Aperture's Blog, page 105

February 6, 2018

The Fragility of Existence

With uncompromising directness, Margaret Courtney-Clarke photographs the lives and landscapes of Namibia.

By David Goldblatt

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, Gottlieb plays traditional Damara music at the funeral of Ouma Juliana ǂÛ-khui ǁAreses on the family farm beneath the Dâures. Uis District, Erongo Region, 6 December 2014

© the artist

Except perhaps for a thread of elegance that runs through most of her work, not any of Margaret Courtney-Clarke’s earlier photography prepared me for the work in her book Cry Sadness into the Coming Rain (2017). No hint of what she has done here could I find in my memory of our collaborations of the late seventies. Nor could I link what she has done in the past few years in Namibia with her photography on the art of African women in traditional societies. Fifteen years of work, unaccompanied journeys into remote parts of Africa, hardships, fevers and great risks resulted in three seminal and definitive books, yet all of them differed fundamentally from what we have here.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, While Marta Rooinasie lives out her day in the nearby Klein Spitzkoppe Mountain digging for tourmalines, her Africanis dog Skrikkie (Afrikaans for “little fright”) guards her home, poultry and pigeons. Erongo Region, 9 January 2015

© the artist

Margaret returned to Namibia, the country of her birth and upbringing, in 2008 to live in Swakopmund on the edge of the Namib desert. Recovering from a life-threatening illness and the effects of its treatment, one might be forgiven for thinking that she would adopt a quiet life and write her memoirs. Instead, in photographs quite unlike anything she (or others) had done before, she embraced the reality of the Namib desert and its people with an extraordinary energy, acuity and devotion.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, Ashanti Gaises was born and raised in Khorixas in north-eastern Namibia and has moved south with her baby in search of work. She drags a bag of cardboard boxes from an illegal dump on the outskirts to the DRC. Swakopmund, 4 March 2014

© the artist

The photographs she produced are about existence. They come from an awareness of the fragility of her own existence and from a symbiotic grasp of the ancient rhythms of the desert and the coast, the ways of life of its people, the traces of their passing and the seemingly inexorable advance of corporate and mining development. The photographs are bare of nostalgia, fat or facile certainties. They are eloquent of raw existence and offer faint glimmers of hope, of life scratched from an appallingly inhospitable terrain in the face of overwhelming societal transition. Yet these photographs attain a searing grace which is in no sense false to the reality but is, on the contrary, a rare synthesis of what is there with an intensely heightened and uncompromisingly honest vision.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, A morning at the “amphitheater” in the sand dunes. Dorob National Park, 26 April, 2016

© the artist

Margaret’s relationship with the people she has photographed in this work is practical and intimate, never patronising, almost that of family rather than of compassionate observer. It is of a piece with the wholeness of her embrace. Using the sand of the desert she built a dwelling of sandbags with a family who had no home. She is a trusted friend of the women and children who scavenge the garbage dumps. She puts children into school and confronts municipal officials over their treatment of landless people. Deep into the desert she goes to friends and she knows their life. She celebrated her birthday with a family of peasant farmers who slaughtered a goat in her honour. When she heard of two children who had died of snakebite, she raised money for their coffins and travelled 230 kilometers on a rough desert track to be at their funeral.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, Tattered by wind and burnt by the sun, an effigy made by Tolikie Dausab is meant to attract buyers/tourists to his pile of rose quartz stones on the side of the road. A road grader returns to camp for the night. Uis District, Erongo Region, 8 August 2015

© the artist

In her earlier work Margaret’s concern was the art of African women. In this work her involvement is with the people themselves and their place. Like a pulse in the background her involvement throbs with anger and love. Anger at the stunting of lives, the blunting of hope, the desecration of the Namib and her own frailty, when there is so much to tell. Not the least of which is love.

David Goldblatt is a photographer based in Johannesburg. This text is reproduced from the foreword to Margaret Courtney-Clarke’s photobook Cry Sadness into the Coming Rain, published by Steidl in 2017.

The post The Fragility of Existence appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 1, 2018

Framing Justice

How do photographs tell the story of citizenship in the United States? Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture magazine’s summer 2016 issue, “Vision & Justice,” recently asked this question to her class at Harvard University. Here are five reflections from participating students.

Wayne Miller, Sgt. Johnie Morgan and his Korean wife, Blue (nickname for Lee Yong Soon) greet the former’s mother after arriving in the US, Seattle, Washington, 1950

© the artist and Magnum Photos

The Racial Assimilation of America’s “First Korean War Bride”

By Nathan Cummings

On November 5, 1951, Life magazine published an article that claimed to profile “the first Korean war bride to arrive in America” along with her new American GI husband. Although the woman’s real name was Lee Yong Soon, the article referred to her as “Blue,” a nickname she had been given by American soldiers in Korea during her work there as a telephone operator.

Life’s breathless coverage of Lee’s arrival in Seattle reflects an imminent shift in American attitudes and policy toward Asian immigrants. Only thirty years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had explicitly excluded foreign-born Asians from the category of “free white persons” in a series of cases including Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), making them ineligible for citizenship. A year after Lee’s arrival, however, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (also known as the McCarran-Walter Act) repealed this category and allowed certain categories of Asian immigrants—in particular, the wives of American soldiers—to become naturalized. As “America’s first Korean war bride,” Lee represented this future prospect. Even so, the Life article reflected the paternalism and ethnocentrism that defined white Americans’ apparent embrace of Lee and her fellow “war brides.”

In the article, photographer Wayne Miller captures Lee’s arrival in Seattle as she and her husband, Sgt. Johnie Morgan, are warmly welcomed by Morgan’s parents. One full-page photograph is captioned: “Homecoming kiss squeezes Blue between Johnie and his mother.” The image embodies the simultaneous assimilative pressure and cultural isolation experienced by Korean military spouses. Sgt. Morgan and his mother flank a smiling Lee, symbolically adopting her into their domestic unit; yet the photograph’s vertical hierarchy—along with the oddly romantic aura of the sergeant kissing his mother—casts Lee as a juvenile member of this unit, subordinated beneath parental control. The intimacy of the Morgans’ kiss further suggests a level of cultural connection that Lee is unable to access, leaving her paradoxically marginalized, even though she’s “squeezed” at the center. Moreover, the tight, symmetrical framing furthers this narrative: with her body obscured by a Western military coat, Lee is reduced to an isolated Asian face swaddled within the fabric of her new country. Her forward gaze reflects the implicit burden of this position—she must choose between isolation and assimilation, as the article’s use of Lee’s American nickname suggests.

In Miller’s other photographs, Lee is shown performing a vision of domestic life in the United States: eating dinner with the Morgans and cooking her husband’s favorite “Carolina-style” gravy. Published in the pages of Life, these images would have helped create what historian Grace M. Cho calls a “fantasy of honorary whiteness,” which acted to erase Korean military spouses’ cultural heritage in the eyes of the American public. In her 2008 book Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy and the Forgotten War, Cho argues that Korean spouses were expected to accept and participate in this “willful forgetting of . . . the violent and intimate history shared by Korea and the United States.” Even though the category of “free white persons” was no longer a prerequisite for foreign-born Asian citizenship, whiteness remained an aspirational ideal that Asian immigrants like Lee were expected to pursue.

Nathan Cummings studies American history and literature at Harvard University.

Bill Hudson, A 17-year-old civil rights demonstrator, defying an anti-parade ordinance of Birmingham, Alabama, is attacked by a police dog, May 3, 1963

© the artist and AP Photo

In Birmingham, Enduring Emblems of Authority and Violence

By Josiah Corbus

The German shepherd lunges, teeth bared. The black adolescent grimaces, midriff exposed. The white policeman clenches both fists: one wielding his predator, the other clutching his prey.

Bill Hudson’s May 3, 1963, photograph tells a story that arrays white authority and its attendant violence, emblematized by the police dog, against an unarmed black teenager. As the policeman yanks the boy, Walter Gadsden, a seventeen-year-old student at Birmingham’s Parker High School, to the right, the dog lunges to the left, creating a diagonal line that bolts across the frame. Hudson, an Associated Press photographer who was in Alabama to cover the Birmingham Children’s Crusade, captures the instant before the spearhead of this diagonal—the dog’s open maw—pierces the boy’s stomach, thereby leaving viewers to imagine the impending tear of flesh.

The next day, Hudson’s photograph ran on the Saturday front cover of nearly every major newspaper in the country. The New York Times printed it above the fold and across three columns, below the headline, “Violence Explodes at Racial Protests in Alabama.” Upon seeing the photograph, President John F. Kennedy said he felt “sick” and dismayed.

James Bevel, Martin Luther King, Jr., and other Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leaders had come to Birmingham hoping to expose the violence of Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor’s racist regime. Hudson’s photograph and others depicting the May 3 police crackdown achieved this objective and forced viewers across the country to confront the harm that violent policing had inflicted on young African Americans engaged in nonviolent resistance. These images mobilized public opinion. As Diane McWhorter, a scholar of the Birmingham campaign, has argued, they “shifted international opinion to the side of the civil rights revolution.” This shift contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, among other legislative achievements.

The broad resonance and persuasive power of Hudson’s photograph stems from the ways its visual story connects to longstanding experiences of authority and violence in the United States. Historian Walter Johnson has explored how the structure and perpetuation of slavery depended on violence, including the use of hunting dogs to track down so-called fugitives. In the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, African Americans continually faced the threat of violence. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, public lynchings and their visual reproductions enforced white racial hegemony. Hudson’s image highlights how state-sanctioned violence against African Americans persisted into the mid-twentieth century. In today’s world, where images and videos of struggles between police and African Americans have proliferated, Hudson’s depiction of white authority wielding violence on black bodies feels all too familiar.

Josiah Corbus is a senior at Harvard College, where he studies American history and literature, and directs an educational enrichment program for underserved local youth.

Edward S. Curtis, Maricopa women gathering fruit from Saguaro cacti, Arizona, 1907

Courtesy the Library of Congress

“Aliens” in America

By Ted Waechter

John Elk was an alien. Likely a survivor of repeated forced removals, Elk renounced the Winnebago tribe, to which he was born, about a year before trying to vote in Omaha, Nebraska. But in Elk v. Wilkins (1884), the Supreme Court ruled that he was not a U.S. citizen because, like other “Indians,” he “owed immediate allegiance” to his tribe, an “alien” nation.

Though at the time naturalization laws varied by state, they often required indigenous people to reject their tribes and prove they had “adopted” the habits of “civilized life.” In citizenship ceremonies, men were directed to trade their bow and arrow for a plow, symbolically abandoning the “life of an Indian,” as Frank Pommersheim writes in Broken Landscape: Indians, Indian Tribes, and the Constitution (2009), for the “life of the white man—and the white man lives by work.” Naturalization thus entailed reconstituting oneself racially through rules and rituals that discursively linked citizenship, civilized-ness, and whiteness. The indigenous person thereby embodied the dual definition of an alien given by Ulrike Küchler, Silja Maehl, and Graeme Stout in Alien Imaginations: Science Fiction and Tales of Transnationalism: both a noncitizen foreigner and something inhuman, removed from civilization.

This dual meaning of “alien” is at work in Edward S. Curtis’s Maricopa women gathering fruit from Saguaro cacti (1907). Taken near Arizona’s Gila River, home to the Maricopa since the sixteenth-century, the photograph foregrounds three women and a towering saguaro. Curtis exaggerates the saguaro’s height by severing it at the top of the frame, making it appear so tall that it dwarfs the women by comparison. Land domination is central to notions of civilization and humanity in Judeo-Christian theology, but nature dominates the Maricopa in Curtis’s composition. Because these tiny-looking women are nameless racial types, their faces obscured by shadow, they stand in for all members of an “uncivilized” race.

In Maricopa women Curtis rhymes the women’s bodies with the saguaros behind them, and both the human figures and cacti are rendered in similar shades of gray. Their shadows are identical. And the saguaros’ grooves and ridges find both formal and textural equivalents in stripes and folds in the women’s dresses, patterns on their baskets, and streaks in their hair. By likening the Maricopa women to cacti, Curtis makes indigenous bodies appear as inhuman features of the landscape. But how can natives be foreign? Believing Native Americans to be a “vanishing race,” Curtis makes them foreigners from a distant time. He deliberately hides evidence of missionary contact, which had begun years prior, and as Brenda McLain and Tobi Taylor explain in a 2006 issue of American Indian Art Magazine, he uses the tropes of Pictorialism—a nostalgic, soft-focus style of photography—to portray “Indians as ancient relics fixed in a permanent, ahistorical past.”

Turn-of-the-century discourse linked citizenship, civilized-ness, and whiteness through narratives of the land: whites claimed it for the mission of manifest destiny, dominated it as an index of humanity, and even incorporated plows in citizenship ceremonies. Whites justified the disenfranchisement of indigenous people by representing them as aliens, inhuman foreigners—yet their age-old relationship to the land undercut assertions of their foreignness. By portraying Maricopa women and thousands of other indigenous subjects as extratemporal relics of the past, Curtis subverts indigenous people’s history and casts them as foreigners from a distant time, alien invaders of the present.

Ted Waechter is a senior at Harvard College.

Dorthea Lange, Baseball players in a huddle, Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California, 1942

Courtesy the Online Archive of California, Berkeley, California

Home Field Disadvantage

By Christopher Chow

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the eviction of Japanese Americans to U.S. concentration camps for the “protection against espionage and sabotage.” Several months later, on Memorial Day 1942, Fred Korematsu was arrested in San Leandro, California, for evading eviction. Yet Korematsu, who had previously attempted to alter his appearance with plastic surgery, resisted again. In federal court, he argued that the executive order violated the Fourteenth Amendment. But the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the order in the 1944 case Korematsu v. United States. This ruling legitimized the cultural hysteria that discounted the citizenship of Japanese Americans for racist fears linking their biological ancestry to treachery.

During the same cultural moment, the photographer Dorothea Lange sought to dignify Japanese Americans living in internment. In one photograph from Manzanar, California, she depicted a group of eight boys holding each other closely. The extended caption reads: “Baseball players in a huddle. This game is very popular with 80 teams having been formed to date. Most of the playing is done in the wide firebreak between blocks of barracks.” Lange’s description preserves the anonymity of the boys: with turned backs and hidden faces, they might be any baseball players in a huddle. The absence of social markers in the photograph foregrounds the boys’ national belonging. No matter their ethnicity, they participate in American culture by playing the nation’s favorite pastime.

But internment policies displaced Japanese American families from their homes to concentration camps without regard for their belonging. In the photograph, shacks and telephone poles form a repetitive middle ground before the backdrop of the mountains. The built elements of the landscape mark Manzanar as the site of a concentration camp, and accordingly, the boys as Japanese American interns therein. Lange both documents the emotional emptiness of their displacement and appears to sympathize with them; she centers their bodies within the barren camp at eye level. This framing underscores the open bleakness of internment life, but it also directs focus to the contrasting intimacy of the boys’ huddle. The boys stand anchored here, contained within the camp, but convivial in their spirit nonetheless.

Outside the boys’ circle, Lange observes the tragic irony of Japanese displacement. The conspiracy of their enclosed formation and anonymity touches on the fears of spying that justified the decision of Korematsu v. United States. And like Fred Korematsu, who tried to hide his identity, the boys here are concealed, too. But while they cover their faces and themselves with each other’s bodies, they huddle neither to evade eviction nor hide from American troops. The boys are merely strategizing for their next home run: they are players of the national sport, yet victims of a national suspicion they did nothing to deserve.

Christopher Chow studies history and literature at Harvard University.

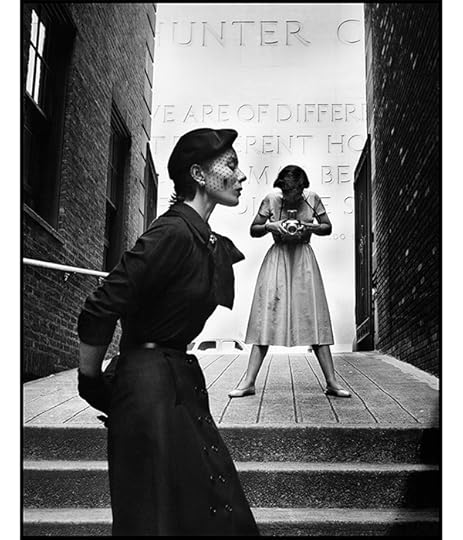

Paul Fusco, Women in mourning were joined by their husband in protesting against police brutality, NYC, 2000

© the artist and Magnum Photos

The Veiled Truth

By Larisa Owusu

On February 4, 1999, four undercover NYPD officers in the Bronx mistook Amadou Diallo, a Guinean immigrant, for a serial rapist. By the end of the confrontation, Diallo fell victim to forty-one shots, nineteen of the bullets piercing through his body, obliterating his spleen, kidney, liver, aorta, intestine, and spinal cord. The reason for this use of excessive force? The officers assumed that Diallo was reaching for a gun. In fact, he was searching desperately for his wallet to prove his identity.

Over a year later, at a protest against police brutality outside the United Nations, a protester held up a sign that read: “Go ahead and shoot. I’m black so it must be justified.”

One of the most striking details of this photograph by Paul Fusco, who covered the demonstration, is a veiled woman. The woman’s obscured face mirrors how every facet of Diallo’s encounter with the police officers was veiled, unclear: Diallo’s mistaken identity as a rapist; the undercover police officers; Diallo’s desperate last attempt to reveal who he really was. The contrast between the darkness of the veil, and the light that strikes the photograph she holds of Diallo’s face, serves as a stark reminder of the official portrait Diallo urgently tried to reach for in order to bring light to his identity. The black hands caressing his image seem to suggest a silent understanding: “I see you. I acknowledge you. I stand for you.” Unlike in his fateful encounter with the officers, Diallo, in Fusco’s photograph, is finally visible.

Ten years before Diallo died at the hands of NYPD officers, the Supreme Court case Graham v. Connor (1989) created a set of standards that determines when an officer can use excessive force. In 1984, in Charlotte, North Carolina, Dethorne Graham, a diabetic, was falsely accused of theft after leaving a convenience store where he was trying to buy some juice. A Charlotte officer, M.S. Connor, stopped Graham’s friend’s car, and in the ensuing altercation, Graham was injured. Following District and Appeals Courts rulings in favor of the police, the Supreme Court argued for the concept of “objective reasonableness,” a test based on the Fourth Amendment’s standards against unwarranted search or seizure. The court officially stated that the decision to use force “must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight.”

But, how effective is “objective reasonableness”? The court’s decision itself serves as a veiled conclusion. It is yet another way to conceal the injustice of unwarranted excessive force. The solution to police violence is not to put more power in the hands of aggressors. Amadou Diallo is proof of that. The 282 black individuals who lost their lives to police in 2017 are proof of that. Instead, the solution is, finally, to see past the veil, and to acknowledge black bodies as worth saving.

Larisa Owusu is a Ghanaian American first year student at Harvard University.

Read more from Aperture, Issue 223, “Vision & Justice.”

The post Framing Justice appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 31, 2018

Peter Hujar’s Italian Reverie

From the underground art star, a delicate picture of youth.

By Joel Smith

Peter Hujar, Boy on Raft, 1978

© The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC, and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In the early 1970s, in New York, Peter Hujar shuttered the commercial studio on Madison Square he’d been operating for a few years, moved into the East Village loft he would call home for the rest of his life, and turned his back on the hustle of fashion photography. Hujar’s enduring status as an underground art star is owed to what he called his “personal work,” which consumed him from then until his death in 1987—in particular, portraits of the famous and infamous among his generation of artists based downtown (which, by some counts, was the last).

But to associate Hujar only with portraits is to miss out on an oeuvre of great depth and variety. Rather than being a portraitist who did other work besides, he was a well-rounded artist for whom portraiture provided a moral anchor: it was his model for art making as the fixing and framing of a moment of intense identification with a subject. Empathy was Hujar’s emotive signature, whether he was shooting a drag performer under studio lights, the dappled surface of the Hudson River, or a cube of compacted scrap metal.

Hujar photographed this teenager on a chunk of Styrofoam in an Italian coastal town in the summer of 1978. A look at the contact sheet (one of over fifty-seven hundred of Hujar’s at the Morgan Library & Museum) reveals that artist and subject occupied separate spaces: Hujar was on the promenade, watching locals roughhouse on the rocky shore below. The boy—who appears in just one frame, marked with a red dot—is exposed to the elements, but to the camera he gives only a deeply shaded profile. Anonymity makes him readable as a focus of either desire or projection: self-portrait as a youth on a precarious raft.

Hujar was forty-three that summer, with one book to his name (the largely overlooked Portraits in Life and Death from 1976), and he was intensely aware that the slow maturation of his art had left him behind the curve of such nakedly ambitious peers as Robert Mapplethorpe. But here, under the warm natural light of a place where no one knew him, he was at his freest and at his fullest strength, and the world of beauty was his oyster.

Joel Smith is the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Morgan Library & Museum and contributor to Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, published by Aperture in 2017.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, through May 20, 2018.

The post Peter Hujar’s Italian Reverie appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 30, 2018

American Prospects

Tina Barney zooms out in a new series of landscapes.

Tina Barney, High School Band, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, 4th of July on Beach, 1989. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, Tennis Court, 1988. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, Weekapaug Surf, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, Bike Parade, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, Bay Street, 1988. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, Fun Slide, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Tina Barney, The River, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery

Known for her lush and precise portraits of upper-echelon American families, Tina Barney, in a new body of work, has reimagined her subjects at a distance. In Landscapes, her current exhibition at Paul Kasmin Gallery, she pans out from the individuals themselves, placing landscape at the forefront. Although many were taken in the last year (with a few, previously unseen works from the ’80s), Barney’s East Coast landscapes strike a similar mood as her previous work. In an interview from 1995, Barney noted that her photographs “are based on nostalgia, not only on the nostalgia of this place as opposed to the West Coast where I was living, but also nostalgia for my own childhood.” More than two decades later, in these large-scale color prints, Barney depicts classic scenes celebrating American traditions: Fourth of July parades, state fairs, tennis courts, beachside barbecues, and a high school sporting event sprinkled with cheerleaders and marching band players. Barney’s landscapes expand upon the theatricality of American wealth and prosperity, and widen the stage she has been working on throughout her career. Even in the most still moments or sparsely-populated scenes, these works appear choreographed by tradition.

Tina Barney: Landscapes is on view at Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, through March 3, 2018.

The post American Prospects appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 25, 2018

The Fearless Lynsey Addario

Katie Couric interviews the lauded photojournalist about her adventures abroad and her challenges at home.

Lynsey Addario, Taimaa Abazli, 24, holds her new baby Heln in their tent at the Karamalis camp in Thessaloniki, Greece, 2016

© the artist

Lynsey Addario has been kidnapped twice, was ambushed by the Taliban, and is one of the few photojournalists who has experience working in Afghanistan. A Pulitzer Prize winner, Addario regularly shoots for publications such as the New York Times, National Geographic, and Time. Her biography, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War (2015), is currently being developed as a movie to be directed by Steven Spielberg, and is slated to star Jennifer Lawrence. Most recently, Addario has been focusing on the lives of Syrian refugees, including the lives of three babies whose families have been seeking refuge in Europe.

In an interview with Katie Couric at the annual ICP Spotlights luncheon last November, Addario confided, “Most of the time I’m photographing, I’m weeping.” Her immense empathy carries into the projects that she takes on. Addario used her MacArthur fellowship to concentrate on maternal health and mortality, and she speaks passionately about documenting the tragic effects breast cancer in Uganda. Her photographs do nothing to hide the horrors to which she bears witness, but they emphasize a shared humanity, a social responsibility too often neglected by those who can afford to ignore the world’s cruelties. Addario allows—even compels—viewers to see themselves on the other side of her lens, despite differences of race, gender, age, or nationality.

—Annika Klein

Lynsey Addario, Captain Emily Naslundm, patrols through the village of Soorkano, Afghanistan, May 7, 2010

© the artist

Katie Couric: Let’s start at the very beginning, as Maria von Trapp would say. Why did you decide to become a photographer?

Lynsey Addario: I started photographing very young. I was timid. I was terrified to photograph people. Then, in 1999, the Associate Press asked me to do a story on transgender sex workers in the Meatpacking District. There had been series of murders in that community, and when Mayor Rudy Giuliani received a report about these murders, he had allegedly called them “the throwaway community.” I spent about six months of every single Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night in their apartments, going out on the streets with them. I realized that most people don’t have any idea that they’re human beings, that they have a life.

When I first started, the camera felt so obtrusive. I was too shy to walk up to people and take their picture. But now, my camera is exactly the reason I can walk up to people because I have an excuse.

Couric: How has your work evolved over the years? I imagine that you probably look back to some of your earlier work and think, Ugh.

Addario: I went to Afghanistan when it was under the Taliban in 2000, and it was one of the first difficult trips I had taken, one of the first times I had traveled to a war zone. I was twenty-six years old. I borrowed money from my sister, and I called my mom the night before leaving, and said, “Mom, I’m going to Afghanistan tomorrow,” and she said, “Okay, honey! Have a good time!”

I was one of the few people who went into Afghanistan under the Taliban and actually photographed there because photography was illegal at the time. Families would open up their homes and school their little girls at home, which was illegal under the Taliban. I look at these photographs and think, “Ugh, if I could have these opportunities today, with the technical skills I have now, then it would be such a different body of work.”

Lynsey Addario, An Iraqi woman walks through a plume of smoke rising from a massive fire at a liquid gas factory as she searches for her husband in the vicinity, Basra, Iraq, May 2, 2003

© the artist

Couric: Do you remember the experience of going to Iraq and being so up close and personal?

Addario: In 2003, the only way to get into Iraq—if you didn’t have a visa from the government, from Saddam before he fell—was to sneak in through Iran into northern Iraq. I didn’t go with the military because I wasn’t sure I would have the courage to be with them. I had never been in full-on combat. I thought, Why don’t I go to northern Iraq, and if there’s a humanitarian crisis, I’m well positioned. I didn’t think I’d see combat there.

About a month in, there was a proxy war going on with Ansar al-Islam, which was linked to Al Qaeda, and they were being fought by Kurdish Peshmerga backed by American special forces. We started covering that war. There was one day when the Americans fired dozens of cruise missiles into Iraq, into their area. We as journalists—for the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, there was a group of us—went to that area where the cruise missiles were fired because we wanted to see if there were civilian casualties.

I was photographing, and, suddenly, the locals started warning us to get out. We reconvened the journalists; there were about fourteen of us. We said, “Okay, we should go.” Everyone is warning us to leave. I was standing next to this TV camera man, and we were shooting side by side this truckload of Peshmerga. I got this feeling in the pit of my stomach, and I dropped my camera, and ran back to the car, and I shut the door, and a car bomb went off at that truckload of Peshmerga. The guy that I had been standing with was killed.

We didn’t know what happened. In those moments you have no idea, all you know is that you have to get out. We fled to a school where there were wounded being unloaded. A taxi driver pulled up and he said, “Is anyone here a journalist?” I said, “I am.” He said, “I have the body of a journalist in the back of my car. Can you help me identify him?” I thought I was going to throw up, and I ran to the back of the school and just started crying and thinking, “I don’t want to do this for a living. This is horrible.”

Lynsey Addario, An Iraqi man leans against a wall as he walks along rows of remains of bodies discovered in a mass grave south of Baghdad, now laid out in a building in Iraq, May 29, 2003

© the artist

Couric: Did you identify him?

Addario: No, I couldn’t look. I asked Elizabeth Rubin, who was there, to look, because she was much more seasoned than I was. There was no way to get out of the country because I didn’t have another visa for Iran and Saddam Hussein had not fallen. So I had to stay, but I was terrified.

Couric: There have been many other terrifying situations, I know. One was the Korengal Valley. What were you doing there, and why was it such a scary place?

Addario: In 2007, Elizabeth Rubin for The New York Times Magazine wanted to do a story about why there were so many civilian casualties in Afghanistan.

If we had the best military in the world—

Couric: So-called “smart bombs.”

Addario: Right. We were trying to figure out what was going on, so we asked to go to the heart of the war, where it was most dangerous, and the U.S. military was dropping the most bombs. Elizabeth and I went to the public affairs officer, and said, “Hi, we’d like to go to the Korengal Valley.” We were already in Afghanistan. The guy just looked us over and said, “Mm, it’s not really a place that’s fit for women.” And we’re like, “Why?” And he said, “There’s no place for you to sleep, and there’s no place for you to go to the bathroom.” And we looked at him and were like, “Well, where do men sleep? Where do men go to the bathroom?” He said, “They sleep in bunkers.” And we said, “We can do that.” He got flustered because, at that point, women in the military were not allowed on the front lines, but there was no rule for journalists. He said, “Come back tomorrow,” and we went.

We spent two months living on the side of the mountain with the troops. At the end there was Operation Rock Avalanche, which was a battalion-wide operation. We were airlifted in Black Hawks, and jumped out of Black Hawks in the middle of the night on the side of the mountain, and walked for a week with everything we owned on our backs. On the sixth day, we were ambushed by the Taliban.

Lynsey Addario, Soldiers with the 173rd Airborne, Battle Company, on a battalion-wide mission in the Korengal valley on the Abas Ghar ridge line, October 23, 2007

© the artist

Couric: Another place we were going to talk about was when you were meeting the Taliban, when you were really frightened—understandably so. Paint a picture for us.

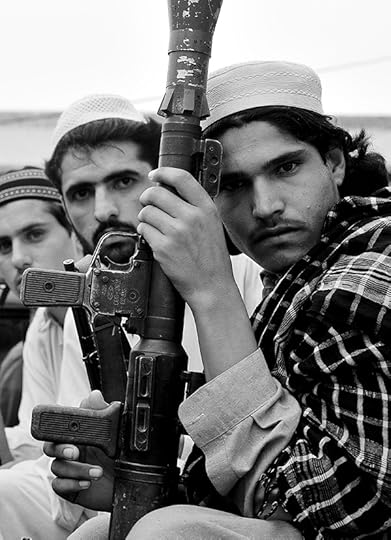

Addario: Exactly a year later, Dexter Filkins, who is now with The New Yorker but was with the New York Times at the time, called me up and said he had this great story on the Talibanization of Pakistan. My husband, who was my boyfriend at the time, said, “You’re not going to meet the Taliban.” I was like, “No, absolutely not. Why would I do such a thing?”

Of course, a month later, we were invited to meet Haji Namdar. They said the one thing you can’t do is to bring a woman. Our translator, who was basically Taliban, said, “Can’t Mr. Dexter take your camera and take photos?” And I was like, “No, Mr. Dexter can’t.” [Audience laughs.] They dressed us up as husband and wife. All Taliban will understand is that you can’t leave your wife in this strange village, so you have to go together.

Couric: How did he explain that his wife happened to have a camera?

Addario: We go to Haji Namdar’s compound, and I’m fully veiled—I can’t see anything. I go in this very small room with fifteen to twenty fighters and they all have their weapons and rockets. It’s very awkward because women don’t leave their house in this part of the world. I’m stumbling in, and sit down behind Dexter, who says, “Hey, Haji Namdar, man, thanks for welcoming my wife. She happens to have a camera, do you mind if she takes a few photos?” [Laughs.] At that point, the fact that there was a woman in the room was so awkward that it didn’t matter what I did.

Lynsey Addario, Pakistani Taliban fighters in Bar Kambar Khel, in the Pakistani tribal area near the border of Afghanistan, July 4, 2008

© the artist

Couric: Let’s talk about your scariest experience of all, which was in Libya. Why were you there, and what was going on at the time?

Addario: When the Arab Spring started in Egypt and Tunisia, I was on assignment for National Geographic in Iraq. But, eventually, I went into Egypt and crossed illegally into Libya. In many of these cases, that’s how you cover an uprising, because the government doesn’t want journalists there. Almost immediately, the war started. None of us thought there would be combat, because we expected it to be an uprising, like in Egypt. None of us had flak jackets or helmets, or any of the combat gear that we needed. But there was a call to arms, and, suddenly, we started moving forward on the front line with some of the rebels. It was unbelievable, it was not like anything I’ve ever seen because there was no place to hide. It was in completely flat desert. We were with guys who had no training at all. Often the journalists had more experience in combat than they did. Gaddafi had his military still. There were air strikes, helicopter gunships, mortars, sniper rounds, and they were hitting us from all sides. Often, the rebels would just turn around and leave when things got really bad, and the journalists were just sort of there. I was working on the front line for about two weeks.

Couric: And then what happened?

Addario: On March 15, 2011, I was working with Tyler Hicks, Stephen Farrell, and Anthony Shadid—all for the New York Times. The front line was moving in very quickly, so we knew Gaddafi’s troops were moving in, and that we had to pull back towards Benghazi. Originally, we were in two cars, which journalists often do in case one of the cars breaks down, but the driver of the second car, his brother was shot, so he stopped in the middle of the battle and said, “I quit.” There were four of us in one vehicle. To ask four journalists how long to stay in one place is quite complicated because everyone had a different idea of safety and different needs journalistically. We went back to the hospital to measure civilian casualties, and then we went back to the front line, when we knew it was about to fall. Mortar rounds were locking into our position, and civilians were fleeing. Eventually, by the time we made a decision to leave, we ran directly into one of Gaddafi’s checkpoints. Our driver panicked, stopped the car, and jumped out. They were all pulled out of the car. I, as the only woman, am often left sitting in the car. It was the second time I had been kidnapped, and the same thing had happened in Iraq.

At that moment, the rebels that we were covering started opening fire on the checkpoint. We were caught in a wall of bullets, and I knew I had to get out of the car. I crawled across the back seat and jumped out where Tyler, Anthony, and Steve had jumped out. Eventually, we ran for cover to a small cement building. Once we got behind that building, we were told to lie facedown in the dirt. We each had a gun put to our heads, and our hands and our ankles were tied together. They were about to execute us when the commander walked over and said, “You can’t kill them, they’re American.” We were very lucky because, obviously, there are a lot of people who don’t feel that way.

We were put in vehicles and placed on the front lines for hours while bullets and bombs rained around us. They laughed at us because we were tied up and couldn’t get out. For the next few days, we were beaten up, blindfolded, remained tied up, threatened with execution. As the only woman, I was groped repeatedly. Then we were transferred to a glorified prison-apartment in Tripoli, and we were released after six days.

Lynsey Addario, Opposition troops burn tires for cover during heavy fighting, shelling and airstrikes near the main checkpoint in Ras Lanuf, Eastern Libya, March 11, 2011

© the artist

Couric: As you were going though that horrific experience—I’m sure it was very scary for your mom, your husband, for your friends, your family—and most of all, for the four of you. Tell me about when you realized that you were finally going to be released?

Addario: There was an incredible guilt involved, because I knew my family was suffering. That is one of the hardest things about putting my life at risk. It’s not about me, and what happens to me, and if I get killed. That’s a consequence of doing this work. It’s more about, What do you leave behind? I’ve lost a lot of friends, and I’ve seen how it tears apart their families, and that’s very difficult.

Couric: You wrote a piece about being pregnant and doing your job in The New York Times Magazine. Tell us why you wrote it, and the backlash that you got as a result.

Addario: When I got pregnant, I was terrified. It was right after Libya—about six weeks after I was released from captivity. My husband and I had talked about having a family at some point, but as a woman and a professional, I was terrified of what that would do to my career. There were no role models. I didn’t know a single woman who did what I do who even had a boyfriend, much less a child. For me, the natural reaction was to hold on to my identity, and to work as much as I possibly could before I gave birth. I went to Senegal. I was in Saudi Arabia. I was in America—I did a road trip.

No one talked about how hard it is; everyone just talks about how beautiful it is to have a child—which it is, of course, but it’s very, very difficult. I felt like I needed to be honest. I wrote about going to Kenya to cover a drought, and going to Somalia, which was a war zone, when I was six months pregnant.

I received a lot of criticism. My response is: first of all, there are male journalists who get killed with children at home, and no one says, “What were they doing in a war zone?” It’s just as bad to lose a father as it is to lose a mother. Second, in these places that I cover, there are women who are pregnant and having children, and no one talks about the conditions for them. All they talk about is, “How can a girl from Connecticut go to Somalia when she’s pregnant?”

Lynsey Addario, Killis Camp, Turkish–Syrian Border in Turkey, October 22, 2013

© the artist

Couric: Tell us about the sexism you’ve faced early in your career. Do you feel that it’s gotten better as you’ve proven yourself to be so competent?

Addario: I kept thinking, when I started out, that there would be more and more women in the field—and there just aren’t. There are women who decide the lifestyle isn’t for them, but I also think that editors need to start assigning women, and putting more faith in women. When I look around in the field, it’s mostly white men, and that, to me, is a problem. We need local people to tell their own stories. We need people of color. We need women. And it’s just not happening.

Couric: As a woman, you’ve been able to have access to some extraordinary situations that men wouldn’t have access to. These are some of your proudest photographs as well.

Addario: In 2009, when I won the MacArthur, I wanted to focus on maternal health and maternal mortality. At that point, 550,000 women were dying in childbirth every year, around the world. Now, 800 women die every day around the world. That is extraordinary because 98 percent of those deaths are preventable.

Once, in Afghanistan, on the way back from some very remote hospitals and clinics, we saw these two women on the side of the mountain. Anyone who’s familiar with Afghanistan knows that a woman is always accompanied by a man. We didn’t see a man, so we assumed something was wrong. It turned out the woman on the right was in labor, and her water had broken. Her husband’s first wife had died in childbirth. He was so determined not to lose her that he borrowed a car, and that car broke down. I brought the family to the hospital and she delivered safely.

Lynsey Addario, Nazer Begam and her pregnant daughter Noor Nisa, 20, wait for transport to hospital, after their car broke down, November 14, 2009

© the artist

Couric: You stepped in and helped the woman in Afghanistan. It must be so difficult not to get emotionally invested in these stories. I’m sure you want to help every person you photograph.

Addario: Most of the time I’m photographing, I’m weeping. This picture is out of focus because when the daughter came in and saw her mother in the coffin, she didn’t even know that her mother had cancer. All of the attention went to preventing HIV/AIDS. Cancer was overlooked. This little girl came in and looked in the coffin and saw her mother, and I was crying so hard that I couldn’t even take the picture.

Couric: Why is photography so powerful? As someone who is a communicator and a storyteller myself, when can photographs tell a story that a documentary or television news story can’t?

Addario: It’s the moment that brings you to the heart of the image, and the emotion that is captured in that one second. I’ve been photographing a lot of Syrian refugees for the past five, six years. When the public hears about Syrian refugees, or refugees in general, you just generally turn the page, and you are like, I don’t even know how to connect with that story because it’s so far away. And, for example, I’ll take a picture of this mother and her children to show you she’s a mother—

Couric: The shared humanity.

Addario: An entry point. That’s constantly what I’m trying to do—to bring you into that moment and that emotion.

Katie Couric is an American journalist and author.

This interview is adapted from a live conversation at the International Center of Photography Spotlights luncheon on November 7, 2017.

The post The Fearless Lynsey Addario appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 23, 2018

Where the Homeless Sleep

Anthony Hernandez takes a hard look at the neglected landscapes of Los Angeles.

By Stephen Hilger

East Los Angeles–born Anthony Hernandez has long recognized the underprivileged people and disregarded spaces of his hometown in his photographs. The artist’s photobooks published between 1995 and 2017 provide an anthology of overlooked, ordinary, and deprived public life in his native city. While Hernandez’s intention of giving visibility to this segment of society has been consistent, his photographic style has undergone important shifts during his fifty-plus-years calling. Despite these formal changes, however, Hernandez has persistently aimed to picture life in Los Angeles from an atypical perspective. Allan Sekula likened his imagery to “a city grid opening up to the east, and thus a reversal of the usual understandings of Los Angeles topography, which always approach downtown from the west, and rarely take in the view from the other side of the river.”

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #62, 2010

Courtesy the artist and MACK

In Hernandez’s most recent title, Forever (MACK, 2017), he returns to this familiar territory, examining the most neglected landscapes throughout points east and south of downtown LA. The fifty-five closely cropped color photographs in the book are different from the sweeping, cinematic images of Los Angeles one may be accustomed to seeing. Instead of buying into the glamorous projection exported through motion pictures and via self-aggrandizing digital screens, Hernandez takes what he has described as a “very hard look” at the urban landscape, and at the “hard spaces” its citizens occupy. With Forever, Hernandez returns to a longtime subject, photographing the spaces inhabited by the homeless in Los Angeles and beyond. The first photograph in the book reveals a worn-out broom leaning against a white-washed yet stained wall, and soiled sheets of cardboard jutting out past the foreground. As in William Henry Fox Talbot’s seminal picture of the broom at Lacock Abbey, the photograph attests to everyday life. A crucial difference is that Hernandez’s broom positioned against a dead-end concrete wall appears more confrontational as opposed to Talbot’s, positioned by an open door.

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #31, 2011

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Made two decades earlier, Hernandez’s first monograph, Landscapes for the Homeless (Sprengel Museum, 1995), presents the viewer with the visual evidence of homeless encampments between or underneath the sprawling freeways of Los Angeles. Invisible to the multitudes traveling through the city in motorized vehicles, these sites are made conspicuous in Hernandez’s saturated color photographs of the denizens’ bedding, clothing, cooking utensils, and other possessions within the brushy foliage. Landscapes for the Homeless depicts the social condition of homelessness without human subjects. It is the absence of the dispossessed in these “landscapes” that charges the scenes. Borrowing from Walter Benjamin, the “photographs become standard evidence for historical occurrences, and acquire a hidden political significance. . . . They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way.” The lack of human presence marks the perhaps most significant transformation of the artist’s working process. While Hernandez’s earliest views from the street emphasized city dwellers adrift in the city by foot, his “landscapes for the homeless” are as hauntingly absent of people as the city views by Eugène Atget. This signature emptiness has remained in every subsequent series that Hernandez completed since that landmark work.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #1, 1988

© the artist and courtesy Yancey Richardson, New York

When Hernandez started out as a photographer in the sixties, he roamed streets, beaches, and other public spaces to compose street photography–style portraits of the city’s residents. By the late seventies, Hernandez began to photograph people waiting for the bus throughout Los Angeles with a 5-by-7-inch view camera; in the process, he created a new style of street photography more attuned to the urban landscape. These photographs remained unpublished for thirty years, until they appeared in the monumental book Waiting, Sitting, Fishing, and Some Automobiles: Los Angeles (Loosestrife Editions, 2007). The coveted volume, published by John Gossage’s imprint, features forty-two exceptional duotone, gatefold reproductions of Hernandez’s black-and-white photographs from the late seventies and early eighties. Waiting, Sitting, Fishing, and Some Automobiles includes four distinct yet related photographic series that portray the systematic use of public space in Los Angeles. The large-format views open up the pictorial space and render details not possible with a smaller negative. In the book’s first sequence, “Public Transit Areas,” the viewer can glean small details like chewing gum littered on the sidewalk by waiting riders and motor oil–speckled roadways. Pedestrians recede from the foreground to the middle ground, transforming his images of people waiting into urban landscapes. The following two series in the book also depict Angelenos waiting: in “Public Use Areas” office workers take their breaks in overbuilt corporate plazas, while in “Public Fishing Areas,” people pass time at lakes and watering holes in the city’s furthest environs. In the final selection, “Automotive Landscapes,” Hernandez pictures auto-repair shops, used-car lots, and junkyards—the locations where the defining machinery of daily life in Los Angeles is maintained.

During the early nineties, on a walk through the city after his own car broke down, Hernandez noticed a crowd waiting in line at a social-services office. Although he had passed the scene often in his own vehicle, he experienced things differently by foot, where he could observe architectural details from the vantage of the people waiting in line at the welfare office. Hernandez photographed the tile façade that wraps around the building, recording what the people saw as they moved through the line. A detail view of the tile grid enfolds the book Waiting for Los Angeles (Nazraeli Press, 2002). The image is highly formal—a straight-on depiction of square colored tiles—yet the significant shift in perspective places the observer within the social space of the subject, simultaneously representing both an abstract and real view.

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #36, 2009

Courtesy the artist and MACK

As in Waiting for Los Angeles, Hernandez assumes the perspective of the subject—the vantage point of the homeless—in Forever. While the “landscapes for the homeless” made by Hernandez two decades earlier created views of an outsider looking in, Hernandez’s new photographs look out from the sites where the homeless sleep. The artist perceived what the inhabitants see as he positioned his camera on the ground where they sleep, cook, and maintain their makeshift shelters. An essay by Hernandez’s wife, Judith Freeman, written in dialogue with him, gives context to the photographs by transporting the reader along the photographer’s itineraries through the city. The conversational format is evocative of the dialogue between Lewis Baltz and Hernandez in Landscapes for the Homeless, titled “Forever Homeless,” which served as inspiration for the title of the new book. In the original text, Hernandez claimed, “the homeless stand for the failure to face the future. Maybe forever homeless is the future.” In 1995, the year when Landscapes for the Homeless was published, the global homeless population was estimated to be 55 million people. Twenty years later, it had nearly doubled to 100 million. To document the homeless sites in Forever, Hernandez didn’t need to discover hidden enclaves of the dispossessed; so many of these campsites now appear in plain sight, in the harsh, bright light of the midday sun. As the photographer learned through firsthand observation, “the most neglected landscapes are left for the most neglected people.”

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #56, 2009

Courtesy the artist and MACK

The bulk of Hernandez’s work has focused on what Baltz described as the “defeated” majority; however, in the course of five decades of photographing and the publication of more than a dozen books, there is an important exception. Rodeo Drive, 1984 (MACK, 2012) brought to light Hernandez’s photographs of luxury shoppers or wannabes in a brilliant series of corporeal color photographs. They compose the last series in which Hernandez depicted people, and the first photographs by the artist in color. Hernandez took aim at “the winners, the lumpen rich, enjoying the spoils of their victory on Rodeo Drive.” With the inclusion of Rodeo Drive, 1984, Hernandez’s archive provides an even further-reaching visual atlas of the socially diverse and divided metropolis.

Stephen Hilger is a photographer also born in Los Angeles, a place he frequently photographs. His recent monograph, Back of Town (SPQR Editions, 2016), chronicles the disappearance of a neighborhood in New Orleans. He teaches at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he is chair of photography.

The post Where the Homeless Sleep appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 19, 2018

The Honesty of Petra Collins

The young photographer is celebrated for her raw and real depictions of femininity. But can images ever be trusted?

By Gideon Jacobs

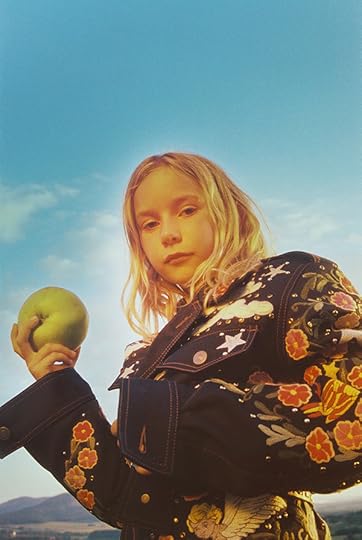

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

Petra Collins was five years old, in 1998, when Britney Spears’s “. . . Baby One More Time” was released. She was seven when Survivor first aired. She was almost eleven when Paris Hilton’s sex tape went public (conveniently, just a few weeks before Hilton’s television debut in The Simple Life), and eleven when Facebook launched. She was fourteen when Pornhub launched. She was seventeen when Instagram launched. She was nineteen when Kodak declared bankruptcy.

Collins’s generation—of which I’m a slightly older member—grew up in a cultural era defined by a potent combination of high commercialism and consumerism, seller enthusiasm and buyer naiveté. Seemingly caught off guard by new forms of media and technology, many still believed what they saw on the covers of magazines, on TV, on the internet, on their friends’ brand-new social media profiles. Sure, there was some baseline distrust of images—iconoclasm is as old as the icon—but savvy cynicism wasn’t quite as mainstream as it is today. It’s almost as if, in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it wasn’t fully understood, or maybe was simply ignored, that Photoshop is a powerful manipulative tool, that reality TV is an oxymoronic term, that the pictures from your ex’s vacation might not be telling the whole story. When Collins burst onto the scene at the start of this decade with her “real,” “raw,” “honest” photographic explorations of femininity, beauty, and sex, although she was borrowing heavily from many who came before her—Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, and Ryan McGinley, to name a few—it felt a little revolutionary.

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

Now, years later, but still just twenty-five years old, Collins has published Petra Collins: Coming of Age (2017), an attempt to put her meteoric rise to renown into a larger cultural and artistic context. Dubbed her first monograph, the book mixes Collins’s words and photographs with interviews, essays, and messages from other prominent voices, all reflecting on one subject: Petra Collins. Across the board, the guest contributors, from artist Laurie Simmons to writer Karley Sciortino, are unabashedly adoring. Model Diana Veras’s note begins, “Well first of all you’re fucking amazing and all your work has blown me away recently.” These sentiments would ring false, and their inclusion would feel tacky, if they weren’t expressed with such sincerity and urgency. What quickly becomes clear, when flipping through this book or browsing the comments section below a @petrafcollins Instagram post, is that many fans of Collins don’t just like her work; they’re thankful for it.

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

It’s this—the feeling that Collins has somehow given us something that we needed, or has finally said something that we’ve all been thinking—that has made her, for better or worse, a poster child. Having tapped into a wishful shift away from the inauthentic and fake, perhaps it’s no coincidence that her popularity has grown right alongside the recent revival of analog technologies like vinyl records and film cameras. Collins’s early work feels unmediated, like peeks behind the scenes. These images of teens hanging out, applying makeup, taking selfies—performing for their own cameras, not Collins’s—positioned her as a kind of visual truthsayer, an artist working to debunk the myth of the hairless body, the unblemished face, emotional invulnerability, uncomplicated happiness, perfect families, perfect romances, perfect lives.

But the most powerful force fueling Collins’s widespread fandom stems from her firsthand understanding of just how uniquely damaging it must be to grow up female in a Western world of false idols. (This is an experience I cannot directly speak to, but I hope it’s important for people of all genders to consider—with awareness and empathy—what it’s like to be a woman in a patriarchy.) Constructing a sense of self is a process of comparison, of establishing some idea of how one fits into the sociocultural context in which they live. So how could a young woman not feel alienation and shame when surrounded by imagery in which she fundamentally cannot see herself represented? But, to that same point, how could a young person of color not experience something similar? Or, for that matter, a young trans person of any race? Petra Collins: Coming of Age mostly features thin white women, a fact that feels incongruous with the goal Collins plainly lays out in her introduction: “This book is extremely personal, but I hope that when you look at it you can see yourself in it, too.”

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

The nagging question that will always sit just below the surface of any conversation about Collins is whether images, even ones made with an impulse to convey truth, can ever really be truthful, particularly because her photographs are celebrated for their “honesty.” That is, if Collins’s audience expects her to close the gap between who we are and how we are portrayed, are they bound to be disappointed? And if her mentality and work are, in large part, a reaction to feeling lied to by the images she was exposed to growing up, why should we trust images now, even hers?

Or maybe there’s another, more pressing question: If Collins is after honesty, at least in some sense, why is she a photographer? And why is she now working for fashion brands (Gucci, Bulgari, Juicy Couture) that are among the worst offenders of producing and propagating images that lie between their teeth? There’s a moment at the midpoint of Petra Collins: Coming of Age, in her dialogue with artist Marilyn Minter, that approaches an answer. Referring to media as the vehicle “that gives us all of our information,” Collins says, “It’s our duty to change it by working inside of it.” This statement of intent signals that her work, whether documentary or commercial, is never really without agenda. But it’s also an admission of her overall project’s inherent shortcoming—that her pictures are, at the end of the day, still pictures, part of the very thing they hope to undo.

Gideon Jacobs is a writer who has contributed to The New Yorker, The Paris Review, It’s Nice That, and BuzzFeed, among others, and previously was Creative Director at Magnum Photos.

Petra Collins: Coming of Age was published by Rizzoli in October 2017.

The post The Honesty of Petra Collins appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 17, 2018

Take the J Train

In Andre D. Wagner’s new photobook, an intimate chronicle of black life on New York City’s subways.

By Jessica Lynne

Andre D. Wagner, Gates Avenue, Brooklyn, New York, 2014

Courtesy Creative Future

I can’t quite remember the first time I encountered one of Andre D. Wagner’s photographs. It might have been during an afternoon perusing Instagram. It might have been during one of my many conversations with friends about exciting young photographers. Or maybe I read an early profile of the Brooklyn-based photographer. But, I’m not upset that I can’t recall that specific moment. Which is to say that, somehow, Wagner’s images feel as if they have always been here, inviting viewers to marvel at the quiet beauty of even the most familiar scenes.

Andre D. Wagner, New York, 2015

Courtesy Creative Future

Wagner’s photographs emit a sonic vibration that pulsates beyond the eye as he captures scenes from New York—particularly his neighborhood of Bushwick, the streets of SoHo, and the subway—that move toward a poetic vision of the city and its residents. The Omaha, Nebraska, native, who has a background in social work, tells me that taking photographs is always part of his daily regimen. And although he has a studio, you’ll rarely find Wagner shooting inside. Instead, his thousands of recent images are the result of hours-long city strolls. Last summer during a break from work, I walked past Wagner in SoHo as he watched the crowds pass by, camera in hand. Caught up in the chaos of tourists, it took me a few seconds to recognize him, but I’m sure he saw me before we eventually said hello—his eye somehow able to find a center in the busy New York shopping storm. He is nothing if not an artist who knows how to find a moment’s kinetic energy.

Andre D. Wagner, New York, 2014

Courtesy Creative Future

His debut monograph, Here for the Ride (2017), invites us to look closely at the environ of the city’s vast subway system. Here for the Ride is comprised of sixty-two black-and-white images that were taken over a three-year period, primarily along the J train, the line off which Wagner lives. It’s a line that starts in the capitalist heart of the city, the Financial District, and then runs eastward through Brooklyn and Queens, across some of New York’s most disenfranchised neighborhoods. In the wrong hands, such a story might be reduced to clichés of pity, of voyeurism. Resisting didactic social commentary, Here for the Ride offers us a world unto itself that hums with intimacy and possibility: a daughter leaning on her mother’s shoulder, caught in a moment of rest, or two showtime dancers intertwined in their choreography.

Andre D. Wagner, Lorimer Street, Brooklyn, New York, 2014

Courtesy Creative Future

Wagner is not the first photographer to position the New York City subway as subject in his images. Walker Evans and Bruce Davidson each chose the subway and its passengers as a site for mapping urban life: Evans in the early twentieth century, using a hidden camera, and Davidson in the 1980s, capturing the decade’s franticness. Indeed, for image makers, it’s difficult to fully comment on the rhythm of New York without paying attention to its massive public transit system. Wagner has found the romance in it all, the gentleness that emerges when working from a nuanced space of subjectivity. In this way, I’m reminded of the late Charles “Teenie” Harris, a photographer who chronicled black Pittsburgh from the 1930s to the ’70s. Many, though not all, of Wagner’s subjects are black folks. Like Harris, Wagner has found a way to record moments of black urbanity that emphasizes an expressiveness that runs counter to stifling narratives about blackness and urbanity we are too accustomed to seeing in mainstream newspapers and media outlets—if and when blackness is represented at all.

Andre D. Wagner, Gates Avenue, Brooklyn, New York, 2014

Courtesy Creative Future

What does it mean, then, to glean a vocabulary of abundance from Wagner’s photograph of four smiling black boys in their backpacks? From a father exiting a train car with his two daughters? In the introduction to her recent book, Listening to Images (2017), Tina M. Campt argues that quietness is a sonic methodology that provides a tool for contemplating the registers of the photograph. As she notes, “the quotidian is not equivalent to passive everyday acts, and quiet is not an absence of articulation or utterance.” That is, it’s not enough to see the image. Instead, we must also contend with what lives beyond the image, the world in which the image is located. Wagner’s Here for the Ride is a project of great care and skill from an artist who understands his role as a storyteller and attends the many utterances contained within his pictures. It’s a narrative of quiet wonder.

Jessica Lynne is the coeditor of ARTS.BLACK.

Here for the Ride was published by Creative Future in 2017.

The post Take the J Train appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 12, 2018

The Other Side of Gordon Parks

A new exhibition reconsiders the legendary photographer’s fashion and portrait work.

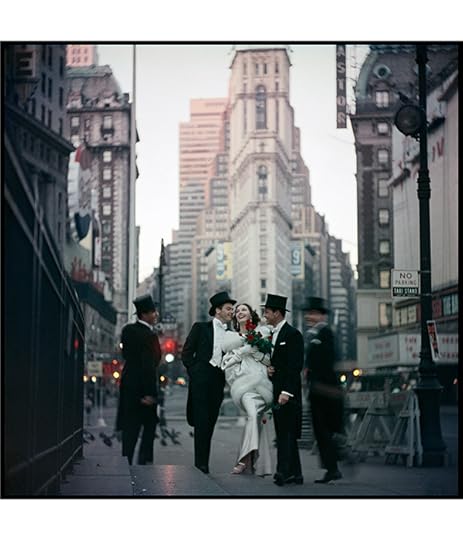

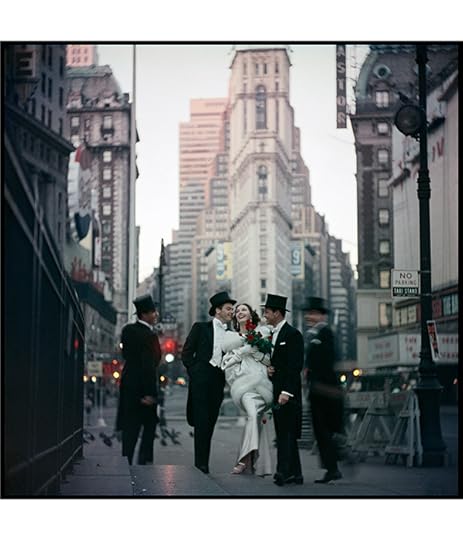

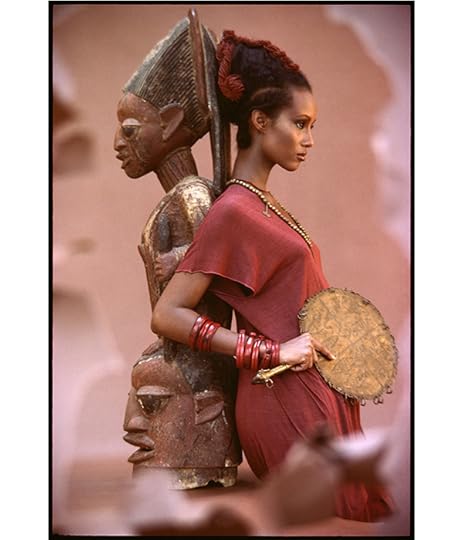

Gordon Parks, Cocoon Cape, New York, New York, 1956 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Untitled, 1978 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

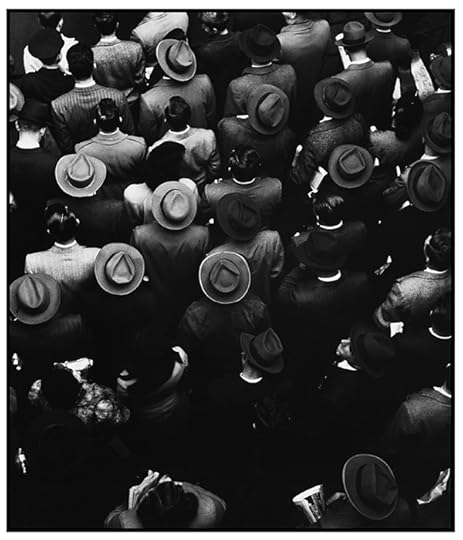

Gordon Parks, Ferry Commuters, Staten Island, New York, 1946 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

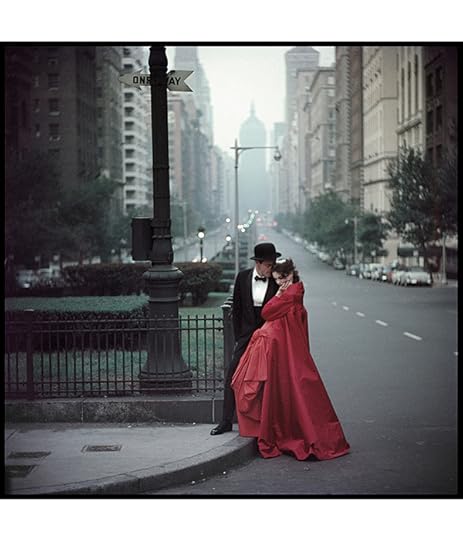

Gordon Parks, Untitled, New York, New York, 1957 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Evening Wraps, New York, New York, 1956 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

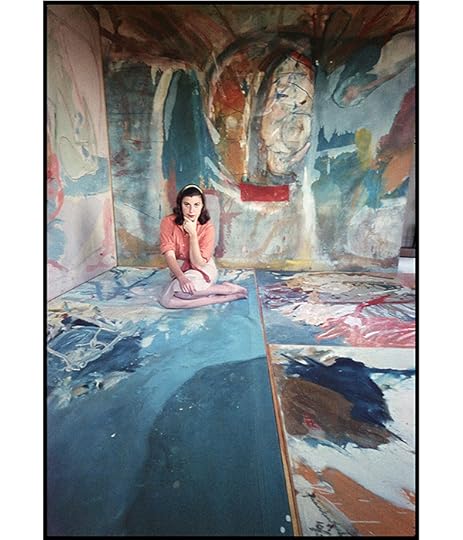

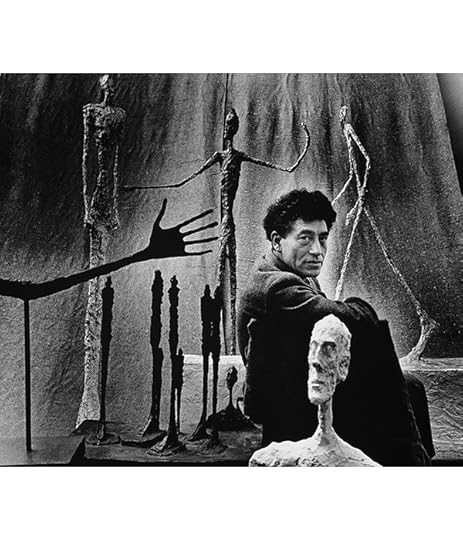

Gordon Parks, Alberto Giacometti and His Sculptures, Paris, France, 1951 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Untitled, New York, New York, 1956 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Bettina and Frances McLaughlin-Gill, 1950 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

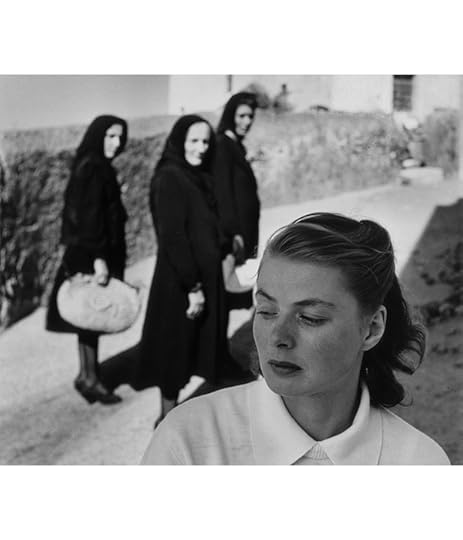

Gordon Parks, Ingrid Bergman at Stromboli, Stromboli, Italy, 1949 © and courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation

“Even from the beginning, Parks challenged prevailing rules about how to photograph fashion, including objects, group poses and streetscapes that beckoned with the allure of a desired lifestyle or career,” writes the photography historian Deborah Willis of Gordon Parks. A new exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery, Gordon Parks: I Am You, Part 1, displays Parks’s fashion work from the 1950s and ’60s along with portraits of artists in their studios—Helen Frankenthaler, Alexander Calder, and Alberto Giacometti, to name a few. Parks, who is best known for his velvety black-and-white photographs of the civil rights era, was also an innovative fashion photographer, often taking to New York’s streets for his atmospheric shoots. His artist portraits, however, are quiet and considered, letting the artists disappear into their creations.

Gordon Parks: I Am You, Part 1 is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, through February 10, 2018.

The post The Other Side of Gordon Parks appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 11, 2018

Jamie Hawkesworth Doesn’t Believe in Boundaries

A rising photography star bridges the divide between art and fashion.

By Adam Murray

Jamie Hawkesworth, Preston Bus Station, 2016

© the artist

Last fall, I met the photographer Jamie Hawkesworth at Central Saint Martins, London, to reflect on his recent exhibition, Landscape with Tree at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam. The college was a fitting location for such a discussion, as it was during my time as a lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire in the northwest of England that I first encountered Hawkesworth’s work, when he joined the undergraduate photography course in 2008. His deservedly quick rise from novice student to the photography establishment is long documented, with key moments often discussed, such as his work in the Preston Bus Station, his longtime collaboration with fashion designer J.W. Anderson, and his commissions for fashion and current affairs publications. All of which have contributed to his Huis Marseille exhibition, for which he was given free reign of the entire building—sixteen spaces filled with well over 150 hand-printed C-type prints.

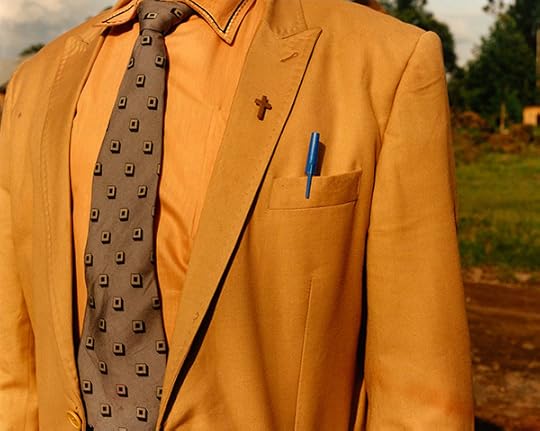

Jamie Hawkesworth, Congo, 2016

© the artist

Built around 1665, the Huis Marseille is housed in the former residence of French merchant Isaac Focquier. The combination of seventeenth-century architecture, eighteenth-century interior embellishment (including intricate stuccowork), and a room with a painted ceiling depicting Apollo among the clouds, accompanied by Minerva and the nine muses and twenty-first-century reconstruction, makes for an unusual yet compelling setting for photography. This being Hawkesworth’s first major exhibition, I made the trip from Manchester to Amsterdam for the opening weekend. As I walked into Huis Marseille, I was confronted by an ambitious body of work, which had the feel of an early-career retrospective.

Jamie Hawkesworth, Congo, 2016

© the artist

One gallery featured seven prints from a reportage project in the Democratic Republic of Congo commissioned by the Wall Street Journal. On the main wall hung three photographs: a young girl peering around a wall, a close-up of a torso clothed in a turmeric-colored blazer, and a green landscape with a single tree in the center, from which the exhibition’s title is derived. Each print was monumental in scale, allowing viewers to see every tiny detail that Hawkesworth’s 6-by-7-cm negatives have been able to capture.

Jamie Hawkesworth, Rio, 2016

© the artist

The focus for another space—this one dominated by a rich gold and red décor and the Apollo ceiling—was a project originally commissioned for Mastermind, a niche fashion publication directed by Marie-Amélie Sauvé. In this body of work, the beaches of Ipanema, Brazil, provide the backdrop for a styled editorial that features street-cast teenagers alongside models dressed in Louis Vuitton’s 2017 Resort collection. A less minimal curatorial style was given to a long, narrow space that displayed every photograph from Hawkesworth’s recently published photobook Preston Bus Station (2017)—139 images of people that he fleetingly encountered during his many visits to the Preston Bus Station in Lancashire.

Jamie Hawkesworth, Preston Bus Station, 2016

© the artist

The trend for producing “fashion exhibitions” in photography spaces has long been used as a way of bringing in large audiences through the network of press platforms that the photographer is already part of. No doubt Hawkesworth’s work is most often seen in a fashion context, a context that gave the work a major audience at an early stage. But for Hawkesworth, this does not come without its frustrations. “I do feel pigeonholed and I struggle to understand why people still distinguish between art and fashion,” he says. “My approach is always to try to take on work regardless of the context, where I feel like I am going to appreciate these pictures.”

Jamie Hawkesworth, Russia, Endless Rhythm, 2015

© the artist

Landscape with Tree was a seductive exhibition in a seductive space, not an exhibition intended to bamboozle the viewer with overcomplicated contextualization or a gimmicky hang. As Hawkesworth explained, “I liked the idea that you moved through someone’s sensibility, through many different rooms, but it all felt like one perspective. Nanda van den Berg [the curator] and I spent time walking through the space and instinctively identifying what work lent itself to each particular room.” Hawkesworth used the word “instinctive” many times during our conversation, which is not a flippant way to justify decisions that have not been given much thought: this has always been his approach. It is very much about actively responding to the time and place that he is in, exactly the behavior that the viewer was encouraged to engage in when in the exhibition.

Adam Murray is a lecturer at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, and Manchester Metropolitan University. He recently cocurated North: Fashioning Identity with Lou Stoppard, on view at Somerset House, London, through February 4, 2018.

Jamie Hawkesworth: Landscape with Tree was on view at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, from September 9 through December 3, 2017.

The post Jamie Hawkesworth Doesn’t Believe in Boundaries appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers