Aperture's Blog, page 28

June 16, 2023

What Is the Relationship between Literature and Photography?

The title of a recent exhibition at Musée des beaux-arts in the Swiss town of Le Locle (MBAL), The Pleasure of Text, is borrowed from Roland Barthes’s famous 1973 essay. A quote from that text stands out in the center of the room displaying paintings from the MBAL collection, depicting women engrossed in the act of reading: “The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body will follow its own ideas—for my body has different ideas than me.” This physical dimension of reading pleasure is exemplified in an installation by the Swiss duo Andres Lutz and Anders Guggisberg, who have created a new space in the museum’s former library, blending sculpture and automatic painting. The installation features a selection of their Bibliothèque Imaginaire (1999–2020), consisting of hundreds of wooden books that viewers are encouraged to explore. While the volumes cannot be read, the tactile experience of reading remains, and the text within them becomes a product of the viewer’s imagination.

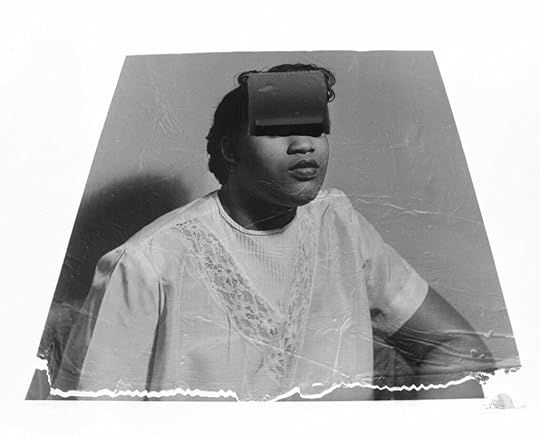

Melissa Catanese, Montage with eyes, from the series Voyagers, 2023

Melissa Catanese, Montage with eyes, from the series Voyagers, 2023© the artist

The Pleasure of Text is Federica Chiocchetti’s inaugural exhibition as the director of MBAL and holds a few surprises for those familiar with her academic and curatorial work. Especially with The Photocaptionist, the editorial and curatorial platform she founded and directs—Chiocchetti was also guest editor of Aperture’s 2019 issue of The PhotoBook Review on “photo-text-books”—she has focused on the relationship between text and images in literature and photography. This exhibition features the works of approximately thirty international artists in dialogue with pieces from the museum’s permanent collection. Instead of an exhibition solely dedicated to the theme of text-images in the context of photobooks, The Pleasure of Text takes a broader approach to the experience of reading by exploring the intersection between photography, photobook publishing, and other art forms that combine text and image making.

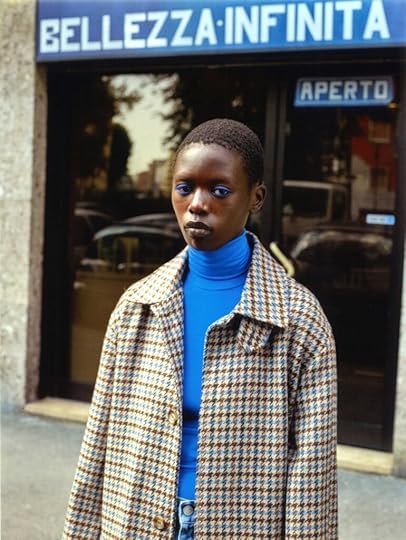

Luca Massaro, Bellezza Infinita, from izionario Vol. 1, Milano, 2023

Luca Massaro, Bellezza Infinita, from izionario Vol. 1, Milano, 2023© the artist

In a project titled Lady Readers, Sara Knelman presents a series of photographs featuring women reading. It remains unknown what these women are reading. One striking image depicts a girl, somewhere between childhood and adolescence, sitting on a bench while reading a magazine, with her face concealed by cascading light blond hair. Melissa Catanese contributes to the same theme with her video piece Voyagers, based on her book of the same name published in 2018 by The Ice Plant. The video presents a selection of images of people reading from Peter J. Cohen’s collection, utilizing the book’s pages to offer the viewer a subjective sensory experience with the text.

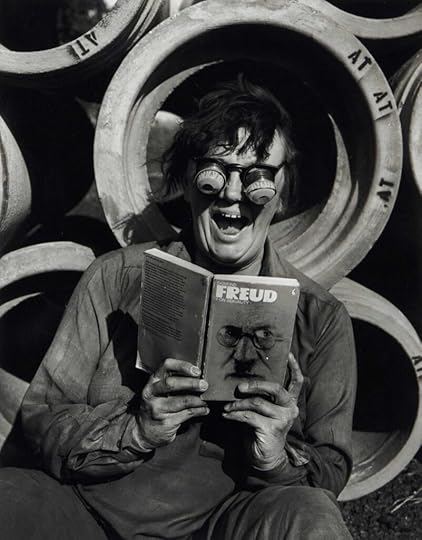

Jo Spence in collaboration with Terry Dennett, Remodelling Photo History: Revisualisation, 1981–82

Jo Spence in collaboration with Terry Dennett, Remodelling Photo History: Revisualisation, 1981–82© Estate of Jo Spence and courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London/Rome

The idea of reading (whether text or image) as a space of freedom and emancipation, particularly for women, is a prevalent theme throughout the exhibition. As Virginia Woolf wrote in her essay “How Should One Read a Book?,” “Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.” A photograph by Jo Spence captures this sentiment. The image portrays the artist, disguised as a domestic worker, reading Sigmund Freud’s On Sexuality, wearing googly eye glasses with a comically bewildered expression. It serves as a visual metaphor for the feminist response to the accusations against Freud, who was accused of shifting the blame for sexual abuse from men to women and their imaginations.

Related Items

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists

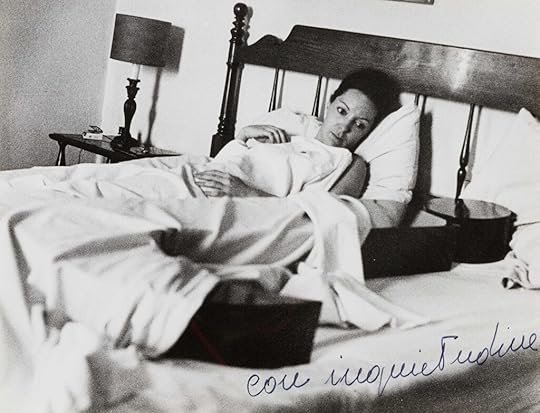

Shop Now[image error]Other notable examples of a relationship between text and writing include the works of Brazilian artist Lenora de Barros and Italian artist Ketty La Rocca. De Barros portrays herself in a photographic sequence from 1979 titled Poema, where she wedges her tongue between the gears of a typewriter. La Rocca, on the other hand, presents a series called Photograph with Js (1969–1970), in which she interacts with a sculpture shaped like the letter J, from the French word je, meaning I. As La Rocca explains, “The ‘you’ has already begun at the border of my ‘I’.”

Chloe Dewe Mathews, In Search of Frankenstein, 2016

Chloe Dewe Mathews, In Search of Frankenstein, 2016© the artist

The exhibition concludes with works that directly relate to the curator’s passion for the text-image theme. Nelis Franken’s Perfect Forests (2020–23) is a leporello featuring black-and-white images of locations associated with technology companies, interspersed with texts generated using artificial intelligence. Luca Massaro showcases ten large canvas prints from his book Dizionario Vol.1 (Dictionary, 2023), capturing various words and letters in juxtaposed settings. Chloe Dewe Mathews, as part of the overlapping festival Alt+1000, explores the landscapes of Swiss mountains and the network of anti-atomic bunkers constructed within them in the 1960s, juxtaposing them with passages from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a novel conceived during her stay at Lake Geneva. The path design by Chioccetti also includes a series of photographs by Anne Turyn titled Lessons & Notes (1982), displayed in the room dedicated to children’s activities. The photographs depict a primary school classroom where children learn to read and write, featuring questions written on the blackboard against a backdrop of blurred figures.

Ketty La Rocca, Con inquietudine (With concern), 1971

Ketty La Rocca, Con inquietudine (With concern), 1971© Estate of Ketty La Rocca/Michelangelo Vasta

Throughout Chioccetti’s and Dewe Mathews’s exhibitions, the continuous interplay between image and text highlights that concepts of the two can overlap. Pictures possess a lexicon, grammar, and syntax of their own, just as words, sentences, speeches, and stories can create mental images. In both cases, the resulting knowledge is most valuable and enduring when it stems from a pleasurable experience of exploration and understanding.

The Pleasure of Text is on view at Museum of Fine Arts Le Locle, Switzerland, through September 18, 2023.

June 12, 2023

The Possibility of Home

A panel of solid black is interrupted by fragments of human form: an elderly woman stepping halfway into the frame, her expression animated by something in the dark. Down by her side, a sliver of a child’s face peeks out with one curious eye. In front of them, a floral-patterned bandana levitates in midair, as though to suggest the presence of some phantom we can’t see. In Passing, taken in 1969 in San Francisco’s Chinatown, reflects the intuitive gaze of a longtime local. It is a mode of looking that is at once attuned to the intricate sociality of one’s own community and unconcerned with accommodating the needs of an outside viewer, registering instead rich stretches of ordinary life as darkness.

The artist, Irene Poon, spent many years photographing the neighborhood of her youth, weaving dreamy images out of the fleeting faces and encounters of everyday life. As her contemporaries Charles Wong and Benjamen Chinn had begun to do a decade earlier, and previous generations of Chinatown photographers, such as Mary Tape, had done as early as the nineteenth century, Poon used her camera to replace the distant, exoticizing gaze of the tourist with that of an intimate insider caught up in the same quotidian rhythms as her subjects. But her work also goes further: Poon’s most striking compositions feature dense black areas that shroud and fragment her subjects, like blind spots made visible.

Left: Irene Poon, In Passing, 1969; right: Irene Poon, Memories of the Universal Café, 1965

Left: Irene Poon, In Passing, 1969; right: Irene Poon, Memories of the Universal Café, 1965© the artist and courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

In Memories of the Universal Café (1965), a forearm hovers, disembodied, over a table of food. In Fire Crackers Await (1969), a woman in apron and slippers floats in negative space at the bottom of a staircase. Often, the enveloping blackness shows up as background while figures linger at thresholds—doorways, balconies, windows—a recurring motif, marking the unseen interiors from which they emerge and into which they can retreat. Poon usually lets in just enough details to suggest that the negative spaces aren’t empty but rather full of presences we can’t see. Curiously, Poon honed this aesthetic of visible invisibility just as the political awakening of the Asian American movement swept through the campuses of the Bay Area and beyond, including Poon’s own alma mater of San Francisco State College.

What does it mean at this historic moment to turn one’s camera toward the banal details of ordinary life, to center the familial figures of children and grandparents, and, what’s more, to cast them on the edge of spatial indeterminacy, to allow them to go dark? If the Asian American movement sought to forge a clear political identity for Asians in the United States—as multiethnic, oppositional, anti-assimilative—then Poon’s work opens onto the obverse: the messy, exploratory, unfinished private spaces and relations that sustain such acts of public self-definition. If Asian America is built on generations of activism, Poon’s shrouded compositions remind us that it is also built on generations of what the performance scholar Summer Kim Lee calls “staying in.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Staying in, writes Lee, “critiques the compulsory sociability and relatability demanded of minoritarian subjects to go out, come out, and be out.” To stay in isn’t to cut off relations with others but only to refuse to be relatable—that is, to act in ways that conform to the standards and values of an outside public. For Asian Americans, to stay in means to slip out of our assigned roles within a visibility predicated on binaries of injury and protest, trauma and resilience—as entrenched as ever in our era of anti-Asian hate. Staying in opens up other registers of sociality: of rest, pleasure, play. It encapsulates the banal, domestic, familial spaces and relations that make up the substance of our lives but leave little trace in history.

As one of the few places to register this history of “staying in,” Asian American photography before and since Poon has found inventive ways to engage with such interior spaces and relations, often against the demands of public visibility, sociability, even legality. Take, for example, the phenomenon of the composite family portrait, which emerged in the early twentieth century to create what the art historian Thy Phu calls a “counterarchive” of familial intimacy in the era of Chinese exclusion. In the 1920s and ’30s, a time when Asians were effectively banned from entering the United States, Chinese American photography studios used collage techniques to piece together portraits taken thousands of miles apart, visually reuniting family members separated, sometimes for a lifetime, by racist immigration policies.

May’s Studio, Untitled, San Francisco, ca. 1920

May’s Studio, Untitled, San Francisco, ca. 1920© and courtesy Wylie Wong Collection of May’s Studio Photographs and Special Collections, Stanford University

Ricardo Ocreto Alvarado, Dancing Couples, California, ca. 1950

Ricardo Ocreto Alvarado, Dancing Couples, California, ca. 1950© and courtesy Janet M. Alvarado, San Francisco

May’s Photo Studio, which was opened in 1923 in San Francisco’s Chinatown by the husband and wife Leo Chan Lee and Isabelle May Lee, made such portraits for those in their community. One example shows a family of six posing against the backdrop of an ornate interior. The wife and husband sit at the center, on either side of a table, a set of teacups between them, as though they will momentarily turn toward each other to take a sip. But the illusion of togetherness is broken by the flatness and unnatural glow of the husband, the only one in Western attire. A closer examination reveals the rough outline that snakes along his head and shoulders like stitches, a sign that he has been cropped from another photo, a place an ocean away. At a moment when studio portraiture had become a government tool to track Asian bodies via the introduction of photograph identification documents, Chinese American studios found a different use for photography: to weave together dream interiors of familial wholeness and imagine a utopian space without borders.

Ricardo Ocreto Alvarado provides another vision of “staying in” through his photographs of house parties in the 1940s and ’50s. Alvarado, who had no formal photography training and worked as an army hospital cook by day, brought his Speed Graphic camera to countless gatherings of friends, family, and relatives within San Francisco’s growing Filipino American community. Taken in an era when segregation kept people of color out of many restaurants, clubs, and other mainstream social settings, Alvarado’s photographs center the private home as a precious site for nourishing an otherwise impossible social world.

What does Asian America look like from the inside? What does it mean to live in the blind spots of American history?

In one photograph, a sparsely furnished room is offset by its buoyant inhabitants spilling out from the top of the frame. Handsomely dressed parents, children, and relatives gather in loose rows as though for a group shot, but only half look at the camera; the others are engrossed in their own micro-dramas—eating, crying, daydreaming—creating a rich tapestry of crisscrossed gazes. Near the center of the group, the beaming host turns away from the camera to offer up a heaping plate of lechón (roast pig) to her guests, further derailing any attempt at a standard pose.

Alvarado’s interior scenes often include other minority friends and coworkers, from the same area in San Francisco, whose communities overlapped and merged with Alvarado’s own. A live band of Filipino, Black, and Latino musicians play at a house party; interracial couples dance, hands loosely interlaced, in a living room draped with streamers. These figures, open and carefree before the camera, owe their casual radiance perhaps to a sense of safety in the presence of the photographer. Like Poon, Alvarado inhabited the spaces he photographed, resulting in images that tend not toward public display but shared interiority, the pleasure of enclosure, the relief of “staying in.”

Julie Quon, Amanda, from the series Nine to Thirteen, 2011

Julie Quon, Amanda, from the series Nine to Thirteen, 2011Courtesy the artist

Julie Quon, Nolan, from the series Nine to Thirteen, 2011

Julie Quon, Nolan, from the series Nine to Thirteen, 2011Courtesy the artist

Like their fleeting subjects, photographs of Asian American interior life—real and imagined—occupy a tenuous place in American art history. Both the work of Alvarado and May’s Photo Studio were buried away for decades and rediscovered only by chance. Alvarado’s daughter stumbled upon some three thousand negatives in the basement of their home after her father’s death in 1976. A young art student on a walk encountered and rescued from a Chinatown dumpster the archive of May’s Photo Studio in 1978, after its owners had passed away. Still, home spaces, familial relations, the vast terrains of quotidian time: these remain abiding interests in Asian American photography. In recent years, a younger generation of artists has waded into the interior world of “staying in,” finding new strategies to contemplate the secret histories it enfolds, the legibility it withholds.

Often, these photographers begin with the site of their own home, using the camera to perform an excavation of the everyday, to see anew the banal details that usually fade into the background. In the series Of Light, Dust and Passing (2011), Julie Quon photographs her family home in New York’s Chinatown, where her parents have lived since 1980. Still living with them at the time, Quon lingered over ordinary objects bathed in early morning light, seeking out the incidental traces that index her parents’ particular presence, without needing to show their faces: her mother’s slippers under the chair, her father’s cigarettes hidden behind the radio, the makeshift dust covering over the washing machine. These still lifes reflect Quon’s architecture training with their clean lines and geometric compositions, but they are also portraits, years in the making, that patiently tease out the inner lives of their elusive subjects through a visual vernacular of the quotidian.

Miraj Patel, Sunday Morning, 2020

Miraj Patel, Sunday Morning, 2020Courtesy the artist

Tommy Kha, Stations (Kitchen God), Whitehaven, 2015

Tommy Kha, Stations (Kitchen God), Whitehaven, 2015© and courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

Miraj Patel takes the portrayal of the family home in a different direction, using elements of performance and self-portraiture to create playful, moody meditations on immigrant life in American suburbia. He began the series Do you see what I see, when I look at me? (2020–present) while cloistered at home with his parents during the first year of the pandemic. In one image, Sunday Morning (2020), Patel snuggles in bed with his parents and dog, reenacting a childhood ritual; this unusual arrangement of bodies contrasts humorously with the generic, symmetrical furnishings of the room. Other photographs show Patel creatively misusing various corners of their home. These performative interventions heighten a sense of incongruity between the Southern California house, a symbol of assimilation and upward mobility, and its Indian American inhabitants. “In trying to fit into the cookie-cutter formula,” Patel pondered, “what is this third thing we exist as?”

Likewise, Tommy Kha, whose family was part of the Chinese diaspora in Vietnam before immigrating to the United States, recalled noticing as a child that his house was “set up differently” from those of his friends: “every room had different walls and textures.” In his series Shrines (2013–ongoing), Kha explores this distinctive heterogeneity by tracing the presence and placement of religious and ancestral shrines, first in his own home, then in the homes and businesses of others across Memphis and New York. Kha calls the mismatched assemblage of incense holder and offerings in Stations (Kitchen God) (2015) “my mom’s curation”; set amidst other details bearing her touch over the years—a large burn mark on the counter, aluminum foil lining the stove tops and range hood—it forms a palimpsest of immigrant life. “It was a part of my childhood,” Kha said of the shrine, “but no one ever explained the ritual to me.” The project thus began with a reconfiguration of Kha’s own vision, a shuffling of the background into the foreground. For the past seven years, Kha has photographed more shrines—in restaurants, stores, and multigenerational homes—in an effort to locate and survey a shared, everyday Asian American iconography.

Jarod Lew, Please Take Off Your Shoes, 2021

Courtesy the artist

Jarod Lew similarly tries to find a shared language of the home in his series Please Take Off Your Shoes (2016–ongoing), which took him to the houses of relatives, friends, and strangers around Michigan and San Francisco. Lew, whose work is featured in a portfolio in this issue, began the series as much to seek community as to make pictures, an interest reflected in the deeply collaborative nature of his process. “A lot of these photographs stem from conversations I have with the person I’m photographing, building trust, coming up with ideas of portraying them in a way they’re comfortable with,” Lew told me. Like Quon, Lew looks to still life as the key to portraiture. In his unwavering attention to some of the most mundane sights of domestic life—furniture covered with sheets, a plate of cut fruit, shoes by the entrance—there is an argument about the home itself as performative, a rich sensory world that wordlessly conveys entire histories of intimacy, relation, and feeling.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

What does Asian America look like from the inside? What does it mean to live in the blind spots of American history? For over a century, Asian American photographers have explored these questions by crafting ways of seeing that paradoxically protect from the trap of visibility, the trap of being defined by external policies and historical flashpoints. By treasuring the least remarkable recesses of everyday life, these photographs enact radical shifts in vision. To see ourselves in the shared spaces of staying in, unburdened by legibility or relatability—this, they suggest, is the only kind of seeing that will free us.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.” Xueli Wang’s research was supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.

June 8, 2023

Aperture Appoints Esther McGowan as Director of Development

Aperture announces the recent appointment of Esther McGowan as Director of Development. In this position, McGowan will lead fundraising initiatives and build philanthropic support for Aperture’s celebrated photography program, including Aperture magazine, an extensive catalog of photobooks, traveling exhibitions, limited-edition prints, the annual Portfolio Prize, and the Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards, as well as partnerships and public events.

As a key member of senior staff, McGowan will collaborate on a new strategic plan, helping set the future direction of Aperture and grow funding in support of it. She will lead the development team and work closely with the Executive Director and Board of Trustees to advance Aperture’s capital campaign, supporting the transition to a new, permanent home on 380 Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 2024.

“Along with our Board of Trustees and colleagues, we warmly welcome Esther McGowan to Aperture,” stated Sarah Meister, Executive Director, Aperture. “With an accomplished record of building engagement and support for artists and mission-driven arts organizations, Esther joins us at a pivotal moment in Aperture’s history. She will play a vital role in advancing fundraising to activate our capital campaign as we prepare for our new home and continue to broaden and nurture our growing community around photography.”

“I have long been a fan of Aperture’s publications and exhibitions, and have been inspired by photography from a young age,” added McGowan. “Aperture’s role in the field is essential, and I am thrilled to contribute to this important work and help expand its reach.”

Before joining Aperture, McGowan had served as Executive Director for Visual AIDS since 2017, and as Associate Director since 2012, where she developed strategic partnerships, initiated Board growth, increased staff, expanded programming and archival practice, and created diversified revenue for the HIV/AIDS arts organization. She has held positions as Development Director and worked as a freelance fundraiser for multiple nonprofit cultural groups, including the Center for Fiction, Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Arts International, and the Alliance for the Arts.

June 7, 2023

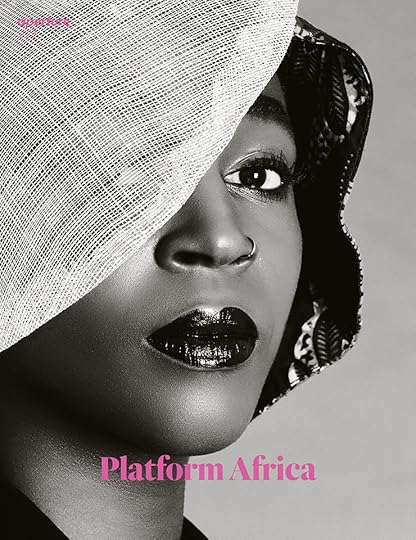

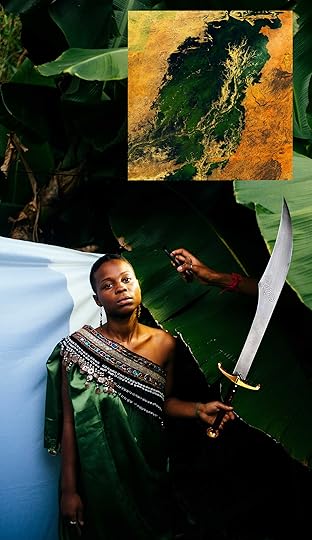

The Quest to Protect the Father of Ivorian Photography

Paul Kodjo’s work was headed for the dustbin of history—not the proverbial trash can but the actual garbage. The 2022 documentary Je reste photographe (I remain a photographer) shows a scene with the Ivorian photographer, his daughter Esther Kodjo, and the film’s director, Ananias Léki Dago, in a wooden cabin that the elder Kodjo built in a forest in Elubo, Ghana, where he retired. The trio are sifting through a dusty iron trunk filled with deteriorating papers and negatives, along with dirt, leaves, dead spiders, and cockroaches. “Ananias, this is what’s left of my work. I’m giving it to you. Do whatever you can with it,” Kodjo says. “Or else, I’m throwing it away.”

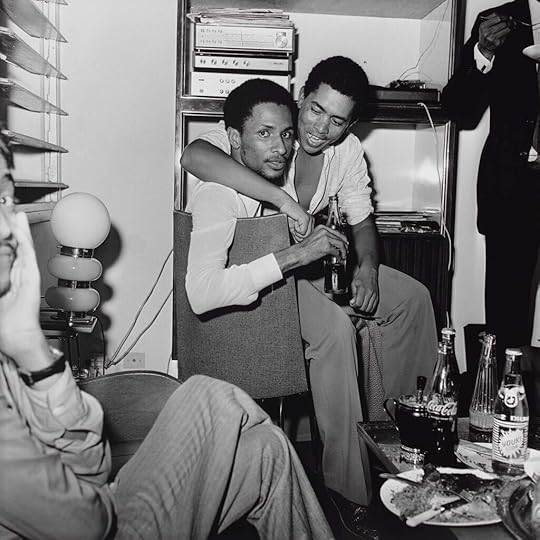

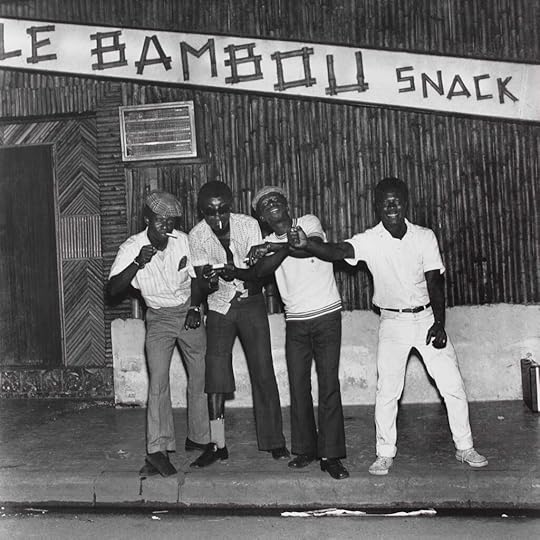

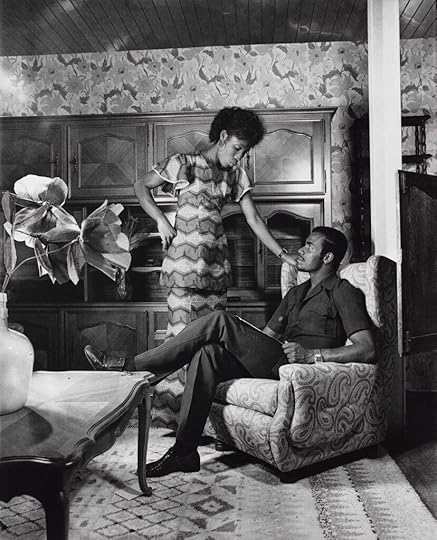

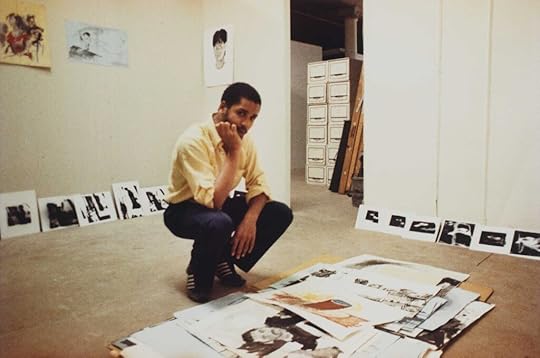

Léki, who is also a photographer, has been working to restore, archive, research, and promote Kodjo’s work internationally since they met in 2002. Kodjo’s photography from the 1960s and 1970s features fresh, emotive, black-and-white portraits of young people in the streets of Abidjan, Ivory Coast, and in gleaming domestic settings. Kodjo, who died in 2021, began his career in 1959, on the eve of Ivory Coast’s national independence, following French colonial rule, and his images capture a mood of aspiration during a postindependence economic boom. Look what Kodjo could do with angles, as in his electric 1970 photograph of a Black model in front of a boxy building. It strikes me as a visual chiasmus, a moment of reversal caught on camera. The tall building is clearly bigger but the model seems to rival its grandeur.

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s  Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s “I want his story to be known around the world,” Léki told me over Zoom last winter. Most of us would have never known of Kodjo’s photography without Léki. But this is not a savior story, not a rescue narrative, not the artistic neocolonialism that often governs records of African art. It’s a political commitment involving an Ivorian artist protecting and fighting for the legacy of another living Ivorian artist. Léki has opened new vistas onto Kodjo’s cultural, historical, and aesthetic impact on photography in Ivory Coast and around the world.

“People thought that he was already dead—dead physically and also photographically or artistically,” Léki said. “From what I know from the history of photography, I’ve never heard of another African who saved another African’s archives.” He continued: “For me the message of that is also political. It’s unique: an African photographer who helped another old African photographer, who restored negatives without any validation from the West until they bite. It’s a victory. I’m not in the big system. Paul Kodjo is not a product of the Western. Malick Sidibé is a product of the Western. Seydou Keïta is a product of the Western.”

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970sYou Look Beautiful Like That: Studio Photography in West and Central Africa, an exhibition recently presented by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto, includes only two images by Kodjo, but these stand out among the very well-known work of Malian photographers Sidibé and Keïta, as well as Cameroonian photographer Michel Kameni, among others. Kodjo’s images are photoromans, an innovation that boomed in the mid-twentieth century and features textual narrative paired with photography. Kodjo, who was born in 1939, began using this kinesthetic format in the late 1960s and early 1970s for work published in the magazine Ivoire Dimanche. With its use of scripts, castings, settings, and amateur and professional actors, this cinematic approach to still photography is no surprise given that he studied film in the 1960s in Paris and once wanted to be a filmmaker.

Kodjo’s story is part of an intergenerational narrative about the difficulties of keeping Black archives alive in an oftentimes exploitative art industry.

“Kodjo wasn’t necessarily a studio photographer. He creates these beautiful cinematic mise-en-scènes,” says Julie Crooks, the AGO’s curator of arts of global Africa and the diaspora who organized the show. “It’s very filmic. It blurs the line between reality and fiction and lands somewhere in between.”

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970sThe exhibition’s main title is translated from the Malian phrase “I kany¨ tan.” It was popularized by Keïta and was previously used as a title for an exhibition, traveling from 2001 to 2003, of works by him and Sidibé. The words stress, as Crooks tells me, “the idea of collaboration between client and photographer, which is different than the kind of ethnographic images that we associate at that time through the lens of European photographers that create these damaging stereotypes of African peoples.”

Related Items

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 227

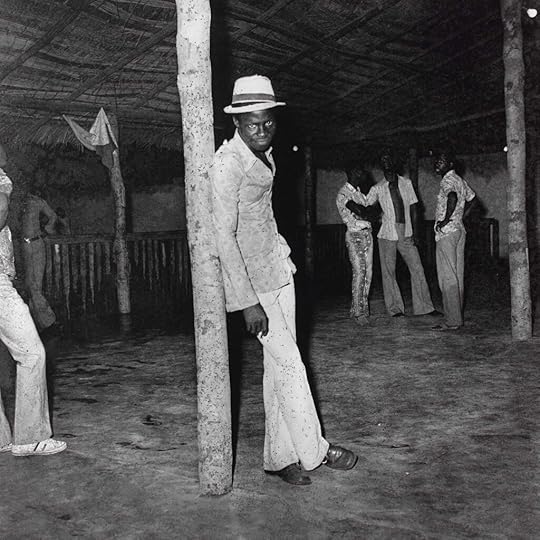

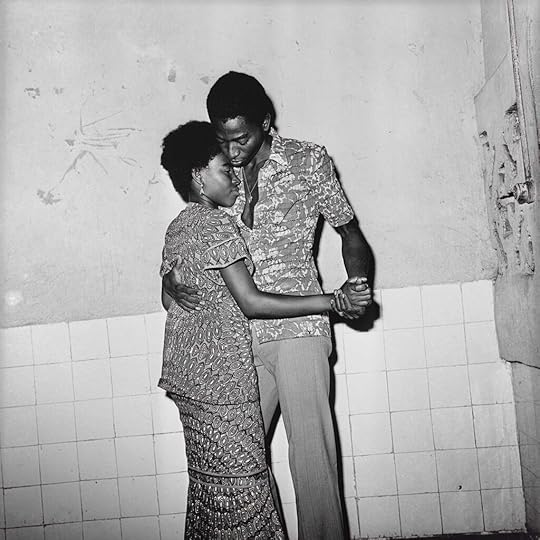

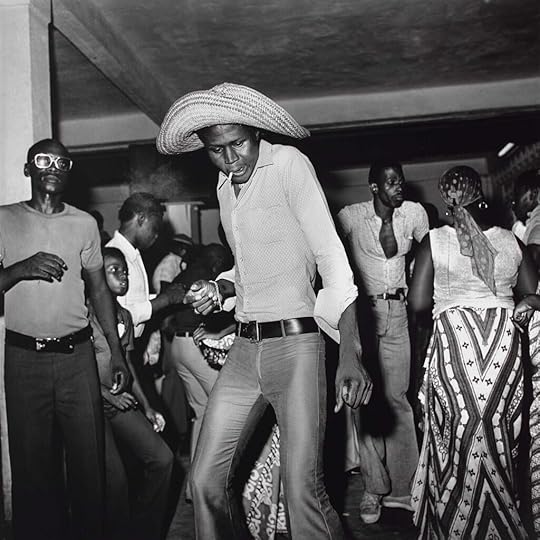

Shop Now[image error]Self-presentation, modernity, aspiration, self-propulsion, confession, and the politics of respectability are at the heart of studio-photography practices. Studio photography limns the line between self-determination and conformism, intimate and public life, performance and the mundane. By contrast, Kodjo’s photos of nightlife and youth culture especially are edgy, resisting cultural norms of the time. “Crazy, unbridled, carefree, and cheerful,” says Léki in the documentary, narrating over a slideshow of Ivorians dancing, partying, flirting, touching, swaying, smoking, self-fashioning, hugging, and posing. Kodjo also worked for the press, photographing the political elite, and he was the only Black African photographer to cover the May 1968 revolution in France, assigned by a government news agency created by then President Félix Houphouët Boigny.

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970sAll photographs © Estate of Paul Kodjo and courtesy Les Rencontres du Sud

Often referred to as the “father of Ivorian photography,” Kodjo rocketed to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s with his photoromans. But after much popularity, he disappeared from public view. “He was born in the period that people didn’t understand what he was doing,” Léki told me. “He was faster than his contemporary people.” He seeks to put Kodjo back on the map. The restoration process, which was carried out in France, has been long—and many negatives were lost. But the 3,120 photographs that remain tell a powerful story about Ivorian history and aesthetics. Kodjo’s story is part of an intergenerational narrative about the difficulties of keeping Black archives alive in an oftentimes exploitative art industry. “I know some institutions in the West are not happy because they’re like, What is this Black young man doing? Is he challenging us? I want to control the narrative,” Léki insisted. “I don’t want anyone to take that from me—or from us.”

You Look Beautiful Like That: Studio Photography in West and Central Africa is on view at the Art Galley of Ontario, Toronto, through June 11, 2023.

June 6, 2023

How Do Asian American Photographers Envision New Possibilities for the Future?

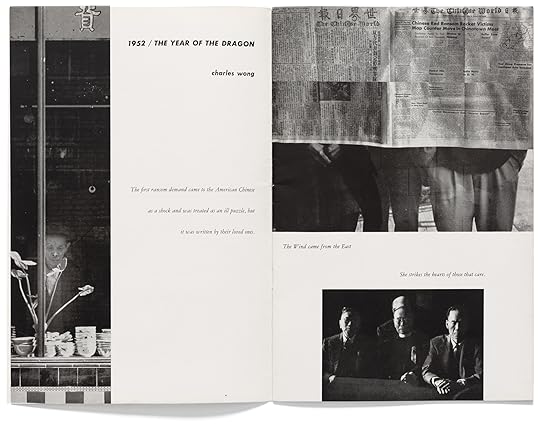

In the summer of 1953, Charles Wong’s photo-essay “1952 / The Year of the Dragon” was published in the fifth issue of Aperture. The impetus for Wong’s piece—a carefully designed sequence of photography and poetry—was an extortion scheme that had plagued the immigrant community in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The perpetrators peppered vulnerable immigrants with fake notices about kidnapped family members in China. Cut off from communication by the Communist Revolution, many of the scheme’s victims opted to pay an expensive ransom, while others made the difficult decision to forsake their loved ones to imagined captors. The themes of Wong’s work—immigrant displacement, vulnerability, memory, and intergenerational trauma—reveal wounds of the Asian American immigrant experience that feel no less raw today. Wong’s piece might be read as a statement about the impossible choices and pain of forgetting that building a new life in this country continually demands.

Spread from Aperture, Summer 1953, with photographs by Charles Wong

Spread from Aperture, Summer 1953, with photographs by Charles Wong  Photographer unknown, Portrait of a Chinese woman with daguerreotype, ca. 1850

Photographer unknown, Portrait of a Chinese woman with daguerreotype, ca. 1850© the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

As guest editor of this issue of Aperture, I have found solace and inspiration, throughout my research, in seeing how generations of artists have used the medium of photography to grapple with questions of visibility, belonging, and what it means to be Asian American. Just as there is no single point where Asian American experience converges, photography produced by Asian American image makers encompasses disparate ways of viewing the world—and demands to be approached as such. But to seek connection and coherence among these perspectives is to acknowledge a shared story of immigration to the United States that relates to a long legacy of exclusionary policies and struggles for recognition and citizenship. Being and becoming Asian in America is an unfixed, constantly evolving, and expansive process, and photography plays an essential role in envisioning it.

Since the first Asian immigrants arrived in America in the mid-nineteenth century, social visibility has conferred vulnerability. Our modern-day system of passport controls was based upon nineteenth-century forms of visual policing developed specifically to regulate the movement of Chinese and Japanese bodies, the first national methods of biometric identification to utilize photography. Falling under the gaze of the camera was an experience shared by most Asian immigrants, not primarily as a hobby of self-documentation or leisure but as a bureaucratic fact of racialized surveillance and policing. Under the threat of deportation or detention, many early immigrants opted for self-effacement and erasure as strategies for survival. A daguerreotype from 1850s California that shows a young, working-class Chinese woman cradling a picture of an absent loved one in her hand is a rare exception. The dearth of historical photographs portraying Asian men and women at ease speaks to contested ideas of place, identity, and belonging that continue to shape our collective image of the United States.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

The author Ocean Vuong once identified a generational divide in the aspirations of Asian Americans. To paraphrase Vuong, first-generation immigrants saw life in America as such a privilege that they were content to put their heads down, work, fade into the background, and live a quiet life—so much so that they expected their children to do the same. But with the second generation, there came a desire to be seen. A great paradox for these children of immigrants, many of whom seek agency and self-expression through art, was that they betrayed their parents in order to subversively fulfill their parents’ dreams.

This issue provides an opportunity to discover generative ways of seeing that are rooted in connection and empathy.

For this younger generation of artists and immigrants, the desire for visibility is about more than individual self-fulfillment. It arises from a want to understand a past that continues to act on us and forms part of who we are but remains unspoken and closed off from view. This phantom pain of forgetting creates its own particular sense of loss—so clearly articulated in Wong’s piece—that marks where immigrant hopes intersect with intergenerational melancholy. Whether one arrived generations ago or today, being Asian American requires coming to terms with absences, omissions, and silences, as well as with the complications of human choices that entail various acts of abandonment. It involves negotiating the in-betweenness of here and there, past and future, breaks of language and culture—or, as the creators of the recent film Everything Everywhere All at Once imagine it, multiverses that can fracture a sense of self across infinite chains of unrealized possibilities.

Corky Lee, Sikh Man with US Flag at a Post-9/11 Vigil, New York, 2001

Corky Lee, Sikh Man with US Flag at a Post-9/11 Vigil, New York, 2001Courtesy Corky Lee Estate

Stephanie Syjuco, Pileup (Brass Bells), 2021

Stephanie Syjuco, Pileup (Brass Bells), 2021Courtesy the artist; Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco; and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

This issue of Aperture explores the myriad ways in which Asian American image makers have approached questions of visibility and belonging on their own terms. They create works that reveal the full complexity and diversity of stories that make the experience of being Asian in America. They creatively navigate the tension between being seen and unseen as strategies of survival, play, and reclamation, from the pursuit of anonymity or effacement during times of exclusion to self-fashioning and commemoration. And in the spirit of the late photographer and activist Corky Lee, they are working toward what he called “photographic justice” by exploring areas of hope, celebration, and connection alongside doubt, uncertainty, and sorrow across generations. What comes into view in these pages is not a single story or image but a kaleidoscopic refracting of shared patterns and impressions that is connected to the specifics of an evolving Asian American identity and its potential.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

How might we acknowledge the invisible wounds of US warfare and imperialism in Asia? Artists have employed diverse approaches to reflect the trauma inscribed on our bodies and psyches, from landscape to portraiture, abstraction, and conceptual practices. Toyo Miyatake’s photographs show the mundane highs and lows of Japanese Americans’ daily lives while interned during World War II at the Manzanar concentration camp in California. They are testaments to the resilience of a community and the ways in which art perseveres even in the darkest hours. In reenactments of Vietnam War battles, An-My Lê draws on the landscape tradition to investigate how history seeps into the present. Yong Soon Min explores the emotional terrain of displacement in self-portraiture that marks the body as a repository for personal and national histories. And while both Annu Palakunnathu Matthew and Stephanie Syjuco turn to archives for source material, their projects pursue different ends: Matthew’s animations collapse time by merging immigrant family photographs from different generations in an act of suturing or repair; Syjuco calls attention to the evidence gathered to quantify, categorize, and understand the Philippines in order to question the unseen power structures still embedded in national archives and museums today.

Family is central to the stories of Asian American lives, but what new visions of our loved ones—what entirely different multiverses, of what could have been and what is possible for the future—might emerge from the push-pull of picture making? In the early 1960s, the Low family in New York City used cut and paste to create an ideal world in which family members separated by immigration policies are reunited in one image. In the same vein, Leonard Suryajaya’s theatrical tableaux and Guanyu Xu’s layered domestic spaces are filled with symbols of hope, history, and affection. From the vibrant, dignified portraits taken at May’s Photo Studio in the early to mid-twentieth century to Michael Jang’s wryly observant photographs of his suburban family in the 1970s and the haunting series Half Self-Portraits made collaboratively by Tommy Kha and his mother in the beginning of this century, photography acts as a prism, allowing us to glimpse the dazzling humor, ambitions, desires, and regrets of our expanded families and ourselves.

Photographer unknown, Low Family Portrait, ca. 1961

Photographer unknown, Low Family Portrait, ca. 1961Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America Collection

Janice Chung, Grandma’s Room, Flushing, Queens, 2013

Janice Chung, Grandma’s Room, Flushing, Queens, 2013Courtesy the artist

Reconciling this yearning to be seen—to find meaning, be acknowledged, and, finally, belong—with the habits of opacity is part of the process of being and becoming Asian in America. It has taken me time to realize that there is agency and subjectivity in both positions. That there are emotions that cannot be expressed or articulated but are deeply felt. Photography has the ability to help us navigate what we choose to bring to the surface and what we hold back. It can address losses that are difficult to name by making visible, with attention and respect, the actions and concerns of previous generations. Perhaps it is this fundamental act of care that will aid us in moving from personal experience to greater collective action and solidarity.

It is my hope that this issue provides an opportunity to discover generative ways of seeing that are rooted in connection and empathy. It is through the work of artists that we can change our perceptions of the past and heal generational wounds.

In seeing one another and recognizing the beauty and creativity of these endeavors, we take part in a project of reclaiming agency and humanity.

Charles Wong is now over a hundred years old and still living with his partner, the photographer Irene Poon, in San Francisco. It has been seventy years since his photo-essay was published in Aperture. The two don’t have cell phones or email, but Wong sent a handwritten note on the occasion of this issue: “This is a brave project, and is heading into the 2024 elections. We are with you.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

June 1, 2023

The Photographic Traces of Luc Tuymans’s Ghostly Paintings

In the late 1970s, when Luc Tuymans started painting, the pursuit was seen as quixotic, archaic. Painting had been declared dead, superseded by Pop and Conceptual art—that is, if we disregard both the bold and wildly colorful brushstrokes of the neo-expressionists and the Transavanguardia, including Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente, as well as the cleverly thought through paintings of the older Germans Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Anselm Kiefer, who each engaged with the Nazi era in their own ways. In any case, Tuymans, born in 1958 and raised in Belgium, outside of Antwerp, was quite removed from all these conversations.

Tuymans was born into the TV generation, with, as he later put it, “an overdose of images and a lack of meaning.” World War II may have been always present in the media for him, but it remained far from comprehensible. He was three years old when Adolf Eichmann was on trial in Jerusalem—the German SS Obersturmbannführer was being made to answer for the murder of millions of Jews. It was the first such trial to be piped into living rooms across the world. The TV cameras captured a bespectacled man who felt he was not guilty of anything but bureaucratic diligence and obedience. The philosopher Hannah Arendt, covering the trial for the New Yorker, would describe his crimes as “the fearsome, word-and-thought defying banality of evil.” The most terrifying thing about Eichmann, for her, was his normality, so at odds with the atrocities he oversaw; he was somehow both monster and administrator.

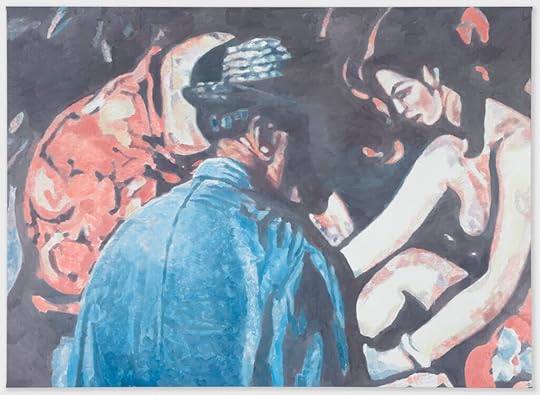

Luc Tuymans, Allo! III, 2012. Oil on canvas

Luc Tuymans, Allo! III, 2012. Oil on canvasIt is precisely this discrepancy, this mismatch between harmlessness and horror, that Tuymans would later address in his paintings. It’s almost as if the trial served as a kind of blueprint for his work, which stands out from that of his peers through its uncanny sense of paralysis. Over the next thirty years, he created paintings whose ghostly, pallid morbidity evokes history and triggers memories—yet transcending mere illustration and eschewing the sensationalism artists’ engagement with the Holocaust can involve. Instead, Tuymans’s paintings speak through their very silence. His only apparently immaterial portraits and interiors convey a particularly dark energy, an ominous atmosphere in which evil is palpable but never exactly present. He models his work after photographs and film stills taken from a wide variety of sources, such as books and postcards, but also photographs or footage taken by himself or others. Tuymans’s art transforms these into something more complex and sinister than historical documents. They gain a ghostly presence that tells of trauma and of death. Death, though always inherent in photography as a medium, here acquires an indefinable, sickly quality that is strangely undead.

Using subjects from the Nazi era early on in his career, the artist set a tone that permeates his oeuvre to this day: seemingly arbitrary, often zoomed-in image sections and laconic titles illustrate topics that elude any poetry. Our New Quarters from 1986 shows a schematically roughed out, anonymous building—giving no indication that it’s actually a courtyard from the “model” concentration camp Theresienstadt, depicted on a postcard that Tuymans saw printed in a book by Alfred Kantor, a Jewish Czech artist who survived three concentration camps. One of these camps was Schwarzheide, of which Kantor made a drawing he then cut into strips to hide it from the SS guards. In 1986, Tuymans used a small section from that composite drawing that depicts a few treetops for a painting titled Schwarzheide; he took up the subject again in 2019. Viewers unfamiliar with its background story remain in the dark.

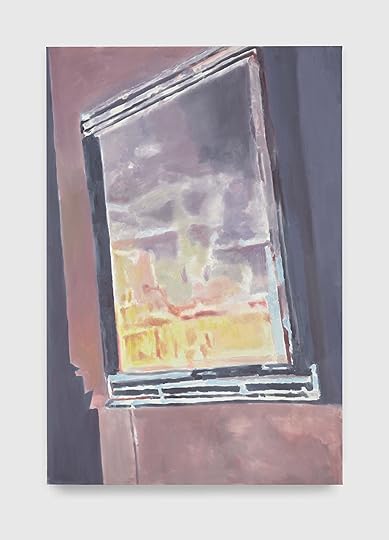

Luc Tuymans, The Frame, 2023. Oil on linen

Luc Tuymans, The Frame, 2023. Oil on linen  Luc Tuymans, Bell Boy, 2003. Oil on linen

Luc Tuymans, Bell Boy, 2003. Oil on linen His painting of a fallen skier whose face remains unrecognizable is similarly unsettling and strange. However innocuous its title—An Architect (1998)—seems, the figure sitting in the snow and turning to us is disturbing. Based on Tuymans’s interest in the Third Reich, we might guess that this is Hitler’s chief architect and armaments minister Albert Speer, whom the artist painted based on historical photographs again and again—along with other Nazi rulers such as Himmler, Heydrich, and Hitler himself. Here, Tuymans used a still from private footage by Speer, in which his face is clearly recognizable despite the poor quality of the film. Tuymans, however, anonymized the architect, rendering identification impossible. Painting him at leisure also creates a stark contrast to his role at Hitler’s side. His snowy fall, on the other hand, points to the downfall of the Nazi regime, of whose brutal “final solution” Speer claimed to have known nothing. Tuymans took a similarly reductive approach to his portrayal of Reinhard Heydrich in his 1988 painting Die Zeit. Heydrich chaired the Wannsee Conference, where the mass murder of European Jews was plotted and decided. The source of this painting came from the propaganda magazine Signal, which dedicated a special issue to Heydrich when he died of sepsis after an assassination attempt by Czech agents. The original photo shows the Nazi sleek and determined in a white fencing jacket with SS badges. Tuymans reduced the image to a few white surfaces, hiding the yellowy face behind sunglasses and posing him as if stuffed in front of a kind of filing cabinet. The typical mixture of anonymization and allegory is at work here too: the man may be unrecognizable, but even detached from his historical context you can sense an abstract threat whose chilling silence sets your imagination reeling.

Installation view of Luc Tuymans: The Barn, David Zwirner, New York, 2023

Installation view of Luc Tuymans: The Barn, David Zwirner, New York, 2023One might say that Tuymans copied his approach of modeling paintings after photographs and then blurring them from Gerhard Richter. But unlike Richter, who experienced the war himself as a child in Dresden, Tuymans explicitly explores questions of power, representation, and memory—and how they are reflected in images. The Flemish artist certainly also works with blurring and reducing, but whereas Richter used family photos for his paintings on the Nazi era (such as Uncle Rudi [1965], the subject in his Wehrmacht uniform), Tuymans is not concerned with his own personal history, but with the way images, like morgues, can contain rigid and incomprehensible horrors. It is important to note that, at the beginning of the 1980s, Tuymans gave up painting for film for four years. His experience working with a camera, which he used to shoot his own footage but also filmed television broadcasts, often makes his later paintings look like close-ups, or frozen scenes or images, which he also produces in series.

As mysterious and reduced as Tuymans’s paintings appear at first glance, so much in them speaks of the brutality to which their photographic originals silently bore witness.

When asked why he remains captivated by World War II, Tuymans once said that when he was growing up his family constantly talked about this era over dinner. And yet: “Added to this was the tabooing of these events on the grounds that it’s impossible to depict their horror in its entirety.” This is how he came to paint small, excerpted images with a conscious degree of distance and indifference that conveys instead a feeling of what happened, of where it happened. What he thus manages is to interpret visual material artistically and “bring it to the point at which—through the aesthetics of depiction on the one hand and the ethics of what is depicted on the other—it can be interrogated at length. This is the foundation of my painting, which through seeks to give form to feeling, to the inexpressible.”

Luc Tuymans, Big Brother, 2008. Oil on canvas

Luc Tuymans, Big Brother, 2008. Oil on canvasTuymans also applies this attitude to topics beyond the Holocaust, such as the Ku Klux Klan, Belgium’s brutal colonial history in the Congo, or 9/11. Images of the last are familiar to us, but he depicted it through a large-scale, classical-looking still life, which offended some people. But it is precisely this distance that demonstrates the power of Tuymans’s method, which is free of nostalgia and irony, making it inexhaustible. His images of images strip the photographic sources of their realistic sharpness and undermine photography’s only recently destabilized claim to truth. Although they remain chilly, because they grant an immediate proximity to—almost an involvement in—historical events, Tuymans creates an atmosphere that takes your breath away.

He succeeds in doing so even when he draws on images of fiction. The Valley (2007) is part of a series based on the 1960s sci-fi horror movie The Village of the Damned, whose parable of mind control is reflected in a boy’s absent gaze and clean-cut aspect. Photographed from the film in extreme close-up, the boy’s face embodies a sense of emptiness and threat in Tuymans’s customary cold blues and grays. But Tuymans also makes use of contemporary pop culture. Based on a photograph the artist took of his television set, the work Big Brother (2008) shows the dormitory of the titular reality show that films its contestants 24 hours a day. Michel Foucault’s analysis of “discipline and punishment”—Tuymans’s central focus, if you will—takes on an absurd dimension here. Instead of in a concentration camp or some boarding school, the people lying in this image are in a TV studio, voluntarily giving away their human dignity to a questionable TV genre. Issei Sagawa (2014), Tuyman’s painting of the Japanese man who murdered and cannibalized a Parisian student in 1981, also stems from a TV documentary. Tuymans took the picture with his smartphone. It shows Sawaga before he committed the crime, wearing a mask and a pith helmet. The transfer of the snapshot into a quickly applied painting reflects the blurring of the video itself, which achieves an eerie effect: the figure appears spooky and frightening, seething with violence and delusion.

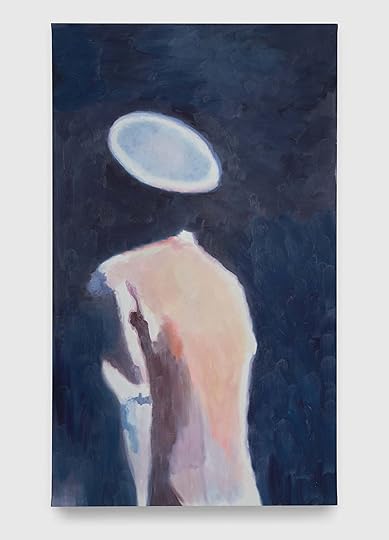

Luc Tuymans, Italy, 2020. Charcoal on paper

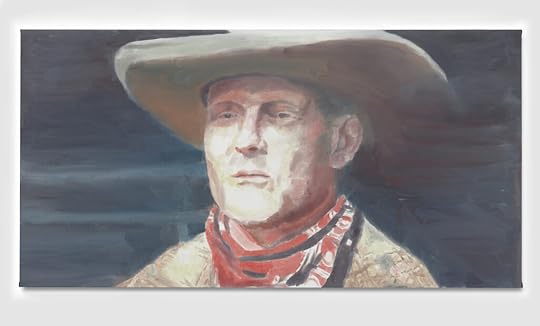

Luc Tuymans, Italy, 2020. Charcoal on paperTuymans’s fascination with monstrous characters continues. The cowboy in Still (2019) corresponds to the ominous figure in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive whose stubbornly white, ice-cold visage shows no feelings. It is hardly surprising that Tuymans has now directed his attention to the pandemic, since silences, standstills, and unconscious biases in our unfolding history conjointly form something like the DNA of his images. Italy (2020) shows a dark, empty piazza above which hovers the digital play button of an online video. Apparently taken directly from a screen, Tuymans’s piece alludes to a present that has come to a standstill, now accessible only via the internet. And when he called his 2022 exhibition at David Zwirner’s Paris location Eternity—the second in a trilogy of exhibitions across Hong Kong, Paris, and New York—he was also referring to a temporality that’s not subject to any chronology. The painting Eternity (2021)—a red shimmering ball that could be the sun or some kind of magic orb—is actually based on the model that the physicist Werner Heisenberg used to design the hydrogen bomb.

Luc Tuymans, Still, 2019. Oil on canvas

Luc Tuymans, Still, 2019. Oil on canvasAll works © the artist and courtesy David Zwirner

Violence, destruction, horror, and death. As mysterious and reduced as Tuymans’s paintings appear at first glance, so much in them speaks of the brutality to which their photographic originals silently bore witness. In Camera Lucida (1980), Roland Barthes describes the paradox that photography can capture for eternity a moment that has passed immediately afterward, which is why photography prematurely mortifies life: “Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.” Tuymans translates this catastrophic paradox of photography into painting. By engaging in memory work, he keeps us aware that barbarity could break out again at any moment. His paintings somehow exist between times, impossible to be pinned to one particular past. With their strange incorporeality they reach into our world, and these spirits Tuymans keeps evoking will never let us go. Where photography can keep us at a distance, his painting grabs us by the throat. Without any consolation, beyond poetry and nostalgia, they convey the chill of horror, the power of trauma that continues to throb inside of us and is far from defeated.

Translated from the German by Florian Duijsens.

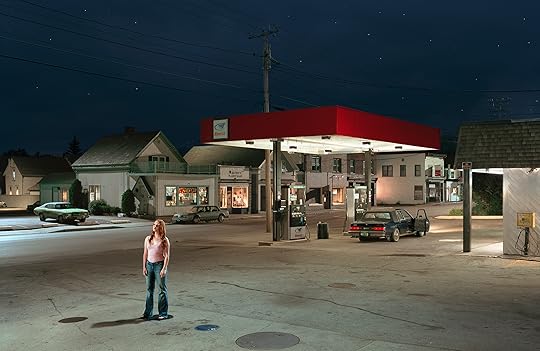

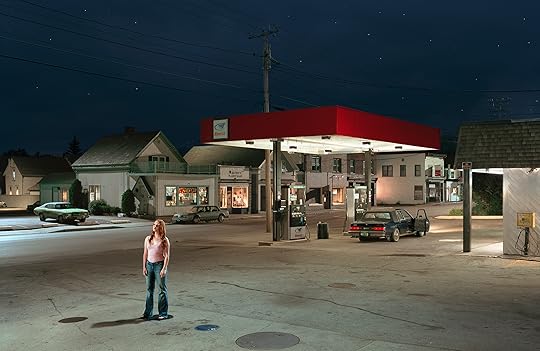

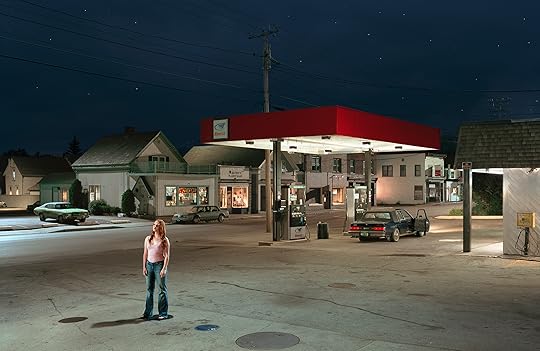

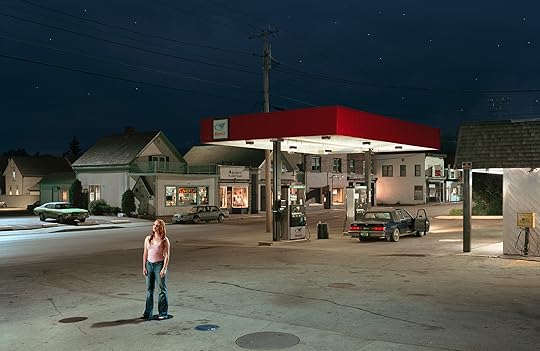

Gregory Crewdson and Lauren Ambrose on the Making of an Iconic Photograph

In 2003, Gregory Crewdson visited the set of Six Feet Under to shoot a campaign for the acclaimed HBO series depicting a family-run funeral home. There, he met Lauren Ambrose, who was starring in the show. Crewdson made a photograph of Ambrose in his signature cinematic style, a photograph that has never before been seen, released, or published—until now.

For one week only, Aperture will host a Gregory Crewdson special edition print sale of Untitled, Unreleased #4 (2003) to benefit the Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Like many independent movie theaters across the country, the Triplex faces an uncertain future. When news of its possible closing spread, a group of people living in or with ties to the Berkshires quickly came together and started a non-profit to buy the theater.

The Triplex is currently the only full-time working movie theater in Great Barrington, or for forty-five minutes in any direction. But its legacy looms larger than that. For Crewdson and many others, the theater is associated with the late legendary film critic Pauline Kael, who lived in Great Barrington. Kael was a family friend of Crewdson’s, and he used to see movies there with her, especially in her later years. Many other local artists, writers, and filmmakers have their own anecdotes about Kael frequenting the theater, and there are even discussions about renaming it after her. A young Wes Anderson famously screened Rushmore there for her, and then wrote about the experience in the New York Times.

Crewdson and Ambrose are among the local residents who are actively trying to save the theater. Crewdson recently came across the Ambrose picture in his archives, and was struck by its beauty and magical quality, and what a time capsule it had become. He decided to use it to benefit the cause. The picture was made when Crewdson was embarking on the body of work that would ultimately be made across eight productions, shot on an 8 x 10 camera with his full cinematic lighting team and a production crew of over a hundred people. Beneath the Roses remains his most elaborate and lengthy undertaking to date. Here, Crewdson and Ambrose speak about the intergenerational experience of movie theaters, art in the Berkshires, and the making of an iconic image.

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 Collect a signed printed by Gregory Crewdson, with proceeds supporting The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA, and Aperture. View product

[image error]

[image error]

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 Collect a signed printed by Gregory Crewdson, with proceeds supporting The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA, and Aperture. View product

[image error]

[image error]

Out of stock

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 Out of stock Description Orders will ship by July 7, 2023.Starting June 2, for one week only, Aperture will host a Gregory Crewdson special edition print sale in benefit of The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA. The picture, made by Crewdson 20 years ago, features actress Lauren Ambrose, and has never before been released, published, or shown publicly.

The Triplex, like so many small independent movie theaters across the country, faces an uncertain future. When news of its possible closing spread, a group of people living in or with ties to the Berkshires quickly came together, started a non-profit to buy the theater and save it. The small movie house is currently the only full time working movie theater in town, or for 45 minutes in any direction. But the Triplex’s legacy looms larger than that. For Crewdson, and many others, the theater is associated with the late legendary film critic Pauline Kael, who lived in Great Barrington. Kael was a family friend of Crewdson’s, and he used to see movies there with her, especially in her later years. Many other local artists, writers, and filmmakers have their own anecdotes about Kael frequenting the theater, and there are even discussions about renaming it after her. A young Wes Anderson famously screened Rushmore there for her, and then wrote about his experience in The New York Times.

Gregory Crewdson and Lauren Ambrose are among local residents who are actively trying to save the theater. By a stroke of serendipity, Crewdson had just recently come across the picture he made featuring Ambrose in his archives and was struck by it, its beauty and magical quality, and what a time capsule it had become. He decided to use it to benefit the cause. The picture was made in 2003 when Crewdson was just embarking on the body of work that would ultimately be made across 8 productions, shot on an 8 x 10 camera with his full cinematic lighting team and a production crew of over a hundred. Beneath the Roses remains his most elaborate and lengthy undertaking to date. This is the first time Crewdson has made an unreleased work from the series available as an editioned print.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003, Digital pigment print, 8.2 x 12.7 in. (image) 11 x 14 in. (sheet), will come signed by the artist. The special edition will remain open and available for one week only, through June 9th at 11:59 PM ET. The price of the print is $250. Details

GREGORY CREWDSON

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003

Digital Pigment Print

Signed by the artist

Image Size: 8.2 x 12.7 in.

Sheet Size: 11 x 14 in.

© Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson (born in Brooklyn, 1962) is a graduate of the Yale School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut, where he is now director of graduate studies in photography. His series Beneath the Roses is subject of the 2012 documentary Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters. Crewdson’s awards include the Skowhegan Medal for Photography, National Endowment for the Arts Visual Artists Fellowship, and Aaron Siskind Foundation Fellowship. His prior books include Twilight (2002), Beneath the Roses (2008), Cathedral of the Pines (Aperture, 2016), and An Eclipse of Moths (Aperture, 2020). Crewdson is represented internationally by Gagosian Gallery.

Lauren Ambrose: I’m interested in how you came to be a part of Save the Triplex. My husband Sam [Handel] is working very closely on this project. And we immediately got involved when we heard what was going on, because basically, it makes immediate sense why the Triplex needs to be owned by the community in a nonprofit format.

Gregory Crewdson: Absolutely, I mean, I grew up in Brooklyn, but my family started coming to Becket when I was young and eventually built a small log cabin there. We were very isolated in the woods, and one of my central experiences from childhood was going to movies in Great Barrington or Pittsfield. And that continued ’til I grew older. And I’m not sure if you’re aware that my family was very close with Pauline Kael, the film critic. My mother was and still is very close to Gina, her daughter. And when Pauline was starting to get older, I actually would go to movies with her in Great Barrington; and so, I have so many deep connections with this place and movies, you know, in my mind. And not just with this movie theater, but with the kind of ritual of going to a movie with my family, driving down our hill in the woods, and coming into town for a special event. So for me, a lot of wanting to be a part of this and supporting the Triplex is tied up in these deep memories of the Berkshires.

Ambrose: Yeah, and not wanting to lose that, for myself, but certainly also for my children. I mean, I grew up in New Haven, but going to the movies, you know, going to a small independent movie theater—for me it was the York Square Cinema in New Haven, which of course has since closed.

Crewdson: Oh, that’s crazy. I used to go there a lot too. I saw Blue Velvet at that theater for the first time.

Ambrose: For me, it was going to the new releases, going to the less mainstream or foreign films that opened up a whole world of storytelling. They would have revivals, and they’d have the midnight showings of Rocky Horror on Saturday night; stuff that was tied into the community, stuff that was tied into Yale, and I know that’s very much the dream for what the Triplex can be. I was attracted to living in this area because of Tanglewood, and studying there when I was a teenager. I feel like the town having a good movie theater was another reason to move here and raise children because, you know, going to movies, like you said, the event of it is just so special.

Crewdson: It’s a very different experience than any other form. That kind of collective thing of going to a place, leaving the world, and having an experience that’s kind of a collective dream in a way.

Ambrose: It is truly an intergenerational meeting place, the movie theater. And it’s democratic. Everyone can buy a movie ticket and have access to stories. And it feels like social infrastructure. And frankly, an antidote to loneliness. To be able to share emotions and laughter and tears and all the things that the movies transport us to, as a group. And, in a place like the Triplex, with some space for discussion and debate. I mean, what a special thing that you were probably introduced to with Pauline. What a lucky thing to have had a companion that could ask you questions about film; it must have really opened your mind.

Crewdson: Yes, I mean, definitely; I think Pauline was like a central figure in my life in terms of my relationship to movies and maybe even one of the reasons I wound up moving here.

Lauren Ambrose on the set of Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003

Lauren Ambrose on the set of Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003Courtesy Crewdson Studio

Gregory Crewdson and Lauren Ambrose on the set of Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003

Gregory Crewdson and Lauren Ambrose on the set of Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003Courtesy Crewdson Studio

Ambrose: It’s striking that this community, including you with this generous donation, is coming together to continue this legacy and to continue to have this experience. It’s actually pretty inspiring, the outpouring of hope and support.

Crewdson: This picture feels really fateful. It’s been waiting all these years for the right moment. I should say that Juliane and I were trying to piece together the chronology of the making of this picture. So, you and I first met on the set of Six Feet Under when I did the picture—

Ambrose: Yeah! And I couldn’t believe it because there were all of these people from the Berkshires all of a sudden on our set in LA.

Crewdson: I know, I know [laughs].

Ambrose: You were shooting that amazing poster for what I think was our third season.

Crewdson: To this day, by the way, it’s the only thing I ever did like that, ever, and it was because I was such a huge fan of the show.

This picture feels really fateful. It’s been waiting all these years for the right moment.

Ambrose: We were so excited.

Crewdson: And I was mentioned on the show, right? Which I had no idea about. That was previous to shooting the campaign. I was just watching the show on TV like everybody else and I was like, Did they just say my name?

Ambrose: Yes, and it was either me or a character that I was in a scene with that mentioned you. Because my character was a photography student at an art school—or she became that. And there was an opportunity to mention you. I just remember all of us: me, Peter Krause, Michael Hall, and Rachel Griffiths were watching you guys bring in metric tons of soil and flowers and we were like, What is happening right now?! [laughs]. It was so exciting.

Crewdson: It was around that same time I was just beginning Beneath the Roses, and then we connected up in Great Barrington because you had moved there, right?

Ambrose: Yeah! Yeah.

Crewdson: And I asked you to be in a picture. And my original conception for it—I don’t know if you remember, but there were all these local teenagers in the picture. And I always loved the picture but there were so many distractions. And I felt that I messed up the picture.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Ambrose: And there were going to be moths or something, in the light . . .

Crewdson: Yes.

Ambrose: And it felt like some version of a dental X-ray where I had to hold incredibly still during the super-long exposures.

Crewdson: [Laughs] Yes, yes, oh God.

Ambrose: Also amazing to me that your crew is comprised of so many people in the Berkshires, so, it was this “community art project” at the time, and now it’s supporting this community art project. Also so fitting of course is that your work is so incredibly cinematic, and shooting that photo, for me, other than the dental exam part of it, was also just like being on a film set, because of the scale of your operation, which was like a Spielberg set or something, where it’s lit down the entire street. And there’s a DP and a camera operator and grips and electrics and all the same equipment and all the same lingo and all of the same process, basically, but only for one still image. It’s very touching to me that all these years later the picture is now in service of a cinema.

Crewdson: Everything has its time, you know? So the strange thing is, I felt like I just—independent of all this—I had gone back to that picture a few months ago, strangely, and I was like, This is such a beautiful picture, but it has to be more isolated, it has to be quieter. So I pieced back the picture together, as we do, with different composites, and focuses, and removed all of the other figures, and I was like, my God, is that so beautiful? And it also captures a moment twenty years ago. Twenty years ago.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Ambrose: And I can’t quite look at it, like fully look at, and I have to, like, partially look at it, because I’m in it [laughs]. No, really, it is very beautiful and striking what you guys have done with it. It’s very beautiful.

Crewdson: So, weirdly, when we started becoming involved with the Triplex, and I was actually at Yale, swimming at the pool, and I just thought of it. I was like, oh my God, there’s this picture we’ve been working on, and you happen to be in it, and we both live in the Berkshires, and Sam had contacted us, and I was like, this has to be it. It was fate. I couldn’t be happier and I am a firm believer in timing and fate. It feels like there’s a reason that this is the moment to bring this picture out into the world.

Ambrose: Yeah, I’m thrilled about it.

Crewdson: Can you believe it’s been twenty years since we made that picture?

Ambrose: No. It’s proof time is relative [laughs].

Crewdson: But time moves on. And so many great things happen in life in the meantime.

Gregory Crewdson’s Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003, a digital pigment print, 8.2 x 12.7. in. (image) 11 x 14 in. (sheet), will be signed by the artist. The special edition will be available through June 9 for $250, or paired with a subscription to Aperture magazine for $310.

Gregory Crewdson Releases a Limited-Edition Photograph to Benefit the Triplex Movie Theater

In 2003, Gregory Crewdson visited the set of Six Feet Under to shoot a campaign for the acclaimed HBO series depicting a family-run funeral home. There, he met Lauren Ambrose, who was starring in the show. Crewdson made a photograph of Ambrose in his signature cinematic style, a photograph that has never before been seen, released, or published—until now.

For one week only, Aperture will host a Gregory Crewdson special edition print sale of Untitled, Unreleased #4 (2003) to benefit the Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Like many independent movie theaters across the country, the Triplex faces an uncertain future. When news of its possible closing spread, a group of people living in or with ties to the Berkshires quickly came together and started a non-profit to buy the theater.

The Triplex is currently the only full-time working movie theater in Great Barrington, or for forty-five minutes in any direction. But its legacy looms larger than that. For Crewdson and many others, the theater is associated with the late legendary film critic Pauline Kael, who lived in Great Barrington. Kael was a family friend of Crewdson’s, and he used to see movies there with her, especially in her later years. Many other local artists, writers, and filmmakers have their own anecdotes about Kael frequenting the theater, and there are even discussions about renaming it after her. A young Wes Anderson famously screened Rushmore there for her, and then wrote about the experience in the New York Times.

Crewdson and Ambrose are among the local residents who are actively trying to save the theater. Crewdson recently came across the Ambrose picture in his archives, and was struck by its beauty and magical quality, and what a time capsule it had become. He decided to use it to benefit the cause. The picture was made when Crewdson was embarking on the body of work that would ultimately be made across eight productions, shot on an 8 x 10 camera with his full cinematic lighting team and a production crew of over a hundred people. Beneath the Roses remains his most elaborate and lengthy undertaking to date. Here, Crewdson and Ambrose speak about the intergenerational experience of movie theaters, art in the Berkshires, and the making of an iconic image.

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 Collect a signed printed by Gregory Crewdson, with proceeds supporting The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA, and Aperture.

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 Collect a signed printed by Gregory Crewdson, with proceeds supporting The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA, and Aperture. $250.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003 $ 250.00 –1+$250.00Add to cart

View cart Description Orders will ship by July 7, 2023.Starting June 2, for one week only, Aperture will host a Gregory Crewdson special edition print sale in benefit of The Triplex, an independent movie theater in Great Barrington, MA. The picture, made by Crewdson 20 years ago, features actress Lauren Ambrose, and has never before been released, published, or shown publicly.

The Triplex, like so many small independent movie theaters across the country, faces an uncertain future. When news of its possible closing spread, a group of people living in or with ties to the Berkshires quickly came together, started a non-profit to buy the theater and save it. The small movie house is currently the only full time working movie theater in town, or for 45 minutes in any direction. But the Triplex’s legacy looms larger than that. For Crewdson, and many others, the theater is associated with the late legendary film critic Pauline Kael, who lived in Great Barrington. Kael was a family friend of Crewdson’s, and he used to see movies there with her, especially in her later years. Many other local artists, writers, and filmmakers have their own anecdotes about Kael frequenting the theater, and there are even discussions about renaming it after her. A young Wes Anderson famously screened Rushmore there for her, and then wrote about his experience in The New York Times.

Gregory Crewdson and Lauren Ambrose are among local residents who are actively trying to save the theater. By a stroke of serendipity, Crewdson had just recently come across the picture he made featuring Ambrose in his archives and was struck by it, its beauty and magical quality, and what a time capsule it had become. He decided to use it to benefit the cause. The picture was made in 2003 when Crewdson was just embarking on the body of work that would ultimately be made across 8 productions, shot on an 8 x 10 camera with his full cinematic lighting team and a production crew of over a hundred. Beneath the Roses remains his most elaborate and lengthy undertaking to date. This is the first time Crewdson has made an unreleased work from the series available as an editioned print.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003, Digital pigment print, 8.2 x 12.7 in. (image) 11 x 14 in. (sheet), will come signed by the artist. The special edition will remain open and available for one week only, through June 9th at 11:59 PM ET. The price of the print is $250. Details

GREGORY CREWDSON

Untitled, Unreleased #4, 2003

Digital Pigment Print

Signed by the artist

Image Size: 8.2 x 12.7 in.

Sheet Size: 11 x 14 in.

© Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson (born in Brooklyn, 1962) is a graduate of the Yale School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut, where he is now director of graduate studies in photography. His series Beneath the Roses is subject of the 2012 documentary Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters. Crewdson’s awards include the Skowhegan Medal for Photography, National Endowment for the Arts Visual Artists Fellowship, and Aaron Siskind Foundation Fellowship. His prior books include Twilight (2002), Beneath the Roses (2008), Cathedral of the Pines (Aperture, 2016), and An Eclipse of Moths (Aperture, 2020). Crewdson is represented internationally by Gagosian Gallery.

Lauren Ambrose: I’m interested in how you came to be a part of Save the Triplex. My husband Sam [Handel] is working very closely on this project. And we immediately got involved when we heard what was going on, because basically, it makes immediate sense why the Triplex needs to be owned by the community in a nonprofit format.