Aperture's Blog, page 86

June 25, 2019

Desire and Loss, from Stonewall to the AIDS Crisis

Working with vintage gay erotica, Pacifico Silano is committed to understanding how trauma and queer identity commingle.

By Rowan Renee

Pacifico Sliano, Boundless Blue, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

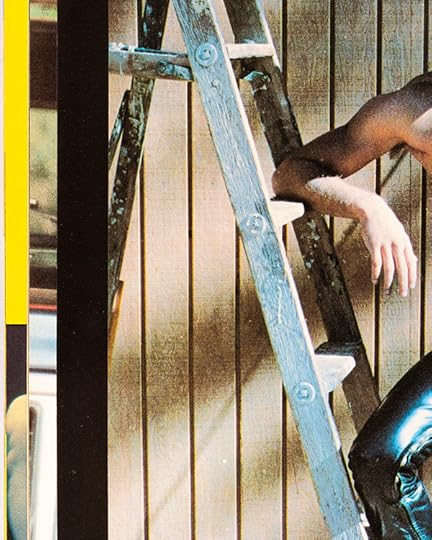

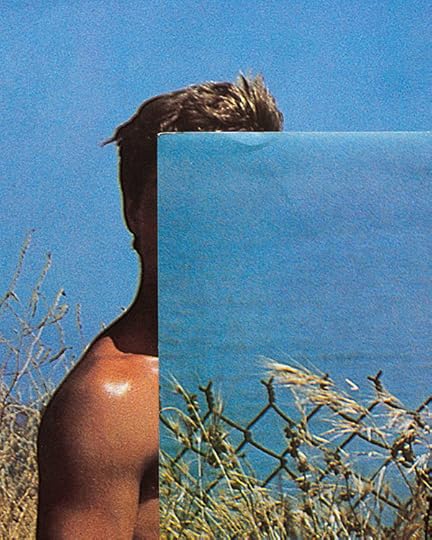

Fragments of bodies—a gently draped hand, the slope of a bicep, a wedge of exposed chest—emerge from fields of vibrant color in Pacifico Silano’s Speaking Little, Perhaps Not a Word. These large-scale photographs, on view at the Bronx Museum’s new Block Gallery in Tribeca, are composed from layers of ephemera sourced from gay erotica and pornography produced between the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the peak of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

The simultaneity of queer desire and loss is inextricable from these images. Silano works with his own personal collection, as well as with the late Whitney curator Richard Marshall’s archive (recently acquired by New York University’s Fales Library). While he often researches the lives of the male models and porn stars pictured, Silano obscures their identities and withholds narrative details. Many of the men pictured likely died as a result of AIDS-related complications. However, the impossibility of ascertaining further information about their fate foregrounds a more ephemeral absence.

Silano situates the viewer in the same position as the publications’ original consumers, many of whom may have also passed, and whom we become aware of through the traces of handling that remain on the page. Re-photographing these remnants is a means for Silano to put his own identity into historical context; yet, embedded within the artistic process, this becomes more than just viewing. It becomes a reparative act steeped in a deep commitment to understanding how trauma and queer identity commingle.

Pacifico Sliano, Leather Shine, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Over the course of nearly a decade, Silano has developed a photographic practice to elevate those lost not only at the height of the epidemic, but also by the systematic suppression and erasure of the archives that contain their memory. Silano himself encountered censorship just last year, when municipal officials asked him to remove images deemed too suggestive from a public commission along the beach walk in Bal Harbour, Florida. Instead of complying, Silano withdrew from the project, thus curtailing the programming planned to build visibility and public dialogue in Miami-Dade, the county with the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the country.

Silano’s exploration of loss is by no means devoid of pleasure. What Silano has accomplished in these works is a deft sleight of hand, redirecting the object of our desire from sexual gratification to something more elusive. At a distance, his photographs draw us in with ebullient color, merging expanses of blue sky and glistening boulders with the soft curves of men’s bodies. Up close, a lace-like pattern of interlocking dots, vestiges of the now-obsolete offset printing process, overtake the compositional field. An errant staple, a dog-eared corner, or a shadow cast by a slight crease interrupts the mechanical artifacts with the mark of human touch.

At forty-by-fifty inches, the scale of enlargement shifts the images towards abstraction. The materiality of the printed page becomes engrossing, locking the viewer into meditative study of subtle collisions of color and texture. In At Twilight (2019), which is void of the human figure entirely, a blue-grey slit bisects the center of the image, cutting across the gradient of purples and oranges surrounding the sunset silhouette of outstretched branches. The folds and creases that run along the magazine’s spine break apart the continuity of the image. For a moment, one slips away from longing to recuperate the lives of unknowable figures, to the rapt exploration of formal elements. This shift of focus offers a visual respite from the weight of grief.

Pacifico Sliano, At Twilight, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Sodomy between consenting adults in private was not decriminalized at the federal level until the 2003 Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas. With this ruling some kinds of gay sex gained constitutional protections; however, people living with HIV could still be held criminally liable simply for having sex. In 1986, states began passing HIV-specific legislation intended to criminalize a broad range of consensual sexual activities based on the potential for HIV exposure, regardless of actual risk or transmission. In addition to HIV nondisclosure laws, sentencing enhancements were passed that apply more severe punishment to crimes committed by people living with HIV, based solely on their health status. In following decades, substantial medical advancements have furthered understanding of how the virus is transmitted, and increased accessibility to treatment options and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has effectively reduced the risk of sexual transmission to zero.

Despite the fact that HIV no longer poses the same deadly threat that it once did, thirty-four states still have HIV-specific legislation and/or sentencing enhancements on the books. Some states, including New York, do not have HIV-specific criminal laws, but do have legal precedents for prosecuting people living with HIV for potentially exposing another under general criminal law statutes. In New York, people living with HIV within the criminal justice system can lose their right to medical confidentiality, and be fined for violating public health laws and subjected to indefinite civil commitment, where the state involuntarily detains someone deemed “sexually dangerous,” not as punishment for crimes committed, but as a preventative measure against future crimes.

Pacifico Sliano, Blue Void, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Silano’s tight control of the photographic medium operates as an anchor to the present, rooting the viewer firmly in the act of looking. Speaking Little, Perhaps Not A Word is not an exhibition about the history of the AIDS crisis, but rather about the living impact of the epidemic on contemporary lives. Like the traces of men’s figures that shift across Silano’s compositions, the escalating fear at the height of the public health crisis left behind tangible artifacts that we are still grappling with today.

As we celebrate Stonewall’s fiftieth anniversary this month, and the legislative gains that have decriminalized certain kinds of gay sex, we cannot lose sight of the scope of consensual sex practices that are still subjected to severe policing and punishment. Speaking Little, Perhaps Not A Word is a timely exhibition that meditates on the complexities of queer desire—especially how legacies of loss merge with pleasure to form new languages of queer eroticism. Not only can one get lost in the narrative history behind Silano’s photographs, but also in their seductive shapes, colors, and forms. This careful balance of melancholy and grace creates a powerful space for contemplation. Within it, we can find the necessary nourishment to take on the next fight.

Rowan Renee is a genderqueer artist currently working in Brooklyn.

Pacifico Silano: Speaking Little, Perhaps Not a Word is on view at the Bronx Museum’s Block Gallery through June 29, 2019.

The post Desire and Loss, from Stonewall to the AIDS Crisis appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 24, 2019

Paolo Di Paolo’s Paradise Found

An Italian photographer of Hollywood stars, now in his 90s, finally makes his debut.

By Heval Okcuoglu

Paolo Di Paolo, Gina Lollobrigida and Giorgio De Chirico, 1961, from the book Gli inconvtri impossibili

© Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

“For pleasure,” Paolo Di Paolo, the ninety-four-year-old Italian master of photography, explains when asked the intention behind his 1950s and ’60s portrayal of Hollywood stars and key personalities of the Italian art, fashion, and cinematography worlds. Decades later, Di Paolo’s unseen archive of photographs “born out of boredom” is a testament to a socially and politically capricious period in time, when Italy was coming out of the stupor and mental ferment of the Second World War. In his own special way, Di Paolo—a best-loved photographer for the acclaimed Il Mondo magazine, where he published more than five hundred photographs—witnessed and documented all layers of society in their hopes and contradictions.

Di Paolo’s first exhibition, Mondo Perduto (Lost World), currently on view at the Spazio Extra MAXXI in Rome, brings together more than 250 images, many of them previously unseen—part of an immense archive found by chance by his daughter, Silvia, in a cellar about twenty years ago. “Can you imagine my face, when instead of a pair of skis I was looking for in my parents’ home, I found these photos made by my father?” says Silvia Di Paolo, “It took more than twenty years to convince him to show these photos to the world.”

Paolo Di Paolo, Marcello Mastroianni, n.d.

© Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

Shortly after the closure of Il Mondo in 1966, Di Paolo, feeling that he was “no longer in tune with the times, with the society that was coming into being,” abandoned his camera and, at forty-one years old, returned to his philosophical studies and the publishing world, launching a collaboration with the Carabinieri, the national gendarmerie of Italy, for which he edited around twenty books and forty-three calendars—his inestimable archive ending up forgotten in a cellar. “It must be understood in relation to a new era, a society that was being transformed,” Di Paolo explains. “At a certain time, Italy had embarked upon a new Renaissance in form and spirit after twenty years of utter darkness. The strength and enthusiasm that motivated us young people was overwhelming: Our happiness was intoxicating. When I decided to give up photography, a career that had allowed me to express fully the joy of being part of a creative society during that happy time, it felt like waking up from a dream and being anxious.”

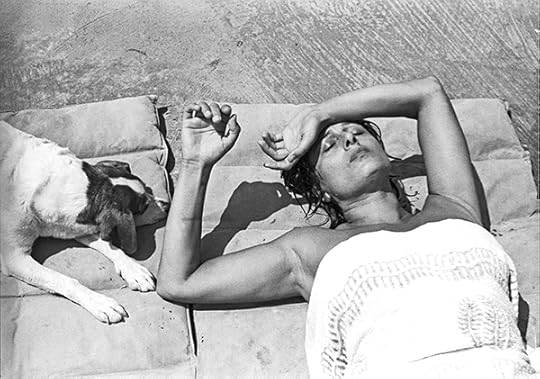

Paolo Di Paolo, Anna Magnani at her villa in San Felice Circeo, Rome, 1955

© Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

Curated by Giovanna Calvenzi, Mondo Perduto is organized into five different segments to intersect and establish dialogue with another. All the photographs in the exhibition seem to be cosmically tethered to one another. The first segment, “Society/Rome,” focuses on the city emerging from the poverty and illiteracy of the ’50s and the sparkling international high society frequenting the capital, while the second, “Society/World,” features impressive shots from Di Paolo’s reportage in Japan, Iran, and New York.

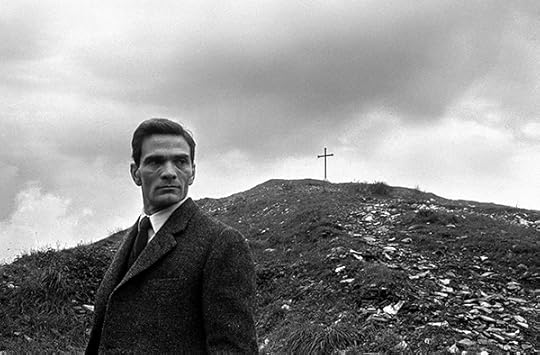

Paolo Di Paolo, Pier Paolo Pasolini on the Monte dei Cocci mountain, Rome, 1955

© Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

With each of his portrait subjects, Di Paolo created a relationship based on empathy, trust, and collaboration. “Artist/Intellectuals” shows the private and intimate moments of film stars, writers, artists, and aristocrats, to whom he was granted access through his personal relationships. Whether it is enigmatic director Pier Paolo Pasolini visiting Monte dei Cocci—where ancient Romans built a hill by methodically piling up broken oil jars—actress Kim Novak ironing in her room at the Grand Hotel, or director Michelangelo Antonioni walking while reading a newspaper, each Di Paolo image embodies an acute sense of Zen, signaling an almost mystic bond between the photographer and the subject. It’s hard not to feel the chemistry as a viewer.

A special group of pictures in the “Film” segment is dedicated to Italian actress Anna Magnani. Another group is devoted to Pasolini, and fully expresses the director’s complex psyche. Pasolini was portrayed at the tomb of philosopher Antonio Gramsci in the Non-Catholic Cemetery, at home with his mother and, in Basilicata, and on the film set of Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 1964), where Di Paolo was the only photographer allowed. These portraits lead to another group of photographs from La Lunga Strada di Sabbia (The Long Road of Sand), a travel journal from 1959 documenting Italian seaside resorts. Here, the magazine Successo, edited by Arturo Tofanelli, had the idea for an innovative pairing of Di Paolo and Pasolini for the project. One of the most iconic images portrays Pasolini walking on the Cinquale beach in Viareggio, Tuscany, while observing young bathers.

Paolo Di Paolo, Fashion foto, Tor di Nona, Rome, 1957–58

© Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

Di Paolo sounds amazed when asked about the attention and positive feedback the exhibition has been receiving. “The audience members have proven to be more sensitive than one might have thought,” he muses, upon hearing that the exhibition has been extended for three additional months. “Visitors who didn’t live through that happy period in Italian society still recognized that that period was responsible for shaping them—that they owe a debt to my generation based on pride in their ancestry. That was an intoxicating surprise to discover. A large audience had discovered my lost world and experienced it with pleasure and felt that they were its rightful heirs.” Mondo Perduto offers a lucid and privileged journey in time to Di Paolo’s masterfully captured moods, characters, vanity, and most of all, truth. It is indeed hard not to find pleasure in that.

Heval Okcuoglu is a writer and translator based in London.

Paolo di Paolo. Mondo Perduto is on view at Spazio Extra MAXXI, Rome, through September 1, 2019.

The post Paolo Di Paolo’s Paradise Found appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 20, 2019

Aperture Launches “Orlando” with Tilda Swinton in a Series of Events

Last month, Aperture Gallery opened an exhibition of work featured in Aperture magazine’s Summer 2019 issue, “Orlando,” guest edited by Tilda Swinton. The opening was capped off over the following week by a screening of Sally Potter’s 1992 film adaptation of Orlando at Metrograph, and a discussion between Swinton and critic B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library.

Tilda SwintonMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Hilton Als, Tilda SwintonMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Stefano TonchiMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton at the New York EDITION Hotel. Griffin Lipson/The New York EDITION

Zackary Drucker, Collier SchorrMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Ethan James Green, Jordan HancockMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Antwaun SargentMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Chris Boot Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Chris BootMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Thomas Dozol, Tilda Swinton, Michael StipeMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

RoseLee GoldbergMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Zackary DruckerMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Slobodan Randjelovic, Jon Stryker, Michael FamighettiMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Waris AhluwaliaMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Collier SchorrMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Brendan Embser, Michael Famighetti, B. Ruby Rich, Tony WhiteMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Cathy Kaplan, Amelia LangMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Lynn Hanke, Frank Arisman, Andy LewinMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Lynn HankeMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Isabelle McTwigan, Lisa Israel, Edward BarsamianMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Catherine George, Henny GarfunkelMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Evan Moffitt, Rajendra RoyMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Peter Barber, Jeff Gutterman, Michael FamighettiMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Hannah GompertzMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Brendan Embser, Zackary Drucker, Sawyer Devuyst, Jari JonesMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Emily Mayer, Sandro Kopp, Elizabeth MayerMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Edward BarsamianMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Cathy Kaplan, Duane Michals, Tilda Swinton, Chris BootMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Maria Cornejo, Lisa IsraelMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Justin Vivian Bond, Henny GarfunkelMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Michael Mahan, Jodi Peikoff, Jerry StaffordMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Martine Gutierrez, Nomi Ruiz, Sawyer DevuystMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Kathy Ryan, Chris Boot, Hilton AlsMadison Voelkel/BFA.com

Balarama Heller and Daniel Arnold Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Maria Cornejo Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Isabelle McTwigan, Evan Amzuri Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Nomi Ruiz, Zackary Drucker, Tilda Swinton, Martine Gutierrez Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton, Chris Boot Madison Voelkel/BFA.com

Tilda Swinton in conversation with B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

Tilda Swinton in conversation with B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

Tilda Swinton and B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

Tilda Swinton in conversation with B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

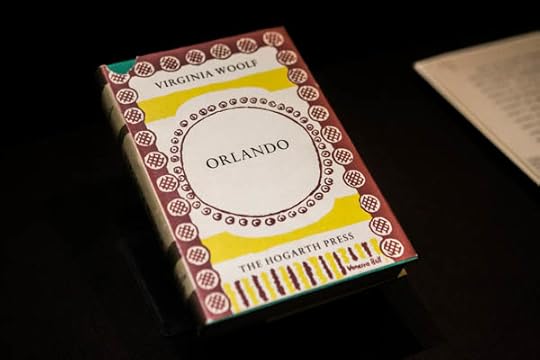

A first edition of Orlando© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

A one-night-only display from the Library's Berg Collection© Sarah Stacke/The New York Public Library

Opening Reception: Orlando at Aperture Gallery

On Thursday, May 23, guests gathered at Aperture Gallery to celebrate the launch of the Summer 2019 issue of Aperture magazine and coinciding exhibition, Orlando, guest-edited and curated by Tilda Swinton. The project draws upon the central themes of Virginia Woolf’s prescient 1928 novel—gender fluidity, consciousness without limits, and the deep perspective of a long life—to offer a collection of images and writings that celebrate openness, curiosity, and human possibility.

In attendance were Waris Ahluwalia, Hilton Als, Antwaun Sargent, Tilda Swinton, Stefano Tonchi, and artists Dawoud Bey, Zackary Drucker, Ethan James Green, Duane Michals, Elle Pérez, and Collier Schorr, among others. Guests enjoyed prosecco by Monsieur Touton.

Addressing the crowd, Aperture Executive Director Chris Boot thanked Swinton: “Thank you especially to Tilda Swinton for putting this project together with us in the echoes of time, Orlando, and Virginia Woolf.” Boot extended thanks to Aperture’s Board of Trustees, Members, Patrons, and staff, as well as to Slobodan Randjelović and Jon Stryker. He went on to thank ROOT Studios for supporting the production of Mickalene Thomas’s work in the Orlando issue, and launch partners The New York EDITION and Mercedes-Benz.

Swinton followed with an introduction to the project. “When we first had this idea of making something around Orlando, I sent out an invitation to an extraordinary group of people, each of whom I was a superfan,” she remarked. “Everybody came towards it with a sense of real personal thrill and autobiography, and that really was meaningful to us.” She went on to express gratitude to Aperture. “Orlando forever, and forever Aperture. Because truly, where else could something as completely supersonic as this idea take flight? This is a glorious space, and everyone who works here is to be lauded for keeping it alive.”

Orlando is on view at Aperture Gallery through July 11, 2019.

Film Screening: Orlando at Metrograph

On Tuesday, May 28, a screening of Sally Potter’s 1992 film, Orlando, was held at Metrograph in New York City, followed by remarks by Tilda Swinton. The film features Swinton as Orlando, an immortal nobleman who is shocked one day to awake and find himself transformed into a woman. Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel, the film boldly takes liberties with the text, a cinematic equivalent of Woolf’s own searching literary inventions.

To a sold-out theatre, Swinton reflected on the legacy of Orlando. “It goes on inspiring,” she remarked. “Of course this film was inspired by Virginia Woolf’s book of 1928, and now we have all these other artists who were inspired by Sally’s film, and maybe in twenty-five years there will be something, I don’t know, some interpretive dance inspired by the Aperture magazine issue ‘Orlando.’” Later in the evening, Swinton introduced a screening of Derek Jarman’s 1990 film, The Garden, one of her many collaborations with the director.

In Conversation: Tilda Swinton and B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library

On Wednesday, May 29, Tilda Swinton was joined by scholar B. Ruby Rich at the New York Public Library for a discussion on the “Orlando” issue of Aperture magazine. The two discussed Woolf’s legacy, the multitude of roles Swinton has played throughout her career, and the actor’s collaboration with artists who made new work reflecting on the themes of Orlando.

A one-night-only display of several items including unique photographs, correspondence, and a first edition of Orlando—all of which are housed in the Library’s world-renowned Berg Collection, was on view.

The New York Public Library is home to one of the largest collections of Virginia Woolf’s archives, with holdings including original manuscripts (among them, a typed fragment of Orlando), rare first editions, unique photographs, and the author’s walking stick.

Stream the conversation here.

________________

The Opening Reception of Orlando was photographed by BFA.

Supporters

Orlando is made possible, in part, with the support of Slobodan Randjelović and Jon Stryker. Aperture also thanks ROOT STUDIOS for supporting the production of Mickalene Thomas’s work in this issue.

Launch Partners

The post Aperture Launches “Orlando” with Tilda Swinton in a Series of Events appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 19, 2019

What is a Photo-Text Book?

Since the nineteenth century, photographers and writers have collaborated as equals—to varying degrees of success.

By Federica Chiocchetti

Larry Sultan, Business Page, 1984, from the book Pictures from Home (Abrams, 1992)

Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco and Estate of Larry Sultan

Quite literally, it is a book where photographs and words share equal ontological dignity, or, less academically, equal importance in contributing to the narrative of the project and where text is not a mere introduction, postface, or essay on the photoworks. Perhaps it is the ultimate nightmare for all the iconophobic writers and textophobic photographers out there.

Let’s consider two examples: the twenty-four-volume New York Edition of Henry James’s fiction, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1907–9, with a photogravure frontispiece for each volume by Alvin Langdon Coburn; and the first edition of Robert Frank’s photobook Les Américains, published by Robert Delpire in 1958. James’s fear that a too-detailed image would overwhelm the retina of the reader, killing their imagination and disturbing his own literary picture, led him to give the then young Coburn strict instructions. Human figures were forbidden. James wanted the pictures to be “not competitive and obvious,” but ambiguous and general, “to shroud their documentary quality,” in the words of Ralph F. Bogardus; James desired them to work well as “mere optical symbols or echoes, expressions of no particular thing in the text,” serving as “empty” images that “the reader must fill out through their own imaginative and interpretive activity,” Bogardus notes in Pictures and Text (UMI Research Press, 1984).

At the other end of the spectrum, as Roger Hargreaves compellingly recounts in his contribution to the Photocaptionist column Image-Text Photobooks in a Nutshell (ITPIAN), the true first edition of Frank’s The Americans was swarming with text, in French, edited by poet Alain Bosquet and showing “a decidedly European take on contemporary America.” Hargreaves describes the heavily textual first edition as “a rare example of a photobook buried inside another book” and as “a cautionary tale of the potential failure of text to work with images.” He praises the replacement of the texts, for him clearly an awkward presence, with a dedicated Jack Kerouac essay as a happy solution, when The Americans was printed stateside a year later.

Man Ray and Paul Éluard, Facile, Éditions G.L.M., Paris, 1935

Another sign of textophobia was spotted by Patrizia Di Bello and Shamoon Zamir in their brilliant introduction to The Photobook: From Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond (I. B. Tauris, 2012). In particular, they shed light on the curious contradiction between Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s definition of the photobook as “a book—with or without text—where the work’s primary message is carried by photographs,” presented in their acclaimed trilogy The Photobook: A History (Phaidon, 2004, 2006, and 2014), and their inclusion, nonetheless, of “too many examples” of books where text plays a fundamental role, such as Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor’s An American Exodus (1939), and Bertolt Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War primer, 1955). “Photography and text always interact, even if the text is mostly elsewhere,” write Di Bello and Zamir. “They work within a dialectical relationship.” My deus ex machina helping me come through this diplomatic tussle hopefully unscathed is Lesley A. Martin, who, in her piece in the Photobook Phenomenon catalogue (Editorial RM, 2017), “Invitation to a Taxonomy of the Contemporary Photobook,” announces that “the seeds are currently being sown for the ‘genre-fication’ of the photobook” and elaborates on a number of taxonomical pathways or tracks.

Paul Strand, Worker at the Co-op, Luzzara, Italy, 1953, from the book Un Paese (Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1955)

© Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

So, here’s my proposition: the photo-text book is a distinct and diverse species within the larger genre of the photobook that deserves proper scrutiny, precisely to transform the above phobias into philias. While it is true that words can narrow and direct the meaning of an image (the Latin origin of the term caption means “seizure”), when they exert the function that Roland Barthes defines in Image, Music, Text (1977) as “anchorage,” it is also true that they can enhance the image’s ambiguity and operate as “relay.” Don’t get me wrong: purely visual photobooks are bliss, but the idea here is to show that photo-text books don’t bite; they are just a specific category that offers the opportunity to expand the audience of the photobook beyond its own bubble, as I touch upon in my Editor’s Note.

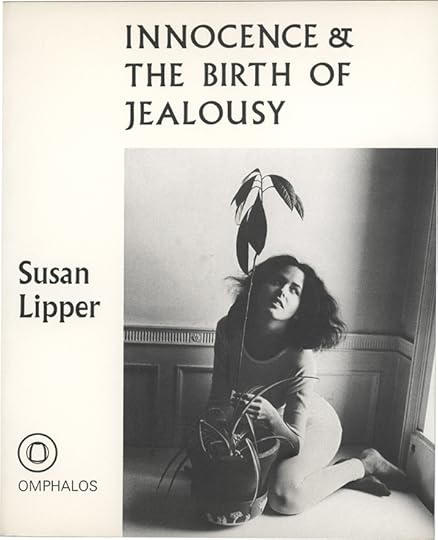

Susan Lipper, Innocence & the Birth of Jealousy, Omphalos Press, Rushden, Northamptonshire, UK, 1974

It is important to highlight that this track is not new, and its origins date way before Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. A regained momentum of “formidable hybridization that conjoins literature and photography” is undeniable, as noted by Rick Moody in his review of Teju Cole’s Blind Spot (Random House, 2017) for PBR’s issue 013, and confirmed by the amount of contemporary photo-text books presented in this issue, as well as in PBR’s previous issues. Photo-text books are deeply rooted in the history of photography. To be persuaded, we only need to look at the spate of fascinating nineteenth century photographically illustrated books, or pictorial books, as they were called at the time, in which words and images mingle more or less harmoniously; many have been recently included in great exhibitions, such as Poetic Images at both ICP (2003) and George Eastman House (2004) and Photolittérature at the Fondation Jan Michalski (2016). I believe the time is ripe to explore the track or subgenre of photo-text books, researching the past, surveilling the present, and speculating on the future.

Duane Michals, Narcissus, 1974, from the book Real Dreams: Photo Stories (Addison House, 1976)

Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

As I type this sort of photo-text book manifesto, I am immediately afflicted by what Thomas O. Beebee, in The Ideology of Genre (1994), describes as the paradox of genres: “they seem real and at the same time indefinable,” perhaps due to their promiscuity. Depending on the criteria we focus on, such as authorship, types of texts, or image-text dynamics, we already encounter a varied spectrum of photo-text books: collaborative versus retrospective, anthological versus monographic, photo-poetry versus photo-essay, hierarchical versus democratic, and so on and so forth. For the purpose of this introductory survey I cannot by any means even attempt exhaustion, and I am obliged to redirect you, dear reader, to my research, which combines a taxonomical investigation with a history of photo-text theory through practice and will hopefully be published in the next year or so.

Bahman Jalali and Rana Javadi, Days of Blood, Days of Fire, Zamineh, Tehran, 1979

As a profound lover of the photobook, when I started the column on the Photocaptionist I intentionally gave it the somewhat tautological title of Image-Text Photobooks in a Nutshell. I wanted to preserve the term photobook and underline the fact that a photograph is not like any other image, but, as discussed by Umberto Eco in “Critique of the Image” (1982), it is misleadingly analogous to the retinal image. Then, I started to use “photo-text” more and more, encouraged by the introduction of the eponymous new category for the Prix du Livre given during Les Rencontres d’Arles with the support of the Jan Michalski Foundation for Writing and Literature. It’s simpler and perhaps more effective.

Recently on Facebook I read an interesting comment by photographer Vasantha Yogananthan in reply to Colin Pantall’s critique that “within photography so many people are working with the ambiguity of images and if you use a fictionalised text, there is less room for that kind of ambiguity also you need a good story. And that is difficult.” Yogananthan replied that “it depends greatly on how the fictional text relates to a sequence of images. The text could indeed be narrowing the possible readings of a picture, but (if done well) it could, on the contrary, add ambiguity/complexity to an edit/ sequence of images. That said, it is harder to do a successful photobook with text than with no text.” I agree, and I would like to take his comment as an opportunity to continue the conversation elsewhere and explore why it is harder.

Barbara Kruger and Stephen King, My Pretty Pony, Knopf in association with Library Fellows of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1989

We have invited a chorus of scholars, photographers, curators, and writers to contribute to an annotated and incomplete bibliography of the photo-text book—titles that have laid the groundwork for this burgeoning genre, from some of the earliest offerings, as in Bruges-la-Morte, to more recent works, such as (Other) Adventures of Pinocchio. This compilation is by no means comprehensive or even consistent in its listings, but rather a first, necessarily idiosyncratic step toward exploring the genre’s diversity in all its glorious hybridity, from photo-literature to photo-poetry, through the photo-essay and more experimental compositions. It is inevitable that books have also been selected according to personal taste; additionally we have leaned toward books that are pioneering, or that have eccentric image-text dynamics, which don’t necessarily manifest in every page. We tried our best to cover a broad geographical area, within the obvious linguistic limitations of a photo-text book when its words belong to a language unknown to the reader. There are omissions of some landmark books: Rodchenko and Mayakovsky’s 1923 collaboration on Pro eto. Ei i mne (About This. To Her and to Me); Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland, Changing New York (1939); Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941); Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Octavio Paz’s Instante y Revelación (1982); W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (1992); Elisabeth Tonnard’s Two of Us (2007); Roni Horn’s Another Water (2011); and Alec Soth and Brad Zellar’s House of Coates (2014). The list goes on.

Needless to say, our efforts represent a minor scratch in the surface of future research and analysis. We would like to express our most sincere grazie mille to this issue’s contributors for their most generous participation in this photo-text extravaganza, and look forward to continued dialogues and ideas about both the history and the future of the photo-text book.

Federica Chiocchetti is a writer, curator, editor, and lecturer who runs the Photocaptionist.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post What is a Photo-Text Book? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The PhotoBook Review 016: Editor’s Note

What’s the point of having an obsession if you can’t share it with other people?

By Federica Chiocchetti

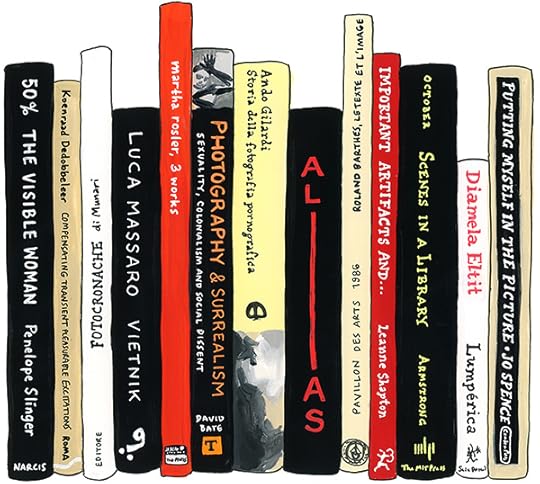

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf 1112: Federica Chiocchetti, 2019

Courtesy the artist

In the first issue of The PhotoBook Review (2011), Jeffrey Ladd closed his Editor’s Note by raising a glass to an obsession: the photobook. I confess to having a further obsession, within that obsession: “photo-text” books, where images and texts are equally prominent.

As a labyrinthine flaneuse, I never seek truth but my Ariadne. What follows is a fragmentary attempt to reconstruct my “clinical record,” understand the thread that drew me toward photo-text intersections, and explain why I find them so alluringly addictive. In doing so I will connect my trajectory to the content of this issue and the titles from my ideal bookshelf. Ideal, indeed . . . Richard Burton said that “home is where the books are.” Alas, I have given up on understanding where I live; I might never see these spines together on the same shelf, so a massive thank-you to Lesley A. Martin, Jane Mount, Samantha Marlow, and the Aperture team for making me feel at home within these pages.

Anamnesis:

Please allow me to indulge in the hashtags, as in these schizo-verbo-visual-bombarding times, I find them a useful typographic tool to keep our fragile attention alive.

#literature Italo Calvino’s words in his 1955 “The Adventure of a Photographer,” as well as Julio Cortázar’s 1959 short story “Las babas del diablo,” triggered my fascination with photography more than any image did (apologies to all the image makers in the audience).

#photographytheory Even more pathologically, the philosophical discourse around photography shaped my research interests in a sort of “death-of-the-author mode” toward what Joan Fontcuberta described as “the virus of fiction.” I developed a curiosity for eccentric, somewhat surreal imagery that interrupts, departs from, or plays with our perception of what we tend to call reality.

#complit The fascinating field of comparative literature infected me with further masochistic research methodology: why simplify your life by focusing on one discipline, epoch, geographical area, or even one author, when you can have a complex and diverse blast by mingling multiple arts and authors from different linguistic regions and periods? I am indebted to Professor David Bate, whose seminal 2003 book Photography and Surrealism (discovered through David Evans’s terrific Critical Dictionary [2011]), among his others, taught me how to unpack an image through words and encouraged me to not give up on the difficulties of genre studies within photography. The only novel on my ideal bookshelf is Diamela Eltit’s Lumpérica (1983), an uncanny, claustrophobic, and almost plotless text, impossible to categorize.

#Brecht&Benjamin Although we might remember them as chess rivals, from the famous 1930s Svendborg photographs, Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin shared very similar views on photography. “What we must demand from the photographer is the ability to put such a caption beneath his picture as will rescue it from the ravages of modishness and confer upon it a revolutionary use value,” explains Benjamin in “The Author as Producer” (1934). While writing an essay on Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War primer; Eulenspiegel Verlag, 1955) for my modern literary theory course, I stumbled upon the above sentence. I would only realize a couple of years later the almost shamanic impact it had on the development of the Photocaptionist.

#degenerateart In one random online search I came across a quirky workshop organized by the then emerging platform Self Publish, Be Happy in London. It was called “Degenerate Art,” and its aim was to respond to the eponymous exhibition organized by the Nazi Party in Munich in 1937. The teacher was no less than Adam Broomberg. He made us create a collaborative photo-text zine where the obnoxious words of the exhibition’s catalogue and imagery from an anonymous archive of vernacular Nazi Germany prints, a blind buy on eBay, mingled in a quite disturbing way.

#identitycamouflage I never stopped following the incredibly prolific duo Broomberg and Chanarin, and I have included on my bookshelf their marvelous book ALIAS: None of the Artists Exist, which is also the catalogue of their 2011 edition of Kraków Photomonth. It is inspired by my favorite writers (Pessoa, Borges, and Bolaño) and it explores another fetish of mine: pseudonyms, heteronyms, and alter egos. Similarly, the artist book Compensating Transient Pleasurable Excitations by Koenraad Dedobbeleer (Roma Publications, 2014) is a catalogue of an imaginary exhibition that irresistibly evokes something that never took place. Luca Massaro’s brand-new self-published Vietnik is a clever visual bildungsroman where, lurking behind his semiotic images, made by his alter ego, we find layers of the young artist’s influences, such as Bob Dylan, Luigi Ghirri, Robert Frank, and Frank Ocean.

#scriptovisualvertigo It is hard to define exactly how my encounter with the artistic and theoretical practice of Victor Burgin has shaped my interest in photo-text intersections, but undoubtedly it has. To honor his contribution to the field, an interview about his forthcoming books was fundamental for this issue. Another important book is Martha Rosler’s 3 works (Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, 1981), which contains her experimental photo-text piece The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75), a deadpan critique of the poverty of representation in political documentary. David Campany recently recommended me a great book: the catalogue of a 1986 Parisian exhibition, Roland Barthes: le texte et l’image, that celebrated the author’s writings about art and visual culture by displaying them juxtaposed to the original artworks, from Arcimboldo to Wilhelm von Gloeden. And how could I not include Bruno Munari’s 1944 groundbreaking, witty journey into Photo-Reportage (Domus Publishing Group).

#photocaptionist I was sinking in heavy photo theory at the British Library in the first year of my PhD, when one night I had a strange dream of a grumpy old bloke whose job title was “Photocaptionist.” His occupation consisted of composing creative short texts in response to the photographs he would receive from artists, institutions, and random individuals. I thought that creating an editorial and curatorial platform to explore photo text intersections could be a more playful way to deal with my research. One day I will ask my analyst to interpret that dream.

#thirdsomething When my eyes land on a book spread where images and words interplay, even before thinking about whether they do so successfully or not, I get truly excited by the opportunity for a more enriching viewing and reading experience. As I look at the images, I miss reading the words, so I go back to them and I start missing the images again. In this constant ping-pong, or tension, a third unattainable object, which Sergei Eisenstein called, in relation to montage in film, literature, and art, a “third something,” develops. And it’s only in my mind. Aren’t we often attracted by the presence of an absence? Photo-text pairings are a springboard to dive into our own imaginary world of afterimages and afterwords.

#phemerson I had the pleasure of curating an exhibition of Peter Henry Emerson’s photogravures and pictorial books with a focus on his writings during my fellowship at the V&A, where, brilliantly enough, the Photographs section is part of the Word and Image Department. This opportunity, together with the study of Carol Armstrong’s book Scenes in a Library (MIT Press, 1998), introduced me to the wondrous world of nineteenth century photo-text books. Delphine Bedel showed me one of the first essays ever written on photobooks by Elizabeth McCausland, “Photographic Books” (1942). It was a nice surprise to read that McCausland considered Emerson’s Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads (S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1886) “an organic relation between text and pictures,” which for her was “the basic characteristic of the photographic book.”

#imagetextithaca Another game changer was to find out that I was not alone in my obsession: Nicholas Muellner and Catherine Taylor crafted an entire MFA program around image-text intersections at Ithaca College. I treasure the memories of participating in their symposium in 2015, where I met phototext wizard Jason Fulford, whose commissioned collaboration with the fantastic Elisabeth Tonnard is presented in this issue’s centerfold. Muellner and Taylor also recently launched the publishing house ITI Press, and I am grateful to 10×10 Photobooks cofounder Olga Yatskevich for interviewing them. No end to the surprises in the photo-text world. In 1987 an international association called Word and Image Studies was founded with a dedicated journal and series of conferences to “foster the study of Word and Image relations in a general cultural context, and especially in the arts in the broadest sense.” Maybe I can go there for rehab.

#femininemasculine Photo-texts are particularly useful for deconstructing ideology in our society. Gender dynamics and bourgeois heteronormativity are another deep preoccupation of mine. Four books on my ideal bookshelf relate to this theme. I hope an English language publisher will decide to translate Ando Gilardi’s Storia della fotografia pornografica (History of pornographic photography; Bruno Mondadori, 2002), as it’s a rare and amusing study of the origins of pornography that enables us to better understand how it has organized power dynamics differently over time as compared to today. Penny Slinger’s 1971 book 50% the Visible Woman (Narcis Publishing), with its psychoanalytic confrontational photocollages and tissue overlays, is an unsettlingly amazing book that introduces a different language for the feminine psyche to express itself. (Thank you to Susan Lipper for showing it to me.) Jo Spence doesn’t need any introduction. Her brutally honest, tragicomic, autobiographical photo-texts paved the way for the disruption of sexual stereotypes and photo-therapy. Leanne Shapton’s Important Artifacts And . . . (Sarah Crichton Books and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009) is the perfect post-breakup photo-text antidote.

#photopoetry A specifific category within photo-text books, in which the challenges of making a successful object are even higher, given poetry’s idiosyncratic DNA. I would like to thank David Solo for inviting me to collaborate on activating his photo-poetry books collection, for his contribution to the Annotated Bibliography, and for his continued constructive criticism.

Time to find a cure for my photo-text addiction.

Treatment:

Be contagious; spread the “virus.” After all, what’s the point of having an obsession if you cannot share it with other people? Discussing photo-text books at the legendary bookshop Shakespeare and Company during last year’s Paris Photo, within Too Many Pictures’ Photobook Week, was a real learning experience in terms of considering new audiences for the photobook. I believe that promoting the concubinage of words and photographs in book form is one of the possible remedies that will help the photobook cross its own bubble border and encroach on the wider soil of a literary audience.

Federica Chiocchetti is a writer, curator, editor, and lecturer who runs the Photocaptionist.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The PhotoBook Review 016: Editor’s Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 17, 2019

Drew Nikonowicz: Building Your Own 4×5 View Camera

Join photographer Drew Nikonowicz for a two-day workshop intended for photographers interested in learning about large format photography, while building their own 4×5 – courtesy of Standard Cameras. This DIY approach will lead to a deeper understanding of image-making both inside and outside the camera. Regardless of your background, this workshop will leave you with all the knowledge and tools you need to successfully shoot with a large format camera. Drew founded Standard Cameras in 2018 as a platform to empower photographers everywhere to improve their skills through affordable equipment and valuable educational content.

Participants will begin by assembling their own Standard 4×5 as a group, while familiarizing themselves with their new 4×5. After assembly is complete, they will have an opportunity to practice making photographs with both a standard film back and Polaroid film back. Large format is a slow process, which forces the user to focus on each image in a radically different way. With Drew’s guidance, participants will receive advice on how to approach image-making with large format through hands-on practice, and later discussions on compositional and conceptual considerations while shooting. Participants will take home a hand-made Standard 4×5, several Polaroid photographs, and information on large format equipment.

Drew Nikonowicz (born in St. Louis, Missouri, 1993) earned a BFA degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia in 2016. His work employs analog photographic processes as well as computer simulations to deal with exploration and experience in contemporary culture. He has exhibited both nationally and internationally. In 2015 he received the Aperture Portfolio Prize and the Lenscratch Student Prize. In 2017 Nikonowicz completed a one-year residency at Fabrica Research Centre. He now lives and works in the United States in Saint Louis, Missouri as an artist and owner of the company Standard Cameras. His first photobook, This World and Others Like It, was co-published by Yoffy Press and Fw:Books in 2019.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Build your own Standard 4×5 within a small group setting

Learn the essentials to using a large format camera to make quality photographs

Practice shooting with large format Polaroid film and standard sheet film

Hear about local New York resources for processing, scanning, printing, and more

Materials To Bring:

Tripod (preferred, but not necessary)

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $700 and includes one Standard 4×5 Camera. Tuition also includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition*. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

*A discount will only be given on the price of tuition covering instruction ($500), not the price of the camera ($200)

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Friday, October 4, 2019

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of ten students is required to run this workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Drew Nikonowicz: Building Your Own 4×5 View Camera appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 13, 2019

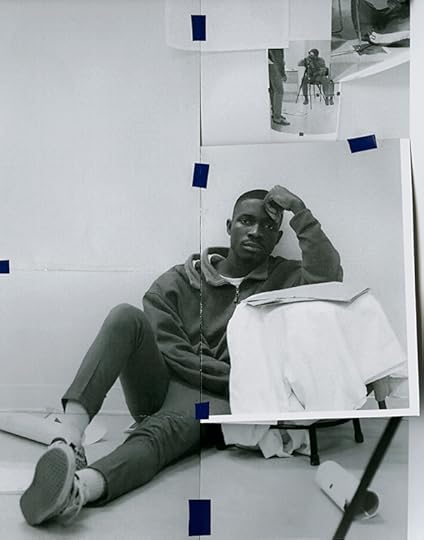

Introducing: Luther Konadu

For the latest installment of “Introducing,” Aperture speaks with Canadian artist Luther Konadu, whose constructed photographs riff on the work of Carrie Mae Weems and Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

By Brendan Embser

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

He had me at the green tape. One morning I was on the subway reading a magazine when I flipped to a page with a portrait of a man with curly hair. The man had a tattoo on one of his biceps and a rakish mustache. He held in his hands a sheaf of photocopies, and the portrait itself looked like a photocopy, but one that was assembled into a grid with tape, Kelly green and slightly uneven. On the edge there was a pink Post-It, attached with the casual elegance of a well-placed accessory. Before I saw the credit line, I knew who had taken this picture. The magazine was the New Yorker. The subject was the musician Helado Negro. The photographer was Luther Konadu.

Although he says he hasn’t had any training in photography, Konadu knows how to take a picture. Like other subjects of Konadu’s personal work—mostly young and black, friends or friends of friends—Helado Negro, the recording name for Roberto Carlos Lange, gazes out from Konadu’s portrait with a kind of inquisitive confidence. He could be Konadu’s friend, even though, at the time the picture was made, the two had just met. “Luther’s photography appears casual,” the critic Antwaun Sargent told me, noting that Konadu’s process recalls the work of Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya. “But linger on his images and what is recognizable is their precise and thoughtful construction.”

Konadu was born in Ontario to Ghanaian parents. When he was 23, he moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where he has a studio practice and runs the online publication Public Parking. He’s also a writer-in-residence for Gallery 44, a photography space in Toronto. In April 2019, he won a New Generation Photography Award from the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. One of the prize jurors, Deanna Pizzitelli, noted Konadu’s “keen sense of design” and the way his images seem to “reinvent” his subjects. “In his work, we experience narrative as something unfixed and unfolding,” Pizzitelli wrote, “one that includes text, fragmentation, and re-photography.”

Coralie Kraft, a photo editor at the New Yorker who commissioned the portrait of Helado Negro, was also drawn to Konadu’s use of re-photography—and to the tape. “We are so quick to look at someone and put them in a box, whether they’re your colleagues, friends, or family,” she says. “But tape can be removed or swapped.” Personal identity is mutable; often, as Konadu shows, identity is a construction of groups, of the people around us, all of these elements cut and folded and pasted together. Helado Negro was born in Florida to Ecuadorian immigrant parents and Kraft wanted a portrait that spoke to the interlayering of self and society. “We specifically had Luther play with the physicality of the image,” she says.

Luther Konadu, Helado Negro (Roberto Carlos Lange), 2019

Photo illustration for the New Yorker

When it comes to his influences, Konadu wears his heart on his sleeve. His pictures have the intensity and introspection of Weems’s portraiture and Sepuya’s mirrored choreography of camera and studio. But there’s also those folded and unfolded aerogram-prints by Moyra Davey, with their firm green squares of tape. There’s Andrzej Steinbach’s multipanel cast of characters. There’s LaToya Ruby Frazier’s documentary work that sometimes melds with performance. “I’m interested in taking off from what they’ve begun and seeing what I can contribute to it,” says Konadu. And as for the photograph itself? “I’m always trying to make a photograph look more like a photograph, an object, as opposed to a portal into the realities of those who appear in my images.” Making the surface more “haptic”—more tactile—is a means to “snap viewers out of the illusion of representation” and to create a tension between the real and the fictional. Scanning copies likewise creates a “veil,” as Konadu calls it. “I essentially want viewers to second-guess what they’re looking at.”

Konadu had been a fan of Helado Negro’s music before he took the singer’s portrait. There’s one song he likes, “2º Dia,” that he listened to on repeat. And even though he doesn’t speak the language—the song is entirely in Spanish—“I’m there with him. I can somehow empathize and connect.” Konadu says his editorial work might be a space to “extend the family,” to continue his interest in the collectives and identities of Indigenous, black, and queer subjects. That family is full of gazes, sometimes questioning, sometimes just hanging out and working through things. Antwaun Sargent added that he admires Konadu’s physical approach to photographs, which, he says, heighten an exploration of power and agency. “His subjects,” notes Sargent, “are looked at, but they look back, too.”

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019

Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine. All works courtesy the artist.

The post Introducing: Luther Konadu appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 12, 2019

A Trailblazing Fashion Photographer’s Turn to Collage

In the 1970s, Deborah Turbeville eschewed highly-sexualized photographs in favor of haunting portraits.

By Shonagh Marshall

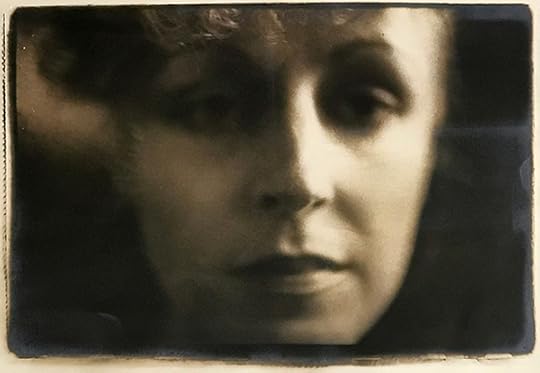

Deborah Turbeville, Untitled, 1978

©️ Estate of Deborah Turbeville; courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, and Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

The Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan says that history can help you make sense of the present. “It may help you like a sign on a road that says ‘dangerous curve ahead’ and makes you drive more carefully,” she noted back in 2016. MacMillan was speaking about media and politics, but her words rang through my mind as I visited the exhibition Deborah Turbeville: Collages, currently on view at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York.

Deborah Turbeville was one of the most revered fashion photographers working during the 1970s and ’80s, and her legacy has shifted the way we view women in fashion imagery. Beginning as fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar, Turbeville’s entry into image making in 1966 was a six-month photography workshop taught by Richard Avedon and the art director Marvin Israel. Her editorial fashion shoots would later be featured in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Nova, and the New York Times Magazine, among others, and she also worked with advertising clients such as Comme des Garçons, Guy Laroche, Valentino, and Calvin Klein.

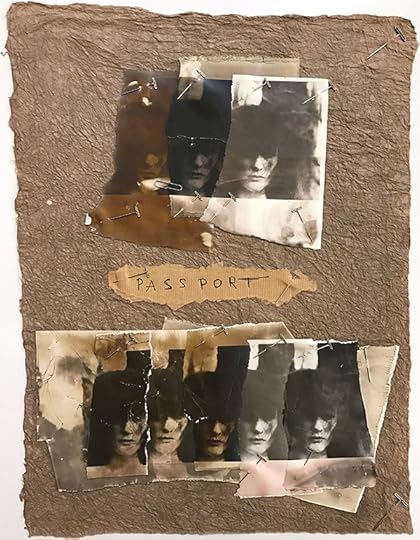

Deborah Turbeville, Untitled (Women in the Woods “Passport” collage), 1977

©️ Estate of Deborah Turbeville; courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, and Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

Within an atmosphere of fashion photography dominated by highly sexualized, saturated images of women taken by men, Turbeville’s images are haunting. Shooting mainly in black and white, she portrayed women as specters; her subjects play the role of distant relatives whose pictures we might hang on our mantle. In the exhibition, these images are collaged, cut, and stuck to mounting paper as she saw fit, which adds to their archival aspect. You are always aware of her hand in the construction and capture.

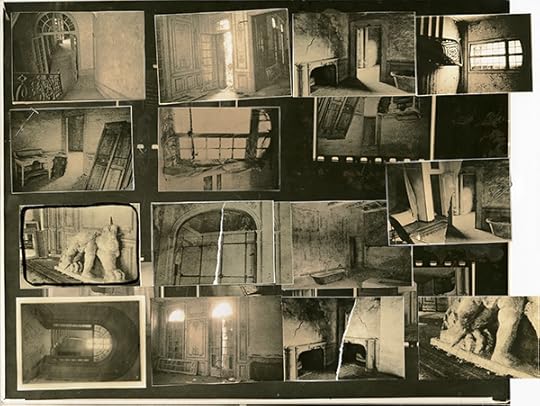

Turbeville began making collages in the late 1970s while working with Israel on her first book, Wallflower (1978). He encouraged her to play with her images and negatives; as a result she made ensembles—taping, pinning, Xeroxing, and cutting. (Some of the originals made for Wallflower are included in the exhibition.) This process allowed her to crop images with tape around the 35mm frame and layer others up, giving an air of work-in-progress. In a piece titled Chateau Raray (ca. 1984), images of a melancholic interior overlap and tussle for space; two protrude from the black backing mount. Shot in the house where Jean Cocteau made La Belle et La Bête (1946), the piece draws attention to the importance of location to her photographs.

Deborah Turbeville, Chateau Raray, ca. 1984

©️ Estate of Deborah Turbeville; courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, and Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

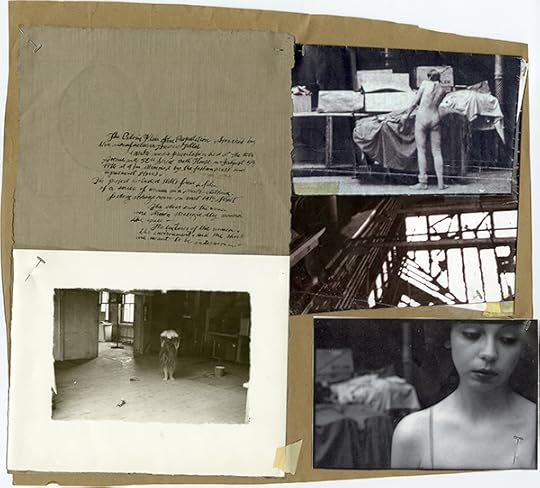

Perhaps the most striking element throughout Turbeville’s work is the women she captures. “I can’t deny that I design the background,” she told the New York Times in 1977. “A woman in my pictures doesn’t just sit there. In what kind of mood would a woman be, wearing whatever? I go into a woman’s private world, where you never go.” In the two collages that include images created for the Charles Jourdan shoe campaign in 1974, the models’ physicality draws you in, each scene playing out as if from a silent movie. The women pose amongst the mannequins in the Woolf Form Dummy Factory wearing Betsey Johnson clothing, the shoes being sold barely visible. One element of Turbeville’s enduring relevance is her sense of humor—she was disdainful about fashion.

Deborah Turbeville, Untitled for Calvin Klein, ca. 1976

©️ Estate of Deborah Turbeville; courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, and Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

In another image for Calvin Klein, in 1976, a woman bends double, her hair tumbles to the floor, and kicked off in front of her are two shoes, visual breadcrumbs amongst the desolate architecture. Turbeville’s women don’t “work”; they sprawl and lounge in faded country mansions, in woods, and in bathhouses. They are fragments of history even at the time they were shot, yet they are distinctly feminine—feminine from a feminine perspective—and so, in turn, there is something relatable about them.

Fashion photography has always been a reactionary space to carve up and redefine identity. And, like MacMillan’s historical road signs, fashion photographs act as useful ephemeral markers. The “dangerous curve ahead”—the exploitative imagery prevalent at the time Turbeville was working —was, until very recently, the industry norm. In the wake of recent social movements such as #MeToo, the time seems ripe to redefine representation.

Shonagh Marshall is a curator and writer, specializing in fashion, and based in New York.

Deborah Turbeville: Collages is on view at Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, through June 29, 2019.

The post A Trailblazing Fashion Photographer’s Turn to Collage appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 10, 2019

10 Magnum Photographers on their Obsessions in Images

What keeps a photographer returning to a particular subject, theme, place, or person?

From deep-seated beliefs that have driven photographers like Susan Meiselas toward career-long documentary explorations, to the humanist personal investigations of Elliott Erwitt, Magnum photographers demonstrate an unwavering commitment to their work for decades.

For the June 2019 Square Print Sale, Magnum photographers have chosen a single image that reflects the issues, working practices, and visual signatures that have consumed them throughout their careers.

For five days only, purchase these signed and estate-stamped, museum quality images, while supporting Aperture Foundation.

Selected by Aperture’s editors, here are ten highlights from the Magnum Square Print Sale.

Eve Arnold, A mother holds her child’s hand; a baby’s first five minutes, Port Jefferson, Long Island, New York, 1959

© Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos

Eve Arnold

“I realize now that through my work these past twenty-five years I have been searching for myself, my time, and the world I live in.”—Eve Arnold, The Unretouched Woman, Random House (1976)

Jonas Bendiksen, Gagra beach at dusk, Abkhazia, Georgia, 2005

© Jonas Bendiksen / Magnum Photos

Jonas Bendiksen

“I’m not really all that interested in photography itself. What I’m passionate about is what you can do with photography. What societal, psychological, emotional, or aesthetic questions can you ask with it? How can viewing or taking pictures make you react or feel? What stories can you tell, what mysteries can be pursued? Those are the things that get me out of bed in the morning and cause me to, still, desperately want to be a photographer.”—Jonas Bendiksen

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, USA, 2000

© Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“I am obsessed with dogs—because they remind me of people, but with more hair.” —Elliott Erwitt

Paul Fusco, Robert Kennedy funeral train, USA, 1968

© Paul Fusco/Magnum Photos

Paul Fusco

“Although I made this image early in my career, it remains a reflection of my desire to champion the underdog. The woman in the field is sending off Bobby Kennedy, a man who fought against oppression. Though I cannot know the thoughts of this woman, she symbolizes the common American citizen in the act of honoring a civil rights hero.” —Paul Fusco

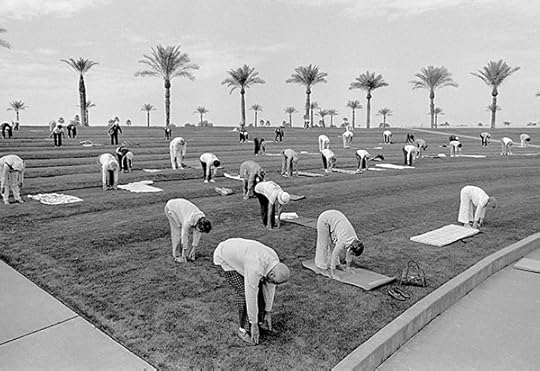

David Hurn, Sun City, Arizona, USA, 1980

© David Hurn/Magnum Photos

David Hurn

“I am not sure I have ever felt the need to use the word obsession—for me, it feels intrinsically unhealthy. But I do like passion, or maybe more accurately, enthusiasm. Whenever I travel I instinctively photograph, so I never have ‘holidays’ as such. However, some events are so uplifting that parts of these happenings become a sort of holiday. I enjoyed the early morning efforts in Sun City of seniors determined to keep fit, it was totally inspiring. I have photographed the ‘pursuit of health’ many times. It has always put a smile on my face, and a feeling of delight, whilst doing it.” —David Hurn

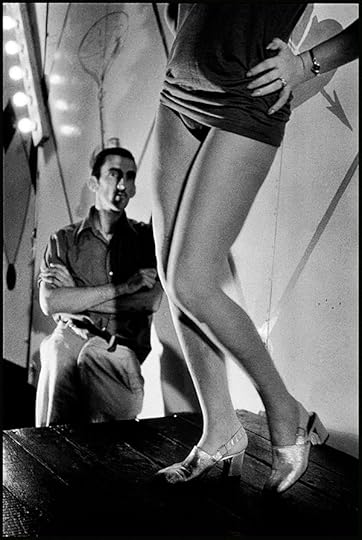

Susan Meiselas, Gawker, Tunbridge, Vermont, USA, 1974

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“He looks at her. She may or may not be looking at him. He dreams and delights in her moves. She may or may not be moving for him.” —Susan Meiselas

Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Café, Tokyo, Japan, 1996

© Gueorgui Pinkhassov/Magnum Photos

Gueorgui Pinkhassov

“A barmaid standing in the open door of a cafe caught my attention. As I was trying to focus my lens, the door slowly began to close. ‘Be quick,’ I told myself. A moment later the door’s glass barricaded my view but a salutary ‘pourquoi pas?’ urged me to make another shot. If a camera is your weapon, ‘pourquoi pas?’ is the flag you raise. Without it, you can achieve nothing.” —Gueorgui Pinkhassov

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001

© Alessandra Sanguinetti/Magnum Photos

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“While I was working on On the Sixth Day, exploring the life and death of farm animals, I came across a man who lived with his horse. It would come and go as it pleased, so sometimes he’d put sugar on the table to lure it back in for the night. I’ve been drawn to photographing animals, especially farm animals, since I was a kid, and always while doing so I’d be filled with a nostalgic, wistful feeling. I never understood the root of that feeling until I read John Berger’s amazing essay, ‘Why Look at Animals?’ in which he wrote: ‘With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.’”—Alessandra Sanguinetti

Marilyn Silverstone, First lady Jacqueline Kennedy returns from a state visit to the Lake Palace Hotel, Udaipur, India, March 1962

© Marilyn Silverstone/Magnum Photos

Marilyn Silverstone

“Marilyn was drawn to photographing women: powerful women like maharanis, queens, political figures, as well as ordinary women working in the fields, gathering food, being mothers. She was not interested in creating ideals or role models, but in capturing women in specific places (villages, palaces, offices) as they navigate their world. Her photographs reveal women being themselves. At the same time, they reveal women who seem to embody the landscapes around them. This photo is startling in its intimate portrayal of a young woman whose face was known to millions. Glowing with delight and a sense of freedom and possibility, she enjoys a new role, a different culture, and landscape. ‘It’s been a dream,’ Jackie said of her tour of India—her first goodwill trip as the First Lady.” —Vivian Kurz, Director of Dilgo Khyentse Fellowship/Shechen, The Estate of Marilyn Silverstone

Jacob Aue Sobol, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010

© Jacob Aue Sobol/Magnum Photos

Jacob Aue Sobol

“To me the camera has always been a tool to find and depict love to a point that it became an obsession. How close can I get to a love that feels true in my images? Is this the love I have been searching for myself these past twenty years? Is this the love of my life? I photographed young couples in love across the planet to remind us that we are all the same, to remind us that what we have in common is greater than what separates us. That young couples in love from Beijing share the same love as young couples from Moscow, Paris, or New York. And, even after this obsessive search for love came to an end, I found Martin and Pernille in my own neighbourhood in Copenhagen.”—Jacob Aue Sobol

Magnum’s Square Print Sale, Obsessions, is now online through June 14, 2019. For five days only, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch square prints are exceptionally priced at $100. By using this link to make your purchase, proceeds from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

The post 10 Magnum Photographers on their Obsessions in Images appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 8, 2019

Reckoning with Canada’s History of Whitewashing

Two artists delve into a national archive, revealing a counter-history of colonialism, trauma, and erasure.

By Laurence Butet-Roch

Morris Lum, PA-1599-114-31, 2018, from the series Subtle Gestures, 2017–18. Stan Wong and Lou Wong wearing Western clothing at barbeque, Calgary, Alberta, April 8, 1969. Photograph by Ken Sakamoto, Calgary Herald

Original photograph courtesy Glenbow Museum, Calgary, and Calgary Herald

How do institutional archives create national narratives? On the occasion of Toronto’s month-long photography festival, Gallery 44, an artist-run nonprofit, asks just this. The curator, Gabrielle Moser, an assistant professor at the Ontario College of Art and Design University, focuses on settler–colonial image-making and its resistance. Moser brought together five artists, all with ties to the Canadian state, whose works rupture the welcoming, tolerant, multicultural story the country likes to project. Rather than pointing out what’s missing from institutional memory, these artists bring to the surface what is already there, but has been misread, misinterpreted, or misrepresented.

Deanna Bowen, a Toronto-based interdisciplinary artist, appropriated footage from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) with the intent of demonstrating how that reporting served Canada’s desire to show itself as tolerant and multicultural. The footage relates to Bowen’s own family, former enslaved people and their descendants, who fled all-black towns in the United States in the early twentieth century and found themselves in Northern Alberta. Bowen’s colleague Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn, who grew up in Montreal and now lives in Stockholm, has been mining the nearly five-hundred photographs her great-grandfather brought from Vietnam. The differences between his album and the Vietnamese art holdings of North American and European institutions reveal divergent values and hierarchies. Both projects are the result of ongoing investigations of and engagement with the radical potential of archives. Bowen and Nguyễn discuss these topics here, accompanied by the curator, Moser, who draws parallels between their works.

Jacqueline Hóang Nguyễn, Untitled, 2018, from the series Presence in Absentia. Sand. Installation at Gallery 44, Toronto. Photograph by Darren Rigo

Courtesy the artist and Gallery 44, Toronto

Laurence Butet-Roch: Archives often conjure up images of an austere environment to which only a select few, usually members of the privileged and ruling white patriarchy, have access or a demonstrated, vested interest. How did you, whose identities intersect a variety of marginalized communities, come to see their artistic and disruptive power?

Deanna Bowen: I’m a super sentimental grandkid of a family that has always been very much preoccupied with history in one way or another. A lot of what I’ve been doing for the last twenty odd years has been about making sense of that. Once one starts doing genealogical work, all these other historical materials appear and become intrinsic to understanding who those people were and who their community was. It was a doorway into grasping the ways in which trauma impacts the telling of our story.

Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn: I come from the other end of the spectrum. I grew up in an environment where family history was never talked about. It was always hush-hush. As new immigrants, we feel that we shouldn’t look back. Rather, in order to be the “model minority,” we ought to be looking forward, investing at all cost in the education of the children, who would then ensure the future of the family through their professional success. So I came to archives much later in life and not by way of the personal. In 2012, I started investigating the world’s first UFO landing pad built in the Prairies of Alberta in 1967. Looking for context, I did research in the national archives and library in Ottawa, as well as in private archives. I was struck by how white they were. It was especially surprising because 1967 marked this paradigm shift in the country from a privileged Northern European migration to the implementation of the points-based system, where an applicant can gather points in different categories such as education, language skills, age, etc. up to a certain threshold that will grant them rights for immigrating. Yet, despite how celebrated diversity has since become, it isn’t reflected in the archives. That realization came in conjunction with finding an album of photos my dad took when he moved to Canada in 1973. This was in essence the representation that was missing from the official archives. He was engaged with student activism, organizing protests in front of parliament. He was an immigrant body who displayed political agency in the public sphere. All of these reflections about representation of self, community, and national identity came clashing together.

Bowen: I also quickly found myself working in very white archives as well. The narrative about Amber Valley, the black settlement in Northern Alberta my family belonged to, rested on the presumption that despite racial differences everyone got along. That this was a lie became more and more apparent as I dug into the archives, making notes of sociopolitical context of the time. Archival materials explicitly detailed antiblack hostility—threats of mob violence and lynch mobs, documented political interference, media smears about black savagery, inferiority, and so on. Over time, I have come to understand that the family myth of peaceful cohabitation was partially true, in that it reflected a practical negotiation for living in harsh climates. The life and death realities of homesteading and the extreme weather of the region made it necessary for my family (and the greater settlement community) to negotiate an uneasy civility between racist neighbors and government officials as a means of survival. In other words, the archive turned out to be a means to measure the accuracy of the constructed family myth versus reality. Yet, at the same time, navigating the white archive also demonstrated how data about my community was often lost, hidden, or buried. Overall, I got this sense that we were not valued because we were largely absent.

Deanna Bowen, still from The Promised Land, 2019. Original footage from Heritage, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1962

Courtesy the artist

Hoàng Nguyễn: I’m still trying to make sense of the colonial relationship between photography and Indochina. I have this notebook where my great-grandfather has written about our family history from the 1700s and a collection of five-hundred photographs he gathered that range from the late 1910s to the end of the Vietnam War. While one has to keep in mind who has access to the camera—members of the upper middle class—this is a rare instance of the Indochinese documenting themselves during a period when colonial powers and then photojournalists produced the imagery of what Vietnam is.

Gabrielle Moser: I came from a much more traditional academic background, where I spent seven years studying photographic colonial archives. My interest in bringing this group of artists together came from this experience, thinking about what to do with images in state hands that for the most part go unseen by the larger public. The archive I looked at for my dissertation included seven-thousand images, but only two thousand of them had been seen by a wider audience at the time. Wondering about how to engage with these ethically and responsibly, I began looking at how artists handle archives. The artists gathered here work with a variety of collections in very different ways, but each think about how they can develop narratives about history, identity, sovereignty, and belonging that run counter to the official ones.

Jacqueline Hóang Nguyễn, Untitled, 2018, from the series Presence in Absentia. Sand. Installation at Gallery 44, Toronto. Photograph by Darren Rigo

Courtesy the artist and Gallery 44, Toronto

Butet-Roch: Speaking about strategy, Jacqueline and Deanna, you’ve both employed a wide array of methods to manipulate archival materials. For instance, Jacqueline, you’ve facilitated sessions where you invited peers to scan and caption pictures from family albums for The Making of an Archive project, as well as transformed photographs taken from the collection of relatives. Similarly, Deanna, you’ve worked with moving and still images, as well as textual sources, and in turn reenacted, re-staged, or re-interpreted them. How do you determine which is the best way to make the usually unseen teachings of these documents come to life?

Bowen: While some of it hinges on aesthetics, I constantly strive to analyze how the state has shaped how our story has been told. Re-enacting and re-staging events comes from a desire to have a bodily understanding of what was going on at the time. Often the only way to really understand the weight of a moment and its representation is to re-stage it, record it, and then publicly re-present it again. There are also photographic documents that I bring forward as living images because the emotions they speak to are better represented that way, like that of my mom and her siblings and cousins at a funeral. I felt a still moving image was the best way to present the active grief that my mom experiences.

At Gallery 44, I’m showing the full-length appropriated version of a thirty-minute narration of my family’s migration that was produced by the CBC in 1962. It involves family members singing gospel hymns that have been strung together to create that story. It has all the aesthetic values of 1960s black-and-white television. It reads like a variety show. It’s heavily romanticized. It’s fundamentally inaccurate. But it’s important to bring forward because it’s the best kind of example of how the reality of our black experience in Canada has been erased to make space for a blackness that’s been produced and disseminated by the state.