Aperture's Blog, page 116

June 8, 2017

Camerawork Now

For Akinbode Akinbiyi, new technologies have helped and hindered the development of photography in Africa.

By Rahima Gambo

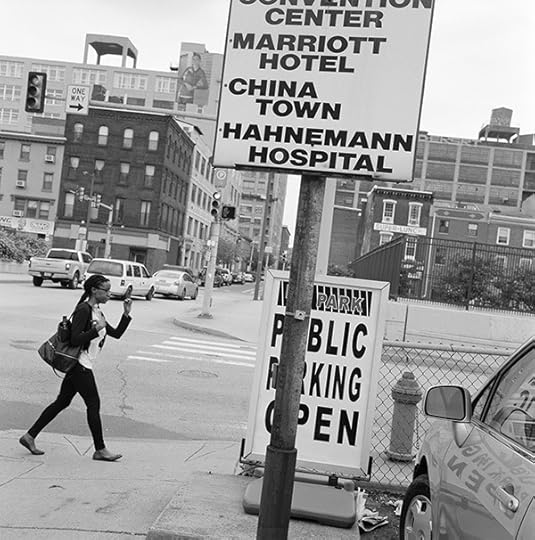

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Passageways, Involuntary Narratives, and the Sound of Crowded Spaces, 2015–17

Courtesy the artist

The first time I saw Akinbode Akinbiyi was in a little digital square. It was a documentary about his practice and he was peering down through his Rollei at a Johannesburg street. Then I met him at the LagosPhoto Festival where we exchanged few words, but found instant recognition. Years later, he was my assigned mentor for the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg Photographer’s Master Class. His advice has always been poetic and lyrical with a crystalline core of unflinching honesty, just like his images.

Rahima Gambo: When and how did your journey into photography begin?

Akinbode Akinbiyi: It started in an uncertain, still-colonized Lagos of the 1950s. My parents were forging a path into what was then an uncertain future. This uncertainty made us—their four children—aware of our surroundings, looking, listening, trying to understand. My practice as a photographer started in the pages of National Geographic, the West African edition of Drum magazine, and the Black Photographers Annual. After university, I took up photography as a hobby but soon grew much more serious. It was very much a learning-by-doing process. I soon discovered the powerful work of Japanese post-Second World War photographers and then Latin American photographers. The photographers who struck me most deeply were those from the continent: David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, Peter Obey, and, somewhat later, Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé.

Gambo: Your projects seem mostly to dwell on urban Africa, yet you live in Berlin, Germany. Does geographical proximity matter in your practice and mentorship activities?

Akinbiyi: Proximity does matter, but it need not necessarily be physically close. What matters is being sincere and aware of the inner impulses that course through us all when making images. It is not the environment that determines the approach, but rather how you stand in relation to yourself and what you want to say, to see, to create. My approach to mentoring is to gently urge younger colleagues to hear their inner voices, see their inner eye, and take it from there. The location of teaching is of little importance.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Passageways, Involuntary Narratives, and the Sound of Crowded Spaces, 2015–17

Courtesy the artist

Gambo: Can you describe the photography education landscape in Africa in the beginning of your career and how it compares to today?

Akinbiyi: In the early 1970s, there were few if any institutions devoted to photography. Art institutions focused on drawing, painting, and sculpture. Those who wanted to learn photography usually assisted established photographers or went abroad to recognized institutions. The Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, founded by David Goldblatt in the late 1980s, was one of the first photographic learning institutions on the continent and an influential one that has brought forth a wealth of articulate and incisive photographers ever since. Hence, one finds that South Africa, the leading economy on the continent, has a relative wealth of art institutions that today promote and teach photography. Internationally recognized South African photographers have had a synergic effect on their country and further afield. Other regions too have brought forth talent, such that today North, West, East, and Central Africa are on the map as much as South Africa, though oftentimes not in the number of recognized photographers. This is due to the uneven development in photography education and the many serious problems that beset many countries in Africa.

The powerful surge of the digitally mobile age has encouraged a willingness to photograph and record ubiquitous happenings, subsequently uploaded to various Internet sites. This has led to a kind of facile regard towards photography and being a photographer.

This one development, the easy access to photographic equipment and its even easier dissemination, has helped, and at the same time hindered, the development of photography on the continent. Helped, in that photography has become even more democratic, even more widespread than ever before. Hindered in the almost insurmountable number of images now produced, downloaded, viewed.

A careful scroll through these archives of downloaded visual data makes very apparent the superficiality of much that is produced. Clichéd images from a sensibility dulled by extreme overkill. However, a few resonate, give evidence of aspiring talent in the jungle of unending visualizations.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Passageways, Involuntary Narratives, and the Sound of Crowded Spaces, 2015–17

Courtesy the artist

Gambo: Why did you begin to focus on developing photography education and mentorship in Africa?

Akinbiyi: One workshop led to the next until I was actively involved in establishing a network of teaching centers called “Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa” across the continent. The role model was the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. The Goethe-Instituts in Lagos, Khartoum, and especially Johannesburg have been critical in this development. Johannesburg provided seed funding to get the whole program of Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa off the ground. The intention was to encourage young practitioners to get a formal photographic education based on a set curriculum and with the intention of becoming professionals.

Gambo: Can you describe your photography education and mentorship work in Sudan? How has it impacted the photography scene there?

Akinbiyi: Khartoum, Sudan, is a secret almost too precious to be mentioned. The city at the confluence of the two Niles—the White and the Blue Nile—is a like a jewel hidden in the tales of woe that so often come out of our continent. Due to the years of economic, and in many ways cultural, embargo, photography in Sudan was not particularly developed. In 2013, I took part in a series of workshops where participants were eager to learn. Their enthusiasm was a joy to experience, and in a very short time, the quality of work by these young aspirants leapt forward. Their work was exhibited at the 2016 Mugran Foto Week and in two rooms at the National Museum in Sudan.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Passageways, Involuntary Narratives, and the Sound of Crowded Spaces, 2015–17

Courtesy the artist

Gambo: What is the future for young African emerging photographers?

Akinbiyi: The future is bright. Still, a major challenge is avoiding the pitfalls of being too attuned to the Internet, to the ready-made images that constantly flood screens and social media sites. Too many of these images are like a visual version of highly toxic fast food. The same Internet does however afford an insight into serious photography, if used and applied with a sense of purpose. This brings up the vexed question of how many have this diligence and sense of purpose, how many are so passionate about photography as to want to seek out past masters and their techniques and motivations. Opportunities are few and the Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa are still in the early stages. Some participants cannot afford the low fees being charged and workshops are infrequent. One constant weakness I see is the lack of research so many emerging photographers bring to their chosen subject matter. Almost as if they enter blindly into the foray of going out there and taking, making images.

Gambo: Can you tell us a little bit about your work at documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel?

Akinbiyi: The work is very much about spirituality, how it manifests physically in our daily wanderings and doings, so quietly and often unnoticed, that we are often surprised when it gently comes through.

Rahima Gambo is a documentary photographer based in Nigeria and winner of the 2017 Fourthwall Books Photobook Award.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Camerawork Now appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

At a British Photography Biennial, Glimmers of Optimism

The FORMAT Festival has put Derby on the U.K.’s cultural map. But can it survive Brexit?

By Isabel Stevens

Sadie Wechsler, Eruption, from the series Part 1: Redo, 2013

© the artist

If there is one image that encapsulates how many people in the West feel right now, it might be a dystopic vista in Sadie Wechsler’s series Part 1: Redo. In Eruption (2013), the signature picture for FORMAT, a photography festival presented this spring in Derby, a city in central U.K., a group of people stand watching the world around them burn. A forest is ablaze in the distance. Smoke suffocates the air. The onlookers just stand there, resigned, staring.

At a time when many exhibitions, from the Whitney Biennial in New York to Richard Mosse’s recent installation Incoming at the Barbican feel like urgent protests, it’s unusual to find glimmers of hope in a photography biennial. Wechsler’s work was part of a group exhibition at QUAD Gallery titled Ahead still lies our future, curated by Louise Clements and Hester Keijser. With images like Wechsler’s, and Ester Vonplon’s photographs of melting glaciers, the exhibition described a world at risk, but, inspired by philosopher Hannah Arendt’s 1958 book The Human Condition, it also refreshingly embraced humanity’s ability to change and adapt.

Sohrab Hura, from the series The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer, 2013–ongoing

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Under the festival’s wider theme of “habitat,” Ahead still lies our future focuses on the environment. Ursula Biemann’s film Forest Law (2014) documents how indigenous people of the Ecuadorian Amazon have succeeded in battling mining and oil companies that exploit the rainforest’s resources (In a series of landmark legal cases at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the rights of nature were upheld by law.) Lisa Barnard’s roving, interactive digital essay about gold considers the “excrement of the gods,” while Sohrab Hura’s photographic series The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer (2013–ongoing) explores the daily rhythms of life in Barwani, a city in one of the hottest and driest areas of India, but without the resolute despondency one might expect.

It’s particularly surprising to find these notes of nuanced optimism in Derby, which, in last June’s referendum, voted in favor of Brexit. The relatively affluent streets of the city’s center, and in particular the sleek arts complex QUAD—funded partly by European Union in 2008—don’t particularly betray the frustration and deprivation that underscored much of the Leave vote. But, neglected by successive governments after the demise of the coal mining industry in the 1980s, many towns and villages throughout the county of Derbyshire tell a different story: they have high unemployment and very little public transport or investment.

Sohrab Hura, from the series The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer, 2013–ongoing

© the artist/Magnum Photos

FORMAT is the largest photography biennial in the U.K. The 2017 edition brought photographs—including the work of fifty emerging international artists selected from an open call—not only to Derby’s museums but also to all types of venues, including the city’s Cathedral, a castle, and even a pub. British cities that have large, established cultural festivals are generally thriving artistic hubs like Brighton, Manchester, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and, of course, London, all of which are Remain strongholds. As Monica Allende, acting director of FORMAT, told me this spring, the festival highlights the polarization of the cultural landscape. “We have all these mental barriers in this country. It’s very challenging for FORMAT to persuade people from London to come to Derby. It’s not a place people identify as being a ‘cultural city.’” For Allende, this idea of a habitat as a bubble loomed large. “Are we paying attention when we go outside our immediate spaces? Are we taking the time to pause and have a look around and to have a conversation?”

As a curator, Allende’s priority was to bring to light Derby’s forgotten past. Another of the festival’s exhibitions, People, Places, and Things, showcased the archive of one of Britain’s oldest photographic studios, W. W. Winter, set up in Derby 150 years ago. The images offer a glimpse into the lives of people who came to the studio to have their portrait taken, as well as the city’s factory floors, shopwindows, and street parades. While a time machine like this could all too easily slip into nostalgia for Britain’s “glorious” lost past—a nostalgia baldly co-opted by Brexiteers in the racist, anti-immigration elements of the Leave campaign—the exhibition displayed the diversity of Derby’s citizens from the 1960s onward.

Discipula, from the series STRATA, 2017

© the artists

Flâneur: New Urban Narratives was an open-air installation of photographs by three artists asked to respond to the local East Midlands area. Their photographs were presented in cubes that people could walk around and illustrated both disenfranchisement (Tom Hunter’s somber exploration of ex-mining communities) and hope (Liz Hingley’s focus on their still-thriving brass band culture). This project, like the QUAD Gallery, was partly funded by the EU; its next stop after Derby is Mansfield, a former mining town that recorded one of the highest Leave votes.

Tom Hunter, from the series Flâneur in the Ancient Landscape, 2017

© the artist

As I left the biennial to return to London, I wondered about the economic fallout from Brexit and its impact on cultural events like FORMAT in places like Derby. One of Allende’s key concerns was to reach beyond the confines of the art and photography worlds, not just by bringing work into the streets and everyday locales. The biennial producers made sure to engage with local businesses, looking beyond traditional outreach arts projects to commissioned bespoke ales from a local brewery with the theme of habitat in mind.

“I want to leave things that are the beginning of the conversation. It was important to create networks of independent and creative people in the city. Five years ago, much of Derby’s city center was boarded up,” Allende said. But what will the next edition of FORMAT look like in two years, when the U.K. has left the EU? Whether the U.K. government will pick up the funding shortfall from the EU is one of the questions on many people’s minds—and not just concerning arts funding. Despite the message of hope that the festival brings, Allende is wary about being too optimistic. “We don’t know what the future will hold,” she said, “but it’s likely that the people of Derbyshire will be some of the first to suffer.”

Isabel Stevens is the production editor of the film magazine Sight & Sound.

FORMAT Festival was presented in Derby, U.K., from March 23–April 23, 2017.

The post At a British Photography Biennial, Glimmers of Optimism appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 6, 2017

Myles Loftin Wants to Change the Conversation About Black Youth

Picturing friends and family in vivid colors, the nineteen-year-old photographer reframes representations of masculinity.

By Will Matsuda

Myles Loftin, 08, from the series HOODED, 2017

© the artist

Most people know Myles Loftin through his Instagram feed @goldenpolaroid. Loftin, who is only nineteen years old, has been using images to push back against stereotypical representations of black teens. His photographs—soft, bright, and a bit rebellious—are shared widely on social media platforms like Tumblr, where one post has garnered over 72,000 notes. Varied representations of black teens produced by black teens are important in any context, but the power of Loftin’s images lie in their vast reach.

A rising sophomore at Parsons School of Design, Loftin has shot for Urban Outfitters, Rookie, and The Fader. His recent series, HOODED (2017), challenges the negative, even deadly, perceptions of black boys wearing hooded sweatshirts. The series brings to mind John Edmonds’s Hoods (2016) images, which also examine the racially-coded nature of the hoodie; depicting only the backs of men’s heads, Edmonds suggests that even though black men are constantly watched, they are rarely seen. Loftin has a different approach: his frames explode with the joy and laughter of young men.

Matsuda: Your series HOODED really took off this year. How did it come about?

Loftin: I was scrolling through Twitter one day and I saw a tweet comparing the Google searches for “four black teens” and “four white teens.” The results for “four black teens” were mostly mug shots and courtroom shots. For “four white teens,” the results were stock photos of teens playing and laughing. That annoyed me. It’s upsetting that when someone is trying to find a picture of some black teens, the only thing that comes up are those pictures. It’s the first thing they see. I wrote this down in my journal and it sat there for a while. Last semester, I used this idea for a final project at Parsons. And then Milk published it!

Myles Loftin, 04, from the series HOODED, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: The series also challenges a lot of ideas about black masculinity.

Loftin: It was natural for me because I don’t think I fit into the stereotypes about black men. A lot of my friends, and the people in the project, don’t fit either. They were just being themselves. Being yourself is a rebellion when the traditional representations of black male identities are hypermasculine and non-emotional. You’re not allowed to be intimate at all.

Matsuda: Sometimes when a project goes viral, it can get stripped of its context and turned into clickbait. Have you been happy with how HOODED has been presented and described?

Loftin: It has been good for the most part. I feel like some places went a little far with the clickbait. Saying “This Gorgeous Photo Series Crushes Stereotypes About Black Masculinity” isn’t really true. That makes it seem like I’m doing so much more than I actually have. It was only a project. It’s just a small part of this conversation.

Myles Loftin, Untitled, from the series Potential Intermission, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: This project seems more explicitly political than your other work. Has the current political climate affected your ideas about photography?

Loftin: I’m interested in conversations about representation, so I’m mostly photographing my friends and family. By photographing the people around me, I feel I am creating a more honest and accurate representation of people of color. Usually, I see watered down or exaggerated versions of who we are. I want to show what the people close to me are like. It’s more honest.

HOODED was my first political project. Before that I was just taking portraits of my friends, but I feel like I might do a project on the political situation. There’s so many racists who now feel they can say whatever they want with Donald Trump as president.

Myles Loftin, Synclare, from the series Synchilla, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: But, even before HOODED, I think your work is political because you’re showing a different perspective on the many ways black teens can simply exist in the world.

Loftin: Yes, definitely.

Matsuda: How do you think images can fight back against these emboldened racists?

Loftin: The narratives of people of color are often created for them, not by them. This has led to the development of a system that automatically sees us as inferior. I think that visual art affects people in a different, maybe more personal way than words. An image can be a great way to fight back against racist narratives. That’s what I’d like my images to do.

Myles Loftin, Matthew and Darius, from the series Poolside Portraits, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: There’s been so much discussion about “bubbles” and “echo-chambers” on social media. Do you think your work can connect with the people who disagree with you? Do you want it to?

Loftin: The Internet is one of the best tools to get your art seen by the people who really need to see it. When HOODED was published and shared on Facebook, there were many people commenting and agreeing with the very ideas that I was trying to argue against in my photos. I can only hope that my work gets through to those people. It may not happen immediately, but at some point I’d like it to influence a change in their thoughts.

Matsuda: Does your large social media following influence the kinds of images you make?

Loftin: Social media puts my work in front of more people and it gets me more work. Most of the work I’ve gotten has been through people who saw my work online. I’m not changing my work for my followers; I don’t make work just so 19,000 people will like it.

Matsuda: What photographers are you looking to for inspiration?

Loftin: Tyrone Lebon, Tyler Mitchell, Harley Weir, and Tim Walker.

Myles Loftin, Crimson, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: That’s a pretty young crowd. Do you find yourself drawn mostly to young photographers?

Loftin: I really like looking at the work of young people because that’s mainly the work I’m interacting with on social media. A lot of the people I follow are around my age. Young artists come together because we share the same issues with being exploited by publications and companies who try to get you to work for free or for essentially no money. We’re not taken seriously! We’re not paid enough, if we get paid at all. That stuff brings us together.

Matsuda: Do you have any advice for emerging photographers?

Loftin: Value yourself and your work. Know what your talent is worth—and don’t settle for less. That’s so important to understand as a young photographer. When you know how much you’re worth, you’ll work really hard to get people to understand that.

Will Matsuda is the social media associate at Aperture Foundation.

The post Myles Loftin Wants to Change the Conversation About Black Youth appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 5, 2017

How Do Magnum Photographers Connect With Their Subjects?

Robert Capa once said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” In the years since Capa co-founded Magnum Photos, in 1947, Magnum photographers have continued to shape the world’s visual narratives by getting closer than anyone else. For five days only, get signed and estate stamped, museum quality, 6-by-6 inch prints by acclaimed Magnum photographers for $100. Use this link to make your purchase and a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

Selected by Aperture’s editors, here are ten highlights from the Magnum Square Sale.

Olivia Arthur, India, 2017

© Olivia Arthur/Magnum Photos

Olivia Arthur

“I had intended to make a portrait of Loren on her own, but she took me to a house she shares with other members of the hijra society—India’s ancient transgender community—and it was buzzing with people. They were all quite enthusiastic about having a photographer there, and after I had done the portrait, they started dancing and we all sat around talking a little. It was at that time that Loren, sitting in this embrace with Sheshan, caught my eye, and I took my camera back out again to take this image. It’s a situation that I feel has happened to me often: in the moment when the formality of the photoshoot is over, everyone feels a bit more relaxed. It’s as though I need to finish taking pictures in order to really start taking pictures. It’s not that I was so close to them in this moment, as I was only there for a relatively short time, but that I got to a point when they could let their barriers down and share their own closeness with the camera.” — Olivia Arthur

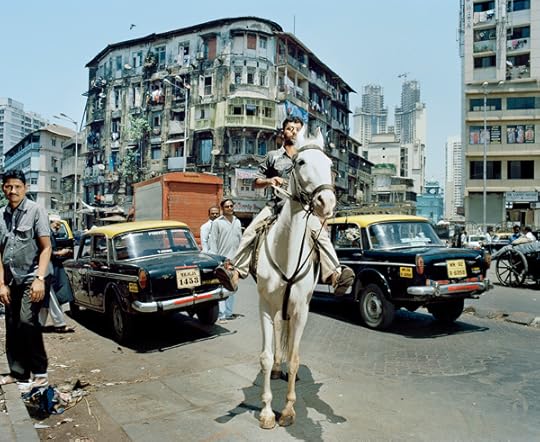

Max Pinckers, The Horse to be Sacrificed Must be a Stallion, from the series, Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty, 2014

© Max Pinckers/Magnum Photos

Max Pinckers

“The man on the white horse in the middle of this image is clearly the center of attention. Bystanders know this and either attempt to discreetly remove themselves from the image frame in one swift body movement, or choose to become part of it by remaining still and addressing the camera with a faint smile or inquisitive glance. It is in the actions and reactions of the extras that a photographer’s presence and intentions can become apparent, something that would have been lost by following Robert Capa’s famous maxim. In this case, the man leaning into the edge of the image acknowledges the excluded space outside of the frame. The two men behind the horse are conscious of the scene that is taking place and choose to contribute, taking up their right to play an active role for a brief moment. These small gestures hint toward the construction of an image, and prick through our willing suspension of disbelief.” — Max Pinckers

Carolyn Drake, Ukraine, 2006

© Carolyn Drake/Magnum Photos

Carolyn Drake

“I made this image of Olya at a Ukrainian boarding house, where about sixty girls, judged to have disabilities, lived together tucked away on the edge of a forest near Ternopil. In the afternoons, as the weather warmed and the workday finished, the girls often plugged in a boombox on the balcony and spread out across the courtyard to dance. This was the only time of day when the girls’ attention drifted away from me, the visitor, toward another place. This image plays sweetly into the illusion that photography allows the viewer to get close to someone, to have access to them, through their image. It’s a fantastical escape mirrored by Olya, who appears to also be escaping into the music.” — Carolyn Drake

Elliott Erwitt, New York City, USA, 1955

© Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“In thinking about getting closer, weddings come to mind … at least initially. Afterward, and down the line, all bets are off.” — Elliott Erwitt

Jean Gaumy, Dune of Pilat, Arcachon Bay, France, 1987

© Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos

Jean Gaumy

“I was on a Jeanne Labrune film (La part de l’autre, 1987), with Maïté Nahyr, one of the actresses in Fellini’s film City of Women (1980). I asked her, between two scenes of shooting, to come to the great Dune of Pilat with me. I was photographing Maïté from afar, up against the wind, in the middle of vast emptiness. This man and his dog appeared, confidently, passing very close by. She, them, and me. Close, afar. Different distances that worked perfectly for me.” — Jean Gaumy

Martin Parr, Mar del Plata, Argentina, 2014

© Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

Martin Parr

“I love Mar del Plata. It is safe to say the Argentines do as well. With seventeen kilometers of beaches and two thousand hotels, it is by far the biggest resort in the country. Indeed, it may be the biggest resort in the world. The real sun lovers, generally over fifty, are out in the hot January sun by 9 a.m.; this was a great time to shoot and to come up close on some of the real characters.” — Martin Parr

Robert Capa, Pablo Picasso with his nephew Javier Vilato and Françoise Gilot on the beach, Golfe-Juan, France, 1948

© Robert Capa and International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

Robert Capa

“In these images of Picasso and his family, Robert Capa stresses the everyday human side of the man. These are warm friendly images with sharp flashes of the typical Capa gaiety. In this group of pictures, the hopeful aspirations of millions of family snapshot albums is realized by a master journalist photographer.” — Edward Steichen

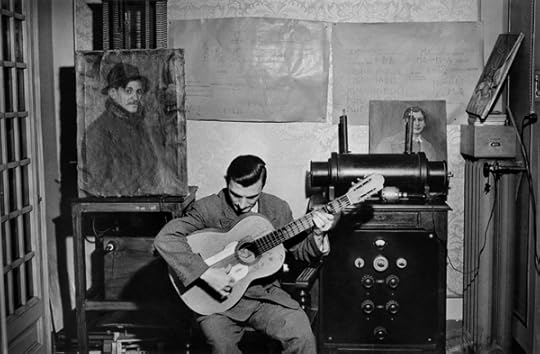

Inge Morath, Pablín, nephew of Picasso, strums guitar next to a portrait of his uncle painted by Picasso’s great friend, Sebastià Junyer, Barcelona, Spain, 1954

© Inge Morath/Magnum Photos

Inge Morath

“Inge’s interests in exploring different regions, and their cultures, often led her into homes of local artists and writers. On one such occasion, she found herself on an assignment in Barcelona for the French magazine L’Oeil. Picasso’s sister, Lola Ruiz Vilato, amused by Inge’s shaky Spanish (over the phone), agreed to be photographed and invited her home. Inge was greeted by music, drinking, and conversation among Lola’s many children.

In this photo of Pablín, Inge creates not only a literal, but also an emotional invitation for the viewer to ‘get closer,’ so we can observe the subject’s surroundings. Pablín sits next to a portrait of his uncle, Pablo Picasso, with a deliberate visual narrative that showcases familial closeness.” — Sana Manzoor

Jonas Bendiksen, Altai Republic, Russia, 2000. (Alternate Take)

© Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

Jonas Bendiksen

“I’ve always tried to follow Capa’s adage about getting closer. The irony is that my most well known image of a crashed spacecraft with butterflies was taken from afar with a big, long telephoto lens. Without that, the butterflies would be all but invisible in the image. I did, in fact, try some images with a wide angle lens, but the pictures just got worse and worse the closer I got. But there is wisdom in Capa’s idea outside of the frame as well. The best photographs are of the things that are close to you – in terms of what you are passionate about, what engages you. When I took this picture, in 2000, I was in the midst of a big love affair with Russia and the former Soviet Union. I had moved there to live in the middle of my story every day. This is an outtake that’s about 10 frames after the more well-known image. The same boys are ripping copper wire from the top of the rocket but, in this picture, a villager on a horse has shown up. I wonder if there was an even better picture that I missed if I’d gotten the horse in the frame when the boys were standing up.” — Jonas Bendiksen

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Cecilia, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1995

© Alessandra Sanguinetti/Magnum Photos

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“Back in 1993 I lived on a third floor, in an old building, on a narrow street, in downtown Buenos Aires. My bedroom had a little balcony that faced straight onto another third floor balcony of the building across the street.

Every day I’d see three young sisters hanging the washing out to dry on the railing, sweeping, playing, or throwing the keys down to someone waiting to get in. I started taking pictures of them when they came out, and we would wave at one another. The narrowness of the street between us made it seem like they were closer than they were. Eventually, I crossed the street and rang a few doorbells (there were ten third floor apartments). To everyone that replied I’d say I was the girl from in front that took pictures, until I rang the right bell and they let me in. This started a yearlong relationship with them and their Mom. We’d call each other from balcony to balcony and once in a while, we’d defy the gap and play ball over the traffic below.” — Alessandra Sanguinetti

Magnum’s “Closer” Square Sale runs from Monday, June 5, 2017 at 8 a.m. EST until Friday, June 9, 2017 at 6 p.m. EST. Signed and estate stamped, museum quality, 6-by-6 inch prints from over seventy artists will exceptionally be available for $100, for five days only. By using this link to make your purchase, a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

The post How Do Magnum Photographers Connect With Their Subjects? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 1, 2017

Inside Aperture’s Annual Patron Cocktail Party

Elizabeth and Bill Kahane, hosts of Aperture's Annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party

Guests mingle at Aperture's Annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party

Larry Fink and Bill Kahane

Guests mingle at Aperture's Annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party

Guests view photographs at Aperture's Annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party hosted by Elizabeth and Bill Kahane

Chris Boot, Aperture's executive director, and Larry Fink

Elizabeth and Bill Kahane with Mike and Doug Starn

At Aperture’s Annual Patron Cocktail Party, held on May 24, 2017, Patrons, friends, and artists celebrated Aperture’s wonderful community while listening to the music of photographer Larry Fink. The evening’s hosts were Aperture trustee Elizabeth Kahane and her husband, Bill.

Guests toured the Kahanes’ private collection, including a recent commissioned portrait by Doug Starn and Mike Starn, generously donated to the 2016 Aperture Benefit Auction.

At sunset, Larry Fink and friends played a fabulous jazz set on the Kahanes’ rooftop with its panoramic views of Central Park. Over champagne and hors d’oeuvres, guests mingled with Aperture editors, trustees, and artists, including Elliott Erwitt, Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao, and Doug Starn and Mike Starn.

Aperture Patron Members gain insider access to publications, exhibitions, artists, and programs while supporting the foundation’s mission to connect the photo community and its audiences with the most inspiring work, the sharpest ideas, and with each other—in print, in person, and online.

For more information, click here or contact Hillary Beson at 212.946.7146 or membership@aperture.org.

The post Inside Aperture’s Annual Patron Cocktail Party appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Lives of Samuel Fosso

The acclaimed photographer pushes self-portraiture into new realms of gender-bending theatricality.

By Yves Chatap

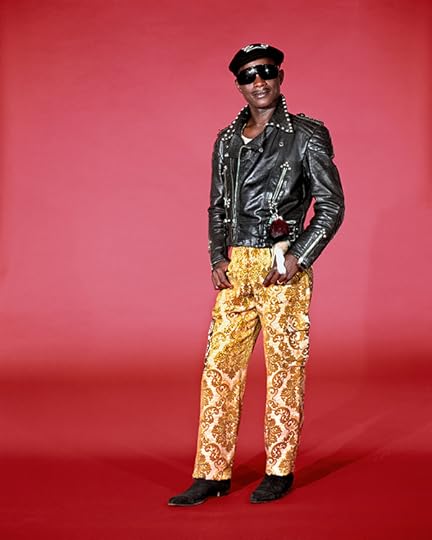

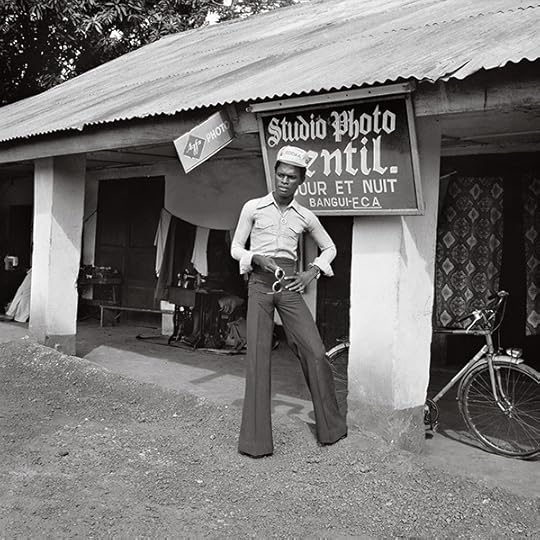

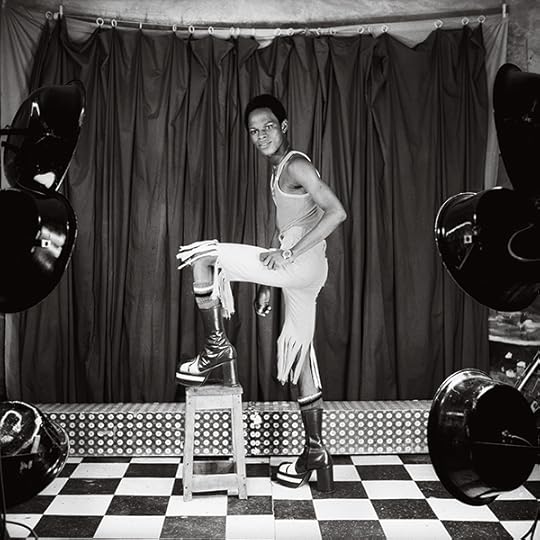

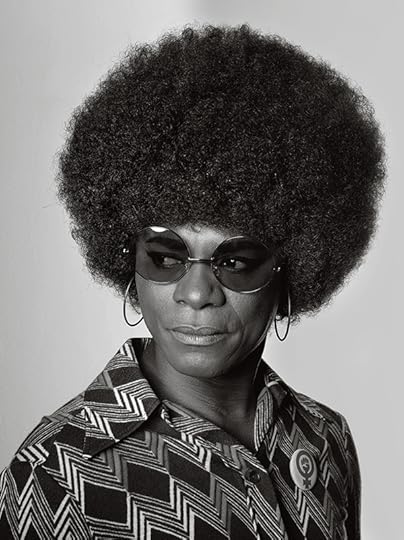

Samuel Fosso, The Rocker , 1997, from the series Tati

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

It all began with the high heels. In 1976, as a precocious teenager, Samuel Fosso traveled from Bangui, Central African Republic, where he operated his own photography business called Studio Photo Gentil, to visit his family in Nigeria. There he discovered a pair of platform boots similar to those worn by the popular Nigerian highlife musician Prince Nico Mbarga on the cover of his record albums. Fosso’s grandmother agreed to buy him the boots, and upon returning to Bangui he completed the look, ordering a pair of bell-bottoms from a local tailor. “I put on my new outfit and went out. In the street, I ran into a priest who said, ‘You look handsome. You look like an astronaut. Do you want to reach heaven?’ And I answered, ‘Yes!’”

For more than forty years, Fosso, like Cindy Sherman, Iké Udé, and Yasumasa Morimura, has focused on one subject: himself. In the 1970s, after making pictures for clients, he would finish off rolls of film by staging imaginative self-portraits, wearing sunglasses, bathing suits, and fashions that would have challenged the conservative sensibilities of ’70s-era Bangui. By playing with the cultural codes of style and pose, Fosso evoked the power of personal transformation. His early experimental images remained private until 1994, when he was invited to participate in the first edition of the Bamako Biennale. Since then, often using a team of stylists, Fosso has pushed his self-portraiture into new realms of gender-bending theatricality.

Ahead of his solo exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery in June 2017, Fosso spoke with Paris-based curator Yves Chatap about studio photography, artistic influences, and taking on the roles of a lifetime.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait, 1976–77

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Yves Chatap: Your earliest exhibition dates back to the first Bamako Biennale in 1994. Can you tell us about that experience?

Samuel Fosso: For the first edition of the Biennale, emissaries were sent all over Africa to find photographers. There was a French photographer, Bernard Descamps, who discovered my work while visiting Bangui and invited me to participate in this exhibition. When we met, I was already working in color, but Descamps wanted to see my black-and-white images from the 1970s, which he then submitted to the jury. That’s how I got my first show at the Palais de la Culture in Bamako, which was inaugurated by then president of Mali, Alpha Oumar Konare.

During my stay in Bamako, we did workshops. Six months later, I learned that I had won first prize, which I was awarded in September 1995 in Paris, where I went for the first time. It was then that I had my first exhibition in Paris, with Martin Parr and Marie-Paule Nègre.

Chatap: How did this first visit to Europe go?

Fosso: It gave me the chance to meet photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, who congratulated me and advised me about my work. I didn’t know him, but that encouraged me to carry on, as did the support of Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, because I came to understand that my process was an asset that I shouldn’t overlook.

Chatap: When did you become aware of the work of other African photographers?

Fosso: Before coming to Bamako, I didn’t know any other African photographers like Malick Sidibé or Seydou Keïta, but they seemed to have known my work, because my photographs were hung before I arrived. I have to admit, I didn’t know I was making artistic photographs. It was a discovery for me. It was a big surprise to have Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta coming to give me advice on my work and to encourage me about my future as an artist-photographer, explaining that it was rare to see a photographer photograph himself. I thanked them for their advice and encouragement and was able to get to know their works during the exhibition.

All of that opened my eyes. Once I got back to Bangui, I continued working, because I said to myself, If I don’t produce anything, they will forget about me. Those meetings still frame my career today.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait, 1976–77

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: Let’s go back to the beginning. How did you get started in photography?

Fosso: I was born in Cameroon. As a child, I suffered from paralysis, and my mother was too ashamed to have my picture taken like other babies. I was cured under my grandfather’s care in eastern Nigeria, but then war broke out in Biafra in 1967. It was then that my uncle brought me first to Cameroon, then to the Central African Republic, where we worked making women’s shoes. On our street, there was a studio photographer who I began to spend time with. I asked him to teach me photography. I spent five months as an apprentice, after which I wanted to have my own studio. The problem was making prints without wasting too much paper because, as my uncle said, “You don’t do business for loss, you do business for gain.” But I found out that the owner didn’t want me to leave because he had stopped losing money when I started working in his studio. After learning that, my uncle told me to find a space for my own studio and he bought me an enlarger.

Chatap: You mentioned your childhood and your illness. Isn’t your self-staging today a form of therapy for that suffering body?

Fosso: It is indeed, because body movement is part of health, if you think about athletes, for example. For my body, it was the distress of illness and healing, but also the cure that my grandfather worked on me—perhaps I had to suffer from that. When you look at my work, it’s my body that is looking at me. It’s my way of seeing. Perhaps it’s my illness. I don’t know. But what matters is that it is my natural body.

Chatap: Do you see your grandfather as a hero?

Fosso: For me, yes, my grandfather is a hero because I am not the only person he had to heal. He was a healer his whole life and he took care of the mentally infirm. Whenever anyone brought an insane person to my grandfather, after two weeks the person would begin to respond and to recover their natural state and normal consciousness. Then, the family could come take them back. At that time, money was hard to come by, so people paid him in hundredths of a shilling. My family couldn’t really make ends meet. He healed many people. The whole village considered him a hero. He was an important figure who the village asked for advice on major decisions. For me, he’s a hero, and he is deserving of the term.

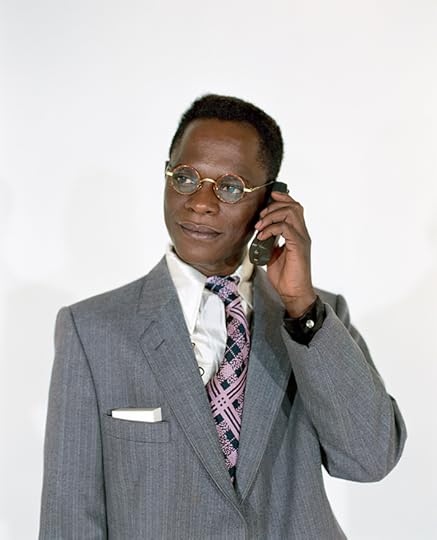

Samuel Fosso, The Businessman, 1997, from the series Tati

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: Why put this personal history into images?

Fosso: Simply because Westerners have never believed in traditional medicine. I bear witness to the idea that the healer can treat many things. It’s a way of educating about the practices of traditional medicine that have long been rejected.

Chatap: What was the motivation behind your first self-portraits in the 1970s?

Fosso: I opened my own studio on September 14, 1975. I started taking pictures of myself to make up for the absence of photography in my childhood. I used the last frames on rolls of film because I didn’t want to waste them. When I closed the studio for the day, I would take pictures of myself and send the images to my grandmother in Nigeria. I had clothing custom-made based on things I saw in magazines, mostly Afro-American ones.

Chatap: Your inspirations in adventurous fashion can be seen in your first images in the 1970s. Did you have icons in mind when you made those photographs?

Fosso: If you take the example of Nico Mbarga—I was mostly inspired by him, especially by his outfits. I had clothing made, and I bought shoes called talons dames that you couldn’t find in central Africa. As for Fela Kuti, it was political because there were denunciations. We still weren’t free, and so we couldn’t just do whatever we wanted. From 1977 to 1980, and especially before democracy, conditions weren’t easy, particularly because of the political denunciations. That scared me because I didn’t want to get arrested.

Chatap: So, you were aware that your approach could have political consequences?

Fosso: I was aware that there were political consequences and, as a result, I couldn’t just do whatever I wanted.

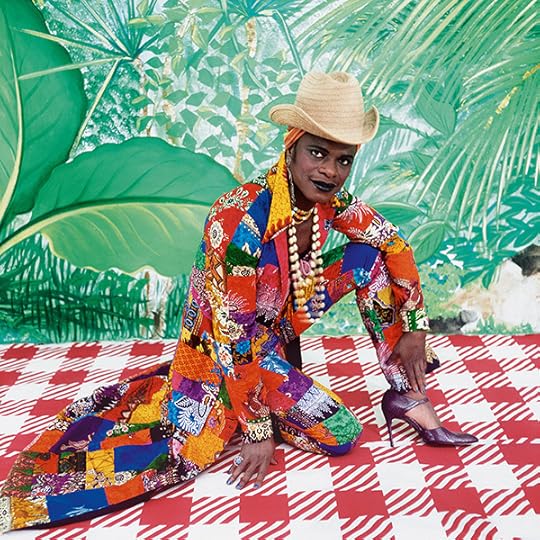

Samuel Fosso, La Bourgeoise , 1997, from the series Tati

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: In 1997, three years after you participated in the Bamako Biennale, you were commissioned by the Paris department store Tati to make a series of images. Tati contains some of the most famous images of your career. It’s about archetypes and characters, from the rock star to the businessman to the bourgeois woman. In this series, what message did you want to deliver?

Fosso: It’s a discourse about segregation and slavery and a demand for independence and freedom. I gathered all these ideas together, as you can see in the image La femme libérée américaine dans les années 70 (The liberated American woman of the 1970s), which I made before my first visit to the United States, and in the series African Spirits (2008), which follows the same path. In African Spirits, there is a desire to inscribe within the museum space all those figures who have marked the history of blacks in Africa and in America. It should be known that they all fought for civil rights and liberties for blacks. This is a heritage that we must not forget. I had to pay homage to them because they have allowed us to be free, in a way, and to give them their place in history so that our children may remember what has happened in the past and what is still happening today.

Samuel Fosso, La femme libérée américaine dans les années 70 (The liberated American woman of the 1970s), 1997, from the series Tati

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: Your series Mémoire d’un ami (Memory of a friend), about a neighbor in Bangui who was burglarized and killed, and Le rêve de mon grand-père (My grandfather’s dream), about your grandfather, are highly personal explorations. When you work with your body, do you experience it as a subject body or an object body?

Fosso: When I work, it’s always a performance that I choose to undertake. It’s not a subject or an object; it’s one more human being. I link my body to this figure, because I want to translate its history. I consider my body as a human being, but always belonging to other subjects, to the person who I am in the process of reproducing.

Chatap: And, technically, how do you work in the studio?

Fosso: I work with a team consisting of costumers, makeup artists, and an assistant photographer to carry out my shoots. Before, as I said, I did photography without realizing that I was an artist. I created my self-portraits on my own with an eight-to-ten-second delay timer. Now my work is easier, since I use a remote-controlled camera, which lets me see if my pose matches the image that I want. It’s an advantage over the past, because the technique is the same but the shot is different in relation to the work.

Samuel Fosso, Mémoire d’un ami (Memory of a friend), 2000

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: You returned to Bamako in 2007 for a retrospective of your work. What were your impressions of that experience since the first Biennale? In particular, what was your relationship with the young photographers who saw you as le grand maître (the great master)?

Fosso: By 2007, things had developed very quickly, and this retrospective was important because I had changed since 1994. I had produced other works in keeping with the earlier series, so returning to Bamako in 2007 for a solo exhibition was a point of pride. I met many Malian photographers who wanted to meet me and talk about photography. They called me “the great master.” And the BBC had produced a documentary film about me in 2002. We discussed photography and the way that I made my images. This solo exhibition that began in Bamako toured all over the world for the next two years thanks to the French Ministry of Culture. My impressions of the young photographers were overall positive because they understood the importance of African photography. That left a strong impression on me because I knew that African photography would not die.

Samuel Fosso, African Spirits, 2008

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: In 2013, you made the series Emperor of Africa, in which you performed as Mao. The images were based on famous paintings of the Chinese leader. Why did you make this series?

Fosso: After enslavement by the West, there was colonization, then political independence, which is absolutely not economic independence and still besets us today. We find ourselves with China profiting from our lack of means without providing sufficient financing in return.

In Africa, no one realized what China would become on the continent. Every African country has been seized by China. I see what they’ve made of their own country with the production of coal and pollution. They came here with a fifty-fifty proposal to rebuild Africa, on the pretext that Europe no longer has the means to do so. Now, you see that they are destroying and looting the continent’s natural resources for their own interest, Africa having been unable to develop its own means of local production. But if China went away, what would Africa become without its money? That’s where the title emperor comes from, in view of the history of that country that has only ever lived under an imperial system.

Chatap: When you talk about relations between Africa and Asia, is there not a kind of fatality about the future of Africa, and also of the individual?

Fosso: This series translates the observation of a form of repetition of history around questions of autonomy and the exploitation of resources. We cannot accept the implantation of the Chinese empire in Africa out of fear of reproducing the past. Among African states, relations are complicated and agreements difficult, so if we ourselves can’t manage to find common ground, nothing will change.

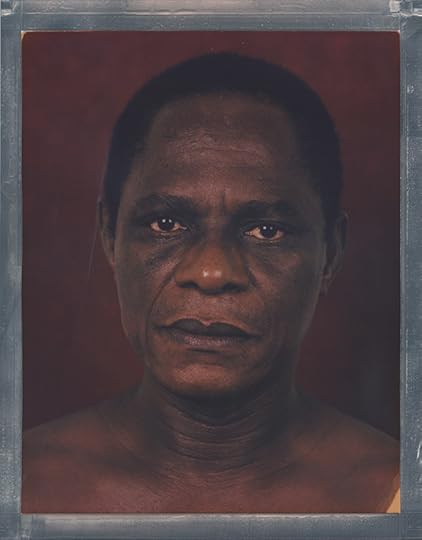

Samuel Fosso, SIXSIXSIX (detail), 2015

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

Chatap: In your latest series, SIXSIXSIX, the body is no longer in costume. The artist is without makeup. Why did you choose to orient yourself in this direction?

Fosso: This series collects 666 images in total, each of which is unique. It’s a work where photographic material has nothing to do with analog prints. The challenge was to make 666 different self-portraits with a different bodily expression in each.

In this series, there is unhappiness and happiness, misfortune and good fortune. I was very inspired by these two aspects. SIXSIXSIX refers to the number of misfortune. By that I mean in terms of what I’ve encountered in my life up to now. After my illness came the Biafra war; millions of people died, and I was fortunate to be saved. I went to the Central African Republic where I experienced the same thing during the conflicts of 2014, in which I could have died. So, 666 is a number of misfortune and at the same time is a number of good fortune. For all that I’ve been through, God has been with me and has saved me.

Chatap: In SIXSIXSIX, do we see Samuel Fosso or someone else?

Fosso: It’s neither the body that smiles, nor the body that cries, but a representation of life and all the misfortunes that strike us deep within. In the end, it’s about buried emotions that we ourselves create, and about exorcising my own resentment in the face of this situation. From 1976 to 2014, I have never been at peace in my life when faced with the actions of those who always sow misfortune among children and innocents.

Yves Chatap is an independent curator based in Paris. Translated from the French by Matthew Brauer.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Lives of Samuel Fosso appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

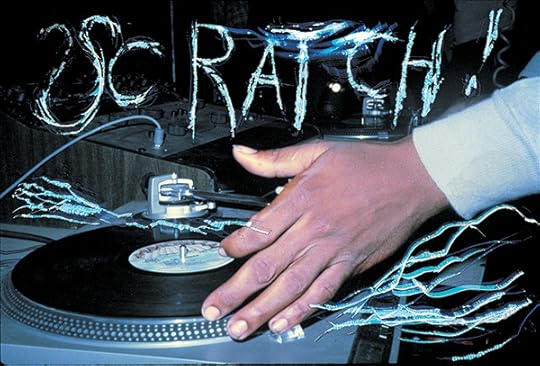

Picturing the Early Days of Hip-Hop

Bronx legends Charlie Ahearn and Grand Wizzard Theodore discuss the rise of Hip-Hop at the Ecstasy Garage Disco.

By Miss Rosen

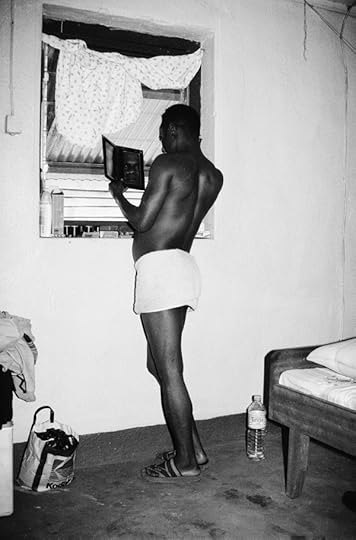

Charlie Ahearn, DJ AJ 2 from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Hip Hop came of age inside the cinderblock walls of the Ecstasy Garage Disco in the Boogie Down Bronx. By 1980, it was the place to be as the flyest DJs and MCs honed their skills among their peers. In tribute, filmmaker Charlie Ahearn has teamed up with Grand Wizzard Theodore, inventor of the scratch, to recreate their weekly slide show as the centerpiece of Ahearn’s exhibition Scratch Ecstasy, currently on view at P.P.O.W. Gallery. Miss Rosen, who worked with Ahearn on his 2007 book, Wild Style: The Sampler, speaks with Ahearn and Theodore about the interplay between sight and sound in the development of Hip-Hop culture during its formative years.

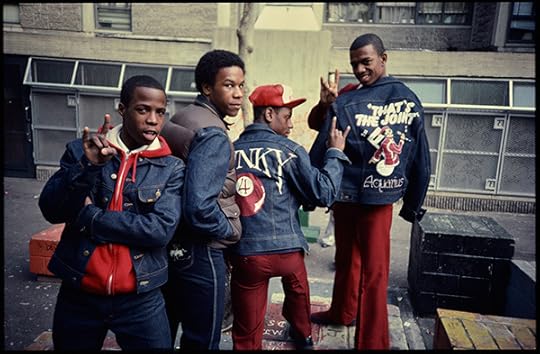

Charlie Ahearn, Funky four with Busy Bee at The Valley jam from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Miss Rosen: Could you tell us about the Ecstasy Garage Disco? What as the scene like?

Grand Wizzard Theodore: It was a place for groups like the Fantastic Five, the Cold Crush Brothers, and the Funky 4 + 1 to hone their craft. We had the audience so we were able to do what we loved. The Ecstasy Garage was like a gym for practicing and making ourselves better.

Charlie Ahearn: The Ecstasy Garage was like my clubhouse. It was completely dark in the room. The only light in the room was a single, sixty-watt light bulb that was over the DJ section. Listening to Grand Wizzard Theodore play music, I thought, “This is so experimental and so advanced intellectually and it’s being done by teenagers for teenagers in this really devastated place in the Bronx and nobody is playing any attention to it.”

The Ecstasy was a complete world unto itself. At some point early on, people recognized that they could do this themselves, that they could make money from it, that they could become famous from it, and that they could become stars. It was really bringing money into their households, and they had control over this. They had the means of production.

Charlie Ahearn, Fab 5 Freddy’s Campbell’s Soup Can homage to Warhol from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Rosen: How did you guys first connect?

Theodore: Busy Bee Starski met Charlie Ahearn and brought him around all of us. They said they were making a movie, Wild Style (1983). Once Charlie started taking pictures, we all took to him right away. We got to talk to him and he got to talk to us; we got to learn about each other and it was pretty cool. It was like, “Hey, take all the pictures you want.”

Rosen: What was the inspiration for the slide show?

Ahearn: I started bringing my slide projector stuff because I wanted to become part of the house, like the DJ. Usually I used rolls of paper on the wall behind the DJ. It was often projected as double slides and it was done as a performance. I was very inspired to see people like Kevvy Kev and Busy Bee seeing themselves up on a large screen over the DJ booth. They were superstars.

Charlie Ahearn, Scratch DJ from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Rosen: The slide show you made for Scratch Ecstasy opens with pictures from the original slide show, which is very meta. You were creating a social media experience for the people, taking pictures of the times and showing them.

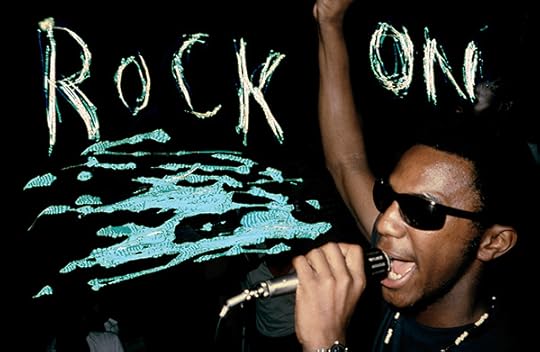

Ahearn: The very next week! Every week I would have a couple of new rolls to add to the slide show and I would take things out that weren’t as good. I would always have shots that were either out of focus, too dark, or too bright. I thought, “This costs a lot of money. I’m going to make things out of these slides.” My idea was, “Let’s make the slides that were really bad the best slides instead of throwing them away.”

Rosen: So that’s where your version of “scratching” comes in.

Ahearn: It’s not very documentary, is it? It’s a way of saying, “Well, we’re making a show here, let’s do the best we can with what we’ve got. Let’s take these things that are not the best images but add things to them that make them really memorable.” Like the Busy Bee photo that says “ROCK ON.” It was too dark. So I scratched on it with a screwdriver on the reverse side.

Fred [Brathwaite aka Fab 5 Fredddy] and I would be sitting around talking about what we’re going to do [for Wild Style], and I’d take out these slides and Fred would be like, “Give me one of those!”

Charlie Ahearn, Funky Four in their Bronx neighborhood from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Rosen: How did the slide show influence the creation of Wild Style?

Ahearn: I had a stack of color Xeroxes of pictures I was taking for the movie and I would take them and pin them on the wall in order. I would go, “It opens in a subway yard and it ends over here somewhere at the amphitheater. Okay, what else is going to be in the movie?”

I’d have all these images and I wasn’t writing the script: I was creating a storyboard. The movie was to give a shine to a series of moments that people could be themselves on the film. The whole point of making the movie was to escape from plot and escape from dialogue and those other conventions of filmmaking and think of it more like a kung fu movie.

My first kung fu movie had way too much dialogue in it. [Laughs]. You don’t need all these plot points because people are in the present when they are watching the film. In a sense, it’s a series of moments when people have their two minutes where they are clearly being themselves and whatever got them in this place doesn’t matter. We’re moving through this—as you would in real life.

Rosen: The Scratch Ecstasy slide show has the same basic narrative arc as the film. We start at the Ecstasy Garage and travel through the creation and release of Wild Style. What’s it like looking back at these pictures?

Theodore: These photos remind me of where I came from, of how I grew up in the Bronx in a single parent home, gangs all around, abandoned buildings, buildings being set on fire, the city not wanting to put any money into the Bronx, all the graffiti all over the place, seeing the Bronx look like a war zone, poverty, drugs—all of this was my every day life. Seeing those pictures reminds me of how far I’ve come.

Charlie Ahearn, Rock on Busy Scratch from the series Scratch Ecstasy, 1980

© the artist and courtesy P.P.O.W.

Rosen: How did you choose the music for the Scratch Ecstasy slide show?

Theodore: I went to Charlie’s house and the first thing he did was show me the entire slide show. Then I pulled together a bunch of songs and he started to pick out the songs. He was like, “Oh wow I remember that song. We’re going to keep that one.”

Ahearn: Everything was played at the Ecstasy Garage. The songs I picked [like “Heaven and Hell is on Earth”] were made to create a feeling. There are different passages in the party and only some DJs knew this. The labels were covered and you didn’t know what was playing. The DJs wouldn’t tell you. Now everybody knows but at that time these were secret cuts. I wanted music that had this mystery to it.

I do play “Good Times” because we see Chic in the pictures and we’re going to the Roxy with Grand Master Flash. We’re not at the Ecstasy Garage anymore. We’ve entered the pop world. We’ve changed. I wanted it to be a performance by Theodore. What you hear is not edited. It’s a straight performance of the entire twenty minutes that Theodore mixed. You have to break it down to a feeling. Soundtrack is the heart of movies.

The music is by the world’s greatest musicians. You look at who’s playing on that list and you’ve got Booker T & the MGS with the organ. Is that Hip Hop? You’re damn fucking right it’s Hip Hop.

Miss Rosen is a journalist covering art, photography, and books for Vogue Online, Dazed Digital, The Undefeated, Feature Shoot, and Crave Online.

Charlie Ahearn: Scratch Ecstasy is on view at P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York through June 24, 2017.

The post Picturing the Early Days of Hip-Hop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 30, 2017

Martine Syms: Conscious Resistance

In photographs and videos, an artist pushes back against reductive stereotypes of black life.

By Amanda Hunt

Martine Syms, Stills from Notes on Gesture, 2015. Single channel video, 10:27 minutes (loop), color, sound

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Another week, another video depicting the execution of a black man at the hands of a police officer goes viral. Another black man rendered absent: Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile … when do I stop? And what of the black women who are prematurely disappeared? It is with this horrific backdrop of continued abuse of power—which has resulted in 559 deaths at the hands of U.S. law enforcement in 2016 alone (as of July 8, 2016), only a fraction of which have actually been visualized—that I can begin to talk about the positive power of Martine Syms’s art, feminism, and photographic presentation of black women, black life, black power.

Syms’s work, foremost, is a conflation of image and text—both are primary to her practice. For a number of years Syms was the director of Golden Age, a Chicago-based project space focused on printed matter. She later founded Dominica Publishing, an imprint for artists that continues today. This fundamental relationship to and engagement with language connects all of her endeavors. As with her writing, Syms’s development of a visual aesthetic references the structures of cinema and television. The artist states that she is creating a relationship between image and text in order to produce a resultant “third meaning.” Now based in Los Angeles, Syms is closer to the Hollywood apparatus; this proximity is evidenced in her art, almost having become a character itself. But the most constant character of all is that of a black, female protagonist.

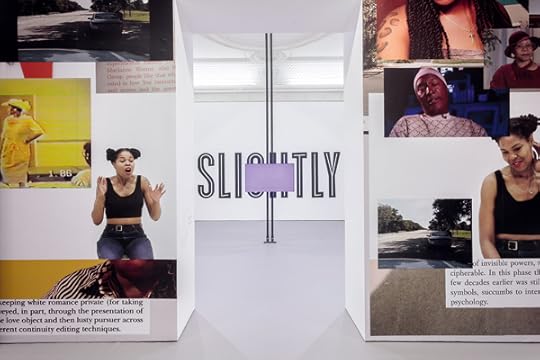

Martine Syms, Fact & Trouble, installation at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Vertical Elevated Oblique (2015), Syms’s first solo exhibition in New York, at Bridget Donahue, offered an overtly technical installation comprising video, photographs, and staged objects, as well as a space for books from Dominica Publishing. For Notes on Gesture (2015), the featured video, Syms employed a female, black actor to enact gestures readily associated with black women and blackness. Interspersed with shocks of text (“DON’T JUDGE”; “WHEN IT AIN’T ABOUT THE MONEY”), Notes on Gesture is an exercise in nonverbal expression. The video essentializes the essentializing: black women as sassy, finger-snapping, mm-hmming folks. Gestures of blackness are often co-opted, but here we do not know which gesture is authentic or which acts as a quotation. Syms presents an intentional flatness to the image that supports the myth and refutes the dimensionality of its subject. But is this body and identity really just an empty vessel of expression?

The installation of Vertical Elevated Oblique smartly collapsed language and image, layering pop culture with enduring symbols of both Hollywood (industrial stands used in film production now held up Syms’s photographs) and the black resistance (a flock-covered black panther, originally intended as a support for a glass tabletop, co-opted from the Black Panther movement by the home and now repurposed by Syms).

Martine Syms, Stills from She Mad: Laughing Gas, 2016. Four-channel video installation, 6:59 minutes (loop), color, sound

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Syms’s photography-based work is a conscious resistance that rejects what we see in the media— a construction of what is real— and flips the balance simply by the fact that it is Syms behind the camera, creating her images. If images of black people are going to continue to be fed into an endless and cruel cycle of stereotype, we may as well control the output—present them as mundane and normal, insert them into history, and reassert them in the contemporary. Syms’s video She Mad: Laughing Gas (2016), modeled on a silent film, Laughing Gas, from 1907, does exactly that. We follow Syms-as-protagonist to the dentist, where she engages with the hygienist, gets high on the titular gas, and is ultimately denied coverage for the visit by her insufficient health insurance. A distinctly American experience.

The power of what Syms does is not only in its visual strength, but also in its political implications in an art world marked by a dearth of diversity in proprietors and artists alike, and in a media universe that suppresses (whether consciously or not at this point) positive images of black life. Syms, by simply representing “herself”—and specifically black women—in the context of institutional, commercial, and codified spaces, is asserting her presence. And that, by nature, is feminist and political.

Amanda Hunt, formerly Assistant Curator at the Studio Museum of Harlem, is Director of Education and Public Programs at MOCA Los Angeles.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Martine Syms: Conscious Resistance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 25, 2017

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Glimpse of India

Spanning decades, an exhibition of the iconic photographer’s work in India reveals the fraught nature of photojournalism.

By Emma Kennedy

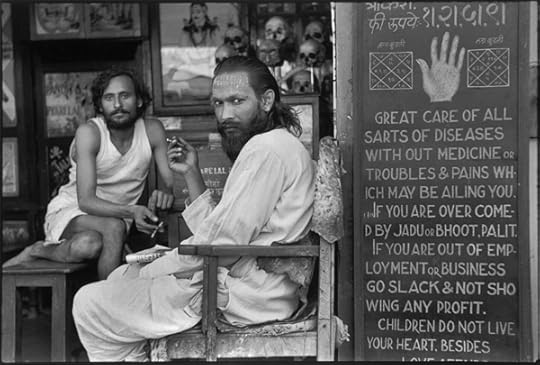

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Astrologer’s Shop, Bombay, Maharashtra, India, 1947

© the artist/Magnum Photos

In 1947, Henri Cartier-Bresson embarked on a major three-year trip to Asia, to photograph on behalf of Magnum Photos. The same year, he cofounded Magnum and his early artistic work from the 1930s and ’40s was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in an exhibition organized by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. In part thanks to his first wife, the Javanese dancer Ratna Mohini, Cartier-Bresson was particularly interested in Asia and the massive social and political changes resulting from the postwar collapse of colonial empires. Cartier-Bresson’s first stop was India, just after the country gained independence from Great Britain. Centered on his images of Mahatma Gandhi and his funeral procession, the exhibition Henri Cartier-Bresson: India in Full Frame, currently on view at the Rubin Museum in New York, is a sweeping chronicle of the iconic photographer’s sojourn in India.

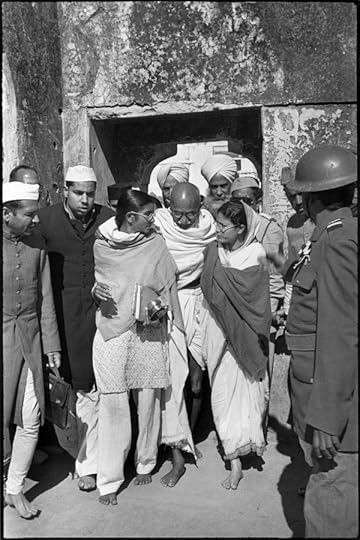

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gandhi leaving Meherauli, Delhi, India, 1948

© the artist/Magnum Photos

The day before Gandhi’s assassination, Cartier-Bresson photographed the leader, who had been fasting to call for an end to the violence over the India-Pakistan partition, as he was physically—and perhaps emotionally—supported by his nieces. Cartier-Bresson returned the next day to interview Gandhi about the fast. On January 30, 1948, hours after their conversation, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist. In the aftermath, Cartier-Bresson returned once again to Birla House to document Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s announcement of Gandhi’s death. Cartier-Bresson’s quiet pictures of Gandhi’s body lying in state led to a commission from Life to document the funeral. (The February 16, 1948 issue included nine of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, compared to only five by Margaret Bourke-White, despite her close relationship to the magazine.) Cartier-Bresson captured silence and grief in a moment of chaos and noise. In Train Carrying Gandhi’s Ashes (1948), for example, a single figure stands in a mass of bodies with a look of anguish inscribed on his face.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Train Carrying Gandhi’s Ashes, Delhi, India, 1948

© the artist/Magnum Photos

India in Full Frame, curated by Beth Citron, touches upon Cartier-Bresson’s well-documented awareness of his privileged position as a white, male foreigner. As he photographed the funeral proceedings—the cremation and scattering of the ashes—Cartier-Bresson attempted to remove himself from his place of advantage; he tried not to photograph the crowd from above, as he did not wish to project a western gaze. Cartier-Bresson’s awareness, however, does not extend to all his work in India, and the exhibition does little to challenge the photojournalistic frame within which he was working. By this omission, the suggestion is that Cartier-Bresson’s images from India avoid the clichés of journalistic photography.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Untitled, Madura, Tamil Nadu, India, 1950

© the artist/Magnum Photos

In the exhibition, a handful of photographs lack context that would help them subvert such clichés. An untitled photograph from 1950 shows a malnourished child held by a woman, presumably his or her mother. The woman’s hand—monumental in comparison to the child’s frail body—cradles the head of the child, but little detail is provided by either the photographer himself or the curator. In effect, the child becomes a nameless, starving body and fuels the West’s stereotyped, reductive perception of India. As Jacque Rancière has noted, there are “too many nameless bodies, too many bodies incapable of returning the gaze that we direct at them, too many bodies that are an object of speech without themselves having a chance to speak.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Street photographer in the old city, Delhi, India, 1966

© the artist/Magnum Photos

While most of the photographs presented in India in Full Frame are situated more closely along the photojournalistic line than the artistic, works like Astrologer’s Shop (1947) and Street photographer in the old city (1966) resist the journalistic sensibilities Cartier-Bresson largely employed in India and lean more toward his earlier, surrealist work. Such images exist outside the typical visual associations of photojournalism, such as starving children and beggars with emaciated bodies. Street photographer (1966) displays Cartier-Bresson’s surrealist sensibilities by combining an imagined and real background. The work is a subtle, perhaps unintentional nod to the history of Indian studio photography practices.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Refugee camp, Kurukshetra, Punjab, 1947

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson portrayed India as he found it, capturing the business of everyday life. He photographed everything from refugees performing their daily exercises, to women spreading saris out in the sun to dry. While India in Full Frame is centered on the mythic figure of Gandhi and the outpouring of emotion after his death, the exhibition also reveals Cartier-Bresson’s struggle to interweave art photography and photojournalism—an unwavering commitment, as he put it in his 1952 essay, “The Decisive Moment,” “to preserve life in the act of living.”

Emma Kennedy is the editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Henri Cartier-Bresson: India in Full Frame is on view at the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, through September 4, 2017.

The post Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Glimpse of India appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 24, 2017

Aerospace Folktales

From Allan Sekula, dreams and illusions of the postwar American economy.

By Drew Sawyer

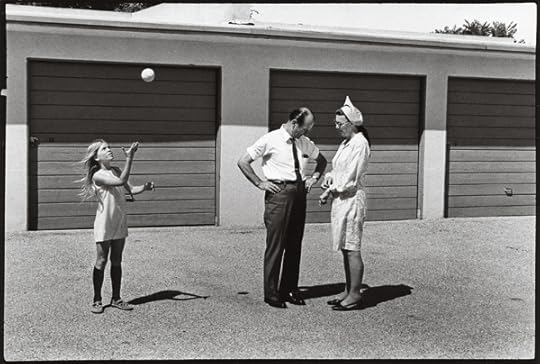

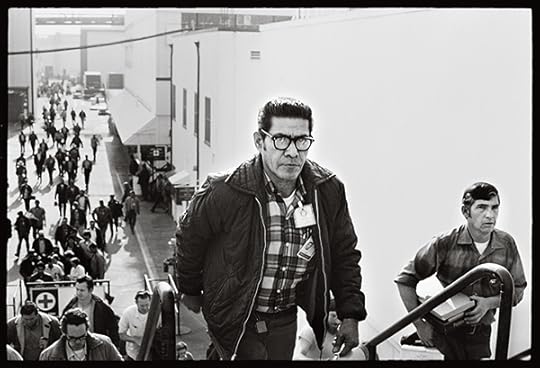

Allan Sekula, from Aerospace Folktales, 1973

Courtesy Allan Sekula Studio and the Columbus Museum of Art

In 1973, a year that marked the beginnings of a national recession and the signing of a peace treaty to end the Vietnam War, Allan Sekula’s first major work took as its subject an aerospace engineer who had been laid off from Lockheed, then the single largest defense contractor in the United States. By combining intimate scenes of family life in a small Los Angeles apartment with various personal documents—family photo albums, a rental agreement, bookshelves filled with classic literature, the engineer’s CV, and job rejection letters—Aerospace Folktales explores the daily life of this unemployed white-collar worker and his family as their class identity is being thrown into question. Sekula then goes on to disrupt the usual objective distance of social observation and documentary politics by revealing that the unemployed worker is in fact his own father. The result is a group portrait of an artist and his family in relation to each other and to their surrounding social and economic structures.

Allan Sekula, from Aerospace Folktales, 1973

Courtesy Allan Sekula Studio and the Columbus Museum of Art

At its peak, in 1967, Southern California’s vast aerospace industry accounted for nearly half a million jobs. But the waning of the Vietnam War and of the Apollo space program, along with a recession, brought a sharp falloff in military and NASA procurements that resulted in a succession of layoffs during the early 1970s. Many of those employees were, like Sekula’s father, professionals and experts who had risen to the middle class after World War II by obtaining undergraduate and graduate degrees. Sekula forces both his subjects and viewers to consider the dissolution of the postwar American dream, and the artist himself wonders in an accompanying text what will become of his career as an “art engineer” once he completes his graduate degree.

In its original installation at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), in 1973, Aerospace Folktales consisted of 142 black-and-white photographic images and text cards, along with four sound recordings of interviews between the artist and his father, his mother, and his mother’s friend (whose husband was also unemployed). Sekula hung the 142 photographs in a single row with text cards breaking the sequence into smaller groups that suggested the narrative flow and format of a silent movie. In this first exhibition, the audio played in an adjacent room, but in a 1974 installation at the Brand Library &Art Center in Glendale, near the Lockheed plant, the speakers were hidden behind potted plants in the gallery. At UCSD, Sekula performed a reading of an explanatory text, typed on seven pages of letter-size paper and titled “a commentary,” serving as a general narration but also “filling in for earlier omissions … because of the limited representational range of the camera.” In 1984, the year he published his seminal book Photography Against the Grain, Sekula edited the work down to fifty-one photographs, often grouped as diptychs or in grids of four, and three sound recordings.

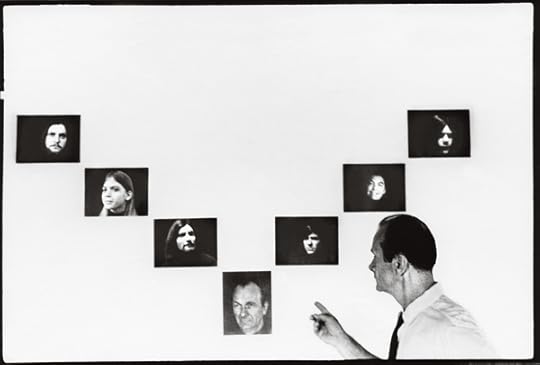

Allan Sekula, from Untitled Slide Sequence, 1972

Courtesy Allan Sekula Studio and the Columbus Museum of Art

Sekula referred to the work, with its deconstruction of the essential elements of a film, as a “disassembled movie.” He had already begun to experiment with this format in his 35mm slide show Untitled Slide Sequence from 1972. Here too he turned his camera on aerospace factory workers, but without the typical veneration associated with pictures of such laborers taken by photographers for the Office of War Information or popular magazines like Fortune during the 1940s. Instead, he chose to capture the workers just as they were leaving their shifts at a General Dynamics Convair Division factory in San Diego, where several of them likely helped produce the F-111 military planes that flew in Vietnam. The twenty-five images in this sequence depict a range of employees as they climb the staircase to a pedestrian overpass and are directly confronted by the artist’s camera. Sekula had originally envisioned Aerospace Folktales as a slide show as well, but ultimately decided to keep separate image, text, and audio “tracks,” allowing their formal discontinuities to underscore the contradictions inherent in the documentary genre as well as in contemporary life—both are their own kinds of folktales or mythologies.

To continue reading, buy Aperture Issue 226, “American Destiny,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Drew Sawyer is the William J. and Sarah Ross Soter Associate Curator of Photography at the Columbus Museum of Art, where he organized Allan Sekula: Aerospace Folktales and Other Stories, currently on view through July 2, 2017.

The post Aerospace Folktales appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers