Aperture's Blog, page 59

March 22, 2021

11 Photographers on Seeking the Unexpected in Their Work

The “unexpected moment” is one uniquely suited to photography. The camera has the ability to capture a split second of time, to freeze the frenetic, ever-moving world around us. Since the medium’s earliest days, photographers have embraced this quality, allowing happy accidents and unusual turns to lead to some of history’s most memorable images.

The latest edition of the Magnum Square Print Sale, The Unexpected, brings together over one hundred prints by an international group of photographers celebrating the unpredictability of life.

Through March 28, 2021, collect these signed and estate-stamped, six-by-six-inch, museum-quality images for $100 each. When you purchase through this link, you directly support Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations. Below are highlights from The Unexpected: The Magnum Square Print Sale.

Jonas Bendiksen, Shinjuku, Tokyo, 2016

Jonas Bendiksen, Shinjuku, Tokyo, 2016Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Jonas Bendiksen

“I was in Tokyo working on a chapter of an ongoing project, and had finished photographing for the day. Tokyo is a city packed with light, movement, and intensity, so I still had my camera on me and ready, just in case. I was starving and heading to dinner but had to wait at one of these huge zebra crossings in Shinjuku. They’ve been photographed so many times before, so figuring that to make a picture I would be happy with here would require more time and effort than I had blood sugar for, I wasn’t paying much attention. Then this zebra-dressed woman placed herself right in front of me. Click. Thank you. Sometimes you get more luck than you deserve.”

Sabiha Çimen, Students having fun on an artificial lake on the weekend, Istanbul, Turkey, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, Students having fun on an artificial lake on the weekend, Istanbul, Turkey, 2018Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sabiha Çimen

“The Qur’an school is an ordered, structured, and predictable environment for learning, so during holidays and break times, when these girls are allowed to be led by their own whims, they seek the fresh air of the outdoors without any particular plan or direction. There, they can let the day take them away to other shores, where the wind carries their dreams on unpredictable currents of imagination.”

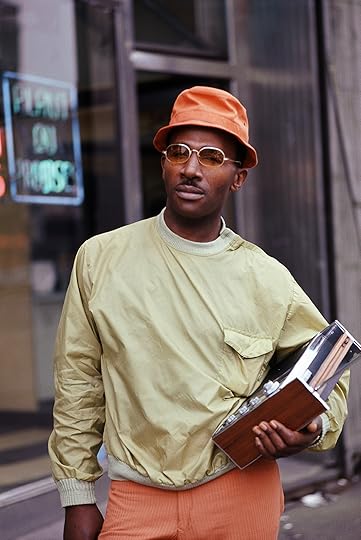

Ernest Cole, New York City, circa 1971

Ernest Cole, New York City, circa 1971Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Ernest Cole

“One of the strangest phenomena of street photography is when the photographer appears to engage in a form of cultural prophecy. The collision of today with tomorrow requires an uncanny ability to sense the future in the present.

Ernest Cole’s 1971 image of a New York hipster predicts the B-boy stylings of the mid-1980s: the dinky hat, the sportswear, the early version of a stereo beatbox. The unexpected pose of the proto-B-boy seems to leap forward decades to the pages of style magazines like the Face and i-D.

And the new culture is neatly complemented by Cole’s parallel pictures of graffiti adorning the New York streets, years before books began to collate and document that burgeoning art form. How strange it must have been for Ernest Cole to watch the development of hip-hop culture during the 1970s and 1980s—an identity that he had presciently foreseen in the late 1960s.”

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, 1955

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, 1955Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“To me, photography is an art of observation. It’s about finding something interesting in an ordinary place. I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see, and everything to do with the way you see them.”

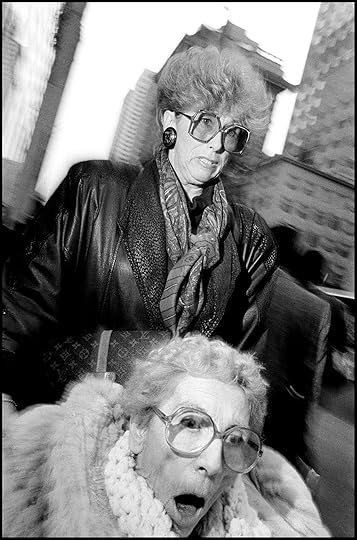

Bruce Gilden, New York City, 1990

Bruce Gilden, New York City, 1990Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bruce Gilden

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the expressions on the faces of these two seemingly related women, as the younger one was pushing the other along Madison Avenue in her wheelchair. Whatever the reason, her mouth was wide open. The scene spoke to me about the mother-daughter relationship; I imagined that the daughter had had enough and was perilously pushing the older woman over a cliff.”

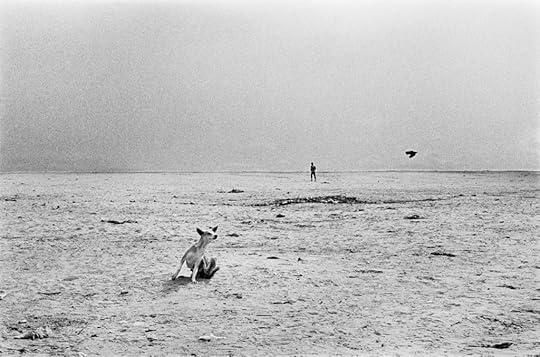

Sohrab Hura, Yusuke, Cambodia, 2008

Sohrab Hura, Yusuke, Cambodia, 2008Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sohrab Hura

“I thought I had photographed only the dog and the man, until I processed my negatives.”

Susan Meiselas, ‘Molotov Man,’ Sandinistas at the walls of the Esteli National Guard headquarters, Esteli, Nicaragua, 1979

Susan Meiselas, ‘Molotov Man,’ Sandinistas at the walls of the Esteli National Guard headquarters, Esteli, Nicaragua, 1979Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“It was on July 17, 1979, the day before Somoza fled Nicaragua, that I photographed Sandinista Pablo ‘Bareta’ Arauz, whose name I didn’t know at that moment. He was throwing a Molotov cocktail at one of the last remaining National Guard garrisons.

Back then I was working with two cameras, one loaded with black-and-white film and the other with color. I missed the shot of Bareta’s decisive gesture in black and white, but captured him in color. The image that became known as the ‘Molotov Man’ was reproduced and painted all over the country, before appearing on matchbooks commemorating the first anniversary of the Sandinista revolution.

Twenty-five years later, Bareta’s likeness was adopted as the ‘official’ symbol of the fight against the Somoza dictatorship. In 2018, the ‘Molotov Man’ was printed on T-shirts worn by university students protesting now against the Sandinista President Daniel Ortega.

An image can have multiple lives, which in this case, neither Pablo nor I could predict or control.”

Inge Morath, Mr. Gross, one of the managers, tried to run a travel service for a while, Chelsea Hotel, 23rd Street, New York City, 1968

Inge Morath, Mr. Gross, one of the managers, tried to run a travel service for a while, Chelsea Hotel, 23rd Street, New York City, 1968Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Inge Morath, in Camera Austria, no. 19/20 (1985)

“Photography is a strange phenomenon. In spite of the use of that technical instrument, the camera, no two photographers, even if they were at the same place at the same time, come back with the same pictures.”

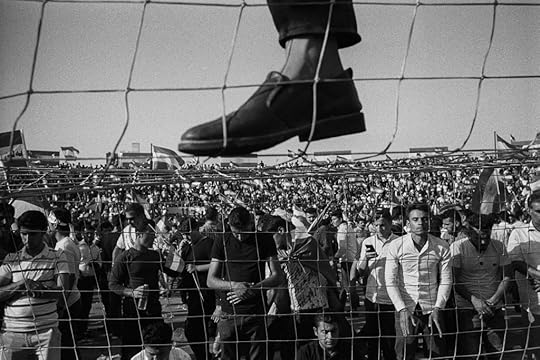

Emin Ozmen, People gather in a stadium during a large rally before the independence referendum in Erbil, Iraq, September 2017

Emin Ozmen, People gather in a stadium during a large rally before the independence referendum in Erbil, Iraq, September 2017Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Emin Ozmen

“For a long time, I wanted to keep control over what my future would be made of. This feeling that I had a sense of direction reassured me. However, during my studies and throughout my career as a photographer, I have come to realize that the most important moments in my life, which had a positive impact on my destiny, were the moments I hadn’t anticipated. It’s a feeling certainly shared with many people, quite banal in itself. But I am now aware that I need to leave more room for the unexpected. It is often by chance that the most beautiful things happen: in life and in photography.”

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Bhayi alembathwa lembathwa ngabalaziyo, 2020

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Bhayi alembathwa lembathwa ngabalaziyo, 2020Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Lindokuhle Sobekwa

“The series Ezilalini (The Country) grew out of my project I carry Her photo with Me, a handmade photobook about my sister Ziyanda. As I investigated her disappearance, I traced her footprints back to Tsomo, in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, which is my ancestral home and where my sister grew up. Unexpectedly, this journey provided the opportunity to reconnect with my family, identity, and culture: engaging parts of myself and my history that I had not considered before, or perhaps had avoided thinking about. Tsomo has a deep meaning to my family, and to me personally, but I feel it is a place I don’t know very well. There is also a feeling of conflict for us there; to this day, my grandmother curses Johannesburg as a place that swallowed her children.

The title of this image is Bhayi alembathwa lembathwa ngabalaziyo, relating to the idea that only the pot knows how hot the fire is.”

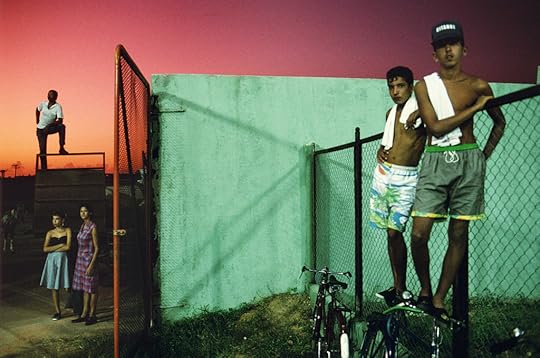

Alex Webb, Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, 1993; from the book Violet Isle (2009, with Rebecca Norris Webb)

Alex Webb, Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, 1993; from the book Violet Isle (2009, with Rebecca Norris Webb)Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Webb

“I only know how to approach a place by walking. For what does a street photographer do but walk and watch and wait and talk, and then watch and wait some more, trying to remain confident that the unexpected, the unknown, or the secret heart of the known awaits just around the corner.”

The Magnum Square Print Sale, The Unexpected, is available from March 22 to March 28 at 11:59PM PT. Collect signed and estate-stamped, six-by-six-inch, images for $100 each through Aperture’s affiliate link.

March 18, 2021

How a Museum’s Photographic Archive Honors Generations of Chinese American Lives

In late January 2020, as a fire tore through the building at 70 Mulberry Street, in New York’s Chinatown, the staff of the Museum of Chinese in America feared the worst. They watched from a park across the street as firefighters worked deep into the night to contain the blaze. This five-story corner building was once a schoolhouse; now it housed a dance center, a senior citizens’ center, a vocational training office, an athletics association, and the museum’s off-site collections. Luckily, there were no fatalities. By morning, the building was a smoldering husk, and it would be weeks before they would be allowed back inside. Many figured that if the fire hadn’t ruined the collection, then all the water surely had.

Jadin Wong wearing a qipao, ca. 1939–41

Jadin Wong wearing a qipao, ca. 1939–41Courtesy Wally Wong

The museum, located a few blocks away on Centre Street, was started as a salvage operation of sorts. In the late 1970s, Jack Tchen and Charlie Lai began noticing all of the stuff old-timers were leaving out on the streets as junk. Luggage, clothing, personal papers, things that had outlived their usefulness. But Tchen, a historian, and Lai, a community organizer, saw these items as part of a broader history. Perhaps whoever owned this old suitcase or sheaf of menus never perceived themselves that way—as having a history, or participating in a broader story of belonging, let alone an American one. What began as Tchen’s and Lai’s dumpster diving resulted in a museum that today contains some eighty-five thousand items. They are random items, yet they collectively articulate the diverse experiences of Chinese in America.

In the months following the fire, curators and archivists were allowed to reenter 70 Mulberry. Somewhat miraculously, the bulk of the collection could be restored and saved—T-shirts, concert posters, hand-painted signs, old passports and immigration documents, paper fans, cigarette cartons. These are items which might be worthless in purely monetary or market-driven terms. Yet they are irreplaceable, indexing immigrant histories, traditions, and practices that have yet to be written. Very few of these objects were meant for archival preservation. Old signage or furniture once served a primary function for the nearby merchants who couldn’t understand why a museum would want such things. Instruments were meant to be played. Costumes were for performance. Irons and washboards were merely tools of the laundryman’s trade.

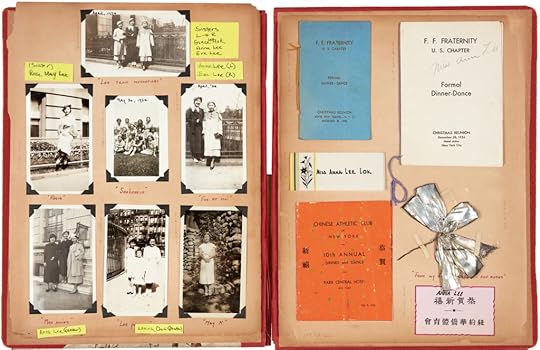

Pages of Ging Hawk Club Album, 1930s

Pages of Ging Hawk Club Album, 1930sCourtesy Alison Shue Lee

Unlike other parts of the collection, the museum’s holdings of photographic prints, slides, and negatives communicate a clear desire to leave something behind, despite the lingering possibility that the people on both sides of the camera may have regarded this U.S. chapter of their lives as a temporary, transient one. These images articulate aspirations or desires that the subjects themselves might not have felt brazen enough to speak aloud: the family looking their spiffiest for a holiday portrait; professional headshots for modeling or singing gigs; school children obediently reciting from their workbooks; the tourist measuring himself in front of a statue of some supposedly great American. There is a photograph of the Chinese Musical and Theatrical Association, which opened on Pell Street in 1931. Associations such as this one functioned as community centers and schools, ways of maintaining a tie to centuries-old traditions of storytelling and performance. In this photograph, taken at a fundraiser in 1946, the performers huddle together onstage. Some radiate pride, smiling, sitting up as straight as possible. Others look shy or uncertain; perhaps they’d prefer to have a picture taken without all this makeup on. They are flanked by performers holding Chinese and U.S. flags.

Emile Bocian, Stephen Cheng and the Dragon Seeds, ca. 1971

Emile Bocian, Stephen Cheng and the Dragon Seeds, ca. 1971Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

While studying at Juilliard, Mary Mon Toy was told that an Asian could never become an opera singer. There is a studio portrait of her from the 1950s, when Mon Toy had defied expectations to become a pioneering Asian American performer on Broadway. A finger is pointed artfully toward the sky; she gazes far past the photographer. Where will her vision take her? I’m particularly drawn to a photograph of Stephen Cheng, an idealistic singer who, in the 1960s and 1970s, sought to connect the United States and China through a fusion of jazz, rock, and Chinese traditional music. He even dabbled in reggae. In one of the only surviving photographs of his band, the Dragon Seeds, from a 1971 concert at the Museum of Modern Art, Cheng appears to be swaying to a groove, eyes and wide smile conveying a sense of bliss, as his band plays behind him.

In the United States, whites first encountered Chinatowns in major cities in the mid-1800s and early 1900s as an exotic, potentially dangerous portal into other worlds. In the early twentieth century, there were best-selling guidebooks about the savagery and old-world quirks of Chinatown in San Francisco and New York, as well as “slumming tours” that brought daring tourists down dark alleyways, past knife-wielding gangsters, and into opium dens. Some of the most famous images of San Francisco’s Chinatown, from the 1890s and into the first decade of the twentieth century, were taken by Arnold Genthe, a German-born photographer who lived and worked there at that time. He often hid his camera from sight as he took photographs so as not to be noticed by the locals. Yet his work presented a skewed version of immigrant life. He frequently cropped out the presence of Western culture, such as white people or English-language signs or advertisements, in order to preserve an alien, inscrutable quality in Chinatown.

Emile Bocian, Marcie (left) and Maureen “Peanut” Louie (right) at the U.S. Open at Forest Hills Stadium, 1977

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

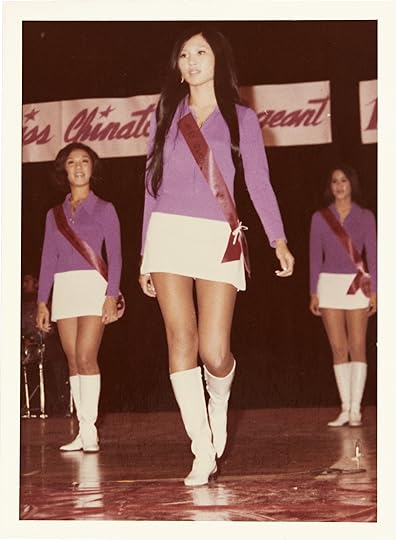

Miss Qwong Yee Wo in the Miss Chinatown Pageant, October 10, 1971

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

As various waves of immigrants slowly adjusted to life in the United States, the reality was often more mundane than those sensationalistic representations from the past. In the early 1980s, Bud Glick began taking pictures around Chinatown as part of the New York Chinatown History Project. His images document the neighborhood’s shifting generations, as the old-timers were passing on, and younger folks, horsing around with Black and brown neighbors, or posing in their punk-rock T-shirts, were beginning to explore new identities. In one of Glick’s pictures, a middle-aged woman at a laundry stares off into the distance, a moment’s reprieve during the busy workday. She leans on the counter and looks as though she is in a trance. Is this the life in the United States she once dreamed of? Among the collection’s newest acquisitions is a portfolio of 2020 images from Mengyu Dong documenting Chinese American communities participating in Black Lives Matter protests. Dong follows a group of young activists at a march in Washington, D.C. Their bilingual signs blend into the broader landscape of protest that these images depict. But they hint at how this community will continue to change and evolve from within.

Related Items

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Irina Rozovsky’s Majestic Photographs of Prospect Park

Learn More[image error]There is a photograph of the Chinese American tennis player Marcie Louie at the U.S. Open in 1977. It’s unclear whether she’s competed yet. She hugs her racket and smiles. She is with her younger sister, Maureen, who will eventually become a tennis pro too. But Maureen’s arms are folded, and her grin is a bit harder to read. She looks impatient. Perhaps she is tired of being photographed. Maybe she’s just not accustomed to it yet. It reminds me of how tedious it felt to pose for my parents’ pictures when I was a child. I couldn’t understand why we needed so many pictures.

A few years ago, I began collecting photographs of Asian American life. As with any excursion into found materials, I was drawn by the storytelling questions that emanated from these scenes of mustached teens waiting for a movie; kids on a playground beating up a peer; a seemingly generic family portrait, only the father is dressed like a greaser. Who were these people? Where did they live? Did they get along with their neighbors? What did they imagine, if they allowed themselves that privilege? My collection involves an element of fantasy, too, a naive hope that I would reconnect with honeymoon photographs my parents lost when they were new to this country.

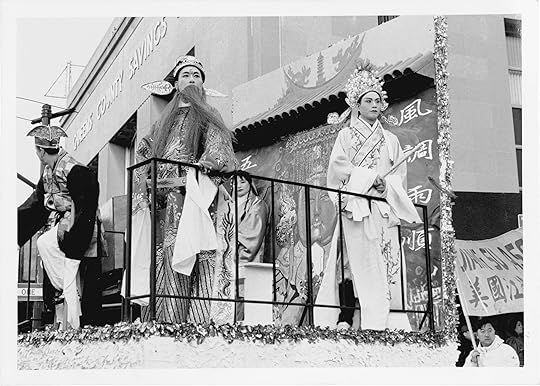

Kitty Katz, Onlookers at a Lunar New Year Celebration, 1992

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

Kitty Katz, Four performers standing on a stage with costumes, 1993

Courtesy the Museum of Chinese in America

For those from the Chinese diaspora who came to the United States in the twentieth century, photography was a tool for imagination and self-fashioning. It holds a special status in the inventory of immigrant things—a way of stopping time, commemorating one’s presence, perhaps capturing a snippet of one’s new life that can be mailed back to everyone across the sea. Especially in the predigital age, photography recorded a sense of acculturation, expressing a desire to register your presence in front of a national landmark or a momentous scene. A sense that you would someday look back, once you had the time. Perhaps it becomes art or a statement about history only to the later generation. In the moment, it’s just a desire to stand in front of the statue or totem that everyone else is standing in front of.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Voices & Memories.”

March 17, 2021

The Photographer Who Embraces South Africa’s Lavish Colors

Every spring, the aging jacaranda trees lining the suburban avenues of Johannesburg, one of the most wooded cities in the world, produce intense violet blooms. The Colombia–born artist Juan Orrantia’s photobook Like Stains of Red Dirt (2020), his first about South Africa since settling in the country in 2008, opens with a flash-lit photo of the underside of this subtropical tree with long arching branches. The tree’s spring profusion of purple-blue flowers feebly registers in his photograph, partly because of his vantage point, but primarily due to Orrantia’s chromatic interference with the scene: the grey-brown branches of the tall tree are a dirty pink on the page in his book.

This formula, of quotidian scenes obliquely seen and strangely colored, is reiterated throughout Like Stains of Red Dirt. The book includes lavish spreads depicting, among other things, an evening thunderstorm rendered in volcanic tones, and an unidentified patch of dirt that may as well be on Mars. Most of the images were taken in and around the photographer’s apartment in the leafy neighborhood of Killarney, and they feature his partner, anthropologist Pamila Gupta, and their nine-year-old adopted daughter, Padma, in a mix of candid and staged poses. These portraits are juxtaposed with domestic still lifes, close-up botanical studies, and urban landscapes that together suggest a life of unassuming suburban privilege.

Juan Orrantia, The scramble for Africa, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, The scramble for Africa, 2017–19Orrantia’s photographs achieve their punch through a seven-color printing process known as heptachrome. He was introduced to this process—which adds orange, green, and violet to the traditional color printing model of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—by Artes Gráficas Palermo, a Madrid prepress and printer, which suggested heptachrome to translate Orrantia’s in-camera and digital postproduction experiments with color into print. (In 2019, Orrantia’s mock-up of Like Stains of Red Dirt won the Fiebre PhotoBook Festival’s Dummy Award.)

“I was really shocked when I saw on paper what I had previously only seen on screen,” says Orrantia of the first printer’s proofs he received. “Some of those colors are hectic to get on paper.”

Color is integral to Orrantia’s book about family, home, and the difficult process of integrating into an alien culture. What does it mean to belong? Is belonging even possible? Orrantia raises these questions in his opening image of a South American tree that, loved as it is in South Africa for its annual outburst of color, is nonetheless classified as an invasive species. In a country where settler and immigrant identities are hotly contested, and the ethics of representation is central to public debates about photography, especially portraiture, Orrantia found a liberating subject in his hometown’s floral abundance.

“When I wake up every morning, I look out from my balcony in Killarney and I see all of these plants that have nothing to do with the place, but are completely about the place,” he says of the subjects that allowed him to overcome his hesitation in taking photographs in South Africa. As Orrantia explains, the jacarandas were introduced as both ornamental plants and barriers to filter the dust that once swept off the profuse tailings from the city’s now-defunct gold mines. Similarly, the foreignness of the garden city created by waves of white settlers in Johannesburg has, over time, become normalized. Interested in playing with the natural-artificial binary, Orrantia’s pimped botanical photographs of rose bushes and palm trees render these naturalized aliens as strange and other again. “But, you know, it’s not the plant’s fault,” Orrantia recalls an academic supervisor jokingly remarking of his photographs and their links to South Africa’s colonial history.

Juan Orrantia, Red hair (or finger to the pencil test), 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, A garden here is not just a garden #1, 2017–19

Like Stains of Red Dirt had its genesis in the University of Hartford’s MFA in photography program, which has a strong emphasis on photobooks. Orrantia entered the program after a substantial detour—a visual anthropologist by training, he has a PhD from Yale University. Orrantia visited Johannesburg in 2008, intending to connect with his supervisor, who was on a research sabbatical there. Orrantia had no connection to South Africa and anticipated a short stay. He shortly met two influential people at the University of Witwatersrand: Gupta and the photographer Jo Ractliffe, then a lecturer at the Wits School of Arts.

Orrantia’s introduction to Ractliffe—the subject of a career survey currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago—was perhaps inevitable. Orrantia’s doctoral work, which photographically explored issues of memory and violence in Colombia, dovetailed with Ractliffe’s work examining the aftermath of South Africa’s Cold War–era conflict with Angola for her book Terreno Ocupado (2008). A friendship quickly developed. “I remember Jo always telling me that I was asking too much of a photo,” Orrantia says of Ractliffe’s influence. “I had these ideas in my head, and I slowly learnt how to photographically express them, to not force them into the photograph.”

Juan Orrantia, Predictable cathedrals of thunderclouds in summer, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Predictable cathedrals of thunderclouds in summer, 2017–19A supportive mentor, Ractliffe also directed Orrantia to the Market Photo Workshop, a photography school established by David Goldblatt in 1989. The rigor of the discussions at the photography school, especially around issues of history and representation, proved bracing, and concretized Orrantia’s resistance to making photographs in South Africa. After completing his doctorate, Orrantia began photographing in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony neighboring South Africa that was wracked by civil war throughout the 1970s and ’80s. “I did not know much about Mozambique at all, but I had this idea, some sort of imagined familiarity, that their history was closer to where I was from.” (Orrantia’s black-and-white photographs from Mozambique are compiled in a limited-edition book, There was heat that smelled of bread and dead fish [2018], and reveal his ongoing quest to visualize quietude.)

Orrantia subsequently photographed in Guinea-Bissau, a former Portuguese colony in West Africa, and Colombia, where he explored the vestiges of the violent drug trade in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range. In 2017, he enrolled in Hartford’s international, limited-residency program, and a year later began tentatively making photographs in and around his Johannesburg home; he also visited Tokyo to participate in a remote MFA meeting. He met Japanese photographers Yurie Nagashima and Mikiko Hara. “Seeing the work of Hara and having that conversation with her really opened up my thinking to what a color photograph can do,” he offers by way of an extended rebuttal to my question about the influence—possible or not—of Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen.

So what can a color photograph do? As Edward Steichen ventured in a press release announcing the Museum of Modern Art’s first-ever color photography show in 1950: “For the perennial experimenters, the seekers for greater freedom from the discipline of the purely descriptive photographic technique, new horizons of abundant promise are indicated, provided the ‘coloriferous’ is not mistaken for the colorful.” For Orrantia, color is not simply about vivid hues and sparkling luminosity. Color is about cognition. “Color,” he says, “allowed me to think.” It also enabled him to embrace his home.

Juan Orrantia, Baobab study (hand and wax print at sunset), 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Baobab study (hand and wax print at sunset), 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Jacaranda, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Jacaranda, 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Still life of dried Proteas and plastic flowers, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Still life of dried Proteas and plastic flowers, 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Aloe and palm, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Aloe and palm, 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Moths (in the bush), 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Moths (in the bush), 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Red dirt with tree stumps, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Red dirt with tree stumps, 2017–19 Juan Orrantia, Christmas lights, 2017–19

Juan Orrantia, Christmas lights, 2017–19All photographs from the book Like Stains of Red Dirt (Dalpine, 2020). Courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

March 16, 2021

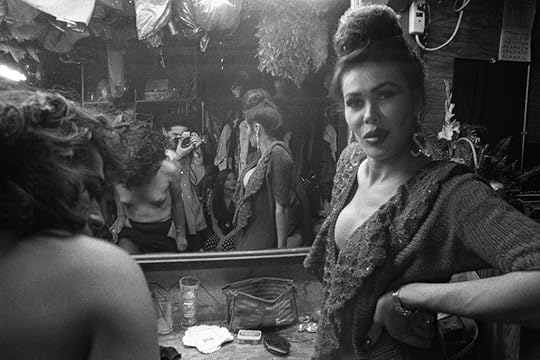

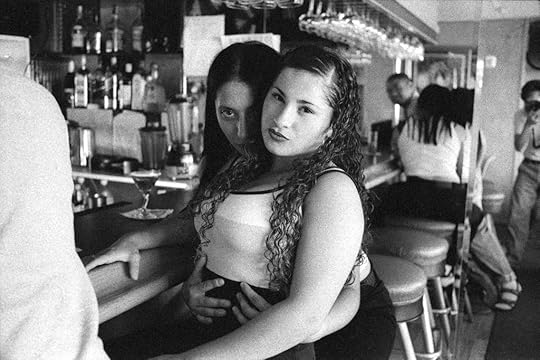

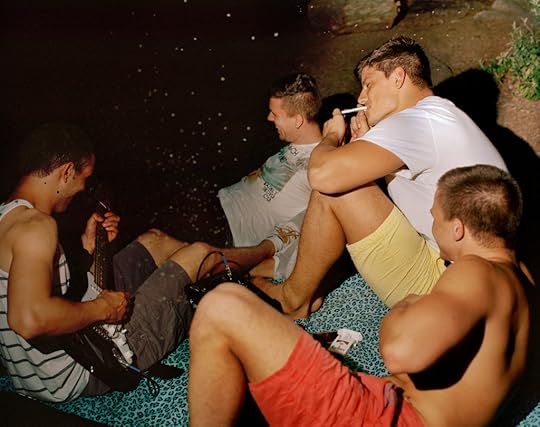

The Glamorous World of LA’s Vanished Queer Underground

If the photographer Reynaldo Rivera didn’t exist, a Hollywood more interested in queer and Latinx people might have invented him. As detailed in Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City (2020), Semiotext(e)’s marvelous new monograph, Rivera sidestepped tragedy through talent and will. He made transformational photographs of subjects transforming themselves, many now dead in places now shuttered or, worse, disappeared. What separates Rivera’s work from that of his peers—the loving slums of Nan Goldin, the horny social-butterfly lepidopterarium of Christopher Makos, Alvin Baltrop’s formal observations, the personality crises of Peter Hujar—might be a rejection, or perhaps disinterest, in distance. Rivera’s photographs of trans women and drag artists, of artists and scenesters and lovers and friends, in and out of LA’s legendary Latino bars and party houses, thrill with presence without flaunting their access. “If people are busy living out myths you don’t like,” Samuel R. Delany writes in his wild epic novel Dhalgren (1974), “leave them to it.” Rivera’s subjects were busy. They were living. He clearly loved them. He made real myths with them.

Reynaldo Rivera, Richard Villegas Jr., friend, and Enrique, Miracle Mile, 1996

Reynaldo Rivera, Richard Villegas Jr., friend, and Enrique, Miracle Mile, 1996In Rivera’s photograph Richard Villegas Jr., friend, and Enrique, Miracle Mile (1996), two men embrace each other in a well-lit bathroom—while another man nearby pisses into a urinal—all so busy in their joy. Another shows off the pride of a patron at the Silverlake Lounge in 1995, his cowboy drag as white and spotless as the toilet seat his boot rests on, at least in Rivera’s frame. There’s an image of “Vanessa” cross-legged and offering an expression of feeling herself so supernatural it transcends place and time, and so natural it could only come from a person truly at home. The run of photographs of Tatiana Volty, her story lovingly recounted by Luis Bauz, is tale-ready for its close-up.

Such intimacy arose from estrangement. Rivera’s mother was born in Mexico and left for Stockton, California, when she was sixteen and pregnant, where she met his father, also Mexican-born and two decades older. They quickly married and separated; Reynaldo and his older sister, Herminia, shuttled between houses and Southern California border towns. Their father kidnapped them when Rivera was five and ditched them with his family in Guanajuato, in a small house with no running water and an abusive grandmother. After four violent years, they returned to their mother and the American racism of Glendale, California, in the 1970s.

Reynaldo Rivera, Gaby, Reynaldo, and Angela, La Plaza, 1993

Reynaldo Rivera, Gaby, Reynaldo, and Angela, La Plaza, 1993Rivera’s father occasionally interfered with his reintegration by hijacking his adolescent son for extended stays in the San Joaquin Valley, where he worked seasonally at a Campbell’s Soup cannery or picking cherries. Rivera stayed in the rundown SROs with him, worked the fields, befriended homeless people in town and robbed stores with them, and found himself spellbound by the photography books he uncovered at thrift stores. In sixth grade, back at home with this mother and beguiled by the lives and work of Golden Age glamour girls like Lucha Reyes, he was arrested for selling drugs; by fourteen, he’d left high school and returned to Mexicali. He worked at his father’s liquor store until his father shot a gangster, who died in the street, prompting his father to disappear with Rivera’s green card. Fortune reunited them at a bus station in Calexico, and they returned together to the Stockton cannery. Rivera’s dad had a side hustle fencing stolen goods, including a Yashica that Rivera stumbled on one summer day. “And then the genie came out of the bottle,” he said. “I thought if I could capture these moments, keep them on file, I could find some kind of order. … It was a kind of alchemy. It became my thing.”

He got a Pentax K1000 and took pictures of Herminia; he returned to Mexico City in 1983, went to the bedroom in which someone had killed his step-grandfather with a machete, and photographed the blood stains across his sheets and framed pictures of saints for a series that empathically struggles against making a crime scene into a still life. Back in Los Angeles, he found worlds of people building lives for themselves by whipping up their own orders of alchemy. He photographed the icons Siouxsie Sioux and Sade and Annie Lennox, sometimes selling his work to the LA Weekly.

Reynaldo Rivera, Girls, El Conquistador, 1997

Reynaldo Rivera, Girls, El Conquistador, 1997On La Brea, Miss Alex lip-synched for tips at the Latino drag bar La Plaza; in Mexico City, she authored a highly fictionalized newspaper column detailing her exploits among the Hollywood elite. Through Rivera’s lens, she inhabits both worlds at once.

Tina, the face of the artsier bar Club Mugy’s, sometimes impersonated Michael Jackson (thus, in Chris Kraus’s formulation in her perceptive essay for the monograph, working as “a man, dressed as a woman, impersonating a man”), and sometimes called on her Thai identity to showcase pan-Asian displays of femininity, from dragon lady to geisha. Such indeterminacy could get performers canceled today, but in the late ’80s and early ’90s, artists on the outskirts looked everywhere they could for a reflection. They developed a visibility, almost photosynthetic in how it distilled nutrition from flashes of recognition. Rivera photographed them in dramatic black and white, often straight ahead and center-framed, with the photographer in their mirrors’ reflections. Rivera’s subjects display the fruits of their labor—their glittering gowns, their tits, themselves—in dusky arrangements that call to mind LA noir and Hollywood screen tests, but mostly, embrace shadows as just another kind of light.

Reynaldo Rivera, Vanessa, Silverlake Lounge, 1995

Reynaldo Rivera, Vanessa, Silverlake Lounge, 1995All photographs courtesy the artist

In a riotous back-and-forth at the close of the book, Rivera and international treasure Vaginal Davis carry on and gossip about the stars of these demimondes, the party people of pregentrified Silver Lake and Echo Park, like Alice Bag and Taquila Mockingbird, and all the dead and deadly serious and drop-dead glamourous. (The pair deserves a genius grant to host double-decker tours of Los Angeles.) There’s sometimes a rush of ruin porn when it comes to these matters: all the wreckage from AIDS and crack and America’s lethal relationship with its transgender family members, all the bars lost to landlords’ greed and our refusal to see nightlife as anything other than a source of “urban revitalization.” Self-invention and self-harm so often fit together, like a hand in a white silk glove. These photographs demand resistance to all that. They marvel at what was made, not how cinematic it looked in destruction.

“We were all thought to be superficial,” Rivera writes of the people around him. “The majority of the city was not white and was not here to be a star or to be in the industry, the majority of us were either born into this dream world or ended up here for other reasons.” Those reasons are all over the faces of the people Rivera photographed—people making the myths that really power Los Angeles. They still exist and must endure.

Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City was published by Semiotext(e) in December 2020.

March 12, 2021

In Okwui Enwezor’s Final Exhibition, an Urgent Portrait of American Life

Okwui Enwezor imagined the exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America as a direct and necessary intervention into the 2020 presidential election campaign in the United States. If the show had opened as planned, at the New Museum in New York last October, it would have been poised to interrupt—albeit from the margins of high culture—the chaotic, overheated, and largely empty rhetoric of the political campaign with an elegant articulation of substantive artistic responses to the harrowing and unrelenting experience of extreme anti-Black violence in this country, coalescing rather beautifully with months and years of critical thinking and crucial protest from the Black Lives Matter movement. But Enwezor died in 2019 at the age of just fifty-five, following a long fight with cancer. Nothing went as planned last year, and so the show was postponed.

Now, after the inauguration of Joe Biden, the staggering loss of more than half a million people in the US alone due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the truly shambolic end to Donald Trump’s one-term presidency, and yet more unconscionable racist violence, Grief and Grievance has finally opened under different circumstances—thanks to the artist Glenn Ligon and the curators Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, and Mark Nash, who served together as advisors. The delay has added to the exhibition’s strength. Creating a semblance of distance while making plain all the things that remain unchanged, the lag time has only deepened the many dimensions of meaning and illuminated the layers of complexity that have been carefully worked into the show. This is especially evident in the role film and photography play, with a series of exceptionally strong image-based artworks plotting their own delicate path through Grief and Grievance—drawing on, while at the same time dismantling, virtually all of the usual narratives, traditions, categories, and disciplinary boundaries of these art forms.

Deana Lawson, Jouvert, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 2013

Deana Lawson, Jouvert, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 2013 Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Enwezor, a big thinker known for his maximalist approach to space, was born and raised in Nigeria. He came to the US as a young man—fiercely intelligent, sartorially sharp, unapologetically cosmopolitan—and studied political science. Then he made a place for himself in New York City’s downtown poetry scene. Much of his eventual curatorial work was notably focused on photography. Landmark shows (such as In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present in 1996; Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography in 2006; and Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life in 2012) delved into the vast milieus of African image-makers, many of whom were legendary in their wider worlds but largely unknown in the US and Europe. These artists’ works were tangled up in literature, music, and the legacies of colonialism and national liberation politics. Knotted historical threads—in addition to the studios, clubs, magazines, and collectives that had brought these artists and the contexts of their work to attention—were always present in Enwezor’s exhibitions. As Gioni, the New Museum’s artistic director, has noted in the various talks and texts around Grief and Grievance, the only institutional position Enwezor ever actually held in New York, a city he called home, was as adjunct curator at the International Center of Photography.

For a show of thirty-seven artists, Grief and Grievance is remarkably well-rounded in terms of style, material, and media. Some of the exhibition’s moments of force and clarity come through paintings and sculptures that create the formal language to convey palpable trauma and irrepressible joy; and through works such as Tyshawn Sorey’s Pillars (2018), Theaster Gates’s Gone Are the Days of Shelter and Martyr (2014), and Okwui Okpokwasili’s Poor People’s TV Room (Solo) (2017), which mesmerize primarily through sounds that drift through the different rooms, pulling you in for a time and then haunting you as you move away from them. But if you find your way through the exhibition as I did—starting in the lobby gallery, with the incredible precis created by screening Garrett Bradley’s stunning short film Alone (2017), in the same room with Terry Adkins’s majestic large-scale X-ray images of memory jugs and Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s horrifying sculpture of a cattle squeeze; then climbing up through the second and third floor galleries, through rooms devoted to works by Carrie Mae Weems, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deana Lawson, and Dawoud Bey; and coming back down to end in the coda of Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016)—then clearly, a thesis emerges on the uses of photography in relation to race in America.

Dawoud Bey, Fred Stewart II and Tyler Collins, from the series The Birmingham Project, 2012

Dawoud Bey, Fred Stewart II and Tyler Collins, from the series The Birmingham Project, 2012 © the artist and courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, and Rennie Collection, Vancouver

Beckwith’s revelatory essay in the catalogue, “My Soul Looks Back in Wonder,” fleshes out this thesis, exploring how early photography served to objectify Black bodies and commodify their suffering. Pseudoscientific images were used as supposed evidence to create racial categories and sustain the myth of white supremacy. Postcards with lynching pictures were traded as awful souvenirs. With the story of Emmett Till, and the pictures of his open casket and his mother’s grief, images of Black mourning began to shift the position of documentary photography and photojournalism, “refashioned,” writes Beckwith, “as potential tools in justice work.” Photographs of the Civil Rights movement began the process of restoring dignity, complexity, and the fullness of Black experience, aspiration, and deep historical knowledge. What stubbornly persisted, however, was the interminability of Black suffering and the continued ubiquity of its imagery, ever present to this day. “Living with trauma and acute grief,” Beckwith concludes, “is our black life, our dexterity, our inheritance.”

Grief and Grievance presents tremendous examples of the works artists have made from that inheritance. Bradley’s video, about her friend Aloné—a single mother in New Orleans and a subject of fulsome Renaissance-level beauty, who is measuring the decision to marry her beloved and to foreclose her bright future by becoming the bride of an imprisoned man—ties the legacy of slavery directly to today’s carceral state. The work carries the force and truth of documentary with the composure and poise of fiction. And the glimpse we get of Aloné’s maybe future husband, a man passing by the camera at a distance (his smile a flash and then gone), electrifies, no matter how much we may think we know better.

Sable Elyse Smith, 8345 Nights, 2020

Sable Elyse Smith, 8345 Nights, 2020Courtesy the artist; JTT, New York; and Carlos/Ishikawa, London

Sable Elyse Smith’s elusive series of family portraits—the images are taken in prisons against brightly painted murals, the pictures nearly swallowed up by huge frames of black suede—offer a thread. Tug on it and an entire economy of incarceration unravels, including the racist policies that have kept it going. An excerpt from LaToya Ruby Frazier’s monumental series The Notion of Family (2001–14) conveys the material, emotional, and psychological destruction of an archetypal postindustrial town more bracingly than any economist or sociologist could. The extreme intimacy and tender gestures that Frazier captures in her photographs, packed as they are with details and contexts, stick in the mind for ages—especially here, with an unforgettable image like Mom Holding Mr. Art (2005) echoing the possible fate of Bradley’s Aloné. In paintings by Julie Mehretu and Jack Whitten, photographs of police brutality and white nationalist violence are almost totally sublimated and overwhelmed by the marks of their makers, yet they remain as traces. And on numerous occasions, the still and moving images present in Grief and Grievance allow the world to come rushing into an all-too-often inward-looking discourse, adding a globalized perspective and exposing many connections from the American experience to the repercussions of the Atlantic slave trade and the long, unsettled history of colonialism.

As Mehretu noted in a panel discussion a few days after the opening of Grief and Grievance, Enwezor planned for the exhibition to open in a liminal space, on a threshold. “It’s interesting that this show comes about during the time where the United States really failed for the world, and exposed itself as a colonial project, a continued colonial project,” she said. “Okwui took this opportunity, with the words and the language around the exhibition, to give it this intellectual framework,” to show “how the US is a participant in this larger, colonial, transnational reality, and how it’s in that state. It’s not in a postcolonial state whatsoever, as many places on the continent, in Africa, and in the Global South aspire to be.”

Installation view of Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016, in Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America

Installation view of Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016, in Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in AmericaPhotograph by Dario Lasagni. Courtesy the New Museum

As our inheritance, Enwezor left behind landmark exhibition histories, as well as robust catalogues, substantial writings, and resonant terms such as “the racial sublime” and “the colonial sublime,” alluded to in the work around Grief and Grievance. But mainly, he left us with a lot of work to do. Until this show, I had never seen Jafa’s Love Is the Message on a screen bigger than my phone. I was living outside of the US when it was first presented, shortly after the 2016 US presidential election, and I missed years of chances to see it in person. The projection at the New Museum is mural-size, the soundtrack all-consuming; Love Is the Message has rightly been called the Guernica of our time. An elastic approach to time binds the work together—Angela Davis striding in glorious slow motion, the pause before Barack Obama begins to sing “Amazing Grace,” the seemingly sped-up chaos of gratuitous police violence, a child crying out as a father figure schools him in how to survive as a Black boy in this country.

In Jafa’s film, as elsewhere in Grief and Grievance, it’s not so much catharsis or transcendence, but the maximum intensity we can bear: this weight and this light, this horror and this joy, this stunning achievement and this cruel, baseless punishment—all of it our doing. A young woman asks, momentously: “What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as we loved Black culture?” Maybe the real intervention of Grief and Grievance is to demand that we imagine a good answer to that question, and then make it so.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America is on view at the New Museum, New York, through June 6, 2021.

March 11, 2021

Irina Rozovsky’s Majestic Photographs of Prospect Park

Prospect Park is, of course, a wonderful vast green space in the heart of Brooklyn. It hosts millions of visitors every year. There are playing fields; there are ponds and woods and a ravine with cascades; there are glades and knolls; there are spots for barbecuing and tennis and drumming; there is a bike loop and a bridle path and an ice-skating rink; there is a zoo with sea lions and poison dart frogs; and, at the park’s eastern edge, there is a carousel where for more than a hundred years young children—my three sons included—have ridden in circles on wild-eyed wooden horses. Each season changes what’s there and what goes on—sledding on Sled Hill in the winter; fishing in the lake in the summer; looking out, in the spring, for the almost invisible American woodcock. Always there is a lot to do and, more pertinently for the photographer, a lot to see.

The spectacular possibilities cannot be understood without a brief ethnology of the place. To the northwest of the park lies Park Slope, a neighborhood of brownstones and, in the main, affluent white families. To the southeast lies Flatbush, the old Dutch country village that these days is densely built-up and densely populated by working-class and middle-class residents, many of whom are of Afro-Caribbean origin. Other neighborhoods, economically and culturally diverse—Windsor Terrace, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Crown Heights, Kensington, Prospect Heights, Ditmas Park, Borough Park—either adjoin the park or are close by. Hundreds of thousands of human beings of almost every sort and provenance are able to resort to Prospect Park on foot. Subway trains bring in families from more remote parts. If a park may be defined as a specifically urban space, at Prospect Park both elements of this definition—the urban and the spatial—are markedly, perhaps even quintessentially, available to perception. Enter (for In Plain Air, a project that spanned 2011 to 2020) the Moscow-born, American-raised photographer Irina Rozovsky.

Note that the photographer finds herself in an unusual position. Photography is precisely one of the recreational activities that Prospect Park users engage in. The formal distance between observed and observer, and the hierarchy implied by this opposition, is, if not erased, then radically modified by a strange mutuality. Going to the park is an act of self-publication. When you step into a space where you observably do as you please, you assert your autonomy. It is an assertion that is particular to the jurisdiction of this special green acreage, beyond the borders of which very different rules and powers apply. The situation of the photographer in the face of this assertion is not dissimilar to the situation of the witness. We all need to be seen in a just light, and Prospect Park can offer such a light, and a photographer can capture it.

At the core of this visibility is, paradoxically, the peculiar privacy that being in the park confers. Privacy, certainly in Western culture, is normally associated with seclusion and secrecy—the closed door and what happens behind it. The privacy of these Brooklyn park-goers is founded on something else: an understanding that the gaze of the other—even if prolonged, even if mediated by a camera and made permanent by a photograph—makes no moral claim on its subject. Rozovsky’s images express this social practice. They refuse the curiosity of the sidewalk pedestrian or the tourist or the voyeur. They accept, and proceed from, a certain responsibility. The responsibility in question is the artist’s duty of carefulness.

All photographs from the series In Plain Air, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, 2011–20

All photographs from the series In Plain Air, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, 2011–20Courtesy the artist and MACK

Carefulness, in this artistic sense, is not just a matter of technical diligence or some heightened awareness of the complexity of the subject matter. (Prospect Park, as we have seen, is an extremely complex subject.) Rozovsky’s human subjects, as they fish or fool around, are defenseless to the onlooker; and yet her photographs exercise no sway over them. This is the product of a careful eye, which is to say, an eye that is neither seduced by its own power nor subservient to the social constraints in which it partakes. The photographic subject makes his or her claim to self-rule, and the photographer responds to that claim, and transcends it. A unique relation is inaugurated. An ethics of seeing is revealed.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “In Plain Air.”

Irina Rozovsky’s photobook In Plain Air was published by MACK in March 2021.

One Year after the City Shut Down, Aperture Presents “New York”

One year after New York City shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Aperture magazine releases “New York,” an extraordinary issue honoring the city through photographs and essays by visionary artists and writers, reminding us of how much there is to discover, and relish, when New York comes roaring back.

New York is a city of improvisers—and there has been no shortage of creative solutions to surviving the trauma of the pandemic and meeting a moment of social unrest and public demands for social justice and equity. The “New York” issue features newly commissioned portfolios by Farah Al Qasimi and Roe Ethridge, alongside never-before-seen photographs by Rosalind Fox Solomon and Saul Leiter. Acclaimed photojournalist Philip Montgomery speaks with Kathy Ryan about covering the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic; Hua Hsu writes about how photographs at the Museum of Chinese in America tell a story of resilience; and Tanisha C. Ford profiles Jamel Shabazz, the legendary street photographer, whose indelible images from the 1980s are icons of style and joy.

Coinciding with the “New York” issue, Aperture and Rockefeller Center are collaborating on a month-long photography program celebrating New York, in the heart of the city. The program will feature a virtual talk series, a pop-up store, and public art exhibitions. See below for the full schedule.

Tanisha C. Ford in conversation with Jamel Shabazz

Tuesday, March 30, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

Since the early 1980s, Jamel Shabazz has photographed New York’s street life and hip-hop culture with joy, verve, and style. His work not only captures the essence and pureness of hip-hop culture in New York, but also the deep connections he has with his subjects and community. In this conversation, Shabazz and Ford will discuss Shabazz’s career, his lasting legacy, how quarantine has given him time to rediscover hidden gems in his archive, and the installation of work at Rockefeller Center through April.

Artist Talk with Irina Rozovsky

Thursday, April 8, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

For ten years, Irina Rozovsky has been making lyrical portraits of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park—both of the landscape and its visitors—perfectly capturing the democratic nature of the space. From images of women fishing to family barbeques to young couples in the grass, In Plain Air (2011–20) is a lover letter to Prospect Park and all those who spend time there.

Presented in collaboration with Aperture, Rockefeller Center, Parsons the New School for Design, and MACK. Additional support for this program is provided by MPB.com.

Widline Cadet and Rafael Rios on Family, Friendship, and New York

Thursday, April 22, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

In this conversation Nicole Acheampong, assistant editor of Aperture magazine, will speak with photographers Widline Cadet and Rafael Rios about their work featured in the “New York” issue, and on crafting intimate portraits of friends and family. In her series Soft, Cadet makes dreamlike, black-and-white photographs of friends embracing in New York City parks, while Rios’s Family series captures vibrant flashes of his extended Puerto Rican family’s everyday life in Brooklyn. Both artists, commissioned by Aperture to make new work for this issue, have expanded their long-term projects to offer new ways of seeing the tenderness and tenacity of community, a vital offering at a moment of social distancing.

A Lightbox Installation of Photographs by Jamel Shabazz

On view at Rockefeller Center from March 27 to April 30, 2020

An outdoor exhibition of New York City street and subway photographs by Jamel Shabazz, who has methodically created street portraits throughout the city for forty years. Fourteen of Shabazz’s portraits will be displayed in the heart of the city, installed on seven-foot-tall lightboxes across Rockefeller Center’s public plazas.

Aperture Pop-Up

At Rockefeller Center from March 27 to April 30

This special pop-up space will feature new limited-edition prints by artists featured in the “New York” issue, Aperture’s new book releases and best sellers, special artist-signed publications, and more.

Related Items

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Collector’s Edition: Roe Ethridge

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]One Year after the City Shut down, Aperture Presents “New York”

One year after New York City shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Aperture magazine releases “New York,” an extraordinary issue honoring the city through photographs and essays by visionary artists and writers, reminding us of how much there is to discover, and relish, when New York comes roaring back.

New York is a city of improvisers—and there has been no shortage of creative solutions to surviving the trauma of the pandemic and meeting a moment of social unrest and public demands for social justice and equity. The “New York” issue features newly commissioned portfolios by Farah Al Qasimi and Roe Ethridge, alongside never-before-seen photographs by Rosalind Fox Solomon and Saul Leiter. Acclaimed photojournalist Philip Montgomery speaks with Kathy Ryan about covering the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic; Hua Hsu writes about how photographs at the Museum of Chinese in America tell a story of resilience; and Tanisha C. Ford profiles Jamel Shabazz, the legendary street photographer, whose indelible images from the 1980s are icons of style and joy.

Coinciding with the “New York” issue, Aperture and Rockefeller Center are collaborating on a month-long photography program celebrating New York, in the heart of the city. The program will feature a virtual talk series, a pop-up store, and public art exhibitions. See below for the full schedule.

Tanisha C. Ford in conversation with Jamel Shabazz

Tuesday, March 30, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

Since the early 1980s, Jamel Shabazz has photographed New York’s street life and hip-hop culture with joy, verve, and style. His work not only captures the essence and pureness of hip-hop culture in New York, but also the deep connections he has with his subjects and community. In this conversation, Shabazz and Ford will discuss Shabazz’s career, his lasting legacy, how quarantine has given him time to rediscover hidden gems in his archive, and the installation of work at Rockefeller Center through April.

Artist Talk with Irina Rozovsky

Thursday, April 8, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

For ten years, Irina Rozovsky has been making lyrical portraits of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park—both of the landscape and its visitors—perfectly capturing the democratic nature of the space. From images of women fishing to family barbeques to young couples in the grass, In Plain Air (2011–20) is a lover letter to Prospect Park and all those who spend time there.

Presented in collaboration with Aperture, Rockefeller Center, Parsons the New School for Design, and MACK. Additional support for this program is provided by MPB.com.

Widline Cadet and Rafael Rios on Family, Friendship, and New York

Thursday, April 22, 7:00 p.m. ET, Register here

In this conversation Nicole Acheampong, assistant editor of Aperture magazine, will speak with photographers Widline Cadet and Rafael Rios about their work featured in the “New York” issue, and on crafting intimate portraits of friends and family. In her series Soft, Cadet makes dreamlike, black-and-white photographs of friends embracing in New York City parks, while Rios’s Family series captures vibrant flashes of his extended Puerto Rican family’s everyday life in Brooklyn. Both artists, commissioned by Aperture to make new work for this issue, have expanded their long-term projects to offer new ways of seeing the tenderness and tenacity of community, a vital offering at a moment of social distancing.

A Lightbox Installation of Photographs by Jamel Shabazz

On view at Rockefeller Center from March 27 to April 30, 2020

An outdoor exhibition of New York City street and subway photographs by Jamel Shabazz, who has methodically created street portraits throughout the city for forty years. Fourteen of Shabazz’s portraits will be displayed in the heart of the city, installed on seven-foot-tall lightboxes across Rockefeller Center’s public plazas.

Aperture Pop-Up

At Rockefeller Center from March 27 to April 30

This special pop-up space will feature new limited-edition prints by artists featured in the “New York” issue, Aperture’s new book releases and best sellers, special artist-signed publications, and more.

Related Items

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Collector’s Edition: Roe Ethridge

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]March 5, 2021

At Beaches around the World, a Photographer Finds Hope and Home

Reality is a rhythm often confirmed by its disruption. And for Venezuelan photographer Silvana Trevale, venturing to the sea is a lifelong strategy for embracing the moments when her rhythms are rattled. Throughout her childhood, Trevale would spend weekends at her grandmother’s home in the coastal town of Mamporal, Venezuela. Here, a young Trevale learned how to consult the horizon. “Water is hopeful,” she tells me, “it’s an opening, a relief, and it’s beautiful.”

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Trevale has continually made her way to water. But now, living in London, she dwells on shores far from the earthy sands of Mamporal: “For obvious reasons, every shore I’ve seen this year has had fewer people, no matter where I was. Somehow, this made it all the more dreamlike. It made me feel like every scene I saw was a vestige of a now distant world.”

For the past decade, Trevale has crafted a photographic practice that treads the line between documentary and portraiture, reality and fantasy. This syncretization bridges Trevale’s predilection for beauty and mystery with the immense value she places on understanding an image’s context. Trevale knows what happens when ideas are not tended to with specificity. She is familiar with the casualties that transpire as an entire world is swallowed up by a homogenizing narrative. Her dedication to detail is impulsed not by the desire to preserve, but rather the desire to knowingly (and lovingly) remember.

Silvana Trevale, Flujo de mar, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Hands in water, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Trevale’s most expansive body of work, Venezuelan Youth (2017–21), is a series that documents an early awakening of her country’s young people to the realities of political, social, and economic conflict. Reflecting on this body of work, her words concede the longing that sits at the poignant heart between her relationship to photography and remembering: “Whenever I’ve photographed something beautiful, my body feels lighter. I feel like in my camera, I carry the pieces of a childhood that was not explicitly mine, but could have been. When I come back to Venezuela, so many people who were a part of my upbringing have left. I keep returning to see my childhood through.”

Over the course of the past year, Trevale has photographed at the beaches of Ireland, Greece, Italy, and Venezuela. Brought together in the series Aproximaciones (2020–21), her beachside photographs show invigorated bodies engaging water through movement, play, and submersion. Like Trevale, we can think of the ocean as an opening—a break from the logic of land. In this light, these activities are pure release, uninhibited and liberatory. But there’s a simultaneous truth to be found in the way the ocean (and even the shore) guides and nurtures all the activities that happen there.

The ocean possesses a sense of the real embodied by rhythms and fluctuations that are far from human. As forces of gravity are suspended, it introduces an alien spatial-temporal order that penetrates every body that enters it. It holds us, and it leads us toward bonds of motion that ease the strangeness of being in water. Simply said, the ocean grants us access to ways of being that cannot be experienced on land.

Trevale practiced gymnastics for fourteen years, so it’s second nature for her to admire the ways people inventively and intentionally move their bodies in space. In her portraiture, her subjects most often appear self-possessed, upright, and imbued with sumptuous elegance. But in Aproximaciones, water inspires a new cadence in Trevale’s mode of perception—one that lingers on the moments of intuitive deliberation and stillness in which a motion is held and enjoyed.

Related Items

The Photographer Who Erased Time

Learn More[image error]

After a Revolution, a Chilean Photographer Mourns the Martyrs

Learn More[image error]

A Photographer’s Visual Poem about Solidarity and Protest

Learn More[image error]In nonoceanic, human time, we often fail to notice the pauses that structure the rhythms of our everyday. In the ocean, this feeling is amplified—all that is solid and still can be experienced as the denial of flow. But in Aproximaciones, stillness is when we are at our most human: it’s the flashing image of what is most recognizably ourselves. And when we are not ourselves, the ocean at least gives us the courtesy of shrouding our bodies in water—refracting/abstracting the unfamiliar gestural language that emerges in dialogue with the ocean.

In October 2020, the need to quarantine derailed Trevale’s original intention for Aproximaciones to be a series exclusively about the ocean. Her continent-spanning practice was reduced to a single bedroom in Lecce, Italy. Here, Trevale hesitantly began to photograph her own body for the first time in her professional career.

On first glance, these images allude to traditionally “studied” approaches to the body. However, Trevale’s touch is gentler—containing that rare queerness and discomfort that accompanies most earnest encounters with embodiment. Her images make no attempt to perform “rigor” in the masculine sense of the term. In other words, she does not dominate or even “master” her body as a formal, photographic object. Instead, her works are intimate approximations that capture the sense of a process, rather than a final, exquisitely constructed image: “My body is myself, but it is also a process.”

As part of Aproximaciones, Trevale’s photographs of her body are paired with portraits of plants that grow beside her home in Caracas. “This is the first time I’ve ever been intrigued by plants,” she tells me. “I’ve developed this compulsive need to photograph them. I feel that by evidencing that they are here, I also evidence that I am here.”

Silvana Trevale, Transforming flower, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Self portrait, London, January 2021

The sentiment is noble, such a simple thing to cherish: because this flower is here, I must be here as well. But it’s not simple—not in a time of global pandemic, and not when your homeland is a place you canno st easily return to.

In a literary sense, we think of plants as symbols of change and growth—creatures from a realm where mutation is law. Like the ocean, plant life operates in a spatial-temporal landscape world apart from the linearity and fixed identity of personhood.But how does knowing this change our understanding of ourselves? How can we possibly become flowers or plants? At least in the ocean, we can swim.

This is perhaps where touch and sight can grasp at vital truths that exist beneath the surface. There’s a depth to the ways we come to understand ourselves under our own fingertips or through our own lenses. Often, it requires swimming in aloneness—an ocean with no water to float on, no intuitive sense of rhythm, and no clear shores to swim to. Yet touch and sight, when reflected onto the self, have the capacity to transform our bodies into allies—companions in a process of perpetual becoming: “Somehow, it felt brave to take these photographs, even though the result might seem timid,” Trevale says. “I think the pandemic has taught me to see myself as the closest point-of-access to a notion of home, and to realize that this is something worth exploring.”

All photographs created using FUJIFILM X-T4 Mirrorless Digital Camera with an XF16-55 2.8R LM WR.

Silvana Trevale, Irish teenagers, Dalkey, Ireland, September 2020

Silvana Trevale, Irish teenagers, Dalkey, Ireland, September 2020 Silvana Trevale, Light through water, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Light through water, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Mother’s hand, Venezuela, February 2021

Silvana Trevale, Caracas Leaf, Venezuela, February 2021

Silvana Trevale, Mariposa, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Mariposa, Corfu, Greece, August 2020 Silvana Trevale, Elderly couple love, Lecce, Italy, October 2020

Silvana Trevale, Elderly couple love, Lecce, Italy, October 2020

Silvana Trevale, Greek boys wrestling in the sea water, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Venezuelan boys happy at the beach, near Mamporal, Venezuela, February 2021

Silvana Trevale, Sun Blast, Lecce, Italy, October 2020

Silvana Trevale, Sun Blast, Lecce, Italy, October 2020All images from the series Aproximaciones, 2020–21, for Aperture. Courtesy the artist

March 4, 2021

8 Photobooks by Contemporary Women Photographers

Since its founding in 1952, Aperture has elevated the voices of women artists and published important works by female photographers, including inspiring volumes by Nan Goldin, Deana Lawson, Sally Mann, and more. Now, in celebration of Women’s History Month, we’ve gathered eight essential titles by today’s leading contemporary women artists.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Every winter, on the day of Epiphany, members of the Russian Orthodox church plunge themselves three times into the Volga River to remember Christ’s baptism. Astrakhan, Russia, 2012

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Every winter, on the day of Epiphany, members of the Russian Orthodox church plunge themselves three times into the Volga River to remember Christ’s baptism. Astrakhan, Russia, 2012Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Caspian: The Elements by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Between 2010 and 2015, Chloe Dewe Mathews traveled through the beguiling region surrounding the Caspian Sea, photographing throughout Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran. Documenting the vastly diverse peoples, politics, and geographies of Central Asia, centering always on the great inland sea, Dewe Mathews found that elemental materials like oil, rock, and uranium have become integral to daily life. In photographs that range from stark and primordial to lush and mysterious, Dewe Mathews records the rituals and components of this resource-rich area—such as immersive acts of healing in water and oil, the almost mythological presence of flames, and drastic changes in landscapes and cities due to sudden economic shifts.

Brought together in the 2018 volume Caspian: The Elements, Dewe Mathews’s investigation is a powerful document of the ways humans are inextricably linked to this enigmatic and much-coveted land. As Sean O’Hagan writes, “Sooner than we think, these images will become historical, a record of a place that no longer exists in quite the same way, but that nevertheless thrives against all the odds in a time when, in much of the world, the age of miracles has passed into myth.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008Courtesy the artist

The Notion of Family by LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first photobook, The Notion of Family, offers an incisive exploration of the legacies of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Examining this impact throughout the community and her own family, Frazier intervenes in the histories and narratives of the region. Setting the story across three generations—her grandma Ruby, her mother, and herself—Frazier’s statement becomes both personal and political. Documenting the struggles and interactions with family and the expectations of community against the demise of Braddock’s only hospital, Frazier reinforces the idea that the history of a place is frequently written on the body as well as on the landscape.

In The Notion of Family, Frazier knowingly acknowledges and expands on the traditions of classic black-and-white documentary photography, enlisting the participation of her family, her mother in particular. In the creation of these collaborative works, Frazier reinforces the idea of art- and image-making as transformative acts, means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives—both those of her family and of the community at large.

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2017

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2017Courtesy the artist

In recent years, Rinko Kawauchi’s photographs of the tender cadences of everyday living have begun to swing further afield from her earlier work. Contemporary Japanese photography has not often been concerned with the natural landscape; the seemingly ever-expanding cityscape of Tokyo was more of a preoccupation up until 2011, a moment when the presumed order of things—natural, civic, and otherwise—was upended by the combined disasters of tsunami, earthquake, and human miscalculation. Kawauchi’s most recent work is not a commentary on natural disaster and unnatural aftermath. It is, however, an acknowledgment of larger forces at play.

This shift was first marked in the 2013 publication Ametsuchi, in which Kawauchi concentrated on the volcanic landscape of Japan’s Mount Aso and the historic Shinto ritual sites as a larger reflection of spirituality. Kawauchi has gone on to expand her inquiry even further in Halo. Throughout the volume, Kawauchi photographs three main themes: Lunar New Year celebrations in China (where a five-hundred-year-old tradition calls for molten iron hurled in lieu of fireworks), the southern coastal region of Izumo, and her ongoing fascination with the murmuration of birds along the coast of Brighton, England. The resulting images knit together a mesmerizing exploration of the spirituality of the natural world, contemplating cycles of time, implicit and subliminal patterns of nature and human ritual, and the larger spiritual forces at play.

Justine Kurland, Orchard, 1998

Justine Kurland, Orchard, 1998Courtesy the artist

Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures

The North American landscape is an enduring symbol of romance, rebellion, escape, and freedom. At the same time, it’s a profoundly masculine myth: cowboys, outlaws, Beat poets. Photographer Justine Kurland, known for her utopian images of American landscapes and their fringe communities, sought to reclaim this space with her now-iconic series Girl Pictures. Taken between 1997 and 2002, Kurland photographs staged scenes of teenage girls as imagined runaways, offering a radical vision of community and feminism.

Kurland portrays these girls as fearless and free, tender yet fierce. They hunt and explore, braid each other’s hair, swim in sun-dappled watering holes. Yet throughout all of Kurland’s photographs, her subjects pay no mind to the camera, or to the viewer, existing outside of patriarchal expectations and ideals. Kurland imagines a world at once lawless and utopian, an Eden in the wild. “I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls,” writes Kurland. “Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it—one of them, a girl made strong by other girls.”

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016Courtesy the artist, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph

Over the last ten years, Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors, to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s landmark first publication, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. Last year, Lawson went on to become the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson’s images portray the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

An-My Lê, Rescue, from Small Wars, 1999–2002

An-My Lê, Rescue, from Small Wars, 1999–2002Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain

Throughout her thirty-year career, An-My Lê has photographed sites of former battlefields—spaces reserved for training for or reenacting war—and the noncombatant roles of active service members. Lê is part of a lineage of photographers who have adapted the conventions of landscape photography to explore the structures of conflict that have long informed American history and identity. Yet she is one of the few who have experienced the sights and sounds associated with growing up in a war zone, having evacuated her home country of Vietnam as a teenager in 1975.

In 2020, Aperture and Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art copublished the first comprehensive survey of Lê’s work, On Contested Terrain, featuring formative early works, as well as her well-known series Small Wars, 29 Palms, and Events Ashore, and Lê’s most recent photographs from the US-Mexico border. “Lê’s photographs are balanced, quiet, and nuanced works of art that offer the viewer an opportunity for contemplation,” Dan Leers writes. “She invites us to examine our own perception of, and involvement in, war as something that is not straightforward or clear-cut.”

Diana Markosian, The Disappointment, 2019

Diana Markosian, The Disappointment, 2019Courtesy the artist

Diana Markosian: Santa Barbara

In Santa Barbara, Diana Markosian recreates the story of her family’s journey from post-Soviet Russia to the US in the 1990s. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Markosian’s mother, Svetlana, placed an ad through a Russian agency that read: “I want to see America, and meet a kind man who can show me the country.” After corresponding with a man who responded named Eli, Svetlana moved to America with her two young children. Markosian’s family settled with Eli in Santa Barbara, California, a city made famous in Russia when the 1980s soap opera of that name became the first American television show broadcast there.