Aperture's Blog, page 26

September 1, 2023

La Dolce Vita According to Sam Youkilis

Italy is a weird place. It’s a country full of contradictions, where monuments of the past tower ominously over the present, where violence, beauty, and sensuality are inextricably intertwined. With this ineffable nature, it’s hard even for Italians to agree on proper representation. They have, however, perfected a nostalgic, idealized way of portraying their dolce vita, a postcard version born of the post-World War II economic boom, with sweet songs, vibrant Vespas, luscious food, beautiful clothes, perpetual summer, and a sense of serendipity. Like all stereotypes, it carries a dash of truth—with so much more beyond it.

Sam Youkilis is a born-and-bred New Yorker, with a background as a travel photographer. After studying photography at Bard College with Stephen Shore, he turned his lens on his community, documenting it in a diaristic way. New York has its own specific kind of insularity, though—the city famously being a sort of miniature of the wide world—and Youkilis felt the need to overcome it. Through travel, he began laying the foundation of his vision, with that clean graphic framing and a penchant for finding the poetic in the mundane.

Sam Youkilis, Breakfast in Venice, ItalySam Youkilis, Bruna, Monopoli, ItalyHis quantum leap happened with Instagram, particularly when the vertical “stories” format was introduced. It was the perfect medium for what we could call “micro-videos”: small fragments of reality that live somewhere between a still and moving image. When presented in series, they can create complex, layered narratives. Youkilis was one of the first artists to perfect a language consubstantial with the medium used to distribute it, achieving something similar to what photography did for print magazines not so long ago.

Today, half a million people and counting follow Youkilis’s Instagram account, and his aesthetic, embraced by traditional media and fashion brands alike, will soon be celebrated in a debut monograph due out this fall.

Italian summer happens to constitute much of Youkilis’s work. So, after a spike in post-COVID tourism—maybe coincident with the slow-burning fresco of Northern provincial life in Call Me by Your Name and the dramatic beauty of Sicily as seen in The White Lotus—it’s fitting to discuss all things Italian with an artist who interprets a very personal and seductive version of la dolce vita.

Sam Youkilis, 38°, Amalfi Coast, ItalySam Youkilis, Bagheria, Sicily, ItalyChiara Bardelli Nonino: How did you develop your distinctive video style?

Sam Youkilis: It happened quite organically as a natural departure from my photography. It started with video portraits and eventually became larger scenes of moving imagery. A lot of it is very spontaneous and reactive and I’m forced to frame and compose in seconds but some of it is a bit more meditated and slow. I feel it’s very much like that. I leave the house with no other plans but to take pictures, I’ll find a frame I like and wait for things to happen within that. And most of the time, it does. The camera has a strange way of conjuring things.

Bardelli Nonino: When did Italy enter the frame?

Youkilis: Well, there’s a family tie to it, even if sadly I’m not Italian. My parents met in Italy, got married there, and bought land in Umbria forty years ago, where I now live and am fixing a house. I’ve been visiting since I was a kid, learning the language, taking in the culture, and the Italian way of being.

Bardelli Nonino: What kind of artistic references shaped your idea of the country?

Youkilis: I draw a lot of inspiration from film. Most of all, Pasolini and Fellini. I think it’s an older Italy that I reference and look for. It has also something to do with the generation of Italians that I’m drawn to shoot, a way of life I think is on the verge of disappearing. There’s definitely an interesting tension between the sort of romanticized, visually striking, dolce vita Italy, and the overtourism and the more neglected aspects, like a certain hopelessness in the younger generations of Italians.

Generationally, a lot of these modes of behavior and ways of being are getting lost. It feels important to archive all of this in the present as these traditions are threatened.

Bardelli Nonino: Italians are definitely complicit in this nostalgic vision of the country (after all, we made it into a very recognizable brand), but there’s definitely a feeling among millennials and Gen Z, especially minorities, of being stuck there, of a lack of representation.

Youkilis: I get that there’s that imbalance in my work, but it isn’t deliberate. I work in a very organic way; I wander and follow my instincts and record the things that I’m drawn to. I want to show the humanity of the world I find daily, to record what I find funny and beautiful, ordinary and mundane. In Italy especially, I find the gestures, the pace, and sensibilities of an older generation more interesting. I also think the power photography has to preserve and memorialize is an important tool. Generationally, a lot of these modes of behavior and ways of being are getting lost. It feels important to archive all of this in the present as these traditions are threatened.

Bardelli Nonino: In general, the idea of Italy abroad has been largely shaped by a Mediterranean, Southern aesthetic, and Naples is very much a focus of your work.

Youkilis: I fell in love with Naples immediately, the first time I went, and it has been a huge source of inspiration for me over the years. Recently, I’m having a little bit of trouble making work there. It is such a visually rich place with so much to offer but I’m finding a lot of the output pretty homogenous. Plus, there’s an oversaturation of Napoli-themed images online. And still brands are hiring me for all these commercial campaigns with that in mind, so I am really specific about working in a certain way. Sometimes I suggest looking at local artists’ work to see if a brand is sure that it is my point of view they are after.

Sam Youkilis, Naples, Italy

Sam Youkilis, Naples, Italy  Sam Youkilis, Naples, Italy

Sam Youkilis, Naples, Italy Now and then I get criticized for “orientalizing” the Southern Italian way of life, but I do see the same tropes, motifs, and subjects in many Italian works as well. I don’t think I am using Italian culture as a prop, even if I have an outsider’s point of view.

Bardelli Nonino: Why do you think fashion was so quick to embrace your way of seeing?

Youkilis: I think storytelling-wise, it’s more interesting to focus on the craft, on the makers, on the cultural context in which the brand lives. It gives a sense of place to what they do that can’t be achieved by bringing the brand to a beautiful location that they have no connection to. I say “no” a lot, though, if I don’t feel I can produce something meaningful or have a say in the casting or creative direction. I am sure the fact that I’m being embraced by the fashion industry has also to do with the slight shift in beauty standards. The last thing I want to do, though, is use people I spend a ton of time building relationships with to sell clothes. Some of them have become quite iconic, like the man with the Tutto Passa (Everything goes) tattoo, but sometimes companies tread on the very thin line of stereotyping, especially in places so recognizable, like Napoli.

Bardelli Nonino: Are you ever afraid of misrepresenting your subjects, of getting them lost in translation?

Youkilis: I think it has a lot to do with the way images are disseminated and consumed today. I try to build a relationship with almost everyone I shoot, to be respectful. I try to explain where and how the work is going to exist. I don’t include captions because I want to build an open space for conversation, and I don’t want to impose my interpretation, but then I am releasing my work into this sort of ether where I can’t control it anymore. I can explain to a person that I’m going to make a video of them while they’re putting suntan oil on at a beach in Napoli and I’m going to publish it on Instagram. And they’re super excited about that, about getting a million views. But I can’t really explain to them that three months later I might be fighting with an Australian company that’s selling skincare and using this image as an example of what not to do.

Sam Youkilis, Naples, ItalySam Youkilis, A Vaporetto Ride in Venice, ItalyBardelli Nonino: Does your work change its meaning depending on who is looking?

Youkilis: Honestly, I don’t think so. And I have to say that one of the most meaningful things to me is that most generations of Italians can relate to it. I remember talking to the image director at a very famous fashion house in Italy who told me, “My mom, my grandma, and I, we all follow you.” And I ended up working with them. I loved it.

Bardelli Nonino: There’s a witty, humorous undertone in your work. Can it be misinterpreted?

Youkilis: It’s inherently part of my work, in a very sincere way. I want the viewer to feel like they’re seeing the world the way that I’m seeing it. I’m not seeking humor or making fun, but I think the things that I’m drawn to are often quite funny. I guess there’s also humor, to an extent, in some of the most stereotyped representations of Italy. I am obsessed by the visually alluring side of it, but I know it can also feel contrived. I guess my voice is to be found in that gap between sincerity and performance.

Bardelli Nonino: Do you consciously play with Italian clichés?

Youkilis: I used to do an exercise where, before going to a place, I’d search the geotag on Instagram or Google. So when I post from Pisa, for example, I’ll play with the classic “holding the tower with my hands” trope, trying to upend that image. Then again, I think it’s clear that I’m obsessed with Italian food, Italian traditions, and Italian people, so a lot of my work is also genuine appreciation.

Sam Youkilis, Naples, Italy

Sam Youkilis, Naples, ItalyAll photographs © Sam Youkilis 2023 and courtesy Loose Joints

Bardelli Nonino: Food is a huge part of your work, I guess because it’s also a huge part of Italian culture: the rituality, the aesthetic of it, the regional traditions and of course the exhausting fights over the right way to prepare a dish . . .

Youkilis: My dad owned two restaurants when I was growing up, so I was very much living and working in them in my teenage years. When I finished undergrad, and no one would hire me to do photo work, I started offering to shoot for free for restaurants. I was also actively working as a bartender, selling wine, and as a server, so I think my love for food comes from all of this. Italy is perfect for that love: the focaccia in Genoa tastes different than the one in Camogli, tomatoes are cooked in thousands of ways. What makes the country so special is how much things can change in towns five kilometers (three miles) apart, and how much pride each takes in its traditions. This defensiveness of customs, this stubbornness, makes Italy one of the most compelling places. At the same time, this fervent desire to maintain tradition stops Italy from moving forward in some ways.

Bardelli Nonino: Have you read The Leopard, by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa?

Youkilis: Yes!

Bardelli Nonino: There is this famous quote in it that is used all the time to describe Italy. It’s sort of a cliché: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Youkilis: I think it’s perfect.

Somewhere by Sam Youkilis will be published by Loose Joints in November 2023.

Evelyn Hofer’s Tender Gaze

The critic Hilton Kramer asked, in a 1982 New York Times review of Evelyn Hofer’s work, if it was possible “in this age of publicity for a photographer to be both famous and obscure at the same time?” This question comes to the fore in a show dedicated to Hofer currently on view at the Photographer’s Gallery, London, as it marks her first solo exhibition in the UK, after a vibrant career spanning more than four decades that included numerous commissions for Vogue, Vanity Fair, and the Sunday Times Magazine. Hofer, who died in 2009, was popular among her artist peers and more commercially minded clients, but out of favor in museum and gallery networks (she is notably absent in institutional collections).

Evelyn Hofer, Waitress, Garrick Club, London, 1962

Evelyn Hofer, Waitress, Garrick Club, London, 1962  Evelyn Hofer, Seminaries, Dublin, 1966

Evelyn Hofer, Seminaries, Dublin, 1966  Evelyn Hofer, Phoenix Park on a Sunday, Dublin, 1966

Evelyn Hofer, Phoenix Park on a Sunday, Dublin, 1966Born in 1922 in Marburg, Germany, to a wealthy family, Hofer fled the Nazis with her family, in 1933, during the First World War, moving between Mexico, Spain, and Switzerland. After short stints working in photography studios, where she refined her technical skills, she mentored with Hans Finsler, a Swiss photographer associated with the New Objectivity movement of the 1920s and 1930s. Hofer moved to New York in 1944, where she first began to receive magazine commissions. This retrospective showcases the brilliance and breadth of Hofer’s oeuvre. Hers is the eye of a documentarian, but it is not distant and unfeeling. Her approach is the opposite: a tender, inquisitive, open perspective. So much was worthy of Hofer’s attentiveness, and her photographs show viewers that she was a keen student of the everyday, capturing the lives of those she met on her travels as well as the fabric and structure of the cities she focused on, such as London and Dublin.

Hofer photographed waitresses in the Garrick Club, a private members’ club in the center of London. Two children—one perched outside on a wall, and the other partially visible indoors behind a curtain—stare curiously at her lens in Notting Hill, an area with a sizable Caribbean community who arrived to help with the British postwar labor shortage. In Dublin, we are introduced to footballers in a park after a match who wear muddy shorts. 1960s New York is brought to life in color, with a quartet of images focusing on shop fronts and signs throughout the city, showcasing the lives of working-class inhabitants.

Evelyn Hofer, Yayoi Kusama, New York, 1964

Evelyn Hofer, Yayoi Kusama, New York, 1964The exhibition also offers glimpses into Hofer’s distinctive approach to photographing interiors and inanimate objects, such as Marianne Moore’s gloves or a bowler hat perched on a shelf in front of a window advertising stout. Both serve to tell the story of a life, whether of a famous actress or an unknown gentleman in a London pub. Books, magazine covers, and newspaper spreads, all placed in vitrines, offer further context to Hofer’s practice, often focusing on her commercial and commission-based work, such as her city-focused book collaborations with the writer V. S. Pritchett, as well as a project with novelist and political activist Mary McCarthy on the past and present of Florence.

Hofer at times focused on other artists. One image, taken in Jackson Pollock’s studio in the 1980s, shows Lee Krasner’s paint-speckled shoes; Hofer would also make portraits of Andy Warhol and Yayoi Kusama in the 1960s. She was commissioned by Life magazine in 1974 to produce a photo story on newly married couples at New York City Hall, titled One Day in the Life of America. This body of work, hung on one wall of the gallery, recalls August Sander and his typological approach to portraiture. Made over the course of one morning, Hofer’s photographs feature newlyweds of different ethnicities and ages against the same muted background. She captures a variety of poses and different fashions of the era in vibrant color, an effect achieved through her use of the dye-transfer printing process, where cyan, yellow, and magenta dyes are applied by hand to an emulsion layer.

Evelyn Hofer, Four Young Men, Washington, 1968

Evelyn Hofer, Four Young Men, Washington, 1968  Evelyn Hofer, Soldier in Uniform with Girlfriend, New York, 1974

Evelyn Hofer, Soldier in Uniform with Girlfriend, New York, 1974  Evelyn Hofer, “Little Italy,” Mulberry Street, New York, 1965

Evelyn Hofer, “Little Italy,” Mulberry Street, New York, 1965  Evelyn Hofer, Self-Portrait with Gigi, 1974

Evelyn Hofer, Self-Portrait with Gigi, 1974On a 1966 trip to Dublin, Hofer photographed James Joyce’s death mask, resulting in a tightly cropped, haunting image. Another photograph, Saul Steinberg with a Younger Self, also asks us to consider time’s passing and our mortality; it features the well-known illustrator, in 1978, holding the hand of a cardboard-cutout image of himself as a young boy (an image from more than fifty years earlier). This image lingers long after you see it. Time is key to thinking about the method Hofer used: her four-by-five-inch, large-format camera required patience with meticulous planning and study for each shot. We are lucky to have had a documentarian as technically skilled and as tender as Hofer. If one wants to delve deeper, beyond this exhibition, an excellent publication on Evelyn Hofer, Encounters (2019), edited by Susanne Breidenbach, offers more photographs in all their richness and complexity. One attendee in the audience-feedback section of the gallery noted that they anticipated Hofer’s name would be mentioned alongside Sander’s as a genius of her craft in years to come. Hopefully, this show will bring her work into the spotlight, far from obscurity.

Evelyn Hofer is on view at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, through September 24, 2023.

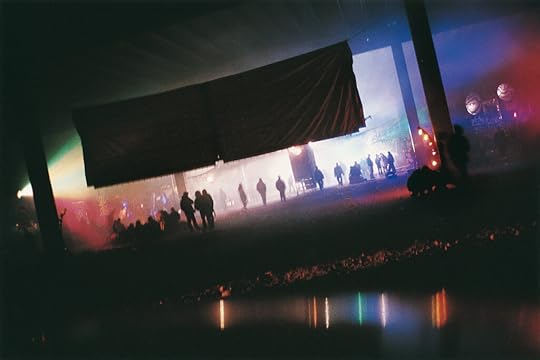

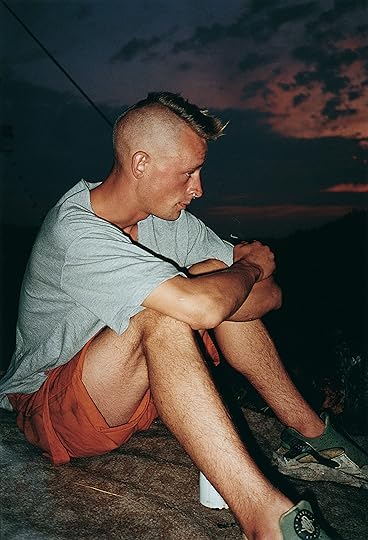

Finding Euphoria and Community in Rave Culture

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Fall 2016 issue, “Sounds” under the title “No System.”

Vinca Petersen didn’t set out to be a photographer. Her pictures began as a visual diary, documenting her leaving home at the age of seventeen, moving into a London squat, and becoming involved in the free party scene that blossomed across Europe in the 1990s. She has built up an impressive archive that records the techno-fueled raves and the lives of the travelers who organized them, but she started taking pictures primarily as a way of recording her own life, preserving her memories of the parties, memories which otherwise—as anyone who has danced all night will know—tend to become a bit blurry.

In the U.K., free parties grew out of the rave explosion of 1989, when crowds of up to twenty-five thousand people would gather in the English countryside for illegal all-night events fueled by MDMA and techno music. Although the primary impetus was hedonism, it developed into an exhilarating wave of mass civil disobedience in which Britain’s young briefly united and partied in defiance of the Conservative government, which throughout the 1980s had thrived on divide and rule. When the authorities finally realized this was a battle they couldn’t win and consequently relaxed restrictions on dancing and drinking, most of these revelers returned to the cities and to newly legal, all-night dance clubs. But a marginalized minority—with no jobs to fund expensive nightclubs, and a liking for the vagabond lifestyle—took to the road and continued putting on free techno parties in the countryside. They organized themselves as sound systems—a term taken from reggae music that encompasses DJs, rappers, huge speakers, and all of the technology needed to put on a party anywhere, indoors or outdoors.

Petersen had become involved in this scene while still in her teens in London. She did some modeling and as a result met the renowned fashion and documentary photographer Corinne Day, whose work had reacted against the gloss and artifice of the 1980s by exploring a different kind of beauty: young and edgy, but also awkward and flawed. The raw, personal style of Petersen’s photographs fit into this new aesthetic, and Day encouraged her to make more, giving her protégée film and even cameras. In 1994, when new, draconian laws were passed to suppress free parties in the U.K., most of the sound systems Petersen knew fled to mainland Europe. She followed soon after, taking her camera with her, and remained on the road for nearly a decade. Everyone in the free party scene had their own stories, their own reasons for staying on the move, from ideology to a simple lack of money to a yearning for freedom. Petersen enjoyed the lifestyle: “I liked the earthiness of it all, and the traveling. I loved the practicalities, like finding somewhere to park for the night, finding water, going to a new supermarket to buy food, and cooking together. For me it was about a desperate need for community, I think.”

Life on the road wasn’t easy. They wandered through France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany, banding together with other sound systems to put on huge parties in remote countryside locations in the summer, then separating to seek out smaller, more urban venues, such as empty warehouses, when the weather got colder. The travelers played what Petersen describes as a constant game of cat and mouse with the police. As a result, they were wary of outsiders, especially those taking pictures. Cameras were routinely confiscated at parties, or film was removed. Of the few pictures by other photographers that exist of this scene, most were taken surreptitiously, and seem distant. Petersen’s images, by contrast, have been taken by an insider. Working with small, inconspicuous cameras, she sometimes didn’t even look through the viewfinder before clicking the shutter; other times she’d leave a camera on a bar overnight and retrieve it in the morning to see what had been recorded.

All photographs by Vinca Petersen, from No System (Göttingen: Steidl, 1999)

All photographs by Vinca Petersen, from No System (Göttingen: Steidl, 1999)Courtesy the artist

The resulting pictures are intimate, warm, but also unflinching, celebrating the travelers without romanticizing them. Petersen shows the damage as well as the highs of drug use, the litter and destruction the travelers left in their wake, as well as the euphoria of their parties. It’s a time and place that already feels distant: a world without cellphones and distracting screens.

Petersen’s fellow travelers often criticized her for hiding behind a lens, saying that it stopped her from being fully present in the moment. “A photograph, especially if it’s not a digital one,” Petersen remarks, “is a recording of the moment for another point in time. I used to struggle with that. But then over the years, of course everyone started asking me for copies.”

Eventually she put together a book, No System (1999), going back on the road for another year in order to obtain permission from everyone featured before it was published. A second edition was published in 2020, and Petersen hopes that a new generation will see her pictures as a guide to an alternative way of life.

Related Items

Aperture 224

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]August 25, 2023

The Defiance of South African Women Photographers during Apartheid

“How do we refigure the archives?” the late scholar Bhekizizwe Peterson once asked about the legacy of the colonial-apartheid memory project in South Africa today. Bringing to bear the multiplicity of the country’s official records—as a space of opportunity but also omission—Peterson’s inquiry invites imaginative ways to redress fixed and obscure narratives that still linger. The recent group exhibition Defiant Visions, curated by Marie Meyerding for apexart in New York, which closed in July but is still on view online, shines a light on the perspectives of women during apartheid, accentuating cracks in the archive and exposing new possibilities for these histories.

Defiant Visions brings together five photographers and two filmmakers whose divergent accounts of apartheid magnify the intricacies of women’s everyday under white-minority and patriarchal rule. It also exposes the effects of race, gender, and class structures on lives, namely Black women. The exhibition covers the 1950s to the 1990s, a time marked by resistance campaigns, an emergent field of Black photojournalism, and the shift to democracy. On view include a 1950s magazine archive spotlighting the biography and photography of Mabel Cetu, and Deborah May and Georgina Karvellas’s short documentary film You Have Struck a Rock (1981), about the 1956 Women’s March in Pretoria against pass laws for Black women.

The extensive and brutal forced removals of Black and brown people across South Africa are given nuance in Jansje Wissema’s 1970s account of District Six, a mixed-race community in Cape Town that was proclaimed as whites-only, resulting in the displacement of thousands of its residents. Meanwhile, Zubeida Vallie’s and Lesley Lawson’s photographs meditate on the quiet and more action-oriented moments of the 1980s, an era defined by increased resistance efforts against the state’s repression. Also included is a sweeping collection of Mavis Mtandeki’s images chronicling Black women’s lives in the period surrounding the country’s first democratic election in 1994.

Earlier this summer, I spoke with Meyerding about some of the artists gathered in the apexart exhibition and how their practices can help us make sense of apartheid, photography, and history-making at large.

Mavis Mtandeki, UWCO Members at the Second Funeral of King Sabata Jonguhlanga Dalindyebo at Bumbane Great Place, Eastern Cape, October 1, 1989

Mavis Mtandeki, UWCO Members at the Second Funeral of King Sabata Jonguhlanga Dalindyebo at Bumbane Great Place, Eastern Cape, October 1, 1989Stefanie Qaba Jason: What prompted Defiant Visions?

Marie Meyerding: I was working on my doctoral thesis, which is on women and photography in apartheid South Africa. From the start, I wanted to make my research accessible to a larger audience beyond the small academic bubble. The title of the show is derived from Darren Newbury’s important 2009 book Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa, which traces how photographers documented the violence that dominated anti-apartheid imagery—but this book focuses primarily on well-known male photographers. So, in Defiant Visions, I wanted to foreground the work of largely ignored women photographers and showcase their vision of everyday life during apartheid. On display is work created from the 1950s until the 1990s, which has been produced by Black and white women. Many of the resulting black-and-white images portray women and expose issues of intersectionality, which are moments where various social classifications such as race, gender, or class overlap, resulting in systemic oppression.

Apexart’s exhibition style doesn’t allow any captions to go directly with the works in the space, so it was clear to me that I needed to find other ways of contextualizing the photographs. Some of the ways in which I did this are the timeline, which you’ll encounter when entering the space, and a table and chairs, where you can take your time to read through different photobooks. I also decided to include a documentary, You Have Struck a Rock. The film is a collage of images and songs, interviews, filmed scenes, and photographs, recalling the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria and its aftermath.

Related Items

Aperture 227

Shop Now[image error]

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic

Shop Now[image error]Jason: How did you become interested in this history?

Meyerding: I did my masters at the Courtauld Institute of Art in a special option course on documentary photography, film, and video in contemporary art. I wrote my master’s thesis on Candice Breitz, a South African photographer and video artist, and found that in her work she deals a lot with the representation of women. Then I asked myself if she drew inspiration from other women photographers from South Africa. Once I started doing research on women photographers working in apartheid South Africa, there was very little research that I could find, apart from some articles which were crucial for me by Kylie Thomas or Patricia Hayes. But I thought, This cannot be true; women must have been more involved with photography. That was the start of my PhD. Now I’ve submitted my PhD thesis to the Department of African Art at Freie Universität Berlin, which is the only department on African art in the German-speaking university landscape. What I can already tell you is that from the rise to the fall of apartheid, women were involved with photography.

Jansje Wissema, District Six photographed before the removal, early 1970s

Jansje Wissema, District Six photographed before the removal, early 1970sJason: Can we speak about the archival nature of this exhibition? I’m thinking of the black-and-white photographs, the archives presented, and some older technical equipment, like the VHS and the slide projector. What comes forward is a sort of commentary on South African archives, or maybe archives at large.

Meyerding: For me, archives are a source of invaluable information that require a lot of time to be spent in to uncover histories which are not traceable in online databases or keyword searches. Many of the women who you’ll encounter in Defiant Visions won’t appear in any keyword directories, so you really need to sit down and go through the archives and try to find out more about them. Through the presentation of the photographs or the film, I wanted to show the way the works would have been shown at the time when they were produced or distributed. Most importantly, I wanted to convey a sense of the materiality of these works, so that you get a feel for the size and the colors of Zonk! magazine, that you hear the clicking of the slide projector, that you see the film on an old TV, and also that you get a sense for the contextualization and the seriality of the photographs as they appeared and continue to appear in photobooks.

Jason: I’m also interested in the period that bookends this exhibition: 1948 through 1994. We see a timeline of the events across these dates as soon as you walk into the space.

Meyerding: Displaying this timeline was crucial for me for making Defiant Vision accessible to a larger audience, because not everyone walking into the space knows what apartheid was. It gives you a setting for the works on display and also explains some of the abbreviations visitors encounter in the photographs on display. It gives a bit more of context to people who are not familiar with apartheid and the history of South Africa.

Mabel Cetu, Unidentified photographer, Zonk! African People’s Pictorial, October 1956

Mabel Cetu, Unidentified photographer, Zonk! African People’s Pictorial, October 1956Jason: The show makes important contributions to research on photographers such as Mabel Cetu. It also opens with Cetu’s works and archival material relating to her life. Could you share more about the recovery of these archives and your presentation of in the exhibition?

Meyerding: Mabel Cetu is considered South Africa’s first Black woman photojournalist. Though her name is often mentioned in research on the history of photography in the country, her work has not always been attributed in official archives. When I started doing some research on Cetu, I spent several days in the British Library leafing through microfilm of magazines like Zonk! African People’s Pictorial, which was the first mass-circulated magazine directed at Black people in South Africa. When I found Cetu’s photographs, I was thrilled, especially because Cetu’s work was mostly published uncredited at the time.

Mavis Mtandeki, Jean Benjamin at the United Women’s Congress General Council Meeting at a Church in Bellville, 1989

Mavis Mtandeki, Jean Benjamin at the United Women’s Congress General Council Meeting at a Church in Bellville, 1989Jason: Mavis Mtandeki’s photographs are given critical attention in the exhibition. The show also includes the photography book Sights of Struggle: The History of the Tambo Village Women, which you coproduced with Mtandeki.

Meyerding: Mavis Mtandeki is the photographer I spent most time with over the course of several years. When I started my dissertation research, we were in touch via WhatsApp for over a year because of Covid-19 restrictions, so I couldn’t go to South Africa. We only met in person in 2021 and had numerous meetings where she showed me her archive, which included a lot of photographic prints and other materials. I was able to raise money to digitize and then publish parts of her archive. We digitized her archive with the Photography Legacy Project, led by Paul Weinberg, so her archive will be available online soon, once we have completed the metadata.

The publication Sights of Struggle includes Mavis Mtandeki’s photographs and some texts of mine that give more context to the photographs, which is the result of long conversations with Mavis Mtandeki. I’m grateful that this publication worked out, because Mavis Mtandeki and I helped each other to create a book through mutual exchange and support. Earlier this year, we had book launches in Cape Town, in the city center and Tambo Village, and Berlin. I’m thrilled to see how people engage with her work in the exhibition and through the different ways of presenting her photographs.

Lesley Lawson, Minding a laundry press, dubbed “the abortion machine” because it caused so many miscarriages, Johannesburg, 1984

Lesley Lawson, Minding a laundry press, dubbed “the abortion machine” because it caused so many miscarriages, Johannesburg, 1984Jason: How did apexart’s geographical location in New York, the space, and the potential audiences encourage your curatorial vision for the show?

Meyerding: I worked with an exceptional team at apexart who offered support in making this exhibition happen and helped me get around some difficulties in producing a show in a small space, with many works, on also a small budget. What is also crucial is that apexart produces shows that are accessible both in New York City and online, enabling an international audience to see the show not only now but also in the future.

Lesley Lawson, Trade unionists celebrate the unbanning of the ANC, Johannesburg inner city, February 2, 1990

Lesley Lawson, Trade unionists celebrate the unbanning of the ANC, Johannesburg inner city, February 2, 1990Jason: Do you have any plans to show the exhibition in South Africa?

Meyerding: No. Unfortunately, apexart exhibitions don’t typically travel to other institutions. This is also why I’m even more grateful for the opportunity of visiting the show online, because apexart produced a Matterport, where you are able to walk through the space and have a look at each work individually in quite a good quality. I was surprised at how well that’s possible. Online you will also find the exhibition essay, details of all the works that are on display, and videos of the curatorial 3D tour as well as the public programs that accompany the show. I hope that the photographers whose work is on view will gain greater attention and that the show will spark further uncovering of histories of women’s involvement with photography, be it in South Africa or elsewhere.

Defiant Visions was on view at apexart, New York, from June 1 to July 29, 2023.

August 17, 2023

Toyo Miyatake’s Indelible Record of Life inside the Manzanar Internment Camp

The week after Trump won the presidential election, I attended an Asian American community meeting in Manhattan where one of the attendees told me the following story. The day after the election, he ran into a senior partner at his work, jubilant about the results. Now, the older man said, we can finally round up the gays, the Muslims, and the immigrants. Shocked by this brazen declaration, my new acquaintance pointed out that he was gay himself, and the children of immigrants. When he returned to his office, he saw an email. It was not an apology. The partner wrote that Korematsu v. United States—the 1944 Supreme Court decision justifying the Japanese American prison camps—was still good law.

This senior partner wasn’t alone. I remember waiting for a flight at an airport and watching Fox News pundits suggest that the prison camps provided a precedent for us to register and imprison Muslims. Then ICE started taking children who had traveled across the border and throwing them in Fort Sill in Oklahoma, which once imprisoned some seven hundred Japanese Americans. I thought the camps were ancient history, an Asian American friend bemoaned to me at a coffee shop. But they weren’t.

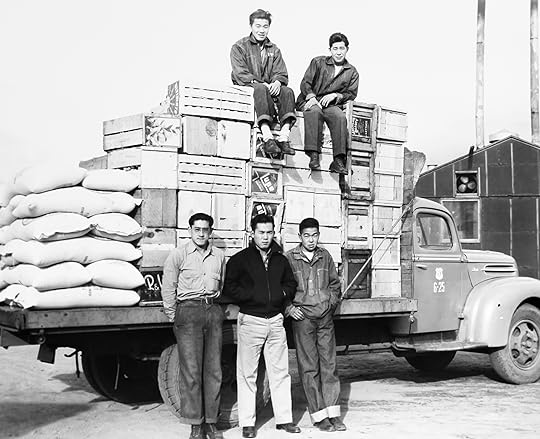

Toyo Miyatake, Manzanar Food delivery crew making delivery to the mess hall, ca. 1942–45

Toyo Miyatake, Manzanar Food delivery crew making delivery to the mess hall, ca. 1942–45  Toyo Miyatake, Internee-run beauty salon under the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprise, ca. 1942–45

Toyo Miyatake, Internee-run beauty salon under the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprise, ca. 1942–45 In 1942, Toyo Miyatake left his studio in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo and brought his wife and four children to the Manzanar concentration camp in the central Californian desert. Cameras were prohibited, so Miyatake snuck in a lens and fashioned a wooden box into a body for his surreptitious camera. “As a photographer, I have a responsibility,” he told his teenage son Archie. “I have to take all the pictures in Manzanar to keep a record of what’s going on here.”

An unusual candidate for incarcerated auto-ethnographer, Miyatake had been a well-known Pictorialist before the war: a friend of Edward Weston’s, a collaborator of the cinematographer James Wong Howe, and winner of an award from the International Photography Exhibition in London. His métier consisted of poetic abstractions. His landscapes captured no humans, just the delicate shadows of bushes, falling like brushstrokes over snow-covered hills. The figures in his Little Tokyo cityscapes exist only as silhouettes. His dancers, gestures of shadow and motion. But there was another Miyatake: the much less expressionistic professional photographer who ran a commercial studio. He courted his wife by taking her picture, yet his most libidinous portrait shows Michio Ito, the charismatic performer who danced alongside Martha Graham and inspired W. B. Yeats’s Noh theater experiments. In Miyatake’s portrait from 1929, Ito seems capable of conveying modernist ferment through just a hairstyle and a glance. His hair hides his face in a center part, but even this obscured gaze communicates an erotic recalcitrance. He looks like he’s arrived from the future, the way silent-film actors sometimes do—or at least from the grungy glam 1990s of the actor Leslie Cheung.

What did Miyatake, driven by a mission to document an abhorrent experience, decide to preserve?

In 1942, Ito was deported to Japan as an enemy alien, and Miyatake banished to Manzanar, a dreamy aesthete and studio portraitist in a prison wasteland. When viewing the colonial archive, we often search for how oppressed people understood their own predicament. For life at Manzanar, we can simply look at Miyatake’s photographs. What did this man, driven by an ethical mission to document an abhorrent experience, decide to preserve? A baseball batter readying for the pitch. Children cradling their dolls, borrowed from a toy loan center. Smiling majorettes twirling their batons in the air. When I’ve taught the literature of the Japanese American imprisonment, it is precisely these details that trip students up—the sense that daily life continues, even in a concentration camp. In Farewell to Manzanar (1973), Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston describes her brother’s playing in a prison swing band. In Citizen 13660 (1946), Miné Okubo writes that the prisoners at the Topaz camp in Utah “went wild with excitement” over a snowball fight. Why, my students essentially asked, wasn’t everyone constantly miserable?

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Obviously, we shouldn’t undersell the camps’ fundamental crappiness. These permitted types of recreation were ways of assimilating prisoners into American nationhood (baseball!). When Miyatake was at Manzanar, sewage tainted the drinking water with E. coli. Residents died in the sweltering 110-degree heat. Military police fired on a rioting crowd, killing two. “Manzanar was a devil’s playground,” said Fukiko Elisabeth Komatsu, imprisoned with her mother and siblings, “and the dust storms came through at 60-miles an hour to make our lives even more harsh and miserable.” Nor did Miyatake live at the Tule Lake concentration camp, the prison for the radicals, which Konrad Aderer’s documentary Enemy Alien (2011) calls the Guantánamo Bay of the Japanese American incarceration experience. There, prisoners were shackled in the camp stockade, shot at by battalions of tanks, or simply executed in broad daylight. We might describe these prisons using the work of the theorist Giorgio Agamben, who writes that during crises such as the Third Reich and, arguably, post-9/11 America, groups can become stripped of their legal status and reduced to what he calls “bare life.” My students were essentially asking, “Why weren’t the prisoners diminished into pure abjection?” The answer is that Agamben was wrong. The men locked up at Attica prison wrote poetry. People in refugee camps, which activists wryly call the most permanent form of architecture, still find ways to care for one another, make art, and live life. Miyatake photographed women getting their hair done.

“Although Miyatake lived in the hothouse environment of simmering anger, fear and suspicion that some Manzanar chroniclers have described,” the author Nancy Matsumoto writes, viewers may be “disappointed,” because “his photographs bear no signs of violence or anger.” The enigma of his images is their mundanity, which we can better understand if we compare them to those of Manzanar taken by two of America’s most famous photographers, Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. A landscape photographer uninterested in portraiture or politics, Adams wanted to show that the prisoners weren’t terrorists but smiling schoolgirls, Norman Rockwell–esque nuclear families, and proud men in uniform. What did Adams omit? Any cultural difference, as well as the barbed-wire fences and guard towers.

Toyo Miyatake, Three-generation family, son enlisted in the US Army, ca. 1942–45

Toyo Miyatake, Three-generation family, son enlisted in the US Army, ca. 1942–45Dorothea Lange called Adams’s efforts “shameful.” Her photographs, which were censored and impounded by the military until 2006, depict Manzanar as a stark, perpetually dusty prison. As in her migrant portraits, she displays a novelistic ability to capture her subject’s gaze, the solemn look or glance cast slightly askew, insinuating some private turmoil. While Lange’s images are generally seen as better than Adams’s, both had one thing in common. They took photographs of their own projections. Adams saw the prisoners as model Americans, Lange as people experiencing injustice. Miyatake did not understand the Japanese Americans as political idealizations—and that is exactly what perplexes us about his work. He saw little need to glorify, humanize, or even individualize the prisoners. For he was one of them.

One Miyatake photograph shows a crowd facing the monument at the center of the Manzanar cemetery. The obelisk fills the left third of the image, a white geometry, its paleness continued by the flecked outline of the Sierra Nevadas. Aside from a girl looking toward the camera, we cannot see any of the mourners’ faces. Their bodies form a black mass barely recognizable as people. They turn away from us. They will not tell us what they know.

Avoiding the poles of didacticism and aesthetics, Miyatake documented outside such binaries. “Not yes or no, it could be maybe,” the artist Hirokazu Kosaka says in the 2002 documentary Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray. “It’s not white or black but infinitesimals of gray. That’s what Miyatake was trying to create.” Some of his images lack any people, depicting Manzanar as a barren environment. Barracks tile and recede to the background, but instead of a horizon opening to a broader world, the foreground is encased by Mount Williamson. Not unlike in Hokusai’s prints of Mount Fuji, the peak is a spectral crystal, a gargantuan mass always visible but never foregrounded, the inescapable reality of imprisonment banished to the unconscious.

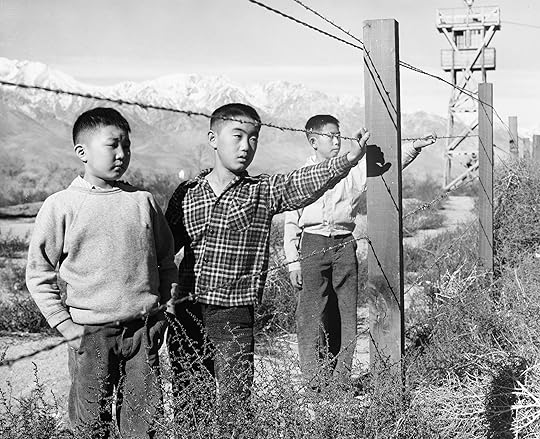

Toyo Miyatake, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire, 1944

All photographs courtesy Toyo Miyatake Studio

It is not necessarily that Miyatake preserved some authentic truth. Another photographer who once worked at his studio, Jack Iwata, composed similarly quotidian photographs of daily life in these prison camps, but his images occasionally suggest more emotional range, both stark drama (American soldiers holding bayonets as cars enter Manzanar, black smoke rising up in plumes from a fire at the Tule Lake camp) and joy (a woman wearing a crown declaring her the Queen of Manzanar). Seen beside them, what emerges in Miyatake’s photographs is a meticulous reticence, a refusal of the evocative flourishes he once adopted as a Pictorialist. He became the diarist of a society, one who, whether because of personal temperament or camp surveillance, did not photograph the violence of the prison. Instead, he documented weddings, graduations, newborns entering the world in a prison. Both he and the photographer Corky Lee were forced by Pacific wars and spatial segregation into becoming community archivists, but they traveled in opposite directions. Lee had a flair for adventurism and famously captured Chinatown protestors brawling with cops. Miyatake spent the Manzanar riot in his barrack. Lee was a radical who gradually adopted expressive and inventive forms of mise-en-scène, but Miyatake left behind his lavish romanticism and the formal poses of his portraits. Unlike Lange’s brooding depiction of ruminating prisoners, what is most mysterious about Miyatake’s photographs is that we do not know how to make them available for our own emotional use.

Unlike Lee, Miyatake rarely took photographs that overly implied a political message, but there are exceptions. In a photograph for the 1944–45 Manzanar yearbook, a hand holds up pliers, positioned as if to sever the barbed wire slicing the background. His most famous photograph, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire (1944), shows three boys considering the steel fencing that diagonally intersects the frame. A guard tower stands behind them. Unlike Miyatake’s more quotidian portraits, this image vibrates with implied psychology and the sense that these imprisoned children also serve as symbols of some sort. There is a less famous version of this photograph in which only one of the boys touches the wire. He bends back slightly, his shoulder tucked back awkwardly, and connects a single finger to the wire, as if feeling for the prick of the barbs. In the more well-known image, two of the boys raise their hands and almost lean on the wire, like dancers lined up on a ballet barre. They are testing the boundary.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

While it is tempting to reduce Miyatake’s photographs to documentation, Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire was more constructed than it appears, the scholar Jasmine Alinder writes: the boys actually stood outside the camp and looked in. Many prisoners found the incarceration experience too terrible to talk about, so perhaps we can read the photographs as not only describing the implied barbarism of locking up children but representing their future selves wondering how to probe the repressed past. Akemi Ookas, the daughter of one of the boys, reconvened the three subjects, now in their eighties, for the 2017 documentary Three Boys Manzanar, a project not unlike Lee’s 2014 restaging of Andrew J. Russell’s 1869 golden spike photograph—taken in Utah to commemorate the completion of the transcontinental railway—to include descendants of Chinese rail workers.

If the boys stood outside looking in, this meant Miyatake positioned himself inside the prison. When the war ended and the camps opened, some, rather counterintuitively, did not want to leave. They may have had nowhere to go. The push toward incarceration had been driven by corporate agribusinesses, which seized more than a quarter of a million acres of Japanese American farms. Leaving meant relinquishing the community of the prison camps for the very racist world that had imprisoned them. Consider a man named Joe Takeda, who returned from the Gila River prison to his San Jose pear orchard, where assailants poured gasoline on his home and shot at his car. Miyatake did not leave immediately. He stayed and documented those who lingered. Ralph Merritt, Manzanar’s director, warned the now-free residents against “crowding into the seven southern counties of California” and creating “another Japanese problem.” Miyatake did the opposite. He spent the remainder of his life photographing Little Tokyo. With both the Pictorialist movement and his fine arts career having molted away, he trained his camera on the weddings, families, births, and deaths of those who lived there. “So, the ancestors are looking down. / The poet, and/or his poem, is looking up,” writes the poet Brandon Shimoda, whose family members were imprisoned in Utah, Montana, and Wyoming. “We are in between.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

August 8, 2023

Japan’s Unparalleled History of Photography in Print

Not long ago, Daido Moriyama told me that his favorite way of encountering photographs is in a book or magazine. Nobuyoshi Araki has emphasized that “the photobook—not too big—is still the best way to show photographs.” And Tomoko Sawada has proclaimed that her photobooks are “works of art in their own right.” Indeed, many Japanese photographers understand books, as well as magazine features, as the ideal means of presenting their artistic output, often putting them on par with framed photographs on a wall. The importance of the printed page to Japanese photography cannot be overemphasized.

Over the last twenty years, images by a growing number of Japanese photographers have been shown in exhibitions worldwide. Simultaneously, the international photography community has begun to accept the photobook as a valid form of artistic expression, discovering, in the process, the innovativeness and significance of Japanese publishing. Yet there are still few comprehensive English-language books that consider the history of and specific sociocultural context for Japanese photography. Publications such as the 2003 exhibition catalog The History of Japanese Photography, by Anne Wilkes Tucker, Dana Friis-Hansen, Ryūichi Kaneko, and Joe Takeba, and my own book Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography since 1945 (2018) include select photobooks and periodicals but do not focus on them. The short-lived but influential 1960s journal Provoke was examined in a 2016–17 touring exhibition and related catalog. Even so, the history of Japanese photography magazines has remained largely underexplored.

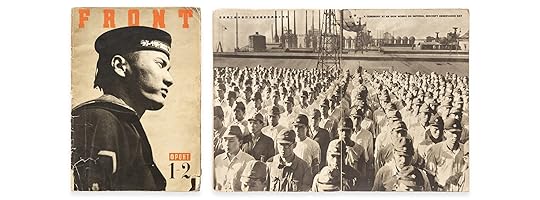

Cover of Front, Volumes 1 and 2, 1942, and spread from Front, Volumes 10 and 11, 1944, with photographs by Ihei Kimura

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s–1980s (Goliga, 2022; 500 pages, $100), by Ryūichi Kaneko, Masako Toda, and Ivan Vartanian, sets out to change this by investigating one hundred years of photographic history in Japan, told through carefully chosen issues of camera and photography magazines. The book unfolds with an introduction describing the authors’ approach and objectives. As an exhaustive overview is impossible, they aim to convey “one story of Japanese photography through the printed pages of periodicals . . . intentionally avoiding a western-oriented approach to ideas of photography, authorship, reading, and the relationship of images.” It offers readers a chance to “see Japanese magazines within a Japanese context.” Some selection criteria are explained. The stories and features highlight significant moments within the history of Japan and its photography scene, shedding light on the connection between magazines and photobooks as well as the roles of photographers and editors. Nude photographs—apart from those of women who were active participants in the creation of their photographs—were excluded, whereas camera advertisements that provide an indication of how technology developed over the years were deliberately left in. Linguistic and design challenges, such as having Japanese spreads, which are read top to bottom and right to left, reproduced in an English book, are addressed in an honest way, conveying the authors’ awareness of their role in presenting Japanese photographic culture to “Western” readers.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

This comprehensive volume is divided into three parts, eight chapters, and twenty- four thematic subsections in roughly chronological order. Starting with the first camera-related publications of the nineteenth century through to those released at the end of the golden age of Japan’s camera industry in the 1980s, the book immerses the reader in the work of internationally famous photographers, along with figures such as Shōji Ueda and Hiromi Tsuchida, who remain overlooked outside of Japan. The selection makes visible the diversity of Japanese imagery and approaches while also showing how magazines were a male domain that mostly excluded female photographers.

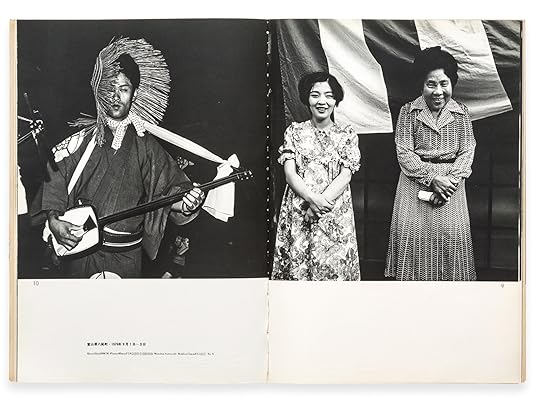

Spread from Asahi Camera, November 1936, with photographs by Nakayama Iwata

Spread from Asahi Camera, November 1936, with photographs by Nakayama Iwata  Spread from Camera Mainichi, September 1977, with work by Issei Suda

Spread from Camera Mainichi, September 1977, with work by Issei Suda The authors have also compiled photographers’ writings that accompanied their images in the magazines, ranging from the realist master Ihei Kimura’s descriptions of his documentary approach toward photographing farming villages in Akita to an imagined, humorous dialogue, with erotic undertones, between a photographer and his subject by Araki. Often translated into English for the first time, these texts reveal how words were often significant components of the visual layouts.

The book immerses the reader in the work of internationally famous photographers, along with figures such as Shōji Ueda and Hiromi Tsuchida, who remain overlooked outside of Japan.

Reproductions from difficult-to-access early magazines that appear in the book are particularly valuable. Hanzai Kagaku, from 1932, features captivating montages that were created collaboratively. An editor provided photographers with a theme: for example, “evoke the atmosphere of the train terminal” using specific motifs, such as a “bustling train platform.” The resulting photographs were published as artistic collages with the editor’s original prompts, creating a fascinating interplay of image and text, of assignment and photographic interpretation. The 1940s war propaganda magazine Front contains striking photographs by Kimura and designs by Hiromu Hara. It is also refreshing to see iconic photographs from the 1960s to 1980s in their original context, including Araki’s first major work, Sacchin, from 1964, Takuma Nakahira’s Fūkei (1970), Masahisa Fukase’s Ravens (1976–82), and Kikuji Kawada’s series Los Caprichos (1972).

Spread from Camera, October 1949, with work by Shōji Ueda

Spread from Camera, October 1949, with work by Shōji UedaAll photographs from Ryūichi Kaneko, Masako Toda, and Ivan Vartanian, Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s–1980s (Goliga, 2022)

The idea for Japanese Photography Magazines was born when Kaneko and Vartanian collaborated on an earlier project about 1960s-to-1970s Japanese photobooks. Vartanian realized that “a discussion of photobooks required a considerable understanding of photography magazines, because that culture was the context and system through which the photobooks from Japan were greatly informed.” Japanese Photography Magazines, a seven-year undertaking, is a well-researched, balanced, and sensitively designed book that provides a compelling story and convincingly presents the magazine format as a major, genre-defining space.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Japanese Photography Magazines is also the last major contribution by the legendary Kaneko, whose death in 2021 shocked the Japanese photography community. In addition to being thirty-second in the lineage of monks in charge of the Tokyo Buddhist temple Shogyo-in, he was a pioneering historian, teacher, and curator of Japanese photography, and an avid collector of magazines and books. Without Kaneko’s expertise and collection, this impressive publication would not have taken shape. It will, hopefully, contribute to more in-depth research on overlooked Japanese photographers and Japan’s unparalleled photography culture, beyond the “fetishizing” of vintage prints and photobooks as collectors’ items.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America,” in The PhotoBook Review.

August 4, 2023

Reagan Louie on Surviving the American Dream

In the 1970s Reagan Louie moved to San Francisco to take a teaching job. The city still had a countercultural flair, and Louie, who at the time considered himself something of a rebel, began documenting the streets and vibrant businesses of its Chinatown. He later traveled to China, connecting to his family’s history and capturing the country’s rapid pace of change. By now, he has spent more than fifty years exploring issues of migration, cultural transformation, and intergenerational dialogue through photography.

As the son of immigrant parents, Louie’s decision to take an art path was a bold one. He studied with such major figures as Robert Heinecken and Walker Evans, and considers Chauncey Hare, the photographer-activist who famously abandoned the art world to focus on the plight of workers, a mentor, even though technically Hare was Louie’s own student. Louie also often felt estranged from the art world. After graduate school at Yale, he almost gave up on art, taking odd jobs digging sewers before pushing himself to return to photography so that he could pursue his original “intent to understand and discover the world.”

In 2022, Louie’s work was included in one of three inaugural exhibitions related to the Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI) at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, an ongoing initiative dedicated to the study of Asian American art. Here, Louie speaks with Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, codirector of AAAI, about his artistic journey and the stakes today for Asian American visibility.

Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Henry Chong Rice Shop, 1979

Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Henry Chong Rice Shop, 1979  Reagan Louie, Jiao, Hefei, China, 1980

Reagan Louie, Jiao, Hefei, China, 1980 Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander: Let’s talk about this particular moment we’re in, which is both difficult and celebratory for Asian Americans.

Reagan Louie: Yes. Our talk is taking place at the beginning of the Lunar New Year and a few days after two mass shootings by Asian American men. For me, it represents the kind of ultimate American assimilation—these two men shot and killed as Americans, not as Asians. The tragedy illustrates a lot of things that I felt. They were unseen and isolated. That reveals to me this irony of the promise of the American dream, which can never be fully realized by people of color. They can never become white. For Asians, that foreclosure is double, because we’re still perceived as being quite exotic and inscrutable, and, therefore, forever alien.

This is, I think, what my work is about—being both Asian and American. It’s kind of like a Venn diagram, where the Asian circle and the American circle overlap. That union between the two circles of identity is what matters. Perseverance is the hallmark of my life, a quality I share with all Asian American artists, if not all artists. I’m not really sure where it comes from. But surely it has to do with survival, this profound need we have, or I have as an artist, and the success, if I’ve had any successes—I’ve had some—has been accompanied by many moments of feeling unseen and marginalized. In fact, I first believed that I had to turn my back on my Chinese culture to achieve the American dream, to be successful.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1 View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Alexander: You’re reflecting on your more than fifty-year-long career from a certain vantage point. In the early phases of your career, how much do you feel these factors of identity, both from your position as an Asian American and from how you and your work were seen, impacted the way that you moved through school or the art world? I’m thinking, of course, of your early experiences with Robert Heinecken and, later, Walker Evans, both of whom you studied with. To what extent did these questions come up then for you?

Louie: Almost never. Because at that time, it was all about formalism, and any other conversation was irrelevant. In the 1970s, there was no interest, like there is now, in any of the other questions, particularly around identity. There was always this struggle going on between my Asian side, which was almost the opposite sometimes of American behavior and values, which had privilege over your Eastern ideas or values or culture. You had to be extroverted, boisterous in America, not stoic. Hubris always triumphs over humility, and individualism over the collective. So these were all dynamics that were internal in the work I did.

Until college, I was a pretty indifferent student. I wasn’t your typical model Asian American student. I nearly flunked all my math and science classes. But somehow, in my first year, I took an art class as a gut course. But I was enchanted. It opened me up to new ways of looking and being and understanding the world, a new way of communicating, and I developed a curiosity that has remained to this day. This was a moment when the world was changing. I’m a child of the 1960s, and there was a bit of a rebel in me. I was seeking truth and light and beauty and all that. I was a romantic. I still am in a lot of ways.

This fusion in using the camera to find my Chinese, non-Western self comes with many obstacles, including adopting its logic and its values.

Alexander: That also makes me think about going back even further into your life—your mother and your father, and their roots, and how you came to be.

Louie: There was no precedent for becoming an artist. Growing up, I recall going to a museum only once. My family didn’t have time or interest in cultural matters, really. They were too busy making a living, like most people in that generation. So when I decided to become an artist, and not become a lawyer or a doctor, or at least a pharmacist, and studied art instead, I really knew deep down I had to abandon my family for the moment. Abandon those obligations, familial obligations of being the oldest son, and all those expectations that come along with it. I had to turn away from my Chinese self. I mean, literally, physically. I just didn’t see them for a while.

I chose this tool, photography, which is the quintessential Western invention, a paradox that both estranged me from my Chinese self and my family but also gave me a way back to discover and to integrate those two selves. This fusion in using the camera to find my Chinese, non-Western self comes with many obstacles, including adopting its logic and its values, the machine logic, which you kind of resist.

There’s a critical divide that needs to be recognized, or reckoned: immigration to America before 1965, and after. I’m a boomer. My generation’s experiences are more connected to that first wave of Chinese immigration that began in the nineteenth century. But I’m somewhere in the middle if we consider that the Chinese American experience is a continuum from the 1800s until now. My father was born in China. Even though I’m fourth generation on my mother’s side, which is very unusual, I identify as a second-generation citizen because my mother’s family really grew up in isolation, away from the surrounding communities. My first language is Cantonese. We lived in a pretty enclosed world. Both waves of Chinese immigrants came for the same reasons—for a better life for their families, for themselves. But we faced very different kinds of receptions. The pre-1965 immigrants faced open hostilities, physical violence, whereas the post-1965 generation was welcomed, albeit with more subtle forms of racism and suspicion.

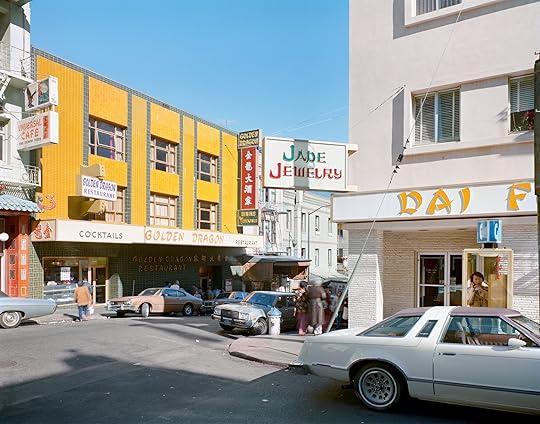

Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Golden Dragon Restaurant, 1979

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Alexander: We see that continuing through today, especially during the pandemic. So, in order to pursue photography, you essentially had to turn away from your family. But then, it comes back around that your work is, in many respects, largely about your family—and family in general. I wonder if you might share a little about that process, from arriving at your subject matter in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the earlier part of your career to how you ended up in China.

Louie: There was no way I could explain, even to myself, why I wanted to be an artist—and especially to my family. They took comfort that I went to good schools, and then later on, I became a professor—so that’s how they saw me. Art? They just couldn’t figure it out.

It was only when I came with my father to China in 1981, into his village that he had left when he was nine years old, that my photography made sense to them. That’s when the circle closed, and I really understood for the first time what my work meant to me, what I was trying to do. Eventually, I reconnected with my family.

I moved to San Francisco to accept a teaching job at the San Francisco Art Institute in the 1970s. San Francisco was a beautiful place then. It was still basking in the afterglow of the ’60s. I began photographing in San Francisco’s Chinatown really out of convenience. I lived there, and it looked exotic. I lived around the outskirts, the border of Chinatown and North Beach, in this alleyway called Fresno Alley. Its claim to fame was that my building was the location of a Woody Allen film. It was still really boho life there. You saw the North Beach poets still wandering around, trying to channel Ginsberg.

Reagan Louie, Aunt in SRO, San Francisco Chinatown, 2005

Reagan Louie, Aunt in SRO, San Francisco Chinatown, 2005  Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Jackson Street, 1979

Reagan Louie, San Francisco Chinatown, Jackson Street, 1979 While I began photographing there out of convenience, it was also a place of my ancestors and memories. Many of my family members, including my grandfather and father, lived and worked in Chinatown initially. I deployed a nineteenth-century stand camera, 4-by-5. I wanted to contrast the incredible detail that camera renders with the motion blurs of people’s movements. I saw them as my ancestors, as ghosts.

Chinatown led to China. In 1980, I answered an ad in a Chinese newspaper to study in China. That’s when I began my forty-year odyssey. Unbeknownst to me, what I was doing was attempting to find another way, a truer life. Again, finding your cultural roots, or even thinking about that as a source for your art, wasn’t heard of then in high-art circles. That was taboo, really. I thought that’s what I was doing, but I didn’t tell myself that was the goal. In fact, I said the opposite: I was taking my educated eyes to picture this new exotic world. I couldn’t really acknowledge the real reason for going to China, my need for some kind of authenticity.

Alexander: Why do you think it is that it took both you and your father going to China for him to understand your practice more fully?

Louie: It was less what we spoke about than our actions. Toisanese especially, and my family in particular, are very laconic. My dad, me, my son, we’re all men of few words. So what spoke to me was watching him become a nine-year-old again. He had tears in his eyes most of the time. I saw his gentleness, which I had never seen, because to survive as an Asian male at that time, when I was growing up (and still, maybe), you had to be a tough guy.

With the two eras of Chinese immigrants, the work that’s produced by the artists of those eras really manifests their time, the conditions they faced. The art made in internment camps, photographically—like the pictures made by Toyo Miyatake—is a declaration that they were here. Right? They weren’t going away. I feel really strongly about that. Whereas the work being made now, which is wonderful and celebratory, it’s about living life out loud.

Reagan Louie, Vegetable Garden, Wing Wor, 1983

Reagan Louie, Vegetable Garden, Wing Wor, 1983  Reagan Louie, Betelnut Stand, Taiwan, 1997

Reagan Louie, Betelnut Stand, Taiwan, 1997 Alexander: Why do you think it was difficult for you to acknowledge that the need for authenticity was a primary driving force for you to go back to China?

Louie: Again, I drank the Kool-Aid. It was all about formalism and nothing else.

Alexander: Many of the early Chinese immigrants to the United States came from a specific province, Guangdong. This is to say, there are many distinct provinces in China with their own dialects, mores, and histories. Yet here, sometimes, there’s a tendency to view China, this massive country, as a kind of monolith.

Louie: Before I began working in China, I vaguely knew that China was vast and diverse, filled with different dialects and cultural practices. But I didn’t realize to what extent until I got there. I really detest anything pan-Asian right now. I don’t even like the word Asian American.

Alexander: Speaking of the term Asian American, we got to know each other through the Asian American Art Initiative, a project I codirect. Your work was included last year in the exhibition At Home/On Stage: Asian American Representation in Photography and Film, curated by my colleague Maggie Dethloff at the Cantor. I recall that you wrote beautifully in a private note to Maggie and me about what it means to be included in an exhibition like that, even when you don’t love the term Asian American.

Louie: I was struck by how much art in the exhibition came from suffering pain and grief, which I could identify with. We know the pain and suffering caused by internment, or the history of violence directed at Asian Americans, which continues to this day. But equally important for me was the daily pushing against grief and loss that we face, that’s faced by every Asian American every day—racism and discrimination, not being fully seen, just those daily microaggressions against people of color. But in the exhibition, we see Asian American artists pushing back against all that discrimination and hate; from their pain and hardship they made tremendous meaning. Art that gave them solace. Which is why all the work for me is filled with healing joy. It was never bitter. The art in the show reminded us that beauty and grace can arise from pain and loss. It’s that irrepressible human spirit.

Reagan Louie, Beijing, from the series Towards a Truer Life, 1987

Reagan Louie, Beijing, from the series Towards a Truer Life, 1987  Reagan Louie, Chengdu, 2002

Reagan Louie, Chengdu, 2002 Alexander: Recently there’s been a lot of critique of the racially specific exhibition model. From your perspective, working all these decades both within and on the perimeter of the art world, what’s your thought on this kind of model of inclusion in the museum space?

Louie: Super complicated question. I refuse to do this, to perform our Asian-ness. Right? I think it’s great that museums and institutions are recognizing that we’re coming from a different place than just formalism. But I am skeptical sometimes about putting in one or two pictures of an Asian American artist, or whatever. How much difference does that really make? Is it really transformative? I’ve seen too many instances where it’s not. In fact, it’s reductive. It diminishes the work of that artist, seen in that context. If you truly want to make a statement, you’ve got to make the big move. Turn the entire museum inside out. Not just one or two pictures but an entire show. That’s what’s going to pull in new audiences.

Maybe this is a good moment to give you an example of an experience I had with all this in the ’70s. I was a photographer during the very beginning of photography as a fine art. At the top was MoMA, in New York. The museum had a generous portfolio-review policy. The drill was you’d drop off your portfolio and return to pick up the work a few days later. The first time I dropped off the work, it was a tray of color slides I’d made while I was in California that year after I’d returned. They were of places around Sacramento, where I grew up, and they were very formal, beautiful pictures—and I was surprised when I was invited to come in and speak with the curators. They thought the pictures had a sweet quality and asked me to keep them updated. But the reception for my work made in China was much chillier. I couldn’t articulate what it meant.

I’m embracing values that I once rejected. Inclusion, not exclusion. Authenticity, not artificiality.

As I’ve talked about, I didn’t know why I had gone back to China. And there were awkward silences with the curator when the conversation veered away from formal aesthetic issues. At one point, I remember I was trying to talk about my feelings, to try to communicate what was at stake for me. The curator was dismissive. He said he didn’t care about my feelings, only his. It just shut down that conversation. I was really pondering whether I had what it took to be an artist. I was really dejected after that encounter. I tried to step away from art and tried to quit. I applied to business school. I was convinced I didn’t measure up. And I was also tired of always being in debt.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});