Aperture's Blog, page 47

December 19, 2021

How Photographers Navigate the Challenges of Working on Assignment

In the introduction to his 1978 book, Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960, John Szarkowski proposes that, in the midst of the twentieth century, photographers’ aims, ambitions, and outputs quickly shifted away from the traditionally “professional,” and instead firmly toward the “personal.” “The role of the professional is by nature social; [their] livelihood depends on the production of work that others find useful,” he writes, explaining that with the rise of general interest, photo-heavy magazines such as LIFE, Look, Picture Post, VU, and others from the 1930s onward, photographers were provided with both a structure and a platform that could support them financially and, at the same time, accommodate their creativity and guide the direction of their work. Szarkowski suggests that for approximately twenty-five years there was “a coincidence of interest between the creative photographer and the mass publisher,” which often centered around issues of broad social concern. “But by 1960,” he notes, “it had been largely lost.”

Earlier this autumn, while speaking with the documentary photographer and photojournalist Natalie Keyssar—whose work regularly appears in Time, the New York Times, National Geographic, and elsewhere—about challenges she’s faced on assignment, I was reminded of Szarkowski’s argument. “As a teenager in North Carolina, I was very interested in social justice,” she explained. After moving to New York and completing an undergraduate degree in painting and illustration, she found herself turning toward photojournalism. “I realized that if I just sold what I was making to rich people to hang over their sofas, that sucked. And I didn’t want to spend eighteen hours a day alone in a studio. So eventually, I applied to do an internship with two photojournalists who took me under their wing, gave me a camera, and basically said, ‘Just don’t lie and go shoot.’”

Natalie Keyssar, Desiree, center, puts her horse through a “giro” with the rest of the team during practice, French Camp, California, July 1, 2021, for National Geographic

Natalie Keyssar, Desiree, center, puts her horse through a “giro” with the rest of the team during practice, French Camp, California, July 1, 2021, for National GeographicCourtesy the artist

Keyssar’s earliest assignments were mostly for daily newspapers and tabloids, and eventually she worked her way up to shooting regularly for the New York Post. Most of the assignments Keyssar received from the Post were straightforward—broken water mains, press conferences, and so on—but then she got what she regards as one of her hardest assignments, which also became her last for the paper. “It was about ten years ago, and I was told to stake out an elementary-school teacher who had written an op-ed piece for the Huffington Post in which she talked about her previous experiences as a former sex worker,” she said. At the time, the New York Post was regularly plastering their front page with sensationalist headlines about the woman, referring to her as the “hooker-teacher.” “She was this totally amazing woman,” Keyssar continued, “with two master’s degrees, who was educating children as a New York City Teaching Fellow in a school in the South Bronx, who had conducted ethnographic research and written about sex workers’ rights in the past—and they sent me to wait outside of her apartment.”

Natalie Keyssar, Marissa Regla poses for a portrait on her horse after practice, French Camp, California, 2021

Courtesy the artist

Natalie Keyssar, Caracas–based neighborhood dance team “Moni Dance” hop a fence on a rooftop, Caracas, Venezuela, 2019

When Keyssar arrived, she discovered a gaggle of male photographers already standing at the address in the rain, so she moved away from the crowd. “I strongly identify as a feminist, and as somebody who was pro-sex-worker rights, so internally I was freaking out; it was all so predatory,” she said. “The paper was putting a lot of pressure on me to do this, and I was so young that I didn’t have the words to argue with them about it.” Then, while Keyssar was standing by herself having what she describes as an existential crisis, the woman finally arrived home holding an umbrella. “The men were being really aggressive, so she blocked them all with her umbrella. But because I was standing apart from them, it left my shot wide open—and I just did nothing. My body was just like, ‘Nope.’”

Keyssar is often asked by students where she draws an ethical line when it comes to her work. “My rules are pretty straightforward—don’t lie, don’t cheat, and do no harm,” she said. “But in terms of that particular assignment, I was so young. I wish that I could say that I’d already consciously decided that I’d never take that picture, but to be honest, I was just grateful that my body made the right choice in that moment. I was just not going to make that photograph, and I realized that I couldn’t do that kind of work anymore.”

Poulomi Basu, from the series Centralia, 2010–20

Poulomi Basu, from the series Centralia, 2010–20Courtesy the artist

Ethical concerns and considerations have always proved to be challenging territory for photographers on assignment, beyond just the realm of photojournalism, yet many contemporary photographers identify the biggest problems stemming from systemic issues in the media industry and culture at large. Indian-born artist and activist Poulomi Basu, whose ten-year-long transmedia project Centralia was shortlisted for the 2021 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, recently explained: “The primary reason I’ve found assignments hard is because of the limited time that I’ve been given to be in a certain situation. I steer away from photojournalism these days, because I found it to be very unbalanced when it came to giving long, sustained assignments to people of color.”

Currently based in England, Basu began her career in India. “I never really found myself at home in photojournalism, but it just so happened that I was based in India, so I was suddenly pigeonholed into this box that I should be doing little stories from there,” she said. Several years ago, she was commissioned by a major international publication to shoot a story on leprosy in India. “It was horrendous, because we only had one or two hours to be in the community. This is a bunch of women who have been ostracized, living in this really isolated, lonely home in exile, and I only had an hour and a half to photograph them,” she said. “I literally felt like I was robbing them of their time, their dignity, and their life. It was the most awful experience; I went back to my hotel, broke down, and said to myself, ‘This is the end of my career in photojournalism.’”

Since then, Basu has been able to more firmly define and understand her position, values, and obligations as a practitioner. “I’m a postcolonial artist and activist. I don’t just parachute into places and bring back ‘news’ or whatever; I have a responsibility towards the people who are my race, my color, and general humanity at large,” she said. “If people aren’t going to invest in photographers of color doing long-term assignments—if you can’t share meals with the people, if you can’t spend time with them, immersing yourself in the community—then as far as I’m concerned, it’s no way to do any kind of reporting. That story was published as the cover of the magazine, but I never even bothered to get a copy of it for myself, because I was so horrified by the whole experience.”

Poulomi Basu, from the series Centralia, 2010–20

Courtesy the artist

Basu is still approached with commissions on a regular basis, which she often turns down. “Even in the last few months, I’ve had an editor say to me, ‘So when are you going to be in India next?’ And I’m like, ‘Are you joking? I live in the UK–give me work here!’ It’s so humiliating,” she explained. “I’ve been given some assignments in the West, but it’s very rare, and I’ve never been given an assignment to go into a white community. The industry is so deeply racist, I can’t tell you.”

The photographer Quil Lemons partially echoed and then broadened these sentiments far beyond the industry itself. “I always think that it’s interesting that, when I get pitched stories, a lot of them are Black,” he said. “At this point in my career, I find myself not really wanting to have any labels put onto anything that I do. I think that you should just feel the art and it shouldn’t matter. And we all wish we didn’t have to be talking about our Blackness all the time. But in being a Black photographer, the fact is that my Blackness often comes before my photography, which is so annoying and can also be very limiting.”

Quil Lemons, Say Less, 2021

Quil Lemons, Say Less, 2021Courtesy the artist

Lemons first gained attention several years ago through his self-initiated project Glitterboy (2017), and has since been regularly commissioned by publications such as Vogue, Variety, i-D, and GQ. (In March 2021, at the age of twenty-three, he became the youngest person ever to photograph for the cover of Vanity Fair, which featured Billie Eilish.) When asked what his most challenging assignment has been thus far, Lemons responded that it wasn’t about making pictures. “It’s literally just being Black. It’s knowing how hard it is to exist and survive as a Black person in the world, let alone have a career. I don’t know anyone else’s experience, but I do know what it is to live in my body, and it’s not easy; it’s a lot—mentally and emotionally,” he said. “That’s why I always commend anyone who’s Black and operating in this space—because I know what I’m up against, and I can only imagine what they’ve had to deal with. I don’t shy away from the responsibility that comes with all of this; I just want people to acknowledge that this is what we have to think about every time we pick up that fucking camera.”

Quil Lemons, I Hope You’re Ready, 2021

Courtesy the artist

Quil Lemons, First (Andia Jai Anderson), 2021

At the same time, Lemons recognizes that there has been some progress. “I think it’s really interesting to come into contact with an industry that until recently has ignored people that look like me, and ignored a perspective,” he said. “And in the last two years, there seems to be a shift happening, with the industry saying that they’re going to support young Black creators and be more inclusive—just with me being in that space, you can see that change happening.” But he also recognizes that, for lasting progress to be made, like it or not, the brunt of the responsibility may still ultimately end up on photographers themselves. “I also feel that my generation of photographers is not adhering to certain limitations or expectations,” he continued. “Maybe the industry now is finally catching up and realizing that you don’t have to put people into a box. But as creators, we have to make sure we’re not just used as token symbols, and we also have to push for and create more structural changes for ourselves. We’re all trying to do that, but it’s hard—we need money, we need capital, we need support on a very deep level to make sure that this doesn’t become just a blip in time. We need to learn how to come together, to support and protect one another in ways that we can’t have our shit be stolen.”

“When I was in New York in 2017, I had a major identity crisis,” said Ashish Shah, one of the most influential and sought-after fashion photographers in India, who has recently photographed major campaigns for brands such as Alexander McQueen and Byredo. At the time, he was in the midst of a six-month internship at 2b Management, which represents photographers such as Peter Lindbergh and Ellen von Unwerth. “I was working for a lot of French people there, and I saw their amazing love for and appreciation of their own culture.”

Ashish Shah, Sovena, 2021, for Mumbai Noise–Byredo

Ashish Shah, Sovena, 2021, for Mumbai Noise–ByredoCourtesy the artist

Shah realized that his own work up to that point, and fashion photography in India in general, rarely celebrated or even reflected the country’s rich culture or contemporary reality. “What we were doing for the longest time in India was trying to make Indians act like Westerners. We were shooting Brown women with black hair, and yet all of our reference points would be of blonde supermodels; we wanted an Indian model to act like Cindy Crawford or Claudia Schiffer. I don’t know whose fault it is, because India is such a new country when it comes to fashion photography, consumer culture, and so on, but there wasn’t really any acceptance of what was Indian. When I talk about acceptance, what I mean is accepting the reality of what my country has to offer, and understanding that there is a beauty to it.”

On returning to Mumbai in 2018, Shah started working with designer Sanjay Garg’s India-based fashion brand, Raw Mango, which is deeply invested in promoting and celebrating what is truly Indian. “Because of him, I started to accept my own people and culture,” Shah said, “and how Indian bodies are. I began to really understand Indian draping, Indian postures, Indian gestures and expressions, how Indians sit in a certain way, how there’s a certain amount of carelessness in our body language, how men have a huge feminine side, and so on—that really opened my eyes.”

Ashish Shah, Home Story, 2021, for Architecture Digest India

Courtesy the artist

Ashish Shah, Moomal, 2020, for Raw Mango

As a result, Shah began to embrace the surrounding environment, letting it dictate his aesthetic rather than attempting to “correct” or manipulate it to suit Western expectations. “I started shooting in natural rather than artificial light, appreciating the hazy quality, the unique tonalities, and the color palettes of Indian light,” he said. “One of the challenges that I’ve been facing lately is that no matter how much someone wants to celebrate India, still there is a very strong [stereotypical] perception of us.” Shah is regularly approached by some of the biggest international brands and publications to photograph in India, but he says that they often request a “colorful” version of the country: “That highly-saturated imagery which Steve McCurry and others flooded the international market with for so long is crazy. Contemporary India doesn’t look like that—that India doesn’t really exist—and it has become a big problem for us. I have to explain this to clients outside of India all the time. I want my images to have nuance—to accept, appreciate, and celebrate Indian culture, heritage, and the realities of India now.”

In Mirrors and Windows, Szarkowski writes, “As the magazines grew older and their procedures more regular, it became increasingly difficult for even the most determined photographers to use the magazine as a vehicle for their personal views of the world.” Yet today, photographers continue to find new and innovative ways to negotiate that territory between producing “social” and “useful” work—while at the same time allowing their photographs and careers to be vehicles for personal views, visions, interests, and intentions.

“Recently, I’ve been increasingly making all of my processes more collaborative, which inherently requires my active presence and authorship to be in conversation with the active presence and authorship of the people I’m photographing,” Keyssar explained. “The starting point for me now is being honest about my own practice, and my own capabilities. What I’m asking of myself is honesty, not objectivity.”

Natalie Keyssar, Katherine poses for a portrait with her daughter at her in law’s house in El Observatorio, Caracas, Venezuela, 2018, for California Sunday

Natalie Keyssar, Katherine poses for a portrait with her daughter at her in law’s house in El Observatorio, Caracas, Venezuela, 2018, for California SundayCourtesy the artist

“Greater engagement and creating a groundswell is very important—to be able to go back to communities and see change happening,” Basu reflected. “I’m not saying that everyone has to do it, but I don’t come from the elite or a first-world country, so my perspective is very different when it comes to these things. There’s no point in my work being in these big publications or famous galleries if it doesn’t, in some form, go back towards the community. As an activist, I don’t just care about the pictures or the photo project; I care about the bigger world that exists outside of it, and how I can help, activate, and empower people through it.”

For Lemons, it’s also a matter of capitalizing on his newfound position of influence to create meaningful change, understanding, and opportunities for others. “I’ve had a lot of great opportunities and experiences myself, but I’m really trying to go for something bigger. How do I do something with this platform that’s actually impactful, something beyond the scope of myself?” He also recognizes that there is something especially unique and powerful about his chosen medium. “Photography has become this really interesting touch point—because we all see it, we all use it, we all understand the act of making an image, and we all have a basic understanding of what is beautiful. And maybe that’s the solution with all of this—to keep making this work, and maybe people will see us.” Lemons then swiftly corrected himself. “In fact, I’m not really asking for people to see us—I’m like, ‘You are going to see us.’ That’s the difference—it’s a declaration, where we’re firmly standing in our existence.”

December 16, 2021

Joiri Minaya Unravels the Fantasy of Tourism

Who’s she smiling at? What’s she selling? What’s she hiding? She’s wearing the Caribbean blue sea. The hills. The palm trees. The flower: a third eye.

Joiri Minaya created Woman-landscape (On Opacity) #4 (2020) as part of a series in which she collages vintage postcards advertising the Dominican Republic, superimposing samples of commercially available “tropical prints” and archival images in a way that strategically obscures an easy knowability of the subject. Minaya, born in New York and raised in the Dominican Republic, is a multidisciplinary artist whose work investigates the body within constructions of gender, identity, social space, and landscape, complicating hierarchies through hybridity, challenging otherness, and, most recently, thinking through opacity.

Joiri Minaya, Woman-landscape (On Opacity) #4, 2020

Joiri Minaya, Woman-landscape (On Opacity) #4, 2020It feels fitting to write about Minaya’s works from an airplane heading to Santo Domingo airport. From the moment I enter the airport, the thick humidity will hug my body. The landscape will inhabit me. I will inhabit it. Although I’m traveling to the Dominican Republic to do research, when I mention the trip to folks, they assume I am going on vacation, escaping to a decadent pleasure space where the sun always shines and everything is for sale—including the women featured in the postcards. Minaya’s photographs disrupt these reductive perceptions of the Caribbean.

In an interview, Minaya spoke about her interest in expanding “identity labels” when discussing and making her work, which, she says, “is about identity but it’s not about identity.” She is interested in subverting the assumptions and expectations people make when they identify her as Caribbean or Dominican. To do this, she uses popular visual forms that perpetuate limiting notions of Caribbeaness or Dominicaness, such as the tourist postcard.

Joiri Minaya, Ayoowiri / Girl with poinciana flowers, 2020

Joiri Minaya, The Upkeepers, 2021

The Woman-landscape series draws on Édouard Glissant’s essay “For Opacity,” in which he explores the concept of opacity—a call to move away from transparency toward the untranslatable, the unknowable—as a way to disrupt identity hierarchies. In her work, Minaya asks why we have to label, and be trapped in labels. She takes Glissant’s notion of the “right to opacity” as a way to dismantle difference, to blur the borders of difference, the colonizer and the other, the tourist and the local, the past and the present. In Continuum II (2021), she juxtaposes a well-known painting by Canadian artist François Beaucourt, formerly known as Portrait of a Negro Slave (1786) and recently retitled Portrait of a Haitian Woman, with an image of a brochure of Bávaro, a touristic town in the east Dominican Republic.

Joiri Minaya, Continuum II, 2021

Joiri Minaya, Continuum II, 2021All images courtesy the artist

In the midst of a global climate emergency that presents an urgent need for ethical tourism, Minaya’s nuanced work, which disrupts and questions the hierarchy between figure and landscape through a kind of visual camouflage, is incredibly timely. The artist weaves the figure into the landscape and the landscape into the figure, signaling, urging, revealing our interdependence and kinship with fruit, palm trees, flowers, the sea.

Minaya has remixed the postcards and archival photographs to create un choque, defined by Gloria Anzaldúa in her book Borderlands/La Frontera as a “cultural collision”—a conflict between how we perceive and are perceived. Much like Anzaldúa, who is known for innovatively remixing theory, poetry, and personal narrative “to carve and chisel her own face,” Minaya reclaims an everyday visual vocabulary, revealing the breadth and depths of the worlds she depicts with unapologetic fierceness.

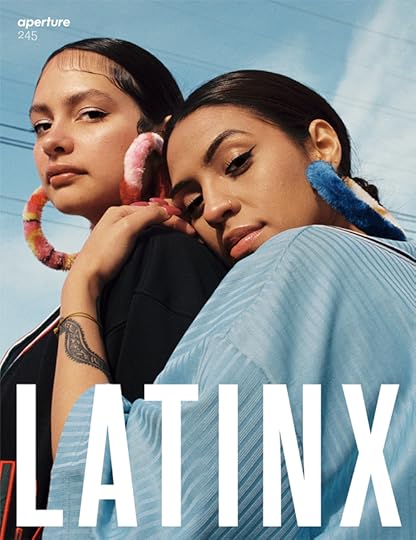

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “Dominican Postcards.”

December 13, 2021

Announcing Tommy Kha as the Recipient of the 2021 Next Step Award

Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, in partnership with 7|G Foundation, are excited to announce Tommy Kha as recipient of the 2021 Next Step Award. As the winning artist, Kha will receive a $10,000 artist’s grant and publish a photobook with Aperture, accompanied by an exhibition at Baxter St at CCNY.

The Next Step Award supports US-based artists at critical junctures in their artistic development. Reconsidering equity across the country and in arts institutions, the award also supports the presentation of diverse opinions, as well as timely lens-based work that is relevant to today’s visual culture and society across a wide array of genres or approaches.

“Baxter St’s ongoing support of Tommy Kha’s artistic development, from workspace resident in 2018 to now, underscores Baxter St as an incubator that identifies and supports strong emerging or evolving voices deserving of greater recognition,” says Jil Weinstock, director of Baxter St. “Kha’s work distinguishes itself for his rigorous and complex approach to self-portraiture that poignantly explores the confluence of identity, connection, and belonging. We are thrilled to see how his practice will evolve with the Next Step Award and Baxter St’s ongoing support during this critical stage in his development.”

Tommy Kha, Constellations (XVIII), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, Constellations (XVIII), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)Tommy Kha has been granted this award for his series Soft Murders, a collection of several ongoing and interrelated bodies of works, including Canada 1984, Facades, Half Self-Portraits, South Portraits, and Yellow Pearl. Kha says that his interest lies in “the disjointed mapping of Asian diaspora, set primarily against the backdrop of the American South,” filtered through his family’s history of fleeing countries and wars.

“Our appreciation for Tommy Kha’s achievements and our conviction that he is ideally positioned for the Next Step Award is underscored by the fact that he was recommended by several of the distinguished individuals we invited to join our nominating committee,” says Sarah Meister, Aperture’s executive director. “Aperture is delighted to continue this partnership with Baxter St and 7|G to expand the ways we support emerging voices in the field.”

Kha was chosen out of an extremely competitive list of artists, nominated by a diverse group of artists and curators who brought expertise and artistic experience to the selection process. The nomination committee included Derrick Adams, Zalika Azim, Sergio Bessa, Antawan I. Byrd, Jesse Chan, Ivan Forde, Lyle Ashton Harris, Sheree Hovsepian, Sarah Kennel, Amanda Maddox, Marvin Orellana, Nandita Raman, Legacy Russell, Phil Taylor, Hank Willis Thomas, Eugenie Tsai, Diya Vij, and Jessie Wender.

The roster of nominated artists who submitted to the prize included David Alekhuogie, Matías Alvial, Zalika Azim, Nathan Bajar, Jonas Becker, Chris Berntsen, Kennedi Carter, Pradeep Dalal, Dominique Duroseau, Lloyd Foster, Genevieve Gaignard, Camilo Godoy, S*an D. Henry-Smith, Sandy Kim, Clifford Prince King, Bria Lauren, Ian Lewandowski, Joshua Rashaad McFadden, Azikiwe Mohammed, Pau Pescador, Stephanie Powell, Susannah Ray, Jacqueline Silberbush, Dianne Smith, Meg Turner, D’Angelo Lovell Williams, and Suné Woods.

Tommy Kha, May (A Costume Drama), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, May (A Costume Drama), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, Stops (II), Marsha P. Johnson State Park, Brooklyn, 2020, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, Assemblies I (or Me Crying in Three Takes), Brooklyn, 2020, from the series Facades (2015–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, New Lin’s Chinese, Memphis, 2019, from the series Yellow Pearl (2012–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, New Lin’s Chinese, Memphis, 2019, from the series Yellow Pearl (2012–ongoing) Tommy Kha, Tourist (Bruised Eye), Southport, Connecticut, 2016, from the series Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, Tourist (Bruised Eye), Southport, Connecticut, 2016, from the series Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, May (with Her Half Self-Portrait), Whitehaven, Whitehaven, Memphis, 2017, from the series Half Self-Portraits / Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, May (Mirror, Mother, Mirror), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from the series Half Self-Portraits / Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, May (Summoning the Kitchen God), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2015, from the series Half Self-Portraits / Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)

Tommy Kha, May (Summoning the Kitchen God), Whitehaven, Memphis, 2015, from the series Half Self-Portraits / Soft Murders (2011–ongoing)All photographs courtesy the artist

December 8, 2021

Greg Tate and Arthur Jafa on Ming Smith’s “Acts of Love” in Photography

The photography of Ming Smith has haunted the international art form like a specter for over four decades. Artist Arthur Jafa has been on record as Smith’s most enthusiastic hype man for half that time, routinely referring to her as the greatest of African American photographers, if not of contemporary art photographers in general. In 2017, he put his admiration and advocacy on “front street,” per the vernacular, by including a survey of Smith’s work in his epic traveling “solo” show A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, an exhibition which debuted at London’s Serpentine Galleries and has since toured several European cities, including Berlin, Prague, and Stockholm.

Smith was born in Detroit and raised in Columbus, Ohio; her father was a dedicated amateur photographer. She began her own photographic journey into the art world shortly after graduating from Howard University and moving to New York to work as a model. She quickly garnered a series of significant “firsts”: the only female member of the Kamoinge Workshop for Black photographers founded by Roy DeCarava, and the first Black woman photographer to have her work purchased for MoMA’s permanent collection. Smith exhibited sporadically in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but jazz fans internationally were made aware of her work via over a dozen album covers for recordings by her former husband, saxophonist David Murray, on the Italian label Black Saint and the Japanese imprint DIW. The selections were an eclectic mix of self-portraits, jazz subjects, and more oblique personal work.

The work that has most inspired and intrigued Jafa has been images in which Smith foregrounds blurred figures of Black folk. In his book Black and Blur (2017), critical theorist Fred Moten (Jafa’s good friend and intellectual confidant) provides myriad novel ways of thinking about blurring in contemporary Black art-making as an artistic and political strategy—one frequently bent on poetically illuminating, through sublimation and subterfuge, the impact of anti-Black violence (historic and systemic) on post-traumatic Black subjects, Black interiors, and Black communities.

Smith’s strategic deployment of blurring in rendering her varied Black subjects and communities is seen by Jafa as an act of love and loving protection from predation by a policing white gaze. It is also testament to Smith’s creative affinity for the freedom-seeking music produced by her generation of jazz artists—that revolutionary group of outliers from California, the Midwest, and New Haven, Connecticut, who collectively transformed the music’s sonics and expanse of conceptual vision in late-1970s New York. These musicians embraced Smith as a creative compatriot and fellow traveler and she, in turn, immortalized them in her artful and liminal documentation of their effigies and performances.

In our conversation, Jafa opens an initial emphasis on Smith’s musicality and visual sonorities into a more complicated discussion about her work’s explorations of what we’d call the “maroon fugitivity” of Black postmodernity and post-traumatic modern Black folk.

Ming Smith, Coney Island Detailed, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island

Ming Smith, Coney Island Detailed, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney IslandGreg Tate: Brother J!

Arthur Jafa: I’m here, I’m here, I’m here.

Tate: We’re talking about the presence of music and sound in Ming’s work.

Jafa: [hums a refrain]

Tate: That series of album covers that Ming did for David Murray in the 1980s, was that your first exposure to her work?

Jafa: Well, no, it actually wasn’t. The first time I saw her work was in The Black Photographers Annual, that featured the work of several members of the Kamoinge group. In each issue, everybody would get one or two photos; then maybe they would have three or four photographers who would get a bit more of an extended space, like a little portfolio section. If I remember correctly, Ming had five or six photos in one issue. So that was my first exposure to her work, and I thought it was pretty amazing.

Tate: It had an impact immediately.

Jafa: Yeah, definitely. My ongoing obsession at the time was like, Where are the photos of Black cultural modes? I knew Ming was great. No doubt about that. But being great and being somehow bound up with a quest for a thing—they would call it a “mother tongue”—they’re not exactly the same thing; Black artists can be great without the thing being inherently Black. But Ming’s thing was super Black. She definitely made an indelible impression on me. She was the standout of The Black Photographers Annual, and not just of one volume, but of the entire series. Later, when I moved New York, I became aware of the David Murray album covers and stuff like Home [David Murray, 1982].

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976Tate: What is the relationship between Black visuality and Black musicality, in your critical sense? What’s the path that binds the two?

Jafa: I was always interested in a certain kind of transformative proximity. Meaning, I was fascinated by the pressure that the music put on the visualizations which, more often than not, had to do with album covers at that point. But there was a pressure the music put on the visualization, to come up with something that seemed simpatico or consistent with the nature of the music.

There’s a long history of jazz photography that’s quite amazing, like many of the Blue Note covers and things like this, that are very distinctive, to say the least. But nevertheless, much of that photography, even though I think it’s good photography, didn’t necessarily feel like it was uniquely Black in its modalities, in its expressive and technical modalities. You know what I mean? So the first time that I saw work that I thought actually was tapping into something was, like I said, album covers. And particularly things that Ming shot, and at the same time, I sort of stumbled on Hart Leroy Bibbs [journalist and photographer from Kansas City, Missouri; 1930–1994]. Bibbs, in some ways, may be the predecessor. His work seemed to be preoccupied with the photography of jazz and Black music performing. Then, the other person one would have to reference would be Roy DeCarava, who had, as a subset of his larger body of work, jazz photography. In particular, there are some really incredible pictures of Coltrane and his ensemble.

From the beginning, from the inception of jazz, you had identifiable musical phrases, songs, melodies, things like that. Then, when you get to bebop, you start to feel an abstract relationship to melody and figures. But then you start to get to free jazz and you start talking about a blurred figure, a figure that isn’t so discretely defined as a figure against a background, then you start talking about the slow shutter speed. In visual terms, you would start with Roy DeCarava. You can see it from his crisply defined but moody figures. In his photos of Trane, there is a kind of impressionism and expressionism that starts to enter into the photography. There’s DeCarava’s John Coltrane on Soprano [1963]. The combination of low light levels, like you would have in clubs, not being able to use flashes, and having to open up the shutter speed, together with people’s movements being more agitated, would generate some of these sort of blurred figures that I’m talking about.

I don’t know if DeCarava went into these spaces and said, “Hey, I’m going to slow my shutter down and create this effect that’s going to seem more commensurate with the music,” or if it just was a technical solution. But one thing that becomes really clear is that Ming, Hart Leroy Bibbs—and I would also put Spencer Richards in this group of photographers—realized that there was an equivalency between this music flow and these blurred figures, which erases much of the distinction in between foreground and background.

Ming Smith, Male Nude, New York, 1977

Ming Smith, Male Nude, New York, 1977Tate: Well, part of the rhetoric around free jazz is that it’s cosmic energy music, music concerned with invoking and evoking spirit possession. The kind of vibratory resonance. Anyone who’s been to a really electrifying performance of the freer music knows that it does open up a heightened sense of the optical as well as the auditory, and expands our sense of the spiritual and the soulful. So we definitely see a connection between that idea of energy music and Ming’s work that has the blur, has a similar kind of vibratory harmonics going on. How would you relate that to what’s going on in her nonmusic practice?

Jafa: The two places that you see this pronounced vibratory quality are in the photos, like we said, of musical figures, and the other place would be in the photography of churches. In both instances, you’re talking about a kind of heightened experience. You’re also talking about lowlight situations, or at least situations where a flash would be inappropriate. Versus, one could be “discreet” in a pool hall or something like that, but it would have more to do with being discreet than the appropriateness in a cultural sense, in the appropriateness of a flash. Certainly not outside, or when people are posing.

The typical Western visual dynamic has to do with figure and ground relationships. Like, what is the figure? What is the subject? What is the object? What is the background? What is the foreground? There’s really two ways you can get at blurring the distinction between the foreground and the background. One way is the shutter speed, which means that the figure itself is being smeared, in a sense, on the negative, or the target. And the other way that you can get at it is tonally. Basically, the foreground figure is high-lit. You know what I mean? It’s generally edged by the light in a certain kind of way. In the most elemental sense, it’s what you see in classic Hollywood cinema—the subject is keyed by the light. Even if it’s an interior, the sunlight is hitting their face, and the background will fall off behind them. So they actually are brighter than the background.

If you talk about Ming’s work outside of the church and outside of the music thing, what you see her doing is something akin to what DeCarava does, with these flattened midtones. Or everything is in a high key. She erases or destroys this background-foreground relationship by making the figure or the subject not brighter than the background. Some of Ming’s most incredible photos—I’m thinking of things like in the telephone booth in Harlem—they’re striking precisely because of that. In many instances, her figures are silhouettes. There’s a heightened sense of shape. If you’re going to have a figure that’s not brighter than the background, things like shape become one of the primary tools that’s being utilized to create formal complexity, to create differentiation in the visual field.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978Even in some of Ming’s Sun Ra pictures, what you actually see is a combination of these two techniques. You see the blur and, as in DeCarava, these flattened midtones. What’s unique about Ming is her ability to use this shutter thing to erase much of the distinction of the boundaries or the edge between the figure and the background, but at the same time, have it be very precise in this articulation of form. It’s a very, very, very difficult thing to do, because as soon as you lower the shutter speed, you reduce the sharpness of the figure. Man, it’s crazy that she can actually do that so consistently, know what I mean? It’s one of the great mysteries of her photography that I’ve always been curious about—what her actual settings are. And then, even when you have the shutter speed, it’s not just the figure moving. It’s like, how much motion you induce to the figure by the camera shaking, to a certain degree. Which is another way that the shutter speed winds up manifesting itself.

Now the other thing, which I think goes even further to this question, is completely tethered to insights taken from Robert Farris Thompson’s African Art in Motion [1974]. Thompson talks about the classic natal context in which African artifacts are being exhibited. In the West, where the object has no agency, it is on a pedestal; the eye can move around the object, which is static. The object is frozen, in a sense. It has no ability to move or to relocate itself in space, he says. In the classic or the natal African traditional context, that artifact moves around the viewer as much as the viewer moves around the artifact. And that dual movement produces a blur. You don’t want to have one static thing, like a kind of open appraisal. That’s what the shutter speed is, the length of appraisal, the time in which one will actually look at a thing. And if you extend that length of time and you move, you’re going to get a blur. Then, in the church or the performance, there’s the motion that’s being induced by the actual movement of her hands—meaning not holding the camera perfectly static. That’s in space-time terms too, like a target that’s distended. It’s the classic thing of people posing for a photo. You always say, “Be perfectly still.” Right? Ming’s technique is based on a complete disavowal of both of the classic tenets of the photographic capture. And I think that lines up perfectly with the deep philosophical implications of this inverted or subverted figure, foreground-background, figure object relationship that Robert Farris Thompson articulates in African Art in Motion. So these things are not accidental.

Ming Smith, Cadillac Man, New York, 1991, from the series Invisible Man

Ming Smith, Cadillac Man, New York, 1991, from the series Invisible ManTate: When you were talking about shapes and silhouettes, I thought of that great Amiri Baraka line, “the shapes in the darkness had histories,” from his book Tales [1967]. With Ming and Baraka, you recognize this quest into the underground of the Black working-class environment. They both have created these magnificent bodies of work that put you inside of a particular kind of Black populated darkness, an Abyssinian field of communal interaction. There’s been hundreds of Black photographers who have shot in the hood. But there’s something extraordinary that Baraka and Ming pull out of their intimate engagement with what I call “real Black life.” It’s so rarefied.

Jafa: They’re both more into the dark places. There is a direct correlation between this idea of darkness, just like literal darkness—in technical terms—and how your eyes adjust to the darkness at a certain point. And that darkness is both figurative and literal at the same time.

The one photography book that Baraka was involved with is In Our Terribleness [1970], by Fundi, who was also in The Black Photographers Annual. And one of the things that’s really distinct about his work, too, is the darkness; and the darkness that he achieves is not just from the light level being down, but it’s also completely bound up with this flattened tonal thing between the foreground and the background. You also see that in Carrie Mae Weems’s work, the way she’s playing with the figure against the dark ground.

Some of the way I term it is “super bad,” like when people shoot things that are not just bad, like in technical terms, but they’re like unrepentantly bad! And the technical badness starts to function on the meta level. It’s almost like the Black man’s heaven is the white man’s hell—some shit like that. It’s like when James Brown said, “I’m bad, I’m super bad,” this whole idea that we’re going to invert these values. It’s this interconnected space where the metaphoric becomes literal, becomes a new point of reference to any kind of norm. So the whole question becomes: what is the default status for Blackness? And it, of course, is darkness. Because Blackness is not the same thing as Darkness, but Blackness as it’s structured in the West is inherently going to be always in proximity to Darkness, because Darkness functions as all kinds of things, like positively and negatively. It functions as black. Deprivation. Not having power. But it also functions as stealthiness. Doing things under the cover of darkness. You don’t really think of runaway slaves as running away in the day. You think of them as running away in the night. Steal away, steal away; you think of people stealing away in the night.

Ming Smith, Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972

Ming Smith, Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972Tate: Under cover of darkness.

Jafa: Yes, under cover of darkness, exactly. As soon as you make a photograph that starts foregrounding things like darkness, it’s inherently bound up with issues of self-determinacy and of freedom.

Tate: I remember what the photographer Jules Allen was saying about Ming; this was the first aesthetic appreciation of her I ever heard from anybody. He just said, “She’s the best of us.” I know you certainly concur with that. But I’m wondering, if we want to talk about aesthetic benchmarks established by Black artists, what’s going on in her work that generates an aspirational response? What’s she doing that’s so singular and powerful?

Jafa: Her capacity to control the dual technical strategies and abnormal technical strategy of slow shutter speed, and the flattened tonal range, to erase the typical relationships between figure and background, foreground and background, are unparalleled.

Tate: I’ve heard you talk about it in terms of Black cinematography, this whole notion of a “God particle.” I’m also asking, what is it about her relationship to Black subjects in the visual fields that Black people occupy in the world that is just so potent and so poignant? Let’s talk about the existential or the emotional aspects of what her photographs generate for you.

Jafa: I mean, what you see in the work, which is what you see so often in the works of any Black artist—let’s talk about music, as an example. That field has been so defined, so structured by Black phonic expressivity, that even the most casual Black-produced music is doing certain kinds of things that Black people take for granted, in terms of them affirming what we consider beautiful. And then there’s people, like an Aretha, or an Albert Ayler, or Jimi Hendrix, who seem to go that further distance—they’re always bound up with the limits to which they are willing to go to affirm aspects of Black sonic beauty or taste, which would be considered, at best, on the margins of appreciation in other musical modalities. Vibrato. Undertone. Overtone. Things like this. It’s on the edge of those things. In other words, it becomes like the space in which a Black person in the space of other values, or maybe dominant values, nevertheless will hold the line in foregrounding schemes in their work.

In photography, that thing which is taken for granted in the musical arena, around which we have basically structured ourselves, is much less prevalent. So, when I talk about these foregrounds, backgrounds, and things, that’s the gist of it. Nobody else has gone as far as Ming in terms of her commitment to doing it. The existential dimensions have to do with the way in which the technical parameters of what she’s doing are, in fact, structured by a commitment to being in those spaces that Black people occupy. The spaces that are underlit. And because they are underlit, and because they are secret spaces and things like this, they require the technical approaches to be aligned with those spaces.

Ming Smith, Farewell to Alvin Ailey (Mother), New York, 1989

Ming Smith, Farewell to Alvin Ailey (Mother), New York, 1989So, as opposed to saying, “People, come outside in the sun so I can photograph you,” it’s like, “No, I’m going to go into these dark spaces with you.” And the technique that would conventionally be considered what you would have to do to rescue the photography, to make a suitable picture, is thwarted. It’s like saying, “No, I’m going to put the pressure on myself of actually coming to where Black people are,” rather than bringing Black people into what would be considered a technically appropriate relationship to the photography.

You see a lot of consequences of this commitment to going into the spaces that Black people occupy, or are forced to occupy, or left to occupy. For example, we know one of the more egregious aspects of the very mechanism itself, photography, is surveillance. Right? Black people get tight around photos, in a certain respect, because they are being surveilled, and there’s always a danger that the photograph can be used as evidence against you in some fashion. But as soon as you say, “I’m going to go into the spaces in which Black people feel comfortable that they’re not being surveilled”—meaning dark spaces, underground spaces, spaces in the woods—the photographer is now introducing into that space the instrument par excellence of surveillance. What that means, then, is you have to be willing to embrace techniques that, in a sense, void the ability of the photograph to function as evidence. In many of Ming’s photos, you can’t identify anybody.

Tate: Photographer as a predator for The State.

Jafa: Exactly. You can’t identify anybody in them. They couldn’t be used in a court of law, because you can’t make out people’s faces! What you’re left with are things like the line of a person’s body, a person’s postural semantics, things like that, which cannot be used as evidence. You can’t be like, “That person stands like X, Y, and Z,” you know what I mean, when you can’t really see who it is. It’s amazing how in a large percentage of Ming’s photos, you can’t identify a single person!

Tate: It’s this rendering of evidence of things unseen.

Jafa: Absolutely.

Ming Smith, Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere, 1991

Ming Smith, Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere, 1991Tate: They operate in this meta-dimension. Some call it “Blacknuss.”

Jafa: Or, as you say, in planes and shadows. It’s not true of all of her pictures. But I mean, Male Nude [1977]. The person’s back is to the camera. And then it’s quite literally a figure against a background, and it looks a little dark. And not because the person is Black. I’m saying the tones are pressed together. Or Farewell to Alvin Ailey Ailey (Mother) [1989], you can see those people’s faces, but that would have something to do with the nature of it. That’s a more straightforward document of that event. But then you go to Dakar Roadside with Figures [1972]—you can’t use that to say who that person is. Not at all. And the same with Family Free Time in the Park [1982]—they’re silhouettes. You go to What’s It All About? [1976]—that kid is on the cusp of silhouette. You can certainly identify him there. But he’s on the cusp of silhouette.

These are pictures that I would say—like God, Mary, Jesus [1991]—that I think typically get presented in Ming’s work as evidence that she can take a decent photo. They look more conventionally like the photojournalism that we associate with Black photography, which I think most people do. But when you come to Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere [1991], which is one of her masterpieces, you can’t fuckin’ identify nobody in that. It’s really interesting, the tension in so many of these photos between saying it’s X, Y, and Z, that you can’t identify the person. It’s not clear of all of them. But I’m saying it’s something you see quite a bit of. It’s a high percentage of her photos. Or Cadillac Man [1991]. These are clearly pictures that are about how bodies occupy space. But they don’t identify who the bodies are.

Ming Smith, Family Free Time in the Park, Atlanta, 1982

Ming Smith, Family Free Time in the Park, Atlanta, 1982All photographs courtesy the artist

Tate: Ming has a romance with the mystery of Black people as shadows moving in a shadow world.

Jafa: And, I would say, she is very invested in Black fugitivity, the fugitivity of Black people.

Tate: A fugitivity that’s not bound up with escape but a kind of self-illumination.

Jafa: A Yeah, totally. Circular breathing. It’s like this whole question of shape, man. Shape and silhouette. How pronounced it is. She can do all kinds of things. But this is something she does that hardly anybody else can do on this level. I don’t know another photographer who can do work in this modality with this level of specificity and precision. Look at Abhortion [1978]. If these photos are not about the whole idea of fugitivity, I don’t know what else they’re about. She takes a picture of a person next to, I guess she’s next to a traffic light, and where she’s not in silhouette, her hair is blocking her face. These are masks, people who are masked. There’s a certain masquerade dimension to these photos.

And in Prelude to Middle Passage [1972]. This is a photo in which the figure is defining the background. It’s framing the background! [Laughs] The background is not framing the figure. The figure is framing the background. In Invisible Man, that’s the blur. The traces. The phantom. The fugitivity of people willing to be free from being fucked with. You can’t fuck what you can’t see. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee; you can’t fuck with what you can’t see!

This conversation was originally published in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) under the title “The Sound She Saw.”

December 7, 2021

What Can Photographs Tell Us about Latinx Identity in the US?

On the hot and humid afternoon of May 10, 1974, in Dallas, Texas, my mother, Dolores, known to everyone as Lollie, visited with my great-grandfather Juan Sosa, who went by the anglicized name of John. My mother brought John his lunch as he lay bedridden from illness and age. She told him that she was pregnant and going to have a daughter. He cried, perhaps realizing he would never see the baby, and with tears in his eyes said, “How wonderful, mija.” She left the room, and when she returned shortly after to pick up his tray, he had passed away. I was born four months later. Although I never knew John, I always liked to imagine his last encounter with my mother and felt connected to him through that story.

Juan Sosa in Western Union uniform, Dallas, ca. 1920

Juan Sosa in Western Union uniform, Dallas, ca. 1920

Courtesy of Evelyn Aguirre and Dolores Cuello Tompkins

When I was invited to guest edit this issue on Latinx photography, the first pictures that came to my mind were not the many artworks and documentary images that I have had the fortune of working with as a curator, but rather the personal photographs that have helped me piece together the story of my family’s history as Latinos in the United States. One is an image of John, whose photograph appeared in the local paper when he saved a family from a burning building during his route as a bicycle messenger for Western Union. John was born in 1899 in the Comanche territory of Oklahoma, before it was a state.

His ancestry was both Mexican mestizo and Indigenous to the Comanchería. He and his family made their way to Dallas after the turn of the century; John served in both World War I and World War II and made his living as a hotel cook.

Matchbook photograph of Ricardo and Consuelo Cuello at Pappy’s Showland, Dallas, 1945

Courtesy of Evelyn Aguirre and Dolores Cuello Tompkins

Luisa Flores and Anita Sosa López making tamales at Christmas, Dallas, ca. 1950s

Other family photographs that came to my mind are images of my grandfather Ricardo Cuello and his brothers in military uniform, as all of them served in World War II and the Korean War. I thought of a photograph printed on a matchbook from a nightclub called Pappy’s Showland of my grandparents Ricardo and Consuelo, known as Chelo, from the 1940s, when they were still teenagers but newly married, their hair piled up in pompadours and their clothes in keeping with the pachuco style they always wore. And I remembered all of the photographs of my extended family shown cramped into small homes, laughing, smiling, and celebrating birthdays and holidays, especially the big tamaladas at Christmas that doubled as yearly family reunions.

The photographers in this issue bring visibility to Latinx experiences—from politics to families and communities, from youth and counterculture to spaces of intersectional identity and expression.

These are, of course, family photographs. But, perhaps, we might think of them as part of a larger history of vernacular Latinx photography—a national project yet to be undertaken within our annals of historicizing the American experience. The countless personal photographs of the more than sixty million Latinx people in the United States today craft the familial origin stories of how we came to be constituents of this country. They are records of our presence that collectively chart the paths and routes of Latinx people—from those whom the border crossed generations ago to those who cross the border today.

The journey is one of negotiating between two cultural worlds that stretch one’s identity across transnational histories, customs, value systems, and languages. Often, this journey is one that rides the edge of visibility. We are frequently the people who live in the background—the laborers who toil in the sun and the kitchens, the heroes and heroines whose legacies you don’t know, the families whose lives are disregarded in movies and on television, the artists whose work you are unfamiliar with, the young people in urban centers across the country who remix fashion, music, and style into hybridized subcultures, and the invisible children who are trapped, alone and afraid, in the migrant detention centers of our borderlands. We are the people who live amid the collective Latinx fight for social, political, and economic justice in the United States.

Photographers unknown; left: Young man wearing a zoot suit, 1944; right: Portrait of Ramona, 1944

Photographers unknown; left: Young man wearing a zoot suit, 1944; right: Portrait of Ramona, 1944Courtesy the Shades of L.A. Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

There is no single story to tell about Latinx people. While rooted in the commonalities of heritage, transnational histories, and lived experiences, Latinx communities are heterogeneous, with shared yet pluralistic identities. This complexity can make it hard to picture Latinx culture. Despite the richness and nuance of Latinx visual production, images of Latinxs in mainstream US culture and media are few and far between. Latinxs, while being a part of the fabric of the United States since its inception, and ubiquitous in urban centers and rural areas alike, are often rendered largely invisible through ongoing systems of erasure, exclusion, and disenfranchisement.

Yet Latinxs in the United States are the largest ethnic group in the country—made up of people of all races, classes, and gender expressions. Our family histories are tied generationally to the land the US occupies, or are linked to multiple waves and periods of immigration to this country, often prompted by the destabilization brought on by imperialistic US military and economic intervention into Latin American countries. Latinx experiences are intersectional and integral to our understanding of the complexities of the populations in the United States and the American hemisphere. It is important to know that there are more people of Latin American descent in the United States than in any individual country in Latin America, with the exception of Brazil and Mexico. Equally significant is the fact that Latinxs will represent 30 percent of the US population by 2030. While Latinx people are critically important to comprehending the past, present, and future of the United States, we are not well represented within the nation’s cultural, historical, and political landscapes. The photography of, by, and about Latinx people has not been widely circulated, nor has it been widely published, collected, or preserved. A deep lack of visibility for this multifaceted community persists.

Related Items

Aperture 245

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]My hope is that this issue of Aperture provides an opportunity for discovery. Photography from the nineteenth century to 2021 presents a push-pull of image making across a spectrum of history and futurity. The photographers in this issue bring visibility to Latinx experiences—from politics and bifurcated nationalisms to families and communities, from youth and counterculture to spaces of intersectional identity and expression. Collectively, their images cast a greater net for the multiple ways of seeing Latinx people, creating a visual archive whose edges are yet to be defined. As the canons of art and history must be pushed to meet the world we live in, so too must the systems that support its visual documentation—from academia, to museums, to the market, and beyond.

The diverse forms of Latinx image and culture making that have unfolded across the expanse of the nineteenth century through the twenty-first are, indeed, vast. While a consistent return to the familiar topics of borders, migration, and identity remains pertinent and germane, the photographers and artists in this issue take a broader perspective on the Latinx archive across time. Their work addresses dialogues relevant to the processes of visibility and belonging that are not fixed but ever evolving. We glimpse archival images that speak to a range of Latinx histories, contextualize documentation from watershed social and artistic movements, trace lineages of photographers making space for queer and gendered bodies, and advance critical work signposting the medium of photography within the larger field of Latinx art. This issue also explores the world through portfolios of contemporary photography that shed light on social spaces—from intimate portrayals of home and family to the collective experiences of the streets and nightlife—as well as on the in-betweenness, or nepantla, of transnational, multiracial, and postcolonial positionalities.

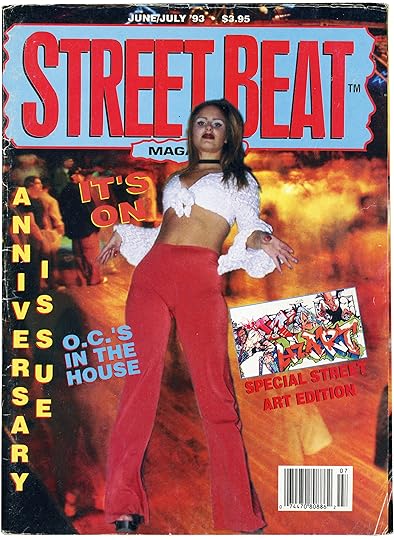

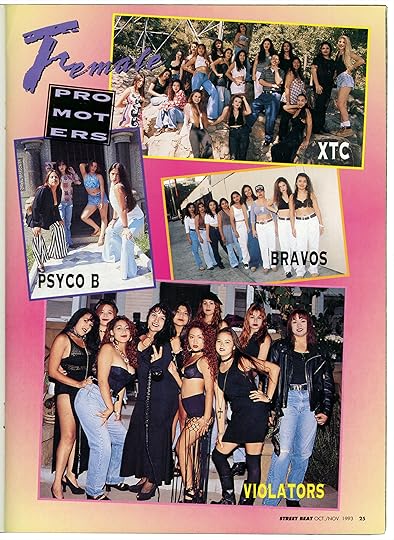

Cover and page from Street Beat, 1993

Collection of Guadalupe Rosales

Here, we merely scratch the surface of a field that calls out for deeper work. I yearn to know more of what the Latinx photographic archive encompasses. What might emerge when we pull back with a wide lens to mine historical images from the earliest periods of US colonization of Latin American sovereign lands, yielding the first Latinx peoples? I want to see photographs of the poet and nationalist leader José Martí rallying Florida cigar workers in support of Cuban independence in the 1890s alongside images of the labor leader Dolores Huerta organizing farmworkers in California from the 1950s to today. I want to posit images of Pedro Albizu Campos in resistance to the US government and industrial monopolies in Puerto Rico in the same breath as the Flores Magón brothers strategizing the Mexican Revolution and fighting US corporate land grabs in Mexico while living in Los Angeles.

How may we expand our understanding of US history by recognizing and elevating these stories of resistance orchestrated from within our borders? What might we learn about Latinx culture when we can look at it across the span of more than one hundred years? What continuums emerge when we see images of young people styling their own personas—from the self-aware studio portraits of the outlawed Californio Tiburcio Vásquez in the 1800s, to the urban portraits of street-fashioned, 1940s pachucos and pachucas, to the cholos and cholas captured by John Valadez’s 1970s lens, to the work of the artist Guadalupe Rosales striving to recover a visual archive of Southern California Latinx youth culture in the 1990s? How may we understand the power of image making when we see young Latinxs rendering themselves visible through dress, style, self-possession, and acts of personal agency?

William Camargo, We Gonna Have to Move Out Soon Fam!, Anaheim, 2019

William Camargo, We Gonna Have to Move Out Soon Fam!, Anaheim, 2019Courtesy the artist

When we visually name and mark forms of cultural erasure such as gentrification—a process that displaced my family not once, but twice from their historic Mexican American communities in Dallas—in the way that William Camargo’s images do, can we halt the expunging of our presence and narratives? I would have liked to have known such images when I was growing up, and to have felt their influence on my nascent sense of self.

For me, the Latinx journey is not only a process of visibility but also a process of belonging. The stinging instances that serve to remind me of that continue even today, but I will never forget one of the first times that I became aware of such attitudes. When I was about eight years old, the father of an Anglo friend of mine, on learning about my family, said to me, “You’re Spanish? All wetbacks should go back to Mexico.” I didn’t understand what he meant, but I knew his words were intended to hurt. I asked my mother, and our conversation went something like this:

“Are we from Spain?”

“No.”

“What is a wetback?”

“It’s a bad word to say that people like us swam across the Rio Grande to get here.”

“Did we swim across the Rio Grande?”

“No.”

“Will they make us go back to Mexico?”

“I don’t know.”

“Are we from Mexico?”

“Not really. We are from here, but our family is from there.”

“Do we still have family in Mexico?”

“No.”

“What would happen if they made us go to Mexico?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think that will happen, but it has happened before. But you are American, you belong here.”

While that encounter was almost forty years ago, I rarely forget that the place where I belong is embedded within a continual process of belonging. The more images I come to know of the Latinx experience—from among our monumental archive— the greater that space for belonging becomes.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “You Belong Here.”

December 3, 2021

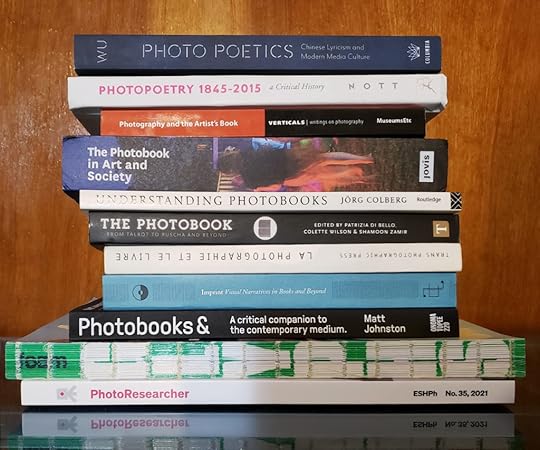

Why We Need Photobook Criticism

In her 1964 essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag wrote, “The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.” Since then, critics and readers have continually asked, Why is it a book? How does it work as a book? and similar queries about artists’ books and photobooks.

Over the past two decades, this inquiry has expanded significantly with the explosion of books about photobooks, and more recently, online coverage of photobooks. While this coverage offers a wealth of information, often including images or videos of the books, most of the treatment tends to be promotional (with commentary more or less amounting to, This is good, I recommend it, here’s a summary) or descriptive, and more about the photographs than the book. Some might as well be reviews of an exhibition containing the images from the book—leaving open the question of how, or if, the work functions differently as a book. Furthermore, because a significant portion of photobook reviews leverage content provided by the publisher and/or the artist, multiple reviews often reflect the same perspective and information, instead of conveying an evaluation of how a particular reader responds and why.

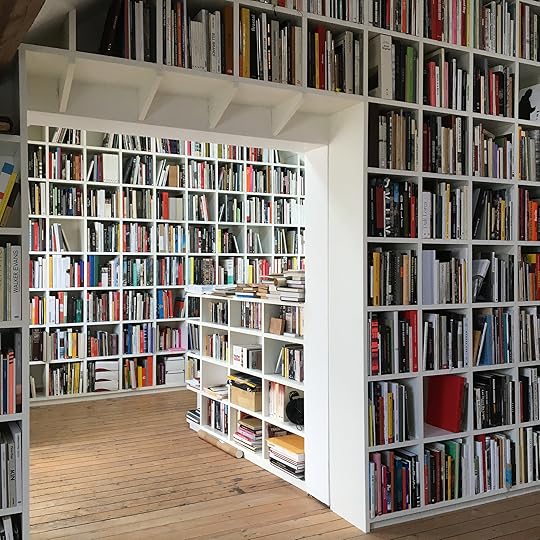

Courtesy David Solo

Courtesy David SoloWhile these reviews are important and helpful, a wider range of writing—namely, critical analysis of the photobook—lacks the same kind of platform. This includes discussion of the choices made not only in the content but in the arrangement of the book itself, as well as other design choices that shape the experience of the reader. This deeper criticism can also more adequately explore the relationship between images and text—how the two come together, how collaboration works, and how they shape or challenge the interpretation of the associated content. Criticism should offer a wide set of voices and opinions, analyze work from different cultural viewpoints, and position the work across a wider historical landscape (including both photographic and other art forms).

This is not to say that all writing must do all these things. But I do argue that a richer diversity of writing needs to be encouraged and supported so it can be made available to audiences who are, or who might be, interested. Without robust critical frameworks and debate—and platforms to support and distribute such writing—the audience of the photobook cannot mature or expand. Other art forms have had centuries, or even millennia, of critical discourse. Mainstream coverage of literature, poetry, music, film, etc. includes reviews as well as more structured criticism, producing a range of judgments supported by objective examination of the work’s detailed elements (for example, Carol Rumens’s poem of the week in The Guardian). The photobook has yet to achieve that level of legitimization and recognition.

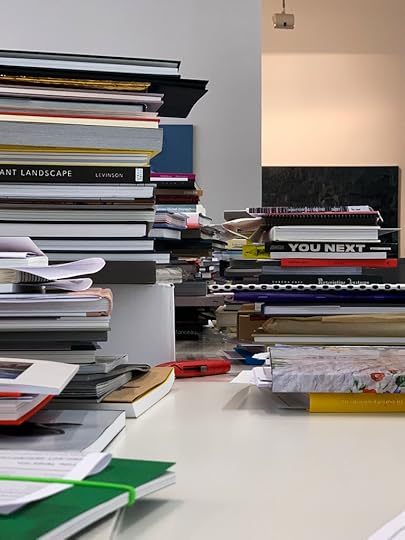

Jody Quon and Sonel Breslev, shortlist jury members of the 2021 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, New York, 2021

Jody Quon and Sonel Breslev, shortlist jury members of the 2021 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, New York, 2021Courtesy Lesley A. Martin

Objectives for Criticism

Richer photobook criticism will serve a range of audiences and objectives above and beyond the advocacy function addressed by many current reviews and lists. Criticism would help to inform readers, and to demystify those photobooks that would otherwise seem totally opaque.

While the current audience for reviews is generally well-versed in the lifecycle of books and the components of their design, there is a wider audience for whom this is a foreign realm. In order to help expand the audience of the photobook, criticism must empower a wider community to pick up a book, see and understand what the makers were trying to do, decide whether they agree with the choices, and assert whether they think it worked and why. That’s very difficult when you don’t know what the menu of possibilities may have been. Without access to the insight that criticism provides, for many readers, the photobook’s medium-specific language is an impediment to opening, let alone enjoying it.

In a related fashion, more robust criticism would also serve as additional feedback (beyond sales and top ten lists) to the artists, designers, and publishers involved in the making of photobooks. An ever wider set of options in dimensions, materials, bindings, inserts, and other features are available, yet there has been limited discussion of how well those choices shape the experience of the book and contribute to the overall success of the work. As with the prior objective, this element of criticism is also oriented around addressing the experience of the reader.

Criticism can also explore in more detail the historical positioning of work—both within an artist’s body of work and across the wider range of photobook history—and contextualize both content and design choices across cultures and time periods. Growing attention around the explicit and implicit signals sent by visual material and design choices like typography and layout in turn requires discussion of these topics as seen in different eras and by different communities and cultures.

Photobook criticism can also engage with a wider set of questions facing the art world, the general book world, and society more broadly. Such topics include:

the communities (those of the maker[s], subjects, and intended audience) associated with a book and how those connections influence the reception of the work;the question of how to extend the dialog across languages and localities, and how to sustain a conversation about work being made locally across the globe;whether there are or should be different frameworks for discussing activist, protest, and socially engaged work;alternative financial, production, and distribution models;zines and related works that may be more ephemeral, or more about working out an idea, experiment, or messageRelated Items

Has the Photobook Become More Interesting than Photographs Themselves?

Learn More[image error]

A Photographer Traces the Ghosts of Loss and Trauma in Southern Africa

Learn More[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]State of the World

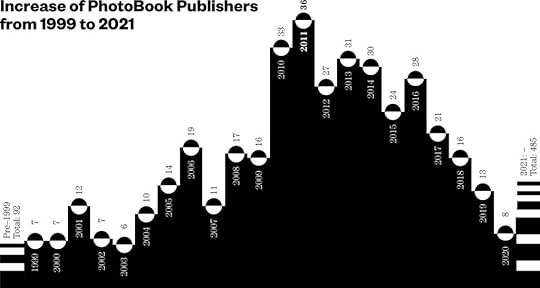

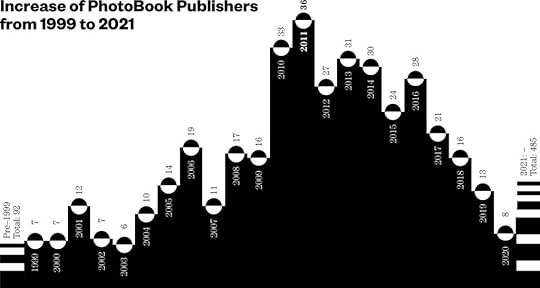

Within this landscape of what criticism is or can be, it’s worth looking at where we are and have been over the past twenty years, during which the volume of writing about photobooks has expanded greatly. The primary intent of this essay is not to say that there is a gap—there is and has been excellent criticism of photobooks—but to argue that the coverage remains skewed toward the promotional/advocacy end of the spectrum. There is still much that can be done to both deepen this discourse and widen its reach.

Photobooks are currently shown and discussed in a wide range of forums. As described elsewhere in this issue, books about photobooks have exploded over the course of the last twenty years—from those that provide generalized lists, to those bound by a thematic, regional, or monographic scope. While some provide rigorous analysis (the two Autopsie volumes by Manfred Heiting and Roland Jaeger published by Steidl come to mind), most are in the form of lists of the authors’ choices within the given scope and include merely a description, some background on the work, a focus on the images, and perhaps sequencing. Other elements of book design and experience tend not to get as much attention. The flood of annual “top ten” lists is even more focused on the question of what the selector responded to positively, and most social media posts are also about promoting or recommending the book. Many artists, publishers, and booksellers present their books online, sometimes with discussion or background of the project from a content perspective. Several online review sites have sought to fill some of the gap by providing promotion as well as more extended reviews and in some cases more structured analysis of the books. Several books, often aimed more at makers, have looked at specific elements of photobook design. PBR and other photography-focused journals have also occasionally provided extensive looks at elements of the photobook lifecycle and design process. The most recent issue of PhotoResearcher considered questions of the reception of photobooks in depth.

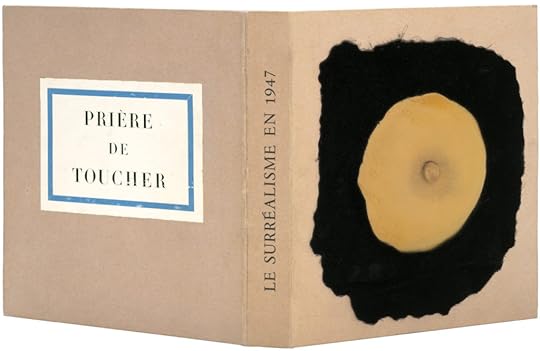

The world of photobooks overlaps significantly with the broader world of artists’ books (there’s another long-standing debate about the nature and breadth of that relationship). The critical discourse that has been taking place in that sphere over the past fifty years takes up many of the same questions and wrestles with similar challenges. Compared to those of photobooks, reviews of artists’ books often pay more attention to the physicality, materials, and composition of the book as an object, but still primarily maintain a descriptive vs. evaluative standpoint. While the examination of the interplay between image and text in general has a long history, the photograph has only recently entered the fray. Academic study of artists’ books and photobooks from both a practice perspective and an art and book historical perspective is also expanding with research and publications emerging.

Courtesy Lesley A. Martin

Courtesy Lesley A. MartinA Path Forward?

So what are some suggestions for what we might do?

Establish and encourage paid platforms for critical writing from diverse, global sources with wide availability. The critical discourse can be in a variety of forms including writing (in print and/or online), live conversation, panels, and video. Maintain an online listing of platforms that provides examples for aspiring writers and a guide for those looking to consume such content.Create and maintain resources for writers who want to write more expansively about photobooks (understanding process, book design, fact checking, etc.). This should include examples of successful critical writing, resources to help answer questions, and perhaps checklists of issues to consider.Develop and support opportunities in photobook-related activities (launches, online discussions, lists, etc.) that include more critical, analytical discussion. In doing so, make the choices and roles associated with the book more visible, and invite critics and other voices to discuss those choices and their impact on the reading experience.Create partnerships to enhance translation and distribution solutions to connect artists, writers, and makers globally.Cooperate with artists’ book communities, organizations, and initiatives to jointly pursue these objectives and activities.Some of these are simple and some are in progress to varying degrees. The Book Art Review was launched last year (of which I’m a cofounder with Corina Reynolds and Megan Liberty with the Center for Book Arts in New York) and in February coorganized the Contemporary Artists’ Book Conference to explore these questions. The Photobook Sessions were organized by the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation and Camberwell College of Arts, UAL in May and continued some of these threads with more focus on the photobook.

The objective here is to continue describing and supporting what more can be achieved through a greater range of critical discourse about photobooks, and to encourage both writers and platforms to explore these topics and seek opportunities for collaboration.

This article originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review, Issue 020, under the title “Why Is This a PhotoBook? A Call for a Richer PhotoBook Criticism.”

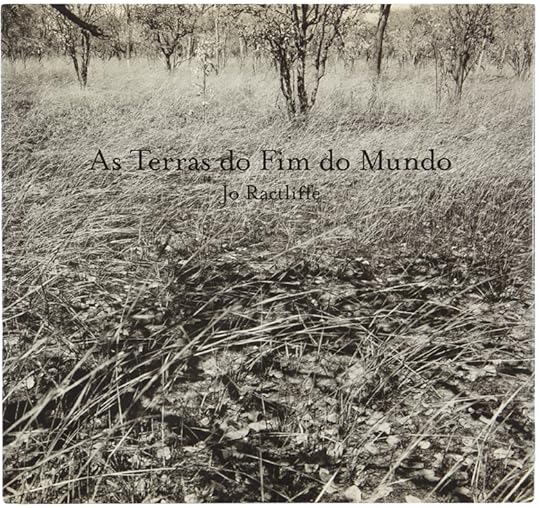

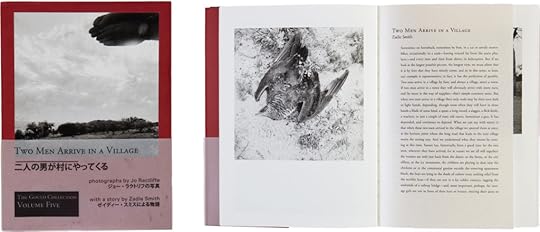

A Photographer Traces the Ghosts of Loss and Trauma in Southern Africa

Nearly four hundred pages into Jo Ractliffe, Photographs: 1980s – now (Steidl and the Walther Collection, 2020), the first comprehensive survey of the South African photographer’s thirty-five years of artmaking, is a graceful short story by Emmanuel Iduma. “Rendezvous: A Fiction” follows the journey of an unnamed man in an unnamed town who is searching for signs of the father he lost to war decades prior. It is strewn with footnotes, by which Iduma intersperses this story with close reads of key photographs by Ractliffe. These asides provide the momentum for an understated narrative of family mourning and the long shadow of war. “She stands facing seven dangling overalls, held by long strips of twine and tethered to narrow branches,” Iduma writes of Ractliffe’s photograph Roadside stall on the way to Viana (2007). “Presences without bodies, exoskeletal men. They are hung there as if in readiness. Later, when the ghosts come, they will need to be clothed.”

Jo Ractliffe, Roadside stall on the way to Viana, 2007, from the series Terreno Ocupado, 2007

Jo Ractliffe, Roadside stall on the way to Viana, 2007, from the series Terreno Ocupado, 2007They will need to be clothed. So much of Ractliffe’s photographic practice has hinged on clothing ghosts. She attends to the ghostly imprints that political violence has left on the landscapes of South Africa in the wake of apartheid, and on those of Angola in the wake of civil war. Photographs: 1980s – now narrates this career-long commitment, culling work from each of the artist’s major series, such as Crossroads (1986), depicting the titular township where bulldozers razed people’s homes to the ground during the State of Emergency, and Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting), made during the artist’s visit to the farm that had once served as headquarters for the apartheid government’s covert hit squad. In these and many other photographic series, Ractliffe focuses her lens not on explicit scenes of human violence but rather on the signs of its haunting: the riven terrain where somebody’s shack once stood, a lone man in the background taking the measure of what is lost; or the ominously blurred gate that marks the way to Vlakplaas, a terror best glimpsed askew.

Jo Ractliffe, Torreno Ocupado (Warren Siebrits, 2008)

Jo Ractliffe, As Terras do Fim do Mundo (Michael Stevenson Gallery, 2010)