Aperture's Blog, page 92

February 21, 2019

Remembering Xavier Barral (1955–2019)

Aperture remembers the life of an influential figure in photobook publishing.

By Lesley A. Martin and Darius Himes

Xavier Barral at Paris Photo, 2017. Photograph by Ramón Reverté

When The PhotoBook Review was first launched in 2011, Xavier Barral was an obvious choice as the publisher best suited to launch the ongoing Publisher Profile column. The stated intent for the column was to “profile publishing houses that are contributing to the international photography book scene and who see the book as a primary means of expression within the broad field of photography.” Barral was a major figure in the French photobook community, but his impact was truly felt internationally. He had a keen and inimitable sense of the book as an object, and for the way photographic intention could be elevated by the judicious selection of materials, the right mode of reproduction, the proper balance of elements on the page. Barral brought an innate sense of elegance to every book, without ever reverting to the staid or expected, and his books ranged from the beautiful to the exquisite. Éditions Xavier Barral was a co-publishing partner of Aperture and it was a point of pride for a book that we originated to be selected as suitable for the XB list. It was with profound sadness and a sense of loss that we heard of his passing this past weekend. The publishing community is less lovely and less complete without him. In tribute to him, we repost Darius Himes’s column from November 2011. —Lesley A. Martin

Ramón Reverté, Lesley A. Martin, Xavier Barral, and Klaus Kehrer at Paris Photo, 2017

Photograph courtesy Ramón Reverté

Editions XB, based in Paris, France, was founded in 2002 by Xavier Barral, a photographer and former art director. The first book Barral published was Word for Word, a co-edition with the Centre Georges Pompidou on the work of French minimalist artist Daniel Buren. In many ways, this book set the tone of the publishing house. As an artist, Buren was regarded as visually and spatially audacious, and is known as an abstract minimalist who is concerned primarily with what he calls the “scene of production.” For his book with Barral, this “scene” became the printed book. Word for Word is a glossary of sorts, thumb-tabbed like a large dictionary, covering one hundred key words, from A for “affichage sauvage” (fly posting) to Z for “Zigzag.” It is a pleasure to hold and behold.

Sergio Larrain (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2013)

A creative marriage of content and form is precisely the point of a book, in Barral’s eyes. As a publisher, he actively strives to “recapture the pleasure of a book” and set the physicality of the object on center stage. Great art books are akin to “sculpture, or like portraits,” he stated in a conversation with me by email. “Books will become more and more expensive to produce, the cost of paper will never cease to rise, and they will become a luxury good,” says Barral. “The role of the digital book will be essential. I have nothing against the digital book. On the contrary, I see it as a solution to the dynamism of information and a field of fantastic exploration!” The paradox, he offers, “is in how it serves the art photography book. The digital book pushes the printed book to distance itself from accepted standards, to distinguish itself. The imprinted form becomes a choice.” This distancing from accepted standards is evident in the titles published since the inception of Editions XB. In the last few years, Barral has worked on projects with Jean Gaumy, Sophie Calle, David Lynch, Philippe Chancel, Takashi Murakami, and a second project with Daniel Buren.

Speaking about the nature of collaborating with artists, Barral shares that “Every collaboration has been gratifying. I publish authors not only because I want to defend an idea, a work, but also because they teach me, because they help me. And likewise, I push the artists. Through the books, I think I can go farther precisely because they surprise me. . . . I become a kind of conductor, advancing towards an objective. I see all my books as parts of a whole.”

Josef Koudelka, Wall (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2013)

Two books which exemplify this collaborative spirit were published this past year: Antipersonnel (2011), by Raphaël Dallaporta, and A Criminal Investigation (2011), by Yukichi Watabe. Dallaporta was born in France in 1980 and was the winner of the 2010 Young Photographer ICP Infinity Award. In many ways he represents a new generation of photographers who are consciously engaged with photographs and their relation to the printed word—whether following the dictums of scholarship or the mores of literature—and who see the book as a lasting, important form of expression. Dallaporta’s long-term projects can loosely be termed “documentary,” as they are concerned with real-world situations, but he consciously borrows a visual language from varied sources beyond the recognizable tropes of journalistic photography. His photographs and subsequent books are the result of collaborations with professionals from a wide range of fields, including social work, forensic pathology, and, for Antipersonnel, a landmine-clearing project.

Martin Parr, Life’s a Beach (Aperture/Éditions Xavier Barral, 2013)

Also based on a real-world situation, albeit one from some decades ago, A Criminal Investigation, by Yukichi Watabe, looks and reads like a crime thriller, with the following text appearing on the back cover:

On January 14th, 1958 the disfigured and mutilated body of a man was discovered near Lake Sembako, Japan. Two Tokyo detectives were sent to help local authorities quickly wrap up what seemed to be a routine case. It turned out to be anything but.

From the outset, the question presented by this book is whether the story is fictional or historical. Watabe (1924–1993) was a freelance photographer who was granted special permission to accompany the two detectives on a murder case involving a dismembered body. The vocabulary Watabe wields is an elegant blend that draws on both film noir and the handheld, Magnum-inspired journalism of the era. Many of the photographs read like film stills, with the elder detective cast as the main protagonist of the story. The murder case was indeed real. Through the active storytelling devices of brief journalistic notes deeply enhanced by powerful editing, sequencing, and the design of the book, A Criminal Investigation borders on a true graphic novel in photographs.

Barral’s conscious attention to the printed book as a platform for creative expression in collaboration with artists and designers is what will distinguish Editions XB from other art and photography book publishers in the twenty-first century. —Darius Himes

At the time of the publication of this piece, Darius Himes was assistant director of Fraenkel Gallery and a cofounder of Radius Books, and had recently coauthored Publish Your Photography Book (Princeton Architectural Press, 2011). He is currently the International Head of the Photographs department at Christie’s.

The post Remembering Xavier Barral (1955–2019) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 20, 2019

Collapsing Time and Space in Black and White

Ray K. Metzker spent his career exploring the boundaries of photography in order to break them.

By Max Campbell

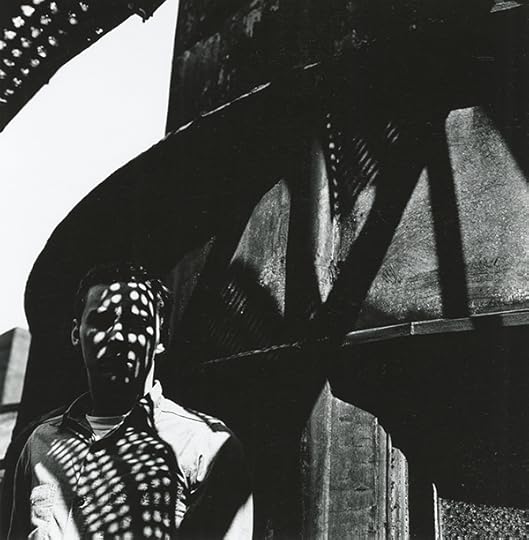

Ray K. Metzker, 63 CM-12, Early Philadelphia, 1963

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

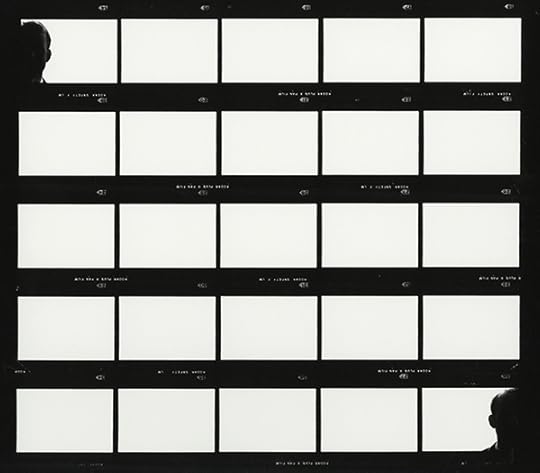

Twenty-three empty frames divide the left and right side of Ray K. Metzker’s likeness in 67 DH, Early Philadelphia (1967). Each is numbered and, under every other one, “Kodak Safety Film” or “Kodak Plus X Pan Film” can be read, written upside down. On first glance, the image might appear to be a contact sheet of blown exposures or an empty template. But at either end, silhouetted features—hair, ears, shirt collar—punctuate the emptiness, turning a roll of film into a single image.

Ray K. Metzker, 67 DH, Early Philadelphia, 1967

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

This contact-sheet-as-self-portrait is on view to the public for the first time among more than fifty photographs surveyed in Ray K. Metzker: Black & Light at Howard Greenberg Gallery. Like 67 DH, which makes a subject out of what is in between by stretching the study across twenty-five shots, the works in Black & Light draw attention to the evolution between various experiments in Metzker’s half-century career. It is in transitions from one formal exploration to the next where the restlessness, frustration, and persistence that set Metzker apart are most clearly on display.

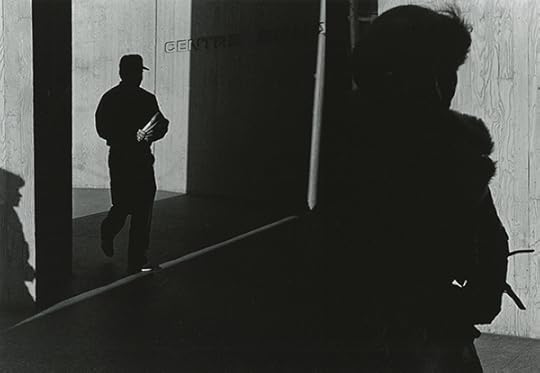

Ray K. Metzker, 82 QO 21-22, City Whispers, 1982

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Here street photography hangs near intricate darkroom compositing. Scenes from Chicago, where Metzker studied under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind at the Institute of Design, mix with others from Philadelphia, where he went on to teach at the College of Art. Faces get close to brushing the camera’s lens; cars, building facades, and interior scenes recede into geometric impressions. A range of action and observation is mounted on the wall here like a score. We can sense Metzker’s interests in theater and music clearly in stark shots of people posted under industrial structures and exchanging passing glances on street corners. In certain images, subjects are found in such dramatic relief that they seem to have been photographed across footlights.

Ray K. Metzker, 68 FD/68 FD, Couplets, 1968

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Black & Light, which is presented on the occasion of Howard Greenberg’s new representation of the photographer’s estate, of course does not provide the context that might be available in a museum retrospective. But the show does present works spanning Metzker’s career, and a look at the rolling innovation that defined it. In two early photographs, a man and a woman stand behind what appear to be thin curtains, some obstruction on the street Metzker has chosen not to avoid. A few years later, he would seek a similar effect in early experiments, holding up film negatives to photograph through and abandoning a dedication to the power of the decisive moment.

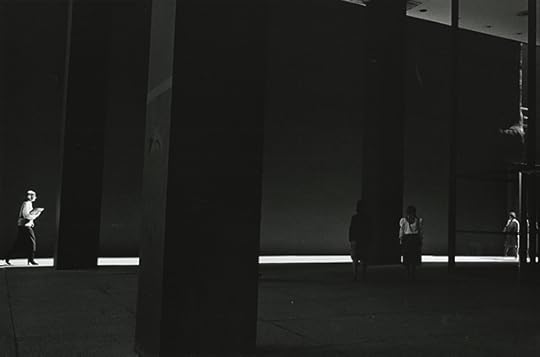

Ray K. Metzker, 58 EA-20, Chicago – Loop, 1958

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Throughout his career, Metzker identified the boundaries of photographic images so that he could restructure them. It was an inclination that grew out of what Keith F. Davis describes in The Photographs of Ray K. Metzker as an “impatience with the static perspective of the single image,” a frustration with “the essentially realist notion of the photograph as a passive ‘window on the world.’” Metzker might take a photograph and advance the film only partially, muddying the temporal divisions inherent in his camera and film. At Howard Greenberg, a grid of Metzker’s “Pictus Interruptus” images shows him grappling with the too-perfectness of landscapes, lifting things into his frames in order to disturb familiar forms. The objects blot out and mix into architecture in the distance, collapsing space between his vantage and the landscape. Clear indications of people and landscape leave his frames entirely in some later works, where solarized prints, torn and collaged, make rough white paper edges look like photographic highlights.

Ray K. Metzker, 65 A-2, Early Philadelphia, 1965

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

As Davis writes, Metzker’s work encourages us to “think about the adventure of perception in new ways.” His techniques for compositing underscore a tension between the static stipulations of photography and the current of action one might find on the street. Describing the “Pictus Interruptus” work, Metzker explained that he sought disturbances, things that were “foreign in subject but hauntingly right for the picture, the workings of which seem inexplicable, at the very least, a surprise.” Physical aspects of perception were also of interest, and Metzker took to translating them into images. It is an eyeball in rapid motion that charts the world before us, he observed, and holding that energy within the pictures required reaching for and often developing new frameworks.

Ray K. Metzker, 82 KS-4, City Whispers, 1982

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

During different phases of his work, Metzker described photography both as a vacuum cleaner used to suck up every detail and as a process like collecting butterflies. The two analogies account for time in very different ways, and we can find a shifting relationship with the delicacy and voraciousness of photography in Black & Light. Formal approaches are adjusted like a watch because, as Metzker explained, photography was for him a way of examining the world by reaching out, touching, and then transforming meaning. “What catches my attention and leads me to trip the shutter,” he once said, “is the first step in a process that may or may not lead to anything that quickens the heart.” The individual works often do. And an opportunity to chart the many directions in which Metzker reached provides a delight of its own.

Max Campbell is a writer and photographer based in New York.

Ray K. Metzker: Black & Light is on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, through March 2, 2019.

The post Collapsing Time and Space in Black and White appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Three Women Photographers Reclaim the American Landscape

Susan Lipper, Kristine Potter, and Justine Kurland deconstruct the mythology of the Wild West.

By Rebecca Bengal

Justine Kurland, One Red, One Blue, 1999

© the artist and courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

In her influential 1985 essay “Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men,” Deborah Bright called for women artists to “recoup landscape photography for themselves in response to its long-time character as an exclusive white male preserve.” The cherished ideal of the Wild West, metaphoric repository of the American dream, seemed particularly hunted and besieged: Ronald Reagan was in office, and images of the cowboy president riding horses and chopping wood on his Santa Barbara ranch were prevalent, propping up stereotypical colonial ideas of dominance and expansion. “Landscape images are the last preserve of a nation’s myths about nature, civilization and beauty,” Bright wrote.

Certainly plenty of American women photographers working in landscape-at-large have been cracking apart those myths since, as seen in Sally Mann’s photographs of Civil War battlefields, and LaToya Ruby Frazier’s depictions of steel industry wastelands in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, to name a few. In that vein come two auspiciously titled new books of black-and-white photographs centered on American landscape by women photographers: Domesticated Land (MACK, 2018) by Susan Lipper and Manifest (TBW Books, 2018) by Kristine Potter.

Susan Lipper, Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Lipper’s Domesticated Land is the third in a series of monographs the New York–based photographer has made on road trips in America since the 1990s. In this installment, she travels to the California desert, rendered postapocalyptyic in sun-bleached tones. In the image that wraps the front and back cover of Domesticated Land, a desert junkyard of tin cans rusts in the sunlight, the detritus of past westward migrations leaving an ominous trail for those who follow. While born in Dallas, Potter was based in New York for years, prior to moving to Nashville in 2017. For Manifest, she traveled to Colorado, photographing wilderness and the men who wander it. On the cover of the book, a male subject is mostly camouflaged by leaves and corresponding shadows; they shield and protect him in a harsh and unknown landscape.

Kristine Potter, Topher by the River, 2012

Courtesy the artist and TBW Books

Lipper and Potter focus specifically on the American West. Their books join other recent monographs by women that take as their subject this complicated history and landscape. In her first monograph, Deep Springs (MACK, 2017), begun when she was completing an MFA at Yale, Sam Contis traveled to the then all-male liberal arts college of the same name, located in the California desert east of the Sierra Nevadas. Her sensual, gestural pictures of young men in a rugged landscape reveal atypical depictions of masculinity in the West. In her photographs the region remains romantic, but the view is personal and intimate, focusing not just on bodies in relation to landscape, but specifically the textures of clothing, skin, dirt, blood.

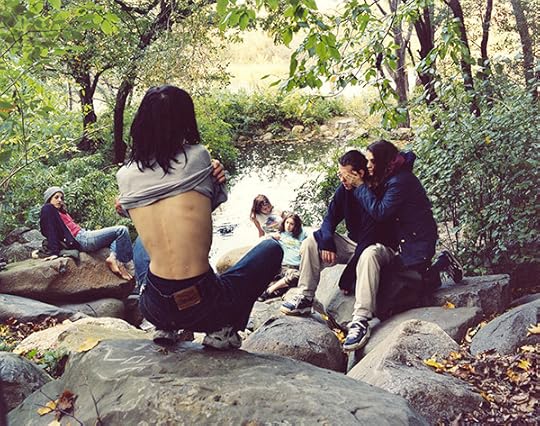

Wilderness, the road, and the individualist promise embodied by the West have occupied much of Justine Kurland’s career, too, starting with her Girl Pictures series of staged photographs, which were recently shown in an anniversary exhibition and republished as a limited-edition photobook in an edition of two hundred copies, which sold out rapidly (Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 2018). Seen afresh in 2018 and by a new generation, her girls took on new resonance as they forged through woods and roadside wastelands and made those places their own, reclaiming male-dominated adventure narratives in the process. What began as revisions of fictionalized myth for Kurland launched a career trajectory into a years-long, documentary minded exploration of the American road as place and ideal, an interrogation of manifest destiny.

On her annual cross-country migrations, often accompanied by her young son, Kurland photographed the tropes of the Westward road: trains dissolving into the vast landscape, horses and cars and their mechanics and drivers and hitchhikers—America’s grizzled and troubled dreamers and drifters, most of them and the Contemporary American Landscape men. “What is power in this wounded world?” Kurland asks, quoting her own son’s question; “I could ask the same of the road.”

Justine Kurland, Boy Torture: Love, 1999

© the artist and courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

The drifters who wander through Kristine Potter’s pages could practically be some of the same men. Potter has made masculinity the subject of previous series: her photographs of soldiers training at West Point are connected to a long line of male relatives who served in the military. Her latest work, photographed in Colorado, is also rooted in personal history—her great-great-grandparents were sharpshooters who started their own traveling show, in the style of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show—and Manifest grapples with both the history of landscape photography Bright cites, and the legacy of westward expansion, justified by national ideology. “The mythic image of the West abetted the profound and sustained violence required to render this region to the nation, in a process that in turn stripped from the West the lifeworld of its indigenous peoples,” writes Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa in the afterword.

Potter’s landscapes are luminous but anxious, alluring but frightening. There’s a sense of paranoia in the pacing of Manifest. Darkness offers comfort: shadows shelter those for whom to be exposed means to be vulnerable. Midway through the book, a photograph of an empty road under a full moon, in multiple shades of silver, is the most serene image in the book—here, the night delivers calm. In daylight, appearing like portents on the ground and repeating within Potter’s sequence are images of water, a river, and the mini narrative of a man surfacing in it, attempting to make his way across. Will he make it? There are flashes of the pastoral—a man sunning on a rock in a stream, sunlit weeds, those river rapids—but idyllic nature is often a goal, not the present tense. It is the distant view, in the book’s final image, of the snow-capped Rockies, seen from a still-green part of the country, obscured by other woods, another wilderness to cross first. Here is manifest destiny realized, Potter seems to suggest—or, to answer Bright, the cancer of the Marlboro Man.

Kristine Potter, Drying Out, 2015

Courtesy the artist and TBW Books

When Susan Lipper began her road trip trilogy of photobooks in the 1990s, she had returned from a three-year residency in the UK. Grapevine, first published in 1994 by Cornerhouse, takes its name from a hollow in rural West Virginia, where Lipper made pictures that were both diaristic and documentary. Her next photobook in the series, trip (Dewi Lewis, 2000), worked photographs made in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas into an imagined journey that subverted the classic male road trip, and made her own presence a character. Between trip and Domesticated Land, Lipper says, she invented a new photographic persona, not terribly unlike herself: a liberal New Yorker who “has not lost faith in America fulfilling its utopian promise,” and who also seeks to shuck off its consumerist culture. Her protagonist heads to the California desert, culminating at Zabriskie Point, unnamed but resonant nonetheless. Here presented as a kind of final frontier—blighted, scorched, blinding, largely uninhabited—the landscape takes on an alien aspect, and the objects pictured within it offer telling clues.

As in trip, in which Lipper made her own presence palpable on diner plates and motel mirrors, she places herself in the narrative of Domesticated Land. A car’s side mirror is visible at the right edge of one frame, for instance, and these moments where the photographer is seen offer tangible proof that this world is being watched, that someone is bearing witness to what is happening to this dry, cracking earth. Interspersed at intervals throughout the book are pages containing brief quotations, which clue the reader in to the mindset of this traveler, which is aligned with Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and a legacy of American women pioneers who, as feminist theorist Annette Kolodny writes in one epigraph within Domesticated Land, tend to approach the harsh land with the goal of “locating a home and a familial human community within a cultivated garden”: a domesticated land. It’s a gentler approach, but still centered around bending landscape to human will—and isn’t that a version of colonial sensibility, too? Instead of the utopia her traveler seeks, Lipper finds the dried pages of a book, littered fragments of construction material, discarded refrigerators and washing machines, baked asphalt, an abandoned house that could be a suburban tract home out of Robert Adams’s The New West—all grim portents. Soldiers and military tanks appear on the horizon; here, seemingly, is the foregone conclusion of the land, the government takeover of the desert.

Susan Lipper, Domesticated Land, 2018

Courtesy the artist and MACK

And yet the book makes room for a kind of hope. Lipper’s lone protagonist is also seemingly rescued by the company of a band of wanderers. Perhaps they are a literal band (she also quotes song lyrics by a desert musical group, the Sibleys), but regardless, their faceless presence in the images adds a welcome mutinous thread as they inspect the traces of civilization. They are the human community of which Kolodny writes, and seeing them delivers a little surge of possibility. Could they collectively rebel against the feds encroaching and imposing an armed rule over the natural world? Some of the solace in the book comes from the bleakness of the images, the depictions of the continuous desert itself, suggestive of something Adams also said in his New West period: that “all land, no matter what has happened to it, has over it a grace, an absolutely persistent beauty.” In any case, if this land is to survive humanity’s most destructive impulses, perhaps a first step is to undo the Marlboro Country mythology of the West: to question, to see again, to see anew.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 015 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Three Women Photographers Reclaim the American Landscape appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 14, 2019

For Alex Majoli, Photojournalism and Performance are Inseparable

The photographer’s psychological portraits cast a unifying light around the world.

By David Campany

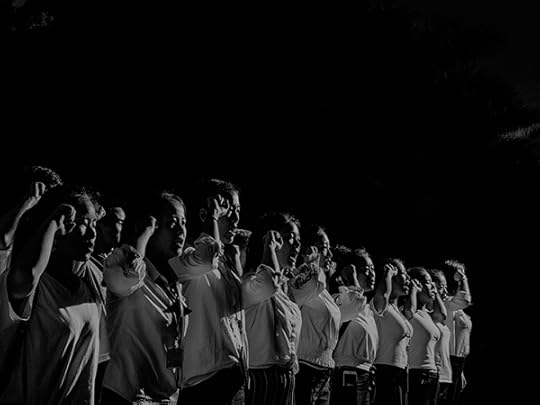

Alex Majoli, Scene #2774, Guangzhou, China, 2016

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Europe, Asia, Brazil, Congo. For eight years, across continents and countries, Alex Majoli has photographed events and nonevents. Political demonstrations, humanitarian emergencies, and quiet moments of daily life. What holds these disparate images together, at first glance at least, is the quality of light and the sense of human theater. A sense that we are all actors attempting, failing, and resisting the playing of parts that history and circumstance demand; and a sense that we are all interconnected. Somehow.

Alex Majoli, Scene #8667, London, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Majoli’s photographs result from his own performance. Entering a situation, he and his assistants slowly go about setting up a camera and flash lights. This activity is a kind of spectacle in itself, observed by those who may eventually be photographed. Majoli begins to shoot, offering no direction to people who happen to be before his camera. This might last twenty minutes, or even an hour. Sometimes the people adjust their actions in anticipation of an image to come. Sometimes they are too preoccupied with the intensity of their own lives to even notice.

Majoli uses very strong flash lighting. It is instantaneous and much brighter than daylight. It illuminates what is near but plunges the surroundings into darkness, or something resembling moonlight. Spaces appear as dimly lit stages and, regardless of the ambient light that existed, everything seems to be happening at the sunless end of the day. Just when the world should be preparing to sleep, it offers a heightened performance of itself.

Alex Majoli, Scene #9928, Republic of Congo, 2013

© the artist/Magnum Photos

The term “theater” implies a stage; a stage implies an audience; an audience implies performance; and performance implies artifice. Photography has always had fraught relations with all these concepts. This is because it is a medium that can be used with minimal preparation or intervention. It can set itself apart from the world it depicts, or at least fool itself it can, and this was for a long time enshrined as the protocol for realist reportage photography. In order to be true and authentic, a reportage photographer had to be present in the world but without interference. It was an aspiration at once noble and impossible, of course.

Alex Majoli, Scene #1350, Shenzhen, China, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Majoli’s approach to image making constitutes a profound reflection upon the conditions of theatricality that are implicit in both photography and a world we have come to understand as something that is always potentially photographable. If the world is expecting to be photographed, it exists in a constant state of potential theater. Whether it is a surveillance camera, a smartphone camera, or a photojournalist’s lens, the omnipresence of photography has created a heightened state of camera-consciousness. Even when this consciousness does not affect those in front of the camera, it affects those looking at the resulting images. In photographs we do not see people, we see people who have fulfilled their potential to be photographed, to become light, with all the inevitable theatrical transformations this can entail. This does not negate the documentary potential of the image, although it does imply that documentary itself ought to accept the theatricality of its own premise.

Alex Majoli, Scene #9546, Republic of Congo, 2013

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Majoli accepts this newly complex condition, responds to it and reflects upon it. And from this perspective it is perfectly understandable that the points of departure for his project come from experimental theater, and in particular Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, first performed in 1921. Its “plot” concerns a theater director, and actors who, while rehearsing their play, are interrupted by strangers. The presence of these strangers, with their complicated relationships and difficult histories, forces the director to rewrite the play in order to accommodate them. The layers of theatricality build up, and the audience has to adjust constantly. But the play would be little more than an empty game about theater, were it not for the fact that Pirandello has deep moral questions to pose to the audience. What is our relation to the demands of strangers? What adjustments are we obliged to make? How do we reset the “plot” of our life, our society?

Alex Majoli, Scene #2233, India, 2015

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Is there a correct position from which to grasp Alex Majoli’s proposition? Are we to suspend any documentary claim and engage with these pictures as fictions, like film stills or theater publicity photographs? Are we to understand these images as psychological portraits of people and circumstances, made by a photographer concerned with some higher truth relating to the contradictory promise of a new global consciousness? Would this global consciousness be the ghostly return of the humanist promise of universal rights and values, asserted in the face of shameful and catastrophic inequality? Perhaps these are not so much ways to read Majoli’s photographs than questions to think about while looking at them.

David Campany is a curator and writer based in London.

This piece is adapted from Alex Majoli: Scene (MACK/Le Bal, 2019). Alex Majoli: Scene is on view at Le Bal, Paris, from February 22 to April 28, 2019.

The post For Alex Majoli, Photojournalism and Performance are Inseparable appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 13, 2019

Family Workshop

On February 1, 2019, thirteen photography students from colleges and universities in New York City were invited to Aperture Foundation’s Chelsea gallery for a workshop inspired by Aperture magazine’s winter issue, “Family.” Participants were joined by Rhea Combs, Curator of Film & Photography at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and photographer Kathryn Harrison. The workshop began with Aperture magazine’s managing editor, Brendan Embser, introducing the day’s speakers. The first session of the workshop was led by Combs, who discussed how the notion of family motivates her work as a curator. Combs started out by showing images from her own personal family archive, and continued on to discuss more historical images from the museum’s collection. Combs provided meaningful insight into the way she looks at photographs, discussing how images “convey a fissure, or another layer into the subject’s personality.” Combs concluded her session by answering insightful questions from the students while emphasizing the need to rupture the notion that family photographs may not always be deemed “museum quality.”

The second session of the workshop was a master class by Kathryn Harrison. As a young photographer who has recently received her MFA from Yale, and whose work has been featured in publications like the New York Times, Aperture, and Format, she was able to provide a range of advice from how to be a working photographer to how to balance work and personal life. Harrison walked the students through her own photographs, showing them projects from her undergraduate degree as well as her most recent work about her family. Even when Harrison is not making work directly about her mom and her brother, all of her work is deeply rooted in the notion of family. For the remainder of the workshop, Harrison led students through portfolio reviews. She looked at each student’s body of work, giving them feedback and helpful advice. She told the students that “it is important to photograph the way the world looks now. In twenty years, it will look completely different.” Harrison’s openness about her own work and her words of encouragement inspired students to continue making work and be confident in the direction their projects are going in.

Significant support for this program and the “Family” issue of Aperture magazine is provided by the Kanakia Foundation, the Anne Levy Charitable Trust, and the Reba Judith Sandler Foundation.

Further generous support is provided, in part, by the Board of Trustees and Members of Aperture Foundation, the Grace Jones Richardson Trust, the Jane Smith Turner Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

Explore Workshops

The post Family Workshop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 7, 2019

Documenting the Weaponization of Water Along the U.S.-Mexico Border

In remote stretches of desert, Richard Misrach and Guillermo Galindo record traces of volunteer efforts—and attempts by Border Patrols to stop them.

By Josh Kun

Richard Misrach, Agua #1, near Calexico, California, 2004; Water placement by the organization Water Station.

© the artist

Last month, four volunteers for the Arizona-based humanitarian aid group No More Deaths were convicted on misdemeanor counts of trespassing after entering the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge without a permit in 2017. Charged with threatening “pristine nature” (in the words of U.S. Magistrate Judge Bernardo Velasco), they left canned food and jugs of water in an uncompromising expanse of protected desert in order to help long-journeying migrants suffering from dehydration and malnourishment.

Richard Misrach, Wall, Jacumba, California, 2009

© the artist

The volunteers knew the statistics of the pristine desert all too well. Since 1999, more than three thousand migrant deaths have been reported to the Pima County medical examiner, but as so many have pointed out, those numbers are necessarily low. Bodies decompose fast in the desert sun. The story of migrant death along the U.S.-Mexico borderlands always carries an even grimmer footnote: there are many more. The deserts of Arizona and California are many things to many people, and they are also certainly graveyards, landscapes now defined by human remains scattered amidst saguaro cacti and lowland brush, disintegrating into dust in heat-stunned canyons and gulches.

The Border Patrol has never liked the work of No More Deaths or their California counterpart, Water Station, which for years has installed large blue barrels full of six-gallon water jugs in remote stretches of terrain. Agents have been known to shoot up barrels, slice open and empty jugs, and destroy canned food.

Richard Misrach, Bullet-ridden water station, Carrizo Creek Gorge, California, 2014

© the artist

Richard Misrach, Migrant grave site, Carrizo Creek Gorge, California, 2014

© the artist

When Richard Misrach traveled the California and Arizona deserts in 2014, taking photographs that would find their way into Border Cantos, he worked closely with both organizations. He hiked with No More Deaths volunteers in Arizona, photographing them near Arivaca on a trek to deposit water jugs. In his Agua series, he shot over four dozen images of water station barrels and beacon flags, including one barrel dripping red paint into bullet holes left by the Border Patrol. Installed next to a fallen shade tree in the Carrizo Gorge, the water station is only feet from a cross of white stones, a makeshift migrant grave.

Richard Misrach, Lee S., No More Deaths, near Arivaca, Arizona, 2014

© the artist

Richard Misrach, Water placement by the organization No More Deaths, near Arivaca, Arizona, 2014

© the artist

As part of his Border Cantos collaboration with Misrach, composer Guillermo Galindo turned these visual traces of volunteer aid and the attempts to stop them into musical instruments and sonic outcries. In his Water Station Scores, Galindo superimposed forensic data of human remains over Misrach’s water station photographs. In his Sarape Tracking Flag, he printed a musical score on a tattered water station beacon. But his crowning intervention is Fuente de Lagrimas (Fountain of tears), a blue water station barrel that slowly drips water onto a slab of rusting metal floor. When the drops hit, you can hear the weaponization of water in the age of militarized border enforcement. Galindo compares it to “rain falling onto a tin roof,” but this is no symphony of shelter. This is a grueling drip-drop rhythm for a place where shelter is scarce, help has become a criminal act, and no Samaritan is safe.

Guillermo Galindo, Fuente de lágrimas (Fountain of Tears), 2014

© the artist

Click here to purchase Border Cantos at a discount. For the duration of the sale, Richard Misrach and Guillermo Galindo will donate 100% of their royalties to the Arizona humanitarian group No More Deaths.

Josh Kun is an author, journalist, and curator. He is the director of the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Southern California, where he is also professor and chair in Cross-Cultural Communication. He is a 2016 MacArthur Fellow, and wrote the introduction and epilogue to Border Cantos (Aperture, 2016).

The post Documenting the Weaponization of Water Along the U.S.-Mexico Border appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 6, 2019

The Hard Truths of Family Life

In Florida, Kathryn Harrison photographs her mother and brother with fearless intensity.

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist

When Sally Mann started photographing her kids and husband thirty years ago, it was probably the most interesting case of a photographer turning the lens on their immediate family since John William Draper covered his sister’s face in flour and made her sit perfectly still for sixty-five seconds in 1840. It may not be an exaggeration to say that Mann made us look at our own family members differently, as people we know intimately and, at the same time, as actors in a drama more vast and complicated than we can grasp or hope to control. She didn’t discover all of that, but she made it newly visible. Work of that power ought to produce progeny and spawn, and hers has.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist

One of the most recent—and promising—cases is a woman named Kathryn Harrison. She’s thirty. She’s not the brilliant and scandalous author Kathryn Harrison who wrote The Kiss (1997), just same name, same spelling. “I have run into that many times,” she said on the phone recently. “I just say, ‘Not me.’ But I do think it’s kind of fascinating that she’s a writer who also does very personal work.” As for Sally Mann, “I’ve met her once, at a show. I don’t think she would remember me. But she’s one of the leading ladies in my life. It’s her work. It’s her fearlessness in putting those images out into the world.”

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist

Harrison is also a Southern woman (from Florida) who takes pictures of her immediate relatives. Many involve her chronically ill mother, a major force in her life, but her new work focuses mainly on her brother, Ray, who suffers from schizophrenia. “He got into drugs and got sent to an institution. We didn’t get to spend any time together for some really important years.” The pictures are searingly intimate. They seem to have been taken from closer than you’re supposed to stand. Yet, they don’t leer.

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist

“Some people have said, ‘It’s so exploitative,’” she told me. “But he wants it, too.” He being Ray. The work is almost a collaboration between artist and model. “He’ll call me and say, ‘I want to make a picture of this!’” A self-made artist’s book by Harrison (yet to be published) has Ray’s drawings and writings in it. “My brother only draws when he’s high,” she said. “In that sense, his drawings are all very dark. Vines growing out of a pot, every time.” She basically let him art direct the book: “In the beginning, I was shooting medium-format, and he would show up on my college campus, in Sarasota—always on foot. He would take me to all of these hidden places, where he’d overdosed, or where a guy did this crazy thing.”

Kathryn Harrison, Untitled, Sarasota, Florida, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist

Harrison admires the painter Caspar David Friedrich, and she allows her brother a certain romantic drama, even in his self-accelerated decay. In one of my favorite pictures by her, Ray is seated on an overturned plastic recycling bucket in the driveway. He is shirtless, in camo shorts, giving himself a random haircut with a buzzer. Hair clumps fall and lie on the asphalt at his feet. It is the trashiest thing a person could possibly do, yet he sits on the bucket as on a throne, glaring at you like a king whose time you are wasting. “He presents himself with all of his chaos,” Harrison said. She does the same.

John Jeremiah Sullivan lives in North Carolina and is a writer for The New York Times Magazine.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Hard Truths of Family Life appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 31, 2019

The Pleasures of Domestic Comfort

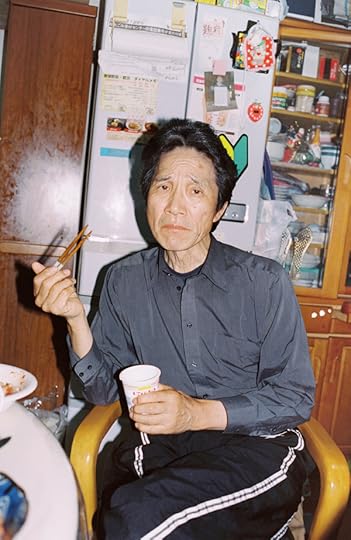

At home in Japan, Motoyuki Daifu captures his family with gleeful candor.

By Dan Abbe

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

© the artist

In one image from Motoyuki Daifu’s series Project Family (2007–ongoing), the photographer’s mother eats at a table that’s practically overflowing with vessels of all kinds: bowls, bags, coffee mugs, sauce bottles, food containers, a small tub of candy. The table tilts slightly upward, producing the vertiginous feeling that everything might just slide off and into the viewer’s space. The aggressive and nonchalant combination of vibrant colors, a mountain of domestic clutter, and a figure hardly paying any attention to the camera characterize Daifu’s series, which he calls an exploration of “the extraordinary within the ordinary.” His work plays across these two areas of experience, at times gleefully mixing them together.

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

© the artist

Daifu started working on Project Family while living with his mother, father (a professional photographer), and four siblings in a suburban development in Yokohama, Japan’s second-largest city, located just outside of Tokyo. The project began as part of a photography school assignment, and he notes that other students felt some discomfort with the work, because his house was different from theirs. Daifu knows that his photographs can also be surprising to foreign audiences expecting a “refined and clean” image of life in Japan, but he’s adamant that his family home is hardly unusual. “You can find homes like this all around,” he says. “I don’t think these conditions are anything special.”

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

© the artist

Daifu says that each member of his family appears in his work as a “character,” and the consistent use of flash gives his photographs a theatrical or posed quality, as if he were an outside observer. Daifu’s parents face his camera directly, and their placid expressions hardly differentiate themselves from the various objects that appear in the series. Yet the vast majority of these situations—including the stack of tires that can be found in one image—are not staged.

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

© the artist

His other works also deal with intimate spaces: Still Life (2012–16) extends the exploration of objects in Project Family, while Lovesody (2008) documents Daifu’s romantic relationship with a young mother. Although Daifu moved out of his family residence five years ago and now lives in Tokyo, he continues to photograph in, and now around, his old home. While he’s tried photographing other suburban developments, he’s inexorably drawn back to the specific landscape of his own Yokohama neighborhood. Reflecting on questions of access, Daifu says that a photographer can get something from almost any place if they really want to, but that “a relationship is a place that no one else can enter.” He adds, “There’s something there that only I can photograph. I think maybe it’s better to take a place I know, and get to know it better.” What kind of approach is this? In Daifu’s case, perhaps it means getting closer to the familiar—while also estranging it at every turn.

Motoyuki Daifu, Untitled, 2010–17, from the series Project Family

© the artist

Dan Abbe is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he is researching photography in Japan in the 1970s.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Pleasures of Domestic Comfort appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

How to Make Books that Sing Like Sinatra

Keith Smith on the elaborate art of sequencing pictures.

By Lesley A. Martin

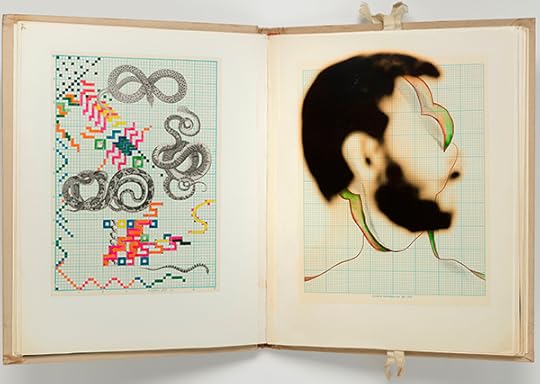

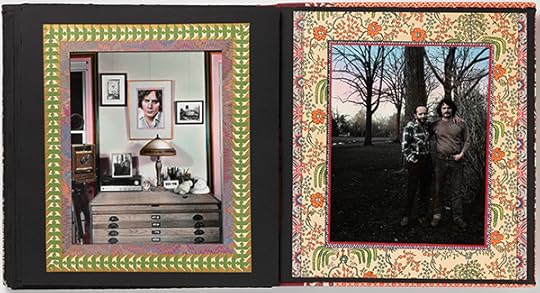

Keith Smith, Book Number 296, December 2015

Courtesy the artist and the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Keith Smith is a quintessential book maker—an artist fixated with the possibilities of the book form. In the course of creating over three hundred books, beginning with his first book of photo-etchings in 1967, he has explored the endless variations by which visual images and texts can be gathered together. He has worked with the classic Western codex, sometimes amended to include translucent pages, tipped-in images, and other customizations; made interventions in existing books (Book Number 15, 1970); and created wildly imaginative books-as-performance (and as-meal—Book Number 67, Bachelor’s Cook Book, 1977, a “conceptual book” featuring a recipe for making and freezing a seven-course meal in pouches stapled together). The majority of his works fall into the books-as-sculpture category, playing with unique structures and bindings, including triangular books, books as screens, books as fans, books with elaborate die-cut pages, and several featuring pages turned via elaborate systems of strings laced through holes punched into the pages (Book Number 91, 1982), among other experimentations. While a number of his books contain no images or texts at all, relying exclusively on the physical structure of the book as both form and content, photography anchors many of his projects, including taped-in gelatin-silver images and contact sheets as well as early experiments in Xerox, halftone screens, and other reproduction processes. The images frequently depict his friends and their families, his house-turned-studio, and his partner and frequent collaborator, Scott McCarney. Often, the photographs are used in combination with texts, sketches, watercolors, and other collaged elements to commemorate his community and relationships in book form.

In addition to Smith’s ongoing output of book objects, few artists have written as obsessively about the mechanics and metaphysics of how books work, including fifi ve volumes on nonadhesive binding methods (beginning with volume I in 1989 and ending with volume V in 2003), one volume on Text in the Book Format (Book Number 120, 1989), and the ne plus ultra of artist book geekery, Structure of the Visual Book (Book Number 95, 1984). In the fourth edition of this extensive, 432-page volume, Smith dissects and defines the many factors that influence the way an image performs within a book. The writing is at times belabored, but the dedicated reader is rewarded with rich veins of lyrical, compelling insights on the alchemy of making books. Sections include “The Book as Physical Object,” “The Process of Turning Pages,” “Picture Relationships,” “Movement,” “Time in Books,” and “Evolving a Series or Sequence,” to name just a few. This is a book for anyone interested in a deep dive into the syntax and structural elements that contribute to a book’s “visual flfl ow,” a term Smith borrows from his late mentor Nathan Lyons, photographer, educator, and founder of the Visual Studies Workshop. (Lyons, of course, was another great elaborator on the gestalt of images in a sequence, as activated via the printed page.)

The brief exchange below peels back the outermost layer of analysis Smith offers in the book, touching on the nuances of a sequence of images versus a group or series of images; the importance of pacing in directing a reader/viewer’s experience; and other finer points of shaping a loose set of pictures into an engaging visual book experience.

Keith Smith, Book Number 11, Up, 1969

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Lesley A. Martin: I’d like to start with a basic question about Structure of the Visual Book (Book Number 95). The book is dedicated to Nathan Lyons and one of the chapters is an homage to him; throughout the book there are references to other photographers, like Ken Josephson and Minor White, who were also seriously thinking through the idea of sequencing and multiple picture formats. Which other photographers or writers who were focused on the language of images and editing photographs for meaning were important to you when you wrote this volume?

Keith Smith: The people you mentioned were no inspiration to me in my ideas for sequencing. Music, especially sonatas, symphonies, and Richard Wagner’s leitmotifs, were my only influences, not photographers. There was one poet: Marianne Moore. I write about her in my book Text in the Book Format [Sigma Foundation, 1989]. Marianne Moore devised enjambment of line: breaking a thought or sentence, and completing it on the following line. In this manner, Ms. Moore pulls the reader from line to line through the poem.

By 1974 I had made fifty-three books using my ideas of how to take the viewer from one page to the next. I never saw any other artist or photographer’s books. I worked out my own ideas of what is a book, based on structure in music. I mention 1974, because that is the year I first saw a sequence by Nathan Lyons, when he published Notations in Passing [MIT Press]. I was elated. Here was the only book, outside of my own, I felt, that utilizes sequence to construct order. They create a series. Nathan and I try to “pull the reader” through the pages of our books, but not in the manner of a flip-book! It is not a straight-line progression that Nathan or I create. We go back and forth in time/action, and proceed by cause and effect, not by linkage forward. Cause and effect is sequential; linkage is serial.

I studied Notations in Passing (as I still do) to see what all elements Nathan utilized to take the reader from one picture to another, and not necessarily an adjacent image. He would take the viewer to a picture eight or ten pages ahead, or previously seen. . . . As Nathan often said, one must define one’s terms. Two cannot converse without common definitions. When someone says, “I am going to sequence these pictures,” what do they mean? An order could be a group, a series, or a sequence. To a cinematographer, the term sequence is a series of pictures, not an order by which Nathan defines his sequence.

Most books set up an arithmetical order, from A to B to C to D. To Nathan and me, this is a series. Some people order a book by selecting thirty various prints of the same subject matter. That order is A to A to A to A. In effect, there is no order. You could shuffle them up. They are held together only by a common theme (and the binding of the book). A bunch of pictures with the same subject matter is a group. Not a series, not a sequence. It is the simplest form of order. It might be all pictures of fast food restaurants.

Now, if you show thirty pictures of fast food restaurants, and you show them in the order of starting at First Avenue, then restaurants on Second Avenue, then Third Avenue, the group of pictures of restaurants is now also a series, since it now has an order: A to B to C to D. So, it is a group and a series.

But a sequence can start in the middle of an action, eventually showing the complete action, much as an Ingmar Bergman film. One can start a sequence in the middle of the action/event, then change to a different subject matter. That interlude might move along as a series or a group, then return to the original (sequential) action. Then it might go back to the second subject matter or event, with a single picture/page, which might be a variation on the second picture in the book. Studying each picture for motif, one receives hints of relationships to recognize the composition of this complicated structure, much as a symphony or fugue has layers of specific order built in. Richard Wagner was the master of musical motif: a few notes to symbolize a character, a place, or an event. Nathan is the master of visual motif. There is no guesswork, no arbitrary adding or subtracting of pages, but an exquisite creation of order.

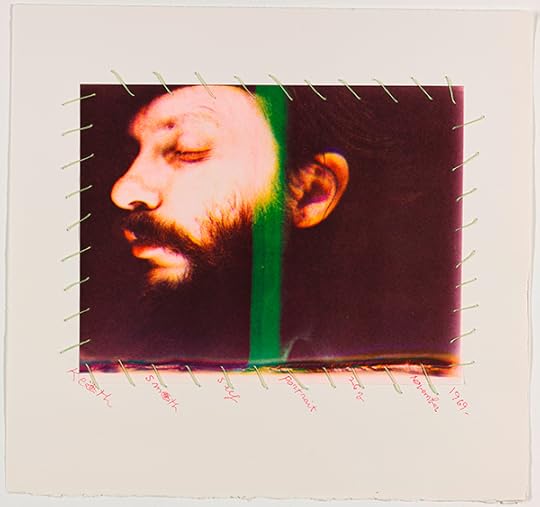

Keith Smith, Self Portrati, November 1969

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Martin: The section called “Picture Relationships” begins with the statement: “There are no single pictures. . . A picture does not exist in isolation. Every picture is a compound, or an implied compound picture.” You go on to explain not just the way that images, in sequence to one another, are the building blocks that create meaning, but also how important it is to consider all the elements. How the materials used in a book can affect how an image is read and the different ways that texts can contextualize an image, in addition to how images interact with one another across the book as a whole. Do you consider the book itself to be, in essence, a “compound picture”? Can any one of these elements function without the other? Are any to be considered more critical than any others to making a book of photographs?

Smith: Yes. Pictures in a book are like words in a dictionary. It is not in the amount of words one uses, but in the choice of the words you choose, and more importantly, not only the order in which you place them, but the total that is revealed by that order. Take any poem or sentence you love. Now shuffle up the words. It is garbled. All the words are there! But the meaning, or a lot of the meaning, is lost. It is order that is the most important element of a sentence, not the words in that sentence. The same is true in a book. The book is more than the sum of its parts. . . . Each individual picture has power, but each must be submissive to the total experience, which is the book. The book has to come first, and sometimes choice images must be discarded in order to create a better totality. Pictures are not that important in a picture book! They are just one element. Pacing is just as important! If you play a common tune on the piano, such as “Happy Birthday to You,” and give equal volume, identical pacing, same inflection to each note, the tune is incomprehensible. Pacing, volume, pitch, emphasis, feeling, all go together (along with the melody) to create the tune. The individual notes are not that important! The same is true in a book. Pacing, mood, pauses, building to climaxes are just as critical as the meaning within each individual picture. The gaps between the pictures must be composed, and many things are left unsaid, composed in the gaps by the reader’s imagination.

Keith Smith, Book Number 82, Keith Smith at Home, 1982

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Martin: What is it that really activates a “sequence” of images? How can you tell when you see a really good sequence of images versus something that falls flat?

Smith: Study a poem by a fine poet. If you study it, reread it over years, you will all of a sudden see things you never saw before. They have always been there, but you did not see! You did not hear! And what a joy when you do find something new. That is one of the beauties of a poem over prose. The poet invites the reader back, because one cannot possibly get everything in one reading. Yet, I have had few people over the years look at one of my books for more than a single viewing. Someone who looks at a sequence, as opposed to a series or a group, could not possibly know what all is said from a single viewing. I go over Nathan’s books time and time again, and find things. It is a joy. Certainly the same is true for a composer’s music. Even the renditions by a great singer. In one of my books, I speak about structure in the singing of Frank Sinatra:

Sinatra is known for his phrasing, more than any modern singer. I have listened to Sinatra for years. Then I heard something I never picked up on before. In “Only the Lonely,” the lyrics are, “The songs I know, only the lonely know. Each melody recalls a love that used to be.” Sinatra sings it as a dirge. And, he pauses ever so briefly after the second syllable of the word “melody,” introducing a word within a word: Mellow is not in the lyrics, but in the phrasing. . . The book artist can do this in a book, not only within text, but by manipulating pictures in a book. (Nathan speaks through phrasing/pacing, as well as within his pictures.)

“Try creating duality for yourself.” I often would tell students, “copy musicians, not visual artists, it is less obvious.”

Lesley A. Martin is creative director of Aperture Foundation.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 015 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post How to Make Books that Sing Like Sinatra appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 24, 2019

Whatever Happened to Corporate Extravagance?

Susan Ressler revels in the immaculate offices of days gone by.

By Jennifer Piejko

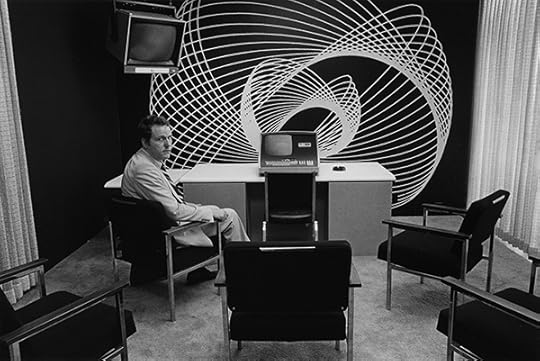

Susan Ressler, System Development Corporation, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

Coworking spaces, open-plan postindustrial lofts, lounge areas, telecommuting—today’s flexible desk culture has wiped nearly every semblance of the traditional corner office into oblivion. Companies favor the open-source, the perma-lance, the OOO, but always online. So, only forty years after they were taken, Susan Ressler’s photographs of corporate headquarters seem more an anthropological study than a blueprint for a contemporary workplace. The guarded quarters of powerful transactions display a controlling exactitude.

Susan Ressler, Atlantic Richfield, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

A recent exhibition at Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego—based on Ressler’s book of the same name, Executive Order: Images of 1970s Corporate America—considered corporate interiors that flaunt gleaming veneers and plush corners waiting behind sets of spotless glass double doors. The photograph Atlantic Richfield (1980), for example—part of the Los Angeles Documentary Project, a National Endowment initiative for documenting the city—radiates wealth and broadcasts financial success, all bold geometric details and extravagant materials. ARCO, as Atlantic Richfield oil company had come to be known, tightly controlled its public-facing quarters, all smoothed-down fabrics and quiet hallways. Ressler documented its lobby space, decorated with of-the-moment details of high design. The wall-to-wall carpet is freshly vacuumed, and all footsteps have been erased. A fortress of dark leather club chairs surrounds a coffee table polished to an impeccable shine; a minimal wall work, a blank pie chart, hangs on the wall behind them. An Alexander Calder mobile dangles above, its kinetic dance the only element emitting evidence of any oxygen in the room.

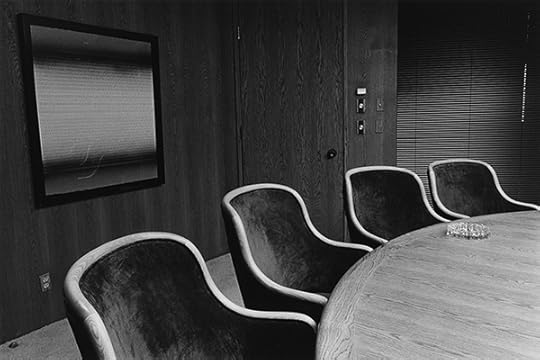

Susan Ressler, Filmways, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

The pared-down rigidity in Filmways submits to a notion of inclusivity and openness, but only on the company’s terms: the dark panels enclosing the conference room appear to be lacking in natural light, and the neat row of chairs are an indirect invitation to sit at the table. The seating in The Capital Group, Inc nods to a less-formal setup, but reinforces the closed nature of the circle of participants, while photographs like Systems Development Corporation, Wednesday, and Honeywell (all 1980) project precise images of industry sophistication.

Susan Ressler, The Capital Group, Inc., 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

The Dallas ARCO Tower, forty-nine stories of imposing smoked glass anchoring ARCO Plaza downtown, opened in 1983. In 1977, ARCO had merged with the copper mining Anaconda Company, a major investment in copper mines in the American West. By the mid-1980s, only a handful of years after Ressler made Atlantic Richfield, it become clear that ARCO’s finesse in extracting oil failed to translate into the same success in copper extraction. The Anaconda land was partitioned and sold off, and in 1985, ARCO was acquired by a Dutch trader, who soon passed it off to Sunoco. Scraping by as the no-frills gas station, ARCO was sold to and absorbed into BP Amoco by 2000. In 2008, it was decreed that the once-powerful oil company owed $187 million to the Environmental Protection Agency for restoration of the towns of Butte and Anaconda, the company’s territories in Montana that included the Berkeley Pit, once the “richest hill on Earth.” Perhaps presaging the company’s own oversteps, it is now classified as a Superfund site.

Jennifer Piejko is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles.

Executive Order: Images of 1970s Corporate America was published by Daylight Books in April 2018.

The post Whatever Happened to Corporate Extravagance? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers