Aperture's Blog, page 89

April 19, 2019

2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Jack Latham

In the age of fake news, Jack Latham investigates the secret society that has inspired conspiracy theories, protests, and attacks since its founding days in 1872.

by Emily Stewart

Jack Latham, The Phantom Patriot, Nevada, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

In the redwood forests of Monte Rio, California, sits an expansive 2,700-acre retreat where, every summer, an elite invitation-only social club founded by a group of male artists, writers, actors, lawyers, and journalists meets. The Bohemian Club, founded in 1872, has inspired conspiracy theories, protests, and attacks since its founding days. In Jack Latham’s new project, Parliament of Owls, he investigates the secrecy of the club and the wider political effects this has caused.

What happens when the country’s top lawmakers, politicians, artists, lawyers, and businessmen meet behind closed doors? What secrets are being swapped, plans being made? For years these questions have been at the root of protest groups and journalists hoping to expose the truth. Latham takes the viewer on a journey of discovery, showcasing the town surrounding Bohemian Grove (the club’s rural outpost) and its people. His photographs also depict the rise of Alex Jones—conspiracy theorist and founder of InfoWars—and how his break-in at the Grove led him to become a household name with the antiestablishment crowd. In 2000, Jones released alarmist footage of the club’s “Cremation of Care” ceremony, which inspired the attempted attack led by “Phantom Patriot” Richard McCaslin two years later.

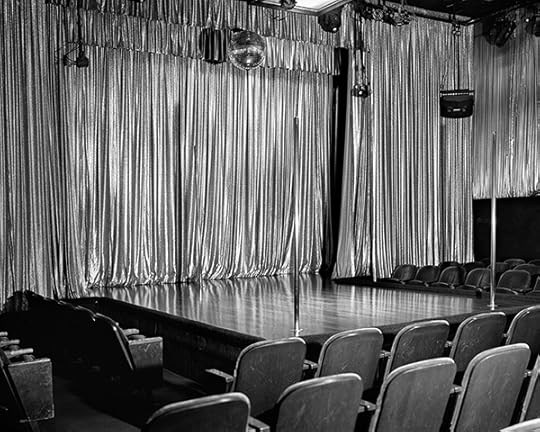

Latham describes his work as “an attempt to explore the dangers within society when voids of context are challenged.” His images are beautiful and thought-provoking, often leaving the viewer feeling mystified and intrigued. Because nonmembers aren’t allowed inside, Latham instead photographs spaces that are in some way tied to the club and its members—for instance, his image of an empty, glittery stage was taken in a strip club owned by two members. In one of Latham’s photographs, three Bohemian Club members can be seen standing on a viewing platform inside the Grove. The image is taken at such a distance that the members almost disappear into the surrounding forest, solidifying the fact that for the majority of us, the club will always be a remote mystery.

Jack Latham, Viewing Platform, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Main Stage at the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre, San Francisco, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Great Grey Owl, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Mary as Nixon, Camp Meeker, 2018, from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham (born in Cardiff, 1989) is a Welsh photographer based in the United Kingdom. His work primarily focuses on aspects of storytelling throughout society, which he presents using large-format photography or realizes within photobooks. Latham is the author of Sugar Paper Theories (2016), which was shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation and Kraszna Krausz photobook awards. He is currently working on his latest project, Parliament of Owls, which focuses on Bohemian Grove, a private men’s club in Northern California.

Emily Stewart is the manager of education and engagement programs of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

The post 2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Jack Latham appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Zora J Murff

Zora J Murff evaluates the fallout of prejudicial housing policies within the larger narrative of violence perpetrated against African Americans.

by Michael Famighetti

Zora J Murff, Chris (talking about fear), 2017, from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff has emerged as a distinguished voice in photography dealing with the complex intersections of race and American society. Earlier works have focused on a facility for incarcerated youth, where he was employed, by exploring notions of visibility and interrogating a system that rendered his young subjects invisible. For his recent series At No Point in Between, Murff turned his attention to the historically black neighborhood of North Omaha, Nebraska, a cityscape shaped by “redlining” and other prejudicial housing policies. Through his mix of emotionally resonant portraits, vacant landscapes, and fraught archival materials, Murff locates his investigation of this particular place within a larger American narrative of violence perpetrated against African American citizens. His project has been informed by viral videos of police shootings of these horrific documents he reflects, “They are injurious, yet informative, shifting how I navigate my own black body through this world.” But Murff never entirely reproduces images of trauma. Instead, he offers fragments, suggestions, hints. By “creating a collection of images scrutinized in both their historical and contemporary contexts,” he notes, “I metaphorically connect the body and the landscape, fast and slow violence.”

Zora J Murff, Under dark daylight (cross), 2018; from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff,, Dark pages written white (cleared), 2018; from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff, Terri (talking about the freeway), 2018; from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff,, Surveyors, 2018; from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff (born in Des Moines, Iowa, 1987) combines his education in human services and art to explore how photography is intertwined with social and cultural constructs. Murff, who is visiting assistant professor of photography at the University of Arkansas, received his MFA in studio art from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and a BS in psychology from Iowa State University. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and featured in Aperture, the New Yorker, Vice, British Journal of Photography, and the New York Times. In 2019, he was named an honoree for PDN’s 30: New & Emerging Photographers to Watch, selected for the Light Work Artist-in-Residence Program, named the Daylight Photo Award Winner, and selected as a LensCulture Top 50 Emerging Talent with his collaborative partner Rana Young. Murff has published two monographs, Corrections (2015) and LOST, Omaha (2018).

Michael Famighetti is the editor of Aperture magazine. All images courtesy the artist.

The post 2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Zora J Murff appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Guanyu Xu

Reclaiming domestic space through installations in his parents’ home, Guanyu Xu explores queer identity and censorship across China and the US.

by Taia Kwinter

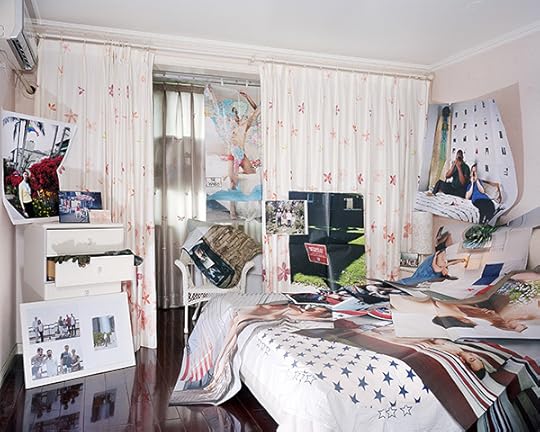

Guanyu Xu, Space of Mutation, 2018, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

In Temporarily Censored Home, Guanyu Xu quietly intervenes in his parents’ house, creating queer installations in secret across the heteronormative domestic space. Xu inserts countless made and collected photographs—including images from family albums, torn ads and editorials collected as a teen, and portraits of himself and other gay men—in complex tableaux to create a collective visual portrait. In some rooms, small and large photographs meticulously fill an area, covering every visible inch of the scene. In others, huge prints drape over furniture or hang from the ceiling, layered and multidimensional across the walls and floor.

The act of return and intervention is not uncommon in photography; marginalized and misrepresented groups have a long history of visual reclamation and redefinition to form a portrait of the self that was once controlled. This is particularly powerful for Xu, who grew up in China—a country with severe censorship laws and regulations surrounding LGBTQ+ visibility and content—and in a conservative household: his parents do not know he is gay. Xu now lives in the United States, and uses these installations as a comparative examination of the two countries, where his intersectional experience of the US meets his conservative familial and social experience of China.

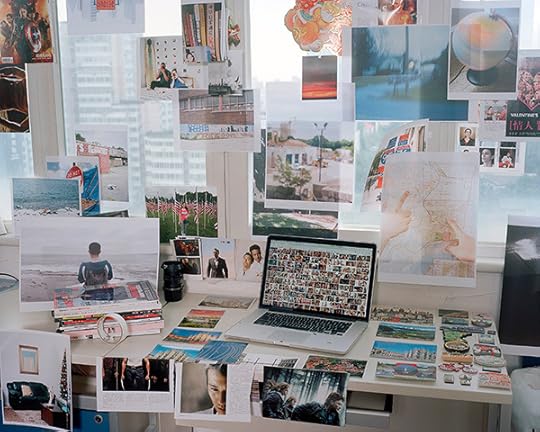

It is hard to fathom how Xu’s parents remained unaware of the installations, which are without doubt incredibly time-consuming to create and then dismantle. Any practical uses of the home become impossible—bedroom drawers overflow with photographs; open doorways are blocked by hanging posters; all surfaces of an office, including the computer desktop, are consumed by images. Xu’s interventions reveal a painstaking process to create a domestic space that finally acknowledges him. They grab the viewer gently but urgently: see me here.

Guanyu Xu, Parents’ Bedroom, 2018, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

Guanyu Xu, My Desktop, 2018, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

Guanyu Xu, Behind My Door, 2018, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

Guanyu Xu, Worlds within Worlds, 2019, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

徐冠宇 Guanyu Xu (born in Beijing, 1993) is an artist currently based in Chicago. He was the recipient of the Fred Endsley Memorial Fellowship and James Weinstein Memorial Fellowship, and a finalist for the Lucie Foundation Emerging Artist Scholarship and Luminarts Cultural Foundation Visual Arts Fellowship. Xu’s work has been exhibited internationally, at venues including Aperture Foundation, New York; the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, Colorado; New York Photo Festival; Union League Club of Chicago; Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Santa Ana, California; and Embassy Tea Gallery, London. His photography has also been featured in numerous publications, such as Aint-Bad Magazine, Musée Magazine, Der Greif, and China Photographic Publishing House.

Taia Kwinter is the managing editor of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

The post 2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Guanyu Xu appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 15, 2019

California on Fire

Carolyn Drake’s photographs of the 2018 wildfires point to the human role in creating a new, terrifying normal.

By William Finnegan

Carolyn Drake, Forest view at sunset, two months after the Ferguson Fire, Yosemite West, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Every fire has a narrative. For major wildfires, there are numbers to help frame the narrative, and usually a name. But all fires start long before they start, in the sense that the ground must be prepared, literally, for the conflagration to come. Fuel, weather (and behind weather, climate), the natural landscape, the built landscape, suppression efforts past and present, prevention schemes, politics—these factors and many others, interacting and colliding, create a context and prehistory for each major fire. The fire itself burns and then takes its place both in recorded history and in the natural history of its epoch. That epoch, now, is the Anthropocene—the epoch of a world made by humans.

Carolyn Drake, Wawona campground in Yosemite National Park, two months after the Ferguson fire, Yosemite West, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

To make these images in California’s disaster-struck areas, Carolyn Drake chose the long moments after a series of major wildfires. The flames and smoke, the panic and news crews, are gone. The land is charred, ashes are sifted, burned-out residents return, campgrounds reopen. The fury and violence of the vast event recede, and the world that’s left behind becomes specific again, inviting contemplation. Three big wildfires broke out in Northern and central California in July 2018 and burned through the following weeks. Drake tracked and photographed the aftermaths of all three.

Carolyn Drake, Archaeologists search for a jar containing the ashes of a widow’s husband after her house burned down, Redding, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

The Ferguson Fire was started by a vehicle’s overheated catalytic converter in dry vegetation beside a highway in Mariposa County. This was in the Sierra foothills southwest of Yosemite National Park. The fire burned into the park, and its smoke filled Yosemite Valley, the most popular (and most photographed) destination in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The valley was closed and evacuated. It became a staging area for firefighting operations. Roughly three thousand firefighters were thrown at the fire. Two died. One was a bulldozer operator, killed when his vehicle rolled down a mountainside. The other, a captain of an elite crew whose members work in the most dangerous areas of wildfires, was killed by a falling tree. Nineteen other firefighters were injured. The Ferguson Fire took more than a month to contain. It burned almost ninety-seven thousand acres.

Carolyn Drake, Fire roads cross privately owned mountains, three weeks after the Mendocino Complex Fire finished burning, Spring Valley, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

The Carr Fire was started by a flat tire, which sent a wheel rim onto asphalt, where it generated sparks, igniting dry vegetation. This occurred in the mountains west of the city of Redding. Three days later, the fire jumped the Sacramento River and entered Redding, forcing the evacuation of thirty-eight thousand people. That same evening, a fire whirl developed—a tornado-like column of superheated air that can be generated by intense wildfires. The Redding fire whirl contained winds exceeding 143 miles per hour. The wind tore roofs from houses, bark from trees, and toppled high-tension power-line towers. The fire whirl was reported to be forty thousand feet tall. The Carr Fire killed eight people, including three firefighters. It burned more than a thousand homes. Insured losses were estimated at $1.5 billion. The cost of fire insurance is said to be soaring in California, moving beyond the reach, effectively, of many residents in fire-prone areas.

Carolyn Drake, Lounge in the Usona Forest Fire Station, Mariposa County, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Finally, the Mendocino Complex Fire started as two vegetation fires in the chaparral-covered mountains near Clear Lake, about one hundred miles north of San Francisco and fifty miles from the coast. The ignition point is still under investigation. In hot, dry, windy conditions, the fire burned for nearly two months, ultimately consuming more than 450,000 acres, which makes it the largest wildfire in California history. It destroyed 280 structures, most of them rural residences, many in unincorporated communities like Spring Valley. One firefighter died. He was a battalion chief from Utah, killed by a falling tree. The firefighters struggling to contain the Mendocino Complex Fire were hampered by a manpower shortage—many of their brethren were off working other fires. Nevada state prison inmates, among others, were deployed to fight the enormous blaze, and suppression costs ran to more than $200 million.

Carolyn Drake, Rod on the foundation of his burned home after the Mendocino Complex Fire, Spring Valley, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Wildfires are getting bigger, hotter, more frequent, more destructive. Of the ten most destructive fires (measured by destroyed structures) in the history of California, six have occurred in 2017 or 2018. The single deadliest and most destructive, the Camp Fire, in Butte County, is still smoldering as I write, in November 2018. This fire, which essentially destroyed the small city of Paradise, California, on November 8, killed eighty-eight people, with 249 more still listed as missing. It burned more than thirteen thousand homes, and archaeologists are working among the ruins now to find any traces, such as teeth, of the perished. The second most destructive California wildfire, the Tubbs Fire, in Napa and Sonoma Counties, did its gruesome thing in October 2017. It killed twenty-two people and burned more than five thousand structures, including some 2,900 homes in the city of Santa Rosa.

Carolyn Drake, A creek overpass, one month after the Carr Fire, Redding, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Why this biblical plague of fire? It is the Anthropocene, and we must look to our own agency. The climate is hotter and, in California, much drier than in the recent past because of the greenhouse effect, which is caused, primarily, by the burning of fossil fuels. In the American West, as in other places, logging practices have produced vast amounts of slash—woody debris that burns more readily than the mature forests it replaced. Overzealous fire suppression policies have contributed, paradoxically, to the proliferation of bad fires. They have left a tree-choked landscape, where natural fires caused by lightning have been unable to do their ecological job of thinning.

Then there is the mass migration of people into what land-use jargon calls the wildland-urban interface (WUI)—the zone where residences abut forests or other combustible vegetation. This is by far the fastest-growing land-use type in the United States. More than one hundred million souls now live in the American WUI. These people accidentally start a great many fires, and their presence makes firefighting harder and more dangerous. Natural fires cannot be allowed to burn themselves out anywhere in or near the WUI.

Carolyn Drake, Charred landscape, one month after the Carr Fire, Redding, California, for Aperture, 2018

© the artist/Magnum Photos

These calamitous trends and policies form some of the context, the prehistory, of the wildfires that rage in our day. These problems are national, if not international; climate change is, of course, global. But here is Stephen Pyne, the preeminent American scholar of fire, on California, its particular problems, and the larger picture:

California is a special case. It’s a place that nature built to burn, often explosively. If people vanished, fires would still thrive. … But people have worsened the scene. They have introduced flammable grasses, overgrazed in the mountains and felled forests in ways that overturned the prior system of ecological checks and balances. … And then Earth’s keystone species for fire decided to burn fossil biomass, which has cascaded effects throughout the planet and unhinged the climate. We used to think fire history was a subset of climate history; now climate history is becoming a subset of fire history.

I see this dilemma, this mess, in Drake’s pictures. They are not about simply the harsh aftermath of natural disasters. They are about the role of humans, and of Drake’s own observing eye, in this burning world we’ve made.

William Finnegan is a staff writer at The New Yorker and winner of a 2016 Pulitzer Prize for his memoir Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life.

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post California on Fire appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Photographs that Defined the Iranian Revolution

Forty years after the Iran’s turbulent political transformation, a look back at the images that captivated the world.

By Haleh Anvari

Bettmann, Ayatollah Khomeini Stepping Down from Plane, 1979

Courtesy Getty Images

February 2019 marked the fortieth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. The last major revolution of the twentieth century, which toppled an ancient monarchical system and ushered in an Islamic theocracy was a widely photographed event. By the time of the revolution in 1979, Iranians had been exposed to photography for more than a hundred years; it wasn’t uncommon for ordinary middle-class people to own cameras. A professional cadre of photojournalists followed the royal court and the country’s growing pop-culture personalities, providing news photographs for the daily newspapers and numerous weekly magazines. But it was the revolution, followed by the American hostage-taking, and then the eight-year war with Iraq, that propelled Iranian photographers into new territories, transforming them into serious practitioners of new genres.

Photographs of the first year of the revolution helped fix the inevitability of a new Iran in the eyes of the world and the psyche of the Iranian nation: the crying Shah leaving the country as one of his officers threw himself at his feet, Ayatollah Khomeini descending the steps of the Air France chartered aircraft that carried him back to Tehran, executed generals’ and ministers’ corpses lying naked on mortuary slabs, published daily in newspapers. For all Iranians there must be a number of images that mark for them the progress and development of the revolution. For me, these photographs are searing reminders of the nascent days of the new regime and the blossoming of Iranian photojournalism.

Two photographers whose careers changed because of the revolution were Maryam Zandi and Bahman Jalali. They were both young amateur photography enthusiasts who had secured jobs as in-house photographers in National Iranian Radio and Television, which published its own magazine.

Monday, December 11, 1978, was the day of Ashura, the second of two consecutive holy days of mourning in Iran, when processions of black-clad men take over the street to mark the martyrdom of Imam Hussein by flagellating themselves with chains to the sounds of beating drums. The revolutionaries, well aware of the immense symbolism of these days, had arranged a large demonstration.

Iranian Radio and Television had called a strike in sympathy with the anti-Shah demonstrators. Zandi was at home when she heard about the big protest march. She felt these strange new times had to be recorded, but there was no one to look after her two-year-old daughter. So she threw her camera bag on her shoulder, and her baby girl on her hip, and headed out into the street.

Crowds already filled the streets and the square around Tehran University, punching their fists in the air, shouting slogans against the Shah and dictatorship. Zandi decided to climb upon a bus shelter to get a better view, but couldn’t do so while holding her daughter in her arms. So she asked a woman standing nearby if she would hold her child for a little while. “On one condition,” said the woman. “If you shout ‘long live Khomeini.’” Zandi passed the child into the stranger’s arms and yelled: “Of course, long live Khomeini!” as she climbed atop the shelter. She doesn’t remember how long she stayed there, but she does remember being scared when she saw the crowd from above. She had never seen so many people in one place.

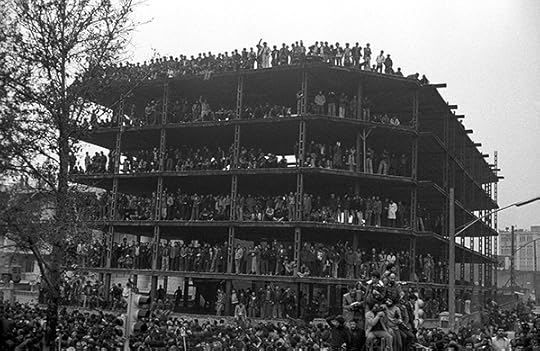

Bahman Jalali, Iran Revolution, Tehran, 1979

© and courtesy Rana Javadi

Numerous photographs of the Ashura demonstrations show the multitudes marching with their banners. But one of the most memorable images of that day depicts a half-finished five-story building overrun by onlookers seeking the perfect vantage point. Filling every floor, men and women flesh out the spaces where walls should have been. Taken by Bahman Jalali, the image of a half-finished building close to the Azadi monument suggests a striking metaphor: the country’s incomplete project of modernity imagined by the Shah, interrupted by tiers of people, hopeful, excited with merely a skeletal idea of what they want. None of them knows how this half-finished structure will look when the project is complete.

Bahman Jalali wasn’t a photographer by training. Before the revolution, he had studied politics and economics at Tehran University. He traveled with the architecture students on their many road trips around Iran, taking photos of traditional houses. When the unrest began in 1978, he and his wife, Rana Javadi, who had picked up the photography bug from him, joined the throngs in the streets to photograph the events. She could move freely among the women and provided a different point of view.

Jalali, who went on to establish Iran’s first university course in social documentary photography, may have sensed the uncertain nature of the revolution; in another photograph that resonates deeply with many Iranians who, four decades after the event, are questioning the outcome of their revolutionary actions, he shows a young man waving a banner atop a traffic sign that reads “Choose your direction before you reach the bridge.”

Another couple were also busy recording the events in the streets of Tehran in those days: Kaveh Golestan, the son of one of Iran’s celebrated film directors, Ebrahim Golestan, and his wife, Hengameh. At the outbreak of the revolution, Kaveh Golestan had already established himself as a photographer with a talent for accessing challenging social documentary subjects, such as the sex workers of Tehran’s red light district. With Hengameh at his side, he photographed the scenes of bloody conflict, while she focused her camera on the women.

By January 1979, the Shah was forced to leave. The photographs of his unceremonious departure were captured solely by Iranian photographers, according to Jafar Daniali, who worked as a staff photographer for the daily newspaper Ettela’at. As he recalled in an interview with an Iranian publication, he and a handful of his colleagues managed to get past the guards and into Mehrabad airport, while two busloads of foreign journalists were held back because the Shah did not want the foreign press there.

Daniali, who had made his way under the plane’s stairs, describes how weak the Shah’s legs appeared, and how he heard him groaning as he boarded the plane to leave the country and end a 2,500-year-old monarchy. The various photographs of his departure were circulated widely around the world, paving the way for the next stage of the revolution: the return of Ayatollah Khomeini from his fifteen-year exile, first in Iraq and then briefly in France. A cleric and critic of the Shah, he arrived back in Iran aboard an Air France–chartered plane in a posse of his followers.

The numerous photographs of his descent from the airplane mark what Iran’s Islamic government refers to as the “succession of the revolution.” The image has such iconic value that in recent years, a two-dimensional reenactment of the famous descent has become a regular feature of the celebrations: soldiers carry a cardboard cutout of Khomeini down the steps of a plane, creating a somewhat flat, if not altogether bizarre, tribute.

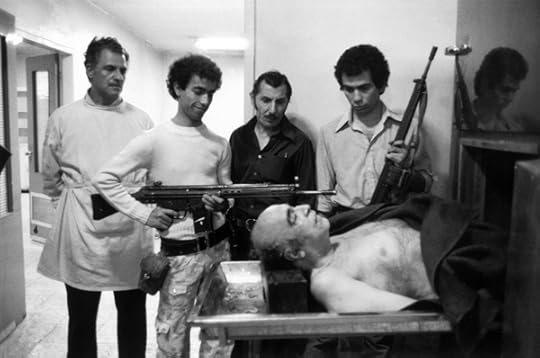

A. Abbas, The corpse of ex-Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda lies at the morgue, Tehran, Iran, 1979

Courtesy Magnum Photos

The late Abbas Attar, a longtime member of Magnum Photos, had left Iran at an early age, but he visited the country both before and during the revolution as an established international photojournalist. Of all his images of the revolution, his photograph of Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, Iran’s prime minister from 1965 to 1977, in a morgue might be the most unnerving. Hoveyda, who was famous for wearing an orchid in his buttonhole and smoking a pipe, did not leave the country when the Shah left. He gave himself up to the revolutionaries because he felt he had not committed any wrong.

Like many of the Shah’s generals and high-ranking officials, he was judged as “corrupt on earth” and executed by the revolution’s merciless hanging judge Sadegh Khalkhali, who had a penchant for five-minute trials and executions in makeshift situations. Hoveyda was apparently shot dead during the recess in his trial in the basement of Qasr prison. It has been suggested that his corpse was returned to his chair for the reading of his verdict. Abbas’s unsettling photograph of the morgue shows Hoveyda surrounded by four men, two of them posing with their assault weapons (which were not used in his execution) with triumphant smirks. The composition echoes the photograph of the dead Che Guevara, positioned so gleeful men with rifles could record themselves in a macabre memento mori.

Kaveh Kazemi, Defiant Revolutionary, 1979

Courtesy the Artist

Iranian women were an intrinsic part of the Iranian Revolution. They would become its icon. A photograph by Kaveh Kazemi—one of the only academically trained photographers of the revolution, who had trained in the UK in the seventies—shows a militiawoman holding her hand out of the impenetrable blackness of her chador, while brandishing a G3 weapon. The towering chador, apart from being an immensely powerful image in its own right, heralds what is to come in the Islamic hegemony that will be forced on the country, as well as how it will be represented visually for decades afterward. The Iranian black chador, worn by the pious and political, became a favorite of visiting photographers depicting the revolutionary spirit of Iran.

On March 8, 1979, less than a month after the succession of the revolution, Iranian feminists chose International Women’s Day to demonstrate against enforced veiling. Joined by the American feminist Kate Millett, who had come to Iran inspired by the role of the women in the revolution, they braved heavy snow in the streets of the capital,to show their dismay at Ayatollah Khomeini’s announcement that the wearing of hijab would be required of all women in Iran.

Their hopes of greater equality and freedom after the revolution were dashed by this fundamentalist slogan during the march: “Ya roosari ya toosari”—wear a scarf or be smacked on the head. The photographs of this march are an exotic reminder, for the younger generation who grew up with mandatory rules of modesty, that compulsory veiling was not accepted without a fight by secular Iranian women.

The early days of the revolution saw power struggles between the various revolutionary factions in Tehran. There were also serious incidences of ethnic unrest in other areas of the country. In August 1979, dissenting Kurds in the northwest of the country were punished with impunity. Some of the captured rebels were taken to Sanandaj Airport to meet their fate in one of Khalkhali’s notorious courts.

A series of images captures the execution of eleven men who are shot dead by a firing squad in Sanandaj airport. The photographer even records the point-blank shots that ensure the men are dead once they hit the ground. But the most powerful image, known as Firing Squad in Iran, shows the men in various stages of being hit by bullets: some are already on the ground, others bent double by the force of the bullet entering their body. This photo was distributed by United Press International without crediting the photographer, and became the recipient of the only anonymous Pulitzer Prize ever awarded in Spot News Photography in 1980. No one knew the photographer’s identity until 2006, when the Wall Street Journal revealed the photographer to be Jahangir Razmi from Ettela’at newspaper. Razmi’s editor in Tehran had decided at the time that his identity should remain secret for his own safety during the vengeful early days of the revolution.

Jahangir Razmi, Firing Squad in Iran, 1979

Courtesy United Press International

On November 4, 1979, another event affected the growth of homegrown photojournalism. A group of hardline students supporting Ayatollah Khomeini climbed over the walls of the U.S. embassy compound in Tehran and took fifty-two American diplomats and citizens hostage for 444 days. They paraded the hostages, blindfolded, with arms tied, to be photographed by the international press. This was an opportunity for the regime to use visual media to convey its independence from the West—specifically, its anger toward the United States (already deemed “the Great Satan”), which had propped up the Shah.

One such image, of a man—a hostage—in a white shirt, with a thick white blindfold wrapped in layer after layer around his head, as if he is readied for execution, became the emblem for the US television show Nightline, a program hosted by Ted Koppel and created specifically to follow the state of the hostage crisis. These photographs would form an image of Iran as barbaric and hostile in the minds of American viewers, which to this day has proven difficult to erase.

After the hostage-taking, many foreign journalists, including Michel Setboun, who had come to Iran early on to record the revolution, decided to leave. They handed over the job of covering the still-volatile country to local photographers, who stepped in to supply the foreign media with the images they needed. Setboun passed his SIPA mantle to Reza Deghati, whom he connected to the agency. “There were these young Iranian photographers that grew up with us. It was time to let them take over. They could speak the language; all they needed was a connection to the outside media, which they didn’t have before,” he says. With that, Iranian photojournalism took another step forward. The hostage-taking was not only good for Iranian local photographers; it was also one of the first landmark events that consolidated the hold of the Islamists on the way the country would proceed. Iran’s foreign policy took an irreversible turn into isolationism and belligerence toward the world.

By 1980, the eight-year war with neighboring Iraq had begun, providing Iranian photographers with a chance to experience war photography, and allowing the new Islamic government to tighten its grip on internal politics with the sophisticated use of photography as one of the sharpest tools in their propaganda toolbox.

Four decades on, photographers like Maryam Zandi and Kaveh Kazemi have been given rare permits to publish photobooks of their images of the days of the revolution. According to their publisher, the younger generation of Iranians are very interested in images that depict that cusp in their history. The treasury of photographs by these local photojournalists provides them with a chance to review their history independently from the official narrative and provide a fuller picture of those turbulent days.

Haleh Anvari is a writer based in Iran.

The post The Photographs that Defined the Iranian Revolution appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 12, 2019

How to Make Art at 30,000 Feet

For nearly a decade, Nina Katchadourian has made images on airplanes using only a cell phone and found objects.

By Ellen Pong

Nina Katchadourian, Topiary, 2012, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

Overlooking a seaside courtyard of ornately manicured hedges and potted shrubs, Nina Katchadourian’s Topiary (2012) pictures meandering garden-goers on a sun-drenched summer’s day. From a lily pond at the center of the scene springs the focal point of the image: a towering, Brancusi-like form of stacked green spheres. The “sculpture,” as the artist confirmed at a talk she recently gave at Fridman Gallery, is actually a row of green peas that Katchadourian was snacking on during one of many flights she’s taken over nine years of traveling between exhibitions, professorial positions, and her home bases of New York and Berlin.

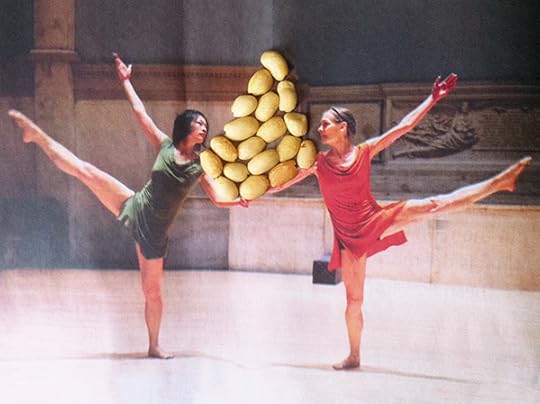

Nina Katchadourian, Dancers, 2012, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

Using rephotography and found objects, the artist makes the most of the mundane. Drink napkins, airplane food, in-flight magazines, paper toilet-seat covers, and countless near-silent hours spent sitting stiffly upright become the fertile grounds for Katchadourian’s series Seat Assignment (2010–ongoing), a body of absurdist cell phone images made exclusively while flying on airplanes. This series was on view in the artist’s recent solo exhibition, Ification, at Fridman Gallery in New York. It was presented alongside video, audio, and sculpture works that are equally amusing—including a functional, Frankensteinian popcorn machine that speaks with the assistance of a custom-written Morse code translation program (Talking Popcorn, 2001). Ification framed a thoroughly entertaining experience of Katchadourian’s diverse art practice, reminding us that an exhibition is never really a “show”unless there’s popcorn involved.

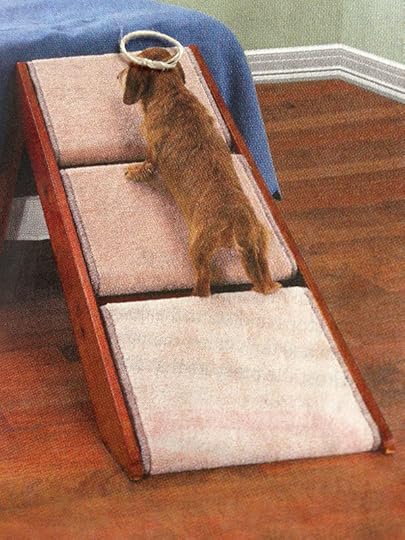

Nina Katchadourian, Ascension, 2013, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

Deadpan and parodic humor deftly manipulate otherwise unimpressive objects and imagery in Seat Assignment. The result is a bootleg canon of art-historically (mis)informed images, hung à la the nineteenth-century salon. In Ascension (2013), a tissue-haloed dog climbs into bed using a ramp marketed for elderly pets, eagerly welcoming a long and peaceful rest. In an intimately sized portrait titled St. Edward (2013), a downward-gazing Edward Snowden dons a similar napkin-shred nimbus. Katchadourian now categorizes the expansive series according to recurring themes, many of which draw from art and photography genres—Landscapes, Athletics, and Proposals for Public Sculpture—and others that don’t (among them, Buckleheads and Sweater Gorillas).

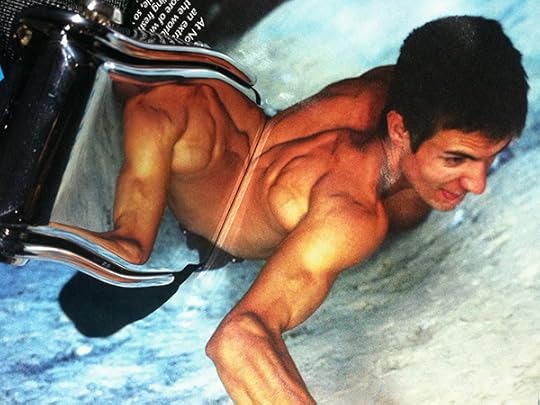

Nina Katchadourian, Centaur, 2012, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

Appropriating images from SkyMall, travel magazines, and whatever else has been abandoned by prior passengers, Katchadourian defies reasonable doubts against the artistic possibilities of cell phone photography, advertisements, and literal garbage. The images in Seat Assignment, as low-resolution as they may be, are sharp depictions of the artist’s intuition for a playfulness that resists being tired. Operating in a conceptual mode reminiscent of John Baldessari’s dot paintings, they provoke viewers to see the ordinary anew by making evident all we take for granted in our everyday visual field. They could even stand in response to a hypothetical Yoko Ono instruction poem:

Collect a piece of sweater lint. Throw it into the sky.

1964 summer

Nina Katchadourian, Pink Volcano, 2011, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

For as much as the series can be viewed as a set of individual images, it also can be read as the documentation of a performance. When asked how other passengers react to her process of making images, the artist recalled that over the estimated 275 flights she’s taken in the past nine years, only three people have ever inquired about her work. Whether disinterest or politeness undergirds these numbers, Katchadourian’s insistence on the airplane-as-studio is nonetheless a quiet provocation of business as usual, raising poignant questions, as the artist herself has mentioned, on the fraughtness of post-9/11 air travel. Within a space colored by the rhetoric of paranoia, anxiety, and terror, what does it mean to make lavatory self-portraits in the Flemish style?

Nina Katchadourian, Lavatory Self-Portrait in Flemish Style #13, 2011, from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing

Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Fridman Gallery

Katchadourian carves out a rare space for humor in the often tedious worlds of both airplanes and galleries. The images in Seat Assignment are not particularly complicated or technically sophisticated, but they forego these traits for a self-awareness and transparency made all the more refreshing by their context. Because while we often look to art as an escape into alternate realities, Katchadourian’s images are only momentary illusions. They ground us in the presentness of paper waste, dry pretzel snacks, and unflattering airplane lighting, but they also insist on the expansive potential for joy and pleasure amid the smallness of these everyday mundanities.

Ellen Pong is the editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Nina Katchadourian: Ification was on view at Fridman Gallery, New York, from February 24–March 31, 2019.

The post How to Make Art at 30,000 Feet appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Don McCullin Doesn’t Want You to Look Away

From the Troubles in Northern Ireland to the wars in Southeast Asia, McCullin’s images defined the conflicts of the twentieth century.

By Aaron Schuman

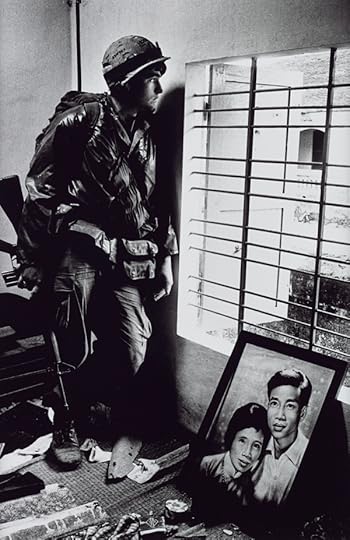

Don McCullin, The Battle for the City of Hue, South Vietnam, US Marine Inside Civilian House, 1968

© the artist

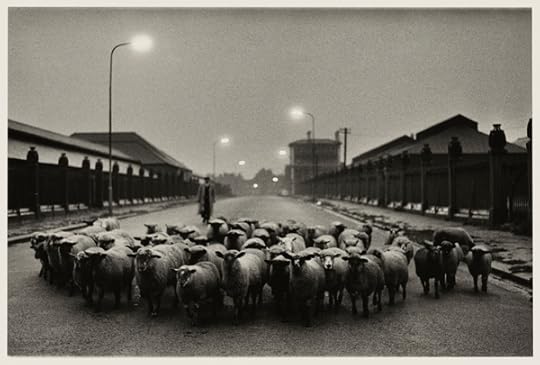

In the first of the ten galleries that make up the staggering retrospective Don McCullin, currently on view at Tate Britain in London, hangs a prescient photograph taken by McCullin in 1965, entitled Sheep Going to the Slaughter House, early morning, near Caledonian Road, London. A gloomy gray haze hangs heavily in the dawn air as a shadowy figure in a long coat and flatcap marches a tightly packed herd of sheep, more than forty strong, along a wide, straight road to their deaths.

Seen through the eyes of McCullin, who grew up among the ruins of Blitz-scarred north London in the early 1940s, and would later photograph for the Observer and The Sunday Times Magazine, what might have otherwise been depicted in previous centuries as a rather quaint and pastoral image of British shepherding life is infused with a haunting sense of postwar horror. Thick black fences, buzzing streetlamps, elongated factory-like buildings, and blocky towering structures line the street with an impeccable, cold regularity, inevitably evoking the startlingly bleak pictures of concentration camps taken only twenty years earlier, and which have resounded within our collective unconscious ever since.

Don McCullin, Sheep Going to the Slaughter House, early morning, near Caledonian Road, London, 1965

© the artist

In the making of the photograph McCullin firmly positioned himself directly in the herd’s path, situating the picture and the viewer precisely between his subjects’ immediate present and the brutal fate that soon awaits them, unflinchingly recording their last living moments: some bow their heads in resignation, others look anxiously into the distance, and, most distressingly, several of them look us straight in the eye.

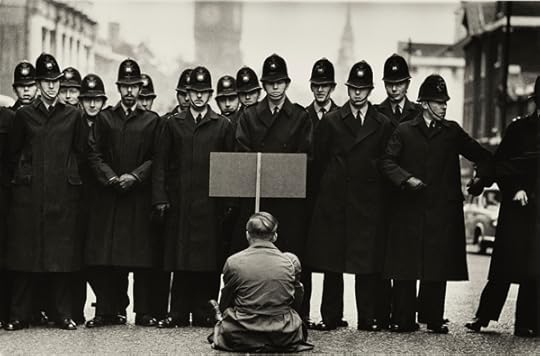

McCullin’s exhibition is densely hung in a relatively linear fashion with his own handmade gelatin-silver prints, and proceeds chronologically through a remarkably diverse career that spans more than sixty years—from his documentation of the teddy boy gangs that loitered in the streets of his childhood neighborhood in the 1950s, to anti-fascist protesters in Trafalgar Square and the building of the Berlin Wall in the early 1960s.

Don McCullin, Protester, Cuban Missile Crisis, Whitehall, London, 1962

© the artist

He covered wars waged in Cyprus, Biafra, the Republic of the Congo, Vietnam, and Cambodia in the late 1960s and early ’70s; the Troubles in Northern Ireland; the rise of homelessness in London’s East End; the plight of industrial cities in the north of England throughout the 1970s; the war zones of Beirut, Bangladesh, and Iraq in the 1980s and ’90s; the AIDS pandemic in Africa in the early 2000s; and the ruins of Syria in the 2010s. And more. The sheer geography he traversed, the quantity of miles and the range of experience, is astounding. Yet throughout, a particular motif—direct and unwavering eye contact—persists, punctuating the show with a relentless and penetrating power.

When I visited the exhibition earlier this year, I was astonished to find that the galleries were absolutely packed, a tightly knit queue of enrapt visitors shuffling along the walls at a slow but steady rate, and growing discernably quieter and more subdued from one gallery to the next. McCullin’s photographs are captivating for both obvious and unnerving reasons, as they depict moments of human conflict, cruelty, suffering, desperation, depravity, and destruction with a wide-eyed and unapologetic directness.

Don McCullin, Northern Ireland, The Bogside, Londonderry, 1971

© the artist

It was heartbreaking to watch visitors move from one horrific scene to the next casually and in time with the surrounding throng. But occasionally, when a subject’s gaze reached out from the frame, this collective procession would come to an abrupt halt. Each one of us was struck not only by the force of what we were looking at—an instant of connection and recognition, often caught moments before death—but also by the unsettling fact that as viewers we were just looking, while the person facing us could look no longer. McCullin’s photographs demand that you stop and take a breath.

“I want people to look at my photographs,” McCullin once stated, trying to explain the complex motivations behind his work in the simplest of terms. “I want to create a voice for the people in those pictures. I want the voice to seduce people into actually hanging on a bit longer when they look at them, so they go away not with an intimidating memory but with a conscious obligation.” Despite such intentions potentially seeming naive or idealistic, especially today, within the hyper-skeptical, oversaturated, and often cynical media landscape, Don McCullin insistently serves as a troubling yet poignant reminder that we are still capable of being conscious and connected, and must therefore recognize our obligations as both spectators and citizens of the world at large. McCullin tells us, as he told himself in the field time and time again, “You have to bear witness. You cannot just look away.”

Don McCullin, Local Boys in Bradford, 1972

© the artist

Aaron Schuman is a photographer, writer, lecturer, and curator based in the U.K. His latest book, SLANT (2019), was recently published by MACK.

Don McCullin is on view at Tate Britain, London, through May 6, 2019.

The post Don McCullin Doesn’t Want You to Look Away appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 10, 2019

Foreigners in a Foreign Land

Arguiñe Escandón and Yann Gross travel to Peru in search of connections to nature.

By Emmanuel Iduma

Arguiñe Escandón and Yann Gross, Untitled, from the series Tamamuri, 2018–ongoing

Courtesy the artists and Wilde, Geneva

In summer 2016, Arguiñe Escandón sent Yann Gross, a Swiss photographer who often works in the Amazon, a postcard with a photograph by Charles Kroehle. It was one of many pictures the German photographer made while documenting Peru between 1888 and 1891. Escandón, a Spaniard and a photographer herself, added a friendly warning: “I hope you won’t end up like him.”

Although much is known about Georg Hübner, the German ethnographer and photographer with whom Kroehle traveled in eastern Peru, Kroehle’s fate has been open to speculation—some say he disappeared after he was shot with a poisonous arrow in the rain forest. As Escandón and Gross considered their predecessors’ earlier photographs, they saw an opportunity to make collaborative work. Almost a century and a half later, they traveled in Peru with the legend of Kroehle as a kind of anti–field guide.

Arguiñe Escandón and Yann Gross, Untitled, from the series Tamamuri, 2018–ongoing

Courtesy the artists and Wilde, Geneva

While Hübner and Kroehle intended to produce a visual documentation of Indigenous Peoples and to send back prints for sale, Escandón and Gross were not as unquestioning of the implications of being foreign and the ties between power and representation. “We didn’t want to bring back trophies, but tried to understand a bit more, even if the result was that we realized that we were totally ignorant,” Gross said. “It was a good lesson in humility.”

They traveled along the Pachitea, Ucayali, and Nanay Rivers, living among the Ashaninka, Shipibo-Conibo, and Cocama peoples, who must fight for the guarantee and acceleration of communal land titling, based on their rights of self-determination, and for alternative development plans that respect existing ecosystems. Escandón and Gross are rightly ambivalent about Kroehle and Hübner, who were complicit in more than one form of colonial exploitation, working with rubber barons, fur traders, and gold diggers.

Arguiñe Escandón and Yann Gross, Untitled, from the series Tamamuri, 2018–ongoing

Courtesy the artists and Wilde, Geneva

The question for Peru, then as now, is how it might reckon with the pressures of global capitalism while addressing the fact that its resources are taken from Indigenous Peoples, whose claim to the territory is several thousand years old. The scale of the Peruvian Amazon—comprising 60 percent of the country, while occupied by only 5 percent of its population—makes parts of it prone to be allotted to companies engaged in mining, oil exploration, and hydroelectric megaprojects. “A concept is needed,” Gross said, mindful of the impact of climate change and decreased biodiversity, and the worldviews of the peoples he and Escandón spent time with, “where you are part of an ecosystem and in balance. It’s to be face to face with other elements and not above it—a concept of equality, more relational than hierarchical.”

Arguiñe Escandón and Yann Gross, Untitled, from the series Tamamuri, 2018–ongoing

Courtesy the artists and Wilde, Geneva

If, as the artists have noted, Gross’s earlier photographs from the Amazon were documentary in nature and Escandón’s were invested in psychology, their collaboration, Tamamuri (2018–ongoing), has produced a mix of both enthusiasms. The photographs they have returned with so far—whether a portrait or a detail of marshland, whether varnished with light silver or delicate blue—convey the intricacy and totality of an ecological surround.

Escandón and Gross are as foreign as their predecessors. Yet work of this kind, invested in sensation instead of a romantic representation of an unfamiliar culture, is an inward rather than outward exploration—an intrepid adventure that nevertheless rejects the logic of the explorer as discoverer. Their photographs mark a process of participation. Foremost on their minds was the possibility that they could find a through line connecting self and environment, image and history.

Emmanuel Iduma, a critic and novelist, is the author, most recently, of A Stranger’s Pose (2018).

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Foreigners in a Foreign Land appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Celebrates Ethan James Green at the 2019 Spring Party: Young New York

Stefano Tonchi, Ethan James Green Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tali Lennox Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Alek Wek and House of Yes performersMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Party guestsMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Dara Allen, Ethan James Green, Torraine Futurum Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Micol Sabbadini, Andrea Franchini Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

DonChristian, Martine Gutierrez Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Phyllis Posnick, Ethan James Green Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Ang Rand, Matthew DomescekMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

House of Yes performance at the Paradise Club, The Times Square EDITIONMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

House of Yes performance at the Paradise Club, The Times Square EDITIONMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Adam Eli Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tali Lennox, Carly Mark, Richie Shazam KhanMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

The scene at the Paradise Club, The Times Square EDITIONMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

James O'Shaughnessy, Missy O'Shaughnessy, Tony White Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Nina Rosenblum, Cathy Kaplan, Daniel Allentuck Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Isabella Isbiroglu, Alexandra Ben-Gurion Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Rebecca Roberts, Lauren Lanier, Leslie Simitch Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Erwin Olaf, Nion McEvoy, Shirley den Hartog Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Stefano Tonchi, Ethan James GreenMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Sonalde Desai, Hemant Kanakia Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tim Doody, Sarah Haimes Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Melinda Green, Ethan James Green, Mark GreenMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Performer from the House of Yes

Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Ben Pundole, Alek Wek, House of Yes performer Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Alek Wek, Brendan Embser, Nkechi Ebubedike Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Sarah Cascone, Lulu Krause Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Sally Borno, Rebecca Roberts, Jordan Hancock, Ethan James Green Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Sophia Narrett, Alice Hines Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Nion McEvoy, Cathy Kaplan Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

The scene at the Paradise Club, The Times Square EDITION

Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Maya Margarita, MerlotMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Alex Arauz, MarcsMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Antwaun Sargent Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tali Lennox, Carly Mark Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Richie Shazam Khan, Ethan James Green Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Peter Goldberg, Stevie Triano Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Chris Boot, Mary Ellen GoekeMike Vitelli/BFA.com

Julia Wagner, Isabelle McTwigan, Brendan Embser Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Brendan Embser, Ethan James Green, Chris Boot Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Ethan James GreenMike Vitelli/BFA.com

Dara Allen Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Michael Hoeh, Lisa Rosenblum, Nina Celebic, Nina Rosenblum, Daniel Allentuck Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Jessica Craig-Martin Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Tom James, Natalie Gaisser, Christine Ramsbottom, Meghan Michelle Gallagher, Tyler Rhode, Scott Robinson Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Zsela Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Marcs Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Tammy Hsu, Jinny Choi Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

DJ Greg Poole (Homecoming) Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Torraine Futurum, Adam Eli, Maya Margarita Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Richie Shazam KhanMike Vitelli/BFA.com

Sam Pritzker and guest

Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Dara Allen Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

Antwaun Sargent, Ethan James Green Mike Vitelli/BFA.com

On Friday, April 5, Aperture celebrated Ethan James Green and the release of his first monograph, Young New York, at a festive party at the Paradise Club presented by The Times Square EDITION in New York City. The night featured specialty cocktails, a creative feast, and a performance by the House of Yes, based on William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Aperture Executive Director Chris Boot toasted Green, stating: “A book can change an artist’s life, and can contribute in a significant way to culture and consciousness.” Boot extended thanks to Green and to his community, as well as to the book’s supporters, including Alexander McQueen, Peter Barbur, Michael Hoeh, Cathy Kaplan, Noel Kirnon, Fred Ohm, Missy and Jim O’Shaughnessy, and Drs. Stephen and Marsha Silberstein.

Young New York editor Brendan Embser spoke about the impact of Green’s work. “You’ve shown queer people that we are beautiful, that we exist,” Embser said, noting that the book grew out of Green’s portfolio in Aperture magazine’s “Future Gender” issue, guest-edited by Zackary Drucker. “I wish I had a book like this when I was a teenager. But I can just imagine all the queer youth out there who are going to find Young New York and suddenly see themselves.”

“Your work makes what we believe about ourselves become real,” remarked Spring Party cohost and model Dara Allen, who is featured in multiple portraits in Young New York. Torraine Futurum added that Green is “someone who, as he rises, brings people along with him, and tries to give them the same opportunities that he has.”

The House of Yes gave an energetic show for dinner guests, followed by an after-party with music by DJ Greg Poole (Homecoming), and a performance by Brooklyn-based multimedia artist Martine Gutierrez. Guests were decked out in colorful and show-stopping ensembles. In attendance were Great Bowery’s Leslie Simitch and Jordan Hancock, W magazine’s Stefano Tonchi, Vogue’s Phyllis Posnick, artist Erwin Olaf, supermodel Alek Wek, artist and model Tali Lennox, artist Carly Mark, writer and activist Adam Eli, Richie Shazam Khan, artist Ryan McNamara, and critic Antwaun Sargent.

Green’s brother, Joel Green, said: “As an older brother, it might be strange, but this feels like a hero moment for me. Ethan is someone who embodies the essence of hard work, who has overcome so many obstacles, to get to a point where he can fully express himself, and who he is, and what he can give to the world.”

The event was photographed by Jessica Craig-Martin and BFA.

The 2019 Aperture Spring Party was made possible with generous support from:

Sponsors

The Times Square EDITION

Great Bowery

Cohosts

Dara Allen, Adam Eli, Torraine Futurum, Meghan Michelle Gallagher,* Great Bowery, Sarah F. Haimes,* Jordan Hancock, Parker Kit Hill, Michael Hoeh, Cathy M. Kaplan, Joshua Lewin and Kaavya Viswanathan,* Sam Pritzker,* Lisa Rosenblum, Thomas R. Schiff, Stefano Tonchi, Alek Wek

Spring Party Committee

Anonymous, Peter Barbur and Tim Doody, Audry X. Casusol, Allan Chapin and Anna Rachminov, Jessica Craig-Martin, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Hemant Kanakia and Sonalde Desai, Richie Shazam Khan, Tali Lennox, Andrew E. Lewin, Carly Mark, Nion McEvoy, Ryan McNamara, Paula Naughton, Erwin Olaf, Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy, Phyllis Posnick, Michael Schulman, Jasper Soloff, Lisa Stone Pritzker, Julia Wagner, Paul Zaentz, Zsela

* Aperture Connect Council Member

Partners

BFA

Mikkeller Brewing NYC

Click here to purchase Young New York.

The post Aperture Celebrates Ethan James Green at the 2019 Spring Party: Young New York appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 8, 2019

The Photographer Giving New Life to Ocean Plastic

Along the coast of South Africa, Thirza Schaap collects discarded bottles and shopping bags to create fanciful sculptures.

By Sara Knelman

Thirza Schaap, Sunday stroll, from the series Plastic Ocean, 2017–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

From her home in Cape Town, where she’s lived for the last six years, Dutch artist Thirza Schaap can walk to the ocean in seven minutes. The waters are wild and cold there, too rough for leisurely swimming. Drawn to them nonetheless, Schaap began walking the beaches with her black-and-white poodle, Iso, and was struck by the perpetual mass of plastic debris washing up on the shore, often caught up in watery strands of seaweed. It always looks, she says warmly, “like there has been a party.”

Thirza Schaap, Road trip, from the series Plastic Ocean, 2017–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

In 2016, Schaap started photographing found plastic sculptures and sharing her pictures on social media. As response to the work grew, she carved out a daily habit, foraging for plastic while out on morning rambles, then going home and making fanciful, pastel-hued arrangements on a table in her garden, and finally photographing her impromptu sculptures. Her lighthearted constructions contain familiar, everyday objects: bottles and lids, balloons, shoes, forks and spoons, toothbrushes, straws, and, of course, the ubiquitous plastic bag. Through Schaap’s collaboration with a writer friend, the resulting photographs take on evocative titles: Sunday stroll, Long stocking, Beehive.

Thirza Schaap, Split ends, from the series Plastic Ocean, 2017–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Despite their sweet allure, Schaap’s images are also deeply troubling. There has, after all, been a global party, and these pictures are glimpses of its ugly aftermath, shards of the unsustainable volume of refuse from our collective voraciousness. As sites of celebration so often appear the morning after, Schaap’s compositions are full of spent enjoyment, of things now devoid of use, faded, deflated, or broken. These things have been thrown away, but they persist, unable to decompose, resisting deletion.

Globally, we produce about 340 million tons of plastic each year, and a huge proportion of it ends up in our oceans. There are multiple “great garbage patches” floating languidly around Earth’s vast waters, the largest of which, off the coast of Hawaii, holds about 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic and weighs close to 80,000 metric tons. Like a large planetary orb, it continually pulls new objects into its sphere, perpetually accumulating remnants of our modern consumer culture.

Thirza Schaap, Beehive , from the series Plastic Ocean, 2017–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Schaap’s project Plastic Ocean (2017–ongoing) is a whimsical attempt to rescue a few stray fragments from this fate. A habit and a discipline, it has also become a meditative ritual tied to Schaap’s deep commitment to living a plastic-free life. Schaap, though, is not keen on pointing fingers or instilling guilt. There’s a groundswell now of antiplastic backlash, and Schaap finds inspiration in the community of people working to make things better. As melancholy reminders of the detrimental consequences of our entrenched habits of convenience, her images encourage the possibility, however inconvenient, of changing the way we live for the betterment of the planet and future generations.

Sara Knelman is a curator, writer, and the director of Corkin Gallery, Toronto.

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Photographer Giving New Life to Ocean Plastic appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers