Aperture's Blog, page 94

January 4, 2019

The Time is Always Now

A recent exhibition considers the legacy of James Baldwin and the civil rights era in photographs.

By Ben Sloat

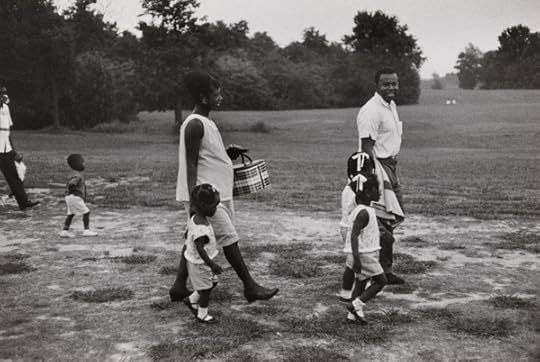

Bruce Davidson, Untitled (Tennessee), 1962

Courtesy Harvard Art Museums

Time Is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America, co-organized by Harvard Art Museums and Harvard’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, is an urgent and disarmingly intimate exhibition of photographs, all black-and-white, spanning the lifetime of James Baldwin. Curated by Makeda Best in a manner that suggests the visual pace of a musical score, images from the exhibition demonstrate the photograph’s uncanny ability to immerse the viewer within the distinct psychology of past moments. Part historical reflection and part call to action, Time Is Now acknowledges Baldwin’s enormous cultural legacy by including diverse components such as an essay and books by Baldwin, a sculptural installation on Harvard’s campus by Teresita Fernández, and a series of companion events for the larger community. Last fall, I spoke with Best about the project.

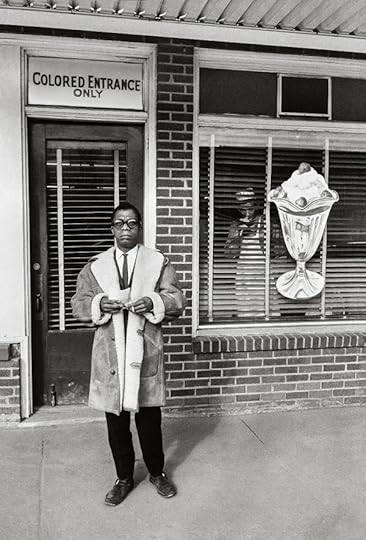

Steve Schapiro, James Baldwin, Colored Entrance Only, New Orleans, 1963

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Ben Sloat: T. S. Eliot once said that “the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.” I thought of this idea in relation to your exhibition, in which there’s an unsentimental recognition of the past, but also a demonstration of how these historical works bridge to our contemporary life, maybe providing a kind of guidance.

Makeda Best: That quote’s interesting, because it relates to Baldwin. The title Time Is Now is a quote by Baldwin. Someone once asked him, “When is the time?” And he said, “The time is always now.” It’s a similar sentiment; there is no past, time is always present, there’s always a present for action. Baldwin was very enmeshed in the impact of everyday life, and how incidents in everyday life transform you forever. The Danny Lyon and Marion Post Wolcott photographs in the exhibition both engage a theme in Baldwin’s work—how humiliation or other forms of psychological terror are used as a tool of oppression.

Sloat: Just as in the sole image of Baldwin in this show—Steve Shapiro’s 1963 image—Baldwin is dressed as a celebrity during the height of his fame in the 1960s, but he is still denied entry to a restaurant in the South.

Best: Yes, while being followed around by a Life magazine photographer.

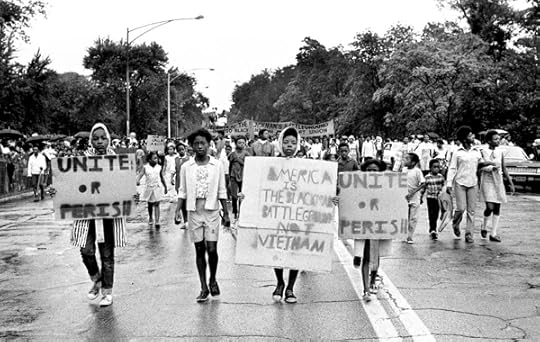

John Simmons, Unite or Perish, Chicago, 1968

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: One thing that strikes me about this show is the tether to forms outside of the photograph: there’s a nod to literature, to the magazine, to Nothing Personal (1964), Baldwin’s book collaboration with Avedon, to music, to a companion sculptural installation by Teresita Fernández. Can you talk about the expanded purview of the show?

Best: That was directly inspired by Baldwin. I was looking at someone who, as an activist, modeled so many different types of interactions. I think that’s useful for us to think about today when we think about how to be an activist. There isn’t just one form. It doesn’t mean that you don’t stick to your discipline. Baldwin wasn’t necessarily doing all those different things, but he did think very deeply about how that impacted his own work. He was an active participant in observing all of those other forms. I wanted to show that as a model for the young people who visit this exhibition. That you can participate in different communities, and how important that is to sustain.

Joanne Leonard, Untitled, ca. 1965

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: Can you talk about your approach to putting this exhibition together?

Best: I had this limitation I put on myself of Baldwin’s life dates, so I really had to compress my thinking. His lifespan is important for us to consider because there are so many moments in those decades that directly influenced not only his life, but all of what happened in history. I tried to visualize what were the kinds of incidents that mattered in those decades. I began looking at what those moments were that foreshadow the traumas and the uprisings that would come later.

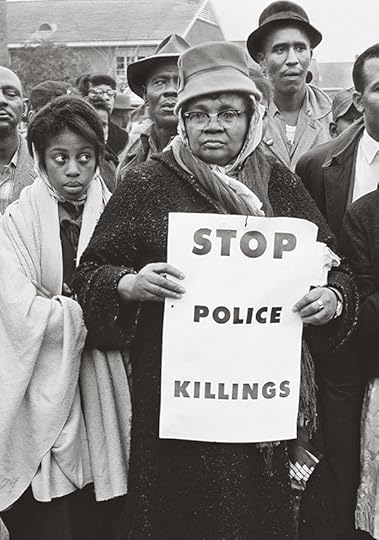

Steve Schapiro, Stop Police Killings, Selma, 1965

Courtesy Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Sloat: You have both an MFA in photography as well as a PhD in art history. How does that studio art background inform your curatorial decision-making in this show?

Best: I’m interested in images that create movement, on a page, or on a wall. I wanted there to be moments where you had to physically move your gaze and other moments where you had to stop. These moments of stopping, of movement, of direction, that definitely comes from my practice of photography and thinking of how images communicate.

I think I’m taking a risk here, since I’m relying on the viewer a lot to sit with this. There isn’t a lot of wall text, so I’m hoping there’s an intuitive way that people might approach this, which also comes from a studio practice. It’s an intimate exhibition; I wanted you to be close to people, and sometimes far away. That kind of dialogue I think also comes from a studio practice.

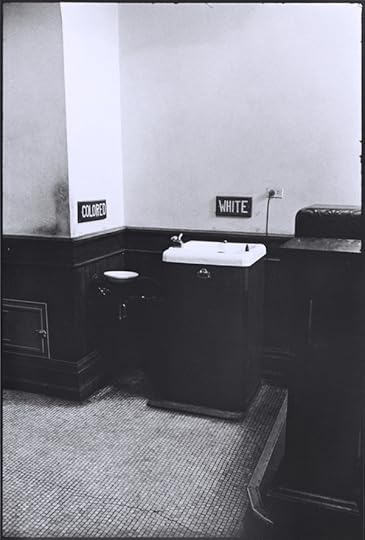

Danny Lyon, Segregated drinking fountains in the county courthouse in Albany, Georgia, 1962

Courtesy the Cleveland Museum of Art

Sloat: What has emerged as unexpected for you from the experience of this show?

Best: The Danny Lyon image [Segregated drinking fountains, 1962] has become more and more important to me—the fact that you had to stoop, no matter how tall you were, the various levels of dehumanization to get to that water fountain. It was small, it was unrefrigerated—that you had to turn the knob. Versus this big thing that was elegant, that was refrigerated, that you would just push this button and a nice big arc of water would come out. People look at the signs that say “White” and “Colored,” but it’s not even about the signs. Look at these facilities which were just poor. And then you look at what’s next to you.

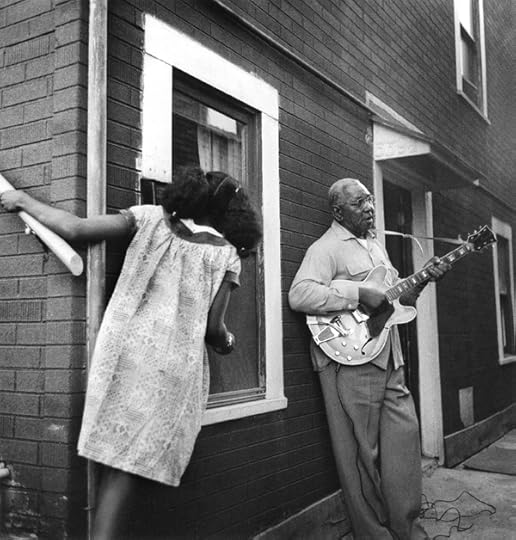

John Simmons, Window Writing, Chicago, 1969

Courtesy the artist

Sloat: I find myself often caught in a one-to-one gaze with the portraits in this show. It’s a kind of a reacquaintance with the presence of the moment of the photograph being made, even with images that are historically iconic, like those of Robert Frank, Roy DeCarava, and Diane Arbus.

Best: This was a decision that was really inspired by Baldwin’s writing. He constantly writes about looking in someone’s eyes. I wanted you to focus in on a few images where you would be confronted with someone, that it would inspire that kind of looking. One of the reasons that this show resonates so much now, is that’s what we’re seeing today. We’re learning how much our everyday lives matter. How much that can totally transform who we are, the path that we take. These simple incidents that are important.

Sloat: I wanted to conclude with this quote by Baldwin: “To be locked in the past means, in effect, that one has no past, since one can never assess it, or use it: and if one cannot use the past, one cannot function in the present, and so one can never be free.”

Best: Yes, it’s a compelling idea of freedom, through our past.

Ben Sloat is an artist and writer based in Brookline, Massachusetts. He is the director of the MFA in Visual Arts program at Lesley Art + Design in Cambridge.

Time Is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America was on view at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, from September 13 to December 30, 2018.

The post The Time is Always Now appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 3, 2019

We Are Family

For the members of the legendary House of Xtravaganza, family is about love, identity, and protection.

By Mikelle Street

Father Jose Xtravaganza and Mother Gisele Xtravaganza, 2018

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

It took a picnic in New York’s Central Park for Coko Xtravaganza to understand what the House of Xtravaganza meant when they called each other family. Having been inducted into the crew in 1983—after discovering house members on the piers on Manhattan’s West Side and at the downtown nightclub Paradise Garage—Coko thought they were simply a group of friends with a name.

“But Carlos and Tito used to throw an annual picnic for the house, and that was really the tipping point for me,” Coko, now the grandmother of the house, said during a recent photoshoot with photographer Stefan Ruiz. “That’s when the family thing really clicked, and I finally felt a part of something real. It came to the point where I would kill for one of them.”

Left to right: Dominique Silver Xtravaganza, Yusef Junquera, Rorí Xtravaganza, G Xtravaganza, and Manuel Xtravaganza

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

Founded in 1982, the House of Xtravaganza (formerly Extravaganza) is one of the original houses of Manhattan’s ballroom community, in which queer people of color compete in balls centered around voguing, fashion, and identity performance, and group themselves into houses to share knowledge, resources, and also, at times, protection. This community was chronicled in Paris Is Burning (1990) and is at the center of the documentaries How Do I Look (2006) and Kiki (2016). The Xtravaganzas distinguished themselves early on, having been founded as the first all-Latinx house in a majority black scene, with a penchant for appearing in the mainstream. At its core, Xtravaganza has always been a true family, thanks to the cultivation of the first mother of the house, Angie Xtravaganza, who died in 1993.

Exclusive Xtravaganza, 2018

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

Danni Xtravaganza became mother of the house in the mid-1990s. “I remember I would walk into Danni’s apartment and see nine or ten sleeping bags on the floor, someone cooking, and someone else running off to work,” Jose Xtravaganza, onetime Madonna choreographer and current father of the house, says of those early years. According to Jose, that legacy lives on to this day, with parents and elders helping to house their children in need: “If there were no more balls, there would always be Xtravaganza, because this is about family to me.”

Grandfather Hector Xtravaganza and Grandmother Coko Xtravaganza, 2018

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

As the ballroom community has steadily grown and mainstreamed over the past three decades—FX’s television series Pose counts several Xtravaganzas working in front of and behind the camera—other houses have developed organizational structures more akin to corporations or franchises. This family, though, has remained true to a hierarchical structure that includes grandparents, elders, one mother and one father, and children. The chapter structure popular elsewhere in the ballroom community, with its multiple leaders, has been avoided.

Alexia Xtravaganza, 2018

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

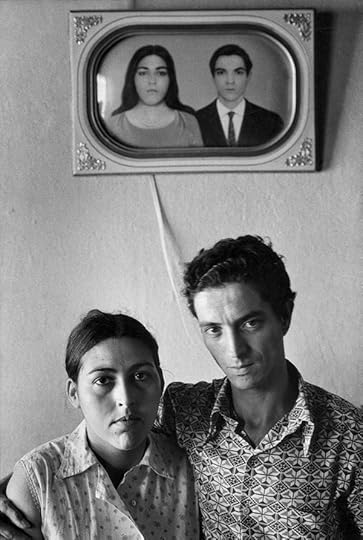

Like any other family, tradition and legacy are mainstays of the house. Birthdays, holidays, vacations, and events like the annual AIDS Walk bring them together, along with the yearly picnic, revived by Coko in 2013. There is an Xtravaganza legacy that lives on today of “impossible beauties”—a descriptor from the 1980s for the family’s extraordinarily beautiful trans women who pass as cis. For grandfather Hector Xtravaganza, the family came to mean so much that he changed his legal last name. In Ruiz’s images of House of Xtravaganza, the photographer attempts to capture that sense of created family, respecting the individuality of each member while putting their shared bonds at the forefront.

Hector Erazo, 2018

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

“It was really getting this overwhelming response of positivity and love that drew me to Xtravaganza,” says Angie Xtravaganza, who took on the name of the original mother of the house when she joined in 2009. “It’s one thing to have that from your biological family, but they have to love you. These are random people who have no claim to you; they don’t have to love you and don’t have to care about you, but they take the time to love you and take care of you and appreciate you.” It’s this purposeful choice that makes their love all the more meaningful.

Mikelle Street is a writer based in New York.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post We Are Family appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 21, 2018

Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2018

From the images that inspired Sofia Coppola’s films to Zanele Muholi’s visual activism, here are this year’s highlights in photography and ideas.

Zanele Muholi on Resistence

In an interview, the visual activist speaks about courage, rethinking history, and the politics of exclusion.

Back in the Days

Guadalupe Rosales and her archive of Chicano life in Los Angeles.

Sofia Coppola on Pictures

The acclaimed director reveals the photographs that inspired her films.

The Spirits of Fire Island

Matthew Leifheit conjures history and fantasy in the fabled gay enclave.

Alec Soth Revisits His Legendary First Book

How the American photographer fell in love with photography.

The Woman Behind the First Photography Gallery

Helen Gee risked everything to open Limelight in 1954, selling prints by Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, and Robert Frank.

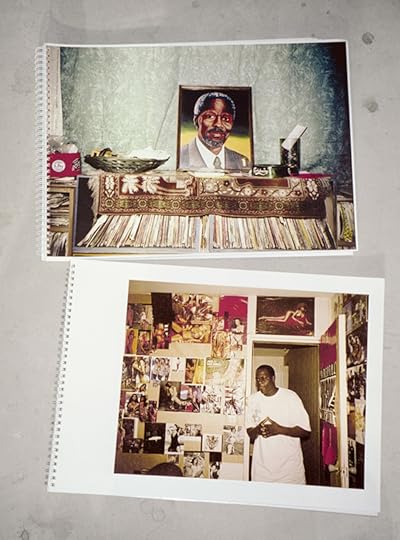

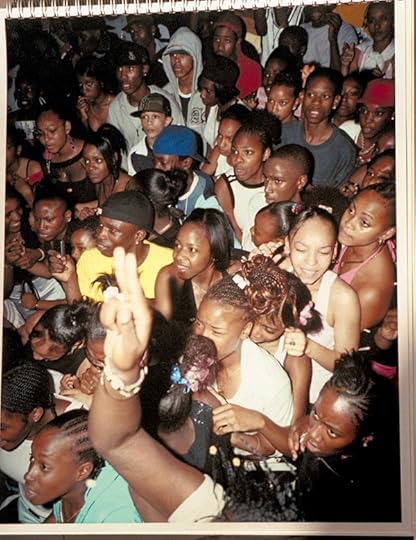

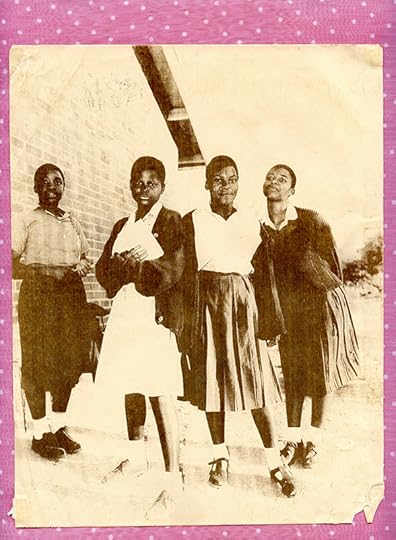

Black Balloon Archive

Liz Johnson Artur’s intimate workbooks honor communities across the African diaspora.

Along the Shores of the Caspian

From Russia to Turkmenistan, Chloe Dewe Mathews photographed the rituals and resources of a much-coveted territory.

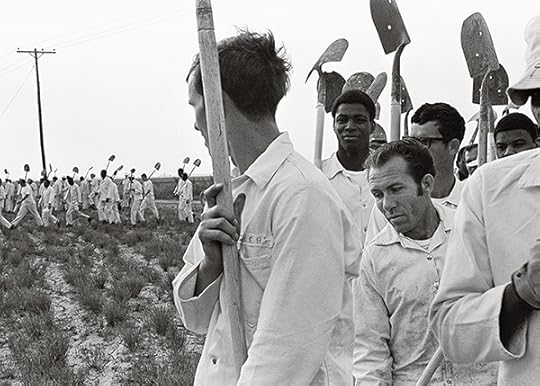

Bruce Jackson: On the Inside

When a folklorist set out to document life in American prisons, he found the enduring segregation of the Old South.

What Does Photo Editing Look Like?

In the digital age, locking down a sequence of images in print can seem like an act of resistance.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2018 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 20, 2018

What Does Photo Editing Look Like?

In the digital age, locking down a sequence of images in print can seem like an act of resistance.

By David Campany

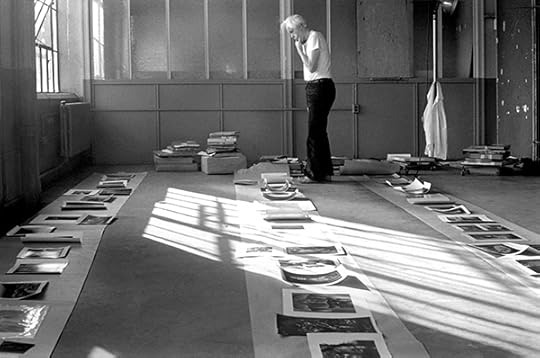

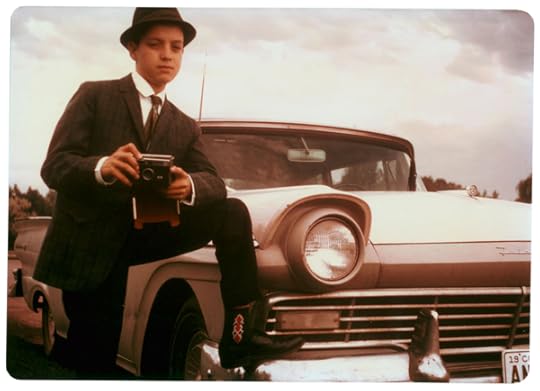

Henrik Malmström, Editing OK Cloth Shop (Kominek Books, 2018), 2014

Courtesy the artist

For some photographers, editing is the heart of the matter, the place where the real work is done, and a source of great pleasure. For others it is secondary, or a problem, and may even lead to anguish. But unless the photographs are absolutely singular, with no intended relation to any others, sooner or later there will be editing. If the photographer does not do it, someone else will have to. And there is certainly no such thing as a photobook without editing.

It was in the 1920s, with the flourishing of the illustrated press and the growth of popular cinema, that the role of editing became crucial to visual culture. All those images had to be sifted and arranged. The tasks of editing were soon professionalized in various fields, each according to their media-specific needs, including magazine and book publishing, filmmaking, and art history. Conventions for selecting and sequencing were established by the mainstream press and cinema, and rejected or subverted by the various avant-gardes wanting alternatives from society, from images, or both. And in that rich setting, new kinds of photographic books emerged that were more emphatic in their choice and arrangement of images than mere collections of individual pictures.

George Peet, Minor White editing photographs for the Celebrations exhibition

and Aperture vol. 18, no. 2, M.I.T. Warehouse, 1972

© the artist

The now-canonized photobooks from the interwar years were of course quite anti-canonical at the time, and many were experiments in what can be done with photographs on the page. Visual primers for the new media age such as Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold’s Photo-Eye (Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fritz Wedekind & Co., 1929); László Moholy-Nagy’s Painting, Photography, Film (Bauhaus Bücher 8, Al-bert Langen Verlag, 1925) and 60 Photos (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1930); freeform books like Moi Ver’s Paris (Editions Jeanne Walter, 1931) and Germaine Krull’s unbound album Métal (Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, 1928); and Walker Evans’s groundbreaking American Photographs (Museum of Modern Art, 1938; discussed on page 10) were all shaped by the possibilities of montage as reflexive provocation, something that would make audiences think rather than passively consume a smooth flow. These books were also responses to the modern citizen’s daily experience of images, which was speeding up, fragmenting, even becoming overloaded. (Although these feel like our problems here in 2018, we’ve had nearly a century of speed, fragmentation, and overload.)

Where filmmakers and film critics worked up sophisticated theories of editing, still photographers did not. There is no photographic equivalent, for example, of the 1920s Soviet theories of montage developed by Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, and Dziga Vertov (all men, although the unsung heroine from that period is Elizaveta Svilova, who edited and appears in Vertov’s 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera, a work every editor of movies or photographs should see).

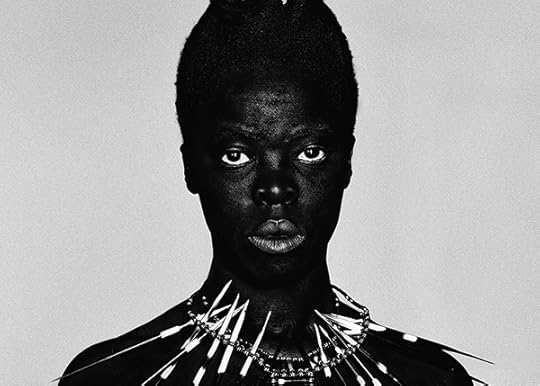

Lesley A. Martin, Editing Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (Aperture, 2018), July 2016

Courtesy the artist

It is surprising how rarely any of the great photo editors of the last century—Stefan Lorant of Picture Post and Lilliput magazines, John G. Morris of Life magazine, or Robert Delpire, to name just a few—spoke or wrote with any real insight about how they worked. Two unusual exceptions were actually art historians, Aby Warburg and André Malraux, although neither paid much attention to photography beyond how it reproduces and arranges all the other arts on the page. Warburg’s highly idiosyncratic methods, arranging diverse images on panels to explore multidirectional affinities and themes, are discussed widely today. Sara Knelman considers Malraux’s highly influential and highly manipulative books of art reproductions for this issue of The PhotoBook Review. Illustrated art history books are rarely considered “photobooks,” but there’s every reason they should be. Another key voice has been Keith Smith, whose 1984 study Structure of the Visual Book remains one of the few sustained attempts to think through the relations between images. You’ll find Aperture editor Lesley Martin’s exchange with Smith here, too.

Is it possible to express what happens in the mind when one photograph is placed next to another, and another, across pages? Are there theories that editors of photographs work with? Working assumptions? Unwritten rules? Or are there just private preferences? Does the role and task of an editor shift significantly if editing for the front page of a newspaper, or a magazine essay, versus an artist’s own book? Can the craft of an editor be recognized, like a signature style, or does it disappear in the result? Does an editor know why they think one arrangement “works” and another does not? Can they articulate it? Can editing procedures be classified, and named?

Lesley A. Martin, Editing Stephen Shore: Selected Works, 1973–1981 (Aperture, 2017), May 2016

Courtesy the artist

There was a moment in the 1960s and ’70s when it seemed image editing would be approached theoretically. Structuralism, semiotics, and the revival of interest in rhetoric in French and British academies transformed the way culture was thought about. Methods first developed for studying language were applied to images, with highly suggestive results (notably Roland Barthes’s early writings on photography, and Judith Williamson’s Decoding Advertisements in 1978). Complex theories of narrative structure emerged as ways to understand everything from folktales to Hollywood cinema. But something about the arrangement of still images seemed to resist scrutiny. Beyond photography’s attempts at linear storytelling or radical juxtaposition (both of which are usually pretty creaky), analysis seemed to hit a brick wall. This didn’t prevent extraordinary things being done with the editing of images. On the contrary, the 1960s and ’70s saw the second great expansion of experimental approaches, which are still influential. Think of the diverse publications of Hans-Peter Feldmann, Martha Rosler, Allan Sekula, Edward Ruscha, or John Baldessari. But at the same time, photography was entering the museum largely on the basis of exemplary single images, not even bodies of work, and this also stalled critical discussion at the borders of the image.

There were deeper difficulties, too. Most combinations of photographs are more like poetry than prose. For all that they show and express, they also announce their gaps, indirections, and enigmas. They do not explain effectively and are not very good at argument. Instead, image combinations suggest. In their punctuated way, they do not have the flow that can be attained by cinema and some types of literature. The individual images never entirely overcome their essential isolation from each other. There is always a tension—aesthetic, cognitive, intellectual—between what is irreducibly singular about a photograph and the part it plays in the larger whole. This is the challenge and the pleasure that photo editing presents. It is also the reason why analyzing it proves difficult. Only vague things can be said about it in general, so the more specific one can get, the better. There can be no overarching theory.

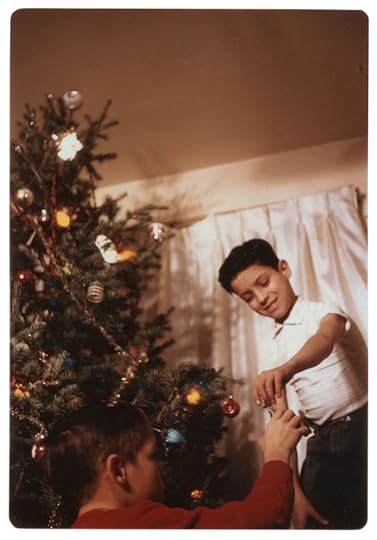

Lesley A. Martin, Editing Josef Koudelka: Gypsies (Aperture, 2011), November 2010

Courtesy the artist

The range of ways that images are put together today is wide, especially in book form, which for many photographers has now come to be the space in which comprehensive expression of an artistic vision is most possible. Everything, it seems, is being dared and tried. Why? Well, these are strange and desperate times, and who knows what works best, and what forms best express an age of uncertainty? Moreover, there is barely a mainstream of photo editing conventions anymore—certainly not of the kind that was established by the mass-market magazine photo-story that dominated for decades. Today there is no fixed order to kick against. If there is a mainstream, it is that mutating flow in which the order of images experienced daily is more likely to be determined by the algorithms of ideology, preference, taste, and commerce than by a conscious mind, let alone a creative or critical one. When any image might relate vaguely to any other, the very gesture of locking down a sequence in print, once and for all, which almost any photobook demands, can seem like a small act of resistance.

David Campany is a curator and writer based in London.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 015 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post What Does Photo Editing Look Like? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Strong Women

Hannah Starkey’s cinematic, psychologically astute portraits define the contemporary flaneuse.

By Sara Knelman

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, May 1997, 1997

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

In Hannah Starkey’s recent pictures, London’s East End seems less made up of concrete and steel than conjured from reflections, graphic projections, and the intensity of compressed space and glowing color. The purposefully anonymous women in them—silhouetted by a nightclub marquee, shaded by a shock of pink hair—are integral to the visual world they inhabit. We might see them as images among images, equally resonant of the aspirations and expectations suggested by the city’s surfaces around them, on billboards and hoarding, in shopwindows, or even divined from the hinted-at lives of other city wanderers.

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, January 2013, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Starkey has been making singular, large-scale photographs of women in public for over twenty years, since moving to London from her native Belfast. She doesn’t make many pictures, and there are often very long stretches of walking and watching before a handful of new ones takes shape. Often hiring actors or collaborating with friends or strangers, Starkey casts her subjects as anonymous flâneuses, neither specific nor typological. The anticlimactic blankness of their static postures—standing, sitting, staring—and the familiar, transient spaces in which they pause mark them as both actors in the pictures and agents in the world. They might appear to us as posed icons of beauty and desire, but they are also self-aware individuals struggling into formation against the environments—architectural, visual, social—that project and reflect them.

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, November 2015, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Despite their sharp stillness, Starkey’s images are incredibly dynamic. Though they’ve often been described as cinematic, their charge comes from the possibilities and surprises only a still image can yield, from the pleasures and challenges of looking carefully at an arrested moment. (To allow your eye to wander freely and completely, her images are best seen at their intended scale, usually around 4 by 5 feet.) In one of Starkey’s earliest photographs, a young woman sits in a café, her hand held up to an oblong mirror. She appears to be admiring her own pretty reflection, but a closer look reveals a moth pinned delicately beneath her fingers. Reflected in the mirror, an older woman in red curlers watches with a faint but unmistakable frown. A more recent image refracts elements from a mosaic of mirrors: architecture, trees, graffiti, pavement, a young woman taking a selfie—and the photographer herself, there with her camera poised. Whatever sleights of hand might be at play—the trick of the angled mirrors, the camera’s perspective, or digital manipulation after the fact—the pieces, again, don’t quite add up. What are we to make of all these apparent signs and symbols? Are they haphazard, coincidental? Do they relate a story, or foretell a future? Or are they performances of seduction?

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, April 2006, 2006

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

For all of Starkey’s suspicion of the negative effects of mass media imagery, particularly of and on women, there’s a joyfulness and an affection for looking and seeing in her pictures. In this spirit, we might detect autobiographical resonances, glints of a shifting mind and eye across the slow accumulation of pictures. This is especially palpable in the more recent work, which thrives on the loose, vibrant mood of the street. There’s a great freedom, after all, a special pleasure of escape in the act of being in public, of watching and being watched. In 1930 Virginia Woolf made up the excuse of buying a pencil as a way of enjoying a solitary walk across London, recounted in her vivid essay “Street Haunting”: “As we step out of the house on a fine evening between four and six, we shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one’s own room.” She returns home with a pencil and the intense emotional energy of other people it might, with great effort and a bit of luck, recollect, reconfigure, and record.

Sara Knelman is a writer, curator, and lecturer living in Toronto.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Strong Women appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 19, 2018

American Solitude

An exhibition in Paris reveals the extraordinary power of Dave Heath’s midcentury photographs.

By Violaine Boutet de Monvel

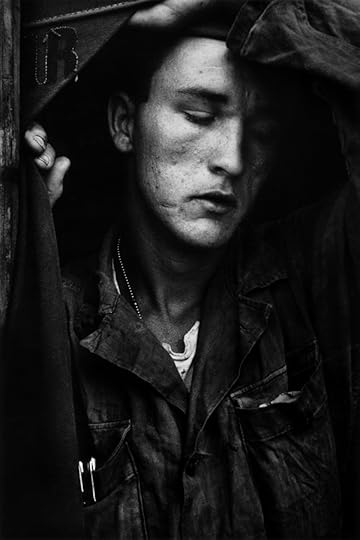

Dave Heath, Howard Crawford, Jr., Korea, 1953–54

© the artist/Collection Torosian, and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

In the fall of 1952, at the age of twenty-one, Dave Heath was drafted into the US Army. He trained as a machine gunner to fight overseas during the Korean War, serving in the South against the communist North. Although peace still has yet to be declared between the two Koreas, the July 1953 Armistice Agreement implemented an immediate ceasefire. Until the end of his military service, Heath dedicated his off-duty time to photography, documenting the melancholy among his fellow soldiers. He was particularly drawn to the quiet intensity of their self-absorbed expressions while resting, further crystallizing a strange stillness in their bodies. Closing themselves off, if only for an instant, GIs would allow their minds to wander away from the hostile surroundings. Lost in silent thoughts, longings, or fears, they just waited, perhaps, to finally go home, while others never would; thirty-three thousand of them had already given their lives in “The Forgotten War.” This very peculiar look, when one’s field of vision temporarily deserts the outside world to turn inward instead, became the leitmotif of Heath’s candid style.

Dave Heath, New York City, 1960

© the artist/Collection Torosian, and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

Once Heath returned to the United States in the spring of 1954, he traveled from Philadelphia to Chicago and New York, where he stayed until 1970. This fall, Le Bal in Paris presented over 150 pictures from this period in Dialogues with Solitudes, the late photographer’s first European retrospective. It is titled after A Dialogue with Solitude, a photobook published in 1965 that took Heath four years to conceive. (The original maquette is on display at the exhibition’s entrance, along with some of his portraits of soldiers in Korea.) In the book, a masterpiece of visual poetry, street photographs from distinct places and times are juxtaposed to summon pure emotions, which the show also pays homage to by following no chronology. Vibrating like the many tones of a poignant scale of solitude, the pictures at Le Bal are arranged around narrow white blocks to evoke Heath wandering the streets like a true Baudelairean flaneur (and the “spleen” or gloom that comes with it).

Dave Heath, Washington Square, New York City, 1960

© the artist/Collection Torosian, and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

While close to the humanist trend that developed at the time, Heath’s practice didn’t share the latter’s air of innocence. His desire to become a photographer was originally sparked by Ralph Crane’s “Bad Boy’s Story,” a photo-essay published in Life magazine in May 1947. It followed Butch, a young orphan in Seattle, whose difficulties in relating to others strongly resonated with Heath’s own journey: Heath was abandoned by his parents when he was only four years old, which left him to yearn for intimate connections that he contrastingly sought behind a camera. While he took his lonely quest to the streets and their random encounters, the absent eyes of ordinary people caught in moments of complete introspection could only mirror his own emotional homelessness. “I believe it all goes back to the loss of my mother,” he told Michael Torosian in a 1987 interview, republished in the exhibition catalogue. “I’ve been creating this work, trying to get to the point of mourning, but it sucks me down more and more instead of releasing me.”

Dave Heath, Elevated in Brooklyn, New York City, 1963

© the artist/Collection Torosian, and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

In New York, Heath’s search led him straight to Washington Square and the 7 Arts Coffee Gallery, where members of the beat generation regularly met at the time, including the poets and writers Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. He photographed both men reading, along with other leading figures. This community of nonconformists, who didn’t believe in the postwar American dream and who sought artistic freedom away from materialism, offered Heath, for the first time in his life, a sense of belonging. Like the beatniks, Heath was simply more attuned to the shadows. His remarkable printing technique—a combination of burning and bleaching that he borrowed from W. Eugene Smith—further isolated the everyday strangers he crossed paths with through sharpened black-and-white contrasts, beautifully highlighting the depth of their inward gaze.

Dave Heath, Washington Square, New York City, 1960

© the artist/Collection Torosian, and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

In 1970, Heath moved to Toronto, where he taught at Ryerson University. He died in 2016, leaving behind an outstanding body of work, which, after an interlude of obscurity, would have sunk into oblivion if it weren’t for the growing attention it has gained over the last few years. His “inner landscapes,” as he referred to his portraits, touch the awe of the sublime in a Romantic sense. Instead of contemplating the decline of civilization through the reign of nature, Heath contemplated the desolation of the soul, to which the eyes are the windows, and tried to overcome it through photography. “When you live a life where you feel you don’t belong, everything in chaos,” he said, “maybe you sense that the control over the chaos is the structuring of art.”

Violaine Boutet de Monvel is a writer and translator living in Paris.

Dave Heath: Dialogues with Solitudes is on view at Le Bal, Paris, through December 23, 2018.

The post American Solitude appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 13, 2018

Gordon Parks, a Brazilian Child, and an Exposé that Shocked the World

A 1961 photo-essay about the struggles of Flávio, a twelve-year-old Brazilian favela dweller, elicited unprecedented response. But should an American publication have tried to “rescue” a boy from poverty?

By Laurence Butet-Roch

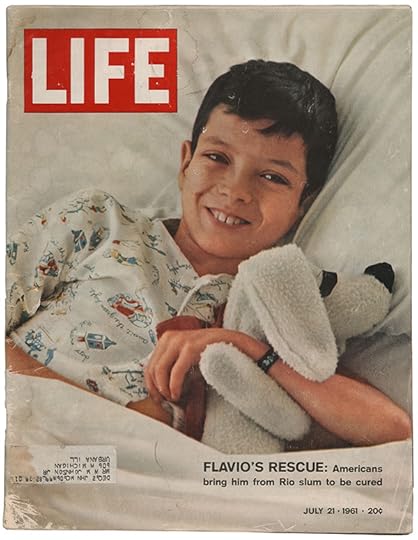

“The Compassion of Americans Brings a New Life for Flavio,” Life, July 21, 1961. Cover photograph by Carl Iwaski

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

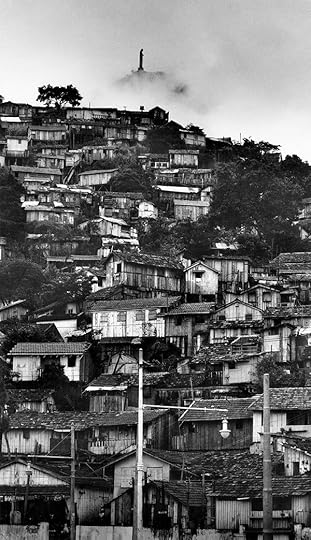

The artistic career of Gordon Parks (1912–2006), which spans nearly seven decades and a variety of mediums, is so rich and diverse that it refuses simplification. Even singular projects resist linear interpretation. Case in point: the Flávio story. On assignment for Life magazine in the early sixties, Parks traveled to Rio de Janeiro with the mandate to produce a visual exposé on poverty that would elicit empathy. Eschewing instructions from the magazine’s editorial leadership to follow an impoverished father, he chose to focus on an adolescent suffering from bronchial asthma and malnutrition, Flávio da Silva, who lived in dire conditions in Catacumba, a hillside favela near an affluent enclave of the city. Nearly sixty years later, a new book and exhibition, Gordon Parks: The Flavio Story, reconsider the legacy of this famous encounter.

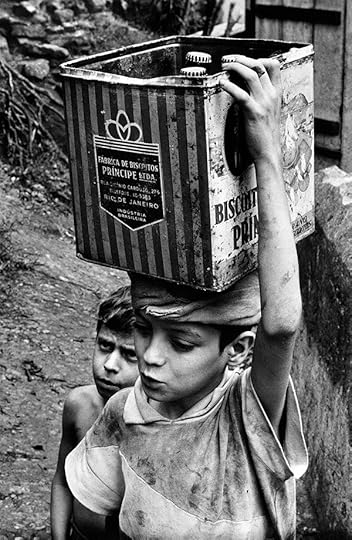

“Breathing hard, balancing a tin of water on his head, a small boy climbed toward us. He was miserably thin, naked but for filthy denim shorts. His legs resembled sticks covered with skin and screwed into his feet. Death was all over him, his sunken eyes, cheeks and jaundiced coloring. He stopped for breath, coughing, his chest heaving as water slopped over his bony shoulders. Then jerking sideways like a mechanical toy, he smiled a smile that I will never forget. Turning, he went on up the mountainside,” Parks wrote in his autobiography Voices in the Mirror (1990). “This frail boy bent under his load said more to me about poverty than a dozen poor fathers.”

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

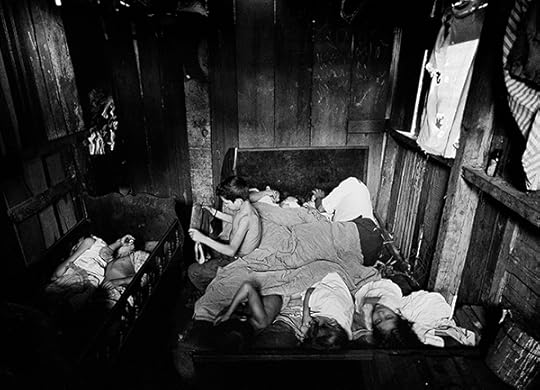

For the next eighteen days, according to the diary published alongside the feature, from March 22 to April 9, 1961, Parks would climb that very mountainside to photograph the young boy and his family. Bleak images show Flávio struggling to breathe in bed, caring for his siblings, and getting through his daily chores. He appears, in many ways, to be the man of the house, responsible for the family’s survival despite his own illness. It’s a portrait of resignation. There are no smiles being exchanged, no hints of love, joy, or even playfulness, aside from a small image of Flávio and his brother kicking sand on the Copacabana Beach, where Parks took them after learning they had never been, despite living only ten minutes away from it.

Published under the headline “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty,” the photos pulled at Life readers’ heartstrings. They sent letters of sympathy, offering money and help. The Children’s Asthma Research Institute in Denver wrote to promise pro bono care for the ailing teenager. Parents imagined how they would feel if this were their child. Life couldn’t have hoped for a better response. Thirty thousand dollars (the equivalent of roughly $250,000 today) were collected. The family was resettled in a nicer neighborhood. Flávio was flown to the United States to receive treatment at the aforementioned hospital. Life made sure to document these efforts in a report printed five weeks later, entitled “The Compassion of Americans Brings a New Life for Flávio.”

Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story dissects this feel-good narrative. Curators Paul Roth, from the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, and Amanda Maddox, from the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, in partnership with the Gordon Parks Foundation in New York and Instituto Moreira Salles in Rio de Janeiro, interrogate the context in which the feature was created, look at reactions it spurred in Brazil, and explore the lasting consequences of what was at the time referred to as a “rescue.” Earlier this fall, I spoke to Roth about the alleged power of photography, the influence and responsibilities of publication owners, editors, photographers, and readers, and the necessity to reject easy, black-and-white interpretations of iconic works.

Gordon Parks, Flavio da Silva, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Laurence Butet-Roch: The Ryerson Image Centre, as a photo institution set within a university, has the responsibility to provide exhibitions that examine the medium and its practices. Last year, you featured the project Collaboration by Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler, which offers an alternative history of photography grounded in a range of collaborative processes. Before that, you hosted an exhibition of historical images of Canada from the New York Times archive in a bid to discuss the representation of the country in news media. And before that, you programmed Attica USA 1971: Images and Sounds of a Rebellion, curated by Philippe Artieres for Le Point du Jour, which recontextualized the coverage of the Attica prison riots, to name a few recent memorable exhibitions at the RIC. How does Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story fit within that mandate?

Paul Roth: Before I even came to the Ryerson Image Centre, I had the idea of organizing an exhibition about this reportage, which was once Gordon Parks’s best-known photo-essay. But, the truth is, I’m not sure we could have curated it this way at any other institution. It fits so perfectly with our mandate of trying to interrogate what photography is, how it communicates, and how people understand it. To unpack The Flávio Story, to place it in historical context and reveal its social impact, we’re showing Parks’s photographs alongside images by many other makers, professional and amateur, and with documentary materials that many institutions would be reluctant to exhibit. This includes lots of publications, corporate and institutional records and correspondence, Parks’s original working materials, and images that have never been printed, that we found in the course of our research.

Gordon Parks, Family’s Day Begins, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

More importantly, we discuss The Flávio Story not just as a classic picture story with extraordinary images, but also as the product of Parks’s midcareer ambitions, as an ambitious corporate media project, for its stunning appeal to Life’s middle-class audience, and for the controversy of its publication in Brazil. Now, obviously, many museums and curators have become more flexible and open in their examination of historically important artistic projects, in making their checklists and in exhibition display, in order to better contextualize the stories they tell. But for many others, especially older institutions, it can be hard to make these shifts.

Our partners at the Getty Museum are trying, as we speak, to figure out how to handle a lot of the display choices that we’ve been able to make more easily at the RIC, because we aren’t bound by the same traditions and ideas about audience, and thus we can think quite differently. Ultimately, it seems to me that our goal in this time and place is to find new ways of telling the stories of photography, so that we not only retell the stories that the artist or photographer told, but that we also question how the stories were told, and how they have been understood. Because of this, we’re actually asking our audience to come to a Gordon Parks show where a majority of the pictures are not by him!

Gordon Parks, Flavio After Asthma Attack, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Many uphold The Flávio Story as one of the few examples of photography’s purported power to effect positive change. Here, you challenge that conclusion.

Roth: It’s really up for debate. Looking at Parks’s story and the effort to save Flávio only as a cautionary tale would also be too easy. Some of my colleagues here in Canada have analogized it to the residential schools program, whereby indigenous children were ripped away from their parents and dropped off in abusive spaces to have their culture removed. To this day, Flávio doesn’t see his experience that way. He shared his point of view with us over several interviews. Instead, he’s angry that he was taken away from the place he was brought to!

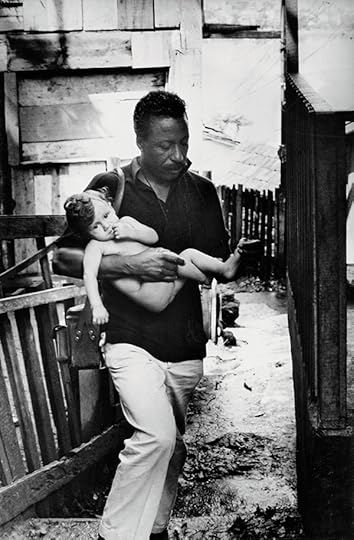

The initial situation he was taken from was so perilous. He was twelve years old, on the verge of dying due to asthma, had a terrible relationship with his parents, was physically abused, and lived in a swirl of psychic violence that we can hardly imagine. So for him, being on the cover of a big American magazine, getting toys and clothes, being deposited with a family that he liked better than his own, felt like winning the lottery. He was so incredibly distraught when he eventually had to leave his new life in Denver. He acknowledges that something wrong happened to him, but to him it isn’t that Gordon Parks and Life interfered in his life, but that he wasn’t permanently adopted by any of the people involved, like Gordon Parks, Ruth Fowler, the executive assistant to Life’s publisher, José Gallo, the longtime business manager at the Rio de Janeiro bureau of Time Inc. assigned to assist Parks as reporter and interpreter on the Flávio story, or the family he lived with in Denver. He asked all of them to adopt him. They all said no. They all felt that they were doing the right thing by returning him to his own family in the country of his birth. But Flávio didn’t want to go home to his family. Photos taken by José Gonçalves, his surrogate father in the United States, bear witness to these emotions.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Having said that, Flávio was fourteen years old at that point, and one could argue that he had no way of understanding the complexity of his situation. All the people involved were already terribly worried that they were going to cause him harm. They obsessed over that, the magazine’s employees included. Yet at the same time, they didn’t really understand, they couldn’t. And, it’s important to remember that they weren’t doing all this for purely innocent or altruistic reasons; they had very complicated motives. All this to say that an uncomplicated absolutist read of this story, positive or negative, is not only misguided, but also not really that illuminating or interesting. Like all claims made about the power of photography, it’s much more revealing to look at the fragility of those declarations than to take them at face value. That’s why I love this story so much: there are so many moments and details you can interrogate.

Jose Gallo, Gordon Parks carrying Zacarias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: The first part of your investigation rests in scrutinizing the context in which this photo-essay was commissioned by Life. It was part of a series entitled “Crisis in Latin America,” which was launched with an introduction that began: “The messianic eyes of Fidel Castro, hypnotic and hungry for power, summon up a new and nightmarish danger for the U.S.” This came six weeks after the failed CIA-supported Bay of Pigs invasion and as the Kennedy administration was pitching the “Alliance for Progress” economic interventionist policy for Latin America. Knowing the strong relationship between Life’s owner, Henry Luce, and the American leadership, should it be apprehended as propagandist?

Roth: Certainly, but it’s complicated. Henry Luce was many things, including an absolute anti-communist crusader. At the same time, he was also a self-proclaimed humanist. In other words, his corporatism and paranoid defensive foreign policy coexisted with his human-uplift politics. He embodied the idea of American exceptionalism. He built many magazines to carry this message forward—principally Time, Life, and Fortune—which became citadels for the people he employed, many of whom were political liberals, thereby empowering them. So, in a sense he created a paradoxical situation: On the one hand, he stated very clearly to his editors and reporters that he needed them to be propagandists in this war—these are words he actually used—believing that their role was as important as any army’s. However, and this is no surprise, many of Time-Life’s staff and contributors resisted Luce’s politics for a variety of different reasons.

Paulo Muniz, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Where does Gordon Parks fit within that milieu?

Roth: Gordon Parks didn’t directly oppose these ideals per se; rather, he was opposed to the tedium of politics and what that would mean for his pictures. He had enough power by this point in his career, in 1961 when he was assigned to make pictures for this Latin America story, to fight back a little. He felt that it would be dull for Life’s readers to see a programmatic set of pictures that exemplified the editors’ political convictions. So, while he fulfilled some of their demands, which came in the form of an assignment list of desired images, Parks more or less ignored the editors. Rather than build his picture story around the father, as he had been assigned, Parks chose to focus on Flávio.

You can feel this uneasy marriage between the assignment and the images Parks actually brought back in the text that accompanies the photographs in Life magazine. The first block of text is very much what the editors wanted to get across about communism. The lead writer, Timothy Foote, presented poverty as a compelling pretext for the United States to solve, in order to prevent Latin American countries from being swallowed whole by communism. The cover headline, “Shocking Poverty Spawns Reds,” is telling. Yet, at the end of the photo-essay, an additional text is provided by Parks himself, a direct yet emotional diary of his experiences.The politics have been drained out of the pages and replaced by a language that buttresses the emotional impact of the pictures.

This is why this story is so complicated. Yes, Henry Luce was trying to support Kennedy; and many Time-Life staff members certainly voted for him and wanted him to succeed, believing that the Alliance for Progress would be a force for good in South and Central America. But they also had a more human reaction to this story of a single child suffering in poverty. When Life’s readers responded in kind, the staffers got excited because they could now help a single family, as a kind of proxy for all the people of Latin America.

José Gonçalves, Untitled, Denver, Colorado, 1963

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: The ideals you speak of, the context in which this work was created and seen, and the readers’ response evoke the white-savior complex, especially given how the humanist instincts of the magazine and its readership were then celebrated, just five weeks after the original picture story was published, in a self-congratulatory follow-up story: “The Compassion of Americans Brings a New Life for Flávio.”

Roth: I think that’s certainly true. The reaction expresses several things at once. For one thing, the magazine was just bluntly kissing up to their readers. At that time, Life’s publishers were increasingly concerned about their subscription and newsstand sales. In fact, circulation numbers were at their highest in the magazine’s history, just over seven million per week. With each copy passed between families and neighbors, it’s been estimated that anywhere from thirty-five million to one hundred million people saw every issue. But the publishers were still very worried, because it’s 1961 and television is increasing its market share and taking more advertising dollars from the magazines. There’s also a more crowded competitive space among weekly publications. So that’s why the cover featured Flávio smiling, in a clean bed, with a stuffed dog. The message was: you, the readers of Life magazine, contributed to saving this boy’s life.

Another reason Life was drawn to this intervention is that it helped them to visualize a journey from poverty and suffering to middle-class life, which was kind of an obsession with the magazine—because of who their readers were. The layout of the “rescue” issue is actually organized to reflect that ascent: Flávio and his family climb down the hillside of their favela, enter their new home, they get new furniture and clothes. Flávio flies to the United States, he’s diagnosed and treated by the best doctors, he learns how to play with other children, he learns how to speak English, then he starts making new friends.

So this story of redemption from poverty served many purposes for Life. The magazine could demonstrate its own power and reach, while also suggesting to its readers that by reading Life, they could contribute to the betterment of the world. Furthermore, the intervention suggested that John F. Kennedy’s policy—a continental foreign-aid program designed to save families like Flávio’s—could be successful.

José Gonçalves, Untitled, Denver, Colorado, ca. 1963

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Still, this story encountered some criticism, initially and almost immediately, from the Brazilian government and media.

Roth: When North American media outlets do a story on poverty or war on the other side of the world, we, the North American readers, typically only care about our own reaction to that story. Very few people would even wonder whether there’s a response in the media of that place. In 1961, the press in Brazil immediately condemned the Flávio piece. They knew what Life and the story represented: a stalking horse intended to promote a financial aid policy that wasn’t fully supported within Brazil. There were opinion columns, news articles, even editorial cartoons.

One publication, O Cruzeiro, launched a two-pronged attempt to attack and debunk the story. First, they critiqued Parks’s photo-essay by flipping Life’s idea on its head, by sending their photographer Henri Ballot to depict poverty in the U.S., in New York, where Time-Life kept its corporate headquarters. O Cruzeiro’s counterattack was deliberate and overt. When they published Ballot’s photographs of a Puerto Rican family living in poverty on the Lower East Side, their page spreads were designed to echo corresponding page spreads in Life, so that the repetition of Parks’s visual tropes would undermine his pictures and reveal Time-Life’s motives. In response to that, Life’s sister publication Time retaliated with an article alleging that Ballot staged one of his hardest-hitting photographs. And that wasn’t the end of it! O Cruzeiro fired back and commissioned Ballot to debunk Gordon Parks’s photographs. He interviews the da Silva family in their new home and even takes them back to their shack in the favela in a bid to demonstrate how Parks’s reportage was staged.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1976

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Was Parks aware of the Brazilian backlash against his photo-essay on Flávio?

Roth: Yes. Interestingly, Parks did in fact set up a lot of his shots, working with the family to depict their lives, though that’s not altogether atypical of this kind of press photography. Ballot, a fellow photojournalist, knew this fact; hence he knew he could attack Parks in this way. He takes a particular stab at the Life picture story’s central image of Flávio getting out of bed before his family. In order to get the picture, Parks had to manufacture a high vantage point in this tiny shack, so he set up something to stand on. He had the family stage the scene in broad daylight so he would have enough light to expose his film. And his contact sheet shows that he made twenty-plus frames of this moment, with Flávio, suffering from asthma, holding his arms up for as long as it took. Parks, like a lot of photojournalists, wouldn’t think of this as dishonest. He needed to make a picture that conveyed what it’s like for Flávio to get up first in the morning. He doesn’t see it as fake, and in many respects, it isn’t.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1976

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Henri Ballot’s photo-essay brings to mind the work that Gordon Parks subsequently did in Harlem in 1967, on the Fontenelle family, to illustrate American poverty. How did his time with Flávio and the O Cruzeiro riposte inform that series?

Roth: Certainly the Flávio story inspired that later story. However, while both Life and Parks later compared the two photo-essays, I wasn’t able to find any direct evidence in the Life corporate archives that his editors said: “Let’s redo the Flávio story in Harlem.” There are clear parallels, but also differences. There’s something darker, much more stark and harrowing, about Parks’s coverage of the Fontenelle family, with the exception of his iconic, melancholy image of the mother talking to a social welfare bureaucrat, surrounded by her children. By comparison, the Flávio story is a story of hope, and is quite romantic in its pictorial values and composition. I don’t know that Parks set out to romanticize or exoticize either of the families. He was working within the visual idioms of the times. While he certainly related to Flávio on some level, he must have seen himself even more in a couple of the Fontenelle boys. He grew up very poor in Fort Scott, Kansas, and then in St. Paul, Minnesota. Entering adulthood, he lived briefly in poverty in Harlem himself. He knew the Fontenelle story better, so perhaps that fostered more of an edge in his style. Or maybe, having passed through the experience with Flávio, he was more jaded as the 1960s were drawing to a close.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1976

Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

Butet-Roch: Why is it relevant to reflect upon such works and their impacts half a century later?

Roth: As a great photographer, filmmaker, writer, and composer—and also as a pioneering black American—Gordon Parks is somewhat like Jackie Robinson. Just as baseball historians exhaustively look at his career, you can exhaustively look at Parks, his work, and his place in history. There’s just so much there. He worked in so many different genres and with different media. At the end of it all, what he really boils down to is a great storyteller, one well worth examining and understanding.

In many ways, Flávio was his greatest story. It just couldn’t be contained. It was so compelling that the audience took it over and carried it forward. That makes it unusual. Yet at the same time it’s paradigmatic of his photojournalism.

It’s no surprise that Parks’s photographs had such a significant effect on Life’s audience. He wanted to move people, to shake them up, to take them into the lives of this distant family. He was intent on conveying the suffering of poverty. He succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of his editors. In a way there was nothing new about his approach. Characterizing poverty by representing the life of a single individual or family had been done before; taking readers from the developed world on an armchair journey to pockets of the developing world is a mainstay of documentary photography.

This idea, that photography has the power to change people’s lives for the better, is the mythology that gives us hope and makes so many of us look at similar pictures year after year. We believe that by looking at these images, we can change things, we can relieve the relative guilt we have over our affluence by looking at the lives of others. The Flávio story endures because the pictures affected Life’s readers so much that they decided to try to change fate. The fact that things didn’t work out as expected is what makes it so resonant and revealing, even today.

Laurence Butet-Roch is a photographer, writer, and educator from Toronto.

Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in July 2019.

The post Gordon Parks, a Brazilian Child, and an Exposé that Shocked the World appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 12, 2018

Between Pictures and Concrete Objects

Anthea Behm discusses feminism, photograms, and what it means to “hover” in the world.

By Carmen Winant

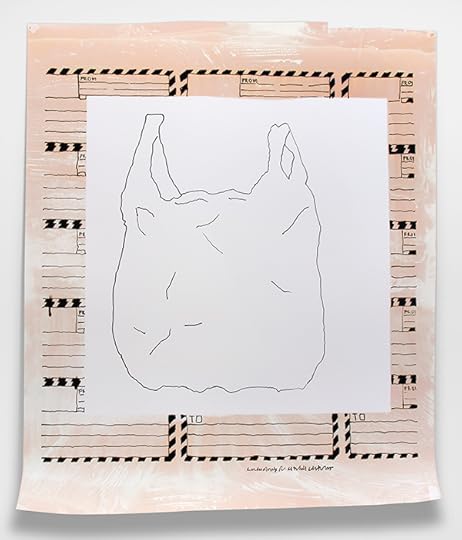

Anthea Behm, Rage for Order, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Anthea Behm is a difficult artist. I mean that in the best sense: her work is beautiful, agitated, and restless. In the five years that we have been friends, I have never known Anthea to make work that resembles anyone else’s. Her new series in particular—which we will be discussing here—refuse singular description. They exist, perhaps most succinctly, in the nexus of feminism, twentieth-century art history, concretism, and the phenomenological experience of a life lived.

Carmen Winant: I am so moved by this new body of work, Anthea, which I know is ongoing and not yet complete. I’d like to start by asking you about how you carve out an in-between kind of definition for your practice, and then talk a bit about your unique process—which I think we could say that you have invented, to some degree—and finally discuss the work in relation to feminism.

I thought it would be useful to start with two words: “concrete” and “hovering.” I’ve heard you use both of these terms in describing your work, and yet they strike me as contradictory. Can you speak to this, and the notion of making things that, in your words, “hover between pictures and concrete objects”?

Anthea Behm: When people talk about the “concrete arts,” be that sculpture or photography or poetry, they have this idea of something that is all in itself and is not bound up in other things. There’s an idea that this makes something more “what it is”: a photograph that’s itself an object rather than about another object. But that’s actually a bizarre idea of what things are: that something could just be in itself and not be relational. What doesn’t hover in relation? What isn’t always connected to other things and people? The single plane of the world, with all its striations and variegations and hidden ducts and lost folds, that’s what the concrete is.

Hovering is onomatopoeic for me, not in terms of sound, but in terms of effect—as a word that registers the affect of process, becoming, the constant movement of the layers and relations of the world. When I use the word “hover,” it’s to get at this idea of simultaneity, of our liminal connections to multiple spaces, times, and things. Hovering is ontological in this sense—it’s what I think of objects doing, and what we are, as humans in the world.

Anthea Behm, Showing the hand, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Winant: So in this sense, photograms are perhaps more in contact with the world? Less a picture of a thing, and more an impression of the thing itself.

Behm: I do consider photograms to be in contact with the world, but not more in contact than a picture, because it’s this binary split between a picture of a thing and an impression of the thing itself that I don’t recognize. Photograms are “in contact” not because they are solely themselves and representational photography is relational, but because being in contact with the world is always some mix of enclosure and connection. To be in contact with something is to form a picture of what has impressed itself on you. The picture is a kind of, I don’t know, a kind of attempt to come to terms with the fact of your embedded-ness in life, with the fact that impressions are always being made on you and you are always making impressions on things.

The philosopher Branka Arsić writes about a nineteenth-century idea of the “camera obscura of the earth,” in which all things come to bebecausetheir exposure to the sun is refracted by the shadows of other things and beings, which they process, or “develop,” in the nighttime. I love this idea of the world itself as a kind of photograph—and thus to be in contact with the world, one must have what the world already has, which is both things and impressions.

Anthea Behm, Wilendur, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Winant: The photographs themselves are cut on slight biases, and hung without frames, pinned only on top corners so that they curl upwards at the bottom. As a result, they literally hover. Can you speak to these formal decisions, and how they answer back to such ideas?

Behm: There is an immediate relationship between the viewer and the paper, which I like—not to fetishize the paper in itself, but as another object in (and of) the world. The photographs are made on resin-coated paper, which is basically plastic-coated paper, and like the plastic bag or tablecloth represented in the Mirror Lamp Hammer series, the photographs can move easily in—and through—the world. They are not hard, stable objects, but flexible and nimble, which I hope is also reflected in the potential readings of the work.

The way the work is presented also reflects how I make it in the studio. For one thing, I am constantly moving for work or other opportunities, making movement and circulation not only at stake in the work, but also my embodied experience. And because the work is so large-scale, I’ve had to create temporary darkroom spaces. So, unlike a conventional darkroom, I only have a couple of red safelights. This makes it difficult to see what I’m doing and the way the paper is cut is a result of this. I am trying to control these actions and processes in the darkroom, but chance enters in, and it’s this messiness between—or hovering, to invoke it again—that I am interested in. Of course, I could have also recut the paper after it was fixed, but I am interested in showing these tensions and economies of production.

Winant: And what of their verticality?

Behm: They are made vertically for the most part, and I think a lot about painting and drawing when making this work. I enjoy making these like paintings—not framed yet, hung with a support that allows the surface to be worked on. And then I can move them straight from the studio to exhibition, just as you might with a painting. I also go between working with and against the paper. “Against,” in terms of pushing it to do things it is not meant to do, and “with” in terms of letting it do what it wants. It is the latter reason that I don’t pin the work in the bottom corners. Being roll paper, it has a “natural” curl, and this is something I don’t force flat . . . at least I haven’t had a reason to yet.

Anthea Behm, #4 from DUST series, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Winant: How do online, Photoshop, and darkroom processes come to meet in these pictures?

Behm: It varies from work to work. For example, with the Mirror Lamp Hammer series, I find most of the images I work with online. I search, drag, copy, and organize archives of images. I then import these images into Photoshop and make sketches for works that I then create through analog processes in the darkroom. This primarily involves painting and drawing with chemistry and light. It is important to me that these processes are highly controlled, but at times, like with the cutting of the paper or painting with chemistry, my control is exceeded by the conditions of the darkroom or material.

Winant: In those instances, it seems, you begin to “show your hand,” so to speak, and that’s not always done in photography, where the idea of a “good” photograph is sometimes that the artist’s hand disappears to allow the image to come through.

Behm: Exactly, and it was against this conception that Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray and others foregrounded their place in the making of images by featuring hands in their early experimentations with paper and light. I think it’s interesting how this gesture of “showing the hand” (either the hand itself or in glimpses of the apparatus) has come to be equated with a kind of self-reflexivity. It’s as if just revealing yourself and/or how you made the thing automatically means some form of transparency.

Winant: Though “showing the hand” doesn’t always mean a heightened level of authenticity, accountability.

Behm: Right. Showing the hand doesn’t necessarily reveal anything about the social conditions that drive the relationships between us and the things our hands do or take part in. In fact, it might work as another element of concealment. Like, look at my left hand that’s showing you how the work is made, but don’t look at my right hand, which is abusing the power I have as a subject, or further still, as an institution. I’m interested in working through this complexity somehow by simultaneously revealing and concealing the hand. Whether through an image or process, the hand is at once in a position of becoming revealed and concealed.

Anthea Behm, #6 from DUST series, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Winant: Your two new series are DUST (named after the space where they were made as part of the Plates of the Present residency in Paris) and a still-untitled work in progress featuring nude images of Charis Wilson taken by Edward Weston. The first also uses nudes, from Man Ray, combined with forms from Moholy-Nagy. Each of these so-called “masters” of the form has justified their use of female bodies as “formal investigations”; your work troubles that explanation. How did you come to work with this material, and feel the need to problematize it?

Behm: The first work in photography I ever did was about the female body. It was about how I can inhabit a body that, as much as it was mine, often felt taken away from me. It wasn’t only taken away in the obvious ways—by gazes that objectified me or men who thought they had as much right to my body as I did—but also in surprising ways: by women and their assumptions about other women, and what it meant to be a feminist or fail to be a feminist.

Winant: Perhaps we can return to the idea of hovering here: how we move between different, slippery notions of self, and self-affirmation.

Behm: I love how you put that, and there is something potentially liberating in that slipperiness. But this is where “hovering” can become pejorative, when bodies (along the spectrum, in very different ways) can be stuck between desires and codes and prescriptions. It feels at times, quite viscerally, like there is no good way to be in a body. So often our bodies can seem overdetermined and unavailable, even when we think we are “reclaiming” ourselves and founding new intimacies. I don’t yet know how to answer your earlier question about the origins of this new work, how to say what exactly brings me to a material or subject, because it’s so many different strands and motivations.

Anthea Behm, #7 from DUST series, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Winant: Do you think of your project as intending to “rescue” these women? From perennial muse-hood?

Behm: It would be good if we thought of them beyond just being muses, but I don’t want this work to be some kind of “rescuing” gesture, as if they needed rescuing, as if I were in a position to rescue them, as if history had moved to such an extent that we could now look back with clean hands. Because we don’t have the time or space to get into the different types of feminism here, I would just say that I don’t want to condemn how different women respond to patriarchy, because I think we should stay focused on patriarchy itself, on how we’re all finding different ways of living in a world that is, at some real level, shaped by heterosexual male ways of seeing, and how we can continue the ongoing liberation movements to surpass that condition.

Winant: Women can oppress one another, too.

Behm: Of course. And of course there are people in the world who refuse this either/or of man/woman. My intention here is not to use “women” as a homogenous category, or overlook the intersectionality that is required when discussing issues of gender. Indeed, those complications are central to my thinking. For example, one of the things that interests me about Charis Wilson in Weston’s photos is how blissfully unaware she seems of the fact that she’s rolling around on colonized land. As if her reclaiming of her body and her right to present herself depended on the layers of dispossession that the photo wants to keep buried in the sand. Some of what I’m curious about is the capacity of images to excavate these layers and intersections. And to complicate it further, there is something still formally significant about the work of these “masters.” I’m not trying to dismiss them entirely.

Winant: Right, your claim is not totalizing.

Behm: That would go against the subtleties, fragments, and layers that I want to expose on the single plane of the photograph. I’m not trying to make a final statement about the misogyny of history. I’m trying to break apart the past and rearrange it in some manner. I’m drawing my way toward this.

Carmen Winant is an artist, writer, and the Roy Lichtenstein Chair of Studio Art at the Ohio State University.

The post Between Pictures and Concrete Objects appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 6, 2018

Aperture’s 2018 Holiday Gift Guide

This year, Aperture has published books by Diane Arbus, Judy Glickman Lauder, Deana Lawson, and Hank Willis Thomas, among others. Aperture publications have explored how photographers have chronicled their relationships to family, the garden’s rich history in photography, and more. From iconic monographs by master photographers, to groundbreaking, never-before-published work, we offer titles for everyone on your holiday list.

For the Collector

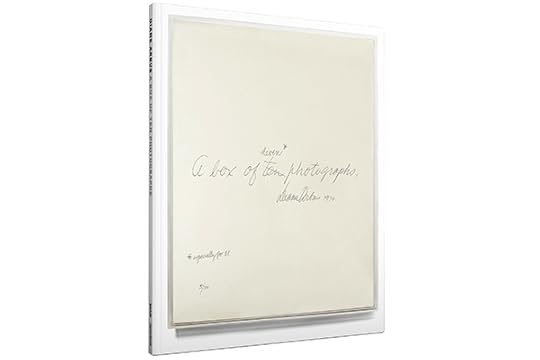

Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs

In 1971, Artforum featured the work of a photographer for the very first time. On its cover and in a six-page spread, it announced the publication of a portfolio by Diane Arbus, and in the words of the magazine’s editor Philip Leider, “the portfolio changed everything . . . one could no longer deny [photography’s] status as art.” The only instance in which Arbus curated her own work for the public, Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs is a stunning large-format reproduction of the artist’s iconic portfolio.

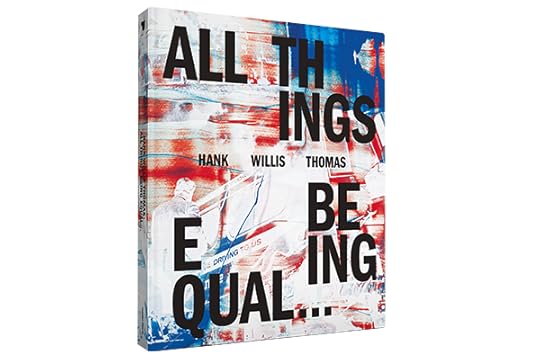

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal presents a survey of the artist’s prolific and extraordinary interdisciplinary career, with a particular focus on his ability to critically dissect the flow of images that comprise American culture. His work’s powerful themes include race, gender, and the commodification of identity through popular media, sports, and advertising.

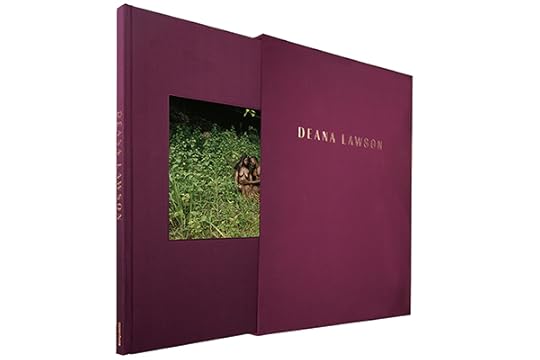

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (Limited Edition)

One of the most compelling artists of her generation, Deana Lawson’s photographs portray the personal and the powerful. This special, signed, limited-edition version of her highly anticipated first volume, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, features rose-gold gilded pages, a luxurious slipcase, and a custom tipped-on C-print of Lawson’s iconic portrait The Garden (2015).

Family Matters

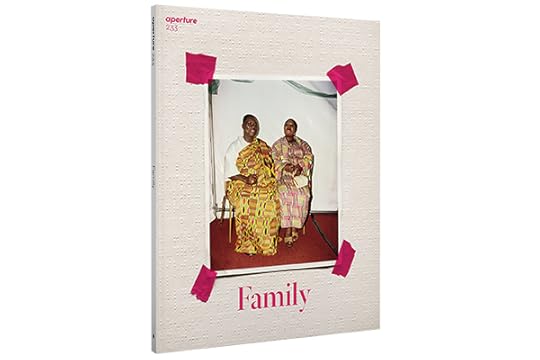

Aperture 233, “Family”

The Winter issue of Aperture, “Family,” considers how artists and photographers have chronicled their relationships to their families and chosen communities, and takes an expanded view of what families can be.

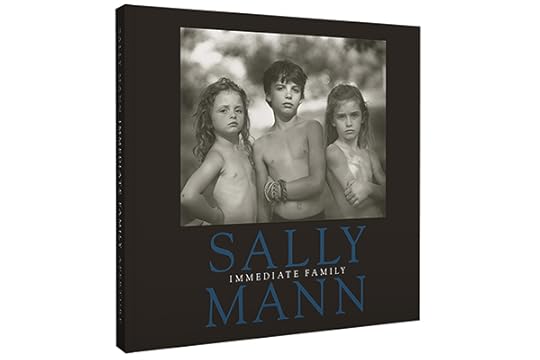

Immediate Family by Sally Mann

First published in 1992, Immediate Family has been lauded by critics as one of the great photography books of our time. Sally Mann’s extraordinary, intimate photographs of her children reveal universal truths—such as the eternal struggle between a child’s simultaneous dependence and quest for autonomy—while embodying the individuality of her own family.

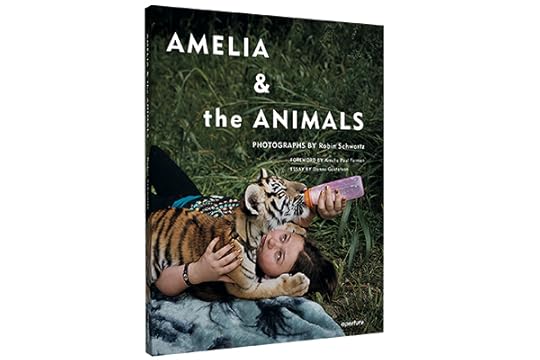

Amelia and the Animals

Since the age of three, Amelia has been the muse of her mother, Robin Schwartz. Amelia and the Animals is Schwartz’s second monograph featuring collaborative photographs of Amelia among the animals. The resulting photographs serve as a meditation on the nature of interspecies communication and as evidence of a shared mother-daughter journey through their invented worlds.

Remarkable Storytelling

Judy Glickman Lauder: Beyond the Shadows: The Holocaust and the Danish Exception

Over the past thirty years Glickman Lauder has photographed the intensity of the death camps in Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. Beyond the Shadows responds to the mass murder of Jews during the Holocaust, while telling the uplifting story of how the citizens and leadership of Denmark, under occupation and at tremendous risk, defied the Third Reich to transport the country’s Jews to safety in Sweden.

Chloe Dewe Mathews: Caspian: The Elements

Chloe Dewe Mathews spent five years spent roaming the borderlands of the Caspian Sea. In this resource-rich region roiled by contested geopolitics, Dewe Mathews found that elemental materials like oil, rock, and uranium are central to the mystical, practical, artistic, religious, and therapeutic aspects of daily life. Caspian: The Elements explores the deep links between the peoples of the Caspian and their enigmatic and coveted landscapes.

As it may be

Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter has traveled to Egypt regularly since the beginning of the revolution in 2011, making intimate pictures of Egyptian families. In 2017, she revisited the country with the first draft of this book, inviting others to write comments directly onto the photographs. In As it may be, contrasting views on country, religion, society, and photography arise between people who would otherwise never cross paths.

For the Adventurous

The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip

The road trip is an enduring symbol in American culture that has spurred some of the most important photographs in the history of the medium—from images by Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Berenice Abbott to Robert Frank’s 1950s odyssey The Americans. From Stephen Shore to Ryan McGinley, hundreds of other photographers have continued the tradition. The Open Road is the first book to explore the photographic road trip as a genre.

Highway Kind

For several years Justine Kurland, known for her utopian photographs of American landscapes and their fringe communities, and her young son, Casper, traveled in their customized van, going south in the winter and north in the summer. Her life as an artist and mother is finely balanced between the need for routine and the desire for freedom and surprise. Kurland’s deep interest in the road, the western frontier, escape, and living outside mainstream values pervades this stunning and important body of work.

A Wild Life: A Visual Biography of Photographer Michael Nichols

A Wild Life is the story of National Geographic photographer Michael “Nick” Nichols, told with passion and insight by author and photo-editor Melissa Harris. Nichols’s story combines a life of adventure with a conviction about how we can redeem the human race by protecting our wildlife.

For the Foodie

Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography

From basic sustenance to savory repasts, food awakens the senses and touches both private and public life. This is the first book to cover food photography’s rich history—not only in fine-art photography, but also in crossover genres such as commercial and scientific photography and photojournalism.

The Photographer’s Cookbook

In the late 1970s, the George Eastman Museum approached a group of photographers to ask for their favorite recipes and food-related photographs, in pursuit of publishing a cookbook. Forty years later, this extensive and distinctive archive of recipes and photographs was published in The Photographer’s Cookbook for the first time. And it does not disappoint: from Ansel Adams’s Poached Eggs in Beer to William Eggleston’s Cheese Grits Casserole, the book provides a time capsule of the era’s contemporary photographers as well as a fascinating look at how they depicted food, family, and home.

For the Outdoor Enthusiast

The Photographer in the Garden

From famous locations to the simplest home vegetable gardens, from worlds imagined by artists to vintage family snapshots, The Photographer in the Garden is the first volume to trace the garden’s rich history in photography, examining the complex relationship between photography and nature.

Picturing America’s National Parks