Aperture's Blog, page 111

September 26, 2017

In Putin’s Russia, an Island of Tolerance

Dasha Yastrebova captures a fleeting moment in Moscow’s queer underground.

By Miss Rosen

Dasha Yastrebova, Stylist Natasha Sych, 2007

Courtesy the artist

In 2007, when the Solyanka Club opened in Moscow, it was a time of great hope. The first generation of post-Soviet teenagers came of age in a moment when anything seemed possible, mostly because the government was willing to overlook many social and cultural activities. Solyanka, a restaurant during the day and a nightclub after dark, burst forth. It quickly became the home for an underground, bohemian community of artists, photographers, designers, musicians, performers, and filmmakers who embraced those whom the Russian government persecuted, specifically queer culture, drag queens, and people who identified as transgender. Even then, Solyanka was an island of tolerance in a country plagued by prejudice and persecution.

At the age of eighteen, while shooting for magazines like Russian Vogue, Dasha Yastrebova started going to Solyanka. She photographed there for a year, and most of this work has never been seen before. Here, Yastrebova speaks about this intriguing moment in Russian history, a period of personal and creative freedom that has since disappeared.

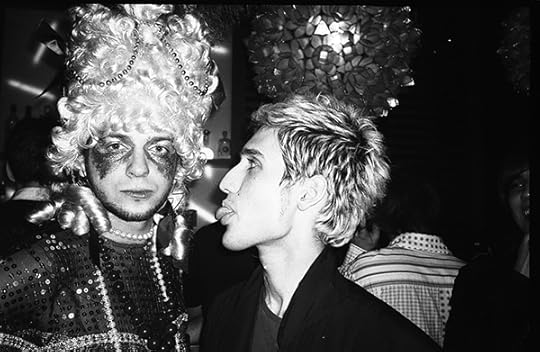

Dasha Yastrebova, Agasfer, the founder of fetish gay parties in Moscow, and Andrey Yarden, jeweler, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Miss Rosen: Thinking back to Moscow in 2007, you must have felt as if you were living the high before the fall. How would you describe the political and social changes the city was going through?

Dasha Yastrebova: There was a feeling of rising, a flourish in the air. Young people were not forbidden to do anything, as the government did not perceive the new generation of teenagers as a threat. The country was not liberal; there were no new liberal laws; there was the same authority, but the government overlooked some parts of social and cultural life. So, temporarily, young people had a chance to freely express themselves, and we were too young, inspired, and energetic to believe it would come to an end.

Before the 2008 financial crisis, entrepreneurs funded cultural events, in which we could participate. The government allowed advertisements for cigarettes and alcohol, for example, and I worked several on Philip Morris campaigns.

We had a lot of free time, were interested in everything, and wanted to do something useful. Many new vehicles for expression began to appear: the first youth magazine was Look At Me; the first art-place was Moscow Contemporary Art Center Winzavod; and the first nightclub, Solyanka. Young people felt that there was an untilled field of opportunities. There were people from the older generation who also wanted change. It was also the beginning of a dialogue with the authorities—it was actually possible to pitch your ideas. The new generation was realizing its strength and potential.

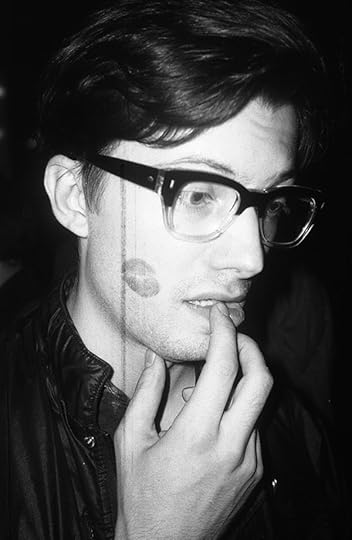

Dasha Yastrebova, Roman Mazurenko, best known as editor-in-chief of Look At Me magazine, who also launched a Russian version of the magazine Dazed & Confused, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Rosen: Could you talk about the new Moscow you wanted to build? What did you want to see your country achieve?

Yastrebova: We were the first post-Soviet generation of teenagers and we wanted this Soviet spirit to be washed off quickly. Everything was destroyed and was in desolation; there were no places built for the youth. We lagged behind, but there was a desire to develop and to move forward.

With the advent of the first youth websites, we began to learn about the cinema, modern directors, new music, style, and fashion—how through appearance one could change cultural. For us, appearance was a manifesto, and we dreamed that all this would grow to become a mass movement.

Then, a chain reaction began. At Solyanka, designers, fashion designers, and musicians, were all discussing how it would be great to open a showroom, launch a production, record an album, shoot a video, open cultural spaces, et cetera. We wanted to do something for the city and the people, but no one knew how to execute such projects. It was a time of great experiments.

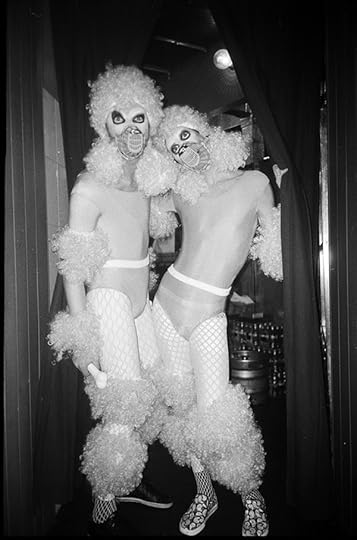

Dasha Yastrebova, Dancers in costume, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Rosen: How did the Solyanka embody the spirit of the times?

Yastrebova: At Solyanka, we learned that we were not the only “strange” ones. Solyanka was not just a club. You felt that you were inside a new flow—that it was historical, and something important was happening. On weekends, the streets near the club were filled with people. Sometimes we did not even go inside. Instead, we drank and talked on the street. People of all ages, social statuses, and subcultures gathered there: oligarchs, artists, gays, skinheads, artists, transgender people, and students. Back then, within certain spaces, all of these groups mixed and communicated without any barriers or prejudices.

During the day, Solyanka was a restaurant: three large halls with a stunning vintage, Bohemian atmosphere. It felt like you were in a different country. There were meetings and events there. We watched movies and discussed them, made friends, and dreamed of new projects and a better future.

Dasha Yastrebova, Ramona, an epic fan of fashion and a member of the gay band C.L.U.M.B.A, the morning after a party, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Rosen: How did taking photographs in this environment inspire or influence your development as an artist?

Yastrebova: Prior to this experience I had only a moments, fragments way of thinking. This was the first time I made a more long-term project. Solyanka gave me an opportunity to do something cohesive.

We did not believe in stereotypes, and the boundaries of our personalities blurred. We were interested in everything. Solyanka was an opportunity to interact with people openly. I could say, “Show me your boobs”—and the person did it. I felt the world was plastic. People were open to doing crazy things; they wanted to do something strange. We all wanted to go beyond our comfort zones.

Dasha Yastrebova, Masha Galaxy, trash-character and performer, the star of all parties, and a legend in Moscow, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Rosen: What made you decide to stop shooting at the Solyanka after just one year?

Yastrebova: At one of the parties, the security guard beckoned me, saying, “Dasha, come here, look what happened here! Maybe it will be interesting for you to take a picture.” I went into the dressing room and saw that there was a girl without pants on. I asked the guard, “Why is she naked?” She was unconscious. She looked really bad, most likely from mixing drugs and alcohol. I took a couple of photographs and left, and couple of hours later, I saw the same girl in the main room lying on a big sofa. No one cared.

I understand now how terrible it was but, at the moment, I was too drunk and took a few more pictures. When I developed a film, I was in shock. How it could happen in such a place? Why didn’t anyone cover her up or take her to a safe place? Why didn’t anyone call an ambulance? I had many questions, including, Why did I just walk up and take a photograph of a girl who is in a situation that I would not want to be in? I decided that this was the final picture, and that I needed to move on.

Dasha Yastrebova, Unidentified Lovers, 2007

Courtesy the artist

Rosen: This project was just ten years ago, but in some ways it must feel like another lifetime. As an artist, what is the greatest lesson you learned in this environment?

Yastrebova: I began to understand more about humanity in general. I realized that, despite their differences, people could have common ground. Understanding the fluidity of human consciousness helped me to avoid stereotyping people. Everything is possible.

I also learned that there could be equality, sense of freedom, both internal and external, between people regardless of social status. Tolerance and inner freedom—this, perhaps, was the main lesson.

Miss Rosen is a journalist covering art, photography, and books for Vogue Online, Dazed Digital, The Undefeated, Feature Shoot, and Crave Online.

The post In Putin’s Russia, an Island of Tolerance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 22, 2017

The 2017 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

Aperture and Paris Photo are pleased to announce the shortlist for the 2017 PhotoBook Awards.

The shortlist selection was made by Gregory Halpern, whose ZZYZX won the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award in 2016; Lesley A. Martin, Creative Director, Aperture Foundation and Publisher, The PhotoBook Review; Kathy Ryan, longtime director of photography at the New York Times Magazine; Joel Smith, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York; and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

Established in 2012, the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards celebrate the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography, with three major categories: First PhotoBook, Photography Catalogue of the Year, and PhotoBook of the Year.

Mathieu Asselin, Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation (Verlag Kettler) 2017

Zackary Canepari, REX (Contrasto Books) 2016

Teju Cole, Blind Spot (Penguin Random House) 2017

Sam Contis, Deep Springs (MACK) London, 2017

Debi Cornwall, Welcome to Camp America, Inside Guantánamo Bay (Radius Books) 2017

Albert Elm, What Sort of Life Is This (The Ice Plant) 2017

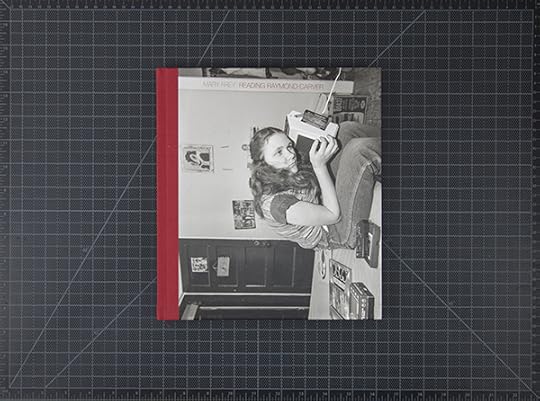

Mary Frey, Reading Raymond Carver (Peperoni Books) 2017

Jenia Fridlyand, Entrance to Our Valley (Self-published) 2017

Darren Harvey-Regan, The Erratics (RVB Books) 2017

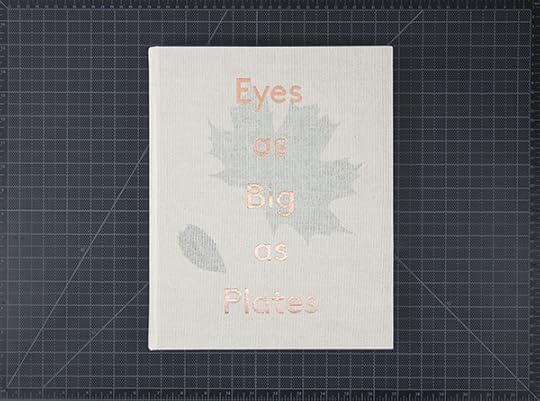

Karoline Hjorth and Riitta Ikonen, Eyes as Big as Plates (Forlaget Press) 2017

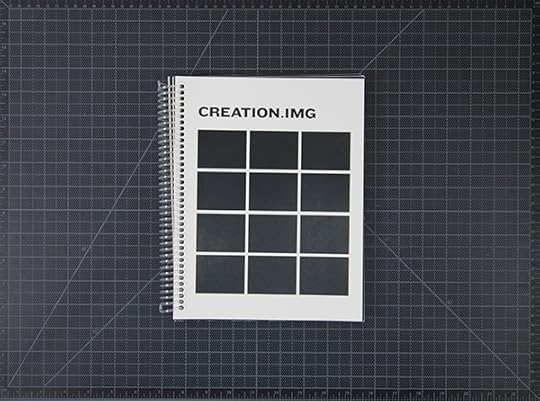

Dawn Kim, Creation.IMG (Self-published) 2016

Laura Larson, Hidden Mother (Saint Lucy Books) 2017

Feng Li, White Night (Jiazazhi Press) 2017

Cecil McDonald Jr., In the Company of Black (Candor Arts) 2017

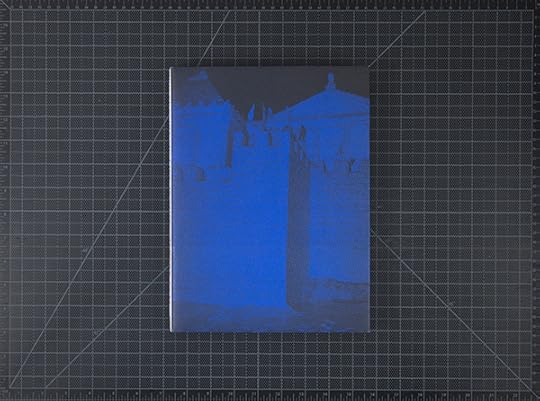

Virginie Rebetez, Out of the Blue (Meta/Books) 2016

Claudius Schulze, State of Nature (Hartmann Books) 2017

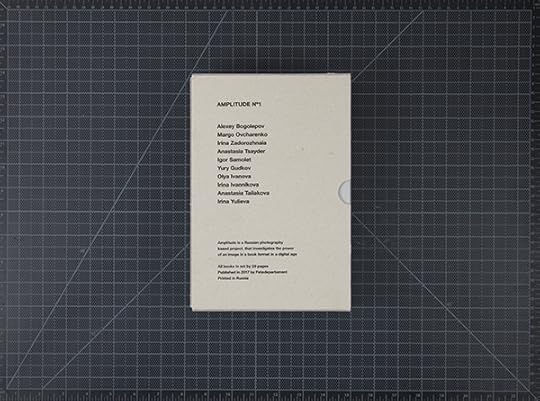

Nadya Sheremetova, ed.; with Alexey Bogolepov, Margo Ovcharenko, Irina Ivannikova, Anastasia Tsayder, Igor Samolet, Yury Gudkov, Olya Ivanova, Irina Zadorozhnaia, Anastasia Tailakova, and Irina Yulieva; Amplitude No.1 (FotoDepartment) 2017

Senta Simond, Rayon Vert (Self-published) 2017

Alnis Stakle, Melancholic Road (Self-published) 2017

Mayumi Suzuki, The Restoration Will (Self-published) 2017

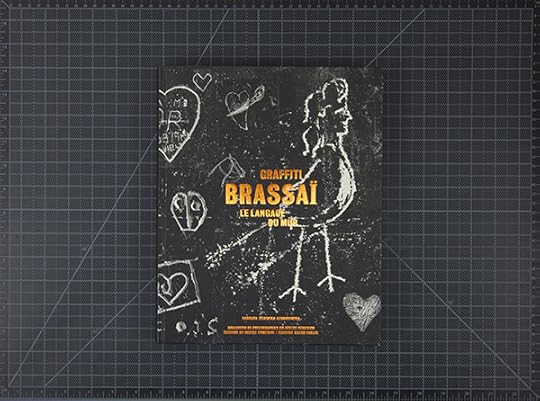

Brassaï: Graffiti, Le Langage du Mur,Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska (Éditions Xavier Barral) 2016

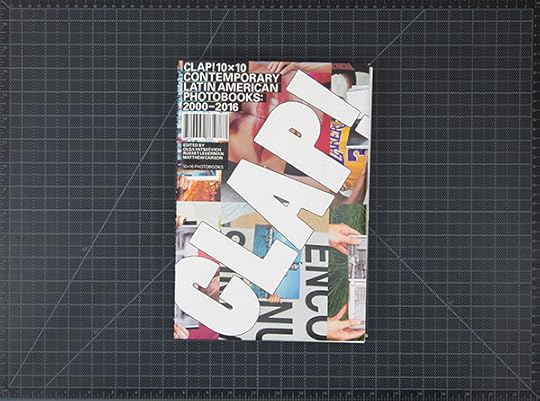

CLAP! 10x10 Contemporary Latin American Photobooks: 2000–2016, Olga Yatskevich, Russet Lederman, and Matthew Carson (10x10 Photobooks) 2017

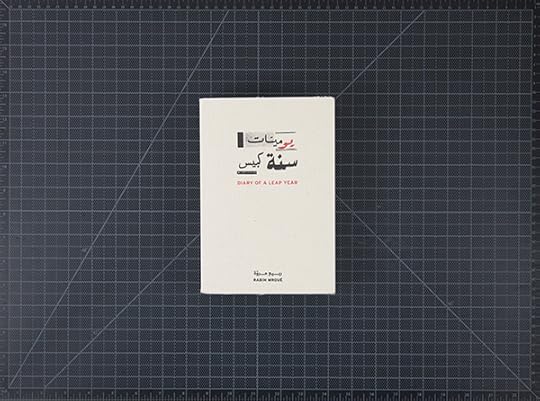

Diary of a Leap Year, Rabith Mroué (Kunsthalle Mainz and Kapth Books) 2017

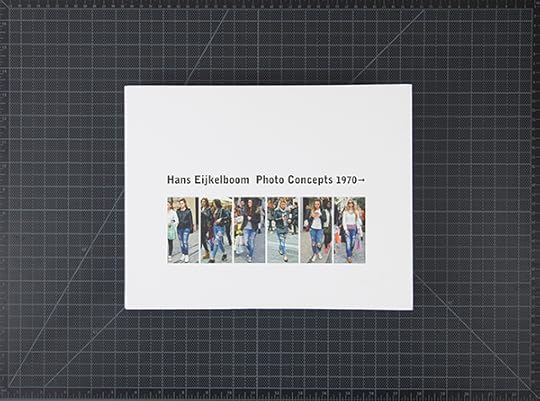

Hans Eijkelboom: Photo Concepts 1970, Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, Wim van Sinderen, Gerrit Willems and Dieter Roelstraete (Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft mbH) 2016

New Realities: Photography in the 19th Century, Mattie Boom, Hans Rooseboom (Rijiksmuseum/Nai) 2017

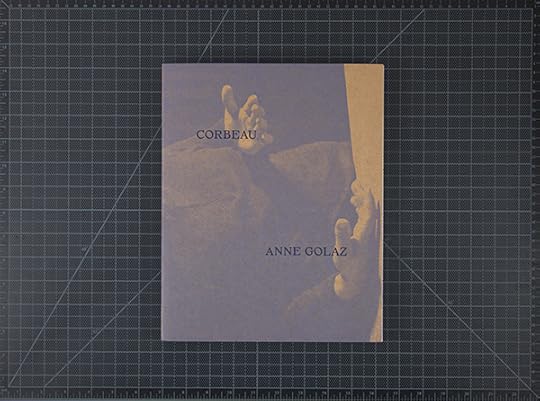

Anne Golaz, Corbeau (MACK) 2017

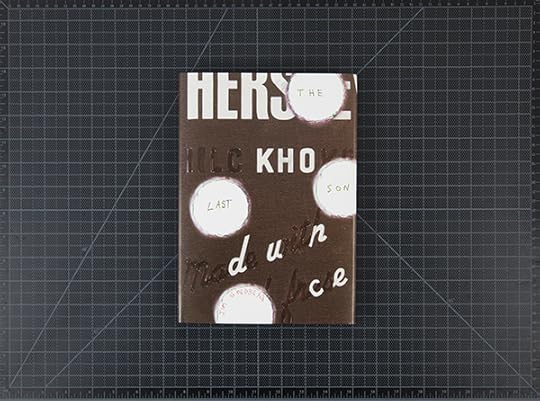

Jim Goldberg, The Last Son (SUPER LABO) 2016

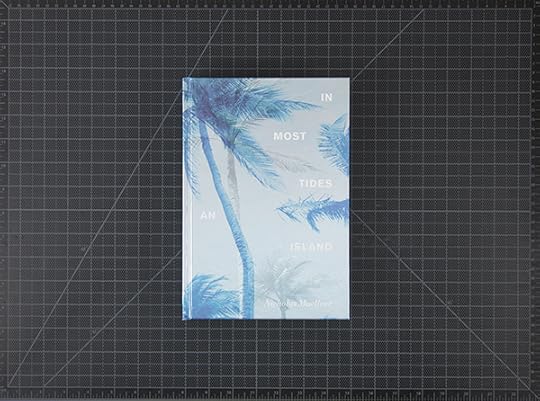

Nicholas Muellner, In Most Tides an Island (SPBH Editions) 2017

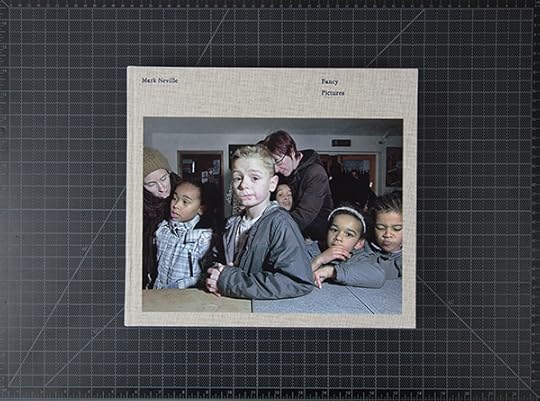

Mark Neville, Fancy Pictures (Steidl) 2016

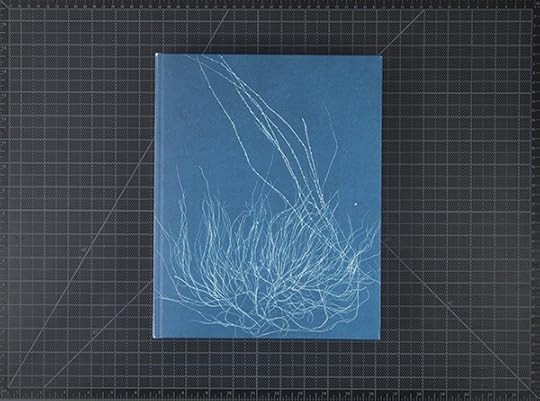

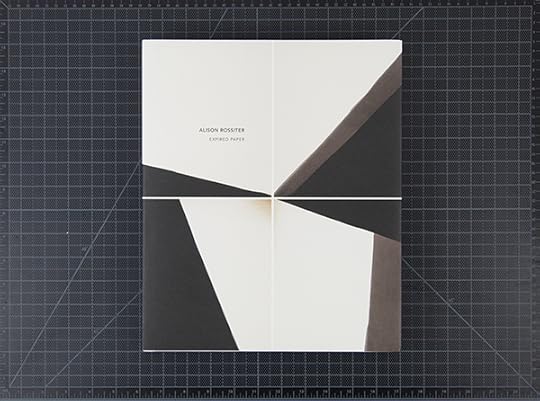

Alison Rossiter, Expired Paper (Radius Books and Yossi Milo Gallery) 2017

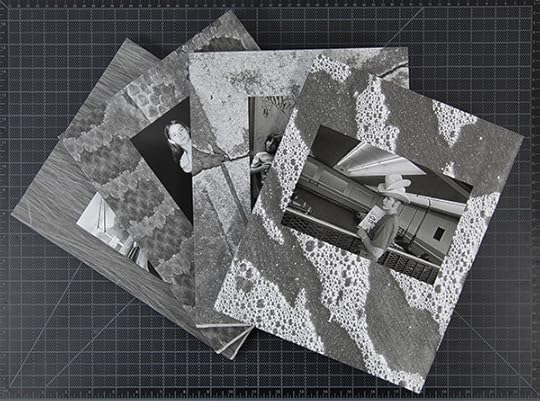

Paul Schiek, ed., Mike Mandel, Susan Meiselas, Bill Burke, and Lee Friedlander, Subscription Series No. 5 (TBW Books) 2017

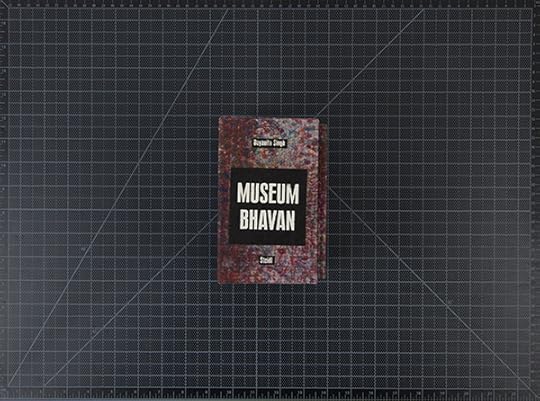

Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan (Steidl) 2017

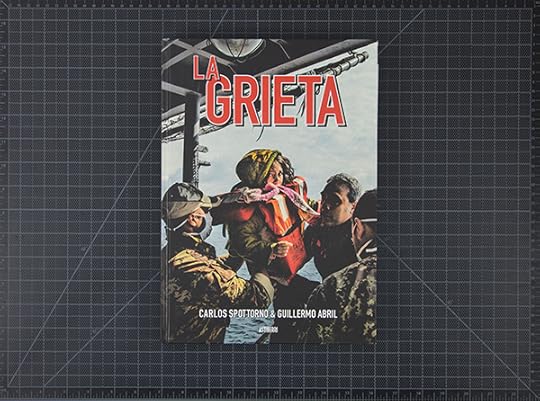

Carlos Spottorno and Guillermo Abril, La Grieta (The Crack) (Astiberri Ediciones) 2016

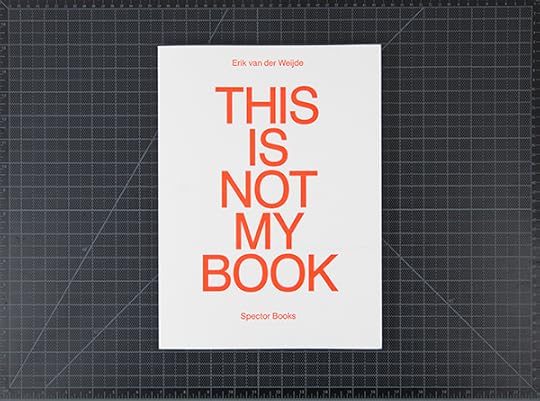

Erik van der Weijde, This Is Not My Book (Spector Books) 2017

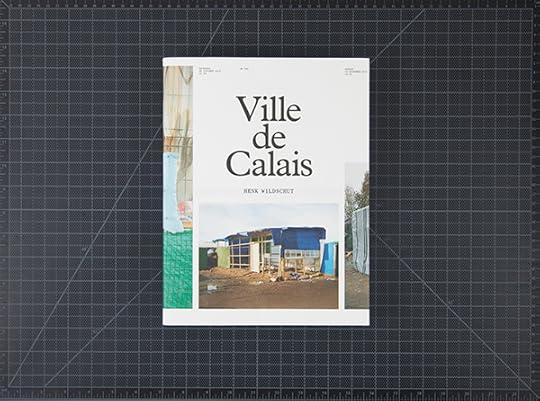

Henk Wildschut, Ville de Calais (Self-published) 2017

First PhotoBook

Mathieu Asselin

Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation

Publisher: Verlag Kettler, Dortmund, Germany, 2017

Designed by Ricardo Báez

Zackary Canepari

REX

Publisher: Contrasto Books, Italy, 2016

Designed by Teun van der Heijden

Teju Cole

Blind Spot

Publisher: Penguin Random House, New York, 2017

Designed by Alex Merto

Sam Contis

Deep Springs

Publisher: MACK, London, 2017

Designed by Sam Contis and Lewis Chaplin

Debi Cornwall

Welcome to Camp America, Inside Guantánamo Bay

Publisher: Radius Books, Santa Fe, NM, 2017

Designed by David Chickey

Albert Elm

What Sort of Life Is This

Publisher: The Ice Plant, Los Angeles, 2017

Designed by Albert Elm

Mary Frey

Reading Raymond Carver

Publisher: Peperoni Books, Berlin, 2017

Designed by Hannes Wanderer

Jenia Fridlyand

Entrance to Our Valley

Self-published, New York, 2017

Designed by Jenia Fridlyand

Darren Harvey-Regan

The Erratics

Publisher: RVB Books, Paris, 2017

Designed by Zoé Aubry & Vincent Sauvaire

Karoline Hjorth and Riitta Ikonen

Eyes as Big as Plates

Publisher: Forlaget Press, Oslo, 2017

Designed by Greger Ulf Nilson

Dawn Kim

Creation.IMG

Publisher: Self-published, Brooklyn, 2016

Designed by Dawn Kim

Laura Larson

Hidden Mother

Publisher: Saint Lucy Books, Baltimore, 2017

Designed by Guenet Abraham

Feng Li

White Night

Publisher: Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2017

Designed by Cheng Yinhe

Cecil McDonald Jr.

In the Company of Black

Publisher: Candor Arts, Chicago, 2017

Designed by Matt Austin

Virginie Rebetez

Out of the Blue

Publisher: Meta/Books, Amsterdam, 2016

Designed by Chi-long Trieu

Claudius Schulze

State of Nature

Publisher: Hartmann Books, Stuttgart, Germany, 2017

Designed by SIB

Nadya Sheremetova, ed.

With Alexey Bogolepov, Margo Ovcharenko, Irina Ivannikova, Anastasia Tsayder, Igor Samolet, Yury Gudkov, Olya Ivanova, Irina Zadorozhnaia, Anastasia Tailakova, and Irina Yulieva.

Amplitude No.1

Publisher: FotoDepartment, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2017

Designed by Anton Lepashov

Senta Simond

Rayon Vert

Self-published, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017

Designed by Florence Meunier

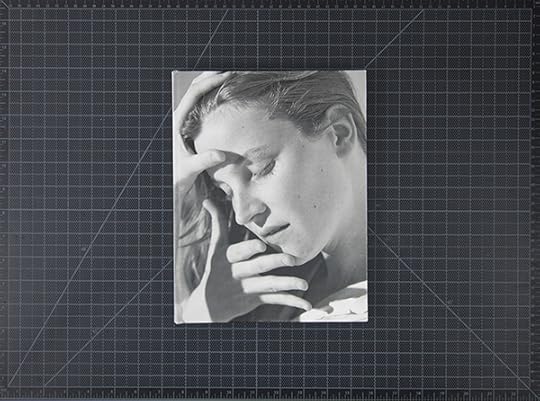

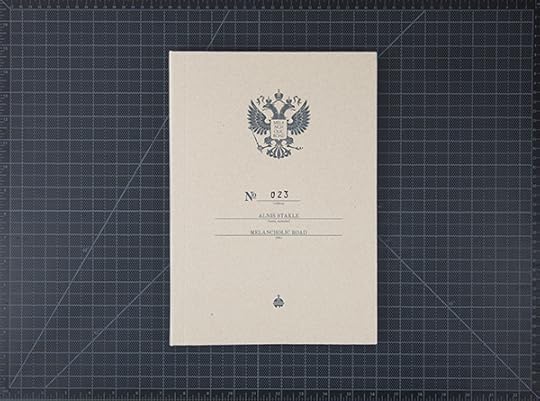

Alnis Stakle

Melancholic Road

Self-published, Riga, Latvia, 2017

Designed by Alnis Stakle

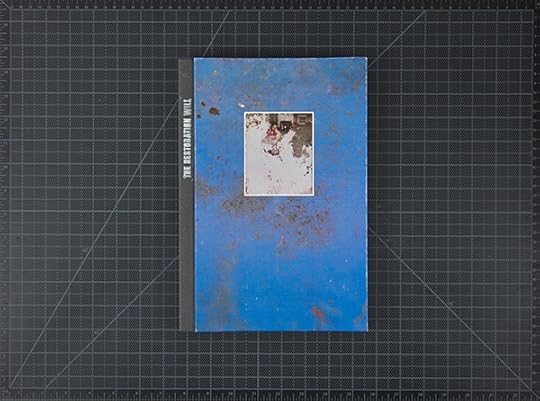

Mayumi Suzuki

The Restoration Will

Self-published, Tokyo, Japan, 2017

Designed by Yumi Goto and Jan Rosseel

Photography Catalogue of the Year

Brassaï: Graffiti, Le Langage du Mur

Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska

Éditions Xavier Barral

Paris, 2016

Designed by Xavier Barral and Coline Aguettaz

CLAP! 10×10 Contemporary Latin American Photobooks: 2000–2016

Olga Yatskevich, Russet Lederman, and Matthew Carson

Publisher: 10×10 Photobooks, New York, 2017

Designed by Ricardo Báez

Diary of a Leap Year

Rabith Mroué

Publisher: Kunsthalle Mainz and Kapth Books, Beirut, Lebanon, 2017

Designed by Studio Safar

Hans Eijkelboom: Photo Concepts 1970

Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, Wim van Sinderen, Gerrit Willems and Dieter Roelstraete

Publisher: Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Cologne, 2016

Designed by Jaap van Triest, Amsterdam

New Realities: Photography in the 19th Century

Mattie Boom, Hans Rooseboom

Publisher: Rijiksmuseum/Nai, Amsterdam, 2017

Designed by Irma Boom Office (Irma Boom/Tariq Heijboer)

PhotoBook of the Year

Anne Golaz

Corbeau

Publisher: MACK, London, 2017

Designed by Anne Golaz and Lewis Chaplin

Jim Goldberg

The Last Son

Publisher: SUPER LABO

Kamakura, Japan, 2016

Designed by Jim Goldberg

Nicholas Muellner

In Most Tides an Island

Publisher: SPBH Editions, London, 2017

Designed by Andrew Sloat

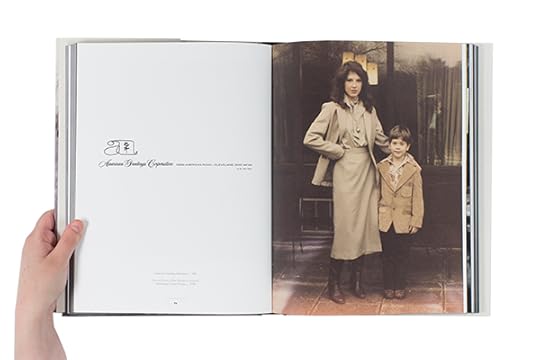

Mark Neville

Fancy Pictures

Publisher: Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, 2016

Designed by Duncan Whyte

Alison Rossiter

Expired Paper

Publisher: Radius Books and Yossi Milo Gallery, Sante Fe, NM, 2017

Designed by David Chickey

Paul Schiek, ed.

Mike Mandel, Susan Meiselas, Bill Burke, and Lee Friedlander

Subscription Series No. 5

Publisher: TBW Books, Oakland, CA, 2017

Designed by Paul Schiek and Lester Rosso

Dayanita Singh

Museum Bhavan

Publisher: Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, 2017

Designed by Dayanita Singh and Gerhard Steidl

Carlos Spottorno and Guillermo Abril

La Grieta (The Crack)

Publisher: Astiberri Ediciones, Bilbao, Spain, 2016

Erik van der Weijde

This Is Not My Book

Publisher: Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, 2017

Designed by Fabian Bremer and Pascal Storz

Henk Wildschut

Ville de Calais

Self-published, Amsterdam, 2017

Designed by Robin Uleman

The post The 2017 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 21, 2017

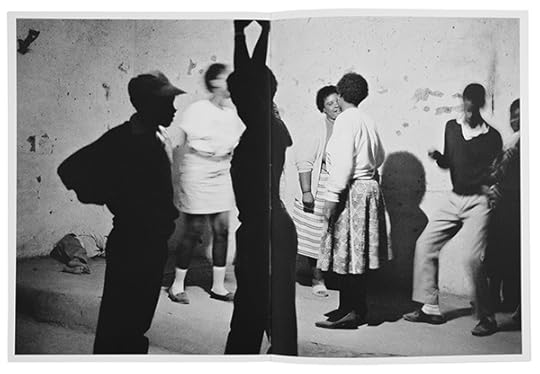

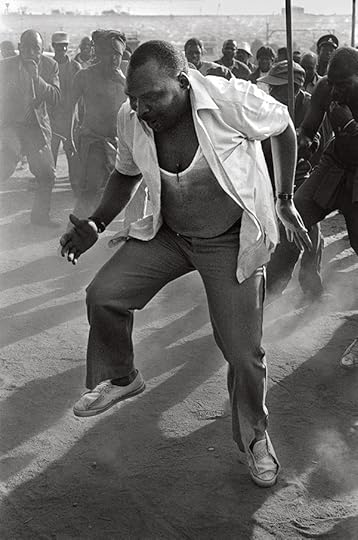

The Humanist Visions of Santu Mofokeng

In a series of photobooks from the revered South African photographer, stories of grace, beauty, and dignity.

By Ashraf Jamal

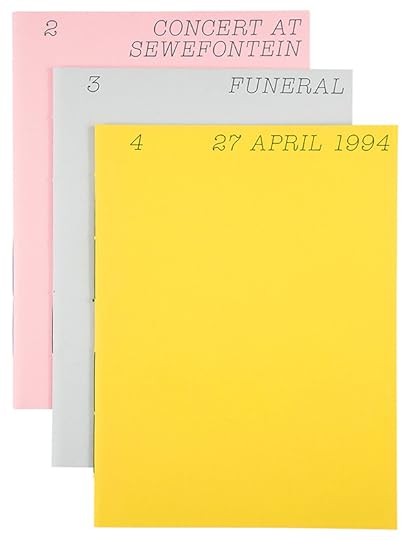

Santu Mofokeng, Stories: 2–4, Concert at Sewefontein—Funeral—27 April 1994

Steidl. Göttingen, Germany, 2016

Why is it that the funereal—the specter of death and dying—still clings to black experience in South Africa? Why is its photographic record still caught in these pathological optics? For all the talk in South Africa of transfiguration and transformation, a psychic shift from death to life, liberation remains in abeyance. Hopelessness continues to conspire against hope, injustice against justice. The photographic record of black South African resistance to oppression has largely been shaped by this paradox, and that includes the images that Santu Mofokeng has relayed to us since the beginnings of his career as a photojournalist.

A street photographer who turned photojournalist in the 1980s, Mofokeng, like many others, devoted himself to recording the struggle against apartheid. But his images are never overdetermined by a political agenda: while many other photographers have captured the spectacle of protest, Mofokeng has captured the more subtle sublimity of the body in pain, or the body transfigured—by political belief, by faith. He is widely celebrated as the spiritual painter of South Africa’s tormented body politic, and his uniqueness lies in his ability to capture a subject’s aura, their life hidden from view. In Stories, his multivolume, multiyear book series—the latest installment of which is titled Stories 2–4 (2016)—each individual book is devoted to a singular photo-essay. Through this, the stories of lives hidden or commonly subtracted are elevated and restored to a greater dignity, beauty, and grace.

Santu Mofokeng, Stories: 2–4, Concert at Sewefontein—Funeral—27 April 1994

Steidl. Göttingen, Germany, 2016

Each of the three volumes of black-and-white images in Stories 2–4 is thin and almost improvisational in feel, but printed with great care using lavish five colors on uncoated paper. The photo-essays comprise three gatherings in or near a South African township called Bloemhof, from the late 1980s to the early ’90s: a concert at Sewefontein; a burial; and a record of South Africa’s first democratic election, on April 27, 1994. These stories are about a collective imaginary. In a photograph from the concert, we see young men together in a line, their bodies thrumming to a beat, faces joyous. But seeing this grouping, we also remember other human chains—those of serfdom. Music, while transfigurative, is also reminiscent of human suffering. This, after all, was the origin of the blues. So while Mofokeng’s photographs are irrevocably tied to the perversities of South African history—inequality, indentureship, and psychic and physical brutalization—they’re also a challenge to global serfdom and ongoing racial inequality, in search of what Paul Gilroy has termed a “planetary humanism.”

The most potent image from these three stories is of a funeral gathering: the grieving and penitent all have their backs turned to the camera—except for one man who is bent, crumpled, drawn to the earth instead of the sky. Upon first seeing this image, I was reminded of Gustave Courbet’s painting A Burial at Ornans (1849–50); there, too, we see a gathering with a central bowed figure. The marked difference, however, is the neatly edged black hole readied for the dead in the fore- ground of Courbet’s painting. No such hole is visible in Mofokeng’s photograph, but it still feels gnawingly there; it is the grave’s absent presence that is embodied in the bent, grieving man. It is the void of which Frantz Fanon unceasingly reminded us—the indistinction which nullified black experience, emptying it and leaving little room for the imagination, for hope.

Santu Mofokeng, Untitled, from the series Pedi Dancers, ca. 1989

© the artist and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

For Fanon, colonization bound up the black experience with its own extinction; its sense of itself would always be tainted, compromised, emptied. It is this dark intuition that shapes Mofokeng’s image of grief. But it is also present in the photograph of the men at the concert—and, in retrospect, we know betrayal also resided at the very heart of a national hope, the subject of the third volume in this set: the country’s first democratic election. Here, Mofokeng gives us an empty street with a placard that reads “The Power to Fight Black,” reinforcing the bitter irony that has dogged hope and compromised black experience in South Africa since 1994.

To Mofokeng’s great credit, however, his visual record refuses to err on the side of hopelessness and despair. Rather, as Monna Mokoena, the director of Johannesburg’s Gallery MOMO, notes, “Santu’s great secret is that he is a poet who uses the camera to tease out of life its deepest meanings.” Mofokeng has never been seduced by the didacticism of reportage. Reflecting on his own photographic take on South Africa’s first democratic election, Mofokeng speaks of “an uneasy sense of euphoria . . . a combination of anticipation and dread, excitement and anxiety.” It is this twist—this glitch, this ghosting—of a profound psychic unsettlement that gives his deceptive record of everyday life in South Africa its enduring potency.

Ashraf Jamal is a cultural analyst and writer based in Cape Town.

The post The Humanist Visions of Santu Mofokeng appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 20, 2017

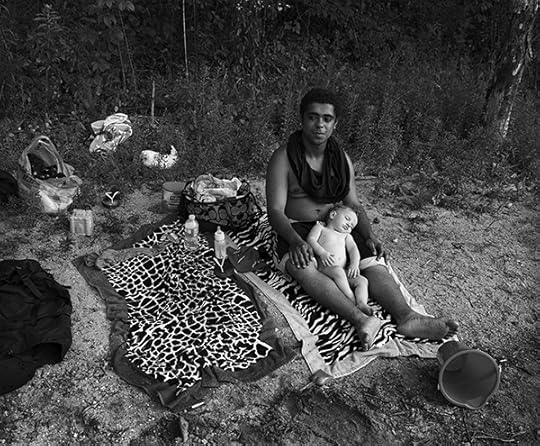

The Fate of Thoreau’s Pond

In Walden, Massachusetts, photographer S.B. Walker meditates on the cruel contradictions of modernity.

By Robin Kelsey

S.B. Walker, Combing hair after a swim, August 2010

© the artist

Although photobooks live and die on the meaningful coherence of selection and sequence, sometimes a single image goes straight to the gist. The last of the beautiful black-and-white photographs making up S. B. Walker’s Walden (2017) does this. Concluding a series that implicitly pits recollections of Henry David Thoreau’s classic paean to simple solitude, Walden (1854), against recent encounters at the famous pond, the final picture offers a rebus for the gulf between Thoreau’s day and ours. In the distance, we see a topos of nineteenth-century pictorialism, a bosky lakeshore, a strip of fog, and a mirror image of the shore in still water. This softened world and its reflective quietude promise to cure, counter, or redeem the clanking tumult of modernity. But in the foreground this pictorialist revival gives way to a sampling of twentieth-century abstraction. Reflected sky and melting ice merge in a white expanse, on which an even whiter plastic Target bag lies crumpled. The result is a mash-up of Kazimir Malevich, Marcel Duchamp, and Jasper Johns, a white on white, interrupted by a target-covered readymade. Taken as a whole, the picture strands us between incompatible modern paradigms.

S.B. Walker, Target bag, ice melt, March 2011

© the artist

Did Walker intend all this? I have no idea. But his book unquestionably meditates on historical rifts, on the cruel contradictions of modernity and the clever descents of modernism. The historical rifts leave Walden Pond in an incongruous state. The pictorialist background refers to a prior century but also signifies the restorative pleasures that the pond continues to deliver. Walker’s photographs show us people sunning, swimming, reading, and cavorting along the pond’s shores. In his generally fine essay accompanying the photographs, the great Alan Trachtenberg remarks on “the absence of signs of human pleasure,” but it seems to me they are rather plentiful. These pleasure seekers are sundry in appearance and style, making the book an occasion to celebrate the values of diversity and tolerance. But as the Target bag reminds us, modernity has not been kind to the ecology of Walden Pond or to the sensible politics of Thoreau. The book abounds in traces of ecological callousness and degradation. People have come to enjoy precisely what their enjoyment will destroy. The Target bag may be a witty riff on modern art, but it is also trash.

Many of the book’s photographs follow this semantic structure, juxtaposing signs of recreational pleasure with signs of banality or loss. We encounter an image of a woman playing a didgeridoo, surrounded by tree roots exposed by erosion, with plastic fencing sagging behind her. The prospect of this woman finding a quiet place by Walden Pond to play her instrument warms the heart, but the land itself looks trampled and bleak.

S.B. Walker, Didgeridoo, May 2011

© the artist

Despite the visibility of inclusiveness and recreation, and the enlivening rhythm of the book’s layout, the book has a melancholic tenor. One could ascribe this to the poignant traces of ecological degradation, imaginatively measured against a healthy Walden Pond of yore. But for me that’s not quite right. For me, the melancholy stems less from an attachment to a certain pond and more from an attachment to a certain kind of photography. The photographs are saturated with signs of the medium’s past. Echoes of the likes of Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Sally Mann are rife. Here is a photographer who has learned from the pantheon what gritty realism you can make of a tattooed amputee, what haunting banality you can get from an artificially illuminated football field, and what uncanny disquiet you can extract from a dark bag left in the woods. The echoes are in the captions as well as in the photographs. The title of Black man, white baby (2013), a picture of two figures relaxing together on a zebra-print towel, seems like a caption from another time.

S.B. Walker, Black man, white baby, July 2013

© the artist

S. B. Walker knows his craft. He knows how to make photographs, and how to string them together. On this score, Walden is a remarkable achievement. But here’s the rub: the photobook is more than craft. For its definitive practitioners, the photobook has been a timely intervention, a vital cultural shock. Walker Evans, William Klein, Frank, Arbus, Mann: their photographs, when introduced to the world, looked unfamiliar and stirred up trouble. Yes, I know: this is an absurdly high bar, and if I could make photographs as well as S. B. Walker can, I would probably give up my day job. But as I went through his book, I found myself wanting the photographs to offer more critical reflection on the distance between 1950s and 1990s photography and what photography must be today. Signs of the digital life-world appear in Walker’s book, but only as an iconography of people using smartphones.

S.B. Walker, The Milky Way, October 2010

© the artist

Don’t get me wrong: employing older technologies is by no means a capitulation to dumb nostalgia. Mann used large-format black-and-white to blow the roof off family photography. But when encountering a photobook I want to experience the choice of means as working in concert with the historical argument the pictures relate, and that argument must make sense of the present. As I tell my students, to emulate Robert Frank is not to make photographs that look like his; it is to pursue the hidden logic and necessary means of one’s own time. I’m not sure that Walker’s book shows us that.

Robin Kelsey is Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography at Harvard University.

Walden was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2017.

The post The Fate of Thoreau’s Pond appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 19, 2017

You Can Never Be Too Rich

In Lauren Greenfield’s chronicle of American wealth, the desire for status is insatiable.

By Nancy Isenberg

Lauren Greenfield, Limo Bob in his office, Chicago. Bob owns a one-hundred-foot limo that made the Guinness Book of World Records for being the world’s longest limousine, 2008

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

What is class? Is it something we can graft onto our bodies through plastic surgery? Is it every commodity, big or small, luxurious or cheap, that we buy, and that comes to symbolize us? Is it the desperate need to impersonate those who seem to have more things and more fame than we possess? Is it about power?

In Generation Wealth (2017), Lauren Greenfield’s brilliant photographic journey through the labyrinth of American class presumption in the present century, the reader/observer is overcome by the sheer weight of hollowness. Yes, the paradox is intentional. The book traces its serial themes from shopping to the cult of celebrity to dynastic comfort, a world where money is everything. Even a twelve-year-old girl in Los Angeles gives evidence of an obsession with every tawdry cliché: “But I want the world; I want designer clothes; I want eternal happiness, the fountain of youth. . . . I want the best of everything.” I want, I want.

Lauren Greenfield, A VIP guest “makes it rain” with hundreds of dollar bills on a sold-out Saturday night at Marquee, routinely ranked as one of the top-grossing nightclubs in the United States, Las Vegas, 2012

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

In her introduction, Greenfield emphasizes the unnerving appeal of reckless abandon. Look around. It is pervasive. As we become a more unequal and less democratic society, Greenfield writes, “we have experienced a democratization of the signifiers of wealth.” The new American Dream, the ultimate goal for every man, woman, and child, is to achieve an ever more lavish lifestyle, or at least the illusion of one.

The watchwords of this mesmerizing book are crave, commodify, and consume. The people we meet in this book are material girls, toddler beauty-pageant stars, Disney World royalty, Botox babes, anorexic models, amateur pole dancers, and professional strippers. Women and pets are treated comparably—as accessories to wealth. Even a sad-faced Imelda Marcos. The images reflect the self-hatred that grows from the experience of spiritual prostitution. Sexual exploitation is pivotal in the book’s depiction of class, with the underlying message that women are the unconscious (and some conscious) mascots of a cruel system; they represent rapacious desire and property meant for display. And meant to be controlled.

Lauren Greenfield, Christina, 21, a Walmart pharmacy technician, en route to her wedding in Cinderella’s glass coach, drawn by six miniature white ponies and with bewigged coachman, Walt Disney World, Orlando, Florida, 2013

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

Annika, the aforementioned twelve-year-old, eagerly exploits her mother. She tries to extract all she can from her: “I sometimes feel angry,” says the mother, “because I feel like her goal is to get as much out of me as she possibly can, without any regret.” Jackie is the third wife of timeshare mogul David Siegel. They became (in)famous for building a ninety-thousand-square-foot home in Florida that they called Versailles. It is hard to resist seeing Jackie as a cheap version of Marie Antoinette. The caption for a photograph that emphasizes her four breast augmentation surgeries and an over-the-top diamond-and-sapphire necklace quotes Jackie: “You never can be too rich or have big enough boobs.” One of the most disturbing images in the entire book is of Jackie’s daughter Victoria, also twelve, who stands in front of a portrait of her father: he is dressed in royal robes, the crowned head of Jackie reflected in the mirror beside him. Victoria died of a drug overdose at the age of eighteen.

There is very little optimism to be squeezed from the pages of this compelling and curious book. The one bright spot in Generation Wealth is the section devoted to the people of Iceland, who have experienced both economic boom and fall, and subsequent to that, an emotional reattachment to a simpler way of life. Alas, the only American story that offers a usable counternarrative to unrepentant greed and gluttony is that of a reformed Wall Street trader named Sam Polk. He grew up in the lower middle class, but was able to graduate from Columbia University and find work in the financial district. For a time, he was dazzled by the men in his financial fraternity—“They all had these money clips . . . they’d pull them out and have a thousand in fifties.” He came to realize that even with a $3.6 million bonus in a single year, he “hadn’t helped anybody else.” So, he left his firm, moved to Los Angeles, and started an organization called Groceryships, which helps mothers living in food deserts. At the end of his rollercoaster ride along the class ladder, he cannot believe “how hard it is to people living in poverty to simply exist. . . . Somehow, we have created one of the most unequal cultures that has ever existed.”

Lauren Greenfield, Swiss publishing magnate Jürg Marquard, 65, with his wife, Raquel, 47, and stepdaughter, Bianca, 21, at their vacation home in the tower of the iconic Badrutt’s Palace hotel, St. Moritz, 2010. In 2005 he took Donald Trump’s starring role in a Swiss version of The Apprentice, 2010

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

What do we learn from this book that exposes the reality of class? In many ways, it is an old story. The themes Greenfield pursues, timely though they are, are not actually new. When I hear young Annika expressing her thoughts, I flash to actor Paul Muni in the film Scarface (1932). Muni’s character buys expensive suits, steals the boss’s mistress, and kills his way to the top of a crime organization; he looks out his window and sees his private version of the American Dream, a neon sign blinking the words, “THE WORLD IS YOURS.” Insatiable desire is something Western culture equates with childish behavior, and with primitive urges. If the 1990s gave us “the inner child,” the 2000s have given us a full-blown “baby-fication” of mass culture. What had already devolved into semiconscious craving has now become instinctual.

The class system in America has contributed to a new, more perverse social leveling. Social mobility has not improved; instead, it is the roles of adults and children that have apparently been inverted. The glorification of youth that we trace back to the roaring ’20s, and that was refashioned in the hippies heyday in the ’60s, has come to a point in which adult values of rationality and self-discipline have been thoroughly undermined. There is no such thing as delayed gratification anymore.

Lauren Greenfield, Celebrity plastic surgeon Dr. Frank Ryan, 39, prepares to give Botox injections to Shannon Tweed, 43, a former Playboy Playmate and wife of Kiss lead singer Gene Simmons, Beverly Hills, 2000

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

Greenfield’s book is reminiscent of two works by Vance Packard, the best-selling author who came to prominence in the late 1950s and influenced millions. His book The Status Seekers hit bookstores in 1959, and he was still thriving when he published The Ultra Rich: How Much Is Too Much? in 1989. In the first book, Packard defined status seekers as “people who are continually straining to surround themselves with visible evidence of the superior rank they are claiming.” He made the point that heightened stratification endowed Americans with a distinctive trait: they routinely looked for ways to separate the “elect from the non-elect.”

Americans have long adhered to the myth that they thoroughly broke free of the class system of Great Britain, when in fact they have only magnified it in their quest to define social status through material symbols. Class in America is not, and never has been, solely about income levels—it is a condition reproduced from parent to child. That is, children are not merely heirs to the class status of their immediate forebears; they are symbols of bloated excess for the rich and symbols of deprivation for the poor. The vaunted middle class that we imagine to be the very definition of American society, and that brings us both stability and provides a moral anchor, is neither as stable nor as well-anchored as we have been led to assume. Packard’s disturbing revelation about the vast middle is memorable. He writes: “The middle classes are all affectation and conceit and pretense and concealment.” Here he is quoting British prime minister Lord Melbourne, from the early 1830s. Melbourne’s point was that middle-class people were shapeshifters in terms of their values, because they were constantly striving to get ahead.

Lauren Greenfield, Lil Jon, 33, sporting a diamond and platinum grill that reportedly cost $50,000, at the 2004 Soul Train Awards, Los Angeles. Lil Jon is a rapper, producer, and DJ who has worked with Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Usher, and Britney Spears, 2004

© the artist and courtesy INSTITUTE

Americans have never embraced social equality. They have long held contempt for those who wallow just beneath them. It is not only the Texans who love “bigness”; there are a host of New Yorkers of the same grasping need for ostentation—no better represented in this example than the brash, insensitive, real estate man who built himself a Fifth Avenue penthouse in the style of Louis XIV and went on to become president. “He won votes by talking about how great he is,” writes Greenfield. Historically, class has always been about conspicuous display, or pride in the family name; the lower classes have often sought to imitate their social betters by looking for similar means of self-expression. (This is one reason why the dual businesses of designer fashions and imitation knockoffs thrive.) Greenfield also gives us the rapper Lil Jon with his $50,000 diamond grill on his front teeth, which effectively captures another old but accurate depiction of the American personality: it was Frances Trollope, a visitor to the country almost two-hundred years ago, who acidly remarked that all Americans were braggarts.

The message is that Americans, in the past, never felt secure in their class identity, and they still do not in the present day. They are constantly negotiating their place in the world: everything they buy and display and everything they utter about themselves becomes a desperate attempt to say, “I am somebody.”

Nancy Isenberg is the T. Harry Williams Professor of American History at Louisiana State University and the author of White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (2016).

GENERATION WEALTH by Lauren Greenfield is on view at ICP Museum, New York, from September 20, 2017–January 7, 2018.

The post You Can Never Be Too Rich appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 14, 2017

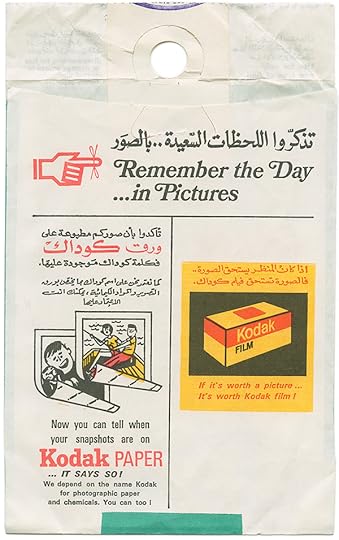

The American Dream in Saudi Arabia

In Ayesha Malik’s new photobook, a California-style suburb in the heart of oil country.

By Annika Klein

Ayesha Malik, Suha after work in the commissary parking lot, December 2011

© the artist

In Ayesha Malik’s first book, ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields, few of her photographs show rigs, pumps, or other industrial equipment. Instead, she presents smiling families, golfers, palm trees, verdant landscapes, Christmas lights, and picnics—all through “a dusty-rose filter,” as she describes in the preface. Malik spent her childhood in Dhahran, an American enclave built exclusively for Saudi ARAMCO employees in the late 1930s. Inside the compound, which was modeled after a California suburb, families from around the world send their children to American schools, play baseball, and speak English. Women are allowed to drive, and wear Western clothing. Here, cultures that usually clash blend together, and identity outgrows simple, nationalistic terms.

Only months after the U.S. enacted a travel ban on residents from seven Muslim-majority countries, Malik and I sat down to discuss the complications of cultural identity and the power of compassion.

Ayesha Malik, Early-morning view along Rolling Hills Boulevard, November 26, 2016

© the artist

Annika Klein: ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields includes old family snapshots, which are laid out in the same way as your own photographs, floating on the page with captions in the back. Why did you decide to organize the book this way?

Ayesha Malik: While laying it out, I wanted it to be genuine and intuitive, and not based on what people might expect to see. I thought a lot about my own memories in Dhahran and how I felt connected to the people I photographed; I saw a little bit of myself in them. Growing up, my dad took snapshots of our lives. I imagined how these kids felt similar to how I did. Not much changes in Dhahran. The old pictures create an atmosphere of nostalgia and a space for readers to think about their own memories.

Ayesha Malik, Baseball player in the dugout, October 21, 2016

© the artist

Klein: You said the word “genuine.” But when I think of something like a corporate compound, or even a suburb, I think of it being artificial.

Malik: In art school, while making work, I remember somebody using the word “theatrics.” And it was funny because it is theater, in a way. But it was my life, my normal, my “genuine.” The cookie-cutter houses, the manicured grass were artificial, but the life I led was not.

I don’t think anyone in the ’30s could have predicted what would come out of this manicured environment in Saudi Arabia. If you go deeper into ARAMCO’s history, there is a story of human connection, but that isn’t always true. It’s history is not without faults, as in a promotional film from Standard Oil of California circa 1948, titled Desert Venture. Aspects of the film reinforce orientalist and neocolonialist stereotypes. The relationship has evolved and grown. Most Aramcons are mindful of those stereotypes. Of those who aren’t Saudi, many actively try to learn about and respect Saudi culture, integrating it into their lives. In ways seen and unseen, it becomes part of who they are. People spend lifetimes there. My family did.

Ayesha Malik, Kodak envelope, ca. 1980s–90s

© the artist

Klein: Along with vintage family photographs, you also include ephemera, such as Kodak envelopes with and film receipts. One of the most memorable examples is a hilarious, charming fan letter that your sister wrote to Leonardo DiCaprio. How did you decide which archival documents to include?

Malik: The Kodak envelopes, for example, are familiar to many Americans, but they’re probably not familiar with the Kodak envelopes with Arabic writing. It creates a psychological space for the work and also a physical memory. Looking through this book and touching these inserts, the reader will probably feel like they’re looking through my personal stuff, which is intentional.

I use my sister, Sara, as an example throughout; the fan letter is a moment of humor. Many girls here experienced similar emotions as teenagers, and I like the fact that she explains, “Oh, in Saudi Arabia, no one comes here.” We had a movie theater that played old movies and huge sections would be missing. The censors would cut out the whole kissing and romance scenes, and we were left wondering, Why is this movie over in twenty minutes? What happened? Now, access to Western media has changed because of globalization and the Internet. But, at that time, I longed to watch Western films, and I really wanted to go to the States. When we would visit, the first thing we’d do was get junk food and watch bad TV.

Ayesha Malik, Aramco mom, December 2011

© the artist

Klein: How would you describe your nationality? How does the theme of identity play into your work?

Malik: My dad would identify as American because he spent a long time studying, living, and working in California. We’re ethnically Pakistani. I’m not necessarily Saudi by nationality, or by blood, but it’s a huge part of my identity. I’m American according to my passport, but, sometimes, when I’m in America with kids who’ve never left the country, I feel different from them. Then, when I’m in Pakistan, I feel American. Sometimes the technicalities of identity are flawed because how you identify yourself is usually more complex than what people see.

There are many Saudi women in this book, but some of the portraits don’t visually say “Saudi”—or what we are trained to understand “Saudi” to be. Newspaper and magazine editors often won’t choose those images where Saudi women aren’t wearing veils because they don’t see Saudi—they just see nothing. To some, this suggests a loss of culture or identity to a more a homogeneous image. We crave these obvious signifiers of identity because it lets us consume people and cultures like any other commodity. I was asked, for example, for a photograph I had taken at ARAMCO’s private beach. The person described it as the photograph of Western and Muslim women. It was an awakening moment. I thought, well, those aren’t necessarily two separate entities. I am both Western and Muslim. Who is to say, in that photograph, that the women in bikinis aren’t Muslims or that the women in abaya aren’t Western? It is all speculation. Images always fail to tell whole stories and express identities. I stopped using that photograph because I realized it plays into a stereotype.

I also remember a man looking at one of my photographs and saying that the woman was wearing a symbol of oppression (the abaya) and holding a symbol of freedom (a smartphone). He was a seemingly modern, left-thinking guy. To me, that is a problematic way of thinking. It is simplifying and divisive. We need new ways of seeing and interpreting.

Everyone is always looking for that perfect image to illustrate it all, and I don’t think it exists. I don’t believe in the nice neat package of identity. I hope that the ephemera and the text included encourages people to reconsider what they think they’re seeing. Throughout the book, I’m asking people to stop and think, What are you seeing? Are you seeing this American town, or are you seeing something that’s more complex and nuanced than that?

Ayesha Malik, Sprinkler rainbow on Tarut Drive, October 20, 2016

© the artist

Klein: Looking at these rosy pictures reminded me how rare it is to hear about the positive things that come from Saudi oil, especially in left-leaning, Western circles. The oil boom seems to have improved many lives in that region, at least on an economic level. On the other hand, the leaflets included in the book tout oil production as an unequivocal good, which does not account for the ecological ramifications. What are your views on the effects oil has on the environment?

Malik: I know from my father that, when he worked on projects, environmental protection was always considered. I became more conscious with age and the increasing mainstream media coverage of the ecological effects of oil, global warming, and climate change. There is no denying the childhood Dhahran gave me and so many other kids. My experience was very “rosy,” as you described it. But I do have an issue with the negative impact drilling for oil has had on the earth. It has come at a cost.

It is worth noting that Saudi ARAMCO is part of an initiative with the state of Saudi Arabia called Vision 2030, which aims to reduce dependency on oil by looking to new economic sources and developing different sectors, part of which includes renewable energy. ARAMCO is also helping fund artists who are talking about the impact of oil on society, cultures, and the environment, such as Saudi artist Ahmed Mater, who actively criticizes those consequences, and not just specifically in regards to Saudi Arabia. Those conversations have to be had, even it if makes people uncomfortable. And no, I didn’t receive any funding from Saudi ARAMCO.

Ayesha Malik, Mrs. Bumstead’s charm bracelet, October 21, 2016

© the artist

Klein: In your interview with Elizabeth Renstrom of VICE, included in the book, you mention that many kids growing up in the U.S. don’t have the same opportunity to live with people from so many different countries.

Malik: I grew up with people from around the world, and we would make jokes about the Palestinian kid, the Jordanian kid, the American kid, et cetera. Coming into the States, I realized people don’t always get those jokes. In Dhahran, if you embrace it all, I think you develop a sympathetic, empathetic worldview. Friends telling you about their parents in Syria, or their family in Palestine—those are the stories I heard growing up. It’s a way of seeing the world that’s bigger than what’s just around the corner.

Ayesha Malik, Tank farm, Saudi Arabia, December 24, 2012

© the artist

Klein: How does growing up in such an international environment make you feel about the recent wave of this anti-immigrant feeling, and particularly Islamophobia?

Malik: It’s scary, and it touches on the darkest impulses of society. It’s about as un-American as it gets. I’m Muslim. What are you saying about me and my family, and my family’s family, and the people I feel connected to? They’re just regular people building their lives. It feels like a personal attack. Empty, stereotypical statements—they make me angry. You can’t color any group of people.

Annika Klein is the editorial assistant of Aperture magazine.

ARAMCO: Above the Oil Fields was published by Daylight Books in 2017.

The post The American Dream in Saudi Arabia appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 13, 2017

Pictograms of Lars von Trier

In still lives and portraits, Casper Sejersen reinterprets the script of Nymphomaniac.

By Remi Coignet

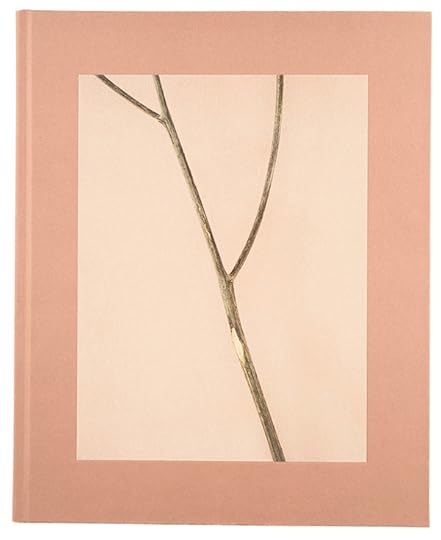

Casper Sejersen, Belongs to Joe, MACK, London, 2015

Belongs to Joe, by Danish photographer Casper Sejersen and author Cecilie Høgsbro, is a book created on the set of Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac (2013)—a powerful, erotic, and at times, deeply disturbing movie about Joe, a woman who defines herself as a nymphomaniac. She tells the story of her sexual life, from childhood to maturity, to a man who takes her in after finding her injured. This serves as the framework for a powerful reflection on addiction, art history, mythology, and even fly-fishing. Belongs to Joe is by no means an illustration of the movie, and is even less a by-product of it; instead, it is a standalone work inspired not by the film but by its scenario. This work, unique in its own right, nonetheless manages to remain faithful to the charged, transgressive ethos of its source. Sejersen, who is known for his work shooting fashion for such magazines as Dazed and Purple, spoke about the creation of this uncommon book.

Rémi Coignet: How did you get in touch with Lars von Trier?

Casper Sejersen: I was hired to do the commercial campaign for the posters and promotional material. I saw the casting, and I thought I should not just do the campaign. So I asked his producer [Louise Vesth] if I could do a kind of behind-the-scenes book about the film. And she said, “Forget about that. Lars will never allow anything like that. He’s not interested.”

And then she sent me the manuscript, because Lars wanted me to read it before I did the campaign. I read it in one day and was totally blown away. Then his producer called me back and said, “Now Lars thinks it’s his idea, this behind-the-scenes book, so you are allowed to do it.” I responded, “Yeah, but Louise, I have read the manuscript now—I can’t do a behind-the-scenes book after that. I can’t do pictures of actors in trailers putting on makeup. It will be too light. Now I want to do my own art project, not based on the film at all, but based on the manuscript.” She just said, “No, that’s an art project—he will never allow it.” So I told myself, “OK, forget about that.”

She called me two days later and said, “OK, Lars thinks it’s a brilliant idea. He only has one wish: that he not be a part of it. And he will only see the final result. So you can do whatever you want. We will support you, but it’s your own art project.”

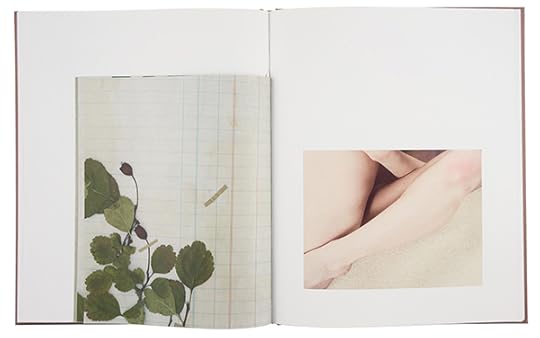

Casper Sejersen, Belongs to Joe, MACK, London, 2015

Courtesy the artist and MACK

RC: Was the writer Cecilie Høgsbro involved in the project from the beginning?

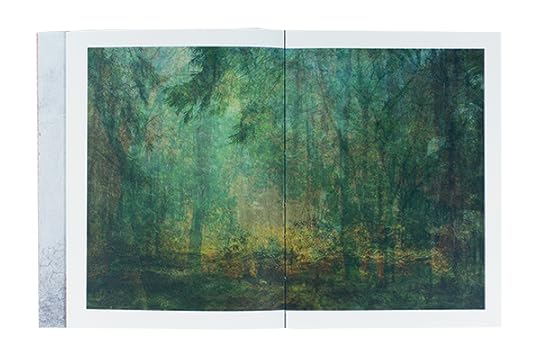

CS: No. First I did the pictures because the film’s promotional campaign was shooting in Cologne, where they filmed. I think I went there eight times because the actors were there at different times. I set up a studio in Cologne, where I did the pictures for my book. And when I came back to Copenhagen, to my own studio, I did all the still lifes. Some of them are my interpretations, and some are the real props from the film. So it was a mix of that and the nature pictures in the book. Those are not the locations from the film. I could see that all the inspiration for the walks that Joe has with her father in the film came from the area where Lars lives, north of Copenhagen. So I shot in this area where he did his own walks. I was trying to dig into his brain—to find where he gets his thoughts from, his ideas and inspiration.

Casper Sejersen, Belongs to Joe, MACK, London, 2015

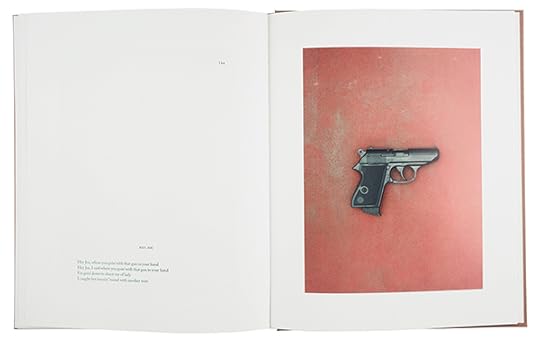

RC: And how did the script and text come into the work?

CS: When I got the idea for the book, I could see that there were so many routes and so many pictures you could do. I was really quick to lock down the specific pictures I wan to do for the book based on the script. I made that list and made the pictures. After I did all the pictures, I showed the to Cecilie. So first she saw the pictures, and then she began, as I did, with inspiration from the script. We wanted to have some things that were our interpretations of the script—some things that were really kind of factual, almost scientific, and others that were fiction, which were our take on it. Maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not. And then Greger Ulf Nilson, the designer for the book, had the clever idea of using different typography to show the different layers. Greger did the layout the same way that Cecilie did the text and I took the pictures. He is really a graphic designer who thinks; he set up the rules before he started, so once he started to lay it out, there was only one way for it to happen.

RC: The aesthetic of your images—the colors and light—is completely different from that of the movie. Why?

CS: Louise, the producer, asked me if I wanted to see the dailies. My answer was, “No, I don’t want to have any interference.” I wanted to use what I think can be the power of still photography rather than film—because if I had tried to do it the same way as the film, it would have just been a superlight version of it. So from the beginning, I had in mind that the photos I wanted to do should be shot almost like pictograms. So if it’s a fist or it’s a gun or it’s a tree, it should be a kind of pictogram version of that—I wanted to do it very simple. So it has this aesthetic from a science book or from an encyclopedia, for example.

RC: How did the actors contribute to the book, and how did the work with them happen?

CS: Again, from the beginning, I made the choice that I would only photograph the main characters. So it’s just Joe in her three states: as a child, as a young woman, and as a mature woman. And then I wanted to use Shia LaBeouf as a stand-in example of a man. I didn’t want to use him as his character in the film—he should just be the picture of a man, and the same with the one picture of Stellan Skarsgård. I wrote letters to the actors, and especially to Charlotte [Gainsbourg], to explain my vision to her. And she was really supportive. Stellan got on board right away. The parents for the young girl got it. Stacy Martin also got it immediately after talking to Charlotte. Shia has this Hollywood background, so it took a longer time to convince him. He thought my project was a celebrity project, and I was just using his name. But in the end, it worked out.

Casper Sejersen, Belongs to Joe, MACK, London, 2015

RC: The book is divided into several chapters—even physically, with the herbarium in a smaller format and thinner paper, and the forest pages printed with glossy, varnished images. Does that echo the chapters of the movie?

CS: Yes, in a way. I think it was both a choice and not a choice. Not to compare myself with Lars at all, but maybe I work in a similar way. As I tried to explain, I have to have some rules before I do anything. Also, I could see that Joe is just a collector in the film, and it’s all about low forms of collecting. I told Greger that it would enhance different collections in the book if they had slightly different aesthetics.

RC: The movie, which is brilliantly done, uses a classic narrative: in one room, one person tells a story to another, and then you have flashbacks. Belongs to Joe deals with the same issues as the film, but in a more metaphorical way. Does the weakness of photography in telling a story become a power if you focus on the concepts behind the story? You were talking about pictograms; I would say concepts.

CS: Yes. I think photography can exist outside of time in a way that allows you to dwell on something. You can have a picture of a specific expression on a face, or specific objects. Then you can just look at it again and again. I’m not saying that I like photography better than film, but there are differences between what they can and cannot do. The power of photography is that you can really dwell on the small details. And, for me, that has so much power. You can just add so many things, whereas when you see a film, it’s all about the music, the voices, the edit. And that makes film really powerful. But then you have these frozen moments, where you have to use your imagination about what’s happening just before or just after: is she pained here, or is she pleased? In a film, you will know in another way, because you can also hear a voice, and you can hear the music. The power of photography is that you have to use your imagination a little bit more.

Casper Sejersen, Belongs to Joe, MACK, London, 2015

Courtesy the artist and MACK

RC: I get the feeling from your work that, even when actors are being portrayed, they look like still lifes.

CS: Yes, exactly. That was also really a specific choice, because you could have done this book in many ways. If I had been another photographer, I might have done it more reportage-style or more candid. So it was really an important choice to go as far away from what film can do as possible, to try to have a really new take on the material.

RC: What was the reaction of Lars von Trier to the final result?

CS: Lars is not a man of many words. He liked it. I got the sweetest and shortest letter from him. It was just one sentence: he just said, “I love the book,” and that was it.

Rémi Coignet is editor-in-chief for The Eyes magazine. He is the author of two books, Conversations and Conversations 2 (2014 and 2016, The Eyes Publishing), collections of his interviews with distinguished photographers.

The post Pictograms of Lars von Trier appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 12, 2017

The Urban Riders of North Philadelphia

Mohamed Bourouissa explores how a neighborhood on the verge of gentrification etches out marks of distinction.

By A.M. Weaver

Mohamed Bourouissa, still from the video Horse Day, 2015

© ADAGP and the artist and courtesy kamel mennour, Paris/London

Born in Algeria, Mohamed Bourouissa began his career by documenting his friends in Paris’s suburban banlieues and staging photographs that express the tension of marginalized populations. In this sense, his current exhibition at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, Urban Riders, is a continuation of his previous work. The Urban Riders project provides an in-depth look at a community and brings nobility to the equestrian enterprise of African American men and youth situated in Strawberry Mansion, a neighborhood on the verge of gentrification in northern Philadelphia.

The story of the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club goes back about a century, and may even have roots in the American south. Bourouissa first heard about the club through Martha Camarillo’s book Fletcher Street (2006); Camarillo is currently working on a documentary film on the same topic. For eight months, in 2014, Bourouissa immersed himself in this community. Bourouissa does not engage much in the history of the club but, instead, presents its day-to-day activities and the horsemen involved.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Skin and Paper, 2014

© ADAGP and the artist and courtesy kamel mennour, Paris/London

At the entrance to the Roberts Gallery, a space for temporary exhibitions at the Barnes Foundation, sits a crudely fashioned display of Bourouissa’s notes and sketches from his time at Fletcher Street. To the right, the wall is plastered with posters from Horse Day, a pageant organized by the artist in 2014. Held in an vacant lot, Horse Day displayed the skills of the horsemen as well as the horses’ regalia. Several artists constructed the horses’ festive gear, which included a bridle and saddle made of CDs as well as a spectacular ensemble made of strips of red and silver Mylar.

The next area is a viewing room of a split-screen, documentary-style film chronicling day-to-day activities, including interviews with the Fletcher Street club members. The film features a horseman named Peewee riding a horse bedecked with Mylar gear made by Max Lussenhop and Billy Dufala. It closes with clips of a fictitious race between a vintage 1970 Buick and a horse—both of which are driven by Peewee. The horse outpaces the car, and wins the race. This last scene brings to mind the African American folktale of John Henry. Labeled a “steel driving man,” Henry’s prowess and energy was pitted in a race against a steam driven hammer used to construct the railways in the 1870s. John Henry won the race, but ultimately died from exhaustion afterward. Despite conflicting tales and scholarship, Henry, like the Urban Riders, remains a symbol of stamina and strength.

Mohamed Bourouissa, still from the video Horse Day, 2015

© ADAGP and the artist and courtesy kamel mennour, Paris/London

Bourouissa sees a connection between urban neighborhoods in the United States, Guadeloupe, Algeria, and immigrant communities in Paris. He is interested in marginalized people, and in making the marginal visible. In the case of Urban Riders, he portrays the horsemen in their effort to hold onto and to continue building a tradition integral to their community in the midst of gentrification. What struck me deeply about Bourouissa’s film were the words of a youth who considers himself not an urban cowboy, but a horseman. He states that the term “horseman” represents the pride he has in caring for and training horses—a badge of honor. (Part of the agenda of the Fletcher Street Riding Club is to teach youth responsibility.)

In the last gallery, Bourouissa has printed images on flattened car parts. They bring to mind modern and post modern sensibilities, such as Conrad Marca-Relli’s collage-on-canvas works and Robert Rauschenberg’s metal-and-silkscreen art. Unlike his modernist predecessors, Bourouissa’s works are slick and refined: the car parts are carefully honed and the images on them blurred, but readable. The largest relief sculpture in The Hood series is The Ride (2017), a twenty-four-foot panoramic view of the Fletcher Street neighborhood. Bigger is not necessarily better, however. More satisfying are a few large, but more moderately sized sculptures Keason (2017) and Boy with the Hood (2017).

Mohamed Bourouissa, Keason, 2017. Black-and-white gelatin silver print on car metal plate, body part, spray paint, and lacquer

© ADAGP and the artist and courtesy kamel mennour, Paris/London

Bourouissa’s attraction to urban sub-cultures was fueled, in part, by his postcolonial studies of Frantz Fanon, who’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961) analyzes the Algerian War of Independence waged against French colonial rule. Fanon is still considered a leading voice in outlining the trajectory of decolonization, and Bourouissa understands the connectivity between postcolonial strivings and the African American and African diaspora experience. He connects urban dwellers of color across continents, their struggles to maintain their dignity, and communities that are often marginalized, or under siege.

The Fletcher Street stables and club are located in a section of Philadelphia earmarked for gentrification. There have been a number of art projects such as the mural Tribute To Urban Horsemen (2005) by Jason Slowik, and Camarillo’s Fletcher Street, which focus on the horsemen and their humble, yet notable, enterprise. A number of stables throughout Philadelphia remain active in various states of functionality. But will the legacy of the Fletcher Street horsemen survive the transition of the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood? Probably not. Yet, the documentation by artists such as Bourouissa exemplifies how communities etch out marks of distinction that evolve over years and, in the case of the Fletcher Street Urban Riders Club, a century.

A. M. Weaver is an independent curator and journalist based in Philadelphia. She has recently organized the exhibit Gardens of the Mind: Echoes of the Feminine View for the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

Mohamed Bourouissa: Urban Riders is on view at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, through October 2, 2017.

The post The Urban Riders of North Philadelphia appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 8, 2017

What Does it Take to Make a Successful Photobook?

Each year, we call on photobook makers and artists to submit to the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. From the hundreds of books that arrive from around the globe, a jury of industry leaders selects thirty-five shortlisted titles, and finally, in Paris, a final jury selects three winners. From there, the shortlisted books are exhibited around the world, ensuring maximum exposure for all titles, including the winners in each category. Below, six winning and shortlisted artists and editors reflect on their experience of being part of the prize and lend their advice to up-and-coming photobook makers.

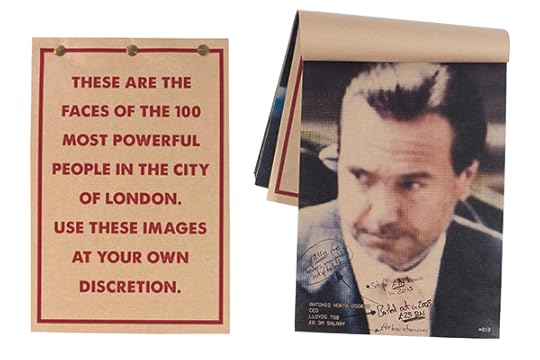

Daniel Mayrit, You Haven’t Seen Their Faces, RIOT BOOKS, Madrid, 2015

Do you feel that being shortlisted (or winning) in a category of the PhotoBook Awards has had an impact on your work and the reception of your book?

Daniel Mayrit (Winner, First PhotoBook, 2015): To begin with, the book sold out within a day of receiving the prize. But I’ve also shown the work in over a dozen exhibitions in the last couple of years because most curators remember encountering the book for the first time at the PhotoBook Awards, or maybe read an interview published in the days after the announcement. So pretty much everything related to You Haven’t Seen Their Faces (2015) took off from there.

Amy Elkins (Shortlisted, First PhotoBook, 2016): Being shortlisted definitely boosted awareness for Black Is the Day, Black Is the Night (2016), and had an impact on book sales. And I’m quite certain it is what led to me being nominated for the Mack First Book Award, along with being shortlisted on a number of best of 2016 book lists.

Kazuma Obara (Shortlisted, First PhotoBook, 2014): I submitted Silent Histories (2014) as a handmade book in an edition of forty-five copies; being shortlisted allowed me to tell the story to a wider audience. The exhibition gave me an opportunity to meet a great publisher during Paris Photo. This led to making a new edition of the handmade book [published by Editorial RM in 2015].

Kazuma Obara, Silent Histories, Self-published, Kyoto, 2014

Myriam Ziehli (Shortlisted, First PhotoBook, 2012): Being shortlisted in 2012 was a really nice experience for my work and my career—I still was at school and [once I was shortlisted] I had orders from all over the world. For me, it was also a way of digging into the topic and strengthening my skills and my convictions that the book is a great way of showing my work, and distributing it easily.

Donald Weber (Shortlisted, First PhotoBook, 2012): I do not encourage artists to enter too many awards and prizes, but this is a legitimate prize and one I would certainly encourage all book makers to enter. There is a trade-off between competition organizers and those who enter; we feed off of each other’s legitimacy, which is a way to secure and sustain visibility. Of the hundreds of yearly awards, prizes, contests, and competitions every year, I’d say there are a handful of worthy, qualified outlets, and this is in the top. What the prize does is declare a certain stamp of approval, a benchmark of “good work” or quality to an audience that perhaps wasn’t familiar to begin with. It is not unlike the Oscars, where movies frequently tag themselves with “Academy Award Winning Actress,” etc. to give a shorthand of approval, a stamp of an authority that something is valid and worth your money.

Barbara Tannenbaum (Shortlisted, Photography Catalogue of the Year, 2015): Being shortlisted helped TR Ericsson’s career by drawing international attention to the first monograph and first major publication on his work. It similarly enlarged the audience and provided recognition for the achievements of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s programs and for my own work as a curator. How fabulous to know that the jurors, all highly respected professionals at the top of the field, have looked at the book! And if you make it to the shortlist, your book is presented to the most interested and knowledgeable audience, and enters into dialogue with the year’s other best productions.

Amy Elkins, Black Is the Day, Black Is the Night, Self-published, Los Angeles, 2016

Do you have any advice for photobook makers—especially for first-time book makers—in general?

Donald Weber: Yes! I am an inveterate supporter of the book dummy, regardless of how well polished it is. The craft of cutting and pasting makes me physically closer to my work, to understand the materiality and textural composition of the story I am trying to tell. Sticking things into a sequence helps me understand the rhythm of the book, how pictures react against each other and what they induce as you flip through it. These dummies become part of my “forensic imagination,” documents of thought, of communication, of emotion, of whatever it is I need to communicate with a designer in order to adequately represent what needs to be said.

I highly recommend the collaboration of others in this process, not just a designer, but also other artists, writers, and scientists. The collaborative mess of spitballing ideas is super fun and enlightening. What do others have to say, and how can it improve your work?

Myriam Ziehli: My advice is: think about the book as a medium and not only a way of putting images together. How does the content match conceptually with the book form? And second: think about the whole economy of the book making . . . it’s very important to keep in mind that the book form is strongly linked to distribution. So in my process, I try to make books that are cheap to produce and to sell. . . . I choose a paper and a book materiality that makes sense for me. But I would also be very happy to discover a copy printed in black and white and on another paper. . . . That’s why I put the PDFs of my books on my website with all the paper and size information.

TR Ericsson: Crackle & Drag,TR Ericsson, Arnaud Gerspacher, and Barbara Tannenbaum

Barbara Tannenbaum: Share your work and get others’ opinions, prepare mock-ups and then refine, refine, refine. Edit and sequence, then re-edit and re-sequence. Give it time to gel and mature.

Daniel Mayrit: Don’t rush it. Think carefully about the reasons for making every single decision regarding the making of the book, from design to binding to printing. Every single detail matters. Print as many dummies as you think necessary and do listen to other people’s opinions. That first idea you had when you first thought about making a book months ago isn’t necessarily the best one. It took me quite a bit to understand that, but collaborating with other people is the best thing that happened to the book.

Amy Elkins: There is such an amazing book making / book loving community. I would definitely recommend reaching out to book making friends you have and tapping into that resource. My friends who make and publish books were such an invaluable resource throughout the entire process. Book making and all that goes into it before and after can be overwhelming, but there are so many generous people out there. Don’t be afraid to reach out.

This year’s PhotoBook Awards submission deadline is September 15, 2017. Enter here.

The post What Does it Take to Make a Successful Photobook? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 7, 2017

Art and Activism in a Contested Democracy

In spring 2017, Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, led a series of classes at the Brooklyn Public Library on the relationship between photography, citizenship, and the law. Here are five reflections from participating students.

Russell Lee, Japanese-American evacuation from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-American child who will go with his parents to Owens Valley. Los Angeles, California, 1942

Courtesy the Library of Congress

Taiyo Na

To make the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II more palatable to the public, the federal government used euphemistic terms such as “evacuation,” “assembly,” and “relocation centers.” It was in this context that Russell Lee’s 1942 photograph bore the following caption: “Japanese-American evacuation from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-American child who will go with his parents to Owens Valley.” It’s a deflective description, but the image itself offers the viewer far more tragedy, injustice, and pathos.

In this photograph, a Japanese American child with a face in disarray stands next to a soldier. The image presents a relationship, a binary and a hierarchy. An overstuffed bag, perhaps the mother’s and “only what we could carry,” occupies the space between the child and the soldier. Between them, there is also a chasm of citizenship, race, and exclusion: the child will board the train in the background to reside in a federal prison in the middle of a desert, and the soldier will enforce that removal. Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 Supreme Court decision, validated the internment of Japanese Americans for the reasons of “emergency and peril.” Under the guise of an “evacuation” and perceived threats to national security, who are the children “tagged” and forcibly removed today? A process of classification always precedes state-sanctioned exclusion. When the waiting is too long and the “tag” unwarranted, its impacts are life and death, and a democracy unfulfilled.

Taiyo Na (Taiyo Ebato) is an educator, writer, and musician based in Brooklyn.

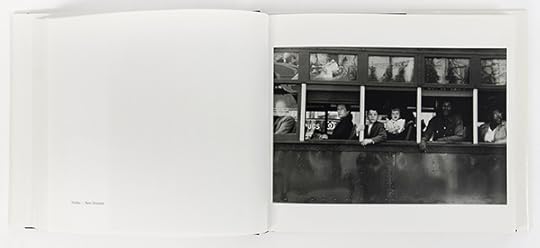

Spread from Robert Frank, The Americans, 1958

Aperture Foundation Library

Jonathan Michael Square

In 1955, one year after the passing of Brown v. Board of Education, Robert Frank photographed a streetcar in New Orleans. The Supreme Court had declared separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional, a death knell to legalized racial segregation. Starting in 1955, Frank traveled across the U.S. taking the photographs that would later be collected in The Americans (1958). Despite the optimistic zeitgeist of the Eisenhower era, Frank showed the racial and socioeconomic hierarchies that still divides us.

New Orleans, where Frank photographed the streetcar, also figures into a pivotal Supreme Court decision, Plessy v. Ferguson. In 1892, Homer Plessy, a creole man of color, bought a first-class ticket, and boarded a “whites only” car. He was arrested and charged with violating Louisiana’s Separate Car Act of 1890. The case reached the Supreme Court, where segregation was upheld. When Frank took this photo in the middle of the next century, public transportation in New Orleans was still separated by race.

In this photograph, the viewer must confront the gaze of Frank’s subjects, both black and white. There are many photographs of “whites only” signs segregated South from this era. But social stratification does not have to be marked or articulated. Inequality had become so inscribed in the American psyche and the national visual grammar that it could be enforced and internalized without explicit instruction. It would not be until the activism of Rosa Parks later that year, and the passing of Boynton v. Virginia in 1960, that buses and trolleys across the nation would gradually be desegregated.

Jonathan Michael Square is a writer and historian who currently teaches at Harvard University, where his work explores the intersection of fashion and slavery in the African Diaspora.

Lucia Hermo, A Call for Help, 2015

Courtesy the author

Carmen Hermo