Aperture's Blog, page 127

January 4, 2017

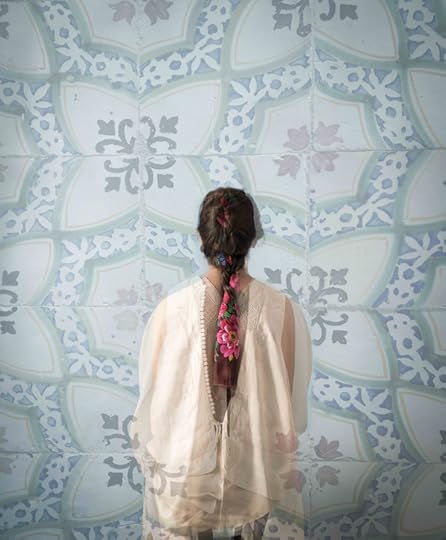

Spotlight: Eli Durst

In Eritrea, a young photographer pursues a cinematic vision.

By Alexandra Pechman

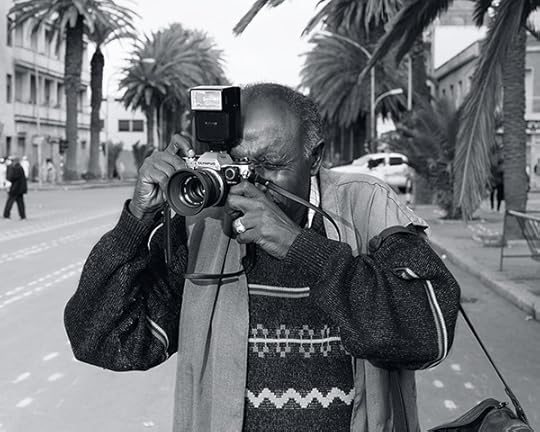

Eli Durst, Photographer, from the series In Asmara, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Eli Durst spent his summers during high school and college assembling asylum applications at the Austin immigration clinic where his mother works as a legal advocate, often for refugees from Eritrea. Durst took passport photographs and met dozens of people who had crossed the U.S. border from Mexico after landing there by circuitous journeys and illegal means, fleeing Eritrea’s authoritarian government and standstill economy. Yet, some Eritreans spoke wistfully about the underrecognized allure of Asmara, the nation’s capital and a time capsule of early twentieth-century colonial Italian architecture.

In the 1930s, following four decades of colonization, Italian fascist forces imposed the charge of futurism on Asmara through hundreds of new buildings, often shaped like the era’s latest technology: airplanes, radios, trains. The invasion of British troops in 1941, during World War II, brought an end to the Italian colony and the architectural explosion. Today, buildings remain remarkably undisturbed after years of war and undemocratic regimes.

“That really interested me, this kind of a duality of people’s love for this place while they are doing everything they can to leave,” Durst told me recently. In the summer of 2015, Durst visited the city for the first time, arranging for the brother of an Eritrean translator who works with his mother’s clinic to serve as a guide. He showed Durst the city for a few days, but then was forced to report for military training—another reason Eritreans leave the country.

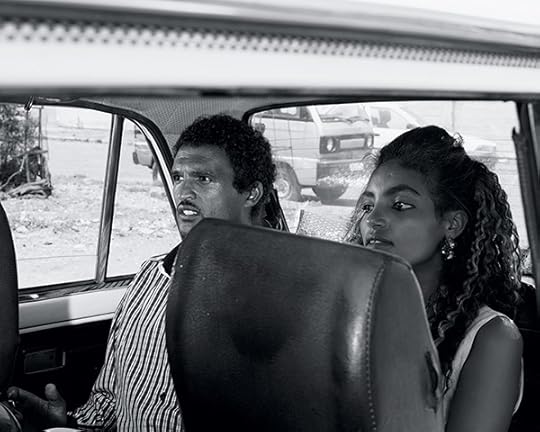

Eli Durst, Samson and Winta, from the series In Asmara, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Durst toured Asmara using a 2003 architectural survey, but found he was not allowed to photograph iconic buildings. Though still standing, the majority have fallen into disrepair. A 1930s swimming hall he wanted to photograph had, he learned, been closed for a decade, and buildings converted for government use were restricted. With limited accessibility, Durst focused on silent details, and took cues from the cinematic styles of Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, and, most of all, Michelangelo Antonioni. “I couldn’t not see it that way,” Durst said. “Asmara looks so much like the world I’ve seen in these midcentury Italian films. Antonioni, particularly, conveys a certain beauty with an underlying tension, where you have this setting but it’s disintegrating.”

Durst’s sharply contrasted black-and-white images from Asmara are often devoid of people, though the sense remains that someone has just left or is soon to appear in the frame. The Roman lettering of AMOR on a building reflects up from a puddle of standing water. Untouched coffee cups crowd a brimming ashtray on a table. A place setting of food awaits a diner.

“All you can talk about is how beautiful it is, because everyone is afraid of being critical,” Durst said. Eritrea has no free press and one of the world’s worst records for free speech. Journalists who speak out against the government are imprisoned, email and Internet use are closely monitored, and foreign journalists are not allowed to enter the country. (Durst traveled under a tourist visa.)

Durst, a native Texan, took photography classes at Wesleyan University. After graduating in 2011, he moved to New York to learn more about photography, working at Griffin Editions and as an assistant for Joel Meyerowitz, whom he cites as an influence. Durst later attended the Yale University School of Art for his MFA, where he began to work on his Asmara portfolio.

Eli Durst, Steak, from the series In Asmara, 2015

Courtesy the artist

The retouched passport photographs that Durst took over the years in Austin (and now uses in his work, with applicants’ consent) punctuate the series and connect Durst’s engagement with Eritreans in Austin and Asmara. Other images have faces and bodies that are clipped, cropped, or seen at a distance.

In a photograph taken in the dining room of his nearly unoccupied hotel (tourism to Eritrea is made difficult by a government wary of Western agitators and influence), a waiter in suit and tie stands in front of a contemporarily dressed man seated alone among empty tables.

Durst’s trip coincided with Ramadan, and on Eid al-Fitr local photographers take pictures of celebrating families. One took notice of Durst. “All the younger photographers had digital and he had this old Olympus,” Durst said. “He saw me and I stood out. He took my picture and then pulled me aside and led me around the city.” The man didn’t speak English and Durst was without a translator, so during their hour-long tour Durst never learned his name. In Durst’s image of their encounter, the unknown photographer, his face obscured by the Olympus, trains his analog lens on Durst, a seeming nod to the obscured face of Thomas in the popular imagery from Blow-Up (1966), Antonioni’s seminal meditation on the medium of photography.

“With Antonioni, there are these complicated and often very scary political undercurrents,” Durst said. “That photographic tension exists in his films. That’s what was driving me.”

Alexandra Pechman is a writer based in Rio de Janeiro and New York.

Eli Durst is the winner of the 2016 Portfolio Prize. His exhibition In Asmara is on view at the Aperture Gallery through February 4, 2017. Click here for more information about the Portfolio Prize, now open exclusively to Aperture subscribers.

The post Spotlight: Eli Durst appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

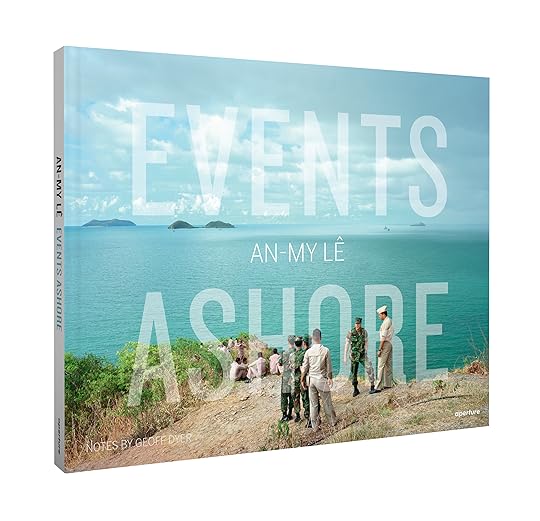

John Berger’s Intimate Greatness

Aperture remembers the life of John Berger, whose narrative approach to art criticism reached far beyond photography.

By Geoff Dyer

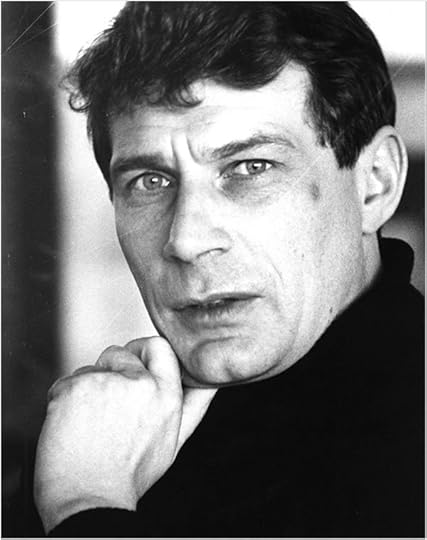

Jean Mohr, John Berger, 1967

Courtesy the artist

I became interested in photography not by taking or looking at photographs but by reading about them. The names of the three writers who served as guides will come as no surprise: Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, and John Berger. I read Sontag on Diane Arbus before I’d seen any photographs by Arbus (there are no pictures in On Photography), and Barthes on André Kertész, and Berger on August Sander without knowing any photographs other than the few reproduced in Camera Lucida and About Looking. (The fact that the photo on the cover of About Looking was credited to someone called Garry Winogrand meant nothing to me.)

Berger was indebted to both of the others. Dedicated to Sontag, the 1978 essay “Uses of Photography” is offered as a series of “responses” to On Photography, published the previous year: “The thoughts are sometimes my own, but all originate in the experience of reading her book.” Writing about The Pleasure of the Text (1973), Berger described Barthes as “the only living critic or theorist of literature and language whom I, as a writer, recognise.”

For his part, Barthes included Sontag’s On Photography in the list of books—omitted from the English edition—at the end of Camera Lucida (1980). Sontag, in turn, had been profoundly shaped by her reading of Barthes. All three had been influenced by Walter Benjamin, whose A Short History of Photography (1931) reads like the oldest surviving part of a map this later trio tried—in their different ways, using customized projections—to extend, enhance, and improve. Benjamin is a constantly flickering presence in much of Barthes’ writing. The anthology of quotations at the end of On Photography is dedicated—with the kind of intimate relation to greatness that Sontag cultivated, adored, and believed to be her due—“to W. B.” At the end of the first part of Ways of Seeing Berger acknowledges that “many of the ideas” had been taken from an essay of Benjamin’s titled “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” (This was 1972, remember, before Benjamin’s essay became one of the most mechanically reproduced and quoted ever written.)

Photography, for all four, was an area of special interest, but not a specialism. They approached photography not with the authority of curators or historians of the medium but as essayists, writers. Their writings on the subject were less the product of accumulated knowledge than active records of how knowledge and understanding had been acquired or was in the process of being acquired.

This is particularly evident in the case of Berger, who did not devote an entire book to the subject until Another Way of Telling in 1982. In a sense, though, he was the one whose training and career led most directly to photography. Sontag had followed a fairly established path of academic study before becoming a freelance writer, and Barthes remained in academia for his entire career. Berger’s creative life, however, was rooted in the visual arts. Leaving school possessed by a single idea—“I wanted to draw naked women. All day long”—he attended London’s Chelsea and Central schools of art. In the early 1950s he began writing about art and became a regular critic— iconoclastic, Marxist, much admired, often derided—for the New Statesman. His first novel, A Painter of Our Time (1958), was a direct result of his immersion in the world of art and the politics of the left. By the mid-1960s he had widened his scope far beyond art and the novel to become a writer unhindered by category and genre. Crucially, for the current discussion, he had begun collaborating with a photographer, Jean Mohr. Their first book, A Fortunate Man (1967), made a significant step beyond the pioneering work of Walker Evans and James Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), on rural poverty in the Great Depression. (A Fortunate Man is subtitled “The Story of a Country Doctor,” in homage, presumably, to the great photo-essay by W. Eugene Smith, “Country Doctor,” published in Life in 1948.) This was followed by their study of migrant labor, A Seventh Man (1975), and, eventually, Another Way of Telling. The important thing, in all three books, is that the photographs are not there to illustrate the text, and, conversely, the text is not intended to serve as any kind of extended caption for the images. Rejecting what Berger regards as a kind of “tautology,” words and images exist, instead, in an integrated, mutually enhancing relationship. A new form was being forged and refined.

A side-effect of this ongoing relationship with Mohr was that Berger had, for many years, not only observed Mohr at work; he had also been the subject of that work. Lacking the training as a photographer that he’d enjoyed as an artist, he became very familiar with the other side of the experience, of being photographed. With the exception of one picture, by another friend—Henri Cartier-Bresson!—the author photographs for his books have almost always been by Mohr; they constitute Mohr’s visual biography of his friend. (The essay on Mohr included here records Berger’s attempt to reciprocate, to make a sketch of the photographer.) His writings on drawing speak with the authority of the drawer; his writings on photography often concentrate on the experience, the depicted lives, of those photographed. Barthes expressed the initial impetus for Camera Lucida as photography “against film”; Berger’s writing on photography hinges on its relationship to painting and drawing. As Berger has grown older, his early training—in drawing—rather than fading in importance has become a more and more trusted tool of investigation and inquiry. (Tellingly, his latest book, published in 2011 and inspired in part by Spinoza, is called Bento’s Sketchbook.) A representative passage in “My Beautiful” records how, in a museum in Florence, he came across the porcelain head of an angel by Luca della Robbia: “I did a drawing to try to understand better the expression of her face.” Could this be part of the fascination of photography for Berger? Not just that it is a wholly different form of image production, but that it is immune to explication by drawing? A photograph can be drawn, obviously, but how can its meaning best be drawn out?

This was the goal Barthes and Berger shared: to articulate the essence of photography—or, as Alfred Stieglitz had expressed it in 1914, “the idea photography.” While this ambition fed, naturally enough, into photographic theory, Berger’s method was always too personal, the habits of the autodidact too ingrained, to succumb to the kind of discourse- and semiotics-mania that seized cultural studies in the 1970s and ’80s. Victor Burgin—to take a representative figure of the time—had much to learn from Berger; Berger comparatively little from Burgin. After all, by the time of About Looking (1980), the collection that contained some of his most important essays on photography, Berger had been living in the Haute-Savoie, France, for the best part of a decade. His researches—I let the word stand in spite of being so thoroughly inappropriate—into photography proceeded in tandem with the struggle to gain a different kind of knowledge and understanding: of the peasants he had been living among and was writing about in the trilogy Into Their Labours. Except, of course, the knowledge and methods were not so distinct after all. Writing the fictional lives of Lucie Cabrol or Boris—in Pig Earth (1979) and Once in Europa (1987), the first two volumes of the trilogy—or about Paul Strand’s photograph of Mr. Bennett (p. 44), both required the kind of attentiveness celebrated by D. H. Lawrence in his poem “Thought”:

Thought is gazing on to the face of life, and reading what can be read,

Thought is pondering over experience, and coming to a conclusion.

Thought is not a trick, or an exercise, or a set of dodges,

Thought is a man in his wholeness wholly attending.

In Berger’s case, the habit of thought is like a sustained and disciplined version of something that had come instinctively to him as a boy. In Here Is Where We Meet the author’s mother remembers him as a child on a tram in the London suburb of Croydon: “I never saw anyone look as hard as you did, sitting on the edge of the seat.” If the boy ended up becoming a “theorist,” then it is by adherence to the method described by Goethe, quoted by Benjamin (in A Short History) and requoted by Berger in “The Suit and the Photograph”: “There is a delicate form of the empirical which identifies itself so intimately with its object that it thereby becomes theory.”

This is what makes Berger such a wonderful practical critic and reader of individual photographs (“gazing on to the face of life, and reading what can be read”), questioning them with his signature intensity of attention—and, often, tenderness. (See, for example, the analysis of Kertész’s picture A Red Hussar Leaving, Budapest, June 1919.) To that extent his writing on photography continues the interrogation of the visible that characterized his writing on painting. As he explains at the beginning of the conversation with Sebastião Salgado: “I try to put into words what I see.”

This essay is adapted from the introduction to John Berger’s Understanding a Photograph , published by Aperture in 2013.

Geoff Dyer’s most recent book is White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World (2016).

The post John Berger’s Intimate Greatness appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 22, 2016

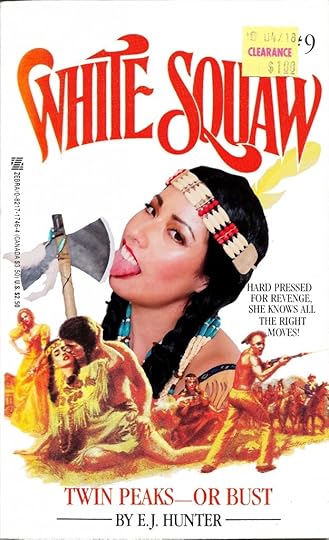

The Accidental PhotoBook

Denise Wolff

We are at a moment when the community of photobook makers and collectors is expanding rapidly, yet also becoming more insular. We’re ever searching for that handmade artist book created just for the art fair, available in limited copies that are going fast. For many years, the Martin Parr/Gerry Badger Photobook: A History and other books about books have served as a shopping list, bestowing value on the included volumes. Looking back through The Photobook: A History, however, it’s worth remembering that they cast a wide net, including among the shimmer of possibilitys and Sleeping by the Mississippis, mass market books, commercial books, books on food, and propaganda.

It’s been over a decade since the first and second volumes of The Photobook: A History came out, and our community has developed a finely tuned connoisseurship of the artist monograph. For this reason, it is a good time to consider other types of books that use photography, but are not considered photobooks qua photobooks—books that are unlikely to end up on anyone’s yearly top-ten list (and never aimed to). These books are often outside the photobook radar for a variety of reasons, whether they be too idiosyncratic, mass market, or useful (cookbooks, lifestyle, science), but their impact relies heavily on photography. Some of these fall into a guilty-pleasure category, but many, freed from an artist’s agenda and the conventional earmarks of an artist book, present a more direct use of photography and are successful in their own right. In the pages that follow, we have invited photobook aficionados to talk about their favorite niche within the larger universe of photo-illustrated books, and a handful of others to introduce their favorite non-photobook photobook—their own guilty pleasures. In short, this issue will address the unlikely, even accidental, photobook.

My own interest in the category of the accidental photobook began with cookbooks. I bought the 1958 Time Life Picture Cookbook as a joke. Maybe it appealed to me as a reaction against the kinds of photobooks I engage with on a daily basis. From there, I gathered many more cookbooks of a similar ilk—those that had clearly paid as much attention to the staging and photographing of the food as to the presentation of recipes. When the habit grew from a few books on a shelf to an entire bookshelf, I had to admit, it was no longer ironic, but true love. I take more pleasure in a few of these cookbooks than I do with some of the more proper photobooks, many of which are languishing on my shelves in Mylar sleeves. The following are a few of my favorites.

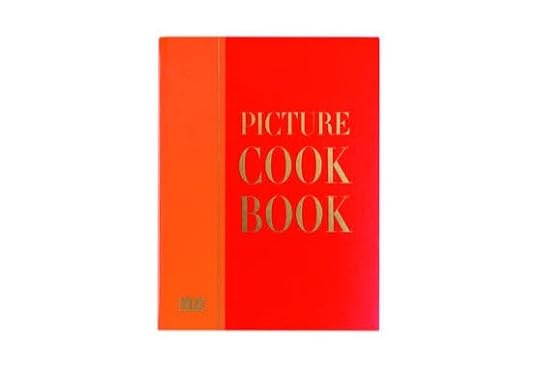

LIFE Magazine ⋅ Time Life Picture Cookbook

Time Inc. ⋅ New York, 1958

Some context is needed to fully appreciate the Time Life Picture Cookbook. Picture cookbooks became popular in postwar America. Women were supposed to get back into the kitchen with new vigor, entertaining needed to start again, national taste and culture had to be re-established. Photographs, particularly of food and feasts, were part of that. The most well-known was the 1950 Betty Crocker Picture Cookbook. It’s bound in a loose-leaf ring binder and chapterized into subject files, so you can quickly get to the Pie section and remove the recipe for cooking. Throughout, decadent color photos burst at the seams with American bounty. Buffet-style spreads are in full force and meant to feed an army of guests: epic picnics and breakfast feasts, rows of frosted cakes and jellyrolls, and salads galore. They are more exuberant than they are appetizing, speaking more to tastefulness (or perhaps the lack thereof) than taste itself. The photos are often set in the home, showing the newest appliances and wares. Here, America presents itself as plentiful during the Cold War, in direct contrast to communism. Despite all the messaging, the book remained a functional cookbook, one that was bought primarily for the recipes and was engineered to be useful. The pictures are a punchy bonus. The tables and counters full of food are aspirational, but still seem achievable.

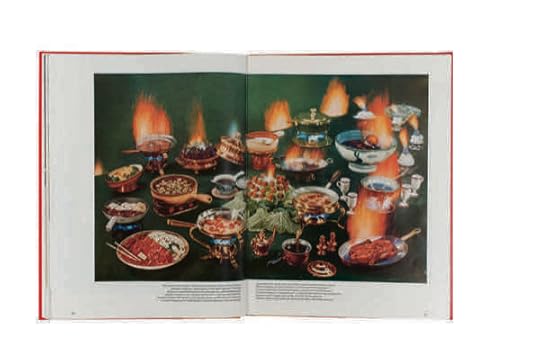

LIFE Magazine ⋅ Time Life Picture Cookbook

Time Inc. ⋅ New York, 1958

By 1958, the Time Life Picture Cookbook had become decidedly more about the pictures. Sure, it contains lots of recipes, but at fourteen inches tall, this is not the book you’re reaching for in the kitchen. It’s not being bought or produced for the recipes, which are all run together, small. The pictures, however, go across the double-page spreads gloriously, presenting a tableau of food more aligned with still life than with interiors. The production on each shoot is impressive, not accomplishable by any home cook anywhere, with twenty plates of flambé presented in the same shot for the “Flaming Foods” chapter opener or with pineapples frozen into blocks of ice for “Cooking on Ice.” The pictures here are spectacular in the truest sense of the word. They present a wonderful fantasyland of food. Scales and hourglasses appear with perfectly textured Baked Alaskas and Petits Fours in pastel and desert backgrounds, depicting low-calorie and time-saving desserts. The book still operates within lifestyle and taste, but instead of presenting recipes you can accomplish with the help of this book, the Time Life Picture Cookbook is something you would more likely display in your home rather than actually use. Hence, the book is more photobook than recipe book. And the pictures are a joy to look at beyond their nostalgic value. The watermelon on ice with roses is a gorgeous still life that still holds up today; the “Drinks and Hors D’oeuvres” opener could pass as an Irving Penn (it’s by H. I. Williams). Time Life would go on a decade later to publish the Foods of the World Library, which also focused on the photographs—though more documentary in hopes of creating an armchair travel experience of culture through food.

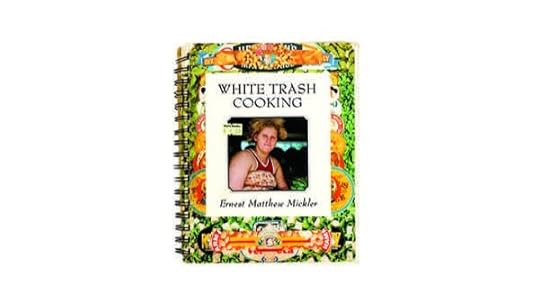

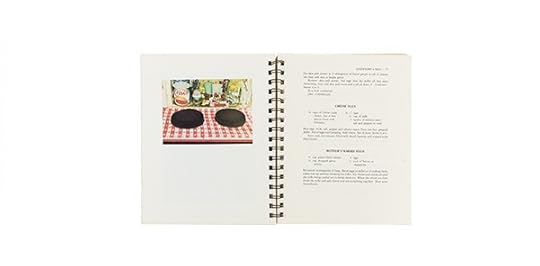

Ernest Matthew Mickler ⋅ White Trash Cooking

The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press ⋅ Berkeley, CA, 1986

White Trash Cooking (The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press, 1986), by contrast, is the antithesis of the Time Life Picture Cookbook, a spoof, but one with a great deal of love at its heart. (The Jargon Society, founded by the late North Carolinian poet and Black Mountain College alum Jonathan Williams, was better known for publishing avant-garde books of poetry and photography.) The book is a satirical counterpoint to the more serious cookbooks of the day that had begun fetishizing freshness and local ingredients with the rise of Chez Panisse. The recipes, like Tutti’s Fancy Fruited Porkettes, Mock-Cooter Stew, Oven-Baked Possum, and Four-Can Deep Tuna Pie, are written in a down-home voice. But through the tongue-in-cheek, it is clear there is genuine affection for the people and respect for the country dishes. Nothing reflects this more than the surprise center section of color photographs, taken by the author, Ernest Matthew Mickler, on his travels through the South as he collected the recipes. There is no irony here. The pictures are casual, direct, and elegiac. They reference FSA pictures from the region and resemble William Christenberry’s pictures of Alabama with their sense that this way of life is becoming a memory. Bushels of peaches, old stoves, rusty bedframes in the landscape, people on porches, cornpones on the stove show a different kind of local lifestyle. Though the pictures would still work in a traditional photobook context, in the cookbook they operate to both cut the edge of the White Trash Cooking’s joke, and to deepen the satire against other lifestyle cookbooks, by revealing something much more sincere. In the last picture, the two devil’s food cakes cooling on the counter look like black portals into another time. That Mickler could convey such depth in front of a tub of Crisco is remarkable. Publishers first rejected the book and the New Yorker refused to run an ad for it, but it became an instant classic.

Ernest Matthew Mickler ⋅ White Trash Cooking

The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press ⋅ Berkeley, CA, 1986

Today if you walk through the cookbook section of any store, you will notice that the books there look a lot like art books. This trend may have started out of necessity; with the rise of digital books, printed books needed to justify their existence and amplify their shelf appeal to entice consumers. To achieve that, publishers have reached into the bag of tricks established in art and design books, including photobooks. An early adopter of this recent trend is Breakfast Lunch Tea (Phaidon, 2006). This was the first cookbook wholly originated by Phaidon, after its success with Silver Spoon (a buy-in with Editoriale Domus for the 1950 Italian classic Il Cucchiaio d’argento). It is no surprise that this book takes the form of an artbook since this is what Phaidon knows best. Toby Glanville, a wonderful British portraitist, took the photographs and presents an utterly lovely portrait of a bakery: those who work there, the regulars, the purveyors, the ingredients, the process, and the finished food. Glanville’s unusual color palette, striking angles, and unassuming portraits make for a beautiful book. This, combined with the high quality paper and printing, elevate the cookbook into more of a photobook. Phaidon continued this type of treatment in their future cookbooks, and many other publishers have followed in their wake.

Brooks Headley ⋅ Brooks Headley’s Fancy Desserts: The Recipes of Del Posto’s James Beard Award-Winning Pastry Chef

W. W. Norton ⋅ New York, 2014

Perhaps in reaction to this movement, Brooks Headley’s Fancy Desserts (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014) is a serious cookbook, but also pokes fun at today’s delicate pastry cookbooks with their restrained color palettes and selective focus. Instead, the Fancy Desserts pictures, a collaboration between photographer Jason Fulford and illustrator and author Tamara Shopsin, are playful, each with their own deadpan joke, and shot almost entirely against a plain white background. The red cover says it all with sticky hands, sauce poured out from proportionally tiny creamer, dripping chocolate from poorly painted fingernails, and a rather unappetizing mystery dough (cheese, actually). The book feels more punk than lighthearted with clever inside references and, at times, a gross-out take on pastry, more akin to a food fight than a white table experience. We rarely see the fragile and fancy final dishes, just the crazy process, complete with a condensed milk bomb. The book is purposefully not tasteful, deflating the very notion of fancy, and subverting the increasingly precious cookbooks-as-artbook genre. The fact that the book accomplishes this with art stars Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin at the design helm is a large part of its genius. Sadly, the publisher just released a paperback edition replacing the original cover with a more expected picture of fancy dessert. Chickens!

Denise Wolff is a senior editor at Aperture. Some recent books she has commissioned include The Photographer’s Cookbook (2016); The Photography Workshop Series books; and Seeing Things (2016), a children’s book by Joel Meyerowitz.

The post The Accidental PhotoBook appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 21, 2016

Laurie Simmons and Molly Ringwald are Playing with the Big Boys

The iconic actress and legendary photographer talk about cameras, color, and what it means to be a woman in the arts.

Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll/Day 30/Day 2 (Meeting), 2011

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Laurie Simmons and Molly Ringwald are a bit of an item. In the past year, Ringwald interviewed Simmons on WYNC’s Studio 360; for a conversation in Lenny Letter, Simmons turned the spotlight on Ringwald, the breakout star of the John Hughes classics Sixteen Candles (1984) and Pretty in Pink (1986), who recently appeared in the stage adaptation of Terms of Endearment. On the first Tuesday in November—when New York was still bubbling with the anticipation of possibly electing the first woman president—I attended the ICP Spotlights Awards luncheon, where Ringwald celebrated Simmons, the honoree. Amidst the soft clatter of dessert forks and champagne flutes, the duo discussed not only Simmons’s iconic work, but also what it means to be a woman in the arts.

At the beginning of their conversation, Simmons mentioned that, in the ’70s, she saw an opportunity for women artists to disrupt the male-dominated, documentary-focused field of photography. Most famously, her photographs elevate miniature objects—houses, dolls, furniture—playthings of girls who are destined for domesticity. She shows us ourselves through the very tools that confine women to certain standards of behavior, beauty, and ambition. In Aperture’s current issue, “On Feminism,” Simmons writes that How We See (2015), her recent project, “is partly concerned with directives in language and the expectations imposed by pronouns like he, she, it, they, them.” She examines what a universal “we” could imply at a time when classes and cultures are becoming increasingly isolated. What we see, and how we see is who we are. —Annika Klein

Laurie Simmons, Big Camera/Little Camera, 1976

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Molly Ringwald: You don’t necessarily consider yourself a photographer, but more of an artist who uses a camera. Why did you decide to use the camera instead of a different medium?

Laurie Simmons: I came to New York after a very formal, rigorous art school education. Conceptual art, process art, and video and were bursting wide open. My education, which was printmaking, painting, and sculpture, just didn’t seem relevant in 1973–74. Conceptual art was about people picking up a camera because they had to document what they were doing. Fashion photography was also exciting then between Deborah Turbeville, Chris von Wangenheim, and Helmut Newton. And I just thought: A camera—maybe that’s an interesting tool.

I wasn’t aware of a lot of women photographers at the time so I thought, maybe this path is a little clearer for me than painting or sculpture or art history; as it was taught to me, most of its characters were male. I, like a number of other women artists at the time, saw something that we might be able to invent, or at least mold.

Ringwald: How did you start taking pictures? Did someone actually teach you the technique?

Simmons: Kind of, yes. I shared a loft with the photographer Jimmy DeSana who died of AIDS in 1990. We got a two hundred foot long loft in SoHo for no money—everyone loves that, or hates it. [Laughs.] We put a dividing wall in between and I had a darkroom, and he had a darkroom. Basically, I started with a book and tried to figure out what to do. I had walked out of a photography class in art school because I thought, frankly, photography wasn’t art. I just dismissed it. Jimmy DeSana taught me everything I knew. And when he wasn’t around, there was this thing called the Kodak Hotline, and you could call and there was a guy on the other end who sounded like an astronaut. I called so many times that I started disguising my voice and putting on different accents because I thought, this guy’s not going to answer any of my questions. Between Jimmy DeSana’s instruction and what I learned from the Kodak man, I was really self-taught.

Laurie Simmons, Blonde/Red Dress/Kitchen, 1978

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: Could you tell us about your work from that time?

Simmons: My first show was at Artists Space in New York in 1979 and it got reviewed in the Village Voice, which is still one of the most exciting things that has ever happened to me. It was reviewed by Ben Lifson and he called me a feminist artist. The article was called “Robert Frank and the Track of Life.” Even though I was a baby booming feminist I was so floored, because I was surprised to be referred to as a feminist artist.

Ringwald: Did you consider yourself a feminist?

Simmons: Yes, I did. But I didn’t think that I was making art about that, nor did I want to because I felt that the generation before me had marginalized themselves by calling themselves feminist artists. Like a lot of women in my generation, I wanted to play with the big boys; I wanted to do everything that was available to do; I wanted to hang in museums, which is what eventually led me to make big prints.

Laurie Simmons, Walking Cake I (Color), 1989

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: When you look back on the work now, do you see it as feminist art? I say that in a good way, because I don’t think “feminist” is a bad word.

Simmons: I don’t think “feminist” is a bad word, and it’s starting to become clear to me that a number of young women do think it’s a bad word. I’d like to know why, but I think I was making work about memory. Those pictures were not a critique about a housewife being entrapped, enmeshed in her own possessions, or being trapped in her own home. I loved the images from Life magazine. These were the kinds of pictures that drove me crazy.

Ringwald: “I courted an angel and married a cook.”

Simmons: Which is incredible. My father was a dentist who had an office in his house. He had huge magazines—Look and Life—and I was reading that stuff when I was really young. He used to invite my and me sister into the office to read. He had a great fish tank, and these beautiful magazines. My visual brain started to work in his office. I had a memory of that period of time being so idealized, and I lived in suburbia—it was so beautiful on the surface. I wanted to make work that was as beautiful as the work in Life magazine. I wanted my pictures to look like that.

The most striking feature of my childhood home was that everything was color-coordinated. In the most amazing way. I am programmed to see color-coordination because of how rigorous the steps were that everybody took to make sure that the world matched in some way.

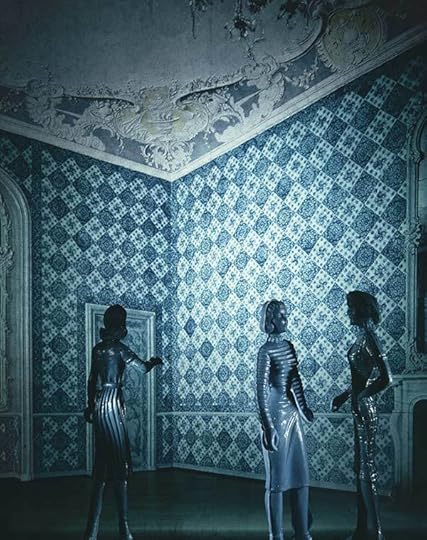

Laurie Simmons, Blue Tile Reception Area, 1983

© the artist and courtesy Salon 94

Ringwald: Have you used the color coordination from your youth in your art?

Simmons: Yes. I love shooting in black-and-white, but I am most conversant in color. As a child, I could identify people’s lipsticks. If you had to have your shoes dyed to match your dress, I didn’t have to use the color chart.

Ringwald: You got married in 1983. Do you feel that getting married and having children affected your art in any way?

Simmons: I’m really glad you asked that question, because if someone asked me that question twenty years ago I would have refused to answer. I felt that all artists should be on a level playing field: men and women, gay and straight. People were not asking men that question. Now I think it’s important to answer the question because there are many young women artists who feel like it’s not appropriate to have children. A number of them have come to me and asked me my thoughts about it, about the idea of being an artist and having a child. Of all of the things that everyone says about Hillary Clinton, I haven’t heard anyone criticize her for being a mother. Or Ruth Bader Ginsburg, or Meryl Streep, or Margaret Thatcher. So why this question exists in the art world is really baffling to me.

Laurie Simmons, Jane, 1988

© the artist and courtesy Salon 94

Ringwald: Going back to the idea that being a feminist can have a bad connotation, being a mother can also be seen as a negative connotation. Why would being a mother influencing your art be considered a bad thing?

Simmons: I don’t know if being a mother, per se, influenced my work. Although, when I was making the ventriloquism series in 1987, I made three trips to a ventriloquist museum down South, and photographed hundreds of dummies against a background. In hindsight, it did occur to me that I was moving the dummies around and carrying them, and then going back home and picking up a child who weighed relatively the same. Often times, I think the artist is the last person to know what the connections really are.

When I was making the work, I was coming into my full-blown, adult political awareness. What I was thinking about was: who’s actually speaking? Who’s really speaking when we read the newspaper? Who’s really speaking when we listen to a politician? Who’s really speaking when we listen to newscasters? Where is the information coming from? It was the moment when I became mature enough to understand all the information that was coming at me.

Ringwald: What was the inspiration for the series Walking and Lying Objects that you recently revisited for your video with New York magazine?

Simmons: This was my friend Jimmy DeSana in the camera, which was from the movie The Wiz (1978). We borrowed it from the Museum of the Moving Image. We both knew that he was dying of AIDS. Not something that we talked about a lot, but this was an homage to him in the sense that he taught me everything I knew, and he loved posing for it. It makes me so happy that people associate this picture first and foremost with my work because it’s so much about him, and my relationship with him. The reason I thought about doing objects on legs is the ventriloquist series had been so much about the brain, and I wanted to think about brawn, and the way that we as women, or people, have to heft, hold up the possessions of our life—we become subsumed by them, we hold onto them. This is more of a classic feminist statement than the early dollhouse pictures.

Laurie Simmons, Walking Camera I (Jimmy the Camera), 1978

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: That feeling of carrying around a lot—I feel like that every day. Every day I find myself carrying so much stuff, and I think it is purely psychological, like I need to manifest everything in what I’m actually carrying, and this series reminds me of that.

Simmons: You need to take your life with you. A lot of people feel that. It was a long time ago now, but I was starting to think about aging and the ways I could portray that without hitting you over the head with it.

Ringwald: I’ve always thought that being an artist would make you less susceptible to the idea of aging. Is that a fallacy?

Simmons: Yes. One of the great things about being an artist is that we’re never going to retire. I will work on whatever I can work on until the very end. It would be impossible to be a woman in our culture—you’d have to live under a rock—not to think about issues around aging. The U.S. is manic about youth. It doesn’t mean that everyone hates the age that they are or wants to be young, but it’s there for us to see every single day. As an artist, I think of all the work that I want to do, that’s left to do. Everyone is just battling the idea of a limited amount of time.

Laurie Simmons, Music of Regret, Act 2, 2006

© the artist and courtesy Salon 94

Ringwald: And that’s universal. Tell me about your first film, The Music of Regret.

Simmons: It was a musical in three acts, and it was a way to say goodbye to all of the work I had done until then. I wrote the lyrics, Michael Rohatyn wrote the melodies, which are beautiful. There was a moment there where I thought, this is it, I’m a lyricist. The dummy is an image of me, and then I cast Meryl Streep to play the dummy.

Ringwald: How did you end up with Meryl Streep in your project?

Simmons: I’ve known her for years. Her husband is a very well-known sculptor. I knew that Meryl liked to sing—this was before Mamma Mia! (2008). And I knew that if I played the songs that she would say yes, and she completely fell in love with the songs. She was going to be able to sing with Adam Guettel, who wrote The Light in the Piazza (2003) and was also the grandson of Richard Rogers.

Laurie Simmons, Yellow Hair/Brunette/Mermaids, 2014

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: Was it daunting at all, your first experience directing Meryl Streep?

Simmons: Well, you don’t direct Meryl Streep. [Big laugh from audience.] You just stand there and she does her thing perfectly. That was really not a directing experience.

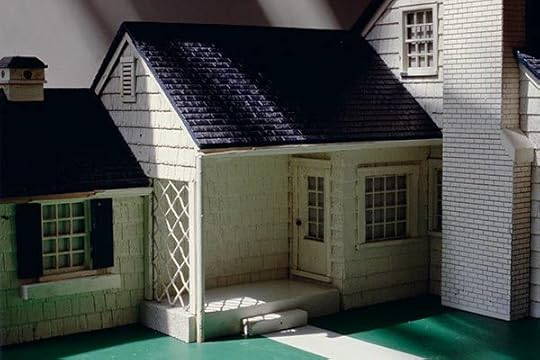

In White House/Green Lawn (1998), which very few people have seen, I just moved around an architectural model, that just felt like the essence of a kind of suburban feeling. I often really like to shoot without figures or dolls, which is interesting for me because if I’m exhibiting the work, and standing in the gallery and people come in, they’re coming in looking for a doll. They’re looking for a figure. It’s almost amazing to see people’s eyes glaze over, like “where’s the doll? I’m out of here . . .” But I need to do it. And I do it periodically. I just make really empty spaces.

Ringwald: Why do you do it?

Simmons: Because it feels right to me. Sometimes the places I want to be don’t have figures in them, and I feel like that’s where I am when I look through the viewfinder.

Laurie Simmons, White House/ Green Lawn (View I), 1998

© the artist and courtesy Salon 94

Ringwald: Sort of like the difference of being an introvert and an extrovert. These images seem more introverted and peaceful.

Simmons: Exactly. And someplace where I like to go stand. The experience of shooting through a viewfinder—and this is more true for me when I’m shooting still photographs than when I’m shooting film—I really feel like I’m there. Whatever the camera factors out, or what I lose in my peripheral vision makes me feel like I’m physically standing in this place, which reminds me of the feelings that I had when I would sit on my mother’s lap and she would read a book, and I had this very profound, overwhelming desire to be in that book.

Ringwald: It evokes the same thing in the viewer. I tend to gravitate to authors who don’t describe the person physically in detail so I can event my own image.

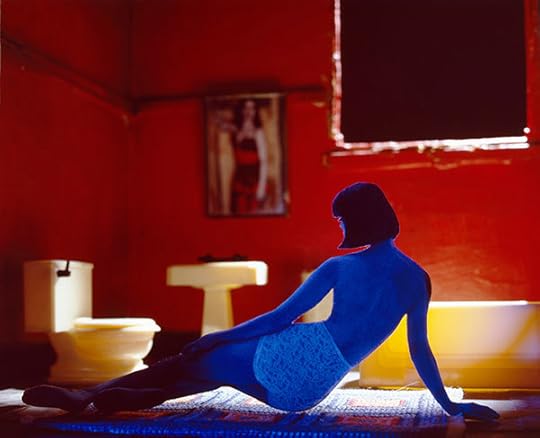

Going back to interiors, what about your series Long House?

Simmons: I started cutting out figures and putting them in a house with furniture. Instead of being pristine, it felt more like a bordello. I loved shooting in a very different kind of space.

Laurie Simmons, Long House/Red Bathroom/Blue Figure, 2004

© the artist and courtesy Salon 94

Ringwald: In the picture with the red bathroom, she’s wearing very sexy granny pants on.

Simmons: That’s because she’s cut out from a magazine. This is both embarrassing and very practical, I saved all my fashion magazines, my Mademoiselle, Glamour, Seventeen, and I have huge stacks of them. They’re an incredibly great resource. This series got me into a more cartoon, noir sort of world.

Ringwald: How long does it usually take you to do a photograph?

Simmons: I work in series. So when I get an idea, I set it up and I shoot, and I shoot, and I shoot. A series can go on for two years, or one month. I’m sure a lot of artists would share these feelings with me, but I know when things begin and I know when they’re over.

Laurie Simmons, Color Pictures/William Baziotes, 2009

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: Most people don’t realize this, but along with dolls and puppets, you’ve also experimented with nudes and pornographic imagery.

Simmons: When I finished making my movie, I felt I’d left so much work behind, and I felt like I needed to start with no nostalgia and with a naked person. So I downloaded free internet porn which is probably college girls who needed extra money. I’ve only shown that work once. I have a hundred of them; I love them all. But women who thought they knew my work were so shocked that I put them away very quickly.

Ringwald: People were upset by it?

Simmons: I think they were puzzled. People thought they knew who I was and I wasn’t that person.

Laurie Simmons, How We See/Ajak (violet), 2015

© the artist and courtesy ICP and Salon 94

Ringwald: This is a question from the audience. You transition from black-and-white to color from your early work. Did this choice have to do with the idea of the time that black-and-white connotes the real and color could create a more constricted fantasy world?

Simmons: I’ve never thought about it that way before, but I have to praise whoever wrote that question. I often think about when Dorothy went to Oz and basically the lights were turned on and her fantasy life was exposed in beautiful emerald living Technicolor.

What I really want to get to is my most recent pictures, they’re called How We See, where the fashion model’s eyes are closed.

Ringwald: They’re so beautiful, and so creepy. But they’re striking; you can’t stop looking at them.

Simmons: It’s that classic there’s something wrong with this picture. And there is. They’re eyes are closed. It speaks to so many of the things I’m thinking about identity politics, and the idea that the person that we meet on the internet, the person who we project on the internet, may not be the person we think it is at all. I’m interested in false identity and the way we’re able to mask identity.

Annika Klein is the Editorial Assistant at Aperture magazine.

This interview is adapted from a live conversation at the International Center of Photography Spotlights Award Luncheon on November 1, 2016.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Laurie Simmons and Molly Ringwald are Playing with the Big Boys appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 20, 2016

Renée Cox: A Taste of Power

Renée Cox knows a thing or two about style. A former fashion model for Glamour and photographer for Essence, Cox had an early career in New York defined by the rapid pace of commercial assignments. In her thirties, turning to fine art photography, she began the first of several self-portrait series, portraying a multitude of stylized, powerful, and iconoclastic black women. These avatars—historic characters, fierce mothers, cosmopolitan socialites, and Afro-centric superheroes—are imbued with sexual agency and resolute confidence. Cutting a distinctive path in contemporary photography, Cox’s icons narrate a field of vision where black women perform for the world on their own terms.

Running in parallel to Cox’s photography is the evolving image of black women in popular American media and culture, including such icons as Angela Davis, Grace Jones, and Beyoncé. But the widespread consumption of images can erase a subject’s political message. In her classic 1994 essay “Afro Images,” Davis, a distinguished philosopher and activist, recalls that it was “both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo.” Just as Davis sought to retake her own identity, Cox, in her photography, reimagines the lives of black women as central to debates about equality and respect. Here, Cox speaks with Uri McMillan about racial icons, stylish images, and the pursuit of power.

Renée Cox, Chillin’ with Liberty, 1998, from the series Rajé

Courtesy the artist

Uri McMillan: Let’s begin with your journey from working in the milieu of fashion photography in New York and Paris for magazines like Glamour, Cosmopolitan, and Vogue Hommes to switching exclusively, in the 1990s, to fine art photography after the birth of your first son.

Renée Cox: I had an interest in photography from the day in high school when they made a mistake and put me in the advanced class. I was supposed to be with the beginners because I’d never done it before. So, I learned the practice of being in the darkroom and shooting right away. It was kind of nice, that moment when you’re young and you realize, Oh! That’s what my talent is.

Uri McMillan: What was your first job?

Cox: At Fiorucci, at the time a very trendy store on Fifty-Eighth Street in New York. I also did a little bit of modeling. My biggest modeling job was for Glamour in the early 1980s, posing as the girl who just graduated from college and was looking for a job in New York City—that was me. Brigitte Lacombe shot it. During the course of the four-day shoot, the fashion editor—Phyllis Posnick, now at Vogue—asked me if I had ever considered working at a fashion magazine. Previously, I had met with Deborah Turbeville, who gave me the blueprint. So, I didn’t have to think twice; I immediately jumped on it.

I did fashion for ten years. During that period, I shot a lot for Essence. If you look back at Essence in the 1980s, when it looked cool, that was usually me shooting. As a result, Spike Lee summoned me to shoot his poster for School Daze (1988) and some album covers—Gang Starr and the Jungle Brothers, for instance. I had a good little thing going. But then I got to the ten-year mark, had my first kid, and hit thirty. I was doing a lot of editorial then, and that work only had a twenty-eight-day life span. After that it was done.

McMillan: There’s no longevity to it, no permanence to the work.

Cox: Zero. I mean, maybe if you do the book, twenty years out. But that’s about it. I started thinking to myself, I can be an artist, too. I have things to say. Then I quickly realized I needed to go to grad school for anybody to take me seriously. I left the fashion industry for the School of Visual Arts, and then on to the Whitney Independent Study Program, arriving in this intellectual land where people spoke in tongues. The program started in September. By October, I knew I was pregnant. I came in and said, “I’m pregnant—with my second child.” People looked at me like, “Oh my God, are you sure? What are you going to do?” I was outraged. I had been through grad school and was not cutting my career off; I was just getting started. That’s how the series Yo Mama (1992–94) came about. I decided I’m going to give you pregnancy in your face—and that’s what I did. In other societies, women have allowed the males to dominate. I was like, No. Women are fucking strong. You make somebody in forty weeks; that’s pretty phenomenal. That’s the power of a woman.

McMillan: Let’s talk about icons and iconography. A large part of your practice has been the creation of new and affirming self-representations for black diasporic peoples, as a visual corrective to both art history and history writ large. And this has often taken the form of larger-than-life iconoclastic black female heroines, such as Rajé in your series Rajé, as well as portrayals of self-possessed erotic subjects. Who are your icons? What makes a powerful image? What are the complications in transforming black women into icons?

Cox: For me, the icon comes from within; it’s very organic. It’s a reaction. I refuse to be put down, squashed, or made invisible. I’m here, seven feet tall, larger than life. The thing that I use is the gaze. Ninety percent of the time, I’m looking back at the viewer looking at me. It’s about creating freedom. I’m not one of these black artists who’s trying to run away from blackness. There is no postblack. There’s no post; it’s only the present.

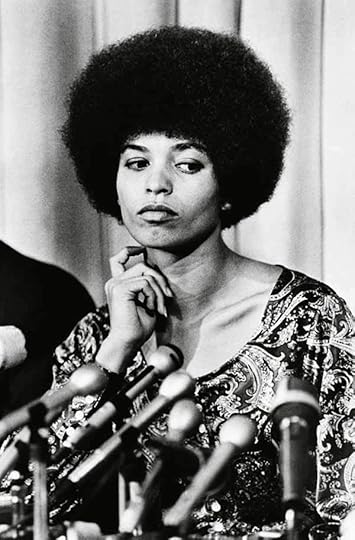

Photographer unknown, Political activist Angela Davis at press conference, September 23, 1969

© Bettmann/Getty Images

McMillan: In regard to the black-power era of the late 1960s and early ’70s, no one’s image has been circulated as much as that of Angela Davis. She is perceived as the embodiment of an era, or in her words, “a nostalgic surrogate for historical memory.” Yet, she has been very critical of the way her image travels. In her 1994 essay “Afro Images,” she discusses her alarm at the way indelible images of herself, such as the FBI’s notorious 1971 wanted poster, or photographs of her speaking to crowds of protesters, were later decontextualized and dehistoricized.

Cox: She became an icon—for her hair.

McMillan: Right. She was reduced to her now stylish Afro, transforming a “politics of liberation to a politics of fashion.” What are your thoughts on Angela Davis as the prototypical black feminist icon?

Cox: At the time, she was doing something very revolutionary, but it becomes flattened when you only get the superficial sound bites about the Panthers that appeal to ignorant people. This flattening has happened with my work as well. The Rajé series, for instance, had a lot of meaning and depth behind every one of those images. Yet, people would say to me, “How often do you work out?” What do you mean, how often do I work out? This is not a Jane Fonda workout video! If you’re a fit black woman, there’s this whole exotic longing for the other.

[image error]

Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, 1984

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York, and courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

McMillan: Grace Jones, on the other hand, is an icon of a much different order, understood as sine qua non to the 1970s downtown party network. Similarly exoticized for her sleek athleticism, she’s a striking counterpart to your own work, particularly her distinct dynamism as a visual subject. You also have amazingly similar geographic trajectories—Jamaica, Syracuse, Paris, and New York City.

Cox: We definitely had a lot in common, for sure. She obviously had a lot of insight in how she wanted to be portrayed. Yet, I can’t negate the fact that she collaborated with Jean-Paul Goude. He’s the one who can present the idea of using her in Peugeot advertisements and the company says, “Whoo, yeah!”

McMillan: Finally, perhaps inevitably, we come to Beyoncé. To consider Beyoncé as a feminist icon is a bit ironic, since she initially expressed ambivalence to the term feminist and to her songs, such as “Bootylicious,” being labeled feminist anthems. She has now apparently embraced the term—she showed off an enormous light-up sign reading FEMINIST at a 2014 concert—and also through specific angles, such as sampling Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 TED Talk “We should all be feminists.” I am curious as to your thoughts on her, particularly since she has become the black female icon.

Cox: Before speaking with you, I said to my assistant, “Let me try to be politically correct here. I don’t want the ‘Bey-hive’ coming after me.” She’s talented and has a good team around her to make her look good. I give her that. But … [laughs].

Ezra Shaw, Beyoncé performs during the Pepsi Super Bowl 50 Halftime Show, Santa Clara, CA, February 7, 2016

© the artist/Getty Images

McMillan: Visually, her very clear recycling of black-power sartorial aesthetics, in her performance of “Formation” for the 2016 Super Bowl, circles us back to Angela Davis. In my opinion, it was a bit problematic.

Cox: Yes, because it’s not coming from any real place. I didn’t hear her say “Stop killing black young men” and see her put her fists up in the air. No, she didn’t do that. I’m sorry, but to me that was pure nothingness. How did that performance represent the Black Panthers? The Black Panthers were trying to get breakfast for kids and trying to protect their communities, before they were destroyed by Hoover and the FBI. You’re just talking about the sensational part of the Panthers: the guns, the black leather jacket, and the black beret.

McMillan: So her “feminism” is just on the surface?

Cox: “I’m a feminist.” “Put a ring on it.” Oh, okay, great. Come on! I don’t even call myself a feminist. I just believe that women should have the same rights as men, and be treated and paid accordingly. Simple. I hate to say it, but the whole feminist movement was for white women who lived in the suburbs, and in some ways they killed it for themselves. Men have been treating women badly for centuries. So continue with the chivalry.

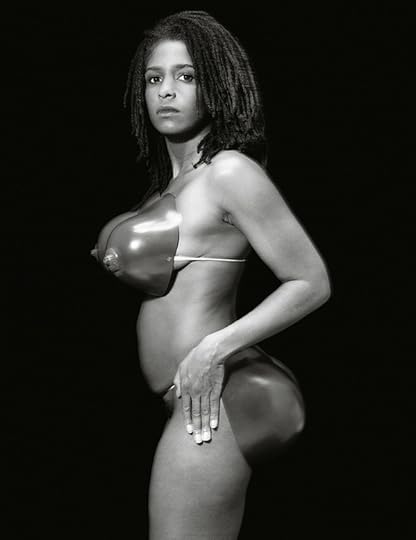

McMillan: What resurfaces in Beyoncé are the manifold historical tensions between white and black feminisms, academic and mass feminisms, and the presence of unruly black female bodies in the visual sphere. In your own work, you’ve often brought history to the stage. Take Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus, a Khoikhoi woman who was born in South Africa in the late eighteenth century and later paraded around Europe as a form of public entertainment. Her story is ground zero for the grisly objectification of the black female body, as well as its visual coding as grotesque, fleshy excess, dark fantasy, and pathology. Which makes it all the more remarkable that your restaging of this history—and body—in Hott-en-tot is playful while revealing the hyperbole and stereotypes embedded in these erotic fantasies. By deconstructing the black female body, you reveal the indelible, sticky myths behind it.

Cox: I was horrified when I first read about her and found out she was taken to Europe and toured around like a specimen, as if to justify colonization. I’m certainly not ashamed of her; that’s how some of our people look.

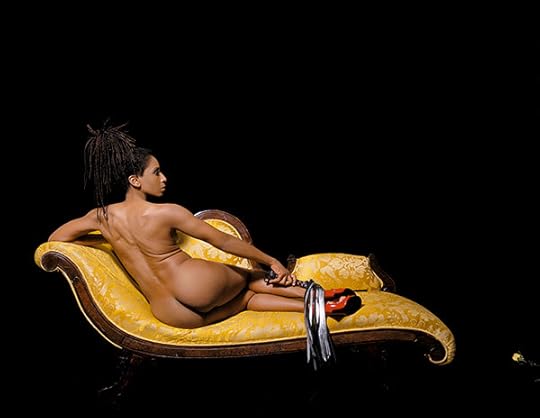

Renée Cox, Hott-en-tot, ca. 1993–94

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: How did you make this image?

Cox: It came together in a costume store. I saw the big tits and the big ass in plastic! And I said, “Aha, there it is,” and took it back to my studio, and shot it. That’s Hott-en-tot. That’s how it came about.

McMillan: Nobody would ever think about tracing that costume back to a figure like the Hottentot Venus. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen a random white teenager wear those body parts during Halloween, and not think anything about it being controversial or offensive.

Cox: Well, that’s the lack of awareness. They don’t know the story of the Hottentot Venus. They don’t know what their European brethren and sistren were doing back then, how they were exploiting people.

McMillan: I taught Suzan-Lori Parks’s 1996 play Venus this past spring; literally none of my students had ever heard of the Hottentot Venus. I did have one black female student who was really moved by it. She said to me, “Thank you so much for teaching this and for making me realize I’m not a freak.” I was stunned.

Cox: I would have been, like, “Girl, why did you think you were a freak anyway? Who told you you’re a freak, and why did you believe them?” But, that’s how the woman was built. End of story.

[image error]

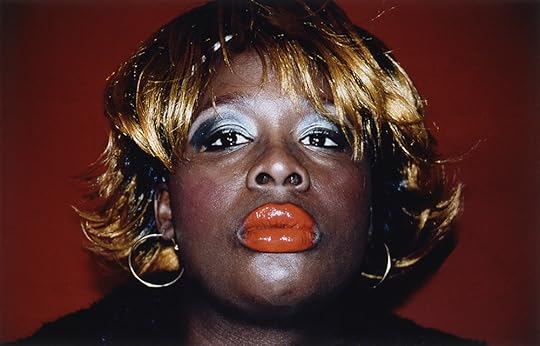

Renée Cox, Miss Thang, 2009, from the series The Discreet Charm of the Bougies

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: The spectacle isn’t about her. It’s actually about the people who made her into one.

Cox: Exactly. That was the thing that I liked about Haile Gerima’s Sankofa (1993) and Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013). I heard people say, “Why are we doing another slavery movie?” Because some of us were slaves, and were treated very badly—that’s why. You know, I went to this plantation down in South Carolina, Magnolia. You’ve got to drive a mile before you get to the big house and the vegetation is so dense, you can’t even see your hand in front of you if you held it out. I’m saying to my son that these people had to cut this down and level it. A mile’s worth of land; flat as a golf course now. Then, we get up to the big house, and they wanted thirty dollars from me to go on a tour. I was like, “Are you kidding?” They had not seen the likes of me before. You have white people walking around with their baby strollers, saying, “The gardens are so lovely.” Yet, for me, this is like Auschwitz or Dachau; it’s a death camp. I went off. I said, “When you see a black person coming up the drive, you need to roll out the red carpet. You need to have people outside going, ‘We’re so sorry that our ancestors were so degenerate and did the thing that they did.’” That’s really what needs to be happening, not asking me for thirty dollars to go on some damn tour.

Renée Cox, Baby Back, 2001, from the series American Family

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: In that spirit, you transform dispossession into self-possession. Baby Back continues such work, staging the reclining black female nude—a contested object in its own right, since the female nude is usually associated with the white female body. You use black portraiture as a counter- narrative to upend Manet’s Olympia. Black women move from the margins of the frame to the center. Yet, even here, there is a subversive edge—the fire-engine-red patent-leather high heels, and the black leather whip, which references BDSM subcultures as it also alludes to histories of enslavement.

Cox: Exactly. If anybody’s going to be using the whip, it’s going to be me. It’s not going to be used on me. I’ll be using it. Okay? [laughs]

McMillan: And the shoes?

Cox: Well, they’re sexy.

Renée Cox, Missy at Home, 2009, from the series The Discreet Charm of the Bougies

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: In your ongoing series The Discreet Charm of the Bougies, there is a provocative metatextuality happening. You stage yourself as the paradigmatic black housewife, a woman of stature, class, and status—signaled by the pearls, poodle, and especially the nameless white female servant. Yet, that is partly undercut by the haunting of that character by the huge photograph she owns: Yo Mama, your own picture, featuring you as a nude mother clad in nothing but black high heels, holding your son. What were your motivations for this series?

Cox: The Discreet Charm of the Bougies is a psychodrama. The star’s name is Missy. She lives a very privileged life. She is very much self-aware, but she is very much alone. She’s got a white maid, but she’s blasé about it. It’s expected, in a way. Throughout this series, you see her going from living in this depressive, unconscious state to becoming enlightened and realizing she can live a life of joy. Obviously, it’s my own personal journey. Because for me, one of the key things was when I realized I didn’t need anybody to validate me except myself.

McMillan: In Lady of the Night, Missy is reincarnated as an eroticized version of herself, seemingly liberated from her pristine surroundings and conservative attire. Missy’s attainment of power is linked to gaining sexual power, as well.

Cox: Right. In The Jump Off, she’s in bed with a guy, with the pills and the rum—because she’s Jamaican—but she also has a book about Maroon society. Yet, she’s caught up in a lifestyle, and at that juncture of the series, she doesn’t yet know how to get out. Her transition occurs when she’s traveling over in Asia, in Bali, and Cambodia, and the wig that she’s been wearing the whole time is gone.

McMillan: You said you don’t call yourself a feminist, but power, and specifically the power women generate for themselves, has been one of your enduring themes. How have your ideas about power evolved since you first began taking photographs?

Cox: Once you have the power, you always have the power. The power comes from within. It’s not a state of mind: the real power comes from the heart. All women have it. It’s a matter of cultivating—and realizing—that power. You have to feel it.

Uri McMillan is Associate Professor of Performance Studies at UCLA and the author of Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance (2015).

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Renée Cox: A Taste of Power appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 19, 2016

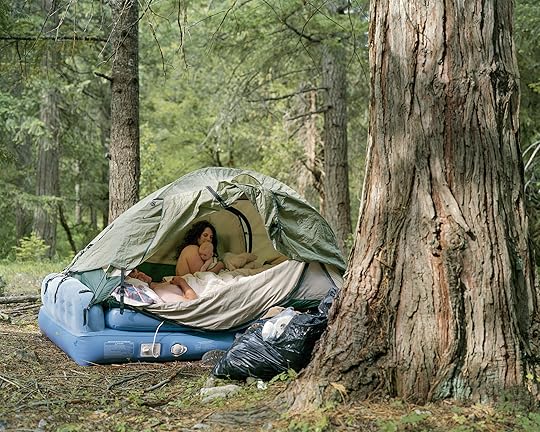

Raised on the Road: Justine Kurland in Conversation with Her Son, Casper

After years traversing the U.S. in a van, the photographer and her son sit down for a candid interview.

Justine Kurland, Spit Bubble, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Casper McCorkle: How does this quote by William Carlos Williams reflect your road trips in your opinion?

Justine Kurland: Lynne Tillman begins her stories “Still Moving” with this quote from a poem he wrote about the wind: “I am bound more to my sentences the more that you batter me to follow you.” Highway Kind starts with photographs of trains and if you think about it, all the words in a sentence are like a train, and maybe both a sentence and a train are like the wind—they move along a path. Lynne Tillman’s stories blow against my photographs in a way that stirs up meaning.

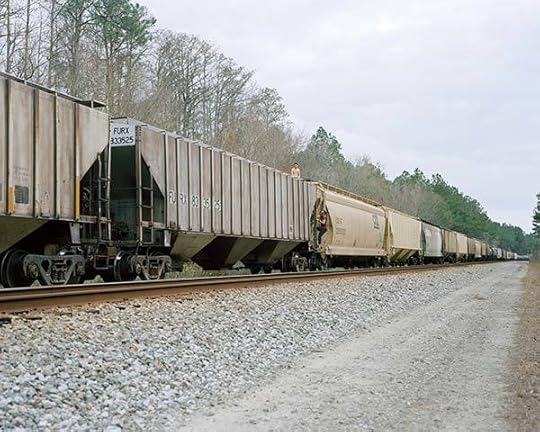

McCorkle: I think that makes a lot of sense. I like it. In Waldo Farm Train Hoppers (2011)—where was this?

Kurland: Waldo Farm is outside Gainesville, Florida. It’s kind of like a commune—a bunch of punk, train-riding kids go and stay there for free in exchange for work. The guy who owns the place is also a photographer, but he used to be a philosophy teacher. Every night he has all the kids sit in a circle—they call it “temple”—and they read philosophers like Hegel. These kids might have dropped out of school and haven’t had a lot of education but because they’re all working together, they can understand some really deep, complex ideas.

McCorkle: Could I ask a question? You said the leader used to be a philosophy person or whatever. What philosophy does he believe in? Do you know?

Kurland: I think maybe anarchy or Marxism. When I was there they were reading Hegel, who wrote this book called Phenomenology of the Spirit (1807), which later became a model for Karl Marx. It’s about the master–slave relationship. Part of the philosophy is that everyone should live off the labors of their own work, and that mastery is achieved through labor.

Do you remember going to these different places to look for trains to photograph?

Justine Kurland, Waldo Farm Train Hoppers, 2011

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: Yeah. I think I always used to—it was called a shutter, I think, right? I used to . . .

Kurland: You would press the shutter for me?

McCorkle: Yeah. I have a question about basically all of the train pictures. How long did you normally have to wait until a train came, and did you know when the trains would come by?

Kurland: Sometimes we would wait so long. Sometimes we would wait all day. We met rail fans who helped us. Do you remember those guys?

McCorkle: I remember that, yeah!

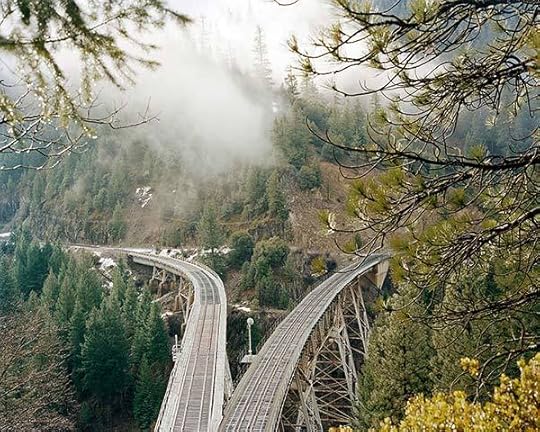

Kurland: There was one guy in Colorado who used to work for the railroad, so he knew the schedule. And there were these designated spots, the Donner Pass or the Tchepatche Loop, or the Caliente Pass, or in the San Gabriel mountains where we met other people. There was a guy in California who brought us some place in the mountains. And remember? We got chased by cows.

Justine Kurland, Union Pacific at Donner Pass, 2008

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: They threw us into a bush?

Kurland: That was a different story. We were chased by dogs, and I threw you over the fence into a bush so the dogs couldn’t get to you.

McCorkle: You’re a great parent.

Kurland: When I showed my photographs to the rail fans, they weren’t impressed because they had zoom lenses and tried to photograph the trains in a particular ways. But I’d want the train to disappear into the landscape. I wanted to talk about how the train had become part of the landscape.

McCorkle: I have a question. What’s your favorite photo out of all of these that you made?

Kurland: I think the last photograph in this book is my favorite. It’s this guy. You know why I like him? His hair and his bone structure—he looks exactly like what you’re going to look like when you grow up.

Justine Kurland, What Casper Might Look Like If He Grew Up to be a Junkie in Tacoma, 2013

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: Oh god, he’s so ugly!

Kurland: No, he’s super handsome, what to you mean he’s ugly?

McCorkle: He’s ugly!

Kurland: He’s super handsome, he’s a foxy dude.

McCorkle: What happened to his hair?

Kurland: It’s just a style. I think that’s my favorite picture because I like to imagine you when you grow up and you’re my age. Sometimes I think about what if you’re my age and I’m your age.

Justine Kurland, Watermelon Still Life, 2012

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: If I’m like forty and you’re like one? What is he doing?

Kurland: He’s a junkie. Actually when I met him he asked me if he could put his drugs in my van for a little while.

McCorkle: And what did you say?

Kurland: I said, “No thank you.”

McCorkle: What drugs?

Kurland: I don’t know. I didn’t ask him. I’d like to think you’ll have a better life than this guy. The last part of the book gets pretty depressing.

What’s your favorite picture in the book?

Justine Kurland, Keddie Wye, 2009

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: The overpass picture.

Kurland: The Keddie Wye?

McCorkle: Yeah. I remember being there and how rickety it was. I really like that the fog makes the railroad tracks the only thing you can see, and I really like the white rocks and the white wood.

Do most of the people who you photograph want to be photographed?

Kurland: I ask people to let me photograph them, and a lot of the times they say, “No.” But I never photographed anyone who didn’t want to be photographed.

McCorkle: You photographed me when I didn’t want to be photographed.

Kurland: You’re the only person I photographed who didn’t want to be photographed. But when you really didn’t want to be photographed, you just kind of walked away.

Justine Kurland, After Weston, 2010

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: Okay.

Kurland: It’s true. The times I photographed you when you didn’t want me to, we would make a make deal. And a deal is a deal.

McCorkle: You know what I really like about this book? It doesn’t stick to one theme. It has a theme of cars, and trains, and me when I was little, and it’s just really cool.

Kurland: The back of this book has some of the snapshots I took between the other photographs.

McCorkle: I remember this one. Well, of course I was asleep. But I remember going in the back of the van and then waking up when you were still sound asleep and dreaming. I also remember waking up to that really awesome noise of the rain on the roof. Sometimes I was asleep and I slept for a long time and you were driving and I was still in the back.

I remember you taking so long to write this thing called “Now We Are Six” and I really like the writing of it. I think it’s really good. It really describes the road trip experience. And I think these two photos just go really well with your writing, especially the van when it’s sort of dirty.

Kurland: Do you remember this one where you’re brushing your teeth? We used to talk about you brushing your teeth professionally?

Justine Kurland, Untitled (Sleeping in Van), 2006

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: Yes, and there was a spit bowl, oh god.

Kurland: We didn’t have a sink so you had to use the water out of the jug and a spit bowl.

McCorkle: In the picture with the birds, I remember being there, and it was kind of cool and really scary.

Kurland: When I showed you these pictures for the back of the book you described this photograph formally. You talked about the birds and your hair being chaotic—do you remember saying that? It was a good way to describe the photograph.

McCorkle: And also the signs. The buildings are neat and organized and then there’s basically chaos. It looks like the birds have wrecked havoc. They have destroyed the landscape. These signs look dirty and then over here it’s all nice in that direction the birds are headed in.

Kurland: What do you think overall of the book? Would you do anything different if you could?

Justine Kurland, Untitled (Birds), 2008

Courtesy the artist

McCorkle: No, I really like what you did with the book.

Kurland: Do you wish we were still on the road?

McCorkle: No, I like my friends and I have a good school.

Kurland: You’re glad we got off the road?

McCorkle: I think we got off the road at a good time. When elementary school started in first grade, I think that was a good time.

I wish I could teleport to some of the places we’ve gone and sleep in the van. But the one thing I didn’t like about being on the road was the six hour, eight hour trips. But yeah if I could just teleport anywhere with the van, I would definitely do that a lot. Like on the weekends, just teleport to the sand dunes, teleport to Red Rock Canyon, all the places in your photographs, and see what changed. You know what I mean?

Kurland: Yeah. It was a long time ago for some of these places.

When you look through these pictures, do you think it was a happy childhood?

McCorkle: I don’t know. Yeah, I think. Yeah.

Kurland: When you grow up and you have kids will you bring them on road trips?

McCorkle: Maybe. Probably not, I don’t know. I don’t know if I could be a photographer, but if I could, if I had all the money for gas, and they were little, I probably might. And if their mom wanted to go or whatever.

The post Raised on the Road: Justine Kurland in Conversation with Her Son, Casper appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 15, 2016

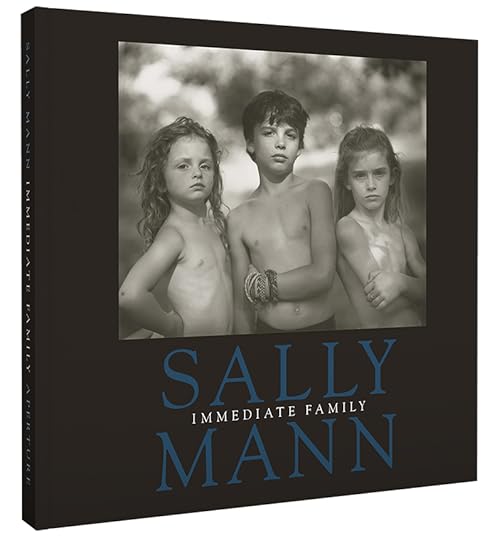

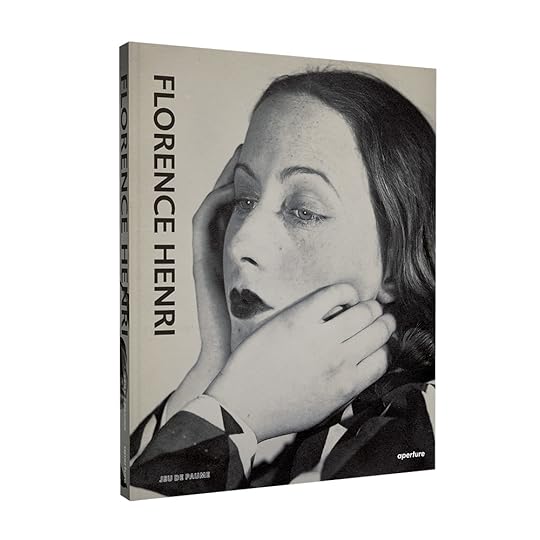

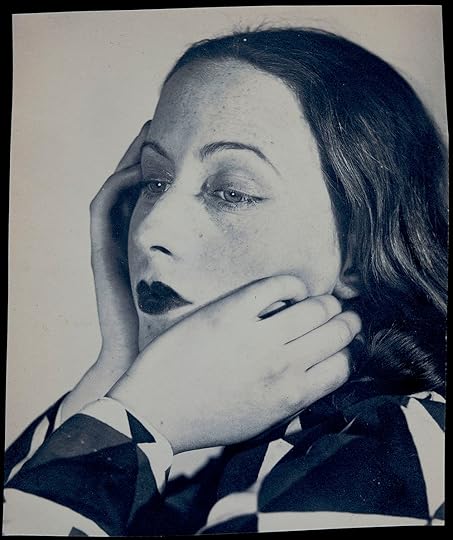

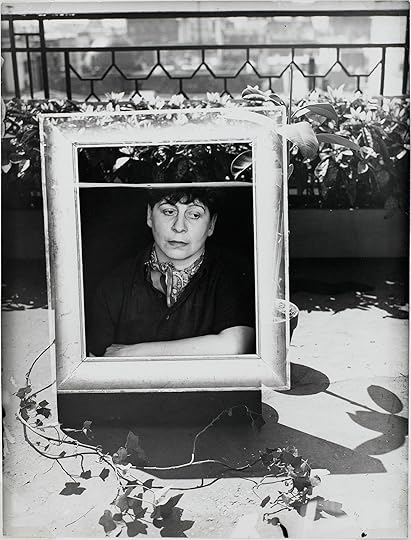

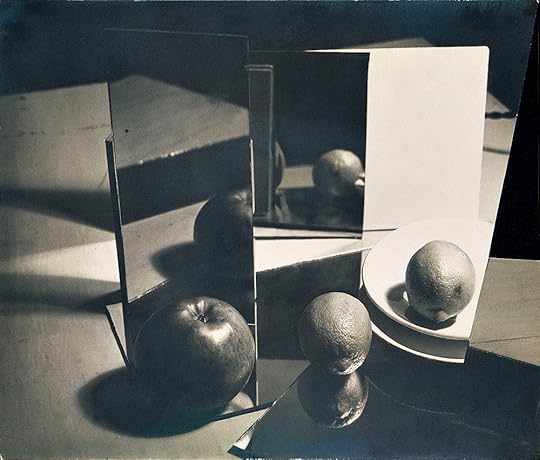

13 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

From Florence Henri’s little-known avant-garde photographs of the 1920s to Susan Meiselas’s piercing documentary photography of the 1970s, we’ve compiled a list of Aperture photobooks by women photographers that are sure to inspire.

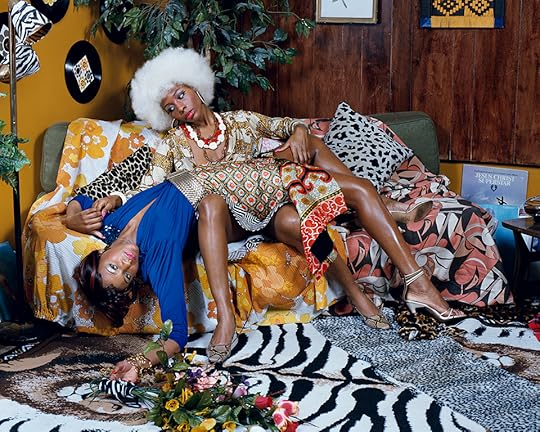

Over the course of her storied career, Mickalene Thomas has worked in a variety of mediums, drawing inspiration from the women around her. Muse: Mickalene Thomas Photographs is the first book to gather together her various approaches to photography. From cultural icons like Beverly Johnson and Vonetta McGee to her family members and lovers, each of Thomas’s “muses” grapples with and asserts new definitions of beauty.

Mickalene Thomas, Remember Me, 2006

Mickalene Thomas, Negress #3, 2005

Mickalene Thomas, A Moment's Pleasure #2, 2007

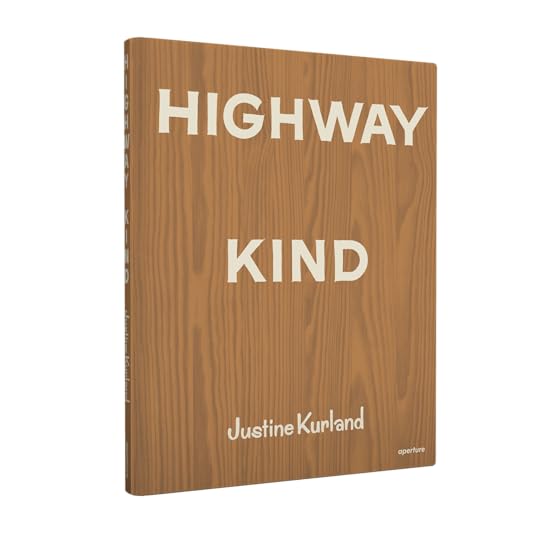

Since 2004, photographer Justine Kurland and her young son, Casper, have traveled in their customized van across the United States. As Kurland balances life as an artist and mother, her son heavily influences her subject matter. Exploring the idea of the American dream juxtaposed against reality, the photographs in Highway Kind are equal parts raw and romantic.

Justine Kurland, Baby Tooth, 2011

© Justine Kurland

Justine Kurland, 280 Coup, 2012

© Justine Kurland

Justine Kurland, New Family, Black Bear Ranch, 2011

© Justine Kurland

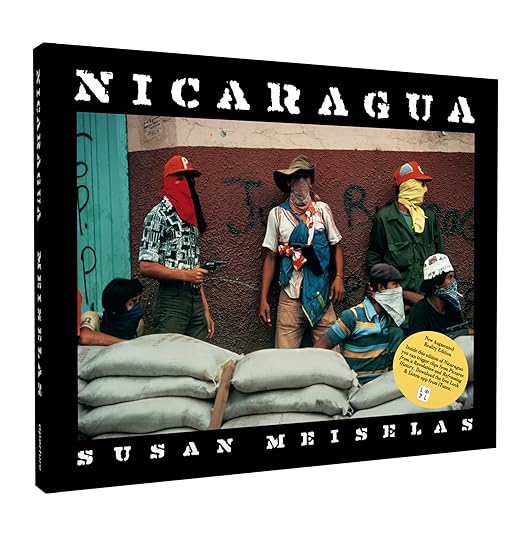

In the late 1970s, Susan Meiselas traveled independently to Nicaragua to document the Somoza regime during its decline. The images she made would transform her career. Originally published in 1981, and reissued in 2016 with an augmented reality (AR) function, Nicaragua: June 1978 - July 1979 remains a seminal contribution to the literature of concerned photojournalism.

Susan Meiselas, Monimbo woman carrying her dead husband home to be buried in their backyard

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Muchachos await counterattack by the Guard, Matagalpa, 1978

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Street fighter in Managua, 1979

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

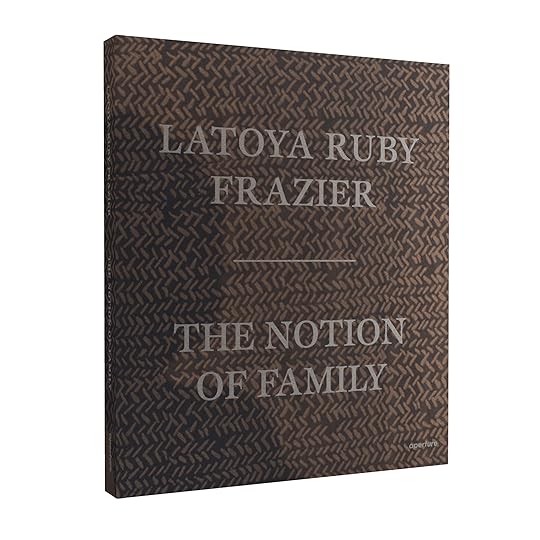

The Notion of Family, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s first book, offers an exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Enlisting the participation of her family—and her mother in particular—Frazier reinforces the idea of art and image-making as a transformative act, a means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives, both those of her family and those of the community at large.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme (Floral Comforter), from Momme Portrait Series, 2008

© LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and J.C. in Her Kitchen, 2006

© LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Bottom (Talbot Towers, Allegheny County Housing Projects), 2009

© LaToya Ruby Frazier

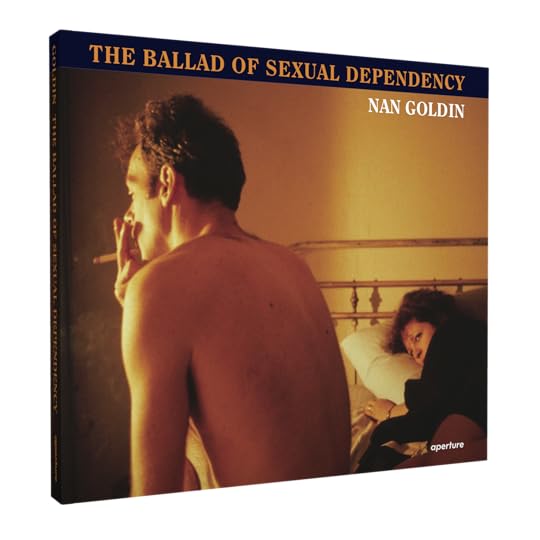

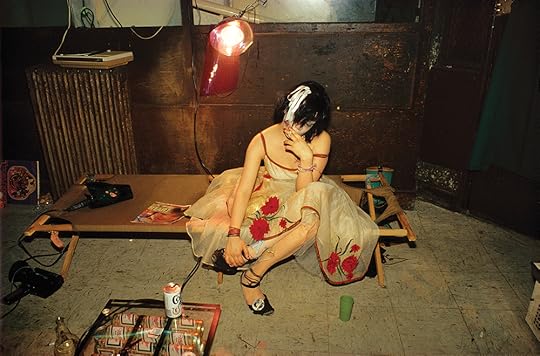

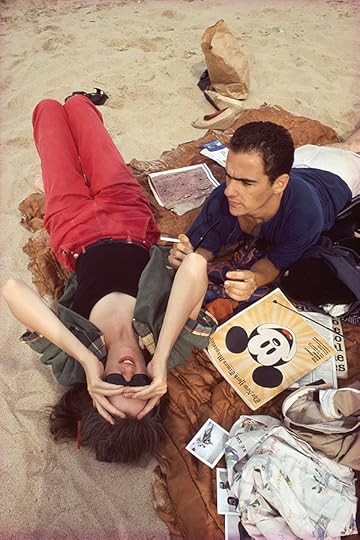

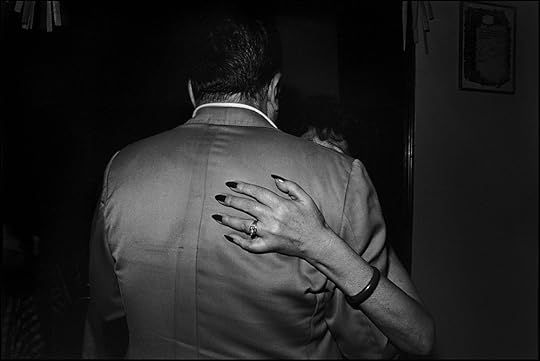

Nan Goldin's The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a visual diary chronicling the struggle for intimacy and understanding between Goldin’s friends, family, and lovers. Aperture first published her irreverent and visceral images as a book in 1986. The influence of Ballad on photography and other aesthetic realms has continually grown, making the work a contemporary classic.

Nan Goldin, Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979

© Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, The Hug, New York City, 1980

© Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, C.Z. and Max on the beach, Truro, Mass., 1976

© Nan Goldin

Provocative, seductive, and surprisingly fresh, this collection of Jo Ann Callis’s work from the mid-1970s investigates the nude body and sexuality. Callis utilizes twine, belts, tape, and other everyday materials in an intimate exploration of pleasure and eros. Other Rooms is as beautiful and delicate as it is mysterious and disconcerting.

Jo Ann Callis, Hand in Honey, 1976–77

© Jo Ann Callis, Courtesy Rose Gallery

Jo Ann Callis, Woman with Black Line 1976–77

© Jo Ann Callis, Courtesy Rose Gallery

Jo Ann Callis, Woman in Crimson Slip, 1978

© Jo Ann Callis, Courtesy Rose Gallery

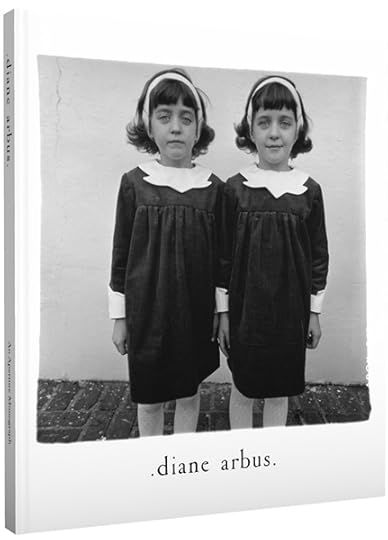

One of the best-known female photographers of her generation, Diane Arbus was already a legend among serious photographers when she died in 1971. In 1972, Aperture published Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, and offered the general public its first encounter with her momentous achievements. The response was unprecedented. Universally acknowledged as a timeless masterpiece, this book will transform the way you see the world.

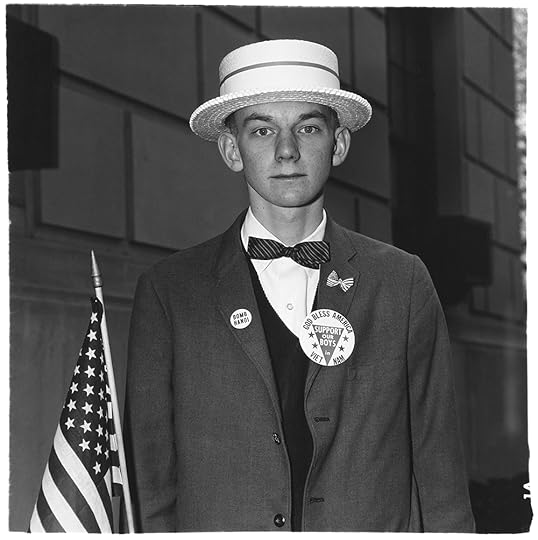

Diane Arbus, Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C 1967

from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (2011)

Diane Arbus, Woman with a veil on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C 1968

from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (2011)

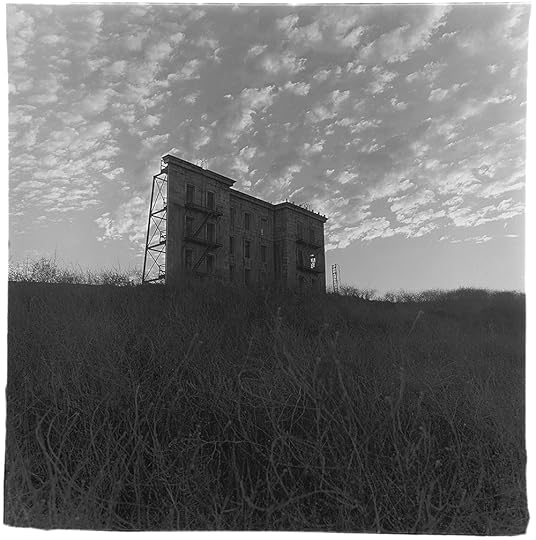

Diane Arbus, A house on a hill, Hollywood, Cal. 1963

from Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (2011)

Mary Ellen Mark is renowned for the emotional power of her pictures. Though she died in 2015, she remains one of the most respected and influential photographers of our time. Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment distills over fifty years of Mark’s experience and wisdom, providing photographers with a unique chance to learn from Mark’s astonishing life and career. The book was printed just before she passed away.

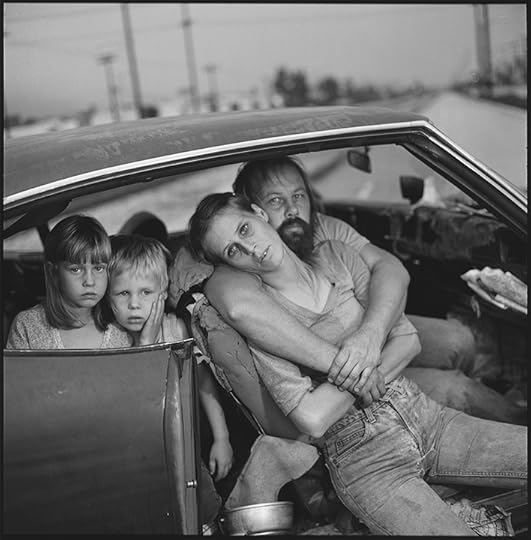

Mary Ellen Mark, The Damm Family in Their Car, Los Angeles, California, USA, 1987

© Mary Ellen Mark

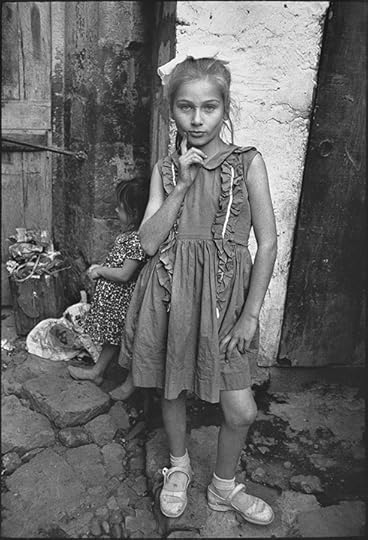

Mary Ellen Mark, Beautiful Emine posing, Trabzon, Turkey, 1965

© Mary Ellen Mark

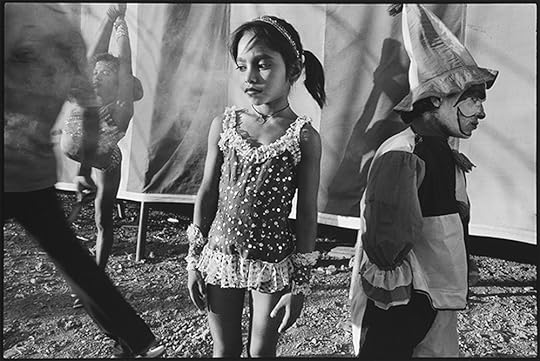

Mary Ellen Mark, Pinky and Shiva Ji, The Great Royal Circus, Junagadh, India, 1992

© Mary Ellen Mark

During the height of the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1970s, Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz was taking great risks to continue her work, which violated the regime’s strict regulations. She dared to visit brothels, psychiatric wards, and boxing clubs, where women weren’t welcome. In Paz Errázuriz: Survey, over 170 photographs by Errázuriz are compiled for the first time.

Paz Errázuriz, Club Buenos Aires, Santiago, from the series (In twos) Tango

courtesy the artist

Paz Errázuriz, Evelyn IV, Santiago, from the series Adam's apple, 1987

courtesy the artist

Paz Errázuriz, Atáp, Ester Edén Wellington, Puerto Edén, from the series The nomads of the sea, 1995

courtesy the artist