Aperture's Blog, page 84

July 31, 2019

From an Italian Photographer, the Bygone Days of Bohemian New York

Ugo Mulas captured the swinging 1960s art world defined by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg.

By Jesse Dorris

Ugo Mulas, Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

It often takes an immigrant to show America to itself. Italian photographer Ugo Mulas only visited here, but his view of New York in the mid-1960s changed the way we see the city and the bohemian enclave it stands for. That world—with its sizable lofts, oversize ambition, and stance that life could be art and vice versa—only barely exists today (if at all) in neighborhoods like Chelsea, where more than one hundred of Mulas’s images hang at Matthew Marks Gallery in Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene, a thoughtful exhibition organized by curator Hendel Teicher.

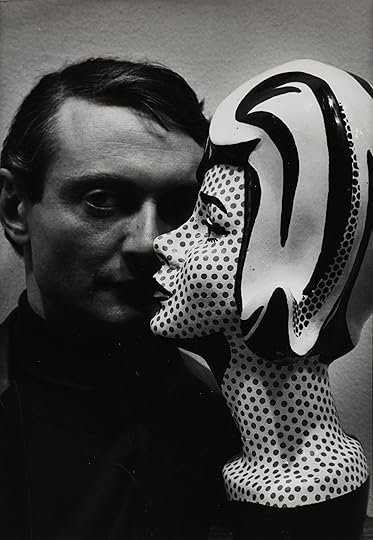

Ugo Mulas, Roy Lichtenstein, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Born outside of Milan in 1928, Mulas thought he’d become a lawyer, but he abandoned school after falling in love with Milanese nightlife, photographing people posed at the infamous Bar Giamaica with a borrowed camera. By 1954, he was the Venice Biennale’s official photographer; ten years later, he’d developed a style: inquisitively formal, full-frontal, and based on long nights watching theater rehearsals. He made definitive portraits of Alexander Calder, David Smith, and Lucio Fontana. And he formed crucial friendships with figures like Leo Castelli and Andrew Solomon, whom he met at the 1964 Biennale and who convinced him to take a trip to New York.

Ugo Mulas, Jasper Johns, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

“He didn’t speak much English,” Teicher told me, “but you don’t have to speak much English as a photographer.” Instead, Mulas sat in artists’ lofts, around dinner tables, and in studio rehearsals, galleries, and clubs. “I feel impersonalized,” Mulas once remarked. “Thus I try to understand what is happening around me, doing it through my photos.” He returned in 1954 and 1967, and produced an epochal catalogue of what he saw, 1967’s New York: The New Art Scene. Teicher pulls from this book and unpublished work from the time for her show, which greets viewers with fascinating maquettes of the manuscript, before opening into zones for Mulas’s studies and collaborations with a who’s who of New York’s midcentury artistic characters.

Ugo Mulas, Roy Lichtenstein, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Each zone centers one of Mulas’s formal innovations: printing an entire roll of film as a single image, thus transforming time spent watching an artist work into a flip-book, or a skyscraper with parties or workspaces glimpsed through rows of windows, or even from a distance, a kind of Mondrian grid. Favored images earn pride of place next to contact-sheets-as-photographs: Marcel Duchamp, Mulas’s first artistic love, standing between drapes like a magician appearing; Barnett Newman, standing stiffly in a suit and pointing to a vast, empty canvas as if to say, “that’s enough.” A series of action shots of Roy Lichtenstein integrates fascinating photographs of comic book scraps taped to the walls with glamor shots of the artist pressing his face to dotted busts and other merchandise, a self-conscious blurring of the lines between product and producer. Mulas’s portraits of Andy Warhol manage to find something new in someone overexposed even then, with a 1964 photograph drawing attention to the fragile veins in his hands, those physical tools Warhol worked so hard to make irrelevant.

Ugo Mulas, Police stop a dancing party at Andy Warhol’s Factory, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

“Mulas always gives you enough information to understand what kind of character you are dealing with,” Teicher says. And what characters! Juxtaposing photographs of Warhol’s world—a police raid on the Factory with a man thrusting his ass out beside another man pounding a bottle of beer—with those of Robert Rauschenberg’s tells you everything you need to know about the difference between the two artists. Rauschenberg’s vast loft includes domestic clutter and a long table of friends invited for Thanksgiving dinner; other photos study Trisha Brown arranging her body in practice, or Rauschenberg half-naked in shadows, mid-thought and yet in costume (for Spring Training). In these images, life and work are as carefully balanced as Mulas’s compositions.

Ugo Mulas, Jasper Johns, 1965

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Watching Jasper Johns changed Mulas’s idea of what should be shown. In as intimate a moment as is possible between two artists, Mulas captured Johns from behind in the act of creation. The power dynamic—one artist transforming the labor of another into work of his own—unnerved him. “If the painter agrees to be shot, the photo is purely for public relations purposes,” Mulas later explained. “If the painter refuses and I succeed in convincing him, the photograph is an act of violence.” Mulas rarely photographed artists at work again; his portraits of Johns instead show Johns wrapped in sweaters and staring down his gaze, or pressing a sweating face into the canvas as if it were a pillow or a lover.

Ugo Mulas, Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol, 1964

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Mulas left New York and returned to documenting the Italian art world; an accomplished writer and critic, he finished the series Verifications, a kind of meta-manifesto, shortly before he died of cancer in 1973. The images in The New Art Scene now look like arguments for—more so than evidence of—a world that takes artistic practice seriously. One hopes someone new is able to come to New York today and not only make this argument, but win it. But it’s surely more difficult now than it was for Mulas. “One needs to realize that my point of view is not only optical, but mental above all,” he once said. Which is to say that maybe this world was a state of mind after all.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene is on view at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, through August 16, 2019.

The post From an Italian Photographer, the Bygone Days of Bohemian New York appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Delirious Cities: The 2019 Aperture Summer Open

The city is an ever-changing landscape, a place of contested freedom, a laboratory of identity, a supermarket of desires. When the architect Rem Koolhaas first published his 1978 manifesto, Delirious New York, he wrote of density and ecstasy, of the epic visions of Manhattan skyscrapers and the otherworldliness of capitalist congestion. Through their photographs, videos, and lens-based installations, the twenty-three artists selected for the 2019 Aperture Summer Open propel Koolhaas’s curiosity into the present, defining the contours of metropolitan life in the twenty-first century. Together, they offer urgent statements about how images are shaping the contemporary city as an endless project, a delirious machine for living.

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled, 2018–19

Courtesy the artist

Sara Abbaspour

Originally trained as an urban designer, Sara Abbaspour makes photographs in the Iranian cities of Tehran and Mashhad, as well as on Hormuz Island. Her lush and cinematic images, characterized by crystalline highlights and a mysterious sense of drama, explore mental states of connection and contemplation. Abbaspour is influenced by the American photographer Mark Steinmetz and the late Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, whose poetic films were associated with the Iranian New Wave of the 1960s. “In my work, I wonder about entanglements of life rippling outside the frame of my vision and the silent internal conversations of the people I photograph,” Abbaspour says. “I study the poetics of spaces and states in transition, the concealed burden of history on a nation’s back, and the wonders of a people floating in precarious eternity.” In these images from an ongoing series, Abbaspour is also thinking through the idea of psychogeography, first proposed in 1956 by the French theorist Guy Debord. A member of the movement Situationist International, Debord and other artist-flaneurs were keen to think about how urban spaces inform behavior and feelings. A flaneur herself, Abbaspour is aware of the undercurrent of political tensions in her work. “But,” she says, “in an era of intergovernmental and political hostility and projected identity politics, I believe that an apolitical or poetic expression can be the most profound political response.”

Laura Barrón, La Paz, 2016, from the series Absentia

Courtesy of the artist

Laura Barrón

“All my work has been a continuation of a discourse about nostalgia, absence, and loss—themes that constitute moving targets in one’s life,” says Laura Barrón. In 2013, after a decade of living as a Mexican immigrant in Canada, Barrón decided to learn about the cities that her fellow Latino Canadian friends grew up in. She participated in residencies in several cities, usually for about seven weeks at a time. La Paz City, a subseries of Absentia, explores “vertigo in relation to the precariousness of its territory and urban landscape.” The dizzying upside-down images of dense urban spaces verge on abstraction, making one wish for the stability of understanding—and of home. Absentia, she says, “has become a meditation on historical trauma, national or cultural identity, and the desire to change one’s life forever by changing one’s surroundings and nationality.”

Rydel Cerezo, Undercover, 2019, from the series Am I a Sea

Courtesy of the artist

Rydel Cerezo

The sin and the service, the modesty and the majesty. Since Spaniards celebrated the Philippines’s first Catholic Mass in the island town of Limasawa on March 31, 1521, the contradictions of Catholicism have been ever present in Filipino life. For Rydel Cerezo, a queer Filipino from an immigrant family, the inability to fully escape the religion is a consequence of the holy entanglement of colonial enterprise and Catholic imperialism. “I am interested in the history of the church that served as a tool involved in the colonial mission and now acts as a space for bodies to commune with one another in the Diaspora,” Cerezo says of his autobiographical series Am I a Sea, which considers the trauma and love delivered by the Catholic Church. Cerezo uses his family members and a palette of bold primary colors to restage moments of Catholic ritual in an attempt to “probe the familiar space of the church in relation to the living post-colonized body.” Although church leaders speak of compassion and forgiveness, respect for the fully realized lives of queer Catholics often falters before the reverence for tradition. Cerezo’s photographs, blending the staged with the documentary, renew what Catholics call “the mystery of the faith.”

Alex Huanfa Cheng, A boy with a flower, 2018, from the series Chinese Wonderland

Courtesy the artist

Alex Huanfa Cheng

Seven years ago, Alex Huanfa Cheng left his hometown in Hubei, China, to study photography in France. From a distance, Cheng began to see his home from a new perspective. “China is an evolving country and is full of contradictory duality,” he says. In his series, Chinese Wonderland, created while visiting home and traveling throughout the country, Cheng pictures scenes of leisure and everyday life in playful juxtapositions. In one image, a boy brushes up against a small tree of pink flowers, blossoming amid a landscape of half-demolished buildings and rubble. In another, Buddhist statues and temple furnishings stand before an industrial background. Telephone wires crisscross behind them through a hazy, gray sky. With wry humor, Cheng photographs small moments layered with inconsistencies, noting that “this kind of complexity is precisely what makes contemporary China so exuberant and fascinating.”

Rose Marie Cromwell, Bike Accident, 2016

Courtesy of the artist

Rose Marie Cromwell

Miami is Rose Marie Cromwell’s subject and canvas. She photographs in Little Haiti, Liberty City, Allapattah, Bay Point, Edgewater, and Wynwood, each neighborhood and district filled with people from different countries, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and each—perhaps with the exception, more recently, of the rapidly gentrifying Wynwood— underrepresented in the media. “I want to convey the sense of disorientation that I feel in Miami,” says Cromwell. To create that feeling, Cromwell sometimes stages scenes of her own, as she looks for the “performative” in the everyday. “I’m interested in how we create space for intimacy, spirituality, and a sense of community in these areas meant more for industry and commerce.”

Esther Hovers, Overview E – Timeframe: 0’ 04”, 2015–16, from the series False Positives

Courtesy the artist

Esther Hovers

Created in collaboration with intelligence surveillance experts, Esther Hovers’s series, False Positives, pictures eight different algorithmic “anomalies” around the business district of Brussels, mimicking images used to detect social deviance in public spaces. Described as “signs in body language and movement that could indicate criminal intent,” the “anomalies” rendered in Hovers’s photographs and pattern drawings become like blueprints of potential state control. In their banality and clarity—businessmen on sidewalks, joggers on streets—the images are all the more sinister, especially in Brussels, the capital of the European Union, whose stated goals are to “offer freedom, security and justice.” “False Positives is set around the question of normal behavior,” says Hovers. It’s an investigation of “how power, politics, and control are exercised through urban planning and the use of public space.”

Mateo Gómez García, Fruits, 2017, from the series Paraiso

Courtesy of the artist

Mateo Gómez García

Since 2009, when he returned to his native Colombia after studying cinema and photography in Buenos Aires, Mateo Gómez García has documented the changing visions of Colombian society—both subtle and dramatic—often driven by the politics of drugs and violence. His 2014 series, A Place to Live, considers the complexities of life in suburban Bogotá, which over the last decade has seen a rise in new housing developments and shopping centers. A 2016 commission for the California Sunday Magazine profiled religious communities in Bello, a town near Medellín. In his newest series, Paraiso, Gómez García deploys a language of absurdity as a riposte to ideas of optimism propagated by the Colombian media. “I refuse to consider the image shared by the media as the mirror of my reality,” Gómez García says. His photographs become enigmatic metaphors, with a kind of visual flexibility that moves between documentary truth and fiction. “This work is an approach to the new Colombia,” says the artist. “A fragile and ephemeral paradise, a folkloric dream of a society without memory.”

Délio Jasse, Darkroom, 2019

Courtesy of the artist

Délio Jasse

Before moving to Portugal at the age of eighteen, Délio Jasse grew up in Luanda, the capital of the oil-rich nation of Angola, routinely named one of the most expensive cities in the world for expatriates. Angola’s fortunes have traveled with the velocity, the sudden rises and hurtling falls, of a roller-coaster: three decades after a catastrophic civil war, the country rebounded with an oil rush only to be followed, in 2014, by a crash with the collapse of oil prices. In 2013, Jasse began making photographs in Luanda, tracing how architecture, as curator Marta Jecu puts it, “is a container of time.” Working in a variety of analog formats, Jasse photographed Luanda’s colonial relics, its modernist architecture, and its new “international corporate style”—buildings constructed in the era of rapid globalization—which together create a palimpsest of streetscapes and memories. Jasse’s images of Luanda, he says, “point to the past” while also alluding to “a utopian architectural future for one of the fastest-expanding African cities.”

Lilly Lulay, Still from the video Istanbul, up and down, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Lilly Lulay

Lygos, Byzantium, Constantinople, and now Istanbul—for three millennia, Turkey’s iconic metropolis, once the largest in the Western world, has been the capital of an empire and a bridge between worlds. In 2015, ninety-two years after the founding of the Republic of Turkey, Lilly Lulay created a moving “collage” while at a residency in Istanbul. She gathered images ranging from iPhone snapshots, to black-and- white analog prints, to slides from the 1970s. She reproduced the images at postcard size and made cutouts and interlayered prints. Some viewpoints are unique, she notes, whereas others are just the stereotypes of the city, repeated across time and throughout individual albums. Lulay’s resulting video, Istanbul, up and down, traverses the city’s streets and is attuned to a spirit of change, architectural mashup, and constant movement as scenes from different eras overlap and merge. “Setting the cutouts in motion was a means to reflect this constant process of deconstruction and new construction,” says Lulay. It’s a tribute, a portable museum, a postcard sent to no one in particular and everyone at once.

Noritaka Minami, Facade I, 2011, from the series 1972

Courtesy the artist

Noritaka Minami

In the 1960s, emerging from the devastating impact of World War II on Japanese cities, a group of architects began to develop a visionary movement called “Metabolism.” Based on the idea of growth and regeneration of organisms, the manifesto “METABOLISM/1960–Proposals for a New Urbanism” became a signal text of postwar urban design in Japan, with its dynamic master plans and prefabricated housing. Since 2010, Noritaka Minami has photographed the Nakagin Capsule Tower, a thirteen-story tower designed by Kisho Kurowawa and comprised of “removable” cubes, each one only 107 square feet. Built in only thirty days in 1972, the tower became the most prominent of the Metabolist structures, at first a symbol of progressive design, but years later a retro-futuristic relic. Some capsules retain their original furnishings, whereas others are uninhabitable; after Kurokawa’s death in 2007, residents voted to demolish the building. Minami’s images describe the irony of individuality under a once-optimistic regime of structure. “The building is a reminder of a future that was never realized in society at large and exists as an architectural anachronism within the city,” Minami says. “Despite Kurokawa’s plan to mass-produce the capsules, this structure became one of a kind in the world.”

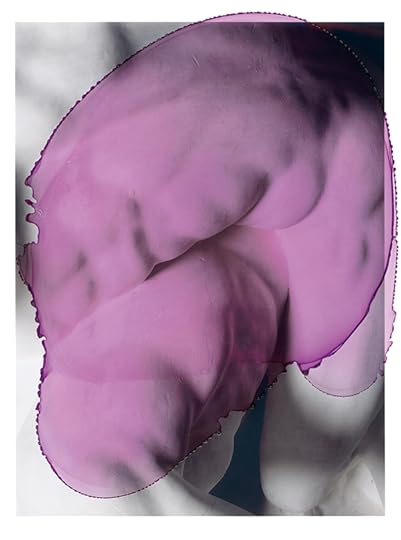

Alice Quaresma, Ocean Sound, 2018, from the series Tempo

Courtesy the artist

Alice Quaresma

Known for its sweeping views and golden beaches, Rio de Janeiro has in recent years been beset by recession and political upheaval, and an uptick in narcotics-related violence and police killings. Alice Quaresma, in attempting to process her relationship to her homeland, culls black– and-white photographs of downtown Rio de Janeiro from her personal archive, and paints shapes, often in primary colors, on top of them, thereby transforming the city’s architecture. Tempo, Portuguese for “time” and the title of Quaresma’s series, invokes the relationship between past and future. “The geometry hides the past, the old Brazil, opening a gate for new possibilities and new horizons,” says Quaresma, whose use of bright hues brings to mind similar interventions by the late painter Ellsworth Kelly. “The bold colors come to provoke action and attitude.”

Adam Pape, Untitled, 2013–18, from the series Dyckman Haze

Courtesy the artist

Adam Pape

Dyckman Street divides the upper Manhattan neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood. Named for the Dutch farmer William Dyckman, the street is also the byway between Fort Tyron Park and Inwood Hill Park, enclaves in the city that form the backdrop for Adam Pape’s photographs in his series, Dyckman Haze. “The park is the city’s subconscious, where its citizens can indulge in the desires and urges not meant for the public streets,” says Pape. This land was once occupied by Native American tribes, and Pape notes that his title “juxtaposes the colonial past with contemporary intoxication”—“haze” is a state of mind and a potent strain of marijuana famous in the Heights. Like the artificiality of natural spaces in the city, Pape’s black-and-white images stage a theatrical view of everyday “performances and private rituals.” His dramatic, glassy lighting transforms the banal gestures of smoking, sitting, kissing, sleeping—even the ominous lurking of a skunk—into dream states. As a series, Pape says, Dyckman Haze is like a fable about the precarious public spaces in cities today and the impulsive thrills of the night.

Carlo Rusca, Untitled, 2015-2019, from the series Turistica

Courtesy the artist

Carlo Rusca

Locarno, Switzerland, a town at the northern tip of Lake Maggiore, boasts pristine views and a balmy climate, where palm trees grow at the foot of the Alps. Carlo Rusca—who grew up there, and after some time away, moved back in 2016— presents a more complicated vision. Turistica is “a visual journey dedicated to all the small tourist destinations and to their lonely citizens,” says Rusca. His silvery photographs show darkness, nighttime, fog, and a noirish mist. In one, sheep crowd into a paddock, and a truck with a ramp looms ominously in the background. In another, two figures float on a sidewalk grate that disappears into fog. Through Rusca’s use of black and white, his images withhold the lushness of Locarno’s landscape; there are no sapphire lakes or royal– blue mountains. Instead, he portrays modern apartment buildings, lit by streetlamps, where the only sign of life is two dimly glowing windows. As Rusca says, “I always felt my nights in Locarno monochromatic. I’m still searching for my colors.”

Josh Schaedel, Peacock & Cat, 2018, from the series It’s Almost Not Worth Talking About

Courtesy the artist

Josh Schaedel

“In a city as dictated by car culture as Los Angeles, there is no way of escaping the billboards, window vinyl, flashing signs on top of cars in traffic, whole painted sides of buildings, and advertisements in all shapes and sizes that flash by as you drive around,” says Josh Schaedel. As Thom Andersen argues in his 2003 film Los Angeles Plays Itself, which compares the real- life city to the way it’s portrayed in cinema, LA is a city built on its own mythologies—and on its images. Schaedel’s series, It’s Almost Not Worth Talking About, interrogates the validity of making new images of LA. Looking for the in-between, the unexpected, or the overlooked, he hopes to break the spell cast by the self-conscious staging of events and experiences for instant broadcast on social media. “I try to flatten the space and time that separate the fabricated realities of the constantly shifting representations found in advertisement, from real experience,” Schaedel says. “I want to create a space where the banal feels surreal.”

Michele Sibiloni, Hoima, 2017, from the series Nsenene Republic

Courtesy the artist

Michele Sibiloni

Since 2010, Michele Sibiloni has lived in Kampala, where he has made photographic projects about night guards in the Ugandan capital, as well as about Kabalagala, a neighborhood known for its raucous nightlife. While making the photographs in Nsenene Republic, his latest series, Sibiloni became captivated by the world of the nsenene, or grasshoppers—a delicacy, basis of income, and potential food resource for the future. Twice a year, after the rainy season, grasshoppers migrate en masse, and each night people stay up late to gather and sell them. “The ubiquitous presence of the grasshoppers, the overall green shade dispersed by the night mist, and the smoke of bonfires create an otherworldly scenario, enhanced by the oddness of the hunting techniques and self-made equipment,” Sibiloni says of these pictures, made in Kampala and the city of Masaka. The hunting of grasshoppers is located “on a very precarious edge between past and future, tradition and innovation, and can shed some light on Ugandan identity as well as on new prospects for the whole planet.”

Chanell Stone, Potted Earth, 2019, from the series Natura Negra

Courtesy the artist

Chanell Stone

In her practice, Chanell Stone explores the “re-naturing of the Black body in the American landscape.” Stone’s self-portraits and environmental studies—made in Los Angeles, Oakland, and New York, locations where she has lived—seek to reconnect Black subjects in inner-city environments with what she calls “urbanized nature.” Scenes that appear like verdant, rural landscapes in Natura Negra I are actually tenements in Oakland. The seemingly archetypal high-rise buildings in Natura Negra II are from MacArthur Park in Los Angeles and Chelsea in Manhattan. “I was motivated by a sense of ownership and reclamation of these structures, no matter how monolithic they are in American society,” Stone says. “I am invested in showing the beauty of these environments and the Black presence within them.” By collaging Mylar prints and fragmented impressions, Stone also comments on the interlayering of urban experience and guides the viewer to what is seen and unseen. The collages float from their backgrounds in order to “call to the liberation of these environments from their restrictive settings” and to reclaim spaces of imagination and memory against waves of gentrification. As Stone says, “I create dialogues around these themes in my work to create space for the Black body in the canon of photography.”

Leonard Suryajaya, Arisan, 2017

Courtesy of the artist

Leonard Suryajaya

“I had to make something happen there,” Leonard Suryajaya says of the apartment lobby in Medan, Indonesia, where he made the riotous tableau Arisan. Visiting his home city after the 2016 US presidential election, and noticing elaborate Chinese New Year decorations everywhere, he invited a group of subjects to pose in traditional Indonesian costumes in response to the Women’s March in Washington, DC. “I strive to show solidarity and the many different possibilities of rendering femininity, while also defying the rigid traditional views of what’s feminine,” Suryajaya says, noting that the title refers to a type of microloan in Indonesia. Suryajaya, who moved to the US at the age of eighteen as a queer immigrant in a same-sex marriage, uses photography to test definitions of family, community, and selfhood. Whereas Arisan rises to Kabuki-level theatrics, in Good Neighbors, Suryajaya employs spectacular textiles and masquerade to describe an undercurrent of racial tension during a residency for artists of color in Woodstock, New York. The subjects, including Suryajaya himself and his partner, Peter, riff on cultural stereotypes, including the fad for Asian beauty products such an “expensive pacifier” that’s like a “face workout.” Good Neighbors, he says, with its offering of flowers, is a way to say, “Hi, guys. We come in peace.”

Dustin Thierry, Crowd of onlookers at the Candy World Ball, Paris, September 2018, from the series Opulence

Courtesy the artist

Dustin Thierry

In the 1970s and ’80s, turning away from the increasingly white-dominated drag balls that were once part of a multiracial, queer demimonde in New York City, black and Latinx performers began to organize ballroom houses and dance subcultures of their own. Based on traditional family structures, but fiercely competitive, houses would go head- to-head in “voguing” balls, where performers “walk” in categories such as Town and Country, High-Fashion Evening Wear, and Executive Realness. The phenomenon was introduced to mainstream audiences through Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning and more recently by the television series Pose, which is set in the 1980s and centers the stories of trans and queer people of color as gender pioneers two decades before the contemporary visibility of trans politics. In 2018, Dustin Thierry began to track how the ballroom voguing scene has expanded to Amsterdam, Berlin, Milan, and Paris in his series, Opulence. Although LGBTQ+ activists have successfully fought for equality in cities and countries around the world, Thierry notes that homosexuality is still strongly stigmatized within the Caribbean community, and Caribbean people are often objectified in places as seemingly open-minded as Amsterdam. Opulence, for Thierry, is therefore a “living archive of feelings,” a testimony to the energy of queer life, and an international connection to the spectacular presence, beauty, and diversity of the African diaspora.

Bryan Thomas, Larry and Laron, 2019, from the series Sunrise/Sunset

Courtesy the artist

Bryan Thomas

“Though the white liberal imagination likes to feel temporarily bad about black suffering,” the poet Claudia Rankine wrote in 2015, “there really is no mode of empathy that can replicate the daily strain of knowing that as a black person you can be killed simply for being black.” Rankine’s searing essay appeared in the New York Times Magazine only days after the shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, that killed nine African Americans. But her words about mourning as a “condition” of black life in the United States continue to resound for the photographer Bryan Thomas, a Florida native who, in the aftermath of the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, began to wonder about grief, personal memorials, and the recognition of African American life and death in the United States. For his series Sunrise/Sunset, Thomas pictures the production and frequent appearance of custom-made T-shirts commemorating individual lives lost to gun violence in Miami. Many say “Sleep in Peace” and mark dates of birth and death with the words “Sunrise” and “Sunset.” Screen-printed with vibrant pictures and worn by family members and friends, the T-shirts become, as Thomas notes, “an act of protest against the ways in which African American lives are often misrepresented and, sometimes, entirely forgotten.”

Sally Tosti, from the book Distressed Cities, 2019

Courtesy the artist

Sally Tosti

The rise and fall of Detroit has been treated as a bellwether for politicians and a metaphor for artists, especially since the recession of 2008. But Sally Tosti’s recent photographs of the city and its streetscapes, with their clarity and open-ended, nonjudgmental tone, move away from the spectacle of decay toward an evolving archive-in-the-making that allows buildings, as she says, “to speak volumes about the lives lived in and around them.” Since 2014, Tosti has photographed Detroit, assembling her images into photobooks that become miniature exhibitions. This book, the fourth on Detroit and the latest addition to her ongoing project Distressed Cities of America, examines how redevelopment initiatives attempt to improve the city. Tosti photographed in multiple locations, including Eastern Market, Seven Mile, Hamtramck, and Highland Park. She found abandoned houses, but also colorful murals—signs of life and small gestures that signal a form of commitment to the place. “When I return to a city that I have previously photographed, I look for changes since my last visit,” she says. “By photographing these neighborhoods, I strive to bring attention to their plight and hope this attention will initiate change.

Shelli Weiler, Balloon Wishes, 2018, from the series ENJOY house

Courtesy the artist

Shelli Weiler

Is every destination now just a backdrop for an Instagram post? The photographs in Shelli Weiler’s series, ENJOY house present escapist amusements as settings for enacting bizarre performances and what she calls “readymade fantasies selling the idea of immersive art experiences.” For these high-gloss images, Weiler photographed dogs and slides, children and balloons, boxers posing for a fight and stairways to nowhere. Lifted was taken at the Museum of Pizza in the William Vale hotel in Brooklyn, as a boy rises into Pizza Heaven—another photo-op. Balloon Wishes, taken inside the Color Factory in SoHo, centers on a girl being scolded for deflating balloons emblazoned with children’s dreams. These made-for-Instagram “selfie factories,” meant both for “influencers” and common citizens (sometimes at a cost upward of $38), act as “film sets devoid of narrative.” Such environments, Weiler says, “codify the semblance of perfection through symbols and mass, and yet remain a sort of semantic desert.” By imposing an illusion of objectivity, Weiler turns the impulse of documentary fact-finding on its head, creating portals for new, perhaps futuristic experiences in the social-media hall of mirrors.

Yana Wernicke, Untitled, 2017–18, from the series Bombay Dream

Courtesy the artist

Yana Wernicke

In 2015, while at a residency in the Indian city of Pune, Yana Wernicke was working on two projects centered on women, when she kept hearing about young people moving to India’s film capital. “Mumbai has a magnetic pull on young men and women who are moving there from all over the country to become actors or directors or work in the film industry,” she says. Three years later, she began photographing aspiring actors in Mumbai, mostly women “doing smaller jobs—like regional Marathi TV, commercials, theater, and online productions.” Wernicke collaborates with the actors in their often-spare apartments to allow for a more intimate exchange. As a young woman herself, Wernicke can relate to the challenges they face. “The idea of taking a risk and trying to work in a creative business environment has some strong parallels to the photography world.”

Hal Wilsdon, It’s Milk, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Hal Wilsdon

An Art Deco tumbler, adorned with lilies, sits in the corner of green velvet upholstery, perhaps the arm of a plush chair or sofa. Two pale hands grasp each other behind a pinstriped suit. A leather checkbook, complete with an antiquated calculator, lies on a wooden desk next to a gold pen. Each of these photographs speaks to Hal Wilsdon’s reckoning with authority, with traditional ideas of success: the marble lobby, the executive suite. “This ‘path to success’ doesn’t really exist for me, or for a lot of people,” says Wilsdon. “Whether it’s because of their gender, age, race, or class, this hypermasculine power trip of big business is effectively inaccessible.” For these photographs, marked by their clarity and geometric precision, Wilsdon sought out archetypal settings of corporate life: board rooms of major corporations, country clubs, courthouses, and horse-racing tracks. Wilsdon thought she would find lavish design, an alluring world of important people doing important things. But it was just a trove of fool’s gold: “I forced my way in to see what I missed, and there wasn’t much there.”

The 2019 Aperture Summer Open is on view at Aperture Gallery through August 29, 2018.

Delirious Cities is curated by Brendan Embser, managing editor, Aperture magazine; Matthew Leifheit, artist and editor of MATTE magazine; Chiara Bardelli Nonino, photo editor, Vogue Italia and L’Uomo Vogue; Azu Nwagbogu, director of African Artists’ Foundation and LagosPhoto; and Guadalupe Rosales, artist and founder of Veteranas & Rucas and Map Pointz.

Collect works from Aperture’s Summer Open artists today. Proceeds from the sale of prints directly support the participating artists in addition to Aperture’s publications, public programs, and exhibitions. Click here for more information, or contact prints@aperture.org.

The post Delirious Cities: The 2019 Aperture Summer Open appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 30, 2019

Hellen van Meene Wants You to Fight Your Fears

Revered for her portraits of young women, the photographer speaks about the poetics of intimacy and the rewards of taking on a challenge.

By Heval Okcuoglu

Hellen van Meene, No. 470, 2015

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

For more than twenty years, Hellen van Meene has been making photographs of teenagers, capturing the mystical nature of their transitional stages of physical and psychological development in all its introverted glory. Each van Meene photograph inhabits that famous distinctiveness of a classical Dutch painting, as if a secret is being revealed in a small whisper only to the gazing eye under an exquisite light. Working in analog and principally in small format, the sense of intimacy in each of her portraits is palpable. In the later phase of her career, the Dutch photographer explored the subject of intimacy through portraying dogs, as she considers that they share the same kind of intrigue and kinship as her beloved teenagers.

I recently spoke with Van Meene following the opening of her latest exhibition, The Bird in Borrowed Feathers, her first solo show in London since 2008. Comprising new works presented together with a number of pieces from the past decade, the exhibition finds glimpses into these intimate inner worlds and brings their fragility to light in ways that are sometimes surreal and unsettling, often uncomfortable and challenging, but always deeply sensitive and sincere.

Hellen van Meene, No. 357, 2010

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Heval Okcuoglu: I have always wondered why you photograph young people in the way you do.

Hellen van Meene: As an artist, I have spent over twenty years making the work that I do. In all these years that I have been making photographs, I have never made decisions based on commercial angles. I always followed my heart to make photographs. I have always focused on teenagers because that was my first instinct. Teenagers are still that for me. A teenager for me can be eight years old to twenty-five; sometimes you don’t really see someone’s age on their face. I always felt I related more to young people, not because they are young and people say young is beautiful, but because of the transparency and openness they have. I love to capture these younger faces.

Okcuoglu: What have you learned from decades of experience photographing young people?

Van Meene: The biggest surprise was that even though they are from different countries, have different upbringings, or are subjected to different rules, in the end, happiness, sadness, or shyness is the same for everyone. It is only the way one approaches them that is completely different. In some countries, I couldn’t communicate in their language, but they still understood what I wanted from them. That was an eye-opener that convinced me that I could do this anywhere. I can still make the photos I want, even though I don’t have the right words for it. That’s very liberating. It comes back to intuition and connection.

Hellen van Meene, No. 458, 2014

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Okcuoglu: Your fascination with dogs is also very well documented in your work. In what way is it different from your work with young people?

Van Meene: It’s actually the same. I never realized how easy it was to photograph them because I was afraid of dogs. Dogs can read people so well. Their ability to sense things is the same as that of children. It is because they haven’t learned to distrust their instincts by behaving themselves in the way that adults do. Children are very close to their senses. We still have them too, but we have learned to make them flat, because in day-to-day life people don’t appreciate it so much. Dogs and children do have a lot in common, because they are true to what they are and what they feel.

Okcuoglu: Materials and textiles are an echo from traditional painting that finds expression in your work. Many of your subjects are dressed in exquisite fabrics. In that sense, how does fashion manifest in your work?

Van Meene: It’s just an extra detail in the photos that is necessary. I don’t use clothes like jeans or T-shirts because they are very modern in a way, and that’s something I don’t want in the pictures. I don’t want the clothes to draw attention, that’s about it. Jeans are not so poetic. I try to find vintage clothes or new clothes that looks vintage, and clothes help me to draw the photos more into my story. I want the clothes to be there, but they should also disappear at the same time.

Hellen van Meene, No. 501, 2017

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Okcuoglu: You always exhibit your work in small format. Why is that?

Van Meene: The format is based on intimacy. I have always believed that this intimacy works with the photos that I make. It is not about revealing so much. If I print them really large, it doesn’t make so much sense. I like the fact that they are not big.

Okcuoglu: Do you have rituals you repeat before or after every shoot?

Van Meene: I have this crazy thing. After the photos are done, I never make a contact sheet. I should be the first one to see the photos myself and if I do a contact sheet, then I may not get to be the first one. It’s just a feeling. Once the photos appear and I see the negatives, it really makes me happy.

Hellen van Meene, No. 503, 2018

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Okcuoglu: Do you think photography can help confront our fears and overcome them?

Van Meene: In 2016, my mother got ill and the next year, she passed away. I couldn’t make any new photos, and I needed to find a new way of making them. I was taking care of her before she died, so I felt very lost and sad, and then I was depressed once she was gone. I love costume drama, so I was watching Lady Macbeth one day. It’s a dramatic film about death and murder. In one scene, she murdered her father-in-law with poison. The coffin was upright with the dead body in it, and she was standing next to it in a beautiful dress. I saw this image and I thought, Oh, my god, I need to do that. I need to make photos of people in stand-up coffins.

I researched where this phenomenon came from and then found out that around 1839, when photography was just being invented, in America, people made photos of the deceased, not when lying in coffins as we do now, but by raising it upright with the dead body in it, positioning the family members around it, as they felt it was the last time to make a photo of the deceased. Photography was new and no one had the money to make photos like we do now, so that was the last moment to have a picture taken with the deceased. They only did this for a short while in that period. It was very caring. Nowadays we are very much afraid of working with the dead, but back then it was normal, maybe because people died more often then. It was the combination of my mother’s death and these coffins that made me think that I have to do this.

So I called the undertaker who organized my mother’s funeral, and I said I wanted to borrow a coffin. He said, “Yes, it’s fine come over,” and I remember I felt very awkward going there because six months ago, we carried my mother’s coffin. And here I was now, asking for a coffin to make photos with it. I put the coffin in my car, and the next day I had to get some groceries because the photo shoot was a day later. After I had placed the groceries next to the coffin, I thought, “What the hell am I doing? This is insane. Driving around with an empty coffin.” It is a very good thing to take care of your fears. I made the photos, not with deceased people of course, because that’s too much of a struggle. It was like remembering someone for the last time. It was such a poetic feeling. I loved it. When I started making the photos of the dogs, I was afraid of dogs because I had been bitten. I always think you have to challenge and fight your fears. You can’t run away from them; instead, you confront them.

Hellen van Meene, No. 497, 2017

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Okcuoglu: What does it mean to be free in photography?

Van Meene: Looking back at my career, I never made decisions based on making photos I knew would sell a lot. I always followed my instincts. Two weeks ago, I was in Berlin and it has been nine years since I asked girls in the streets myself if they wanted to be photographed. Around 2010 I started to work with magazines for editorials, and you work with a model agency in order to find new faces. I pick the ones that give me a certain chemistry, but I don’t go into the streets myself anymore. You only have two days and you don’t have the time to find great faces, and so that spoilt me. It was easier. When I was working on my latest project, Seven Sins, there, I felt how tough and great it was at the same time, because I still get to find great faces. When you follow your instincts and what makes you happy, it doesn’t feel like a job. Sometimes it’s a bit silly, but I go and push myself into these difficult situations, because I know in the end, I will be rewarded.

Hellen van Meene, No. 423, 2013

Courtesy the artist and James Freeman Gallery

Okcuoglu: Finally, I would like to ask you about your experience as a woman in the industry.

Van Meene: Sometimes it’s a bit distressing that men the same age as me get more chances than women, especially in photography, as there are a lot of very famous, good women photographers. Men do get more exhibition opportunities than women. If the curator is a man, he always looks for a person who resembles him, that’s the way it works. It is kind of disappointing when you Google museums and see how many solo shows of women there are compared to the male solo shows. I think it should be about the quality of the work.

Heval Okcuoglu is a writer and translator based in London.

Hellen van Meene: The Bird in Borrowed Feathers is on view at James Freeman Gallery through August 3, 2019.

The post Hellen van Meene Wants You to Fight Your Fears appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 25, 2019

Venus & Mercury

Roaming the halls of Versailles, Viviane Sassen’s new photomontages consider royal intrigue and the limitless potential of the human condition.

By Jerry Stafford

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The Palace of Versailles has been fetishized by photographers since Eugène Atget—“a Balzac of the camera,” in Berenice Abbott’s words—first fixed the crumbling statuary of its gardens in his romantic gaze early in the twentieth century. More recently, Luigi Ghirri created photographic puzzles of the place that shift between fiction and fantasy, Candida Höfer explored its social architecture, and Robert Polidori captured its epic decorative constructs. For her most recent work, Viviane Sassen has applied her distinctive visual style to the storied location.

Versailles, as imagined by Louis XIV, began to take form in 1661; in 1682, it became the principal royal residence of France until the start of the revolution, in 1789, under Louis XVI. It offers a visual history of French architecture from the seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth. The centerpiece of the monumental palace is the Hall of Mirrors, commissioned by Louis XIV to prove the artistic and political superiority of France to the world. Its seventeen mirror-clad arches reflect seventeen arcaded windows that overlook the extensive gardens, with their symmetrical flower beds and classical statuary, landscaped by André Le Nôtre.

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Over six months, and on those privileged occasions when the palace was closed to the thousands of daily visitors who invade the grounds, Sassen roamed the empty mirrored halls of the palace alone, detailing the rococo chambers and the extravagant gardens, exploring both its most famous attractions and those secret spaces inaccessible to the public, including the private rooms of the king’s mistresses, the small libraries, the servants’ quarters, and even the Galérie des sculptures et des moulages, where weather-worn sculptures are repaired or shrouded from the bite of winter. Her body of work (or rather her work of bodies), titled Venus & Mercury (2019), was commissioned by the Palace of Versailles and curated by Alfred Pacquement, the palace’s curator of contemporary art, and Jean de Loisy, director of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris, as part of an ongoing series of artist collaborations with the estate.

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

By her own admission, Sassen is an intuitive photographer who does not always come to a project with a specific concept or strategy, but allows the work to evolve over time and take on meaning as the process unfolds. However, she was immediately intrigued by the systems and signifiers of power and sexuality at play in the royal court, and particularly those inherent in the omnipresent statuary that populates the interiors of the palace and punctuates the geometry of its gardens. The rigidity and the restraints of court etiquette, with its hierarchical structures, became the entry point for an exploration of historical division and conflict, while at the same time conjuring in the artist memories of her own adolescent sexual awakening. “I had been there once before as a young teenager, when I was about fourteen,” Sassen recalls. “It was the first time I had visited Paris with my parents, and the palace made a huge impression on me. There was something about the statues in the garden. I found it an extremely romantic place and fantasized about what had happened there.”

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

As suggested by her photomontage techniques, which are reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s disjointed fantasies and Hannah Höch’s subversive collages, Sassen has always been drawn to the surreal. During her research, Sassen was particularly captivated by metal prosthetic noses from the period that were used by victims of syphilis—an affliction rampant in the royal court—whose own noses had been eaten away by the disease. This forbidden and forgotten relic of sexual decadence and deformity acted like a talisman for the artist. Sexuality and decay, disfigurement and dilapidation permeate Sassen’s vision as she gazes on these frozen totems of privilege, class, and power and liberates them from the sociopolitical and historical codes to which they have been bound by convention and academia.

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Venus & Mercury proposes its own vertiginous mirrored labyrinth in which disembodied halves are reflected and morph into unexpected wholes; bodies are severed and faces sliced in direct conflict. Sassen seems to be proposing new mutations within her gallery of biomorphic, almost hybrid creatures. Her photomontages echo the assemblage sculptures of German artist Isa Genzken, which transform and transfigure familiar objects and invite the viewer to consider a new way of being, a new way of seeing beyond the constraints of a binary system of values and aesthetics. They welcome us into a nonlinear narrative as a tribute, a reminder, and an open question. In the same way that Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, which follows the long life of a young nobleman across centuries and genders, plays with possible realities and challenges social impossibilities, Sassen’s work on Versailles infiltrates historical corridors of power to offer a more universal consideration of the limitless potential of the human condition. “I try to make images that have the ability to free your mind in some way and to look at something from a different perspective,” Sassen reflects. “I always try to avoid too much context. I isolate these things in order to make them more abstract. My images are like a hall of mirrors; they reflect back at you what you already have inside.” In her own visionary sculpture garden, these figures are no longer frozen in time and space. Restored and repaired, they are alive and resonant with new meaning. Stripped of wealth, gender, and history, they inhabit an ambivalent space, a world in-between.

Jerry Stafford is a writer and creative consultant based in France. All sculptures belong to Musée du Louvre and Château de Versailles.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Venus & Mercury appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 23, 2019

Father Figure

Masahisa Fukase transformed the ritual of the family portrait into a source of play—and a memento mori.

By Tomo Kosuga

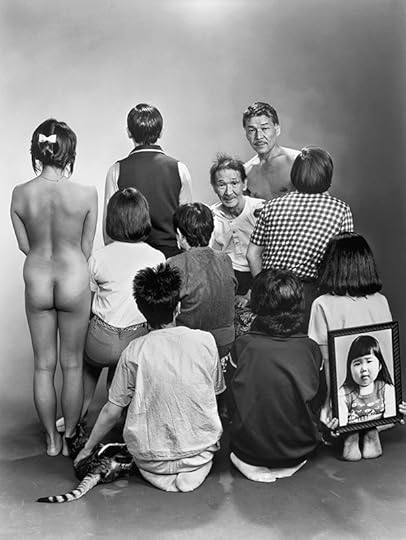

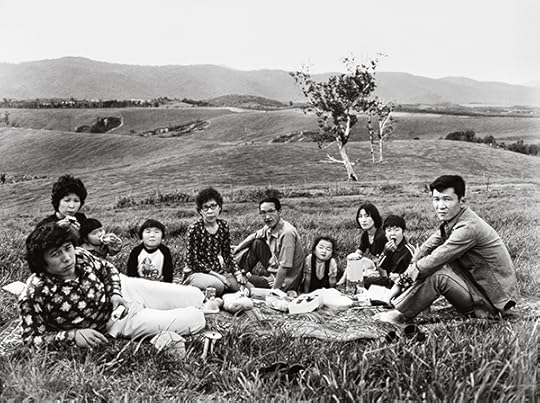

Masahisa Fukase, From the upper left: model A, Toshiteru, Sukezo, Masahisa. From the middle left: Akiko, Mitsue, Hisashi Daikouji. From the bottom left: Manabu, Kyoko, Kanako, and a photo of Miyako, 1985, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

The Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase is best known for his celebrated photobook Ravens (1986), a work in which he projected his sense of isolation and sadness, arising from his 1976 divorce, onto the figures of ravens. More than thirty years have passed since the publication of Ravens, and it is still lauded as one of the most monumental achievements of Japanese photography. But in 1992, Fukase suffered a traumatic brain injury that brought an end to all of his creative endeavors; it also resulted in the greater part of his photographic works, excepting Ravens, falling into oblivion for the next twenty-five years. Considerable scope remains for reassessing what Fukase was trying to accomplish in the course of his forty-year-long career as a photographer. Two works made over long stretches of his life, Family (1971–89) and Memories of Father (1971–87), are essential for any understanding of his photographic art.

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Memories of Father, 1971–87

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Fukase, who died in 2012, left a large and varied body of work, both personal and ludic. He was born in the small town of Bifuka, in the Nakagawa district of Hokkaido, the eldest son of a family that ran a provincial photography studio, which had been in operation since his grandfather’s time. His father, Sukezo, had hoped that Fukase would take over the family business, and made his son help with the processing of prints from the tender age of six. In one recollection, Fukase notes that “the grudge” he harbored toward photography had its beginnings around this time, suggesting an ambivalence about his first encounter with photography and the way his life seemed to have been decided for him. In 1952, at age eighteen, Fukase left home in order to get formal training, entering the photography department of the College of Art at Nihon University, in Tokyo. After graduation, he stayed on in Tokyo and took a job as a commercial photographer—not, in the end, going back to run the family business. While working at this position, Fukase threw himself into improving his photographic expression, and gradually started making a name as a conceptual photographer, getting his works published in magazines like Camera Mainichi and Asahi Camera.

In 1964, he married Yoko Wanibe. The autobiographical photographs he took of his domestic life with her have often been compared to Japanese I novels, with their self-revealing, confessional tone; his images were, in fact, the cause of continual friction between husband and wife. Wanibe stated, in 1973, that “in the ten years we lived together, he really only looked at me through the lens of the camera, and the photographs that he took of me were unmistakably depictions of himself.” As Fukase himself noted: “In the end, a kind of paradoxical situation came about in which we seemed to be together only for the sake of my photographs. This by no means made for marital bliss.”

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

In 1971, suffering considerable existential torment, Fukase began making periodic journeys back home to Hokkaido, after a long absence. In the locale of his native village—the very starting point for his whole being—Fukase started to explore the source of the creative energy that poured endlessly out of him, the compulsion to obsessively take photographs of the people he loved—even to the point of hurting them. The photographs he made over this roughly twenty-year period include the ones seen in Family and Memories of Father, both published in book form in 1991. Family is essentially an album of commemorative family portraits, all taken inside the family’s studio on anniversaries. Memories of Father is a collection of photographs, taken over a decade and a half, of his father, following Sukezo’s life and death through to cremation, interspersed with shots of the family’s daily life.

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Memories of Father, 1971–87

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Having in the 1960s turned his personal life with his wife into art, Fukase now took up the most ordinary, mundane, and everyday format: the family album. Yet in Family, he includes a number of nude and seminude women, photographed in the 1970s, who have nothing whatsoever to do with his family. He seems to be inviting the viewer to enjoy a kind of joke—at the same time perhaps performing a type of self-parody, underlining how he is the failed, degenerate, third-generation son. In 1985, after a blank of ten years or so, once again his father appears in the photographs, by now markedly older. Fukase understood, as he himself wrote, that “every member of the family whose inverted image I capture on the film inside my camera will die. The camera catches them, and in that instant it is a recording instrument of death.” He elaborated on this idea: “Time passes inexorably, and death comes to us all. It comes to old people, to young people, to children, to me. For me, everything is a commemorative photograph, to be eventually stuck in a battered old photo-album.”

For Fukase, a photograph was not something to record the successful moments of a life fully lived: rather, it was to record the time spent until the unavoidable day of death eventually provides a fitting end point. Fukase was surely well aware from early on that Memories of Father would be brought to a final full stop by Sukezo’s death. He saw photography as a macabre art, one that allows the viewer to exist, in some sense, unbound by the progression of time.

Masahisa Fukase, From the upper left: Masahisa, Toshiteru, a photo of Suzeko, Takuya. From the middle left: Akiko, Mitsue, and Hisashi Daikouji. From the bottom left: Manabu, Kyoko, Kanako, and a photo of Miyako, 1987, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

In 1987, Sukezo died, after having succumbed to pneumonia. On the night before the funeral, a heavy snowstorm covered the town of Bifuka in snow. Fukase gathered the whole family together, some dressed in their mourning clothes, and once again took a commemorative photograph. In the position his father used to occupy, he placed a photographic portrait of Sukezo, which Fukase had taken in 1974. The person in the photograph has a restrained smile, even though the occasion is now his own funeral. The suggestion seems to be that commemorative photographs have to be taken of all family events, and all commemorative photographs have to be marked by beaming smiles. Even though Sukezo himself is deceased, he has been brought back to life by that instrument of death, the camera. Now he is being photographed again—allowing him to stare out at the viewer, even though he exists only within a photograph—death canceling out death.

Two years later, in 1989, Fukase’s brother divorced, and the brother’s wife and their two children moved to Tokyo. Fukase’s younger sister and her husband moved away to Sapporo. His mother took up residence in a nursing home for the elderly. What had begun in 1971 as a lighthearted parody of a family photo-album had gradually changed over the course of twenty years and met an entirely unexpected end: the family itself scattered to the winds, their photographic studio closed—the end of an era that had lasted eighty years.

Masahisa Fukase, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

In these works, Fukase uses the camera as a kind of pistol, puncturing the boundaries of time. The bullet moves at an extremely slow speed, seemingly almost motionless, eventually reaching its desired target. The dead body that lies on the ground is the corpse of the past. Fukase pulled the metaphorical trigger over and over again, first on his wife, then on his family. His shots pass through them all over a period of several decades. In effect, what we look at when we view Fukase’s photography is a heap of the remains of the past, a grave marker composed of layers upon layers of images. The viewer gets an intimate sense of the disintegration of Fukase’s father, of the photography studio, and of the entire family, but also becomes conscious of the strange, rather macabre ease with which the photographer invites us to go back and forth through time with these photographs, the only thing left to us now that he—the practitioner of this art—is also dead. In the same way that the reappearance of Sukezo in a photograph of his own funeral seems to negate the effect of death, the members of Fukase’s family actual corpses of the past—come to life in these photographs and stare unflinchingly straight out at us.

Masahisa Fukase, From the left: Hisashi Daikouji, Kanako and Miyako, Manabu, Mitsue, Sukezo, Kyoko, Akiko, Takuya, and Toshiteru, 1974, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Tomo Kosuga is founder and director of the Masahisa Fukase Archives. His book, Masahisa Fukase, was published in 2018 by Éditions Xavier Barral. Translated from the Japanese by Lucy North.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Father Figure appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 18, 2019

How “Earthrise” Changed the Way We See The World

One of the most influential environmental photographs ever taken almost didn’t happen. In this excerpt from Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe, Marvin Heiferman tells the story of William Anders’s Earthrise.

William Anders, Earthrise, 1968

Courtesy NASA

Earthrise—one of the best known and most widely reproduced of all science photographs—was a fluke. On Christmas Eve, 1968, after three days of space travel, America’s Apollo 8 spacecraft was on its fourth orbit around the moon when Frank Borman, the commander of the mission, began to reposition it so that the topography below could be better filmed to document potential future landing sites. During the brief time that the capsule’s windows faced away from the lunar surface, astronaut William Anders looked through them and was startled by what he saw: “Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders grabbed a Hasselblad camera, loaded it with 70 mm Ektachrome film, and hastily shot off a couple of frames to capture an unanticipated and spectacular sight: Earth’s seeming ascent above the moon’s rough surface.

After splashdown on Earth and once Anders’s film was processed, one image from it, circulated worldwide by the media, left viewers awestruck. Serene, if a little disquieting, the photograph presents the marbled, blue-and-white planet’s fragile beauty that, seen from a distance, hints at Earth’s insignificance in the vastness of space. Wonder and intimations of the sublime are the frequent by-products of science photography, and the most paradigm-changing of images can be simultaneously mind-boggling and sobering. “Wonder is tinged with awe . . . and it’s also tinged with fear,” science historian Lorraine Daston wrote. “It’s an uncomfortable emotion. You don’t have wonder. Wonder has you.” Once it does, and thanks to photography, we keep on looking.

Click here to learn more about Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe.

The post How “Earthrise” Changed the Way We See The World appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 17, 2019

Introducing: KangHee Kim

Unable to leave the United States due to visa restrictions, this South Korean photographer makes images of surreal escapism.

By Cassidy Paul

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim wants to take you to another world, one where single palm trees emerge from a sea of clouds, perfectly crescent moons appear in cotton candy-hued skies, golden rays of light shine over streetscapes and domestic interiors, and clouds peek through windows and scaffolding. Kim is most widely known by her Instagram handle, @tinycactus. While her dreamlike, otherworldly images perfectly capture the digital aesthetic of today—soft color palettes, minimalist compositions, and an almost uncanny, eerie quality—they were the result of something much deeper.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Kim immigrated to the United States with her family at the age of fourteen. When her lawyer missed critical deadlines in applying for Kim’s green card, she was unable to secure citizenship. Eventually, she was granted protection under DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), but it came with the major caveat: due to visa restrictions, Kim has been unable to leave the U.S. for over a decade. Her images of “surreal escapism,” as she refers to them, have since become a form of visual therapy. “To be in DACA is living in limbo,” Kim says. “I desire to be unbounded in my photographic practice. Creating these fictional scenes allows me to feel a little bit liberated.”

Kim studied painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art, graduating in 2014. It wasn’t until her senior year that she began using photography as a creative outlet, enjoying the freedom that came with the minimal equipment required. One of her ongoing series, Street Errands, began in 2016 and was born out of the mundane daily encounters of living in New York. “I realized, instead of waiting for miracles, I could instead create the magical moments in my imagination,” Kim says. “I construct my own form of escapism.” To create these photographs, she uses Photoshop to merge and manipulate multiple images from her travels in New York, California, Colorado, and Hawaii. Rather than preplan the scenes, Kim lets intuition guide her—creating cohesion with a uniform aesthetic and color palette, and the returning motifs of moons, clouds, oceans, and skyscrapers.

The early years of Kim’s Instagram feed feature standard day-to-day documentation—she joined in 2012—with hints of her future experiments intermixed in the form of non-photoshopped, early versions of her dreamy photographs. Now, with just under 300,000 followers on Instagram, Kim is among a generation of photographers for whom the platform has become their main source of notoriety. As a result, her images have proliferated across the Internet, earning her commissions from brands such as Adidas, American Express, Air France, and Nike, as well as publications ranging from TIME and the New York Times, to Bloomberg Businessweek.

But for Kim, widespread popularity has a double edge, and she now feels conflicted about showing her work on Instagram. “It’s certainly helped me in many ways to get where I am now. At the same time, the flow of the Internet is uncontrollable,” she says, noting that the deeper, more personal ideas can get lost. However, she adds, “It’s fine with me if some people are missing out on the backstories, as long as they can relate their own experiences.”

Navigating the line between the everyday and fantasy, Kim’s photographs make the impossible possible: they create a space for her desire for freedom, while accepting the reality of her situation. Ultimately, Kim explains, her work “seeks to actively create something new with what I have for myself. These images give me illusions of traveling to unknown places that are familiar yet totally new. I’d like to remain optimistic and hopeful. Appreciating what I have in the present seemed to be one of the ways to do that.”

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

KangHee Kim, from the series Street Errands, 2016–present

Cassidy Paul is the social media editor of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

The post Introducing: KangHee Kim appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

One Giant Leap for Mankind

Fifty years ago, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong made history as the first person to set foot on the moon’s surface. In Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe, author Marvin Heiferman reflects on the significance of the photographs made during the Apollo 11 mission.

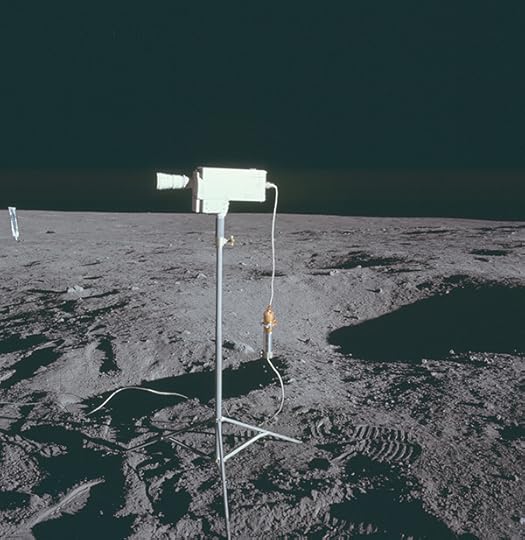

Boot prints with camera on the Lunar Surface, 1969

Courtesy NASA

One of the simplest and most haunting photographs ever made was taken on July 20, 1969, when astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped off Apollo 11’s lunar module and placed his left foot on the surface of the moon. The image was taken by fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin. It was Richard Underwood, NASA’s chief of photography in the 1960s, who taught the astronauts how to expose, frame, and focus their shots.

“Your key to immortality,” he said to motivate them, “is in the quality of the photographs and nothing else.” The images they captured—on six missions over the course of a three-year period—ranged from workaday documentation to the extraordinary. And as more astronauts landed on and explored the moon’s surface, the more footsteps they left behind. What was startling and novel the first time it was photographed became a pictorial constant. In 2011, conspiracists who claimed that these pictures were faked were proven wrong when a NASA lunar orbiter captured the sharpest images of landing sites ever taken and revealed the astronauts’ footsteps to still be there—where, it is estimated, they will remain for at least a million years.

Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin Deploys Apollo 11 Experiments, 1969

Courtesy NASA

Neil Armstrong, An Apollo 11 Hassleblad image from film magazine40/S–EVA, 1969

Courtesy NASA

Buzz Aldrin, An Apollo 11 Hassleblad image from film magazine 40/S–EVA, 1969

Courtesy NASA

Marvin Heiferman is a writer and curator based in New York.

Click here to learn more about Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe.

The post One Giant Leap for Mankind appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Revolutionary Roads

From Addis Ababa to Johannesburg, Guy Tillim photographs the streets named for Africa’s military leaders.

By Sean O’Toole

Guy Tillim, Leopold Takawira Street, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016, from Museum of the Revolution (MACK, 2019)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Guy Tillim’s new book of color photographs, Museum of the Revolution (MACK and Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2019), gathers his ambulatory work made on walking excursions along major avenues in several African cities between 2014 and 2018. Extending on the drift initiated in his book Avenue Patrice Lumumba (Prestel, 2008) and enabled by his receipt of the 2017 HCB Award, his new photobook contains numerous diptychs or triptychs—as if one frame is insufficient to contain the quotidian abundance of postindependence life in such major African cities as Addis Ababa, Harare, Johannesburg, Libreville, Luanda, and Nairobi.

Guy Tillim, Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 2016, from Museum of the Revolution (MACK, 2019)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

The book opens with a fractional view of a military parade in Maputo, martial pageantry being a feature of Tillim’s work since the 1980s. It is followed a few pages in by a four-part study taken in 2017 at a busy intersection in the Mozambican capital. It has just rained in this photo; Avenida 24 Julho, a major artery named for the day (July 24, 1975) Mozambique’s month-old socialist government nationalized education, health, and legal services, is waterlogged. In one frame a woman wearing a floral skirt and pink heels purses her lips as she waits to cross the uneven tarmac; in another a pudgy man with a lanyard tucked into his shirt pocket is caught midstride, ignoring the red light. In postsocialist Mozambique, some people jaywalk.

Strikingly, none of the Maputians appearing in Avenida 24 de Julho, Maputo (2017) seems remotely aware of or even interested in the white South African photographer looking at them. The same is true of Tillim’s photographs taken on Haile Selassie Avenue in Nairobi, or Boulevard du Général de Gaulle in Dakar, where he witnessed a military procession. None of Tillim’s photos exhibit that reciprocal involvement and recognition—or even conflict—that defines Garry Winogrand’s in-your-face street photography. Paul Graham’s indifferent pedestrians come to mind, although Tillim’s invisibility and irrelevance to his photographic subjects is piquant in liberated Africa.

Guy Tillim, Boulevard du Général de Gaulle, Dakar, Senegal, 2017, from Museum of the Revolution (MACK, 2019)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Tillim was in his early teens when, in June 1975, Mozambique gained its independence from Portugal following a decade of strife and armed conflict. In 1986, working as a photojournalist, he visited Maputo to document the funeral of Samora Machel, the rebel fighter who became Mozambique’s first president. Machel had just died in a mysterious plane crash in neighboring South Africa. His death was deeply felt. Among the photographs Tillim took during his press trip, one somehow foreshadows his preoccupations in Museum of the Revolution. It portrays a group of female mourners, many wearing headscarves, queuing to view Machel’s body as he lay in state in Maputo’s colonial-era city hall.

Guy Tillim, Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016, from Museum of the Revolution (MACK, 2019)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

This early photo anticipates Tillim’s current interest in cityscapes and the human bodies that activate them. But this photo is important for another reason. The endpapers of Museum of the Revolution reproduce a large painting housed in a four-floor museum along Avenida 24 Julho. Produced by North Korean artists for the 1978 launch of the Museu da Revolução (or Museum of the Revolution, from which Tillim’s book derives its title), the painting describes a jubilant crowd of black Mozambicans greeting a parade of soldiers in neat olive fatigues led by Machel.

Writing about this painting in 1983, New York Times journalist Joseph Lelyveld—a friend and supporter of photographers Ernest Cole and David Goldblatt—revealed that Machel had been “unhappy” with the painting, in particular the artist’s rendering of eyes, which “looked more Korean than African” and required “considerable retouching at the President’s behest.” Pyongyang remains a prominent sculptor of memory in postcolonial Africa, its artisans famously contributing to the production of architect Pierre Goudiaby’s puzzling African Renaissance Monument in Dakar.

Guy Tillim, Simmonds Street, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2014, from Museum of the Revolution (MACK, 2019)

Courtesy the artist and MACK

In some places, notably Luanda, where Tillim wandered around Avenida 4 de Fevereiro in 2016, the African metropolis now more resembles China than Europe. But the pervasive influence of forces beyond the continent is not the focus of Tillim’s roaming, detail-interested study of time and progress in urban Africa. If there is a defining image, it is a diptych from his forsaken birth city, Johannesburg. Taken in 2013, it records a car park slowly being demolished. Passersby don’t even look at the spectacle. Of course, Johannesburg is not alone in feeling the bite of diesel-driven excavators; cities everywhere are continuously atrophying and being remade. Tillim’s book records this infrastructural life force, both with marked dispassion and an affecting curiosity.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and editor based in Cape Town. He has contributed essays to photobooks by, among others, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Margaret Courtney-Clarke, David Goldblatt, Jackie Nickerson, and Mikhael Subotzky. He has published one book of fiction, The Marquis of Mooikloof and Other Stories (Double Storey, 2006).

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Revolutionary Roads appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Look Inside Aperture’s Third Annual Patron Weekend in Hudson Valley

Aperture patrons and friends gather at the “Apple House.” Photo courtesy of William Kahane.

Lyle Ashton Harris discusses his work at his Germantown studio. Photo by Kodie-Ann Walcott.

Chris Boot holds Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs, an Aperture publication, with Lyle Ashton Harris. Photo by Amelia Lang.

Amelia Lang introducing Letha Wilson at her studio in Craryville, New York. Photo by Kodie-Ann Walcott.

Letha Wilson sharing images with the Aperture group that reflect the confluence of nature and architecture in her work. Photo by Amelia Lang.

James Casebere in his studio, surrounded by the architectural models that he uses as props in his work. Photo by William Kahane.

Back balcony at Simon Lince and Cary Leibowitz’s home. Photo by Kodie-Ann Walcott.