Aperture's Blog, page 103

March 28, 2018

America on the Brink

Zoe Leonard’s retrospective investigates the politics of image making.

By Rebecca Bengal

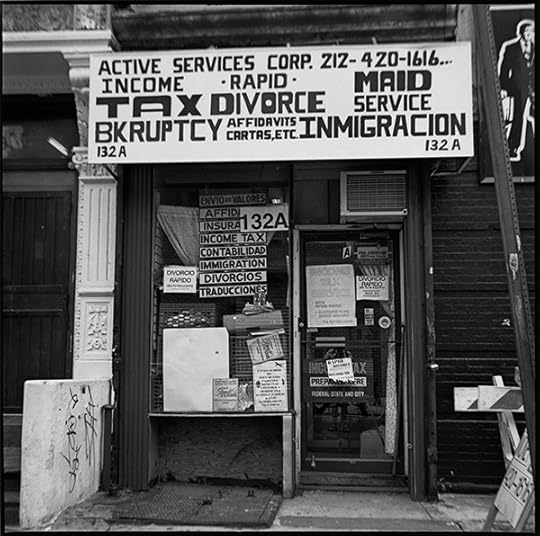

Zoe Leonard, Income Tax, Rapid Divorce, 1999

Courtesy the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York

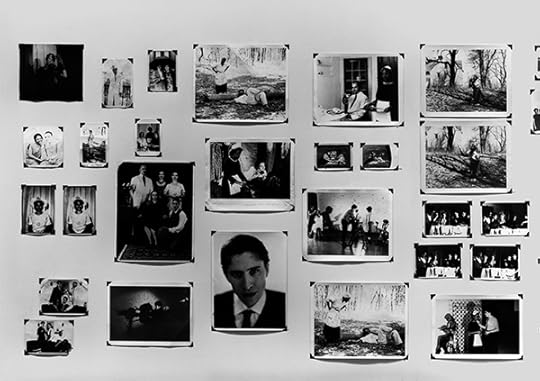

“Why does she look so surprised at the flowers?” a man asked of his companion on a recent afternoon at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He bent closer to the glass to inspect a publicity still–style photograph of a woman wearing a maid’s uniform, brandishing a vase of florals and an exaggerated, startled expression—an image from The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96), Zoe Leonard’s photographic narrative of the fictionalized subject of a faux documentary by Cheryl Dunye. In photographs and film, Leonard and Dunye invent the story of Richards, an African American lesbian actress in twentieth-century Hollywood, who gets work playing slaves and maids (as in the aforementioned still), comes to fame for her role as the “Watermelon Woman,” lives a thinly closeted existence, becomes an activist in the civil rights movement, and, after her career is derailed by racism, slips into obscurity.

“Ah!” the man said. “A burlesque-y show. It makes sense.” He parsed through more of Leonard’s prints, presented as an archive of found photographs, in a glass-topped display box: pictures of Richards performing onstage topless, in a skirt made of bananas, lounging with her supposed lover in a park, blowing smoke rings under a spotlight. “I never heard of her before,” he continued, seemingly baffled that he hadn’t.

It’s a testament to the successful verisimilitude of Leonard’s staged photographs, created to mimic various vernacular and formal styles over the decades—snapshots, press clippings, a luminous series of black-and-white portraits that make for an affecting rendering of a very conceivable life—that they can inspire such genuine befuddlement. Leonard’s work, on view in Zoe Leonard: Survey, her first solo exhibition at the Whitney, invites that kind of pliable, multi-tiered appreciation.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive (detail), 1993–96. 78 gelatin silver prints and 4 chromogenic prints

Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art

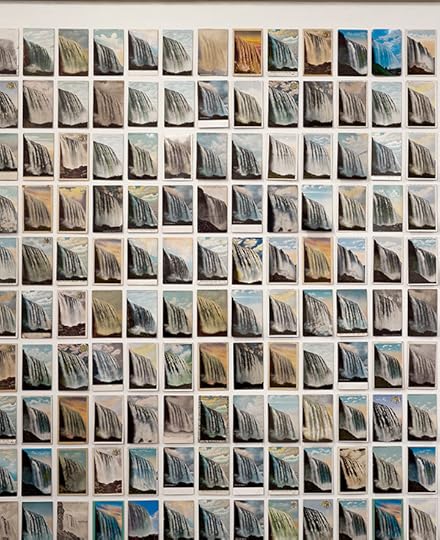

Leonard’s massive display of vintage postcards of Niagara Falls, You see I am here after all (2008), speaks to the desire to see the thing that everyone else has seen, and to own it, and the impossibility of doing so. The tangible image recorded in a postcard is what visitors to the falls will keep, and likely, it’s what drew them there in the first place, perhaps via the mailing of a similar postcard, signed—as the ones here are—by Alice, Edna, Bert, “Father,” and “A True Friend.” (The title comes from a line handwritten on one of the cards.) The postcards—hand-colored, glitter-covered, color-saturated—reveal changes over time, preferred angles, rainbows appearing in the mists. Leonard makes towers of postcards that share the same picture; they form their own waterfall. Museumgoers sit down on benches, stare: rippling along the wall, the waterfall postcards are nearly as calming and mesmerizing as the real thing.

In another room, more Niagara postcards are stacked on a workhorse table and arranged in piles corresponding to the various vantage points and depictions of the falls. Here, they speak to the collecting and archiving of memory. Barred from getting too close to the table, one has to crane in order to read their straightforwardly descriptive and accidentally evocative titles: Brink of American Falls, American Falls From Below, American Falls from Canada. On an adjacent wall, Leonard’s own photograph of Niagara Falls, made from above, is a gelatin-silver print that depicts a boat at the foot of the falls, caught in the horseshoe semicircle. You can sense the roar in the dark grain of her print; it swings between terror and beauty.

Zoe Leonard, You see I am here after all (detail), 2008. 3,851 vintage postcards. Installation at Dia: Beacon, New York. Photograph by Bill Jacobson

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

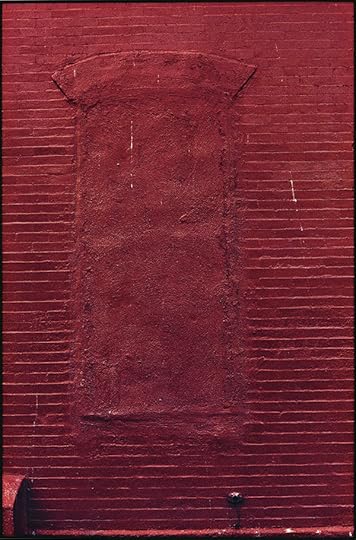

Elsewhere her other photographs likewise exist on dual planes. The forty photographs that make up The Analogue Portfolio (1998–2009) depict small storefronts—on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in Poland, Cuba, Mexico, and Uganda—with crude hand-painted signs advertising cell phones, fried pastries, back-to-school shoes, bolts of fabric, and quick divorces, as well as sidewalk displays of still more shoes, brooms set in sandbags, mattresses in stacks. At the outset, they are the sorts of pictures a traveler might take; similar to William Eggleston, Leonard finds her subject matter in the quotidian and renders it in dye-transfer printing: the lurid, glorious, and now-extinct process previously used in commercial photography. Eggleston was attracted to the vivid, saturated color of dye transfers; Leonard is, too, but she reclaims the original purpose of the process, as if “advertising” these benign, independently run laundromats and barbershops in an artistic context. The series includes a photograph of a wooden drink stand painted bright red, save for its hand-painted Coca-Cola logo and a similar wooden, handmade, shack-like structure, painted pink, that bears a sign reading “ARTIST.” Leonard effectively places corporations and individuals—in particular, artists—on equal footing.

Zoe Leonard, Red Wall, 2001/2003

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

These streets—ephemeral, endangered—are a mapping of the world, and of Leonard’s place in it. The wall text that opens Survey explicitly encourages all kinds of mapping, through place and time. In the first room, a row of blue vintage suitcases, one for each year of the artist’s life, includes space, perhaps superstitiously, for just one or two more; in still another room, stacks of a Kodak-published book on amateur photography. The installation How to Make Good Pictures (2016) shows the evolution of changes in the cover photo, design, and then, markedly, its title, which changes to How to Take Good Pictures. The verb switch from “make” to “take” signals a shift from the idea of creating a picture to “capturing” one. The stacks sit across from Leonard’s photographs, made from her own family’s pictures taken near the Statue of Liberty, records of recent immigration.

On personal and artistic terms, the show is a record of the various work that Leonard, born in 1961, has been making for decades, some of which has previously appeared at the Whitney, including Strange Fruit (1992–97), her installation of sewn dried fruit skins, dedicated to her friend David Wojnarowicz, which anticipates the Whitney’s retrospective exhibition of his photographs opening this summer. The museum’s physical place in the world has changed since Leonard began showing there: her first Whitney Biennial was in 1993; her most recent, 2014. In 2016, one of her best-known works, the poem “I want a president,” was blown up and wheat-pasted along the High Line park just north of the Whitney. Leonard had written it in response to Eileen Myles’s run for president in 1992, as an independent, but most notably, as a woman and as a lesbian. Now the poem hangs on the wall of her survey, in a smaller, 8-by-10-inch format.

Zoe Leonard, Untitled, 1989

Courtesy the Artist

One by one, visitors approach the work, aim their phones at it. Some stop to reread. As I did, I started thinking again about Fae Richards, whose invented but very real-seeming life is mapped in the other room, surrounded by Leonard’s photographs of anatomical wax models and chastity belts. “I want a dyke for president . . . I want a Black woman for president. I want someone with bad teeth and an attitude, someone who has eaten that nasty hospital food, someone who cross-dresses and has done drugs and been in therapy. I want someone who has committed civil disobedience.” Leonard and Dunye created a perfect candidate—it’s a shame that she is imaginary, and a shame that they had to let their protagonist die, to serve a verisimilar, documentary truth. Looking at those photographs, you do believe in her. After all, she exists everywhere. Fae Richards for President!

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

Zoe Leonard: Survey is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through June 10, 2018.

The post America on the Brink appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 27, 2018

David Goldblatt and the Legacy of Apartheid

For more than fifty years, the South African photographer has documented the structures of a divided society.

By Violaine Boutet de Monvel

David Goldblatt, Young men with dompas (identity documents that every African had to carry), White City, Jabavu, Soweto, Johannesburg, November 1972

© the artist

David Goldblatt’s first retrospective in France, currently on view at the Centre Pompidou, unfolds across 250 photographs ranging from 1946 to 2016. The acclaimed eighty-seven-year-old South African photographer has spent his entire career capturing the ordinary—though at times dramatic—manifestations of the deep racial divide afflicting his country. “I want the most with the least: straightforward photography leading to what Borges, in regard to writers and writing, called ‘a modest and hidden complexity,’” he notes in the text viewers read upon entering the show. Words have always been significant to Goldblatt, whose photographs are systematically supplemented with highly detailed titles and captions. He has also authored all the wall texts punctuating his Parisian survey, which is arranged in two parts. The first includes past series touching upon the contrasted fates of black and white communities during the apartheid era (1948–94). The second is dedicated to his lifelong project Structures, which documents the urban and architectural traces of ethnic segregation throughout South Africa.

David Goldblatt, A plot-holder, his wife and their eldest son at lunch, Wheatlands, near Randfontein, Gauteng, September 1962

© the artist

Born in 1930 into a family of Jewish immigrants who had fled European persecution, Goldblatt grew up in Randfontein, a typical gold-mining city of the Witwatersrand area, where Africans from all over the continent would come and work for low wages (and still do). Determined to become a magazine photographer, he self-taught himself and took his first pictures at the early age of sixteen, some of which are exhibited here. They portray tailings heaps, on which he used to play and contemplate miners at work, then unaware of their particular circumstances. Two decades later, he provided powerful metaphors for the strain and misery many have endured—to the benefit of but a few—with simple depictions of facilities and tools in his mid-1960s series On the Mines. The image Shovels retrieved from underground, Central Salvage Yard, Randfontein Estates, Randfontein, 1966, for instance, depicts a huge stack of spades with the following caption: “Virtually every grain of sand in the mine dumps that made the Witwatersrand landscape was in a rock that came off the shovel of a black miner underground.”

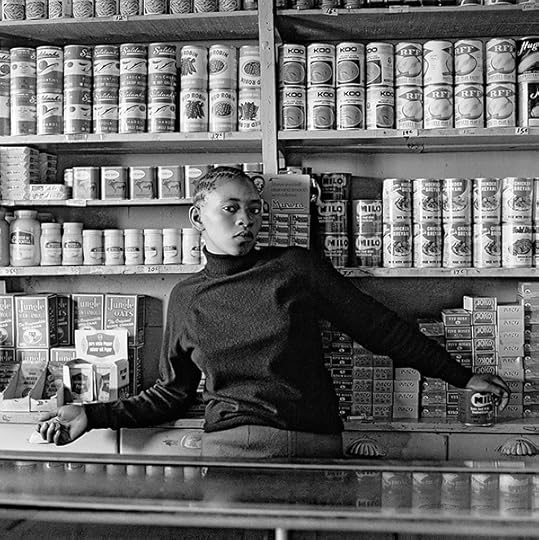

David Goldblatt, Shop assistant, Orlando West, Soweto, Johannesburg, 1972

© the artist

In his 1960s series Some Afrikaners Photographed, Goldblatt concurrently focused on the lives of Dutch-descended farmers, also known as Boers, the primary supporters of the Nationalist Party responsible for apartheid policy. The diptych Kleinbaas with klonkie, Bootha Plots, Randfontein, Transvaal (Gauteng), January 1963 follows two boys playing outside. The first picture immortalizes the children seated together on a four-wheeled cart, whereas the second turns around this ideal of innocence and friendship to reveal instead an image of unmistakable racial subordination: a little black servant pushes his little white master up a hill to ride again. “Apartheid was a grey matrix of legislation and regulation hanging over the country, penetrating, restricting, controlling, cramping every aspect of life. Nothing and no one escaped it,” Goldblatt comments in a wall text nearby.

David Goldblatt, Saturday afternoon in Sunward Park. Boksburg. April 1979

© the artist

The exhibition continues with a stunning ensemble of early 1970s portraits, which were originally commissioned by the South African magazine Optima. They mostly represent segregated people in Soweto, a township bordering Johannesburg. Often concerned with the way people compose themselves—consciously or not—in front of his camera, he actually kept direct eye contact with all the subjects of these photographs. Many of the pictures were taken within the confined interiors of “matchbox” houses, the precarious accommodations provided to black workers by the apartheid government, which otherwise forbade them to own property. That said, the crepuscular view of Sunset over the playing fields of Tladi, Soweto, 1972 even more powerfully conveys the claustrophobic feel of this repressed existence. It shows children playing and posing on wrecked cars in the middle of a junkyard, a scene of sublime desolation behind which a humble skyline disappears into a haze of dust. In contrast, the series In Boksburg, which Goldblatt realized at the turn of the 1980s in a typical white suburb, extends a full horizon of possibilities for its inhabitants. For instance, the idyllic Saturday afternoon in Sunward Park, Boksburg, April 1979 represents a shirtless man mowing his lawn on a radiant day—a routine weekend for some, an unreachable dream for others until the end of the twentieth century.

David Goldblatt, Woman smoking, Fordsburg, Johannesburg, 1972

© the artist and Centre Pompidou

While Goldblatt’s style and method vary from one series to the next, the constant impartiality and benevolence of his gaze are perhaps what best describe his unique approach to social documentary photography at the crossroads with fine art. He never judges his subjects, but seeks to expose the most insidious dynamics of discrimination in the everyday—that is, in the simple ways people and their surroundings present themselves before his eyes. His work is all the more subtle in that it doesn’t always engage head-on with politics, or at least at first glance. For instance, his little-known mid-1970s series Particulars consists of rather formal close-ups, which highlight the body language and garments of either black or white people randomly encountered in the streets and parks of Johannesburg. Among them, Man sleeping, Joubert Park, Johannesburg, 1975 literally embodies the sense of constriction and bareness that pervades the entire exhibition: a black man curled up on a sunburnt lawn shields himself behind the tightly interlocked fingers of his hands. The series overall offers an extremely intimate counterpart to Goldblatt’s colossal ensemble Structures, in which people’s skin colors eventually translate into divergent architectures.

David Goldblatt, In commemoration of and protest against farm murders, Rietvlei,

on the N1 near Polokwane 19 June 2004

© the artist

As if to remark upon his country’s newfound, but tenuous, democratic freedom, Goldblatt started taking color photographs in the early 2000s, for only about a decade. A dozen are presented here. Among them, 5:52 AM, Going to work in 2012 shows a continuous stream of buses on their way to Pretoria from the remote former Bantustan of KwaNdebele—one of the so-called “homelands” that were created under the apartheid regime for black South Africans to inhabit, often against their will. This fairly recent image dismally echoes an older series, The Transported of KwaNdebele, which was made in 1983–84 and documented from the inside the excruciating six-hour-long bus commute of the Ndebele people going every day to Pretoria for work. Deploring this unbearable persistence of racial inequities, as well as the corruption and unprecedented unemployment that his country also faces after Jacob Zuma’s controversial nine-year-long presidency (he was forced to resign just a week before the retrospective’s opening), Goldblatt has since returned to the intensity of black-and-white photography. “Apartheid has gone,” he concedes; “its half-life will continue beyond knowing.”

Violaine Boutet de Monvel is an art critic and translator living in Paris.

David Goldblatt is on view at Centre Pompidou, Paris, through May 13, 2018.

The post David Goldblatt and the Legacy of Apartheid appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 21, 2018

Bruce Jackson: On the Inside

When a folklorist set out to document life in American prisons, he found the enduring segregation of the Old South.

By Brian Wallis

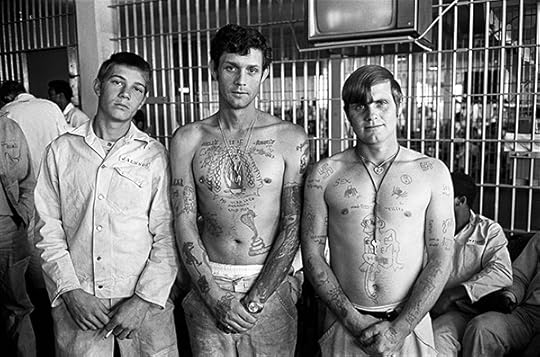

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

Among other things, the American prison system is designed to keep a purportedly disagreeable or disposable portion of the population out of sight and out of mind. The same walls that keep prisoners in are intended to keep prying eyes out. The secret lives of prisoners—their living conditions, their social systems, their codes—are, in the free world, virtually invisible, and, therefore, unknowable. Breaking through these barriers, folklorist and photographer Bruce Jackson has, for over fifty years, tried to get inside the penitentiary walls to tape-record, film, and photograph inmates, not only to document their unique cultural forms and social microcosms, but also to make a clamorous case for prison reform and prisoners’ rights.

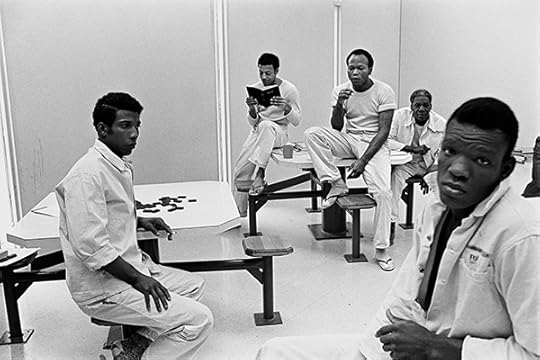

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

Like many documentary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, Jackson developed a unique approach to infiltrating and re-presenting otherwise unknown aspects of seemingly impenetrable and forbidding subcultures. Between 1964 and 1979, he compiled extensive studies of the social behavior of prisoners in Texas and Arkansas state prisons, and his research was presented in dozens of scholarly books, essays, films, and audio recordings. In 1964, while a visiting fellow at Harvard University, he first traveled to Ramsey prison farm, near Rosharon, south of Houston; it was Freedom Summer, a period of especially high racial tension in the South. Jackson’s goal—as noted in his 1965 text “Prison Folklore”—was to record “the ways of prison life, the factors that make for an independent world: the language and code, the stories and sayings, and, sometimes, the songs.” Following in the footsteps of early folk song collectors like Alan Lomax and Paul Oliver, Jackson was gathering the remnants of a rapidly disappearing African cultural tradition lingering in the diaspora in the forms of oral histories, toasts, spirituals, gospel music, blues, and work songs.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

The archipelago of southern prison farms that Jackson encountered in East Texas from 1964 to 1967 consisted of vast tracts of forests and farmlands, often located on the sites of former slave plantations. Under the watchful eyes of mounted prison guards, segregated work details of inmates, in matching white uniforms, labored from dawn to darkness building roads and levees, picking cotton and tobacco, planting bottomlands and felling trees, swinging axes in unison to the chants of traditional work songs. Cadenced work songs were a survival technique, intended to synchronize the prisoners’ labor, pace them under the scalding sun, and keep slower workers from falling behind. In the free world such music had been forced away or co-opted by commercial interest, but in the isolated prison work crews and chain gangs this anachronistic music survived. “I was interested in the black convict work songs,” Jackson recalled, “because they go back to a slavery-time musical tradition which in turn goes back to an African musical tradition. It’s a pure, unbroken line of musical performance and style, and the way music and physical labor integrated with one another.”

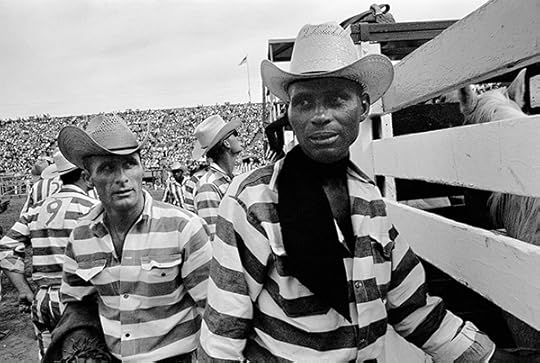

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

In March 1966, Jackson joined with folk singer Pete Seeger and his family to film the last vestiges of African American work songs at Ellis prison farm, near Huntsville, Texas. The mesmerizing thirty-minute, black-and-white documentary film they produced, Afro-American Work Songs in a Texas Prison, records the chants and the rhythmic chopping, with very little narration. It’s the only known film record of a tradition that, by the following year, had literally vanished.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

In this context, Jackson began taking photographs, initially as notes or aides-mémoire, and later to illustrate his many publications. Jackson was interested in capturing whatever elements of prison folklife could be recorded, using whatever documentary instruments were necessary to gather this information as thoroughly as possible. According to Jackson, “Documentary work entails a responsibility to an external reality. For me, that external reality is broad and complex. Human experience is not one thing, it is everything: it is what you have for breakfast, what you wear, what you make, and the stories you tell. So, what I was trying to do was to use as many instruments as I could to look at and to preserve as many aspects of that world as I could, to let other people see what I saw. Photography was equivalent to my tape recorder.” Jackson’s photographs formed a crucial part of the research for his several classic books on prison life, including In the Life: Versions of the Criminal Experience (1972), Wake Up Dead Man: Afro-American Worksongs from Texas Prisons (1972), and “Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me”: Narrative Poetry from Black Oral Tradition (1974).

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

True to his training as a folklorist, Jackson tended to be more practical than poetic about his photography, saying, “What I wanted in my photographs was the sense of what it was like if you were standing where I was standing.” Jackson’s photographs from the antiquated East Texas prisons meticulously catalog the various components of the bureaucratic penal system: the entry, or sally port; the chain-link and razor-wire perimeter; the warden’s office, with its boar’s head decor; the uniformed guards, mounted on horseback with rifles; the prison yard, where inmates are forced to strip down; and the endless parched fields, where the prisoners work. A retrospective volume of Jackson’s photographs, Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas (2013), reproduces these brutal pictures with merciless fidelity. And they are astonishing, in part, because they seem so alien and anachronistic.

Bruce Jackson, Texas and Arkansas prison photographs, 1965–78

Courtesy the artist

These stark black-and-white photographs capture the primitive social conditions and enforced slavery-like labor of a not-so-distant version of criminal justice. They show legions of prisoners with raised shovels and hoes marching to work in the fields; they show uniformed guards with rifles monitoring the workers from high on horseback; they show inmates in striped prison costumes performing at a local rodeo; and they show inmates at ease in anonymous and poorly lit prison lunchrooms, confronting boredom. Pictures of paunchy white prison guards sipping iced tea while a field of hunched-over, white-suited African American prisoners pick cotton are not only images of a bizarre cultural remnant of the Old South, but also are records of the deliberately dehumanizing, almost medieval, caste system that survived in American prisons as late as the 1970s.

To continue reading this story, buy Aperture Issue 230, “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Brian Wallis is a writer and curator based in New York.

The post Bruce Jackson: On the Inside appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 20, 2018

No Country for Young Men

In a society with strict definitions of manhood, how are photographers portraying Iranian masculinity?

By Haleh Anvari

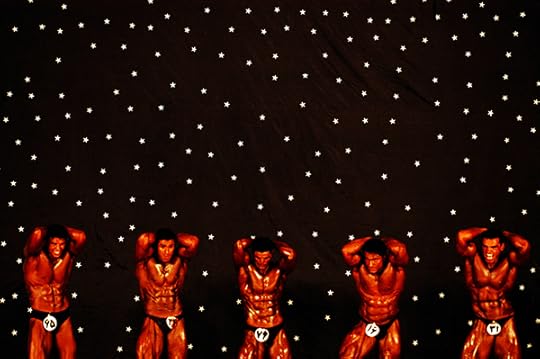

Abbas Kowsari, Tehran/Azadi Stadium, April 22, 2006, from the series Masculinity A

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran’s image abroad has been defined by its politics. In this newsroom universe, Iranian women have been front and center in the frame, the Western gaze seeking their exotic attire and problems. Iranian men, on the other hand, have been strangely absent from this picture, unless they are bearded politicians or directors of art-house movies. Young Iranian men, in particular—perennially present in their own cities in the countless murals of fallen heroes of the Iran-Iraq War—became invisible to the world, their issues lost in the daily economic and political maelstrom of the country.

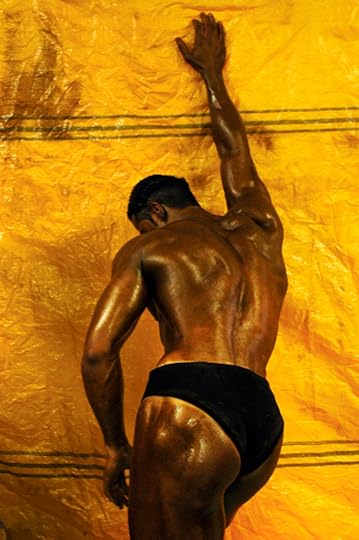

Abbas Kowsari, Tehran/Azadi Stadium, April 22, 2006, from the series Masculinity A

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Abbas Kowsari, one of Iran’s prominent photojournalists, noticed the lack of representation of men in images about Iran while working as an assistant to the late Sadegh Tirafkan, who addressed issues of masculinity in his internationally celebrated art photography. “Maybe it was because of the wars that Western powers were starting in the region,” Kowsari says, referring to the consecutive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. “There was more interest in women’s issues and women photographers taking photographs of women.”

Abbas Kowsari, Tehran/Azadi Stadium, April 22, 2006, from the series Masculinity A

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

In 2006, Kowsari began to focus on Iranian men in a series of photo-essays titled Masculinity. These images feature bodybuilders preparing for the stage (from oiling up to parading their pumped-up muscles) and wrestlers (who enjoy hero status in Iran because of the regular medals they bring home) captured in the moments before and after competition. “I really wanted to show that men can also feel fatigued or defeated,” Kowsari says. His photography addresses both the vanity and the vulnerability of men. His latest project, begun in 2015 and ongoing, documents male public bathhouses that operate in the poorer parts of Tehran.

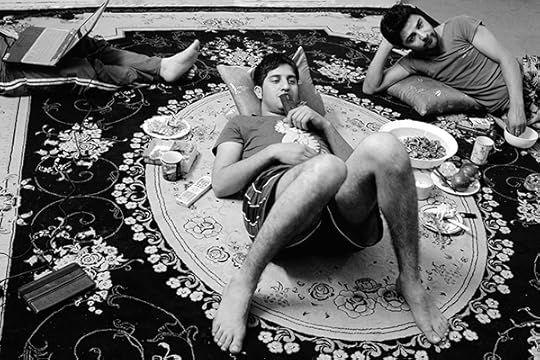

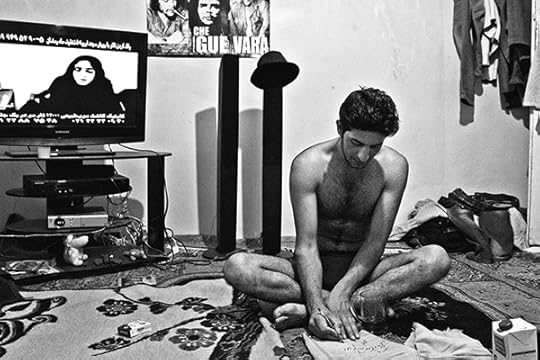

Najaf Shokri, Untitled, 2009, from the series Bachelors

Courtesy the artist

While Kowsari’s work records men in public spaces, Najaf Shokri’s series Bachelors (2009) looks at the private spaces of a group of friends in the town of Karaj, some forty kilometers from the capital. Young men are seen whiling away their time at home, uninhibited and often half naked. Out of work and in retreat from the policed streets after the 2009 postelection turbulence in Iran, they depict a generation’s lassitude. It is surprising how relaxed and open these men are in front of the camera. “They were happy that I was photographing them,” Shokri says, “as if their lives became more meaningful by being photographed.”

Najaf Shokri, Untitled, 2009, from the series Bachelors

Courtesy the artist

Although Shokri’s photo-essay has been picked up for group exhibitions in the United States and Canada, he cannot show these photographs in Iran, as they reveal too much skin. Despite the fact that his series is reminiscent of the work of Larry Clark, in the intimate portrait it provides of friends, Bachelors is being both subjected to censorship inside the country and largely dismissed by the outside world, due to a tendency to favor stories from Iran that are told through images of its women.

Behzad Jaez, Khan Passageway, Qom, 2015, from the series Turbanites

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

In another cloistered environment, Behzad Jaez has recorded the lives of young men usually hidden from view: seminarians in religious schools across the country, whom he began photographing fifteen years ago. These are the aspiring ayatollahs of the future—potentially the elite clerics who will lead the country’s politics through religion. Jaez’s series Turbanites (2014) was exhibited in Tehran last fall and published as a book by Nazar Art Publications in 2017. But this glimpse into the austere lives of these religious students has aroused the ire of his secular friends, condemning his choice to photograph the young clergy, who they feel should not be valorized. Jaez notes, however, that this community is not as monolithic as it may seem: “Ironically, not all of these guys decide to take the robe when they finish their studies,” he explains.

Behzad Jaez, Jahangirkhan Seminary, Qom, 2014, from the series Turbanites

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Aspects of Iranian men’s lives provide a wide scope for social documentary work about Iran as a whole. Men, especially the young, face overwhelming demands in a traditional society that defines manhood as a role of protecting and providing. In a country where the government is failing to create enough jobs, reduce rampant economic corruption, or prevent the current frightening increase in drug use, these men face challenges that are as complex as the issues that afflict the women and ultimately affect the whole population, regardless of gender. Photographers who choose to focus on the country’s men accept that their images may not find a regular spot in international exhibitions on Iranian photography as easily as works by photographers who zoom in on Iran’s women. And they know that these images of Iran’s masculine population almost never make it to the front pages of major publications in the West. In the gaze of foreigners and Iranians themselves, Iran is no country for young men.

Haleh Anvari is a writer based in Tehran and a regular contributor to the Guardian.

Read more from Aperture Issue 226 “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post No Country for Young Men appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

What Makes a Family?

An exhibition explores how black photographers portray their communities and kin.

John Edmonds, American Gods, 2017. Courtesy the artist

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008. Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York

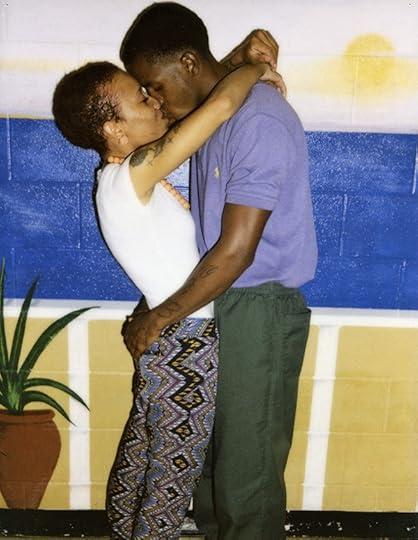

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family, 2013

Courtesy the Columbus Museum of Art

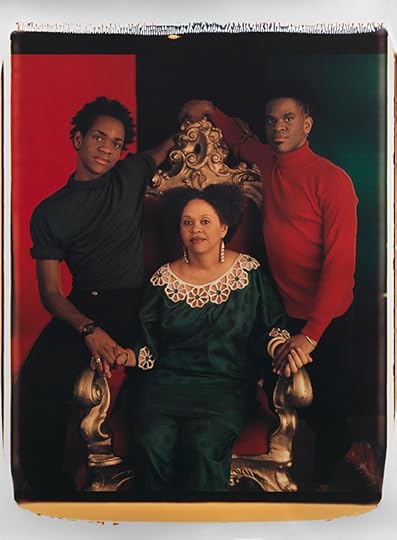

Carrie Mae Weems, from the series Family Pictures and Stories, 1981–82. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Lyle Ashton Harris, Mother and Sons II, 1994. Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

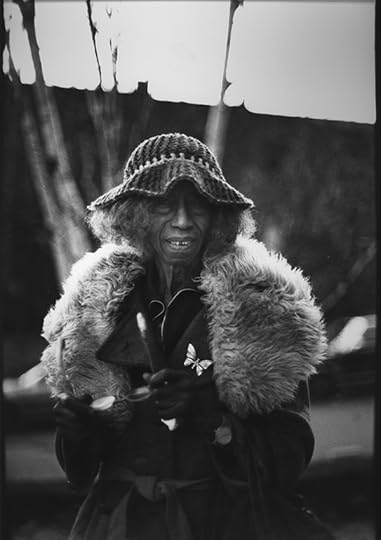

Ming Smith, Auntie Esther, Pittsburgh, ca. 1993, from the series August Wilson. Courtesy the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

When Roy DeCarava set out in mid-twentieth century Harlem to undertake what would become the landmark photobook The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), he employed photography as “a creative expression to meditate on everyday life and family,” says Drew Sawyer, head of exhibitions and curator of photography at the Columbus Museum of Art. The artists featured in the exhibition Family Pictures–LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deana Lawson, Carrie Mae Weems, John Edmonds, and Gordon Parks among them–work in a similar vein, pushing against traditional notions of documentary photography in radical and intimate depictions of domestic life.

Family Pictures is on view at the Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio through May 20, 2018

The post What Makes a Family? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Inside a Japanese Legend’s Latest Book

At the Japan Society, Aperture Members enjoyed a rare glimpse into Naoya Hatakeyama’s artistic process.

On Wednesday, February 28, Aperture Members and Trustees gathered at the Japan Society to celebrate the release of Naoya Hatakeyama’s book Excavating the Future City, copublished by Aperture and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Following a brief introduction by Yukie Kamiya, director of Japan Society Gallery, Members had the rare opportunity to hear Hatakeyama in conversation with Aperture’s creative director, Lesley A. Martin. Hatakeyama, speaking through a translator, mentioned artists such as Stephen Shore as early influences on his work. The pioneering use of color by Shore’s generation and their turn “toward the social landscape” informed Hatakeyama’s photographs of environments altered by human construction and industrial intervention.

Much of Martin and Hatakeyama’s talk revolved around the artist’s best-known series, Blast. From 1995 to 2006, Hatakeyama photographed quarry explosions, capturing from a natural formation to the raw material for construction. A stop-motion video, Twenty-Four Blasts (2011), was projected in the front of the room, bringing to life his original series. Hatakeyama also shared how his practice was deeply marked by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

The evening brought supporters of Aperture Foundation and Japan Society together to engage with an artist who, as Kamiya noted, is able to “focus on the transformation of the city . . . and still find what is [uplifting] after a hopeless situation.” Hatakeyama concluded the event by signing copies of the book.

Naoya Hatakeyama (born in Iwate Prefecture, Japan, 1958) is included in some of the most important public collections in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. He co-represented Japan in the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001, and presented his first solo museum exhibition outside of Japan in 2002 at Kunstverein Hannover. Hatakeyama’s work was also included in Japan Society’s presentation of In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11 in 2016, originally organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Excavating the Future City is copublished by Aperture and the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) on the occasion of Excavating the Future City: Photographs by Naoya Hatakeyama, curated by Yasufumi Nakamori and on view at Mia through July 22, 2018.

Click here to join Aperture’s membership program or contact our membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post Inside a Japanese Legend’s Latest Book appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 15, 2018

Being and Belonging at MoMA

Behind the scenes of the museum’s latest showcase for new photography.

By Annika Klein

Aïda Muluneh, Strength in Honor, 2016

© and courtesy the artist and David Krut Projects, New York and Johannesburg

Two questions have been central to photography since its inception: how do we see, and how do we see ourselves? This year, the Museum of Modern Art takes a contemporary approach to these inquiries by asking “how photography can capture what it means to be human,” as a matter of identity and representation. I recently spoke with Lucy Gallun, curator of Being: New Photography 2018, about how photographers are using both conceptual and personal approaches to reckon with the history of portraiture and beyond.

Annika Klein: I wanted to start with the previous iteration of New Photography, Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015, which you also cocurated. It focused on a post-internet view of images, often ones with a digital element. Three years later, why have you picked a theme that focuses on subjectivity? What’s the shift there?

Lucy Gallun: Ocean of Images took place on the thirtieth anniversary of the New Photography series. The series started in 1985 with an exhibition simply called New Photography, organized by John Szarkowski, who was then director of the Department of Photography at the Museum. Prior to the thirtieth anniversary, the new chief curator of photography, Quentin Bajac, decided to expand the scope of the exhibition and hold it a bit more infrequently—approximately every two years instead of every year. Historically the show had presented the work of between three and six participants, and usually the participants’ work was shown on its own, and there wasn’t necessarily the opportunity to look at themes across the artistic practices.

On the occasion of Ocean of Images, we included nineteen artists, gave the show a title, and, as you mentioned, we were really looking at wider themes across the included works, including issues of dissemination and the circulation of images at that moment. The show included works in a variety of formats: some were framed photographs and others took different forms, including projected video, sculpture, and site-specific installation, among others. It was a diverse show: artists at different stages in their careers, from different countries, and very different types of work.

When I started thinking about work for the next exhibition, I was struck by the work of artists considering ideas of representation in diverse contemporary contexts. It seemed to me that many artists were focusing on specific issues of citizenship or nationality, gender, sexuality, specific cultural heritage, and considering the stakes of representing oneself or others in this particular political or cultural moment. Unlike the last iteration, in which most attention was directed to the format of the physical objects, here the focus is on something specific to the subject of these photographs, a subject that is more inward or personal even as it addresses being in the world.

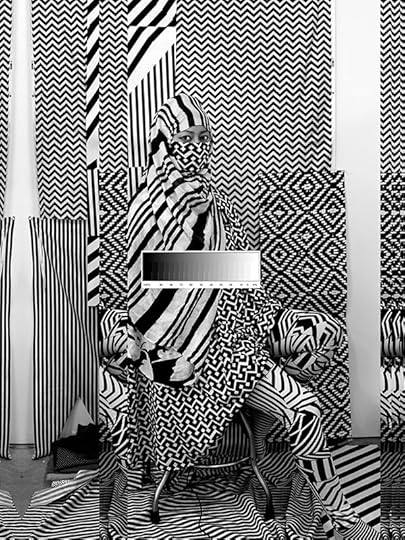

Stephanie Syjuco, Cargo Cults: Cover-Up, 2013–16

© and courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and Ryan Lee Gallery, New York

Klein: Do you think the stakes of image making feel higher than when you were working on the last show?

Gallun: No. The stakes of image making have always been quite significant. But there are issues that are specific to this moment, and depending on the circumstances or situations in which the artist is working, or the questions they are hoping to raise, their approaches can be quite distinct from one another. In some cases that means drawing attention to the ways photography has addressed particular markers of nationality, or classification or identification around perceived racial or ethnic categories, such as in the Cargo Cults (2013–16) or Applicant Photos (2013–17) series by Stephanie Syjuco. In other cases, such as the unique objects constructed by Em Rooney, artists are drawing attention to how a photograph might be a very personal object, how it might serve as a memento or keepsake, reminding us of a special individual experience. In all cases, there is an awareness of the questions raised around representation and, to address such questions, the artists are thinking about the history of representation, particularly through photography. Even in their contemporary approaches, they’re aware of certain characteristic elements that have been traditionally deployed in portrait photography, for example, and they are working with or through those expected elements.

Andrzej Steinbach, Untitled, 2017, from the series Gesellschaft beginnt mit drei

© and courtesy the artist and Galerie Conradi, Brussels and Hamburg

Klein: Could you give a couple examples of the new ways they’re playing with representation?

Gallun: A number of the works deploy conventions that have traditionally been associated with studio portraiture, but they might interrupt or disrupt or underscore those conventions.

For example, there are seven images in the exhibition from a larger series called Gesellschaft beginnt mit drei (Society begins with three) (2017), by Andrzej Steinbach, in which the artist employs the format of a group portrait. All of the people are gathered together and are looking at the camera, but Steinbach has only depicted one figure in full in each picture, so the other people who would be around that figure are partially cropped out of the frame. As we follow along from each picture to the next, we start to see that the individual figures have actually switched places within the group and that they’ve also switched clothing over the course of the series. Confusion starts to set in and we might start to feel disoriented; we’re reminded that individuals are always changing, they’re always mutable, their relationships to others are always changing. These figures push against or defy easy interpretations of what they represent. Typically, we might look for specific characteristics in each member of a group portrait—who’s sitting where, who’s wearing what—but when they subtly switch in this way, that mechanism is interrupted.

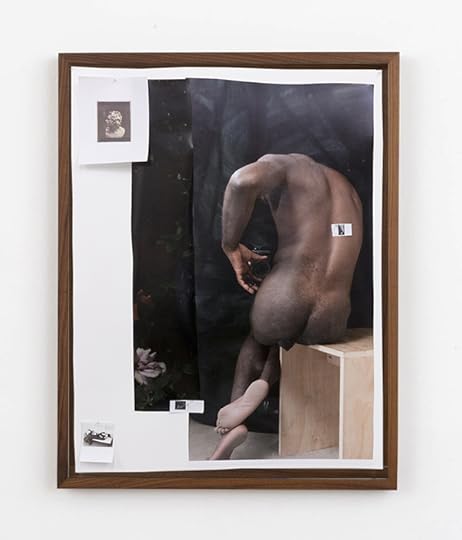

Another artist, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, often foregrounds elements of the studio itself that we, as viewers, don’t typically pay attention to in a portrait. Often that means the relationships between the photographer and the model. The camera apparatus is usually quite visible, and the layered aspects of his studio process are brought forward through multiple pieces of photographic paper that are collaged together in one work, or the use of a mirror to bring together many planes into one composition. The process that goes into making a picture is evident in the final image. In other pictures, he foregrounds the platform or the drapery against which a model would pose. The model themself might not be visible at all, but their presence is palpable. At the forefront always are his own relationships to his models (traditionally something that is kept hidden), underscored by the presence of his camera apparatus or his own hand on the camera lens.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Untitled, 2017

© and courtesy the artist; courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, and Document, Chicago

Klein: Even though this exhibition has a very different focus than Ocean of Images, it seems similarly concerned with semiotics—in the sense of how images create and denote meaning. This has been a prominent conversation among image makers since, at the very least, when New Photography started in 1985. How are these artists questioning systems of meaning in new ways, as opposed to how they might have been in 2015, or any time since this exhibition series has been running?

Gallun: I anticipate when people think about a show that’s about representation, they’ll expect to see maybe a lot of portraits. And, indeed, there are many works that we would immediately call out or identify as “portraits.” But there are also works in the show where there is no figurative imagery at all. In such cases, there might be particular objects or other signs that stand in for a particular person. Sometimes those are quite personal objects, such as a work by Em Rooney that consists of a welded metal ladder with photo keychains dangling from the rungs— an homage to a family friend who had passed. In fact, a physical photograph is an object that stands often as a precious or valued object: we might frame it and put it in a special place, for example, so that a physical object stands in for a person.

There’s one project in the exhibition—a large project, we’ve excerpted it—by Shilpa Gupta, in which she gathered together representations of one hundred people who had changed their surnames for different reasons, some political, some personal, some emotional; these are each represented by a picture that has been sliced in half, and the two halves of the picture are near each other in these clusters, but they are read as separate. Often, the pictures that represent each of these individuals are not figurative depictions, but other imagery that has been captioned with short text notations about the particular stories behind those names.

In other cases, a mask might stand in for a person. For example, Sofia Borges often takes photographs in museums or archives or zoos, or other places where things or beings are put on display. Her pictures—which are usually at an immense scale and rendered in brilliant hues—emphasize the spectacle inherent in that way of looking or of understanding “reality.” A couple figures in a display case representing a particular era or culture are meant to stand in for all the lives that were part of that culture. Or when looking at an ancient mask, we’re somehow transported into the head of that person, and we understand it as a representation of that moment in time or that life.

Sofia Borges, Painting, Brain and Face, 2017

© the artist

Klein: The exhibition text talks about “personhood.” Could you say more specifically what that means?

Gallun: I actually quite like that word. We have a sense of what it might mean just because we’re familiar with the word “person” and we’re familiar with the idea of “selfhood,” so maybe we interpret it as the state of being a person, in a straightforward way. It also traffics in other, specific fields: It might be used in philosophical terms, imagining when a person begins to exist—in a more philosophical sense. It’s also used in legal terms, quite often in terms of the rights of a person, and when such rights might be in place. Some works in the exhibition address imagery of birth and death, and living in the world, in a more existential, philosophical way. Other works refer to particular rights that a person may or may not have in a society, and in those cases, audiences might consider the legal characteristics of the term.

Sam Contis, Junction, 2015

© the artist

Klein: These New Photography exhibitions introduce artists who aren’t in the MoMA collection and who haven’t shown at the museum. Is there an artist who you’re particularly excited to be showing at MoMA for the first time?

Gallun: I can’t call out one artist [laughs]. But one thing that I will point out is that the artists are at very different stages in their careers. Some of the artists are what one might call “emerging”: they might be younger artists, or showing in New York for the very first time. Other artists are at a later stage in their careers, but their work hasn’t been presented at this museum.

Klein: Such as Aïda Muluneh?

Gallun: Yes, she’s one. Or Matthew Connors. Both these artists have been working in the field for some time, supporting the field of photography. Muluneh is the founder and director of the Addis Foto Fest and also the founder of DESTA, an organization that supports arts initiatives. In that way, she has been directly linked to the circulation and the support of photography. Connors has been the chair of the department of photography at MassArt for a number of years.

Matthew Connors, Pyongyang, 2016, from the series Unanimous Desire

© and courtesy the artist

Klein: Contemporary photography is a broad field, especially when you’re including image-makers and photo-based artists. What’s the most difficult part of curating a “state of the union” exhibition, such as this one, that people will look to and say, “This is what was happening in 2018”?

Gallun: I think you’ve alluded to it in the question. The hope is that viewers will not perceive the show to be a “state of the union,” in that it’s not meant to be comprehensive in any way. There are, of course, any number of artists that it would have been wonderful to include. I do hope that the selection is diverse, in terms of the stages of the artists’ careers, and also their very different approaches. Especially with a theme like this, about representation at this moment, one thing I want to underscore is that these artists are really all very aware of difference, and are looking at diverse circumstances and experiences. So, in this way, it’s not at all a universalizing idea, but instead looking at specific and quite distinct ideas of being.

Joanna Piotrowska, XXXIII, FROWST, 2013–14

© the artist

Klein: Someone walks into MoMA who maybe didn’t study art, or maybe isn’t incredibly versed in contemporary photography, and they enter this show. What do you hope they take away from it?

Gallun: Many works in the show will be prints, framed and hung on the wall. In that way, the language will not necessarily be surprising to visitors. These are formats we typically associate with photography. But even in works that use these standard formats, the artists are often working against or disrupting the particular characteristics that we associate with those standards, complicating them so that they are not so easily legible. And right away, visitors will also find references to the contemporary world—issues of migration or gender play, for example—and they might be surprised by or touched by the ways the artists address these issues. All the works speak to how, through photography, we might capture ideas of being human at this moment.

Annika Klein is the editorial assistant of Aperture magazine.

Being: New Photography 2018 is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 18–August 19, 2018.

The post Being and Belonging at MoMA appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 14, 2018

What New York Photo Editors Want to See

The curators of the Aperture Summer Open discuss what inspires them in photography today.

The curators of the 2018 Aperture Summer Open: Marvin Orellana, Antwaun Sargent, Siobhán Bohnacker, and Brendan Wattenberg

Photograph by Katie Booth

Katie Booth: Every year, Aperture calls on photographers from all over the world to submit their work for a juried exhibition here at Aperture Gallery. This year’s Summer Open will be curated by a fantastic group of editors and writers; among them is my colleague, Brendan Wattenberg, the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

Brendan Wattenberg: Thanks, Katie. The theme of this year’s Summer Open is The Way We Live Now. We’re looking for bodies of work by photographers who are addressing society in innovative ways, through fashion, through the environment, through portraiture, through documentary photojournalism: all kinds of photography that speak to our moment. We want to be open-minded. We want to take a broad approach and see what’s out there. (Submissions are currently open through April 4, 2018.)

This year, we have three amazing editors and writers who will join me on the jury for the 2018 Aperture Summer Open: Siobhán Bohnacker, a senior photo editor at The New Yorker magazine; Marvin Orellana, a photo editor at New York magazine; and Antwaun Sargent, a writer, critic, and contributor to newyorker.com, Artsy, Vice, Surface, and Aperture, among many other publications. They are some of the most creative and exciting editors and thinkers in contemporary art and photography today, so it’s a huge privilege to work together and curate this show as a team.

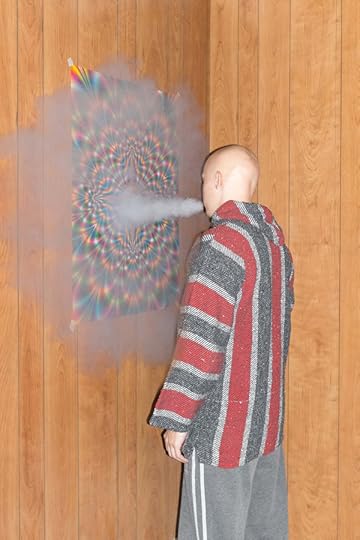

Brandon Nichols, Selfie, 2015

Courtesy the artist. Nichols’s work was presented in the 2016 Aperture Summer Open

Booth: To start off, could you talk a little bit about your own point of view as writers, as critics, and as editors?

Siobhán Bohnacker: It’s a real pleasure to be part of the team curating the Summer Open this year. I’m especially excited because it gives me a chance to work outside of the weekly format of The New Yorker. It’s a different way of looking at work, separate from having to think so strictly about specific stories for the magazine: a bit more of a relaxed look at what artists are making.

Marvin Orellana: It’s one thing to work at a magazine and have deadlines, but it’s not just that. You’re constantly having to assign to very specific subjects. So this will be an opportunity to invite photographers to allow us to enter the different worlds that they all inhabit.

You know, the world is so big, and there are so many big forces shaping us and in so many different ways. What are we not seeing? I really want photographers to think about what that would be. I want to feel shocked. I want to know: What is happening in your country, in your part of the world? It will be very exciting to see.

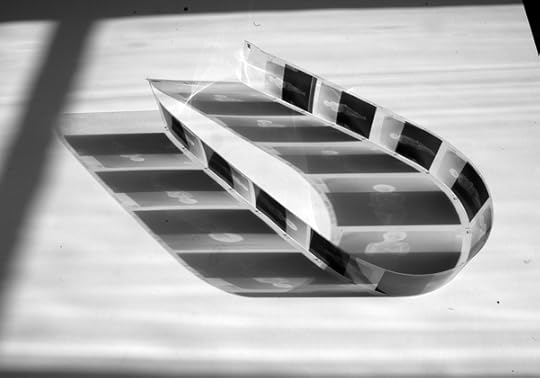

Junsheng Zhou, Representation of a refused negative film, 2014

© the artist. Zhou’s work was presented in the 2016 Aperture Summer Open

Antwaun Sargent: I’m also really excited about this opportunity to see what photography means right now to different photographers around the world. I just came back from Marrakech, where I saw this wonderful photography show called Africa Is No Island, featuring forty-two African photographers, and a lot of work I’d never seen before, which really made me excited about the types of submissions we might receive and to think about what photography can do today.

And with a theme that’s so broad, we can think about how photography encounters identity, or politics, or culture. As Siobhán said, I’m excited to see work I’ve never seen before, but I’m also thinking through the possibilities of this show. Hopefully we will meet really good photographers who are pushing those types of conversations.

Eva O’Leary, Molly, 2015, from the series Happy Valley, 2014–15

Courtesy the artist. O’Leary’s work was presented in the 2015 Aperture Summer Open

Bohnacker: A great example of a photographer doing just that is Eva O’Leary, who was in the 2015 Aperture Summer Open. I’ve worked with Eva a number of times, most recently on a project about a beauty convention in Los Angeles. Eva was ideal for that assignment because her work is so much about how young women conceive of their public identities versus their private identities. Her work has this kind of uncanny feel to it aesthetically, so she was great for this story about young girls and young boys going to these conventions and experimenting with makeup as a means to figuring themselves out.

In that respect, with the Summer Open, there’s a real Venn diagram between all of our fields. And the people who come to see an exhibition like this could very well be people who might assign photographers in the future or want to write about their work or collaborate with them in some way.

Sargent: Hopping on the Eva train, so to speak, I wrote about her work after seeing the Aperture show. I was interested in the way that she was thinking about beauty, but she also has a series of work that talks about her hometown. And the way that she is thinking about those moments where you’re looking at photography and you’re looking at magazines and you’re looking at images in the world, trying to find yourself. So, there is a dialogue between editors and writers and what is seen on the walls at an exhibition like the Summer Open, and this can lead to conversations and assignments around different bodies of work.

Chris Maggio, Untitled, 2014

© the artist. Maggio’s work was presented in the 2016 Aperture Summer Open

Wattenberg: Marvin, you’ve had a very interesting career. You’ve worked at The New York Times Magazine, and you were a photographer yourself, back in school.

Orellana: No one’s supposed to know about that! [laughter]

Wattenberg: Well, you know what it’s like behind the lens!

Orellana: I give my utmost respect to all photographers out there, because, yes, being on the other side, it’s a challenge to try and capture what’s in my head—this idea or fantasy of a photograph. But when you’re on the ground, obviously, the situation can be very different. I always feel like that is the hardest part of being a photographer. How do you walk into a situation and make something that hopefully will be remembered, be iconic, transcend the page, so that when we print it in the magazine, it’s not just something that we, as a publication, feel proud to present to the world, but that we feel like will also add to the bodies of work of those respected photographers? A lot of what we do, at least in the magazine, is to think about how certain assignments will also shape the way a photographer goes on to work or takes on the next stage of their career.

Jon Henry, Untitled #5, Parkchester, New York, n.d.

Courtesy the artist. Henry’s work was presented in the 2017 Aperture Summer Open

Booth: For all the brave souls who are working so hard to get their work seen, a question for all of you: When you’re looking at a portfolio, what is it that makes that body of work cohesive? What advice could you give photographers in pulling their work together, presenting it to editors, or a picture desk, or even to a writer like yourself, Antwaun? What are those qualities?

Sargent: One of the things that I’m always trying to find in photography, across a range of subjects and genres, is that it tells a story. You can tell if the photographer is truly invested in a body of images if it tells a story that moves you.

Bohnacker: And if the photographer has a distinct voice. I get so many unsolicited pitches—

Orellana: Sorry, Siobhán, I didn’t mean to send you those! [laughter]

Bohnacker: And there are some real tropes that I see, in terms of subject matter, for sure. Some things have been photographed to death, but depending on who is making that image, it can be told in a very different way from the next person. So, just as in fiction writing, where the writer’s “voice” distinguishes the writing, it’s the same thing with visual art making.

But on a practical note, in terms of storytelling, to speak to Antwaun’s point, I don’t think that necessarily means photographers should need to submit a very tight edit. I mean, that’s what we as editors are here for. I think, often, that photographers are not the best editors of their own work. So, I think they should leave the edit wide enough so that an editor can actually get in there and shape the narrative a little bit.

Shane Rocheleau and Brian Ulrich, Martin + Scene at the Former Bluebird Theatre, n.d.

Courtesy the artists. Rocheleau and Ulrich’s work was presented in the 2017 Aperture Summer Open

Wattenberg: Exactly. That’s how we like to work at Aperture as well. To see a wide amount of work and then think collaboratively about how to make the best presentation.

Bohnacker: I’ll speak often to the editors at Aperture or to writers like Antwaun, to find out what other people in the field are seeing. Or, if I’m looking for somebody making work on a certain subject. I might not know anyone, but maybe Brendan has been researching this very subject matter, and he’ll be able to give me a tip.

Wattenberg: Or vice versa.

Noritaka Minami, Tract No. 3279 (California City, California), 2016

Courtesy the artist. Minami’s work was presented in the 2017 Aperture Summer Open

Booth: There are so many calls for entries and numerous opportunities for juried exhibitions, but this one is very unique. Could you speak to some of the ways that the Summer Open is an incubation space for Aperture to meet new artists, for us to become familiar with what’s really out there?

Wattenberg: I’ll give you one example from Aperture. In 2015, the Summer Open theme was Black Mirror, which included the work of a fantastic young photographer named Farah Al Qasimi. The following year, we published a portfolio of Qasimi’s work in Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue. And during this time, she has been doing so well. She had a breakout show at Helena Anrather gallery last fall; Siobhán commissioned her for a fiction piece for The New Yorker; and she’s been reviewed in Artforum and a number of other magazine. So, it’s great to see photographers participate in the Summer Open and then follow their careers. I think that’s one of the most valuable things that can come from an open like this.

Farah Al Qasimi, S with Floral Fabric, 2015

Courtesy the artist and The Third Line, Dubai. Qasimi’s work was presented in the 2015 Aperture Summer Open and published in Aperture, issue 225, “On Feminism”

Sargent: Aperture’s gallery is in Chelsea, so photographers have the exposure of showing their work in a community where we have some of the best artists working today, who are showing their work down the street and around the corner. And there will be so many different people around and in the art world that will see the work and want to engage the work, whether that is in a magazine story or critically, through text, or people who might want to collect the work. All of that is possible given the location of where the show will be.

Bohnacker: There are few places I would commit so much of my personal time to, but I totally get behind everything Aperture does. I think in terms of programming, across books, exhibitions, and the magazine, Aperture is rigorous in investigating photography now.

Matthew Herrmann, Analog Upsample #2, 2016

© the artist. Herrmann’s work was presented in the 2016 Aperture Summer Open

Booth: One last question: Why should people submit to the Summer Open?

Bohnacker: You get to come to the party! [laughter] No, because it’s exciting to be part of a group show in Chelsea, in New York, and so many people will come and see this exhibition. I mean, we work with all kinds of people—dealers, curators, editors, writers—so it’s like a—what’s that phrase?

Wattenberg: One-stop shop.

Bohnacker: One-stop shop!

Orellana: Every opportunity counts, and there’s no reason why you shouldn’t submit your work. It’s important for us to see your work, to be aware of what you’re doing. So, please submit!

Bohnacker: And, doesn’t it feel like a critical and urgent time to support artists expressing themselves? The way in which we are living now is just so strange and interesting. Aside from the professional-connections element to it, I think just making work and sharing that with people who care is important.

Sargent: This is a show that’s going to be about what it means to image the world and the people who live in it. So, I would hope that young and emerging and established photographers around the world will want to show their work in dialogue with other photographers who are having a conversation about how we live now.

Katie Booth is the digital manager at Aperture Foundation.

Submit your photographs to the 2018 Aperture Summer Open now through April 4, 2018, at 12 noon EST.

The post What New York Photo Editors Want to See appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Can a Feminist Embrace Araki?

At the Museum of Sex, a new look at the prolific—and provocative—Japanese photographer.

By Russet Lederman

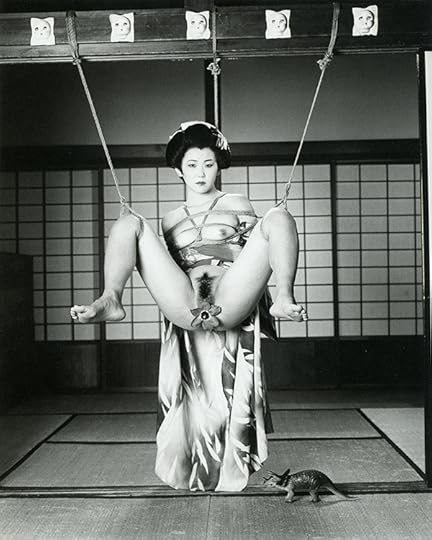

Nobuyoshi Araki, Marvelous Tales of Black Ink (Bokuj ū Kitan) 068, 2007

Private Collection

Being a feminist and an admirer of the work of Nobuyoshi Araki are two viewpoints that do not easily fit well together—especially in our current era of #MeToo. Araki, one of Japan’s most celebrated photographers, is a controversial figure whose work has been derided for its pornographic and sexually demeaning depictions of women. How, then, to reconcile this popular and occasionally apt perception of Araki as misogynistic with a pro-women attitude? Surprisingly, the current Araki retrospective at the Museum of Sex does a lot to address this question.

Acknowledging this prevalent, mostly Western view of Araki’s photography as sexist and devoid of meaning, the curators at the Museum of Sex have justifiably chosen to frame their exhibition with a direct confrontation of the controversy surrounding his work. Organized by the major themes that have defined the artist’s nearly fifty-year career, The Incomplete Araki covers two floors in a presentation that examines the paradoxes within his copious and consciously branded output. Traveling through the show elicits fluid opinions and conclusions in the viewer, at times seeming to confirm Araki as bluntly misogynistic while at others reframing him as a deeply private sentimentalist. Both perceptions are equally valid when assessing the slippery factual and fictional persona that Araki has cleverly nurtured into “Ararchism”—a portmanteau of “anarchy” and “Araki.

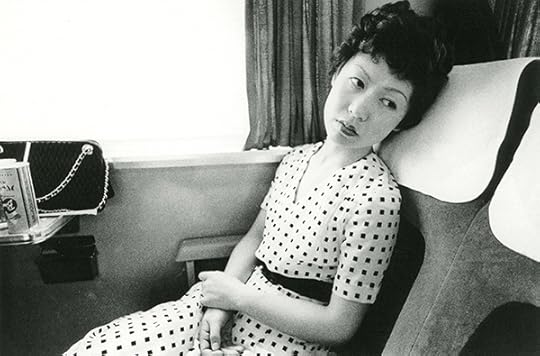

Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

On entering the exhibition on the museum’s second floor, the outspoken, incendiary side of Araki is in full view as one moves down a darkened hallway adorned with rope knots suggestive of kinbaku-bi (Japanese rope bondage art) to confront a lone spot-lit photograph of a suspended, bound kimono-clad woman with her legs splayed, her genitals barely covered by a flower. Conscious of their audience, the curators at the Museum of Sex are literally roping in the viewer’s attention with the most sensational work before slowly unfurling a more nuanced reading of Araki.

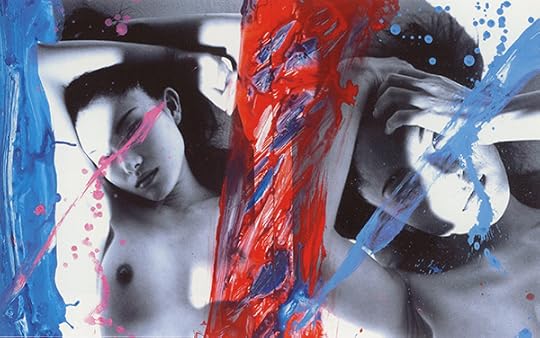

Nobuyoshi Araki, Tokyo Comedy, 1997

Private Collection

With the initial shock in place, the photographs that follow in the second floor galleries vacillate between large-scale black-and-white and color images of bound women alone, women having sex, models in a studio setting with Araki, and more intimate, date-stamped images that include bound women as well as Tokyo cityscapes, the photographer’s back terrace, his adored cat Chiro, and cloud-filled skies. Expanded wall texts and interspersed video interviews draw attention to the contradictions on display: details on Araki’s relationships with his models (both consensual sexual participation and one anonymous model’s accusation of sexual harassment), notes on his relentless self-branding and cultivated celebrity status, comments on his freewheeling merger of fact and fiction, and a historical explanation of kinbaku-bi are a few of the issues tackled.

Nobuyoshi Araki, KaoRi Love (Diptych), 2007

Private Collection

If exiting the exhibition without continuing to the third floor, the feminist who admires Araki would be inclined toward an overwhelmingly negative evaluation, having gleaned only subtle hints at Araki’s full range. But a signal of what is to come can be found on the last gallery wall of the second floor. Less dramatic than the nudes, but critically important, is a copy, and associated page-turning video, of one of Araki’s early Xerox Photo Album books. Its modest and roughly printed monotone images are juxtaposed on the same wall with similarly unadorned, more personal portrait and landscape prints from his 1995 Endscapes series. Herein lies a key to a broader, more complex reading of Araki that unfolds in its full intensity on the next floor.

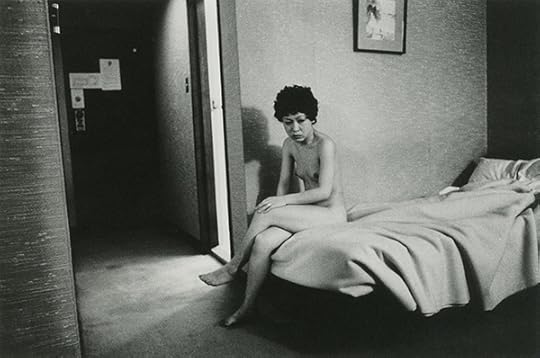

Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

In contrast to the dark and theatrically lit second floor, the upper-floor gallery is awash with an even light that serves to showcase a spectacular room-size case filled with over 450 books from Araki’s prolific photobook production. Presenting the tomes cheek-by-jowl with only their covers visible, the display cleverly includes several interspersed videos of book interiors. The overall impression is a sea of books that covers every stage of Araki’s career, which serves to introduce several of the more introspective thematic obsessions presented on the gallery walls surrounding the case. Foremost is a selection of prints associated with Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey (1991) books, each chronicling an important period in Araki’s tender relationship with his now-deceased wife, Yoko. Black-and-white images of a young Yoko on her honeymoon share the walls with her flower-filled casket—all reflective of the gentle romanticism of a man in love.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

A less sensational yet still highly sexual perspective is found in the group of Erotos images that examine Araki’s unabashed fixation on the dichotomy of Eros (the impulse toward life and sex) and Thanatos (the impulse toward death). Verging on the abstract, these close-up images of organic and flower forms suggest the sensuality and ephemerality of life without the aggressive sexuality found in the bondage photographs. A curatorial pairing of sexually brazen nineteenth-century ukiyo-e woodblock prints—one with specific references to kinbaku-bi—next to staged photographs of bound women provides further analysis of Araki’s contradictory forces. As Araki observes, “Photography, in a way, is a modern ukiyo-e.” However, he is quick to point out that he likes to take photographs similar to shunga (erotic ukiyo-e), but has yet to reach that level of mastery.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Colourscapes, 1991

Courtesy the Museum of Sex Collection

Paradoxes and obsessions shape Araki’s world, which blurs the boundaries between respectful depictions of women and pornography. Whether presenting a spectacularly lit photograph of a bound woman, a group scene of drunken, sexualized debauchery at Tokyo Lucky Hole (Araki’s favorite bar in Shinjuku’s Kabukicho district), or a tender photograph of his late wife, Araki is a complex persona and artist who should be more fully explored in the U.S. beyond his provocative, audience-arousing bondage photographs. The Museum of Sex is apparently the only institution in the U.S. willing to take on this challenge. As a retrospective, The Incomplete Araki is indeed incomplete—as any retrospective of his would be, given his immense output—but it is nevertheless a window into a fascinating artist. While the exhibition lures visitors with the more provocative and titillating photographs, its lasting imprint dispels many of the one-dimensional viewpoints that otherwise keep Araki’s work from being embraced by a broader audience.

Russet Lederman, a researcher and writer, teaches art writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki is on view at the Museum of Sex, New York, through August 31, 2018.

The post Can a Feminist Embrace Araki? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 7, 2018

Are You Listening, America?

Eugene Richards’s new film shares stories of overlooked citizens.

By Melissa Harris

Eugene Richards, Grandmother, Brooklyn, New York, 1993, from the book Americans We

Courtesy the artist

Eugene Richards always pays attention, close attention, while stealthily drawing almost no attention to himself. His countertenor voice floats or pitter-patters slightly above a whisper. He’s tall and lanky, yet seems to take up almost no physical space. His serene demeanor belies an explosive intensity. His instincts are those of both predator and prey—the one who hunts for the stories, and the one who has seen too much, and thus emanates a vulnerability to which people relate, respond.

And he knows this country and its people—“Americans We,” as he titled one of his books—having spent much of his life documenting from America’s heartlands to its peripheries, its blue-collar and most down-and-out neighborhoods, its industrial landscapes and its institutional landscapes—hospitals, jails, and the like. He engages. Always. Conversing, photographing, and on some occasions filming and videotaping those people he meets with a story to tell. Curious? Absolutely. But also aware of the efficacy of keeping a record, bearing witness—his own record, his memory, having been irreparably damaged after he was brutally beaten by likely Klansmen, when he lived in Arkansas (from 1969 to 1972).

Born in 1944 in Dorchester, Massachusetts, Richards made his hometown and its people an early focus in his book Dorchester Days (1978). But that came after his time as a VISTA volunteer health worker in Arkansas’s Mississippi River Delta, after which he became a reporter and social worker in Eastern Arkansas. There, he and other ex-VISTA volunteers founded RESPECT, which helped organize and distribute food and clothing to the poor. Out of this work evolved his first book, Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta (1973). Later, at the request of his then wife, the writer and poet Dorothea Lynch, who was dying from breast cancer, they together chronicled her illness and created the book Exploding into Life (1986). Its disquietingly poignant texts (hers) and images (his) revealed cancer’s physical and social realities long before the disease was openly discussed as it is now. Only a few years before, they had collaborated (again, Gene’s images, Dorothea’s writing) on 50 Hours (1983), a book that experientially moves through illness, protests, births, and other life events occurring mostly in Seabrook, New Hampshire. In other words, from the beginning, Gene has intimately focused on issues of social justice and health that challenge America and its citizens.

Eugene Richards, Final treatment, Boston, Massachusetts, 1979, from the series Exploding into Life

Courtesy the artist

He continued with Below the Line: Living Poor in America (1987), and then came his riveting coverage of Denver General Hospital’s emergency room in The Knife and Gun Club (1989). Gene’s portrayal of the drug scourge in inner-city America, in his devastating Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (1994), was a scathing indictment, through interviews and images, of our so-called “war on drugs” and its accompanying slogan, “Just say no.” Recognizing both the uselessness and the ultimate indifference of such inept policy, the book instead examines how crack-cocaine addiction ultimately destroys the very fabric of disenfranchised, vulnerable communities, and must be addressed in terms of this, and the poverty from which it emerges.

Myriad magazine stories (many collected in The Fat Baby, 2004) and other book and film projects consider everything from river blindness to mental illness (A Procession of Them, 2008) within and outside of the US. His stories embrace individuals of all races, genders, ethnicities, and ages, including two films on the elderly—Clarence, a Nebraska farmer, and Melvin, a farmer in North Dakota, respectively—in But, the Day Came (2000) and The Rain Will Follow (2016). Gene’s searching book Stepping through the Ashes (2002) evokes the ghostly World Trade Center site soon after the horrors of 9/11. There, he photographed while his wife and partner on many projects, film and print producer Janine Altongy, interviewed first responders and others. War Is Personal (2010) contemplates the excruciating toll of the war in Iraq on those who fight, and on their families at home—again through images and interviews. The story side of war becomes even more prominent in his 2015 play, In a Far Away Mind.

Eugene Richards, Still House Hollow, Tennessee, 1986, from the series Below the Line

Courtesy the artist

Gene has a habit of making work that defies categorization, and is often prescient in form and/or content—as is the case with his new film, Thy Kingdom Come, which will have its world premiere at Austin’s SXSW Film Festival on March 10, 2018. Begun in 2010, the film questions the very nature of documentary. The cast comprises individuals from the town of Bartlesville, Oklahoma, as themselves, and an actor: Javier Bardem, in character as a priest, yet most essentially himself. The film opens in such a way that announces its conceit.

Visually, it is quintessentially Eugene Richards. Camera angles, at times askew, intensify the raw intimacy of what we are experiencing. Ambient light conspires with the layering of images. Stark contrasts resonate with stark truths. Windows and mirrors compositionally and metaphorically play with transparency, opacity, and reflection. Shadows seem to have matter, and the tangible—a hand, a cat—feels almost illusory.

It turns out that the people who Bardem and Gene meet and speak with in the no-longer-thriving oil town of Bartlesville, home of Frank Lloyd Wright’s only skyscraper, are desperately hungry for someone to talk to. This has always been Gene’s forte: sensing where the stories are and then, of course, how to tell them. Trusting his gut, he has often been led by his assignments to experiences entirely unanticipated when he began. Such is the case with Thy Kingdom Come, which all began with Terrence Malick and To the Wonder (2012).

Ben Affleck and Javier Bardem in To The Wonder, 2012

Courtesy Magnolia Pictures

Melissa Harris: What is the genesis of Thy Kingdom Come?

Eugene Richards: It was in 2010, so it’s tough to remember exactly, but the first call was from Nick Gonda, Terrence Malick’s producer. He asked me if I wanted to be involved on a film with Malick. Terry and I had met briefly in the 1990s and I loved his film Badlands (1973), so I was very honored to be asked to be a part of this. At the time of Nick’s and my first conversation, the film was untitled and the script not something to be discussed—except that one of the characters, to be played by Javier Bardem, would be a priest experiencing a crisis of faith, and a lot of it would be set in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, where Malick in part grew up.

As part of this film, their idea was to incorporate real people, local townspeople, in scenes interacting with the parish priest, Javier, in order to give the film a broader sense of reality or atmosphere. These were meant to be short scenes shot on video that might later be edited into the final work.

Harris: When did you first go out to Bartlesville to scout, to find your subjects?

Richards: I first went in August 2010 on a kind of research trip and met Father Lee Stephens, Bartlesville’s Episcopal reverend, who said he would introduce me to people he knew who he thought might be interested in speaking with us. That’s how we began to meet people.

Father Lee was a really good guy, very interested in social justice, and in association with his Episcopal parish, he ran a program focused on helping those struggling economically and emotionally. Father Lee had this great term—“future story”—that he used when talking to people. His idea is that there’s no point in always dwelling on the past. He tries to help them know that there is the possibility to get their lives under control. This was a big part of his ministering.

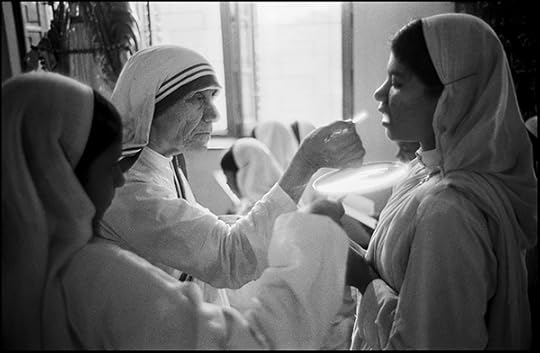

Mary Ellen Mark, Mother Teresa giving communion in the Mother House, Mother Teresa’s Missions Of Charity, Calcutta, India, 1981

© the artist

Harris: Did Malick have a clear idea of what he wanted his priest to be like—both his fictional priest (played by Javier Bardem) in To the Wonder (2012), and then what he was hoping to get from your footage with Bardem?

Richards: Terry Malick very much liked Mary Ellen Mark’s Mother Teresa photos . . . He, in fact, lent me one of her books. He thought a priest should act in the hands-on manner of a Mother Teresa—at least the one pictured in the photographs. But I had to tell him about what I had actually seen, for example, when I photographed in the emergency room in The Knife and Gun Club (1989). The priest would have to come in and talk with the person while they were critically ill and talk to the families, to find out what their wishes were. That’s what I said to Terry; it isn’t so much a physical thing as it is a listening process. I told him that I saw the priest’s first role as listener—as did Father Lee, as did Javier, in time.