Aperture's Blog, page 128

December 9, 2016

Don’t Touch Our Hair

Coinciding with Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, students in Sarah Lewis’s Harvard University class “Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship” contributed essays on images of social unrest. Here, Jeneé Osterheldt reflects on the protests of black girls in South Africa, the policing of black women and girls’ hair, and the importance of Solange.

Carlota Guerrero, Album cover for A Seat at the Table by Solange

Courtesy the artist

Don’t touch my hair

When it’s the feelings I wear

Don’t touch my soul

When it’s the rhythm I know

Don’t touch my crown

They say the vision I’ve found

—Solange Knowles

She should have been in class learning the Pythagorean Theorem, but the only right angle Zulaikha Patel was looking at was the one that gave her agency.

At Pretoria High School for Girls, in South Africa, little black girls were being told their hair was a dirty distraction. So Zulaikha and her friends did the math and took a stand in August, protesting patriarchy and white supremacy. An image of Zulaikha, tiny black fists up and fro out, in a powerful stance in the face of security went viral.

The image of this thirteen-year-old girl, naturally shorter than the white men towering above her, signified not just the physical inequality of the situation but also our literal inequity as black women and girls. Her oppositional gaze is not just challenging the man in her way; she’s bucking systemic racism. And her image dominated social media because this was not only a South African song cry: this was the battle cry of black women and girls.

Zulaikha Patel protesting discriminatory hair policies at Pretoria High School for Girls, South Africa, 2016

Courtesy Twitter/lennoxbacela

Women like Chastity Jones of Mobile, Alabama. Jones was told to cut her locs if she wanted to work at Catastrophe Management Solutions. Locs “tend to get messy,” the white HR manager told her. But had she been white, perhaps they would have told her she was chic and refined like the models on Marc Jacobs runway this season. Everyone has the right to black culture except black folks.

People say it’s just hair. But it’s an extension of one’s self and an expression of identity. To police our hair is to deny us agency. If we can’t run our own hair, we certainly have no ownership of ourselves. But America has a tradition of robbing women of their bodies. Add blackness to womanhood and you are marked less than a citizen twice over.

In September, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled there was nothing racist about banning Chastity Jones from wearing locs, citing discrimination had to be based on characteristics that didn’t change, and the hairstyle didn’t qualify as “immutable.”

So because we can loc, twist, braid, weave, fry, dye, and lay to the side our hair, we should tame its power to indulge whiteness? Aren’t we a woman and a sister?

Again and again, the laws remind us we are just as commodified as the Greek Slave, our very womanhood to be bought, sold, broken and dictated to by white rules.

Perhaps that’s why we all grabbed a chair in September when Solange Knowles released A Seat at the Table. Her cover image, a direct celebration of #blackgirlmagic with a revolutionary gaze, does not need white validation.

She carved out the space black people have long been denied. She claimed and celebrated our power. When she sings “Don’t Touch My Hair,” she demands our autonomy. She sings a song for Zulaikha, for Chastity, for black women and girls worldwide.

Don’t touch my pride

They say the glory’s all mine

Don’t test my mouth

They say the truth is my sound

—Solange Knowles

Jeneé Osterheldt is a Nieman Fellow at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Harvard University.

The post Don’t Touch Our Hair appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 8, 2016

Beyond Binary

What does photography offer the trans feminism movement?

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Andrea Bowers, Trans Liberation: Beauty in the Street (Johanna Saavedra), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

She is striding down the middle of the empty street. She is striding down the street flanked by palm trees. She is striding down the street in a gray dress and strappy, red, open-toed shoes. She is striding down the street coming toward us. She is striding down the street holding a brick in one hand.

This large-scale, life-size photograph of Johanna Saavedra—a trans, Latina activist—is part of Andrea Bowers’s series Trans Liberation (2016), produced in collaboration with artist and organizer Ada Tinnell. Trans Liberation features three trans women activists of color—Saavedra, CeCe McDonald, and Jennicet Gutiérrez—photographed with weapons (brick, hammer, rifle) and in postures that nod to historical representations of revolutionary insurrection. Saavedra’s brick, for instance, references both a famed graphic from the student/worker uprisings of May 1968 in France and the brick thrown by African American trans pioneer Marsha P. Johnson at the 1969 Stonewall rebellion, which helped ignite the gay liberation movement in the United States. Even as the photographs confidently portray these women as stunning, beautiful, and strong, by some accounts they are not considered women at all—recently enacted bathroom laws mean their use of certain public ladies’ rooms is illegal, and they would not have been welcomed at the (now defunct) Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival with its “womyn-born-womyn”-only policy.

In another photograph, McDonald—who was convicted of manslaughter after defending herself in a racist, transphobic attack outside a bar in Minneapolis in 2011 and, despite entreaties by trans activists, served nineteen months in a men’s prison—is portrayed as an avenging angel of liberation in a flowing gown with wings spread out behind her and a sledgehammer tucked into her belt. Bowers, whose practice has long rotated around the imaging of social justice struggles, writes, “I wanted to document these activists because I believe they are some of the most powerful and courageous activists of this time. Over 70 percent of hate-motivated murders are against trans women, and 80 percent of those are trans women of color.” Gender might not be “real,” to cite theorists of social construction, but gender-based oppression certainly is.

Andrea Bowers, Trans Liberation: Building a Movement (Cece McDonald), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

The photographs comprised only one component of Bowers’s multimedia exhibition, entitled Whose Feminism Is It Anyway?, at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, in spring 2016, but they were the show’s breakthrough centerpiece. The titular question is a direct quote from an influential essay by trans activist/writer Emi Koyama that discusses the racism that accompanies some trans-inclusion debates, as various camps stake their claims not only to who owns feminism, but who owns (and who is excluded from) the very definition of womanhood. The category of “woman” has never been singular or stable, and many—because of normative ideals about anatomy, about body size, about race, about age, about disability—have been barred from its rigid confines. Trans women of color continue to fight hard to change these conversations, fights allegorized in these portraits by the weapons wielded by Saavedra, McDonald, and Gutiérrez.

Bowers is perhaps most well known for her carefully wrought drawings (some of which were on display in Whose Feminism Is It Anyway?), but to document these figures as mythic heroines she turned decisively to photography, with its special capacities to depict not only the purported “real” but also to render visible “unreal” or fictive states of being. It is one of the first lessons to impart in any history of photography class: despite the vaunted truth value of a photograph, it is always the result of a partial, packaged, and framed viewpoint. The photograph’s alleged transparency is as mediated and produced as any other form of representation.

In a related vein, these photographs perform a denaturalizing function. Trans activism asks us to rethink the supposed truth of the binary gender system—one that sorts people at birth into two inviolable categories (boy or girl) and permits no crossing between them during a lifetime. In addition, sexist systems of inequality privilege men above women, as well as masculine above feminine; to counteract these strictures, trans feminism advocates for the flourishing of a range of genders and promotes solidarity between all kinds of women, including those who were born female and those who were not. Trans feminism also considers how gender intersects with race, class, ability, and age. It is thus worth asking: What does photography as an artistic resource, a visioning technology, and a tool of activist organizing have to offer the trans feminist movement? Current debates about the porousness and flexibility of gender identities hinge in part on questions of visibility and self-presentation—that is, how one looks, as well as how one looks back, is crucial. These are issues that photography is uniquely suited to address.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley.

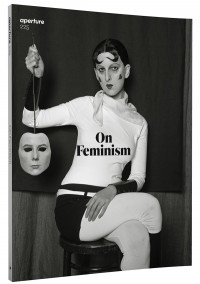

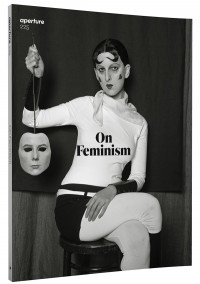

To continue reading this article, buy Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

“On Feminism”

The winter issue of Aperture, “On Feminism,” arrives at a moment when the power and influence women hold on the world stage is irrefutable, and the very idea of gender is central to conversations about equality across the country, and around the globe. “On Feminism” focuses on intergenerational dialogues, debates, and strategies of feminism in photography and considers the immense contributions by artists whose work articulates or interrogates representations of women in media and society. Across more than one hundred years of photographs and images, “On Feminism” underscores how photography has shaped feminism as much as how feminism has shaped photography.

FRONT

Redux

Brian Wallis on Leonard Freed’s Black in White America, 1968

Spotlight

Eli Durst’s In Asmara by Alexandra Pechman

Curriculum

By Martha Rosler

Dispatches

Maria Nicolacopoulou on Athens

BACK

Object Lessons

Les Femmes de l’Avenir, 1900–1902

WORDS

On Feminism

Contributions by Catherine Morris, Zanele Muholi, Laurie Simmons, Johanna Fateman, Zackary Drucker, and A. L. Steiner

Modern Women: David Campany in Conversation with Marta Gili, Julie Jones, and Roxana Marcoci

The artists who redefined the course of twentieth-century photography

The Feminist Avant-Garde

In self-portraiture and body art, experimental pioneers of the 1970s

By Nancy Princenthal

Sex Wars Revisited

Lesbian erotica as critical rebellion

By Laura Guy

A Taste of Power: Renée Cox in Conversation with Uri McMillan

From Angela Davis to Beyoncé, the icons and avatars of black style

History Is Ours

The legacy of protest in video and performance

By Eva Díaz

On Defiance

How women have resisted representational photography

By Eva Respini

Beyond Binary

New visions of trans feminism

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Our Bodies, Online

Feminist images in the age of Instagram

By Carmen Winant

PICTURES

Cosey Fanni Tutti

Introduction by Alison M. Gingeras

Gillian Wearing

Introduction by Jennifer Blessing

Yurie Nagashima

Introduction by Lesley A. Martin

Hannah Starkey

Introduction by Sara Knelman

Katharina Gaenssler

Introduction by Yvonne Bialek

Josephine Pryde

Introduction by Alex Klein

Laia Abril

Introduction by Karen Archey

Farah Al Qasimi

Introduction by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Martine Syms

Introduction by Amanda Hunt

Elle Pérez

Introduction by Salamishah Tillet

$24.95

The post Beyond Binary appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 7, 2016

The Radical Power of the Black Feminine Gaze

Carrie Mae Weems’s unwavering vision sparks dialogue about violence, mourning, and strength.

By Ladi’Sasha Jones

Carrie Mae Weems, Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me – A Story in 5 Parts, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Black feminists, Black women artists, and Black feminist artists have a laborious tradition in witness work. They imagine futures unseen. They engineer poetic tools of resistance and provocative encounters. Through their paintings, sculptures, images, performances, fabric works, moving images, and writings, Black women convey the essential connections between the body and spirit with compassion for states of mourning and healing.

Carrie Mae Weems’s interdisciplinary practice of portraiture, documentation, and storytelling is a part of this legacy of women who work in remembrance and refusal. Her current two-site exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery is a sharp, meditative assembly of ideas and questions that extend her career-long disruption of conditioned perception and viewership. In her new series, Usual Suspects (2016) and Scenes & Take (2016), Weems tackles power structures as represented by American media, and state-sanctioned violence.

Carrie Mae Weems, Scenes & Take (The Bad and the Beautiful) (detail), 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The evolution of Black feminist cultural production and political thought has sought to articulate the intimate relationships between the body and power, the body and violence, the body and capitalism. Weems has frequently drawn upon these dialectic relationships. One of her recurring devices, a Black woman avatar—who is present in photographic work from the Kitchen Table Series (1990) to The Museum Series (2006–ongoing)—relies on the strength of a Black feminine gaze. The avatar confronts viewers with scenes and sites both startling and familiar. This avatar, an enigmatic character whose sightings we have all come to relish, is a witness and a guide.

In a 2009 interview with the photographer Dawoud Bey, Weems said, of the avatar, “Carrying a tremendous burden, she is a black woman leading me through the trauma of history. I think it’s very important that as a black woman she’s engaged with the world around her; she’s engaged with history, she’s engaged with looking, with being. She’s a guide into circumstances seldom seen.” Weems continues, “She’s the unintended consequence of the Western imagination. It’s essential that I do this work and it’s essential that I do it with my body.” Her avatar doesn’t wander or drift about; she is determined. She is a lens, a way of seeing. We look and journey with her.

Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Blocked 2), 2016

© the artist and coutesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Black women have always been at the forefront of national dialogues around state-sanctioned murders and the rituals and processes of mourning. Weems’s approach in addressing the murders of Black children, women and men at the hands of America’s policing citizens is to forge an unmistakable reckoning. From Usual Suspects (2016), a grid of nine panels featuring descriptions of deadly encounters, to the enlarged fragments of police reports in the series All the Boys (2016), Weems conspicuously displays the fruit, the evidential repetition, of racial injustice.

“The history of Black women is a long study in mourning,” Jessica Millward stated recently. “The mourning takes on an added layer, however, when those sworn to serve and protect proceed to hunt and kill furthering African Americans’ long distrust of the government.” In the face of racial violence, the Black feminine gaze is a radical aesthetic, a technology that generates its own framework for the production of art, culture, and resistance. At this moment in America, a Black feminist vision is consequential for the future, and Carrie Mae Weems’s feminist vision has never been more timely.

Ladi’Sasha Jones is a writer and arts administrator from Harlem.

Carrie Mae Weems is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, through December 10, 2016.

The post The Radical Power of the Black Feminine Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 5, 2016

W.M. Hunt: Talking Pictures

“The most enjoyable afternoon of stories both personal and professional—he will delve into the photography world in the most unusual way. Learning should always be this fun.”

—Elaine Goldman, collector of photography and past workshop participant

W. M. (Bill) Hunt led a one-day workshop at Aperture Foundation, intended for people who look at photographs and who want to challenge and heighten both their sense of seeing and their ability to talk about what they see.

The workshop offered photography lovers an insight into Bill’s personal collection and how he came into collecting. During the first half of the workshop, Bill discussed the challenges of finding a great photograph in a world filled with good photographs. He shared personal stories and encouraged the workshop participants to “find what excites you, and pursue it.” Bill explained to participants that a great photograph will do three things: make the hair on the back of your neck stand up, make your heart beat faster, and keep your feet planted in front of it. In his lecture, Bill showcased a wide variety of photographers including Richard Misrach, Bill Brandt, Sally Mann, and Nathan Lerner.

Participants had the pleasure of meeting Chris Boot, executive director of Aperture, and debated the role of photography in today’s current economic, political, and social state. During the second half of the workshop participants discussed photographs that they thought were great and why they felt that way. Bill challenged the participants to find photographs that were not necessarily their favorites but ones they thought were extraordinary. Peggy Roalf, former editor and curator at Aperture, joined the conversation and gave her opinion about what makes a photograph great, using Josef Koudelka’s work as an example. Gwyneth Degraf, former workshop participant, was also asked to speak with the group and shared photographs made by Damon Winter.

W. M. Hunt is a champion of photography and frequent presenter both in the U.S. and internationally, from Shanghai to São Paulo. He is a longtime adjunct professor at the School of Visual Arts, New York, and organizer of the W. Eugene Smith Talks at Aperture and the Your Picture . . . series for PDN’s PhotoPlus. Hunt’s Three Ring Circus: American Groups Before 1950 was exhibited in New York last year in collaboration with the ICP after traveling to Arles, Bologna, and Houston. His book The Unseen Eye: Photographs from the Unconscious (Aperture, 2011) was the basis for a large show that debuted at the Rencontres d’Arles, France, then toured to the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland; FOAM, Amsterdam; and the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

The post W.M. Hunt: Talking Pictures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 2, 2016

William Christenberry, Poet of the Ordinary (1936–2016)

Aperture remembers the life of the Southern photographer, whose work evokes the power of passing time.

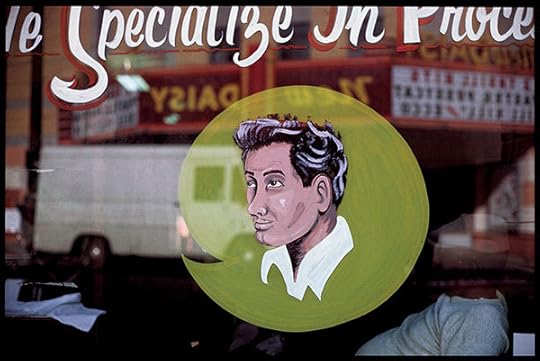

William Christenberry, Processing, Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee, 1966

By Walter Hopps

In 1963, as director of the Pasadena Art Museum in California, I mounted a retrospective of the work of Marcel Duchamp, which was widely reviewed. I had put together a catalog and a poster for the show, and I was very proud of both of them, but we sold precious few, and almost none by mail order. One day, my secretary was going through the mail, and she said, “Here’s a strange one. Somebody in Memphis, Tennessee, has written requesting a catalog, and he’s sent fifteen dollars.” I said, “Who the hell in Memphis, Tennessee, would want a Duchamp catalog?” Duchamp, at the time, was not exactly a household name in the South. Because the catalog cost less than fifteen dollars, I told my secretary to throw in a poster as well.

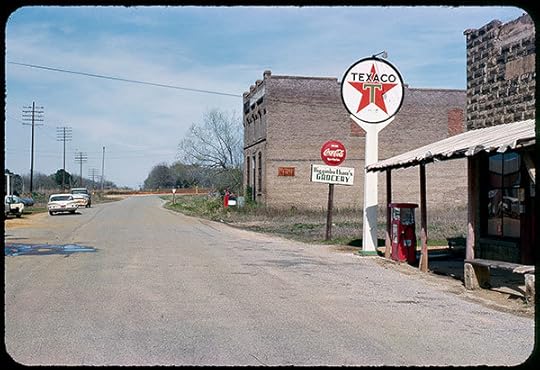

William Christenberry, Signs in Landscape, near Marion, Alabama, 1975

Years later, I was in the atrium of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington one day when a lanky-looking man came up to me and said, “Excuse me. You’re Walter Hopps, aren’t you? I just wanted to thank you for that Duchamp poster you sent me.” He told me his name and explained that he was living in Washington now. I asked him what he did, and he said, “A little bit of everything. I draw. I make sculpture. I’ve done paintings. I take photographs.” In an age when everyone else looked like a hippie, he was short-haired and straitlaced and very polite in a southern way. I asked him if I could come by sometime and see his work. When I got to his house, I looked at everything he’d been doing, but the minute I saw the photographs—both black and white and some small ones in color—a light went on in my head, and I knew that they were special. As Walker Evans once said, they were like perfect little poems. I often wondered afterward whether I ever would have met Christenberry if I hadn’t sent him that Duchamp material. He was shy—it might have taken years.

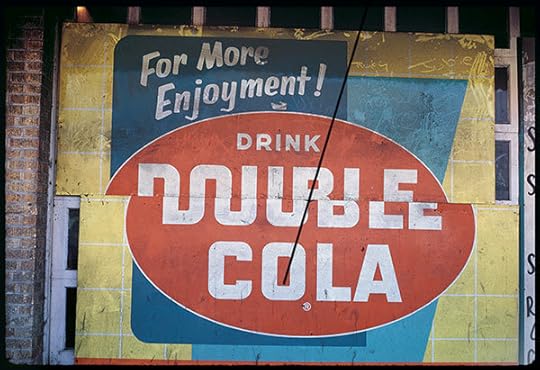

William Christenberry, Double Cola Sign, Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee, 1966

William Christenberry was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in 1936, and spent a lot of his childhood in Hale County. He went to the University of Alabama at a time when many of the teachers there were former students on the GI Bill. One of those teachers turned out to be important in his life, a graduate of the California School of Fine Art named Lawrence Calcagno. Calcagno turned out not to be one of the majors himself, but he was a sophisticated, mature person, and he opened up all kinds of things for Christenberry. He sent him to the library and forced him to look at art he’d never heard of before. A couple of years after college, Christenberry moved up to New York to look for work. He got a job at Bella Fishko’s gallery. That didn’t work out. Then he got a job cleaning Norman Vincent Peale’s church. That was too depressing. Next he was taken on as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. That was too boring. Finally, he heard that Walker Evans was working at Time-Life and Fortune magazine. This was late in Evans’s life, and he had been almost forgotten. Christenberry went over to the Time-Life Building and met with him. Evans, who never had a son, took to Christenberry right away—especially when he realized that his family lived right down the road from the people he’d photographed for his book with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Evans had documented the lives of sharecroppers in the area; Christenberry’s family was just one rung up the ladder—they owned the land they worked on. So that was a real connection between Christenberry and Evans, and it was Evans who encouraged Christenberry to go back to the South for his work.

William Christenberry, Building with Nehi Sign, Stewart, Alabama, 1965

Agee, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, called for the use of the most humble materials to create a lyric poetry of everyday experience. Words “are the most inevitably inaccurate of all mediums of record and communication,” he said. “Words cannot embody; they can only describe.” To convey the dignity of the lives observed, one must form a montage of details—scraps of iron, the wood from a table, a broken chair, chickens. This is the aesthetic principle that Christenberry has been developing since the 1950s, and he has done so in an extraordinarily wide variety of media. He has also devoted considerable attention to one particular fringe element of the American South: the Ku Klux Klan. Curator Thomas Southall has written of Christenberry’s Klan pieces, “This creation, like his other work, has a way of giving physical form to intangible feeling. We are left not with a simple polemic or documentary statement, but with a new sense of how complex and deeply rooted prejudice is.” For Christenberry, these fetishistic works seem to constitute a kind of exorcism of racism.

William Christenberry, Child’s Grave with Pink Rosebuds, Hale County, Alabama, 1975

What fascinated Christenberry about Duchamp was that Duchamp could make art out of anything. He was, to use the French word, a bricoleur—a fix-it man, an improviser of modest and humble materials, who can patch your chair or fix your chicken coop. In Christenberry’s work, Duchamp’s and Agee’s ideals come together: even the most modest of farmers knows inherently how to survive. If the plow breaks, he knows how to mend it. If he can’t find tar paper for his roof, he figures out how to insulate with newspapers. His life is an improvisation. When Christenberry saw all the found materials in Duchamp’s work—the old bottle racks, the bicycle wheels—he felt an instinctive rapport. It makes Christenberry nervous to call what he does art. For him to take a good picture is simply a matter of getting the right kind of crop planted and then harvesting it on time.

What a harvest.

This essay was originally published by Aperture in William Christenberry (2006).

Walter Hopps (1932-2005) produced a number of legendary exhibitions, including the first retrospectives in America of Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell, and Kurt Schwitters, and was the founding director of the Menil Collection in Houston.

The post William Christenberry, Poet of the Ordinary (1936–2016) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 1, 2016

Elle Pérez

In the Bronx, New Haven, and Baltimore, nightclubs are spaces of queer liberation.

By Salamishah Tillet

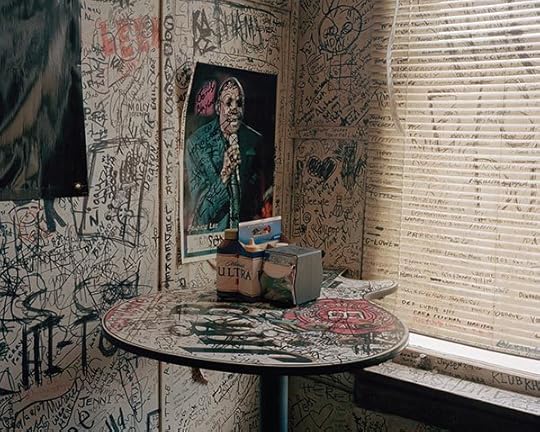

Elle Pérez, Karila, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Euforia Latina. Bronx Underground. Autonomous queer spaces now disappeared from the American urban landscape. Rather than have them live on as remnants in the minds of those who found haven there, Elle Pérez insists on their presence. Her photographs are a form of counter-memory, a practice that philosopher Michel Foucault describes as actively reviving the past to resist historical obscurity and narrative death.

Pérez was born the year before Jennie Livingston released Paris Is Burning, a 1990 documentary initially heralded for its provocative characters and its unprecedented exposure of New York’s queer, black, and Latino ballroom culture to mainstream America. In retrospect, what was seen as the film’s innovation can now seem to be racial and class exploitation: Livingston neither turns the camera back onto herself nor turns it over to the stars. “As a twenty-two-year-old from the Bronx watching Paris Is Burning for the first time, it was like falling in love with yourself through a white gaze,” Pérez told me. “That’s what I am fighting against in my work.”

Elle Pérez, Curtain Peek, 2014

Courtesy the artist

And yet, Pérez’s photographs are more empathetic than embattled. Her close-up shots, a few staged, mostly improvised, capture the offscreen rather than the nightclub’s main attraction. Those moments before the moment. A stairwell before going in or leaving the party. Backstage pageant prep. Peering from behind the curtain. A Selina catsuit hanging midair. A slow inhale. A tight embrace.

That her photographs are from different places might matter for the official record. Some are taken at Euforia Latina, the Latin club night held at Baltimore’s popular Club Hippo, which first opened in 1972. Others are from the Bronx Underground, a punk show hosted at the First Lutheran Church of Throgs Neck, in the Bronx, for fourteen years. Both places permanently closed their doors in 2015, shortly after Pérez captured them for posterity. “In the beginning, I thought I was photographing for the future,” Pérez said. “Because these people would have been left out of the history of punk.”

That her photographs refuse their geographical specificity is the point. These images flatten space, giving us a sense that we are watching both the entertainers and their spectators in media res and waiting for each other. Even more poignantly, Pérez’s black-and-white portraits dislodge these scenes from their respective years of 2014 and 2015 and situate the viewer fully in the present or transport us back to the neopunk scene of the early 2000s or to the roaring Harlem ballrooms of the 1980s. Here, we are all part of an intimate experiment in out-of-timeness in which space and temporality are deconstructed, each moment rendered eternally new.

Elle Pérez, Kirsten, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Pérez’s counterarchive then becomes an alternative to erasure. Taken together, these photographs create their own imagined community, to use the phrase coined by historian Benedict Anderson, in which people are joined by shared experiences or collective memories rather than by the more traditional borders of the nation-state. Unlike the racial and sexual othering in Paris Is Burning, Pérez, working in settings of emotional familiarity, takes her subjects, their queerness, and their blackness and brownness for granted. By doing so, she recenters all LGBT individuals as normative, everyday, and utterly beautiful.

Amid the euphoria and exaltation there is now a stinging sadness as we juxtapose Pérez’s images against the backdrop of those brutally murdered on Latin Night at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub this past June. And while Pulse’s owner defiantly vows to keep its doors open, Pérez’s photographs are their own form of memory-justice, ones that we need now more than ever.

Salamishah Tillet is an associate professor of English and Africana Studies and a faculty member in the Alice Paul Center for Research on Gender, Sexuality, and Women at the University of Pennsylvania.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

“On Feminism”

The winter issue of Aperture, “On Feminism,” arrives at a moment when the power and influence women hold on the world stage is irrefutable, and the very idea of gender is central to conversations about equality across the country, and around the globe. “On Feminism” focuses on intergenerational dialogues, debates, and strategies of feminism in photography and considers the immense contributions by artists whose work articulates or interrogates representations of women in media and society. Across more than one hundred years of photographs and images, “On Feminism” underscores how photography has shaped feminism as much as how feminism has shaped photography.

FRONT

Redux

Brian Wallis on Leonard Freed’s Black in White America, 1968

Spotlight

Eli Durst’s In Asmara by Alexandra Pechman

Curriculum

By Martha Rosler

Dispatches

Maria Nicolacopoulou on Athens

BACK

Object Lessons

Les Femmes de l’Avenir, 1900–1902

WORDS

On Feminism

Contributions by Catherine Morris, Zanele Muholi, Laurie Simmons, Johanna Fateman, Zackary Drucker, and A. L. Steiner

Modern Women: David Campany in Conversation with Marta Gili, Julie Jones, and Roxana Marcoci

The artists who redefined the course of twentieth-century photography

The Feminist Avant-Garde

In self-portraiture and body art, experimental pioneers of the 1970s

By Nancy Princenthal

Sex Wars Revisited

Lesbian erotica as critical rebellion

By Laura Guy

A Taste of Power: Renée Cox in Conversation with Uri McMillan

From Angela Davis to Beyoncé, the icons and avatars of black style

History Is Ours

The legacy of protest in video and performance

By Eva Díaz

On Defiance

How women have resisted representational photography

By Eva Respini

Beyond Binary

New visions of trans feminism

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Our Bodies, Online

Feminist images in the age of Instagram

By Carmen Winant

PICTURES

Cosey Fanni Tutti

Introduction by Alison M. Gingeras

Gillian Wearing

Introduction by Jennifer Blessing

Yurie Nagashima

Introduction by Lesley A. Martin

Hannah Starkey

Introduction by Sara Knelman

Katharina Gaenssler

Introduction by Yvonne Bialek

Josephine Pryde

Introduction by Alex Klein

Laia Abril

Introduction by Karen Archey

Farah Al Qasimi

Introduction by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Martine Syms

Introduction by Amanda Hunt

Elle Pérez

Introduction by Salamishah Tillet

$24.95

The post Elle Pérez appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 29, 2016

A Portrait of the Artist as Claude Cahun

On the cover of Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue is a photograph by Gillian Wearing, who recreated a 1927 self-portrait by the French writer and artist Claude Cahun. Rediscovered in the 1990s, Cahun was known for her gender bending, theatrical photography. “Wearing, like Cahun, conceives of gender as multivalent,” Jennifer Blessing writes in an introduction to a portfolio of Wearing’s previously unpublished early work. Ahead of her latest exhibition, Wearing spoke about Cahun, feminism, and her “spiritual family” of artists with Nicholas Cullinan, director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, where Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask opens in March 2017.

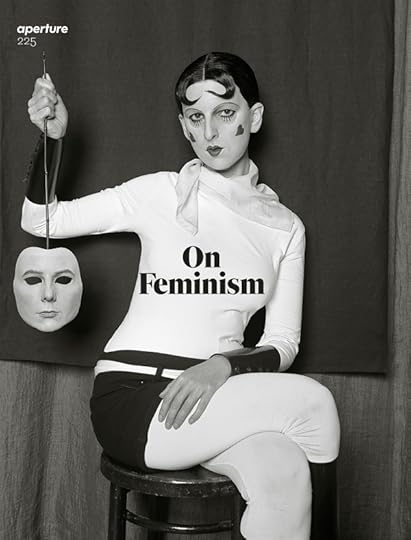

Gillian Wearing, Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Nicholas Cullinan: I wanted to begin by asking you about Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face, from 2012. When did you first discover Claude Cahun’s work, and what has it meant to you over the years?

Gillian Wearing: I read about Cahun in the mid-’90s; I think it was in an article in the Guardian. Her work was being written about as if it were a new discovery, although it was more of a rediscovery, as her photographs had been bought at an auction in the 1970s after her partner, Marcel Moore, passed away. The photographs seemed very playful, and also very apt for that moment, something that has not gone away over time. In fact, we are now finding new ways to look at her work.

In the ’90s I thought about her work as performed versions of the self—something that now feels innate and even commonplace to anyone with an Instagram account. I can track my own sensibility to this from my teenage years onward; I felt compelled to take photographs of myself posing in order to crystallize a perfect image of myself, and mainly for my consumption only. It was not always about vanity and creating an illusion, but also trying to get close to how I might look or be at a certain point in my life. A lot of this is captured in my series My Polaroid Years, which look very much like selfies but were all taken with a Polaroid camera between 1988 and 2005. So when I became aware and interested in Cahun’s work, I felt there was some kind of affinity, a need that she had to take images of herself that I related to.

It’s only fairly recently I found out that she did not exhibit her photographs, and that she saw herself primarily as a writer. We don’t entirely know why she took the images, although some fragments of her photographs did appear in her collages. With very little to guide us, a lot of what we can say and think about Cahun and her photographs is only conjecture.

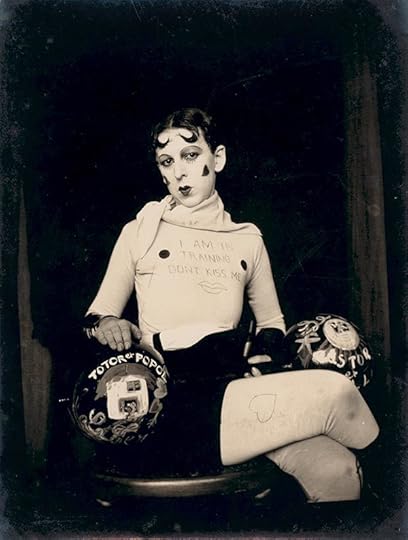

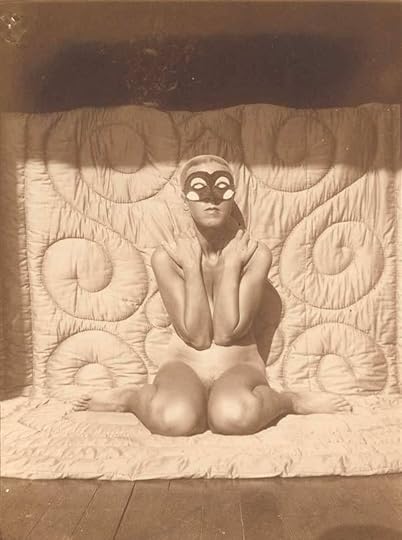

Claude Cahun, I am in training don’t kiss me, ca. 1927

© Jersey Heritage and courtesy Jersey Heritage Collections

Cullinan: Leading on from that, why did you choose this particular image of Cahun’s to re-create? Could you talk a bit about the process behind making this work?

Wearing: I chose it because it was quite an emblematic photograph. I liked the way her face, which was painted, already resembles a mask, and that led me to thinking about introducing a mask of my own face into the work. So both of us are represented as masks in the image.

The whole process in creating the photograph takes about four months. A mask is made of Cahun’s face that will fit my face. So the sculpting of her face is done over a cast of mine. In the shoot I wanted to create a pose similar to her original one, with the head tilted down, the legs crossed. I didn’t want to have the text of “I am in training don’t kiss me,” as this image is about our relationship and shared interests in the masquerade. I shoot with film rather than digitally, and it was a ten-hour shoot. I think film makes me much more thorough. I know I can’t see the images before they are processed, so I try and have as many choices of shots and lens changes as possible.

Gillian Wearing, Me as Arbus, 2008

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: It’s fascinating that you take on the roles of artists, as well as your mother, father, sister, and brother, and yourself at different ages. So, is Cahun part of your “family,” so to speak?

Wearing: In my series Me as … (2008–13), apart from Cahun, Warhol, Arbus, and Mapplethorpe, there is Weegee, Sander, and Fox Talbot. I classify them all as my spiritual family.

Cullinan: How have Cahun’s example and the way she addresses issues of gender politics, identity, masquerade, performance, and self-portraiture through her work resonated with you?

Wearing: Like a lot of people, apart from my scant knowledge of her in the ’90s, I didn’t really have much exposure to Cahun until the last fifteen years, when quite a few books have been published on her life and work. And it is within this time that I realized she was an activist, as well as an artist, writer, etc; that she was prescient in her ideas of renegotiating what gender means, and that it can be neutral. So there is a really interesting convergence of her life and art.

Gillian Wearing, Self-portrait as my brother Richard Wearing, 2003

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: Is the fact that both of you work primarily using photography as your medium significant, or is photography simply a vehicle to explore both portraiture and self-portraiture?

Wearing: I have always classified my work as portraiture, from my filmic works to photography and sculpture. You could say the terminology is the vehicle. The word portrait is a very open term; it allows for experimentation, discovery, and the fact that almost anything can be a portrait, whether it is of a human face or a bouquet of flowers.

Gillian Wearing, Self-portrait of me now in a mask, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: I want to ask you about the exhibition we are working on here at the National Portrait Gallery, which will open next March: Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask. Of course, in doing this, we are generating an intergenerational dialogue between two woman artists. As such, does you consider yourself a feminist? Do you identify in particular with one or more periods/waves of feminist art?

Wearing: Yes, I am a feminist. I believe in equality, and I believe anyone who thinks the same is a feminist. I am indebted to many women over the years who have achieved change for other women through feminist art, politics, and writing. I don’t identify with any one period, as I identify with different things over different moments in time.

I remember what I consider the first feminist artwork I became aware of: Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79). It seemed very radical, both as an idea of what art was and that something that would have normally been private was being put on display. I think women artists have really pushed that envelope in terms of the personal being art. In my own work over the years, people have said to me, “You can’t show that, it’s too revealing.” This has happened with the confessional works and even with my series Signs, both from the early ’90s. But I am glad I never took heed, because art is about challenging and changing dominant cultural hegemony. I feel the same way about Cahun’s work. She has left us with these images that show how she was disrupting ideas of gender and reconstructing what identity means, which is very topical at this moment in time.

Claude Cahun, Self-portrait (kneeling, naked, with mask), ca. 1928

© Jersey Heritage and courtesy Jersey Heritage Collections

Cullinan: Can you share with readers a bit more about how this exhibition has taken shape, particularly your research trips to Jersey, where Cahun lived for the last twenty years of her life, and your curatorial involvement and “collaboration” with Cahun in the new works you are making for it?

Wearing: The exhibition has really brought me much closer to Cahun’s work and to her life. By going to Jersey with curator Sarah Howgate from the NPG, I saw the house where she lived, which was next door to the church where she was buried, which was next to the beach where she walked her cat on its lead. It was so unusual to have such a huge part of someone’s life in this small area of land. I was able to imagine those portraits of her being shot on the beach, at the cemetery, or on the wall of her garden, and from that create my own idea of her biography as an artist. Also, the Jersey Heritage Trust has the largest collection of Cahun’s works, many of which we have borrowed for the exhibition. The whole trip was a real treat, this tiny island with a treasure trove of this great artist’s life and work.

Nicholas Cullinan is the director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, where Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask will be on view from March 9 to May 29, 2017.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

“On Feminism”

The winter issue of Aperture, “On Feminism,” arrives at a moment when the power and influence women hold on the world stage is irrefutable, and the very idea of gender is central to conversations about equality across the country, and around the globe. “On Feminism” focuses on intergenerational dialogues, debates, and strategies of feminism in photography and considers the immense contributions by artists whose work articulates or interrogates representations of women in media and society. Across more than one hundred years of photographs and images, “On Feminism” underscores how photography has shaped feminism as much as how feminism has shaped photography.

FRONT

Redux

Brian Wallis on Leonard Freed’s Black in White America, 1968

Spotlight

Eli Durst’s In Asmara by Alexandra Pechman

Curriculum

By Martha Rosler

Dispatches

Maria Nicolacopoulou on Athens

BACK

Object Lessons

Les Femmes de l’Avenir, 1900–1902

WORDS

On Feminism

Contributions by Catherine Morris, Zanele Muholi, Laurie Simmons, Johanna Fateman, Zackary Drucker, and A. L. Steiner

Modern Women: David Campany in Conversation with Marta Gili, Julie Jones, and Roxana Marcoci

The artists who redefined the course of twentieth-century photography

The Feminist Avant-Garde

In self-portraiture and body art, experimental pioneers of the 1970s

By Nancy Princenthal

Sex Wars Revisited

Lesbian erotica as critical rebellion

By Laura Guy

A Taste of Power: Renée Cox in Conversation with Uri McMillan

From Angela Davis to Beyoncé, the icons and avatars of black style

History Is Ours

The legacy of protest in video and performance

By Eva Díaz

On Defiance

How women have resisted representational photography

By Eva Respini

Beyond Binary

New visions of trans feminism

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Our Bodies, Online

Feminist images in the age of Instagram

By Carmen Winant

PICTURES

Cosey Fanni Tutti

Introduction by Alison M. Gingeras

Gillian Wearing

Introduction by Jennifer Blessing

Yurie Nagashima

Introduction by Lesley A. Martin

Hannah Starkey

Introduction by Sara Knelman

Katharina Gaenssler

Introduction by Yvonne Bialek

Josephine Pryde

Introduction by Alex Klein

Laia Abril

Introduction by Karen Archey

Farah Al Qasimi

Introduction by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Martine Syms

Introduction by Amanda Hunt

Elle Pérez

Introduction by Salamishah Tillet

$24.95

The post A Portrait of the Artist as Claude Cahun appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 22, 2016

Separate Cars on the Open Road

Coinciding with Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, students in Sarah Lewis’s Harvard University class “Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship” contributed essays on the relationship between images of social unrest and landmark Supreme Court decisions. Here, Ian Askew reflects on Robert Frank and the freedom to travel.

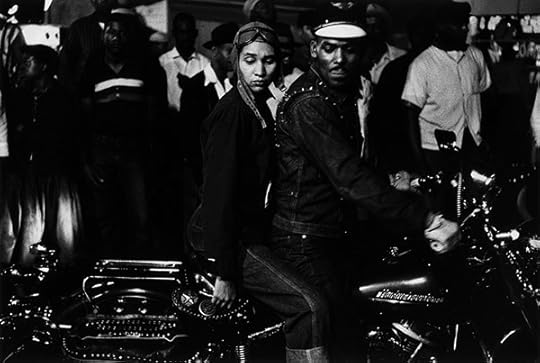

Robert Frank, Indianapolis, 1956

© the artist, from The Americans, 1958

On April 13, 1896, Supreme Court Justice David Brewer left Washington, D.C. for his home in Leavenworth, Kansas, following news of his daughter’s untimely death. In all likelihood Brewer traveled by train, and in a car for only white passengers. Meanwhile, in D.C., the case of Homer A. Plessy v. John H. Ferguson was being argued in front of the eight remaining judges. Given Justice Brewer’s record, it’s likely he would have sided with Justice John Harlan, the single judge to dissent in the seven-to-one landmark ruling that upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine and would define the partially reconstructed United States. This decision would cement that public, specifically mixed-race spaces would be accessible but inhospitable to black citizens of the United States. For black activists, the ruling instilled a narrative that citizens seeking equality should do so through desegregation and by gaining access to shared facilities. Plessy sought to give black citizens the same kind of access to transportation, and therefore the nation, enjoyed by Justice Brewer.

Nearly sixty years later, in 1956, as Rosa Parks continued Homer Plessy’s legacy by fighting for equal access to public transportation in Montgomery, Alabama, the Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank visited Indianapolis, Indiana. Frank was there capturing images that would eventually be collected in his landmark 1958 photobook, The Americans. The book was a revelation to many, and featured images of the country as seen through a foreigner’s eye. Frank captured the essential complexity of American culture, a vision not advertised to the world, and revealed the growing pains of a country still in transition.

Frank’s 1956 image Indianapolis provides one of the book’s many revelations. His portrait of a young black man and woman, presumably a couple, presents a starling portrayal of black aspiration and style. Two young people sit astride a motorcycle. In their posture and downcast eyes, they perform a brand of coolness that seems to predict the aesthetic of the Blaxploitation films that would follow in the 1970s. Light darts off of the studded shoulder of the driver; the man and woman appear fused to the machine. The couple’s focus beyond the frame allows the viewer to consume their coolness, their modernity, their self-possession without meeting or confronting their gaze.

Frank’s image asks nothing of the audience but their attention. At the time, images of black neighborhoods and segregated public spaces, purveyed by popular media, served as “proof” of the failings of segregation, and argued that separation was tantamount to the death of black potential. Frank’s photograph does none of this. Instead, Frank pictures black people on their own terms, embodying the potential of travel—that most American ideal of freedom. They are not Plessy insisting on a place in the train car or Rosa insisting on a seat on the bus. They have a machine, and they’re ready to claim the open road.

Ian Askew studies history and literature at Harvard University.

The post Separate Cars on the Open Road appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 17, 2016

The Lyrical South of Shane Lavalette

Echoing the languid melodies of the South, Shane Lavalette finds fragments of oral tradition in the visual world.

By Tim Davis

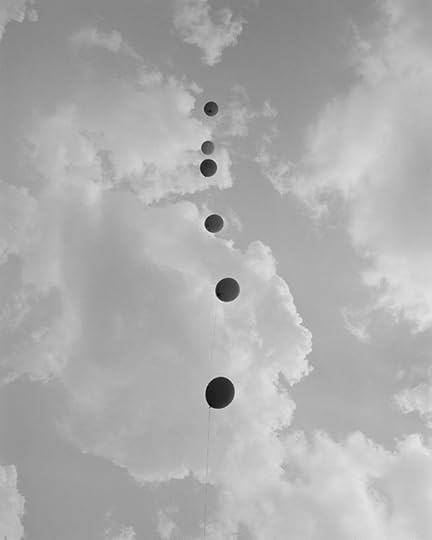

Shane Lavalette, Domonique at Sunset, 2010

Courtesy the artist

Barons and earls traveled the world after gold and rubber and souls. They built big building wings and echoey halls, which they filled with curiosities: animal skins, sacred relics, and paintings of their armies’ exploits. The houses became museums. And in most cases, they still are. Walk through those labyrinths of gilt-framed canvases and you see occurrences. Things happen. Important things. A dove flies into a virgin’s bedroom window and she knows she’s been impregnated by God. Sailors cling to life and succumb to death on a ramshackle raft made from the mast of a wrecked French frigate. A severe wealthy man fans his finery. That was what painting was for: to yell “Echo!” from the heights of power, myth, and experience and let it ring in our ears down in the fancy rooms below.

Shane Lavalette, Ground Zero, 2010

Courtesy the artist

Along came photography, and out went the assumption that a work of art had to describe the apexes of experience. The camera is uncaring and undiscriminating. It likes all things (excepting the darkness) equally. The camera doesn’t care whether the man in front of it is a royal or a rube, or if that man is entirely inside the picture’s frame. It is fixed in one instant, from one vantage point, limited to places one human being can actually go while carrying equipment. It is not good at describing the scope of an important battle or sacred revelation, as any one photograph is always a diminishment of a great, epic event: one mouth’s utterance, rather than a heavenly choir. The camera didn’t care for history, mythology, religion, but its interpretation of painting’s lesser genres—still lifes, portraits, landscapes, folks in the fields—was not a diminishment. The camera raised those subjects up. And it did it over and over, with total devotion.

Shane Lavalette, Ready to Roll, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Shane Lavalette is the latest inheritor of photography’s devotion to the lyric potential of the barely occurring. A northerner, commissioned by a great southern museum, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (with a big new wing of its own), to make a project about the South, Lavalette took as his point of entry the vernacular music of the region. It makes sense. Mark Twain was so moved by the sounds of southern voices he wrote in Life on the Mississippi that “A Southerner talks music,” and the oral is the South’s profoundest point of access. American music comes from the South. Blues, jazz, country, rock ’n’ roll, you know the story. From Stephen Foster to Sly Stone, the South is our musical source and subject.

Shane Lavalette, Ashley at Ben Burton, 2010

Courtesy the artist

And yet a photography project about music sounds like an opera about Helen Keller. The camera, being so single-mindedly visual, is an illogical tool to address music. Lavalette smartly decided not to make a documentary about musicians. He instead scoured the landscape looking for the feeling coming from the music. By avoiding the sanctioned, probing tropes of ethnomusicologists and photojournalists, this young northern artist avoided the conundrum Ma Rainey is supposed to have described: “White folks hear the blues come out, but they don’t know how it got there.”

Shane Lavalette, Binoculars, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Lavalette digs roots instead of picking flowers. He hunts for analogies, hints, circumlocutions. He is not preparing the epic history painting of Southern music; he is finding cunning, lyric fragments of an oral tradition in the visual world and letting them rattle together in his carrying case. There is smoke in the grass, but no fire. Skies only hint at tornadoes. A fence finds itself in fragments. The girls are pretty, the boys are rogues, but the photographer doesn’t fall for feints or flirtations. A tiny toy church sits mysteriously in a field, reminding us of Flannery O’Connor: “I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted.”

Shane Lavalette, Church, 2011

Courtesy the artist

This is a project about a project. Lavalette is accruing meaning about southern music by eschewing information. He moves through those “minor genres”—portraits, landscapes, agricultural scenes, still lives—content to let the project as a whole gather significances along the way rather than laying out a thesis and filling in bullet points. The pictures in Lee Friedlander’s Jazz People of New Orleans are about music not because they have musicians in them, but because they are formally polyrhythmic and alive. Shane Lavalette’s pictures are visually straightforward, obsessively clear, and devoted to the metaphysical idea that direct observation can be beamed through a lens to a viewer. They are quiet pictures that build to a boisterous whole. They speak from the endlessly renewed place of the photographic expeditioner who loves the world and knows it’s a well that never runs dry.

Tim Davis is a writer and artist who teaches photography at Bard College.

Shane Lavalette’s most recent book, One Sun, One Shadow, is self-published.

The post The Lyrical South of Shane Lavalette appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 15, 2016

A Chance Encounter with Mark Morrisroe

After years in a Boston attic, Mark Morrisroe’s dreamy, unpolished early work is on display in a rare exhibition in New York.

By Matthew Leifheit

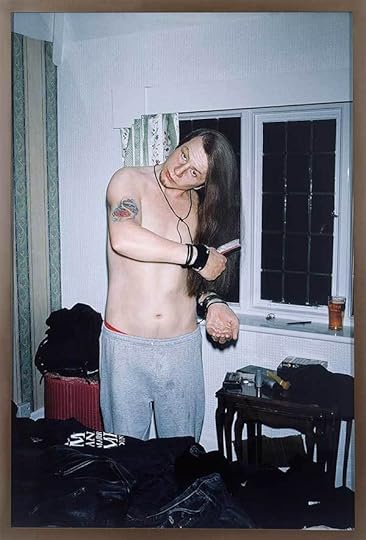

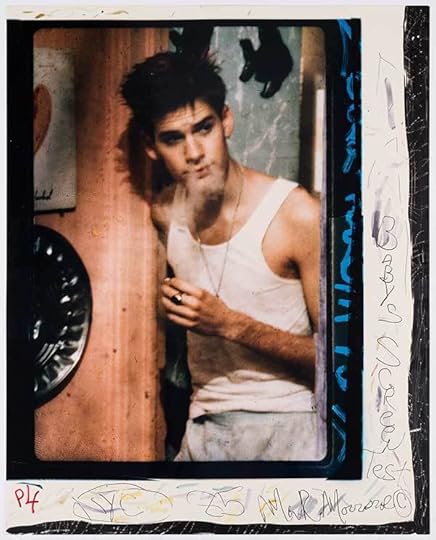

Mark Morrisroe, Baby Steffenelli (John S.), 1985

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

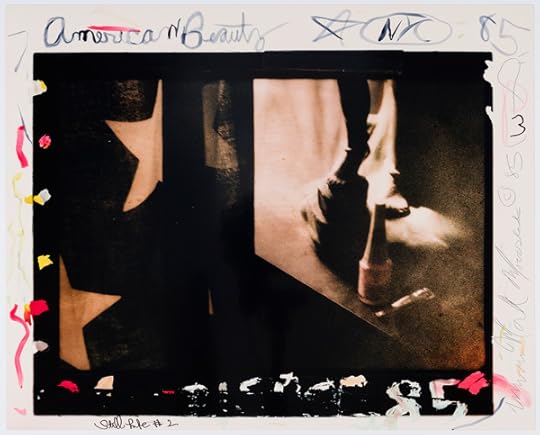

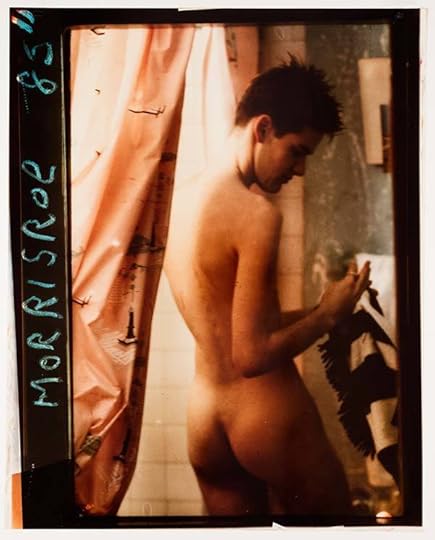

At the end of the stairway to the lower galleries of Alexander and Bonin’s new location in Manhattan’s financial district, there is a grainy color image of two men frozen in ecstatic embrace. Titled Untitled (John S. and Jonathan), the C-print, made in 1985 from sandwiched negatives, has some kind of life about it—an electric draw produced by its nubile highlights and off-kilter framing. The image is by Mark Morrisroe, who died in 1989 at the age of thirty, and it’s printed with a wide border, enshrined in frenetic pen marks, scratched emulsion, out-of-focus confetti in darkroom colors, traces of multiple negatives, and otherwise fanciful processing. Stashed in the attic of a private home in Boston for over thirty years, these unique works are now on view to the public for the first time.

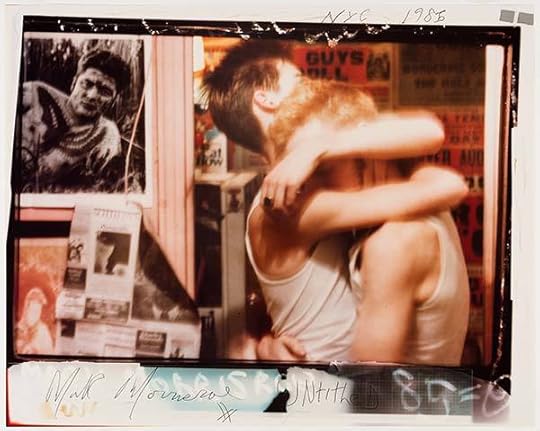

Mark Morrisroe, Untitled (John S. and Jonathan), 1985

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

The taller of the two figures in Untitled (John S. and Jonathan) is John Steffenelli, a subject with teen heartthrob allure who appears in three of the eight pictures on view in Mark Morrisroe: Works from 1982–85. The red-haired boy on the right is distinguishable as the artist Jack Pierson, former boyfriend and frequent muse of Morrisroe’s. “It was my first intense gay relationship,” Pierson told me recently. “It was two years solid of living together and then I moved to New York to get away from him. I mean we were both drug addicts and alcoholics. But he was, as far as I’m concerned, much worse than me. So it was kind of lunacy to be around him.”

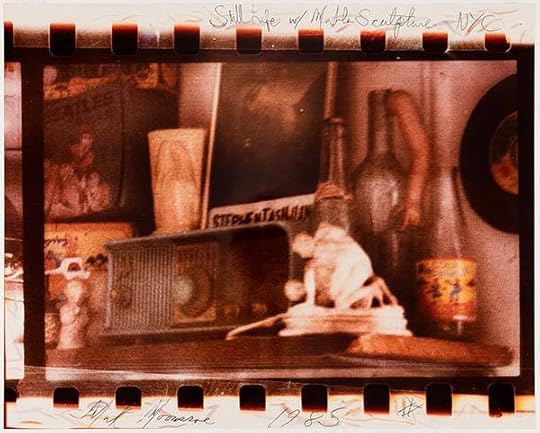

Mark Morrisroe, Still Life with Marble Figures (In the Home of Stephen Tashjian NYC), 1985

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

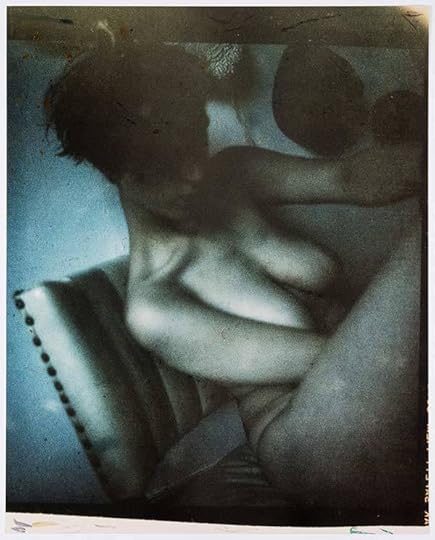

A climate of lunacy is apparent throughout much of Morrisroe’s work, particularly in his so-called “sandwich prints.” Figures dissolve into shadow and film grain, encircled in multilayered jabs of neon marker scrawling stars, symbols, dates, and locations, creating a dream world that is alive with sex and freedom. Standing amid such colors provides a glimpse into a more bohemian time, when artists in downtown New York were redefining the expressive possibilities of identity and gender in art making. (Always preferring the margins, Morrisroe himself moved from Boston to Jersey City.)

Mark Morrisroe, Janet Massomian, 1982

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

These pictures also reanimate a brief, seemingly hedonistic era in advance of the AIDS crisis, which felled a generation of artists, including Morrisroe. Despite his short career, Morrisroe managed to leave behind more than six hundred color photographs and thousands of Polaroids, an archive replete with a sense of urgency, a sense that time was running out. Yet, for an artist of Morrisroe’s cult following, there are few opportunities to see work in depth. The only comprehensive Morrisroe retrospective in the U.S., presented in 2011 at Artists Space more than two decades after his death, was based on a 2010 survey mounted by the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland, where Morrisroe’s estate has been housed since being acquired by Collection Ringier in 2004. Because the vast majority of his work is held in Winterthur, only the few scattered pictures he sold or gifted during his lifetime tend to crop up in exhibitions. (Six additional sandwich prints are featured in Human Interest, the Whitney Museum’s installation of portraits from the collection.)

Mark Morrisroe, American Beauty, 1985

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

The works on display at Alexander and Bonin were consigned through a neighbor of Morrisroe’s in Boston. “What he told me is basically that when Mark needed money to pay the rent, his neighbor would buy a photo,” gallerist Ted Bonin said. “The funny thing is, he never framed them, they were never exhibited, they were kept in a folder in his attic along with some Nan Goldins.” Even though eight C-prints might not compare to a retrospective, this modest exhibition is a rare opportunity. Unlike its digital counterpart, analog photography has a clear path of indexicality, where the light that touched the subject was absorbed by the negative and reborn onto paper. Seeing the end stage of this intimate process in person makes the prints appear more alive. In fact, they carry a human trace of the past: as is so unusual in contemporary photography, the margins allow us to actually see the artist’s hand.

Mark Morrisroe, John Steffenelli in the Bath, 1985

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin Gallery

If you ask the gallery staff, there are more Morrisroe prints to be seen in the back room. Since the exhibition opened in October, collectors have approached Alexander and Bonin with an offering of smaller works by Morrisroe, discrete Polaroids and the gauzy gelatin-silver prints he made from them. Perhaps these new finds, when collected, will be the basis of more exhibitions to come.

Matthew Leifheit, a graduate student in photography at the Yale School of Art, is the publisher of MATTE magazine.

Mark Morrisroe: Works from 1982–85 is on view at Alexander and Bonin, New York, through December 22, 2016.

The post A Chance Encounter with Mark Morrisroe appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers