Aperture's Blog, page 30

May 4, 2023

Two South African Artists Reflect on the Memories of Apartheid

On May 10, 1994, South Africans inaugurated Nelson Mandela as their first Black president, bringing to an end the country’s notorious system of apartheid. Nearly thirty years later, crucial questions remain about ensuring equal rights for all South Africans. How might these citizens account for the trauma of violent racial segregation? How can they reconcile personal memories with official state accounts? And what role can artists play in creating new avenues for those personal and national narratives?

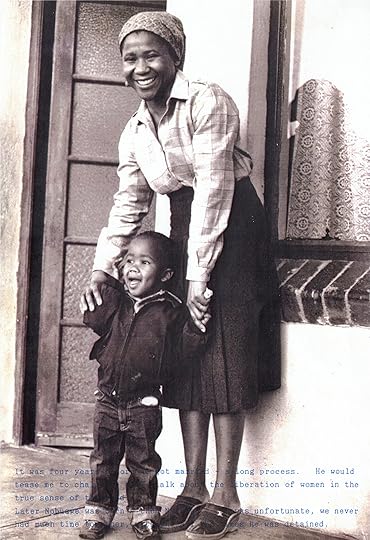

Sue Williamson, Caroline Motsoaledi I, 1984, from the series All Our Mothers

Sue Williamson, Caroline Motsoaledi I, 1984, from the series All Our Mothers Sue Williamson, A Tale of Two Cradocks (detail), 1994

Sue Williamson, A Tale of Two Cradocks (detail), 1994 The exhibition Tell Me What You Remember, curated by Emma Lewis and currently on view at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, thoughtfully addresses these questions as they surface in the work of South African artists Sue Williamson, who was born in 1941 and grew up under apartheid, and Lebohang Kganye, who was born in 1990, the year that then president F. W. de Klerk unbanned the African National Congress, setting in motion apartheid’s dismantling. Importantly, the landmark 1994 general elections created a generational divide between those who directly experienced the horrors of apartheid and those who have grown up in its aftermath (often referred to as “born frees”). Bringing together an artist from each side of this divide, the exhibition highlights how each thinks about memory in relation to both trauma and healing, as well as the subtle differences in their approaches.

Entering the gallery, visitors are greeted by images of women who lived through apartheid. Williamson’s contributions include multiracial portraits from her series All Our Mothers (1983–ongoing), which documents—with real emotional force—everyday people who fought against that system. The entryway to the exhibition also includes Kganye’s larger-than-life portraits of matrilineal ancestors from her series Mosebetsi wa Dirithi (2022), which the artist has beautifully rendered in carefully quilted swatches of fabric. This first moment of Tell Me What You Remember is the only one where Kganye’s and Williamson’s work is directly in dialogue; the rest of the exhibition is divided evenly between the two artists.

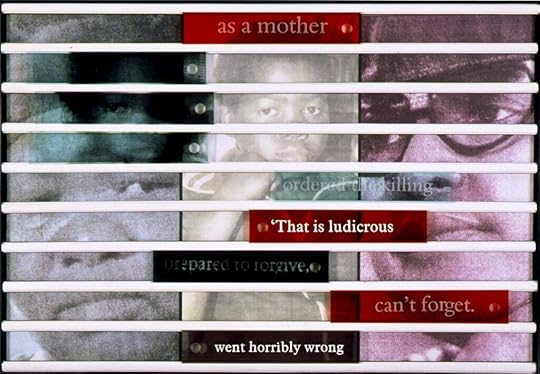

Sue Williamson, Truth Games: Joyce Seipei – as a mother – Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, 1998. Laminated color laser prints, wood, metal, plastic, Perspex

Sue Williamson, Truth Games: Joyce Seipei – as a mother – Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, 1998. Laminated color laser prints, wood, metal, plastic, Perspex Sue Williamson and Siyah Ndawela Mgoduka, That particular morning, 2019, from the series No More Fairy Tales, 2016–19. Two-channel video, color, sound

Sue Williamson and Siyah Ndawela Mgoduka, That particular morning, 2019, from the series No More Fairy Tales, 2016–19. Two-channel video, color, soundCourtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, Johannesburg, and London

In her multifaceted practice, Williamson explores the ways that apartheid laws affected individual lives and communities, and her side of the exhibition is organized into areas loosely categorized as “Testimony” and “Memory Work.” Her works in the latter section center on the effects of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and demonstrate the exhibition’s focus on the complexity of living memory. In the video installation That Particular Morning (2019), Doreen Mgoduka and her son Siyah Ndawela Mgoduka discuss the loss of Glen Mgoduka, a police officer whom apartheid police murdered in 1989 to cover up the role of white police colleagues in activist assassinations. More than a retelling of that trauma, the video stages a long overdue, and at times strained, conversation in which the two talk about how the death of Doreen’s husband and Siyah’s father has affected their relationship. Throughout much of the dialogue, Doreen sits back in her chair with her hands clasped or arms crossed as Siyah gestures broadly and occasionally wipes away tears. Each is captured by a different camera, although the two videos are projected onto one screen. This approach illustrates their different access to memory, and the difficulty of bringing the two perspectives into a seamless narrative.

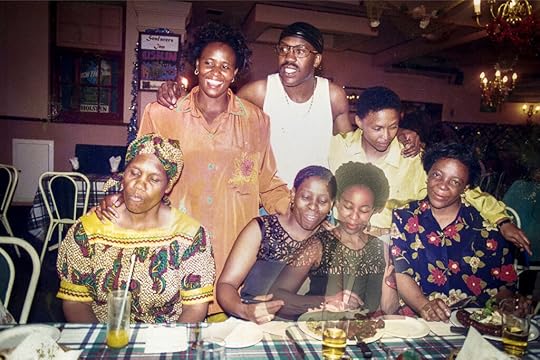

Recreating images from family albums, Kganye returned to the sites of the photographs, often putting on the same outfit that her mother had worn and assuming her mother’s pose.

Reflecting an important theme of the exhibition, That Particular Morning seems to ask, what does all of this sharing of memory add up to? This question links many of Williamson’s works. For instance, in the series Truth Games (1998), she directs this question at the TRC hearings, in which victims of apartheid violence were brought together with perpetrators who confessed their crimes in the name of national “healing.” In each of these works, a press photograph from a well-publicized case is sandwiched between a photograph of an accuser on one side and a defendant on the other. Movable Perspex slats partially block the images, demonstrating how words can obscure the truth, or perhaps that full transparency remains forever out of reach. Similarly, Memorial to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (2016) resembles a tombstone upon which the alternating and repeating phrases “can’t remember” and “can’t forget” are printed onto glass. The difference between the inability to forget and the desire to not remember marks the power differential in the TRC process as well as the problems inherent in transforming personal memories into collective histories.

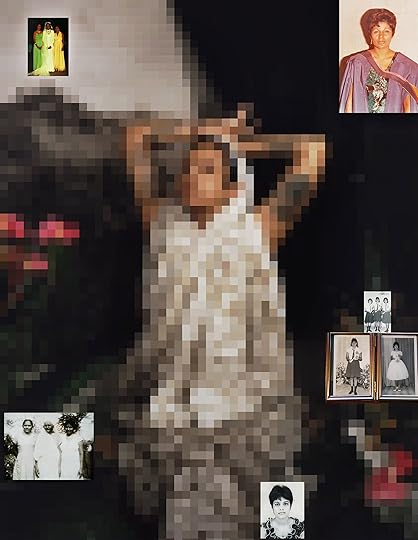

Lebohang Kganye, Setupung sa kwana hae II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013

Lebohang Kganye, Setupung sa kwana hae II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013 Lebohang Kganye, Ke tsamaya masiu II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013

Lebohang Kganye, Ke tsamaya masiu II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013In contrast, Kganye’s practice largely addresses apartheid indirectly, leading with explorations of her family’s archive. In the exhibition, works grouped together under the label “In Search for Memory” suggest the urgency and poignancy of such searching. For example, the sudden death of the artist’s mother in 2010 inspired a series called Ke Lefa Laka: Her-Story (2013). Recreating images from family albums, Kganye returned to the sites of the photographs, often putting on the same outfit that her mother had worn and assuming her mother’s pose. What began as separate images of reenactment transformed into photomontages of the two women, with the figure of Lebohang creating a ghostly double of the elder Kganye. The longing in these montages is especially apparent in Setshwantso le ngwanaka II (2013), where Kganye, wearing a red dress and a tender smile, mirrors her mother’s gesture of beckoning to a toddler who is the artist herself. These images bring to mind performance scholar Joseph Roach’s notion of surrogation, a process through which individuals—or collectives—perform the past to enact a sense of continuity. But as Roach points out, the process is always marred by the deficit or surplus created when a new person steps into an established role.

Lebohang Kganye, Setshwantso le ngwanaka II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013

Lebohang Kganye, Setshwantso le ngwanaka II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013 Lebohang Kganye, Re intshitse mosebetsing II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013

Lebohang Kganye, Re intshitse mosebetsing II, from the series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2013Rather than lament this lack of seamless continuity, Kganye makes works that revel in it, embracing the idea that family albums and, more broadly, family stories, are spaces of fantasy and creative possibility. In a short video titled Pied Piper’s Voyage (2014), she performs stories, gleaned from family members, about her grandfather’s journey from farmland in the Orange Free State to Johannesburg in search of work. As in the series Her-story, Kganye dons her grandfather’s clothes, but in this work, the doubling is even more theatrical: The artist moves among cardboard set pieces that are scaled-up photographs from the family archive. Posing alongside the black-and-white, two-dimensional set pieces, she enacts both the disjunct between the present and the past as well as the mutability of memory, demonstrating how an artist can rearrange elements of the past at will.

If Kganye’s work illustrates the power that artists have in restaging the past, the series In Search for Memory (2020) extends this idea into a speculative future. The works, photographs of miniature dioramas, are based on Ta O’Reva (2015), a science fiction novella by the Malawian writer Muthi Nhlema. In Nhlema’s apocalyptic setting, South Africa has collapsed in a sequence of events that began with a race riot and resulted in the spread of a deadly contagion. Kganye’s works picture some of the novella’s most powerful moments, as in the image He could hear the voices of his ancestors (2020), in which a little boy hides under a kitchen table as his father is being murdered by a white farmer, or The stranger stood before what to him was a monstrosity (2020), in which a reanimated Nelson Mandela surveys the nation’s ruin, an outcome that occurs in spite of a lifetime of sacrifice. If the images gesture to Afrofuturism, they are also resolutely dystopic.

Lebohang Kganye, Untouched by the Ancient Caress of Time, 2022, from the series In Search for Memory, 2020–22. Fiberboard, cardboard, light

Lebohang Kganye, Untouched by the Ancient Caress of Time, 2022, from the series In Search for Memory, 2020–22. Fiberboard, cardboard, lightCourtesy the artist

In her essay on Williamson in the exhibition’s catalog, the writer Nkgopoleng Moloi describes the artist’s work as “the unfinished project of emancipation.” Tell Me What You Remember proposes that both Williamson and Kganye participate in this project, whether mining collective or personal archives or picturing possible futures. In either case, the artists powerfully engage memory as a material, pointing to its potential for transformation.

Sue Williamson & Lebohang Kganye: Tell Me What You Remember is on view at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, through May 21, 2023.

May 2, 2023

How Tommy Kha’s Mischievous Portraits Challenge the Idea of Belonging

Tommy Kha told me about a moment, not too long ago, when he was photographing his mother and she asked him: Why is art always so sad?

She fled Vietnam in the eighties, raising Tommy and his sister in Memphis. When they were children, the history that had delivered their family to America was passed down in fragments and gestures. It was a story that was never told. Rather, it was carried through expressions or habits, with a tendency toward conversational dead ends, and in the chasm between shouting and silence. In her closet, Tommy’s mother had kept photographs from when she was younger, some from Vietnam but most taken in Ontario, her first home in North America, in the eighties. Washed-out snapshots of friends gathered around plates of food or birthday cakes, self-portraits on a pier, at the beach, with enormous stuffed animals, or perched in a tree. These pictures weren’t art, she was suggesting to Tommy, just moments from a past she never discussed.

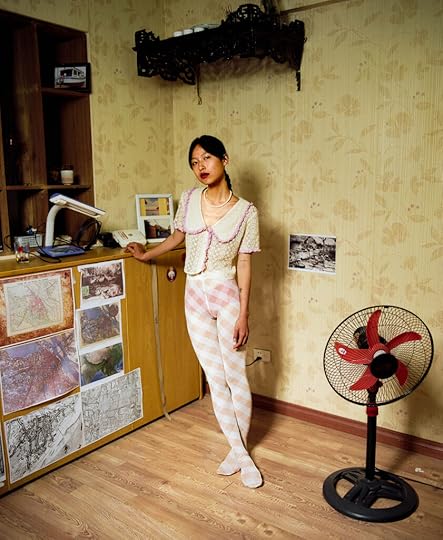

Tommy Kha, May (Acting), Mom’s Bedroom, Whitehaven, Memphis, 2013

Tommy Kha, May (Acting), Mom’s Bedroom, Whitehaven, Memphis, 2013  Tommy Kha, Constellations VIII, Prop Planet, Miami, 2017

Tommy Kha, Constellations VIII, Prop Planet, Miami, 2017 As Tommy pursued his own path as an artist, he and his mother settled into a routine. She would make him food, and then he would take pictures of her, usually inside her home or in her backyard, making these overfamiliar settings feel mysterious and alien. She frequently looks troubled in these images; maybe she is just annoyed. People need to smile more, she told him.

I don’t find Tommy’s work sad at all. A life-size cutout of Elvis Presley with Tommy’s face slapped over the iconic singer’s? This is hilarious, mischievous, surreal stuff. That’s not where he’s supposed to be, which is part of how his art seizes you. The compositions are gorgeous and meticulous, with Kha masterfully capturing these soothing, garish auras in the naturally occurring colors of our world. But there’s often something a bit off. A flourish—visual jokes, out-of-place expressions, a glimpse of a cutout of his own face—that marks his presence.

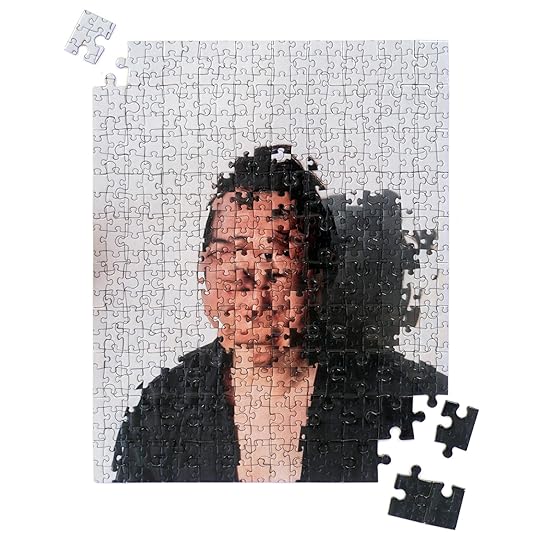

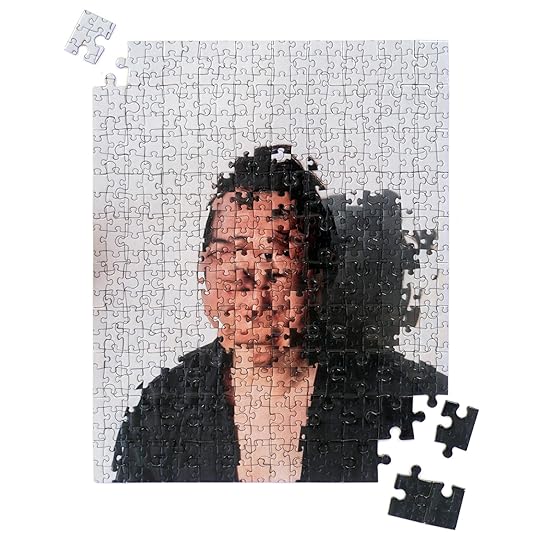

(Re) Assemblies, 2023 A limited-edition puzzle of one of Tommy Kha’s idiosyncratic self-portraits from the monograph Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (2023).

(Re) Assemblies, 2023 A limited-edition puzzle of one of Tommy Kha’s idiosyncratic self-portraits from the monograph Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (2023). $150.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

(Re) Assemblies, 2023 $ 150.00 –1+$150.00Add to cart

View cart Description Aperture is pleased to release this special limited-edition puzzle by the artist Tommy Kha on the occasion of the publication Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (2023). In this first monograph, the result of the Next Step Award, a collaboration between Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, in partnership with 7|G Foundation, the artist explores the personal psycho-geography of his hometown and weaves together self-portraits and classically bucolic landscapes punctuated by the traces of East Asian stories embedded in the topography of the American South. In assembling a visual record of the struggle to find his own voice and to create a fragmented portrait of his family, Kha challenges the cultural amnesia around Asian lives and experiences in recent American histories. (Re) Assemblies, 2023 brings together a limited-edition puzzle of one of Kha’s idiosyncratic self-portraits. DetailsLimited-Edition Puzzle

Size: 8 x 10 inches

Edition of 150

Signed and numbered by the artist

Tommy Kha (b. 1988, Memphis, TN) lives and works between Brooklyn and Memphis. He received his MFA from Yale University in 2013, and is the recipient of the 2021 Aperture–Baxter St Next Step Award.

When Tommy began taking photographs, he was inspired by the work of Nan Goldin to document his friends, many of them performers and musicians, as they made their racket around town. To better pull focus for his self portraits, he toted around an Elvis cutout. But over time, inspired in part by Claude Cahun, Reka Reisinger, and Tseng Kwong Chi, he began incorporating the cutouts themselves, producing a different kind of self-representation. On one hand, these self-portraits dramatize his sense of dislocation—of not belonging, maybe even invading, or judging, these scenes of pure Americana. They suggest an insolubility, the impossibility of assimilating, whether into a nation or an everyday background. He experimented with printing his face on pillows or puzzles so that he was, quite literally, fragmented. But all of this felt playful too. His family and friends cradled his cutout, played dress-up with a reproduction of his face, as if poking fun at its overly serious, some might say inscrutable, expression.

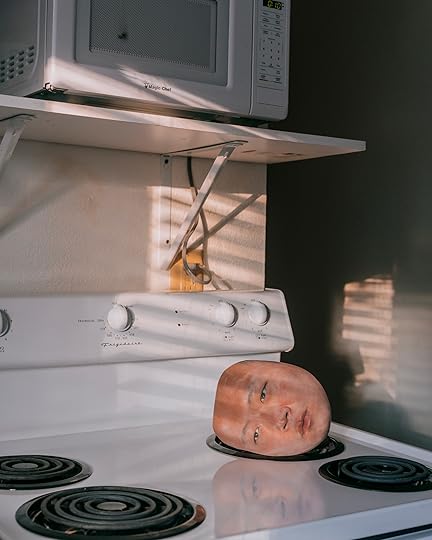

Tommy Kha, Headtown (XII), Midtown, Memphis, 2021

Tommy Kha, Headtown (XII), Midtown, Memphis, 2021

May (Pattern Drafting), London, Ontario, ca. 1984

May (Pattern Drafting), London, Ontario, ca. 1984

Most of the photos in this book were taken by Tommy. Interspersed are faded snap-shots from a photo album his mother passed onto him and his sister a few years ago with little explanation or context. The pictures are full of friends and acquaintances from her early years in Ontario, most of whom the children do not know. Some of the photos are reproduced here in full; others have been cut to lift figures from backgrounds and are arranged into collages, leaving only jagged, island-like clusters of new immigrants against a blank expanse.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

The children of immigrants learn of the world first through the oft-limited horizons of those around us. We don’t see ourselves in the culture, so we learn how to breach America by studying our families, our parents, and nearby elders. Photography was the only form of art they participated in, only it wasn’t art, it was just something to do. It was a ritual, a place to put their memories, fleeting visions of the new world to mail back to the old one, if anyone was still there. There were minor details of self-presentation, like a cherished piece of clothing or a carefree smile, perhaps the only gestures of self-fashioning that felt comfortable in those days. The fact that Tommy’s mother had kept this album all these years communicates enough.

Tommy Kha, Stations (Viet Hoa Market), Cleveland Street, Memphis, 2021

Tommy Kha, Stations (Viet Hoa Market), Cleveland Street, Memphis, 2021And you realize: this isn’t just Tommy’s book, and the photos from the eighties aren’t just there to provide context about his world. These snapshots sit effortlessly alongside his austere pictures of Memphis and his carefully staged family portraits. Together, they offer us a sense of collaborative possibility, a wondrous back-and-forth between present and future, a collaboration that goes unremarked upon, since there are certain aspects of the past that we never talk about. Instead, the images in this book speak to one another in glances, smiles, echoes. What we inherit isn’t just language but the angle you hold your head when you listen.

Tommy Kha, Mine IX, Den(tist Room), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017

Tommy Kha, Mine IX, Den(tist Room), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017  Tommy Kha, May (with Her Half Self-Portrait), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017

Tommy Kha, May (with Her Half Self-Portrait), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017 There are photos of Tommy’s mother in the corner of her father’s home dental office, where he practiced in private for family and friends after not being able to establish his license in the US. A cutout of Tommy’s face is nestled in the chair. He doesn’t belong there. Then again, the room itself indexes an entire history of not belonging. Elsewhere, mother and son lie next to one another in a living room, gazing in different directions. Her face is weary, perhaps because that’s what she thinks she’s supposed to do with her face. She’s playacting. But sometimes, she looks back at the camera, at Tommy, and she understands that they are there at the same time, sharing a moment, even if neither of them can put to words what that is.

These pictures aren’t sad; they’re hopeful. They luxuriate in the ongoingness of family and history. Nothing is resolved. But what draws us forward are moments of reckoning, as generations take turns telling a shared story. A fragment will never join with the whole. It is a new whole.

Tommy Kha, Exchange Place VI, Midtown, Memphis, 2019

Tommy Kha, Exchange Place VI, Midtown, Memphis, 2019  Tommy Kha, May (or Half a Self-Portrait), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017

Tommy Kha, May (or Half a Self-Portrait), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017 This essay originally appeared in Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (Aperture, 2023).

April 28, 2023

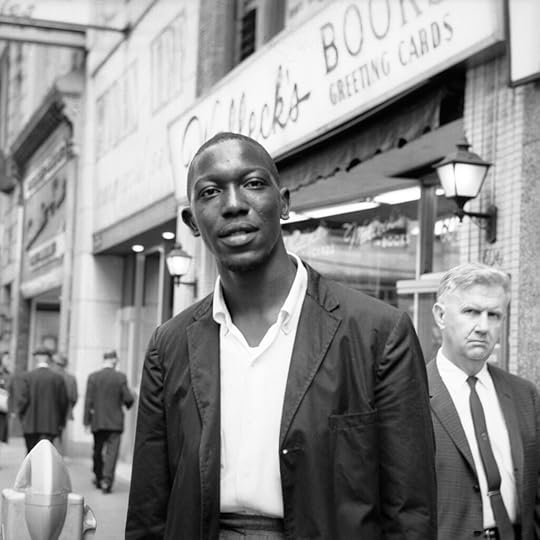

A Midcentury Portrait of Black Culture in Pittsburgh

Sometime in the middle of the last century, Charles “Teenie” Harris became known for often taking only one picture of his subjects, and was aptly nicknamed “One Shot” by the former mayor of Pittsburgh David L. Lawrence. “He was fast,” Charlene Foggie-Barnett, the Teenie Harris community archivist at the Carnegie Museum of Art, told me over Zoom in late October 2022. “He’d run in and say, ‘Get together, everybody, I’m only gonna take one shot.’” With a determined energy, Harris took “one shot” many, many times in his long career, capturing the ordinary beauty of Black life in the city.

Professionally, Harris started out at the Washington, DC–based Flash Weekly Newspicture Magazine, but he had been exposed to photography since he was a small child. For more than forty years, Harris was the leading photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the country’s largest Black newspapers. At the Courier, he worked on assignments ranging from the civil rights movement (protests, rallies, and marches) to local events such as birthdays, community meetings, cultural programs, and sports activities. Intersecting with the lives of innumerable Pittsburgh residents as a street photographer, studio photographer, and photojournalist, he made note of what he saw as a member of Pittsburgh’s Black communities, touching on themes of sexuality, religion, intimacy, memory, slavery, and more. He lived for ninety years, nearly the twentieth century in its entirety. His work poses the question, How can photography be conceived as a history of experience?

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Greyhound buses going to the March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC, 1963

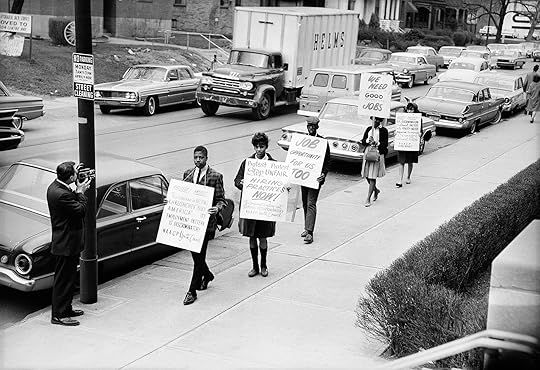

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Greyhound buses going to the March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC, 1963  Charles “Teenie” Harris, Protesters, Pittsburgh, ca. 1963

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Protesters, Pittsburgh, ca. 1963 Harris’s presence in Pittsburgh’s historically Black Hill District, Speed Graphic camera in hand, was ubiquitous. As exclaimed in He’s a Black Man!, an early 1970s Sears Public Affairs radio series, “There may very well be a Black person in Pittsburgh who hasn’t had his photo snapped by ‘Teenie’ Harris, but that would more than likely be a Black person in Pittsburgh who hasn’t had his picture taken at all.”

Through Harris’s eyes, the pressures of historic events including the Great Depression, the Great Migration, Black freedom struggles, civil rights campaigns, World War II, and Jim Crow were given rich visual references. Harris captured the contours of political life: a Black elder named Mary Reid holding a note defaced with swastikas, reading “Kill All Blacks” and “Stop Niger [sic] Take Over”; a billboard advertising the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign demanding low-income housing and a moratorium against redevelopment in the Hill District; and a 1970 broadside of the Black Panther manifesto. He also photographed cultural icons when they passed through a deeply segregated and heavily policed Pittsburgh, a city he rarely left: well-known musicians (Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington), politicians (John F. Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt, Richard Nixon), civil rights leaders and organizers (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael), dancers (Josephine Baker), singers (Lena Horne, Sarah Vaughan, Eartha Kitt), and athletes (Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Willie Mays). As the art historian Nicole Fleetwood writes in her 2011 book Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness, “Harris’s lens provides an alternative visual index of black lived experience of the twentieth century, one that does not rely on the familiar device of photographic iconicity.”

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Possibly the Loendi Club, Pittsburgh, ca. 1930–45

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }In 1937, Harris opened his own studio. In addition, he regularly freelanced for advertising agencies and insurance companies in order to make ends meet given the scant resources on offer from the Black press. Still, roaming around Black Pittsburgh, he made photographs that were just for him, for the sake of his craft, which often exceeded the limits of documentary photography and reportage. Harris’s practice combined the ordinary, uniquely vibrant character of Black life, including such shiny events as family portraits, weddings, baptisms, and funerals, with the more quotidian subjects of work and birth. He took pictures inside hotels, nightclubs, homes, restaurants, boxing rings, and kitchens; on tree-lined, brick-paved, stoop-filled streets; at railroad yards, police stations, demolitions, groundbreakings, and picnics. He never stopped taking pictures.

The Carnegie Museum of Art’s permanent Teenie Harris collection contains more than seventy thousand negatives from Harris’s working career, spanning from the 1930s to the 1980s. Tens of thousands still need to be digitized; among the selection here are several previously unpublished images, part of a major scanning project underway at the museum. Some images from Harris’s formidable photographic archive are online and searchable. They have woozily long titles describing what they depict (partly because the recording of this information is ongoing). Over the past twenty years, since the institution purchased the Harris archive in 2001 from the artist’s estate (a wish of Harris’s before his death), the Carnegie has searched for more details and identifications. The catalog listings, which continue to evolve as new information becomes available, come from oral histories done with people who appear in Harris’s photographs or from research via the Pittsburgh Courier or Flash Weekly Newspicture Magazine.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Untitled, Pittsburgh, ca. 1962

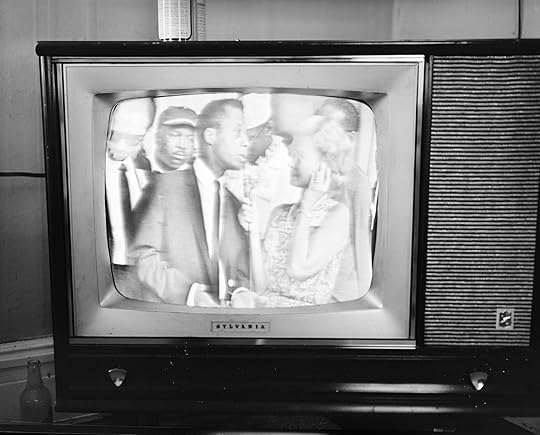

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Untitled, Pittsburgh, ca. 1962  Charles “Teenie” Harris, A television playing coverage of James Baldwin at the March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC, 1963

Charles “Teenie” Harris, A television playing coverage of James Baldwin at the March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC, 1963 Instrumental to the contemporary and historical Harris moment, as well as to the Carnegie, is Foggie-Barnett, who knew Harris and was photographed by him as a child in the Hill District. She describes Harris as a friend of her parents, Bishop and Mrs. Charles H. Foggie, who were civil rights leaders. “Teenie was just an everyday occurrence,” she recalls, with pride. “It was not uncommon, for a lot of people, to have Teenie pop up at any time.”

In 2006, when Foggie-Barnett read in the newspaper that the Carnegie Museum of Art was looking for children photographed by Harris, she was the only person who showed up at the museum. “Part of the concern, of course, was what is the Carnegie doing with these images?” she says. The recording of this history is urgent, but the critique of big institutions, which often excluded and exploited the Black community, is just as pressing. Many of Harris’s acquaintances are nearing the end of their lives, but they still express an unsurprising distrust of institutional archives or a fear that they may not say the “right thing.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Foggie-Barnett ended up creating an oral history with the museum. “The archive had come almost exclusively unidentified to the Carnegie,” she says. “And so, the first-person interviews and people talking about their lived experiences as seen through Teenie’s lens was the way they were building the information of the archive. I got so excited by and so appreciative of how the staff treated the information. They were very delicate in how they asked questions and were very clear and sincere about what their intentions were,” she explains. “I started bringing some people with me that they couldn’t get to come down. And a lot of those were elderly people, like my original childhood hairdresser [Gloria Golden Grate], who had her own shop but was also one of the first Black models in Pittsburgh.”

Foggie-Barnett began volunteering at the museum in 2006 and was hired in 2010 as the community archivist. She is now a well-respected steward of the Harris archive, involved in preserving, curating, and broadening the collection’s scope and community relevance. Along with the archivist Dominique Luster, she co-organized In Sharp Focus: Charles “Teenie” Harris, a permanent exhibition in the Carnegie’s Scaife Galleries that opened in January 2020. As a researcher studying the Harris archive, Foggie-Barnett conducts oral histories and coordinates outreach by bringing exhibition prints to nursing homes, delivering lectures in schools and on campuses, and giving tours of the exhibition.

Looking at the subjects in Harris’s pictures, we see people who find comfort and trust in a world where comfort and trust are never guaranteed.

At its core, Harris’s picture-making practice was aimed at a Pittsburgh in transformation, shifting from a steel-producing hub of industrialism to a city best described as postindustrial. As the city changed, many tensions around segregation and desegregation, for example, unraveled at the Highland Park pool. In the 1940s and 1950s, civil rights organizers in Pittsburgh staged demonstrations involving interracial swimming. As the historian Joe William Trotter Jr. notes in his essay “Harris, History, and the Hill,” published in the 2011 catalog Teenie Harris, Photographer: Image, Memory, History, white people harassed the swimmers. Harris photographed many outdoor and indoor pools: some give off a sense of leisure (glamorous poses, a hand on the hip), others focus on sports (boys lined up at the edge of a pool for a swim meet), but all are overburdened by the historical fact that municipal swimming pools were crucial sites of racial violence during segregation. The corresponding fear of Black people “contaminating” whites loomed large.

Harris wanted you to see, but he also wanted you to listen to the stories he was presenting in his art. “He is leaving clues, he is revealing story lines and truths,” says Foggie-Barnett. “He’s making a statement.” Harris trains the eye to notice more idiosyncratic acts, that mental montage of stills ever blowing in our head, at the edges of memory.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Swimmers, Pittsburgh, ca. 1971

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Swimmers, Pittsburgh, ca. 1971  Charles “Teenie” Harris, Sabre “Mother” Washington, a formerly enslaved person, on her 109th birthday, in her home on Conemaugh Street, Pittsburgh, 1954

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Sabre “Mother” Washington, a formerly enslaved person, on her 109th birthday, in her home on Conemaugh Street, Pittsburgh, 1954 A single Harris photograph can take the form of a transgenerational account of the present. In one image, from December 1954, Sabre “Mother” Washington, a formerly enslaved woman, stands in her Conemaugh Street home on the occasion of her 109th birthday. The image would be remarkable on its own, but Washington, seemingly having just stood up from her floral-patterned chair for the picture, and with her shadow imprinting the living room wall behind her, gives the impression that she

is hovering, evoking the hauntings of the slave trade.

In other photographs, in which people aren’t always as readily identifiable, some looking directly at the camera and others seemingly posed, subtleties break through the frame: a Sylvania television playing footage from the 1963 March on Washington, forcing the viewer to take note of the technologies of representation. Harris’s oeuvre chronicles historic events but also what the art historian Cheryl Finley calls, in Teenie Harris, Photographer, “glimpses of everyday life and the people who gave it vitality, dignity, and purpose.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Harris often provided visual language to interstices only he could see. Swirling night scenes—the subtle shift in brightness as lights twinkle over a foggy steel mill; sparsely populated urban landscapes; the subdued, anxious excitement of people standing around Greyhound buses for a march—reveal an aesthetic perspective that is an essential element of his work, cementing Harris’s position as not only a photojournalist and studio photographer but an artist. Harris’s rendering of Black skin and epidermal intensity was yet another sign of his creative virtuosity. Foggie-Barnett informs me that Harris used dodging and burning techniques in the darkroom so that Black skin would develop in rich shades.

As The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords, a 1999 documentary film by Stanley Nelson, illuminates, Black print culture played a determining institutional role in fighting white supremacy, especially during the twentieth century. Photographs are not only visual archives of the past but the axis on which people represent themselves, or see themselves represented. In Teenie Harris, Photographer, the historian Laurence Glasco describes Harris as a people person who often used comedy as a way to deflect attention from his four-by-five-inch handheld camera. Looking at the subjects in Harris’s pictures, we see people who find comfort and trust in a world where comfort and trust are never guaranteed, especially considering the ethnographic exploitation at the time by many American photographers slumming it for the shot.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Untitled, Pittsburgh, ca. 1962

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Untitled, Pittsburgh, ca. 1962All photographs courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund

Yet another important instance of Harris’s representation of the ill-represented: “He has an array of photos of the LGBTQ+ community that most people didn’t know existed,” Foggie-Barnett tells me. In 2018, Black Artists’ Networks in Dialogue (BAND) Gallery, in Toronto, exhibited Harris’s work in a show called Cutting a Figure: Black Style through the Lens of Charles “Teenie” Harris, which featured midcentury scenes of queer and transgender aesthetic culture, such as the drag performers “Gilda” and “Junie” Turner in feathered costumes. “These images reveal the complete trust his subjects had in Harris,” reads the online blurb. “Any spectacle related to outlandish dress is overshadowed by Harris’s intimate and familial treatment of his subjects.”

Harris’s work was, and is, part of the fabric of the continued making of a heterogeneous Black narrative in Pittsburgh and beyond. One finds oneself changed by his visually quiet sociability. “He is the keeper of our history,” Foggie-Barnett says. She encourages those who are young to explore Harris’s archive and ask questions about what it means for them and their future. What remains will be up to them.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

The Photographers Who Envisioned Queer History and Resistance

On the evening of February 9, 2023, in a standing-room-only presentation for a raucous audience at the LGBT Center in Manhattan, Joan E. Biren (JEB) did something for the first and last time in thirty-nine years: a live performance of her Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–the present (1979–1985). The Dyke Show, as it is more popularly called, is a slideshow comprised of hundreds of portraits, documentary images, and erotic photography by artists ranging from Alice Austen to Tee Corinne. Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, an exhibition curated by Ariel Goldberg and currently on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York includes a digitized version of The Dyke Show and seeks to carry on the ambition, enthusiasm, and intergenerational through lines of JEB’s work.

The exhibition is overwhelming—in the best way—in its six distinct but inextricably connected sections. These include photography by Lola Flash alongside ART+ Positive (a small artist collective dedicated to fighting AIDS phobia); documentary images from the vast archive of artist and educator Diana Solís; a selection of images of African American lesbians from the Lesbian Herstory Archives; snapshots, correspondence, and newsletters that showcase sundry trans networks; and Electric Blanket, a slideshow installation of images related to HIV/AIDS, from portraits of dead loved ones to photo essays to protest slogans and statistics.

Images on which to build, which was originally presented at the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, showcases artists and collectives that participated in, and ultimately built, robust trans and queer image cultures with lasting influence. The title card for each section looks and feels like a vintage activist button, reminding us that these projects were never only “art for art’s sake.” And neither is this exhibition. Indeed, in form and content, Goldberg’s mission is in keeping with their predecessors’: the work is offered in the spirit of education, inspiration, and interconnection.

I recently spoke with Goldberg, who exudes passion and purpose. “When I started to approach people, my tenor was one of humility,” they told me. “I never thought I was discovering anyone; I was simply bridging the gaps of historical erasure for all those artists and culture workers who have been ignored by incomplete photographic histories.” The result of their gap-filling is a sort of interstellar vastness as moving as it is galvanizing.

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Delaware Dykes for Peace, Jobs, & Justice, ca. 1979, from The Dyke Show

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Delaware Dykes for Peace, Jobs, & Justice, ca. 1979, from The Dyke ShowCourtesy the artist

Kerry Manders: What was the impetus for this exhibition?

Ariel Goldberg: The fire—fueled by anger and disbelief—really started in 2015 when I was finishing my book The Estrangement Principle about the label “queer art” and asking: what’s my queer lineage in photography?

I knew it had to be deeper than Robert Mapplethorpe and his Hasselblad. I was starting with how modes of representation are contested in queer history, reading Isaac Julien and Kobena Mercer, thinking about Lyle Ashton Harris and others who were pushing back against an elite white gay male history. I wanted to learn about everything that doesn’t assimilate into the commercial fine art world.

The fire was also ignited when I read Sophie Hackett’s article on The Dyke Show by JEB [Joan E. Biren] in the “Queer” 2015 issue of Aperture. That gave me a concrete example of what we could find if only we looked.

Manders: Your mission was to recover and re-present those artists.

Goldberg: I started this research in part because I wanted to experience the slideshows that I was told I can’t see anymore because they were live events. You can reconstruct historical multimedia projects like The Dyke Show if you are devoted to the long process and move at the speed of trust with the people who made them.

Diana Solís, Flexing our Muscles: Gathering of Friends, Greenview Street, Lakeview, Chicago, IL, 1981

Diana Solís, Flexing our Muscles: Gathering of Friends, Greenview Street, Lakeview, Chicago, IL, 1981Courtesy the artist

Manders: Can you give us a snapshot of this moment in time on which your exhibition focuses? How do you differentiate it from what came before?

Goldberg: The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet. Right before this, visual records of trans and queer life most often belonged to the state—like arrest records—or were tabloid-y, sensationalized news stories of gender “discovery.” There were criminalizing narratives, or even outright destruction—families destroying personal archives of their queer relatives and even people destroying their own archives for fear of discovery. Even Diane Arbus’s photograph of Stormé DeLarverie was too controversial for Harper’s Bazaar to publish in 1961.

Manders: Where and how did you find these artists? Can you pull back the curtains on the “making of” this exhibition?

Goldberg: It’s multifaceted—there’s no template. My methods depend on the person I’m researching. I do the maximum amount of research I can before engaging in dialogue with an artist or archivist.

The artist Nicole Marroquin, whom I met at a Magnum Foundation event, introduced me to Diana Solís. Ever since, I leave each conversation with Diana—and the many artists and scholars working with them—with more names of people and events to look up, more books and articles to read. I remember the first time I visited Chicago, Nicole said I must read this book Chicanas Movidas, and has since shared articles in English on the Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericana y del Caribe. I still have a lot of learning to do about Chicago social movement history, Chicana, Mexicana histories of the Midwest, and Latin American feminist history if I’m to even fathom Solís’s work.

I apply to get travel funds that are available through archives to go to personal papers. I basically riffle through boxes and boxes of stuff. I try to zoom out and understand who was supporting the photographers’ work. Especially when I was just beginning in JEB’s papers, I started to see repeated names like Tee Corinne and Morgan Gwenwald, and patterns of relationships.

Morgan Gwenwald, Working on the “Keepin’ On” exhibition, 1991. Left to right: Paula Grant, Jewelle Gomez, Georgia Brooks

Morgan Gwenwald, Working on the “Keepin’ On” exhibition, 1991. Left to right: Paula Grant, Jewelle Gomez, Georgia BrooksCourtesy the Artist

Manders: That’s lovely. You built this exhibition via a network of relationships you found in the archives, which you then translate in your curatorial choices. Interconnection and overlap are key elements of the show.

Goldberg: Yes! When I was working with Diana Solís on the edit of their photographs, I remember getting excited when I saw, in the background of a photograph taken at Mujeres Latinas en Acción, matted photographs on the wall behind the table where a group of women were having a meeting. That group included Diana’s mother, their friend Diane Ávila, and her mother, too. When I asked whose photos were on the wall, Solís responded it was their own work and likely their students’ work from the photography class they were teaching at Mujeres in the late 1970s.

The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet.

This scene is what I am hoping to achieve with the exhibition broadly: creating a space for people to gather and make connections about photography and art’s critical role in organizing across generations. At the openings in Cincinnati and New York, artists and archivists from different cities were getting to meet and appreciate each other through the varied contexts of each other’s work.

The goal was not only about finding material, but also about meeting and connecting people who were not already acquainted. Personally, the ongoing power of this work is the relationships and mentorships I’ve been lucky to cultivate through this process.

Manders: That makes me think of one of the various resonances of the exhibition title—images on which to build relationships. This exhibition seems to be as much about community as it is about art.

Goldberg: Aldo Hernández, one of the organizers of ART+ Positive, reminded me that their work was about communities and collectivities, not about individuals and careers. It was about organizing and doing as much as you could with what little you had. He once said to me, “Oh, we were foam core queens!” And I thought, That kind of sums it up, getting work out there in the ways that were most affordable and easiest to schlep around.

One of my design challenges was to honor the Lesbian Herstory Archives foam core exhibition boards alongside framed archival ink-jet prints. I wanted to show that these practical materials traveled. They’ve been to student centers and volunteer-run archives. That ding on the corner of the foam core board—that wear and tear—is filled with the love of the previous audiences receiving the work.

Related Items

Aperture 229

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Manders: What have you learned in the process of curating this exhibition? What are some crucial takeaways?

Goldberg: The first, most beautiful lesson is that organizing as image makers takes so many different forms.

On the one hand, I’m looking back. I’m doing all this inspiring time travel and celebrating the ways in which our predecessors came together and solved problems. AIDS activists learned the science for treatment—and tirelessly fought for the funding.

On the other hand, I’m thinking in the present tense. We are in a horrifying conservative backlash right now that could really be immobilizing. How can I work and pay my rent, but also bring my skills to all the amazing grassroots organizing happening right now, from prison abolition, defunding the police, affordable housing, canceling student debt, Palestine—all of which are interconnected struggles—to the current onslaught of anti-trans legislation? How can I be of service?

Installation views of Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, 2023

Installation views of Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, 2023Photographs by Object Studies

Manders: Now you’re reminding me of the rest of the quotation from which you borrowed your title. In an early review of JEB’s Dyke Show, Carol Seajay claimed these were “Images on which to build a future.” This exhibition, like the image cultures it showcases, is as interested in doing as it is in being.

Goldberg: A lot of trans and queer image making was all about self-determination beyond representation.

For example, Loren Rex Cameron, who was a part of the FTM support group in San Francisco, took pictures of people at different stages of transitioning, and those pictures played a part in educating people about hormones and surgeries. His photographs give us a way to understand how people were using photography to share non-pathologizing transgender medicine and build stronger movements.

The “doing” also speaks to how I wanted to share materials about the joy of gathering! I don’t want to lose that aspect of it. I’ve learned that didactic projects are also about community building and fun. Look at ART+Positive’s Queer Beauty series that Lola Flash photographed: people were spelling the phrase with their naked bodies! This isn’t dry material! Enjoyment in education is part of the work.

Diana Solís, Women Free Women in Prison, March on Washington, 1979

Diana Solís, Women Free Women in Prison, March on Washington, 1979Courtesy the Artist

Manders: I’m struck by the breadth of this exhibition—the fullness of your curatorial essay and exhibition text and even acknowledgments. We’ve joked about our shared “maximalist tendencies.” It’s not an inability to edit but, instead, a commitment to community, pedagogy, and material history.

Goldberg: Captions are a great metaphor for my work. I felt inspired to begin research for this exhibition while I was working on my photo history book Just Captions: Ethics of Trans and Queer Image Cultures. The caption is my rallying call to learn the names of people who appear in images. To then ask questions about how they were showing up for movements. Beyond the literal, I think of captions as an expandable poetic space, as curiosity for multiple narratives.

The show demonstrates how people were supporting and making culture. The columns in the exhibition space are wheat pasted with a single flyer or newsletter page from each of the six sections of the show. The Electric Blanket slideshow call for photographs, Rupert Raj’s Metamorphosis, which was the inspiration for Lou Sullivan’s FTM Newsletter. I want to show how these projects addressed their audiences. Wherever possible, I included a review of the slideshow or exhibit, in part to prove the work was recognized in feminist, trans, and queer communities.

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Connie Panzarino, New York City, 1979, from The Dyke Show

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Connie Panzarino, New York City, 1979, from The Dyke ShowCourtesy the artist

Portrait of Bet Power (now Ben Power Alwin), April 1990

Portrait of Bet Power (now Ben Power Alwin), April 1990Courtesy the Sexual Minorities Archives, Miscellaneous Photography Collection and Digital Transgender Archives

Manders: That makes me curious about the echoes and reverberations of these image cultures. How do we see their influence in the years after? And today?

Goldberg: We see the influence of these image cultures where artists are distributing their work in unconventional, non-institutional ways that also foreground material struggles and support their peers. Publishing hard-to-find materials online, with captions, for example, and making it freely accessible, as Sky Syzygy’s Gender.Network website does.

I am excited by contemporary work that tries to understand, through photographs, the texture of the lives that we’re now celebrating, as opposed to relying on iconicity and fantasies. If we insist on context as part of the work, we can resist the erasure of material struggles that often happens when queer culture is appropriated into mainstream culture.

The exhibition highlights inherited strategies of practical resistance, ways to fight the violence and stigma and discrimination that come with a denial of queer and trans life and history. Image makers and archivists in the timeframe I’m looking at realized that they have skills in documenting and preserving queer history and organizing, and needed to put those skills to use.

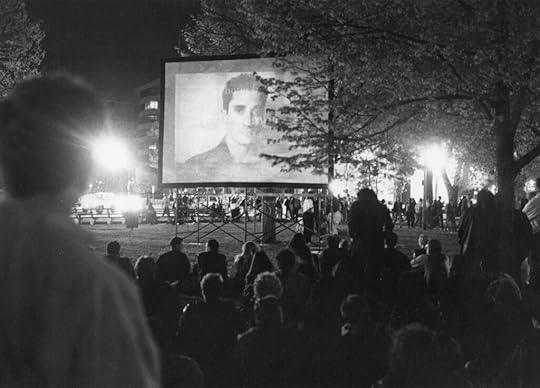

Allen Frame, Documentation of Electric Blanket: AIDS Projection Project, Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C. Eddie Marookian by Robert Williams on screen, 1993

Allen Frame, Documentation of Electric Blanket: AIDS Projection Project, Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C. Eddie Marookian by Robert Williams on screen, 1993Courtesy the artist

Manders: Can you give us a contemporary example of that formula in action?

Goldberg: Here’s one that was really moving: this student, Avery Camp, is in a class I’m teaching at the New School, and we went to the archives at the LGBT Community Center in New York to look at periodicals. Their assignment was to make a newsletter, message, poster, or sign. Avery made a flyer with information about how to volunteer for the Trevor Project, which is currently dealing with a high volume of calls and a lack of volunteers.

I asked the museum to distribute Camp’s flyer at the exhibition. J. Soto, director of engagement and inclusion at Leslie-Lohman, printed it in a handbill size for visitors to take and spread the word. That’s the legacy right there. You don’t need a lot of people to get something done. It’s not that complicated. Let’s do something now.

Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s is on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, through July 30, 2023.

April 21, 2023

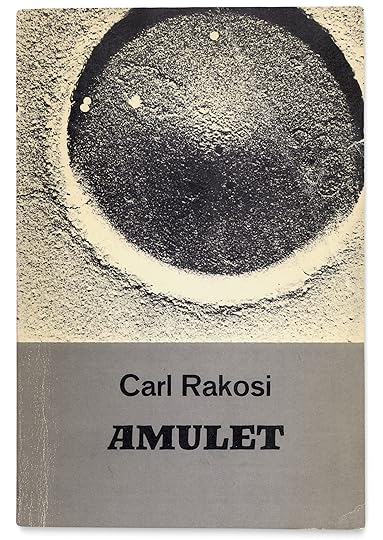

A Literary Publisher’s Bold and Original Photographic Covers

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 217, “Lit,” winter 2014.

New Directions, one of the most significant publishers of modernist literature, was founded on a failure. In 1933, James Laughlin, a twenty-year-old Harvard freshman and aspiring poet, traveled to Italy to study with Ezra Pound at his so-called “Ezuversity.” After assessing the younger man’s work, Pound deemed him hopeless and suggested Laughlin “do something useful. . . . Go back [to school] and be a publisher.” Three years later Laughlin took his advice, which surely would have demoralized most young writers, founding New Directions in his college dorm room. Using a hundred-thousand-dollar familial gift—Laughlin was a Pittsburgh steel heir—his first publication was titled New Directions in Prose and Poetry. An anthology, it featured William Carlos Williams, Elizabeth Bishop, Marianne Moore, e.e. cummings, Henry Miller, and Pound himself.

Cover of Carl Rakosi, Amulet, 1967

Cover of Carl Rakosi, Amulet, 1967  Cover of Julien Gracq, A Dark Stranger, 1950

Cover of Julien Gracq, A Dark Stranger, 1950 Laughlin would go on to publish a coterie of twentieth-century writers, including T.S. Eliot, Djuna Barnes, Tennessee Williams, Edith Sitwell, Nathanael West, John Hawkes, Kenneth Rexroth, Octavio Paz, Robert Duncan, Gary Snyder, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gertrude Stein, and Robert Creeley. Unlike some other American presses, Laughlin was interested in publishing foreign writers, and New Directions reprinted Herman Hesse, Rainer Maria Rilke, Franz Kafka, and Guillaume Apollinaire; Laughlin was Nabokov’s first American publisher. This whole article could be about those books and how they came to shape an essential cultural ethos. Instead it is about their significant, if less examined, covers and how they came to do the same. Ironically, given how influential the New Directions look came to be, Laughlin morally objected to the idea of people “buying books by eye.” In the preface to a 1947 collection of New Directions book jackets, he wrote, “It’s a very bad thing. People should buy books for their literary merit. But since I have never published a book which I didn’t consider a serious literary work—and never intend to—I have had no bad conscience about using [designers] to increase sales.”

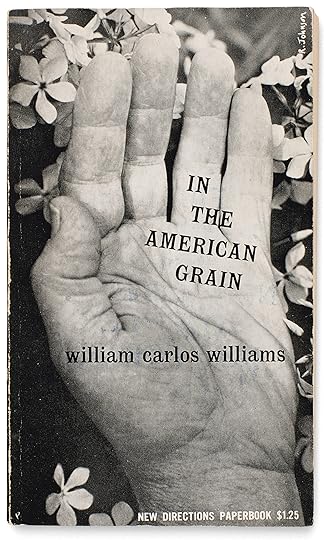

New Directions covers are easy to spot but difficult to describe. They are black-and-white. They are stark, contemplative, inky, and dreamlike. They often feature cropped images—usually taken by the designers themselves and rarely credited—printed full bleed, appearing to strain against the margins that hold them. From the 1940s through the mid-1960s, the covers were designed by a small handful of art directors and freelancers, most notably Gilda Hannah, David Ford, Rudolph de Harak, and Gertrude Huston (Laughlin’s wife). In some cases, they are simple and straightforward, illustrating the title (Stand Still Like a Hummingbird by Henry Miller, which features . . . a hummingbird arrested in flight), or picturing the author (Selected Cantos by Ezra Pound).

These early photographic covers are arrestingly original—and influential in their use of photography as integral to the cover design.

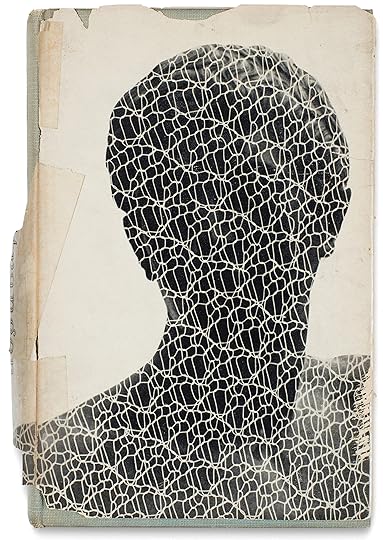

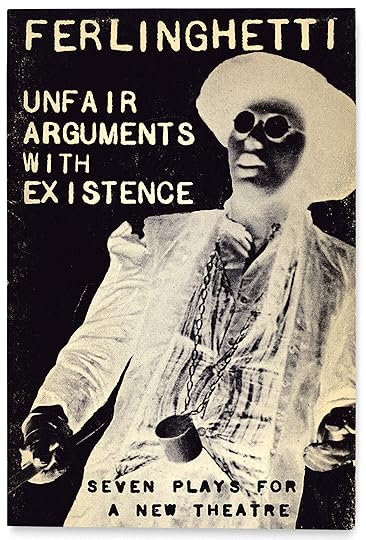

In other cases, they flirt with abstraction: double exposures (Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre), extreme close-ups (Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima), long exposures (A Season in Hell by Arthur Rimbaud), negative images (Unfair Arguments with Existence by Lawrence Ferlinghetti), reticulated negatives (Confessions of Zeno by Italo Svevo), blur (The Lime Twig by John Hawkes), photogram and photo-collage (A Dark Stranger by Julien Gracq), and heavily contrasted images (The Happy Birthday of Death by Gregory Corso) proliferate within their ranks. In rare cases, the covers feature pure photographic abstraction (New Poems by Eugenio Montale). Titles and author names are at times marginalized, pushed to the edges of the frame or otherwise worked into the composition of the image. These early photographic covers are arrestingly original—before this point in publishing, book covers tended to feature billboardesque typography on a plain background—and influential in their experimentation with the plasticity of the printed image and use of photography as integral to the cover design.

Cover of Yukio Mishima, Confessions of a Mask, 1968

Cover of Yukio Mishima, Confessions of a Mask, 1968  Cover of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Unfair Arguments with Existence, 1963

Cover of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Unfair Arguments with Existence, 1963 Perhaps due to Laughlin’s lack of interest in visual appeal, New Directions never had an institutionalized creative mandate. Instead, its earliest book covers reflect the vision that emerged from one man’s sensibility, Alvin Lustig. Laughlin met Lustig in 1940 while visiting Tennessee Williams in Los Angeles. At the time of their meeting, the young designer was working as a freelance printer and typographer, doing jobs on a letterpress that he kept in the back room of a drugstore. (Their mutual friend, the noted writer, intellectual, and bookseller Jacob Zeitlin introduced the men.) Less than a year later, Lustig designed his first New Directions cover. In an interview for this article, Lustig’s widow, Elaine Lustig Cohen—who also worked at New Directions and photographed for, designed, and collaborated on a handful of covers herself—explained that her husband had full creative reign. “There was no such thing as an art director,” said Lustig Cohen. “James did it all. Every time there was a new book, he told Alvin to do the jacket. James either liked the result or he didn’t.” This lack of interference was in keeping with Laughlin’s treatment of manuscripts, which were barely edited before being sent off to print; perhaps Laughlin’s response to Pound reflected a tendency to trust other people’s instincts with his life project.

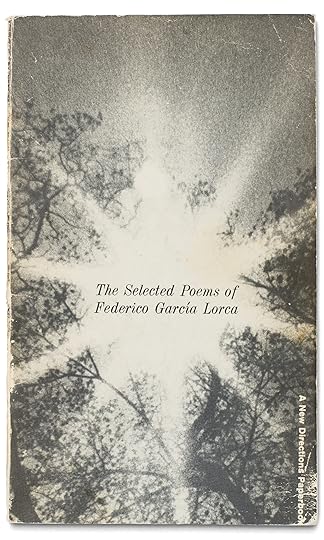

Lustig is not especially known for his photographic covers—he worked with largely abstract collage strategies that referenced, and sometimes used, type metal from a print shop—but he did set the tone for New Directions (and indeed, the book design industry) by moving away from purely text-based covers and utilizing pared-down, graphic images that referenced the printing process. When he died at the age of forty in 1955, Gilda Hannah (then Kuhlman) succeeded him as the in-house designer. During her tenure, New Directions covers became almost entirely photographic. It was an all-in-one, streamlined job: Hannah took the majority of the photographs, occasionally commissioning an image or buying from stock, made the design and type decisions, and chose the book’s paper. She produced the cover image for The Selected Poems of Federico García Lorca using “a defective Leica” in order to achieve lens flare, went uptown in Manhattan to photograph a “relatively non-responsive” Jorge Luis Borges in his hotel room for an early edition of Labyrinths, and collaged her photograph of the Statue of Liberty for Kafka’s vertiginous Amerika cover. By the time she parted ways with the publisher in the early 1960s, citing Laughlin’s notorious lack of prompt payment, New Directions had established a recognizable and effective formula for its covers, begun by Lustig and propagated by Hannah and a small handful of freelancers (including the early Pop artist Ray Johnson): a graphic black-and-white photograph matched with modest text.

Cover of Federico García Lorca, The Selected Poems of Federico García Lorca, 1968

Cover of Federico García Lorca, The Selected Poems of Federico García Lorca, 1968  Cover of William Carlos Williams, In The American Grain, 1956

Cover of William Carlos Williams, In The American Grain, 1956All photographs courtesy New Directions Press, New York

In addition to New Directions, there were other pioneering, modernist publishers during and after this era. Knopf, and their imprint Pantheon Books, published significant fiction and poetry, including Ezra Pound; Grove Press published Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, and the majority of the Beat writers (including Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, which New Directions had turned down for being too sexually explicit). Meridian Books printed writers like Grace Paley, Thomas Pynchon, and Ralph Ellison before going out of business. Independents such as the Jargon Society, Capra Press, Black Sparrow Books, Graywolf Press, and North Print Press, founded between 1951 and ’74, each modeled themselves in some way on New Directions. While these other publishers also tried out new design strategies—Grove Press was particularly innovative—they did so inconsistently, shifting back and forth between black-and-white and color, abstract design, photographic images, and text-only covers. New Directions managed to experiment with design without losing uniformity; they articulated a recognizable visual treatise that also boosted sales. As avant-garde poet Eliot Weinberger wrote in his 1997 obituary for Laughlin in Jacket magazine, “In my adolescence, the black-and-white photographic covers of ND books were unmistakable on the bookstore shelves, and I would buy any of them at random, knowing that if ND had published it, it was something that had to be read.” This holds true decades later for any reader of modernist literature; an early- to midcentury New Directions book is instantly identifiable on a crowded shelf.

Related Items

Aperture 217

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Conversations

Shop Now[image error]Today, Laughlin’s theory that a cover is just an advertisement for its book, the “serious” content, would be considered diminishing and unimaginative. Covers matter beyond the stores where books are purchased or passed over; readers return to them hundreds of times over as they tunnel through a book. Cover design (especially involving photographic images) has become inexorably entangled with the experience of encountering, and traveling through, literature.

These several decades of New Directions’ photographic book covers, often the most original when they were simplest, did something truly modern: by using pictures to describe words rather than the other way around, they jettisoned the artificial boundaries between the two. They remind us that both text and image require a kind of literacy; we often speak of “reading images,” for instance, and poets challenge us to “see” words on the page. Both text and images have the potential to objectify and document our lives in a different way from, say, painting or sculpture (which are rarely utilized in a “nonartistic” sense). Denise Levertov, who published more than thirty books of poetry with New Directions, put it best in her early-1970s essay “Looking at Photographs,” written in response to a request from this magazine: “I have come to see that the art of photography shares with poetry a factor more fundamental: it makes its images by means anybody and everybody uses for the most banal purposes, just as poetry makes its structures, its indivisibility of music and meaning, out of the same language for utilitarian purposes, for idle chatter, for uninspired lying … photographs teach the poet to see better.” Levertov could have illustrated her essay with the cover of The Cosmological Eye, the first book of Henry Miller’s published in the United States—by New Directions—in 1939. Superimposed atop a full-bleed, black-and-white photograph of clouds is a single, open eye. It belongs to James Laughlin.

Hervé Guibert’s Passionately Restrained Photographs

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 217, “Lit,” winter 2014.

I shall always refuse to be a photographer: this attraction frightens me, it seems to me that it can quickly turn to madness, because everything is photographable, everything is interesting to photograph, and out of one day of one’s life one could cut out thousands of instants, thousands of little surfaces, and if one begins why stop? — Hervé Guibert, The Mausoleum of Lovers, Journals 1976–1991

When Hervé Guibert died in 1991, he had just turned thirty-six. A year before, the writer, journalist, and photographer had opened his autobiographical novel, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, with the declaration that he had AIDS, but went on to insist that he “would become, by an extraordinary stroke of luck, one of the first people on earth to survive this deadly malady.” When the book caused a sensation (magnified by the fact that one of its characters was a thinly disguised Michel Foucault, whose HIV-positive status contributed to his death in 1984), Guibert became the strikingly handsome, articulate, and very public face of AIDS in France. He didn’t avoid the spotlight, but it made him famous in a way he never wanted to be, and the attention exhausted him even before the disease left him frail and nearly blind. that extraordinary stroke of luck eluded him. Two weeks before he succumbed, he tried to commit suicide with an overdose of pills but failed.

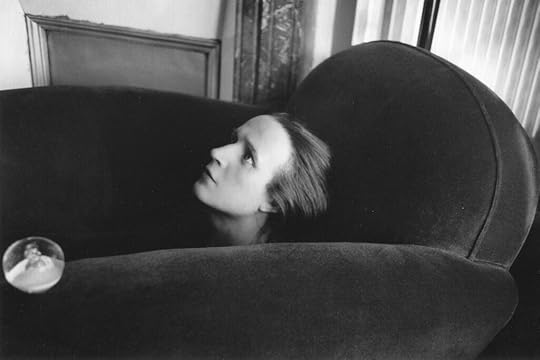

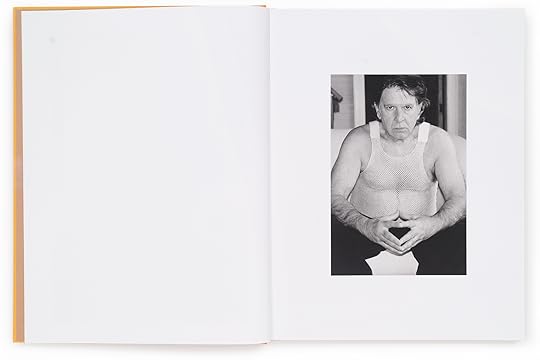

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait (Self-portrait), 1976

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait (Self-portrait), 1976 Hervé Guibert, Sienne (Siena), 1979

Hervé Guibert, Sienne (Siena), 1979Wildly prolific, Guibert was driven, compulsive, and rarely satisfied. He wrote twenty-three other books, nearly all of them in the ten years before his death (only a handful have been translated into English). In The Mausoleum of Lovers, a collection of journal entries published posthumously in 2011 and just translated, he often sounds melancholic, if not desperate, but then much of it was written as an open letter to an inconstant lover who was allowed to read the journals as they were written. Melodramatic moments—furious, passionate, delusional—alternate with cooler observations, often about photography, which was, along with writing, a highly personal form of expression for Guibert. “The photo that someone other than I could take, that isn’t bound to the particular relation I have to this or that, I don’t want to take it,” he writes.

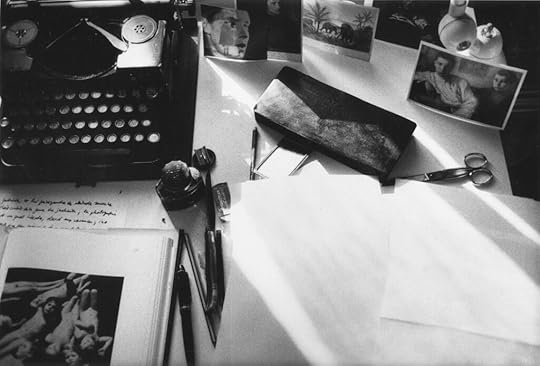

Very little of his photographic work has been published or exhibited in the United States, so the larger body of work remains rather elusive. Still, much of what has appeared is striking: emotionally warm, even a bit sentimental at times, but stylistically cool and confident. His images range from artful interiors and landscapes to pictures of friends, family, and lovers. The mood is usually hushed and intimate. Working in a distinctive black and white that tends toward soft platinum grays, he made what feel like visual diary entries, quick but thoughtful notes, often recording his immediate surroundings—his desk, his mantel, his bookcase—with the same descriptive intensity he brought to photographs of boys in his bed. Even in his most seductive self-portraits, Guibert never seems show-offy. The work is restrained and subtle—as if it were made not with a public in mind but for himself and a small circle of friends. We often feel we’re peeking into a private and somewhat privileged world, where much is revealed and just as much withheld.

Hervé Guibert, Agathe, 1980

Hervé Guibert, Agathe, 1980 Hervé Guibert, Isabelle, 1980

Hervé Guibert, Isabelle, 1980In Ghost Image, a 1982 collection of Guibert’s brief essays on photography, reissued this year by University of Chicago Press, he writes about photographers he admires. They’re an idiosyncratic pantheon that includes Diane Arbus, Pierre Molinier, F. Holland Day, George Hoyningen-Huene, and Duane Michals, the last of whom seems especially influential on the selection of images included here. Clearly, he looked long and hard at his precursors and his contemporaries, but some of his most telling essays are dialogues with his critical self, an accusatory voice that he never allows to have the last word. When that voice points out that much of his work “oozes homosexuality,” he shoots back:

“How could it be otherwise? It’s not that I want to hide it, or that I want to boast about it arrogantly. But it’s the least I can do to be sincere. How can you speak about photography without speaking of desire? If I mask my desire, if I deprive it of its gender, if I leave it vague . . . I would feel as if I were weakening my stories, or writing carelessly . . . The image is the essence of desire and if you desexualize the image, you reduce it to theory.”

Guibert’s criticism can stray into knotty intellectual territory, but he steers clear of dry, deadening theory. What’s most engaging about his work in writing and photography is its frankness and sincerity—qualities the contemporary avant-garde has little use for. Even his restraint feels passionate—an elegance at once instinctive and hard-won.

Hervé Guibert, Table de travail (Work table), 1985

Hervé Guibert, Table de travail (Work table), 1985 Hervé Guibert, La tête de Jeanne d’Arc (The head of Joan of Arc), n.d.

Hervé Guibert, La tête de Jeanne d’Arc (The head of Joan of Arc), n.d. All photographs courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Related Items

Aperture 217

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Why Are We Seeing So Many Photographs on Book Covers?

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” spring 2020.

The British writer Rachel Cusk’s celebrated Outline trilogy, published between 2014 and 2018, concerns a series of journeys a writer named Faye takes in Europe. In one, Faye encounters a woman who is obsessed with the works of a painter. “What she was trying to say was that she wasn’t interested in them objectively, as art,” Cusk writes. “They were more like thoughts, thoughts in someone else’s head that she could see.”

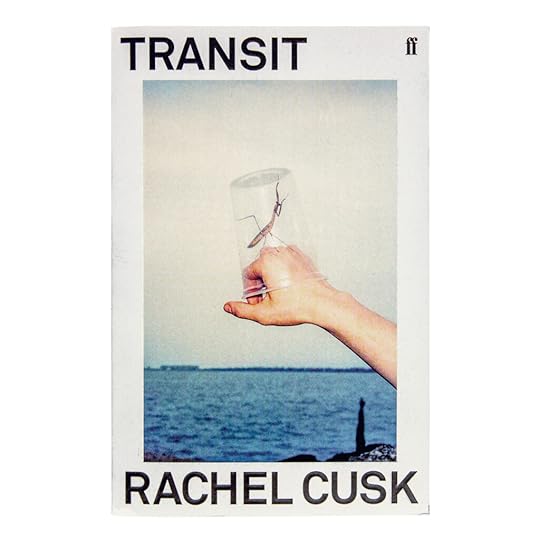

A recent spate of well-regarded novels has taken the use of photographs in book jacket design into new territory, structuring a relationship between word and image. The U.K. Faber and the U.S. Picador editions of Cusk’s trilogy, designed by Rodrigo Corral, make use of still lifes by the fashion photographer Charlie Engman. The thick white border and the bold black all-caps text frame an image that offers a way into thinking about what the individual titles of the trilogy might refer to—Outline, Transit, Kudos. But after reading the book, you realize how provisional the cover’s illustrative nature is. Corral’s design was in reaction to reading Cusk’s prose: “It isn’t super linear,” he says. “It’s more about being part of the journey.”

Rachel Cusk, Transit (2018), with photograph by Charlie Engman

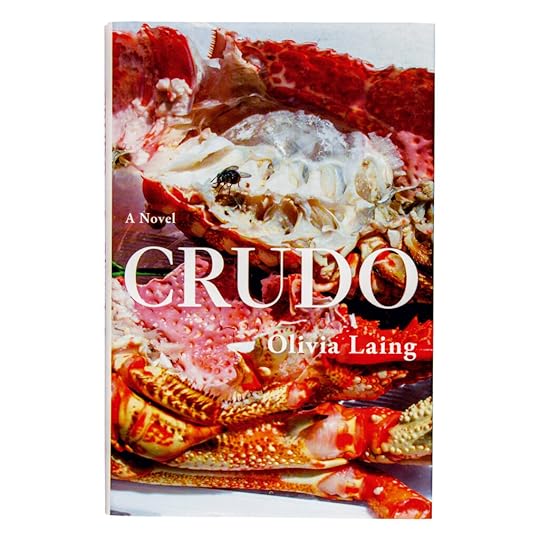

Rachel Cusk, Transit (2018), with photograph by Charlie EngmanThe U.S. edition of the American writer and T Magazine editor Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life (2015) and the U.K. edition of the British writer Olivia Laing’s first novel, Crudo (2018), turn this observation concrete. Both novelists were inspired to use photographs for their book jackets after seeing them in galleries. Yanagihara saw Peter Hujar’s Orgasmic Man (1969); Laing saw Wolfgang Tillmans’s astro crusto (2012). Laing has noted that Tillmans’s image of a postprandial crustacean shell connects to a scene in the book where her lead character, Kathy, smashes a crab open with a hammer.

But the principle of using someone else’s work to frame your own rises above the evident linkage. Laing’s use of the American writer Kathy Acker as her protagonist—partly quoting Acker’s work, largely fictionalizing her life—is a feature of her style of autofiction, but it is also bound up with how writing is described in the novel: “She wrote fiction, sure, but she populated it with the already extant, the pre-packaged and ready-made.” Laing’s Kathy is described as “Warhol’s daughter,” someone who is “happy to snatch what she needed but also morally invested in the cause.”

It’s a description that is as much about image use in publishing as it is about writing. The cover of A Little Life reproduces Hujar’s photograph of a close-up of a man’s face at the point of orgasm; although shorn of its title, the ambivalence about whether it’s a face in agony or ecstasy is ramped up. Yanagihara has described the cover as a “sensation—of witness and also of trespass—that I wanted the reader to feel as well.” A Little Life opens in New York in the early 1980s, a time when Hujar was still working, and chronicles the lives of four young men with a tight focus on private and inner worlds as represented by the cover. One of the four, JB, is an artist, and the photographs he takes of his friends—depicting them in his artworks without their consent—is what begins his distance from them. “Tonight, I am a camera, he told himself, and tomorrow I will be JB again.”

Related Items

Aperture 238

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]The novel’s Instagram account, set up by Yanagihara and her social-media manager, has spawned similar reactions in readers—not through posting portraits of their friends as the book’s character does, but by posting portraits of themselves with the book itself. As one London-based reader’s body extends out from the jacket, it’s as if a novel can be slipped on and off like an alternate, temporary identity or a thing worn. It’s a performance that resonates with something the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin wrote: “That the self is a condition of disguise and that we can move back and forth in terms of sexualities, in terms of social being, in terms of all kinds of sense of who we are.”

Cover of Olivia Laing, Crudo (2018), with photograph by Wolfgang Tillmans

Cover of Olivia Laing, Crudo (2018), with photograph by Wolfgang TillmansWhat these book jackets illuminate is the way the contemporary novel, both in content and cover, performs the idea of the self continually collapsing back onto other ideas, other images—as if somehow the prose operates as a written means of interconnectedness between visual ideas, a kind of long-form resort to the pictorial. It’s a queer way of defining things, a privileging of final looks over how things might first be written down. It seems somehow reminiscent of record covers and not book jackets, of the photographs Steven Patrick Morrissey once chose for the singles and albums The Smiths released, or of the covers Peter Saville once designed for Joy Division and New Order that made use of sourced photographs. Perhaps it is the realization that novels are now the sleeve notes of our time.

April 18, 2023

Announcing the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Aperture’s support of emerging photographers and other lens-based artists is a vital part of our mission. The annual Aperture Portfolio Prize aims to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography—identifying contemporary trends in the field and highlighting artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Aperture’s editors reviewed over one thousand submissions, and we are thrilled to announce the shortlisted artists for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize:

Samantha Box

Brian Lau

Akshay Mahajan

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn

Ziyu Wang

These artists join the ranks of illustrious winners and artists shortlisted for the Portfolio Prize in past years, including Felipe Romero Beltrán, Dannielle Bowman, Alejandro Cartagena, Jessica Chou, Eli Durst, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Natalie Krick, Daniel Jack Lyons, Mark McKnight, Drew Nikonowicz, Sarah Palmer, RaMell Ross, Bryan Schutmaat, Donavon Smallwood, Ka-Man Tse, and Guanyu Xu.

The 2023 Portfolio Prize winner, to be announced on Friday, May 12, will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize and a $1,000 gift card to shop for gear at mpb.com, and present an exhibition at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York. Each runner-up will receive an online feature.

Alongside the five shortlisted artists, twenty finalists were selected by Aperture’s editors. The finalists and shortlisted artists will each receive a virtual portfolio review session with an Aperture editor, who will provide thoughtful and constructive feedback on their work.

The twenty finalists are:

Hannah Altman, Sasha Arutyunova, Kerr Cirilo, Rose Marie Cromwell, Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo, Natalie Ivis, Hassan Kurbanbaev, Camille Farrah Lenain, Drew Leventhal, Morgan Levy, Jesse Ly, Kavi Pujara, Guarionex Rodriguez, Hyunmin Ryu, Agnieszka Sosnowska, Mika Sperling, Kai Wasikowski, Jaclyn Wright, Leafy Yeh, Rana Young

Samantha Box, One Kind of Story, 2020, from the series Caribbean Dreams

Samantha Box, One Kind of Story, 2020, from the series Caribbean Dreams Brian Lau, House in Flurry, 2020, from the series We’re Just Here For the Bad Guys

Brian Lau, House in Flurry, 2020, from the series We’re Just Here For the Bad Guys Akshay Mahajan, from the series To die is to turn in gold

Akshay Mahajan, from the series To die is to turn in gold Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Untitled (Girl with Pearls), 2022, from the series As You Grow Older

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Untitled (Girl with Pearls), 2022, from the series As You Grow Older Ziyu Wang, Lads, 2022, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boy

Ziyu Wang, Lads, 2022, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boy

April 14, 2023

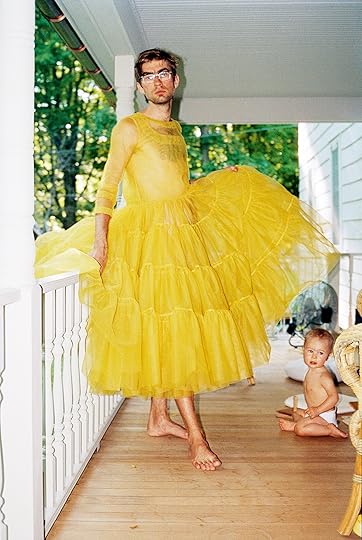

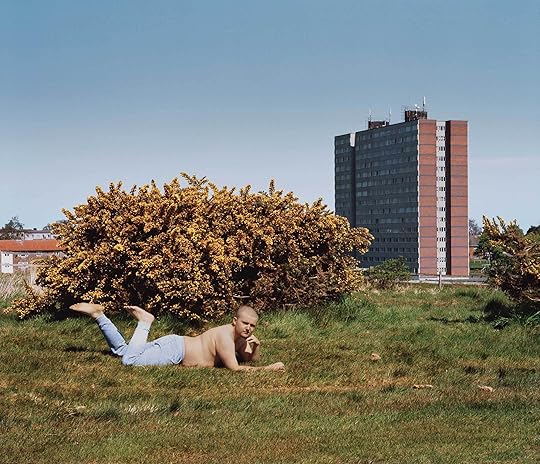

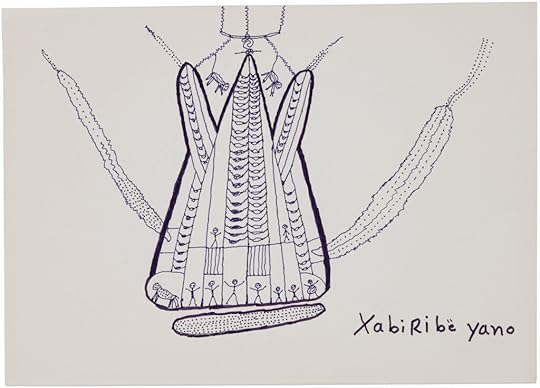

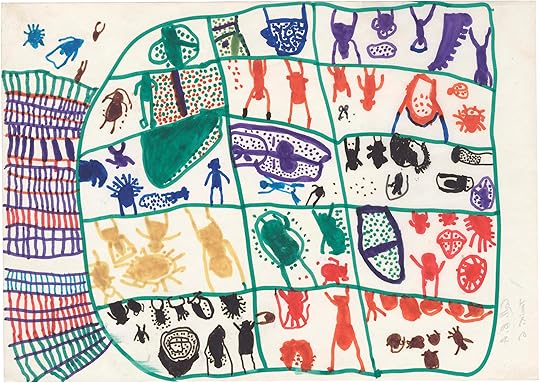

The Delight and Absurdity of Domestic Photography

Throughout the pandemic, the popular conception of home became a place of unrelenting monotony—a site of confinement, despair, potentially even breakdown. Creativity was stifled when stuck in one’s living room. It was impossible to maintain professional output while sharing a space with one’s children. To many women, this new obsession with the inside, the domestic, was both frustrating and amusing. Home was now a space confining both sexes. And yet, female artists have long centered home as a site for probing discussions and creative explorations. The resultant works often deal with the themes that contributed to women’s very presence at home in the first place: sexism, pay disparity, childcare inequality, patriarchal conditioning and control.