Aperture's Blog, page 98

August 9, 2018

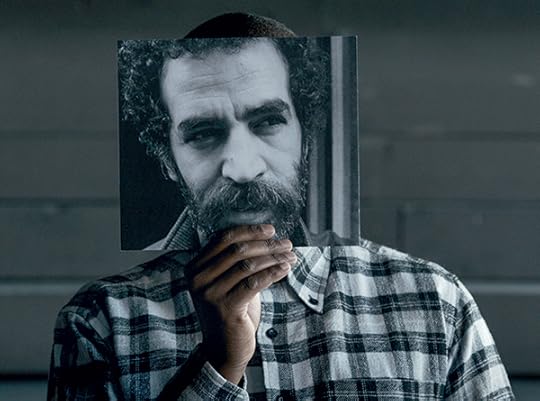

Demanding Justice for Shahidul Alam

In Bangladesh, the brutal arrest of a prominent photographer incites an international outcry.

By Brian Palmer

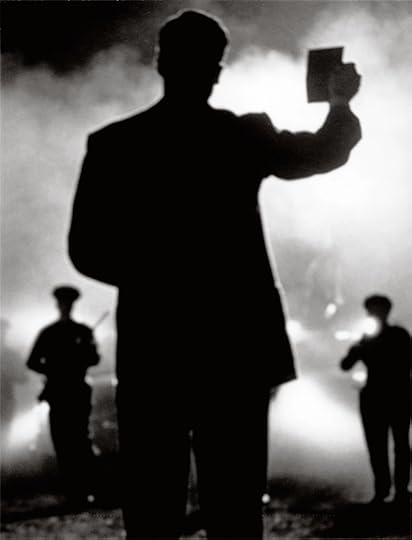

Shahidul Alam, Jubilant people take to the streets after the dictator agrees to step down, Dhaka, Bangladesh, December 4, 1990

© the artist/Drik Images

On August 5, 2018, Dr. Shahidul Alam, the preeminent Bangladeshi photojournalist and human rights advocate, was abducted from his home by dozens of police officers. Alam had given a frank interview to Al Jazeera about protests that had erupted in Dhaka days after two youths were killed by an out-of-control bus. Alam reported on the brutal backlash against demonstrators by vigilantes, presumed to be aligned with the ruling party, the Awami League. But Alam, a veteran advocate for genuine democracy, did not stop there. The protests are about more than just road safety, he told the interviewer; the “unelected government” has been “clinging on by brute force. The looting of the banks, the gagging of the media . . . the extrajudicial killings, the disappearances, the need to get protection money at all levels, bribery at all levels”—these are the root causes of the current popular outrage and unrest.

The government charged Alam under the International Communication and Technology Act for “giving false information to different media and for provocative comments,” said a police official interviewed by Al Jazeera. According to his partner, Rahnuma Ahmed, and his attorneys, Alam has been beaten and tortured by his abductors. After a city judge remanded Alam to police custody for seven days, Bangladesh’s High Court ordered that he be sent for medical treatment. On the morning August 8, was taken to a government hospital, but was returned to police custody the same afternoon. Alam is still in custody, incommunicado, as of this writing.

In 2002, Aperture published a story about Chobi Mela, a biannual international photography festival in Dhaka founded by Alam, a chemist by training but a journalist/photographer/educator/activist by inclination. This was only the second time Alam and his team had held the event, a wildly ambitious, multiday, multivenue mix of exhibitions, panels, workshops, and parties across Dhaka. It is a city known for frequent, crippling transportation strikes and stunning population density. Alam also chose to hold the event during the holy month of Ramadan, when many businesses—and all restaurants—are closed during daylight hours.

Shahidul Alam, For the first time in the history of Bangladesh, a fair and free election. A stamp on a ballot paper in exchange for Nur Hossain’s death, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1991

© the artist/Drik Images

There were hitches, big and small. Customs officials impounded shipments of photos slated for exhibition. Ominous rumblings came from government departments. Venues fell through. None of this mattered. With the help of his team—his students at the school he started, Pathshala; their instructors; colleagues; and his partner, Ahmed—as well as festival attendees from around the world, Chobi Mela succeeded. Photographers, curators, editors, and artists from Malaysia, Singapore, Norway, the US, India, and many other countries showed work, exchanged ideas, shared meals, learned, bonded. “This whole thing defies gravity,” Alam said at the time. And indeed it did.

Alam had set out to do something audacious: to create an international festival of photography in the “majority world,” the nations and regions of the Global South whose stories have historically been framed by European and American journalists. He wasn’t simply out to compete with the famous conclaves in the US and Europe. Alam’s goal was—is—to transform the very nature of international documentary photography and photojournalism by building a hub for these fields in South Asia. He has done that. The event draws participants from dozens of countries. The tenth Chobi Mela is scheduled for February 2019.

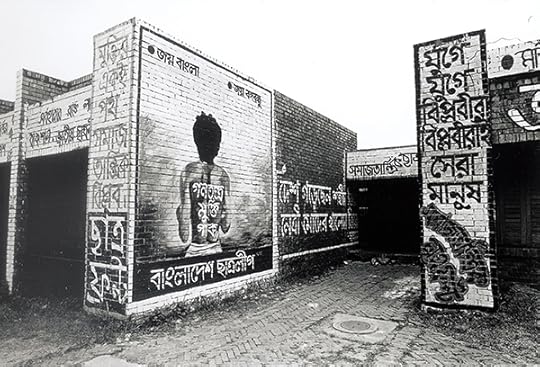

Shahidul Alam, Nur Hossain had written on his back “Let Democracy Live.” He was the first to die. A mural on a campus wall is painted in respect, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1990

© the artist/Drik Images

Since Alam’s arrest, social media has erupted with messages of support from around the globe, with the hashtag #freeshahidulalam. Dozens of international NGOs, among them Amnesty International, PEN America, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Human Rights Watch, have called for his release. Several petitions are circulating, including one by change.org. This and more pressure is needed to secure his freedom.

Alam will undoubtedly thank the thousands of people speaking out against his unjust detention. But he would also remind us, immediately, that protesting students and journalists have also been beaten and jailed. We should be advocating for them just as loudly.

Brian Palmer is a visual journalist based in Richmond, VA.

The post Demanding Justice for Shahidul Alam appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 8, 2018

The Tunnel is Made of Light

In a series of haunting Polaroids, Ryan Spencer draws upon neo-noir movies set in Los Angeles.

By Dana Stevens

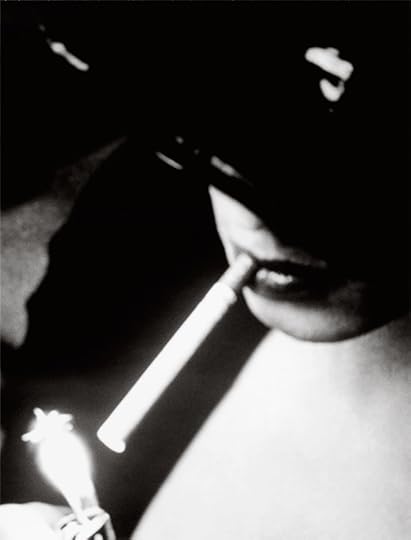

Ryan Spencer, Untitled, 2016, from the series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light

Courtesy the artist

In one image from Ryan Spencer’s recent series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light (2016), a man holds up a camera to the lens, as if to photograph the viewer. At least, we assume, based on the blinding white circle emanating from the object in his hands, that it must be a camera. In Spencer’s work, light obscures as much as it illuminates.

Ryan Spencer, Untitled, 2016, from the series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light

Courtesy the artist

These pictures, taken with a 1970s-era Polaroid Land camera using Fuji FP-3000B instant film, capture still images from dozens of neo-noir movies set in Los Angeles. In this encounter between black-and-white camera and color TV screen, light takes on unexpected forms, sometimes enshrouding entire images in a pale gray wash—as in an image from Brian De Palma’s The Black Dahlia (2006) of a figure, perhaps a child, whose face and shoulders are barely discernible through a thick veil of what looks like smoke or fog—and sometimes creating a lens-flare halo that renders an otherwise sinister figure weirdly beatific. Such effects distort or mask the stills’ original meanings—Which movie is each image from? Does knowing the answer make a difference in how you see it?—and place them in the service of a new, obscurely glimpsed narrative. The ambient glare can suggest an interrogation room, a crime scene, or a traffic pull over. Spencer chose only movies made in the 1990s or later for a reason: reminders of the civil unrest at that time in Los Angeles, of the trial of O. J. Simpson and Los Angeles Police Department officers’ brutalization of Rodney King, thread their way through these unsettling photographs, many of which seem to either precede or immediately follow some decisive instant of transformation, be it sublime or terrible.

Ryan Spencer, Untitled, 2016, from the series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light

Courtesy the artist

The city whose archaeological traces these images show us, filtered first through the medium of narrative cinema and then through the gaze of one Polaroid-wielding viewer, never properly existed, on-screen or off. LA comes to life— lurid, uneasy, often menacing life—only in the meeting of these two recording media and the excess of luminosity their encounter produces. The photographs that stay with me most from this haunting series affect the viewer like the glowing eyes of a coyote in a still from Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004): they are both sources of light and holes into which our gaze disappears. Whether it emanates from a gun, a cigarette lighter, a glittering nighttime cityscape, or a mysterious offscreen source, the light in No Light functions as a doorway to some other space, behind or beyond the image itself.

Ryan Spencer, Untitled, 2016, from the series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light

Courtesy the artist

This conversation between photography and movies was initially sparked by neither medium, but rather by a piece of music—Black Love, the 1996 Afghan Whigs album— that struck Spencer as “incredibly cinematic in its themes. I always thought of it unfolding as the suicide note of a doomed protagonist, sort of the way that Sunset Boulevardis told from the point of view of the narrator who we see floating dead in the pool.” The images in No Light arrive from a similarly impossible place; if they do form themselves into a story, it’s one told by a ghost.

Dana Stevens is the movie critic for Slate.

Read more from Aperture, Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Tunnel is Made of Light appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 3, 2018

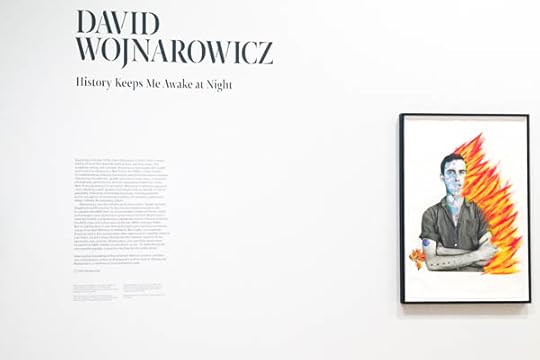

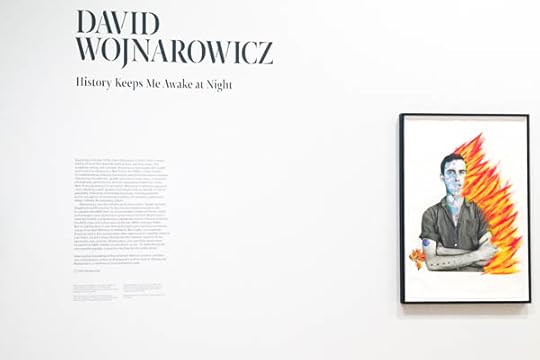

Inside the Revolutionary Work of Artist and AIDS Activist David Wojnarowicz

On July 25, Aperture Members joined the Whitney Museum of American Art for an in-depth discussion and exploration of the work of controversial artist, writer, and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz in the full-scale retrospective exhibition History Keeps Me Awake at Night, on view through September 30, 2018, at the Whitney.

Members connected with Wojnarowicz’s graffiti, sculpture, film, conceptual photography, and profound neo-expressionist paintings, which document and illuminate outsiders, friends, lovers, and strangers affected by government inaction and conservative politics in the 1980s through the 1990s. The symbols and images in Wojnarowicz’s art not only break through to an authentic reality, disrupting the oppressive social order of the time, but also celebrate beauty, love, and the natural world.

The tour concluded with Wojnarowicz’s iconic letterpress edition, Untitled (One Day This Kid…) (1990–91), featuring an image of the artist as an innocent and smiling child, encompassed by bold text describing Wojnarowicz’s dysfunctional family, and the condemnation of societal homophobia the boy in the photo will inevitably endure in his life because he is gay.

Aperture’s book Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, begun in collaboration with Wojnarowicz before his death in 1992 and first published in 1994, engaged what the artist would refer to as his “tribe” or community. Brush Fires is also the only book that features the breadth of Wojnarowicz’s work with photography.

Aperture Members receive an up to 30 percent discount on publications, such as Brush Fires, and meet up with other photo-enthusiasts, editors, scholars, and photographers at events in New York and beyond. Click here to join our growing community and receive invitations to experiences like this one.

The post Inside the Revolutionary Work of Artist and AIDS Activist David Wojnarowicz appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 2, 2018

A Pioneer of Latinx Identity

Laura Aguilar’s unapologetically queer bodies.

By Yxta Maya Murray

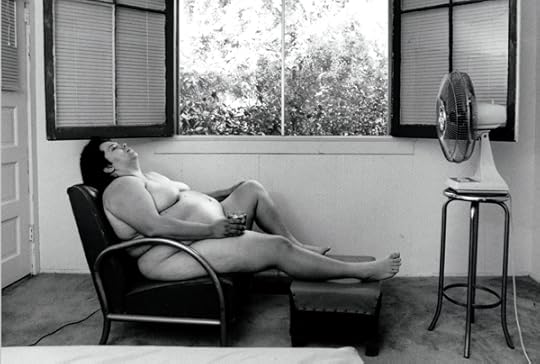

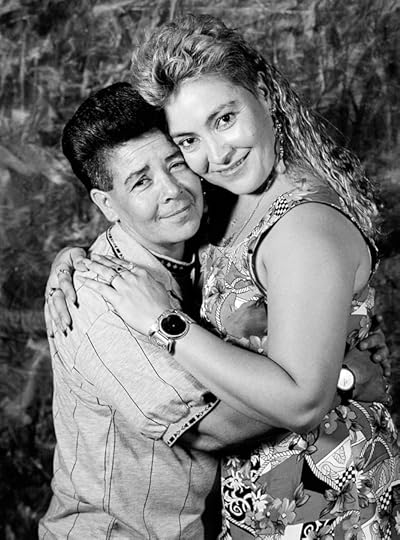

Laura Aguilar, In Sandy’s Room, 1989

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Photographer Laura Aguilar was one of the pioneers of Latinx identity. In her fin de siècle pictures, Aguilar depicted “Latina lesbians” in pompadours, families all cuddled together, and nonbinary babes showing off their bodies. In creating this community of images, she left us a foundational text for how we invent and collaborate on brown selfhood today.

Laura Aguilar, Plush Pony #2, 1992

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

The term “Latinx” first appeared on the web around 2004, according to scholar Arlene B. Gamio Cuervo. The term descends from the appellations Latina/o, Xicanx, Chicanx, Latin@, and Latine, which rebelled against the gender-assuming “Latino” and “Latina,” and the grumble-inducing but always popular “Hispanic.” Latinx evokes a pan-gender brownness that possesses blurry edges, queer sensibility, and an intersectionality of affections and oppressions.

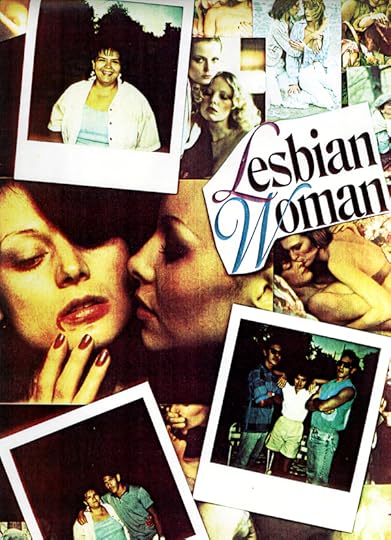

Laura Aguilar, Xerox Collage #2, 1983

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

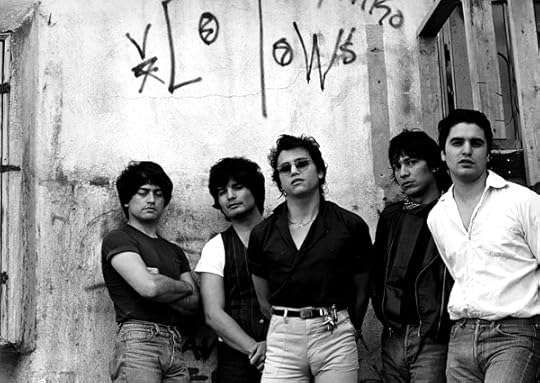

Today, these values are expressed by artists such as the conceptualist Rafa Esparza, who makes built environments out of tierra alongside his father, who had expressed discomfort with Esparza’s sexuality. They also imbue the photo art of Guadalupe Rosales, whose work engages found snapshots of manifold Latinx party crews, as well as that of trans musician/banshee Elysia Crampton and critical race burlesque performer Xandra Ibarra. Each of these creators burns down the cells in which supposedly discrete Latin American personas have been segregated. In so doing, they live out some of “Latinx”’s promise, which was imagined decades earlier in Aguilar’s coruscating photography.

Laura Aguilar, Los Illegals, 1984

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Born in San Gabriel, California, in 1959 to the Mexican American Paul Aguilar and the half-Irish Juanita Grisham, Aguilar was dyslexic, large-bodied, lesbian, and of a complex racial background. Around 1988, Aguilar produced the famous Latina Lesbians suite, which describes identity as an evolving community invention. In her own self-portrait, she’s shown smiling in her bedroom, wearing shorts and a cowboy hat. Beneath the picture, she’s written: “Im not comfortable with the word Lesbian but as each day go’s by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA.” And in Yolanda, an unsmiling, square-jawed heartbreaker, wearing jeans and a navy Izod polo, poses with her hands in her pockets. Under her image it says, “My latina side infuses my lesbian side with chispa & pasión.”

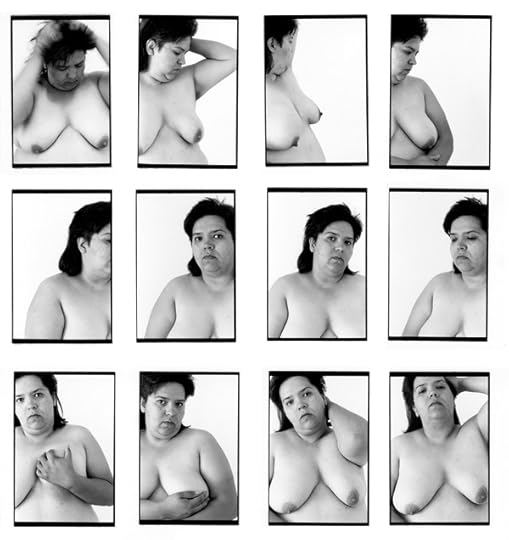

Laura Aguilar, Clothed/Unclothed #14, 1991

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Aguilar’s art gained energy and texture as the ’80s crested into the ’90s. In her early ’90s Clothed/Unclothed series, she represented a Latinx woman with a little sign reading “Fuck Your Gender” affixed to her vagina. Aguilar included this model within a panoply of other portraits that are naked, multiracial, queer, and beguilingly interfamily. From 1996 to 1999, Aguilar made some of her most well-known works: Her Nature Self-Portrait and Stillness portfolios reveal Aguilar undressed in the southern California desert, positioned next to rock pools, burned trees, and stone outcroppings. Her body’s lush curves and vibrant attitudes—arms up, dancing; standing with her hands on her hips and staring into the forest—do not hide the frailty of her skin, or the vulnerability of her breasts. To be a brown, gay, full-framed woman in the world takes courage, these images say, and you have to invent a self that the hegemony insists does not, and could not, exist.

Laura Aguilar, Plush Pony #15, 1992

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

With their gentleness and beauty, the Nature Self-Portrait and Stillness photos glimpse at Latinx melancholy experienced avant la lettre. These works cap off Aguilar’s decades-long study of the ways in which exclusion and anguish helped forge the brown and contingent self. In one of the installments of 1993’s Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt Her series, Aguilar stands nude before the viewer while mouthing the barrel of a gun: “So don’t tell her Art can’t hurt,” she printed neatly beneath the portrait. “She knows better. The believing can pull at one’s soul. So much that she wants to give up.”

Laura Aguilar, 12 Lauras, 1993

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Aguilar created other narratives of agony, too—the 1990 Three Eagles Flying shows her standing before a black background, with her head wrapped in the Mexican flag, her breasts bared, the U.S. flag tucked around her waistline, and a rope tied around her throat. And Aguilar fearlessly demonstrated how poverty and neoliberalism shaped identity with their own carving knives in 1993’s Will Work for #4, which portrays her standing under the word “Gallery” (perhaps she was at Santa Monica’s Bergamot Station) and holding up a sign that says Artist Will Work for Axcess.

Laura Aguilar, Stillness #25, 1999

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

In the way back of the ’80s and ’90s, Aguilar taught us that living as Latinx meant looking hard at what’s within, while also reaching out to the larger world. Like the writings of Audre Lorde,Cherríe Moraga, and Gloria Anzaldúa, her work presaged the vision of contemporary artists who embrace unbounded community, not to mention the intersectional activism of Black Lives Matter and #NoBanNoWall. Aguilar died tragically at the age of fifty-eight in a hospice in Long Beach, California, on April 25, 2018, and deserves to be remembered as a foremother of the modern Latinx state. Without her photographs, this morphing and creative identity would not exist in its current form.

Yxta Maya Murray is Professor of Law at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, and the author of the novels The King’s Gold (2007) and The Good Girl’s Guide to Getting Kidnapped (2010).

The post A Pioneer of Latinx Identity appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Camera as Portal

Shani Jamila, Larry Ossei-Mensah, and Teju Cole discuss travel, mobility, and the meaning of images.

By Laura Raicovich

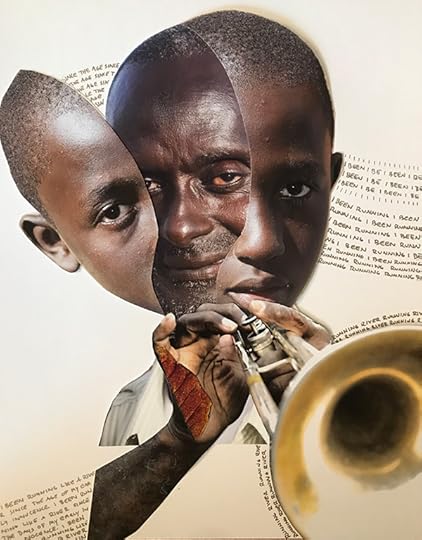

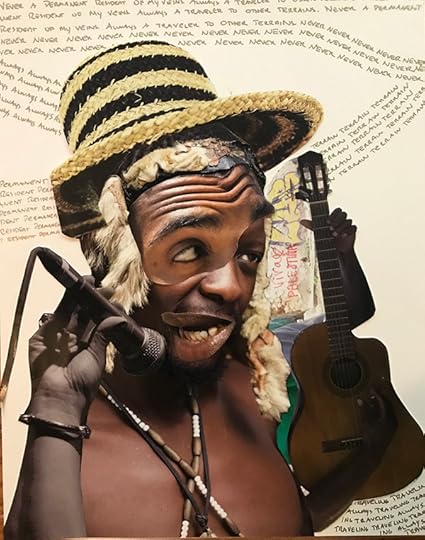

Shani Jamila, Been Running Like a River, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Sitting on one of the easternmost shores of the United States, I close my eyes and listen to the Atlantic surf. Round and tumbling, like wet fabric flapping in strong wind. I am thinking of the violence witnessed by this ocean and this shore. This meeting point of water and land brought people ready to claim territory for a faraway king, not caring that Algonquins and so many other native tribes had lived on this terrain for thousands of years. The colonists also captained boats of human cargo from Africa to create wealth for themselves and the monarchy. Waves of immigrants from the world over have made their homes here. Every day people continue to cross invisible borders to seek a better life; many are making forced migrations brought about by the realities of power, war, and wealth exerted upon them. With the water in front of me, I’m thinking about how to live on these shores in the wake of these histories that are so very present.

Artist Shani Jamila has her own answers, answers that center diaspora and mobility, physical and intellectual, in photographs and collages that capture people and landscapes in foreign lands, as well as here in the United States. Having traveled to nearly fifty countries, she tells stories and makes meaning of the structures we have created to see ourselves and our differences in this globalizing world. The photographs and collages are both documents of travel and a visual journal of her thinking through space and time. The collages mash up faces, eyes, noses, and surreal abstractions of the human body, many of them making music, connecting what is similar and familiar rather than foreign. They represent the pleasure of movement, and they are resistance.

Jamila’s solo exhibition Portals (2017–18) has a title both evocative and profound. I imagine the portal of her camera, door to other lives and new experiences, even the door of no return, the edge of precarity and loss, the unknown. These are her gifts to her viewers. In the spirit of the exhibition, Jamila, curator Larry Ossei-Mensah, writer and photographer Teju Cole, and I got together to talk about the show, photography, meaning, and travel. What follows is an edited excerpt of this conversation that addresses mobility and its implications, particularly for black bodies in our times, and the meaning of images produced by Cole and Jamila. Both, in their diaristic approach to photography, contend with how constructions of home, borders, and nationality, among other intensely felt notions, are largely figments of imagination that, while powerfully experienced, are equally slippery when parsed. Further, Jamila and Cole both confront subjective and objective visibility of themselves as photographers, seers, and artists. The result is a complex discussion that emerges from the wake, in Christina Sharpe’s terms, often asking: “How are we beholden to and beholders of each other in ways that change across time and place and space and yet remain? Beholden in the wake, as, at the very least, if we are lucky, an opportunity (back to the door) [back to the Portal] in our Black bodies to try to look, try to see.”

Shani Jamila, Ulises Double Portrait, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Laura Raicovich: Shani and Larry, you both grew up in the States, right?

Shani Jamila and Larry Ossei-Mensah: Yes.

Raicovich: And Teju, you came to the United States when you were seventeen, having grown up in Lagos. How is your experience of travel inflected by that personal history?

Teju Cole: Larry grew up with African parents in the US, Shani grew up with African American parents, I grew up with African parents in Africa . . . But we three very much have a share in a kind of black global cosmopolitanism that becomes the lingua franca between us. The first fact is that we’re black and traveling.

Ossei-Mensah: A lot of my travel has been guided by curiosity and a desire for understanding. I do a lot of listening. I visit with artists and try to figure out how I extrapolate what I’ve learned and put that into the work that I do, whether an exhibition or essay.

Jamila: No matter how many times I step on a plane, I never get jaded about the idea that we’re able to traverse from one part of the world to another in a matter of hours.

There’s a privilege that comes with having an American passport in terms of our ability to be mobile, or the lack of a need for visas in a number of countries, or in terms of how you’re received once you get there. Once people hear your accent, sometimes the way you’re treated will change from the way the black folks who are indigenous to that country are treated. It can be jarring. So, it’s a privilege to travel, but then I think it also causes you to check your privilege internally.

Cole: That’s right. What’s particularly interesting to me is the impossibility of being a neutral black traveler. I think what we have to offer to history, historiography, to writing, to photography is our inherent subjectivity. If a lot of heteronormative white patriarchy is predicated on an impossible neutrality, we’re present to give light to that. When you walk into any library in any of the fine schools you folks have graduated from, 95 percent of the books are by straight, we’ll assume, white men. The standard pose is, these are the facts about this particular subject, I have no influence on any of this. When I started my work, it became clear to me that objectivity was neither interesting nor possible.

Jamila: It’s a pretense.

Cole: We know that we cannot leave behind our subjectivity, nor the subjectivity of our interlocutors, because we’re always already subjective. That’s what it means to be black in this country, to be in a position that isn’t the mainstream, and then that inflects every travel experience.

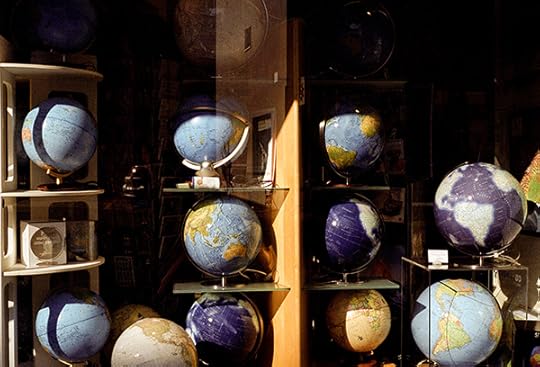

Teju Cole, Zurich, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Raicovich: Is the representation of that subjectivity happening through the photograph?

Jamila: The way that’s influenced me as a photographer is that when I’m making portraits of people, I’m aware of what it means to be a subject who’s been objectified as well. So I pay attention to the cultural context in a specific country and their cultural attitudes around the idea of photography. Because even the language of photography is often very imperialist: I’m taking your picture, I’m capturing this image.

Cole: Or militaristic: I’m shooting you.

Jamila: Right.

Cole: I’ve got you in my sights.

Jamila: Yes . . . there are all these things to be aware of and to negotiate.

Shani Jamila, Matanzas, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Raicovich: One of the remarkable things that bridges Shani’s and Teju’s work is a commitment to a very specific type of storytelling: a storytelling that is not facile. It is certainly legible, but not uncomplicated. It’s demanding of us, and requires a commitment to a type of image-making that is both evocative and without nostalgia for places traveled and people encountered. I want to explore why this might be so.

Cole: One of the really fascinating things about photography is its testimonial quality. Every photograph seems to declare, “I was there when it happened.” In an effort to subvert that, I’m usually there when nothing happens. Even when something is happening, I’m turning to the part where nothing is happening, because the stillness of the ongoing indecisive moment can be more revelatory.

But, you also simply cannot escape the fact that we carry cameras with us all the time, and working in this quasi-testimonial, quasi-diaristic form means that you’re actually catching a lot of life on the fly.

Shani Jamila, Long Live, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Ossei-Mensah: I think Shani’s photographs bring you closer to her. They’re a portal to how she’s seeing the world, how she’s experiencing the world, and how that’s shaped who she is as a woman right now.

Cole: I think one of the strongest things that immediately comes across is the sociality, maybe even the extroversion, of the many people you’ve encountered. But then, there is definitely a sense of you that’s somehow embedded in there. When you look at a photo, the body of the photographer is implied, even if not present, because somebody’s going around doing that and seeing things. Photos have to be—they generally have to be the result of adventure. One must be in the world making images.

Jamila: This idea of implied bodies also undergirds my collage work. They are largely sourced from portraits that I’ve made in the course of my travels and merged into surrealist images. I want to catalyze conversations about what it means to be at home and how identities are formed in a globalizing world.

Even in my film that’s playing in the back room [of the Portal exhibition], Altar—there’s a point midway through where my body leaves and then all you see is shadow and silhouette.

Raicovich: So, you’re denying it, you’re denying access.

Jamila: My body is interchangeable, almost as an avatar. The film was shot in three different locations throughout Italy. I wanted to find places that were once sacred, but they’re now desecrated or no longer considered sacred. It felt like an apt metaphor for our bodies in this country. I inserted myself into these spaces and this organic sort of processing began.

I was far away from the US at a moment where I felt like, as an artist, I needed to be able to give witness and to document and to fight for our human rights—the most fundamental of which is the human right to life.

Cole: You have images in here that are not simply taken by you, but in which you’re the subject. It’s like you’re saying that you’re not going to pretend that there was a disembodied eye that took these. In fact, here you are in the picture, a picture either taken automatically by the camera or with the help of someone else. And so, you’re asserting that what actually matters is not to press the shutter, but the agency involved in selection.

Jamila: Right. It’s all stills—everything in this exhibition is photo based, whether it’s the collages or the film or the photos themselves. They’re all part of a multilayered conversation about what it means not just to preserve ourselves, but then also to be in response, constantly, to whatever it is that’s happening in the world . . . in any given moment, in any cultural context.

Teju Cole, Black Paper, 2017. Performance at Performa 17, New York

Courtesy Shani Jamila

Raicovich: I want to connect what Shani said about the film and using your physical body in space to Teju’s recent performance at Performa 17, Black Paper.

Cole: I had to put my body out there and express the fact that this was a moment that called for an extreme experience. It was a question of, what’s actually at stake here? Bodies are at stake. And it is visceral, it is physical, it is corporeal, it is personal, it is on your skin. The anger is in my body when this guy’s trying to like gin up violence against Muslim people who are our families and our neighbors. That anger is not just for me.

A lot of it was thinking about what is happening in darkness, what is visible in darkness and what’s not. So, very much a burial in fact.

Jamila: They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds, as the saying goes.

Cole: I find myself thinking about ancestors a lot more, just because we need help. One’s own personal ancestors, but then there’s questions of people who spoke to the moment.

A friend texted me like, “Man, fuck all this! All I can deal with right now is John Coltrane.” People are really desiring quality, like sitting with friends and listening to Nina Simone. You want somebody who’s really speaking to the deeper thing.

Jamila: Well, it’s necessary to just remember ourselves. We’re not all fight all the time. Like who are we when we’re not just engaged in this battle? And so, Nina Simone and John Coltrane will save your life.

Cole: Saved mine.

Jamila: Yeah, mine too.

Teju Cole is a novelist, essayist, photographer, and photography critic for The New York Times Magazine.

Shani Jamila is a Brooklyn-based artist, photographer, and cultural worker. A selection of her collages is currently on display at the Manifesta European Biennial of Contemporary Art in Palermo, Italy, through autumn 2018. Portals was on display at Art@UJC in Battery Park from October 2017 through March 2018.

Larry Ossei-Mensah is an independent curator and cultural critic and a cofounder of ARTNOIR .

Laura Raicovich is a writer and art worker based in New York City.

The post The Camera as Portal appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 30, 2018

Library as Studio

Where do artists go for inspiration? For some, it’s a museum, for others, it’s the stacks.

By Deirdre Donohue

Since 2010, thanks to artist Nayland Blake, founding chair of the ICP/Bard MFA program, I have had the privilege of teaching a class with the program’s advanced photographic practice students. Each autumn, I hand out blank catalogue cards and ask the MFAs to define the word artist on one side and librarian on the other. Then the cards are tucked away into an envelope and we revisit them in the last class of the semester. Over time, I have evolved my own definitions that are derived from these conversations—and still evolving.

An artist creates intellectually edifying (informative and inspiring) content of any kind.

A librarian creates enduring, intellectually mediated, and hospitable access to edifying (informative and inspiring) content of any kind.

The relationship between artists and libraries is one that cannot be well understood in such a simple exercise, but is one that I continue to explore.

What attracts artists to libraries as subjects? Often it is the notion of the library as memory—sometimes as an institution with the authority to select and preserve a canon, sometimes as a microcosm of all human society—and, as in the case of Taryn Simon, I would daresay that it is a celebration of the reorganization of knowledge that can/must happen within its walls.

In fact, there are many artists working in this space. I have selected a finite number of (mostly) photo-based projects that utilize images of—or from—libraries as a springboard to exploring larger philosophical questions that libraries can serve to elucidate.

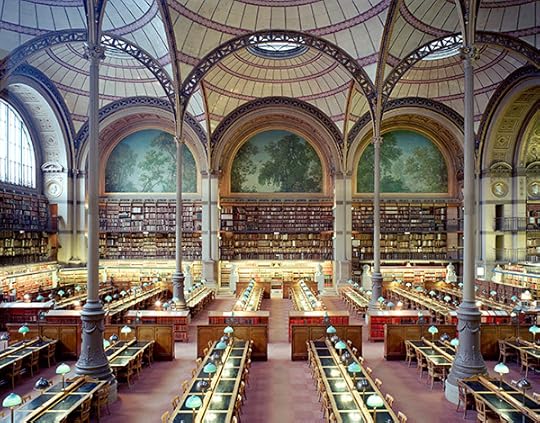

Candida Höfer, Bibliotheque nationale de France XXIII 1998, 1998

© the artist, Köln / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Alain Resnais, Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956

Toute la mémoire du monde (All the world’s memory) is a meditation on the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) with a thoughtful script by Remo Forlani. The film declares the BNF, as France’s national library, to be encyclopedic—and not just an encyclopedia of a single European nation, but of the entire world as seen through the acquisition of knowledge and goods that characterizes colonialist enterprise.

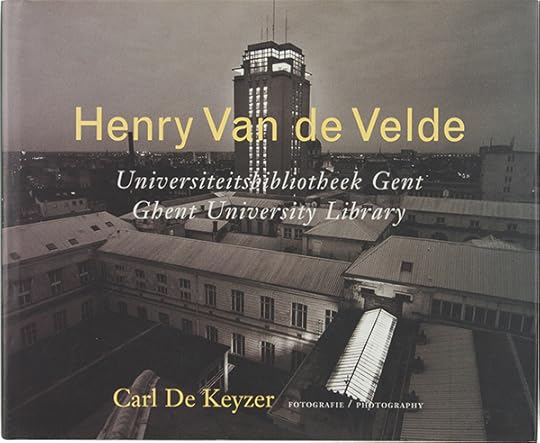

Carl De Keyzer, Henry Van de Velde: Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent/Ghent University Library 1797–1997

Ghent University Library, 1997

Carl De Keyzer, a Magnum photographer, was commissioned to document the two-hundredth birthday of the Henry Van de Velde Library in Ghent, Belgium, much as Alain Resnais commemorated the Bibliothèque nationale. The resulting images have a marked affinity: dramatically lit, dark, Gothic. It is actually a view of a library as a chaotic storehouse, and portrays its stewards and researchers in a kind of mannered way, with deep shadows and awkward moments of research and unconscious thought.

Philipe Gronon, Catalogue de la table des matières (A–Z), 1996

Philippe Gronon, Catalogue de la table des matières (A–Z), élément no. 4, Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée nationale Paris, 1996

French photographer Philippe Gronon is a keen observer of utilitarian objects that are mysterious or generally unnoticed, yet stand in as symbols of a collective past. Two of his eponymous series of such objects portray those ubiquitous, mysterious elements in libraries called card catalogues, and reading/writing tables, which bear the subtle marks of human intellectual effort over time.

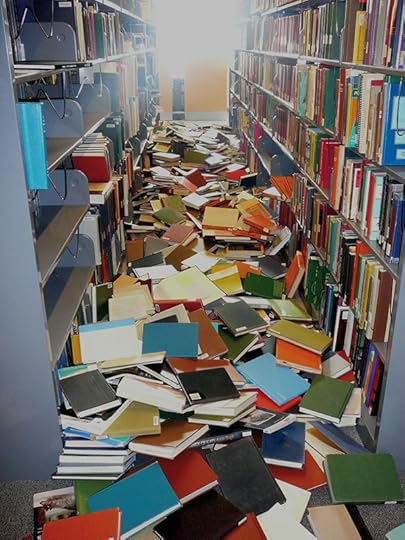

San Jose earthquake, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Public Library, San Jose, California, October 30, 2008. Image by Carole Correa-Morris

Melissa Dubbin and Aaron S. Davidson, Fallen Books , 2008

Fallen Books, published by onestar press, is a collection of images taken not by the artists, but by the discoverers of libraries after earthquakes have shaken them. Each photograph is catalogued according to the level of the earthquake on the Modified Mercalli scale, and its location. While it is an index, and there is evidence of humans, it is chiefly a thought experiment about one very specific condition of stewardship: that libraries strive for order within chaos, but also preserve the documents of that chaos and add it, in order, to the shelves.

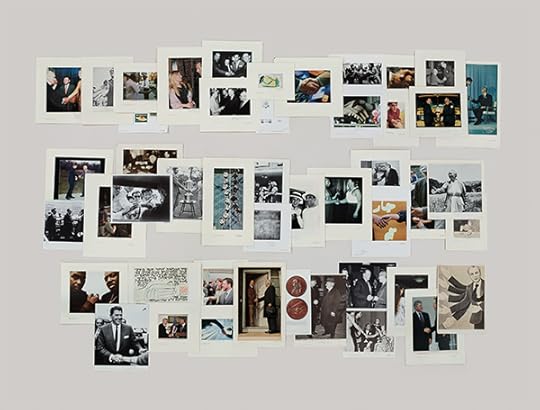

Taryn Simon, The Picture Collection, 2013

Taryn Simon, Folder: Handshaking, 2012

© the artist, Courtesy Gagosian

Taryn Simon’s series The Picture Collection is a conceptual project that turns out to be a love letter to the work that librarians do. Simon is an artist who researches, studies, and reads thoroughly into each one of her projects, so we cannot be astonished by the depth of what went into her elegant, formal exhibition of the selected folders: an examination more of the taxonomy underlying the collection, studying its archives, selecting folders, and simultaneously developing the online database Image Atlas, created by Simon and the late computer-programmer Aaron Swartz.

Deirdre Donohue is the Managing Research Librarian in the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs of the New York Public Library (NYPL). Prior to joining the NYPL, she was the Stephanie Shuman Director of Library, Archives, and Museum Collections at the International Center of Photography in New York.

The post Library as Studio appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Editor’s Note

Libraries multiply the audience for a book—almost without limit.

By Dierdre Donahue

In October 2017, the Tate announced the acquisition of a remarkable collection of photobooks. These books are known to many photobook enthusiasts because a considerable number of them are included in the marvelous series The Photobook: A History, written by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, as well as in some regional examinations of photobooks in Latin America and China. Parr and the Tate (with the support, in part, of Maja Hoffmann of the LUMA Foundation) have made it possible for Tate Library visitors to study these photobooks in person, turning the pages, comparing them side by side, making their own microscopic discoveries.

Having spent half my career as a librarian at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, a school and museum of photography, I have naturally thought deeply about photobooks in libraries, as well as libraries’ relationship with artists. Libraries and photography have been dancing together since Henry Fox Talbot and Anna Atkins recognized the medium as especially well suited for reproduction and, once those reproductions were bound together, as a vehicle for the distribution of information. Many photobook collections, in institutions such as the New York Public Library and the British Library, accidentally became great photobook libraries because of the pervasive use of photography as the kind of information that libraries aim to collect comprehensively. When we think of Eugène Atget or Walker Evans, we don’t think of them as suppliers for picture collections in libraries, yet that is what they were. Photobook libraries can also begin as one collector’s passion, transferred by some means into an institution and then appended with the results of others’ passionate collecting. The institution’s stewards then make judicious decisions about how to keep the collection safe, make it discoverable, and continue to add to it.

The greatest part about the young medium of the photobook is that it is so vast that it’s impossible to know fully. Every day I learn of new wonders from the past, present, and even future. This issue of The PhotoBook Review presents a few souvenirs of that daily serendipity: friends I have met in the library, books encountered, and ideas that have percolated there.

For example, I was first introduced to the artist Ishiuchi Miyako by the wise ICP alum Hisashi Murayama, who gingerly handed me Apartment (1978) and said that it was the greatest photobook ever made. It is truly among them, I acknowledge, and I am excited to have a new essay by this remarkable artist to read, thanks to the collaborative ethos of 10×10 Photobooks, a group of photobook aficionados on whose board I have had the pleasure of serving for a number of years. Other former ICP colleagues have likewise impacted my expanding photobook knowledge. ICP faculty Stephen Ferry showed me early maquettes of the book that became La Batea, a work about gold mining written by him and his sister Elizabeth Ferry. I am delighted to have it reviewed in these pages. Ed Grazda, also an ICP faculty member and one of my wisest teachers, is also featured here, as an avid photobook collector. What a fortunate thing it is to be a librarian, where I learn from such brilliant people every day and get paid to do it!

With subjects such as artists and photobook libraries, the greatest challenge as guest editor was whittling down the choices to a rational number to include. The photobook repositories I survey range from very old and established ones to one that is merely months old. (It would be a great service to put together a really comprehensive guide, as the George Eastman Museum staff did for photography collections in 1998—but that remains a project for another time.)

At the New York Public Library, I think a lot about all the collectors whose collections formed the basis of the material we are handing over to new readers each day, and even more about who, in the future, will add their collections to the treasure trove guarded by the lions. Including collectors’ voices recognizes their part in the ecology of the photobook and library community. What I would like is for everyone who collects books feverishly, as I do, to never forget that libraries multiply the audience for a book almost without limit. It’s also worth noting that photographers too would benefit from thinking about libraries and collectors as a critical part of their community and audience—they can be an invaluable part of the support system for bookmakers everywhere.

Dr. S. R. Ranganathan, a mentor for all librarians, published his five laws of library science in 1931, and the fifth and final law is: “A library is a growing organism.” I think this tenet should both guide and check any collector—to grow and learn and create new relationships among items in the collection, and check that there is sufficient room to add to it and build its audience.

That is the spirit I hope fuels this issue.

Deirdre Donohue is the Managing Research Librarian in the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs of the New York Public Library (NYPL). Prior to joining the NYPL, she was the Stephanie Shuman Director of Library, Archives, and Museum Collections at the International Center of Photography in New York.

The post Editor’s Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 25, 2018

Shirin Neshat’s Dreamlands

An artist and filmmaker contends with Iranian identity.

By Negar Azimi

Shirin Neshat, Still from Looking for Oum Kulthum, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Shirin Neshat is an image maker of ample gifts. Born in Qazvin, Iran, she moved to California in 1974 to study art. In 1990, eleven years after the (fateful) Iranian Revolution, she returned to Iran and soon began work on her debut photographic series, Women of Allah (1994). Like poetry to decipher, these stark black-and-white portraits of women, many of whom have text inscribed on their bodies, offer up complex emotional registers. Some of her subjects carry firearms, evoking a battle recently waged, or a battle to come. Since then, Neshat’s work has taken a zigzag journey from photography to video installation and, finally, to cinema.

Few artists have made such a seamless transition to creating feature films, and yet Neshat makes her restless movement between forms appear natural—necessary, even. From one work to the next, the aura of Neshat’s distinctive signature remains. Some critics have burdened her work with the specter of speaking for or about the fates of women, or women from the Middle East in particular. But a true accounting of Neshat’s art, and the rich range of her references, reveals that ambiguity is the land in which her work resides. As a self-described nomad, Neshat says, “we have this ability to approach different places and people and subjects and make them our own.”

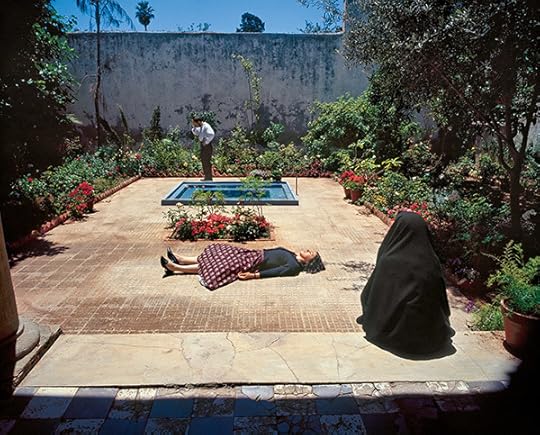

Shirin Neshat, Stills from Women Without Men, 2009

© the artist and courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Negar Azimi: Shirin, as an artist you’ve brought images into the world that are burned into the mind. They’re literally stuck—certainly in my own. They’re images of such iconicity, of such jaw-dropping beauty and enigma. I’m thinking, for example, of the stark juxtaposition of the male and the female singer in Turbulent. Or Rapture, in which you see women marching defiantly into a murky sea. Your gift for composition is significant, and you’ve created a visual vocabulary that I think is all your own. Where do these images come from?

Shirin Neshat: I think that at root I’m an image maker and the images I’m drawn to are paradoxical, full of contradictions. Perhaps the only way I can explain it is that this is how I feel about everything around me. I feel like I’m full of contradictions, life is full of contradictions, and there’s a good and bad in everything. I never see anything in between.

Shirin Neshat, Still from Looking for Oum Kulthum, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Azimi: Your images are emotionally potent, but ambiguous too. Those women marching into the sea—are they running away from something? Or are they walking into the sea because they want to? Is the woman in the unforgettable first scene of Women Without Men flying, or is she in fact falling? That ambiguity is part of the power of your visual language.

You made an evolution from being a still photographer to authoring filmic videos and video installations. Now you make cinema. First, can you tell me a little about how you came to be a photographer?

Neshat: I guess I’ve become very good at building a profession out of things that I’ve never studied or had formal training in. This doesn’t mean that I’m naturally talented at any of them! But I do have a tendency to experiment. When I was making the series Women of Allah, I was not a photographer, but I was really struck by the power of the photojournalism that had documented the Iranian Revolution. No painting, sculpture, movie could have captured the spirit of the religious fervor.

Then, slowly, I moved from making images that had this borderline photojournalistic approach to storytelling, but without really knowing how to do it. I think the video installations in some ways prepared me. Videos like Rapture or Turbulent were like moving photographs; there was no real logic of filmmaking to them. Slowly, I had a protagonist. Then I had a beginning, middle, and end. There was a real director behind the vision. Over time, my work became more cinematic, and I felt like trying to tell a story rather than just create an environment. That led to my first entry into filmmaking, which was Women Without Men (2009).

Shirin Neshat, Still from Women Without Men, 2009

© the artist and courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Azimi: You note that images of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 were consequential, and somehow led you to the medium of photography. I immediately conjure Abbas’s haunting photographs of the revolution and its aftermaths, and Bahman Jalali’s too. But outside of that moment, what was your visual coming of age like? What marked or influenced you?

Neshat: Most of my young adulthood was spent in the United States, so my education was very much Western. I was away from Iran for so long, and was out of touch with what was happening there culturally. I was most influenced by American or European photographers, and Western art history. Later, I started to go to Iran. I was curious about the revolution and the changes taking place in my family. I spent a lot of time speaking to friends who had become involved with the revolution. But I wasn’t really in dialogue with artists. My family wasn’t really artistic.

When I came back to the United States, I worked at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, and I was around people like Kiki Smith, Mel Chin, Vito Acconci, and David Hammons. My mind and life were divided, literally, between the bohemia of New York and what was going on politically in Iran.

Later, my life changed again. I now had an Iranian partner, my collaborators became Iranian, and I studied Iranian cinema. I began to see the similarities and differences between how I made sense of the revolution and its legacies, and how those who had lived in Iran made sense of it all. I saw a vast difference. I have a more diasporic or exilic … a kind of accented point of view. And a very Western, absolutely conceptual approach—never, ever to do with realism. So what I’m trying to say is that my New York life had everything to do with the evolution of my ideas. My subjects were Iranian, but I was never really inspired or influenced by Iranian artists.

Shirin Neshat, Still from Looking for Oum Kulthum, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Azimi: The question of influence is endlessly interesting. At the moment I’m thinking about the late avant-garde theater director Reza Abdoh, who was also of Iranian American background. And not unlike with your own work, there are many competing claims on his. Some say that his work was influenced by aspects of Shia Islam, like the Ta’ziyeh passion play. Others look at it through the lens of Artaud and his theater of cruelty. And yet others argue that it’s just deeply American, more informed by American TV than anything else. So the question is, can it be all of these things? Can one’s work be a collage, especially for someone like you with, as you said, an exilic background, a sort of pastiche of influences?

Neshat: Influence is such a mystery. I do believe there are elements in my work that have to do with my experience as a kid in Iran. I left when I was seventeen. But I feel like that Iranian part of me has deeply informed my work nonetheless, even though I’m very American too.

To continue reading, buy Aperture Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Negar Azimi is a senior editor of Bidoun.

The post Shirin Neshat’s Dreamlands appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 18, 2018

Photographs Do Not Stop Wars

The celebrated photojournalist James Nachtwey has covered global conflicts for four decades. But in his current retrospective, politics is an afterthought.

By Wilco Versteeg

James Nachtwey, A Palestinian throws Molotov cocktails at Israeli army troops. Occupied Palestinian territories, Ramallah, West Bank, 2000

© James Nachtwey Archive, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

Memoria, a large-scale retrospective at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, provides the occasion to review James Nachtwey’s era-defining, forty-year career. The exhibition presents 139 large, framed prints from a body of work that covers disease, war, famine, and death, from South Africa and Palestine to 9/11 and American prisons. On the heels of these riders of the apocalypse, we are led along Nachtwey’s signature-style photography: beautiful, close-to-the-bone images of immense suffering in high-contrast black and white or saturated color. One cannot help but be amazed by Nachtwey’s outlook and his sensitivity to what makes a great photograph. Yet, while Nachtwey’s astonishing oeuvre has accrued credulous praise over several decades, it’s essential to retain a critical eye and consider the chilling discrepancy between the intentions of this exhibition and the actual presentation of the work.

James Nachtwey, A bedroom becomes the frontline in a brutal civil war. Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1993

© James Nachtwey Archive, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

Nachtwey fashions himself as a witness who sets out to photograph the crises that are tearing the world apart. In Memoria, we encounter the clichés and myths often associated with war photographs: victims regain their dignity through photography; viewers cannot help but feel compassion; and, by looking at the horrors of the past, viewers will not forget what happened. The act of memory is elevated here to an inconsequential political gesture: passive remembrance, it seems, takes the place of active political engagement. However, at MEP, the actual political context is relegated to a booklet. The accompanying catalogue, consisting of images and a celebratory essay, struggles with the same lack of in-depth context. The various sections of the exhibition are announced on the wall, but besides some quotes by and on Nachtwey, the exhibition space does not provide any didactics.

This radical separation between the photographs and their context evacuates the political from images that are nothing if not political. For instance, one theme in Memoria is “Famines,” as if famine exists in and of itself and is not the result of a complex web of political and natural disasters. Upon consulting the booklet, we learn that the pictures shown under this category were taken in Sudan and Somalia between 1992 and 2004. Instead of allowing the viewer to engage with the history and politics of two distinct nations, these beautiful images are heaped on top of each other, leaving them to speak for themselves as politically powerless icons of suffering.

James Nachtwey, A mother stands at her child’s bedside. Darfur, Sudan, 2003

© James Nachtwey Archive, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

Seeking to portray a crisis in a comprehensive way, documentary photographers must use a familiar and accessible visual language. As Memoria makes clear, Nachtwey’s language is one of iconic transcendence, of the obliteration of the individual in the search for the universal. But that universalizing power also creates a weakness: the impossibility of entering deeply into the details of a conflict. Take, for example, a heartbreaking series on the intergenerational aftereffects of Agent Orange in Vietnam from 2004 to 2012. Natchtwey’s images of parents and their disabled children beg for contextualization that is otherwise lacking throughout Memoria. The accompanying booklet provides some context, but seems to ascribe emotions and motives to those portrayed that are impossible to verify and that, to me, seem to fit too perfectly into Nachtwey’s discourse of dignity and compassion. A text in the booklet describing the Agent Orange series states that “workers and rice farmers with few resources and no available remedies have redeemed the outrage with caring and with love.” Heroic as it may sound, it seems to deny the suffering of these individuals. This is even more problematic because we are talking about the results of imperialistic warfare.

Memoria suffers from a reliance on the photographer as auteur. While in our daily media consumption, we often encounter photographs without being aware of who made them, in the exhibition space the photographer is promoted to an oracle, a mythical figure who through his experiences becomes a sage. Our understanding of documentary images is still too often determined by the terms set by photographers or their willing critics. Words become a stumbling block in understanding the work of one of the greatest war photographers the world has known. Why not heed D. H. Lawrence’s famous dictum “never trust the teller, trust the tale” for documentary photography too? By placing the photographer firmly in the exhibition’s center, and not the photograph, the possibility to understand the singularity and interconnections between the many conflicts Nachtwey covered is harmed.

James Nachtwey, A woman wanders the ruins of the city. Kabul, Afghanistan, 1996

© James Nachtwey Archive, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

Nachtwey’s work needs words, but not necessarily those of the photographer himself. A recent example that is not featured in Memoria is Nachtwey’s collaboration with Time in documenting the American opioid crisis: here abundant images are contextualized with interviews, providing an ingenious example of documentary storytelling for the twenty-first century. Other examples are Susan Meiselas’s recent exhibition at Jeu de Paume, Mediations, showing how some of her work became iconic through a complex process of international publications over the years, and how some images were used by the people they portray as a form of political empowerment—or Christoph Bangert’s book War Porn (2014), which invites the reader to investigate mechanisms of censorship and self-censorship. In both projects, the visitor or reader plays an active part, whereas in Memoria the viewer is kept at a distance, in awe in front of Nachtwey’s works. Activating the visitor by showing how these images were made, and how they became the icons they are, might have done more justice to the complexities of the production, distribution, and reception of contemporary documentary photography.

James Nachtwey, Ash, smoke, and shattered glass rained down on Lower Manhattan following the destruction of the World Trade Center. New York, 2001

© James Nachtwey Archive, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

We need to accept that photographs do not stop wars from happening, and do not feed those starving to death—that our remembering past conflicts does not prevent us from waging new wars, and that, bluntly said, those whose “dignity” we celebrate in photographs could not care less for our compassion while reading a newspaper or visiting an exhibition on a Sunday afternoon. While it has been repeatedly stated that images of the Vietnam war, for instance, galvanized protest and, thereby, show that documentary photography is politically relevant, academic research has not been able to prove that images played a role in starting or furthering protest. Rather, many of the war’s most iconic images were only published when critique of the war had become common currency among intellectuals and politicians, and was no longer seen as treasonous or unpatriotic.

Our fascination with and aestheticization of suffering should not be an end in itself, but instead a starting point in attempting to understand the intricacies of worldwide conflicts and our role in them. Memoria is, in fact, a moving-away from politics, from history, and from complexity. What remains are stunning images, high points in contemporary documentary photography, but how should we contend with that when war and suffering are involved?

Wilco Versteeg is a researcher in visual culture and war photography at Université Paris Diderot.

Memoria: Photographies de James Nachtwey is on view at Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, through July 29, 2018.

The post Photographs Do Not Stop Wars appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 17, 2018

Can You Hear Me?

Bouchra Khalili wants to make a platform for migrant and minority voices—but when do images become theater?

By Violaine Boutet de Monvel

Bouchra Khalili, Still from The Tempest Society, 2017

© the artist/ADAGP and courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris

In 1970, while presenting their newly formed Dziga Vertov Group to a packed audience at Yale University, the French filmmakers Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin compared their conception of militant cinema to the blank blackboard in the lecture hall: a space of possibility for all attendants to discuss and take part in the construction of knowledge. This anecdote inspired Blackboard, the title of Moroccan French artist Bouchra Khalili’s first survey, at Jeu de Paume in Paris. Made over the past decade, the ensemble on display includes two series of photographs, a series of silkscreen prints, and eight documentary projects running on small monitors or projected onto large screens, which together unfold over four hours of mostly single-channel video.

In the introductory wall text of her survey, Khalili cites Pier Paolo Pasolini’s civic notion of poetry as a major influence. During the Second World War, the late Italian writer and director started composing poems in Friulan—an endangered language spoken in northeastern Italy—to oppose the growing linguistic and cultural hegemony in his country. To varying degrees of success, Khalili has also committed her practice to giving a platform to socio-political minorities silenced all over the world: carrying discourses of unyielding resistance, no less than twenty-five languages and dialects can be heard throughout the exhibition.

Bouchra Khalili, Still from Mapping Journey #1, 2008

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

One example is The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), a multi-projection installation comprising eight videos concurrently running on four double screens, which are suspended from the ceiling in the middle of a dark room. Seven men and one woman, who were forced into exile for economic or political reasons, recount their clandestine journeys to reach Europe from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Palestine, Afghanistan, Sudan, Somalia, and Macedonia. Each account takes the form of a static shot displaying a map, onto which one of the migrants factually retraces the complex itinerary of his or her own perilous expedition. Only a hand appears on screen, maneuvering a red indelible marker, whereas their voices are relayed through a single pair of headphones per video. This creates a palpable sense of disconnect for the visitors deprived of sound while waiting for their turn, even though the speeches are also subtitled in both English and French. Despite this sense of detachment, the overall cinematic simplicity of this installation makes it the most engaging work on display. Not being able to see the narrators’ faces draws full attention to the uncanny twists and turns of the maps in the making, which reflect the true resilience of people willing to risk their lives to meet, perhaps, more favorable fates.

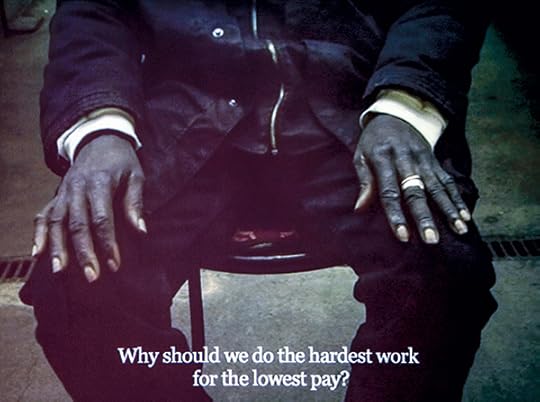

Bouchra Khalili, Still from Chapter 1: Mother Tongue, 2012, from The Speeches Series

© the artist/ADAGP and courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris

Unapologetic resistance continues in the video trilogy The Speeches Series (2012–13), which was produced in Paris, Genoa, and New York. Titled Mother Tongue,Words on Streets, and Living Labour, respectively, each chapter, playing on its own screen, shows five different people who share personal manifestos, touching upon their denied rights and citizenship as immigrants in their chosen countries. Most discourses were authored in English, French, Italian, or Spanish through preliminary one-on-one interviews with the artist, and the participants’ voices are relayed through two pairs of headphones for each screen. “America is a prison for its immigrants. The bars of this prison are injustice, racism, lack of moral values, and loneliness,” a man called Kante declaims in French about the life of hardship faced by undocumented workers in New York. “I don’t know what the American dream is, but now is not the time to dream, now is the time to rise up,” he fiercely concludes. From one portrait to the next, Khalili’s didactic use of video editing makes speech emerge as an emancipatory gesture. For instance, close-ups on the protagonists’ hands alternate with wider views of busy city streets, where discourses privately echoing one another finally unite in a collective voice.

Bouchra Khalili, Lost Boats, Fig. 2, 2012, from The Wet Feet Series

© the artist/ADAGP and courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris

Vestiges of resistance from recent, yet untold—if not forgotten—history inform all the photographs on display. In The Wet Feet Series (2012), realized in Florida, nine pictures of seemingly random stranded boats and rusted containers capture (metaphorically, at least) traces of the dreadful “wet foot, dry foot” policy, which applied to Cuban immigrants from 1995 to 2017. The ones who managed to reach the American shore were allowed a chance to stay, but if intercepted in national waters, they were immediately sent back to Cuba. The fifteen photographs of Foreign Office (2015) document the former, and now-deserted, headquarters of many liberation movements in Algiers. Throughout the 1960s, the city offered asylum to political opponents from all over the world, including members of the African National Congress and the Black Panther Party. As the authorities currently in place have favored different national narratives, this cosmopolitan part of Algiers’s revolutionary past is little known to younger generations.

Bouchra Khalili, Hôtel El Safir, Ex-Aletti, Algiers City Center. Residence of the Black Panther Party delegation during the 1969 Pan African Festival of Algiers. Fig 1: Entrance of the former casino, 2015

© the artist/ADAGP and courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris

Taking this into account, Khalili further explores if not the moral obligation, then perhaps the uncertainty of historical transmission in Twenty-Two Hours (2018). The forty-minute-long video brings together the figure of Jean Genet—the late French writer and activist who clandestinely traveled to the United States in 1970 at the Black Panthers’ request, in order to take part in the “Free Bobby Seale” campaign—and Douglas Miranda, a former Black Panther who was involved in Genet’s tour. Archival footage, shared memories, and Miranda’s interview are narrated and supposedly orchestrated by Quiana and Vanessa, two young African American women, prompting the audience to question the role of witnesses, in general, and the nature of their discourses.

Nevertheless, this video fails to properly engage the viewer, but not only because of its unsuitable duration for an exhibition context. (It is worth noting that the majority of these works, which are all scripted, could have benefited from a scheduled screening program, in order to garner proper attention. The longest one—The Tempest Society [2017]— runs for one hour alone, which feels rather unsuitable in the context of an exhibition, where on-the-move viewers might find it difficult to take in.) What’s more, the sharp grasp on reality that Khalili’s earlier works so strongly possess gets lost under thick layers of overly scripted, theatrical cosmetics, which turn all potential witnesses into amateur actors lecturing some play. Over the past three years, the artist’s theoretical fascination with the aesthetics of Pasolini, Godard, and Gorin appears to have reached a literal level. No matter how politically engaged her pieces’ participants are individually, their voices have become inaudible, and their subjectivities disturbingly subsumed by affected didacticism—ultimately raising the question that punctuates the entire survey: who really speaks when someone speaks?

Violaine Boutet de Monvel is an art critic and translator living in Paris.

Bouchra Khalili: Blackboard is on view at Jeu de Paume, Paris, through September 23, 2018.

The post Can You Hear Me? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers