Aperture's Blog, page 78

December 18, 2019

Revisiting African Portraiture, Through the Female Gaze

Sandrine Colard and Laurence Butet-Roch examine the history of how African women have been pictured, and in turn, how they look back at the viewer.

By Laurence Butet-Roch

A double entendre is at the heart of Sandrine Colard’s latest curatorial achievement, the exhibition The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture, recently on display at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. The title can indeed be interpreted in two ways. Immediately, it speaks to how a woman appears to us, the spectators, in an image; what we can infer from her style, her posture, her expression. Such a reading brings forth the responsibility we have, as members of the public, in interpreting these different cues to (re)construct the identity of the sitter, and to imagine the conditions of the photographic encounter. Yet moving through the three sequential sections of the show—“The Birth of a Gaze,” which covers colonial representations during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; “The Visual Soliloquy,” which focuses on the studio work of celebrated mid-century African artists, such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere; and “Self-Possessed,” which highlights the different themes that contemporary photographers on the continent explore through portraiture—another understanding emerges. It is not only the way that the women look to us, but also the way they look at us, at the photographer, and what this gaze conveys. Colard explained to me exactly how this expanded understanding of the female gaze reframes the history of the medium.

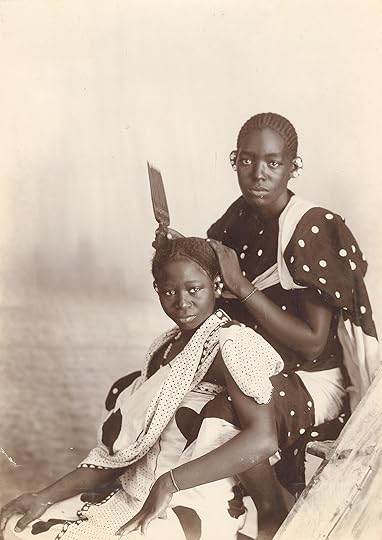

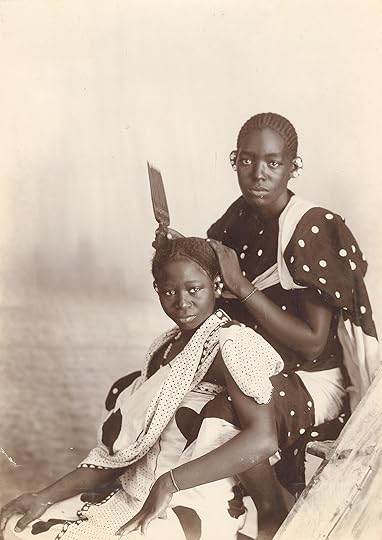

A. C. Gomes & Sons, Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Laurence Butet-Roch: What makes this particular moment ripe for examining the history of African portraiture through the perspective of the female gaze?

Sandrine Colard: Looking back at the role of art, including photography, in depicting African women and women of African descent is very tied to the arrival of new curators from these very communities. In the last year, there was the exhibition Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present at United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn, cocurated by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Catherine E. McKinley—which showed a selection of images from McKinley’s collection and centered African women—as well as Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, based on Denise Murrell’s dissertation, which started at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University and traveled to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. These exhibitions, which present a different view of photographic and art history, exist because the profession is changing thanks to the diverse profiles of new curators.

And, in regards to The Way She Looks, it harks back to when I was doing my PhD in art history at Columbia University. Each time there was a discussion about a Black character in art, especially a Black female character, it always revolved around issues related to the body and its exploitation. I’m a Black woman, and most of my peers and myself don’t think of ourselves as only that, a body. When we consider this disconnect, this show is both overdue and obvious. While the question of the body remains relevant, there’s room for another history of Black women, where we see that they had (and have), even in difficult circumstances, the power of shaping the way they want to be seen.

Butet-Roch: Your notion of the female gaze includes women photographers’ visions, but also the gaze that female sitters return to the photographer. What can be learned from paying attention to the gaze of the sitters?

Colard: When you look at colonial images of African subjects from the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries, only one woman is named; the rest are labeled according to their ethnographic “type.” Yet if you were to ignore the captions, and when you really look at these people—not just glance—the range of expressions and gazes is a testament to their humanity, and it completely defeats the caption that tries to reduce them to a type. In fact, it ridicules the caption. Take the image by Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin entitled Bakgatla: when you look at how this woman poses, you see that there’s a lot more to her than what the caption suggests. Of course, since we were not there and we have no account of the photo session, we’ll never know exactly how the photographic transaction went. What we do know is that the photographer was undertaking the ambitious project The Bantu Tribes of South Africa, which was conceived as an encyclopedia of ethnographic “types” and “primitive” people. Many of his photographs don’t match the anthropographic aesthetic of the time. Maybe it was because the photographer deliberately strayed away from it, or, more likely, because the women he encountered, via their gaze, refused to be reduced and encapsulated by a type.

Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin, Bakgatla, South Africa, early to mid 20th century

Courtesy The Walther Collection, Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg, and The McGregor Museum, Kimberley

Butet-Roch: Beyond revealing the complexity of the relationship between the photographer and the sitter, how do these gazes involve the viewer and interrogate the act of looking?

Colard: I really love Ariella Azoulay’s concept of the responsibility that we have toward the images, even one hundred years later. When all the images were hung on the wall, I was deeply moved, because I felt that they were looking back to ask for meaningful engagement from the viewer. I’m a strong believer that we have a responsibility to the subject, not only when we’re the photographer taking the picture, but also in regard to how we use the photos afterwards, how we present them, how we frame them, and the discourse that we build around them. I’ve had a sense that in the last few decades, we have attributed so much power to the colonial gaze. We read images from Africa through that lens only, to the point that we became blind to anything else the subject within the image was expressing.

Bearing this in mind, it was very important for me to include a historical perspective in the exhibition, because so often, when we discuss the great contemporary photographers—such as Zanele Muholi, Joana Choumali, or Aida Muluneh—they are presented as if they came out of a vacuum, that there was nothing before them. Such a timeline is not doing justice to the agency of the sitter, nor to the work of some of these artists’ predecessors. Only very recently was the photographer Felicia Abban recognized in the Western Hemisphere. She was a portraitist who had her own studio in Accra, Ghana, from the 1950s on. This changes everything, and I’m sure that more research will demonstrate that she was not the only one.

Butet-Roch: How can that expanded notion of the female gaze disrupt our understanding of the role of women in photography, on the one hand, but also our perception of African women as “powerless” in their representation?

Colard: It actually also tells us a lot about the art world. Take for instance how Seydou Keïta has become this icon and darling of the art world in the West. For the longest time, he was considered an artisan, that is until he was adopted by the art world of the West and became an artist. Yet, when subjects were stepping inside his studio, they were as much of an author as he was. They picked him to photograph them, they often chose and created the clothes they were going to wear, they brought the person with whom they wanted to be seen, and so on. Take the image of the two women that came dressed in the same way; the patterns and textiles are not trademarks of Seydou Keïta, but rather an expression of the sitters’ bonds of friendship, kinship, and solidarity. You can see this agency of the subject in the work of another African portrait photographer, Malick Sidibé. These observations contradict the Western art discourse, which tries to package him as this author who was in total control of everything he was portraying.

Butet-Roch: Why is it important to prioritize the agency of the sitter?

Colard: When we don’t recognize people, it’s very dehumanizing. Last year, the book Sexe, Race et Colonies was released. It’s a collective work featuring the analysis of respected French historians on the visual sexual exploitation of non-Western women in the French colonies. Despite its good intentions, this book insulted me. The cover of this beau-livre featured the title in neon, referencing brothels. More importantly, the texts further victimized the women photographed by failing to recognize the power they had, thereby reinforcing the stereotype of African women as powerless.

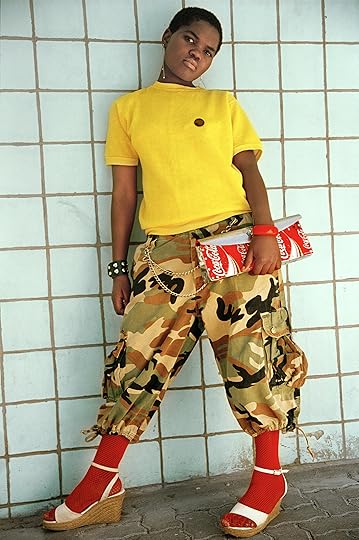

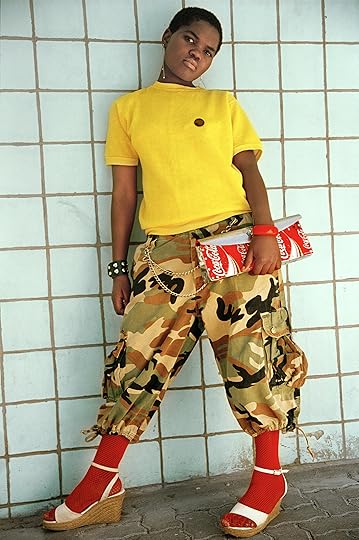

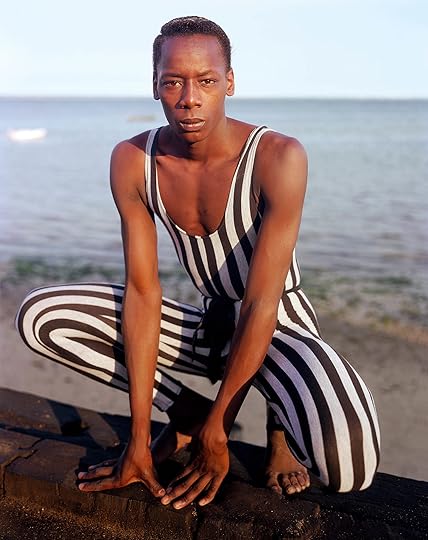

Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, Nonkululeko, from the series Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder, 2003

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Butet-Roch: Speaking mainly about the colonial archive component of this show, you wrote for the wall text accompanying the exhibition that it promises to bear witness “to the emergence of an African female photographic gaze and subjectivity without ignoring or erasing the harmful objectifications of the past.” This rings true for the rest of the show as well. How did you balance these two objectives—especially given that you did not want to continue giving critical attention to works that have subjugated African women—in the colonial archive section, but also in the modern and contemporary sections?

Colard: I was very intentional in my selection, looking for images that geared toward this visual exploitation of the female body, but that also provide room for further reflection. In one corner of the exhibition room, there’s an image of an odalisque-like woman. She’s paired with an image of a woman who returns a very oppositional gaze, thereby suggesting the spectrum of responses to being photographed that existed in the nineteenth century. You had all kinds of situations in the studios, from consent to coercion. I’m dedicated to demonstrating that even in the sometimes small area in which these women could express themselves, they used varied expressions to convey how they felt about the situation.

Butet-Roch: The concept of dignity reverberates throughout the exhibition. You mention it in reference to Guy Tilim’s work where the “‘subjects’ dignified bearing diverges from the norms of humanitarian ‘crisis’ photography,” as well as in relation to an 1870s portrait by Barnard that presents his sitter in the formal setting usually afforded to European subjects.

Colard: Let’s start with Guy Tilim. I hesitated about including the image Fiorinda Ngoma, Her Mother Rosalia Nahamba (Holding Baby Filomena Lasinda) and Her Sister Rosali Sindali, Holding Baby Guerra (2002) until I read the 2014 article “One hundred years of suffering? ‘Humanitarian crisis photography’ and self-representation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo” by Aubrey Graham. The article touches on photojournalists in warzones and how they sometimes perpetuate the very things they think they’re denouncing. The article was written from the standpoint of the subjects. The author notes how in certain images, the women changed the way they posed if they were in front of a foreign war photographer. In that choice—deciding to pose in a certain way—there’s agency, and therefore, dignity. In this case, the young woman in the foreground brings her hand to her face, which historically, within her culture, signifies sorrow. Even if this image presents her as a victim, which in some respect she is, she also made a choice of expressing that in the way that she wanted.

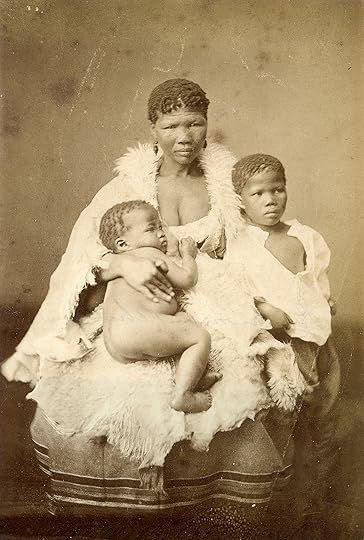

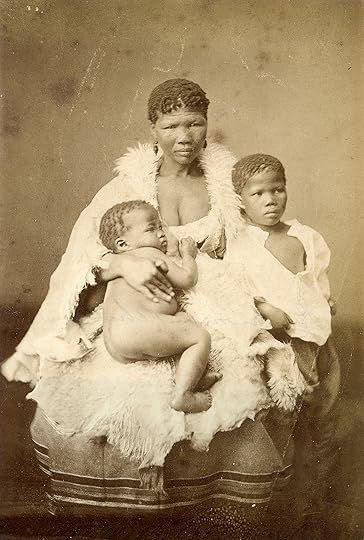

Samuel Baylis Barnard, Bushwoman [sic] and Children, South Africa (Portrait of !Kweiten ta //ken), 1874–1875,

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Butet-Roch: While in the Barnard portrait, it’s arguably the photographer’s choice of placing the subject within a formal setting that is understood, through a colonial gaze, as “elevating” her.

Colard: In this image, the woman, whose name is !kweiten ta ||ken, is not represented in the usual anthropological codes of the time, but rather according to European codes, which make her appear “dignified.” However, what I think is interesting is that it makes us reflect on how the anthropological portrait is intended to entirely dissolve the subject. The subjects are never named, so they’re not commemorated, nor even presented as individuals. They’re a type. Sometimes, the more you are imaged, the less visible you become. Images of Africans at the turn of the nineteenth century were primitivizing in order to justify the presence of the colonizer as a “civilizing” force. Yet, this image by Samuel Baylis Barnard is valorizing her aesthetically, and the fact that the caption includes her name is very charged with meaning. When you are represented as a nameless “type,” you are generalized, and in fact, you are undergoing the exact opposite of a portrait session, which seeks to seize you and no one else. Naming her is individualizing her, recognizing her uniqueness, and therefore making her the opposite of a type.

Butet-Roch: Perhaps because I read it recently, I had the following quote by bell hooks in mind when going through the exhibition: “Understanding marginality as position and place of resistance is crucial for oppressed, exploited, colonized people. If we only view the margin as sign marking the despair, a deep nihilism penetrates in a destructive way the very ground of our being.” The photographs produced by African artists from the later part of the twentieth century until now seem to heed to that call in a variety of ways. Could you speak to that?

Colard: This quote reminds me of Frederick Douglass and the double consciousness. The “benefit” of being part of a marginalized or minority community is that you always have double insights into the world around you. Even though it’s painful, this position is an extremely rich one, as we can see in the works of many contemporary artists who are using the genre of portraiture to talk about more than simply the representation and interpretation of the body. Imagine if, as a Black woman artist, I was only allowed to talk about the body. That’d be extremely restrictive. Hence, it was important for me to show the diversity of what they could do with the portrait genre, how it could be used to talk about issues that concerned them. For example, Mimi Cherono Ng’ok talks about homecoming, the uncanny, and what it is like to look at your family members as strangers when you come back from somewhere else.

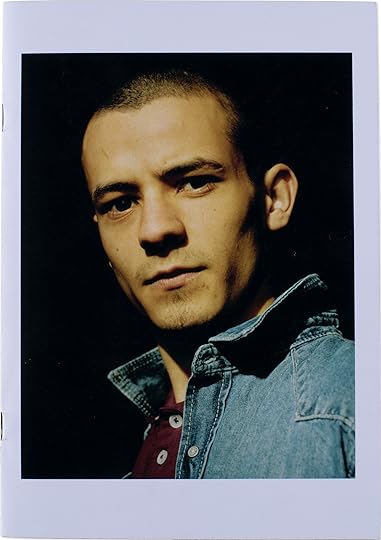

Butet-Roch: Mikhael Subotzky once recounted how he and Thabiso Sekgala discussed what makes a good portrait work. He said that they both felt that it was the “duality of the subject being both present and distant” that is “engaged with the photographer and comfortable, but also pining to be somewhere else and seemingly happy to display this longing in their manner and stance.” What do you feel makes a portrait work?

Colard: Indeed, it seems that what exceeds the control of the photographer is what is of interest for me in a portrait. The unexpected is what makes the portrait work, because it needs to be a collaboration. The photographer can’t and shouldn’t have all the keys.

Laurence Butet-Roch is a photographer, writer, and educator living in Toronto. She is currently pursuing a PhD in environmental studies at York University, examining the discourses perpetuated by visual representation of environmental contamination in mainstream media.

The post Revisiting African Portraiture, Through the Female Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Revisiting African Portrature, Through the Female Gaze

Sandrine Colard and Laurence Butet-Roch examine the history of how African women have been pictured, and in turn, how they look back at the viewer.

By Laurence Butet-Roch

A double entendre is at the heart of Sandrine Colard’s latest curatorial achievement, the exhibition The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture, recently on display at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. The title can indeed be interpreted in two ways. Immediately, it speaks to how a woman appears to us, the spectators, in an image; what we can infer from her style, her posture, her expression. Such a reading brings forth the responsibility we have, as members of the public, in interpreting these different cues to (re)construct the identity of the sitter, and to imagine the conditions of the photographic encounter. Yet moving through the three sequential sections of the show—“The Birth of a Gaze,” which covers colonial representations during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; “The Visual Soliloquy,” which focuses on the studio work of celebrated mid-century African artists, such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere; and “Self-Possessed,” which highlights the different themes that contemporary photographers on the continent explore through portraiture—another understanding emerges. It is not only the way that the women look to us, but also the way they look at us, at the photographer, and what this gaze conveys. Colard explained to me exactly how this expanded understanding of the female gaze reframes the history of the medium.

A. C. Gomes & Sons, Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Laurence Butet-Roch: What makes this particular moment ripe for examining the history of African portraiture through the perspective of the female gaze?

Sandrine Colard: Looking back at the role of art, including photography, in depicting African women and women of African descent is very tied to the arrival of new curators from these very communities. In the last year, there was the exhibition Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present at United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn, cocurated by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Catherine E. McKinley—which showed a selection of images from McKinley’s collection and centered African women—as well as Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, based on Denise Murrell’s dissertation, which started at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University and traveled to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. These exhibitions, which present a different view of photographic and art history, exist because the profession is changing thanks to the diverse profiles of new curators.

And, in regards to The Way She Looks, it harks back to when I was doing my PhD in art history at Columbia University. Each time there was a discussion about a Black character in art, especially a Black female character, it always revolved around issues related to the body and its exploitation. I’m a Black woman, and most of my peers and myself don’t think of ourselves as only that, a body. When we consider this disconnect, this show is both overdue and obvious. While the question of the body remains relevant, there’s room for another history of Black women, where we see that they had (and have), even in difficult circumstances, the power of shaping the way they want to be seen.

Butet-Roch: Your notion of the female gaze includes women photographers’ visions, but also the gaze that female sitters return to the photographer. What can be learned from paying attention to the gaze of the sitters?

Colard: When you look at colonial images of African subjects from the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries, only one woman is named; the rest are labeled according to their ethnographic “type.” Yet if you were to ignore the captions, and when you really look at these people—not just glance—the range of expressions and gazes is a testament to their humanity, and it completely defeats the caption that tries to reduce them to a type. In fact, it ridicules the caption. Take the image by Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin entitled Bakgatla: when you look at how this woman poses, you see that there’s a lot more to her than what the caption suggests. Of course, since we were not there and we have no account of the photo session, we’ll never know exactly how the photographic transaction went. What we do know is that the photographer was undertaking the ambitious project The Bantu Tribes of South Africa, which was conceived as an encyclopedia of ethnographic “types” and “primitive” people. Many of his photographs don’t match the anthropographic aesthetic of the time. Maybe it was because the photographer deliberately strayed away from it, or, more likely, because the women he encountered, via their gaze, refused to be reduced and encapsulated by a type.

Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin, Bakgatla, South Africa, early to mid 20th century

Courtesy The Walther Collection, Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg, and The McGregor Museum, Kimberley

Butet-Roch: Beyond revealing the complexity of the relationship between the photographer and the sitter, how do these gazes involve the viewer and interrogate the act of looking?

Colard: I really love Ariella Azoulay’s concept of the responsibility that we have toward the images, even one hundred years later. When all the images were hung on the wall, I was deeply moved, because I felt that they were looking back to ask for meaningful engagement from the viewer. I’m a strong believer that we have a responsibility to the subject, not only when we’re the photographer taking the picture, but also in regard to how we use the photos afterwards, how we present them, how we frame them, and the discourse that we build around them. I’ve had a sense that in the last few decades, we have attributed so much power to the colonial gaze. We read images from Africa through that lens only, to the point that we became blind to anything else the subject within the image was expressing.

Bearing this in mind, it was very important for me to include a historical perspective in the exhibition, because so often, when we discuss the great contemporary photographers—such as Zanele Muholi, Joana Choumali, or Aida Muluneh—they are presented as if they came out of a vacuum, that there was nothing before them. Such a timeline is not doing justice to the agency of the sitter, nor to the work of some of these artists’ predecessors. Only very recently was the photographer Felicia Abban recognized in the Western Hemisphere. She was a portraitist who had her own studio in Accra, Ghana, from the 1950s on. This changes everything, and I’m sure that more research will demonstrate that she was not the only one.

Butet-Roch: How can that expanded notion of the female gaze disrupt our understanding of the role of women in photography, on the one hand, but also our perception of African women as “powerless” in their representation?

Colard: It actually also tells us a lot about the art world. Take for instance how Seydou Keïta has become this icon and darling of the art world in the West. For the longest time, he was considered an artisan, that is until he was adopted by the art world of the West and became an artist. Yet, when subjects were stepping inside his studio, they were as much of an author as he was. They picked him to photograph them, they often chose and created the clothes they were going to wear, they brought the person with whom they wanted to be seen, and so on. Take the image of the two women that came dressed in the same way; the patterns and textiles are not trademarks of Seydou Keïta, but rather an expression of the sitters’ bonds of friendship, kinship, and solidarity. You can see this agency of the subject in the work of another African portrait photographer, Malick Sidibé. These observations contradict the Western art discourse, which tries to package him as this author who was in total control of everything he was portraying.

Butet-Roch: Why is it important to prioritize the agency of the sitter?

Colard: When we don’t recognize people, it’s very dehumanizing. Last year, the book Sexe, Race et Colonies was released. It’s a collective work featuring the analysis of respected French historians on the visual sexual exploitation of non-Western women in the French colonies. Despite its good intentions, this book insulted me. The cover of this beau-livre featured the title in neon, referencing brothels. More importantly, the texts further victimized the women photographed by failing to recognize the power they had, thereby reinforcing the stereotype of African women as powerless.

Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, Nonkululeko, from the series Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder, 2003

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Butet-Roch: Speaking mainly about the colonial archive component of this show, you wrote for the wall text accompanying the exhibition that it promises to bear witness “to the emergence of an African female photographic gaze and subjectivity without ignoring or erasing the harmful objectifications of the past.” This rings true for the rest of the show as well. How did you balance these two objectives—especially given that you did not want to continue giving critical attention to works that have subjugated African women—in the colonial archive section, but also in the modern and contemporary sections?

Colard: I was very intentional in my selection, looking for images that geared toward this visual exploitation of the female body, but that also provide room for further reflection. In one corner of the exhibition room, there’s an image of an odalisque-like woman. She’s paired with an image of a woman who returns a very oppositional gaze, thereby suggesting the spectrum of responses to being photographed that existed in the nineteenth century. You had all kinds of situations in the studios, from consent to coercion. I’m dedicated to demonstrating that even in the sometimes small area in which these women could express themselves, they used varied expressions to convey how they felt about the situation.

Butet-Roch: The concept of dignity reverberates throughout the exhibition. You mention it in reference to Guy Tilim’s work where the “‘subjects’ dignified bearing diverges from the norms of humanitarian ‘crisis’ photography,” as well as in relation to an 1870s portrait by Barnard that presents his sitter in the formal setting usually afforded to European subjects.

Colard: Let’s start with Guy Tilim. I hesitated about including the image Fiorinda Ngoma, Her Mother Rosalia Nahamba (Holding Baby Filomena Lasinda) and Her Sister Rosali Sindali, Holding Baby Guerra (2002) until I read the 2014 article “One hundred years of suffering? ‘Humanitarian crisis photography’ and self-representation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo” by Aubrey Graham. The article touches on photojournalists in warzones and how they sometimes perpetuate the very things they think they’re denouncing. The article was written from the standpoint of the subjects. The author notes how in certain images, the women changed the way they posed if they were in front of a foreign war photographer. In that choice—deciding to pose in a certain way—there’s agency, and therefore, dignity. In this case, the young woman in the foreground brings her hand to her face, which historically, within her culture, signifies sorrow. Even if this image presents her as a victim, which in some respect she is, she also made a choice of expressing that in the way that she wanted.

Samuel Baylis Barnard, Bushwoman [sic] and Children, South Africa (Portrait of !Kweiten ta //ken), 1874–1875,

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Butet-Roch: While in the Barnard portrait, it’s arguably the photographer’s choice of placing the subject within a formal setting that is understood, through a colonial gaze, as “elevating” her.

Colard: In this image, the woman, whose name is !kweiten ta ||ken, is not represented in the usual anthropological codes of the time, but rather according to European codes, which make her appear “dignified.” However, what I think is interesting is that it makes us reflect on how the anthropological portrait is intended to entirely dissolve the subject. The subjects are never named, so they’re not commemorated, nor even presented as individuals. They’re a type. Sometimes, the more you are imaged, the less visible you become. Images of Africans at the turn of the nineteenth century were primitivizing in order to justify the presence of the colonizer as a “civilizing” force. Yet, this image by Samuel Baylis Barnard is valorizing her aesthetically, and the fact that the caption includes her name is very charged with meaning. When you are represented as a nameless “type,” you are generalized, and in fact, you are undergoing the exact opposite of a portrait session, which seeks to seize you and no one else. Naming her is individualizing her, recognizing her uniqueness, and therefore making her the opposite of a type.

Butet-Roch: Perhaps because I read it recently, I had the following quote by bell hooks in mind when going through the exhibition: “Understanding marginality as position and place of resistance is crucial for oppressed, exploited, colonized people. If we only view the margin as sign marking the despair, a deep nihilism penetrates in a destructive way the very ground of our being.” The photographs produced by African artists from the later part of the twentieth century until now seem to heed to that call in a variety of ways. Could you speak to that?

Colard: This quote reminds me of Frederick Douglass and the double consciousness. The “benefit” of being part of a marginalized or minority community is that you always have double insights into the world around you. Even though it’s painful, this position is an extremely rich one, as we can see in the works of many contemporary artists who are using the genre of portraiture to talk about more than simply the representation and interpretation of the body. Imagine if, as a Black woman artist, I was only allowed to talk about the body. That’d be extremely restrictive. Hence, it was important for me to show the diversity of what they could do with the portrait genre, how it could be used to talk about issues that concerned them. For example, Mimi Cherono Ng’ok talks about homecoming, the uncanny, and what it is like to look at your family members as strangers when you come back from somewhere else.

Butet-Roch: Mikhael Subotzky once recounted how he and Thabiso Sekgala discussed what makes a good portrait work. He said that they both felt that it was the “duality of the subject being both present and distant” that is “engaged with the photographer and comfortable, but also pining to be somewhere else and seemingly happy to display this longing in their manner and stance.” What do you feel makes a portrait work?

Colard: Indeed, it seems that what exceeds the control of the photographer is what is of interest for me in a portrait. The unexpected is what makes the portrait work, because it needs to be a collaboration. The photographer can’t and shouldn’t have all the keys.

Laurence Butet-Roch is a photographer, writer, and educator living in Toronto. She is currently pursuing a PhD in environmental studies at York University, examining the discourses perpetuated by visual representation of environmental contamination in mainstream media.

The post Revisiting African Portrature, Through the Female Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

How a No-Frills Zine Transformed a British Town

For ten years, Adam Murray and Robert Parkinson have celebrated the hyperlocal through their expansive photo project.

By Holly Black

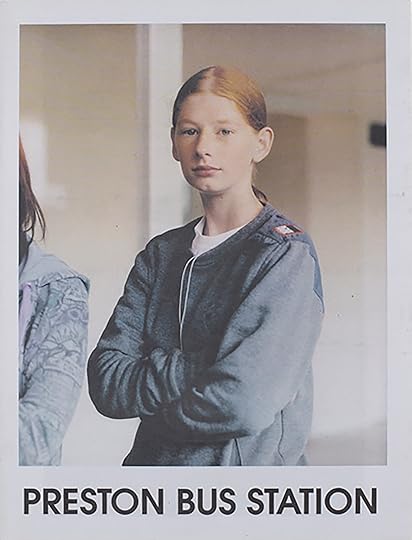

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

Britain’s ubiquitous graffiti-strewn carparks, rundown bus stations, and no-frills pubs might not seem like obvious subjects for artistic scrutiny. But these seemingly innocuous places hold a special kind of magic for Adam Murray and Robert Parkinson, who started documenting them a decade ago in Preston, the northern city where both artists lived and worked at the time. Now, the pair looks over the legacy of their collaborative project with a new book, Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019, presenting a slice of the huge amount of imagery they produced.

Murray and Parkinson met through University of Central Lancashire and quickly struck up a friendship through a mutual interest in photography, identifying the city’s relative lack of visual culture—particularly compared to its music and nightlife scenes. To fill this gap, they began producing a modest black-and-white, hand-stapled zine called Preston is my Paris as a way of celebrating largely overlooked areas of the city and the people that populate them (Murray is now a lecturer at Central Saint Martins and Manchester Metropolitan University; Parkinson still mainly works as a photographer). This DIY approach included new and found photos and random bits of ephemera, collated with little editorial intervention, along with modest distribution that consisted of handing the zines out for free.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

“It was pretty simple, there wasn’t much concept—it was just for fun!” says Parkinson, who had no background in photography and only began shooting at Murray’s suggestion. “I picked up a camera two weeks after I graduated,” he adds, “and my first roll of film was in the first zine. We learned as we went along—simple things, like the fact you need multiples of four pages. We would print out a mock-up and everything would be out of sync. We had no idea about those things.”

This small-scale project—with a self-effacing title that Murray describes as “nicked off of a Clarks shoes advert that made British cities look like exotic places”—grew a local following, thanks largely to conversations initiated by the pair as they traversed the city looking for people and places to photograph, from young clubbers to older couples like Iris and John, who were snapped following a jovial chat in the pub. “It was a form of hyperlocal social media, because people would pick up the zine to see if they or anyone they recognized was in it,” Parkinson explains.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

Murray and Parkinson’s self-published labors of love stand out because they are born out of two individuals who really understand the city that they live in. Their celebratory approach, with plenty of subjects actively embracing the presence of the camera, eludes any sense of voyeurism; it is unselfconscious and self-assured in a way that only comes from being comfortable in your environment—and perhaps a little bit naïve. In fact, Parkinson says that he is amazed by some of the images that he made with such a fresh eye, which can be hard to replicate “once you have trained yourself out of it.”

As the zine gained traction, so did new opportunities for Preston is my Paris to become a full-fledged imprint. Within their first year of publication, Murray and Parkinson mounted an exhibition in a disused shop, holding workshops and a pop-up portrait studio and relying on local foot traffic to get the message out. They also produced a newspaper showcasing the work of photographer Jamie Hawkesworth, whose images of Preston Bus Station celebrate its Brutalist architecture and the people who travel through it every day in alluring, saturated hues. Printing a paper both allowed for full color and was a format that many in the local community were familiar with and might be more likely to pick up. “It all comes back to understanding the city and how people might engage with what you’re doing,” says Murray. “In Preston, it is not necessarily on the top of people’s priority list to seek out art and culture, but that doesn’t mean they are not interested.”

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

As far as Parkinson is concerned, Preston is my Paris—a project that has gone on to produce over forty books and numerous commissions around the world—is a far cry from the platitudes that are so often offered by museums and cultural institutions in an effort to appear locally relevant. “There’s lots of talk of ‘socially engaged’ photography, which comes across as a bit elitist,” he says, “because when you think about it, that is what all people-focused photography is. If you’re taking their photos, you’re meeting them, talking to them, and getting their stories.”

The anniversary book reflects this outlook. “We had so much material,” says Murray. “But a lot of people haven’t seen the work, so we wanted to produce an edited portfolio of images, and also include our wider reflections on the project.” As a result, they invited a range of individuals to include their thoughts on Preston is my Paris and its legacy, including Jamie Hawkesworth (whose photos are featured) and Iris Lunt, who became a subject after she met the pair in her local pub. While their personal accounts exemplify the intimate, friendly atmosphere that Preston is my Paris fostered, City Council Leader Matthew Brown takes a broader view, commenting on the zine’s ability to capture “the reality of life in our city at that time,” as well as the changes the area has endured over the last decade.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

For Murray and Parkinson, the new publication offers a chance to look back, but also to gain new audiences, who will hopefully feel inspired by the project. “One of the main purposes was to encourage people in Preston to do more. They might like what we’ve done or hate it, but either way, the hope was that it would encourage them to do their own thing,” says Murray. Parkinson echoes this sentiment: “We want people to really see the area. There’s something interesting in any town in Britain, you’ve just got to find it.”

Holly Black is a freelance arts journalist based in London and an editor at large at Elephant magazine

Adam Murray and Robert Parkinson’s Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019 was published by Dashwood Books in November 2019. More information about the project can be found on the Preston is my Paris website.

The post How a No-Frills Zine Transformed a British Town appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Joel Meyerowitz Reflects on the Magic of Provincetown

The artist looks back on a town that has long captivated his imagination, through every flowering of identity and sexual politics.

Joel Meyerowitz, Friends and Family, 1987

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

Provincetown. Land’s End. Beyond it, the wide Atlantic. People have been coming here to get away from it all since the Pilgrims came ashore in 1620. The Pilgrims stayed for five hard winter weeks at the end of the sandbar in the Atlantic known as Cape Cod before sailing across the bay to what is now Plymouth.

But for the rest of us who find our way here—travelers, artists, writers, playwrights, actors, poets, straight, gay, lesbian, gender-nonconforming, black, white, foreign, anyone who wants to move from the urban pressures to the spacious and spiritual beauty of the Outer Cape—Provincetown is where your identity and sense of “home” come to ground.

Joel Meyerowitz, Darrell, 1983

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

There is something about communities coming together at “land’s end” that creates compassionate understanding; tolerance and acceptance become the foundation of the community. P’town, as the locals call it, has been welcoming these various seekers since the nineteenth century, or even earlier. Portuguese fishermen from the Azores, picked up as crew members by Yankee whalers, settled and built a fishing community in Provincetown early on, and later, at the end of the nineteenth century, artists from New York and Boston found low-rent fishing shacks to paint in during the summers. Then, around 1910, came poets and writers and playwrights. Eugene O’Neill’s early plays were put on in the local theater. The word got out that there was a place of great natural beauty with endless sandy beaches, dunes, forests, and hidden ponds in the woods that were left over from glacial deposits of the last Ice Age, with water so pure you could drink it while swimming. A place where you could walk through the dappled light of the woods and up and over a sand dune to dive naked into the briny waters of the Atlantic.

Joel Meyerowitz, Elias and Joelle, 1981

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

Joel Meyerowitz, Ariel, 1984

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

Apart from nature, there was in P’town an animated and joyous street life, a little like Eighth Street in Greenwich Village, which brought a spicy urban flavor to this natural paradise. There were great dance clubs and bars, good music, lots of art galleries and parties, readings, and openings, all on a scale that perfectly fit the landscape that surrounded it. During my time there in the 1970s and ’80s I knew, or often saw in town, Norman Mailer, Robert Motherwell, Mary Oliver, Myron Stout, Michael Cunningham, Stanley Kunitz, Jack Pierson, John Waters, Annie Dillard, and many others. Before them there were Marsden Hartley, Hans Hofmann, Milton Avery, even Andy Warhol, and many more young artists who got the call.

What always surprised and pleased me was how kind the townspeople and shop owners were, considering the flood of day-trippers, as well as the seasonal influx of the creative crowd and summer visitors. That generosity extended to the daily circus of sexual expression that played out in the streets and hotels, the guest houses and summer rentals, in a town that, after the summer’s end, returned to the three thousand or so permanent residents who remained there through the dead of winter.”

Joel Meyerowitz, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1977

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

Joel Meyerowitz, Elizabeth and Melinda, 1981

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

The town lived through the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and stood strong through every flowering of identity and sexual politics of the last thirty-five years. And it did so with grace and humanity. What in many places would be judged as “other” was the norm in P’town. My kids grew up there in the summers and saw its diversity for themselves; they learned about acceptance and tolerance firsthand and have carried these lessons into their lives.

I went there originally to explore how the Cape’s light seemed to illuminate nature from within. What I discovered was the manner in which the light penetrated and exposed people’s mystery, revealing their true identities in such a way that everyone became beautiful.

This text appears in Provincetown as the artist’s introduction. Click here to purchase Provincetown.

Click here to collect limited-edition prints from Provincetown.

The post Joel Meyerowitz Reflects on the Magic of Provincetown appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 17, 2019

Spirit of the Age

Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s iconic novel Orlando, the artists in Aperture’s “Orlando” issue explore the limitless territories of identity, history, and consciousness.

By Tilda Swinton

Tilda Swinton as Orlando in a preproduction image made by director Sally Potter to help secure funding for the film Orlando, spring 1988

Courtesy the artist

Jacques Derrida’s l’avenir: the unforeseeable that will appear, although we cannot control our expectation of what it will be.

It’s 2019, the wheel has turned, and here I am again, marveling at Orlando and its impact—not only on my own life, but also on the lives of a host of my colleague-artists.

When I sent out my calling cards to the extraordinary collection of individuals whose work you open here and now, between these covers, it was with an invitation to share the inspiration of a book, a novel: Virginia Woolf ’s 1928 “writer’s holiday,” her wild-goose chase of a fantasy.

The response was universally overwhelming. And overwhelmingly personal.

Woolf calls the book a biography and refers constantly to its diligent biographer’s task and the specific challenges therein, recording the life, with deadpan sincerity, of a young nobleman whom we meet under an oak tree, in an ancestral park, during the reign of Elizabeth I. During Orlando’s journey, he encounters the love of the ancient queen and a broken heart on the frozen Thames in the court of James I, learns to distrust the envy and cupidity of poets, serves as King Charles’s ambassador to Constantinople—there transforming with unremarked ease into the form of a woman. She sips tea in drawing rooms with Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, and Jonathan Swift; succumbs to the stifling Victorian age by breaking her ankle while running on a wild moor in a crinoline; marries an adventurer; loses and regains her estates; and, in the early twentieth century, delivers both a son and her great poem (the work of over three centuries).

How could one such fable inspire in the depths of so many disparate creative souls the sense of it being their own biography? How could one size fit all in such a way?

Maybe this is, indeed, a magic carpet of a book. It can transport so many of us so profoundly into the heart of our experience of living life again and again and again: an enchanted mirror in which to see oneself. A book about agelessness that honors our every age. A robust and reliable fellowship—all moments having, as Woolf might argue, an equality of weight, of buoyancy, of heft; all moments can do with the company of her wise, experienced perspective.

When I was a teenager, it read to me as a book about writing. Later, in my twenties, as a book about reading. Having just put the book down again, on January 31, 2019, I find that this febrile, synthetically hallucinogenic transport of a fable has slip-slid again and now reads to me as a book about revolution, about the dismantling of everything it touches, about a recalibration of perspective and will. A book about looking up.

Lenare, Vita Sackville-West, ca. 1920s

Courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University

Our very first sight of the adolescent Orlando is of him swinging at the decapitated head of a Moor, brought back by a crusading forebear and hung in the rafters of the family’s great house as a trophy. This mindless, violent sport notwithstanding, there are frequent references throughout the book to Orlando’s discomfort at the brazen barbarism of his patrician milieu. He/she regularly ducks under the silken ropes of court enclosures in all centuries to seek the company of people in backstreets, huddled about braziers. In the East, Orlando learns perhaps the most profound lessons of all from the itinerant gypsies with whom she lives, who are embarrassed for her that she has ancestors who must have thieved their great wealth, who had the “vulgar ambition … to possess bedrooms by the hundred,” and who were only able to trace their lineage four or five hundred years, whereas their own families, nomadic peoples who had built the pyramids, went back two or three thousand.

Colonialism, then. Inherited wealth. The illogical snobbery of class. The nonsensical vagaries of xenophobia. Orlando meticulously detonates each one. Beyond everything, the question of a properly responsive “civilized” self appears to me, today, as a principal preoccupation of this synesthetic portal of a book.

It is also, of course, a vivid record of the processes of making art—the urge to interpret and describe. The imagistic vortex of Woolf ’s mind, as manifested in Orlando, is a gift to artists. It seems a large part of the reason for the deeply felt enthusiasm of this gathering of eyes and minds and hearts in these pages. And at the core of Orlando is the steady, dual pulse of two undeniable influences: the weather and the spirit of the age.

We live at a moment of stilled consciousness. All our hackles are stimulated, our noses urgently—to the wind. We’ve been straying around perilous corners recently, and there be dragons.

We tell ourselves it must have been rough in past centuries, that the Black Death, the Russian Revolution, the Great War were surely something of a challenge, that more recent developments are survivable. But we are stumbling. It’s a next-level shit show—maybe not entirely what Pharrell Williams was thinking about, but somehow best described as a room without a roof.

Maybe the questions before us right now number among some of the most profound possible: What is a society? What is a social conscience? What is social responsibility? What is a human? What future can we envisage for ourselves? What is hope?

And, certainly, this particular moment we live through, this 2019, these days, these vertiginous times—with more than Chicken Licken, whose ancient folktale has him convinced the sky is about to fall in, running for cover, for shelter, for safer, higher ground— call for a new breath and a fresh commitment to the life we mean to build here while we can.

So many lines are being drawn, differences cast in stone, daggers unsheathed, territory marked, positions owned, dignities abused.

I propose, in general and in this issue of Aperture, a contrary tack: openness, all fences down, all go molten, all arms wide.

I’ve been thinking about how certainty is becoming our nemesis. How doubtlessness is killing our ability to expand as a society and as individuals. How the once essential search for a definable, and immutable, identity has become stifling to our sense of development and the possibilities of finding true fellowship with other complex, variously wired, hesitant, sensitive beings.

Paul Strand, Bent Grass, Machair, South Uist, Hebrides, 1954

© Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

Woolf believed the fundamental creative mind to be androgynous. Obviously, the most celebrated context within which we have come to see Orlando referenced concerns that of transformation, especially in relation to gender: as Orlando himself/herself so memorably remarks (in the film) at the critical moment of transformation, “Same person. No difference at all. Just a different sex.”

However, beyond this field of discourse—and, it has to be said, in the era of the all-gender bathroom—I have come to value the landscape of this beloved book far less as being only about gender and far more as being about the profound flexibility of the fully awake and sensate spirit. I embrace its visionary perspective as an invaluable parable about true freedom—from the imperatives of nationality, of history, and of class, as well as of gender. A directive to the existence of an authentic and responsive soul: consistent and evolving, inviolable and pure.

And now, within this issue’s panoply of colors and tastes and imaginings, I see, afresh, once more, Orlando as a story about the life and development of a human striving to become liberated entirely from the constructs of prescriptive (tired old binary) gender or social norms of any kind.

We offer on the previous spread two formal portraits by the Lenare studio in London, the go-to stamp of high-society identity, taken some forty years apart: a three-year-old girl and a pearl-bedecked lady, linked by the avatar of Orlando that they share, one in Woolf ’s book, the other in Sally Potter’s film. I’m proud to clarify: Vita Sackville-West in the pearls and me in the organza with the ribbon in my hair. Two Orlandos, here among so many others: the future ahead of them, as ours lies before us now, ready for the making.

To consider this story’s limitlessness, its sense of innate and empowered boxlessness. To consider the wider territories of identity, of dream, of heredity, of consciousness, of memory, of history, of fantasy, of the limitations of mortality, of life itself. To consider the consolation of the wilderness of the future. This was the invitation offered to our contributors here.

It has been my profound privilege to lay the table for this feast.

Tilda Swinton is the guest editor of Aperture’s “Orlando” issue.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Spirit of the Age appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 12, 2019

12 Photographers on How They Conceptualize Their Work

Over the course of her career, curator and lecturer Sasha Wolf has heard countless young photographers say they often feel adrift in their own practices, wondering if they are doing it the “right” way. She was inspired to seek insight from a wide range of photographers about their approaches to making photographs, and, more important, a sustained body of work. Their responses are compiled in PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice. Below, twelve artists respond to the first question in the interview series:

What comes first for you: the idea for a project, or individual photographs that suggest a concept?

Robert Adams, Sally, Weld County, Colorado, 1984

Courtesy the artist

Robert Adams

Thinking up a project and then making pictures that fit does not, in my experience, usually result in the best pictures. Most of the books I’ve published have started with just walking and photographing, free of any plan.

Dawoud Bey, A Woman Waiting in the Doorway, Harlem, NY, 1976

Courtesy the artist

Dawoud Bey

My work always begins with an idea, with something that I need to talk about. I make my photographs in order to provoke a conversation around things that I am invested in. The challenge is how to give those concerns a resonant and coherent form so that the viewer becomes interested and invested. I want the things that matter to me to matter to the viewer.

Elinor Carucci, Bath, 2006

Courtesy the artist

Elinor Carucci

Somehow both things are happening: I can have an idea for a project and then take individual pictures that will lead me to change the project. Many times I will take pictures that I think are about one thing, but they end up being about another thing—then I listen to my own pictures and understand what my project is about. At that point, I have the idea for a project that I follow and develop.

Siân Davey, Garden Gate, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Siân Davey

My first series [published in 2015] was about my youngest daughter, Alice, who was born with Down’s syndrome. It was ignited by feelings of anger at how I felt others perceived her. I felt a need to articulate and disseminate these feelings. In that sense, the concept preempted the work.

The series I am currently working on, about my youngest son, Joseph, was inspired by an August Sander picture I saw in a gallery in Paris. Seeing the Sander print felt like a transmission—in that moment I knew exactly what I needed to do. I have always worked in medium format (6-by-7) but decided, like Sander, to work in large format (8-by-10). Working this way strips everything down. All I am left with is myself, Joseph, and our shared histories revealing themselves in that single moment.

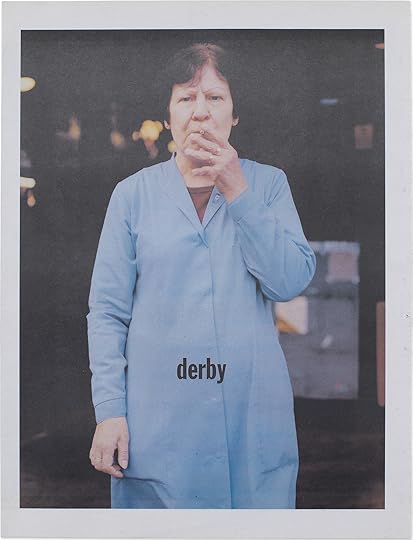

Paul Graham, Woman Smoking Cigarette, Belfast, 1988, from New Europe

Courtesy the artist

Paul Graham

They go hand in glove. If you are a photographer who works with life, then you have to put yourself into the territory where that imagery and your thoughts might coalesce, because you need the vital lesson that first key image provides. Not the first image, but the first key image, the one that unlocks the door. The one you stumble over. It might surprise you by coming in from left field, taking things in a completely different direction, but that’s the beauty of working with the world, with the moments that time hurls your way. It’s a collaborative dance between the artist and life itself, so embrace the partnership. Often the world’s complexity is far more interesting than your concepts. If you can have the humility to admit that, you’ll do well.

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from ZZYZX, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Gregory Halpern

My answer to this is a little messy, but working through the messiness of that process is part of the joy of fumbling my way toward clarity. It may begin with an idea, but sometimes it’s simply a hunch, or a feeling. I don’t clearly understand the evolution of the process until the work is done, and I like to take my time working on projects—A [2011] and ZZYZX [2016] each represented about five years of work, respectively. Finding out where the work will go is what keeps them going.

Once I begin to understand what will hold the work together, even if it’s just a loose binding structure at first, then I am able to narrow my field of vision, or “material,” to whatever is within the parameters of the “project.” Once I have loosely defined parameters, I am free to be as obsessive as possible within that framework. I want parameters narrow enough to make the work compelling and cohesive, but broad enough to allow myself, and my viewer, the pleasure of being able to find their own way through the work.

Todd Hido, #2479-a, 1999, from House Hunting, 2001

Courtesy the artist

Todd Hido

I always find the concepts in my work through making pictures and sorting them out, which clarifies my ideas. Most often I am using my intuition up front. The process of analyzing comes later.

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Utatane, 2001

Courtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi

Most of the time the photographs tend to be a prelude to the concept. With my earlier works Utatane and Hanabi [both 2001], for example, I carefully selected photographs to use from the pool I had accumulated after a number of years of shooting—all the while thinking about how to structure the pages of a book. To bring each to completion, at the end I went out and photographed additional shots to create the imagery I wanted to depict. For Halo [2017], a more recent work, I felt that I could achieve the desired aesthetic by amalgamating photographs I had taken for different projects—culminating in compiling the series into book form.

Catherine Opie, Untitled #6 (Immigration March, Los Angeles, CA), 2006

© Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Catherine Opie

Normally the idea of the project comes first. When I begin to make a body of work, surprises or different situations often happen that allow me to think within the original idea but still experiment. So I like to start with a concept, but I also like the freedom of how it can transpire during the making of the work.

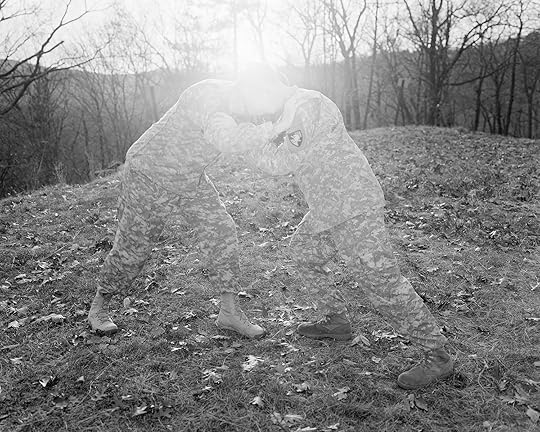

Kristine Potter, Untitled, 2009, from The Gray Line

Courtesy the artist

Kristine Potter

If we want to talk about long-term projects, I typically begin with a conceptual architecture that loosely defines where I’m going and whom I’m looking to find. When I first began work on Manifest [2018], for example, I thought it would be comprised entirely of portraits. But you’ll notice that the body of work is full of landscape pictures: those evolved because the area, Colorado’s Western Slope, was so sparsely populated that I would sometimes go a few days without making a portrait. There I was, in this incredible landscape that had all kinds of photographic history, holding a 4-by-5 camera. It came so naturally—and I can’t imagine this work existing without the landscapes—but that wasn’t the original plan. For me, it is increasingly important to avoid treating my initial concepts as a formula or something to illustrate. These ideas are necessarily loose and the magic usually happens at the margins.

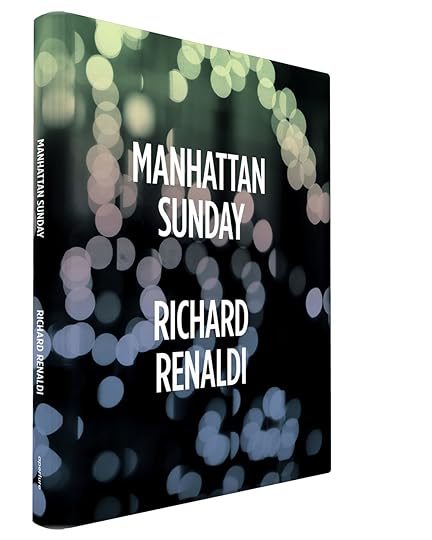

Richard Renaldi, 07:51, 2015, from Manhattan Sunday (Aperture, 2016)

Courtesy the artist

Richard Renaldi

For much of my career I have focused on specific projects. I think of an idea and execute it. Either the project develops sufficiently or eventually I drop it. I have nearly as many unfinished projects as completed ones. Sometimes, one project gives rise to another. For example, a portrait series I worked on for a number of years, photographing at Greyhound bus stations across the country, led me to attempt group portraits of strangers sitting together on public benches. Those images relayed themselves into a new idea, to shoot pictures of two or more strangers posing intimately with the stipulation that they must physically touch one another. This became the genesis for Touching Strangers [2014].

Alec Soth, Peter’s Houseboat, Winona, Minnesota, 2002, from Sleeping by the Mississippi, 2004

Courtesy the artist

Alec Soth

I usually start with a vague idea. But after the first exposure, this idea invariably is transformed. I’m reminded over and over again of William Carlos Williams’s “no ideas but in things.” By the time I’m done shooting, the original idea is barely recognizable.

Responses have been edited for space. To read the full interviews, order your copy of PhotoWork here.

The post 12 Photographers on How They Conceptualize Their Work appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 11, 2019

Santu Mofokeng’s Pensive Visions of Land and Ritual

In a new series of photobooks, the revered photographer conjures the mysteries of faith in South Africa.

By Sean O’Toole

Santu Mofokeng, Animal Festoon, Mautse Cave, Clarens, 1996

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

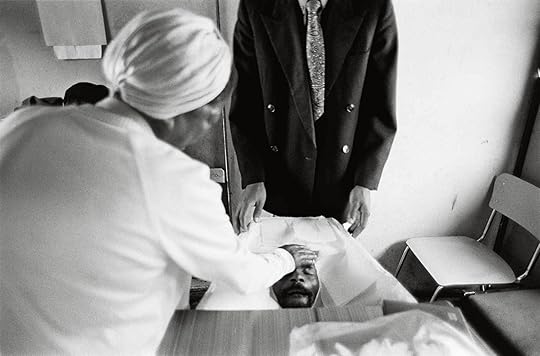

In October 2004, a few months after a handful of his black-and-white street photographs were presented in an exhibition of South African photography in Tokyo, Santu Mofokeng agreed to meet me at his Johannesburg home. The plan was to pick up on our conversations in Japan, as well as to talk about an image he had recently taken of his older brother Ishmael, which he was showing at a local gallery. Titled Eyes-Wide-Shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens (2004), the head-and-shoulders portrait presents an aging man, with a graying Colonel Sanders goatee, wrapped in winter clothes. Two figures pass behind him, blurs in the murk of a cave. His eyes, too, are distorted, but it is nonetheless possible to detect a slight deviation in his sight. Ishmael’s right eye peers straight into the lens, but his left eye does not. It looks elsewhere, at something beyond the conjecture of words. Call it a decisive finality.

When I arrived at Mofokeng’s house, the photographer was slumped on the pavement, crying. Ishmael, he said, was dying. He motioned me into his home, pointed to a seat, and handed me a stack of postcard-size photographs. “My children cried when I showed them these.” The photographs, cheap machine prints, offered a sequential record of a road trip Mofokeng had recently undertaken with his brother to Motouleng Cave, an immense sandstone overhang near South Africa’s border with the mountainous country of Lesotho. The caves there are popular with hikers and urbanites interested in ayahuasca spiritual medicine—ceremonies. Motouleng, though, is different.

Santu Mofokeng, Prayer Service at the Altar on the Easter Weekend at Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 2006

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

The cave, whose name in the central South African Sotho language loosely translates as “place of the beating drums,” has a special significance for followers of the country’s traditional animist religions. It is venerated as a place of salvation and healing. Ishmael had recently been diagnosed with tuberculosis, an opportunistic infection that is the leading cause of death among people with HIV.

“Of the many beliefs in townships, most people believe there are two kinds of HIV virus and AIDS,” Mofokeng wrote in 2011. “There is the genuine kind, identified worldwide by epidemiologists, which responds to treatment using scientifically approved methods and medicines. The other kind is transmitted by a ‘worm’ and is passed on to a person by witches, enemies, jealous relatives, friends, and so on.” Ishmael believed he was a victim of the latter, that his decline was attributable to witchcraft.

Santu Mofokeng, Eyes-Wide-Shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 2004

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

The drive from Johannesburg to Motouleng takes roughly four hours. The final approach is made on foot. It was an arduous trek for Ishmael, who avoided naming the illness that had brought him to the cave. He collapsed. One of the small photographs I cradled in my lap depicted this: Ishmael lying in a meadow, resembling one of the war dead photographed by Timothy H. O’Sullivan. Mofokeng bundled his brother into a wheelbarrow like a sack and pushed him to the cave, where, in the presence of resident healers and fellow pilgrims, he was fortified by the immensity of his encounter with tradition.

Three years later, in 2007, in a Johannesburg gallery during a walkthrough with me of Invoice, his first, largely self-curated survey exhibition, Mofokeng offered a shorn summary of his visit to the cave with his brother. “They gave him water and holy ash,” he said. “He felt better and said thank you to me for bringing him to Motouleng. He walked back to the car without assistance. It didn’t take him long, and he died. Anyway.”

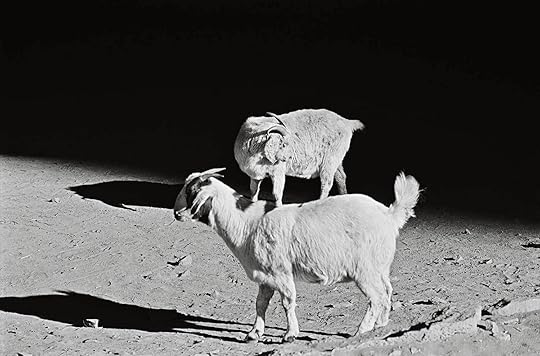

Mofokeng quickly moved on to another photograph, which depicted two goats, sacral animals roaming the same cave, in 2004. He pointed to the optical illusion at play, of one goat seemingly balancing on another. He linked the photograph to his portrait of Ishmael. “I don’t know if Ishmael’s eyes are open or shut.” These two pictures, along with another of a horse hidden in shadow taken near a Buddhist retreat in 2003, he explained, were descriptive of his attempt to photograph magic. “Can you capture it?” he asked. “No.”

Santu Mofokeng, Sacral Animals, Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 2004

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

Mofokeng is now sixty-three. His career is signposted by the standard markers of achievement—photobooks, exhibitions, awards, a growing body of interpretive writing—but among his peers, he remains something of an enigma. Make no mistake: Mofokeng is widely admired, particularly by younger South African photographers like Jabulani Dhlamini and Lindokuhle Sobekwa, but he is not a household name, at least not like his elder, the renowned South African photojournalist Peter Magubane.

“I find the term so weird, a painter’s painter, but if I was asked who is a photographer’s photographer, I’d say Santu,” explains the artist Mikhael Subotzky, who as a young man looked to white South African photographers working in a humanist, rather than activist, tradition of documentary—notably David Goldblatt and Guy Tillim—as models. “I am trying to think if there was a reason why,” he adds. “In some ways, it was as simple as Santu’s work wasn’t as accessible to me.”

There are various reasons Mofokeng’s work hasn’t always been available. He initially worked in news, that most ephemeral of photographic modes, covering the civil strife that gripped South Africa in the 1980s, the final decade of apartheid. Mofokeng tired of the genre’s rhetorical conventions, of producing “images bespeaking gloom, monotony, anguish, struggle, oppression,” as he wrote in 1993, and joined the African Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Starting in 1988, he spent most of the next decade working in relative obscurity, documenting rural tenant farmers, collecting photographs of South Africa’s forgotten black middle class, and—crucially—refining his writing skills.

Santu Mofokeng, U-Drive Rent-a-Car, Little Switzerland, 1996

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Mofokeng worked with the revisionist historian Charles van Onselen at Wits. The environment of the institute, which Mofokeng described as “enabling,” cultivated in him a belief in his photographs’ value. It also highlighted the need to answer basic questions: What are you doing? Is this what you mean? Coming up with explanations wasn’t easy—writing was not Mofokeng’s métier, at least not initially—but the process allowed him to take ownership and responsibility for his photographs.

In 1996, he signaled the end of this withdrawal by initiating his long-term project photographing in the caves that would later attract his brother. “When I first became a professional photographer, I started working on a project called Fictional Biography, a sort of metaphorical biography of my life, going to places I would ordinarily go, making photographs of things I ordinarily do or see,” Mofokeng told the Swiss curator and art historian Corinne Diserens in 2011. Entering the caves, he said, was his way of concluding a body of work he had started in the mid-1980s.

In 2002, Mofokeng’s photography was featured in the curator Okwui Enwezor’s landmark Documenta 11 exhibition in Kassel, Germany, and, almost a decade later, Diserens organized the first international survey of his work, Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng, Thirty Years of Photographic Essays (2011). Comprised of some two hundred photographs, and presented first by the Paris photography space Jeu de Paume, followed by a multicity European tour, the exhibition was organized into loose thematic clusters. Heralded by Train Church (1986), his breakthrough series of close-up portraits of religious worshippers on crowded passenger trains in Johannesburg, and fully announced by Chasing Shadows (1996–2014), a photographic essay largely made in the caves of central South Africa, Mofokeng’s interest in spirituality formed a major component of the survey. The latter essay, with its explicit focus on spirituality, includes his portrait of Ishmael. “Once in a while I make portraits,” Mofokeng told Diserens in an interview, “and some of them I’m proud of, but I can’t say I’m a portrait photographer.”

Each section of Diserens’s exhibition was introduced with text panels written by Mofokeng. They reiterated a long-held faith. “Most of the time, when I’ve looked at catalogues or exhibition texts in which experts come in and talk about my work, I don’t like it,” Mofokeng told the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2002. “I was raised by a parent (my father died when I was four) who instilled in me a religious thing about always searching for meaning and purpose in everything we do. This informs my enterprise and the work that I do—I’d like to be the interpreter of my work.”

Santu Mofokeng, Soweto, 1985

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, a twenty-four-year-old Magnum Photos nominee, tells a story about a visit with Mofokeng around 2013: “I wanted to show him my best pictures, which I had printed out. He looked at a few pictures. ‘You can photograph, but what have you written?’ I said nothing. ‘Take those newspapers and go read. Next time I meet with you, show me what you’ve written.’ I was very young, and I thought photography is something you don’t need to read or write about. He was teaching me.”

Sobekwa first encountered Mofokeng’s work while studying photography in high school. His teacher showed him a copy of Chasing Shadows. He says he felt a connection looking at the images. In an essay appearing in the book, Enwezor describes Mofokeng as “heir to the great black South African photographers such as Alf Khumalo, Peter Magubane, Ernest Cole and Bob Gosani, as well as to David Goldblatt.” He writes that “Mofokeng’s observational approach, his scrupulous skepticism toward the dramatic image,” is most allied to the “urban disquiet” of Cole and the “cool distance” of Goldblatt.

Mofokeng contradicts this. Magubane’s documentation of the apartheid government’s violent crackdown on a 1976 student revolt in Soweto, conceived in the 1930s as a segregated black settlement abutting Johannesburg, was particularly influential. “It was Magubane who made photography a respectable occupation,” Mofokeng told me in 2014. While Goldblatt was “an inspiration,” he said it was while working as a printer for Magubane’s mentor, the Germanborn photojournalist and documentarian Jürgen Schadeberg, in 1986, that he had a “light-bulb moment.” His series Train Church, made while journeying by train to and from work with Schadeberg, materialized this insight. Its blurred chiaroscuro lighting became a hallmark of Mofokeng’s photography.

South Africa’s passage to a nonracial democracy, however imperfect, has tended to inspire fabulist narratives about the role of color film in portraying the fullness of the new country. After the first nonracial elections in 1994, documentary photographers started to use color more frequently. By 2000, as South African photography gained wider visibility, some artists and critics began to argue that black-and white imagery was ethically oppressive and, conversely, that color dignified. Mofokeng rejected this argument as expedient and market-driven. In a 2013 note he explained how “my work and that of lefties, groups and archives, and other activists and organizations, along with their efforts, were being insulted and thrown out like so much apartheid paraphernalia and baggage.” The meaning of color in postapartheid photography certainly merits consideration, but not at the expense of some basics. While his black-and-white images are better known, Mofokeng also worked in color; selections from his color landscape series Graves (2012) were shown at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

Santu Mofokeng, In Town, Towards Selby, ca. 2011

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

The Cape Town–based photographer Jo Ractliffe first became aware of Mofokeng around the time he joined the nonracial and activist inclined photography collective Afrapix, in 1985. Best known for her ravaged landscape pictures depicting the troubled passage to freedom in South Africa, Namibia, and Angola, Ractliffe doubts the curatorial projection of thematic certainties onto Mofokeng’s work. She describes his fragmentary and investigative output as hard to pin. “People tend to make his work seamless in a way that I don’t think it is at all,” she says. Ractliffe considers Mofokeng not coherent in the way Goldblatt was coherent, or his contemporaries at Afrapix were. She singles out his first book of photographs, Taxi-004: Santu Mofokeng (2001), an unpolished hodgepodge of text and image that the photographer played a key part in orchestrating.

“Books are a way of domesticating meaning,” Mofokeng has stated. For all its failures, his first book is nonetheless striking for an autobiographical essay titled “Lampposts,” which threads through the layout, making a case for the equal import of Mofokeng’s writing. The essay details his impoverished upbringing in Soweto, his introduction to photography in the early 1970s, his careers as a darkroom technician and a photojournalist in the 1980s, his vague immersion in activism, as well as his subsequent pursuit of a personal vision. It even features an episode involving Ishmael, who, in 1976, saw his younger brother being beaten by white bullies on the streets of Johannesburg’s city center in retaliation for protests in nearby Soweto. “I was never an activist,” writes Mofokeng. His photojournalism from the late 1980s, nonetheless, includes strongly partisan documentation of street protests, striking mine workers, and police repression, as well as the tenth-anniversary commemoration of the 1976 Soweto uprising.

This long-ago-forgotten activist work forms part of the photographer’s new twenty-one-volume anthology, Santu Mofokeng: Stories (2019). The outcome of a multiyear collaboration between Mofokeng, the bookmaker Lunetta Bartz, the editor and New York Public Library curator Joshua Chuang, and the German publisher Gerhard Steidl, the series is a major restatement of Mofokeng’s career. Its selection of 584 photographs draws upon an archive of approximately 32,000 frames. The earliest photographs date back to 1985; the most recent are from 2011. There is a somber finality to this closing bracket. In 2013, Mofokeng began to lose his voice. He was later diagnosed with a degenerative illness known as progressive supranuclear palsy. He is now confined to a wheelchair, unable to speak.

Stories is a major expansion of the public archive of Mofokeng’s practice, but in other ways it also efficiently clarifies older work. Photographs that once appeared singular, or unhinged from context, or too instrumentally bound to grand themes of struggle and belief, are now revealed to have emerged from very particular projects. Some have to do with indigenous customs (Pedi dancing) and localities (notably, Soweto and Bloemhof), and were made over a number of years. Others, though, are strikingly time-bound—like Concert at Sewefontein, his experiential photo-essay on youth and pleasure in rural South Africa on a Friday night in 1988, or Funeral, a remarkable sequence on the tenant farmer Miriam Maine’s burial on November 21, 1990.

Santu Mofokeng, Dukathole Funeral, Germiston, 1988

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Stories includes two volumes devoted to Mofokeng’s work between 1996 and 2010 in Motouleng and Mautse Caves. “I grew up on the threshing floor of faith,” writes Mofokeng in the introduction to the volume titled Caves. (The books are otherwise spare in design, and most don’t contain captions.) “A faith that is both ritual and spiritual—a bizarre cocktail of beliefs that completely embraces pagan rituals as well as Christian beliefs. And while I feel reluctant to partake in this gossamer world, I can identify with it.” This passage is from a 2011 text he wrote for Chasing Shadows. The word reluctant is telling. Mofokeng’s work in the caves was bound by an ambivalence and an agnosticism; this attitude framed his participation in a ritual he understood intimately, but could not believe in.

“Apartheid was a roof,” Mofokeng wrote in a text accompanying his exhibition Invoice. “The demise of apartheid has brought to the fore a crisis of spiritual insecurity for the many who believe in the spiritual dimensions of life. Today, this consciousness of spiritual forces, which helped people cope with the burdens of apartheid, is being undermined by mutations in nature. If apartheid was a scourge the new threat is a virus; invisible perils both.”