Aperture's Blog, page 29

May 19, 2023

Eikoh Hosoe’s Mythic Worlds

It is said that the kamaitachi spirit resembles a weasel, rides on a whirlwind, flies through the air, and moves so incredibly fast that before you know it it’s already gone. With strong and sharp claws, the invisible beast attacks suddenly and sucks blood from its victim’s wounds.

Such a kamaitachi, half-naked and with its clothing blown up by the wind, jumps high in front of a group of curious farm children. Darkly surreal, a female head appears under a male arm and stares at the viewer, her eyes wide open. An androgynous figure runs across Tokyo. A young woman sits pensively between portrait paintings and striking busts with crying faces. Hauntingly poetic and depicted in high-contrast, these scenes tell of human physicality, sexuality, and a wide array of emotions. The images, by the legendary Japanese photographer and filmmaker Eikoh Hosoe, are expressive, subjective, and mythic; they whisper, speak, and shout fantastical stories that engrave themselves in the viewer’s mind.

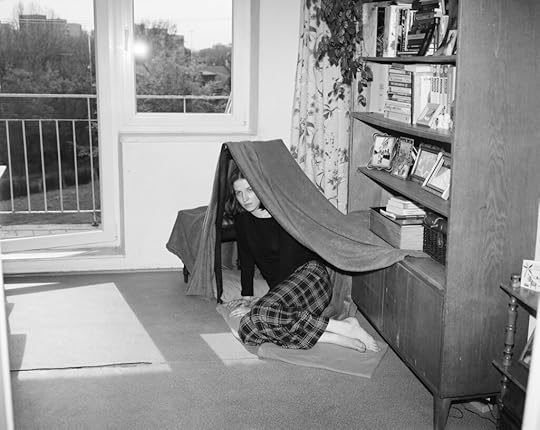

Eikoh Hosoe, Kazuo Ohono, a visit to the home of Yutaka Haniya III, 1995

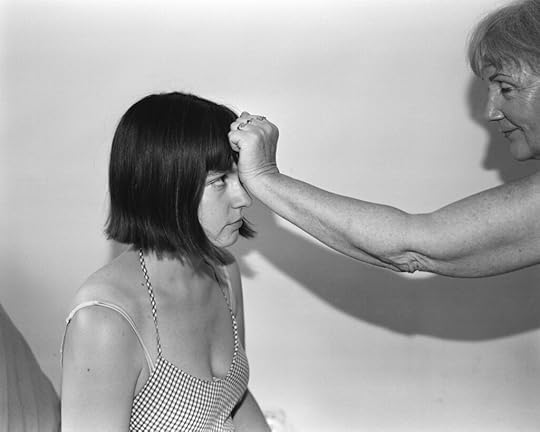

Eikoh Hosoe, Kazuo Ohono, a visit to the home of Yutaka Haniya III, 1995  Eikoh Hosoe, Sawako Goda II, Artist, 1972

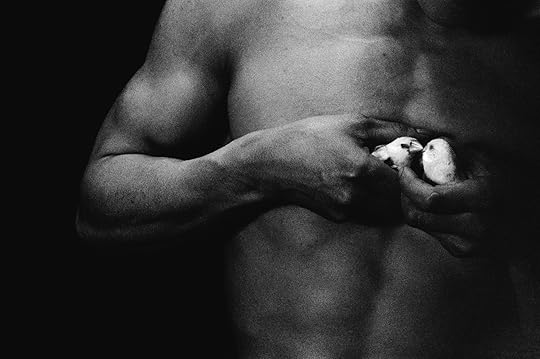

Eikoh Hosoe, Sawako Goda II, Artist, 1972 Brought up in a Shinto shrine where his father was a priest, Hosoe, who was born in 1933, came to photography at a young age. He borrowed a camera that belonged to his father, who supplemented his income during World War II by taking photographs at festivals and graduation ceremonies. In 1951, as a teenager, Hosoe won the inaugural Fuji Photo Contest and first gained widespread attention in the photography world with his 1960 solo show Man and Woman, at the Konishiroku Photo Gallery, featuring stylized nude compositions that reflect his career-long interest in the human body. Hosoe’s fascination with the body’s forms, movements, and eroticism is evident also in what was to become his best-known series: Ordeal by Roses (1961). The theatrical photographs featuring the writer, actor, and ultranationalist Yukio Mishima, a tireless promoter of his celebrity image who would commit ritualistic suicide through seppuku disembowelment a few years later, convey a sense of dark eroticism. “The series made me famous, and I started to work with Light Gallery in New York,” Hosoe told me recently. Selling prints overseas enabled him “to live a good life and get married.” And, he recalls, “Mishima came to my wedding and gave a rather ironic speech.”

For his equally striking series Kamaitachi (1965–68), Hosoe collaborated with Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of the experimental dance form butoh. The work is linked to the photographer’s childhood memories of the war, when he was evacuated to the rural Tōhoku region. Hijikata, who grew up there, embodies the kamaitachi spirit of folklore said to haunt the rice fields. The dynamic scenes show the dancer running in the fields, dramatically jumping, hiding, or “stealing” a local farmer’s baby, and they also often mirror Hosoe’s own physical involvement, taking photographs while running or from unusual vantage points. Even today, elderly people in the village remember the photoshoots.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Soon after, Hosoe began to work with Ohno Kazuo, the other founding figure of butoh; this collaboration was to last for more than forty years. Another highlight in Hosoe’s oeuvre is the series Simmon: A Private Landscape (1971), which features the artist and actor known as Simmon Yotsuya—a stage name inspired by the artist’s love for Nina Simone’s music and the Yotsuya district of Tokyo. The beautifully made-up, effeminate actor was a participant in Juro Kara’s avant-garde Situation Theatre troupe (Jōkyō Gekijō). Hosoe photographed Simmon Yotsuya in different areas of Tokyo, including around Kannon Temple in Asakusa. His energetic poses and facial expressions are juxtaposed with the urban landscape, blurring the lines between the real city and passersby, on the one hand, and the performative and photographic narrative on the other. This results in an expressive aesthetic that links the performer’s inner “private” side with the outer “landscape.” In contrast to Kamaitachi, Hosoe has described the series as a recollection of his adolescence when he had returned to Tokyo: “I have created works based on special encounters with photographic subjects. At that time, I had met Simmon Yotsuya—through him, the adolescent scenery of Tokyo awakened from my memories and was turned into a work of art.”

Eikoh Hosoe, A Private Landscape #13, 1971

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Hosoe communicates memories and personal realities, challenging conventional notions of photography. In 1950s and 1960s Japan, his work embodied the hunger for a subjective and experimental form of photography in opposition to the then dominant trend of social realism. The photographers’ group Vivo, named after the Esperanto word for “life” and cofounded by Hosoe in 1959, is an early manifestation of this hunger. Like Hosoe, its five other members, Kikuji Kawada, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, Akira Tanno, and Shomei Tomatsu, had participated in a group exhibition titled Jūnin no me (Eyes of Ten) at Konishiroku Photo Gallery two years earlier, organized by the photography critic Tatsuo Fukushima. The Vivo artists shared an office, a manager, and a darkroom in East Ginza, Tokyo. Despite existing for only two years, this office became the epicenter of a new subjective style of photography, whose protagonists were soon referred to as the Image Generation and became highly influential in the history of Japanese photography. As the critic Kotaro Iizawa once wrote, the Vivo members “gave the image its independence.”

Dramatic and dreamlike, Hosoe’s imagery remains radical, powerful, and moving—it deserves to be discovered by a wider audience.

Whether presented individually or as a series, in exhibitions or photobooks (often designed by key figures of Japanese graphic design, such as Kohei Sugiura and Tadanori Yokoo), Hosoe’s photographs grab viewers and lead them into a cinematic world. None of the series have a beginning, ending, or story line; however, most of them convey a strong narrative quality. But whose stories do they tell? They are born out of collaborations, while also recording a specific time and place. The narratives are based on Hosoe’s artistic choices in terms of photographic angle, perspective, light, shadow, background, and printing techniques in the darkroom just as much as they come into existence through the facial expressions, spontaneous gestures, and movements of the photographic subjects. Hosoe creates an inspiring atmosphere in which the performers and the photographer engage in a fantastical Ping-Pong match, passing ideas back and forth to each other.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

In a recent monograph titled Eikoh Hosoe: Pioneering Post-1945 Japanese Photography, edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, the curator Christina Yang proposes viewing Hosoe’s expansive practice as “exquisite world-making”—I suggest attributing this act of “world-making” to Hosoe as well as to the people in front of his lens, situating both on a par with each other. It is no coincidence that the subjects of Hosoe’s best-known photographs are strong characters who enjoy working with their bodies and faces, be they dancers, actors, or public figures such as Mishima, who transformed his physique through bodybuilding. Hosoe is aware of the photographic subjects’ power during the creative process; unlike his peers, he has credited Hijikata, Mishima, Simmon Yotsuya, and others, acknowledging them as equal collaborators. With many of them, he developed a friendship. When I asked Hosoe a few years ago what he likes best about photography, he pointed first to his subjects, responding that “the most interesting and attractive aspect of photography is the simple joy of the people who are photographed. I have always liked human relationships.” Storytelling in Hosoe’s photography is based on an indescribable fantasy world that exists between the photographer and photographic subject(s); a unique moment of space, time, and feeling is captured on camera, during the vivid exchange of ideas.

Eikoh Hosoe, Kamaitachi #17, 1965

Eikoh Hosoe, Kamaitachi #17, 1965  Eikoh Hosoe, Man and Woman #33, 1960

Eikoh Hosoe, Man and Woman #33, 1960All photographs © the artist and courtesy Akio Nagasawa Gallery

This March, Hosoe will be ninety years old. With his distinct visual language, pioneering collaborative approach, and relentless activity promoting photography in Japan—including through education and copyright protections—he has been one of the country’s most influential photographers since the postwar era. Hosoe has inspired his peers as well as younger generations of artists. Kikuji Kawada, a legendary photographer himself, who is best known for his experimental photobook Chizu (The Map, 1965), described Hosoe as someone who “searched for a new world of thought based on the eye,” creating “dramatic evidence and unforeseen stories within overwhelmingly photogenic and poetic frames.” It is telling that, having aspired to be a diplomat and also having won Tokyo’s very first English speech contest as a child, Hosoe chose the Japanese character ei for his pen name, Eikoh, which is also used in the term eigo, “English,” suggesting internationality. According to Kawada, both the Vivo office and what is now the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum would probably not have been founded without Hosoe. Daido Moriyama, who at the beginning of his own photographic career in Tokyo assisted Hosoe, argues that before Hosoe, the Japanese photography world was dominated by a type of photography that had “a strong sense of documentary and was strictly not staged. Hosoe confronted this, creating theatrical, staged photographs based on collaborations with the photographic subjects. It was a major achievement.”

With his openness, beginning in the late 1950s, to viewing photography as a form of creative collaboration, Hosoe was well ahead of his time. After early attention in the United States and Europe, however, his work has not been exhibited on a large scale outside of Japan. Dramatic and dreamlike, Hosoe’s imagery remains radical, powerful, and moving—it deserves to be discovered by a wider audience internationally, including all current and future photography lovers.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

A Festival in Kyoto Dazzles with Photography and Architecture

If tourists flock to Tokyo to be wowed by its urban acceleration, Kyoto provides the inverse as a serene city showcasing the splendors of ancient Japan. During the height of the pandemic, the city saw an influx of new residents seeking more space and a less frenetic lifestyle. With new galleries opening and support from the local government for the arts, it continues to evolve as a vibrant center of contemporary culture.

Kyotographie, a photography festival held annually (excepting interruptions due to the pandemic), smartly takes advantage of the city’s overwhelming number of shrines, temples, gardens, and other alluring architectural destinations. Founded in 2013 by Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi, the festival staged its eleventh edition in April, loosely themed around the idea of borders. Projects addressed both literal and metaphysical spins on this idea, including a series on migration and one on elderly people isolated by dementia. (Japan had only recently fully reopened its own borders after three years of pandemic-related restrictions for foreigners, and tourists were out in force.) In a photography field crowded with festivals, Kyotographie distinguishes itself through clever site-specific exhibitions within many of the city’s stunning, and usually off-limits, locations. The event is as much a photography festival as it is celebration of the city’s majestic architecture and cultural heritage.

Installation view of Kazuhiko Matsumura, Heartstrings, Hachiku-an (Former Kawasaki Residence), 2023. Photograph by Kenryou Gu

Installation view of Kazuhiko Matsumura, Heartstrings, Hachiku-an (Former Kawasaki Residence), 2023. Photograph by Kenryou Gu  Installation view of A dialogue between Ishiuchi Miyako and Yuhki Touyama: Views through my window, Kondaya Genbei Chikuin-no-Ma, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi Asano

Installation view of A dialogue between Ishiuchi Miyako and Yuhki Touyama: Views through my window, Kondaya Genbei Chikuin-no-Ma, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi AsanoThe impressive Nijo-jo castle tops any visitor’s must-see list for the city. Built in 1603 by the shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa, it is a magnificent complex of buildings and gardens. One building features famous “nightingale floors,” designed with dry wood to chirp when walked on and alert its eminent residents of an impending ninja ambush. Where tourists won’t find themselves, though, is in the castle’s normally closed Okiyodokoro, the kitchen area where, centuries ago, samurai gathered to eat.

The architect Tsuyoshi Tane was initially apprehensive about designing a photography exhibition of work by the fashion photographer Yuriko Takagi within this storied space. Tane, whose studio is in Paris, is known for elegant designs that absorb the particulars of local context into their execution and thoughtfully harness the specificity of place. His design for the Estonian National Museum follows the straight line of a former Soviet-era runway on which the building is constructed; his firm’s completed Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art, in Japan, features a “cider gold” roof, a reference to the region’s robust apple production.

Yuriko Takagi, Gateway, Yuriko Takagi × Nanao Kobayashi, Japan, 2023

Yuriko Takagi, Gateway, Yuriko Takagi × Nanao Kobayashi, Japan, 2023 ©︎ the artist

Installation view of Yuriko Takagi, Parallel World, Nijo-jo Castle Ninomaru Palace Daidokoro Kitchen and Okiyodokoro Kitchen, 2023. Photograph by Kenryou Gu

Installation view of Yuriko Takagi, Parallel World, Nijo-jo Castle Ninomaru Palace Daidokoro Kitchen and Okiyodokoro Kitchen, 2023. Photograph by Kenryou GuThis holistic approach is also present in Tane’s work inside Nijo-jo castle. Takagi and Tane had long wanted to collaborate after meeting in 2017 during a public program for an Issey Miyake exhibition in Tokyo. For four decades, Takagi, who once worked as a fashion designer, has photographed the collections of Miyake, Commes Des Garçons, Dior, and Yohji Yamamoto, among others, to create sumptuous, dreamlike fashion imagery. Her work on view in Kyoto sought to unite what she sees as fashion’s parallel worlds: luxury haute-couture creations and traditional, functional, yet beautiful styles of dress found in a range of cultures around the world.

Placing art in iconic spaces can be fraught. Historical spaces have a way of taking the limelight. They also come with a litany of restrictions. Constraints, however, are often generative, allowing for new ideas and possibilities—even if that means you cannot attach anything to a wall, or to the floor, or you are required to call upon a specially appointed staff member to open and close a sliding door.

And then there’s the weight of tradition. Tane was at first apprehensive about the “very Japanese” architecture of the castle, as he put it, and concerned that viewers wouldn’t be able to ignore the context and focus on the photographs. However, as he worked on the project, he says he became enamored with the “strong presence” of the building and saw the project as a “lifetime opportunity.” To present Takagi’s photographs, he leaned not away but into tradition, devising an installation based on shoji, traditional Japanese screens. In one cavernous room, photographs were printed on rice paper and presented in a large-scale configuration that allowed viewers to walk around the images.

Installation view of Yuriko Takagi, Parallel World, Nijo-jo Castle Ninomaru Palace Daidokoro Kitchen and Okiyodokoro Kitchen, 2023 Photograph by Kenryou Gu

Installation view of Yuriko Takagi, Parallel World, Nijo-jo Castle Ninomaru Palace Daidokoro Kitchen and Okiyodokoro Kitchen, 2023 Photograph by Kenryou GuTakagi’s work moves “beyond the image,” Tane says. “It is about texture imagination and the journey.” And the installation had a transporting effect, as the main room opened onto smaller ones where additional photographs were presented as a field of unglazed prints situated atop metal pedestals. “I wanted to play with shadows and darkness, and follow the geometry of the Japanese construction,” Tane noted. With only natural light filtering into the space, the tonality of the prints seemed to match the dim but warm atmosphere of the interior, recalling Junichiro Tanizaki’s classic 1933 essay collection In Praise of Shadows, a treatise on what Japanese aesthetics were losing with the advent of electrical lighting and modernity.

The presentation at Nijo-jo may have been a high-water mark of site specificity, but it was not alone. Joana Choumali, a resident of the festival, presented at the Ryosokuin Zen Temple a series of mixed-media fabric works featuring images of West African landscapes that she made during morning walks in her hometown of Abijan, Ivory Coast. The series was installed on the floor in an arrangement of custom-made wooden boxes with the feel of domestic furniture, and continued in two tea houses beside a painterly Edo-era garden.

Joana Choumali, MAYBE I GREW UP A LITTLE TOO SOON, 2022

Joana Choumali, MAYBE I GREW UP A LITTLE TOO SOON, 2022 © the artist

Installation view of Joana Choumali, Alba’hian, Ryosokuin Zen Temple, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi Asano

Installation view of Joana Choumali, Alba’hian, Ryosokuin Zen Temple, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi AsanoAn exhibition of works by Yu Yamauchi, who explores the natural landscapes of Yakushima island, was staged in a large machiya (townhouse) built a century ago by a Shinto shrine carpenter. A selection of images by Ishiuchi Miyako, a giant of postwar photography in Japan, was paired with photographs by Yukhi Touyama in a modest exhibition staged inside a space belonging to a wholesaler of obi—a business that has been operating for nearly three hundred years. This presentation teased out an intergenerational dialogue between two photographers reflecting on family loss—although Ishiuchi, considering her position as an artist and feminist cultural force, warranted a castle of her own.

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s #5, 2002

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s #5, 2002Courtesy The Third Gallery Aya

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s #39, 2002

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s #39, 2002  Installation view of Yu Yamauchi, JINEN, Kondaya Genbei Kurogura, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi Asano

Installation view of Yu Yamauchi, JINEN, Kondaya Genbei Kurogura, 2023. Photograph by Takeshi Asano Yu Yamuchi, Existence #11, from the series JINEN, 2023

Yu Yamuchi, Existence #11, from the series JINEN, 2023© the artist

All installation views courtesy Kyotographie 2023

The festival’s decision to make the architecture and local context as much a part of the festival has the benefit of highlighting not only the histories and stories embedded in the locations, but also the work of exhibition making that often goes unseen and uncredited—the many collaborations between artists, curators, and designers. The dynamic pairing of images and architecture underscored how photography transports viewers into other worlds and temporalities. In an era when so much is mediated by the screen, the spirit of this festival is entirely physical, almost performatively so. You have to be there to take off your shoes, step inside, look carefully, and be taken away.

Kyotographie 2023 was on view at multiple locations in Kyoto, Japan, from April 15 to May 14, 2023.

May 12, 2023

Vân-Nhi Nguyen’s Bold Perspective on the Lives of Young People in Vietnam

A young woman sits on a plastic-covered bed in a cheap motel room. She is dressed without pageantry or occasion, in a black tank top and a pair of shorts. A small tattoo is visible on the inside of her elbow. She is barefoot. Her gaze is one of neither confrontation nor seduction. “See me as I am,” she seems to be saying. “Look at me as I look at you.” Behind her, a poster depicting a flat, computer-rendered landscape of a beach is tacked to the wall. This could be Vietnam, but it could also be anywhere tropical.

What does it mean to grow up in a country violently marked by colonization and war? For Vân-Nhi Nguyen, the twenty-three-year-old Vietnamese photographer who took the untitled image as part of her 2022 series As You Grow Older, it is a disorientating experience, one that overwhelms her emotionally.

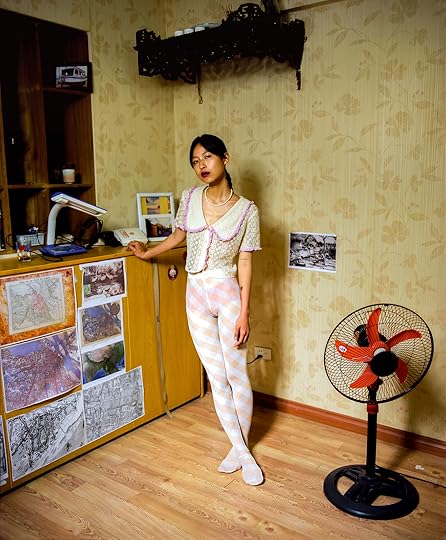

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Girl in Pearls), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Girl in Pearls), Vietnam, 2022  Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Between Two Centuries), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Between Two Centuries), Vietnam, 2022 “Our history has been wiped clean every single time from thousands of years of colonization,” she told me in a recent conversation. “It strips us of our identity so that, even now, young Vietnamese people don’t even know who they are to begin with, to even tell a story. When you actually look at the history of Vietnamese people, we didn’t really gain any sense of our own identity until our independence in 1975, which was forty years ago. That’s still within a human’s lifetime.”

Nguyen’s relationship to photography has been complicated. Initially, art was more a means to escape a conventional life and less a way to express herself. “Art, in general,” says Nguyen, “is not something too important to public education in Vietnam. I think it’s fair to say that people need to stay alive first. Not just in Vietnam, but, typically, it’s understandable that people can’t look for anything else if their stomach is empty or their beer is not cold.”

Under Nguyen’s lens, the flattening stereotypes of Vietnamese culture are never present, even if she is perfectly aware of them.

At sixteen, she began taking photographs, and soon, while in college, found a place for herself with commercial and fashion-oriented work. But Nguyen eventually came to see that this type of image making was essentially meaningless. She was equally unimpressed with the clout that the camera lent her socially, and, in a radical gesture, she put it down when she was twenty and stopped producing altogether for two years. “Photography became to me something so shallow and so superficial,” Nguyen says. “I hated the emptiness of images I saw scrolling Instagram, and I hated the cleanliness of the fashion images in magazines. Everything was too sterile and dishonest.”

That time was a fallow period for Nguyen, who spent it looking at photography books, studying not only her peers but those who came before her. One of her biggest influences is the photographer Deana Lawson, whose portraits of Black American men and women, often at home, are striking in their ability to capture a kind of out-of-time noble or aristocratic manner.

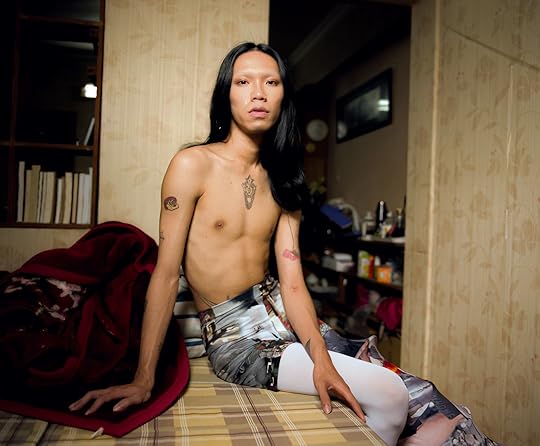

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled, Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled, Vietnam, 2022  Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Ba Cô (Three Aunties), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Ba Cô (Three Aunties), Vietnam, 2022 As Zadie Smith wrote in a 2018 essay for Lawson’s Aperture monograph: “Deana Lawson’s work is prelapsarian—it comes before the Fall. Her people seem to occupy a higher plane, a kingdom of restored glory, in which diaspora gods can be found wherever you look: Brownsville, Kingston, Port-au-Prince, Addis Ababa.” To Nguyen, this kind of framework was a revelation. She asked herself: What am I even doing if I can’t put my people on a pedestal?

Nguyen’s photographs in As You Grow Older are a serious attempt at exactly that. She asked friends, colleagues, and acquaintances to pose for her, sometimes staging them in intimate settings such as their bedrooms, other times in unfamiliar spaces. In one memorable photograph, three women stand defiantly in the center of the frame, each striking an identical pose, their hands on their hips, like a line of chorus girls. But the image is unsettling in its power, even though its setting—a dimly lit hallway of an apartment walk-up—is ordinary, almost bland. Nguyen was, in fact, referencing a pose from a historical image she had come across, of three Vietnamese women on the verge of being executed by European settlers, their necks shackled together by chains.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

“Even though that image was taken by a white person, a settler, the women looked as though they owned the space,” Nguyen observed. In her pictures, masculinity, too, is its own kind of pure beauty: two young men lean against each other at night on the banks of the Hong River; another young man poses calmly on a bed, shirtless. Nguyen has a knack for seeking out the idiosyncrasies of those around her, to find intimacy with her gaze. Under her lens, the flattening stereotypes of Vietnamese culture are never present, even if she is perfectly aware of them.

Lately, Nguyen has been productive, completing the first portion of a series of photographs called Under the Sun, taken by the Siem Reap River in Cambodia earlier this year, and is at work on an upcoming show this August with Aperture. Her relationship to photography is still complex. “I feel like I’m in a marriage,” she says of her art. “Some days, I can feel intense passion for it that feels like I could survive off photographs and images alone, and some others, I just want to stop altogether and never touch a camera again.” But she is spending more time deepening her craft. She allows herself to fall in love with people and places. She is open to where photography will take her next.

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Dan Ni), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Dan Ni), Vietnam, 2022  Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Vietnamese Pieta, By the River), Vietnam, 2022

Vân-Nhi Nguyen, Untitled (Vietnamese Pieta, By the River), Vietnam, 2022All photographs courtesy the artist

Vân-Nhi Nguyen is the winner of the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize. A solo exhibition of her work will be on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York in August 2023.

This piece appears in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian In America,” under the column “Spotlight.”

A Photographer’s Final Collaboration with His Father

“To me, photography recontextualizes and embraces death,” explains the photographer Brian Lau. In 2019, Lau’s father had an abrupt stroke, and passed away the following year due to brain cancer. Before his passing, Lau and his father began a collaborative series, We’re Just Here for the Bad Guys, a deeply personal exploration of family, grief, and Asian American identity.

Lau, who was born in Honolulu and is currently based in Seattle, is a self-taught photographer. Like many of his generation, Lau’s formative experiences with photography stemmed from online platforms such as Tumblr and Flickr that were prominent in youth culture in the early 2010s. “Most of my education with photography has been from the popularization and influence of these online platforms,” says Lau. “Many of my peers I found and formed friendships with were due to these social platforms and found communities.” In 2022, Lau founded the online platform Arcanite Pictures, dedicated to highlighting the work of emerging artists.

Brian Lau, Dad’s Shave (A Week After Surgery), 2019

Brian Lau, Dad’s Shave (A Week After Surgery), 2019Lau’s relationship with his father was a tumultuous one. Lau’s father, who had been incarcerated during his youth, left his son and family behind in 2010, when he returned to Vietnam in pursuit of a new life. Yet, when faced with the news of his father’s stroke, Lau made the decision to travel to Ho Chi Minh City with no return date in sight. Lau spent several months with his father’s new family, finding himself faced with an unfamiliar set of customs and family dynamics. It was in his final month there that Lau’s father made a proposition: work together to create a series of photographs documenting what was ultimately an unsuccessful journey to recovery.

Throughout We’re Just Here for the Bad Guys, Lau weaves together black-and-white images of his father’s life in Vietnam alongside landscapes of the Pacific Northwest made after returning home. Drawing upon the idea of the family album, Lau is less interested in the idea of direct representation, instead offering a more ambiguous, open-ended (or, unanswered) depiction, which Lau describes as “acts of evidence being unearthed.” In photographing his father in tightly framed, small interior spaces, Lau brings us into this newly intimate space between them, while simultaneously blocking our view beyond the frame—making a direct link between their changing relationship, his father’s condition, and his history with the prison system.

Brian Lau, House in Flurry, 2020

Brian Lau, House in Flurry, 2020Despite being shot across various locations and years, Lau’s series creates an amorphous blend of time and place. A dark cave leads to a bright opening; his father, post-surgery, attempts to play a song on a guitar; a house is sunk roof-deep into a curved landscape; a family dinner is imbued with a sense of anxiety when lit with flash. In one image taken during Lau’s first winter without his father, a flurry of snow is illuminated with flash at night in a suburban neighborhood, giving an almost ghostly, spiritual presence. “This series became more of a reflection on the relationship between my father and me, one of mutual interpersonal grievances, and a practically ouroboran cycle of shame and alienation,” explains Lau. “I began to look at the pictures as an attempt to answer the ambiguities left in his wake, and the lack of emotional closure we shared.”

Photographs exist with almost opposing realities: they stop at a moment in time, and yet live on indefinitely, constantly transforming alongside us as we grow, learn, and change. We’re Just Here for the Bad Guys narrows in on this tension, acting not only as a means to process grief—the loss of a father, the dysphoria of his Vietnamese lineage, a deteriorating sense of home—but also as a way to make sense of Lau’s relationships. “Finding the story, and unraveling what had happened and the many infinite layers in our relationship that ended so abruptly took the most time and patience,” says Lau. “It took years and I’m still finding answers.”

Brian Lau, Parent’s College, 2022

Brian Lau, Parent’s College, 2022 Brian Lau, Last Supper, 2021

Brian Lau, Last Supper, 2021 Brian Lau, Dad’s Cave, 2019

Brian Lau, Dad’s Cave, 2019 Brian Lau, Dad’s Song, 2019

Brian Lau, Dad’s Song, 2019All photographs from the series We’re Just Here for the Bad Guys. Courtesy the artist

Brian Lau is a runner-up for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Samantha Box’s Pictures of Dreams and Diaspora

To make the Jamaican national dish of ackee and codfish, first you have to find ackees, a fruit that’s poisonous before it’s fully ripe but delicious when cooked with garlic, onions, peppers, and tomatoes. One of the purveyors of canned ackee, originally native to West Africa, is the company Caribbean Dreams. “Which struck me as being hilarious,” says the photographer Samantha Box. “Because it’s like, who’s dreaming of what? What are these dreams? What does it mean for this thing to be called Caribbean Dreams when it’s a symbol of Jamaican culture?”

Box set these questions in motion with her still life The Jamaican National Dish (2019), part of an ongoing series she began in 2018 called Caribbean Dreams: Constructions. She was fascinated by the botanical and social history embedded in fruits and vegetables, particularly the names, which trace the triangular trade routes between Africa, North America, and Europe beginning in the seventeenth century. The word ackee, for example, derives from a word in the Akan language group, spoken by people in present-day Ghana, but the scientific designation, Blighia sapida, refers to British naval captain William Bligh, who brought the fruit from Jamaica to England. Ackees and yams were transported by enslaved Africans, and took root in the new world, a symbol of both horror and survival.

Samantha Box, The Jamaican National Dish, 2019

Samantha Box, The Jamaican National Dish, 2019Food markets in the Bronx, where Box lives and works, have become the prop warehouse for the series, with barcodes and receipts providing evidence of the commodification of diasporic cuisine. “Everything gets flattened into a price,” she says, “including the person who’s ringing things up, the people who own the place, the people who are buying the things.” Box lit her photographs like Dutch still lifes, what she calls a “record of empire,” and set several against a backdrop created from details of a painting by the nineteenth-century Trinidadian artist Michel-Jean Cazabon, who idealized the British colony’s lush landscapes. The reproduction is rough and seams in the backdrop are visible. “I wanted the background to be something that everybody knew was fake,” she says. Yet in this scene-setting that plays with art and commerce, a hybrid kind of truth emerges.

Box was born in Jamaica to a Black Jamaican father and an Indian Trinidadian mother. “I’m descended from the enslaved and the indentured, and other people who were brought together in this crucible that is the Caribbean,” she says. Her parents met at the University of the West Indies. They had a “deep, abiding love and passion” for organic chemistry. In the early 1980s, her father was offered a job at an American pharmaceutical company and the family moved to Edison, New Jersey. It was the kind of immigrant community where people from a variety of backgrounds were writing a new chapter of their lives, often with great sacrifice. “That trope that people had in the ’80s of the cab driver who has a PhD, that’s who I grew up around,” Box says. “I think quite literally the guy who delivered our newspapers was an engineer.”

As a child, Box read National Geographic and Natural History, the magazine published by the American Museum of Natural History. She studied biology at Cornell, but decided to try a semester at City College of New York, where she took up photography and studied with Shawn Walker, an early member of the Kamoinge Workshop, the collective of photographers that included artists such as Anthony Barboza, Louis Draper, and Ming Smith. Box sent a cold cover letter (“the best in my life”) to Contact Press Images to inquire about an internship. She ended up working there as an technician for nearly ten years, during which time she made piercing long-form photo essays about queer youth and the Kiki scene in Manhattan, influenced in part by the Buffalo photographer Milton Rogovin.

Samantha Box, One Kind of Story, 2020

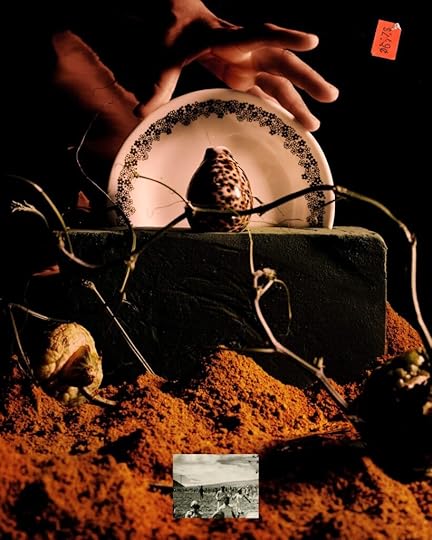

Samantha Box, One Kind of Story, 2020Caribbean Dreams: Constructions is the fruition, you might say, of Box’s lifelong preoccupations with what it means to create diaspora in the United States—and to be created by diaspora. In One Kind of Story (2020), she draws upon images of her grandmother, great-grandmother, and great-aunt, while centering herself in a pixelated self-portrait modeled after a photograph by Felix Morin, a studio photographer who worked in Trinidad in the late nineteenth century. An inset photograph in Navel (2022) depicts a strike in the 1930s by sugarcane cutters in St. Kitts, an act, she says, of “self-emancipation” undertaken by the descendants of enslaved Africans.

All of these layers in Box’s work offer a riposte to the questions immigrants are frequently asked about their origins. Where are you originally from? And where were you from before that? These questions assume the essentialism of homelands, but elide the hybrid narratives that emerge from the crucible of places like Jamaica or Trinidad, homelands embedded in the history of forced labor and capitalist enterprise. Sometimes, as in Box’s dizzyingly recursive “constructions,” family lineage can be expressed in snapshots or passport stamps, barcodes or botanicals. Memory has a way of returning through the senses. The writer Bryan Washington has published his own recipe for ackee and saltfish, a dish his mother used to make, and one he only came to appreciate as an adult. “Our meals are associated with memories, but that’s not to say that we can’t carve out new ones,” he says. “The things that we run away from can be the same things that call us back home.”

Samantha Box, Edges, 2020

Samantha Box, Edges, 2020 Samantha Box, Navel, 2022

Samantha Box, Navel, 2022 Samantha Box, Multiple #3, 2018

Samantha Box, Multiple #3, 2018 Samantha Box, Four Hands, 2020

Samantha Box, Four Hands, 2020 Samantha Box, Portal, 2022

Samantha Box, Portal, 2022All photographs from the series Caribbean Dreams: Constructions, 2018–ongoing. Courtesy the artist

Samantha Box is a runner-up for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

How a Young Chinese Photographer Subverts Traditional Gender Roles

Ziyu Wang grew up in Xinyang in a traditional Chinese family, meaning that he was constantly aware of the gendered expectations that his parents have for him. “My father had hoped I would become a government official, because in his eyes, this was a symbol of masculine power,” Wang says. “As a result, I took a photo of myself wearing a suit against a blue background, as in China, all government officials have ID photos with this backdrop.” But what might it mean for Wang, who is queer and now lives and works in London and Shanghai, to upend these expectations, and to challenge himself and others through photography?

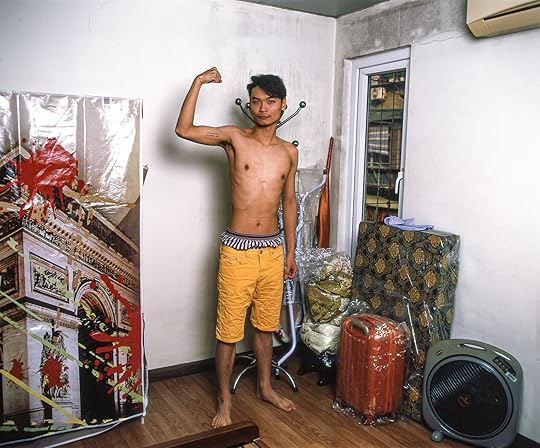

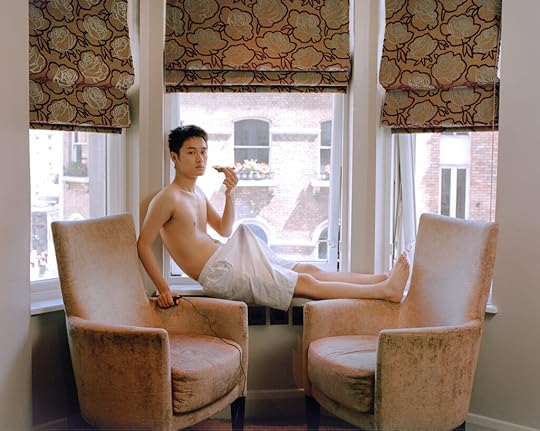

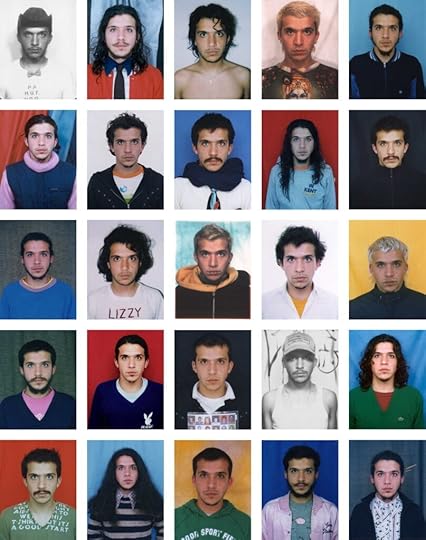

Ziyu Wang, Lads, 2022

Ziyu Wang, Lads, 2022In his playful self-portrait series Go Get ’Em Boy (2021–22), Wang performs traditionally masculine archetypes in front of the camera, embodying different characters to point out the often absurd assumptions of traditional gender performance, in China and elsewhere. The reflexive nature of self-portraiture allows Wang to explore these themes and remain authentic to his own life. Informed by gender theorists such as Judith Butler, whose germinal writing in the 1990s framed gender as a form of performance, Wang inflects ideas of “gender parody” into the context of Asian men, subverting stereotypical ideas to capture gay, Asian men in the role of “alpha” males. In Lads (2022), Wang poses in a line with other Asian men, all shirtless, flexing, ordered from largest to smallest physique. It’s a striking image that, on one hand, cleverly confronts stereotypes of Asian masculinity as it relates to the body while, on the other, questioning the viewer’s expectations of what a “man” should look like.

While Wang employs a supporting cast of characters, the focus in Go Get ’Em Boy remains on how he himself can personify these masculine archetypes. “I believe that using myself as the subject allows me to create a deeper connection with the viewer, as they are able to see me, my body, and my emotions in a way that they might not be able to with an image of someone else,” he notes.

Wang’s photographic influences include Hans Eijkelboom’s With My Family (1978), a series wherein the Dutch photographer took self-portraits with real families, interloping as a fake father figure. “What I love about this series is Eijkelboom’s ability to subtly shift identities and insert humor into a familial context,” Wang says. He also cites Yushi Li’s self-portraiture work as a touchstone of photography that deals with tangential ideas of gender and race, using a similar approach.

Ziyu Wang, Go Handstand, 2022

Ziyu Wang, Go Handstand, 2022Wang approaches image-making with levity and wit. “Humor and playfulness are key to making conversations about masculinity and gender identity more inclusive,” he says, which “allows for detachment and questioning, connects with audiences, and creates a more accessible and relatable experience.” However, the pleasure of viewing Wang’s parodies of masculinity (for example, being held in a pose of extraordinary athleticism by two conspirators in morph suits), belies the use of humor as a critical device. “I had been pretending to be heterosexual in my parent’s presence,” Wang says. “It struck me as absurd.”

While Go Get ’Em Boy is foremost a playful refraction of his own lived experiences, Wang is aware of the broader ideas communicated by his work. “Many young Chinese people are often pressured to conform to cultural and societal expectations surrounding gender, sexuality, and identity,” remarks Wang, who has come across similar experiences of familial prejudice in conversations with his queer, Chinese friends in London. This experience of having to live a double life—being able to be openly queer in London, but not China—is something he wants to explore in a future body of work. “Overall, I want to bring attention to the struggles faced by the queer, Chinese community.”

Ziyu Wang, Wedding Rehearsal, 2021

Ziyu Wang, Wedding Rehearsal, 2021 Ziyu Wang, Untitled 1, 2022

Ziyu Wang, Untitled 1, 2022 Ziyu Wang, With My Daughter, 2022

Ziyu Wang, With My Daughter, 2022 Ziyu Wang, With My Buddies, 2022

Ziyu Wang, With My Buddies, 2022All photographs from the series Go Get ’Em Boy . Courtesy the artist

Ziyu Wang is a runner-up for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Akshay Mahajan Searches for Mumbai’s Past Lives

The city of Mumbai—once Bombay—has long suffered an identity crisis. Before Bollywood and the Bombay Stock Exchange, the rise of cotton mills and Gothic facades, and the fall of the Raj, the territory was a gift, a seventeenth-century dowry from the Portuguese to the British. This rather bureaucratic maneuver set the stage for Mumbai’s many evolutions: first as an archipelago of seven islands, then a colonial port, and then a modern metropolis. With each mutation, a grand narrative was developed and preserved with great care: on paper, celluloid, and stone. But for those willing to look closely, the city is full of cracks.

Akshay Mahajan, Certain things about a place become its memory, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, Certain things about a place become its memory, 2022  Akshay Mahajan, Empty pedestal, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, Empty pedestal, 2022 The historian Gyan Prakash once said that Mumbai “can be read in the detective novel form.” It may not come as a surprise, then, that the protagonist of Akshay Mahajan’s ongoing series To die is to be turned to gold is on a citywide search. Recalling an old urban legend, the title underscores the city’s image as a place of extremes. As the saying goes, those who move here either prosper or die trying, ultimately turning into gold themselves. But ask any Mumbaikar: the dead don’t die so easily.

“Within the city’s postcolonial reality is a pre-colonial memory,” explains Mahajan, who called it home before moving down the coast to Goa. “I refer to these as ghosts.” Using a mix of portraits, street photographs, landscapes, and still lifes, he envisions Mumbai through the eyes of a young sculptor who walks the city in search of a muse. One could imagine him as a student at the Sir J. J. School of Art, a pioneering Indian arts institution founded in the nineteenth century, where several photographs from the series are set. The city and school have been historically intertwined; a popular story claims that the gargoyles mounted on Mumbai’s most recognizable Gothic structure, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, were student art projects.

Akshay Mahajan, They say unusually in the case of the artist and their muse, the passing of time only seems to amplify, rather than fade perception, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, They say unusually in the case of the artist and their muse, the passing of time only seems to amplify, rather than fade perception, 2022  Akshay Mahajan, The Fine Arts department at the JJ School of Arts, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, The Fine Arts department at the JJ School of Arts, 2022 For Mahajan—who has a special interest in archives, colonial histories, and urban forms—the series is an experiment with historical continuity and memory. Relics are reinterpreted, replicated, and used as reference material, as the sculptor’s attention seesaws between the colonial and the contemporary, the center and the margins. He understands his debt to Mumbai’s past, but can also intuit its failures and contradictions. In one photograph, Laxmi, a longtime professional nude muse at the school, leans against the plinth of a marble statue. She then reappears in another image as the subject of two student paintings. The sculptor’s eye attempts to preserve Laxmi within the record; instead of disappearing, she multiplies. “There must be a room somewhere with hundreds, if not thousands, more,” Mahajan adds.

New statues emerge, mills are turned into luxury malls, and colonial offices are repurposed as investment banks. Nonetheless, repetitions continue to appear. An image depicting a young student sitting in front of two Greco-Roman replica statues bears an uncanny resemblance to one made over thirty years ago by the photographer Raghubir Singh for his own Mumbai book. All the elements are there: the replicas, the hardwood floor, and nearly the same corner of the sculpture department. Another photograph of a boy on horseback riding into the Arabian Sea seems to mimic an equestrian statue of King Edward VII. Once a centerpiece of the city’s colonial urban plan, the nearly seventeen-foot-tall bronze king now sits in a nearby zoo. If the politics of India is increasingly a politics of revisionism, Mahajan enacts an attentive close reading. “Every successive boom has come at the cost of a class of people who were never pedestalized as statues,” he says. In their search for a Mumbai beyond received frameworks of colonial architecture, art, and commerce, the photographer and his invented guide share the same vision, that “one sculpts bottom up.”

Akshay Mahajan, One sculpts bottom up, with slabs of clay, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, One sculpts bottom up, with slabs of clay, 2022 Akshay Mahajan, It’s hard to rid oneself of these traces, like wet sand, Bombay sticks to your ankles, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, It’s hard to rid oneself of these traces, like wet sand, Bombay sticks to your ankles, 2022 Akshay Mahajan, Bust in plastic, 2022

Akshay Mahajan, Bust in plastic, 2022All photographs from the series To die is to turn to gold, 2022–ongoing. Courtesy the artist

Akshay Mahajan is a runner-up for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

May 5, 2023

Photographs That Show the “Fire and Thunder” of Contemporary Life

The Image Equity Fellowship, in partnership with Google, Aperture, For Freedoms, and FREE THE WORK, aims to support the next generation of image makers of color in the US. Throughout a six-month fellowship, a group of twenty artists made new bodies of work with the dedicated mentorship of Lebanese filmmaker and photographer Ahmed Klink; American artist and 2016 Guggenheim Fellow Lyle Ashton Harris; photographer and documentarian Bee Walker; multi-hyphenate creative Mahaneela; and Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. An exhibition of their work Through Fire and Thunder opens at Pioneer Works on May 12, 2023.

“The role of the artist is to dream up a world where we collectively transcend the limits of inequitable systems,” notes the exhibition’s curator Adama Kamara of Creative Theory Agency. “We rely on them to cast light on our experiences through the fire and thunder, but also to imagine a world on the other side.” The Image Equity Fellowship and subsequent exhibition grow from Real Tone, Google’s efforts to more accurately and beautifully represent people of color on camera and in image products, and has since developed into a collective of imagemakers capturing their communities through the lens of identity, belonging, movement, coming of age, home, and beyond.

Jamil Baldwin, For Olivia “Olee” Lee, 2022

Jamil Baldwin, For Olivia “Olee” Lee, 2022Jamil Baldwin

“This is my ode to the lives of Jabari Benton, Jonathan Sandoval-Aleman, Millard Frazier Jr., and Olivia Lee,” says Jamil Baldwin of his series Tenacity. Baldwin’s poignant black-and-white images begin as photographs of family members from his group of friends, who are seen at sites of importance for loved ones who have passed away, holding images that Baldwin has printed and framed. Each image reappears within the image being held, creating a recessive effect where each family photographed is therein holding the next. This gesture, Baldwin notes, reflects “what it is to be held by your community of friends and family; a reminder that grief isn’t held by any one individual.” Baldwin then soaks the silver-gelatin prints in water, to a point where the image begins to dissolve and abstract. These abstractions, for Baldwin, reflect the process of losing a loved one. “In some ways I don’t want Black bodies to be the anchor for conversations about death and grief and adversity. This series is really about love, but to know love as deeply as I know it, you need to know the depths of loss.”

Miranda Barnes, Untitled #1, 2022

Miranda Barnes, Untitled #1, 2022Miranda Barnes

When Miranda Barnes graduated from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in 2018 with a degree in Humanities and Justice, she was unsure how photography would fit into her career plans. That year, she was commissioned for a New York Times story about Memphis for the fiftieth anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. “It gave me the confidence to pursue photography as something I could use my background for in a more visual sense,” says Barnes, a self-taught Caribbean American artist who grew up in Brooklyn. In the years since, she’s taken on a range of commercial and editorial work across the country, including for Nike, Apple, Vanity Fair, and TIME, developing an approach that draws from the visual language of street portraiture and environmental and vernacular photography. The intimate and vibrant work in her sub-series Labor Day Parade—which focuses on the West Indian Day carnival that takes place in Brooklyn every September—forms one part of a much longer-term project exploring celebration, community, coming-of-age, and Black subcultures across the country, including Cotillion and Debutante Balls. For Barnes, who has been photographing the parade since she was a teenager, style is as much about individual expression as it is about community relations and history, which is why people, in celebration and communion, are always at the center of her work.

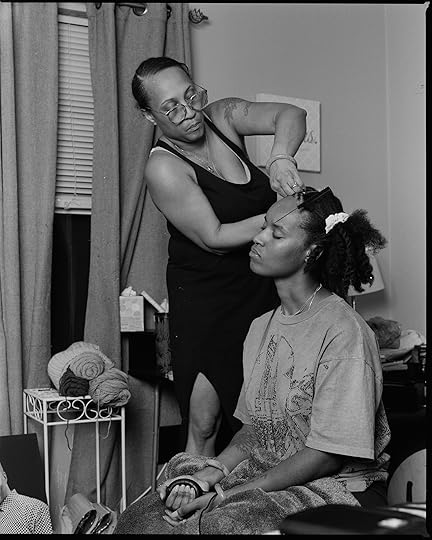

McKayla Chandler, Only Mama’s Hands, Minneapolis, MN, 2023

McKayla Chandler, Only Mama’s Hands, Minneapolis, MN, 2023McKayla Chandler

Growing up in Minneapolis, McKayla Chandler’s mother would often braid her and her three sisters’ hair, and then photograph the styles as references for her circle of local clientele. However, it wasn’t until 2020, when Chandler moved back home due to the pandemic, that she rediscovered her mother’s braid book, the photographic ledger of all the different styles she had braided, and realized the artistic potential behind it. Chandler’s series, MOBETTA, uses her mother’s braid book as a launch point into a documentation of contemporary braiding styles and culture. Chandler’s work captures the innate beauty and expressiveness of braiding as an art form and a means of self-expression, but also the symbolic potential of braiding styles as vessels for personal and communal history. Just as the braid book preserved a moment in her own family’s story, Chandler sees her project as a work of “archiving in real time.” As she notes, “There’s so much erasure that happens, especially in the Black community, especially being in America. One way to preserve this history is to just make sure you’re taking those photos, and understanding the importance of being able to pass these things down.”

Neesh Chaudhary, The Dream of the Heron, 2023

Neesh Chaudhary, The Dream of the Heron, 2023Neesh Chaudhary

Neesh Chaudhary’s series Diluted explores the physiological and emotional impact of colorism in Indian culture. “The color of your skin is still something that defines your place in society,” Chaudhary says. “But what’s so complex is that it’s something that’s also perpetrated by the victims themselves—it’s ingrained in society in a way that’s just become natural.” In several staged scenes shot on film and then digitally stitched together, Chaudhary envisions the tensions within the interior landscape of her heroine, who has been split between her natural self and an idealized, European beauty-standard alternative. Throughout her photographs, the power dynamics of these two “selves” is constantly shifting—in some moments, the heroine blissfully ignores her alternate, in others, she sits vulnerable while her other takes on a dominant role—pointing to the fluidity of these anxieties and self-perception, and that the ways one sees themselves is always changing. In the concluding photograph of the series, Pranama, Chaudhary plays on the traditional act of bowing at the feet as a form of respect and reverence. Her heroine’s alternate bows at her feet, reversing the roles of reverence in a moment of reclamation for her true self. As Chaudhary states, “It’s taking a strong cultural tradition and turning it on its head, asking: How can we have this tradition about respect for one another, while simultaneously having this cultural view that judges someone based on their skin tone, something they can’t control?”

Nykelle DeVivo, birth of the purple moon, 2023

Nykelle DeVivo, birth of the purple moon, 2023Nykelle DeVivo

Tha Crossroads is one part of DeVivo’s ongoing series that explores the different ways Black people throughout the diaspora connect to the spirit. The source of DeVivo’s inspiration comes from the Kongo cosmogram—a core symbol in Bakongo spirituality that depicts the cyclical nature of the physical and spiritual worlds. In this iteration, DeVivo narrows in on the point at which the spirit rises, whereas they describe, “birth and potentiality reach their ultimate point.” Working with a mix of photographic techniques including Polaroids and burning and layering images, DeVivo is less driven by the representative nature of photography, instead stating, “I’m more interested in the ephemeral or emotional space we connect to through image-making.” Throughout the photographs, a purple moon births into the world; two bodies intertwined call to sexuality and pleasure as a space of connection; and the recurring motif of sparks offer a visual representation of the spirit’s birth into the physical world. For DeVivo, who has family connections to Southern vodou, Creole heritage, and Hinduism, the creation of these photographs feels tied directly to their lineage. “I call my art practice my spiritual practice,” says DeVivo. “It’s a place where I can commune with my ancestors.”

Emanuel Hahn, California Dreaming, 2023

Emanuel Hahn, California Dreaming, 2023Emanuel Hahn

In America Fever, Emanuel Hahn intersects Korean cultural and historical elements with mythologies of the American West in an exploration of Korean American immigrant experiences in the 1970s. The title refers to citizens in postwar Korea who, inspired by the image of American culture, desired to immigrate to the US for a better life. Hahn’s staged scenes reflect the luster and romance of an American West coming out of the Hollywood age. Inspired by artists such as Alex Prager and Gregory Crewdson, who created their own worlds through cinematic techniques, Hahn’s work reflects upon the duality America has to offer: a hopeful, yet potentially dangerous, future. “I wanted to do that for the Korean American community, depicting this specific time and place in our history that hasn’t really been seen or celebrated,” Hahn says. One image from the series, Jultagi,references a historical Korean performance in which an entertainer tells witty stories while walking a tightrope. Hahn depicts a man dressed in Western clothes walking towards the camera, and his future, while a woman, dressed in traditional Korean attire, has her back turned, reflecting longingly on her past. “The tightrope acts as a metaphor for the immigrant experience,” says Hahn. “There’s no room for mistakes, but it’s also a performance.”

Eric Hart Jr., Range (Mister, Mister Series), 2023

Eric Hart Jr., Range (Mister, Mister Series), 2023Eric Hart Jr.

Eric Hart Jr.’s sitters are aware of your gaze, their own performance, and the inequalities that have long haunted photography. “I’m interested in dissecting what it means to perform as a man, as a queer man, as a Black queer man,” says the Brooklyn-based artist and NYU Tisch School of the Arts graduate. Using a highly stylized approach, Hart’s portraits reimagine Black men against a range of historical circumstances, racist visual tropes, and critical and cultural references, including Du Bois’s “double-consciousness,” Fanon’s anti-colonialism, New York City’s Ballroom scene, and the photographer’s own upbringing in Georgia. In addition to a growing body of commercial work for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, and the Washington Post, his debut monograph, When I Think About Power (2023), explores power and its relationship to the Black queer experience––using theatricality, overtly produced elements, and dramatized black-and-white imagery. Hart’s more recent series, Mister, Mister (2022–23), builds on this idea while widening its scope, using constructed scenes and postures to comment on artifice, photographic representation, and its historical associations. “So much of power is performance, and I think performance is so broad,” Hart says, explaining his proclivity toward artists that produce work that feels made, including Zanele Muholi, Kerry James Marshall, and Dana Scruggs. “I have so much more to say.”

Vikesh Kapoor, The Day After, 2023

Vikesh Kapoor, The Day After, 2023Vikesh Kapoor

Vikesh Kapoor is a singer-songwriter and a photographer. “My medium changes depending on the kind of story I want to tell,” he says. The story Kapoor is telling in his latest photographic series is a story about his family, specifically the lives of his parents, Sarla and Shailendra, who were married in 1969 and immigrated from India to London and New York before settling in Pennsylvania. They were doctors. “We’re a Team,” a promotion from the Lockhaven Hospital declared in an announcement about the couple. Beginning in 2018, Kapoor decided to make a record of his parents, photographing them at home and drawing upon family albums and documents, in an effort “to explore their life aging, as immigrants.” He discovered letters his mother wrote to his father after their engagement and portraits from their wedding day. All of these details suddenly held new meanings when Sarla died on January 11, 2023. Grief can be distorting and illuminating. A woman’s hands as she steams milk or a man’s blazer worn to a funeral: the fragility of the body and the resilience of memory. One photograph shows an altar before which Kapoor’s family told stories of Sarla. At the center is a portrait Kapoor made of Sarla posed against a plain white backdrop, poised and self-possessed—a final collaboration between mother and son.

Adeline Lulo, Lydia, Washington Heights, New York, 2022

Adeline Lulo, Lydia, Washington Heights, New York, 2022Adeline Lulo

“When you visit a Dominican household, you’re welcomed with open arms, and treated like family,” says Adeline Lulo. “Visitors are welcomed with a kiss on the cheek, and conversations flow over freshly brewed cafécito.” This particular sense of warmth and hospitality is the focus of Lulo’s project A La Orden (At Your Service), in which she photographs intimate scenes of the interior life of immigrant families who have migrated from the Dominican Republic to New York. Images of walls and shelves adorned with family photos, flowers, and reliquaries tell a rich story of past and present, while portraits of family and friends are captured with care and reverence. Lulo, who herself has roots in Washington Heights, the Bronx, and the Dominican Republic, sees this work as a love letter to the Dominican community. “This is my way of giving them their flowers,” Lulo says. “By sharing these stories and images, I hope to create a space for reflection, conversation, and healing for the Dominican community, while preserving a piece of Dominican history for future generations.”

Tiffany Luong, But we just got here, 2022 (Re-imagining 1948)

Tiffany Luong, But we just got here, 2022 (Re-imagining 1948)Tiffany Luong

Tiffany Luong stages imagined moments in her family history in order to expose the personal weight and lingering effects of immigration. Her series Reclamation is a restorative work; having been never told the details of her grandparent’s journey from Taishan (Toisan in Cantonese), China to the United States, Luong was motivated to fill in the gaps herself. Through intensive research through resources like the National Archive Record Administration, Luong surfaced her grandparents’ immigration documents and entry interviews, and began to piece together an idea of their history. “Reclamation is me trying to figure out what made my grandparents who they were, what made my parents who they are, what made me who I am, and finally what I’m passing down to my own children,” Luong says. The images, made between Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and California, while informed by her historical research, seek to inhabit the emotional space of her grandparents during their immigration rather than adhere to an idea of historical fact. Luong notes, “I realized that I didn’t have to do an accurate documentation, because I don’t actually know what happened exactly. Instead, I could have artistic license and freedom. That was an important revelation—although I wanted to tell a true story. I don’t know the truth, because no one ever told me.”

Maya June Mansour, I’m Still Here, 2022

Maya June Mansour, I’m Still Here, 2022Maya June Mansour

In her ongoing series Light Brown Butterfly,Maya June Mansour investigates the lasting physical and emotional impact of an act of sexual assault she experienced in her youth. Mansour was prompted to begin the projects after being diagnosed with an ovarian cyst that formed as a result of internalized stress and anger from the event. Working between a variety of mediums, from 35mm film to Polaroids to multi-frame cameras, Mansour’s series of self-portraits depict the non-linear process of healing, describing each of the photographs as “pages from a journal.” Beauty is an integral part of the work and her creative process, acting both as a tool of self-care as well as an exploration of the spiritual attributes beauty can offer. “I want victims or survivors of sexual assault to feel seen in a way that they haven’t before,” she says. “I’ve never really resonated with the stories or the phrase #MeToo before, so this is my version of that.” The mirror, a recurring motif, integrates Mansour’s emotional journey of reflection to create this work, while also asking viewers to consider their own life and position as it pertains to sexual violence and patriarchy. In I’m Still Here (2022), a small mirror featuring Mansour’s reflection is almost invisible against the larger interior space, hinting at the ways in which trauma can often be invisible on the outside. “When you have that kind of trauma it becomes a part of you, it informs everything,” Mansour says. “This photograph shows how it’s almost easy to look at a person and not see it—but once you see my face in the mirror, it’s impossible to miss.”

Da’Shaunae Marisa, Charm, 2023

Da’Shaunae Marisa, Charm, 2023Da’Shaunae Marisa

Da’Shaunae Marisa’s mother was the family photographer. When Marisa was in kindergarten, her mother gave her a disposable camera to document her friends. That was the beginning. Marisa grew up in Cleveland and although she has extended family in Ohio, Georgia, and Virginia, they weren’t close until Marisa’s mother was diagnosed with cancer, which would become “the reason for an overdue reunion.” Marisa’s work is about connectivity, about “finding all the similarities between different cultures and generations.” But it’s also about how emotions can be stored in the body and the face, protected most of the time, released only in spaces of trust and intimacy. After her mother passed away in May 2020, Marisa made a series of sensitive portraits with the muted color palette of Ohio’s early-spring light, probing questions about grief and survival. For her newest project, she invited her own family, a friend’s family, and twin brothers she met in South Africa into the studio, working with a large format camera and a Lomography Instant Back, often taking upwards of two hours to make detailed composite portraits. The long studio process allowed for deep discussions about grief “and how each family member processes that differently.” Sometimes you only see a fraction of what a person is thinking or feeling, if that’s all they can give. Sometimes, as in Marisa’s patient, collaborative portraiture, you can catch glimpses of their true self.

Giancarlo Montes Santangelo, te recuerdo, asi incompleto, 2022

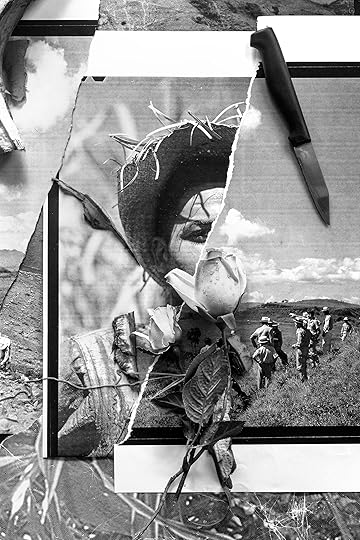

Giancarlo Montes Santangelo, te recuerdo, asi incompleto, 2022Giancarlo Montes Santangelo

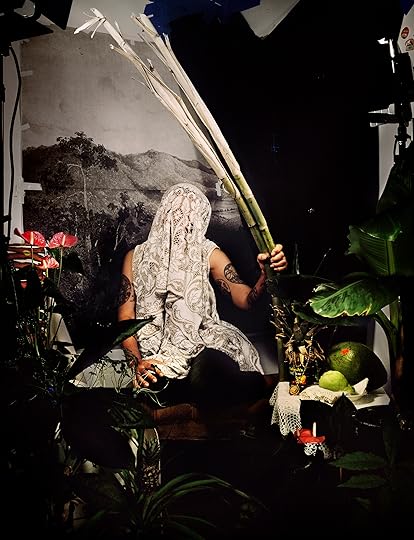

When Giancarlo Montes Santangelo searched the Library of Congress for photographs of Puerto Rico, he discovered an excess of images that appeared to frame the island’s history through a nationalist perspective. He began to wonder about the impact of these images, many from the early twentieth century, on larger cultural stories, “and how these stories settle into the present.” Montes Santangelo’s mother was born in Argentina and his father was born in Puerto Rico; they met in Washington, DC. The artist’s dual heritage has, in part, prompted an ongoing inquiry into archives, both public and personal, that might fill in missing chapters of history about the Caribbean and Latin America. But he’s also drawn to photographs that resist interpretation. In his work, multiple, often competing narratives are drawn together in layers. For some pieces, he collects and collages photographs, enlarges the collages to create studio backdrops, then sets up his studio to make yet one more image. For others, he poses himself or friends in performative actions that recall the strategies of artists Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Whitney Hubbs. There’s a “spectrum of experience” Montes Santangelo notes about his intricate collages, which consider ritual, pain, masculinity, and spirituality. “My own body is affected by those images and can affect those images,” he says. “I’m trying to create a space where I can open up those histories but also contribute to them.”

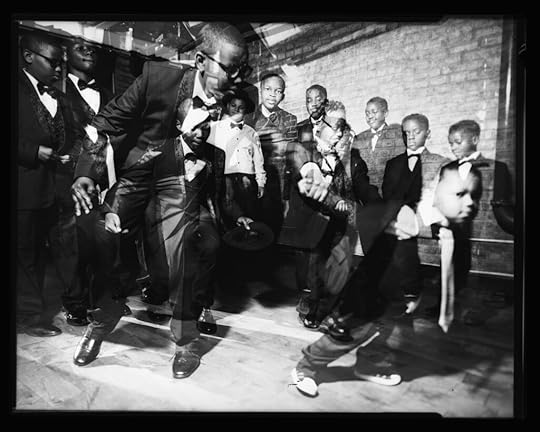

Xavier Scott Marshall, Untitled (Harlem Ballroom), 2023

Xavier Scott Marshall, Untitled (Harlem Ballroom), 2023Xavier Scott Marshall

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Cotton Club in Harlem hosted a dizzying array of iconic Black musicians and performers, but Black patrons were not permitted entry. Xavier Scott Marshall was questioning that double standard—a space where a Black man in a suit could only be seen as the entertainment or “the help”—when he encountered a Harlem community program called We Do It Too, which teaches boys to wear suits, invites guest speakers and mentors, and generally invites boys to “come into their manhood in a confident way.” As Marshall began photographing the boys in their suiting, he thought about James Van Der Zee’s classic Harlem portraiture and Ming Smith’s experimental approach to portraying musicians. He also thought about W. E. B. Du Bois’s concept of “double-consciousness,” the sense, as Du Bois wrote in 1897, “of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” For these young boys from economically challenged backgrounds, would suiting be a form of “class armor”? Would a suit equalize the playing field? Marshall used a 4×5 camera to make double exposures and processed the film by hand, allowing for subtle imperfections to remain part of the final images. “I wanted to glorify them while also paying homage to the past,” Marshall said of the Harlem boys. Instead of dancing for patrons, in these photographs, the boys are dancing for themselves.

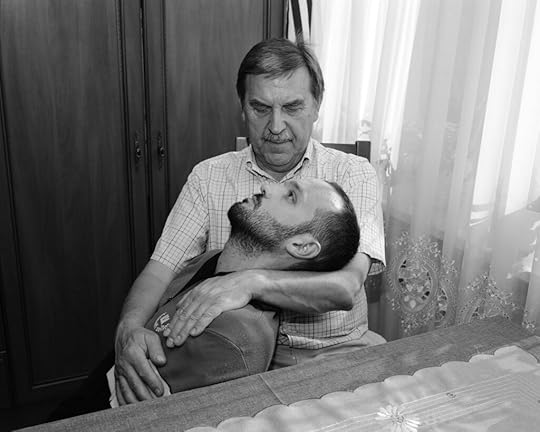

Ricardo Nagaoka, Caress (Justin), 2022

Ricardo Nagaoka, Caress (Justin), 2022Ricardo Nagaoka

Growing up in Asunción, Paraguay, as the grandson of postwar Japanese immigrants, photographer Ricardo Nagaoka found himself surrounded by narrow and patriarchal models of masculinity. “As I tried to perform that very form of masculinity,” Nagaoka says, “my body felt what it meant to be seen as less than because of my race.” Through constructed images featuring close friends, chosen family, and collaborators, Nagaoka attempts to pry open masculinity’s historical and cultural baggage, as well as its performance, to push for a broader understanding of gender and queerness. His quiet and intimate imagery draws from personal experiences: “Whether it’s a memory of touch, a glimpse of a gesture, or a translation of my emotional state,” he explains, “my work relies on intuition during its making process.” Nagaoka brings in a range of visual references and ideas when constructing his photographs—from the work of Catherine Opie, Masahisa Fukase, Sam Contis, and the twentieth-century Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu, to the broader legacies of New Topographics and the Pictures Generation. After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2015 and then spending nearly a decade outside art education institutions—working with the New Yorker, TIME, and FT Magazine—Nagaoka will start his MFA at the University of California Los Angeles this year. “I want my work to continue these conversations, and to be contextualized within academic, institutional, and cultural understandings of how we define masculine performance,” he says.

Nasrah Omar, Proteus Effect XXVI, 2023

Nasrah Omar, Proteus Effect XXVI, 2023Nasrah Omar

Nasrah Omar is drawn to the limits and possibilities of world-building, both online and in real life. In her series Proteus Effect (2021–ongoing), iridescent slime oozes in from a French window, amethyst runic stones scatter over a game board, a head appears just above the surface of a bioluminescent body of water. “I’ve always thought of photography as an apparatus to manipulate reality,” says Omar, who was born in India, graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 2012, and now lives in Queens. “The imagery explores how virtual spaces become deeply affective and integral to the composition of layered identities, agendas, and ideologies.” Through photographic tableaus, references ranging from spiritualism to Tumblr, and collaborative portraits with queer Muslim Bangladeshi activist and model Nova A, Omar explores how constructed ecosystems are able to challenge power structures encoded within technologies, often expressed through surveillance systems, algorithmic biases, and censorship. Among her influences are thinkers who’ve drawn potent links between digital systems and real-world imbalances, including Legacy Russell, James Bridle, and Zainab Aliyu, who co-taught a class Omar took at the School for Poetic Computation in New York. At its heart, the world built by the series is an experiment in imagining—as Omar says—“how the digital world can be an avenue to create agency for marginalized persons.”

David López Osuna, Andre Guerrero, 2023

David López Osuna, Andre Guerrero, 2023David López Osuna

The sterile environment of a chain restaurant is nothing like the places where California-based photographer David López Osuna grew up eating. As an undergraduate at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, he began noticing that much of the work he was seeing didn’t relate to his own experiences, or was overly influenced by commercial media. That’s when he began photographing the fast-food industry—particularly the people behind the counter, their relationship to their communities, and their attempts for fair working conditions. “I come from a family of working-class people,” Osuna says. “I’m the first person in my family to actually pursue a career as an artist.” What began as a project documenting corporate chains like McDonalds soon evolved into a more community-centered approach, focused on two family-owned restaurants in the greater Los Angeles area. Osuna spent months documenting their owners, patrons, and staff, using an intimate and interpersonal approach that contrasted with the sanitized worlds envisioned by corporate advertising. Having worked as a lighting assistant for similar commercial projects, Osuna is familiar with how these consumer fictions are manufactured; his work remains focused on real people and the lives they attempt to conceal or embellish. “As an artist, I’m very concerned with the role that corporations have in the lives of working-class people,” he says.

Walé Oyéjidé, Le père, la fille et le ballon, 2022

Walé Oyéjidé, Le père, la fille et le ballon, 2022Walé Oyéjidé

When COVID-19 began to hit statewide, Walé Oyéjidé, like many other artists at the time, found himself turning to his domestic space and those he shared it with to create new work. The resulting series, Joy and Daughter at the end of the world, is an intimate yet joyous reflection of life with his ten-year-old daughter in these precarious years. Weaving together a mix of stated scenes and naturalistic images, Oyéjidé depicts the sense of imagination of a child at this age, bringing a sense of play and fantasy to each of his photographs. For Oyéjidé, who has a background in film and fashion, the beauty in his photographs is a deliberate attempt to challenge narratives around fatherhood that are often negative—particularly for people of color. The role of collaboration between himself and his daughter further bolsters this idea, allowing her to have a direct hand in her own representation, as well as transforming photography into an act of father-daughter bonding. “We all connect in whatever ways we can,” says Oyéjidé. “But as an artist, the tools that I have are storytelling or photography.”

Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola, Mom & Ola, December, 2022

Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola, Mom & Ola, December, 2022Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola

Tosin Popoola moved from Nigeria to the US in 2014 and bought his first camera on eBay the following year. During college, he discovered the work of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. His photography, he says, which encompasses fashion and portraiture, is about “feelings, everyday life, little moments.” Several years ago, he decided to begin making pictures of his family, many of whom had emigrated to the US and settled in Ohio. “I wanted to honor them and introduce them to the world,” he says, but also to document “the changes in my parents’ faces.” Not everyone in his new portraits is a family member in the strictest sense, but all are like family in their bonds to the photographer. Here, we see regal postures and gazes, gleaming skin and perfect manicures, brown swag fabric flowing against a white studio backdrop, and the kinds of clothes Nigerians are known to wear on Sundays or special occasions. In one image, Popoola’s mother wears a vivid pink gown originally made by an aunt. Popoola’s youngest brother, zigging and zagging in the background, makes a cameo in a few pictures, adding a dash of kinetic energy to the formal studio scenes, which Popoola created with a large-format camera. “It just happened,” Popoola says of his brother’s sudden appearance. So, everyone said, “You know what, just jump in.”

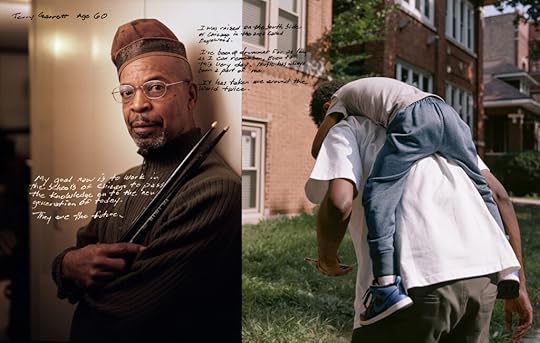

C.T. Robert, Terry, 2022

C.T. Robert, Terry, 2022C. T. Robert