Aperture's Blog, page 88

May 2, 2019

How to Capture an Intimate History

For Jane Evelyn Atwood, who has photographed sex workers and prisoners, it’s all about the balance between intuition and occasion.

By Claire Debost

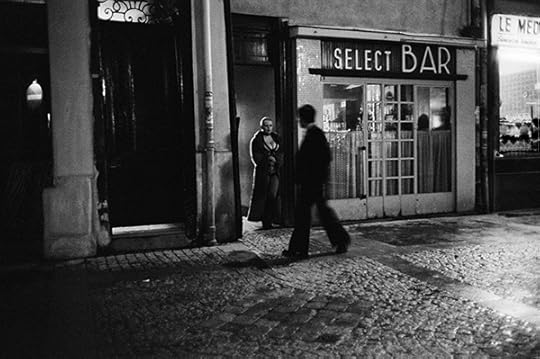

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Blondine in front of the door, Rue des Lombards, Paris, 1976–77

Courtesy the artist

Jane Evelyn Atwood is not the kind of documentary photographer who leaves once she has the right pictures. Instead, Atwood spends years getting to know her subjects and their communities. Atwood’s bodies of work are photographic essays, perhaps in their purest form—where the power of each image lies in the seemingly impossible balance between an intimate instant and a glimpse of history.

An American born in 1947, Atwood moved to Paris in 1971, and has been based there ever since. In 1975, after encountering a woman named Blondine, Atwood began photographing sex workers on rue des Lombards and in the Pigalle neighborhood by night, while working at the local post office by day. Atwood received her first W. Eugene Smith award for this work in 1980. Other major personal projects have included an eighteen-month reportage of a French Foreign Legion regiment (1983–85); a three-year project in Haiti (2005–8); and a ten-year investigation of women in prison across North America and Europe (1989–1999).

In early 2019 Atwood’s photographs of James Baldwin were part of the exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, curated by Hilton Als, at David Zwirner gallery in New York. A series depicting transgender sex workers, Pigalle People (1978–79), was shown at the 2018 edition of Les Rencontres d’Arles in France, and is currently on view at the Maison Doisneau, Gentilly. I recently sat down with Atwood to look back on forty years of not only image making but also activism, love, and loss.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Prisoner in the prison workshop, Les Baumettes prison, Marseilles, France, 1991

Courtesy the artist

Claire Debost: Last spring, Too Much Time (2000), your book focusing on the condition of women in over forty prisons throughout Europe and America, was adapted into a play by Fatima Soualhia Manet, an actor and director. Could you talk about these translations or adaptations from the experience of these women in prison, first to photographs and then a play?

Jane Evelyn Atwood: It was a fantastic experience. I was fearful, but even when I was actually doing the work, there was something so surreal and unbelievable about what I was witnessing and experiencing that it felt theatrical. A playwright couldn’t have made up better stories, yet they were real, they were real people. When I was working on the project, I would have these women in front of me and they would tell me everything because—and I say this without pretension—they knew that I was a way that they could have their voices heard, and they had never had that before. That’s why I made a book that was so full of captions and text. I felt that if I had a “duty” (and I dislike that word), it was to not betray those women with all the information I had gathered from them, and to tell it to other people who know nothing about prison, to tell what it’s really like to be inside.

For the play, I thought a simple mise-en-scène would make this even more theatrical, would work on the stage, and it would prolong the life of the book. What was really intelligent about Fatima was that she realized that it wasn’t just the story of prison and the women who were in there; it was also the story of the photographer who goes into these prisons and has this experience. So, she incorporated that into the prison stories, and that’s what makes this play different from everything else out there. Our play stands apart because it combines video, photography, and theater. And nothing is made up, so it’s that much more shocking, that it’s not fiction—and it’s still completely up to date, because conditions have only gotten worse. It’s timeless, for the moment.

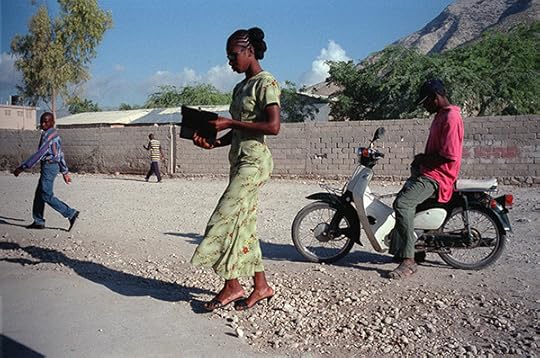

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Street scene, Gonaïves, Haiti, 2005

Courtesy the artist

Debost: A lot of your work touches on social issues, such as domestic abuse or prostitution, yet the images are sensitive and personal. How do you begin to work on a project and how does it evolve?

Atwood: I see something. All of my projects start with a visual cue. That can be in real life, in a newspaper, in a magazine, or even on TV sometimes. Every once in a while, I have an assignment that turns into a personal project. For example, Haiti was originally an assignment but it wasn’t enough for me, so it became a personal project. Then I get “bitten” by the subject and very quickly I know whether I want to begin the personal project or not. As soon as I know that I want to do it, I do everything I can to organize my life around the project: finding the money, finding where and when I can do it. With most of my subjects, I want to photograph because I have a lot of questions myself. My photography is about interrogations: it’s always questioning and wanting my questions to be answered.

This is contrary to what a lot of people say about me. They say I’m an activist and I’m a feminist—of course I am a feminist, as all intelligent women must be today. But, really, the very first activist story I did was quite late in 1987, with the photo-essay on a French man named Jean-Louis, who was dying of AIDS. He was the first person in all of Europe to allow himself to be photographed and published in the press saying he had AIDS. Before that, there was nothing contentious about prostitutes when I was making the work Rue des Lombards in 1975, even though later some feminists made it their cause. But it was a testimony—it was like, wow! I saw these incredible women and this is what I experienced with them and I’m giving it to all of you. I wasn’t trying to change anything or take a position on it.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Jean-Louis, the first person with AIDS in Europe who allowed himself to be photographed to appear in the press saying, “I have AIDS.” Paris, 1987

Courtesy the artist

Debost: Even as you discuss your process, it is clear that you spend years on every project you work on. Too Much Time, for example, took almost ten years to complete. Have you developed deep relationships with some of the people you have photographed along the way?

Atwood: Well, it’s true that, with many of the projects, I’ve had some sort of “bonding experience” (as you say in the States) with certain people. Blondine, who I met while working on Rue des Lombards in the ’70s, was the most important; not only because she was such a remarkable person but also because the prostitutes on the rue des Lombards were the first people I photographed. I didn’t know what I was doing, and Blondine was very patient with me; she would wait while I was trying to focus my camera. But I think also that was maybe the reason that she let me in; I wasn’t a threat to her. I didn’t have a carte de presse or a ton of equipment, and I could hardly speak French. She was curious about me just as I was curious about her.

I continued that very privileged friendship with Blondine until she died in 2013. It was Leonard Freed who told me once, “You’re choosing a kind of photography that is very lonely; you can’t take these people home with you.” I never forgot that. He meant that it’s a special kind of friendship. I was privileged that Blondine let me into her world, and I let her into a part of my world, the photography part. But she’s the one who said, “Don’t invite me to your house.” She protected me from herself at the beginning. She said, “You’re a cavette,” meaning a “straight” person, someone not in the milieu of prostitution, “and I’m a street prostitute.” She was setting the boundaries, and she was right because it wasn’t always la vie en rose. Sometimes she threatened me; she was an irrational person who had no rules.

Then there was Jean-Louis, the man I photographed for my AIDS project in the late ’80s, who was very special. Our friendship only lasted four months and ended because he died. I said to him once, “You know, I’ve only seen you once not wearing pajamas.” We went out one night because he wanted to show me a gay restaurant. The effort to do that almost killed him. That was the only time I ever saw him in real clothing. We were in this creative bubble, making photos, but when somebody is dying there is no bullshit. If you get along, immediately everything is out there. He talked about things that were very intimate that he probably would never have talked about with other people without knowing them for a long time, but he didn’t have a long time.

I do feel it’s important to have some kind of boundary as a photographer or you can get in trouble, especially as a woman. I know other photographers who have no boundaries at all, that’s their way of doing it. I try to always impose myself as The Photographer and not as something else.

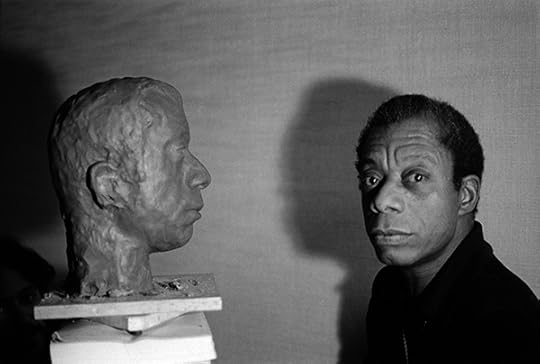

Jane Evelyn Atwood, James Baldwin with a bust of his likeness by Lawrence Wolhandler in his hotel room, rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, 1975

Courtesy the artist

Debost: Some of your photographs were recently included in the exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, curated by Hilton Als. What was your relationship with James Baldwin? Can you tell me more about these intriguing photos of Baldwin with a sculpted bust of himself?

Atwood: I was so lucky. It’s thanks to Larry Wolhandler, who is one of my closest friends and who was in Paris studying sculpture at the Beaux-Arts. It was at the very end of 1975. I had just bought my camera, and suddenly he called me one day and said, “You’ll never believe who I’m sculpting.” “Who?” I said, and he answered, “James Baldwin, and he said that you can come with your camera and photograph him!” In high school, and at Bard, I had studied James Baldwin, and he was a huge star. He was like a hero to me. He used to stay in a very fancy hotel on rue des Grands-Augustins. Larry and I went there often; he was always with a group of guys who worshipped him. We would go to this one restaurant in Saint-Germain-des-Prés: we would all drink whiskey and smoke, and listen to Jimmy. We had many nights like this. You could listen to him all day and all night. He was an extraordinary person.

He died on December 1, 1987. Jean-Louis had also just died. A friend of mine who was also a photographer called me and said, “Have you heard about Jimmy?” I was still devastated by Jean-Louis’s death, and was very fragile, and then there was the news about Jimmy. I felt like the world was coming to an end.

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Blondine in the hallway. Rue des Lombards, Paris, 1976–77

Courtesy the artist

Debost: You talk about the boundaries between you and the people you photograph. What about the responsibility that you owe to them and to yourself when putting the photographs out in the world? Are there times when you have questioned whether to publish a photograph or not, and how do you work with that?

Atwood: The truth is, when you ask permission to take photographs, it can’t be conditional; you can’t let other people make decisions about which photograph you can and can’t use. It’s difficult but that’s the truth. You have to earn enough trust from the people you photograph so that they trust you to choose the right photographs. That means you have to follow the photographs for the rest of your life; you have to become a control freak and follow how and when those photos are being used, with what captions, et cetera—and that’s a whole lot of work that many people aren’t ready to do. And now with the internet, it’s practically impossible because you can’t really control images, but you can do your best.

You can never satisfy everyone. Even people who may have loved you when you photographed them might be angry at you about which photograph you use. There was a prostitute in my very first book, Daily Nightlife (Nächtlicher Alltag, 1980), who’d signed the release, who I had spent a lot of time photographing. But when the book came out she was furious. She yelled, “You bitch! You put me in a pornographic book!” It was no secret that she was a prostitute; everyone knew it, and my book was a book about prostitutes. But I didn’t put her photograph in the second book because I didn’t want to have any problems, and I certainly didn’t want to make her life unhappy. Who knows, really, why she said that; maybe it made her see what she’s doing, and she was confronted with the reality of her life.

When I make a book, I try to be very fair about how many of a certain kind of photograph I’m going to use. I’m not going to overdo the horrible, grotesque pictures. For Jean-Louis, I had a lot of photos that I didn’t use because he was so thin, he was like a skeleton. I included a couple of photographs like the one of his back, which shows how sick he was, and that’s enough—but you have to show it, too. You can’t be sentimental about AIDS or cancer, you have to show what it is. But one or two photos is enough. It’s dosing, and dosing is very important.

Claire Deboost is an editorial work scholar in Aperture’s books department.

The post How to Capture an Intimate History appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 30, 2019

Aperture and LensCulture Celebrate the Opening of “Beyond Boundaries”

On Thursday, April 26, LensCulture and Aperture communities gathered at Aperture gallery for the opening of a wide-ranging exhibition.

© Thomas Rommé

© Thomas Rommé

© Thomas Rommé

© Thomas Rommé

© Thomas Rommé

On Thursday, April 26, the opening reception for Beyond Boundaries: LensCulture Discoveries in Contemporary Photography was held at Aperture Gallery. Beyond Boundaries is a wide-ranging group show that doubles as both a celebration and a survey of global image making today. With 101 participating photographers hailing from over thirty-four countries, this exhibition is a visual reflection of the beating hearts and curious minds of LensCulture’s vibrant community.

It was thrilling for guests to welcome a number of the participating photographers to the opening, who had flown in from all corners of the globe to see their images hung in Aperture’s exhibition space. If you didn’t make it to the opening, the show is on view through Thursday, May 2, 2019.

AnneCharlotte Guinot, a Juror’s Pick from the LensCulture Art Photography Awards 2018, traveled from Mexico. “Encountering my photograph on the wall among all the other amazing photos from all over the world, executed in such a beautiful design in such a wonderful space, was an experience that I will remember forever,” she says. “Photography is an art form with infinite possibilities, and this exhibition gave us all a taste to explore those possibilities even more. I am so proud to be part of this unique and beautiful exhibition.”

Marc Ohrem-Leclef, an Art Photography Awards Juror’s Pick, reflects, “As an image maker, it is wonderful to see your work shown on gallery walls and be able to share the work with a wider audience. This is especially true and meaningful with Aperture Gallery, the famed gallery and foundation in NYC. The history and gravitas attached to this space is especially humbling, and encourages me to continue my work and set the highest standards for its future iterations.”

LensCulture is one of the most far-reaching resources for discovering the best in contemporary photography around the world. Beyond Boundaries is part of an ongoing commitment to offer recognition, exposure, and career-changing opportunities to photographers of all levels.

Participating Photographers:

Alexander Sobol / Alexandre de Mortemart / Alison Romanczuk / Alla Sokolova / Amy Friend / Anne-Marie Weber / AnneCharlotte Guinot / Antigone Kourakou / Antonio Pulgarin / Ash Shinya Kawaoto / Aude Carleton / Balder Olrik / Beth Caron / Brett Leigh Dicks / Camila Berrio / Camillo Pasquarelli / Carol Allen-Storey / Cassio Vasconcellos / Cate Wnek / Charlie de Keersmaecker / Damion Berger / Daniel Chatard / Daniel Lyons / Danielle Dean / Dario Calmese / David Pace / David Wadelton / Diana Thorneycroft / Dick Sweeney / Dustin Thierry / Edgar Martins / Ekaterina Zershchikova / Elena Paraskeva / Emrah Karakoç / Evelyn Bencicova / Feiyi Wen / Fernando Morales Roca / Florian Ruiz / Garrett Grove / GIllmar villamil / Ingvild Kristine Melby / Jacob Burge / Jacopo Brunello / Jan Ung / Javier Arcenillas / Jayesh Joshi / Jeannie O’Connor /Jerry Takigawa / Joan Sorolla / Joshua Sariñana / Julia Fullerton-Batten / Juul Kraijer / Karine Roué / Katerina Stratos / Klaus Lenzen / Laura Pannack /Lebohang Kganye / Luciano Díaz Godoy / Magda Kuca / Marc Ohrem-Leclef / Mariagrazia Beruffi / Marina Black / Marinka Masséus / Mary Berridge /Matjaz Krivic / Maxine Helfman / Michelle Rogers Pritzl / Mikhail Grebenshchikov / Myriam Boulos / Oli Kellett / Oluwasegun Oladele-Ajose / Pablo Solórzano / Paolo Galletta / Peggy Washburn / Peter Franck / Rachel Liu / Rafael Goldchain /Rebecca Najdowski / Rene Habermacher / Rhiannon Adam /Rick Olivier / Roberio Braga / Rodd Owen / Sara Jurado / Seunggu Kim / Sonya Whitefield / Soomin Ham /Sophie Gabrielle / Stanislava Novgorodtseva / Szymon Barylski / Tabitha Barnard / Tania Franco Klein / Tania Ruda / Tobin Jones / Tonay Roy Sagar / Vanessa Filley / Vikesh Kapoor / Vladimir Zivojinovic / Walter Plotnick / Yorgos Yatromanolakis / Zhou Chengzhou

International Jury:

Alona Pardo, Barbican Art Gallery

Anne Farrar, National Geographic Traveler

Bruno Ceschel, Self Publish, Be Happy

Catherine Edelman, Edelman Gallery

Corey Keller, SFMOMA

Cristina de Middel, Magnum Photographer

Daphne Palmer, Fraenkel Gallery

Deborah Klochko, Museum of Photographic Arts

Francesca Morosini, GQ Italia & WIRED

Francis Hodgson, Prix Pictet

Hannah Watson, Trolley Books

Ihiro Hayami, T3 Tokyo International Photo Festival

Jennifer Murray, Filter Photo

Jim Casper, LensCulture

Joanna Milter, The New Yorker

Karen McQuaid, The Photographers’ Gallery

Laura Moya, Photolucida

Lucy Conticello, Le Monde’s M Magazine

Manila Camarini, D La Repubblica

MaryAnne Golon, The Washington Post

Michael Famighetti, Aperture magazine

Molly Roberts, National Geographic magazine

Mutsuko Ota, IMA Magazine

Richard Renaldi, Photographer

Shoair Mavlian, Photoworks

Stephen Mayes, Tim Hetherington Trust

Todd Hido, Artist

Xavier Soule, Agence VU & Galerie VU

The post Aperture and LensCulture Celebrate the Opening of “Beyond Boundaries” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 29, 2019

The Woman Behind the First-Ever Photograph of DNA

Under-appreciated during her lifetime, physical chemist Rosalind E. Franklin’s mysterious and groundbreaking photograph helped transform the science of genetics.

By Marvin Heiferman

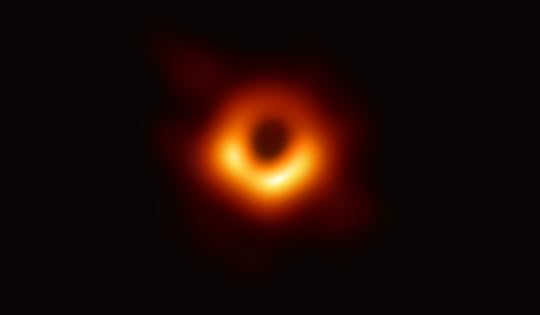

The first image of a black hole, 2019.

© Event Horizon Telescope collaboration et al.

After weeks of a well-orchestrated media build-up, the recent release of the first image of a black hole proved to be as stunning as promised. The minimalist image—depicting the gassy orange fumes of a Dunkin’ Donut–shaped celestial event, wrapped around a bottomless void of deep space—is spectacular and resonant with meaning. The emptiness at its center presents a powerful symbol of the malleability of time and space and the startlingly fragile nature of the present.

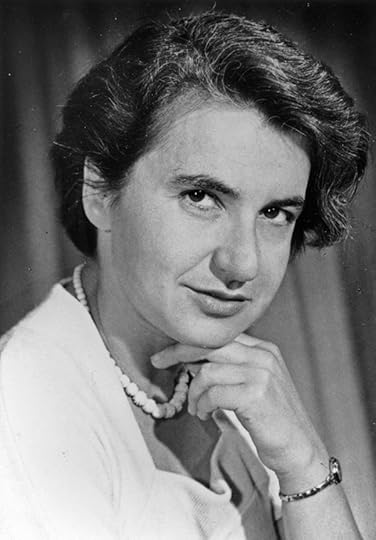

Among the fascinating aspects of the image is that much of the work in developing the algorithm that made its capture possible is credited to Dr. Katie Bouman, a twenty-nine-year-old scientist. Historically, women’s visibility and the proper crediting of their work has been a controversial issue in the sciences, but Bouman became Internet-famous as soon as the black hole image was released. Just as quickly, she became a victim of online trolling, as naysayers set out to undermine her contribution to the making of what is certain to be one of the twenty-first century’s most consequential images. This recalls another ground-breaking picture and woman, physical chemist Rosalind E. Franklin, who for most of the twentieth century was under-appreciated for her pioneering work in producing the X-ray diffraction “double helix” image of cell DNA, aka Photo 51, which helped transform the science of genetics.

In the following short essay, “The Story of Photo 51,” historian Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette, writes of Franklin’s 1952 accomplishment and her iconic image’s genesis and import. This essay appears in the forthcoming book, Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe by Marvin Heiferman (Aperture, Spring 2019).

Raymond G. Gosling and Rosalind E. Franklin, Photograph 51, 1952.

© 2015, Linus Pauling and the Race for DNA, Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries

Peer deep into this photograph’s heart, eye, vanishing point. Despite the beauty, no hammered stare, of any length, unlocks meaning or maker. The image (inviolate) defies casual analysis. Perhaps, you wonder, identification of topic or photographer is irrelevant. No clues visible (except perhaps to a biologist). Ah, now you read the label. The shoulders sigh (aesthetic surmises fade), the eye winks (no joke), and a scientist strides onto the stage and grips the podium (serious stuff).

This is the iconic X-ray diffraction photograph of DNA taken by physical chemist Rosalind Elsie Franklin and PhD student Raymond G. Gosling. The genetic material glimpsed in Photo 51 connects all living things and the image thus metaphorically captures human past, present, and future. It also marks an important milestone in science. In the last half-century, research that drew from Franklin’s photograph has brought advances in biology, medicine, paleontology, and many other parts of life.

Under a microscope, cells reveal their own truths, possessing the potential to separate conception from context. By convention, science (which makes the invisible visible) renders the visualizer invisible. Discoveries are disassociated (divorced) from he (or she) who stained the cell, mixed the reagents, pushed the buttons, coded the data. In an era when cameras record every baby step and every entertainer’s misstep, it may be difficult (if you are outside that world) to comprehend a culture in which (in theory) the photographer does not attach to the image. Analysis matters. Publication matters. Claiming credit first matters. The photographs themselves are allegedly, well, just part of the work.

This particular image had led Franklin to conclude in 1952 that the strands of DNA might form a helical structure but she was cautious and wanted more data. And therein lies the back story: Franklin’s own vanishing point.

Novelist Josephine Tey once accused historians of flattening the past into a “peepshow,” drawing historical actors as “two-dimensional figures against a distant background.” Let us pull Franklin into the foreground, replace the center of the image with her face (three-dimensional), and consider whether knowing about the photographer matters.

Photographer unknown, Rosalind E. Franklin, ca. 1956

© World History Archive/Ann Ronan Picture Library

In January 1953, Maurice Wilkins, one of Franklin’s colleagues in the laboratory at King’s College, London, shared her photograph (without her knowledge) with two other scientists also in the DNA hunt. James Watson and Francis Crick (the men who, in another famous picture, seem to be ogling a curvy “double helix” model as if it were a naked Venus) interpreted the image (and other material attributed to Franklin). Watson, Crick, and Wilkins raced into print, pushed Franklin aside, and achieved fame and fortune. Franklin was allowed to stand at the back of the stage: her article was the third in the journal issue. Watson’s arrogant dismissal of Franklin’s work continued for decades after her death. Credit should go to the flyboys, the creative geniuses, not the others. “Technical stuff” was “woman’s work.”

Franklin had grasped the image’s essential truth, before others saw it, but the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously. Die too soon and you never get to wear a fancy dress. Watson, Crick, and Wilkes made the list four years after Franklin’s death. It is left to history to reconsider (some would say “redress”) such matters. Scientific encyclopedias up through the 1990s included “Franklin, Benjamin” but not “Franklin, Rosalind.” Newer works now recognize Rosalind’s contributions and dissect the social and cultural attitudes that reinforced and stood silent at her marginalization.

The notion that a photographer’s identity might, as a matter of cultural practice, be detached from her photograph may seem an anathema within the world of art, where exhibitions celebrate the vision of those who hold the cameras, even if their names are unknown. Credit is a cultural practice: a matter of grace and humility when shared, a matter of despicable boorishness when unfairly stolen. Fortunately, there is a form of historical geometry: a line (reinforced) attaching Franklin to this photograph and its meaning in time.

At first glance, such context remains obscured from the viewer. The photograph’s mysterious, cloudy strands loop themselves around our eyes and engender thoughts of beauty. But for those who value integrity, well, pull on that line and reach for Rosalind E. Franklin. No vanishing point to memory or to our common humanity. Credit due.

Marvin Heiferman is a writer and curator based in New York. Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette is a historian who explores the boundaries of science, politics, and the public.

The post The Woman Behind the First-Ever Photograph of DNA appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 25, 2019

Aperture Announces Free Publication for Historic Convening at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute

Download the free curriculum, including thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice.

Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1847–52

© The Art Institute of Chicago

Aperture is pleased to present “Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum,” a free publication released on the occasion of Vision & Justice: A Creative Convening on Art, Race, and Justice, a landmark two-day conference taking place at Radcliffe on April 25–26, organized by Professor Sarah Lewis. In 2016, Lewis guest edited Aperture’s summer issue, “Vision & Justice,” a monumental edition of the magazine that sparked a national conversation on the role of photography in constructions of citizenship, race, and justice.

The 80-page “Civic Curriculum,” edited by Lewis, will be made available at the conference, and includes thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice. Highlights include a wide-ranging conversation between filmmaker Ava DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young; an interview between Lewis and Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative; and Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s essay on Frederick Douglass. Amanda Gorman, first Youth Poet Laureate of the United States, wrote for the publication; “Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum” also includes contributions by Elizabeth Alexander, Alexandra Bell, Robin Bernstein, LaToya Ruby Frazier, For Freedoms, Doreen St. Félix, Naomi Wadler, Darren Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis.

“Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum” takes its conceptual inspiration from Frederick Douglass’s landmark Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress,” about the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation, and addresses both the historic roots and contemporary realities of visual literacy for race and justice in American civic life.

“American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice,” said Lewis, who is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard. “When I was asked to guest edit a special issue of Aperture magazine, inspired by my course, which has led to this convening, I could think of no other theme. Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil.”

“Sarah Lewis’s work literally has transformed the way we see American history, especially with regard to citizenship,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University.

Click here to download “Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum”.

“Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum” was made possible by generous support from the Lambent Foundation. Vision & Justice: A Creative Convening is supported by the Ford Foundation, and cosponsored by the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, the Harvard Art Museums, and the American Repertory Theater.

The post Aperture Announces Free Publication for Historic Convening at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 24, 2019

The Pain and Pleasure of Queer Life in Egypt

Mahmoud Khaled considers the legacy of the “Cairo 52,” the men who were arrested in 2001 at a gay-friendly nightclub.

By Brendan Embser

Mahmoud Khaled, Splashed Memory of a night Out (detail), 2010–18

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

For gay men, the nightclub is often a place of refuge and revelry. But one night in May 2001, the Cairo police raided the Queen Boat, a gay-friendly nightclub on the Nile, and dramatically upended the lives of fifty-two men. They would become known as the “Cairo 52.” In jail, they were told to strip off their clothes to show if they were wearing colored underwear, thought to be a sign of gayness, although all were wearing white. They were then subjected to invasive procedures by doctors to “determine whether or not they were gay.” Some were forced to record confessions admitting to their homosexuality. Images of the Cairo 52, covering their faces with white cloth to protect their identities, would become emblematic of the persecution of gay men in Egypt, where homosexuality isn’t explicitly outlawed, but where gay people can be arrested for “debauchery.”

The Queen Boat incident, and the images of the Cairo 52, have long been on the mind of Mahmoud Khaled, a young Egyptian artist based in Cairo and Oslo. In 2017, for a commission by the Istanbul Biennial, Khaled made a project called Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017), a fictional tribute to one of the Cairo 52, who, in Khaled’s imagined biography, relocates to Turkey and makes a new life for himself in Istanbul. Two photographs from the collection of the “proposed museum” were included in Khaled’s solo exhibition I want you to know that I am hiding something from you (the title is a reference to Roland Barthes’s 1977 book A Lover’s Discourse), presented at Helena Anrather Gallery in New York in fall 2018. The exhibition included numerous beguiling works that meditate on queerness in the Middle East and beyond—a staged conversation between two men on Grindr, a series of photographs from the now-shuttered gay nightclub Splash in New York, a video of a man getting a tattoo scored with Jacques Brel singing “Ne me quitte pas”—and announced the arrival of a formidable talent in contemporary art.

I recently spoke with Khaled about the legacy of the Queen Boat incident and the politics of revelry and desire in queer life.

Mahmoud Khaled, Perfect Lovers (Alexandria), 2014, from the collection of The Unknown Crying Man House Museum, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Brendan Embser: Were you aware of the Queen Boat incident at the time it happened? And how has that episode influenced your thinking and some bodies of work that you’ve made?

Mahmoud Khaled: Yes; I remember waking up one day in the morning and reading about the raid in all the newspapers. I was in university, and I saw the images of the fifty-two men all over the place that day. I think this memory is very iconic for my generation. The incident was more reduced to a very abstract image for me; then the Human Rights Watch report was released afterwards with all the details of torture and investigation—all these horrific details made that reduced image very politically and emotionally charged.

The image I’m referring to is the “crying man,” dressed in white and covering his face with a white fabric to protect his identity; we only see his hand and his ear and a tiny part of his hair. This image later became the point of departure for a project I did in Istanbul. The image became established in the newspapers, and because the media was orchestrated by the government, everything was very well planned in terms of outing and destroying the reputation of the fifty-two men who were arrested by releasing all their information, names and professions and addresses and everything, even before the court finalized the case.

This image of the crying man, which is of course a very anonymous person, became representative, and up until now the New York Times, the Guardian, whenever they wanted to write a story about the gay scene in Egypt they would use this image. It became like a stock image for the political situation of the gay scene in Cairo. This crying man became almost like the “Jesus” of the community.

Mahmoud Khaled, Gift Shop at The Unknown Crying Man House Museum, 2017. Commissioned by the 15th Istanbul Biennial

Courtesy the artist and Sharjah Art Foundation

Embser: What was the political atmosphere like leading up to the incident? Was there a sense in the late 1990s or early 2000s that a crackdown was imminent?

Khaled: One theory is related to the government and their relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood, because the Muslim Brothers used to brand themselves as the power that could protect Islamic and society values, et cetera, while the government was not marketing themselves as such. So every now and then the government has to arrest a bunch of gay men to show that they are protecting the values of society more than the Muslim Brothers, and that you can do that without aligning yourself with radical Islam. So gay people are always a card they play with in their political games.

When the Human Rights Watch released their report, it was like a horror show for everyone because you could get the sense of all the details of what happened—and think to yourself that this might happen to you the day after. Everyone was so conscious of what they were doing, where they were going, what kind of parties. It also started to become an identity, and the existence of these feelings became so politicized. Even if you didn’t think of homosexuality as an identity, you had to start thinking about it as an identity, because this might lead to you being in prison.

Embser: Let’s take the image of the crying man, which has, as you said, become kind of an icon or stock image. Can you describe your project to make a museum for this unknown man?

Khaled: I developed a certain relationship with this image and tried to make it more poetic. By him hiding his identity in the image, he is also saying a lot—he’s giving us a lot of information. So because this image has been totally abstracted and stigmatized, I tried to make a monument for it. House museums commemorate the legacy of certain individuals, writers, politicians, collectors, et cetera, who are no longer with us, but whose houses become remarkable—they need to be transformed into exhibitions, in order to keep alive the legacy of the person who used to live there. So that’s how I started to think of the house museum: as a memorial that could commemorate the existence of that man who is stigmatized and unknown. The main artistic desire was to make this image more human.

Embser: And the idea is to give him back his life.

Khaled: Somehow, yes.

Mahmoud Khaled, Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man, 2017. Commissioned by the 15th Istanbul Biennial

Courtesy the artist and Sharjah Art Foundation

Embser: And where exactly is this museum?

Khaled: It is a proposed/imagined museum that can happen in any city in the world except Cairo, because almost all the fifty-two men, when they were released, they left the country. It was impossible for them to continue living in Cairo because their names, addresses, and professions were published in the newspapers and they basically lost their lives. They mostly all asked for asylum in many different places, so now these fifty-two men are all over the world. And any of their houses can be transformed into a house museum that can commemorate the event and the victims, which is why this house museum can happen anywhere in the world—except Cairo.

The whole idea of the museum is to think of exile in a productive way. The first proposition of this museum happened in Istanbul in 2017 as part of the Istanbul Biennial. It’s a proposal for a monument that is coming out of exile, but not necessarily a bad exile. I didn’t want to imagine a person who left Cairo and lost his way in the world; I really didn’t want to imagine a bad exile. The protagonist I constructed in the project was obviously a well-off man who could afford to buy a modernist villa in a middle-class neighborhood in Istanbul, where he could stage the whole world in his own exile. So what the installation is trying to do is to give you an experience of a staged world of someone else. His art, his desires, his basement, which he actually transformed into a darkroom, his taste in music, the kind of plates he uses to eat at dinner parties and stuff like this. I wanted to imagine someone who managed to construct his proposed idea of the world in his own exile/house.

Mahmoud Khaled, The Crying Man (memorial), 2001–15. Wood, mirror, vinyl, archived online found image, and text

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: The image itself is also represented in an artwork, is that right?

Khaled: The point of departure of the project started in 2015, when I showed an object made out of wood and a hand-painted mirror in a group show in Cairo accompanied with the following caption: “Proposal for an object that can operate as a memorial displayed in the entrances of middle-class houses in Cairo, commemorating a group of fifty-two happy young men dancing on a floating structure in Zamalek.”

I wanted an object that can act as a subtle gesture of remembrance to be placed in an entrance of a house in Cairo, because that’s where people normally place a mirror so they can see themselves when they enter the house and leave the house. Then two or three years later I had the chance to make this three-floor house “museum” for the Istanbul Biennial, where this gesture/object could be placed at the entrance—and that’s the only place where you can see that image of the crying man painted in the entire installation.

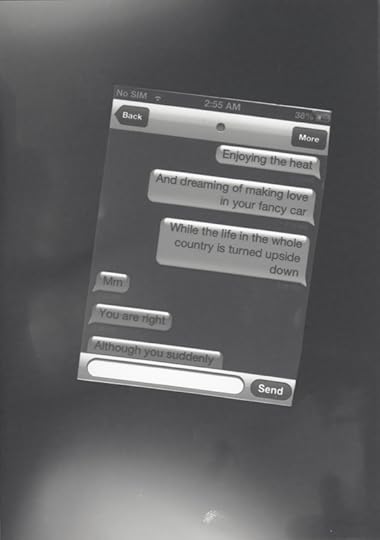

Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow? (detail), 2013

Courtesy the artist and Ibraaz

Embser: That idea of imagined lives is also played out in the conversation you staged on Grindr in a 2013 piece called Do You Have Work Tomorrow?. When I saw this work in your exhibition in New York, I didn’t know, at first, that the conversation was fictional. I read it like you would a text and found it extremely powerful and poignant. I later learned that the piece was initially commissioned by the web platform Ibraaz. How did the production of this work come about and how did it change when you showed it in a gallery?

Khaled: This work is inspired by a real experience, but it is based on a script I wrote and it is all fictional. I staged the conversation with myself. I was talking to myself on two phones, and then I took the screenshots and that’s what I proposed to Ibraaz. Probably they were expecting an image! Like an actual photographic project. Later on I was thinking about the physicality of the image of this work. I like to be in the process of creating a physical image, because now we deal with immaterial images all the time. We have images on our phones but we can’t touch them, we can’t smell them, we can’t exchange them physically. I wanted to transform online, immaterial work into a real physical work with traditional photography format.

So these black-and-white images were developed in a darkroom, which removes the time and place from the work, which is something I wanted when I was working on the piece. It’s too immediate when you look at the piece online as a screenshot: you can tell when it was produced through the layout of Grindr—this was 2012 and 2013—it looks different than what we’re using now; even the phone screen size is different. Once you see the image, you immediately can tell when this thing was happening. I wanted to remove this from the work and complicate this relationship between the image and the time and place it was produced in. That’s why the idea of the black-and-white print came out, which also gives a strong physical existence to the image. Framing every single moment of this conversation was also important for me, conceptually, because normally our relationship with texts, on WhatsApp or iMessages, are just memory—you don’t capture it or frame it.

Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow?, 2013. Series of 32 screenshots of a staged conversation on an iPhone, transformed into black-and-white photographs. Installation view at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2018. Photograph by Kristien Dae

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: The framing seems to give value, in the art gallery sense and in the reception of the work, because the frames somehow demand that you take the panels very seriously as individual objects but also together as a thread.

Khaled: Exactly, I agree! Also, if you think about the screenshot itself as text, there’s no form. It’s formless, completely. When I went to the darkroom to print, the performativity of printing the images created a form, an effect, created some depth to the background of the text, which needed to be highlighted by the “frame.”

Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow? (detail), 2013

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: The conversation starts out in the typical way these conversations tend to do, but then it takes a few turns toward the immediate urban context, with the car on the street. Soon, when the flirtation veers into politics, there’s a feeling that the platform is being misused. Grindr is supposed to be for sex, not politics. Could you talk a little bit about the texture of the dialogue?

Khaled: This piece started by imagining myself as a film director. I wanted to film a scene and have two men talking together, for example in a bar. It’s exactly the same in this piece, but I didn’t want them to talk in a bar—I wanted them to talk on their phones together. You can tell from the details of the conversations that it’s Cairo, but the work doesn’t deliberately say that. It’s a city, and we don’t know exactly when. But it’s happening apparently in a city that is under curfew, going through a strong political change. There’s a lot of violence going on from how they describe the situation in the conversation. In the meantime, both of them are trying to normalize this abnormal moment and still look for love and flirt and talk about sex, but still the political atmosphere is dominating the conversation.

So the dialogue fluctuates, jumping between politics, love, desire, and class. But it’s still also talking about location, about locating who you are talking with and how important it is to know how far away that person is standing. The idea of moving and talking about the car as a mobile vehicle (although it was parked in the context of this conversation), instead of talking about a house in a specific fixed location, is because they’re both supposed to be out in the street, protecting their properties and neighborhood. This is a very stressful kind of duty, but it comes out of that intense, precious, and liminal political moment their city is experiencing. Also you never know what’s going to happen if you’re holding a stick or a knife for the first time in your life to protect your house—you don’t know who’s going to come and attack you. But in the meantime, while you’re supposed to be doing that, you’re still trying to find normalcy in this moment and looking for love and intimacy in this situation. The conversation is trying to imagine this scene between the two men and also trying to speak about the overdominant political discourse.

Mahmoud Khaled, Do You Have Work Tomorrow? (detail), 2013

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: What the piece manages to achieve through text is the kind of intimacy you get by listening to audio. Like when you listen to a podcast, the voices come so quickly into your ear and your mind. With this piece, you get us to switch modes so that when you read the text it’s almost like listening to a private conversation made public.

Khaled: Yeah—and also retaining the text, taken out of the phone, is a very violent act. Because all the texts we have are very private. Taking someone else’s phone and looking at the conversations they’ve had on Grindr or WhatsApp is a very violent act. So taking this and putting it into a gallery was a way of trying to stress this tension between public and private in the materiality of the text.

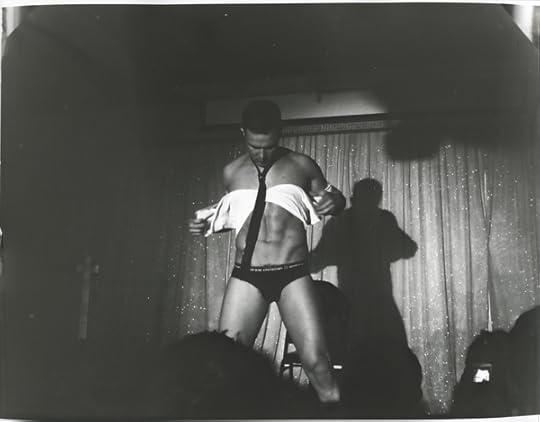

Mahmoud Khaled, Splashed Memory of a night Out (detail), 2010–18

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: In a way, the opposite of this work, in the ludic sense, is a series of black-and-white pictures taken several years ago at Splash, the former gay nightclub in Manhattan. Did you revisit these images specifically for your exhibition?

Khaled: Yes; for me this is the highlight of the exhibition since it is the only work I made for the occasion of the show. I had this material in my archive for more than ten years, and I love them—they are very attractive and exciting images. But I didn’t know what to do with them. They’re very seductive, and I was quite obsessed with the content of the images because they’re all like sexy bodies and party and fun. But I wanted to get over my obsession with the images to process them conceptually in a proper way and understand why I want to work on them.

I didn’t remember at all where or when or why I went to that club, but then I realized that this happened in 2008 and it was my first time in New York, and I went to Splash because I got an ad online or a pamphlet in the street saying that they were doing a fundraiser. The go-go dancers were collecting money and all this money would go to AIDS research. They announced it in a really nice way and it seemed like so much fun, so I went there with no expectations. I didn’t even know Splash was such a big-deal place for the gay scene in New York back then. So I had a PowerShot camera, because in 2008 the cameras on our phones weren’t that advanced. Eventually I had around four hundred pictures.

Mahmoud Khaled, Splashed Memory of a night Out (detail), 2010–18

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: All from one night?

Khaled: Yes! I spent a long night there [laughs]. But then I didn’t know what to do with this, because it was just a fun party and they didn’t really mean anything to me conceptually, and I really didn’t know how to process it. But when I was working on that show, I made a mock-up for the space, to imagine how to lay out the exhibition in the gallery. But I felt like something was missing in the experience of the curatorial narrative, and it was something to do with my relationship to New York and my relationship to sexuality and understanding the body, and then I felt the urgency of working on these images to complete the cycle of the show and the experience of it.

There’s an intentional strong contrast between this work and the Grindr text. The Grindr work is basically an anti-image. At the end, it’s all text and it’s formatted in a way that makes it look like a classical old photograph in a white cube gallery, but you actually don’t see a pictorial work in the frame. While in Splashed Memory of a night Out, you see clearly composed images, composition, body as a subject and an object, the cut, the framing, and the lighting and all this.

When I Googled Splash and realized that it had closed in 2013 and there was a heated discussion about the gentrification of Chelsea, the images became more important to me. I started to think that the images are not just beautiful images of a bunch of men dancing. They definitely had gained a different meaning. I worked with a great technician in a photo lab and we found a way to transform these very low-res images taken by an old digital Canon PowerShot into large-format negatives, and then take the negatives into the darkroom and work on printing them. So at the end, the presentation of this work is one piece composed of twenty images. They have to be presented all together. I always have to have a reference for a presentation, so I imagined a big theater showing these images at the entrance of it in order to celebrate that history—it’s like the archive of that theater. I wanted to present it in a way that I think shows the history of that club in New York, like an archive celebrated in a way that also celebrates an era in the history of the city.

Mahmoud Khaled, Splashed Memory of a night Out (detail), 2010–18

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Embser: Do you see a connection between the image of the crying man and those images from Splash in some form?

Khaled: Yes and no. I think in Splashed Memory of a night Out, the images are celebrating bodies and sexuality and freedom, but also you could tell from certain images that there are buckets full of money with stickers that say “AIDS” on them, so you know that all the celebration and fun is also a form of activism and resistance. It has different layers. The crying man is starting from a very oppressed point of departure and going into a very emotional, poetic, productive and protective place, which is the house of the crying man.

Embser: The Queen Boat incident happened at a moment when queer men were seeking a space for revelry, a space like Splash, and perhaps a space that only exists in the imagination of the two men whose dialogue you constructed in the Grindr piece. What has the pursuit of revelry meant to you?

Khaled: It’s obviously a human need that we all share, but specifically for groups like LGBTQI there is a political urgency for it. It’s basically a celebration of existence and togetherness, and a transformation of the banal and the quotidian into an organic form of resistance.

Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

The post The Pain and Pleasure of Queer Life in Egypt appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

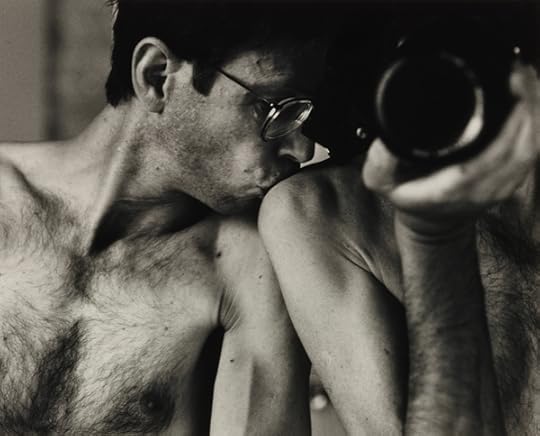

Let Us Now Praise David Lebe

A long-overdue exhibition expands the canon of gay photography.

By Matthew Leifheit

David Lebe, Angelo on the Roof, 1979

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In 2017, Peter Barberie, Curator of Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, extended a somewhat cryptic invitation to me. “I’m working on an exhibition with a little-known photographer named David Lebe, whose work I love,” he wrote. “I would like to show you.”

A few weeks later I hunched tentatively off the train from New York and found my way to the museum, where, leaning seductively on mahogany shelves in a viewing room for works on paper, I discovered David Lebe’s hand-colored gelatin-silver print Seth (1985). It alone was worth the trip. The delicately wrought tones of Seth, its large format, and the intricacy of its analog compositing all make for an example of photographic ingenuity that would be considered momentous by any standard.

David Lebe, Seth, 1985

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Seth turned out to be just the beginning. Relatively few people knew about Lebe until this year, when the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened the career survey Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue attempt to complicate the narrow canon of gay photography of the 1970s and ’80s on an institutional level by forging new space for a septuagenarian artist and his rich and varied body of work.

“A lot of queer artists in the 1970s and ’80s turned to photography as their medium of choice,” Barberie said. “That is a story that is still being told, it’s still unfolding, and there are many voices who are part of that story. This exhibition is just one iteration.” Barberie was speaking to a standing-room-only crowd gathered one afternoon in February to hear a public conversation with Lebe soon after the exhibition’s opening. “One of my goals for this exhibition, and I think the most important one, is to give support and space to this tremendously moving body of work. But I also want to make a contribution to our understanding of queer art during these crucial decades.”

David Lebe was a fixture of the Philadelphia art scene in the 1970s, and his center-city home on South Fifteenth Street was a gathering place for friends, students, and others involved in the arts. He studied with Ray K. Metzker and Barbara Blondeau and was a close friend and roommate of the artist Barbara Crane; the Bauhaus-y ethos of experimentation handed down from Moholy-Nagy at Chicago’s Institute of Design—of pushing mundane circumstances past their furthest logical conclusion—can be felt in every part of Lebe’s work.

David Lebe, Scribble #6, 1987

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Lebe was known for developing a certain kind of “light drawing” that melded details of the real world and male bodies with gestural marks drawn in with a pen light during long exposures. Some of these images are in the Philadelphia Museum’s collection, and they were Barberie’s introduction to Lebe’s work. They were also the primary focus of perhaps the only other comprehensive exhibition of Lebe’s work, a show called Truth Fantasy, which was staged in 1986 by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and accompanied by a small, staple-bound catalogue. In his essay for that publication, curator Tom Beck writes, “Autobiography is the key to [Lebe’s] work, which has shifted from time to time among photograms, light drawings, and male nudes.” Beck adds, in a seemingly personal note amid otherwise dry curatorial text, “Until the age of 25, David Lebe lived a closeted life; his life was about keeping a secret. Finally, he vowed to be open and honest about his homoerotic personal and aesthetic life.”

When Lebe discovered he had AIDS in the late 1980s, the diagnosis would almost have amounted to a death sentence. Soon after finding out, he met Jack Potter, who also has AIDS, and they fell in love. Though their lives were in Philadelphia, they withdrew to upstate New York, a decision they made in an attempt to improve their fragile immune systems. They moved to an area that has been cultivated since the mid-twentieth century by Anthroposophists, members of a philosophical organization whose adherents follow, to varying degrees, the teachings of the Austrian-born philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophy promotes holistic living and Steiner made advancements in biodynamic farming, so the community uniquely provides a wide range of the organic crops Lebe and Potter need for their macrobiotic diet. “Jack came very close to dying, and David also declined, but amazingly they rallied with new drug combinations that became available after 1995,” Barberie writes in the catalogue. Today they are remarkably healthy and full of zeal and appreciation for life, though they face a range of physical challenges that mean, among other things, that they spend most of their time at home.

David Lebe, Jack Watering, from the portfolio Jack’s Garden, 1996

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In November 2017, I took a train and then a cab to Lebe and Potter’s home near Ghent, New York, to see more of Lebe’s work in person. Everything in their house and their life together was organized just so, as if the house were an artwork. Rooms had been painted and repainted many times over to match or contrast the landscape perfectly, as well as the particular character of light and the objects and artworks inside.

We toured Potter’s garden, which was past its prime after a cold spell the week before, but purple flowers still blossomed on a few bushes near the ground. (He commented that they were bracts rather than flowers. Bracts, I later learned, are ornamental or colorful leaves that protect a smaller, more fragile bloom within, which I guess was the reason they survived the freeze.) We went inside, and I looked at prints with Lebe in an immaculate attic studio as Potter prepared dinner: mixed whole grains topped with natto, a traditional Japanese dish that he’d made himself by fermenting soy beans, a food they’d come to early in their macrobiotic diet.

Up in the attic, I experienced a second, slower revelation than I had in the museum’s viewing room. I began by looking at Lebe’s hand-colored botanical photographs, which are a technical marvel. The exact combination of spliced, projected negatives, contacted photogram objects, and hand coloring that was required to make these pieces in the darkroom is mystifying. The works are surreal in their spare landscapes and gradient skies, lost children of the psychologically inflected figurative paintings Jared French made in the mid-twentieth century and the botanical photograms of Anna Atkins a hundred years before.

David Lebe, s/m–Leather Contingent, from the portfolio The Second March on Washington for Lesbian & Gay Rights, October 11, 1987

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

I also leafed through an album of pictures from the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, in 1987. Lebe made the pictures using high-speed recording film, a black-and-white process known for its usefulness in low light and its unpredictability in terms of grain. Four-by-six prints were arranged in a modestly sized album, with the names of the people in the pictures written underneath in ballpoint pen. Lebe told me this was the first LGBT march on Washington where AIDS was a part of the agenda, but when I looked at the faces of the people in the photographs what I saw was joy instead of fear or anguish.

Barberie, too, feels these early works are essential to Lebe’s message. “Lebe discovered he had AIDS soon after the march,” he writes. “Over the decade that followed, he produced diverse photographs that grapple with the disease and its impact, and which together form the crucial part of his artistic achievement.”

David Lebe, Morning Ritual No. 28, 1994

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

It wasn’t until the current exhibition, however, that I saw one of the central pieces in Lebe’s work, a series called Morning Ritual (1994), made after he and Potter moved to the mountains. These smallish, black-and-white pictures exude tenderness through gestures of caring and intimacy, but also make the daily routines of the couple, whose health was still extremely perilous, into little photographic gifts of fine tonality and formal invention. If photography is often an honorific form, these pictures honor the quietest moments in Lebe’s life. They appear to genuflect for these times, and as part of a daily practice also mark time as it passes. They insist delicately, day by day, We are still here.

Robert Mapplethorpe, the go-to gay photographer of all time, naturally comes up in comparison to Lebe’s work and the culture of the 1980s. Lebe photographs flowers in black and white, and also deals with the erotic male body, sometimes explicitly. This is the case in a series of photographs of the porn star, activist, and writer Scott O’Hara, a friend and muse who Lebe photographed, often masturbating, in a series of four sittings between 1989 and 1996. During these years, pornography took on a new importance for gay men as a means of safe sex, free from the existential anxieties a hookup might incur. Of his photos of O’Hara, Lebe wrote, in 2013, “They are about, in part, the refusal to give up on life or on life’s pleasures. A triumph of spirit over AIDS.”

David Lebe, Bernard, Grady & Me, 1986

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art originated Mapplethorpe’s infamous 1988–89 retrospective that later went on to upset conservatives throughout the United States. Lebe saw the exhibition—and even appears in the 2016 HBO documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures examining Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio, which was installed at the ICA in a glass case built purposefully too high so as to prevent children from seeing the images. In February, during their conversation, Barberie asked Lebe what his reaction to the show had been. “I was doing male nude work at the same time he was, and so it wasn’t as if I saw his work and thought, Oh, it’s OK to do that. I was already doing that. It’s just that nobody saw it like they saw his work,” Lebe said. “I wasn’t searching out people who I thought would make startling or interesting photographs. My inspiration for photography always came from my life and myself.” Lebe recalled seeing the work of Minor White and Duane Michals, but not being certain if they were gay. “And that was frustrating and annoying,” he said. “So from an early time I just decided to be open in my work, and just let people know that I was gay and that the work came from that experience.”

All too often, museums and galleries show overexposed work by already famous artists, the ones who have been affirmed in the history of photography, like the recent museum and gallery exhibitions of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston in New York, or the Guggenheim’s two-part yearlong Mapplethorpe show. This is precisely why Lebe’s career-spanning retrospective being staged at a major museum is essential. Lebe is now incontrovertibly part of the history of twentieth-century queer artists. Given the number of voices silenced by HIV and AIDS, it is crucial to look back and celebrate the important work that queer artists made despite personal and political adversity. As a gay artist born in the late 1980s, at the height of fear about the American AIDS crisis, the trauma of the previous generation looms like a kind of silence of arrested potential. We can still hear that silence, and we could use more saints.

Matthew Leifheit is a photographer and the editor of MATTE magazine. He is a cocurator of the 2019 Aperture Summer Open.

Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through May 5, 2019.

The post Let Us Now Praise David Lebe appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 19, 2019

Alice Proujansky: Teaching Visual Literacy Through Photography

This one-day workshop is intended for photo educators and photographers looking to build their skills in the classroom.

Led by Aperture Teaching Artist and author Alice Proujansky, and grounded in Aperture’s On Sight curriculum, this workshop will teach participants how to decode and encode images, and how to interpret photographs using flexible, engaging inquiry techniques that make material accessible to middle- and high-school students. Through this workshop, participants will understand the ways that images communicate, how students can infuse their own photographs with meaning, and ways to move beyond art history lectures toward truly thoughtful interpretative conversations that encourage students to make personal connections with visual imagery.

The Aperture On Sight curriculum is designed to teach visual literacy through working with photography and creating photobooks. The curriculum builds students’ abilities to communicate as visual storytellers, develops them as creative and critical thinkers, and builds their capacity for academic and professional success.

The curriculum relies on the equation form + content + context = meaning as a framework for twenty lesson plans that guide teachers working with students in grades six through twelve.

Alice Proujansky is a documentary photographer and teaching artist, and the lead curriculum writer for Aperture On Sight, Aperture’s photography and visual literacy curriculum. Her photographs of women, labor, birth, and leftists have been published widely, and she has received support from the International Women’s Media Foundation, the Magnum Foundation, the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Women Photograph, and others. Her book Go Photo! An Activity Book for Kids was published by Aperture in 2016.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Learn engaging strategies for teaching visual literacy

Receive lesson plans, inspiration, and project ideas

Plan a photobook project for your students

Tuition:

Tuition for this one-day workshop is $250 and includes lunch and light refreshments.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Friday, July 5, 2019

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of ten students is required to run this workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Alice Proujansky: Teaching Visual Literacy Through Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2019 Portfolio Prize Winner: Mark McKnight

Mark McKnight’s black-and-white images of bodies and landscapes challenge Eurocentric ideas about male beauty—and aim to make “straight” photography a little less straight.

by Brendan Embser

Mark McKnight, if water forgets how to play mirror, 2018, from the series Decreation

Mark McKnight is a modern-day modernist. His black-and-white photographs of skin and sand, brick and tar, with their rich tones and sparkling light, are redolent of twentieth-century masterworks, those pictures by men like Edward Weston who cast the world in silver-gelatin. Weston once said the camera should be used for recording the “quintessence of the thing itself, whether polished steel or palpitating flesh.” But for McKnight, who was born in Los Angeles to a New Mexican, Hispana-identified mother, something was missing from Weston’s vision. Something that would ignite a flame of recognition in a young queer man with ideas about male beauty more expansive than the Eurocentric standard. Something that would make “straight” photography a little less straight.

McKnight began to photograph hirsute, softer-bodied men, often people of color, deliberately obscuring their identities so as to render them as “armatures for concepts of loss, desire, vulnerability, and entropy.” His subjects are people he knows intimately, partners or close friends. In his photographs, the body, the physical world, and the built environment begin to merge. “I like when the body starts to look like another thing, when it transcends itself. When it becomes undone,” McKnight says. By overprinting his images, he buries certain details while accentuating others. It’s a strategy “for making the body look less like a body, whether it’s concrete or metal.”

“The flame started first by amazement over subject matter, that flame which only a great artist can have,” Edward Weston wrote back in 1930. For McKnight, the choice of queer bodies as an ongoing subject—the flame itself—is simply about photographing men he found beautiful, and who looked more like himself. “I wanted to represent these subjects with the grace that Weston would have afforded,” he says. McKnight didn’t set out intending to “right some art historical wrong,” but he admits he couldn’t find the subjects of his desire represented in the history of photography. Until now.

Mark McKnight, Burned Map (or: Body), 2018; from the series Decreation

Mark McKnight, Decreation, 2018; from the series Decreation

Mark McKnight, Untitled, 2018; from the series Decreation

Mark McKnight, Earthskin, 2018; from the series Decreation

Mark McKnight (born in Los Angeles, 1984) was born to a New Mexican mother who struggled with their Southwestern, diasporic roots. In turn, McKnight grappled with reconciling his own identity, both as a mixed-race person of color and as a gay man—particularly one who neither exemplified nor desired the idealized, Eurocentric cultural standard of male beauty that is perpetuated even within gay culture. Since McKnight was raised in an environment that privileges white, heterosexual masculinity, his work operates as a site of resistance to those values. McKnight completed a Fulbright Scholarship in Finland in 2009, and he has also completed artist residencies at Storm King Art Center (2017) and Light Work (2019). In 2018 McKnight gave the first in a series of public lectures titled “Queer Eye,” in which he confronted the shortsighted legacy of “straight,” modernist photographic practice while proposing a queered historical revision; that same year he held two solo exhibitions that received favorable national reviews. His work was the subject of both a two-person gallery exhibition at Roger’s Office in Los Angeles and a multi-museum survey and catalogue. His most recent group exhibition, Close to Home (Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles, 2019), dealt with the themes of identity and abstract narrative. His work is currently represented by James Harris, Seattle.

Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine. All images courtesy the artist.

As winner of the 2019 Portfolio Prize, a portfolio of McKnight’s work will be published in an upcoming issue of Aperture magazine as be exhibited at Aperture Gallery.

The post 2019 Portfolio Prize Winner: Mark McKnight appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Teresa Eng

In her lyrical, dreamlike images, Teresa Eng asks—what does modern China look like to a child of the Chinese diaspora?

by Cassidy Paul

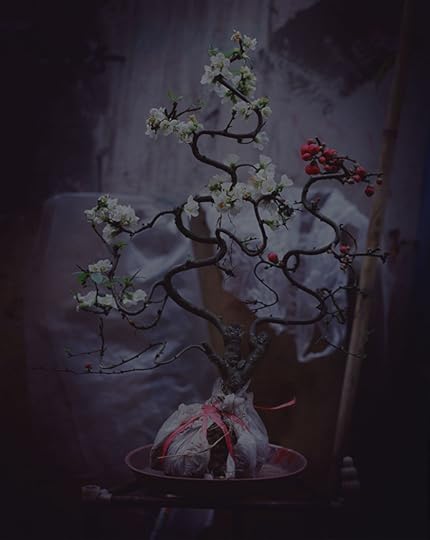

Teresa Eng, Junction, 2016, from the series China Dream

What does modern China look like to a child of the Chinese diaspora? That question at the heart of the lyrical, dreamlike images Teresa Eng has created throughout the country. Eng’s parents were part of the mass exodus of Mainland Chinese who fled to Hong Kong during the Communist revolution in the 1950s, and eventually immigrated to Canada. Growing up in Vancouver, Eng was only able to construct her vision of China from the cultural norms and traditions she experienced. It wasn’t until traveling there in 2013 that Eng was confronted with the stark contrast to her imagined state, finding instead a landscape in a constant state of fluctuation.

Drawing from the cultural preconceptions she formed in her youth, Eng began photographically exploring the country of her ancestors, looking to better understand her heritage. The resulting series, China Dream—named after a popular slogan Xi Jinping used, alluding to the American Dream—evokes cycles of reconstruction and reinterpretation of the past happening in China due to the immense development occurring throughout the nation. “The rate of development in China is so quick that the buildings I photographed have long been demolished and replaced,” Eng writes. “Historical monuments and buildings destroyed during the Cultural Revolution are being rebuilt haphazardly—often as facsimiles of the originals.”

Each of Eng’s vertical compositions feels like one part of a larger narrative, and viewing them gives a similar sensation to remembering flashes from a dream. In one, an ornate bonsai tree sits abandoned in a trash-filled alley. A head of infinite ink-black hair swirls off frame, mimicking the curved modern architecture of a similar image. Chinese graffiti gets scratched into the leaves of plants. And a never-ending series of overpasses and roads link over one another like a knot floating above the city. Eng’s photographs live at the in-between of moments, covered in a hazy, ambiguous veil that balances between reality and dream—reflecting her own personal experiences in ever-changing China. As Eng writes, “These observations allow me to make sense of the world around me.”

Teresa Eng, Wave (Hair), 2016; from the series China Dream

Teresa Eng, Chinese Graffiti, 2013; from the series China Dream

Teresa Eng, Wave (Blossom), 2016; from the series China Dream

Teresa Eng, Station, 2017; from the series China Dream

Teresa Eng (born in Vancouver, Canada, 1977) lives and works in London. Her photography deals with transition and change: she tends to revisit a place over time, allowing the temporal and physical distance to process her thoughts while new and existing strands of ideas merge. Eng’s first self-published book, Speaking of Scars, was shortlisted for the 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Award, and her work has been featured in publications such as Vogue Italia, British Journal of Photography, Dazed & Confused, Raw View, Invisible Photographer Asia, Photoworks, and L’Oeil de la Photography. In 2018, Eng was a finalist for the Photographie Grand Prix at Hyères 33e festival of fashion and photography.

Cassidy Paul is the social media editor of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

The post 2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Teresa Eng appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2019 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Jack Latham

In the age of fake news, Jack Latham investigates the secret society that has inspired conspiracy theories, protests, and attacks since its founding days in 1872.

by Emily Stewart

Jack Latham, The Phantom Patriot, Nevada, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

In the redwood forests of Monte Rio, California, sits an expansive 2,700-acre retreat where, every summer, an elite invitation-only social club founded by a group of male artists, writers, actors, lawyers, and journalists meets. The Bohemian Club, founded in 1872, has inspired conspiracy theories, protests, and attacks since its founding days. In Jack Latham’s new project, Parliament of Owls, he investigates the secrecy of the club and the wider political effects this has caused.

What happens when the country’s top lawmakers, politicians, artists, lawyers, and businessmen meet behind closed doors? What secrets are being swapped, plans being made? For years these questions have been at the root of protest groups and journalists hoping to expose the truth. Latham takes the viewer on a journey of discovery, showcasing the town surrounding Bohemian Grove (the club’s rural outpost) and its people. His photographs also depict the rise of Alex Jones—conspiracy theorist and founder of InfoWars—and how his break-in at the Grove led him to become a household name with the antiestablishment crowd. In 2000, Jones released alarmist footage of the club’s “Cremation of Care” ceremony, which inspired the attempted attack led by “Phantom Patriot” Richard McCaslin two years later.

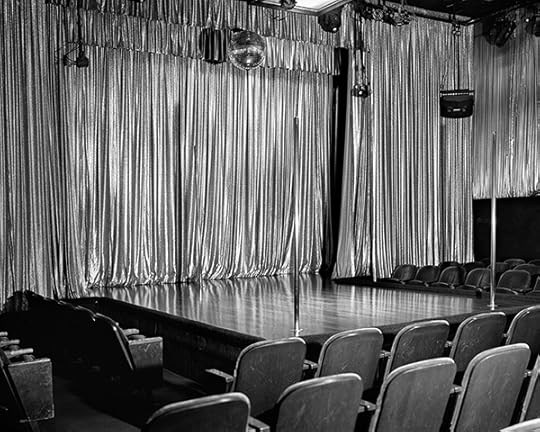

Latham describes his work as “an attempt to explore the dangers within society when voids of context are challenged.” His images are beautiful and thought-provoking, often leaving the viewer feeling mystified and intrigued. Because nonmembers aren’t allowed inside, Latham instead photographs spaces that are in some way tied to the club and its members—for instance, his image of an empty, glittery stage was taken in a strip club owned by two members. In one of Latham’s photographs, three Bohemian Club members can be seen standing on a viewing platform inside the Grove. The image is taken at such a distance that the members almost disappear into the surrounding forest, solidifying the fact that for the majority of us, the club will always be a remote mystery.

Jack Latham, Viewing Platform, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Main Stage at the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre, San Francisco, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Great Grey Owl, 2018; from the series Parliament of Owls

Jack Latham, Mary as Nixon, Camp Meeker, 2018, from the series Parliament of Owls