Aperture's Blog, page 65

October 26, 2020

What “Greater New York” Got Right about Photography in the Age of Instagram

Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger loved whiskey and bourbon, so when the two young, Stanford-educated developers started a photo-sharing app, they dropped a couple vowels and called it Burbn. In the spring of 2010, with location-based services like Foursquare competing for venture capital, Burbn raised $500,000 in seed funding. Users could check in at a bar and post a photo, or just post a photo on its own. “I was excited about being able to help people tell their stories when they’re out and about,” Krieger later recalled in an interview with CBS This Morning. “Not when they’re at their computers at home, you know, downloading one hundred photos from their last weekend, but that instant right then and there.”

The first photograph Krieger uploaded to the app, which he and Systrom renamed Instagram, was an off-kilter view of San Francisco’s South Beach Harbor. Systrom posted a picture of soup, a taco stand, a puppy, and a cocktail. On October 6, 2010, Instagram arrived in Apple’s app store, and before the end of the year, one million users had joined the platform. Less than two years later, in April 2012, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram for $1 billion in cash and stock. The rest isn’t history, it’s the present. It’s the obsession of the art world. It’s the flotsam of celebrities and brunch. It’s the filters, the FOMO. It’s pics or it didn’t happen.

But what happens to art photography when everyone is a photographer?

Michele Abeles, Plant, hand, paper, table, lines, numbers, 2009

Michele Abeles, Plant, hand, paper, table, lines, numbers, 2009© the artist and courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

That was the question in the spring of 2010, when MoMA PS1 opened its third iteration of the quinquennial exhibition series Greater New York, a survey of work by sixty-eight artists in New York’s metropolitan area, many of them photographers who have since earned remarkable prominence in the art world, journalism, and visual culture. Begun in 2000 to mark the merger of PS1 and the Museum of Modern Art, the 2010 edition of Greater New York arrived at an inflection point in photography, in the year that Instagram was founded and Apple introduced the iPhone 4 (with its rear-facing, selfie-enabling camera), but also at a moment when museums and art institutions were breaking down the parochial borders between medium-specific departments, and when artists were rapidly exploding traditional disciplines by using pictures as just another tool at hand.

The exhibition, as MoMA Director Glenn Lowry wrote in the foreword to its accompanying catalogue, was meant to give audiences a “proleptic sense of the promises of the future.” Ten years later, the inclusion of artists such as Hank Willis Thomas, Deana Lawson, David Benjamin Sherry, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Michele Abeles, K8 Hardy, Daniel Gordon, and Xaviera Simmons appears prescient. When it came to anticipating the future of photography, how did Greater New York get so much right?

David Benjamin Sherry, Minted Sensoria, from the series Birth In Futureverse, 2009

David Benjamin Sherry, Minted Sensoria, from the series Birth In Futureverse, 2009Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Connie Butler, one of the curators of Greater New York, remembered having conversations with artists and curators at the time about how photography was changing, how new technologies were influencing the circulation of images. “There was a growing feeling of a crisis in photography because of it,” Butler, who is now the chief curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, told me recently. “At the time it was like, Oh my god, how are we going to sort this out? Everyone’s taking pictures.”

Butler and her cocurators—Klaus Biesenbach, the former director of MoMA PS1 (and current director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), and independent curator Neville Wakefield—put out a broad call for artists through submissions on the MoMA PS1 website, inviting artists for presentations, and making numerous studio visits in the New York area. “It was an attempt at a kind of democratizing structure, where we could cast the widest net, so I think that’s also reflected in the range of photography we got,” Butler said.

Butler recalled that the curators sat in a room at PS1 with hundreds of Post-its and papers on the wall as they shaped the exhibition, bringing together artists working in video, sculpture, painting, performance, and photography—and others who produced genre-defying installations. Butler noted the vast difference in approach among the photographers and lens-based artists, some of whom were looking reflexively to the medium’s history. Mariah Robertson, for example, contributed one-of-a-kind, abstract compositions on metallic paper, experimenting with kaleidoscopic shapes and layers, and employing analog processes “that have been marginalized in the wake of digital photography,” as the curators write in the catalogue. David Benjamin Sherry similarly drew on old-fashioned practices in his color-drenched landscapes, made in the darkroom even though they could have been more easily achieved in Photoshop. “Sherry’s refusal to concede to the convenience of technological innovation,” the curators noted, “points to a nostalgic desire to preserve the painstaking, laborious processes of the past.”

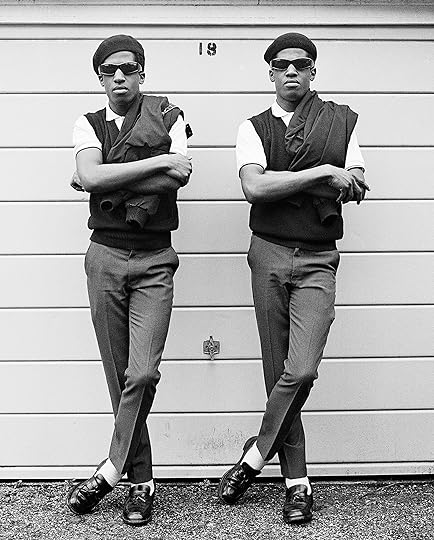

Hank Willis Thomas, Farewell Uncle Tom, 1971/2007, from the series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968–2008

Hank Willis Thomas, Farewell Uncle Tom, 1971/2007, from the series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968–2008Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Among the most resonant contributions to Greater New York were works by Hank Willis Thomas, Deana Lawson, and LaToya Ruby Frazier, whose diverse approaches are united, Butler said, by “images of Black life and Black bodies and Black domestic life.” Several years before Greater New York, Thomas began exploring “commodity culture” in the United States and the impact of advertising on perceptions of Black identity. In Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America (2006–ongoing), he removes the slogans from popular magazine ads featuring Black subjects, allowing images of Black and white figures to float untethered to brand associations as a way of interrogating stereotypes.

Lawson, known for her monumental portraiture, created a site-specific installation of found photographs, Assemblage (2010), composed of four-by-six-inch Walgreens prints of images found in archives or pulled from personal collections, a “biological mass” that she called a “visual regeneration of human histories and futures.” Assemblage staged a dramatic, tactile encounter, and asserted, like many other works, “the potential physicality of photography,” as Biesenbach noted in his introduction to the exhibition. (Lawson was recently awarded the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s 2020 Hugo Boss Prize.)

Deana Lawson, Assemblage, 2010. Installation view at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew Septimus

Deana Lawson, Assemblage, 2010. Installation view at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew SeptimusCourtesy MoMA PS1

Frazier presented works from her series The Notion of Family (2001–14), an epic, profoundly personal photographic essay about her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, and the impact of gentrification and environmental degradation on the lives of her grandmother, her mother, and herself. (Aperture published this project as a book in 2015.) Frazier, who won a MacArthur Fellowship in 2015, and who now teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has since covered the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, for Elle; and the closure of a GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio, for the New York Times Magazine.

Thomas and Frazier both have active social practices, and political advocacy is “an extension of their work,” Butler noted. Thomas cofounded For Freedoms, an organization advocating for direct action by artists in political discourse. Frazier transformed her trenchant photojournalism into gallery and museum exhibitions, including The Last Cruze, organized in 2019 by the Renaissance Society in Chicago, which centered the voices and lives of people affected by economic decline in the Midwest.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Aunt Midgie and Grandma Ruby, 2007

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Aunt Midgie and Grandma Ruby, 2007© the artist

“They are really thinking about how their work lives in the world,” said Eva Respini, the chief curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA), referring to Thomas, Frazier, and Lawson, as well as to Xaviera Simmons and A. L. Steiner—whose work is rooted in the queer community, and who was also featured in Greater New York. “They continue to stay true to who their communities are, what their worldview is, and an insistence that making art or making photographs or making images is a special part of understanding who we are as people,” Respini said, adding that a decade later, people are increasingly seeking art grounded in lived experience and reflecting historical and contemporary injustices.

Respini, who is organizing a major survey by Deana Lawson at the ICA in 2021, was a curator in MoMA’s photography department at the time of Greater New York. Although she didn’t work on the exhibition directly, she was influential in organizing New Photography 2009; and with Roxana Marcoci, she cofounded Forums on Contemporary Photography in February 2010, an ongoing series of discussions with curators, artists, editors, and scholars. Those discussions felt urgent, Respini explained, because artists were rethinking the role of photography. “It really felt like there was a shift happening in the medium,” she said.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Notion of Family, 2001–14. Installation view at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew Septimus

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Notion of Family, 2001–14. Installation view at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew SeptimusCourtesy MoMA PS1

When Drew Sawyer, a curator of photography at the Brooklyn Museum, thinks of the year 2010, “I think of a range, or a multiplication, of different platforms for photography.” The publisher Michael Mack founded MACK Books in 2010. Le Bal, the venerable space for photography in Paris, opened in 2010. This was a time, Sawyer said, when many artists were exploring process-based approaches to the medium, “which one could read as a reaction to the digital. But also, as a reaction to the death of those very processes.” Sawyer noted that this “multiplication” of platforms coincided with the rise of the “poetic or lyrical documentary mode.” MACK’s most successful books—Alec Soth’s Songbook (2015), Gregory Halpern’s XXYZX (2016), and Sam Contis’s Deep Springs (2017)—exemplify that lyrical turn in photography. MoMA’s Being: New Photography 2018, organized by Lucy Gallun, represented a triumph of the trend, featuring Contis, Carmen Winant, Matthew Connors, and Joanna Piotrowska; the critic Arthur Lubow labeled Contis’s work in his New York Times appraisal of the survey as “daringly retrograde.”

Sawyer added that 2010 was also the year New York’s New Museum presented Free, an exhibition about the internet, public space, and collective experience. Free, which opened that October, was curated by Lauren Cornell, former executive director of Rhizome, a platform for digital art founded in 1996. (Caterina Fake, cofounder of Flickr, a predecessor to Instagram, contributed to the Free online catalogue.) Where the photography in Greater New York previewed aspects of the social-engagement art that would become integral to museum programming in New York and beyond, Free was more theoretical, and embodied a tenet of Artie Vierkant’s 2010 essay, “The Image Object Post-Internet,” a condition defined as “inherently informed by ubiquitous authorship, the development of attention as currency, the collapse of physical space in networked culture, and the infinite reproducibility and mutability of digital materials.” Free, like other projects, such as Charlotte Cotton’s Words Without Pictures (2009), channeled a spirit of profound introspection around the future of image-making.

Xaviera Simmons, Superunknown (Alive In The), 2010. Installation view MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew Septimus

Xaviera Simmons, Superunknown (Alive In The), 2010. Installation view MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Matthew SeptimusCourtesy MoMA PS1

For Xaviera Simmons, showing in Greater New York was “in a tradition.” She recalled that in 2010, the galleries at PS1, a Romanesque former schoolhouse, were “rougher” than they are today, yet the exhibition was as prestigious as an artist residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem or showing in the Whitney Biennial. Simmons had studied at Bard College with Stephen Shore and An-My Lê, and was trained with large-format cameras and analog film. Around 2010, however, she wanted to think about “how a modern photograph could be produced.”

Simmons began collecting pictures online, particularly images of migrants packed into boats and crossing bodies of water, which she sourced from sites such as Human Rights Watch. She worked on them in Photoshop, to make them “my own,” while continually asking larger questions: Who migrates? Who collects? What is the role of the witness? The resulting work, Superunknown (Alive in the) (2010), is a grid of forty framed images, a choral record of perilous voyages. Arriving five years before the images of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean proliferated around the world, Superunknown remains among the most moving and prophetic works of Greater New York. As the exhibition’s curators noted, Superunknown “renders each individual photograph into a visual metaphor for longing, loss, memory, and despair, both for the image-maker and the migratory participant.”

Group portrait of Greater New York artists at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Jason Schmidt

Group portrait of Greater New York artists at MoMA PS1, 2010. Photograph by Jason SchmidtCourtesy MoMA PS1

One of the last spreads in the Greater New York catalogue is a striking group portrait of the curators and participating artists. Their poses are stylish or ironic or formidable. There’s Hank Willis Thomas in an orange hoodie. Deana Lawson in a navy sweater and bold lipstick. Daniel Gordon in red-and-white stripes. Members of the Bruce High Quality Foundation behind exaggerated masks. Klaus Biesenbach, with his black tie and silver hair, back row center. It’s the kind of assembly that only happens once, and in retrospect, marks the coming together of a generation, a group of artists who, Glenn Lowry accurately predicted, “advance, expand, and overturn notions of contemporary art.”

Any exhibition, especially a sprawling survey, is a message in a bottle. Some drop to the ocean floor. Some return, years later, to our own shores, to the present, full of surprising insights, memories, and wisdom. Looking back, Connie Butler realized that Greater New York did have an impact. “We did get something right,” she said. “It doesn’t always happen.”

Naima Green’s Ode to Fleeting Pleasures

Naima Green has a thing for the moon, and for the tides. In her first public film work, The intimacy of before (2020), the artist fashions a dusk-lit self-portrait: her skin glistens behind bath steam, and the sea acts as the short film’s baseline soundtrack, waves lapping at Green’s voiceover narration. “It felt like I was being pulled by a magnet towards the sea,” she says in near-whisper. She’s been sitting with Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) since the start of 2019, and in The intimacy of before, I see echoes of one of the book’s heady passages: “ . . . the ghostly vague light drifting upward from the street competed with the silver hard sweetness of the full moon, reflected in the shiny mirrors of our sweat-slippery dark bodies, sacred as the ocean at high tide.” Green’s film, commissioned by Fotografiska New York, provides a captivating anchor for her first solo museum exhibition, and the show’s title, Brief & Drenching, makes Zami’s influence explicit; it’s lifted from one of the book’s final phrases.

Naima Green, Self-Portrait (I like you), 2017

Naima Green, Self-Portrait (I like you), 2017I recently spoke by phone with Green about Brief & Drenching, her ode to portraiture—of the self, of the home (one gallery room is a recreation of her living room), and of the queer communities that make both self and home most legible. From Pur·suit (2018), a studio portrait series-turned-playing card deck of fifty-four queer womxn and trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people; to a birthing stool handcrafted by Green; to her snapshots at New York City’s historically LGBTQ-centered Jacob Riis beach, Green’s work seeks out a soft place for the transient self to land and wander. As Green intones over the short film’s narration, in a quiet murmur that drenches the whole exhibition, “Is it too much to want a tender and complete intimacy?”

Naima Green, Still from The intimacy of before, 2020. Single-channel video installation, 8:30 minutes, color, sound

Naima Green, Still from The intimacy of before, 2020. Single-channel video installation, 8:30 minutes, color, soundNicole Acheampong: One of the pieces in the exhibition that’s stuck with me is the video installation The intimacy of before. I’d love to know more about your filmmaking process. What drew you to that medium?

Naima Green: About four years ago, right after the 2016 election, I had just started my MFA program at ICP-Bard and was taking a video course. I was fresh out of a breakup, fresh off of the despair behind the election, and I made a video just with my tripod. It was me in my apartment; it was almost like a sketch video. The concept behind it was around grief and loss and using these pearls with the same action that appears in The intimacy of before: pulling the pearls out of a menstruating vagina, eating the pearls, and almost choking on them. At the time, it wasn’t anything that I wanted to share or show, but I knew that it was an idea I wanted to work on again, and in a different way. So, this time, I worked with collaborator Jessie Levandov. We filmed in July over the course of two days, and it was just me and her.

In that gallery room, the second one you pass through in the exhibition, it’s all about different ways of thinking about a self-portrait, but also the intimacy of being at home with me. In this time of quarantine, I’m thinking about the touch and comfort we now have to provide for ourselves. I’m definitely thinking about grief and loss and transformation and rebirth and purging and really sitting with myself in this time.

Naima Green, Cynthia and Travis, 2019

Naima Green, Cynthia and Travis, 2019Acheampong: A word you mentioned just now, purging, feels resonant, because there was so much in the exhibition that felt close to bursting. In the film, you narrate about drinking too much wine, standing in the water until your feet are numb—so there’s this extremity of submergence. There’s the portrait Cynthia and Travis (2019), where you have the swell of the pregnant belly. But on the other hand, there’s this insistent purging as well. Can you speak on that tension?

Green: The release and the “holding too tightly”—I’m interested in those ends of the spectrum, which in some way are the same act, just on opposite sides. Intimacy and community are about the overflow in some ways. I think about the Riis portraits. Untitled (Riis) (2019) was the result of a thirty-second interaction. These moments are so temporary. You refer to Cynthia and Travis; I think that photograph was taken three weeks or less before [the couple’s son] Tenoch was born. I’m thinking about the stuff of life that happens on the brink of a change. Even in Pur·suit, something that feels really important is that none of these images are providing fixed narratives about who these people are. There is a constant change, an evolution. Last weekend, I saw one of the people that I had photographed for Pur·suit in 2018, and they said to me, “That felt like so long ago.” Thinking about the self, and what we’ve been through even in 2020, 2018 feels like lifetimes ago.

Acheampong: Absolutely.

Green: I have since moved out of the apartment I’d lived in for six years, the apartment where all the MumboJumbo portraits (2014–18) were taken. We filmed The intimacy of before a few weeks before I moved, and so, having that moment and having that video is also a way to remember the very end of a long time in a space that I called home.

Naima Green, Freddie and Laurent, from the series MumboJumbo, 2018

Naima Green, Freddie and Laurent, from the series MumboJumbo, 2018Acheampong: So much of the film feels fluid, like it’s being moved by currents of water. Likewise, a lot of your photographic work captures bodies in fluid motion. In the MumboJumbo portraits, there’s sometimes a pleasurable blur, a figure in backbend. I’m curious about your relationship to movement and transition in your photographs.

Green: For a long time in my work, I would say until maybe 2016, I was really focused on the stillness of a portrait. I’m thinking about some of my earlier Jewels from the Hinterland portraits (2013–present), where there might be a subtle movement—maybe someone is lifting their big toe in a certain way—but it’s still really about the body in a still posture, claiming their environment. There was a shift when I started including my own body in my work, around 2017. The movement comes through for me in subtle ways. I’m interested in a breathing portrait or the way that someone might wipe water off of their chin, or the way that they might hold the wind in a certain way. How do you exist within the natural environment?

The Riis portraits really are when motion comes through in a new way for me. I was talking to a friend of mine, Jenna Wortham, and she said to me after she saw this show, “You are thinking about and celebrating people and bodies while they’re still living.” Photographing our bodies and our existing in spaces of leisure and joy and pleasure is really crucial to me, because so much of the way that Black bodies are understood and digested is in death. We’ve been on the brink of something for so long. This overflow and this oversaturation of Black death in the media cycle feels like this bursting; like, how much more can we take? I’m not watching the news right now, because mentally, and emotionally, I can’t digest any more.

When I’m thinking about the movement and lives of the people that I’m photographing, it’s like, where is the pleasure in our lives? And how much of that pleasure, prior to COVID-19, existed in community, in space together, at the beach, at a party, in a home.

Naima Green, Untitled, 2017

Naima Green, Untitled, 2017Acheampong: There’s a lot of the textual and the literary woven throughout the exhibition, from the Open Tabs portraits (2017–19) and the Audre Lorde reference in the exhibition title, to your own poetic narration in the film. Do you see those insertions as photographic in their own ways, or as counterpoints to your visual project?

Green: They offer a different entry point into the photographic and the visual field. For example, I have a sound library that I’ve kept for the past four or five years. Just recording sound as I’m walking down the street; or maybe on the subway, I hear someone playing a song. I record my dreams when I wake up in the morning, when I can remember them. I used to write them all down, but then that just got too arduous. I went through hours of dream recordings and pulled out themes and memories that felt like they would add to the visuals of the video. A lot of them had to do with the water and being at the beach. I feel like they offer a different texture, and a different tone.

All of the audio, with the exception of my voiceover, was taken from my phone. The voiceover, we re-recorded, but the origins of those stories and of those clips and sound bites are from my phone.

Acheampong: Which seems relevant to the transient themes throughout the exhibition—that all these recordings are taken on the go or, at least, taken in a way that you can transport.

Green: Mm-hmm. And it’s also about what you find and what you encounter as you’re moving around your life. So, I’m not going out with all of my sound equipment looking for sound. It’s more like, I’m on a really long walk, and I hear something that I want to remember. It’s a more natural way for me to engage with the things that I’m hearing in my life.

Naima Green, Come Back to Bed, 2017

Naima Green, Come Back to Bed, 2017Acheampong: I also wanted to know more about your encounter with Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. How did that text come to coincide with this body of work?

Green: I moved to Mexico City in January of 2019, right after the New Year. I started reading that book right after moving. When I really enjoy a book, I read it slowly, because I want to make it last forever, and that’s pretty rare for me, but it’s happened recently, with Zami. I learned so much about . She’d lived in Cuernavaca, Mexico—I had no idea. She’d also lived really close to where I’d lived in Brooklyn. I finally finished Zami at the top of 2020.

The line “brief and drenching” is on the last page of the book—in maybe the last paragraph, the last two to three lines. It felt so apt for the way that living in Mexico really changed my life. I felt like I was being rinsed and I was being washed in a culture and a people. I was able to move slowly; I was able to recognize that there is so much more that I want for myself and that I can have. I think, sometimes in New York, you have to be really rich to have what you want. And so, you just start grinding until maybe one day, hopefully, you can create the picture of the life that you might want for yourself. And living in Mexico City, I’m like, Oh, all of the light that I want is here, and I can have it in my apartment. All of the places that I want to go, I can get there by bus, and it’s not so crazy expensive that it’s prohibitive. Or I can go see the monarch butterfly migration two years in a row and experience the beauty and the magic of that. In thinking about Lorde’s life and the way that she moved; it felt so aligned with that moment that I was in.

Also, when thinking about queer life, in the same ways as when thinking about Black life, our lives often do end quicker and younger than other people’s. So, the title is also a way of thinking about, in this moment, who knows how long I’m going to live? I hope that I have a long life, but I’m really maxing out on the joy and the pleasure and the leisure and the resistance and making sure that the people I love—and even the people I don’t know—are celebrated and that our lives are pictured in those subtle pleasantries of the day-to-day.

Naima Green, Sara Elise & Amber, from the series Pur·suit, 2018

Naima Green, Sara Elise & Amber, from the series Pur·suit, 2018Acheampong: I’m curious about the size and scale of your images. You’re working with playing cards, Polaroids, a lot of prints that can be cupped in the palm of your hand. How do you want viewers to interact with the portraits? For myself, the size required me to really come close to the wall and have that kind of intimacy with the physical space.

Green: My intention is just that: to encourage—I was going to say “force,” but that is a strong word—to encourage people to step into the work. To actually hold a picture close to your face or to really move your body into the work.

I was drawn to the playing card format because you can put it in your pocket or bag, you can bring it with you to the beach, you can have a game on you at all times, but also have this community and this support around you at all times. Pur·suit has taken on a much broader life than I could have ever imagined. I get messages from people who have said to me, “I don’t live in a place where it’s safe for me to be out and queer and affirmed, and someone sent me this deck, and I’m reminded that there are so many people in the world who are like me.” Pur·suit is equally for that and also the pleasure of having a deck of playing cards and recognizing, “Oh! I went on a date with this person” or “This person’s my ex” or “I’ve seen that person in Bed-Stuy,” and those two degrees of separation that happen. I like the idea that the deck straddles this line: it’s framed beautifully as a fine art object, but it’s also the same format as an object that you can get in a bodega for $3. It takes on many different lives.

I started working with Polaroids because it helped me, as someone who is more type A. I’m always thinking about the postproduction and how to really elevate the photograph. Having a format like Polaroid, where I’m not doing anything to that portrait, frees me up in a different way. It allows me to accept what comes out of a camera in a different way, but also, when thinking about the self-portraits, accept myself in a different way, in this raw form: this is who you are, this is how you look in this image,and that’s it. And that’s okay and that’s beautiful. And how can you extend grace towards that, even if you don’t like what you might see in that moment?

Naima Green, I like you, September 22, 2018

Naima Green, I like you, September 22, 2018Acheampong: We’re getting to witness you extend that grace to yourself as well as to anyone who interacts with the work. You are documenting and fostering so many safe spaces across your work. There are the photographs at Riis beach, which has itself been a safe space for many queer people. And then, in reading about your portrait-making process for the Pur·suit portraits, I noticed an emphasis on how you wanted everyone you photographed to feel at ease. You had a pre-shoot ritual to invite them into that safety. As a final note, can you share how in your photographic practice, as well as in your life and the chaos that is 2020, slash America, slash just being a Black person moving through this world at any time—

Green: It’s like, slash, slash, slash! [Both laugh]

Acheampong: —what does safety look like and feel like for you?

Green: That’s a great question. Safety looks like setting boundaries with people that I love. Safety is taking this weekend and saying, “Actually, I’m not working this weekend.” I work all the time. I work seven days a week. I’m trying to change my relationship to work. So I’m going to go, in the beginning of fall, to experience what these mountains look like, what this lake looks like, and just live in that and live in these beautiful sunsets and live in the full moon and just enjoy my life in this way. And allow myself to enjoy the leisure and the pleasure that I’m wanting to share and foster in my work. To give that to myself too, in a more formalized way.

Safety looks like baths. Taking baths and soaking. Safety looks like really centering, and sharing my time with people that I love and care about and who respect me and who want to see me thrive and grow in the same ways that I want to see them thrive and grow and change. Safety looks like therapy and acupuncture.

Riis is a site of my work, but it’s also a site of some of the deepest joy and comfort that I experience in my body. So, safety looks like going to the beach, it looks like being near the water.

Acheampong: Yes, the water. In your film, you said, “I need the water,” and you said it three times.

Green: Yes. I’m recognizing for myself the things that I do need, the things that make me feel more whole.

Naima Green: Brief & Drenching is on view at Fotografiska New York through February 28, 2021.

A Photographer’s Visual Poem about Solidarity and Protest

It feels impossible to reduce the events of 2020 to one theme. It’s COVID-19. It’s the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many other Black Americans. In the U.S., it’s a cultural reckoning with our own racist histories—and our need to do better. It’s the economic crisis. It’s a presidential election of existential proportions. And it’s the unavoidable sense that these experiences are inextricably linked.

In 2016, Yu-Chen Chiu began a long-term project, America Seen, which she describes as a “visual poem about the social landscape of the U.S. during the Trump administration.” Examining the country’s tumultuous social and political moment, the series explores the varied nature of America. Now, a new series, Separated, Together (2020), serves as a continuation of that project.

Weaving together three main experiences—society under COVID-19, protests in response to the murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and a modern reassessment of historical monuments—Chiu examines not only the new chapter the U.S. faces today, but also the ways historical narratives shape our future. “Many things got magnified during the pandemic and social movements this year. I never imagined to see this kind of America, everything is surreal,” Chiu said recently. “I feel the responsibility as a photographer to capture what’s going on at the moment.”

Born and raised in Taiwan, Chiu moved to the United States to pursue her master’s degree in 2003, going on to become a permanent resident in 2015. After earning a degree in English literature from Chinese Culture University in Taipei, she studied film production and new media at New York University and photography at Cooper Union and the International Center of Photography. Working in the documentary genre, Chiu’s experience as an immigrant for half her life has become a foundational part of her photographic practice. “I am always drawn to the notion of identity and belonging,” Chiu says. “I use my own experience as a starting point to take photographs.”

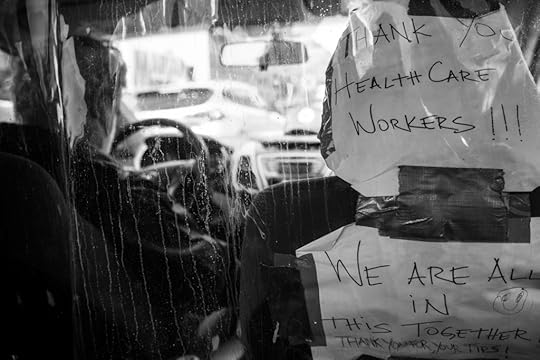

Most of the photographs from Separated, Together come from Chiu’s daily observations of her surroundings in Brooklyn, where she is now based. Like for many adjusting to life under quarantine, taking walks became a permanent fixture in her routine. Bringing her camera along, Chiu allowed an intuitive process to guide her exploration—capturing moments that arouse her curiosity, from sights she had never seen before to moments of extreme mundanity. “Photography is about experiencing and observing life to understand myself and my relationship with the environment,” Chiu explains. “Instead of forcing something to happen, I take my time to blend myself into the situation and circumstances that come to me.”

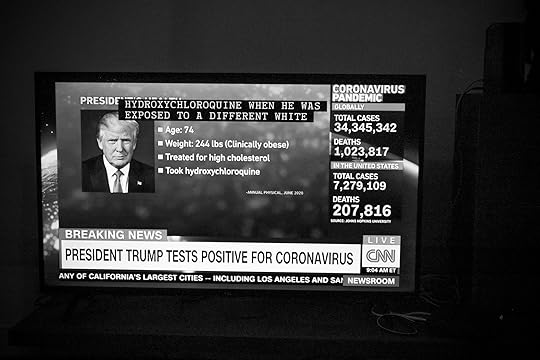

Throughout all of Chiu’s black-and-white photographs is a subdued, contemplative atmosphere. At times, there is an overwhelming stillness, which extends into her accompanying video pieces (the only components of the series in color). Although the reality Chiu captures is familiar, viewing these works gives a similar sensation to flashes from a dream or memory. Fog overtakes a surreally empty Brooklyn Bridge. A trio of children, almost completely lost within the frame, peek out the window from behind protective bars. Chalk squares indicating social-distancing guides are spread across a concrete courtyard—a sight that would have been almost incomprehensible a year ago, but is immediately recognizable today. A candlelit sign reading “Vigil 4 Martyrs of the George Floyd Rebellion” sits quietly at the center of a frame, illuminating the dark background.

In one frame, posters of Black men, women, and children who have been killed are displayed across a fence, a dried bouquet between them. In another, the news splashes across a TV screen, floating in a darkened room. Signs of the pandemic become, at once, both messages of separation and reassurances of solidarity. The American flag, in particular, is a recurring symbol throughout the series: from a sweeping field of them at a 9/11 tribute in Stanford, New York; to those held during protests with the words “Black Lives Matter” written across them; to flags ominously standing next to a “Trump 2020” sign in an empty field.

Among Chiu’s ruminations on the present, she introduces images of historical monuments and memorials, particularly those associated with racial injustice. Chiu’s goal was to examine the ways these monuments exist in our public space, as well as how our ever-changing perspective of history alters these monuments’ meaning. “Our definition of ‘greatness’ changes by our eras. I intentionally wanted to document monuments of figures such as Columbus, Robert E. Lee, George Washington, whose achievements are being redefined today,” Chiu states. “It was important to use these images to act as a pause, a reflection on the pandemic and protests. To me, they are all related concepts of solidarity, freedom, and patriotism.”

Chiu’s photographs do not seek to provide any answers or solutions to the crises we face today. In a time of social distancing, when many of us are more separated than ever, Separated, Together instead offers a poetic rumination on our collective experiences. “I hope this can be a catalyst to let us rethink what’s happening now and continue the conversation,” she says. “I see my work as a remedy for these unsettling times.”

All photographs from the series Separated, Together, 2020, for Aperture

All photographs from the series Separated, Together, 2020, for ApertureCourtesy the artist

The Photographer Who Spins Black Girls’ Lives into Gold

As a Black woman born and raised in Ithaca, New York, Nydia Blas has long been accustomed to carving out space in a predominantly white city, seeing a “magical outlook” as a necessary tool for resilience. At the age of eighteen, she started college as a single mother, and she used whatever was at her disposal to make work, without the luxury of time or a dedicated studio. While her images were often misunderstood or misinterpreted by the predominantly white male faculty, she never stopped creating, because she knew she needed to express her voice. It was exactly this mentality that led to her acclaimed series The Girls Who Spun Gold, which was born out of the conversations and collaborative creativity shared by members of the Girl Empowerment Group that Blas set up as a means of supporting young women of color in Ithaca.

In 2019, Blas took a teaching position at Spelman College in Atlanta, a move that marked a turning point in her life. “Atlanta is a super-magical space,” she says. “I am surrounded by Black folks every day, which is completely different to where I’m from.” She admits that her preconceptions of the South meant she never imagined she would end up moving there. “I saw it as this horrific place where all these terrible things happened, in terms of the European acts of African slavery,” she adds. “Enslaved Africans used the stars to escape to the North.”

Blas explores these contradictions—and the significance of the stars—in her new series The Souls of Black Folk. The name is taken from W. E. B. Du Bois’s influential 1903 essay that explores the notion of “double consciousness,” in which being African American is to be “looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” Turning her lens on her family, Blas sought to understand the new and unfamiliar city of Atlanta through them. The ensuing images include intimate portraits of her relatives adorned in gold or bathed in red light, interspersed with visions of the night sky and the natural beauty surrounding their new home.

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black Folks

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black FolksIn one scene, Blas’s stepson sits with his eyes closed, wearing what appears to be a gilded cape. “It is actually a tree skirt,” Blas explains. “It immediately seemed very space-like to me, and I related it to the costumes worn by Sun Ra, and these ideas of Afrofuturism. My work is temporal and a reflection of what I’m thinking about and how I feel at the time. That photo sums up how I was feeling about Atlanta.”

The allure of gold has been an ongoing concern for Blas. It has made its way into a number of her pictures, from iridescent clothing to metallic liquid spread across the skin. She first began using gold glitter while an undergraduate, as a way to cover the bodies of victims in photographs of lynchings. For Blas, it was a way of countering the violence and “returning the bodies to a state of value, which had been taken away,” while simultaneously engaging with the spiritual qualities and gaudy artifice of the material. As she explains, “value is a fallacy itself, because our value changes depending on our setting and for whose use.”

For Blas, this idea of desirability and utility is linked to the experiences of Black women, who have so often found their voices undervalued and overlooked. When she first exhibited The Girls Who Spun Gold, for example, she was taken aback by the response: “The project felt so personal, and yet it resonated with so many people around the world, who felt that they were in a space where they were excluded.”

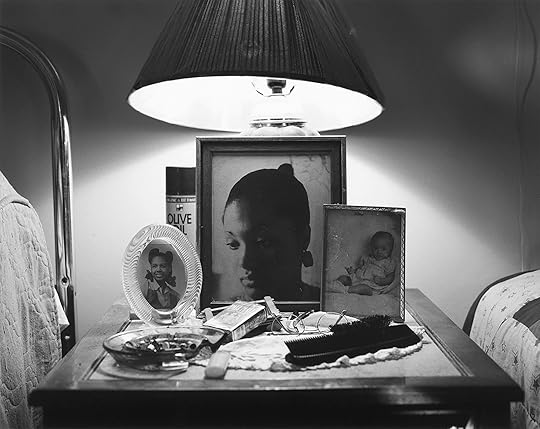

Nydia Blas, Band Uniform, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold

Nydia Blas, Band Uniform, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun GoldAlthough Blas photographs a multitude of subjects, she attests that Black women remain at the heart of her work. “I have always been surrounded by amazing women. I was raised a lot by my great-aunt Beverly, and she introduced me to so many things that are intrinsic to my practice today, like having access to pictures of our family at her home,” she adds. “Just being able to see photographs of my ancestors had a big impact on me.”

In creating her own images, Blas is forging a sense of belonging and community that extends far beyond herself and her camera lens, even in the most trying circumstances, including going through a divorce. “The Souls of Black Folk sees me turning the camera on my husband, my stepson, and my daughter, yet now I need to figure out how to talk about the work,” she says. “Even though I’m going through this tough period, I have now had more time to connect with and support the girls featured in The Girls Who Spun Gold. This space is now open in my life to give back to them.”

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black Folks

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black Folks Nydia Blas, Gold Cap, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold

Nydia Blas, Gold Cap, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black Folks

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Souls of Black Folks Nydia Blas, Secrets, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold

Nydia Blas, Secrets, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold Nydia Blas, Gold Glitter, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold

Nydia Blas, Gold Glitter, 2016, from the series The Girls Who Spun Gold Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2017, from the series The Trouble with Being a Mama

Nydia Blas, Untitled, 2017, from the series The Trouble with Being a MamaAll images courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

Why Do These German Citizens Dress up as Native Americans?

Here are the Indianer bodies: braid-framed German faces and shirtless, toned torsos. And here are the material goods, products of a curious labor of desire: bright canvas tipis, brain-tanned deerskin, perfectly crafted feathers, quilled and beaded clothing that mimics Karl Bodmer paintings from the 1830s. Bodies and goods join together in performances, as drums pound, legs step, and voices sing—or sometimes just yell. Document these things and you have archives—a museum stuffed with mannequins, a wall hung with moccasins, a computer full of images.

For German hobbyists who participate in the Indianer subculture, which revolves around Native Americans, their devotion culminates in annual summer camps where they show off their skills and live the Indianer life for a week. Their scene (for it is truly that) originated with the late nineteenth-century writings of the German author Karl May, whose characters—the Apache chief Winnetou and his German sidekick Old Shatterhand—inspired Europeans’ fanatical affection for North American Indians.

Into that scene, carrying a camera, steps Krista Belle Stewart, an Indigenous Syilx Nation artist based in Berlin. What Stewart enters, on visits made over a period of several years, is multiple layers of the uncanny. The hobbyists’ dedication to authentic detail seems at first to evince a deep respect for Native cultures. But the escapism also embodies a reassuring flight from compromised German histories. Stewart’s presence reminds them that there are moral quandaries surrounding history and appropriation yet to be considered. Indianer, shrinking in number and uneasy, know this to be true.

Krista Belle Stewart, Coke Finger, Grimma, Germany, 2007

Krista Belle Stewart, Coke Finger, Grimma, Germany, 2007What of Stewart herself, sitting with a friend in a replica of a Plains Indian lodge in a German field? “What’s weird about the experience,” she told me, “is that they are real . . . but I can’t quite believe it. Because we are real too.” She spoke of returning to her homelands after each trip, a cleansing restoration for an Indigenous sense of self pushed a touch off-kilter. After visits in 2006 and 2007, Stewart stepped back from her explorations of Indianer culture, unable to reconcile the contradictions. She returned in 2019, though, and quickly rekindled old relationships. One hobbyist, who had made Stewart a dress more than a decade earlier, retrieved it from a subsequent owner and gifted it to her.

That dress and a silver arm cuff gifted to the artist by another German enthusiast are the only two objects situated vertically in her 2019 exhibition Truth to Material, held at Nanaimo Art Gallery in British Columbia. For the rest of the installation, Stewart arranged images of four different scales in an asymmetrical grid on a vinyl-covered floor. Stewart’s bare walls reject the exotic and documentary photographic traditions associated with Indigenous subjects. Instead, viewers teeter over the images, positioned in a vertiginous uncanny.

The floor also brings viewers into an Indigenous judgment. In many Native cultures, one does not step over another’s body or belongings. To do so is a sign of disrespect, even a provocation. Such stepping is the essence of the exhibition, and for good reason. As Stewart observes, when Indigenous people contemplate Indianer life, they laugh. And then they feel anger. She is aiming for the complete package—not simply wonder, irony, and humor, but also a sense, understood but less often experienced, of Indigenous indignation.

Krista Belle Stewart, Crazy Ranch, Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany, 2019

Krista Belle Stewart, Crazy Ranch, Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany, 2019 Krista Belle Stewart, The Week, Geheimer Ort, Germany, 2019

Krista Belle Stewart, The Week, Geheimer Ort, Germany, 2019 Krista Belle Stewart, Letzter Tag der Woche, Geheimer Ort (Last day of the week, Secret place), Germany, 2019

Krista Belle Stewart, Letzter Tag der Woche, Geheimer Ort (Last day of the week, Secret place), Germany, 2019 Krista Belle Stewart, Heike’s Photo, Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany, 2019

Krista Belle Stewart, Heike’s Photo, Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany, 2019  Krista Belle Stewart, Truth to Material, 2019. Installation view at Nanaimo Art Gallery, British Columbia. Photograph by Sean Fenzl

Krista Belle Stewart, Truth to Material, 2019. Installation view at Nanaimo Art Gallery, British Columbia. Photograph by Sean FenzlAll images courtesy the artist

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “Truth to Material.”

Two Photobooks Consider the Pervasive Fantasies of Whiteness

On February 23, 2020, Ahmaud Arbery, a twenty-five-year-old African American man, was shot while running in a suburban neighborhood outside of Brunswick, Georgia. A video recording of the incident shows two white men following him in a pickup truck, confronting him, and firing their guns three times. Arbery was dead when police arrived. No immediate arrests were made, and for seventy-four days the men remained free. Only after the release of the video sparked public outcry were they charged with murder.

Arbery’s killing has prompted anguished talks about the peril faced by African Americans in “running while Black” or, more bleakly still, “living while Black.” But the initial reluctance of some Georgia authorities to charge the men, even with the existence of potentially damning video footage, is also a devastating illustration of what the photographer and writer Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa calls “the governing equation of whiteness to innocence.”

Buck Ellison The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 1975, 2019

Buck Ellison The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 1975, 2019Courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

Being white, as Daniel C. Blight reflects in his timely and perceptive book The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization (2019), is about much more than skin color. It is a “stubborn and often invisible power structure,” a ubiquitous ideology of domination, privilege, and violence that hides in plain sight as a default “natural identity” for white people. It is also a way of seeing the world. And as Blight observes, the camera has been deeply implicated in the promulgation of the white gaze virtually since its invention in the nineteenth century. The Image of Whiteness features excerpts from projects by various artists, such as Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Hank Willis Thomas, alongside insightful dialogues with key thinkers on race, including the writer Claudia Rankine and the philosopher George Yancy. Blight aims to explore how the white imaginary is developed and perpetuated across Western culture and to also consider how photography can help reveal whiteness “for the set of representational fictions that it is.”

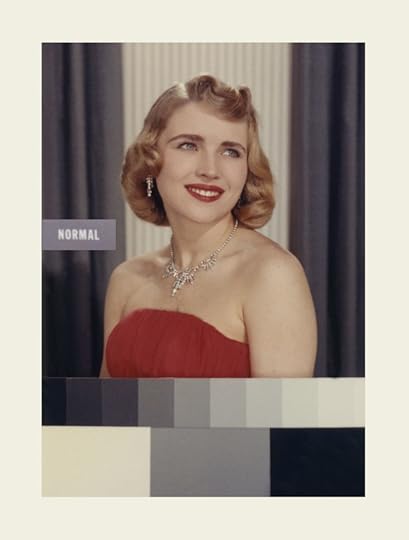

To those ends, the book presents Michelle Dizon and Viêt Lê’s project White Gaze (2018), which appropriates archival imagery from National Geographic, unpacking and disrupting the visual language of racial hierarchy encoded in each picture. In another contribution, Broomberg & Chanarin look to the loaded history of Kodak’s Shirley test cards and the false equivalence of whiteness with universality that they fostered.

Broomberg & Chanarin, Shirley 1, from the series How to Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light, 2012

Broomberg & Chanarin, Shirley 1, from the series How to Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light, 2012Courtesy the artists and Lisson Gallery, London and New York

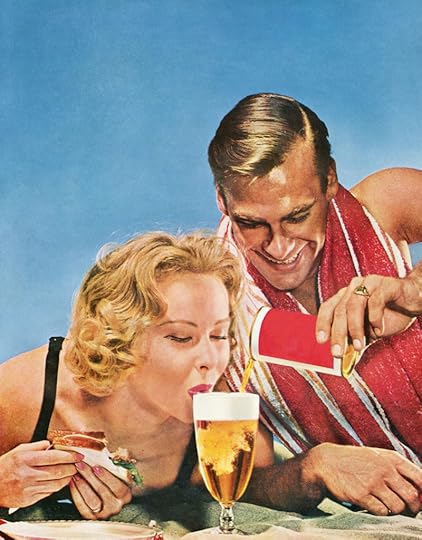

Hank Willis Thomas, You Don’t Have to Try So Hard!, 1958/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915–2015

Hank Willis Thomas, You Don’t Have to Try So Hard!, 1958/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915–2015Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Some artists whose works appear in the book explore race through strategies of erasure. Ken Gonzales Day digitally removes the hanging bodies of Black or Brown victims from archival pictures of lynchings that took place in the United States. Nate Lewis obscures the faces of people of color from news footage of Trump rallies. The result of these works is to turn attention to the white figures in the images—the grinning spectators jeering at the (now absent) dead body, and the Trump supporters engaged in what appears to be a verbal assault on Black onlookers. Both projects offer vivid proof of Yancy’s observation that whiteness is a “parasitic” condition that survives by creating a menacing racial “other”—the Black body—on which it can assert sovereignty.

White power and privilege are also the governing themes of Buck Ellison’s recently published monograph Living Trust (2020). Ellison’s photographs, a selection of which appears in The Image of Whiteness, seem to document the habits and tastes of the white upper-middle class. There are photographs of lacrosse matches and Range Rovers, a young man in performance fleeces of various colors, and Christmas-card portraits of well-groomed families. But these are mostly artificial scenarios constructed by Ellison using paid actors and models. The images highlight how wealth has historically enabled members of the upper socioeconomic classes to present a veneer of bland respectability to the world, irrespective of their private prejudices.

Ellison devotes a section of the book to a series of family portraits purportedly showing Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s controversial secretary of education, and her brother, Erik Prince, founder of the notorious private military company Blackwater. Few private pictures of the family exist in circulation, and in lieu of these, Ellison presents his own confected portfolio. A group picture, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 1975 (2019), shows four blond siblings lounging in a 1970s-era living room decorated with mahogany furnishings and characterless paintings, the room displaying not so much wealth but the Protestant rectitude of the Prince family’s strict Calvinist beliefs. The imagined portraits strive to convey normalcy, but there’s an unsettling undercurrent to them that hints at what F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator in The Great Gatsby calls the “vast carelessness” of the rich.

Buck Ellison, Dick, Dan, Doug, The Everglades Club, Palm Beach, Florida 1990, 2019

Buck Ellison, Dick, Dan, Doug, The Everglades Club, Palm Beach, Florida 1990, 2019 Courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

In the image Erik with Kitty, Blackwater Training Center, Moyock, North Carolina, 1998 (2019), Erik, as a young man yet to found a security force implicated in the massacre of seventeen Iraqi civilians, sits on the grass, playing with a kitten while sporting tactical pants and a bulletproof vest. Another photograph, titled Dick, Dan, Doug, The Everglades Club, Palm Beach, Florida, 1990 (2019), shows four men out on a manicured golf course: Two golfers haggle over the position of the ball near a hole. The third golfer has his back turned and is pissing on the green. An unnamed caddy looks on impassively.

Ellison’s photographs describe whiteness as its own paradisal domain—a world where people of color are banished from sight, and where actions have no visible consequences. It is a fantasy, albeit one that some, such as the killers of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and far too many others, seem to aspire to as a reality.

This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the column “Viewfinder.”

Who Was Richard Avedon?

Often, the individuals who are best known and most public are, in fact, the least knowable and most inscrutable. The masks that ensure their legends often obscure their tortured private lives. Among photographers, few were more conspicuously famous or notoriously private than Richard Avedon (1923–2004). Following a meteoric rise as a young fashion photographer at Harper’s Bazaar in the late 1940s, and later at Vogue and other magazines, the intensely driven Avedon glided through mid-century New York high society with the glamorous authority and savoir faire of a movie star. He transformed notions of style, celebrity, women’s fashion, and photography itself.

But around 1969, after nearly two decades of literally dominating the covers and glossy pages of leading fashion magazines, Avedon turned abruptly and increasingly to innovative forms of photographic portraiture—often large, minimalist, and unsparing in detail. And it was those experimental portraits, more than his groundbreaking fashion work, that ultimately won Avedon the plaudits which he so craved from art galleries and museums.

In the new book What Becomes a Legend Most: A Biography of Richard Avedon, noted photography critic Philip Gefter explores the intricate backstory of Avedon’s private life and the evolution of his career to make a case for him as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

Paul Himmel, Dick Avedon, Cherry Grove, ca. 1946–48

Paul Himmel, Dick Avedon, Cherry Grove, ca. 1946–48Courtesy Lizzie and Eric Himmel

Brian Wallis: You have just published a massive biography of Richard Avedon, a project that has absorbed you for over five years. Let’s talk about the project of biography in general. Does writing a biography make you end up loving or hating your subject?

Philip Gefter: I went through stages, as with any relationship. There were moments when I loved him. There were moments when I was completely annoyed by him. There were moments when he disappointed me. And then, there were moments when he was utterly redeemed. [laughs]

Wallis: After all that, what do you think is the value in tracing someone’s life? What did you learn, and what do you want to communicate to readers?

Gefter: Well, that’s a good question. In the case of Avedon, specifically, I had always felt that he was a far more significant artist than he was generally considered. In fact, it was only toward the end of his life that he was finally acknowledged as such. And I always was curious about him personally: what was the combination of qualities that formulated his unique sensibility? That was really the essential question for me, that’s what I set out to try to answer.

Wallis: In arguing for Avedon’s cultural significance, you say at one point that there were various forces arrayed against him, forces that would deny him his status as an important artist for most of his life. And you say at the very beginning of your book that your principal goal is to make a case for Avedon’s rightful place in “the pantheon of twentieth-century arts and letters.” Why is this important to do? And why now, in particular?

Gefter: From the time I went to art school at Pratt in the early 1970s, I was aware of a general prejudice against photography. It was considered a second-class medium, not much more than a graphic art. And during the ’70s, I watched with interest the elevation in stature of photography in the art world. So I always felt the need to defend photography as a medium. I studied and understood its history and was fortunate enough to meet many interesting photographers. I’ve always loved the photographic image. In the end, I truly believe that photography reflects something profoundly existential about who we are.

That said, the reception of Avedon’s work in the 1970s and ’80s seemed to me to be representative of the prevailing derogatory attitude toward photography. And his struggle to be recognized as an artist was not his alone. Like many photographers of that time, Avedon suffered a genuine artist’s quest to have his work recognized. And he had to endure a number of prejudices about the medium he chose.

In particular, he suffered the prejudice of being a commercial photographer in the art world, where there was a very distinct church-and-state divide between art and commerce. Today, of course, art is commerce. But fifty years ago, there was still some semblance of integrity about the making of art without the goal of simply making money.

Burt Glinn, Richard Avedon photographing Veruschka in his studio, 1966

Burt Glinn, Richard Avedon photographing Veruschka in his studio, 1966Magnum Photos

Wallis: But by that time, Avedon was a very successful photographer.

Gefter: Yes, Avedon was one of the most famous photographers in the world at that time, but he was also known as a fashion photographer which, in the art world, was a joke. So, he tried various approaches to hurdle that negative reputation. For instance, there was Avedon’s show at Marlborough Gallery in 1975, which was a signal moment in his career and, even in the photography world, was a bit of a phenomenon. He showed his large, wall-size group portraits for the first time together. But art critics dismissed the show as high-style formulaic imagery that didn’t really rise to the level of Art with a capital A.

So, one issue I wanted to raise in this book was this: At what point would the critics and scholars finally acknowledge that Avedon’s approach was not merely a formula but an artist’s signature style? That was something I was intent on putting forward.

Wallis: Why was Avedon’s exhibition of portraits so controversial?

Gefter: In the 1970s, in New York in particular, street photography and new forms of documentary photography were ascendant. Nothing could have differed more from Avedon’s approach. He was a studio photographer, and his work was all set up—even the spontaneity was contrived in advance. And that whole approach to photography was thoroughly dismissed at the time. Later, in the 1980s and through the early twenty-first century, studio practices were taken seriously by artists and photographers, and given increasing stature in critical writing and thinking. But that required a substantial shift in thinking about photography as art.

One other thing: I had always believed that Avedon insinuated himself into the art world to satisfy his own ambition or ego. But I was surprised and relieved to learn that, for every single museum show he had—at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum, and the Met—he had always been invited by the curators or museum directors. In fact, even in the case of the Marlborough show, he was invited. He didn’t go to them. They went to him. That’s a significant shift in mind because, in fact, in some ways he was accepted by aspects of the art world and its institutions—more so than we’d thought previously.

Wallis: On the other hand, from your detailing of his relationship with John Szarkowski, the photography curator at MoMA, for instance, it’s clear that these were long-running campaigns of flattery and persuasion by Avedon, through which he attempted to capitalize on the rising interest in photography by certain curators at specific museums.

Gefter: Yes, that’s true. When Dick and John Szarkowski met in the early 1960s—I’m going to call Avedon “Dick,” if you don’t mind. I mean, everybody called him Dick. I think of him as Dick, not that I knew him.

Wallis: I think after a five-year relationship, you’re entitled to do that.

Gefter: [laughs] Yes, well . . . When Dick and John Szarkowski met in the early ’60s on the occasion of the Jacques Henri Lartigue show at MoMA, they established a very cordial relationship. In the late ’60s, Szarkowski went to Dick’s studio several times; he had come to recognize Dick’s work as being significant and, in fact, invited him to have a retrospective. Then, Dick and John began a conversation about what this retrospective would be. The problem is that Dick, because he was obsessive and self-promotional—and wanted to be in total control of everything related to his work—eventually alienated Szarkowski. Two years into this conversation about the retrospective he would have at MoMA, Dick agreed to have a retrospective at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Well, this didn’t sit well with John Szarkowski at all, because it preempted the uniqueness of his planned show at MoMA. And John was very territorial. So, understandably, that began a process of alienation. Thereafter, Dick was never really accepted at MoMA. Having spoken to the curators there going back to John’s era, I know that they basically dismissed Avedon as being too commercial. They simply dismissed his work. They didn’t acknowledge it as art.

Wallis: That dismissal must have been devastating to Avedon.

Gefter: Yes. I think he spent the rest of his career trying to get John Szarkowski’s attention. He did have a small exhibition at MoMA in 1974. Finally, John deigned to give Dick a single room on the first floor, where he exhibited a small series of portraits of his dying father. But it was nothing compared to the planned retrospective, which was supposed to be a large show covering several galleries.

Wallis: So, instead of focusing on Avedon’s incredible fashion photography, Szarkowski presented his own version of Avedon, as an incisive documentary portraitist in the mode of Diane Arbus.

Gefter: Right. That’s an interesting point. I never thought of it exactly in those terms.

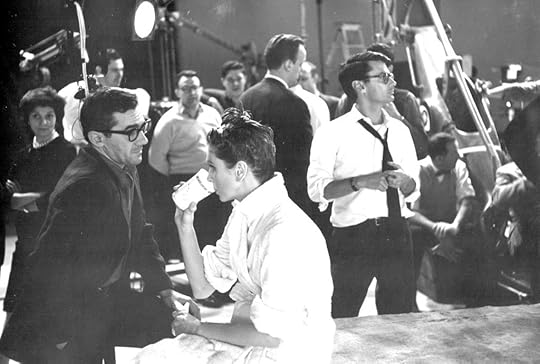

Richard Avedon on the set of the CBS TV special The Fabulous Fifties, 1959

Richard Avedon on the set of the CBS TV special The Fabulous Fifties, 1959Courtesy Earl Steinbicker

Wallis: In the case of his only show at MoMA, it also seems like a punishing gesture on Szarkowski’s part, one that focused on Avedon’s own self-loathing and self-doubt by forcing him to confront the incriminating stare of his dying father.

Gefter: Well, I think Avedon was trying to work something out with his father. I mean, he hated his father. His father was autocratic and dictatorial; and he tried to teach Dick some very hard lessons as a child. Clearly, Dick was not the son that his father wanted. I mean, Dick was scrawny, unathletic, pensive, and poetic. And his father wanted a “son.” I mean he wanted a guy, a tough guy.

So, while you may perceive in Avedon’s portraits his father’s withering stare, I see it differently. I think that he was watching his father wither away, to the point where his father had no more control of himself as a person dying. That’s my take.

Wallis: That’s brutal. And an interesting take on Avedon’s portraits in general. What distinguishes his portraits as significant to you?

Gefter: Avedon was of the generation that was on alert to the profound threat of the atomic bomb. And more and more, I think he started photographing his subjects like specimens under the forensic scrutiny of his lens, trying to identify a strain of existential dread that runs through the species at the thought of our annihilation.

No one is smiling against the white nuclear backdrop in his portraits. I don’t think he was aiming for emotional contact with his subjects—as compared with, say, the psychologically embroiled approach of Diane Arbus. That was not what he was after. He was after a clearer, more clinical, more objective observation consistent with the postwar, postnuclear condition. I don’t know that he conceived it exactly the way that I’m describing it. But I think that he did bring this forensic attention to the people he photographed.

He also endured being considered a celebrity photographer for years. And it irked him, understandably, as he got older and became more intentional about his work. He would say, “Don’t think about who they are, just look at their faces.” And what he meant by that is that we are all going to die, whether by nuclear annihilation or natural causes, whether we are the former king of England or the most glamorous actress in the world.

Wallis: What, then, did Avedon mean when he said that all his portraits were self-portraits? Was that an arrogant way of describing self-expression or was it, again, a competitive way of dominating other people?

Gefter: Well, not only did he create a visual pantheon of celebrities, he also photographed the anonymous everyman in the American West, and everybody in between. So, I think he was definitely taking his own measure against the person he was photographing.

But in terms of the portrait as self-portraiture, his body of work manifested a direct, clear-eyed approach, stripping the frame to nothing but a face-to-face confrontation with his subject. The visual economy and the straightforward elegance was pure Avedon. That was his signature. That was the artist in the work—hence the self-portrait. It isn’t arrogance. In all art, you see the identifying traits of the artist. In the genre of portraiture in photography, look at Nadar, or Julia Margaret Cameron, or August Sander—each body of work is a self-portrait of that artist.

Wallis: But Avedon’s portraits often seem artificial, soulless, or even mean-spirited. How do you align that attitude with his proud description of them as self-portraits?

Gefter: Well, I think Dick struggled his entire life with his self-esteem. It was a complicated thing. He had enormous confidence in his work, in his eye, in his sensibility. But his self-esteem was constantly on a roller coaster. He endured prejudices as a child. He endured anti-Semitism, and I think he endured homophobia.

So, that mean-spiritedness some people claim to be characteristic of his work wasn’t intended to make other people look bad. Rather, I think he was searching in the faces of others for that strain of existential dread that he felt himself. Maybe it was a kind of projection onto the visages of the people he was photographing. I think that is also what he was talking about in terms of his portraits being self-portraits.

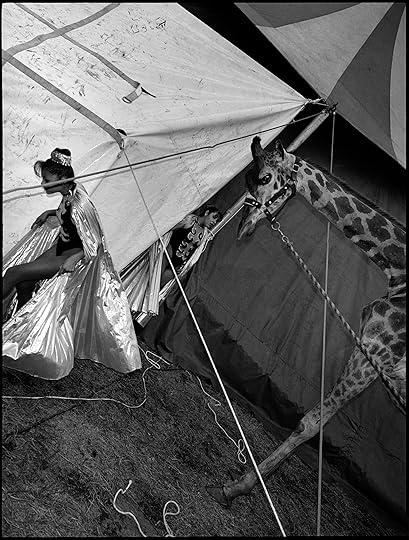

Sam Shaw, Richard Avedon with Dovima following the shoot at Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, 1955

Sam Shaw, Richard Avedon with Dovima following the shoot at Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, 1955Courtesy Sam Shaw Family Archives

Wallis: How would you compare that forensic projection in his portraiture to the seemingly light-hearted and spontaneous spirit he evoked as a fashion photographer?

Gefter: One of the key things I discovered about Avedon, which was key for me as his biographer, is that as an adolescent, he wanted to be a poet. That was a very serious pursuit for him throughout his teenage years. He was avidly writing poetry, and had his work published in newspapers and magazines. When he was seventeen, he won first place in a New York City–wide high-school poetry contest. And he was the coeditor of his high-school literary magazine—with no less a classmate than James Baldwin. But at some point, he was swatted down by a high-school teacher who said that Dick’s poetic language was largely derivative, the result of the magazines he was reading at home. That comment affected him so profoundly and adversely that he just didn’t have the courage to stay with it.

So, I think he brought to his early fashion work this lingering poetic impulse. This is one of the unique ingredients that helped him to revolutionize the fashion photograph in the 1950s. He brought the model out of the studioand into the street—not that he was the first to do so—and he did that with élan, against the spectacular backdrop of postwar Paris. He said, “My Paris never existed. I fabricated it.” Not out of whole cloth exactly, but out of swatches of Ernst Lubitsch, the films of René Clair, the songs of Cole Porter, and the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. He became a kind of impresario of the fleeting visual metaphor, as if a breeze always seemed to be blowing through the frame in his early fashion work. There’s a special kind of spontaneity he was able to achieve, in which the highly constructed and artificial image is made to appear entirely authentic. He said, “I was photographing my own elation. And it got whipped up to the point where I was able to give some emotional dimension to the couture itself.”

Wallis: Was this improvised spontaneity in fashion also the basis of what you call “the Avedon woman”?

Gefter: Yes. “The Avedon woman” is not my term. It was an actual phrase that was used, a kind of cultural trope in the ’50s. The Avedon woman was perceived as a free-spirited, imaginative, curious, provocative, slender, almost androgynous and very urbane female figure. And you can see that type being formed in the models he chose, especially Dorian Leigh, Dovima, and various others. I consider Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s to be the quintessential Avedon woman. Irving Penn famously said, “Avedon’s greatest creation has been a kind of woman. She’s a definite kind of person. I know her. I’d recognize her if she walked into this room. She’s sisterly, laughs a great deal, and has many other characteristics. . . . It’s a kind of woman I’m talking about projected through one very powerful intellect and creative genius.”

Wallis: What do you think was so appealing to Avedon about fashion photography in the late 1940s, as opposed to other applications of photography he could have pursued?

Gefter: To go back to the notion of the poetic impulse, I don’t think fashion was what Dick wanted to do, necessarily. I mean, what he really wanted was to be part of the cultural life surrounding fashion. Initially, when he was twenty-one, he made up his mind to work for Harper’s Bazaar, and he just sort of bulldozed his way in. In a way, that was very impressive for a young ambitious kid.

Harper’s Bazaar was one of the best magazines when he was growing up, and they were publishing really good literature. His parents subscribed to it. So he would be reading short stories by Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. Christopher Isherwood published Sally Bowles in Harper’s Bazaar in 1938.

The magazine was a way for Avedon to understand serious culture in a very direct way. He took fashion as being part of that world, and made something of it, and was being paid for it. But ultimately, that wasn’t his goal as an artist. I think portraiture was a much clearer, more direct way for him to bring his poetic observational impulses to his work, but that only came later.

Wallis: Well, that turn toward portraiture—if you want to call it that, since he never really gave up fashion—seems more evident after about 1959, which, as you note, was the year that Robert Frank’s book The Americans was published. And since you have also written a book titled Photography After Frank [Aperture, 2009], are you positing a general shift around 1959 toward a very different approach to thinking about photography as an art form?

Gefter: Yes. It’s a very good question, since both Robert Frank and Dick published books in 1959—Frank’s Americans and Avedon’s Observations. At the time, Dick was well aware of Frank. Not because Frank was prominent. In fact, nobody really knew who Frank was outside of a very small coterie of artists and Beat poets in Downtown Manhattan. But Frank had studied briefly with Dick’s mentor, Alexey Brodovitch. And Brodovitch even wrote one of the recommendations for the Guggenheim Fellowship that enabled Frank to make The Americans. And so, Dick was aware of him. But Dick was uptown and out in the world, and Robert Frank was downtown and quietly doing what he was doing. Still, Dick understood instinctively that Frank was the real thing: he was an artist and a photographer’s photographer.

When The Americans was published, it was a true artist book, authentic documentation of America as Frank was experiencing it. It was a modest publication, but it was something. And Dick recognized that.

Meanwhile, in the very same year, Dick published this very splashy coffee-table book—with a fancy slipcover, and pedigreed to the nth degree. Alexey Brodovitch designed it. Truman Capote wrote an essay. And the people Dick photographed were celebrities. So it had all the right elements to be a pop-cultural event. And it was well-received by the general public. But it was fatuous.

Installation view of Richard Avedon: Evidence 1944–1994, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 1995

Installation view of Richard Avedon: Evidence 1944–1994, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 1995Courtesy the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Wallis: Ouch. Then Avedon’s second book, Nothing Personal, in 1964, was an attempt to use his photography to make a statement about the urgent and topical issue of Civil Rights. And throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Avedon kept trying to make these more socially engaged works, but they often came off as misfires. He seemed to fit the model of what Tom Wolfe called a “limousine liberal,” well-meaning but out of touch. How do you assess the meaning and value today of these quasi-political works?

Gefter: I posit in my book that Nothing Personal was Dick’s direct response to The Americans. What Dick was trying to do, the only way he knew how to do it, was to “portraitize” a set of social issues of that time. He went down South and photographed individuals who were directly involved with or who represented the Civil Rights struggles. Nothing Personal was well-intended, but as an artist, Dick had not yet come into focus. He was groping. I consider it a worthy first draft in the evolution of his more realized artistic intentions.

He was not very successful at this new, more intentional approach to photography until he began his mural portraits in the late 1960s. The first project, in 1969, was of the Chicago Seven, the antiwar protesters who were accused of conspiracy to disrupt the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. That panoramic portrait—of Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Tom Hayden, and the others—certainly crystalized some of the key social and political conflicts in the United States at that time. In that work and other examples of his radical portraiture—including his mural of the Warhol Factory members, and his series of portraits of leading political figures, which he published as “The Family” in Rolling Stone in 1976—constituted a very systematic attempt to create a new kind of portraiture. And he did. I mean, no one had ever seen portraits like those before. They were literally larger than life; they became not only documents but monuments, in a way. I think that Dick’s portraiture became much more intentional after that.

Anyway, Dick was always looking over his shoulder at Robert Frank and wanting his approval. And Frank always considered Dick a “Sammy”—based on the character Sammy Glick in Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel What Makes Sammy Run?, which became a film in 1959. A Sammy in Robert Frank’s day would be what a yuppie was in our day.

Wallis: It’s funny, when I read that in your book, I recalled that the photographer Louis Faurer, who was close with Robert Frank at the time, used to mock Frank by calling him a Sammy.

Gefter: I wish I had known that. [laughs]

Wallis: Avedon’s portraits of Robert Frank and June Leaf seem like the absolute antithesis, in some ways, of his fashion work. But at the same time, you see what Avedon was doing is exactly what he did in his early fashion work, which is finding fashion wherever it exists in daily life, and acknowledging the sort of disheveled nature of Frank and Leaf as the new prototype, the new beauty.

Gefter: Well, I think you’re using the word fashion in a broader sense than couture. Or style. The thing is, yeah, you’re absolutely right. That signaled a new time.