Aperture's Blog, page 96

October 25, 2018

Everything is Light

In her recent photography, Mona Kuhn evokes LA’s iconic architecture and landscapes.

By Sara Knelman

Mona Kuhn, AD 7809, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

Los Angeles seems literally made of light. Most days, an unbroken blaze shines down from cloudless skies where palm trees casually sway, casting every detail of the city’s surfaces in forensic focus until they eventually disintegrate into the pink-hued explosion of sunset. Even as the light fades, neon signs illuminate shop fronts and sidewalks, parades of hazy red-and-white orbs make freeways glisten, and, viewed from the surrounding hills, the whole sprawling mass shimmers quietly. The bright lights of movie theater marquees beckon toward projected illusions inside and remind us that cinema chose Hollywood, in part, for its year-round promise of gleam. As the film industry flourished in the 1910s and ’20s, architects flocked here too, entranced equally by the city’s special quality of light and by the avant-garde spirit of freedom and inventiveness that inspired new ideas about “modern” living.

Mona Kuhn, AD 6046, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

Mona Kuhn, a German-Brazilian transplant to the city, often works at the intersection of light and architecture. In her series, She Disappeared into Complete Silence (2014) (which draws its name from Louise Bourgeois’s first monograph), the lines and shapes of an anonymous house frame images of a desert setting. A sharply angled overhang looks out toward a graph of mountain ranges and cuts a black triangle across a swath of sky. Watery reflections undulate beneath a room’s blurry scaffolding, and refracted doorways lead to the arid earth outside. Mirrorlike, silvery folds and a spectral figure recur, beacons in an ominous landscape. Shot in a modernist structure built by architect Robert Stone outside Joshua Tree National Park on the fringes of LA, Kuhn’s images are mirage-like, visions borne of a thirst for otherworldliness.

Mona Kuhn, AD 6705, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

For Schindler House (2015–ongoing), Kuhn turned to a more specific architectural and social history. Designed and built by Rudolph Schindler, the West Hollywood house was a masterful experiment in communal living (intended for two couples), with private rooms and shared spaces dispersed around a pinwheel axis. Completed in 1922, it quickly became a place for working out other modernist ideas, as well as a hub for intellectuals and bohemians. Kuhn’s pictures of the house evoke the moment it was imagined, in soft, veiled vignettes. Like walking through a dream, the house appears as a memory of some lost, ideal past, both haunted and romantic. Yet at the same time, the images are unfinished and tentative, sketches for a potential future not quite realized.

Mona Kuhn, Schindler House #2, 2018, from the series Schindler House, 2015–ongoing

© the artist

Sara Knelman is a writer, curator, and educator based in Toronto.

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Everything is Light appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 19, 2018

Peter d’Agostino Wields the Film Still Like a Scalpel

An artist considers the psychological ramifications of media images.

By Brian Wallis

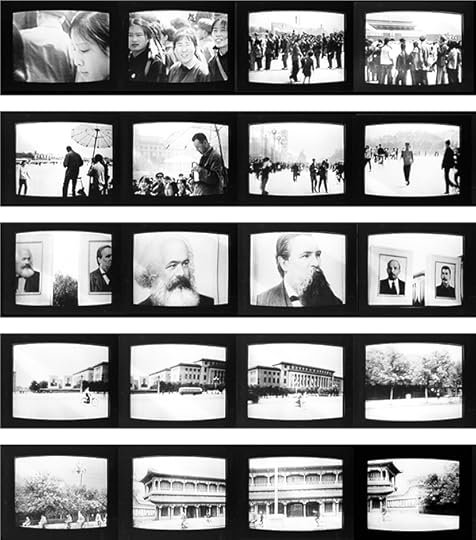

Peter d’Agostino, CHUNG: “Still” Another Meaning (detail), 1977

Courtesy the artist

In his 1970 essay “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills,” French theorist Roland Barthes argued that the essence of film lay not in the motion or flux, but in the potential arrest of movement characterized by the film still. This move allowed Barthes to propose a structuralist theory of film in which the disruptive still is the key to filmic language, the punctum that pierces the narrative reading and reveals its obtuse meaning. In a stirring last line, Barthes proclaimed that such a “mutation of reading and its object”—text or film—was “a crucial problem of our time.” Taking up this challenge in the mid-1970s, Californian media artist Peter d’Agostino embarked on a series of photographic projects that deliberately interrogated the semiotics of film through a structural analysis of film stills, or what he prefers to call “stilled images.”

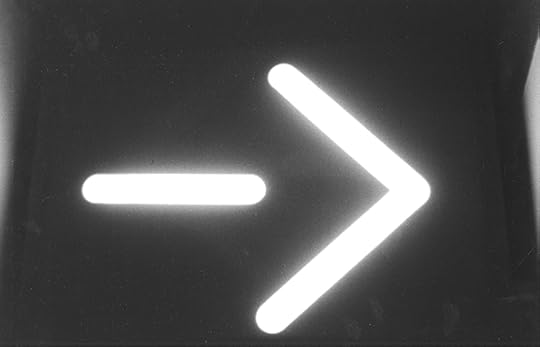

Peter d’Agostino, ALPHA (detail), 1976

Courtesy the artist

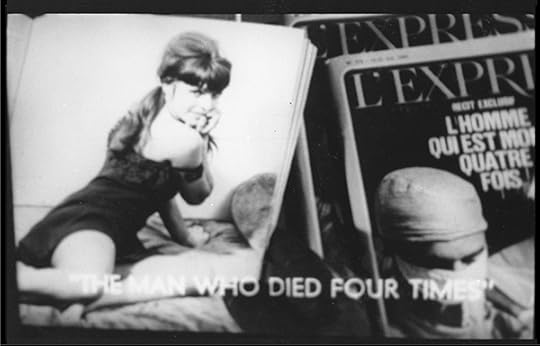

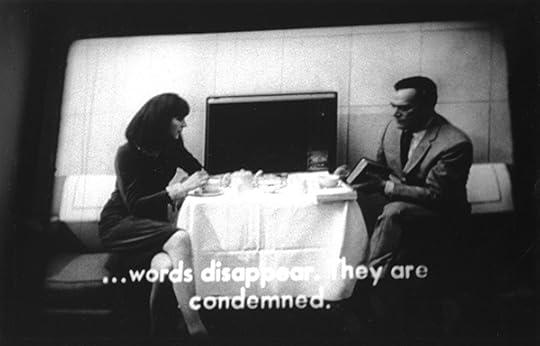

The heady mystique of the art-house underground of subtitled foreign films pervades d’Agostino’s slim artist book ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG (1978), subtitled A Photographic Model: Semiotics, Film, and Interpretation. In this largely photographic book, d’Agostino documents several of his own disruptive interventions, time-based media installations that took as their raw material stills from three New Wave films, classics even then: Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Trans-Europ-Express (1966), and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Chung Kuo, Cina (1972). For the first project in d’Agostino’s book, ALPHA (1976), the artist reduced Godard’s dystopian sci-fi film to thirty-six stilled frames on a single contact sheet. From this, d’Agostino distilled eight photographs to summarize the film’s attention to, on the one hand, the formal events of light and time, and on the other hand, the dissolution of language. For the second chapter, TRANS (1977), d’Agostino analyzed Robbe-Grillet’s dazzling film-within-a-film by slowing the action, lingering on certain details, and incorporating the responses of the audience, filmed in real time. The third section, CHUNG: “Still” Another Meaning (1977), employs stills from the opening of Antonioni’s lengthy documentary, commissioned by the Chinese government, to consider why China censored the film and harshly rejected the filmmaker’s depiction of “their” reality.

Peter d’Agostino, TRANS (detail), 1976

Courtesy the artist

But ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG also contains a dazzling appendix of pertinent metacritical texts by Robbe-Grillet, Umberto Eco, Lew Thomas, Kristine Stiles, Hal Fischer, and others, showing that d’Agostino is above all a media experimenter and theorist. In addition to his many innovative and interactive installations, d’Agostino has written extensively and compiled several significant anthologies, including Still Photography: The Problematic Model (1981), with Lew Thomas; The Un/Necessary Image (1982), with Antonio Muntadas; and Transmission: Theory and Practice for a New Television Aesthetics (1985). Some writers have related d’Agostino to a loosely affiliated Bay Area group around the publication Photography and Language (1976), for which his contact sheet from ALPHA served as the cover image, or described d’Agostino as a “conceptual photographer,” a phrase he rejects. But as he said to me recently, “I am an artist working with/utilizing photography, not a photo/language or conceptual photographer.”

Peter d’Agostino, ALPHA (detail), 1976

Courtesy the artist

By no coincidence, ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG—which doubled as a catalogue of d’Agostino’s 1978 exhibition at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, where he then taught—functions in a similar way to his other anthologies: it combines specific examples of media practice with clear theoretical texts to advance a radical critical thesis. As the press release for the 1978 showing of the project at Artists Space in New York stated, “[ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG] is a model of the interrelationships of various means of symbolic communication, visual as well as verbal. In terms of the media, it utilizes the similarities shared by film, photography, video and the written word.” In ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG, d’Agostino wields the film still like a scalpel, to dissect the social, cultural, technological, and even psychological ramifications of media images. The goal for d’Agostino, as for Barthes, was the delineation of a semiology of film and photography, as a social language, a system of signification in everyday life.

Brian Wallis is a curator and writer based in New York.

The post Peter d’Agostino Wields the Film Still Like a Scalpel appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 17, 2018

Along the Shores of the Caspian

From Russia to Turmenistan, Chloe Dewe Mathews photographed the rituals and resources of a much-coveted territory.

By Arnold Van Bruggen

Chloe Dewe Mathews, In the oil boomtown of Aktau, a woman looks out to sea. Aktau, Kazakhstan, 2010

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

What was this?

At the start of my traveling life and journalistic career, in 2001, I dipped my toes into the waters of the Caspian Sea, in an attempt to recover from a weekend spent on the Iranian coast in a rambling house in a gated community. Opium and hash smoke filled the air, and alcohol flowed freely in large gatherings that tried to circumvent the regime’s strict rules. At the edge of the sea, I felt a kind of oily substance, a thick, briny, lukewarm liquid, so unlike the clean and bracing water surrounding the North Sea island where I grew up. A woman, completely covered, was bathing a little farther down the beach in the ripples that constitute the surf there. I looked out across the sea and contemplated the treasures on the other shore: the legendary city of Baku, surrounded by oil fields; strict, isolated Turkmenistan; the gateway to the Caucasus at Derbent; and the endless steppes of Russia and Kazakhstan, with the countless mouths of the Volga Delta in between.

Seas ignite wanderlust. A toe in the water is a connection to the opposite shore, even if it is miles away. As a child I used to stand on the North Sea beach and imagine Iceland on the horizon, taste the molecules from the Sargasso Sea, and feel the chill from the Arctic Ocean. In my imagination I saw the opal-blue waters of Fiji flecking the gray seas of the north. Here, on a beach in Iran, I wanted to go to Russia, to the fairy tales of Central Asia, and see how this sea influences the peoples on its shores. Chloe Dewe Mathews did just that and discovered that although the sea is relatively small, and its coasts might seem worlds apart, the countries are bound together.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Employees of a fish-curing factory that vacuum packs strips of dried vobla, or Caspian roach, and distributes them across Russia to be eaten as a snack with beer. Kamyzyak, Russia, 2012

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

A short distance to the north, the Caspian Sea becomes lighter, sweeter, fresher. Standing on the beach on the Russian side you can see the ferries attempting the crossing, the freighters ploughing through the water. I imagine myself as a small dot on a zoomed-out map of the world, standing next to an apparently insignificant sea without an exit, without perspective. The Caspian Sea is an anomaly, a self-contained system. All the water from Russia’s mighty Volga, which is Europe’s largest river, flows endlessly into the sea, heavy with historical and cultural significance, eventually breaking on the shores of Iran and Turkmenistan and evaporating. The sea acts as an enormous engine, transforming all it touches into steam and salt.

Hard, almost ruler-straight borders divide the land around the sea into fifths, although what these borders have to do with any kind of reality remains a mystery. The borders in this region should be as fluid as its peoples. The dozens of tribes from the Caucasus, the nomads from the Russian steppes, Kazakhstan, and beyond are the result of thousands of years of migration, conflict, and the rise and fall of empires. If you fast-forwarded through the tribal history of the countries surrounding the Caspian Sea, you would see the different peoples washing over the land in waves. From the east came the Tartars, the Mongols, and the Turks, from the south came the Persians, from the north the Cossacks and the Russians. National borders have existed for less than a century. Access to water and, in the last hundred years, to oil and gas are the only real, literally fluid borders that count here.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, A young woman poses before entering the icy water. Astrakhan, Russia, 2012

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

The Caspian Sea has never belonged to anyone, unlike the Mediterranean Sea, which the Romans called Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), or the Black Sea, which the Ottoman Empire ruled in various constellations. Russia has never completely owned the Caspian, although it has come close. Neither the Persians nor the Turks have ever ruled it. Genghis Khan’s nomads got the farthest, but even they never conquered the Caucasus, which the Russians have managed to do to a greater or lesser extent over the last 250 years. The sea belongs to no one—or at least, which part belongs to whom is still under dispute. Despite years of negotiations, the five countries around the sea have failed to reach an agreement. Envy and geopolitics surrounding oil and gas dominate the water. Is the Caspian a lake or a sea? The countries disagree. If it is officially a sea, Turkmenistan, according to international law, may lay an underwater pipeline to Azerbaijan. If it is a lake, then Russia remains the most important transit country for oil and gas. In a complicated game of chess between the five countries, with Russia and Iran at the fore, this body of water’s fate hangs in the balance.

The Caspian Sea is a place of real-life fairy tales. One of these can be found about halfway down the west coast, on the southern border of the Russian Federation, in the autonomous Republic of Dagestan. Here lies Derbent, one of the oldest cities in the world. Embroiled in a fight between trade (as Russia’s gateway to the East) and separatism and Islamic terrorism, it is a city of faded glory, of tensions and uncertainty. But what a city! To the west rise the hills and then the mountains of the Caucasus, the highest mountain range in Europe. Look carefully and you can see traces of the city even in the mountains, like long arms trying to pull passing travelers into its embrace. At one time there were miles of city walls. Looking down from the castle, you can see more of these arms reaching into the labyrinth of the city below.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, At a beach café, Azerbaijani soldiers question a local man. Lankaran, Azerbaijan, 2010

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Like a spider, Derbent has woven a web between the sea and the mountains, in order to prevent travelers and, hopefully, any invading army from escaping. The walls that cut through the city do not end at the coast, but march straight into the sea, creating a safe artificial harbor and ensuring no black-market vendor or malicious outsider can pass unnoticed. It’s a city straight off the pages of a children’s storybook, a city just as you would have liked to have drawn it. A city with an oriental history, with a Russian and then a socialist layer laid over it, and where now the messy, random, modern buildings seem to defy any form of logic. A city where the Caspian coast is used as a beach and a bar but also where empty factories, old harbors, and shipwrecks dominate, making their own mountain range of concrete posts, steel hulls, and graffiti, just as in so many other places on the Caspian Sea.

Perhaps the most appealing fairy tale of the region is that of Kara-Bogaz Gol (which literally translates as “black gullet”), the Turkmen sea waterfall through which the Caspian pours and then spreads over a wide bay, where a merciless sun evaporates the water faster than the Volga can replenish it. This has created a fascinating area of extremely salty water, salt pillars, and crystals that the residents eagerly harvest. In his book Engineers of the Soul (2012), Frank Westerman describes the writers who, under Stalin, were meant to prepare the minds of the Soviet citizens for communism. Konstantin Paustovsky, one of the great twentieth-century Russian writers, chose Kara-Bogaz Gol as his topic. In fantastical terms, he cites the many stories about the sea waterfall—how sailors described the coast of Asia as a towering wall and the cascade as a maelstrom. A “sea waterfall” sounds like a fantasy from the time when the Earth was still considered flat, something that would have been drawn on old maps next to dragons and deep-sea monsters. But in the Caspian Sea, it is reality.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, A larger-than-life-size photograph of Turkmenistan’s president, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, towers over a hotel guest. Awaza, Turkmenistan, 2012

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

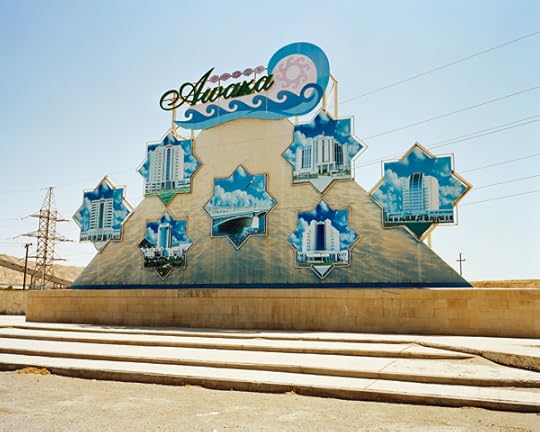

In any other country, you would expect Kara-Bogaz Gol to be a world-famous attraction. Not here. In authoritarian Turkmenistan, you need a special permit to visit. But farther to the south rises a new mythical land: Awaza, Turkmenistan’s answer to Dubai—or “Turkmen Las Vegas,” as Dewe Mathews discovered. Every country around the Caspian Sea would like to copy Dubai’s success, the fairy-tale city rising out of the Arabian desert. Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Iran, Turkmenistan, and Russia all regard Dubai’s incredible transformation into an ultramodern cosmopolitan metropolis as a rags-to-riches tale worth imitating. In this, everyone believes they have found a unique route to new national success. But construction alone is not enough. In Turkmenistan, the resorts are empty, and the country’s dictatorship stifles the type of freedom found in Dubai, as one of Dewe Mathews’s images attests, featuring a larger-than-life-size portrait of the leader looming in a baroque interior. In the meantime, the world’s greatest inland sea, fed by Europe’s largest river, empties itself desolately over a sea waterfall and into a salt desert.

This Volga is much more than a river. This is Mother Volga, on which nearly all old Russian cities are situated, the lifeblood of the Motherland. Many Russians, rich and poor, travel to the river to eat, drink, and fish. Here, and in the sea, swim the sturgeon from which Russia’s black gold, the coveted roe that makes caviar, can be mined. The Volga Delta, with its thousands of arms and lakes and abundance of birds and animals, is therefore also a perfect place for wealthy Russians to pit their strength against nature. Putin and Medvedev come here for male-bonding weekends and roar up the rivers in motorboats; they fish bare-chested on the bank, organize hunting parties, or dive below the surface to photograph the wildlife, so that the whole of Russia will know their president and prime minister can measure themselves against Mother Volga.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, In Turkmenistan, the foreign ministry has expressed plans to transform the luxury beach resort of Awaza into a “Turkmen Las Vegas.” Awaza, Turkmenistan, 2012

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Those in power in the Kremlin form a striking contrast to the inhabitants of the delta and the Caspian coasts, from the extravaganza of Baku, “Turkmen Dubai,” and elite Russian resorts to those of small villages, cities, former Soviet farms, and abandoned factories. Most Caspian residents still live at subsistence level and are self-sufficient; they fish and work their land, and survive the changing regimes. The wide, beckoning sea offers few alternatives on the other sides.

When looking through Dewe Mathews’s work on the Caspian, from its often-impoverished denizens to its decadent visitors, from the worshipping of holy water to its reserves of holy oil, you can’t deny the fact that the Caspian is a magical place. Think about it: when dipping your toes in the water of any sea or lake, there she is, the lady in pink on the other side, dipping hers in the ice-cold water. There are the sunbathers, draping their towels between the rotting concrete remnants of some factory; there are the empty, shiny palaces, misplaced but waiting for those toe-dipping tourists. Seas are magical places. A sea connects cultures, even those that are miles apart. People move close to it, bathe, swim, build ships, start trading, go fishing, and look and sail across and start dreaming away. In the meantime the water flows past in an endless swirl from the Volga to Kara-Bogaz Gol.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Two women pause by an upturned boat.

Kamyzyak, Russia, 2014

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Just before the Volga pours into the sea, Russian Orthodox state priests declare the Mother River’s water holy. The sins of the past year are washed clean in the ceremony and illnesses disappear while the water, in the harsh Russian climate, undergoes the endless transformation from liquid to ice, from river to sea, from fresh to oily and salty, from seawater to salt desert, and then returns as cloud, rain, and water vapor. The never-ending cycle begins again.

Arnold van Bruggen, a writer and filmmaker based in Amsterdam, is cofounder of Prospektor, a documentary production company.

This essay is from Chloe Dewe Mathews: Caspian: The Elements (Aperture and Peabody Museum Press, 2018) and was translated from the Dutch by Alison Eradus.

Chloe Dewe Mathews’s exhibition Caspian: The Elements will be on view at Aperture Gallery from October 25 to November 30, 2018, and at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University, from April 27, 2019 to January 5, 2020.

The post Along the Shores of the Caspian appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 11, 2018

Outside, Looking In

Barak Zemer pictures intimate moments of isolation in the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles.

By Kate Palmer Albers

Barak Zemer, Aquarium, 2015

© and courtesy the artist

How do human beings—and human bodies—experience a culture that is structured around separation? How many ways can we be outside, looking in? And what are the consequences, conversely, of occupying inner spaces? Bodies in states of transition, and subjected to degrees of impermeability, are at the heart of Barak Zemer’s photographic interests. The title of his recent body of work, Aquarium (2012–16), sets the tone for a range of disorienting states of looking, states of containment, and, often, states of incongruity. Those dark and luminous spaces of immersion and separation act as metaphors both for his experience of Los Angeles and, more broadly, for a heavily structured and mediated experience of daily life in the twenty-first century. As he puts it, “The aquarium is how we live, encapsulated.”

Barak Zemer, Lotus, 2014

© and courtesy the artist

Zemer was born in Israel, in 1979, and relocated to LA for graduate school, in 2011, where he found the flux of his encounter as a foreigner echoed and mirrored in the basic structure of this most decentralized city. The rich sensory porousness that had characterized Zemer’s daily life in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv was abruptly replaced by an isolation fostered by LA’s urban infrastructure and pervasive car culture. The contrast was initially—and to some degree remains—a shock. Of his experience in LA, Zemer says, “I’m trying to deal with it. We’re closed in a car, we’re all bubbled from each other. It’s as though someone planned it for us to be unable to look at or experience somebody else. And the camera fights that. It recognizes the closed thing.”

Barak Zemer, Ramp, 2014

© and courtesy the artist

As a result, Zemer photographs prolifically, finding his subjects in the course of daily life, on his travels around the United States and internationally, and at tourist sites like zoos and aquariums that he habitually seeks out wherever he goes. For Transit, his 2018 exhibition at LA’s Night Gallery, Zemer culled a tightly conceived edit from some fifteen thousand images he’s made in the past few years alone. In those photographs, one feels again and again the sense of something just out of reach, a consciousness in which disorientation has become routine. In Passenger (2015), an older man’s face is partially lit by the blue glow of flight—an inverse of the aquarium. In Ramp (2014), the white industrial haze of a Los Angeles morning fails to fully mask the slight oddities of street life. Aquarium (2015) depicts a seated woman with her cellphone, appearing comfortably, if incongruously, submerged. Is she taking a photograph, looking out? Or is it a selfie? In Lotus (2014), lacquered and bejeweled fingernails offer a closed bloom from the darkness, and in Head (2016), a statue seems to have shed a lifetime of tears. The organic and the artificial repeat and replay, in ever-shifting configurations.

Barak Zemer, Passenger, 2015

© and courtesy the artist

In both the vast archive of his images and the radically reduced selection that has become Aquarium, the current U.S. political environment is never pictured directly. However, as Zemer comments about the series as a whole, “If it succeeds in being about the human experience, then it’s always about politics.” In Zemer’s work, that feeling finds its way into moments of disconnect, of uncertainty, and of absurdity.

Kate Palmer Albers is a professor of art history at Whittier College, Los Angeles.

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Outside, Looking In appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 3, 2018

Sara Cwynar’s Contemporary Nostalgia

On the occasion of her solo exhibition in Minneapolis, the Canadian artist speaks about color and consumerism in the information age.

By Gabriel Ritter

Sara Cwynar, Tracy (Cezanne), 2017

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Gabriel Ritter: Can you speak a bit about your latest body of work, the Tracy pictures? Tell us how this series came to be and how you met Tracy.

Sara Cwynar: I’ve been photographing Tracy for ten years, and she is a good friend, but I’d never really shown any pictures of people until a couple of years ago. I picked Tracy because she also comes from a design and art-direction background and she poses kind of ironically, with the knowledge of a history of representations of women in mind. I always hate when people say, “My model was a collaborator,” but in some ways that was actually really true of Tracy.

Ritter: Do you see the current series as an evolution from your earlier work?

Cwynar: I think Flat Death (2014) was more about how photography works, how it tricks us in a way. With the Tracy pictures, I was thinking more about the kind of power dynamics that go into who we see as opposed to just what. I was thinking about how anachronistic portraits are from the 1950s heyday of advertising, which only portray certain kinds of people in objectifying ways. What does it mean to see an ironic, remade version of that? Every artist has their insecurities about their work, and one of mine is that it reads as too design-y or too much about a certain outmoded aesthetic sensibility, which is only a part of what I’m doing. I always try to connect it to lived experience a bit more, and using an actual person was the most immediate way to do that.

Sara Cwynar, Red Rose, 2017

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: There is a flatness to the images you make, but also what I would call an excessive materiality in the way that you build up your sculptural arrangements. I wonder, do you see this duality between the object and the image, or the reproduction and physical reality, as core to image making now in the digital age?

Cwynar: I’m responding to an overwhelming amount of images all the time. The films deal better with that because they can keep up with this influx of information, which is very much of the digital age. That’s partly why I started making films, to try and capture this hectic, insane, macro pace a little bit more—the way that it feels like there’s so much stuff but you can’t grab on to anything.

Ritter: Could you speak a bit about your own collecting and how that figures into your photographic process? How do you go about selecting and acquiring the various objects that then find their way into your images?

Cwynar: For most of the objects that repeat in my work, I find them first in the real world and then obsessively troll eBay to find every other version of, for example, the jewelry boxes or the Avon presidential cologne bottles. I used to think I should only find objects in the real world, and there should be some surprise or chance involved, but now I think that I should use the power of the internet to explore the full range of these objects.

For the Tracy pictures, I had made a bunch of portraits of her and I had them hanging on the walls for a really long time; I would pull from objects that I had saved and see what kinds of connections could be made. For example, the Tracy photos have all these historical representations of women, snapshots of real women, and a lot of discarded, high-modernist-era designed objects. I was thinking about some shared fate of these representations of women and these objects, how they had both faded out of view or become devalued a bit by the time I found them—a connection between the way we treat objects and the way we treat humans.

For this series, I wanted to shoot through layers of glass stacked on the floor and have various objects come in and go out of focus depending on where I placed them on, between, or under those planes of glass. So I actually built these glass structures on my studio floor to photograph through. I put my camera on a giant studio stand, so the camera can be about six feet in the air, and I photographed down through the layers of stacked glass and objects. This creates an intense layering effect and changes the focus of the different objects. It helps to mesh the disparate elements into one image.

Sara Cwynar, Avon Presidential Bust (Washington, Gold, Lincoln, Gold), 2017

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: What is it about these specific objects or images that draws you to them? What about them warrants further investigation?

Cwynar: I like objects that are lightly faded in color and texture from what they were initially intended to be. Color can take you back to a specific time period, like the way mustard yellow is so 1970s. I’m always trying to find certain colors and textures that do that. I also think a lot of objects from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s even, have simpler designs, so they’re easier to work with graphically in some ways, which is interesting to me, as a former graphic designer.

I’ve also thought a lot about kitsch and how a lot of what design or advertising does is try to erase the real fact of living: the everyday materiality of us being in bodies, that we’re going to die eventually, and that there are many unpleasant things about being human. Advertising erases that passage of time. It makes everything feel like it’s possible if you just buy the right things and it kind of glosses over the reality of being human in favor of a more idealized view of the world.

Sara Cwynar, Tracy (Gold Circle), 2017

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: You’ve not once mentioned the words “nostalgic” or “sentimental,” but those for me get at what you’re describing. Is there a certain nostalgia or sentimentality that you’re going for?

Cwynar: I’m not trying to make nostalgic work, but I am trying to walk a fine line between what nostalgia means and how design works, and also how we perceive the future versus how we just repeat the same things in slightly different forms. The overwhelming choice of our time is paralyzing for a lot of people. I actually think there’s something really contemporary about this kind of nostalgia.

Ritter: A lot of the work you do looks at color and its relationship to notions of femininity and consumerism. They’re all kind of wrapped up within advertising, as you were describing. What trends do you see materializing from the research you’re doing into color and the beauty industry?

Cwynar: I’ve been researching the beauty industry a lot and especially the way that color has been used to sell things. There’s a long history of inventing new colors to sell the same things. I’m just trying to make clear the ways that color has a politics, how it gets used as a tool to convince or seduce, and how that often gets forgotten about.

Sara Cwynar, Still from Cover Girl, 2018

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: It’s instrumentalized.

Cwynar: Yes, that’s a good word. All of these things—color and the beauty industry and design—really latch on to creating something that seems like it’s missing, and then solving that problem, like finding a gap. Like the rose gold iPhone, for example. Nobody needed a new iPhone, but they created a gap and then filled it by inventing—but they didn’t invent anything, they just changed the color.

Ritter: In the found images and magazine clippings you use, you often emphasize the use of halftone dots in print reproduction. It’s a specific aesthetic that you like to exploit that connotes a datedness to past forms of reproduction that high-resolution digital printing seems to almost eclipse.

Cwynar: Yeah, that’s true, and Flat Death was sort of about this, too—the way that images congeal into looking good, but could fall apart if you looked closer. Even any billboard that you see now, if you were actually able to get close to it, it looks like shit, but you’re always far enough away from it that you can’t tell. Once something exists in the world, it seems like it was almost inevitable, or it’s right in a way because it was printed or produced or put out there and people approved it. But actually it’s just a series of often subjective human decisions and specific technologies that led to that outcome.

Sara Cwynar, Tracy (Grid 1), 2017

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: Do you see your work as questioning historical concepts of beauty and femininity by reexamining those particular decisions?

Cwynar: Yes, but those are just some elements of it. I’m trying to dismantle this often-idealized kitsch, or often very nostalgic Western context of photography, which tells us who we think we are, and often with great bias. I’m trying to think of all the different ways that that is a false history. But I also love all these materials and I even really loved the rose gold iPhone in a way—I really wanted it. I’m trying to be clear about my own ambivalence, and how you can see the way the strategies of design and advertising are working but still be seduced by them, still want to be seduced by them somehow. Even in exposing some of the problems in the history of image making, I’m still making beautiful images, and I want them to contain some of the pleasure that made those things work in the first place.

Ritter: By drawing attention to that ambivalence, and using it critically, you don’t have to deny yourself that inherent pleasure. Instead, you can rearticulate it in your own vocabulary.

Cwynar: There’s a great pleasure in making this work, and I also want there to be pleasure in looking at it. I don’t want it to be a dry conceptual project; I want it to contain some of the emotional seductive qualities that advertising has. Part of the reason why I started making videos was that in some ways, it’s easier to be seduced by moving images than still ones because they operate in a more emotional register. I want there to be some of the same pleasure that has maybe led us astray at times in the pictures.

Sara Cwynar, Still from Soft Film, 2016

Courtesy the artist, Cooper Cole, Toronto, and Foxy Production, New York

Ritter: That is a nice segue into speaking about your videos. Could you talk about your shift to filmmaking over the past few years?

Cwynar: It’s been three years since I started making videos. I thought about it for a long time before, though. I wanted to be able to actually say what I mean a little bit more. My book Kitsch Encyclopedia (2014), which is kind of my first art project, has all this text and writing, and I was sort of missing that in the photos. You can access a more heightened emotional tone or valence in video than you can in photography, and that seemed really exciting to me.

Ritter: And, as you were describing, you can have that textual layer, you can have the voice-over. The way that you use these critical texts is somewhat novel because you’re using a mixture of other people’s words and your words. You’re also putting them in an actor’s voice, and at the same time, you’re there, almost like a coach, correcting them. The overlapping voices and constant interruptions break any sense of cohesive narrative, which re-creates much of what you’re working toward visually. It’s difficult to have that richness, that layered experience solely in a photographic image without it becoming too didactic. I feel like critical theory informs so much of your thinking and image making that naturally, when you come to filmmaking, text becomes your dialogue.

Cwynar: I would read and read and then make a photograph, and so much would get lost. I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing, but video definitely allowed for the source material to be more present. The same way I’d use a photograph in a different way than it was intended for, I want to think about how theory can become kitsch or theory can become this easily digestible way of understanding the world. In a way, theory is a privileged realm that seems really difficult to access, or at least it did to me for a long time and still does in some ways, but actually it’s just another way of repackaging and representing the world, the same way images do. I wanted to use it in the same way I’d use an image. For example, I’ll misquote people, or use something Lacan said in a way that wasn’t really the way he meant it. I know it drives theory people crazy, but I think there’s a power in it. It’s really satisfying to use words in a similar way to images and have a form that can accommodate both of those things, which can really only happen in video. Sound also changes the way an image looks. To have this kind of didactic, male voice of authority telling you something while you’re looking at the images really changes them. And then I come in and say who’s really in charge.

Gabriel Ritter is curator and head of contemporary art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Sara Cwynar: Image Model Muse is on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art through January 20, 2019.

The post Sara Cwynar’s Contemporary Nostalgia appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 2, 2018

Inside Member Tour of Kendall Messick’s Home Collection

On September 15, Aperture Members visited the home of artist, filmmaker, and collector Kendall Messick.

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Yu Yan © Aperture

Members had the opportunity to explore Messick’s impeccable historic town house in Jersey City, New Jersey, filled with collected photography, art, and antiques from around the world. Artists in the collection include Irving Penn and Robert Rauschenberg. Messick also discussed his project Impermanence, photographs documenting the remains of his art collection after a fire ravaged his home and belongings.

Messick’s book, film, and touring exhibition called The Projectionist explore Gordon Brinckle’s lifelong fascination with an era in American culture almost forgotten: the age of the grand movie palace. A highlight of Messick’s personal collection was objects and remnants from the “Shalimar” theater—such as the original 1940s-style box office—which was constructed in the basement of Brinckle’s modest Delaware home.

Aperture Members meet up with other photo-enthusiasts, editors, scholars, and photographers at events in New York and beyond. Click here to join our growing community and receive invitations to experiences like this one.

The post Inside Member Tour of Kendall Messick’s Home Collection appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 27, 2018

Unpacking Ed Ruscha

A new exhibition offers an inside look at the artist’s book-making practice.

By Abigail Cain

Ed Ruscha, Pool #7, from the portfolio Pools, 1968

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Ed Ruscha’s artist books confounded archivists and artists alike when they were first published. In 1963, the Library of Congress mailed back the copy of Twentysix Gasoline Stations he’d submitted (a rejection the twenty-six-year-old artist memorialized in a cheeky Artforum advertisement). That same year, Artforum’s editor Philip Leider pointed out that the book—cheaply printed and composed of twenty-six black-and-white photographs of gas stations along Route 66—was “so curious, and so doomed to oblivion, that there is an obligation, of sorts, to document its existence.” Of course, that confusion was the intended effect. “People would look at it and say, ‘Are you kidding or what? Why are you doing this?’” Ruscha told the New Yorker in 2013. “That’s what I was after—the head-scratching.”

Ed Ruscha, Conoco, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1962, from the book Twentysix Gasoline Stations

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

A new exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center, part of the University of Texas at Austin, doesn’t lessen Ruscha’s artistic ambiguity, but it does pull back the curtain on his process. Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance marks the first showing of the Ransom’s Ruscha collection, acquired in 2013. (The Los Angeles artist has divvied up his papers between a number of institutions, including the de Young Museum and the Getty Research Institute.) Although Ruscha’s oeuvre is broad—encompassing painting, printmaking, photography, even video—the Texas archive contains materials tied specifically to his pioneering artist books and two public library commissions, a panoramic landscape for Denver Public Library and a series of site-specific word paintings for the Miami-Dade Public Library.

Archaeology and Romance narrows its focus to the sixteen artist books Ruscha made between 1963 and 1978. More than one hundred and fifty objects are displayed across the Ransom Center’s first floor, including rare copies of publications such as Business Cards (1968) and Babycakes with Weights (1970) and a case, over twenty feet long, that allows the accordion-folded Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) to stretch out to its full length. But it’s the preparatory materials accompanying these publications—studio notebooks, paste-ups, even invoices for printing and binding—that offer the most intriguing glimpse into the artist’s mind.

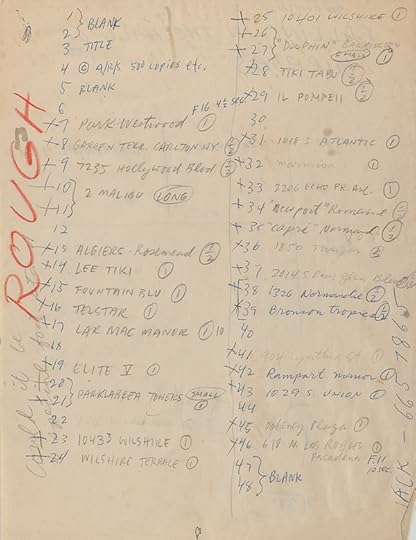

Ed Ruscha, Preliminary notes, Some Los Angeles Apartments, 1965

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Jessica S. McDonald, photography curator at the Ransom Center, was among the first to comb through the archive. Ruscha, she discovered, was a consummate multitasker. “Something I found surprising was just how much he was working on at any one time,” McDonald told me recently. A page of notes relating to his 1965 book Some Los Angeles Apartments also sports a few lines at the bottom, reading “Fourteen Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass.” That offhand note went on to become, three years later, a book titled Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass. (There are also some other delightful, apparently discarded, book ideas, including Several Ash Trays, a Speedometer, & a Fish.) “Finding those traces all through the works,” McDonald explained, shows that Ruscha’s process “was more of a web than any kind of linear progression.”

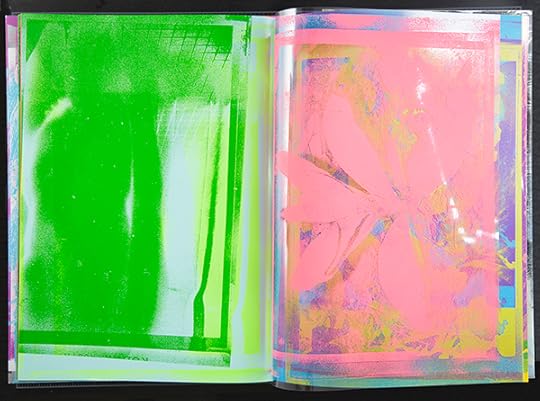

Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass was the first of the artist’s books to include color photography. Sorting through the materials related to the project, McDonald came across Ruscha’s handwritten specifications for the book. In underlined block letters, he had written “THREE COLOR NO BLACK.” Color photographs are typically produced using four layers of ink—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—but in this case, he eschewed the final, black layer. It was an unorthodox printing choice that could, perhaps, have been a money-saving measure—except that Ruscha also added fifty-two blank pages to the book, indicating he wasn’t particularly worried about the expense. “If that decision is what I think it is, that’s a really kind of brilliant experiment,” McDonald said. “It’s a way to get the pictures to look really bright and a little bit unsettling, in that you can’t quite ground them in the shadows. I just didn’t expect to see that, because his photos are usually so straightforward.”

Ed Ruscha, State Board of Equalization, 14601 Sherman Way, Van Nuys, 1967, from the book Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

This lack of artistry is one of the hallmarks of Ruscha’s artist books. “The photographs of gas stations are bad photographs on purpose,” McDonald noted. “He’s trying to do the opposite of what a photographer trying to make an artistic photograph would be doing.” In a 1965 Artforum interview concerning his second book, Various Small Fires and Milk (1964), Ruscha explained that it didn’t even matter to him who took the photographs. “In fact, one of them was taken by someone else,” he said. “I went to a stock photograph place and looked for pictures of fires, there were none.” For his 1967 book Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, Ruscha went so far as to hire a commercial photographer to capture the aerial shots.

Compared to his paintings, Ruscha has said that the books were “easy.” “I didn’t have to struggle, and I felt like I was operating on blind faith more than on any kind of decisions. It was as though somebody else was designing them.” That self-assurance is also visible throughout the archive. McDonald came across a sheet of paper, labeled “ROUGH” in orange crayon, outlining the order of Some Los Angeles Apartments. Despite the label, “it’s not rough at all. It’s precisely how the book is,” McDonald said. “So if he’s somebody whose rough draft is essentially pretty darn close to the final draft, then that shows a certain level of confidence.”

Ed Ruscha, “Rough” layout sequence, Some Los Angeles Apartments, 1965

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Archaeology and Romance chronicles an artist becoming increasingly sure of his vision. For Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Ruscha took far more than twenty-six photos, narrowing his selection to images he felt were devoid of feeling; for Real Estate Opportunities, published in May 1970, he took just four rolls of film in total. “A lot of people who would intentionally call themselves a photographer, somebody trying to make ‘good photographs,’ might get one good picture in forty-eight,” McDonald said. “He just needs to get the information. He’s not trying to make a great picture. By 1970, he already knows what he needs—he just goes out and gets it.”

Abigail Cain is a writer based in Brooklyn.

Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance is on view at the Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas, through January 6, 2019.

The post Unpacking Ed Ruscha appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 25, 2018

Disobedient Domesticity

In suburban LA, Sophie Tianxin Chen produces scenes of the mundane and perverse.

By Jennifer Piejko

Sophie Tianxin Chen, Untitled, 2018

© and courtesy the artist

Wary cartographies comprise Los Angeles. The city’s relentless sprawl—spreading itself thin over five hundred square miles—evades any attempt to cultivate a singular identity. The area we consider LA is cut into eighty-eight little cities (Culver City, Inglewood) often patched together to approximate neighborhoods and informal districts (the Westside, East LA). Greater Hollywood is at the center, both in geography and mission, the metonymic scene hosting the storied studios, the Walk of Fame, and the iconic sign at the foot of the Hollywood Hills. Just over it, though, North Hollywood, in the San Fernando Valley, has become infamous for a parallel path to notoriety: since the 1970s, the Valley has been the hub for pornography production and distribution. The area’s low-lying, nondescript seediness and latent unease have fascinated establishment Hollywood (Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights), portraitists (Larry Sultan’s The Valley series, shot on location a few blocks from where he grew up), and hustlers of every stripe.

Sophie Tianxin Chen, Dog Day, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

“The 818” (area code shorthand for the Valley) is also home to another singularly postwar, American climate: suburbia. The Chinese-born photographer Sophie Tianxin Chen found herself at these crossroads of normative domesticity and acute malaise when, after finishing her MFA at UCLA, a campus-village located in LA’s Westwood neighborhood, she relocated to the Valley, landing in Burbank. Describing her new residence as an “armpit town,” she began to identify it by its “mediocrity in every way … middle-class family houses, old-fashioned diners with elderly customers, front yard decorations for every holiday.”

Sophie Tianxin Chen, Man Working, 2017

© and courtesy the artist

Having a child and becoming a caretaker while maintaining a studio practice at home only distilled these feelings of isolation. Chen longed to puncture the heaving, long stretches of dullness, much like Sultan’s pornographic film subjects who wait hours in rented tract houses for a single moment of action in front of the camera. “I kept hoping for a stranger’s phone call telling me my dogs had gotten loose to happen,” she said. “My six-week-old fell off the bed and was taken to the hospital by an ambulance. These disastrous events brought me moments of relief.”

Sophie Tianxin Chen, Good Job, 2015

© and courtesy the artist

Chen used what was in front of her, staging mise-en-scènes of the unremarkable for her large-format camera: rag dolls scattered over sandstone, bleached by the sun; bananas rendered in wholly nonsensical colors; a diaphanous cascade of plastic hangers suspended from the ceiling. Giving birth had her ceding a certain amount of control: “I am now less polite or shy in my work; it’s become more raw and careless.” The forfeiture has allowed for a self-objectification as well, stretching out her body for maximum unsentimental exposure to her own camera’s roving lens. Like the town’s X-rated permeations, Chen’s late-afternoon delights feed into our voyeuristic appetites for pleasure, drama, and perversion. If watching alone isn’t enough to satisfy you, then build a scene that will.

Jennifer Piejko is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles.

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Disobedient Domesticity appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 21, 2018

The 2018 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

Aperture and Paris Photo are pleased to announce the shortlist for the 2018 PhotoBook Awards.

The shortlist selection was made by Lucy Gallun, associate curator in the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art; Kristen Lubben, executive director of the Magnum Foundation; Yasufumi Nakamori, PhD, incoming senior curator of international art (photography) at Tate Modern, London; Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review; and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

Established in 2012, the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards celebrate the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography, with three major categories: First PhotoBook, Photography Catalogue of the Year, and PhotoBook of the Year.

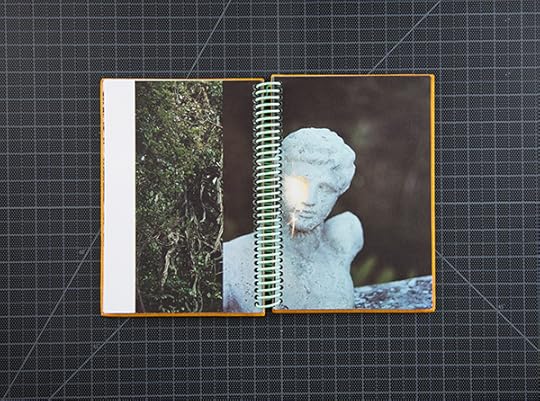

Edén Bernal, Exilios (Exiles) (Inframundo) Mexico City

Edén Bernal, Exilios (Exiles) (Inframundo) Mexico City

Nacho Caravia, Mamá (Self-published) Barcelona, Spain

Nacho Caravia, Mamá (Self-published) Barcelona, Spain

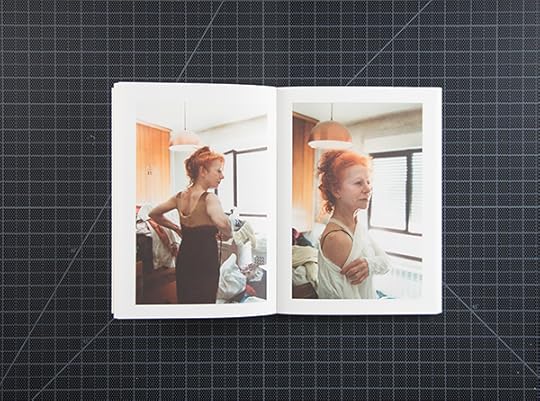

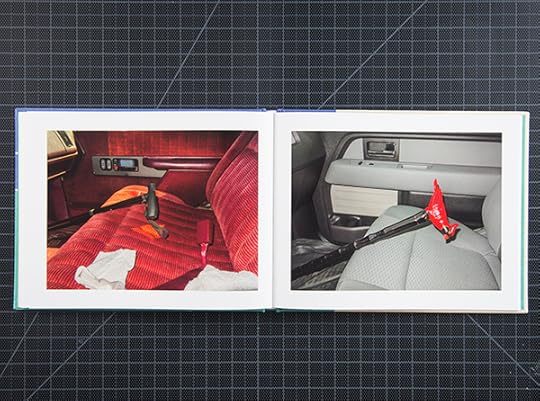

M L Casteel, American Interiors (Dewi Lewis Publishing) Stockport, England

M L Casteel, American Interiors (Dewi Lewis Publishing) Stockport, England

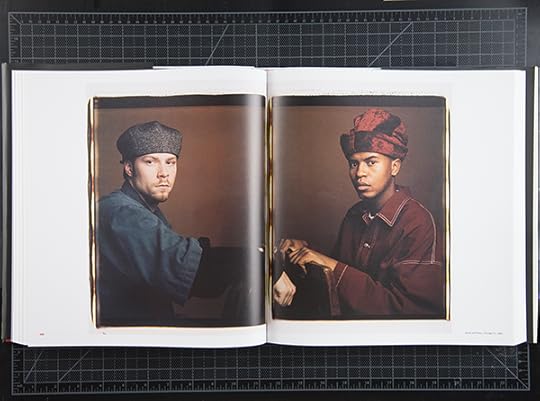

John Edmonds, Higher, (Capricious Publishing) New York

John Edmonds, Higher, (Capricious Publishing) New York

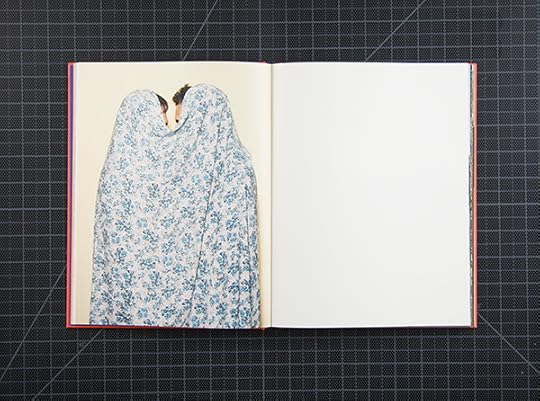

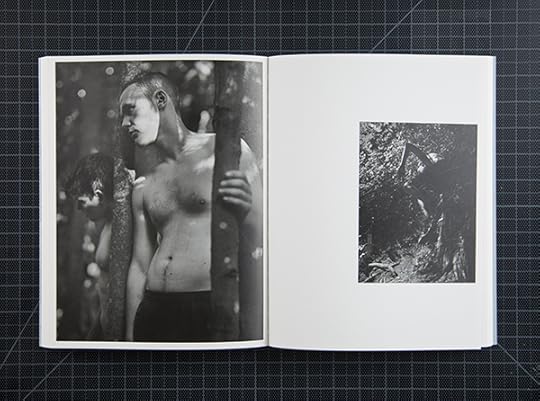

Matthew Genitempo, Jasper, (Twin Palms Publishing) Santa Fe

Matthew Genitempo, Jasper, (Twin Palms Publishing) Santa Fe

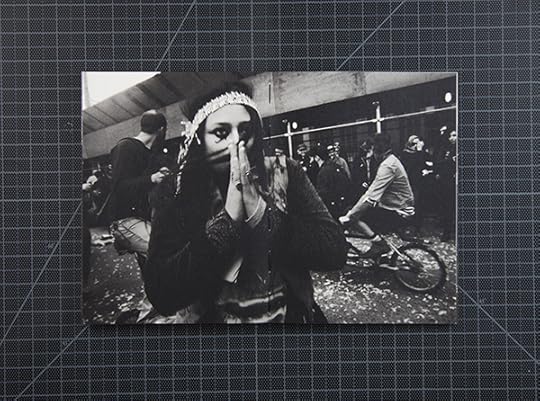

Julie Glassberg, Due to unforeseen circumstances, this book has no title (Bike Kill) (Ceiba Editions) Siena, Italy

Julie Glassberg, Due to unforeseen circumstances, this book has no title (Bike Kill) (Ceiba Editions) Siena, Italy

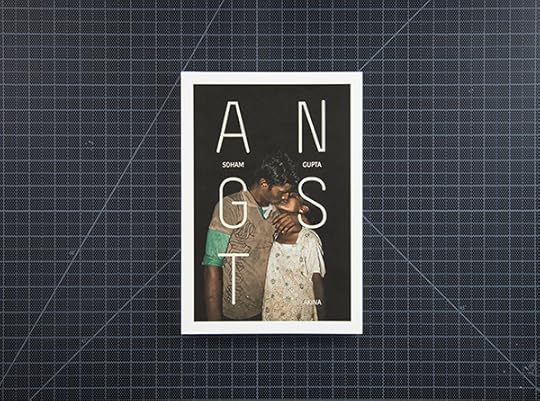

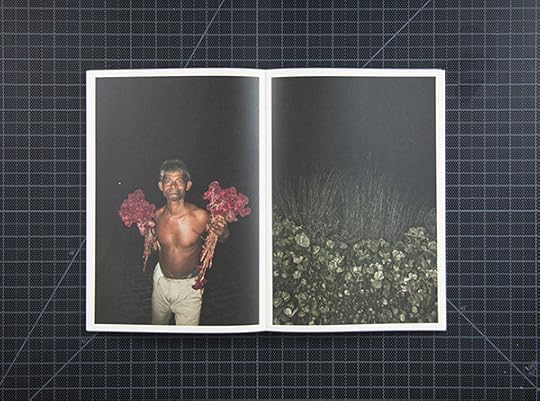

Soham Gupta, Angst (AKINA Books) London

Soham Gupta, Angst (AKINA Books) London

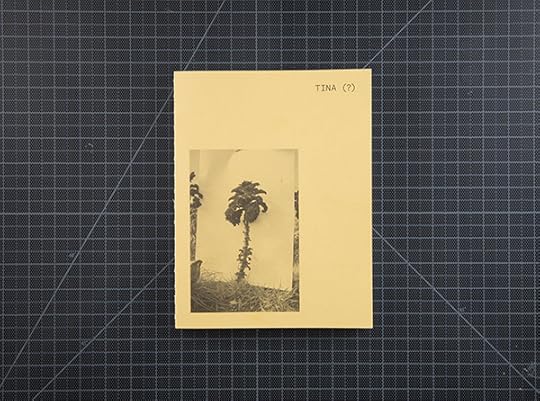

Yann Haeberlin, Tina(?) (Self-published) Geneva, Switzerland

Yann Haeberlin, Tina(?) (Self-published) Geneva, Switzerland

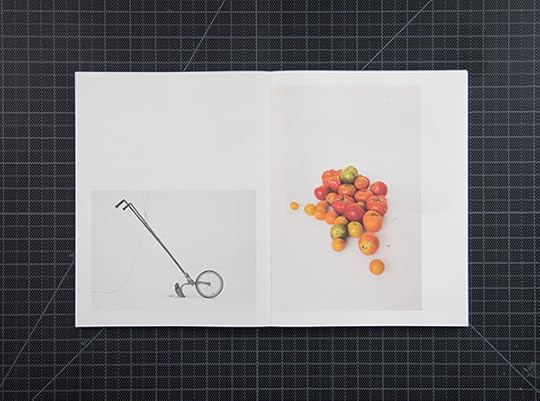

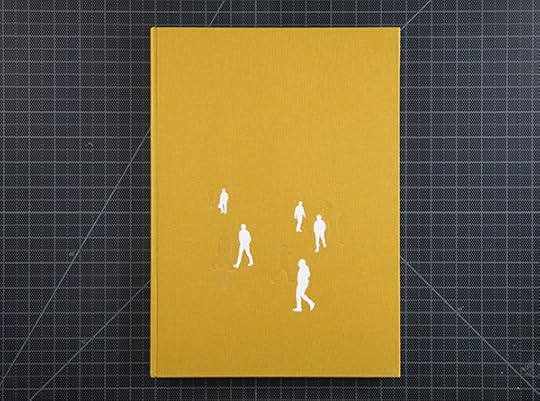

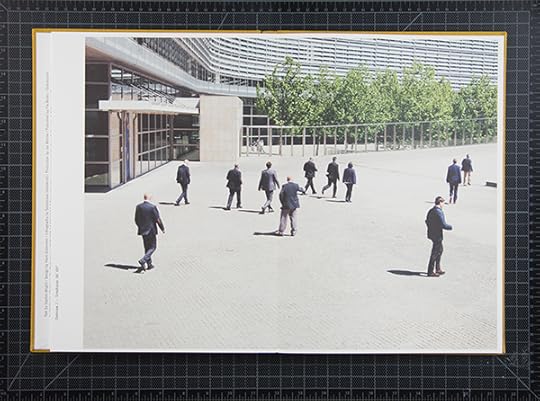

Esther Hovers, False Positives (Fw:Books) Amsterdam

Esther Hovers, False Positives (Fw:Books) Amsterdam

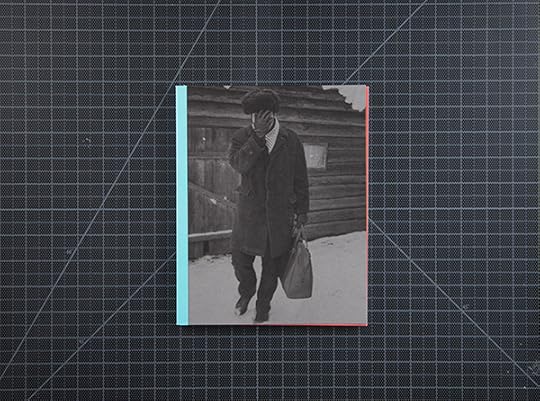

Maria Kapajeva, You can call him another man (Kaunas Photography Gallery) Kaunas, Lithuania

Maria Kapajeva, You can call him another man (Kaunas Photography Gallery) Kaunas, Lithuania

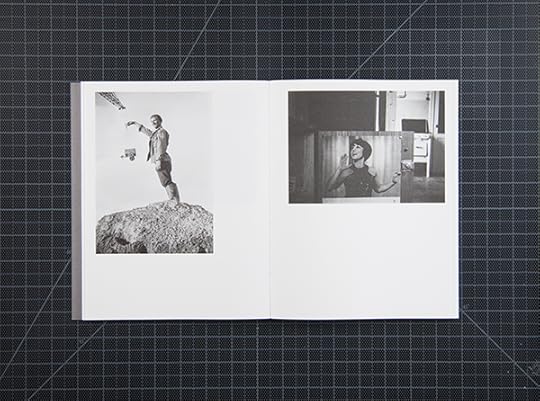

Mariken Kramer, The Eyes That Fix You in a Formulated Phrase (Multipress) Oslo, Norway

Mariken Kramer, The Eyes That Fix You in a Formulated Phrase (Multipress) Oslo, Norway

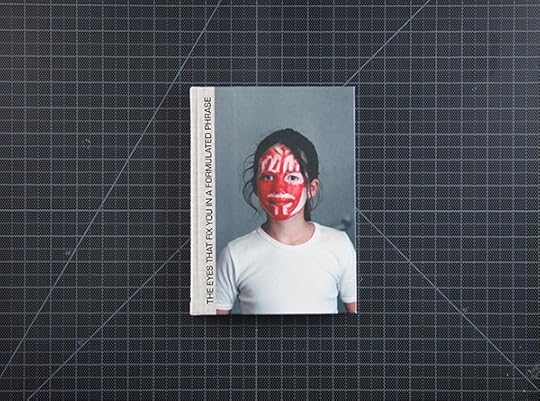

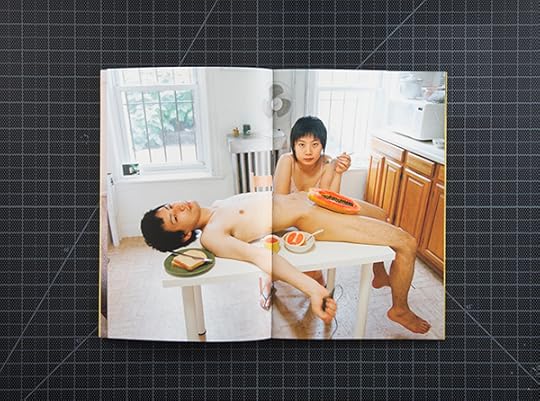

Pixy Liao, Experimental Relationship Vol. 1 (Jiazazhi Press) Ningbo, China

Pixy Liao, Experimental Relationship Vol. 1 (Jiazazhi Press) Ningbo, China

Margo Ovcharenko, Country of Women (Empty Stretch) Moscow

Margo Ovcharenko, Country of Women (Empty Stretch) Moscow

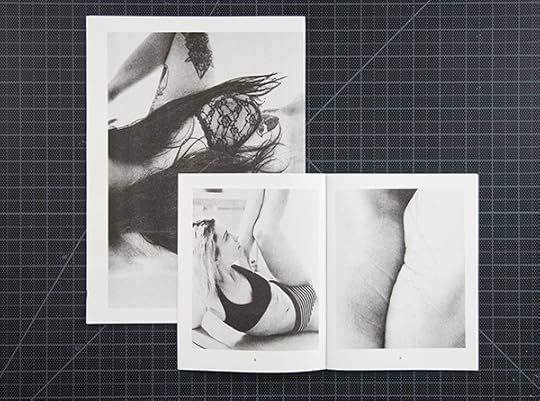

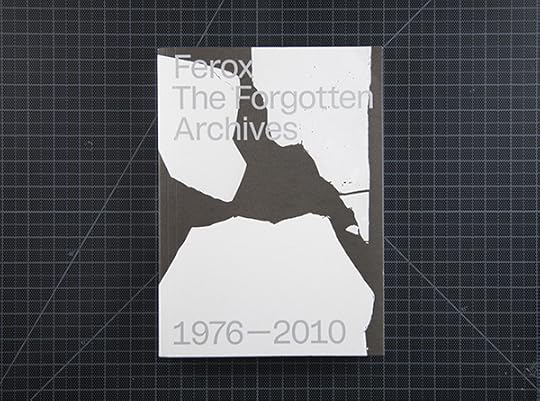

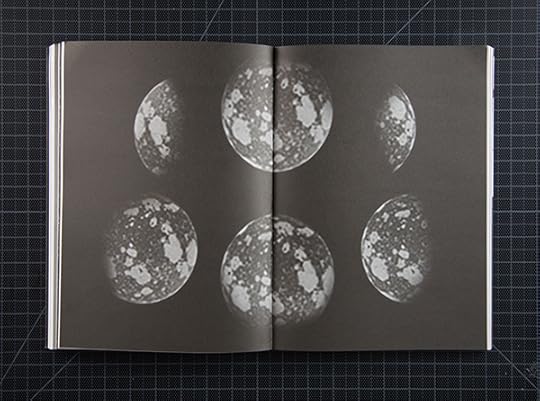

Nicolas Polli, Ferox, The Forgotten Archives (1976–2010) (Ciao Press) Lausanne, Switzerland, and (Skinnerboox) Jesi, Italy

Nicolas Polli, Ferox, The Forgotten Archives (1976–2010) (Ciao Press) Lausanne, Switzerland, and (Skinnerboox) Jesi, Italy

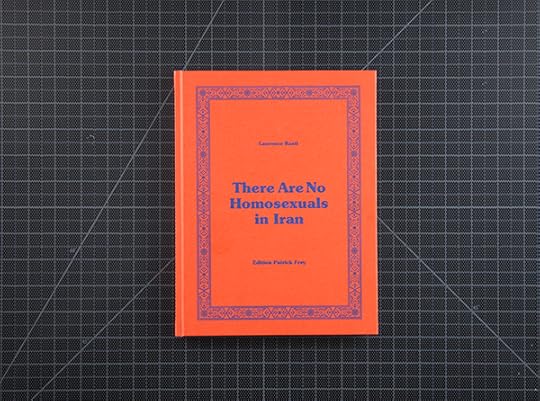

Laurence Rasti, There Are No Homosexuals in Iran (Edition Patrick Frey) Zürich, Switzerland

Laurence Rasti, There Are No Homosexuals in Iran (Edition Patrick Frey) Zürich, Switzerland

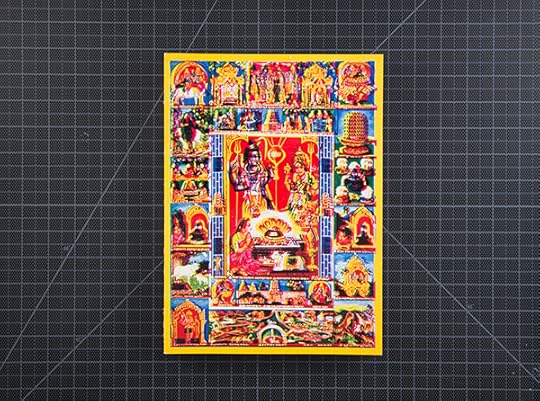

Nick Sethi, Khichdi (Kitchari) (Dashwood Books) New York

Nick Sethi, Khichdi (Kitchari) (Dashwood Books) New York

Clara de Tezanos, Piedra-Padre, Universo (Self-published) Guatemala City

Clara de Tezanos, Piedra-Padre, Universo (Self-published) Guatemala City

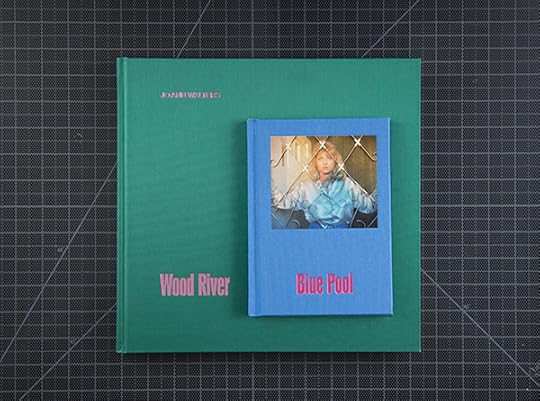

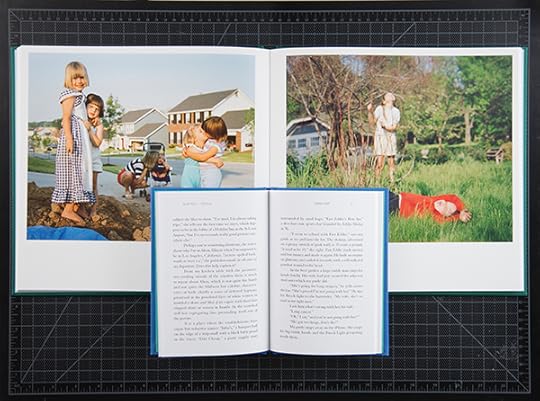

Jo Ann Walters, Wood River Blue Pool and Blue Pool Cecilia (Image Text Ithaca) New York

Jo Ann Walters, Wood River Blue Pool and Blue Pool Cecilia (Image Text Ithaca) New York

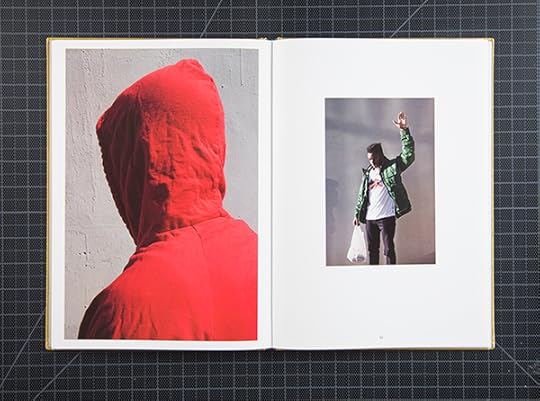

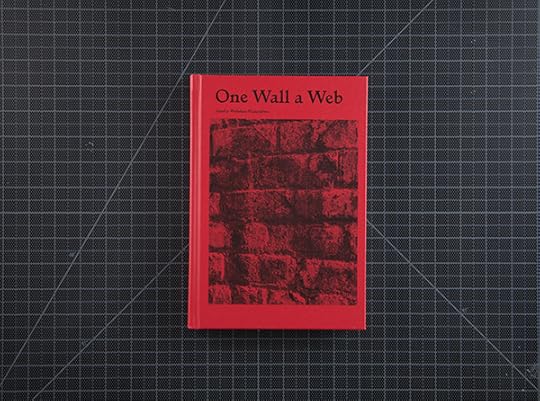

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, One Wall a Web (Roma Publications) Amsterdam

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, One Wall a Web (Roma Publications) Amsterdam

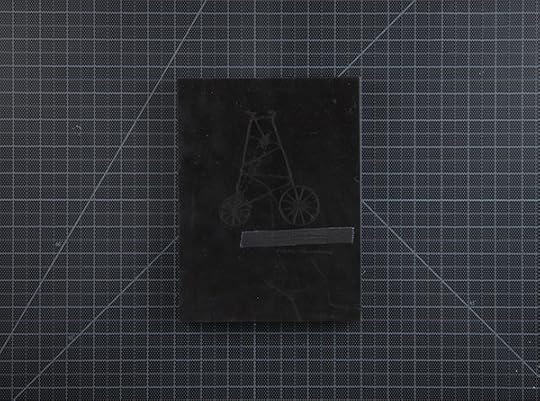

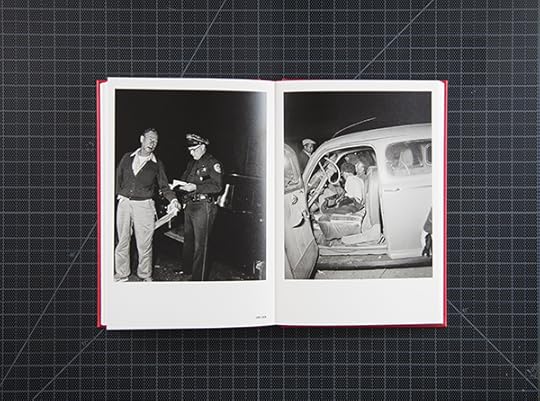

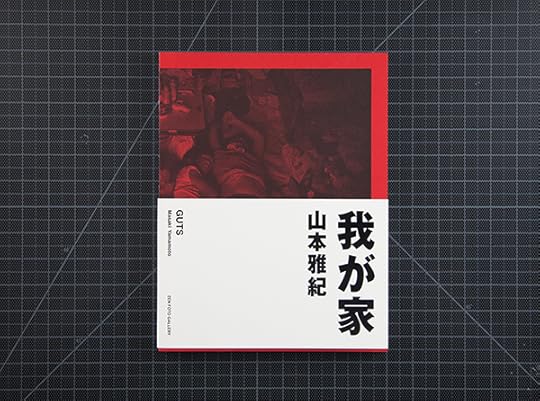

Masaki Yamamoto, GUTS (Zen Foto Gallery) Tokyo

Masaki Yamamoto, GUTS (Zen Foto Gallery) Tokyo

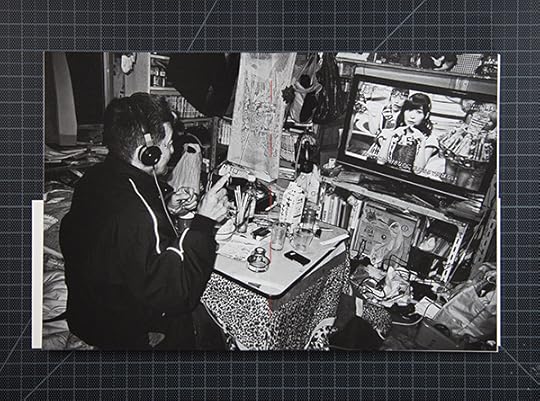

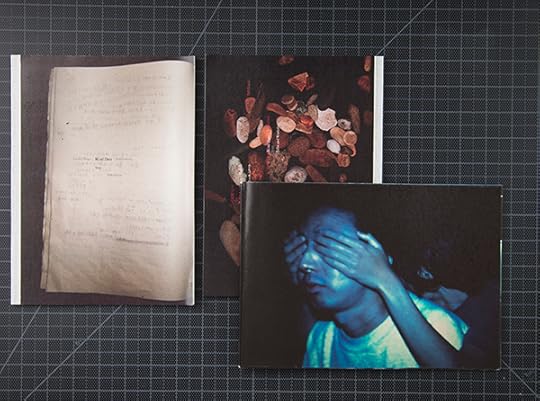

Lieko Shiga, Blind Date Exhibition (T&M Projects) Toyko

Lieko Shiga, Blind Date Exhibition (T&M Projects) Toyko

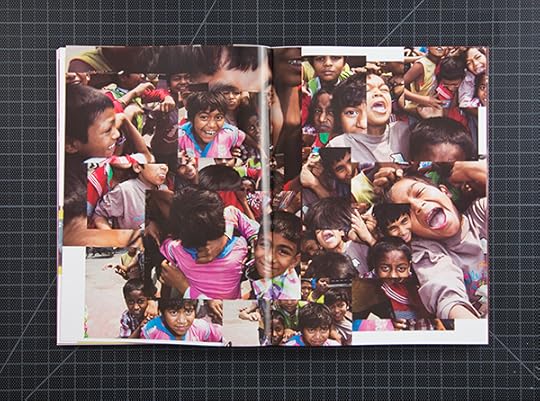

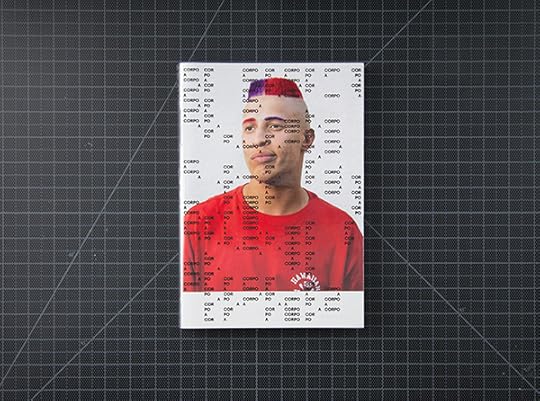

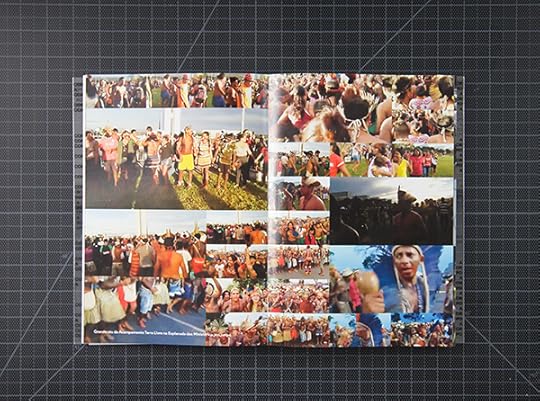

Thyago Nogueira, ed., Bárbara Wagner, Garapa Collective, Jonathas de Andrade, Letícia Ramos, Mídia Ninja, and Sofia Borges, Body Against Body: The Battle of Images, from Photography to Live Streaming (Instituto Moreira Salles) São Paulo, Brazil

Thyago Nogueira, ed., Bárbara Wagner, Garapa Collective, Jonathas de Andrade, Letícia Ramos, Mídia Ninja, and Sofia Borges, Body Against Body: The Battle of Images, from Photography to Live Streaming (Instituto Moreira Salles) São Paulo, Brazil

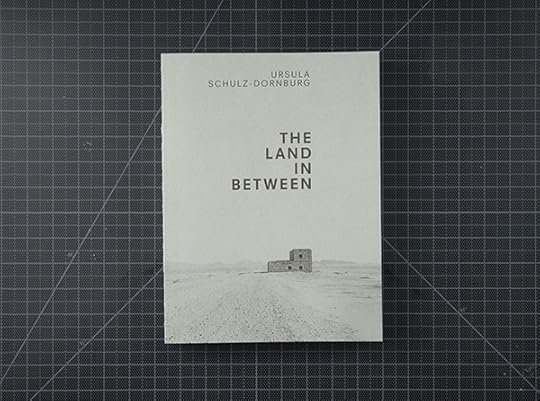

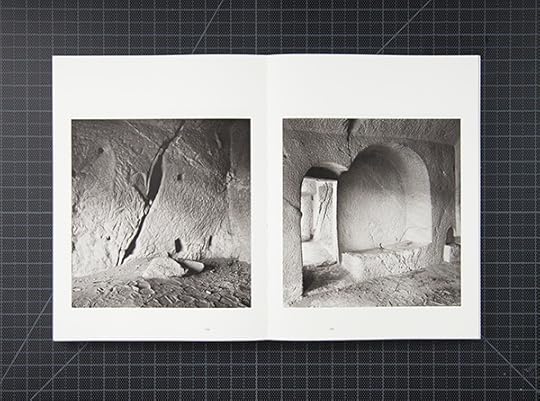

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, The Land in Between (MACK) London

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, The Land in Between (MACK) London

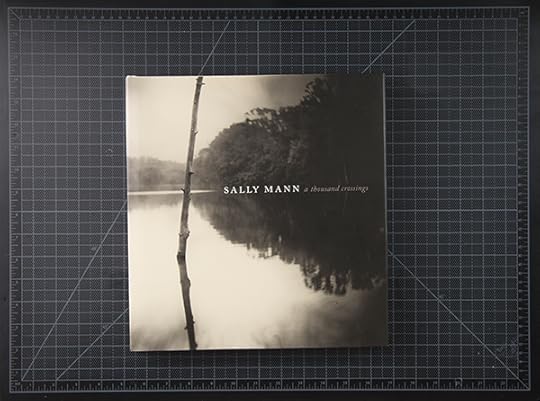

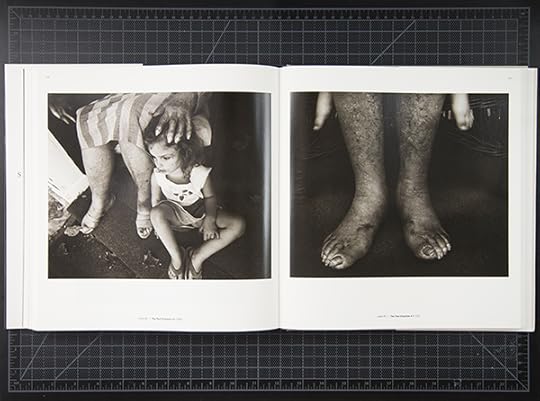

Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel, Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in association with Abrams, New York)

Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel, Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in association with Abrams, New York)

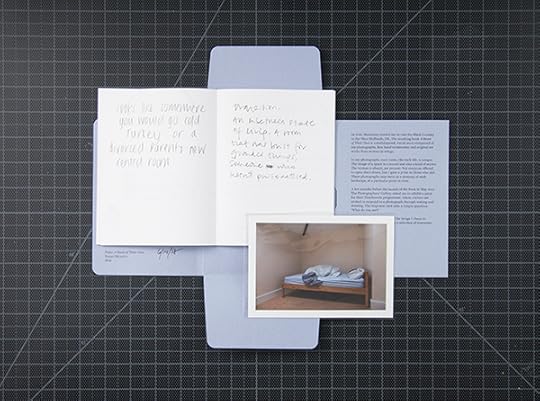

Susan Meiselas, A View of a Room (Here Press) London

Susan Meiselas, A View of a Room (Here Press) London

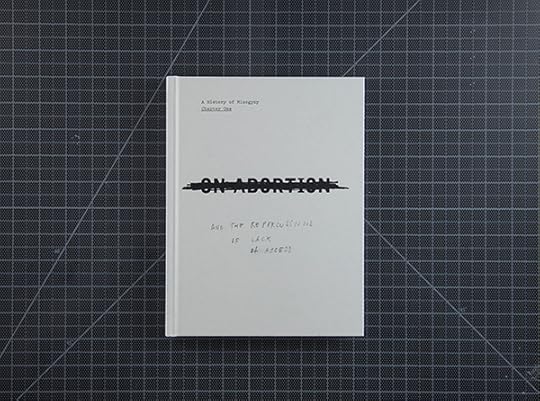

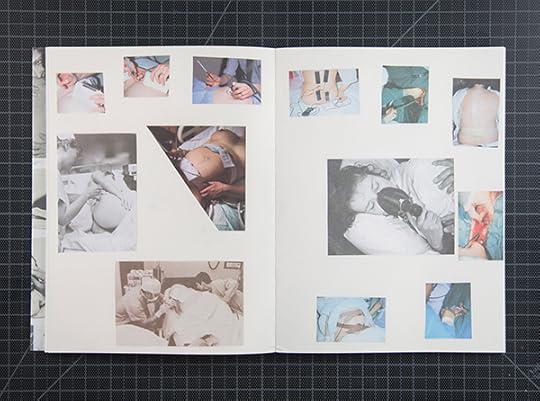

Laia Abril, On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing) Stockport, England

Laia Abril, On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing) Stockport, England

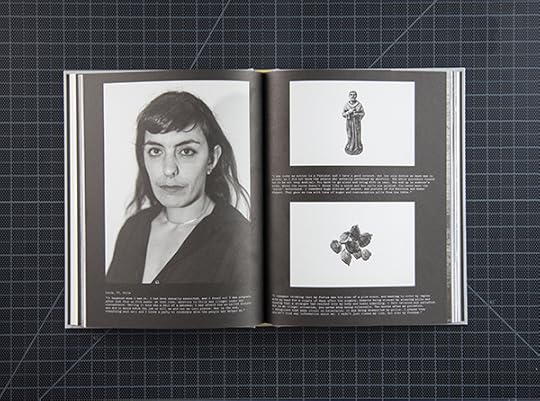

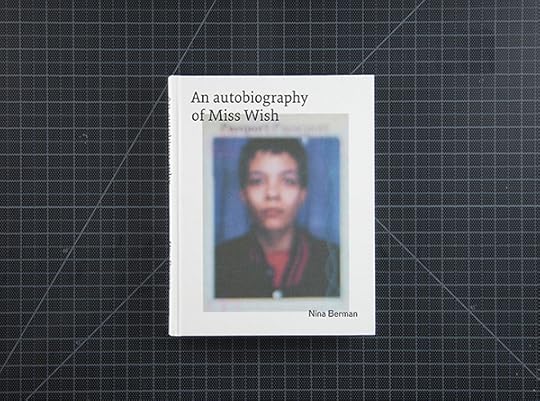

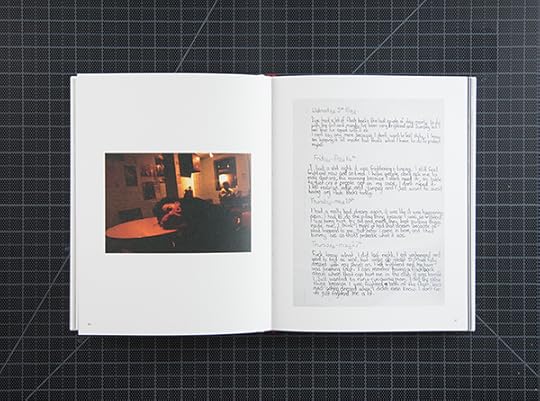

Nina Berman and Kimberly Stevens, An autobiography of Miss Wish (Kehrer Verlag) Heidelberg, Germany

Nina Berman and Kimberly Stevens, An autobiography of Miss Wish (Kehrer Verlag) Heidelberg, Germany

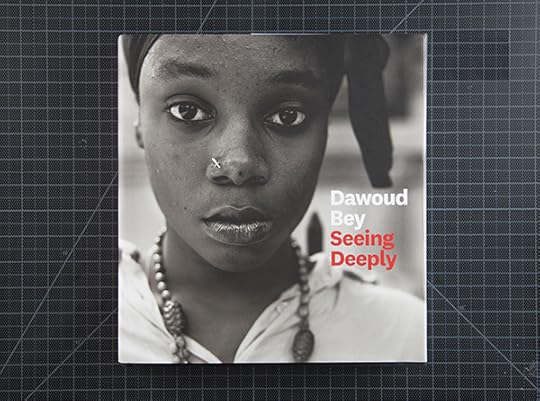

Dawoud Bey, Seeing Deeply (University of Texas Press) Austin

Dawoud Bey, Seeing Deeply (University of Texas Press) Austin

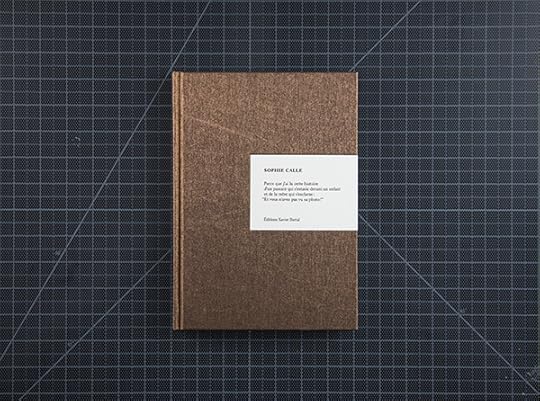

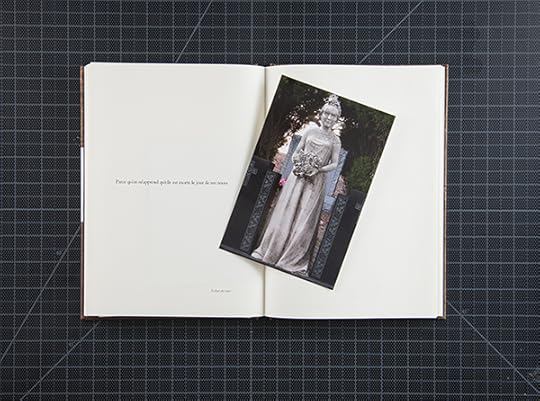

Sophie Calle, Parce que (Éditions Xavier Barral) Paris

Sophie Calle, Parce que (Éditions Xavier Barral) Paris

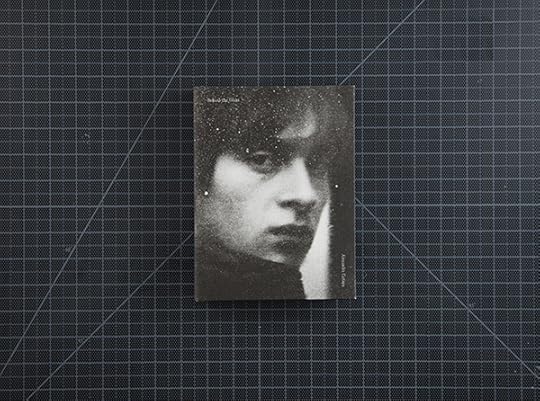

Alexandra Catiere, Behind the Glass (Chose Commune) Paris

Alexandra Catiere, Behind the Glass (Chose Commune) Paris

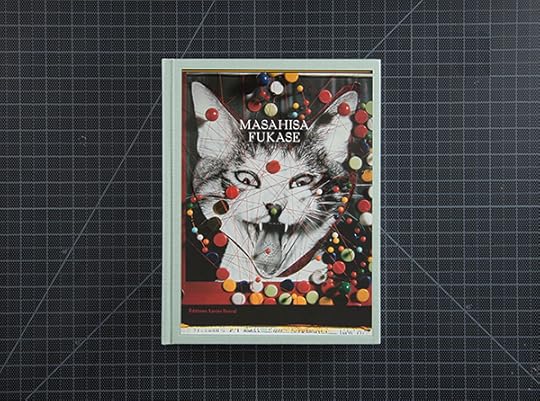

Masahisa Fukase, Simon Baker, and Tomo Kosuga, Masahisa Fukase (Éditions Xavier Barral) Paris

Masahisa Fukase, Simon Baker, and Tomo Kosuga, Masahisa Fukase (Éditions Xavier Barral) Paris

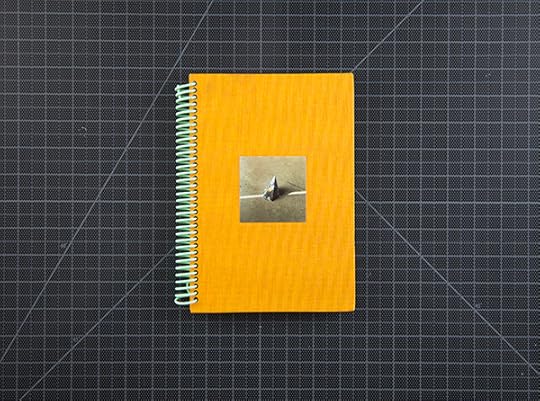

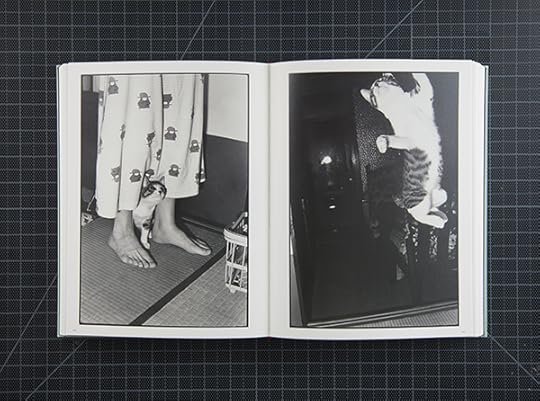

Sohrab Hura, Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!! (Ugly Dog [Self-published)]) Delhi, India

Sohrab Hura, Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!! (Ugly Dog [Self-published)]) Delhi, India

Raymond Meeks, Halfstory Halflife (Chose Commune) Paris

Raymond Meeks, Halfstory Halflife (Chose Commune) Paris

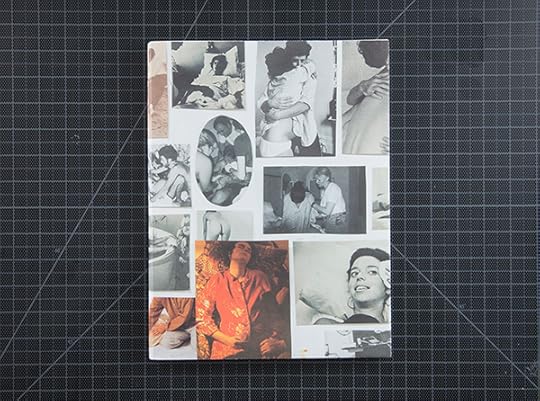

Carmen Winant, My Birth (Self Publish, Be Happy Editions) London

Carmen Winant, My Birth (Self Publish, Be Happy Editions) London

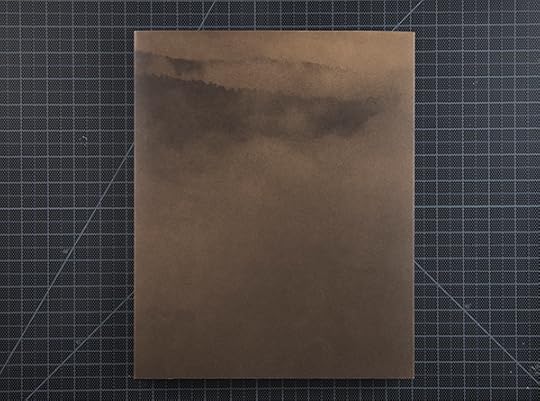

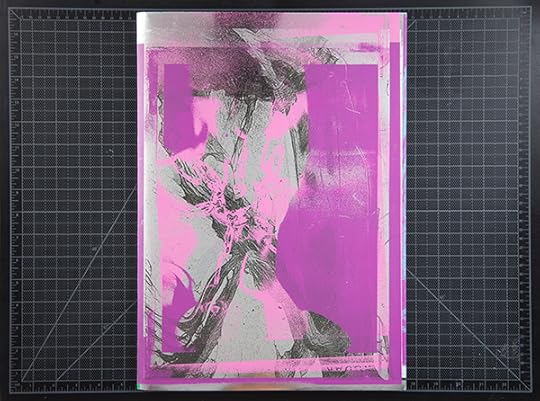

Daisuke Yokota, Inversion (Akio Nagasawa Publishing) Tokyo

Daisuke Yokota, Inversion (Akio Nagasawa Publishing) Tokyo

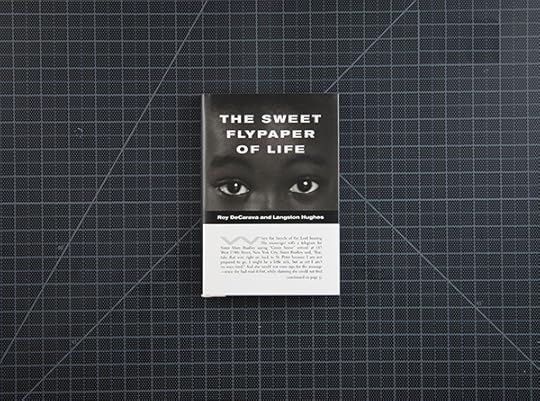

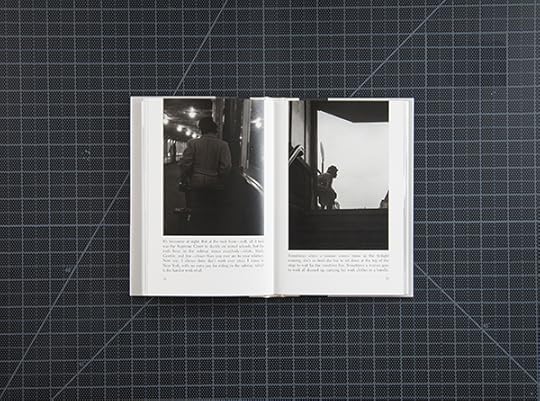

Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (First Print Press) New York Originally published 1955; reissued in paperback

Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (First Print Press) New York Originally published 1955; reissued in paperback

First PhotoBook

Edén Bernal

Exilios (Exiles)

Publisher: Inframundo, Mexico City

Nacho Caravia

Mamá

Publisher: Self-published, Barcelona, Spain

M L Casteel

American Interiors

Publisher: Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, England

John Edmonds

Higher

Publisher: Capricious Publishing, New York

Matthew Genitempo

Jasper

Publisher: Twin Palms Publishing, Santa Fe

Julie Glassberg

Due to unforeseen circumstances, this book has no title (Bike Kill)

Publisher: Ceiba Editions, Siena, Italy

Soham Gupta

Angst

Publisher: AKINA Books, London

Yann Haeberlin

Tina(?)

Publisher: Self-published, Geneva, Switzerland

Esther Hovers

False Positives

Publisher: Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Maria Kapajeva

You can call him another man

Publisher: Kaunas Photography Gallery, Kaunas, Lithuania

Mariken Kramer

The Eyes That Fix You in a Formulated Phrase

Publisher: Multipress, Oslo, Norway

Pixy Liao

Experimental Relationship Vol. 1

Publisher: Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China

Margo Ovcharenko

Country of Women

Publisher: Empty Stretch, Moscow

Nicolas Polli

Ferox, The Forgotten Archives (1976–2010)

Publisher: Ciao Press, Lausanne, Switzerland, and Skinnerboox, Jesi, Italy

Laurence Rasti

There Are No Homosexuals in Iran

Publisher: Edition Patrick Frey, Zürich, Switzerland

Nick Sethi

Khichdi (Kitchari)

Publisher: Dashwood Books, New York

Clara de Tezanos

Piedra-Padre, Universo

Publisher: Self-published, Guatemala City

Jo Ann Walters

Wood River Blue Pool and Blue Pool Cecilia

Publisher: Image Text Ithaca, New York

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

One Wall a Web

Publisher: Roma Publications, Amsterdam

Masaki Yamamoto

GUTS

Publisher: Zen Foto Gallery, Tokyo

Photography Catalogue of the Year

Blind Date Exhibition

Lieko Shiga

Publisher: T&M Projects, Toyko

Body Against Body: The Battle of Images, from Photography to Live Streaming

Thyago Nogueira, ed., Bárbara Wagner, Garapa Collective, Jonathas de Andrade, Letícia Ramos, Mídia Ninja, and Sofia Borges

Publisher: Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil

The Land in Between

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Publisher: MACK, London

Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings

Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel

Publisher: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in association with Abrams, New York

A View of a Room

Susan Meiselas

Publisher: Here Press, London

PhotoBook of the Year

Laia Abril

On Abortion

Publisher: Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, England

Nina Berman and Kimberly Stevens

An autobiography of Miss Wish

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany

Dawoud Bey

Seeing Deeply

Publisher: University of Texas Press, Austin

Sophie Calle

Parce que

Publisher: Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Alexandra Catiere

Behind the Glass

Publisher: Chose Commune, Paris

Masahisa Fukase, Simon Baker, and Tomo Kosuga

Masahisa Fukase

Publisher: Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Sohrab Hura

Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!!

Publisher: Ugly Dog (Self-published), Delhi, India

Raymond Meeks

Halfstory Halflife

Publisher: Chose Commune, Paris

Carmen Winant

My Birth

Publisher: Self Publish, Be Happy Editions, London

Daisuke Yokota

Inversion

Publisher: Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo

Jurors’ Special Mention

The Sweet Flypaper of Life

Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes

Originally published 1955; reissued in paperback

Publisher: First Print Press, New York

The post The 2018 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 20, 2018

Fashion Photography in the #MeToo Era

Are fashion photographers responsible for producing truthful images?

By Lou Stoppard

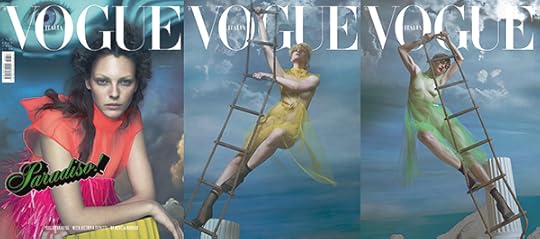

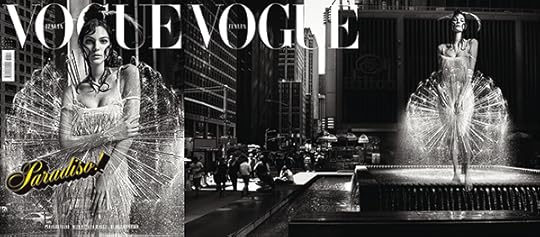

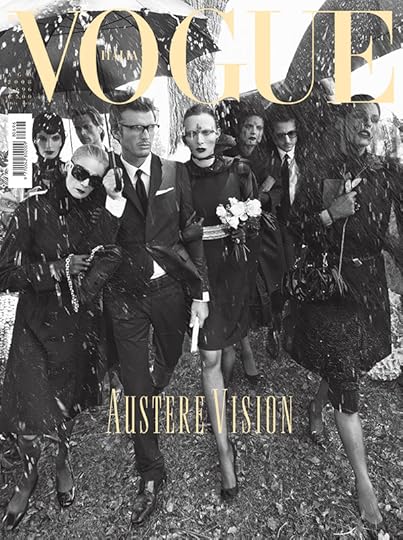

Mert & Marcus, cover of Vogue Italia, September 2017

“I’m not the UN, I’m just a fashion photographer,” says Mert Alas, who, along with his collaborator Marcus Piggott, is known for an uncompromisingly charismatic, glossy style of image-making. He’s commenting on the demand on fashion photographers today to be aware, engaged, political, and, perhaps as a result, increasingly cautious.

In October, it will be a year since allegations against Harvey Weinstein were reported in the press. In this post–#MeToo and Time’s Up era, fashion—which has had its own abusers and brave accusers—is under more scrutiny than ever. That’s good; powerful companies, and powerful men, should be held responsible for their actions. But fashion is in a particularly complex position, partly because fashion itself has never been so fashionable. It’s now a huge part of pop culture, watched by millions and commented on by many. While other industries can express a desire to change through words—expressions of remorse, discussions of new regulations, announcements of new appointments and sanctions—fashion is judged largely on what people see. Images have never been under so much scrutiny, and that scrutiny is shaping the kinds of photographs we see and dictating trends, content, and mood.

Mert & Marcus, cover of Vogue Italia, September 2018

To Alas, despite all the many victories of this modern time we live in, when it comes to imagery, we’re getting more closed-minded. He and Piggott started out in the mid-nineties and fashion was not the industry it is today. Then, shoots lasted days, rather than well-organized hours, and were often conducted by groups of friends for niche titles with a DIY, anticommercial mentality. It would have been impossible to imagine that such images would ever be subject to enormous levels of analysis, or could be digitalized and republished and reblogged by thousands, and taken as a definitive comment on society, politics, women, men, beauty, life. Today, images are simply more seen. And photographers are no longer regarded as image-makers, but increasingly as spokespeople for a set of values. “We used to go for a smaller audience and we had less pressure,” says Alas. “As the audience is so wide now, I feel there is an urge to please everyone. If you stick to your point of view you can always get a good shot.”

Photography, like fashion, is in fashion—it’s everywhere. Some like to say we’re all photographers now, uploading our own personal photo shoots onto Instagram. An average of sixty million images are uploaded to the app each day. Our eyes have never been so accustomed to digesting and dismissing images. Fashion photographer Sølve Sundsbø has seen the resultant spotlight on his industry grow: “I think it’s very important that photography, and fashion photography, are under scrutiny—I don’t think that there is any point being defensive about it. But I think what is interesting is the language and understanding that it’s being scrutinized with. When you go to school you learn how to analyze written texts, you look at books, you read poetry, you analyze written statements, you analyze geography, but the one thing you don’t really get to analyze is images—and if there’s one sense we use more than anything these days, and over the last thirty, forty, fifty years, it’s our sight; we consume images nonstop. But most of us don’t have a way of understanding images; we simply have an old notion that a photograph should tell the truth. And that notion is the underlying premise for most discussions about photography.”

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, April 2014

In her germinal book On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture.” A lot has changed since Sontag wrote that in 1977, but the point she makes is as true as ever. As Sundsbø says, we look to fashion photography in search of some kind of reality. Increasingly, we not only expect that something exists that looks like the picture, but also demand that fashion photography only show things that could exist—hence why we criticize images that do not present a realistic body image, or suitably diverse casting, or a sort of moral sensibility that seems in line with the politics of the moment. Such comments are, of course, important. But they also establish guidelines and tricks for companies to hide behind: make a “diverse” campaign and hopefully no one will look behind it and ask about the demographic of your management board, or the working conditions in your factories. It is a veneer of an ethical industry. “There is a degree of expectation in the current moment that every individual shoot has to be representative in so many ways, and occasionally this feels like pressure to put political or ideological considerations before creative ones,” says Alas. “I personally do cast in a diverse way, but this is because of my artistic point of view. If there is a lack of representation of different kinds, maybe we need to see more points of view rather than token casting choices.”

In an age of “fake news,” it is understandable that people want to be able to trust the imagery they see. But increasingly, imagery that is fantastical or whimsical is seen as out-of-date or off topic. Glamour cannot thrive in this mood. Maybe that’s appropriate, given the uncertainty and difficulty of the times we live in. But it’s also hard to see how imagination can thrive, either. Prioritizing photography as a medium that should be dedicated only to truth-telling also defines the tools of the trade as simply a camera, relegating it to some kind of recorder or note-taker. It ignores the opportunity areas that have come with new technologies like retouch software, apps, and Photoshop. These can be dynamic tools for innovation but are often dismissed as opportunities for trickery, despite the desires of photographers to use them artistically. As Vinoodh Matadin said, when discussing his and Inez van Lamsweerde’s early experiments with digital manipulation in an interview for my book on collaboration, Fashion Together, in 2015: “It was almost like you could finally paint in photography. We never started using digital just to retouch people.”

Inze & Vinoodh, cover of Vogue Italia, October 2018

In this climate, there has been a move away from “mise-en-scène” fashion photography, and the representation of dreams or nightmares, to a more documentary-like approach. There is a thirst for something “real” or “raw,” hence the current vogue for imagery that looks natural, clean, quiet, and almost entirely unchoreographed: girls shot by the side of the road, or in quotidian settings, as if they were just stumbled upon. But “real”-looking photography is problematic, too. “The fact that people always believed images should show the truth has always been the strength of fashion photography—it made people believe what they saw in the pictures,” says Sundsbø. In other words, it helps sell bags and dresses, because people really think that they could look just like the girl in the picture. “But now, people are starting to realize the imagery maybe isn’t as true as they first thought, and they almost seem angry about it. One way fashion has reacted is to go toward reality—well, making it look more like reality. But people have to understand that the reality in fashion photography right now is no more real than a fully fledged Helmut Newton Amazon woman in the South of France.” Indeed, you may see an image of a carefree-looking girl, shot in an unexceptional town. But still, that girl is a paid model. Hours will have been spent on getting her to look artfully undone, and art directors and location scouts will have spent days hunting for just the right spot to take the image. Oh, and she’s wearing thousands of dollars’ worth of clothes.

Seven Klein, cover of Vogue Italia, October 2017

Lucy Moore is director of the photography bookshop Claire de Rouen in London, which specializes in fashion and design and regularly supplies to icons of the industry. She’s observed the change in mood in fashion photography. “I have definitely noticed a turn away from an interest in the constructed or abstracted image in the shop’s visitors—instead they focus on archival social documentary and portrait photography as well as self-representation,” she says. “For a very long time, fashion photography needed to generate desire in a very small coterie of wealthy people, who actually had the means to realize their dreams. But with the dramatic turn-of-the-corner into a commercial world where digital space is where the power is won, and where the majority of the users of that space are young, communicative, and not afraid of sparring with their thoughts, maybe aspiration is more about forming alliances—being part of a specific group—than about standing out or entering the rarified world of the elite in a very visible way.”

As Moore observes, most fashion is now consumed in digital spaces: fashion shows are watched on live streams, clothes are bought on e-retailers, and photo shoots and magazine covers are most widely seen on Instagram. Fashion images have thus come to reflect the off-the-cuff, intimate mood on the digital space. That said, it is perhaps ironic that the most criticism of fashion photography—as unrepresentative, or in bad taste, or overedited—occurs on social media, where increasingly users’ own uploads and selfies are as manipulated, tweaked, and tuned as high-budget fashion images. Social media also has its own rules and regulations, which are shaping the future of fashion imagery. It is often described as an area of unbridled freedom and democracy, but really it is rife with censorship. “Image-makers are definitely becoming more daring while, generally, platforms are far from being accepting or willing to facilitate this progress,” say Stefano Colombini and Alberto Albanese, the duo behind Scandebergs, who offer cinematic, narrative-driven images. “Instagram, for instance, is heavily subjected to censorship because of the wider audience it reaches daily.” The most notorious example of this is the ban on showing female nipples, which is surely undermining fashion photography’s long history of breaking down taboos around nudity. “Also,” Colombini and Albanese continue, “with ‘engagement and reach’ being the most important marketing strategy points for brands, images are increasingly being created to be easy to read, rather than complex ones that would reach a smaller audience. It is important to preserve the complexity of every artist’s visual language.”

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, July 2005

One wonders how some of the more provocative, politically charged images from Vogue Italia’s history, such as Steven Meisel’s shoots exploring society’s obsession with plastic surgery or violence against women, would fare on Instagram in this age of outrage. Social media allows for instant commentary—a quick like or dislike, dictated by a tiny movement of the thumb and a millisecond of thought. “If you do even the smallest mistake, your career might be over,” says Sundsbø. Mert Alas tries to stay brave. “Fashion photography is a tool for escapism, a break from reality, a little dream. I feel like there is a fear of being politically incorrect, and fear creates moderation. Quite frankly I hate moderation—I’m a man of excess!—so I still search for that little dream and try to portray it in our photography.”

So, what is next? Will the taste for the “real” disappear? Will glossy glamour ever feel right? And will fashion ever be able to handle sex? That’s debatable. “I’ve heard men in the fashion industry say they are ‘scared’ of making sexual work. But I hope this doesn’t last. Humans need to be sexual,” says Moore. Sundsbø has had editors shy away from sensual imagery, even in a case where a female portrait subject chose her own dress, which happened to be semitransparent. Somewhere along the way, some people seem to have forgotten that Me Too isn’t saying that sex is bad; it is saying that exploitation is bad. The answer certainly isn’t tasking female image-makers with coming up with a totally new style of imagery. It has become fashionable to talk about a “female gaze,” which is almost becoming an aesthetic in itself, with its own set of limitations and recognizable tropes. “It’s important to not fall into that easy trap,” says photographer Julia Hetta. “What’s important is that we really feel we believe in the picture.”

Steven Meisel, cover of Vogue Italia, August 2008

In the end, the diversity we demand to see within pictures should be reflected in the photographers themselves and the style of images we see: they should be surprising, unexpected, ambitious, and—the most unattainable goal—new. Sundsbø remains optimistic: “Every person hopes that the next thing you do will be the best thing you’ve ever done—whether it’s the next meal that you have, the next purchase you make, or the next person you meet. I have to believe that the next picture I do will at least be better than the picture I did yesterday—you have to have that hope.”

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London. This article was originally published in Vogue Italia‘s September 2018 issue.

Aperture, in collaboration with UNSEEN Amsterdam’s Living Room Series, will present a panel discussion on the “Elements of Style,” featuring Lou Stoppard, on September 21, 2018.

The post Fashion Photography in the #MeToo Era appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers