Aperture's Blog, page 107

December 14, 2017

On the Side of Truth

The Kenyan photojournalist Priya Ramrakha covered twentieth-century icons from Malcolm X to Miriam Makeba. Nearly fifty years after his death, a new exhibition reveals the scope of his pan-African vision.

By Bongani Madondo

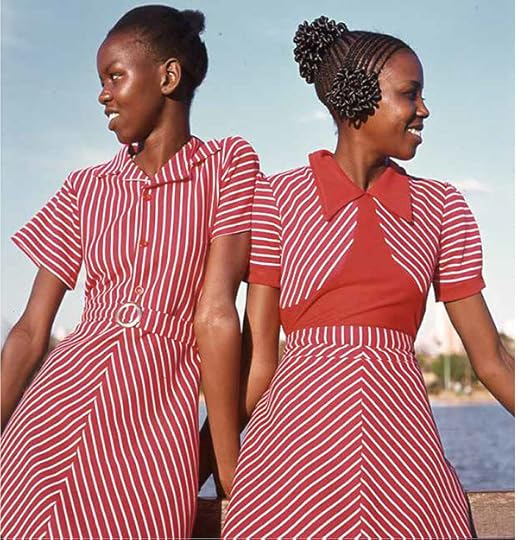

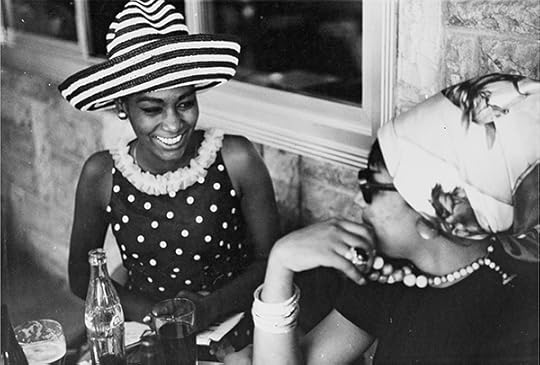

Priya Ramrakha, Models, ca. 1965

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

If he had some kind of supernatural powers, the archivist and filmmaker Shravan Vidyarthi would make sure the world, especially Africa, never forgets the name Priya Ramrakha. With the exhibition Priya Ramrakha: A Pan-African Perspective 1950–1968, cocurated by Vidyarthi and the scholar and curator Erin Haney, and recently presented at the FADA Gallery at the University of Johannesburg, the moment has arrived to illuminate Ramrakha’s story from a decades-old archive.

Ramrakha (1935–68) started working as a photographer as a teenager. He was a gifted and subtle documentarian, and yet he remains relatively unknown in his native Kenya and beyond. Born into a Kenyan-Indian family, by age eighteen he was working as a photojournalist for his uncle G.L. Vidyarthi’s rebellious Nairobi newspaper, the Colonial Times. From there, Ramrakha quickly made his name. Against the grain of the British, state-owned press, Ramrakha sought to capture his subjects with an acute and penetrative, yet sympathetic, eye, and his earliest efforts focused on the anticolonial nationalist movement, the Mau Mau war, and the Kenyan populace at large.

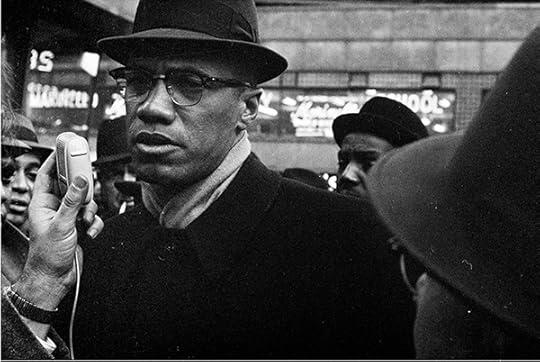

But Ramrakha was never just a one-dimensional protest photographer. His work, evident in the yellowing press cuttings of the late 1950s and early 1960s, is imbued with a jocular sense of humor, cinematic poetics, and the urgency of journalism, and paints a portrait of the artist as a young genius. At twenty-five, he crossed the Atlantic and headed to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in photography at the Art Center College. The America of the ’60s was a hotbed for all sorts of immigrant intellectuals, artists, and exiled students, mostly coming from what then was called the “third world,” and who were gripped in vicious struggles for independence. In New York, he photographed Malcolm X; in LA, Ramrakha was drawn to the civil rights movement, and met a veritable mix of activists, including Nation of Islam organizers, Martin Luther King Jr., and the South African siren Miriam “Zenzi” Makeba—of whom he made a series of intimate, frill-free, and yet alluring portraits.

Priya Ramrakha, Malcolm X and Nation of Islam protestors, New York, 1960

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Back home during the raging ’60s, as the African continent was gripped by the radicalizing fervor of rock ’n’ roll, soul music, and the quest for freedom following Ghana’s 1957 independence, Ramrakha got a freelance gig shooting for both Time and Life magazines. His work for them is unique for its unadorned yet uncomfortable portrayals of independence movements across Africa and the military takeovers that followed. Like Robert Capa, or the Polish metafictional writer Ryszard Kapuściński, Ramrakha’s immersion reveals the story of an embedded man. Although he was anticolonialist, the situations he shot and the access he gained make it difficult, at first, for the eye to discern with which side he was embedded. But, Ramrakha was embedded on the side of truth.

The exhibition in Johannesburg contained a series of battlefront portraits in Biafra, Nigeria, which tells two stories at once: the story of what’s framed in war, and what’s left out. On one hand, he tells the story of the gruesomeness of war; on the other, the story of the man who shot some of Africa’s vicious contemporary battles for self-determination. How did he get so close, so intimate, and so participative? What were the personal risks he worked in and through to beam war back to the world?

These are questions every artist—not that he referred to himself as such—has to contend with, then and now; they go to the very heart of his biography. In 1968, Ramrakha was shot dead in Owerri, Nigeria, caught in the crossfire between federal Nigeria’s army and the secessionists in Igboland’s Biafra. A CBS film crew captured his final moments; the correspondent Morley Safer tried to carry him to safety, but Ramrakha died before they reached an aid station. He was thirty-three years old.

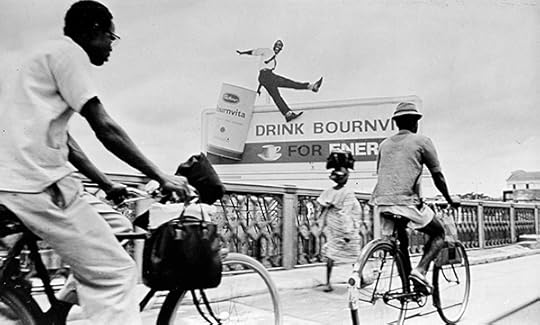

Priya Ramrakha, Bicyclists, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1950

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Although Ramrakha was definitely attracted to war, he also retained a lyrical aesthetic and warmth for ordinary people and their sense of dress, laughter, and the poetic lack of drama that shapes humanity’s daily mundanities. It is a poignancy drawn out of his love for people, especially fellow Africans. To Vidyarthi, a Georgetown University-trained filmmaker, Ramrakha’s life is both a pan-African archival story as much as a personal one: Vidyarthi is related to Ramrakha through his father, who was the photographer’s first cousin. Since 2004, Vidyarthi has been working on Ramrakha’s archive, searching for material for a documentary film, African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha (2007).

I recently spoke with Vidyarthi and Haney about Ramrakha’s legacy and his first-ever exhibition, which could not have come at a more apt and urgent moment: South Africa once again finds itself in the eye of the storm, as fierce, tertiary students lead “decolonialization” debates and take on identity politics body armor. Who is and is not an African? What role do you play, as an artist and seer, in relation to the tumultuous times around you?

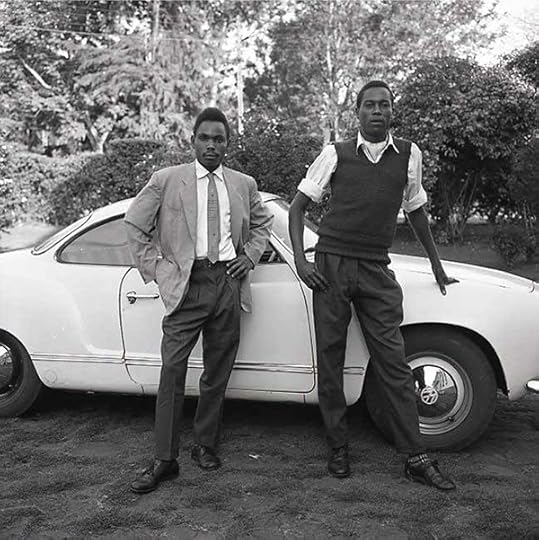

Priya Ramrakha, Two men, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1958

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Bongani Madondo: Why a pan-African show now? Is this a climb on the vogue-ish public discourse on decolonization revived by the student and youth movements in the U.S. and South Africa in the last three years?

Shravan Vidyarthi: This project has been a long-term labor of love, dating back to 2004, when, in Nairobi, I first began the work of recovering the neglected archive of Priya Ramrakha, who was my father’s cousin. My initial research led to the production of African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha, a documentary film I directed and produced, in which I sought to bring attention to Priya’s remarkable story and photographic output. Ramrakha was a total outlier for his time. In the 1950s, he left Kenya to briefly study in the U.S., and then, in the 1950s and ’60s, he photographed all around the African continent, the U.S., and Europe for Time and Life. Priya was largely drawn to communities during the rise of anticolonial resistance and nationalism, and he focused often on ordinary people doing quietly heroic things, sometimes at great costs to life and family, as well as to the lesser known leaders and visionaries. He was not beholden to political marquee names, although he documented the major players, such as Malcolm X, with grace.

As to the question of current debates in South Africa and the U.S., there has been a surprising dovetailing, but we have been working on this project far longer. Erin’s research in West Africa and my own in Kenya brought together joint efforts like our forthcoming book on Ramrakha, as well as educational programs we are working on.

Priya Ramrakha, March, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1964

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Erin Haney: In 2015, VIAD (Visual Identities in Art and Design) at University of Johannesburg asked us to create an inaugural exhibition of Ramrakha’s work, with a view to featuring more stories from the continent. So there are many points of urgency that we recognize, and it is not about coopting present struggles and activism around decolonization (be it in South Africa or elsewhere), or jumping on trendy bandwagons; rather, it is about being attentive to histories often neglected or sidelined in the mainstream.

We have been focused, here, on opening up a broader critical dialogue, by way of engaging Ramrakha’s visual archive. For us, the objective as curators was to situate current struggles and challenges within an extended, layered, and essentially pan-African story of colonial disentanglement.

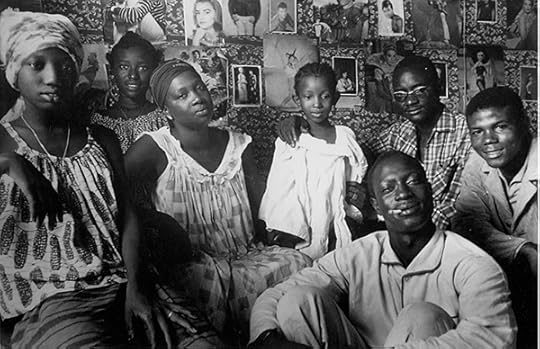

Priya Ramrakha, Family gathering, Accra, Ghana, ca. 1966

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Should our references of pan-Africanism always be a rear-window view, always looking and celebrating the past with scant attention to a changing Africa globally? Have you factored in the current winds of “wokey” Pan-Africanism coursing through South Africa today?

Haney: Pan-Africanism in Kenya and in other places was inherently futurist and collaborative, even with its ambiguities and omissions. Pan-Africanism has never been cut off from the rest of the world, in time or space. From each of our own experiences, we see how there is still a critical absence of visual material around these stories, and much intellectual and creative work needs to go in to a necessary and critical rethinking of the period, and its politics. Our view is that history is a work of the here and now and not a fossilized past.

Seeing the responses of people in Johannesburg—the younger “born-frees” and the older generations—it was clear that the exhibition brought out distinct stories, especially in light of the public debates around decolonizing education and the sidelining of African histories that is commonplace. It’s part of a messy and ongoing dialogue—hopefully that connects with the deeper frustrations and misrepresented histories that are so profoundly troubled and debated in South Africa, and which have powerful resonances in the U.S. as well.

Vidyarthi: That said, present day Kenya does a terrible job of celebrating its pan-African heroes and helping young people connect with them, and their aspirations and ideals. Ramrakha’s work reveals important political collaborations across racial lines, especially in the pre-independence era. All of this is almost impossible to remember today. Very few people in Kenya, whether of African or Indian descent, know of the relationships forged between African and Indian freedom fighters, or the extent of those collaborations and solidarities. Symbolically, his work is rendered all the more relevant, especially in a place like Kenya where Kenyan Indians have been vilified as “non-indigenous” bourgeoisie.

Priya Ramrakha, Miriam Makeba, New York, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: I’m particularly interested in the discovery of the photographs of the singer Miriam Makeba within the Ramrakha archive. So much love in there.

Vidyarthi: To be clear, the Makeba images have been part of Priya’s broader archive all along. They are one of many tremendously exciting subjects, most of which were never published. The inclusion of the Makeba images is, of course, an important point of connection for a South African exhibition, and one that demonstrates the kind of pan-African and international conversation that has linked independence movements across the continent, as well as associated civil rights and antiracist movements in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Priya Ramrakha, Ladies, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1964

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Did Priya have a close relationship with Makeba at all? Looking at some of those images, the viewer is confronted with intimacy, and a sense of warmth in the subject and her surroundings.

Vidyarthi: No, but by all accounts, he was incredibly good at gaining the trust of his subjects. He would have been a student in Los Angeles during this time, and would probably have been excited to meet Makeba, given his connection to the anticolonial press in Kenya, and his interest in (and coverage of) the civil rights movement in the U.S.

Madondo: What did he think of Makeba? Are there any letters or diaries he kept that might shed a light?

Vidyarthi: Priya’s scrapbooks are essentially a visual record. Unfortunately, we don’t have any letters or diary entries around his interaction with Makeba. Some of these encounters demand a measure of imagination, which is so often an aspect of revisionary historical work!

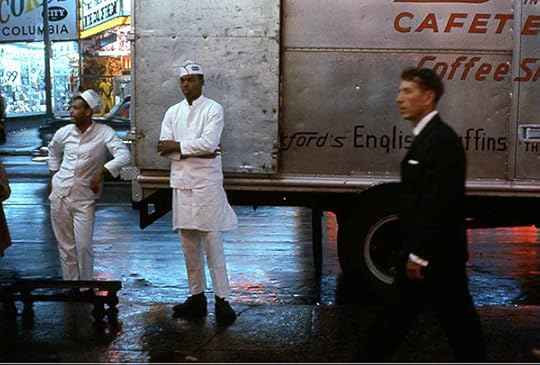

Priya Ramrakha, Deliveries, Manhattan, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Is this a posthumous retrospective or a fraction of Priya’s work?

Vidyarthi: It is retrospective in the sense that we are looking back at a particular continuous time and view of this person’s work, but not at all an exhaustive reflection of his career. As we are working on the book we are still digging through the archive, discovering fascinating images, and piecing together their stories.

Priya was killed in the Nigerian Civil War in 1968. Prior to that, he shot thousands of photographs. Thus, the exhibition is a selection that presents a broad overview of his practice, and will give audiences an opportunity to rethink and revisit a set of experiences and political moments that continue to resonate today, as the legacies of colonialism are grappled with and negotiated.

Priya Ramrakha, Rally for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign, Los Angeles, 1960

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Who, specifically, discovered these photographs?

Vidyarthi: Priya’s images were scattered across the globe. Priya’s friends had some in the U.S. and the U.K. Some were in the Time and Life archives. The most elusive, thousands of negatives and prints, were concealed in the depths of Priya’s cousin’s garage in Nairobi. Over the ten years working to gather and collate the archive, I have interviewed numerous people connected with Priya and his time. All of the photographs are presented for the first time in over fifty years.

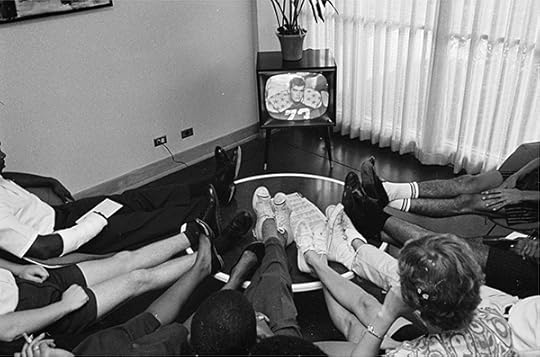

Priya Ramrakha, Football watchers, Los Angeles, 1961

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: What state were they in?

Vidyarthi: Fortunately, many of the negatives, contact sheets, and clippings were in great condition because of Nairobi’s dry climate.

Madondo: What exactly was discovered: prints or negatives?

Vidyarthi: Both, and some letters, documents like passports, death certificates, Time and Life correspondence.

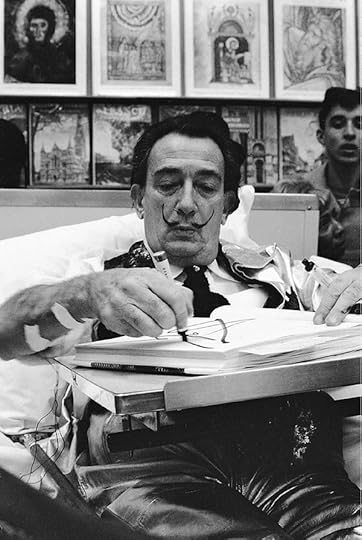

Priya Ramrakha, Salvador Dali, New York, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: How do we know the images have never been published before?

Vidyarthi: Some images in his archive have been published in Time and Life. Others were published in Drum magazine’s East Africa edition, and in Kenyan newspapers. The majority have not appeared in any publications that Ramrakha worked for, to the best of our knowledge.

Madondo: Is there a possibility that Priya shot these while on commission (say for Life) and that the photographs were not used during his time there?

Vidyarthi: We don’t know for sure, yet. It would appear that Ramrakha shot these either in New York, or at the University of California, Los Angeles, where Makeba might have been performing and visiting a cohort of continental African students there in 1961 or 1962. Ramrakha was in both places, and he attended the Art Center College in LA at that time.

Priya Ramrakha, Kenyan subjects rallying for land rights and political equality, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1950

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: As a photographer in those tumultuous times, roughly from 1960 to late 1968, was Priya associated with any cultural or liberation movement?

Vidyarthi: Not that I am aware of. I would say that Priya’s political drive is reflected in his photographic practice, in the kinds of stories he told, many of which are located around experiences of race, civil rights, anticolonial struggles, and experiences of independence. As one of the first African photographers for Time and Life, he was in a unique position to counter, to some degree, reductive views on African political struggles and experiences. Significant in this regard is, I believe, the attention he gave not only to key political figures and “big moments,” but also to the everyday experiences of African people.

Priya Ramrakha, Local and international press corps, Independence day, Nairobi, Kenya, December 12, 1963

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: What’s next for this exhibition?

Vidyarthi: I’m thrilled that a selection of works from the recovered archive were finally on public display, and I am honored that an African audience has been able to experience images that have lain dormant for over half a century. VIAD, who commissioned and made a deep investment in this project, and the FADA Gallery were extraordinary in their commitment to see this work come to public light. We are all looking forward to seeing the work travel within South Africa, and hopefully soon to Kenya, as well as in Europe and the U.S.

Bongani Madondo is the author, most recently, of Sigh, the Beloved Country (2016). He is an associate researcher at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, as well as contributing editor at the Johannesburg Review of Books.

Priya Ramrakha: A Pan-African Perspective, 1950–1968 was on view at the FADA Gallery, Univeristy of Johannesburg, from October 5 to November 1, 2017.

The post On the Side of Truth appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture’s Holiday Gift Guide

This year, Aperture publications have explored how fashion photography can serve as a vehicle for social change, how photography empowers transgender communities, the black dandy movement, our relationship to food, and more. From iconic monographs by master photographers, to groundbreaking, never-before-published work, we offer titles for everyone on your holiday list.

For the Collector

Intimate Distance: Twenty-five Years of Photographs, A Chronological Album

Intimate Distance is the first comprehensive monograph charting the career of acclaimed American photographer Todd Hido. Though he has published many smaller individual bodies of work, this book gathers his most iconic images for the first time and brings a fresh perspective to his oeuvre with the inclusion of many unpublished photographs.

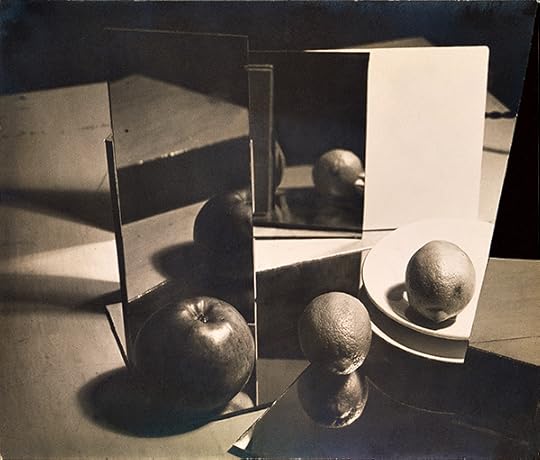

Illuminance Limited-Edition Box Set

Rinko Kawauchi’s work has frequently been lauded for its nuanced palette and offhand compositional mastery, as well as its ability to incite wonder through careful attention to tiny gestures and the incidental details of her everyday environment. In Illuminance, Kawauchi continues her exploration of the extraordinary in the mundane. This limited-edition boxed set includes a specially bound copy of the artist’s monograph Illuminance (Aperture, 2011) and two beautiful prints of images found in the book, all presented in a clothbound case.

Stephen Shore: Selected Works, 1973–1981

Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places is a canonic body of work—a touchstone for those interested in photography and the American landscape. Remarkably, this series of photographs has yet to be explored in its entirety. Over the past five years, Shore has scanned hundreds of negatives shot between 1973 and 1981. In this volume, Aperture has invited an international group of fifteen photographers, curators, authors, and cultural figures to select ten images apiece from this rarely seen cache of images.

John Chiara: California

John Chiara creates his own cameras and chemical processes in order to make unique photographs that use the direct exposure of light onto reversal film and paper. Each resulting image is a singular, luminous object. This highly anticipated first book includes the surreal and thrilling landscape and architectural photographs for which the artist has become known. John Chiara: California features pictures taken in the artist’s hometown of San Francisco and other locations along the Pacific Coast.

Great Storytelling

The Notion of Family

Now available in a paperback edition, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first book, The Notion of Family, offers an incisive exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania.

Jonas Bendiksen: The Last Testament

Imagined as a sequel to the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, The Last Testament features visual accounts and stories of seven men around the world who claim to be the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

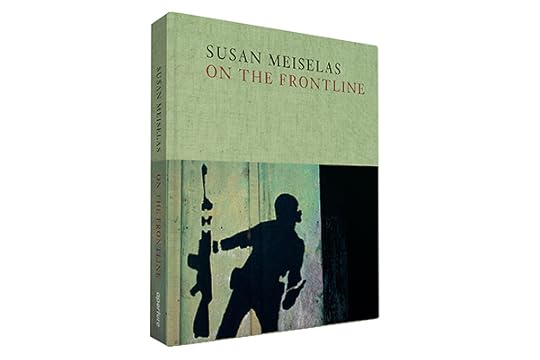

Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline

Susan Meiselas, one of the most influential photographers of our time and an important contributor to the evolution of documentary storytelling, provides an insightful personal commentary on the trajectory of her career.

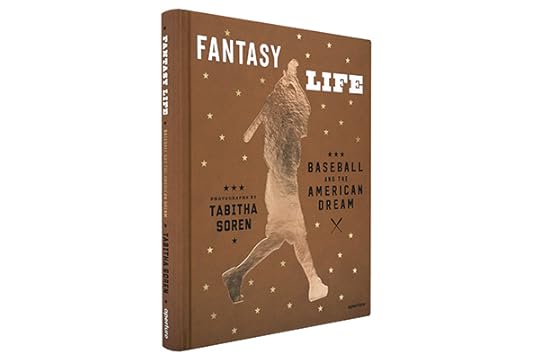

Tabitha Soren: Fantasy Life

In 2002, Tabitha Soren began photographing a group of minor league draft picks for the Oakland A’s. Fifteen years after that first shoot, Fantasy Life portrays a selection of these stories, gathering together a richly textured series of photographs taken on the field and behind the scenes at games, along with commentaries by each of the players and memorabilia from their lives.

Intersectional Inspirational

Future Gender

The Winter 2017 issue of Aperture magazine is dedicated to the representation of transgender lives, communities, and histories in photography. Guest edited by Zackary Drucker, the artist, activist, and producer of the acclaimed television series Transparent, “Future Gender” considers how trans and gender-nonconforming individuals have used photography to imagine new expressions of social and personal identity, from the nineteenth century to today.

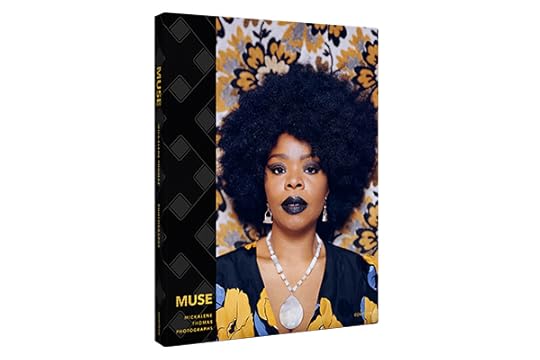

Muse: Mickalene Thomas Photographs

Mickalene Thomas, known for her large-scale, multi-textured, and rhinestone-encrusted paintings of domestic interiors and portraits, identifies the photographic image as a defining touchstone for her practice. Thomas’s portraits draw equally from 1970s black-is-beautiful images of women such as supermodel Beverly Johnson and actress Vonetta McGee to Édouard Manet’s odalisque figures.

On Feminism

The winter 2016 issue of Aperture, “On Feminism,” focuses on intergenerational dialogues, debates, and strategies of feminism in photography, and considers the immense contributions by artists whose work articulates or interrogates representations of women in media and society. Across more than one hundred years of photographs and images, “On Feminism” underscores how photography has shaped feminism as much as how feminism has shaped photography.

Question Bridge: Black Males in America

Question Bridge assembles a series of questions posed to black men, by and for other black men, along with the corresponding responses and portraits of the participants. The questions range from the comic to the sublimely philosophical: from “Am I the only one who has problems eating chicken, watermelon, and bananas in front of white people?” to “Why is it so difficult for black American men in this culture to be themselves, their essential selves, and remain who they truly are?”

Wanderlust

Highway Kind

Since 2004, Justine Kurland, known for her utopian photographs of American landscapes and their fringe communities, and her young son, Casper, have traveled in their customized van, going south in the winter and north in the summer. Her life as an artist and mother is finely balanced between the need for routine and the desire for freedom and surprise. Kurland’s deep interest in the road, the western frontier, escape, and living outside mainstream values pervade this stunning and important body of work.

The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip

The road trip is an enduring symbol in American culture. As photographers have embarked on trips across the United States with the express purpose of making work, they have created some of the most important photographs in the history of the medium: from images by Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Berenice Abbott to Robert Frank’s 1950s odyssey, The Americans. From Stephen Shore to Ryan McGinley, hundreds of other photographers have continued the tradition. The Open Road is the first book to explore the photographic road trip as a genre.

This Is Mars: Midi Edition

This Is Mars offers a thrilling visual experience of the surface of the red planet. The award-winning French editor and designer Xavier Barral has chosen and composed images, drawn from the comprehensive photographic map of Mars made by the U.S. observation satellite MRO (Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter), to revel in the wonder of Mars.

Foodie

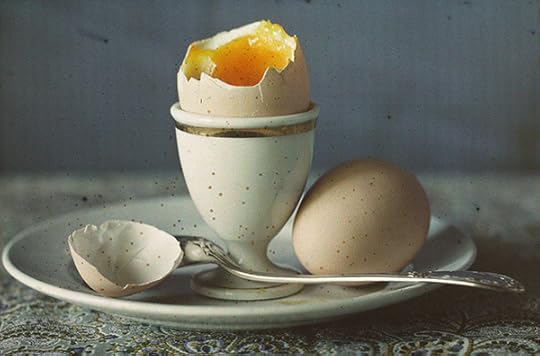

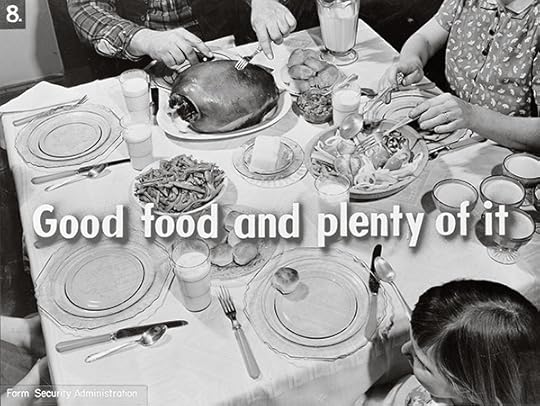

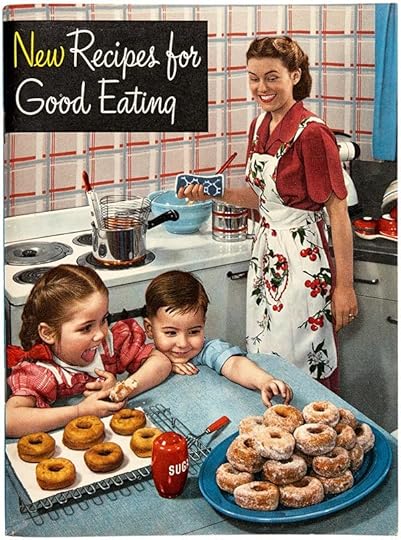

Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography

From basic sustenance to savory repasts, food awakens the senses and touches both private and public life. This is the first book to cover food photography’s rich history—not only in fine art photography, but also in crossover genres such as commercial and scientific photography and photojournalism.

The Photographer’s Cookbook

Playing off George Eastman’s famous recipe for lemon meringue pie, as well as former director Beaumont Newhall’s love of food, the cookbook grew from the idea that photographers’ talent in the darkroom must also translate into special skills in the kitchen. An extensive and distinctive archive of recipes and photographs are published in The Photographer’s Cookbook for the first time.

Downtown Kid

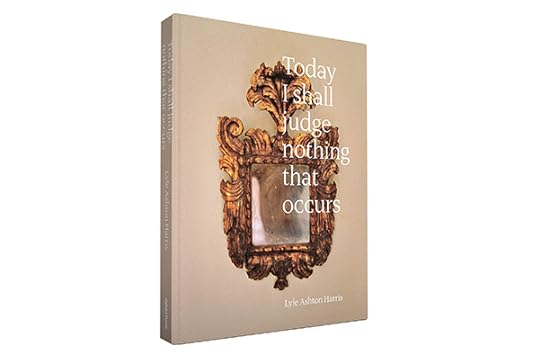

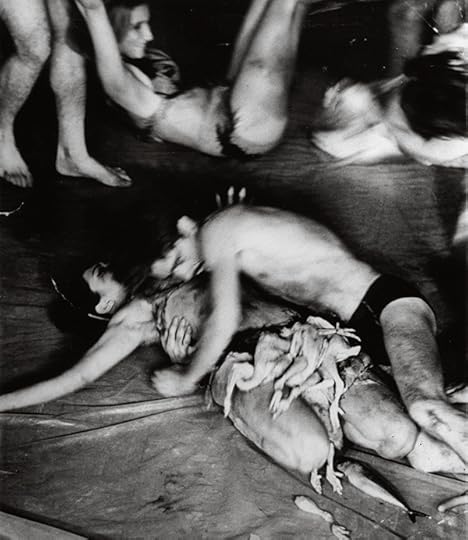

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, a radical cultural scene emerged in cities across the globe, finding expression in the galleries, nightclubs, and bedrooms of New York, London, Los Angeles, and Rome. In Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs, the artist’s archive of 35 mm Ektachrome images are presented alongside journal entries and recollections by contributors such as Vince Aletti, Rashid Johnson, and Sarah Lewis.

Manhattan Sunday

Drawing heavily on personal experience, Richard Renaldi captures that ethereal moment when Saturday night bleeds into Sunday morning across the borough of Manhattan. This collection of portraits, landscapes, and club interiors evokes the vibrant nighttime rhythms of a city that persists in both its decadence and its dreams.

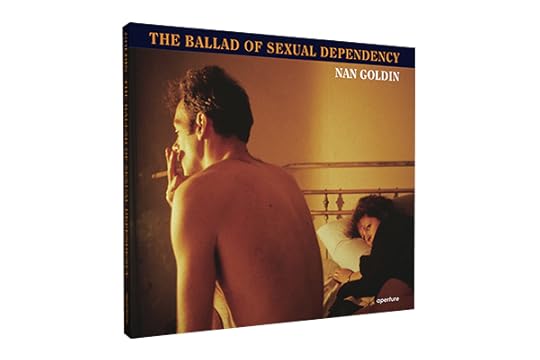

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a visual diary chronicling the struggle for intimacy and understanding between friends, family, and lovers—collectively described by Goldin as her “tribe.” Her work describes a world that is visceral, charged, and seething with life. First published in 1986, this reissue recognizes the persistent relevance and freshness of Nan Goldin’s cutting-edge photography.

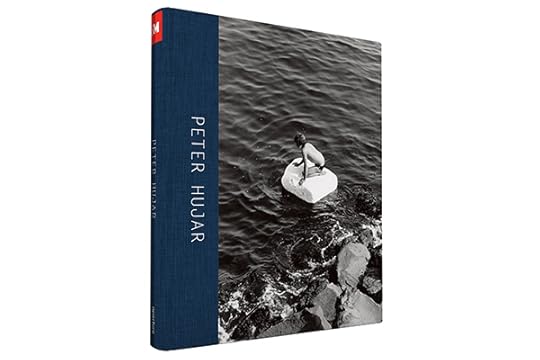

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life

Underappreciated during his lifetime, Peter Hujar is now a revered icon of the downtown art scene. He is best-known for his portraits of New York City’s artists, musicians, writers, and performers, which feature characters such as Susan Sontag, William S. Burroughs, David Wojnarowicz, and Andy Warhol. Hujar and was admired for his completely uncompromising attitude toward work and life.

Inner Child/Actual Child

Seeing Things, A Kid’s Guide to Looking at Photographs

Aimed at children between the ages of nine and twelve, Seeing Things is a wonderful introduction to photography that asks how photographers transform ordinary things into meaningful moments. In this book, acclaimed and beloved photographer Joel Meyerowitz takes readers on a journey through the power and magic of photography.

The Martin Parr Coloring Book!

Photography and Pop-culture buffs, get out your crayons and colored pencils! Martin Parr’s colorful, tongue-in-cheek photographs—his comedy of contemporary manners—have been transformed into a coloring book.

Go Photo!

Go Photo! features twenty-five hands-on and creative activities inspired by photography. Aimed at children between eight and twelve years old, this playful and fun collection of projects encourages young readers to experiment with their imaginations, get messy with materials, and engage with the world in new and exciting ways.

Nature Lover

A Wild Life: A Visual Biography of Photographer Michael Nichols

A Wild Life is Michael “Nick” Nichols’s story, told with passion and insight by author and photo-editor Melissa Harris. Nichols’ story combines a life of adventure, with a conviction about how we can redeem the human race by protecting our wildlife.

Picturing America’s National Parks

Picturing America’s National Parks brings together some of the finest landscape photography, from America’s most magnificent and sacred environments. Photography has played an integral role in both the formation of the National Parks and in the depiction of America itself. This book traces that history and delights readers with stunning photographs of the best American landscapes.

Cape Light

Cape Light, Joel Meyerowitz’s series of serene and contemplative color photographs taken on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, quickly became one of the most influential and popular photography books in the latter part of the twentieth century. Now, over thirty-five years later, Aperture is pleased to bring back this classic collection in its original form.

Fashion Forward

Fashion Photography: The Story in 180 Pictures

Fashion photography captures our desires and fantasies about how we present ourselves to the world, while reflecting the changing values of our culture and society. Fashion Photography: The Story in 180 Pictures explores the profound influence that fashion photography has had over the past eight decades, presenting its evolution as a language, and a genre, while showcasing some of its most glamorous moments.

Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style

Suits that pop with loud colors and dazzling patterns, complete with a nearly ubiquitous bowtie, define the style of the new “dandy.” Described as “high-styled rebels” by author Shantrelle P. Lewis, black men with a penchant for color and refined fashion ave gained popular attention in recent years. Lewis’s carefully curated selection of contemporary photographs surveys the movement across the globe, with all of the vibrant patterns, electrifying colors, and fanciful poses of this brilliant style subculture.

Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Louise Dahl-Wolfe opens a window onto the work of one of the most influential fashion photographers of the twentieth century. After being discovered by Edward Steichen and having her work exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1937, Louise Dahl-Wolfe went on to revitalize the Hollywood portrait and invigorate fashion photography of the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.

Design Savvy

Rinko Kawauchi: Halo

In recent years, Rinko Kawauchi’s exploration of the cadences of the everyday has begun to swing farther afield. In Halo, Kawauchi expands this inquiry, this time with photographs of the southern coastal region of Izumo, in Shimane Prefecture and interweaving them with images from New Year celebrations in Hebei province, China, plus her ongoing fascination with the murmuration of birds along the coast of Brighton, England. Kawauchi mesmerizingly knits together cycles of time, implicit and subliminal patterns of nature, and human ritual.

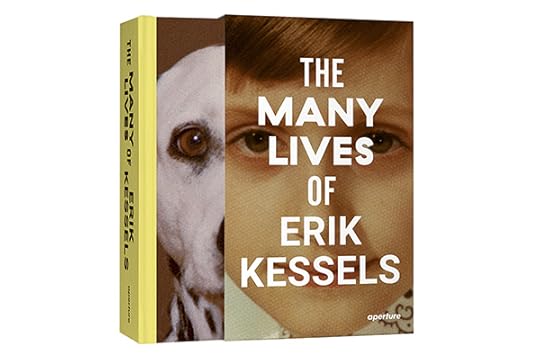

The Many Lives of Erik Kessels

The Many Lives of Erik Kessels presents the highly anticipated first illustrated survey of this pioneering and influential curator, editor, and artist whose varied experiments with photography and photographic archives reconsider the medium’s vernacular and narrative possibilities in today’s inundated image landscape.

Self Publish, Be Happy: A DIY Photobook Manual and Manifesto

An economic and cultural revolution has shaken the photobook world in the last five years: self-publishing. An army of photographers operating as publishers have had an instrumental role in today’s photobook renaissance. This book offers a do-it-yourself manual and a survey of key examples of self-published success stories, as well as a self-publishing manifesto and list of resources.

Classic Cat

Bruce Davidson: Survey

This survey focuses on the work that has made Bruce Davidson one of the most influential documentary photographers to this day. In his work, Davidson prizes his relationship to the subject above all else. From his profound documentation of the civil rights movement to his in-depth study of one derelict block in Harlem, he has immersed himself fully in his projects.

Elliot Erwitt: Home Around the World

Elliott Erwitt: Home Around the World offers a timely and critical reconsideration of Erwitt’s unparalleled life as a photographer. Produced alongside a major retrospective exhibition, the book features examples of Erwitt’s early experiments in California, intimate family portraits in New York, major magazine assignments, long-term documentary interests, and ongoing, personal investigations of public spaces.

Lisette Model

Lisette Model is an unsurpassed introduction to one of the twentieth century’s most significant photographers—a woman whose searing images and eloquent teachings deeply influenced her students who included Diane Arbus, Larry Fink, and many others.

The post Aperture’s Holiday Gift Guide appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

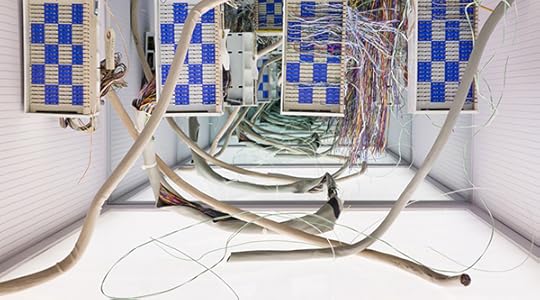

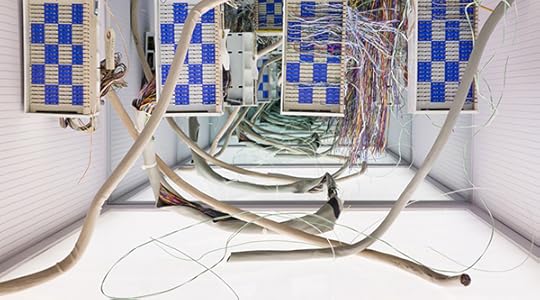

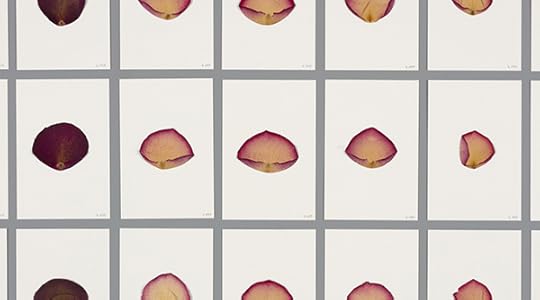

Inside Sarah Meyohas’ Cloud of Petals

Sarah Meyohas, Bell Vitrines, 2017. Photography by Lance Brewer. Courtesy Red Bull Arts, New York

Reagan Brown © Aperture Foundation

Sarah Meyohas, Most Beautiful Petals, 2017. Photography by Lance Brewer. Courtesy Red Bull Arts, New York

Reagan Brown © Aperture Foundation

Reagan Brown © Aperture Foundation

On December 4, 2017, Aperture Members at the Connect level and above met with New York–based artist Sarah Meyohas for a special tour of her first large-scale exhibition and virtual reality experience, Cloud of Petals, at Red Bull Arts New York. The exhibition is the culmination of an extensive yearlong project, which employs both defunct equipment and the latest technology to question ideals of beauty.

The tour began with a 16 mm film, in which workers at Eero Saarinen’s Bell Works in Holmdel, New Jersey, choose the most beautiful petal from individual roses, and create images of them. The 100,000 rose petals collected and imaged then became a data set fed to an artificial intelligence algorithm capable of creating infinite new petals.

After the film, Meyohas spoke with Aperture Members in front of an archival grid of 3,289 petals. She discussed the project’s evolution, the film’s production, and how she discovered Bell Works, former site of the venerable Bell Labs, where, among breakthroughs such as satellites and lasers, information theory was born.

Meyohas then led Members to four glowing boxes salvaged from discarded wall paneling and wiring from the Bell Works switchboards. The tour culminated with Aperture Members trying on the six virtual reality headsets, which allow the viewer to interact with AI-generated rose petals floating through the digital void.

Multimedia artist Sarah Meyohas (French-American, born 1991) uses networks of information, power, value, and communication in her work. Recent projects include creating the cryptocurrency Bitchcoin in 2015, and in 2016, trading stocks while stationed at 303 Gallery. Meyohas has been featured in the New York Times, Time, Wired, Vice, Fortune, Artspace, and the Atlantic, and she has appeared on CNBC, PBS, and CBC. Meyohas holds a BA in international relations from the University of Pennsylvania, a BS in finance from the Wharton School, and an MFA from Yale University.

Click here to join Aperture’s membership program or contact our membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post Inside Sarah Meyohas’ Cloud of Petals appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 12, 2017

You Get Me?

Mahtab Hussain’s tender portraits question the image of South Asian Muslim men in Britain.

By David Campany

Mahtab Hussain, Young boy, white boxing gloves, 2010, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

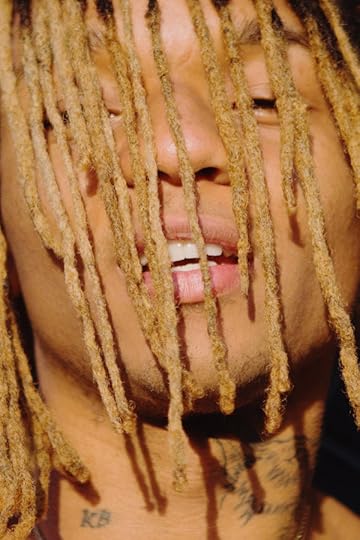

Xenophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment helped drive the momentum behind the U.K.’s June 2016 vote in favor of Brexit. How, then, can British artists create counternarratives that offer nuanced representations of unfairly maligned populations? Mahtab Hussain, a British photographer, has recently created a visual record of his community, which has been neglected by the art establishment and media alike. Recently published in the monograph You Get Me?, Hussain’s series features emotionally layered portraits of young South Asian Muslim boys and men, and often examines the performance of masculinity. The book’s title references the trend for British Asian men to identify with black urban experience. As Hussain writes, “The phrase You Get Me? also embodies it all. It can be seen as aggressive and confrontational, yet it expresses a glimmer of vulnerability too, that uncertainty when voicing one’s thoughts and opinions, asking the real question behind it all: Do you understand me?”

Mahtab Hussain, Shemagh, beard and bling, 2010, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

David Campany: Mahtab, you’ve just published the book You Get Me? with MACK. I’ve heard it was a long time coming. How and where did this project begin? I guess it’s tied very closely to the story of your own youth?

Mahtab Hussain: My identity as a young British Pakistani boy was never in question. Until the age of seven, I was oblivious to race, class, and ideals of difference. Although I was conscious of racial violence and tension between whites and blacks, my father was very open about talking through his experiences, which helped me to understand, to an extent. But, crucially, I was never directly affected. I went to school surrounded by others like me, a mix of ethnicities—Indian and Pakistan—and where we were the majority. And then it all changed. My parents divorced when I was six. This forced not only a family separation, but also a community separation too, as we were essentially ostracized. My father moved to Druids Heath in Birmingham, a very poor, white, working-class community, and my mother to Handsworth, which had a predominately black and Indian demographic.

Living with my father in Druids Heath thrust racism directly into my life. My brother and I were the only British Pakistani boys at the local Catholic school. Our first day was met with violence and racial remarks, and it was the first time the word “Paki” was directed at me. Questions were asked: “When would I go home? Why had I come here?” Questions that I had never thought about before, about my race, class, and culture. We were always looked upon as a problem, or at least positioned in a place of difference. It was obvious to me then that my identity was under threat, and for ten years I hated being brown—this color that brought unwanted, often violent attention.

Mahtab Hussain, Friends, curry sauce n’ chips, 2012, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: When did photography begin to interest you?

Hussain: Well, truly, at seventeen. I decided to live with my mother and deliberately enrolled at Joseph Chamberlain College (the British equivalent to American high school), which had a predominately Pakistani intake, to study photography. On my first day there, I was confronted with another form of discrimination. This time I was ridiculed not for my skin color, but for my attitude, personality, even culture. I was told I was too white, I was “fish and chips,” a “John,” I spoke too gently, too posh, like a white boy. I retaliated saying they were too black, and it was at the college that I first heard the phrase “wagwan,” Jamaican slang for “What’s going on?” It staggered me that for ten years I battled with my own identity crisis and continue to do so. My contemporaries were undergoing the same crisis. I regret now never turning my camera on my friends at college, but it was a subject too close at hand. And even at this stage in my life, I was still very much ashamed of being a “Paki” and all the stereotypes that came with that name.

Mahtab Hussain, Boy in grey hoodie, 2012, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: But somehow you wanted to become a photographic artist . . .

Hussain: The idea of becoming an artist came as an undergraduate at Goldsmiths College in London, studying for a degree in History of Art during my second year. I had chosen to study postcolonialism, and this introduced me to black artists who analyzed and responded to the cultural legacies of colonialism, racism, class, and gender. Yinka Shonibare, Chris Ofili, Carrie Mae Weems, Sonia Boyce, Lorna Simpson, and cultural theorists like Stuart Hall, Edward Said, and Frantz Fanon. They turned my world on its head, forcing me to question the absence of Asian/brown artists, a voice was missing in art history.

All this ignited a deep-rooted passion. I felt connected not only to the work which these extraordinary artists were making, but also to the historical narrative they were exploring and dissecting. In other words, I experienced the transformative possibilities of art. I started to think about my experiences as a child and what identity really meant to me, and how complex this concept was for many British Asians. I wanted to create a visual history about my identity and community, a community which had seemingly been forgotten by the art establishment. That was in 2002. It took me five years, however, before I ventured back into photography, and inevitably my first series would directly address identity politics, race, class and gender. That project became known as You Get Me?

Mahtab Hussain, Green chalk stripe suit, 2017, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: One can say to oneself: “I’m going to directly address identity politics, race, class and gender.” But in practice what did that mean for you? How did the images come about? What were you looking for in this series? Did you know straight away how to approach it photographically?

Hussain: I wanted to make a body of work that countered the narrative that I have been fed over the last twenty years by external forces. I wanted to show the complexity of the community, their humanity, their struggle in trying to find their sense of self in a world that actively tells them that they do not belong—a world that also asks them who they are, while comparing their differences. The men in my series are from working-class backgrounds. Some even see themselves as a subclass. This is what I mean by identity politics—visually articulating how these men are defining themselves and why. Race is important here, too, as the series begins to ask the question about what the audience is seeing. Certain portraits allow the viewer to gaze upon them, while others challenge what they are looking at. Do you see them as simply men? Are they British men? Asian men? Muslim men? I guess at the beginning I was looking for all the stereotypes in my head: the boy with the dog, the man in the car, the thuggish looking chap, the gangster wannabe, the man smoking the joint. I was collecting these characters.

I had a strong idea as to how I wanted to present my work. At the time, I was working at the National Portrait Gallery and was heavily influenced, in particular, by seventeenth-century court and society paintings. It was the gaze that I was drawn to, that direct look at the audience. For me, that was power in its purest sense, knowing that someone was going to look at you, judge you, but you too were able to judge them. So, their gaze was important, and I often asked my sitters the question, “How do you want to be seen?” That is how I began to make the work. I walked the streets looking for striking individuals. It could be the way they walked, a piece of clothing that I liked. There had to be this level of attraction. All the men in the series have a level of beauty, and this was important to me, too.

Mahtab Hussain, Black hat, black glove and bling, 2012, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: These portraits are horizontal.

Hussain: I deliberately framed all the work in a landscape format for many reasons. I wanted to get close while being able to include some of the environment. But I also wanted to make a comment on advertising campaigns, the billboards, television, and computers screens—formats that are filled with visions of male beauty, with those who belong and own such spaces—ideas around representation, or the lack of it, and the importance of seeing yourself reflected in society. The work then moves beyond the narrative of the disenfranchised youth. It becomes an enquiry into male beauty, masculinity that visually articulates how these men are defining themselves as men to each other and to a wider society. When I look back at the portraits, I wonder what masculinity would look like in their ancestral homes. So, in a sense this performance of masculinity, male peacocking even, has a strong cultural influence from British/Western/Urban culture.

Mahtab Hussain, Muscles, blue dothi, 2011, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: I’m struck by the fine balance in the portraits between confidence and vulnerability. Between self-assertion and inner complexity. You mentioned that there had to be something outward that first attracted you to photograph each man. But you’re going beyond that, getting to that place where we feel that outward appearance can never quite carry inner complexity. Is this how you see it?

Hussain: Yes, exactly. I feel there is a very fine balance between external confidence and inner vulnerability; the outward appearance is a type of performance, acted out in public environments, on the streets—bravado at its best. The environment here is key. I firmly believe the types of portraits made in You Get Me? would be completely different in a studio setting, too constricting for the sitter to perform or magnify this outward appearance, or subjectively exude different meanings based around pride, success, uncertainty, or fear. What is interesting is that there are very few portraits made indoors, or in domestic environments, places which may have given rise to a greater show of vulnerability. In order for that to be truly articulated, it was vital to include interviews alongside the portraits. I wanted to address the challenge of navigating dual identities, whether social, religious, or ego-related, dealing with hate, violence, or stereotyping. On top of all that, these people are also having to navigate what it means to be a man, not only in their community, but also within the rapidly changing modern Western world.

Mahtab Hussain, Young boy in white shirt, 2012, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: Yes, it is really a rich and complex combination of images and words. At what point did You Get Me? begin to take on this form?

Hussain: In order to make the work I had to engage in conversation, which was part of the process of gaining trust in order to make the portraits. I really enjoyed these exchanges. However, it was in 2010 that the idea of including these voices came to me. I say came to me, but actually I was asked by various curators, directors, and picture editors if I had interviewed the sitters. At the time, I was a little reluctant to interview the sitters because I wanted to position the work as fine art portraiture. I felt if I included their voices it would start to ghettoize and position the work as documentary. But I guess this thought is just a hangover of previous work that I have seen and did not want to replicate. I also did not want people to feel sorry for these men, as often the conversations were very dark. I realize now how important it was to include these statements: it helped inform the work but also empowered the community, by retaking control of their narrative.

Mahtab Hussain, Checked top, striped top and cap, 2010, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: The portraits certainly become much richer when seen in the light of the various voices in the book. All portraits are inevitably ambiguous things, as the title of your book suggests. “Getting” a person through a two-dimensional image of their momentary outward appearance to a camera is always so fraught and, in a way, it seems to me this is a large part of what your project is about. But I wonder if the “me” of the title also refers to the idea that the portraits might amount to clues about the photographer who made them. That is, you, Mahtab. And if this is autobiographical, what kind of self-portrayal is it?

Hussain: Yes, it is difficult to define a person by their portraits alone. It is an impossible task. However, my intention was not to collect individual portraits, but to build a body of work that represents the community through a collective narrative. When making the portraits of these men, I never felt it was fraught as I fully immersed myself as one of them. Their words echoed the voices I had heard all around me as I was growing up. So, yes, in a way you are right that in part this project is autobiographical and the “me” sits squarely to represent this in my work. I feel in an abstract way they are all self-portraits because I am reflecting upon my community. I have felt that real art comes from within, and can then serve a bigger purpose. When I started the project, I was trying to discover my identity, where I belonged in my own community and in a wider society. In the end, I realized that it’s not something that can be arrived at easily. It is a journey that we are all on. I’m just attempting to reflect upon where we currently stand. You get me?

Mahtab Hussain, Young man asleep, 2010, from the series You Get Me?

Courtesy the artist

Campany: I get you. In many ways, the richness of the book is in the nuances. There are no specific pairings of images with words, so the reader/viewer is left to piece the puzzle together, and not all the pieces are there. It’s a community with all the richness and contradictions of any community. For example, there’s quite a range of views in the book around masculinity, sexuality, power, belonging, and integration. How much of an eye did you have to keep on the balance of those views as you brought the book together?

Hussain: I did not put too much pressure on myself when I was making the work. It was really about trying to build a color palette so that when it came to editing the book and exhibition there would be enough material to play with. Each portrait embodies all those elements or views you speak of, but the book has also been broken down subtly into small chapters to reflect specific issues. I left the work for about a year or two in order for it to settle.

At this stage Michael Mack, my publisher, saw the series, and as I was showing it and talking to him about the work, I felt very uncomfortable. You see, the series at that point included environmental details, broken sofas, graffiti tags “repping” various postcodes, dirt on the street, and deprived areas. However, I was talking about power, pride, noble sitters who should be envied for their strength and beauty, so the sequence as it existed seemed to be jarring, and made you feel sorry for the community rather than wanting to connect with them. I remember calling Michael and telling him that I wanted to remove these pieces for that very reason, and he paused for a moment and said, “I agree, you’ve made a very wise decision.” It was great to have Michael truly understand a body of work that took a very long time for people to comprehend and see exactly what I was trying to achieve.

David Campany is a writer, curator, and artist based in London.

You Get Me? was published in 2017 by MACK.

The post You Get Me? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 7, 2017

The Queen Unleashed

Lyle Ashton Harris’s archive offers a queer vision of the 1980s and ’90s.

By Catherine Lord

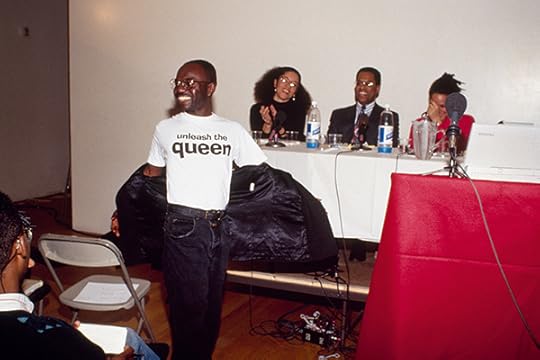

Lyle Ashton Harris, Marlon Riggs, Judith Williams, Houston A. Baker, and Jacqui Jones, Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, December 8–10, 1991

© the artist

Lyle remembers Marlon Riggs doing a runway walk in a dazzling white T-shirt with black letters that spelled “UNLEASH THE QUEEN.” Lyle has the photograph to prove it. I have no photograph and no memory of the T-shirt but am nonetheless certain that Marlon wore a black jacket, stood behind a podium, and daringly read a text straight from his laptop screen. Lyle didn’t photograph that performance, and so he doesn’t remember the laptop, or, for that matter, the text, which soon became the widely published “Black Macho Revisited: Reflections of a Snap! Queen.” Lyle remembers Marlon fierce, Marlon fabulous, Marlon laying claim to public space for the young and queer and black at an event for public intellectuals that leaned distinctly away from the arts toward academic discourse. I remember Marlon’s nerve. He had written his talk on the plane and had no way to present it but to read from a screen. I’d never seen a fellow procrastinator pull off that trick. It was 1991. People still used paper. Laptops were heavy. There was no easy way to scroll down a text. Marlon held his laptop in the air and managed, though his hands were a little shaky and so, just at the start, was his voice.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, 1991

© the artist

Same event, two performances (at least). Although Lyle and I are just little slices in each other’s archive, Marlon’s performance was a formative moment in our respective and respectful creative lives. It was at the Black Popular Culture conference organized by Michele Wallace and held at the Dia Center for the Arts in SoHo. I punctuate Lyle’s photographic archive as a terrible haircut on a middle-aged white woman in the audience, listening to Kinshasha Conwill, then director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. I was in row ten or so, not back row and not front either, trying to learn—which I did—while being a present but non-colonizing ally. Besides, I’m shy and I wasn’t in the in-group of speakers. Neither Lyle nor I remember exactly what Conwill said, just that she bluntly and boldly addressed some questions and discontents on the relationship between queerness, race, and representation, and that whatever she said caused a buzz of resistance. The year 1991 was a turning point for queer and for black and for mixing up those labels to contest fixed identities with a spectrum of practices, skin hues, ethnicities, and nationalities. We had gone through some of those changes together, Lyle and I. When I met him, around 1987, he had just graduated from Wesleyan and though he’d spent the summer at a well-known photography workshop program in Maine, he wasn’t yet an artist but rather a promising snow queen.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle and Iké, Narcissistic Disturbance exhibition opening, Otis Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, February 3, 1995

© the artist

While everyone else devoted themselves to rocks and the zone system, Lyle stayed in his motel bathroom screwing around with whiteface and a tutu. Those antics alone, I figured, were worth the price of admission to CalArts. As I was the dean then, I saw to it that Lyle was admitted, despite the fact that the photo faculty, then rather conservative in their distaste for anything documentary, and perhaps for young black queens with a mouth on them, was less than enchanted. In his few years as a CalArts student at the end of the 1980s, Lyle created the space he needed. As a young student, any number of clueless comments by white faculty or by other students could have stopped him in his tracks, but Lyle’s photographs show him collaging another world—rigorous in its politics of race and sexuality, insistent that pleasure was the point of the project, and cognizant that sociality was not only the way to get there but in itself a method of working that could be documented. The photographs in Lyle’s archive—which weren’t what Lyle showed faculty as his Work—were a way of offering narrative and representation to the inhabitants of the world he was helping to invent. The snapshots construct a universe of queer and color, of joy and heartbreak, haircuts and T-shirts, meds and books, beds and pets, doorknobs and drinks. Such lists put flesh on gossip, give the backstory that drives and cements subcultures. The photographs and the act of celebrating through photographs are cultural resistance. This is what intellectual history looks like.

Catherine Lord is professor emerita of studio art at the University of California, Irvine. This feature is adapted from the Aperture book Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs.

On Friday, December 15, Lyle Ashton Harris will be joined by an intergenerational group of artists and writers for a night of conversation and performance at the Whitney Museum. Tickets are available to purchase here.

The post The Queen Unleashed appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 6, 2017

Wayne Sorce’s Nostalgic America

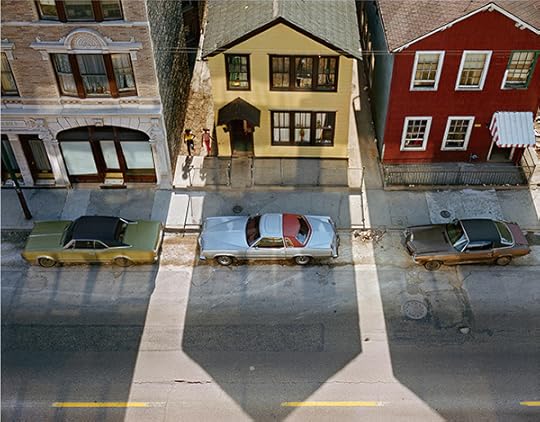

Wayne Sorce, East Chicago, 1977. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, Halsted Street, Chicago, 1978. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

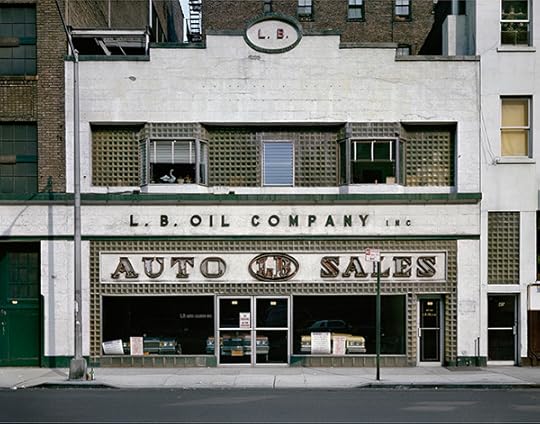

Wayne Sorce, L.B. Oil, New York, 1984. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

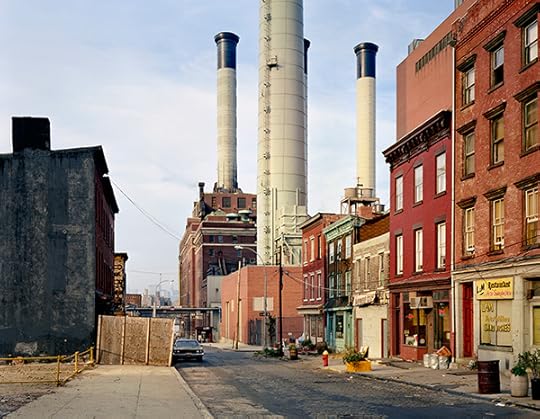

Wayne Sorce, Vinegar Hill, New York, 1985. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, Five Bros, 1982. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, El Platform, Chicago, 1978. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, Dave's Restaurant, New York, 1984. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, Parklane Hosiery, 1980. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

Wayne Sorce, Fort Dearborn Coffee, Chicago, 1977. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

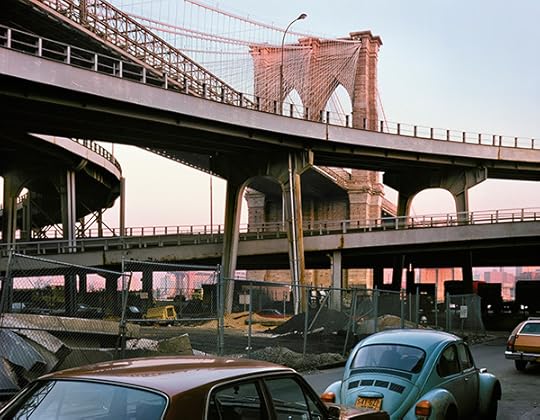

Wayne Sorce, Brooklyn Bridge, 1985. Courtesy Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla

“For me, photography is very important in that it exists because of everything else,” Wayne Sorce stated in a 1973 issue of Camera magazine. For Sorce (1946–2015), his photographs were embedded in the identity of the cities in which they were taken, namely Chicago and New York. The exhibition Urban Color, currently on view at Joseph Bellows Gallery in La Jolla, California, presents selections of Sorce’s masterful work from the late 1970s and early ’80s. With their primary-color palette, old Cadillacs, retro store fronts, neon signs, and midcentury street corners, Sorce’s images contain a uniquely American sensibility, akin to the paintings of Edward Hopper. Like Stephen Shore and Walker Evans, Sorce flattens space, filling his images with graphic architecture and wry signage. While photography might exist because of everything else, such nostalgic images of America are enduring because of photographers like Sorce.

Wayne Sorce: Urban Color is on view at Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla, California, through December 30, 2017.

The post Wayne Sorce’s Nostalgic America appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 30, 2017

In Kashmir, Hope Blooms

Bharat Sikka offers a poetic portrait of a disputed region.

By Emma Kennedy

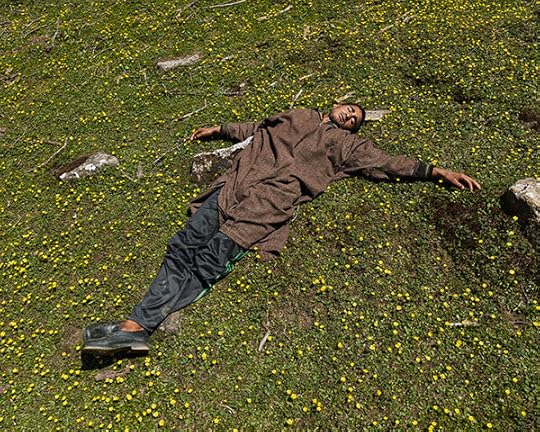

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2016, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Bharat Sikka first visited Kashmir as an adult, in 2014, at the age of forty. Raised in India, Sikka is best known for photographs that explore the nation’s recent economic and cultural shifts. Over several trips to Kashmir, Sikka has created a body of work that transports the viewer to its mountains and valleys. Oscillating between intimate portraits of men and sweeping landscapes, Sikka presents a poetic view of this disputed region.

I recently spoke with Sikka, who now lives between India and Europe, and he described his new photobook, Where the flowers still grow (2017), as “an emotional response” to Kashmir. The book acts as a recollection of emotions and experiences in Kashmir, allowing readers travel with Sikka on his journey. He focuses in on vivid details: the pink and purple blooms of spring, fresh footprints in the snow, a makeshift wooden fence. Amidst these idyllic scenes are the men of Kashmir, gathering wood, atop their horses, or reclining in a field of yellow flowers. The homes and interiors that appear in these pages are often deserted, as if the men belong to the snowy mountains, not in the cabins patched with sheets of tin. To Sikka, the men are just as much a part of the landscape as the pine trees.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2015, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Emma Kennedy: What is the meaning behind the title of this series?

Bharat Sikka: Where the flowers still grow—a glimpse of hope in a disturbed area. Kashmir is known as one of the world’s most beautiful mountain valleys, but it has gone through so much turbulence and political conflict that nobody thinks about it in that way anymore.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2016, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Kennedy: There are no children or women in the images. Why do you focus only on men, often in isolation in the landscape?

Sikka: Almost all my projects—from the beginning, starting with Indian Men (1999–2003)—are about men. I am naturally drawn towards photographing men, especially as subjects. I feel I have more to say about them, although they do make me uncomfortable. In Kashmir, I came across more men than women. It became about the relationship of a man with his space, and I wanted to make the narrative specifically about these men living in their land. In the series, I felt that men played a dominant role, just by their visual presence, especially outdoors, and their constant physical engagement in the political conflict. I had a stronger emotional response to the men. I was perhaps more intimidated by them.

On my first trip to Kashmir, I just photographed men as I found them in the landscape. The style was instinctive based on what I’d shot before: just positioning the person in their environment, and telling a narrative about them through their space—that’s very me. The people are very isolated there, and there are many reasons—some political—why I decided to isolate them in the landscape, which knows nothing of national borders and political rivalries.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2014–16, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Kennedy: This series came into being, in part, because of your discovery of Mirza Waheed’s novel The Collaborator (2011). How did the book help you conceptualize the physical and emotional landscapes of Kashmir?

Sikka: I haven’t read the book. During that first trip, my wife read it and told me the story, which is about a young boy and his struggles with his own sense of self in this turbulent region. I didn’t want to interpret the story, but by being in that space and moment, it made a lot of sense. And then I came across this one boy carrying sticks who reminded me of the book’s protagonist, and it started from there. The whole story is about this young boy, another reason why the project has just been about men. The book helped me gain clarity about how to proceed.

Kennedy: The image of the man in yellow with his back to the camera reminds me of the iconic nineteenth-century painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich. Could you talk a little about your influences for this series and your practice in general?

Sikka: I love this reference. I do look at paintings, and was influenced by Edward Hopper quite a lot in my earlier projects. For Where the flowers still grow, a lot of the influence came from my earlier projects. I also wanted to reinvent, and at the same time use my own style, and bring a narrative to the whole project.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2014–16, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Kennedy: Another of your series, Space in Between (2003–7), also explores the Indian landscape. How do you think about landscape and geography?

Sikka: I am really drawn towards spaces. Even when I take portraits, I place the subjects in their environment, and I often wonder if the picture is more about the space and if the person is just a prop in it. In Space in Between, I was really interested in how India was evolving geographically. In that series and in Matter (2006–ongoing), I explore how India is losing its culture as we become more globalized and homogenized. I think India is confused and now looks dull and grey, especially in the urban areas. It’s not the exotic country that it was years ago. Industrial revolution never took place in India, and nothing was ever planned, or made in a logical way, and now all of this is decaying and cities are overpopulated and polluted.

Kashmir is an extremely beautiful place and has been photographed and documented in many different ways, mostly as pin up calendars with incredible landscapes, sunsets and flowers, or in a very documentary style.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2015, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Kennedy: The landscapes you capture have a specificity to them, but they also refer to the larger history of landscape photography. For example, your images of valleys and mountain ranges recall those of Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams, who photographed the grandeur of the American West. If I hadn’t known it was Kashmir, I probably wouldn’t have been able to identify the geographic location. How important is it that the viewer knows where the photographs were taken?

Sikka: I come from a strong Indian background. I spent my first twenty-four years in India, and hadn’t really discovered the world of fine art photography until I went to school at Parsons. I was exposed to all these photographers, even the contemporary ones like Joel Sternfeld and Stephen Shore. Then, when I reflected back on India, I really wanted to show a totally different side of it and how it could be seen in a completely new way. That is also an important part of my work, to move away from my Indian contemporaries and how they’ve explored India. I wanted to move away from all the stereotypical images that are associated with India, especially the ethnic ones.

Bharat Sikka, Untitled, 2016, from the book Where the flowers still grow

© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Kennedy: The cover image for Where the flowers still grow is almost completely black. It is such a dark image compared to the others in the series and its presence (or perhaps its “absence” of photographic information) really surprised me. Could you talk a little about this image and how it became the cover?

Sikka: I grew to really like the cover. First, because it was ambiguous and unexpected. Second, the white dot is actually a distant star in a dark sky, and reminds me of a light, like a glimmer of hope, which is similar to the idea behind the title of the book. Third, it reminds me of a conversation I had with my driver Shabir about meteorites—how its pieces fall from the sky, and how people in the past have become rich by finding them, and how he too hoped to find one someday.

Emma Kennedy is arts professional and former editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine. She is based in New York.

Where the flowers still grow was published by Loose Joints in 2017.

The post In Kashmir, Hope Blooms appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 21, 2017

Michael Marcelle’s Surreal New Jersey

How Hurricane Sandy set the tone for an uncanny photobook.

By William J. Simmons

Michael Marcelle, Sister Smile, 2015

Courtesy the artist

As the photographer Gregory Crewdson notes in his afterword to Kokomo (2017), Michael Marcelle’s new photobook, when faced with trauma, “reality never feels ‘real’ in the same way again.” It would be easy to read Marcelle’s images as indices of some mental strife or survivor’s guilt, with their brightly lit and grotesque interiors reminiscent of a Roman Polanski movie screened in a West Hollywood gay bar.

Kokomo emerged in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, and although Marcelle’s childhood home in Belford, New Jersey was not destroyed by the October 2012 storm, the surrounding community was devastated. This biographical narrative notwithstanding, Kokomo also makes a statement about constructed photography. Marcelle’s work follows that of Crewdson, Laurie Simmons, Roe Ethridge, Sue de Beer, and Jimmy DeSana; yet, as with the best young photographers working with tableaux (like Cynthia Talmadge or Tommy Kha), there is something idiosyncratic and personal that resists pure imitation. There is something entirely unique, for example, in Marcelle’s relationship to queerness; it is restrained, coy even, but wildly evocative like the weepiest melodrama.

By coincidence, as I prepared for this interview last month, massive fires raged in Northern California, where my parents’ house was among the few untouched (homes only a half-mile away were destroyed). I imagine, to quote The Sound of Music (1965), that the Marcelle and Simmons families must have done something good, perhaps in another life.

Michael Marcelle, One Month Before, 2012

Courtesy the artist

William J. Simmons: Your book begins with text, and many of the images have a narrative/lyrical presence that implies a potential story. Of course, there is the reality of Hurricane Sandy, but I am also thinking of unseen stories. How do you engage with the history of photography as both a fragment of the real and a space of imagined projection?

Michael Marcelle: The text that you mention is lyrics from the Beach Boys song “Kokomo,” which have been redacted and given a new context, accentuating the ominous non-space of the hallucinatory seaside utopia described in the song.

I’m interested in keeping the connection between fantasy and reality in these pictures in a very tenuous and uneasy state. It would’ve been incredibly boring and problematic to document the aftermath of this storm in a “real” way. So, instead, I used my own personal experience as an anchor to create something new out of the destruction rather than simply record it. I wanted to see how far I could abstract my own family’s narrative into something alien, yet also deeply personal, something that could act as an echo to the devastation. How far could the personal be pushed into oblivion?

Michael Marcelle, One Year Later, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Simmons: Constructed photography—I’m thinking of Robert Mapplethorpe, Jimmy DeSana—and portraiture by artists such as Catherine Opie, have been privileged media for queer people, perhaps as a result of some desire for the “real” of the photograph when homophobia has denied this kind of connection to representation. And you are engaged with each of these photographic lineages. Yet, refreshingly, there is nothing in Kokomo that explicitly or obviously enunciates queerness. Where might you locate a queer sensibility in your restrained combination of multiple modes of photography?

Marcelle: I’ve always viewed the queerness in my work as acting on a psychic, almost supernatural level. The earliest connections I can recall having with queer culture have less to do with my own sexual desires and more with glimpsing into a secret, strange world. Growing up as a fat, stuttering, gay, goth kid in New Jersey, my own queerness became inexorably linked to what I found escape in: the cheap spectacle of VHS genre films, the pageantry of Marilyn Manson, the occult world-building of Kenneth Anger. Queerness was a feeling, a sense of color, light, extremity, and horror. In my photographs, I’m just trying to emulate that feeling, to describe that world over and over again.

I think there’s a predominant sensibility in a lot of art made by gay men that sets up a more traditional relationship between the male body and the inherent desire within as the point of queerness in the work. But in my photos, I’m trying to create an entirely queer world, where everything is charged with a feeling of otherness, of a throbbing strangeness. I think that lends itself to slipping between modes of picture making while still being able to maintain an aesthetic continuity. I don’t see a difference between a portrait or a still life or a landscape, so I try to fill each picture with the same potency.

Michael Marcelle, Poinsettias, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Simmons: I’m intrigued by the idea of the uncanny here—people often use that term for photographs that just “look” surreal, but here I think you’re actually working with the term as it was defined—something both strange and familiar, something intimate and distant that bursts into our everyday consciousness. One of the few other artists who managed to do this is Cindy Sherman—not only in her “disaster” pictures from 1986–89, but even in her film stills, where we work constantly and in vain for figure out the movie that we “know” we’ve seen before.

Marcelle: I would say the sense of uncanniness in these photographs is driven by a desire to subvert the typical structure of the home-based photography genre, where the artist presumes their life is inherently interesting enough to make work around it. I don’t think I’m particularly interesting on a personal level, so rather than focusing on the specific details of my life or my family, I focused on the act of picture-making itself, which I found incredibly freeing. I wanted to decontextualize the familial and the banality of the suburbs into something utterly strange and hallucinatory, with family members in constant states of mutation and landscapes slipping in and out of consciousness.

Michael Marcelle, Our Backyard, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Simmons: In Camera Lucida (1980), Roland Barthes discusses at length a photograph of his mother who has passed, but he refuses to reproduce the photograph, which instills a sense of nostalgia that we as readers or viewers cannot access. But we are learning every day—as with the Charlottesville white supremacist march, in August—that looking back in time or longing for the past is rarely, if ever, progressive. I still find myself nostalgic for nostalgia—a longing that once seemed harmless. What is your relationship to nostalgia?

Marcelle: A lot of my interest in the uncanny has to do with nostalgia, which I’ve always considered as basically synonymous with death, only in a more narcotic, saccharine form. The pictures in Kokomo are drenched in a kind of inverted, uncanny nostalgia, where the past, present, and future have merged, so death is looming over everything. I started the project as a way to describe the feeling of coming home to a world that had turned upside down, but as time went on the focused changed to ultimately be more about family and death.

When I was in grad school, the dean sat in on one of my early crits. He was really not feeling the work at all, and said that the pictures felt like work about magic that was made by someone who doesn’t believe in magic. He clearly meant it in a negative way, but I actually think it’s one of the most accurate descriptions of my work I’ve ever heard. My work is about using all these cheap special effects and theatrical lighting as a way to hide from death, to reach, but ultimately miss, immortality.

William J. Simmons is Provost’s Fellow in the Humanities at the University of Southern California and a Mellon Predoctoral Fellow in Women’s History at the New York Historical Society.

Kokomo was published by MATTE Editions in 2017.

The post Michael Marcelle’s Surreal New Jersey appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 16, 2017

Why Aren’t There Any Famous Asian American Photographers?

Three young artists discuss the histories, struggles, and complexities of making photographs in America today.

By Will Matsuda

Tommy Kha, Unity, Memphis, Tennessee, 2013, from the series A Real Imitation

Courtesy the artist

The first time I saw a Rinko Kawauchi photograph, it felt a little like home. I connected with the softness, the warmth, the subtle hints of Japan. Like everyone in the photography community who comes from a “diverse” background, I’m always looking for images that the industry rarely provides—images that reflect my experiences, made by people who look like me. But, that doesn’t happen very often.

In the hands of a white elite, photographs have long constructed ideas of racial Others in America, and have preserved and propagated white supremacy. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Edward Curtis presented Native Americans as a people nearing extinction, which contributed to the movement to erase them from American social consciousness. In the Jim Crow South, photographs of lynchings were printed onto popular postcards. From the late nineteenth century through the early twentieth century, anthropologists used photographs as “evidence” that colonial subjects in Africa were inferior. During the same period, American photographers, funded by the U.S. Bureau of Science, photographed hundreds of Filipinos, ranking their subjects on a hierarchical scale from savage to civilized.

Because American photographers have utilized photography as a tool of racial oppression, images made by people of color are vital. Today, a new generation of Asian American photographers is answering the call.

Mary Kang, 28, was born in South Korea, raised in Austin, Texas, and now lives in New York. She began by working in photojournalism, but now shoots fashion and music editorials. Tommy Kha, 28, from Memphis, Tennessee, now lives in New York and makes self-portraits. Jessica Chou, 32, was born in Taiwan and raised in Los Angeles, where she now lives now, and works in editorial and documentary settings.

I recently spoke with Kang, Kha, and Chou about the histories, struggles, and complexities that make Asian American photography a crucial part of American culture. Despite their differences, themes of belonging and community unify their work. And while these photographers are all of East Asian descent, the stories of Asia, in all its vastness, are not represented here. Kang, Kha, and Chou’s images don’t directly address grievances. Instead, they make visual space for nuanced dialogue.

Jessica Chou, Bruce and Sherry, 2013, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Courtesy the artist