Aperture's Blog, page 97

September 11, 2018

The Last Humanist

Sabine Weiss’s photographs brought style and serendipity to the streets of Paris and beyond.

By Violaine Boutet de Monvel

Sabine Weiss, Place de la Concorde, Paris, 1953

© the artist/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GRP

On June 6, 1944, the one hundred fifty-six thousand soldiers from the Allied forces who landed on the beaches of Normandy, France, under heavy Nazi fire, each carried a three-day supply of compact, lightweight food. The U.S. troops’ rations included chewing gum from the American brand Wrigley, which had reserved its entire production for GIs fighting overseas during the Second World War. As they progressed on the western front (and more supplies were sent their way), D-Day survivors offered extra gum to the children greeting and soliciting them for leftovers, French people having endured years of severe food shortages due to German occupation. This friendly gesture might not be the kind of capital-H History recorded in books, but the story has nonetheless passed from one generation to the next: the Allies did not just liberate the country, Americans also brought candy. Courtland E. Parfet, a former GI who took part in the Normandy landings, eventually returned to France in 1952 to create Hollywood, his own brand of gum sticks, which still exists to this day.

Sabine Weiss, Enfant, Paris, 1952

© the artist/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GRP

The same year, the Swiss-born, Paris-based photographer Sabine Weiss captured a French boy relishing one of these sticky treats through a sequence of three black-and-white photographs. Each titled Enfant, Paris (1952), they portray the child with an ear-to-ear grin, mischievously chewing gum and rubbing his little hands with satisfaction. Taken while Weiss was strolling around the capital with a medium-format Rolleiflex camera, these candid pictures are currently exhibited in Les villes, la rue, l’autre (The cities, the street, the other) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which gathers about eighty vintage and, for the most part, previously unseen photographs from Weiss’s own archives. (The ninety-four-year-old recently donated some of them to the Pompidou; a catalogue coedited with Éditions Xavier Barral was also published on the occasion, with reproductions of over one hundred pictures.) The overall ensemble extends from 1946, when she moved to Paris from Switzerland to assist the renowned German fashion photographer Willy Maywald, to 1962, at which point she left her personal work aside, taking up commissions for Vogue, the New York Times, Life, Paris Match, Esquire, and others.

Sabine Weiss, Dun sur-Auron, 1950

© the artist/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GRP

Born in 1924, Weiss is the last living representative of humanist photography, a typically French trend related in style to the serendipities of the street—like that child chewing his gum. Far from documenting newsworthy events, let alone historical milestones, humanists shifted their focus onto everyday situations and people in candid, often poetic compositions, which touched upon the misery and optimism that characterized postwar France. In 1952, Weiss had already embarked on a career as an independent photographer when she met Robert Doisneau by chance in the Parisian offices of Vogue. Impressed by her work, he recommended her to the Rapho agency. She joined it the following year and her career immediately took off with landmark exhibitions: some of her photographs were included in Postwar European Photography (1953) and The Family of Man (1955), both curated by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, and she had her first solo show at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954.

Sabine Weiss, New York, 1955

© the artist/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GRP

The vast majority of Weiss’s personal work from the postwar period, however, ended up in boxes in her Parisian studio, and as a result her early humanist photographs have yet to be thoroughly studied and exhibited. Les villes, la rue, l’autre chiefly highlights Weiss’s certain taste for evanescent silhouettes or reflections through the rain, mist, snow, and night. While her pictures taken in Paris constitute more than half of the show, they would capture a rather dim City of Light if it weren’t for the fleeting yet palpable joie de vivre among its inhabitants, ranging from homeless people and street children to fishermen, storekeepers, and even horse-racing gamblers. Between 1955 and 1962, Weiss also traveled numerous times to New York, where everything that she couldn’t find in Paris would catch her attention—a father devouring cotton candy next to his son after a circus spectacle, the neon lights of giant billboards piercing through the dark in Times Square—in other words, the dynamism and apparent prosperity of the restless metropolis.

Sabine Weiss, Paris, 1955

© the artist/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GRP

For all the pleasure the images afford, what this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue lack are sharper perspectives by which to approach Weiss’s humanist aesthetics. By reducing the photographs on display to vaguely formal or simply geographical considerations, with basic introductory titles such as Villes de brume et de lumière (Cities of mist and light) or just the names of said cities, the presentation somewhat neglects the fundamentals: the profoundly humane quality of these works and their sociopolitical charge. Still, the best may be yet to come. Last year, Weiss gave the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne, close to her Swiss birthplace, her entire archives, which will enter the museum’s collection by 2021. Hopefully exploring them will not only uncover other long-lost gems from her past, but also offer much-needed insights into her early personal practice and allow us, as she notes in the foreword of her recent catalogue, “to see the simplest details that express everything and bring out the essential.”

Violaine Boutet de Monvel is an art critic and translator living in Paris. All translations are the author’s own.

Sabine Weiss: Les villes, la rue, l’autre is on view at Centre Pompidou, Paris, through October 15, 2018.

The post The Last Humanist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 10, 2018

Zanele Muholi On Resistance

In an interview, the visual activist speaks about courage, rethinking history, and the politics of exclusion.

By Renée Mussai

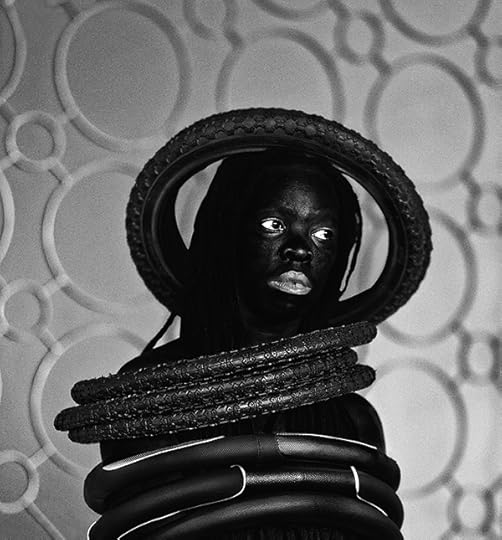

Zanele Muholi, Bona, Charlottesville, Virginia, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Renée Mussai: Let’s begin by talking about how the images in Somnyama Ngonyama offer a repertoire of resistance, both for yourself and for empowering others. Collectively, they represent an invitation to see yourself in a different light. You take on the image archive in the racial imaginary, addressing a range of personal experiences, social occurrences, cultural phenomena, past histories, and contemporary politics through self-portraiture. Each portrait poses critical questions about social (in)justice, human rights, and contested representations of the black body, confronting the viewer with a stance that is at once personal and political. How does the project sit within your wider bodies of work?

Zanele Muholi: My practice as a visual activist looks at black resistance—existence as well as insistence. Most of the work I have done over the years focuses exclusively on black LGBTQIA and gender-nonconforming individuals making sure we exist in the visual archive. (In Faces and Phases, I focused exclusively on LBTQ individuals, for instance, bearing in mind that gender politics are complex, and fluid; the acronyms are always shifting and changing.) The key question that I take to bed with me is: what is my responsibility as a living being—as a South African citizen reading continually about racism, xenophobia, and hate crimes in the mainstream media? This is what keeps me awake at night. Thus Somnyama is not only about beautiful photographs, as such, but also about bringing forth political statements. The series touches on beauty and relates to historical incidents, giving affirmation to those who doubt whenever they speak to themselves, whenever they look in the mirror, to say, “You are worthy. You count. Nobody has the right to undermine you—because of your being, because of your race, because of your gender expression, because of your sexuality, because of all that you are.”

Zanele Muholi, Ziphelele, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mussai: I see at the heart of your project the desire for remedial, permanent inscription into a wider visual narrative, and to affect future histories through visual interventions. We have spoken in the past about how your affirmative portraiture practice evokes W. E. B. Du Bois’s Paris Albums 1900. Challenging the historically racist imaging machine—though with a distinctively heteronormative focus—Du Bois’s strategic assemblage of several hundreds of photographs depicting African Americans in turn-of-the-century Europe similarly represented a site of resistance, enhancing existing visual histories that had tradition-ally rendered certain communities not only invisible, but inferior. I’m thinking of your Faces and Phases (2006–) series in particular, but I feel this equally holds true for Somnyama; the many “faces and phases” you conjure not only bear witness to your own existence, but persist, and insist on, making a claim for humanity. Inviting us into a multi layered conversation, each photograph in the series, each visual inscription, each confrontational narrative depicts a self in profound dialogue with countless others: implicitly gendered, culturally complex, and historically grounded black bodies.

Muholi: Somnyama is my response to a number of ongoing racisms and politics of exclusion. As a series, it also speaks about occupying public spaces to which we, as black communities, were previously denied access—how you have to be mindful all the time in certain spaces because of your positionality, because of what others expect you to be, or because your tradition and culture are continually misrepresented. Too often I find we are being insulted, mimicked, and distorted by the privileged “other.” Too often we find ourselves in spaces where we cannot declare our entire being. We are here; we have our own voices; we have our own lives. We can’t rely on others to represent us adequately, or allow them to deny our existence. Hence I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified, brave enough to take on that visual text, those visual narratives. To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.

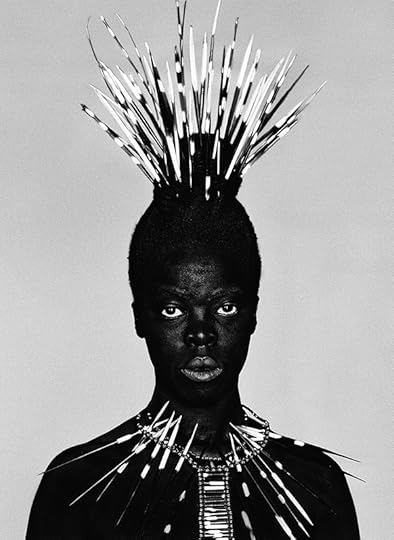

Zanele Muholi, MaID X, Durban, South Africa, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mussai: Yes. Gordon Parks’s notion of the camera as his choice of a “weapon . . . against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs” comes to mind, as well as Audre Lorde’s potent rejection of being “crunched into other people’s fantasies . . . and eaten alive.” And perhaps most relevant, Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s bold declaration to use “Black, African, homo-sexual photography” as a weapon to resist attacks on his integrity and existence on his own terms. I’ve been thinking further about the idea of “weaponizing” one’s practice lately, in relation to Somnyama—not necessarily in a militant fashion, but as a visually seductive call to arms, a protective mantle, a necessary reclamation. An occupation, manifesto, and invitation. These portraits are, essentially, about courage: the courage to emerge; the courage to reflect; the courage to exist, insist, resist; the courage to step in front of the camera—to literally “face oneself.” While you have featured in your work before, you refer to these earlier images as “portraits of the self,” as opposed to the self-portraits in Somnyama. Why did you choose to become an active participant and image-maker at this stage in your career? Why now?

Muholi: I wanted to use my own face so that people will always remember just how important our black faces are when confronted by them—for this black face to be recognized as belonging to a sensible, thinking being in their own right. And as much as I would like a person to see themselves in Somnyama, I needed it to be my own portraiture. I didn’t want to expose another person to this pain. I was also thinking about how acts of violence are intimately connected to our faces. Remember that when a person is violated, it frequently starts with the face: it’s the face that disturbs the perpetrator, which then leads to something else. Hence the face is the focal point in the series: facing myself and facing the viewer, the camera, directly. Coming from South Africa, I doubt that it would have been possible to execute this project as a black person prior to 1994, for instance, because of the apartheid system and laws that were in place.

Zanele Muholi, Sthembile, Cape Town, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mussai: Given both the personal nature and sociopolitical critique that underpins so many images in the series, I imagine that’s especially true. Was there a specific event that inspired the first portrait in Somnyama?

Muholi: In 2012, I was on an artist residency in Italy, where I stayed in a very, very beautiful place: an old castle. But every morning I’d be woken up by gunshots. Even though the space was protected, and we were guaranteed our safety, these continuous gunshots were unnerving for me. When I inquired, I was told they came from hunters, hunting for boars. The catch of the day was described as a “wild, black pig.” At the same time, there was controversy around [the soccer tournament] UEFA Euro 2012: black Italian players were subjected to overt racism, with “monkey” chants and bananas being thrown at them on the pitch. It made me think of how we are perceived as black people—and how black bodies are routinely exposed to danger. Anything black is always positioned as wild, animalistic, uncontrollable.

It’s a painful notion, and I don’t want to go too deep into it, although it does not go away. Only recently, in December 2017, one of the most important photographs in our history—the famous image of Hector Pieterson by South African photojournalist Sam Nzima—was abused by Selborne College in East London, South Africa. The original image shows Hector’s lifeless body being carried by his fellow student Mbuyisa Makhubo on June 16, 1976, when South African police opened fire on marching schoolchildren in the township of Soweto. To illustrate a flyer for a class of 2017 event, Pieterson’s head was removed, and the faces of Makhubo and Antoinette Sithole, Pieterson’s sister, were replaced with dog heads. If an iconic image exposing the violence of the apartheid regime can be turned into a caricature, then what have we learned (or gained) in twenty-three years of democracy, with regards to the ethics of image production—or in terms of empathy and understanding, forty-one years after the Soweto uprising? This is the reason why Somnyama exists.

Mussai: Unfathomable, to think that not even an image this deeply emblematic of the anti-apartheid struggle is protected from parody. It also serves as a testament to the urgency and unabiding relevance of the series in this contemporary moment. I want to return briefly to the inaugural portrait: I vividly recall you telling me about a new project back in 2012, then tentatively titled the Black series before it became Somnyama. When you returned home to South Africa after Italy, you created Sthembile, Cape Town (2012), in response, correct?

Muholi: Yes. I used materials that spoke to my presumed cultural identity as an African, while referencing a particular historical mode of representation. All of this stereotyping inspires a deep-seated hatred of the black body, from head to toe: facial features, eyes, lips, everything. It could either be wild, as in uncultured, savage, or how your hair is defined as “nappy,” “dirty”—all those things. In August 2016, there was a high-profile case in South Africa at the Pretoria High School for Girls where pupils were reprimanded by one of the teachers because of their Afro hairstyles. As a student, how are you expected to concentrate if your educator tells you that your natural hair is “untidy”? You see this person on a daily basis, in a space where you are supposed to be receiving an education.

Mussai: And, instead, you are effectively told to police your expressions of blackness.

Muholi: Exactly.

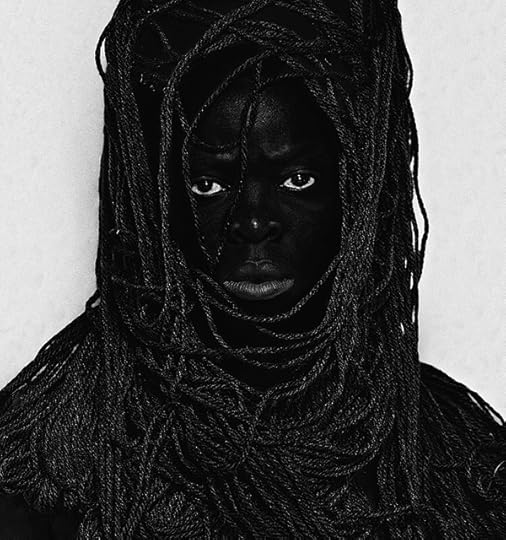

Zanele Muholi, Dalisu, New York, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mussai: It’s poignant to me that the inaugural portrait in Somnyama was inspired by an experience in Europe, as this sense of “otherness” becomes so much more . . . pronounced, perhaps, or dangerous, when you find yourself in spaces where your blackness is often experienced as the defining marker of difference. How has being on the road, constantly in transit, and living a nomadic life affected the series over the years?

Muholi: It’s obviously different between here and there. In America, Europe, or Africa, the experience is never the same. But that judgment, that discrimination, that lingering sense that you are not supposed to be here, persists—having to continually justify your presence. Especially at hotels, the ritual of checking into your room can be so traumatizing. Sometimes you’ll be the last person attended to; at other times, you are made to feel as though you are lost, or looking for directions, rather than treated as a paying guest.

Mussai: And these experiences are then translated into Somnyama?

Muholi: Yes. I made a portrait following one of my negative hotel experiences in September 2016 in New York, with strings of wool framing my face, like a scarf. The title of this piece, Dalisu, New York (2016), means “make a plan.” A majority of the photographs in Somnyama Ngonyama are based on my personal experiences. On their own, they might not appear extreme, but they accumulate; all those minor irritating questions add up to something. Sometimes it feels as if you’re inside a web—a web covering your face that you have to constantly peel back in order to breathe. Yet you are still giving yourself access to see—to check if what you are seeing or hearing is real. Dalisu talks about the feeling of being strangled alive. I felt entangled and confined, confused and angry. At the same time, it’s an affirmation to myself and others like me—a call to action. A reminder to ourselves not to allow anyone to undermine us, or to be restrained by exterior forces or others.

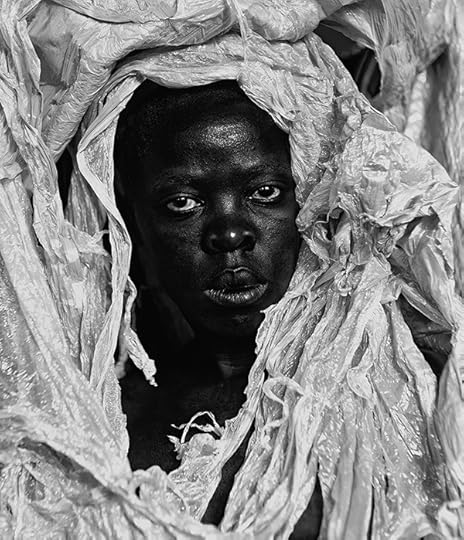

Zanele Muholi, Kwanele, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Mussai: Conceptually, this recalls another portrait in the series, Kwanele, Parktown, Johannesburg (2016), where your face is enveloped by layers of plastic wrap.

Muholi: Kwanele responds to the experience of traveling through immigration at different airports where one is often racially profiled. The plastic around my face is the same material that covers my suitcase. So the image speaks about the need for protection, as well as the sense of feeling exposed, stripped of one’s dignity, and continuously scrutinized when passing through border control. In those moments, one often feels like a piece of trash as one moves from one space to the next. It speaks to the painful inconvenience of being delayed by these reoccurring experiences—humiliated, and unnecessarily exposed, as though you have committed a crime. Over and over, security guards will interrogate you: “Where do you come from? What’s the purpose of your visit? How long are you going to be here for? Who invited you?” And so on. You answer all of their questions, and you listen. But you are also very tired because you have been traveling overnight, and you think to yourself, I feel like my bag right now; I feel like trash; I don’t deserve to be asked all these questions.

While you watch another person, who might be of a different race or ethnicity, pass through the border without being troubled, for you, the questions continue: “What are you doing for a living?” “I take photographs . . .” “What type of photographs? Please show me.” But you are not supposed to open your phone at security, acknowledging the sign that says, “No mobile phones.” As you know, I don’t travel for leisure—this is work, always. The portrait is about traveling as a black person, as a photographer.

Renée Mussai is senior curator and head of archive and research at Autograph ABP, London.

This interview is adapted from Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, now available from Aperture.

The post Zanele Muholi On Resistance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Are We All Cyborgs?

From biohacking to vitamins, photographer Matthieu Gafsou’s latest series questions the relationship between human bodies and technology.

By Annika Klein

Matthieu Gafsou, Businessman Igor Trapeznikov, a member of Russia’s transhumanist movement, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

What does it mean to improve human life? Does improvement mean to be as healthy as possible, as productive as possible, to live as long as possible? For adherents of transhumanism (often abbreviated H+), these are some of the main goals. Or, as philosopher Max More wrote in 1990, it is “a class of philosophies of life that seek the continuation and acceleration of the evolution of intelligent life beyond its currently human form.” Eight years later, More, along with an international cohort, wrote the Transhumanist Declaration and founded an organization now known as Humanity+. But in the quest to evade or delay death, what gets lost along the way? Swiss photographer Matthieu Gafsou, whose previous series have focused on religion, drug abuse, and the meeting of technology and nature, explores these questions in his book H+, which eerily catalogues the spectacle of body modification and optimization. Recently, I sat down with Gafsou to discuss how these threads coalesce, and how his newest work weaves an exciting, and often disturbing, web of what our future may hold.

Annika Klein: Many of the technologies you show in H+ are so ubiquitous—such as contact lenses or protein bars—that few people would think of them as biohacking in the sense that one would think of, say, someone like Kevin Warwick, who has a computer chip implanted in his arm. Yet the main difference here is really just how long these technologies have existed. Why is getting a pacemaker seen as “normal,” while having a computer voluntarily connected to your nervous system is extremely eccentric? How did you determine the scope of your project?

Matthieu Gafsou: For me, this was one of the interesting topics about transhumanism. Is it an extension of actual medicine becoming more extreme, or is something changing in our relationship with technology, or even changing human nature? Even after working on this project for four years, I’m not sure that I have an answer to give, but we are already used to using technologies and having technology related to the body. It’s not something new. It’s a long process and now we are arriving at this moment called transhumanism, which is an old dream resurfacing about eternity, about humanity. It was important for me to have this historical dimension in the project.

Matthieu Gafsou, The intra-uterine device (IUD) is a contraceptive invented in 1928 by Ernst Gräfenberg, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Klein: And that’s why you included things like contact lenses, or an IUD, right?

Gafsou: Yes, exactly. They’re very banal, we see them every day, but in these cases, the objects are directly related to the body. It’s not about science; it’s more about technics and technology. Maybe transhumanism is a new word for something that is not that new. The perfect transhumanist object is the smartphone: even if it isn’t (yet) inside the body, it is always near the flesh and it creates a relationship of dependency. It gives many abilities, but it also steals from us: we lose memory or space orientation.

Klein: One of the scariest—or most exciting, depending on your viewpoint—parts of this project is realizing how we are already changing our bodies without thinking about what that means philosophically. This embrace of medical technology—take orthodontic braces, for example—is an interesting contrast with, say, the natural food movement. I can imagine many parents having no qualms with putting their child in braces, but not wanting them to eat GMOs.

Matthieu Gafsou, Classic orthodontic treatment using braces, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Gafsou: The food chapter of this project was more about how food can become a prosthesis for the body. Transhumanist food is generally vegan and non-GMO, but what was really important to me is the lack of pleasure related to this kind of food. For me, the body should remain the place of pleasure and feelings. Transhumanism is a way to live longer, but also sometimes means forgetting what makes us human beings. I was reading a French anthropologist, David Le Breton, who also wrote a text for H+, about how food and nootropics are chemical prostheses. To answer your question, our society can be seen as techno-progressivist: it connects technology and social improvement, and this is something I was also curious to dispute.

Klein: It’s unusual to have a body of work that is cohesive, and yet spans portraiture, documentary, and studio photography. The light, too, changes between a dark background with an illuminated scene or object and a strong, sometimes overexposed flash. Why did you vacillate between these different techniques and modes?

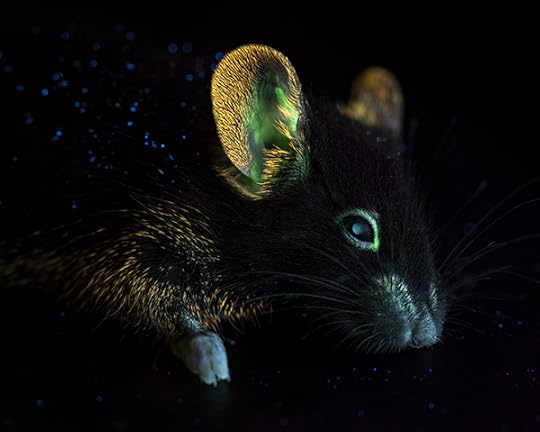

Matthieu Gafsou, Mice that have received a gene responsible for bioluminescence glow when exposed to UV rays, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Gafsou: I like the idea of nonnarrative and fragmented language because it resonates with how we are connected to data or information today. I am also passionate about the notion of rhythm inside a book or exhibition, and I believe that different typologies of photographs really help to create meaning. Seen alone, some of my pictures might not mean much, but when you connect those together in a network, they make sense in a complex way. I also knew that my project was going to be incomplete, because there are too many topics related to transhumanism—too many new objects, experiments, people emerging every day.

Regarding the variation between darkness and light in this series, I can say many things. It is a mystical way of showing things and it refers to a religious idea. I wanted to have this connection with religion in H+, as my belief is that transhumanism is a new religion. Finally, this alternation of white and black reveals some anxiety. The bright light leaves nowhere to escape, and the dark could engulf us. Many of the philosophical questions raised by transhumanism, such as death, eugenics, or an increase of social disparities, are disturbing and can cause anguish.

Matthieu Gafsou, “Total” foods are not dietary supplements but food substitutes, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Klein: You also borrow a lot from the language of product photography, which isn’t usually mixed with documentary.

Gafsou: Yes—this was to contaminate my body of work with an aesthetic coming from the business world, as transhumanism is also a very big business. Most of GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) are already involved. I think it is interesting because art photography language also has stereotypes. Being contaminated by a commercial language makes the work a bit more ambiguous. Am I doing publicity for those products or thinking about them as an artist? Am I an activist or a critic?

Klein: You have a master’s degree in philosophy and literature. Which authors and books were you reading and thinking of while working on this body of work?

Gafsou: I’ve been reading the cyberpunk writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. Then there’s Douglas Coupland and Donna Haraway, the American intellectual. Le Breton, who I mentioned earlier, and his book called L’adieu au corps (2013), which translates roughly to “forgetting the body.” An American reference for me is Theodore Kaczynski, known as the Unabomber. He’s not a transhumanist at all, but his book Industrial Society and Its Future (1995) is really interesting as a way to question our dependency on technology—even if the guy was extreme. Then there’s Philip K. Dick, who speaks a lot about how living beings look more and more like the inanimate, and how the inanimate looks more and more lifelike. Some philosophers, too—Peter Sloterdijk, Jürgen Habermas. What was really difficult with this project was to deal with this huge amount of information available. It took me a long time to process the data, to classify it and to forget about what seemed nonrelevant.

Matthieu Gafsou, Incubator, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Klein: The part of this project that relates to reinventing the self via reinventing the physical body makes me think of this very American, Enlightenment-era idea of anything being achievable through work and progress. Was this something you had in mind?

Gafsou: Yes. Transhumanism fits completely into this kind of ideology, along with Silicon Valley, and libertarianism. Transhumanism fits our society of information, of neoliberalism, of start-ups, of business. This is a bit frightening, too. You think of transhumanism as a philosophical or intellectual movement, and you discover that it perfectly fits into business. Ayn Rand’s idea of yourself against the world, doing what you are able to do—it totally matches with transhumanism.

Klein: Besides life expectancy, how does health play into this?

Gafsou: I was surprised that, for some people I met, what we would consider a healthy body is for them a sick body. The line between healthy people and sick people is not that easy to draw.

Matthieu Gafsou, STIMO (Epidural Electrical Simulation with Robot-assisted Rehabilitation in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury) aims to improve the motor skills of people with injured or diseased spinal cords, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Klein: Do you mean that people who subscribe to transhumanism think that a body that’s not augmented with technology is a sick body, even if medically it’s not a sick body?

Gafsou: Yes. And this idea is really fascinating, because it helps us to understand how transhumanism can be seen as a prosthesis for the soul! I believe we all have weaknesses, and the biggest of those is our common fear of death. It makes us look fragile, pathetic, and beautiful at the same time. If you consider transhumanism, it anesthetizes the fear but prevents us from learning to live by facing the inescapable. We can see this movement as a new opium for the people.

Matthieu Gafsou, Laboratory designed by French architect Dominique Perrault on the campus of EPFL, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Galerie C, Switzerland, and MAPS

Klein: On the other hand, someone who does not adhere to transhumanism might think that someone who implants a device that is not deemed medically necessary into their body has a sick body. It goes both ways. With all this on your mind, what’s keeping you up at night? What are you most concerned about?

Gafsou: Just after the end of the project, a few months ago, I started thinking about how transhumanism is just a way to accelerate the process of consuming too much, not thinking about the way we are using resources, and is also about individualism. I started working on this project because I’m going to die, of course, and I was fascinated by transhumanism because I am fragile (as maybe we all are). I still am. But the more I worked on it, the more I wanted to be free from it. I’m not saying I’ll refuse to have a pacemaker; I’m saying that choosing life extension or immortality as a goal in life seems presumptuous and perhaps even immature.

Annika Klein is assistant editor of Aperture.

H+: Transhumanisms was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2018.

The post Are We All Cyborgs? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 5, 2018

Energy Charts and Cosmic Light

Working between portraiture and documentary, Khalik Allah’s new book tracks Harlem by night.

By Jovonna Jones

Photographer and filmmaker Khalik Allah’s monograph begins with a manifesto entitled “Camera Ministry.” He writes: “I shoot people who find them-selves in the worst possible situation, but I recognize their invulnerability and reflect it back to them. These are psychic x-rays. I consider my photographs energy charts.” This empathic insight notably was brought to bear in his film Field Niggas (2015), an acclaimed documentary about New Yorkers facing homeless-ness, substance abuse, and harassment on 125th Street and Lexington Avenue. Souls Against the Concrete (University of Texas Press, 2017) compiles 105 analog portraits made on those street corners over three years, foregrounding Allah’s long-held commitment to cinematic storytelling and nocturnal light. Rather than frame his nighttime Harlem subjects through terms of social abjection, vulnerability, and redemption—an over-determined lexicon typically used to regard people who occupy the streets—Allah practices a visual language of impenetrable self-possession. He acknowledges metaphors of darkness as both freeing and debilitating, but tables them. Instead, light is his driving concept and technical method, in service of what he terms soul consciousness.

Khalik Allah, Untitled, 125th Street, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York

As a child of the 1990s growing up between Queens and Harlem, Allah found his practice shaped by two sites of knowledge: the camcorder and the corner. He started out by capturing the everyday lives of his family, the streets, and anything around him—“the rays of [their] lives.” But it was the philosophy of the Five Percent Nation, or the Nation of Gods and Earths, that would define Allah’s photographic mission and form. Harlem serves as the Mecca for the Five Percent Nation, a cultural-religious movement founded by a former student of Malcolm X in 1963, and popularized by the legendary hip-hop group the Wu-Tang Clan (whom Allah photographed early in his career). Members ground their teachings in tenets such as “Black people are the original people of the planet Earth,” and “each one should teach one according to their knowledge.” They are committed to the social and ideological liberation of African Americans, and Allah’s work bears traces of their influence.

Khalik Allah, Untitled, 125th Street, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York

Since the early 2000s, Allah has created five documentary films concerned with collective consciousness and self-possession within a racist and classist social order: The Absorption of Light (2005), Popa Wu: A 5% Story (2010), Urban Rashomon (2013), Antonyms of Beauty (2013), and Field Niggas. In Souls Against the Concrete, Allah centers on the individual, seeking out the moments when a person’s inner life creates both tension and harmony with their surround-ings. The series opens with an elevated and unfocused city shot of 125th and Lexington, taken from the vantage point of an overpass overlooking the intersection. The scene stretches from the cross of the Iglesia Pentecostal to the Pathmark retail sign beaming up across the street. Traffic congeals on both sides of the road, shooting two dotted, receding vectors of white and red light that dissipate where the night sky meets the city’s horizon.

Khalik Allah, Untitled, 125th Street, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York

Nearly eclipsed by the activity of traffic and dwarfed by signage, two micro-stages take shape on the concrete. On the sidewalk, three figures stroll through the frosty light from a convenience store. At the major intersection, three more figures lean against a parked car, while another starts down the crosswalk past a chorus of headlights. Abundant yet sparing, artificial light organizes and renders the figures complete in their concealment. For his portraits, Allah wields competing light sources, luminosities, and gradations with flexibility and precision, keen to the ways people conduct visible energy, yet protect their sacred interiority. Fluorescent light becomes corporeal in some portraits and abstracted in others. Glows emerge through a person’s face, their gaze, and the angle of their pose, whether contemplative, elusive, playful, or performative. The lucent coordinates featured in the opening street view reoccur through-out the work: they frame a dapper man between sips of his beverage and drags from his cigarette; they’re cradled in a woman’s palm as she gives her hair a quick pat. Distant and contained forms of light become two-dimensional shapes or planar gradients behind a muse, appearing chromatic and translucent, even cosmic.

Khalik Allah, Untitled, 125th Street, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York

Allah maintains a theatrical, narrative space within this landscape-format book, with each portrait appearing widescreen against a facing page of black ink, forcing the eyes on a single subject. But unlike a documentary with credits and captions, Souls Against the Concrete includes no titles, no photo index. (The project ends with a heartfelt acknowledgments section, simply thanking everyone who cocreated the work.) At the intersections of portraiture and documentary, Allah breaks through the limited visual conditions of the night to figure light differently through the human form, and to portray the streets freely through light. As he writes, “I shoot at night to remind people that we’re in outer time, outer space. Time is over, and the world has ended. Only the Light continues.” Here, light animates the prolific outer-worldliness of people—people deemed out of time and at risk. People who “shoulder the world’s blame” and live to refuse it.

Jovonna Jones is an art critic and doctoral student at Harvard University. She researches black aesthetics and the history of photography.

The post Energy Charts and Cosmic Light appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 28, 2018

Back in the Days

Guadalupe Rosales and her archive of Chicano life in Los Angeles.

By Carribean Fragoza

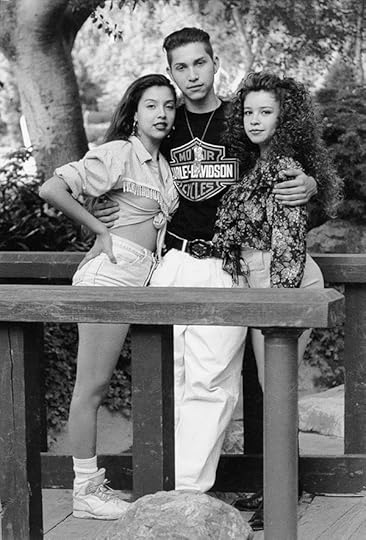

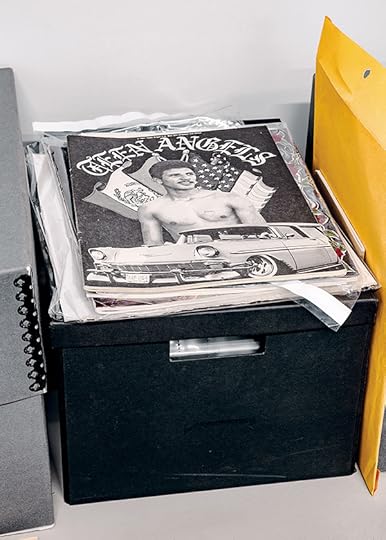

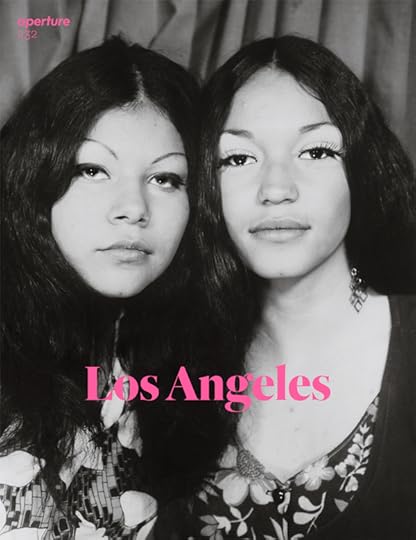

Photographs in Guadalupe Rosales’s studio, 2018

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

Guadalupe Rosales moved to New York with little more than a stack of wallet-sized photographs to remind her of home. She’d left Los Angeles in 2000, a few years after her cousin, Ever Sanchez, was stabbed to death at a party. Nearing her twenties, at the beginning of a new millennium, she decided to relocate her life to New York, where she’d remain living for over a decade. During that time, as she came of age away from the violence that had marked her youth, she held on to those photographs not only as reminders of unresolved trauma, but also as important links to her past. The photographs, given to her by family and friends she had grown up with in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights, were all made in a similar “glamour-shots style” using hazy filters. In the pre-selfie era, young people would flock to their local malls wearing coordinated outfits, sharply outlined lips and eyebrows, and meticulously teased perms to pose with friends in front of ambient backdrops. The diffused lighting spared them from blemishes, including emotional ones, and saturated the images with sentimentality that with time would turn into acute nostalgia.

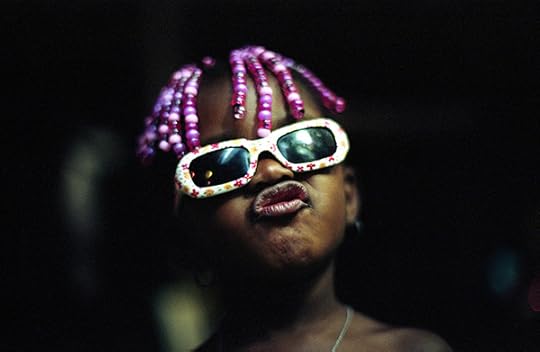

Photographer unknown, Booker and friends, 1992

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Eileen Torres

For Rosales, these photographs were placeholders for a history that had yet to be told. Their pull eventually compelled her to come back home to LA. “I was thinking a lot about my crew days,” she told me. “And I was always attracted to photographs not just for their images, but also for the notes written on the back. They were like relics; they reconnected me.”

In 2015, Rosales started Veteranas y Rucas, an Instagram archive focused on youth culture in LA’s Latino neighborhoods. Its point of view is from the women’s perspective. She posted photographs from her own collection, along with brief anecdotes, in hopes of eliciting feedback. Before long, she had a steady stream of followers that eagerly shared photographs and memories of their teenage party days in LA in the 1990s. Then, in 2016, she developed a second Instagram project, Map Pointz, to collect images and memories of Southern California raves and party crews.

Photographer unknown, Mind Crime Hookers party crew on 6th Street Bridge, Boyle Heights, 1993

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales

Rosales’s project is twofold: The physical collection of objects that she keeps in her studio consists of thick binders and albums filled with hundreds of party flyers, photographs, and party paraphernalia such as glow-in-the-dark beaded necklaces, pagers, and customized backpacks, along with stacks of magazines that document various youth subcultures. But it’s also her Instagram projects, Veteranas y Rucas and Map Pointz, that have quickly grown into expansive and generative digital archives of photographs that document scenes of LA. Both have become multigenerational as followers share photographs of family members and themselves, tracing as far back as the 1910s. In all of the images, we see young women and men expressing and embodying Mexican American culture through fashion and posture in their homes, in the streets, and, of course, at parties. The photographs and comments in combination begin to shape the narrative of these deeply rooted communities that have largely remained unrecognized at best and criminalized at worst.

Swing Kids party crew from San Gabriel Valley, 1994

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Deborah Meza

However, Veteranas y Rucas, says Rosales, was not originally conceived as an archive. While in art school at the University of Chicago and far from home, she began with the idea of creating an installation of a teenage raver’s or party crew member’s bedroom. But she was also thinking of her work as a broader historical project, using photographs and other objects as documents to show what it was like to grow up in 1990s LA as a young woman of color. “I started the work with the intent of finding material on my own time in the 1990s,” says Rosales. “But if you don’t have the material, you can’t use it.”

Though Rosales’s process of collecting photographs of these unrecognized communities has largely been guided by instinct, it is in step with the work of radical historians such as José Esteban Muñoz, who called for building an “archive of the ephemeral.” In his groundbreaking 1996 article “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts,” Muñoz posits that contrary to traditional archives that exclude marginal communities—the poor, queer, and colored—an ephemeral archive allows us entry into transient spaces, such as dance floors and cruise spots, where we can begin to find their stories.

While the invisibility of these and other marginalized communities, especially youth, has all but erased them from official history, it also once protected them. The 1990s were dangerous times for young people of color in LA. It was a decade of increasing economic disparity, police brutality, and social turmoil that led up to and followed the 1992 LA riots, along with gang violence and rampant anti-immigration policies that prompted days of student walkouts.

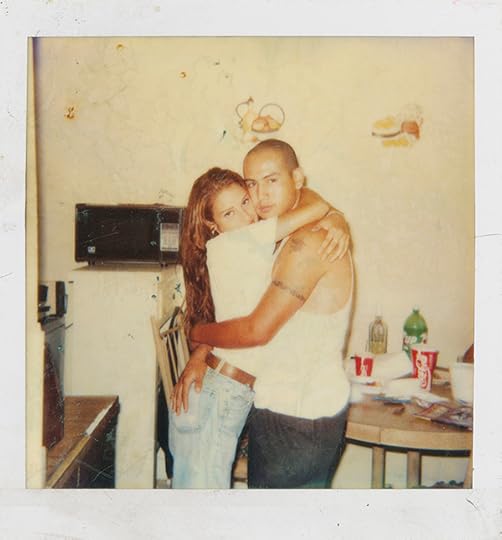

Photographer unknown, Guadalupe Rosales’s cousin, Ever Sanchez (right), and unidentified woman, East Los Angeles, 1995

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales

“Kids went underground. At raves and parties, we were creating safe spaces for ourselves when everything like the riots and Prop 187 was going on,” Rosales recalls, referring to Proposition 187, a 1994 ballot initiative that would prohibit undocumented immigrants from accessing public services such as education and health care. Rosales attended many of these parties when she wasn’t going to protests and marches with her mother and sister. Effectively, it was in the underground that youth like Rosales created a world of their own, away from the institutional establishments that had betrayed them.

Map Pointz focuses on the rave party scene. The name refers to what in the 1990s were the coordinates of a party location that could only be accessed by following a specific set of instructions. Flyers often directed partygoers to call a phone number to learn where they would receive an address for the event, usually only hours before the doors opened. The purpose was to keep the location secret from unwelcome party crashers, including police, parents, and rivals.

Party crews would often drive out into the far reaches of Greater Los Angeles, even venturing into Southern California’s Inland Empire. “Sometimes we didn’t even know where we were going. We’d just carpool and end up in places,” recalls Rosales. Very naturally, party culture intersected with Southern California’s distinct car culture. Veteranas y Rucas includes many photographs, from across several decades, of young Chicanxs posing with cars, as if this recurring shot marked a coming-of-age or, for women, a display of empowerment. Photographs of young people cruising along LA’s Eastside boulevards in customized cars show a weekly urban pageantry of polished chrome, jewel-toned fiberglass, sculpted hairstyles, and the finest hoochie garb. They were parties on wheels.

Shrine to Ever Sanchez, Guadalupe Rosales’s studio, 2018

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

As these underground parties proliferated and became more sophisticated, they developed an ephemeral infrastructure that suited LA’s decentered and transient character. According to Rosales, partygoers became party-promoters who created entrepreneurial opportunities for themselves; amid a barren landscape, they took warehouses gutted by deindustrialization and transformed them into temporary venues for large-scale events, turning these underground scenes into businesses. They taught themselves, and each other, skills as they photographed, laid out, and published their own magazines. They designed their own flyers, booked venues, and found creative ways to promote carefully planned events. “These parties were being organized by teenagers using their own resources,” Rosales says. “Schools were not providing us skills. The party scenes allowed us to develop these skills.”

Photographer unknown, Booker (right) from the Together We Stand crew and friend (left) from Mind Crime Hookers, Whittier, California, ca. 1993

Courtesy Guadalupe Rosales and Eileen Torres

Concurrent with the rise of these cultures, print magazines like Low Rider, Street Beat, Teen Angels, and Urb thrived as they documented the various scenes and effectively trained new generations of publishers and photographers. Rosales met one of these photographers, Eddie Ruvalcaba, on Instagram and soon began collaborating with him on an installation project at Commonwealth and Council, a gallery in downtown LA. Ruvalcaba was a self-taught photographer for Street Beat. His portfolio extends beyond party scenes, including photographs of daily street life, as well as striking images of the 1992 LA riots and their aftermath. This collaboration is an example of how organic partnerships can grow out of collective archive-building processes such as Rosales’s, which are, in fact, part of a growing movement of nontraditional, DIY archive projects dedicated to recovering lost histories.

Magazines in Guadalupe Rosales’s studio, 2018

Photograph by Mike Slack for Aperture

Rosales and Ruvalcaba held one other thing in common: they were both still coming to terms with the trauma of violence and drug addiction that came to afflict so many of their generation.This is also what brings so many Instagram followers to share their experiences with Rosales, as they attempt not only to ruminate on memories of times past, but to make sense of the chaos they experienced. More than just Instagram projects, Veteranas y Rucas and Map Pointz also involve a process of healing, which is why Rosales continues to hold onto them so closely. She says that though she feels some pressure to conserve the objects in the collection she is building, she is not ready to hand them over to a formal or institutional archive. “The project is still evolving, and it’s still a part of me. I feel responsible for these things.”

Even today, Rosales guards the stack of wallet-sized photographs, keeping it within arm’s reach in her studio as if it were a deck of tarot cards. The ink of the neatly written notes on the back of the photographs is now smudged but still clearly says, again and again, “Keep in touch.” And she does.

Carribean Fragoza is a writer from South El Monte, California. Her fiction, poetry, and essays have been published in BOMB, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and LA Weekly.

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Back in the Days appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 27, 2018

A Range of Vision

Aperture’s free On Sight curriculum brings together students of different backgrounds in Los Angeles.

Annabel Z., Untitled, from the series GIRLS, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Harvard-Westlake

In April 2018, Aperture educator Alice Proujansky traveled to Los Angeles to be part of a collaboration between Harvard-Westlake School and East LA’s Humanitas Academy of Arts and Technology (HAAT). Coming from opposite sides of LA, and using Aperture’s On Sight curriculum, students met at HAAT to look at each other’s work, and find common ground through photography. Activities included playing a “telephone” game from Proujansky’s book Go Photo! (Aperture, 2016), during which they shared cameras, taking turns photographing in response to each other’s images.

The ongoing collaboration began in October 2017, when the two classes met at Harvard-Westlake. There, each student planned out a thematic project using a “mind map,” a visual thinking tool that allows students to explore new themes and ideas for their projects. The two teachers—Adriana Yugovich of HAAT and Harvard-Westlake’s Joe Medina—also planned an exchange of photographs, made using film cameras provided by Harvard-Westlake.

Roman, Untitled from the series LA, 2018

Courtesy the artist and HAAT

The students’ resulting pictures are quiet, clean, playful, and strange. Students worked with a range of digital cameras for their themed projects: some of the resulting photographs are technically precise, while others are blurry, or show signs of digital grain. Sometimes the photographs are carefully observed and thoughtfully constructed, other times casually noticed. The range of vision is broad, which is fitting, as these teenagers are about as diverse a group as any in Los Angeles.

“With the help of Aperture On Sight, we investigated how photographs work as symbols and metaphors,” explains Medina. “It provided us with a way to at least start a conversation and try to understand each other using photography as a groundwork. Otherwise, these kids never would’ve come in contact with each other even though they live in the same city.”

Pablo G, Untitled, from the series Dreamer3, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Harvard-Westlake

This breadth of vision points to a teaching approach that is both structured enough to support students in seeing clearly, and flexible enough to accommodate a range of visions. Aperture On Sight, a free, open-source curriculum, was written by Proujansky; Sarah McNear, then deputy director of Aperture; and a team of teaching artists, and was tested over two years in seven New York City schools.

Yugovich says, “I was super excited to know there is a sequential curriculum for teenagers because it is really hard to teach photo at the high school level. There’s no textbook, there’s no test, there are no standards, really. This was great because it’s got hooks, it’s not boring. A lot of the stuff out there is very technical or basic, and nowadays everyone’s a photographer—kids are composing pictures all the time and they’re not thinking about it.”

Heidi T., Untitled, from the series Sense of Place, 2018

Courtesy the artist and HAAT

While Aperture’s previous community education focus was providing direct services in New York City schools, the organization has now finished testing the curriculum and is providing professional development workshops and education consulting. The team writes curriculums, sends artists to visit classrooms, and works with teachers to adapt lessons to their needs.

In 2018 alone, Aperture On Sight has been used by 450 students in kindergarten through twelfth grade at schools across the country, including Harvard-Westlake and HAAT, as well as at Avenues: The World School in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, MS 136 Charles O. Dewey in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and Success Academy’s middle schools throughout New York City.

The curriculum is free to use; contact Alice Proujansky at edupartners@aperture.org for more information.

The post A Range of Vision appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 23, 2018

A Hidden History of Abortion

Laia Abril’s new book provides a harrowing record of women’s struggles to access family planning.

By Kristen Lubben

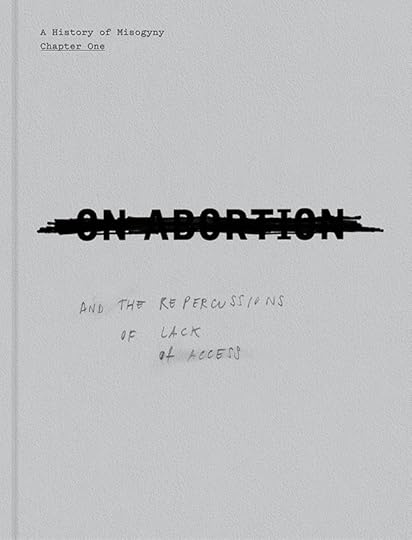

Laia Abril, On Abortion

Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, UK, 2018

Every year, forty-seven thousand women die from botched illegal abortions. On the front cover of Spanish photographer Laia Abril’s excellent new book on the subject, the official title, On Abortion, is vigorously crossed out in black marker and below, handwritten in pencil, is the essential problem: “the repercussions of lack of access.” It is not abortion itself, but barriers to access—laws, secrecy, shame—that cause these deaths and innumerable other tragedies for women and their families. The series title at the top magnifies the project’s scope even further: “A History of Misogyny, Chapter One.” Misogyny is a chronicle with many, many chapters, and the control of women’s fertility is one of its canonical texts.

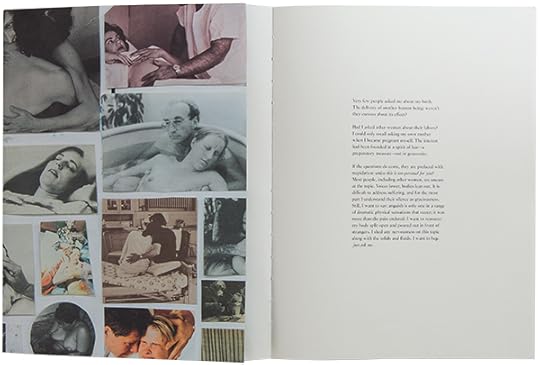

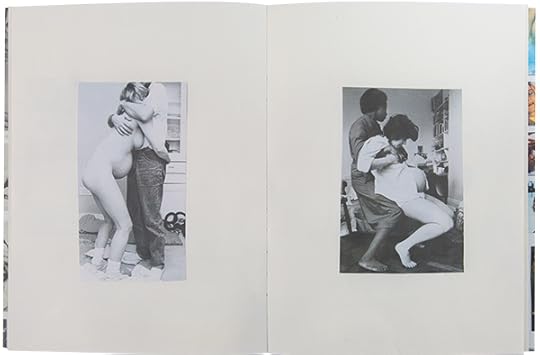

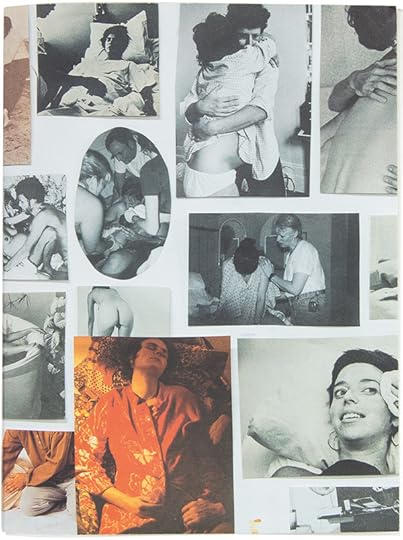

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

How can photography reveal hidden histories? One strategy that artists have used is to reconstruct narratives or fill in overlooked chapters of history using archives and found photographs. But what about stories that are so secret that they were never photographed in the first place? Abril, first trained as a journalist, came to the conclusion that conventional reportage was too limited and confining a strategy for telling the stories she wanted to tell. In On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018), a wrenching and beautifully designed book, she takes on the ambitious—and radical—project of making invisible histories visible.

The book opens to endpapers made up of nineteenth-century advertisements for abortion and fertility cures for “married ladies” who “wish to be treated for obstruction of their monthly period.” These are bracketed by more recent color ads from Peru with offers to treat the same ancient malady, using the same euphemistic wording, over a century later. In between these endpapers is a painstaking recounting that peels away the layers of pretense and hypocrisy that have rendered this enduring history obscure.

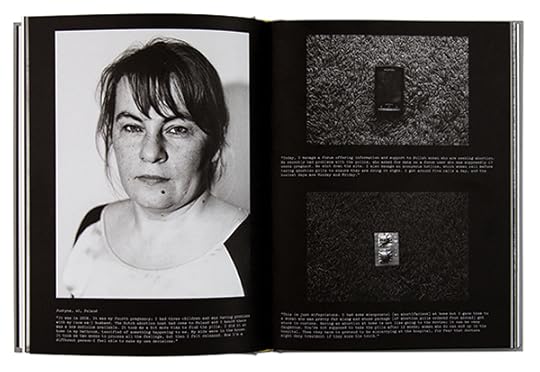

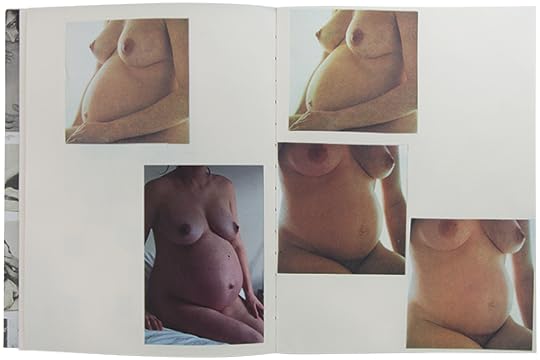

Laia Abril, Magdalena, thirty-two, Poland, from the book On Abortion, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

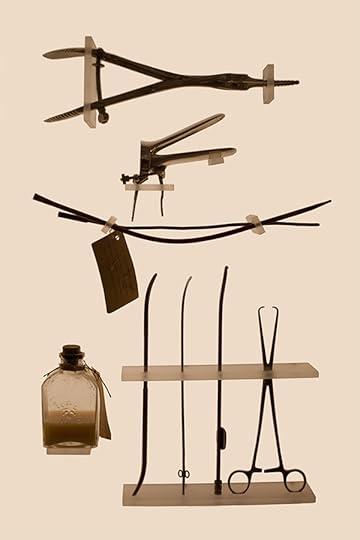

A series of objects from a medical museum, many of which look like torture devices, demonstrate the ancient and gruesomely inventive history of fertility control. These still lifes are followed by profiles of women who survived illegal abortions. Their unabashed frontal portraits stand in contrast to the heavily blurred faces of women who died from their botched abortions. It is a subtle but profound design gesture that draws a distinction between participating subjects (the brave women who have chosen to partner in Abril’s project of demystification) and those who are powerless to consent to the use of their images. Abril also includes photographs that she staged or recreated based on documented cases. The book’s rigorously ethical treatment of vulnerable subjects, combined with its disregard for the conventions of documentary photography, offers an updated and useful model for photographers grappling with the ethics of representation, who are often overly concerned with technical issues and not concerned enough with the impact on those photographed.

Interspersed throughout are photographs that piece the overarching story together: methods of self-induced abortion, mug shots of early twentieth-century abortion providers, a drone that airlifts abortion pills into countries where they are outlawed, and the ultrasound of a nine-year-old Nicaraguan girl raped by her own father and denied a termination of her pregnancy. Each episode in this history is treated with a distinctive design solution—different paper stocks and sizes, unfolding flaps and layers—which keeps the viewer engrossed in what could otherwise be an unrelenting experience. On Abortion first appeared in exhibition form, a fact that contributed to the book’s inventive and experimental design.

Laia Abril, Spreads from the book On Abortion

Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, UK, 2018

While the book is detailed, it is not especially graphic, a surprise given the long history of weaponized photographs on both sides of the abortion debate. Where violent images are used, they are heavily altered. At the book’s center, in a section called “Visual War,” is a vivid red color photograph of an aborted fetus from an anti-abortion website, pixelated to the point of abstraction. Lift that photograph and you find another iconic image: the naked body of Geraldine Santoro, face down in a hotel room after bleeding to death from a botched abortion attempt in 1964. This black-and-white crime scene photo became an icon of the American pro-choice movement, and has appeared in every edition of the women’s health bible Our Bodies, Ourselves. The chilling photograph accompanies the rallying cry that “we won’t go back” to the time of back-alley abortions, when deaths like Santoro’s were all too common. Abril has chosen to reproduce the image so faintly that it is barely visible—easily legible if it is burned into your consciousness, as it is for many American women, but otherwise more idea than image, only readable because of its accompanying caption.

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

Abril says that her project aims to “visualize the comparison between the present and the past, so we understand that things are not as certain as we think—so we don’t forget what is in the past and don’t get too comfortable in the present.” In the United States, where hard-won abortion rights are being eroded, the wire hanger has become a symbol whose referent has largely faded from our collective memory. Abril’s absorbing, galvanizing, and beautifully constructed book is a timely reminder of what is at stake—not just here in the United States, but globally.

Kristen Lubben is the executive director of Magnum Foundation.

The post A Hidden History of Abortion appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 20, 2018

Koudelka’s Prague, Fifty Years Later

When Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia’s capital in August 1968, Josef Koudelka was one of the first on the scene.

By Melissa Harris

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

That everything has happened by chance might seem an odd way to begin a discussion with a photographer whose focus, intensity, precision, and sheer will are evinced in every aspect of his being, not to mention in every project he has ever undertaken. And yet this is where Josef Koudelka has chosen to begin our discussion of the work he did that one extraordinary week in Prague, August 1968, when “the big Soviet army invaded my country, everybody was against them, and everybody forgot who he was—if he was a Communist, if he was young, or old, if he was anti-Communist. Everybody was Czechoslovak. Nothing else mattered. Miracles were happening. People behaved like they never had before; everyone was respectful and kind to each other. I felt that everything that could happen in my life was happening during these seven days. It was an exceptional situation that brought out something exceptional from all of us.”

Unrelentingly alert, Koudelka is poised “to seize these chance occasions, because they can be the most revealing.” He works with an open mind and heart, knowing intuitively when, as Arthur Miller once wrote, “attention must be paid.” His acute, almost feral instincts left him with little choice but to go immediately out on the street and start photographing when Prague was invaded by Soviet-led Warsaw Pact tanks on August 21, 1968.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Koudelka is an unsentimental photographer who approaches his work without preconceptions, and with phenomenal energy and humanity, and whose own essence appears profoundly intertwined with a hunger for personal freedom (seemingly satiated). And consistent with this spirited way of being in the world is his respect for the freedom and individualism of others. Koudelka is not at all interested in talking about his photographs, or in insisting on a way of thinking about them, or advocating a particular point of view. He is, however, “interested in the picture that may tell different stories to different people,” and in what others find in his images.

Ultimately, it is all about seeing, and so the synergy between photography and painting, for instance, is a given for him—this I learned when I brought up Piero della Francesca, issues of perspective, balance, weight, and form, and how space is broken up. Consider the faces of the people in Koudelka’s photographs; look at his rendering of the gestures, the expressions of the courageous Czechoslovak people as they attempt to resist invasion, and how these photographs, taken quickly and at great risk, are so exquisitely composed. None of this is by chance.

The chance in this work is that he had returned from photographing Gypsies in Romania the day before; that a friend called him up to tell him the Soviets had indeed entered Prague, so he was one of the first to witness what was occurring; that he actually had film; that the Soviets never took his film; and that the work got out of Prague and was published one year later to commemorate the invasion. And so we begin . . .

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Melissa Harris: Can you tell me a little bit about your life before 1968, before what became known as Prague Spring? Not just photographing, but what else was important to you, and whether or not you were political.

Josef Koudelka: No, I was not political. To be political in Czechoslovakia meant being in the Communist Party, which I was not. But in the period of ’68, everybody in the society became involved in politics. Czechoslovakia had been a country where nothing was possible, and suddenly, at that time, everything was possible, and everything was changing very quickly. However, what was happening in Czechoslovakia was not about revolution. It was about regaining freedom. It was the writers who first started calling for more freedom, and who, in doing so, also expressed the feelings and desires of the whole society.

Harris: Milan Kundera’s speech supporting freedom of expression at the Fourth Congress of the Czechoslovak Writers’ Union in June 1967 is so powerful:

All suppression of opinions, including the forcible suppression of wrong opinions, is hostile to truth in its consequences. For the truth can only be reached by a dialogue of free opinions enjoying equal rights. Any interference with freedom of thought and word, however discreet the mechanics and terminology of such censorship, is a scandal in this century.

Koudelka: With the abolition of censorship, everything started to change. Seven days after the Soviet invasion in Prague, we heard that one of the key conditions in the Soviets’ agreement to remove their tanks from the streets of Prague was the reestablishment of censorship.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: What was important to you at that time?

Koudelka: The same as today: to do what I wanted to do. There was no political freedom in Czechoslovakia. I found my freedom through doing my work. I worked as an aeronautical engineer and at the same time I was taking photographs. I loved airplanes as much as I love the camera, but in 1967 I left my job because I realized that I could not grow much more as an engineer and I wanted to try to go as far as I could in photography. In order to be permitted to quit my job and become a photographer, I needed to officially join the Czechoslovak artists’ union, which was difficult, but I succeeded in 1965. I had already started photographing Gypsies and the theater in 1962, and continued photographing these subjects before and after the invasion of Prague. I’m always looking at many things simultaneously.

Harris: What drew you to the Gypsies?

Koudelka: I’ve always loved folk music. When I went to Prague to study I played the violin and bagpipes in a group. We used to play at traditional folk festivals. There, I met Gypsy musicians and got to know them. That’s when I began to photograph Gypsies. I think my interest in folk music helped me when taking photographs. While visiting their settlements I often made recordings of Gypsy songs. Gypsies are good psychologists: they probably understood that if I liked their songs, then I must have liked something more.

I could never have photographed the Gypsies the way I did if, in 1963, I hadn’t by chance acquired one of the first 25 mm wide-angle lenses that came to Czechoslovakia. This lens changed my vision. My eyes, my vision became wide angle. It enabled me to work in the small spaces where Gypsies lived, helped me to separate the essential from the unessential and to achieve in bad light the full depth of field that I had always wanted. By my understanding and respecting the rules of its proper use, it determined the composition.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: And what about your theater work?

Koudelka: When Otomar Krejča founded the Theater Beyond the Gate in 1965, he asked me if I wanted to work with him. One of my conditions for agreeing was that when taking photographs, I could move freely among the actors on the stage. I wanted to be able to react to situations between the actors directly onstage, photographing the performance in the same way I photographed life outside the theater. I hoped to get at something real within the artificiality of the theater. By working with Krejča in this way, I learned to see the world as theater. However, to photograph the theater of the world interests me more.

Harris: Were you aware of photojournalism at the time?

Koudelka: In 1968, I knew nothing about photojournalism. I never saw Life, I never saw Paris Match. When I photographed the Soviet invasion, I did it for myself. I was not thinking about a photo-essay or publishing.

Harris: I read a great quote by Ian Berry, who I gather was the only Western photographer in Prague that week. He said: “The only other photographer I saw was an absolute maniac who had a couple of old-fashioned cameras on string round his neck and a cardboard box over his shoulders, who was actually just going up to the Russians, clambering over their tanks and photographing them openly. He had the support of the crowd, who would move in and surround him whenever the Russians tried to take his film. I felt either this guy was the bravest man around or he is the biggest lunatic around.” Apparently, Josef, this brave lunatic was you.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Koudelka: It must have been a dangerous situation but I didn’t feel it. For me, the people with real courage were those seven Russians in Moscow—the only ones out of millions—who protested that week in Red Square against the invasion, knowing they would be arrested and go to prison. I think what happened in that time was much bigger than me, much bigger than all of us. The invasion was tragic, but if it was going to happen, I’m glad I was there to witness and photograph it. During the invasion, I took photographs but didn’t develop them. There wasn’t time for that. It was only later that I processed everything. I left some photographs with the photography historian Anna Fárová. She showed them to various people, including Václav Havel. He offered to take them to America—where he had been invited by Arthur Miller—but then he was not allowed to go. Several photographs were eventually taken out of the country by Eugene Ostroff, curator of the photography department at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Fárová had shown them to him. Ostroff showed them to his friend Elliott Erwitt, who was then president of the photo agency Magnum Photos. Erwitt wanted to know whether there were photographs other than the ones he had seen, and whether I would be willing to send the negatives to Magnum. I wasn’t too keen on that—having lost my negatives previously.

Harris: What had happened earlier with your negatives?

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968 © the artist/Magnum Photos

Koudelka: I wanted to take a photograph of the Soviet tanks and soldiers alone in Wenceslas Square after the people of Prague had decided not to demonstrate so as not to give the Soviet occupiers a pretext for a massacre—the Czechs realized they were being set up. In my photograph of the hand with the watch, you don’t see the Soviets . . . I climbed to the top of one of the buildings, and the Soviets saw me. They thought I was a sniper and started to chase me. I ran through hallways into another building, and by chance found that a friend of mine was living there. I left all the film I had shot that day—about twenty rolls—with him, just in case the Soviets caught me when I left the building. The next day I returned to get the film, but he had given the rolls to someone to take to Radio Free Europe in Vienna. I wanted to kill him. So when things had quieted down, about two weeks after the invasion, and while I still had my passport (which I had only just gotten for the first time during the Prague Spring), I went with this guy to Vienna. I wanted to get my film back. Radio Free Europe had already sent five rolls to their office in Munich. We were told they were not interested in the material. I was happy to get the rest of the rolls and I brought them back to Prague, but I never got back the five other rolls.

Anyway, to go back to what happened later with Magnum, in the end, the negatives got safely out of the country and arrived in New York. Magnum supervised the printing of the photographs and their distribution all over the world.

I happened to be in London in August 1969 with a theater group that I was photographing. We went out one Sunday morning (the first anniversary of the Soviet invasion) and someone bought a copy of the Sunday Times, and there were my pictures. That was the first time I saw the pictures published. To protect my family and me the photographs were credited to an “unknown Czech photographer,” and for its internal use, Magnum stamped the backs of my pictures simply with “P.P.”—“Prague Photographer.” Then I received the Robert Capa Gold Medal for the work—anonymously—and this was announced on the Voice of America radio station. Lots of people in Prague listened to that when it was not blocked, and some of my friends began to ask me if the pictures were mine. I started to be afraid that the Czech secret police would find out that I was the author of these pictures. Magnum arranged for me to get permission to leave Prague in 1970 by inviting me to photograph Gypsies in Western Europe, and then I was given asylum in England.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: This work both covers and bears witness to the Soviet invasion of Prague. Do you think of it as evidentiary?

Koudelka: Yes—which is why the Soviets and Czechoslovak government were not very happy that the pictures exist. These photographs are proof of what happened. When I go to Russia, sometimes I meet ex-soldiers who occupied Prague during that period. They say: “We came to liberate you. We came to help you.” I say:

“Listen. I think it was quite different. I saw people being killed.” They say:

“No. We never . . . no shooting. No. No.” So I can show them my Prague 1968 photographs and say: “Listen, these are my pictures. I was there.” And they have to believe me.

Harris: How did you feel when it finally became known that you are the author of the 1968 invasion photographs?

Koudelka: I didn’t really feel anything when people eventually understood I had taken those pictures. I was happy that Communists in Czechoslovakia could not say that I had only become known because of these pictures, because by the time people found out I had taken those photographs, I was already known for other work.

The first week of the resistance to the Soviet invasion was fantastic, but it didn’t last. What happened during the next twenty years was less heroic. The government became increasingly oppressive, destroying the lives of many Czechoslovak people, and trying to eradicate any memory of the Prague Spring and the resistance. I was in the Czech Republic ten years ago for Magnum’s exhibition about 1968. More than half of the young generation there didn’t know anything about the events of 1968, and most of the population that did know chose to forget. But so much has changed since then. The Prague Spring played a role in the eventual fall of Communism, so the events had significance beyond Czechoslovakia. The Czech publisher has ordered four thousand copies of my new book Invasion 68: Prague (2008).

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: Why did you wait forty years to do this book?

Koudelka: Nobody was interested in publishing this type of book. I wasn’t either. For me, it was much more important to produce new work.

Harris: So why now?

Koudelka: Again, it all happened by chance. I was in Prague in early 2007 talking to my publisher, who asked me about projects I was doing that winter. I answered that I wanted to finally finish the dummy of the next Gypsies book I’ve been working on for the past forty years. He said that the following year was going to be the fortieth anniversary of the Soviet invasion, and suggested that we do a book on that.

Harris: What are some of the differences in the way you structurally conceive your books—for instance, Gypsies [=(1975), Exiles (1988), and Invasion 68?

Koudelka: Gypsies is the result of an approach that could be called construction, in the sense that I made a conscious effort to cover the spectrum of life . . .

Harris: . . . in the sense that this body of work suggests a common experience, aspects of human life that we all share?

Koudelka: You could say that. And when I thought there was something missing, I made an effort to find and photograph it.

Exilesis the title that my editor, Robert Delpire, gave to a group of photographs we selected in the mid-1980s mainly from those I made after I left Czechoslovakia.

Josef Koudelka, Defending the Czechoslovak Radio Building, Prague, August 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Harris: So the approach was in part about recognizing relationships among photographs that already exist, and in this case, the images cohere around the concept of exile?

Koudelka: Being exiled insists that you must build your life from scratch. You are given this opportunity. When I left Czechoslovakia, I was discovering the world around me. Of course, one is still drawn to certain people . . .

Harris: To me, the images comprising Exiles have a distinct choreography. The sensibility seems based in gesture and a dispersal of movement. At times there are several focal points— the feeling is not linear. So the book as a whole radiates a vitality that is different from both the intimacy of the Gypsies work, and the more reportage-like Invasion 68. What were your goals with the Invasion 68 book?

Koudelka: My aim was to present the Soviet invasion of Prague in all its complexity, and to render the atmosphere of those seven days while respecting the chronology of events. I worked with the Czech graphic designer Aleš Najbrt. Together we selected the strongest photographs and came up with the structure of the book.