Aperture's Blog, page 87

June 6, 2019

Aperture Celebrates MUSE at its 2019 Gala

On June 3, at its annual fundraising Gala, Aperture Foundation celebrated MUSE, the ideas and people that inspire us in photography, and honorees The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Mickalene Thomas, and Racquel Chevremont. The event was generously sponsored by Barrett Barrera Projects, Christie’s, Foto Care, and Ingram Content Group.

Zachary Tye Richardson, honorees Racquel Chevremont and Mickalane Thomas, Shiona Turini

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala honorees Racquel Chevremont and Mickalane Thomas

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Dario Kelis, Antwaun Sargent

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Kelly Peck with sponsor Susan Barrett of Barrett Barrera Projects

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Aperture executive director, Chris Boot with Gala cohost Elizabeth Kahane

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gina Gershon, Ben Sinclair

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Chris Boot with Aperture trustee Missy O'Shaughnessy and Jim O'Shaughnessy

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Honoree Michael Ward Stout of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation with Joan Berkowitz

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Kristin Riepenhoff, Carissa Barnard, Aperture trustee Tom Schiff, and Mary Ellen Goeke

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas Sr.

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

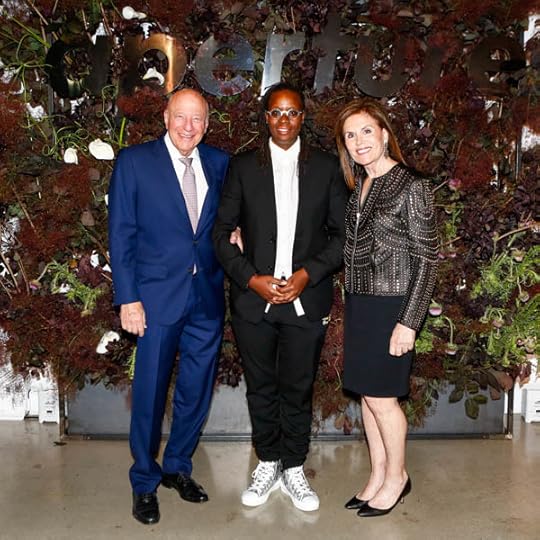

Steven Leber, honoree Mickalene Thomas, Bonnie Lautenberg

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Kristin Riepenhoff, Carissa Barnard, Aperture trustee Tom Schiff and guests

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Melonie Bennett, Judy Lauder, Leah Zimmerman, Alice Momm

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Aperture magazine editor Michael Famighetti with Kathy Ryan

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Guest with Aperture trustee Michael Hoeh

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Stefano Tonchi

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Mickalene Thomas with DIOR Lady Art #3

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Artists Matthew Porter and Hannah Whitaker

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Keanna Quinn of Honey + Vinyl

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Shiona Turini, honoree Racquel Chevremont, Zachary Tye Richardson

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

William Kahane, Annie Sandler

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Aperture trustee Stuart Cooper, Becky Besson

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Alima Lee

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Alan and Louise Weil

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Eliza Soros, Melissa Schiff Soros

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Mariane Abraham, Gala cohost Elizabeth Kahane, Lina Iris Viktor,

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Antwaun Sargent, Ethan James Green

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Mayfield Brooks, Zachary Tye Richardson

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Gala guests

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Guest with Amelia Critzer, Lori Grover, Liz Grover

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala cohost Tilda Swinton

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Lauren Fern, Ron Hartleben

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Guests viewing auction artworkSansho Scott/BFA.com

Ian Wardropper, Elizabeth Stribling, Guy RobinsonSansho Scott/BFA.com

Honoree Mickalene Thomas, Shiona Turini

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Christie's auctioneer Robbie Gordy

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Aperture trustee Elaine Goldman, Kendall Messick, Diane Ackerman

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala cohost Cathy Kaplan with honoree Michael Ward Stout

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Stewart Shining, Burt Lipsky

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Aperture director Chris Boot, honoree Mickalene Thomas

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Alida Latham, Aperture executive director Chris Boot

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Andrew Wingert, Yancey Richardson, Annie Armstrong

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Sheree Hovsepian, honoree Mickalene Thomas, Shari Loeffler

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Guest with Aperture trustees Allan Chapin and Cathy Kaplan, Anna Nilsson

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala performer Rhonda Ross, Barbara Stehle, honoree Mickalene Thomas

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Glitter Fluide application on guest Sheree Hovsepian

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala cohosts Celso Gonzalez-Falla and Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Mary Ellen Goeke, Katherine Siegwarth, Kristin Riepenhoff, Carissa Barnard

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Honorees Racquel Chevremont and Mickalane Thomas, Shiona Turini, Zachary Tye Richardson

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Lina Iris Viktor, Mariane Ibrahim, Eva Therond

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Stephen Shea, Stewart Shining

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Sponsor Darius Himes of Christie's

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Rhonda Ross, Honey + Vinyl

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Auctioneer Robbie Gordy of Christie's

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Honorees Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Gala cohost Cathy Kaplan with honoree Michael Ward Stout

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Rhonda Ross

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Keanna Quinn of Honey + Vinyl

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Shiona Turini, Zachary Tye Richardson

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Akima Sane, Anaka 444

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Terrence Eldrige, Rhonda Ross

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Ian Wardropper, Aperture trustee Sarah McNear, Jeff Rosenheim

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Annika Zee, Anika Larsen

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Shiona Turini, honoree Racquel Chevremont, Zachary Tye Richardson

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Nina Chanel Abney, Jet Black

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Kelly Peck with sponsor Susan Barrett of Barrett Barrera Projects

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Logan Jackson, Carly Mark

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Aperture trustee Jessica Nagle with DIOR Lady Art #3

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Guest with Silvina Sterin

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Peter Kayafas

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Leslie Simitch, Stewart Shining

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

William Kahane with Gala cohost Elizabeth Kahane

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Casey and Lauren Weyand

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Shira White

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Lavon Kellner

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Stewart Shining, Christina Burns

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Chris Boot, Rhonda Ross, Keanna Quinn of Honey + Vinyl

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Tony White, Aperture executive director Chris Boot

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Rhonda Ross

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Cathy Kaplan and honoree Michael Ward Stout

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Zachary Tye Richardson, honorees Racquel Chevremont and Mickalane Thomas, Shiona Turini

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Honoree Mickalene Thomas, Lola West

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Aperture trustees Cathy Kaplan and Jessica Nagle

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Dan Fethke, Alex Rapport

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Gala cohost Cathy Kaplan

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Nicole Chapoteau, honoree Mickalene Thomas, Shiona Turini

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Honrees Mickalane Thomas and Racquel Chevremont

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Lesley Martin, Aperture trustees Andrew Lewin and Elizabeth Kahane, William Kahane

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Dan Allentuck, Susanna Singer, and Aperture trustees Cathy Kaplan and Willard Taylor

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Darius Himes of Christie's with Aperture trustee Jessica Nagle

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Daniel Milder, Barbara Stehlé

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Sheree Hovsepian, Shari Loeffler

Ryan Kobane/BFA.com

Aperture trustee Willard Taylor, Ian Wardropper

Sansho Scott/BFA.com

Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, and Tilda Swinton were this year’s Gala cohosts. Swinton, who greeted guests in an introductory video, thanked the honorees, and Aperture. “Vivre Aperture forever,” she stated. “May we all continue to know what an oasis of sanity and culture it is.”

Robert Mapplethorpe is one of photography’s great muses, whose legacy continues to echo through the art of photography, and in the work of many artists. Under the expert guidance of Mapplethorpe’s friend Michael Stout, and Eric Johnson, the foundation has supported AIDS and HIV medical research and so many arts initiatives across the worlds of art and photography. In a special tribute, Cathy M. Kaplan recognized the work of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, calling Mapplethorpe “a singular photographer who really changed the shape of what photography can do and mean.”

Aperture honored Mickalene Thomas for her brilliant use of the photographic image to assert new definitions of beauty and black female identity, celebrity, and sexuality, and Racquel Chevremont, Thomas’s partner, muse, and collaborator on Deux Femmes Noir, a platform for supporting new opportunities for artists of color to achieve greater prominence in the art world.

Zachary Tye Richardson and Shiona Turini expressed heartfelt thanks to Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont for their achievements. “These women walk the earth with a divine purpose, challenging the norm, assaulting the commonplace, and empowering black women in these forms,” Turini said. “Their work is an extension of their pioneering souls. Collectively, their incredible cultural impact has penetrated not only our thoughts and convictions, but a global consciousness as well.”

Robbie Gordy, of Christie’s, presided over a live auction, featuring works by Thierry Cohen, Ethan James Green, Seydou Keïta, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Mapplethorpe, Vik Muniz, Erwin Olaf, Matthew Pillsbury, Matthew Porter, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Paul Strand, and Mickalene Thomas.

Following the auction, The Photo Party guests joined the celebration and everyone enjoyed a performance by Honey + Vinyl featuring Rhonda Ross, rhythms by Alima Lee, glitter applications by Fluide, and artisanal mezcal cocktails by Gem & Bolt. In attendance were Nina Chanel Abney, Dara Allen, Susan Barrett of Barrett Barrera Projects, David Breslin, Michael Carl, Stuart Cooper and Rebecca Besson, Gina Gershon, Elaine Goldman, Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Susan Gutfreund, Darius Himes of Christie’s, Jeffrey Hirsch of Foto Care, Sheree Hovsepian, Mariane Ibrahim, Matthew Pillsbury, Phyllis Posnick, Lisa Rosenblum, Antwaun Sargent, Drew Sawyer, Thomas Schiff and Mary Ellen Goeke, Ben Sinclair, Melissa Schiff Soros, Elizabeth Stribling, Stefano Tonchi, Lina Iris Viktor, and Shen Wei.

The 2019 Aperture Gala and Auction was generously supported by:

Underwriters

Judy and Leonard Lauder

Leader Committee

Susan Barrett, Barrett Barrera Projects, Elizabeth* and William Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan* and Renwick D. Martin, Lisa Rosenblum,* Thomas R. Schiff*

Gala Committee

Joe Baio and Anne Griffin, Peter Barbur* and Tim Doody, Maria Love Brisbane, Audry X. Casusol, Allan Chapin* and Anna Nilsson, Sb Cooper* and R. L. Besson, Richard Edwards and Kevin Ramnaraine, Fine Art Frameworks, Foto-Care Ltd., Gladstone Gallery, Elaine Goldman* and John Benis, Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla,* Agnes Gund, Hermès of Paris, Darius Himes, Christie’s; Michael Hoeh,* Elizabeth R. Kabler, Hemant Kanakia* and Sonalde Desai, Darlene Kaplan and Steve Zuckerman, LaVon Kellner, Christopher and Alida Latham, Bonnie Lautenberg, Raymond Learsy, Mark and Elizabeth Levine, Marina and Andrew* Lewin, Anne Stark Locher* and Kurt Locher, Nion McEvoy,* Sarah McNear* and Ian Wardropper, Jessica Nagle* and Roland Hartley-Urquhart, Philip C. Ollila, Ingram Content Group; Missy* and Jim O’Shaughnessy, Melissa Schiff Soros, Severn Taylor* and Scott Switzer, Willard Taylor* and Virginia Davies, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee, Casey and Lauren Weyand, Yancey Richardson Gallery

*Aperture trustee

Sponsors

[image error]

Partners

Artsy, BFA, Emily Thompson Flowers, Fine Art Frameworks, Fluide, Gem & Bolt

The post Aperture Celebrates MUSE at its 2019 Gala appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 3, 2019

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision

Do you know where you’re going next with your photography–or where it’s taking you? This intensive weekend workshop will help photographers begin to understand their own distinct way of seeing the world. It also will help photographers figure out their next step photographically–from deepening their own unique vision, to the process of discovering and making a long-term project that they’re passionate about. A workshop for serious amateurs and professionals alike, it will be taught by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, a creative team who often edit projects and books together-including their new Aperture book, Brooklyn: The City Within.

This weekend workshop will begin with a public artists’ talk on Friday, September 27 at 7:00 p.m., which all participants are required to attend, and an optional pre-workshop assignment due on Thursday, September 26 at 11 p.m. It will continue with reviews of each participant’s work on Saturday morning, which will spark a larger discussion about various photographic issues, including the process of photographing spontaneously and intuitively, how to edit (select and sequence) photographs instinctively, how to work in cultures different from one’s own, and how long-term projects can evolve into books and exhibitions. The first day of the workshop will end with a group-editing exercise and a photography or editing assignment. Sunday will be dedicated to reviewing each participant’s assignment, as well as a series of presentations about bookmaking and exhibitions. The workshop will end with an informal Q&A with Alex and Rebecca.

NOTE: This workshop is for photographers who collaborate with the world, not for those who dramatically alter or change their images digitally.

Alex Webb has published sixteen photography books, including Aperture’s The Suffering of Light, a survey book of thirty years of his color photographs. He’s exhibited at museums worldwide including the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the High Museum of Art, Atlanta; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A Magnum Photos member since 1979, his work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and other publications. He has received numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007. His most recent books are Aperture’s La Calle: Photographs from Mexico and the collaboration Slant Rhymes with Rebecca Norris Webb.

Originally a poet, Rebecca Norris Webb often interweaves her text and photographs in her six books, most notably with her monograph, My Dakota—an elegy for her brother who died unexpectedly—with a solo exhibition of the work at the Cleveland Museum of Art (2015), among other venues. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker and the New York Times Magazine, and is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Rebecca is an NEA grant recipient, and she’s currently working on her eighth book, Night Calls, where she’s following the route of her 99-year-old, country doctor father’s house calls through the same rural Indiana county where they both were born.

Alex and Rebecca on Instagram: @webb_norriswebb

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Learn how to begin to find your own photographic voice

Learn more about selecting and sequencing your photographs intuitively

Learn how projects evolve into books and exhibitions

Materials To Bring:

Roughly 30 PRINTS (Please bring prints, NOT digital files). These don’t have to be finished prints. Small inkjet or machine prints, the latter like those made at a drugstore, are fine. The image is what matters most, not the quality of the print.

Optional: For those who choose the editing assignment, please bring 45–100 small prints (no larger than 4 by 6 inches or 5 by 7 inches) on Saturday, from one or two projects, including work that you hope one day will become a book.

Optional: For those who choose the photography assignment, please bring your digital camera on Saturday, because you’ll be photographing that afternoon after class (you’ll need a laptop to edit your work Saturday evening, which you’ll leave at home or at your hotel). You’ll also need a portable hard drive or thumb drive to bring your assignment to the classroom on Sunday morning.

Tuition:

Early Bird Discount: Now until July 1, 2019, tuition will be $600 (originally $650). Tuition includes lunch and light refreshments.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Monday, August 19, 2019

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run this workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 30, 2019

Christopher Street Revisited

In the 1970s, Sunil Gupta photographed moments of desire and liberation in New York’s gay capital.

By Jesse Dorris

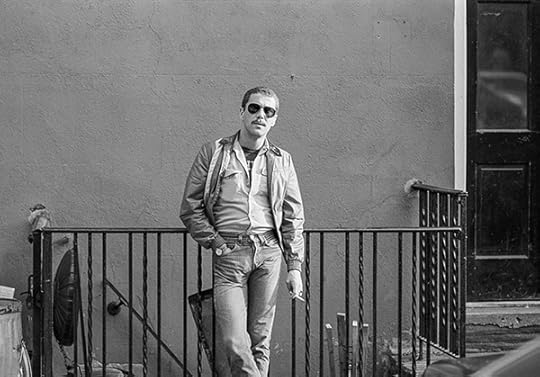

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #22, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

In 1976 and in his early twenties, the New Delhi-born photographer Sunil Gupta left his adopted home of Montreal and came to New York to earn an MBA. The better part of his time, however, was spent conducting business of a very different kind: cruising around the gay mecca of Christopher Street. Camera in hand, and scoping out the men who, like him, had arrived from various elsewheres, Gupta began making pictures of people who wanted to see and be seen, and to see what might happen. Sometimes Gupta’s snapshots were preludes to sex, sometimes instead of it. Other times, the images display other forms of desire, each empathetic and honorable. There’s a curiosity, a need to know in his photographs, which were collected last year in the book Christopher Street 1976 and now presented in a thrilling show at Hales Gallery.

Gupta went on to study under Lisette Model at the New School and take his place among the most accomplished photographers, editors, and curators of his generation, exploring the way identities flower under various sexual, geographical, and historical conditions. But Christopher Street is where it all began. His subjects are engaged in an unprecedented moment in which it seemed possible to build a world of their own. He shows inner lives, barely concealed within the downturned face of a mustachioed man with his hands in his pockets, and outer ones as well, as other men cruise the lens right back, or laugh with each other, unbothered by the stranger with the camera. They were often just engaged in the everyday and extraordinary act of simply existing as gay. In each photograph, Gupta somehow projects a protective and versatile desire: to remember and be remembered at once.

Gupta and I recently walked through his exhibition and then sat for tea, talking about global gay identity, the magic of the darkroom, and cruising as a creative act.

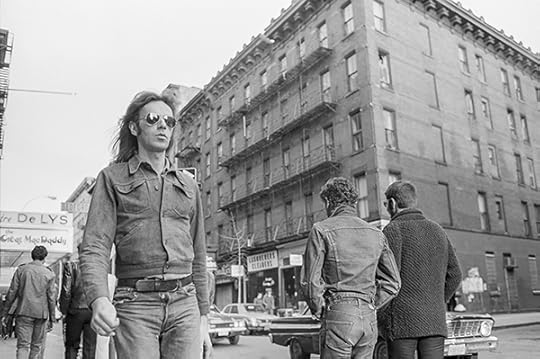

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #36, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Jesse Dorris: When was the last time these have been shown as a group?

Sunil Gupta: There are about sixty in this that we used for the book. It’s difficult to have exhibitions of all sixty, so in 2015, we tried about twenty-two 8-by-10 prints, which were up at sepiaEYE in New York, and then traveled to Houston.

Dorris: What was it like pulling these out again?

Gupta: I was shooting these at a time when I was just doing it part-time. I was here in New York in business school, and I was just doing street photography. It came out of my gay activism in my undergraduate years and became kind of a serious hobby. It became a natural thing to shoot. I was just on the street corner. Street photography was very fashionable then because of the post-New Documents show with Garry Winogrand and others at the Museum of Modern Art. Then I dropped out of my MBA and began taking photography classes.

Dorris: What was it about photography that called to you?

Gupta: At the very beginning it was kind of a poor man’s cinema. In India, I grew up with Bollywood cinema. It was big and colorful and melodramatic, with sweeping narratives and music. But I was never in a place where I could imagine making anything like that. In Montreal, where my parents moved from Delhi when I was fifteen, I was doing my undergraduate degree, and gay liberation came along in 1970 and we started a student’s union movement around it. I became interested in using the camera and I had a literature-oriented buddy who liked cinema. Basically we made fictional narratives about still frames and tried to make up stories about people like us who were young, single, gay men. Montreal was a much smaller town, and after going to the same bars every weekend for a few months, you’ve kind of seen everyone. So we invented fictional names and backgrounds for people. They had two lives going on: their lives, and what we thought about.

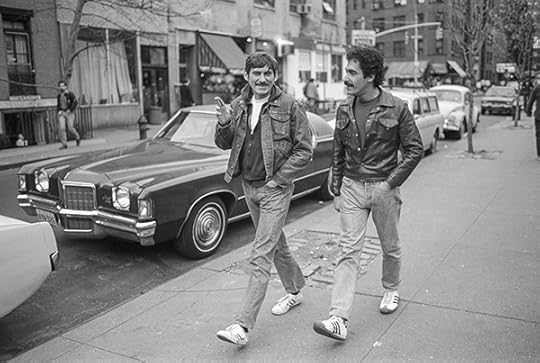

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #43, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: You said this was coming out of the liberation movement and that kind of activism. Did you see taking these portraits as a political act? Or was it an act of desire?

Gupta: Most of my photography was initially for public consumption. It wasn’t like snapshots of us. I was photographing gay politics. I went to demonstrations. The campus group Gay McGill was trying to go out into the town and become more relevant to the city. We produced a little paper called Gayzette, so the pictures appeared in that.

Photography came to represent political action and the fiction kind of took a back seat for a while after this. When I was in New York in 1976, I just got drawn into the whole moment of early ’70s documentary stuff that was happening here, in terms of the photography and also the gay scene, both of which suddenly exploded in front of me here. It was quite different than what I had seen in Canada or anywhere else.

Dorris: Tell me what it was like.

Gupta: I lived in London Terrace and all along here was this rough, big scene happening. There were clubs, the Eagle and some other places. In the daytime it was equally busy, just people going by, and obviously I couldn’t have them all, so the next best thing was to photograph them all [laughs]. And fortunately, in this part of Manhattan, the streets all faced the light, so it was great for that.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #21, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: And did people see that were taking the photograph?

Gupta: Yes, they could see me coming, camera pointed, because I was looking through the viewfinder. For me it was like cruising; I was used to going up to people anyways. I used to be quite aggressive in bars, I would just walk up to people. Most people are just waiting to be asked anyway [laughs]. I was impatient.

Dorris: So this is ’76, the height of visibility as a political activity.

Gupta: There was none of this negativity. Sex wasn’t risky; New York City was pretty safe. There was some gay bashing around the fringes, but there was a community response to that so it felt like it could be handled.

Dorris: Why were you taking pictures on the streets rather than at the piers?

Gupta: I think because it gave me photographic structure. It was originally part of a larger idea of street corners in New York. I did this and I also did it further up in the 30’s here in Chelsea. I was very energetic. I just walked up Eighth Avenue up to Thirty-Second or something and the whole world changed, the way New York changes from block to block. I stood on that corner and there were very different people walking by. I thought I would end up with a range of different sights, with different people populating different street corners, but this one became of greater interest to me.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #37, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: It’s really hard to look at these without thinking about the doom that was around the corner. I’ve been thinking about this a lot as everyone is mounting their Stonewall shows and contemporary queer art shows now. I’ve been thinking about if there’s a way of looking at this work without thinking about AIDS and the ’80s.

Gupta: I hope so. It’s meant to be a bit celebratory and not a memorial. I left in ’77 for London and never came back, so I wasn’t here for that terrible time. I thought, in safety, that this was an American disease, we’re never going to get it. The Atlantic is going to save us.

Dorris: How come you never came back?

Gupta: The person I was with moved to England and I was sort of holding on to him. I did regret that I had to leave New York, it felt like a step backward at the time, because London didn’t have this. He promised me it did, but I got there and it wasn’t like this at all. The pubs all closed at 10:30 p.m. And if you held anyone’s hand in a pub, they’d throw you out.

Dorris: Even in Vauxhall or Chelsea or places like that?

Gupta: They didn’t exist. There was only Chelsea. And Earl’s Court was the hub. Britain has this weird history of decriminalizing in ’67-ish and then in the ’70s, the police responded by increasing the number of arrests and entrapments. There was huge police activity against gay men in London in the ’70s. They’d try to catch you out in public places, in parks and toilets. There was a lot more fear and hiding in London.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #56, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: How did the punk scene, fashion, music, et cetera, all affect your work?

Gupta: You know, it made me very aware that I wanted to do something gay. Because in my experience in art school in the ’80s, nobody wanted to do this subject, which made me want to do it even more. I feel really caught in that gay moment, even still. I’m very of that time. People say to me, “Shouldn’t you grow out of this? You’re supposed to mature into something more holistic,” but I still persist in seeing it through my gay identity, my lens. And now we see it all transformed into queer, and now there’s a new problem, that everybody’s queer. And I feel like being gay again. Although, my last book was called Queer [laughs]. That was a mistake, actually; it should have just been Gay.

Dorris: Well now you have your next title!

Gupta: Right, Back to Gay!

Dorris: That would be an amazing reclaiming of a gay identity.

Gupta: I was very invested in identity politics because you know, I was a bit older when I went back to art school, so I was like twenty-four, not twenty, and then for my MFA, by the time I graduated in ’83, I was thirty. The rest were just twenty-three or something. So I was aware of things like Robert Mapplethorpe, which you couldn’t mention in class. When Mapplethorpe happened, Doug and I were like, “We don’t really like this, but we have to go out and support it.”

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #42, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: So you didn’t like it, but you supported it anyway?

Gupta: I didn’t have a problem with it. I just felt like it over-dominated. It became “the gay work” and I didn’t think penises were the issue for most of us, certainly not for me or Doug. It wasn’t our sex life that was the problem; there were other problems.

Dorris: You’re taking pictures not at the piers, or the bathhouses, or the parties, but before and after or instead of. They’re clothed on the streets, present in the world, not in the underworld the way Mapplethorpe’s are.

Gupta: There’s been that other battle in the gay subculture, making a place for work that’s not body-centric like that. All of these gay magazines that existed everywhere in the West, their centerfolds all seemed all the same and there was no way to shift it. And you get to this horrible period of very white, hairless models. It was kind of weird.

Dorris: I always thought that was a reaction to AIDS. It was “clean,” “healthy,” no secrets, nothing hiding, everything’s been wiped down. That’s how that world always seemed to me.

Gupta: Yeah, that’s true.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #54, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: I watched a video you made at the Tate where you talk about the darkroom and the magic that happens in there. Could you tell me more about that? What happens in there?

Dorris: In the dark, there’s that final emergence of the image. Being able to control it tonally and all of that, that kind of physics and chemistry is still a bit mysterious and magical. I used to be quite nerdy about darkrooms and chemistry. I had a whole kit of measuring tools. I used to buy raw chemicals, I wouldn’t buy commercial developers, I always mixed them up.

Dorris: Why did you want to do it yourself?

Gupta: Just to have more control with the contrast and things. It’s a lot cheaper also, because chemistry doesn’t cost anything when it’s in a raw state. It’s not complicated, you just have to mix things up. And it was like being a kid, you know, grown-up toys, measuring things, making potions. That was loads more fun and entertaining and you felt better after it. But if I’m sitting for twenty hours in front of a screen, on Photoshop, you just have a backache after it. And it’s so infinite, Photoshop, I find it quite horrible. There’s just no obvious end in sight. In a darkroom there’s a point at which you say, “Okay I’ll fix it now.” In Photoshop you could come back tomorrow and do something else to it. It’s a bloody nightmare.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #50, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: You’re taking sidewalk pictures again?

Gupta: What happened was between 2004 and 2012, I was based in India and I got very involved in reinventing my new gay liberationism and all of this. And as a photography person, I saw that both of these areas needed developing in India when I got there.

Dorris: Were you there when the Supreme Court legalized homosexuality?

Gupta: I was there the first time that it happened. And I joined one of the groups that was involved, which put on shows and festivals and films. I had a photography show. We’d make a call for video and photography and people would rush out and make something locally. The first time we did it, ninety percent of it came from California, and almost nothing from Asia. But a couple years later there was a lot of local stuff. And the curating principle was how to make all the entries look good and put it all up. It was not about choosing the best. So that was great fun. And then we had the first gay pride in New Delhi, so that was fun too.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #10, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: What was that like? Did you photograph it?

Gupta: Yeah, it’s in this other, bigger book. There were rumors spread about possible attacks. When we went to the start of the march, there were maybe about twelve of us who arrived a little bit earlier. We were wondering if there would be any more, really, because of the fear and anxiety of being outed. It was still illegal then. We were a small group of people and a vast army of camera crews and police on-the-ready. So finally, a few hundred people did turn up and nobody was attacked. There’s a new battle to keep it a people’s march. We all have a stake in it, it’s like a big co-op. The consensus so far is that there shall be no branding of anything. No NGOs, no GMHC, and definitely no corporate branding.

Dorris: That’s inconceivable from a Western perspective [laughs].

Gupta: In Bombay they haven’t been able to sustain it, so it’s been corporatized, and therefore bigger. Ours is still littler and a bunch of straggly people walking around. And a bunch of drag queens making a racket. But it’s getting bigger in numbers.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #59, 1976

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: Is there a new project on the horizon for you?

Gupta: Yes, I’m trying to attach myself to a Canadian research institute around the forest and migration, which will be the next five years, I anticipate, if I get the funding. I’ve become more into academic research. I just got a PhD.

Dorris: Congratulations! In what?

Gupta: On my own work [laughs], so that was kind of easy. This is a new, third kind of PhD in England. There’s the second one, which was my practice, where you make a body of work and write about it. And now there’s a third one. If you’re an older person like me and if you have at least ten years’ worth of work, you can retroactively write about those ten years, so I picked my last four exhibitions and theorized about them from the vantage point of today. It makes you catch up on the literature about your subject. For example, queer theory has come such a long way in these ten years.

Dorris: So the migration issue is something that’s calling to you?

Gupta: Yeah, my topic was queer migration. I’ve always thought of my experience as a departure from India to Canada and then to New York and England and then I left to India again. But from a contemporary point of view, the more recent idea is to think of it more as an arrival than a departure. In a way, coming to Canada in ’69, a month after Stonewall, I arrived into an identity in a way that wouldn’t have been possible. If I hadn’t left, I would never have been like this. This identity wasn’t happening in India; they missed the whole “gay thing.” They’ve gone from nothing to queer, they didn’t have LGBT. But I really praise my situation in that way, as an arrival.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

Sunil Gupta: Christopher Street is on view at Hales Gallery, New York, through June 1, 2019.

The post Christopher Street Revisited appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

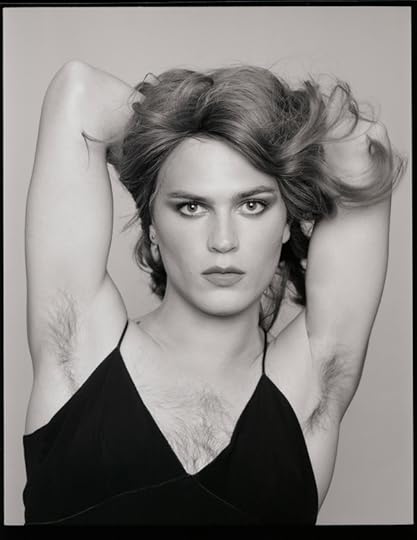

Can this Young Photographer Dissolve the Drama of Gender?

With his queer, neoclassical portraits, Michael Bailey-Gates wants to start a revolution.

By Horace D. Ballard

Michael Bailey-Gates, Los Angeles, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Akin to Caravaggio, the humanist Baroque painter of the double-edged scene, Michael Bailey-Gates serves ambiguity atop ambiguity to get at the underlying truths of living in a pre-apocalyptic world. This is accomplished most directly by Bailey-Gates’s capacious understanding of the work of the close-up and a refracted, almost restrained use of color. The close-up has become visual lingua franca in the age of the selfie. It was Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman in the 1970s and ’80s who borrowed the close-up from cinema to speak truth to power in a divided Thatcher-era, Reaganomics world. Whereas Goldin’s close-ups are of half bodies, writhing together so that the tail-end of one sits on the mouth of another in a Mobius strip of nonlinear, undefinable narrative arch, Bailey-Gates’s close-up always includes the eyes of the subject(s) and often the knees. This redoubled fixation on the computational apertures onto human experience and the joints which propel action through the world is startling.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Self-Portrait, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Through Goldin and Sherman, we learned that the close-up lends a humanist lens with which to view an event, but occludes knowledge of everything else in the frame. The close-up provides deep information about a single situation, but renders everything else in fractals. The close-up under their respective kneading became symptomatic of Western culture’s slippage into the postmodern. Bailey-Gates flips this existential form born of cultural angst on its ass—turning transgression into emo transliteration for this new post-postmodern milieu. The close-up in the social media era is now referential of the early-modern painted allegories that were neither sacred texts nor portraiture, but instead a third genre, one conscious of the subject’s transition from human to critical referent. Whether in studio shots, movement studies, genre scenes of bodies in nature, or staged images lit by candles and studio lights, Bailey-Gates frames a close-up that is neither the caress of a third lover nor the blatant impatient stare of the voyeur, but rather the wink of collusion by a knowing accomplice.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Jane and Me, 2018

Courtesy the artist

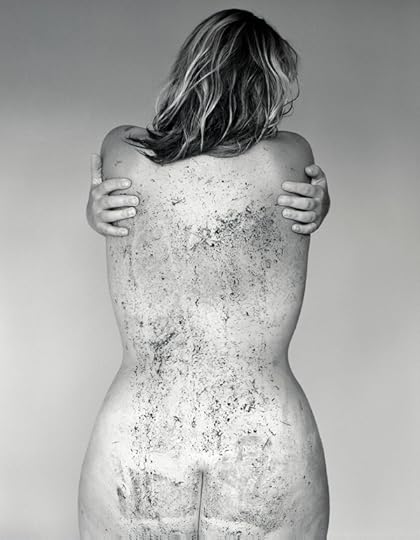

The existential drama of gender and being dissolves before Bailey-Gates lens. Bailey-Gates’s photographs don’t so much interrogate gender as bypass it. With these photos, I’m not just unconcerned with reading the gender of the bodies before me, it’s also futile. The photographic close-up is now an opportunity to collaborate, to collude, to build the little life of a narrative where there was none. The subject becomes less important for who and what they are and dearer to us because of the network of intimacies and experiences they represent.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Zoe covered in mud, 2017

Courtesy the artist

This post-postmodern matrix of ever-expanding intimacies and experiences is what links and distinguishes Bailey-Gates’s attentions to and from the lush austerity of George Dureau or the slick provocations of Robert Mapplethorpe. There is something quintessentially New York about Mapplethorpe; something indelibly Cajun about the New Orleans born-bred-and-died Dureau. There are no tell-tale signs of where Bailey-Gates’s images are conjured from, only a decisive when: the now of our imaginings. I can’t help but see this distinction as one of color, that shifting and shifty attenuator of form and light. Both Dureau and Mapplethorpe are hip to the close-up game: using intimate acts as a way to turn the circus tent and the bathhouse into a studio. Both employ light as a way of rendering the nude or leather-clad body as sculpture, with all the tricks and displacements neoclassicism provides in a postcolonial world.

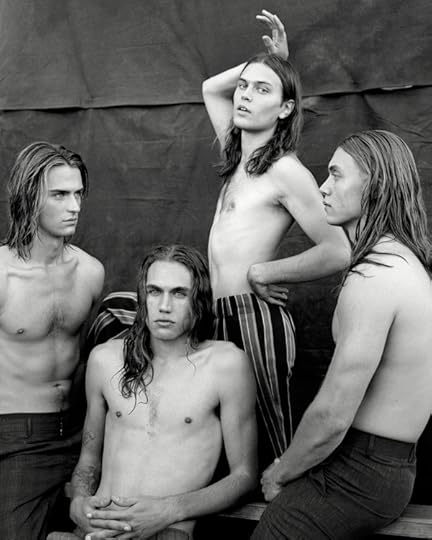

Michael Bailey-Gates, Los Angeles, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Yet both photographers were decidedly male and decidedly gay, with a decidedly uninterrogated male gaze. Both men often photographed their subjects against light backgrounds so the formal taxonomy of limb-to-limb ratios could be enacted. This doesn’t mean their work sucks or is unimportant, it just means the images have no desire to appeal equally to canonical and individual standards of beauty. Their work is not interested in providing a modulated, inclusive vision of truth. Bailey-Gates does not fall into this myopia. Entanglements of power and dependency — electric, historic, proximate — form the compositional landscapes of Bailey-Gates’s formal intersubjectivity. Whether shooting from above and looking down on subject(s) giggling on a bed, or from below with subject(s) carousing above, or shooting bang dead-on, the camera’s aperture filling with the light from subject(s) eyes, Bailey-Gates gives us an expansive gaze — often photographing against dark or riotous backgrounds so that the composition is sonic rather than lucrative and tight.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Saskia and myself, 2019

Courtesy the artist

And while Mapplethorpe and Bailey-Gates are both referential (Mapplethorpe to Thomas Eakins; Bailey-Gates to Marc Jacobs looking at Mapplethorpe looking at Thomas Eakins), only Bailey-Gates is able to mobilize color as a way of referencing past and coeval commercial and editorial modes of looking. These images capture the criticality of pop culture citation and the body’s relation to luxe fashion as both an experience of material and an imagined fluidity of pigment. It seems to my eye that color and citation function in a Bailey-Gates photograph as analogues to critical relations to gender: something we step in and out of, something we try on, wear, perform, then discard if it prevents the kind of encounter we crave.

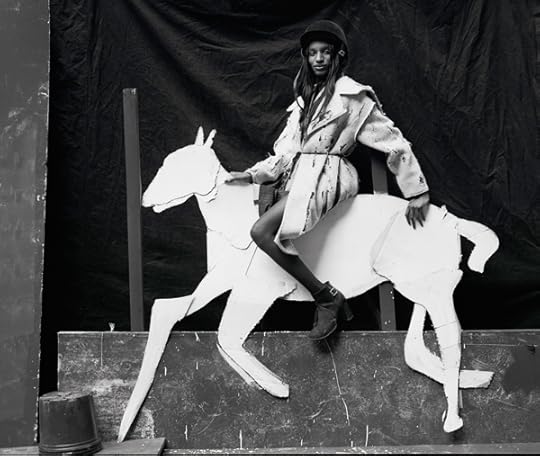

Michael Bailey-Gates, Torraine Futurum with a white horse, 2017

Courtesy the artist

It is the worst-kept secret in culture that sculpture, fashion, and the photograph are the same boi in a new wig. The triplets arise from the same impulse to capture and sustain the body mid–free fall as it navigates Time. These three visual modes provide a body or a subject added dimensionality as it moves. Judith Butler reminds us that gender is constituted in these visual and material mediations through time and space. Neither fixed nor periodically stable, gender is for Butler a tenuous “locus of agency” that provide an illusion of coherence via a stylized sense of repetitive acts. To put it more succinctly, gender is its own dimension through which the human subject as form walks in and out of with every word, act, and thought.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Bobbi and Me, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Back to color. For Bailey-Gates, color is applied across these photographs conscientiously in order to suture the photographic event in Time. The black-and-white images do not read as matte or neutral, but as substantial poetic forms in which our expectations are meant to be affirmed then subverted. The photographs with warm palettes leave the realm of deep time and position us in the immediate present where a decision is about to be made and we are about to bear witness to its unfolding. Color implicates the viewer in the mutual creation of a communal gaze that is joined and spread digitally. I cannot tell where the spiraling web of fashion affecting Instagram affecting ourselves and our posts to Instagram affecting what’s on trend begins. What Michael Bailey-Gates’s images convey, however, is the enduring importance of this ever-widening gyre to include more narratives and more bodies in the “visual tectonics” of culture. But where will it lead?

Michael Bailey-Gates, The Rosemont Girls, 2019

Courtesy the artist

In a future time, say two, three generations from now, cyborgs will recover the photographs of Michael Bailey-Gates as the first flourishing of themselves. Cyborgs, you understand, don’t have sex. They don’t need to, as the network they are all tuned into for their being is a constant and consistent matrix of connection and interrelationality. They also don’t do clothes. But the cyborg body is a pleasuredome of expanse served in circuited refractions of genderplay and agency, and the digital photograph serves this up with all the jolt of mainlining caffeine. They keep their humanoid shape as homage to us, their great grandparents.

Michael Bailey-Gates, Rob, Shun, Yves, Tzef, and Bobbi on my table, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Bailey-Gates knows this. Bailey-Gates’s surname will flicker in neon Helvetica across the cyborg chest—between the on and reset switches of memory. The transmodalities of the cyborgian mind-space continuum allow them to conjure the pages of MATTE from thin air in order to learn when the photograph in the digital age stopped serving facets of reality and began inventing futurities. Bailey-Gates is going to be a band name of epic post-hip-hop-punk potentiality in this future age. Draft an email to your children’s children. Tell them you peeked this visual revolution first.

Horace D. Ballard is Curator of American Art and Research Curator for Photography at the Williams College Museum of Art.

This essay originally appeared in MATTE magazine, issue 53, 2019, and is republished courtesy the author.

The post Can this Young Photographer Dissolve the Drama of Gender? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 22, 2019

Tilda Swinton Guest Edits Aperture’s “Orlando” Issue

Vivane Sassen, from the series Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg. All sculptures belong to Musée du Louvre and Château de Versailles

Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando (1928), perhaps the author’s most whimsical, begins as a tale of a young nobleman in the age of Queen Elizabeth I. Orlando, improbably, lives for centuries and along the way mysteriously shifts gender, a radical plot point that is rendered—in an even more radical gesture—as a nonevent. After having Orlando traverse time and geographies, Woolf concludes the narrative in her present day, October 1928, on the eve of the book’s publication.

In 1992, director Sally Potter adapted the novel for the screen and cast Tilda Swinton, the guest editor of Aperture’s summer issue, in the role of Orlando. The film version, like all translations of a story from one medium to another, takes its liberties, extending Orlando’s life decades further, leaving her in the early 1990s.

With this issue, Swinton continues that journey.

She calls upon Woolf’s central themes—gender fluidity, limitlessness, and the deep perspective that is earned from a long life—and connects them to our present day. The film Orlando arrived at a moment when debates around identity, representation, and society shook the culture, notably with the controversial 1993 Whitney Biennial, referenced in a conversation between writer Maggie Nelson and artist Shannon Ebner. Those debates still resound as a new generation of photographers push to challenge institutions and representational codes, insisting on their own narratives, their own visions.

In “Orlando,” we move through portals and across time. Reflections by the acclaimed authors Michael Cunningham, Marina Warner, and Lynne Tillman underscore the prescience of Woolf’s playful experiment from the 1920s, while filmmakers and critics Sally Potter, Isaac Julien, and B. Ruby Rich—who, along with the iconoclastic auteur Derek Jarman, defined queer cinema aesthetics in the 1980s and ’90s—consider the power of rendering narratives like Orlando on-screen. Lynn Hershman Leeson melds art making and futurism. And Viviane Sassen approaches classical statues at Versailles as if they were living subjects, creating hybrid bodies for her newest series Venus & Mercury (2019). “I try to make images that have the ability to free your mind in some way and to look at something from a different perspective,” Sassen says. “My images are like a hall of mirrors; they reflect back at you what you already have inside.”

At Swinton’s prompting, a group of artists made work expressly for this issue. Mickalene Thomas’s Orlando-inspired portraits unite fashion, the classical muse, and nineteenth-century painting. Paul Mpagi Sepuya confronts the depiction of the Moor on the first page of Woolf’s book. Elle Pérez, channeling Woolf’s devotion to her lover Vita Sackville-West, for whom Orlando was written, makes portraits that read as love letters to fellow artists. Carmen Winant assembles collages that layer the images Woolf originally selected to illustrate the pages of Orlando. Jamal Nxedlana travels through Johannesburg with the gender binary–flouting artist duo FAKA. And Walter Pfeiffer and Collier Schorr delve into their own archives to create revealing new image sequences of bodies in states of youthful transition.

“Woolf wrote Orlando,” Swinton notes, “in an attitude of celebration of the oscillating nature of existence. She believed the creative mind to be androgynous. I have come to see Orlando far less as being about gender than about the flexibility of the fully awake and sensate spirit. This issue of Aperture will be a salute to limitlessness, and a heartfelt celebration of the fully inclusive and expansive vision of life exemplified by the extraordinary artists collected here.”

Today, when many are turning inward, or calling for borders, when suspicion abounds about those unlike ourselves, a story such as Orlando, which celebrates the expansiveness and possibilities of human experience, is a much-needed parable.

Pre-order Aperture, issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. “Orlando,” an exhibition guest-curated by Tilda Swinton, is on view at Aperture Gallery from May 24–July 11, 2019.

The post Tilda Swinton Guest Edits Aperture’s “Orlando” Issue appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 20, 2019

Free Zine-Making Workshop with 8-Ball Community

Join Lele Saveri, founder of 8-Ball Community, for a free one-day workshop intended for young professionals, students, and creatives who are interested in creating and producing zines. Throughout the day participants will experiment with sequencing and editing, as well as learn about different printing, binding, and formatting techniques that go into zine production. Participants will look at both current and past issues of Aperture Magazine to draw inspiration for their own zines.

The first session, June 15, is reserved exclusively for students, ages 15–24. You will be asked to show a student ID upon registration.

The second session is open to all.

Materials will be provided. Light refreshments will be served throughout the day.

8-Ball Community Inc. is an independent not-for-profit organization that—through free, open-access platforms and events—nurtures and supports a community of artists. We provide virtual and physical meeting sites for people of all ages, genders, and backgrounds. Our mission is to generate collaborative and educational exchange through public access television and radio stations, an imprint, a self-publishing fair, a public library, an internship program, a residency, and a series of workshops in art-related trades. 8-Ball Community operates free of elitism and is governed by its participants.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Materials to Bring:

Participants are encouraged to bring printed or digital photographs they would like to include in their zine

Tuition:

Tuition for this one-day workshop is FREE. Please note, there are only 20 spots for each session.

REGISTER HERE

Registration for Session 1 ends on Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Registration for Session 2 ends on Wednesday, June 19, 2019

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

CANCELLATION

If you choose to withdraw from the workshop, please do so 2 days before your scheduled session to allow Aperture to fill your seat. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Free Zine-Making Workshop with 8-Ball Community appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 17, 2019

Barbara Ess is Always Watching

An artist investigates the aesthetics of surveillance at home and on the U.S.-Mexico Border.

By Izzy Leung

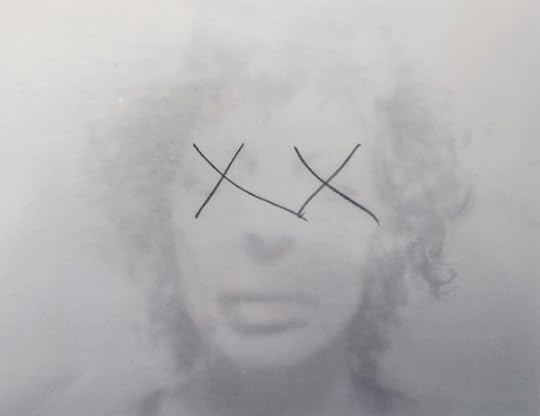

Barbara Ess, Peekaboo, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

“There’s something very odd about trying to stop the world,” Barbara Ess says. Ess began her career not as a photographer, but as an experimental filmmaker and musician, engaging with mediums that embrace time rather than trying to stop it. While participating in international collectives and film festivals, Ess began using single-frame stop-motion cameras to create films, which she then turned into zines. A fresh dedication to photography was born as she then began self-publishing books featuring isolated still images such as This Happened Yesterday (1979) and Human Life (1979). Ess became fascinated with the divisions between movement, stillness, and sound.

Barbara Ess, Fire Escape, 2011, from the series Shut-In

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

Ess is also interested in the distance a camera creates and what viewing life from afar accomplishes, or as she describes, the chasm between self and other, the “in-here” and “out-there.” She has tackled this subject in past work, most notably in the book I Am Not This Body (1991), published by Aperture. Someone to Watch Over Me, recently on view at Magenta Plains in New York, features work made over the past nine years that explores themes of distance, subjectivity, and mediation. (Ess was my teacher when I was a student at Bard College.) Spanning both floors of the gallery, the exhibition included seventeen photographs, two videos, and a sound piece. Three series—Surveillance, Remote, and Border—employ photographs captured from live-stream footage; another body of work on view, Shut-In (2018–19), was created while Ess was isolated in her apartment for a month with bronchitis.

Barbara Ess, Beach (from Balcony), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

Someone to Watch Over Me explores the divide between where you are and where you are not—what it’s like to witness events outside one’s window or one thousand miles away. “I asked someone once, how is the world where you are not? You never know,” Ess told me when we spoke recently. “When you walk out of a room, what’s it like when you’re not there?” In Someone to Watch Over Me, Ess captures images in unorthodox ways: placing a small telescope before a lens, using a broken point-and-shoot camera and taking screenshots from her computer. Each method of image-making derives from a source of mediation, distancing Ess further and further from the actual world in which her subjects reside.

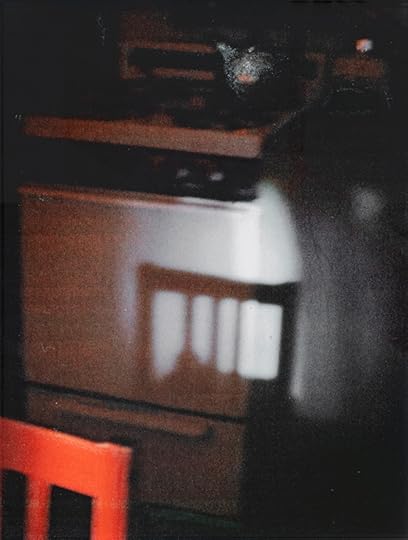

Barbara Ess, Kitchen, 2011, from the series Shut-In

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

In Shut-In, which was installed in the basement level of the gallery along with several images taken from traffic and weather cameras, Ess depicts details of her apartment and the view into neighbors’ windows, only to show that their blinds are drawn. Vases and air conditioning units become the focus, obstructing viewers from gaining entrance into their lives, and drawing the attention back to Ess. These are the only photographs directly representative of the artist’s personal life. Ess created the images using a standard inkjet printer, drew on them with crayons to alter the texture, rescanned them, and then printed them large. Even Ess’s still images feel as if they are moving. The lo-fi quality vibrates in its graininess, producing the same stir-crazy feeling one might experience after a month of being stuck inside an apartment.

Barbara Ess, Attenti al Cane (Cyan Dog), 2007

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

To Ess, the thematic center of the show was in two photographs, most visible when exiting the gallery, Peekaboo (Seeing Not Be Seen, 2014/2019) and Attenti al Cane (Cyan Dog) (2007). Peekaboo, a silvery self-portrait of Ess, was the only image in the exhibition depicting a full face, yet Ess has drawn two Xs marking out her eyes, negating the ability to see her image fully. The two black Xs are both a punk gesture, as well as a reference to Rosalind Franklin’s photograph of DNA, Photo 51 (1952), according to Ess. Here, she is both fact and fiction, present and not, captured in a fog. Sitting below Peekaboo is Attenti Al Cane, or “Beware of Dog” in Italian, a blurred image of a German shepherd. The dog “acts as both a protector as well as some kind of surveillance, a watch dog, a seeing eye dog,” Ess explains. The original function of the dog is buried in the layers of distance from the dog itself. “This separation gives you some emotional and mental distance, from your subject, to roll around in your mind and your eye,” she says.

Barbara Ess, Rio Grande, 2012

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

Back on first floor were images from the Surveillance and Border series, all pulled from livestream footage on the U.S.–Mexico border. To have access to cameras monitoring the border along Texas, Ess signed up as a “Deputy Sheriff,” where she was tasked with reporting suspicious behavior. The resulting video from a heat-sensitive camera, Crossing (2011), is shockingly pastoral in comparison to a neighboring image, a sign warning passersby of an electric fence. The camera pans across trees blowing in the wind, and down a river, catching a pack of galloping horses, all while following a man as he tries and ultimately succeeds in entering the United States by crossing the Rio Grande. While Ess didn’t have any agency in what she saw, aside from what she decided to record, the video embraces the beauty in the mundane, of watching and waiting from a distance. It’s easy to imagine that someone who would sign up to survey the border would be eager to report illegal activity. Instead, Ess found interest in the forms of the water and the trees, and the deceptively small narratives of the people she encountered.

Izzy Leung is a photographer and former Aperture work scholar based in Brooklyn.

Someone to Watch Over Me was on view at Magenta Plains, New York, April 7–May 12, 2019.

The post Barbara Ess is Always Watching appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 15, 2019

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Camp

James Bidgood’s queer and candy-colored photographs were camp before camp was stylish.

By Jesse Dorris

James Bidgood, Bullfighter, ca. 1960s

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

Reveries, the Museum of Sex’s retrospective of James Bidgood’s photographs, film, and ephemera, tells the story of an American narcissus, a boy entranced by the beauty of his own vision. Largely self-taught, Bidgood transformed tricks both male and mechanical into proofs of better, queerer worlds. Forced perspective mixed with male-on-male affection, with smears of glitter and Vaseline that blurred the male gaze into a horny swoon. It won him immortality, but became all that he could do.

James Bidgood during World War II, standing outside his father’s tavern with his dog, Jack, ca. 1940s

Courtesy James Bidgood

Bidgood seems to have been born (in 1933) the way certain boys are: an early personal photo in the show offers him smiling near a dog and looking somewhere over the rainbow. In Madison, Wisconsin, during the depths of the depression, he harangued his mom to buy him an expensive paper doll collection; he spent afternoons watching the Technicolor Follies fantasias. Then, at the age of eighteen, he moved to New York, ready for stardom, and while he was homeless for a while, he always says that his tight pair of Levi’s kept him out of the rain.

James Bidgood as Terry Howe “mixing” at Club 82 as Carol Channing, ca. 1950s

Courtesy James Bidgood

In the 1950s, Bidgood made himself at home at Club 82, a drag club in the Village that an article in the March 1968 issue of Man to Man magazine recalled as a favorite of Judy Garland, Liz Taylor and Eddie Fisher, and the Gabors. “Male couples are usually in evidence,” notifies author Raoul MacFarlane, “but they are vastly outnumbered by heterosexual pairs, and to the surprise of management and everyone else, the 82 has become a favorite with suburban women’s club groups.”

Costume for Junior League Mardi Gras Ball Pageant designed by James Bidgood, ca. 1960s

Courtesy James Bidgood

Perhaps they were window shopping. Bidgood frothed his Follies memories into elaborate set and lighting designs for the stars of Club 82, and his costumes for them and his own drag alter ego, Terry Howe. A delightful image of Howe has survived, boothed among vast heterosexuals in a clenched pose. The appeal is irresistible. By the early 1960s, the women took his gowns uptown, gentrifying them into jaw-dropping creations paraded around the Junior League Mardi Gras Ball, prefiguring similar appropriations by the recent Met Gala.

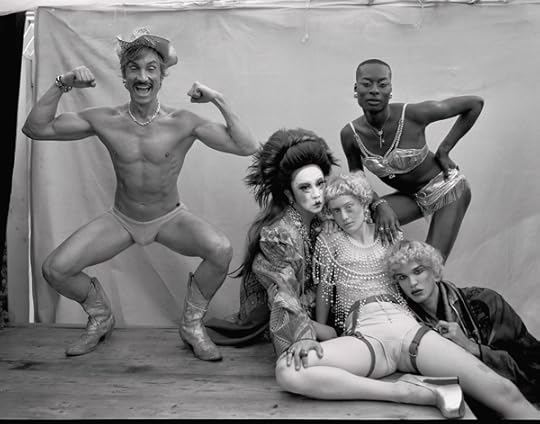

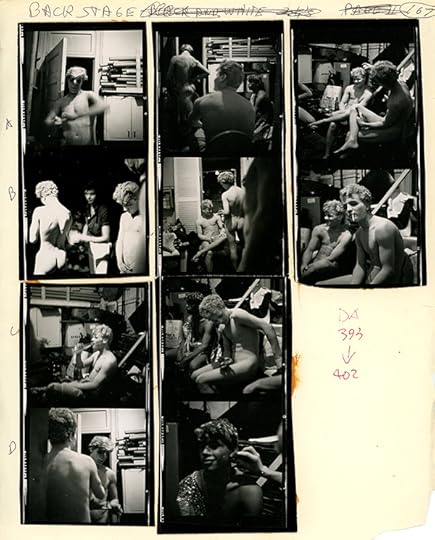

Backstage during the filming of Pink Narcissus. Contact sheet, ca. 1960s

Courtesy James Bidgood

They probably didn’t ask, and Bidgood probably didn’t tell, but after the party was over the couture would trickle downtown—well, West really, to his flat in Hell’s Kitchen—where he’d refashion his vision with wit and thrift into glamourous backdrops for gay porn. Left cold by the aw shucks naturalism of Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial shots of twinks in posing straps, Bidgood desired his hustlers as noir heroes, photographing Jay Garvin from below in a clam-shell G-string with bejeweled nipples and a lobster in each hand that looks made of lamé. Bruce Kirkman beckons from behind chiffon boughs of willow; it made the cover of Muscleboy, a magazine subtitled Incorporating Demi-Gods that not only was the closet thing to porno the government allowed, but also offered sets of slides or art prints for a small fee, thereby seeding queer imaginations wherever the post office delivered.

James Bidgood, Setting Down White Boot, First Cover, ca. 1960s

Courtesy of ClampArt, New York

Like Jack Smith’s film Flaming Creatures (1963), Bidgood’s magnum opus Pink Narcissus is less a slice of life than a smorgasbord of candy-colored novelties; like Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954), no definitive version exists. It’s a feast, starring Bidgood’s likely lover Bobby Kendall as a hero among homemade urinals that baptize the faces of bikers who themselves almost drown in pools of pseudo-semen and also threaten toreadors while Charles Ludlam hawks and licks “pissicles” from a cart. The film does have an odd puritanical streak, in which pleasures of the flesh inevitable lead to ruin—but what pleasures!

James Bidgood, Willow Tree, ca. 1960s

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

Sadly, by the time the government allowed hardcore porn, Bidgood was still hypnotized by his vision, and hadn’t or couldn’t yet finish. “The big boom of porn culture,” says curator Lissa Rivera, “wasn’t his style. It wasn’t elaborate. It wasn’t something that was going to take seven years to shoot and have jewels.” It was, as they say, just too much. Producers wrenched the film from him and made a lousy 1971 print Bidgood took his name off. Meanwhile, audiences lapped up Warhol’s faux verité and the hedonism of Wakefield Poole. Bidgood went back to window dressing, and has shown little work since.

James Bidgood, Smoking, Sandcastles, ca. 1960s

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

The bud of Pink Narcissus would bloom in the work of Pierre et Gilles and David LaChapelle and Ryan Trecartin and Greer; its gauzy shimmer shines in films like Blade Runner and Soft Cell’s Non-Stop Exotic Video Show and Prince’s Sign o’ the Times. The pink-and-blue palette prefigures the “bisexual lighting” lately gracing Janelle Monáe. While drag queens have for decades mined his work for their art, it must also be noted the exclusive focus on male bodies in racialized fantasias would likely get the film “cancelled” today.

James Bidgood, Valentine, ca. 1960s

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

But the ripples of Bidgood’s influence appear in most every artsy earnest queer on Instagram who gazed into Bidgood’s pool and saw themselves. And what remains is a wide-eyed, world-building tribute to the beauty of narcissism. “He wasn’t being ironic,” says Rivera. “He was interested in the fantasies he had since he was a boy. He’s elevating men who don’t get elevated: queer men, hustlers, people from the drag world. He loved them in this emotional visual sense. He still loves that way.”

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

James Bidgood: Reveries is on view at the Museum of Sex, New York, through September 8, 2019.

The post Extremely Loud and Incredibly Camp appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 10, 2019

The Enduring Legacy of Frederick Douglass

Isaac Julien’s latest film explores the life and work of a man who believed in the power of photographs to transform American society.

By M. Neelika Jayawardane and Phillip White

Isaac Julien, The Lady of the Lake (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

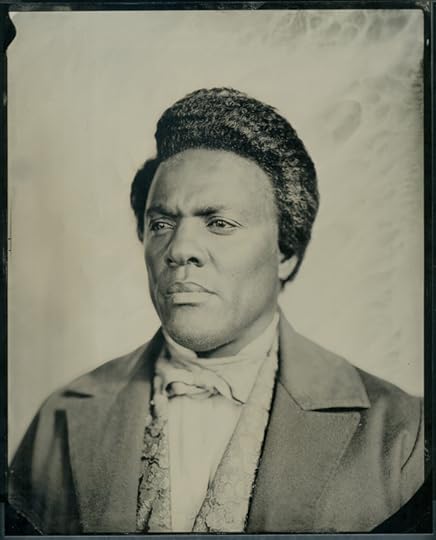

Isaac Julien’s latest multiscreen film installation Lessons of the Hour–Frederick Douglass reflects on the life and work of the nineteenth-century abolitionist, as well as Anna Murray Douglass, Helen Pitts Douglass, and several other powerful, single-minded women involved in campaigning against slavery. Commissioned and acquired by the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, New York, where it was presented this spring concurrently with an exhibition at Metro Pictures in New York, Lessons of the Hour asks audiences to engage in call-and-response with Douglass, and the wealth of images and self-constructed narratives he left behind. It is both an homage to the enormity of Douglass’s sacrifice in the service of his “race” and a reflection of the limits of attempting to transform the violence inherent in racism using rational approaches.

Isaac Julien, The North Star (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

Today, it is widely accepted that Frederick Douglass was the most photographed person of the nineteenth century—even more so than Abraham Lincoln, whose portrait had pride of place over the Douglass-Murray household’s fireplace, along with photographs of fellow abolitionists and supporters of women’s rights. In 2016, a new Douglass photograph was rediscovered during routine repairs for a scrapbook, which had been stored in the Special Collections of Rochester Public Library’s Local History and Genealogy Division. The scrapbook was created by William H. James, a postal carrier who lived in Rochester, New York, where Douglass and his first wife, Anna, lived from 1847 to 1872. Like all Douglass photographs, this latest find also portrayed a man fashionably dressed, poised, a gentleman of his era.

Between 1841 and 1895, Frederick Douglass sat for about 160 photographs. He viewed photography as a “democratic art” and praised its ability to bring the power of image-making and self-representation to a greater public. Douglass recognized that new photographic technologies made it possible for a larger public to enjoy images in their own homes, and allowed us to project, to the world, the self as we wished to be seen. He also understood that just as modes of travel and transport gave the Western subject freedom to be mobile—and thus further solidified their subjectivity—so too had the mobility of images: “The facilities for travel has sent the world abroad, and the ease and cheapness with which we get our pictures has brought us all within range of the Daguerreian apparatus.”

Isaac Julien, Lessons of the Hour Project Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (After Fredrick Douglass II), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

But as Thulani Davis reminds us, in the foreword to For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights by Maurice Berger (2010), “In every decade since escaped slaves began to produce narratives of their lives in bondage, there have been one or two African-Americans whose lives and images have appeared in the mainstream and have been characterized as representing our experience.” These couriers had to bear the burden of taking with them, wherever their image and narrative journeyed, a message intended to show white America (and fellow Black people) that to be Black was in opposition to prevailing white supremacist views, while—as Davis argues—anticipating how white audiences would likely receive one’s image and one’s person.

Isaac Julien, J.P. Ball Salon 1867 (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

Julien’s video work does not allow audiences to walk away with an untainted perspective about photography, as would a man who came into his full subjectivity at the moment when the technology was made more accessible to the public. Rather, it is a painful reflection of the ways that photographic technologies, in which Douglass so fervently believed as a tool for transforming racist views, continue to be used—by individuals, institutions, and structures under which we all live—for subjugating Black communities. Instead of aiding our efforts at directing and amalgamating our subjectivity, photography continues, in the twenty-first century—just as it did within the early years of invention—to be used for surveillance, documentation, and further denigration of those regarded as racialized others.

Isaac Julien, Lessons of The Hour London, 1983

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

The photographic images in the entryway of Metro Pictures gallery were both intimate and expansive, consisting of small tintype portraits that harken our collective historical memory of nineteenth-century photographs, and large, lush color stills from the video works. To these, Julien added black-and-white photographs documenting protests that followed the killing of Colin Roach, a twenty-three-year-old black man who was shot to death at the entrance of an East London police station in 1983. (Julien’s 1983 film, Who Killed Colin Roach? engages more fully with this brutal incident.)

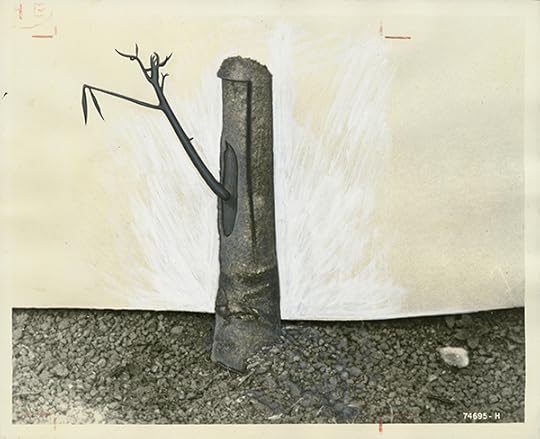

But the main attraction is Julien’s new video installation, filmed at the Royal Academy of Art in London, which splices reenacted montages of Douglass’s glorious, powerful presence, and samples three of his most powerful lectures: “Lessons of the Hour,” where Douglass addresses lynching in the South; “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July,” where he questions the meaning of freedom to those in bondage; and “Lecture on Pictures,” where he marvels at the power of photography to empower its subjects, giving them autonomy over how wished to represent themselves. He believed that these “truthful” depictions would win over stereotypical depictions that aided white supremacy.

Isaac Julien, Serenade (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

When Douglass reflects on freedom, or lynching, we also see footage of cotton fields that fill the screens, or a great, hulking tree, which creaks with its burden. Toward the end, as Douglass questions the legitimacy of the Fourth of July as a universal celebration for all Americans, we see some of the screens fill with grainy, contemporary video. This is aerial surveillance footage, made by the FBI, of the Baltimore riots of 2015 following the acquittal of all police officers involved in the death of twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray, who suffered a severe spinal cord injury while in the back of a police van in Baltimore on April 12, 2015, and died a week later as a result.

Isaac Julien, Helen Pitts Class of 1859 (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

In order to provide a more complex view of Douglass, Julien worked on developing what he calls his tableaux vivants in which he details Douglass’s relationships with the women in his life. These intimate, intertwined portraits indicate that this great man’s accomplishments were accompanied primarily by the kindness, financial support, intellectual companionship, and emotional care of women. Douglass’s first wife, Anna Murray, a born-free black woman, was married to Douglass for forty-four years, bore their five children, and maintained their home and family while Douglass traveled throughout the United States, and during a two-year journey in Great Britain. Following Anna’s death in 1882, two years later, Douglass married Helen Pitts—educated, white, raised in an abolitionist family, twenty years his junior.

Isaac Julien, Lessons of the Hour Project Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow (After Anna Murray Douglass), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

Anna Murray appears in several of Julien’s photographs, sometimes accompanying her husband on a train or together with a group in a parlor. In one sumptuous image, she is seated on her own; she appears as a woman as determined and forward-thinking as any of her counterparts—though she did not have the advantages of being able to read and write in a world that made literacy a requirement for proving one’s humanity. That Murray and Pitts were not only facilitators in Douglass’s journey, but collaborators in the political work of self-fashioning, is evident in scenes where Anna Murray is shown at her hand-cranked sewing machine, attending to a royal blue velvet garment, which allows Douglass to carry himself regally as he gives public lectures. We know that Douglass’s life and work were financially dependent on others and their charity. When Julien’s video work shows Helen Pitts at her desk, reading correspondence and writing, we know a small part of what it must have taken to generate that support.

Isaac Julien, J.P. Ball Studio 1867 Douglass (Lessons of The Hour), 2019

© the artist and courtesy Metro Pictures, New York

Douglass maintained his complicated perspective—which, in the twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois named “double consciousness”—throughout his life. Douglass seemed fully aware of where he came from, and what his extraordinary education, along with others’ financial and emotional support, allowed him to accomplish. He often contrasted his life as a barefoot child of slavery, dressed in rags, to the well-dressed visitor of the White House, an exemplar of respectability. Julien’s film adds necessary complexities to versions of history that often portray great men like Douglass as exceptions. Julien also complicates Douglass’s laudatory commentary on photography, showing how this remarkable tool—so often subverted by powerful systems of authority—can still move us to reclaim freedom and dignity.

Neelika Jayawardane is associate professor of English at the State University of New York-Oswego, and research associate at the Visual Identities in Art and Design, University of Johannesburg. Phillip White is a former lecturer in the School of Education & Human Development at University of Colorado Denver.

Isaac Julien: Lessons of the Hour–Frederick Douglass is on view at Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, through May 12, 2019.

The post The Enduring Legacy of Frederick Douglass appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 6, 2019

Introducing: Karolina Karlic

For the second installment of our new series, “Introducing,” Aperture speaks with a photographer tracing the globalization of rubber from the Amazon to Ohio.

By Annika Klein

Karolina Karlic, Emilly Farias in the Michelin rubber groves, Bahia, Brazil, April 2014

In 1987, when Karolina Karlic was four years old, her family moved from Wrocław, Poland, to Detroit. Her father had been hired as an engineer, and Karlic spent her childhood in a city troubled by racial tension and economic decline. Later, in California, Karlic studied with photographer Allan Sekula, whose work traces the connections between labor, industry, and the environment. Karlic’s first major body of work, Primer (2008–13), reflects upon growing up in the motor city, and investigates the industry that first brought her to the U.S.

“In the Ford archives, I located many photographs that were made with the intent to report back to headquarters,” Karlic recalls. Her research on American auto manufacturing eventually led her to the archives of tire companies back home in Michigan, and in Akron, Ohio. These corporations fuel the economy and enable globalization: commerce would break down without jets and trucks to deliver goods, and these vessels still rely on rubber tires. Though some rubber is synthetic, a surprising amount—about half, some thirteen million tons annually—comes from a rubber tree indigenous to the Amazon.