Aperture's Blog, page 113

August 10, 2017

The Unsung Hero of South African Photography

In searing and poetic images, Andrew Tshabangu chronicles Johannesburg in the age of democracy.

By Bongani Madondo

Andrew Tshabangu, Portrait of a Young Thwasa, from the series Bridges, 2008

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

Andrew Tshabangu’s two decades-plus visual repertoire, the best of which was showcased earlier this year at Johannesburg’s Standard Bank Gallery and Gallery MOMO in Footprints, is provocative and ultimately liberating. With its exploration of blackness as a lived, if banal and mundane experience (just as it is with any other racial group), Footprints, which was curated by Thembinkosi Goniwe, is also notable for its simplicity and aching, often sweeping quietness, and clarity. In “The Value of Andrew Tshabangu’s Photography,” an essay in the accompanying monograph, published by Fourthwall Books, the curator, critic and novelist Simon Njami tells us that Tshabangu’s journey began in the place where he was born, namely, South Africa. “While biography is never a trivial part of the analysis of any artist’s work,” Njami writes, “in Tshabangu’s case the contextual elements seem to render fundamental clues to a deeper understanding of his universe.”

Who is Andrew Tshabangu and why does he matter? Tshabangu was born in 1966 in Soweto, Johannesburg, where he currently works and lives. His lifelong visual subject is the city and its satellite township on the southwest frontier of the African megalopolis. Tshabangu studied photography in the Eastern part of the city, at the Alexandra Community Art Centre, in 1990; he later studied photojournalism at the Institute of Advancement for Journalism, shortly in the wake of the new democratic dispensation. He would go on to make his name as a photojournalist mainly at the then-exulted New Nation, an alternative weekly published by the South African Catholic Bishops’ Conference.

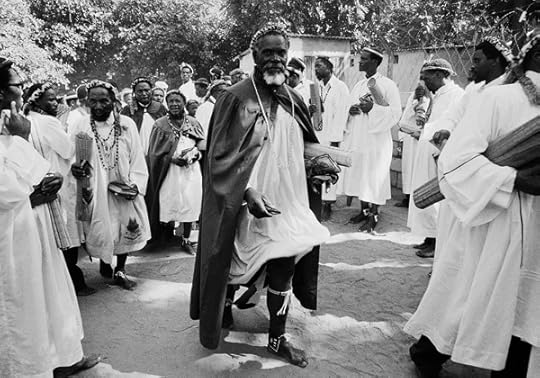

Andrew Tshabangu, Shembe Church Elders, from the series Bridges, 2008

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

“Without doubt,” writes Njami in Footprints, “a journey into the past is always necessary to get a better understanding of any photographic practice.” Njami then lets loose an obvious fact: “Tshabangu is black, and yet this biographical detail could seem almost irrelevant.” It isn’t—at least in the South African (or global) context. On March 21, 1960, six days before Tshabangu’s birth, the South African Police mowed down hundreds of unarmed civilians who were marching peacefully in Sharpeville to protest against the Pass Laws. When he was ten years old, in June 1976, half of Soweto, and by extension the country, was engulfed in fire as students marched against the government’s enforcement of Afrikaans as the language of instruction across the education system. The white regime again responded by shooting the youths and setting raging dogs on them. But, instead of heading into exile, like many teens slightly older than him who skipped the country at that time, Tshabangu, who grew up in a Catholic family, prayed and wished for inclusion in the one calling he felt would offer salvation to his tumultuous country—the priesthood.

Time would pass until he found other ways to tell and preach about the conditions of his people. Upon leaving high school, he applied to Wits University’s School of Dramatic Art, to study performance. “Alas, I was terrible at it. I was rejected, ” he told me recently. “And yet I kept on searching for ways I could train as a creative and tell my people’s stories. Hence I arrived at the Alexandra Community Art Centre where I took up taking up photography. It was not a complex decision to make.”

Andrew Tshabangu, Butchery, Traders and Taxis, from the series City in Transition, 2003

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

In a way, Footprints is both an accumulation, as well as a visual testimony, of the journey he has walked. Thematically divided into six chapters, “City in Transition,” “Bridges,” “Emakhaya,” “Hostel Interiors,” “Hostel Exteriors,” and “Water is Ours,” the exhibition and catalog comprise selections of Tshabangu’s photographs taken since 1994, a year of both personal and political resonance. The beginning of South Africa’s democracy, 1994 also marked the beginning of the end of foreign, NGO-supported African, feminist, and workerist independent media engaged in the antiapartheid movement. Tshabangu is a survivor of that “struggle photography” culture spawned by the activist literary titles such as Staffrider, Weekly Mail, Labour Bulletin, New Nation, and Learn & Teach, and he is stoically steeped in the social documentary mode exemplified by Afrapix, a collective of politically-conscious photojournalists active from 1982 to 1991. His work refuses easy categorization and defies agitprop politics, while remaining cognizant of his subjects’ undeniable blackness; his project, per the Du Bois-esque adage, is the soul of black folks.

Andrew Tshabangu, Naledi-Bree Street Bus, from the series City in Transition, 2004

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

Stylistically, and by this I mean in terms of both aesthetic veneer and disciplinary strictures, Tshabangu can be said to have evolved within the social documentary genre. Early on, as testified by the section “City in Transition,” his camera was trained on black folks’ mobility—by taxi, train, or on foot—in and out of the city. Confident, he moved on to focus on a people dealing with the meaning of freedom via their age-old mysticism and African spiritual practices, before breaking out into the hostel dwellers’ digs and rural environs. By all intents, even in the post-1994 work displayed in Footprints, Tshabangu is a man of the 1980s, and in character and language, he appears stuck in there. There’s nothing extravagantly contemporary, hip, arty, current, or fashionable about his photographs, and yet his work is revolutionarily refreshing for its timelessness. It shouldn’t work wonders, but it does. There’s a backstory to this.

In the immediate postapartheid years, from 1994 to 2004, cultural spaces in South Africa metamorphosed from the tyranny of the apartheid-era single story—benign blacks doing nothing but enduring suffering from evil whites (when not burning everything in sight)—to an idealized narrative, One Nation Under a Groove. Of course, the entire project was optimistic at best and fictive at worst. Artists, the media, and the general public were exhorted to imagine the country anew. The process of re-imagining demanded of the newly democratic country to move the narrative from who we are to who we can be. In that period, the theory held that the past is a divisive if ugly country, a place we had better hurry to escape from, just in case it derails our march into cultural and social nirvana. Like all modern cultural and artistic expressions, photography as art or document found itself exposed and manipulated for propaganda purposes—this time propagating the Rainbow Nation Groove.

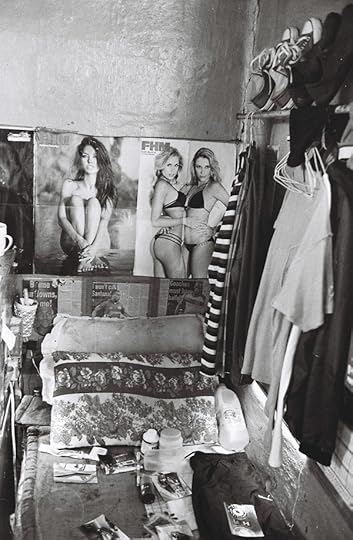

Andrew Tshabangu, Fantasy, from the series Hostel Interiors, 2009

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

In Tshabangu’s South Africa, the South Africa in his Footprints, photography, literature, and all modes of storytelling were no less besieged by the end of apartheid’s reconciliation project. Everyone was besieged. The new age of political correctness had arrived. Exhortations to ideological good manners grew all the louder. No matter what the economics and historical baggage your life might have been shaped by, the message was clear: You have to forget the past, you have to love thy neighbor, you have to believe in the untested miracles of the Nelson Mandela’s fantastical promise.

All attempts at wholesale loving and cultural kumbaya, with no solid legal or spiritual recourse to past injustices, kicked off with blistering immediacy in mid-1994. This is the era on which Tshabangu focused his lens. It was around this time that a question arose (with an implicit “nay” as its answer), a question that persists to this day, as galleries and commercial media wrestle with the conundrum: Does social documentary as a means of visual expression still matter? Is socially engaged art devoid of creative imagination? Is it propaganda?

Andrew Tshabangu, Women Praying at the Crucifix, from the series Bridges, 2001

Courtesy the artist

Out of the cultural turbulence brought about by the politics of hope, social documentarians such as the Afrapix vanguard Omar Badsha, Paul Weinberg, Cedric Nunn, Santu Mofokeng, and Peter McKenzie, among others, all Ernest Cole’s affective heirs, were relegated—while simultaneously valorized by academic theorists—into museum fare and college syllabi. Only the newspaper- and street-hardened, photo-punk collective called the “Bang Bang Club”—which specialized in photographing the police’s jackboot behavior, the disruption of workers and church organisations work, random shootings and arrests of young black males, and the township youth’s militant response to it—achieved glorious infamy.

The “Bang Bang” crew—notably, Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva—were mostly white men working in the black townships. They were treated with suspicion, even though they were often the most reliable visual agents the burning ghettoes could hope for to beam tales of their daily woes to the outside world. (They were later immortalized in The Bang Bang Club [2010], a Hollywood flick that curator-critic Khwezi Gule eviscerates in his essay “Bureaucratization of Memory” in Okwui Enwezor and Rory Bester’s exhibition catalog Rise and Fall of Apartheid [2013]. Gule calls out the photographers for “aestheticizing” as well as “commodifying” township folks’ suffering.) Through all these changes and aesthetic re-imaginations, Tshabangu pushed on quietly, alchemically, working through the raging trends, walking throughout the streets of Johannesburg, almost anonymously.

Andrew Tshabangu, Mielies, Stove and Heater, from the series Hostel Interiors, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

A twenty year survey (“and not retrospective,” Tshabangu insists), Footprints is perhaps the most fully realized and groundbreaking solo photography exhibition in South Africa in recent memory. Tshabangu circumvents all the cherished tropes of twentieth-century popular “black life” in Africa: sex, drugs, alcohol, cars, and witchcraft, or the joie de vivre of the stylized natives, as per Malick Sidibé’s postindependence nouveau noir aesthetic affirmation. Groundbreaking as Sidibé’s James Brown-inflected portraiture (in West Africa) and some of Drum magazine’s 1950s shebeen and fashion show photospreads (in South Africa) were—especially to the racist gaze that never expected outward self-celebration and dandified genius from the native—ultimately that vision was, and is still, susceptible to the single story trap, too.

Tshabangu directs his camera to the same hard done Africans, street idlers, and Johannesburg’s legendary traffic-disregarding minibus taxis at the ranks, or in motion, though he chooses to show neither the ugly nor its opposite, poverty chic. Take, for example, his hostel series, subdivided into “Interiors” and “Exteriors.” His photographs of the exteriors of the low wage workers’ compounds entitled Hostel Exterior I–IV (2008) give off an indifferent feel: trains of architecturally lackluster dwellings, windswept rows of laundry hung out to dry, no people in sight. In an interior view, Mielies, Stove and Heater (2011) depicts a kitchenette upon which stands a table decorated with a check-cloth covering, a bunch of mielies resembling a ponytail of a city slicker or Mafia hitman hung up above a whitewashed wall, and a long electric cord snaking around the table down to a makeshift tin stove that might work as both a tea-heating appliance or a DIY heater. It’s a stripped-down atmosphere: it’s minimalist without the trendy implication; here, minimalism implies a lack of material possessions, but also a willful commitment to “make it” by any means necessary.

Andrew Tshabangu, Brazier, Joubert Park, from the series City in Transition, 1994

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

At the core of Footprints is a narrative of spiritual and ritual experience. The work speaks for itself like nothing else in current in South African social documentary. Why? The composition is specifically an oxymoron—motionless, mystical cinema, 1930s black-and-white Hollywood, a style reminiscent of Isaac Julien’s earlier work, and the process by which he has revisited his iconic film, Looking for Langston (1989), nearly thirty years later, with the emphasis on stills rather than video. There’s Tshabangu’s three-part series Brazier, Joubert Park (1994), which is is imbued with cinematic visual attributes. In the three frames, we see a random woman. She could be a grilled corn trader. She’s dashing across the frame carrying a random box. Behind her is a loose cast of several figures, figures almost blurred off under a haze of smoke, or cast behind a huge transparent smoke curtain. They are going about their interests, around open-fire braziers with raging fire emitting smog and additional smoke.

Brazier, Joubert Park is tricky, perhaps even throws up its own visual phantom jive. It’s as if, after printing it in the darkroom, Tshabangu continued to paint the cloud curtain of smog in it to trick the eye, or emotionally swindle us to connect with the image in a visceral way. Nothing could be further from the truth. Unlike the exuberant and performative visual language of say, Zanele Muholi, neither Tshabangu, nor his curator and gallery, are interested in moving the work from its reportorial grounding. That might seem to foreclose other readings, but, conversely, it also proves to be the only way Tshabangu’s magical realist work assumes its poetic potency, when not otherwise exulting in transcendental otherworldliness.

Andrew Tshabangu, Boy at the Window, from the series Emakhaya, 2004

Courtesy the artist and Gallery MOMO

Tshabangu grew up with ambitions of serving as an ordained priest. Instead, he might have become something else within that pantheon of the spiritual realm: the visual marabout. Haunted by this idea of humanity and dignity as something that can be imbued, passed on, gifted to, rather than an innate virtue and spiritual property, I revisited Footprints a month after it opened. The second time around, I started from the end and moved my way to the beginning, like loving backwards. Both the photographs as objects and the photographed spirits—shadows and figures, eyes daring the camera to get it wrong, or eyes trained far off beyond the horizons of the soul—are more than visual metaphors of a country. The work opens up like a flower, drawing the viewer into an omni-enfolded space from whence the bud, spurred by the gardener’s care and caress, reveals its secrets: bare, undemanding beauty. Which strains credulity, for what sort of beauty is undemanding? Yet, that is what bestows on Footprints its unimpeachable artistic and social gravitas. Tshabangu’s images pry the lid from our position as passive viewers. In other words, although we cannot simply swap places with his subjects, in looking at his photographs, we are participants, gazing at ourselves.

Bongani Madondo is the author, most recently, of Sigh, the Beloved Country (2016). He is an associate researcher at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, as well as contributing editor at the Johannesburg Review of Books. Footprints is on view at Gallery MOMO, Cape Town, through August 20, 2017, followed by a presentation at Iziko National Gallery, Cape Town.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Unsung Hero of South African Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 9, 2017

10 Exhibitions to See This Fall

From Malick Sidibé to Stephen Shore, here are the must-see photography exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and beyond.

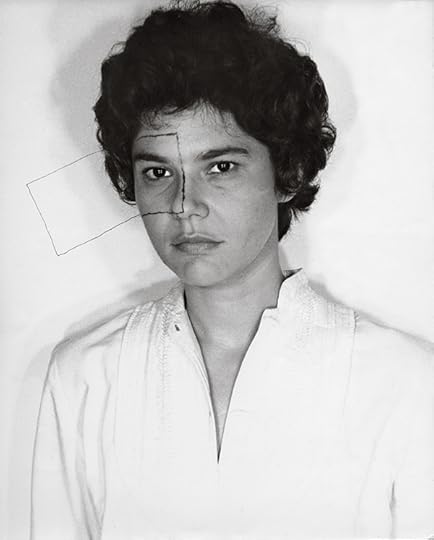

Liliana Porter, Untitled (Self-Portrait with Square), 1973/2012

© and courtesy the artist

Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985

The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

September 15–December 31, 2017

As part of the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, which will involve dozens of museums across Southern California, the Hammer will open a survey of more than one hundred female Latin American artists. Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 focuses on a turbulent twenty-five-year period when much of Latin America suffered under forms of military dictatorship, and the emboldened work of female artists, in particular, challenged the status quo. While the work ranges across a wide variety of practices, a number of important artists celebrated for their photography, including Liliana Porter, Regina Silveira, and Paz Errázuriz, will be featured.

Stephen Shore, Santa Fe, New Mexico June 1972

© the artist

Stephen Shore

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

November 19, 2017–May 28, 2018

This ambitious survey, featuring numerous unpublished and previously unexhibited works, covers five decades of Stephen Shore’s photography. It begins, of course, with the gelatin-silver prints from his teenage years—famously purchased by MoMA when he was fourteen—and includes his photographs of Andy Warhol’s factory, his pioneering work with color photography, his eventual transition to digital tools and social media, and everything in between. As Britt Salvesen writes in Stephen Shore: Selected Works, 1973–1981 (2017), “he was trying to understand the meanings people attach to places, things, and practices—pondering their scope of knowledge, sense of urgency, and expectations of satisfaction.”

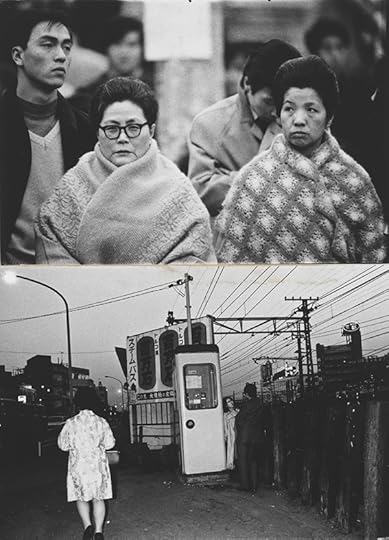

Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled, 1971, from Tokyo

© the artist

Araki. Tokyo

Pinakothek Der Moderne

October 26, 2017– March 4, 2018

Nobuyoshi Araki’s series Araki. Tokyo is composed of formative photographs made from 1969 to 1973, included in one of his earliest books, Tokyo (1973). Araki, known for his erotic depiction of Japanese culture, made these photographs as if producing a diary. The twenty-eight diptychs to be featured at the Pinakothek Der Moderne juxtapose intimate portraits of nude women with the bustling streets of Tokyo. Araki. Tokyo foreshadows Araki’s recent work made after going blind in one eye, which more blatantly examines the disparity between sight and memory.

Manuel G. Barrera Jr., Evening vigil at LAPD Parker Center, ca. 1971

© the artist and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

La Raza

Autry Museum, Los Angeles

September 16, 2017– February 10, 2019

La Raza, the bilingual newspaper published from 1967–77 in Los Angeles, was an essential platform for the visibility of the Chicano civil rights movement. Spanish for “the people,” La Raza envisioned a multicultural image of Latin American identity in the midst of a revolution. Photographers were a crucial part of the movement, incentivizing readers to join the cause through images of determined artists and activists. This exhibition at the Autry Museum will feature an extensive archive of over 25,000 images from the Chicano Studies Research Center of UCLA, illustrating an often-overlooked vision of American history.

Lauren Greenfield, Secret Moneii, 28, a stripper at Magic City who made nearly $20,000 during her first week at the club, Atlanta. Before coming to Magic City, the single mother of two was working two jobs and struggling, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Institute

GENERATION WEALTH by Lauren Greenfield

ICP Museum, New York

September 20, 2017–January 7, 2018

“I’m looking at how the values of our culture have shifted in a way that affects people beyond socioeconomic status, race, or nationality,” Lauren Greenfield, director of the celebrated 2012 documentary The Queen of Versailles, said in a recent interview with Aperture. GENERATION WEALTH, Greenfield’s first major retrospective, presents her twenty-five-year, multimedia exploration of consumerism—in the U.S. and abroad. The exhibition originated at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, and includes photographs, first-person interviews, and documentary film footage, all of which reveal the tremendous level trust she has built with her subjects.

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Stapedia variegata. Asclepiadaceae, 1923

© the artist and Archiv Annund Jürgen Wilde/ADAGP, Paris

Albert Renger-Patzsch: The Perspective of Things

Jeu de Paume, Paris

October 17, 2017–January 21, 2018

This exhibition of 190 photographs marks one of the largest to date of the work of photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch, a crucial figure in the New Objectivity movement during the Weimar Republic in 1920s Germany. In his stark images of nature, architecture, and commercial items— from orchids to shoe-factory machinery—Renger-Patzsch sought to precisely depict the “essence of the object.” His 1928 photobook, Die Welt ist schön (The world is beautiful), helped define the movement. Albert Renger-Patzsch: The Perspective of Things will also include a selection of the photographer’s postwar works.

Walker Evans, Truck and Sign, 1928–30

© The Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Walker Evans

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

September 30, 2017–February 4, 2018

A major retrospective of Walker Evans’s vernacular style comes to San Francisco this fall and will include more than four-hundred works from the 1920s to the 1970s that illuminate the seminal photographer’s facility for capturing the everyday. SFMOMA will mount the exhibition’s only U.S. engagement, following a presentation at Centre Pompidou. The museum’s new senior curator of photography, Clément Chéroux, curates a textured look at Evans’s practice, including not only his photographs, but also personal items such as postcards and clipped images that influenced him.

Sarah Charlesworth, Still Life with Camera, 1995, from the series Doubleworld

© The Estate of Sarah Charlesworth

Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

August 20–November 26, 2017

Can pictures be more important—and more powerful—than reality? Sarah Charlesworth (1947–2013), along with her Pictures Generation peers, revisited this question throughout her career. Charlesworth’s first major retrospective in Los Angeles, Sarah Carlesworth: Doubleworld, organized by the New Museum, surveys four decades of work across ten series. In 1977, Douglas Crimp included Charlesworth in the now-legendary Pictures exhibition, among artists such as Sherrie Levine and Laurie Simmons, who shared her fascination of representation and symbolism, as well as in how images are constructed and distributed. “I use images drawn from the culture,” Charlesworth said in 1990, “because I’m interested in each piece being an interface between my personal subjectivity and a given world.”

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Staircase at Villa Farnese II, Caprarola, 2016

© the artist and courtesy of the Polo Museale del Lazio-Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Italian Tourism

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Gates of Paradise

Japan Society, New York

October 20, 2017–January 7, 2018

More than four hundred years ago, in the 1580s, Jesuit missionaries sent four Catholic-convert Japanese boys on an eight-year tour of Europe. After discovering a fresco portraying this envoy, Hiroshi Sugimoto retraced their steps, and captured the sites that this “Tenshō Embassy” visited. Conceived by the artist, Hiroshi Sugimoto: Gates of Paradise couples new, unseen work by Sugimoto and classical masterpieces from Japan. Considering the history of cultural exchange between East and West, the exhibition celebrates the Japan Society’s 110th anniversary. In addition to these black-and-white photographs, Gates of Paradise also includes several Japanese screens, which depict Christian and Western themes, from the same era.

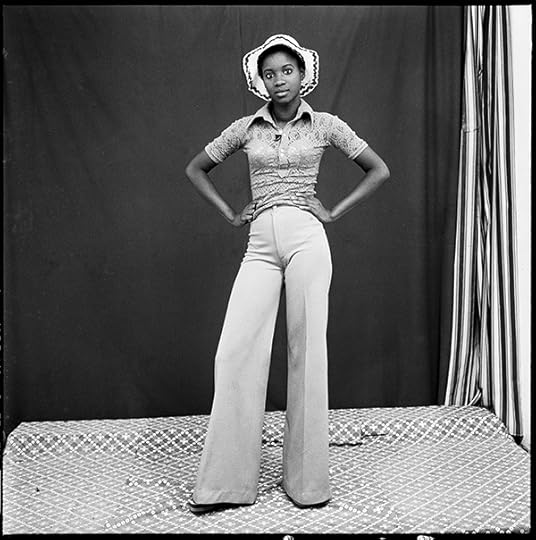

Malick Sidibé, (Je l’appelais) La gazelle / Avec mon chapeau et mes pattes d’éléphant, 1974

© the artist and courtesy Magnin-A

Malick Sidibé: Mali Twist

Fondation Cartier, Paris

October 20, 2017–February 20, 2018

Known as the “eye of Bamako,” the late photographer Malick Sidibé (1936–2016) fused the American rhythms of James Brown with the fashions of 1960s-era postcolonial West Africa. Two decades after his first solo exhibition at Fondation Cartier, Sidibé’s vivacious studio portraits and a dizzyingly spectacular account of 1960s nightlife in Mali’s capital return to the glossy Jean Nouvel-designed museum in a retrospective organized by André Magnin and Brigitte Ollier. Sidibé was famous for staying out late, and his most iconic photographs project irrepressible joie de vivre. “I was the only young reporter in Bamako taking photos at surprise parties,” Sidibé once said, referring to the clandestine gatherings organized by the city’s youth. “I was always on the lookout for a photo opportunity, a lighthearted moment, an original attitude, or some guy who was really funny.” If the preview this spring at Red Hook Labs was any indication, the expanded version is not to be missed.

The post 10 Exhibitions to See This Fall appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 3, 2017

Can African Critics Rewrite the Story of African Photography?

M. Neelika Jayawardane speaks with Emmanuel Iduma about the influential role—and responsibility—of art criticism in Africa today.

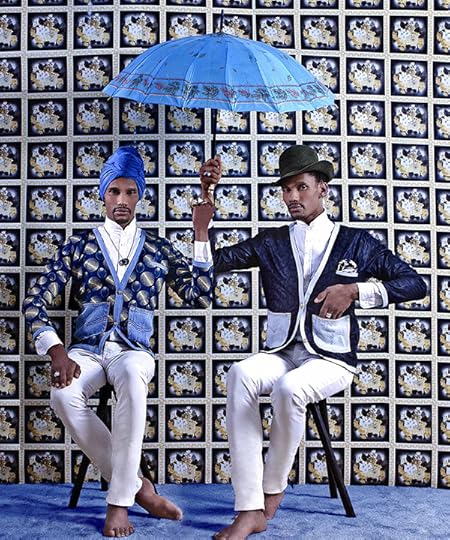

Namsa Leuba, Untitled I, 2011, from the series Cocktail

Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Since the early 1990s, when Malian photographers Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta began to attract international attention for their stylish, midcentury portraiture, there has been an upwelling of interest in photography and lens-based media from African and African diaspora artists. Today, more than two decades after the first Rencontres de Bamako (commonly known as the Bamako Biennale), in 1994, as photography from Africa has become intrinsically tied to the global flows of art fairs, biennials, and magazines, certain geographies on the continent have remained locations of aesthetic innovation. Cities like Accra, Addis Ababa, Cairo, Lagos, Nairobi, Bamako, Dakar, Johannesburg, and Cape Town are now home to multiple exhibition platforms and educational programs, and have become centers of photography, despite financial and political pressures. Platforms and events—such as LagosPhoto in Nigeria, Addis Foto Fest in Ethiopia, RAW Material Company in Dakar, Kulte Gallery & Editions in Rabat, and the roving Àsìkò Art School and the Photographer’s Master Class—are producing their own cartographies of knowledge about art through distribution channels across Africa and beyond.

Within this ecosystem of image production, art writers play both peripheral and central roles in creating counternarratives and producing new ways of thinking about African photography. Writing about African photography has, traditionally, been the realm of an exclusive group of North American and European academics and critics. However, just as the camera, in the hands of an African photographer, produces a different image of “home,” African and African diaspora critics who write about photographs of their home produce necessary interventions in academic and critical writing. By ensuring that Africa-based and diasporic writers’ thoughts are published, we as writers create a home for our own ways of thinking about our images of self. With these thoughts in mind, I recently spoke to Emmanuel Iduma, an art writer whose work I’ve been following with deep respect for several years. — M. Neelika Jayawardane

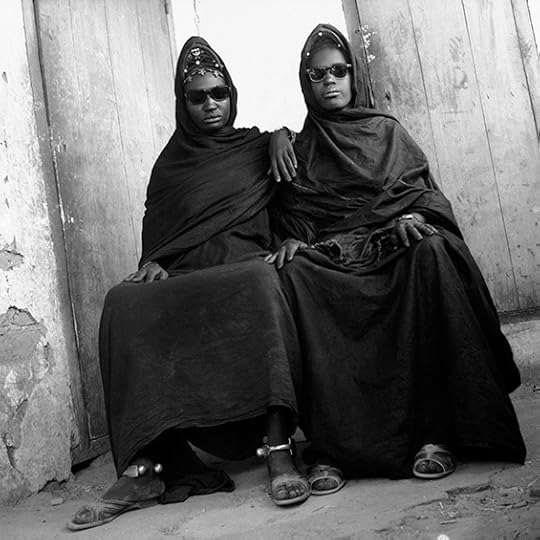

Oumar Ly, Untitled, Podor (Senegal), 1963–78

© the artist and courtesy (S)ITOR

M. Neelika Jayawardane: Last year, in a conversation at the Armory Focus: African Perspectives in New York, we spoke about writing about art. There, I wanted to open up a discussion about the role that art writers might play in enriching dialogue and shifting pervasive attitudes—in the geopolitical West—about African art and African artists, given the surge of interest in contemporary African art in recent years. You have been involved in several platforms for photography and art writing in Africa, Europe, and North America, in particular Invisible Borders and the online magazine The Trans-African. What is your approach to writing about photography?

Emmanuel Iduma: In my writing on photography, I am probably closer to a novelist than to an art historian. I begin each essay on a photograph or a photographer with the assumption that I’m trying to tell a story, and to elucidate an experience. For instance, my essay on LagosPhoto for Aperture’s “Platform Africa” issue begins with a quote from the Nigerian novelist and playwright Sefi Atta, who asks, “Who was I to think that art could save anyone in Lagos?” The photograph, in my thinking, is connected with how it was made, where it was first published, or the event that occasioned it. What has always drawn me to thinking and writing about photographs is the sense that the people depicted are their truest selves in the light of another’s imagination—the photographer, the person who looks back. I always wonder about the tenuous relationship between image and text, especially what the text, in approaching an image, cannot unravel.

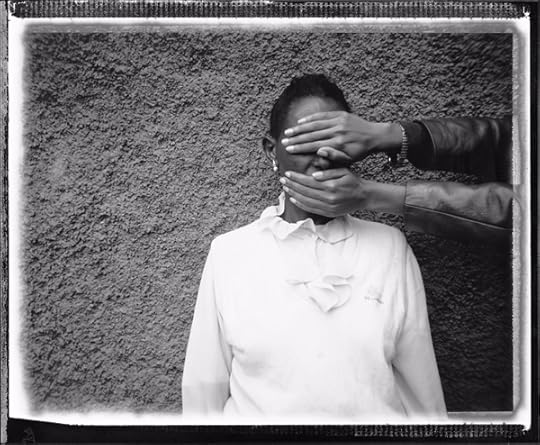

Nomusa Makhubu, Imfundo Impahla neBhayibheli (Education Apparel and the Bible), 2007/2013

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: How people are “depicted are their truest selves in the light of another’s imagination” is a great sentence about photography! What about the long legacy of colonial ethnography, in which the colonial imagination and the regimes of fantasy surrounding the African other actually became intrinsic to colonial propaganda, scientific study, and education, and formed the basis for white supremacist ideology? Would you be able to unpack the ways in which this influential body of photography informs our own picture of ourselves?

Iduma: As writers, thinkers, and image makers, we have to be willing to confront the ambiguity of our relationship with the archive, to realize that, more often than not, our bodies were pictured in denigrating ways. And how we were seen has shaped our perception of who we are. I hope for my work to begin by engaging with this complicity, but then surpassing and counteracting it. I think now of a certain photograph by the South African artist Nomusa Makhubu, Imfundo Impahla neBhayibheli (Education Apparel and the Bible) from The Self Portrait Project (2007/2013). In the image, she projects her silhouetted body on a colonial photograph of five men and a boy, taken by A. James Gribble in South Africa. It’s a metaphorical lodestar for me. At once repudiation as reclamation, the outline of her body is imposed on the archive; but equally, she can no longer be seen apart from it.

Edson Chagas, Marcel D. Traoré, Tipo Passe, 2014

Courtesy the artist and APALAZZOGALLERY

Jayawardane: Yes, Makhubu did not pick a simple archetype from colonial images. As a contemporary South African artist and academic, she is well aware of the imprint of that colonial archive on the ways in which her present body and person are “read,” seen, and acted upon, especially in the Cape. She inserts herself into the narratives handed down to us from family members and authority figures, who tell us what our collective memory should be, and draws attention to how photographs like this were used to illustrate how the “native” could be “civilized”—and made docile—through European clothing and educations. Those ideas return to us through what we today call “respectability politics”: we all, and especially young, black men, still get told that if we dress the part and behave the part, we won’t run afoul of the law, or get harassed by the state.

Shifting the center of image production is important, but it is equally important to ensure that interpretation and the critical dialogues around those images now also include writers, academics, and critics from “home spaces.” Why it is just as important for African and African diaspora writers to write about African and African diaspora photographers?

Iduma: The question is one of accessibility. How might our writing on photography reach an audience in our “home spaces?” What sort of writing style can help us achieve that? More importantly, what publications are open to that kind of writing, in which lucidity is privileged over jargon? Considered together, all three questions point to insisting on work in which the means of production is controlled by African writers, editors, and critics interested in the long term—a fifty-year argument, I would say. It is a question of how the lineage of criticism expands from Transition to NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art to Chimurenga, from a journal that celebrates African art as an academic discipline to one in which culture takes a pan-African, mainstream bent.

And then, besides presentation, why is art writing by African and diaspora writers urgent? Is there a political necessity they express in their writing that is otherwise unclear in criticism by white writers? My inclination is to say yes. We begin our writing in response to despair we feel in our body. Art writing in any form isn’t exempt from that.

Dawit L. Petros, Single Cube Formation No. 4, Nazareth, Ethiopia, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Jayawardane: When you write, do you begin by reading all you can find about the photographer and possibly interviewing her or him? Do you share a draft with the photographer to get feedback, or do you feel it is important that you remain autonomous? If the latter, can you speak about the importance of maintaining that autonomy and objectivity?

Iduma: I do my best to read all I can find on the photographer. However, because I have often written about photographers who are fairly young, and whose work hasn’t already received a lot of critical attention, the process of research hasn’t been as exacting. I rarely interview the photographers—I often share what I have written with them, but only at a later stage. I wrote recently about the work of Dawit L. Petros for the exhibition catalog published to accompany his solo show at the Kansas City Art Institute. Another essay, for The Walther Collection’s exhibition catalog Recent Histories (2017), focused on photographs by Mame-Diarra Niang, Michael Tsegaye, and Edson Chagas. For ARTNews, I have written about the work of Aida Muluneh, Iké Udé, Oumar Ly, Zina Saro-Wiwa, among others.

My work has also included writing on images published in newspapers and websites, which require a different kind of research. For example, “If I Could See Your Face” in the November 2016 issue of The Trans-African, or earlier in the March Issue, “Image of Displacement.” In those instances, I read almost everything I could find on the manner in which the photographs were made, and proceeded from there. I do not wish to be ignorant about those portrayed or the event depicted, but I also see the value in reaching a dead end in the historical or journalistic record. From there I make detours, guided by the conceit of my imagination.

Like Nomusa Makhubu, I also return to images of my Nigerian forebears in the National Archives of the U.K., aware of the ethnographic, patronizing gaze of the colonial photographer. To write about those images—to respond with my experiences as a decolonizing body—is to turn the archive on its head.

Emeka Okereke and Emmanuel Iduma, A Walk in a Daraa, 2014

Courtesy the artists

Jayawardane: You have participated in several road trips with Invisible Borders, which began in 2009. Did the intimacy of that geographic journey with other writers and photographers open possibilities for creative communication? Or create conflicts that exposed the fact that people’s vastly different expectations and boundaries?

Iduma: I participated in four editions of the road trip project, each time with a different set of participants. In 2011 we traveled from Lagos to Addis Ababa; Lagos to Libreville in 2012; Lagos to Sarajevo in 2014; and, in 2016, across fourteen Nigerian states. The travels placed exacting demands on how you work and how your body responded to that work—this was a promising challenge for us, from an organizational perspective. For me, as a writer, the trips offered an opportunity to reflect on what it meant to be a stranger, to move as a stranger through African countries. But, I have been uninterested in recalling the closed lines of communication during the trips—the grouses and disagreements. I think some of that might have resulted from the nature of the project, and its constraints. Whether or not they were inevitable is a different matter.

Aida Muluneh, Local Understanding, 2016

Courtesy the artist and David Krut Projects

Jayawardane: Who are the photographers or works you’ve most enjoyed writing about? Can you speak about what was enriching about these particular experiences or interactions?

Iduma: One of my favorite essays in The Trans-African is “Face in the Archive.” Since about 2012, I have spent a considerable amount of leisure time browsing the images from the Colonial Office of the National Archive on Flickr, especially those from Nigeria. One of the first images that struck me was that of three Kamberi boys, in a village somewhere in today’s northwestern Nigeria. In the photograph, a boy looks back at the camera. His glancing back bore, in my estimation, a particular anxiety. What I came up with, by the end of writing the essay, was that the task of decolonization isn’t quite done.

Eric Gottesman, Beletu, from the series If I Could See Your Face, I Would Not Need Food, 2000

Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: The scholars and writers whose work I encountered during my literature degrees were enormously influential: James Clifford’s The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. And without Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and Chinua Achebe, and Edward Said to give us the language of decolonizing our own practices and minds, where would we be? Without feminist theory, I’m not sure I’d have the critical acumen necessary for speaking about why power structures and the gaze—and whose gaze—are necessary parts of a conversation about any photograph. Njabulo Ndebele’s Rediscovery of the Ordinary helped me understand that a photograph that seems to be about “nothing” contains so much. Who are some of the writers you look to? Whose writing influences you?

Iduma: I am enthused by the work Teju Cole has done in the last two years as photography critic of The New York Times Magazine, the rigor and reach of his essays. Maaza Mengiste has written a number of short essays on photography, some in the Guardian, which are compelling and prescient. One of my favorite books on photography is Double Negative by Ivan Vladislavić, a response to David Goldblatt’s photographs. I like to think that my work is possible because of books by John Berger and David Levi Strauss.

Emeka Okereke and Emmanuel Iduma, A Walk in a Daraa, 2014

Courtesy the artists

Jayawardane: In January 2016, you and a couple of other collaborators—fellow writers and editors Serubiri Moses and Ndinda Kioko—began a new online journal The Trans-African. It is dedicated to the reflections of independent art writers from Africa on the photographs, images, and other visual cultures of Africa. In our Armory Show conversation, you mentioned that you were interested in the work of “recuperation,” which is possible through archival work. You mentioned that the thought process as a writer is an imaginative endeavor, which does “not merely involve linear time, but time as in a dream, or a photograph.” This was especially important considering that the much of our history have a life outside archives, and outside the Web.

Iduma: “The past does not change, nor our need for it. What must change is the way of telling,” writes Anne Michaels. I wonder about a way of telling that reflects on histories that, as Brent Hayes Edwards once wrote, fell on the wayside. This work can only be done when one looks back, when the future casts its shadow on the past. Consider, for instance, the similarities in how dissident men in Nigeria are pictured upon arrest. You have General Ologbosere in 1899, Isaac Adaka Boro in 1966, and Mohammed Yusuf in 2009: all three are bound, placed between armed soldiers, and stripped to the waist. Writing about those photographs (in my essay “Regarding Insurgency”), I wasn’t particularly interested in their villainy, or the morality of their claims, but in the nature of their disillusionment with the status quo, which is a particular Nigerian anxiety. The work of recuperation is really an attempt to study the present. If we don’t cultivate skepticism for the historical record, we run the risk of perpetuating narratives tainted by colonialism and patriarchy.

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Untitled, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Jayawardane: In a more recent conversation at the School of Visual Arts, you mentioned that there are “pitiably few” platforms for writing about African art outside of academia. “I knew I was a product of the academy in terms of my education and research interests,” you said, “but I also knew I belonged to a literary tradition invested in the mainstream, in writing that’s accessible in language and form.” Thinking about this media environment, can you speak about the significance of The Trans-African?

Iduma: The Trans-African is a journal published by Invisible Borders. For most of last year, Moses Serubiri, Ndinda Kioko, and I published essays on visual culture. We used our home countries—Uganda, Kenya, and Nigeria, respectively—as the basis of our reflections. In July of last year, we had a three-way conversation on “Writing and The Trans-African.” It’s a good starting point to understand the guiding principles for the journal. There are thirty-plus essays on the site, which I’m proud of.

For now, the journal is on a fundraising hiatus. To put it simply: we founded the journal as a non-traditional platform for criticism. The influences for the journal are more literary than academic. By thinking through wide-ranging sources—poetry, philosophy, history, fiction—we expected our writing on visual culture, such as album covers, photographs, and film, to expand the scope of African literature.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York–Oswego and arts contributor to Al Jazeera English. Emmanuel Iduma is a Nigerian writer based in New York and editor of Saraba Magazine.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives. Limited edition prints by Nico Krijno are available from Aperture Foundation.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Can African Critics Rewrite the Story of African Photography? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 2, 2017

At Documenta, Blurred Lines Between Art and Politics

An ambitious exhibition grapples with the conditions of our time—but can images provoke social change?

By Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Victoria Island, Lagos, 2006

Courtesy the artist

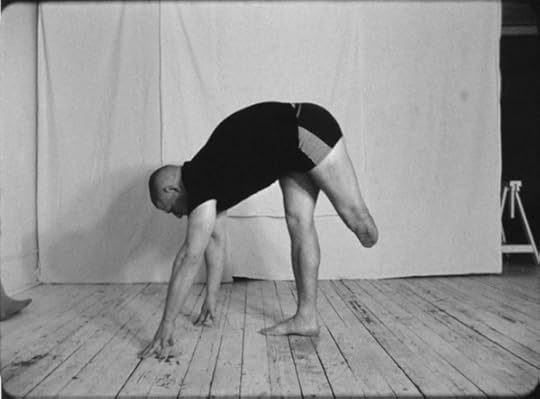

Some of the most provocative images in the latest edition of the quinquennial exhibition Documenta, first presented this spring and summer in Athens, show a man kneeling on top of a table with a hoop and a stick in his hands. He wears a moustache, has scars on his face, and his torso is bare. In a series of twelve black-and-white photographs, which until last month were all squished into a tight spot on an upper floor of EMST, the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, he strikes various poses animated by anger, bemusement, and agony. The figure in the photographs could be an avant-garde artist—male, of course—experimenting with modes of conceptual performance and minimalist sculpture in the makeshift lofts and factory spaces of downtown New York in the early 1970s. In fact, he is the revolutionary anthropologist Franz Boas, mentor of everyone from Margaret Mead to Claude Lévi-Strauss, and famed for the ethical foundations he laid for the field. Though still underappreciated, Boas was also crucial for his tireless disputations against eugenics and other bogus theories of racial superiority, which, in the first half of the twentieth century, bent scientific findings to fascist doctrines.

Franz Boas posing for a figure in “Hamatsa Coming Out of Secret Room,” 1895

Photographer unknown. Courtesy the National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

The Boas photographs date back to the turn of the twentieth century; the photographer is unknown. The images were taken as studies for a sculptor who was helping Boas to build a diorama for what is now the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., part of the Smithsonian Institution. The diorama—one of the fabled “life group” displays for which the anthropologist became known—was meant to represent the Hamatsa, a dance performed by initiated members of the Kwakwaka’wakw tribes of northwestern Canada. Set on the threshold of the human and spirit worlds, the dance demanded performers to emerge from the “mouth” of a supernatural, cannibal creature. (Because expectations are perhaps higher at Documenta than anywhere else, a colleague who admired the inclusion of the Boas photographs quipped, to the side, “I mean, they could have shown the diorama, too. That would have been amazing.”)

Ulrich Wüst, from the series Flachland, 2013

© and courtesy Loock Galerie, Berlin

Throughout his career, Boas returned again and again to the notion that indigenous peoples, as the subjects of ethnographic study, had much to teach the anthropologists who all too often depicted them as primitive. According to the writer Claudia Roth Pierpont, who profiled Boas in The New Yorker in 2004, “he demolished the standard claim that Indian and Eskimo speakers used different sounds for the same word at different times, and showed that the purported vagueness of ‘primitive’ speech was actually a characteristic of the primitive ears of anthropologists, who transcribed different approximations of what they heard at different times.” In the context of Documenta—organized by Adam Szymczyk with a team of some two dozen curators and staged, in Kassel, where the event was established in 1955, and, for the first time, in Athens, a city beleaguered by messy politics and financial strain—the Boas photographs carry many curatorial assertions and arguments, about art’s role in reckoning with colonialism, injustice, and conflict.

Hans Eijkelboom, Par 79 October 16, 2006 Boulevard Haussmann, from the series Paris, 2007

Courtesy the artist

The Boas photographs are also emblematic of an exhibition that draws on photography both for its record-keeping, archival function, and for its malleability. As a medium, photography is uniquely fit to capture the process of long term artistic pursuits, such as Hans Ejikelboom’s dizzyingly repetitive, typological photographs of street fashion from the 1970s until today, which double as a ruminative and sustained critique of global capitalism. Ejikelboom’s Photo Notes 1992–2017, on view in Kassel’s Stadtmuseum, brings direct, almost overwhelming evidence of his project into the exhibition space. But at Documenta, other such labor-intensive projects often, by necessity, happen far outside of the museums or galleries where people otherwise encounter them, learn about how they transpired, and consider what they mean, and so the work enters those places as small pieces of a much larger puzzle.

Ulrich Wüst, from Stadtbilder (Citybuilder),1980–83

© the artist and courtesy Loock Galerie, Berlin

The archival function of photography in this Documenta is wonderfully represented in the pairing of archival material showcasing Maya Deren’s research on voodoo rituals in Haiti with a portrait of the voodoo painter Andre Pierre, whom Deren met in the 1940s. Photography as a record of long term projects finds expression in two expansive series by Moyra Davey and Akinbode Akinbiyi, which register, respectively, transmissions through the mail system and public space. A bit of both applications—the archive and the time-based study—comes through in Douglas Gordon’s intriguing film on Jonas Mekas, I Had Nowhere To Go (2016), which relies so heavily on the black space between barely moving images that it might well be a series of photographs.

Ahlam Shibli, Untitled (Heimatno. 27), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17

Rathaus Kassel, March 3, 2017. Murat Çakır’s presence as a translator is required at the wedding of Çiğdem Yalcin and Göksel Akgül at Kassel City Hall because the groom, originating from Izmir in Turkey, doesn’t speak German. The young people met during the bride’s vacation in Turkey and decided to establish themselves at the center of her life. Mr. Akgül will work in Kassel at the bride’s father’s advertising agency. Mr. Çakır considers this photograph of the wedding ceremony important because the presence of the translator demonstrates that Germany is, and has been for long a time despite all political denial, a country of immigrants. The bride’s father is called Hüseyin Yalcin and belongs to the second generation of guest workers. The witnesses are Jessica Seitz and Senem Korkmaz

© and courtesy the artist

The works on view in Kassel’s Neue Gallery plot out a notably coherent argument and worked, for me, as the key to unlocking the meaning of this two-city, seventy-venue exhibition. Woven into the Neue Gallery display are Tina Modotti’s photographs of a radical Indian agronomist exiled to revolutionary Mexico who was experimenting with wheat production, and Sunil Janah’s photographs of the Bengal famine in 1945, a documentary project he undertook alongside Margaret Bourke-White. Extending a thread that runs throughout Documenta, these works explore the effects of hardship and hunger. In the Neue Neue Gallery, Kassel’s old Brutalist post office, two very different, but equally ambitious, photography projects occupy large spaces on the upper and lower floors. Upstairs, Ulrich Wüst’s black-and-white photographs of abandoned East German cityscapes before the fall of the Berlin Wall are classical and restrained, yet packed with drama and tension. Downstairs, Ahlam Shibli’s portraits of successive waves of immigrants to Kassel tell, in their extensive captions, a rich and complex history of assimilation, rejection, homesickness, and shocking violence.

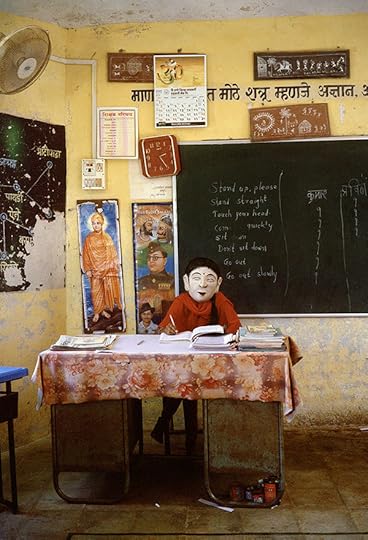

Gauri Gill, Untitled, from the series Acts of Appearance, 2015–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

But photography as a tool of contemporary art shimmers in Gauri Gill’s Acts of Appearance (2015–ongoing), a series of lush, large-scale color portraits of the residents of a village in Maharashtra, which is known for making Adivasi masks. Instead of requesting the likenesses of gods and demons, however, Gill asked the residents—including the master mask-makers Subhas and Bhagavan Dharam Kadu, their families, and fellow volunteers—to make masks that portray their own lives. Then, she painstakingly orchestrated medium-format portraits of the makers wearing their masks in everyday settings. The resulting images unfurl narratives—vast commentaries on time, leisure, work, pleasure, hopes, dreams, fears, and futures—without uttering a word. Gill’s photographs occupy the same threshold between human and spirit as the Boas photographs enacting the Hamatsa dance, and depict the frozen moment of an elaborate performance to be a powerful—and politically consequential—thing indeed.

Artur Żmijewski, still from Realism, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Around the corner from Wüst’s photographs is a room filled with a six-screen video installation by the Polish artist Artur Żmijewski. His work is as galvanizing in Kassel as it was in Athens, where he showed the video Glimpse (2016–17), a silent, black-and-white excursion into the evacuated refugee camps of Calais, among others. The film walks a fine line between documentation and provocation, exposure and voyeurism: Żmijewski riffles through the belongings that people have left behind, daubs a black man’s face with white paint, and hands a broom to another man as if to put him to work. Żmijewski’s work in Kassel, Realism (2017), shows six men with amputated limbs, moving about their days, exercising, going to work, and returning home. The films, both silent, were shot on 16mm film and transferred to video; both toggle between moments of pathos, beauty, and pure repulsion. At times, Żmijewski nearly seems to push viewers away.

Artur Żmijewski, Realism, 2017. Six-channel video. Installation view at Documenta 14, Kassel

Courtesy the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Żmijewski’s films capture the essence of Documenta 14, and epitomize the role of photography—and, by extension, related styles of filmmaking—throughout the sprawling exhibition. Adam Szymczyk and his curatorial team appear relentlessly concerned with pulling together two modes of image making: the document of an action and the action as art. If the argument posed by the theme of this Documenta, “Learning from Athens,” is to urge us all to become political actors, Szymczyk’s treatment of photography seems to insist that images must occupy our social and political lives. Following the line of photographs from Athens to Kassel, art and politics are endlessly intertwined.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer, critic, and contributing editor of Bidoun.

Documenta 14 was on view in Athens from April 8–July 16, and is on view in Kassel, Germany, from June 6–September 17, 2017.

The post At Documenta, Blurred Lines Between Art and Politics appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 27, 2017

A Readymade World in the Heart of the Country

In a studio outside of Cape Town, photographer Nico Krijno refashions sculpture and performance.

By Matthew Leifheit

Nico Krijno, Edible plants growing outside my studio, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Douglas Sirk once said, “I’ve always trusted my audience to have imagination, or else they should get out of the cinema.” Nico Krijno, an artist who lives with his wife and young daughter on a farm outside of Cape Town, South Arica, seems to follow Sirk’s plea for the indirect, the open-ended, the gleefully imaginative. A selection of his photographs, characterized by botanical motifs and emphasizing Krijno’s uniquely lush mode of fracturing and flattening space, was featured in Aperture’s “Platform Africa” issue. In the accompanying essay, Sara Knelman wrote, “With a background in theater and film, Krijno is more inclined to invent new worlds than record this one.” And it’s true—a sense of play and a freedom of space permeates this work, but it’s devoid of specific geography, especially as geography might relate to a clearly defined politic. The work provides no answers; instead, it generates new and endless questions.

I first started speaking with Krijno in 2014 after admiring his work online, and eventually wrote the foreword to his first book of photographs, Synonym Studies (2015), which was subsequently was shortlisted for the Aperture Foundation-Paris Photo PhotoBook Awards. Since then, I’ve lived for the publications he’s been releasing on an almost yearly basis, as well as his presence on Instagram, where, with casual nonchalance, he releases scads of photos of astonishing quality and range.

Nico Krijno, Conductor, from The Fluid Right Edge, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Matthew Leifheit: What’s going on in your life?

Nico Krijno: I live out on a farm, an hour outside of Cape Town. I guess the move was brought on after the baby came, we just needed a change, and we felt it would be the best place to raise a child, which it is! The idea was to slowly migrate from the city, but life had other plans, so we made the move. It’s idyllic, but also very tough, and can be very testing on a relationship when two people are in such close proximity 24/7 while we are raising our daughter together.

It’s also slightly tricky to be based here and to make work from such a rural setting. I’m cut off from a face-to-face peer group to talk about work with. I think that’s important, the mirroring. It energizes. I don’t want to be the guy who goes to all the openings; I don’t want that life. For me it’s just about making the work, and I think the rest can be a distraction. There might come a time in the future where I would like to live in the “Big Smoke” again, or at least close to the real smoke. I don’t have a gallery in South Africa, and I don’t do a lot of commercial work here.

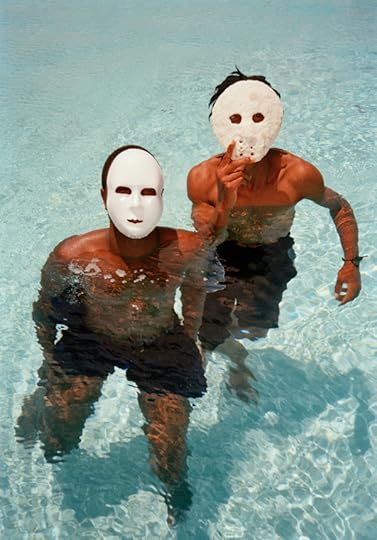

Nico Krijno, Boys in pool with masks, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: What relationship does your work have to where you are?

Krijno: Because the work is so self-involved and personal, where I am plays a huge role. I think about it a lot, and I haven’t come up with a good answer yet. When I was in London recently, I had a show, and I was walking through the streets every day. It was familiar because I used to live there. But it was also seen through updated eyes, and I thought, What would my work be like if I still lived there? Because when I lived there, I was doing completely different things. But I was just finding my feet. I was making videos, and I was shooting models in my bedroom to pay the rent. If I was living in London now, I wouldn’t have all the time I have. And I do like washing my eyes in nature. I like the peace and quiet and the wildness of living this close to nature, not just looking for parking or free Wi-Fi. But it’s very important to keep a good balance.

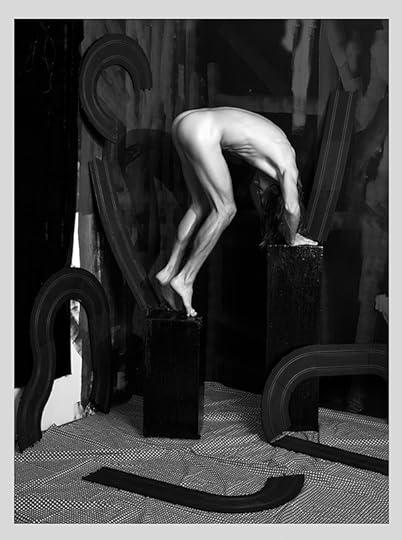

Nico Krijno, Sculpture Study as Wooden Performance, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: “Washing your eyes in nature”? Is that a thing people say in South Africa or did you just come up with that?

Krijno: Just feels right. Must have heard it somewhere.

Leifheit: From an outsider’s perspective, it does seem like you have a lot of space.

Krijno: I work from this tiny old cottage, probably an old farm worker’s cottage. It’s not very big, and when the sun is out I try to build my setups outside. I’m so happy to be able to do that. Because the light’s fantastic and I can schlep my lights and flashes outside with me. And when you’re in a city, and you have a tiny little studio on a busy street, you can’t have all of that.

Because I have the luxury of space, I’ve got a lot of junk and props and materials piled in my studio yard that I mine from. I go to the dump a lot, and I collect stuff—objects that speak to me, old wood, building rubble, et cetera. And they sort of amass outside. When I’m finished I take them back to the dump. People look at me strangely, like, Why are you taking things from the dump and bringing them back again?

I also like this life because it gets me to do things like gardening and building. I do a lot of physical labor, such as chopping wood or mixing concrete. Those are the things I want to be doing, they get me away from the desk, and also away from the studio. I want to be doing these things that I think we’ve all lost, which are important. These things give me a lot of time to process and think about what I’m working on.

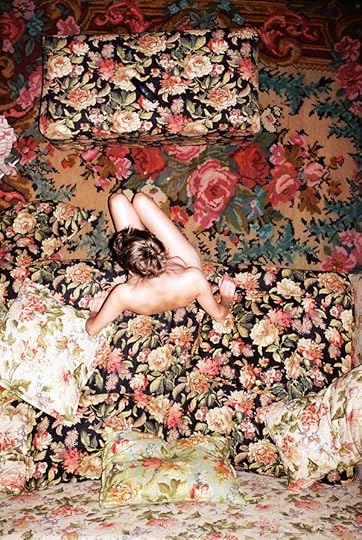

Nico Krijno, Migonne in the flowers from above, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: In your work, there is so much variation: there are things happening outside, in the studio, and in between—and there are things constructed in Photoshop. Everything could fit into the world of your vision and your work, which I find very liberating and exciting. You also make the tools of Photoshop apparent sometimes, like Lucas Blalock does. In the world we’re living in, appropriation and even sampling seem like dated terms to me. This is all material in your purview, material that you make your own and exceed. And there’s something exciting about that.

Krijno: The variation is what’s important to me. It’s all about a building up of a visual rhythm. Really it’s just the way my head works. Someone once told me in critique that my work is “too much.” There’s just too much variety in the work: a face, a table an object, some flowers. Where does it begin and where does it end? How are people supposed to engage and access the work? Maybe this person was looking for a clear and linear series—the kind where there are fifteen essentially similar images to really hit the point home. There’s work out there that does that to great effect, but I just don’t think in those straight lines. Maybe I think in circles that link up, forming some kind of Technicolor dream chain. I like to show an idea, and what also lies behind that idea, and sits right next to that idea.

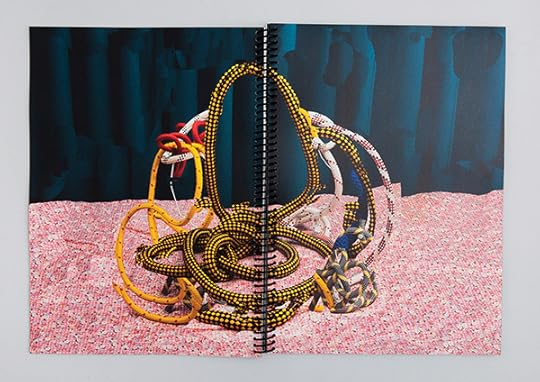

Nico Krijno, The Porthole, spread from the photobook New Gestures, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: Are the books you’ve published, Synonym Study and New Gestures, and the unpublished books you’ve shown me, The Fluid Right Edge 1 & 2, the core of what you’re doing?

Krijno: Yes, I think books are extremely important to the process, to making sense of the work as an outsider and to myself as well. They are the definitive lines in the sand for me. Because I don’t work in series, everything sort of bleeds into each other.

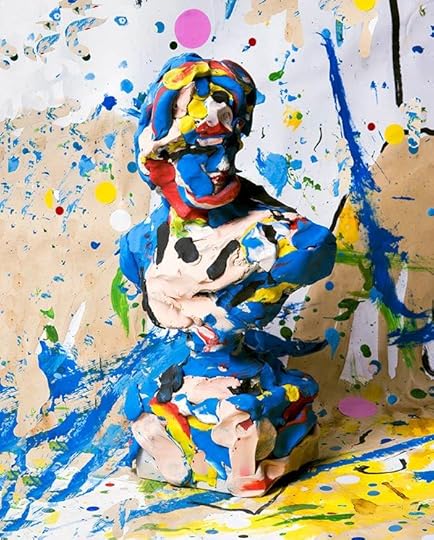

Leifheit: You make sculptures, too.

Krijno: I make sculptures, but I’m really just interested in photographing them. I’m interested in how the meanings of cast off objects can change. Dousing them in paint and removing their original use completely. And I am interested in fooling the eye. You’re not sure what you’re looking at, a painting or a photograph. I like the trickery, but I do make it quite obvious.

Leifheit: So part of the meaning of what you’re doing comes from the use of readymade objects, and of mashing them into something new?

Krijno: My work is very, shall we say, busy? But I don’t like to live with a lot of objects and trinkets and things. I prefer the photograph of them. I prefer a photograph of a sculpture to the sculpture itself.

Nico Krijno, Sculpture Study as Self-Portrait, from The Fluid Right Edge, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: Yes, there’s the flatness, and a reductive quality to all photographs, but there’s a sense of democracy that comes with that. I also noticed that your butt recurs a lot in one of these new books, which is really working for me. And you’ve been in your photos before. How are you using yourself in the work?

Krijno: I’m starting to do it more and more. I see the work as a performance, with the camera as the viewer. I’m very physical in the studio; it’s like sculptural gymnastics. I’m in my body, and I feel it’s important to break that wall and become a sculptural object in the photograph. I don’t think about it at all; it just feels right.

Leifheit: A sculptor once told me, “I’m just trying to keep my practice one step ahead of what I can understand or explain.” With photography, if you allow yourself to be present in a situation and react to it, you can learn from what the camera takes in.

Krijno: That’s what happens when I’m editing a book. I see two images that are literally bounding off one another, and they might have been made in different years. I make so much work, and there really is something in the sum of the parts that happens when you look at all the images together. I have a lot of critique for the books I’ve made in the past, but I’m just trying to make better books. That’s why I’m making a book in two volumes. And I like to keep things simple when I make a book, in terms of the layout.

Nico Krijno, Sculpture Figure Study with Clay, from New Gestures, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: It’s about the photographs.

Krijno: Yeah, it’s not about the design. It’s about the photographs. They’re picture books. And the works are not going to be propped up by any text, because I don’t think like that. I really think in images. It would be great if someone looks at the work and writes a great piece. But then I find that these are the only words that enter the work. Because the work is so abstract, sometimes these are the only words that stick. I find that it’s best to just ask questions, and not have too many answers.

Leifheit: Photographs are always, in the end, a mystery, and I think your books end up that way, too. They are mysteries I want to engage with.

Krijno: That’s what I want them to be. My images are part of the “Platform Africa” issue of Aperture, which is an honor, but somewhat strange to me that I’m included in that conversation. Because I don’t work in the typical South African tradition like some of the well-known and respected South African artists—like Zanele Muholi, Pieter Hugo or David Goldblatt. Their work is extremely important; I just don’t make that kind of work.

Nico Krijno, Two Telephones, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: I expect the editors wanted someone who wasn’t going to fit peoples’ expectations of what photography in South Africa might be. I don’t actually think all art needs to be an activist project, which seems to be a common sentiment these days.

Krijno: But especially in South Africa, that’s the sort of the narrative that gets driven at the university level. Which is why I never studied photography here. I studied filmmaking and acting. You’re told that if you want to make it, you have to talk about the white guilt. The past, you know?

We live in a traumatized country that will take a century to heal itself. And I’m grateful for the local artists engaging with these issues in direct ways. But I don’t see myself as a South African artist. I’m just an artist. And being here feeds into the work, but I can’t post-conceptualize and overlay issues between black and white on my work. Because I know it so well, these textures and these people. And I deal with it on a daily basis. I am just trying to reinvent the world and make it strange and new again.

Matthew Leifheit is the publisher of MATTE magazine.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives. Limited edition prints by Nico Krijno are available from Aperture Foundation.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post A Readymade World in the Heart of the Country appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 25, 2017

John Divola’s Upside Down Formalism

With dark humor, the photographer plays with perception, space, and surface.

By Travis Diehl

John Divola, Untitled 90UJ, 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

The titles of the two series by John Divola currently on view at Gallery Luisotti in Los Angeles could hardly be starker: the Five Prints Portfolio (1987), outdone for emptiness by Untitled (1990). These titles outline the bare minimum of photographic formalism—flat, rectangular prints—which his work then attempts to pry apart. Each of the five vertical photographs in Untitled has a vellum-smooth surface, mottled with abstract whites and grays. On closer inspection, the pictures show the brushed-on unevenness common in “alternative process” photographs, as if the chemistry had been slopped on by hand. Ditto the uneven top edge of three of the five images, which resemble mesas on a horizon. In fact, the subject of the photographs turns out to be a backdrop smudged with flour; what seems to be ragged tiers are actually brush strokes along the curled edge of the paper, held to white panels with pushpins. Divola introduces a confusion between additive and subtractive, positive and negative; it’s a “process” photograph, after all—if not quite an “alternative” one. The series offers a two-dimensional subject, a grisaille abstraction—the texture of a ridged, dripping black surface bearing its own dust-thin layer of gray marks—that then peels into depth.

John Divola, Untitled 90UC (detail), 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

Divola, born in Los Angeles, is known for photographs that document his vandalism-style interventions in abandoned buildings and other interstitial spaces with a wry eye towards painting’s collapse into photography. In the mid-1990s, he made a series titled As Far as I Could Get, comprising vertical landscape shots of a lone, distant, running figure with his back to the lens. Divola set the camera’s timer, then sprinted down its field of view. No matter how much distance Divola puts between himself and the film plane, the image always snaps flat. The grayscale images in Untitled, are also remnants of a weird performance. The clouds of grayish white that drift across the compositions, formless and out of focus, are also the main formal element of each: fogging the black ground, puffing up the scene into space-time. The suspension of this dust cloud places Divola’s series (like many of his others) within the space of an action. The flour hangs like a kind of fleeting sculpture, a distribution of matter in midair—and thus points to the gesture that put it there. How strange, artificial, and temporary is art, Divola seems to say. His dry titles take on a gallows humor.

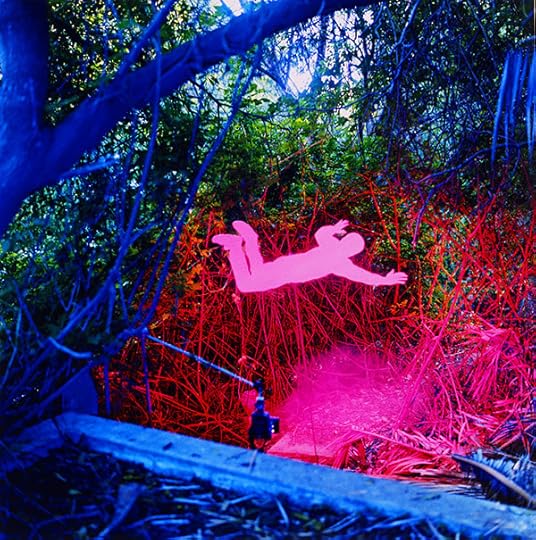

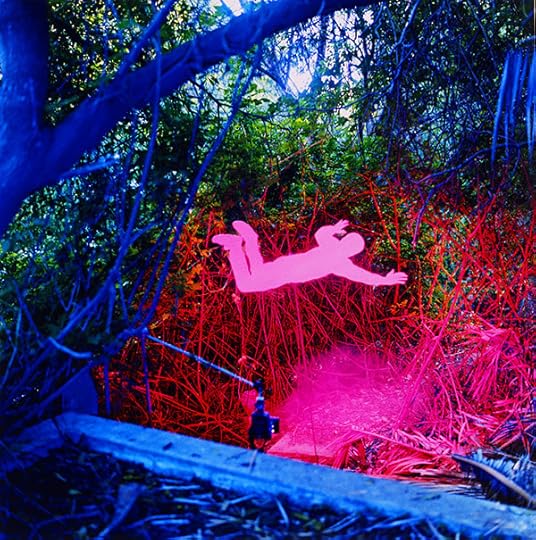

John Divola, Flying/Falling, 1984

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

In the Five Prints Portfolio, with brilliant dye-print color, Divola emphasizes “prints” and their icy flatness. Near the center of each square frame, hemmed in by the foliage of a forest or backyard, are pale, paper-like objects saturated by colored light. A cutout of a howling wolf—Wolf (1983)—is lit with red, and the strip of sky at the frame’s top—an echo of Untitled—burns orange. In Flying/Falling (1984) a human silhouette plummets toward a smoky pink patch of depressed reeds—or else they’re blown upwards, as if by a strong wind or a small explosion, by the pink strobe’s pop. This indeterminacy between flat and round, dead and alive, is the core vertigo of the photograph. In Cyclone (1984) a little cone, blasted with magenta light, stands upright in a spot of bare ground in the woods. The light source is visible: a flash, wrapped with a gel, hanging from the tip of a c-stand, which is not so different from the bare branches around it. Red light fills a branch, canting across the top right corner of the frame, as well as some of the leaves in the middle ground. But it’s a sunlit sky that punches cyan through the background. We’re in the woods, but not too deep.

Travis Diehl is a writer based in Los Angeles.

John Divola: Physical Evidence is on view at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles, through September 9, 2017.

The post John Divola’s Upside Down Formalism appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

John Divola’s Upside-Down Formalism

With dark humor, the photographer plays with perception, space, and surface.

By Travis Diehl

John Divola, Untitled 90UJ, 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

The titles of the two series by John Divola currently on view at Gallery Luisotti in Los Angeles could hardly be starker: the Five Prints Portfolio (1987), outdone for emptiness by Untitled (1990). These titles outline the bare minimum of photographic formalism—flat, rectangular prints—which his work then attempts to pry apart. Each of the five vertical photographs in Untitled has a vellum-smooth surface, mottled with abstract whites and grays. On closer inspection, the pictures show the brushed-on unevenness common in “alternative process” photographs, as if the chemistry had been slopped on by hand. Ditto the uneven top edge of three of the five images, which resemble mesas on a horizon. In fact, the subject of the photographs turns out to be a backdrop smudged with flour; what seems to be ragged tiers are actually brush strokes along the curled edge of the paper, held to white panels with pushpins. Divola introduces a confusion between additive and subtractive, positive and negative; it’s a “process” photograph, after all—if not quite an “alternative” one. The series offers a two-dimensional subject, a grisaille abstraction—the texture of a ridged, dripping black surface bearing its own dust-thin layer of gray marks—that then peels into depth.

John Divola, Untitled 90UC (detail), 1990

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

Divola, born in Los Angeles, is known for photographs that document his vandalism-style interventions in abandoned buildings and other interstitial spaces with a wry eye towards painting’s collapse into photography. In the mid-1990s, he made a series titled As Far as I Could Get, comprising vertical landscape shots of a lone, distant, running figure with his back to the lens. Divola set the camera’s timer, then sprinted down its field of view. No matter how much distance Divola puts between himself and the film plane, the image always snaps flat. The grayscale images in Untitled, are also remnants of a weird performance. The clouds of grayish white that drift across the compositions, formless and out of focus, are also the main formal element of each: fogging the black ground, puffing up the scene into space-time. The suspension of this dust cloud places Divola’s series (like many of his others) within the space of an action. The flour hangs like a kind of fleeting sculpture, a distribution of matter in midair—and thus points to the gesture that put it there. How strange, artificial, and temporary is art, Divola seems to say. His dry titles take on a gallows humor.

John Divola, Flying/Falling, 1984

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti

In the Five Prints Portfolio, with brilliant dye-print color, Divola emphasizes “prints” and their icy flatness. Near the center of each square frame, hemmed in by the foliage of a forest or backyard, are pale, paper-like objects saturated by colored light. A cutout of a howling wolf—Wolf (1983)—is lit with red, and the strip of sky at the frame’s top—an echo of Untitled—burns orange. In Flying/Falling (1984) a human silhouette plummets toward a smoky pink patch of depressed reeds—or else they’re blown upwards, as if by a strong wind or a small explosion, by the pink strobe’s pop. This indeterminacy between flat and round, dead and alive, is the core vertigo of the photograph. In Cyclone (1984) a little cone, blasted with magenta light, stands upright in a spot of bare ground in the woods. The light source is visible: a flash, wrapped with a gel, hanging from the tip of a c-stand, which is not so different from the bare branches around it. Red light fills a branch, canting across the top right corner of the frame, as well as some of the leaves in the middle ground. But it’s a sunlit sky that punches cyan through the background. We’re in the woods, but not too deep.

Travis Diehl is a writer based in Los Angeles.

John Divola: Physical Evidence is on view at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles through September 9, 2017.

The post John Divola’s Upside-Down Formalism appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

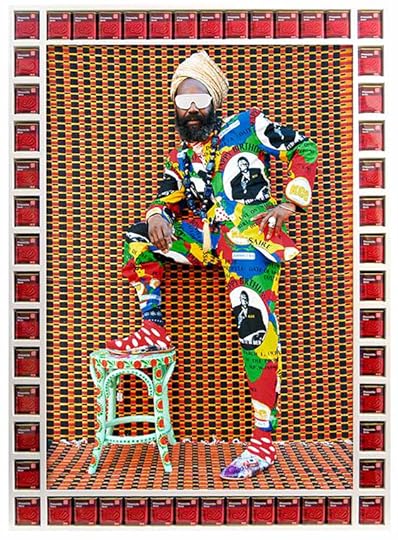

July 19, 2017

10 Photographers Who Celebrate Black Identity through Fashion

“The word dandy may evoke ideas of bygone white men in waistcoats and multilayered blouses with puffy sleeves,” writes Shantrelle P. Lewis, in her new book, Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style. Historically, dandyism has been outside the traditional tropes of masculinity—queer, in a sense—dandies also threatened the existing class structure by dressing up. A Black man employing this strategy is even more radical and subversive. By looking sharp, the Black dandy fashions a sense of pride, positivity, and self-worth that can transcend circumstances, as well as societal perceptions. He defies monolithic understandings of what it is to be a man—particularly a Black man—through a colorful and complex dance between race, class, gender, power, and style. Today, the fashion of Black dandies is more a nod to the style of their well-dressed grandfathers than the likes of Oscar Wilde or Beau Brummell. With styles as diverse as their subjects’, each of the following photographers portrays a striking relationship to dandyism.

Sara Shamsavari, Samson Soboye, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Sara Shamsavari

Sara Shamsavari has long photographed London’s Rude Boys as a way of shattering stereotypes of immigrants. Born in Tehran, Shamsavari is a British artist concerned with cultural identity and social justice. A bit of history—in England, eighteenth-century enslaved Africans were often dressed lavishly to reflect well on their owners, and they soon began personalizing those uniforms. Fast-forward to the 1960s, when waves of Black immigrants flocked to the UK from Anglophone countries in the Caribbean and West Africa, bringing their colorful and vibrant styles with them. The Rude boys were arbiters of style as soon as they arrived from Kingston, Jamaica. Modern-day Rude Boys come from all over and continue to influence global fashion.

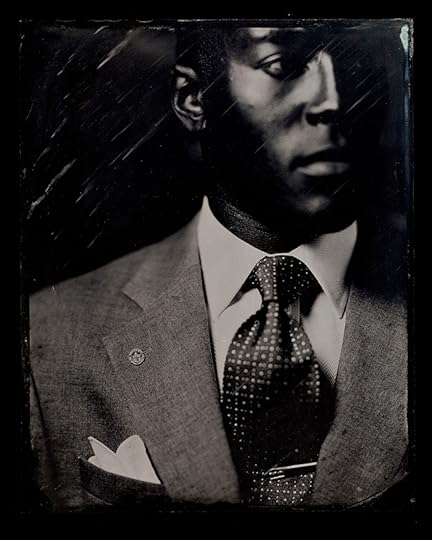

Jody Ake, Untitled, 2003

Courtesy the artist

Jody Ake

Jody Ake, born and raised in the South but now living in Portland, Oregon, creates rare and delicate ambrotypes. Developed in the 1850s as a less-expensive alternative to the daguerreotype, the ambrotype is a labor-intensive process that requires creating, exposing, and processing an image on a glass plate over about fifteen minutes. Ake’s historic-looking portraits of twenty-first-century Black men convey self-actualization and identity. On first glance, it may even be easier to believe that the images were created in a past century than in the last decade.

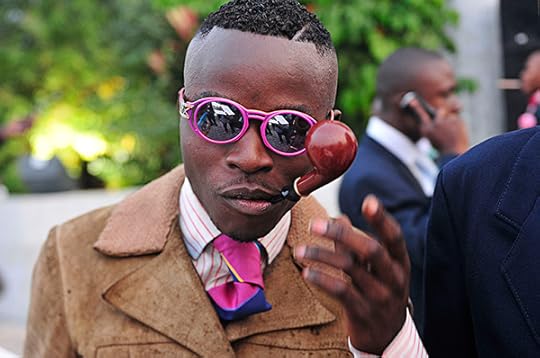

Daniele Tamagni, from the series Gentlemen of Bacongo, Brazzaville, Congo, 2008

Courtesy of the artist and Marie Finaz Gallery

Daniele Tamagni

Daniele Tamagni photographs one of the oldest sartorial movements, the Sapeurs. It dates back to the late nineteenth century, when Europeans first colonized the Congo, and locals imitated their mannerisms and dress. Over the past hundred years, this cult of extravagant clothing and elegance became known as La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (The Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People) or La Sape. Tamagni’s series Gentlemen of Bacongo (2009) has influenced style-based social movements around the world.