Aperture's Blog, page 121

March 8, 2017

Full Color Feminism

A former Riot Girrl, Becca Albee’s photography unpacks the politics of color.

By Annika Klein

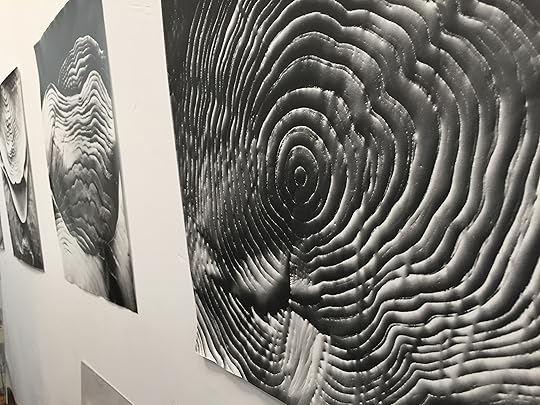

Becca Albee, Eyre, MR, 2015. Installation at 356 S. Mission Rd, Los Angeles, 2015. Photograph by Brica Wilcox

Courtesy the artist and 356 S. Mission Rd

In early October, when I spoke with Becca Albee about the roots of her artwork in activism, feminism, and ’90s punk, little did we know what was ahead: an upset of an election and a resurgence of mainstream feminism, including “Pussy Hats” on the runway. Rooted in a curiosity about physical materials from negatives to newspapers, Albee investigates the mechanisms of history. Her most recent work, now on view as prismataria at Et Al in San Francisco, considers color—seemingly formalist, but deeply political. When color, or a sensitivity to it, has been long associated with women, what does it mean to be neutral?

Annika Klein: How does your musical background—specifically feminist punk and Riot Grrrl—influence your approach to photography?

Becca Albee: Playing music in the early ’90s, when I was living in Olympia, Washington and attending Evergreen State College, was formative. In part because of the political climate—there was a sense of urgency, and with music, there was almost an immediacy in communication. I was self-taught and learned from, and created with, my friends. I was able to blend together my interests in biography, art, and politics within a larger community. When writing lyrics, I could reference an individual or an issue, and through metaphor, layer the narratives. The music originated from a feminist core—which is to say, placing feminism at the center of my work, rather than patriarchy. There was no separation between what was and was not my art: I made zines, I made songs, I made images.

In the late 1990s, when I started to make more visual art than music, I hung on to the same starting points that I did with songwriting, which was a concept that was initiated by an impulse: experience, historical, material. Those were all things that I was making music with and about, and ultimately is how I start my projects.

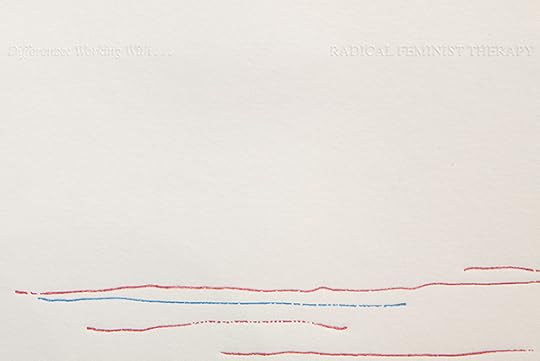

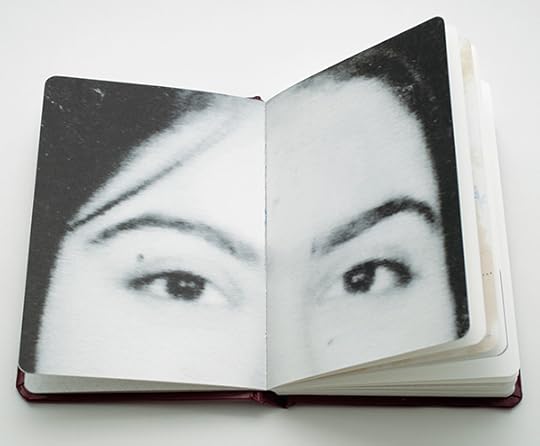

Becca Albee, Radical Feminist Therapy, 12. Difference, Working With… (detail), 2016

Courtesy the artist

Klein: Your series Radical Feminist Therapy: Working in the Context of Violence shares its name with a book by philosopher and feminist therapist, Bonnie Burstow. What is your relationship to Burstow’s book?

Albee: At Evergreen, I took a course called “Women’s Health and Healing.” Radical Feminist Therapy was one of my textbooks from that class. A foundation of the book is that there should be a general understanding that the patriarchy is a violent society, and the importance of recognizing the impact of oppressions and multiple oppressions. I still have my copy of the book, where I wrote numerous notes in the margins with color pens. For this print series, I removed all of the printed text and left my marks: the underlines and notes. Each print represents all of the markings from a single chapter.

Klein: Most artists, especially photographers, want their work to be shown in perfectly neutral lighting. In your most recent exhibitions, why did you install a light that changes colors?

Albee: There is a Works Progress Administration mural in San Francisco called the Prismatarium, which was created in 1939 by Hillaire Hiler. It’s a circular room, with gray walls and a color wheel painted on the entire ceiling. Hiler was a psychoanalyst, color theorist, and painter. For him, color is about psychology. The Prismatarium was originally purposed as a ladies’ lounge. In the WPA proposal for the mural, he wrote that everyone knows “the fair sex” has a higher connection to color. The proposal also references a light fixture that would rotate through cyan, magenta, and yellow—which he considered to be the primary colors. From all accounts, that light fixture was never made. So, I fabricated this rotating light fixture and created photographs that are meant to be viewed in this cyan, magenta, and yellow light.

Becca Albee, Untitled, 2015. Installation at 356 S. Mission Rd, Los Angeles. Photograph by Brica Wilcox

Courtesy the artist and 356 S. Mission Rd

Klein: You mentioned that the Prismatarium was intended only for women, and you have also have photographed color-based products, such as Aura Soma, that are clearly marketed to women. How does you interest in color relate to you interest in feminism?

Albee: I researched different lifestyle-oriented, color-related methods or therapies, looking at the gender constructs surrounding the marketing of color and its relationship to capitalism. For Aura-Soma, you go to a specialist, and there are numerous bottles with two different color liquids presented in a lighted grid, and you pick the three or four bottles that you’re drawn to. It is clearly marketed to women—the perfume bottles, the colors. The session is somewhat like a Tarot card reading, but you’re supposed to buy your selected bottles as “color therapy for the soul.”

What do you do when you are both attracted to and repulsed by something? In some cases, I created photographs in the most desirable way possible because I wanted the work to exist within this paradox around color: you can be circumscribed and exhilarated by it; limited and animated by it.

Becca Albee, Radical Feminist Therapy, 12. Difference, Working With… (detail), 2016

Courtesy the artist

Klein: Newspapers are a recurring theme. What attracts you to this analog media?

Albee: I am interested in how we experience information, what actually gets filtered through and presented, what images we are shown, and not shown. The handheld newspaper is a historically important format that I first used for a project called Newspaper & Flowers. In 2006, I started to digitally replace journalistic photographs from newspaper clippings with photographs of flowers taken by my grandfather, Ellis Albert Resch (1903–1974), who had worked at the New York Times as a low-level assistant in his late teens. In the years before his death he took hundreds of photographs of flowers, which I obtained a decade later. At the same time, I was collecting articles that angered me—most were about the Bush Administration and U.S.-involved conflicts. Eventually, I merged the two together.

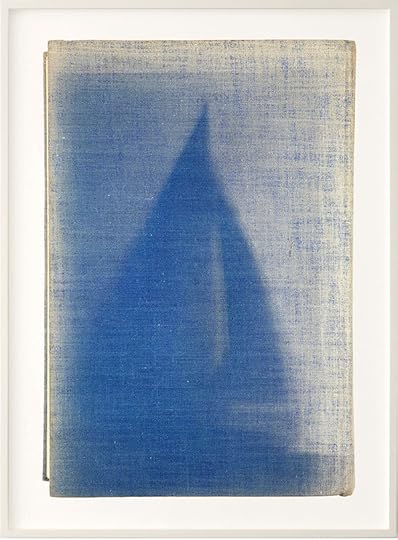

Becca Albee, Cradle of the Deep, Joan Lowell, 1929, 1st Edition, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Klein: Your series Joan Lowell: The Only Woman also considers the historical impact of news by referencing the scandal of Joan Lowell’s fraudulent memoir, The Cradle of the Deep.

Albee: The project began after I read a paper that my father, a historian, wrote about Joan Lowell’s 1929 literary scandal. Lowell was a twenty-six-year-old actress who wrote a bestselling autobiography about growing up on a ship with her sea captain father and an all-male crew. In her book, Lowell positions herself as a child heroine, defying her gender expectations. In a review, Lincoln Colcord, proved that Lowell did not grow up at sea. This review initiated a very public demise. Ultimately, I created photographs, sculptures, and a video performance using Lowell’s constructed biography, the scandal, and related objects as material. Lowell was a complicated character and I was interested in her construction of her own biography and her adamant life-long defense of her narrative. And also how she was scrutinized and brought down and who was able to capitalize on her failure. Who’s benefitting from this?

Klein: Do you think that, in general, women are told that they’re fake or that their credentials are questioned more often than men’s?

Albee: You could look at the U.S. presidential election as the most glaring and blatant occurrence of this double standard—which in this case is so publicly violent and where an unqualified misogynistic, racist, classist, narcissist is even being considered for the most powerful elected office in this country. So yes, absolutely.

Annika Klein is the Editorial Assistant at Aperture magazine.

The post Full Color Feminism appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 7, 2017

Visions of Unity: Six Visual Protests

From coalitions to exhibitions, here’s how artists and institutions are making their voices heard.

By Giada De Agostinis

How do artists stand up for what they believe in? With the rise of right-wing politics in the U.S. and Europe, people across all seven continents have felt a renewed urgency to fight for civil liberties. Though the pundits and politicians may have changed since the 1960s, many of the same issues are at stake. Now, in 2017, there are new channels with which to express dissent—easily shared on the screens, but rarely expressed by museums. As visual protests take shape internationally, they rely on the power of unity. Here are a few initiatives to keep an eye on.

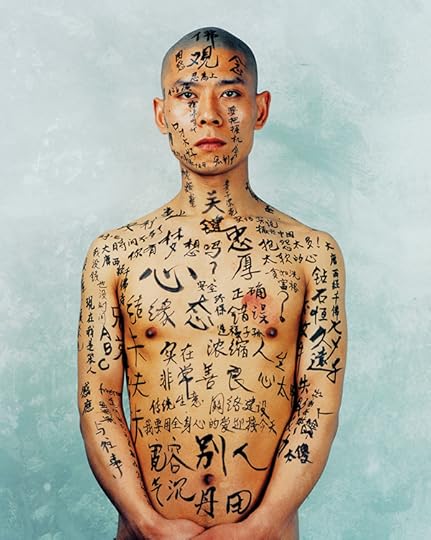

Zhang Huan, 1/2 (Text), 1998

© Zhang Huan Studio and courtesy Pace Gallery

Pace/MacGill Gallery, 32 E 57th St, New York, NY

Through April 29, 2017

Celebrating the first amendment, Speech includes works by Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Jim Goldberg, Gregory Halpern, and others. Documenting historic moments, such as Peter Hujar’s Gay Liberation Front Poster Image (1970), the exhibition also includes more intimate representations of opposition, like the illuminating A Man Talking to God (1975) by Duane Michals. The work on display is a reminder not to take the pride of verbal expression for granted, and a few posters from recent protests are also included.

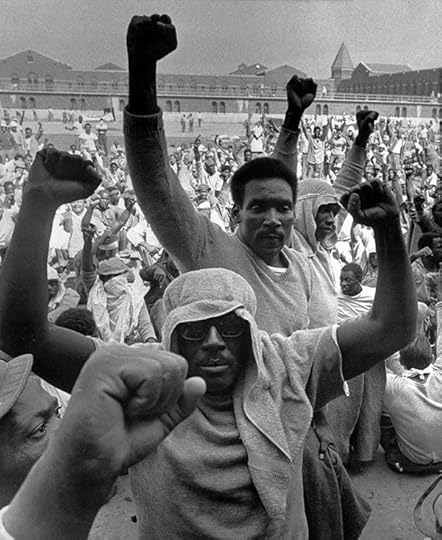

Bob Schutz, Clenched fists at Attica State Prison, Attica, New York, September 10, 1971

Courtesy the Associated Press

Ryerson Image Centre, 33 Gould Street, Toronto, Ontario

Through April 9, 2017

Power to the People is a series of exhibitions covering the civil rights movement from the 1960s to 2016, and exploring images and videos of protest. Attica, USA: 1971 chronicles the prison riots in western New York, where 2,200 inmates rebelled in demand of better living conditions. Also on view, Birmingham, Alabama: 1963 shows Dawoud Bey’s portraits of victims who survived the infamous bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church.

Spread from Amak Mahmoodian, Shenasnameh, 2016

Courtesy 10×10 Photobooks

Through April 3, 2017

10X10, a non-profit organization committed to engaging with the photobook community, has launched an open call for photobooks, zines, and other printed materials focused on political protest. Their aim is to collect works produced with the intent of showing disaffection and dissent and to amplify the diverse voices of resistance. A selection of the submissions will be shown at the Carnegie Museum during the PGH Photo Fair in April.

EJ Hill, Surrendered (A Harrowing Descent), 2016

Courtesy the Studio Museum in Harlem

The Window and the Breaking of the Window

Studio Museum of Harlem, 144 W 125th St, New York

Through April 2, 2017

African American artists have long participated in protests and responded to threats against their freedom, artistic and otherwise. This exhibition borrows its name from one of Pope.L’s Skin Set drawings, Black People Are the Window and the Breaking of the Window (2004), which questions the understanding of racialized language. Pulling from the permanent collection, the exhibition features works by Devin Allen, Alice Attie, Deborah Grant, Steffani Jemison, and Kerry James Marshall, among others.

Mark Titchner, Hands Off Our Revolution (detail), 2017

Courtesy Mark Titchner and Wilma Gold

February 16, 2017—Ongoing

Led by artist Adam Broomberg, this initiative includes more than 200 artists, musicians, writers, and art professionals from forty countries. Stephen Shore, Richard Misrach, Walid Raad, and Wolfgang Tillmans have already pledged their support. The project confronts the rise of right-wing populism by creating a series of contemporary art exhibition and events, the first of which will be announced in March.

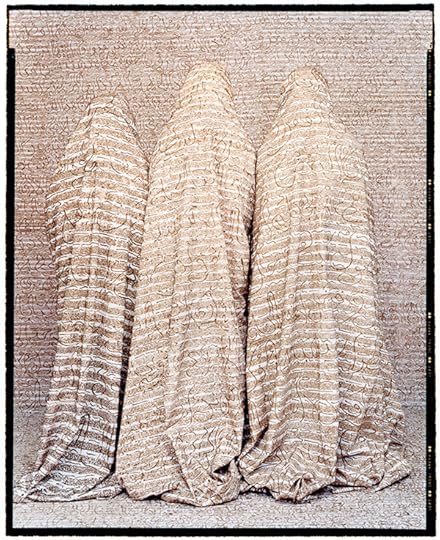

Lalla Essaydi, Les Femmes du Maroc #26B, 2006

Courtesy of Jenkins Johnson Gallery

Jenkins Johnson Gallery, 464 Sutter St, San Francisco

Through March 11, 2017

This exhibition compresses time and space to address current concerns about civil rights. One of the earliest works on view, Gordon Park’s 1963 photograph of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech shows the National Mall flooded with protesters. More recently, in Chicago, Carlos Javier Ortiz’s provides an account on urban life and gun violence. The exhibition also includes several paintings and non-documentary photographs, such as Aida Muluneh’s contemporary take on African body art.

Giada De Agostinis is an Editorial Work Scholar at Aperture Foundation.

The post Visions of Unity: Six Visual Protests appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 3, 2017

Recap of Aperture’s Patron Weekend in San Francisco

Richard Learoyd's work in the group exhibition "Collected" at Pier 24. Photo by Melissa O'Shaughnessy.

John Chiara discussing his upcoming Aperture publication. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Todd Hido's studio. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Sean McFarland discussing work in his studio at the Minnesota Street Project. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Klea McKenna's work and studio at the Minnesota Street Project. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Portrait by Erica Deeman. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Aperture patrons touring "Danny Lyon: Message to the Future" with de Young curator Julian Cox. Photo by Emily Grillo.

Interior of Todd Hido's home and studio. Photo by Melissa O'Shaughnessy.

![Bosker-Gideon[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445481987i/16657920.png)

![Bosker-Gideon[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1489571624i/22227188._SX540_.jpg)

Aperture trustees and patrons at Piccino in San Francisco. Photo by Gideon Bosker.

“Everything worth photographing is in California.”—Edward Weston

The weekend of January 26 through 29, a group of twenty-four Aperture Foundation trustees and patrons enjoyed a weekend in San Francisco, to both check out the contemporary photography scene and pay homage to the city that launched the first issue of Aperture magazine in 1952.

The weekend kicked off with a preview of PHOTOFAIRS, a new art fair dedicated to presenting fine-art photography from international galleries and artists making work around the world. To mark Aperture magazine’s latest issue, “American Destiny,” the Aperture booth at PHOTOFAIRS featured an exhibition of limited-edition prints and commissioned work inspired by America’s social and economic landscape.

On first day, the group was welcomed at SFMOMA by Clément Chéroux, Corey Keller, and Erin O’Toole, who gave an overview of the museum’s Pritzker Center for Photography, the Collection Study Center, Photo Interpretive Gallery, and an in-depth tour of Japanese Photography from Postwar to Now. The Diane Arbus: In the Beginning exhibition was also on view and the group enjoyed comparing and contrasting the installation of Arbus’s work in San Francisco and the presentation at the Met Breuer in fall of 2016. Following the tour, a curated menu spotlighting local chefs at new restaurants was enjoyed at In Situ. The group continued down Market Street toward the Bay for a visit at Pier 24. Pier 24’s director, Chris McCall, led a walkthrough of the exhibition Collected, featuring selections from ten local, dedicated collectors of photography. Following Pier 24, John Chiara welcomed Aperture at his studio and loft space, presenting one-of-a-kind prints from his Manhattan and Hudson River Valley series. Chiara talked about the forthcoming publication he is working on with Aperture, California, capturing the light and landscape along the West Coast.

On day three, Fraenkel Gallery director Frish Brandt presented an impressive selection of masterworks, including Diane Arbus, Sophie Calle, Richard Misrach, Edward Weston, and Garry Winogrand. Todd Hido invited Aperture inside his home and studio in the East Bay, where he told stories about exploring suburban America, and the inspiration for his landscape work. Entrepreneurs and collectors Deborah and Andy Rappaport introduced Aperture to Minnesota Street Project and the Artist Studio Program, “affordable and economically sustainable spaces for art galleries, artists and related nonprofits.”

At the Project, artists Sean McFarland and Klea McKenna invited Aperture into their studios and Erica Deeman presented an exhibition of striking portraits that address visual expectations and historical portrayals. The last stop of the day was a visit to Paul Sack’s vast collection of photography, spanning the history of the medium from its beginnings to about 1975. Stemming from Sack’s career as a real estate investor, every image in his collection includes an ownable or leasable building.

On the last day of the trip, the de Young Museum’s chief curator of photography, Julian Cox led a tour of Danny Lyon: Message to the Future, an impressive and timely exhibition with over 175 photographs, related films, and ephemeral materials documenting social and political issues.

The Aperture trustees and patrons had a tremendous time exploring the photography scene in San Francisco, and linking the history of the medium with the contemporary and tight-knit photography community.

Click here to join Aperture at the Patron Circle level, and enjoy access to trips like this one.

The post Recap of Aperture’s Patron Weekend in San Francisco appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 2, 2017

America’s Destiny in Pictures

What is the role of the photographer in our new political order? Alejandro Cartagena, Nancy Isenberg, Fred Ritchin, Julian Stallabrass, Jose Antonio Vargas, Susan Meiselas, and Sarah Lewis respond.

Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #51, 2012

Courtesy the artist

Alejandro Cartagena

For most of the last century, the United States of America, at least as we have perceived it from Latin America, followed a formula to avoid (or to hide) blatantly corrupt governments. Was it the way the law seemed to be enforced? Was it the obscene amount of money that supposedly made things better? Was it just propaganda that portrayed the United States as a place to realize your dreams? I don’t really know, but it worked—until now. Somehow, as we say here in Mexico, se les viró la tortilla—the tortilla got flipped. It seems like a scene from a bad Hollywood movie. In Mexico we turn on our laptops with pirate IP addresses to watch American TV to contemplate the current state of things. Are we Latin Americans surprised of what is happening in the United States? I have to say, not that much. From here, the “American destiny” seems to be exactly that of the rest of the American continent: daily doses of in-your-face corrupt politicians, demagoguery, lies, and nepotism.

In a recent trip to San Francisco, after the travel ban was enforced, I found myself a bit scared to go to the United States. Just crazy. I went ahead and erased all social media from my phone and my search history from my laptop. I was stepping into a new type of war zone where anything could happen. I made a point to myself only to watch Fox News–type media. I wanted to see America becoming great again. In Latin America we see this happen all the time. I wanted to get a feel for the formula being used to create this “better” world. Such propaganda made me think of the urgency I feel here in Mexico to photograph the urban sprawl in the outskirts of most Mexican cities, or the tough travel and working conditions of Mexican day labors in Northeastern Mexico. It is through these images that we as photographers commit to visualize the lives of those who lack the power to represent themselves.

If the official story of the United States is now going to be written by the people in power, there is a pressing need to have photographers, artists, and writers create alternative story lines that can balance out those coming out from the regime. Photography can empower introspection, giving more options to the American people. Options, as we have been told, create possibilities of a better future. If the “American destiny” wants an opportunity to fulfill itself in a “good way,” it’s time to start looking inwards to the mess the country is in and see what you can say about it, even if Mr. T deems it fake news.

Alejandro Cartagena is a photographer based in Monterrey, Mexico.

Arthur Rothstein, Eroded land on tenant’s farm, Walker County, Alabama, 1937

Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

Nancy Isenberg

I discovered a long history of seeing the poor through the metaphors of wasteland, vagrancy, idleness, inferior breeding, and impoverished minds while researching my book White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (2016). The oldest image, The Mapp of Lubberland or the Ile of Lazye (ca. 1670), portrays an imaginary territory where sloth is contagious and men are drained of the will to work. In the 1930s, when 40 percent of the American population were landless tenant farmers, WPA photographer Arthur Rothstein captured what Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace called “human erosion.” A hapless man is dwarfed before a barren landscape scarred with massive gullies. At the same time, the gully became the symbol of downward mobility. Land was never just a source of wealth, but the measure of civic identity and good breeding. Hence, people who lived on bad land—hillbillies and rednecks (people associated with swamps)—were dismissed as degenerate stock.

This is why the “eugenics mania” of the early twentieth century targeted poor white women as perfect specimens of white trash and perfect subjects of state-mandated sterilization. Nor did class language disappear. Orval Faubus, a controversial governor of Arkansas, embodied the conflicted message of social mobility. He was a poor country boy who rose to become one of the political elite. And yet, in the 1957 Life magazine spread about his rise, one photograph featured Taylor Thornberry, his cross-eyed kin in overalls. This one image made its point with perfect clarity: inheritance and pedigree mattered greatly, even in modern America. The country boy could never really escape his inferior roots.

“American destiny” has never been about the entire population, only those considered worthy enough of inheriting our country’s wealth and benefits. Planters in the antebellum South compared themselves to fine stallions, while eugenicists heralding IQ tests celebrated the rise of an aristogenic class of educated professionals. Sadly, even today we have not escaped this unappealing legacy. The best predictor of success in the United States remains the wealth and privilege passed down from ancestors/parents to children. Photography can play a valuable role in unmasking the truth behind the myth that all are created equal.

Nancy Isenberg is the T. Harry Williams Professor of History at Louisiana State University.

Peter van Agtmael, Max Pons, a biologist and manager of the Nature Conservancy in Brownsville, where the land is bisected by a border fence, Brownsville, Texas, 2016.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Fred Ritchin

We now live in the world of “post-truth” and “alternative facts,” where much of the media is characterized by the U.S. administration as the “opposition party.” At its best the media, and especially photography, have served as credible witnesses to contemporary events, able to focus large segments of society on issues of importance.

Given, however, the diminished credibility of all news media today, what is a photographer of the journalistic persuasion to do? First of all, it seems that the medium needs to be reinvented. Only in photojournalism could someone working today in the style of the 1930s be awarded the World Press Photo award for the photograph of the year (see last year’s Robert Capa-like winner by Warren Richardson, for example). Documentarians and photojournalists must learn from the strategies used by artists, cinematographers, novelists, and poets—“f/8 and be there” is hardly convincing as a strategy when some four billion people are doing the same thing, often calling into question the credibility of all imagery with uncertain standards of fairness. Curators and editors must learn to practice a sophisticated form of metaphotography to make sense of the trillions of photographs and videos online so that the vast amounts of knowledge stored within them can be intelligently shared. And, most of all, everyone must stop communicating only with the groups with which they already agree. The wall that Trump is threatening to build between Mexico and the United States has already been put in place separating many of the denizens of the red states and those in the blue, between those living in rural and urban America; we live in different conceptual universes.

As for the U.S. economy, photographers have hardly begun to look at the systems that underlie much of what is happening, from automation to imports to the disintegration of labor unions, to the ways in which the very rich manipulate the political and economic systems. We need a “USA, Inc.” project, a more extensive version of Philip Jones Griffiths’s 1971 Vietnam Inc., to begin to understand our societal failures and potential. Right now the great hoax is that the Internet makes all things knowable; it certainly does not.

Fred Ritchin is Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography and author of the Aperture book Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (2013).

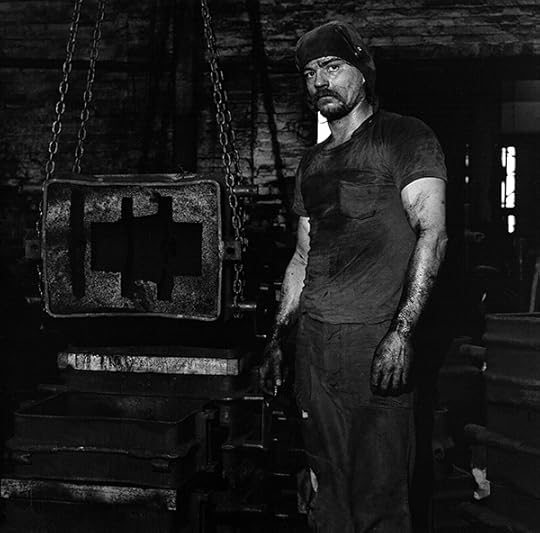

Milton Rogovin, Working People, Amherst Foundry, 1978-87

Courtesy the Rogovin Collection

Julian Stallabrass

In 1993, Sebastião Salgado published his monumental book, Workers, an elegiac testimony to a global world of manual labor that he saw passing away amid the tide of automation. With an economist’s eye, Salgado teased out in stories and text the structural relations of exploitation between corporation, boss, overseer, and worker, between consumers and producers, and between the global north and south. Behind the detail of the individual stories that made up the book, Salgado glimpsed a destiny in the form of an ending, and mourned two endangered activities: manual labor and humanist photography.

What would a photographic project about work’s destiny look like now? It would face the difficulty that among those enslaved to tailoring their human capital to corporate agendas, “work” has permeated everything, even and especially holidays, and involves regular self-display. Salgado’s project, as is true of other humanist photographers, like Milton Rogovin, was in good part about revealing what was hidden at a time of deep political reaction that sought to bury laborers in invisibility. While much remains actively concealed, one can imagine a project now taking the form of an analytical collage of found fragments, cast in the bright colors and cosmetic filters of digital self-advertisement.

Is there an American destiny in this work, which diverts the utopia of self-fulfillment to serving commercial conformity? The word’s grandeur, like that of fate, may momentarily swell the Trumpian chest, and seem apt to describe an empire in decline, with all its attendant dangers. Yet it is paradoxical when applied to the empire of neoliberalism. Destiny suggests that a destination is held in sight, in the way that the eyes of socialist-realist heroes were fixed upon the coming dawn. Yet neoliberalism outlawed such dreams: there can be no direction except that of the untrammeled market, which is nothing other than the rule of contingency. Even in neoliberalism’s present frailty, no future is glimpsed—only a return to an imagined past, oddly similar to Salgado’s Workers, in which brown skins are swapped for white and women for men, in a strange and barely plausible oil- and coal-begrimed nostalgia.

All cultural workers, including those who work with photography, should be building counter-narratives and subjecting “work,” “destiny,” and especially “America” to corrosive analysis. They could also point towards positive liberations from work dissolve the idea of America in its web of global social relations, and wrench the trajectory of capital away from the only destination it appears to offer: catastrophe.

Julian Stallabrass is Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Michael Conti, Great!, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Jose Antonio Vargas

Politics used to begin and end with the relative passiveness of red and blue lawn signs. Now weaponized words, heavy with histories of derogating others — “illegal,” “alien,” “tranny,” “gang-banger,” and “terrorist” (to describe Muslims exclusively) — have been accepted in the national discourse, all in the name of making our country “Great.”

As Toni Morrison said, “The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, midwifery properties for menace and subjugation.”

In a world where the news has become a frontline of the American culture war, we must understand and honor the power of language if we are to live free of this menace. The words we choose to use do more than represent an idea. They represent who we are: our values, opinions, and the level of our love and empathy for others.

How can we communicate with one another when we are not speaking the same language? Where words fail us in this national crisis of communication, images transcend. This series of photos by Michael Conti entitled Great! (2017) is part of an ongoing effort by Define American to change the way we talk about our fellow Americans, to see each other for our stories, our work, our full lives.

An image can convey how a Wisconsin potato planter might love his undocumented siblings in the New Jersey tomato fields. How an embattled police officer might love the Black and Brown people they are sworn to protect. How a young immigrant, who will be part of 88 percent of our country’s population growth in the future, can feel love for a generation of older Americans who have seen their ways of life change at an unprecedented, exponential speed.

It will take radical empathy for the mainstream to trust the experiences of all those outside as authentic—and to give them the space to speak. It will take radical empathy for people of color to not quickly call White people “racist,” personalizing systemic racism. In order to understand one another, we must see one another first.

Jose Antonio Vargas is a journalist, filmmaker, and CEO of Define American and #EmergingUS.

Susan Meiselas, Sultan from Turkey, stitching button holes, Hickey Freeman, Rochester, New York, 2012

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

The Rochester chapter of the Magnum Photos project “Postcards from America” led me to the home of Hickey Freeman, one of the oldest and last surviving manufacturers in the nation. For more than one hundred years, the company has drawn on the finest tailors, first from Eastern Europe, then from Italy and Turkey, and now the world. The company has a long-standing history of supporting immigrant workers, through both seeking out master tailors and, more commonly, providing new workers with the skills to do the job.

Hickey Freeman is an institution that has weathered the near collapse of domestic American industry. In 1899, when the company was founded, nearly all clothing purchased by Americans was made in the United States; today it is just 2 percent. On a grand scale, the company has seen each new wave of U.S. immigrants come through its doors. Today, Hickey Freeman is the only apparel company left in Rochester, which was once a booming textile and apparel production center of America. It employs workers from nearly forty countries, all in one factory. These immigrants are the lifeblood of the company—each so specialized in a task that collectively it takes 160 actions to make a jacket.

Susan Meiselas, Sugar drive to process cane at Falk/Rexnord, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2013

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Another project addressing the current state of American manufacturing took me just beyond the boundaries of downtown Milwaukee. In the surrounding suburbs, I drove around past huge anonymous boxes, manicured so as not to expose the mystery of what was being made inside. Few gave permission to come inside, but those who did offered a tour which often revealed an object whose function was nearly impossible to identify and too abstract in purpose for an outside observer’s eye. The pieces were remarkably odd. I couldn’t tell what a small piece or larger futuristic structure would become.

Unlike Hickey Freeman, the vast majority of the workers in Milwaukee were American, a striking number of them women. They all seemed removed from the objects they were responsible for creating. Their work environment is more insular. They too focus on a single piece with great care, but perhaps with less connection to the larger whole object they are contributing to, or to where it might in fact end up.

What is “Made in America,” and who is making it? This is what I am now just beginning to explore. Can the impact of globalization be turned around, especially in mid-America? This is the great question. There is the reality of broken lives and now new promises. Time will tell what the future holds for both.

Susan Meiselas is a photographer and member of Magnum Photos.

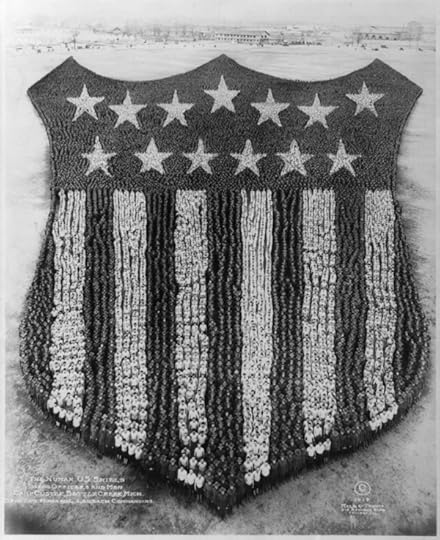

Mole & Thomas, The Human U.S. Shield; 30,000 officers and men, Camp Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan, 1918

Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

Sarah Lewis

We often consider measuring a life by data—information gleaned from the census, statistics from social science metrics, demography—who lives where—and analyzing health disparities. We measure a life through mortality rates or earning power—the value of our labor. During times of crisis we often realize the power of images to measure progress in American life.

This is a concept that Frederick Douglass spoke about during the Civil War in a speech entitled “Pictures and Progress.” Douglass —whose work is, apparently, being recognized “more and more,” and here perhaps I should emphasize that he left us in 1895—understood that photography was both an artistic medium and a tool, an instrument of measurement that would help expand our concept of citizenship. When Douglass gave this speech, it was also the dawn of the photographic age. If combat might end complete sectional disunion, America’s progress would require encounters with pictures because of the images they conjure in one’s imagination, he argued. Douglass—the most photographed American man in the nineteenth century—was making a case for the epiphanic power of images to shift our vision of the world.

Much of the work by image makers of the last century has expanded the notion of citizenship by altering the living portrait of the nation. One could say that we are refuting the living portrait of the country laid out in 1918 by photographer Arthur Mole. In that year, Mole gathered 10,000 men from the army to create a portrait of American destiny through the image of Woodrow Wilson. On the grounds of Camp Sherman in Ohio, Mole turned human beings into dots, a collective into a single, undistorted image, with rigid exactitude. To take the photograph, Mole created towers nearly eighty feet high and took a week to plan, placing lace edging on the ground to mark where each person would stand. The image depended on Mole’s having bi-level vision: he paid close attention to individuals to create a sweeping, collective image. The dehumanizing exactitude with which Mole made individuals conform to the image of the national figurehead—some men fainted during the shoot—hints at the fragility of the idea of national identity. Mole created this among many other collective portraits—with sitters ranging from 10,000 to 30,000—during a time when the country was striving, struggling, and rioting over attempts to impose a reductive face on U.S. nationalism.

The men in Mole’s portrait of 10,000 Americans are exclusively white. If it can be argued that one effect of the American Civil War “was to replace the sentiment of section with the sentiment of nation,” as Louis Menand writes in The Metaphysical Club (2001), then one effect of America’s involvement in World War I was to expose the nation’s attempts to conflate the concept of “nation” with racial whiteness.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the idea of America’s “manifest destiny”—the idea of expectant hope about the providence of America’s westward expansion—coincides with the birth of photography in the mid-nineteenth century. America at this time had a limited visual template for citizenship. The initial idea of American citizenship, after all, had been connected to whiteness and the ability to own property. The ways in which we’ve since expanded our concept of citizenship, of progress, and of destiny would become deeply tied to the new medium. For, as Douglass knew, it is during moments of encounter in the crucible of crisis that we see the role that pictures play in auguring American destiny.

Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture’s “Vision & Justice” issue, is an Assistant Professor at Harvard University in the Departments of History of Art & Architecture and African and African American Studies.

Read more from Aperture Issue 226, “American Destiny,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post America’s Destiny in Pictures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 1, 2017

Along the Route of Fidel’s Funeral

When Fidel Castro died in November, photographer Noah Friedman-Rudovsky followed the final journey of Cuba’s comandante.

By Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, The faces of a diverse nation lined up to watch Fidel’s remains pass by, Cuba, 2016

Courtesy the artist

What’s the geography of a life? The town where one’s born and where one is raised; the far-off cities or nearby states to which one later treks for pleasure or need; the house or humble flat where one ends up, and as they say, reproduces, dies: these are the sites, for most humans, that chart the trip from sunrise to ‘set. Some people’s maps expand little beyond where they start; some stride the globe. The details of most maps, either way, concern few beyond their subjects and their kin. Those of some people—the sort about whom biographies are written—occupy many more. A few maps, because of their worldly itineraries and their impacts, become allegories: they exemplify journeys that symbolize key currents in, or crucial truths about, their nations or age.

Fidel Castro Ruz was one such person. When Cuba’s late comandante died in November, at ninety, he had for nearly six decades been both his country’s foremost celebrity and its plenipotent leader. He was a villain to those who fled his rule, a hero to those who admired his courage and ideals, and an outsized figure on the world stage. His map touched places ranging from South Africa, where he is loved for sending Cuba’s troops to fight Apartheid in the ’70s, to Miami—the city his cousins built to loath him. But in Cuba itself, his story is also simpler. It is the tale of a rancher’s son, from the island’s rural east: a country boy who launched a revolt in that region’s Sierra Maestra mountains, and after his revolution’s victory in 1959, rode up this huge 700-mile island’s spine to seize its distant capital of Havana.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, Cubans gathered along the length of the nation’s highway for days to watch Fidel’s ashes make a cross country trip back to the region where we has born and where the revolution began, 2016

Courtesy the artist

When Fidel’s brother Raúl made a momentous speech to announce his death in that same city, fifty-six years later, the route between Cuba’s eastern heartland and its capital was the map every Cuban thought of—the map of both Fidel’s life and his revolution. On November 25, 2016, Raúl Castro spoke not as Fidel’s brother but as the current head of Cuba’s Communist Party. Raúl announced the “physical disappearance” of the party’s eternal comandante and then described how Fidel’s passing would be marked by his country. Fidel’s funeral cortège would trace the same route as their revolution, said Raul, but in reverse. Fidel’s remains would be cremated, per his wishes, and his ashes would be carted, behind a small Jeep like the one he rode to Havana in 1959, back from whence he came. This humble procession, over nine days of national mourning during which no alcohol would be sold or music performed, would roll Cuba’s length to bring the comandante home. Each mile of the way, Cubans lined the road. Noah Friedman-Rudovsky—a photographer whose experience with lefty leaders in Latin America includes working as personal photographer of President Evo Morales of Bolivia for the past decade, but who has been documenting life in Cuba for longer than that—accompanied the comandante’s ashes for their whole route.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, The ashes of the physically large Fidel were carried in a small, understated box, draped by a Cuban flag and dragged by a military Jeep, 2016

Courtesy the artist

The cavalcade of official grief got under way in Havana, with a mass gathering of Cuban citizens and visiting dignitaries in the great concrete expanse of the capital’s Plaza de la Revolución. As it did, the nation’s TV screens, which would for nine days devote round-the-clock coverage to Fidel’s farewell, aired the convocation’s boring speeches. But that night and the next morning, as the Jeep toting Fidel’s ashes left behind the dignitaries in the capital to commune with rural Cubans in el campo, live shots of the procession interspersed archival images from Fidel’s life, many of them rendered in slow motion and accompanied by aching string music. The images overlaid with the government’s official slogan of mourning, Yo Soy Fidel (“I am Fidel”). They recalled the main moments in a life—or at least the ones the state wanted Cubans to recall—that began in 1926 on the ranch of an immigrant from Galicia, Spain who got his start as an overseer in the sugar fields of Cuba’s Oriente before he grew rich owning them.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, The slogan “I am Fidel” rang out across the country, Cuba, 2016

Courtesy the artist

It was the ambition of Fidel’s mean rancher dad that saw him and his brothers sent to the top Jesuit boarding school in Cuba’s eastern capital of Santiago. It was Fidel’s own that took him from Cuba’s second city to its first, to attend law school at the University of Havana. As a brash and brilliant student activist, he became a prominent and fiery critic, leading with his barrel chest, of Cuba’s corrupt leaders in the 1940s. But then it was back home in Santiago where he launched his career as a revolutionary that saw him, in 1953, lead a doomed attack on an army barracks in which several of his friends were killed but that Fidel managed, by a form of luck either dumb or destined, not merely to survive but to declare to his countrymen, during his ensuing trial for treason, that “history will absolve me.” That saw him return to eastern Cuba, after a stint in jail and a stint in Mexico, in a little boat whose twelve surviving invaders stole into the mountains and gathered around their leader, like hirsute apostles of Christ, to convince Cuba’s poor and its liberals of his cause. That saw him ride west toward Havana, in his little Jeep and to the exulted cheers of all. That saw his revolution’s ambit quickly grow, for his crew of believers and zealots, to include such quixotic tasks as eliminating illiteracy on his poor island (which Fidel’s volunteers quickly did). After he nationalized Cuba’s land to estrange Havana from Washington, and then found a new Soviet patron, Castro expressed not relief but frustration when humanity avoided the nuclear precipice of October 1961: he was peeved that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev backed down from launching missiles at the Yanks.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, Girls paint the words “I am Fidel” in marker in the town of Bayamo, Cuba, 2016

Courtesy the artist

This hard-headedness—what Cubans dub gallego and Brits would call bloody-minded—was always there, too. It’s what saw Fidel, in the revolution’s early decades, betray a grave intolerance for Cubans who were less Communist, or more gay, than he was. It’s also what helped him, when the Soviet bloc fell and with it the rusting Cuban economy’s lifeblood, not merely retain his firm grip on power but sustain his state’s vaunted systems for providing free healthcare and good schools for all Cubans. And it’s what also saw him, against all odds and after perhaps 600 distinct attempts on his own life, die not from an assassin’s bullet, or a poisoned cigar, but of old age in bed.

The life story reads like a fable. This befits a man who counted among his best friends Gabriel García Márquez. One used to wonder, hearing tales of Fidel dining in Havana with magical realism’s foremost exponent, what the comandante and novelist spoke of. It was hard not to suspect, learning of how Cuba planned to mark his demise, that one thing Fidel himself discussed with “Gabo” was how to imbue the aftermath of his death, long foretold, with optimal narrative symmetry and heft. The number of days of mourning proclaimed by Raúl—nine—wasn’t accidental: in Cuba, nine days is the sum of time that adepts of santería, the Yoruba-derived faith that is one of the island’s religions, believe a person’s soul takes to leave its body. And so it was, as Fidel’s soul rose from the little box wrapped in a Cuban flag, that his Jeep pulled his ashes the length of the island’s carratera central—its national highway—and through cities whose every name resounds, in Cuba’s history or Fidel’s story or both, with its own meaning.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, School children were bussed in en masse to attend the caravan, Cuba, 2016

Courtesy the artist

The caravan rolled past the old slave port that birthed Cuban rumba—Matanzas—and through the central city—Santa Clara—where Fidel’s great lieutenant during the revolution, Che Guevara, attacked a train to break the dictator Fulgencio Batista’s forces. It rolled from Sancti Spíritus to Ciego de Ávila to Camagüey; from Las Tunas to Holguín, and to Bayamo—the eastern city, site of a famous battle in Cuba’s nineteenth-century war for independence that now lends its name, in “La Bayamesa,” to its national anthem. Each mile of the way, Cubans lined the road. Friedman-Rudovsky rose before dawn to be ready when the cortège departed whichever well-guarded rural army base Fidel’s ashes spent the night, riding in, or often atop, a car rolling with them.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, On the final night of mourning, Cubans filled the plaza in Santiago de Cuba for official remarks by Raúl Castro, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Some of the faces his lens found belonged to people who had to be there: rural nurses or farmworkers employed by the state, bused to the roadside as a duty. Others—townspeople and students, retirees, and layabouts—came because they wanted to. Their tears said so; their aunts and cousins’ presence did, too. Theirs was a farewell to family, signaled with waving flags or smartphones: the parting of a grandfather who, resented or cherished or a complex mix of both, had earned the pause his death prompted. And as the comandante’s posthumous retinue reached the base of the Sierra Maestra by Santiago, the great square in Cuba’s oldest city filled, at sunset, with thousands of mourners. Some chanted “Yo Soy Fidel!” Many wore armbands noting the date in 1953—July 26—when Fidel launched his doomed attack on the Moncada army barracks here.

That night, Raúl Castro gave another speech to the assembled. He declared, in a homily to his brother’s role in Cuban history, how Fidel had decreed that no park or avenue or public site be named after him, so as to “avoid any manifestation of a cult of personality” in Cuba. This may have beggared belief: Raúl was invoking a man who thought it fit to dominate his country’s airwaves and its public sphere, for decades, with his hours-long speeches. But this was Fidel’s wish.

Noah Friedman-Rudovsky, A young military serviceman salutes the fallen leader’s caravan, Cuba, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Cuba now enters a new and uncertain age. Havana’s recent rapprochement with the administration of former president Barack Obama signaled a recognition, here, that attracting foreign capital—if not necessarily embracing capitalism—is increasingly key to the island’s future. Cuba now confronts a new leadership in Washington, whose buffoonish head has already tweeted his unwillingness to deal with his island neighbor. How the drama between these two will go is hard to say. But as Cuba’s ruling party confronts this new foe, Cuba will be without the leader who defined its modern history.

The morning after Raúl’s final speech, in a cemetery not far from where he and his brother went to high school, Fidel’s ashes were buried next to the grand mausoleum of José Martí, the poet-laureate of Cuba’s nineteenth-century war for independence. The simple granite boulder under which they were laid was inscribed with a single word—FIDEL. That is now his official monument. But the larger monument, at least in the days after he passed, was the faces of his people—weary or hopeful, wary or sad—who looked on. As his remains passed on their final journey, the people of Cuba saw themselves reflected in his ashes’ glass case or in the sympathetic lens of a photographer who, filling that map with them, was there for it all.

Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, who has written on Cuban history and arts for many years, is the author of Island People: The Caribbean and the World (2016).

The post Along the Route of Fidel’s Funeral appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Exhibition

A student photo exhibition can be a rewarding public culmination for your Aperture On Sight students The execution doesn’t need to be complicated. Here are a few options:

A slideshow of a selection of the class’s photographs, set to appropriate music or accompanied by live or recorded student narration explaining what the class has done. Project each image for about four seconds: long enough to understand what you’re seeing. Keep slideshows to about three minutes. This could take place during a school-wide performance.

A gallery walk, with nicely printed student photographs on tables with Post-it notes on which visitors can write comments, as well as student books. This works well for parent-teacher conferences.

A formal exhibition at the school, in a café, at a library, or in a local politician’s office. Students can select and sequence photographs to hang on a wall, then use photo paper, an ink-jet printer, and frames or map pins. Include wall text and captions/titles printed on clear shipping labels.

A presentation of the student work and books with a talk in which a teacher or other adult interviews a panel of students about their projects.

The post Exhibition appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Resources

The resources below are provided as additional information for teachers:

“What’s going on in this picture?”: How to use visual thinking strategies in the classroom.

More information about Aperture On Site at Your Site!

Suggested photobooks for your library.

Sample: Letter to a Visiting Editor.

Blurb: Tips and tutorials.

Telephone Game: A fun activity for the classroom from the book Go Photo (Aperture, 2016).

Aperture’s educational publications.

The post Resources appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Workbook

The post Workbook appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Lesson 20

In the last lesson of the program, students finalize their digital books and participate in a group critique, sharing honest and kind feedback about one another’s projects. Students will now know how to create a photobook, from concept to practice, along with the basic skills needed to use an online publishing program.

The post Lesson 20 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Lesson 19

In lesson nineteen, students use online bookmaking software to bring their projects to life. Using their book dummies as a guide, students learn to use online tools to create digital versions of their books. Students also have time to write artist statements and captions for their images.

The post Lesson 19 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers