Aperture's Blog, page 33

February 8, 2023

11 Essential Photobooks for Black History Month

Samuel Fosso, ‘70s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Samuel Fosso, ‘70s Lifestyle, 1975–78Courtesy the artist and JM.PATRAS/PARIS

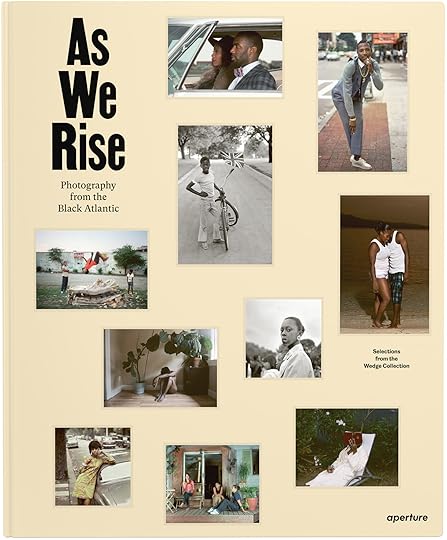

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits; to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa; to J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s landmark series documenting Nigeria’s rich hairstyle traditions, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite, A school for one of the many modeling groups that had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s, ca. 1966

Kwame Brathwaite, A school for one of the many modeling groups that had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s, ca. 1966 Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the 1950s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color. Born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling agency for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Until recent years, Brathwaite has been under-recognized. This is the first-ever monograph of his work. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation. . . . [They] were the woke set of their generation.”

Ernest Cole, Sometimes check broadens into search of a man’s person and belongings, South Africa, ca. 1960s

Ernest Cole, Sometimes check broadens into search of a man’s person and belongings, South Africa, ca. 1960s© Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole: House of Bondage (2022)

First published in 1967, Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage has been lauded as one of the most significant photobooks of the twentieth century, revealing the horrors of apartheid to the world and influencing generations of photographers around the globe.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Cole photographed the underbelly of apartheid in South Africa—often at great personal risk. Methodically documenting the daily atrocities and indignities for the Black majority under the apartheid system, Cole pictured its miners, police, hospitals, schools, and more. In 1966 Cole fled South Africa and smuggled out his negatives, becoming a “banned person” and settling in New York. A year later, House of Bondage was published.

Over fifty years later, a new edition of House of Bondage brings this powerful and politically incisive document to a contemporary audience. Retaining Cole’s original writings and photographs, this edition adds unpublished work found in a cache of negatives recently returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. It features never-before-seen photographs of Black creative expression and cultural activity taking place under apartheid—recontextualizing this pivotal book for our time.

Related Items

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic

Shop Now[image error]

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Shop Now[image error]

Ernest Cole: House of Bondage

Shop Now[image error] Deana Lawson, Binky & Tony Forever, 2009

Deana Lawson, Binky & Tony Forever, 2009Courtesy the artist; Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago; and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Over the last decade, Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors, to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s landmark first publication, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited-edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-in c-print.

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013Courtesy the artist and Webber Gallery, London

Zora J Murff: True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) (2022)

Zora J Murff’s photographs construct an incisive, autobiographic retelling of the struggles and epiphanies of a young Black artist working to make space for himself and his community.

Since leaving social work to pursue photography over a decade ago, Murff’s work has consistently grappled with the complicit entanglement of the medium in the histories of spectacle, commodification, and race, often contextualizing his own photographs with found and appropriated images and commissioned texts.

True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) continues this conversation, examining the act of remembering and the politics of self, which Murff describes as “the duality of Black patriotism and the challenges of finding belonging in places not made for me—of creating an affirmation in a moment of crisis as I learn to remake myself in my own image.”

Micaiah Carter, Adeline in Barrettes, 2018

Micaiah Carter, Adeline in Barrettes, 2018Courtesy the artist

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Twins II), New York, 2017

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Twins II), New York, 2017Courtesy the artist

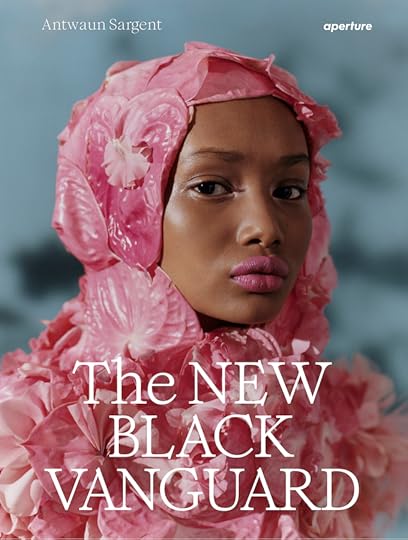

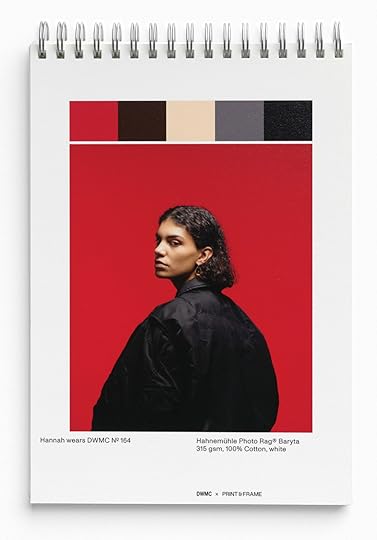

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019)

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in fashion and art today. The book highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation—including Tyler Mitchell, the first Black photographer to shoot a cover story for Vogue; Campbell Addy and Jamal Nxedlana, who have founded digital platforms celebrating Black photographers; and Nadine Ijewere, whose early series title The Misrepresentation of Representation says it all.

From the role of the Black body in media; to cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture; to the institutional barriers that have historically been an impediment to Black photographers, The New Black Vanguard opens up critical conversations while simultaneously proposing a brilliantly reenvisioned future. “Often in this culture, when we think about the work of Black artists, we almost never think about, How do we celebrate young Black artists? And I wanted to change that,” Sargent states. “I wanted to say that what was happening right now with these very young artists is significant. It has shifted our culture, it has shifted how we think about photography, and it has shifted who gets to shoot images.”

Related Items

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph

Shop Now[image error]

Zora J Murff: True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis)

Shop Now[image error]

The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion

Shop Now[image error] Ryan McGinley, Black Trans History Ball, February 2021

Ryan McGinley, Black Trans History Ball, February 2021Courtesy the artist

Souls of a Movement, An Honoring of the African Diaspora, February 2021

Souls of a Movement, An Honoring of the African Diaspora, February 2021Courtesy Souls of a Movement (Carlos von der Heyde)

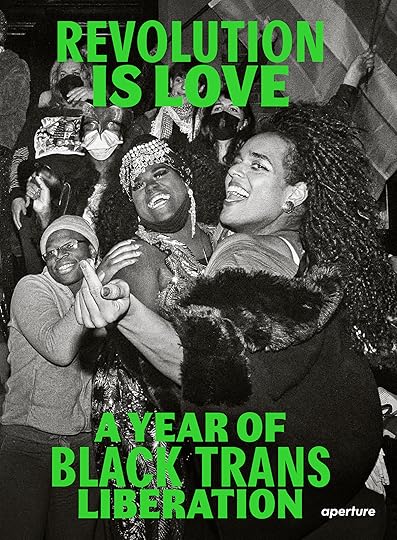

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation (2022)

In June 2020, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Brought together by the urgent need to center Black trans and queer lives within the Black Lives Matter movement, over the following year, thousands of people across communities and social movements gathered in solidarity, resistance, and communion.

Gathering work by twenty‑four photographers from within the movement, Revolution Is Love is the potent and celebratory visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City—and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community. As Qween Jean reflects in an interview from the volume: “We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social justice movement. We’ve existed.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2070386), 2017

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2070386), 2017Courtesy the artist and DOCUMENT, Chicago, team (gallery inc.), New York, and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Mirror Study for Joe (_2010980), 2017

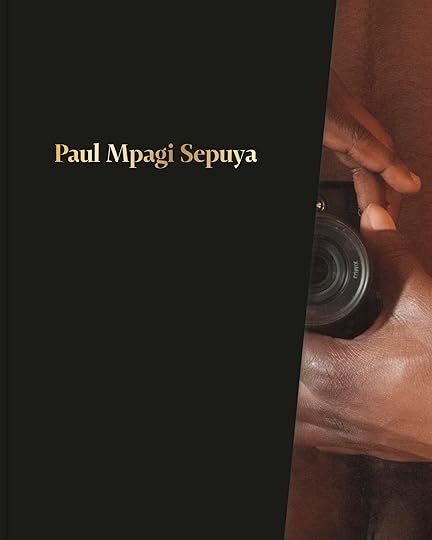

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Mirror Study for Joe (_2010980), 2017 Paul Mpagi Sepuya (2020)

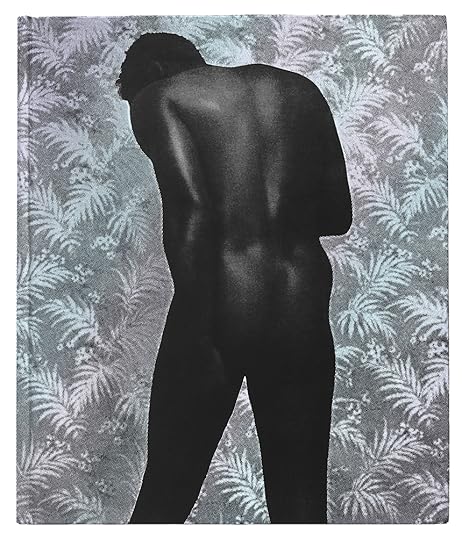

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s studio portraits challenge and deconstruct traditional portraiture by way of collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, all through the perspective of a Black, queer gaze. Although the creation of artist books has been a long-standing part of his practice, this 2020 volume is the first widely released publication of Sepuya’s work.

For Sepuya, photography is a tactile and communal enterprise, with his multilayered scenes coming together through groups of his friends, fellow artists, collaborators, and himself. Moving away from the slick artifice of contemporary portraiture, Sepuya’s frames are filled with the human elements of picture-taking, from fingerprints and smudges to dust on mirrored surfaces. Sepuya pushes this even further by directly inviting us to look inside the studio setting—while also considering the construction of subjectivity.

[image error]Shikeith, O’ My Body, Make of Me Always a Man Who Questions!, 2020Courtesy the artist

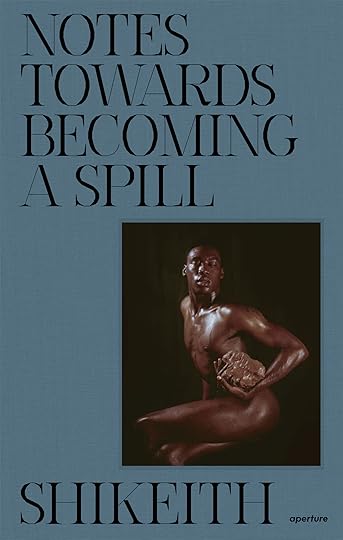

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill (2022)

In his striking studio portraits, multimedia artist Shikeith envisions his Black male subjects as they inhabit various states of meditation, prayer, and ecstasy. In work he describes as “leaning into the uncanny,” Shikeith’s subjects’ faces and bodies glisten with sweat (and tears) in a manifestation and evidence of desire. This ecstasy is what critic Antwaun Sargent proclaims “an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world.” Brought together in the artist’s first monograph, Notes towards Becoming a Spill redefines the idea of sacred space and positions a queer ethic identified by its investment in vulnerability, tenderness, and joy.

Related Items

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation

Shop Now[image error]

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Shop Now[image error]

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill

Shop Now[image error] Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978Courtesy the artist

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem, to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

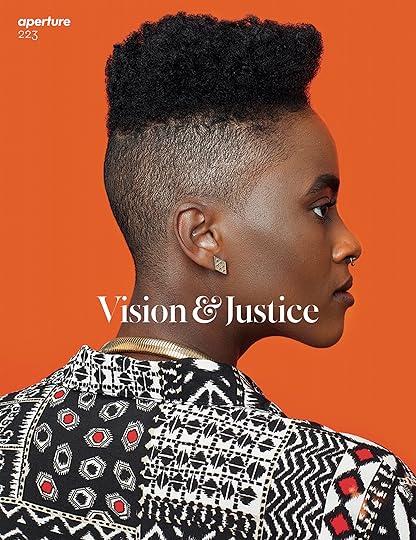

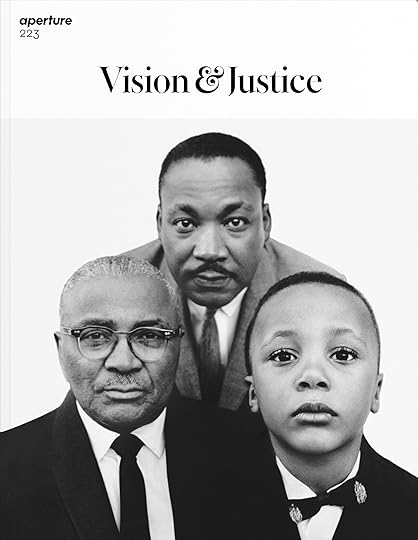

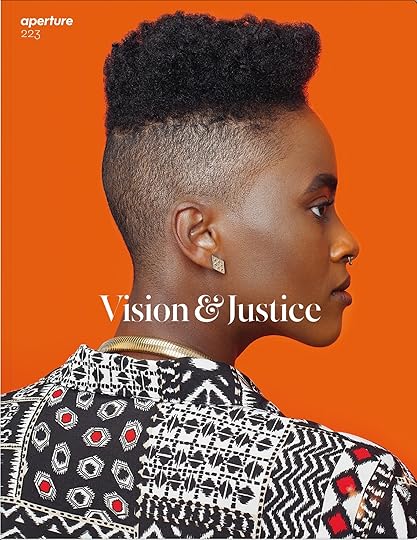

Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice ” (Summer 2016)

The art historian, curator, and writer Sarah Elizabeth Lewis guest edited Aperture’s summer 2016 issue, “Vision & Justice,” a monumental edition of the magazine that sparked a national conversation on the role of photography in constructions of citizenship, race, and justice. The issue features a wide span of photographic projects by artists such as Awol Erizku, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Deana Lawson, Jamel Shabazz, Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis; alongside essays by some of the most influential voices in American culture, including Vince Aletti, Teju Cole, and Claudia Rankine. “Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil,” writes Lewis, “but America’s progress would require pictures because of the images they conjure in one’s imagination.”

In 2019, Aperture worked with Lewis to create a free civic curriculum to accompany the issue, featuring thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice. Taking its conceptual inspiration from Frederick Douglass’s landmark Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress” (1861)—about the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation—the curriculum addresses both the historical roots and contemporary realities of visual literacy for race and justice in American civic life.

Related Items

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 223

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]February 3, 2023

What Uta Barth’s Images Tell Us about the Limits of Sight

In the fall of 1996, Uta Barth exhibited her then-new series Field and Ground at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York. Barth was living in Los Angeles, having joined the art faculty at the University of California, Riverside, in 1990 after earning her MFA at UCLA in 1985. The critic Mark Van de Walle reviewed the show in Artforum, invoking Barth’s relationship to the minimalism of Agnes Martin, the play between photography and painting in Gerhard Richter’s blurred paintings, and the sensitivity to light shared by Vermeer. Even in her foundational work, Barth was understood in relation to a long and significant history of artists. Van de Walle mused that Barth’s photographs, “by virtue of being pictures of nothing in particular, manage to be about a great deal indeed.”

At the time of that show, I had just moved to New York, as a recent college graduate, and happened to be working at a photography gallery down the hall from Tanya Bonakdar Gallery. I wasn’t reading Artforum regularly and had only just begun to learn about photography, but I must have stopped in to look at Barth’s show dozens of times. I still remember stretching my breaks during the workday as long as I thought I could get away with, to sneak in a few more minutes with Barth’s photographs. I would stare at them, and consider what they were telling me about photography, about seeing, about how to signal what matters.

Uta Barth, …from dawn to dusk (December), 2022

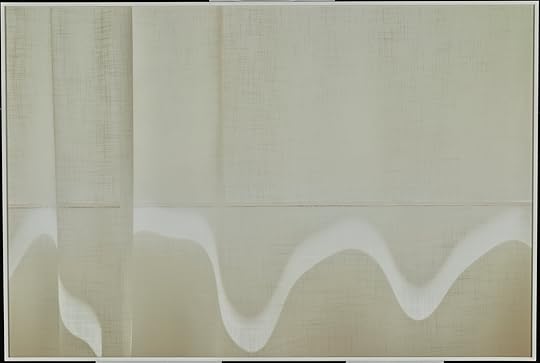

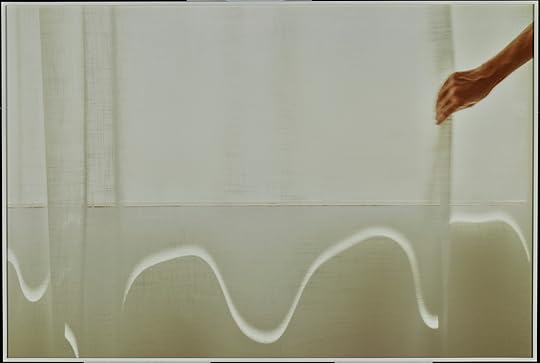

Uta Barth, …from dawn to dusk (December), 2022 Uta Barth, white blind (bright red) (02.13), 2002

Uta Barth, white blind (bright red) (02.13), 2002Both of those early series—Field (1995–96) and Ground (1994–97)—feature prominently in Barth’s current major exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision, curated by Arpad Kovacs. Filling the entirety of the museum’s West Pavilion photography galleries, the exhibition is a generous and expansive look at the artist’s key bodies of work from the 1990s up through the present. It opens with …from dawn to dusk (2022), a work commissioned by the Getty. On view for the first time, these new images crystallize the artist’s ongoing fascination with the fleeting effects of light on place and the potential of photography to sequentially capture and reflect this human, and bodily, experience. Notably, in a side gallery, Kovacs also includes Barth’s early and experimental work from the late 1970s and ’80s: rarely seen collages, self-portraits, iterative sequences of space, and experiments with light and its blinding capacities—all early traces of ideas that will persist and play out for decades.

Installation view of Uta Barth: Peripherial Vision, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2023

Installation view of Uta Barth: Peripherial Vision, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2023 Photograph by Kayla Kee

Field and Ground established Barth’s commitment to disrupting the conventional habits of photographic seeing. Here, the camera’s focus is not associated with objects but with space, foregrounding color, compositional arrangement, and a fundamental question about how both photographic and human vision affect perception and experience. Barth does a lot with a little: a wall, a light fixture, the edge of the frame, a window, or light as it lands. These elements form relationships that are as intricate and nuanced as they are spare. Later works, such as …and of time (2000), …and to draw a bright white line with light (2011), and Compositions of Light on White (2011) express the refinement of these ideas, along with Barth’s exquisite attention to the most ordinary domestic surroundings. In Barth’s photographic world, the soft glow of a shifting line of light becomes everything. That these photographs are made in her own home quietly establishes the grace of our everyday, most immediate, and most personal surroundings.

Uta Barth, Untitled (…and of time, 00.4), 2000

Uta Barth, Untitled (…and of time, 00.4), 2000

Uta Barth,…and to draw a bright white line with light (Untitled 11.2), 2011

Uta Barth,…and to draw a bright white line with light (Untitled 11.2), 2011

Among Barth’s great strengths is her ability to play with options, to present variations on a theme, not as variations in and of themselves but as a true reflection of and insight about how we look, and how it feels to look, again and again, over time. This dedication plays out intensively in the series white blind (bright red) (2002) and Sundial (2007), both of which are given whole galleries. These rooms most effectively shift the psychology and mood of the exhibition from the meditative and contemplative beauty of the ordinary to something more visceral and acutely destabilizing, even strange. The installation of white blind (bright red) is purely linear. An even line of photographs depicting gnarled tree branches in winter, punctuated by color inversions, shocks of entirely red or nearly black frames, and washed-out images of the same branches, barely visible, surround the viewer.

Uta Barth, Sundial (07.4), 2007, from the series Sundial

Uta Barth, Sundial (07.4), 2007, from the series SundialThe effect, moving from image to image, mixes sight with both the memory of sight and with literal afterimages—a convergence of vision and its effects, which, Barth seems to suggest, are really one and the same. She made these photographs during a period of convalescence, looking out a window from her bed, recovering from an illness. We may think of vision as occupying a largely conceptual realm—the eye and the mind—but Barth shows a distinct bodily awareness of vision. Both may be as universal as the other, but an acute sense of the physicality of vision, and visual processing, feels like the greater revelation. Standing in the gallery, I can envision my own self, lying in bed, looking out the window, again and again, waiting in a space of vulnerable limbo, to be well.

Sundial offers a similarly complex and slightly surreal vantage point on what it might mean to spend a lifetime looking closely, or even a few minutes. Barth invites us to stare with her, tracking the warm play of late afternoon light on the refrigerator, the floor beam, the edge of a cabinet. Soon enough, like a familiar word spoken over and over, the everyday becomes strange, and it is evident that total attentiveness to the real can be slightly hallucinatory.

Uta Barth, Thinking about…In the Light and Shadow of Morandi, 2018

Uta Barth, Thinking about…In the Light and Shadow of Morandi, 2018In their foregrounding of the complex physicality that can be associated with vision, Sundial and white blind (bright red) offer a contrast to several of the other series featured in the show, where mindfully contemplating the subtle passage of light feels more aspirational, like what one’s best self does, the most focused, clearest, and attentive version of vision. But, Barth shows, vision also comes from sick and tired bodies, aging or just-awoke-and-still-disoriented eyes. This sight is wrapped up in our bodies, this sight is unstable, this sight second-guesses itself. Remarkably, no matter which version of sight she is prompting viewers toward, Barth’s photographs do not just depict these experiential states. Rather, they make the viewer’s re-enactment of them possible. Ultimately, both are equally part of our existence and relevant to an experience of a world that is, at once, visual, perceptual, felt, lived, embodied, subjective, flawed. And, yet, coherent.

Uta Barth: Peripheral Vision is on view in Los Angeles at the J. Paul Getty Museum, through February 19, 2023.

Gordon Parks’s Strident Vision of Stokely Carmichael and the Black Power Movement

On June 16, 1966, Stokely Carmichael, who had just been elected head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), appeared at the Meredith March Against Fear in Greenwood, Mississippi. Carmichael, alongside leaders including Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer, had resolved to continue the weeks-long protest march begun by the voting-rights activist James Meredith, who, while on his solitary walk from Memphis to Jackson, had been shot by a white supremacist. Facing a crowd that evening, Carmichael grabbed a microphone and said, “We been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!” The marchers cried back, “Black Power!”

The white establishment wasn’t happy with Carmichael’s language, and photographs taken during his speech didn’t soothe its fears. The photographer Bob Fitch had captured Carmichael baring his teeth as he forcefully gesticulated, his features underlit like those of a villain in a silent movie. News outlets cautioned against a rise in reverse racism, and the polls saw a white backlash that November when many Anglos interpreted “Black Power” as a call to violence.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Watts, California, 1967

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Watts, California, 1967During this tumult, Gordon Parks met Carmichael in Berkeley while on assignment for Life magazine, where he was the first Black staff member. This Vogue alum was so impressed by Carmichael that he went on to shadow him into the following year. Five pictures would illustrate Parks’s 1967 Life profile, “Whip of Black Power.” While some of the article’s photographs have been collected by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the rest of Parks’s photographs and contact sheets had not been exhibited or published until the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, staged its 2022 exhibition Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power and published an accompanying catalog.

Parks wanted to draw Stokely Carmichael’s full character as a multidimensional person.

“When I came to Houston, a Parks project was on my list. I went out to the Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York, and I knew immediately that this was the project we had to do,” the associate curator of photography Lisa Volpe recently told me. “It has such resonance with the Black Lives Matter movement and the entire long history of the civil rights movement. I jumped at the opportunity.”

Gordon Parks, SNCC Office, Atlanta, Georgia, 1967

Gordon Parks, SNCC Office, Atlanta, Georgia, 1967Volpe appreciated that Parks initially questioned Carmichael’s ideas: in Life, he pressed Carmichael about whether he was “preaching violence”—a charge Carmichael eloquently rebutted, even as he emphasized the need for Black self-defense. Parks eventually warmed to the concept of Black Power, ending his essay with uneasy admiration for Carmichael, and the images he took countered Fitch’s sensationalizing depiction. In Stokely Carmichael, Lowndes County, Alabama (1966), Parks captured Carmichael canvassing Lowndes, which was 80 percent Black but, due to white violence, had no registered voters of color. Carmichael helped form the pro-voting-rights Lowndes County Freedom Organization, whose mascot was a pouncing black panther. When he snapped Carmichael on one of the county’s gravel roads, Parks drew on his fashion background, highlighting the activist’s combat boots and preppy pullover emblazoned with the feline, which would later be adopted by the Black Panther Party.

Related Items

Aperture 249

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]As Volpe sifted through Parks’s contact sheets, she encountered a cascade of images similarly deploying detail to bring the viewer into Carmichael’s mission-driven world. A 1967 picture shows a man securing the scene at a November rally in Watts, Los Angeles: dressed in a slim gray suit, he talks intently into a walkie-talkie while a large crowd sits expectantly on the ground to hear Carmichael speak. Another photograph documents SNCC’s Atlanta office, whose walls are papered with leaflets and pamphlets, one of which reads “The Black Panther Is Coming!”

Parks accompanied Carmichael on the car trips that brought him to these mobilizations, at one point snagging an image of him driving through town while laughing with his unseen companions. Volpe’s research revealed that Carmichael usually sat at the wheel, because he’d been trained in defensive driving. “Stokely always wanted to be in the driver’s seat because that was the position of responsibility, and he was caring for his SNCC colleagues,” she says.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, 1967

Gordon Parks, Untitled, 1967All photographs courtesy Gordon Parks Foundation

Carmichael died in 1998, but his words are very much alive today. The 2022 documentary Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power was recently acquired by the streaming service Peacock; the newly created Black Migrant Power Fund seeks to support Black-led, migrant-focused nonprofits; and the artist Hank Willis Thomas recently installed his monumental sculpture All Power to All People (2017), which combines a hair pick with the Black Power salute, in New Orleans’s Lafayette Square. Parks’s Life photographs form an essential part of the Carmichael and Black Power archive.

“Parks was very aware that the vast majority of Life’s readership was white,” Volpe says. “But he understood that it was his voice that could humanize people like Stokely Carmichael, who had been shown in such a terrible, one-dimensional manner. He wanted to draw Stokely’s full character as a multidimensional person. And, in the end, you can see Parks really took in Black Power, interpreting it in his own way.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

An Artist’s Photo Archive Tells a Story about Race and Labor

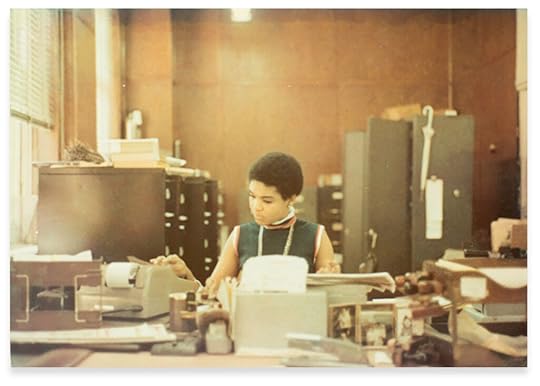

Archival images can find us in the most discreet and serendipitous ways—stashed in a forgotten book, orphaned at a flea market, tucked in the sleeves of a photo album. Their scenes are portals to a different time, and often, with patience, they are a compass for our present one. At least this is how the artist thinks and speaks of them. Her series Toward a History of Women of Color in the Workplace (2018–ongoing) is a result of the artist’s search for answers about her past and her place as a mixed-race person in the United States. She found these images—a collection of prints from around 1969, when her mother worked as a secretary—among her family’s belongings, wrapped inconspicuously in plastic pharmacy bags.

Sifting through them struck a chord: “I enjoyed going to work with her as a child when I had days off from school,” Mestrich says of her mother, Lydia, who raised her alone, “so it was fascinating to see this visual record of her first office job.” Inspired, Mestrich talked to her mother about the images, tried to track down the photographer, and became engrossed with contextualizing them.

Qiana Mestrich, Lydia is using a desktop calculator and unaware of the camera, ca. 1969

Qiana Mestrich, Lydia is using a desktop calculator and unaware of the camera, ca. 1969The photographs helped Mestrich feel closer to her mother, who emigrated from Panama to the United States in 1969, in her early twenties. When Lydia arrived in New York, she found an opening on the assembly line at a perfume factory. The work was grueling, and she didn’t stay for long. Through a friend from her English classes, Lydia got a job as a secretary at Rugol Trading Corporation. “She quickly had to be independent,” Mestrich notes of Lydia’s early days in the city. “She made this community of girlfriends who were all immigrants from Latin America, and they were all in the same boat of trying to make it on their own.”

Rugol, a wholesale hardware company, no longer exists. Its former office building, at 55 North Moore Street, has been converted into million-dollar co-ops. And the neighborhood it once called home—Tribeca—is now more famous for luxury lofts and restaurants than warehouses. Mestrich’s series captures a transitory phase in the area’s past—after the demise of commercial outlets and factories but before it became an artists’ haven and, later, a bastion of wealth. They show her mother and her colleagues working and milling about in an industrial workshop turned office space. In one photograph, provisional walls separate each employee’s desk area and fluorescent lights dangle from the high ceilings. A white column plastered with a baseball poster—Mestrich’s mother is a fan of the sport—interrupts the flow, another reminder of the space’s makeshift nature. “It wasn’t built to be an office,” Mestrich says to me as we huddle over her laptop. She points out Lydia, hunched over a desk in the far-left corner, and then her mother’s coworker, fiddling with a typewriter.

Related Items

Aperture 249

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Another photograph of Lydia—this time smiling while seated at her desk—expands the office topography. Behind her stands a row of green-tinted filing cabinets and two-door storage closets. Precariously stacked reams of paper sit on top of some, while others display notes held up with magnets. Lydia smiles warmly at the camera, her hands clasping a document. These images convey a familiarity between subject and photographer. Lydia told Mestrich that they were taken by her coworker, an African American man who worked in the mail room. (Mestrich has tried to get in touch with him but hasn’t yet been successful.) He would happen upon his colleagues, sometimes asking them to pose, other times snapping candids. His proximity to his subjects lends the photographs an affectionate warmth. They are the kind of pictures friends take of one another, endearing attempts to capture the ephemeral.

How does spending time with the archive enhance our understanding of the role women of color play in the workplace—yesterday, today, and tomorrow?

In that same photograph of Lydia at her desk, follow the trail from her slender fingers to her earlobe and you can see a thick band of bracelets decorating her wrist, then a globular gold earring. Mestrich takes joy in observing her mother’s style, which serves as a window into late 1960s fashion. This was the era of the Black Power movement, “Black is beautiful,” Woodstock, and the Harlem Cultural Festival. The photographs in the series reflect Lydia’s elegance and her varied wig collection. In some images, she wears her natural hair coiffed into an Afro, in others, she dons a tall wig with a chic side part. Fellow employees have similarly sophisticated garbs. Take the photograph in which Lydia’s coworker nibbles on a piece of birthday cake: See the coworker’s outfit, a checkered dress cinched at the waist with a wide belt. Look at Lydia, seated at her desk, in a white collared button-down under a gray dress. A string of pearls hangs from her neck, connecting the two garments.

Qiana Mestrich, Lydia poses for a portrait in the boss’s chair, ca. 1969. All photographs from series Toward a History of Women of Color in the Workplace, 2018–ongoing

Qiana Mestrich, Lydia poses for a portrait in the boss’s chair, ca. 1969. All photographs from series Toward a History of Women of Color in the Workplace, 2018–ongoingCourtesy the artist

Toward a History of Women of Color in the Workplace begins with Lydia, but Mestrich doesn’t want it to end there. The time she has spent with her mother’s archive has inspired more questions about the professional legacy of women. She thinks of the 1980 film 9 to 5, its vision of office spaces including no one who isn’t white, and compares that to her mother’s reality and her own as a working artist. I can’t help but think of Mestrich’s project alongside Ling Ma’s, Raven Leilani’s, and Natasha Brown’s novels, works that have, in recent years, tried to capture the office experiences among women of color. In the spirit of tethering archives to a community, Mestrich, a recipient of the 2022 Magnum Foundation’s Counter Histories grant, has started an Instagram account for these photographs. She hopes they will inspire others to submit family pictures of working mothers, aunts, and grandmothers. “We are the backbone of these companies,” Mestrich says.

If there is a broader goal for the series, it’s to possibly answer questions about gender discrimination, pay discrepancies, and the continued lack of representation of Black women in leadership roles: What can images from 1969, or throughout the past century, tell us about the contemporary moment? How does spending time with the archive enhance our understanding of the role women of color play in the workplace—yesterday, today, and tomorrow?

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

February 2, 2023

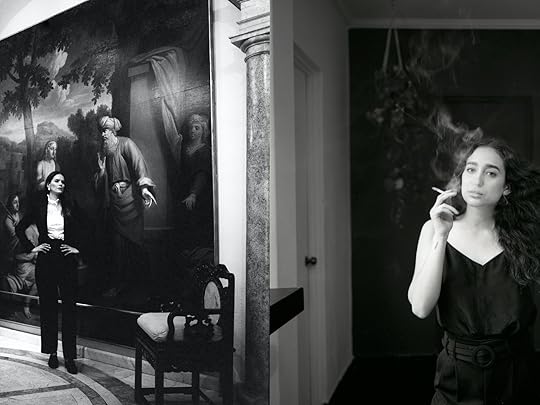

A Photographer’s Desire to Change How She Sees the World

Last fall, after graduating from Yale’s MFA program in photography, the artist Anabelle DeClement started a new job working at a photo shop in Manhattan, where she spent her days engaging with photography enthusiasts of all stripes. Despite the varied clientele, however, DeClement noticed a pattern: much of the small talk offered up by her customers had a decidedly nihilistic bent. People seemed deflated by the world around them, often remarking, “Well, the world is ending,” or, “I mean, nothing matters”—deadened, space-filling remarks indicating a pervasive feeling of hopelessness and impotence.

DeClement’s newest project, under the double moon (2022–23), is a reaction to that despondency. “I’ve been thinking a lot about how easy it is to get caught in a way of seeing the world, or get caught in one way of being,” she told me over the phone in January. Her newest body of work is adamant that we have the capacity to change the way we see the world around us. “It’s about the desire for a collective perspective shift,” she said. In order to question the order of things, she continued, “Sometimes you have to be taken out of yourself.”

But what does it mean to change your perspective? Casting about for an example, DeClement stumbled upon an article about the actor William Shatner and his long-awaited visit to space. While aboard the capsule, Shatner experienced the “overview effect,” a term coined by philosopher Frank White that describes “a cognitive and emotional shift in a person’s awareness, their consciousness, and their identity” when they view our planet from space. For his part, Shatner cried when he looked out at the luminous world below him. “I had to go off some place and sit down and think, ‘what’s the matter with me?’” he told NPR last year. “And I realized I was in grief.”

With under the double moon, DeClement repositions herself in relation to the world around her. Navigating what initially seems like two opposing stances, DeClement seeks out a degree of detachment in order to ground herself in the world again, as only through distance can we start to understand the broader contours of our experience. This push and pull—distance, then intimacy—is borne out in her compelling photographs.

Related Stories Featured Ashish Shah’s Languorous Portrait of the Indian Countryside

Featured Ashish Shah’s Languorous Portrait of the Indian Countryside

Featured The Double Life of a French Armenian Photographer

Featured The Double Life of a French Armenian Photographer DeClement, who grew up in New Jersey, spent her time at Yale creating work that centers on the relationship between reality and surreality. Her photographs often play into the viewer’s expectations in order to subvert them. Moreover, nature is a central “voice” in her work, as she puts it, and her images force a mental confrontation about how we’ve chosen to interact with the people and places around us.

Throughout all of DeClement’s work, mirrors crop up with notable frequency. Composition-wise, she said, she likes playing with reflections because they confuse the frame, creating unexpected layers that draw the viewer in and force them to engage further with her photographs. Thematically, the visual echoes represent a state of being that DeClement wants to buck. “Sometimes we get stuck in a pattern of reflecting off one another,” she told me, “Where we’re just reverberating the same energies and perspectives.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Everything feels ephemeral right now. People are exhausted by darkly entwined political and cultural atmospheres—not to mention the critical but overwhelming message that the world around us is actively dying. It’s easy, DeClement noted, to slide into the endemic feelings of futility. So how do we fight to keep perspective? For DeClement, the answer lies in her photographic lens on the world. “This project is a way of saying, Well, maybe that’s all true, but there are also all these other things going on at the same time,” she told me. “Even within a catastrophic future, there’s still desire and hope and the need to connect.”

Anabelle DeClement’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera and EF-X500 flash.

All photographs by Anabelle DeClement from the series under the double moon (2022–23), for Aperture

All photographs by Anabelle DeClement from the series under the double moon (2022–23), for Aperture

January 31, 2023

Why Ramón Reverté Believes a Photobook Needs a Great Story

Ramón Reverté serves as the editor in chief and creative director of Editorial RM, a prestigious illustrated-book publisher based in Barcelona and Mexico City that specializes in Latin American art and photography monographs, with occasional ventures into publications that take on the history of the photobook genre, such as El fotolibro latinoamericano (The Latin American Photobook, 2011) and New York in Photobooks (2016). The independent scholar and critic María Minera describes having had “the privilege of collaborating” with Reverté twenty years ago. “I realized that I was, without a doubt, next to one of those editors for whom books, far from being commercial products, took on a dimension close to works of art,” she states. “Every detail, every image, every caption, every comma was studied with the attention that I imagine was proper to the monks of the Middle Ages who made illuminated manuscripts. His works, one after the other, are testimonies of a deep love for those endangered objects that are books in general and art books in particular.” Minera reconnected with Reverté recently to talk about the role of an editor and his unabashed passion for the photobook.

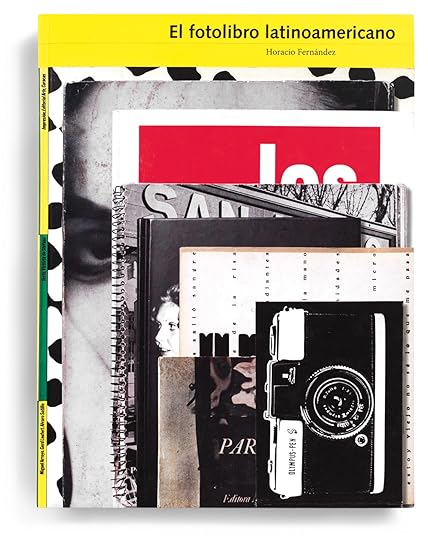

Cover of Horacio Fernández, El fotolibro latinoamericano (The Latin American Photobook; RM, 2011)

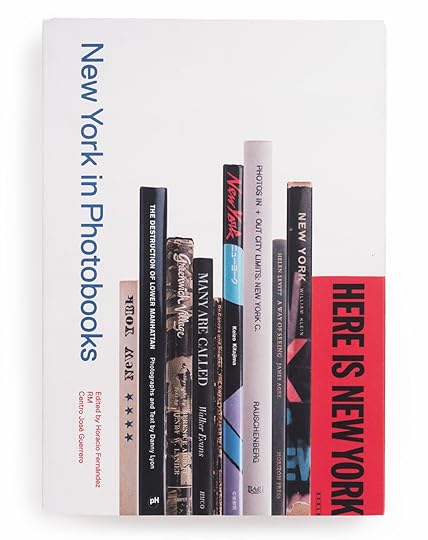

Cover of Horacio Fernández, El fotolibro latinoamericano (The Latin American Photobook; RM, 2011)  Cover of Horacio Fernández, New York in Photobooks (RM, 2016)

Cover of Horacio Fernández, New York in Photobooks (RM, 2016) María Minera: Editorial RM is not a publishing house dedicated exclusively to photography, but I get the impression that over the years you, as an editor, have become more immersed in the photographic world, without leaving behind other forms of art. Do you feel this is the case?

Ramón Reverté: Yes. On a personal level, I like everything that has to do with illustrated publications, but what interests me most is photography in book form. Two things have happened: On the one hand, there’s my own focus on photography and my growing knowledge of the genre of the photobook, because I am a compulsive buyer of books. Then there is also a kind of gravity; the more photography books RM publishes, the more people and institutions follow us, and that gives us more possibilities to make books.

Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandón, Flores, 2019, from Aya (RM, 2019)

Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandón, Flores, 2019, from Aya (RM, 2019)  Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandón, Red, 2019, from Aya (RM, 2019)

Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandón, Red, 2019, from Aya (RM, 2019) Minera: I also have the feeling that in the last twenty or twenty-five years, the interest of the public, but also of the publishing world, in photobooks has grown. There were always photographers interested in the book format because it is ideal to present photographic images, but I’m seeing more and more bookstores filling up with photography books. Do you think so too?

Reverté: Yes, although we have to consider that the photobook was born with photography, going back to Anna Atkins, for example. But it is true that with the publication of Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919–1939 by Horacio Fernández, in 1999, there has been a lot of interest from the public, and especially from photographers, because of the ease of showing their work through a book and reaching other parts of the world. At the end of the day, galleries are in a fixed location. An exhibition is ephemeral. But a book has a very big potential. At this moment, it is also technologically much easier than ever to make photobooks, and there is an average level that is very good. But I would also call it a time of crisis, because everybody thinks they are capable of making great photobooks—and they do not realize that making a photobook is not merely a photographic and design exercise, but that there has to be a very powerful story behind it.

The hand of the editor, the editor who really shapes the photobook, is paramount.

Minera: Yes, you see a lot of uninteresting photobooks right now. Maybe it has to do with the fact that editing is no longer appreciated. Robert Gottlieb, a famous editor, said that the editor’s relationship with a book should be invisible. However, in literature there are very famous cases of editors who told an author to change the end or eliminate a hundred pages. And thanks to those interventions, they are extraordinary books. I feel that we tend to downplay the absolutely essential role of the editor in the photobook. Would you agree with Gottlieb? Should the hand of the editor not be seen?

Reverté: I do not agree at all. I get very involved. Especially in the conceptual part of the book. It’s inevitable that I get into it, in depth. I often select the designer and that clearly directs the book toward a specific style. And, in addition, there are economic factors that constrain a book to so many pages, and to a higher or lower quality of printing. But the hand of the editor, the editor who really shapes the photobook—and I don’t know any good editor who doesn’t—is paramount.

Cover and spread from Graciela Iturbide, Juchitán de la mujeres, 1979–1989 (RM, 2011)

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Minera: Do you weigh in on content issues, telling the photographer what images to keep and which ones to remove?

Reverté: It’s never an imposition. I tell the photographer: “Look, you have the last word, but I’m going to tell you with total transparency what I think.” In the end, all books are different. I actively participate and never fail to say something that goes in favor of the book. But there’s a very clear hierarchy, and the one who always ends up deciding is the author. In editing, the problem often lies with images that are not especially good on their own but that are extraordinary when put into a sequence. At times, the author cannot see them because they are too close, too involved. And the editor—because of the perspective they bring—can make those decisions very easily.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.Minera: Many authors look to you because they like the books you make and want to be part of that lineage. Do you also develop certain projects yourself ? Could it be that you find some photographs somewhere—maybe at a flea market—and then decide to make a book?

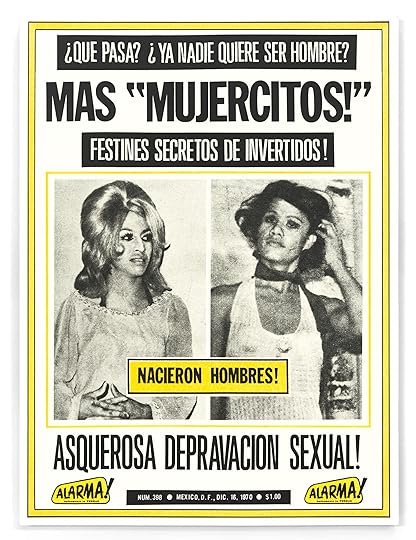

Reverté: Yes, both. Personally, I really like to make books that seem natural to me. For example, Mujercitos (2014) is a book I made with Susana Vargas. She wanted to do a mostly textual book about the phenomenon of photographs of men who dress as women—called mujercitos in Mexico. I said yes, but I suggested a change to the equation: instead of a book with 10 percent images and 90 percent text, we made it the other way around. I also want to make a book by the Spanish photographer Javier Campano, who made a series of incredible Polaroids that I discovered by chance through a friend. I am convinced that it will be a very important book—and by important, I do not mean that it will sell a lot, but that it is a book that is really needed. So, there are books that come ready-made, other books that you propose, some others that come without form and you give them form, others that come almost finished and we do nothing.

Cover of Susana Vargas, Mujercitos (RM, 2015)

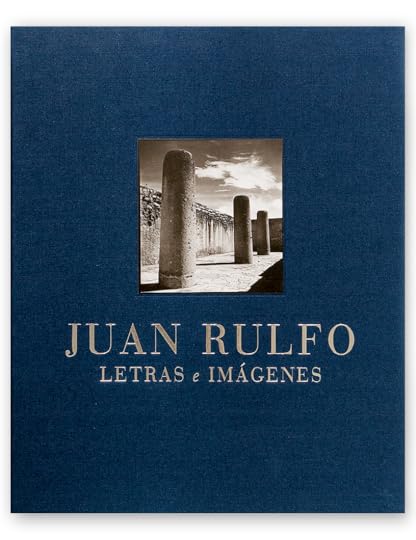

Cover of Susana Vargas, Mujercitos (RM, 2015)  Cover of Juan Rulfo, Letras e Imágenes (Letters and images; RM, 2001)

Cover of Juan Rulfo, Letras e Imágenes (Letters and images; RM, 2001) Minera: I imagine your passion for collecting photobooks informs your approach as a publisher, right? Did you start collecting at the same time that you began publishing, or was it an earlier interest?

Reverté: It started at a very young age. In my house, as my father was a publisher, Santa Claus always brought us books. So books have always been very important to me. I’ve kept all my books since I was a child, and I keep them in perfect condition. From children’s picture books, I moved on to the world of comics. I have an enormous collection of Spanish comics from the ’70s and early ’80s. And from there came the art and photography book—in general, the visual book. These books give me enormous visual pleasure—more so than reading, actually. From that passion came an interest in making art books. The first book of photography I did, in 2001, was about Juan Rulfo, who besides being a wonderful writer was an incredible photographer. Little by little, things escalated with one opportunity after the other, and a growing closeness to and love for the world of photography.

Minera: You have said that the books you make are the ones you would like to see out there. Part of your impulse as a publisher seems to be the thought of books that do not exist but are necessary.

Reverté: Yes, I don’t fancy doing books that already exist in some way or another. It often happens to me that I am looking for a specific subject, or I know someone’s photographic work and I see that there’s nothing similar around. It gives me great satisfaction to make that book. I publish the books I would like to have.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Minera: With the overproduction of photobooks that we talked about earlier, how do you seek, as a publisher, to separate yourself from the rest? How are you defining a particular path for RM?

Reverté: Well, there is a very clear editorial line, which is, above all, to publish mostly books from Mexico and Latin America and Spain. In other words, our catalog is almost entirely made up of authors from the Hispanic world. That makes us very singular. It makes no sense for me to publish books by French, American, or Japanese authors when there are already incredible publishers in those markets, whereas in Latin America, there is a lot of talent but very few publishing possibilities. Spain is doing a little better now because there are several publishing houses, and it is, after all, a richer country. But not Latin America, so there are extraordinary book proposals that come to us every week from Mexico and Latin America. And unfortunately, we can’t take all of them. We have to be selective.

Minera: And how are those books received in the European market, for example, or in the United States?

Reverté: They are increasingly well received. There is a knowledge that goes beyond the older, classic Latin American photographers now. And also because the language we use when making the books—I am referring to the graphic language—is very similar to the contemporary graphic language of other countries. People understand the language of the book from a design point of view. What matters is that the book is spectacular.

Graciela Iturbide, from Piedras (Stones; RM, 2019)

Graciela Iturbide, from Piedras (Stones; RM, 2019)  Spread from Yvonne Venegas, Pencil of Nature (RM, 2023)

Spread from Yvonne Venegas, Pencil of Nature (RM, 2023) This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference,” in The PhotoBook Review.

January 25, 2023

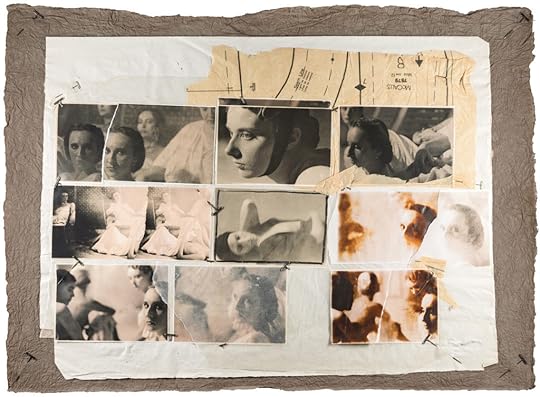

The Strange and Beautiful World of Deborah Turbeville’s Photo-Novella

“Fashion takes itself more seriously than I do,” said Deborah Turbeville in an interview with The New Yorker in 2011. “I’m not really a fashion photographer.” Turbeville, who was born in 1932, first entered the industry as an assistant and sample model to the fashion designer Claire McCardell before becoming a magazine editor—a job for which she had contempt. “I’d get a note from some senior fashion editor saying, ‘We find your arrival half an hour late for Bill Blass appalling,’” Turbeville explained in a 1993 interview. “I just stopped going.” When she was in her mid-thirties, she took a photography seminar with Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel, impressing her teachers with her strong point of view, despite her lack of skill or technique. It was here that she found her calling.

Turbeville’s vast body of work, which spans several decades and was published in the pages of various fashion magazines and books, as well as exhibited in museums and galleries across the world, is known for its darkness and mystery. Lanky models with haunted eyes stand despairingly in abandoned settings. Beauty was, in Turbeville’s imagination, not just bright and happy but melancholic and brimming with travesty. She was fond of distorting the images, playing with the developing process to create an artificial patina of time, and distressing the prints with tears, folds, and scratches. Photographs she took just two decades ago look as if they were from another century, unearthed in a Paris flea market.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.Two years ago, Turbeville’s archive was acquired by MUUS Collection. Discovered among the thousands of artworks was the manuscript of an unpublished novella, titled Passport: Concerning the Disappearance of Alix P, that tells the story of a fashion designer who, at the height of her career, is institutionalized and disappears from the public view. Over time, Amanda Smith, MUUS Collection’s director of archives, realized that Turbeville had created collages corresponding to the novella, on which typed portions of the text had been cut and pasted alongside Turbeville’s photographs, each one marked numerically on the back. Soon, Smith realized that nearly the entire novella had been given this treatment, comprising 136 separate collages—though it’s possible, Smith says, that they will discover more. Now, for the first time, a selection of them is being published, here in Aperture. “It was a bit like a puzzle,” Smith explains of piecing it all together.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }The photo-novella reveals a strange and beautiful world. Photographed in France, Italy, Poland, the United States, and the Czech Republic, the images display Turbeville’s appreciation for decadence and decay. (Her Paris studio “was an opulently decrepit, near-vacant flat near the drag bars of Pigalle,” wrote Judith Thurman in the New Yorker interview; in the New York Times, Margalit Fox described Turbeville’s New York apartment, in the Ansonia, as a place where the photographer “left generations of old paint unstripped, speckled mirrors unsilvered, threadbare tapestry unrestored and tattered curtains unmended.”) Turbeville’s writing is sensory and impressionistic, tinged with a cinematic flair and slightly reminiscent of Marguerite Duras. Rooms are portrayed with the precision expected from a photographer known for her atmospheric use of architectural spaces. The moods of various scenes are exquisitely evoked. Yet even though Turbeville painstakingly conveys Alix’s footsteps echoing in barren corridors (“they have an eccentric sound . . . the heels . . . the combination of the heels and floor . . . the rhythm . . . the punctuation . . . the footsteps grow stronger and more emphatic”), very little interiority is granted to her protagonist, who is surrounded by models (or “mannequins” as Turbeville calls them), artists (assistants for hair and makeup), and various high-ranking people in the fashion world. Women are the ones with power in this universe. Men are objects of desire.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Alix’s abruptly timed sojourn in the sanatorium is equally disorienting. She is isolated, lonely, and unconnected to her previous life. One wonders what exactly Turbeville’s own relationship to the glamorous world she occupied was, how she handled the superficiality of fashion, with its unrepentant greed for excess and beauty. The novella doesn’t end neatly: in her manuscript, Turbeville offers several different conclusions to the story of Alix—but maybe that was the point. She was more interested in capturing the slow unraveling of a woman not too dissimilar from herself (Alix is unmarried and childless), the quiet devastation and sorrow that Alix feels coursing below the surface of all the abundant allure and influence in her life. It couldn’t have been easy as an independent woman to survive a world that prized youth and beauty so highly. Turbeville’s sensitivity to this milieu and what she produced from it are extraordinary and truly rare.

Related Stories Portfolios An Artist’s Clever Reuse of the Fashion Image

Portfolios An Artist’s Clever Reuse of the Fashion Image  All works by Deborah Turbeville from Passport, ca. 1990

All works by Deborah Turbeville from Passport, ca. 1990© the artist and courtesy MUUS Collection

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

January 20, 2023

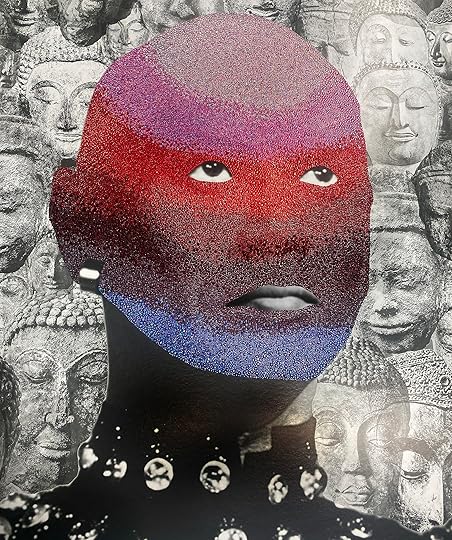

How a Photographer Connects with His Thai Australian Heritage

The emotional resonance of a found photograph has long fascinated Nathan Beard. The Thai Australian artist, who is based in Boorloo (Perth), looks to existing imagery to explore the threads of personal histories, as well as the wider context of Thai culture, specifically the flattening and condensing that occurs when it is consumed through a Western lens.

Beard’s interest in reclaiming old photographs was piqued in 2013 when he discovered several long-forgotten family albums in his mother’s home in Nakhon Nayok, Thailand. The building had sat abandoned for more than twenty years, and the artist embarked on reopening the house while on a residency at Speedy Grandma gallery in Bangkok. The albums—which feature photographs of his mother, aunt, and other relatives he had never met or can barely remember—serve as a visual record of his fragmented childhood memories and stories passed on through the family. “It was a rich source material to work with,” he says, “not only to connect to my mom and her family, but to explore tenuous ideas of identity and how I position myself culturally as someone of Thai and white Australian heritage.”

Nathan Beard, Tender Ruin (i), 2022, from the series Tender Ruin, 2021–22

Nathan Beard, Tender Ruin (i), 2022, from the series Tender Ruin, 2021–22Beard looked to the excessive adornment found in many elements of Thai culture as a way to recontextualize these images. He saw similarities between the precious mosaics and antiquities found in Buddhist temples and the rhinestones in his mother’s domestic shrines. The obsession with bedazzling extended to Bangkok’s markets, where everything from T-shirts to phone covers were embellished. “I began decorating reproductions of these photographs with Swarovski crystals to give them a material presence, one that is venerated, but also alludes to the pop culture of contemporary Thailand,” the artist explains. This process is evident in series such as and Siamese Smize (2018) and Ad Matres (2014–17), in which some photographs feature gems applied to faces as shimmering tears, not simply abstract motifs, a treatment that was reserved for relatives Beard had met in person, creating a melancholic connection to a fractured family tree.

The artist further develops this in his latest body of work, A Puzzlement (2022), which was recently on view at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) and will travel to the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney later this year. The series takes the theatrical and cinematic productions of The King and I as its starting point. The Orientalist fantasy of an English governess falling in love with a Thai monarch was introduced in the 1950s in the United States and Europe to great acclaim, but the film was banned in Thailand due to its misrepresentation of the king.

“Watching The King and I was the first time I vividly recall my mom’s culture being reflected back to me through a Western lens,” says Beard. In A Puzzlement, headshots, film stills, and ethnographic images are blown up to more than six feet square, and are once again laboriously embellished. “Painstakingly applying the crystals is almost a meditative act, where I am obliterating the subject entirely by creating a shimmering void,” he adds. “I’m ostensibly creating a crystal mask, which not only elevates the image, but points to the facade of cultural identity and authenticity. It is interesting to try and complicate the legacy of all of these objects and images.”

Nathan Beard, Mongkut (1956), 2021, from the series A Puzzlement, 2022

Nathan Beard, Mongkut (1956), 2021, from the series A Puzzlement, 2022  Nathan Beard, AFG Kerr (1939), 2022, from the series A Puzzlement, 2022

Nathan Beard, AFG Kerr (1939), 2022, from the series A Puzzlement, 2022 These carefully applied ombré layers feature seven Swarovski tones, all with the term Siam in their names (such as “Light Siam Shimmer” and “Siam Nightfall”). The outdated and exoticizing terminology points to the contexts of the images the crystals adorn, such as a film still of Yul Brynner, who played King Mongkut in both the film and stage adaptations of The King and I in the 1950s, and a photograph of Prince Chulalongkorn taken by John Thomson, who in 1865 became the first Western photographer permitted to take portraits of the Thai royal family. Beard also includes a portrait of Arthur Francis George Kerr from 1939, which he came across while conducting research at Kew Gardens in London. Kerr is known as the “father of Thai botany” in Eurocentric circles, and his study and propagation led to several plant species being named after him.

In bringing together these images, Beard presents the many contradictions and conflicts that arise from ideas of Thai identity, even those that are state-induced. “King Mongkut introduced policies of Westernization to strategically avoid colonization,” says Beard, “whereas Kerr built this huge archive of native Thai plant species, including notebooks and amateur photography, which are stored in Kew.”

Nathan Beard, Noi, Resting, 2014

Nathan Beard, Noi, Resting, 2014This cultural cross-pollination, and the huge part that photography has played in it, informs other aspects of Beard’s practice. In addition to his work with found photographs, he shoots original imagery to document his regular trips to Thailand, including photographs of the abandoned family house and the surrounding countryside, where he shot intimate portraits of his mother in the series Departures (2016), and, more recently, a sensitive record of her funeral following her unexpected death in 2019. The ensuing series, Tender Ruin (2021–22), helped the artist begin processing his grief.

“These images are my impression of Thailand,” he says. “I only seem to have a drive to document when I’m there, to supplement the archive I have inherited.” The artist often presents his photos as assemblages—referencing not only family albums, but also the multiple tabs and windows on a computer screen—as if he is trying to sort and make sense of his own collected memories.

In another experimental approach, Beard uses images of Thai objects on display in museums around the world as source material to create 3D-printed sculptures, some of which are featured in A Puzzlement. The result is a deft comment on the distorted way cultural, and often sacred, objects are presented in ethnographic and museum contexts.

Similarly, Beard’s White Gilt (2019–20) series uses popular Thai motifs of wai hand gestures, nail bars, and orchids to consider ideas of cultural authenticity and exoticism. His beautiful, yet slightly sinister, images of manicured hands and floral stems are shown among shots of his parents’ wedding, postcards, travel promotions, and Buddhist statues. Such assortments speak to the mundanity of tropes used to represent Thai identity, but also the implicit violence of homogenizing and neatly packaging an entire culture. “Those original family photographs unlocked all of these associations for me,” says Beard. “The idea of cultural identity is contingent on so many different and disparate things.”

Nathan Beard, Retirement, 2014

Nathan Beard, Retirement, 2014  Nathan Beard, Floral Extension 2, 2019, from the series White Gilt, 2019–20

Nathan Beard, Floral Extension 2, 2019, from the series White Gilt, 2019–20  Nathan Beard, Floral Extension 1, 2019, from the series White Gilt, 2019–20

Nathan Beard, Floral Extension 1, 2019, from the series White Gilt, 2019–20  Nathan Beard, Rampai, Samniang, Ratana, Pornjit, 2017, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17

Nathan Beard, Rampai, Samniang, Ratana, Pornjit, 2017, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17 Nathan Beard, Siam Shimmer, 2018, from the series Siamese Smize, 2018

Nathan Beard, Siam Shimmer, 2018, from the series Siamese Smize, 2018  Nathan Beard, Prakhong, 2017, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17

Nathan Beard, Prakhong, 2017, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17  Nathan Beard, Sompong, 2015, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17

Nathan Beard, Sompong, 2015, from the series Ad Matres, 2014–17  Nathan Beard, Untitled, 2014

Nathan Beard, Untitled, 2014All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

January 19, 2023

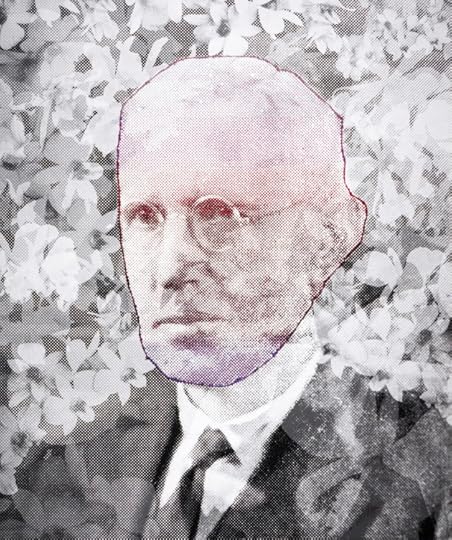

The Cairo Photographer Whose Studio Became a Dream Machine

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” fall 2017.

I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues. —Richard Avedon

Who was Van Leo? The question haunts anyone who sets out to write about him. He left behind so much for us to admire. And yet he gave us so very little. Of himself, I mean. So many unanswered questions loom. The temptation to fill the gaping holes is huge. Was he a pioneering modernist, one of the most questing and idiosyncratic photographers the Middle East has known? A man-boy narcissist whose greatest quirk was to close his studio for a few hours each day to snap photographs of himself? A savvy technician with an outsize passion for Hollywood-tinged glamour? An oriental orientalist?

When he passed away, in 2002, at the age of eighty, the Armenian with the fantastical stage name bequeathed a vast treasure trove to the American University in Cairo—several thousand prints and negatives, eclectic props and furniture, Post-it notes and shopping receipts, and drafts and obsessive redrafts of letters, both sent and unsent. Van Leo had attended the university for only a year or so in the 1930s before dropping out (he’d always been a below average student), and yet he was convinced that they would soon create a museum in his honor. An overenthusiastic autoarchivist, he told himself that nothing he’d ever touched was insignificant enough to throw out. Still, these life scraps hardly shine a light onto the photographer’s soul.

Van Leo, Drury Smith of South African Concert Party, Cairo, 1944–45

Van Leo, Drury Smith of South African Concert Party, Cairo, 1944–45By the time I met Van Leo, in 2001, his studio had been shuttered. His body was broken, and he was living in his childhood home in Cairo, a narrow apartment at 7, 26th July Street. Inside that dark rectangle—dark because he was thrifty and strained to keep his electrical bills down until the end—he no longer walked, but shuffled. He was alone, and there was little, beyond my twenty-year-old presence, to indicate what decade it was. A wall calendar hung crisply in the kitchen from a particular year in the 1940s—I can’t remember which. Van Leo himself was cordial, occasionally charming—in at least four languages—but he was wary. Cairo had changed, he said, and he didn’t know whom to trust anymore.

*

Levon Boyadjian was born in Jihane, Turkey, on November 20, 1921, the youngest of three children of Alexandre and Pirouz, Armenian émigrés whose family name roughly translates to “one who paints.” Like so many Armenians unmoored after the genocide, they moved to Egypt—to Alexandria first, and then on to Zagazig, a medium size town on the Nile. It’s tempting, when looking at images of baby Levon from this period, all dolled up, to see the rumblings of future vanities.

Van Leo, Self-Portrait, Cairo, January 8, 1945

Van Leo, Self-Portrait, Cairo, January 8, 1945  Van Leo, Self-Portrait, Cairo, November 1, 1942

Van Leo, Self-Portrait, Cairo, November 1, 1942 The Boyadjians eventually settled in Cairo, landing on what was then Avenue Fouad, an elegant thoroughfare in the Haussmannian style that extended from the manicured topiary of the Ezbekieh Gardens to the Egyptian High Court of Justice. As a teenager, young Levon interned at Studio Venus, one of dozens of photography studios run by Armenians in that city. (The Armenians had a well-known proclivity toward the craft.) Some say that Levon was pushed out of Venus when the owner—his name was Artinian—began to feel threatened by his young disciple’s precociousness. Whether this piece of lore has a kernel of truth to it is unclear. It doesn’t really matter; it’s the first of so many myths to come.

Van Leo would never have called himself the Cindy Sherman of Egypt, but between 1939 and 1944, he took hundreds of untitled self-portraits, assuming myriad personae.

It should be said that there were two photographers in the Boyadjian household, and when Levon and his brother set up shop in the family apartment in 1941, they called it Studio Angelo, in deference to the chatty older brother. The living room served as the lobby; the bathroom, the darkroom. The pair’s first customers were entertainers passing through Cairo during World War II who traded glamour shots for free advertising space in local playbills. Downtown Cairo was brimming with dancers, stage actors and actresses, clowns, and strippers—there to boost the morale of the marooned troops who were stationed in the city, soldiers from across the British Empire, as well as Americans. And yet, from the beginning, Angelo—gregarious, gambling, womanizing—was Dionysus to Levon’s bashful Apollo. While the creative partnership might have appeared happy from a distance, the two couldn’t have been more opposed.

*

In 1947, the brotherly collaboration fell apart, and Levon set out on his own, taking over a large space a few blocks from the family home, from a photographer who had left Egypt for Armenia. Studio Metro had six big rooms—“six big rooms!” he would intone, over and over, to me and anyone in earshot, decades later. It was there, at 18 Avenue Fouad, that Levon Boyadjian became Van Leo, star maker and star. The name “Van Leo,” a fabrication of his own, conjured certain Dutch masters, lapsed European royalty, and good breeding in general; it had the cadence of greatness. In the archive, there are at least half a dozen typeface experiments for the new, exotic nom de plume—thick and regal, skinny and modern, cursive and confident. Sometimes there’s a dash between the “Van” and the “Leo.” A persona is finding its way.

Van Leo, Self-Portraits, Cairo, August 25, 1939

Van Leo, Self-Portraits, Cairo, August 25, 1939

Van Leo would never have called himself the Cindy Sherman of Egypt, but between 1939 and 1944, he took hundreds of untitled self-portraits, assuming myriad personae. In these, his own body was putty—he would grow his beard, shave his head, even put on weight, while experimenting with costumes, props, and lighting. He appeared as a gangster or prisoner; as Jesus Christ, the Wolf Man, or Zorro. In one, he has the mien of a young Vladimir Lenin; another evokes the 1940s film The Thief of Baghdad. Several are surrealist tinged, betraying Van Leo’s encounter with a short-lived Egyptian Surrealist circle of the 1930s and ’40s known as Art and Liberty. “My father used to get very angry,” he admitted in 1998. “He’d tell me: ‘Did you make the studio for yourself or for the customer? Stop making photos of yourself!’” And yet it’s precisely these works in which Van Leo turned the camera on himself that began to bring him a measure of international fame in the late 1990s, shortly before we met.

In the photographer’s archive, there’s a little flip-book with dozens of postcard-size images pasted in. And yet the bulk of the self-portraits had never been printed at all. What purpose did they serve? Did they appeal to his vanity? Were they by-products of his ongoing efforts to hone his craft? Samples to show customers? Flights of fancy? It’s impossible to say. The elaborate masks Van Leo wore, one after another, were less transformative than obfuscatory. They open a door to delirious wonders, but don’t give us the key.

Van Leo, Self-Portraits, Cairo, June 26, 1940

Van Leo, Self-Portraits, Cairo, June 26, 1940