Aperture's Blog, page 119

April 12, 2017

Frédérique Destribats on Children’s PhotoBooks

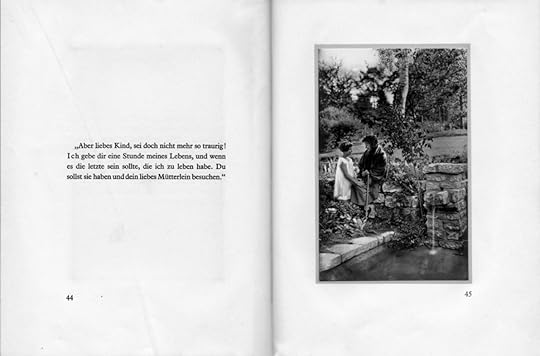

Lulu Meusser, Seelchens gute Tat (Berlin: Hermann Meusser, ca. 1920)

As photography developed in the wake of its invention in 1839, constant improvement in processing and printing techniques, quality and production, accelerated the distribution of the photobook and contributed to its success. Naturally feeding on this history, photographically illustrated books for children were introduced by the end of the nineteenth century. Their expansion was encouraged by such events as the gradual introduction of laws implementing compulsory schooling, which led to a rising demand for illustrated books from the growing numbers of young readers and educational institutions.

The first photographically illustrated books for children came in the form of photo albums carefully created and crafted by parents. These would sometimes be published for a larger audience, as was the case for Seelchens gute Tat by Lulu Meusser (privately published by Hermann Meusser in Berlin circa 1920)—a charming example of an early photo album for young people, with original photographic prints and a creative, if somewhat conformist, story about motherless girls and their quest to reach heaven. Youth literature, which had long focused on matters relating to religion, morality, conventional behavior, and education, experienced a shift in the twentieth century, opening up to whimsical storytelling and design, while also introducing sensitive societal issues.

Photographically illustrated books for children evolved over time and came to encompass every photographic style and genre: straight documentary photography; fabricated images and staged scenes with children, animals, figurines, etc.; visual and graphic experiments; photomontage; and so on. Whether professional or amateur, famous or anonymous, a long list of authors, poets, illustrators, and artists have explored the children’s photobook genre. Illustrious names include Laure Albin-Guillot, Claude Cahun, Edward S. Curtis, Dominique Darbois, Robert Doisneau, Tana Hoban, Frank Horvat, Eikoh Hosoe, André Kertész, Danny Lyon, Duane Michals, Sarah Moon, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Claude Roy, Cindy Sherman, Edward Steichen, William Wegman, and Ylla, to acknowledge but a few. Their topics ranged from the magical to the ordinary, with a large range of creative stories, artists’ books, textbooks, illustrated dictionaries, pictorial alphabets, how-to manuals, and educational guides covering the full range of youth-related concerns and interests. These books not only function as tools allowing children to nurture their imaginations and improve their understanding of the world, they also constitute fascinating commentaries on society. An extensive history of the genre would show that children’s photobooks are in tune with, and often even ahead of, their time.

Since the mid-1980s, however, photography has largely disappeared from children’s and young adults’ bookshelves. The medium seems to have been mostly abandoned for these audiences, while the number of titles intended for the same demographic but based on text and hand-drawn or digital illustrations—graphic novels and manga, for example—has steadily grown. I find this odd, considering that this is a time when the flow of images has been growing; it’s a disconcerting development for a genre that has proven to be highly creative and innovative.

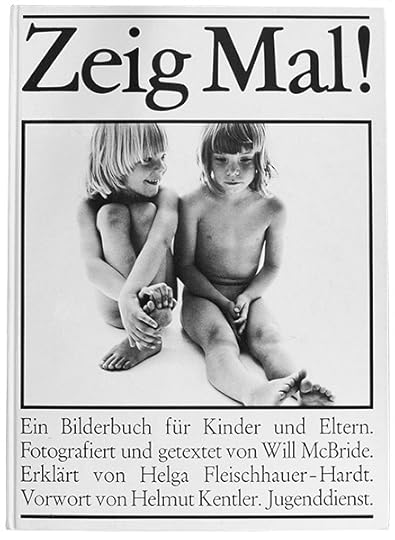

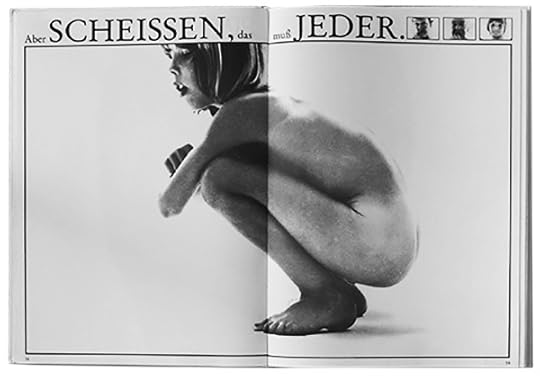

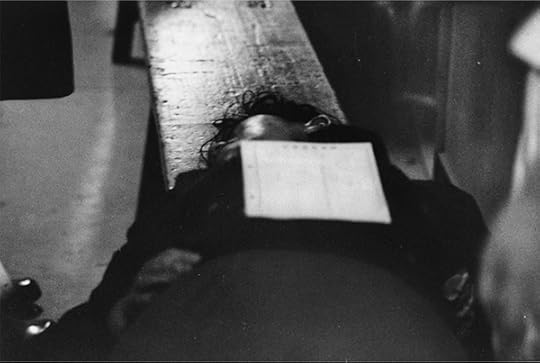

Will McBride, Zeig Mal! (Wuppertal, Germany: Hammer, 1990)

Here are but two examples of photobooks from the late twentieth century that strike a decidedly sociological tone, while eschewing the potentially infantilizing tone of books for children. First is Zeig Mal! (Show me!), which was released by the Wuppertal Evangelical Youth Book Publisher in 1974 and is a stunningly poetic, realistic guide to sexual education. The large-format book is illustrated with black-and-white photographs by Will McBride, keen observer of sexuality and proponent of sexual liberation. A foreword by child psychologist Helga Fleischhauer-Hardt advocates the need for psycho-pedagogical, ethical, and enlightened sex education. Delicate close-ups of nude babies, toddlers, kids, teens, and adults in candidly tender scenes, in the many stages and variants of our sexual lives—parts of the universal, natural cycle—are printed alongside spontaneous quotes from children, used as captions for the images. Nothing is deemed “too adult” (although the English version, released six months after the original German, was slightly “polished”). The book was, for the most part, well-received upon its release, and McBride was initially praised for his photographs. Soon enough, however, this uninhibited approach ignited morality fires. The book faced sensationalistic critics and multiple accusations—including that it allegedly had pornographic intent—and was finally removed from the market in 1996. Incidentally, so has photography from subsequent such publications, generally to be replaced by hand-drawn illustrations.

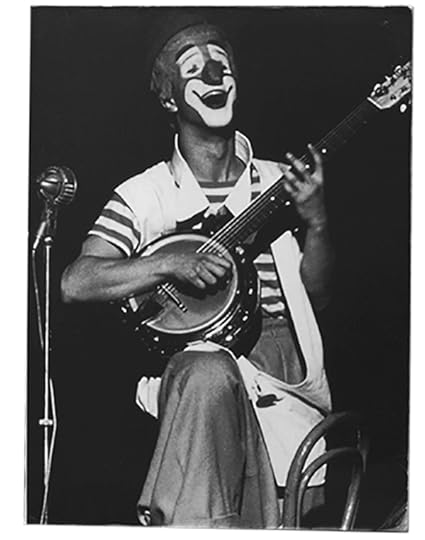

Jesper Höm and Sven Grønlykke, Børnenes Billedbog Forlaget Per Kofod (Denmark: Helsingør, 1996)

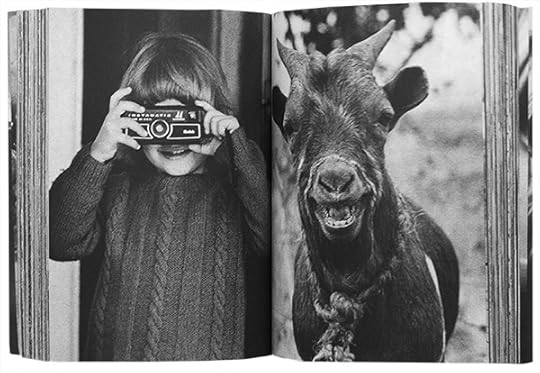

Børnenes Billedbog (The children’s picture book) by Jesper Höm and Sven Grønlykke is a relatively small yet thick volume of black-and-white images and no text, save for the title and copyright information. Originally published in Denmark in 1975, it has been reissued several times, including in the United States as For Kids Only: An Adventure in Reading without Words. The raw production and average printing set it apart from the graphic, colorful design standards of most children’s photobooks. This little-known and poetic photographic ode is a gem: it contains roughly five hundred full-bleed pages of photographs from all over that display a collection of plants and animals, still lifes, children and dolls, clowns and skeletons, bits and pieces of everyday life, and details of all kinds, loosely composed in short sequences or free associations. It’s a whimsical, kaleidoscopic vision of the world. Nothing is explicitly suggested or narrated—rare for a children’s book. Readers are simply invited to ruffle through the pages at will and create their own associations, stories, and interpretations, on their own or with the help of a grown-up.

Frédérique Destribats is a translator for numerous photography books, publications, and magazines, including ELSE magazine, published by the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland. She is the guest curator for the forthcoming second issue of Co-Curate Magazine.

Lulu Meusser

Seelchens gute Tat

Hermann Meusser • Berlin, ca. 1920

Will McBride

Zeig Mal!

Hammer • Wuppertal, Germany, 1990

Jesper Höm and Sven Grønlykke

Børnenes Billedbog

Forlaget Per Kofod • Helsingør, Denmark, 1996

The post Frédérique Destribats on Children’s PhotoBooks appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 11, 2017

Around the World in Six Photographs

Renowned travel writers and editors on the photographs that transport them.

Brian Finke, Don Lorenzo Angeles taking a break with a machette, Mezcal Real Minero, Santa Catarina Minas, Oaxaca, Mexico, 2016

Courtesy the author

Tara Guertin

Brian Finke’s work was on my mind for fifteen years before I commissioned this photograph. I first noticed Finke in the late ’90s, soon after I moved to New York, when we were both in our mid-twenties. Over the next decade and a half, I watched him refine his sharp, high contrast style while straddling the art and editorial worlds. Cheeky and dark, his photographs are impressively consistent and instantly recognizable.

When Brian and I finally met in 2013, I was working as the photo director at the then fledging travel magazine AFAR. On a visit to New York, he and I chatted over a few bourbons at a local barbecue joint. Brian shoots vices, often sex-related, but not always: frat boys half naked, dripping in beer; women in hip-hop videos or beauty pageants; and marijuana producers. I considered him for many assignments, but AFAR focuses on experiential travel, rather than these nefarious pleasures. Nothing seemed right. So I waited—until a story about one of my own weaknesses crossed my desk.

Mezcal wasn’t something Brian was particularly familiar with, but I had a feeling that the Mexican liquor and its culture would be right up his alley. He returned with a body of work that thrilled me. Recently, we met again. Waiting for me on the bar was a glass of mezcal, neat, and a print of this photograph. Maybe Brian has discovered another vice?

Tara Guertin is Director of Photography at AFAR.

Brigitte Lacombe, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Dharamsala, India, 2003

Courtesy the artist

Pico Iyer

Every portrait is a self-portrait, so they say; I cherish that idea every time I look at the oversized photograph that beams down on my desk. As I chatted with the Dalai Lama in his home in 2003—I’ve been lucky enough to visit him there regularly since 1974—my old friend Brigitte Lacombe sat quietly on a sofa, taking everything in. Then she asked His Holiness if he’d mind stepping out onto his terrace for five minutes. Silently, as relaxed and full of soft smiles as he was, she snapped a few frames on a small camera. When she sent me the result, I noticed one eye all kindness, one all penetration—on both sides of the lens. No amount of fancy equipment or elaborate setup can conjure something as piercing as this.

Pico Iyer is the author, most recently, of The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere (2014).

Photographer unknown, William Finnegan, Padang Padang, Bali, Indonesia, November 6, 2015

Courtesy the author

William Finnegan

I was in Bali for work, but the surf was big, so I borrowed a board. This photograph was taken at a fabled country spot called Padang Padang. It was my first wave of the morning. At the captured moment, I am about to make a mistake. Farther down the reef, Padang has two bowling sections—shallow spots where the wave becomes a violent barrel—and the correct line of attack for those sections is high on the wave’s face. When I look at this image, my heels dig into the floor, my shoulders turn—what I should have done. But I was unfamiliar with the reef, and the board, and instead I held the low line you see, which did not work out well. What did work out well: several hours later, while I was hiking back to the road, a local teenager accosted me with a laptop computer. He had been shooting pictures from a cliff above the break, he said. He sold me this shot, on a flash drive, for eight bucks. It’s been on my laptop, haunting me gently, for the year since.

William Finnegan is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author, most recently, of Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life (2015).

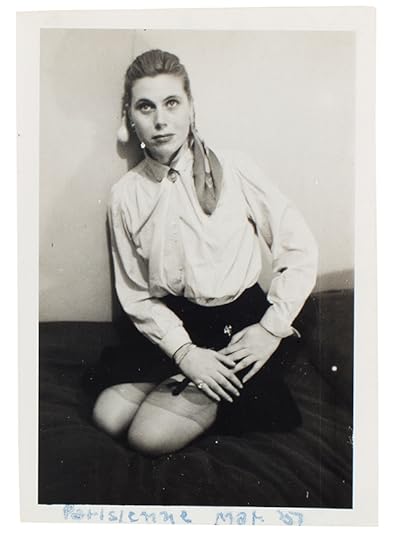

Samuel Levine, Parisienne, 1951

Courtesy the author

Sasha Levine

My older sister found this photograph of a Parisian woman in an old album, tucked away in our childhood home. She scanned it and reprinted the wallet-sized image at about three feet tall. It hangs in my bedroom in a simple, handsome walnut frame, catty corner from a second picture of the same woman reclined in an even more suggestive pose. My grandfather, Papa Sam, took these photographs in 1951, just two years before my father was born. He was thirty-seven years old and still a bachelor, traveling to Europe after World War II to import cameras for his family’s pawnshop in downtown Boston. Rumor—or dark family secret—has it that he may have had a German lover, of whom his parents didn’t approve. Perhaps there were others, too, including this Parisienne. I never met my Papa Sam, but my father tells me that he never thought of himself as an artist. I wonder what he’d think about having his work hanging in his granddaughter’s home.

Sasha Levine is the Digital Editor of Departures magazine.

Steve Berman, La Gioconda, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Stephanie Rosenbloom

I go to Paris once a year and one of my favorite things to do is walk alone on quiet streets and through lesser-known museums. This photograph, by my friend and colleague Steve Berman, was taken in the Louvre, perhaps the city’s busiest and best-known museum. Visitors who have come to see the Mona Lisa are gazing at camera lenses or at themselves rather than at the centuries-old da Vinci masterwork at their backs. In an age of Instagram and Twitter, this image, a gift to me from the photographer, serves as a personal reminder to look outward; to be present; to experience, not tweet, the moment.

Stephanie Rosenbloom writes the column “The Getaway” for the New York Times.

Betsy Karel, Hanging Gardens, 2006

© the artist and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Suketu Mehta

I don’t know the people in this photograph by Betsy Karel, which hangs in the living room of my Manhattan apartment, but I know them. They could be any of the groups of retired men that go for a daily walk: before the sun starts loaded for bear in the morning, or after it has admitted defeat and is sliding down the Bombay sky. The place is Hanging Gardens, green oasis of my boyhood. I can’t listen to what’s being said in the photograph, but I know the dialogue. The Parsi wit in the black cap has just cracked an off-color joke about a politician or film star. They’ve known each other for half a century now, and done what they’ve needed to in life. They can now leave their wives and their grandchildren behind to enjoy this daily constitutional, argue agitatedly about the state of the country, and laugh uproariously at the Bawa’s remarks. On the right is a group of youngsters also hanging out, but not having half as much fun as the geezers. This is a photograph that makes me look forward to growing old.

Suketu Mehta is Associate Professor of Journalism at New York University and the author of Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found (2004).

Read more from Aperture Issue 226, “American Destiny,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Around the World in Six Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Dispatches: Istanbul

In Istanbul’s photography scene, the anxious aftermath of a violent year.

By Kaya Genç

Charlie Kirk, Okmeydani, Istanbul, Berkin Elvan protest, 2013

Courtesy the artist

“A photograph can be incredibly intimidating for cops,” Tuğba Tekerek, a Turkish journalist, told me recently. “They can use it to crush you.”

The last twelve months have seen Turkey navigate an accumulation of violent incidents and growing surveillance; with them, the environment for photographers has changed for the worse. In this country, which occasionally tops the New York–based Committee to Protect Journalists’s annual list of the world’s leading jailers of journalists, taking pictures is an increasingly political and dangerous act.

Tekerek, arrested twice last year for photographing people in public spaces, was speaking from experience. When we met at a Caffè Nero one quiet morning last September, Istanbul had not fully awoken from the nightmares of 2016. ISIS suicide attacks on Istanbul’s main shopping avenue in March and in its airport last June, followed by a coup attempt by a religious cult that ended up killing hundreds of civilians in July, unsettled the city.

“Taking pictures here has turned into a big problem only in the past three years, following Gezi,” she said, referring to violent protests around Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park in 2013. Intent on documenting human rights violations, Tekerek often photographs in civic areas—the corridor of a courtroom, the garden of a police station. But these are the kinds of images likely to land the reporter behind bars. On the occasions Tekerek has been taken into custody, police officers have asked whether she is a terrorist studying the area for an attack. Twice, cops confiscated her camera and placed her in a locked room. Tekerek’s supposed crime, meanwhile, stays the same: her pictures contain images of uniformed or plainclothes police officers.

Bülent Kılıç, A young girl wounded with tear gas after the funeral of Berkin Elvan in Istanbul, March 12, 2014

© the artist/AFP/Getty Images

Charlie Kirk, a British photographer, made the same discovery when he arrived in Istanbul in the summer of 2012, following a career as a derivatives lawyer. “I was amazed by the number of protests on İstiklal Avenue,” Kirk recalled. The 2013 protests at Gezi Park were a revelation for him. His first night photographing, on May 29, when tens of thousands packed the avenue and helicopters dropped tear gas on them, was burned onto his mind. Kirk produced a series of images using what the Australian photographer Rob Vallender describes as Kirk’s gonzo style: an aggressive approach toward his subjects, whose unsuspecting faces he illuminates with an off-camera flash. With raw and clear-eyed realism, Kirk captured protests in the wake of the suppression of the Gezi uprising and the unrest in ethnically diverse Istanbul neighborhoods. He plans to publish his protest photographs in a book, but not in Turkey, where he fears censorship.

A few days after speaking with Kirk in September 2016, I paid a visit to the offices of Geniş Açı, a collective and formerly a prestigious photography magazine that ceased publication after producing fifty issues between 1997 and 2006. Refik Akyüz and Serdar Darendeliler, the duo who run the initiative, had sad news to share: the World Press Photo traveling exhibition, which they had been responsible for organizing at Forum Istanbul since 2009, usually opens every August, but there was no attempt by World Press Photo to renew the contract for an exhibition in 2016.

“The photography community here is used to attending the premiere every year at the end of August,” Darendeliler said. “People were telephoning us to ask when the opening would be.”

Mauricio Lima, A doctor rubbing ointment on the burns of a 16-year-old Islamic State fighter named Jacob in front of a poster of Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, at a Y.P.G. hospital on the outskirts of Hasaka, Syria, August 1, 2015

© and courtesy the artist

Akyüz and Darendeliler felt that the nonrenewal must have been political. In particular, they suspected the presence of a singular image by Mauricio Lima in the exhibition as possibly being the cause. Lima’s photograph shows a doctor treating a sixteen-year-old ISIS militant at a hospital in northern Syria. A framed portrait of Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdish armed movement PKK, hangs in the background. (Turkish officials consider PKK—which routinely attacks Turkish security forces—and ISIS to be equally violent terrorist groups.) When Lima’s photograph won the World Press Photo Contest’s first prize in the general news category in February last year, Akyüz and Darendeliler received an email from the organization’s Amsterdam office, inquiring whether the image would cause an issue. But World Press Photo, in response to my question about the exhibition, stated, “Our exhibition requires local partners for it to be organized in each location and local partners are not always available.”

“We have never encountered censorship while editing our magazine,” Akyüz said. “In 2007, we organized an exhibition in Bursa, with lots of nude images. The mayor, a member of the conservative ruling party, came to visit, looked at the images, and just walked by.” In 2015, Bülent Kılıç’s photograph of a young girl wounded during clashes in Istanbul received a World Press Photo Award and was exhibited without any problems.

Whether censorship or conservative caution was at play with the failure to present the exhibition in Istanbul, the atmosphere is more stark in eastern Turkey. Tuğba Tekerek told me of photographers who, when attempting to take pictures in war-ridden areas, were met with willful intimidation from military snipers. In one case, a photographer visibly shaken by the riot gear and machine guns was asked by a special operations police officer, “Why are you so scared of my machine gun? Your camera is more powerful than my gun, and much scarier.”

Kaya Genç, a novelist and essayist based in Istanbul, is the author of Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey (2016).

Read more from Aperture Issue 226 “American Destiny,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Dispatches: Istanbul appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 6, 2017

A Witness to Resistance

From student demonstrations to farmers in revolt, Kazuo Kitai captured the social tumult of 1960s Japan.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

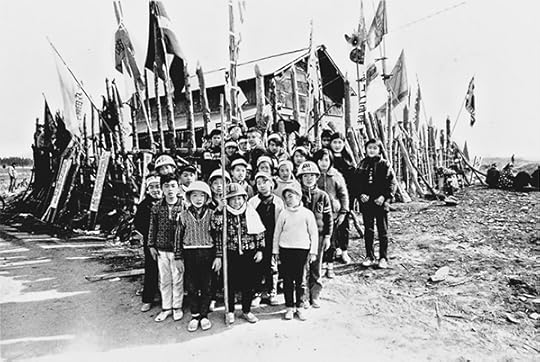

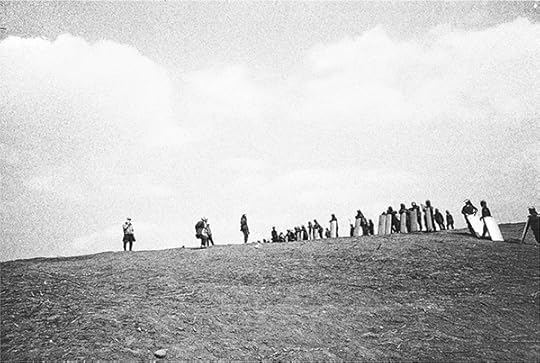

Kazuo Kitai, Childrens’ Resistance Corps, 1970, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

“I wanted my pictures to be just the opposite of what passed then for excellence,” Kazuo Kitai remarked in the introduction to Barricade, his 2012 monograph. His blurry, out-of-focus snapshots from the 1960s were radical in style and substance. In 1965, at the age of twenty, Kitai published his first book, Resistance, which pictured the 1964 demonstrations near the U.S. Navy base in Yokosuka. From 1966 to 1967, he worked exclusively for political student groups, documenting their protests. When Zenkyoto, or All Student Union, came to power in 1968, he joined the students occupying Nihon University. The following year, he moved to a village east of Tokyo called Sanrizuka, where local residents clashed, often violently, with the government over the construction of a new airport. In the ’70s, Kitai left Tokyo and shifted focus to photograph rural landscapes and families. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke with Kitai about his engagement with photography and protest.

Tsuyoshi Ito: How did you first get into protest photography?

Kazuo Kitai: In 1964, during my second year at Nihon University, an acquaintance invited me to photograph the anti-nuclear submarine demonstrations. I shot seven rolls of film that night, and developed them right away. I thought, “Wow, these aren’t bad!” I continued my photographing protests, but at first my subjects weren’t pleased with my photographs. At the time, the student movements were treading water. But things began to heat up in 1968 when the All-Campus Joint Struggle League formed and the Barricade Strike demonstrations started taking place throughout Japan.

Ito: Were you working independently?

Kitai: At first, yes. The Asahi Journal and Asahi Graph magazine were covering the student movement and selling quite well. The editors were pleased, but found the accompanying photographs, shot from afar with telephoto lenses, to be sterile and lacking. My first assignment was shooting inside the barricades of the student protest at Nihon University’s College of Art. The publication dedicated a six-page spread to my photos. They titled it something ridiculous like, “Violent Radical Student Protest.” No one on the outside knew what the conditions were like inside the barricades. People were interested in that. My photographs started to develop a good reputation, and I soon had a monthly assignment.

Kazuo Kitai, In front of the Basement Gates, Yokosuka Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964–65

© the artist

Ito: You published several books on the student protests. How were they received by your subjects?

Kitai: Barricade (1968) was one of my first collections of protest photography. At first, there was tension in the air. But as time passed, people became accustomed to life inside the barricade. It was common to see laundry hanging out to dry, people’s beds, and living spaces. Many of my photographs from inside the barricade depicted daily life. I thought that was cool, but the student protesters didn’t like those photos. On the other hand, the collection Agitators (1968), contained intense scenes of protest, and was a hit among the students.

Ito: What was your next stop after photographing the student movements?

Kitai: In the late ’60s, the government had plans to build a new international airport (near Tokyo), Narita, and the farmers in the area fought to defend their land from appropriation. I began visiting Sanrizuka, a farming village at the center of the struggle. I contacted the editors of the Asahi Graph with a proposal that I stay and shoot in Sanrizuka for two years, and they agreed. From 1969 to 1972, I photographed the daily lives of farmers as well as their protests.

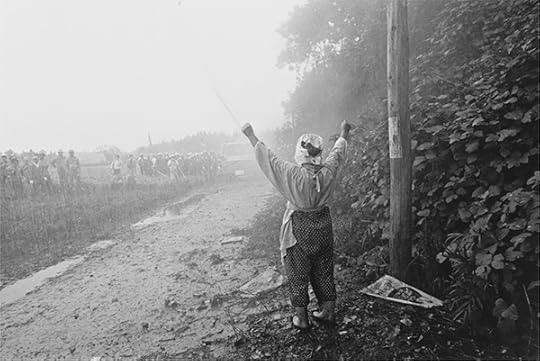

Kazuo Kitai, Old Lady Faces the Water Cannon, 1970, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

Ito: How did that experience influence your photography?

Kitai: My perspective changed completely. A common perception is that photographs simply record events as they unfold. But I came to believe that a photograph is a conversation between the photographer and the subject. That really influenced me, and even today I try not to force my shots. I prefer that both my subject and I both act naturally, and I think my photographs capture that.

Ito: What was the political climate at the time of the student protests?

Kitai: There were two major student movements at the time: the Liberal Revolutionary Student Movement, which was very political, and the All-Campus Joint Struggle League, which was more focused on the democratization of universities. I photographed them both. Requests started to pour in from newspapers, always wanting more and more provocative photographs. But I wasn’t really interested in that type of photography. I was living with the protesters, but I never really got radicalized. I wasn’t there for the action.

Slowly, the photos that were requested of me and my idea of what my photography should be began to diverge. And I was fine with that. I realized that if I wanted to become a professional photographer, I would have to be serious about my craft. Shooting a demonstration is simple. There’s always something happening, you just point and shoot. I wanted to come up with a theme that resonated with me, and the first thing that came to mind was Eugène Atget and his photography of everyday people in Paris. That really appealed to me and I thought I could try something similar.

Kazuo Kitai, Women Facing the Police on a Hilltop, 1971, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

Ito: But before you changed direction, you were very involved in the protests?

Kitai: Behind the barricades I threw Molotov cocktails along with the student protesters. In Sanrizuka I was ready to be arrested at any time. I was a photographer, but I was also a part of the resistance.

Ito: So you wanted to bring about societal change through your photography?

Kitai: I never even considered that. Of course photography is a form of expression. It has the power to influence people and even change society. But I never took a picture with that in mind. I think that if you take photographs with that kind of intention, then your product will be necessarily altered.

Ito: You didn’t see your photography as political expression?

Kitai: Politics is power and violence. Strength passes for power in politics. But I was only armed with what I could express through my lens. There was no overlap between politics and the pictures I was interested in taking. I don’t like depressing photography. I prefer photos with more humanity—photos that encourage empathy with the subject. You can see this in my series To the Villages (1973–81).

Kazuo Kitai, Washi Village, Agawa district, Kochi prefecture, 1973, from the series Mura e. / To the Village, 1973–81

© the artist

Ito: The human element is important to you?

Kitai: Yes. I don’t have many critically acclaimed photographs, even from my days as a protest photographer. But my subjects would often ask me to send them prints. It was a different time then, as opposed to now where photos are readily available to anyone. My subjects would keep it as a memento, showing their friends, “Look at this picture that one famous photographer took of me!” I knew how important it was for them, so I made it a priority.

Ito: How did your subjects react upon seeing To the Villages?

Kitai: They loved the photographs, same with the farmers and protesters from Sanrizuka. I think it was because I lived with them. I understood them and respected their lifestyle, and my photos mirrored their own perspective in an intimate way. It was popular at the time to appeal to viewers by highlighting someone’s hardships—showing the wrinkles on their sunburnt faces and their leathery hands. But the subjects themselves didn’t like that. I prefer to highlight the good side of people, to capture their presence and the reality of their existence.

Tsuyoshi Ito is founder and managing editor of A/fixed, a leading resource on the history of Japanese photography.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s will be released in April 2017.

The post A Witness to Resistance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 5, 2017

Inside the 2017 Aperture Spring Party and Dinner

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

[image error]

[image error]

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

[image error]

[image error]

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Will Matsuda/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Carly Lovejoy/Aperture © Aperture

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/PMC © Patrick McMullan

On March 31, Aperture’s Spring Party and Auction was awash with brightly colored ensembles, whimsical fedoras, turbans, and many a bow tie. Celebrating the pre-launch of Aperture’s forthcoming book Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style, the more than 325 guests who attended were treated to an evening with Shantrelle P. Lewis, Dandy Lion’s curator and author. The event was co-chaired by Taymour Grahne, Darius Himes, and Thomas R. Schiff. During an elegant Host Committee Dinner on the rooftop of the NoMad Hotel, guests were seated at the table with Dandy Lion contributors, including Lewis, Iké Udé, Erik Carter, Ouigi Theodore, Rose Callahan, Sara Shamsavari, and Dandy Wellington.

At the Spring Party, guests danced late into the night under a disco ball at Aperture Gallery, where The Library Exhibition is on view. Accompanied by a surreal dance performance, the Afro Cuban rapper Kool A.D. got the crowd moving, along with the old-school hip-hop played by DJ Lumumba a.k.a. Revolution. The print Flower Girl by Hassan Hajjaj, in a unique red Michelin tire frame, as well as a pet portrait session with Richad Phibbs at the Humane Society of New York, were sold in the silent auction. Guests also vied for the special raffle items, including two custom bow ties designed by Lewis herself and a copy of Dandy Lion, signed by select contributors.

Courtesy of Patrick McMullan Company, click here to view Host Committee Dinner photos and click here to view Spring Party photos. Additionally, view all of the PHHHOTO booth photos by clicking here. If you would like to support Aperture, but weren’t able to join the fun at the Spring Party, we invite you to donate to Aperture’s Annual Fund.

For this brilliant and stylish event, Aperture wishes to thank co-chairs Taymour Grahne, Darius Himes, and Thomas R. Schiff; Shantrelle P. Lewis; Christie’s; all of the contributing dandies; AIPAD; Destination Artists Touring Agency; Patina Rentals; Patrick McMullan Company; PHHHOTO; photograph magazine; Stella Artois; Ziobaffa; KOOL A.D.; and DJ Lumumba a.k.a. Revolution.

Special thanks to the Host Committee and the Spring Party Committee, and to all of the Aperture staff, work scholars, volunteers, and ambassadors for their time and dedication.

Host Committee

Andrew Craven

Anne Stark Locher and Kurt Locher

Barbara and Donald Tober

Bradford Richardson

Cathy M. Kaplan*

Chris Boot and Tony White

Dandy Wellington

Darius Himes, Christie’s*

Darlene Kaplan and Steve Zuckerman

Darnell Moore

Ed Messikian, Fine Art Frameworks

Elaine Goldman and John Benis

Emily Bierman, Sotheby’s

Howard Greenberg

Iké Udé

Jessica Nagle and Roland Hartley-Urquhart*

Kasper and Linda Lindenbaum

Lori Grover

Magic Group Media*

Malú Alvarez

Michael Hoeh

Missy and Jim O’ShaughnessyNion McEvoy

Ouigi TheodorePatrick McMullan

Peter Barbur and Tim Doody

Raymond Learsy

Rita Anthoine

Rose Callahan

Sb Cooper and R.L. Besson*

Shantrelle P. Lewis and Tony Oluwatoyin Lawson

Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla*

Drs. Stephen and Marsha Silberstein

Susan Gutfreund

Tabitha Soren

Taymour Grahne*

Thomas R. Schiff*

Whit Williams

Willard Taylor and Virginia Davies

*Leader

Spring Party Committee

Alice Finnerty

Aliza Sena

Esther Zuckerman

Mike Tan

Sam Pritzker

Sarah F. Haimes

The post Inside the 2017 Aperture Spring Party and Dinner appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 4, 2017

The Surreal Landscapes of California City

From the air, photographer Chang Kim discovers a city that never was.

By Geoff Manaugh

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160616_05, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

In his recent book, The City That Never Was: Reconsidering the Speculative Nature of Contemporary Urbanization (2016), architect and urbanist Christopher Marcinkoski writes about the strange fate of entire cities created for the speculative possibility of future financial gain. For Marcinkoski, these are places of urban development predicated not on real, existing demand in the current marketplace, but on projected possible consumer interest in an unrealized tomorrow. They are cities for people who don’t exist yet, funded by “increasingly complex transactional instruments” whose value is divorced from anything resembling civic good or democratic well-being.

The resulting developments often fail before reaching the point of being even partially inhabited, Marcinkoski warns. At times, they are abandoned long before construction is complete, deserted by their heavily leveraged investors and left in an eerily half-finished state that has no clear resolution. The result is a kind of zombie urbanism, both undead and stillborn at the same time.

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160629_05, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

California City is roughly two hours north by northeast from the desert edge of Greater Los Angeles. It was launched in 1958 as the dream of real-estate developer Nat Mendelsohn, who saw it not just as a healthy investment, but as a place that would someday exceed Los Angeles itself in both scale and quality of life.

By land area alone, California City is today the third largest municipal area in the state of California. Yet outside of its small, developed core—complete with a park, fast-food restaurants, liquor stores, and a pharmacy—it is fantastically, surreally, even unsettlingly incomplete. You can drive through California City for twenty minutes or more without even knowing it’s there.

Chang Kim, Utopia incomplete 160603_16, California City, CA, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Seen from an aircraft, however, as in this ongoing series of aerial images taken by photographer Chang Kim (born in Korea in 1974 and now living in Los Angeles), California City’s true scale is revealed. It is, in fact, a bewildering array of gridded streets and culs-de-sac—many named after American automobile companies, such as Buick, Oldsmobile, and Pontiac—scratched into the arid terrain. At times, it seems endless, an immersive geometry textbook of primary shapes all but invisible from the ground, extending forever. The houses meant to appear along these roads and avenues never materialized, of course; the residents meant to live there have yet to arrive.

Sites like California City—or the many failed superdevelopments discussed by Marcinkoski—have, in a sense, become ruins in advance of their own construction. Although radically incomplete, these ghostly locations are not so much remnants of a place or city that once was; they represent the spatial by-products of abandoned financial transactions. They are 3-D receipts for business deals that went nowhere, tragic accounting errors in urban form.

Geoff Manaugh is the author of BLDGBLOG and A Burglar’s Guide to the City (2016).

The post The Surreal Landscapes of California City appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 31, 2017

Against Occupation

Japanese curator Rei Masuda discusses how postwar Japanese photographers adapted to a new era.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Shinjuku Contemporary, 1967-68

© the artist

In 1960, the U.S. and Japan re-signed a security treaty known as Anpo, which maintained U.S. dominance in East Asia, and allowed American troops to be stationed in Japan—indefinitely. In a few short years, the U.S. had flipped from being an enemy to an ally. At the same time, American culture was becoming increasingly pervasive in the country. Protests were staged across Japan in response to these societal shifts—and photographers were soon engaged.

Rei Masuda, head curator of photography at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, has long studied the rich photography of this period, producing traveling exhibitions such as Gazing at the Contemporary World: Japanese Photography from the 1970s to the Present that have introduced an international community to key ideas and figures. Here, Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed speaks with Masuda about his work about post-war photography from Japan.

Tsuyoshi Ito: What first drew you to photography, and which photographers had an influence on you?

Rei Masuda: In 1989, while I was attending university, there was an exhibit on the 150-year anniversary of the invention of photography. More than the photographs themselves, it was that visceral expression of culture and history that inspired me. When I was young, I greatly admired Walker Evans and Robert Frank.

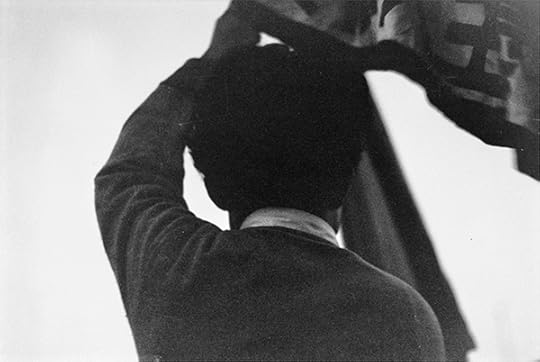

Kazuo Kitai, Flag, Yokosuka, Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964-65

© the artist

Ito: When people think about the radicalism of 1960s and ’70s Japan, student protests are usually the first thing that come to mind. Many segments of society were taking part in the political movements. What’s your take on this highly fluid period during which not only students, but also ordinary citizens from all walks of life, were spurred to action? What kind of influence did that dynamic have on photographers?

Masuda: During the ’60s and ’70s there were many influences on photographers, not the least of which was the protest against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, known as Anpo. That time of unrest gave birth to many exceptional documentaries criticizing the heavy-handed powers that prevailed. In the decade that followed (i.e., the 70s), Japanese society became ever more complex, as did the causes of unrest. Protests expanded to include anti-Vietnam War activism, campaigns to return Okinawa to Japanese control, and anti-Narita Airport movements, among others. Just as in the ’60s, photographers were there to document it. The photography magazine Provoke is often seen as a symbol of these times, but it hardly stood alone. Photographers were documenting events, people, and movements in various, unique ways. It was really a special era.

Kazuo Kitai, Sanrizuka Protesters, 1969, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969-72

© the artist

Ito: During the ’60s, when Anpo was ratified, the aims of both photographers and ordinary citizens had a common cause. At that time, what attracted you to Provoke?

Masuda: Provoke rejected the established photographic aesthetics. Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira were embracing a radical new form of photographic expression. This style was a reflection of the times, of the counterculture and political movements that were peaking in the late ’60s.

Ito: The campaign against the Anpo Treaty was one of the more visible aspects of Japanese–American relations, and the most polarizing social issue of the time. Many Japanese people appreciated American artists and desired American material affluence, but simultaneously resented the pervasive American presence in Japan. What kind of influence did this have on Japanese photography?

Masuda: Japan’s relationship with America was inextricably linked to both photographers and photographic works produced at the time. This is especially evident when looking at the work of photographers like Shomei Tomatsu, for whom the American occupation of Okinawa was a major theme, and Miyako Ishiuchi, who grew up in Yokosuka, in the shadow of an American military base. They were a generation apart and not geographically close, yet Japanese–American relations had an impact on both of them, and not just on their characters. I can’t say that all Japanese photographers were affected in the same way, but the changes in post-war Japanese society are certainly reflected in the people and photography of the time.

Kazuo Kitai, Injured Protestor, Yokosuka, Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964-65

© the artist

Ito: Are there any other photographers that come to mind when you think of American influence on Japan?

Masuda: Take Daido Moriyama, for example. You can clearly see the influence of American contemporaries like Andy Warhol in his photography. At first glance some of his work seems critical of America as well. Though I think that it is more a criticism of America’s influence on and occupation of Japan, rather than America itself. If you consider his formative years, it’s easy to see how he could have such mixed feelings. As a teenager during World War II, he knew that should the war continue, his fate would be to give his life for his country in the fight against America. In post-war Japan, during the occupation, his view necessarily changed as he lived in close contact with the former enemy. Photographers of the day had very complex and unique relationships with America.

Tsuyoshi Ito is founder and managing editor of A/fixed, a leading resource on the history of Japanese photography.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s will be released in April 2017.

The post Against Occupation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 30, 2017

The Joy of Photography

An exhibition in Amsterdam revisits Ed van der Elsken’s passionate vision of twentieth-century life.

By Wilco Versteeg

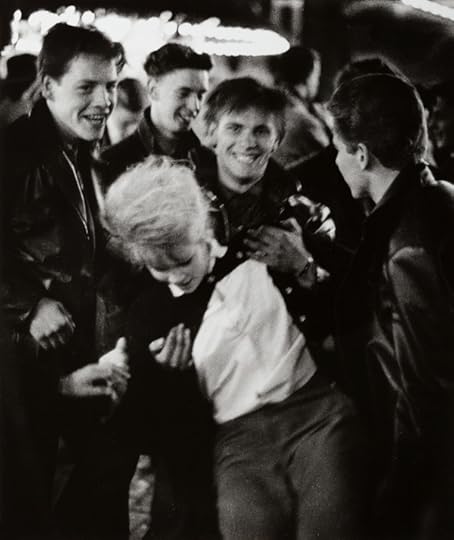

Ed van der Elsken, Nieuwmarkt Fair, Amsterdam, 1963

© the artist and courtesy the Ed van der Elsken estate and Nederlands Fotomuseum

The most famous photographer in the Netherlands, Ed van der Elsken showed the Dutch as they like to see themselves: diverse, open, and rebelliously normal. In the decades after World War II, his photographs effectively defined Dutch identity. Van der Elsken’s idiosyncratic style of street and documentary photography displays his tenderness and love for the world, which is why Camera in Love (De Verliefde Camera), the title of the Stedelijk Museum’s retrospective, the largest exhibition of the photographer’s work in twenty-five years, is well-chosen.

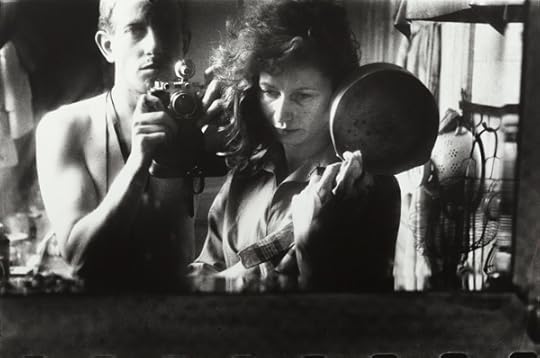

Ed van der Elsken, Selfportrait with Ata Kandó, Paris, 1953

© the artist and courtesy the Ed van der Elsken estate and the Nederlands Fotomuseum

Camera in Love highlights the joy that is apparent throughout van der Elsken’s photography. Many treasures are to be found. In the big, central rooms, his famous photographs are displayed as prints, while the more intimate, adjacent rooms present the genesis of his well-known photobooks through personal notes, contact sheets, and dummies. The exhibition also includes much of van der Elsken’s video work, which is often as personal as his photography. Bye (1990), for instance, shows the photographer in the last stages of a terminal disease.

Ed van der Elsken, Vali Myers with cigarette, Paris, 1953

© the artist and courtesy the Stedelijk Museum and the Nederlands Fotomuseum

The variety of the work allows everyone to choose their own version of van der Elsken. He documented the life and existential crises of youngsters flocking to the Paris in Love on the Left Bank (1956); photographed Equatorial African life in Bagara (1958); and took dramatic and iconic close-ups of musicians in Jazz (1959). Known for his big mouth and upfront attitude, van der Elsken often provoked the people he met on the street. His best work catches the expression when a subject realizes a camera is aimed at them, but before they are able to strike a pose. Today’s street photographer, by contrast, is challenged to find a way around the banality and self-censorship that comes with the ubiquity of the camera.

Ed van der Elsken, Girl in the subway, Tokyo, 1984

© the artist and courtesy the Stedelijk Museum and the Nederlands Fotomuseum

Van der Elsken’s more political work—documenting riots, police violence, and the down and out—is not overtly didactic. While showing the marginalized, his engagement is not systematic and does not provide a clear-cut critique of capitalist society. But what is most striking is the intimacy of his portraits. Of a photograph of Dutch counterculture writer Simon Vinkenoog and his girlfriend enveloped in each other’s arms, Nan Goldin writes, in the accompanying catalog, “They are so naked, I can feel the flesh.” In fact, the connection between van der Elsken and Goldin is revelatory. “I realized I had just met my predecessor. My real predecessor,” Goldin continues. “The feeling was similar to that of meeting a lover, or of finding a brother.”

Ed van der Elsken, Bargirls, Cebu, Filippijnen, 1960

© the artist and courtesy the Stedelijk Museum and the Nederlands Fotomuseum

Van der Elsken introduced a crucial pivot in documentary photography, and Camera in Love marks a renewed interest in a photographer who, in Dutch culture, is never far away, but who can only be fully understood in an international context and alongside such seminal image makers as Weegee and Edward Steichen. With the full breadth of van der Elsken’s work, Camera in Love is the most spectacular photography exhibition in the Netherlands has seen in decades.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD candidate at Université Paris Diderot.

Ed van der Elsken: Camera in Love is on view through May 21, 2017 at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

The forthcoming issue of The PhotoBook Review (Issue 012/Spring 2017), guest edited by independent curator Daria Tuminas and developed in partnership with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, focuses on the intersection of cinema and the photobook, inspired in part by Ed van der Elsken’s landmark work in both photography and film. Complementary issues will be available on site at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam as well as at the Aperture Gallery, New York, beginning April 3, 2017.

The post The Joy of Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 29, 2017

Video Response: Amos Mulder on Inka and Niclas Lindergård, The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth

Amos Mulder is a video artist whose works include visual responses to found footage, texts, and photographic images; he describes his series as “video haikus,” adding that “I love to explore these parallel universes and catch their atmospheres and governing principles in short films. While rooted in the history of cinema, these films are also inspired by (and combined with) other nice things such as music, photography, and philosophy.” For this issue, he accepted guest editor Daria Tuminas’s assignment to create a video response to Inka and Niclas Lindergård’s The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth. The video work, created with a single camera, ambient light, and—echoing the artists’ process as featured in the book—no visual effects added in postproduction, is presented here.

The post Video Response: Amos Mulder on Inka and Niclas Lindergård, The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 28, 2017

How Soon Is Now?

A sprawling exhibition showcases Wolfgang Tillmans’s restless curiosity—about everything.

By Aaron Schuman

Wolfgang Tillmans, Central Nervous System, 2013

© the artist

Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017, which opened last month at London’s Tate Modern, is a genuinely overwhelming and immersive experience. Incorporating works made between 2003 and 2017, the show spreads ivy-like across the walls and vitrines of fourteen of the museum’s immense galleries, charting Tillmans’s wide-eyed engagement with new forms of technology (photographic and otherwise), artistic practice, geopolitics, notions of “truth,” community, media, migration, and more. Tillmans insists that the exhibition is in no way a retrospective, but is instead a new and complex artwork in itself. “I spend all of my days thinking about these objects,” he explained at the press preview in February, “and making this show reminded me that art is at the center of what I do; it’s about the Now.”

Wolfgang Tillmans, Juan Pablo & Karl, Chingaza, 2012

© the artist

Throughout the exhibition—in the “Playback Room,” for example, where various bands’ studio recordings can be absorbed at their highest fidelity, or in Instrument (2015), a video and sound piece that converts Tillmans’s rhythmic footsteps into a throbbing soundtrack—music and photography are aligned and celebrated. The exhibition itself functions as a brilliant visual album, with each gallery serving as a distinct “track” with a particular mood, tempo, or theme. And like an accomplished musician, Tillmans is careful to avoid being too literal or pedantic. “I don’t expect anybody to understand this exhibition,” he remarked. “It’s about resonances, and the connections between us.”

Such connections have long been at the foundation of Tillmans’s work, and were foregrounded in his 2003 Tate Britain exhibition called If one thing matters, everything matters. As both that title and his signature installation strategy (constellations of prints of various scales and mediums, hung at different heights and by multiple means, from traditional frames to bulldog clips) suggest, he is not particularly concerned with the power of any individual image, but rather with the relationships between and collective effect of groupings of observations and encounters as captured through photography.

Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017, installation at Tate Modern, London

Courtesy Tate Photography

The first two galleries at Tate Modern meditate on new forms of digital image production. A series of kaleidoscopic collages, Double Exposure (Fespa Digital / Fruit Logistica) (2012), juxtaposes images from trade fairs for digital printers with those from trade shows for fruits and vegetables. In an adjacent gallery, amongst photographs of the artist’s own studio, a large-scale, framed print of Tillmans’s defunct color photocopier—CLC 800, dismantled (2011)—exposes the elaborate inner-workings of the most basic of contemporary image-generating machines. And, later in the exhibition, several spaces are exclusively dedicated to Tillmans’s experiments with photographic materiality, abstraction, and repetition, incorporating many of his darkroom manipulations and photo-paper sculptures from four ongoing series: Lighter, Paper Drop, Silver, and Abstract Pictures.

Wolfgang Tillmans, paper drop Prinzessinnenstrasse, 2014

© the artist

But Tillmans’s interests extend far beyond explorations into photography’s nature and permutations. His genuine dedication to both political and cultural engagement are also strongly highlighted, through displays of his prolific contributions to pop and print culture via books, posters, album covers, and magazines, as well as through works that address today’s political tensions and humanitarian crises. In the final gallery, a photograph of a shipwreck left by refugees on the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa hangs among images of various airport border controls and sublime seascapes of the borderless Atlantic Ocean. These of-the-moment concerns are presaged by earlier series such as Neue Welt (2012) and truth study center (2005–ongoing). The former represents Tillmans’s own travels through five continents, but in a dreamlike way, with the intention of exploring “the surface of things as they appear in those lucid first days of being in a new environment.” The latter consists of photographs, newspaper clippings, and documents that explore how political and socical “truths” are constructed and distributed, from mainstream media justifications for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to far-out conspiracy theories.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Lampedusa, 2008

© the artist

But it is in one gallery (Room 11), which lacks any obvious theme, where Tillmans improvises most freely and is at his most virtuosic. According to the exhibition leaflet, this is a space where Tillmans “highlights the coexistence of the personal, private, public and political spheres in our lives.” Here disparate images intermingle and harmonize: tender nudes, wispy clouds, a grid of small portraits (including those of Patti Smith and Morrissey), a group of Black Lives Matter protesters, complex still lifes, a seductively lit windowsill, and probably the most beautifully rendered photograph of a man’s buttocks and scrotum as one is likely to encounter. The space visually sings, overwhelming not only one’s vision, but the totality of the senses.

Although Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 encompasses large social, cultural, and political issues, the exhibition is ultimately about how such concerns touch even the smallest moments in our everyday lives and reverberate to the core of human experience. “The artist is the hand that plays,” the painter Wassily Kandinsky once wrote, “touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” Walking out of Tate Modern and back into “the Now,” one’s soul can’t stop buzzing.

Aaron Schuman is an artist, writer, and curator based in the United Kingdom.

Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 is on view at Tate Modern, London, through June 11, 2017.

The post How Soon Is Now? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers