Aperture's Blog, page 36

November 4, 2022

Tom Sandberg’s Elusive Photographs Show Mysteries in Plain Sight

In Japan, where I’ve made my home for thirty-three years, I often see people bowing to a telephone as they speak into the receiver. Ceremonies are held in temples every year for sewing needles that have given themselves up to make a kimono. My Japanese wife, while growing up in Kyoto, was taught to apologize to a table if she kicked it in a fit of six-year-old pique. Nothing, in short, is unworthy of the humbled reverence we call attention. Objects have lives, and the divisions we draw between animate and inanimate are a human-made creation; that’s one reason why the moon in Japan is offered the same honorific suffix as the emperor.

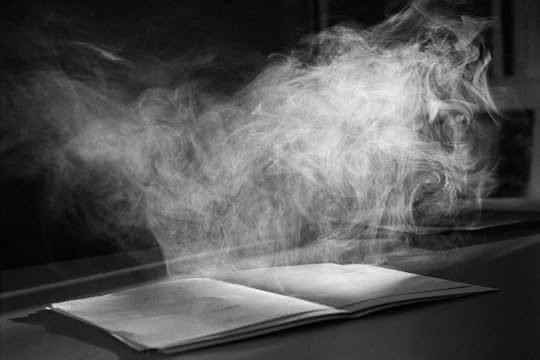

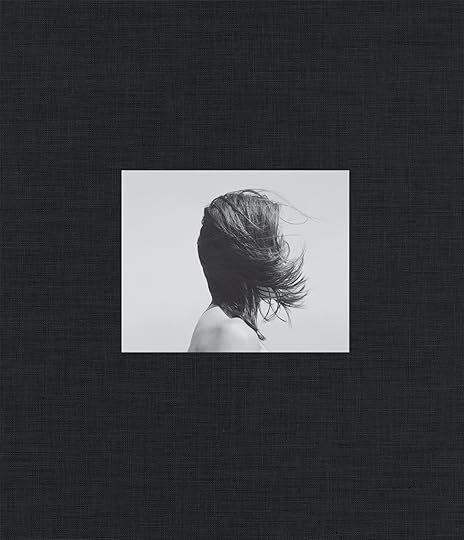

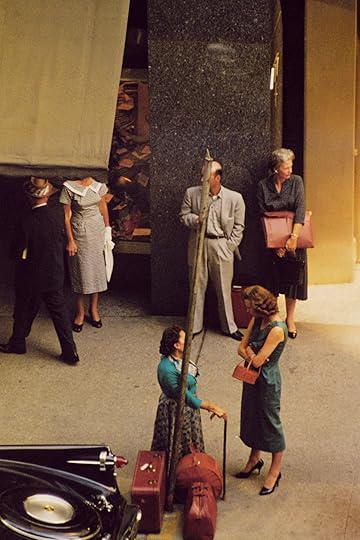

Much of that spirit comes back to me whenever I spend time with the work of Tom Sandberg. The Norwegian who pioneered photography in Scandinavia was always, it seems, training his lens on the objects that we overlook: Not the people enjoying lunch, but the paper bag beside them, so vivid we can almost hear it crinkle. Not a jet cutting through the heavens, but the emptiness that surrounds it. There are vehicles—cars, planes, and buses—in much of his work, and yet the images are about movement of a subtler kind: misty and precise as smoke rising from a stick of incense, they focus not on the cars outside but on the way a wind stirs a filmy curtain and, maybe in so doing, stirs us.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007 Tom Sandberg, Untitled, ca. 1994

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, ca. 1994This mix of specificity and absence is deepened by the fact that, though he was granted the honor of a solo show at New York’s MoMA PS1 in 2007, Sandberg liked to call his younger self a “small gangster from Norway.” In video interviews, I see a grizzled, watchful figure, contained and serene in the snow as he waits to find images with his predigital Pentax.

He organized happenings on the Oslo music scene and, in his youth, chose to sustain himself on donations of food from friends who worked in restaurants. In the early 1970s, he earned money as an assistant dogcatcher and loading frozen pig carcasses onto trucks. At that same time—photography not being regarded as much of an art in Norway—he began studying the craft at Trent Polytechnic in England, where he encountered an old master who produced large-scale black-and-white analog evocations of light, Minor White.

Much like his mentor, Sandberg grew fluent in the art of suggestion. His pieces are mostly untitled. They sit calmly in the midst of all they do not disclose. Thus, very often, they take us beyond the eye to somewhere deeper inside. I don’t know what to make of the reflections of all those faces in a bus, and when I look at his clouds swirling against blackness, smoke gets in my eyes. As with classic pen-and-ink drawings, these images invite us to complete the picture ourselves—or perhaps they simply ask us to live uncomplainingly with what we cannot hope to fathom. Everywhere in the world we take for granted, Sandberg might be pointing out, are enigmas as open as that paper bag. “I photograph just about everything,” he told the BBC in 2006. He even took his camera with him when he went shopping.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2006

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2006 Tom Sandberg, Untitled, ca. 1999

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, ca. 1999Photography, he also said, is “a complex dialogue between shades of gray.” He labored long and hard, or more than forty years, to find a thousand shades of “gray and matte,” working with the same type of film and developer throughout. In the process, he often gave us a universe in which there seems to be no color at all.

Or, phrased more precisely, he appeared to be listening, with all his being, to a universe that at moments offers us the silent treatment and at other moments speaks in whispers, in spectral trails of smoke, or murmurs through faces barely discernible in the rain. Some of his blacks are so inky they seem as if they were shouts—“Keep out!” Elsewhere, we lose all orientation in fields of silver and a whiter shade of pale.

Sandberg offers us attention so scorched of excess—and of explanation—that it comes to us as a secular prayer.

This dogged, undeviating artist—the son of a photojournalist—might, in fact, be trying to release us not just from the simplicities of black and white but from the black-and-white way in which we too readily strive to tame the universe. His work is about emotion, but the kind that cannot be pushed into any pigeonhole (or reduced to words). Sandberg was the first photographer to buy a house in the artists’ colony set up on Edvard Munch’s old estate outside Oslo. When he bought his first medium-format camera, he told a visitor there, “I started dreaming in six-by-seven.” That same visitor described the studio as “a white forest of rolls of large prints from the Picto lab in Paris.”

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2006

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2006 Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2004

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2004There’s something of an alien’s gaze in much of the work; this is how a brother from another planet might apprehend a hand, a child’s pigtails, a pair of sunglasses. When we do see figures in a landscape, they’re nearly always alone, small, against a backdrop of machines and high buildings: a classic vision of alienation. You don’t have to observe Sandberg’s work for long before noticing how still lifes, through his eye, are gnarly with texture and rhyming patterns. Yet the human body—in his nudes or portraits of babies—comes to seem just a shape, a cluster of tubes. Naked bodies are the opposite of erotic here.

What all this means is that he moves us to respond to photographs differently from how we usually might, which is why I write of listening as much as seeing: when I look at his airplane on an icy day, I can feel the slippery ground under my feet and the hard flakes of snow in my face more than I can make out anything visually. With his persistent images of clouds and smoke, it is the same: they’re not something just to be seen but rather to be reflected on. Sandberg can find what looks to be a giant lizard in the harsh terrain of a mountainside; he can give us pure canvases of light akin to a Mark Rothko work or a James Turrell Skyspace. In one of my favorite images here, we get not just the heavenly geometry of an illuminated tunnel, but a question: how much is this Nature’s work, and how much humans’?

Tom Sandberg, John Cage, 1985

Tom Sandberg, John Cage, 1985There’s something close to religious about this ghostly work, even though the clouds he presents are seldom celestial or shot through with heavenly rays. At heart, he’s giving us not just the world but all that cannot be shown and can never be seen. We hover between the earthly and something else. In that regard, it is surely no surprise that one of his great portraits is of a haunted, visionary John Cage, the man who wrote the book on silence and reminded us, in works such as 4’33”, that what the artist offers us is not the whole picture; his collaborator is circumstance.

Cage was a great believer in randomness and in the way that everything around us can, if seen or heard in the right way, be taken as a work of art. We don’t need to rely on simple distinctions between what is interesting or beautiful or important and what is not. It is the eye—of audience as much as artist—that makes a picture and, in so doing, makes the world.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2010

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2010 Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007 All photographs from Tom Sandberg: Photographs (Aperture, 2022). Courtesy Tom Sandberg Foundation

Of another caretaker of mysteries, Cage once told an interviewer, “As the words become shorter, Thoreau’s own experiences become more and more transparent. They are no longer his experiences. It is experience. And his work improves to the extent that he disappears. He no longer speaks, he no longer writes; he lets things speak and write as they are.” That chimes beautifully with what I find in Sandberg’s disappearances. Nothing comes between us and what we’re seeing. We’re getting reality—or mystery—unmediated. Or so, at least, he makes me feel.

The more I look at Sandberg’s work, in fact, the more I find myself disappearing, too, into the resistant images he shares with us, lost amid those cityscapes where humans seem tiny to the point of insignificance. And the longer I inhabit his eerily alive abstracts, the more I come back to some of Cage’s meticulously inexplicit koans: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.” And “Is there such a thing as silence?”

“Beauty is now underfoot,” Cage also wrote, of his friend Robert Rauschenberg, “wherever we take the trouble to look.” That could be the perfect epigraph for this book. Sandberg himself once quoted Rauschenberg: “I don’t know where I’m going, but I know I’ll get there on time.” Some of Sandberg’s images are so distinct, we can’t look away from them; others are so elusive, we look and look and still don’t know what we’re seeing. In all his work, Sandberg, who died at sixty, fourteen years into the new millennium, offers us attention so scorched of excess—and of explanation—that it comes to us as a secular prayer.

Related Items

Tom Sandberg: Photographs

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 244

Shop Now[image error]This essay originally appeared in Tom Sandberg: Photographs (Aperture, 2022).

October 24, 2022

August Sander and the Disquieting Facts of Modern Life

New Objectivity—in German Neue Sachlichkeit, a word which also connotes “fact”—was used by the curator G. F. Hartlaub in a 1925 exhibition at the Mannheim Kunsthalle to define a generation of painters who came after Expressionism. It described artists who shared a keen interest in realist representations of modern life, which at times resembled a form of reportage. These artists produced portraits of urban bohemians and professionals, like Otto Dix’s Portrait of Writer Max Hermann-Neiße (1925), still life paintings, such as Rudolph Dischinger’s Grammaphone (1930), or political or social satires. A recent exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris, entitled Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, attempted to explore how artists produced new forms of culture that reflected the massive changes of an unstable era. These artists, however, did not necessarily share ideology or politics. Some veered left, others right. “Objectivity,” it seems, had more than one side.

August Sander, Workmen in the Ruhr Region, ca. 1928, from August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Aperture, 2022)

August Sander, Workmen in the Ruhr Region, ca. 1928, from August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Aperture, 2022) Curated by Angela Lampe and Florian Ebner, this compelling exhibition placed New Objectivity within larger aesthetic and social contexts of 1920s Germany. There were standard examples of neue sachlichkeit paintings, like those from Hartlaud’s exhibition of Georg Grosz, Dix, Max Beckmann, and Alexander Kanoldt, as well as other artists who later became associated with the term like Walter Schulz-Matan, whose fascinating painting The Faience Collector (1927) portrays a seated man obscured by his own earthenware. Organized into eleven thematic groupings (Rationality, Utility, Montage, and Standardization, for instance), the exhibition opens up to a variety of other aesthetic trends in Germany that have some relationship to New Objectivity. What, for example, is its relationship to Bauhaus design? Or how does the political and economic chaos of the twenties, as expressed in New Objectivity, tumble into the well-known horrors of the 1930s and 1940s? Facts, it turns out, are never simple.

August Sander, Usherettes, 1926–1932, from August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Aperture, 2022)

August Sander, Usherettes, 1926–1932, from August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Aperture, 2022) All Sander photographs © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne—August Sander Archiv, Cologne, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

The exhibition title, with its slashes, is further telling of the curatorial method and aims, as it implies that the exhibition is split in a variety of different concerns that relate to one another. Those slashes also perhaps represent the shutter of a camera opening and closing: each a different perspective on the same reality, a series of snapshots of a chaotic period. That is particularly evident in the only name singled out in the title: although not in Hartlaub’s original exhibition—no photographers were—August Sander is often associated with New Objectivity, particularly through social connections to artists like Otto Dix (whom Sander photographed).

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022, with works by Otto Dix

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022, with works by Otto DixPhotograph by Bertrand Prevost

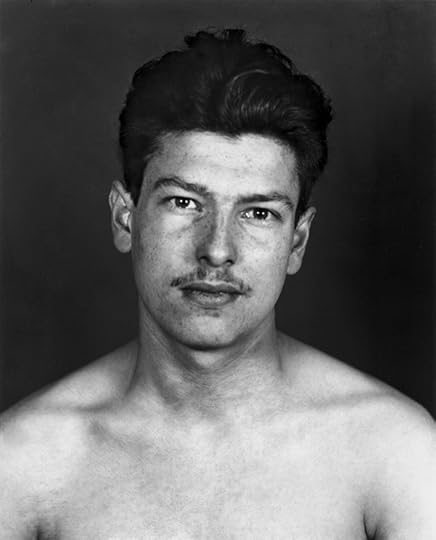

A massive presentation of Sander’s prints cuts through the exhibition, a sort of exhibition-within-an-exhibition. Around 1920, Sander started a project titled People of the Twentieth Century, a compendium of all types, kinds, and classes of people from the areas in and surrounding the Germany city of Cologne (a new edition of the compendium has recently been reissued by Schirmer/Mosel and Aperture). He organized it into seven main categories: Farmers, Skilled Tradesmen, Women, Classes and Professions, Artists, the City, and a final category the Last People, which included the transient populations, and even corpses. Sander’s pictures are blank, factual. They straddle a line between art and artlessness, between depiction and documentation. He captures his subjects—from bourgeois children to the homeless—with little room for ambiguity, or even aesthetic contemplation, either in situ or against neutral backdrops. They include disabled miners, the wives of architects, street musicians, unemployed men, bakers, and mixed-race circus performers. He is best known for portraits of labourers and of men in suits.

Related Items

August Sander: People of the 20th Century

Shop Now[image error]

From August Sander, Stirring Portraits of Nazis and Jews

Learn More[image error]“Work like Sander’s could overnight assume unlooked-for topicality,” writes Walter Benjamin. “Whether one is of the Left or the Right,” he continues, “one will have to get used to being looked at in terms of one’s provenance . . . Sander’s work is more than a picture book. It is a training manual.” Sander’s first publication, The Face of Our Time (1929), which was a selection from his larger ongoing project, was confiscated and destroyed by the Nazis in 1936. After being interrupted by the Third Reich, he continued his project for another twenty years.

It is within the context of Sander’s work—its documentation of modernisation and urbanisation, its sociological aim of classifying people of all walks of life in a dignifying way—that the exhibition attempts to present the facts of German art in the 1920s. It does so by also including other artists, photographers, and designers. There are, for example, photographs by Albert Renger-Patz of industrial objects, often aestheticizing their formal qualities, including his canonical Glasses (1926–27), which is juxtaposed with a still life painting of the same subject (and year) by Hannah Höch. There is a section devoted to the industrial design and architecture of the era, from architectural photographs by Werne Mantz to a complete reconstruction of Maragrete Schütte-Lihotzky’s “Frankfurt Kitchen” (1926). Further images of Walter Gropius’s architecture, as well as Marcel Breuer chairs, are also displayed, filling out the kind of radical experiments in modern life that are often associated with the Bauhaus. One of the final sections, “Transgressions,” focused on non-normative expressions of sexuality, from queer representations, such as the lesbian cabaret images of Jeanne Mammen, to Otto Dix’s violent and misogynistic sexual fantasies. These are presented as the social and aesthetic “facts” of the era, though the exhibition spends less time on the conservative elements, the painters Hartlaub called “classicists.”

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022Photograph by Bertrand Prevost

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022

Installation view of Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2022Photograph by Bertrand Prevost

The emphasis in “Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander”— on the facts—on that somewhat untranslatable word sachlichkeit—indicates something that many of the cultural producers of the era were considering: how to build a new way of living based on what they saw around them. The exhibition suggests that artists, architects, designers, and photographers attempted to take the facts of their circumstances and produce something new from them. The problem, as Walter Benjamin wrote in an unfinished critique of New Objectivity, is, “that the fashionable appeal to ‘facts’ is a two-edged sword.” While the exhibition focuses on the twenties instead of forecasting the end of a story that we all know too well, it hints that certain ideas, within the hotbed of their cultivation, sprout in untended ways. And, thus, it becomes, for us in our contemporary moment, another form of “training manual,” to use Benjamin’s term for Sander.

Germany / the 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander was on view at the Pompidou Center, Paris, from May 11 through September 5, 2022.

October 21, 2022

At a Photography Festival in Houston, History Confronts the Present

On September 4, 1949, shortly after closing a benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress near the upstate New York town of Peekskill, the singer and activist Paul Robeson was hustled into a car and told to lie on the floor, to protect himself against an assassination attempt. Anti-Communist rioters and Ku Klux Klan sympathizers had ambushed the departing audience, hurling rocks the size of tennis balls. Pete Seeger, who opened for Robeson with a new protest song called “If I Had a Hammer,” was in a car with his wife and two small children. The police stood by as a riot engulfed the country roads; the windows of Seeger’s car were shattered, and more than one hundred and forty people were injured. At home, Seeger washed the glass out of his children’s hair. In the 1950s, Robeson and Seeger were accused of Communism and blacklisted. “I remember a high-up official in the Communist Party,” Seeger recalled of the Communist writer V. J. Jerome. “He said, ‘Pete, don’t you realize this is the beginning of Fascism taking over in America? You know they have concentration camps for people like us already set up?’”

Dorothea Lange, Hayward, California – Two children of the Mochida family who, with their parents, are awaiting forced evacuation, 1942 Courtesy the Library of Congress, Washington, DC

Dorothea Lange, Hayward, California – Two children of the Mochida family who, with their parents, are awaiting forced evacuation, 1942 Courtesy the Library of Congress, Washington, DCSeeger and Lee Hays’s song “If I Had a Hammer,” the rousing folk standard once seen as taboo socialist agitprop, was on the mind of Steven Evans, the executive director of FotoFest in Houston, when he and the curators Amy Sadao and Max Fields put together the 2022 edition of the organization’s biennial. Spanning photography, video, and lens-based art, and subjects with overlapping themes of social justice and civil rights—including the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, the 1954 US-backed coup in Guatemala, the enduring surveillance state in Washington, DC, and the extraordinary rise of photo-sharing platforms—If I Had a Hammer, titled after the song and installed in Houston’s Silver Street Studios, exemplifies the hand-wringing mode of numerous exhibitions mounted in the wake of the Trump presidency and the COVID-19 pandemic. “If I had a hammer,” the lyrics go, “I’d hammer out a warning.” At FotoFest, there’s both sound and fury, and an urgent sense that we must interrogate history if we are to survive the present.

Installation view of If I Had a Hammer, Houston, Texas, 2022, with works by Bruce Yonemoto (left) and Dorothea Lange (right). Photograph by Ryan Hawk

Installation view of If I Had a Hammer, Houston, Texas, 2022, with works by Bruce Yonemoto (left) and Dorothea Lange (right). Photograph by Ryan HawkCourtesy FotoFest

The history lessons are robust. If I Had a Hammer opens with an enormous, wallpaper-style print of a Dorothea Lange photograph. Taken in Oakland in March 1942, three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it portrays a shop owned by a Japanese American who would later be forcibly relocated by the US military to an incarceration camp. “I AM AN AMERICAN,” a sign reads in the shop’s windows. (The majority of incarcerated Japanese Americans were born in the US and therefore citizens by birth.) After working for the Farm Security Administration to photograph the crisis of migrant workers during the Depression—Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936) being her emblem of the era—Lange took up another government assignment when the US entered World War II. She documented Japanese American families preparing to leave Oakland and San Francisco, and, with instructions from the US War Relocation Authority not to show barbed wire and other unsettling details, she made photographs inside Manzanar, a prison camp in the California desert.

At FotoFest, there’s both sound and fury, and an urgent sense that we must interrogate history if we are to survive the present.

Unlike her images from the 1930s, which were published widely at the time, Lange’s work for the WRA was not made public during the war. In 1942, she was discharged by the agency. Her photographs were accessioned by the National Archives in 1946 and digitized fifty years later; today they’re available to download from the National Archives Catalog. “I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot,” she wrote in 1943, in a letter to Ansel Adams, who photographed at Manzanar after Lange’s departure, “even if I accomplished nothing.” Yet, as If I Had a Hammer illustrates, Lange’s accomplishment is vivid on its own—the exhibition includes a generous number of new prints made from Library of Congress scans—and accrues dimension when viewed in conversation with Toyo Miyatake’s contrasting account of Manzanar.

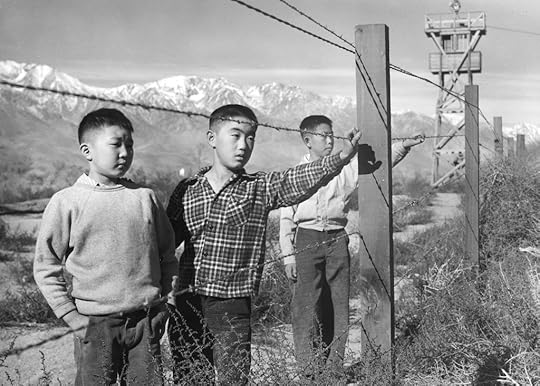

Toyo Miyatake, The boys behind barbed-wire fence cut through the semi-arid land and eyes of the National Guardsmen gleamed from the towers along the fence. From left: Norito Takamoto, Albert Masaichi, Hisashi Sansui, 1944

Toyo Miyatake, The boys behind barbed-wire fence cut through the semi-arid land and eyes of the National Guardsmen gleamed from the towers along the fence. From left: Norito Takamoto, Albert Masaichi, Hisashi Sansui, 1944 Courtesy Toyo Miyatake Studio

Miyatake, who was born in Japan in 1895 and ran a flourishing portrait studio in Los Angeles before the war, cleverly slipped parts into the camp to build a camera, which was banned. He made clandestine photographs until he was found out. Ralph Merritt, the camp’s director, later permitted Miyatake to set up frames himself, but the shutter release had to be pulled by a white person. (Eventually, this rule was dropped.) Miyatake’s photographs are both sober and shocking. One of the most famous, from 1944, portrays three boys with tragic expressions alongside a barbed wire fence, their searching looks conveying their state of anguished captivity. In the background looms a guard tower and snowcapped mountains. Did this scene really occur in the United States, home of the “free”? Or is this the most American of scenes, a visual metaphor for the paradox that “freedom” is balanced atop the pillars of incarceration, forced labor, and terror against the unfree?

Mike Osborne, Security Perimeter / H St NW, 2019, from the series Federal Triangle, 2019

Mike Osborne, Security Perimeter / H St NW, 2019, from the series Federal Triangle, 2019Courtesy the artist

Bruce Yonemoto, Untitled (NSEW 4), 2007, from the series Untitled (NSEW)

Bruce Yonemoto, Untitled (NSEW 4), 2007, from the series Untitled (NSEW)Courtesy the artist

Evans notes that the dialogue between Lange and Miyatake forms the “emotional center” of the Biennial. Certainly, in light of the devastating child-separation policies at the Southern US border and the recent construction of tent camps for migrants sent to New York, Lange and Miyatake’s images feel as frighteningly relevant as ever. Between the presentation of their works, on opposite ends of an immense hallway, are numerous photographic statements that spin out themes of freedom, resistance, and political determination at varying frequencies. Bruce Yonemoto’s stately portrait series Untitled (NSEW) (2007) reimagines soldiers who served in the Civil War, with models of Asian descent posing in the style of nineteenth-century cartes de visite and dressed in costume uniforms originally used in D. W. Griffith’s notorious film Birth of a Nation. Mike Osborne’s Federal Triangle (2019–ongoing) profiles government institutions and street scenes in Washington, DC, with the sinister eye of a film-noir auteur. Keisha Scarville installed fabric prints that float from the ceiling and summon the darkness of the American landscape from the perspective of a fleeting Black female presence, blurring, as she says, “the specificity between the body and the terrain.”

Keisha Scarville, Untitled (Door), 2016, from the series Placelessness of Echoes (and kinship of shadows)

Keisha Scarville, Untitled (Door), 2016, from the series Placelessness of Echoes (and kinship of shadows)Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

Installation view of Ryan Patrick Krueger, Yearbooks, 1953–1964, 2022. Photograph by Ryan Hawk

Installation view of Ryan Patrick Krueger, Yearbooks, 1953–1964, 2022. Photograph by Ryan HawkCourtesy FotoFest

David Kelley, China-East Asia, Inner Mongolia, Group of People, Society, Adult, Adults Only, Aspirations, Beautiful People, Business, Colleague, Dancer, Employee, Fashion Model, Armed Forces, Happiness, Inner Mongolia, Manual Labor, Military, Mongolian Culture, Teamwork, Success, Togetherness, Men, Military, Women, Working, Young Women, 2020, from the series Rare Earth Image Bank

David Kelley, China-East Asia, Inner Mongolia, Group of People, Society, Adult, Adults Only, Aspirations, Beautiful People, Business, Colleague, Dancer, Employee, Fashion Model, Armed Forces, Happiness, Inner Mongolia, Manual Labor, Military, Mongolian Culture, Teamwork, Success, Togetherness, Men, Military, Women, Working, Young Women, 2020, from the series Rare Earth Image BankCourtesy the artist

Several of the most intriguing projects in If I Had a Hammer concern archives and preexisting images as the raw material for introspection. Ryan Patrick Krueger scoured eBay using search terms such as gay interest and male affection to assemble large collages that interrogate the queer vernacular imagery in the decades before Stonewall. Working in Mongolia, a global capital of mining for elements essential to the production of digital devices, David Kelley hired local actors and posed them for portraits in the style of commercial stock photography, then uploaded the final versions to iStock, adding search keywords in an ironic gesture of recirculation.

Fred Schmidt-Arenales, an artist in residence at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells a story about the 1954 coup in Guatemala, a political disaster engineered in part by the CIA and the United Fruit Company. Schmidt-Arenales’s grandfather was a correspondent in Guatemala for the New York Times and later a State Department diplomat. For his project The New York Times on Guatemala (2022), Schmidt-Arenales scanned articles from the newspaper that covered the coup and redacted certain texts and images. The thirty-nine framed prints, organized chronologically according to the article datelines, become an homage to Sarah Charlesworth’s Modern History series from the late 1970s. Schmidt-Arenales also invited four other artists, David Ramírez Cotón, Daniel Hernández-Salazar, Camilla Juárez, and Jorge de Léon, to make their own responses to his grandfather’s 1950s-era photographs. Among these, de Léon’s two-screen video, Untitled (image 4 and 17) (2022), of nine people (including a wry young boy) on a steep city street, clapping endlessly, is a charming and absurd vision—and one of the highlights of the exhibition.

Jorge de Léon in collaboration with Fred Schmidt-Arenales, Video still from Untitled (image 4 and 17), 2022, from the series Coup transcription

Jorge de Léon in collaboration with Fred Schmidt-Arenales, Video still from Untitled (image 4 and 17), 2022, from the series Coup transcriptionCourtesy the artists

Liz Rodda, Video still from Turn Your Face Toward the Sun, 2016, from the series Heat Loss. Found video, found audio, 5 minutes, 42 seconds

Liz Rodda, Video still from Turn Your Face Toward the Sun, 2016, from the series Heat Loss. Found video, found audio, 5 minutes, 42 secondsCourtesy the artist

The FotoFest Biennial, which extends across Houston in numerous galleries and museums, also includes a reinstallation of the 2020 edition, African Cosmologies, which was on view for only a few weeks before the pandemic forced institutions to close. The opportunity to see both biennials simultaneously provides a rare and kaleidoscopic platform for contemporary photography. Contributing to this is the experience of encountering emerging talent in the exhibition Ten by Ten, featuring artists selected from FotoFest’s portfolio review; Alejandro González, Will Harris, and C. Rose Smith make especially strong impressions.

The complex, finely calibrated messages of If I Had a Hammer provoke difficult questions about what art can actually do for society beyond illustration. Against the edifice of power and corruption, would an artwork alter the course of history? Would a biennial change the mind of a staunch partisan? Amid the noise of political anxiety, Liz Rodda’s cryptic piece Turn Your Face Toward the Sun (2016), assembled from found video and audio, offers a critique of willful optimism. As a camera pans across magazine images of stilettos, parquet floors, handsome furniture, and well-placed art books, a young woman whispers what she calls “positives affirmations.” The sound is muffled, yet the clichés resound as commands. “Move on, it’s just a chapter in the past,” she says. “Don’t close the book, just turn the page.”

If I Had a Hammer, the FotoFest Biennial 2022, is on view at the Silver Street Studios and Winter Street Studios in Houston through November 6, 2022.

A Biennial in Cincinnati Pictures the Earth in Crisis

Water coursed through the opening weekend of the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, Ohio—visually and metaphorically. Established in 2012 as “a month-long celebration of photography, film, and lens-based art,” with dozens of exhibitions and events in Greater Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, Dayton and Columbus, Ohio, this is its first iteration since the pandemic. My visit started with a water-themed exhibition by Tony Oursler at Michael Lowe Gallery titled Crossing Neptune, which features dozens of works from the artist’s archive: photos, videos, objects, and three of Oursler’s video sculptures that together express the complex mythic, religious, elemental, and ecological aspects of H2O. The display is as generously haunting and witty as the chattering, animated objects for which the artist is known. With half of it occupying a subterranean gallery bathed in a soft blue light, the experience is immersive.

Unknown artist, Gulf Coast Community Unknown artist, Service Association volunteers sell water-filled shoe inserts, June 30, 1985

Unknown artist, Gulf Coast Community Unknown artist, Service Association volunteers sell water-filled shoe inserts, June 30, 1985Collection of Tony Oursler

FotoFocus takes place at various venues and touched off with a two-day symposium at the beginning of October. The latter concluded with a keynote lecture by the filmmaker Jeff Orlowski-Yang, who spoke about his documentary Chasing Ice (2012), which follows a group of photographers who use groundbreaking time-lapse cameras to capture the speed and extent of melting glaciers due to climate change. It was a chilling presentation, especially when Orlowski-Yang showed horrifying yet sublime clips of skyscraper-sized ice blocks collapsing into the sea. The talk generated an incisive audience question: “I’m an artist, but after seeing what you’ve captured on film, it seems like nothing else matters. How can we go on making art?”

Mary Mattingly, Pull, 2013

Mary Mattingly, Pull, 2013Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

Many of FotoFocus’ exhibitions, panels, and artist talks tiptoed around that question, with works located between aesthetics and activism. The Biennial’s title, World Record, encompasses the dynamic, suggesting the buoyant popularity of the Guinness Book of Records while alluding to that term we’ve heard so often the last few years: unprecedented. During the weekend of the opening, Hurricane Ian was pummeling the southwest coast of Florida. With wind speeds placing it just shy of a Category 5 storm, it was one of strongest to strike the US. Meanwhile, California’s water year, used to measure hydrologic records, concluded on September 30, and the state’s Department of Water Resources declared the drought from 2020 to 2022 “the driest three-year period on record.” Few of us would be surprised if these records break before the next Biennial.

Installation view of On the Line: Documents of Risk and Faith, Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, 2022, with works by Mauro Restiffe Photograph by Wes Battoclette

Installation view of On the Line: Documents of Risk and Faith, Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, 2022, with works by Mauro Restiffe Photograph by Wes BattocletteThis backdrop might suggest the Biennial would comprise a series of dour exhibitions, but FotoFocus exudes visual verve and curatorial energy. The Oursler show was a heady, intoxicating brew of pop-culture references and mysticism: the artist’s archive includes anonymous vintage photographs of hydrotherapy, mermaids in makeshift costumes, the Loch Ness monster, wishing wells, beached-whale carcasses, and historic floods. There is a vitrine holding ornate bottles of holy water. Kitsch mingles with metaphysics in a balance necessary to survive contemporary crises.

Paulo Nazareth, Untitled, from the series Notícias de América, 2011–12

Paulo Nazareth, Untitled, from the series Notícias de América, 2011–12Courtesy the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo/Brussels/New York

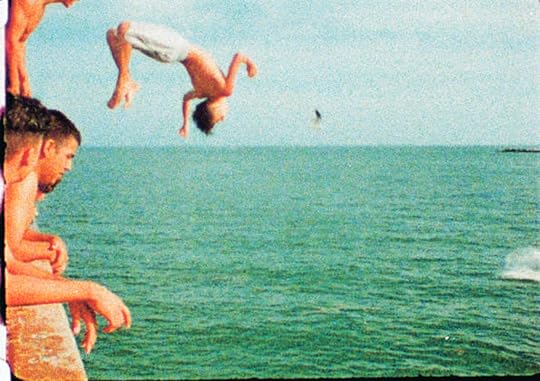

Land and sea both figure in FotoFocus’ centerpiece exhibition, On the Line: Documents of Risk and Faith at the Contemporary Arts Center. Curated by Harvard Art Museums photography curator Makeda Best and FotoFocus artistic director Kevin Moore—who also organized the Oursler show—On the Line uses the line as a metaphor for something that might be crossed, inviting us to assess risks and rewards both personally and politically. This approach offers plenty of opportunity to include works related to borders, including by An-My Lê, Paulo Nazareth, and Jim Goldberg. Borders are often conceptually liquid, as Dara Friedman makes plain in Government Cut Freestyle (1998), a silent 16 mm film of young people gleefully jumping into the ocean from a pier in Miami Beach. The exact location, identified on the wall label, is South Pointe Park, a spot home to the “government cut”: a manmade shipping channel.

Dara Friedman, Stills from Government Cut Freestyle, 1998. 16mm silent film loop, transferred to DVD, 9 minutes, 20 seconds

Dara Friedman, Stills from Government Cut Freestyle, 1998. 16mm silent film loop, transferred to DVD, 9 minutes, 20 secondsCourtesy the artist

During his symposium conversation with Best at Memorial Hall, on October 1, Moore acknowledged Friedman’s piece as a curatorial catalyst for the exhibition and noted its emphasis on human play and sociopolitical complexity. A similar performative precociousness is conveyed in the first works we encounter in the show: images documenting David Hammons and Dawoud Bey’s infamous Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), in which Hammons sells snowballs on a street corner, and Francis Alÿs pushing a hefty ice block through Mexico City in his equally famous Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (1997). These performative acts of futility reminded me of Orlowski-Yang’s lecture, in which he noted that in the face of collapse, you cannot sit complacently: doing something is an expression of hope.

Francis Alÿs, Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), Mexico City, 1997. Video documentation of an action, 5 minutes

Francis Alÿs, Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), Mexico City, 1997. Video documentation of an action, 5 minutesCourtesy the artist and David Zwirner

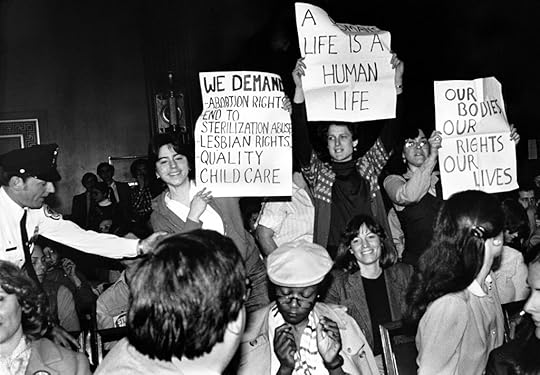

Action is very much the operative word in the exhibition Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, a compelling look at historical activism by queer and trans image-makers also on view at the Contemporary Arts Center. Curator Ariel Goldberg features six artists and group projects that are as much about forging community and disseminating important information as they are about making art, and as such offer a counter to our view of social media as a political catalyst, albeit an illusory one. Diana Solís’s photos form an archive of Chicana feminism in the 1970s; Lola Flash’s vibrant, unearthly color studies are rooted in club culture and AIDS activism; and The Dyke Show (1979) by JEB (Joan E. Biren) is an astounding compendium of lesbian imagery and ideas that the artist presented in person as a slideshow, at venues across the United States. The human connection attached to such projects, among others in the gallery, is important to reconsider in the age of facemasks, quarantine, and rising queer- and transphobia.

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Zap Action Brigade at July 1981 Senate Hearing on an Abortion Ban Bill (protestors, left to right: Sarah Schulman, Stephanie Roth, and Karen Zimmerman), 1981. Still from JEB’s slideshow performance Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–1984

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Zap Action Brigade at July 1981 Senate Hearing on an Abortion Ban Bill (protestors, left to right: Sarah Schulman, Stephanie Roth, and Karen Zimmerman), 1981. Still from JEB’s slideshow performance Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–1984Courtesy the artist

FotoFocus exists in this spirit of bringing people together to discuss the implications of images. I, for one, would not have experienced Orlovsky-Yang’s frightening and vital work about climate change had I not traveled to Cincinnati. Nor would I have heard him say that despite the enormity of the crisis, he still holds hope for change—and the ability of artists to depict and inspire it.

World Record, the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, continues at various venues in Cincinnati, Ohio, through 2023.

October 19, 2022

Aperture Celebrates 70 Years at Its 2022 Gala

On October 17, Aperture’s annual fundraising gala celebrated the organization’s seventieth anniversary and the wide breadth of Aperture’s influence on the field of photography. Acknowledging this milestone, Executive Director Sarah Meister introduced a short video celebrating Aperture: “Since its founding seventy years ago, Aperture has been an inspiration and a guide for photo-curious people everywhere. I am proud to lead an organization supporting artists and shaping the conversation around the ways in which photographs help us see one another and our world more clearly.”

Jeffrey Hoone, Hank Willis Thomas, Deb Willis, Lyle Ashton Harris, Sarah Meister, Dawoud Bey, Cheryl Finley, Colette Veasey-Cullors, Kwame S. Brathwaite, Nicole Fleetwood, Ari Marcopoulos, and Kara Walker

Gala Co-chairs Yesim Philip, Antwaun Sargent, Kara Ross, and Helen Nitkin, with Cathy Kaplan and Sarah Meister (center)

Stuart Cooper, Becky Besson, Sheela Murty, and Vasant Nayak

Judy Glickman Lauder, Celso Gonzalez Falla, and Cathy M. Kaplan

Antwaun Sargent, Deb Willis, Tyler Mitchell, and Cheryl Finley

Sarah Meister, Tom Schiff, and Mary Ellen Göke

Wesley Garlington

Previous NextThe night served as a joyous moment of reflection and an opportunity to look forward to exciting advancements. The event was co-chaired by Helen Nitkin, Yesim Philip, Kara Ross, and Antwaun Sargent, and coincides with the “70th Anniversary” issue of Aperture magazine released last month, which explores the uniqueness of this moment. The issue features original commissions by leading artists and photographers alongside celebrated, incisive writers who were tasked with exploring the Aperture archive. The result, editors of the magazine note, “reveal[s] that however much photography and this magazine evolved, sometimes radically, Aperture remained committed to thinking about the meanings of pictures, and all that might encompass.”

The evening also looked ahead to Aperture’s future home, a new space located on the Upper West Side that will serve as a hub for connecting artists and ideas with members of Aperture’s expanding community. The move will take place in 2024, and act as the home base for the organization’s production of the flagship magazine alongside books, exhibitions, limited-edition prints, public programming, and digital initiatives. In welcoming remarks from the night, chair of the board of trustees Cathy M. Kaplan said enthusiastically, “It marks the beginning of an exciting new chapter in Aperture’s long and distinguished history.”

Lesley A. Martin and Tim Davis

Lesley A. Martin and Tim Davis Tim Davis, Matthew Porter, and Hannah Whitaker

Tim Davis, Matthew Porter, and Hannah Whitaker Celso Gonzalez-Falla and Camille Clech

Celso Gonzalez-Falla and Camille Clech Matt and Martha Sharp

Matt and Martha Sharp Kate Cordsen and Marie Aiello

Kate Cordsen and Marie Aiello Virginia Shearer and Peter Barberie

Virginia Shearer and Peter Barberie Tommy Kha and Phil Taylor

Tommy Kha and Phil Taylor Richard Renaldi

Richard Renaldi Adraint Bereal, Brendan Embser, Cassidy Paul, Stephen Molina Contreras, Gus Aronson, and Silvana Trevale

Adraint Bereal, Brendan Embser, Cassidy Paul, Stephen Molina Contreras, Gus Aronson, and Silvana Trevale Sarah Meister, Elizabeth Kahane, and Rebecca Bengal

Sarah Meister, Elizabeth Kahane, and Rebecca BengalPhotographs courtesy The Self Portrait Project

Steven Contreras, Philip Montgomery, and Myriam Boulos

Steven Contreras, Philip Montgomery, and Myriam BoulosThe night began with a cocktail hour featuring drinks from Tito’s Handmade Vodka and Stella Artois Beer and a silent auction of limited-edition prints from Aperture’s commemorative 70 x 70 print sale. As guests transitioned to dinner upstairs, they were welcomed by Aperture staff members and remarks from Meister, Kaplan, and Aperture Creative Director Lesley A. Martin.

Dinner was served by PINCH and guests enjoyed musical sets by Wesley Garlington, Matt Ray, Danton Boller, and Joél Mateo. An additional live auction led by Christie’s followed dinner featuring works by Sebastião Salgado, Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, An-My Lê, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and Richard Learoyd.

The celebration continued into the night at the Aperture Etcetera Afterparty with lively DJ sets from artists Awol Erizku and Stefan Ruiz. The Self Portrait Project’s unique photo booth captured the celebratory mood of the night while guests danced the night away over drinks and dessert.

Proceeds from the Gala support Aperture’s Stevan A. Baron Work Scholar program, award-winning publications, educational initiatives, exhibitions, and public programming. You can still support Aperture’s essential work here.

Dr. Arlen Cullors and Collette Veasey-Cullors

Dr. Arlen Cullors and Collette Veasey-Cullors Elizabeth and William Kahane

Elizabeth and William Kahane  Jon Stryker, Sarah Meister, and Slobodan Randjelović

Jon Stryker, Sarah Meister, and Slobodan Randjelović Dawoud Bey and Cathy M. Kaplan

Dawoud Bey and Cathy M. Kaplan Peter Barbur and Tim Doody

Peter Barbur and Tim Doody David Leven and Stella Betts

David Leven and Stella Betts Awol Erizku

Awol Erizku

October 13, 2022

In Tavares Strachan’s Collages, Double Meanings and Colliding Histories

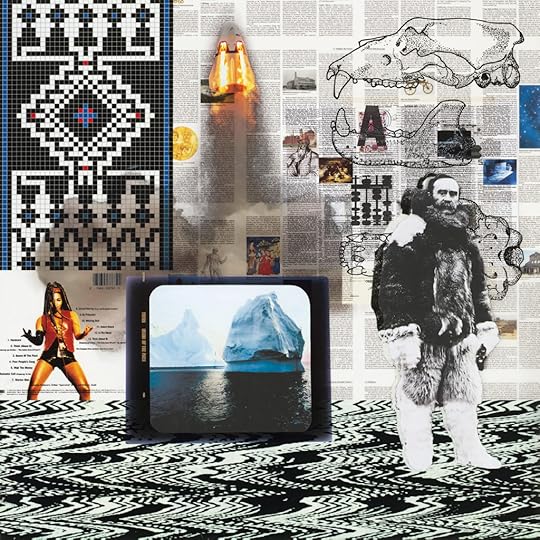

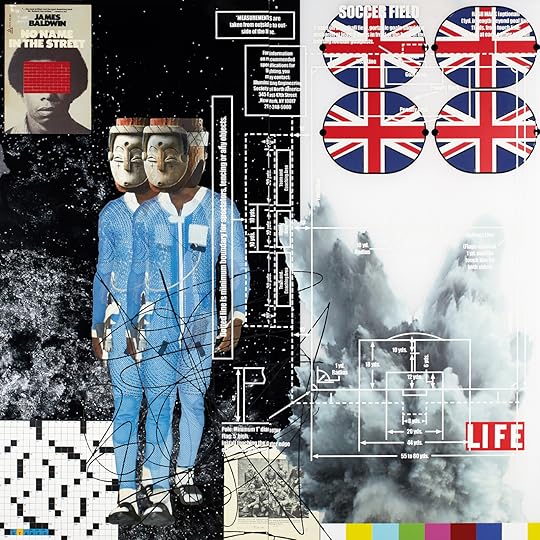

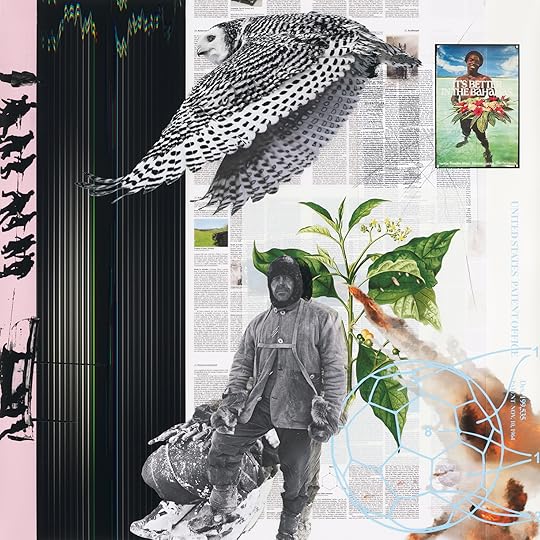

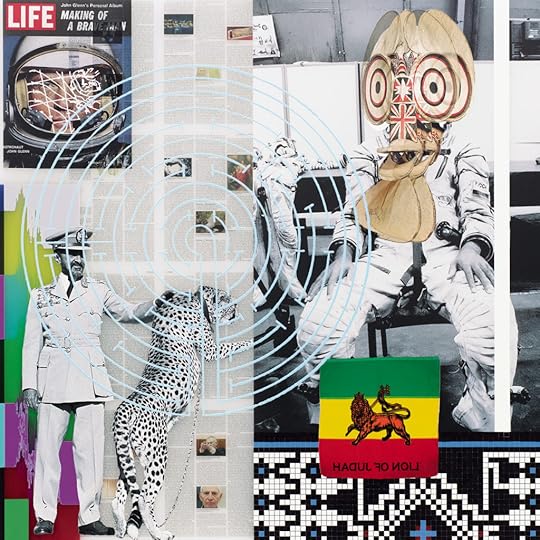

The artist Tavares Strachan makes enormous neon sculptures, immersive installations, and accumulative two-dimensional series that layer historical photographs of monarchs, explorers, and musicians over and under drawings, advertising images, traditional geometric patterns, and technological glitches such as the smudges from a printing error or the wavy lines and test patterns of television broadcast interruptions. His best-known projects take performance to an outrageously global, even cosmic scale—moving a four-and-a-half-ton block of ice from the Alaskan Arctic to a freezer in the courtyard of his Bahamian elementary school, in 2006, or placing a 24-karat gold canopic jar bearing the bust of Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut chosen for a national space program, into a SpaceX rocket that has been orbiting Earth since 2018.

Tavares Strachan, Rocket, 2018, from the series Notes on Exploration

Tavares Strachan, Rocket, 2018, from the series Notes on ExplorationStrachan speaks of his work in terms of a West African street festival where dance, poetry, music, and the performing arts are jumbled together in an exuberant whole. It’s hard for him to separate out any one medium, to speak of photography, say, or sculpture, in isolation from his other modes of making. As he explained to me one day in early June, speaking from his studio in New York, so much of what he is trying to do, as someone who was raised in an Afro Caribbean home (he grew up in the Bahamian capital of Nassau) but graduated from high powered Western institutions (RISD, Yale), is about reconnecting the experiential elements of the former that were pulled apart by the organizational systems (and colonial undertones) of the latter.

Tavares Strachan, No Name in the Street, 2020

Tavares Strachan, No Name in the Street, 2020  Tavares Strachan, It is Better in the Bahamas, 2018, from the series Notes on Exploration

Tavares Strachan, It is Better in the Bahamas, 2018, from the series Notes on Exploration Strachan compares the process of making the pieces in series such as Notes on Exploration and The Children’s History of Invisibility (both 2018) to the loose structures of 1960s jazz, “with a little bit of dub and a little bit of hip-hop,” he says, adding that “those genres speak to each other.” They respond to a rift or a clue. “I think, visually, I’m doing something similar with images, textures, the pieces of a story.” These works have the appearance of large-scale collage, but more often than not, they are made from images printed on layers of Mylar and vinyl mounted on acrylic or museum board. Strachan also calls them poems, assembled from a language that is never innocent or transparent but can be wrestled into a form that speaks to (and about) systems of power.

Tavares Strachan, The Stranger, 2018

Tavares Strachan, The Stranger, 2018 Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

A work such as The Stranger (2018), for example, might begin with an image of Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia who galvanized public opinion, inspired the Rastafarian movement, and, incidentally but tellingly, kept massive pet cheetahs as his preferred symbols of power. From there, Strachan builds the surface sonically, adding a delicate line drawing of a maze; a Lion of Judah flag, which he used to see everywhere in his neighborhood as a kid growing up; a Life magazine cover featuring the astronaut John Glenn alongside a headline about women’s intimate apparel; and a photograph of himself in a cosmonaut suit, his head obscured by an oversized, performative mask. He’s particularly drawn to materials with double meanings, such as Native American textile patterns that not only are decorative but also serve as maps or other such communication channels.

“Duality allows for a certain level of elasticity in how we think about the world,” Strachan says. “Instead of spending all this time thinking about how we are different, it allows for thinking about sameness, about overlapping and intersecting, about all kinds of complexity. My own history, my erased history through colonialism, my new history as someone who’s been living in the United States for some time in a society that wants you to decide you are one thing or another—all of that goes into the work.”

Related Items

Aperture 244

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies.”

Hank Willis Thomas’s Tribute to the Photographers Who Inspire His Vision

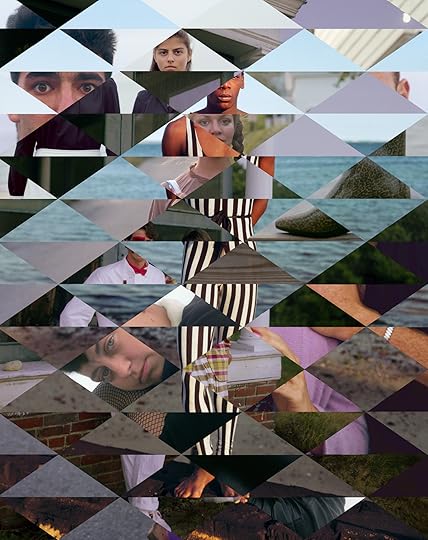

For Aperture‘s “70th Anniversary” issue, seven photographers were invited to consider a single issue, an article, an idea, or even an omission, from a decade of the magazine’s history. In an original commission, Hank Willis Thomas reflects on the 2010s.

Kwame Brathwaite, the Harlem photographer who helped popularize the clarion slogan “Black is beautiful,” was known as the “Keeper of the Images.” His pictures of Black models and musicians from the 1960s are essential documents that radiated from New York during an era of Black and African independence campaigns. Although known to scholars and archivists, Brathwaite’s work didn’t reach a wider audience until Aperture’s 2017 “Elements of Style” issue. As an elder statesman of the Black freedom movement, Brathwaite became the “keeper of the stories, too,” Tanisha C. Ford wrote. “If he didn’t share this history, it would be lost to time.”

Hank Willis Thomas, Wendy Ewald & Eric Gottesman: We’re Talking About Life and Culture, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas, Wendy Ewald & Eric Gottesman: We’re Talking About Life and Culture, 2022  Hank Willis Thomas, Dave Swindells: Taking pictures definitely kept me going, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas, Dave Swindells: Taking pictures definitely kept me going, 2022 The artist Hank Willis Thomas is also a keeper of the images. “Sometimes I see myself as a visual-culture archaeologist or DJ,” he explains. “All of my work is about framing and context.” In this series of collages, which reference traditional quilt patterning, Thomas draws on stories from Aperture in the 2010s, a decade during which looking back was as vital as looking forward. He sets in kaleidoscopic motion an energetic range of associations and styles: Joel Meyerowitz’s stately portraits from Provincetown in the era before AIDS and Nick Sethi’s dizzying chronicle of a festival for a transgender community in India; Renée Cox’s self-portraits about power and Dave Swindells’s endless nights on London’s dance floors. Revivifying history, remixing the present. Thomas sees these collages as a collaboration with peers and mentors he’s long admired. “The process of weaving these images has been revelatory,” he says. “Through this blending, I was able to engage more intimately with the images, the subject matter, and the journey of the image maker.”

Hank Willis Thomas,

Joel Meyerowitz: On the Beach

, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas,

Joel Meyerowitz: On the Beach

, 2022  Hank Willis Thomas, Robert Voit: New Trees, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas, Robert Voit: New Trees, 2022  Hank Willis Thomas, Renée Cox: A Taste of Power, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas, Renée Cox: A Taste of Power, 2022  Hank Willis Thomas, Nick Sethi: The Third Gender, 2022

Hank Willis Thomas, Nick Sethi: The Third Gender, 2022All photographs for Aperture. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue.”

October 6, 2022

Can the Photo-album Hold Cultures Together?

Last May, my children discovered my photo-album from college. As they laughed at images of me in my early twenties wearing big twist outs and patterned head wraps, or of their dad with his tight fade and tighter shirts, I realized how unfamiliar to them this intimate object of mine was. For me, each plastic-covered page revealed one or more carefully curated stories from my young adulthood. In contrast, my daughter, who was born in 2012, and my son, born in 2015, saw the album quite differently. For them, it was a random assortment of images and an artifact that offered a glimpse into their parents’ yesteryear.

But that experience was also a rite of passage. As they visited my early adulthood, I flashbacked to my own poring over of my parents’ albums when I was a child in the 1980s. Unbeknownst to me at that time, I was, in fact, participating in an intergenerational ritual that I would later share with my own children: the impromptu celebration of the family archive.

Covers of Aperture: Spring 2013, with photograph by Christopher Williams; Spring 2015, with photograph by Ren Hang; Summer 2016, with photograph by Awol Erizku

Covers of Aperture: Spring 2013, with photograph by Christopher Williams; Spring 2015, with photograph by Ren Hang; Summer 2016, with photograph by Awol ErizkuIn many ways, my children’s curiosity was part of a larger trend. While the physical photo-album itself seems to have been replaced with Instagram feeds or camera phone folders, it has simultaneously been repurposed. Now, it is less a method to freeze time and more a muse for artists in their own contemporary practices. I imagine this turn is, in part, an intervention into the rise of the selfie as a primary means of personal expression and social-media influence in the 2010s. Lest we forget: Kim Kardashian’s photobook, Selfish, featuring countless selfies of Kardashian traveling, with her family, and in swimsuits, was a New York Times bestseller in 2015.

Rather than compete with spectacle and surplus, contemporary photographers have revived an even earlier form—the portrait—to enact everyday protest.

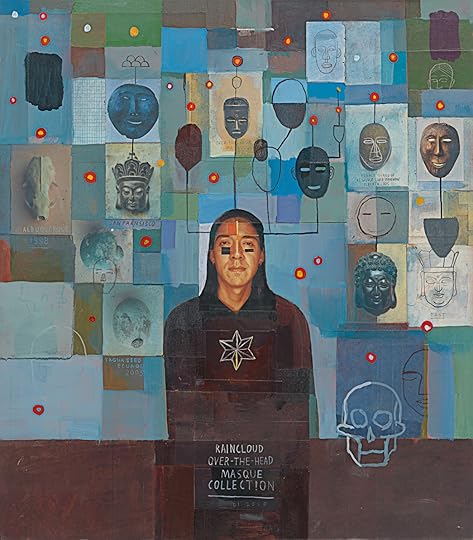

Whereas the selfie emerged in the last decade as our ultimate symbol in an era of instant access and casual self-importance, the picture album, as a series of either snapshots or collective self-portraits, suddenly felt far humbler and more intimate. Though the Russian Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur has been documenting the everyday lives of Black immigrants in London, Brooklyn, Kingston, and Accra for more than three decades, the album was the conceit she used when she chose to connect these images together in The Black Balloon Archive, on ongoing series that she began in 1991. Described by Ekow Eshun in the Winter 2018 Aperture as “a family album for the diaspora,” this format enabled Johnson Artur to capture multiple people, periods, and places. Seeing her subjects as “my neighbors,” she visualizes the feeling of Black belonging, offering them a home space in which each can gather together, as Eshun notes, “on one’s own terms.”

Such inclusion was not always guaranteed. In its earliest conception, the family album indicated the wealthy economic status and high social standing of the Victorian-era elite in the 1850s. A hundred years later, photo technology had advanced so much that the baby-boomer generation saw photographs as indispensable. But in today’s world, “What does that same device have to offer the contemporary artist?” as artist Carmen Winant asked in “Into the Album,” her essay that also appeared in the Winter 2018 issue. “In what ways can the family photo-album behave as a kind of confirmation—or assertion—of our very survival, dignity, and existence?”

Kimonwan Metchewais, Raincloud, 2010, from Aperture, Fall 2020

Kimonwan Metchewais, Raincloud, 2010, from Aperture, Fall 2020 Courtesy the Kimowan [McLain] Metchewais Collection, NMAI. National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution

As a contemporary artist herself, Winant ended up turning to Glenn Ligon’s much earlier queering of the family album in A Feast of Scraps (1994–98) and Lorraine O’Grady’s disrupting of linearity in her Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994) as both radical reclamations of the genre as well as inspirations for Winant’s own feminist practice. Likewise, Jack Halberstam reminds us of the family album as a counter-archive. In his Winter 2017 Aperture essay, “Eric’s Ego Trip,” he writes about the powerful gift that Reed Erickson, a wealthy, white trans man known for his philanthropy, gave to the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, in Los Angeles.

I find optimism in the desire among contemporary artists and scholars to resurrect this family genre. Their considerations of these older photo-albums are not overly sentimental or nostalgic. Instead, they turn to this earlier format to better reflect our ever-expansive notions of gender, race, sexuality, and belonging, and to reject those racially homogenous and heteronormative notions of the American family that continue to thwart us as a nation.

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]And yet, the 2010s were also the decade of the spectacular. In addition to selfies, there was no shortage of random, often viral, images for us to click, like, or upload. At the same time, such distractions did nothing to ease the grief, and rage, that we felt as we watched unarmed Black people being killed by the police online or played on a twenty-four-hour loop.

In this “information overabundance,” as Fred Ritchin lamented on these pages in the winter of 2012, such excess made it difficult for us “to focus on any one image, or set of images.” In other words, the proliferation of photos and video content ended up minimizing the power of a single picture and its ability to foment activism akin to that of the civil rights and the antiwar movements of the 1960s. Instead, the oversaturation compromised “the credibility and authenticity of photographs that purport to frame the real,” he wrote. In such an age, only the viral video, like the one heroically filmed by seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier of George Floyd’s murder, has inspired mass protest.

But rather than compete with spectacle and surplus, contemporary photographers have revived an even earlier form—the portrait—to enact everyday protest. Across Aperture issues from this decade, the ordinary is the alternative to oversaturation.

Farah Al Qasimi, Arun (Rose Studios Satwa), 2014, from Aperture, Winter 2016

Farah Al Qasimi, Arun (Rose Studios Satwa), 2014, from Aperture, Winter 2016 Courtesy the artist

The large-scale portrait is the medium of choice for Farah Al Qasimi, a photographer and native of the United Arab Emirates. Her bright, color-saturated images of people at beauty salons, shopping malls, and traditional pharmacies in her home country have become her signature style and were exhibited in 2020 on one hundred New York bus shelters. “Her Instagram feed is a glorious mix of high art and everyday image inundation,” Kaelen Wilson-Goldie wrote of her work in the magazine’s Winter 2016 issue, “On Feminism.” “And between them, the boundaries are blurred.”

This dissolution between the real and the staged is also a defining trait of four very different artists—Kimowan Metchewais, Zanele Muholi, Buck Ellison, and Tyler Mitchell—whose portraits are revelatory. Though Cree artist Metchewais passed away in 2011, Aperture’s more recent reprisals of his work affirm the power of the small photograph self-portrait to upend longstanding racial stereotypes. His specific use of Polaroid portraits not only afforded him a malleable medium to dissect, rearrange, and then display on large-scale paper but also gave him a “visual sovereignty” that contested the willful erasure of and violence against Indigenous communities by the State. Muholi’s Brave Beauties (2014), on the other hand, is a series of portraits about Black trans women in South Africa that calls attention to the way in which Black queer or lesbian South Africans are vulnerable to gender-based violence. “Today, lesbians in South Africa are brutally murdered,” Muholi told Deborah Willis for Aperture’s Spring 2015 issue, “Queer.” “‘Curative rape’ is used on us. That forces me to redefine what visual activism is.” Muholi adds, “Art needs to be political—or let me say that my art is political. It’s not for show. It’s not for play.”

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017, from Aperture, Fall 2017

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017, from Aperture, Fall 2017 Courtesy the artist

In contrast, Ellison uses models to re-create those intimate moments among the white elite in which racial and class hierarchies are reinscribed. And by giving us access to the inner worlds of such white privilege, Ellison reveals and gravely reminds us how power is informally yet consistently wielded, even in the prosaic space of a dressing room or family driveway.

And in the decade-ending “Utopia” issue, I had the good fortune of exploring how Mitchell’s aesthetic flips white privilege on its head. He lingers in the imaginative possibilities of Blackness, often capturing his friends and fashion icons from throughout the African diaspora in relaxed settings and in nature. “Inherent to photography, especially when you think of it historically, is a strong hierarchy, where the photographer is the one with all the power, the one who is seeing,” he told me. “And the person being seen has almost no power. So, for me personally as a photographer, I ask myself, ‘What are the things I can do to lessen these inherent hierarchies in the photography-shoot structure of seeing and being seen?’” In his oeuvre, the wide-scale portraits become landscapes in which Black people find a haven, and the ability to rest is rendered as justice.

As for my children, they are now obsessed with the technologies of their age. TikTok, Zoom backgrounds, and iPad screenshots are their preferred forms of self-expression. As I struggle to find a way to store those images, I have begun to print out a select few from my phone and put them in our brand-new photo-albums as a way of safeguarding our memories for the future.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue,” under the title “Everyday People.”

October 5, 2022

Saul Leiter’s Ravishing Color Photographs of New York

Among the great or later-to-be-great New York photographers of the middle of the last century, Saul Leiter bested them all in caring the least about fame or legacy.

“I wasn’t burdened by importance,” he said a few years before his death in 2013, synopsizing a devotion to unfettered autonomy that has itself come to shape his legacy. What his reticence meant, practically speaking, was that many thousands of the pictures he took over almost seven decades were never developed, printed, or seen during his lifetime, despite the fame that came thundering to his doorstep with the 2006 publication of Saul Leiter: Early Color. “Before he died, he said that what we had seen of his work was just the tip of the iceberg, and we’re really only now finding out what he meant,” said Michael Parillo, the associate director of the Saul Leiter Foundation, which has been hard at work to bring more of Leiter’s color photography into the world.

These previously unpublished selections of 35mm slides confirm and extend our sense of the stubborn singularity of Leiter’s color language. You might occasionally mistake a Stephen Shore for a William Eggleston or a Helen Levitt for an Evelyn Hofer, but it’s not easy to see a Leiter for anything else. His quietly elaborate layering of urban surfaces and his predilection for puncta such as red umbrellas, traffic lights, gently sloping car tops, and fractured window lettering are as instantly recognizable as a Giorgio Morandi bottle—as is Leiter’s enduring subject, the East Village neighborhood where he spent almost his entire adult life. Leiter wasn’t exactly a visual hermit; he took pictures in Paris and Rome, Brooklyn and Harlem. But his principal ambit was tightly and purposively bounded, the dozen or so blocks around his modest artist’s-garret apartment, streets he turned into the whole world, a photographer’s rendition of William Carlos Williams’s localist modernism.

It was a happy accident to see these unknown Leiter pictures for the first time last fall, during the run of Luigi Ghirri: The Idea of Building, a highly focused look at the work of the Italian photographer, organized by the painter Matt Connors at Matthew Marks Gallery. Connors writes that Ghirri, working from within Conceptualism, was “reading the physical world but also writing it,” making images that reassemble the built landscape recursively within the frame of the lens. Leiter, emerging from Abstract Expressionism, accomplished something strikingly similar on his own terms, rapidly and somehow instinctively on the street and then deliberatively in the editing, though he remained coy about his own considerable powers of stage management.

“I believe that there is something in you that strives for order and within that order there’s a certain kind of mishmashy confusion, and you bring this mishmashy confusion, if you succeed, into some kind of order,” he said. “There’s an element of control. There’s also an element that just kind of happens, if you’re very lucky.”

Leiter was the kind of artist who established the conditions for that luck, earning, as Emily Dickinson put it, “fortune’s expensive smile.”

All photographs by Saul Leiter, Untitled, early 1950s–1961

All photographs by Saul Leiter, Untitled, early 1950s–1961 Courtesy the Saul Leiter Foundation

Related Items

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York.”

Mark Steinmetz Portrays the Gestures of Love between Mother and Daughter

For Aperture‘s “70th Anniversary” issue, seven photographers were invited to consider a single issue, an article, an idea, or even an omission, from a decade of the magazine’s history. In an original commission, Mark Steinmetz reflects on the 1980s.

“Mothers and daughters! Are there any fantasies or ideal images left to us in this tough-minded age of psychological realism?” So begins the historian Estelle Jussim’s essay for Aperture’s Summer 1987 issue, “Mothers & Daughters,” a catalog in magazine form that accompanied a traveling exhibition of photographs about mother-daughter relationships. “That Special Quality,” the suggestive subtitle offers—is it a definition or a dare? The issue is organized neither chronologically nor typologically. It’s not ethnographic or sentimental. Yet “Mothers & Daughters” relies on both of photography’s elemental impulses: the desire to see others and the desire to memorialize. There are lines of poetry by Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, and Alice Walker. There are backyards, weddings, beaches, kitchens, embraces, American flags, sashes that read “Votes for Women,” looks of impatience, and gazes for posterity.

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, February, 2021

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, February, 2021Mark Steinmetz began taking pictures of his wife, the photographer Irina Rozovsky, and their daughter, Amelia, in 2017, when Amelia was an infant. While looking through “Mothers & Daughters,” Steinmetz was thinking about the 1980s as a time when the domestic became a concern in photography: Aperture’s issue preceded the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition The Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort by four years. Among the portraits by Robert Adams, Judith Black, Jill Freedman, Rosalind Fox Solomon, and many others presented by Aperture, Steinmetz was drawn to a street picture by Garry Winogrand—the concluding note of the issue—of a woman walking outside a Doubleday bookshop on Fifth Avenue in New York, distracted yet propulsive, a small child on her back, a beaming daughter holding her hand. “I don’t think I’m a nostalgic person,” Steinmetz says of the photographs he made of Amelia’s young life and the gestures of love between mother and daughter. “I got married, and we had a baby. So, I’m just photographing around me. It’s inevitable. I also think my daughter is a star.”

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Jersey City, NJ, September, 2019

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Jersey City, NJ, September, 2019 Mark Steinmetz, Sledding, Commerce, GA, January, 2022

Mark Steinmetz, Sledding, Commerce, GA, January, 2022 Mark Steinmetz, Our Kitchen Window, Athens, GA, August, 2020

Mark Steinmetz, Our Kitchen Window, Athens, GA, August, 2020 Mark Steinmetz, Amelia’s Shadow, Athens, GA, October, 2020

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia’s Shadow, Athens, GA, October, 2020 Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, March, 2021

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, March, 2021 Mark Steinmetz, Irina and Amelia, Jamaica Plain, MA, March, 2017

Mark Steinmetz, Irina and Amelia, Jamaica Plain, MA, March, 2017 Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Paso Robles, CA, December, 2018. All photographs from the series Irina & Amelia, 2017–ongoing, for Aperture

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Paso Robles, CA, December, 2018. All photographs from the series Irina & Amelia, 2017–ongoing, for ApertureCourtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue.”

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers