Aperture's Blog, page 100

June 19, 2018

Inside Aperture’s Fifth Annual Patron Cocktail Party

Russet Lederman, Jon D. Smith Jr., Andrew E. Lewin, and Jeff Gutterman

Willard Taylor and Chris Boot

Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan addresses guests

Edward Messikian and Melissa O'Shaughnessy

Susanna E. Singer, Ren Martin, Cathy Kaplan, and Harriette Silverberg-Natkins

Scott Switzer and Maeva Freeman

Bernard Lumpkin and Aperture executive director Chris Boot

Maeva Freeman and Severn Taylor

Rita Anthoine and Mark B. Levine

Emily Grillo, Mary Ellen Goeke, and Thomas R. Schiff

Guests mingle at the home of Aperture trustee Willard Taylor and his wife, Virginia Davies

On Wednesday, June 13, Aperture Patrons, board members, and special guests gathered for the fifth annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party at the home of Aperture trustee Willard Taylor and his wife, Virginia Davies. As the sun set, guests enjoyed a cocktail reception on Taylor’s terrace overlooking the Hudson River. “All of this is in the cause of changing artists’ lives and exciting people about the narrative of photography,” Aperture executive director Chris Boot said during remarks. “In addition to sharing a passion for photography, photographers, and artists, we really enjoy the discourse and spending time together,” board chair Cathy Kaplan said of Aperture Patron events.

Aperture Patron events bring together Members, trustees, and photographers. To join Aperture’s Patron Program, click here or contact Jean Son at json@aperture.org or 212.946.7146.

The post Inside Aperture’s Fifth Annual Patron Cocktail Party appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 13, 2018

John Chiara: Experimenting with Photography

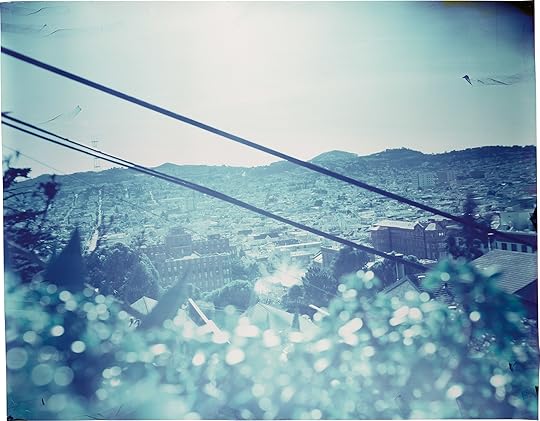

John Chiara, Grizzly Peak Boulevard at Claremont Avenue, Oakland, 2011; from John Chiara: California

(Aperture/Pier 24 Photography, 2017)

John Chiara, Kansas Street at 22nd Street, San Francisco, 2004; from John Chiara: California (Aperture/ Pier 24 Photography, 2017)

Join photographer John Chiara for a two-day workshop intended for photographers who are looking to have fun and experiment with photography. Whether you’re a novice, professional, or enthusiast of photography, this workshop will display a raw, hands-on, alchemist approach to the medium. Known for making large-scale photographs with hand-built cameras—the largest being 50 by 80 inches—Chiara will teach participants how to make one-of-a-kind images using a variety of cameras and techniques.

On the first day of the workshop, participants will photograph the New York City landscape using both large-scale, 4-by-5, and small pinhole cameras. Chiara will guide participants on how to set up the cameras, locate the perfect scene, and photograph the landscape. Using these techniques, participants will learn how to slow down their approach and take all aspects of the scene into consideration when making an image. Participants will spend the second day of the workshop in the darkroom developing their images. Chiara will teach participants how to work in the darkroom and develop their images using black-and-white processing methods. The workshop will end with a group critique back at Aperture. Participants will take home their own one-of-a-kind photographic print.

John Chiara (born in San Francisco, 1971) received a BFA in photography from the University of Utah in 1995 and an MFA in photography from the California College of the Arts in 2004. Chiara was Artist in Residence at Budapest Art Factory (2017); Crown Point Press, San Francisco (2006, 2016); Porch Society, Clarksdale, Mississippi (2013–14); Gallery Four, Baltimore (2010); and Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California (2010). In 2011 and 2013, the Pilara Foundation in San Francisco commissioned work that was included in two group exhibitions at Pier 24 Photography: HERE. and A Sense of Place.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Discover and learn how to use various cameras and methods of photography

Learn basic darkroom techniques

Create a personal one-of-a-kind photograph (that you get to take home!)

Materials to bring:

Participants will be notified regarding required materials

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $600 and includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of ten students is required to run this workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post John Chiara: Experimenting with Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Hidden Mothers

Through uncanny vintage photographs, Laura Larson tells a story of love and attachment.

By Carmen Winant

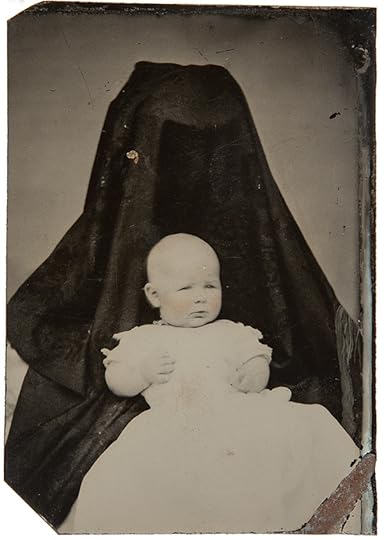

Photographer unknown, ca. 1860s–70s

Courtesy the collection of Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr.

When I moved to Ohio in 2014 for a teaching job, I had no idea what kinds of artists and friends I might encounter. One of the first people I came to know was Laura Larson, a professor of photography at Ohio University, who was living in Athens, Ohio. She gifted me her new book, Hidden Mother; I’ve been wanting to write about the way it moved me ever since. In the slim volume, Larson braids together her personal narrative of adopting her now nine-year-old daughter with a history of nineteenth-century photographs of “hidden mothers”: children propped up for the camera by their mothers, who are literally dislodged from the image through drapery, plate scratching, or other methods of erasure. The writing behaves at once as memoir, poetry, biography, and creative nonfiction, keeping company with the likes of Maggie Nelson, Sarah Manguso, Wayne Koestenbaum, and, of course, Roland Barthes. But its content, which moves through the tender and the uncertain to arrive somewhere in between, feels entirely its own.

Carmen Winant: I am struck by how, as you describe in this book, you came to meet your daughter through pictures. She was in an orphanage in Addis Ababa; you were across the world in Athens, Ohio. As someone who spent their life dealing in pictures—and perhaps being skeptical of their capacities to transmute truth or evidence—did this experience affect your understanding of photographs?

Laura Larson: I received approximately fifteen photographs of Gadisse during the legal process of the adoption with a two-month gap between the first photograph and the second set of images. Bear in mind I had already waited nine months while my application was being processed and that time had passed relatively easily. But, once I had an image, I became a mother, Gadisse’s mother, and she became my daughter. It felt real to me and disconcerting, too—extraordinary to feel this intense attachment based solely on a photograph. I’ve spent so much time as an artist thinking critically about the medium; I’m not a sentimental person, and here I was, drowning in affect! There’s a speculative aspect of becoming a parent, wondering who this little person’s going to be, what will their life be like? Gadisse’s photographs supplied a screen, a real face, for those projections. I struggled to navigate those fantasies, those questions, and those very intense fears because my rudder, my skepticism, was gone.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1920s–30s

Courtesy Laura Larson

Winant: I keep thinking of this line, toward the end of the book, when you come to meet Gadisse in person: “When we first met, I hesitated to pick her up, pausing at the threshold when we became real.”

Larson: Right. Strangers were making these photographs—government officials, agency employees, visiting families. I was jealous and sad because of the contact they had with her and here I am on the other side of the world with a few digital files. Those photographs varied wildly in quality since they were all made by amateurs and this added to the strangeness of the experience. I found myself getting frustrated. Get closer! Use the flash! You could really tell when the photographer spent time with her and when she was just another child of many who was documented. There’s one photograph of her—I don’t write about it in the book—where there’s a small dry-erase board propped in the frame with her name written on it. That picture destroyed me. All of this intensified her vulnerability for me, my distance from her. So, when I do finally meet her, here is this very real person and those photographs are a very faint approximation of her. I still recognized her but I didn’t know her at all. I had anticipated this but it’s something else to see and hold your daughter for the first time after looking at her photographs for seven months.

Winant: There is a direct relationship between photographic process and healing explored in these pages. You write of the early chemistry: “During the Crimean War, collodion was also used as a kind of liquid skin to dress and seal wounds on the battlefield.” I’m struck by this fact, that the same chemicals that were used to make the Hidden Mother tintypes were used to save lives, keep limbs together.

Larson: I was really taken by the idea of how collodion’s capacity to repair a body, to make it whole again, circled back to representation—in this case, of mothers, of mothers and children, of adoption. With the hidden mothers where the emulsion is scratched off, that’s a tear in the collodion, a wound. I’m thinking of the book as a form of feminist triage! The book mends these bonds that are disguised or marginalized or severed in the photographs. You can physically repair a wound and tend to psychological pain, but trauma steeps in the body and scars remain. It’s a way of thinking of healing in a more complete way, that it’s ongoing, never resolved.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1860s–70s

Courtesy the collection of Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr.

Winant: Can you speak to this in a more direct way, as it relates to your daughter?

Larson: Yes, this all comes back to the stream of photographs of Gadisse. I grew attached to her and the bond felt whole but that bond was predicated on some delicate psychological suturing. There’s another connection here too with the role of attachment in adoption. Attachment plays a fundamental role in child development but with adoption, it’s a critical aspect of healing. Forming a bond with a new parent is key to a child’s emotional health and their capacity to recover from trauma.

While I was writing the book, I took a workshop on wet collodion to get some insight into the process. This is where I learned of its role as a surgical binding agent. What I love about wet collodion is its messiness, its stickiness—there’s so much power in this liquid material. There’s something poetic about how bodily the process is; a comparison could be made to birth. Those plates stand for a physical touch between the photographer and the subject, which in turn echoes the touch of the subjects’ bodies. It’s moving to think about how healing can come from a substance so mercurial and how images—photographs of bodies—emerge from this fragile economy of light and chemistry.

Winant: Can you talk a little bit about the structural form this project takes? The short, interweaving sections recall Barthes’s figures, so notable in A Lover’s Discourse (1977). This form allows you to weave together distinct narratives: your own personal history, and a larger, photographic one.

Larson: Barthes looms large in this work—his notational forms, short chapters, circling structures, prismatic effects. There hadn’t been any scholarly writing about hidden mother photographs, so for a while, I internalized a pressure to position the practice within a critical framework. I realized at a certain point that the writing could be organized around my experience as a photographer, rather than as a historian or critic, and that was enormously freeing. I know the physical demands of making a photograph, that it’s a form of emotional exchange, and the ethical and political questions around representation, and the pleasures of experimenting with shooting and printing. I wanted my identity as a maker of photographs to run up against my identity as a mother-to-be.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1860s–70s

Courtesy the collection of Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr.

Winant: When did this book begin to come into focus?

Larson: The project was seeded by an essay I wrote when I was assembling my adoption dossier. I was introduced to the hidden mother photographs at the same time and I knew I wanted to tell the story through these images. The photographs were like a release valve for all my longing, a distraction from the situation at hand, and I could take shelter in them. I didn’t want to write a conventional memoir or a confessional. I’m an intensely private person, so considering its subject, I think it’s a reserved work. The photographs allowed me to spin out the different parts of the story.

Winant: Had the adoption been formalized when you began to write? So much of it takes place in the beginning months, the back and forth, the bureaucracy, the anticipation.

Larson: I actually wrote the book when Gadisse was four. We were still in the moment when childcare is so physically demanding. The adoption process is so disorienting, it would have been impossible to write the book when she was a baby. During those early years as a single parent, I had no time to make work, to get to the studio, but I could sneak time to write. Not that this is a small thing! When I was weaning her from co-sleeping to being in her own bed, I would sit on the floor of her room by the door. It would typically take her an hour to fall asleep and she needed me close by. So, in the dark, I would write on my laptop, pieces of ideas, between comforting her, singing. It started with writing around and about each of the photographs. The book grew from these fragments and the fragments were tied to the actual experience of mothering. Its structure developed as a constellation from that writing, rather than linear essay.

Winant: Has that informed the way you work in the studio as well?

Larson: Writing this book has fed back into my studio practice in really positive ways. Historical research plays an important role in my work but typically as a point of departure. In working directly with appropriated imagery, I’ve shed some baggage around authorship, baggage I didn’t even know I had, and I’m excited about where this is taking the work.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1920s–30s

Courtesy Laura Larson

Winant: I’ve been making a lot of work about motherhood lately, and all that attends it. It is an area that’s made me nervous. I’ve worried that I might cloister myself, that I might not be considered serious. Can you talk a little bit about taking on motherhood—not to mention adoptive motherhood, and single motherhood—as the subject of this work?

Larson: I share these fears, too. The motherhood ghetto is one of the ghettos where women’s work is placed. So, with that understanding, I felt less anxious about that space because I know those terms of marginalization well and I’m committed to resisting those terms, the outskirts, so to speak. I’ve been very fortunate to have mentors who were role models not only as artists and scholars but mothers as well: Patricia Mathews, Martha Rosler, Mary Kelly. To be honest, I was more terrified of writing an autobiographical work—to share my experience publicly, especially the loss of my own mother, with whom I had a difficult relationship. I felt vulnerable writing an autobiographical work that takes Barthes’s writing as its model. To answer your question, I wanted the book to weave together the strands of experience that shaped my desire to be a mother and how they’re intimately tied to my work as an expression of how I want to live in the world.

Winant: Perhaps it is because I am not close to this experience, but I cannot recall reading any narratives about adoption, especially in this context. I only realized that during my first reading of your text. It feels like a void.

Larson: Adoptive motherhood is understood as a second choice, the option available if you can’t get pregnant and, to a certain extent, if you become a single mother by choice. Since I was in my twenties I’ve known I wanted to be a mother, and adoption intuitively felt more primary. For me, it represented a decision to feel connected and to see mothering as an intentional, political act even with the knowledge that I will fail. Adoption is a serious and ongoing reckoning with privilege.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1860s–70s

Courtesy the collection of Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr.

Winant: Yes, the line you’ve written—“With the uncertainty of our legal case, this sense of fate unmoors and my fears bloom that I am complicit in another mother’s loss”—stayed with me. It certainly complicates the already complicated terrain of motherhood, within and outside of artwork.

Larson: On a fundamental level, I think the desire to have children is a selfish act. I don’t mean this in a judgmental way. In our case, there’s no escaping the losses that are the very condition of her adoption and the implications for our life as a transracial family.

Winant: The hidden mother photographs themselves strike me as so desperately sad, and laced with trauma. They play to my deep fear that mothers need fade into the background, literally disappear for the sake of holding up their children. You approach them with more nuance in your writing.

Larson: Many of the photographs are so casually and profoundly violent. I didn’t think I had much to add to this other than to say, look at this, and let those images speak for themselves. Why not photograph the mother and child together? Some of the photographs are so extreme that it veers into black comedy—who are these monsters? Those ruptures open up the cultural schizophrenia around mothers. But, I found so many images where the bond between mother and child was so undeniably there—a mother playing peekaboo with the camera, the infant’s gravitational pull toward the mother’s obscured body—and I love these moments of insistence. I’m here! She’s here! Loss is a defining feature of mothering but I read ambivalence in these images as well. I know that I was already anticipating those feelings.

Photographer unknown, ca. 1860s–70s

Courtesy the collection of Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr.

Winant: Right—as you say, “Like a hidden mother, I was bound to and separated from my daughter.”

Larson: Yes. Her first mother is hidden too, and to a lesser extent, the women who cared for her in Addis Ababa. I took great comfort in the photographs I received of Gadisse with the house mothers. I liked seeing her held by these women even though it was also very painful. It’s important to know that the nannies are mothers too and providing care for children is how they support their own. The work of mothering isn’t tethered to biology and I wanted the book to account for that labor in a broader framework.

Winant: A substantial portion of the book revolves around descriptions of Gadisse’s image, before you came to meet her in person. Can you speak about the decision to include only a single image of your daughter, at the book’s end? Neither of your faces appear; her little body is turned toward the laptop camera.

Larson: Hidden Mother is my story and I purposely withheld images of Gadisse because she’ll tell her own story someday. She hated having her photograph taken as a baby so the Photo Booth application on my laptop was the only way I could make photographs of us. In the photograph, we’re embracing, but her body’s turning to see herself on the screen, away from me. The photograph crops out our faces but you can see our bond through the touch of our bodies. It’s my nod to Lacan’s mirror stage (and to Mary Kelly too) as refracted through adoption—the moment when the child recognizes their identity as separate from the mother’s. We’re bonded, but she’s already moving away from me, like all children do. Gadisse came to me already separate, and separated from her first mother. Her experience of the world will be radically different than mine because of her race so I’m thinking of that rift, too.

Courtesy Saint Lucy Books

Winant: I’m struck here by your consideration of Barthes’s writing on his mother, Henriette, whom he mourns, seizing on a single picture of her five-year-old self. Though, you write, “He doesn’t reproduce the photograph in the book, and the text pivots on its deliberate withholding. Echoing this loss, he suggests that the medium itself is an invocation of the maternal—a subject and experience both present and lost.”

Larson: Barthes’s casting of photography as a maternal medium is so radical because it doesn’t privilege the idea of birth as the apotheosis of mothering. By this I mean the studium is all cause and effect while the punctum is wild and eschews this tidy economy. He insists on the looping and irrational rhythms of photography’s attachments, and this certainly rang true for my experience of feeling like a mother through those photographs. His sentences about seeing Henriette restored in the Winter Garden photograph—how looking back is one and the same with the present. He’s writing of losing her but there’s this devastating sense of how her wounds—I’m thinking of her parents’ divorce—become Barthes’s, too.

Winant: You make reference to Barthes’s withholding in the book specifically when you write about the second set of images you received of Gadisse, the images that showed her as thriving, two months after you received her referral photograph.

Larson: The first photograph was devastating, which made the second set so shocking in their difference. Those photographs are my Winter Garden photograph. I would never print them, out of respect for her privacy, but those images do contain her ineffable self. I part ways with Barthes’s mournful refusal by including the photograph of us, even if it’s a modest disclosure. Its reveal comes at the end of the book. It’s our happy ending even though it alludes to the complications that we face.

Carmen Winant is an artist, writer, and Assistant Professor of Visual Studies and Contemporary Art History at Columbus College of Art and Design.

Hidden Mother was published by Saint Lucy Books in 2017.

The post Hidden Mothers appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 12, 2018

Hale County Revisited

In photographs and a new film, RaMell Ross offers a poetic vision of Southern life.

By Salamishah Tillet

RaMell Ross, Ida Mae, 2012, from the series South County, AL (a Hale County), 2012–14

Courtesy the artist

“Their faces were secret, soft, utterly without trust of me, and utterly without understanding,” lamented journalist James Agee after meeting a young African American couple in Hale County, Alabama, in 1936. “And they had to stand here now and hear what I was saying, because in that country no negro safely walks away from a white man.”

Appearing quite early on in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), the landmark text and photobook that Agee and photographer Walker Evans collaborated on to explore the impact of the Great Depression on Southern sharecroppers, Agee’s account of his encounter with these African American residents of Hale County is one of just a handful of descriptions of black life in their over-four-hundred-page epic work.

RaMell Ross, Here, 2012, from the series South County, AL (a Hale County), 2012–14

Courtesy the artist

Agee leaves that scene with regret for bothering them, and, more importantly, flooded by a distance that he feels is impossible to close. “I nodded, and turned away from them, and walked down the road without looking back.” Evans, on the other hand, appears to have been even more alienated. Despite the intense portraits of rural poverty that he produces, there is not one image of an African American in the entire book.

Although photographer and filmmaker RaMell Ross is not directly responding to the absence of Hale County black life in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his series South County, AL (a Hale County) (2012–14) and his corresponding experimental film, Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018), provide a poignant and subtle counterpoint to Agee’s and Evans’s willful blindness. Less concerned with maintaining the illusion of objectivity that typifies Evans’s detached, social documentary–style black-and-white photographs of rural tenant farmers and their families, Ross is not encumbered, but rather he dives into the lives of his subjects. His images—both still and moving—travel between the highly intimate and the breathtakingly panoramic in order to offer up an experience as dynamic and sweeping as contemporary Southern life itself.

RaMell Ross, Antonio, 2012, from the series South County, AL (a Hale County), 2012–14

Courtesy the artist

No longer exclusively shaped by the strident laws of Jim Crow, the New Black Belt of twenty-first-century America through Ross’s eyes is marked by possibility, minor movements, familial ties, and the everyday stillness of a black person, or an African American people, just trying to get by. Though his subjects face adversity—racial, economic, and gendered—he is far more interested in lingering in the quotidian, in those rarely captured moments not of mass resistance, but instead of far more ordinary instances of quiet refusal.

RaMell Ross, iHome, 2012, from the series South County, AL (a Hale County), 2012–14

Courtesy the artist

In South County, such occasions are captured through ambiguity. A well-dressed older African American woman wiping her eyes. A tear? A bead of sweat? Her fatigue buttressed and staved off by her sartorial respectability. In Antonio (2012), we witness a young African American man sprawled out on the ground. Exhaustion? Submission? Coercion? His fate somehow both filling in the outline of other black boys and men—Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, whose deaths we have mourned collectively—and his ability to get back up, a potential defiance against our recent past. iHome (2012) is both forward-looking and backward-searching; part mediation on slavery as America’s founding sin and part homecoming, Alabama’s prodigal black children return home to reclaim both land and landscape and render them anew.

Still from Hale County This Morning, This Evening, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Hale County This Morning, This Evening pushes against our temporal expectations even more. Shot over five years, the film, in title and method, remaps time as a way of reorienting the viewer’s relationship not just to the South, but to Ross’s black subjects, too. Following the stories of two young African American men, Daniel and Quincy, with whom he became acquainted when he worked as their GED and workforce readiness teacher, Ross consciously tried to re-create the mundane, the banal, or the quiet moments that he experienced working with and learning from his students.

Still from Hale County This Morning, This Evening, 2018

Courtesy the artist

“If you just sit there and watch someone for a very long time, you tend to forget and begin to participate in the person’s life and not judge them,” Ross tells me. “It took three years of me living there to shed all of those platitudinal photographs and all of those empty images of the South and the people there that are ingrained into the ways that people understand that region. I used the camera as an investigation into my way of looking, as opposed to fulfilling these visions of things to which I had previously been introduced.”

Still from Hale County This Morning, This Evening, 2018

Courtesy the artist

“Quiet,” writes literary critic Kevin Quashie in The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (2012), “is a metaphor for the full range of inner life—one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears. The inner life is not apolitical or without social value, but neither is it determined entirely by publicness. In fact, the interior—dynamic and ravishing—is a stay against the dominance of the social world; it has its own sovereignty.”

And while Daniel and Quincy do not govern the legal and social apparatus that ultimately limit their life chances in Alabama, Hale County This Morning, This Evening lingers in the spaces of their self-navigation and self-invention. Such stillness has a political power all its own.

Salamishah Tillet is the Henry Rutgers Term Chair Professor of African American Studies and Creative Writing at Rutgers University and a regular contributor to the New York Times.

Read more from Aperture Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Hale County Revisited appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 8, 2018

Into the Darkroom

At Ted Partin’s studio, Aperture Connect Members take a peek behind the curtain.

On Thursday, May 17, Aperture Connect Members met with photographer Ted Partin at his studio in Long Island City. The evening, which began with refreshments, was an opportunity for five of Aperture’s younger patrons to speak with Partin about his life and work. Partin, who received an MFA in photography from the Yale School of Art in 2004, introduced the small group to his first black-and-white photographs, made with an 8-by-10-inch camera. The group also looked at Partin’s experimentations with Cibachrome, a photographic process that yields film transparencies instead of negatives. Partin, rather than developing the images onto photographic paper, created unique, large-format transparencies with extremely vivid colors and light; for instance, an image of a standing woman illuminated in a lush forest struck the group as peculiar, surreal, and graceful. These resulting one-of-a-kind photographs have become even more rare since Cibachrome shut down production in 2012. (Partin keeps a stockpile of film in his freezer.) The studio and darkroom tour provided an opportunity for young photography enthusiasts to learn about the technical specifications of shooting with large-format film.

Aperture’s Connect Members particularly enjoyed an open discussion of the photographer’s large-format techniques in relation to an ongoing body of work. As members contemplated Partin’s framed color photographs of young, beautiful, and often nude women, the warm tones, intimate bedroom settings, and openness in the women’s gazes sparked a conversation about the relationship between Partin and his subjects. He explained that he will often meet the women and request portrait sessions via Instagram. Keeping in mind the stereotypical portrayal of women as passive subjects, Partin aims to create a collaborative, empowering exchange. The women in his photographs are self-possessed and unposed, and his large-format techniques facilitate a slow, methodical way of making pictures with the women rather than taking pictures of them.

Finally, Members gathered around images of women obscured in black, murky tones, as if Partin had snapped the shutter with the lights off. Following an error in the darkroom around 2011, Partin spent a year refining another unique large-format process, making what he calls “dark pictures.” In order to see the image in detail, Members had to view each photograph from different angles and distances, much like a nineteenth-century daguerreotype. The group then discussed the ways in which Partin’s “dark pictures” further subvert the viewer’s gaze and expectations of looking at women. After the studio tour concluded, the group retired to a neighborhood bar for a more casual conversation over drinks.

Click here to become an Aperture Connect Member today and to receive an invite to the next meet-up this September!

For more information on Aperture’s membership program, visit our website or contact the membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org.

The post Into the Darkroom appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 4, 2018

13 Photographers on What Freedom Means to Them

Highlights from the Magnum Square Print Sale

Photography has long been a tool of freedom, enabling many to find a voice, discover their identity, and exercise freedom of speech. From Bruce Davidson’s and Leonard Freed’s images of the US civil rights movement, to Newsha Tavakolian’s nuanced portrayals of everyday life in Iran, Magnum photographers are documenting the search for and limitations of freedom, as well as their personal expressions of creative freedom.

This week, for five days only, get signed and estate-stamped, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by acclaimed Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase and a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

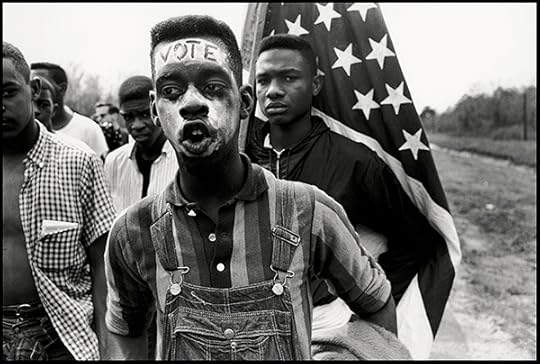

Bruce Davidson, Alabama, 1965

© the artist /Magnum Photos

Bruce Davidson

“From 1961 to 1965, I bore witness to various demonstrations in the civil rights movement. In this photograph, a group of civil rights demonstrators march from Selma to Montgomery to fight for the right to vote. Freedom was then, as it remains today, something that had to be fought for.” —Bruce Davidson

Bieke Depoorter, Istanbul, Turkey, 2015

© the artist /Magnum Photos

Bieke Depoorter

“I used to think that I was a street photographer. I pushed myself to take photos on the streets, but in a way, it never felt comfortable. I always had the feeling that I was ‘stealing’ photos from people. With Ou Menya, my project in Russia, things changed. I entered people’s homes to photograph the intimacy of families, and for the very first time, I felt both connected and at ease with the medium, as well as toward the people I was photographing. Although I may have been physically ‘trapped’ inside the house for the first time I felt free. The relationships I built with the people I photographed was crucial to this evolution. I now see photography as a conversation, even though we don’t often share the same language.” —Bieke Depoorter

Leonard Freed, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. being greeted upon his return to Baltimore after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, October 31, 1964

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Leonard Freed

“Dr. MLKing Jr.: an icon of peace and freedom.” —Elke Susannah Freed, daughter of Leonard Freed

Paul Fusco, Robert Kennedy Funeral Train, USA, 1968

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Paul Fusco

“The freedom to make pictures is essential to my being. When I boarded the train that carried RFK’s body from New York to Washington for his burial in the Arlington National Cemetery, the press corps was not allowed to take pictures within the cars themselves. I was frustrated by my inability to record the event—until the train came out of the tunnel and into the light, and I saw the tracks lined with folks wanting to say goodbye to Bobby. By turning my camera outside of the train, and photographing these people, I created my own freedom to chronicle this important event in a way I had not anticipated when I received the assignment from Look magazine at the time.”—Paul Fusco

Hiroji Kubota, Wounded Knee, South Dakota, 1990

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Hiroji Kubota

“December 1990 was the one hundredth anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre. In this image, Native Americans travel to a gravesite to honor members of the Sioux tribe who were slaughtered in 1890. At the time the Sioux, led by Spotted Elk, had been trying to migrate from one campsite to another when they were intercepted by the 7th Cavalry Regiment.”—Hiroji Kubota

Susan Meiselas, Wall, Managua, Nicaragua, July 1979

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

Dear Parents: I’m sure you’ve noticed my odd behavior over the past months. I no longer go to parties. I appear and disappear. This is because I’ve become a revolutionary. . . . Our country is full of misery and backwardness. All Nicaraguans have the sacred mission to fight for the freedom of our people.

Excerpt from a letter written by Edgard Lang Sacasa to his parents. His father, Federico Lang, was a wealthy Nicaraguan businessman and supporter of Somoza. Edgard was killed by the National Guard on April 16, 1979, just before the FSLN overthrew the Somoza dictatorship on July 19, 1979.

“Watching from afar as events rapidly unfold in Nicaragua today, I can’t help but think of the dreams that propelled the Nicaraguan people nearly forty years ago, and what they continue to demand and deserve as they struggle again for their future.” —Susan Meiselas

Diana Markosian, Doud, Age 11, Wolfsburg, Germany

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Diana Markosian

“It was night when Doud boarded a small rubber boat. It was his first time seeing the ocean, and now he was amongst a group of refugees, escaping their homes in search of freedom elsewhere. Doud didn’t know how to swim and feared the boat would sink. A year later, now in Germany, he is with a handful of other refugees learning to swim as a way of overcoming their fear of water associated with the journey they made to Europe. When I look at this image, I see the trauma that accompanied Doud’s sacrifice. It’s a constant duality for me: there’s no freedom without that risk.” —Diana Markosian

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Village of Jayyous, West Bank, Palestine, 2003

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“I made this picture on my first trip to Palestine. I remember how coming upon this scene felt like a mirage. All around it were checkpoints, barbed wires, Israeli military jeeps, and the hum from the construction of the separation wall; this woman seemed oblivious to it all as she calmly filled her bucket with olives.

The wall now cuts through this village, making 75 percent of the land inaccessible to her and to the farmers who’d worked the land for generations. I dedicate this picture to her and to a future where Palestinians are free from the Israeli occupation of their land and lives.” —Alessandra Sanguinetti

Alessandra Sanguinetti’s profits from this sale will be donated to Lajee Center, a local cultural center in Aida Refugee Camp in Palestine’s West Bank: http://lajee.org.

Alec Soth, Cambridge, Minnesota, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alec Soth

“After the most recent US election, I stopped traveling and stayed home in Minnesota. I also stopped photographing strangers. I preferred to drive into farm country without talking about politics or ideology. But I was also aware that my ability to do this sort of apolitical wandering was the result of the enormous freedom and privilege with which I was born. Every landscape, no matter how subdued, can be seen as a political landscape.” —Alec Soth

Newsha Tavakolian, Iran, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Newsha Tavakolian

“The young woman in red hesitates as she enters the water. Perhaps this is the first time she has seen the open sea. I did not ask her. I just watched. Her two female family members rest in the sand, their feet in the water.

Everywhere in the world, freedom and eternity find one another on the far horizon of the endless sea. Freedom is often described with big words, but we encounter it every day in the little things we do.” —Newsha Tavakolian

Larry Towell, West Bank, 2000

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Larry Towell

“Freedom is something you must struggle for even if you don’t achieve it in your lifetime.” —Larry Towell

Alex Webb, Miami Beach, Florida, 1989

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Webb

“In the late 1980s, I often found myself stuck in the Miami airport en route to Haiti, a vibrant and troubled Caribbean country I’d been photographing for a decade. From time to time, election-related riots would engulf Port-au-Prince in violence, and force the shutdown of its airport. While stranded in Miami, I started to take a closer look at Florida—this strange and often confounding state of immigrants and senior citizens, land speculators and migrant farm workers, theme parks and strip malls, alligators and sun seekers. Born out of the frustration of waiting to return to Haiti—and the freedom to wander wherever the Floridian light led me—this series of photographs ultimately became my third book, From the Sunshine State.

Would I have seen this beach scene unfold before my eyes if I hadn’t already spent years photographing in Haiti, with its tropical light and volatile weather? This particular afternoon on Miami Beach, a gust of wind caught this boy’s tangerine-colored towel as he rushed off the beach before the storm. Only later did I notice how the sweep of his beach towel echoes the sweep of the dark clouds overhead.” —Alex Webb

Christopher Anderson, Untitled, New York, New York, USA, 2014

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Christopher Anderson

“Free enough to take pictures of things that don’t matter, like spilt cherries on a crosswalk, for instance. . .” —Christopher Anderson

Support Aperture today through the Magnum Square Print Sale, open online June 4–8, 2018.

The post 13 Photographers on What Freedom Means to Them appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 31, 2018

BookMaker Symposium

Aperture Foundation presents the BookMaker Symposium a day filled with presentations and discussions by key members of the photobook community. Participants will hear from designers, printers, editors, artists, and more, on ways to successfully edit, design, and produce a photobook. The day will consist of short and sharp presentations offering different perspectives on the ecosystem of the photobook. Whether you’re new to bookmaking or have previous experience, this symposium is intended for photographers of all skill levels looking to take their work to book form.

The day will begin with mini-presentations by industry leaders, including Christina Labey and Jason Burstein, cofounders of Conveyor Arts; Craig Mathis from Printed Matter; João Doria, graphic designer and printer; Kris Graves, founder of Kris Graves Projects; and David La Spina, Dana Faconti, and Michael Vahrenwald from ROMAN NVMERALS. In the spirit of creating a space for artists to support one another and share ideas, the day will conclude with a small reception where participants and speakers can get to know one another.

Schedule:

11:00 – 11:10 AM: Introductory Remarks

11:10 – 11:40 AM: Kris Graves from +KGP

11:45 – 12:15 PM: Jason Burstein and Christina Labey from Conveyor Arts

12:20 – 12:50 PM: João Doria

12:55 – 1:25 PM: Sophie Mörner from Capricious

1:25 – 2:30 PM: Lunch Break

2:30 – 3:00 PM: Craig Mathias from Printed Matter

3:05 – 3:35 PM: Nelson Chan from Aperture

3:40 – 4:10 PM: Small Publishers Panel with ROMAN NVMERALS, moderated by Lesley A. Martin

4:10 – 5:00 PM: Reception

schedule subject to change

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Tuition:

Tuition for this symposium is $75.

First 20 people to register will receive a free copy of Self Publish: Be Happy

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a $5 discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, August 23

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop or symposium will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops and symposiums are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the day of the event they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop or symposium with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops and symposiums must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop or symposium less than two weeks prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops and symposiums. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop or symposium up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of forty participants is required to run this symposium.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post BookMaker Symposium appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 30, 2018

Sofia Coppola on Pictures

The acclaimed director reveals the photographs that inspired her films.

By Philip Gefter

Paul Jasmin, Laura, Los Angeles, 2009

Courtesy the artist and WM Artist Management

“I never thought I would be a filmmaker. It wasn’t something I ever planned,” Sofia Coppola recently told the Guardian. “I felt frustrated at art school. I had so many interests—design, photography, music.” By turning to film she no longer had to choose. The form allowed Coppola to engage all her passions, especially photography, which has been central to shaping her cinematic language. From Coppola’s debut with The Virgin Suicides (1999) to Lost in Translation (2003) to Marie Antoinette (2006), the filmmaker has turned to the history of photography for inspiration for the interiors, costumes, and atmosphere of her films. Storyboards, replete with photographic references, were key to Coppola’s most recent—and controversial—film, the Civil War–era The Beguiled (2017), for which she won the Best Director Award at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. Each of her six feature-length films is visually distinctive, and yet it’s possible to identify in all of them a directorial signature, one that might be characterized by visual calm and compositional clarity.

One sunny morning in early January, writer Philip Gefter sat down with Coppola at her home in Lower Manhattan to discuss the influence of photography on her filmmaking. On the walls hung a number of framed photographs: a William Eggleston of a girl lying in the grass holding a Brownie camera; a Tina Barney from the series Theater of Manners (1997); a Lee Friedlander nude; an Andy Warhol polaroid of Tina Chow. These pictures provided clues not only about Coppola’s knowledge of photography, but also about the subtlety of her sensibility—and became a starting point for their conversation about the look and feel of film.

Guy Bourdin, Untitled, for Charles Jourdan, Fall 1977

© The Guy Bourdin Estate

Philip Gefter: I wonder if you think that there is a tension between photography and film—the still image versus the moving image. Is photography threatened by film? Will video render the still image extinct?

Sofia Coppola: For me, photography and film are two totally different things. My filmmaking begins with images from photography, so I think of it as a starting point for making a film. I love photographs.

Gefter: Yes, I can see that by looking around the room. You mentioned, too, that you have a print upstairs by Helmut Newton of Charlotte Rampling, nude, sitting on a table; also, a picture by Larry Sultan of his father swinging a golf club indoors. So, obviously, you collect photographs.

Coppola: But not in a serious way.

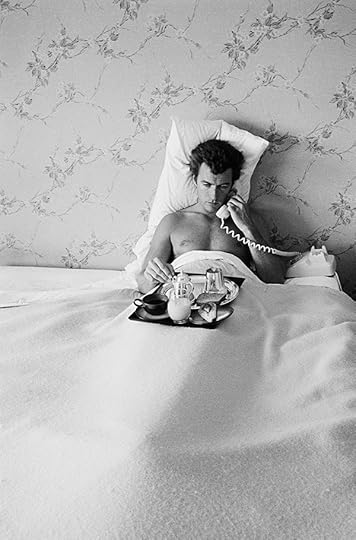

John R. Hamilton, Clint Eastwood, Breakfast in Bed, 1958

© the artist

Gefter: Did you study photography or film?

Coppola: I went to CalArts in the fine art program. I wanted to be a painter but I wasn’t good at it, and my teacher wasn’t encouraging, so I went to ArtCenter, in Pasadena, where I met Paul Jasmin, who taught photography. I sat in on his classes. Then I started spending time in Japan, where a kind of girly snapshot photography was popular in the early ’90s. A friend of mine had a magazine called Dune, and he would hire me to do little fashion jobs in Tokyo—snapshot-like pictures of my girlfriends. I never had the patience to learn very much technically, but I could take snapshots. That’s the extent of it.

Larry Sultan, Dad on Bed, 1984

Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan, MACK Books, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Gefter: Your first film, The Virgin Suicides, was about teenage girls. How did you make the transition from taking snapshot-like photographs to making movies?

Coppola: Paul Jasmin encouraged me. He thought I had a point of view that was worthwhile, and Dad [Francis Ford Coppola] was always talking about writing. I wasn’t planning on being a filmmaker, but when I read Jeffrey Eugenides’s novel The Virgin Suicides (1993), I loved it and thought I would try adapting it. I ended up writing the script and putting a book of visual references together—photographs—to show how I wanted to make the film.

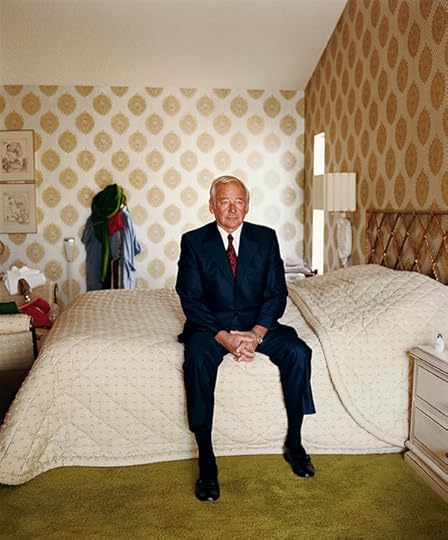

Gefter: Where did the visual references come from?

Coppola: My relationship with photography started as a teenager in the ’80s, looking at fashion magazines. I would also go to art fairs with my mother. Mom encouraged me to start collecting photography because it was the more affordable art at that time. At one art fair, I first saw the photographs of Bill Owens—his series on suburbia—so when I started working on Virgin Suicides those Bill Owens pictures became a reference. I bought one print—an image of girls at a school dance with stars hanging from the ceiling. That picture was definitely in my mind when I worked on the film.

Bill Owens, Eighth Grade Graduation Dance, 1973

Courtesy the artist

Gefter: And, so, the book of photographs you put together—how did you use it for the look of the film?

Coppola: I made these color-xerox books, which included Bill Owens’s photographs from Suburbia (1973); also ’70s Playboy photography, with the nature girl, soft style; and Eggleston colors. The story in the film is a memory, recreated in faded snapshots. I worked with Ed Lachman, the cinematographer, showing him photographs of what I wanted the film to feel like. That’s how I start every movie, sitting with the cinematographer and the art department, looking at photographs, and saying, “This is the look or feeling,” so everyone is informed by it. It’s always the starting point for me, the images.

To continue reading, buy Aperture Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Philip Gefter, the author of Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe (2014), is at work on a biography of Richard Avedon.

The post Sofia Coppola on Pictures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 23, 2018

What’s In An Image?

Sharing, surveillance, and data are changing the way we look and see.

By Marisa Olson

Shelly Silver, What I’m Looking For, 2004

© the artist

In the fall of 2016, two American pop cultural icons became unwitting touchstones in the discourse surrounding the contemporary relevance of data. Naturally, I’m speaking of Kim Kardashian and Donald Trump, both reality-TV celebrities and entrepreneurs. Kardashian was the victim of a horrific gunpoint robbery in her Paris hotel room, only to be brutally victim-blamed in the media for her constant sharing of selfies containing metadata that might lead criminals to her whereabouts. Trump arguably stole the US presidential election by not only bucking the odds—as they had been laid out in predictive national-poll results leading up to Election Day—but also by carrying out essentially civilian psy-ops through contracts with big data firms like Palantir and Cambridge Analytica, whose official tagline is “Uses data to change audience behavior,” and who were also behind the recent buyer’s remorse–laden Brexit vote. While Kardashian’s photosharing practices—a staple of her brand—came under heavy scrutiny, Trump’s big-data battle was armed by info. The firms gleaned from millions of social-media users’ online posts, from photos to text posts to likes.

In fact, today we are seeing a simultaneous and paradoxical blurring of the boundaries between photographs and their associated (formerly meta-)data, and between a media user/consumer’s clinging to a right to privacy versus a tendency to rampantly overshare. This blurring—whether in the name of branding, neoliberal critique, perceived activism, social/familial bonding, or a desire to be validated, i.e., “seen” (given the Pew Trust’s designation of the Millennial generation as that of “Look at Me”)—somehow persists in aligning recognition with the scopic apparatus.

Natalie Bookchin, My Meds, from the Testament series, 2009

© the artist

Make no mistake: The fact that I describe these simultaneous developments (one social, one formal/technological) briefly and in the same breath should not discount the fact that they are both epic in their ramifications and wholly different, even if their coincidence is worth exploring. After all, as artist and writer Trevor Paglen said in a “1,000 Words” feature in Artforum, the intervention of AI and algorithms into photography over the last decade has displaced the human eye in the act of seeing, and has become, in his estimation, “more significant than the invention of photography” itself.

When I think of a photograph today, I think of the actual image floating askew, like some intergalactic curtain, aimless over the liminal threshold between public and private. A steganographic decoy, the site of cathexisquadata for the photographer’s or poster’s (who’s who again?) attendant fears and fantasies, mirror images of twin drives etched into the photo like a watermark in invisible ink.

We began to hear horror stories about this right after 9/11. Terrorists swapping JPEGs that were literal fronts for the cryptic messages buried inside the files. Meanwhile, the “if you see something, say something” administration was erecting a theater of security in which airport lines, public transportation, teenage bedrooms, online profiles, and selfie phones were all players in the newfangled Globe Theatre. Soon millennials and Gen Z social-media users were born, many after 9/11 or too young to remember a time before such visibly increased state surveillance in the name of “homeland security,” for whom a “photo” was almost exclusively a digital object. This is the era in which reality-TV shows like Big Brotherare no longer shocking outliers, but as my colleague Gene McHugh once said succinctly of postinternet art, the medium has shifted from novelty to everyday banality.

Joseph Maida, from his reflection “Pictures without Words” in Public, Private, Secret: On Photography and the Configuration of Self, 2018

© the artist

I would argue that we’re in an era of photography marked by data ennui. Consider a morning in the life of my own media consumption: Yesterday I checked my email only to find a shockingly prescient promotional message with the subject line, “Is being online fun anymore?” Then I read an article about Roomba vacuum cleaners autonomously collecting data about their owners’ home layouts and lifestyle. After this, I came across a well-received tweet by someone proposing that blood-alcohol levels and their GPS coordinates be collected on people’s social-media posts. Finally, I read Paglen’s article, which points out the politically repressive implications of machines attempting to “recognize” photographic subjects (their race, gender, and age, for instance) according to normative criteria. Somewhere in these scattered scenes, the concept of consent melts away in the hazy playtime of convenience and fooling around online.

Earlier this year, a study out of the Max Planck Institute quantified this data ennui in regard to the privacy risks that users take in posting photos, which are often at odds with their own stated privacy preferences or policies. They were able to identify sixty-eight categories of risk (far more than I think many of us typically realize—part of the point) in the form of information that machines are able to glean in photos. This includes details like recognizable geographic features in the background, a wedding ring suggesting relationship status, objects in the image that might indicate medical history, a child’s hand holding an object that might indicate parental status, and many more elements to which people might not give a second thought. The study’s authors were advocating for what they called a “Visual Privacy Advisor,”distinct from general, categoric text descriptors that could algorithmically recognize and warn users that images posed privacy risks. The machines could see better than humans or could be trained to care more.

Zach Blas, Fag Face Mask, October 2012, from the series Facial Weaponization Suite

©the artist

October 20, 2012 , Los Angeles, CA

Negotiating participation in image culture in an era of constant state surveillance and self-broadcasting is not easy. For the last fifteen years, there’s been increasing pressure to participate in both arenas, to some extent. One is compelled to submit to surveillance “for the greater good,” if not to participate in various layers of sousveillance—sous being the French counterpart to sur, a looking from below rather than above. Citizens’ countersurveillance has thus only amped up in the six decades since the phrase “the whole world is watching” has been in circulation, following the rapid proliferation of cameras under the doctrine of media convergence.

It’s not just the word photo that is up for redefinition today. There is a casual slippage between many of the terms we previously used to ground ourselves—in the art world, the sphere of computing, and in digital culture writ large. For instance, I’ve written previously about how one of the primary symptoms of network culture, in the post-internet era, is a slippage between the definition of transparency-as-visible in surveillance contexts to transparency-as-invisible in computing parlance. We also tend to conflate participatory art and participatory media, assuming equal levels of informed consent on the part of participants.

And that is the ultimate question raised above: to what extent are people informed participants in the sphere of photography today, and subsequently, in the world of image-embedded data? The participation question might be the easier half to address: there is a tug of war between a desire to expose and a desire to be protected. But to be informed feels nigh on impossible in the undertow of the theoretical singularity invoked by rapidly advanced encryption, AI, and surveillance technologies and their deployment.

Joseph Maida, from his reflection “Pictures without Words” in Public, Private, Secret: On Photography and the Configuration of Self, 2018

© the artist

Regardless of the everydayness or banality of the photos at stake (or perhaps because of this uncannyness), the more one thinks about it, the more one feels like the subject of a Hollywood virtual-reality production. The piece of paper, the screen, the pixel, the contact lens, or the neural implant stands in for the representation that is perceived to be not-there/previously-there/ there-not-there—whether it is ultra-high-resolution or the kind of “lossy-copy” Hito Steryl has called the “poor image” (a digital artifact accelerating toward a thing of the past; an accidental fallacy). No matter how generous one is in theorizing the materiality of conceptual or digital or performative or time-based or otherwise “ephemeral” media, we have to remember that it is not only image quality that distinguishes digital from analog; it is data, the code itself. The digital is always already a medium of doubles, if not duplicity—not necessarily because it is simple to forge, as we easily assume when we swap the term “Photoshop” for “digital,” or forget how long predigital cinema carried out special effects—but because alphanumeric code is one language now capable of telling a story altogether different or adjacent to the images that overlay it.

Those of us interested in photography and new media have spent much of the last fifteen years theorizing and aestheticizing digital archives, but we would be remiss not to recognize that individual photos are now archives. That is, not just indices of their immediate metonymic namesake (the light that winked them into being, or the space/time event to which the photo bears an immediate, proximate, and consummate relationship) but also carriers (carrions) of whole libraries of information. Consider this in context of a society with ubiquitous image-making devices, where taking and sharing images is de rigueur. People are walking around with databases of databases of databases, ready to post them to public databases that will be hosted on other civic or corporate databases, for analysis by other unforeseen data firms, with unknown aims. The disparity of access to public and private information, the corporate colonization of the net that seeks to monopolize the space, and the looming legislative threats to net neutrality that hover over the landscape of cloud computing only compound this vista. Suddenly the once-novel concept of “database aesthetics” sounds not only trite but Pollyanna.

Artists and other supporters of the photographic arts (by which I mean good old-fashioned point-and-shoot, then print-on-paper photography) who are, at this point, still reading might feel that their practice has been sidestepped in this essay. On the contrary: One of the reasons I so related to the email that asked, “Is being online fun anymore?” is that I once made internet art, cofounded a “pro-surfer” net art community, and curated new-media art at a time when the internet felt like a more utopian, adventurous, less litigious, more neutral place in which the art we were all making had neither become co-opted by corporate channels nor was up for comparison (by us or anyone else) with social media. Likewise, I do not mean to cast “fine art” photography as a fledgling outlier kicked to the curb by the evil internet. In fact, I would invoke the French dramatist Antonin Artaud in arguing that in this era of questionable “truthiness” and threatened arts funding, the nation is in greater need than ever of the arts, if not art therapy.

Ann Hirsch, Here For You (Or My Brief Love Affair with Frank Maresca), 2010

© the artist

Few people realize that it was Artaud who coined the term “virtual reality” in 1933, when articulating the concept of the theater and its double in his initial manifesto on the Theatre of Cruelty. Artaud wanted artists to show everyday viewers what was at stake; to create a moment in the middle of all the other moments of buzzing from here to there, one that virtually re-creates or doubles the everyday, but allows us to bifurcate and peel off our consciousness from the imitation—not unlike a nightmare that allows us to wake up from a worst-case scenario and be relieved it didn’t happen, a sort of reverse wish-fulfillment.

I am not one of those who believe that civilization has to change in order for theater to change; but I do believe that theater, utilized in the highest and most difficult sense possible, has the power to influence the aspect and formation of things.

That is why I am proposing a theater of cruelty … Not the cruelty we can exercise upon each other by hacking at each other’s bodies, carving up our personal anatomies, or, like Assyrian emperors, sending parcels of human ears, noses, or neatly severed nostrils through the mail; but the much more terrible and necessary cruelty which things can exercise against us. We are not free. And the sky can still fall on our heads. And theater has been created to teach us that first of all … But it should not be forgotten that if a theatrical gesture is violent, it is also disinterested; and that theater teaches precisely the uselessness of the action which, once accomplished, is never to be done again.4

“Never to be done again” would be nice, but this, too, may be Pollyanna and reaching for the stars. Nonetheless, I like Artaud’s idea of deploying the creative work to split use from uselessness and violence from healing.

Marisa Olson is an artist, writer, and curator.

This essay is adapted from Public, Private, Secret: On Photography and the Configuration of Self, now available from Aperture.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

The post What’s In An Image? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 21, 2018

Mary Virginia Swanson: Beyond Print: The Life of Your Photobook Beyond Publication

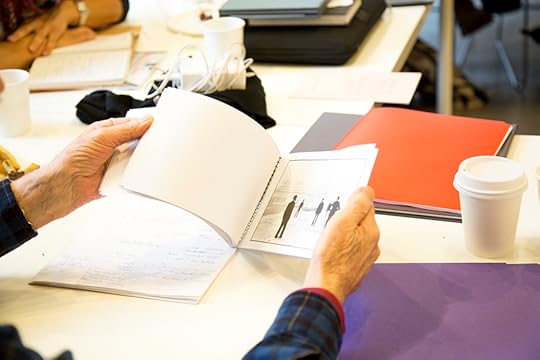

Mary Virginia Swanson led a two-day workshop at Aperture Foundation, working with photographers who were interested in how to build their audience, establish value for their work, and extend the life of their photobook beyond publication. The workshop focused on ways newly published photographers can conduct targeted research; from examining existing and desired audiences to discussing the possibility of exhibitions, participants broadened their perspectives about methods that will aid in securing exposure and longevity for their work.

On the first day, Swanson introduced the photobook market and explained how to research and build an audience. She discussed the importance of knowing your audience, the value of extending the work into exhibition form, and how to build a dialogue beyond the printed work. Then Swanson took a brief intermission from the discussion, and participants had the pleasure of visiting sepiaEYE gallery—upstairs from Aperture—and viewing various prints and photobooks on display, as well as speaking with the gallery director, Esa Epstein. In the afternoon, participants presented their photobooks and works in progress, and practiced marketing concepts to the group, in addition to strategizing methods of targeted research.

On the second day, participants continued to present their works in progress for photobooks and beyond. Swanson provided valuable critique and advice to participants in regards to their work and the existing art markets, including academic, fine art, and commercial. Swanson explained simple but useful ways that one could adjust their social and media platforms to better target their audience and market to it. In the afternoon, Swanson shared examples of her favorite photobooks and publishers with participants, explaining that every publisher has something different to offer—and thus that not every publisher will be the right fit. The workshop concluded with a discussion about the various types of exhibitions and their usefulness, social media tools, and educational programming that could be tied to a photobook project. Participants left the workshop with a wealth of new knowledge and a plan on how to tackle the task of executing and marketing their work beyond print.

Mary Virginia Swanson is an author and educator who helps artists find the strengths in their work, identify appreciative audiences, and present their photographs in an informed, professional manner. She draws from her thirty-year career spanning the fine-art, documentary, photojournalism, publishing, and licensing arenas to lend sage advice to artists at all professional levels. Swanson coauthored with Darius Himes the acclaimed Publish Your Photography Book, which was revised and updated in 2014 (Princeton Architectual Press). Visit mvswanson.com or @maryvirginiaswanson.

Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers