Aperture's Blog, page 123

February 28, 2017

Lesson 9

Lesson nine engages students in how to approach, photograph, and interact with subjects. This lesson encourages students to take what they have learned in previous lessons—truth, symbols, form—and use these tools while collaborating with others when making portraits. The works of Richard Renaldi, Robin Schwartz, and Wayne Lawrence help students understand that there are a number of approaches to making portraits.

The post Lesson 9 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Lesson 8

The eighth lesson introduces the use of text and the ways in which it can work with photographs. Students learn that text can be used to tell a more complete story rather than simply act as a caption for an image. Dawoud Bey’s series Class Pictures is a perfect example of text being used in concert with photographs to tell a story. Students consider both the text and the images separately and then together. Students will be able to write brief, personal narratives to accompany their pictures, as well as understand that photographs and text can work together to describe someone both internally and externally.

The post Lesson 8 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 24, 2017

The Subversive Fantasies of Ren Hang (1987–2017)

Aperture remembers the surprising, defiant work of the Chinese photographer. Despite China’s strict censorship, Hang’s playful vision cleverly pushed the limits of self expression.

By Stephanie H. Tung

Ren Hang, Untitled, 2013-14

One of China’s most distinctive young photographers, Ren Hang makes cool, saturated images that are tightly composed and lit with stark flash. Prominently featuring red lips, black hair, and supple flesh, his photography creates a world where sex, desire, and the joy of voyeurism create a visceral effect. Although most of his recent solo exhibitions have been held outside of China, viewers have gravitated toward his work when it has appeared in group shows in Beijing and Shanghai.

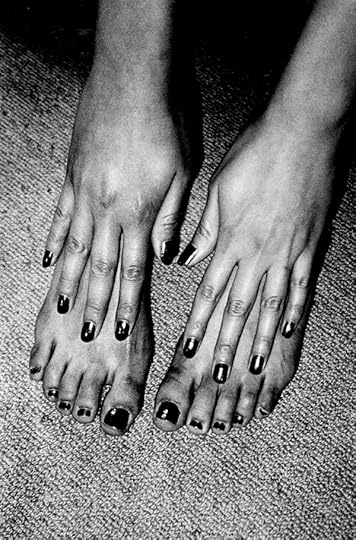

Ren Hang, Untitled, 2014

Born in 1987, Ren Hang left his home in Changchun city in Northern China to study advertising at the Communication University of China in Beijing. He began photographing his friends as an escape from the tedium of class. Using a small Minolta point-and-shoot camera, Ren Hang acts as director, moving hands and legs, lifting girls on top of girls, and arranging flowers on top of men. The subjects are all close friends or models he interviews beforehand who trust and respond well to the photographer’s demands. The resulting photographs—untitled and dated only for convenience—do not consciously attempt to address queer identity in China but rather function as a form of play or performance in a place where any explicit declaration of same-sex orientation is still considered risky and nude photographs are routinely labeled pornographic.

Ren Hang, Untitled, 2013-14

Since his first photographs from 2008, Ren Hang’s images have shifted from seemingly candid shots of individual nudes to more complex compositions involving groups of people interacting with each other and props. Though he acknowledges a debt to the frank displays of sex by photographers such as Juergen Teller, Nan Goldin, and Araki Nobuyoshi, Ren Hang identifies most with the dark absurdity of Shuji Terayama, a filmmaker best known for his surreal theater and cinema. Like Terayama, Ren Hang explores the erotic through startling juxtapositions that evoke fantasies: “My work is all about sex, lust, and porn,” says Hang, “but I’m not quite at the point where I can make people feel desire yet.” Though Ren Hang’s photographs often depict same-sex relations, in his work gender and sexual preference dissolve as he directs the models into provocative arrangements and compositions. The nude bodies become so strange and fluid and bare that it is difficult to pin any label on them.

Ren Hang, Untitled, 2013-14

Ren Hang has learned to adapt to the censorial conditions of working in China. He develops and scans his film at private studios to avoid obscenity charges and has become keenly aware of the potential for censorship. Still, he is often harassed online, and his works, when on public view, have been spit upon or taken down, leaving only empty frames. Yet when asked if he wants to continue working in Beijing, Ren Hang responds: “Yes, of course; even though China refuses me, I don’t care. China is still pretty conservative, but it’s the same elsewhere, and not even young people are exempt [from sharing these views]. As long as I like photographing, then I’ll still photograph.” Precociously self-aware, Ren Hang is part of a new generation of young photographers in China daring to push the limits of society from within with bold, defiant work.

Stephanie H. Tung is a PhD candidate focusing on modern and contemporary Chinese art at Princeton University. She was a contributing author to The Chinese Photobook , published by Aperture in 2015.

This essay was originally published in Aperture Issue 218, “Queer.”

The post The Subversive Fantasies of Ren Hang (1987–2017) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Defying Stereotypes, One Post at a Time

The four artists in Torrent Tea are redefining narratives of Black and Queer bodies on the Internet.

By Roula Seikaly

Rafia Santana, Worked, 2015

Courtesy the artist

In mid-January, Torrent Tea opened at Portland’s Newspace Center for Photography. Here, four emerging artists—Texas Isaiah, E. Jane, Devin N. Morris, and Rafia Santana—reject racist stereotypes of Black bodies—the mammy, the athlete, the rapper, the slave. Focusing on websites and other forms of accessible media, such as zines and GIFs, the artists reclaim digital space as a site for celebrating Blackness and Queerness, accomplishment, and empowerment. In an email interview, I spoke with curator Ashley Stull Meyers about the project’s origin, the potential for visual imagery to defeat racist and sexist stereotypes, and how curation extends to virtual platforms.

Roula Seikaly: Tell me about the exhibition title, Torrent Tea.

Ashley Stull Meyers: “Torrent Tea” is a play on the two central themes of the exhibition. One, content that moves subversively through social media and web-publishing channels, for example Facebook and Instagram. And, two, the intimate conversations that happen within Black, Queer communities. The artists in the exhibition have a practice of web-hosting much of their creative output—critique, revisionist art histories, self-portraiture—as a way to politicize social media platforms, which are often banal. This critical work is frequently missed by communities not literate in memes and hashtags, or who don’t lend a discerning eye to Tumblr and Facebook.

E. Jane, NOPE (A Manifesto), 2015

Courtesy the artist

Seikaly: You’ve identified artist E. Jane’s NOPE (a manifesto) from 2015 as the beginning of this project. How did you come across it? How did it inform the thesis for this group exhibition?

Meyers: E. Jane wrote the manifesto during graduate school as a refusal of their work being considered exclusively under ire of identity politics. I think that is a fight that most, if not all, Black and Queer makers fight—to have their work read with the critical respect afforded to cis-gendered, white, male artists. They wrote, “I am expansive in my Blackness/ And my Queerness/ As Blackness and Queerness/ Are always already expansive.” I think all four artists are emphatic about that. They each “reject the colonial gaze as the primary gaze.”

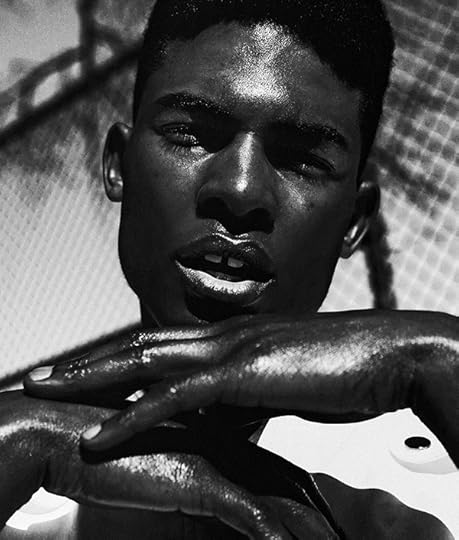

Seikaly: Texas Isaiah describes his practice as one attempting to create both communicative and safe space for his subjects, himself, and the audience. What are your thoughts on those terms — “communicative” and “safe” — when artists of color explore Blackness and Queerness online? Are they mutually exclusive, given the rabid racism, misogyny, and homophobia that informs so much of online interaction?

Meyers: No space is entirely safe. What the Internet presents is a greater opportunity to skirt or manipulate oppressive sociopolitical systems in a more earnest way than is possible in blue chip galleries and mega-museums. Traditional exhibition spaces come with barriers to access and problematic funding expectations that aren’t solved by virtual space, but the Internet is at least more adaptable to those issues. Texas Isaiah may have been discussing “safe space” in the literal sense because he photographs other Queer people of color in the physical spaces they’ve carved out for themselves, but the general sentiment still applies.

Devin N. Morris, Untitled (Red), 2016

Courtesy of the artist

Seikaly: You’ve worked with Newspace to develop a lecture series that expands on conceptual aspects of the exhibition. One topic is “slowness.” Could you elaborate on what that is, and why it’s important?

Meyers: A primary goal of Torrent Tea and its programming is to expand the dialogue around these makers beyond what’s imitated in the entertainment industry and popular culture. There are works in the exhibition that take to task the ways cis, white, straight celebrities and entertainers “perform” Blackness for social and monetary gain. Rafia Santana’s Black Power Project is caricatured GIFs of pop cultural figures like Kylie Jenner, Iggy Azalea, and Macklemore, who profit from things like AAVE (“black speak”) or beauty products that help them imitate the Black female figure, such as big butts, big lips, and certain hairstyles. The artists in Torrent Tea seek to criticize the celebration of Blackness and Queerness only when they aren’t attached to actual Black or Queer persons. They want to call out these problematic imitations as well as broaden the social perception.

“The Slowness” was a lecture by Dr. Kemi Adeyemi from the Department of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies, at the University of Washington. It provided historical context to the way Black and Queer people navigate a Western society founded on neoliberalism. In short, Dr. Adeyemi connects the trope of “slowness” as negatively associated with Blackness to its contemporary reclamation in Queer nightlife, particularly a slow jams party in Chicago called Slo Mo, which was founded in 2012. She asserts in her dissertation and upcoming book that slowness is a way of situating Queer, Black bodies within a political, social atmosphere that tests their physical and emotional endurance. As part of the exhibition’s culminating event, Bart Fitzgerald, a local Queer thinker, will discuss the Black body as inherently Queer, and the Queer body as inherently sacred.

Texas Isaiah, Jocquese, 2016

Courtesy of the artist and Swagger Like Us, San Francisco

Seikaly: The exhibition defies stereotypes of Blackness, Black bodies, and Queerness that are created and promulgated by our consumerist, commodity-driven society. Can this work, and work like it, defeat ideas and imagery that are deeply entrenched in our visual culture?

Meyers: No. White, Western misinterpretation of Black bodies won’t be defeated by a photograph, especially within the constraints of capitalism. But, an impactful first step to exposing caricatures, both tragic and camp, is to let Black and Queer bodies lead the production of their own images and narratives. Torrent Tea is portrait heavy: all the photographs are either self-portraits or portraits taken with intimate groups of collaborators. Cis-gendered, white bodies have no business constructing the narratives around queer people of color. Torrent Tea doesn’t have the answers, but the principles are on target and I’m proud of that.

Seikaly: Much of your writing and research considers the Internet as an exhibition space alternative to the white cube. Given that pursuit, why curate an exhibition in a physical space?

Meyers: As much as I love non-traditional structures for art and exhibition making, a physical experience of viewing art still holds tremendous value. For Torrent Tea, about three-quarters of the work was printed or made into an object for the first time. The other quarter was shown digitally, on iPads or as projections. E. Janes’s manifesto, for example, became an inkjet print on satin that they conceptualized as a “flag”—an object of declaration. This symbolism gives the work an added ideological dimension without betraying its origins. I hope that this installation still feels true to the original host platforms. Texas Isaiah’s work is hung in a grid that is reminiscent of Instagram. Devin N Morris’s photographs were installed in a pattern that alludes to “swiping” through digital images. The irony of showing immaterial work in a physical space doesn’t escape me, but in this case it felt important to very literally make room for Queer people of color who are too often neglected by arts institutions.

Roula Seikaly is a curator and writer based in San Francisco.

Torrent Tea is on view at Newspace Center for Photography, Portland, through February 25, 2017.

The post Defying Stereotypes, One Post at a Time appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 23, 2017

Valérie Belin’s Uncanny Visions

The French artist’s most recent work explores the dark side of pop culture and beauty.

By Annika Klein

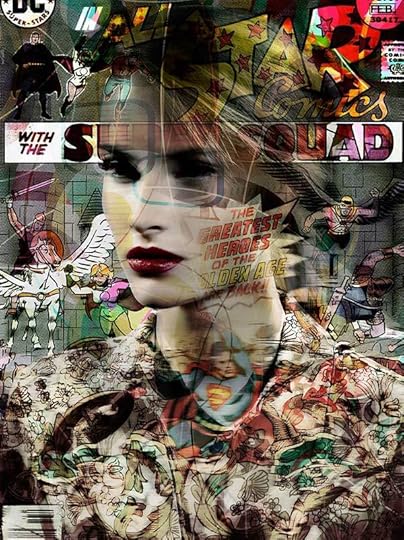

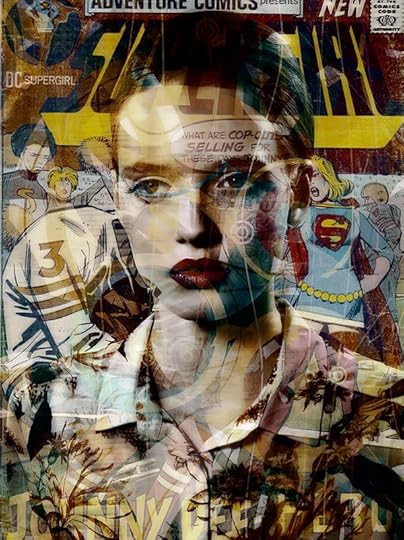

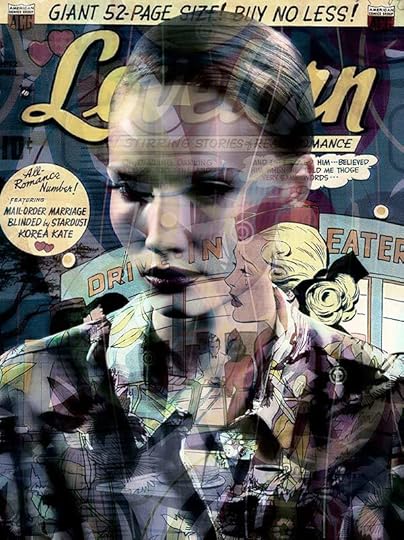

Valérie Belin, Golden Girl, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

In Valérie Belin’s latest series, All Star (2016), currently on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York, Belin places the faces of pale, idealized women against a background of digitally collaged, 1950s comic strips. The unidentified, unnamed models appear passive, almost forlorn, with eyes cast down or obscured by shadow. Rife with scenes of chaos and destruction, the composition and graphic quality of the images evokes nightmarish magazine covers, but each print stands about five-and-a-half feet tall—miniature billboards in scale. How confusing, how chaotic, how layered—and yet, how consumable.

Born in France in 1964, the Paris-based Belin’s work centers on questions of surface, artifice, consumerism, and the indexical nature of images—that is, the often fraught way that photographs relate to the object they depict. She said she has long been haunted by what she refers to as “the stereotype,” Belin told me recently in an interview by email, and how people either conform to or reject norms of gender and appearance—for example, bodybuilders both male and female, transgender women, and Moroccan brides imprisoned in ceremonial garb. “My subjects all have cliché status,” she explained.

Valérie Belin, Super Girl, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

This straightforward solo exhibition gleams in Edwynn Houk’s tony Fifth Avenue gallery. One of the more striking pictures, Super Girl (2016), is typical of the series. Belin has placed the model in accordance with the “two-thirds” rule of photography, a cliché of composition. Alluding to her previous series, Belin burned the shadows of flowers into the model’s white collared shirt. Around her face, cheerleaders pump yellow pompoms as football players take the field, and a Supergirl figure shows a sliver of her thighs between her red boots and blue minidress as she shouts into the model’s ear. It’s not clear what she’s shouting. But her diminutive, almost oxymoronic title, reminds me that, during the 2016 Olympics, world-class athletes still had to demand that male commentators refer to them as women, not girls.

Belin explicitly deals with the feminine, in both style and subject. Presaging the layering critique of her recent work, Black Eyed Susan (2010–13), situates portraits of women styled with ’50s-inspired hair and makeup against floral backgrounds. Belin says she sees the battle for feminism as already won by an older generation, and she doesn’t consider her work to be overtly political. At the same time, she knows the art world doesn’t treat women equally. Asked how her work relates to other female-identifying artists who have worked with photography and abstraction, such as Anna Atkins, she replied: “Parity does not exist. One could even say that in many cases the work of a woman artist is taken seriously only if it touches on the female condition. The theme legitimizes the work’s artistic status.”

Valérie Belin, Confessions of the Lovelorn, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the All Star series is that all of the models look so alike. Yet this is intentional. Referring to a 2003 series titled Mannequins, Belin notes, “A very recognizable beauty is dissolved into an empty plasticity.” The eerie similarities between Belin’s portraits of mannequins, and the ways in which Western culture routinely objectifies women’s bodies, are striking. When Belin depicts “real” women as digitally manipulated specters, however, it’s difficult to separate them from the similar images so common in advertising. In her influential book, The Beauty Myth (1990), Naomi Wolf argues that images of female beauty are used against women’s advancement. Instead of being presented with pictures of women who vary in weight, age, race, ability, and class, we see “a dissemination of millions of images of the current ideal.” In 2017, thanks to the Internet and digital media, make that billions. In using these idealized images of women, is Belin making a much-needed critique, or feeding the machine?

Annika Klein is the Editorial Assistant at Aperture magazine.

Valérie Belin: All Star is on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, through March 4, 2017.

The post Valérie Belin’s Uncanny Visions appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 22, 2017

Learning to See: Photography at Black Mountain College

How a small, liberal-arts college became a birthplace of modern photography.

By Diana C. Stoll

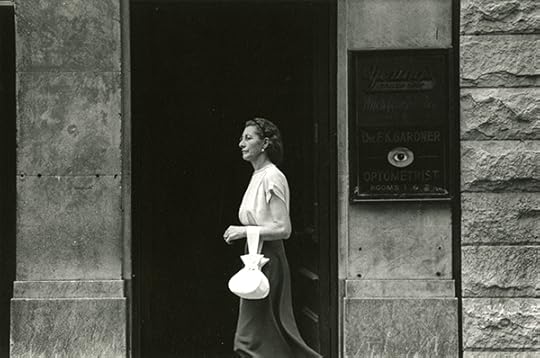

Harry Callahan, Asheville, North Carolina, 1951, 1951

© the Estate of Harry Callahan and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

The impact of Black Mountain College on the history of twentieth-century arts is still coming to light. A small, liberal-arts institution that ran from 1933 to 1957 in rural North Carolina, the school brought some of the most inventive minds of a generation—including European intellectuals fleeing the ravages of World War II—into contact with an intrepid student body that was ready to change the cultural gears of history.

The backbone of Black Mountain’s curriculum was the arts program, famously shaped and directed by Josef Albers from 1933 to 1949. Before coming to America, Albers had studied and taught at the Bauhaus, where he developed an understanding of Werklehre—the noble, “handicraft” aspect of art. He brought this pragmatic approach to his teachings at Black Mountain College. While at the Bauhaus, Albers created a series of semi-experimental photocollages (a selection of them is currently on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art). His interest in photography as an art and as a mode of seeing continued upon his move to the States. “Photography,” Albers once observed, “is still a child among the crafts”; indeed, its newness might well have been part of the medium’s allure for him.

Albers’s foundational classes at Black Mountain were by many accounts transformative. One of his students, Hazel-Frieda Larsen (later Archer), joined the school’s faculty in 1949 as the first full-time instructor in photography. Among her students, in turn, were several who would go on to become fixtures in the pantheon of American modernism: Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Stan VanDerBeek among them. Numerous photographic luminaries had teaching stints at the college, including Harry Callahan, Barbara Morgan, Beaumont Newhall, Arthur Siegel, and Aaron Siskind. The school’s focus on open learning processes led to intertwinings of disciplines and media; students of photography might well also be students of mathematics, poetry, architecture, weaving, or any number of other subjects and skills.

Although there is much ongoing scholarship and curatorial interest in Black Mountain College, the teaching and practice of photography at the school has received surprisingly little attention. Begin to See: The Photographers of Black Mountain College, curated by Julie J. Thomson for the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, is in fact the first survey exhibition of the school’s photography. The show includes images by students and teachers across the history of the school, from snapshots of the campus to portraits to experimental abstractions, as well as a trove of fascinating archival materials. Begin to See is accompanied by a catalog with informative essays by Thomson and by Michael Beggs, former researcher at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. I spoke with Thomson shortly after the opening of the exhibition.

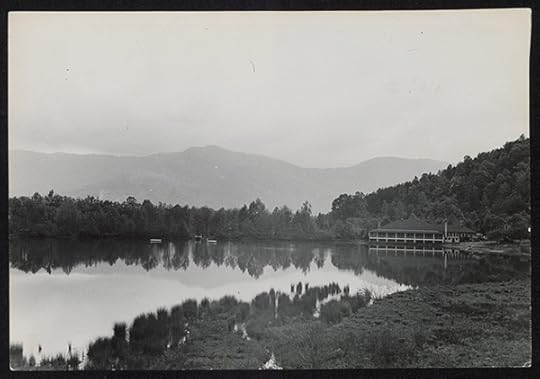

Will Hamlin, Dining Hall and Lake Eden, n.d.

Courtesy the Martin Duberman Collection, Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina and Christopher Hamlin

Diana C. Stoll: Under the initial guidance of Josef Albers, Black Mountain College emphasized the skill of seeing, starting at the most primary levels: color, form, matière (Albers’s term for textural and material interaction—a centerpiece of his instruction). Were all the school’s students exposed to these ideas?

Julie J. Thomson: The cultivation of seeing, and exercises that created the conditions for the development of seeing, were central to Josef Albers’s teaching.

Black Mountain College was a liberal arts school that placed the arts—visual art, drama, music, and dance—at the center of the curriculum. That didn’t mean that everyone was required to take art courses, although many did. The faculty and visiting artists gave evening lectures, which were well attended. Faculty members and their spouses could also attend classes, and even those who didn’t might hear about them during meal times. So there were many ways people were exposed to the ideas circulating.

The title of the exhibition was inspired by a description of Black Mountain College’s summer 1951 session, which focused on photography. It says: “The world is open wide to the photographer who can see. And one can never be bored if one can see.” This statement was one of many things that made me want to know more about photography at Black Mountain College.

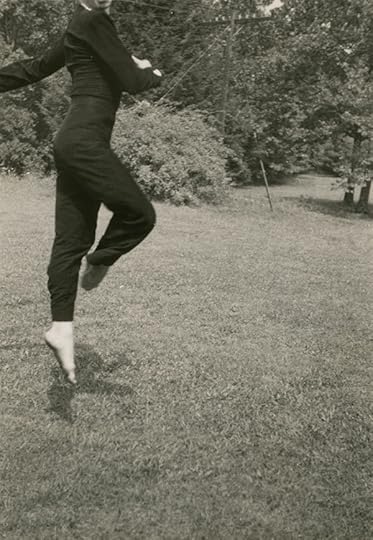

Jonathan Williams, Beauty and the Beast: Joel Oppenheimer and Francine du Plessix Gray, Black Mountain College, 1951

Courtesy Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Collection and Thomas Meyer

DCS: What role specifically did photography play in the drive toward visual intelligence at Black Mountain?

JJT: Seeing something and seeing it through a camera are different experiences. Photography offered a different way into seeing and learning to see. In his 1943 lecture “Photos as Photography and Photos as Art,” Albers spoke about how the camera sees differently than our eyes, and showed at least one example of how a camera flattens space. I think that many of the individuals who made photographs at Black Mountain College built on what they had learned about design and seeing (in Albers’s and Larsen’s classes) while experimenting with how the camera sees things too.

DCS: How was the photography curriculum formed at Black Mountain College—and how did it evolve over the years?

JJT: Photography began as an informal workshop in the 1930s, primarily with Albers offering students feedback. Early on, other photographers were invited to visit and give lectures or instruction, photograph the college, and sometimes show their photographs. In the late 1930s Black Mountain students—including John Stix and Claude Stoller—brought darkroom equipment and some knowledge of photography to the school; it seems that this helped lead to the formation of a photo study group. For other students, the opportunity to have conversations about photography, to borrow a camera, or to have access to a darkroom allowed them to discover, explore, and cultivate this interest.

It’s worth mentioning that Albers’s matière studies also had a relationship to photography: many of those materials were ephemeral, and so were documented with photographs.

In 1942 Albers wrote a letter to the editor at U.S. Camera magazine: he was soliciting work from photographers, but he was also letting readers know that photography was taught at Black Mountain College and that photography was considered part of the arts at the school. It was something he wanted a broader audience to know they were doing and teaching.

Then in 1943 at Black Mountain College, Albers gave the lecture “Photos as Photography and Photos as Art,” the most substantive record of his thoughts on photography, and his only lecture on the subject. Following that, starting in 1944, photography courses begin to be offered during the summer sessions.

In the summer of 1949 Hazel Larsen taught photography as a tutor, and that fall she was appointed to the faculty as the first regular photography instructor. The following year, she and four of her students produced Five Photographers [a booklet featuring photographs and statements by each of them]. Like Albers, Larsen was interested in cultivating students’ ability to see, to be attentive to what was around them. According to accounts from her students, she was an inspiring teacher—some even spoke of her teaching as spiritual.

DCS: You’ve divided Begin to See into sections: “Available Light,” “Performing for the Camera,” “Bearing Witness,” “Place,” and “Experimentation.” How did you shape these categories?

JJT: Of course, many of the photographs that I’ve selected could be viewed in more than one of the sections I’ve identified. I’m suggesting these themes—some of which are self-explanatory—as ways to look at these photographs, but I am wary of labeling them too strictly, because labels sometimes are limiting, and cause us to stop looking.

I see the photographs in “Performing for the Camera” as collaborations between photographer and subject. Jonathan Williams made a number of memorable portraits at Black Mountain that might fall in this category, including his 1951 image of fellow students Joel Oppenheimer and Francine du Plessix (later Gray). Oppenheimer bares his teeth at the camera and looks like he’s about to pounce, while du Plessix stands elegantly statuesque in the background with a sneer signaling disgust. It has become one of the iconic photographs of Black Mountain College. The “Place” images reveal photographers seeing and experiencing places in a way that allowed them to see and experience the larger world, and allowing us to see it through them. A wonderful example in the show is Harry Callahan’s 1951 Asheville, North Carolina. Callahan had photographed people walking on city streets starting in 1943 in Detroit, and would return to this theme throughout his life. When he came to Black Mountain to teach in the summer of 1951, he ventured into downtown Asheville, where he made a photograph of a woman walking in front of a door. The ovals of her bag, eyeglasses, and the optometrist’s sign echo one another; the folds of her skirt add to the sense of her being in motion. The composition is remarkable.

DCS: There’s an interesting overlap between Black Mountain College and the founding of Aperture in 1952.

JTT: There is. Aperture’s founding statement envisions a forum in which to communicate about photography and to share experiences. This was also the type of space Black Mountain College provided for photography and photographers.

Four of Aperture’s founders had connections to Black Mountain College. Barbara Morgan and Beaumont Newhall were invited to teach, and Nancy Newhall came with Beaumont; she provided photographic advice and worked with students. Dora “Dody” Harrison (Warren, later Weston Thompson), another of the founders, was a student in the 1940s. While her practice of photography began after her time at Black Mountain, she later acknowledged Albers’s classes as influential.

Beaumont Newhall lectured about the history of photography during the three summers he and Nancy were at Black Mountain College (1946, ’47, ’48); in 1947 he also taught a technical course in photography. Black Mountain gave Newhall his first experiences teaching at the college level. In 1947 and 1948, he was revising his 1938 book on the history of photography into what would become The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (published by MoMA in 1949). So the Black Mountain College community was one of the early audiences for his approach in that revised edition.

Hazel Larsen Archer, Merce Cunningham, n.d.

© Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and courtesy the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

DCS: We can’t talk about Black Mountain College without mentioning the summer of 1948, a synchronous gathering of creators, including John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, the Newhalls; and among the students: Ruth Asawa, Ray Johnson, Kenneth Noland, Arthur Penn, and Kenneth Snelson. Who was taking pictures that summer?

JJT: Each semester at Black Mountain College was different due to the people who were there, both faculty and students. In the summer of 1948, photographs were made by Albers, Larsen, Trude Guermonprez, Clemens Kalischer, the Newhalls, and Kenneth Snelson, among others. Rudy Burckhardt visited that summer also, at the encouragement of the de Koonings, and showed his city movies.

Sadly, there was a fire in the darkroom that September, and many of Larsen’s negatives were destroyed.

Hazel Larsen Archer, Ray Johnson (back of head), ca. 1947–48

© the Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and courtesy Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

DCS: Black Mountain College’s existence spanned World War II, and many of the school’s teachers (including Josef and Anni Albers) had fled Europe to the relative safety of rural North Carolina. In 1944—at the height of the conflict—visiting photographer Josef Breitenbach addressed the students, saying: “Photography is showing us the world in all its facets, conveying the insight necessary to understand our time.” Were there ways in which Black Mountain students contended with the politics of their time through photography?

JJT: People at Black Mountain College were very aware of political events—particularly those faculty members who had left Europe due to the Nazis. The school’s approach was deeply invested in the idea of democracy and democratic procedures. John Dewey himself said: “Black Mountain is a living example of democracy in action.” The faculty was interested in creating citizens and open minds that would engage with the world. I see this as leading toward a personal politics for individuals.

The beliefs and ideals formed while at Black Mountain College became part of the individual visions of the photographers, but perhaps in a more abstract than a directly illustrative way. In the Begin to See catalog, I discuss the concept of the “personal vision” of a photographer, which was something that both Albers and Breitenbach spoke about at Black Mountain College. It was this idea of achieving a personal vision that Albers used as a way to discuss photography reaching the level of art. This personal vision, combined with the camera as a way to experience the world, can lead to remarkable photographs.

Diana C. Stoll contributes regularly to Aperture Online. She edits books for Aperture, the Museum of Modern Art, and other cultural institutions, and is the co-author of The Desert and the Cities Sing (Chronicle Books, 2016).

Begin to See: The Photographers of Black Mountain College is on view at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville, North Carolina, until May 20, 2017.

The post Learning to See: Photography at Black Mountain College appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 16, 2017

Robert Cumming Invents the Photograph

Constructing sets that look functional but are intentionally useless, an artist parodies the seamless illusion of images.

By Sarah Bay Gachot

Robert Cumming, Watermelon/Bread,1970

Courtesy the artist

In the early 1970s Robert Cumming spent a lot of time in movie memorabilia shops in Hollywood. These shops—filled with flotsam and jetsam from the classic era of Hollywood cinema—were a curious brand of cultural repository for the young artist from Massachusetts, schooled in the Midwest. Cumming honed in on studio photographs, 8-by-10 black-and white contact prints commissioned in the name of maintaining continuity between scenes, or for testing particular hairstyles or wallpaper samples. The slightly battered stills—bent, inked with notes, and often hole-punched—were nonetheless beautifully photographed, and they had infinitely more detail than the movie-goer ever saw onscreen, as images traveled by at twenty-four frames per second.

Cumming was discovering the curious language of film illusion. A small set light tucked into a corner of an otherwise domestically tepid living room; dolly tracks installed on a wooden platform leading up to a bucolic indoor “marsh” of ferns, grasses, and pine trees surrounding a canoe; a crewmember caught adjusting a fake pine bough on a tripod at the edge of the frame (his ghostlike arm blurred from the long exposure). Cumming wondered: Why in the world did they have to construct that entire marsh for that canoe indoors? That’s some pretty intense work when they could have just gone outside…. The photographs were certainly strange enough to pay attention to, and soon he was buying stacks of them for twenty-five cents apiece. Years later, he would say that it was stills like these that inspired him to dissect the mechanics of photographic perception.

Robert Cumming, Quick Shift of the Head Leaves Glowing Stool Afterimage Posited on the Pedestal, 1978

Courtesy the artist

As a painting student in the 1960s, one of Cumming’s influences was Robert Rauschenberg, whose paint on canvas with collage, then photo-silkscreens and three-dimensional Combines, Cumming took as some of the fuel that drove him to study photography and printmaking. Later, as an MFA student at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, he took courses with photographer Art Sinsabaugh, known for his work with the massive 12-by-20-inch “banquet” camera.

Soon after receiving his master’s degree in 1967, Cumming moved into three dimensions completely, and began by teaching himself a variety of sculptural practices. He made constructions that were functional-looking, but were intentionally useless; they often involved piping, threaded aluminum, hooks, hinges, and grommets on cotton duck, burlap, and canvas. (Few survive, but they look terrific in photographs.) He bought an 8-by-10 view camera in 1968—captivated by the precise detail of the large negative (echoes of Sinsabaugh)—and made use of that unwieldy beast to document his three-dimensional work. Soon enough, he was creating those sculptures for the camera, rather than to exhibit on their own.

Robert Cumming, Institutional Faucet, 1971

Courtesy the artist

His photographs from the 1970s are a parody of the seamless illusion of film: he leaves subtle “tells” in the frame that reveal his mechanics—intentional mistakes and offscreen tools appear in the image. What unravels lets loose far more absurdity than a set light, paper fern, or plaster rock betrayed in an 8-by-10 studio still. In the diptych Decorator Test (1974), a visual cacophony of stripes covers a corner of wallpaper, floorboards, and steps. A swatch of more pattern is clamped to a tripod—Cumming’s riff on the professional photographer’s test target, used to gauge how accurately a camera depicts reality. Looking closely, however, one sees that this is not reality at all: the “wallpaper” glistens and buckles like plastic-adhesive shelf liner in the upper-left corner; the baseboard is just two flimsy pieces of wood, one wide and one thin, leaning up against the wall. Cumming wanted the viewer to get to know, personally, the process of perception—perhaps to ward off the onset of visual inertia. The pictures unfold slowly over time; the more you look, the more you see.

French philosopher Hubert Damisch mandated in his 1963 essay “Five Notes for a Phenomenology of the Photographic Image” that a true artist should never fall prey to the artificiality of photographic illusion. According to Damisch, photographs were not really “invented” in the early nineteenth century; the camera obscura had existed for centuries, and the lens even longer. It was the desire to fix the image that was new—a latent image was revealed, developed, and preserved; it wasn’t magic: lenses and cameras complied to a spatial system dependent on distance and curvature of glass. Cumming was highly sensitive to these mechanics—for instance, the ability to transform a three-dimensional object with heft and depth into a flat representation. He celebrated this as a skill to be learned and exploited, rather than subverted as opaque—to simultaneously maintain and destroy illusion and quirks of vision with photography.

Robert Cumming, Decorator Test (detail), 1974

Courtesy the artist

Cumming illustrates what one thinks one sees in a glance when an involuntary imagination ruptures reality: a silhouette of a cactus for a rabbit head, for example (as in Theatre for Two—Easy Analogies, 1978), or paper towels from a dispenser as pages on the platen of a typewriter (Institutional Faucet, 1971).

Cumming’s images undermine the idea that a photograph, upon first glance, is as reliable as anything that reaches the unique receptors leading to our sensorium—eyes, nose, ears, mouth, skin, the liminal areas between the world around us and the world of cognition. He explores the moment of seeing, and delivers us wildly imagined permutations of the moment that follows: when perception is either uncontrollably, automatically processed or mistakenly processed based on remembered experience. But always with a robust and fathomless imagination.

Sarah Bay Gachot is an independent curator, writer, educator, and artist living in Los Angeles, California.

Read more from Aperture Issue 211, “Curiosity,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Robert Cumming Invents the Photograph appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 15, 2017

Erotic Voyeurs of Japanese Photography

Three celebrated photographers push the limits of sexuality and surveillance.

By Russet Lederman

Kohei Yoshiyuki, Untitled, from the series The Park, 1971

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

What may seem erotic and even offensive in the West is viewed quite differently in Japan. A naked body does not always suggest sexuality or eroticism. Sometimes it invites voyeurism. By pairing Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama, two icons of Japanese photography, with the lesser-known Kohei Yoshiyuki, Acts of Intimacy: The Erotic Gaze in Japanese Photography, currently on view at The Walther Collection, invites New York audiences to contemplate personal and cultural definitions of intimacy and eroticism—subjective concepts that shift as the exhibition unfolds.

In the early 1990s, Nobuyoshi Araki gave the legendary photographer Robert Frank a handmade notebook of photographs during Frank’s visit to Japan. Later editioned as a series, 101 Works for Robert Frank (Private Diary) (1993) is the first work one encounters upon entering Acts of Intimacy. Presented in two closely gridded chronological rows that snake across the front section of the gallery and into a smaller side room, these intimately scaled prints—all date-stamped at the lower right corner—offer an encyclopedic view of Araki’s expansive visual vocabulary.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled, from the series 101 Works for Robert Frank (Private Diary), 1993

Courtesy The Walther Collection

Included are Araki’s typically notorious images of nudes, couples having sex, and provocatively bound women. But we also discover tender images of his cat, Chiro, the back terrace of his apartment, cityscapes, urban crowds, and cloud-filled skies. One of the last images is entirely black, except for the date stamp. Photographed from 1992 to 1993, using a snapshot aesthetic, these images mark Araki’s emergence from a long period of mourning following the death of his beloved wife, Yoko. There is eroticism here, often calculated to enhance Araki’s carefully crafted public persona as a photographer-provocateur, but the overriding perspective is the beguiling voyeurism of Araki’s private world made public.

Voyeurism creeps more aggressively into the show, and shifts our understanding of both Araki’s and Moriyama’s works, as Kohei Yoshiyuki’s series The Park (1971–79) comes into view. In comparison to Moriyama and Araki’s decade-spanning careers, Yoshiyuki’s fine art photography career is extremely short and based on this one series. Primarily a commercial photographer, Yoshiyuki stumbled upon the bizarre subject of hidden sexual encounters while out on late night walks in Tokyo parks. Armed with a 35mm camera, infrared film, and flash, Yoshiyuki’s images show straight and gay couples engaged in secretive sexual activities in the parks’ dimly lit areas.

Kohei Yoshiyuki, Untitled, from the series The Park, 1972

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

One wouldn’t think much of these grainy photographs, which were first published in the weekly tabloid Shukan Shincho, and decades later as a book, except that within view are groups of voyeurs who circle the couples. Yoshiyuki spent months befriending these spectator-participants, pretending to join them as they clandestinely observed the amorous trysts of unaware couples. The voyeurs’ extreme behavior, which often included attempts to touch the couples, reveal an aberrant underbelly that contrasts with polite Japanese social norms. What proves the lasting intrigue of these images—which some have suggested might be “yarase,” a Japanese journalistic practice of presenting elaborately staged images for the express purpose of selling magazines—are the layers of voyeurism and surveillance they suggest: The park voyeurs watch the couples, Yoshiyuki watches the voyeurs, and the gallery viewer watches all.

Daido Moriyama, Untitled, from the series a room, 2015

Courtesy The Walther Collection

Moriyama, largely celebrated for his grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus urban aesthetic, is less often associated with eroticism. But for those who remember his Eros photographs, first published in 1969 in the seminal postwar Japanese photography journal Provoke, the sixty-seven images shot from the 1980s to the present in Moriyama’s series a room (2015) suggest a revisit to familiar territory. Filling the gallery’s back wall in a tight grid, a room, as with Eros, depicts nude women posed against rumpled sheets in the privacy of a bedroom space. Among the fragmentary views of exposed breasts, splayed legs, and skirts lifted to reveal various styles of women’s underwear, there are also images of overflowing ashtrays, stuffed animals, and ordinary household trappings. When viewed within the shadow of Yoshiyuki’s The Park, a room feels like peeking into a neighbor’s home from a window across an alley.

In his essay that accompanies the exhibition, curator Christopher Phillips points to Japan’s long history of publishing sexually explicit imagery. But the shifting of readings—from eroticism to both fetishistic and mundane voyeurism—gives Acts of Intimacy a more fluid and nuanced reading than the subtitle “the erotic gaze” suggests. Context is everything. The inclusion of Yoshiyuki acts to broaden our understanding of Moriyama and Araki, and reframes all three series within contemporary debates about pervasive surveillance, and the spectacle of private moments shared on public platforms.

Russet Lederman, a researcher and writer, teaches art writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Acts of Intimacy: The Erotic Gaze in Japanese Photography is on view at The Walther Collection, New York, through April 2, 2017.

The post Erotic Voyeurs of Japanese Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 14, 2017

Redefining the Image of Black Masculinity

In our recent Instagram contest, Aperture asked photographers to submit images that redefine the black male experience. Inspired by the prolific, Jamaican-born street photographer Ruddy Roye, who has collaborated on their #BlackMaleReimagined project, the contest was organized with the Campaign for Black Male Achievement, a national network that seeks to improve the lives of black men and boys in the U.S. In a recent interview, Roye, who was also featured in Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, spoke about the importance of complicating the visual narratives surrounding black men. “When I first came to this country, I met all of these stereotypes: That black men were never fathers, we were never teachers or educators,” Roye said. “By showing these images, I inspire other other black men to say, ‘I can be that person.'”

Here are the winners of the #BlackMaleReimagined contest, selected by Ruddy Roye together with Aperture’s editors, and accompanied by each photographer’s personal reflections.

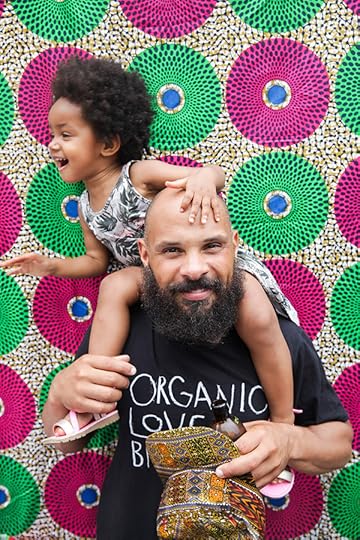

Ken McFarlane, Erik & Erik II, Philadelphia, PA, from the series From the Root to the Fruit, 2016

Courtesy the artist

“Despite the ongoing narrative that black men are absent from the home, I have intimate knowledge of a different narrative. My grandfather was in the home with my father. My father was in the home with me, and I am in the home with my son. I’ve known Erik, an entrepreneur and business owner in Philadelphia, for a number of years. When I met his son, Erik II, the reflection of father in son was so bright that I knew I had to add their reflections to my project From the Root to the Fruit. My mission was not to reimagine the black male, but to reclaim the image of the black male. We have the power to shape our own collective image in our own authentic reality. We can amplify our voices using images of strength, dignity, pride, and success to drown out the cacophony of negative imagery surrounding the black body.” —Ken McFarlane (@365ken)

Christian Padron, blindé, Los Angeles, CA, 2017

Courtesy the artist

“My friend and I had been discussing the idea of masking pain. Tendencies toward denial, withdrawal, and self-isolation are common in reaction to deeply felt emotional pain, especially for black men at this current time. My friend—the subject in the image—even discussed feeling trapped in his house sometimes because of events happening across the country. I tried to capture a creative way of representing this isolation. The title of the photograph, blindé, translates to ‘shielded’ in English. I think these images matter today to provide more accurate context for the black experience. It’s important to debunk stereotypes and create new definitions of black manhood that include emotional responses to trauma and pain.” —Christian Padron (@gangitmo)

Brandon Stanciell, Thinker of Tender Thoughts, Skid Row, Los Angeles, CA, 2015

Courtesy the artist

“The vision for this picture was influenced by a poem, ‘Thinker of Tender Thoughts,’ by Shel Silverstein. In the poem, a man appears to have flowers growing from his hair, and when he approaches society, they laugh at him. He then goes back home and cuts the flowers off his head. In this portrait series, I encourage the viewer to keep the flowers growing. It’s easy to have your ideas and yourself be tainted by the opinions of your peers, but don’t let it destroy you. People these days have this idea that all black men are hypermasculine, aggressive human beings, when we’re not. We feel, too. We cry, too. It’s okay to look soft, it’s okay to be soft. Images like this help people to see black men in a more sensitive and relatable setting.” —Brandon Stanciell (@themanwholovedflowers)

Honorable Mentions

Craig Bernard, from the series #SWEATANDHYPE, Notting Hill Carnival, London, 2016

Courtesy the artist

“The picture is from a project I’ve been working on for a while called #SWEATANDHYPE. It’s from London’s Notting Hill Carnival, which has been going on since the early 1960s. I’m a chef by trade, and when I have time, I go out and make pictures. This past year, it’s been quite unstable politically and socially. I responded to this by taking my camera to various marches and protests in London. There have been several marches under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter, antiausterity, anti-Trump, and many others. When I made this picture, I saw two people embracing. It wasn’t until a few days later, when I was editing, did I realize that there was maybe a bit more weight to the picture—a relevance to the times, you could say, in terms of black men and black women coming together, and that fear of having that togetherness cut short because your life is seen as having a less-than-positive relevance. Maybe the #blackmaleimage can include black women.” —Craig Bernard (@craigobernard)

Richard Louissaint, Okai and Naima at La Caye during BAM DanceAfrica, 2016

Courtesy the artist

“Okai is a friend and musician I have been documenting for a while. This picture came about spontaneously, as I had set up a photo booth as part of From Haiti to Africa last year during the BAM DanceAfrica street festival. He came by with his wife and daughter. Given that his daughter is a ball of energy, getting her to pose was difficult, so I just grabbed three frames and this one stuck out the most. This is the image of men I see in my life—cousins and friends with their sons and daughters enjoying their time. Mainstream media has shifted very little in its portrayal of black men. You have to look to alternative programs and online to find nuanced portrayals, or to a film like Moonlight that breaks through and was created by a person of color.” —Richard Louissaint (@haitianrich)

Dana Scruggs, Vince Harrington, 2014

Courtesy the artist

“I’m enamored with capturing black men and the black male form. As a black female photographer, I thought that I would have a unique perspective to contribute. There aren’t as many of us working and being recognized in comparison to white male (and female) photographers that dominate the art, commercial, and fashion photography industries. The idea that black men are violent, lazy, and absent as fathers is a stereotype that permeates our society. The belief that they are different and less valuable is the reason why black men (and women) are being killed by the police at higher percentages than any other demographic. Creating positive depictions of black men is important because, essentially, we need to reimagine the black male experience for people who’ve only viewed it negatively.” —Dana Scruggs (@danascruggs)

Joni Sternbach, 09.08.24 #4 Len, Montauk, NY, 2009

© Joni Sternbach

“In my series Surfland, I often go to beaches and randomly meet people who are curious about my project and agree to be photographed. Len was one. We met by chance at Radars, a surf break in Montauk, in 2009, and he agreed to participate. Images of black male surfers are scarce and rather unconventional, even in this day and age. In addition, breaking stereotypical molds of who is a surfer is important. So much of our world is defined by imagery, and beliefs are often reinforced that way. Creating ambitious and positive imagery of black men puts the word out there.” —Joni Sternbach (@jstersurf)

The post Redefining the Image of Black Masculinity appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 9, 2017

After the Avant-Garde

How has feminist photography changed since the 1970s?

By Isabel Stevens

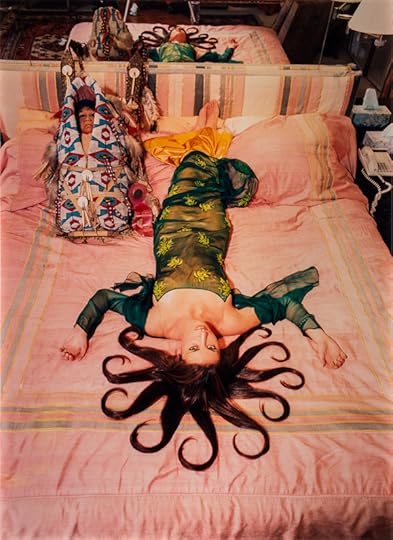

Daniela Rossell, Medusa, from the series Ricas y famosas, 1999

© and courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

“Normally my museum tells a sad story,” Kathryn A. Wat, chief curator of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C., told me last month. She was preparing to open a new exhibition from the museum’s collection, Terrains of the Body, at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Historically, Wat said, women painters and sculptors fought for success against huge odds. “But in photography, it was different. Women were working in the medium from the very beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. I’m interested in that trajectory.”

After an American presidential election campaign rife with misogyny, and with racism and nationalism on the rise in Europe, Terrains of the Body, which features work by an roster of international female photographers and is drawn entirely from the NMWA collection, feels as relevant as ever. For those with any doubt as to why exhibitions like this and museums like the NMWA are still necessary, I recommend a dip into the Guerrilla Girls’ investigation downstairs at the Whitechapel. Their poster exhibition presents data the anonymous feminist activist group gathered in 2016 from the 101 European museums and art spaces that answered their questionnaire. (282 declined.) One sobering statement looms large: “Only two museums have 40% or more women artists in their collection.”

Hellen van Meene, Untitled (79), 2000

© the artist and courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery

Several recent exhibitions in Europe have thrown the spotlight on women photographers. Seeking to rewrite a more inclusive official history, the surveys Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, in 2015, and the more intensely thematic compilation The Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, traveling in Europe for several years and recently presented by the Photographers’ Gallery in London, make a persuasive case not only for gender-specific exhibitions but also the ongoing need for gender parity in institutional collecting. (Marta Gili, Julie Jones, Roxana Marcoci, and Nancy Princenthal discuss these ideas in Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue.)

Terrains of the Body is different. First of all, the photographers include acclaimed contemporary artists such as Shirin Neshat, Rineke Dijkstra, Candida Höfer, Anna Gaskell, and Hellen van Meene. The powerful position of these artists in today’s museums and art market is in stark contrast to the relative anonymity of their forbearers in The Feminist Avant-Garde (Cindy Sherman and Francesca Woodman aside), which emphasizes just how much has changed in the last forty years. And then there are the images themselves. Whereas the photographs made during feminism’s second wave are often characterized by their violence, defiance, and all-out badass nature, the work of the contemporary photographers in Terrains of the Body is more dreamy and surreal. Justine Kurland’s Edenic images of women in nature, for example, have an otherworldly feel to them. Meanwhile, Anna Gaskell’s vision of a pair of legs upside-down in a tree could be straight from a fairy tale, as could Janaina Tschäpe hallucinatory bedroom scene of a woman with a strange, balloon-like hand.

Nan Goldin, Self-Portrait in Kimono with Brian, NYC, 1983

© and courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

“I think this dreaminess came out of an impulse in the 1990s of developing a narrative, a story, which would let you do almost anything,” Wat said. “These women are building whole new worlds, they’re selecting locations and finding costumes and controlling their imagery.” Reclaiming the female body, wresting it away from entrenched notions of what it should look like and how it should behave, is still a vital activity for these artists. Hellen van Meene hunts the streets for ordinary teenage girls to photograph. “These girls aren’t the ‘perfect’ size. I’m not interested in a simple beautiful picture. You see that and forget it,” van Meene explained.

Marina Abramović, The Hero, 2001

© Marina Abramović Archives

Feminism in this exhibition, and in many artists’ work today, is not as easy to define as it was forty years ago. It’s implicit in Candida Höfer’s vast interior of a Venetian palace—look closely and you’ll spot Höfer’s tiny reflection in a mirror. It’s explicit in the duo Mwangi Hutter’s photographs Shades of Skin (2001). “She’s being very pointed in the critique that she’s making as a young woman who emigrated from Kenya to Germany and who experienced racial discrimination,” Wat said of Ingrid Mwangi, who works collaboratively with her partner, Robert Hutter.

Wat and Whitechapel curator Emily Butler conceived of Terrains of the Body as an “extension” of that earlier era, with the key figures of Marina Abramović and Nan Goldin forming the bridge. When Wat was researching the exhibition, she also noticed a desire among the artists in the NMWA collection to fragment the body. Three artists—Shirin Neshat, Mwangi Hutter, and Adriana Varejao—all isolate hands, specifically. “There’s something very particular about Shirin Neshat’s use of a hand,” Butler noted. “In Iran, it’s one of the only parts of a body that a woman may show.”

Shirin Neshat, On Guard, from the series Turbulent, 1996

© the artist and courtesy the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Neshat’s work is chillingly urgent. As I write this, protests across the United States and in London are taking place against the discriminatory travel ban that the Trump Administration has imposed on refugees and nationals from seven Muslim-majority countries, including Iran, Neshat’s birthplace. A few weeks ago, millions of people across the world participated in the Women’s March.

But what now? Now we need more: More female photographers in institutional and private collections; more exhibitions and books exhuming forgotten figures; more solo exhibitions to present their work in depth. As Mwangi Hutter and Shirin Neshat in Terrains of the Body, and Lorraine O’Grady and Ana Mendieta in The Feminist Avant-Garde remind us, there needs to be a broader platform for female photographers of color, and for all artists and work to addressing marginalized perspectives. And how about exhibitions across the United States of photographers from the seven banned countries? That, too, would be a start. In the words of Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, it’s time to make more noise.

Isabel Stevens is the production editor of the film magazine Sight & Sound.

Terrains of the Body: Photography from the National Museum of Women in the Arts is on view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, through April 16, 2017.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post After the Avant-Garde appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers