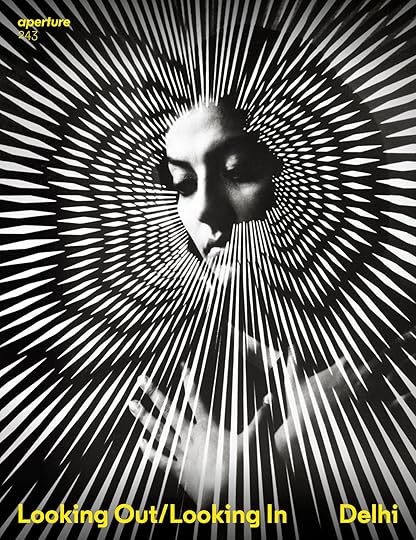

Aperture's Blog, page 55

June 17, 2021

The Photographers Crafting Visionary Narratives of the African Diaspora

In May 1803, a slave ship bound for St. Simons Island, off the coast of Georgia, neared its final destination. On board were seventy-five captives belonging to the Igbo peoples of West Africa. As the ship approached the island, the Igbo rose up in revolt, forcing the white crew to jump overboard, running the vessel aground. On land, according to a contemporary account, the Igbos “took to the swamp.” Rather than risk being returned to captivity, they lined up hand in hand and walked into the water where many of them drowned.

Variations on the story of the Africans who found liberation through suicide have been told over successive generations across the Atlantic world, from the United States to South America and the Caribbean. In the process, the tale has taken on the resonant power of myth. Some versions have the Igbos returning to Africa by walking on the waves or along the seabed. Others describe them taking to the sky and soaring back to their homeland. Echoes of the story can also be heard in popular culture. It is the base material for Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon and Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust. Beyoncé references it in a scene in her Lemonade film. And in Black Panther, Michael B. Jordan’s character, Erik Killmonger, alludes to the tale with his dying words: “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships, ’cause they knew death was better than bondage.”

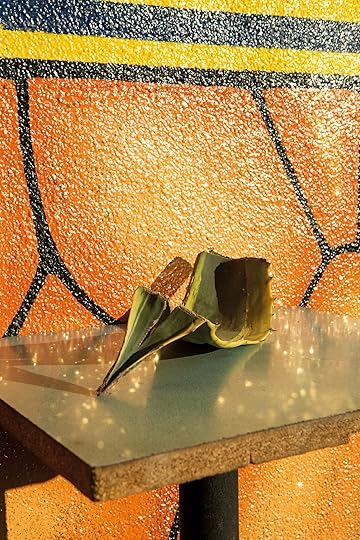

Adama Delphine Fawundu, Black Gold of the Sun, Lagos, 2018

Adama Delphine Fawundu, Black Gold of the Sun, Lagos, 2018Courtesy the artist

Real-life events turned folklore, such as the story of the Igbo slaves, along with myths, legends, and spiritual beliefs drawn more widely from the history and culture of the African diaspora, have increasingly become a powerful source of inspiration for Black artists and creative figures. A trio of recent photographic projects illustrates renewed attention to these stories.

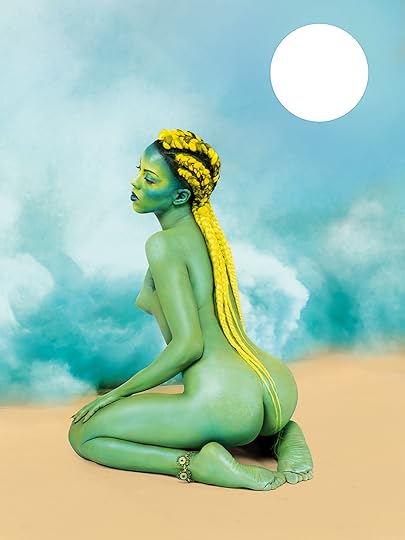

Ayana V. Jackson’s series Take Me to the Water (2019) is inspired by mythological African water deities such as Mami Wata and Olokun, spirits venerated in Africa and the diaspora for their power to heal and liberate those who summon them. In addition to African legends, Jackson’s project draws on the fable of a Black Atlantis created by Drexciya, the enigmatic 1990s Detroit techno duo. In the group’s telling of it, Drexciya is also the name of a colony located on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean populated by the descendants of pregnant African women thrown overboard from slave ships. The women’s fetuses learned to breathe through the embryonic fluid of their mothers’ wombs and were born able to live underwater. In Jackson’s pictures, the Drexciyans craft their clothes from human detritus: a bodice of spoons, a skirt of flip-flops, a veil of black netting. But they are defiant, noble creatures, glorious proof of how Black life might have flourished without the depredations of the slave trade.

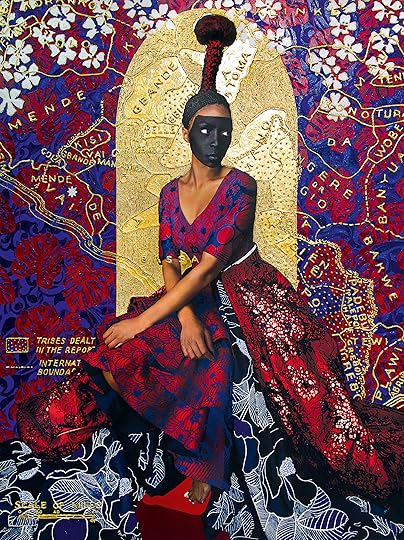

Similarly, the artist Adama Delphine Fawundu merges myth, memory, and spiritual belief in her photography-based multimedia project Sacred Star of Isis (2017–ongoing). Fawundu’s family origins lie in Sierra Leone, and in the series, she invokes the presence of West African deities such as Mami Wata while photographing herself in Argentina, upstate New York, and other locations where her forebears were scattered by slavery. These works suggest the possibility of new narratives and networks that can be formed from traditional myths and beliefs despite the efforts of the slave trade to sunder Africans from the heritage of their homelands.

Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh, 2017–18, from the series A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred

Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh, 2017–18, from the series A Haven. A Hell. A Dream DeferredCourtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Lina Iris Viktor draws from African cosmologies as well as Aboriginal dream paintings and other sources of Indigenous and non-Western myths and beliefs in her art. Viktor was raised in London by Liberian parents who were forced to flee the country amid civil war in the 1980s. The dazzling, gold-embossed pictures of her series A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred (2018) offer a mythological history of the country, conjuring Liberia as an uneasy utopia, both a paradise lost and a cautionary tale about the pathology of colonization.

In their shared tendency to blend historical fact and lyrical folklore, and to juxtapose the spiritual, the supernatural, and science fiction, we might usefully group the art of Jackson, Fawundu, and Viktor under the heading of the “Black fantastic,” works of speculative fiction that draw from history and myth to conjure new visions of African diasporic culture and identity. The scholar Rosemary Jackson describes the “fantastic” as a form that reaches beyond the boundaries of realism and dispenses with “rigid distinctions between animate and inanimate objects, self and other, life and death.” The fantastic, she writes, “has to do with inverting elements of this world, re-combining its constitutive features in new relations to produce something strange, unfamiliar, and apparently ‘new,’ absolutely ‘other’ and different.”

The Black fantastic shares terrain with genres such as Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism, artistic realms with their own expansive takes on Black experience. But to my mind, the Black fantastic is less a movement or a rigid category than a way of seeing shared by artists who grapple with the legacy of slavery and the inequities of racialized contemporary society by conjuring new narratives of Black possibility. The roots of the Black fantastic emerge from pioneering authors, musicians, and filmmakers of the 1960s and ’70s such as Octavia E. Butler, Henry Dumas, Amos Tutuola, Sun Ra, and Ousmane Sembène. But a raft of prodigiously talented contemporary practitioners is now taking the lead, among them the artist Wangechi Mutu, the novelist N. K. Jemisin, and musicians such as Solange and Kamasi Washington.

Juliana Huxtable, Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm), 2015

Juliana Huxtable, Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm), 2015 Courtesy the artist and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Art Resource, New York

This perspective stretches from, say, the enigmatic tableaux of the South African artist Mohau Modisakeng, whose Land of Zanj images (2019) are rich with historical allusion, to the explorations of race, gender, and queer sexuality conducted by the likes of Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Mickalene Thomas with her 2019 Orlando series made for this magazine, and Juliana Huxtable with her 2013 Nuwaubian Nation photographs. In those latter images, Huxtable inserts herself into digitally rendered landscapes inspired by the Nuwaubian Nation, an African American religious sect whose credo borrows from Islam, ancient Egypt, and stories of alien visits to Earth. Huxtable, who describes the portraits as “self-imaginings,” depicts herself as an otherworldly, green-skinned being, a figure whose very form critiques existing social norms and categorical distinctions while gesturing to alternate, more mutable states of identity.

But why are so many figures being drawn to art that ostensibly seeks to escape from, rather than contend with, the long history of anti-Black racism in the West, especially in the era of Black Lives Matter and the international protests triggered by the killing of George Floyd?

The success of Marvel movies and television shows including Stranger Things and Game of Thrones, to name just two, makes clear that fantasy is a dominant cultural language of our times. One of the unanticipated consequences of the superhero and sci-fi boom is that it has given space for Black artists to explore Black life in ways that are more allusive and audacious than hitherto possible. For example, the dazed and sardonic tone characteristic of recent shows and movies such as Us, Atlanta, Get Out, and Sorry to Bother You can surely be taken as a response to the horror and absurdity of a world in which Black people can be harassed, arrested, or killed while going bird-watching, cycling, jogging, or lying asleep in bed at night.

Isaac Julien, Place des Cineastes – Roundabout, 2005, from the series Fantôme Créole

Isaac Julien, Place des Cineastes – Roundabout, 2005, from the series Fantôme CréoleCourtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Fundamental to the Black fantastic is a skepticism about the claim that modern liberal democracies are built on ideals of tolerance, rationality, and equality. Those values feel profoundly flawed in their application when you consider how the wealth and advancement of the West were built on four hundred years of the slave trade, and how the intellectually and morally corrupt arguments of racial hierarchy used to justify slavery still poison our societies today. Artists working from the perspective of the Black fantastic are intent on both critiquing Western notions of progress and, in riposte, offering counterimages of Black imaginative reach.

The British Guyanese artist Hew Locke has had a long fascination with the role that public monuments play in the formation of Western cultural identity. For the past two decades, he has been photographing statues of prominent historical figures from Queen Victoria to Edward Colston, the slave trader whose bronze effigy was recently toppled by Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol. Locke then embellishes the pictures with objects, creating elaborate fetish figures whose often-problematic relationships to race and empire are now made visible. For his 2018 New York–based iteration of this project, he reworked the statues of public figures such as George Washington, Peter Stuyvesant, and J. Marion Sims. Each of the men he selected benefited from slavery or the exploitation of people of color, and in covering them with totems and tchotchkes, Locke reveals what their power was built on. An illustration by William Blake of a slave being tortured dangles from the forearm of Washington, a reminder that the United States’ first president owned over one hundred souls.

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Icarus 13, Astronomy Observatory, Namibe Desert, 2007

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Icarus 13, Astronomy Observatory, Namibe Desert, 2007© the artist and courtesy Galleria Fonti, Naples

By contrast to such brutal and dispiriting histories, some of the still photographs from Isaac Julien’s 2005 film installation Fantôme Créole depict a legacy of cultural renewal in late twentieth-century Africa. In the 1960s and ’70s, nation after nation in Africa secured independence from colonial rule. The optimism of liberation triggered a creative flourishing across the arts of Africa and the diaspora, from the novels of Chinua Achebe and the photography of Malick Sidibé to the films of Ousmane Sembène and Med Hondo. Julien’s images capture some of the thrilling, futuristic structures inspired by that period. Built in the 1980s, the Place des Cinéastes, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, for example, a towering monument of shapes representing stacks of film reels, telephoto lenses, and other camera equipment, is an homage to the country’s independence- era role as the heart of filmmaking in Africa. Julien confines his study to Burkina Faso, but across the continent, you can find buildings of similarly audacious design. Ghana’s flying saucer–like International Trade Fair Centre, in Accra, and the extraordinary La Pyramide commercial center in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, speak to a shared desire to break free of European aesthetic strictures in favor of an exhilarating architecture of freedom and the fantastic.

Visionary architecture also plays a key role in the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Icarus 13 series from 2007. The project purports to document Angola’s first space mission, complete with images of a spectacular rocket launch from mission control in Luanda. The photographs are imaginary, courtesy of the artist, who creates what have been described as “pliable fictions.” But the settings are real. A dome-shaped cinema from the independence period doubles as an astronomical observatory, while the towering mausoleum for Angola’s former leader Agostinho Neto becomes a sleek rocket headed to the stars.

With works such as Julien’s and Kia Henda’s in mind, we can think of the Black fantastic as a project of liberation. For much of the history of Western thought, the peoples of the African diaspora have functioned as a synonym for the primitive and perpetually underdeveloped. Writing in the nineteenth century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel dismissed the continent as “enveloped in the dark mantle of Night,” its people only representative of “natural man in his completely wild and untamed state.” Even today to talk of Africa, or the culture, myths, and beliefs that have spread from there across the Atlantic world, is to invoke the antithesis of Western modernity. In collapsing distinctions between fact and fiction, science and the supernatural, the Black fantastic also dissolves the false connection between Blackness and backwardness. Instead, it makes clear that belonging to the African diaspora means being a participant in a shared endeavor of artistic imagining and world making that stretches back hundreds of years into the past and reaches always into the future.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” under the title “The Black Fantastic.”

June 11, 2021

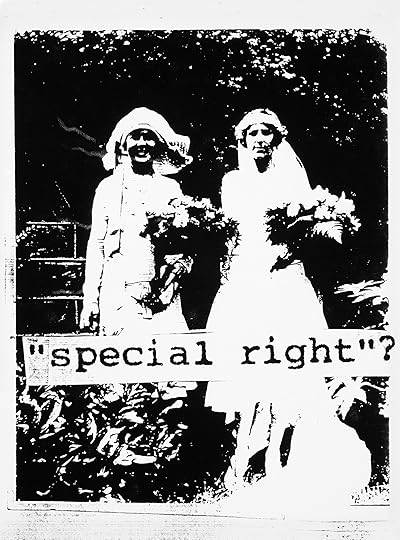

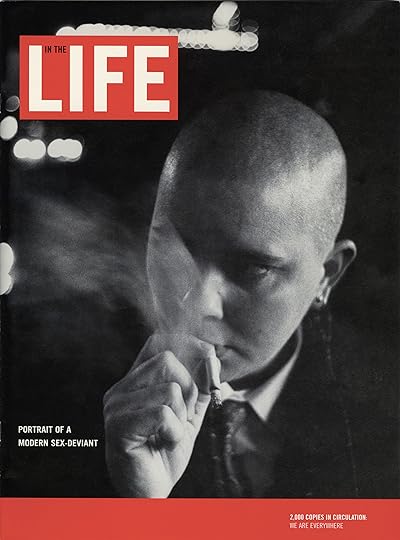

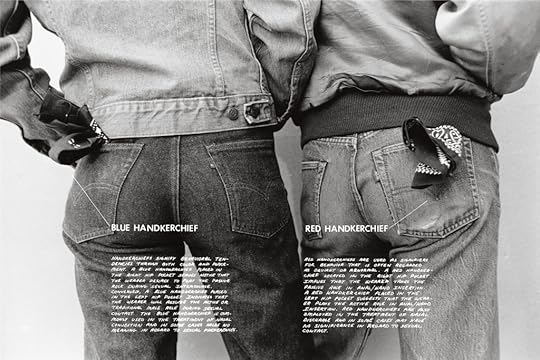

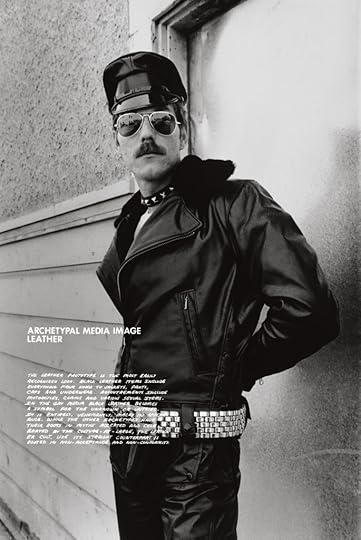

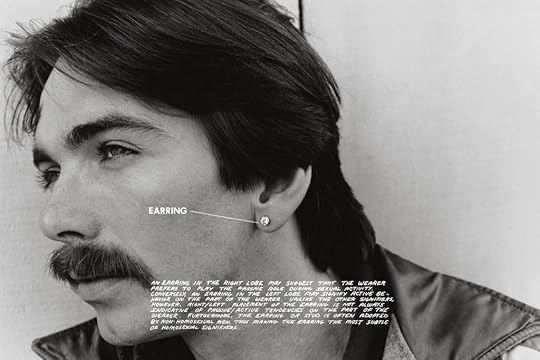

Sunil Gupta’s Vision for a Queer Politics of Belonging

On November 26, 1982, the Guardian, in its Third World Review section, ran a piece with the startling headline “They Dare Not Speak Its Name in Delhi: Sunil Gupta on the Secret Suffering of India’s Homosexual Community.” At the time, being gay in India was still illegal, as decreed by Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, instituted in 1861 during the British rule of India. “One of the best kept secrets in India is the practice of homosexuality, although there is no lack of practitioners from all social classes,” Gupta writes, noting the constant “fear of discovery” and that Indian society “requires the individual to dedicate his/her life to presenting a conventional puritanical public image.” Accompanying the concise text is a single black-and-white image taken by Gupta, picturing a lone man in a kurta, his face cropped from the frame and his body angled away from the camera toward the gardens of the grand Mughal mausoleum Humayun’s Tomb.

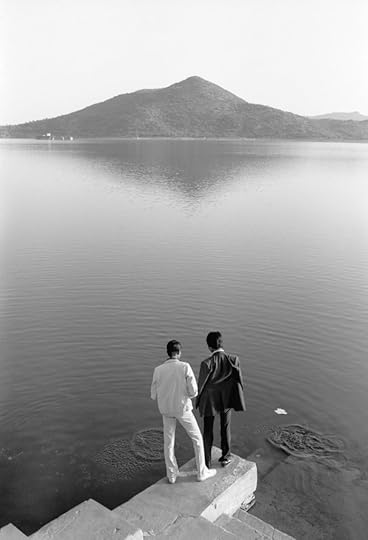

Gupta, who was born in New Delhi, immigrated with his family to Canada in 1969, at the age of fifteen. Having aspirations of being a social-justice photographer in the mode of W. Eugene Smith, he traveled back to India in 1980, receiving a student award from Thames Television to document poverty in the rural Ajmer district of Rajasthan. While transiting through Delhi, Gupta, who had come out by the age of seventeen in Montreal, was curious about urban gay life there and wanted to take some pictures. He quickly realized through a friend, the historian Saleem Kidwai, that a gay underground did exist and that to connect with it all that was needed was “one telephone number.” It was “all word of mouth,” Gupta told me last year. “No one wanted to be in a picture.” Gupta was staggered by how men had accommodated themselves to this situation, where it was not polite “in a Delhi drawing room” to discuss living an out gay life. Frustrated, Gupta made some staged photographs that imagined anonymous men purportedly cruising in various locations around Delhi. The image reproduced in the Guardian comes from this group of fewer than ten gelatin-silver prints that, until recently, were rarely exhibited or published, and were later christened as Towards a Gay Indian Image (1982).

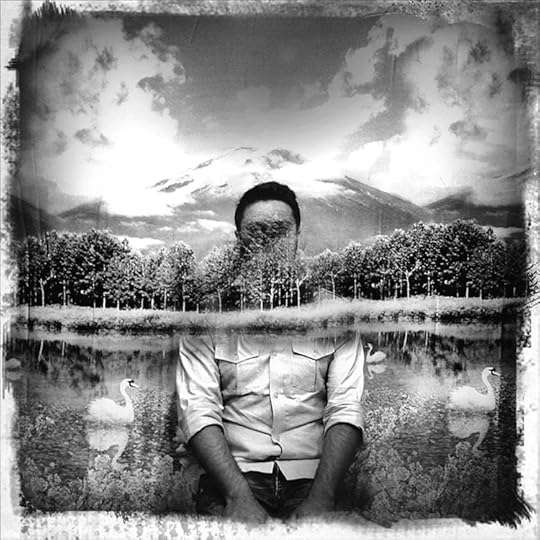

Sunil Gupta, Towards an Indian Gay Image, Lake Pichola, Udaipur, 1983

Sunil Gupta, Towards an Indian Gay Image, Lake Pichola, Udaipur, 1983Unlike the other bodies of work that Gupta had in his portfolio at the time, either straightforward photojournalism or personal photography projects, these images were conceptually driven. They are constructed photographs, with Delhi not merely a backdrop for the experiences of the gay men Gupta directed but a subject itself. Gupta was aware that gay men navigate a city with a distinct agenda driven by searching for a partner or lover. He marked gardens of historical monuments in Delhi as furtive destinations for these men, who, in those unaccounted hours between when work would end at five o’clock and dinner was served at seven, stepped outside their domestic, conventional family lives to have a casual tryst.

For ethical reasons, Gupta decided against simply taking documentary pictures of men who were actually cruising at these locations, as it was “too revealing of people who did not want to be seen.” Instead, he insisted on the visual presence of historical landmarks, recalling a strain of nineteenth-century colonial photography that exulted in the beauty of archaeological sites often evacuated of people, effectively erasing all indications of the society in which they existed. (A rare documentary image of gay subjects, looking out at a lake, which Gupta made from an elevated vantage point in Udaipur, was later used for the cover of Jeremy Seabrook’s 1998 book, Colonies of the Heart.) By explicitly foregrounding and orienting the bodies of his volunteers, either alone or in pairs, their gazes averted from the camera toward these monuments, Gupta inverts and refutes this historical gesture of erasure, expressly confirming the presence of these men and the culture of cruising that was a part of the fabric of Delhi.

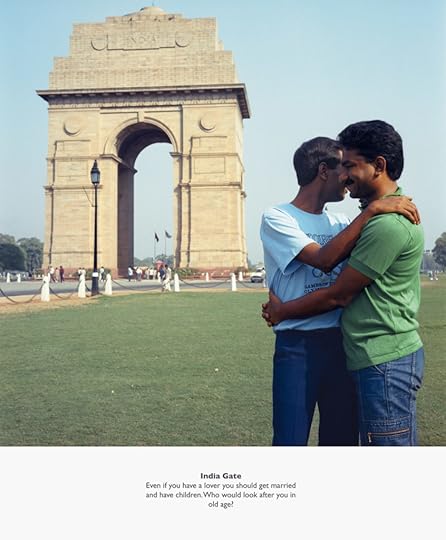

Sunil Gupta, India Gate, 1987, from the series Exiles

Sunil Gupta, India Gate, 1987, from the series ExilesThese experimental pictures are the natural precursors to Gupta’s better-known series Exiles, which he shot from 1986 to 1987. Gupta, who was living in London at the time, returned to India to make photographs at cruising sites. He actively tried to involve the men who volunteered as subjects, printing contact sheets in London and sharing them to ensure that he had their consent to print the photographs, with the understanding that the images would not be shown at the time in India. As an art student, Gupta had not seen any representations of gay Indian men in art, as if, he recalled, “there were no gay Indians.” He was not interested in the casual homosocial interactions visible on the streets of the country that the photographer William Gedney sensitively captured during his two trips to India, in 1969 and 1979. “Exiles was about locating Indian cis men in an international gay landscape,” Gupta told me. “I was very keen that my subjects were explicitly gay men, that the images showed such men for the historical record. We were there.”

Sunil Gupta, Nehru Park, 1987, from the series Exiles

Sunil Gupta, Nehru Park, 1987, from the series ExilesThe geography of Exiles is more expansive: Gupta traversed Delhi, photographing in color. Each image is accompanied by a caption that states the location followed by a few lines from recorded conversations Gupta had with assorted men. The texts do not correspond to the images directly but are drawn instead from disparate thoughts and reflections. One reads, “It must be marvelous for you in the West with your bars, clubs, gay liberation and all that.” Another says, “I am tired of being alone with no prospect of meeting anyone I like. I’m nauseated by the party and park scene.” By contrast, “I love this part of town. It’s got such character and you can have sex just walking in the crowd.” AIDS is mentioned in one caption, but Gupta notes that while there was awareness about the illness in Delhi, “it seemed very distant . . . and everyone thought it was a uniquely American problem”—a situation that was compounded by the Indian Health Ministry’s prolonged public dismissal of the disease.

The hesitancies, anxieties, struggles, and curiosities of men in Delhi portrayed in Exiles offer a stark contrast to Gupta’s own personal experiences in the West. A decade earlier, in 1976, Gupta was standing on street corners in downtown New York taking the photographs that now make up his celebrated series Christopher Street. These gay men were, as he says, “dressed up and showing off.” Confidently, they stride by, unabashedly wanting to be seen, their demonstrative sense of self appearing in direct opposition to the faceless protagonists of Exiles. Christopher Street has received a belated adulatory reception, with a 2019 exhibition and an accompanying book.

Related Items

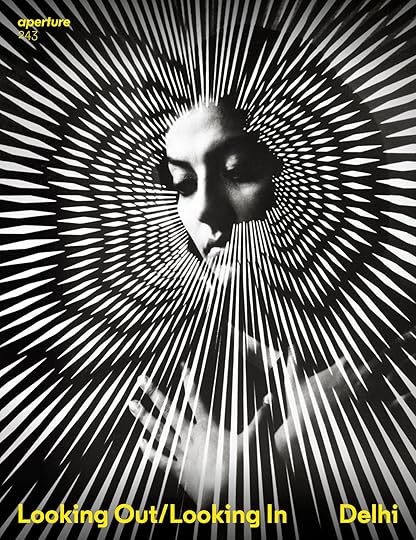

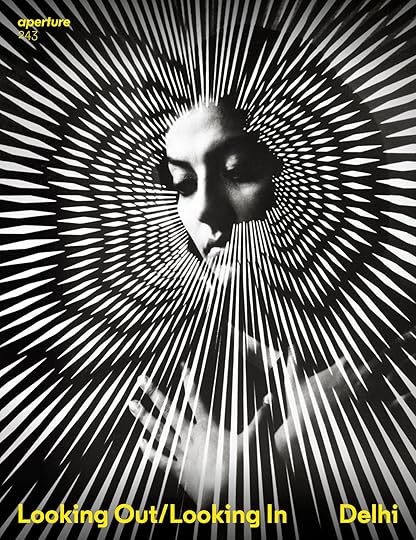

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

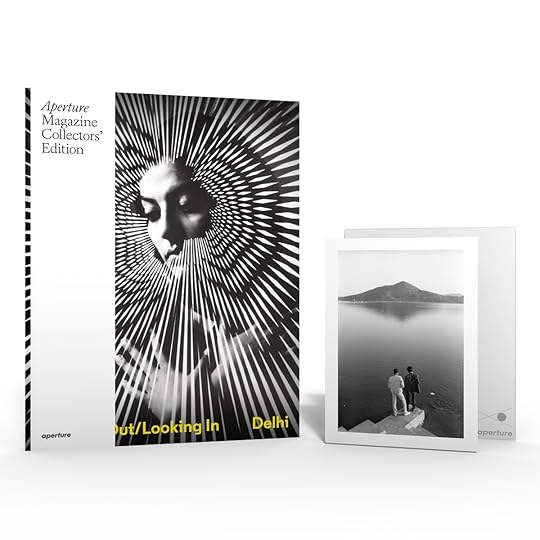

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Sunil Gupta

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Work from Exiles was publicly exhibited for the first time in 1987, as part of The Body Politic: Re-Presentations of Sexuality at the Photographers’ Gallery, London. As Gupta describes it, the work just “sank.” Despite the curator’s attempts to be inclusive, there seemed to be no interest in material from beyond the West. Finally, in 2004, Gupta showed Exiles, along with three other bodies of work, in New Delhi, at the India Habitat Centre, as a belated, affirmative homecoming. In the intervening decades, things had begun to change for LGBTQIA Indians: Shortly after Gupta completed Exiles, the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (AIDS Anti-Discrimination Movement, known as ABVA), the first HIV/AIDS activist organization in India, was founded in 1988, in Delhi. In 1991, ABVA published Less Than Gay, a groundbreaking report demanding the repeal of all discriminatory legislation singling out homosexual acts by consenting adults in private, including Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. While the first petition was unsuccessful, throughout the 1990s and into the early twenty-first century, the battle for LGBTQIA rights continued, with the establishment of newer organizations and collectives and with more reporting in the mainstream media.

Gupta encountered this shift in attitude during the run of his 2004 exhibition at Habitat. The curator Radhika Singh had organized complementary movie screenings, and she invited two organizations to participate, including a queer student group based at Jawaharlal Nehru University. The following year, Gupta returned to India, noting that he wanted “to become part of the changing face of Delhi. And to reconnect with a long-lost gay childhood.”

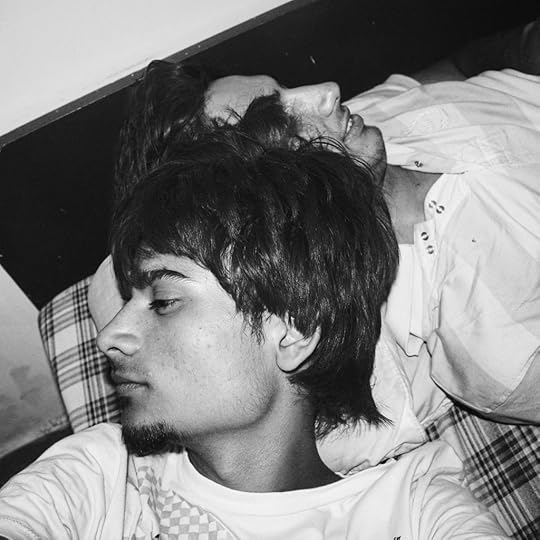

Sunil Gupta, Akash, 2012, from the series Mr Malhotra’s Party

Sunil Gupta, Akash, 2012, from the series Mr Malhotra’s PartyAll photographs by Sunil Gupta © the artist/DACS and courtesy Hales Gallery, New York; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi

Energized, Gupta started working on a new, strikingly different series of portraits, each made on the streets of Delhi. This time, the subjects faced the camera unfazed, calm, resolute, and self-assured within the melee of the city. The people in these photographs—from an extended network of young people he began to spend time with in South Delhi—want to be seen, and, as Gupta noted, are “‘real’ people who identify their sexuality as ‘queer’ in some way.” The title Mr Malhotra’s Party (2007) is a reference to Pegs ’N’ Pints, a local nightclub that held a gay night every week, even though signs posted outdoors advertised a private party under a fictitious person’s name, a subversion of Section 377. The moniker Gupta chose for the host of his “party” was Mr. Malhotra.

Exiles and Mr Malhotra’s Party are, in fact, twinned projects. Gupta was no longer confronted with the clandestine lives of gay men. Instead, the people pictured in Mr Malhotra’s Party assert that they are not disembodied subjects, their forthright presence a testament to the urgent need to contest prejudice and intolerance. Between these two bodies of work, a transit is captured from the isolated, invisible, and private to the collectively proud, visible, and public. As the writer and activist Gautam Bhan has noted, “Cities belong to different publics, no single identity, no single way of life, no one sense of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ can dominate a metropolis. It is in such a city that sexuality could, should, must be able to take its different paths, where it can reach for dignity rather than a bare life.” Bhan wrote these words in 2017, in a dark time, when the 2009 ruling by the Delhi High Court that had struck down portions of Section 377 as unconstitutional had, in 2013, been overturned by India’s Supreme Court.

As the mood shifted, Gupta recalled, from “euphoria to gloom,” he began work on Delhi: Communities of Belonging (2016), a collaborative venture with his husband, Charan Singh, whom he met in 2009 at an HIV/AIDS-awareness community gathering in Delhi. Approached by a U.S. publisher to develop a book on queer life in India, Gupta and Singh focused their efforts on Delhi, photographing seventeen subjects in their homes and workplaces. The pictures are softer, quieter, and at times banal, and read as a sequence of nonintrusive glances. These images reveal how individuals and couples have negotiated and built worlds for themselves, which they inhabit fully without shame. Passages of text accompany the suite of photographs, and, unlike the chorus- like captions of Exiles, they are accounts of the subjects’ lives in their own words. Finally, on September 6, 2018, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the application of Section 377 was unconstitutional, calling it “irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary.”

Anoop Ray, Untitled, Noida, 2010, from the series Friends and Their Friends

Anoop Ray, Untitled, Noida, 2010, from the series Friends and Their FriendsCourtesy the artist

“Sunil has been a key advocate for photographers of color and queer photographers throughout his expansive career,” says Mark Sealy, the director of Autograph ABP, a photography space in London, who curated Gupta’s 2020 retrospective at the Photographers’ Gallery. “His work should be viewed primarily through the lens of an activist—one who understands fully what it means to live in a world full of intolerance and hatred.” A younger generation of photographers across India, whose work is confident, unflinching, and hot, has unequivocally taken up these concerns that Gupta pioneered.

Pulkit Mogha’s 100 Nudes project (2019) has amassed scores of amateur nude selfies voluntarily sent in by South Asian men. Roshini Kumar’s series Bad Company: The Secret Lives of Good Girls (2018) imagines an underground world of unbridled female pleasure, with women exploring the limits of their sexuality. Others have taken a more localized, quasi-documentarian approach: Sandeep T K, Indu Antony, and Soham Gupta have photographed the transgender communities of Kerala, Bangalore, and Kolkata, respectively. Members of the LGBTQIA community in eastern India are pictured in Soumya Sankar Bose’s elegant group of moody portraits Full Moon on a Dark Night (2014–ongoing), in which the sitters are swathed by inky black shadows, metaphorically attesting to the psychological traumas they have suffered because of persecution and marginalization.

Soumya Sankar Bose, Howrah, 2016, from the series Full Moon on a Dark Night

Soumya Sankar Bose, Howrah, 2016, from the series Full Moon on a Dark NightCourtesy the artist

“Today, there is a great explosion of queer photographers and photography in a way that was not possible not so long ago. It has also become diverse in terms of gender fluidity and race,” Gupta says. The younger generation’s insistence on an inclusive politics of community, the coexistence of differing subjectivities that exist outside of conventional heteronormative narratives, follows the legacy of Gupta’s work and activism. In the series Friends and Their Friends (2010–15), Anoop Ray sensitively records the simple and immediate joy of unexpectedly falling into a community that nourishes and sustains. Ray had just moved from a small town to Delhi when he started to take these pictures. “In the metropolitan city,” Ray says, “I saw new relationships and the myriad of expression they held.”

With passion and resolve, these photographers depict their own experiences of community. They are fragile and vulnerable formations, networks of kinships and shared solidarities transgressing generations and borders. For Gupta, the momentum is belated but timely. “Whereas it has taken years for museums to notice work by me and my LGBT contemporaries, our queer graduates are appearing in major museum exhibitions,” Gupta says. “In the 1990s, I thought identity politics had had its day, culturally speaking, but clearly, it’s having a revival. Better late than never.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “We Were There.”

Arundhati Roy Sees Delhi as a Novel

“A novel gives a writer the freedom to be as complicated as she wants—to move through worlds, languages, and time, through societies, communities, and politics,” Arundhati Roy recently wrote. Having risen to international fame with her Booker Prize–winning novel The God of Small Things (1997), Roy is a singular voice in contemporary literature, producing riveting works of fiction, along with a prodigious output of essays that address class, gender, and politics with a moral clarity and urgency that reflect her role as a committed activist.

Born in a small town in Northeastern India, Roy moved to Delhi to study architecture, a background that would shape her work as a writer. Here, the filmmaker and essayist Shohini Ghosh speaks with Roy about the links between the space of a novel and the built environs of the city as well as the political crises and large-scale farmers’ protests that have shaken Delhi and reverberated around the world. Their conversation is illustrated with images by Mayank Austen Soofi, known for his popular Instagram account called “The Delhi Walla,” and a photographer whom Roy considers to be one of the city’s finest, most tender chroniclers. (This conversation took place before the second COVID-19 wave hit India. Read more from Roy on the impact of the health crisis.)

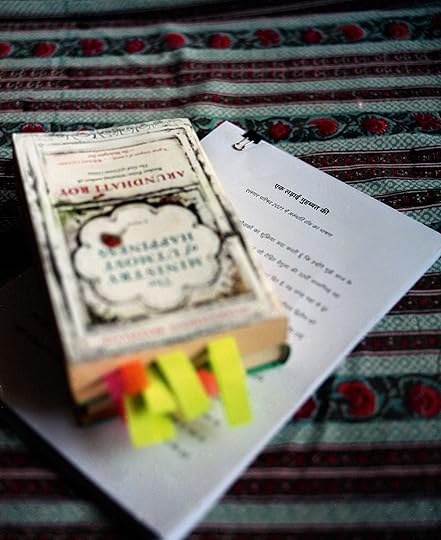

Roy’s copy of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness and a manuscript for a speech about “fighting for love,” New Delhi, February 2021

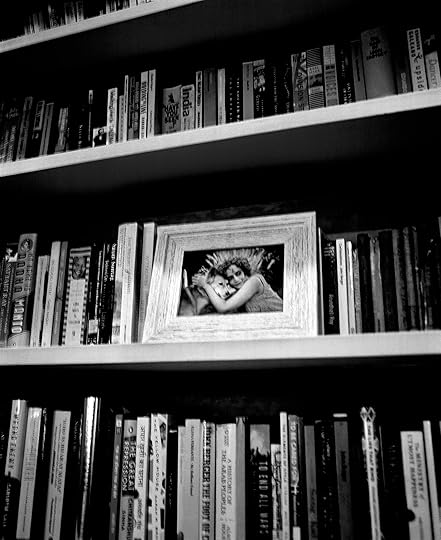

Roy’s bookshelf, New Delhi, February 2021

Photographs by Ashish Shah for Aperture

Shohini Ghosh: How did you end up coming to Delhi?

Arundhati Roy: It was a well-plotted escape from the village and the small town nearby where I grew up in Kerala. As a child, I was surrounded by concentric layers of fear and dread that came from within my home and family as well as from the community. My mother had married “outside” her community—the very closed, casteist, moribund, and elite Syrian Christian community of Kerala—and then she had committed the double crime of getting divorced. So my brother and I, while we did not belong to any socially oppressed caste or community, were made to understand, in a million different ways both subtle and crude, that we did not belong in the home we lived in or the society to which my mother’s family belonged. To me, the message was clear: “Nobody will marry you.” It made me feel, from a very young age, Why the heck would I want to belong? Why would I want to marry any of you? I yearned to escape.

Ghosh: How old were you?

Roy: I fled in 1976, when I was sixteen. I knew I needed to get an education that would make me financially independent. I chose to study architecture. I had been deeply impacted by the ideas of the architect Laurie Baker, who built the school my mother founded and continues to run. I studied there for many years. “No-cost architecture” is how Baker described his work—the most beautiful buildings that were built so cheaply that they threatened the building industry. So at sixteen, as soon as I finished high school, I was on a train to Delhi to sit for the entrance exam to SPA, the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture. The journey was three days and two nights long . . . and I arrived in a different world. When I turned seventeen and was in my second year, I stopped going home. I never went for years. I worked my way through college—of course, I could do that then. Now, things have changed. Now, higher education is closing its doors to those who have no money. Every day, I feel gratitude to this city that liberated me. Now, I do go back home to Kerala. Those old wounds have healed, but they still lurk close to the surface of my skin.

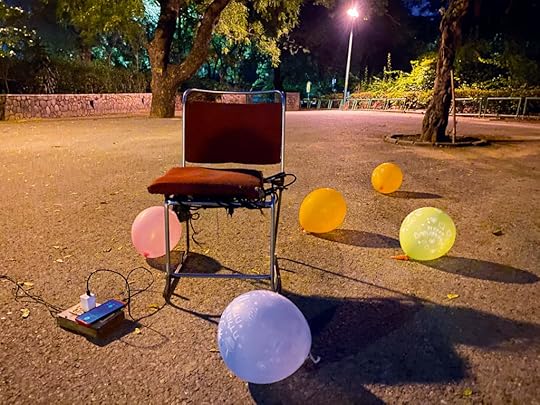

Mayank Austen Soofi, The litter left behind by picnickers around a security guard’s chair outside a public garden, August 2019

Mayank Austen Soofi, The litter left behind by picnickers around a security guard’s chair outside a public garden, August 2019Ghosh: What images of the city do you most remember from that time?

Roy: I remember the excitement of pulling into the railway station. The smell of freedom and the excitement of anonymity. Anonymity is impossible in villages and small towns in India. For me, that was the greatest gift anybody could give me. The infinite possibilities of naughtiness. I was so ridiculous though. When I first arrived, I had no sense whatsoever of the scale and size of a big city. So I went to the auto- rickshaw rank at the railway station and asked a driver if he could take me to Mrs. Joseph’s house. I still laugh out loud when I think about it. Mrs. Joseph was my mother’s sister—a good and decent Christian—who lived in Delhi then. I was to stay with her. She wasn’t thrilled about her nonpedigreed niece’s arrival and made that very clear. So I made it a point to inflict myself and my indecency on her as often as I could.

I was also very frightened of the city. This is because of the films I saw growing up. At the time, in virtually every Malayalam film, the heroine got raped. The rape was always lovingly choreographed, in elliptical ways . . . reflections in the ceiling fan, flowers dropping off their stalks, or whatever. Utterly destroyed women. As a result of this, I grew up believing that every woman gets raped. It was just a question of where and when. So in that auto rickshaw, on my way to Mrs. Joseph’s house in Delhi, I clutched a knife hidden in my bag. I was fully prepared to meet my womanly future. The first few days in the city were intimidating . . . but then . . . the school of architecture. Anarchist heaven. I knew I had escaped forever. I would be safe in a dangerous sort of way.

Mayank Austen Soofi, A homeless dog always seen sitting on a centuries-old stone bridge that runs over an artificial lake, February 2021

Mayank Austen Soofi, A homeless dog always seen sitting on a centuries-old stone bridge that runs over an artificial lake, February 2021Ghosh: Before you wrote The God of Small Things, you wrote two screenplays: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1988) and Electric Moon (1992). Did the city play a role in shaping you as a writer?

Roy: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones is about students in architecture school—stoned, bell-bottom-wearing hippie kids in the 1970s. Annie is actually a man, Anand Grover, who is repeating his final year for the fourth time, the victim of one professor’s vendetta. Annie’s a little eccentric, a little defeated. He rears chickens and rabbits in his hostel room and is obsessed with how to handle what he calls “rural–urban migration.” Although I opted for architecture because of a kind of desperation to begin to earn a living, the five years I spent there have laid the foundation for the ways in which I see and think.

By the time I was in my final year, I was almost as interested in urban studies as I was in architecture. My thesis was not a design thesis. It was about the city, postcolonial Delhi, how it came to be what it is, what it does to the people who live in it. The city and the noncity. The citizen who is welcome and for whom the city and its laws are made.

The noncitizen who is unwelcome and lives in the cracks between institutions, who subverts laws as well as the imagination of the urban designer. Who shits on top of the sewage system. That lens, that way of looking at our cities, has remained with me through my screenplays and my novels. To me, the city was and is a fascinating, never-ending story. It’s a novel with characters who appear and disappear, shaping the physical space around them.

Mayank Austen Soofi, Protesters in an area reserved for women during a late night candle- light vigil against the Citizenship Amendment Act, February 2020

Mayank Austen Soofi, Protesters in an area reserved for women during a late night candle- light vigil against the Citizenship Amendment Act, February 2020Ghosh: When you wrote The God of Small Things, you were living in Delhi and writing about a place that was far away in space and time. How did that work out?

Roy: It didn’t seem to matter one bit. The village I grew up in, the pickle factory, the landscape, the people, the green river, the coconut trees that bent into it, the broken yellow moon reflected in it, the flash of fish—I am made up of all that. I am that. No matter where I go. I knew every plant and worm and fish and insect; they were characters in my life. As oppressive as the humans around me were when I was growing up, the river and the insects, the rain and mud were my pals. But perhaps the physical landscape of Kerala was conjured up more vividly in The God of Small Things because it was so different from the place that I was living and writing in.

Ghosh: For me, the experience of reading The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was like learning to navigate a copious landscape. In one of the chapters in the book, a character called Khadija takes one of the protagonists, S. Tilottama (or Tilo), on a journey across a city in Kashmir. They travel, and I quote, “through a maze of narrow, winding streets in a part of a town that seemed to be interconnected in several ways—underground and overground, vertically and diagonally via streets and rooftops and secret passages—like a single organism. A giant coral or an anthill.” This could well be a description of the teeming metropolis that is Utmost Happiness, in the alleyways of which the many interconnected narratives of the novel unfold. Did your training as an architect and urban planner have an impact on structuring the novel?

Roy: Yes. The city as a novel—the novel as a city. Truly, I think like that. And I don’t just mean the physical landscape of both cities and novels. I mean it more in the manner of how something is designed, and then that design is subverted, ambushed, enveloped, and turned into something else, and then all of that becomes a part of another design, and on it goes. Something like the way the shapes of cities inscribe themselves spatially on the surface of the earth as distinct from the amorphous countryside that surrounds them. They have a form, a logic that is not immediately obvious, except, of course, imperial cities that were created by fiat and decree. But those, too, are subverted. In the novel, too, this happens often to the narrative. And yet, it’s only once you begin to live in the novel-city of Utmost Happiness that you understand that the apparent chaos is designed. It, too, has its underground, overground, and diagonal pathways that interconnect. It has its own complicated logic.

If you remember, there is a passage in which Tilo thinks about the city . . . It’s a sort of wakeful reverie. She thinks of cities like starlight traveling through the universe long after the stars themselves have died— “fizzy, effervescent, simulating the illusion of life while the planet they had plundered died around them.” So there’s that awareness not just of the city, but of the meaning of the city. Right now in Delhi, the confrontation between the city—the seat of political and economic power—and the countryside, and the plundered planet is playing out in a literal way. As we speak, millions of farmers have risen in protest against three new farm laws that will put the levers of control of Indian agriculture in the hands of major corporations. Over the last twenty years, hundreds of thousands of farmers caught in a debt trap have committed suicide, many by drinking the pesticide they are being forced to use to grow crops that the market wants but their land does not support. And now, with these new laws, they are facing an existential crisis. Hundreds of thousands of farmers have arrived on the outskirts of Delhi. It’s being called the biggest protest in human history. The government has barricaded the city with concrete barriers, concertina wire, and iron spikes, and the area is being patrolled by thousands of police and paramilitary. The borders are no longer just national borders. New battles are unfolding. In Utmost Happiness, those conflicts are folded into one another—the freedom struggle in Kashmir, the rise of Hindu nationalism in India, and the many conflicts, environmental and political, that are displacing and devastating people in myriad ways. All these are connected to one another like a maze of city streets.

Related Items

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Sunil Gupta

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Ghosh: In its magnificent embrace of people (living and dead), creatures (birds, mammals, bugs), and places (from the dystopian to the paradisal), Utmost Happiness imagines a world where the nonhuman is integral. Even in The God of Small Things, the world in which the narrative unfolds is as important as the protagonists themselves. In your universe, it seems to me, the human predicament is inextricably linked to the nonhuman.

Roy: Not everybody notices that, actually. I remember somebody telling me that she thought the hum and scurry of insects and other creatures in The God of Small Things were like a background music score. She could hear them. I am incapable of looking at the world, or even thinking about it, with only humans at its center. How can we take anything—any discourse, any ideology, any religion even—that is exclusively about human beings seriously? It’s a sort of violence. A futile, blinkered, foolish violence.

Of course, in The God of Small Things, the landscape and its nonhuman populations wrap themselves around the human protagonists. But even in Utmost Happiness, the nonhumans are an integral part of life. There is so much nonhuman activity even in our most densely populated metropolitan cities, and it’s not just pets on leashes. There are crow conferences, street-dog conclaves, horse confabulations, monkey madness. All you have to do is keep your eyes and ears open—and yes, your heart too—and whole other cities and city-stories will make themselves known.

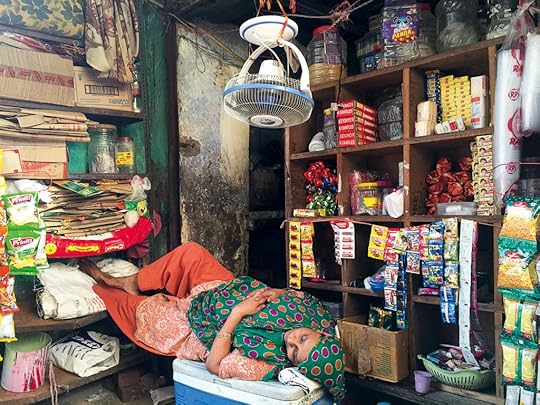

Mayank Austen Soofi, A grocer enjoying her siesta, May 2018

Mayank Austen Soofi, A grocer enjoying her siesta, May 2018Ghosh: The COVID-19 pandemic and the complete lockdown in March 2020 transformed the images and imagination of the city. As a majority of the inhabitants locked themselves in, you ventured out into the streets. What did you see?

Roy: I saw what the rest of the world saw, except not just on my cellphone screen. When Modi announced the world’s strictest, cruelest lockdown, giving 1.3 billion of us just four hours’ notice, it became obvious that he had absolutely no idea about the country he is the prime minister of. He was just copying what was being done in the United States and Europe but in a more authoritarian, autocratic way. The previous week, he had asked people to come out on their balconies and bang their pots and pans and ring bells! Like people had in Europe. How many people have balconies in India? It was ridiculous. Lockdowns in affluent Western countries were to enforce physical distancing. But here in India, in the densely populated slums and shantytowns, it enforced the opposite—physical compression. The day after the lockdown was announced, India spilled its terrible secrets for the world to see. Millions of working-class people hidden away in the crevices of big cities—the noncitizens of my architecture thesis—working for a pittance in informal, unregulated jobs, found themselves out of work, unable to pay rent for the cramped tenements they lived in. A mass migration began—biblical in its scale. Millions of workers and their families began walking thousands of miles home to their villages. On the way, they were beaten by the police, hosed down, killed by trains as they walked on railway tracks, held in containment camps. As soon as I saw the streets of our city turn into this river of COVID refugees, I went out. I saw the scenes on the Delhi–Uttar Pradesh border. I walked part of the way with some of the walking people.

Mayank Austen Soofi, Arundhati Roy walking late at night in the historic quarter of Old Delhi, November 2016

Mayank Austen Soofi, Arundhati Roy walking late at night in the historic quarter of Old Delhi, November 2016All photographs courtesy the artist

Ghosh: Well over a year later, what has been the consequence for the city?

Roy: The result of this lockdown that wasn’t a lockdown is that the virus spread across India. Fortunately, it hasn’t proved as devastating or as fatal as it has been—and continues to be—in more affluent countries. But the lockdown caused an already severely slowing economy to crash. The urban economy collapsed. India’s GDP shows deep negative growth. In all this devastation, even though agriculture is generally in crisis, during the COVID pandemic, farmers continued to work their fields, so we did not have a food-production crisis. But if all this awfulness isn’t enough, now farmers, too, have been dealt a blow from which they may not recover. Unless we all stand with them and force the repeal of these new laws. So here’s the latest chapter in the story-city and the city-story. Last year, millions of workers were forced to leave the city. This year, millions of farmers have arrived at its outskirts. Between these two events lies an epic tale. The story of our times.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Looking Out/Looking In: Delhi,” under the title “Arundhati Roy: The City as a Novel.”

June 10, 2021

How Three Photographers Are Working through India’s COVID-19 Crisis

koī haath bhī na milā.egā jo gale miloge tapāk se

ye na.e mizāj kā shahr hai zarā fāsle se milā karo

(You’ll be refused a handshake if you go for an ardent embrace.

This city’s in a fresh temper, keep your distance when meeting.)

—Bashir Badr

It has been a year of looking out windows and doors that frame the world like crude viewfinders, of observing caution and of seeing from afar. For lens-based practitioners, distance, the defining condition of the COVID-19 pandemic, is an aesthetic concern as much as a hygienic one. Photographers interpret and render subjects through intimacy, remoteness, or even just an acknowledgement of the space in between. The camera’s manipulability can extend the human eye and, therefore, presence to cover spans proscribed during a time of contagion or bring its details into focus. As India battles its second wave of the novel coronavirus, photographers are either out on the streets documenting the crisis or confined to their homes, focusing on their loved ones. In my rented apartment in the hard-hit Indian capital of Delhi, I’m on the phone with photographers who’ve retreated to their hometowns, and they tell me that the temporal distance between when their work was originally shot and the present appears disorienting. Will the city they photographed exist on the other side of the pandemic?

Prarthna Singh, Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh: One Hundred Days of Resistance, New Delhi, 2020

Prarthna Singh, Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh: One Hundred Days of Resistance, New Delhi, 2020Courtesy the artist

Prarthna Singh has held onto the moment of the protests against India’s amended citizenship law through the bonds she forged there a year and a half ago while making Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh: One Hundred Days of Resistance (2020). She exchanges voice notes with a young woman she befriended there who lost her mother to the virus. “Perhaps without this collective grief, I wouldn’t have noticed this tender aspect of the work I do,” Singh says. Though she has been on assignment in between the Indian government’s strictly enforced national lockdowns, 2020 allowed her to step back and reflect. Ironically, it has brought her closer to her subjects, many of whom exist at the edge of visibility: “Photography is a starting point, the camera just an opener. My practice doesn’t stand in isolation,” she says. “It’s the relationships formed because of it that make me believe in its worth.”

Singh is based in Mumbai, although she spent two months of India’s second wave with her parents in Jaipur. Two of her current projects include a series on people held as illegal immigrants in Assam’s detention camps, and a collaboration with journalist Snigdha Poonam comprising images of young voters in the run-up to India’s 2024 general election. She hasn’t changed her approach in the wake of the pandemic, continuing to have involved conversations with those she photographs, mask and all. At home in Jaipur with her parents, she turned down commissions requiring her to be outdoors for the sake of their health. But there are other consolations. “I’ve been photographing my mother a lot, which I’d never done,” Singh says. “Now I have this fear of losing my parents.”

Aditi Jain, Maze of Binaries, New Delhi, 2019

Aditi Jain, Maze of Binaries, New Delhi, 2019Courtesy the artist

Family members are a natural subject during this housebound period. In her hometown of Bhopal, Aditi Jain has also been photographing her mother, as well as the latter’s paintings and craftwork, as a way to retain the creative momentum she worries has been adversely affected by the pandemic. “I’ll shoot in my garden, even birds on the terrace. I’m someone who needs to be photographing all the time,” she tells me. In the course of developing her series Maze of Binaries (2019), on Delhi’s transgender community, Jain became deeply attached to her subjects. Given the current context, when those already marginalized by the state face further financial precarity and emotional turmoil, maintaining these long-distance friendships has become even more important. As we discuss COVID-19 and how she sees an artist’s role in times of distress, Jain brings up the work of her idol, pioneering photo-essayist W. Eugene Smith, whose photographs, she says, “communicate that pain does not belong to an individual person but is felt by society.”

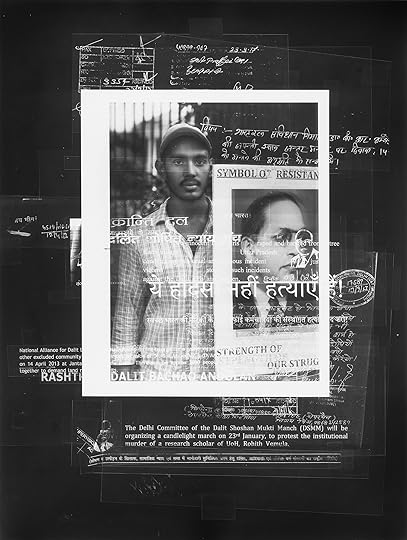

It’s a sentiment shared by Uzma Mohsin when she asserts that “the role of art is to address crises.” Sensitivity to sociopolitical upheavals permeates Mohsin’s transparent photomontages that combine citizens’ applications to organize protests in Delhi with portraits from Jantar Mantar, the city’s iconic protest site. No dissenting crowds can congregate there now. Mohsin herself is away from the capital, in her native Aligarh, making visual journals and photograms in the absence of a darkroom. (During the Citizenship Amendment Act protests in December 2019, Aligarh Muslim University made headlines when its students stood up to the regime and faced its wrath.) Staying home is working out for Mohsin. “I received a grant to do a photographic study of Aligarh and its significance as a locus of liberal Muslim life,” she says. “Right now, since I can’t meet people, especially older folk I’d need to speak to for this project, I am reading a lot of history.”

Uzma Mohsin, Songkeepers, New Delhi, 2018

Uzma Mohsin, Songkeepers, New Delhi, 2018© the artist

Made toward the end of the first term of the Hindu fundamentalist Narendra Modi–led government, Mohsin’s series Songkeepers (2018) appears prescient and impossible to replicate now. I wonder aloud whether the Delhi we emerge to will be the same one we sheltered from. “A lot has changed since I accessed those Right to Information applications in Delhi’s police headquarters,” Mohsin says. “Now the city’s government buildings are inaccessible. As the virus keeps us apart, there’s a sense of being kept at a distance by the state too.”

Mohsin is referring to the Central Vista Redevelopment Project that anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has characterized as “the mausoleum of the spirit of Shaheen Bagh.” Ostensibly a renovation of the central administrative complex designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker in the early decades of the twentieth century, the project is, in fact, an ominous signal. The Central Vista has served as the chief node of the postindependence capital of New Delhi for more than seventy years. Its reconstruction is widely understood as the architectural erasure of a secular, democratic republic and its replacement by the ninth city of Delhi—the heart of a Hindu nation.

The adjustment of focal length integral to photographic practice has, over the past two years, become a mode of ordinary living for humans worldwide, as proximities are modulated at various scales—literal and symbolic. The angles and distances at which Singh, Jain, and Mohsin capture Delhi’s oft-ignored citizens enhance the city’s peripheral vision. I ask the three photographers if the pandemic made certain compositional choices challenging—if, for example, the close-up might go out of style for a bit. Jain and Mohsin agree. Singh shrugs; the close-up was never her favored shot anyway. “I maintain space between myself and my subjects,” she says. “I prefer giving them room to breathe.”

Read more about Aditi Jain, Uzma Mohsin, and Prarthna Singh’s photography in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In” (Summer 2021).

In Delhi, Dynamic Images and Shared Solidarities

We are described into corners, and then we have to describe our way out of corners.

—Salman Rushdie, in an interview with W. L. Webb

In April 2019, as the general elections in India dominated the media, an international team of astronomers published the first photograph of a black hole, silhouetted against a disc of glowing gas surrounding this cosmic void, the threshold beyond which not even light can escape. The image showed us what we thought could never be seen, almost two centuries after the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce used a camera obscura to take the world’s first photograph, looking out from his second-story workroom. These acts of imaging have generated a radical, fundamental warping of the space-time of human consciousness and triggered a cultural “event horizon,” by mapping the existential coordinates of memory, genealogy, ecology, aesthetics, history, and geography.

The “aura” of images proliferates beyond time and space, exemplified in this issue by works from both within and outside Delhi, and by various eras, cultures, and media. My mandate as guest editor was to build on previous city-centric issues of Aperture, but as a curator managing a collection, visiting personal repositories, and researching in state and private archives, I am aware that image making is always in the process of expansion and reflection, regardless of frame, paradigm, and aesthetic scaffolding. Through continued engagement with Aperture’s editorial team and independent artists, and while considering the possibility of addressing new audiences, we have tried to offer visual convergences, juxtapositions, and inversions, hoping to explore the forever growing parameters of place and to suggest the migratory, the mutable, the transient.

Sumit Dayal, Studio Self-Portrait, Srinagar, India, January 2009

Sumit Dayal, Studio Self-Portrait, Srinagar, India, January 2009Courtesy the artist

Delhi, where I live and work, serves as only one complex node of visual possibility, but it can proffer a conceptual prism for the diffraction of evolving photographic practices, perspectives, and forms in and outside the region, with innumerable offerings yet to be made. This city, for me, is also bound to family, one that moved here from Mumbai half a century ago. It is where my thespian grandfather, using the backdrop of medieval ruins, staged productions of the famous play Andha Yug (The Age of Blindness) that draws on the Mahabharata, a classical Indian epic about warring royal clans who clash in a momentous battle. Andha Yug, written in 1953 by the renowned Hindi litterateur Dharamvir Bharati, can be read as a fierce castigation of the politics and politicians complicit in the atrocity of Partition, and as an allegory that continues to reverberate in the present with Delhi’s political position as the seat of assertions and abuses of power.

In this issue, the urban environment is a locus for the dynamic intermeshing of place, personal history, art practice, and radical critique, as seen in Shohini Ghosh’s interview with the writer-activist Arundhati Roy and in Christopher Pinney’s interview with the photographer-activist Shahidul Alam. It was my privilege to invite Alam to the city for a lecture, pre-lockdown, in 2019, and I was absolutely dismayed when the state and its machinery prevented his journey. Undeterred, Alam delivered a riveting talk via Zoom from an airport lounge. Even this interpersonal media may now be regulated.

The social mapping of urban terrain— its people, persuasions, seductions, illusions, and claims—is presented through fascinating interrelationships: Roy compares the city to a “novel with characters who appear and disappear, shaping the physical space around them.” Latika Gupta’s exploration of films/moving images by Anamika Haksar and Priya Sen looks in and delineates how these works capture an “old” and a “new” Delhi through the city’s restless, granular meta-histories as well as its embodiment of urban aspiration and dream, idealism and pragmatism.

Gulmehar Dhillon, Haal Mureeda Da (Plight of His Disciples), New Delhi and Gurgaon, 2019–ongoing

Gulmehar Dhillon, Haal Mureeda Da (Plight of His Disciples), New Delhi and Gurgaon, 2019–ongoingCourtesy the artist

The lines of sight generated by this issue are intended to manifest through associations and touchpoints that highlight many other sites and works of resistance, albeit not in this single issue. To name a few: the work of Masrat Zahra; the cross- exposed portrait/landscape of a war-torn occupied Kashmir, now acknowledged to be one of the most militarized zones on Earth, by Sumit Dayal; the careful amalgamation of Dalit as well as feminist histories by the Nepal Picture Library; and even the Partition-related photographs by stalwarts such as Rashid Talukder in Bangladesh. The iconography of resistance grows by the day, and it has been an important vector, contributing to the creativity of subcontinental image makers who may or may not self-identify as cultural nomads, their visualizations an organic means of seeing the world, being in the world, and inscribing the world.

Many worlds within and outside Delhi are under threat of being erased. In the 1980s, I would find myself on the steps of the city’s iconic modernist buildings, such as the arts hub Triveni Kala Sangam, designed by Joseph Allen Stein, built in 1963. The modernist legacies of such constructions in the country have been captured by a handful of pioneering photographers, including Madan Mahatta, Lucien Hervé, and Werner Bischof. Mahatta’s documentation of the buildings— which highlight revolutionary architects of that era who used local materials and occasionally amalgamated American and German cultural strands, as suggested by the architecture critic Kaiwan Mehta—is increasingly resonant as the present government is destroying many iconic edifices in a grievously misplaced, myopic bid to further “modernize.” “Nationalism diminishes us, because . . . its principal human activity is war,” states Stein. Perhaps the internationalism of the mid-1950s that he was a part of in India must now be read against the backdrop of a larger community experience, and the uncertain future of urban heritage that is seen or indicated in Mehta’s piece through the work of Rajesh Vora and Akshay Mahajan.

Related Items

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Sunil Gupta

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Contemporary practice also leans on postindependence modernist trajectories in the visual arts that fostered interdisciplinary initiatives such as the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), founded in Bombay (now Mumbai) between 1969 and 1972, which brought together painters, filmmakers, a cinematographer, an animator, a psychoanalyst, and the resident artist, Krishen Khanna. VIEW provided resources such as books, slides, and cameras, editing and projection facilities, a darkroom, and an etching press. It was a unique creative space in India that supported multimedia art based on aesthetic and conceptual collaborations among skilled exponents in various fields. Simultaneously, in print culture, we saw the rise of certain image- rich publications, particularly the Illustrated Weekly of India, explored in an essay by Sabeena Gadihoke as one of the first magazines available in the subcontinent. Designed in accordance with trends in international magazines, the Weekly featured news, analysis, commentary, and photo-essays as well as articles on popular culture. Priding itself on its role in developing a progressive public sphere, it followed a formal pictorial aesthetic even while it supported photojournalism.

The Pictorialist tradition was established by many regrettably under-acknowledged artists, including the virtuoso O. P. Sharma, whose work is included here with an essay by Diva Gujral. Sharma was also the founder of the India International Photographic Council, in 1983. The genre persisted in India postindependence and in South Asia through the numerous camera clubs and hobbyist associations that are still active today, and can also be seen in newer initiatives such as Film Foundry in Nepal. Sharma’s early experimental images that deviate from the pictorial are juxtaposed in this issue with more recent stark, dissenting counternarratives. Uzma Mohsin uses montage to layer images of the human actors protesting for their beliefs with textual evidence of claims and counter-claims surrounding these events, which occur within an intensifying ethos of toxic supremacist hate speech, erasure of civil liberties, and punitive crushing of dissent.

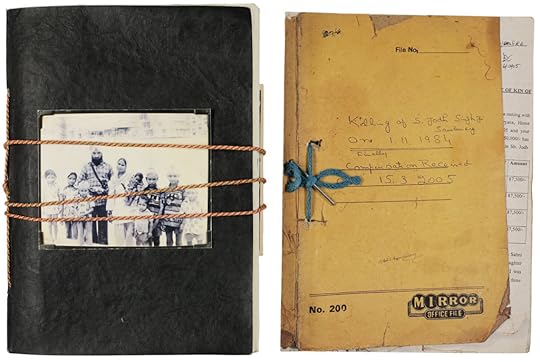

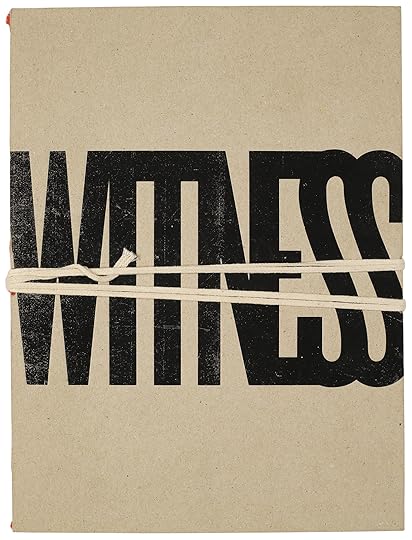

Cover of Witness: Kashmir 1986–2016, Nine Photographers, edited by Sanjay Kak (Yaarbal Books, 2017)

Cover of Witness: Kashmir 1986–2016, Nine Photographers, edited by Sanjay Kak (Yaarbal Books, 2017)Ishan Tankha depicts the antigovernment, leftist, rural Naxal movement of the late 1960s through humanist images of its comrades taken from 2007 to 2015. Tankha’s images also point to recent moves by the state to attack, imprison, and subjugate the newly identified, present-day “urban Naxal.” Activist energies, and different forms of forensic yet poetic analysis, also manifest in the grounded work of Sheba Chhachhi, the contributions of Sunil Gupta, and the images of Aditi Jain, who all explore the construction of feminism and queer identities and lend voice to the censored, the cast down, the silenced.

My interest in learning from contemporary regional practices and lens-based artists began a decade ago through PIX, an exhibition and publishing initiative for visual discourses from or about South Asia. Anshika Varma’s focus on artist collectives in the broader South Asian region underscores how diverse artistic collaborations become a means of crossing frontiers and cultures—especially when current political tensions make those actual journeys difficult or impossible. These collectives raise questions about South Asian identity at a time of mass separation, uprooting, and exile, and hence, the very meaning of so-called national identities and related conflicts.

Varma’s contribution is also indicative of important festivals in the region—Chobi Mela, Photo Kathmandu, Chennai Photo Biennale, and Yangon Photo Festival, among others—that manage, against serious odds, to systematically document the simultaneous reification and expansion of the local, the domestic, and the Indigenous. These events and institutions can be read alongside earlier histories, such as those of the contested and short-lived biennials of photography that were organized by the Lalit Kala Akademi (National Academy of Art), in and outside the city, in 1989 and then 1993.

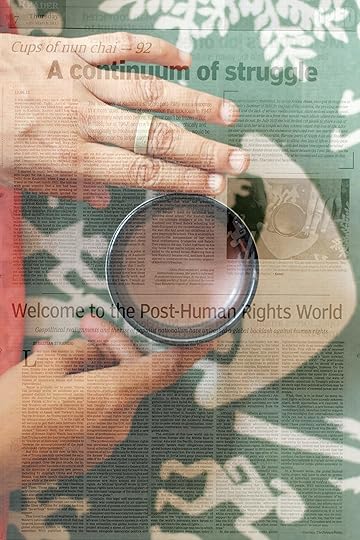

Alana Hunt, Cups of Nun Chai, 2010–ongoing

Alana Hunt, Cups of Nun Chai, 2010–ongoingCourtesy the artist

The thematic trajectories encountered in this issue are both internal and external, abstract and intimate, as seen in the work of Srinivas Kuruganti, who focuses on South Asian diasporic communities in the United States. A continuing exploration of the interpersonal is also seen in the flourishing genre of photobooks—even unpublished ones such as Gulmehar Dhillion’s anti-Sikh riot diary of 1984—and is further discussed by Deepali Dewan in conversation with Indu Antony and Kaamna Patel, who present the entanglements of memory as well as sociopolitical critiques. This form is increasingly oriented toward shaping a more inclusive political imaginary and hospitable, yet complicated, definitions of home and community—profound connections of which are seen in imagery from the protests at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi by Prarthna Singh, which mark the ever-fraught identity politics of an outdated “nationalism,” and harness the revolutionary embrace of shared solidarities. And they also make me consider the hallowed space of publications brought out by Yaarbal Books around Kashmir’s past and present, including Witness: Kashmir 1986–2016, Nine Photographers (2017), edited by Sanjay Kak, and Cups of Nun Chai (2020) by Alana Hunt.

While the photograph is usually thought of as a concluded moment, the theorist Ariella Azoulay asserts that photography is an ongoing event that is “subject to a unique form of temporality— it is made up of an infinite series of encounters.” The images in this issue invite our continued engagement and encourage us to contemplate events happening elsewhere. But what is it that we, as image makers, as participants, or as spectators, ultimately encounter in photographs? At a time when Delhi, as other cities and towns in India, has experienced the devastating effects of pandemic through another shattering surge—drone footage of overcrowded and ad hoc crematoriums; floating, abandoned bodies in the Ganga river; a government in denial about the scale and cause of mortality and the appalling lack of beds, oxygen, and ventilators—one may scrutinize, yet again, the true nature of images being relayed day after day.

The visuals we generate embed “event horizons” that reveal the multiple dimensions of the “real.” And so, whatever our location, we might agree that, in myriad ways, lens-based practices serve as an uncompromising reminder of our finitude as well as our plenitude, in this or any other “age of blindness.”

This essay and photographs originally appeared in Aperture magazine, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In.”

June 9, 2021

A New Digital Platform Asks What Truth Means in Photography

Chris Boot: Earlier this year, you started a website for photography debates and as a meeting place for ideas, Truth in Photography, which has just launched its second edition. Can you start by telling me why the focus on truth?

Alan Govenar: Issues of truth are more pressing than ever. We’re all looking for truth, particularly as it relates to current events, news, photography. The possibilities for manipulation of the truth have never been greater, given the technological advances over the last decades. Truth in photography is a question, not an answer. Truth in photography is a perception. It’s a feeling. In many ways, it’s intangible.

Boot: It’s clear from the second edition that the arguments and issues are evolving. It ranges from Nigel Poor’s work within the prison system, The San Quentin Project, that began as a feature in the “Prison Nation” issue of Aperture magazine and is now a book, published by Aperture.

There’s a piece about the Bronx Documentary Center, another about the girls of Quran schools by the Magnum photographer Sabiha Ҫimen.

Govenar: She is one of the most fascinating new contributors. What’s particularly interesting is that she is a young photographer, and this work related to the Quran schools is her most personal. She told me that in these photographs, she sees herself. She attended Quran schools. Her sisters attended Quran schools. And what she has been striving to depict in her photographs is a sense of what the girls are experiencing, how they manifest their inner lives. Growing up, she was told by her mother that the headscarf was liberating, that if she wore a headscarf, then she could mix in the world. But her mother was also committed to her getting a secular education. So, for her to go into the Quran schools—not only is she in some sense realizing a truth about herself, but she’s also looking at how these girls dress essentially the same, how they engage in group activities, what their fantasies are.

Sabiha Çimen, Nehir (18) embraces her soulmate at a picnic in Istanbul, Turkey, July 15, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, Nehir (18) embraces her soulmate at a picnic in Istanbul, Turkey, July 15, 2018© Sabiha Çimen/Magnum Photos

Boot: Her text is incredibly powerful. It’s probably relevant to mention that she’s Turkish and grew up in Istanbul, so she’s right at that crossroads of the secular West and the Muslim East. What she has to say about her adoption of the scarf and how that changed her and made different kinds of photographs possible is a moving piece of writing in addition to the photographs.

Her work, in a way, is both core to a kind of changing set of values in photography, which, judging by the content of Truth in Photography, you’re thinking about and monitoring. And clearly, the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements have had an enormous impact on the field. Do you see a new ethics for photography emerging, and if so, how would you describe the contours of that?

Govenar: I think the awareness, the consciousness, of ethics in photography have become more apparent, more visible. Photographers are having to discuss ethics, perhaps in a way that they have not before. But historically, for me, the ethics of photography are never neutral. Photographers and photography take a position, a point of view that’s inherent to the framing in which the images are made. This has always been an issue. Issues of truth are time-honored and time-debated, maybe time-disregarded. But we now face this floodgate of images daily. We have to somehow try to make sense of them.

Boot: It does feel like the words “cultural revolution,” as they apply to what’s happened in the last few years and particularly last year, have real meaning here. Would you agree with that?

Govenar: I would. But I think in a larger sense, it’s not only those issues. It’s the systemic issues, because so much of the production of photography, particularly as it relates to photojournalism, is driven by magazine editors, newspaper editors, online news editors.

And then the other spectrum is fine art photography—or what we like to think of as fine art photography, when in fact, for me, it’s a kind of artificial hierarchy that emerges in photography beginning with Stieglitz. While photography is perhaps, intrinsically, the most democratic of all art forms—anyone can make a photograph if you have a camera, and it’s become easier—but photographs are not considered equal. The technical and aesthetic criteria by which we judge them is also part of the issue: How do we see the image? How do we feel the image?

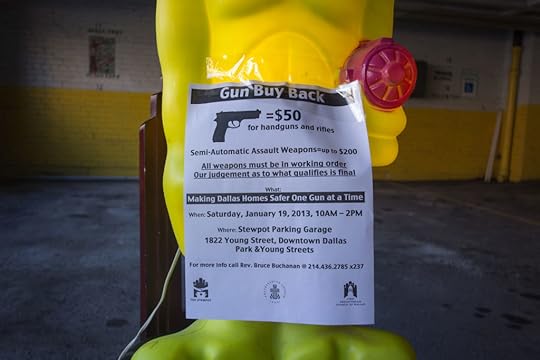

Those are the issues that are not often discussed. But then how are the subjects that photographers focus on prioritized? One of the areas in the spring edition that we introduced is this idea of the struggle for gun control. I was very surprised to find, in searching the Magnum photo archive, that there were no photographs ever made of gun buybacks, which have been happening for decades in the United States and in other places around the world. We’re featuring a portfolio of work by Alessandra Sanguinetti of the March for Our Lives protests. She photographed one of these demonstrations. They were held all over the country.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Analy High School students stage a walk out during a nationwide protest for gun control. Sebastopol, California, March 14, 2018

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Analy High School students stage a walk out during a nationwide protest for gun control. Sebastopol, California, March 14, 2018© Alessandra Sanguinetti/Magnum Photos

Boot: You’re identifying a gap in the perspective. I mean, it does seem like Magnum, and not Magnum alone, but a generation of photographers who perhaps have taken advantage of, let’s call it photographer’s privilege—they could go anywhere and had the privilege of viewing others the way that they were not viewed. That was, in a sense, the essence of photography for many years. These quixotic individuals who could adapt and fit in and record without necessarily having a responsibility to their subjects—although I do very vividly recall a conversation with Philip Jones Griffiths several years ago, where he discounted any photographs that were made without the implicit consent of the subjects, i.e. that his idea of photography was rooted in the sense of serving the subject rather than just catching the subject.

But that generation of photographers is deeply challenged by this new environment. Magazines and the media generally have to think differently about who they commission and what viewpoints they adopt, with much more attention paid to the subjects, paid to whom the subjects would wish to be recorded by, obviously with a drive towards more inclusivity and balance in their commissioning practices. Is that something you encounter in your work, this sense of the older generation being profoundly challenged by new thinking?

Govenar: Consent and context are critical in the making of photography, in the publishing of photography, in the exhibition of photography and its presentation in various media. It’s always been a concern of mine. I founded Documentary Arts in 1985 to have a holistic approach, a way of seeing the still photograph as important, but also to focus on not only, how an individual image can become iconic, but on issues of context and the ways we can contextualize the image in different media. To really understand what is happening around us or what we are experiencing, we need to also listen to audio, or see film, or video. If there is truth in photography, it’s in the multitude of perspectives. And that isn’t limited to the factual media. Sometimes it’s in the interpretation. Sometimes there’s more truth in fiction, than in what appears to be factual. Ultimately, truth in photography is intangible, it’s about what we sense, what we identify with, or perhaps know through the realm of experience.

Fanta Diop, Protestors peacefully march from Union Square to 86th Street in New York City to protest for Black Lives Matter and against police brutality after the murder of George Floyd, June 2, 2020

Fanta Diop, Protestors peacefully march from Union Square to 86th Street in New York City to protest for Black Lives Matter and against police brutality after the murder of George Floyd, June 2, 2020 © Fanta Diop/Bronx Documentary Center

Boot: One of the things that occurs to me about the future of photography is, well, take New York City, for example. You’re out and about with your camera in New York. Subjects are not passive. There are rules of respect and consent that go with the territory of a highly empowered society, let’s call it that. Whereas the history of photography is marked by colonialism and photography served colonial purposes., While much of that has changed, there has been a different attitude to subjects and consent from photographers working in places where people don’t have a voice in the same way.

It occurs to me now that you have to treat every subject the way you would your mother, your brother, another New Yorker. You just can’t have a hierarchy depending on where you are photographing.

Govenar: Part of what we’re trying to do is present the work of professional photographers side by side with the work of community-based photographers and vernacular photography. In the 1980s, I started writing about this concept of community photography. Until that point, discussions of community photography were largely focused on content, what was in the picture. What I was interested in was the process through which these photographs were made. I had received a commission from the Dallas Museum of Art to create a project called Living Texas Blues, and, and at that time, there was a two-volume history of Texas photography being published by Texas Monthly Press. And there was not a single African American photographer represented. When I talked to the curators who were both at major institutions in the state, they said, “Well, we only had time to work with existing collections, and we couldn’t identify any known African American photographers in an existing collection.”

That was in 1985. And that’s when I founded Documentary Arts. Our first major project was focused on African American photography. It’s when I went to New York to meet with Cornell Capa to discuss some of these issues with him. He introduced me to Deborah Willis, who’s been a colleague for decades and who’s been very enthusiastic about the work of Documentary Arts.

In 1995, my wife Kaleta Doolin and I founded the Texas African American Photography Archive. In the first edition of Truth in Photography, we featured a selection from the sixty thousand images that we collected and form the core corpus of this archive. But the bigger point here is that we have worked to present community photographers, who were actively involved in their communities. On the Truth in Photography website, you can hear the voices of the photographers and watch video of people in their communities talking about their work. So, in a sense, what’s being advocated today, which is consent, context, and transparency about the nature of the interaction between the photographer and his or her subjects, the collaborative portrait—all very important ideas—this is the way community photographers have historically worked.