Aperture's Blog, page 52

August 10, 2021

From Rome to Disneyland, Catherine Wagner Finds “Clues” to Civilization

A giant marble head of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great, seemingly wrested from a larger sculpture, sits on a pedestal. Both are encased in a narrow enclosure, a telephone booth–like stall that in turn is minimally braced by metal scaffolding. Around it are stone body parts, pieces of what was once was a complete sculpture of the man, enveloped in an irregular matrix of boxes that resembles an unfinished Eames shelving unit.

Catherine Wagner photographed Constantine Fragments (2014) at the Musei Capitolini in Rome, while she was in residence at the American Academy, and the picture elegantly breaks down concepts of power and history, literally into pieces. It is historical evidence captured in situ, broken yet organized and protected, however provisionally.

Catherine Wagner, Artemis / Diana, 2014

Catherine Wagner, Artemis / Diana, 2014Wagner’s photography is consistently about foundations of culture, so it is fitting that her first solo show at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco would survey the core of her artistic inquiries. While the show covers a lot of ground—the photographs span four series from 1982 to 2014—Clues to Civilization is but one possible remix of her practice. The works from the different decades are arranged associatively, revealing a long-term project rather than discrete series.

“The foundation of the work is built from an idea about how knowledge is transferred and how we look at the times and culture in which we live, hence the title, Clues to Civilization,” Wagner told me recently, as we walked through the exhibition. I have a long relationship with Wagner, starting with her inclusion in a project-based, institutional critique group show I curated for the de Young Museum in 1999. We’ve been in dialogue about art and life ever since. She is gracious, hardworking, and a masterful and highly entertaining storyteller. Each of her photographs has a narrative within its carefully realized composition.

Catherine Wagner, Gendered House, 1995

Catherine Wagner, Gendered House, 1995Wagner’s mid-1990s Realism and Illusion series was the result of her rare behind-the-scenes access to international Disney theme parks. The project was commissioned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, where the work was first shown in 1997. “When I received the call, I said, I think you have the wrong person,” she said, referring to her unfamiliarity with the Americana aspect of Disney: Wagner’s father was German and her mother was from the Philippines; Wagner grew up in the Bay Area. “I’m from an immigrant family, my parents knew nothing about this as an American culture,” she said. “I’d never been to Disneyland. I came without that background that Disneyland was this happiness place.”

She approached the theme parks with a critical, conceptual lens, revealing the architectural, design, and cultural norms imparted by these corporately controlled fantasy lands. Southern California Landscape (1995), for example, shows a faux Alpine village on a reduced scale, with artificial snow–dusted mountains at the perimeter. Hovering over the scene in the background are life-size trees. “I was a kid in a candy store,” she said. “Not that I wanted to ride all the rides, but [I wanted] to be able to engage with the ways in which architecture was presenting itself.”

Nature is also built here, as in Japanese Elephants (1995), a black-and-white picture in which the animatronic pachyderms at Tokyo Disneyland have Hello Kitty–like grins. The color pigment print Tokyo Wildlife (1995) captures the blur of motion of more realistic looking animals. “My mom loved this piece because it reminded her of the Philippines,” Wagner said.

Catherine Wagner, Dream Kitchen, 1995

Catherine Wagner, Dream Kitchen, 1995Like many artists, Wagner has been shifting her practice over the last year. “During the pandemic, I really started to look at my archive,” she said. In revisiting older works, she made the decision to present the pictures at a larger scale and with revised titles. In 1995, she printed Minnie Mouse’s Kitchen; Mickey’s Toontown, Disneyland, Anaheim, CA at a modest scale. In the current exhibition, the work is shown as a monumental 40-by-50-inch archival pigment print—more than twice its original size—and retitled Dream Kitchen. It’s a strategy that nudges towards expanded interpretations and a more elemental focus.

Catherine Wagner, “Pirouettes Turned My Life Around” (Creative Writing Class), 1986

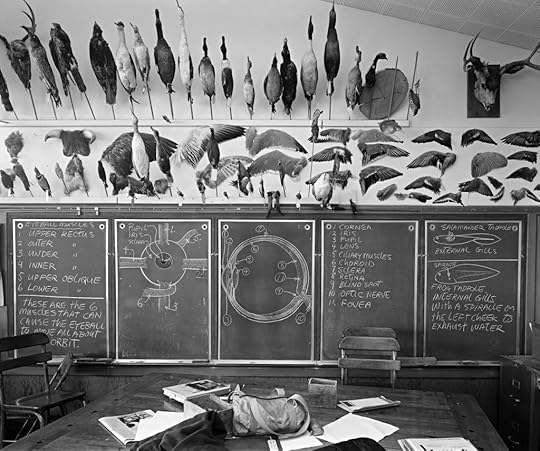

Catherine Wagner, “Pirouettes Turned My Life Around” (Creative Writing Class), 1986This strategy is also effective in works from Wagner’s noted American Classroom series, begun in 1983 and originally printed on gelatin-silver paper. Here they are presented as new, crisp black-and-white pigment prints, again at a larger scale and with new titles focusing on subject matter—world maps, science experiments, and a desk densely etched with student scrawls. The last provides the witty title for “DH Lawrence Kicks Ass” (University Humanities Classroom) (1983–87). Wagner knows much about academic settings: she has been teaching at Mills College since 1987 and currently chairs the college’s art department.

Clues to Civilization includes works that Wagner made in Italy after she received the Rome Prize in 2013. Her fellowship resulted in photographs of antiquities in Roman museums that uphold historical gender codes. She points to two color pictures, Philosophers’ Hall and Emperors’ Hall (both 2014), each showing museum galleries filled with busts. “In Philosophers’ Hall, we see ‘great men,’ yet there isn’t a woman in it,” she said. “I walked over to another room where I see a presentation of a woman. They’re remembered in the wall didactics as ‘Busto Femenino,’ the bust of a woman, whereas the men would be titled their name.”

Catherine Wagner, “Optic Nerve” (7th Grade Science Room), 1983–87

Catherine Wagner, “Optic Nerve” (7th Grade Science Room), 1983–87All photographs courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco

Such clues to civilization are evident in each series here. Most were made through opportunities to photograph internationally, in a range of culturally resonant sites, and in response to what she would find there. “I’m not shooting fast,” Wagner said. “None of this work is street photography, I’m either working with an 8-by-10 camera or extremely deliberately. There’s an athleticism to have to construct these ideas and carry them through in situ.” Seeing the career-spanning photographs offers a space to survey an artist’s aesthetic and conceptual strategies. “I work hard to make the photographs beautiful,” Wagner said. “Whether or not you are interested in this, beauty is the thing that pulls you in. Then you have to wrestle with what is there.”

Catherine Wagner: Clues to Civilization is on view at Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, through August 14, 2021.

July 29, 2021

The Dazzling Black-and-White Photographs of India’s Premier Darkroom Artist

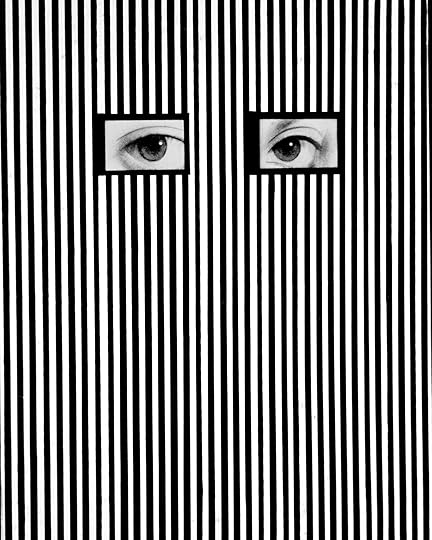

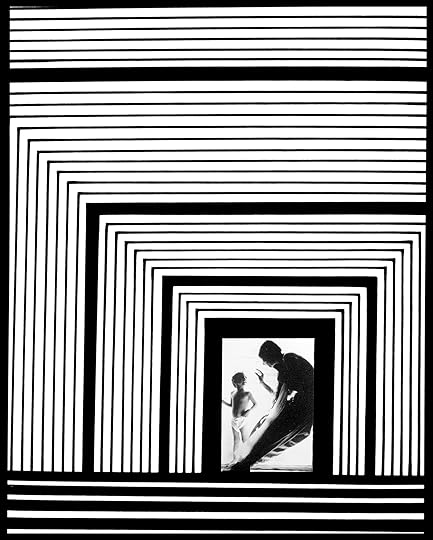

In the varied archive of O. P. (Om Prakash) Sharma, who has been practicing and teaching photography in India since the 1950s, human forms are inserted into labyrinths of geometric patterns, repeated in multiple postures across the photographic frame, and cast into eerie inversions of light and dark. In The Open Door (1968), a man leans against an unseen wall to speak more intimately with a quizzical child, making a motion of explanation with his right hand as his legs lean long across the framing rectangle. Transformed through Sharma’s methodical darkroom work, the conversing figures are enclosed in a maze of repetitive bands, an effect produced by creating a photogram and turning it into a black-and-white negative on high-contrast film.

O. P. Sharma, Twins, 1976

O. P. Sharma, Twins, 1976Sharma’s images are painstakingly produced, often with multiple layers of photograms, solarization, combined prints, or reflections that create dreamlike spaces. Even if these techniques sound impenetrably complicated and laborious, they are essential components of the Pictorialist’s tool kit. And, as is also often the case with Pictorialists, Sharma’s practice is difficult to pin down: it is forged out of many different themes, techniques, and visual vocabularies. He is as much a prominent portraitist as he is a darkroom alchemist, testing the limits of experimental processes such as multiple printings, photograms, and collage, while, occasionally, developing his own techniques, including a meticulous method for multiple solarization. “Pictorial photography is the mother of all branches of photography,” Sharma noted in a 2020 interview, declaring that its biggest contributors are amateurs “who spend their time, money, energy and their life to discover new things.”

O. P. Sharma, Far Away Look, 1990

O. P. Sharma, Far Away Look, 1990By the mid-twentieth century, Pictorialism was considered passé in the United States and relegated to the terrain of the amateur. But South Asian practitioners such as J. N. Unwalla, A. L. Syed, and Sharma in India, along with Lionel Wendt in Sri Lanka, kept the style alive. That these bodies of work have only recently been revived in writings and histories of photography around the world speaks to the enduring power of the U.S. model for so-called photographic progression: even within India, as camerawork has gone through the global motions of modernism, photojournalism, and documentary, the country’s vast and prolific network of Pictorialists has remained under-addressed in the prevalent literature.

O. P. Sharma, Who is there, 1975

O. P. Sharma, The Open Door, 1968

Despite this near erasure of many successful practitioners in India, Sharma has been one of the country’s most enthusiastic proponents of the medium of photography. It was Sharma who wrote in the late 1980s to the Photographic Society of America and the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain requesting that August 19 be recognized as World Photography Day to mark the anniversary of the French government purchasing the patent for the daguerreotype in 1839. The first World Photography Day was celebrated in 1991, a likely result of Sharma’s personal efforts. Sharma, who was born in 1937, in Agra, moved to New Delhi in 1958, where he has been teaching photography ever since: at the Modern School from 1958 to 2000 and also, since 1980, heading the photography department at Triveni Kala Sangam, a prominent visual and performing arts institution. Sharma’s publications range from handy primers on the technical aspects of the camera to expositions on the oeuvres of Unwalla and Syed, his stylistic predecessors. In his many decades as an educator, Sharma will have taught hundreds, if not thousands, of students the intricacies of darkroom experimentation. Across his lifetime, his work has been shown in close to forty solo exhibitions, mostly in galleries and photographic societies in India as well as in the United States, Pakistan, and Norway.

O. P. Sharma, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, 1964

O. P. Sharma, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, 1964All photographs courtesy the artist

How are we to locate a practice as expansive as this?

Sharma’s work does not speak of South Asia as an empty photographic scene reliant on Europe and the United States for cues. It presents us with an active cosmopolitan global system of photography to which postcolonial photographers contributed localized visual languages, literature, and pedagogy. The range of Sharma’s influences—from the Armenian Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh to the Soviet Constructivist Aleksandr Rodchenko, from Man Ray to Unwalla and Syed—is a testament to the cultural interconnectedness of this world. It does not pander to the primacy of New York as a photographic ground zero. To the contrary, it speaks to the preservation of darkroom experimentation in alternative geographies, where photographers such as Sharma have maintained the memory of photography as a careful, laborious, and tactile act of creation.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “Light Work.”

Donavon Smallwood and Bryan Schutmaat on "Languor"

July 22, 2021

The Artists Who Tried to Warn Us about AIDS

When does an epidemic begin, and when does it end? It’s now commonplace, at least among those privileged enough to have received the COVID-19 vaccine, to talk of a “postpandemic world,” as if nearly nine thousand people worldwide weren’t still dying every day from the virus. The novel coronavirus’s origin may be a subject of debate in right-wing conspiracy circles but, like most other viruses, it was likely around long before it was ever observed in humans.

This year marks the first anniversary since COVID-19 became a global pandemic, and forty years since AIDS was first reported. The latter milestone has occasioned a number of retrospective exhibitions, including More Life at David Zwirner in New York, though as a timeline on the gallery’s website acknowledges, deaths from AIDS-related complications were recorded in the US as early as 1969, fifty years after scientists believe it jumped from nonhuman primates. These dates tell us much about who was considered worthy of attention; no one seemed to notice AIDS until it affected middle-class white gay men. The Zwirner timeline focuses heavily on the institutional controversies that followed artists who engaged with HIV/AIDS as their subject matter, particularly after 2000, when protease inhibitors made HIV manageable for those with financial means and access to health care. Yet at least fifteen million people have died from complications of the virus since then, mostly in developing countries. As artist and activist Gregg Bordowitz reminds us in the epitaph to his current survey at MoMA PS1, “The AIDS Crisis Is Still Beginning.” COVID-19 may never end.

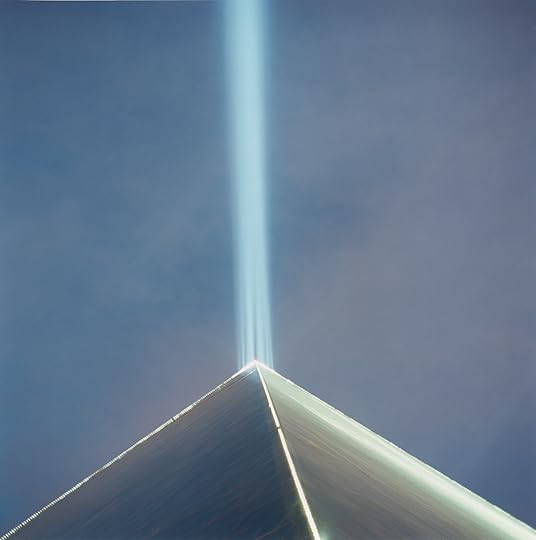

Derek Jarman, Still from Blue, 1993. Photograph by Liam Daniel

Derek Jarman, Still from Blue, 1993. Photograph by Liam DanielCourtesy Basilisk Communications

More Life is a historical show, although AIDS is not yet history. Its selections safely invest in the established canon. At Zwirner’s two Chelsea locations, two cinematic masterpieces—Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1989) and Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993)—will be familiar to many. Several vitrines contain materials from the Silence=Death and subsequent Gran Fury collectives: ephemera, including the iconic “Silence=Death” poster that the groups wheat-pasted around New York and distributed at protests until their disbandment in 1995. At the gallery’s Upper East Side jewel-box space, a selection of photographs by Mark Morrisroe, the late punk prince of Polaroid photography, likewise showcases the work of a widely acknowledged genius. Little unifies these disparate artists save the virus that ended their lives—and, perhaps, a particular sensitivity to the evanescence of light, that essential ingredient of film and photography.

Blue is a poetic conflation of an ophthalmological condition with the anatomy of cinema. Toward the end of Jarman’s life, Kaposi sarcoma lesions—a common complication of HIV/ AIDS—developed on his pupils, causing flashes of blue to interrupt his vision. The entire seventy-five-minute run of the film is a single frame of International Klein Blue, the rich azure developed in 1960 by Yves Klein, then best known as the creator of The Void (1958). Jarman plumbed the blue void for centuries of poetry and song, recited by the artist and his friends, in which the color of sea and sky is charged with meaning. By using his own literal vision as the subject for a film, Jarman frames light as the force that animates both our bodies and our cameras. The intense hue seared itself into my eyeballs and made the outside world seem sepia-toned for some time after I left the gallery, as if I had come face to face with my own mortality.

Still from Marlon Riggs, Tongues Untied, 1989

Courtesy Frameline and Signifyin’ Works

Donna Binder, Women of ACT-UP demonstrate at NIH, 1990

© Donna Binder

Blue eyes haunt Marlon Riggs, too. Throughout Tongues Untied, the filmmaker narrates his own painful journey from shame to self-acceptance as a Black gay man, including his years of fetishizing white men. “I was intent on a search for my reflection—love, affirmation—in eyes of blue-gray-green,” he says, only to discover that, by pursuing those eyes, he had rendered himself “invisible” in the process. The film interweaves Riggs’s story with poetry written and performed by Essex Hemphill, among others, and sketches of Black gay life that are alternately tender, comic, and devastating. In one sequence, from footage purportedly on loan from the “Institute of Snap!thology,” a group of men demonstrates how to communicate through diva snaps, which can serve as both punctuation and prose. Anti-gay and racist slurs interrupt moving reflections on Riggs’s attempts to articulate his own identity. If Tongues Untied concerns itself with light, it sheds some on what society would prefer to shroud in darkness; released the same year that legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced “intersectionality” into the lexicon of critical race theory, the film confronts the challenge of speaking to, and making visible, an identity that is doubly marginalized.

In Camera Lucida (1980), Roland Barthes proposed that every photograph has a punctum, a “sting, speck, cut, little hole” that centers our attention. His first example, notably, was the hand of a young Black boy resting on the thigh of a French colonial explorer in an 1882 photograph—a “speck” of interracial homoeroticism that seems, at least for Barthes, to cut through whatever else the picture was intended to relay. In Blue and Tongues Untied, these cuts come from body parts—eyes, lips, fingers—that both articulate and absorb the world around them. Their power to do so can be transferred to the devices of film and photography: cameras enable these filmmakers to isolate and reproduce aspects of their physical experience so that we may briefly inhabit them.

Mark Morrisroe, The Boy Next Door (Beautiful But Dumb), 1983

Mark Morrisroe, The Boy Next Door (Beautiful But Dumb), 1983© Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection)

Cuts can be found all over the surface of Mark Morrisroe’s large-format “sandwich prints,” Polaroid double negatives that he layered one atop the other. Their rough edges seem to mimic Morrisroe’s own scars and the scruffy scenes he photographed with affection. The selection on view at Zwirner includes several iconic self-portraits, as well as images of his friends Jack Pierson, Tabboo!, and Lynelle White. There are drag antics and painterly views of the sky, fuzzy with clouds or darkening at sunset. Light in these photographs always seems to be fading, and it’s tempting to see them as talismans of Morrisroe’s own life, which ended when he was barely thirty.

More life, tragically, is the one thing these artists wanted but wouldn’t have. Still, by staging such a resolutely retrospective exhibition, Zwirner chose to ignore the work of artists still living with and fighting against HIV/AIDS. In the process, a particular history of the epidemic has been retread. Women are also notably absent from the show—not just from these three exhibitions but also another four shows of work by Ching Ho Cheng, Frank Moore, Jesse Murry, and Hugh Steers, due at the gallery’s London and New York spaces in September. It’s an immense amount of time and space to afford such a narrow view of history. As Sarah Shulman argues in her monolithic new book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (2021), the voices of gay men—and particularly white gay men—have prevented many others from being heard. The AIDS crisis is still beginning, and how we address it now may affect if it can ever end.

More Life is on view at David Zwirner’s New York galleries through August 3, 2021.

In Central India, A Photographer Documents the Persistence of Protest

There is a lesson that every child in India learns at school: the narrative tableaux, from the early life of the Buddha, called “the four sights.” On his first journey outside the palace walls, Prince Siddhartha saw an old man bent with age, then a man afflicted with disease, then a corpse, and, finally, an ascetic. Siddhartha had so far been protected from the world because of a prophecy made at his birth that he would renounce home and seek enlightenment. The four sights awoke him to suffering, and the prophecy was fulfilled: Siddhartha left home, and, at the end of his search, he became Gautama the Buddha, or the Enlightened One.

When I was young, I received this story as a fatalistic narrative about inevitability. But later, this story took a turn and became one about visual culture: it matters what you see, and what you see can change you and determine the history of the world.

Given the scenes of suffering in India, it would be right to ask, Why aren’t there more Buddhas? But there is also a different question: How is one to see the world as it is?

Delhi-native Ishan Tankha is a regular observer of the power of the state and the persistence of protest. When I recently corresponded with him, he had been up since five AM, camera at the ready, following one of the leaders of the farmers protesting the new government laws that favor corporations. These farmers have been stopped from entering the capital; tens of thousands have camped at the Delhi border for months since the demonstrations began in November 2020.

Tankha has long been working to depict news that is rarely covered by Delhi’s mainstream media outlets. A Peal of Spring Thunder (2007–15) is the result of a long labor documenting the presence of guerrillas in Chhattisgarh, a state in central India. These insurgents are often called Naxalites, after Naxalbari, a small village in Bengal where, in 1967, an uprising of landless workers inaugurated a chain of peasant rebellions in different parts of India. The rebels in Naxalbari were inspired by Maoist ideology and the idea of an armed peasantry capturing state power. The title for Tankha’s project echoes the report from Radio Peking in June 1967 hailing the Naxalbari uprising: “A peal of spring thunder has crashed over the land of India.”

When he went to Chhattisgarh the first time, in 2007, Tankha had expected and hoped to find “rebels in a thick jungle, walking in a single file at dusk, hidden campsites and weapons, an ambush.” Instead, the man who came for him in the village had a bow and arrow. He wore only a lungi wrapped around his middle and a torn vest. The landscape was dusty and bare. Nearly everyone Tankha met was suffering from, or had recently had, malaria. In these photographs, we see the guerrillas Tankha traveled with. Smiling tenderly with rifles at hand, they present themselves as doing what needs to be done, including the business of quietly asserting their humanity.

Since 2009, the guerrillas in Tankha’s pictures have been hunted by approximately one hundred thousand Indian counterinsurgency troops. In 2010, these insurgents were described by the then prime minister Manmohan Singh as “the biggest internal security challenge” facing India. Not all of the people in A Peal of Spring Thunder are armed fighters; many of them are just the rural populace, dirt-poor, a part of the Indigenous Adivasi population of India, people who the troops often also mistreat and torture as if they were not citizens of India in any meaningful sense. The land that the Adivasis farm is mineral-rich, and most of their struggle involves opposing the corporations eager to displace them. In Tankha’s series, you see the land, you see mines, but you do not see schools or hospitals—there are no schools or hospitals. There are roads, but, critics say, the roads exist to bring in troops and take out the minerals.

Tankha’s work on this project, not least because it has been carried out over such a long time, is in a variety of formats: 35mm, black-and-white negatives, 4-by-5-inch color negatives, digital images. When traveling to Chhattisgarh on assignment, or sometimes on his own steam, Tankha used whatever materials, including cameras, he could access. Formally, this gives variety to his work. It promotes a form of seeing that is opposed to the singular, mechanized gaze of the state or the strictly binary reporting of the hypernationalist media that offers endless paeans to the military-industrial state.

All photographs by Ishan Tankha from the series A Peal of Spring Thunder, Chhattisgarh, 2007–15

All photographs by Ishan Tankha from the series A Peal of Spring Thunder, Chhattisgarh, 2007–15Courtesy the artist

When looking at these images, I see that Tankha makes visible the state’s victims. But he has also exposed, as it were, the state’s enemies. When I asked him whether it wasn’t dangerous for the cadre to have their pictures taken for publication, Tankha answered that when he showed concern, the fighters pointed out that “if they were to be caught by the security forces, they would most likely be killed on the spot, picture or no picture.” Which, I guess, is also a way of seeing the world as it is.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “A Peal of Spring Thunder.”

9 Photographers on Keeping Their Eyes Open to the World around Them

“The camera can be a way of connecting to people and places while also expressing yourself,” writes photographer Susan Meiselas at the beginning of Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids, a new book of ideas for young readers to engage with the world through the camera. Broken into twenty-three short, thematic chapters—ranging from “Alphabetography” and “Light,” to “Movement,” “Neighborhood,” and more—each idea starts with a prompt, illustrated with pictures by students from around the world, and followed by the words and images of professional artists who share their ways of seeing. “When you point your camera at a person, a place, or a community, think about what you want to convey,” Meiselas writes. “Who is the picture for? The people in the picture? Yourself? Or both? What are you sharing? What are you giving back? This is what I always ask myself.” Playful and meaningful, this book is for young would-be photographers and those interested in expressing themselves creatively.

Below, we’ve gathered five highlights from Eyes Open.

Light: Can you capture how light shapes, hides, exaggerates, and transforms where and what it touches?

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2011, from the series Illuminance

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2011, from the series IlluminanceCourtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi

“I want imagination in the photographs I take. You wonder, ‘What’s going on?’ You feel something is going to happen.”

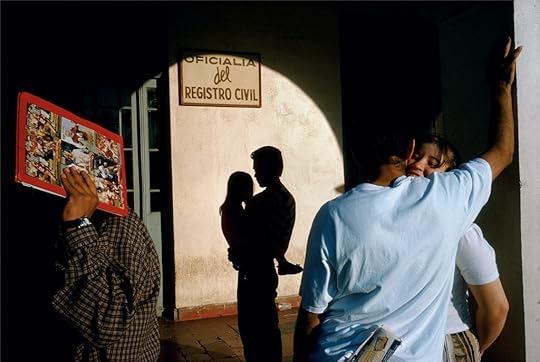

Alex Webb, Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, 1996

Alex Webb, Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, 1996Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Webb

“When I look at a scene, I am sensing not just what seems to be happening in front of my eyes and the various shapes that fill the frame, but I am also aware of . . . the color of light, the angle of light: how a shaft of light, or a particular tone of light, can utterly transform a situation.” —Alex Webb

Animals around You: When you see animals in the world around you, think about their state of being, their conditions, their habitat. How do they live: enclosed, roaming, wild, domesticated?

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2010

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2010Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Gregory Halpern

“Animals are like humans in the sense that they want and need the same basic things. But humans hide their feelings, whereas animals reveal fear, anger, and affection so readily.”

Sage Sohier, Boy in Barn with Cat and Pony, Rowley, Massachusetts, 1992

Sage Sohier, Boy in Barn with Cat and Pony, Rowley, Massachusetts, 1992Courtesy the artist

Sage Sohier

“People are proud of their animals and like to show them off. Animals are active, funny, and surprising, so people tend to be much less self-conscious in front of the camera.”

Portraits in a Place: Can you place yourself in a landscape that is meaningful to you?

Graciela Iturbide, Self Portrait, Botanic Garden, Oaxaca, 1999

Graciela Iturbide, Self Portrait, Botanic Garden, Oaxaca, 1999Courtesy the artist

Graciela Iturbide

“Photography for me is just an excuse to get to know the world. When you are an artist or a photographer, you always need to establish a connection to the place where you are. Without the camera, you see the world one way; with it, you see the world another way.”

Personal Space: How does a room express the personalities of those who live there?

Alec Soth, Untitled 36, Bogotá, Colombia, 2003

Alec Soth, Untitled 36, Bogotá, Colombia, 2003Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alec Soth

“When I’m in someone else’s house—what kind of books do they have? What are they reading? It’s just another way to try to glean who this person is. What’s going on inside of them? We only have so many clues. We see how people dress. We see their mannerisms. And an interior provides all of this other information.”

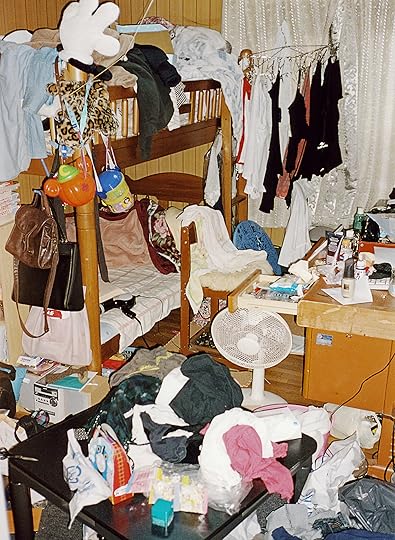

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project FamilyCourtesy the artist

Motoyuki Daifu

“I have a relationship to the space that no one else has. There’s something there that only I can photograph. I think maybe it’s better to take a place I know and get to know it better.”

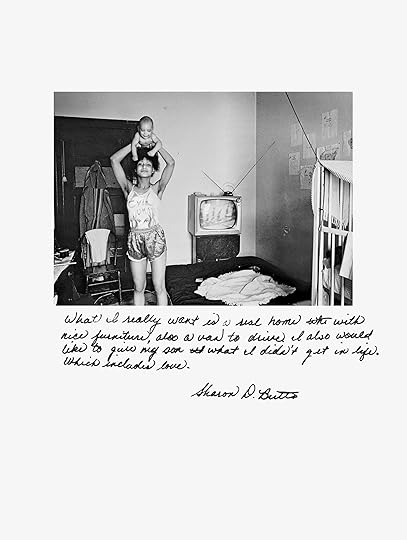

Me: Can you share a story about yourself that goes with and beyond what the picture shows?

Jim Goldberg, Sharon D. Butts, San Francisco, California, 1979

Jim Goldberg, Sharon D. Butts, San Francisco, California, 1979Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Jim Goldberg

“A lot of photographs are taken from the outside looking in. And I was interested in something else—letting people describe experiences in their own words, from the inside, with pictures that sometimes went with, and sometimes went against, what they were saying.”

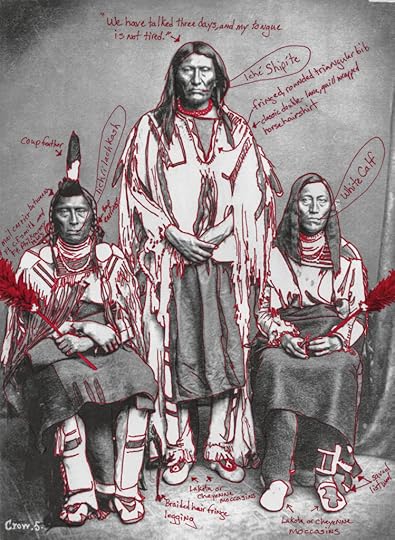

Wendy Red Star, Long Horse, Sits in the Middle of the Land, and White Calf, 2017

Wendy Red Star, Long Horse, Sits in the Middle of the Land, and White Calf, 2017Courtesy the artist

Wendy Red Star

“Even though I grew up in the community and on the reservation, this is how I’m learning more about my heritage. I’m patching pieces of our historical timeline back together as a way of archiving the culture and history of my people, which are not widely known.”

This text originally appeared in Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids (Aperture, 2021).

July 16, 2021

Judith Black’s All-American Summer Vacation

Who would have thought the title of Vacation could, in our present moment, propose so quixotic an idea? Released by Stanley/Barker on the frayed edges of a pandemic-weary spring, Judith Black’s new photobook is a tease. The photographs collected within took seed in 1986 when Black was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, allowing her to take off from her job as a photo technician at Brandeis University and document that most all-American of rites: a cross-country road trip. The starting point was her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which previously set the scene for her 2020 photobook Pleasant Street, an intimate portrayal of her family life (also published by Stanley/Barker). From there, Black departed for New York, Michigan, and Chicago, moving westward to San Francisco with a new set of cameras—and four children—in tow.

Judith Black, Erik, Dylan, Hank, California, August 17, 1986

Judith Black, Erik, Dylan, Hank, California, August 17, 1986The open road is a prism through which generations of photographers have envisioned the United States. Moving freely through the American landscape and its pockets of life is a privilege afforded to few, and the canon of photography that makes transience its tenet is dominated by a male and white lens. Principal among them is Robert Frank. He set out from New York in 1955 (also with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship) and returned two years later with a suite of images that would become The Americans, his work of monolithic influence. First published in France in 1958 and in the U.S. the following year, the book depicts a thrumming spectrum of realities, its staggered cadence determined by what Jack Kerouac called in the preface “intermediary mysteries.” Frank’s project overwhelmingly asserts the primacy of chance encounters, whereas Black offers a sort of spiritual opposite. She instead uses the trip to center her children, extended family, and friends—portraits of whom make up the heft of the book.

Judith Black, Maggie and Matt, My sister and new baby, Seattle, Washington, March 1, 1986

Judith Black, Maggie and Matt, Seattle, Washington, January 11, 1992

Shown on the cover of Vacation, set against an image of wild daisies and hemlock flowers, is a photograph of a sleeping infant, his somnolent consternation hinting at the mysterious activity of his mind. From there, across single- and double-image spreads, we see subtle evolutions of life. Black’s children are seen early on in the book wading into rivers and posing at tourist attractions, each one wearing the mantle of an inchoate youth in both expression and dress. As we turn the pages, this innocence gives way to a steadier physicality and self-assurance, a way of comporting themselves that reflects the passage of time. Similar shifts appear in Black’s images of family and friends, who accrue their years within familiar haunts. Black is an avid researcher of vernacular family photo albums, but her own method of photographing with medium- and large-format press cameras—often loaded with Polaroid Type 55, known for capturing exceptional detail—requires exacting technical precision, time, and collaboration with the sitter, diverging from the spontaneity of the average snapshot found in such albums. The cumulative effect of time is laid bare not just through her tenacious recording of growth spurts but also by virtue of her meditative approach. This is no shoot-from-the-hip photography but a marriage of technique and subject matter.

A photograph that strikes me, in particular, is a portrait of Black with her daughter, Johanna, taken in 1995 in Chico, California. In it, Black crouches furtively in the foreground. Her floating head is indistinct, lost in the aperture’s shallow depth of field, while Johanna looms above her, eyes lit and in high detail, addressing the camera with a well-versed directness (she appears dozens of times in her mother’s various projects). To me, the positioning of the two women signals a reverence from mother to daughter, making visible the ineffable will to uphold and make luminous one’s child.

Judith Black, Johanna and Self, Chico, California, March 27, 1995

Judith Black, Johanna and Self, Chico, California, March 27, 1995In an essay in Aperture magazine’s summer 1987 issue, “Mothers and Daughters,” in which Black’s work was included, the feminist writer Tillie Olsen, in collaboration with her daughter Julie Olsen Edwards, describes the potential of a maternal connection to afford a “lifelong at-homeness with each other’s bodies, the sensuality, the easy tactile expression of connection.”

This idea of “at-homeness” reverberates throughout Vacation. The sights that line Black’s trip are given short shrift and seem merely to provide a mise-en-scène for her to record the tacit bonds of family. Surveying the recursive nature of these photographs, and Black’s apparent indifference to spectacle, so potentialized by a cross country trip, I am reminded of Annie Dillard’s 1982 essay “Total Eclipse,” which details her pursuit of a solar eclipse. Dillard is seduced by the promise of the extraordinary, only to demur: “One turns at last even from glory itself with a sigh of relief. From the depths of mystery, and even from the heights of splendor, we bounce back and hurry for the latitudes of home.” Attentive to this tug of the familiar, Vacation coheres an overarching verity for Black: that those close to us are often ballast amid the irrepressible magnitude of life.

Judith Black, Til and Robbie, Ithaca, New York, February 15, 1987

Judith Black, Maggiore’s Inn, Saratoga, New York, August 17, 1996

With its specter of grief and lost pleasures, this past year has left many of us longing for a return to the swim of life and to revel in its vibrancy. For many, this season also restored ties that bind us and provide a tonic in the worst of times. Where absence was felt, family albums and snapshots took on a new charge, providing a thread to what used to be. These mediations of experience and people are, for Black, physical “touchstones,” containing within each of them, she writes, “sweet memories and histories.” Portraits of family, even as inadequate documents of life, assert what matters.

Judith Black, Dad and Gaye, Chico, California, January 15, 1992

Judith Black, Dad and Gaye, Chico, California, January 15, 1992 Judith Black, Dylan and Laura, His 22nd Birthday, Cambridge, Massachusetts, August 23, 1996

Judith Black, Dylan and Laura, His 22nd Birthday, Cambridge, Massachusetts, August 23, 1996All photographs © the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Black continued her project after returning to Massachusetts, where, in 1987, she became the head of the photography department at Wellesley College. Vacation ultimately spans twenty-three years, her coordinates mapping buzz cuts and births alike. For Black, the swim of life does not course along some distant shore; its ebb and flow is felt in the everyday, whether a passing embrace at a breakfast table or a child hiding between the cushions of a sofa. Vacation sets up a precept of emancipation from the domestic sphere; Black, however far she travels, is always home.

Judith Black: Vacation was published by Stanley/Barker in 2021.

July 12, 2021

Life Is Good for You in William Klein’s New York

Faced with the complexity and contradiction of New York, photographers tend to take a position, to form a coherent response, especially when making a book. Nearly all New York photobooks do this, from Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland’s Changing New York (1939) and Daido Moriyama’s 1971/NY (2002) to György Lörinczy’s New York, New York (1972) and Ken Schles’s Invisible City (1988). But what if one doesn’t have a clear position? Since a book is built up from individual images, what if each photograph is a singular expression and they just accumulate, leaving the sense making up to the viewer? These are the questions provoked by William Klein’s bewildering opus Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, published in 1956.

Art history tends to reduce Klein’s New York work to a handful of punchy and gritty street shots, but the book itself always surprises. For every picture of anarchic kids clowning or billboards exhorting, there are as many visions of tenderness, elegance, and affection. Each seems to be made with conviction, but there is no point of view that unites them all. In fact, Klein’s book signaled a break with the modernist idea that an artist should even need such a thing as a unified position.

Spread from Vogue, July 1959, with photograph by William Klein

Spread from Vogue, July 1959, with photograph by William KleinCollection of Vince Aletti

His teeming vision emerged at the onset of Pop, a movement that would quote, mimic, and mirror back the contradictory iconography of postwar popular culture. Klein pioneered for himself a kind of hyper-photography, bouncing between genres. In this one book he is historian, urban geographer, sociologist and anthropologist, Weegee-like newshound, cool Walker Evans inspired surveyor of the urban fabric, high-society photographer, fashion visionary, and even abstract artist.

Indeed, fashion and abstraction were key to the book’s genesis. Born into a Jewish family on the edge of Harlem in 1928, Klein left the United States for Europe, in 1946, to become a painter. He returned in 1954 at the invitation of Alexander Liberman, art director at Vogue. In Paris, Liberman had seen a show of Klein’s abstract photographs and paintings. Klein was not trained in photography but had endless curiosity. At first, Liberman gave him still-life assignments. Shoes, hats, the season’s fabric swatches. They lent themselves to inventiveness, and Klein gained a reputation for stylish problem-solving. He would soon photograph Vogue’s models with the same creative verve, leaving the studio and taking them out into the unpredictable world outside.

Liberman also bankrolled Klein’s wish to shoot the streets of New York with complete freedom. He developed and printed his photographs at night, transforming his errors of exposure, focus, and motion blur into expressive devices. With the new photostat machine in the Vogue office, he made high-contrast copies of each image in multiple sizes and used them to create a dummy of the eventual book. Klein did his own layout and the jacket design. He also wrote the hilarious and insightful captions, which were printed as a separate pamphlet, attached to the book’s spine by a cord.

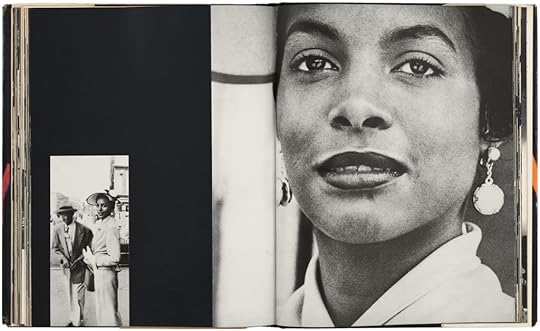

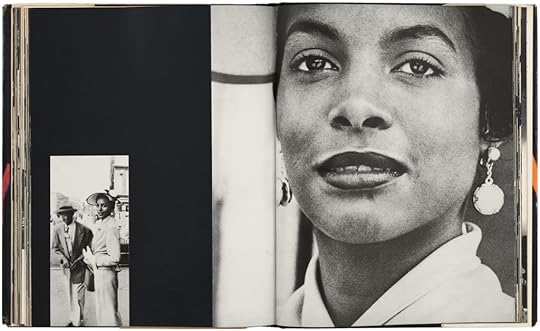

Spread from William Klein, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Photography Magazine, 1956)

Spread from William Klein, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Photography Magazine, 1956)Collection of the author. Photographs by Fabrizio Amoroso

Every spread has a different arrangement, and the book overall is impossible to remember. With each viewing, the emphasis falls somewhere new. For me, of late, the energy of Klein’s many Harlem photographs has my attention. Throughout his career, Black experiences have been a key thread (he went on to make groundbreaking films about Cassius Clay, Eldridge Cleaver, the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers, and Little Richard). Klein’s captions speak clearly of Black resilience in the face of white racism. His Harlem images range from the almost chaotic to the stately, but he is always present to his subjects. Never attempting to be invisible, Klein is unmistakably part of each situation—interacting, collaborating, sharing, and celebrating. There’s nothing voyeuristic, and certainly nothing objective, about his images. These are willfully immersive photographs, and all the richer for it. New York is performed as much as documented, with human life a constantly improvised theater.

To the purist defenders of documentary and fine-art photography in the United States, this was all deeply off-putting. Only recently has the country come to appreciate Klein’s artistic achievement and global influence. At the time, no U.S. publisher would touch Life is Good & Good for You in New York. It was tumultuous and wild, with swerving bebop rhythms of editing and no calming white borders. The most adventurous American photobook to get published in the 1950s was probably Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life, from 1955. Klein’s book had ten times the photographs, no narrative, and a jumble of styles. Back in Paris, it was the young upstart editor Chris Marker who persuaded Éditions du Seuil to issue it, with co-editions published in London and Rome. Today it tops many lists of the most influential photobooks.

I have never understood Klein’s views about New York, and this has never bothered me. One can see in his book a premonition of the city’s future urban hell, but of resilience and reinvention too. Sixty-five years on, it remains a vision against which the city can measure itself.

Life is Good for You in William Klein’s New York

Faced with the complexity and contradiction of New York, photographers tend to take a position, to form a coherent response, especially when making a book. Nearly all New York photobooks do this, from Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland’s Changing New York (1939) and Daido Moriyama’s 1971/NY (2002) to György Lörinczy’s New York, New York (1972) and Ken Schles’s Invisible City (1988). But what if one doesn’t have a clear position? Since a book is built up from individual images, what if each photograph is a singular expression and they just accumulate, leaving the sense making up to the viewer? These are the questions provoked by William Klein’s bewildering opus Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, published in 1956.

Art history tends to reduce Klein’s New York work to a handful of punchy and gritty street shots, but the book itself always surprises. For every picture of anarchic kids clowning or billboards exhorting, there are as many visions of tenderness, elegance, and affection. Each seems to be made with conviction, but there is no point of view that unites them all. In fact, Klein’s book signaled a break with the modernist idea that an artist should even need such a thing as a unified position.

Spread from Vogue, July 1959, with photograph by William Klein

Spread from Vogue, July 1959, with photograph by William KleinCollection of Vince Aletti

His teeming vision emerged at the onset of Pop, a movement that would quote, mimic, and mirror back the contradictory iconography of postwar popular culture. Klein pioneered for himself a kind of hyper-photography, bouncing between genres. In this one book he is historian, urban geographer, sociologist and anthropologist, Weegee-like newshound, cool Walker Evans inspired surveyor of the urban fabric, high-society photographer, fashion visionary, and even abstract artist.

Indeed, fashion and abstraction were key to the book’s genesis. Born into a Jewish family on the edge of Harlem in 1928, Klein left the United States for Europe, in 1946, to become a painter. He returned in 1954 at the invitation of Alexander Liberman, art director at Vogue. In Paris, Liberman had seen a show of Klein’s abstract photographs and paintings. Klein was not trained in photography but had endless curiosity. At first, Liberman gave him still-life assignments. Shoes, hats, the season’s fabric swatches. They lent themselves to inventiveness, and Klein gained a reputation for stylish problem-solving. He would soon photograph Vogue’s models with the same creative verve, leaving the studio and taking them out into the unpredictable world outside.

Liberman also bankrolled Klein’s wish to shoot the streets of New York with complete freedom. He developed and printed his photographs at night, transforming his errors of exposure, focus, and motion blur into expressive devices. With the new photostat machine in the Vogue office, he made high-contrast copies of each image in multiple sizes and used them to create a dummy of the eventual book. Klein did his own layout and the jacket design. He also wrote the hilarious and insightful captions, which were printed as a separate pamphlet, attached to the book’s spine by a cord.

Spread from William Klein, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Photography Magazine, 1956)

Spread from William Klein, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Photography Magazine, 1956)Collection of the author. Photographs by Fabrizio Amoroso

Every spread has a different arrangement, and the book overall is impossible to remember. With each viewing, the emphasis falls somewhere new. For me, of late, the energy of Klein’s many Harlem photographs has my attention. Throughout his career, Black experiences have been a key thread (he went on to make groundbreaking films about Cassius Clay, Eldridge Cleaver, the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers, and Little Richard). Klein’s captions speak clearly of Black resilience in the face of white racism. His Harlem images range from the almost chaotic to the stately, but he is always present to his subjects. Never attempting to be invisible, Klein is unmistakably part of each situation—interacting, collaborating, sharing, and celebrating. There’s nothing voyeuristic, and certainly nothing objective, about his images. These are willfully immersive photographs, and all the richer for it. New York is performed as much as documented, with human life a constantly improvised theater.

To the purist defenders of documentary and fine-art photography in the United States, this was all deeply off-putting. Only recently has the country come to appreciate Klein’s artistic achievement and global influence. At the time, no U.S. publisher would touch Life is Good & Good for You in New York. It was tumultuous and wild, with swerving bebop rhythms of editing and no calming white borders. The most adventurous American photobook to get published in the 1950s was probably Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life, from 1955. Klein’s book had ten times the photographs, no narrative, and a jumble of styles. Back in Paris, it was the young upstart editor Chris Marker who persuaded Éditions du Seuil to issue it, with co-editions published in London and Rome. Today it tops many lists of the most influential photobooks.

I have never understood Klein’s views about New York, and this has never bothered me. One can see in his book a premonition of the city’s future urban hell, but of resilience and reinvention too. Sixty-five years on, it remains a vision against which the city can measure itself.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers