Aperture's Blog, page 126

January 19, 2017

Picturing Dissent: 50 Years of Protest Photographs

The photograph has long been instrumental to the act of protest. Though photographs have always played a defining role in our collective memory, they have never been more immediate or reproducible. Advancements in technology have given rise to new avenues for self-documentation and citizen journalism, while social media has allowed us to bear witness in real-time. Just as the protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989 are widely remembered in relation to Magnum photographer Stuart Franklin’s iconic “Tank Man” photograph, the viral Facebook Live videos showing law enforcement deploying water cannons on a crowd of activists throw the spotlight on recent protests at Standing Rock.

In anticipation of the Women’s March on Washington on January 21, 2017, Aperture’s editors highlight images of protest that are a testament to the ever-evolving visual language of dissent.

Sharon Hayes, In the Near Future, Vienna (detail), 2006. Multiple-slide projection installation

Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin

Sharon Hayes

“Sharon Hayes draws on the tradition of women performing actions in public spaces as a challenge to gender norms, male power, and the patriarchal monopoly on authorship. For Hayes’s series In the Near Future (2009), she had herself photographed in public spaces carrying placards from historical protests, such as one that reads “I AM A MAN,” from the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, and another demanding “Ratify E.R.A. NOW!,” from the failed struggle to adopt the Equal Rights Amendment in the late 1970s. Hayes’s photographs, depicting herself as a lone picketer protester adopting a pastiche of historical issues, bring up discomfiting issues of artistic agency and political efficacy, as the collective and performative nature of protest becomes a gesture of remembrance.” —Eva Díaz

Eva Díaz is Associate Professor, History of Art and Design, at the Pratt Institute. Sharon Hayes’s work originally appeared in Aperture 225, “On Feminism.”

Radcliffe Roye, Colours, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Radcliffe Roye

“Roye is especially concerned with what it means to belong. To that end, injustice and inequality are at the center of his focus . . . He has walked in rhythm with foot traffic all over the United States in the past few years, hoping to show ‘the faces of those whose lives are spent living in protest.’ The resulting series, When Living Is a Protest, reminds us that to walk is to bear witness, for we are pilgrims, all.” —Garnette Cadogan

Garnette Cadogan is a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia. Radcliffe Roye’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 223, “Vision & Justice.”

Mehmet Kacmaz, Protesters holding a sign calling for the resignation of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during protests in Gezi Park, Istanbul, June 2, 2013

© the artist/NAR and courtesy Redux Pictures

Mehmet Kacmaz

“When a small group of protesters occupying Gezi Park in Istanbul, opposed to its proposed transformation into a shopping mall, were teargassed by the police, Turks were outraged both by the disproportionate use of force and by CNN Türk’s failure to report on the protests. Referencing CNN Türk’s decision to air a documentary about Antarctic penguins instead of the protests, a gas-mask-wearing penguin became an unofficial protest mascot, and Turkish activists adopted a disciplined process of self-documentation, producing photos and videos that demonstrated the peaceful nature of the protests and the disproportionate responses of the police and the military.” —Ethan Zuckerman

Ethan Zuckerman directs the Center for Civic Media at MIT and is a principal research scientist at MIT’s Media Lab. Mehmet Kacmaz’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 214, “Documentary Expanded.”

Laura Hanna, Untitled (Tijuana), 2007

Courtesy Hanna Archive

Laura Hanna

“I was filming on-site in Tijuana when I took this picture. One man stares ahead while the other reads a gossip magazine, possibly avoiding my gaze. Resting under their makeshift shelter, they tell me that many here are orphans.

“Outside the frame: a man squats along the hillside, his face buried in a scavenged Marie Callender’s fettuccini alfredo; a Caterpillar tractor buries waste from a massive mountain; people scurry at its base, collecting copper pulled from wire (it’s in high demand); seagulls swarm. Some here describe journeys made to the United States to work construction. They slept in canyons outside construction sites. When their jobs were done, they were deported.

“A friend once described his hometown of Tijuana as a future city. Now, I wonder how many more people find themselves here, on the front line.”—Laura Hanna

Laura Hanna is a filmmaker, media activist, and political organizer. Her photograph originally appeared in Aperture 224, “Sounds.”

Jeff Lautenberger, Occupy demonstrator in Tulsa, Oklahoma, October 15, 2011

© the artist/AP Photo and courtesy The Tulsa World

Jeff Lautenberger

“When revolution is understood not as a will to seize or preserve power but instead as a reorganization of the body politic, revolution emerges as a language that is constantly shaped by those who use it, as we have seen in the last decade around the globe . . . The future of journalism cannot be limited to journalism as a profession but to our capacity to imagine new forms that will help transcend the genealogy of colonies, mandates, and sovereign states and their knowledge regimes. This is what makes our historical moment so exciting. All around the globe, people are inventing—and sharing with others—different forms of colaboring, cothinking, comapping.” —Ariella Azoulay

Ariella Azoulay is the author of Civil Imagination: The Political Ontology of Photography (2012). Jeff Lautenberger’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 214, “Documentary Expanded.”

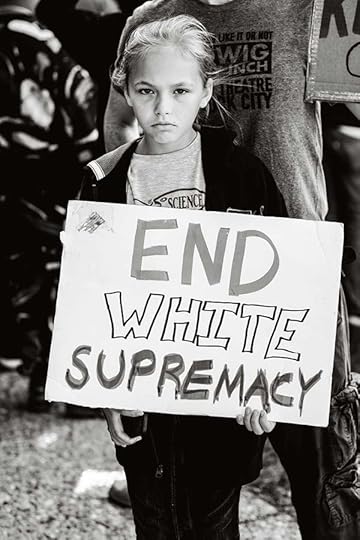

Devin Allen, Daughter of Michael A. Wood, Jr., retired Baltimore police officer who spoke out against corruption and excessive force in the Baltimore Police Department, Million Man March, Washington, D.C., October 10, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Devin Allen

“From scenes of a community’s joy to scenes of anger and protest, Allen’s work expresses a profound cultural shift toward grassroots, proletarian ideals that in recent years have influenced millennials across the country. Resonating with a long history of social justice photojournalism, his images reveal influences of the Black Lives Matter ideology, both as a political program and as an ethos. In Allen’s more confrontational photographs, the sense of injustice and indignation conveyed by the people who populate his images is palpable. These are people who understand that through action and mobilization it is possible to create change.” —Aaron Bryant

Aaron Bryant is the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Photography at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. Devin Allen’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 223, “Vision & Justice.”

Mídia Ninja, Barricade protesting the FIFA Confederations Cup Brazil, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, from the project Ruas de Junho (June Streets), 2013

Courtesy the artist

Mídia Ninja

“During the 2013 protests, Mídia Ninja became one of the most instrumental collectives to provide on-the-scene coverage: Several videos posted on Twitcast reached as many as one hundred thousand viewers. With a huge portfolio documenting conflict situations, they were able to confront major news providers whose coverage had been critical of the protests, forcing some to adjust their content and provide a more nuanced portrayal that included not only scenes of vandalism on the part of protesters but also scenes of police violence.” —Ronaldo Entler

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo. Mídia Ninja’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 215, “São Paulo.”

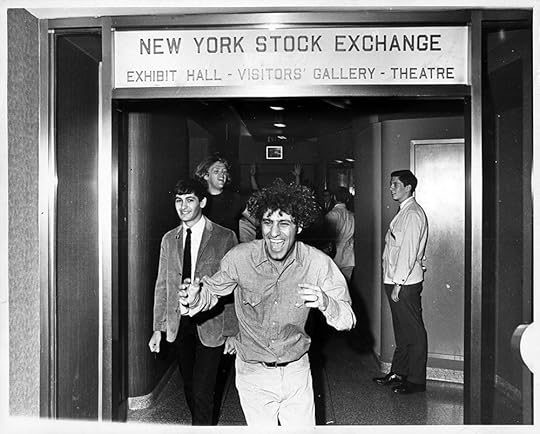

Arty Pomerantz, Bruce Dancis with Abbie Hoffman after a stunt at the New York Stock Exchange, 1967

© the artist and courtesy the New York Post

Arty Pomerantz

“At first, we only had the oral history to inspire us. In 1989, I was organizing some ACT UP activists to disrupt trading on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange to protest the high price of AZT, the first drug approved to treat AIDS. We knew that activists had done this only once before, in 1967. Abbie Hoffman had led some Yippies in a counterculture prank, throwing dollar bills from the visitors’ gallery onto the trading floor below. We drowned out the opening bell with marine foghorns and threw fake hundred-dollar bills that read “FUCK YOUR PROFITEERING” as our homage to Hoffman. Finding this photograph online years later completed the circle. I know that joy well when all of your planning pays off and your activism succeeds. I too smiled as I was led out of the exchange, and I pumped my fists as the price of AZT was lowered three days later.” —Peter Staley

Peter Staley is a long-term AIDS and gay rights activist, first as a member of ACT UP New York, then as the founding director of Treatment Action Group (TAG). Arty Pomerantz’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 224, “Sounds.”

Goshka Macuga, Preparatory Notes, 2014. Installation view at the New Museum, New York, 2016

Photograph by Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio © the artist and courtesy the New Museum

Goshka Macuga

“Rights for women to be treated as equal citizens have been won over many centuries, a process requiring countless protests and demands for recognition, and in struggles marred by frustration and defeat. Yet equality has not been accomplished. Parity in wages and income between men and women has not been attained, and sexism and violence against women are still prevalent. Hell, studies show that women are still doing more housework than men.”—Eva Díaz

Eva Díaz is Associate Professor, History of Art and Design, at the Pratt Institute. Goshka Macuga’s work originally appeared in Aperture 225, “On Feminism.”

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events, 1971

© the artist and courtesy Osiris, Tokyo, and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Takuma Nakahira

“Takuma Nakahira, who got his start in photography and criticism only around 1965, had by the end of that decade already become one of the most influential figures in contemporary culture in Japan. Nakahira’s incisive writing cut apart standing views in literature, film, politics, and especially photography, and he published both articles and photographs at a feverish rate. He wanted a relation between these two activities that could come closer than complementarity—a joint force of action, perhaps . . . Provoke: Provocative Materials for Thought—the short-lived photography journal that Nakahira helped to found, which blazed its trail across the Tokyo cultural scene in those years—took its name from such intertwined desires. Writing and photography should illuminate the world, explosively, and they should set each other ablaze as well.” —Matthew S. Witkovsky

Matthew S. Witkovsky is Sandor Chair of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago. Takuma Nakahira’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 219, “Tokyo.”

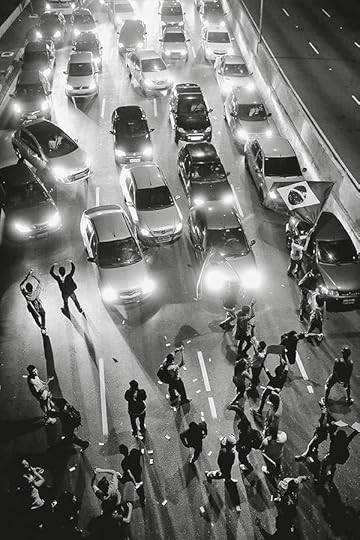

Keiny Andrade, Demonstrators block traffic on 23 de Maio Avenue during a protest against raising public transportation fares, São Paulo, June 20, 2013

Courtesy FotoProtestoSP

Keiny Andrade

“One of the more stringent collectives to rise out of the unrest of 2013 is FotoProtestoSP. Its thirty members include several well-established veterans of Brazilian photojournalism, such as Maurício Lima, Marlene Bergamo, Fernando Costa Netto, Keiny Andrade, Ignácio Aronovich, and José Francisco Diório. Their manifesto radiates indignation with the country’s political structure and asserts a desire to explore the critical power of photography beyond private media platforms and art institutions . . . According to Renato Stockler, one of the group’s members, its objective is to occupy the city’s leisure spaces and to remind residents of the power people have when they unite around a common cause.” —Ronaldo Entler

Ronaldo Entler is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo. Jeff Lautenberger’s photograph originally appeared in Aperture 215, “São Paulo.”

The sun as seen from the Solar Dynamics Observatory, September 17, 2011

Courtesy NASA/SDO and the AIA, EVE, and HMI science teams

Micah White

“In 1922, Alexander Chizhevsky, a maverick Russian scientist, argued that revolutions and social movements are influenced by the eleven-year solar sunspot cycle. He claimed that for the last two thousand years, mass upheavals have tended to occur during periods of peak sunspot activity. Chizhevsky’s heterodox theory of revolution contradicted Marxist historical materialism and landed him in a Stalinist gulag.

“Now fast-forward to September 17, 2011—the first day of Occupy Wall Street. In the very early morning a coronal mass ejection hits earth, triggering spectacular auroras. And while Occupiers establish their Zuccotti Park encampment in Lower Manhattan, the sun is erupting in an abnormally high number of sunspots. Coincidence?” —Micah White

Micah White is the author of The End of Protest: A New Playbook for Revolution (2016) and the cocreator of Occupy Wall Street. This photograph of the sun originally appeared in Aperture 224, “Sounds.”

The post Picturing Dissent: 50 Years of Protest Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 18, 2017

Jason Fulford: CHANCE

Order from Chaos; Surrealist Games; Psychogeography; Impracticality; In Praise of Idleness; Where Function Ends and Play Begins; Dumpster Diving; Keeping It Weird, Photographer as Editor, Scavenger, Author, Comedian, Critic & Wanderer; Maximum Effort for Minimum Result.

In a rigorous two-day workshop, filled with physical and mental exercises, you and Jason Fulford will explore various ways that CHANCE can improve your life (and possibly your photography).

Jason Fulford is a photographer and cofounder of J&L Books. He is a Guggenheim Fellow, and a contributing editor to Blind Spot. He is a frequent lecturer at universities, and has led workshops across the United States and in Japan, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Spain. His monographs include Sunbird (2000), Crushed (2003), Raising Frogs for $$$ (2006), The Mushroom Collector (2010), Hotel Oracle (2013), and Contains: 3 Books (2016). He is coauthor with Tamara Shopsin of the photobook for children This Equals That (Aperture, 2014), and coeditor with Gregory Halpern of The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014).

Fulford’s photographs have been described as open metaphors. As an editor and an author, a focus of his work has been on the subject of how meaning is generated through association.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Participants can expect to:

Experiment with various methods of using chance.

Edit photographs in group and individual exercises.

Discover new perspectives on their own work.

Be tired, and inspired, when it’s all over.

Materials to bring:

25 photographs from your personal work* (from the same body of work if possible)

25 found photographs* (not taken by you)

One object from your house/apartment. The object should be smaller than a football.

Digital camera (smartphone is OK)

Laptop (if possible)

*Image files will need to be sent to Aperture one week in advance of the workshop. More details regarding file requirements will be sent upon registration. Please contact us at education@aperture.org with questions.

Preparation (requested):

Prepare an introduction of yourself that lasts 3 minutes and 33 seconds.

Preparation (optional):

Rearrange the furniture in your house/apartment.

Listen to some Banda polyphonic music.

Watch the film Slacker by Richard Linklater.

See the Francis Picabia show at MoMA (up until March 19).

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $500 and includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, March 15, 2017

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Jason Fulford: CHANCE appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Renegade Video Artist

In the late 1970s, Mary Lucier pointed her camera at the sun and broke the rules of a new medium.

By Kris Paulsen

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979

Courtesy the artist

When video emerged as an artistic medium in the mid-1960s it was, as Mary Lucier puts it, a “renegade” form: low-resolution, ephemeral, woefully connected to the debased cultural products of television, and, for some, hopelessly “narcissistic” in form and content. It was a medium that had no past and seemed to have no rules, except one: never point the camera at the sun. Doing so would permanently burn and scar the vidicon tube inside. Lucier, who has worked across media including film, photography, performance, and choreography in her nearly fifty-year career, made her mark by breaking this rule. Her early video installations, such as Fire Writing (1975), Dawn Burn (1975), and Equinox (1979), which was just recently restored and exhibited at the Columbus Museum of Art, used the medium against itself, overwriting real-time images with indelible accretions of the past.

Kris Paulsen: I want to focus our conversation on Equinox (1979), a seven-channel video installation that was recently restored for the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA) exhibition, The Sun Placed in the Abyss. Before we get there, I want to ask how you got into video in the late 1960s, when it was still a very new medium?

Mary Lucier: I got into video primarily because I was doing performances at the time, in the mid-’60s into the ’70s. I was working with my first husband, the composer Alvin Lucier, and I was involved with the time-based work that was happening at that time in dance and in music, and I thought it was really the most advanced art of its time. I got involved in performance art and I was very close to Shigeko Kubota and Nam June Paik. At some point through their influence, I decided I wanted to use video, so I borrowed a camera and started shooting video and that became a whole thing in itself—not just a part of the performance. So eventually that moved into installation. I had studied sculpture as a college student, and video installation struck me as a form of sculpture. I thought, this is three-dimensional, this is how I want to work.

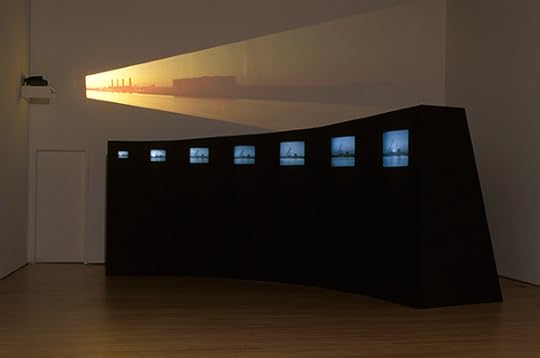

Mary Lucier, Dawn Burn, 1975. Installation view at the Columbus Museum of Art, 2016

Courtesy the artist, the Columbus Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Paulsen: Equinox is on display for the first time since it was commissioned in 1979 for the CUNY Graduate Center. I want to ask about the impulse behind this work and others you made in the 1970s, particularly Dawn Burn. In these works, you break the number one rule of analog video making: you point the camera directly at the sun. Doing so burns a permanent black spot into the vidicon tube. Everything you record from there on out is marked in that same way. In Equinox, you point the same camera at the sunrise for seven days straight. Each day is on a different monitor and shows the day-by-day accretion of tube burns in a series of arc across the frame. What inspired you to break that rule?

Lucier: Well, I have to say the first impulse was probably just to break that rule. In the early 1970s, video itself was still a new medium, and a medium that in many ways was breaking rules with conventional film and other kinds of visual art making. It was not universally liked as a medium. It was renegade and its quality did not match film, even 8mm, of the time. And yet it was very expensive. It had this roguish quality, as if we were doing something that was a little bit elicit. So, since I was already breaking the rules by using video, I then decided I wanted to break its very first rule and see what would happen.

Paulsen: Was the result what you expected?

Lucier: I did tests before I actually made a complete work. So, I did know what was going to happen, more or less, and how the sun was going to scar the internal tube of the camera. That’s the other thing I was certainly interested in—the scarring process and how, if the camera is the substitute for the eye, you’re actually, in a sense, scarring the retina of the camera.

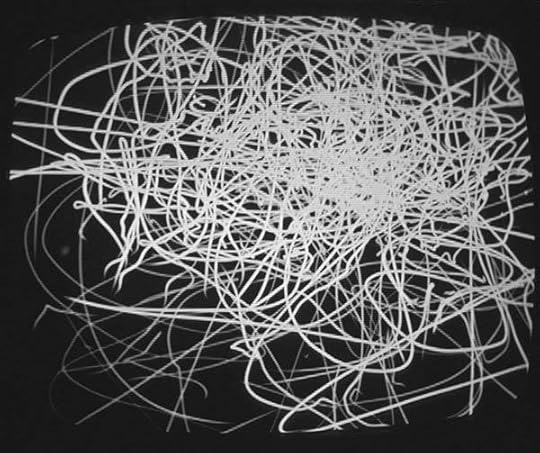

Mary Lucier, Dawn Burn, 1975

Courtesy the artist, the Columbus Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Paulsen: That’s one of the things that I think is so visually, metaphorically, and poetically powerful about Equinox and Dawn Burn. It makes the video image material, and makes the camera into an individual, particular thing. It’s not a disembodied eye but an embodied, unique individual machine, and that camera tube is marked physically by that vision. There’s an incredible double-sidedness or reciprocity in the image: You see the eye that is seeing at the same time as you see the image itself.

Lucier: And obviously the tube retains what I call “the memory of that moment,” and anything else that you look at through that camera with that tube is going to have the markings of that memory, of that moment.

Later, I reused some of the damaged tubes that I burned with lasers in a series of pieces called Fire Writing, where I wrote in the air, so to speak, with laser beams aimed at the camera. I tried to replicate text that was being spoken in the room. The burn marks of the lasers are much more intense—they’re very white. So you have this build up of white calligraphy on the tube that becomes quite extraordinary after a while. I later exhibited them as drawings.

Paulsen: And after a while of recording the light writing with the laser in the room, does the image of the room become completely obscured by the remnants of the laser burn on the tube?

Lucier: It can and the longer it goes on, the more the tube is obscured. But one of the things I did like about it is that even near the very end of that “performance” you can still see faces; you see them through the veil of this calligraphy. I have always liked that.

Mary Lucier, Fire Writing, 1978. Performance at The Kitchen, New York

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: That’s fascinating, since video’s essential properties, at least as they were being discussed around that time in the 1970s, were connected to the idea of an unrelenting present. But you have this way of retaining a kind of past in live image, whether it’s of this physical, embodied memory or these more literal inscriptions within the image. The image becomes thick with time rather than just delivering the real-time image of the present.

Lucier: That’s absolutely true. It actually imprints the moment. It also compresses whatever is happening. Particularly, in the writing pieces, it compresses the entire text. By the time the piece is finished, all the text theoretically is there on the screen even though you can’t read it but theoretically, you could unravel it and read it somehow. That was one of my ideas about it. When I displayed them as other installations, I also left the cap off the camera so that you can see—

Paulsen: Yourself?

Lucier: Your own face through the burn markings.

Paulsen: The present in the background is being renewed but the past is always in the foreground clouding that vision.

Lucier: You’re right: the markings are always in the foreground and then the real-time image becomes kind of background.

Paulsen: In that way, it erases that idea of transparency or immateriality that video images seem to have. We assume that they give us a direct view of the world unfolding in front of the lens. But this camera’s previous life is always going to be present and affect it, rather than the image being constantly renewed again or refreshed.

Lucier: Exactly.

Mary Lucier, Fire Writing, 1978

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: When I was watching you install Equinox at the CMA, you were “tuning” the colors across the seven monitors. It made me wonder about your use of color in Equinox. A sunrise is, of course, a colorful thing, but color seems to be a definite choice, especially since Dawn Burn and Paris Dawn Burn were black and white.

Lucier: Well, everything was moving toward color when I started making video in the very early ’70s. Somebody, maybe Nam June Paik, brought back the first color camera from Japan and everybody kind of flipped and started experimenting with color. The thing about black and white when I made Dawn Burn was that the black markings were so heavy.

Paulsen: Yeah, they are almost sooty.

Lucier: You could look at it as though it was charcoal drawing, let’s say, and when you look at the whole image of the river and the boats and the sun marks on the tube, they’re like black-and-white drawings to me. The marking was very important to me in black and white and how the markings revealed this shape of the earth moving around the sun. It has a very specific shape. It starts as a smallish thing and seems to get larger as it rises in the sky.

Color became the central thing about Equinox. I realized that this summer when I was transferring it from analog to digital and just staring at these images on the screen and thinking, my god—it’s all about color!

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979

Courtesy the artist

Paulsen: You bring up transferring and restoring the work this summer. What was the experience of seeing this work again after almost forty years?

Lucier: It was kind of thrilling. I got very wrapped up in making the transition into digital. I had never thought the color aspect of it as being as critical as it is. When you’re transferring from analog to digital qualities change, and I certainly think this was one of the qualities. The color really popped up in the transition and I was just blown away by how much I enjoyed it.

Paulsen: I wonder if that pleasure was a product of digital transfer or the distance that you’ve had from it. Maybe you were also surprised by the particular look of analog color after it’s been gone from our daily lives for so long? We don’t see those kinds of colors anymore. It moves across the screen in such a fluid way. For Equinox, this was the critical moment for transferring a nearly forty-year-old videotape, which is nearing the end of its lifespan. This is the case for all early video works. I wonder what you are doing to preserve your work?

Lucier: Preservation of video is a major issue now. Even if you successfully transfer something to a digital format and you have it as a digital file, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to play that forever, either. It’s essential to get it all down on digital in some format that I can live with, and then that’ll be its copying format for the future, not the original tape.

And that’s scary because what’s to guarantee that this file will play in even ten years? What’s to guarantee that there’ll be a device that will play it, that you’ll be able to insert it into a computer that accepts that format? Will you always be able to do that?

Mary Lucier, Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: Do you ever think about a kind of “living will” for your works, indicating what you would want or intend for them especially once collected? Would you be willing, for example, to allow them to be shown on flat monitors? Have you thought about contingency plans if these old style analog monitors are no longer in production?

Lucier: Yes, I think there is an advantage of there being a living artist attached to these works as museums collect them. SFMOMA did a huge interview with me, asking how I saw the future of this work, what I wanted Dawn Burn to be. I think that’s very important. If you can catch the artist while they’re still alive and get their take on what they want for the future and what they would allow. You’ve got to be able to think about ways that you can transform the work as the technology transforms. So, I am indeed thinking about that.

Paulsen: This is a particularly important question for works like Equinox and Dawn Burn, which are on analog technology but are also about analog technology.

Lucier: Right, and I really wanted this piece to be in its more or less original context. This was something I talked about with Greg Jones from the CMA: what is the best compromise we can strike between the way it looked originally and the way it could look now and still be authentic? I could never do anything to change Dawn Burn. It exists as is. It is a programed piece. It is fixed. It’s a conceptual piece that cannot change whereas I don’t feel that way about Equinox. I feel that as long as I keep it essentially the same, I could change many interior things. I feel I have the liberty to change them in certain ways if I wished.

Paulsen: So, do you?

Lucier: Embellishments—not to the change the essential concept of it, and maybe not to change the original materials, but to change certain aspects of presentation.

Mary Lucier, Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: Do you think that the work that you’ve had to do around preservation has prompted some of these re-imaginings?

Lucier: It does make you look back at things, and it does open you to the question. I keep thinking of Bruce Nauman, because his pieces keep being redone, and he made a comment about a recent piece he did—a new piece—he hadn’t made a new piece in two years. It’s a version of his contrapposto walk. He said there were things he felt he needed to redo and I applaud that because if there’s anybody who you would think wouldn’t change a thing, it’s Bruce Nauman. It was process art. So I love the idea that he would take the liberty to go back to an older idea and rework it in some way, and I think that’s a great liberty now for many of us because we’ve had some great ideas in the past and they haven’t been used up.

Paulsen: Hearing you talk about Equinox just a little while ago was really wonderful. I loved your surprise realization that the color was different than you had remembered and that it was more important. Its effect on you was different. Encountering a work from the past can give it a new narrative, even to you.

Lucier: Absolutely. That’s a great way to put it.

Paulsen: It’s like a long feedback loop.

Lucier: It’s a loop and you’re allowed to make changes in that loop as it comes around again. There are certain scores written on paper that would do the same thing. Lamont Young, Yoko Ono, John Cage, Robert Ashley, all the composers I knew, wrote scores that weren’t music notes on a staff but were conceptual ideas. I think some of the best scores were like that and I still very much admire that way of working and see the permissiveness to go back into it and to make some changes.

Paulsen: Right, scores are meant to be interpreted—

Lucier: Interpreted!

Paulsen: And played again.

Lucier: Exactly. Who knows, I might change my mind someday. I could imagine completely redoing Dawn Burn. Let’s say, reshooting it from beginning to end. That would be permissible, because in a sense, it’s a score, too.

Mary Lucier, filming site of Paris Dawn Burn, 1977

Courtesy the artist and the Columbus Museum of Art

Paulsen: And it seems like that score gave birth to Paris Dawn Burn and to Equinox, so it is already in a series of interpretations and reopenings.

Lucier: You’re right—you’re absolutely right about that. Probably if I had more opportunities, I could continue doing various iterations of that overall idea. Already Paris Dawn Burn is different from Dawn Burn. Dawn Burn has no sound. Paris Dawn Burn has a wonderful soundtrack with the morning bells of Paris.

Paulsen: That’s the thing about sunrise: a trip around the sun or a rotation around our axis, it’s iterative everyday. It happens again each day but each day it’s different.

Lucier: Each day is different—exactly.

Kris Paulsen is Assistant Professor in the Department of History of Art and Film Studies Program at The Ohio State University. Her first book, Here/There: Telepresence, Touch and Art at the Interface, will be published by MIT Press in February 2017.

The Sun Place in the Abyss was on view at the Columbus Museum of Art from October 7, 2016 to January 8, 2017.

The post The Renegade Video Artist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Surreal Sexuality

In his staged, gel-lit nudes, Jimmy DeSana explored the body as object.

By William J. Simmons

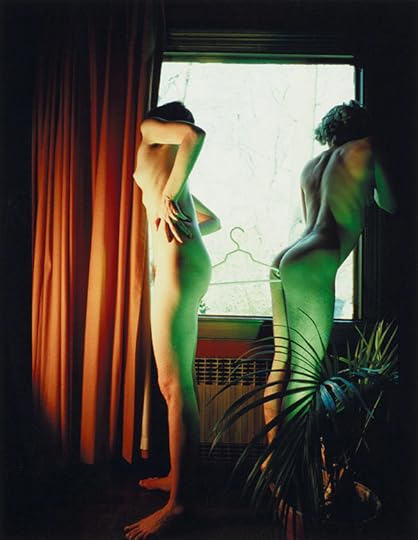

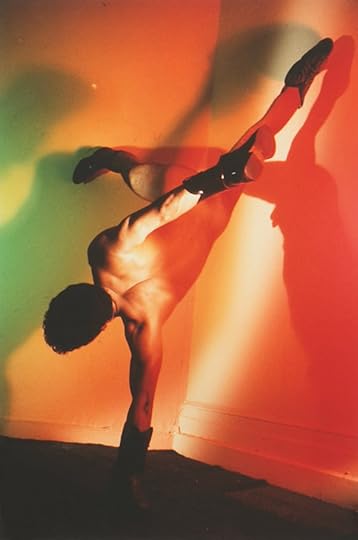

Jimmy DeSana, Storage Boxes, 1980

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94, New York

Lit by raking color that recalls the strangest drag show you have ever seen, Instant Camera (1980) tells an incredible story. A nude woman holding a camera stands atop a nondescript couch, assuming the pose of an ersatz classical statue. Her curved body, muscles taut in an effort to maintain balance, is echoed by a circular nimbus of angelic light. This figure directs her camera toward a contorted entity, whose crumpled pose surely frustrates any attempt to take a picture. A picture of what? Since the second figure’s face is hidden, we can only guess. Lurking somewhere between the mundane and the extraordinary is Jimmy DeSana’s world—a surreal display of the desires coursing through the veins of everyday life.

Jimmy DeSana, Coat Hanger, 1980

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94, New York

Born in 1949 in Atlanta, DeSana moved to New York in 1972 after studying art at the University of Georgia, and immediately became a fixture in multiple worlds that he mediated and processed with ever-present camera. He was a beloved member of New York’s East Village scene, what some have called the last avant-garde. Friends remember him as sensitive and kind. Perhaps most important for a photographer, he never took someone’s picture without permission. DeSana did much of his own printing, and cultural figures as diverse as Kathy Acker, Kenneth Anger, Richard Hell, David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, John Giorno, Debbie Harry, John Lurie, and Patti Astor cherished his portraits both for their commercial appeal and their skilled and flamboyant punk sensibility. His commercial work for venues like East Village Eye, File, New York Rocker, SoHo News, and the Village Voice exhibited the same formal rigor and imagination as his art photography, which he showed at Stefanotti Gallery and Pat Hearn Gallery.

Jimmy DeSana, Contact Paper, 1980

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94, New York

DeSana’s camera was as dear to him as his sexual life; the two were mutually constitutive, and his engagement with the BDSM subculture provided boundless inspiration to him, both as an artist and as a gay man. DeSana complemented his colorful commercial and portrait images with a set of black-and-white silver-gelatin prints depicting BDSM scenes. Published as a book titled Submission in 1979, the photographs are intentionally ambiguous. Refrigerator (1975) is exemplary; composed of intermingling angles and shadows, the photograph cracks open the doors of respectability and shame, and inside we find the body deliciously bound. In his introduction to Submission, William S. Burroughs mistakenly claimed that these were documentary images of sex acts in progress. In fact, each photograph, no matter how lifelike, was staged, with DeSana and his friends acting as models. DeSana is thus at the crossroads of multiple avenues of representation, neither documentary nor purely artistic, neither commercial nor high art.

Jimmy DeSana, Cowboy Boots, 1984

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94, New York

DeSana was an incisively critical of the photographic medium, normative sexualities, and commodity culture as his Pictures Generation colleagues, but the narrative of conceptual photography has been conspicuously devoid of an appreciation of queerness as a critical tool. It would seem that, in art-historical discourse, gay men are only friends, lovers, curators, or artists with a single platform: AIDS. This engenders a ghettoized history that excludes queer artists from these formative years of photo-conceptualism. Revisiting DeSana allows us to repair these oversights and restructure the long-standing Pictures narrative.

Jimmy DeSana, Instant Camera, 1980

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94, New York

As a gay man, a photographer, an artist of the AIDS era, a lover, a son, and a friend, DeSana is as beautifully complex as his work. After he died of AIDS in 1990, DeSana left his estate to his best friend and muse, the artist Laurie Simmons. Simmons told me, “I gave myself twenty years to sort out a lifetime’s worth of breathtaking material. I also felt certain that the work would look as fresh twenty years later as it did at the time of its making.” The resurgence of DeSana’s revolutionary career could not come at a more opportune moment; his oeuvre is exemplary of new outlets for reconstituting the Pictures Generation with queer modes of vision and critique.

William J. Simmons is an adjunct lecturer in art history at the City College of New York, and a PhD student in art history and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

This article first appeared in Aperture Issue 218, “Queer.”

Jimmy DeSana: Late Work is on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, through February 18, 2017.

The post Surreal Sexuality appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 17, 2017

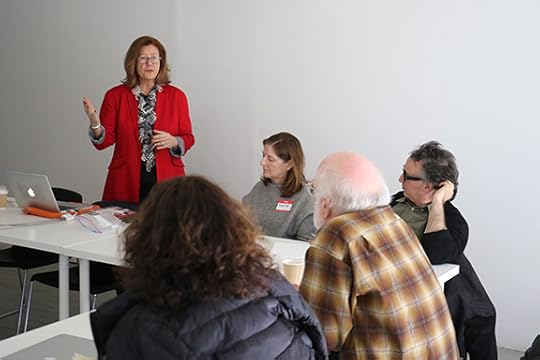

Mary Virginia Swanson: Marketing Your Photographs

Conceiving, researching, and creating long-term photographic projects is an enormous accomplishment. Sharing the work with the public is the next step.

Join mentor and educator Mary Virginia Swanson for a two-day workshop that will teach photographers to identify appropriate audiences for specific photographic projects and how to effectively reach them.

Swanson will explore a wide range of venues for photography in public, institutional, and private sectors while focusing strongly on learning to “read” their websites for clues to the demographics they reach. She will also discuss the importance of building, rather than buying, a mailing list with well-researched individuals, frequency of contact, and best practices for communication, whether via direct contact or utilizing social media platforms.

On the first day, Swanson will present an overview of the different types of venues as well as various audiences that extend beyond the fine-art market. The second half of the first day is reserved for participants to present their project statements, images, and a description of their desired audience. Swanson will offer suggestions on what additional information or services they could provide to the public, such as lectures, workshops, or other educational components in order to enhance one’s relationship with their audience. She will also advise participants on various audiences they may not be aware of in order to expand and diversify their reach.

On the second day, participants will present revised project statements and a list of venues they are interested in contacting, and share why they seem likely to be appreciative audiences for their work. Participants will also share their websites with the group while Swanson leads a discussion on what elements can be improved upon for clarity of intention. In the afternoon, she will discuss how to conduct project-specific research to develop a larger audience, establish a targeted mailing list, and discuss the language of funding and site-specific proposals.

Mary Virginia Swanson is an author, educator, and advisor who helps artists find the strength in their work, identify appreciative audiences, and present their work in an informed, professional manner. During her career, she has worked in the fine art, documentary, photojournalism, and licensing arenas, having launched an innovative agency to manage licensing rights for artists called “Swanstock” in 1990, and launching her consulting business in 2000. Swanson coauthored with Darius Himes the acclaimed Publish Your Photography Book: Revised & Updated (2014). Swanson is known for staying current in today’s diverse marketplace for photographs. Her current book project is Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs (2017), a major update to her earlier Business of Photography: Principles and Practices (2008) that will guide photographers through the changes taking place in nearly every aspect of our industry, preparing them for new opportunities in today’s photography-rich culture. She is the recipient of numerous honors including the 2015 Honored Educator Award and the 2015 Insight Award from the Society for Photographic Education, the 2014 Susan Carr Award for Education from the American Society for Media Photographers, and the 2013 Lifetime Achievement Focus Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography. An active contributor to the photography community, Swanson aids numerous organizations in our industry to provide relevant programming and plan for their future. She is based in Tucson, Arizona, and NYC.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Upon completion of this workshop, participants can expect to be able to:

clearly define their project in the language of their desired audience

establish a targeted mailing list and develop a successful strategy for communication

engage their audience with their work via new and varied opportunities (i.e., print sales, exhibitions, public speaking, workshops, and more)

identify a diverse range of venues to share their work in public, private, and institutional sectors

How to prepare:

In advance of the workshop, participants will need to:

Write a statement about their project in 100 words or less

Define the demographic of that project’s targeted audience. Address questions such as, Who would want to see this work? Where can those people be found? If possible, list specific venues

Send 10–15 images and the project title to education@aperture.org

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $500 and includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, March 29, 2017

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Mary Virginia Swanson: Marketing Your Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 11, 2017

Dispatches: Athens

A collective of artists reimagines contemporary Greece.

By Maria Nicolacopoulou

Georges Salameh, Broken Nose, 2012, from the series Spleen

Courtesy the artist

Art flourishes in times of adversity. In the charged political landscape of Athens, austerity measures and the prevailing division in the European Union have taken an irreversible toll on the city often referred to as the cradle of democracy. Yet, there is a pulse of creative inspiration and artistic production. On ghostlike streets where businesses are closing down and rental signs are ubiquitous, new artist-run spaces have emerged and collectives are being formed.

Depression Era is one of the products of this condition. Formed in 2011 and with almost thirty members to date, the collective operates in a unique format: its members are professional artists, photojournalists, architects, activists, and filmmakers who are joining forces in their free time. By resurrecting and embracing the value of communal ideals, strangers from different backgrounds and disciplines come together to experiment collectively—a configuration quite unknown to the mantra of neoliberalism and individualism heard throughout the art world.

Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Foundation NY.

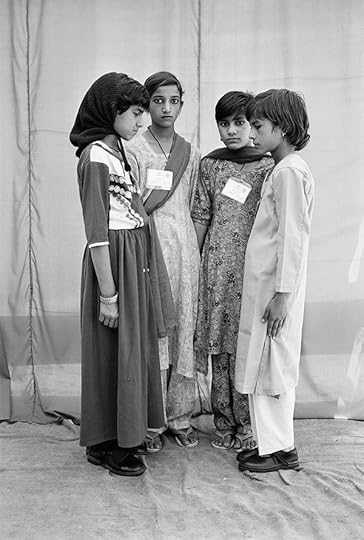

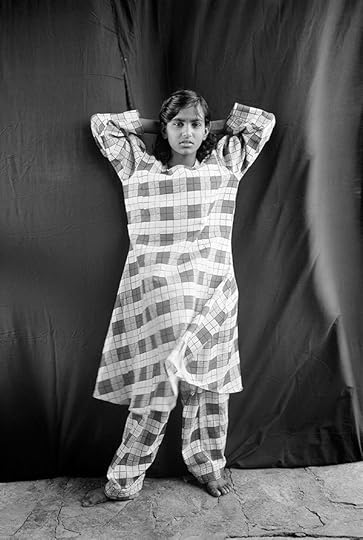

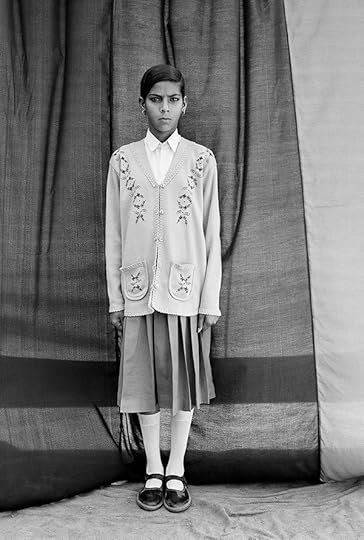

The Kids Aren’t All Right

In a region where women are regarded as an economic burden, Gauri Gill photographs girls in acts of quiet daring.

By Prajna Desai

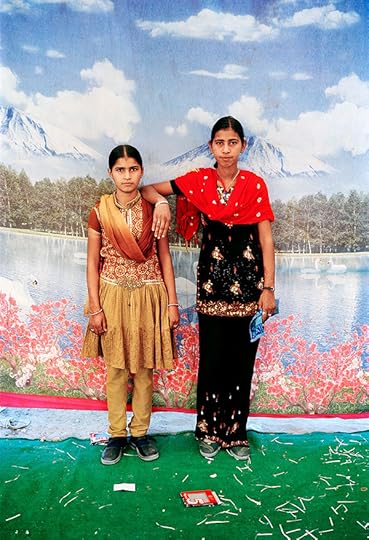

Gauri Gill, Virpal and Sunita, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

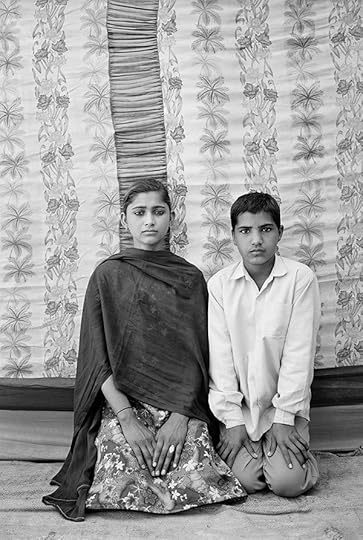

Gauri Gill, Sunita, Kalavati, Sita, and Nirmala, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Goga, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Kanta, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Manju and Parvati, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Indira and Murali, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

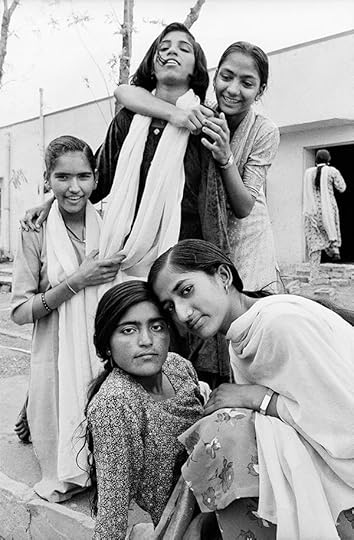

Gauri Gill, Sharda, Baby, and Krishna, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Bhanwari and Licchma, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Sita and Sharda, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Savitri and Poonam, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill, Manju, Amri, Jyoti, Dhaapi, and Maghi, from the series Balika Mela, 2003/2010. Courtesy the artist

One of the best things about Gauri Gill’s photobook Balika Mela (2012), named after a fair for girls in the arid state of Rajasthan in western India, is how it resists the idea that the kids are all right. In the black-and-white portraits headlining the book, rural adolescent girls are sometimes posed solo, with spare accessories—a watch, a newspaper, some plastic flowers. Some pairs and groups hold hands in obvious fellowship, while one wears paper hats. One picture shows a pair playing out heterosexual coupledom. Elsewhere, two girls staring intently into their own ring-around-the-rosie formation appear unconcerned with the world they inhabit. Solidarity, thrill, and resoluteness are all in evidence here. Yet, even while the girls’ frank gazes master the gaping desert light, these economical, almost silver-toned photographs refuse the implication of the girl ascendant.

Gill’s book is a document of her collaboration with the rural non-profit Urmul Setu Sansthan, which organized Balika Mela (Girl’s Fair) in 2003, in the town of Lunkaransar, Rajasthan. Some of the over fifteen hundred girls milling around the fairground wandered into Gill’s spartan, makeshift studio for photo shoots that resulted in the black-and-white images, and several weeks of mentorship in photographic technique alongside discussions about photography. When invited back to a new installation of Balika Mela in 2010, Gill shot a new set in color, injecting unexpected theater into the girls’ hand-embroidered jeans, puffy jackets, and tennis shoes peering out from under loose pantaloons. The most swaggering image is not of the girl straddling a motorbike, but of a pair in blue, the seated girl slouched like a hip-hop artist, her hand lightly clasping that of an impassive escort.

Critics like to cast Balika Mela as a modern replay of the emancipatory mid-nineteenth-century zenana photo studio, where mainly female Indian photographers shot performative pictures of elite Indian concubines from palatial harems who otherwise lived in purdah (wearing the veil). The comparison ignores the fact that her subjects have nothing to do with orientalist identity politics or feudal concubinage. The images do, however, have a feel for the region’s dizzying rates of female infanticide, but also for the corollary: that women just want to be. Their skits of aspiration and quiet daring, while certainly quite a bit of fun, would also become pragmatic weapons while they eventually struggle to get jobs, as some do. Indeed, one workshop participant, Manju Saran, who went on to reject purdah after marriage, also established a successful photo studio. The book concludes with Manju’s first-person account, delivered partly in the third person, like a split personality negotiating the gap between an ideal state of freedom and the knowledge it is not quite hers yet, not unlike Gill’s portrayals of the same.

Prajna Desai is an art historian based in Mumbai and curator of the Call for Entries exhibition for the 2017 FOCUS Photography Festival Mumbai.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Kids Aren’t All Right appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 5, 2017

Here Comes the Sun

At the Columbus Museum of Art, photographers look to the light in the sky.

By Ian Bourland

John Divola, Zuma #21, 1977

Courtesy the Columbus Museum of Art

Charles Baudelaire once derided photographers as “sun worshippers”—mere transcribers, rather than visionary creators. And indeed, for most of its short history, photography has been defined by light—the play of shadow, the capture of tonal range or photonic energy, while the sun has long endured as a metaphor, down to the medium’s first name, heliography, the “sun writing” coined by the Niépce brothers in 1820s France. But can the sun itself be the subject of a photograph? Can it be charted only indirectly, by its various reflections and refractions? Staring into its fiery depths, are we blinded in the act of looking, all recognizable forms obliterated into abstraction?

These questions are taken up in The Sun Placed in the Abyss, the recent exhibition organized by Drew Sawyer at the Columbus Museum of Art, which draws together dozens of works made not in the age of Niépce or Baudelaire, but since 1970. January 27, frame 9 (2012) is an image and a prompt by Zoe Leonard: a field of gray, diffuse but punctuated with a halo of white, like the pinprick orbs that float on the retina on a cloudless day. The photograph is a large gelatin-silver print, but it could easily be mistaken for a painting in its near-total abstraction. The accompanying text reminds us that the sun is “what makes photography possible, but it is impossible to really depict it.” Most of The Sun Placed in the Abyss is a spectrum of solutions to this problem, from dead-on looking to the deep parallax of allegory and irony.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Venus transit, 2004

Courtesy the Columbus Museum of Art

What’s refreshing here is Sawyer’s embrace of crucial horizons in photography that had long fallen out of fashion yet stubbornly persist in many contemporary practices, most notably the Romantic tradition in landscape (think Turner or Bierstadt) or the material splendor of analogue, alternative, or antique processes. To this extent, the obligatory Richard Prince montage, or Anne Collier’s appropriation of kitsch postcards of sunsets, tick the right boxes—of dutiful scrutiny, or knowing irony. But the most interesting conceptual strategy here is Dan Graham’s 67-second super-8 Binocular Zoom (1969-70), which merges otherworldly lens flare with a Warholian banality of city rooftops.

Instead, The Sun Placed in the Abyss shines when it includes photographers who unabashedly take on heliography as a formal route. The Californian Chris McCaw is here, with one of his silver gelatin photograms—the images he makes with military lenses and custom paper in which solar radiation burns holes in the negative. McCaw’s work is in dialogue with peers like Ryan Foerster and forebears such as Hiroshi Yamazaki, whose ’70s-era series Observation: The Sun captures the sun’s arc as a searing tracer on the horizon. Foerster’s Sun Blast (2013) is the monotypic husk of chromogenic chemistry left in the sun—it lands somewhere between surrealist experiment and nuclear incident.

Trevor Paglen, Reaper in the Sun, 2013

Courtesy the Columbus Museum of Art

Contemporary artists who engage with such solar lineage find unexpected trajectories in their otherwise familiar practices. Catherine Opie’s Sunrise and Sunset pictures from 2010 are taken from the deck of a transoceanic voyage on a cargo ship. Opie reinvigorates the genre of sublime seascape, charting distant horizons and moody shifts in light and shadow, but she also visualizes the flows of capital that define the Pacific Rim.

Wolfgang Tillmans looks to the heavens, and follows the transit of Venus across the Sun—a not-quite eclipse usually invisible to the naked eye, but rendered here in lavender hues and on a monumental scale. Others ponder the all-seeing sky. Trevor Paglen’s striking Reaper in the Sun (2013) is a print on the scale of history painting. From across the room it’s as alluring and abstract as a Rothko, but on closer inspection there is a faint trace of a new world order, of two decades of warfare fought from above by unseen forces. Omnipresent and elusive as the sun itself, a tiny drone strafes a bleached sky.

Ian Bourland is an assistant professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

The Sun Placed in the Abyss is on view at the Columbus Museum of Art through January 8, 2017.

The post Here Comes the Sun appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Our Bodies, Online

Feminist images in the age of Instagram.

By Carmen Winant

Petra Collins, from the series Selfie, 2013-2016

© the artist

What are the qualifications of being a feminist artist today? This is an impossible question, which is, in many ways, the point. One of the defining doctrines of third-wave feminism (or fourth-wave feminism, or postfeminism, or whatever you call our current moment) is its persistent unwillingness to be defined. Whether you make abstract photograms or stag films, label your work feminist, and it is.

As a feminist contrivance, this idea is either liberating or naive, depending on whom you ask, and, likely, in which decade you were born. In either case, it’s a jagged break from the secondwave feminist art movement that predated it—a movement that adhered, by its very design, to a strict set of ideological guidelines. Much like the activist organizations from which this movement grew (which aimed to achieve specific goals like legalizing abortion, passing the Equal Rights Amendment, establishing equal pay and free, universal childcare), feminist art of the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s was determined to raze oppressive structures with a new and defined set of rules all its own. “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” Audre Lorde famously declared in 1979. According to both the political and creative arms of the movement, any device that utilized patriarchal means was pointedly unfeminist and thereby an inadmissible agent of real social change.

Mayan Toledano, Emma, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Though born from a desire to achieve equality, some of these mandates around what feminism could and could not be eventually became exclusive, limiting, and problematic. Activist groups such as New York Radical Women came to regularly vote out their leaders for being “unsisterly,” leaders of the National Organization for Women distanced themselves from lesbian feminists—whom Betty Friedan labeled a “lavender menace”—and male children were banned from feminist separatist communes such as Womyn’s Land. At its zenith, this essentialist dogma thwarted the momentous gains of the second-wave movement. At the same time, artists like Betty Tompkins and Anita Steckel, whose paintings were considered too explicitly pornographic and thereby aligned with the patriarchal gaze, were largely excluded from the pale. Hannah Wilke was criticized for being too stereotypically beautiful (and thereby narcissistic) to represent her work’s feminist politics.

Almost half a century later, Instagram, the rise of selfie culture, American Apparel aesthetics, and amateur pornography—channels of visual communication that would have been impossible to fathom within the context of the pre-Internet women’s liberation movement—have come into being. An emerging guard of young, female photographers has carved out a new brand of feminism with a new set of definitions: Amalia Ulman created “hipster lifestyle” porn, to be viewed only within a gallery setting titled International House of Cozy (2015). Arvida Bystrom’s series There Will Be Blood (2012) pictures women in their lacy, period-stained underwear (she also regularly photographs herself and other young women in various states of undress in front of bright, pastel backdrops). Molly Soda’s project Should I Send This? (2015) is comprised of titillating, seminude, and headless selfies that the artist took but never forwarded on to romantic partners. Audrey Wollen’s series Repetition (2014–15) features the artist posing nude or seminude as she imitates and embodies historic works of art made by men such as Bas Jan Ader, Botticelli, and Velázquez. Mayan Toledano’s photographs for her brand Me and You—cocreated with Julia Baylis—are of young women posing topless in bed while wearing Me and You’s most recognizable product: women’s underwear that has the word feminist printed across the backside in pink. These artists frequently collaborate, curate one another into exhibitions, tag and promote each other on social media, and appear as subjects in each other’s work. The commercial, editorial, and creative ventures are part of a larger, allied cohort that is rapidly gaining popular visibility.

Mayan Toledano, Sherris in Palm Springs, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Among them, Petra Collins’s work is perhaps the most prominent. In addition to a creative practice—a recent project is of adolescent girls in the process of taking selfies—Collins counts Vogue, Elle, Wonderland, and i-D magazines as editorial clients, and has shot advertising work for Levi’s, Adidas, Stella McCartney, and Calvin Klein. Across all of these practices, her 35mm images are recognizable as crude and dreamy. Collins’s use of gel filters, pastel palettes, and high grain is uncannily reminiscent of Bob Guccione’s signature Penthouse magazine style, and likewise owes a debt to Ryan McGinley (for whom she has posed on numerous occasions) and Nan Goldin before that. However, unlike Goldin’s women, whose whole bodies project a wild and gleeful pathos, Collins—when she shoots commercially—often zooms in on her subject’s breasts, lips, or asses, their bodies bathed in warm, gauzy light. For all their sexual potency, Goldin’s photographs of Greer Lankton and Cookie Mueller don’t resemble other popular images of women; they feel at once beaten down and ferocious. Collins’s photographs of female subjects for fashion magazines, in which models pose in sauna-soaked underwear and lacy negligees, are notably more domesticated.

Yet Collins consistently makes the case for her work as being driven by her deeply rooted feminist ideals, as do many—if not all—of the photographers of this cohort. The question, then, of what qualifies work as feminist art in today’s cultural landscape circles closely around this group of artists. Bystrom, the Swedish photographer and self-defined “strident feminist” who has posed for Toledano and collaborated with Collins, told Dazed, “You can’t just make ‘feminist art’ because feminism is more like a spectrum of things; it changes and depends on its context.” This notion—that feminism can be whatever you want it to be, and that there are as many feminisms as there are women—appears to sharply contradict the exacting boundaries and idealistic aspirations of the preceding movement. It is, perhaps, the prevailing definition of feminism embraced by Collins and her peers.

Mayan Toledano, Lindsay, Long Island, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Prestel, the publisher of Babe—a 2015 Collins-curated book that includes work by over thirty artists who have been part of her online collective, the Ardorous—promotes the collection as “reflect[ing] an all-accepting, affirming, distinct point of view that teens and young women everywhere can respond to.” Barnes & Noble blurbs Collins as “leading the way in a contemporary girl power revolution that proves feminism and sexuality aren’t mutually exclusive,” and various places online promote the book as “help[ing] us to refocus and remember that we are all a part of the struggle together.” This publisher-scripted language is not far removed from the manner in which the photographers and their surrounding community describe their work. For instance, Collins did an interview with the site StyleLikeU titled “Sorry Not Sorry, Women Have Body Hair” (and subtitled, “Another female power house is stripping down in the name of self-love, femininity, and body acceptance”) while slowly disrobing down to her underwear. Posted on YouTube, it drew several comments by men bemoaning the fact that she never removes her bra.

In her essay “Censorship and the Female Body,” published in 2013 by the Huffington Post, Collins rebukes Instagram’s decision to remove her profile based on a photograph she posted showing her crotch with some exposed pubic hair, writing:

I know having a social media profile removed is a 21st century privileged problem—but it is the way a lot of us live. These profiles mimic our physical selves and a lot of the time are even more important. They are ways to connect with an audience, to start discussion, and to create change…. To all the young girls and women, do not let this discourage you, do not let anyone tell you what you should look like, tell you how to be, tell you that you do not own your body. Even if society tries to silence you keep on going, keep moving forward, keep creating revolutionary work, and keep this discourse alive.

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 2nd July 2014), 2014

Courtesy the artist, James Fuentes and Arcadia Missa

Collins shows real dedication to challenging censorship and promoting body positivity through her work (and is aware that her position is a privileged one), which is focused on reclaiming the female body by utilizing the techniques and tools of the male gaze. Censorship is, of course, a crucial feminist issue, as is sexual expression, freedom, and agency—all addressed head-on by these photographers. The characterization of this particular case of censorship being a “21st century privileged problem” that nevertheless represents “the way a lot of us live,” though, hints at the paradox inherent in much of this work. Can an inclusive and far-reaching feminism develop within the confines of a Westernminded social-media universe that upholds the status quo of capitalism—the begetter of privilege and the patriarchy alike?

If the rhetoric surrounding this kind of imagery is under question, the images themselves flirt with something undeniably interesting: the tension between provocation and objectification. Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” now almost four decades old, might have been written about this very charge:

The erotic offers a well of replenishing and provocative force to the woman who does not fear its revelation, nor succumb to the belief that sensation is enough. The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling.

Mayan Toledano, Tessa in Mizpe, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Locating the boundary between the erotic-as-power and the erotic-as-bondage can be a complex task, as is manifest in a recent project by Amalia Ulman. For Excellences & Perfections (2014), she posted hundreds of hypersexual, blank-faced selfies on Instagram, accruing up to six hundred likes on a single photograph. In describing how young women now self-present in images on the Internet, Peggy Orenstein’s book Girls and Sex (2016) aptly pins the type of account that Ulman’s spoofs as “a commercialized, one-dimensional, infinitely replicated, and, frankly, unimaginative vision of sexiness … [set to] perform rather than to feel sensuality.” By the time that Ulman eventually revealed that she was playing a fictional character in an act of cultural sendup, she had accrued almost 90,000 new followers. In a moment in which feminist art is defined primarily by its immediate context and authorial claims (Ulman herself does not identify her practice as “feminist” or ascribing to any other political categorization), this work—which has been digitally archived by Rhizome at the New Museum and will be exhibited at the Tate Modern this year—could be considered incisive or lacking rigor. In any case, by reveling in the exhibitionism she seeks to critique, Ulman’s work gets to have it both ways.

Feminist curator and critic Helen Molesworth told me recently that “in addition to the understanding that feminism is structured on absence—the absence of women’s experience, of bodies of color—a feminist is someone who is aware that you can’t change the patriarchy just by inserting women into it.” Is the fact that it was made by a woman enough to qualify it as progressive or political? Would we read these same images differently if Terry Richardson or Richard Kern—a mentor of Collins—made them? Is it possible to at once challenge codified systems of feminized beauty while photographing for the very fashion magazines that reinforce them? Can feminism successfully protest sexism through the personal choice of self-objectification, using what Zoë Heller described skeptically in her New York Review of Books essay “‘Hot’ Sex & Young Girls” as “the emancipatory possibilities of hotness”?

Audrey Wollen, Rokeby Venus, repetition of Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez, 2015

Courtesy the artist

When untangling the complex questions posed by the work of these artists, it’s important to recognize that these women deliberately take control of the master’s tools (porn, Instagram, high-end fashion advertising, lifestyle magazines, other corporate and commercial entities) to dismantle the master’s house (patriarchal expectations of gender). Let’s remember that Audre Lorde and the antipornography activist Andrea Dworkin, who passed away in 1992 and 2005, respectively, would have been old enough to be grandmothers to this new generation of feminists. Movements evolve and revolt against themselves; axioms shift over time and in relationship to culture. Rather than ask this group of artists to resemble the feminists that came before them, critics, consumers, and practitioners alike should be promoting an unabashed and exacting dialogue around the politics of looking and image making.

This is a generation that has had access to mobile devices and image-centric web platforms from preadolescence as a part of daily life; this technological and commercial divide naturally shapes their creative instincts, and sets them apart from previous makers. Molesworth concluded our conversation by reminding me, “Though there are some basic operating principles and values, there is no one theoretical position on feminism that works for everyone.” So long as it is self-critically vested in challenging modes of power, feminism can, and must, be a continually evolving phenomenon. No matter the generation of feminism to which one ascribes, expansive and rigorous definitions do exist; let’s set about reclaiming them.

Carmen Winant is an artist, writer, and Professor of Visual Studies and Contemporary Art History at Columbus College of Art and Design.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Our Bodies, Online appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Notes on a Scandal

After weathering the media firestorm surrounding a series of provocative self-portraits, Lebanese photographer Rasha Kahil turns comments from online trolls into a powerful exhibition.

By Rayya Badran

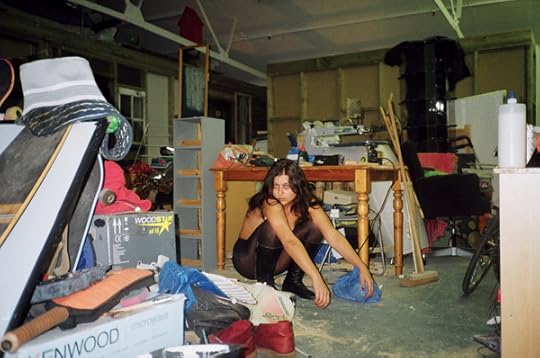

Rasha Kahil, Hackney Wick, E9, London, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

For her photographic series In Your Home (2011), Rasha Kahil a London-based, Lebanese artist, photographer, and art director, depicted herself in seminude poses in people’s homes in London, Berlin, and Beirut. Kahil presented the work in Beirut and Istanbul and self-published the series in London in 2011. Confined at first to art world circles, In Your Home later caught the attention of local Lebanese news outlets when, in 2013, Al-Jadeed TV produced a report on Kahil. Her images became an instant sensation and the coverage subsequently catapulted Kahil into the ruthless public domain of social media. Anatomy of a Scandal, Kahil’s new work, is a multimedia installation that delves into her response.

Rasha Kahil, Kastanienallee, Mitte, Berlin, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Rayya Badran: In Your Home, made between 2008 and 2011, is a series that challenges issues of intimacy and private space. Yet, the later occultation—censorship—of the erotic parts of your body was itself a violation, not merely bestowed upon your body, but also a violation of what your work had intended to do in the first place. Your reprisal of these reworked, retouched works sheds light on the ease with which the Internet can appropriate and deconstruct images at will. Instead of actively challenging them, you chose to surrender, if one can say that, to that noise. I wonder about the subversive potential in such a decision. Radio silence as a position of power.

Rasha Kahil: As the “scandal” happened online, I did choose to stay silent. It wasn’t so much an act of resistance at first, but instead a realization that the power of the Internet, and the free-flow of voices who either choose to condemn or champion, is a torrential force that can only be observed in real time, not one I can actively engage in. Observation was my only recourse; documentation my only tool.

Being at the center of a such a vigorous media storm and witnessing the flurry of comments aimed at my body, my work, my being, was at first extremely harrowing, especially because there were many attempts to contact me directly, rather than just “reading” my person being dissected online. I was hounded by TV talk show hosts who asked me to participate in live TV panels and “defend” my work, give my side of the story. Of course, I was never going to do that, and I chose to remain silent, as not only is attempting to engage with the strength of the online voices a futile exercise, but, of course, agreeing to add my own voice to the discourse would only mean that I was giving validity to the wider discussion.

Therefore, proactive silence was my only course of action, and my strongest tool. I actually found the deconstructed images of my original In Your Home series churned out by the media outlets online—with their liberal use of pixels, black bars, and Photoshop blurs and splodges—quite fascinating. I am not sure “surrender” is the right word, as my silence was my own form of attack: it never crossed my mind to issue an apology to the singular “mass,” as seems so customary an outcome in these types of online scandals.

Rasha Kahil, Caledonian-Road, N7, London, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Badran: Before you moved onto the dissection of people’s responses to your work, and aside from the very polarizing, yet somewhat predictable opinions out there, was there a response among those that were sent or posted that particularly marked you or made you pause? And could you explain why?

Kahil: Yes, it is a comment left on a blog post that I actually used as a stand-alone vinyl piece in the exhibition:

unfortunately, none of Rasha’s so-called artistic pictures meet the conditions needed for a piece of work to be considered as art:

art: something that is created with imagination and skill and that is beautiful or that expresses important ideas or feelings/works created by artists: paintings, sculptures, etc., that are created to be beautiful or to express important ideas or feelings. [from the Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary]

Obviously, these pictures only display vulgarity, fruitlessness and lack of creativity, which are the complete opposites of the two definitions of art mentioned above (that’s just to say a little about her pictures). Plus, they serve no important or noble purpose and are thus pure garbage porn.

Last point I want to make is, looking at this girl’s pictures, all I could possibly see is a stupid, wrathful, disguised feminist rebelling at the very end of the continuum and more importantly, a promising Arab porn star … wow! Very honorable and educational material for generations to come …

It is the violence of the tone in the comment that really struck me. Most of the comments left online were throwaway remarks, using my body as a springboard for “locker-room banter” (as Trump would say, defending this type of discourse). But this particular comment is considered. It reads like a mini-essay, with a moderate intro, a heated argument, and a progressively more vociferous closing statement. There seems to be deep-rooted revulsion towards my work and persona, manifest in an attack not only on my practice, but also my intellect, my body, my gender, and my intentions all at once. It unsettled me deeply, not because it zoomed in on me personally, but because I feel it to be a violent attack on women in general and vocal, outspoken women in particular.

Rasha Kahil, Anatomy of a Scandal, installation at Art First Projects, London, 2016

Courtesy the artist