Aperture's Blog, page 57

May 11, 2021

The Photographers and Designers Who Transformed American Magazines

Since it’s concerned, above all, with context and the printed page, Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine at the Jewish Museum in New York is an exhibition as much about graphic design as it is about photography. From its opening galleries, it focuses on the influence these ways of seeing exerted on one another beginning in the 1930s, when photography began replacing illustration in magazines. The creative push and pull that resulted was exciting, bringing out the best on both sides; Modern Look tracks that synthesis over the next two decades, focusing on key players both on and off the page.

William Klein, Atom Bomb Sky, New York, 1955

William Klein, Atom Bomb Sky, New York, 1955Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In a period when art became increasingly linked with activism, many of its innovators were recent European exiles, fleeing repression and a widening war, including Herbert Bayer, Erwin Blumenfeld, Josef Breitenbach, György Kepes, Herbert Matter, László Moholy-Nagy, and Martin Munkácsi. Kepes, quoted in the Modern Look catalogue, spoke for the group’s most high-minded impulses in 1944, when he suggested that art and design can be functional as well as expressive: “Posters on the streets, picture magazines, picture books, container labels, window displays . . . could disseminate socially useful messages, and they could train the eye, and thus the mind, with the necessary discipline of seeing beyond the surface of visible things, to recognize values necessary for an integrated life.” Whether any of these artists realized the most principled of these goals is debatable, but “train the eye” they collectively and most effectively did.

Because they were in a position to employ and direct so many of their peers, the most influential of the émigrés were the artists and art directors Alexey Brodovitch, who took over the design of Harper’s Bazaar in 1934; and Alexander Liberman, whose life-long career at Vogue began in 1943. Both were brilliant, sophisticated, imperious, and famously volatile, alternately charming and waspish; both helped define the “modern look” as designers, assigners, and mentors.

Martin Munkácsi, Woman on Electrical Productions Building, New York World’s Fair, New York, 1938

Martin Munkácsi, Woman on Electrical Productions Building, New York World’s Fair, New York, 1938Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

The Jewish Museum exhibition’s curator, Mason Klein, introduces Brodovitch in one of the first galleries with the elegant cover, hallucinatory spreads, and a page-by-page digital presentation of Brodovitch’s 1945 book Ballet, an impressionist vision of the Ballets Russes in performance. Before coming to New York, Brodovitch had painted sets for Sergei Diaghilev’s original Ballets Russes in Paris; and once in New York, he adopted the impresario’s most quoted directive, “Étonnez-moi! (astonish me)” as his own. Brodovitch’s work in the show, including spreads from Observations (1959), the book that introduced Richard Avedon to the larger world, astonishes us. He might be given showstopping star treatment, but Brodovitch always shares gallery space with other graphic geniuses—including Bayer, Matter, and Paul Rand—who rivaled him at witty and arresting design.

As for Liberman, although he is represented in the exhibition by reproductions of seven knockout covers he conceived for Blumenfeld at Vogue from 1944 to 1954, the extraordinary still-life and portrait images he commissioned from Irving Penn are shown out of context, leaving the art director’s role vague or unacknowledged.

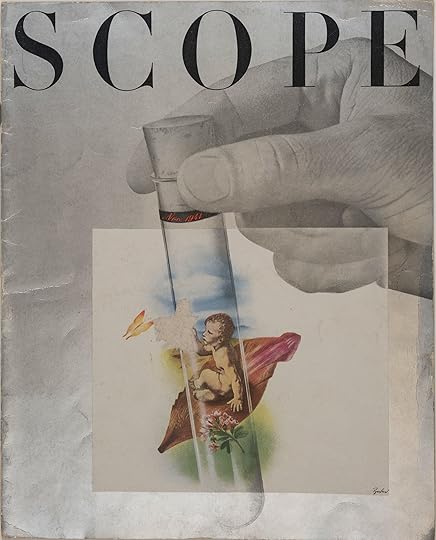

Cover of Scope, November 1941. Designed by Will Burtin

Cary Graphic Arts Collection, Rochester Institute of Technology

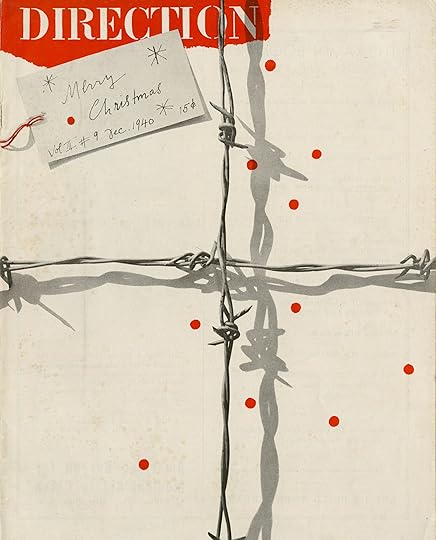

Cover of Direction, December 1940. Designed by Paul Rand

If the attention to these two magazine design legends is predictable, Klein goes to some lengths to overturn expectations elsewhere in his show, primarily by focusing on women photographers: Lillian Bassman, Margaret Bourke-White, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, and Lisette Model. Bourke-White and Model help to open up the show, moving further beyond fashion to include the magazines Life, Fortune, and Flair, and surprisingly inventive industrial titles like Scope and Westvaco Inspirations for Printers. Gordon Parks, one of the very few Black photographers with a substantial career in magazine work at the time, is a lonely outlier here, joined only by Roy DeCarava, with a single, superb photograph of jazz musicians, but supported in spirit by two galleries of atmospheric black-and-white images that close the exhibition on a moody, contemplative note.

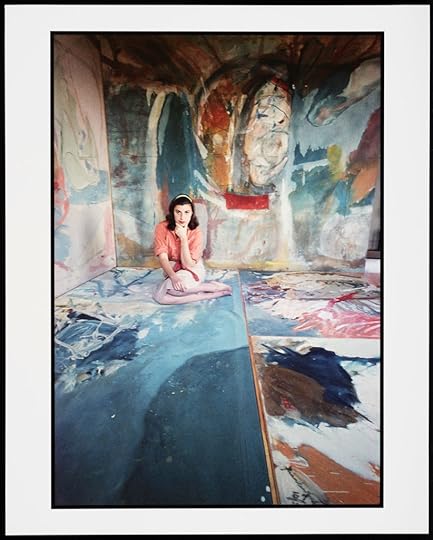

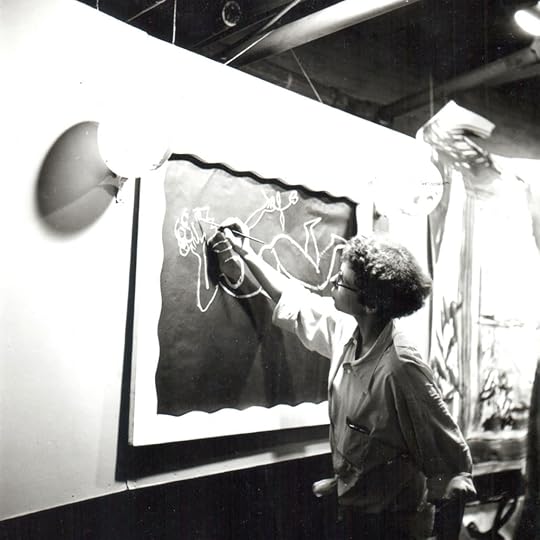

Gordon Parks, Portrait of Helen Frankenthaler, for Life, May 13, 1957

Gordon Parks, Portrait of Helen Frankenthaler, for Life, May 13, 1957© The Gordon Parks Foundation

Setting the Parks photograph alongside works by Louis Faurer, Robert Frank, William Klein, and Saul Leiter—nearly all of it made on the streets of New York—seems intended to remind viewers of socially engaged Photo Leaguers like Model, Sid Grossman, and Walter Rosenblum, seen in these same galleries in 2011’s The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936–1951 (also curated by Klein, with Catherine Evans). The league’s activities may not have been covered by many of the magazines featured here, but its soulful, reportorial style impacted and inspired most of the photographers; and the powerful last passage of Modern Look makes that abundantly clear.

Lillian Bassman, A Report to Skeptics, Suzy Parker, New York, for Harper’s Bazaar, April 1952

Lillian Bassman, A Report to Skeptics, Suzy Parker, New York, for Harper’s Bazaar, April 1952© Estate of Lillian Bassman

Liberman is quoted in the catalogue insisting he wanted to inject “the grit of life into this artificial world” at Vogue. Without making a similar claim, Brodovitch frequently did exactly that at Harper’s Bazaar, and many of the other magazines here (even Fortune at its 1940s best) made grit a specialty. Given the state of the world—with a post-Depression boom quickly swept up in a sobering but invigorating war, followed by an even more aggressive boom—how could they not? Without losing sight of elegance, inventiveness, and style as a saving grace, Klein grounds his show in seriousness, if not grit. But along the way, his focus on the magazine nearly evaporates. Many of the photographs did not appear on the printed page, and those that did are rarely seen in context. The American magazine remains as a force field and an incubator, but its absence in Modern Look as an object of size, weight, and graphic impact is puzzling and disappointing.

Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine is on view at the Jewish Museum, New York, through July 11, 2021.

May 10, 2021

A Message from Aperture Foundation’s New Executive Director

Hello, Aperture.

Today is my second First Day at a New Job, and I’m giddy with anticipation. My first First Day was in September 1994, fresh out of college, when I walked into the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. We used typewriters—on occasion, floppy disks at shared computers, no internet or email!—John Szarkowski stopped by regularly, and people smoked in their offices. Every Thursday morning, the curatorial staff would gather to look at portfolios that photographers had dropped off and mailed in from all over the world. I couldn’t believe how fortunate I was to spend my days around amazing photographs and brilliant people. That feeling never waned—and in my new role leading Aperture, I imagine it never will.

Aperture has been inextricable from conversations around photography since 1952, something I first grasped in high school, where Aperture magazine was both a teaching tool and a source of inspiration. As an undergraduate, I studied with Peter Bunnell, who had worked closely with Aperture’s founding editor, Minor White, soaking up stories of his connections with by-then-legendary figures. I wrote my thesis about Danny Lyon’s portraits, and avidly perused library copies of Diane Arbus’s Aperture monograph (1972), Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 1986), and Sally Mann’s Immediate Family (Aperture, 1992). It would be many years before I purchased my own copies of these books, which didn’t require a major investment, thanks to the fact that Aperture keeps them in print.

Sally Mann, Jessie Bites, 1985, from Immediate Family (Aperture, 1992)

Courtesy the artist

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Aunt Midgie and Grandma Ruby, 2007, from The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2014)

Courtesy the artist

Aperture has also been a significant link between most of my favorite projects over the last decade, most recently with the exhibition and book on one of Aperture’s founders, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (MoMA, 2020). I appreciated the opportunity to fine-tune my ideas for the magazine about Horacio Coppola (in Aperture #213), Regina Silveira (#215), and the Club Fotográfico de México (#236), and to contribute to The Photographer’s Playbook: 307 Assignments and Ideas (2014) and Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph (2021). Nearly all the artists I’ve had the pleasure of working with recently are deeply connected to MoMA and Aperture: Sara Cwynar and Stephen Shore, Dawoud Bey and Danny Lyon, Rosalind Fox Solomon and LaToya Ruby Frazier, Irina Rozovsky and Zora J Murff, Richard Misrach and Wendy Red Star, Hank Willis Thomas and Tina Barney. Last fall, I had the privilege of moderating a conversation with the incomparable Dr. Deborah Willis and the editors of To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2020) and of being a juror for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. Although no one associated with those events knew it at the time, I was applying for this job. The professionalism of the Aperture staff, their sense of purpose, and their commitment to the medium, combined with our shared admiration for all of the artists I mentioned above and many more, made me redouble my efforts to persuade the search committee to choose me as Aperture’s next executive director. I’m so grateful they did.

As a way of getting to know you—our community—and introducing you to our team, I will be hosting a series of seven conversations on Instagram Live. Beginning on May 19, join us every Wednesday at 1:00 pm EDT at @aperturefnd to hear from:

Lesley A. Martin, Creative Director

Denise Wolff, Senior Editor

Michael Famighetti, Editor of Aperture magazine

Kwame Brathwaite Jr., Board Trustee

Sara Cwynar, Artist

Richard Misrach, Artist

Wendy Red Star, Artist

While these conversations are happening, I’m going to send out a survey and ask that you kindly take the time to reply. Among the new programs I’m planning is an Aperture Book Club—and your interests and opinions will guide it! I look forward to hearing from you as we embark on this next chapter in Aperture’s history.

Left to right: Deana Lawson, Sarah Meister, An-My Lê, and Rosalind Fox Solomon at the AIPAD Photography Show, New York, 2019

Collection of Aperture publications at Sarah Meister’s home, New York, May 2021

Photography brings us together, across continents and decades. No medium can equal its ability to register our individuality and represent the various stories that we refer to cumulatively as history. I cherish the time I spent at a museum where we grappled with the ways photographs rest uneasily within the boundaries of art. As the new executive director of Aperture, I am deeply committed to looking critically and closely at what feels familiar and what feels strange in photography, to broadening our understanding of the medium through the highest-caliber publications and programs, and to leading an organization where conversations between artists, editors, and our audience is central. I believe in our capacity and our responsibility to harness the power of this medium, which we are fortunate to champion, in pursuit of a more just, more joyful world.

Yours,

Sarah Meister

April 30, 2021

The Post-Documentary Photographers Who Care about the World

There are no big crowds or large gestures in But Still, It Turns: Recent Photography from the World at the International Center of Photography in New York, which brings together the work of nine photographers to illuminate, as if by aleatory spotlight, corners of the United States in everyday endurance. Instead, the mood is quietly contemplative, a muted melancholy settling over the show like a light fog.

But Still, It Turns—what Galileo reportedly said upon the church’s rejection of his most famous theory—was planned before the pandemic but held until this February. If the exhibition feels prophetic, you might attribute that to the tricks of time. If it feels a bit random, that is no accident, writes curator and photographer Paul Graham in the stylish catalogue, published by MACK. “To some viewers, the artists’ work presented here, with its tributaries and eddies, its non-sequiturs and perambulations, its lack of drama and prize winning moments, will mean it does not appeal,” Graham writes in his essay-manifesto, framing the exhibition as a corrective for what he identifies as the “pendulum swing” of esteemed fine arts photography—“shift[ing] away from the world” in its preference for “constructed, conceptualized and staged imagery.”

Curran Hatleberg, Lost Coast (36), 2014

Curran Hatleberg, Lost Coast (36), 2014© the artist

Graham, a celebrated English photographer, has eighteen monographs and three survey books to his name, including his 1983 portrait of a Britain in industrial decline under Thatcher in A1: The Great North Road (republished as part of a trilogy this spring, also by MACK) and A Shimmer of Possibility, a twelve-volume look at everyday life in the US. In But Still, It Turns, he brings together “photographers who care about the medium and the world, who keep the heart of photography vital and alive” and whose work “give[s] shape to the world, to straighten the disarray, to reveal the fine web that binds us to each other, to this time, to existence.”

Literature has, among other art forms, seized on formal fragmentation to illustrate contemporary experience, and Graham invokes Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk’s notion that “constellation, not sequencing, carries truth.” With But Still, It Turns Graham seeks a photographic equivalent, celebrating each artist’s work as post-documentary, post-narrative: “no editorializing, no words to illustrate: that there is no singular story is the story.” Ian Penman’s catalogue essay takes up the literary form, a scrapbook of reflections interspersed with quotes from other writers and thinkers, and the show includes photobooks as “profound art works in their own right.” Six of the featured photographers’ books, along with a handful of other recent photobooks by artists whose work is not exhibited (including LaToya Ruby Frazier, Zora J Murff, and Carolyn Drake), are under glass at ICP and illustrated at the end of the catalogue, giving a sense that, with more space, these artists might have been included in the show.

Kristine Potter, Drying Out, 2015

Kristine Potter, Drying Out, 2015© the artist

All the photos in But Still, It Turns were taken in the US, many of them sometime during Obama’s second term or Trump’s early presidency. They are united as the works of astute artists using their cameras to lift the veil—without the flourish of a magician or morgue attendant—on an unequal and troubled country. There are moments of joy and tenderness, but overall the mood is quiet and contained.

By embracing the freedom left by the Internet’s erosion of magazine editorials and their narrative imperatives—“no didactic story here, no theme or artifice,” Graham writes—But Still, It Turns equates an oblique, observational aesthetic with sincerity, even truth. That there is no singular story is indeed the story of perspective. Separately, many of the works featured are strong. But I left ICP with a feeling of suggestive absence more than presence. The melancholic fog never parts.

Piergiorgio Casotti and Emanuele Brutti, STL PEOPLE no. 17, 2017

Piergiorgio Casotti and Emanuele Brutti, STL PEOPLE no. 17, 2017© the artists

This absence is most literal in the empty streets of Emanuele Brutti and Piergiorgio Casotti’s Index-G (2016–18), which takes as its subject racial segregation in Saint Louis (the title refers to the Gini Index, a statistical measure of inequality). The series documents the invisible barrier between the 95 percent Black zip code north of Delmar Boulevard, where life expectancy, the wall text tells us, is sixty-seven, and the 70 percent white neighborhood just south where life expectancy is eighty-two. The color photographs taken along the boulevard (one might think of Graham’s A1)—mundane scenes including an American flag, brick walls, an auto repair shop, boarded up storefronts, a nail salon—are shown in jarring juxtaposition with black-and-white portraits of Black Americans and the interiors of vacated home. The absence of the neighboring white residents poses the question: How best to confront whiteness—by picturing it directly, or refusing to give it more time centerstage?

Some may see prescience in these deserted streets. The word is used frequently these days to make sense of the déjà vu of inheritance—of this country’s history building on its own logic. Isolation, alienation, and racial violence are exacerbated by the experience of living with a global pandemic, but they are not novel. Perhaps prescience describes inevitability, further exposed.

Richard Choi, Untitled (Bedside Prayer), 2018

Richard Choi, Untitled (Bedside Prayer), 2018© the artist

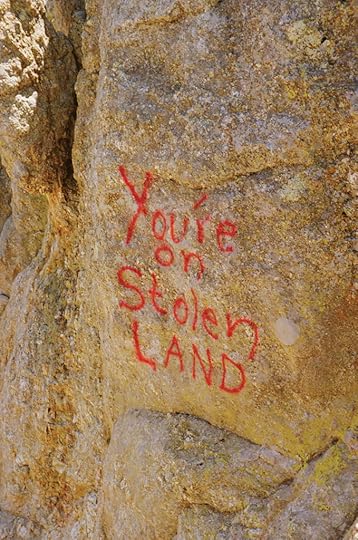

America’s recent confrontations with its own brutality, historical and contemporary, have been notably visual—from the videos of police murder of civilians that ignite uprising as well as conversations about spectacle and the ethics of picturing both atrocity and protest, to monument toppling, efforts to memorialize slavery, and more. Inseparable from social movements for material equity—the interconnected struggles for just housing, education, and healthcare, environmental justice and the redistribution of resources, the abolition of police and prisons—is the question of how we see: ourselves, each other, the world.

Photography has a tendency to reinforce the inequity and violence it reveals and, in some cases, claims to dismantle. In a world dominated by Big Tech, our distrust of photographs is met with further reliance on them. Some photography responds directly or self-referentially to anxieties about how technology affects how we see and who we are, addressing themes such as surveillance and saturation; circulation and manipulation; appropriation and the algorithm; democratization and democracy.

The term “post-documentary” has described many things, including a photography that examines these issues of authenticity and power. It now frequently refers to a poetic or ambiguous style whose meaning or message is not overdetermined. A suggestive rather than more overt aesthetic dominates But Still, It Turns, but the images that linger are the ones that most clearly wrestle with the tensions central to the form.

RaMell Ross, Boys, 2014

RaMell Ross, Boys, 2014© the artist

RaMell Ross’s South County, AL (a Hale County) (2012–20) offers glimpses of intimacy, mediated by the thick air of history. Faces are often partially or fully obscured: a little girl wearing a yellow dress and yellow barrettes crouches behind a flowering bush; another’s softly smiling eyes—both mischievous and shy—peer over the seat in front of her in an otherwise empty school bus. The catalogue notes “a strategic ambiguity” in Ross’s images “that speaks of a pursuit not to frame somebody, to grant them the full dignity of selfhood and perhaps unknowability.” Akin to Édouard Glissant’s notion of the “right to opacity,” Ross’s images are numinous in their respect for the untraversable boundaries of individual perspective.

In 2009 Ross moved to Hale County, Alabama, where he taught photography and coached basketball for many years, using his lens to represent the community while working to free his own perspective. Ross’s own catalogue essay for But Still, It Turns, also fragmentary in form, is a kind of dialogue that shifts between the imperative (“Disautomate the consumption of blackness” and “Consider the indecisive moment.”) and analysis (“If blackness/form is unstable and evolving then the ideas of structure and narrative must evolve correspondingly to accommodate. The site of the image in a time-based chain of interpretation must remain fertile.”).

“To be black is the greatest fiction of my life,” Ross has said. “Yet I’m still bound to its myth. I can’t help but think about . . . how the myth of blackness aged into fact and grew into laws . . . How it became the dark matter of the American imagination.” One might think of James Baldwin on the twin myth—or “moral choice”—of believing oneself white; in “On Being White . . . and Other Lies” (1984) he writes that those who “think they are white,” “who believed that they could control and define Black people[,] divested themselves of the power to control and define themselves.” What might it mean to learn to see again, to define oneself—to imagine—anew?

Vanessa Winship, Untitled (Seth and John, after the Rodeo), Fort Worth, Texas, October 12, 2012

Vanessa Winship, Untitled (Seth and John, after the Rodeo), Fort Worth, Texas, October 12, 2012© the artist

In Vanessa Winship’s she dances on Jackson—a series taken across the US in 2012, and one of the more classical documentary approaches in the show—faces are on full display: open, porous, guarded, seeking. But these are fleeting moments of intimacy, poignant and enigmatic. In one portrait, a father and son in suit-and-tie stand outside a public building—the son elevated by the curb and gently holding the older man’s earlobe between his fingers, the father pigeon-toed and leaning slightly into the gesture. They look away in opposite directions, this moment of sweetness between them, both finite and infinite, sealing the tableau.

Winship’s black-and-white portraits seem to be in conversation with Curran Hatleberg’s light-soaked color narratives in Lost Coast (2014–16)—pictures of warmth and uncertainty in a struggling post-industrial California town—though it’s unclear exactly what is being said beyond a collective, quiet making do. Meanwhile, Gregory Halpern’s ZZYZX (2008–16)—a colorful and carnivalesque, mystical and semi-fictional chronicle in the Mojave Desert—and Kristine Potter’s Manifest (2012–15)—black-and-white portraits of landscapes and lone men in unnerving repose—are also kindred despite their strikingly different styles; both invoke the surreal in their play with the pageantry and brutality of American myth and westward expansion.

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2016

© the artist

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2016

© the artist

“We know that a photograph lives in multiple eras at once: the time of its making, the time of its unveiling, the various eras of its subsequent rediscovery,” Rebecca Bengal writes in her catalogue essay. In Richard Choi’s What Remains (2011–20), short videos of everyday life—a mother praying with her children, a woman winding a clock—jolt with the sound of a camera’s shutter as a still photograph (framed beside the video) is made, the moment plucked from time. Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s All My Gone Life (2014–18)—the artist’s own images from those years mixed with prints of archival negatives he purchased on eBay—are arranged on two stories of the exhibition’s central wall. Some are so small or hung so high as to be frustratingly less legible than others, emphasizing not only the fallibility of perspective but also the distorting passage of time—history’s hold on our vision.

“What makes photography a strange invention is that its primary raw materials are light and time,” John Berger wrote. Ross’s Academy Award-nominated film Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018)—which is screening at the ICP— follows two young men, Daniel and Quincy, to convey a sense of their community without the imposition of a confining narrative. About midway through, there’s a beautiful scene where sunlight streams through trees and smoke as it rises in wisps and blooms—a daytime bonfire burning nearby an old plantation house. Accompanying this everyday fever dream is Ross’s impromptu conversation from behind the camera with a local who’s curious about why he’s filming; we hear bits and pieces about Ross’s project—“We need more black folks making photos in the area and taking pictures,” he says—and the man’s grandson’s scholarship, the dialogue a part of Ross’s practice: “participate, not capture; shoot from not at.” The question “What happens when all the cotton is picked?” then fills the screen preceding a 1913 clip of Black American actor Bert Williams in blackface—the true breaking of the fourth wall. (Filmmaker Garrett Bradley also incorporates footage from Lime Kiln Club Field Day, the earliest surviving feature film with a Black cast, into her 2019 installation America, recently on view at MoMA.)

RaMell Ross, Shaquan, 2012 © the artist

RaMell Ross, Shaquan, 2012 © the artistRoss’s film is a reimagining of what it might mean to represent Blackness and the South. But it is also a freeing of perspective more generally, by way of working with and within its inevitable constrictions—of the physical, the individual, and of time. It is artful and open, demanding and free. This possibility is what the post-documentary round-up of But Still, It Turns urges us to see.

But Still, It Turns: Recent Photography from the World is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through August 15, 2021.

How David Alekhuogie Navigates the Colonial Past

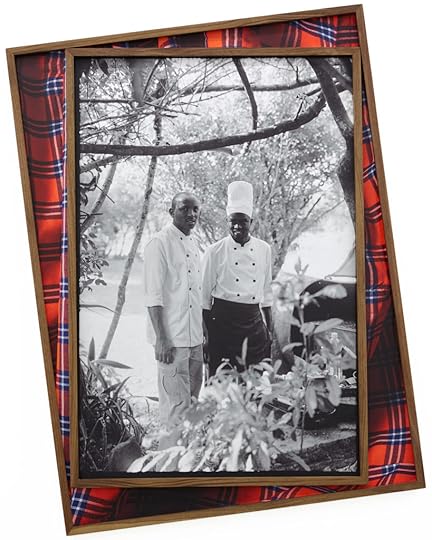

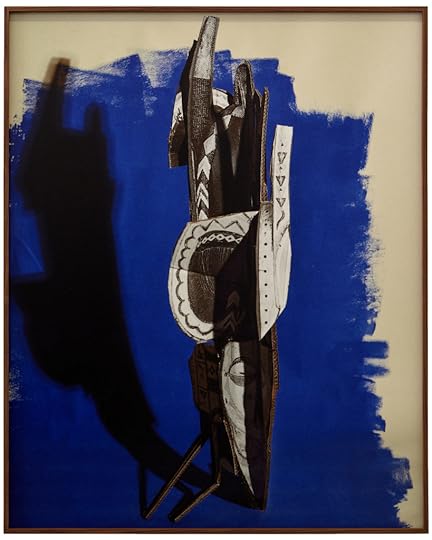

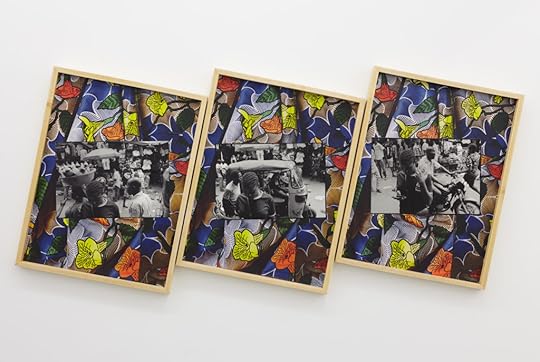

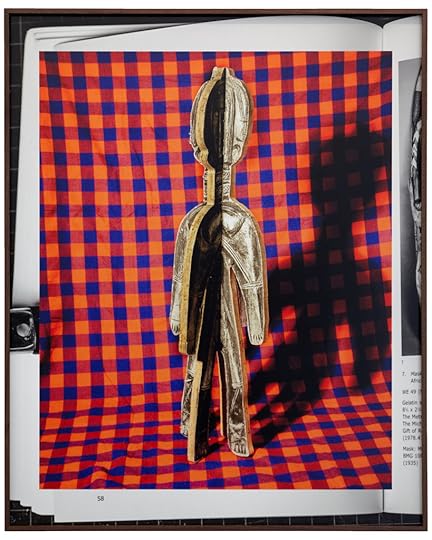

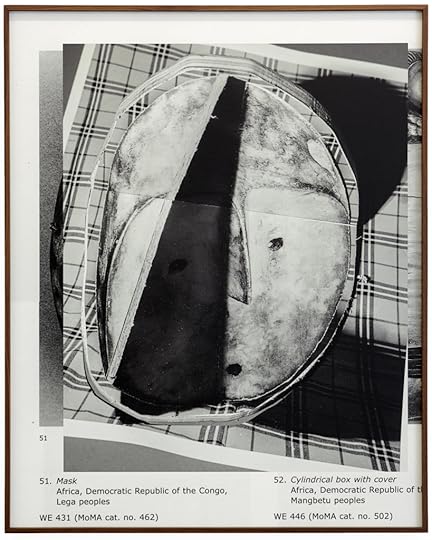

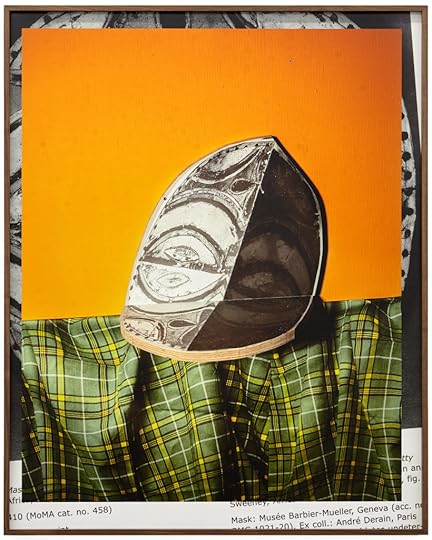

For his recent exhibition at Yancey Richardson Gallery, David Alekhuogie worked with photography, collage, and sculpture to produce a visual meditation on his artistic and cultural lineage. His source materials—cotton jersey fabric, wax print fabric, the 1935 exhibition catalogue of Walker Evans’s photographs of African sculptures—are varied and all approached with a tendency towards abstraction. In one series, titled To Live and Die in LA (2018), his fascination is with the body as landscape and with the ways that the body, when photographed, can indicate the tensions and vulnerabilities of its stance. The most acclaimed of his photographs in that series show the midriff area of Black male bodies, the subject of his earlier work Pull-Up (2017), pictured so that low-slung pants seem like bright tapestries. In 2019, when Alekhuogie first visited Nigeria, where his father is from, he created new photographs using a similar strategy, placing the images against a background of floral wax print fabric.

Talking to Alekhuogie feels similar to looking at his photographs: both indicate the possibility of thinking in multiple directions at once. He is a photographer interested in generative thought and in images that do not overexplain, even if they are informed by moments of vulnerability, masculinity, and disposability—such as an encounter with the police near his studio in Los Angeles, when, with their weapons pointed at him, he felt his mortality in a “hyper-realized way.” What follows is a conversation touching on the key themes in his work, in which my questions served only as prompts for his superlative digressions.

David Alekhuogie, rampart police station 34.0567° N, 118.2670° W, 2018

David Alekhuogie, LA convention center 34.0403° N, 118.2696° W, 2018

Emmanuel Iduma: I want to begin with a quote of yours that was included in your Aperture portfolio in the magazine’s 2018 “Los Angeles” issue. You said, “It’s not always the storytelling. Sometimes it’s the accent, the cadence, the how: how a person is speaking, how they are telling the story.” You are speaking about strategies you used in Pull-Up (2017). But I want to know if you remain interested in rhetoric as a way of understanding your visual work.

David Alekhuogie: Definitely. It’s something I’ve been thinking about even more in some of this newer work. When I was making Pull-Up, I was specifically interested in Abstract Expressionism and the way that American modernism had developed around these ideas of abstraction. I still think about modernity as being constantly defined by our relationship with labor and technology. Yet, that part of it seemed to really discount the way different types of marginalized people in the country function.

I grew up DJing a lot. I was DJing parties. I studied jazz for a while. And I would think about this idea of improvisation and abstraction coming out of this kind of structural space—abstraction as a type of protest, where you’re doing your job, you’re getting from point A to point B. But in getting from point A to point B, you’re going to use this opportunity as an expressive moment. And I had been thinking about the relationship between jazz, modernity, and modern painting, as being . . . I wouldn’t call it erasure, but I would definitely call it a misunderstanding of the contributions of African American, radical Black aesthetics.

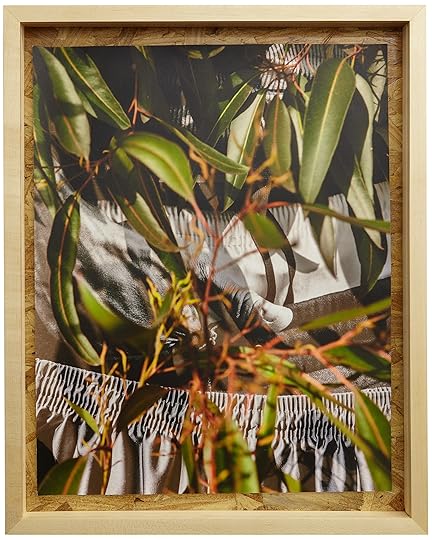

David Alekhuogie, post colonial bush breakfast “no wahala,” 2021

David Alekhuogie, post colonial bush breakfast “no wahala,” 2021Iduma: Let me get a sense of how you got started as a visual artist. You’ve described a potpourri of influences, which is visible in your newest work.

Alekhuogie: A lot of this new work I made during the pandemic. But it is a long time coming. I believe wholeheartedly that African and African American studies departments, at least in the States, are populated with people who are in this kind of coming-of-age moment—or maybe that moment is perpetual. There’s this energy for reeducation, for a point of view that they see as compromise or a line of questioning that they see as incomplete. At least that was my relationship to it. That was the relationship of my peers. It seemed like their own frustrations with that is what pulled them into this research. It became critical.

My new body of work is about this way of thinking through Walker Evans and Frantz Fanon. It’s my way of dealing with seeing myself as the colonized intellectual—like the Black friends who give the liberal elite this sense of authority and moral righteousness. And I started to see these characters play out in this modern thing. Everybody is navigating their own pathologies through the consequences of a colonial past, you know?

David Alekhuogie, Banda Headdress “A Reprise,” 2019

David Alekhuogie, Banda Headdress “A Reprise,” 2019Iduma: I like the idea that, for you, there is the possibility of making the connection between modernism and colonialism. The “modernist movement” in Nigerian art—or what is classified as modernism in Nigeria and art history—is really just at the end of the active colonization process and the beginning of the independent years.

At that time, people were saying that we need to think about what it means for us to have had the education that we’ve had. They evolved the conversation beyond colonialism into something that draws from the experience or the pathology of colonialism. For me, this all comes to a head in the work you did after you came to Nigeria in 2019. Before then, had you ever been here? And what spurred you to travel here?

Alekhuogie: I had wanted to go for a very long time. Originally I felt like I wasn’t permitted to go without my father’s consent. And things like visas, the financial burden, really kept me at bay. Then there came a point when I could afford to travel and stay for extended amounts of time. I got this grant from the Rema Hort Mann Foundation. I also think that the work was doing well at that point. So I think that once I had the resources, I started to really commit to making it happen. Honestly, when you wanna do a thing, you find the resources to do the thing.

Iduma: How did you travel in Nigeria? What places did you visit?

Alekhuogie: I had some friends in Tanzania and Kenya so I went there first. One of my friend’s parents is also Nigerian so we were able to negotiate the visas pretty easily. We went straight to Lagos and Lekki after that. And we were supposed to go to Benin City for a wedding but were not able to make that happen because I had teaching obligations.

David Alekhuogie, Pure Life, 2021

David Alekhuogie, Pure Life, 2021Iduma: You’ve spoken in previous interviews of being interested in the body as landscape. My sense is that your understanding of that concept is evolving or even expanding as, for instance, in the transition from Pull-Up to To Live and Die in LA. I’m curious where you are at this point with that concept.

Alekhuogie: In one way, this has to do with a sexual pathology around a conquered space versus something that is remarkable, uncontrollable, and beyond your comprehension. That is the historical relationship that we have to the landscape and the sublime—this space to be conquered but also this space to be made small or made weak. That was something that I was interested in, in terms of the relationships that we have to people. Because we think about race relations or the various forms of oppression that people suffer globally as being localized. I wanted to ask whether a person’s body could be considered a place, whether it could be occupied or not, and what that would be like politically.

To Live and Die in LA was more a response to what I would call this choice to accept the terms of my situation. I had gone through this traumatic experience near my studio, where the police barged in, and they pointed weapons at me and handcuffed me. It was crazy, you know? I had a bunch of stuff in my hands when they came in. The sun was setting in a way where they couldn’t see me well, and I couldn’t see them well. The sun was shining into my face. I could see that they were pointing a bunch of weapons at me, but I couldn’t see them quite clearly.

In that moment, I felt my mortality in this hyper-realized way. As a writer, an artist, a filmmaker—whatever it is that you’re doing—if you’re talking about these types of lived experiences, you need a certain distance from them. And navigating that distance requires this emotional energy that is at the root of a lot of Black music. At least when I think about how the blues, for example, was historicized, it’s about coming to terms with your own condition.

I was making work for a long time that unknowingly responded to that. I had started to think about the music that I was listening to differently, especially a whole type of politicized music that is really not about action but more about acceptance. I think that those records become anthems. The modern one that I think about now is the Kendrick Lamar track, “Alright.” It’s this political battle cry. It’s about understanding and living in the condition that you’re in and choosing to separate your mind from your body.

I started to think about a lot of literary imagery and musical imagery. And I’m just like, oh, this is all about the same thing. At the time, I was making these concrete sculptures that were like vases or tombstones that went on the floor. I was thinking about these places where people have been shot: they put candles here, they put flowers here. I wanted to make these sculptures that spoke to that idea as decorative objects.

David Alekhuogie, Female figure “A Reprise,” 2020

David Alekhuogie, Female figure “A Reprise,” 2020Iduma: I saw the work you made for Topic. It’s phenomenal. It’s a different kind of formal language from your other work, using a different visual vocabulary. The kind of images that you made form a sort of travelogue, even in how you follow the trail of the Great Migration. You write that your work often comes out of formal investigations of the transitions of kinship. I’m interested in what your work does in relation to kinship, through the language of how, for instance, pants are worn. It is almost a universal code of the Black male body, so to speak.

Alekhuogie: In graduate school, I had been making these tapestries from Nike boxes. I was thinking about them as quilts. Then I started taking these tapestries and making [sun prints] with them so there were negatives and positives.

When I was making that work, I was thinking about all these experiments that people were doing with photography and the camera. I was thinking about the Bauhaus and László Moholy-Nagy. And all those visual strategies and influences are very much visible in the work. But you would see a person who did not have access to that art historical reference, yet they would understand, okay, this sneaker came from this thing during this time, and I remember it. So the work became this negotiation of who was the authority on the work.

With Pull-Up, that line of questioning started to be a part of the work as well because some people would see those photographs and situate themselves in that body. Other people wouldn’t do that. Those pictures are about how a body is objectified. There is one person who is actively becoming the person who is looked at. And then there is another person who becomes the person who is looking.

I’m interested in bringing my people to the space. There are various ways to do that. It doesn’t have to be in the work. It could be in the programming. If you have a bunch of institutions, and if they become the authority on the work, that is going to affect or dictate the value. And that power negotiation is really interesting to me on a practical level.

David Alekhuogie, WE 431/2 “A Reprise,” 2021

David Alekhuogie, WE 431/2 “A Reprise,” 2021Iduma: What makes your practice expansive is the fact that you are thinking about tactility. This attempt to find not just new audiences or new kinships but also new mediums, alternative mediums. In some of the work at Yancey Richardson, the wax prints become a new form or a framing device. I see a through line from the close-ups of the pants to the close-ups of wax prints. You’ve also spoken about your interest in working with tapestry, this sense of stitching. I’m curious how all of that comes together. What is tapestry in relation to wax prints, and how does it expand on the work that you’ve done with the pants?

Alekhuogie: It really comes from a couple of places. In one way, it’s about this internal war that I have where I’m trying to convince people that the way these decorative forms are utilized globally have to do with labor, and they do a lot of narrative work. There’s this hierarchy of crafts that is really frustrating to me. You can see it in how the history is written. It goes back to my interest in quilt making, which, for me, shows a clear relationship between Black aesthetics. There’s this show at LACMA, which positioned these quilts in the same way that you would think about a lot of modernist paintings. It starts to come down to a lot of these essential ideas in American modernism, which really come down to how we deal with labor.

A lot of the strategies that I’m employing in this new show are about trying to flatten what is traditionally thought of as a clear documentary style with something that has the trappings of decorative art. So I can get these two things to collaborate instead of just being this artist making literary allusions. No, this is also a visual experience.

David Alekhuogie, Portrait for George 1, 2, and 3, 2020

David Alekhuogie, Portrait for George 1, 2, and 3, 2020Iduma: Absolutely. And as a final point, the wax prints: Most of the wax prints marketed within Nigeria, for instance, are made outside of it by huge corporations who only recently saw the need to build factories on the continent. So, in the sense of their origin, these wax prints are not African. It’s what you’re saying about the labor that goes into the marketing of these fabrics as African. On one hand, the labor is really market-driven, at least at the point of its origin. But then what becomes interesting, and where the complexity and the tension is, is that they have been imbued with cultural capital by those who wear them. It’s to go back to postcolonial modernism. It’s not simply, this is who we are. It’s what have we become as a result of two contradictory systems.

For me, by using these wax prints to frame the photographs, you claim or even reclaim them as diasporic. And in the sense of the conversation that we need to have about Africa beyond a geographical location about what Africa, or African sensibilities, can become as a result of its diasporic reach.

And To Live and Die in LA—you are taking this phrasing or framing from Tupac, as I heard you say somewhere. The acuteness of that work and that thinking is in how you triangulate Black masculinity, vulnerability, and even disposability. I’m curious about how you sum up or elicit a visual language from such a triangulation. Your mode is abstraction, and you often push beyond realism even if all of it comes from the realistic.

David Alekhuogie, WE 410/2 “A Reprise,” 2020

David Alekhuogie, WE 410/2 “A Reprise,” 2020All photographs courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Alekhuogie: I honestly think—at least, I hope—that most photographers are trying to negotiate this idea of whether they want to be as humanistic as possible while simultaneously trying to be truthful. This is something that I see in my students: there’s this enthusiasm towards trying to speak truth to power. Oftentimes that means being a spectator rather than actively performing. You see it everywhere, like in the George Floyd incident, where the video of this man being murdered becomes this arbiter of change. And the same thing with the Rodney King beating. Or the Emmett Till photograph. The anxiety of photography is really tied up in that, especially now, when people are feeling the need for their work to be politically relevant. And to not just be about their personal experience but more about a kind of shared experience. You have to ask yourself, “What is the cost?” That is what I think about when it comes to art that has the potential to have a social good.

If I have a party, and I play all these records and everybody feels good, there’s no question of whether this was good. Like, hey, no laws might be passed, right? [laughs] But these people feel good in this moment. There is something to that, which oftentimes in a hyper-politicized moment gets overlooked. One of my students told me to watch this movie that is inspired by Tupac’s “Thug Life” tattoo—he uses these letters to symbolize “The Hate U Give.” I watched it on the plane when I was coming back from New York. And I had never felt so emotionally floored. If I hadn’t had my run-in with the police, just in the way that I had so acutely felt my life threatened, I think that I would have responded to it differently.

But that kept me up at night, you know what I mean? I really had to think about how that made me feel. In one way it’s like, yes, this is what it is. But at the same time, it’s crippling. I know that other people go through that too—this sort of social media PTSD. This is the kind of writing I wanna do. I’m curious about people’s relationship to the media in general, and how that informs art and photography.

David Alekhuogie: Naïveté was on view at Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, from March 6–April 10, 2021.

April 29, 2021

The Photographer Who Constantly Transforms

When I first tried to reach Evan Benally Atwood, their phone lay buried underneath a foot of new snow blanketing a cross-country skiing trail at Mount Hood. It was almost spring here in Oregon, so maybe, when the snow began to melt, draining out to the Hood River, past my house, down to the Columbia River Gorge, and then out to the Pacific Ocean, Benally Atwood’s phone would reappear.

A snowy mountain trail is the type of place where Benally Atwood feels compelled to take out their 35 mm rangefinder. They make work throughout the American West, often in the high desert of Central Oregon, which reminds them of where they grew up in New Mexico. They often put themself in the frame, wearing things like cowboy hats and other bits of Western wear, paired with sparkling silver heels or a tsiiyéeł, a traditional Diné (Navajo) hair bun. Sometimes, they don’t wear anything. These signifiers of identity frequently come together in unexpected ways.

Benally Atwood identifies as nádleehí, a Diné word that roughly translates to “one who constantly transforms.” They told me they journaled about what the term might mean for them when they first encountered it: “I never claimed the term two-spirit—it wasn’t something I felt inside. For me, nádleehí is that which is always becoming. I feel more masculine and more feminine today than I did when I first wrote in my journal. I feel blessed to be in my body.”

Evan Benally Atwood, family portrait, 2020

Evan Benally Atwood, family portrait, 2020Benally Atwood describes their gender identity as an act of reclamation of Diné ancestral knowledge. “The Diné have five genders, and have had those five genders since before colonization. The gender binary was pushed on us. In a lot of Indigenous cultures, gender is psycho-spiritual rather than physiological,” said Benally Atwood. But they also noted that they weren’t taught these ideas about gender variance when they were growing up, and they don’t see it widely taught now. This process of reclamation is ongoing and embodied in their photographs.

In the beginning of our conversation, Benally Atwood told me they don’t know what they are taking pictures of most of the time. “It’s a mystery . . . in an Indigenous way,” they said. “A lot of Indigenous communities talk about Spirit as the Great Mystery—the creator of all. So I try to honor the mystery of existence. I try to honor the land that I get to be on.”

As Abaki Beck, a Blackfeet and Red River Métis writer focusing on Indigenous feminisms and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge, told me: “Many Native people, myself included, have an intimate relationship to the landscape. It is where our stories come from, where we gather our medicine, practice ceremonies, or connect with loved ones. Evan portrays this relationship to the land in a vividly intimate way, which stands in sharp contrast to typical photographs of Western landscapes as colonial, touristy, or voyeuristic.”

Evan Benally Atwood, princess bouton, 2019

Evan Benally Atwood, sunrise on chinook, 2020

Benally Atwood grew up in Farmington, New Mexico, a border town to the Navajo Nation. They describe the city as “incredibly conservative,” and left when they were eighteen, after graduating high school. They received a degree in business administration from Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in 2015, and eventually settled on the ancestral lands of the Chinook tribe—Portland, Oregon.

Considering the way Benally Atwood’s work investigates the intersection of queerness and the legacies of colonization, I asked them if they have read Billy-Ray Belcourt’s A History of My Brief Body (2020), a genre-bending collection of essays that explores many of the same themes. “Sort of,” Benally Atwood said. They had it in front of them as we spoke, but still needed to finish it. I read to them aloud from the introduction, which was a nice experience—if you have the chance, I recommend reading a book you like (even a few lines) to a friend over the phone.

“I’m up against decades and perhaps centuries of a literary history that extracted from our declarations of pain evidence of our inability to locate joy at the center of our desire to exist,” Belcourt writes. “With you, I can rally against this parasitic way of reading, this time-worn liberal sensibility. Together we can detonate the glass walls of Canadian habit that entrap us all in compressed forms of subjectivity.”

Evan Benally Atwood, black elks peak, 2020

Evan Benally Atwood, black elks peak, 2020What Belcourt describes here applies to our reading of Indigenous images in “North America” irrespective of colonial borders. In Benally Atwood’s photographs, joy, and also pleasure, operate in a similar way. They rally against the same stifling liberal sensibility that views Native communities exclusively through the lens of pain, and more often than not, erases them entirely. But finding and documenting joy and the places where it can exist in the wrath of colonization is not easy.

“I think for me, nature is the place to access joy. The problem is that nature in the Pacific Northwest is so white-centered. Many of my friends who are trans feminine, Black, and people of color aren’t as comfortable being outside,” said Benally Atwood. As a result, Benally Atwood makes a point of creating portraits of trans feminine individuals outdoors. “I love being able to document and help them see themselves in a beautiful way. Sometimes, taking photos is literally just about going to a place where you want to feel cute and fun.”

On the surface, this intention could be read as lighthearted, but given the historical context, the stakes remain high. “Usually, the narrative of Indigenous people in the landscape is one that revolves around trauma, which gets told and retold,” said Benally Atwood. “These pictures are about creating a narrative ourselves for ourselves.”

Evan Benally Atwood, phoebe, 2020

Evan Benally Atwood, phoebe, 2020 Evan Benally Atwood, a spot on the molalla river, 2019

Evan Benally Atwood, a spot on the molalla river, 2019 Evan Benally Atwood, tani, 2020

Evan Benally Atwood, tani, 2020 Evan Benally Atwood, kerry, 2020

Evan Benally Atwood, kerry, 2020 Evan Benally Atwood, gay head wampanoag beach, 2019

Evan Benally Atwood, gay head wampanoag beach, 2019All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

Can Photographs Help Communicate the Experience of Incarceration?

Prison changes everything. This is what people who have done time understand. On July 2, 2020, my friend Rojai Fentress was released following a conditional pardon by Virginia’s Governor Ralph Northam. Rojai had served twenty-four years of a fifty-three-year sentence, after being convicted at sixteen by a jury of his peers of a murder that he didn’t commit. The day he was released, he told me that he had never been higher than the second tier, prison nomenclature for the series of cells on the second level of the large warehouse-like spaces that are called “housing units.” He said that in the forty years he had been alive, there had never been occasion for him to be more than fifteen feet in the air. Fats, which is what everyone who has done time with Rojai calls him, was describing the particular kind of violence that the circumstances of confinement brought to his life—a denial of what’s possible, even something as simple as looking out over the edge of a mountain.

Baseball game, May 16, 1976

Baseball game, May 16, 1976Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

And yet I know that even within the confines of those small and cramped spaces, he found many opportunities to be free. On the basketball courts, doing pull-ups on the backs of iron stairs, developing an eye for drawing portraits, sharing a complicated meal built around fifteen-cent ramen noodles and cheese crackers. This interior life of men in prison is what is too often hidden, and this is part of what Nigel Poor has given men an opportunity to reveal through her work. When I spoke with Poor about her new book The San Quentin Project, in which men in prison reflect on and demonstrate the richness of their inner lives, she said the book started while she was teaching a class in the Prison University Project (which was an extension of Patten University and is now called Mount Tamalpais College). For Poor, and the men involved, the class was about working with “photographs as a bridge for conversations about their personal histories.”

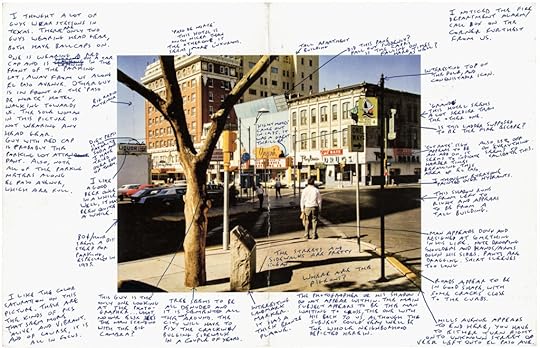

StephenShore, El Paso Street,El Paso, Texas, July 5, 1975, mapped by anonymous

StephenShore, El Paso Street,El Paso, Texas, July 5, 1975, mapped by anonymousCourtesy Aperture; Photograph in work © Stephen Shore, courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

But to fully grasp the interiority that prisoners seek to assert, it’s important to understand what they are asserting it against, particularly Black and Brown prisoners. In “Strivings of the Negro People,” an 1897 article in the Atlantic, W. E. B. Du Bois recognized that he was shut out from the world of others around him by “a vast veil.” The point is that between the world and Black folks, there seems to be something that forces them, us, to have a kind of double vision. Or as Du Bois framed it, a double consciousness, a “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” Prison offers a different, related but more conflicted kind of double consciousness. As philosopher and prisoner James Davis III explains, those in prison have a double- double consciousness. He argues that the Black prisoner enters his confinement with the double consciousness described by Du Bois and then, is burdened by the double consciousness that incarceration imposes—that “concrete veil that obscures his humanity . . . the lack of recognition [as a human] that threatens to alienate him from the inalienable rights with which he was born.” The prisoner understands that, after having been to prison, nothing is ever the same, and so much of the work of living (both inside prison and outside) becomes about remembering and asserting that you can have agency and a life, without either forgetting or being consumed by your memories. Put another way, you walk, handcuffed and shackled, into a prison and become someone that you hadn’t been before.

W. H. Woodside, CO [Correctional Officer] fight, April 8, 1961

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

ID crew, n.d.

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

As a child, I read several memoirs about prison, including Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land (1965), Nathan McCall’s Makes Me Wanna Holler (1994), and a book I had randomly found at the house of an aunt, Albert Race Sample’s Racehoss: Big Emma’s Boy (1984). But these books didn’t prepare me. The philosopher L. A. Paul writes in her book Transformative Experience (2014) about events that substantially revise “how you experience being yourself.” Paul defines an experience as epistemically transformative when the only way to know what the experience is like is to have it yourself. This is why there was no way that Brown, Malcolm X, McCall, Sample, or any of the countless other authors who have written of prison—or even the films that depict life there—can make you know the experience of incarceration. Maybe the point is that these books ultimately aren’t about making you know prison, but rather providing a glimpse of what cannot be understood.

I’ve known the expansiveness and the deep solitude that prisons create. The frustration, the fear. But also the gifts: laughter, grit, possibility. The dilemma of the writer narrating the prison experience is that despite their best efforts, there is always something about incarceration that cannot be fully conveyed. And given this, there is a need for metaphor. The notion that a picture is worth a thousand words is suddenly true when I remember the contraption a man built with wires and a pair of nail clippers to heat water. Prison gives the people who have done time a new way of seeing, a different way to understand the world, which is both a gift and a curse. The San Quentin Project reveals something of that double vision, that sight and insight.

Prison rock band, June 26, 1975

Prison rock band, June 26, 1975Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

What this book establishes, first, is that incarceration does not dim the desire to be full. These photographs—probably taken by correctional officers in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, while some may have been taken by men who were incarcerated at the time—tell a different story of prison. By bringing these photographs to the world, Poor makes an argument for the capaciousness of both the lives that incarcerated men experience and the loss that ripples through their days. One image, Mother’s Day, May 9, 1976, depicts a family reconnecting while visiting San Quentin. Everyone has on a version of their Sunday best, and it is impossible to tell who, if any of them, is incarcerated. In another photo, a group of men pose behind a drum set, with one cat leaning on a guitar that reminds me of the one Prince threw into the sky as he walked offstage after a performance. The image of a Native American, in full regalia in a prison yard, is arresting and makes us pause. What men do to avoid the erasure of prison is as unpredictable as it is vital. Images of men together on a football field, in uniforms and helmets, men lifting weights, even a man whose eye is stitched and swollen closed, are reminders of what the living do. It is only when you see the bars, the narrow corridors of violence, when the angle of the image brings to mind Michel Foucault’s criticisms of the panopticon—where prisoners are controlled by constant observation—that the constraints of prison become part of the point. What is left out of the images reminds us of how much of life in prison remains undocumented.

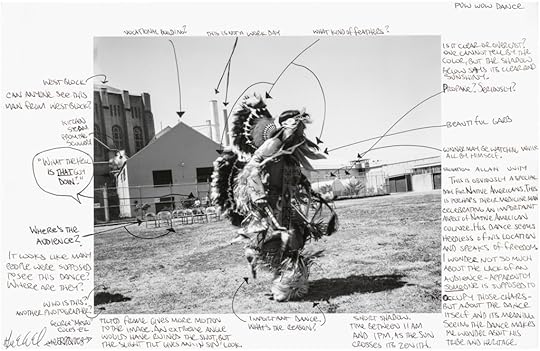

Powwow, n.d., mapped by George Mesro Coles-El

Powwow, n.d., mapped by George Mesro Coles-El© George Mesro Coles-El, courtesy Aperture; Archival image courtesy San Quentin State Prison

Most poignantly, this project allows men inside to begin contemplating—through their stories, annotations, and conversations—the moments that the photographs leave out. The students in Poor’s class not only reflect on their lives or on lives adjacent to theirs but also provide insight into the iconic works of well-known photographers. How do you begin to interpret moments you haven’t begun to live? The San Quentin Project gives us a chance to witness this process of close reading. “That distinct voice,” as Poor says of the guys inside, “is really beautifully communicated to somebody who doesn’t necessarily have the experience.” These voices and these stories create a space of compassion for us all to rest in. And yet, Poor’s project is far more significant than just bringing images that haven’t been seen before to the public. By allowing men on the inside to annotate photographs, she forces readers to become witnesses to how deprivation changes how we see. And the stories, frequently, become a meditation on loss. A man describes a stabbed body as a “once proud castle.” The point becomes a revelation, not just of the stories that this particular photograph might contain but of all the stories that have been buried by prison.

This essay and images were originally published in The San Quentin Project (Aperture, 2021).

A portion of the sales from The San Quentin Project are being donated to Mount Tamalpais College at San Quentin State Prison. This publication is also part of the Million Book Project, which will create curated libraries of five hundred books to be distributed to one thousand prisons and juvenile detention centers in the United States.

April 28, 2021

Peter Hujar, Moyra Davey, and the Performance of Honesty

While browsing The Shabbiness of Beauty (MACK, 2121), in which the artist and writer Moyra Davey places her images among those by the late photographer Peter Hujar (“a risky act,” as she puts it), I thought of a line from Davey’s 2008 essay “Notes on Photography & Accident”—written in an attempt “to rekindle a desire to make images,” and included in her recent collection of essays Index Cards (2020). The essay wanders wonderfully, but circles back to four authors: Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, Janet Malcolm, and Susan Sontag. “Malcolm’s perceptions thrill because they signal ‘truth’ in the way that strange, eccentric details nearly always do,” Davey writes.

Peter Hujar, Diana and John McClellan, 1981

Peter Hujar, Diana and John McClellan, 1981Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

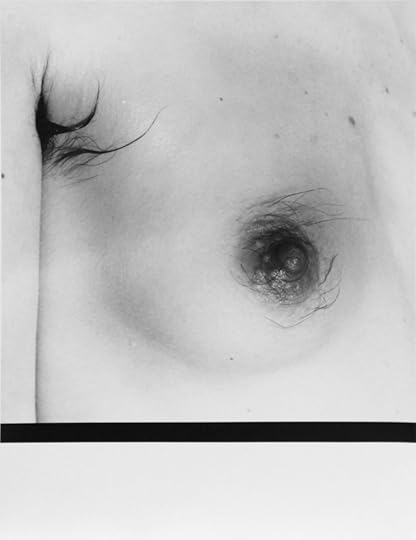

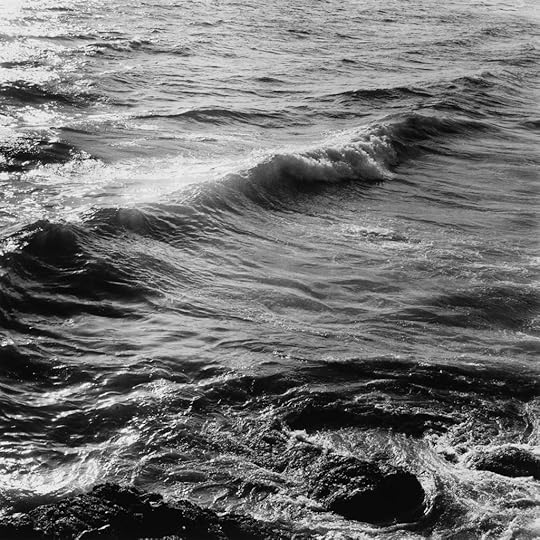

One can apply this notion to photographs. “Strange, eccentric details” help conjure a sense of honesty, of the oppressive mask of polite life slipping, and of a conspiratorial association between the viewer, whoever is revealing something in the photo, and whoever saw fit to capture it, to celebrate it. The warped or broken or peculiar elicits a tenderness—a greater awareness of the act of looking than when one skims the beautiful or the glossy. “Strange, eccentric details” suggests a breaking of some code; a sense of speaking up, shrugging off, being oneself. Hujar’s photographs, both the iconic and the lesser known, which Davey focused on for this project, are full of such details: a mustached artist posing with what looks like two bloody human stumps (it’s Paul Thek, Hujar’s once-boyfriend, preparing his 1967 work Death of a Hippie); or a body of water that looks somehow human—a face, a mouth, appearing in the waves.

Hujar presents his subjects with dignity, showing them both as they are (maybe young and gorgeous, maybe dying) and as they could be (sexual, weird, base, pensive) on a whim. Perhaps this is why Hujar is so great at photographing animals, capturing both the often amusing reality and the majestic possibility of the creature without making the image fetishist or twee. One is simply getting a good, honest look at a chicken. Truth, again. “Animals don’t hold still, except for Hujar,” writes Davey.

Moyra Davey, Plymouth Rock, 2019

Moyra Davey, Plymouth Rock, 2019Courtesy the artist

Davey’s work is also about truth. Her long focus on the everyday has, to me, read as a desire to get to the bottom of things, to leave nothing as small as a stone unturned. It’s about paying attention. Her images in this book are interspersed, with no captions until the end, meaning one sometimes struggles to separate one artist’s work from the other’s, which is the whole point. Davey defers to Hujar’s preferred genres—animals, water, New York City, bodies, babies—and her pictures are rich with the same notes of incongruity or deviation. A dog looks oddly pensive, friends flex their unique forms, dark armpit hair curls elegantly.

The Shabbiness of Beauty, the result of a show at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, is about discussion and dialogue, which makes sense for Davey, an artist who works across writing and photography, often using one to elaborate or spark the other. And yet, it is also about being present; about things (real things, things that are happening before the camera), perhaps more than it is about ideas. It is about consumption (which, as Sontag reminds us, photography always is), and about how we look at images to feed and nurture ourselves.

Moyra Davey, Armpit, 1984

Moyra Davey, Armpit, 1984Courtesy the artist

In mining the Hujar archives, Davey shows us how we all build a sense of who we are through adulation and imitation (through feeling in step with our heroes), and that our past selves can be found as much in the worlds of others (their pictures, writings, notes, songs) as among the memorabilia of our own acts of creation: “Dipping into the archive is always an interesting, if sometimes unsettling, proposition,” Davey writes in “Notes on Photography & Accident.” “It often begins with anxiety, with the fear that the thing you want won’t surface. But ultimately the process is a little like tapping into the unconscious, and can bring with it the ambivalent gratification of rediscovering forgotten selves.” Clearly, various selves also emerged in her trip through Hujar’s history.

The Shabbiness of Beauty is about intimacy and the politics of reflection, which makes sense given the various critiques Davey has made about the contemporary mood for photographs that are giant, egotistical. (“So much of what we see in galleries is responding to the imperative to overproduce, overenlarge, overconsume,” she writes in “Notes on Photography & Accident.”) The Shabbiness of Beauty is quiet, deliberately; it invites speculation, time. As Eileen Myles writes in an essay in the book, “It makes sense that Moyra Davey would wind up expanding into writing—out here in art everything is given (supposedly) but in writing you can’t see the intention. Visual art is mapped on the out there. Writing’s like a cat. I would say Moyra’s a cat photographer.”

Peter Hujar, Sophie Mgcina and Thuli Dumakude – South African Play “Poppie Nongena,” 1983

Peter Hujar, Sophie Mgcina and Thuli Dumakude – South African Play “Poppie Nongena,” 1983Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Hujar never clamored for attention by serving up the obvious (a reason many critics have given for why Robert Mapplethorpe, not Hujar, got the buzz in his lifetime). Hujar never victimized his subjects by feeding the urge to capture their victimization. There is too much respect. These are his friends, his world; him, partly. “We’re here, I’m here,” his pictures seem to say. As Davey writes: “In the 1960s and early 70s, Hujar sometimes preserved the black frame line around his pictures, and said: ‘to print the film frame [implied]: this is not a painting, this is photography. This negative has an edge . . . [it’s] an honesty thing . . .’” The implication: this photograph is something that was made, as well as something that happened. There are two distinct timelines—the one captured in the image, and the one that led to the image’s creation. Such a note from Davey suggests that this is a project about the process of things, about the act of making; the “behind the scenes,” a phrase that has so successfully transcended into marketing speak that it has lost its inference of “truth”—to go back to Malcolm.

But that is what’s at play in The Shabbiness of Beauty, a project first and foremost about truth, about honesty and, to a lesser but equally important extent, the performance of that honesty (not always an oxymoron); the attempt to show the progress, the influence, the relevant factors. Indeed, writing on her style, and that of some of the figures who cross between her and Hujar’s worlds, Davey says, “we are all self-consciously trying to signal that what’s going on behind the camera—the emotional register, the labor register, the thinking register, the mechanical register, the risk factor—is to us as important as the image itself.”

Peter Hujar, Wave, Sperlonga, 1978

Peter Hujar, Wave, Sperlonga, 1978Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Davey continues by claiming that Hujar was “the opposite. Without self-regard, he gifted it all to the subject and the image through patience, framing, razor-sharp focus and crystalline lighting. He apparently gave no direction. . . . He waited for them to give to him whatever it was they were going to give, and then he took it—and after the wizardry of the darkroom, gave it back.” But to me, Hujar’s presence pervades his images. They are palpably sensitive. They summon the spirit of the author; his life, politics, and process; the specter of someone generous outside the frame. That presence is summarized by the title of Nan Goldin’s 1989 curated show Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space in New York, which featured Hujar, alongside close peers such as David Wojnarowicz, and which Davey once visited. This book is another gesture against vanishing, against the idea that Hujar’s work will only be a statement on its own time. In making the images into something new, Davey highlights how Hujar’s work continues to morph, to comment, and to be seen afresh.

The Shabbiness of Beauty: Moyra Davey & Peter Hujar was published by MACK in April 2021.

April 23, 2021

Announcing the 2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Aperture’s support of emerging photographers and other lens-based artists is a vital part of our mission. The annual Aperture Portfolio Prize aims to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography—identifying contemporary trends in the field and highlighting artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, Aperture’s editors reviewed over 1,200 submissions, and we are thrilled to announce the shortlisted artists for the 2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize:

William Camargo

Chance DeVille

Jarod Lew

Anouchka Renaud-Eck

Donavon Smallwood

These artists join the ranks of illustrious artists shortlisted for the Portfolio Prize in past years, including Dannielle Bowman, Jessica Chou, Eli Durst, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Natalie Krick, Jack Latham, Daniel Jack Lyons, Mark McKnight, Drew Nikonowicz, Sarah Palmer, Bryan Schutmaat, Ka-Man Tse, and Guanyu Xu.

The 2021 Portfolio Prize winner, to be announced on Friday, May 14, will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York. Each runner-up will receive an online feature.

This year, alongside the five shortlisted artists, Aperture’s editors selected twenty finalists. The finalists and shortlisted artists will each receive a virtual portfolio review session with an Aperture editor, providing thoughtful and constructive feedback on their work.

The twenty finalists are:

Bryan Anselm, Rachelle Bussières, Amarise Carreras, Ronghui Chen, Golden, Jon Henry, Wing Ka Ho, Kovi Konowiecki, Michal Luczak, Spandita Malik, Steven Molina Contreras, Laura Pannack, Miraj J Patel, Ginevra Shay, C. Rose Smith, Elliott Verdier, Marianne & Katarzyna Wasowska, Wei Zihan, Amani Willett, and Zhidong Zhang.

William Camargo, We Gonna Have to Move Out Soon Fam!, 2019, from the series Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities

William Camargo, We Gonna Have to Move Out Soon Fam!, 2019, from the series Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities Chance DeVille, Mom in a Dream, 2020, from the series David’s Mark

Chance DeVille, Mom in a Dream, 2020, from the series David’s Mark Jarod Lew, The Tethers of Love (Eugene, Miyi, and Qun), 2020, from the series Please Take Off Your Shoes

Jarod Lew, The Tethers of Love (Eugene, Miyi, and Qun), 2020, from the series Please Take Off Your Shoes Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Girls Surrounded by Boys, 2020, from the series Ardhanarishvara

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Girls Surrounded by Boys, 2020, from the series Ardhanarishvara Donavon Smallwood, Untitled, 2020, from the series Languor

Donavon Smallwood, Untitled, 2020, from the series LanguorAll images courtesy the artists

April 22, 2021

Why We Must See Asian Americans in US History

She looks ahead with a steadfast, determined gaze. Perched on a chair beside a small table, she rests one hand on her lap, her bangle grazing a package. She cradles an open daguerreotype case in the other, her fingers wrapped around one portrait in what seems to be a small gesture of longing for absent loved ones.

We do not know who she is. We do not know her name. It is not often that an Asian woman—an immigrant, a worker, perhaps a mother—is pictured, or even rendered visible, especially in nineteenth-century America. What makes this image extraordinary is that it’s most likely from 1850s California: it tells the story of Chinese immigrants who came to America during the California Gold Rush (1848–65).

The portrait was part of an exhibition of daguerreotypes slated to open in April 2020 at the Peabody Essex Museum, but was canceled on the eve of its installation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The exhibition, Gold Rush: Daguerreotypes of Early California was organized by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Jane Aspinwall was the curator of the exhibition at the Nelson-Atkins; I was the coordinating curator at PEM.

We planned to include this daguerreotype and its story in the exhibition to show that Asian Americans have been in this country for a long time. They were just excluded by those who recorded history. Race, class, and gender, alongside a legal status subject to changes in US foreign policy, make photographs like this extremely rare. The only other daguerreotypes of Chinese women I have encountered are the photographs of Miss Pwan Ye-Koo and Lum-Akum, part of P.T. Barnum’s “Living Chinese Family,” at the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Made by Lorenzo G. Chase between 1844 and 1856, they were discovered over a century later in the same attic trunk as the Zealy daguerreotypes of enslaved people of African descent. The images were presumably part of the same Louis Agassiz project that used photography to support pseudo-scientific theories of race.

So what can we learn from the daguerreotype of this woman? What does she want us to see?

Head of Auburn Ravine, 1852. Daguerreotype

Head of Auburn Ravine, 1852. DaguerreotypeCourtesy California State Library, Sacramento, California

She was judged by her appearance and perceived as a temptation to white men before she even stepped foot on American shores. Her plaid headscarf, long-sleeved tunic, and pants mark her as part of the shuishangren (Boat Dwellers), an ethnic minority that mainlanders in southern China looked down upon for their contact with British and American opium traders. They were part of the service industry, providing offshore food, water, laundry, transport, and sex to the foreign merchants who made their fortunes in China. Idealized in Euro-American art and literature as free-spirited and coquettish beauties, shuishangren women moved through the world as objects of desire and subjects of global capital.

Stereotype and stigma followed Chinesewomen to America, shaping their experience and that of generations to follow. In the 1850s, most Chinese women arrived in California with their husbands as part of a large wave of migration in which thousands of people, free and enslaved, journeyed to the new state in the pursuit of gold. These newcomers—arriving from as far as Chile to the south, Australia and Hawaii to the west, and Europe to the east—joined Native, Sonoran Mexican, and other groups already living in the gold region to create one of the most ethnically diverse populations on the continent. Yet racist stereotypes shaped public perceptions and fueled violence against non-white residents as competition over land and resources grew. Images of Chinese women and toiling Chinese men cast them as moral threats to a white society steeped in beliefs of manifest destiny. Newspapers spread rumors about rampant prostitution in Chinatown and the threat of the “coolie” trade, referring to a racialized system of indentured servitude and forced migration used elsewhere in the Americas, despite little evidence that it existed in California at the time.

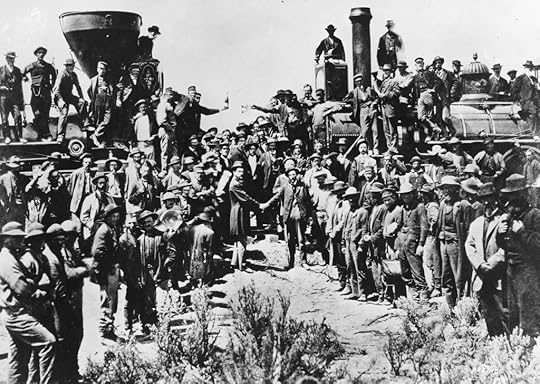

Photograph taken after the ceremonial Golden Spike was driven into the ground in Promontory, Utah, in celebration of connecting the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads, May 10, 1869

Photograph taken after the ceremonial Golden Spike was driven into the ground in Promontory, Utah, in celebration of connecting the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads, May 10, 1869Courtesy the National Archives

Over the next three decades, the bureaucratic regulation of Chinese bodies laid the groundwork for our modern-day immigration system. Early California laws and legal statutes identified any East Asian woman entering the state as a suspected prostitute until proven otherwise. On the federal level, the Page Act of 1875 barred the entry of immigrants deemed “undesirable,” targeting contract laborers and prostitutes from East Asia. Chinese women were the first immigrant group required to carry and produce identification photographs to prove their character, subjecting them to a new form of visual policing. While the Page Act effectively ended the immigration of Chinese women, racially motivated fears about Chinese labor led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the only law to date in American history that specifically prohibits one ethnic group from immigrating to the United States.

The art historian Sarah Lewis writes that American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice. The absence of photographs of the Chinese men and women who helped build California speaks to contested ideas of place, identity, and belonging that continue to shape our collective image of America today. The consequences of this erasure is clear: immigrants have experienced nearly a century of citizenship denied, and Asians who identify as American still live with a deep sense of not belonging. Though the Chinese Exclusion Act was officially repealed in 1943, when the US and China became World War II allies, stringent quotas for Chinese immigration remained in place until 1965. Many Gen X and millennial Asian Americans, myself included, are the first in their families born in America. How do we engage with the democratic ideals of American society when we don’t even see ourselves represented in it?

Corky Lee, Reenactment of the completion of the first transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, 2014

Corky Lee, Reenactment of the completion of the first transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, 2014© the artist and courtesy John Lee

We need to revisit the stories that lie within, and just outside, our picture of American history. Black artists, writers, and curators have paved the way, showing us the power of image-making to expand our worldview beyond stereotypes and demonstrating how deep looking within historical images can reveal the most mundane, everyday acts of resistance. The late Corky Lee knew this as he worked toward what he called “photographic justice.” A chronicler of the joy, grief, and outrage seen in New York City’s Chinatowns, Lee was troubled by the lack of Chinese faces in the 1869 photograph celebrating the completion of the first transcontinental railroad at Utah’s Promontory Summit. His 2014 project to recreate the image with the Asian American descendants of the thousands of Chinese migrant laborers who built the railroad was an act of restoration and acknowledgment of their belonging in this history.