Aperture's Blog, page 85

July 10, 2019

Two Artists Interrogate the “White Gaze” of National Geographic

Pairing archival images and text, Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê pose a razor-sharp critique of colonialism.

By Khairani Barokka

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

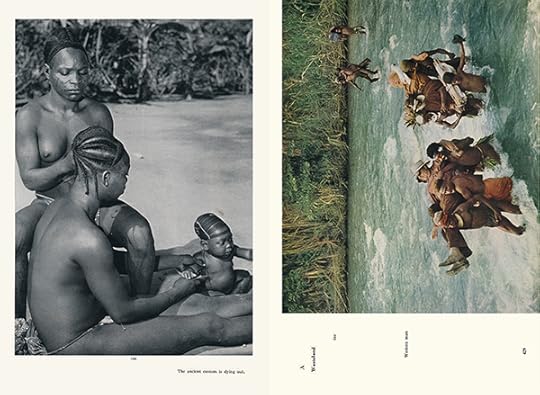

In early 2018, National Geographic ran a piece entitled “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge This.” However, the magazine’s archival behemoth of denigrated bodies and minds still exists, imbuing its photographic subjects with racist notions that still need wider acknowledgment. The National Geographic archive is the cause of true harm on a mass scale, and dehumanizes, exploits, and perpetuates the worldview of our lands as resources for plunder, and our lives as classifiable, capturable, translatable only through the white gaze.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

Artists and scholars Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê’s book White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018) is a work that exposes the National Geographic lens with razor-sharp textual acuity. The authors work harmoniously, with Dizon providing photos chosen from the magazine’s issues and Lê juxtaposing them with original and found poetic text. Their cut-off point for mining the archives was the 1960s: Dizon explains that this is because a more neoliberal version of racism emerged in the 1970s, and in the 1980s text became embedded within the magazine’s images, which doesn’t fit White Gaze’s aesthetics of image-text interplay. Lê, meanwhile, contributes word choice and, crucially, visual spacing, to induce pauses and rhythm for the reader and sustain intended engagement with the photography. The size and positioning of the archival photos in relation to the poetry, timelines, and archival texts are always intentional; the results are deft, cutting. Captions note people “Scrubbed by their missionary guides until they shone” and a woman dancing bare-chested against “the / collector.” A transcribed letter from US President Eisenhower to Indian Prime Minister Nehru, encouraging peacemaking policies, lies opposite a large photograph of what appears to be a white man and woman driven by a South Asian man in a rickshaw—power dynamics persisting through the whiteness of gaze. The text at times excoriates the destructive processes of colonization, and at others adopts the language of the colonizer, or straddles the line between complicit and noncomplicit language. This brings up a slight tension in the act of absorbing the image-text interchange, requiring a subtlety of appraisal.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

In a discussion between Dizon and Lê that ends the book, it is noted that scholar Saidiya Hartman’s notion of “impossible stories” resonates in the dead’s inability to contribute their words to the conversation. I was struck by this impossibility, particularly in the image of the beautiful Polynesian woman captioned “She was destroyed by . . . US military operators.” Would the subject and her loved ones perceive this as a reinscription of violence? Is finding this out impossible, or could she or her family know she is being used in this book—and why or why not? The line between pointing out violent dehumanization in photos and reinstating that harm becomes blurry here; captioning children who could be our own ancestors with “little natives sing and play” is clearly a statement of the photo’s sinister subtext, but also a potential pain for those involved as subjects here, tangentially or otherwise. It is a credit to Dizon and Lê that this lack of power is addressed in their interview, but I found myself craving further discussion on how this affected their process and decisions.

Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê from White Gaze (at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books, 2018)

Courtesy of at land’s edge, Candor Arts, and Sming Sming Books

For these reasons, I found White Gaze most brilliant when a caption turns to the white gazer as at least partial photographic subject, in the sense of bodies or belongings in a frame; for example, “watch / the daughter of an American who buys rubber here for Goodyear.” A pristine mansion’s front yard exists opposite a page proclaiming “Slave labor”; a family gathering of Caucasians watching a film reel is paired with “Absence.” Also significant is the portrayal of resistance to white occupation, whether through the word “Struggle” captioning brown bodies under a colonizer’s flag, or photos 206 and 420 evoking “blacker / English,” language itself as battleground and weapon–textual as well as visual language. At its best, White Gaze illuminates the truth, palpitatingly urgent: “the camera may be a gun.”

Khairani Barokka is an Indonesian writer, artist, and poet. She has published two books, Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis Press, 2016) and Rope (Nine Arches Press, 2017), and her last exhibition as artist was Annah: Nomenclature at the ICA, London (2018).

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Two Artists Interrogate the “White Gaze” of National Geographic appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Human Cartography of Collective Struggles

In his recent photobook, Martín Weber negotiates the past and the future in Latin America.

By Andrea Jösch

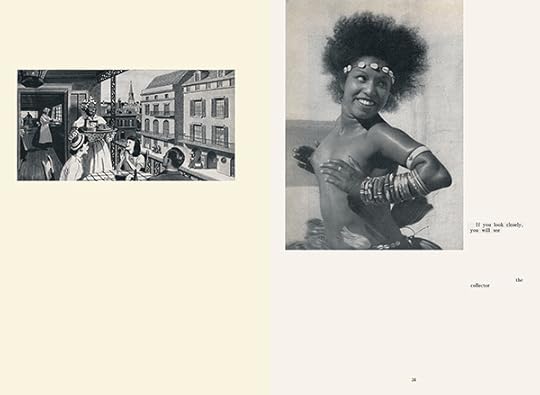

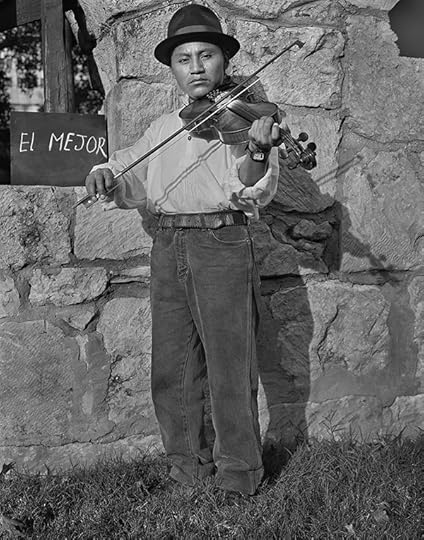

Martín Weber, El mejor./The best., Texas, 1992

© and courtesy the artist

Map of Latin American Dreams by Argentinean photographer Martín Weber (Editorial RM and Ediciones Larivière, 2018) is the result of a long journey (1992–2013) through fifty-three towns and cities in Argentina, Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Peru, Brazil, and Colombia. In the book are 110 monochrome portraits and several personal stories, like diary entries, that are interwoven in the narrative, which includes an essay by artist and educator Robert Blake. The gold color of the cover and silver in the negatives printed in the preface lead us to think about the symbolic space around material/mineral resources and the tragic history of their domination.

Martín Weber, Quiero ser policía./To be a policewoman., Maclovio Rojas, Mexico, 2000

© and courtesy the artist

At the beginning of the book, Weber points out in the travel notes: “Someone once told me that for someone born in exile, every trip is an exile.” And in the postscript: “Perhaps because my parents weren’t part of any armed resistance group against the dictatorships they suffered under, but were instead part of a conscientious opposition, it took me four decades to understand why I was born in Chile, and forty years to accept that I was born in exile.” These phrases, which resonate in the memory of our troubled Latin America, give sense to the images we observe, because the work is not only a question of giving a voice to those who have been denied this possibility, and visualizing the physical and spiritual marks and vestiges that conflicts and struggles have left in people, but also a question of why there are so many abuses, so many silences.

Martín Weber, Viajar a Italia para visitar a mi hija que vive allá./To travel to Italy to visit my daughter who lives there., Cachoeira, Brazil, 2005

© and courtesy the artist

Exile and forced displacement have been, for different reasons, a constant in the reality of our continent for decades, but it is also true that many, most, live or survive in their territories, dreaming that one day something can be transformed. The cyclical worldview of life, on which the belief systems of many indigenous peoples are based, fixes the possibility of the future only if one is aware of the present while looking toward the past. This can be an analogy of the tension between dreaming and living without forgetting—with memory.

Weber stages his photographs with patience and care. Individuals or groups are invited to pose holding a wooden board on which they have written their dreams in chalk—longings, fears, and promises, though almost always colored by violence, poverty, and daily life. This work invites us to build, from the unavoidable relationship between images and texts, a human cartography of common stories and collective struggles.

Martín Weber, Deseo vivir para mi esposa, mis hijos y mis nietos./To live for my wife, my children, and my grandchildren., Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008

© and courtesy the artist

This publication reiterates for us, both in the personal notes of the photographer and in his portraits, the failed policies and the fierce social inequality that invade us, while at the same time accounting for resistance and persistence. It proposes a reflection on time, both photographic time and history’s repetition of events, which seems more like a tragic song, as if dreams have been turned into supplications that are transmitted from generation to generation. The book is a sort of map between two times: the one of the archive and the one of the journey, of reality and dreams, photographs and texts, forgetfulness and memory.

Martín Weber, Mi sueño es morirme./My dream is to die., Medellin, Colombia, 2007

© and courtesy the artist

In 2007, Weber photographed Cristián, the Colombian teenager whose portrait is printed on the cover of this book: “My dream is to die.” He poses with his scars, staring fixedly at the camera; his shot body was found six months later. It’s a tribute, perhaps; a second title, also. It seems that the dreams—of having health, work, land, education, the return of loved ones and the missing, having a decent life, affection—written by the women, men, children, and elderly portrayed by Weber, make us wake up and understand that, for all the differences that exist between cultures and countries, the dream of the majority of Latin Americans is to be able to live with dignity.

Andrea Jösch is academic coordinator of the Master in Photographic Research and Creation program at Finis Terrae University School of Art, Santiago, Chile. She is also editor in chief and founder of the South American photography magazine Sueño de la Razón and coeditor of Ojo Zurdo magazine.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post A Human Cartography of Collective Struggles appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 5, 2019

Marc Feustel on Photobooks After 3/11

It has been four years since the Great Tohoku Earthquake

unleashed a series of tsunami waves which struck a vast area of Japan’s northeastern coastline, and caused a severe nuclear incident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Japan is no stranger to natural and man-made disasters. However, since the 1960s the nation has, by and large, experienced peace and prosperity. Since the post-bubble years of the 1990s, much of Japanese contemporary art has been driven by self representation and aesthetics. But the events of March 11, 2011 (referred to in Japan as 3/11), have profoundly impacted the way art is both made and received in Japan, and today the social and documentary concerns that characterized the postwar years have risen back to the surface.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, photographers from around the country—and indeed the world—flocked to the devastated area. In the following months, book after book was published, seemingly documenting every inch of the devastated coastline. This photographic reaction is both natural and necessary, as if events of this magnitude require images to make it possible for us to begin to comprehend them. However, the sheer volume of these book projects quickly became overwhelming. It was difficult to feel anything but numb when faced with these endless images of devastated landscapes.

It was in this context that projects began to emerge with new approaches to this diffi cult subject. As early as April 2011, Rinko Kawauchi traveled to the earthquake-devastated towns of Ishinomaki, Onagawa, Kesennuma, and Rikuzentakata. From this journey she created the series Light and Shadow, based on her encounter with a pair of pigeons, one black, one white. This became the project’s theme: the dualism of light and shadow, good and evil. While the photographs depict destruction, Kawauchi’s work does not feel like a document, but rather a transcendence of the disaster, where despair already contains the seeds of hope. Two publications have emerged from the series, both titled Light and Shadow: a short, self-published book in 2012, and an expanded edit of the series published by SUPER LABO in 2014.

New approaches were also at work in two projects dealing with the Fukushima nuclear incident that resulted from the earthquake: Katsumi Omori’s Subete wa hajimete okoru (Everything happens for the first time, Match and Company, 2011) and Takashi Homma’s Sono mori no kodomo (Mushrooms from the forest, Blind Gallery, 2011—both of which were reviewed by Ivan Vartanian in The PhotoBook Review 002.) Fukushima is the least likely of photographic subjects as it demands the impossible: to photograph radiation—the invisible. Omori described the compulsion that drove him to Fukushima: “I must go to Fukushima. I must shoot the radiation (though it cannot be shot).” By employing a halation effect throughout his series, he lays bare the limitations of photography in the face of this invisible threat, while also giving that threat a form.

At first glance, Homma’s images of forests and wild mushrooms seem to bear no relation to the nuclear power plant, but their meaning is transformed by a brief text buried at the end of the book. In it, Homma explains that mushrooms absorb radiation faster than other living organisms; those he collected in the forests of Fukushima Prefecture contain much higher levels of radiation than elsewhere in Japan. The experience is unsettling, forcing the viewer back through the images with a very different eye. Tomoki Imai’s Semicircle Law (Match and Company, 2013) uses a similar device. His seemingly anodyne forest landscapes are transformed by a diagram at the end of the book revealing that his photographs were taken on either side of the twenty-kilometer security radius established by the Japanese government around the stricken nuclear plant. Imai himself has said that he thinks these images’ signifi cance will depend on which vantage point the future will bring.

Non-Japanese artists have also been drawn to the affected region. The German photographer Hans-Christian Schink traveled to Japan one year after the quake to photograph the coastline. Tohoku (Hatje Cantz, 2013) provides a complex view of the aftermath of 3/11, in which the tsunami’s impact ranges

from the imperceptible to the brutal—a landscape still caught in the midst of a long healing process. More recently, Antoine D’Agata produced a surprising new book on Fukushima. Over the course of six hundred black-and-white plates, Fukushima (SUPER LABO, 2014) presents a typology of those houses abandoned due to their proximity to the stricken nuclear plant. A far cry from D’Agata’s signature work, the uncharacteristic coolness of these images builds to a foreboding emptiness.

While all the projects mentioned above were created by photographers from outside the Tohoku region, for some the events of 3/11 were of a more personal nature. Iwate-born Kazuma Obara’s Reset Beyond Fukushima (Lars Müller, 2012) goes beyond a documentation of the catastrophe to become a call to action—the book’s subtitle is Will the Nuclear Catastrophe Bring Humanity to Its Senses?—in the grand tradition of the Japanese protest book.

Naoya Hatakeyama is also from Iwate, and his book Kesengawa (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2012; Editions Light Motiv, 2013) is concerned with the destruction of his hometown of Rikuzentakata. Kesengawa has two distinct halves. The first contains photographs that Hatakeyama had been casually producing over the years along the Kesen River, which runs through Rikuzentakata. The

book then shifts into the photographs taken in his hometown in the aftermath of the wave. In the book’s afterword he describes his aim to “bring the event closer to people, to compress the physical distance.” Whereas Homma and Imai’s images are altered by the text that follows them, in the case of Kesengawa, the photographs are transformed by the events themselves. Snapshots made only to be tucked away in a small box in Hatakeyama’s studio suddenly gained great significance—a profound illustration of the ever-shifting relationship between photography and the world.

Lieko Shiga was directly affected by the tsunami. In 2008 the young artist relocated to the small coastal village of Kitakama in Miyagi Prefecture, where she had been given a home and a studio in exchange for taking on the role of official photographer for this small community. Shiga had been working on an ambitious project about her adoptive home when the tsunami struck, destroying much of the community and her studio with it. She went on to fi nish the project, which became a book and an exhibition. Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Beach, AKAAKA, 2013—short-listed as PhotoBook of the Year in the 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards) is not a book about the tsunami, but one whose course was profoundly affected by it. Like many of the projects referred to here, Rasen Kaigan is also concerned with bringing the invisible to light: rather than documenting the surface of her adoptive community, Shiga chose to focus on its fantasies, dreams, and memories—its “essence.” (Shiga also collaborated on the centerfold for this issue—see caption, bottom left.)

Of all the books that deal with the 3/11 tsunami, Tsunami, Photographs, and Then: Lost and Found Project (AKAAKA, 2014—short-listed as Photography Catalogue of the Year in the 2014 PhotoBook Awards) is perhaps that which says the most about photography’s importance at times like these. The book provides an overview of the work of the Lost and Found Project, a group that was formed to attempt to retrieve photographs that had been scattered by the wave, preserve them, and return them to their owners. Initiatives like this one sprung up all along the Tohoku coast, and are a testament to the vital importance accorded to photographs when all has been lost.

An extraordinary breadth of projects and approaches have emerged around 3/11 in the past four years. The books mentioned here all deal with the subject directly, but there are countless others in which these disasters are a powerful, if indirect, undercurrent; the many projects referred to in this piece only represent a beginning. Looking to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, these events remained key themes for decades after the events. Arguably the two most powerful bodies of work on the atomic bombings, Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu (The Map, 1965) and Shomei Tomatsu’s 11:02 Nagasaki (1966), were not published until twenty years after the fact. Today, the resurgence of social concerns echoes the artistic engagement of those postwar years. Perhaps the greatest photobooks to deal with 3/11 are still to come.

Marc Feustel is an independent curator, writer, and editor based in Paris. A specialist in Japanese photography, he has curated exhibitions, including Tokyo Stories (2008), Japan: A

Self-Portrait, 1945–1964 (2009), and Eikoh Hosoe: Theatre of Memory (2010). He writes regularly about contemporary photography and photobooks. marcfeustel.com

The post Marc Feustel on Photobooks After 3/11 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Matthew Carson on Takashi Homma

One of the first things that you may notice about the words on the spine and on the title page of Takashi Homma’s New Documentary is that the title has been struck through. This is a typographic hint that this is not intended to be a new edition of Homma’s 2011 photobook of the same name; however, there is a relationship between the two books. The New Documentary of 2011 was thought to exemplify Homma’s neutral and distant

style. The new New Documentary is a further distillation of that concept through the process of book design and bookmaking.

New Documentary is a compilation of images from the 2012 exhibition Takashi Homma: New Documentary, held at the Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art (MIMOCA), and the 2014 exhibition You reach out—right now—for something: Questioning the Concept of Fashion, held at Art Tower Mito and again later that year at MIMOCA. The clever conceit here concerns the way that the dense multi-platform content from those exhibitions—books, paintings, fashion magazine covers, video, and photo-based silk screens—is worked into this new photobook. Installation shots from the exhibitions are playfully intermingled with the original media, and multiple projects are shown without clear distinction or hierarchy. A tipped-in cover image of a well-known fast-food chain wraps around the spine of this sturdy clothbound book. The same image is again tipped in to the opening pages. Photographs of the restaurant are repeated throughout the book in varying ways: as close-ups, as details, abstracted, in silk screens, and in installation views. Around these images, Homma introduces diverse work from the two exhibitions. He includes familial and vernacular imagery; cityscapes and interiors; an extensive portfolio of his fashion work; and abstract photographs and paintings relating to the visual contrast between forest, blood, and snow, from his First, Jay Comes and Trails series. This is a compilation filled with visual puns and references. What we are seeing here is a photobook as exhibition catalogue (or catalogues), expressing itself as an artist’s book. Homma’s photobooks, like his classic Tokyo Suburbia (1998), have been somewhat confusingly described as being nondocumentary. The fact is, as this book proves, Homma has many styles and is comfortable both communicating and withholding in multiple genres. His work occupies that space between expression and record, personal narrative and document. Working within a realm of loose boundaries, Homma’s unique style has inspired many other photo-based artists to attempt to mimic his distinctive, allegedly unemotional images; not surprisingly, the vast majority of these Homma-san homages have failed, as they try too hard to reimagine his remote style without understanding how emotionally engaged he actually is with his subject matter.

&emsp:New Documentary is a book that you need to spend time with—to break down, unpack, and try to gain access to in its initial remoteness. One needs to understand the simple tricks of the concept underpinning this book. This book is not easy at first: it questions our instincts about what a photograph is and places doubt within us about what we are seeing. But the effort is rewarded by the intimate qualities of Homma’s work.

Matthew Carson is a librarian and archivist at the International Center of Photography. He is a committee member for the Contemporary Artists’ Book Conference at the New York Art Book Fair and a cofounder of the organization 10×10 Photobooks. In 2013, he was a curator of the book component of the ICP Triennial A Different Kind of Order. 10x10photobooks.org

The post Matthew Carson on Takashi Homma appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Foundation

Aperture Foundation

New York, NY

Aperture is a not-for-profit foundation, connecting the photo community and its audiences with the most inspiring work, with the sharpest ideas, and with each other—in print, in person, and online.

Created in 1952 by photographers and writers as “common ground for the advancement of photography,” Aperture today is a multiplatform publisher and center for the photo community. From our base in New York, we produce, publish, and present a program of photography projects, locally and internationally. The Foundation offers public programs including lectures, workshops, panel discussions, and conferences that contribute to and expand the dialogue on photography’s role in our society as well as outreach education for children and teens building visual literacy and aimed to engage diverse new audiences.

POSITION DESCRIPTION

Aperture is seeking a full-time graphic designer, to start as soon as possible, experienced in print and online design, to work with Aperture’s editorial and development staff to produce design projects, and run our design department, maintaining and enhancing the quality distinctiveness of Aperture’s brand, and communications language.

Responsibilities include:

Designing and overseeing book promotion materials, events calendars, exhibition invitations and signage, as well as evites, the program for our annual benefit, display and wall signage, magazine ads, and occasional book covers (requiring work to existing templates as well as original design work);

Prepping files for print and transmitting files to printer and maintaining archives of all pre-press files and PDFs;

Managing design department workflow;

Managing print requirements for house materials;

Assessing design work by outside designers, and proposing first class outside designers for Aperture to add to its roster; and

Managing and supervising an intern and a junior designer, as appropriate, to balance workload.

QUALIFICATIONS

Two to three years’ professional print design and production experience.

Bachelor’s or other degree.

Passion for Aperture’s mission.

Knowledge of online design, website building, CSS, etc.

Strong grasp of issues of contemporary photography and/or the arts a plus.

Ability to work independently with minimal oversight and to thrive under deadline pressure.

TO APPLY

Please send a resume, a link to your design work, and a thoughtful cover letter, outlining how your skills and experience meet the qualifications of the position, your current/most recent salary and/or your salary expectations, and how you heard about this opportunity, to newhire@aperture.org, using the following conventions:

Subject line: Designer

Cover Letter: yourfirstname_yourlastname_coverletter.doc

Resume: yourfirstname_yourlastname_resume.doc

Applications will be reviewed on a rolling basis. NO CALLS, PLEASE

Aperture is an Equal Opportunity Employer

Please also state your availability for an interview on Friday 12 December. Please also note that this is a re-advertisement, where Aperture is reaching out to previous applicants who are invited to re-apply.

The post Aperture Foundation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 3, 2019

Orlando Now

Inspired by Virginia Woolf, Mickalene Thomas imagines a classic, gender-crossing heroine as a fashion muse for the twenty-first century.

By Antwaun Sargent

Mickalene Thomas, Untitled, Orlando, 2019, for Aperture. Suit and gloves: House Of Underwood; necklace: Ayaka Nishi; shirt: Underwood NY; shoes: Top Owens

Courtesy the artist

The 1992 film adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, starring Tilda Swinton in the title role, is a British period drama that begins during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I in the early 1600s. The queen, played prodigiously by Quentin Crisp, fancies a young, boyish, aristocratic poet, Orlando, and grants him the male privilege of estate ownership. The narrative travels progressively through more than three centuries of attitudes, politics, fashions, and, most remarkably, relationships between the sexes.

While the word gender only appears once in Woolf’s work of fiction (in reference to Orlando’s “China robe of ambiguous gender”), the concept of gender is cast radically and rightly as a plaything in the film. Swinton, with delicate quietude and characteristic androgyny, evolves from man to woman in what she has called “a nonperformance.” Her—or is it still his ?—status and authority diminish as director Sally Potter advances the plot, but subjectivity, desires, and matters of the heart remain unbowed to expectation. In one of the saga’s most enduring scenes, Orlando runs into a labyrinth on the lush grounds of an English manor. The camera follows as style, disposition, and century change— apt metaphors for identity in flux.

Mickalene Thomas, Untitled, Orlando, 2019, for Aperture. Dress: BJ Couture; head piece and shoulder piece: Randy Luna; earrings: Rainbow Unicorn Birthday Surprise; heels: Jessica Simpson

Courtesy the artist

It all leaves quite an impression and has inspired a new set of images by the painter and photographer Mickalene Thomas. “I wanted to be Orlando,” she says, explaining that in 1992, when the film premiered, experiments in sexuality, gender, and the social role of each were a crucial revelation in modern cinema. What had been rarely shown on the silver screen prior to Orlando had been privately felt by many, including Thomas, who desired to see cinematic and worldly expressions outside of prescribed binaries.

“The character Orlando, knowing that she was a woman, but was identifying as a male, resonates so deeply,” says Thomas of the moments in the film where the character steps outside of themself and peers directly at the camera as if to say, “I know who you are.” “As a teenager, when I was really coming to terms with my own sexuality, and was very much more androgynous than I am as my adult self, it felt so reassuring, safe, and exciting to see that on-screen.”

Mickalene Thomas, Untitled, Orlando, 2019, for Aperture. Blazer: Corvus; necklace: Randy Luna; headpiece: WXYZ Jewelry

Courtesy the artist

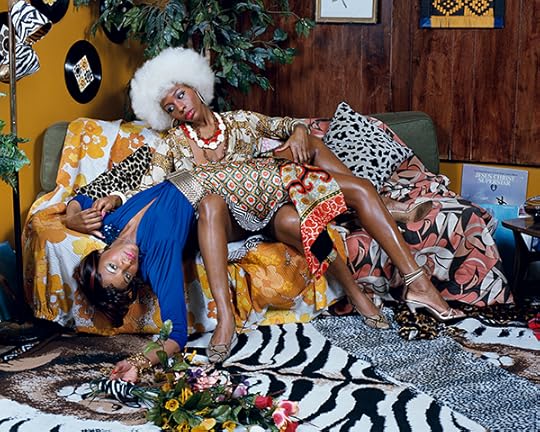

In these studio portraits, Thomas’s muse and partner, Racquel Chevremont, and the performance artist Zachary Tye Richardson extend the long spectrum on which Orlando exists in the imagination, while offering a fresh embodiment of Woolf’s amorphous vision within the context of Thomas’s study of the classical muse. Richardson and Chevremont, wearing ornate suits and beautiful gowns, elaborate wigs and bright jewelry, are cast desirously against a lush collage of plants, pillows, wood paneling, and colorful backdrops. Through Thomas’s eyes, the mise-en-scène has always been an opportunity to display a mélange of masculine and feminine elements, a proxy for the androgyny abounding in nature: her images are an attestation of what is natural.

According to Thomas, the pictures also are gamboling with one of the film’s central themes: passing. It’s something black women, femmes, and anyone existing outside of whiteness have had to rebel against, both racially and sexually, in an effort to claim space for survival and power, to make a world sensitive to their realities. Thomas’s portraits, such as one of Richardson in a blonde wig, a full face of makeup, and a pink lace dress that reveals a defined torso, or one of Chevremont in a black wig that gives her a masculine appeal, complicate notions of passing, asking: Is it worth it when so much of the self has to be given up to exist in tradition?

Mickalene Thomas, Untitled, Orlando, 2019, for Aperture. Shirt and vest: 2WN; tie: Underwood NY

Courtesy the artist

Throughout her career, Thomas has expanded the notion of the muse to include black women in her paintings and photographs, among them past lovers, friends, celebrities, mentors, and her late mother, Sandra Bush. For her Orlando inspired portraits, she draws on the muse-like relationship between Queen Elizabeth I and Orlando, as well as iconic nineteenth-century paintings. Contesting the male gaze, gender, and environmental dynamics in Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (The luncheon on the grass, 1862–63) and Paul Gauguin’s Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892), however, Thomas’s muses also embody the spirit and pageantry of the fa’afafine, a third-gender community in Samoa of boys who are raised as girls.

Thomas dismisses the comfort of neat categorization and applies what feminist scholar bell hooks has called an “oppositional gaze” to the construction of the images that tell a story of black identity play “from inside the circle.” Thomas’s portraits are just expressions of agency and fluid sexuality that represent, through dress, gesture, and environment, the in-between and hard to pin down. The pictures allude to black women loving other black women, and to femmes who love black men, in a world that doesn’t often love any of them back. Like Orlando, these figures, who have not historically been of any value in Western painting, in pop imagery, or on the big screen, now exist profoundly in pose, composition, and style in Thomas’s universe.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer based in New York and a regular contributor to T Magazine and the New York Times. His forthcoming book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion, will be published by Aperture in fall 2019.

Mickalene Thomas’s photographs were produced by ROOT STUDIOS and styled by Paris Warren.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Orlando Now appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Two South African Artists Who Can Be “Anything” They Want

Jamal Nxedlana travels through Johannesburg with the gender-defying artist duo FAKA.

By Milisuthando Bongela

Jamal Nxedlana, FAKA Portraits, Johannesburg, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

“Can we give Fela the other socks, the glittery ones?” Jamal Nxedlana asks stylist and makeup artist Orli Meiri, a short, talkative brunette in bright yellow Y-3 Kaiwa sneakers. She agrees. It’s Sunday afternoon on the calmer side of Yeoville’s ground zero—Rockey Street, where the back seat of a black Toyota Yaris has been transformed into a changing room for Nxedlana’s collaborators this afternoon, FAKA.

Many an artist’s heart has been found, loved, lost, and broken in this infamous oasis of social intercourse, often unfairly considered the Sodom and Gomorrah of Johannesburg by apartheid’s Calvinistic legacies. Today, in the aftermath of the glow of some of its ascended rock-star ancestors—the era-defining singers Brenda Fassie and Lebo Mathosa, the globetrotting trumpeter Hugh Masekela—it has transformed into a neatly sliced pie of religious zealots; hardworking, working-class families from all over Africa; weed dens; struggling creatives; and cyber scammers. Our little scene is unfolding on the doorstep of Times Square, built on one of Yeoville’s many documented intergalactic spiritual portals. A bevy of heterosexual men are drinking and sweating and drinking, following Nxedlana’s motley crew with their eyes.

Jamal Nxedlana, FAKA Portraits, Johannesburg, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Pint-size and protean since 1985, Nxedlana wears an unassuming all-black ensemble and never puts down his camera. He has been diligently creating and archiving small borderless worlds since 2006, both independently and collaboratively with the Cuss Group artist collective—whose projects span various disciplines of cultural production, including audiovisual exhibitions, installations, and the publication of print and digital media—and with Bubblegum Club, the pulsating living-culture website he cofounded and oversees from his Braamfontein offices.

When Fela Gucci (Thato Ramaisa) and Desire Marea (Buyani Duma), who, in 2015, created the performance duo FAKA (a Nguni word meaning “insert it” or “put it in”), eventually emerge from the car in matching outfits from head to ankle—blue-and-pink punctured tube tops, glittery red caps, chunky silver hoop earrings, camouflage booty shorts, and turquoise khunkqu belts—they look like the underage, Black Label beer–drinking, older cousins of the kids in Brenda Fassie’s music video for her 1987 hit “Ag Shame Lovey,” otherwise known as “Midodo.” Nxedlana bought the outfits with FAKA the day before at Small Street Mall, Johannesburg’s working-class shopping haven, where cheap Chinese fashion goes to be resurrected in the limitless fountain of poor black youth.

Jamal Nxedlana, FAKA Portraits, Johannesburg, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Trailing the performative heels of visual artists like Athi-Patra Ruga and celebrities like the 2000s queer South African pop group 3Sum, FAKA are interdisciplinary artists in their own right, and the muses of muses both in South Africa and abroad, raking in nods from the likes of Solange, Donatella Versace, Moses Sumney, and myriad independent music festivals as the queer envoys of gqom, arguably the most influential musical genre in South Africa right now. This attention is owed to the artful confluence of how they appear, where they are, and what they say. Their curated looks often transcend gender, race, and class binaries using uncategorized clothing, makeup, and hairstyles. And perhaps not unlike the title character in Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, they escape the confines of linearity as figures from the ongoing past, becoming somehow all genders, all ages, all times all at once.

Fela stands on the busy pavement looking at the blue sky with a cigarette in one hand and a Black Label quart in the other. An exquisite, waiting Desire sits on a white plastic stool, getting their extra eyebrows did. This person knows love. The way they sit—under a sun so hot it burns like it was hung by a short person—is with a gracious knowing hardly embodied by humans born in the 1990s, hardly deployed by those who are intimate with Internet fame, encapsulated in a tweet put out in July 2018 by Desire: “I am guilty of internalising a narrative that isn’t mine. I was actually very fortunate to have a supportive family who told me that I could be ANYTHING. My aunts and my grandmother invested in my greatness first. I’m learning to embrace that part of my story.”

Jamal Nxedlana, FAKA Portraits, Johannesburg, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

To the observant eye, beneath the unsophisticated sheen of Johannesburg’s new-money basicness is a grime so glorious, so magnanimous, that to name it would be premature. And greedy. Inside this grime is some borrowed sugar from the future-past, the granules of which are a mix of Bantu, the Internet, post-wokeness, and spirit. You will not find FAKA anywhere near a march or a protest. They are a protest, an intervention, and a performance by virtue of being. In a taxi, a mall, or onstage. A perpetual traveling installation of sweet, sweet liberation.

Milisuthando Bongela is a writer and editor based in Johannesburg.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Two South African Artists Who Can Be “Anything” They Want appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 27, 2019

13 Publications that Reimagine Queer Visibility

Pride was born of protest. What began as a commemoration of the 1969 Stonewall riots has grown into a month dedicated to recognizing and celebrating the impact that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals have had on history and culture. Photographs continue to be instrumental in reflecting and shaping representations of LGBTQIA+ communities, and Aperture has a long history of centering queer narratives in its publications and programming. Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, Aperture highlights thirteen publications featuring artists who have radically reimagined queer visibility.

Paz Errázuriz, Evelyn IV, Santiago, from the series Adam’s apple, 1987

Courtesy the artist

Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz is known for spending months or years within a given community, building trust and carefully studying social structures—among them brothels, shelters, psychiatric wards, and boxing clubs—where women were prohibited. In the 1980s, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Errázuriz took pictures of trans prostitutes working in clandestine brothels in Santiago and Talca. “The resulting series, La manzana de Adán (Adam’s apple, 1982–87), shows the intimacies fostered by queer men and trans women in the chosen families formed within brothels,” Julia Bryan-Wilson writes. “Decades before the rise of the phrase trans feminism and the increased mainstreaming of (some) trans bodies, Errázuriz’s La manzana de Adán sought to capture Chilean trans women without shame or stigma.”

Nick Sethi, Attendees of Koovagam Festival, Tamil Nadu, India, April 2016

Courtesy the artist

Aperture 229, “Future Gender,” Winter 2017

Guest edited by Zackary Drucker, the artist, activist, and producer of the acclaimed television series Transparent, “Future Gender” considers how trans and gender-nonconforming individuals have used photography to imagine new expressions of social and personal identity, from the nineteenth century to today.

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980

Courtesy the artist

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency by Nan Goldin, 2012

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Her work describes a world that is visceral, charged, and seething with life. What’s more, Goldin’s work challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis. Goldin herself has said, “I’m bisexual so I can’t really come out as gay. When I’m gay, I’m very gay. And when I’m with men then, you know, I’m with men. I don’t fall in love with people because of their gender.”

Ethan James Green, Maria and Massima, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Ethan James Green: Young New York, 2019

In his serene and sensitive photographs, Ethan James Green redefines beauty and identity for a new generation. Young New York, the artist’s first monograph, presents a portrait of New York’s millennial scene-makers, a gloriously diverse cast of models, artists, nightlife icons, queer youth, and gender binary-flouting muses of the fashion world and beyond. “Green’s subjects are confidently beautiful, masters of style and attitude,” writes Michael Schulman in the book’s essay.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle Ashton Harris by Tommy Gear, Vatican City, 1992

Courtesy the artist

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs, 2017

Throughout the late 1980s and ’90s, a radical cultural scene emerged in cities across the globe, finding expression in galleries, nightclubs, and bedrooms of New York, London, Los Angeles, and Rome. In this new landscape, Lyle Ashton Harris began obsessively documenting the community forming around him, including artists and cultural figures such as bell hooks, Isaac Julien, Nan Goldin, and Catherine Opie, and more. Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs brings together Harris’s archive of 35mm Ektachrome slides alongside journal entries to create a unique visual document of what Harris has described as “the emergence of multiculturalism, the second wave of AIDS activism, and incipient globalization.”

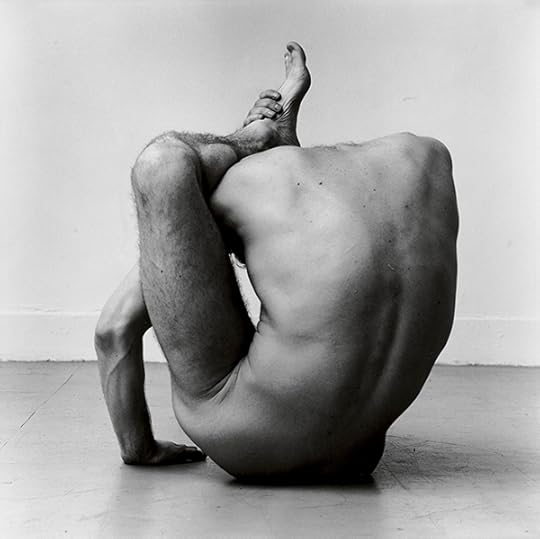

Peter Hujar, Gary in Contortion (1), 1979

Courtesy The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, 2017

Peter Hujar died of AIDS in 1987, leaving behind a complex and profound body of photographs. Underappreciated during his lifetime, Hujar was a leading figure in the cultural scene in downtown New York in the 1970s and ’80s, an inspiration to legendary photographers Robert Mapplethorpe and Nan Goldin. Among his subjects are visionaries such as Susan Sontag, William S. Burroughs, and Andy Warhol. “In many ways Peter Hujar defined downtown for me,” writes photography critic Vince Aletti. “He went places I never dared to, and hung out with people I’d only read about.”

Zanele Muholi, Senzekile II, Cincinnati, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, 2018

One of the most powerful visual activists of our time, Zanele Muholi’s self portraits are radical statements of identity, race, and resistance. Using props and materials found in their immediate environment, Muholi (who uses the pronouns they/them) directly responds to contemporary and historical racisms. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage people to be brave enough to occupy spaces, brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states, “It’s okay for you to be you and love yourself, even if people will deny your existence.”

Erwin Olaf, People of the Labyrinths, 02, 2005

Courtesy the artist

Celebrated Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf’s career began in the early 1980s, chronicling the gay liberation movement. Over forty years, he has established an approach of highly stylized, daring, and often provocative imagery. Erwin Olaf: I Am is the first comprehensive survey of his work, bringing together his earliest images in black and white with his now iconic color work.

Collier Schorr, Untitled (Casil), 2015–18

Courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

Aperture 235, “Orlando,” Summer 2019

Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando tells the tale of a young nobleman in the age of Queen Elizabeth I who lives for centuries, and along the way mysterious shifts gender—a point that is radically rendered as a nonevent. Now, as guest editor of the latest issue of Aperture, Tilda Swinton calls upon Woolf’s central themes, inviting a group of artists and writers to make work inspired by the novel. Featuring work from Collier Schorr, Viviane Sassen, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Elle Pérez, Mickalene Thomas, and more, the issue is, in Swinton’s words, “a salute to limitlessness, and a heartfelt celebration of the fully inclusive and expansive vision of life exemplified by the extraordinary artists collected here.”

Ren Hang, Untitled, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nicolas Hugo, Paris

Aperture 218, “Queer,” Spring 2015

“Queer doesn’t have a look, a size, a sex,” Vince Aletti writes. “Queer resists boundaries and refuses to be narrowly defined.” Over the past three decades, the public conversation about what it means to be queer has evolved, and remains both relevant and necessary to continue. With work by photographers such as Zanele Muholi, Ren Hang, and Catherine Opie, Aperture’s “Queer” issue is an essential primer on the ways in which images have shaped that conversation.

Richard Renaldi, 04:14, from Manhattan Sunday

Courtesy the artist

Manhattan Sunday by Richard Renaldi, 2016

As a young man who had recently embraced his gay identity, Richard Renaldi found a home in “the mystery and abandonment of the club, the nightscape, and then finally daybreak, each offering a transformation of Manhattan from the known world into a dreamscape of characters acting out their fantasies on a grand stage.” In Manhattan Sunday, Renaldi captures that ethereal moment, when Saturday night blurs into Sunday morning in Manhattan, and evokes the vibrant nighttime rhythms of the city.

Mickalene Thomas, Le leçon d’amour, 2008

Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin New York and Hong Kong, and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Muse by Mickalene Thomas, 2015

Mickalene Thomas draws on cultural icons and her relationships with lovers and family alike to subvert the male gaze and assert new definitions of beauty. Thomas, who spent several years estranged from her mother before telling her she was a lesbian, has said of their collaboration, “Using my mother as a model has allowed us time to establish this nice relationship, for me to get to know her. I feel it’s a way of making her happy.” Muse gathers together Thomas’s various approaches to photography in a courageous exploration of gender and sexuality.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (face in dirt), 1990

Courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York

Brush Fires in the Social Landscape by David Wojnarowicz, reissued 2015

Throughout his career, David Wojnarowicz’s use of photography was extraordinary, as were his unprecedented ways of addressing the AIDS crisis and issues of censorship, homophobia, and narrative. As Wojnarowicz once said, “History is made by and for particular classes of people. A camera in some hands can preserve an alternate history.” Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, begun in collaboration with the artist before his death in 1992 and reissued in 2015, explores Wojnarowicz’s profound legacy through the lens of his friends and community, among them Nan Goldin and Kiki Smith.

Shop Aperture’s collection of essential publications by queer artists.

The post 13 Publications that Reimagine Queer Visibility appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

These Queer PhotoBooks Changed My Life

Eleven curators, writers, and artists reflect on images of queer identity past and present.

Minor White, David Ulan, Arlington, Massachusetts 1947, from the book Minor White: The Eye that Shapes (Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Bulfinch Press, 1989)

In honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, we asked some of our favorite queer photographers, writers, and historians to choose a photobook that was important to their development as artists and human beings. Ranging from the early days of photography to the present, these books perform an intimate yet consummately public function: they wait on the shelves of libraries and bookstores to let people know that they are not alone, that queers do have a history, that someone cared enough to write it down. —Brendan Embser and Matthew Leifheit

Jerome Zerbe and Brendan Gill, Happy Times, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1973

Timothy Young on Jerome Zerbe and Brendan Gill, Happy Times, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1973

Happy Times, with its gaily painted cover, is a survey of the work and social world of paparazzo Jerome Zerbe, though it is more than a compendium of celebrities and socialites. With focused looking, images delaminate and reveal kinships: Marlene Dietrich dancing with Clifton Webb, Cary Grant, Lili Damita’s smile, Zerbes’s boyfriend Lucius Beebe, Cole Porter, Katharine Hepburn with her picnic basket, Hermione Gingold doing the Twist, Steve Reeves in the shower, Salvador Dalí with Amanda Lear . . . Maybe history is indeed a big, queer conspiracy—and Zerbe was there to capture it in joyous bursts of light.

Timothy Young is curator, modern books and manuscripts, at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Ann Novotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original; Alice Austen, 1866–1952, Chatham Press, Old Greenwich, Connecticut, 1976

Joan E. Biren on Ann Novotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original; Alice Austen, 1866–1952, Chatham Press, Old Greenwich, Connecticut, 1976

Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original by Ann Novotny (now out of print) is a biography with images from an early documentary photographer who worked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Alice Austen’s photographs of her friends were the first images I ever saw of women that I identified as authentic lesbians, that is, not photographs of women together made by men and for men. Alice’s photos are funny and sexy and when I found them, I felt that I was discovering a true ancestor. Ann Novotny’s book was my 23andMe—only better than genetic testing.

Joan E. Biren (JEB) is a photographer and filmmaker.

Duane Michals, Homage to Cavafy, 1978, from the book Homage to Cavafy: Ten Poems by Constantine Cavafy, Ten Photographs by Duane Michals (Addison House, 1978)

Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Philip Gefter on Duane Michals, Homage to Cavafy: Ten Poems by Constantine Cavafy, Ten Photographs by Duane Michals, Addison House, Danbury, New Hampshire, 1978

When it was first published, in 1978, this book introduced me to the work of Cavafy, a significant Egyptian/Greek poet of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Duane Michals’s photographs-with-text are single narrative images that assert the conditions of inhibited homosexual desire with lyricism, joy, and melancholy, echoing the feeling and attitude of the poems. It is an artistic tribute to the poet by a serious kindred artist—from one artist to another, from one generation to another.

Philip Gefter is the author of Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe; A Biography (2014).

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, 1947, from the book Rites & Passages (Aperture, 1978)

David Benjamin Sherry on Minor White, Rites & Passages, Aperture, New York, 1978

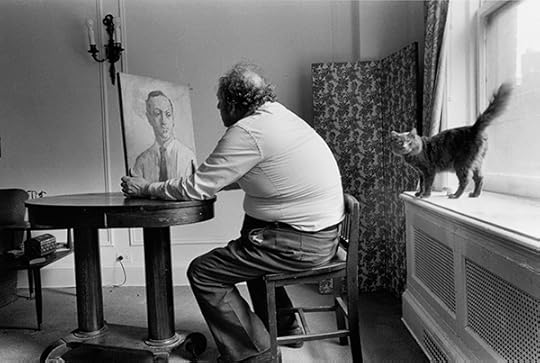

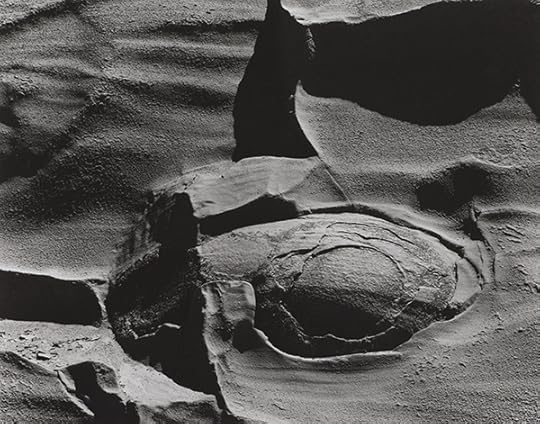

Traversing America as a queer person, camera in hand, in search of meaning and metaphor in our troubled landscape has a certain weight to bear. The road is lonely to begin with; add the juxtaposition of an outsider looking in and trying to navigate the suburban, rural, national park, state park, and campground cultures, all quintessentially heteronormative—it could be said the experience of seeing is heightened, the isolation stronger, the connections between nature more dramatic, and maybe the desire to be loved or to connect with others even more intense, because you’re constantly made aware of your otherness. I’ve often found the strength to pursue this line of work from the varied books of American photographers that line my shelves, though few queer ones come to mind, with the exception of Minor White and specifically his Rites & Passages. White’s work has been an endless road map of encouragement, power, and comfort on some of my darkest nights while alone on the road. His own wandering through the terrain has resulted in a book of countless photographic gifts, each leading to the next: earthly matter, abstract synapses in the universe (or maybe ice forming on a windowpane?), blazing landscapes, erotic portraiture, empathetic abstractions. He creates a mindscape that glimmers with spiritual epiphany, a multitude of cerebral queer experiences that continually awakened him. His work is proof to me that magic is real in the world; queerness is power and the camera can be a tool used to harness the energy.

David Benjamin Sherry is a photographer based in Los Angeles.

Jack Woody, George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931–1955, Twelvetrees Press Pasadena, California, 1981

Jonathan D. Katz on Jack Woody, George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931–1955, Twelvetrees Press Pasadena, California, 1981

My all-time favorite queer photobook has to be Jack Woody’s George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931–1955. It was 1981, the year that Reagan was first elected and the Christian Right began its horrifying ascent. Fairly newly out, I didn’t know Lynes then, but as I leafed through the book on the newly published table at the local queer bookstore, I was transported by a long-dead, preciously gay artist who seemed to me every bit as politicized as I yearned to be. The way the photographs instrumentalized the gaze—and I was just discovering the pleasures of a stare held a beat too long—and the unabashed eroticism were delicious, of course, but so too was Lynes’s evident attention to the power of another kind of gaze to engender feelings of shame, loss, or insecurity.

No matter how explicitly the body was figured in Lynes’s work, it was the question of sight, of being seen or not wanting to be seen, of holding or ducking a look that struck me. Lynes’s work spoke to me because it gave both form and precedent to that dynamic circuitry then investing the newly spectacularized queer body with a host of cruelly competing meanings.

Jonathan D. Katz, an art historian and curator specializing in queer visual culture, chairs the doctoral program in visual studies at the University at Buffalo, New York, and is a visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Minor White, Shore Acres State Park, Oregon, 1959, from the book Minor White: The Eye that Shapes (Princeton University Art Museum in association with Bulfinch Press, 1989)

Shannon Ebner on Peter C. Bunnell, Minor White: The Eye that Shapes, Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Bulfinch Press, Princeton, New Jersey, and Boston/Toronto/London, 1989

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Minor White’s Museum of Modern Art retrospective in 1989, my senior year of high school. As a teenager living in close proximity to the city, I would board the 11A bus to Port Authority from downtown Hillsdale, New Jersey, and visit the museum as often as possible. White’s exhibition was the first photography retrospective I had ever visited, and one of two museum catalogues I somehow managed to purchase as a teenager. But more than that, upon returning home to the privacy of my suburban bedroom, it was where I discovered in a book the name for what had stirred me: homoeroticism, as the catalogue author, Peter Bunnell, calls it. White’s photographs of nude male bodies were obvious, even if shocking, to my eyes, but it was the landscapes—rocks protruding from glistening sandy shores in formations resembling torsos and glory holes, full of transferred desire—that were the revelation. Here was a celebration of homosexuality—what an old-fashioned word, but somehow fitting for White’s expression of gay, white-male modernist sexuality, newly discovered to me and never to be forgotten.

Shannon Ebner is an artist and the chair of Pratt Institute’s photography department.

James Gardiner, A Class Apart: The Private Pictures of Montague Glover, Serpent’s Tail, London, 1992

Deborah Bright on James Gardiner, A Class Apart: The Private Pictures of Montague Glover, Serpent’s Tail, London, 1992

Two cardboard boxes of “dusty negatives and faded letters” from an estate sale fell into the hands of James Gardiner, a collector of gay photographs and ephemera. The resulting compilation, A Class Apart, is a rare (and sexy!) look at homoerotic cruising in London a century ago through the photographs of architect and amateur photographer Monty Glover. Most poignantly, Glover documented his fifty-year love affair with Ralph Hall, the handsome working-class lad who became his muse.

Deborah Bright is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn.

Queer with Class: The First Book of Homocult, MS ED (The Talking Lesbian) Promotions, Manchester, UK, 1992

Laura Guy on Queer with Class: The First Book of Homocult, MS ED (The Talking Lesbian) Promotions, Manchester, UK, 1992

Homocult, self-proclaimed “perverters of culture,” were a Manchester-based collective comprised of working-class queers who were active in the early 1990s. Their printed graphics and graffiti actions, featuring slogans like “Give us your children / what we can’t fuck we eat,” railed against the moral certitude of the political right and continue to offer antidote to the assimilationist agenda of a mainstream LGBT movement. Queer with Class: The First Book of Homocult compiles many of Homocult’s posters into a thin paperback volume. Significantly, as with the broader DIY zine culture to which the book belongs, photography is not a rarefied form here but is put to the work that it does best. Images are lifted from elsewhere, glued alongside text, and blown up on Xerox machines. As the illegitimate offspring of mechanical reproduction, Homocult eviscerate the breeding ground of capital: the heterosexual family. Punk to the end, the first book of Homocult was also the last.

Laura Guy is an Early Career Academic Fellow in Art History at Newcastle University, UK.

Terry Richardson, Terryworld, Taschen, Cologne, 2004

Kayode Ojo on Terry Richardson, Terryworld, Taschen, Cologne, 2004

When I was a student, the only copy of Terryworld had been stolen from SVA’s library stacks. I thought it must be highly coveted, so I was pleased to find a copy for a reasonable price on Amazon.com. When my copy arrived, I noticed some of the pages were stuck together. I’m not sure why I assumed this was because of a man.

In New York, people complain to me about Terry Richardson and his abuse of power because we use the same camera; I’ve brought the camera into the bedroom on a few occasions and exhibited the results. I ask them, if I meet someone cute at a party, is it bad for me to ask them to come back to my apartment to take some pictures? It’s a real conversation-ender.

These days I’m wondering which luxury fashion brands I need to shoot for in order for people to do things for me that they don’t really want to do. Is it Brioni? Missoni? Fiorucci? Was it Gucci? Does sex still sell? Is domination still Gucci?

Anyway, this book contains a lot of pictures of men.

Kayode Ojo is an artist based in New York City.

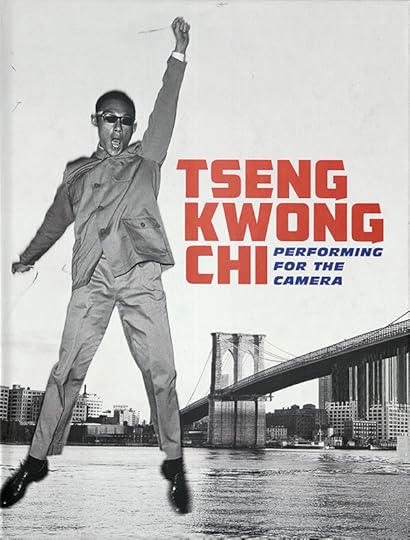

Tseng Kwong Chi, Performing for the Camera, Chrysler Museum of Art, Grey Art Gallery, and Lyon Artbooks, Norfolk, Virginia; New York; and Brooklyn, 2015

Ka-Man Tse on Tseng Kwong Chi, Performing for the Camera, Chrysler Museum of Art, Grey Art Gallery, and Lyon Artbooks, Norfolk, Virginia; New York; and Brooklyn, 2015

My favorite books are the kind you can slip into your winter coat pocket: Langston Hughes and Roy DeCarava’s Sweet Flypaper of Life, or James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, or any Maggie Nelson book. My favorite queer photography books are the kind I can’t carry around or hold easily with one hand while standing on a subway . . . blame it on its being a little too cumbersome—or is it that it would make me blush, red and ears burning (such as Peter Hujar’s Love and Lust)? One that I would say is just as smoldering, beautiful, wild, disruptive, timeless, and urgent—and that I would want to lug around all day, and to pass on, like a lighter—is Tseng Kwong Chi’s posthumous exhibition catalogue Performing for the Camera. It hits many registers: wit and humor, subversion, performance, infiltration, critique. What does resistance look like for a queer Asian American artist working in the late 1970s and 1980s, who was perceived as a perpetual foreigner? There is an insistence on being present, on being both visible and invisible. In the work, you feel his defiant, fiercely intelligent exuberance.

Published in 2015 and as the first comprehensive survey of Tseng Kwong Chi’s work, the book only reminds me of his absence, and all of the occlusions and acts of recuperation, in the canon, the curriculum, and the archive—the epistemic violence, the quiet violence of invisibility. Who writes history? What does a book, if late or overdue, tell us about ourselves, our will to know, and our unknowns?

Ka-Man Tse, a photographer and video artist based in New York, is the winner of the 2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize.

Frances F. Denny, Hope, in the guest bedroom, Bar Harbor, Maine, 2012, from Let Virtue Be Your Guide (Radius Books, 2016)

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

Horace D. Ballard on Frances F. Denny, Let Virtue Be Your Guide, Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2016

I saw the first prints of what would become Let Virtue Be Your Guide in the autumn of 2013. Amid the dying evening light and the white walls, Frances F. Denny’s photographs of family members, domestic interiors, and cultivated landscapes were luminescent in their skillful framing of light, in their unflinching examination of access and class, and their ability to unravel the. distinctions between portraiture and still life. In photobook format, Denny has invited us into her family. In so doing, she offers up an intricate and visceral sense of “home” in a post-archival age.

Horace D. Ballard is curator of American art and research curator for photography at Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine. Matthew Leifheit is a photographer and the editor of MATTE magazine.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Minor White images courtesy of The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White. © Trustees of Princeton University

The post These Queer PhotoBooks Changed My Life appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Rosalyne Blumenstein and the Art of Living

In her newest series, artist and activist Zackary Drucker pays homage to a trans icon.

By Susan Stryker

Zackary Drucker, Rosalyne, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

“My transition from young white boy with a false sense of privilege in the 1970s to young tranny-girl with little or no privilege was a real smack in the face,” Rosalyne Blumenstein wrote in her 2003 autobiography, Branded T. “My spirit and soul seemed to be uplifted and smashed on a daily basis.”

Blumenstein is an icon. I met her, in 1993, when I came to New York as a newbie trans activist from San Francisco and visited the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center, where Blumenstein, a self-described “woman of transexual experience,” lent street cred as director of the center’s pioneering Gender Identity Project, which included an HIV-prevention program for trans people. Blumenstein didn’t invent the word transgender, but she popularized it through her public-health work.

Photograph from the collection of Rosalyne Blumenstein, New York, ca. 1977–82

Courtesy Rosalyne Blumenstein LCSW

I doubt she remembers that brief encounter. Although we are only a year apart in age, I was just getting my feet wet (head first) in the trans scene, while she’d been in the life a long time. Blumenstein lived as I’d been afraid to live as a young teen, struggling with my gender dysphoria, fearing the only way to be the person I was to become would be to abandon everything for a walk on the wild side of Manhattan. Blumenstein’s path from Canarsie, Brooklyn, to Forty-Second Street was shorter than mine would have been from small-town Oklahoma, but she nevertheless had the huevos to transition at sixteen, which I didn’t manage until thirty. She boldly lived what I but timorously imagined.

Zackary Drucker, Rosalyne, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

A generation after her heyday in the demimonde, Blumenstein relocated to Southern California and became, among other things, muse and mentor to LA-based trans multimedia artist Zackary Drucker, who regards Blumenstein as one of her legendary foremothers—an iconically feminine, decidedly binary-gendered incarnation of Botticelli’s Venus. The power of an iconic image is its capacity to simultaneously represent many desires, however contradictory or mutually exclusive, that exceed everything invested in it. For me, Drucker’s recent photographs of Blumenstein embody the fantasy of the fierce, street-smart trans girl who survives into empowered womanhood—a lived reality attested to by Blumenstein’s own compelling photographic archive.

Photograph from the collection of Rosalyne Blumenstein, New York, ca. 1977–82

Courtesy Rosalyne Blumenstein LCSW

Blumenstein is that actualized fantasy and more. The neither/both/other-than of trans-ness layers itself—a powerful, unasked for, and sometimes unwanted gift—atop even the most intransigent of our identifications. As a child, Drucker was enthralled by the fantasy of magical metamorphosis that Tilda Swinton portrayed in the 1992 film Orlando. She sees Blumenstein through that lens: a doubly amphibious, alchemical lady in fiery red, straddling earth and water in open air. Swinton’s own affinity with Orlando similarly lies in her perception of that character’s freedom to break the bonds of binary gender and roam the open territories beyond particular identity. Transgender has long iconized the fantasy of limitlessness.

In practice, flesh—as with any material medium—is not infinitely plastic, nor are our identifications. The cut that accomplishes one intention inevitably constrains another, whether physically or psychically. Yet as Drucker’s images, Swinton’s editorial vision in this issue of Aperture, and Blumenstein’s lived experience all attest, transgender can function as an art of living that enacts, destroys, and elevates the intent it seeks to realize.

Zackary Drucker, Rosalyne, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

Susan Stryker is the author, most recently, of the revised edition of Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (2017).

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Rosalyne Blumenstein and the Art of Living appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers