Aperture's Blog, page 130

October 31, 2016

On Empathy: 10 Powerful Images from Magnum Photographers

Magnum’s Square Sale, Conditions of the Heart: On Empathy and Connection in Photography, now online through November 4, 2016, demonstrates photography’s ability to connect with others. For five days only, museum quality, 6-by-6-inch square prints are exceptionally priced at just $100. By using this link to make your purchase, a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

Can photography promote empathy? Photography’s most acclaimed theorists have long debated this question. More than any other medium, photography asks to be acknowledged as evidence. As Susan Sontag wrote in 1977, “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is what’s in the picture.”

Since 1947, the year Magnum Photos was established, Magnum photographers have been renowned for producing images that provide evidence of the atrocities of war, evidence of the resilience of refugees, evidence of a collective humanity. By chronicling world events and culture with influential narratives that defy convention, Magnum photographers have pushed the documentary tradition toward empathy and transformed lives in the process.

Selected by Aperture’s editors, here are ten highlights from the Square Sale.

Micha Bar Am, The return from Entebbe. Ben Gurion Airport, Israel, 1976

© Micha Bar-Am/Magnum Photos

Micha Bar-Am

“After terrorists hijacked a Paris/Tel-Aviv flight and forced it to land in Entebbe, Uganda, about 2,400 miles from its destination, Israeli commandos freed 268 hostages in a brilliantly planned and executed operation. The original code name for the mission was ‘Operation Thunderbolt’, but after the task force commander, Colonel Yonatan Netanyahu, was killed (Israel Defense Forces’ only casualty during the raid), it became known as ‘Operation Yonatan.’ In this image, passengers are welcomed by their relatives at the Ben Gurion Airport.” —Micha Bar-Am

Bieke Depoorter, Ou Menya, 2009

© Bieke Depoorter/Magnum Photos

Bieke Depoorter

“This photograph was one of the first I took where I finally could feel what photography means to me. Before, I had always treated people as pawns in my photography. I would wait for hours until they came into the right position. But I was never satisfied with the picture and felt that I was missing something… I took this photograph during a trip for my graduating project (Ou Menya), on one of the first nights spent with people I had met on the streets of Russia.

Without saying a word, she took me under her arm, brought me to her tiny house, fed me and showed me how to wash myself in a little basket. Still arm in arm, still in silence, we then went for the most peaceful walk I had ever taken. I remember us standing still over the icy fields. We came home and watched a Russian version of The Bold and the Beautiful. She was in the seat she would sit in every evening, I was in the seat next to her. She gave me pajamas to wear and took a picture of me. I took one of her. Everything seemed so simple, logical and beautiful.

That night I realized that all along I had been missing this connection with people in my photographs.” —Bieke Depoorter

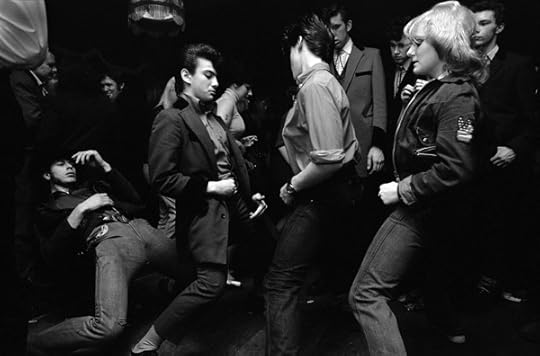

Chris Steele-Perkins, Adam and Eve pub in Hackney, London, U.K., 1976

© Chris Steele-Perkins/Magnum Photos

Chris Steele-Perkins

“All of my working life I’ve been drawn to subcultures, small worlds which have the whole world in them. The Teddy Boys (Teds) were a major subculture in Britain in the mid-’50s and had a revival in the late-’70s, at which point I photographed them. I didn’t want to be like them, but I identified with their energy, their aggression and their style. I was interested in them. I wanted to know more so I hung out, had a few drinks, and soon enough they were not bothered to pose for me. As I became ‘The Photographer,’ I just got on with it.” —Chris Steele-Perkins

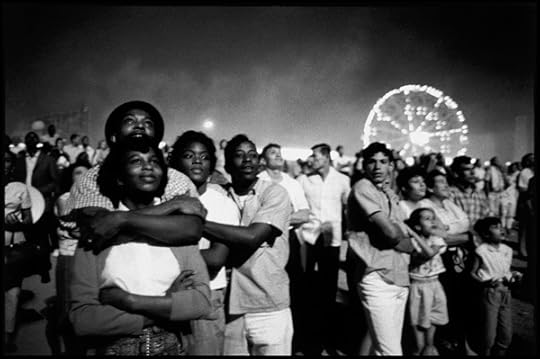

Bruce Davidson, Coney Island July Fourth Fireworks. New York City, U.S.A., 1962

© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Bruce Davidson

“Sometimes they don’t tell stories, they simply speak as images. They express feeling, increase knowledge. Photographs can draw passion, beauty and understanding. And then there is love.” —Bruce Davidson

David Alan Harvey, French teenagers on a boat in the river Seine. Paris, France, 1988

© David Alan Harvey/Magnum Photos

David Alan Harvey

“I was commissioned by National Geographic for a piece for their special issue on France. I decided I did not want to present historic France, but rather modern, young France. French teenagers. So I did what I always do, reduce the scope. I chose one group of Parisian teenagers who formed a sort of gang. A nice gang. Friends. I became part of their group for several weeks. I went to school with them, hung out everywhere with them, saw them succeed, saw them fail. Judith, pictured here with the cigarette, was the leader. There is always a leader. I was especially happy with this shot. It was taken on their graduation day on the Seine in front of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s house. I was always referential to Cartier-Bresson, even when I shot in color during this era. Clearly I bonded with these young French. We were like family when I had to hug them goodbye, which for them was goodbye to their childhood.” —David Alan Harvey

Jim Goldberg, Prized Possession (#2). Democratic Republic of the Congo, Africa, 2008

© Jim Goldberg/Magnum Photos

Jim Goldberg

“This image was taken at the Mugunga refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the time of my visit, in 2008, Mugunga had an estimated 90,000 inhabitants. The UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) was in the beginning stages of moving the entire population two kilometers away from the fast approaching rebel forces.

I climbed a hill on the north side of the camp to get a view of the thousands of makeshift shelters. Sitting alone at the top was Wembe, listening to his radio. Wembe had had this radio ever since escaping a rebel attack in his village, one year before. It was the only possession he was able to keep. Wembe told me that he climbed the hill every day to listen for good news.”—Jim Goldberg

Herbert List, Park of the Palazzo Orsini. Bomarzo, Italy, 1952

© Herbert List/Magnum Photos

Herbert List

“It is speculative for anyone but the ones involved to talk about empathy or emotional connection in a photograph. Once an artist is dead we rely on stories that surround certain images. In some rare occasions we hear from the person in the picture, who might tell us how the picture came about. This image of a shepherd in Bomarzo is such an example. After the book Italy was published with this image on the cover, we found out that the 12-year-old in the image was an orphan boy from Southern Italy. By then he had lived in Germany for the past 40 years and remembered Herbert List very well. He said List had been the first adult to listen to the sad and adventurous stories of his childhood life. The day after this image was taken, List brought him his first bag of candies.” —Peer-Olaf Richter, Herbert List Estate

Max Pinckers, She Will Use the Birds, from the series The Fourth Wall, 2012

© Max Pinckers/Magnum Photos

Max Pinckers

“She Will Use the Birds is a visual interpretation of a passage from Suketu Mehta’s book, Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, a non-fiction account of Bombay’s Bollywood underworld. The passage describes an encounter between a dancing girl and her client, who go on their first date outside of the bar where she works. The dancer invites her man into a taxi, buys a flock of songbirds from a nearby street vendor and lets them flutter around in the car. She then asks her man to play a game with her: catch the birds. This quickly turns into a flirtatious exercise of touching, gasps, laughter and giggles.

When reading stories like this one, it is in the instant imagination of a visual narrative that I find my satisfaction, in which my subjects also play out their own fantasies. When this materializes into a photograph, it is then up to the viewer to form their own interpretation of the scene.” —Max Pinckers

Susan Meiselas, USA. New York City. Little Italy. Dee and Lisa on Mott Street, 1976

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“I remember the day I met the Prince Street Girls, the name I gave a group of young Italian girls who hung out on the nearby corner almost every day. This is Dee and Lisa posing for me – or maybe for themselves. They were great friends, born the same month, they just ‘clicked.’ Growing up in Little Italy, they were always together, at school and on the street – and onwards. A friendship that’s now spanned 50 years.

Back then, I was the stranger who did not belong, but these girls would see me coming and yell, ‘Take a picture! Take a picture!’ For years, I was their secret friend, and my loft became a kind of hideaway when they dared to leave that corner, which their parents had forbidden.

It was important for me to keep on photographing them as they grew up, especially when I came back from abroad where I had been photographing wars. Looking at these pictures now reminds me of how difficult it was to integrate my two lives- family and friends at home, and my life as a photographer on the road. It was often a painful separation, though not one I regret having chosen.” —Susan Meiselas

Carolyn Drake, Crater Lake National Park Vista Point. Crater Lake, Oregon, U.S.A., 2015

© Carolyn Drake/Magnum Photos

Carolyn Drake

“For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go.” — Rebecca Solnit

Support Aperture today through the Magnum Square Print Sale, open online October 31–November 4, 2016.

The post On Empathy: 10 Powerful Images from Magnum Photographers appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 28, 2016

From Stonewall to AIDS, Framing Queer Desire

A recent forum at MoMA reveals a rich, often-overlooked thread of queer history and photography.

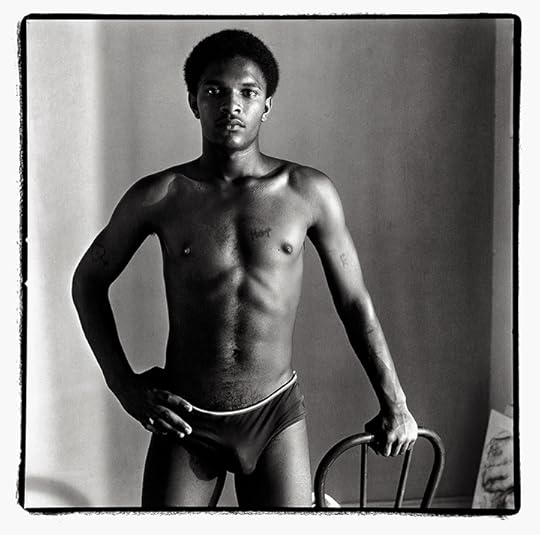

George Dureau, Arthur de Silva, 1988, from George Dureau, The Photographs

© George Dureau and courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery and Higher Pictures

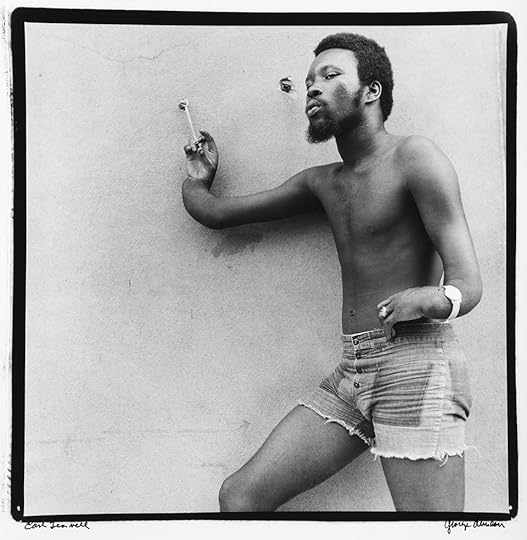

George Dureau, Earl Leavell, 1977, from George Dureau, The Photographs (Aperture, 2016)

© George Dureau and courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery and Higher Pictures

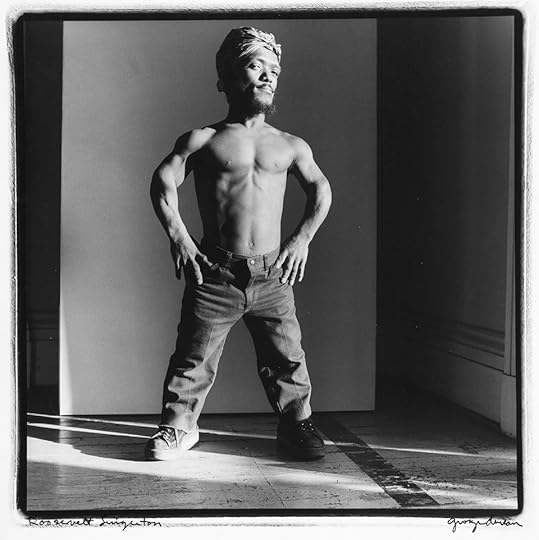

George Dureau, Roosevelt Singleton, 1974, from George Dureau, The Photographs (Aperture, 2016)

© George Dureau and courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery and Higher Pictures

George Dureau, Fred Temnel, 1976, from George Dureau, The Photographs (Aperture, 2016)

© George Dureau, Courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery and Higher Pictures

Jimmy DeSana, Storage Boxes, 1980. From Jimmy DeSana: Suburban (Aperture/Salon 94, 2015)

© and courtesy the Jimmy DeSana Estate/Salon 94

Jimmy DeSana, Four Legs with Shoes, ca. 1980, from Jimmy DeSana: Suburban (Aperture/Salon 94, 2015)

© and courtesy the Jimmy DeSana Estate/Salon 94

Jimmy DeSana, Thimbles, 1983, from Jimmy DeSana: Suburban (Aperture/Salon 94, 2015)

© and courtesy the Jimmy DeSana Estate/Salon 94

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (face in dirt), 1990, from Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, photographs by David Wojnarowicz (Aperture, 2015)

© the Estate of David Wojnarowicz, Courtesy P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York (on subway), 1978-79, from Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, photographs by David Wojnarowicz (Aperture, 2015)

© the Estate of David Wojnarowicz, Courtesy P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz, I Feel a Vague Nausea, 1990, from Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, photographs by David Wojnarowicz (Aperture, 2015)

© The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and courtesy P.P.O.W Gallery, New York

Between the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1990s, what did queer desire look like in photography? In September, the Museum of Modern Art convened a Forum on Contemporary Photography focused on the homoerotic trajectory across two decades of rebellion, liberation, and activism. “Photography has played a central role in the articulation of queer desire,” said Chris Boot, executive director of Aperture Foundation. In his presentation at the forum, which also included panelists Vince Aletti, Philip Gefter, Sophie Hackett, and Lyle Ashton Harris, Boot discussed the work of American and British photographers who pushed the boundaries of representing queer lives and bodies.

“Looking back on the period between Stonewall and the onset of AIDS, we can see how particular photographers shaped a visual language that has become part of the vocabulary of male queer identity,” Boot recalled. “It’s is a thread of photo history we’ve looked at through a series of publications at Aperture—books by and about David Wojnarowicz, Jimmy DeSana, and George Dureau, and with a survey of the work of Peter Hujar coming out next spring. The discussion at MoMA revealed just how rich the subject is, and notwithstanding the attention that Mapplethorpe’s work is getting at the moment, how much there is still to be done.”

Click here to watch a video of the MoMA Forum, recorded on September 15, 2016.

George Dureau, The PhotographsGeorge Dureau, The Photographs is an album of the great photographic portraits made throughout the forty years of Dureau’s artistic career—a New Orleans romance between the photographer and his subjects.

George Dureau, The PhotographsGeorge Dureau, The Photographs is an album of the great photographic portraits made throughout the forty years of Dureau’s artistic career—a New Orleans romance between the photographer and his subjects.$60.00

The post From Stonewall to AIDS, Framing Queer Desire appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 27, 2016

An Evening with William Eggleston at Aperture’s Fall Benefit

“I’ve never felt the need to enhance the world in my pictures, because the world is spectacular enough as it is.” —William Eggleston

Guest of honor William Eggleston Sr. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Bettye LaVette. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Guest of honor William Eggleston Sr. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Richard Renaldi, Bruce Davidson, and guest with Nan Goldin. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Alessio Bax. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Guests enjoying the photoset. Max Mikulecky © Aperture

Judy and Leonard Lauder. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Elizabeth Stribling and Cathy Kaplan. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Bonnie Lautenberg, Steve Leber, Bob Gruen, and Elizabeth Gregory. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Elizabeth Kahane. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Celso and Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla. Jared Siskin © PMc

Guests enjoying the photoset by Emily Thompson Flowers. Max Mikulecky © Aperture

Chris Boot with guest and Thomas Schiff. Jared Siskin © PMc

Lee Friedlander and guest of honor William Eggleston Sr. Jared Siskin © PMc

Aperture's Benefit Auction featuring work by Inez & Vinoodh. Jared Siskin © PMc

Weyes Blood. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Chris Boot. Jared Siskin © PMc

Libby Calloway and Andra Eggleston. Jared Siskin © PMc

Melissa O'Shaughnessy and Anne Stark Locher. Patrick McMullan © PMc

William Eggleston III and Nicholas Eggleston. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Zanele Muholi. Jared Siskin © PMc

Ashlyn Davis, Suzanne Kilpatrick, and Jean Karotkin. Jared Siskin © PMc

Eggleston's grandchildren at the photoset. Max Mikulecky © Aperture

Elaine Goldman and David Raymond. Max Mikulecky © Aperture

Lesley A. Martin with Whit and Nadiya Williams. Jared Siskin © PMc

Christina Caputo with guest, Aliza Sena, and Sarah Haimes. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Michael Schmelling and Jason Nocito. Patrick McMullan © PMc

Aperture Benefit Party atmosphere. Jared Siskin © PMc

Lyle Ashton Harris and Chris Boot. Will Matsuda © Aperture

Darius Himes of Christie's. Jared Siskin © PMc

On October 24, Aperture Foundation’s benefit, “Dear Bill,” honored William Eggleston for his contribution to photography and his lifelong passion for music. Though his name is synonymous with the acceptance of color photography by the art world, William Eggleston is also a virtuoso piano player, and his work has appeared on several album covers. In Aperture magazine’s fall issue, “Sounds,” John Jeremiah Sullivan profiles Eggleston, who, looking at one of his photographs, muses, “either everything works or nothing works”—simple as that. Eggleston’s most recent book, the ten-volume Democratic Forest (2015), contains more than ten thousand photographs and is the basis for Eggleston’s first exhibition at David Zwirner Gallery, opening Thursday, October 27.

Eggleston’s prolific career was the focus of Aperture’s annual benefit, which drew more than six hundred guests and raised approximately $650,000 in support of its publications, public programming, and educational initiatives. The event was cohosted by David Byrne, Sb Cooper and RL Besson, Jeff Garlin, Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Elizabeth and William Kahane, Cathy Kaplan, Judy and Leonard Lauder, Nion McEvoy, Jessica Nagle, and David Zwirner. Over the preceding weekend, the benefit festivities kicked off with a series of exclusive events: visits with photographers Adam Fuss, Richard Phibbs, and Richard Mosse, a cocktail party at Aperture’s Chelsea gallery, a private visit to Yale’s photography collection, and a reception at Steinway Hall.

Taking a cue from vinyl album covers, the Paddle8-sponsored silent auction included square, twelve-by-twelve-inch prints. Thirty-two artists, including Stephen Shore, Rosalind Fox Solomon, Alex Webb, and Penelope Umbrico, contributed prints, all of which sold. Sara Friedlander, Vice President and Head of Evening Sale at Christie’s, presided over the live auction, which featured a commission by Doug and Mike Starn, as well as photographs by Bruce Davidson, Zanele Muholi, and Juergen Teller.

A slideshow of photographs from The Democratic Forest set the stage for live music performances directed by Pat Irwin. Musical performers included Alessio Bax, Bettye LaVette, Weyes Blood, and Lafayette Harris. Chances with Wolves closed with an upbeat DJ set.

Additional party photos are available on patrickmcmullan.com.

Click here to make a donation to Aperture’s Annual Fund.

The 2016 Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction was generously supported by: Christie’s, Foto Care, ropeadope, Steinway & Sons, Emily Thompson Flowers, Espolòn Tequila, Fine Art Frameworks, Ilford, LTI Lightside, and Paddle8.

Benefit Committee

Sponsors

Sb Cooper and RL Besson

Judy and Leonard Lauder

Leaders

Elaine Goldman and John Benis

Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla

Elizabeth and William Kahane

Cathy M. Kaplan and Renwick D. Martin

Anne Stark Locher and Kurt Locher

Nion McEvoy

Scott Mead

Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy

Malú Alvarez

Ann Ames

Rita Anthoine

agnès b.

Peter Barbur and Tim Doody

Dawoud Bey

Allan Chapin and Anna Rachminov

Cheim & Read

Kate Cordsen

Fine Art Frameworks

Randi and Bob Fisher

Arthur Fleischer, Jr.

Foto Care Ltd.

Annette Y. Friedland

Barbara J. Goodbody

Elizabeth Grover

Agnes Gund

Hermès Foundation

Darius Himes, Christie’s

Michael Hoeh

Lynne and Harold Honickman

Ingram Content Group

Darlene Kaplan

Bonnie Englebardt Lautenberg

Susana Torruella Leval and Pierre N. Leval

David Levy and Amanda Bowman

Peter and Susan MacGill

Merideth W. McGregor and Kevin Flach

Patrick McMullan

Joel Meyerowitz

Jessica Nagle and Roland Hartley-Urquhart

Helen W. Nitkin

Lori Perlow

Sarah Gore Reeves and Enrique Norten

Ropeadope Records

Mara and Ricky Sandler

Thomas R. Schiff

Frederick M. R. Smith

David Solo

Steinway & Sons

Michael Ward Stout, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Elizabeth Stribling and Guy Robinson

D. Severn Taylor and J. Scott Switzer

Willard Taylor and Virginia Davies

John C. Williams

Whit Williams

David Zwirner

Additional support from:

Renee Preisler Barasch

Andrew Craven and Rodger Hicks

Jean Karotkin

Kasper

Emily-Jane Kirwan, Marian Goodman Gallery

Philippe Laumont

Mark and Elizabeth Levine

Jack Lueders-Booth

Lauren and Michael Marrus

Jessica May

Sarah McNear and Ian Wardropper

Mauricio Morato

Yancey Richardson

Christine Traina

Tanya Wells

The post An Evening with William Eggleston at Aperture’s Fall Benefit appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 25, 2016

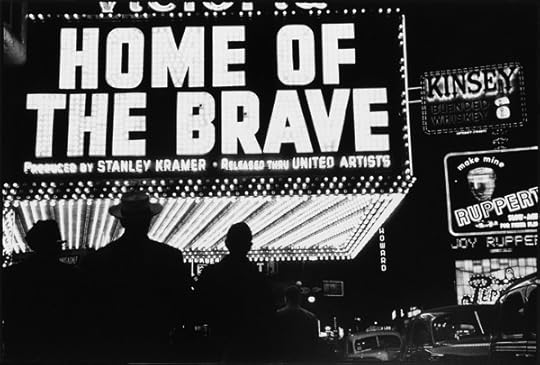

Louis Faurer’s Postwar New York

In the late 1940s, the photographer’s photographer reveled in the contradictory energies of urban life.

By Wilco Versteeg

Louis Faurer, Untitled, New York, 1949

© Louis Faurer Estate

“These photographs make me think of that long gone time—the fifties in New York City,” Robert Frank wrote in 1994 about the photographer Louis Faurer. “His eye is on the pulse.” Frank was writing to the editors of the Japanese magazine déjà-vu, who dedicated a special issue to Faurer. Some twenty years later, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris returns to Faurer, the photographer of the in-between, whose photographs might be a visual expression of T.S. Eliot’s sentiment in The Hollow Man: the shadow falls between the idea and the reality, between the motion and the act, between the emotion and the response.

Louis Faurer, New York, 1949

© Louis Faurer Estate and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Writing in the accompanying catalogue Louis Faurer, Walter Hopps considers the first decade of Faurer’s career as an open space in the history of American photography bookened by Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938) and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), a period otherwise defined by abstract expressionism rather than by photography. The ideological documentary of the Farm Security Administration had left its imprint on the artistic map, while the boom of postwar youth culture hadn’t yet delivered its own expressions in the fine arts. Not only was his career formed during this in-between moment, Faurer’s work itself is concerned with suspension.

Louis Faurer, Win, Place, and Show, 3rd Avenue El at 53rd Street, New York, ca. 1946–48

© Louis Faurer Estate

Even at a safe distance from the battlefields, war made of Louis Faurer the photographer he came to be. Born in Philadelphia in 1916, he came of artistic age during the Second World War. He perfected his printing techniques while serving as a civilian photographic engineer in the U.S. Army Signal Corps for most of the war. Never having photographed an actual battlefield, Faurer nonetheless captured the human and social impact the war had on New York in the last half of the 1940s, exemplified both by survivors recovering from extreme injuries and by the visible increase in wealth often associated with those years.

Louis Faurer, Champion, New York, 1950

© Louis Faurer Estate, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Louis Faurer shows downtown New York as a city reveling in the contradictory forces of postwar financial and political optimism, and witnesses the rise of a more pessimistic and critical counter-culture. He creates a subtle play with text and public space: banks, cinemas, and all kinds of street vendors use the same visual language of typography to sell what they have on offer. Faurer cleverly maneuvered around this overwhelming sensory experience and tried to avoid the irony that made some Depression-era photography so piercing, such as Margaret Bourke-White’s famous Kentucky Flood from 1937. Irony, as a disruptive and distancing communication strategy, does not fit Faurer’s humble and subtle view of humanity. In his work, instead of irony, we are often confronted with a silver lining of lightness around a somewhat darker human condition of constant suspension and expectation.

Louis Faurer, Deaf Mute, New York, 1950

© Louis Faurer Estate

Faurer himself spoke of his “intense desire to record life as I see it” as his only motivation: “As long as I’m amazed and astonished, as long as I feel that events, messages, expressions and movements are all shot through with the miraculous, I’ll feel filled with the certainty I need to keep going.” He offers us a peak behind the masks and appearances of daily life, such as New York (1948–49), in which a wife adjusts the hair of her husband to cover his bald spot, or in the various images of people waiting for an unknown someone or something. Faurer is the photographer of expectation, of finding that Eliotesque shadow that precedes the actualization of a hoped-for future whose impact cannot be yet be grasped. Indeed, the frailty and sweetness of human beings becomes graspable in Eddie, New York (1948), Deaf Mute, New York (1950), and Accident, New York (1952).

Louis Faurer, Accident, New York, 1952

© Louis Faurer Estate, Courtesy Deborah Bell

Even when Faurer portrays the physically, mentally, or financially unlucky, he never does so in isolation. Whereas Diane Arbus, whose work bears resemblance to Faurer’s, at times isolated her subjects from society by photographing them in enclosed environments such as homes or institutions, Faurer grants them their just place in the grand décor of the city. In Faurer’s work, all and sundry contribute to New York: its dwellers, its texts, its windows and mirrors, its reflections, its masks, its fictions, and finally its realities. Long considered a photographer’s photographer, Louis Faurer is a pivotal artist of this in-between period. He de-politicized a documentary aesthetic that preceded him, and opened up new possibilities for the future. In his work, no one is weak or strange. Faurer extends his gift of humility to us, who are then invited to look at the world as he did.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD candidate at Université Paris Diderot.

Louis Faurer is on view at Fondation Cartier-Bresson, Paris, through December 18, 2016.

The post Louis Faurer’s Postwar New York appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 20, 2016

Glamour and Destitution in Los Angeles

In his first museum retrospective, Anthony Hernandez finds melancholy beauty in a city of contrasts.

By Glen Helfand

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #50, 2014

© and courtesy the artist

The paradoxes of Los Angeles, its polarities between glamour and destitution, are not lost on Anthony Hernandez. Since the late 1960s, Hernandez has revealed, with formal integrity and bleak beauty, the harsh realities of his Southern California environs. His retrospective at SFMOMA derives its power from an unerring eye. A native of East LA, Hernandez has been less widely known than other California photographers—he met peer Lewis Baltz in the early 1970s—but this survey makes for a satisfying and timely look at an artist whose innovations are subtle yet significant riffs on key themes in contemporary photography.

Anthony Hernandez, Los Angeles #14, 1973

© and courtesy the artist

The bodies of work on view, ranging from early figurative works to forms of landscape and still life, together form a dour, formally impressive vision that frequently achieves a quiet balance between aesthetic and social concerns. The exhibition initially draws an apt connection to street photography traditions, and the catalog notes that Hernandez met Garry Winogrand in the late 1970s when the elder photographer lived in LA. In the 2013 Winogrand retrospective, also at SFMOMA, Winogrand’s photographs of Los Angeles contained a profound sense of melancholy. In contrast to his pictures of the vibrant sidewalk culture of New York, Winogrand’s LA work reveals a place where those without automobiles are stranded on wide, otherwise empty sidewalks, and in failed Hollywood aspiration.

Anthony Hernandez, Santa Monica #14, 1970

© and courtesy the artist

Similarly, the first powerful iteration of Hernandez’s vision is a 1969–70 series of black-and-white beach photographs that depict sleeping figures adrift on fields of sand—a form of prostrate street photography. Most of the subjects are fully clothed, as though the beach is a safe site to nap, when necessary. In Santa Monica #3 (1970), a male figure seems to be destitute, crawling through the desert with paralyzed legs. In another, even sunbathers appear troubled: bikini-clad women are isolated from their environment and strangely exposed.

Anthony Hernandez, Rodeo Drive #3, 1984

© and courtesy the artist

Nearby is Hernandez’s first foray into color—which became his signature mode—a 1984 series of photographs shot on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. The tony setting, with pops of red and gold, poses a striking contrast to the beach pictures, heightened by the camp factor of ’80s fashion. Still, the figures exude an existential hollowness; they are people slipped into an empty but overpriced lifestyle. Even if their hair is teased to mercilessly comic effect, the success of these pictures is in their cool humanity.

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #74, 2011

© the artist and courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The show then backtracks chronologically to Hernandez’s transitional work in black and white. These photographs, in a section titled Absence and Presence (1978–1990), were shot with a large format camera and depict the vastness of the Southern California landscape. In content and style, they relate to the “New Topographics,” the term that coalesced around a group of photographers including Robert Adams and Stephen Shore, who reimagined the postindustrial American landscape. Hernandez’s Public Transit Areas pictures, from 1979–80, reveal the isolation of Angelenos as they congregate at bus stops on wide, desolate, smoggy boulevards. There’s more formal innovation to two other late 1970s series, Automotive Landscapes and Public Fishing Areas, which show, respectively, rough and tumble car repair shops and prosaic recreation areas from a slightly elevated perspective atop Hernandez’s VW van.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #1, 1988

© the artist and courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The centerpiece is Hernandez’s Landscapes for the Homeless (1988–91), a powerful group of images that capture makeshift domesticity in wooded areas devoid of their inhabitants, who have seemingly gone about their daily business, and left their “homes” vulnerable. There’s a palpable sense of trespassing upon a private space, but it’s a revelation to see a vast pit of cigarette butts surrounding a rumpled blanket, or brushes and combs laid carefully on a plastic bag on the dirt. In its drive to consider urban planning and social observation, Landscapes for the Homeless anticipates such practices as the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

Anthony Hernandez, Pictures for Rome #17, 1999

© and courtesy the artist

Hernandez’s late-’90s work, set in abandoned buildings in Oakland, Rome, and Baltimore, and along the Los Angles river, become more abstract visions of locations buffeted by economic conditions—stalled construction sites, and abandoned buildings and sewage culverts. These photographs are less immediate but more poetic in their power. They provide evidence of beauty within fraught locations—a view from a homeless person’s bed, for example—though the aesthetic value of such a perspective seems as difficult to parse as redressing the social condition. Taken together in the sweep of this exhibition, Hernandez’s persistent vision rewards with its resolve.

Glen Helfand is a writer, curator, and an associate professor at California College of the Arts.

Anthony Hernandez is on view at SFMOMA through January 1, 2017.

The post Glamour and Destitution in Los Angeles appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Limits of Representation

Can Conceptual art speak to activist issues in new ways? Victor Burgin tests the connection between ideas and action.

By William J. Simmons

Victor Burgin, Still from Mirror Lake, 2013. Digital projection, 14:37 minutes

Courtesy the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York

No one is associated more forcefully with a cool academicism than Victor Burgin. His highly theoretical writing, as well as his pioneering use of politically inflected text in photography and video, has been a hallmark of Conceptual art since the early 1970s. However, Conceptual art, in foregrounding its ideas in self-referential forms, is usually understood as devoid of energetic, activist politics. In a recent review in Artforum of John Baldessari’s exhibition at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, for example, Nicolas Linnert makes a shortsighted attack on conceptualism, “What exactly is gained today by continuing to exploit the capacity of images to free themselves from meaning? To avoid a stance?” Linnert suggests that only representational art has any worthwhile affective power, thereby precluding artists like Sarah Charlesworth—who worked with found images and abstraction, often simultaneously—from being considered socially-engaged. Nevertheless, it’s a thought experiment worth applying to Victor Burgin’s concurrent shows shows in New York at Bridget Donahue and Cristin Tierney. What is at stake in both presentations is whether Conceptual art can transcend hyperintellectual concerns and speak to activist issues, and whether artists can express their politics in forms other than pure representation.

Victor Burgin, UK 76 (detail), 1976

© the artist and courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York

Burgin’s exhibition at Bridget Donahue is comprised of archival inkjet prints from the series UK76 (1976) carefully wheat-pasted to the wall. Each photograph, in characteristic Burgin style, consists of text—some found, some composed by the artist, some deadpan, and some florid—placed above an image, each wonderfully reminiscent of film noir in their monochromatic grandeur and allusions to surveillance and violence. Though straightforward, these texts have a lyrical and poetic quality that, no matter their source, becomes strangely poignant. The texture of the paste also lends a corporeal element, as if a very thin skin has affixed the images; in a reference to the original presentation of UK76 four decades ago, the images will be scraped from the walls when the exhibition closes.

Victor Burgin, UK 76 (detail), 1976

© the artist and courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York

One photograph depicts a woman at a bus stop with the same disinterested glance that so interested Walker Evans in his Subway series (1938–41) and Cindy Sherman in her Bus Riders (1976/2000). The text watches over the scene like a forlorn vulture: “Evening is the softest time of day. As the sun descends the butterfly bright colours which flourish at high noon give way to moth shades.” This rapturous prose gives way to the sales points of an advertorial. “The look is essentially luxurious, very much for the pampered lady dressed for a romantic evening with every element pale and perfect.” But, are the unsubtle allusions to whiteness (“pampered lady”; “pale and perfect”) incongruous with the photograph’s black, presumably working-class protagonist? Like any advertisement, the first instinct is to read the text and image as related, despite their obvious dissonance. Yet this isn’t some valorization of the working class, or an elevation of the humdrum daily commute to the status of poetry. We are swept up in beautifully saccharine imagery—we believe the drama—until we discover that the directive to feel moved comes not from true emotion, but from advertising.

Victor Burgin, Still from Prairie, 2015. Digital projection, 8:03 minutes

Courtesy the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

Mirror Lake (2013), one of two digital projections on view at Cristin Tierney in Burgin’s exhibition Midwest, has a similar emotional impact, if more melodramatic. It opens with an interior shot of a train car, a favorite film setting from Alfred Hitchcock to Lars von Trier. A story of interconnected lives enacted by the theft of Native American land ensues, based only on a series of dour, almost ethnographic shots that receive their resonance from applied text. Burgin presents quietly rhapsodic words that emolliate the silence: “There is enchanter’s nightshade and maidenhair fern, blue marsh violet and marsh marigold, orange jewelweed and sarsaparilla, creeping snowberry and wintergreen… The Winnebago once lived here.” There is no joke, no sardonic twist—only a serious narrative (be it fact or fiction) delivered with harrowing and compelling sentimentality.

Victor Burgin, Mirror Lake, 2013. Installation view at Cristin Tierney Gallery, 2016

Courtesy Cristin Tierney Gallery

Burgin allows us to think emotionally and emote intellectually; the distinction between conceptualism and social engagement is no longer a useful division. While his work may not incite protests, from these two exhibitions there emerges an active, politically inflected photographic formalism: the viewer must take a stance, simply by bearing witness to his interplay of feeling and imagery. Revealing Conceptual art’s capacity for excess, emotion, and affect, Burgin’s work is a study of how we relate to traumas both personal and social.

William J. Simmons is an adjunct lecturer in art history at the City College of New York, and a PhD student in art history and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

Victor Burgin: Midwest is on view at Cristin Tierney through October 22, 2016. Victor Burgin: UK76 is on view at Bridget Donahue Gallery through November 6, 2016.

The post The Limits of Representation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 19, 2016

Pushing the Boundaries of Gender Performance

Spanning over eighty years of photographs, an exhibition explores the gender non-conforming potential of the word “they.”

By Alicia Eler

Yasumasa Morimura, Jane Fonda 5 (Barbarella), 1995

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

The singular gender-neutral pronoun “they” was named word of the year in 2016. Judging from the social and historical depth of photography and archival imagery in the exhibition He/She/They, currently on view at ROSEGALLERY, which includes work by more than fifteen artists, it’s crazy to think that it took this long to get American culture at large to recognize life outside the gender binary. Ranging from the early 1930s to the present, the works exhibit a wide array of bodies, locations, gazes, and socioeconomic perspectives, and consider the intersectional influence of race and class on notions of gender.

Lise Sarfati, Malaïka #7, Corner 7th Street and Spring, from the series On Hollywood, 2010

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Since this exhibition is presented in Los Angeles, Lise Sarfati’s Malaïka #7, Corner 7th Street and Spring from the series On Hollywood (2010), is appropriately local and captures a woman trying to make it in the entertainment industry. In this startling photograph, a young woman appears forlorn, perhaps returning from an audition, unsure of what to do next. The actress’s face, and the low-angle perspective, is reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #21 (1978), in which a young woman, who could be any (white) woman, looks intently beyond the frame, with an imposing block of skyscrapers forming the background. Marrying visual art and Hollywood icons, her dress and hairstyle reference Marilyn Monroe and the “dumb blonde” archetype.

Katsumi Watanabe, KW 164, 1965

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

For her series Carnival Strippers (1972–75), Susan Meiselas captured a type of femininity less visible during the women’s liberation era. One of her primary subjects was Mitzi, a woman who worked as a stripper at carnivals; Meiselas documented Mitzi’s public work and private life. Earning money from a performance of sexuality as dictated by the male gaze, Mitzi capitalizes her body under a patriarchal society. Around the same time, Katsumi Watanabe was photographing Tokyo’s queer nightlife scene, creating vivacious images of drag queens, gangsters, prostitutes, and entertainers in Shinjuku Ni-chome, Japan’s largest gay district. His subjects often commissioned the pictures themselves. The locations—outdoors in front of cars or posing inside scuzzy backrooms—suggest a contrast between the dazzling outfits and the milieu, a queer underworld area of Tokyo. Meanwhile, Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s elegant, perfectly contoured black-and-white portraits offer a singular focus on his subjects’ gender presentations. He pictures individuals like Frida Kahlo, as well as the tuxedo-clad authors Salvador Novo and Xavier Villaurrutia. Their gender presentations are both very masculine, but in the context of this show, they could easily be read as trans men or individuals in male drag.

Nikki S. Lee, The Hip Hop Project (1), 2001

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Well-known names of ’90s identity politics appear like anthology entries, though they remain relevant today. Yasumasa Morimura creates images of himself in drag as various female celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor, a critique of both the perceived emasculation of the Asian male body and a global obsession with Hollywood. Nikki S. Lee takes masquerade and cultural identity to another level with her chameleonic (and controversial) self-portrait projects about “passing” in various American subcultures, from hip-hop girls to exotic dancers. In his series Orchard Beach: The Bronx Riviera, Wayne Lawrence portrays glistening beachgoers at the only public beach in the Bronx. Lawrence’s work is among the few representations of African American subjects in the exhibition, but the connection to a critique of gender of this context is unfortunately vague.

Wayne Lawrence, Cathy, Ocean Drive, South Beach, 2010

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Other works in the show focus less on the performance of gender, and more on people who defy normative gender distinctions. Nineteenth-century photographs depict Native American “two-spirit” individuals—those who participate in gender roles not assigned to their sex—but the accompanying text explains that intersex, androgynous, and gender non-conforming people could be held in high regard outside of Eurocentric, heteronormative cultures. In photographs by Mexican artist Graciela Iturbide, Magnolia, who identified as Muxe (Zapotec for homosexual and “genderqueer”), poses for the camera wearing a dress and sombrero, a traditionally male accessory.

Graciela Iturbide, Carnaval, Tlaxcala, Mexico, 1974

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

He/She/They leans heavily on the visual language of portraiture, which might suggest a desire for authenticity in documentation, in contrast to much of the dynamic content found online, where self-expression by social media sensations, celebrities, and everyday people appears to be constantly evolving. The photographs in this show offer a fixed moment in time, declarative and definitive, but also remain open to the many shades of identity, the gender non-conforming potential of the word “they.”

Alicia Eler is a journalist based in Los Angeles. A contributor to New York Magazine, The Guardian, VICE, LA Weekly, Hyperallergic, Art21, and Artforum, she is currently working on her first book, The Selfie Generation (Skyhorse).

He/She/They is on view at ROSEGALLERY, Santa Monica, through November 12, 2016.

The post Pushing the Boundaries of Gender Performance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 17, 2016

Justine Kurland’s Great American Road Trip

Justine Kurland crossed the United States in a weathered van, adding thousands of miles to her odometer while pursuing a chronicle of American drifters.

By David Campany

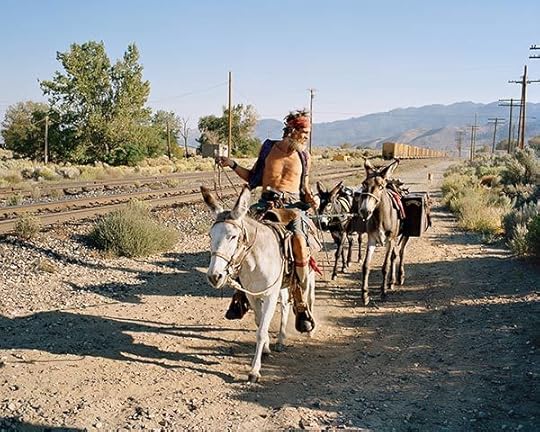

Justine Kurland, 280 Coup, 2012

Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

The actualities and the myths, the facts and the metaphors. Justine Kurland photographs America’s tangled sense of itself. How do we see when seeing has been so anticipated by images? Through the filter of all that has gone before, can a photographer describe lives and places anew? In the last few years Kurland’s pictures have emerged in groupings, with names like This Train Is Bound for Glory and Sincere Auto Care. Gathered here in eloquent sequence is a small sample from her forthcoming book with Aperture.

A train snakes like a toy across the desert between Nevada and Utah. The view looks unchanged for decades but those are boxcars of cheap consumables from China, bound for Walmart. The photographer’s son, Casper, a regular companion on these trips, throws back his head and refreshes himself. He looks like a feral creature, a pioneer, and a twenty-first-century boy, chugging juice from a plastic bottle. The excess trickles down his belly to his diaper. When Casper was six, Kurland took a teaching job. It reconnected her with the work of Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and the long tradition of intelligent documentary photography. For now, this is her idiom—wide, generous, and testing.

Justine Kurland, Black Snake, 2008

Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Her road trips are long and her van is eleven years old. With 250,000 miles on the clock, it gets patched up often. Since nobody feels entirely positive about cars these days, breakdowns and crashes feel like larger symbolic deaths. But as Evans wrote in “The Auto Junkyard,” a 1962 photo-essay published in Fortune, “There is a secret imp in almost every civilized man that bids him delight in the surprises and in the mockery in the forms of destruction. At times, nothing could be gayer than the complete collapse of our fanciest contrivances. Scenes like these are rich in tragicomic suggestions of the fall of man from his high ride.”

The auto yard is a place of pragmatic resurrection. Indeed, the fall of man, or more exactly fallen men, have their own erotic pathos. Kurland’s pictures of mechanics and car culture are touching and affectionate. They leave the ambivalence to us. Casper had his own little fall from Mom’s parked van, catching his mouth on the bumper. That’s his tooth in his hand.

Justine Kurland, Cuervo Astride Marna Burro, Now Dead, 2007

Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

One day she met a man who looked uncannily like Casper, all grown up and coming down from a junkie’s high. With a head full of worries about keeping her boy safe and the knowledge that he won’t be hers forever, she photographed this man. She accepted him, watching him almost pray with his hands around a Coke. Her camera is respectful but it wards off the fears.

And here is Cuervo, on horseback, no car in sight. Kurland got to know him and photographed him over three years. He can hunt, prepare food, and light fires without matches. His past includes drug running and incarceration in Mexico. He has just crossed the Sierra Nevada with his animals. Kurland recalls his words: “I’m a man with a man’s needs, and if you want to get some photography done you are going to have to satisfy my needs.” She walked away. “When I came back he was completely naked. Somehow that was the final straw. I haven’t talked to him since.”

We all know the easy failings of men. The pride, arrogance, narcissism, and fragile vanity. Yet, nobody is quite sure what a man is supposed to be. Myth and history were once on his side but no longer. In these photographs, made with young Casper at her side, Kurland offers her own brave contemplation of it all.

David Campany’s books include the Aperture titles The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip (2014) and Walker Evans (2015).

To read more, buy Aperture Issue 222, “Odyssey,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Highway Kind

Highway Kind$50.00

The post Justine Kurland’s Great American Road Trip appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 14, 2016

Are You Ready For Love?

Four exhibitions celebrate feminist artist Ellen Cantor, who explored the subversive potential of female sexuality.

By Maika Pollack

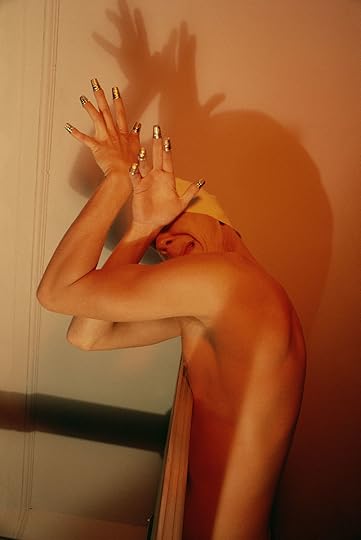

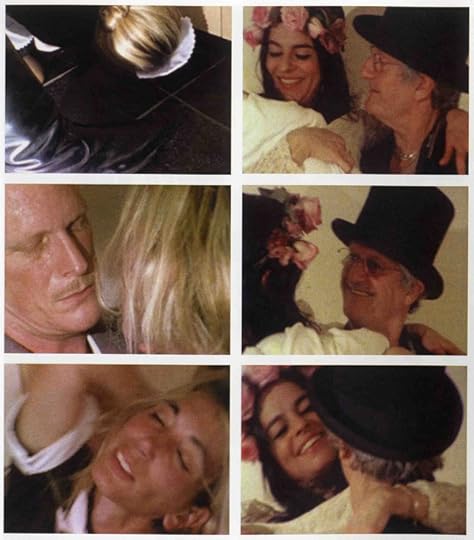

Ellen Cantor, Pinochet Porn, 2008–16

Courtesy the Estate of Ellen Cantor

Dirty Joke or Art? That was the headline in one Swiss newspaper when Ellen Cantor’s show was censored by the mayor of Zurich in 1995. Cantor, the downtown artist who died in 2013, and whose work is featured in four exhibitions in New York this fall, receives more reverence than reproach these days, but she still has an edge. Organized by Participant Inc., Foxy Production, 80 WSE Gallery at New York University, and Maccarone, together with the Cantor Estate, the concurrent exhibitions are complemented by public programs at Skowhegan and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI). The Participant Inc. exhibition, perhaps the opening salvo, sets off Cantor’s interest in explicit depictions of female sexuality as a politically transgressive act.

Ellen Cantor, Within Heaven and Hell, 1996. Video/audio plays over Bil Baird’s “Maiden and Adult Male Goat,” from the original motion picture The Sound of Music, 1965. Installation view at 80WSE Gallery, 2016. Photograph by Jeffrey Sturges

Courtesy the Estate of Ellen Cantor and the Charles H. MacNider Art Museum

Participant Inc. presents several dozen early Cantor paintings and sculptures. With frames bejeweled and bedazzled with pom-poms, glitter, and feathers the paintings depict lesbian orgies, seemingly from above. They also exist as fetish objects and interrupt the serious, presumably masculine dialogue of painting, and conjure what Cantor called a “girl world.” In a separate space, several vitrines display ephemera from the 1995 Zurich controversy in which Cantor’s work was declared pornographic.

Ellen Cantor, Be My Baby, 1999. Three-channel video installation, 12:39 minutes. Installation view at Foxy Production, 2016

© the Estate of Ellen Cantor and courtesy Foxy Production, New York

A revelatory exhibition at Foxy Production displays photo collages made during the 1990s and a three-channel video, Be My Baby, from 1999. The video, with ’90s-era special-effect flourishes, merges reels of 1960s space exploration and 1940s Hollywood movies featuring heterosexual love scenes, and asks how solitary and “masculine” gendered pursuits, like space exploration, can be understood as constructed through the lens of “feminine” and inward-looking experiences like love. It sounds trite, but Be My Baby, in fact, is personal and beautiful. For the six black-and-white photo collages, Cantor used thumbtacks to create grids juxtaposing commercially-developed snapshots of TV screens playing soap operas and porn, revealing an expanded world in which hardcore sex and treacle sentimentality coexist.

Ellen Cantor, Hold Me My Love, I Want to Die With You, 1996. Photo collage, diptych

© the Estate of Ellen Cantor and courtesy Foxy Production

On the other hand, ostensibly the most ambitious of these shows, 80WSE’s Ellen Cantor: Are You Ready for Love?, which features Cantor’s last, incomplete multichannel video work, turned out to be the most poorly curated. The five-chapter Picochet Porn (2008–16) is projected so high and so small as to be unviewable; one “chapter” plays while other projections display the titles of other chapters in bright white fonts, distracting from whatever is playing. (The exhibition does, however, include numerous rich drawings.)

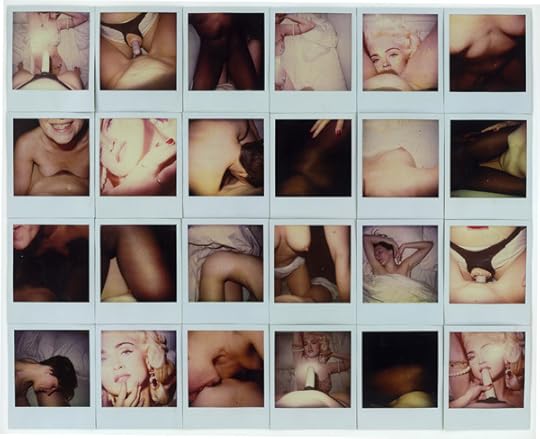

Patricia Cronin, girls, 1993

Courtesy David and Monica Zwirner, New York

At Maccarone, the parade continues with Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art by Women, a restaging of the 1993 exhibition Cantor curated at David Zwirner gallery on the theme of sex-positive feminist artwork. Organized by Pati Hertling and Julie Tolentino (cofounder of the ’90s landmark lesbian bar Clit Club), Coming to Power encompasses several generations of feminist pioneers, from Carolee Schneemann (represented by several photographs as well as her tattered and iconic 1975 Interior Scroll) and Alice Neel (with a very early 1933 painting of a pregnant female nude), to Lynda Benglis, Louise Bourgeois, and Marilyn Minter. Not all the work in this contemporary facsimile is the same as in the original, but all date from before 1993. Together, the works give a quick guide to a second wave feminist genealogy for Cantor’s painting, photographs, and videos.

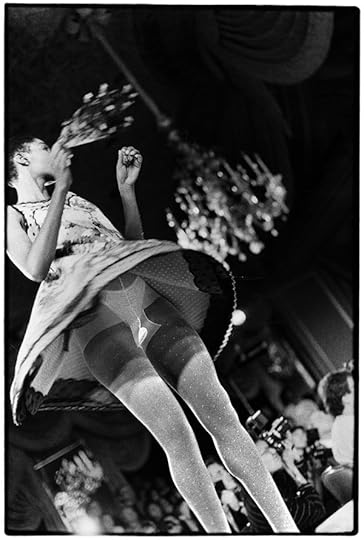

Zoe Leonard, Frontal View Geoffrey Benne Fashion Show, 1990

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

While some photographs in Coming to Power, like those by Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, will be familiar chestnuts to New York audiences, Zoe Leonard’s upskirt shots of fashion shows from the 1990s feel especially fresh in an age of outrage at boasts of assaults carried out by Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. And Patricia Cronin’s grids of Polaroids of herself thrusting a strap-on at the mouth of a televised George H. W. Bush, or pointing her prosthetic dick at a magazine image of Madonna, are great point-of-view shots that remind us of a time when developing film at a lab risked censorship and the immediacy of the Polaroid provided material for radical subversion.

La Chica Boom (Xandra Ibarra) performing Nude Laughing as part of Coming To Power: 25 Years Of Sexually X-Plicit Art By Women, Maccarone, October 8, 2016. Photograph by Julie Tolentino

Courtesy Maccarone

The restaging of Coming to Power also includes a lively rotation of performances and events. Younger artists who make their names on the “rediscovery” of historical artists and events might be seen as agents gentrifying the past. But, one event featuring the dynamic Xandra Ibarra (aka La Chica Boom) brought together a diverse crowd who transformed Cantor’s seeming interest in gender binaries into a more fluid and encompassing community of non-normative gender identity. Ibarra walked the gallery wearing only yellow high heels and a prosthetic chest, laughing hysterically and dragging a large nylon sack behind her. As the crowd surrounded her in a tight knot, both protective and prurient, Ibarra entered the sack and engaged in a seemingly masturbatory episode with the wigs, ballerina slippers, pearls, and furs inside. The moment conjured the radicality of a queer downtown culture and New York communities largely lost to time. Such interventions illuminate contemporary motivations and politics playing out over a body of work belonging to an artist no longer present, and celebrate Cantor’s newfound, and perhaps newly essential visibility, as they also mourn her loss.

Maika Pollack is an art historian teaching at Sarah Lawrence College.

Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art By Women is on view at Maccarone through October 16, 2016. Ellen Cantor is on view at Foxy Production through October 23, 2016. Ellen Cantor, Lovely Girls Emotions is on view at Participant Inc. through October 30, 2016. Ellen Cantor: Are You Ready for Love? is on view at 80WSE through November 12, 2016.

The post Are You Ready For Love? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 13, 2016

Vanguard of the Revolution

In the era of Black Lives Matter, what is the legacy of the Black Panther Party? Stephen Shames revisits his chronicle of American activism.

By Jessica Lynne

Stephen Shames, Kathleen Cleaver, Communications Secretary and the first female member of the Party’s decision-making Central Committee, talks with Black Panthers from Los Angeles, in DeFremery Park, West Oakland, California, July 28, 1968

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Fifty years ago, on October 15, 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland, California. Fifty years ago, it seemed, the world was poised for revolution. And for Newton, the revolution would belong to the people. “The Black Panther Party is simply the vanguard of the revolution,” he declared. It was a statement that perfectly encapsulated the Party’s unprecedented influence in the social, cultural, and political psyche of the United States.

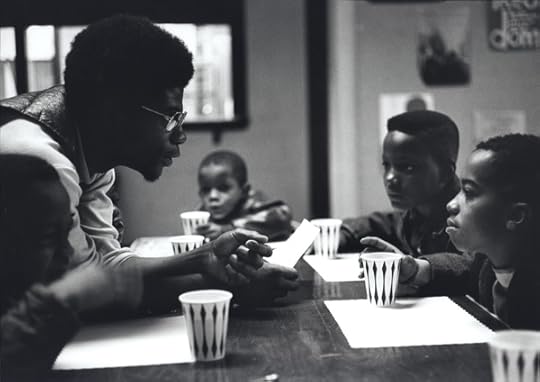

Stephen Shames, Free Breakfast Program, Panther Jerry Dunigan, known as “Odinka,” talks to kids while they eat breakfast on Chicago’s South Side, Chicago, Illinois, 1970

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Hindsight affords a particular kind of clarity. Years after its first utterance, Newton’s claim remains the most definitive statement regarding the ethos that guided the Panthers. Established on the heels of the civil rights movement, the Panthers were a political party committed to dismantling antiblack structures and policies that had afflicted black people for centuries. The Party espoused a Marxist political stance, manifest in programs such as the Free Breakfast for Children Program and the People’s Free Medical Clinics. Yet, the further we travel away from the Panther era, the greater our chance to distort that reality. The Party was not immune to the surveillance of the federal government; former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover made it his mission to cripple the Party through his COINTELPRO program. The legacy of Hoover’s actions—infiltration, assassinations, criminalist discourse about the Panthers—still lingers. Should you ask any two people to share their thoughts on the Panthers, you’re likely to receive divided answers about strategy, effectiveness, and importance. They were radicals. They were freedom fighters. They were dangerous. They were gun-toting fanatics.

Stephen Shames, Memorial mural for Jonathan Jackson, who was killed on August 7, 1970, during an attempt to kidnap California Superior Court judge Harold Haley and three others to exchange for the freedom of his brother, George Jackson, Roxbury section of Boston, Massachusetts, 1970

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

At a time when racial tension again hovers over our national consciousness, Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers, currently on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, reconsiders this revolutionary movement. In the exhibition, Stephen Shames’s photographs are mounted alongside ninety-eight covers of Emory Douglas’s The Black Panther, the newspaper vital to the Party’s communications and outreach. The collaboration between Shames and Seale, together with Douglas’s graphics, forms an illuminating self-portrait of a group of young women and men who sought to create a new, better world for themselves.

Stephen Shames, Black Panther member sells “The Black Panther,” the Party’s newspaper, in the Roxbury section of Boston, Massachusetts, 1970

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Shames’s photographs—vintage and contemporary gelatin-silver prints—are displayed thematically and loosely follow the timeline of the Panthers’ rise and most active periods of operation. Some of the first images on view depict aspects of Newton’s private life, a welcome departure from his highly visible public persona. In one image from 1970, Newton, the former Minister of Defense for the Party, stands in his living room shortly after his release from prison. Another striking photograph from the same day shows Newton and Central Committee Member Elaine Brown sharing a victorious embrace. In a series of four images, Newton and Seale pose for the photographer, unable to hold their laughter as they prepare for a portrait. They are sensitive, precious photographs of two friends, two young, black men who were confronting the perils of a racist, capitalist empire.

Stephen Shames, Black Panther co-founders Bobby Seale & Huey Newton pose in Huey’s penthouse apartment, Oakland, California, 1971

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

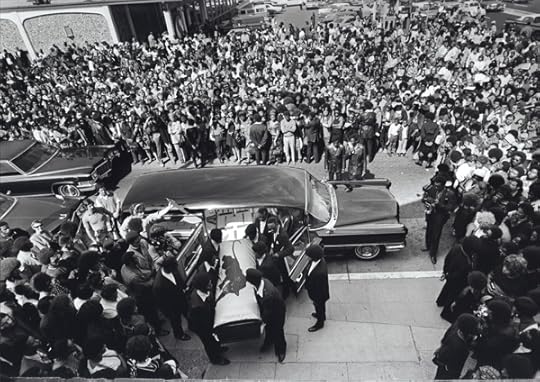

Shames accesses the intimacies of the Party’s interior world, and his photographs evoke a tenderness that is hard to shake. This sense of empathy comes across even in scenes of funeral processions, a testament to Shames’s commitment as a documentarian. We also encounter former Party member Ericka Huggins in the midst of a deep laugh while attending the Party’s Community Survival Conference in Oakland; Party members Ila Mason and Jamal Joseph leading a political education class in Harlem; and a Panther child smiling at the camera in the classroom of the Panthers’ Oakland school. “One thing people don’t understand about the Black Panther Party is that the median age of a Party member in 1969 was nineteen years old,” Huggins notes. The youthfulness of the Panthers was an asset, a potency that enhanced the reach of their radical actions.

Stephen Shames, Black Panthers carry George Jackson’s coffin into St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church for his funeral service as a huge crowd watches, Oakland, California, August 28, 1971

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Shames and Seale’s accompanying book, Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers (2016), chronicles the Party’s founding up until Bobby Seale’s Oakland mayoral campaign in 1973, and privileges the personal accounts of Gloria Abernathy, Kathleen Cleaver, Barbara Cox, Elbert “Big Man” Howard, Ericka Huggins, and Khalid Raheem, among others. The book also incorporates excerpts from Newton’s interviews and speeches into a roundtable of recollections from still-living Party members.

Stephen Shames, Angela Davis, who was a Black Panther for six months, speaks at a Free Huey rally in Defremery Park, Oakland, California, November 12, 1969

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

The exhibition, however, resists sustained analysis in favor of the images. Instead of consistent labels denoting the names, locations, and dates of Shames’s subjects, the decision to display only selected interview excerpts on the gallery walls, drawn from the book, curtails an objective interpretation. (Basic information for each photograph can be found in a gallery guide.) Without the kind of authoritative context a museum or historical institution might provide, this presentation fails to engage with internal rifts and conflicts, a much-needed perspective on gender politics, or the Party’s eventual demise. Perhaps this missed opportunity is a consequence of hindsight. We only immortalize what we think is necessary to immortalize.

Stephen Shames, Children at a Free Huey, Free Bobby rally in front of the Federal Building, San Francisco, California, February, 1970

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Still, the Panthers’ legacy looms large. As we witness the rise of a new group of young, black, activists in the U.S., and as we continue pursuing a vision of liberty that includes all Americans, the story of the Black Panther Party remains a vital point of reference. We see traces of their actions in the interventions of the Black Lives Matter movement, asserting the humanity of black people in the face of incessant state-sanctioned violence, or in the vision of The Black School, a new experimental art school which foregrounds radical black politics and socially engaged art as methodology for educating students. But, the world the Panthers imagined is yet to come. If the lessons of the Party’s successes and failures can offer us any insight, it would be their insistent demand to organize, resist, and ultimately, to act.

Jessica Lynne is a writer and arts administrator based in Brooklyn.

Power to the People: The Black Panthers in Photographs by Stephen Shames and Graphics by Emory Douglas is on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, through October 29, 2016.

The post Vanguard of the Revolution appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers