Aperture's Blog, page 120

March 28, 2017

Publisher Profile

TBW Books

Matthew Leifheit in conversation with Paul Schiek

So often in art—as in life—the decision to prioritize someone else’s dreams, even temporarily, is looked at as if it means one’s own artistic vision and conviction may be wavering. Paul Schiek, a photographer and independent publisher based in Oakland, California, has been curating, writing, and publishing under his imprint TBW Books, in addition to making his own photographs, for the past ten years. He seems to see this varied outpouring as a medium in its own right. His generous vision is perhaps most evident in TBW’s Subscription Series, an annual set of four distinct books that share a common format and design. The series acts like a less ephemeral form of periodical: evolving, sequential, and malleable. Specifically, TBW’s Subscription Series brings to mind Wallace Berman’s Semina—not only because that was also a Bay Area publication that brought together disparate artists under a sort of hand-hewn umbrella, but because Berman himself was an artist bashful about showing his own work. Over the course of an hour in early September, Paul Schiek and I talked about the evolution of TBW Books in relation to his life since 2006.

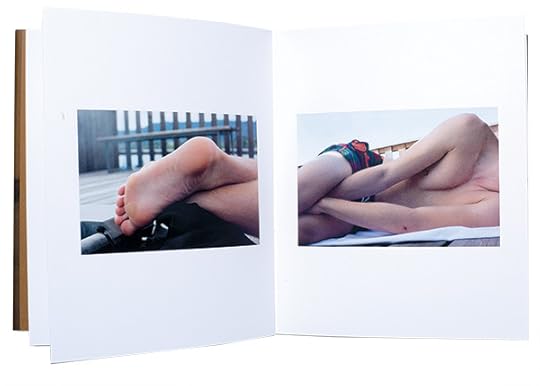

Subscription Series No. 4

Includes Christian Patterson, Bottom of the Lake; Alessandra Sanguinetti, Sorry, Welcome; Raymond Meeks, Erasure; and Wolfgang Tillmans, Utoquai • TBW Books • Oakland, CA, 2013

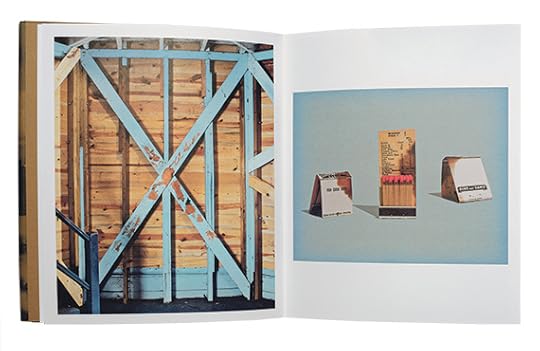

Christian Patterson

Matthew Leifheit: So, the big question: why publish books?

Paul Schiek: I did my undergrad at California College of Arts and Crafts [now California College of the Arts]. I studied under Jim Goldberg and Larry Sultan, and another guy named Abner Nolan. All three of those people had a profound impact on my thinking about photographs and why I make photographs today. We looked at books a lot, and we talked about books, and thought about books. There were classes dedicated specifically to photobook-making, which were really shape-shifting for me.

ML: Had you published zines previously?

PS: I came up in—I hate to use the term—the “punk” world. I grew up being around zines, collecting zines, making little zines. As I was around music, I was taking photos with point-and-shoot cameras. I had no idea what I was doing, but I was taking pictures of what was happening around me and then making things with them. Then, in my senior year at CCA, rather than hanging a show—which was our requirement for graduation—I asked Jim and Larry if they would agree to me publishing a book instead. I thought that was a much more responsible way of distributing my work, because no one knew who I was. No one had any interest in looking at my photos in a gallery setting. The book was called Good By Angels. I had to edit it down to a really concentrated set of images because I couldn’t afford to print five hundred pages. I didn’t have the money for a cover, so I decided to hand-stamp each cover with a rubber stamp. I had watched friends who were in bands do that with their records. It just made a lot of sense to me. Since photography was becoming my medium, I started applying those practices to making books.

ML: When was the first time you thought of publishing someone else’s work?

PS: After school spit me out into the world, I tried to figure out what I was doing. I was making photos, and I wanted to show them, but didn’t know who the audience would be. So that’s when I came up with the idea of the Subscription Series, which was simply to align my work with the work of three other artists. If people were interested in any of the work, then they’d see it all by default. Because they’d subscribed to this thing that’s four books, even if they only wanted one or two of the books, they’d also be forced to look at the book of my own work as well. So that’s how the Subscription Series started. It was a tool, a mechanism, to create a space for people to be exposed to my work.

ML: That method also benefits the other less famous artists you publish.

PS: Yes. By Subscription Series No. 2, I felt that my work couldn’t be in it again. So I started getting other photographers to participate.

We just finished Subscription Series No. 5, which we’re very proud of. Every body of work included is over thirty years old but has never been shown before. We’re also starting to focus a bit more on special editions and singular, one-off monographs. I no longer have much interest in showing my own work; I’m way more excited and fulfilled by working on editing other people’s work, and bringing their ideas to fruition. It’s this evolving sort of thing.

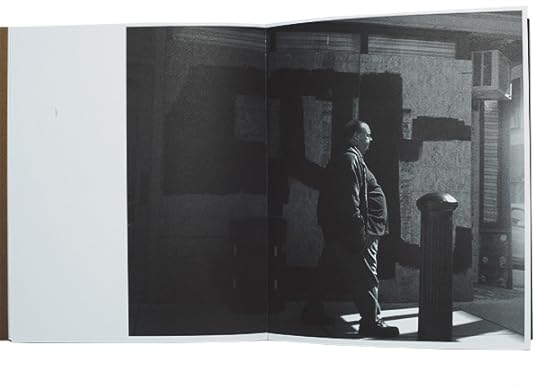

Raymond Meeks

ML: I don’t think that’s a lesser art than going out and taking pictures, actually.

PS: I was taught by Jim and Larry that the actual making of photographs is only 50 percent of it, and the other 50 percent are these small, very deliberate decisions that you make about presentation, editing, sequences, paper choices, installation—all these crucial things that, in certain cases, the photographer might not be good at. They shouldn’t necessarily be expected to be good at all those things. That’s why it’s important for publishers, editors, and designers to be able to step in and round out the project.

ML: How has the Subscription Series evolved?

PS: In the beginning, it was me approaching people I was interested in working with, or friends would introduce me. To this day, reputation and personal relationships with people are a huge factor. It’s also the way I like doing business. I’ve certainly reached out to people I want to work with, and as you know, there are a million e-mails involved. These things take a lot of time on the part of the publisher, and there are people who I started working with four years ago who I might just be publishing now. Sometimes it takes that long for it to gel and get to a place where everybody is comfortable. That’s how this stuff works. In the meantime, my job is to make a better product—become a better editor, publisher, and designer—so that people will continue to trust me.

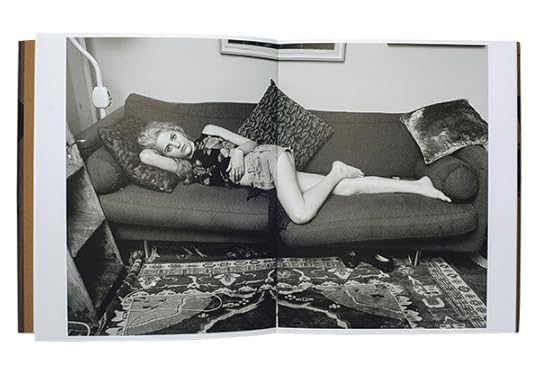

Alessandra Sanguinetti

Wolfgang Tillmans

ML: You’re not just asking people to send you some files—you want to work with artists very closely.

PS: I’m very, very close to the process, out of respect for the book and the artist’s time, but also out of respect for myself and my time. Going back, it was always a dream of mine that doing a studio visit with someone and editing a book with them could be a job. Now I do a lot of different things in the photo world under the umbrella of TBW, and I have a full-time employee, Lester Rosso. I’m really proud that there are two of us working full-time on publishing now.

And so, if I’m just treating it as a business, yes, it’s much easier for me to ask people to send us the files and we put out the book and it’s done. But for me to be fulfilled and stimulated and feel like I’m doing the best job I can do with these books, I need to work as closely with the artists as possible. I enjoy packing orders, I enjoy sending e-mails, I enjoy choosing paper and being on press. I enjoy running to the post office to get more stamps. All the minutia that it takes to run a business—as long as it’s a business that’s surrounded by photography—I’m happy to do. But the most important part of that is getting to work with the artists. When you’re working with an artist, you can have dinner together, they might stay at your house, and then you fly together to do a signing. All those things that some people might call work are, to me, very luxurious. Because there are a million other shitty jobs out there that you can do, and if you’re not doing those and instead you’re talking about photography with another artist and sharing ideas—talking about what photos actually mean to them—that’s a luxury. And that’s why I need to stay super-close to this.

Matthew Leifheit is a photographer, curator, publisher, and interviewer currently studying photography at the Yale School of Art. He has published MATTE magazine, an independent journal of contemporary photography, since 2010. He is also photo-editor-at-large for VICE magazine. matthewleifheit.com

The post Publisher Profile appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Editor’s Note

Denise Wolff

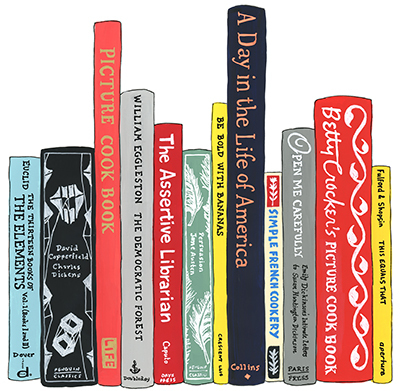

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #968: Denise Wolff

The essential goal of publishing is to make public. But when publishing photobooks, who do we consider our public to be? This is a question I ask myself a lot in my work as an editor: who is this project for and how do we reach them? What many would consider a photobook, those who read this publication might not recognize as such.

As I write this, the top “Photography & Video” book on Amazon is Pumpkin: The Raccoon Who Thought She Was a Dog (2016). The title says it all. A wall calendar is also available! Also in the top ten is a book called People Knitting: A Century of Photographs (2016)—another book whose topic is self-evident and which, I must admit, I’ve added to my cart. Meanwhile, on photo-eye, the top-seller this week is Ron Jude’s Vitreous China (2016), which I bought at the New York Art Book Fair and recommend highly. It is a lovely, unassuming object—delicate, saddle-stitched pages, contained in a gray paperboard clamshell box—with Jude’s pictures of industrial areas in midwestern American cities, accompanied by raw, moving text vignettes by Mike Slack. It was printed in an edition of 375 copies. photo-eye’s other top-sellers include some self-published titles. This snapshot comparison between Amazon and photo-eye reveals that our community exists worlds apart from the greater public. We live in our own photobook bubble.

I may be inside that bubble, but I am also interested in how to make photobooks public, and reach a wider audience. My first experiences of photobooks were the books about life under the sea that we had around the house because of my grandfather’s interest in diving. (In fact, he was the inventor of saturation diving.) As a child, I loved entering the underwater world of corals, sharks, and shipwrecks. I also vividly remember when my mother brought home A Day in the Life of America (1986), and how captivated I was by the different lives and livelihoods across my country, all captured in a single day, morning to night. These mass-market and special-interest books probably shaped my abiding interest in photography more than The Americans did. As a student, another early favorite of mine (a “real” photobook) was Eggleston’s The Democratic Forest (1989)—given to me by a friend, Darius Himes, when I was first learning photography. I was astonished to discover that anything could become subject matter for the camera. These first loves continue to impact what I commission for Aperture now—books like The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip (2014), The Photographer’s Playbook (2014), and the forthcoming Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography (2017). I hope they reach not only the photographic audience, but also a wider public, allowing them to encounter and engage with photography.

This issue is about the accidental photobook— books that use photos, but are not generally awarded the status of photobook proper. As we were putting it together, I discovered that almost everyone in our community had a favorite book in this category that they were eager to share. I am delighted that these humble, unlikely photobooks share these pages with the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist, reflecting the kind of divide I describe above. I hope this collision reminds us how democratic, how generous, how expansive both the medium of photography and the form of the book really are. Enjoy.

Denise Wolff is a senior editor at Aperture. Some recent books she has commissioned include The Photographer’s Cookbook (2016); The Photography Workshop Series books; and Seeing Things (2016), a children’s book by Joel Meyerowitz.

Jane Mount (illustration) makes things for people who love books. idealbookshelf.com

Image credit: Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #968: Denise Wolff

The post Editor’s Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Witness: LaToya Ruby Frazier in Conversation with Kellie Jones

In photographs from Selma to Flint, the unfinished work of the civil rights movement.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Shea Cobb with her daughter, Zion, and her mother, Ms. Renée, outside the Social Network banquet hall, 2016, from the series Flint is Family

Courtesy the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome, and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

Kellie Jones: Let’s start with your 2014 book, The Notion of Family. Did the popularity of The Notion of Family surprise you, especially given the subject matter? Members of your family have been supportive and willing subjects. Sometimes in such exposés we might feel victimhood. How have you crafted your approach differently?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Initially, when I started The Notion of Family, I knew that I needed to make something on behalf of my relationships with my mother and my grandmother, and something that was for me.

Growing up in the 1980s in the Rust Belt in Braddock, Pennsylvania—a time when cities are shrinking, all the factories have been outsourced, all your social services have been cut, the schools are closed, the library is barely functioning—I was already dealing with an invisibility complex. And I didn’t really understand why we were next to this factory, caught in the shadow not only of the Edgar Thomson steel plant, but also caught in the shadow of Andrew Carnegie. What does that mean to have to measure yourself, or try to be seen, through an industrial capitalist?

Even though I was a teenager and I didn’t have the language to articulate what I was seeing, I knew that I was dealing with shadows and invisibility, and dealing with toxicity and pollution, and then dealing with three generations—or really four, but I didn’t meet my grandmother’s mother—of women who grew up in three different social and economic periods. For my grandmother growing up in Braddock in the 1930s it was very different, because it was a bustling melting pot. None of us are fully black, but we’ve led our lives as black women. Then my mother growing up during the 1960s period of segregation, and then myself growing up there in the 1980s during the “war on drugs” and the abandonment.

The Notion of Family is the book of speaking to my younger self as an adult now, understanding what I know now, but also the coming-of-age story of what it means to grow up in a postindustrial, post-Fordist society, and the post-Reagan era. And what does it mean to be a black woman, inserting yourself, talking about the politics, talking about the toxicity, talking about industrial capitalism?

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Mr. Jim Kidd (Campaign for Braddock Hospital; Save Our Community Hospital), 2011

Courtesy the artist, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome, and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

KJ: How was it collaborating with your family?

LRF: It’s a precarious situation. Grandma didn’t like to be photographed. She always said, “Go photograph yourself.” That’s what caused me to start doing self-portraits. My mother, as soon as I came in with the camera, instantly had ideas. But a lot of it revolved around surgery or operations, or having cancer removed from her breast, or just coming out of the hospital, and the same thing for my grandmother, except I didn’t realize that she was dying from pancreatic cancer, because she never said anything. And I’m trying to figure out who I am between these two women, but at the same time our bodies are deteriorating in the landscape, because the three of us all have terminal illnesses.

KJ: Has your practice always combined issues of environmentalism and race?

LRF: When you’re a teenager making portraits, you don’t realize that. You’re just taking the class, trying to get the composition and the formal language. But it became very clear to me the day I went into the Carnegie Library. I pulled out this book, Braddock, Allegheny County. I took it back to my studio, and I’m turning through the pages. I knew the editor. I knew everyone who contributed to it. I knew everyone who wrote for it. And I got to the end and there wasn’t a single African American in this book. And it was published in 2008 and I just couldn’t understand how that was possible. So here I was innocently, quietly making these portraits of my mother and grandmother, and then it all changed when I saw the book. And it hit me: Okay, this has a bigger significance. This is not about you. You’re in it, but really you’re talking about how to rectify the fact that a large population of people has been omitted and erased from history, and continually silenced. So I felt intimidated by it, but I also was so outraged by it. I had a bigger mission.

And that’s when The Notion of Family started to come into my mind, thinking about The Family of Man and what that show meant to American history, and the timing of the show in 1955, and thinking about Emmett Till being killed months later and the power of that photograph, and how images do spark memory, history. Activism starts to take place because images become available of something that wasn’t visible.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint residents and students from Northwestern High School await the arrival of President Barack Obama, May 4, 2016, from the series Flint is Family

Courtesy the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome, and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

KJ: Can you talk about the impact of the MacArthur grant and how that changed your relationship to Braddock and Pittsburgh?

LRF: Prior to the MacArthur I was seen as an angry, disgruntled little black girl who doesn’t know what she is talking about, and doesn’t have the right to talk about civic duty, and isn’t allowed to point out how Braddock is being gentrified, and isn’t allowed to point out the rebranding of it, and how it’s becoming homogenized and not including the people of color, and the working class, and the elderly, who have always occupied this community. I kept being reduced and dehumanized and silenced. It wasn’t until I got the phone call that day and it became public, that all of a sudden Pittsburgh was proud. I was seeing my name in the paper. I had just moved to Chicago, but they were claiming it, and then so was Chicago. I was having to do interviews in both places. One time they said, “Well, is there anything left you would want to say, LaToya?” And I was like, “Yeah, I hope I make Pittsburgh proud.” [Laughter]

August Wilson was on my mind when I received the MacArthur. And when I think about it, even though I’m using photography and performance and video, it is speaking exactly to what he was doing, which was telling and narrating the daily stories and lives of working-class black people that are constantly overlooked. I really believe that if you can talk about the history of this country and the steel industry through Andrew Carnegie and all these other Scotsmen, then you can talk about America and its history through black women, through black men, and through black children.

I’m talking about being working class. I’m talking about being poor. I’m talking about being blue-collar. Our own presidents don’t say “poor” or “poverty.” They say “middle class,” and I’m very agitated about that.

Gordon Parks, American Gothic, Washington, D.C., 1942

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

KJ: You’re certainly bringing that into view for a lot of people. I’ve taught your work in a course on Gordon Parks. I’ve seen you, along with Hank Willis Thomas and Mickalene Thomas, as heirs not only to his photography practice, but also to his sense of interdisciplinarity, as well as social justice. How does your interest in photography and video differ from his?

LRF: Parks’s American Gothic (1942) was one of the first images that I saw by him, in my photography class in undergrad, and it shook me up. To see Ella Watson standing there mimicking Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930)—I realized that this is a photographer in conversation with a painting, and a painter. Then I also noticed: Here is this woman, working in a government building in Washington, D.C., and nobody sees her, and she’s the janitor who’s cleaning and sweeping every night. But Gordon saw her, and it was the first time I realized that I can speak through a photograph. It’s not about taking the picture. It’s about making the image because you have something to say. She was only making what is equivalent now to $15,000 a year, and she had her children.

KJ: And grandchildren.

LRF: And that’s how she was supposed to survive? So that image really pushed me to start to become more accountable and more responsible to what I wanted to say. But importantly, I learned about Gordon Parks from a homeless woman. I was photographing in a homeless shelter and when I handed this woman her portrait she said, “This reminds me of a photographer I saw on TV on PBS. Do you know Gordon Parks?” And I didn’t, but as soon as I left I went and bought all of the books I could get my hands on. It was because of my encounter with all of his works and reading A Choice of Weapons (1966) that I changed. I’m in pursuit of what Gordon Parks achieved. I’m trying to add to that legacy, but add to it as a young woman and a young practitioner giving voice and collaborating with more women, more populations, but also seeing them as equals.

I want to ask you about Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, the exhibition you curated at the Brooklyn Museum in 2014. When I came to Witness and saw the Bruce Davidson, the Gordon Parks, the Charles White, it all really started connecting for me in terms of what I was doing. I realized, Okay, LaToya, you are doing social activist work. I always had this feeling like it just wasn’t enough. And then I saw the exhibition and I realized I was part of a long tradition and a long conversation, and it brought me so much more insight and confidence. Could you talk about the timing of the show and bringing this period, the 1960s, forward through the museum?

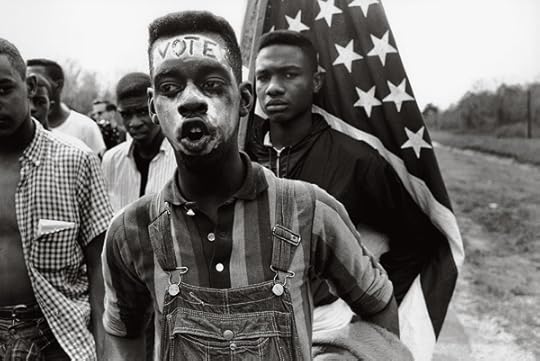

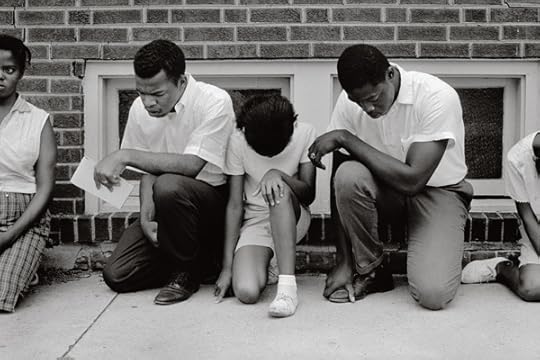

Bruce Davidson, Led by Martin Luther King Jr., a group of civil rights demonstrators march from Selma to Montgomery to fight for black suffrage. A young African American man with the word “VOTE” on his forehead, Alabama, 1965

© the artist/Magnum Photos

KJ: Witness celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, which was about guaranteeing civil rights for all in this country, regardless of race, creed, or color. So we started with that 1964 date.

What was exciting to me was to see so many interesting things that happened in that year artistically. It was Romare Bearden’s breakout moment. He’s been painting for years. He’s in his fifties. People decide they love his collages. He’s also using photographic material in these works.

One of the major things when we think about photography is that most people know the civil rights movement through it, through the photography of Danny Lyon, of Gordon Parks, and through television, but they didn’t know about it through painting and sculpture.

LRF: I was definitely enlightened, and wish I got to study with you. When I was speaking earlier about being held accountable and responsible, not only was I challenging the narrative from my hometown and the narrative that we were all presuming to understand about how the Rust Belt is being developed, or the difference between working-class and creative-class theory, and our complacency as people from the creative sector and industry within that. I was also making it a point to bring people from my community into the institution.

Danny Lyon, John Lewis, future chairman of the SNCC, and others demonstrate at the Cairo pool, which did not allow blacks Cairo, Illinois, 1962

© the artist/Magnum Photos

So you have Witness, and Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960–1980 (2011), which you curated for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, happening right in the midst of this other burst as Obama’s leaving, and you’ve got Black Lives Matter, and you’ve got “riots” coming out because of people resisting police brutality, understanding that the boys in blue could be a gang like the Bloods and Crips. All this realization happening in the American psyche. And the fact that everyone is having this meltdown, even considering Trump and Clinton. We’re just so disillusioned and unhappy, and also desensitized at the same time about the history, the murderous onslaughts that we’ve done in this nation. Am I one of those artists contributing and being a witness to my time?

KJ: You’re definitely a witness to your time. You’re telling us about Braddock. Many of us didn’t know about it. And, like you said, it’s representative of places all over the country, and really all over the world.

LRF: I want to close on the Flint work. I had been tracking the Flint story, and then Mattie Kahn, who profiled me for Elle after the MacArthur, reached out and said she wanted me to cover the story. I initially said, “No way. This is Elle. It’s fashion. Why in the hell would I, of all people, want to deal with you?” Then I started thinking about Gordon Parks. Well, he was with Life; he was with Vanity Fair and Vogue. This is the next step, right? You want to impact mainstream culture, the masses. You want to get these things in front of them. So I decided to go.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Denise and Rodney Clay, Shea’s aunt and uncle, watch President Obama take a sip of Flint water on television, 2016, from the series Flint is Family

Courtesy the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome, and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

And the fact that this is contaminated water: Water is a human right. Water is life. And the fact that no one’s even looking anymore. Clinton is not there. Bernie Sanders is not there. No more free concerts to raise money. As I was packing up to leave, a kid grabbed this poster of Governor Snyder and brought it over to me. He wanted me to see something. He had something to say. He wanted me to document it, and I thought about Witness. I thought about all those photographs, because when I looked at him, I could see that language of the civil rights era, and I couldn’t help but shoot it. Everything from that exhibition came forward and I thought, You have to shoot this. So I grabbed my camera back out and I shot it. I’m thinking about the fact that Gordon was also mindful. Just because people were living in what looks like squalor, which is really the landlord’s fault, they were still educating themselves. They were reading; they were studying; and he was making photographs of people reading their books and studying, in addition to going through the whole system that keeps you trapped. Then there’s the image of Obama drinking the Flint River water. I was dying to get that photograph. I kept asking, “Where is someone I can photograph watching him drinking the water?” I knew I needed it to be this historic image.

Kellie Jones is Associate Professor in Art History and Archaeology and the Institute for Research in African American Studies at Columbia University and the author, most recently, of South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (2017).

This conversation is adapted from a public talk between LaToya Ruby Frazier and Kellie Jones at the Strand Book Store, New York, in October 2016.

Read more from Aperture Issue 226, “American Destiny,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Witness: LaToya Ruby Frazier in Conversation with Kellie Jones appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 22, 2017

2017 Aperture Summer Open: A Conversation With Eric Gottesman from For Freedoms

Aperture is currently accepting submissions for the 2017 Aperture Summer Open, an open-submission exhibition for which all image-makers are eligible. Entries for the exhibition will be accepted until Wednesday, April 5, 2017, 12:00 noon EST.

Curated by Eric Gottesman, Hank Willis Thomas, and Wyatt Gallery of For Freedoms, an artist-run initiative that uses art as a tool for political engagement, this year’s Summer Open invites photographers to submit work relating to the idea of freedom. Aperture recently spoke with Eric Gottesman about photographic liberation.

Eric Gottesman,“The Best Day Of My Life Was The Day I Was Reunited With My Sister.” – Mesfin Muhammad from the series Sudden Flowers

Aperture: How can photography, and particularly images relating to freedom, help us envision the future? How do pictures help us see what or who we can be?

Eric Gottesman: Freedom is not one thing and images cannot define any one idea or concept. They help us draw shapes around an idea; they triangulate and circumscribe. The rectangular frame excludes more than what it displays. Perhaps moving away from the limits of a frame, limited as it is by the history of that frame, is the ultimate form of photographic freedom. I’m reminded of the words of the exiled Assata Shakur: “I can tell you more about what freedom isn’t than what it is, because I have never been free.”

Aperture: Recently you organized an exhibition at Aperture, Collective Thinking, For Freedoms. The exhibition examined the notion of collectivity and how it can serve as a model for artists to work together to share a common message to a diverse and global community. How do you think your experience with this exhibition will inform the Summer Open?

Gottesman: There was so much to talk about! It was fascinating to hear how all these different collectives, working in vastly different modes and contexts, could inform each other’s work. As someone put it on the last panel, we all seem to be addressing the same set of ideas from different perspectives. Often there is this idea that how we relate to one another is in competition with how we express and value individual voices. What emerged from the exhibition, and what I hope will inform the Summer Open, is that collectivity and individuality need not compete. They can coexist. And collectivity can even enable individuality. Difference is of value. We can all be weird together.

Featured Submission: Myriam Abdelaziz, A young woman is waiting for her husband to renew their wows at the Audubon park in New Orleans: a ceremony they do every year since they got married, 2016, from the series “We the People”

Aperture: Considering the current conversations about human rights, climate change, capitalism, and corruption, it feels like representations of freedom are always negative. Does it have to be so?

Gottesman: No. Liberation can be celebratory. It is important to think about both what we must free ourselves from and also what true, utopic freedom might look like. Being free can mean throwing off an oppressive system that prevents us from loving who we love. Or it can mean having an orgy. Or it can mean loving one person for the rest of your life. Or all of these things. It all depends.

Aperture: For Freedoms is an explicitly political arts organization involved in U.S. politics. Clearly, you believe in the power of images to effect change. What do you want to tell artists (from all around the world, not just the U.S.) who are thinking about submitting to the Summer Open?

Gottesman: I think it is a very complicated equation to go from a photograph to social change and it rarely has anything to do with the intention of the photographer. It is more often the case nowadays that images coincide with historical events and can inadvertently contribute to larger movements. The power of photography is not in what it can do but in what we can see through it. I hope those who contribute to the Summer Open will show us something that they see that has never been seen before. We are only explicitly political because we say we want to be explicitly political. What do you want to be? Why do you do what you do?

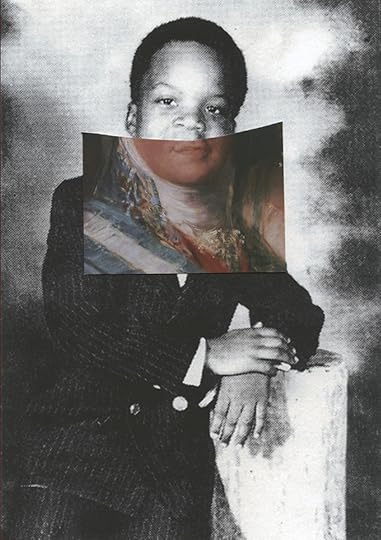

Featured Submission: Gary Burnley, Untitled, 2016, from the series Kings and Queens of Yesteryear

Aperture: What kinds of images are you hoping to see when reviewing submissions?

Gottesman: I hope we see images that surprise us. I love photographs that completely confound any ideas I have previously had. Blow our minds.

For more information on how to enter the 2017 Aperture Summer Open, visit aperture.org/summeropen or contact summeropen@aperture.org.

The post 2017 Aperture Summer Open: A Conversation With Eric Gottesman from For Freedoms appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Behind the Barricades

Student protests shook late-1960s Japan. Hitomi Watanabe bore witness from inside the movement.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Shinjuku Contemporary, 1967-68

© the artist

Hitomi Watanabe began her career photographing in Shinjuku, a Tokyo neighborhood home to Japan’s 1960s counter culture. She then became a member of the Zenkyoto student movement, which occupied the University of Tokyo campus in 1968-69. The students first demanded academic reforms, and then broader, political changes. Her candid photographs lend a strikingly relatable perspective to the struggles and everyday lives of the protesters, and her insider’s vantage on this tumultuous moment afforded her work an undeniable, enduring power. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke to Watanabe about her experience documenting and participating in this influential movement.

Tsuyoshi Ito: How did you get started in photography?

Hitomi Watanabe: A finance magazine I was working for needed someone to take photographs. I had no idea what I was doing, so I went to photography school for two years and started taking photographs in Shinjuku, where I used to hang out a lot.

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Todai Zenkyoto, 1968-69

© the artist

Ito: And from there you began photographing the All-Campus Joint Struggle League (a.k.a. Zenkyoto) at Tokyo University?

Watanabe: Yes, I first met Zenkyoto members in 1968. I had been considering attending Tokyo College of Photography to pursue my studies when the riot police locked down the Tokyo University campus in response to student protests. My friend’s partner, Yoshitaka Yamamoto, had just been elected leader of Tokyo University’s Zenkyoto. He inspired me and I knew that I had to photograph him. Yamamoto gave me insider access and, from that autumn, I was constantly taking photographs there. Other members of Zenkyoto soon became suspicious of my presence, and thought that I was a newspaper reporter or a spy, so Yamamoto made me an armband that read “Zenkyoto” so I could move about freely.

Ito: How did Yamamoto inspire you? What drew you to him?

Watanabe: He had a quiet determination about him. He seemed so ordinary during our everyday life inside the blockade, but when something needed doing, a kind of fire lit inside him. His impassioned speeches at rallies made me want to get inside and photograph as much as I could.

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Tekiya no Sekai, 1967-68

© the artist

Ito: What kind of photographs did you take?

Watanabe: At first I mostly focused on Yamamoto, but soon a warrant was issued for his arrest, and he became understandably scarce. But the leadership didn’t skip a beat, and even in his absence the struggle continued full speed ahead. And I was there the whole time, taking pictures. I didn’t even go home. My family worried about me a lot.

When the police started arresting people in the movement I had to disguise myself. My brother came to meet me in secret and I was able to give him some rolls of film I had shot to keep safe. Later on, I had an exhibition of the photos and my brother, who was working as a journalist, was stunned. He realized what a scoop he could have had if he had published my photos before. But he kept them safe for me the whole time.

Ito: What was the media coverage like?

Watanabe: Outside the barricade there were usually only one or two reporters from the media. There were, of course, many photographers present when the riot police launched their final assault on the barricade, called the Fall of Yasuda Auditorium in 1969. Many of the journalists outside recognized me from my constant presence and took an interest in me. As a photographer aligned with Zenkyoto, I had an interesting perspective. I was strictly a freelancer, but that gave me access to places media reporters were never allowed to go.

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Todai Zenkyoto, 1968-69

© the artist

Ito: It sounds like your photography led to a lot of connections and new relationships.

Watanabe: Yes, definitely, although that was never my intention. Cameras weren’t nearly as widespread back then, and my subjects were always delighted to get prints of the photographs I had taken of them. That helped us build a relationship, and they were then happy to welcome me to their inner circles.

Ito: How long did you cover Zenkyoto?

Watanabe: For two years in total. Even after the fall of Tokyo University, I continued going to events and protests.

Ito: Throughout those years, did you remain as enthusiastic as you were when you began, or did your mood change?

Watanabe: Zenkyoto’s breakup in 1969 was the beginning of the end. Then, things began to fall apart in the early ‘70s. People started getting cynical and apathetic, myself included. Some people lost their minds or went so far as to commit suicide. I spent my time in a deep depression, just drinking in Shinjuku.

Ito: So your life felt empty after those years of emotional struggle.

Watanabe: It wasn’t even the fall of Zenkyoto or the photography itself. I had been a photographer. That was what defined me and gave purpose to my life.

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Shinjuku Contemporary, 1967-68

© the artist

Ito: There were many women alongside the men inside the barricades. Were there differences in responsibilities between the men and the women?

Watanabe: Women weren’t really out on the front lines, but they contributed a lot inside the barricades, like preparing meals. There weren’t any set breakfast or dinner times, so they did their best to get people food when they could. Sometimes speakers would be eating a sandwich while climbing on stage to deliver a speech. Women would also go out to grocery stores to buy more food and supplies.

Ito: What did you think of this division of labor and tasks?

Watanabe: I actually didn’t think anything of it. Men and women have different strengths, and I think that men, being physically stronger, were better suited for front-line activities. Although, women—even high school students—did join in the demonstrations as well. There were occasionally even women-only demonstrations.

Hitomi Watanabe, from the series Todai Zenkyoto, 1968-69

© the artist

Ito: You photographed the Kyoto University barricades and protests, too. Was the atmosphere similar to that of Tokyo University?

Watanabe: At Kyoto University, I photographed the school of literature student protests. Kyoto students were a lot more laid back than their Tokyo University counterparts. Maybe it had something to do with the Kyoto dialect—I’m not sure. They used graffiti as a way of protest, while Tokyo University protesters were more interested in fiery speeches and rhetoric. My time in Kyoto was a lot of fun.

Ito: So the Tokyo protesters were more intense and focused?

Watanabe: Well, even they made time to fool around or read comic books. But yes, things there were more intense. One time they had heard that the riot police were going to stage an assault on the barricade, and they told me I had to leave. I remember watching the attack, seeing riot police storm the building, and helicopters dumping tear gas on the protesters from above. Tears ran down my face as I remembered a girlfriend who was still inside and who I had been laughing with two days before. I couldn’t focus and my shots were blurry, but I kept on pressing the shutter button.

Tsuyoshi Ito is founder and managing editor of A/fixed, a leading resource on the history of Japanese photography.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s will be released in April 2017.

The post Behind the Barricades appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 20, 2017

Back to the Future

A new exhibition in Seattle explores the ambiguity of what is yet to come.

By Roula Seikaly

Kris Graves, Jessica and Keith #2, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Future Isms, an exhibition currently on view at Seattle’s Glass Box Gallery, considers the legacy of visual arts in positing techo-cultural visions of the future—Star Trek’s handheld communicators that foretold smartphones, for example—and what present assertions may suggest about what lies in store for us. I recently spoke with Jon Feinstein, the exhibition’s curator, about virtual exhibition practice as a possible “future ism,” photography as a former “future medium,” and the overlap of visual art and science fiction literature as experimental spaces where ideas of the unknown, utopian, and dystopian alike, filter into our cultural lexicon.

Anastasia Samoylova, Lightnings, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Roula Seikaly: Where did the idea for Future Isms originate?

Jon Feinstein: I’d been wanting to organize a show about the future for a few years. I’d seen a lot of photo-based work about this popping up—such as Jade Doskow’s Lost Utopias (2016)—and I wanted to put my own curatorial angle on it. When the 2016 U.S. presidential election started stirring tension and divisions in this country and beyond, it felt like there was a new way to approach this. We put out the call for work a week or two before Election Day with the idea, initially, that this was going to be the final Humble Arts Foundation online exhibition for 2016.

At the same time, I was working on an unrelated idea for a brick and mortar show at Glass Box Gallery. But when the election results came in, a new sense of urgency came to it all, so I pitched the idea to Glass Box’s director Weston Jandacka. He was excited to change course. The title, Future Isms was borrowed from the title of an early record from Milemarker, one of my favorite bands in my late teens and early 20s. They added keyboards and electronic elements to late-’90s punk/hardcore; I think there are a lot of parallels between their music and lyrics and how I was thinking about this show. Coincidentally, it turns out that the band’s guitar player happened to be a student of Elin O’Hara Slavick, who has a piece in the online version of our exhibition.

Orestes Gonzalez, Dark Shadows from the Trump Towers Invade the Beach, 2012

Courtesy the artist

Seikaly: How do you define the term “future ism”?

Feinstein: For me it’s about “pseudo-futures,” which could have been an alternate title for the exhibition. It’s about representations of the future that borrow from, and riff on past, often expired ideas about the future in classic literature and media, and make them new—because time is continuous. Michael Marcelle, one of the exhibiting artists, references the cloying syntax of old science fiction movies, the premonitions of the future in any work of art, and literature that will ultimately become outdated and feel like a thing of the past.

Seikaly: What were you looking for in the work that you included in the exhibition?

Feinstein: I wanted to avoid a show that screamed “SCIENCE FICTION.” That’s a component, but I wanted things to be a bit more mysterious, unsettling, and less literal. There are no images of steampunk gear-goggles, for example. My intent was for individual images to serve as little nods or chapter markers, leading to building feelings of anguish, and the ambiguity of what might come. The work ranges from straightforward, almost typological cityscapes to collage and humorous, animated gifs.

Griselda San Martin, Through The Wall, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Seikaly: Can the anguish and ambiguity about our political climate and what the future holds be a generative creative experience?

Feinstein: One idea that has come up in many conversations with artists lately—those in the show, and beyond—is that art can be generative, that it can take the craziness of where the world is and where it’s going and use it to fuel the creative process. The photographer Serrah Russell just completed a series called 100 Days of Collage (2016–17), three pieces of which were included in the show. For one hundred days after the election, she made a collage each day, responding viscerally to the strangely unfolding future.

Seikaly: The first photographic processes evolved in the mid-nineteenth during the Industrial Revolution. I think it can be argued that the mechanistic aspect of photography aligned it with future-focused developments in a rapidly modernizing world. Do you think photography is still a medium of the future?

Feinstein: As it relates to this show, I think photography, when interpreted as a technology, could be seen, by some, as a medium of the past. While we might not want to admit it, our iPhones are competing with Digital SLRs, which only a couple years ago outdated film for a majority of photographers. Everything evolves at light speed. On some level, I look at photography less as its own medium of the future, and more as a continuous tool that is constantly taking on new forms and hosts. I don’t think this necessarily means that photography is expiring as an artistic medium, but our understanding and application of light-sensitive imagery—still, moving, or holographic—keeps shifting. I think what’s important is that with making photo-based art, our ideas stay focused, yet malleable so that we can continue having interesting visual conversations.

Daniel Temkin, Saratoga, NY, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Seikaly: Could you talk about the exhibitions you’ve curated online and why Future Isms was pared down and presented at Glass Box?

Feinstein: I’ve been producing exhibitions online with Humble’s co-founder Amani Olu since 2005. Our no-frills project called “group show dot com” quickly evolved into physical exhibitions, and a range of other grant and publishing projects. For years, our online shows had no themes; we liked the challenge of drawing relationships between works that appeared unrelated on the surface. After a brief hiatus in 2013, we re-launched to show quarterly exhibitions around a more defined theme. Our first show in this new format was called Tough Turf: New Directions in Street Photography. It was one of the first street photography shows that included a disclaimer that digitally manipulated images would be accepted. Historically, any kind of manipulation in street photography has been a huge taboo, so we wanted to explore these images. The purists on various street photo blogs called us morons and fools, and we kind of enjoyed that.

Many of our online shows include over fifty images. The online version of Future Isms includes eighty. Even with generous access to two floors at Glass Box Gallery, that would be too many to include with room for the work to breathe. Also, I wanted to include some installations by artists who are local to Seattle, including Max Cleary’s Guy Debord-inspired photography-based sculptures, and Parsley Steinweiss’s photo paper origami fortunetellers.

Ben Alper, Bausch and Lomb

Courtesy of the artist and The Archival Impulse

Seikaly: Are online exhibitions a “future ism”? Do you think there will come a time when virtual exhibitions will successfully challenge presentations in museums or other arts spaces?

Feinstein: I see online exhibitions less as a challenge and more as a way of complementing the experience of seeing art in person, and democratizing who has access to see and participate. Online exhibitions can be more crowded in terms of included images, and often more wide ranging, but at least it allows similar access to people in Nebraska, Nigeria, Berlin and New York City.

Seikaly: Could you describe the various visual strategies the exhibiting artists apply in realizing this work? Where do you see the theme of the exhibition illustrated?

Feinstein: The artists included come from a range of backgrounds and address the open-ended concept of the show with a variety of approaches. Joe Rudko, for example, takes a deeply personal approach using a simple yet chaotic collage of vernacular photographs that spell out “The Weird Feelings Inside of Me” to capture his sense of anxiety about the changing world. Likely one of the more directly political sets of images in the show, Orestes Gonzalez, using a more straightforward process, made a series of photographs of the shadows cast by Trump hotels on a Miami beach, pushing the sunbathers to chase the sun’s waning rays. Made more than a decade ago, Gonzalez’s work is foreboding and current. While Gonzalez and Rudko’s work, like many artists in the show, are grounded in discomfort, some artists tread into more playful territory. Anastasia Samoylova, for example, creates tactile sculptures from digital stock images and then re-photographs them. Her work fuses the history of landscape photography with how we experience the landscape today, largely on screens, in a way that she describes as “bending space and time.” They are lighter, less brooding, and more aligned with a fantasy of how we experience the world.

Michael Marcelle, Orange Still Life, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Seikaly: Do you know of any “future” projects that the artists are working on? When this exhibition closes, it will be in the past, but are there any artists in the exhibition working on projects with an eye to the future?

Feinstein: Daniel Temkin, whose image from Straightened Trees (2016) was one of the first I selected for the exhibition, is working on a new series called The Unprintable. These are digital images that he builds with contrasting colors. Arranged in patterns that are complex at both close and far distances, the images frustrate the interpolation algorithms that map the grid of the image to the pixels of the screen where they are viewed. Zooming in or out, the image seems to change dramatically. Instead of the image itself, we see artifacts of its inability to render at each scale. While not literally “photographic,” it builds on Temkin’s practice of using technology to re-code how we see.

Michael Marcelle’s images are part of an ongoing series, Red Strawberry, which explores the visual limitations of science fiction, specifically its overly saturated, nearly hallucinogenic hues. In Marcelle’s words, “it’s both primitive and futuristic…or maybe a vivid interpretation of the present,” building on an earlier series that used re-created horror tropes as a metaphor for the destruction of Hurricane Sandy.

Griselda San Martin is expanding upon her series of families at the U.S.-Mexican border. The photograph we included in Future Isms shows a couple as they try to embrace through the wall. Looking forward, San Martin has begun expanding on these issues, following the fate and struggles of several undocumented families on the east coast of the United States.

Roula Seikaly is a curator and writer based in San Francisco.

Future Isms is on view at Glass Box Gallery, Seattle, through April 15, 2017.

The post Back to the Future appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 16, 2017

Black and White America

The civil rights-era photographs of Louis Draper and Leonard Freed reveal the complex, poetic lives of African Americans.

By Nolan Boomer

Leonard Freed, They are dancing at a jazz funeral in the streets of New Orleans, Louisiana, 1963

© Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

A young black man in a schoolboy hat playfully grabs a loved one’s chest from behind. The ground is wet, the lighting even, and people move joyously through the warm rain. A brass marching band walks in tow. When the white photojournalist Leonard Freed captured this scene in 1963, he had already been working as a freelancer for several years, accepting commissions from magazines like the Sunday Times Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, and Stern. Especially invested in the lives of black Americans, he photographed communities around the country in the 1960s, eventually using much of it in his landmark photo essay Black in White America (1968).

By the mid-’60s, Louis Draper, a black photographer from Virginia, had also become experienced with portraiture. Draper moved to New York to pursue photography, studying with well-known humanist photographers like W. Eugene Smith and Harold Feinstein. He occasionally received commissions from black magazines like Essence, and in the early ’60s, he exhibited twice at photographer Larry Siegel’s short-lived Image Gallery, then the only photography gallery in New York. Opportunities in the mainstream arts community were few and far between, however, due to discrimination. To promote artistic critique and community, he created a new space, the Kamoinge Workshop, the first black collective of photographers in the United States. It exists to this day.

Louis Draper, Summer, New York, 1961

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

Even though these two photographers most likely never met, the exhibition Black in America: Louis Draper and Leonard Freed, currently on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, surveys relationships between their bodies of work. Curator Barbara Tannenbaum shuffles photographs by the two artists into clusters that show how everyday acts, the media cycle, and activism affected the visibility of black Americans during the civil rights era.

To carry this out, Freed always ensured that his work traveled with context. The title of his photograph They are dancing at a jazz funeral in the streets of New Orleans, Louisiana uses the third-person plural and the term “jazz funeral” (not typically used by people from New Orleans), which hints that this photograph is of interest to his audience because it shows a ritual that departs from the somberness of white American funerals. During “jazz funerals,” solemn music is played during the procession from the house of the deceased to a cemetery, but once the body is laid to rest, the band swells into swingier tunes. The youthful men in Freed’s photograph are swept up in postsepulchral, bittersweet emotion, momentarily hopeful despite the recent loss of a community member.

Louis Draper, Girls Embracing, New York, 1965

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

Showing a less candid and more cryptic sort of joy, Louis Draper created the photograph Girls Embracing, New York (1965). In what appears to be an alleyway, two schoolgirls grasp one another with unabashedly blissful expressions. A woman’s abandoned pair of stubby high heels lies mysteriously next to them. The brick wall behind includes a mangled patchwork of scraped-off posters—only one left intact; it shows a high-contrast image of activist James Farmer preceded by the words, “When this man moves … things change.” What exactly can be read in this interconnection between black female friendship, an absent older, female figure, and a political call to action? This ambiguity is characteristic of Draper. While Freed tends toward overt humanitarian messages, Draper creates a complex juxtaposition, placing a subject against a background of graffiti, billboards, or posters. Through Draper’s lens, the mass media’s coverage of the civil rights movement becomes the background of black New Yorkers going about their daily lives.

Draper occasionally traveled the mid-Atlantic region and abroad, though his practice was centered in his local community of Harlem. Instead of going to overt centers of political action like Freed, many of Draper’s images depict the action filtered through the local cityscape. He could capture moments of everyday life independent of a journalistic agenda, much in the vein of midcentury street photography. The photograph Harlem, New York (1960) shows a middle-aged woman with plum-shaped face waiting idly on the sidewalk. Strangers in trench coats stand close to her, others walk past, yet she peers out at the city as if she is totally alone. She is in transit, possibly thinking about the food in her sack, or whom she will share it with. Carole Kismaric, former editorial director of Aperture Foundation, described in the publication Exposure: Ten Photographers’ Work (1976) the solitude of Draper’s subjects who “revel in their privacy as they experience fleeting moments.” In most cases, a stranger with a camera would destroy any semblance of privacy, yet Draper is able to hold the solitude of his subjects. He maintains thoughtful silence when the time is right, choosing deliberately between privacy and direct interaction with subjects.

Louis H. Draper, Harlem, New York, 1960

© Louis H. Draper Preservation Trust

The depth of Draper’s portraiture has something to do with his careful attention to printing. As Kamoinge member Shawn Walker recollects, Draper’s photos were so skillfully printed that they are practically three-dimensional, lending his subjects an air of dramatic complexity. Freed also cared deeply about the production of his work, much more so than other harried photojournalists. Throughout his career, his wife Brigitte Freed (née Klück) served as his masterful printer. Still, he was expected to meet deadlines and pair his work with writing, sometimes creating work overshadowed by journalistic narrative. This occurs most forcefully in his photograph Black prisoners in an overcrowded communal cell in the Parish Prison-City Prison of New Orleans, Louisiana (1965). The incarcerated black men are photographed as silhouettes, with their arms extended through the cell into the light. While Freed is making an overt, well-intentioned critique of mass incarceration, he does so in a way that fails to highlight the people themselves.

Leonard Freed, A policewoman plays games with community children. Shortly afterward, the officer became pregnant and was assigned a desk job for the period of her pregnancy, 1978, from Police Work

© Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

Despite their differing perspectives, it’s not immediately obvious who took which photographs in the exhibition. Which isn’t to say authorial identity doesn’t matter; when organizing exhibitions of civil rights-era photography, many curators fall prey to the idea that the race of the photographer isn’t of importance if the subjects are black. (And many fine art photography archives preserve the work white photojournalists made at black rights protests, but not those of African American photographers.) Black in America avoids this potential elision by featuring Draper, demonstrating the need for such curatorial evolutions—a particularly pertinent undertaking for institutions in the majority-black city of Cleveland.

How might an exhibition of black Americans during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement look fifty years from now? Certainly the roles of the fine arts photographer and the photojournalist will be entirely different. Politically, things may appear bleak, but one can hope that the democratic potential of camera phones and increased access to photography will create a new sort of archive. One that must circumvent mainstream media and fine art institutions altogether, giving black America what Draper once provided: an assured sense of privacy and a three-dimensional sort of beauty.

Nolan Boomer is an arts and architecture writer based in Hudson, New York.

Black in White America: Louis Draper and Leonard Freed is on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art through July 30, 2017.

The post Black and White America appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 15, 2017

The Provoke Moment

In the first of an ongoing series of interviews about Japanese photography with Tsuyoshi Ito, Curator Simon Baker discusses the radical new vision of the 1960s.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, ca. 1968

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris

Provoke was founded in Tokyo in 1968 by Daido Moriyama, Takuma Nakahira, Takahiko Okada, Yutaka Takanashi, and Koji Taki. The magazine examined Japan’s socio-political situation with a radically inventive style. Although only three issues were published, the publication’s impact would prove to be profound, revolutionizing photography inside and outside Japan. Today, the influence of the work published in its pages can still be seen in new generations of image-makers. This article is the first in a series of interviews about Japanese photography, produced in collaboration with A/fixed, a new publication geared to English-speaking audiences.

Director of the Japanese Photography Project, Tsuyoshi Ito spoke with Simon Baker, Senior Curator of Photography and International Art at London’s Tate Modern, about the legacy of the storied publication.

Tsuyoshi Ito: How would you define or describe the photographers in Provoke?

Simon Baker: Often when people think of Provoke, they think of the magazine. They think of quite blurry, grainy shots of street-level photography. But actually it’s varied, and there are many different approaches even within one photographer’s work. Daido Moriyama, for example, had many different ways of making pictures at this time. If there is a unifying characteristic, it is an openness to chance, to experimentation, and to a radically different kind of photographic image—whether more like a screen print or a film still, an abstract painting, or however else we might think of it. It’s about being open to photography having different characteristics, potentials, and possibilities beyond the descriptive use of the photographic image.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Dog and Mesh Tights, 2015

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: Is there a particular image that you can think of, let’s say, of Daido Moriyama’s, that you have in mind?

Baker: Nakahira’s photobook For a Language to Come (1970) defined Provoke. Even the title suggests that there’s a new visual language that’s available. Nakahira is a great writer, somebody who’s interested in theory, and writing, and thinking about people like Walter Benjamin and Eugène Atget as well as previous generations of photography theorists. But really Nakahira’s aim with that book and title was to suggest a new visual language, a new way of describing one’s experience of the world. What marks out Provoke as avant-garde in the full sense, in the sense we might think of Surrealism, for example, is an attempt not only to make images, but to give a sense of the perspective from which the person making the images is seeing the world. So it’s about experience—how do we experience life in the world around us? In busy urban centers like Tokyo in the late 1960s and early 1970s, you are seeing, in the photography of Provoke, an account of lived experience, which is a very radical kind of image-making. It’s not photography as an objective, descriptive medium. It’s photography as an expressive, subjective, and quite radical medium.

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1968–70

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris

Ito: Can you put the Provoke photographers’ work in the context of what was happening in Japan at the time?

Baker: Well, the photographers associated with Provoke have very different politics. Moriyama, for example, always said that he was not particularly interested in politics. He photographed one student protest, but it wasn’t something that he was doing a lot of. Other members of the movement were engaged with not only student protests, but also with key social issues like the presence of American military bases. Miyako Ishiuchi made a lot of work, slightly later, about Yokosuka, where the American bases were located. And then there are big, pressing issues like the Narita Airport clearances and moving entire populations of people. There is a range of levels of engagement from the quite detached—viewing a world that was changing—to documenting specific protests and political issues. Rather than just the images that were in the magazine, the Provoke moment encompasses all of those different aspects.

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1978–89

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris

Ito: Can you relate their movement to what was happening in other parts of the world?

Baker: The global political upheavals around 1968 were happening in Europe and America (as well as in Japan) and were often student-led. There were demonstrations against the Vietnam War, a major issue that united people from different places in thinking about what American power meant. This had specific meaning in Japan. That global sense of urgent political issues united photographers. Remember that travel and the exchange of ideas were relatively limited. But you do certainly see exchanges of political concepts between Japanese photographers and those working elsewhere. There’s an amazing Provoke book about Che Guevara, for example, which is a very rare, very unusual book. It’s made by Japanese publishers and it keys into a kind of cause célèbre on the Left in Europe, in America, and indeed in Africa and the Caribbean.

Yutaka Takanashi, Shinjuku-ku: Isetan Department Store, October 23 Tammy ¥1,000, Pepper ¥700, 1965, from the series Tokyo-jin (Tokyoites)

© the artist and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

Ito: What kind of influence did Provoke have on photography inside and outside of Japan?

Baker: Soon after the Provoke moment, there were exhibitions of Japanese photography outside Japan. There was the famous New Japanese Photography exhibition at MoMA in 1974. It did not have much Provoke work in it, but included many of the photographers associated with that group. Outside of Japan, there’s a sense in the photography world that things are happening there. But beyond Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, and Eikoh Hosoe, many figures were not able to establish big, international careers. In the catalog for New Japanese Photography, Shoji Yamagishi (who organized the show with curator John Szarkowski), states that people outside of Japan need to understand that photography in Japan is about the series: it’s about groups of images; it’s about the book—and he said this in 1974. I think it has taken a long time for the rest of the world to learn that lesson and say, well, let’s not just focus on one famous image—Moriyama’s Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori (1971) for example—but let’s try to understand where it came from, what the series was, how he was working, what he was doing. The same can be said of people like Yutaka Takanashi and Takuma Nakahira, whose work is now understood through the increasing interest in the photobook. The same goes for Miyako Ishiuchi.

But I think that sense of the breadth, depth, and complexity of Japanese photography has taken a long time to filter through to the rest of the world. Even with the most famous photographers, like Nobuyoshi Araki—we, outside Japan, know relatively little of what he was actually doing in relation to publishing. If you look at early Araki books, there is a lot of text and very little of that has ever been translated for non-Japanese reading audiences. There are some interesting issues in terms of the delays and the problems with creating a broader understanding.

Takuma Nakahira, Circulation: Date, Place, Events, 1971

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris

Ito: For people outside Japan, what is the fascination with Provoke, or about the people around that movement?

Baker: Well, there might be two things. On the one hand, the history of post-war photography for a long time was conceived of and delivered from quite an American-and European-centric point of view. If we think of the shift from William Eggleston and Stephen Shore to Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, it gives a very particular view of what constituted progress, or what constituted something properly creative and avant-garde. But if you consider photography within its own avant-garde character, thinking about things like publishing and series, and the importance of connections to politics and other kinds of art forms, then Provoke seems like an interesting, alternative way of understanding the post-war period and the ’60s and ’70s. There is a cliché that 1972 was one of the best years for Conceptual art, but 1972 was also the year that Moriyama produced Farewell Photography and Hunter, so there are other ways of understanding that moment.

I think non-Japanese curators and historians and, indeed, collectors and critics, can see in Provoke something that they recognize as avant-garde, in that sense of Dada or Surrealism—a group of people working together, sharing ideas, pushing each other to more and more creative achievements. The people associated with Provoke were really investigating what photography could do as a medium, and that makes it really important. The radical potential of the photograph was pushed to these limits much more fully in Japan than in other places at the same time.

Yutaka Takanashi, Funabashi City: Health Center, 1965, from the series Tokyo-jin (Tokyoites)

© the artist and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

Ito: Are there qualities or attributes that are unique to Japanese photography or to the time of Provoke?

Baker: Well, I wouldn’t ever distinguish things by geography and region. I don’t think that everything that was happening in Japan was unique, and I think some of things that were happening there were as a result of the Japanese photographers’ interest in, for example, William Klein—an American photographer based in France—or their exposure to Ed van der Elsken or Robert Frank. The interest in and the power of publishing in Japan was quite significant. Outside of Japan, there weren’t book designers of the same caliber as those working with Moriyama and Takanashi. Yutaka Takanashi’s Towards the City (1974) or Eikoh Hosoe and Tatsumi Hijikata’s Kamaitachi (1969) or Hosoe’s Ordeal by Roses (1961-62), are books that could not have been produced in any other context. That’s the history of the love of paper, of a particular kind of craftsmanship, skilled printing, which indeed are continued in the collotype workshop (at the Benrido Collotype Atelier in Kyoto). When you look at Japanese photobooks of the ’60s and ’70s today, they still look much more sophisticated than what was happening elsewhere.

Tsuyoshi Ito is founder and managing editor of A/fixed, a leading English-Language resource on the history of Japanese photography.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography ’60s-’70s is due April 2017.

The post The Provoke Moment appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 14, 2017

A Love Song for New Orleans

Drawing inspiration from Walker Evans, Stephen Hilger photographed a city’s disappearing neighborhood.

By Matthew Leifheit

Stephen Hilger, Bar, 2011, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Now she’s gone and left me

I’m worried as can be

Oh I’ve searched this world all over

Wonderin’ where she could be

I would ask that she forgive me

And maybe she’ll come back to me

—Louis Armstrong, “Back O’ Town Blues,” 1946

Stephen Hilger’s book Back of Town (2016) begins with an epigraph quoted from the lyrics of Louis Armstrong’s mournful song about the loss of a lover. The photographs that follow depict part of a neighborhood of New Orleans that Hilger came to know as the Back of Town, a historic district devastated during Hurricane Katrina, partially rebuilt then marked for demolition, which he recorded during his time as a professor at Tulane University. Called Lower Mid-City by newspapers and preservationists, the approximately twenty-five blocks these pictures span were razed in 2012 to make room for new hospital buildings. I recently spoke with Hilger about photographing this place as it disappeared, and about how he made the pictures into a book.

Stephen Hilger, Monument, 2011, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Matthew Leifheit: How did this book project begin?

Stephen Hilger: I want to tell you about how I ended up in the Lower Mid-City or in the Back of Town or in this particular neighborhood in New Orleans photographing. But, before that, I’ll just say, I was there and it was very sleepy. There was not a lot of activity, and over the course of four years that I photographed there, there was less and less life. But there was always something, which is part of what kept me coming back. I was at a bar, not necessarily to drink but because it was one of the places on the block that had some life, some people. The bar was called the Outer Banks, and I was photographing the people in the front of the bar, and a man confronted me and said: “What the fuck are you doing?” I tried to explain it to him, but he wasn’t really listening to me, so I went and bought a beer and before long he was back, and I bought him a beer and we talked. I got to know him, and photographed him. Our relationship was based on access he could provide me to his world and access that I could provide him to my world. Our conversation was through the photographs. I feel like he was the sentinel of the neighborhood. He was also a hustler. His name was Brian. He knew the comings and goings of the place and was concerned for me and my safety.

Leifheit: Concerned about your safety or concerned about the way you might be depicting things?

Hilger: Well, he was initially concerned with why I was there, and I explained it to him. I told him that I heard that the neighborhood was disappearing, that it was being torn down, and that I was interested in writing it down—getting to know it and trying to understand it through pictures. There’s a big insider/outsider dichotomy that runs through a lot of things in New Orleans, including photography. I felt it in New Orleans quite a bit in my daily life: You were from New Orleans or you weren’t.

Stephen Hilger, Traveler, 2010, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: You’re from Los Angeles, and you live in Brooklyn. So, why were you in New Orleans?

Hilger: I was teaching at Tulane. The four years I was there, from 2008 to 2012, were the four years I was photographing in this neighborhood. My main activity as an artist during those years was photographing this particular place.

There are a few reasons I wanted to mention Brian. I wanted to photograph the place very completely—in a lot of different ways. The most accessible thing was the street and the exterior of buildings, but then I wanted to go inside and photograph the inhabitants or the drifters passing by. When I was photographing this dying neighborhood, there weren’t really permanent residents—it had reached a terminal stage where people were mostly moving through and squatting. So, I took portraits, photographing Brian on a number of occasions. I met a few other people through him and people saw me through him and it was part of my entree into the place. But Brian’s not in the book, and there’s another half dozen portraits that aren’t in the book. The book is really about the distance that occurs. The more that I’m there, the more that I’m observing, the less that’s there, the farther away things are. It’s not about the particular voices of these people. It’s not even about their particular experiences. But it is about the experience of being in the place more broadly. One thing my friend and mentor, Thomas Roma, said about the work was that it reminded him of veins and arteries and a movement through these vessels. I’ll take that further and say that this is the biology of a sick person, that things are slowing down and things are becoming attenuated.

Brian’s not in it, and I’m talking about that because I think, on some level, I feel that Brian is missing. At the same time, I think that the work is complete. I think it’s OK to feel that missing someone or something, which is really apt for New Orleans, because it’s about a chunk of something being torn away—purposefully forgotten and purposefully erased.

Stephen Hilger, Footprint, 2012, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: In this aerial view, a large piece of land looks like it has been scraped clean. There are faint squares where I imagine buildings must have been. This is where the neighborhood was?

Hilger: Yes, that’s the footprint of the planned demolition, and that is actually one of two adjacent footprints of spaces that were systematically dismantled in order to build new hospitals. What drew me to the place was Charity Hospital, which was one of the oldest public hospitals in the country. It has an infamous place in history because of Hurricane Katrina. Patients were cut off. It was a horrific situation. I was drawn to the building itself. It was a monolithic concrete structure that was very imposing, empty, and there was nothing happening there. I’ve been interested in things that are disappearing, and I often look at architecture, and while I was looking at those things and in neighborhoods that were adjacent to the back of town, I read a New York Times article about Lower Mid-City. Two hundred houses and however many acres having rebuilt itself after Katrina, only to be marked for demolition and subject to what is called “expropriation.” It sounds a little more brutal than eminent domain. One of the ironies about the Back of Town, though, is that it was rebuilt only to be torn down.

Leifheit: To make room for new hospitals?

Hilger: Yes, which was a great thing, but at the expense of people living there. And then there was a hospital that stood empty. There are impulses to think about how photography might serve some purpose to saving the residents’ homes, and I befriended preservationists and other people who were rallying for this. But, ultimately, I realized the place was doomed and damned and there was nothing I could do about it but describe it.

Stephen Hilger, Niche, 2010, from the series Back of Town

Courtesy the artist

Leifheit: Although sometimes it’s essential if communities document their own spaces and lives, in this case it seems equally important that an outsider came in to do this work. And the distance you have as an outsider in this situation is actually beneficial in some ways.