Aperture's Blog, page 81

October 15, 2019

In Sigmar Polke’s Experimental Images, the Negative is “Never Finished”

A striking exhibition in Paris revisits the treasures and dreams hidden beneath the German artist’s unorthodox photographs.

By Carole Naggar

Sigmar Polke, Untitled, 1970–1980

Courtesy Georg Polke Collection and © Sigmar Polke, Cologne/ADAGP, 2019

Like Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke emigrated from East Germany to Düsseldorf, West Germany, during the Cold War. Since the 1970s, he has emerged as a representative of the second generation of artists in postwar Europe. Polke, who died in 2010, is known primarily for his intriguing paintings, but Photographic Infamies, his striking exhibition at LE BAL—an independent platform in Paris centered on the contemporary image in all its forms—presents a never-exhibited corpus of three hundred photographs from the private collection of his son, Georg. The photographs were made from the 1970s to 1986, a period when Polke concentrated on photography as much as on painting.

In these images, Polke violates all the codes accepted by professional photographers. Blurring, overexposure, multiple exposures, reverse effects, superimpositions, solarization, scratching, xeroxing, and copying are only a few of the methods he uses. His unorthodox photographic approach includes printing several negatives in sequence on the same sheet of paper, the use of outdated chemistry that creates unpredictable tonal gradations, and brushing on the developer to obtain a kind of gestural effect, like a quote, a faraway echo of Expressionist painting.

Sigmar Polke, Untitled (Lady Shiva), 1977

Courtesy Georg Polke Collection and © Sigmar Polke, Cologne/ADAGP, 2019

There is a sense of both glee and violence toward the material, a sense that Polke does not care about the final result as much as he cares about the experimentation, the process itself. “It’s the procedures in and for themselves that interest me,” he explained in a 1997 interview with Martin Hentschel. “The picture is not really necessary. The unforeseeable is what turns out to be interesting.” Like a mad alchemist in search of gold that is secreted within the most common metals, Polke constantly pokes at the photographic surface, intent on finding the treasures hidden beneath it, transmuting the most banal shots into something else, something that he would like us to not call art. But unlike the alchemist, Polke may not believe that his quest has an end. “A negative is never finished,” he once said.

Sigmar Polke, Untitled, 1970–1980

Courtesy Georg Polke Collection and © Sigmar Polke, Cologne/ADAGP, 2019

Polke’s material is as varied as the processes he uses: he mixes and matches different sources, from family album pictures and amateur, anonymous photographs to those taken during his travels to New York, Paris, Venice, Tunisia, Afghanistan; images taken under the influence of drugs to publicity shots; news images to scientific imagery. During meetings in the Rhineland art circles of the 1970s, he often passed the camera around, so that he would appear in some of the photographs as a “model.” When, in the early 1970s, he photographed those that slept rough on the Bowery, on New York’s Lower East Side, he modified the pictures during development, adding spots and blurry parts, as if he had wanted to physically replicate the dust covering the men’s bodies. The pictures seem as if they were corroded from within. These images, to me, are especially striking, as they recall the senseless murder of four homeless people on the Lower East Side earlier this month. In a way, far from the condescending stance found in many “humanistic” images of poverty, these seem strangely prophetic.

Sigmar Polke, Untitled (Hannelore Kunert), 1970–1980

Courtesy Georg Polke Collection and © Sigmar Polke, Cologne/ADAGP, 2019

However, on the whole, Polke’s photographs do not provoke empathy in the viewer. Rather, they disturb, because of the ambiguous responses they provoke, sometimes conveying a sense of urgency, crudeness, and vulnerability, sometimes sheer voyeurism, sometimes a strange aloofness reminiscent of surveillance photographs. Far from the “real world” that most photography documents, Polke’s territory is more akin to dreams and the unconscious.

Has Polke photographed what he could not paint? Looking at his images, I was reminded of a reflection made by Maurice Betz, a poet and close friend of Rilke, about the poet’s letters: “the letters are a lining to Rilke’s poetry, but a beautiful lining: if we turn the coat inside out, we’ll see that this variegated, multicolored lining is as rich as the fabric.” It seems to me that, turning the coat inside out, Polke’s photographs are like the lining of his paintings: even though they vastly differ from the latter, we sense that only a painter could have taken—or rather, made—them. In the end, in his photography as in his painting, Polke willfully remains unclassifiable, elusive, and unknowable.

Carole Naggar is a writer and photography historian. Her latest book is Tereska and Her Photographer: A Story (2019).

Sigmar Polke’s Photographic Infamies is on view at LE BAL, Paris, through December 22, 2019.

The post In Sigmar Polke’s Experimental Images, the Negative is “Never Finished” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 4, 2019

Inside the Auction to Benefit Aperture, Presented by Christie’s

Highlights from the first major event of Aperture’s 20/20: A Bold Vision capital campaign.

William Wegman, On and On, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Thank you to everyone who contributed to making the Christie’s New York auction to benefit Aperture such a success.

Many months in the making, the October 2 auction featured over fifty works generously donated by artists, collectors, gallerists, and Aperture patrons—including photographs by Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Walker Evans, Nan Goldin, Todd Hido, William Klein, Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Joel Meyerowitz, Richard Misrach, Vik Muniz, Paul Outerbridge, Herb Ritts, Hank Willis Thomas, Paul Strand, and a large-scale work by Paolo Ventura made especially for this auction.

Christie’s Photographs auction to benefit Aperture on October 2, 2019

Katie Booth/Aperture Foundation

Works sold for over $715,000, and achieved an auction record for William Wegman with the sale of On and On (2015), a large-scale multipanel work donated by the artist.

Proceeds from the auction will directly fund Aperture’s purchase of a new permanent space in New York—a flexible meeting, education, and event space and HQ for Aperture’s global publishing operations.

Darius Himes, Christie’s international head of photographs, leads a guided tour of auction works to benefit Aperture.

Steven Davis/Aperture

Aperture creative director Lesley Martin highlights current and upcoming projects.

Steven Davis/Aperture

Festivities kicked off with a Saturday night cocktail preview and reception for the photography community, including collectors, artists, curators, and longtime Aperture supporters.

In the days leading up to the sale, all contributed works were exhibited in Christie’s new photography galleries, where Darius Himes, Christie’s international head of photographs, and his colleagues led numerous guided tours for museum groups and collectors. Himes also hosted a panel featuring Aperture editors Michael Famighetti (Aperture magazine editor), Lesley A. Martin (creative director), and Denise Wolff (senior editor). Held in the Woods Room at Christie’s, the editors’ presentations laid out the mission and history of Aperture’s original founders, highlighted current and upcoming projects, and dove into recent examples of educational programming and traveling exhibitions. Also presented on-site were rare items from our archive, including an original first issue of the magazine, along with early editions of seminal books in Aperture’s history.

For the latest news about Aperture 20/20: A Bold Vision, follow us on Instagram.

The post Inside the Auction to Benefit Aperture, Presented by Christie’s appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Protected: Inside the Auction to Benefit Aperture, Presented by Christie’s

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: Inside the Auction to Benefit Aperture, Presented by Christie’s appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Inside the Opening Reception of the Audubon Mural Project: Photographs by Gail Albert Halaban

On Thursday, October 3, Aperture patrons, artists, and friends gathered at Aperture Gallery to celebrate the opening of the Audubon Mural Project: Photographs by Gail Albert Halaban.

Guests

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Guest, Jill Fairchild

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Guest, Jennifer Bogo

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Cathy Kaplan, Gail Albert Halaban, guest

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Guests

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Jill Fairchild with family and friends

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Jennifer Bogo, Chris Boot, and Jill Fairchild give opening remarks

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

Steven Davis/Aperture Foundation

The exhibition, on view through October 15, showcases Albert Halaban’s photographs of murals depicting imperiled birds, each loosely based on the watercolors of John James Audubon, the pioneering nineteenth-century ornithologist. The murals, sited in and around the neighborhoods of Harlem and Washington Heights, where John James Audubon lived and worked, were created by a spectrum of artists—from fine-art painters to graffiti artists—and are the result of a collaboration between the National Audubon Society and Gitler &_____.

In 2019, at the initiative of Jill Fairchild, Albert Halaban was commissioned to document a selection of these murals before—given the transient nature of street art—they begin to fade or disappear. Albert Halaban’s resulting photographs place the murals within the context of the community, reminding us that birds and people coexist, and that we both need a healthy environment in order to survive.

Like the murals themselves, the exhibition serves as a fresh way to bring attention to a critically important conservation crisis. More than 350 species of birds pass through New York City each year, seeking out scattered patches of the city’s greenery. Yet Audubon’s new climate report shows that two-thirds of North American birds are vulnerable to extinction because of climate change.

“I thought there should be an artistic and documentary record of the murals, and an exhibition, because these murals are ephemeral, soon damaged by weather or graffiti, and to spread awareness about the project, and the fragility of our bird population. Many of these birds are now endangered species,” remarked Jill Fairchild. “Our lives are enriched by the diverse beauty of birds, and their song. So now, let us celebrate the birds of Harlem.”

Works featured in this exhibition are available for sale, with proceeds benefiting the National Audubon Society and supporting Aperture’s publishing and public programs.

For more information about the Audubon Mural Project or to sponsor a future bird mural, visit audubon.org/amp.

This exhibition is made possible with the generous support of Jill Fairchild.

The post Inside the Opening Reception of the Audubon Mural Project: Photographs by Gail Albert Halaban appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 3, 2019

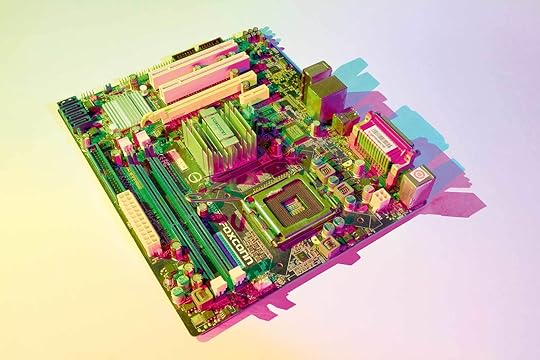

All That Glitters is Fool’s Gold

From the gold rush to e-waste, Lisa Barnard’s new photobook offers a visual biography of a precious commodity.

By Elena Goukassian

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Lisa Barnard’s new photobook, The Canary and The Hammer, is a whirlwind tour of humanity’s relationship to gold, from the Inca Empire to the California Gold Rush to present-day China, where the precious metal is both harvested out of toxic imported e-waste and studied in experimental medical circles. Through photographs, historical documents, and original texts, Barnard offers a non-linear, visual biography of gold and its exploitative, capitalist history. Of the book’s title, she writes, “Much like the canary taken into the coal mines in the twentieth century, gold is the gauge by which we monitor our economic stability. The hammer is the tool that smashes the structures in which it is embedded.” The project serves as the political artist’s response to the 2008 financial crisis, an exploration of our continued preoccupation with the accumulation of wealth.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Elena Goukassian: Did you envision from the beginning that The Canary and The Hammer would span four years and as many continents? Did certain locations and narratives lead to an interest in other locations and narratives?

Lisa Barnard: I really wanted to make a project that reflected the fragmented society that we now inhabit. I was keen to look at how photography could represent visually not only what I was photographing, but also the structure of how I was putting the work together, which felt very chaotic. So, I always knew that the form of the project was going to be anti-formulaic and anti-series [compared to] how the art world works. I wanted to reference this idea of photography being this ubiquitous material, much like gold. (And gold, obviously, is everywhere; it’s very embedded within society.) I wanted to look at how gold as a material reflected our relationship to photography. It was about trying to organize and articulate the impossibility of articulating one truthful event through a traditional series of photography.

To make something that was very fragmented meant following multiple narratives around the world. While working in America, I didn’t realize that a third of the workers during the California Gold Rush came from China. Then I started to research China and discovered that China imported all of America’s e-waste at the time, in 2015. So, of course, then I wanted to go to China. Everything that I researched had a springboard effect of where I wanted to go next.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: How did you decide on the scope of the project?

Barnard: There were, and are, a number of places that I still want to go to. I’ve only touched the surface of this project. I wanted to get to a conclusion, because with this sort of work, if you sit on [a set of research] too long, it’s not valid any longer. You could end up updating the whole project all the time, because capitalism and the relationship between gold and finance move incredibly quickly.

The project is about what I managed to make stick, as far as the access that I had and the people that I met. There were multiple narratives that I could’ve done in order to tell the same story in a different way. I’m really interested in who writes history and how history is written. Most of history comes from men, so an important narrative for me was this idea of the subjugation of women within the narrative.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: In a number of your works in the book, you use gold or fool’s gold in the art-making process—for example, the gold leaf on the back of the portraits of the pallequeras, female sorters of ore for gold pieces at the gold mine in Peru. How did you choose the specific pieces to focus on and how did you decide when to use real gold versus fool’s gold?

Barnard: The gold leaf was a way of trying to give value to the women in Peru. In Edward Curtis’s images of Native Americans, he used a process called orotone, where he put gold leaf on the back of glass plates. I wanted to reference that idea of the camera as a weapon of exploitation, and I wanted to counteract that by placing gold leaf on the back of these women that I spent time with in Peru, to try and give them value, as a way to tell people that I’m aware of the problems of being a European and going in and exploiting Native people for my own ends and for my own storytelling.

The fool’s gold I used on the 3-D renders of asteroids from NASA. I laid gold gesso and then did some screen prints on top of the asteroids. I suppose I wanted to use fool’s gold [to reflect] that the next capitalist expansion is going to happen in space—the plundering of asteroids—and how foolish that whole process will be. My fool’s gold was pointing to the ridiculousness of plundering one planet and then going off and looking for other places to plunder.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: You’ve noted that photography is a part of the capitalist narrative and often used as a tool to exploit. How do you reconcile this reality as a photographer?

Barnard: As a photographer, it’s very difficult for me to discuss using photography. This was an attempt to do it, but it becomes increasingly difficult. How do you justify getting on an airplane, spending a huge amount of money destroying the earth, in order to go and photograph Native people in their own country? How can you justify that? As a white European, I’m finding it increasingly problematic to come to terms with that, and my role within it. How do we justify making photographs as documentary photographers? There’s a very traditional, closed-off way that documentary photography is viewed, and I think it’s important to challenge that as much as possible.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: You seem to challenge this “traditional” view of documentary photography, at least in part, though your incorporation of historical photos and documents. How do you balance the use of archival materials with your own photography?

Barnard: I’m really interested in our relationship to archive. I do lectures on Derrida’s Archive Fever (2005), and I’m interested in the power play with archives. Artists tend to use archives quite randomly and irresponsibly—they dip in, use them, and create a new narrative that’s connected to their narrative that they want to talk about.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: They superimpose their own narrative on archival material.

Barnard: Exactly. And obviously, in relation to colonialism, that’s really problematic, because you’re rewriting. You need to be responsible. I’m interested in this idea of being a responsible photographer in relationship to archive. Archives for me are used purely as text, a way of underpinning a particular idea that I want to discuss. I’m not using them in a way that’s different from their original use. For instance, with Operation Fish, [when, in 1939, the UK evacuated gold bars to a clandestine location in Canada, hiding the nation’s wealth from the advancing Nazis], this was a particular narrative that I knew nothing about. I got in touch with Rodney Agar, and he was really happy for me to use the archive at the Imperial War Museum in London. I was keen to make sure that I used it responsibly, because these were personal photographs that were taken by his uncle [Augustus Agar, an officer in the Royal Navy]. Archives, for me, have a very specific means to an end; I’m not trying to reinvent anything.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: Do you think that gold will ever lose its power over humanity?

Barnard: No, I don’t. Because of gold’s ubiquitous use within the medical and science fields, and within mobile phones and screens and TVs and everything, I think there’s always going to be a need for it; there’s always going to be a desire for gold that is going to outweigh anything else. And there’s only a finite amount on earth. But it depends if we can plunder asteroids, because if the market becomes saturated with gold, it will potentially lose its value. So, who knows what will happen in the future.

Elena Goukassian is a copy editor at Aperture Foundation.

Lisa Barnard’s The Canary and The Hammer was published by MACK in September 2019. Excerpts from the book and additional stories of humanity’s relationship to gold are available on the project’s website, The Gold Depository.

The post All That Glitters is Fool’s Gold appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 27, 2019

Notions of Land

For Indigenous artists, can photographs provide a space of visual sovereignty?

By Wanda Nanibush

Meryl McMaster, Bring me to this place, 2017

Courtesy the artist; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, Montreal

Imagine a lonely warrior slumped over his horse, backlit by a sun setting over rolling hills, or a group of warriors riding off toward the horizon. It isn’t hard for most people to conjure because we have been raised on these romantic images of the so-called vanishing Indian. Photography, which developed hand in hand with colonialism, has largely been responsible for the continued stereotype of the noble savage. What “Indians” are admired for—the idea of being one with nature, one with the land and animals—is also seen as the source of their inferiority and inevitable demise. It is given as the main reason they are unable to survive in modern society: “Indians” are part of nature, not civilization, and, by extension of this argument, less than human.

American photographers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, like Edward S. Curtis and Joseph Kossuth Dixon, to name only the best-known, used photographs to link Indigenous Peoples to the idea of “nature” in order to speak about the end of Indigenous “nobility”—an end that was connected to the introduction of supposed “civilization” in the form of white-settler communities. Photography itself was considered part of the proof of white superiority because of its basis in technological innovation.

All stereotypes have a minor truth to them: in this case, it’s true that Indigenous Peoples have a kinship with land and animals. We do think that all living things have a spirit. The idea that the earth is our first mother and that animals are our kin and can communicate with us through visions, dreams, and signs is central to many Indigenous cultures. But is this all based on clichés and superstitions? No. These facts were deeply misunderstood and parodied for the sole purpose of justifying the removal of bodies blocking the path of settler colonialism; today, this view is used to rationalize the extraction economy as well. In recent photographic works, a number of Indigenous artists are beginning to debunk these colonial “facts” and counter them with deeper understandings of our relations with “nature.”

Robert Kautuk, Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada, July 22, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Robert Kautuk, from Kangiqtugaapik (Clyde River) on Baffin Island, in Nunavut, Canada, uses photography to document the daily life of an Inuit community, in particular their relationship to the land, weather, and animals. For me, a southerner, viewing his aerial photograph Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada (2016), of an ice floe covered in blood after a successful walrus hunt, is almost surreal. South of the Arctic, this is not what our hunting looks like. In Kautuk’s photograph, the red bloodstain spreading across beautiful white ice is set against the deep blues of the Arctic Ocean. There are minute details of hunting gear, a small boat filled with necessary supplies, and people braiding intestines. You want to look closer at this almost dollhouse-scale perspective, which was taken with Kautuk’s Phantom 4 drone rather than his digital single-lens reflex camera.

Kautuk also employs his skills on a digital mapping project called the Clyde River Knowledge Atlas (2015–ongoing), which draws on elders’ and harvesters’ knowledge of local Inuit place names and the environment. The atlas is an important tool for sharing resources on environmental assessments, changes, and uses, and the names for places in the Inuktitut language are critical for determining the locations of people who find themselves in an emergency. Kautuk’s photographs and the new atlas may also have a lasting impact on Inuit communities’ ability to assess the desirability of outside development projects. In 2017, Clyde River won a Supreme Court of Canada fight over the National Energy Board having granted permission to energy companies to do seismic testing for underwater oil in Nunavut. The court justices ruled that the NEB had trampled Clyde River residents’ rights as Indigenous Peoples and had failed to consider the necessity of subsistence hunting for Inuit existence. Clyde River’s former mayor Jerry Natanine, who fought for years to have this Inuit way of life acknowledged and respected, felt vindicated by the ruling.

Kautuk, in his way, is doing the same by preserving the beauty of the land and of the hunt; Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada gives intense presence to Inuit survival. Unfortunately, the hunt, especially of seal, has long been misunderstood by southerners and Europeans, often in the name of environmentalism and ecology. Many people do not understand that grocery-store food is very expensive in Nunavut and often just not available, so hunting is the only way to eat. A diet of whale, walrus, seal, arctic char, and bear is also healthier physically and spiritually for the Inuit people. Hunting is tied to cultural practices that keep alive ways of being that hone the collective spirit through sharing, honoring, singing, and remembering the hunt. In this context, a photograph of a walrus hunt is an act of resistance.

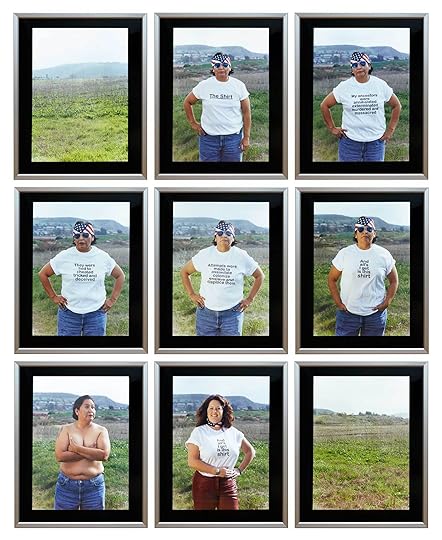

Shelley Niro, The Shirt, 2003

© the artist and courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario

The ways in which photography can express Indigenous presence on the land also include more conceptual, performative work, such as Shelley Niro’s series The Shirt (2003). Niro is a member of the Turtle Clan of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation. The Shirt is a unique set of nine photographs that, taken together, create a narrative of Indigenous sovereignty where women are central. Niro often constructs her photographs by having people perform for the camera; in this case, her friend and fellow photographer Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, of the Taskigi Nation and Diné Nation, faces the lens, confronting the viewer directly. She is photographed in the landscape wearing a series of five T-shirts that sequentially say: “The Shirt”; “My ancestors were annihilated exterminated murdered and massacred”; “They were lied to cheated tricked and deceived”; “Attempts were made to assimilate colonize enslave and displace them”; “And all’s I get is this shirt.” In the sixth image, she appears without any shirt; in the seventh, a smiling white woman wears the final shirt of the series. These seven photographs are flanked by images of the land, underscoring the importance of land rights to Indigenous struggles for self-determination. In Niro’s work, the shirt becomes a souvenir from the highway of colonialism, ripped off the backs of Indigenous women who live there. Because the shirt is an object many people have encountered and is a form of self-expression, statements about the colonial land grab become readable and relatable to a broad, diverse audience.

According to Niro, “The Shirt series came about as I flew over the Texas landscape. I looked out of my window and saw the land below chopped up into squares, each square neatly fenced off from the other. I thought about the ‘Indians’ who fought for that land, as well as the sacrifices made by tribes and nations in their efforts to keep away the settlers from their land and communities. Hulleah’s presence gives the series seriousness and strength.” The presence of a Diné woman in this terrain also draws attention to the connection between violence against Indigenous women and the land: in an extraction-based economy, “man camps”—sites of temporary worker housing—spring up, and violence against the local Indigenous women also rises. Historically, as well, colonization has specifically targeted women, reducing them to the property of men under many policies and laws, including the 1876 Indian Act in Canada. Niro “believes narrative delivers a personal contact with the viewer”; her work asks viewers to be actively and empathically engaged, to place themselves in relation to the narrative as perpetrators or survivors of colonialism.

Jeff Thomas, Bert General Husking White Corn, Six Nations of the Grand River, 1980, from the series Corn Husks

Courtesy the artist

Walking the line between construction and documentary is Onondaga photographer Jeff Thomas, who grew up in Buffalo, New York, and is a member of Six Nations of the Grand River. When Thomas visited the Six Nations reserve in Ontario, Canada, in the 1970s, he was taken with photographing the homes and daily lives of elders, resulting in his series Corn Husks (1976–2011). He states that his step-grandfather “demonstrated how to weave the corn leaves into long strands…. The act of weaving corn leaves into a braid is a symbol of the Indigenous teaching that all living things are interconnected.” Thomas purposely photographs the process of creation rather than the finished product, citing the bodily memory that is the basis of cultural knowledge. In the image Bert General Husking White Corn, Six Nations of the Grand River (1980), the movement of ripping husks from corn is culture in action. Thomas sometimes juxtaposes his images with archival photographs to create more complex narratives; White Corn (2014/2017) is composed of three photographs by Thomas and a fourth taken in 1912 by English anthropologist Francis Knowles, titled Chief Jacob General. These photographs are laid out like a wampum belt, a traditional medium for passing on oral history; Thomas uses photography as memory in place of wampum beads.

The way the physical environment can evoke centuries-old knowledge and function as a kind of memory making for Indigenous Peoples also informs the photographic practice of Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) artist Greg Staats. In the striking work untitled (restraint_constraint) (2015), he delves into the psychological aspects of place. A tree trunk with roots still embedded in the earth but with many severed parts fills almost the entire image plane; only a slight vision of concrete appears in the background. The work evokes a liminal space between the grounded and the uprooted while giving no particular markers of place. Staats describes his practice as “in service to orality of place and natural world mnemonics—objects/images and place share a long wordless relationship reunited to further their cause of holding together the unsaid.” The trunk becomes a poetic rendering of Indigenous Peoples finding their way back home through the trauma of colonialism, which has left many with severed roots.

Greg Staats, untitled (restraint_constraint), 2015

Courtesy the artist

The land as a carrier of traumatic memory also forms a backdrop for Cree artist Meryl McMaster’s latest photographic series, Edge of a Moment (2017), made in Alberta at the Head- Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This spot was once key to Indigenous survival, especially for the Cree and Blackfoot of the prairies. Here, they would run buffalo off the cliff in huge herd hunts; such hunts occurred up until the 1880s. Settlers and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police massacred the buffalo almost to extinction to starve Indigenous Peoples onto reserves. McMaster uses herself as a model, constructing elaborate costumes to wear in these conceptual photographs. In the series, she a wears a coat covered in a printed chicken-feet pattern along with a hat fabricated from prairie chicken feathers. McMaster explains, “The feather bustle we see male traditional dancers wear is modeled after the chicken’s tail feathers. I use their tracks in an abstract way to cover the garment I am wearing within the image. Their absence represents to me not only the dangers of the unsustainable use of the land, but also the human consequences of colonization and settlement.” As McMaster makes clear, photography in the hands of Indigenous artists forms a body of philosophical, poetic, and physical knowledge of our relationship to land and the history of colonial ruptures. Photographs provide forms of visual sovereignty and assert a continued presence on the land, despite centuries of theft and removal.

Wanda Nanibush is curator of Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Notions of Land appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 26, 2019

How to Map a Territory that You Don’t Own

Mitch Epstein discusses Standing Rock, the American flag, and the moment he saw Mount Rushmore cry.

By Rebecca Bengal

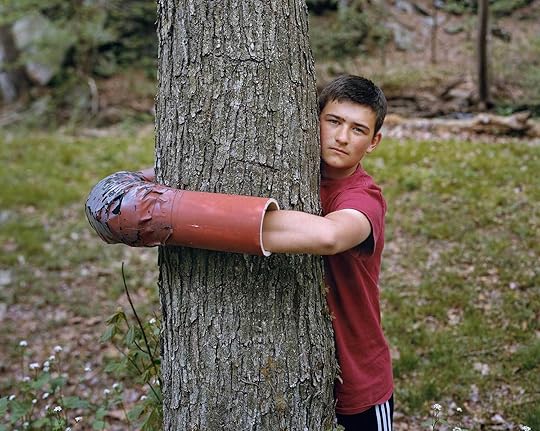

Mitch Epstein, Lancaster Against Pipelines Lockdown Device, Pennsylvania, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Since the mid-1970s, as one of the first artists to significantly embrace color photography, Mitch Epstein has often depicted land and our relationship to it, whether in his early cross-country trips, or in his 2009 book, American Power, an epic chronicle of our attempt to wrest energy from the Earth, or in his meditations on the clouds, rocks, and trees of New York City. He traces the genesis of his most recent project, Property Rights, currently on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. in New York, to the resistance movement that took hold in late 2016 in the wake of the US presidential election. Yet he also refers to the artistic influence of multiple works outside of photography, including Arthur Jafa’s film Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016). Property Rights, though it focuses mostly on threatened landscapes, is part of an established trajectory mapped out over decades of work, fully evident in Epstein’s latest photobook, Sunshine Hotel (2019), which threads recent photographs made as part of Property Rights into an anachronistic sequence that heightens the connections between new and archival photographs.

Mitch Epstein, Standing Rock Prayer Walk, North Dakota, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

I have followed Epstein’s work for many years, but we first began speaking in early 2017, after I returned from a series of trips to the Indigenous-led resistance camps fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Epstein was preparing a visit there, in the wake of President Trump signing orders to advance construction of the Dakota Access and Keystone pipelines. Our conversation would continue over the course of many months, studio visits, and a story collaboration for which we both returned to Standing Rock to follow a four-day prayer walk led by water protector and activist Nathan Phillips. A photograph from that prayer walk, depicting a continuous human line traversing a snowy roadside and bisecting a farm road that leads directly to the Missouri River, is featured in the exhibition alongside images of tree-sit structures high in Pennsylvania white pines, the prehistoric ecology of the Ironwood Forest in the Sonoran Desert, a woman peering through a prototype of the US–Mexico border wall, and others we spoke of here.

Mitch Epstein, Tree Sits, Camp White Pine, Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Rebecca Bengal: The earliest photographs you made as part of Property Rights are from your first visit to Standing Rock. Where did the project begin for you?

Mitch Epstein: The motivation, or the insistence, to go to Standing Rock was the result of having lived through the election and Trump’s inauguration and going with my wife, Susan Bell, to the Women’s March and feeling this surge of resistance, and also to step out into the middle of something that was so divided, at least as it appeared to me.

I had followed Standing Rock in the media and I wanted to go in the fall of 2016, but I had an injury. And then when Trump did an about-face there, I decided I had to go. I went with the expectation that I would make some pictures, but I wasn’t thinking about the long game of making a project. I just went with an open mind and eyes, and also a lot of warm gear because it was probably some of the coldest weather that I ever experienced—the real temperature was ten below and windy when we landed in North Dakota.

Mitch Epstein, William Nelson Williams III ‘Nine-Tails’ and Joshua Flyinghorse, Rosebud Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

When we arrived at the camps, it involved a certain amount of negotiation to be welcomed as a picture maker, but that led me to one of the most profound experiences of being there, which was meeting elders—matriarchs, referred to by some as grandmothers, repositories of deep knowledge, who were in the face of these adverse conditions. I did some video interviews. It was listening to them, to their stories, that encouraged me to think in ways that I hadn’t about some of the historical imbalances, the wrongs. Those conversations and the real righteousness of those voices stayed with me and enabled me to begin to think in a more extended way about how compelling and challenging it would be to do a piece about land in America that would hopefully bring about some new way of looking at it, this notion of who are we to think we can claim ownership of land?

Mitch Epstein, Blue Mesa, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: You recently Instagrammed a research map with pins marking the sites all over the country where you plotted potential locations for these pictures. How did the project begin to evolve for you after Standing Rock?

Epstein: I have a great studio manager, Ryan Spencer, and we’ve brought the process of research into the studio in a way that provides a very broad road map to thinking about what might instigate something for me. We learned about a community in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Lancaster Against Pipelines, which was fighting the construction of a natural-gas pipeline. I reached out to a man named Mark Clatterbuck, and I was expecting to have to go through the kinds of high-stakes visits that I did at Standing Rock to even be admitted to make a visit there, and he just said, “Oh yeah, come on down.”

As soon as I got to Lancaster, what was so interesting was this community that was gathering on a Saturday on this farm and meeting to discuss what options there would be to protest. Many of them were subject to having their lands taken over by eminent domain; these people would otherwise be playing tennis, at the farmers’ market, and yet they were there because they felt strongly. They were not extreme; they were not typical activists. They were like me. I was really touched by that, and I began to see how I could make work in Lancaster. I probably made seven or eight trips down there over the course of a year, and then I spanned out to do much broader research that was more continental in scope.

Mitch Epstein, Ashton-Clatterbuck, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: There’s a wonderful picture of Ashton Clatterbuck—a young activist and the son of Mark and Melinda Clatterbuck—who was arrested during one of the Lancaster actions. You photographed him locked to a tree as if he’s also embracing it [Ashton Clatterbuck, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 2018].

Epstein: I had gotten to know the family for two years, and I was very moved to see the ways in which these tools of resistance were used. This lockdown device was handmade and weathered, and I wanted to make some pictures outside of the actual actions that showed the relationship to those tools, the urgency of that engagement.

We weren’t near a construction site, but all I had to say to Ashton was, “Put yourself in that place where you were when you were arrested.” The way it gets distilled down to its most simplistic form, to lock himself to a tree, was such a perfect metaphor for protecting nature. He was so invested emotionally. He’s at the heart of his adolescence, but he also has the look of an adult. He’s taking on the responsibility of an adult. He’s a bit like Greta Thunberg in that way.

Mitch Epstein, Mount Rushmore National Memorial / Six Grandfathers, South Dakota, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: Trees and rocks, respectively, were the subjects of two recent bodies of your work, and they appear here in these pictures, perhaps most notably in this remarkable photograph of Mount Rushmore, drenched in rain and fog [Mount Rushmore National Memorial / Six Grandfathers, South Dakota, 2018].

Epstein: I think even photography that’s engaging with the world in a representational, descriptive way involves a kind of appropriation. For me, the question was how to take something that’s so imaged and iconized and contrived and bring some kind of fresh reading to it.

When I was twelve, I went on a cross-country trip that included the Badlands, and I remember going to Mount Rushmore and standing in the place the Kodak sign told you to stand and make this perfectly framed, very idealized picture. In 2018, when I made a trip to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, it was interesting because people would either say to me, “Oh don’t go to Mount Rushmore, or we’re not going to talk to you anymore,” or other people would say, “You must go there.” In the end, I made what was sort of an enforced pilgrimage for a white guy. We got a permit from the National Park Service, but after three days of rain, finally we decided to just go scout it.

In this upper altitude in the Black Hills, you have this variable weather, and we were fortunate because the monument itself was coming in and out of cloud cover, and because of the rain, the area wasn’t so trafficked. Then I looked closely at the faces of our presidents, and it was stunning to see the water running down their faces. I mean, that’s pretty straightforward. But it was after our permit time, so we snuck in. You know, I’ve seen North by Northwest; you’ve just got to be clever, right? It’s not like an 8-by-10 is so big, but we had gear and so on; we used our tarps like ponchos. We found a bit of cover from the rain by the elevator that gave a good vantage.

Mitch Epstein, Border Wall, Nogales, Arizona, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: Which I love. And I’m just struck by the fact that although we’re looking at rock—this very photographed and controversial rock—here’s so much that is activated in this picture, so much interplay and surprise here.

Epstein: I think the photographs of mine that endure are ones that engage with time in multiple ways. They’re absolutely of that present that they’re made in. But they have this potential to reference the past and exploit or incorporate it into the tableau of the picture, and also to speak prophetically to the future. Here, when I stepped back, I realized that I could frame these mountain peaks and these carved stone faces, which were a kind of profound violation of the sacred Lakota site known as the Six Grandfathers. The forms themselves are very distinguished, like certain Chinese landscapes. And I wanted to see and to make dead center all the shot rock that was a consequence of the dynamite; all of this is really at the gut of the picture. And at the same time, you see these burgeoning, fertile fir trees.

Bengal: The trees have an almost lifelike energy, as if they’re running up the mountain.

Epstein: They’re shooting up out of the landscape. You’re confronted with the evidence of what it takes to carve a sculpted form like that into stone. But also, the atmospheric quality of the fog alludes to the fact that, in time, these faces are not going to be here anymore. They’re going to erode. This has been a gift in my later work: I see how small I am, how small we all are, and that’s humbling.

Mitch Epstein, Refugee Halfway House, El Paso, Texas, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: And as talk of the president’s border wall and threats to immigration rights escalated, you began to photograph in South Texas and Arizona.

Epstein: I was compelled to spend time in border regions, to look at the cultural exchanges that was very unique to those places: people who were operating under fear and extremism and wanted to protect what they thought would be threatened by immigration. It was not so simple, and also not so simple to try to picture these things.

I made this photograph of a bunk bed in El Paso in 2017 [Refugee Halfway House], when it wasn’t as contentious at the border as it is now. But this was a Catholic mission—this was a place where people could have sanctuary while they awaited their asylum trial to gain immigration status. What spoke to me about this was how it relates to everybody. Everybody deserves and needs a bed, with a pillow and a sheet and a blanket, and a towel. These are the things we take for granted, and they’re so elemental, yet also personalized through the palette of these items and the photograph itself. When you imagine the passage people take, this near-death experience to get into the United States, to have a bed waiting for you.

Mitch Epstein, Bisbee, Arizona, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: There are no people in the picture, but there’s definitely a human impression in the folded towel and the bed made with the flowered sheet. And you see the impression of humans here, too, in all these torn and covered messages [Bisbee, Arizona, 2017].

Epstein: I was driving from Tucson on my way to a site right on the border, and suddenly I drove into this place with a lot of visible prosperity, Victorian houses, a whole town seemingly growing out of the hillside. A few miles down the road, I pass a giant copper mine. There was a clear equation between the big hole in the ground and this town that was clearly built as a result of this mine. I stopped to make a couple pictures, and then I went to a co-op grocery store to get a drink, and there was this message board. I was just struck by the kind of inherent violence of the way the staple gun was holding this palimpsest of papers to the wall. Then I realized there was this accidental confluence of very poetic but also symbolic words that spoke to the moment: nation, see, meditate, water. For me, it suggested a kind of mapping. And again, back to property rights, the consequence of owning land, and using it or neglecting it, is that it becomes battered.

I also think that in photography, the most surprising and thrilling pictures are often the ones that are made out of nothing. So to me, it was also something, especially in this era when we are so married to our screens, to look at paper photographed with film.

Mitch Epstein, Veterans Respond Flag, Sacred Stone Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: The American flag is represented in several of the pictures—“an exclamation point,” you’ve called it—in your picture of Mount Rushmore, upside down on the back of a prayer walker at Standing Rock in 2018 [Standing Rock Prayer Walk, North Dakota, 2018], and most prominently here, also at Standing Rock, but as seen during your first visit in 2017, against the snow and this very blue sky [Veterans Respond Flag, Sacred Stone Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota, 2017].

Epstein: It’s these punctuating details that often lend ballast. This flag was a kind of technical triumph. It was up high and on a ladder; I used a longer lens than I usually do, and it made it an object that’s more sculptural. An 8-by-10 lens only stops action at 1/125th of a second, so you don’t know quite what is going to result. But there’s something very buoyant about the way the flag is catching the light. There’s beauty in distress.

Bengal: I also see it as a positive sign—of resistance taking hold, the wind visibly stirring it up.

Epstein: It’s quite forceful. It really holds its sky.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

Mitch Epstein: Property Rights is on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York through October 5, 2019.

The post How to Map a Territory that You Don’t Own appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 25, 2019

Celebrating Aperture Magazine’s Fall 2019 Issue, “Mexico City”

Hosted by Selina

Pablo López Luz, Emmanuel Faccio, Kevin Hart, Iñaki BonillasSteven Davis/Aperture

Stuart Cooper, Dana TriwushSteven Davis/Aperture

Tom Schiff, Mary Ellen GoekeSteven Davis/Aperture

Lisa Rosenblum, Andrew LewinSteven Davis/Aperture

Meghan Michelle Gallagher, Amanda BeebeSteven Davis/Aperture

Mary Ellen Goeke, Tom Schiff, Sarah Hermanson MeisterSteven Davis/Aperture

Kevin Hart, Elena Navarro, Emmanuel FaccioSteven Davis/Aperture

Rafael Prieto, Sarah BaxbySteven Davis/Aperture

John Roa, Elizabeth BelferSteven Davis/Aperture

Brendan Embser, Alexis Heit, Kelli OrihuelaSteven Davis/Aperture

Kelsey La Porte, Charlotte DawesSteven Davis/Aperture

Chris Boot, Andrea Celda, Christoph WiesnerSteven Davis/Aperture

Whit Williams Jr., Kate Cordsen, Chris BootSteven Davis/Aperture

Michael Famighetti, Artur Walther, Andrea CeldaSteven Davis/Aperture

Guest, Alejandro CartagenaSteven Davis/Aperture

Julian Jordan, Benjamin Petit, Geraldine MoribaSteven Davis/Aperture

Yola Mezcal

Steven Davis/Aperture

Mayra Martel, Elena Navarro, Natalia Priwin, Brendan EmbserSteven Davis/Aperture

Kiyomi Higuchi, Noah Schwarz, Micaela Lade, Richard GreggSteven Davis/Aperture

Sanket Karuri, guest, Pablo López LuzSteven Davis/Aperture

Steven Molina Contreras, Beth Sacca, Stephen Velastgui, Nathalie AraujoSteven Davis/Aperture

Hamant Kanakia, Stuart CooperSteven Davis/Aperture

Madre MezcalSteven Davis/Aperture

Eva Aridjis, Nanci SarroufSteven Davis/Aperture

Christoph Wiesner, Erin O’Toole, Denise Wolff, David SoloSteven Davis/Aperture

Andrew Lewin, Iñaki Bonillas, Bree Zucker, Sarah Hermanson MeisterSteven Davis/Aperture

Anh Tuan Pham, Anna Ritsch, and Isioma-IyamahSteven Davis/Aperture

Steven Davis/Aperture

Fabiola Alhondra, Brian Crumley, Alfredo Poves, Giada De Agostinis, Amanda Boe, Hari MoirisSteven Davis/Aperture

Madre MezcalSteven Davis/Aperture

Tito's VodkaSteven Davis/Aperture

On September 18, Aperture trustees, friends, editors, and artists gathered at soon-to-open Selina in West Chelsea to celebrate the launch of Aperture magazine’s “Mexico City” issue, illuminating the ways Mexican photographers are pushing new visions in the medium.

The night began with an intimate Mexican-themed seated dinner, paired with specialty cocktails by Yola Mezcal. Aperture magazine editor Michael Famighetti gave a toast and welcomed visiting artists featured in the issue, including Iñaki Bonillas, Pablo López Luz, and Mayra Martell—who were all provided accommodations at Selina during the festivities. “The ‘Mexico City’ issue is part of a series of city-based issues that we do, which is about expanding our purview and bringing new people into Aperture’s community,” said Michael. Surrounding Aperture staff were contributors to the magazine’s most recent issue, including Elena Navarro and Andrea Celda—who was introduced and thanked by Chris Boot, Aperture’s executive director. Also in attendance were Sarah Hermanson Meister, Dolph Hogewoning, Christoph Wiesner, Artur Walther, and Whit Williams, as well Aperture trustees Cathy Kaplan, Hemant Kanakia, Stuart Cooper, and Andrew Lewin.

Following dinner, guests made their way up to Selina’s rooftop lounge to join the after-party, where attendees enjoyed stunning views of the New York City skyline, accompanied by music by DJ Mateo López, elixirs by Madre Mezcal and Tito’s Handmade Vodka, and a selection of Mexican candies.

To purchase Aperture’s “Mexico City” issue, click here.

Sponsors

[image error]

The post Celebrating Aperture Magazine’s Fall 2019 Issue, “Mexico City” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 24, 2019

Tommy Kha Isn’t Kissing You Back

The Memphis-born photographer navigates performative intimacy, the legacy of the Mississippi Delta Chinese, and the pitfalls of visual language for queer Asian men.

By Will Matsuda

There is power and vulnerability in a kiss, and perhaps even more so, in the way a kiss is represented. When Tommy Kha photographs himself being kissed by strangers, lovers, and friends, the stakes are high, especially as a queer Asian man. We don’t often get to see bodies like his getting kissed—not in the movies, on TV, or on gallery walls. I met Tommy two years ago, through a conversation for Aperture about Asian American photographers. This time, I spoke with Kha on the eve of his solo exhibition in New York, Return to Sender, about Asians in the American South, the violence of portraiture, and the visual ancestors he works toward—and against.

Tommy Kha, Prince, Midtown Memphis (Return to Sender), 2019

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Will Matsuda: What is it like to be in a room filled with pictures of people kissing you?

Tommy Kha: It’s very out-of-body to have the space to present this long-form project. Some of the photographs have been converted into slide film, and then projected on an old-school Kodak slideshow carousel. I love the noise. It’s a different feeling than seeing them printed out.

Matsuda: Could you tell me about your deadpan gaze in the photographs?

Kha: While I see the kissing pictures as a performance, the kiss is a very real gesture. It’s all an act, but I’m interested in how, unconsciously, reality intrudes.

The kissers choose how they appear on camera, how they kiss me. There are a few little directions, like how to tilt their head so that the light would be better. It’s their secondary gestures that reveal something—their hands on my face, or neck, or physically picking me up.

Tommy Kha, Kati, (Return to Sender), 2013

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Matsuda: How has the work been received?

Kha: Initially, when the work was circulated online in 2013, there was a backlash. Asian people accused me of perpetuating Asian American stereotypes. Our representations are often neutered in Hollywood, presented as asexual, or rendered flat and as background characters. There was an animosity toward the photographs because of my deadpan face. I tried to explain that it was an expression of my power—I could inhabit that space and make a caricature of it.

Recently, the conversation about the work shifted toward a conversation about consent. It’s interesting how this work can be a part of a very important, and different, conversation than when it first circulated.

Matsuda: About consent specifically? I’d like to hear more about that.

Kha: My friends showed the work to their students, and it triggered a few students, because it appeared that I was being taken advantage of, because of my emotionally unavailable look.

But I want to be clear that I’m not telling anyone they are misreading the images, to not reduce their experiences. There is permission, though. The subjects have to kiss me; I am not kissing them back. I always explain the project and its parameters, and then the permission has been granted. In order for these pictures to happen, a “yes” has to happen.

Tommy Kha, Mike, (Return to Sender), 2010

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Matsuda: I’m interested in the way you think about power. I want to be intersectional about this, but as Asian men, we are rarely portrayed as powerful or sexy. So, I’m curious about the ways you often appear as a passive actor, or diminutive, in your images. At the same time, you have agency, because you are the person constructing the image. There’s this interesting tension. What’s at stake for you?

Kha: I think it comes out of growing up in the South within a foreign body. I don’t see enough work that elaborates on the intersections of being queer, Asian, and Southern.

I think the tension arises from having to decode across my identities—I try to avoid using the word “identity,” because it’s a regular cast member in art speak—and the lack of photographic language that can fulfill those totalities. It’s hard to hit all those notes in every photograph. I’ve resigned to compartmentalizing and working in different iterations and approaches.

Tommy Kha, Us (Brooklyn), 2012

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Matsuda: It’s about being seen.

Kha: Yes, more specifically it’s a desire to be seen. In one of the photographs we picked for the exhibition, I am sandwiched between two men who look like Ken dolls on a bed. But you can only see a sliver of me.

The way I stage my photographs confuses people. People ask me how much of it is staged or if part of it is staged. Is the picture real? And that’s part of the question I am asking myself—how does one arrive to their own representation? I am searching for that answer from both sides of the camera. How do I arrive at myself?

Matsuda: I was in a class with Justine Kurland this summer, and she mentioned the idea that a portrait is an act of violence. As someone who does a lot of self-portraiture, do you ever think of it as an act of violence against yourself?

Tommy Kha, Hotel, New Jersey, 2016

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Kha: Right, Sontag wrote about this. She called a portrait a “soft murder.”

Matsuda: Which is the title of your new book. So obviously, you have been thinking about this.

Kha: Yes, oh, I love talking about Sontag, but only when I bring it up [laughs].

I think of depictions of Anna May Wong in Hollywood cinema, or these reenactments of building the Transcontinental Railroad, restaging them with Asian and women’s bodies. Historically, these bodies were almost never imaged—most notably [left out of] the 1869 group portrait made at the hammering of the “golden spike.”

Soft Murders is the culmination of a family album, sourcing familial imagery alongside my collaboration with my mother, as well as a photocopy news article detailing my aunt’s murder.

Sontag said to photograph someone was to violate them, because the camera/photographer could telegraph information about them. What does it mean when the photographer is the perpetrator, and what information can I glean from people who share my DNA? And in picturing these self-portraits, who owns my photographic shadow, and how much of that is influenced by the past’s visual ancestors?

Tommy Kha, McCoys’ Guest Room, Memphis, 2019

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Matsuda: Since the last time we spoke, it seems like you’ve been spending more time in the South.

Kha: I have found myself down there a lot. Having only a finite amount of time, there is this urgency about photographing the South—it’s a rediscovery. I don’t know if it’s the Old South that everyone romanticizes, like William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor.

Matsuda: It’s interesting to hear you say that, because as an Oregonian, my connotations of the Old South are pretty negative. Given your identities, what do you want to preserve?

Kha: Did I tell you I came across a whole community of Mississippi Delta Chinese that have been living there since the 1920s?

Matsuda: Yes! And that seems urgent.

Tommy Kha, September in Reno, 2017

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Kha: Yeah, so I go down for that. I’m also trying to photograph families who had relatives who died during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and ’90s. Those stories are pretty hidden in the South still. Even talking to people now, there is a sense of protection, privacy, and shame. There’s a woman in Arkansas who buried a lot of people who died in her family’s cemetery.

And circling back to the Mississippi Delta Chinese, I wish I knew about them when I was a kid. I would’ve felt like there were people who looked and sounded like me. The issue that I’m having now is that this community is getting older or moving away. The South that they and I have experienced is important, and disappearing.

Back then, they also had to start their own schools because they were subjugated to segregation laws. They couldn’t go to Black or white schools—they had to start their own. A lot of them had grocery stores that catered to both Black and Chinese communities, and they’ve been giving me tours of those stores, or the traces of what’s left of them.

Matsuda: I wonder if there was any hybrid Mississippi Delta Chinese food that came out of those communities?

Kha: Yeah, there actually was a food documentary about this community, and that’s how I found out about them. They spoke about trying to re-create their family’s recipes with the ingredients available to them in the Delta. They did cookouts and things too. I’m hoping to go to one of their cookouts the next time I’m down there.

Tommy Kha, Dog Bed, Fairfield, CT, 2018

Courtesy LMAKgallery, New York

Matsuda: You have to do that! You mentioned that part of the reason you are going down more is because of your family. And last time we spoke, you mentioned how your family hasn’t always approved of your career as a photographer. But your mom is in a lot of the photographs, and even is holding the cable release in a few. Has that relationship changed as a result of your photographs?

Kha: I think photography has helped a little bit. My family is less skeptical. Now they just refuse to be photographed by me. They never really see the photographs. But I’ve been collecting them into a more palpable family album to give them soon. My mom used to be an unwilling sitter, but she has become a great collaborator. Last Monday, we made pictures together and I was introduced to her face masks, which were Japanese Kabuki-inspired. We made a very ambiguous Asian picture.

Matsuda: But if your mom is making time for these sessions, at least on occasion, it seems like she is down to make pictures!

Kha: Yeah, that’s true. My grandma still refuses. She once said, “Please don’t take my picture, but if you do, this is my good side.”

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer based in Portland, Oregon.

Return to Sender is on view at LMAKgallery, New York, through October 20, 2019. Tommy Kha’s next book, Soft Murders, will be released in fall 2019.

The post Tommy Kha Isn’t Kissing You Back appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

At Mariane Ibrahim’s New Chicago Gallery, an Otherworldly Portrait Series

Ayana V. Jackson’s exhibition of radically speculative character portraits inaugurates the midwest home of a leading American gallery.

By Emma Kennedy

Ayana V. Jackson: Take Me to the Water, 2019. Installation view

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

For more than seven years, the gallerist Mariane Ibrahim has provided a vital platform for African diaspora artists, bolstering the careers of, among others, conceptual British Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor, German Ghanaian photographer and textile artist Zohra Opoku, and Nigerian British mixed-media artist Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze. Ibrahim recently decided to relocate her namesake gallery from Seattle to Chicago. The new space opened its doors on September 20, with an inaugural exhibition by photographer Ayana V. Jackson.

While Jackson’s previous work has examined archetypes of nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographic portraiture, her new series Take Me to the Water marks a shift in focus from historical references to speculative fiction. In both still portraits and fluid movement studies, Jackson explores an underwater world, an aquatopia, crafted from West African spiritual legacies and proto-Afrofuturist imaginings. This is Jackson’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. I recently spoke with Ibrahim and Jackson about their longstanding working relationship, the import of Take Me to the Water, and the gallery’s place in Chicago’s flourishing art community.

Ayana V. Jackson, Sea Lion, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Emma Kennedy: Mariane, can you talk about the decision to move the gallery from Seattle. What drew you to Chicago?

Mariane Ibrahim: One disadvantage, that started to become an advantage, is that in Seattle, we were actually isolated from the art market—so removed that you have a different paradigm, where you are developing your business away from all of these centers, away from all of these noises. But you still have the necessity of reaching out to those art markets and being present in those spaces. I had to get closer. We decided on Chicago because it’s central, it has a history, it has diversity. We have to be in Chicago, because Chicago is sophisticated enough to really embrace our program and artists.

I’ve always known that if I was going to open in Chicago, it was going to be with Ayana. Without knowing what work she was going to come up with—but the idea of opening and inaugurating the space with a black American woman was a statement of the direction we’re going in and a way of honoring the contribution of the black American woman in America, and also the history that Ayana is bringing to light.

Kennedy: I’m wondering, Ayana, if you could talk a bit about the work. My understanding is that it’s new work of yours, correct?

Ayana V. Jackson: Yes, it’s definitely new work. Take Me to the Water is marking a pretty significant shift in my practice. I’m dealing with kind of a speculative fiction arena. In previous bodies of work, I was looking at the history of photography or the history of portraiture or the history of fine art and the black body, and therefore referencing materials of existing artworks and/or photographs. This is the first time I’m inventing my characters from scratch. I’m still dealing with the archetype, but in this case, I’m thinking through new archetypes, or archetypes related to older mythologies.

It’s also a shift in that for the first time, I am creating the costumes. With the previous bodies of work, I was using costumes that came from opera houses, that came from costumiers in Paris. This time, I decided to collaborate with two fashion designers to create the costumes. I’m still working with my own body, as usual, I’m still working with black female identities, with the black woman’s body, but in a different, more speculative space. That would be the biggest shift in the work.

Ayana V. Jackson, Serene II, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Kennedy: How are you thinking about your body and performance in this new fictional world? Do you approach it differently than the archival work?

Jackson: Probably in the first couple bodies of work, I was dealing more with the static pose, like the portrait, the still body. The work has always been performative; I’ve never considered it self-portraiture, because I’m always performing a character. But there’s a lot more movement now. Each of my characters does have a static portrait, and you’ll see some of those in Take Me to the Water, but you’ll also see some movement studies. So, each character has multiple manifestations. Because this series is dealing with an undersea colony, this idea of an aquatopia; my characters are existing as much on land as they are existing in the deep, so every one of my characters has a form in movement, whereas that wouldn’t have been the case with previous bodies of work.

Kennedy: I was very intrigued when I was reading about the aquatopia, and the aqua-humanoid characters you’ve mentioned. Can you expand upon that world for us?

Jackson: Are you familiar with the myth of Drexciya? (It’s not common knowledge, though I’m by no means the first artist to deal with the subject matter.) Drexciya was a techno duo from Detroit that was functioning at the end of the eighties and early nineties. They originated before Afrofuturism was a topic, was even given its name. When you think about the forebears of Afrofuturism, you have a black cultural movement that was abstracting from the harsh realities of a place like Detroit or Chicago or the crack epidemic of the eighties and deciding to embrace a new foundation narrative. Drexciya was a band by two guys, and they basically said that they were the children of pregnant women who had been thrown overboard the slave ships, and that because the babies were able to breathe embryonic fluid, they could also breathe the seawater and therefore survive. It’s the idea that there are survivors of the Middle Passage who are living at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean between the triangular slave trade. A friend of mine introduced me to the band. Techno has its roots in Detroit, and Drexciya was among those first DJs, those first founders of techno.

The project considers that aquatopia and other aquatopias that are related to traditional African spirit mythologies. The Yoruba, they have Yemaya, who’s the queen of the saltwater, the photosynthetic layer of the water; then you have Olokun, who’s at the bottom; and then you have Oshun. But then in places like Angola, you have Kianda; in places like Senegal and Benin, you have Mami Wata. I was offered a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (SARF), and I decided that I wanted to consider Drexciya and water-spirit iconography from countries impacted by the slave trade as one aquatopia. Then, I began to imagine a world where you have these ancient water spirits from the continent midwifing these pregnant women and birthing Drexciya. Take Me to the Water is my imagination of these precolonial African water-spirit mythologies intersecting with a twentieth-century black American Detroit imaginary of another aquatopia.

Kennedy: How do you anticipate viewers engaging with the work and this fascinating history?

Jackson: Some people will be familiar with my references, and some people won’t. I think that what I like about the work is that you can interact with my reference materials, or you can embrace it just as portraiture and performance and character-building. I like it when you can enter the work wherever you want.

Ayana V. Jackson, Cascading Celestial Giant I, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Kennedy: I love that. Mariane, I know the gallery started out with a focus on African and African diaspora art and photography, and it’s become more global over the years. What was the impetus for that mission?

Ibrahim: It’s true, my focus was really on African-descent artists and photographers. I think what was really missing [at that time] was the infrastructure for presenting African-descent artists and black artists in commercial spaces, so that they could be visible to the public, written about by the press, eventually picked by museums and institutions, and then finally come to the attention of the mass.

The artists have always been there; there’s no novelty in that. African artists and African American artists have always been there. But at the time, they didn’t have the commercial galleries to invest in them and push them forward. My gallery wanted to shape and change the market for emerging artists and artists from a certain geographic space.

Kennedy: Chicago is very happy to have you here.

Ibrahim: I think the gallery’s pursuit is to bring something different, relevant to the art community that is already so rich in Chicago. You can’t get more diverse than Chicago! I’m literally walking through Chicago with a big smile, because I’m amazed at how much diversity I see every day. And that’s very comforting. Puts us in a really good mind-set, a good setting to be able to develop our business.

Kennedy: Absolutely. The richness of Chicago’s history, specifically its black history, is endless.

Ibrahim: We are beyond excited to have Ayana and her new body of work. They are of a much larger scale. We also are partnering with Expo Chicago, and one of her photographs is going to be part of Override, [taking over a large billboard in the city]. Last year, Override featured Glenn Ligon and Judy Chicago. Ayana will also be part of that landscape, the urban landscape of the city of Chicago. I know she’s too shy to talk about these kinds of things, but it’s really an Ayana Jackson takeover of Chicago [laughs].

Jackson: If she’s going to put me under the bus for being too modest, I’m going to put Mariane under the bus for being too modest. This can be a very cutthroat market, and it’s refreshing and comforting to have someone like Mariane, who takes our careers personally. She takes our success personally; our success is her success and vice versa. I’m super humbled to have the chance to carry her banner as she steps into Chicago for the first time.

Ibrahim: I’m really touched. The last thing that I will say about Ayana, which will summarize everything: she’s the only artist—not that I work with, but the only artist—who can literally, like a compass, put her fist in the center, and reach to Europe, Africa, and America, in terms of the history, like no one else. She has that flexibility to move constantly and go backwards in time, and make a perfect circle on the different narratives that have been told, written, and also untold. That’s also why I think her work is really touching many fields: photography, anthropology, art history, everything. I think she is a great ambassador to our program.

Emma Kennedy is an art history PhD student at Northwestern University. She is a former editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Ayana V. Jackson: Take Me to the Water is on view at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago, through October 26, 2019.

The post At Mariane Ibrahim’s New Chicago Gallery, an Otherworldly Portrait Series appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers