Aperture's Blog, page 63

December 10, 2020

2020 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist: Catalogue of the Year

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation, in partnership with DELPIRE & CO, are pleased to present the shortlisted books for the 2020 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photography Catalogue of the Year Award.

Each year, the Photography Catalogue of the Year category brings together a robust roster of books published by institutions around the world. This year’s list includes both classic exhibition catalogues and new interpretations—from the Yale Center for British Art’s beautifully crafted Bill Brandt | Henry Moore, and Weiss Berlin’s reimagined chapbook series by Anne Turyn, to this year’s winner, the Walther Collection and Steidl’s comprehensive account of the origins and significance of vernacular photography.

This year’s shortlist was selected by a jury comprised of Joshua Chuang (New York Public Library), Lesley A. Martin (Aperture Foundation), Sarah Hermanson Meister (MoMA), Susan Meiselas (photographer, Magnum Foundation), and Oluremi C. Onabanjo (independent curator and historian).

Rahima Gambo Rukkaya and Hadiza, Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2016, juxtaposed with a connect-the-dots style illustration from a school book, from the series Education is Forbidden, 2015–16

Rahima Gambo Rukkaya and Hadiza, Maiduguri, Nigeria, 2016, juxtaposed with a connect-the-dots style illustration from a school book, from the series Education is Forbidden, 2015–16Courtesy of Rahima Gambo and Open Society Foundation

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time and the Other offers a capacious and considered view of contemporary practices across the African continent and diaspora. Published on the occasion of an exhibition of the same name at FotoFest Biennial 2020 in Houston, the catalogue weaves together an inclusive group of thirty-two artists, spanning across four decades of photographic practice, whose works challenge traditional notions of Blackness and transnational histories in relation to concepts of liberty, rights, and representation. Edited by Steven Evans, Max Fields, and Mark Sealy, this handsome and readerly volume features an iconic photo by Rotimi Fani-Kayode across the front and back, and bronze-gilded pages. In addition to each artist’s portfolio is a selection of essays, ranging from epistolary interviews to critical examinations of contemporary exhibition practices around African photography and artists. Reflecting on the combination of essays and selected artists, juror Oluremi C. Onabanjo states, “It offers a rich entry point for someone who is trying to understand contemporary photographic practice and critical discourse surrounding the African continent and diaspora.”

Anne Turyn, Waiting #2 (Federal Building, New York City, 1990s)

Anne Turyn, Waiting #2 (Federal Building, New York City, 1990s)Courtesy the artist

Anne Turyn: Top Stories, Elena Cheprakova and Kirsten Weiss, eds. (Weiss Berlin, Berlin, 2020)

Top Stories, a prose periodical was a chapbook series created by Anne Turyn in the late 1970s. A student of linguistics, Turyn conceived of it as a literary series but welcomed the combination of text and image—a trademark of her own photographic practice. Each issue focused on a single artist, mostly women, some of whom Turyn met through readings and performances—such as Kathy Acker, Laurie Anderson, Constance DeJong, and Pati Hill—and embraced the permeable creativity of the time in blending literary works with art and music. Top Stories and other work are encapsulated in the small, two-toned-cloth softcover book that accompanied Turyn’s exhibition at Weiss Berlin earlier this year. The unassuming format, halftone imagery, and raw typesetting all complement the improvised feeling of the chapbooks. Juror Sarah Meister describes the book as “the perfect marriage of form to content, taking an artist whose career has been flying slightly below the radar and helping to give texture and context to Turyn’s work, while also respecting the original format in which it circulated.”

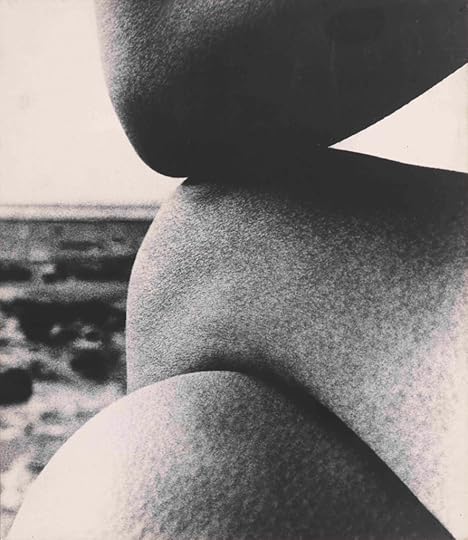

Bill Brandt, Normandy, 1959

Bill Brandt, Normandy, 1959Courtesy the artist/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

According to juror Susan Meiselas, Bill Brandt | Henry Moore is a “masterful work of scholarship.” Accompanying an exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield, UK, this large-scale, richly illustrated book is a thoughtful examination of the interplay between two brillianttwentieth-century artists: Bill Brandt and Henry Moore, brought together while both creating work depicting civilians taking shelter in the London Underground during the Blitz. The book takes the viewer beyond their first encounter and through the artists’ postwar period, sequencing works together to show their intersecting paths. “I love the mix of materials—Moore’s illustrations, drawings, and sculptures in counterpoint to Brandt’s photographs—which highlights the interconnections of each man’s craft,” notes Meiselas. The catalogue makes clear the immediate influence the artists had on one another and “leads the viewer to resee Brandt’s nudes as sculptural form, abstracted into stone by Moore.”

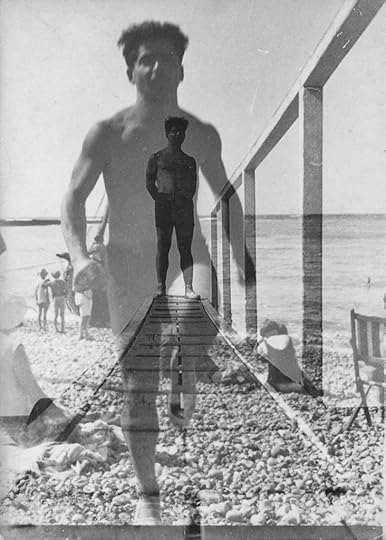

Moi Ver (Moshé Raviv-Vorobeichic), Self-portrait, Yport, Seine-Maritime, France, 1931

Moi Ver (Moshé Raviv-Vorobeichic), Self-portrait, Yport, Seine-Maritime, France, 1931Courtesy the artist

Hommage à Moï Ver offers what juror Lesley Martin calls a “double delight” in the facsimile reprint of a modernist photobook classic, slipcased together with a second volume that offers curatorial insight and rich historical context alongside the original publication. “This is a great way to present the original artifact of the book as it was published, alongside new scholarship and commentary,” Martin concludes. Moï Ver is best known for his canonic 1931 photobook Paris, which buzzes with the vertiginous energy of the eponymous city. That same year, the Lithuanian-born photographer, whose given name was Moses Vorobeichic, published The Ghetto Lane in Wilna. To the contemporary viewer, the subjects might seem dramatically different—the modernist urban center of early twentieth-century art and literature versus the stolid if bustling Jewish quarters of Vilnius, Lithuania (Wilna in German; tragically the city would later be destroyed by Nazi forces). But both were vibrant European capitals in their day, and Ver applied the same avant-garde approaches of images collaged, double exposed, cropped, and placed on the page with idiosyncratic, constructivist verve.

Unidentified photographer (American), Camielle and Tina, ca. 1970 (Detail)

Unidentified photographer (American), Camielle and Tina, ca. 1970 (Detail)Courtesy the Walther Collection

Imagining Everyday Life—a new, comprehensive account of the origins and features of vernacular photography—evolved from a two-day landmark symposium organized by the Walther Collection and held at Columbia University in 2018. With leading scholars and critics from a variety of disciplines and regional perspectives reevaluating ordinary images through the lenses of power, identity, political participation, and ideology, new narratives that have been largely ignored or erased are inserted into the traditional read of the vernacular. In redefining vernacular photography by its social function rather than its aesthetic features, and examining the agency of its makers, Imagining Everyday Life proposes a much deeper and wider discourse around vernacular photography’s history and role. Richly illustrated and supported by texts that are “rigorous without being ponderous,” juror Joshua Chuang states that Imagining Everyday Life “provides a multifaceted snapshot of thought around the problematics of vernacular photography,” and is truly “an essential reconsideration of the topic.”

These text were originally published in Issue #18 of The PhotoBook Review.

The 2020 Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Exhibition will be on view at DELPIRE & CO through December 24, 2020. Read more about the 2020 PhotoBook Award Winners here.

December 8, 2020

Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

“In nature, nothing is perfect. . . . Trees can be contorted, bent in weird ways, and they’re still beautiful.”

—Alice Walker

Two bare-chested young Black men on playground swings. Staring slightly down at the camera, the first young man, with twisted hair and striped boxers peeking out of his jeans, clasps the swing’s chains. Next to him, another young man, swinging in his ripped denim, with his eyes closed. His hands grab the chains in preparation for flight or, perhaps, a return to rest.

In Tyler Mitchell’s photobook I Can Make You Feel Good (2020), a debut monograph based on his first solo exhibition at Foam, in Amsterdam, in 2019, and at the International Center of Photography, in New York, in 2020, the depiction of these young men, partly naturally lit and in leisure themes, is in many ways a definitive aspect of his aesthetic.

Recently Mitchell has photographed a wide range of Black subjects, from the hip-hop artist Vince Staples to skaters in Havana, to take on an even more ambitious project: Black utopia. “People say utopia is never achievable,” he states in the foreword to his book, “but I love photography’s possibility of allowing me to dream and make that dream become very real.”

Tyler Mitchell, Still from Idyllic Space, 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Still from Idyllic Space, 2019The result: young Black men in bright blue jeans, with dark brown to even deeper and richer brown skin tones, taking center stage with a beauty so brilliantly lit by the sun and caught by Mitchell’s eye that the allée of trees behind them all but disappears. Their freeness is intriguing, mainly because it depends on their being outside, making the outdoor backdrop relevant for what is there and what is not. Absent are those racial tragedies that inform my seeing and exist just beyond the photograph’s frame. Rekia Boyd: shot in the head by a white off -duty police officer in Chicago’s Douglas Park in 2012. Tamir Rice: shot in the chest by a white police officer at a Cleveland playground in 2014. Walter Scott: shot in the back while fleeing a white police officer in a North Charleston park in 2015. Among those calamities and, of course, our more recent ones, Mitchell’s insistence on seeing Black people at peace and in play in public is a profoundly radical act.

In this moment of Black Lives Matter, Mitchell’s films and photographs provide counternarratives to those viral recordings, such as Darnella Frazier’s ten-minute video of George Floyd’s murder. But, as his work reminds us of the long history of racism in the United States, it also reveals an alternative. “The African-American ties to this land, unfairly seized from Indigenous people, are ugly and thick,” the historian Tiya Miles wrote in her 2019 New York Times essay on race and environmental justice. “But even in that long, dark tunnel of suffering, African-Americans recognized the capacity of nature to function as a resource—better still, an ally—in the fight for physical and psychological freedom.”

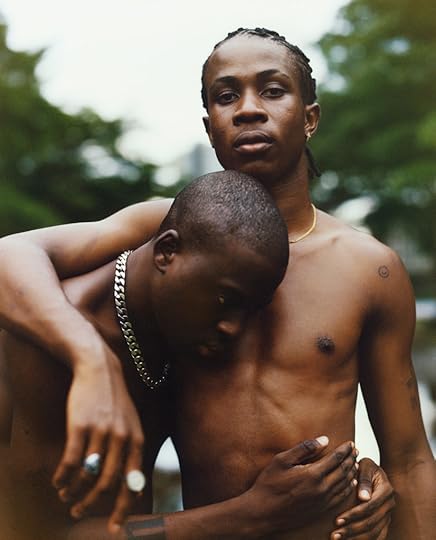

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Warm Embrace), 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Warm Embrace), 2019By showing us Black life as leisure, as repose, as outdoor play, Mitchell continually expands our visual vocabulary of race and space. I search his photographs for more geographic clues. Yet with those young men on the swings, their hairstyles and sartorial details convey only their nowness, not their place. The playground swings tell me something, but not enough. The trees, blurred into a lush mise-en-scène, could be a field, a forest, a farm, or a park. Each potential site has its own racial history, each choice would pose different types of threats for their swinging Black bodies. But in Mitchell’s freedom dreaming, these trees are not used for harm.

With their heads and chests arched forward, their loosely picked-out coils, and the way their jeans hang just so, his Black male models use the trees as a canvas onto which they, not us, can project the artist’s versions of themselves far into the future.

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Family Time in the Park), 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Family Time in the Park), 2019When Mitchell and I spoke on Zoom this August, a week after his book’s release, he was in London, while I chatted from Newark. He was backdropped by potted plants and arching trees that transformed the backyard patio where he sat into a small garden. Knowing that he spent the majority of New York’s pandemic lockdown in his Brooklyn apartment, I thought that any attempt he made to establish a temporary life in another country, and in fresh air, was well-earned.

And yet nature has a way of interrupting our best intentions. Not long into our conversation, a bee started circling him, eventually disturbing him, so that he had to go back inside. Looking back, Mitchell’s desire to remain outside was not just happenstance but fundamental to his autobiography, his aesthetic, and his redefining of Black life.

Two young Black men sitting on the grass. The one at left in a rose T-shirt, eyes down, smile bright. Beside him, his friend, or lover, cousin, or brother, an ambiguity suggested by the unknowable meaning of their near touch. What is clear are their smiles. The young man in the unbuttoned, blue shirt, revealing his bare chest, is mid-turn, hands clutched underneath the ball about to drop. Another man, in a pink, blue, and white striped shirt, zips by them. We see only his back and legs in stride, and his locks swaying, trailed by his matching kite.

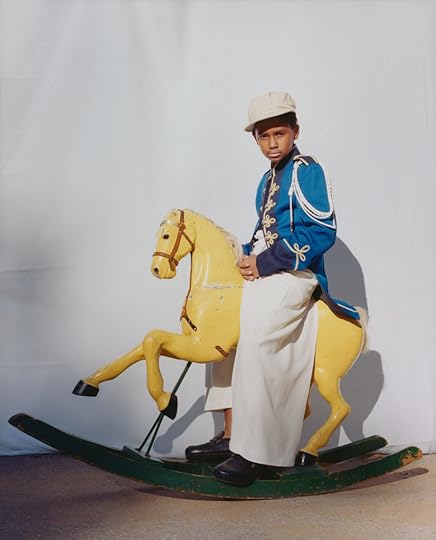

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Boy in Blue Jacket on Horse), 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Boy in Blue Jacket on Horse), 2019Another image. A young Black boy, dressed up in a royal-blue military jacket, his dusty-brown skin quieting the gold braids and buttons adorning the uniform. The white sheet that hangs as a backdrop is reminiscent of Mitchell’s famed September 2018 cover for Vogue, when, at twenty-three years old, he became the first African American artist to shoot the magazine’s cover in its 125-year history, photographing a minimally made-up Beyoncé outside, with only white sheets as backdrops and props. While his clothing and fancy rocking chair intimate an aristocratic flair, the white sheet and outdoor pavement indicate everydayness. Here, these stylized juxtapositions work together to convey Mitchell’s refusal of spatial and sartorial hierarchies.

Inspired by Spike Jonze’s skate videos, Mitchell, in his early work, used his friends and fellow skateboarders as subjects. He documented their aerials and slide tricks with a digital SLR Canon, whose flip switch enabled him to toggle between photography and video. As a result, play was inseparable from the visual languages he was teaching himself. “Of course, there’s the surface level cool and rebel spirit about skateboarding,” Mitchell told Vogue in 2018, “but the thing that makes skaters like artists runs deeper than that: It’s not a sport that’s built on competition, it’s one that thrives on community.”

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Park Frivolity), 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Park Frivolity), 2019Much has been made about how Jonze’s work, along with the casual snapshot style of Ryan McGinley and the gritty youth-culture focus of Larry Clark, has informed Mitchell’s approach. In his own narration, he mentions them, but he also speaks about how Tumblr not only introduced him to creative photography but helped to shape an egalitarian aesthetic. “I think the link for me to Tumblr growing up was a lot more significant than even I realize, in a way,” he tells me. “There, images come to you in a swarm of decontextualization. One thing is next to the next, and they might have nothing to do with one another, but your mind creates a link between two images.” He goes on, “It could be a Rococo painting next to a highly conceptual image of a performance artist. And then it could be next to a very chic modern interior.”

After reading as much as I could about Mitchell, I noticed one crucial aspect of his life that he returns to but that most writers overlook: the role that growing up in the Black South has played in birthing his sense of place and play. “Atlanta, and being from Georgia, frames how I approach my own autobiographical ideas of utopia,” he muses. “Being middle-class, having leisure time in the summers, gave me the opportunity to think about it as a site of utopia, or a potential utopia.” Mitchell notes his aesthetic came out of “that free time and those memories of playing in fields or in parks in Georgia.”

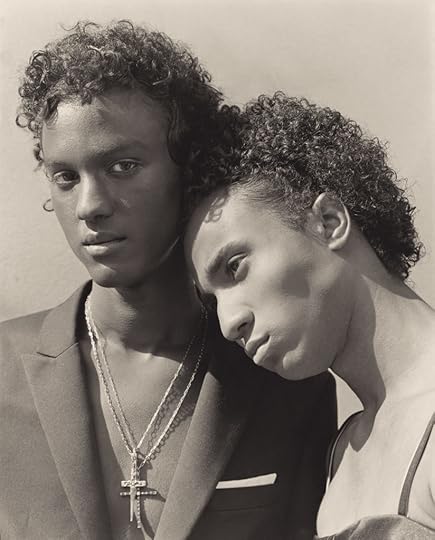

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Curls), 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Curls), 2019In other words, Mitchell’s Black utopianism comes from his nondifferentiation. Taking Tumblr, with its nonhierarchical format, as a political and photographic practice, Mitchell not only toggles between visual mediums but normalizes the celebrity and exalts the everyday citizen. “One of the biggest things I’ve been reflecting on these days is the whole idea of the hierarchy between photographer and subject. I have a tool and a camera that I’m using to convey something or someone,” Mitchell says to me. “And inherent to photography, especially when you think of it historically, is a strong hierarchy, where the photographer is the one with all the power, the one who is seeing. And the person being seen has almost no power. So, for me personally as a photographer, I ask myself, ‘What are the things I can do to lessen these inherent hierarchies in the photography-shoot structure of seeing and being seen?’”

At the same time, his radical flattening of divisions is also a reflection of his expansive worldview, much like the poetry and novels of his fellow Georgia native Alice Walker that seek to celebrate and canonize the diversity innate to nature. “When you see an aerial shot of Atlanta, which I’m really interested in, it’s full of trees,” he says about growing up right outside Atlanta, a city with more green space per resident than any other U.S. metropolis. “You’re in a city whose skyline is really weird. That’s what I grew up around, being surrounded by nature constantly, and near a city with a Black core. A strong Black inner core.”

Tyler Mitchell, Still from Chasing Pink, Found Red, 2019

Tyler Mitchell, Still from Chasing Pink, Found Red, 2019All works by Tyler Mitchell © the artist

Another image. In the book it is fixed, but it is an excerpt from his 2019 film Chasing Pink, Found Red. Here, young Black men and women, eyes closed, bodies dressed in whites, khakis, and browns, nearly touch as they lie together on a red-and-white-checkered picnic blanket. Their stillness recalls the 2015 die-in protests in the early years of Black Lives Matter; their stillness also insists that they rest among each other as a form of self-care and self-protection. While Mitchell’s extolling of Black leisure might be new to some, it is familiar to those of us who have turned to play as both a testament to our humanity and a form of resistance in a world in which our Black lives still don’t matter.

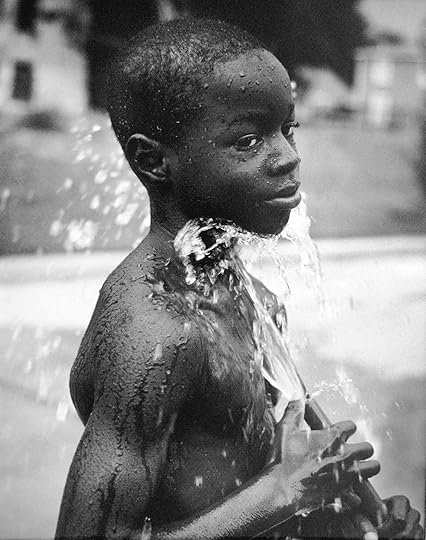

In this way, Mitchell is a student, as he quite earnestly told me, of Earlie Hudnall Jr., a Mississippi-born African American photographer who has spent the majority of his career documenting Houston’s historically Black Third Ward neighborhood. Hudnall’s black-and-white photograph Flipping Boy, 4th Ward (1983), featuring a young Black boy, mid-backflip, in the middle of a Houston street, anticipated Mitchell’s own skateboard montages and Hula-Hoop close-ups. Hudnall’s Cooling Down, 3rd Ward (1997) of a little Black boy gleefully splashing himself with a hose conjures up the joy seen in Mitchell’s images of young Black men flying kites or on swings. And, finally, his Rascals, 3rd Ward (1991), depicting a group of little Black boys proudly standing in front of their bikes, made four years before Mitchell was born, reminds me of the pride of Mitchell’s own regal portrait of the young boy on a play horse.

Earlie Hudnall Jr., Cooling Down, 3rd Ward, Houston, Texas, 1997

Courtesy the artist and PDNB Gallery, Dallas

Earlie Hudnall Jr., Flipping Boy, 4th Ward,, Houston, Texas, 1983

In a statement about his work, Hudnall said that, in addition to his father, who was an amateur photographer, it was his grandmother’s use of a photo-album to record their community’s history that inspired his own interest in documenting quotidian moments rarely seen outside the community. “The love for this common way of life and the memories of those times,” Hudnall recalled, “provided me with the inspiration to become a photographer, just as Grandmother used the photo-album and the family Bible.” Crisscrossing fashion, art photography, and avant-garde filmmaking, Mitchell offers us a Black utopia in which the couture and the common sit next to each other, and in which Black people in London, Brooklyn, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and throughout the African diaspora find one another, as relief and community. And therein lies Mitchell’s gift and genius, to reimagine our world with the possibilities and agency of Black life. “My images are made all over the place,” Mitchell says. “The subjects and the geography just support this aesthetic universe of a utopia. It’s not meant to be pinned down.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Tyler Mitchell: Love for a Common Way of Life.”

The Queer Black Artists Building Worlds of Desire

It is the picture of rebirth, an image of the unease of transition. Profusely the sweat gathers, beading across Prince Luxury’s face and chest. His almond-shaped eyes are shut as his tongue reaches across gold grills capped onto his teeth, licking away moisture from his upper lip. His body is there in the frame, but his mind is elsewhere. Looking at the artist Shikeith’s image titled Prince (2019), you want to see what the figure sees, but you can’t. Luxury’s gaze is hidden behind his eyelids; like an awning, they provide cover. What vision is he masking? An action of his own making? An imagined destination where the sweat of his labor marks him of value? A place where he is the center of his own desire? Of this image, Shikeith has noted that he seems to have caught Luxury in the middle of “an act of deviance.” What is captured is an autoerotic freedom.

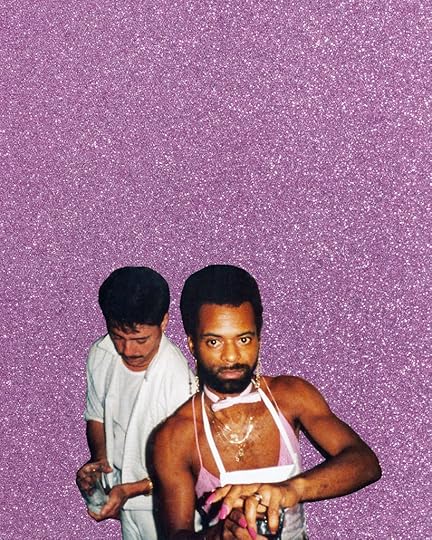

Utopia is not a word that has been widely considered in the contemporary photographic works of Black queer artists. Much of their art has been flattened into the politics of representation. But Shikeith’s impression of ecstasy is an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world. This work has roots in earlier art that explores subjectivities and social spaces beyond cultural and sexual limitations. Alvin Baltrop snapped black-and-white pictures while cruising New York’s collapsing Hudson River piers in the 1970s and ’80s. Those images reveal a secret world—in the liminal post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS space—that existed outside of that era’s dominant sexual appetite and presaged today’s wide embrace of dating apps such as Grindr and Tinder, and casual sex-worker sites like OnlyFans. Shikeith’s portrait of desire also recalls Lyle Ashton Harris’s images that parse gay male subjectivity and want. Harris’s early 1990s performances of masculinity transgressed the binaries of gender and race that governed how a Black man should act. In a self-portrait, Snow Queen #1 (1990), Harris appears in a platinum blond wig; white powder covers his face. His body does not yet exist as normal; there is no place where his body can feel affirmed and complete without the possibility of harm.

Davion Alston, stepping on the ant bed, 2020

Davion Alston, stepping on the ant bed, 2020© and courtesy the artist

While utopia often denotes otherworldly fantasy, unrestricted escapism, or sublime positivity, the late theorist José Esteban Muñoz, in his 2009 book, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, offered the idea of a queer utopia, one constructed with verisimilitude and operating against a history of lack and discrimination. Queerness belongs to the future, Muñoz claims in his study of performance, writing, and contemporary art, noting that it “allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.” Utopia is the search for safe space in counternarratives where queer acts, longings, and urges fulfill personal and communal yearning—and where desire flourishes beyond the confines of mainstream white, gay culture. Such acts offer care and delight, a way out of the margins. As Joshua Chambers-Letson, Tavia Nyong’o, and Ann Pellegrini write in their foreword to the 2019 edition of Cruising Utopia, “For utopia, though it bears many positive qualities, also bears negation, as originating from the Greek for ‘no place’ or ‘not place.’” They add, “Queer utopia is the impossible performance of the negation of the negation.”

“When idealizing what utopia looks like I immediately think of the use of photography,” the photographer Davion Alston explains to me. “This tool mastered the recording of truth, the reflection of what or who could be.” Alston’s recent series stepping on the ant bed (2020) documents the protests in Georgia against the killing of unarmed Black people such as Rayshard Brooks and Breonna Taylor by the police. He describes the work as a way for him to explore “desiring utopia in dystopia.” These black-and-white images capture protesters as they shut down southbound lanes of the I-75/I-85 highway. In the photographer’s prints, faces are intentionally obscured with blue, red, yellow, and green stickers. “Through this covering of faces,” he says, “I am able to think about the protection of identity due to surveillance and speculation as well as redefining what the landscape looks like in 2020.” The images allow for new imaginings of the expressions of the Black body beyond what is sanctioned. Amid the twin pandemics of racism and coronavirus, the pictures offer a look at seeking safety in protest, a way of gathering against governmental failure.

D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Elysian, 2018

D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Elysian, 2018Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

“I made the image knowing I wanted to talk about not giving a fuck,” the photographer D’Angelo Lovell Williams says of Nah (2018). It’s a self-portrait of the artist in a white dress, swimming in a lake, away from the camera, a gesture that refuses capture, finitude. The image is part of a growing oeuvre in which Williams creates scenes of aspiration and connection. “When I think about the formal,” he explains, “I think about themes of class, race, and social hierarchies that don’t allow Black and queer people to explore beauty and desire of each other’s bodies.” His aim is to reframe that censorship, visualizing what Muñoz addresses as a queer performativity that “is not simply a being but a doing for and toward the future.” In Elysian (2018), a figure obscured by parched foliage is seen tenderly pulling a lover into another world, where a moment of intimacy is possible. There is a radical physicality present that explores themes of surreal dualities, kinship, and discovery as a way to transgress the taboo. “I know our history with the natural landscape, and it’s lacking in regard to visual representation,” Williams says. “When themes about my work come up, I hear, ‘Oh, well, your work is sexually explicit.’ The gestures are about rejecting the labels that have been placed on us. I don’t have to abide by censorship on my own body or people’s bodies.” He adds, “It’s about going beyond a sense of the now.”

Photographers such as Daniel Obasi, Nydia Blas, and Naima Green also use the camera to exceed the present precarious conditions of racism, homophobia, and anti-trans violence. In Green’s portrait Diamond, Brower Park (2016), the subject’s eyes are closed. “That gesture offers a different way of thinking into oneself, the landscape, and creating a utopia in really blocking out everything and just being there and taking a deep breath in the moment,” Green explains. The image is from a series of portraits, called Jewels from the Hinterland (2013 ongoing), that captures creatives from across the African diaspora in urban idylls. Hinterland: an area lying beyond what is visible or known. This idea of a private space, only reachable by those in the know, was essential to Green’s pursuit to “create an alternative present” and “reclaim lively, lush urban space as Black space.”

Naima Green, Diamond, Brower Park, 2016, from the series Jewels from the Hinterland

Naima Green, Diamond, Brower Park, 2016, from the series Jewels from the HinterlandCourtesy the artist

Reclaiming urban space as Black space is also at play in Lauren Halsey’s digital collages that present queer Afrofuturist alternative realms. On social media, she borrows the name of the Black ready-to-wear label FUBU (For Us By Us) that, in the 1990s, represented cool urban self-realization, and hashtags her visions #fubuarchitecture. For the artist it seems to be shorthand for what an inclusive and self-reliant Black community could be. Her work thang (2020) zeroes in on South Central, Los Angeles, where Halsey is from. She remakes her neighborhood in her own image. Stylish Black women and men appear, cut from found materials, as do pyramids, unicorns, statues, a Louis Vuitton–monogrammed California bungalow, and advertisements for local businesses such as Urban Books & Thangs. There are statements of empowerment against gentrification: we still here, there (2018) and the sprawling collage work gotta get over the hump? (2010), in which emblems of Black mysticism and informal communion collide. Halsey’s visual world-building sits in a history of queering the medium of collage that has long manufactured dreams, manifesting them through the construction of new material realities.

Lauren Halsey, gotta get over the hump?, 2010

Lauren Halsey, gotta get over the hump?, 2010Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

Like Mickalene Thomas, with her vibrant, collaged living-room tableaux, Halsey, who also draws on the Black cultural aesthetics of the 1970s, has used her collages as sketches for architectural installations such as Kingdom Splurge (2015), which she describes as an “endless becoming that entails liberation through Funk, fantasy architecture, and the experimental development of space.” A similar impulse is at play in Sadie Barnette’s New Eagle Creek Salon (2019). The project pays homage to and reimagines the San Francisco bar her father, Rodney Barnette, opened, in 1990, to serve a multiracial queer community marginalized by the city’s gay nightlife scene. The installation’s bar (activated as a social space), sculpture, and found party photographs of patrons and bartenders are glittering documents of history. Memory here is used in the service of futurity—or, as Barnette writes, the project is meant to “offer space for connection and new energies, to dance and dream.”

Sadie Barnette, Untitled (For Sammy), 2019, from the series New Eagle Creek Salon

Sadie Barnette, Untitled (For Sammy), 2019, from the series New Eagle Creek SalonCourtesy the artist

Muñoz opens Cruising Utopia with a provocation: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer.” It announces that queer people are not yet fully themselves in the world, and the process of trying to get there is the hard work of hope. The violence of the state routinely smashes the self, controlling what is possible—sexually, politically. Given this enduring reality, some queer artists dream in images, in defiance of the straight imagination. Their eyes desire narratives of longing and pleasure, free of trauma, with illuminations of relief. Through their pictures, other ways of existing are possible.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “The Future Will See You Now.”

What Does Utopia Look Like in Photography Today?

This winter, in the wake of a pandemic, global protest movements, and a dramatic presidential election in the United States, Aperture magazine’s new issue, “Utopia,” shows that other ways of living are possible—when the collective will exists.

In “Utopia,” artists, photographers, and writers envision a world without prisons, document visionary architecture, honor queer space and creativity, and dream of liberty through spiritual self-expression. The issue features compelling portfolios by David Benjamin Sherry, Allen Frame, and Balarama Heller—whose respective works span time and geography, from bohemian New York to a Hare Krishna retreat in India—and writing by Antwaun Sargent on Black queer artists’ representations of desire, Sara Knelman on the freeing possibilities of feminist collage, and Salamishah Tillet on Tyler Mitchell’s visions of Black utopia. They all show us that utopia is not a far-fetched scheme, but rather a way of reshaping our future.

In conjunction with the release of “Utopia,” Aperture launches a series of digital programming in partnership with London-based fashion brand JW Anderson. See below for the full schedule.

Tyler Mitchell and Salamishah Tillet on Black Utopia

December 10, 7:00 p.m. ET

Tyler Mitchell’s iconic photographs of Black individuals playing and at ease in public are what Salamishah Tillet calls a “profoundly radical act.” Blurring the line between art and fashion photography, Mitchell’s images capture a Black utopia filled with community, love, and tenderness. In this conversation, Mitchell and Tillet consider what Black utopia looks like in today’s world. See here to register.

Matt Wolf on Creating “Spaceship Earth”

January 21, 2021, 7:00 p.m. ET

For more than a decade, the filmmaker Matt Wolf has won acclaim for his meticulously crafted documentaries that reveal lost histories through deep dives into media archives. In this conversation, Wolf will discuss his latest film, Spaceship Earth (2020), which traces the activities of a counterculture collective known as the Synergists, who spent two years inside Biosphere 2, a self-enclosed ecosystem in the Arizona desert. See here to register.

Feminist Futures with Sara Knelman

February 4, 2021, 7:00 p.m. ET

From the Dada movement to today, artists have deployed the visual collisions of collage to critique, challenge, provoke, and invent their own idyllic realms. In this conversation, writer Sara Knelman speaks with Alanna Fields and others about the freeing, utopian nature of feminist collage. See here to register.

Antwaun Sargent on Black Queer Utopia

February 18, 2021, 7:00 p.m. ET

Antwaun Sargent, artist Shikeith, and others discuss the ways Black queer artists are redefining the notion of utopia. As Sargent explains in his essay “The Future Will See You Now,” Black queer artists are using photography in defiance of the “straight imagination,” and in doing so, creating their own narratives of desire and relief. See here to register.

Read more from Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Through December 14, as part of the Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition, collect a signed print by David Benjamin Sherry for $200.

December 4, 2020

Announcing the Winners of the 2020 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation, in partnership with DELPIRE & CO, are pleased to announce the winners of the 2020 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. From the thirty-five shortlisted, a final jury in Paris comprising of Damarice Amao (Centre Pompidou), Lucy Conticello (M le magazine du Monde), Laurel Parker (Laurel Parker Book), Nicolas Poillot (creative director and image consultant), and Stéphanie Solinas (artist) selected this year’s winning titles.

An exhibition of the thirty-five books shortlisted for the 2020 PhotoBook Awards, as well as installations drawn from Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review guest edited by Dr. Deborah Willis is on view at the DELPIRE & CO bookshop until December 24, 2020.

Coinciding with this year’s winner announcement, a weekend of online conversations with artists and publishers from this year’s shortlist, as well as members of the jury, in discussions of their work and the critical role of photobooks, will take place on December 5 and 6, 2020. See here to register.

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year

Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography

Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis, eds.

Walther Collection and Steidl, New York and Göttingen, Germany, 2020

Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography, edited by Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis (Walther Collection, New York, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany), winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year, “provides a multifaceted snapshot of thought around the problematics of vernacular photography” and is “an essential reconsideration of the topic,” according to shortlist juror Joshua Chuang. Final juror Lucy Conticello added, “The heft and the depth of the research, its striking and insightful contributions sourced from a great number of archives and collections, and fantastic reproductions make this a reference book on vernacular photography that will be around for a long time.”

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year

Gloria Oyarzabal

Woman Go No’Gree

Editorial RM and Images Vevey, Barcelona and Vevey, Switzerland, 2020

In Woman Go No’Gree by Gloria Oyarzabal the artist explores colonialism and white feminism in West Africa through the use of found imagery, archives, and her own photography. “Both substance and form of the book are compelling. The artist advances an excellent dialogue around deconstructing the idea of the gaze and ‘the other,’” states final juror Damarice Amao. “The layout and the intelligent, inventive—even destabilizing—graphic design serve her purpose very well.” In this beautifully and thoughtfully crafted book, Oyarzabal challenges the viewer to engage with their own biases and assumptions.

Winner of First PhotoBook ($10,000 prize)

Buck Ellison

Living Trust

Loose Joints Publishing, Marseille, France, 2020

Living Trust by Buck Ellison was praised for its investigation of the visual language of privilege. Taken together, the series in the book offer a sustained, almost anthropological examination of the ways whiteness and privilege are both recapitulated and broadcast. “Living Trust emerged in our conversations as something that focuses really well on what many take for granted,” shortlist juror Oluremi C. Onabanjo commented. “The book is carefully shaped in relation to the subject, in its form as much as in the artist’s approach to white privilege—a very contemporary subject—and addressed with very personal writing,” concluded Nicolas Poillot, who served as part of the final jury.

Juror’s Special Mention

Ryan Debolski

LIKE

Gnomic Book, Brooklyn, 2020

LIKE by Ryan Debolski explores the experiences and relationships of migrant workers in Oman. But rather than focusing on the defining public image of poor working conditions, Debolski depicts men finding agency and connection to the landscape of the beach and companionship in each other—they are as playful as they are introspective. “The position this work takes is very singular,” juror Stéphanie Solinas affirms, “a book on migrant workers in Oman, where we find a great presence of bodies with a form of sensuality where we expected to find brick walls and deserts. The weave between text and image, bodies and architecture offers a new, unexpected entry into the topic.”

The 2020 Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Exhibition will be on view at DELPIRE & CO through December 24, 2020.

Why Deborah Willis Thinks the Photobook Can Be Transformative

In 1973, Dr. Deborah Willis, then an undergraduate photography student at the Philadelphia College of Art (UArts), submitted an independent research proposal about the contributions of Black photographers to the history of American photography from 1840 to 1940. Willis had sent fifty letters to various collections and libraries, seeking information about photographers such as Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee. “Is a photographer primarily a creative artist rather than a mere recorder?” she asked. “Could these black photographers receive the same recognition their white colleagues received?” Across her prolific career as an archivist, historian, professor, and photographer, Willis has answered these questions about recognition through her groundbreaking studies of Black photographers, her contribution to numerous photobooks, and her support over the years of artists and writers seeking to make space for an expanded, more inclusive history of the medium.

But, for all of the publishers who supported her quest enthusiastically, Willis, the guest editor of Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review, also encountered editors who clung to dated narratives about photography and race. No one said changing minds would be easy, yet Willis was determined. She would go on to win Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowships, and become a revered professor at New York University, where she is now chair of the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts. Willis recently spoke with Brendan Embser, her former graduate student at NYU and editor of Aperture monographs on Deana Lawson and Ming Smith, about her earliest encounters with photobooks and how the photobook as a medium continues to be transformative.

Deborah Willis, Untitled, 2010

Deborah Willis, Untitled, 2010Courtesy the artist

Brendan Embser: When we were launching Deana Lawson’s Aperture monograph two years ago, she gave this beautiful speech. She said she hoped that one day, a young woman would come to the library in Rochester, New York, where she grew up, and discover her book. Her vision was about sharing. That moment, which I found so moving, reminded me of you and your stories about growing up in your mother’s beauty shop in Philadelphia and sharing magazines like Jet. When it comes to photobooks, did you have an experience of going to the library or bookshop and feeling transported by a single book?

Deborah Willis: Yes, I was seven years old. It was Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life [Simon & Schuster, 1955]. We had to pick a library book every week growing up, and I just discovered that book visually. I saw it on the shelf and I took it home. I was so fascinated with the beauty of the light in the photographs. I could see that the lighting and the woman were so beautiful. The bare bulbs in the kitchen. It was intimate; it looked like love. That’s how I grew up, with my family. It was always about love.

Embser: Did you think of the book as a distinct experience visually from the magazines that you were looking at?

Willis: Then, I didn’t. But the connection for me with that book, and with magazines—Black magazines—was the experience of seeing Black people in print. We had National Geographic, which was a different way of seeing Black people, mainly in Africa. But to see Ebony magazine, and Jet, and Bronze, and Hue, and all of the magazines that my parents subscribed to—this was a part of the spectrum, the experience.

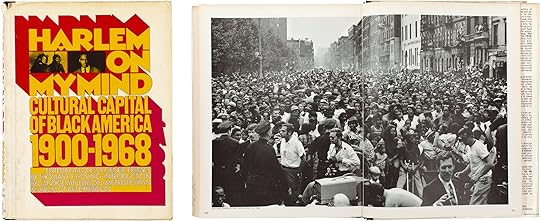

Cover and spread from Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 (Random House, 1968)

Cover and spread from Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 (Random House, 1968)Embser: Do you remember the first photobook you ever bought for yourself?

Willis: The first photobook I bought was the catalogue to the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition Harlem on My Mind [Random House, 1968]. The second book was The Black Photographers Annual [1973–80]. That was really major for me. I was an undergraduate student, looking for a way to examine the history of Black photographers, but also trying to recognize that there was more than what I found in my photo-history books.

Embser: When you worked as an archivist at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, did the Schomburg make a point of collecting photobooks at that time?

Willis: I was conducting research at the Schomburg Center in the mid-’70s, and they didn’t collect photobooks specifically; however, there were numerous pictorials on Black life in the collection. And, there was The Black Book [Random House, 1974] by Toni Morrison, which had photographs in it. I discovered that at the Schomburg. Five years later, when I was hired to be the photo specialist and then became the photo curator there, I saw the gap. I noticed that there was something that I needed to do with organizing and creating the “bio-bibliography,” which would eventually be the first book that I did, Black Photographers 1840–1940: An Illustrated Bio-bibliography [Garland, 1985].

Embser: Were you also acquiring books and objects for the Schomburg? And did you make a point of collecting artists’ monographs, or would that have been the library’s job?

Willis: Yes, I was lucky enough to work with Ruth Ann Stewart, and with Jean Blackwell Hutson—both headed the Schomburg. Ruth was helpful in guiding me through, allowing me to create books that could be used in the archives, where photos were held, but also for the general library, which researches used.

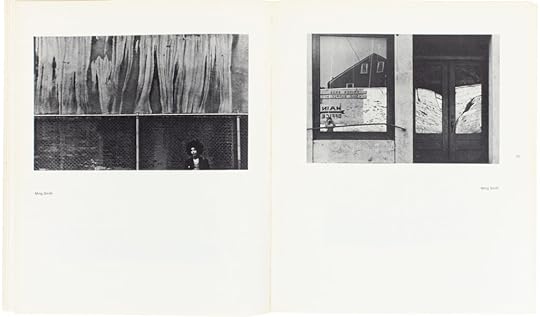

Spread from The Black Photographer’s Annual, Vol. 1 (1973), with photographs by Ming Smith

Spread from The Black Photographer’s Annual, Vol. 1 (1973), with photographs by Ming SmithEmbser: How were you able to find publishers for your own books?

Willis: I had an angel. His name was Richard Newman and he worked at Garland Publishing, which created books on African American histories. Within a month of starting at the Schomburg, Dick called me up and asked me if I would like to do a book on Black photographers. And I said, “Well, I have an undergraduate research paper.” And he said, “Send it to me.” He told me we should create a book that was a resource list of photographers. In the end, I had over three hundred names in there. And that was the beginning—the bio-bibliography from 1840 to 1940. And it was so successful that he asked if I wanted to do another one, and I did, extending that history from 1940 to 1988.

Embser: In addition to these historical studies, you’ve also worked on artists’ monographs. Do you have a favorite from your early career?

Willis: In the early 1990s, Andy Grundberg, at the Friends of Photography in San Francisco, called me and said, “I’d like you to do a book on any photographer. Who would you like to do it on?” I said, “Lorna Simpson.” I was really excited to have that opportunity to meet with Lorna, interview her, create that book at a crucial time in both of our careers and lives. That was Lorna Simpson [Friends of Photography, 1992].

Embser: It sounds like you had key supporters at the beginning of your career. But did you get pushback too?

Willis: Sometimes, publishers battled with me and didn’t believe the history. For my book on Van Der Zee [VanDerZee: Photographer, 1886–1983, Abrams/National Portrait Gallery, 1993], I saved the letters that they sent to me, where they said I was inflating his contributions to the field.

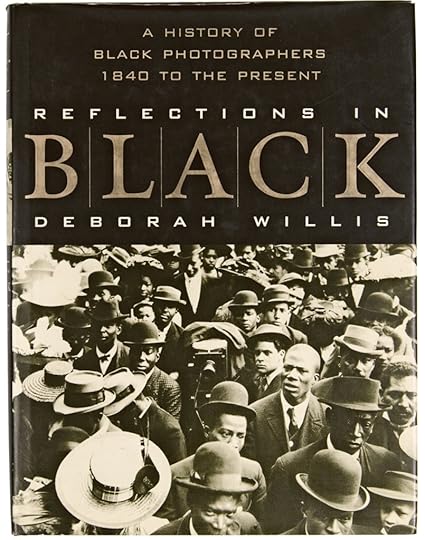

Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present (W. W. Norton & Company, 2000)

Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present (W. W. Norton & Company, 2000)Embser: What exactly would they say?

Willis: Here’s one: “On pages 3/4—Here I feel she inflates Van Der Zee’s achievement. Certainly, others of his time with not much more sophistication or training, accomplished similar technical results. Moreover, such earlier photographers as O. G. Reijlander (to whom she refers later on) used combined-image printing, so Van Der Zee cannot be credited with innovation here. The superlatives (‘astonishing’) need to be toned down.” Or this: “No evidence is given that Van Der Zee possessed issues of Camera Work or otherwise acquainted himself with the work of Strand, Stieglitz, and the photo secessionists. Therefore, it is dangerous to associate his work with new developments in photographic aesthetics, except insofar as it shares a spirit. The problem for me is that I do not find this shared spirit in Van Der Zee’s work . . . One of the unique and potentially most valuable aspects of Deborah’s approach to Van Der Zee’s work is that she deals with it in terms of ethnic consciousness.” [Laughs]

Embser: The word dangerous—I mean, what is that about?

Willis: I know, it’s amazing. The battles I’ve had in publishing had a lot to do with the narratives that people wanted to hold onto. Here is another: “I do not consider Van Der Zee’s photographs radical cultural intervention. Van Der Zee’s photographs didn’t change the way things were: they recorded it. What was surprising, I think, to many white viewers who grew up in a segregated world is that there is this strong, mainstream, upper-middle class tradition that has deep roots in the nineteenth century. It is more about being upper-middle class, irrespective of color.” I could go on and on.

Embser: When you look at the contemporary art world and art publishing right now, after all the work you’ve done, what do you think that publishers can do to better support Black artists and the range of visions that they have for publishing?

Willis: I think the dialogue is really important, what’s happening now. And that discussion increases when we have editors who are sensitive not only to Black photographers in the West, but also look through the lens of African photography, through Asian photography, Latinx, Native American, with a much more critical eye, and to know that there are vital books that need to be encountered.

Sergeant Andrew Martin Chandler of the Forty-Fourth Mississippi Infantry Regiment, Company F, and Silas Chandler, servant, with Bowie knives, revolvers, pepper-box, shotgun, and canteen, ca. 1861–63

Sergeant Andrew Martin Chandler of the Forty-Fourth Mississippi Infantry Regiment, Company F, and Silas Chandler, servant, with Bowie knives, revolvers, pepper-box, shotgun, and canteen, ca. 1861–63Courtesy the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, and NYU Press

Embser: Do you want to say something about your new project The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship [New York University Press, 2021]?

Willis: I’ve been working on this for the past seven years, looking at the experiences of personal memory and public memory, and how photography shaped the history of the presence of Black Civil War soldiers. I wanted to find photographs, letters, and diary pages of Black people who were teachers, preachers, women who were teachers and nurses, Black soldiers who were part of the fight for their own freedom. When I was in school, we didn’t have that discussion. We didn’t talk about Black Civil War soldiers. We didn’t know who fought. And the fact was, there was a strong history that basically was ignored.

I write that the notion of resistance and recovering stories is key to the image of Black soldiers. Cultural historian Alan Trachtenberg wrote that the role of African Americans in the struggle against slavery has been long repressed by guardians of official “privileged versions” of the American past. Racial prejudice has been the major cause of the expunging and erasure of the role of Blacks in determining their own future—and this erasure remains in the interest of some groups invested in continuing and preserving racial inequality.

I wanted to respond to the question of how Black male identity is formed through the photographic image. I found an amazing collection of images at Yale, in Boston, in DC, and here in New York. These collections are available, the photographs are there. Now, there’s an opportunity for people to see that there was a Black presence in the war.

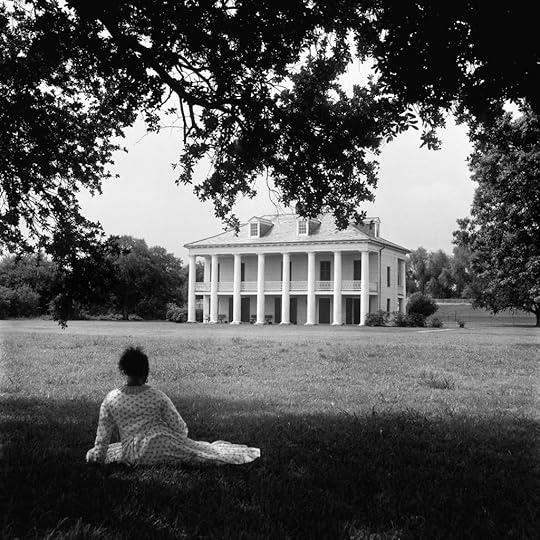

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Embser: One last question for you. This is like a variation on the BBC Radio program Desert Island Discs. So you have three books, and you’re going off to the desert island: one for your granddaughter, Zenzi; one for your son, Hank Willis Thomas; and one for yourself. What are they?

Willis: For my granddaughter to read with her mother, Rujeko, I really love this book called My Mommy Medicine by Edwidge Danticat [2019]. It has pictures, illustrations, text. The narrative is about a child in need of comfort and assurance. I would definitely give Hank, Gordon Parks’s Collected Works: Study Edition [Steidl, 2017]. And I would take with me Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video [Yale University Press, 2012]. It has all of what I love, and it gives the opportunity of seeing, witnessing the Sea Islands, Africa, Europe, experiencing performance, but also looking at folklore and memory. I would spend my time with that on an island, encouraged to create more work, and I would just love that moment.

This piece originally was published in Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review.

Inside an Archive of African Photobooks

I first met Ben Krewinkel in Lagos, Nigeria, when he attended the 2015 edition of the LagosPhoto festival as an exhibiting artist. Guest curator Cristina de Middel had selected his body of work Looking for M. (f0.23 publishing, 2013), a thoughtful and cleverly edited publication that juxtaposes archival images concerning Mozambique’s revolutionary Marxist–Leninist ideology with contemporary capitalist realities found in the cityscapes and on the advertising billboards of Maputo. At this stage in 2015, Krewinkel’s online archive of photobooks on Africa was still in its early stages and only available on Facebook.

In August 2020, I found myself in Amsterdam and eager to see how this recognized archive had evolved from a Facebook page into an important visual reference that problematizes the discourse of visual representations on Africa over time and in print form. I made an appointment to drive to Krewinkel’s home in Haarlem, just outside Amsterdam, where the archive is housed.

Krewinkel studied history in Amsterdam and was an exchange student at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. He specialized in modern Africa, writing a thesis on the role women played in the liberation struggle of Mozambique. He subsequently studied documentary photography at The Photo Academy, Amsterdam, and photographic studies at the University of Leiden, Netherlands, where he wrote a further thesis on the depiction of the so-called “poor whites” in South Africa. He views photographs as fragile historical objects and source material, in much the same way an archeologist views fossilized remains. We had an hour scheduled for our interview but ended up spending nearly three hours, interrupted only once—by the postman, delivering more photobooks.

Spread from Joana Choumali, Hââbré: The Last Generation (Fourthwall Books, 2016)

Spread from Joana Choumali, Hââbré: The Last Generation (Fourthwall Books, 2016)Azu Nwagbogu: Why is the name of the collection “Africa in the Photobook”?

Ben Krewinkel: When I started collecting, my main focus was on books dealing with the struggle in Southern Africa—so in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Angola. Some of the books were issued by the liberation movements, but even more by Western and Japanese photographers who were associated with supportive organizations. When the collection grew, I noticed that only a very small percentage of all the books was actually “African” in its entirety. For instance, even House of Bondage by Ernest Cole [Random House, 1967], which is excellent, was published and designed in North America and Great Britain. Nevertheless, I would consider it an African photobook, given the subject and the photographer’s origin.

I am aware that there is something really monolithic in the title, but the collection spans the whole continent and covers a timeframe of almost 150 years. The largest section consists of books by European photographers, designers, and publishers. So a title such as “African Photobooks” doesn’t do it justice. We are dealing with books by both outsiders and Africans, from and about the continent. Africa in the Photobook follows the changing visual representations of the continent through this print medium and, hopefully, offers some historical perspective on various themes in African history.

Spread from Álbum de familia (InforCongo, 1958)

Spread from Álbum de familia (InforCongo, 1958)Nwagbogu: You aim to “decolonize” these books. How can you achieve this?

Krewinkel: Most of the books in my collection are problematic in some kind of way. I consider photographs as historical sources, and I am aware that many photographs in the past were used in a propagandistic way. The majority were produced by Europeans and were political in aim. Over 150 years, photobooks have expressed constantly changing visual representations of Africa but have also been part of the construction and circulation of ideas and fantasies about the continent and its inhabitants. Books followed the narrow, colonial, and repetitive thematic patterns that often perpetuated the binary oppositions of “self” versus “other.” Most publications produced before the 1960s were there to legitimize and promote the colonial endeavor. But colonial books are nevertheless complex and ambivalent too. One needs to ascertain why certain publications were produced and what the thinking and motives behind them were. To properly study this, you actually need to have access to the archives of photographers or publishers. More important, you want to have information on the sitters and the way they felt about the encounters with the photographer, to learn about the power dynamics between photographer and sitter which, in my opinion, defines whether a work is problematic or not.

Nwagbogu: How does one deal with such contentious material and archives?

Krewinkel: I’m aware that I have to treat the books and their contents very carefully. The cultural theorist Mieke Bal rightly addressed the problem of thoughtlessly republishing problematic, voyeuristic, and even painful content in many of her books. I’m still considering how to deal with this material, but it definitely needs to be contextualized. I also feel that some spreads, however problematic, need to be shown to an audience, so one can learn how these books were used and distributed, and played a role in shaping perspectives on Africa. One has to stress the fact that spreads from such books exemplify the colonial narrative but may not always represent the original intention of the photographers, some of whom were African.

Zanele Muholi, Tumi Nkopane, KwaThema, Johannesburg, 2013, from Faces and Phases: 2006–2014 (Steidl/The Walther Collection, 2014)

Zanele Muholi, Tumi Nkopane, KwaThema, Johannesburg, 2013, from Faces and Phases: 2006–2014 (Steidl/The Walther Collection, 2014)© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson, New York

Nwagbogu: Do books on contemporary photography reflect an image of Africa that is more nuanced?

Krewinkel: For sure, but not all of them. There are still Western photographers who nostalgically recycle the old narrative and thematic patterns, and it irritates me when they claim to show me the “real Africa.” Even the Kenyan photographer Mohamed Amin and South African Peter Magubane have published books full of landscapes, wildlife, and “vanishing peoples.” Fortunately, the last decades show a growth in beautiful and nuanced books from both African and European photographers—such as Yto Barrada, A Life Full of Holes. The Strait Project [Autograph ABP, 2005]; Bruno Boudjelal, Disquiet Days [Autograph ABP, 2009]; Zanele Muholi, Faces and Phases [Prestel, 2010]; Georges Senga, Une vie après la mort [Editions du Garages Dialogues, 2013]; Terry Kurgan, Hotel Yeoville [Fourthwall Books, 2013]; John Kiyaya, Tanzania Photographer and People of Lake Tanganyika [Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd., 2013]; and Crossing Strangers by Andile Buka [MNK Press, 2015]. Then,there are good contemporary books based on archives—such as Jacob Nzudie, Supermarket [Le Bec en l’air, 2012]; Gulu Real Art Studio [Steidl, 2013] edited by Martina Bacigalupo; Commonplace by Tamsyn Adamsand Sophie Feyder [Fourthwall Books, 2016]; and theproject Ebifananyi [YdocPublishing, 2014–17], initiatedand edited by Andrea Stultiens in collaboration with African photographers and artists. And we should not forget Santu Mofokeng’s groundbreaking Black Photo Album/Look at Me 1890–1950 [Steidl, 2013] and his recently published immense box of books, Stories [Steidl, 2019].

Spread from Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen (Brehm Verlag, 1931)

Spread from Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen (Brehm Verlag, 1931)Nwagbogu: Let’s discuss the most contentious photobooks in your archive.

Krewinkel: Wow, where to start? All of the books published before World War II (and many published in the decades following) are contentious in one way or another. The most demeaning photobooks are some of the tourist albums from Algeria, Egypt, or South Africa that show women posing in a supposedly erotic fashion. Also, Frauen des Morgenlandes [Orell Füssli Verlag, 1929] and Negertypen des schwarzen Erdteils [Orell Füssli Verlag, 1930], which were originally published in Switzerland—the latter republished in English as Negro Types [George Routledge & Sons, 1930]—are really difficult to look at because of the ignorance and racist ideology that comes through in both the texts and the photographs. Racist missionary books, such as William Taylor’s Africa Illustrated: Scenes from Daily Life on the Dark Continent [Illustrated Africa, 1895], portrayed Africans as backward, childish, and evil. There is a lot of colonial propaganda in the collection, but the driving force behind the content was dictated by the authors or initiators. The books about the Congo Free State and Belgian Congo, for example, reflect the trinity of the colonial authorities, industry, and the church. Still very racist and grounded on the binary opposition of “us” vs. “them,” even though the books left out explicitly eroticized portraits and, for the most part, deliberately excluded explicit and degrading images of Congolese suffering. Nevertheless, traces of violence are always present.

Nwagbogu: How can photography remediate and decolonize the historiography of Africa?

Krewinkel: I think it is very important to critically revisit old colonial books. By studying them closely, we notice the endless recycling of stereotypes, dominant tropes, and thematic patterns derived from generalized ideas about the continent. However, one must realize that even these books can be easily oversimplified. For instance, from today’s perspective, one can characterize a book like Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen [Brehm Verlag, 1931] as a racist colonial book. Yet it is also a book made by an independent, autonomous young Jewish woman. More important, unlike her contemporaries, Lotte Errell portrayed the Ewe people in a dignified manner, using an informal style. New work can also help to reevaluate and re-address colonial photography. In Joana Choumali’s Hââbré: The Last Generation [Fourthwall Books, 2016], she subtly addresses themes, like scarification and polished teeth, that had been the main subjects of colonial photobooks as well. Hââbré goes beyond representation and gives voice and authorship to the subjects photographed. They relate the effect of scarification on their daily lives.

Retrospectively, we can discover important aspects that were unintentionally included in the books, for example, the small book Álbum de familia [InforCongo, 1958], which was distributed at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, where the Belgian Congo played a major role in the propagandist efforts of the colonial authorities. It was produced by the photographers of InforCongo, who were European as well as Congolese—as in the case of Joseph Makula. The book consists of a systematic juxtaposition of nearly identical scenes capturing Black Africans in the Congo and white Belgians in the metropole. Following a hypocritical humanistic narrative, the book insists on the closeness of everyday life in Belgium and in the Congo and stresses the Family of Man vision of “familial” ties between the Belgians and the Congolese. In reality, the Congolese depicted were part of an elite called the évolués, which constituted an extremely small section of the Congolese population. The world’s fair, and this book, marked the beginning of independence and the decolonization process in Belgian Congo.

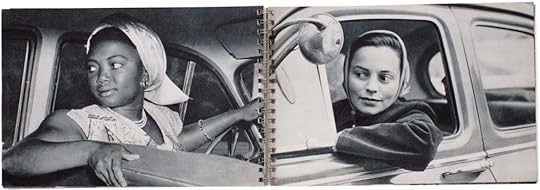

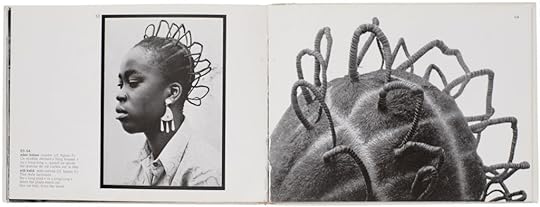

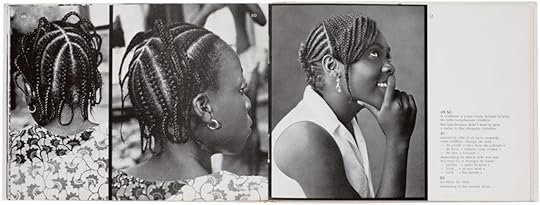

Spreads from Du twist à cocody, ou l’art de la natte (Éditions Dalfoz, 1972)

Spreads from Du twist à cocody, ou l’art de la natte (Éditions Dalfoz, 1972)Nwagbogu: One of my favorite books and definitely a discovery for me in your collection is Du twist à cocody, ou l’art de la natte by Diby Yao Christophe [Éditions Dalfoz, 1972]. What a beautiful volume, and the poem at the end is really telling and poignant. It’s a book that speaks to the value of your collection as one that also highlights and revives largely unknown African voices. What have you learned about this remarkable book?

Krewinkel: Yes, indeed. Du twist à cocody, ou l’art de la natte is a great book from the Ivory Coast. The bookwas printed in France and the text is bilingual, but I’mnot sure who Christophe’s audience was, nor do I knowanything about the photographer. This book deals withhairstyles and reminds me very much of the work by J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, but the photographic style is moreinformal. The women portrayed are much more at easethan women portrayed by colonials. It is a refreshing takeon the topic, and I think you can consider this book as areaction to colonialism and neocolonialism. The authorwrites: “Why do some of our stylish women prefere [sic]bleached hair or wigs to genuine African creations? [. . .]I meet many of you who pretend to be European, tryingto dress and act like white women. Oh, my Black sisters, why are you trying to forget that you are African?”

This piece was originally published under the title “Africa in the PhotoBook” in Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review.

December 3, 2020

The Photographer Who Erased Time

Widline Cadet has been sitting in the light for three seasons. Before the pandemic, she always had something else to do (working away at her MFA at Syracuse University, where she graduated this past spring; and fielding commissions for publications such as California Sunday Magazine), or she had somewhere else to be (residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine or Lighthouse Works on Fishers Island in New York). The demands of social distancing, however, brought an abrupt, ecstatic stillness to her routine; suddenly, she had time to follow the movements of the sun.

“Our living room had this magical light, where I would wake up at seven in the morning, every morning, to just watch the light,” Cadet says of the home in Syracuse she’s recently moved away from. “I spent most of the early spring and summer going to the backyard and watching the sunset, too, for a while.” This fall, stationed in New York City as an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Cadet still tracks the light. In a new body of work, You Won’t Be Here Forever, a burnt-orange glow undulates across photographs taken both Upstate and in the city, flickering in and out of her camera’s gaze.

“I try to erase time as much as I can,” Cadet says of these enigmatic images of unnamed outdoor spaces, strangers, and friends. “I try to be ambiguous about where these pictures were taken, or when, or what’s happening.” Cadet refuses explicit reference to the painful frenzies of 2020. Nonetheless, the aesthetics of social distancing permeate the work: she made most of these photographs on her solitary walks through her former and current cities of residence.

In these images, human subjects are conspicuously distant from the camera. Shoulders slant away, backs are firmly turned, or nature intervenes to shroud them. In one, a profusion of tree branches nearly claims a man as its own, so that his stance—balanced on one leg, the other leg pulled back into a stretch—becomes a kind of sprouting. Even in a rare instance of physical proximity, a portrait of a person in a satin slip and Western hat, the subject looks away from the camera in favor of the trees. Their brown skin and brown hat are beautifully congruent with the lush green of the firs, both where they are sun-dappled and where they are in shadow.

In the absence of interpersonal touch, Cadet’s photographs cultivate a type of alternative intimacy. Disparate textures meet and kiss. A fuzzy, silhouetted head greets crisp, looming bridge beams. A stocky bush caresses the stone wall and wire window grate of a building’s side. Cadet considers these contact points inherently optimistic—signs of natural life and familiar landscapes still converging, even through another season of unnatural isolation. “There’s this serious hopefulness that I have that I try to put into pictures in some way,” she says, and indeed, her gaze on these daily joys feels serious, carefully measured—the inflections of warm, bright light all the more invigorating for the solemnity and solitude that spurred their documentation.

Still, her optimism emanates unbridled. In one photograph, a pair of hands cradles berries from a tree, the palms cupped so patiently they could be outstretched in benediction. This moment joins a constellation of images Cadet has made of Black people in communion with nature. In an ongoing body of work she started in 2017, Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances), “most of the photographs,” Cadet says, “are of Black women and greenery and these abstract landscapes.” In her series Soft (2017) and Home Bodies (2013–ongoing), as well, the surrounding flora often frames her subjects. Cadet calls this mediation of greenery “a way of hiding myself and hiding the figures,” but her hiding practice is less like masking, more like tucking her subjects into a landscape where they can be carefully held. Those subjects are a mixture of Cadet’s loved ones, total strangers, and herself, and Cadet’s avoidance in telling the viewer the difference serves as another way of hiding, holding back her relationship to the figures, so that they may all be ambiguously loved.

In You Won’t Be Here Forever, some amendments needed to be made. “I include my siblings randomly in every body of work that I do. Except for this one,” says Cadet. (She hasn’t been able to see much of her family during the pandemic.) And unlike in Seremoni Disparisyon, Cadet does not explicitly appear alongside her other subjects here. She’s found a new way to hide. In a photograph of her old living room in Syracuse, taken just before she moved out and during one of her seven AM sessions in the morning sunlight, a print of a 2018 portrait, San Tit (Untitled), leans against a wall, turned upside down. It’s partially, perhaps intentionally, obscured by a separate wooden frame and other objects, left last to be packed away before Cadet left the apartment that was her home for three years and her solace for three lonesome months in quarantine.

There’s a painstaking quality to the way San Tit (Untitled) is tucked away, and cut from view is the other young Black woman in the original portrait, on whose stomach the artist gently rests her head. But she is still there. Cadet would like to erase time in her photographs; this one keeps her held in perpetual light, embraced, without distance, by another.

December 1, 2020

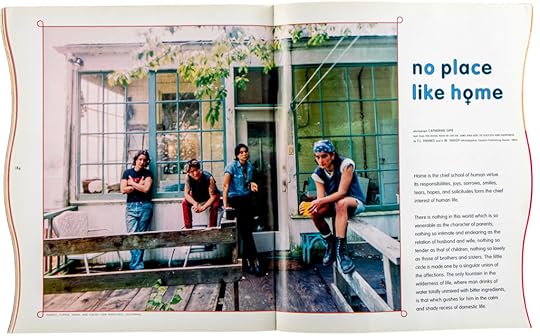

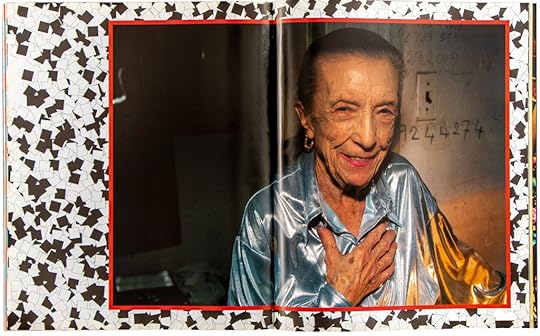

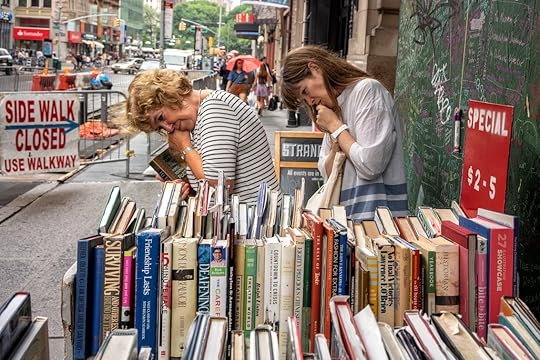

How an Irreverent and Joyful Interiors Magazine Redefined the Idea of Home

It began with photographs of Farrah Fawcett. Raymond Donahue, a young showroom decorator for IKEA, had plastered the walls and ceiling of his bedroom in the small New Jersey bungalow he shared with his mother with black-and-white photocopies of Fawcett’s magazine covers: High Society, Vogue, Good Housekeeping. Nest, a new shelter magazine, sent the photographer Jason Schmidt to capture the room, which made the cover of the debut issue, dated Fall 1997. “I love Warhol’s use of repetition, so I photocopied magazine covers and made wallpaper out of them,” Donahue said to the curator Valerie Steele, who conducted the accompanying interview. “Nest offers its own definitions in celebrating human self-invention at home,” Joseph Holtzman wrote in the issue’s Dear Reader letter. “Our focus will never be on focus groups. We’d love an authentic chunk of your mind, though.”

Nest magazine ran quarterly for twenty-six issues. It was heady, odd, acerbic—sardonic about conformity and corporate America, yet, when it came to decorating, never overly goading or insincere. All tastes were welcome, provided they delighted, or intrigued, or tickled Holtzman, a decorator from Baltimore whose family money afforded him the opportunity to launch such an ambitious magazine.

Spread from Nest 4, Spring 1999, with photographs by Antoine Bootz

Spread from Nest 4, Spring 1999, with photographs by Antoine Bootz“Nest—I could not resist that title. I said ‘Yes’ based only on that, I remember clearly,” says Paola Antonelli, senior curator of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, who profiled the Italian twentieth-century design dealer Fulvio Ferrari for Nest’s first issue. “It was clear he loved other human beings,” she said of Holtzman. “We were all tired of exclusive, staged, rich, haughty, and glossy. We longed for intimate, messy, illicit, stolen, and generous—we wanted to find out how real people lived.”

Nest was seldom cozy. Each issue clashed the refined with the banal or makeshift or extreme; a story on a luxury swimming pool could be followed by a piece on tents in Kosovo, or igloos, or the women confined to the State Correctional Facility near Grants, New Mexico.

In the debut issue, Jan Groover’s photographs of the bathroom at Manhattan’s Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center, painted by Keith Haring in 1989 at the height of the AIDS crisis, appeared a few pages away from David Levinthal’s images of Barbie’s Dream House and Derry Moore’s pictures of Longleat, the home of the Marquess of Bath, who made paintings of all the women he slept with and hung them up his stairs. (Moore, a celebrated interiors photographer and the 12th Earl of Drogheda, and thus a regular at castles and manors, fulfilled Holtzman’s obsession with English aristocratic taste.) The Fall 1998 issue featured a story on the Turin home where Carlo Mollino spent the last fourteen years of his life, pictured alongside his Polaroids of the prostitutes who visited him. Summer 1999 saw stories by Robert Polidori on beehive-shaped mud houses in the al-Shilo village in Syria and Mitch Epstein on the ape house at the Philadelphia Zoo. For Fall 1999–2000, Nan Goldin photographed the artist Nayland Blake in his mother’s bedroom, which he’d wallpapered with over four hundred pounds of gingerbread. The roll call of photographers was impressive—David Armstrong, Martin Parr, Jim Goldberg, Richard Barnes, and Terence Donovan, among others, all made work for Nest—yet only a handful of the image makers, such as Moore, were particularly known for classic interiors photography.

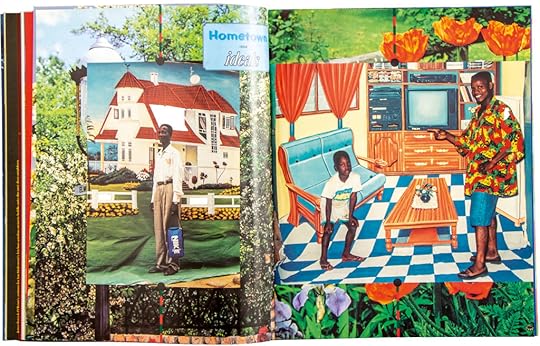

Spread from Nest 7, Winter 1999–2000, with photographs by Philip Kwame Apagya

Spread from Nest 7, Winter 1999–2000, with photographs by Philip Kwame Apagya“I subscribe to a number of shelter magazines—World of Interiors, House & Garden (RIP), Elle Decor (before its recent decline)—but Nest was different,” says the critic and magazine collector Vince Aletti. “When the second issue came out, I’m embarrassed to report that I wrote a fan letter to the magazine advising it to be more appealing to potential readers—not put them off with the sort of abstract design and weird graphics on the cover of the Fall 1998 issue, which no one would have recognized as a shelter mag.” That issue featured a black-and-brown striped cover and a hand-applied cutting of flocked wallpaper, the pattern of which resembled random stains, by the artist Rosemarie Trockel. “It was obvious Nest couldn’t care less about the general audience,” Aletti says. “You liked it or you left it, and most of its core readers loved it. I don’t think I would have called it beautiful at any point, because it was not afraid to get a little ugly, and it went beyond mere beauty.”

The design was “almost baroque,” according to Tom Beckham, who joined Nest ahead of the second issue as design technician, and stayed to the end, quickly becoming graphics director. At points, it veered toward the unhinged—one issue came with four holes drilled straight through it, as if the reader was hanging a particularly hefty picture; while others arrived with scalloped edges or scratch-and-sniff patches. Photographers’ images would often be placed on top of florid, graphic patterns or framed with shouty borders. The magazine was “another iteration of Joe’s interior design,” says Beckham.

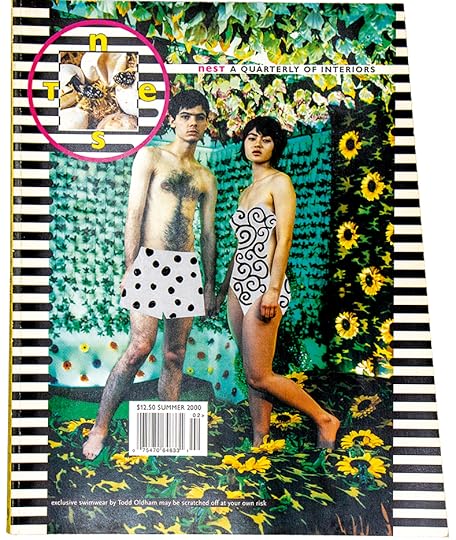

Cover of Nest 9, Summer 2000, with photographs by Nathaniel Goldberg (cover) and Manny Rubio (logo)

Cover of Nest 9, Summer 2000, with photographs by Nathaniel Goldberg (cover) and Manny Rubio (logo)Before launching Nest, Holtzman had considered starting a magazine that was severe and serious. But after Wallpaper launched in 1996, Nest went in the opposite direction. Holtzman took to thumbing his nose at other, less playful titles. The Summer 1999 cover was photoshopped to resemble a comic strip; a thought bubble above the head of a handsome man, nude save for a towel and reclining in a chair, reads, “Hang me. I thought Wallpaper was shooting my apartment.” Behind him, his decorator, clad in a fur stole, is shown thinking, “God willing, my next assignment will be for Architectural Digest.”