Aperture's Blog, page 90

April 5, 2019

Announcing the 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Teresa Eng, Junction, 2016, from the series China Dream

Jack Latham, Mary as Nixon, Camp Meeker, 2018, from the series Parliament of Owls

Mark McKnight, if water forgets how to play mirror, 2018, from the series Decreation

Zora J Murff, Chris (talking about fear), 2017, from the series At No Point In Between

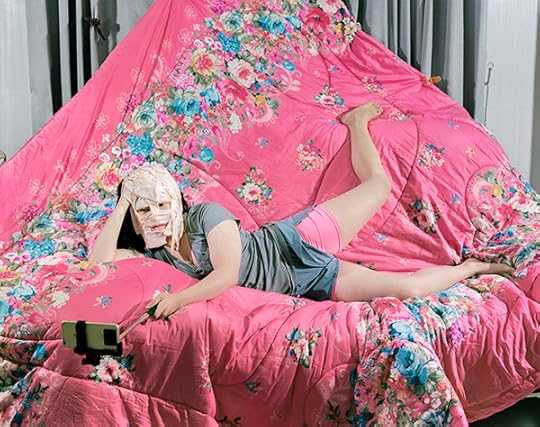

Guanyu Xu, Space of Mutation, 2018, from the series Temporarily Censored Home

This year, Aperture’s editors reviewed over 1,000 submissions during our annual Portfolio Prize competition. With a goal to identity contemporary trends in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition, we are thrilled to announce this year’s five finalists for the 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize.

Teresa Eng

Jack Latham

Mark McKnight

Zora J. Murff

Guanyu Xu

We are delighted to welcome these five finalists to our ranks of illustrious past winners and finalists, joining such artists as Ka-Man Tse, Natalie Krick, Eli Durst, Drew Nikonowicz, Amy Elkins, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Alexander Gronsky, Sarah Palmer, Louie Palu, Bryan Schutmaat, and many others. Our challenge is to now select one winner and four honorable mentions from this impressive group of finalists. The winning artist will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition in New York.

The winner of the 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced on Friday, April 19, and the finalists portfolios and statements will be featured on Aperture Online.

The post Announcing the 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 4, 2019

3 Photo Editors On Why You Should Enter the Aperture Summer Open

Essential advice on submitting to Aperture’s annual open-call exhibition.

Argus Paul Estabrook, Student Protesters March, Seoul, South Korea, 2017, from the series Losing Face

2017 Summer Open Artist

Aperture: Could you describe your point of view as an artist, editor, or educator?

Matthew Leifheit: I edit MATTE magazine and publish books and write and teach, in addition to being a photographer myself, and I think all these activities within photography have a symbiotic relationship—they both influence and are influenced by my practice as an artist. For my own photographs, I hope that I am expressing something visually that cannot be expressed in language, and would mostly like to leave it to other people to put words around my images.

But in terms of subject matter of my art or my publishing, I want to remain as open as possible. I am particularly interested in queer topics and supporting queer-identified artists, but this is not exclusively what I publish or photograph. I strive to have many points of view at once.

Chiara Bardelli Nonino: So much of our experience is filtered through words. A good photograph, at least to me, is something that resembles a wordless, silent epiphany. There’s a power to this immediacy and I think an editor must never forget the responsibility of choosing and showing one image or another.

Azu Nwagbogu: To have a point of view is always a little premature, in my opinion. I would rather consider my role as an enabler of the artistic voice and temperament. If I do have one point of view that I am adamant about, it is that an artist should be an artist and not a journalist or a priest or a moralist. It is important to encourage artists to trust the process of making and to leave it at that and not have to play the multiple roles that contemporary society bequeaths upon them.

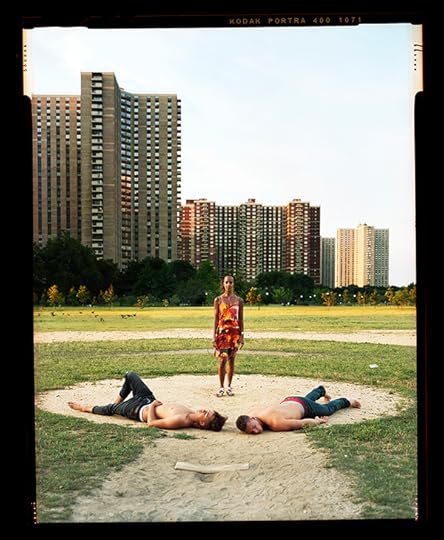

Jon Henry, Untitled #1, Co-op City, New York, from the series Stranger Fruit

2017 Summer Open Artist

Aperture: What do you look for when viewing a body of work?

Leifheit: To quote one of my heroes, Vince Aletti, the best photographs have “something soulful.” It could be a landscape or a portrait or a cameraless darkroom abstraction, but my favorite pictures and bodies of work always have a mystical third element that could be called soul. It’s something indefinable. That said, there are certain things I do look for: that the photographer is in control of their references, that the photographs show an intensive commitment of thought if not time, that the project seems intensely and urgently personal rather than contrived to appear intelligent.

Nwagbogu: Authenticity, whatever that means and however that is defined within the ideas or scope of the work in view. Also, the spontaneous is important. I also want to see if the artist is close to achieving her aims. Without beauty, however you define that, all else is hopeless.

Bardelli Nonino: A clarity of vision, a sense of urgency, the ability to condense complexity and its intrinsic ambiguity in a self-contained space, be it a single image or a project.

Gowun Lee, I’m Here With You, 2017

2018 Summer Open Artist

Aperture: What advice could you give photographers who are considering submitting to the Summer Open?

Bardelli Nonino: Don’t be literal: the theme is as broad and as open to interpretation as it can be. Be a merciless editor: keep only the images that really are essential to tell your story. Allow yourself to be vulnerable.

Leifheit: Concentrate on making your work, not promoting it. The best place to put your energy is into the pictures—artists do not need business cards, promos, or websites if their work is good. It’s a lot easier to make something good and have people love it than it is to foist bad work onto an unwilling audience. Once the work is there, then opportunities like the Summer Open can be a way for more people to discover it.

Nwagbogu: You have much more to gain by applying than not applying. It really is that simple. To borrow an oft-used cliché, it really could be life changing, and I am confident that all the jurors will take a keen interest in each application. The diversity of roles and backgrounds of the jurors means that your work will get noticed regardless.

Matthew Shain, Post Monuments, New Orleans, (General P.G.T. Beauregard, erected 1913), 2017

2018 Summer Open Artist

Aperture: There are so many calls for entry out there. Why should people submit to the Aperture Summer Open?

Leifheit: Editors, curators, and collectors actually pay attention to who is chosen for this show because of Aperture’s reputation and long history of championing the work of new artists alongside established masters. The show is also a great way to grow your community of artists and put your work in dialogue with that of your contemporaries. I think I can speak for all the members of the show’s jury in saying that we will consider your submissions carefully and will be excited to discover new trends in photography from this very competitive pool of talented artists.

Bardelli Nonino: Aperture is one of the most respected voices in photography out there. If you have something to say, I can’t imagine a better platform to be heard.

Nwagbogu: It is a singular opportunity.

Bubblegum Club, Bee Diamondhead, 2017

2018 Summer Open Artist

The 2019 Aperture Summer Open is curated by Brendan Embser, managing editor, Aperture magazine; Matthew Leifheit, artist and editor of MATTE magazine; Chiara Bardelli Nonino, photo editor, Vogue Italia and L’Uomo Vogue; Azu Nwagbogu, director of African Artists’ Foundation and LagosPhoto; and Guadalupe Rosales, artist and founder of Veteranas & Rucas and Map Pointz.

Submit your work now through April 12, 2019.

The post 3 Photo Editors On Why You Should Enter the Aperture Summer Open appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 3, 2019

Does a Woman Have to Be Invincible?

In her latest exhibition, Phoebe Boswell takes self-portraits—and self-healing—to a new level.

By M. Neelika Jayawardane

Phoebe Boswell, Still from Rapture (detail), 2018. Single-channel video

Courtesy the artist and Sapar Contemporary, New York

In the contemporary geopolitical West, we are taught that the body should be made invincible. Despite the fact that women’s bodies and women’s psyches remain locations on which patriarchal, political, and economic violence are projected, we rarely hear narratives that are not solely about strength and resilience, negating moments of vulnerability. Fashioning the self as anything less than “strong” is seen as weakness—a personal and moral failing. But what happens if we find such mythologizing, of being so masterfully in command of our bodies, an impossible task—a nontruth that we no longer wish to support?

Kenyan British artist Phoebe Boswell’s recent multimedia exhibition, The Space Between Things, curated by Renée Mussai and organized by Autograph ABP in London, uses a variety of photographic technologies to meditate on that question. Boswell was born in Nairobi to a Kenyan British father and a Kikuyu mother, but spent much of her formative years in the Arabian Gulf, with what she calls an “expatriate” identity. The Space Between Things included minute cutouts of old family pictures in the entryway to the lower-floor gallery, charcoal wall drawings representing an extended portrait of the self—all based on photographs—as well as drawings of nude female figures and roaring oceans on paper. There was also a series of video works that featured multiple-exposure self-portraits of medical scans, some of which give us a perspective of the artist’s body from a distant vantage point, while others probe the interiors of her organs. Each room of the exhibition was accompanied by sound and spoken word; at times, one could hear sound enveloping the space; at others, one needed to step on sound boards—rectangular pedals installed on the floor—to hear Boswell’s voice reciting lines from her own poem.

Phoebe Boswell, The Space Between Things, 2018. Installation view at Autograph ABP, London

Courtesy Autograph ABP

Accompanying these was a twenty-five-meter-long “extended self-portrait,” powerfully visible on three walls of the ground-floor gallery. These are impressions of her physical and emotional reactions—drawn using soft willow charcoal—based on photographs that the artist took of herself during the three-week process leading up to the exhibition opening. These self-portraits do the opposite of ordinary selfies, so often intended to show us at our finest moments, living our “best lives.” Boswell’s are intimate, self-baring portraits that show her body and flesh sprawled in grief and pain, imperfect and unraveling.

A dramatic series of ruptures in Boswell’s life led to this exhibition, beginning with an accidental injury to her eye. She subsequently experienced an actual heart attack—a physical response to the emotional turbulence she went through as a result of her injury. That wounding, watershed moment forced Boswell to sit meditatively with her physical, psychological, and spiritual self’s vulnerability. How was she supposed to live, now, with a “new” body and an emotional self that could never return to the person she once knew and inhabited? She had to create a dialogue with this new self, “an emotive interrogation of trauma, healing, and the poetics of endurance,” as Mussai writes in the curatorial text; Boswell needed to permit herself to express rage at the cause of the injury that created these ruptures, and give herself moments of longing for return. Between the “before” and “after,” she created a healing, liminal space.

Phoebe Boswell, Ancestors Roar There, 2018

Coutresy the artist and Sapar Contemporary, New York

As she lay in the high-dependency cardiac wing of an East London hospital, “attached to the machine . . . eye bulbous and blurry, delirious,” Boswell remembers hearing the woman in the bed next to hers “calling out to the darkness, ‘Take me to the lighthouse.’” Boswell wondered “where on earth my lighthouse was.” That repeated request—to right one’s vessel in the midst of a storm that could kill, to return to the safety of homeland, guided by a beacon—recalls Virginia Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse, known for its fragmented narrative structure and stream-of-consciousness contributions from several narrators. In the book, a family returns to a summer home after a ten-year absence, each carrying with them unresolved longings they’ve borne all their lives—and the hopes of righting their respective courses.

Like Woolf’s narratives, Boswell’s works depict the storms one must brave in order to make a “crossing,” fraught as they always are, to find communion with others. Healing and recovery may be possible if we accept that our longings for an idealized union with our own lighthouses—which call our lost vessels home—will inevitably be marred by imperfections. Boswell, too, had little choice but to acknowledge that she will never be able to “return” in order to remake a perfect, whole person as she remembers herself.

Phoebe Boswell, Still from Ythlaf, 2018. Single channel video

Courtesy the artist and Sapar Contemporary, New York

Boswell’s video installation Ythlaf (2018), composed of six floor-mounted video screens, shows footage of Zanzibar’s shoreline, taken using her father’s drone. Ythlaf, with its beautiful collection of consonants and vowels, is from Old English; it is composed of yth (wave, water), and laf (remnant, relic). “Water-relic” denotes liminal spaces between land and sea, which provide reliquaries for the energy of each wave. Each screen queries the mysteries of ythlaf; we see a shallow shelf of land welcoming each lace-edged wave, and the great expanse of the Indian Ocean beyond. Boswell’s body drifts like that of a long-limbed starfish. At times, the gentle motion of successive waves pitches her off screen. A sound work activated by visitors’ footfalls on interactive pressure sensors, hidden by black floor mats, accompanied the videos, composed of rhythmic breathwork that mimics wave motion. Pedals stood next to each screen; stepping on them released a looped soundscape of spoken word poetry, The Space Between Things (2018), written and recited by Boswell: “Take me to the lighthouse / There is peace there in the space between things / Take me to the lighthouse / I can rage there / In the space between things.”

In the exhibition spaces upstairs at Autograph, Boswell’s works shifted from these intimate portraits to an operating theater, where she underwent surgery to save her right eye: New Moon (2018) presents actual footage from the surgery, bearing witness to the miraculous, meticulous work that modern technology allows medical personnel to carry out, as well as the vulnerability of an organ as delicate as the eye. Also included in these dark, womb-like spaces was an angiogram of her heart, A Broken Heart (2018), which shows us proof of an injury to the organ. At one station, visitors could put on a pair of headphones to hear the voices of the surgeon and nurses who most recently operated on her eye over a period of about two hours, attempting to fortify it using graft cells. (This was the Boswell’s fourth surgery.) Dubstep played in the background, pacing their labor. With these pieces, she illustrates the ways in which the self—both physical and emotional—is made up of, and by, those around us. Just as other people can injure us to the point where we no longer recognize who we are, they also have the capability to help mend us when we are at our most broken.

Phoebe Boswell, The Space Between Things, 2018. Installation view at Autograph ABP, London

Courtesy Autograph ABP

In the experience of diaspora, we all feel dislocation as we grasp for stability in romantic and sexual attachments, and as we pursue the excellence that one’s community or new country demands, all the while holding together our splintered selves from public view. These tensions in the construction of a diasporic identity are at the heart of Boswell’s practice. Her works unapologetically lay bare the ways in which our psyches fracture and vacillate between a physical world and a world beyond. They portray the poetics of the body’s ability to endure fracturing, without glorifying or essentializing “black women’s strength” or stereotypes about the diasporic subject’s resilience, while also showing a way to speak about our own ruptured selves. Perhaps this can lead us back to our own lighthouses, however fragile and imperfect those journeys may be.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York-Oswego, Research Associate at the Visual Identities in Art and Design (VIAD), University of Johannesburg.

Phoebe Boswell: The Space Between Things was on view at Autograph ABP, London, from December 14, 2018 to March 30, 2019.

The post Does a Woman Have to Be Invincible? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 1, 2019

Introducing: Leonard Suryajaya

In the first of our new series, “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography, Aperture speaks with a queer, Indonesian photographer who makes explosive pictures of his family.

By Cassidy Paul

Leonard Suryajaya, (With Sisters, Aunts, Uncles, and Cousin) Mom as Bodhisattva, 2015

For Leonard Suryajaya, feeling like an outsider was the norm. Growing up in Indonesia as a Chinese minority, Suryajaya was a Buddhist raised by a Muslim nanny and educated in Christian schools. It was when he came into his own sexuality as a queer man that he realized the weight of living in a country that suppressed his freedom of expression and condemned homosexuality, and at the age of eighteen he fled for America.

It wasn’t until 2015, a year after coming out to his mother during a trip back home, that Suryajaya began to explore the complexities of his identity in his work. Traveling to Indonesia once a year, he started photographing various members of his family and his partner, Peter, in elaborately staged scenes drawn from experiences in his youth.

The resulting images in his series Don’t Hold On to Your Bones are vibrant, humorous, dizzying, and deeply personal. In them the absurd meets the everyday—from his father seated among a sea of trophies to his mother posed as a Buddhist figure to a family outing at the beach—and each item and figure seem both at war and at peace with one another. “I relied on my camera to process,” Suryajaya explains. “Photographing my family allowed me to acknowledge my longing to settle the contradictions I experienced about myself.”

Suryajaya knew from the onset he wanted the series to be collaborative, hoping to form a new level of intimacy with his family through the act of photographing. Each frame was approached with a loose concept, allowing his family members and himself to organically create the image together in front of his 4-by-5 camera. Describing the experience on set, he notes, “Everything changes when my family enters. It becomes a bargain and promise between me and them in the end.”

One subject in particular stands out among the rest. Suryajaya’s partner, who is white, is interspersed among his family throughout the series. In one image, Peter and Suryajaya’s mother sit on the bed together, wrapped in a duvet that matches the wallpaper in the background. Their heads rest on one another and they stare lovingly into the camera, which Suryajaya stands behind, directing. “Peter’s role is fluid and complicated,” he explains. “Sometimes he is a muse, an object of desire, a matter of convenience. Other times, he is my partner, helper, supporter, collaborator. Most of the time, he is a stand-in for me.”

At the heart of Suryajaya’s work is a desire to understand the intricacies of his own complicated layers of identity, while working against the backdrop of his cultural and familial expectations. “I’m a queer immigrant to the United States who fled constant cultural and social clashes in Indonesia,” he says. “When I’m home, I feel like I am still a kid struggling to express my autonomy. Naturally, the camera is the only thing that leaves me with any sense of independence.”

Leonard Suryajaya, Familial, 2016

Leonard Suryajaya, Mom and Peter, 2015

Leonard Suryajaya, Candyman, 2016

Leonard Suryajaya, Dad and All of His Trophies, 2015

Leonard Suryajaya, Musing, 2015

Leonard Suryajaya, You, By the Lake, 2015

Cassidy Paul is the social media editor of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

The post Introducing: Leonard Suryajaya appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 29, 2019

In Iran, Images of a Dystopian Water Crisis

Hashem Shakeri’s pastel-hued, otherworldly photographs depict a landscape on the verge of destruction.

By Haleh Anvari

Hashem Shakeri, Hossein, 13, is from Beris, Chaabahar, which is on the sea but lacks secure access to freshwater. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Hashem Shakeri is making a name for himself as one of Iran’s foremost emerging photographers. Trained as an actor and an aspiring filmmaker, Shakeri doesn’t like to be called a photographer; he prefers to be seen as an experimental artist. Whatever label he is given or aspires to, he has captured the attention of the international photographic community with his latest series of photographs about Sistan and Baluchestan, a province in southeastern Iran bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The largest of Iran’s provinces and the birthplace of Rostam, the Persian mythical superhero, Sistan and Baluchestan has a rich cultural history, but the area is also woefully underdeveloped. Thanks to its being on the border of Afghanistan, the province has hosted hundreds of thousands of refugees who escaped the troubles in Afghanistan and have come searching for work in Iran. There is widespread poverty, and major and petty smuggling of people and goods across the porous border is a way of life. This has turned the province into Iran’s “wild east,” where the rule of law is fragile. Shakeri’s recent series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun (2018) focuses on the acute water crisis in the region, which also resonates on a national level.

The water crisis in Sistan and Baluchestan is caused by factors that threaten acute water shortages in all of Iran: a steady decrease in annual rainfall, the rise in population, and shortsighted planning by various governments in water distribution. In Sistan and Baluchestan, the problem points also to a failure in understanding that foreign policy must include environmental issues like water rights. Many in Sistan and Baluchestan believe that Afghanistan’s control of the river Helmand, through the construction of dams and, more recently, irrigation canals, has led to the drying of Hamun Lake, the life source of the Iranian province; the Afghans point to water mismanagement on the Iranian side. Earlier this year I spoke to Shakeri in Tehran about his recording of the drying of Sistan and Baluchestan.

Hashem Shakeri, A family removes soil from the riverbed to use for their home garden. Last year the river that flowed under Nohrab Bridge—a branch of the Helmand—was full of water, but now it is completely dried. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Haleh Anvari: How did you become interested in Sistan and Baluchestan and its environmental problems?

Hashem Shakeri: I have to take you back to when I first became aware of Sistan and Baluchestan Province. About ten years ago I got a call from one of my friends, who told me to hurry to a mutual friend’s house. Her name was Negar. Negar was a childhood friend from my neighborhood; she was a beautiful and gentle girl. I was told that her father had killed her, because she wanted to marry a man and her father didn’t approve. When I got to her house I saw women dressed in a kind of traditional clothing I had not seen before. They were wailing and scratching their faces, mourning in their own traditional way. Their clothes and the women’s behavior made me curious, so I asked where they were from, and I was told that they were Baluchis, from Baluchestan. That’s the first time I heard the name of this province. And something stuck in my head about wanting to know why they were so different.

Six years ago, visual storytelling became important for me, and my priority changed to working on documentary photography to tell the story of different peoples of Iran. I remembered Negar and decided to go see the place for myself. But because of security reasons, Sistan and Baluchestan being on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, I couldn’t go there easily. The place can be unsafe. Border patrol soldiers are regularly kidnapped. The project was too difficult and also too costly.

Then in 2018 I received a scholarship to the Danish School of Media and Journalism. I chose Sistan and Baluchestan as my final project topic. This was the best opportunity for me to cover this topic. I could borrow a medium-format camera from the school, which I couldn’t afford to buy myself. I had a sense that medium format, because of the atmosphere it creates, would be the right camera for this story. I also got the chance to research the subject. This project is my best-planned and best-researched project.

I arrived in the region with an understanding of the place and its situation, because I had the means to research the topic before setting off. I spoke to a number of fixers and used different drivers who facilitated access to a story that is happening very quietly out of sight. As soon as I got there I knew what the title of my project should be: “The Tired and Forgotten Land”—because that is what I was facing. I was looking at a vast emptiness that has a five-thousand-year history and was once known as Iran’s grain store because it was so lush and productive. But in the past eighteen years this place has changed so much, you’d think that all the Persian mythology that tells stories of this green and fertile land must have been lies.

Climate change is happening all around the world, but I believe in Sistan and Baluchestan it is directly affecting the sense of dignity of the people. Here the basic status of humanity is being challenged.

Hashem Shakeri, Four girls from a family in Choutani village take water from a Houtag, or pit dug to gather rainwater. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: When you say humanity’s status is being challenged in Sistan and Baluchestan, is climate change the only factor that is making life difficult for the inhabitants of this region?

Shakeri: In the past eighteen years, climate change has had a direct effect on people’s lives. In 1973, Iran and Afghanistan signed a treaty about the right to the waters of the Helmand River for the people living downstream. The Helmand poured over the border into Iran, filling the Hamun Lake, then turned around again and returned to Afghanistan in a loop.

In 1998 the Afghan government built four irrigation canals to distribute the water of the Helmand River on their side, obstructing it from flowing into Iran, reneging on their 1973 treaty. As a result, Sistan and Baluchestan Province has experienced nearly two decades of drought, which has become acute in the past ten years. Four years ago, the yearly Helmand flood filled the Hamun once again, but it had been dry for so long, the water disappeared into the ground. No doubt mismanagement has added to the crisis. The province is full of half-finished projects.

The majority of the people who live in this province were farmers once, so when the water ran out, it took their livelihood with it. They have turned to smuggling petrol or people across the border. Twenty-five percent of the population has migrated. They move to the nearest place with water. Most of the people from Zabol have migrated to Golestan Province to the north so they can continue as farmers. Some go to Chabahar to the south on the Oman Sea for water, but there is no sweet water there. So they end up being taxi drivers. It’s a case of absolute poverty here. Unemployment leads to addiction and that leads to all sorts of other problems. If I want to record the different ways that lack of water is affecting the lives of people there, I will have to travel to the region several times over three or four years to be able to tell all the stories.

Hashem Shakeri, Until last year, water ran under the Zahak Dam, but now urban sewage runs through it. Teenagers have caught fish from the dirty water, which they sell for bread. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: I’ve heard from a friend who grew up in Zabol that there were so many fish in the river that she used to catch fish with her hands as a child. That’s how much water they used to have. A section of society lived on fishing alone.

Shakeri: I photographed three young men who were fishing under the Zahak dam, right opposite the governor’s office. The dam is now where the city’s waste is collected. I asked them if they were going to eat the fish from this dirty water; they said no, they will sell it to the poorer families who can’t afford anything better. The boys will buy bread for themselves with the money.

A little further under a bridge near the dam, five addicts were hanging out. I spoke to one of them and photographed him—Hoveyda, a thirty-year-old man who was collecting rubbish. He was living in a hole by the pipes running the drinking water supply of the city very close to the governor’s office. But no one does anything. He said he wanted to go into rehab, but feared that he would be arrested because he doesn’t have a birth certificate. These problems are all visible to the authorities, so quite clearly there is a case of mismanagement here as well.

There was a time that the people of this province lived like kings, through their farming. There is a famous wind called the 120-day wind, which can actually last for 170 days. It blows across the province. Sometimes the speed reaches 120 kilometers per hour. It blows across Lake Hamun. Imagine when there was water in the Hamun—this wind would hit the water and return at speed, working like a natural cooling system. Now, the lake is a dustbowl. When the wind blows, it brings only dust. You sleep at night and in the morning your doorway is covered in a heap of dust. This dust is destroying people’s lives. In 2016 this region was one of the most polluted areas. So it’s not just drought, but pollution too. I went to the region once just for the winds but I kept having to stop working, because my mouth would fill up with dust.

Hashem Shakeri, Before the draught struck, part of the Hirmand River moved through the Zahak Dam and entered the Hamun Lake. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: What’s the difference in the problems facing this region and other areas of Iran facing loss of water in a dramatic way, like Lake Urmia, or Isfahan’s Zayandeh Rud?

Shakeri: I have visited these other areas too. I think because these two cases are closer to the capital, they have received a lot of publicity. I decided to go to S&B because as a minority people in a marginal geography, their voice is not heard. It’s like they are screaming but no one is hearing them. The place reminded me so much of Waiting for Godot. It’s years that they are just waiting for something to happen, for a miracle to happen. A people who had a magnificent past are sitting waiting for that past to reappear again. But they seem to be completely dispossessed now. Some of the people here don’t even have birth certificates, because they may have moved over from Pakistan. So they live in homes made of date branches.

Anvari: It sounds like you had so many different social issues that you could have zoomed your lens on throughout this project.

Shakeri: I decided to stick to the water shortage as the main theme of my project so as not to get lost and distracted by the various issues. All the other problems are so grave they need to be looked at separately.

Hashem Shakeri, Poverty, unemployment, and addiction have spread through the region. Hoveyda, 30, lived next to the Zahak Dam, which until recently was full of water but is now contains sewage and garbage. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: Let’s have a look at the form of your photographs. You said it was your first time using medium format. One thing that sticks out to me as someone who sees a lot of photos of Iran is the colors that run across the whole series—a dreamy set of pastels that have a dusty look about them. Are these the colors of drought? Because there is a sublime beauty to them. You have managed to inject some romance into this rather dire situation.

Shakeri: I see myself as an experimental artist more than a photographer. Anyone can take photographs, these days. People are taking amazing photos with their phones, but that’s not art. I thought very hard about how I would treat this story. I do this with every project. I’m a documentary photographer, and visual storytelling is what I do. For me visual storytelling is no different from any other filmmaking or any other medium in art. I have to use whatever I need to be able to tell a dramatic story, which I like to imbue with a poetic atmosphere. My world is without time or geography. A no-man’s-place that can occur anywhere. I’m looking for the human soul, so if I work on climate change in the US, I might create a similar atmosphere.

When I got to the location, I encountered a sharp light and most of my photography happened at midday. So I went up by three or four stops as I took the pictures, so I could escape the sharp light. This overexposure made the impression of desolation that I had about this place possible. I was hugely inspired by Roy Andersson, who creates dead and dramatic atmospheres, and Michael Haneke, who changed my life completely, not only in art but in my personal life. I learned from him about the relationships between people and their states of mind, but also how I can photograph between my own imagination and the reality. I love my own subjectivity.

If there is an incident, even if there are no photojournalists around, many people can capture that image—but how many people can turn it into a story? I think about how I take a photograph subjectively, so as to make the story my own. The more personal it is, the more the viewer can connect to the story and the more awareness it creates.

Hashem Shakeri, Behzad, 5, swings in Takht Edalat Village located along Hirmand River, which is now completely dried. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: Can we say that you have taken the voice of the locals, which you say you hear as a scream, and changed it to a song?

Shakeri: I like that analogy. I like the photos I take to be poetic even if they are about the most bitter and horrific human experiences. Not necessarily beautiful, but what seems aesthetically right to me. Maybe this is my decisive moment, the intuition that I am experiencing at the time. It’s a challenge looking at a disaster and making it beautiful and effective.

Anvari: These photos are certainly not hard on the eyes, considering all the hardship you found surrounding the story. Maybe that’s why they are attracting so much attention, which in turn brings attention to the water and environmental issues that people might turn away from otherwise.

Shakeri: I think sometimes, viewers feel they are having an issue shoved down their throat. With this series, I was surprised that mainly art magazines and even a fashion magazine have asked to publish the images.

Hashem Shakeri, Mohammad, 42, at an abandoned mosque located at the heights of the former Takht Shah Village. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: This makes a lot of sense, specifically about one of your photographs, where a Baluchi man is standing by a rock in the wind. It’s a beautifully evocative photo where the eye is held by the folds of the man’s local outfit. We don’t see any of the horrific issues that you witnessed in this photograph, not the poverty, not the environmental disaster—it looks exactly like a fashion photograph.

Shakeri: Exactly. Medium format’s perspective creates that atmosphere. I tried to work in a minimal way, and the format requires a certain stillness. Plus the fact that I had to be frugal about the use of the medium-format film, because you can’t find it in Iran. So I had to learn to wait for my shot. The photo of the family taking the soil of the dry riverbed for their garden took me twenty hours to get.

Anvari: Apart from the foreign artists you have mentioned, do you see any Iranian photographers’ influences in your work?

Shakeri: Not directly. But no doubt our war photography has had an effect on me, how could it not? People like Abbas Attar, Alfred Yaghoubzadeh, Mohammad Farnood, Kaveh Kazemi, and their war photography have definitely made an impression on my subconscious, because I saw their photos during the war years as a youngster. But I have tried to take it up a level. If you look at the Magnum archive, which I have scoured studiously, up until ten years ago, all the photographers were feeding from the same visual subconscious; you can’t tell their photographs apart. Classic black-and-white. But then it changes by bringing in new photographers who are experimenting with art.

I reach out to other arts. I am a professional actor and have tried to find a common ground between photography and theater, because photography wasn’t going to be enough.

Hashem Shakeri, The Rige Mouri village was near the river, but it is now a wilderness covered with sand and dust. The Saravani family, who have lived in the region for more than 100 years, remember swimming in the river and working in the area. From the series An Elegy for the Death of Hamun, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Anvari: You’ve received a lot of attention outside Iran with this series. What’s been the reaction to this work inside?

Shakeri: I offered the photos free of charge to some Iranian publications but none of them would take them. Even though I am highlighting how Afghanistan is infringing on Iranian rights to Helmand water. This made me very sad. After all, these photos should be seen in Iran by Iranians first and foremost, on huge billboards, so they know what’s going on in Sistan and Baluchestan.

Haleh Anvari is a writer based in Iran.

The post In Iran, Images of a Dystopian Water Crisis appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 28, 2019

Pixy Liao Straddles the Male and Female Gaze

In her playful, collaborative photographs, the Chinese photographer upends the meaning of “muse.”

By Jon Feinstein

Pixy Liao, Open Kimono, 2018

Courtesy the artist

For more than twelve years, Pixy Liao and her partner Moro have been making collaborative self-portraits, playfully contorting gendered displays of power in photography and art history. Liao’s series Experimental Relationship depicts the couple in reversed, often intentionally stiff roles. The scenes recall, lampoon, and flip Liao’s expectations of relationship dynamics inherited from growing up in Shanghai, China: marrying an older man (Moro is five years younger) who would also be her mentor, and enjoying less authority.

The photographs, with Moro and Liao usually looking directly into the lens, place Liao in control. This ranges from subtle interactions—Moro sitting on Liao’s lap—to the hilariously direct, as when Liao pinches Moro’s nipple in homage to the 1594 painting Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses sœurs.

Liao’s latest exhibition, Open Kimono, builds on Liao and Moro’s collaboration with photos made in 2018 while the couple traveled through their home countries of China and Japan. Often clothed in traditional Japanese dress, Liao nods to Japanese Pinky Violence films (a genre in Yakuza films in which the leading roles are female) and Chinese mythology. I recently spoke with Liao about her process and evolution of ideas.

Pixy Liao, Mountain Mirror, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Jon Feinstein: Where does the title Open Kimono come from?

Pixy Liao: Open Kimono is also the title of one of the photos in the show. The show has two parts; one part is from a photo trip I took in Japan in which we both wore kimonos. I’m always fascinated by the sexual attraction of a partially opened kimono. It’s revealing secrets depending on how open it is. The project Experimental Relationship is like opening my thoughts to the public.

Feinstein: “Opening up to the public . . .”—how so?

Liao: I grew up in China. It’s a very different society than the U.S. In the U.S., people like to express themselves and are never afraid to be different. You won’t even be noticed much even if you are weird. In China, people don’t want to stand out. Any difference will immediately be talked about and discouraged. I’m used to hiding my thoughts and just blending in with the group. I felt that revealing my weird thoughts were too risky when I was younger. Experimental Relationship helped me to recognize my real self and get used to revealing my real thoughts.

Pixy Liao, Sento Thinker, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Feinstein: You’ve been making this work for more than twelve years. What’s changed about how you’ve made, or thought about, this work with this new chapter over the past year?

Liao: For the new show, I think it’s the first time I show so many photos from the same photo shoot (eight images). It’s a rare occasion that I actually planned a big photo shoot for this. I found a very old hotel in a town with the smallest population in Japan. For the role in the photos, I was imagining the female Yakuza women in the cult films.

Feinstein: What made you decide to include mostly images shot in 2018 and from the same shoot in this show?

Liao: Last year, I published a photobook including my photos from 2007 to 2017. Many of those photos have been circulating since then. So I thought it would be interesting to see only some new work in the exhibition.

Pixy Liao, The Women in the Red Robe, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Feinstein: Much of this new work was made while traveling, whereas, in the past, my understanding was that it was made in a much less transitory context. Did this impact how the photos were made?

Liao: During our earlier years, Moro and I were students, and then we graduated and we moved every year trying to find a more stable place to live. And after living in the same Brooklyn apartment for eight years, I got bored taking photos in my own apartment. Location is a very important element to inspire me to work. So now I always look for good locations for photos during our trips.

Feinstein: The cable release is present in almost all of your photos. I see it as an acknowledgment of the photographic process, an awareness that the photographer is present, that there’s a sense of fabrication and construction. Most literally I see this as relating to the staging of your relationship, but I think there might be more here.

Liao: I had to use the cable release in my photographs because it’s always just the two of us. Moro is usually the person who holds the cable release. In the beginning, I handed him the cable release because my hand does not have enough power to squeeze the air bulb. It would make my facial expression very painful.

One of the earliest photos in the project, called Relationships work best when each partner knows their proper place (2007), shows me pinching Moro’s nipple while he clicks the shutter, and the cable release extends outside of the frame. Me, him, the audience are all connected by the cable release. I also think it’s like a metaphor for our relationship. Sometimes the one who seems to be in control is actually the one who is being controlled. And I like the fact that he also has control in the image making. After this image, I always leave the cable release in the photo.

Pixy Liao, Relationships work best when each partner knows their proper place, 2008

Courtesy the artist

Feinstein: Like the nipple grab you mentioned, humor seems to be an important part of your work.

Liao: I have to enjoy the process to make it work. The work needs to amuse me in some way. People might think humor means “not serious.” But only when I’m humored can I find my true self.

Feinstein: A big piece of this series is about flipping and rethinking the history of the male gaze and the tradition in art, photography, and cinema of women-as-muse. Has making these images changed how you think about that history?

Liao: This history is a result of our world revolving around men for thousands of years. Men have always been in power for the majority of time and places. So there’s no doubt that the male gaze and women-as-muse has always been in favor. I’m glad to see that now a “female gaze” is getting more recognized these days; that means our world is changing.

Pixy Liao, Untitled (Moro in Dawn), 2018

Courtesy the artist

Feinstein: When I was in school in the early 2000s, I read a passage in Terry Barrett’s Criticizing Photographs about how photographer and critic Diane Neumaier tried to photograph her husband the way historic male photographers like Harry Callahan had photographed their wives—with a sense of muse-ish romance—but found the photos to be “emasculating,” and, in her words, photographic “failures.” The process and experience created new revelations for her about a problematic history of men photographing women. We’re more than two decades past these revelations, yet I think it’s interesting to consider them in the context of your work.

Liao: That is interesting! I never thought that taking photos of Moro could result in photographic “failures.” And if Moro seems less masculine, that is my goal. But my starting point is different than Diane Neumaier’s. I didn’t start by wanting to reverse male photographers photographing their female muses. Before I became a photographer, I had already developed a taste for less masculine males. What inspires and interests me the most are actually photos by gay photographers photographing men.

Also, I think the word emasculating is problematic. It means “deprive (a man) of his male role or identity,” so that means something is being taken away. I wonder why masculinity is man’s most essential quality—I never see it that way.

Feinstein: Has the renewed attention to women’s empowerment impacted how you view this work or your process?

Liao: Even though I personally support the #MeToo movement, I don’t think my exhibition is in response to it. The #MeToo movement might have put more spotlights on females in general, but my process hasn’t been affected by it. I was going to make the work anyways.

Feinstein: With Moro having a great deal of control in making these photos, would you consider this work to be in the “female gaze” or something in between? And how important is that distinction to you?

Liao: I think it’s something in between. Although I’m the mastermind behind the project, Moro is a collaborator. There are so many things that cannot be controlled by me—it all depends on him, like his facial expressions, his body gestures. And he also improvises during the photo shoot. The moment when he clicks the shutter—he was sure of the moment while I was just waiting.

Pixy Liao, Study of A House Husband, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Feinstein: You’re branching out into sculpture and other processes, like risographs, as well. How do these relate to the series and ideas at large?

Liao: The sculpture and risograph piece in the show is part of a larger project I’m working on about female ambitions and leadership, called Evil Women Cult. The two pieces were inspired by the one and only empress in Chinese history, Wu Zetian. What relates to my work is probably my female position. I make work based on my feelings growing up as a girl in China, and how I feel as a woman in today’s world.

Feinstein: The original project title Experimental Relationship refers to a kind of staging of romance, of the roles, gender dynamics, and power often associated with it. Have these stagings changed how you and Moro think about your real-life relationship?

Liao: One thing I have learned is that relationships, even between the same two people, are always changing. The other thing we learned is that role-playing can bring so much fun to a long-term relationship. Making the photos sometimes is taking the role-play to the extreme, doing things that you wouldn’t normally do. And because it is for photographs, that makes it acceptable.

Jon Feinstein is a curator, writer, photographer, and cofounder of Humble Arts Foundation.

Pixy Liao: Open Kimono is on view at Chambers Fine Art through April 27, 2019.

The post Pixy Liao Straddles the Male and Female Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

For This Young Photographer, A “Simple Song” of Images

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.’s photographs capture the private moments hiding in our everyday, public lives.

By Luther Konadu

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., On Ice, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Looking at artist Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.’s photographs over the last few years, I can’t help but feel like I’m missing out on something, like catching the middle of a conversation between friends on public transit, or overhearing one side of a phone call. In the presence of Brown’s photographs, you remain in wonder, speculating within the gaps he leaves for us onlookers. Instead of giving in to photography’s susceptibility to spectacularize or idealize, Brown opts for the uneventful, seemingly inconsequential bits and pieces laden with history and elliptical meaning.

It’s no surprise that Brown’s recent solo show at the Baxter Street Camera Club was titled a simple song—a reference to a Billy Preston track, initially created as a hushed intimate recording, that later became propped up by label heads for commercial success. When I spoke with Brown recently, he described that act of communicating something private in public as being core to his overall practice. “I’m inherently dealing with visibility but privileging the interiority of the individuals and spaces I have access to,” he explained.

Throughout the works in a simple song, Brown manages to be plainspoken, but only enough to keep you at a distance. Every decision, from the images themselves to their idiosyncratic titles and their physical displays, feels highly deliberate and considered. There’s no identifiable beginning or end the viewer might try to piece together into a neat narrative. Over our conversation, we got further into the ways he continues to complicate his photographic practice through sculpture, and what it means to reach beyond the mere flatness of a photograph.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Keep that one metaphorical, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Luther Konadu: You briefly mentioned before we started talking that you might be working on a public installation. Have you ever done anything like that before?

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.: No, I never have but always wanted to. Most everything that we interact with can be repurposed to structure a photograph. Everything is made out of a rectangle. Everything has a square in it. Everything that is a shape, a photograph can somehow occupy. I would like the opportunity to do something public and that can breathe in a different way in terms of who would interact with it and what the work is. A lot of the time, working with photographs, you end up working with them as these precious objects, and I’d like the opportunity to make something physical that can take some use or be impacted by the environment somehow.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Just Beyond, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Konadu: Do you see that as something that is coming out of your recent work, in terms of incorporating relief elements into the photograph, which is otherwise flat on the wall?

Brown: That is an aspect of the recent work. The largest structure in my show at Baxter Street was a piece inspired by an awning, but didn’t end up referencing an awning. It’s made of willow so there’s a natural element involved in its actual structure. It was an object that no matter how I handled it, I could make missteps or not be as gracious with it. I appreciated that one wrong move would not render this piece unseeable; it could still be shown in public space. Similarly, in another piece constructed after a traditional photo panel, a lot of the damages were a result of working through how to make this thing. The wire was coming out of the groove and breaking as I worked with it. I decided to intentionally wound some areas of the work so that it made sense. I think ultimately, because of the reference for that structure and thinking about how that structure may have lived in someone’s house, or may have received some kind of wear over time, it works. The damages don’t stop it from being displayed.

That process reminded me of my mother’s collection of Lenox Angels. Lenox is a brand that makes plates and other dining ware, but they also make angels. They were specifically making these African-inspired angels where each of the angels was given a significant name. One of them represented music, another strength, and agility, et cetera. My mom has collected over fifteen angels and, over time, a lot of them have been broken. In the various houses—three or four homes—my mother has lived in since my parents divorced, those angels have always had a place to be seen in the house regardless of their damage. Sure, these items were intended to be protected, but the sentiment and the act of cherishing them are consistent; therefore, they’ll continue to be displayed. I like objects from that perspective. They don’t have to be perfect. They can exist publicly even as they’ve been transformed by time.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Sssummmmmwhhhhhhhhhhere, 2018. Lightbox print, painted aluminum, and willow

Courtesy the artist

Konadu: The lightbox in the show feeds into this outdoor way of viewing images as it relates to advertising billboards. The scale of it is also something we haven’t seen from you before. It sounds like you are very much in that place of physicality: thinking about how objects in space enact with our bodies, trying to make a linkage between the two-dimensional way of working—collapsing our three-dimensional space into these flat surfaces—now that you are going back into a very physical mode of working. Was it inevitable that you’d take this new turn?

Brown: The very first piece I ever exhibited was in my junior year of college in 2015. And I was thinking about how I wanted to frame it, but something about the work didn’t make sense in a traditional frame. I had this idea to instead frame it in ribbed undershirts that were stained and bloodied by a costume designer. The work was about internal dialogue and conflict, so I wanted to communicate a sense of abuse that was tangible. I knotted and stapled them around the piece and that was the frame. That was my first gesture as an exhibiting artist but also an artist that cared about each element involved in showing my work to people. And so, these dimensional qualities have always existed when I’m making a photograph. The flatness of the picture is something that I love but it’s also a limitation. I love objects and the things they possess; how they can communicate various experiences and time. The objects in my images are oftentimes equally as important as the individuals in them. When I’m making a picture, I’m already thinking about how I can incorporate the space that the photograph is made into the image and beyond the image. The camera limits the frame to a certain view, so how can I embellish what is not pictured here?

Konadu: That’s something I’m always thinking through with my own work. I’m always trying to figure out how I can continue a single image or multiply it in a way that the reference points to different directions. I think a great example of this in your work is a piece you have in the show right now: He gave and he gave … (2018). That piece is almost disorienting. I have to slow down and look at it several times. I like what you are doing there. You are not making it easy for the viewer to passively consume the image. I think that ties into what you were saying about the frame and the image coexisting together.

Brown: I’m invested in how people live with photographs in public and private spaces. When I’m in public, I’m constantly observing spaces where images can or do inhabit and how I can use that in my own work. The same thing happens when I’m in an interior and thinking about how images inhabit people’s private spaces. That piece was inspired by the way my grandmother collects photographs and the frames she uses to organize them. But more specifically, I had already been thinking about family photo panels and how I can use the frame to cause a tension with the photograph. I wanted to use my own photographs that would work in this fractured, compartmentalized, disjointed way, kind of against how the family photo panel was designed to function.

Family photo panels are traditionally used to organize photographic experiences that are somewhat scripted celebratory moments, experiences of accomplishment such as graduations or awards. Experiences are organized very neatly in these frames and I wanted to reference how sometimes experiences in my life are not neat. Things are haphazard. When you recall some of these experiences as a memory, there are certain memories that are pronounced that you are hyperaware of. There are other memories that are lost and not visible in the photograph that your memory creates. That drove the way that I obscured and made visible the images in that piece. The title also helped reveal my inclination behind putting those two images together.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Is it that I desire to see Jesus bend, to witness them at odds or in question? Jesus loves me, but I believe that Jesus is in process too., 2018

Courtesy the artist

Konadu: I like how you play with a discontinuity in your work. Photography can easily fall into a narrative driven space, but you seem to jump in and out in the way you image the spaces, objects, and figures in your work. It sometimes seems like you are showing us something specific, but that leads us nowhere in particular. I’m wondering if you can speak about the usefulness in engaging with discontinuity in terms of how the individuals in your images are read.

Brown: The recent Soul of a Nation exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum was talking about the history of photography as it pertains to black people’s usage of it. It talked about the Kamoinge collective headed by Roy DeCarava, and the ways in which that collective practiced photography w rooted in realityasking reality to prove their thesis. So, they go out and make photos of people on the street and of events and these photographs serve a particular purpose in terms of how you position them through history. But then it started talking about how the next movement of photography by black photographers was led by people like Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who began to consolidate experience into these re-fabricated non-specific moments. So, when you think about Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table series, it’s a completely fabricated moment where she’s thinking about a lot of different things and symbolizing them, as opposed to documenting how these things show up in reality. These are photographers who are conjuring an image within an environment that looks familiar. And so, it teeters on the line of a document versus a studio fabrication. And I think it is within that tradition that I work. I work in ambiguity in the way that someone like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye creates these characters that exist within an environment that can be either real or imagined or someplace in between.

These moments of happenstance where people are at leisure or in dialogue—that’s something I’m interested in when framing my work. I don’t work in series and so working within these structures allows me to imbue these singular images with a relationship to one another, but also with a multiplicity where their biographical context—presenting it on its own—might not allow. I’m making photographs that move around, challenge other images, offset them, complement and broaden the span of the moment and what they can be of service to.

I think that my practice is maybe more akin to how I see painters work with perspective and how you can be placed in multiple places at once. When I first saw Jonathan Lyndon Chase’s paintings, it really shot my mind. The way he depicts the figure is exactly what I want to communicate in my work. He’s able to make the bodies and the space transcend their natural limits and speak to this collective way we experience and recall things. I think other mediums are often more successful in doing that than photography.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Kearra, over it, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Konadu: Some of your images carefully consider color, texture, and composition the way a painter would—I’m taken by those elements. Examples of this are in works like 96 degrees in the shade (2017) or Kearra, over it (2016) or Mommy, Jayden and I at Christmas (2016). It comes to be a deflection of direct observation of sorts from the viewer—we are not seeing a person but instead a picture of them. If I describe this as formalism, it is not simplifying the image but rather form acting almost like a blockade.

Brown: The form is definitely integral to how you navigate the work in terms of defining the viewer’s distance to the piece. There are some photographic works by other artists that are confrontational. They position the gaze in the way that while you are looking at this work, this person who made the work and the people in them are looking at you. Notions of agency and power dynamics are integrated into such works. There are photographs that work to fold you into the experience of that space or event. In my work there are a lot of things that are peppered through the space There are a lot of points that allow you to imagine further about this work because all of the work is about intimacy, maintaining a certain privacy, and discretion; naturally the viewer is not allowed mentally and physically to have a certain proximity to the work.

I think the form helps guide that. I think that process of your body relating to these works is a part of the work itself. When you think about the large awning structure I was talking about earlier, it dictates the distance you have to stand. I’m still working on the language around this but the structure dictates that there’s a certain way that you should behave when guiding these works. I don’t think of that behavioral requirement as abusive or repressive but educational. Here is a way to relate to someone’s life that does not require me to own or know everything, but requires me first and foremost to be respectful. When I’m making these works, I’m thinking about how I interact with others. It foregrounds behaviors within my own life.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., She threatened most people off the dance floor. Fingers now laced quietly along the red countertop., 2018

Courtesy the artist

Konadu: You talk about intimacy and private encounters as being central to your work. How is that sustained as you continue to move outward and become more extroverted with the scale of the work, the sculptural components, and potentially future public works?

Brown: It’s amplified. Sometimes, when I think about these dimensional elements, it comes out of feeling like the photo is not enough to communicate what’s on my mind. But the structures are often like periods or exclamation marks at the end of a sentence that would’ve already exclaimed or ended without those markers. The markers are helpful in contextualizing the work further. The intimacy is still there. Those are the moments I want to photograph. I’m really interested in the parts of ourselves that cannot be articulated or can’t be made available to other people.

Luther Konadu is a visual artist and writer based in Winnipeg, Canada.

The post For This Young Photographer, A “Simple Song” of Images appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 27, 2019

The Photographer Behind John Waters’s Cult Classic “Pecker”

How Chuck Shacochis made Edward Furlong into an art star.

By Lou Stoppard

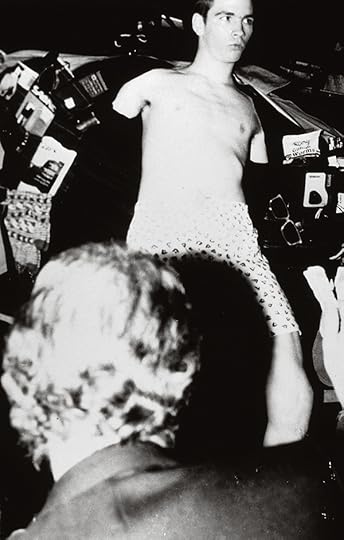

Chuck Shacochis, Matt’s First Time Stripping, 1997

Courtesy the artist

More than twenty years have passed since the release of John Waters’s film Pecker (1998), which tells the story of an aspiring photographer, played by Edward Furlong, whose deliciously gritty black-and-white images of the characters and happenings in Baltimore’s Hampden neighborhood catch the eye of a New York gallerist. Much hullabaloo follows—critics rave over his debut show; an arts writer calls his friends and family “culturally challenged” in the newspaper; his grandmother Memama appears on the cover of Artforum; the Whitney Museum of American Art offers him a show, to be titled A Peek at Pecker; and, eventually, the great and good of the New York art world end up partying in Baltimore, where Pecker decides to stage his own show. The film remains a cult favorite and one in a long line of movies that buoy the cliché that all photographers are eccentric if lovable outsiders.

The images in the film were the work of then twenty-eight-year-old photographer Chuck Shacochis. Briefly, his life intersected with Pecker’s, going from anonymity to the cusp of success. Before filming, he had served Waters various times at the camera shop where he worked in Baltimore. When Waters sought to book Matt Mahurin to capture Pecker’s images—who, in a happy coincidence, Shacochis had on occasion traveled to New York to assist—Mahurin pointed out that, though he was unavailable, there was an ideal person right there in Baltimore.

“On set, John used to refer to me as the Lana Turner of the film—she got discovered from nowhere,” says Shacochis. Underneath all the lampooning of the snobbism and vapidity of the art world, the film is an American-dream narrative, a story about how anyone can make it with sufficient talent and panache. Pecker’s own nonchalance in the face of all the opportunities promised by New York—“God, I don’t wanna be in Vogue,” he says at one point—is ironic, given that Shacochis was unable to turn the images into a viable career, despite the strength of the work and a succession of calls after the film’s release.

Plans to move to New York, including one to enroll at Pratt Institute, never worked out, often due to family issues or financial restraints. “I had people saying, ‘What’s wrong with you? Why haven’t you turned this into insane fame and fortune?’ That happened a lot, and, for a while, I got bitter about it,” he recalls. Shacochis still lives in Baltimore and continues to make portraits in the Hampden area—his work is tender and less sensationalist than the Pecker images. His pictures, he says, are images of “really quiet, nondescript moments.”

Chuck Shacochis, Little Chrissy, 1997

Courtesy the artist

Filming was stressful. While various photographers have produced images credited to fictional photographers in films—Don McCullin for Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 Blow-Up and Steve Pyke and Mick Lindberg for Mike Nichols’s 2004 Closer—the Pecker setup was unusual, as Shacochis was taking photographs on set, rather than in advance, and the prints were being used immediately in the film. After a take, he would duck in and make an image, such as that of Pecker’s kleptomaniac best friend, Matt, played by Brendan Sexton III, dancing on a Baltimore bar. (Matt has turned to stripping after being unable to shoplift unchallenged in the wake of Pecker’s fame.)

After shooting, Shacochis’s film would be rushed to a lab, so that it could be returned to him at the end of the day to be printed in his own darkroom through long nights and then presented to Waters the next morning. Sometimes he’d end up with only a couple of usable frames, such as when he was tasked with shooting two rats having sex; “Every day I’d be like, Please God, please God, let there be something here that can work.” Waters wanted the photographs to look deliberately amateur, so Shacochis printed through a piece of glass that he covered in dirt and tea-bag stains. He made about thirty prints in total and was forced to turn all of the negatives over to the producers when filming ended.

Shacochis also found himself tasked with teaching the somewhat chaotic Furlong how to pass as a half-decent photographer: “I spent a while showing him how to use a camera, and how to move around a darkroom like you know what you’re doing so it didn’t look completely ridiculous—because photographers always complain about that kind of stuff in films about photography, and John was really concerned about it.”

Like nearly all of Waters’s movies, Pecker is a love letter to Baltimore. “It’s an amazing place,” says Shacochis, “but it’s also a giant pain in the ass because there is so much possibility here that just never gets realized.”

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London.

The post The Photographer Behind John Waters’s Cult Classic “Pecker” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 20, 2019

Okwui Enwezor Pioneered a New Kind of Global Exhibition

Through ambitious shows staged around the world, the curator raised the profile of African art and photography.

By Brian Wallis

Okwui Enwezor and Artur Walther, New York, 2011

Courtesy The Walther Collection

When the visionary curator Okwui Enwezor selected a title for the 2015 Venice Biennale, he chose “All the World’s Futures.” For many, this was an optimistic message of hope and prophecy. But for Enwezor, who died last week in Munich at the age of fifty-five, the future was less an abstract ideal than the embodiment of social change, a tangible ongoing project of individuals thinking and working in communal dialogue—a process in which art and art exhibitions played a central role. Unlike many curators, Enwezor understood that each exhibition was an essay or an argument, a brief in what he called his “change agenda.” By this he meant not only rewriting existing art-critical canons, but also introducing a radical rethinking of the role that art—and artists—can inhabit in shaping social and political ideas.

Enwezor was, without doubt, the most influential curator of his generation, noted for bringing an unexpected global perspective to mega-exhibitions like Documenta and the Venice Biennale. From the late 1990s onward, during an era of proliferating biennials and blockbuster exhibitions, he was a master showman. But with his erudition and scholarly demeanor, Enwezor, who was born in Nigeria and moved to New York in the early 1980s, was able to steer clear of the glitzier commercial tendencies of art world spectacles and produce meaningful large-scale interventions. His exhibitions were typified by weighty themes and strong statements from non-Western artists, as well as by contributions from writers, critics, filmmakers, and performance artists. His Venice Biennale featured live readings from Karl Marx’s Das Kapital—all three volumes! Such lively participations always made his exhibitions engaging and entertaining; they were rich with ideas and complemented by the visions of younger artists, as well as by mini-retrospectives of artists who were previously overlooked or marginalized.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait, 1976–77

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Enwezor’s first major curatorial effort was the landmark exhibition In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, which he organized with Octavio Zaya at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1996. In/sight coincided with the rise on the international stage of several African artists whose work is now considered canonical, including Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, and David Goldblatt, all of whom Enwezor wrote about in later books. Then, in an incredible run of large-scale group exhibitions staged from 1997 to 2017, Enwezor organized the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale (1997), Documenta 11 (2002), the 2nd Seville Biennial (2006), the 7th Gwangju Biennale (2008), Meeting Points 6 (2011), La Triennale 2012 at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, and the massive Venice Biennale (2015), along with numerous smaller exhibitions. For Enwezor, the exhibition was an opportunity for interrogation and research, and an extension of the archive—an idea he explored to great effect in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art (2008). He studied the form and meaning and history of exhibitions as what he called “thinking machines.” He noted that his projects evaluated not just the responsibility of art, but “the responsibility of an exhibition as a public forum.”

His organization of Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany, in 2002 was an audacious and innovative breakthrough, widely considered the first truly global exhibition. It was breathtaking in its scope and ambition, with vastly increased spaces, a substantial infusion of non-Western voices, and scholarly research conferences (or “platforms”) organized in advance on four continents, from Lagos, Nigeria, to Saint Lucia in the West Indies. The exhibition—the fifth platform—foregrounded artists and collectives who addressed critical issues pertaining to transnational politics, raising cultural hybridity and cultural migration as key concerns in contemporary artistic practice. The implicit thesis of Documenta 11 was that the physical and psychic displacements of twenty-first-century global realignments could best be understood through cultural forms—the written, filmed, visualized, and performed expressions that shape identity and highlight social injustices in the challenged context of today’s world.

Nontsikelelo (Lolo) Veleko, Cindy and Nkuli, 2003

© the artist and courtesy the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Enwezor was a citizen of world cultures, but throughout his work he returned to the primacy and centrality of African arts, not simply to redress the slights and omissions of lingering colonialist Eurocentrism, but also to assert the complex contemporaneity of approaches based on different histories and modalities. With a comprehensive and methodical agenda, he helped to engineer a profound reconsideration of the arts and culture of the African continent and diaspora. Initially grappling with the lack of a critical dialogue around art of African and African American artists, he cofounded, with Olu Oguibe and Salah Hassan, the critical publication Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art in 1994. He later outlined a bold historical arc, often driven by photography, in exhibitions that traveled internationally, including The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (2001), Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (2006), and Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life (2012). He also curated an important show on African photographic portraiture for The Walther Collection in Neu-Ulm, Germany, titled Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity (2010).

These historical—yet often surprisingly timely—exhibitions were a postcolonial riposte to the conventional narrative of Western cultural dominance. They were also richly modeled investigations that traced the complex artistic genealogies of various African nations to demonstrate how art and photography were vital to self-expression and political self-determination. Enwezor’s exhibitions were frequently described as political, but this sometimes pejorative descriptor made them sound ponderous or didactic. They were anything but that. He understood and validated art as an important means of social activism, a form of translation and transmutation, a talking back to social inequalities and abuses of power. Yet, for Enwezor, who published frequently and championed artists including William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Santu Mofokeng, Yinka Shonibare, Yto Barrada, Lorna Simpson, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, and Lyle Ashton Harris, the real power of the political was the construction of meaning in all things, artistic and otherwise—not merely as a propagandistic affirmation of ideologies, but as a subtler, allegorical way of representing and affirming the political in everyday life.

James Muriuki, Matatus II, from the series Town, 2005

© the artist and courtesy the The Walther Collection

Although Enwezor served as director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich from 2011 to 2018, he was never comfortable in institutions, as an administrator or bureaucrat. He preferred to be, as he said, “unaffiliated.” At Haus der Kunst, a museum constructed by Adolf Hitler to highlight Germany’s nationalist artworks, Enwezor addressed the persistent cloud of World War II in the staging of his last major exhibition, the magisterial Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965, curated with Katy Siegel and Ulrich Wilmes. Enwezor brought together more than 350 works by 218 artists from 65 countries, as well as various scholarly symposia, to radically reconsider the responses of post–World War II artists to the substantive political circumstances of technological change, anticolonial liberation movements, and the international struggle for civil rights and human rights. Overturning any lingering belief in the triumph of American painting and other hackneyed formalist narratives of art history, this exhibition sought to redress the cultural, racial, and national biases of the past and to instate a more nuanced and egalitarian critical approach to modern art.