Aperture's Blog, page 83

August 21, 2019

On the Cover: Aperture’s “Mexico City” Issue

Iñaki Bonillas, Adiós fotografía (Bye bye photography), Mexico City (detail), 2018

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Ghost-like hands reach out from a dark background and create the outline of an invisible camera in Iñaki Bonillas’s Adiós fotografía (Bye bye photography), the cover of Aperture’s fall 2019 issue, “Mexico City,” the fourth in a series of city-focused issues, following São Paulo, Tokyo, and Los Angeles. The staging of this mysterious photograph echoes the relationship between artist and subject. “Here I asked an actress to portray, with her hands only, a photographer in action,” says Bonillas, in an interview with Iván Ruiz for Aperture. “What we see is nothing but the gestures of the hands while taking a picture and the voids that form around those hands where a camera no longer is used—yet it is somehow still there.”

As a young photographer, Bonillas worked for his uncle, the photographer Carlos Somonte, as the assistant to Somonte’s assistant. In that role, he was responsible for preparing every step in the photographic process, aside from actually taking the photograph itself. “This limit allowed me to begin to work in the margins of the notion of the photographic, and to become more interested in the extra-photographic aspects of the medium,” Bonillas recalls. That early education guides the defining works of Bonillas’s career, from the phantom camera in Adiós fotografía to his inventive reworking of the photographic archive he inherited from his grandfather, who moonlighted as a conceptual artist while working as an aluminum salesman.

Bonillas describes himself as an “attic photographer,” adding, “I spend a lot of time looking for traces of images that are hidden somewhere.” Aperture’s “Mexico City” issue is full of photographer-detectives like Bonillas—artists who reconsider the past to tell new narratives, from the personal to the collective. Throughout the issue, artists like Graciela Iturbide, Gabriel Orozco, Miguel Calderón, Jesús León, Pablo Ortíz Monasterio, and Tania Franco Klein, and writers and curators Chloe Aridjis, Álvaro Enrigue, Kit Hammonds, and Sarah Hermanson Meister examine the diversity of Mexico City and its vibrant cultural scenes, reflecting on the ways Mexican photographers are pushing new visions for the medium.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post On the Cover: Aperture’s “Mexico City” Issue appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 20, 2019

What Can Photographs Tell Us About the History of Redlining in the US?

Zora J Murff reflects on the intertwined legacies of segregation and violence in Black communities.

By M. Neelika Jayawardane

Zora Murff, Jerrod (talking about hoods), 2019

Courtesy the artist

Zora J Murff’s new photobook, At No Point In Between, traces the history of redlining in US cities—systematic discrimination that has been implemented over decades as a result of decisions made by individuals, businesses, communities, and local governments to refuse services to Black, low-income, and otherwise marginalized communities. Although Murff reflects on the spectacle of sudden violence—as well as the legacy of segregation and slow violence—that redlining was designed to engineer, his work allows audiences to read images against a background of social conditions and individual lives. Crucially, he shows the myriad ways in which invisible policies continue to operate and impact Black communities. (Murff’s other, concurrent project, which informs his work for At No Point In Between, explores the intersections between historical structures of violence that targeted Black individuals and communities in the US, and how that structural violence is perpetuated today through the juvenile correction system.) Murff acknowledges that his foundational education in counseling and psychology contributed to how he conceptualized his book, likening it to what effective therapy can do. “When you go to see a therapist, they already know what’s wrong with you,” he noted recently, via email. “But they understand that if you find the answer yourself, you can take ownership over it, learn from it, and grow from it.”

Zora Murff, Bound, 2019

Courtesy the artist

M. Neelika Jayawardane: How did you begin to think about redlining? How do you go about photographing something that is not really tangible, a system that is purposefully and systematically designed to not be visible? How does one “picture” something that businesses and policy-makers work hard (perhaps unconsciously) to bury under the rhetoric of security and safety?

Zora J Murff: A little under a year after being deeply impacted by seeing violent video footage of Laquan McDonald shot and killed by a police officer, I visited North Omaha. It was the first time since moving to Nebraska that I entered a new environment as a stranger, and I found that everyone else looked like me. I was also in an environment, for the first time in my life, where that Black majority had existed for a substantial period of time. I was fascinated by that feeling; this was a place where my mere existence was positively acknowledged and affirmed without question. As I passed through, I also noticed many vacant lots that stood as gaps in the landscape; more deeply, they were gaps in time. To me, these vacant lots laid bare truncations in memory within the community. I had a desire to know more, to fumble around in the dark spaces, those amputations in memory.

What I found was that amputations in memory exist so that we “forget” the actors in repetitive acts of racialized terror—but not the terror itself. I came first to the story of Will Brown, who in 1919 was lynched by a white mob for being accused of raping a white woman. Through Will Brown, I found Vivian Strong, the fourteen-year-old girl whose life was stolen by a police officer in 1969 for running away from him.

Next came the articles on the implications of the term “race riots” and how those events critically shaped communities. Then the publications on redlining (John McKnight in the 1960s) and the legal disenfranchisement of communities through the denial of access to wealth-building tools (primarily through homeownership). That led me to reflect on slow violence—insidious legislation, done on behalf of the federal government, which would prove to be an effective (and less identifiable) implement of harm, just as effective as bullets or nooses.

Last came the dissection of lynching photography. I saw photography’s resolute function as a mirroring device: how the image collapses onto itself, all at once reinforcing hatred and buttressing proof of injustice. In that dark space, I ran my finger along the edge of that dichotomy, and what I felt was akin to a Möbius strip, an edge that begins, ends, and brings you back to the beginning. I wanted the path through my work to feel the same way, with the complicated connections between images, histories, and contexts being my key to use photography as an implement to “plot and give figurative shape to formless threats whose fatal repercussions are dispersed across space and time,” as Rob Nixon states in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

Zora Murff, Stripped, 2019

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: You use two appropriated images from a violent crime scene—stills from a phone video of a police killing—as “bookends.” The first image in the book (a tiny, five- or six-square-centimeter color insert positioned at the lower spine of the book) serves as an opening salvo. It shows a grainy image of a man in a turquoise shirt and black trousers running through an open, grassy area. It is Walter Scott, who was chased, shot, and killed by Michael Slager, a white police officer, following a daytime traffic stop for a nonfunctioning brake light. The last image in the book is another postage stamp-size still—that of Slager aiming his gun. The inclusion of these images is sort of an intervention into the traditional format of glossy photobooks. Although one might miss these images if one were carelessly flipping through the book, the power and impact of the narrative they carry—the moment one recognizes them—is unmistakable. Why use these two appropriated video stills to bookend your work?

Murff: My interest in using found or archival footage began as a result of the police killing I mentioned earlier—that of Laquan McDonald, who was shot by Jason Van Dyke, a white police officer; it was recorded by a dashcam. I became preoccupied with the McDonald case once the footage was released to the public. I decided to watch it; this was my first time watching any such footage, and it opened up a type of fear that I hadn’t felt before. I thought about my mom (for various reasons), but one primary reason was because I learned fear through her. The fundamental difference between those two types of fear is the fact that the fear I learned from my mom is based in love: a fear Black parents often instill in their children, because it is necessary for us to have the ability to recognize danger. The fear I felt from the footage was different. It had such depth that it seemed bottomless. With the acknowledgement of his name, Laquan McDonald, I acknowledged those names that were already written and those that would come after. It was in this moment that I was defining myself as an artist. Meanwhile, photography was clearly showing me that white supremacy is at the core of how the technology has been (and still is) used, and an essential part of many US institutions—including those that supported photography itself.

In my book, I chose to use a still from the video of Walter Scott, who was also killed by a white policeman, even as Scott was attempting to run away. I decided to split the still, because it’s the moment before Slager begins shooting. When I speak of layers of history, I think a better term to use might be distention, a statement that Terence Washington makes in his text in At No Point in Between: “the most radical thing is to choose time and its distention.”

The first half of the image establishes photography’s many potentials (specifically as evidence, as archive unto itself, as an object in service to an archive). Hopefully, that gesture carries forward, influencing how everything to come is seen. The second half of the image, of course, reinforces that idea, but brings with it a sort of weight or snap (a connecting of dots, perhaps). I found it crucial to lead the viewer back to the beginning, to recognize that with splitting the image, a fissure is opened, and they can begin to see all of those things that exist underneath images, moments, decisions. I’m asking, “What is the difference between a spectacle lynching, between a murder committed by police, between redlining?” If we retrace our steps back in time, all of those things (to me) become one and the same, stones in the foundation that set the trajectory of the larger, violent structure.

Zora Murff, A Point (3), 2019

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: Can you speak more about your interest in creating an archive?

Murff: When I began entertaining using this specific still in the book, I was thinking about how time and context shift the understanding of images, as well as the concept of archive building. When we look at images or archives, the intent of the maker, I believe, can never fully be erased. I would further posit that time is also always present: both the archive and the image are understood both in and out of time. For these reasons, I always saw this work as my creation of an archive: part archive of a specific place at a specific time, and part my interpretation of things happening in the American sociopolitical landscape between 2015 and 2018.

My motivation for including these images was to try and work through and present pathways to theorizing memory and time, and the gaps I found in both when Black communities have been subjected, long term, to racialized terror.

Recounting the day on which Scott was shot by Slager, Feidin Santana (the citizen who recorded the footage) stated that he “recorded the video so that maybe he [Scott] can feel that someone is there. . . . There were just the three of us in that moment. I couldn’t tell what was going to happen, so I just wanted him to know that he’s not by himself.” Santana made himself a witness, and with the dispersion of the video, made those of us who watched it witnesses too. He was also gathering evidence (thankfully) that would contradict the official story, and possibly lead to Slager’s conviction. The images will always hold that value.

The gravity of the situation, and the constant appearance of Santana’s video on news shows between 2015 (when the shooting occurred) and 2017 (when Slager was convicted), solidified the resulting images as icons. They become ingrained into our collective conscious. Such iconic images have the potential to define a time period. I can almost say with certainty that thirty years from now, many of us alive today will recall this image with ease. These ways of memory-keeping resonate with the way Shawn Michelle Smith, in Photography on the Color Line, describes an archive as something that exists not only as “a record of the past,” but as an entity that “makes a claim on history . . . [as] a vehicle of memory.”

Zora Murff, Jhalisa (talking about self), 2019

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: Your work reveals the rarely documented and rarely examined slow violence that redlining brings about—creating the conditions for the spectacular violence that we see on the news. The smallness of the image of Scott highlights the smallness of his worth—his physical matter, his political power, his social value—to the state. It becomes a metaphor for the perceived smallness of Black lives—redlined into invisibility in America.

Murff: The creation of images—specifically in colonial and American history—has been used to create the perception of an “other.” From prints with renderings of Native peoples in the 1600s to soap advertisements promoting imperialist ideology, images were meant to promote white superiority, a tool to oppress. The white privilege of deciding how nonwhite people were seen, thereby promoting white supremacy, is deeply ingrained in the practice of image-making. Photography is not exempt from that. This isn’t a fatalistic view, because we can, of course, look back and clearly see errors in thinking on both societal and personal levels.

I think about this moment in Lisa Riordan Seville’s afterword in At No Point in Between: “I ask myself what it takes to perpetrate a casual act of photography amid the smell of burning flesh. But I do not ask why I do not see myself among the faces in the crowd. I could come up with reasons other than the truth, which is that because they are white and I am white, I can convince myself our stories are not conjoined. I can write around it. I know that is a failure of sight.”

The photograph she references here is the lynching photograph of Will Brown. In that picture, the men depicted all implicate themselves by appearing in the picture, many of them seeing their presence at this “event” as a point of pride. Their hubris was, of course, met and welcomed; a few of them were tried but eventually acquitted (a narrative too common at that time). Seville’s reflection reminds us that the reading and understanding of images is not absolute, and in that, there’s always hope.

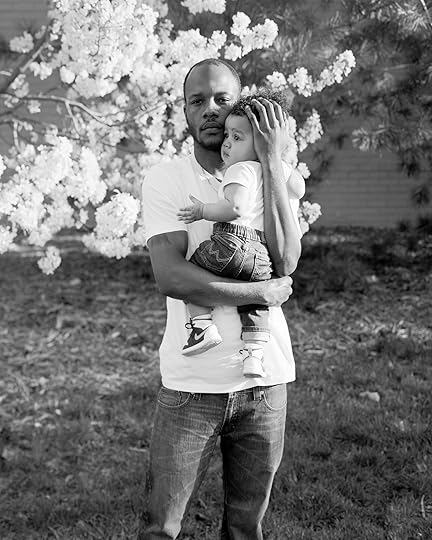

Zora Murff, Jerrod and Junior (talking about fatherhood), 2019

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: There is no directive introduction by the photographer in your book, and no text by contributors that provides factual information that contextualizes the images. One is a poem; the other a reflection. Why these oblique texts?

Murff: When I asked Lisa and Terence to write the texts, I asked them to write around the work rather than writing about it. I didn’t want to give too much away, and both writers found really subtle ways to implicate the viewer: Terence, through masterful, staccato pacing; and Lisa, through a skillful navigation between past, present, self, and society. I felt that to honor the spirit of the work, it was important to me to see their genuine interpretations of the collection of images. They didn’t disappoint.

Zora Murff, Young Man (talking about his future), 2019

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: Your photography makes me think about the labor that engages in powerful, difficult forms of memorialization—labor that resists forgetting, and rather, encourages remembering that moves us to acknowledgement, accountability, and possibly, action. What forms of negation and forgetting is your work attempting to interrupt?

Murff: The early versions of this work were very heavy-handed. I remember hosting a studio visit with a faculty member at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and he spoke a lot about the “volume” of the work. He suggested that I had it up way too loud. He showed me Emily Jacir’s installation ex libris (2010–12) and pointed me to a review of her work written by Cynthia Cruz, who states: “Her photos document the echo of a people; they inhabit the emptiness of that echo.” Before he left my studio, the last thing this faculty member said was, “We already understand this at a high volume. The video footage is loud. The protests are loud. Why does your work also have to be loud?”

For me, the silence is nuance. Rather than tell the viewer exactly what I’m thinking, it is more important to ask them, from the outset, to approach the work with a high level of investment and critical engagement. After all, I think that’s the most that we can ask from audiences.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York-Oswego, and a Research Associate at the Visual Identities in Art and Design (VIAD), University of Johannesburg.

Zora J Murff’s photobook At No Point In Between was published by Dais Books in July 2019.

The post What Can Photographs Tell Us About the History of Redlining in the US? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 19, 2019

From Teju Cole, an Exhibition as “Tone Poem”

Drawing from a Chicago photography collection, the writer continues his interest in presenting the beauty of black skin.

By Emma Kennedy

Whitten Sabbatini, Couple Embracing, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Teju Cole’s first major curatorial project, Go Down Moses, is a triumphant presentation of the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s permanent collection. Founded in 1976 by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP began collecting in 1979 and now has over 15,000 objects. For Go Down Moses, Cole, a writer and photography critic, selected a range of photographs from this vast collection, creating what he calls a “visual tone poem.” Divided between three floors, the show is a visual feast of compositionally striking work and unlikely, yet captivating pairings.

In the first room, Cole intersperses images of landscapes (presumably American ones) with those of body parts. While the juxtaposition is compelling—instigating visual associations between the human form and land—each work is powerful enough in its own right. Cole includes Dorothea Lange’s Toquerville, 1953, Belle Bringhurst and neighbor children, which depicts the back of a gray-haired woman’s head, her tight, twisted bun drawing the eye. In a photograph by Esther Parada, the back and base of the neck of a black person in a simple cloth shirt become a landscape of textual detail. These pieces are compositionally brilliant, yet utterly quotidian.

Christian Patterson, 24th Street Road (Road at Night), 2007

Courtesy the artist

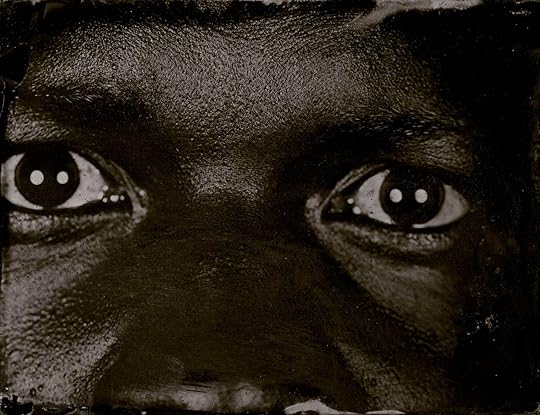

Cole has long thought about photographic representations of black people, as evidenced in his earlier musings on the delicate touch of photographers like Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks, who harnessed the camera’s technology to capture black subjects. Cole’s selections for Go Down Moses illuminate his continued interest in presenting the beauty of black skin. Stephen Feldman’s 1966 Portrait, for example, situates a black man against an entirely black background, where the only visible light is reflected off the sweat on his face; in the resulting profile, only a mouth, nose, and eye are clearly discernible. There are also several works from Myra Greene’s arresting 2007 series Character Recognition; glass ambrotypes present sectioned parts of her body and consider the black body’s role in identity formation.

Myra Greene, Untitled #38, from the series Character Recognition, 2007

Courtesy the artist

The last room of the exhibition features two walls. On the first, longer wall, photographs hang floor-to-ceiling salon-style and range from iconic to lesser-known images, and from banal, everyday visuals to those of violence and destruction. Danny Lyon’s historic 1964 image of the National Guard assaulting photographer Clifford Vaughs is more or less centered in this grouping: a moment of uniquely American violence at the center of Cole’s mini-history of photography. The photograph’s modest size, however, renders it just one small part of a larger whole, especially in relation to its much larger neighbors by artists like An-My Lê, Anthony Haughey, and Alec Soth. The all-too-common nature of violence in the US is on display in Lyon’s striking image, as well as in Cole’s other selections, featuring overturned cars, burning buildings, and even planes in the process of destruction. Alongside these, Cole includes photographs of environmental degradation, American military force, and American consumerism.

On the final, jet-black wall of the gallery, under low light, is Roy DeCarava’s Man in Window (1978). The image is almost too dark to be seen at first glance; under low light, the print’s presentation is radically different from the rest of the exhibition. DeCarava is known for his stunning play of light and darkness and his ability to sidestep the technical camera limitations that typically favor pale skin—and Cole has previously expressed a deep admiration for DeCarava’s use of shadow to reveal the texture, depth, and beauty of black skin. Man in Window is a quiet conclusion. It is an image that encapsulates many of the themes of Go Down Moses, while simultaneously existing outside of the narrative. Cole fittingly considers the image to be his “grace note.”

Melissa Ann Pinney, Selan’s Beauty School, 1988

Courtesy the artist

Go Down Moses asks a timely question: is hope still possible, given the chaos of our present moment? Cole’s words and his curation remind us that moments of change, of upheaval, are not new: this archive tells us that the state of disruption—the chaos in our environmental, political, social, and cultural worlds—has happened before. He also reminds us that photographers have sought hope through their medium since its invention. At the conclusion of his curatorial statement, Cole proposes a new definition of hope, one in which hope is hospitality exchanged in solidarity between the weary. The images in Go Down Moses show us how brilliant and terrifying the world can be—how immense beauty exists with immense pain and destruction. In the end, what Cole offers us through his careful selection of photographs is this hospitality—this hope.

Emma Kennedy is an art history PhD student at Northwestern University. She is a former editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Go Down Moses is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College Chicago through September 29, 2019.

The post From Teju Cole, an Exhibition as “Tone Poem” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 14, 2019

Introducing: Steven Molina Contreras

Between Long Island, El Salvador, and Peru, an American family’s emotional reunion.

By Brendan Embser

Steven Molina Contreras, Mother & I, #2, New York, USA, 2018

Lenin Mejorada was supposed to be away for two weeks. An immigrant from Peru, he was living on Long Island with his family for six years when he made a decision to obtain permanent residency in the US. On December 14, 2017, with short notice, Lenin, a maintenance worker at a Catholic church, left for Peru. His lawyers said the process wouldn’t take longer than two weeks. But after three weeks passed, Lenin missed his return flight home. “We didn’t have an answer,” his wife, Alma Contreras-Mejorada, said. “We didn’t have anything. And then, I was like, what’s going on?”

With her husband away, things were getting tight around the house. Alma asked her son, Steven Molina Contreras, to come home on the weekends to help out with babysitting. Steven, a photographer and student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, started commuting from Manhattan on weekends, mostly to look after his younger stepsister, Abigail—Lenin and Alma’s US-born daughter, who was three years old at the time—while Alma was working at a hair salon.

“My mom started to fill the gap when my stepfather was gone,” Steven told me in July, in a conversation with his mother, two days before Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced a series of “raids” in the US. “Obviously, a young child doesn’t understand why they’re not seeing their family member every day,” Steven said of Abigail. “And her father was gone for those three months.”

“It was more than three months,” Alma corrected.

Steven was born in El Salvador in 1999 and moved to the US when he was six. “By all accounts,” he said, “I was as American as the Pledge of Allegiance I recited every morning in school.” As a child, he distanced himself from his Salvadoran heritage and raced toward assimilation, toward a sense of American identity. When people asked where he was from, he would confidently respond, “I’m from New York.” But his stepfather’s absence prompted a sudden shift in Steven’s relationship to his family. He had to step into the role of father figure; he had to figure out how to be a caretaker. Thinking of Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series (1990) and LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family (2014), he began to photograph his mother and stepsisters, making evocative black-and-white portraits that consider the dynamics of a household living in uncertainty.

“Molina Contreras’s photographs have the power of evoking total recall of private Latinx family moments,” said Yxta Maya Murray, a writer and professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “His ability to capture that intimacy recalls Roy DeCarava’s best portrait work, as well as Paola Paredes’s and Laura Aguilar’s.” In his series Mi Familia Immigrante (2018), Steven envisions his family as both documentary subjects and collaborators. He photographed his mother at moments when she was exhausted, and he gently guided certain scenes with a “performative” eye on composition, as in one of his mother and stepsister at a table, with Steven himself reflected in a mirror, all three trading gazes of introspection and concern.

“The camera starts as an object, a way of making, but becomes another present member of the family, partaking in the in-betweens of her family experience,” Steven observed of Paredes, an Ecuadorian photographer who also works between documentary and staged images. The same could be said of Steven’s own process, and the way his camera is an expressive instrument and a silent observer.

Steven Molina Contreras, 9PM Dinner, New York, USA, 2018

More than three months after leaving for Peru, Lenin returned home. “It was like everyone could finally breathe,” Steven said. “He was a resident. He was here. There was nothing that anyone could’ve done to take him away.” To mark the occasion, Steven made a formal family portrait, even though he’s not in the frame himself; he still thinks of his role as “the photographer.” Signaling a transition, he switched to color, as if the lights had suddenly come on, or a new spectrum of experience had been revealed. He soon decided he wanted to go to El Salvador, to reconnect with his biological father and make photographs of his extended family. “I realized the only way to unobscure my childhood identity was to return to El Salvador alone, with my camera in hand,” he said.

Steven’s Salvadoran family became willing participants in his project. They were glad, he said, that Steven had taken an interest in their lives, and that he was making images that went beyond the typical media representations of violence in El Salvador, a country that faced a devastating civil war in the 1980s, and has in recent years been beset by gang violence—one of the reasons why thousands have attempted to seek safety in the US. In April, over the course of a week, Steven made portraits of his father and his stepmother, his aunt and grandmother, which he collected into a series called Home Again, El Salvador (2019). He visited his father at the car wash where he works and lives, and they went swimming together. He told me he hopes his mother and sisters will return to El Salvador together “as a family unit, in the place where our origins began. I’m continuing to fill out our family tree.”

In Spanish, the word volver means to return, to go back, to start again. Lenin had to go back to Peru in order to return to the US. Steven had to return to El Salvador so that he could go back to his origins, to the beginning of his story. Even though he and Alma were reunited with Lenin, Steven said, “We still face those consequences of being immigrants in this country, having to go through the citizenship process, and having to struggle with the chance that the family we have now is not the family we can always have.”

Yxta Maya Murray noted that Steven’s “eye for detail robs you of your breath.” But in that moment of breath-taking, Steven also gives something back: a window onto the present tension around immigration in the US, and a stirring vision of an American family.

Steven Molina Contreras, Wedding Day, August 2013, Te Extraño, New York, USA, 2018

Steven Molina Contreras, Libertad, Still Life, New York, USA, 2018

Steven Molina Contreras, Mi Familia, New York, USA, 2018

Steven Molina Contreras, New Light, New York, USA, 2018

Steven Molina Contreras, Summer at Home, Rebuilding #2, New York, USA, 2018

Steven Molina Contreras, Papi (Dad) Jimmy, Portrait #1, El Salvador, 2019

Steven Molina Contreras, Self Portrait #1, In My Abuelo’s (Grandpa’s) Home, El Salvador, 2019

Steven Molina Contreras, Papi (Dad’s) Jimmi’s Car Wash/Home #1, El Salvador 2019

Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine and the editor of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018) and Ethan James Green: Young New York (2019). All photographs courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

The post Introducing: Steven Molina Contreras appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In “African Spirits,” A New Visual Vernacular

An exhibition at Yossi Milo Gallery captures the dizzying array of post-independence African photography.

By Imani Noelle Ford

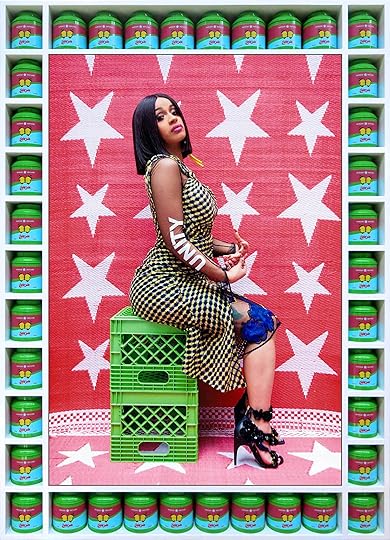

Hassan Hajjaj, Cardi B Unity, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Third Line Gallery, Dubai, and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

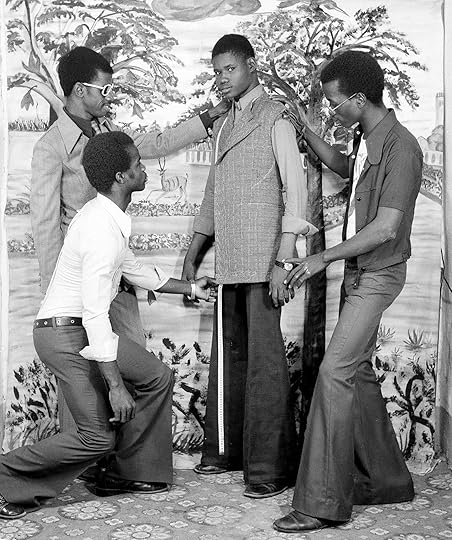

African Spirits, currently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, presents an astutely and carefully crafted panoply of African photography, conveying the mastery and evolution of a bold and—I would add—fly visual vernacular. Juxtaposing approximately sixty-five works from the 1950s to the early 1980s with contemporary pieces by artists across the African diaspora, the exhibition initially overwhelms. Modern prints of black-and-white portraits seemingly clash with the yellowed, aged edges of vintage prints from both celebrated and little-known studios. The image sizes vary, pulling the viewers toward and away from the faces, clothing, and postures of their subjects. But who are these people?

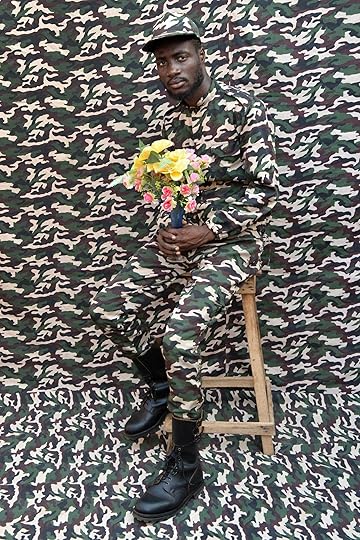

Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou, Untitled, from the series Citizens of Porto-Novo, 2018

© the artist and courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London

Decidedly adorned and decisively posed. Or candidly photographed and sincerely expressive. They are citizens of a new social world, one defined by the transformations of the independence movements that swept Africa in the 1960s. There is motion and agency in these bodies, whether clothed or undressed, choosing if and how they are looked at. The works that constitute African Spirits embrace self-possessed subjects and a reverence for the quotidian, molding the inherently subversive foundation of postcolonial African portraiture.

Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, 1975–78

© the artist and courtesy Jean Marc Patras Galerie, Paris

The title African Spirits is a reference to Samuel Fosso’s series of the same name from 2008, which was recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and presented at its 2017 collection exhibition, Unfinished Conversations. The series is not on view here, but the exhibition does include some of Fosso’s earlier work, alongside that of Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Sanlé Sory, and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, as well as contemporary artists such as Zanele Muholi, Morgan Mahape, Hassan Hajjaj, Pieter Hugo, Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou, and Delphine Diallo.

Delphine Diallo, Afropunk – Pink Fur, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Fisheye Gallery, Paris

An openly queer artist, Diallo gives the show a pop of color with Afropunk – Pink Fur (2016). This portrait of a femme, embodying queer femininity and queer masculinity, complements Mohamed Bourouissa’s nearby image from the series Périphéries, of two men, a boxer and a coach. Pink Fur also converses with Agbodjelou’s Untitled (2012), from the series Musclemen, which depicts three bare-chested men, arms crossed, with different patterns on the fabric of their pants, the backdrop, and the floor. Fosso’s self-portrait works from the series 70’s Lifestyle portray the artist in various costumes of flyness that queer manhood, allowing him to literally and figuratively try on new identity “types,” ultimately fashioning a self as photographer and as subject.

Pieter Hugo, Mimi Afrika, Wheatland Farm, Graaf-Reinet, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Sidibé’s contact sheets ARROSAGE DES TROIS, ADMIS NIARELA, 28-9-68 (1968) and Nuit du 18-19-11-69 (1969) embody the exhibition’s impulse toward quotidian delights. In her book Listening to Images, Black feminist scholar Tina M. Campt defines the quotidian as “a practice honed by the dispossessed in the struggle to create possibility within the constraints of everyday life.” These images are fragmented archives of the subjects at their best, showing up and showing out on the dance floor, embracing the moment and one another. While the quotidian is not spectacular, it is special. African subjects fashioned agency in front of the camera and in everyday life. Hugo’s large-scale photograph Mimi Afrika, Wheatland Farm, Graaff-Reinet (2013), from the series Kin, amplifies the intimacy of Sidibé’s smaller vintages. Hugo captures an older African woman adorned in a pink collared shirt and ornate gold-print headscarf. Most would see her skin’s texture and the beauty in her naked wrinkles as the photograph’s punctum. However, I see the few locks of her hair that she has shed, subtle kinks sitting here and there atop her shirt. The photograph is immaculate in its presentation, yet especially beautiful in its mundanity.

Studio Degbava, Untitled, ca. mid-twentieth century

© Studio Degbava

Similarly poignant, one of the photographs from the lesser-known Studio Degbava depicts a woman throwing her head back in ecstasy. We cannot see her face. To get to know her joy, one must step in close. Arms akimbo, with her hands cinching her dress, she draws attention to her shoes. Left foot turned out, proud and feeling herself. What does it feel like to escape at just the moment of capture? Perhaps like this. Muholi and Mahape’s beaded portrait Somnyama Ngonyama (2019) continues this conversation of expansive feeling. Similar to Black American artist Mickalene Thomas’s Din, une très belle négresse #1 (2012), Muholi and Mahape employ a plethora of cultural artifacts and practices, suggesting that paint and print are no longer enough to communicate the fabulosity and complexity of the Black subject.

Hamidou Maiga, Untitled, 1973

© the artist and courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London

The camera’s introduction to the African continent has fashioned a visual vernacular that persists even as it has morphed from the commercial photo studio of the ’60s and ’70s into the cross-cultural collaborations of today. African Spirits captures the specific aesthetics and ambiguities of African selfhood. We can look to the images of Fosso, Sidibé, their contemporaries, and their successors to access the worlds their subjects crafted in the aftermath of violence, migration, or political independence. Most importantly, we can bear witness to who these subjects decided to become.

Imani Noelle Ford is a visual artist, writer, and scholar from Chicago. Currently based in New York, they will begin a PhD program in English and comparative literature at Columbia University this fall.

African Spirits is on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, through August 23, 2019.

The post In “African Spirits,” A New Visual Vernacular appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 13, 2019

Art School Confidential

Matthew Finn’s photographs of London art students summon the innocent days of the 1990s.

By Lou Stoppard

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

“England, 1997” reads the opening page of Matthew Finn’s new book, School of Art. On May 1 of that year, the left-leaning Labour Party, under the leadership of Tony Blair, won the general election. It was a landslide victory, one that, in numbers, has not since been topped, and it ended the party’s eighteen-year spell in opposition to the right-wing Conservative Party government. Infamously, in response Liam Gallagher, of the rock band Oasis, and his partner Patsy Kensit lay on crumpled Union Jack bedsheets in a photograph shot by Lorenzo Agius on the cover of Vanity Fair, under the headline “London Swings Again!”

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Times seemed good. It was the age of Britpop. The age of Girl Power. My parents watched Titanic. I read Harry Potter. We all listened to The Verve’s “The Drugs Don’t Work,” which was eclipsed at Number One in the UK Singles chart by Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind,” which reentered the charts following his stirring performance at Princess Diana’s funeral (she died in a car crash that August). John’s song stayed there for five weeks before being toppled by the Spice Girls’ “Spice Up Your Life.” The year 1997 was one that changed the UK. The very notion of being British—the thought of what we had, who we were, what we’d lost, and what we could be—had never been so potent, so debated. That year, the nation wore its heart on its sleeve. We were proud but wounded. We were cocky.

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

The subjects of Finn’s book are students of an unnamed art college in London (it’s actually Watford’s West Herts College), and their portraits show them in all their grungy, half-curious, half-insolent glory. But really, School of Art is about the way life changed, that special and strange year. Maybe the project wasn’t always focused this way—when he took the photos, Finn was likely just working instinctively, as capturing students he works with is a central part of his practice. But the choice to publish these now suggests a different, new motivation, a desire to focus the mind on the passage of time.

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

It’s easy to read School of Art through the lens of Brexit. The year 1997 is just shy of two decades before the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, which saw the UK vote to leave the EU and thus plunge itself off a cliff into a sea of uncertainty and division. But it’s better to see this as a book about education, a policy area that receives woefully little airtime in Parliament today, as Brexit talks limp on. Here, 1997 was also a turning point. In November of that year, the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998 was published (enacted in July 1998), which introduced tuition fees across the UK. Before that, university was a time of experimentation, of freedom. “We were able to expand our creativity in any direction we wanted,” writes former student Sonya Bhaji in the book’s foreword. Now, education is something altogether more transactional. Few can afford the luxury of failing, and thus few can afford to truly explore. Now, a young person’s path from school, to university, to endless internships, to work, is highly strategized, highly planned, highly valued.

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

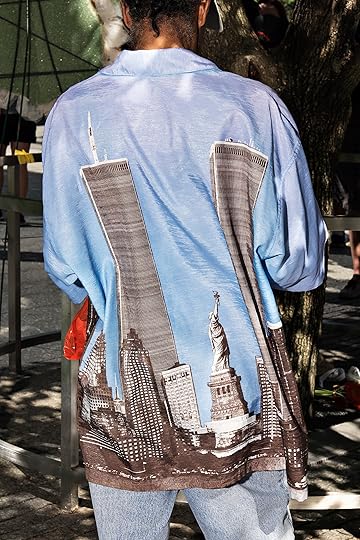

But beyond the politics, there are images. A boy wears a duster coat with “I’m not a trendy asshole, I do what I want”’ and “Pearl Jam” scrawled on the back. That typical angst—propelled by feeling so utterly unique, so totally separate, so smart—raises a smile. We were all young and livid once. In another photograph, a girl wears a Trainspotting t-shirt with the “Choose Life” monologue printed on it: “Choose Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television, choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players, and electrical tin openers. Choose good health, low cholesterol, and dental insurance. Choose fixed interest mortgage repayments. Choose a starter home. Choose your friends. Choose leisurewear and matching luggage. Choose a three-piece suite on hire purchase in a range of fucking fabrics. Choose DIY and wondering who the fuck you are on a Sunday morning. . . .” It goes on. That film, and that speech, is now a cliché in itself, a relic of a time when one had the security to perform rebellion. A time far before urgent news of more pressing issues than one’s own identity, like the imminent climate disaster. What a luxury to choose, or not choose, those things.

Matthew Finn, from the book School of Art, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

It’s fitting that these pictures are being published now, not just for the reasons above, but also because the world of image-making, and image-sharing, is going through a moment of oppressive nostalgia. To a fresh eye, the past might look newer (and undoubtedly safer) than the present. And have the ’90s ever been so in fashion? Look to the runways, where the looks of that age dominate. Look on Instagram, where teens are happily re-gramming pictures of ’90s editorials from The Face or i-D. School of Art cannot simply be read as a savvy comment on all this backward glancing, as it’s undoubtedly shaped by the same impulses. Just then, I found myself tempted to make an Oasis pun, some terrible riff on “Don’t Look Back in Anger,” but maybe that’s apt for this book—a fitting touch of nostalgia, a touch of comradery, a touch of pride, a tiny shot of something that makes one cringe. For those who dream of the better days, of freedom, of opportunity, of a veneer of cool and confidence, and are happy to keep the rose-tinted glasses firmly on, this book will be a tonic.

Really, School of Art is about possibility, about the promise of the future. It lands its punch because, here in 2019, we know how the story went.

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London.

Matthew Finn: School of Art was published by Stanley/Barker in 2019.

The post Art School Confidential appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 7, 2019

Max Pinckers is Raising the Stakes

In his latest book, the photographer asks how news media grapple with fiction and lies in the “post-truth” era.

By Stefan Vanthuyne

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

With each new project that Belgian artist Max Pinckers has worked on, he has raised the stakes a little bit more in terms of questioning documentary photography, and how the genre relates to notions of truth and fiction. As a consequence, book concepts for these projects have become more complex and narratives more layered. And as the books become more ambitious, the role of text also becomes more important. This is evident not only in the amount of text being used, but also, and perhaps more important, in the different sorts of text being used, ranging from the didactic essay and interview (Lotus, with Quinten De Bruyn; Lyre Press, 2016) to found newspaper quotes (The Fourth Wall; self-published, 2012), as well as torn-out newspaper clippings and reprinted blog posts (Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty; self-published, 2014).

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

News stories play a significant part in Pinckers’s work. How news media grapple with concepts such as truth, lies, half-facts, and fictions in what we now call a “post-truth” era is the subject of his praised book Margins of Excess. Self-published in 2018 and made between 2016 and 2017, starting in the midst of the Trump presidential campaign turmoil, the book brings together the stories of six individuals whose own personal beliefs and truths were dramatically exposed as false or deceiving in the mass media. In between these six main stories Pinckers strings together a freewheeling series of small but sensational tales of UFOs, cloned military dogs, crying Virgin Marys, suspicious white vans, accidental bombings, and fictional presidents.

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

For Pinckers, text is primarily a way to contextualize the images, and a tool to steer the reader in a certain direction or interpretation. Margins of Excess is by far Pinckers’s most challenging book in terms of assembling a coherent narrative: he once again cleverly resorts to the use of news stories as a way to frame the work, letting it rub against and bounce off classic media discourse. However, in a very effective way he also uses these news stories as formal support elements to provide the book’s more than three hundred pages with the necessary structure. This is not the first time he’s done that—it’s also modestly present in Will They Sing—but here he takes this ingenious method to a higher level.

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

Each one of the stories begins with a reproduced news article title and introduction on the right page, printed on a slightly thinner, light-gray paper. That these articles aren’t presented as full-on clippings was a deliberate choice by Pinckers. This way he avoided eclectic visual clutter, and instead created a unity between all the chapters’ opening texts on a formal level. After each news title, the following right page contains a portrait of the story’s protagonist made by Pinckers. Then comes a double spread with a full-bleed image and a quote from another news source, reversed out on the photograph and at the top left corner of the left page, as you would find in tabloid press and gossip magazines. Around halfway through each story comes a fully reproduced news article on the subject—on the same thinner paper used at the beginning of the chapter—clearly recognizable as such by a vertical line flanking the text on the left.

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

Every separate story then concludes with a long interview conducted by Pinckers and his wife, Victoria Gonzalez-Figueras, with the protagonist, allowing them to tell their version of the story, followed by a small archive image given to the artists, on the bottom of the right page. These transcriptions are also printed on thinner—but this time yellow—paper. Lacking this interview portion, however, is the very first story in the book, as its hero, Herman Rosenblat, died in 2015, one year before Pinckers started photographing the series. (For the opening portrait, he used a stand-in.) In between the stories, the small tales also have their distinctive and recurring image-text layout.

Max Pinckers, Untitled, 2016–17, from Margins of Excess, self-published, Brussels, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

Equally noticeable in Margins of Excess is when Pinckers purposefully leaves out any form of explanation, as is the case with the meandering series of staged and theatrically lit scenes of people or couples in the street, looking shocked, stressed, anxious, or upset. They are all actors—professional mourners, Pinckers calls them—that he used to re-create the type of imagery the media publish when something horrific occurs, like a bombing or a tragic accident: emotionally charged close-ups of people reacting to the event. Except that such an event never happened, so there is no context to be provided. Here, lack of text is just as important as text.

Stefan Vanthuyne is a writer and photographer. As a researcher he is affiliated with the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, Belgium, where his main topic is the contemporary Belgian photobook.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Max Pinckers is Raising the Stakes appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 6, 2019

Joan Jonas on Her Special Commission for Venice’s Newest “Pavilion”

The acclaimed multimedia speaks about her poetic call to action on behalf of the world’s oceans, the siren call of her long lost Leica, and why Robert Frank and Mary Ellen Mark loom large.

By Laura van Straaten

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, 2019, Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Venice. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy

Photograph by Moira Ricci and courtesy Joan Jonas

Joan Jonas, who represented the United States at the Venice Art Biennale just before the last American presidential election season—when science and facts were still a given and a Trump presidency seemed far-fetched—has returned this go-round with a special commission for Venice’s newest “pavilion.” Though Jonas’s new project, entitled Moving Off the Land II (2019), evokes the form of the artist’s acclaimed image-laden, performative, musical, and sound-based installation from 2015, her challenge here was unique. And that’s because the space for which Jonas has designed the new site-specific work has a quite different mission.

Rather than serving one nation’s cultural—and often political—interests, this new venue is meant to represent the interests of the oceans around the globe in the threat of the climate crisis, caused by global warming, ocean acidification, plastics, and other forms of man-made harm. Ocean Space, as it’s called, is international, or transnational, to the core. Housed in the ancient Church of San Lorenzo, right on a canal, Ocean Space is the brainchild of Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, who has shifted her conservation-focused arts philanthropy TBA21 there from its former home in Vienna. Maja Hoffman’s Luma Foundation, another of the most prestigious European contemporary art foundations, has co-produced Jonas’s inaugural presentation.

Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

As a whole, Moving Off the Land II explores how oceans have cross-culturally served as a totemic, spiritual, and ecological touchstone. Presented in nonlinear fashion, the exhibition has video screens tucked into a loose array of different-sized wooden kiosks. I particularly appreciate the ones that are large enough to enter, so that Jonas’s aqueous imagery assumed my whole field of vision. All around the nave of the former church float Jonas’s paintings of marine life and banners with bits of poetry and scientific facts about the world’s oceans and the creatures of every shape and size therein. I spoke with Jonas shortly after the Benniale festivities surrounding her new project.

Rendering of Ocean Space, due to be completed in the next three years. Designed by Office for Political Innovation, the first phase of the project opened March 2019

Courtesy Andrés Jaque/Office for Political Innovation

Laura van Straaten: I was struck by your use of underwater footage that was imperfect and murky with algae, sediment, and microscopic life. Were you specifically steering away from beauty shots, and a National Geographic or Jacques Cousteau style of underwater photography that draws attention to the craft of image making?

Joan Jonas: Well, I didn’t even think of going in that direction, actually. I wouldn’t want any like Planet Earth and all that. That’s not my thing. What I’m trying to do is very simple. It’s to show what I find interesting: the miraculous and wonderful nature of all creatures that live in the ocean. And for somebody like me, the most accessible place is the aquarium, which is sort of like a fish zoo, where much of this was shot. I don’t like zoos for animals, but I think it’s the only place that people who don’t dive can see many of these creatures.

Van Straaten: You also used underwater footage that was shot by the marine biologist David Gruber and is in fact quite beautiful, including these incredible almost neon-bright seahorses.

Jonas: I met David Gruber through TBA21. His footage shows some more exotic creatures because of what he studies, which is biofluorescence and how fish perceive the world. So he develops special cameras and lenses in order to film that. I’m interested in perception.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land II, at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy and co-produced with Luma Foundation

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

Van Straaten: What was left on the proverbial cutting-room floor when you were mining his archives of footage?

Jonas: I didn’t look at tons of stuff. He sent me some things and then one day, he brought over a whole file. The ones that I chose are all beautiful and fascinating to me—really incredibly beautiful footage of these creatures.

Van Straaten: There’s a nonlinearity, a multiplicity to how you layer images here, where some of the most poignant parts of the Venice exhibition—and the related performances I’ve seen—are when we see you interacting with moving images of underwater creatures not only on the screen behind you, but also projected onto your garments and your face. There are moments where you dance and dart and sway, as if mimicking the movement of the marine life in the swells of the sea. And then in some parts, it’s as if you’re trying to embrace or embody the creatures on the screen behind you—it reads almost as a longing on your part. Can you talk about what you are trying to achieve with your movement in relation to the images behind and quite literally on you?

Jonas: Yes. I’m interested in the surface of the projection. And how do you interrupt that in an interesting way? How do you change the picture? So by bringing other materials in front of an image, and by moving bodies in front of it, that’s one way. This idea of layering—I did it in the piece very elaborately, but it’s the way I’ve been working for a long time. Here, I got more and more into interacting with the fish with my body. It affected me.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land II, at Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, 2019. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy and co-produced with Luma Foundation

Photograph by Enrico Fiorese

Van Straaten: And that visual layering is compounded with the layers of linguistic narrative from various sources.

Jonas: Yes, I read the newspaper and included facts about what’s happening in the ocean and the environment, poems about the ocean, written texts. It’s like a lecture demonstration with me. And I’m juxtaposing one image against another and creating a different narrative by doing so.

Van Straaten: And the still images you used are all pulled from video grabs?

Jonas: Right. I use video because the fish are moving, and I think their movement is so beautiful and works so well with the sound and music.

Van Straaten: Your work has obviously been multimedia for so long—you are a pioneer in video and you employ performance, installation, drawing, painting, music, sound, text, you know, everything you can imagine, but no still photography? What is your stance regarding shooting stills?

Jonas: I don’t have a stance. It’s something that greatly interests me. I’ve always been interested with all of my video projections in the framing device, how to make or alter an image by framing it, just as photographers frame their images. Look at Robert Frank as an example. He sees the everyday and he frames it in a very incredible, beautiful way. So often when I’m working on a piece, I experiment with still imagery and the idea of making a still and framing it. I think that would be the main connection to photography.

Joan Jonas, Moving Off the Land, 2019, Ocean Space, Chiesa di San Lorenzo, Venice. Performance with Ikue Mori and Francesco Migliaccio. Commissioned by TBA21–Academy

Photograph by Moira Ricci and courtesy Joan Jonas

Van Straaten: No camera though?

Jonas: I used to have a Leica a long time ago. In my archives I keep stills that I’ve taken over the years. I almost bought a Leica a few years ago, because I wanted to experiment with digital and analog and work more with stills. I’m very interested in it, and I’m going to return to it probably at some point, in some way. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot for a long time, and I never can get around to it, frankly. And Mary Ellen Mark, who was a friend of mine, was totally enthusiastic about that decision and was actually helping me to buy a new Leica. But, I never followed through.

Van Straaten: Did the mission of TBA21/Ocean Space around the climate crisis make you feel that your image making for this project had to be rooted in documentation?

Jonas: Documentation is just part of my general thinking, part of my language naturally. But I don’t think of it as “I’m going to make this poetic documentary,” like the way Robert Frank works with documentary.

Van Straaten: You mentioned Robert Frank twice now. I understand you were in an early film of his, in 1975?

Jonas: Yes, it was a film called Keep Busy (1975), where there were a group of artists [including Richard Serra] up in Cape Breton. He made it with a man called Rudy Wurlitzer. And we went out on an island and spent like four or five days. There was a lot of improvisation going on. I did some movement. It was funny.

Laura van Straaten is an art journalist based in New York. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Joan Jonas’s Moving Off the Land II is on view through September 29, 2019 at Ocean Space, Campo San Lorenzo, 30100, Venice, Italy.

The post Joan Jonas on Her Special Commission for Venice’s Newest “Pavilion” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 1, 2019

In Film, Are Millennials Having a Moment?

A series at BAM attempts to make a canon of cinema for a generation more interested in dismantling them.

By Jesse Dorris

Fransley Hyppolite, Patrick Declie, and Ashton Sanders in Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight, 2016

©A24 and courtesy Photofest

Once upon a time—let’s say, oh, between the years 1981 and 1996—eighty million or so Americans were born. In their childhood and early adolescence, both the Berlin Wall and the Twin Towers fell. In classrooms and nightclubs, their peers murdered each other at unprecedented, incomprehensible rates. They grew up on the Internet, a commercial space posing as a communication network, and they occupied “third places,” zones neither work nor home but pay-to-be-there hangouts. They claimed unfixed genders or no genders at all, saw AIDS become undetectable for the wealthy and connected, sodomy legalized and abortion criminalized, Britney Spears shave her head and Lady Gaga don a cowboy hat, land a Vegas show, win an Oscar. They heard the dial-up moan-and-grown ghost into the vibration of an iPhone.

Greta Gerwig in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha, 2012

Courtesy IFC Films

The world called them Millennials, and they are having a moment. We Can’t Even: Millennials on Film, a series curated by Ashley Clark at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, tracks this generation’s imprint in and on cinema. Clark has gathered more than two dozen documentaries, web series, indie gems, classics, disasters, and even a masterpiece or two, in an attempt to make a canon for a generation more interested in dismantling them.

Jesse Eisenberg (as Mark Zuckerberg) in David Fincher’s The Social Network, 2010

© Columbia Pictures and courtesy Photofest

Gen-X lodestar David Fincher’s The Social Network (2010), a lightly fictionalized biopic of Facebook cofounder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, is the origin story of a technology—and a habit—that defines us. Not quite the centerpiece, but a key film of the era, it depicts the digital displacement of reality itself in deeply conservative ways. The Social Network, full of young men on their hero’s journeys and presented at angles as if posing for busts, is fueled by Aaron Sorkin’s Boomer babble and scored by Gen-X fury Trent Reznor, allowed only to just tickle the tasteful ivories. “It’s thematically about the changes in technology, rather than an embodiment of them,” Clark told me, pointing to Millennial Eduardo Williams’s 2016 global-minded cybersex thriller, The Human Surge, as a better example of art both of and about its moment.

Natalie Portman in Brady Corbet’s Vox Lux, 2018

© Neon and courtesy Photofest

Vox Lux is another attempt, as Clark puts it, to examine “whether [Millennials] can process bad news at the rate we consume it.” They can’t. There’s just too much of the former and not enough time for the latter, at least in director Brady Corbet’s 2018 fictional biography of a Millennial monster born in gunfire and forged by the markets of commerce and art. Natalie Portman, herself just on the elder edge of the generation, acts as hard as she can as various genres, styles, and tones fail to cohere around her. (Actually, that might accurately sum up the entirety of our strange zeitgeist.)

Lindsay Lohan in Chris Silverston’s I Know Who Killed Me, 2007

© Sony Pictures and courtesy Photofest

It’s tempting to view Portman’s character as an ersatz Lindsay Lohan, who haunts We Can’t Even in three forms: first, as a teen whose eyes are as clear as her skin in Mark Waters’s infectious Heathers-but-make-it-earnest instant classic Mean Girls (2004); then as a Hitchcockian woman in trouble in Chris Sivertson’s outrageously despicable 2007 I Know Who Killed Me; and finally, as ruins to be plundered, a victim of fame-obsessed teenage girl robbers in the banal The Bling Ring (2013), in which Sofia Coppola attempts to eviscerate the vapidity of unearned wealth.

Hamza Meziani in Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama, 2016

Courtesy Grasshopper Film

“I Know is a bad object,” Clark says. “But it interests me to have obviously compromised and deeply unpleasant work next to prestige Oscar winners, and have that conceptually make sense.” It does. A Millennial point of view—rattled and jittery, paralyzed neither by fear of death nor by irony, but instead by sheer overload of self-reflection—begins to come into focus. Bertrand Bonello’s 2016 ode to terrorist chic is shimmering and morally ambiguous but utterly itself. His pack of teenagers blows up buildings and hides in a shopping mall, gathering in wait like The Breakfast Club’s bad apples, as cool as Gregg Araki’s Doom Generation, but so lost in capitalism’s hall of mirrors that all they can do is die, paralyzed by indecision, as they blow up the world.

Kitana Kiki Rodriguez in Sean Baker’s Tangerine, 2015

© Magnolia Pictures and courtesy Photofest

Or not. Sex work, the ne plus ultra of capitalism, might be failing the trans women of color in Sean Baker’s riotous Tangerine (2015)—the rest of their world is surely failing them—but their charisma is so concentrated and specific, it feels like it could only be captured via the tiny funnel of the iPhone camera, on which Baker filmed the feature. More lusciously traditional, if just as radical in content, is Barry Jenkins’s exultant 2016 film, Moonlight. Replete with references to still photographers, like Earlie Hudnall, Jr. and Viviane Sassen, Jenkins not only breathes new life into the hallowed queer coming-of-age-and-out format, but astonishing richness and vitality into the often muddy format of digital film. Meanwhile, Xavier Dolan’s I Killed My Mother (2009) enlists actual still photographs to freshen up its tale of an abused queer teen. Once the narrator’s sexuality is revealed, a larger-than-life poster of River Phoenix, the tragic thinking man’s hunk of Gen X, is shown to have been hanging over his bed the whole time. Like much of Dolan’s work, it’s unsubtle, but it works.

Still from Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis’s Whose Streets?, 2017

Courtesy Magnolia Pictures

The documentaries in We Can’t Even argue that if you’re going to rebuild a world in your own image, you must first know who you are. Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis’s 2017 Ferguson documentary, Whose Streets?; Seyi Adebanjo’s heartbreaking 2013 short for a life cut short, Trans Lives Matter! Justice For Islan Nettles; Cecile Emeke’s 2015 oral history of the modern African diaspora, Strolling; and Wu Tsang’s WILDNESS (2012), a fabulous examination of how representation and gentrification intersect in a Latinx bar for LA’s queer and trans communities (fiercely narrated by the bar itself) all demonstrate what might be Millennials’ true gift: nerve. If awarding children with an endless parade of trophies gives them the confidence to tell these crucial, complicated stories with such prowess and zeal, let’s build trophy factories across the land.

Zoe Renee in Nijla Mumin’s Jinn, 2018

Courtesy Park Circus

“Older generations misunderstand the idea of identity politics,” says Clark, a Millennial himself. “They see representation as self-absorption. And there’s an idea that narrative storytelling devices are played out and conventional. But it’s like, for whom? I’ve never seen a black Muslim girl’s coming-of-age story.” So he programmed one: Nijla Mu’min’s Jinn (2018), a highlight of the series.

Keire Johnson in Bing Liu’s Minding the Gap, 2018

Courtesy Kartemquin

Other highlights include Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2012), in which Greta Gerwig somehow seems to be in Technicolor, despite the black-and-white film stock, as she problematizes the Manic Pixie Dream Girl into a kind of manic depressive Holly Golightly. Today, it seems wiser and weirder than ever. But few works of art in the past twenty (or forty) years have the empathy and aesthetic pleasure of Minding the Gap. Bing Liu’s rightfully beloved 2018 documentary was assembled in real time as he and his skater buddies grew up and fell apart. Shot over a dozen years and set in the golden hours of impossibly tender, doomed light, it deconstructs masculinity more nimbly than gender studies master classes, and for sure will be studied in them. For Liu, manhood arrived in cahoots with cheap editing software, and his careful eye for both the perfect shot and the fearless prompt posit reality television as conscious-raising seminar. It’s the best-case scenario for a life documented from the jump, and a glorious sign of the artistic potential of a generation rewarded and lambasted for just being, and seeing, themselves.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

We Can’t Even: Millennials on Film continues at the Brooklyn Academy of Music through August 6, 2019.

The post In Film, Are Millennials Having a Moment? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 31, 2019

From an Italian Photographer, the Bygone Days of Bohemian New York

Ugo Mulas captured the swinging 1960s art world defined by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg.

By Jesse Dorris

Ugo Mulas, Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

It often takes an immigrant to show America to itself. Italian photographer Ugo Mulas only visited here, but his view of New York in the mid-1960s changed the way we see the city and the bohemian enclave it stands for. That world—with its sizable lofts, oversize ambition, and stance that life could be art and vice versa—only barely exists today (if at all) in neighborhoods like Chelsea, where more than one hundred of Mulas’s images hang at Matthew Marks Gallery in Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene, a thoughtful exhibition organized by curator Hendel Teicher.

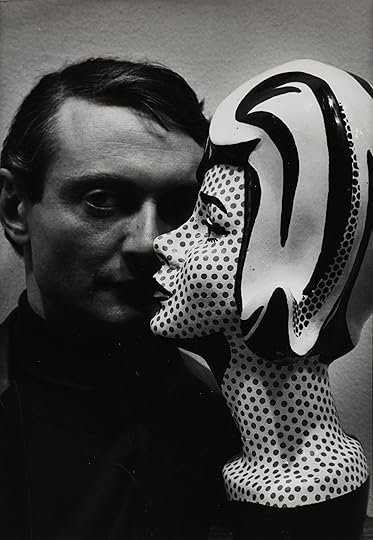

Ugo Mulas, Roy Lichtenstein, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Born outside of Milan in 1928, Mulas thought he’d become a lawyer, but he abandoned school after falling in love with Milanese nightlife, photographing people posed at the infamous Bar Giamaica with a borrowed camera. By 1954, he was the Venice Biennale’s official photographer; ten years later, he’d developed a style: inquisitively formal, full-frontal, and based on long nights watching theater rehearsals. He made definitive portraits of Alexander Calder, David Smith, and Lucio Fontana. And he formed crucial friendships with figures like Leo Castelli and Andrew Solomon, whom he met at the 1964 Biennale and who convinced him to take a trip to New York.

Ugo Mulas, Jasper Johns, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

“He didn’t speak much English,” Teicher told me, “but you don’t have to speak much English as a photographer.” Instead, Mulas sat in artists’ lofts, around dinner tables, and in studio rehearsals, galleries, and clubs. “I feel impersonalized,” Mulas once remarked. “Thus I try to understand what is happening around me, doing it through my photos.” He returned in 1954 and 1967, and produced an epochal catalogue of what he saw, 1967’s New York: The New Art Scene. Teicher pulls from this book and unpublished work from the time for her show, which greets viewers with fascinating maquettes of the manuscript, before opening into zones for Mulas’s studies and collaborations with a who’s who of New York’s midcentury artistic characters.

Ugo Mulas, Roy Lichtenstein, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Each zone centers one of Mulas’s formal innovations: printing an entire roll of film as a single image, thus transforming time spent watching an artist work into a flip-book, or a skyscraper with parties or workspaces glimpsed through rows of windows, or even from a distance, a kind of Mondrian grid. Favored images earn pride of place next to contact-sheets-as-photographs: Marcel Duchamp, Mulas’s first artistic love, standing between drapes like a magician appearing; Barnett Newman, standing stiffly in a suit and pointing to a vast, empty canvas as if to say, “that’s enough.” A series of action shots of Roy Lichtenstein integrates fascinating photographs of comic book scraps taped to the walls with glamor shots of the artist pressing his face to dotted busts and other merchandise, a self-conscious blurring of the lines between product and producer. Mulas’s portraits of Andy Warhol manage to find something new in someone overexposed even then, with a 1964 photograph drawing attention to the fragile veins in his hands, those physical tools Warhol worked so hard to make irrelevant.

Ugo Mulas, Police stop a dancing party at Andy Warhol’s Factory, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

“Mulas always gives you enough information to understand what kind of character you are dealing with,” Teicher says. And what characters! Juxtaposing photographs of Warhol’s world—a police raid on the Factory with a man thrusting his ass out beside another man pounding a bottle of beer—with those of Robert Rauschenberg’s tells you everything you need to know about the difference between the two artists. Rauschenberg’s vast loft includes domestic clutter and a long table of friends invited for Thanksgiving dinner; other photos study Trisha Brown arranging her body in practice, or Rauschenberg half-naked in shadows, mid-thought and yet in costume (for Spring Training). In these images, life and work are as carefully balanced as Mulas’s compositions.

Ugo Mulas, Jasper Johns, 1965

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Watching Jasper Johns changed Mulas’s idea of what should be shown. In as intimate a moment as is possible between two artists, Mulas captured Johns from behind in the act of creation. The power dynamic—one artist transforming the labor of another into work of his own—unnerved him. “If the painter agrees to be shot, the photo is purely for public relations purposes,” Mulas later explained. “If the painter refuses and I succeed in convincing him, the photograph is an act of violence.” Mulas rarely photographed artists at work again; his portraits of Johns instead show Johns wrapped in sweaters and staring down his gaze, or pressing a sweating face into the canvas as if it were a pillow or a lover.

Ugo Mulas, Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Mulas left New York and returned to documenting the Italian art world; an accomplished writer and critic, he finished the series Verifications, a kind of meta-manifesto, shortly before he died of cancer in 1973. The images in The New Art Scene now look like arguments for—more so than evidence of—a world that takes artistic practice seriously. One hopes someone new is able to come to New York today and not only make this argument, but win it. But it’s surely more difficult now than it was for Mulas. “One needs to realize that my point of view is not only optical, but mental above all,” he once said. Which is to say that maybe this world was a state of mind after all.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene is on view at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, through August 16, 2019.

The post From an Italian Photographer, the Bygone Days of Bohemian New York appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers