Aperture's Blog, page 49

October 21, 2021

Aperture’s 2021 Gala Honors Sara Cwynar, Graciela Iturbide, and Dr. Kenneth Montague

On October 19 and 20, Aperture’s annual fundraising gala celebrated the range of its publishing program and the field of photography with three honorees: artists Sara Cwynar and Graciela Iturbide, and esteemed collector Dr. Kenneth Montague. Aperture’s executive director, Sarah Meister, observes, “Since 1952, Aperture has attended to ‘professional and amateur, pictorialist and documentarian, journalist and scholar’ (in the words of its founders). Our choice not to have a theme this year honors the democratic breadth of this legacy, bringing forward individuals who mirror the diversity of photography. We thank each of our honorees for the inspiration they bring to our lives and for their trust in Aperture.”

The two-day celebration began with an intimate in-person gathering on October 19 at Selina in Manhattan, which featured an unforgettable musical performance by Queen Esther. The evening also included cocktails from Yola Mezcal and Ghia and hors d’oeuvres, auction artworks installed in collaboration with Artsy, oysters from Oysters XO, a unique photobooth by The Self Portrait Project, and more.

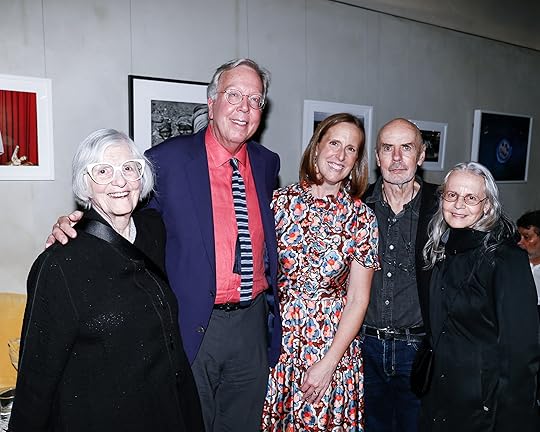

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Dr. Stephen Nicholas, Sarah Meister, Eugene Richards, Janine Altongy

Lyle Ashton Harris, Billy Frae, Nicole Fleetwood

Elle Perez, Brendan Embser, Farah Al Qasimi

Gail Albert Halaban, Lauren Weyand, Casey Weyand

Sara Cwynar

Anastasia Voron with Graciela Iturbide (on-screen)

Dr. Kenneth Montague

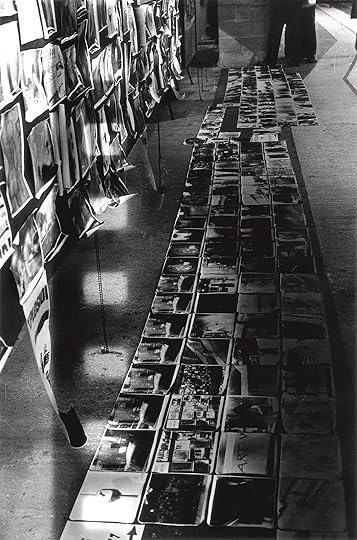

Melissa O’Shaughnessy with prints on display from the Magnum Square Print Sale in Partnership with Aperture

Previous NextSelina also featured a special installation of prints from the Magnum Square Print Sale in partnership with Aperture, which runs through October 24, 2021. Sarah Meister suggested the theme for this year’s iteration, On the Horizon, and the list of participating artists reflects her curatorial vision: Tina Barney, Mitch Epstein, Luigi Ghirri, Naima Green, Sabine Hornig, Susan Meiselas, Richard Misrach, David Benjamin Sherry, Laurie Simmons, Hank Willis Thomas, Aperture trustees Lyle Ashton Harris and Joel Meyerowitz, and so many more.

Rifko Meier, Oysters XO

Rifko Meier, Oysters XO Robyn Stein, Sharon Dye, Cathy Kaplan, Gail Albert Halaban

Robyn Stein, Sharon Dye, Cathy Kaplan, Gail Albert Halaban  Esther Zuckerman and Bob Marshall

Esther Zuckerman and Bob Marshall  Melissa and Jim O’Shaughnessy

Melissa and Jim O’Shaughnessy Sarah Arana, Dr. Kenneth Montague , Liza Murrell

Sarah Arana, Dr. Kenneth Montague , Liza Murrell Michael Paley, Michael Hoeh, John McGovern, Noel Kirnon, Elaine Goldman

Michael Paley, Michael Hoeh, John McGovern, Noel Kirnon, Elaine Goldman  Kristen Gresh and Ivan Abarca-Torres

Kristen Gresh and Ivan Abarca-Torres Michael Famighetti, Nicole Acheampong, Brendan Embser

Michael Famighetti, Nicole Acheampong, Brendan Embser Sarah Meister , Rosalind Fox Solomon, Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Sarah Meister , Rosalind Fox Solomon, Oluremi C. Onabanjo The event at Selina was followed by a virtual celebration on October 20, featuring tribute speeches by Farah Al Qasimi, Julie Crooks, Lucy Gallun, Kristen Gresh, Melissa Harris, Pablo Ortíz Monasterio, Legacy Russell, Trevor Schoonmaker, and Jamel Shabazz. The cohosts for this year’s gala were Julie Bédard, Kate Cordsen, Lyle Ashton Harris, Cathy Kaplan, and Lisa Rosenblum.

Queen Esther

Queen Esther Deborah Willis, Cathy Kaplan

Deborah Willis, Cathy Kaplan Michael Hoeh, Elio Artese

Michael Hoeh, Elio Artese Noel Kirnon, Michael Paley

Noel Kirnon, Michael Paley Robin Schwartz, Penelope Umbrico

Robin Schwartz, Penelope Umbrico Sarah Meister, Cathy Kaplan

Sarah Meister, Cathy Kaplan Legacy Russell, Andreas Laszlo Konrath

Legacy Russell, Andreas Laszlo Konrath Elizabeth Gregory-Gruen, Bob Gruen, Kellie McLaughlin

Elizabeth Gregory-Gruen, Bob Gruen, Kellie McLaughlin Dr. Deborah Willis, Dr. Kenneth Montague, Sarah Aranha

Dr. Deborah Willis, Dr. Kenneth Montague, Sarah Aranha Julie Bédard, Daniel Miranda

Julie Bédard, Daniel Miranda Tiffanie Ho, Nina Celebic

Tiffanie Ho, Nina Celebic Michael Hoeh, Helen Nitkin

Michael Hoeh, Helen Nitkin Cathy Kaplan, Tom Schiff

Cathy Kaplan, Tom Schiff Tim Davis, Giada De Agostinis, Michael Famighetti

Tim Davis, Giada De Agostinis, Michael Famighetti Elizabeth Levine, Mark Levine

Elizabeth Levine, Mark Levine Cathy Kaplan, Andrew Lewin

Cathy Kaplan, Andrew Lewin Rifko Meier

Rifko Meier

About the 2021 Honorees

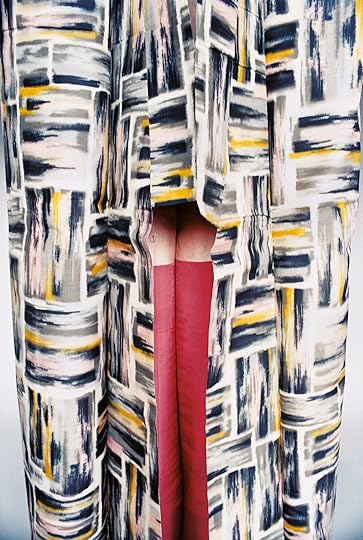

Sara Cwynar’s research-driven and visually complex photographs investigate color and consumer culture. Her images constitute the hallmark of contemporary post–Pictures Generation work—in which photography is pursued in relation to film, sculpture, digital culture, and the cultural and technological history of image-making.

Recognized today as one of the greatest living photographers in Latin America, Graciela Iturbide envisions the rich cultural heritage and diversity of life in Mexico, particularly its Indigenous traditions. Known for her lyrical black-and-white photographs, Iturbide has transformed everyday life into poetic and powerful art for more than fifty years.

Dr. Kenneth Montague started the Wedge Collection in 1997 to acquire and exhibit art that engages multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. Dr. Montague’s 2021 book, As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic, presents the works of Black artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, and the United States, as well as throughout the African continent—serving as a testament to the support provided to artists by collecting and amplifying their work.

For nearly seventy years, Aperture has championed photography as an essential art addressing urgent issues and questions in culture and society. The gala provides critical sustaining support for Aperture’s publications, educational initiatives, exhibitions, and public programming. If you haven’t already, please consider giving a 100% tax-deductible gift today.

October 18, 2021

18 Photographers on What It Means to Embrace the Unknown

Horizons are where the finite meets the infinite; a site of endings and beginnings, anticipation and transformation. The latest edition of the Square Print Sale, On the Horizon, features over one hundred photographers invited by Aperture and Magnum. The selected prints push the boundaries of what we know and see, explore the edges of the photographic practice, and embrace the unknown.

“Photography is a profoundly democratic media, and this Square Print Sale is a rare opportunity for all of us to own work by some of its most creative and inspiring practitioners,” observes Aperture’s executive director Sarah Meister. “The multitude of perspectives gathered here reflect the vitality and breadth of the medium. All of these intimately scaled prints are compelling visual statements that merit close contemplation: whether purchased for oneself or as a gift, these memorable images encourage attentive connection with the world around us.”

Through October 24, 2021, collect these signed and estate-stamped, six-by-six-inch, museum-quality images for $100 each. When you purchase through this link, you directly support Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations. Below are highlights On the Horizon.

Sabiha Çimen, Girls are standing against the waves, Istanbul, Turkey, 2016

Sabiha Çimen, Girls are standing against the waves, Istanbul, Turkey, 2016Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sabiha Çimen

“Like distant stars, horizons always seem to be out of reach, but that’s what dreams are made from.” —Sabiha Çimen

Ernest Cole, New York City, 1972

Ernest Cole, New York City, 1972Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Ernest Cole

“Ernest recognized that the future was going to be a struggle over identity as much as it would be a battle for liberation. Unlike the majority of people of his age, Cole exhibited little or no prejudice towards the subjects of his photographs. Indeed, he seemed to celebrate the extremes of difference on New York’s streets. Everyday was a glorious walk on the wild side.” —Estate of Ernest Cole

Bieke Depoorter, Agata, Paris, France, November 2, 2017

Bieke Depoorter, Agata, Paris, France, November 2, 2017Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bieke Depoorter

“This is the first image I took of Agata, after I met her the night before her twenty-fourth birthday. It was the day I realized that our chance encounter was special, and we would not manage to step away after this one portrait. What followed has been an intense and complex collaboration; a beautiful friendship with much self-reflection and constantly shifting boundaries.” —Bieke Depoorter

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, circa 1950

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, circa 1950Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“People like to point out that this picture was taken from the dog’s point of view. I sometimes wonder whatever happened to that dog.” —Elliott Erwitt

Bruce Gilden, Japan, 1998

Bruce Gilden, Japan, 1998Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bruce Gilden

“It was in a coffee shop in Ginza, Tokyo. I saw a yakuza lighting his partner’s cigarette and after I took one photo of them, I asked if they could do it again to make sure that I didn’t miss it.” —Bruce Gilden

Nan Goldin, Lost Horizon, n.d.

Nan Goldin, Lost Horizon, n.d.Courtesy the artist

Nan Goldin

“Two worlds, like audiences, disperse And leave the soul alone.” —Emily Dickinson

Proceeds from the sale of this print will benefit PAIN, Aperture, and Magnum.

Todd Hido, #5406, from the series A Road Divided, 2006

Todd Hido, #5406, from the series A Road Divided, 2006Courtesy the artist

Todd Hido

“Coming or going? Full or empty? I say going and full.” —Todd Hido

Gillian Laub, Dolly Parton, 2008

Gillian Laub, Dolly Parton, 2008Courtesy the artist

Gillian Laub

“This was an unforgettable day in Los Angeles with Dolly Parton. I have long admired her for both her multitalents and her generous spirit. I’ll never forget the advice she gave me that day. It was right before I was about to get married, and I was anxious. I asked her what her secret is to a long-term successful relationship, since she has been married for decades. She answered: ‘Travel a lot—and not together.’” —Gillian Laub

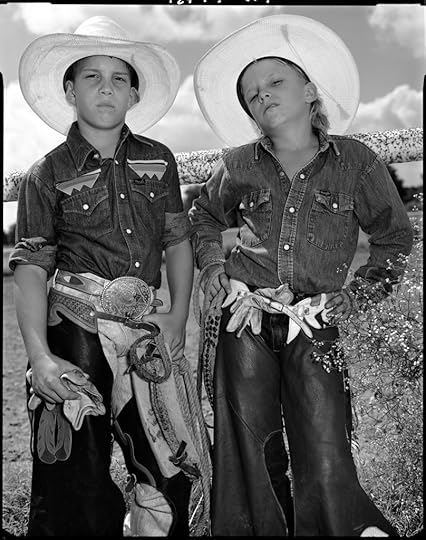

Mary Ellen Mark, Craig Scarmardo and Cheyloh Mather at the Boerne Rodeo, Texas, 1991

Mary Ellen Mark, Craig Scarmardo and Cheyloh Mather at the Boerne Rodeo, Texas, 1991Courtesy Mary Ellen Mark/The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation

Mary Ellen Mark

“DJ Stout, the art director at Texas Monthly, assigned me to spend a month traveling across Texas to photograph small-town rodeos. He chose me for this project because of my work on the Indian circus. There was only one thing that I found terribly disturbing: it was the sport of bull riding, because it was so dangerous. These two young boys were excellent bull riders. You can tell by their attitude that they knew it. Even though they were still children, they displayed a machismo beyond anything I had ever seen.” —Mary Ellen Mark

Yael Martinez, Abuelo-Estrella, An elder from the Cerro de la Garza, Guerrero, Mexico, December 31, 2020

Yael Martinez, Abuelo-Estrella, An elder from the Cerro de la Garza, Guerrero, Mexico, December 31, 2020Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Yael Martinez

“Through narrow, winding, and treacherous mountain terrain, the Na Savi Indigenous communities in Guerrero, Mexico, every December 31, climb the Cerro de la Garza to perform rituals that commemorate the end and beginning of a cycle in life. They perform processions, dances, animal sacrifices, and other Indigenous spiritual practices of gratitude to the earth to ensure good harvests and full rivers, and to protect against water scarcity and the ravages of heat. It is a ritual that seeks to close the past and open the path to new horizons.” —Yael Martínez

Don McCullen, The Steel Town, Consett, County Durham, United Kingdom, 1974

Don McCullen, The Steel Town, Consett, County Durham, United Kingdom, 1974Courtesy the artist

Don McCullen

“When I came back from [photographing] wars, I would immediately throw myself into my own personal journeys, like going to Bradford or Liverpool, or I’d head up to Scotland to do landscape photography. So I never had time to think about posttraumatic stress. This image strikes me for its alien lunar landscape; an environmental disaster which is so uncomfortably at odds with the presentation of this young mother pushing her shiny pram.” —Don McCullin

Daido Moriyama, Hokkaido, 1971

Daido Moriyama, Hokkaido, 1971Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation; Courtesy Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Daido Moriyama

“One day in 1971, on a whim, I traveled to Hokkaido. It was my obsession that urged me—with the wasteland and the wilderness, and with the endless horizon behind it. There is a strong sense of attraction and attachment that I feel to a certain place that may, although not in reality, lie somewhere even further beyond. It is a place in my heart, and my desire to get there, see it with my own eyes, that was driving me.” —Daido Moriyama

Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Bridge at sundown, Tokyo, Japan, 1996

Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Bridge at sundown, Tokyo, Japan, 1996Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Gueorgui Pinkhassov

“Returning to Tokyo several times, I tried to find this bridge. I remember catching a train and getting off at a random station. Everything there intrigued me in its transparent harmony. The departing day fed my melancholy. I sought emptiness. And it colored my picture blue. I accepted it.” —Gueorgui Pinkhassov

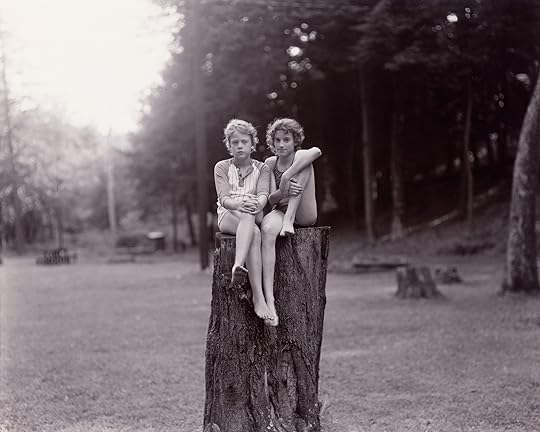

Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Black Cloud. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001

Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Black Cloud. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“A summer storm had just passed over us. As soon as the lightning stopped they both went out, shivering, to watch the wind push the storm clouds away.” —Alessandra Sanguinetti

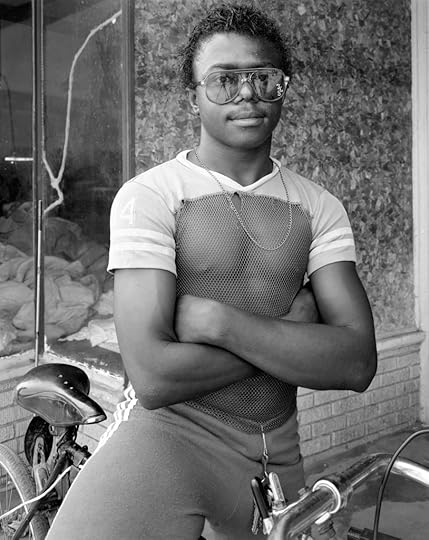

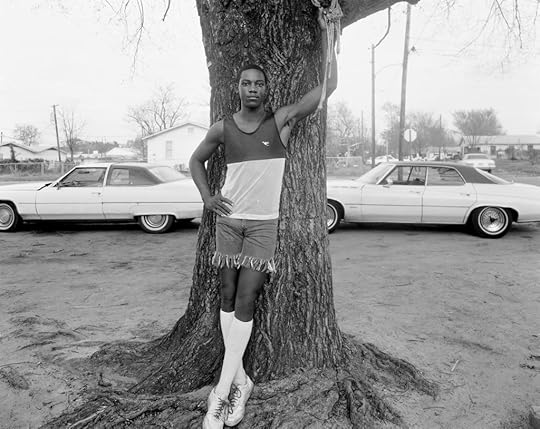

Jamel Shabazz, Best Friends, Brooklyn, 2004

Jamel Shabazz, Best Friends, Brooklyn, 2004Courtesy the artist

Jamel Shabazz

“My father, who was my first photography instructor, provided me with all of the essential tools that I needed to embark on my personal journey as a photographer. He taught me about light, speed, composition, subject matter, and the importance of having concrete themes. The one thing that he would always say is: ‘Carry your camera everywhere you go, have it out and properly set at all times.’ I took that advice and everything else he shared with me and set out on a journey to explore the larger world around me. That was over forty years ago. It would be through the craft of photography that I found my purpose in life, which was to use my camera as a tool to freeze time and preserve the moment as an historical record for future generations. I have often been asked, ‘What do you look for in making an image?’ My answer is simple: I look for love, friendship, and joy.” —Jamel Shabazz

Rosalind Fox Solomon, I Love NY, Staten Island Ferry, 1984

Rosalind Fox Solomon, I Love NY, Staten Island Ferry, 1984Courtesy the artist

Rosalind Fox Solomon

“I’m a composer playing with light and darkness. The camera is my instrument. My parents put me down because I was different. I see myself as an outsider. I’m always a beginner. I approach the woman on the ferry. Saying nothing, I stand before her in a tattered hat and a fishing vest. I focus the camera and take her picture. She ignores me.” —Rosalind Fox Solomon

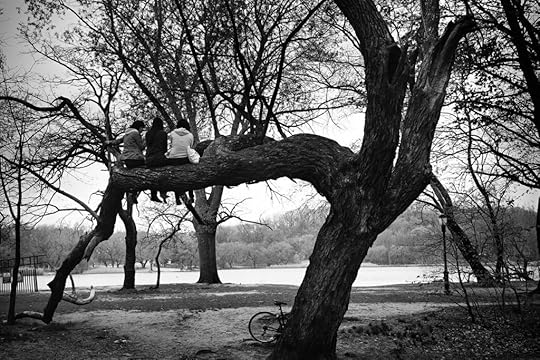

Alec Soth, Bogotá, Colombia, 2003

Alec Soth, Bogotá, Colombia, 2003Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alec Soth

“Nearly two decades ago, my wife and I visited Bogotá, Colombia, to adopt our baby girl, Carmen. During the two months we spent waiting for the courts to certify the adoption, I explored the city. The pictures I took in Bogotá are as much about my daughter’s future as they are about her birth city.” —Alec Soth

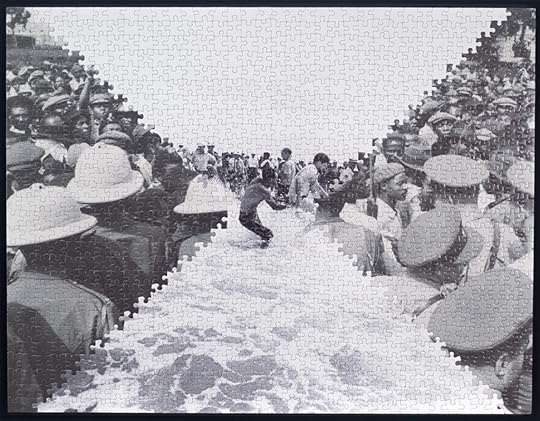

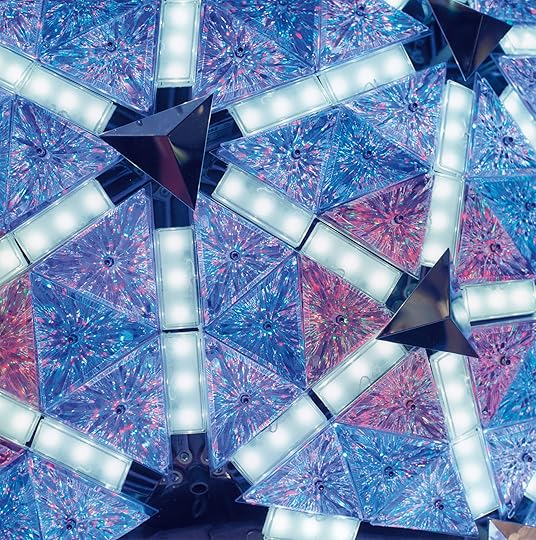

Hank Willis Thomas, Hall of the City of God, 2021

Hank Willis Thomas, Hall of the City of God, 2021Courtesy the artist

Hank Willis Thomas

“I’m looking at puzzle pieces like pixels in a photograph and putting the pieces of history together to make connections to past and present. I’m trying to understand how it all fits together.” —Hank Willis Thomas

The Magnum Square Print Sale in partnership with Aperture, On the Horizon, is available through October 24, 2021 at 11:59 p.m. PT.

October 15, 2021

The Artists Building a Black Cosmos

The visual enjambment we see in collage works entered the collective consciousness through song, specifically the sonic territories mapped and invented by jazz and blues music. Black music made audible ideas that trauma had stifled and muted, and once these sentiments could be heard, it became easier to visualize them and reenact them through images and movement. Black visual artists who do with light what jazz instrumentalists and blues vocalists and hip-hop producers do with sound emerged and began to experiment—pioneers like Romare Bearden early in that tradition, and working artists of today like Jacolby Satterwhite, Lauren Halsey, and Tavares Strachan.

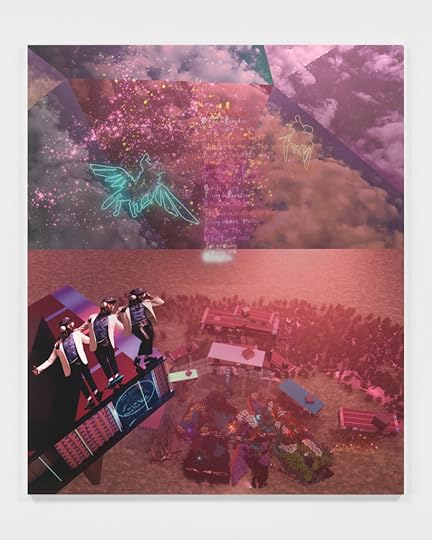

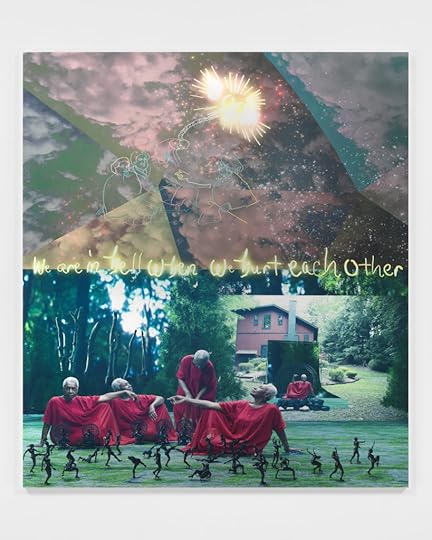

Jacolby Satterwhite, Flying in Paradise, All Above the Business, 2020

Jacolby Satterwhite, Flying in Paradise, All Above the Business, 2020Courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

These artists merge the analog and digital with uncanny ease. The nephew of afro-harpist Alice Coltrane (widow of John Coltrane), Flying Lotus is one of our portals between what’s happening in music and what’s happening to bodies on dance floors and at home, and in factories and offices and schools and prisons and everywhere bodies are sold—and what occurs in the work of Satterwhite, Halsey, and Strachan as a result of the demands the new sounds impose upon how we see ourselves and where we locate the gaze. On Flying Lotus’s album Cosmogramma (2010), harp, bells, voice, synth, and Lil Wayne samples force digital and analog textures to coexist, as if one physical place inextricably united by the texture of desire. He creates a template there for a new grammar of the cosmos. A few years later, we get Jacolby Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire series, videos in which he dances with himself in several dimensions. The same way Black music has purposed sampling as a slick archiving technique which keeps out-of-print music circulating, Black visual intonation takes archives made on paper and film, video, or even cassette tape, as well as the bodies of the artists themselves, and overlays or arranges them to bend time and space and render a paradise of ruins, picturesque detritus.

Collectively, we are at a precipice where we want to embody our gods and ancestors and reclaim their testimonies without reliving their trials. The ancestors we have no names or discernable forms for—because we lost or traded their names on the path to liberation or bondage—we reanimate through fantasy and terrain-making in the visible world using the momentum of music and rumor. The results are unsentimental nostalgias that allow us to see trajectories in Black cultural tradition without overidentifying with their sorrow or mania. It’s as if these artists promise intimately, I’ll be your mirror, and then use that mirroring to deflect everything they are trying to get over and through; they give you your problem back and exorcise their loyalties to struggle and show us that process. Their mazes of Black artifacts and rituals accrue so many personal signifiers for the artists that the weight of their influences is lifted by overfamiliarity, outrun, or so fused with the self as to offer the illusion of having been transmuted.

Jacolby Satterwhite, Black Luncheon, 2020

Jacolby Satterwhite, Black Luncheon, 2020Courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Jacolby Satterwhite / People in Me

There is an element of remothering in Jacolby Satterwhite’s world-making. Beginning with Reifying Desire (my personal introduction to his work), he bends and reshapes his origin story and turns what was stigmatized as mental illness in his mother into a spectacle of her genius for drawing and singing, for “madness” made into domestic mysticism. Satterwhite focuses on her capacity to remain intentional and hopeful throughout her struggles, and how that hope turns to revelry and obsession. He says he maintained an “objective” distance, that he had to take an almost “sociopathic” approach to working with his mother’s archive. Yet the final product is much more vulnerable than he suggests: songs his mother recorded while at home or institutionalized serve as the soundtrack of an imaginary universe where Satterwhite dances. His mother is lucid and self-aware about her troubled mind, and he is loose-limbed and receptive, genuflecting both literally and in spirit, replaying each memory over and over again at different octaves to see if he can detect where it turns, where she goes from full of light to blinded by it. The gestural tapestry created is its own cosmogramma, a method of reinstating the primacy of dismissed or dissembled modes of testifying. He creates a portal using his mother’s voice, her tones, and in this way she accompanies him, collaborating with him posthumously. The exchange is in no way clinical or remote. They are holding hands in their own exclusive universe; she passes him a note, and he only dictates pieces of it to us.

The cosmic reparenting that many Black people are forced to perform as a rite of passage out of or through abandonment demands the ruthless use of personal archives, sometimes to such an extent that the archives become masks to wear while the face is missing. Satterwhite’s mother is so present in his work that she both disappears and becomes omnipresent, the dark matter of his omniverse. (He refers to himself as a “digital hoarder” in one interview.) To experience his work is to experience the opposite of that: someone intently mapping his personal star pattern and then releasing that constellation into the world of the Black myth, freeing himself of his preoccupations by letting them overtake him for a time. Nothing personal, he shrugs, while recreating his entire social life as an infinitely looping virtual reality. His displacement into forms he can control is wise because what becomes hyperfamiliar cannot haunt as much, and generous because both Satterwhite and his mother transmute distress so well that the audience is only let in to revel with them. We aren’t forced to earn it, we don’t have to hold back our awe to make them feel appreciated in this world they create together; we have to surrender to it.

Lauren Halsey exhibition, installation view at David Kordansky Gallery, 2020

Lauren Halsey exhibition, installation view at David Kordansky Gallery, 2020Courtesy the gallery

Lauren Halsey / A New Reality Is Better than a New Myth

Lauren Halsey mixes hoodrich kitsch like neon “check cashing” signs, banana-yellow Afro Sheen aerosols, and technicolor Cheetos logos with sacred cultural iconography and language, including images of musicians Isaac Hayes and Sun Ra, in order to reappropriate the grammar of Black local life. In her 2020 exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery, the effect is both dazzling and sobering. You want to be a member of that society, but you also understand that its weakest links––the economic exploitation, the conflation of stimulation with nourishment––threaten to sabotage all of it. If the state and real-estate mergers and restrictive covenants didn’t dictate the zoning and aestheticizing of neighborhoods, how would historically Black regions of towns and cities be? We’d play more music, surely, and businesses like liquor stores and KFC wouldn’t be more prevalent than fruit stands and mom-and-pops, but at the same time, what does exist would be embraced with love, less a point of shame and more a matter of pride and empowerment. If the liquor store and the fast-food spot are where we convene to discuss free jazz or soul music, and how to build community centers and our own schools, then let them proliferate with all their viscous temptation, simultaneously temping us to resist them.

Halsey invents brand-new environments using the most mundane and familiar ones. She discovers a spectacular mundane, full of soul and glitz and as confident as its detractors. Most importantly, her work, her cosmogramma, dispels the nagging trope in our culture that Black people need a white savior aesthetic to come in and distribute white poise unto Black people or teach us how to be better capitalists, less decadent. Our legacy is one of leaning into ornamentation, orbiting all shades of the light spectrum and, in so doing, being suns ourselves. Halsey rejects energies of lack and collective self-doubt in favor of unapologetic Black opulence. We own everything we touch is her work’s message, so touch this sculpture of a strip mall wrapped in Funkadelic’s royal blue cape and be glad.

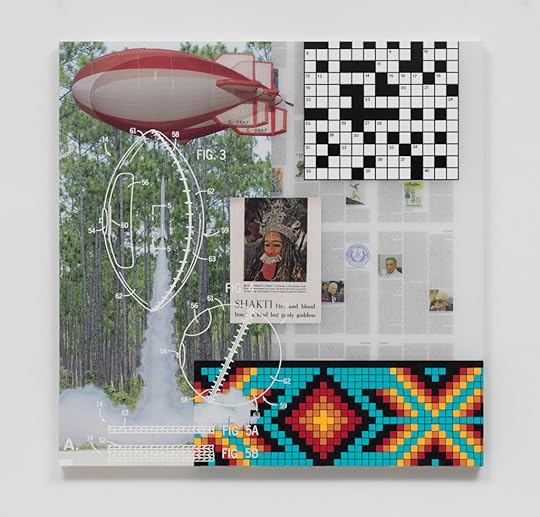

Tavares Strachan, No Name in the Street, 2020Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Tavares Strachan, No Name in the Street, 2020Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New YorkTavares Strachan / Leave No Traces

If Satterwhite and Halsey are constructing whole worlds, virtual and tangible, Tavares Strachan is rendering blueprints for the next world. When those dreams and apparitions inevitably implode or grow bleak and redundant, we will crave the nourishment of their bones, their guts sputtered into elegant retractable horizons we can walk toward, or enter, to reinvent ourselves. Strachan constructs such havens and horizons, letting some of his archives remain 2D, at bay, and a little aloof, so that their syncretism can stretch out playfully, a little languid, not committing itself to a bulkier form. He makes footnotes, not ideologies or fully realized new worlds. And instead of implying outer space and takeoff and launch from the local into the infinite, the way Halsey and Satterwhite do, Strachan includes splayed shards of the natural world turned into speaking objects and humans—astronauts and spaceships mid-launch mingle with African fractals and a portrait of James Baldwin. The visual enjambment is a poetics which loops the notion of cosmogramma back to its roots in order to make that visible or “seen” world look the way our music sounds, and the way our bodies aim to move to the sounds of our music.

Tavares Strachan, The Alchemist, 2018. Photograph by Brian Forrest

Tavares Strachan, The Alchemist, 2018. Photograph by Brian ForrestCourtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

In his 2D collage works, Strachan’s cosmos is a catalogue of irreconcilable ideas: a crossword puzzle, a football diagram, and a goddess all converge in one iteration called The Alchemist (2018). All of this against the quieting backdrop of a forest. He is more of a digital hoarder than Satterwhite, but his incessant collecting is also aimed at a myth of Black minimalism: the streamlined intent that transforms displaced ruins into new land. He objectifies his need for escape and contradicts it with a clear need to be organized and situated with elements that he cannot tame. His cosmos has less of a sense of being willed by tragedy and urgency and feels more like the thinking one gets to engage when they have touched a bit of the Black pastoral, tidy but dissolved on purpose in places, and private in ways that cannot be breached with words, only pierced with focused looking and deliberate turning away.

Strachan, like Satterwhite and Halsey, is thinking about departure, where we go from here. This is a graduation from obsession with escape; this is a less frenzied approach to leaving, but still the stodgy old world has to go, is the idea. Rather than echoing and looping this concept, the most adventurous Black artists are enacting it, architecting a new universe that exiles any traditions they don’t want to uphold. This exclusivity, while perilous in that it could drive the dwellers in these new universes mad with specificity, is also a form of justice. Toni Morrison spoke defiantly about her novels as not being reactionary to the white world, just existing as their own worlds; and when she announced this, it was a thrilling and new notion. Jacolby Satterwhite, Lauren Halsey, and Tavares Strachan are similar in their approach to world-making that centers the image without denigrating it or making it a source of pity and charity or vulgar protest. Jubilation is more effective. Finally, work that doesn’t visibly wonder what the white gaze will make of it. Finally, a Black cosmos nearly impermeable to detractors, and artists dedicated to accessing and occupying that cosmos without destroying or gentrifying it.

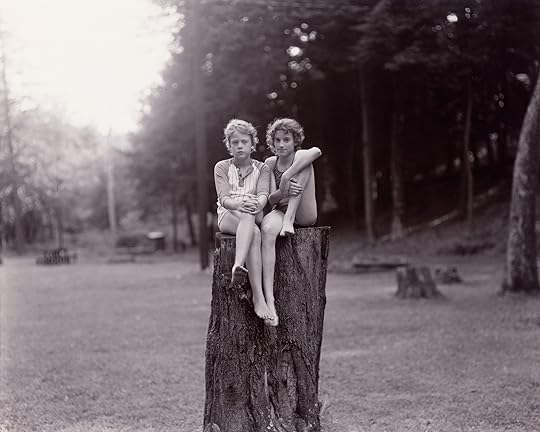

Read more about the visual grammar of Black cosmologies in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies” (Fall 2021).

October 14, 2021

The Luminous Openness of Rinko Kawauchi’s Photographs

The current ecological crisis urges us to formulate new ways of thinking about the real world in which we live. The increasing prevalence of natural catastrophes, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and wildfires, stirs the fundamental conditions upon which the existence of humans depends. In this moment, we are forced to admit that we cannot be free of the inertia of material reality. As Amitav Ghosh puts it in his Great Derangement, “The stirrings of the earth have forced us to recognize that we have never been free of nonhuman constraint.” In a sense, we realize that humans are not free agents but instead are caught within a nonhuman realm—and far from mastering it, we are constrained by it. We feel that we are thrown into vast depths without surfaces or boundaries. We are caught within a truly wild dominion of openness.

Yet we are also, in another way, oblivious to it, because this realm is suppressed beneath the superficial representation of the smoothly functioning everydayness made manageable by the logic of late capital- ism. Contemporary art has often been complicit in this obliviousness. According to Ghosh, “Human consciousness, agency, and identity came to be placed at the center of every kind of aesthetic enterprise.” For that reason, most dominant artistic practices are so bounded by the anthropocentric view that they become impervious to the shock of the ongoing ecological crisis. Even though a natural disaster such as an earthquake urges us to examine the exterior reality beyond human consciousness, artists often appear oblivious to the harsh realness of the world.

As is well known, in March 2011, Japan was horrendously damaged by the tripartite catastrophe of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident known colloquially as 3/11. In the face of this unprecedented event, which inflicted severe harm on those living in the villages and towns in the Tohoku area, Kawauchi responded as a photographer. After that incident, she walked around the area, took photos, and published the results as Light and Shadow (2014). Her response was not directed at the tragedy she witnessed; rather, it was oblique. Her photographs force us to encounter the inert materiality of the world that is emancipated from the glittering surface of the spectacular world.

One of the themes of that book is silence. Depicted in its pages is a pair of pigeons, one black, the other white. The pigeons, who had been uprooted during the tsunami, were in search of safe haven. She writes the following:

Looking at these pigeons, I thought of them as symbols of so many things, especially the dualism of our world. White and black, good and evil, light and shadow, man and woman, be- ginning and end. Throughout existence there have been, and will be, innumerable occurrences of delight and dread.

Because of the devastation, many things, including pigeons, were certainly expulsed from a previously stable habitat. They were uprooted. Yet, on the other hand, an earthquake reveals to us a hidden reality that usually remains submerged beneath the consistent and coherent yet illusory framework of the present world. Such an event urges us to encounter the otherness of the ambiguous realm with its “innumerable occurrences of delight and dread.” A dark and shadowy sphere may have existed prior to the stable consolidation of the present world—an undifferentiated state of heaven (ame) and earth (tsuchi).

The reason I am fascinated by Kawauchi’s photos is that they enable us to be susceptible to the doubleness of reality. The world that we inhabit is not only the self-contained human world. Simultaneously, it is open to the mysterious realm that operates at the edge of the mundanity of the human lifeworld. Her act of photographing is less a way of referring to the appearance of everyday reality than it is a revealing of the luminous open space within which sensuous elements are free-floating. That is to say, in her practice, a sequence of photographs does not fix the appearance of everyday events, but rather evokes the realness of ambiguous ether that existed prior to the fixation of the predominant worldly setting.

Illuminance was published the same year that the catastrophic earthquake happened. I feel it is something like a prophecy of the unprecedented event that totally changed what Raymond Williams calls the “structure of feeling” for all of Japan. Ahead of this shocking incident that revealed to us the fragility of the human world, Kawauchi’s photographs attuned us to its intrinsic frailty.

In an interview, she related the following:

I need many elements to come together in a series to create a mood, not just portraits—including seemingly unrelated subjects, such as landscapes and tiny details, as well as different moods and atmosphere, expressing my own feelings about time passing, the fragility of life. They are metaphorical images, really, [about] how fragile our world is.

The idea that our world is fragile does not mean that it is doomed to extinction. Rather, according to Kawauchi, fragility concerns her feelings about time passing. Perhaps this means that things in our world are perishable. In a way, Kawauchi’s sense of fragility is in accord with Timothy Morton’s statement, “In order to exist, objects must be fragile.” Both of them seem to intuit that everything is ephemeral to the point that it cannot be fixated—in other words, fragile things in this world are not individually fixed objects but rather lose their separateness.

What is remarkable about Kawauchi’s photographs is the way they evoke the sense of mysterious openness at the edge of the everyday human world. One of the images included in this volume depicts an upward-leading stair that middle- and high-school students are ascending, for instance, is photographed in such a way as to show us the vastness of the exterior world that surrounds and penetrates our ordinary living. Illuminance, the title of this photobook, indicates the realness of what is beyond and above our own reach. The fact that something can be illuminated means that some other thing remains in shadow.

What Kawauchi reveals to us is the sensuous realm within which the boundary between things becomes blurred. It is filled with light. David Chandler holds that “Illuminance builds into a sustained meditation on light’s miraculous qualities and revelatory power.” Certainly, light is endowed with an active power that brings something invisible into the visible. Yet, we should not confuse Kawauchi’s revelatory use of the power of light with the violence of light. According to Jacques Derrida, the neutrality of lightning, pure transparency, is often synonymous with the violent oppression that makes everything the same. That is to say, within the neutrally lighted space, “to see and to know, to have and to will, unfold only within the oppressive and luminous identity of the same.”

Kawauchi’s light is quite contrary to this violence criticized by Derrida. Rather, she shows us that there is a different kind of light. In Kawauchi’s Illuminance, Chandler argues, “light obscures as much as it reveals: it reflects, penetrates, dematerializes, and renders things invisible.”

How do we think of light that obscures and dematerializes things? Perhaps it evokes a spacious realm within which things become indistinct, deep beneath the surface of our common perceptual framework. I argue that Kawauchi’s act of photographing captures what Alphonso Lingis calls “luminous openness.” According to him, the light that fills visual space is not transparent; rather, “its radiance fills and thickens the space such that the surfaces of gleaming or shadowy things at a distance are dissolved in it.” Objects within luminous openness are not identifiable nor fixed.

They remain ambiguous. The radiance is sometimes so pervasive that we can demarcate nothing in it. Prior to the construction of the perceptible framework of human consciousness, there was such a luminous openness. Thus, the reason why Kawauchi’s light is different from the violence of lighting is that it allows for the playfulness of sensuous elements—it amplifies the openness and weightlessness of the spacious realm, so as to enable multiple elements to resonate with each other.

Related Items

Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance

Shop Now[image error]

Illuminance Limited-Edition Box Set

Shop Now[image error]

Untitled, from Illuminance

Shop Now[image error]Kawauchi’s practice reminds us of how the conditions in which we exist are fragile and vulnerable. The natural world underneath the human-made world cannot be completely mastered by the act of human will. On the contrary, it stirs and disrupts the human world. In a sense, the world is independent of us, indifferent to our concern. As Dipesh Chakrabarty reminds us, we encounter “the radical otherness of the planet.” This otherness, or the earth’s uncanny aspect, is revealed to be beneath the human lifeworld. It belongs to another kind of reality, the underworld of things, which remains on the edge of human life.

All photographs by Rinko Kawauchi from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)

All photographs by Rinko Kawauchi from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

Illuminance shows us that the world we truly inhabit is withheld from our consciousness, or rather, it reveals that things in the world’s luminous openness are endowed with an aspect that is not empirically observed: the shadowy aspect. To be in shadow is not so much to be in mere darkness, but rather to be vaguely cast in light. Within a realm of illuminance, one that existed prior to the neutral light of violence, the essences of things are manifested—yet, quite mysteriously, the world of things is independent of us. Kawauchi’s work, however, allows us to witness this shadowy realm on the edge of the everyday. Like weeds growing through the cracks in broken pavement blocks, her photographs penetrate the quotidian. In a sense, to be penetrated means to allow things to enter a world; in order for that to happen, that world needs to be fragile. Yet, as Kawauchi reveals to us, fragility is already intrinsic to our world. Eventually, the awareness of fragility means susceptibility to the realm of interpenetration suppressed within everyday human life.

This essay originally appeared in Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance (Aperture, 2021) under the title “The Feeling of Luminous Openness.”

How Takuma Nakahira’s “Circulation” Breathed Life into Photography

“Now, as a result of this project, I can feel that the things that I say and the things that I do are beginning to agree with one another for the first time.”

—Takuma Nakahira, Asahi Camera, February 1972

On the afternoon of September 28, 1971, when Japanese critic and photographer Takuma Nakahira set foot (several days late) in the seventh Paris Biennale, he felt nothing so much as “hollowness” and “despair.” Reporting these sensations for the Japanese weekly Asahi Journal that December, Nakahira explained his dissatisfaction with the state of contemporary art and, indeed, with his own activities as a creator and commentator on art. The laudable artworks on view mostly attacked a social system from which their makers pretended to keep some distance; Nakahira observed that, in fact, this art could only be the very face of such a system, which created a sort of play area for artists to vent futile opposition to the forces of capital flow and authoritarian control. Those forces had a vested interest in shoring up authorial ego when, in fact, it was the art goods and their exchange value that really mattered: individuality was a commodity construct. Yet his own contribution to the Paris Biennale, which he described at length for Asahi Journal and again for the photography magazine Asahi Camera the following February, allowed him guarded hope that art and art criticism could still have a purpose in the world. What was it about Circulation: Date, Place, Events, Nakahira’s piece for the 1971 Biennale, that gave grounds for optimism?

As Franz Prichard recounts elsewhere in this issue, Takuma Nakahira, who got his start in photography and criticism only around 1965, had by the end of that decade already become one of the most influential figures in contemporary culture in Japan. Nakahira’s incisive writing cut apart standing views in literature, film, politics, and especially photography, and he published both articles and photographs at a feverish rate. He wanted a relation between these two activities that could come closer than complementarity—a joint force of action, perhaps. The intended effect of that joint action might be “illumination,” to quote a word favored by prewar German critic and theorist Walter Benjamin, whose essays were first anthologized in English as well as in Japanese in the late 1960s: searing, flashbulb-like insights afforded by a photograph or fragmentary phrases. Provoke: Provocative Materials for Thought—the short-lived photography journal that Nakahira helped to found, which blazed its trail across the Tokyo cultural scene in those years—took its name from such intertwined desires. Writing and photography should illuminate the world, explosively, and they should set each other ablaze as well. Nakahira’s epochal photobook, For a Language to Come (1970), pushed even more insistently at an overhaul of word– image relations. Yet Nakahira remained dissatisfied and, worse, fatigued by his efforts to develop a productive analysis of contemporary culture.

“Has Photography Been Able to Provoke Language?” Nakahira asked in March 1970, around eight months before his book appeared. “Only through human use can a language be given life,” he asserted, for without a subjective viewpoint, language exists as mere symbols and generalities. But to shake a language awake, to deploy it, is also to risk damaging one’s psyche: “This kind of ‘exploding language’ is a language that has been fiercely lived here and now by a single person.” Just such “fiercely lived” insights were what Nakahira sought to produce and circulate, operating calculatedly on the verge of madness. (Prichard has translated that essay and others in the recent reprint of For a Language to Come, as well as in Circulation: Date, Place, Events; issued by the Tokyo house Osiris, both books also have keenly written afterwords by cultural critic Akihito Yasumi.)

In the view of many who have encountered it then or since, For a Language to Come eminently fulfilled Nakahira’s hope for pictures that would give concrete meaning to words while threatening language overall as a system of convention and control. The word tree is general, but a photograph of any tree will be specific, Nakahira argued, with catlike stealth, before pouncing on the surprise conclusion: that close comparison of a single tree in image and word “causes the concept and meaning of tree to disintegrate.” How? Through sentences that leap and dart, and pictures that careen between heavy grays and blinding whites; through sequences of haunting images that overtake the reader, as if the setting for Nakahira’s photographs— the city of Tokyo—were a mental space in which one staggered from desire to trauma, a solitary ego shattered by passion and rage.

Takumi Nakahira, from For a Language to Come (Tokyo: Fudosha, 1970)

Takumi Nakahira, from For a Language to Come (Tokyo: Fudosha, 1970)The effort of making For a Language to Come left Nakahira spent and temporarily uninterested in further photographic projects. One year later, the commissioner for Japanese entries in the Paris Biennale, fellow Provoke veteran Takahiko Okada, convinced him to travel there only after much debate, “at least to do some sightseeing,” as Nakahira disarmingly recalled upon his return. Yet the very fact of Nakahira’s repeated and extensive commentary on his Paris piece suggests the sense of renewal it brought him. Circulation was not only the title of this piece but also its ambition and modus operandi. More literally than did For a Language to Come, the fleeting work raced with an illuminating flash of brilliance through the early 1970s art scene.

Circulation was, in essence, a performance piece in which photographs were the engine of the performance rather than a record of it. This quality is the greatest guarantor of the work’s uniqueness in photographic terms, but there are other reasons to reassess its meanings today. (New prints from the original negatives were shown in New York in 2012 and feature currently in an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.) Rather than send existing pictures to Paris, Nakahira wished to create something “live” during the run of the exhibition. He would hang only pictures taken and printed that very day, making a photo-diary of his Parisian experiences that would cover his Biennale wall in stages. By circulation Nakahira meant his own movements around Paris, the movement of his pictures from darkroom to display, and the perambulation past his evolving piece by visitors to the Biennale, whom Nakahira photographed for this installation as well.

The prints themselves would be “mere remnants” of these circulatory patterns. Nakahira’s description of his procedure, from the February 1972 article in Asahi Camera, suggests a determined resistance to fixity: “To put it concretely, I set myself to photograph, develop, and exhibit nothing but the Paris that I was living and experiencing. My project … was born from this motivation. Every day I would go out into the streets of Paris from my hotel. I would watch television, read newspapers and magazines, watch the people passing by, look at other artists’ works at the Biennale venue, and watch the people there looking at these works. I would capture all of these things on film, develop them the same day, make enlargements, and put them up for display that evening, often with the photographic prints still wet from the washing process.”

Curator Yuri Mitsuda points out, in an essay for the Houston exhibition catalog, that Nakahira was evidently attracted to the wet Parisian streets, for he included many images of them in Circulation, both at the Biennale and in a special section in the January 1972 issue of the Tokyo magazine Design, which stands as the one visual record of the Paris work made at the time. Mitsuda nicely analogizes the washing of city streets with Nakahira’s marathon darkroom sessions to make Circulation, for which he printed, by his own account, some two hundred images each day for a week: the photographer must have spent hours with his hands in chemical baths or running water over his prints to clean them. To focus on wetness is also a way to suggest flow—the process rather than the product. As another hint at Nakahira’s preferences, the few surviving prints are yellow, faded, or blotchy, and one can see that, paradoxically, not enough liquid was on hand to make them; the developer was probably heavily reused, losing its strength, and other sources report that the darkroom apparatus consisted of a bathroom sink and an ordinary wash bucket.

Of course, the Biennale display space became a bigger, brighter, and populated extension of the artist’s cramped and makeshift quarters. This was one of the radical moves Nakahira made with Circulation: evoking at exhibition not an artist’s studio but a photographer’s normally closed and lightproof darkroom, turning that monastic space into a carnival atmosphere. The rows of drying prints that ordinarily hang on a darkroom clothesline, or lie in trays, were here spread out as if at a yard sale, covering the wall and spilling onto other surfaces as Nakahira outgrew his allotted area. This method could also be likened to making public the draft of an essay, showing sheets of jottings for all to read. A quick glance over the shoulder of a Biennale visitor confirms that Nakahira had an eye for written and printed words: “Viva La Muerte!” (Long live death!), “Explosion,” and excerpts from a street poster punctuate the whirl of faces, friends, and street scenes. The first entries for October 12, 1971, meanwhile, include a photograph of the word Paris glued directly after the artist’s handwritten spelling of the city name, inviting a comparison between manual and photographic representations of language; a photograph of a cartoon page below it continues this theme. Here was the visual equivalent for the harmony of critical thought between taking photographs and writing essays that Nakahira would emphasize in explaining the work.

Other stretches of the installation show series of closely related views, like contact sheets turned into exhibition displays. The first step in printing, especially in the news-photographer paradigm that dominated the twentieth century, was contact-printing a roll of film negatives on a sheet of proofing paper to determine which “shots” had the most promise, before enlarging them into final prints. Nakahira did not make contact sheets but instead put that procedure on view, printing up runs of negatives just as they appeared on the film roll. Among these sequential groupings are a street scene with a car and more spilt liquid, and another with a VeloSolex moped rider maneuvering through traffic, both of which look a bit like stop-action cinema. Another sequence shows screenshots from television, intercut with a single photograph of the word hyperreal. There was something hyperreal in this steady accumulation of repetitive and overlapping images, each flowing into the next, doubling back, overlapping, then gushing onward as if from a faucet left running.

There was one precedent for Nakahira’s work in the realm of photography— William Klein—but that precedent gains full meaning only in Nakahira’s highly perceptive and unusual reading of Klein’s work. The “look” of Klein’s photographs— grainy, up close, heated yet acerbic—has been taken by critics since the 1960s as a touchstone for the photographs in Provoke. In a terrifically cogent review from 1967, however, Nakahira argued that it was not really the look but the method that mattered. Graininess and wide-angle lenses did not automatically signify urban anomie; there was no one-to-one correspondence in photographs between appearance and meaning, no key to decoding, indeed no code. What mattered was that Klein had brought forth a particular process of taking photographs in the contemporary city. Viewing it as a dreamscape, even a nightmare, Klein had placed himself in the middle of that mental geography, exposing himself to multiple and colliding vantages with no set idea of his expressive voice. In short, he let his creative identity drift while keeping his critical faculties intact. Nakahira took that approach for a model, as Yasumi points out, and he put into practice his reading of Klein as an authorial cipher passing lucidly yet violently through an unfixed landscape: “The world is not a static, completed universe but rather something which flows and changes its appearance, transforming like a nebula with a movement in viewpoint.”

The trouble was what to do with the photographs, which for all the talk of ceaseless motion would end up having a static form. Photography is hard to think of as a performance medium. Also in the late 1960s, Truman Capote recalled in a breathless sentence seeing Henri Cartier-Bresson at work two decades earlier, “dancing along the pavement like an agitated dragonfly, three Leicas swinging from straps around his neck, a fourth one hugged to his eye: click-click-click (the camera seems a part of his own body) clicking away with joyous intensity.” This comparison, though beautiful in itself, encapsulates all that Nakahira opposed. In the Vietnam era, dead or dying bodies were shown daily in the news media to no apparent effect, and nothing could seem more suspect than a photojournalist sashaying his way through carnage with cameras as breastplates.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs by Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1971, from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs by Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1971, from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events© 1971 Takuma Nakahira and courtesy Osiris, Tokyo, and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Circulation made the city into an extended space of performance, forsaking the projection of a stable authorial ego for the representation of collective and mercurial states of mind: hilarity, terror, alienation, ooze, hyperreality. These changing and changeable pictures came from the city and went back into it, albeit via a public exhibition space. The camera that took them was run through the streets as on a great dérive, a “drifting,” as French philosopher Guy Debord phrased it in his classic book of the era, Society of the Spectacle (another one of his terms, psychogeography, is equally relevant). The perishability of the prints in Circulation marks a singular attempt to analyze reality through its traces without memorializing it. Apparently aimless, this daily circulation in fact summed up the city and the moment in a way that no fixing of photographs in a book or in frames could possibly have done.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 219, “Tokyo,” under the title “Nakahira’s Circulation.”

Ishiuchi Miyako’s Chronicles of Time and History

Through her images of subjects ranging from the American Occupation of Japan and the bombing of Hiroshima, to women’s scarred bodies and her mother’s and Frida Kahlo’s personal effects, Ishiuchi Miyako, born in 1947, has explored the passage of time and history. Like Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama, renowned Japanese photographers who emerged in the 1950s and ’60s, Ishiuchi’s early work was shaped by the residual presence of World War II. Her first series, Yokosuka Story (1976–77), focused on her coastal hometown, the site of a U.S. naval base that was permeated by American culture. Projects that closely followed—Apartment (1977–78), which explored the interiors of Tokyo’s postwar housing, and Endless Night (1978–80), for which she photographed brothels—honed Ishiuchi’s vision as well as her process; for her, the image is a physical object made by hand in the darkroom.

For more recent work such as Mother’s (2000–2005), featured at the 2005 Venice Biennale; ひろしま/Hiroshima (2007); and Frida (2013), Ishiuchi turned to color, taking a forensic approach to examine clothing and objects laden with complex histories, underscoring the idea that the traces of time’s passage are her true subjects. Here, she speaks with Yuri Mitsuda, curator at the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art, about the evolution of her explorations of time, her ambivalence about photography, and how she has negotiated a field dominated by men.

Ishiuchi Miyako, Yokosuka Story #98, 1976–77

Ishiuchi Miyako, Yokosuka Story #98, 1976–77Yuri Mitsuda: Let’s begin with Yokosuka Story. Was this your first show?

Ishiuchi Miyako: When I started out, I was exhibited as part of a group show with Shashin Koka (Photography effect), a short-lived experimental photography group that included Hiroshi Yamazaki and Tunehisa Kimura, among others. [Nobuyoshi] Araki came, and Moriyama—well, maybe Moriyama didn’t make it, now that I think about it. But anyway, Tomatsu, [Masahisa] Fukase, all those guys came and saw it. Araki said, “If you want to show at Nikon Salon, bring some photos over.” It wasn’t really clear to whom he was talking. But when I heard that, I spoke up and said, “Sure, I’ll do it, though only once.”

Mitsuda: Why only once?

Miyako: I didn’t want to be a photographer then, but Nikon Salon was the biggest, most famous, most frequented exhibition space. And here was Araki saying, “If you want to show at Nikon Salon, bring some photos over.” I had just taken my first pictures in Yokosuka. I was absorbed in the darkroom, where I struggled with the photographic materials as objects. They were not only images to me, but materials, and somehow they stood between Yokosuka and myself. But I wanted to show them, and so I thought, Sure.

The title we’d come up with was Yokosuka Elegy. But when we showed it to [Jun] Miki [then the director of Nikon Salon], he said, “No, no, that won’t do. Much too dark.” So he renamed it Yokosuka Story. That was right when Momoe Yamaguchi had that popular song, also called “Yokosuka Story.”

Mitsuda: What did you bring to Araki’s place to show him?

Miyako: 12-by-10-inch prints. About a hundred of them.

Mitsuda: When I’ve asked you before how you started taking photos, you’ve told me, “I haven’t always wanted to be a photographer—it’s more that, from time to time, that’s the equipment I end up using.” It might have been by chance that you ended up taking photos, but nonetheless— at that point you had at least a hundred!

Miyako: That happened once I made the decision to shoot in Yokosuka. Up until then, I had no idea what I wanted to shoot. I went up to Miyako, in the Tohoku region, and I ended up in the station, unable to take a picture of anything. I didn’t know what I should shoot. I just knew people brought their cameras to different places and took pictures. That was the first time I took a camera on the road. I ended up in the waiting area, sitting there wondering why I’d come so far, why I wanted to take pictures here in this faraway place. Then it came to me—what place was I the furthest from really knowing? Yokosuka! Where I’d come from! (I moved from Gumma Prefecture to Yokosuka at the age of six.) So I packed up and went straight back.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Yokosuka Story #5

, 1976–77

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Yokosuka Story #5

, 1976–77Mitsuda: From the very beginning you treated your photographs as objects that one could craft.

Miyako: I threw my whole body into the printing process; to treat a print as something throwaway would be impossible for me. That’s why it doesn’t feel like I’m developing photos. It’s more like I’m making something.

I didn’t learn photography from anyone. I received a pamphlet for a workshop once. It was Tomatsu’s school. I went back and forth about going, but then I saw how expensive it was—200,000 yen for half a year! I decided to do things myself instead. I might try and fail, and I failed a lot. Failing is so important. It’s been such a plus for me, never having been taught photography. Though I’ve been told I hold the camera strangely.

Mitsuda: What is the allure of the darkroom for you?

Miyako: It’s the dyeing process. Dyeing white paper, bit by bit. Each tiny chemical grain, one by one, transforming the paper. I did roll printing, after all, when I was starting out. From the Yokosuka series on, I would start by buying a roll of photographic paper and then cut it as I went. But it always

struck me as crazy that the size of the paper and the size of the film didn’t match. My film was 35mm, and the paper was 4 by 5 or so. When you developed a 35mm image on it, there was so much white. So much white! It was really shocking to me. I developed in two steps. I had to add the black border myself. White seemed like simple excess, and it always stood out, and it really affected the sense of spatial composition to me.

Mitsuda: You considered the paper rather than the image, how the paper had to be incorporated into the finished work.

Miyako: I’d decided my project was not going to be documentary. When you think of Yokosuka, the first thing you think of is documentary. Tomatsu shot it, and so did Moriyama. They all ended up shooting Dobuita Street [the street notoriously frequented by sailors from the Yokosuka U.S. naval base]. That street was America, not Yokosuka. I saw everyone shooting Dobuita and calling it Yokosuka, and I thought, Something’s not right about this.

Ishiuchi Miyako, Apartment #14, 1977–78

Ishiuchi Miyako, Apartment #14, 1977–78Mitsuda: It all seems connected, how you were working then: you wanted to shoot Yokosuka, not Dobuita Street; you wanted to avoid the documentary approach and shoot “your” Yokosuka; you wanted to avoid white borders and use black ones instead.

Miyako: I didn’t want to make my photographs “photo-like.” I wanted to emphasize the presence of the photographic paper itself. I thought it was really something, the sheer physicality of it. To be Tomatsu-like, for example—that meant being documentary. I represented the furthest departure from that kind of thing. What did that really mean? For me, I wanted to present the images right on the walls. I stuck them on with double-sided tape, but they started to fall down, so I bought tacks, enough for 150 photographs.

Mitsuda: Putting all the images into matted frames and lining them up along the wall wouldn’t do.

Miyako: You don’t really look at them that way. You end up moving on to the next image right away. I want to make the viewer stop and really look at each photograph. That’s why I tend to show as few pieces as possible. Like with Silken Dreams (2011). That was an experiment to see how far I could go, if I could display just one image per wall. When I had a show at the [Tokyo Metropolitan] Museum of Photography, people said, “There aren’t enough pieces!” It might have seemed quite paltry to visitors who came just to see images. But I wanted people to look at the pieces more than once— ideally, to look at them again and again.

Mitsuda: Looking at your work again, I’m struck by the themes of the body, of flesh, of flesh and photograph relating to each other. Capturing precisely the way the sensory aspect of a photo- graph, a photograph’s surface, relates to the flesh, to the skin. They have a bodily quality, these prints, even something like the building in Apartment, the feel of the tile, the feel of the dirt, it comes across so vividly. In Apartment, and in Endless Night too, the tile makes an impression. You can think of it as the building’s flesh, perhaps.

Miyako: I considered becoming a tile layer at one point. It was what I would do if I ever quit photography. I’ve always loved tile. It excites me, looking at a black-and-white checkerboard pattern, for example. When I shot Apartment, I did think of it as shooting the body of the building. I felt tender toward it, a certain pity. A building can’t move. It has to stay where it is forever. That’s so sad, I thought. A building has no choice but to sit there and accept everything that happens to it.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Mother’s #3

, 2000

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Mother’s #3

, 2000Mitsuda: Perhaps your pictures feel visceral because of your darkroom process?

Miyako: I don’t know about that, but I have always thought that the darkroom is such a sexual place. Its smell is so strong. And if you do it with bare hands, it’s like you’re having sex. Photography has that quality; it engages the five senses. It possesses something like sexuality.

Mitsuda: So the darkroom had a sexual quality. You can see it in the prints you made, their analog quality. And you also felt the building was a type of body.

Miyako: Yes. I thought of people as being part of the walls. I shot plenty of humans in Apartment, but as if they were part of the walls. Like patterns on the walls. People move away; they disappear. Two years pass and it’s all different. So as the humans pass through, leaving their scents, their body odors, their forgotten possessions, the building remains, silent witness to it all. A wall is a skin, you see. That sense was particularly strong in Endless Night. Those were brothels.

Mitsuda: The Scar (2006) work focuses on actual wounded bodies. It strikes me that the building photos resemble these. You said, “Space is formed from the accumulation of detail,” but you might also say that a body, too, is formed from details fitting together.

Miyako: You can say I’m shooting scars, but that’s not really what I was doing.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Endless Night #71

, 1978–80

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Endless Night #71

, 1978–80Mitsuda: Really?

Miyako: Just like in Endless Night, I wasn’t shooting tile. I was shooting time. The traces of time’s accumulation. Like I did in 1 • 9 • 4 • 7 (1990). I was trying to shoot the traces of forty years’ passage.

When I think of where in the body time builds up the most, it’s the hands and feet. Shooting photographs, you end up shooting surfaces, but I wasn’t shooting hands and feet; I wasn’t shooting scars. I was shooting something invisible to the eye, something on the far side of the images themselves.

Mitsuda: You’re using the word “time,” but, for example, with Yokosuka Story, you have the prewar, the war, the American incursion, and then you were born and eventually picked up a camera—your photography suggests layers of time. It feels less like a span of years and more like history itself. Through Mother’s, all your work strikes me as being personal. After that, there’s ひろしま / Hiroshima and Frida.

Miyako: Hiroshima was an enormous tragedy, socially and historically. I had people who could bring me into that, if you will—I had those girls who’d worn those clothes and left them behind for me. With Frida, too. They invited me, so I went. I didn’t have all that much interest in her because of my limited knowledge.

Mitsuda: That’s a fascinating aspect of your work. You never really had that much interest in Hiroshima. You also say that you never really even had that much interest in photography.

Miyako: I’m a cold fish that way. There’s always a distance from photography, since the beginning.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

ひろしま/Hiroshima #69 (Donor: Abe, H.)

, 2007

Ishiuchi Miyako,

ひろしま/Hiroshima #69 (Donor: Abe, H.)

, 2007Mitsuda: But your photos are so intense, so hot.

Miyako: No, not at all. There’s always something about them that’s cold. Maybe because I never really wanted to become a photographer, never really loved photography itself. With ひろしま/Hiroshima it was a question of what made me able to shoot it. If I hadn’t shot Yokosuka, I wouldn’t have been able to shoot Hiroshima. They’re connected at a fundamental level.

Mitsuda: Looking over ひろしま / Hiroshima, it seems that the images you chose have a certain transparency to them.

Miyako: Well, I shot for luminescence. All of them were shot in natural light. It’s almost seventy years after the war and yet there are still new things, preserved from that time, coming to light—isn’t that amazing? I go to visit and end up getting told, “We have some new pieces.” It’s shocking.

Mitsuda: They’re still alive. These personal effects.

Miyako: Exactly. People can’t bear having them any longer. They can’t bear them alone. So they bring them to the museum, make it so we all can bear them together. This kind of history is lost, usually.

Mitsuda: Your project is so different, though, from something like what [documentary photographer] Ken Domon did, or Shomei Tomatsu. It’s similar in that it’s a way to demonstrate that people’s lives became defined by this event, but it’s such a different approach, taking pictures of people’s clothing but not people.

Miyako: When they were displayed at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, people said, “Oh, they look like high fashion!” Because the images were so pretty, you see.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Frida by Ishiuchi #50

, 2012

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Frida by Ishiuchi #50

, 2012Mitsuda: How do you respond to that? That doesn’t sound like praise.

Miyako: Oh, I disagree. I took it as a compliment. I mean, what’s wrong with that? I shot them to be beautiful. The response was interesting when they came out as a book—people in the fashion industry, who work with clothing, were so enthusiastic. Rather unexpected. Fashion models buying my photos!

It’s because I didn’t shoot the clothes worn by the victims as artifacts. These fashionable young women lived, and while they’re no longer with us, they left these things behind. These clothes are really nice, I thought. So that’s how I shot them. To do them that service. If you look, you can find bloodstains. You can see how they’re torn. They went through the bombing, after all. I read later about Comme des Garçons, about Rei Kawakubo and what they called the “postnuclear look.” I was so surprised. I wasn’t so far off after all, I thought. I’ve learned so many things shooting ひろしま/ Hiroshima. Thinking back over it now, it’s striking me anew. It’s quite an ordeal, this project.

Mitsuda: You mean, an ordeal to keep shooting it?

Miyako: I had no interest in Hiroshima, as you know, to the extent that I didn’t think I even needed to visit it. Now I have this bond with the place, even think of it as a second home. Yet I’m still an outsider. Though it’s because I’m an outsider that I can shoot what I shoot.

Mitsuda: That’s important, isn’t it?

Miyako: It was the same with Yokosuka—I could shoot it because I was an outsider. I’d moved there, after all. I wasn’t born there. And with Hiroshima, I was a complete outsider, so that sense of distance remains. One must be a bit cold to be the one taking photos. Up until recently, I’d never known anyone who’d been directly affected by the bombings. I was able to admit: I don’t know. It is impossible to completely understand [the event]. And in doing that, I was able to take on the burden of responsibility for Hiroshima. I’ve only come to this way of thinking recently. I was being interviewed at a museum, and the woman I was being interviewed with put it that way, that the unimaginable was the unknowable. If you can’t even imagine it, then you know nothing about it.

Mitsuda: It’s like what Wittgenstein said: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

Miyako: Yes, that’s it. The unimaginable signifies that which you can’t conceive.

Mitsuda: It’s like Fukushima.

Miyako: That too. Everything to do with the earthquake in Tohoku.

Mitsuda: I had the thought, looking at Frida, that the distance between you and Frida Kahlo isn’t so great.

Miyako: I’d never had much interest in her, but when I went to Mexico City for the shoot, I came to love her work quite a bit, especially her drawings. The drawings have such lightness to them.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Frida by Ishiuchi #86

, 2012

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Frida by Ishiuchi #86

, 2012Mitsuda: Looking at the things Frida’s absent body once touched, the traces she left behind, her shoes—they’re not unlike scars. The distance between you and the subject in Frida seems narrower than it is with ひろしま / Hiroshima.

Miyako: I think so, too. It became about the everyday life of an individual woman, but in a way, also her life as a whole. She’s always spoken of as being so intense, so willful and passionate. But that’s just one side of her. No one knew Frida as she was in her daily life. Looking at these things, it really struck me. “Ahh, that’s how she was.”

Mitsuda: In Endless Night and other works like that, you were shooting buildings as bodies, shooting the time those bodies held within them. Were you shooting time as it existed within the spaces of the present?

Miyako: Time itself is accumulation. I’m about to turn seventy. It’s pretty shocking. How can one conceive of seventy years’ passage? There’s not much future left. Maybe twenty more years. I know I’m about to disappear. So it becomes even more imperative for me to treat time with importance. To shoot a photograph is to fix time in place. To fix time like that—I’m only interested in fixing time in its accumulation.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

1906: To the skin #60

, 1991–93

Ishiuchi Miyako,

1906: To the skin #60

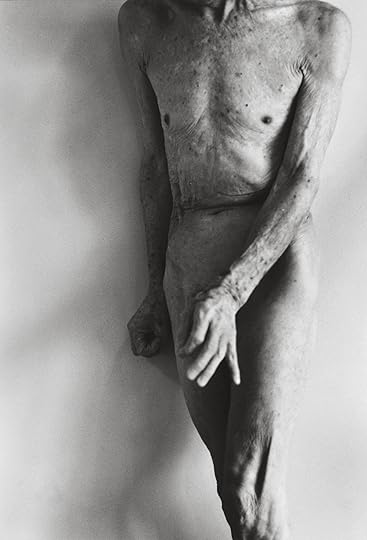

, 1991–93Mitsuda: For 1906: To the Skin (1991–93), you shot Kazuo Ohno. He’s a famous dancer who’d danced with the likes of Tatsumi Hijikata [a founder of butoh dance]. You took nude photos of him, using your signature approach—focusing on different parts, on the surface of the skin.

His body in particular seemed to show the passage of time very vividly. Normally, you think of dancers as young, vigorously moving across the stage and displaying amazing technique and then retiring before time really registers on their bodies. But he continued to dance until he died, dancing even in a wheelchair. And it was so lovely, a kind of dance only he could do.

Miyako: How can I put it? He was like an angel, and so androgynous. As if male and female didn’t matter. There was something very masculine about his flesh, though, his hands and feet. Yet they were smaller than mine!

He was quite willful. It was a difficult shoot. I had thought I was going to photograph his feet and hands, but then I started to have other ideas as I prepared to go. I wanted to take photos of the scars of men. “If you have no scars, then you will pose nude.” That’s what I told him. He was rather obstinate. I asked, “Ohno-san, do you have any scars?” and he said, “No! I have no scars.” So I said, “Could you disrobe for me then?” and all

his clothes came off, just like that! I was a little surprised. He put on some music, and then started to dance. It was overwhelming for me. Though also a pleasure, of course. It felt like rising up to heaven. Just us, no one else around.

Related Items

Aperture 220

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Mitsuda: You put out Main, an independent magazine, from 1996 to 2000, with photographer Asako Narahashi. Did you want it to be like Provoke? There couldn’t have been very many people trying to do what you were doing—starting something run only by women, publishing photography not done on commission, but pieces you made because you wanted to make them.

Miyako: We were tired of the old-fashioned stuff. All that stuff the men were busy making, we wanted to get away from that. We don’t need men, I thought. They’re such a bother to deal with, let’s just do it ourselves. We wanted a venue for the things we were doing right then.

I didn’t have much connection to the photography world. I didn’t really get on with anyone, so I don’t know what they said about us. I was so impudent. I acted from the start like we were equals. And that was so much more interesting. Of course, I can’t say there was absolutely no influence from the Provoke-inspired style, it seeps in, but I can say the influence wasn’t direct.

Mitsuda: Were you ever excluded because you were a woman?

Miyako: Not at all. I mean, Tomatsu loved women. Moriyama too. So there were always women around. I had no interest in them that way, though, as men. There wasn’t one guy who was my type among all those photography guys. Thank goodness. But it can be an ordeal, being a woman. People constantly accosting you. I watched it happen all around me. There were a lot of women who wanted to do something in photography, and one after another I saw their efforts come to nothing.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

a.chiyo #1

, 2015

Ishiuchi Miyako,

a.chiyo #1

, 2015

Mitsuda: Why do you think that was?

Miyako: They underestimated how hard it would be.

In my case, I thought I would do Yokosuka Story and then quit. Like I was getting back at an enemy. Yokosuka was a difficult place for a woman because of the sexual violence that occurred there. Rape was a part of daily life, but nobody saw it as a crime. I did not experience rape myself, but it scarred me. I’m gonna kill you once and for all; that was the feeling. That city, Yokosuka, it had inflicted so much on me, so much trauma, so many scars. If I don’t kill you I can’t move on—that was the feeling I had.

You had to have that kind of intense feeling. I thought I’d do it once and be done, but of course, I ended up continuing. I looked around and thought, Well, now I’ll do Hyakka Ryoran (A hundred flowers bloom, 1976).

Mitsuda: Hyakka Ryoran was an all-woman show you planned for Shimizu Gallery, wasn’t it? So you had the sense that you needed to do things as just women, as women photographers.

Miyako: Of course I did. We wanted to do something just for women, but separate from the women’s lib movement. The mainstream world of Japanese photography was absolutely a boys’ club. People outside Japan noticed it too, and they were right. I had no interest in them, at all. The workshop group was a boys’ club, too, of course, but the form it took was different. They were interesting, at least, Tomatsu and all those guys. They were fun to hang around with. We went out drinking every week on the Shinjuku Golden Street. We had fun drinking together. I got my share of sexual harassment, of course. They were old-school guys, after all. It sounds idiotic saying it like that now, but that’s how it was.

Mitsuda: The excess energy produced by artists, by people engaged in making things—it doesn’t always lead to the most moral conduct.

Miyako: And there were plenty of people who left themselves vulnerable. But never me. I got a reputation as pigheaded, a dragon lady. But I stuck to my guns.

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Silken Dreams #28

, 2011

Ishiuchi Miyako,

Silken Dreams #28

, 2011Mitsuda: If you didn’t, it would come to nothing.

Miyako: They’ll undermine you, drag you down.

Mitsuda: Do you mean how Hyakka Ryoran was thought of as unsuccessful?

Miyako: No, it was just completely ignored. There’s hardly any record that it happened at all. The only attention it got was in [the tabloid] Heibon Punch. They wrote about women taking pictures of men, of women making men strip naked. So that got picked up on television, as a kind of scandal.

Mitsuda: At the time, Diane Arbus was getting a lot of attention as a female photographer.