Aperture's Blog, page 125

February 3, 2017

On Sight – Lesson 1

The first lesson, Hello Photography, introduces students to Aperture On Sight and gets them started working with a camera through a simple photo scovenger hunt. Working in pairs or teams, students learn basic camera core and handing as well as how to pre-conceptualize a subject while remaining open to visual discoveries.

The post On Sight – Lesson 1 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

on sight 1

Lorem Ipsum é simplesmente uma simulação de texto da indústria tipográfica e de impressos, e vem sendo utilizado desde o século XVI, quando um impressor desconhecido pegou uma bandeja de tipos e os embaralhou para fazer um livro de modelos de tipos. Lorem Ipsum sobreviveu não só a cinco séculos, como também ao salto para a editoração eletrônica, permanecendo essencialmente inalterado. Se popularizou na década de 60, quando a Letraset lançou decalques contendo passagens de Lorem Ipsum, e mais recentemente quando passou a ser integrado a softwares de editoração eletrônica como Aldus PageMaker.

The post on sight 1 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

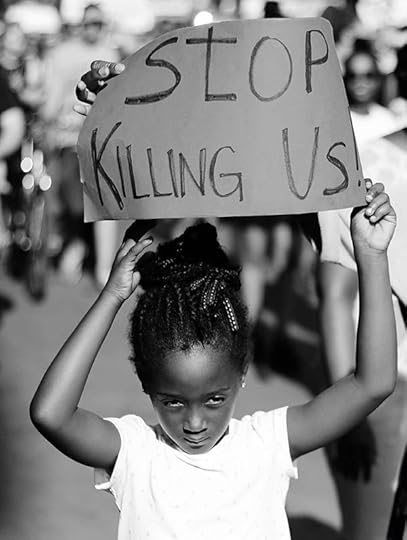

The Revolution Will Be Live-streamed

A new exhibition at the International Center of Photography explores the role of images in modern social movements.

By Will Matsuda

Sergey Ponomarev, Refugees arrive in a Turkish boat near the village of Skala, on the Greek island of Lesbos, November 16, 2015

© Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

In Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change, currently on view at the International Center of Photography in New York, viewers are engulfed in the imagery of six major social issues facing society today: Black Lives Matter, gender identity, climate change, terrorist propaganda, right-wing populism, and the refugee crisis. Each issue is given its own section in the show; a massive glacier breaks apart in James Balog’s video on one wall, while ISIS propaganda videos play in the museum’s downstairs gallery. With its barrage of pictures, this project might aspire to recreate the overwhelming, often contradictory stream of news and ideas we consume through social media every day. I recently spoke with Carol Squiers, one of the curators of Perpetual Revolution, about assembling and displaying the media of our time.

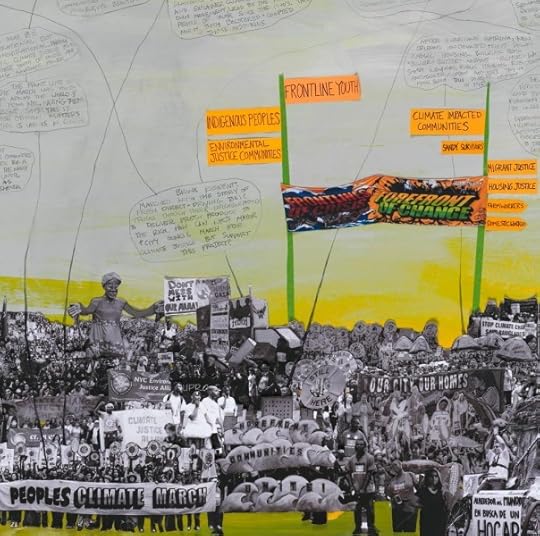

Rachel Schragis, Confronting the Climate: A Flowchart of the People’s Climate March, 2014–16

© the artist

Will Matsuda: What makes photographs of modern social movements unique?

Carol Squiers: Photographs of social movements are now often taken by the people who create the movements, rather than by people whose profession is photography. The participants in contemporary social movements are able to distribute and publish the images themselves—in the way they want—via social media and other web platforms rather than waiting for a magazine or newspaper to notice or report on the cause.

Matsuda: The exhibition is broken up into six distinct themes. Does this division preclude the possibility of intersectionality between, for example, climate change and racial justice?

Squiers: Our goal in the exhibition was to examine the use and character of networked still and moving images within important but discrete subjects, rather than to mount an intersectional critique between the thematic areas themselves. The viewer will be able to discern the intersectionality of certain themes by close attention to the exhibition—one example: the overlapping concerns about race, physical safety and personal freedom are issues important both in the gender and Black Lives Matter sections. Another example: the use by ISIS of economic theories by far-right wing American conspiracy theorist W. Edward Griffin in its critique of the world economy in The Rise of the Khilafah: Return of the Gold Dinar and the ideas and images of far-right conspiracy theorists as they pertain to the election of 2016. We did not aspire to do exhaustive studies of entire social movements—each of the sections could be a museum-wide exhibition of its own.

ISIS distributes school supplies to girls in Mosul, Iraq, 2015

Matsuda: Social media can provide radical transparency. Diamond Reynolds was able to livestream the killing of Philando Castile at the hands of a St. Paul police officer to millions on Facebook Live. However, the same platforms also lead to the creation and easy distribution of violent ISIS propaganda as well as the far-right’s anti-Semitic memes. Why show this offensive, even traumatic material?

Squiers: The exhibition is about the image and social change in a networked environment. Traditionally, social change has meant positive social change. But the network allows for many kinds of social effects, both good and bad. ISIS and the far-right are examples of successful propaganda that have both had enormous global impacts. The study of propaganda has a long history, which is more important now than ever. The point is no longer to just look at images of social change that make us feel good or that we approve of. It’s necessary to look at the range of image production even though some of it is upsetting. The far-right had a major impact on the election and left a lot of people asking how this happened. We can’t provide an answer to that question, but we can look at the images and point out the themes and tropes that are used.

In terms of violence, there is little violence in what we have shown in the ISIS gallery that wouldn’t have been seen in traditional photojournalism. I have written about photojournalism for many years and used that experience as my guide for what was acceptable. The extreme violence you refer to was either edited out, digitally blurred, or otherwise excluded. If you are watching material that is on the Web, you are probably not seeing what is actually in the gallery.

Sheila Pree Bright, Video still from #1960Now: Art + Intersection, 2015

© the artist

Matsuda: Throughout the exhibition, there are lots of screens showing viral video clips, social media feeds, and memes. Is this the new mode that museums must grapple with in exhibiting and representing the media of our time?

Squiers: We set out to look at imagery on the Web with the intention of displaying the images we found on screens of various sizes, which would echo possible primary viewing experiences. Artists and other kinds of photographers are going to continue making images that are objects. Screen-based imagery is an entire category of photography, though, whether it is still photography or not. It exists, and museums will have to figure out what to do with it.

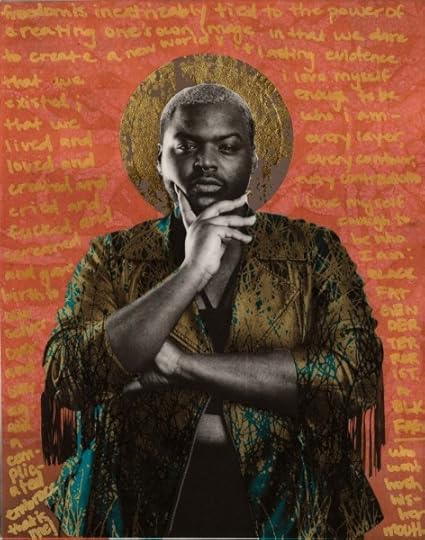

Gabriel Garcia Roman, Jamal, from the series Queer Icons, 2015–16

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: “Perpetual revolution” riffs on the Marxist term “permanent revolution.” This is the idea that the working class must be in a perpetual state of revolution with continuous demands and tactics even when oppositional political forces rule. For many people who were surprised by and are now reacting to the Trump victory and presidency, this seems particularly relevant. Why did you choose this title?

Squiers: “Permanent revolution” got turned into “perpetual revolution.” It refers to these enormous social changes that digital technology is producing. Everything in digital technology keeps changing. It’s endless. Pictures cycle endlessly. Conspiracy theories cycle endlessly. History is not packaged neatly anymore. Now history is this huge field of thousands of images washing over all of us. People feel a need to protect themselves from the tides of pixelated history. We’re trying to look at how images and network culture are perpetuating all of these social changes.

Video still from Trans in Media 2, 2015. Kristen Parker Lovell (left) and Kenyatta Kahn (right)

© Kristen Parker Lovell

Matsuda: The idea that images perpetuate social change is contentious. Can an image change anything?

Squiers: There always been this debate about whether photography can change anything. We think that Lewis Hine’s photos of child laborers helped institute public education. We think that pictures of the West helped develop the national park system. But it’s all really hard to prove. People have so much more access to pictures than they ever had before. Before you had to decide which paper you were going to buy. You’d sit down and open it and those would be the images you consume. Now people can get their ten free articles per month from new sources all over. We still don’t have an answer.

Will Matsuda is the social media associate at Aperture.

Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change is on view at the International Center of Photography Museum through May 7, 2017.

The post The Revolution Will Be Live-streamed appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 1, 2017

Beyond the Wall

Is the U.S.-Mexico border a political calculation or a humanitarian crisis?

By Josh Kun

Richard Misrach, Wall, east of Nogales, Arizona, 2014

© the artist

There is a line between Richard Misrach and composer Guillermo Galindo.

On the cover of this book, it is little more than a keystroke, a simple design flourish to mark an interdisciplinary collaboration: Misrach, photographer, to the left; Galindo, composer and musician, to the right. On the pages that follow, however, that line becomes something else, a hieroglyph of a new coauthored artistic language and a symbol of all the lines that both connect and divide them. It is a line between English and Spanish, between the United States and Mexico, between white and brown, and between sight and sound, looking and listening. It is a line between an American photographer who is perfectly happy driving the nearly two thousand miles of the U.S.-Mexico border in a rented 4×4 with a tripod, a high-definition camera, an iPhone he uses for shooting, and a bottomless supply of trail mix, and a Mexican composer living in the U.S. who is perfectly happy to stay where he is, hundreds of miles away from the border, free from checkpoints, suspicion, and Border Patrol stops.

Richard Misrach, No More Deaths, 2016. Pick-up truck filled with water and food to be placed in remote regions of the Arizona desert

© the artist

The line treats them differently and they treat it differently in return.

It is also, of course, not just a line, but the line—la línea, la frontera, el límite, el bordo—the international boundary first drawn in the sand and along the shifting banks of the Rio Grande to end the Mexican-American War in 1848. Back then, the U.S.-Mexico boundary commission set out to draw a “boundary line with due precision, upon authoritative maps, and to establish upon the ground landmarks which shall show the limits of both republics.” For most of its early years, the border was just that, little more than desert dirt and river currents punctuated by marble obelisks that ran like exclamation points from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico to help remind everyone—the ranchers, the vaqueros, the governors, the generals, the Indians, the tourists—what side of the line they were on. There wasn’t even a fence until 1911, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Animal Industry built one in California to keep “stray Mexican animals” that might be infested with ticks from wandering onto U.S. land. “Such a fence,” the bureau wrote thirteen years before the U.S. Border Patrol even existed, “will also assist the customs officials in preventing illegal traffic between the two countries.” The border of today, with its dedication to security against human and drug traffic, its dedication to the spectacle of national defense, was an afterthought.

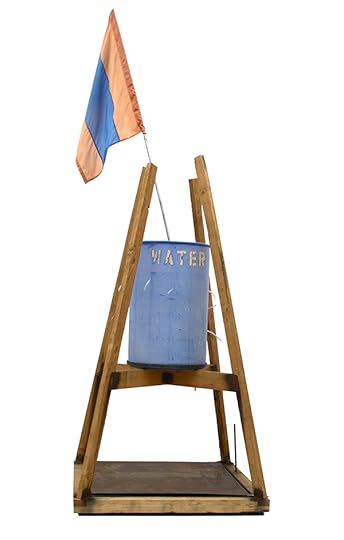

Guillermo Galindo, Fuente de lágrimas (Fountain of Tears), 2014

© the artist

Since the 1970s, Misrach has been photographing the shifting environmental and political landscapes of the American West, the border lurking in the background of his portraits of the new desert frontier but never actually in their frame. Since the 1990s, Galindo has been making music informed by the aesthetic and cultural avant-gardes of the U.S. and Mexico, the border always audible—without it, he would still be living in the Alta California of Mexico—but never pushed too high into the mix. In 2012, their paths crossed when both of them began responding to the effects of the most recent wave of border militarization. Misrach shot the Western landscape as it was being reshaped and remapped by hundreds of miles of new steel border walls, and Galindo turned the detritus of those new walls—animal skeletons, rusting Jumex juice cans—into electro-acoustic instruments.

Richard Misrach, Border Patrol Target #3 (detail), near Gulf of Mexico, Texas, 2013

© the artist

Most materially, the border of these cantos is the one that dates back to 2006, when President George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act and gave a green light to over seven hundred miles of new border construction and surveillance technology, a high security cocktail of imposing steel walls, checkpoint stations, radar towers, ground sensors, thermal imaging, drones, and beefed-up Border Patrol ranks. To “control the border,” between 2005 and 2015, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection paid out over $23 billion in private contracts to companies like Boeing, Raytheon, IBM, and Lockheed Martin, not to mention all of the private architectural design firms hired to make the secure border “aesthetically pleasing” (as the federal mandate put it), and all of the private prison firms—the Corrections Corporation of America, the GEO Group—who profit from upticks in enforcement and detainment. The cost of the new wall was estimated to be $4 to $12 million per mile (dependent on terrain and difficulty of construction), a hefty price tag for any addition, but especially hefty when you consider that it can be scaled by a teenager in seventeen seconds flat, without a ladder. Even a 2008 Army Corps of Engineers blueprint suggested, in fine print, just how impermanent these new walls and fences might be by their very design: “This fence construction is to be dismantled readily.”

Richard Misrach, Effigy #2, near Jacumba, California, 2009

© the artist

The vast industry of this new border extends, informally, into Mexico as well, where drug cartels and human traffickers benefit from the increased desperation and vulnerability of Mexican and Central American migrants looking for safe passage across punishing, burning deserts. This too is part of the border of these cantos, what Pope Francis has called “the humanitarian emergency” produced by overzealous border enforcement and strict detainment and deportation policies. In the past decade, some expanses of desert borderlands have become sun-bleached death zones, blistering and unforgiving sites of mass migrant death and disappearance littered with the personal effects of the missing—miles and miles of trace evidence, forensic clues to lost lives and divided families that mostly lead nowhere. They have also become a particular staging ground for unprecedented femicide, a systemic naturalization of violence against women that the border’s merger of global industry and labor exploitation has helped nurture.

The Arizona-Mexico border can now be mapped the way the Humane Borders organization does it, through RHR maps, or recovered human remains. “Each dot,” their maps read, “represents one RHR.”

The maps are full of dots.

Roy Germano, still from The Other Side of Immigration, 2009

Courtesy the artist

The border wall, then, is not simply the material, built result of politically expedient legislation buttressed by defense budgets and national chauvinism. It is an ideological, social, and economic pressure point where the pulls and pushes of multiple political forces, past and present, converge in volatile and often tragic ways. To speak of the contemporary border is to speak of nineteenth-century U.S. expansionism and twentieth-century economic imperialism, decades of labor recruitment and labor deterrence, post–WWII industrialization and post–9/11 terror wars, pro-trade policies and antidrug policies, Mexican drug supply and U.S. drug consumption, the pursuit of human rights and the violation of human rights, U.S. golf courses with their ninth holes in Mexico and two-bedroom American homes with the border wall in their backyard, and the open frontier of the Old West and the carceral frontier of the New West, where campfires become klieg lights and young mothers carry their infants across live gunnery ranges because, somehow, they’re safer than the open desert.

Richard Misrach, Protest sign, Brownsville, Texas, 2014

© the artist

In her influential 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” art critic Rosalind Krauss noted a new school of American artists making large-scale sculpture that differed from traditional monuments because they were not commemorative or historical; they were the monument’s “negative condition.” Decades later, the border wall has truly become the monument’s “negative condition” but in moral and ethical terms, a statue of un-liberty that funnels the tired into desert bottlenecks and tracks the poor through gulches. It is a monument to the aesthetic and fiscal reaches of political theater, and a thuggish mirror of national and cultural phobias—to the limits, not the depths, of the democratic imagination.

The photographs of Misrach help us understand this. The musical instruments of Galindo help us hear it. When experienced together, however, they have the potential to do something else: to activate our own visions and our own scores for the American monuments that might still be possible to build.

Or tear down.

Josh Kun is a professor at the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism and is the author of Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (2005).

This essay is an excerpt from “Misrach/Galindo,” originally published by Aperture in Border Cantos (2016).

The post Beyond the Wall appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 31, 2017

The Ready-made Dream No One Believes In

In Europe and the United States, Stéphane Duroy charts the course of “big” history.

By Wilco Versteeg

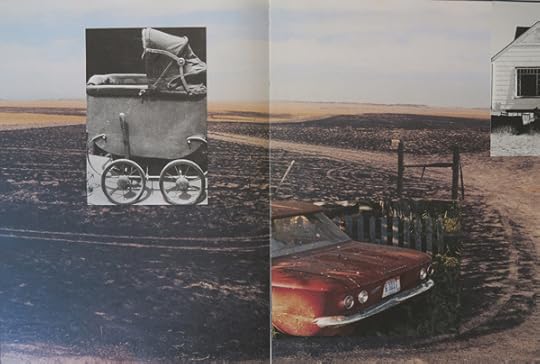

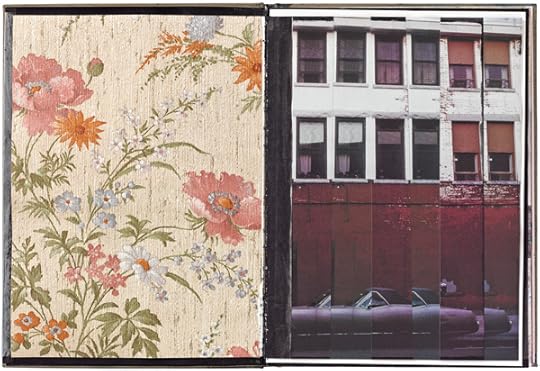

Stéphane Duroy, spread from the book Unknown, 2015

© the artist

Again and Again, Stéphane Duroy’s solo exhibition at Le Bal in Paris, arrives at the right time in history. Having won several World Press Photo awards in the late 1980s and early ’90s, Duroy has become an integral voice in documentary photography, defined by books like Distress (2011) and L’Europe de Silence (1979–89). His artistic development culminates in Unknown (2007–17), an ongoing attempt to exhaust the documentary, artistic, and political possibilities of his work. Seeing Again and Again, the first comprehensive exhibition to present Duroy’s work, is like being taken by the hand on an impressionistic journey through the decline of Europe and the United States.

Stéphane Duroy, Bradford, 1981, from Distress

© the artist

Duroy was born in 1948 in Tunisia, then a French colony, and his life coincides with the major moments of postwar European history. He took up photography in the late 1960s as a means to document national and international upheavals. But Duroy has shied away from exhibitions, instead preferring to share his vision in books that focus on political change in the ’70s in Great Britain, Germany, Eastern Europe, and the United States. Inspired by the writings of Bertolt Brecht, Franz Kafka, and William Faulkner, Duroy’s theme is how “big” history—from World War I to the Holocaust to the end of Communism—is reflected in the daily lives of common people. The title of the exhibition, Again and Again, as well as the character of his work, underscores his historical fatalism. Duroy witnesses the societies of Thatcherite Great Britain, post-communist Eastern Europe, as well as contemporary America, in particular the downtrodden victims of capitalism’s excess, yesterday and today.

Stéphane Duroy, Manhattan, New York, 2004, from États-Unis

© the artist

The first part of the exhibition contains Duroy’s earlier work on the waning of Europe. The gallery walls are covered in demure gray wallpaper with a Second Empire pattern, a motif that returns in pictures such as one showing a chandelier in an abandoned hall in Portugal. One of his most striking pictures shows the falling of the Berlin wall. That epochal event is typically represented by images in which the wall is demolished by a jubilant crowd. Duroy, who has spent extensive periods of time in Berlin, managed the capture the wall while it was falling and suspended in midair; strangely, there are no people in sight. “In 1979, West Berlin became the link between cause and effect, the place where decisions were made about the major tendencies which have created the European tragedy and called our cherished values into question,” Duroy said last year. “Then from 1984 onward, the United States, splendid symbol of hope and great ready-made dream which nobody believes in, closed the circle.”

Stéphane Duroy, spread from the book Unknown, 2015

© the artist

Duroy is a historical pessimist, but this pessimism drives him forward. The forces of history inevitably lead to the trampling of humanity, but Duroy tries to restore this humanity in his latest, ongoing project Unknown, to which the exhibition’s second part is dedicated. Unknown is a Tentative d’épuisement d’un livre, or, in the official translation that reduces the philosophical feel of the original French, “The endless reworking of a book.” (I would have suggested, “Attempt at the exhausting of a book.”) Unknown, begun in 2007, is an impressive twenty-two-foot foldout catalog and an exhibition in of itself. Le Bal presents twenty-nine different versions: Over the last decade, Duroy has reworked Unknown, adding, removing, or manipulating its pages to constantly create new forms and juxtapositions.

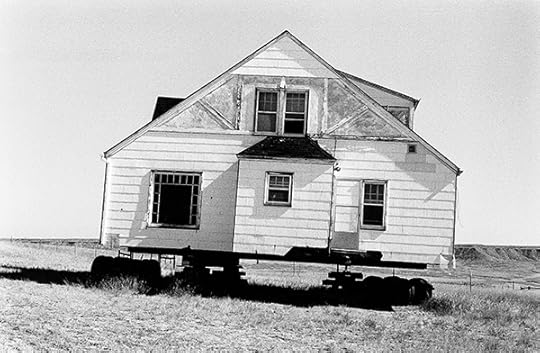

Stéphane Duroy, Billings, Montana, 2003, from États-Unis

© the artist

Duroy no longer describes himself as a documentary photographer, but there is an undeniably documentary impulse at work; while he adds newspaper clippings, paint, and text, his own images remain the groundwork of Unknown. This manic—indeed, exhausting—search for a form that fits our age of economic displacement finds its culmination in his pictures of life in Butte, Montana, a former mining community. One of Duroy’s pictures features a house reminiscent of any of Walker Evans’s images of small houses and barns in decline, except that the house Duroy photographed is on wheels and is being driven to another, perhaps better place. In Duroy’s universe, there is no stability, only, as he says, a “closed theater” of struggles between power and failure, hope and duplicity.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD candidate at Université Paris Diderot.

Stéphane Duroy: Again and Again is on view at Le Bal, Paris, through April 9, 2017.

The post The Ready-made Dream No One Believes In appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 30, 2017

Work, Politics, Survival

Jo Spence rejected categorizing labels of her work and practice and preferred to wander.

By Charlene Heath

Jo Spence, Photo Therapy: My Mother as a War Worker (with Rosy Martin), 1984

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Though we know Jo Spence as an activist, feminist, and socialist photographer, she actually began her career in photography operating a High Street studio business in London between 1967 and 1974. She was perturbed watching parents socialize their young into “ideal children” in front of her lens, and so helped set up London’s Children’s Rights Workshop in 1973. In Spence’s 1986 book Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography she writes about volunteering there, and how she began to explore the role of photographs in establishing certain views of childhood and normative constructions of the nuclear family unit. It’s also where she met Terry Dennett, her long-time collaborator and romantic partner, with whom she began a lifetime engagement with photography and media literacy, studying how photographs operate in the construction of age, class, and gender-based identity.

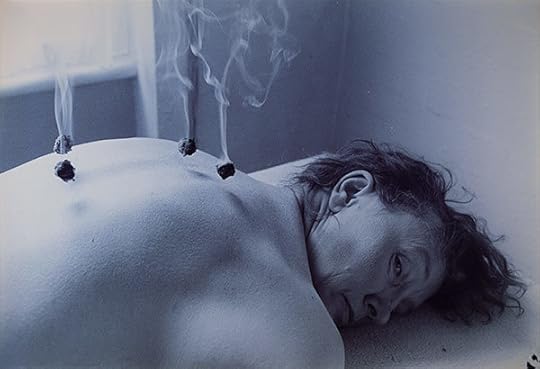

Jo Spence, Alternative Health Treatment using Traditional Chinese Medicine (with Maggie Murray), from The Picture of Health?, 1982–86

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Spence’s political practice unfolded against the backdrop of 1970s London—that myriad of British counter-cultures and concomitant institutions shaped by a general desire to provide an alternative to dominant establishments and their modes of production. In 1974, Spence and Dennett co-founded Photography Workshop Ltd. in their apartment, a place where interested individuals could learn practical darkroom skills, participate in exhibitions, and engage in discussions around photography and photographic education. They also embarked on what would be Spence’s first attempt to work in the classic documentary mode, photographing inhabitants of illegal gypsy encampments throughout London. Spence refers to the project Gypsies and Travellers (1973-5) in Putting Myself in the Picture, stating:

. . . it was the classic introduction to documentary photography for me. I was both privileged and upset to be allowed to look at a world where people worked so hard to survive, whilst labouring under such terrible disadvantages. . . . It never occurred to me to teach people to take photographs of their own lives. . . . In retrospect I can see that although I was a nice liberal humanist, I had no clue as to the history of the gypsy and travelling people, or their real social, economic or political needs.

For Spence, the central question became: How can individuals—namely children, women and working class people—use photography to represent themselves, and take control of their own visual narratives? Although Dennett and Spence continued visiting gypsy communities throughout London, they did so in an old ambulance-turned-darkroom, teaching photography instead of taking photographs. Combining their technical photography skills with theoretical tools aimed at achieving agency-through-self-representation, Spence and Dennett continued teaching the marginalized, operating outside mainstream educational institutions and commercial gallery systems.

Jo Spence, Photo Therapy: The Bride (with Rosy Martin), 1984–86

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

When Spence was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1982, her inclination towards self-representation and education continued, but took on new forms. The Picture of Health? (1982–6) deals with the politics of cancer as she took her physical and mental health into her own hands. By documenting her experience with Western medical orthodoxy, and recording her use of traditional Chinese medicine as an alternative, she continued her critical engagement with institutions and systems that make decisions on behalf of others, and how they treat and represent them. Her collaborative phototherapy work extends these concerns by marrying her holistic health practise of psychodrama with her applied skills in portraiture. By deconstructing and acting out scenarios from her co-counselling psychotherapy sessions—childhood abandonment when her mother was a factory worker during World War II, and anxieties around marriage and the female libido, for example—she complicates the efficacy of dominant, monolithic images of women by piecing together a portrait of herself that is multi-faceted and comprised of many selves.

Jo Spence, Untitled, from Libido Uprising (with Rosy Martin), 1989

© Terry Dennett and courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Spence resisted any notion of feminist or socialist photography as a style of art making during her career, and was reluctant to solely embrace a definition of herself as a capital-A artist. In fact, she preferred to use the term “educational photographer” or “cultural worker” when describing her work. Yet, confrontation with Spence’s work invites the question, Is it art? Activism? Self help? Or, is it all of the above? Responding to a question during the tour of her Review of Work (1985–6), Spence, who died in 1992, resisted any such labels: “Somebody like me wanders, without a category. In a sense, I don’t want a category. I like being a moving target, I feel I’ll survive longer.” The undeniable staying power of Spence’s work lies in her bold approach to picture making drawn from an embodied experience of everyday life, and our inability to pigeonhole it.

Charlene Heath is a Ph.D. student at York/Ryerson University studying Communication and Culture, and the Archivist at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, where she works with the Jo Spence Memorial Archive.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Work, Politics, Survival appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 26, 2017

Roe Ethridge is a Good Southern Boy

The influential photographer, who once worked for JCPenney’s, riffs on nostalgic Americana.

By William J. Simmons

Roe Ethridge, Me and Auggie, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Few contemporary photographers are as productively resistant to categorization as Roe Ethridge, which likely made Kevin Moore’s task of curating Ethridge’s mid-career retrospective a herculean task. Roe Ethridge: Nearest Neighbor, currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, brings together the wide range of his enigmatic pictures in an unconventional manner with little discernable organization. This suits Ethridge’s characteristically paradoxical style—a combination of deadpan and emotional imagery that is neither documentary nor romantic, but sometimes a bit of both. I recently spoke with Ethridge about the multifaceted roots of his practice and his interests in classical music, David Lynch, Andy Warhol, and Lee Friedlander.

William J. Simmons: I’d be interested to hear about your relationship to conceptualism versus your relationship to documentary photography, and how this plays out in your current exhibitions.

Roe Ethridge: I’ll go back to this critical moment of me coming out of art school in Atlanta. At that time, I would have called myself a Conceptual artist using photography, even though going further back to when I started, all I wanted to do was be a photographer. During that time in the early 1990s, I was exposed to the Düsseldorf School through Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky—the Becher students. It was clarifying. It eliminated some of the things associated with being in the South—romantic subjects, selective focus. Or maybe I was exhausted by the dampness, and the rot, and a romantic re-envisioning of a Walker Evans black-and-white, large format photograph. Even with William Eggleston, who was coming through as an influence, I was trying to hold off the seduction of the 35mm that you hold to your eye. I wanted to do something more structural. There was something about those Thomas Ruff portraits and buildings that made so much sense to me.

But I think my first loves were Lee Friedlander and Andy Warhol. Only recently have I been able to let those two names come out together. That almost tells the whole story right there. It’s Lee Friedlander and Andy Warhol—this droll, dry mirror but with composition and content. There’s some concept, there’s some color, there’s an eye. You can see the two trajectories, and they overlap in the concrete poetry that happens in a Friedlander photograph or Warhol’s Brillo boxes.

After getting my BFA, I started assisting catalog photographers in Atlanta. That’s the big photo industry there. I wanted to work in that industry, and I liked that it was the lowest common denominator form of photography, where the aesthetic was only 5 percent of it. The pragmatics of getting it done in a day, or getting the lights so you could see no shadow on the bra, were more important.

Roe Ethridge, Nancy with Polaroid, 2003–6

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Then I moved to New York and started working almost immediately as a commercial photographer. I kept wondering, When are they going to ask me for my license? I’m going to get in trouble! [Laughs.] But I never did. The New York Times sent me checks, and I thought, Oh my God. I just paid my rent as a photographer in New York. I was showing my work, and, at the same time, I was doing this commercial stuff and I realized that sometimes the commercial images were just so much better than my own ideas. I began to see myself as an editor, like Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine, with their processes of selection and appropriation.

At the same time I was reading Walker Percy’s The Last Gentleman, which is about a dude from the South who is going to Princeton. He’s from the South. He’s around New York. I could relate to that notion of being a “good southern boy” in the biggest, baddest city. So the character in the story keeps going into these fugue states, which I guess was a thing that happened to people more often in the forties and fifties than it does now. It’s characterized by far flung travel in an amnesiac state. He kept waking out of this state on a Civil War battlefield in Virginia. At the time I was reading the book, I was going to Lexington, Virginia, to visit friends. I was homesick for Atlanta. So, in this Walker Percy book, he’s talking about the fugue as a mental state. It turns out a fugue is also a musical composition that Bach pioneered.

Glenn Gould famously played Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Basically, it’s two keyboards and he’s playing two at one time. The music, ironically, is the length of a pop song! You start off with a run, a line of notes. So one hand is playing one line of notes, and the other hand is playing another line of notes. And it goes through these variations fifteen times. The keyboards are playing over each other, and there’s this harmony and disharmony. It seems like some things are left to chance and some things are quite intentional, and for me, getting to that place of the musical definition just made everything click. I thought, That is what I’m doing. That’s what I’m up to. It’s more about that sound, the harmony, and disharmony, rather than making meaning or illustrating a thesis. It’s synesthesia. It’s a feeling. It’s a sound. It’s a vibration. It’s not a project. And so all of those things are coming into my young thirty-ish mind at the same time.

All of a sudden, I was like, I’m a photographer, but I’m also an editor. I’m also a lousy conceptual artist or whatever! [Laughs.] I’m a colorist. I’m a pictorialist. I’m a commercial photographer. Suddenly I was allowed to do all of that stuff at the same time.

Roe Ethridge, Coke Bottles, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Simmons: That is almost made literal in your 2016 book, Neighbors, where it starts out in the way that you might assume a normal photobook would, but then you have a movement between those categories, as you described, and a rejection of hierarchies. The images are very disparate. So is this project an illustration of that elimination of hierarchies?

Ethridge: I suppose so, although I don’t like the idea of an illustration.

Simmons: Well, maybe not an illustration, but a literalization.

Ethridge: Let’s look at it this way: This is, as far as Kevin Moore and I were concerned, a thematic survey show. It may not seem quite so because there is so much disparate imagery.

In Neighbors, “Nearest Neighbor” is just a middle section of the book. I was really trying to avoid having this survey show act as the final word. The idea of the book was to problematize the finality of a retrospective and, in a poetic way, to talk about other aspects of what I’m doing as an artist, photographer, father, and storyteller. There were also very grounded things like the kids and me on a walk, and the animals at the sanctuary—two very childlike, very earthbound, things. So there’s a constant juxtaposition.

As far as the salon aspect of the layout, and the hierarchies of it, it was very quickly arranged, on purpose, so that it wouldn’t get a chance to get too organized, though we had already done a layout of the show and knew what images would go into which rooms. So the spreads do relate to the groupings of the images.

Roe Ethridge, Thanksgiving 1984 (table), 2009

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Simmons: Your discussion of music and improvisation reminds me of the scene where they discuss the tritone in Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac, and in some way, André Breton’s notion of convulsive beauty—the obsolete train that can no longer make noise and steam. Do you consider yourself a composer?

Ethridge: Photographic images started working like songs for me. The white cube and the white wall created this place sequencing. That sequence is a lot like writing music—what song follows what, or what sounds follows what. I played in bands in my twenties. I can sort of read music, but it’s mostly self-taught. I mean, I played trombone in sixth grade. [Laughs.] That was embarrassing. It sucks to carry a trombone home in sixth grade.

Roe Ethridge, Durango in the Canal, Belle Glade, FL, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Simmons: That reminds me—I’m interested in hearing more about your relationship to nostalgia.

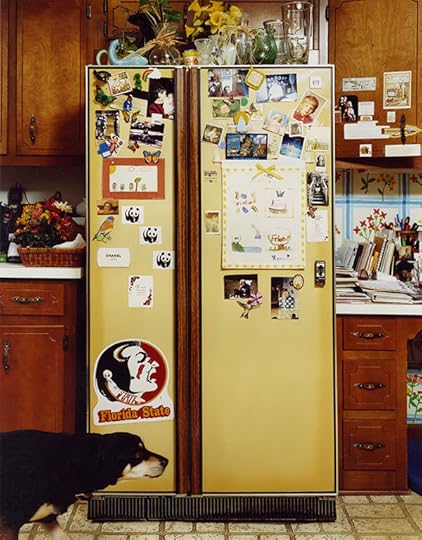

Ethridge: Well, I think there’s a difference between the romantic or nostalgic and the personal. I’m interested in weird America, David Lynch, German objective photography. How am I going to talk about the suburbs and my generic whiteness without coming off like a total dick? I need to address this identity. It’s a problem. It’s like a vacuum—the script that I was handed by my family and that particular southern Christian “good boy” bullshit.

It is such a bad script! I’m so glad that it didn’t happen. But I’m also reconciling with that identity. It’s part of the work in a way, too, but I think I’m talking about the mall, and not the country. I’m talking about working at JCPenney’s as a senior in high school, and then assisting catalog photographers making JCPenney’s catalogs. That’s a weird serendipity. One of the structural models that we were working with on the show was the notion of the department store.

Simmons: No wonder you brought up David Lynch!

Ethridge: There’s the hardware store in the beginning of Blue Velvet! It’s kind of like a pastiche of a Norman Rockwell, but it scares the fuck out of you, or it makes you cry. Blue Velvet is effective in a way, because it is stylized with nostalgic Americana. Then Lynch brings in other things that juxtapose with it and put these themes in stark relief.

Roe Ethridge, Refrigerator, 1999

Courtesy the artist and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati

Simmons: This feels like what you are doing. You can either resist nostalgia or radically choose to fall into it. A lot of your images are intensely emotional, and affecting, and beautiful. But at the same time, you leave room for people to view them ironically.

Ethridge: You have to decide what kind of person you are. I’d like to help people understand the work, but by letting it float, there’s a risk that’s interesting to me. It’s like seeding for the future, and I love that—the idea that it will unfold over time or open up to you on a third read or later when you look at it again.

William J. Simmons is an adjunct lecturer in art history at the City College of New York, and a PhD student in art history and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

Roe Ethridge: Nearest Neighbor is on view at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, through March 12, 2017 and is part of the FotoFocus Biennial, a regional, monthlong celebration of photography and lens-based art in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The post Roe Ethridge is a Good Southern Boy appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Command the Gaze

A girl-powered social media movement becomes an interactive exhibition.

By M. Whiteford

Amal Said, Purple, London, England, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

On January 21, 2017, millions of people participated in Women’s Marches in the United States and around the world, representing 616 diverse marches in 151 cities from Washington, D.C. to Beirut, Lebanon. After a campaign season in which the female body was physically and psychologically abused, scrutinized, judged, and ultimately rejected on media outlets ranging from television to Twitter, women organized around the urgency for a unified and visible stance against the misogyny symbolized by Donald Trump’s ascent to the Oval Office. At the marches, all eyes were on women and their allies, only this time they were the commanders of the gaze.

Dominique Booker, Believe, Berlin, Germany, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

Regardless of their economic circumstance, gender identity, physical ability, or nationality, many women share the experience of being watched, and sense intuitively that their worth and safety can be determined by the capricious nature of another’s gaze. This near-universal experience of being defined as an object, instead of an inherently valuable human being, influenced #girlgaze: a frame of mind, currently on display at the Skylight Studios at the Annenberg Space for Photography. As part of the ongoing #girlgaze project, the exhibition argues that a visual politics that challenges the patriarchal definitions of “female” and “woman” must be embedded in the creative work of people who identify as female, and who advocate for women. Put another way, the artists demand that we must go out to the streets and wield the agency we are afforded with empathic and creative power.

Monica Lek, Turkish Delight, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

The project is made up of an interactive multimedia exhibition of over 150 images that represents a swath of identities, each from the perspective of “people who identify as girls.” #girlgaze was founded by Amanda de Cadenet, a photographer and CEO of The Conversation, an interview series dedicated to women’s voices, and fashion and art photographers Inez van Lamsweerde, Collier Schorr, Lynsey Addario, and Sam Taylor Johnson, as well as model and activist Amber Valetta. This group of prominent photographers envisioned the social media campaign as an expansive way to challenge and redirect the viewer’s attention away from the female body as an object to be consumed in favor of the concept of female agency and multiplicity. Mobilizing social media, Instagram users became active participants in the movement by sharing and supporting photographs made by female-identified photographers. Those visiting the feed will see images of everyday women, such as a snapshot of a young Brit picking up takeout, as well as overtly political photographs, like a startling image of a domestic abuse survivor.

Luisa Dorr, Maysa, Brazil, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

Visitors to the Annenberg exhibition will find the curatorial strategy of the exhibition mimics the experience of discovering pictures via hash tag: photographs are grouped in broad categories. These related images, which include pictures of homeless encampments, race-car drivers, and institutionalized women, are set in conversation with one another on facing makeshift walls, which distinguish the disparate communities without resorting to enclosure. The audience can interact with the material through physical movement, weaving in and out of an open floor plan. In addition, several digital projections are scattered throughout the space and a photo booth welcomes visitors to upload their own portraits to the #girlgaze Instagram account.

Melanie Knight, One Size, Manchester, England, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

Though their backgrounds vary, the artists are united by the use of the camera as a mirror on which to reflect, examine, and scrutinize a woman’s relationship to herself and to the world. In a similar way, the multimedia elements of exhibition create an inclusive space in an equitable display of age, beauty, race, religion, class, and ability.

Francesca Milano, New Romantics, Milan, Italy, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

When I entered the exhibition, I was overwhelmed by the representation of proud faces not normally portrayed with nuance by the media—the infirm, the addict, the obese, the impoverished—none of whom were shown with shame or lack. I lingered on a particular portrait of a gender-ambiguous subject—a bored face staring at her reflection in a vending machine, a thin teenage mustache lining unsmiling lips. I was hypnotized by the capacity for both the photograph and the photographed subject to hold several identities at once, rejecting narrow judgments and definitions constrained by the mainstream gaze. What’s more, here was a portrait of a person in a relatable, everyday snapshot—not a composed, manipulated, or impossible ideal.

Emma Craft, Daydreaming in Silver, Jackson, Mississippi, from the exhibition #girlgaze, 2016

Courtesy the artist and the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles

Our weapons in the women’s fight for equal representation and visibility are potent: the pen, the voice, the camera, and our bodies—our presence on the streets. We must declare: I am Woman. Hear Me, See Me, Let Me Be. Our roar must be directed against the patriarchy, the structures of inequality, and the troublesome gaze that objectifies and endangers our bodies. The Instagram account and the #girlgaze exhibition not only demand this of us, but they also testify to the power of images both to inspire and provoke. #girlgaze implores all participants to stand firmly and meet opponents eye to eye. To be loud. To offend acceptable visions of female decency, behavior, beauty, and body image. To march. If photography is a record of light, the work of #girlgaze chronicles the radiance that emanates from women behind the camera and in the frame.

M. Whiteford is a writer based in Los Angeles, a contributor to Artforum and the managing editor of the Art Book Review.

#girlgaze: a frame of mind is on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles, through February 26, 2017.

The post Command the Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 25, 2017

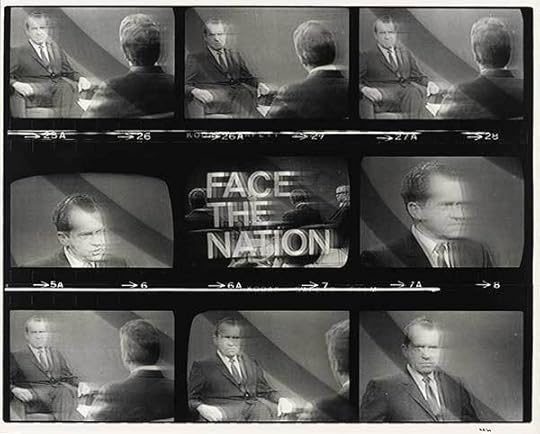

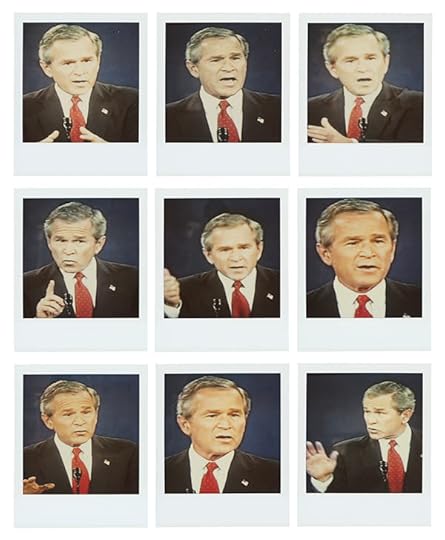

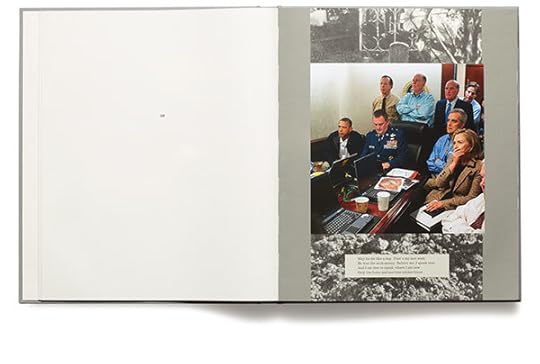

Meet the Press

At the Getty, all the news that’s fit to screen.

By Travis Diehl

Donald R. Blumberg, Untitled, from the series Television Political Mosaics, 1968–69

Courtesy Donald R. and Grace Blumberg

Those seeking to unplug from the ongoing spectacle of Donald Trump’s cabinet appointments may find a grim kind of solace at the Getty Center’s exhibition Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media, where an incisive array of photography and video reminds that the Republican administrations of yesteryear were no picnic either. To wit, one of the Television Political Mosaics (1968–9) by Donald R. Blumberg, like televisions splayed out on a contact sheet, includes row after row of vintage talking heads from the vetting of Richard Nixon’s own unlovable cronies. Others in the series superimpose a faltering transmission of then-candidate Nixon’s profile into a black and gray miasma. Further Zen might come from Blumberg’s Television Abstractions (1968–9), a picture of a grid of sixteen TVs, all tuned to static. The white noise has never been worse, yet this exhibition offers critical insight for those who would turn today’s cameras on today’s screens.

Catherine Opie, Debate, from the series Close to Home, 2004

© the artist and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

The grid—a format employed by half the artists here—is one way to wield the still photo against the moving image. Several works by Masao Mochizuki, for instance, compile dozens of thumbnails shot off television into single prints, from a story about quintuplets to a program on warplanes. The works effectively pause the media barrage, and set TV up for the kind of aesthetic scrutiny to which a photograph is more vulnerable. So too does the shock of the single drama tend to dissipate into deeper, disturbing patterns. In Alfredo Jaar’s Searching for Africa in LIFE (1996), a grid surveying the popular magazine reveals that in sixty years only five covers depict the continent. Jaar’s Untitled (Newsweek) (1995) is more damning. A cover lineup from 1994 comprises a timeline of the Rwandan Genocide; months passed before the magazine gave those mass murders a cover story—during which time O.J. Simpson had three.

Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon), from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, ca. 1967–72

© and courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, NY

In concise but caustic subversions, the artists here zoom in, redact, and collage the supposed authority of the print photograph. Martha Rosler’s well-known series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72), in which scenes from Vietnam haunt fashion shots of well-appointed American bedrooms and kitchens, is here twenty strong. Sarah Charlesworth, in April 20, 1978 (1978), redacted all but the mastheads and photographs on the front pages of national dailies, leaving the prioritizations of their editors as bare as, on the London Times, a lone paratrooper dropping into a blank page. Two decades later, Ron Jude reshot the lo-fi, largely reader-submitted photos of the Idaho Alpine Star, clipping hazy mementos from events of brief, forgotten importance.

Robert Heinecken, TV Newswomen (Faith Daniels and Barbara Walters), 1986

© The Robert Heinecken Trust

Uniquely attuned to media’s aesthetic sleights of hand, other artists perform the work of specialists or consultants. Robert Heinecken finds a typology of newscaster emotion in T.V. Newswomen Corresponding (Faith and Barbara) (1986). His series A Case Study in Finding an Appropriate TV Newswoman (1984) couches a serious analysis of news media in what he calls a “docudrama,” fictionally framed as a commission for CBS, through which superimposed images of male and female morning show anchors become the target of the artist’s satirical physiognomy. One gets the sense that the networks actually do operate on a rubric of superficial qualities thought to convey sexuality and authority. As Heinecken observes, the men appear more often backed by world maps, the women by flowers.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, War Primer 2, Plate 10: President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton along with members of the national security team, as they receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House May 1, 2011, 2011

© and courtesy the artists and Lisson Gallery

The double-entendre of this exhibition’s title betrays its optimism, as if reiterating how reiterative these crises are might break the cycle’s hold. On the other hand, Breaking News might only update a pornographic resignation to media’s horror show. The most graphic images on view are also the most recent. Rosler reprised her Bringing the War Home in the mid-2000s, as America swapped its jungle fatigues for desert. In Broomberg & Chanarin’s War Primer 2 (2011), the pair pasted photographs from America’s antiterror exploits into copies of Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 War Primer, a bitter reprise of WW II-era press photos captioned with four-line epigrams. The sharp verticals of the burning World Trade Center rise out of a ruined German city; the bright red corpse of an Iraqi, hovered over by a US soldier’s camouflaged camera, blocks the blindfolded one of a Frenchman. Under this jarring revision, Brecht’s lilting quatrain feels defeated by having held true for fifty years: “And then to show you all / What came of him, we photographed the scene.” In our war of lens against lens, there’s no end in sight.

Travis Diehl is a writer based in Los Angeles.

Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media is on view at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, through April 30, 2017.

The post Meet the Press appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Shattering the Gold Ceiling

Marilyn Minter brings her brand of glittery feminism to the Brooklyn Museum.

By Maika Pollack

Marilyn Minter, Blue Poles, 2007

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

During these dark times, Marilyn Minter’s brand of empowered woman shines bright. Minter not only shared a bill with Madonna in a conversation at the Brooklyn Museum on January 19, the eve of the Presidential inauguration, but the sixty-eight-year-old artist herself has been a visible presence at a number of anti-Trump protests in New York and Washington, D.C., and her work figures prominently in fundraisers for Planned Parenthood. Minter’s retrospective Pretty/Dirty, curated by Bill Arning and Elissa Auther, currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum, also kicked off a series of ten exhibitions called A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum. These projects feature women artists from Georgia O’Keeffe to the terrific Beverly Buchanan, whose subtle work is presented in the museum’s Sackler Center for Feminist Art concurrently with Pretty/Dirty. Together, the Year of Yes feels timely even if so far—a week into the Trump presidency—2017 feels more like the year of “God, no.”

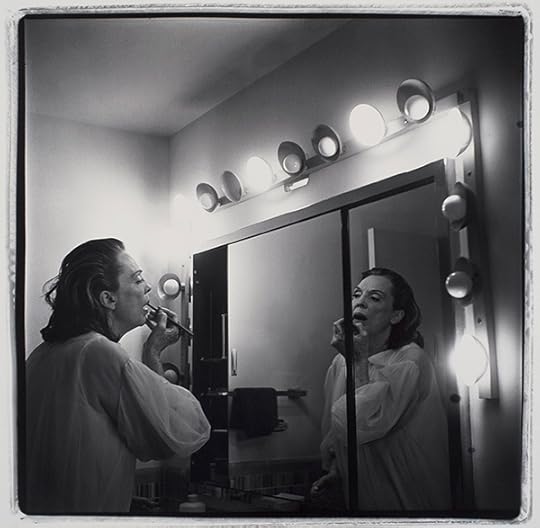

Marilyn Minter, Coral Ridge Towers (Mom Making Up), 1969

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

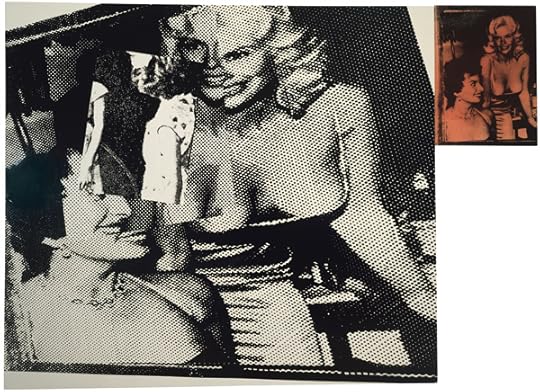

Pretty/Dirty opens with Minter’s 1969 series Mom in Mirror. The mom, in Minter’s black-and-white images, an aged woman the artist describes as a “reclusive Southern Belle,” is defined both by her liver spots and perfectly penciled-in eyebrows. In the 1970s, Minter’s first, somewhat tedious paintings show the life of domestic surfaces: close-ups of linoleum, tinfoil, and plywood. By the late 1980s, we are deep into Minter’s Porn Grid (1989), in which the banality of domestic spaces gives way to the canned shock of rasterized blowjobs—some feature three women to one cock. Trying the same application of paint with yet a third subject, Minter finds food: 100 Food Porn (1990) features phallic corncobs, swollen zucchinis, and items evocative of female genitalia (melons, artichoke hearts). Fingers splay a split salmon like a vagina. Minter, in her application of enamel to metal, is an indifferent painter, but her politics deftly take a page from Joan Semmel’s porn-positive feminism. We’ve recently seen other shows that celebrate women depicting sexually explicit material, in particular, Coming to Power, at Macaronne, in which Minter’s early work also appeared.

Marilyn Minter, Big Girls, 1986

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

At this point, the work in Pretty/Dirty suddenly shifts as we jump a decade forward and find large, photorealistic enamel-on-metal paintings—the Minters we often see at art fairs today. At first they seem to focus on the “flaws” that are edited out of commercial images of women: stubbly armpit hair, or the pink impression sock elastic leaves on white skin. In Blue Poles (2007), a single zit sits between two eyes, dappled with blue glitter. Titled after the iconic Jackson Pollock painting, the work is pretty and carries a low-wattage critique of beauty norms. But soon they lose this grain of commentary: Pop Rocks (2009) is just a woman’s mouth close-up, orgiastic, fellatio-like, on the verge of abstraction. In Drizzle (2010), a model appears with gold paint dripping from her mouth. A mixture of vodka and metallic food coloring create the effect of liquid metal, the wall text informs us. What beauty norm might this critique? It’s not so simple anymore. Instead, the interest of the piece lies in the way gold paint drips from a woman’s mouth—it’s seductive, and silky, and while the pleasure is somewhat sensual and pornographic, the content is just paint meeting body.

Marilyn Minter, Wangechi Gold 4, 2009

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

Another room features Minter’s recent work in fashion, music, and advertising. A concert backdrop created for Madonna, Green Pink Caviar (2009), features women’s lipsticked mouths that that look like Bukkake anemonies, sucking and spitting up various colorful and slimy substances. The series Plush (2014), commissioned by Playboy, celebrates public hair and the nailpolished female hands that caress it. In an adjacent chamber, a video titled Smash (2014) shows a well-heeled woman’s foot breaking a glass wall. The message is clear—as clear as Hillary Clinton hiring the Javits Center with its glass ceiling for her never-consummated victory party in New York.

Marilyn Minter, still from Smash, 2014

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

I remain uneasy about Minter’s signature work. Sure, she is riffing on Baudelaire’s equation of painting with makeup; at best, it’s decadent and rich, smeary and brushy stuff, with technique that might suggest, to some, a feminist Gerhard Richter. Yet Minter’s project also feels limited. Women are all sexy silver body glitter, goo-sucking lips, and alligator eyes. I like that Minter got “hers,” in the sense of commercial and even critical success, and I respect her political commitment: she doesn’t have to be a great artist to be a good feminist. But her images, at least in this later phase of her career, appear too market-ready, and their large scale reads as expensive, deluxe, and ultimately inoffensive.

Marilyn Minter, Glazed, 2006

Courtesy the artist, the Brooklyn Museum, and Salon 94, New York

Minter seats her viewer squarely in a quintessentially male position of power and erotic surveillance—what Laura Mulvey might have called “the male gaze.” Her relationship to Surrealist photography or historical experimental work is shallow, while its relationship to corporate tie-in culture and art-fair capitalism is profound. I find myself wondering if her empowered woman is too easy to assimilate with the often-violent visual pleasure of patriarchal visual culture and winner-take-all capitalism. Meanwhile, Minter’s earliest work is too dull to spark much interest. Pretty/Dirty is an evolutionary step in thinking about how to make art by women a serious and central part of museum culture. A Year of Yes is doing that subtle work, but the bold, ostentatiously successful, “one-of-the-boys” feminism of Minter’s work provides just one model.

Maika Pollack is an art historian teaching at Sarah Lawrence College.

Marilyn Minter: Pretty/Dirty is on view through April 2, 2017 at the Brooklyn Museum.

The post Shattering the Gold Ceiling appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers