Aperture's Blog, page 117

May 23, 2017

The Inspiring, Contested Legacy of Dorothea Lange

A major retrospective surveys the photographer’s career and social activism.

By Sarah M. Miller

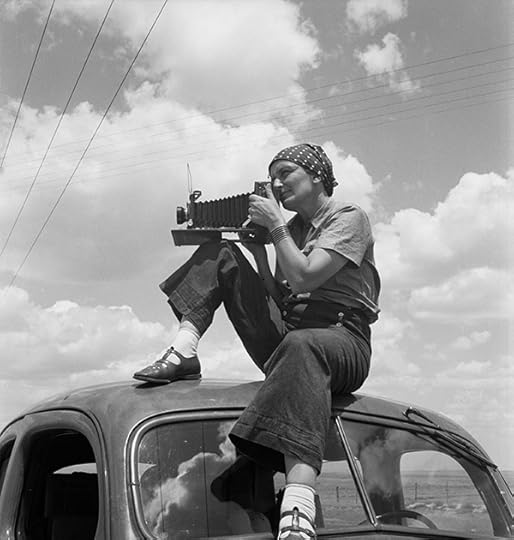

Paul S. Taylor, Dorothea Lange in Texas on the Plains, ca.1935

© The Oakland Museum of California

On May 13, 2017, the Oakland Museum of California opened Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, a major retrospective that surveys the photographer’s career through the lens of social activism. The exhibition draws on Lange’s vast personal archive, housed at the museum. Mixing a wealth of vintage prints with digital prints produced from archival negatives, the exhibition is supplemented with selections of Lange’s field notes, contact sheets, publication mock-ups, books, letters, and ephemera. Prints by three contemporary photographers influenced by Lange—Ken Light, Janet Delaney, and Jason Jaacks—round out the installation and remind visitors how powerfully she set the standard for engaged, empathetic documentary photography. A few weeks before the opening, I visited curator Drew Johnson to discuss the exhibition. The table was set for my arrival with the very first issue of Aperture—a reminder that the inaugural cover was a photograph by Lange.

Dorothea Lange, Shift Change 3:30 pm, Coming out of Yard 3, Kaiser Shipyards, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Sarah M. Miller: Why is the Dorothea Lange archive housed at the Oakland Museum of California?

Drew Johnson: Last year was the fiftieth anniversary of the archive coming to the Oakland Museum. The museum was created in the mid-1960s to unite the existing collections of Oakland’s public history museum, natural history museum, and art gallery. It opened in 1969. Founding curator of photography, Therese Thau Heyman, brought the collection here before the museum even opened, in 1966. Therese approached Lange and Paul Taylor and there were a couple things that appealed to them about the museum. One, it was a local institution. Construction was about to begin, plans were being drawn up. It had been identified as the Museum of California and as a people’s museum. Last, Therese made it a big point that the Lange archive would be made accessible to the general public as well as to scholars and researchers, and that we would make prints from the negatives.

Dorothea Lange, Shipyard Worker, Richmond California, ca. 1943

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Aside from the fiftieth anniversary of the acquisition, what do you hope to achieve with a Lange retrospective?

Johnson: Dorothea Lange has a permanent space in the gallery, but it’s been more than twenty years since we presented an extensive exhibition. Lange has always been relevant to current events. In the oral history interviews that Lange conducted with Linda Reese, Lange says she had seen recent images of migrant workers in the Central Valley, California in the 1960s and, if she didn’t know when they were taken, she would have thought they were from 1935. Nothing had really changed. One of the contemporary photographers included in the exhibition is Ken Light, who photographs Central Valley migrant farmworkers. If the subject wasn’t wearing a 50 Cent sweatshirt, it could still be 1935. And it’s not just about working conditions: Lange saw her mission during the Depression as understanding a refugee crisis in America, and generating empathy for refugees, which is also an issue of great relevance today.

The Lange archive at the Oakland Museum, as opposed to the collections in the Library of Congress and the National Archives, represents her entire career, from 1918 until her death in 1965. Twenty-five-thousand negatives. We spent a long time thinking about how to whittle down this huge archive, and that’s when we decided on the theme of photographer as social activist, and using photography to persuade. Lange is the prime example. Every documentary photographer I meet tells me how Lange inspired them, both in her technique and the issues she documented.

Dorothea Lange, Untitled (Oklahoma Mother in California), 1937

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: How is the exhibition organized?

Johnson: There is an introductory section where visitors look at her early life. She had polio and her father abandoned the family—a possible connections to her great capacity for empathy. Then Lange’s documentary photography is divided into three sections: The Great Depression, World War II at Home (the Richmond Shipyards series, and the evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans), and, last, postwar California which includes her least-known work.

Miller: People rarely discuss Lange’s work from the 1950s and beyond.

Johnson: She had a series of health challenges in the 1950s, but she also did these amazing projects that rarely see the light of day. She was fascinated by what she called the “New California,” this vast spread of suburbia and development. Death of a Valley (1956) with Pirkle Jones, which was about the removal of a community to build Lake Berryessa, presaged modern environmental photography. But she was interested in the development of the inner city, too. She explored it through street photography, as well as the Public Defenders (1957) series, shot right across the street at the Alameda County courthouse. That’s fantastic work, some of her best.

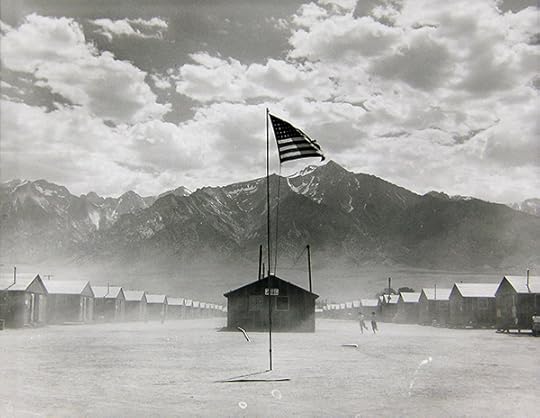

Dorothea Lange, Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Did you discover anything new in the process of planning this exhibition?

Johnson: I did uncover new information about Lange’s photographs of the wartime evacuation of Japanese Americans. The museum’s archive contains some of the best-known images, like the Japanese Owned Grocery Store and Japanese Children with Tags (both 1942), because Lange was working on her own before being hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Most of that series was kept by the National Archives, but we also have a few examples from WRA negative envelopes that Lange seems to have borrowed and never returned.

From this body of work, I dug into the series of Japanese Americans being evacuated from their homes: they’re sitting on their porches with stacks of luggage, waiting to be loaded onto buses. I realized Lange was shooting houses on the site of what is now the Oakland Museum. In fact, some of them were shot from the window of the Alameda County Law Library right across the street. Those Japanese American families were living right here, at 12th and Oak.

Dorothea Lange, Oakland, California, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: The Oakland Museum’s exhibitions always have a strong education component. What will the points of engagement be? Are you planning interactive or educational activities in the galleries?

Johnson: There are two interactive activities. First, visitors will see examples throughout the exhibition of how Lange cropped a negative to increase its power. There will be sample images and movable frames so that visitors themselves can experiment with cropping Lange’s photographs. Especially late in her career, she would take the same negative and crop it three or four different ways. For Public Defender, there would be a portrait from the waist up, and then a version where she would zero in on the eyes, for example. For the other activity, there is a large magnetic bulletin board where visitors can sequence photographs with quotations, statements, and headlines—the way she did. There is a quote on the wall: “I used to think in terms of single photographs. No more.” Both in her home and her studio she had big bulletin boards, where she would group photographs and text in different ways until the sum was greater than the parts.

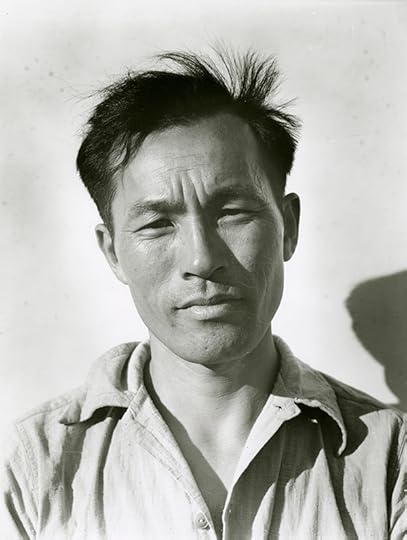

Dorothea Lange, Young Man at Manzanar Relocation Center, 1942

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: That’s an indication of how far Lange scholarship has come. In the ’80s and ’90s, Lange was a target of revisionist scholarship on documentary photography that treated cropping and sequencing like a crime—as though documentary forbade the shaping of information, and as though it were a coup to discover the means by which she editorialized. It’s nice to see her process resurface as a point of engagement, rather than a line of attack.

Johnson: Context and communication were crucial. She was frustrated when her photographs were shown in art museums, put on a wall without context—those images and words from interviews that she went to great pains to take down so precisely. Our thesis is that, through these techniques, she could make the picture more or less emotionally powerful. She could slant the meaning or emphasis in a certain direction. We are not putting a judgment value on that, other than by saying it illustrates her empathy, her desire to effect change, and her emphasis on the photograph’s use over its aesthetics.

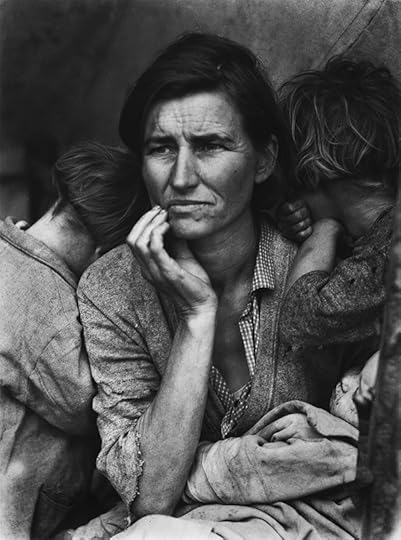

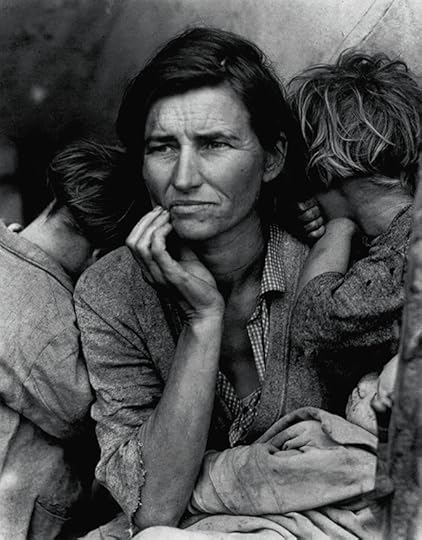

For that reason, we’re actually going to look at how Migrant Mother (1936), her best-known photograph, became de-contextualized over time—and why that is atypical for Lange. How do individuals become icons? Visitors walk past the six preliminary photographs from that day and then come across Migrant Mother in its own niche, Mona Lisa style. After that, there is a case filled with Migrant Mother tchotchkes and memorabilia including t-shirts and mugs. There are also examples of how the image was adapted to later messages, like the Black Panther newspaper, where the mother is rendered as a black woman. On the wall, quotes from various people, times, and contexts form a montage. Roy Stryker says, “You can see anything you want to in her. She is immortal.” Florence Thompson laments, “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t taken my picture.” Lange says, “I do not remember how I explained my presence … I did not ask her name or history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two.”

Normally, Lange prized collaboration, as shown throughout the exhibition. She would talk with someone for fifteen minutes before taking her camera out. She would talk about their kids, talk about her kids. She let the children put their dirty fingers on the lens. It was important that her subjects knew why she was there and what she was trying to accomplish. Lange resisted making icons out of people, and yet this image inadvertently did that and caused distress for Florence and her family.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, 1936

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: It makes sense to address the icon question head on. The way Lange usually interacted with her subjects is often lost in the controversy over Migrant Mother, but the controversy is unavoidable. The photograph has become a flashpoint for cynicism about documentary more broadly—for equating documentary photography with the exploitation of strangers and their suffering.

Johnson: On the other hand, for many people, the image continues to be deeply moving.

In general, Lange does not appear to have been an ideologue. She simply acknowledged problems that needed to be addressed, and said: I have a way to contribute. That said, Lange had convictions that drove her to defy the mandates of her employers, which we show. The WRA didn’t want her version of America to be seen—meaning the racism driving the Japanese evacuation order and the injustice of internment. And before that, the FSA told her not to address issues of racial discrimination in the South. One of the critiques from the ’80s, when documentary photography was under new scrutiny from scholars, was, “Why didn’t she shoot any people of color?” Excuse me?!

Dorothea Lange, Crossroads General Store, ca. 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Will the exhibition be a corrective to that assumption?

Johnson: I hope so. We point out that the FSA specifically instructed her to concentrate on white migrants, according to the theory that doing so would produce more widespread support. But she wasn’t going to have any of that. Her husband, Paul Taylor, was a labor economist at University of California, Berkeley, specializing in agricultural labor. He studied Mexican farm workers for years. When Lange traveled across the South, she was fascinated by it. She shot from across the white side of segregated lunch counter to the black side. And she was attuned to the legacies of slavery and racism in southern agriculture. In the exhibition we juxtapose Ex-Slave with a long memory (1938) with Plantation Overseer and his Field Hands, Mississippi Delta (1936).

Dorothea Lange, Ex-Slave with a long memory, 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: Tell me about the contemporary work in the show.

Johnson: We have chosen three photographers because of the issues they’re interested in, and because they all have connections to Lange. Ken Light’s Valley of Shadows and Dreams (2012) is about twenty-first century migrant farm workers. He is a journalism professor at Berkeley who was inspired by Lange as a young photographer. He has also been running the Dorothea Lange Fellowship at the University of California as a juror, as have I, for the past twenty years.

Janet Delaney is a former Dorothea Lange Fellowship juror and winner. Her work South of Market, San Francisco, Then and Now (1978–86 and 2011–present) is about gentrification, and connects to Lange’s investigation of the “New California.” Jason Jaacks is also a former fellowship winner. He documents the Tohono O’Odham Nation along the U.S.–Mexico border, including how the border wall both affects and divides the community. He also focuses on recently deported Mexican migrants in the area.

Dorothea Lange, The Road West, New Mexico, 1938

© The Oakland Museum of California

Miller: It must have been hard to choose just three?

Johnson: The main idea of the show—photography as activism—is liberating because it allows us see the enormity of Lange’s legacy, but also to zero in on particular ways it has been enacted. For Lange, it was about seeing injustice and getting others to see injustice. All three artists demonstrate that idea powerfully, and each speaks about the influence and inspiration Lange provided.

Sarah M. Miller is an independent scholar, teacher, and critic based in Oakland, California.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is on view at Oakland Museum of California through August 13, 2017.

The post The Inspiring, Contested Legacy of Dorothea Lange appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 18, 2017

Erik Kessels Celebrates the Mistakes of Amateurs

In an excerpt from The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, Simon Baker considers the value of mediocrity.

From The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, 2017

Courtesy the artist

I really don’t consider myself an artist. I make art, but it’s a job . . . this is one profession in which I can be a little bit stupid, and people will say, “Oh, you are so stupid, thank you, thank you for being so stupid.” —Maurizio Cattelan

Amateurs . . . never know what they might end up with, and they don’t particularly care. Nor should you. —Erik Kessels

In 2003 the French writer and critic Jean-Yves Jouannais published one of the most important revisionist histories of art to have emerged in the past fifty years. It was called L’idiotie (Idiocy) and true to the form of the kinds of art with which it was concerned, it was mostly ignored and misunderstood. Primarily it was ignored because no one translated it into English, and the Anglophone world is far too lazy and arrogant to take untranslated French books seriously: they, it is assumed, like public safety warnings on Japanese cigarette packets, are clearly not intended for us. But make no mistake, Jouannais’s book is full of important information. It may not save your life, but neither will learning to read warnings about smoking in kanji.

The gist of L’idiotie, to summarize with brutal brevity, is that there is (and has been) a radical third way for art production that has been dangerously misunderstood and underrated. Looking back to the early twentieth century from today’s vantage point, Jouannais makes clear, it is no longer necessary to posit the binary logic of creative genius (Picasso) versus nominalist genius (Duchamp). Rather, it has always been possible, in Jouannais’s opinion, to avoid the pitfalls of predictable (and successful) art by engaging fully in stupidity, loving mediocrity, and flirting with failure: “art did not become modern,” he claims, “until idiocy became its generative principle.” This strategy (or nonstrategy in most cases) also has the added benefit of dealing with, and resisting, the postmodern disappearance of the author into the work: “Idiocy in art,” he says, “itself a voluntary idiocy, revindicated and instrumentalized, constitutes . . . a manner of resisting disappearance.” But that’s enough bad translation of a brilliant book. Don’t be an idiot; find a copy, look at all the pictures, and then find a French person who’ll tell you what the words say . . .

From The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Anyone who knows Erik Kessels (or his work) should have bells going off in their heads by now. We all know (or at least suspect) that Kessels is not stupid, but then again, he seems to have the ability to do deeply idiotic things in the pursuit of a kind of hard-core resistant art production (up to and including photographing his own penis and then hiding it in a book of thousands of penis photographs). But as Kessels himself writes in his recent book on failure: “If you’re anything like me, you’re called an idiot at least once a day. And that’s OK. Because making mistakes, flirting with disaster and pure, outright failure is how you will get better. Without it, you’re stuck in a zone of mediocrity.” (Jouannais, incidentally, would probably have a problem with this, as he sees mediocrity itself as containing a rich vein of usually untapped creativity: truly stupid artists, perhaps, should have no need to “get better.”)

From The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, 2017

Courtesy the artist

There is, however, a dumb core of Kessels’s practice. Although there is probably no sense in which he’d ever feel licensed, like Maurizio Cattelan, to be “professionally stupid” as an artist. The wide range of Kessels’s activity, from advertising to art direction, graphic design, curating, collecting, and so on, is insurance against the notion of simply being an artist (or even more simply, a photographer). And even the small-scale photobook world, which Kessels has made his home, sees him as everything along the sliding scale from artist/producer to publisher/collector. The dumb core, then, can be found in Kessels’s ability to bracket out and suspend these categories in such a way that normative notions of production and consumption are interrupted or suspended. And this, at a time when the ubiquity of appropriated content has made it almost completely impossible to tell who the next person to stumble from photographic stamp collector to conceptual artist is likely to be. There are brilliant stars in the Milky Way of found imagery (like Kessels’s friend and occasional collaborator Thomas Mailaender), but they’re horribly outnumbered by orbiting lumps of rock dying to be reclassified as planets.

From The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, 2017

Courtesy the artist

But Kessels was not just (or maybe not even) one of the first to mine the infinitely deep shafts of mediocrity constituted by the photographic albums of ordinary people. He seems always to have had the inexplicably positive attitude of a delusional alchemist: certain than he will succeed, where all others before him have failed, in turning giant piles of unremarkable dross into pure gold. In and of themselves, the photographs from which much of his work is assembled are unutterably dull, miserably inadequate, obstinately occupying the space reserved for things diametrically opposed to art. But the apparently impoverished nature of this material is magically reversed by the relentless optimism of Kessels’s dumb humor. Because he is determined not to care about individual images at the level of meaning or value, they become transcendent symbols of potential mobility and the mystical power of failure and stupidity to reverse value systems. This was particularly evident in the works selected for the exhibition and book Failed It! (2016), where Kessels shifts deftly from finding strange pictures that make us think or make us laugh, to finding other people who have already done the dumb legwork for him. Everywhere in Kessels’s work the normative logic of production is replaced by something better: something that refuses to obey the various indices of value that artworks love to be measured by. These include (but are not limited to) originality, uniqueness, expense, size, intention, formal organization, aesthetic sophistication, and even beauty.

From The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, 2017

Courtesy the artist

We could leave Kessels here, staring at us like a lost puppy from the other side of the border between art and rubbish. But Kessels, one suspects, would never abandon a lost puppy (even one that mysteriously failed to register on photographic film), just as he would never suffer the life of an image to be prematurely cut short. Among his most recent work, Unfinished Father (2015) stands out, both for its raw emotional content and Kessels’s evident need to take the real world seriously. Confronted by the long-term illness of his father following a stroke, Kessels constructed the installation Unfinished Father from parts of the vintage car his father was working on before his illness, including the photographs made in the restoration process. But even here, in the man-cave of emotional failure, Kessels makes a virtue of losing the plot: “we can attempt to control our circumstances,” he writes, in the book of the project, “but in the final analysis they control us.” Having proven, time and again, that unleashing the tsunami-like flow of global image culture is an unpredictable and risky business, Kessels finds not only that it’s beyond his control, but that it has flooded his basement.

This essay was originally published by Aperture in The Many Lives of Erik Kessels (2017).

Simon Baker is Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), Tate Modern, London.

The post Erik Kessels Celebrates the Mistakes of Amateurs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 17, 2017

The Loneliness of the Darkroom

In his solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale, Dirk Braeckman turns toward the existential.

By Wilco Versteeg

Dirk Braeckman, E.N.-C.K.-12 – 2013, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Known for his large black and white analog photography of interiors, nudes, landscapes, and otherwise everyday subjects, the Flemish artist Dirk Braeckman doesn’t want his work to be defined by its formal qualities. Rather, the communication between audience and image is central to an artistic practice deeply involved with the material aspects of photography. Through his method and content—and images imbued with a sense of emotional distance—Braeckman criticizes the speed with which photographs are distributed and consumed. In advance of his solo exhibition at the Belgian Pavilion in the 57th Venice Biennale, I spoke with Braeckman about the loneliness of the darkroom, documentary photography, photobooks, and New York.

Dirk Braeckman, 27.1 / 21.7 / 026 / 2014, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Wilco Versteeg: Your work seems to be grounded in nineteenth-century photographic practices, while the performativity of your images and your engagement with the material aspects of photography seem distinctly of our time.

Dirk Braeckman: The nineteenth century informs my work foremost in a formalistic way. I shoot analog and solely black and white, and I make large, tableaux-like prints on baryta paper, but what I do with this is contemporary. I sometimes teach and some students are interested in the darkroom. I wonder if this interest is sincere, or just a nostalgic reflex. For me, this is how I started thirty-five years ago. These have always been my tools of the trade. The world and the distribution of images has sped up dramatically, but I have continued to make images in the same way. Also, the infinite combinations of Photoshop are dizzying to me. I am happy to work in complete solitude, in the darkroom. I don’t suffer anyone or anything around me while I develop.

Dirk Braeckman, B.O.-D.F.-17, 2017

© the artist and courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: So your work comes into existence in the darkroom, more so than during shooting?

Braeckman: The darkroom is where it all happens, but for me, the taking, developing, printing, and exposing of an image are in fact one and the same thing, separated by quite some time. I do not shoot a lot. Sometimes it takes me months, even years, to print a negative. I want to create a distance between the emotions I experienced when shooting and the final print. I have sworn never to tell anything about the time and place in which my images were made. The story of each image is made by looking at them. Each viewer creates his own story: I don’t tell stories, I just create images. The risk of talking too much about your images is that you destroy their core, you destroy what gives them their strength.

Anyone who looks at my images is free to do with them what they want. It is beyond my control. I only control what happens in the darkroom. I think my images take time to comprehend. What at first seems evident, like a curtain, an interior, or a nude, changes when you take the time to let the image work on you. This communication, rooted in the experience of confrontation with a work, is what finally counts. I try to create works that one can return to repeatedly. Works that are, even if that sounds presumptuous, timeless.

Dirk Braeckman, H.M.-H.P.-11, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: Is it important that this encounter, this experience, happens in a museum, or will a photobook do?

Braeckman: By training I am a painter. At art school, a friend told me I could improve my painting by trying to master photography first. I had never touched a camera before that, but to this day I have never laid it down. However, I still look and experience the artistic process as if I were a painter, that’s why my prints are often so big. Looking at a small print is like looking at a small experience. For this reason, I am not too keen on making photobooks, and I have difficulties showing my work on my website. When you see a reproduction of a photo in a book, you are less likely to think of the actual dimensions of the work. It’s just a print of a photo. In Venice, we have tried to make full use of the space. Space and presentation is everything when viewing my work. My works take the physical space they need.

Dirk Braeckman, P.H.-N.N.-11, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: Your work is often approached formally, but what is your relationship to documentary photography?

Braeckman: Documentary photography interests me because I can’t do it myself. I am too shy for it, perhaps. For a short time when I started out as a photographer I filled in as a photographer for a newspaper and soon found that this was not for me. When on assignment, the journalist needed to remind me to finally take my picture. I was too engaged with the situation to think about shooting. When I travel, it sometimes takes a week before I get my camera out. I need to feel connected to a place before I shoot.

All photography is documentary in a way, if we consider artistic practices as telling of the way we deal with images today. In the 1980s and ’90s, I often spent long stretches of time in New York, a city that continues to fascinate me but for which I have less need now, and Berlin. In these places, I took pictures of everything that surrounded me on the street. For instance, the images I made around the fall of the Berlin Wall were never meant to be documentary, but they have become so over time. The passing of time changed the nature of these works. I never printed them, but I am considering making a book of them. For this project, a book would do.

Work that does not have the pretense to be art but becomes art nonetheless inspires me greatly. This is why Luc Sante’s work on New York crime photography has been so important to me. Especially the images that suggest an event are mesmerizing. A murder scene with the dead body already removed, for instance. In my own work, even if people are present, they are just part of the situation but do not stand out. I never make people pose for me; everything comes into existence organically.

Dirk Braeckman, Z.Z.-T.T.-17 #2, 2017

© the artist and courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: Your photographs are often described as autobiographical, even depressing.

Braeckman: The works are dark, no doubt. Some people ask me if I am depressed, and I tell them, “Yes, I am, but not more so than others.” I am not agonizing in my studio. The dark, existential melancholy qualities of the images attract people. I don’t think my work is depressive. Luc Sante said it very well: To him, my works are like unexploded bombs. There is a certain stillness, a timelessness, but they also are full of energy and tension.

Wilco Versteeg: Do you consider your exhibition at the Venice Biennale a highpoint in your career?

Dirk Braeckman: Yes, at least for now. I don’t know what comes next, but this is a big cherry on the cake. I am nearly sixty years old, but I don’t see this as a retrospective moment. I continue to work and to develop artistically. In Venice, I predominantly exhibit new work, but some older prints as well. My work will be unknown to 90 percent of the visitors, so I hope they will get a clear view of my artistic practice. For those who know me, the new works might shed a different light on what I have made before. Works are never finished, not even when they are printed and exhibited.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD candidate at Université Paris Diderot.

Dirk Braeckman represents Flanders at the 57th Venice Biennale, in an exhibition at the Belgian Pavilion, from May 13–November 26, 2017.

The post The Loneliness of the Darkroom appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 16, 2017

In Katy Grannan’s First Film, a Story of Poverty in California

An intimate portrait of the neglected Central Valley, The Nine is surprising and urgent.

By Sylvie McNamara

Katy Grannan, Film Still No. 20 (Wanda, Tears), from The Nine, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Salon 94, New York

At the beginning of photographer Katy Grannan’s first feature film The Nine (2016), the camera peers around a dirty shower curtain. Behind it is Kiki, a black woman with a ragged face, washing her breasts. “The camera sees me every which way,” she observes dispassionately. It’s a disarming moment that sets the tone for this film, a meandering and intimate vérité-style portrait of drifters and junkies living on South Ninth Street—“The Nine”—in Modesto, California. Grannan’s exquisite and authoritative photographic vision provides the film with a surprising beauty, and without falling into tropes of pity or trite aspiration, her depiction of marginalized people makes for a humane and surprising glimpse into lives that don’t often make it to the screen.

Grannan has reluctantly labeled The Nine a documentary, but its genre is vexed. The moods drift through like weather: a brother and sister memorialize their mother by sending silver helium balloons into the sky, and a group discusses a recent murder while a woman in stilettos, lit by car headlights, totters around in the gravel. People play in the river, shoot up, feed the cat, fight, and talk about God, which all adds up to a skillful study of the variety of the everyday—the seamless bleed of often-contradictory experiences that characterize a life.

Katy Grannan, Film Still No. 19 (Blue Boat), from The Nine, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Salon 94, New York

The lives Grannan shows are extreme in their hardship and vulnerability, and the film is concerned with the questions of representation raised by its very existence. Though The Nine includes meta-commentary on the power relations of artmaking, Grannan doesn’t allow the film to become a case study in representational ethics at the expense of focusing on its subjects. At the center is Kiki, who shares a writing credit with Grannan (where her full, legal name, Artimese Fairley, appears for the first and only time). Kiki is in her late thirties and she dreams of being a veterinarian. As a narrator, she is magnetic but unreliable. Her contradictory claims range from her backstory to her drug use; though she no longer speaks to her family, she suggests that her father has promised to buy her a condo. She says she’s clean, but she shoots up on camera in a scene toward the end of the film.

Grannan isn’t concerned with the veracity of these claims, but she is interested in Kiki’s tendency to slip in and out of different realities. “Kiki has fabricated so much,” Grannan told me when I spoke with her last winter. “She’s a master storyteller, but she’s very aware. She has created this shell, this persona, to deflect relationships that she knew would betray her.” Kiki’s signature meld of lucidity and delusion is, in other words, a reaction to dire circumstances. It’s a way to protect herself and control her own narrative.

Katy Grannan, Film Still No. 18 (Kiki Praying), from The Nine, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Salon 94, New York

“I want the viewer to question what they’re seeing,” Grannan said, “whether this is all taking place in Kiki’s imagination—some sort of dream or nightmare state—or if it’s real.” The film’s rambling lyricism mimics Kiki’s reality, and the question of whether The Nine is a dream or nightmare turns out to be a potent one. In a sequence typical of the film’s dissonance, a woman in a cheery blue shirt remarks on her fear of encountering a local criminal: “Even though we’ve got that guy’s picture,” she says, “he could dress up. He’s got one of those faces that he could dress up like somebody.” Grannan then cuts to a woman weaving a flower into another woman’s hair while she confesses her aspiration to open a mud-wrestling club.

These currents of suffering and joy balance the movie and allow it to convey the mood of everyday life rather than only its most pointed moments. The viewer, Grannan said, should “experience the strange way that incredibly ordinary, mundane experiences exist alongside horror,” because witnessing the texture of the characters’ days means that, “You get that there’s a complex history and context for their lives, and you care enough about them to not judge them for whatever they’re doing.”

Katy Grannan, Film Still No. 16 (Purple Eyes), from The Nine, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Salon 94, New York

While Grannan asks viewers not to judge Kiki herself, The Nine’s concern with the presence of the camera in Kiki’s life invites questions about cruelty and exploitation, themes Grannan raises without feigning resolution. Grannan’s exploration of her own entanglement with Kiki’s suffering is made explicit in a moment near the end of the film when Kiki, on her birthday, unravels. After sharing details of her family history, Kiki directly addresses Grannan and her collaborator, Hannah Hughes, telling them that she has revealed parts of herself to them that even her family doesn’t know. Kiki’s biggest fear is that Grannan and Hughes will “leave me and never see me again or you’ll get what you want and … leave.” When Grannan interrupts to try to comfort her, Kiki holds out her hand and commands, “Katy, please hear me out. Please.” She speaks uninterrupted for a while longer, and then concludes, “I don’t want you guys to feel sorry for me. I don’t want anything from you guys, the only thing I want from you guys is … just don’t leave me.”

Katy Grannan, Film Still No. 5 (Dyed Red), from The Nine, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Salon 94, New York

Grannan’s subjects were paid for their time and Kiki, in particular, had control of how she was depicted. It was at Kiki’s insistence, for example, that her vulnerable monologue was included at all. But with that footage, The Nine appears to tacitly acknowledge the long history of white artists distorting their vulnerable subjects and the shared and precarious moral territory of a successful white artist such as Grannan depicting a black woman’s poverty. Grannan is candid about the unresolved ethical questions of her relationship to Kiki; she refuses easy absolution in the form of claims to objectivity, or simplistic ethical formulas, such as “I paid her,” or “she had control.” Instead, The Nine’s open-ended inquiry into whether Grannan’s filmmaking could be causing or distorting Kiki’s pain requires the audience to sit with the complexity of observing another person’s suffering. This is crucial—The Nine would be a manipulative film if it allowed anyone to emerge without questions about how Kiki was depicted and what it meant that they watched.

The nuanced impact of The Nine comes from Kiki’s self-awareness, vulnerability, and her courageous insistence on including the most troubling scenes. Grannan and Kiki are willing to undertake these challenges, in part, I imagine, because of the urgency of the story. People all over the country, and around the world, live precariously. For those of us who are more privileged, Grannan told me, “It’s very convenient to look away, to just pretend none of it exists.”

Sylvie McNamara is a freelance writer and editor.

Read an interview with Katy Grannan in Aperture, Issue 226, “American Destiny.”

The post In Katy Grannan’s First Film, a Story of Poverty in California appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 15, 2017

Rowan Renee’s Defiant Pictures of Trauma

Rowan Renee is a Brooklyn-based artist whose work deals with gender, transgression, and male violence. Their 2016 series Bodies of Wood is presented at Aperture as the centerpiece of a weekend-long collaboration with the Ackerman Institute for the Family and The Voices and Faces Project and explores the role of art-making and storytelling as vehicles to address gender-based violence. Chris Boot, executive director of Aperture Foundation, recently spoke with Renee about the project.

Rowan Renee, The room through eyes that see askew, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Chris Boot: Can you tell us the story behind your project Bodies of Wood?

Rowan Renee: Bodies of Wood is a collection of images made from a place deep within that needs to speak. The drive to make it was urgent, both a longing to access something that was very essential to understanding who I am, but also that this was something that needed to be talked about publicly in order to heal. The taboo of incest in our society is not so much about the violent act itself; it is common and the perpetrators are rarely convicted. The taboo is talking about it. And I think that is because to talk about it, we have to look honestly at a myriad of broken institutions, of false narratives, of interlocking systems of injustice that work together to oppress people.

Boot: Do you see this as a political gesture?

Renee: Yes, in the sense that I believe that bringing light to this issue can bring strength and insight to others who have experienced similar things to talk about their story, and also to understand that being a survivor is a complex identity. In this series, Bodies of Wood, I want to challenge the idea of victimhood and the way that label is often used to make victims seem fragile or to strip them of agency on their path to healing. I want to complicate the narrative a bit, to discuss frankly the pain of abuse and the injustice of the system that is complicit to it, but also the way the energy from deeply painful experiences can be harnessed in so many powerful ways. In that way, I think of Bodies of Wood as a project about transformation.

Rowan Renee, Bodies of wood, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Boot: How has making Bodies of Wood proved transformative for you?

Renee: Bodies of Wood was my third or fourth attempt to address this story. I kept being drawn back to the same moment in my past to make work, and even when I am not dealing with my experiences of abuse directly, I’ve realized that my work is always driven by narratives of power and an attempt to transgress figures or systems of authority. In the process of making this work, I’ve had to sit with my anger as a driving force of my creative process. It’s an emotion that we find uncomfortable, or even dangerous, but I want to suggest that there’s a constructive side to it. It’s been a source of momentum and a place to find strength to break with the status quo. I also think that I have to manage my expectations about how this work, or art in general, creates social change. Through Bodies of Wood, I’ve been learning patience and understanding that the transformations that art usually engenders are slow and within the intimate experiences of individual viewers or readers. Shifting the needle is an incremental process, and the shifts may not be visible for a long time.

Boot: Where did you make the series?

Renee: I made the whole collection of images in about four weeks from December 2015 to January 2016. I was at a residency on a house boat in Sausalito, California. At the same time, I also finished the personal essay that accompanies the images. That’s to say, the process of making it was incredibly fast. In total I took about 180 frames of medium format film and the final edit is eighteen images. Because I was working by myself with an analog film camera, I didn’t have a way to actually see myself in these images until I got the developed rolls back a week later. I think that detail is important, because I feel like each of these images was a leap of faith. I literally couldn’t see what I was doing.

Rowan Renee, The ritual of scrubbing it all out, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Boot: Now that you are going to present the work publicly, how have you reflected on the experience of your residency?

Renee: Looking back on that time, I start to understand what it means to experience artistic inspiration. I think something happened within me where I was able to become uninhibited and tap into some kind of fundamental life force. This is what I mean when I say I want to complicate the narrative of victimhood. While I was working on Bodies of Wood, I felt a profound joy. The feeling was connected to the feeling of freedom. I was no longer bound to these pressures that wanted me to keep quiet about these experiences. One of those forces is my father, who passed away six years ago. But it also was connected to the feeling of my craft. That I had developed a fluency at making images, and that I could wield it with power and confidence. I think you can see that complexity in my images.

Rowan Renee, The brightness where I am bound, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Boot: Could you tell us about how your working process influenced the concept and tone of the images?

Renee: I’ve done a lot of work in the tintype process, which is monochrome. So, working with color was a new thing when I started Bodies of Wood. And, apparently, the way I use color in this body of work is very distinct. Almost every frame has these strange collisions of complimentary colors, often fragmenting the body. There’s also these compositional repetitions. My body is often faceless, flipping back and forth from facing toward the camera and away from it. And then there’s the self-consciousness of the process and the viewer. I worked with a remote release, which is intentionally shown in some of the images. There’s one with fake blood, which is probably one of the most graphic of the images, but the whole apparatus of creating that scene—the dark slide, the remote release, the food coloring and mixing bowls—is shown. For me, this touches on a very important question when doing work around trauma: How do you represent violence without perpetuating it?

Chris Boot is executive director at Aperture Foundation.

Bodies of Wood is on view at Aperture May 20 – May 23, 2017. The weekend events also include:

The Voices and Faces Project’s “Stories We Tell” Testimonial Writing Workshop

Saturday, May 20, 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. and Sunday, May 21, 11:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Bodies of Wood Exhibition Reception and Panel Discussion

Tuesday, May 23, Aperture Gallery and Bookstore

6:00–7:00 p.m. – Cocktail Reception for Rowan Renee

7:00 p.m. – Panel Discussion with Lois Braverman, Rowan Renee, and Mila Zuo

The post Rowan Renee’s Defiant Pictures of Trauma appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 12, 2017

9 Photographers Picturing Motherhood

When it comes to depicting motherhood, stereotypes abound. From the age-old Madonna and Child to today’s celebrity moms beaming from magazine covers, motherhood endures as and subject of both fascination and controversy. For decades, artists have worked to change the ways in which childbearing and child-rearing have been perceived. The following photographs illuminate truths about the experience and potential of motherhood.

Justine Kurland, Baby Tooth, 2011

© Justine Kurland

Justine Kurland

Drawn to the road and its possibilities, Justine Kurland spent the better part of twelve years traveling the United States in a van. Her son, Casper, played a key role in the resulting book, Highway Kind, often accompanying her, and determining the direction of her photographs. Traversing her role as both artist and mother, Kurland’s work reflects a delicate balance between the need for routine and the desire for freedom and escape.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Mom Relaxing My Hair, 2005

Courtesy the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome, and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier collaborated with her mother and grandmother to create an intergenerational exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. The Notion of Family is a statement both personal and truly political—an intervention in the histories and narratives of the region.

Doug Dubois, My mother on the bathroom scale, Oldwick, NJ, 1999

© the artist

Doug DuBois

Doug DuBois photographed his family for over twenty years to produce …all the days and nights. His intimate portraits resonate with emotional immediacy, offering a potent examination of family relations, and what it means to subject personal relationships to the unblinking eye of the camera.

Mary Ellen Mark, Erin (who previously went by her street name “Tiny”) pregnant with Daylon, Seattle, 1985

© the artist

Mary Ellen Mark

“Tiny” (Erin Charles) is unforgettable. Mary Ellen Mark first met the fiercely independent thirteen-year-old living on the streets of Seattle, and continued photographing her for over 30 years. Now in her forties, Tiny has ten children, and Mary Ellen Mark’s Tiny: Streetwise Revisited remains a unique perspective on class, motherhood, addiction, and ultimately, love.

Elinor Carucci, Bath, 2006

Courtesy the artist and Prestel

Elinor Carucci

For her project, Mother, Carucci documented nine years of raising her twins, from the expectance of pregnancy, to the chaos of their youth. The resulting work peels back the sentimental façade of motherhood, revealing the rawness, banality, and beauty of her reality.

Learn more about Mother here.

Sally Mann, Damaged Child, 1984

© the artist

Sally Mann

When Immediate Family was first published in 1992, Sally Mann’s intimate photos of her children—roaming naked and free on their family farm in Virginia—were a dramatic and controversial departure from stereotypical portrayals of motherhood that dominated visual culture at the time.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipoma, CA, 1936

Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange, who documented rural poverty for the federal Farm Security Administration throughout the Great Depression, is perhaps best known for this image. “Migrant Mother,” portraying a thirty-two-year-old mother in a pea-picker’s camp struggling to feed her seven children, would become an icon of the era.

Alice Proujansky, Jen Carnig holds her son Wiley James Carnig Lavoie immediately after his birth at home as her husband Dan Lavoie, daughter Olive Carnig-Lavoie and best friend Lisa Johnson, look on, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Alice Proujansky

Alice Proujansky’s project, Women’s Work, follows women as they navigate childbirth, motherhood, and career, offering insight into the challenges that many mothers face in maintaining their personal and professional identities along the way.

Proujansky is also the author of Go Photo! An Activity Book for Kids.

Robin Schwartz, Rascal, Albino Wallaby, 2010

© the artist

Robin Schwartz

Robin Schwartz began collaborating with her daughter, Amelia, when Amelia was just three years old. Now eighteen, Amelia has become her mother’s muse. Amelia and the Animals depicts their journey into invented worlds and fables, and has brought the two closer. “Photography gives us the opportunity to access our dreams,” Schwartz said, “to discover the extraordinary.”

The post 9 Photographers Picturing Motherhood appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Members Celebrate the Launch of “Platform Africa”

Guests attend the launch of “Platform Africa.” Photo by Will Matsuda

Aperture managing editor Brendan Wattenberg introduces members to “Platform Africa.” Photo by Katie Booth

Helen Jennings, editorial director and cofounder of Nataal Media gives members a tour of Nataal: New African Photography II at Redhook Labs. Photo by Katie Booth

Kwami Coleman. Photo by Will Matsuda

Guests attend the launch of “Platform Africa.” Photo by Will Matsuda

Nikki A. Greene, Monique Long, and Christina Knight. Photo by Will Matsuda

John Gordon Gauld, Chloe Heins, and Quin Heins. Photo by Will Matsuda

On Saturday, May 6, Aperture celebrated the launch of the summer 2017 issue of Aperture magazine, “Platform Africa.” In advance of the launch party at Pioneer Works, Aperture Members at the Connect level and up were invited to participate in a tour of exhibitions at Red Hook Labs and the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, both in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The tour began at Red Hook Labs with a walkthrough of Malick Sidibé: The Eye of Modern Mali with curator Philippe Boutté of the Paris gallery MAGNIN-A. Helen Jennings, editorial director and cofounder of Nataal Media, together with featured artists Kyle Weeks and William Ukoh, then led the group through Nataal: New African Photography II, a survey of nine young photographers working in fashion, video, and performance. At the 1:54 fair, Brendan Wattenberg, managing editor of Aperture magazine, introduced the group to Afronova, a Johannesburg gallery showing works by photographers Phumzile Khanyile and Jodi Bieber. Coinciding with the launch of “Platform Africa,” which will be released on June 6, Aperture presented a series of limited-edition prints by artists featured in the issue, including Malala Andrialavidrazana, who visited New York for the event and spoke to Aperture’s group about her recent photomontages of antique African maps and currency. As the sun set, guests danced in the courtyard to music by Kwami Coleman and sipped wines by Ziobaffa.

Special thanks to: Red Hook Labs, 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, Pioneer Works, Ziobaffa, and all who participated.

To learn more about Aperture’s membership program or to join today, visit aperture.org/join or contact the membership office at 212.946.7108 / membership@aperture.org.

The post Aperture Members Celebrate the Launch of “Platform Africa” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 11, 2017

These Radical Black Women Changed the Art World

Jessica Lynne speaks with the curators behind the Brooklyn Museum’s landmark exhibition about the revolutionary artists who transformed American culture.

Jan van Raay, Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum, 1971

© and courtesy the artist

“If we are going to bring about a better world,” Mary Ann Weathers wrote in her 1969 essay “An Argument for Black Women’s Liberation As a Revolutionary Force,” “where best to begin than with ourselves?” More than a rhetorical device, this salient inquiry encapsulates the heart and pulse of a black women’s liberation movement that sought to disrupt the discourses of second wave feminism—which primarily served the interests of white, middle-class women—and a Black Power movement that, at times, reinforced patriarchal authority. In doing so, a generation of black women such as Weathers sought to assert a political ideology that firmly centered the lives and interests of black women.

It is through this lens of reclaiming power that visitors should consider the exhibition, We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965–85, currently on view at The Brooklyn Museum. Organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Family Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Rujeko Hockley, the museum’s former Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art and now Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition examines the ways in which the cultural production of black women artists during this time period articulated a new message of radical politics. Featuring the work of more than forty artists whose practices span the mediums of sculpture, performance, painting, and photography, the exhibition responds critically to a longstanding gap in the history of art. Following the recent symposium on We Wanted a Revolution, I spoke with Morris and Hockley about the specific ways photography is deployed throughout the exhibition. —Jessica Lynne

Lorna Simpson, Waterbearer, 1986

© and courtesy the artist

Jessica Lynne: This exhibition has been a few years in the making. Could you talk about the impetus of the project and why it was vital for the show to exist within the museum’s series A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum?

Catherine Morris: Several years ago, we started thinking about how the projects we were focusing on pushed against historical orthodoxies, and about second wave feminism, which is the foundation of the Sackler Center. What are the stories that aren’t told? It came down to an exercise of revising revisionism. Revisionist history is one of the most important contributions feminist theorizing has made to the history of art, but it was time to turn that method on itself. We Wanted a Revolution captures that spirit.

Rujeko Hockley: Exactly. A lot of We Wanted a Revolution came out of my work in graduate school and the work I had done about women of color and black feminism outside of the art world. There is an institutional history here vis-à-vis the museum’s community gallery, a space that existed from 1968 to ’86 which was a problematic space in some ways. And a lot of the work in the show is part of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, including a Black Arts Movement collection of work acquired by the museum in 2012. We are building on institutional history and bringing out stories that we ourselves didn’t necessarily know that well.

Morris: This pertains to the subject of photography as well. One of the really important things that comes out, I hope, is the history of art in relation to the tradition of activism—ad hoc organizing, building of coalitions, and direct action. The exhibition starts with the ’60s-era Spiral Movement and AfriCOBRA [African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, founded in 1968]. It ends with Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who, beginning in the 1980s, took up this mantle in a new, intellectual relationship to images, particularly images of black women, but also the overall critique of imagery and interrogation of our assumption of how images are read.

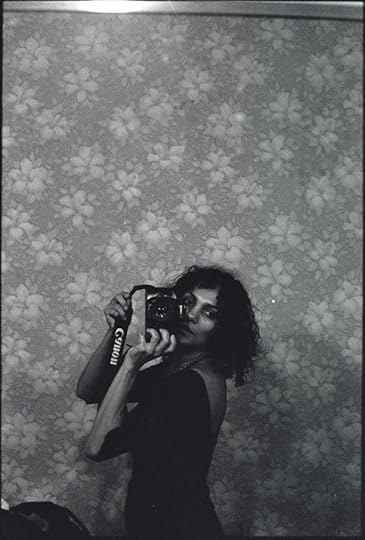

Ming Smith, Untitled (Self-Portrait with Camera), New York, NY, 1975

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery

Lynne: Photographic images exist in a few different ways in the show. We see, for example, performance documentation, formal portraiture, and self-portraiture through the work of artists such as Ana Mendieta and Ming Smith. From a curatorial standpoint, what is gained from using the image in this multifaceted way?

Morris: Photography played a role in the transition from modernist formalism to the emergence of conceptual art. The project I organized with Vincent Bonin, Materializing “Six Years”: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art (2012), points to the very strong links between conceptual practices and politics. Photography is one of those threads by which you can really trace that connection and I think We Wanted a Revolution does that, too.

Hockley: I agree fully. One of my greatest dreams for this exhibition and for the accompanying publication was that it could be taught as a history of American art from 1960 to the 1980s. As Catherine said, during this period, photography became a fully legitimized art form. This is also the period of performance and artists moving out of the studio, of artists moving into public space. And how do you document that? In photographs.

Where We At Collective, Cookin’ and Smokin’, 1972

© Dindga McCannon and courtesy the Dindga McCannon Archives, Philadelphia, PA

Morris: The history of photography in this period is that mash up of the personal and the political, and a transition in conceptual practices. You see that great shot of the women in “Where We At” Black Women Artists [founded in the 1970s] that is purely these folks documenting themselves. And you move back and forth between Jan van Raay’s documentation of Faith Ringgold, Michele Wallace, and BECC [Black Emergency Cultural Coalition] as a public journalistic method, and then you move into Conceptual practices like those of Lorna Simpson, Coreen Simpson, and Ming Smith.

Hockley: The exhibition is about self-determination, about women of color speaking for and to themselves. At the time, there was a lack of interest and understanding of black women coming from the mainstream feminism movement, and a lack of the same from the Black Power movement.

Morris: The exhibition also shows how fully engaged these artists are within the art world. “Where We At” brought in professionals to tell to them about portfolios. There was a very clear interaction between community-based organizing politics and art world politics.

Hockley: And the power of having a group photographer, and using the image, to create an archive. The archive is incredibly important to the show, but it also incredibly important to the people in the show! They kept everything.

Coreen Simpson, Church Lady, Harlem, New York, 1977

Courtesy the artist

Lynne: As you were thinking about how the exhibition might look, was there ever a moment you considered grouping artworks by medium?

Hockley: The artists wanted to speak in their own voices; they wanted to tell their own stories. They also wanted to be contextualized by scholars, and to be read art historically. So, we organized the exhibition by theme—historical moments, exhibitions, collectives, etc. This was a way to remove an overly didactic curatorial frame, but also to let the artists’ moment shine, which created a roughly chronological feel. It became interesting to see the places in the exhibition in which people pop up over and over again, people like Faith Ringgold, but also people like Coreen Simpson.

Howardena Pindell, Free, White and 21, 1980. Installation view at A.I.R. Gallery, 1980

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Morris: The best way to give the exhibition breathing room was to unfold the story in the way it actually unfolded. I don’t think we ever had a discussion about formal relationships that we might want to highlight.

Hockley: But then, that formal approach kind of happened anyway. That was one of the beautiful surprises of installation.

Morris: Yes, it’s one of the reasons I love being a curator—the opportunity to see what the objects will do when you put them in a room together.

Hockley: And to be surprised, to see those moments of synergy. Painting begins the show and we end in new media.

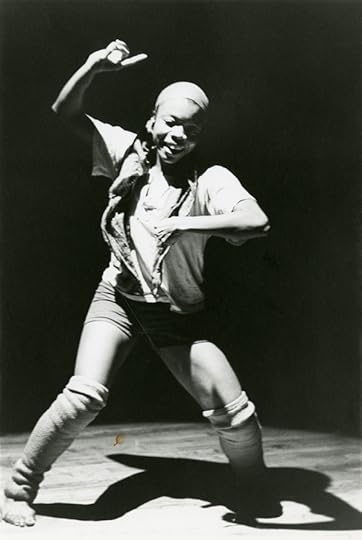

Lona Foote, Blondell Cummings performing “Blind Dates” at Just Above Midtown Gallery, November 1982, 1982

© the Estate of Lona Foote and courtesy Howard Mandel

Lynne: Performance documentation excels within the exhibition. I’m thinking of Senga Nengudi’s Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978). You have treated these works as formal, artistic and photographic art objects. How do you negotiate that within the larger context of this new media moment?

Hockley: The choices that performance artists make at the moment of creation impacts the work forever. Ceremony for Freeway Fets, for example, only exists as photographs. In a film by Barbara McCullough, Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflections on Ritual and Space (1979), which is not in the show, there is brief footage of Ceremony for Freeway Fets. That is the only moving image documentation, of that work. But I don’t think Senga thinks of herself as a photographer. Similarly, Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoisie Noire (1980–83) and Rivers, First Draft (1982) live as photographs, even though O’Grady isn’t a photographer.

Lorraine O’Grady, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Goes to the New Museum, 1981

© the artist / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

Morris: To me, the dicier question always comes up about re-performing. I am much more suspicious about how one can adequately restage something, and if one should. So, these materials, and this way of documenting performance, is absolutely of the time, and that is why it fits in the show.

Hockley: It is different in the dance world than the contemporary art world. What is the difference, for example, between Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup (1981) and the Rodeo Caldonia High Fidelity Performance Theater Collective’s documentation of their performances? Both have different relationships to documentation. I’m sure Chicken Soup has been performed by other people and could be. That is the way that dance exists. Choreography belongs to someone but it is also made to be performed by many different people. I have seen Revelations many times, but never with Alvin Ailey. It is powerful every time.

Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Mexico, 1982

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Lynne: What surprises did you encounter throughout your research?

Morris: We got really excited about some objects that we were able to shake out of the bushes. When you are doing primary research, people come to you. That is one of the most rewarding parts, because you know this is the first of what has to become multiple projects. The Sourcebook has long-term value that will contribute to those future conversations. It will allow other people to understand what we set out to do.

Hockley: And have a broader context. We went to see Linda Goode Bryan [founder of the Just Above Midtown Gallery] and she had her whole JAM archive for us. We live, live, live, live for those moments. One of the most surprising and satisfying things was the connection between research, scholarship, and real things in the world. We saw a reference in an art journal to a piece by Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail (1973). We sent the reference to Saar’s gallery, Roberts & Tilton, and they cross-referenced it with Saar’s impeccable records. Saar was then able to find the piece, and to connect us with the collectors, who live in downtown New York. We went to their house and borrowed it. And now it is in the show!

Carrie Mae Weems, Mirror Mirror, 1987–88

© and courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Morris: And it has never been on public view before. The other thing is, the show continues to reverberate and feel ever more important to the contemporary conversations. When we started this conversation two years ago, we had no idea the election would end the way it would, and that we would need this show. Looking at social media since the show opened, the need that people have for this show is not something you can plan for. But it feels to vitally important.

Hockley: Catherine and I have had an unshakable belief in the necessity of the show from the earliest moment. We were both so invested, to the point of compulsion, probably insanity! Our colleagues at the Brooklyn Museum, they were like, We don’t know what you are talking about, and we don’t understand what is happening, and we don’t know why you keep adding things to the checklist. But we were determined that it had to be amazing. It resonated with us in such a profound way.

Lorna Simpson, Rodeo Caldonia (Left to Right: Alva Rogers, Sandye Wilson, Candace Hamilton, Derin Young, Lisa Jones), 1986

© and courtesy the artist

Lynne: I am certainly also thinking about the contemporary moment. I consider the Sourcebook and the exhibition to be types of black feminist texts. You both remark in your introductory essay to the Sourcebook that feminism, as a word, wasn’t and still often isn’t used within black women’s communities in particular, and yet, this exhibition allows us to understand the lives of these women artists within the very real and urgent ideological framework of black feminism. The Sourcebook in particular functions as an extension of feminist thought. Long after the exhibition is down, there is this text that can circulate and revive itself. And that is equally as important as the work and the stories of these artists, their lives.

Morris: Using the word feminism or not—and I will use it for this conversation as we have yet to find the perfect language—feminism existed and it was happening. The whitestream world of the Brooklyn Museum and the Sackler Center needs to know that. So does everyone else! Walking through the show, and being at the symposium, I thought, “Holy shit, this happened.” Having this exhibition means that history gets rewritten, which it needs to be. And that history needs to be more complex, and more interesting, and more vibrant, and made more pertinent.

Hockley: Instead of being comparative, relational, or responsive to whitestream feminism or accepted narratives of feminist art history, we were committed from the beginning to centering the work and experiences of the women in the show. We were talking about them. This conversation isn’t that long ago. These people are still alive. They are here.

Morris: And they are still making work. They are still working artists.

Jessica Lynne is editor of ARTS.BLACK.

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through September 17, 2017.

The post These Radical Black Women Changed the Art World appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 10, 2017

5 Exhibitions to See in May

From teenage portraits to postwar Manhattan, here are must-see photography exhibitions in New York.

By Amelia Rina

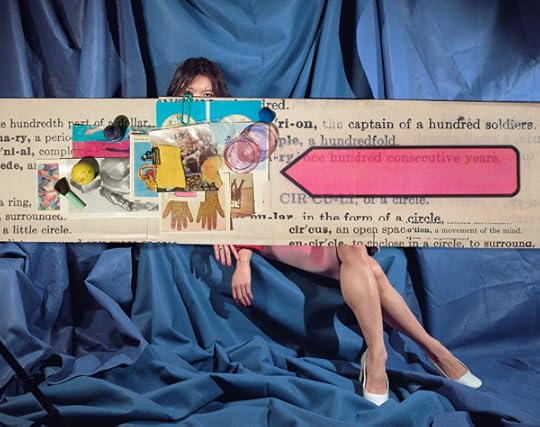

Sara Cwynar, Tracy (One Hundred Consecutive Years), 2017

© the artist and courtesy Foxy Production, New York

Foxy Production, 2 East Broadway #200, New York

Through May 14, 2017

In the past few years, colors described as “Millennial Pink” and “Rose Gold,” hues ranging from bubblegum to salmon, have become increasingly ubiquitous—and ambiguous. In Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar presents an investigation of this color’s propensity to seduce even those who are aware of its capitalist ploy. Her 16mm film Rose Gold (2017) traces the relationships of color, value, consumerism, and permanence, or lack thereof. “I love the rose gold iPhone,” say the voices of a male and female narrators in unison. Photographic portraits of Cwynar’s friend, Tracy, draped over deeply saturated fabric or gridded backdrops reminiscent of 1960s studio photography, present a response to the film’s examination of the aura surrounding rose gold and countless other color trends. Four of these feature superimposed found objects—perfume bottles, nude pantyhose, a golf ball—as well as vernacular and advertising images and fragments of text collected by Cwynar. Together, the works trace the decline of possessions from an object of desire to outdated kitsch, and expose the ephemerality of commercial-driven desire.

Eva O’Leary, Millie, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Crush Curatorial, New York

Crush Curatorial, 526 West 26th Street, New York

Through May 13, 2017

Though many people still recall a time before Facebook, we are already seeing the effects of social media on generations who can’t remember life without it. How does this constant connectivity, with its side effect of negative self-esteem, affect adolescents, an age group burdened with social pressure and uncertainty? Eva O’Leary seeks to answer this question by transforming selfies into formal portraits with a twist. O’Leary set up her 8-by-10 inch camera behind a large, two-way mirror. In her central Pennsylvania hometown, she invited girls ages eleven to fourteen to sit on the other side of the mirror, in which they could see only their reflection. The images project both self-assurance and unease. O’Leary pairs her poster-size portraits with a three-channel video that reveals the girls’ fixing, fussing, shifting, and styling. Unifying the portraits is a background of lapis lazuli, a shade of blue valued since ancient times and often used to represent wealth, signaling the timeworn practice of teaching girls that value is based on appearance.

Todd Webb, 125th Street, Harlem, New York, 1946

Courtesy the Museum of the City of New York and the Todd Webb Estate

A City Seen: Todd Webb’s Postwar New York, 1945–1960

Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Ave, New York

Through September 4, 2017

In 1937, when he traveled to Panama to visit a friend and prospect for gold, Todd Webb encountered the real treasure of his life: his passion for photography. For the next five years, photography became all-consuming. Webb studied at the Chrysler Camera Club in Detroit, where he met Harry Callahan and took a workshop with Ansel Adams. While in New York on his way to serve in World War II, Webb had a chance encounter with Alfred Stieglitz, who encouraged Webb to return to New York after the war. In 1945 he did exactly that, and continued photographing the city over the next fifteen years. The nearly 150 photographs on view at the Museum of the City of New York—which, in 1946, was the first institution to give Webb a solo show—depict a city bustling with industry and grateful to see the end of the war. Two trends emerge: Webb’s fascination with storefronts and signs, both advertisements and those welcoming home the G.I.s, and his attraction to the city’s architecture, towering over him from below, as well as in cityscapes made from the top of the Empire State Building.

![Walead Beshty, Cross-Contaminated Inverted RA4 Contact Print [Black Curl (CYM/Six Magnet/Six Magnet: Los Angeles, California, April 7, 2016, Fujicolor Crystal Archive Super Type C, Em. No. 112-006, Kodak Ektacolor RA Bleach-Fix and Replenisher, 06816), Kreonite KM IV 5225 RA4 Color Processor, Ser. No. 00092174], 2017 Courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1494493150i/22719666._SY540_.jpg)

Walead Beshty, Cross-Contaminated Inverted RA4 Contact Print [Black Curl (CYM/Six Magnet/Six Magnet: Los Angeles, California, April 7, 2016, Fujicolor Crystal Archive Super Type C, Em. No. 112-006, Kodak Ektacolor RA Bleach-Fix and Replenisher, 06816), Kreonite KM IV 5225 RA4 Color Processor, Ser. No. 00092174], 2017

Courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York

Petzel Gallery, 456 West 18th Street, New York

Through June 17, 2017

Throughout his career, Walead Beshty has described the unseen labor behind everyday transactions. For his series Office Work (2017), Beshty skewered office machines, such as a scanner and an iMac, and left them plugged in while the devices attempted to complete their duties in vain. At first glance, four prints hanging on the wall look like they could be the product of an error in a massive printer. In fact, they are giant photograms, folded in half to produce a klecksographic image. The combination of the corporeal and the chemical extends to the series of works in Body Prints (2017), which includes copper-clad glass etched with either the imprint of a body part—for example, a right zygomatic bone and attending soft tissues, a left lateral epicondyle—or a facsimile of a pharmacy prescription for various medications. In Open Source, Beshty demonstrates the tragedy of forced labor and the sinister side of artificial substances.

Cang Xin, To Add One Meter to an Unknown Mountain, 1995

Courtesy the artist and The Walther Collection

Body, Self, Society: Chinese Performance Photography of the 1990s

The Walther Collection, 526 West 26th Street, New York

Through August 19, 2017

In Fen-Ma Liuming Walks The Great Wall (1998), Chinese artist Ma Liuming walks nude along the Great Wall of China. The series, a composite, multi-frame photograph and video documentation, expresses a delicate act of defiance atop a symbol of state power. The combination of body and landscape also appears in Cang Xin’s To Add One Meter to an Unknown Mountain (1995), in which ten artists stripped down and stacked themselves on top of each other; their amalgamated, sculptural form echoes the mountains receding into the misty background. Both works are central to Body, Self, Society, the second iteration of The Walther Collection’s yearlong series on Asian photography and video, which delivers a potent primer on Chinese performance art in the 1990s, a moment of radical experimentation in advance of the market forces that would eventually transform the lives and works of a generation of Chinese artists from the mid-2000s onward. Because of the lack of institutional support, as well as the omnipresent threat of government censorship, these performances were experienced only by small, trusted audiences. The camera, the only witness to the events, became both a stand-in for viewers and the artists’ sole connection to the broader art world.

Amelia Rina is a writer, critic, and editor based in Brooklyn.

The post 5 Exhibitions to See in May appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 9, 2017

The Endless Outer World

Daido Moriyama speaks about his Provoke days and capturing the streets of Tokyo.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

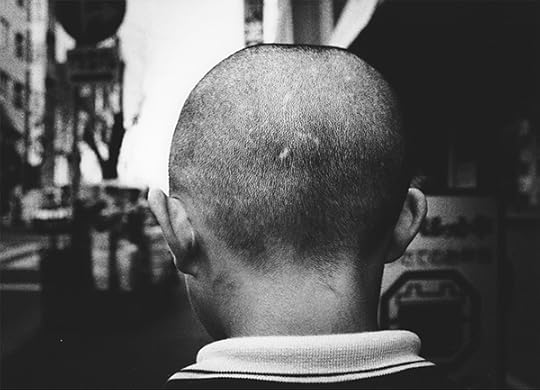

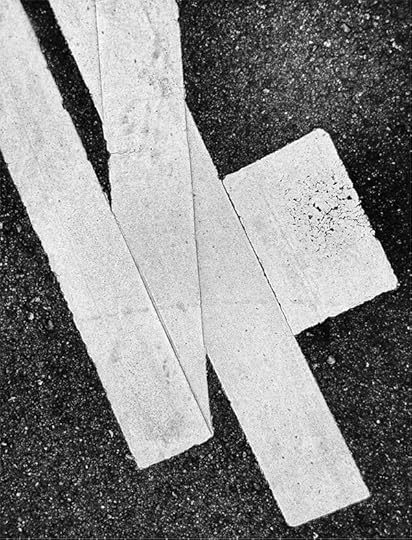

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

By the time Daido Moriyama joined the magazine Provoke for its second issue, he had already perfected the art of the accidental image. Embodying the revolutionary spirit of this late-’60s collective, Moriyama has since become one of the world’s most recognized photographers. His blurry, angular photographs of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district challenged conventional notions of photography. Moriyama’s early mentors included the legendary photographers Shomei Tomatsu and Eikoh Hosoe, but it was Takuma Nakahira who proved to be his greatest collaborator and closest friend. Decades on, Moriyama has continued to photograph Toyko’s streets using a small, handheld camera, inspiring generations of image makers. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke with Moriyama about his time with Provoke.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Tsuyoshi Ito: What drew you to participating in Provoke in the first place?

Daido Moriyama: Takuma Nakahira invited me after the first volume had already been released. Without his invitation to join, I likely would not have been involved. We were best friends and I had a great fondness for him. So rather than being interested in Provoke itself, it was more of an interest in him that made me want to join.

Ito: What was the energy like when you joined for the second issue of Provoke?

Moriyama: Provoke was a lot of fun. Everyone had the similar ideologies about photography, but the way each person expressed it was very different so we all stimulated each other. Since Provoke came at the end of the ’60s, much of it was very political. I had no interest or opinion about politics, so I did not partake in political movements and demonstrations. I focused instead on the need to reform photography. Provoke provided me with comrades.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: How did you get acquainted with Nakahira?

Moriyama: I met Nakahira when he was still an editor working for Shomei Tomatsu, so it was through Tomatsu’s projects that I was introduced to him. Compared to me, Nakahira had an opposite stance on things. Rather than seeing him as a charismatic photographer, I saw him as my only rival and also my only true friend. Never, before or after him, have I had a relationship like that with anyone else. So I thought that if I were doing something with him, then surely it was going to be fun.

Ito: How was it working with Yutaka Takanashi, one of the other key figures behind the magazine?

Moriyama: It was not a daily occurrence for us to see or hang around each other. Our ideologies on photography were also slightly off, but at the root we had a sense of consciousness of each other’s work that tied us all together.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: What was your reaction to Provoke breaking up after the third issue?