Aperture's Blog, page 118

May 4, 2017

Okwui Enwezor on the Recent Histories of African Photography

Okwui Enwezor’s groundbreaking 2006 exhibition Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography redefined the field of contemporary African art. More than a decade later, The Walther Collection is poised to open a major new survey showing how artists working in Africa have continued to push photography and video art into new creative territories. Here, Enwezor, the influential curator, director of Munich’s Haus der Kunst, and former director of the 56th Venice Biennale and Documenta 11, speaks with collector Artur Walther about African photography, past and future.

Zina Saro-Wiwa, The Invisible Man, 2015

© and courtesy the artist

Artur Walther: We have known each other for over fifteen years. You have a long history as a curator, a writer, a scholar, and a teacher. You have made significant contributions to the study of modern and contemporary African art—and African photography and video art in particular. How do you conceptualize your own personal trajectory in relation to the development of these fields?

Okwui Enwezor: Often histories converge, intertwine, diverge, and move in different directions. The development of contemporary art and contemporary African art—and photography and video specifically, has similarly moved in a non-chronological, non-linear fashion. As with any field of study, new ideas emerge and new research illuminates gaps in our information, and provoke new readings, considerations, and revisions. All of this is part and parcel of why one remains engaged and interested in a set of ideas, as well as the underlying principles around which these ideas are formed.

Dawit L. Petros, Untitled (Prologue II), from the series The Stranger‘s Notebook, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Tiwani Contemporary, London

Walther: How did you begin in the field? When would you say the critical mass started developing?

Enwezor: Well let’s think about it this way—about twenty-five years ago, if one were to pursue a frame for African photography, you would have found very little that specifically relates to photography as an autonomous practice. Photography in relation to Africa was often times assigned to the terrain of the ethnography, as documents providing secondary information to more primary information observed in the field. Photography was seen to be an aid to the art, not particularly a part of practice. What I believe, without making any claims of who did it first, is that in the 1990s, a generation of curators, writers, and thinkers who were Africans—and I want to underscore this—made a bid to shift completely away from this ethnographic lens, and its spotlight. We found that the way that this lens thought of Africa was completely at odds with the content.

Mame-Diarra Niang, Satellite 1, from the series Metropolis, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Walther: Your first seminal exhibition on African photography was In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, which took place in 1996 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. How and why did this happen?

Enwezor: Well, the Guggenheim exhibition happened purely by accident. It was not planned. In 1994, or 1995, I was approached by a friend, Octavio Zaya, who was in the process of organizing the Spanish Pavilion for the first Johannesburg Biennale. At the same time, the Guggenheim was involved in an exhibition that was being planned in London at the Royal Academy of Arts, as part of a yearlong season on Africa in the entire United Kingdom. The exhibition was called Africa: The Art of a Continent (1995), and it was a very big exhibition of classical African art. The exhibition had an extremely bold conception; it included everything produced in Africa—East, West, North, and South—and looked at Africa in its entirety. The Guggenheim wanted to bring Africa: The Art of a Continent to New York, and have it accompanied with a contemporary art exhibition.

The museum asked Octavio Zaya and Danielle Tilkin to organize the show, and they said that they couldn’t do it without an African—that’s how I got involved. When Octavio contacted me and we began discussing the exhibition, I said we would need to completely re-conceptualize the show, and that it was very important that the role of photography be introduced into the framework.

Edson Chagas, Untitled, from the series Oikonomos, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Walther: So then going forward to Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, which I feel was an especially important exhibition for building the cornerstone works for The Walther Collection. What was the genesis of that show?

Enwezor: When Snap Judgments opened in 2006, it was the 10th anniversary of In/Sight. For me, it was precisely to make an exhibition that, in a sense, demonstrated the shift in terms of visual production by artists during that decade. I wanted to replicate aspects of what we did in In/Sight, by creating an exhibition that looked at the entire continent again—East, West, North, and South. I wanted to keep making the argument for the cultural complexity of the African continent, and look at the space from the point of view of its diverse cultural composition. So that really was the organizing principle.

Michael Tsegaye, Future Memories #4, from the series Future Memories, 2009

© the artist and courtesy Addis Fine Art

Walther: But since then, now more than ten years later, a lot has changed in the field. Many question whether it’s necessary to keep the continental context, or to group artists as Africans, so to speak. What do you make of this?

Enwezor: I personally question this notion that we don’t have to group. The field of African arts, literature, ideas, is a disciplinary field, and it has to be respected as such. Africa does not need to be given the permission to be part of the world. It is part of the world. It’s a discipline, and there are specializations—just like people who specialize in German romantic literature, or English epic poetry. Until we learn that this is a discipline, it will never be possible to recuperate African artists or African thinking into a “global” field. I say this because such notions are precisely the reason why I entered the field: to challenge and to refuse a conception that doesn’t really consider the diversity of artistic narratives, literary perspectives, and histories within the continent.

For example, there is no one place in the world that has a density of sculptural production more than the Congo—literally every few miles, the conception of sculpture changes. So what we must really do, when we talk about Africa, is be specific. We must speak about Africa with a great sense of its complexity. This premise is what I would say lays the grounds for my specific form of intellectual and curatorial militancy. Because, when we discuss African production only in the context of Western audiences’ recognition, it propagates false narratives. I remember, more than twenty years ago, when I visited Seydou Keïta in Bamako. I asked him “Why did you keep all of these pictures?” There were tens of thousands of them, and he said—“Because they’re good.” He knew that eventually somebody might do something with them, which was very striking. Of course then, the real trip for me is how he was anonymous at first, but now is recognized as a master photographer. That’s critical.

Andrew Esiebo, Untitled, from the series Highlife, 2013–16

© the artist and courtesy Tiwani Contemporary, London

Walther: Yet, despite him being a master, institutions like The Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Museum of Modern Art still have very little African photography in their permanent collections.

Enwezor: Yes—this is what I believe is the loss of these institutions, but a lot of that is changing. Many of these figures in African photography are now being continuously revisited, and reprogrammed—as new scholarship comes into the field, as younger curators join institutions, and as institutions begin to re-think their own positions to the fields that they occupy. For example, in terms of historical African art exhibitions, Alisa LaGamma’s Kongo: Power and Majesty (2015) exhibition is for me a tour de force of curatorial scholarship. When you step into an exhibition like Kongo, you immediately feel that you’re treading on the field of serious and deep scholarship. I’d like for people to bring that same seriousness to the study of modern and contemporary African photography.

Walther: Yes absolutely, and we’re starting to see that happen. But despite the field being much broader now, and continuing to expand, wouldn’t you say that the study of African photography is relatively young?

Enwezor: Well yes, if we were to look at the specific scholarship on what we now call African photography, it is definitely young. It is indeed new. But I think, in terms of the question of production, one would argue that these histories are co-terminus with the rest of the production of photography, from their very inception. If we look at the history of African photographers engaging with the field, it isn’t young at all. We must not forget that in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, there was a whole host of African photographic practitioners and studios making work.

Simon Gush, New Industrial development, Thetsane, Maseru, from the series The Island, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Walther: So, how do you view African photography and video art today?

Enwezor: Well, you know, for very different reasons, I haven’t really given as much attention to photography in Africa over the last ten years—not in as focused a manner as I did with Snap Judgments. Some of my interests have shifted more towards writing, shifted towards new forms of historicizing. As you know, we have produced the exhibition Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 (2016) at Haus der Kunst in Munich. So I’ve not really focused that much on photography as a medium per se, and what is going on within it. I think that right now photography, whether it’s in Africa, Europe, or elsewhere, is at a turning point—photography is embattled.

Walther: Embattled. What do you mean by that?

Enwezor: It’s embattled because photography is being overtaken, as a medium; it is being over-taken by technology and different forms of distribution. There remain many artists that are making work whom I deeply admire, for instance Zanele Muholi and Sabelo Mlangeni amongst others. However, when I reflect on even something like the 56th Venice Biennale, there were very few photographic productions. Right now, I’m excited by artists who use technological media like Samson Kambalu, with his cinematic works and his interest in the Chewa philosophy of the gift, taken from Malawi where he grew up. I’m interested in artists who bring a certain performative aspect to their work. I am also excited by the work of painters like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who are completely occupied by the imaginary. Her works are not photographic in base, they are not references to real people, but completely invented. I’m also drawn to the work of people like Emeka Ogboh, who works with sound, or Ibrahim Mahama, who creates large expansive draped installations. They are all young, born in the late 1970s, ’80s and maybe ’90s—but I’m interested in the ways in which they are kind of evolving these narratives of technology and the handmade in their work. I think it’s so relevant.

Andrew Esiebo, Untitled, from the series Highlife, 2013–16

© the artist and courtesy Tiwani Contemporary, London

Walther: What’s your take on the state of affairs regarding cultural institutions across the African continent? What do you make of the venues, the galleries, and the infrastructures?

Enwezor: Yes, the question of institutions is an interesting one. Generally we’re still dealing with a lack of institutions, or those that were set up before, but have not moved forward—or even institutions that are just holding onto their former selves. This is one of the things that I believe only Africans can solve, you know. We have to give serious thought to reform and building of skills. Without them, there will be a continued erosion due to institutional instability or mismanagement. It’s not a question of production, because there is an abundance of creators and makers throughout the continent. There are models for research and experimental exhibition spaces. There are definitely the young, but somewhat precarious, shall we say platforms—because I would not call Bisi Silva’s CCA Lagos an institution, or RAW Material company by Koyo Kouoh in Dakar, or Azu Nwagbogu’s LagosPhoto Festival, amongst other contexts. I mean, Bavaria has 1,200 museums! What they do in it, I have no idea, but across the continent we don’t have quite this proliferation of models. That’s the next frontier of what to create on the ground. But also, let’s look at the range of amazing writers, critics, and theorists. Who would have thought that the photography critic of The New York Times Magazine would be a Nigerian, Teju Cole? Or who would have anticipated that the work of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie would inspire such a large number of readers, but also listeners, with Beyoncé using her speech on feminism in the song “Flawless.” Honestly, it’s just an incredible moment now in terms of African art and writing. The key issue then is not to isolate the artist from different kinds of production or consider their work in a vacuum.

Okwui Enwezor is the director of Haus der Kunst in Munich. Artur Walther is a collector based in New York and Germany and founder of The Walther Collection.

This interview is adapted from the catalog Recent Histories: Contemporary African Photography and Video Art, to be published by Steidl and The Walther Collection in May 2017. Recent Histories, curated by Daniela Bauman, Joshua Chuang, and Oluremi C. Onabanjo, will be on view at The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany, from May 7–October 29, 2017.

The post Okwui Enwezor on the Recent Histories of African Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 27, 2017

Tokyo Reimagined

As Japan’s capital transformed, Yutaka Takanashi deployed a radical style to picture urban change.

By Tsuyoshi Ito

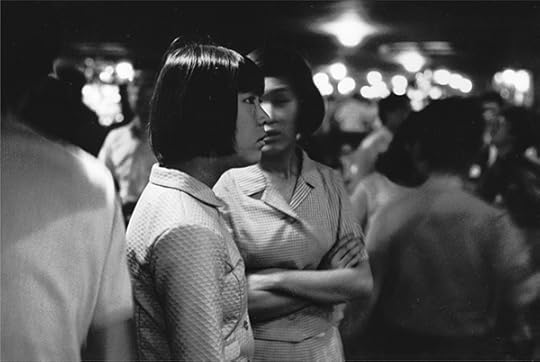

Yutaka Takanashi, from the series Tokyo-jin (Tokyoites), 1965

© the artist and courtesy MOMAT and DNPartcom

Yutaka Takanashi had been a successful commercial photographer for seven years before co-founding the magazine Provoke in 1968. All the while, he had been re-imagining Tokyo with his moody black-and-white photographs, which are famously grainy and angular. His novel approach, encapsulated in the series entitled Otsukaresama (1964), won Takanashi the prestigious Japan Photo Critics Association Newcomer’s Award and, soon after, drew him into the orbit of other (now iconic) photographers, like Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke with Takanashi about his photographic circle in the late 1960s and his pursuit of photography’s potential.

Tsuyoshi Ito: What made you want to join Provoke?

Yutaka Takanashi: Takuma Nakahira invited me because I appreciated and pursued different approaches to photography. I found Provoke’s rebellious attitude interesting. Before Provoke, I perceived older photography as very redundant; there was hardly any creativity to it. Even most of my contemporaries were conservative.

Yutaka Takanashi, Shibuya-ku: Hachikō Square, April 25, 1965 from the series Tokyo-jin (Tokyoites)

© the artist and courtesy MOMAT and DNPartcom

Ito: Moriyama joined the Provoke group for the second and third issue. How did this impact your work? How was working with Nakahira and Moriyama? Had you hoped for a fourth volume?

Takanashi: I thought it was fine that we disbanded. We had explored the range of photographs we wanted to, so to make a fourth volume seemed unnecessary. I continued my friendship with Nakahira, and visited him when he was ill and hospitalized. I was drawn to Nakahira not as a photographer, but as a person. He questioned and challenged things constantly. I didn’t know much about the other members, but because Nakahira was there I decided to join. I didn’t know much about Moriyama, I just heard that someone was stirring up trouble. I thought his photography was pretentious. We weren’t close.

Ito: So, how did you select images for the Provoke volumes?

Takanashi: Koji Taki was in charge of the edits because he was the most organized. I just approved what was presented to me. There were no huge arguments about which photographs to include.

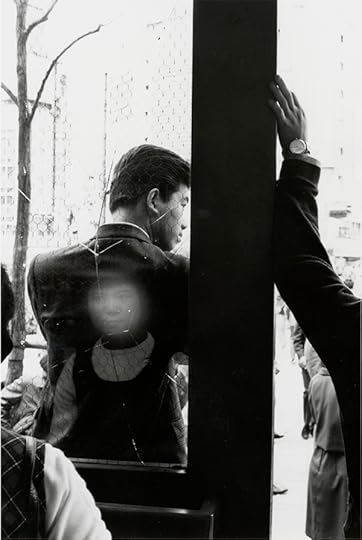

Yutaka Takanashi, from the series Toshi-e, (Towards the City), 1969

© the artist and courtesy MOMAT and DNPartcom

Ito: In the latter half of the 1960s, strikes and protests were on the rise, from student movements to the Narita airport protests. Were you drawn to such themes?

Takanashi: I didn’t have much affiliation with the student strikes. Political or historical scenes were not on my agenda; I just photographed because I liked photography. I was most political when I would go out to dinner and comment on how rowdy it was outside.

Ito: I heard that, when it was first published, Provoke did not sell many copies.

Takanashi: It did not matter whether or not Provoke sold well. My friend from high school was an heir to a publishing company and they helped out with the publications.

Yutaka Takanashi, from the series Toshi-e, (Towards the City), ca. 1970

© the artist and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

Ito: How do you feel about the attention Provoke is receiving today? After quitting Provoke, did you feel as if you were ending an era or simply beginning a new one?

Takanashi: Provoke was truly a revolutionary point for Japanese photography. Although I took it seriously, I still don’t think it was what triggered a revolution. The reason why Provoke was so interesting was because the photographers were so different from one another. The only thing that tied us together was the fact that we were all doing something completely new. But I have always wanted to do new things. I never really changed. Provoke just gave me the opportunity to showcase my ideology.

Ito: Following the breakup of Provoke, your next big landmark was Toshi-e, or Toward the City (1974)—a lionized series about Tokyo, considered to be the last great project of the Provoke era. Why did you want to publish Toshi-e?

Takanashi: I wanted to get Towards the City published because it was boring to just leave the project as disconnected photographs. I think publishing work is more important than gallery shows. I feel more comfortable going through publications, rather than showcasing something as an original, which I find unsettling. I am not very involved with the gallery installation of my work; I just give the okay to proceed with the project. I’ve never felt like I was handing off my child or anything like that. It’s probably because I’m from Tokyo, so it’s easier for me to let go of things.

Tsuyoshi Ito is founder and managing editor of A/fixed, a leading resource on the history of Japanese photography.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s is now available.

The post Tokyo Reimagined appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 25, 2017

Larry Sultan’s California Home Theater

In the Bay Area photographer’s retrospective, family, home life, and American suburbia take center stage.

By Glen Helfand

Larry Sultan, Sunset, from the series Pictures from Home, 1989

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

Location, location, location. The real estate maxim has particular resonance with the work of Larry Sultan, not least because he’s focused on houses and the families who live in them. (His mother, it so happens, was a successful realtor.) But Sultan was also deeply rooted in the aesthetic and conceptual vibes of California—South and North. The former, in the San Fernando Valley, where he grew up, offered the physical and emotional landscape of suburbia, its stucco façades and social dynamics, while the Bay Area, where Sultan’s artistic career thrived, offered guiding photographic and conceptual traditions.

Larry Sultan, Backyard Hercules, from the series Homeland, 2009

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

The title of Sultan’s retrospective, Here and Home, also has a sense of looking back at a location, the romanticized view of where we came from, from where we are now. And the exhibition has the added value of having opened in 2014 in Los Angeles at Sultan’s hometown museum, LACMA (where the show was held over for months), before traveling this spring to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in the region where he was such a powerful force as artist and educator, and where he died, too early, in 2009. In San Francisco, his life and work are currently being celebrated with concurrent exhibitions of his solo and collaborative projects, in particular with Mike Mandel, also at SFMOMA, as well as satellite presentations.

Larry Sultan, Business Page, from the series Pictures From Home, 1985

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

Back in the 1980s, when I was in my late teens, I followed the same El Camino Real trail up California, so the Sultan lens resonates powerfully in me. His work feels like family. But, due to its proximity to Hollywood, the San Fernando Valley is a very particular kind of suburban location. It’s a terrain that has appeared in TV shows and movies. The midcentury suburban modern house from the Brady Bunch is easy to find—five beds, three baths, 2,477 square feet—on Zillow. People magazine reported last summer that the North Hollywood house, now owned by an elderly woman, was burglarized, but “the interior of the Dilling Street home looks nothing like the house on the show, which was created on a set at Paramount Studios.”

Larry Sultan, My Mother Posing for Me, from the series Pictures From Home, 1984

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

In a 2005 interview, Sultan told me that his work consistently involved “taking the construction of the domestic and looking at it as a theatrical subject.” This is abundantly apparent in the influential series, Pictures from Home (1983–92), starring Sultan’s retirement-age parents. There are clues to lifestyle specifics and location in Dad’s Desk (1987), which looks like a well-dressed set: it’s a still life with coupons, golf balls, a calculator, a handwritten banana daiquiri recipe, and a car registration slip with a Calabasas address. Through these objects, and in various portraits, Sultan’s father emerges with the specificity of a well-drawn fictional character, against which the artist measured himself. Sultan’s mother strikes a mythic, muse-like profile in various pictures; she reclines on a chaise lounge, is subsumed by filmy green curtains, or, in My Mother Posing for Me (1984), she stands wearing white slacks that suggest riding pants in front of a lime green wall. As she looks calmly, directly into her son’s camera, her husband, wearing a busily patterned resort shirt, faces the opposite direction, intently watching a Dodgers game on a color TV. Their poses open endless interpretations of marriage and domestic life.

Larry Sultan, Boxers, Mission Hills, from the series The Valley, 1999

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

The exhibition and the catalog feature Sultan’s thoughtful, engaging texts. In one, he recalls his childhood home being rented for a commercial, prepped for camera by a full crew. “When they finished lighting the front of our house it was floating in a soft miraculous glow,” he wrote. “It was a dream house. I thought all of the neighbors who were crowded into our driveway were there to watch our house become a movie star.” This dynamic extended and deepened in Sultan’s last two major series, The Valley (1997–2003) and Homeland (2006–9), also traffic in domestic fictions. The Valley is rooted in the common practice of middle-class homes being rented as sets for porn films, a common practice that he first photographed for Maxim magazine. The terrain and appearance of these houses are strikingly similar to the elder Sultans’ residence. That could be their backyard in Cabana (2000), where rose bushes obscure a sexual act at the edge of a kidney-shaped pool. It could be their remodeled interior in Kitchen, Santa Clarita (2001), in which two naked blonde babes sit on a travertine floor and beam at someone off-camera. They’re almost overshadowed by the elaborate but prefab kitchen island accented with decorative jars, a pie on a glass domed cake stand, and an inset gas range. The porn stars are working in well-appointed, middle McMansions; their break times are moments of leisure and make-up sessions, fictions that are also an uncanny reality.

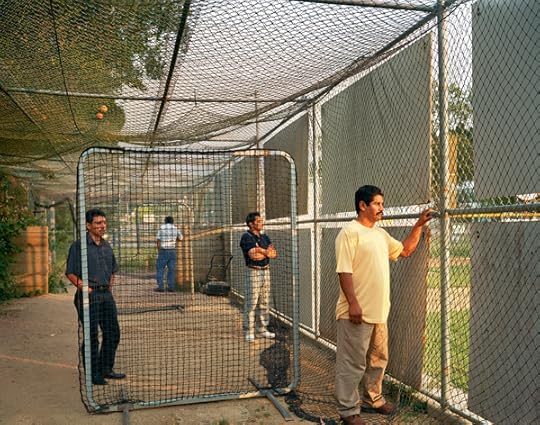

Larry Sultan, Batting Cage, from the series Homeland, 2007

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

In Homeland, his final body of work, Sultan directed the action more emphatically, creating actual fictions by hiring Latino day laborers to appear in a landscape where they seek work. In a gesture that could have come across as exploitative, Sultan generated a dreamy, wistful tone. “I want to investigate the stereotype of the suburbs and complicate that stereotype, make it a richer field,” he said in a 2008 interview with artist Ben Sloat. And so in Antioch Creek (2008), a man sits on beneath a fantastic riot of cherry blossoms, lost in thought, perhaps daydreaming of somewhere else, while in Canal District, San Rafael (2006), a trio of men walk through a field of dry grass behind a recent row of tract homes, each carrying food, perhaps to a potluck. Both photographs suggests that home is somewhere else, and in the current political climate, they offer a complex, humane view into what’s actually at stake in the immigration debate.

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, Untitled, from the series Evidence, 1977

© the artists and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby and Robert Mann Gallery

The SFMOMA iteration of Here and Home begins with Sultan’s appropriation works made in collaboration with Mike Mandel, who also grew up in the San Fernando Valley, and whose work from the 1970s will be featured in a concurrent exhibition opening in May. The centerpiece is their groundbreaking appropriation work, Evidence (1975–77), for which they culled found images from corporate and governmental archives. The curious selections reveal a sense of wit and absurdity in awkward moments and striking, probably accidental, compositions. These works also exude a narrative theatricality, of staging within the common workplaces that are extraordinary in their oddness.

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, Oranges on Fire, 1975

© the artists and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

Mandel and Sultan also collaborated on billboard projects starting in the early 1970s. Perhaps driven by the kind of Southern California reliance on views from the car, they inserted non-sequitur words and pictures, like “Oranges on Fire,” into urban and suburban environments. This series is highlighted in one of a number of satellite exhibitions at Minnesota Street Project. Others include a revival of the Newsroom (1983), in which Sultan and Mandel worked in residence at the Berkeley Art Museum, mining wire service image feeds to categorize official iterations of visual culture, a gesture that seems more complex and relevant in the high speed of current image culture—the new edition features guest editors Dru Donovan, Jason Fulford, and Jim Goldberg—as well as a show of Sultan’s editorial work at Casemore Kirkeby. There are actual celebrities in this mix—Paris Hilton posed in Sultan’s parents’ bedroom in the Valley. “If you put anything in a suburban house … the site functions like an image processor,” Sultan said in 2008. He knew just what to bring home, to place it in that context, and make it indelibly his own—and reverberate far beyond those prefab walls.

Glen Helfand is a freelance writer and Associate Professor at California College of the Arts.

Larry Sultan: Here and Home is on view at SFMOMA through June 23, 2017.

The post Larry Sultan’s California Home Theater appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 20, 2017

Rich, Famous, and Faking it

For twenty-five years, Lauren Greenfield has chronicled the rise and fallout of consumerism and celebrity culture.

By Katie Booth

Lauren Greenfield, Film director and producer Brett Ratner, 29, and Russell Simmons, 41, a businessman and cofounder of hip-hop label Def Jam, at L’Iguane restaurant, St. Barts. Few establishments on the island accepted credit cards, and visitors often carried large amounts of cash, 1998

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Few photographers have cast as unflinching an eye on the outrageously wealthy as Lauren Greenfield. Her 2012 film The Queen of Versailles follows billionaire “Time Share King” David Siegel and his wife, Jackie, as they attempt to build the largest home in America, only to be sidelined by the 2008 financial crisis. But Greenfield’s fascination with the trappings of consumerism began in the early ’90s. On the heels of a National Geographic assignment in Chiapas, Mexico, Greenfield made the choice to focus closer to home: on a group of teenagers in her hometown, Los Angeles. The resulting body of work, Fast Forward: Growing Up in the Shadow of Hollywood (1997), offered a look into youth culture that was at once hopeful, tragic, and wholly American. Present throughout Greenfield’s work over the last twenty-five years is a dedication to bringing forth deeply personal narratives—a testament to the intimate and long-standing relationships she forges with her subjects. I spoke with Greenfield as she prepared for her retrospective, Generation Wealth, currently on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles.

Lauren Greenfield, Jackie and friends with Versace handbags at a private opening at the Versace store, Beverly Hills, California, 2007

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Katie Booth: Did you feel like an outsider in the worlds you’ve entered? How has your own background shaped your photography?

Lauren Greenfield: In a way it was really the opposite. My parents didn’t buy into the materialistic values of LA, but as a teenager wanting to fit in, I still wanted designer jeans, and to have a car at sixteen like my friends did. My work comes from that contradiction: even growing up with parents who did not participate in conspicuous consumption, I was interested in symbols of wealth and glamour. As a photographer, even in the most extreme places, I feel a mix of empathy and ability to relate. The work is about the aspiration for wealth and luxury, and the striving to be “other” than you are. Whether it’s the patients in the anorexia clinic from Thin (2006), or Jackie Siegel from The Queen of Versailles, I had to like the people to spend so much time with them. When I’m with my subjects, I focus on what makes them tick, and their behavior, rather than my status as an outsider. I’m more interested in the common ground, and how we’re all complicit in this story.

Booth: Your photographs expose the dark side of wealth, but typically these people control their own images. What do you think motivated your subjects to let their guard down, such as the Seigel family in The Queen of Versailles? Is it because they trust you as a photographer, or something more?

Greenfield: A lot of the work in Generation Wealth is longitudinal, so I think part of it is developing trust and relationships. Many people who I document desire fame and recognition. More profoundly, people want to share their stories, which I’ve tried to do in a long-term, respectful way. I think with The Queen of Versailles and with Thin, my subjects could sense that I’m not seeking to criticize them. I’m interested in the humanity of their stories, how their stories reflect all of us. In the case of The Queen of Versailles for example, the story of David and Jackie wanting more—a 90,000-square-foot home inspired by the château of Versailles, rather than the 26,000-square-foot mansion they lived in—and being willing to overextend to get it, was an allegory that spoke to, in supersized terms, how many Americans from a variety of backgrounds (and even others I documented internationally in Ireland, Iceland, and Dubai) get wrapped up in the same cycle of addictive consumerism.

Lauren Greenfield, Xue Qiwen, 43, in her Shanghai apartment, decorated with furniture from her favorite brand, Versace, 2005

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Booth: Your work connects threads that might, in another context, seem disparate: alongside images of millionaires and celebrities in Beverly Hills are pictures of migrant workers, squatters, and strippers. Is there a unifying quality or feeling present in your subjects that transcends their socioeconomic status?

Greenfield: Definitely. I’m looking at how the values of our culture have shifted in a way that affects people beyond socioeconomic status, race, or nationality. In the United States, we have a culture that has been deeply influenced by materialism, the cult of celebrity, the importance of image. Globalism and mass media have disseminated these values across the world. I look at how girls are affected, how kids are affected, how people in communist countries are affected, and how we all made the same mistakes that led to the 2008 crash.

Booth: In this project, and much of your work, you focus on women and girls. Juliet Schor, in her introduction to Generation Wealth, notes that “sex greases the wheels of commerce” and that the performance of wealth is typically by men, while “women serve as props and audience for their acts.” Do you agree with these statements?

Greenfield: I think that’s part of the story. I’m interested in how girls are marketed to, but also how they are sold. When girls learn from a young age that their value comes from their body, their reaction is to leverage that value, whether it’s by posting a sexy picture on Instagram, or actually selling their body. In the “Sexual Capital” chapter, there’s a story of Brooke Taylor, a college-educated, Midwestern woman who was working as a social worker making four hundred dollars a week, and who decided to become a prostitute. She makes ten thousand dollars a day, and is happy with her choice. In a world where money is the metric of success, and people don’t feel as bound by traditional conventions of morality, that choice becomes rational. I’m interested in the culture that creates that.

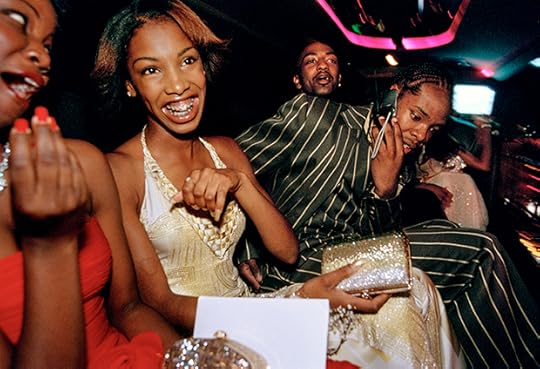

Lauren Greenfield, Crenshaw High School girls selected by a magazine to receive “Oscar treatment” for a prom photo shoot take a limo to the event with their dates, Culver City, California, 2001

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography

Booth: Do you think consumerism places a disproportionate burden on women?

Greenfield: Well, I think capitalism thrives on insecurity, and where you have insecurity, you have a great consumer. If you tell somebody they’re not good enough, but if they buy this product, they will be, that’s a perfect way to sell. Women and girls are particularly vulnerable, because of their insecurity about body image, and self-esteem, but I don’t think they’re the only ones. Boys are becoming increasingly vulnerable because they are being objectified, too. Older people as well. We live in a culture that values youth.

Booth: Your ad for Always, “Like a Girl,” was the first feminine product ad to run during the Superbowl, and was proven to have a positive impact on the way girls perceived themselves. What do you think will be the most powerful effect of bringing all of this work together in the context of a book and exhibition?

Greenfield: I think we’re at a critical moment in history, and our path is not sustainable. Popular culture is ubiquitous and all-consuming. Questioning and discussing this culture makes us less vulnerable to its influence, decreases its power, and increases our agency. “Girl” is often used as an insult and nobody thought about it. That campaign showed how disempowering that is.

Lauren Greenfield, Ilona at home with her daughter, Michelle, 4, Moscow, 2012

© the artist and courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography exhibition

Booth: In On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.” With the rise of social media, how have you seen photography, and images of ourselves, fit into consumer culture?

Greenfield: That’s a prophetic statement. Photography has been completely democratized, and has become part of everyone’s personal branding. The way kids brand themselves is kind of a natural extension of this work. When you ask kids what they want to be when they grow up now, the most common response is “rich and famous.”

Booth: You’ve drawn parallels between David Siegel and President Trump. Many liberals and pundits expressed shock at the impossibility of his win, but, looking through Generation Wealth, are you at all surprised at his massive political following?

Greenfield: I had the same reaction. I was completely shocked. But Trump’s election also validates my work. It looks like a straight line, from the early work in LA, to the rise of celebrity worship and the idea of “fake it ’til you make it,” with the backdrop of inequality and the feeling of the loss of the real American dream and real social mobility. On a personal level, I was surprised, because I was probably in the West Coast bubble like so many others, but I also feel like that makes the work important to think about now. I hope that people have the same reaction, and that this project can shed light on where we’re at now, in a culture that brought about Donald Trump.

Katie Booth is the digital manager at Aperture Foundation.

Generation Wealth is on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles, through August 13, 2017.

The post Rich, Famous, and Faking it appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 19, 2017

Editor’s Note

by Daria Tuminas

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf 1012: Daria Tuminas

A book with “cinematic flair”; “a quasicinematic, nonlinear narrative”; “raw, cinematic, stream-of-consciousness”—you hear these things about photobooks all the time. But what exactly is this cinematic aspect of these publications? And what is the relationship between cinema and the photobook at large?

The historical interconnection goes back to the very beginning of both mediums. As Olivier Lugon points out in Between Still and Moving Images (2012), “already, before the advent of the Lumière cinematograph, paper had been the privileged medium for cinematic movement, from the plates of the phenakistoscope and the zoetrope, to cards for Mutoscope machines, to the pages of flip-books.” The dynamic between the two forms has been explored for nearly a hundred years, from the work of avant-garde artists in the 1920s, to the phenomena of fotoromanzi and photonovels in the 1950s, to cinema theory in the 1970s, and beyond.

At the same time, classical cinema has been radically transformed due to technological change—such as the explosion of digital that resulted in interactivity and virtuality, starting in the 1980s and ’90s. Cinema as something that, in Chris Marker’s words (Immemory: A CD-ROM, 1997), is “bigger than we are, what you have to look up at,” has long vanished. We watch movies on our smartphones, turning cinema into a mobile, manipulable, and intimate matter. Add to that an everevolving number of possible presentation modes, from multiscreen installations to projection domes. With this new state (or should I say “states”?) of cinema in mind, it’s interesting to think about how photobooks have also changed in turn, and to question whether they have mirrored the processes taking place in cinema. David Bate, in Imprint: Visual Narratives in Books and Beyond (2013), claims that “many photobooks operate like silent movies, with a main title, introduction text, and short captions or ‘intertitles’ to signal the direction and flow of the ‘movie.’” While this silent-movie pattern is indeed recognizable in a number of publications, there is probably even more to the relationship between cinema and the photobook now, when physical books have started to cross-fertilize with the digital.

Both cinema and photobooks belong to the history of image seriality and ordering; they can also be analyzed alongside slide shows, photo-essays, and other kinds of sequences. As David Campany outlines in Photography and Cinema (2008), “Any orchestration of images is montage.” Do the principles of montage in all of these different types of assemblies—from the turn of a page, to the click of a slide—correlate? If so, how? Does the photobook borrow from cinematic montage techniques, or does it have its own specific ways of sequencing?

These core questions serve as a framework for inquiry, rather than an attempt at comprehensive answers, for this issue of The PhotoBook Review. They also serve as the impetus for inviting a host of curators, artists, and writers—all of whom have spent time thinking deeply about these matters— to participate. Additionally, I have proposed another angle for discussion in this issue, picking up on an approach introduced by the guest editor of the last issue, Denise Wolff. That issue focused on “accidental photobooks”—those publications that have not been “awarded the status of photobook proper.” Following Wolff’s “recipe,” I would like to open the floor to publications that normally exist in a world parallel to the classic photobook, and yet can address, in their own ways, similar themes: books made by video artists, artists’ books (works of art experimenting with the book form), and books made by film aficionados, experts, and scholars. At times, the photobook world can seem isolated, and the subject of the current issue gives us the opportunity to explore and intertwine with other types of visual publishing. We will see how the book form can play with the moving image, serve as an analytical tool to interpret cinema, or exist in tandem with a video. In addition to the artists and authors who have contributed to this issue, I would also like to express my gratitude to the Mondriaan Fund for their support of my research; to curator Zhenia Sveshinsky, who served as my partner during brainstorming sessions in the early stages of my research; to Johan Deumens, a passionate book lover and gallerist, through whom I was introduced to the wide world of artists’ books; to Hripsimé Visser, who—together with the museum’s public-program team—has shared my interest in the subject and generously supported my initiatives.

Daria Tuminas is a freelance curator and researcher. In 2014, she co-organized a yearly program, Dutch Photography Experience, which included a series of educational events in St. Petersburg as well as an exhibition on Dutch photobooks, Undercover. Tuminas continued Undercover with the next photobook-related project and exhibition, Reading a Photobook, and currently is busy with researching the relations between cinema and photobooks.

Jane Mount (illustration) makes things for people who love books. idealbookshelf.com

Image credit: Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf 1012: Daria Tuminas

The post Editor’s Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A History of White Men in South Africa

In a new film, photographer Mikhael Subotzky takes on two hundred years of white masculinity.

By Ian Bourland

Mikhael Subotzky, Maplank and Naomi, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison, 2004

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Mikhael Subotzky came to prominence in the mid-2000s with large color photographs and monographs that investigated themes of incarceration and punishment in postapartheid South Africa. From scenes in the Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison outside of Cape Town, collected in the series Die Vier Hoeke (2004–5), and in a frontier town prison in Beaufort West (2006–8), Subotzky produced highly-polished, arresting portraits of people and places bearing the legacy of structural violence. A collaborative project on the Ponte Tower—the “hijacked” Johannesburg skyscraper at the center of Ponte City (2008–10)—considered architecture, segregation, and social identity in the urban landscape.

In 2012, with his turn to filmmaking, Subotzky’s practice shifted markedly to more overt considerations of the power of vision itself. His ongoing series of what he calls Sticky-tape Transfers began in 2014 when Subotzky used adhesive to literally prize apart the typically window-like surface of his photographs. Twenty-nine of those collaged transfer images were exhibited earlier this year at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. But at the center of the exhibition was the three-channel feature WYE (2016), on which Subotzky collaborated with the legendary cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein, perhaps best known for his work with German auteur Werner Herzog.

WYE, which was commissioned in 2016 by the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney, is named for a river in the western U.K., immortalized by Wordsworth in the nineteenth century. Over the course of forty-eight minutes, WYE draws together three seemingly discrete narratives by centering on a single coastline in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, where the lighthouse keeper Hare spends his days writing and sounding for metal on the beach. Hare’s section of WYE depicts the discovery—with the help of recurring Subotzky collaborator Hermanus—of a buried chest, left behind by the British settler Lethbridge in 1820. Hare’s uneasy encounter prompts him to write to a woman who has left South Africa for Australia, which is analyzed by an archivist of the future, Feio, who provides voice-over narration. Deftly interweaving the stories of Hare, Lethbridge, and Feio, Subotzky produces a timely and compelling account of the British colonial legacy, and its reverberation in a country still making its uneasy transition to freedom.

Mikhael Subotzky, Still from WYE, 2016. Film projection, 48:30 minutes

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Ian Bourland: WYE is a big jump in genre for you. You made a film in 2012, Moses and Griffiths, but that was more of a non-fiction project. Why was film the medium for this particular project?

Mikhael Subotzky: In the case of both my films—Moses and Griffiths and WYE—the choice of medium just seemed to make sense in relation to what interested me about the subjects. Moses and Griffiths deals with overlapping narratives that seemed better suited to moving images and recorded sound, while with WYE, it felt necessary to write fictional characters to really get inside the colonial mindsets of the past, present, and future.

Bourland: In much of your work, you use acute metaphors of precision and vision that you often also undermine. It seems the “Feio” section of WYE reveals all these blind spots.

Subotzky: Totally. When I was at UCT [University of Cape Town], both my girlfriend at the time and my best friend were studying anthropology. I think I learned a huge amount from what they were reading and the discussions around representational responsibility. At the same time, I felt that the degree to which anthropologists get submerged in theory and react to anthropology’s own very fraught history really shut them down. Feio is a “psycho-anthropologist” of the future whose manner expresses the arrogance of progress, of being freed from bodily needs. And yet the experience of embodiment through the “deep enactment” seduces Feio to some extent. I’ve almost exaggerated the blind spots you mention to undermine this arrogance of progress, which is postulated as a colonialist gaze of the future.

Mikhael Subotzky, Still from WYE, 2016. Film projection, 48:30 minutes

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: There is a moment in WYE where the Hare character is reading an antique letter by a white settler and is embarrassed to be reading it in front of Hermanus, who is black. Is that a reflection of a feeling you had about your work?

Subotzky: I think less in relation to my work but more in relation to being a white South African man. With this project, I wanted to take on white masculinity and collapse or explode it from within the mindset of these three protagonists. I was very much trying to engage with my own sense of shame and guilt in relation to the history of white masculinity, particularly in South Africa.

Bourland: Is the relationship between Hare on the beach and Hermanus indicative of your actual encounters with Hermanus when you were younger? That ambivalence struck me as a sort of typical South African or even white American encounter.

Subotzky: That’s exactly what I was trying to write in that scene. I did it as an exaggeration of that kind of experience; Hare is really like a typical white South African. Hermanus walking up to him is an exaggerated dramatization of how I actually met the real Hermanus. He was behind a wall that he was bricklaying on a building site. He asked me, “What are you doing?” That was the first thing he said to me. And he was genuinely interested in what I was doing with a camera, and then he asked me to take his photograph, and that’s how we got to know each other. In the film, Hare assumes that Hermanus is begging, but he is actually just interested in what Hare is doing—metal-detecting on the beach. Then Hare feels this kind of guilt at the assumption and overcompensates, but he’s very patronizing in explaining what he is doing with the metal detector.

Mikhael Subotzky, Still from WYE, 2016. Film projection, 48:30 minutes

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: There’s an irony, then, with the “Lethbridge” section, which suggests that the British colonialist may be an irrational figure.

Subotzky: Absolutely. Lethbridge comes with that very particular early-nineteenth-century combination of the occult and the scientific. The title WYE alludes to the Romantic era—especially in painting and poetry—and the Romantic way of looking at the landscape, and also to Wordsworth’s poem “Tintern Abbey,” which was written on the River Wye and became a foundational text of the Romantic gaze. With Lethbridge, it was a real balancing act to write him in a way that he wasn’t just a bad person—so you could kind of identify with him—but also to reveal the arrogance that the land was there for him to study and do experiments on, and then he goes mad.

Bourland: The film is set in three time periods on one beach in Port Elizabeth. Is the Eastern Cape especially significant?

Subotzky: I grew up in Cape Town and moved to Johannesburg in 2008 because I hate how pervasive the physical structures of apartheid still are in Cape Town, the sense of separation, everyone pretending they are in the south of France. Grahamstown—the town where I shot Moses and Griffiths which is in the Eastern Cape—is even worse. It’s literally this figure of eight shape with these two bowls: the British colonial town is in one bowl and the black township is in another. WYE really emerged out of Moses and Griffiths. I wanted to link three temporalities and geographies to the gaze of the white colonial body, so using the backdrop of the Eastern Cape and the 1820 Settlers made sense. The beach that 1820s Settlers landed on was literally the beach in Port Elizabeth where we shot.

Mikhael Subotzky, WYE, 2016. Installation view at the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, 2017

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: The 1820s Settlers being the people sent down from England to populate South Africa.

Subotzky: Exactly. And more specifically to populate the particular part of South Africa where there was a lot of conflict between the Afrikaners and the Xhosa. The colonial government was struggling to police that frontier and they really fucked everyone over, including their own countrymen. They brought working-class people over from England to act as a buffer with the promise of land, but it turned out to be poor farming land given to people who weren’t skilled farmers. But the fictional Lethbridge, an 1820 Settler, never makes it off the beach onto the land proper; instead, he goes mad in the liminal zone between the sea and the landscape.

Bourland: WYE connects this history to similar histories around the Indian Ocean and specifically in Australia.

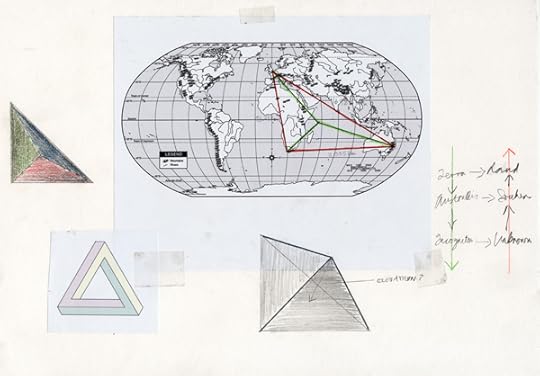

Subotzky: In 2016 I was invited to go to Australia by the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney. In going there, I read The Fatal Shore (1986) by Robert Hughes, an exhaustive, amazing history of the Australian penal colony. I was deeply struck by one of the early chapters called the “Geographic Unconscious,” which describes how the British had to imagine the Australian landscape as upside down, inhospitable, and unfriendly in order to politically justify the use of Australia as a dumping ground for criminals. This “otherization” of the landscape contrasted so strongly with my experience of the way that contemporary white middle-class South Africans idealize the Australian landscape as being “just the same” as ours here, but without all of the “problems.” So it was really that part that got me thinking about the complete turning around of that projection onto the Australian landscape over a couple of hundred years. I literally saw that in my mind on the map as two sides of the triangle. And I drew a line between England and Australia, South Africa, and Australia, and then started thinking about the third side of that triangle, which was the English projections onto the South African landscape.

Mikhael Subotzky, WYE Study 3, 2015

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: WYE follows your recent project Ponte City (2008–14), created with Patrick Waterhouse, which tracks the iconic Johannesburg apartment tower of the same name through photography, installations, and archives. Since you began work on Ponte nearly a decade ago, how do you feel about the direction Johannesburg is moving today?

Subotzky: This is an important moment in our history because the political corruption of our liberation movement is combining with the student protests and a stagnant economy to create a lot of conflict. Issues are coming up that really need to be addressed—how little has changed economically for the majority of people, the pervasive racial problems, and the depth to which colonial thinking has seeped its way into all of our institutions. Some people are very, very pessimistic today. But Johannesburg is amazing. Between my studio in Maboneng and Ponte, which is only a couple of kilometers away, they’re about to open this beautiful new residential building that David Adjaye has designed. There is so much going on that is dynamic and engaged.

Mikhael Subotzky, Boat 2, 2008

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: Have you heard anything in South Africa about the controversy at the Whitney Museum over the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till in the current biennial? Many South African artists, such as yourself and Pieter Hugo, have been thinking for a long time about this question of who can represent whom, who can represent scenes that might actually cause trauma.

Subotzky: Well, I have totally been thinking about it. And those kinds of ideas have been in my thoughts throughout my career. But very, very consciously, I mean, for part of Retinal Shift (2012), I did a wall of a hundred photographs which was called I was looking back; they are all taken from my archive from the eight years of working before that. One of them was a photograph of a prisoner who had been burned to death in a cell. His mother had actually asked me to take that photograph, and even though she was grateful to me for taking it, and it felt very important to her, I felt very uncomfortable. I was literally haunted by the photograph, but I also felt very uncomfortable in terms of the kind of issues that came up around that Dana Schutz painting. I had this instinct that I wanted to smash the photograph; I don’t know where it came from.

In retrospect, it was about writing my own feelings into that work. It had its function in documentary terms, but it also had its function in personal terms for the mother who was so grateful for me giving it to her. But my own trauma of seeing this violently burnt body was written out of that narrative, so I smashed it. And in smashing it—I mounted glass in front of it and smashed the glass—it felt terrifying and felt like I might be reenacting the trauma and violence that was done to that man. But I realized what I was doing in smashing it was covering up the representation that in many ways I wished hadn’t made and kind of “re-shrouding” of that body.

There’s a battle between being sensitive to all the issues of representation, but also wanting to be brave enough to make representations and think about the positive functions that representations can make. And for me, living in South Africa, it would be ridiculous to, for instance, only photograph white people because white people are less than ten percent of the population.

Mikhael Subotzky, Sticky-tape Transfer 13, Quiver Tree / Robert Jacob Gordon, 2014 (detail)

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: In describing your process, there is at times a sense of anxiety or ambivalence that comes out, a masochism towards the work. As a white artist now, is all that there is left to deal with guilt or shame?

Subotzky: We have to engage as citizens. So many white people are on social media commenting and writing in columns and participating in “virtual politics,” but we haven’t delved nearly enough as white people into how pervasive our privilege is. And how we are quite desperate to hang onto it. I think it’s more about shame than guilt. Guilt is very particular; there is nothing one can really do about guilt. Shame can be understood. It’s a starting point in relation to where we are now with the political climate and these student movements. It is something that has to be done before we can move onto actually thinking about our broader place in society.

Ian Bourland, a critic and historian of photography and the global contemporary, is Assistant Professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

WYE was on view at the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, from March 2–April 2, 2017.

The post A History of White Men in South Africa appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 18, 2017

On the Edge of the American Dream

How have West Coast photographers subverted the mythology of California?

By Will Matsuda

John Divola, Untitled (woman watering, striped top), 1971–73

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

When most people hear “Golden State,” they think of sunshine and Stephen Curry, but curator Drew Sawyer was thinking about the 1940s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. He was also thinking about how photographers, since the 1970s, have challenged romanticized images of California. Currently on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery, his group exhibition Golden State includes photographs by Anthony Hernandez, Catherine Opie, Larry Sultan, and other California-based artists. At a moment when California is being heralded as a leader of “the resistance,” these photographers focus on various marginalized communities, demonstrating how not all Californians have access to a utopic, liberal vision of the Golden State. People there are still struggling to be recognized as citizens, to feel like they belong, and to survive.

Christina Fernandez, Lavanderia #11, 2003

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

Will Matsuda: Why an exhibition about California? Why now?

Drew Sawyer: When the gallery asked me to organize a show, it was the day after the presidential election. I knew I wanted to do something that was timely but that wouldn’t feel dated by the time it opened in April. Already within the first week after the election, California was emerging as a state of resistance. There was talk of “Calexit.” In recent years, the state seemed to have become this liberal bastion. But many conservative movements have originated in California, and one would only have to go back ten years to when the state attempted to ban same-sex marriage.

Catherine Opie, Flipper, Tanya, Chloe, & Harriet, San Francisco, California, 1995

Courtesy the artist; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

California, in some ways, represents the country as a whole, and also the country’s ideals. Many of our ideas of California, influenced by Hollywood shows like HBO’s Big Little Lies, have to do with an idealized vision of the American Dream. So I was particularly interested in the contradictions of the state. California has one of the largest economies in the world, and it has one of the greatest number of billionaires. At the same time, it has the highest rate of poverty in the country. It felt necessary to think about these polarities, since the country is so polarized right now.

From an art historical standpoint, the state also seems relevant because many of the California photographers I ended up selecting have had major survey shows in the last few years: Anthony Hernandez at SFMoMA in 2016 and Larry Sultan at LACMA in 2014 (and now currently at SFMOMA). But neither of those shows have travelled to the East Coast. Neither of those artists even have commercial galleries that represent them on the East Coast. It seems like the perfect time to bring this work to New York.

Anthony Hernandez, Rodeo Drive #19, 1984

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Matsuda: The title, Golden State, evokes the usual California connotations: sun, surfers, and LA. But the exhibition seems to attack these romanticized visions straight on with images portraying the hardships endured by Latino day laborers, Japanese Americans facing internment, and other marginalized identities. What were you looking for when you were selecting photos?

Sawyer: I wanted to complicate that idea of California, the one that gets represented so often. You mentioned the Dorothea Lange photographs of the internment of Japanese Americans, and those really were the inspiration for the exhibition. This spring is the seventy-fifth anniversary of the internment. In 1942, the federal government commissioned Lange to document the process of interning over 100,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans. Even before she started photographing the roundups and the camps, Lange photographed Japanese Americans in their homes and at their workplaces. The mandatory internment announcement had already been made, so the people in these photos knew what was coming and knew what they would be forced to leave behind: their homes, their businesses, their jobs, their college educations. Those are the photographs I ended up choosing. In some ways, I think they are the most subversive because Lange really showed the degree to which these individuals were truly American and so fully integrated into the economy and American society.

Dorothea Lange, College students of Japanese ancestry who have been evacuated from Sacramento to the Assembly Center, Sacramento, California, 1942

Courtesy National Archives

Matsuda: I know this history because I am Japanese American and I know Lange’s work. But for people walking into the gallery, the context of internment is not entirely clear. A suburban family poses on a manicured lawn, or two hip guys strike a pose for the camera. There are no captions to explain that these were taken right before their entire communities were uprooted and imprisoned. Don’t you think these kinds of photographs need context?

Sawyer: I did think about that, but of course commercial galleries don’t usually have wall labels, so the full captions are on the checklist and in the accompanying catalog. In the end, I also wanted the show to be beautiful, to be visually enticing, and I think those contradictions are even more interesting. I could’ve shown work that was more explicitly about internment, but I selected a series of portraits that felt more cohesive with the rest of the exhibition.

Matsuda: Right, your focus is on people. But, another common vision of California is the grandeur of the landscape—places like Big Sur and Yosemite.

Sawyer: The landscape, particularly the suburban landscape, does appear. When you think of California photography, you may think of Ansel Adams or nineteenth-century photographic surveys of the landscape. But for me, that is a separate tradition. Since Lange was my starting point, I really wanted to look at images that examine California’s economic systems, and that might be more rooted in cultivated landscapes than in natural ones.

Buck Ellison, Pasta Night, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Park View, Los Angeles

Matsuda: John Divola, Buck Ellison, and even Larry Sultan’s images feel quite suburban. What is it about this setting that makes it a productive backdrop for the exhibition?

Sawyer: I think the idea of suburbia and California are linked with the American Dream. Even looking through the current issue of Aperture, “American Destiny,” a lot of the photographers or photographs are actually from California. But each of those photographers gives a very different picture of suburbia. In John Divola’s work from his San Fernando Valley series, from the early 1970s, there seems to be a certain sense of postwar conformity in the pursuit a middle-class life. I chose several images of people watering their lawn. They are comical but also a bit sad.

Buck Ellison, the youngest photographer in the show by far, has a very different portrayal of suburbia. He’s concerned with depicting a very specific elite, white culture—not the middle class. And to me, his work provides a really interesting dialogue with Dorothea Lange’s photographs. While Lange’s photographs show the failure of liberalism in the face of war, Buck’s photographs seem to capture how certain progressive or liberal ideals have not only succeeded to some extent but also become commodified into identities, brands, and luxuries. In Buck’s staged photograph of the gay couple making pasta, it’s sort of like, “Oh, they’ve won their equality, and now all they want to do is make homemade pasta with their expensive culinary equipment in their beautiful suburban kitchen.”

Larry Sultan, Canal District, San Rafael, 2006

Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan, Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

A lot of Sultan’s work also has to do with home and suburbia too, especially the San Fernando Valley where he grew up. I chose work from Homeland (2006–9) partially because it was his last show and he hasn’t had a show in New York since he passed away in 2009. He shot the work in Marin County, a wealthy and liberal enclave just north of San Francisco where Buck Ellison happens to be from. I thought the series also provided another conversation with Lange’s photographs, since he hired immigrant day laborers to act out scenes in these sort of interstitial suburban spaces, like fields and creeks between housing developments. He made the series both before and after the subprime mortgage crisis, so the landscapes probably took on new meanings for him. And these images of immigrants walking in fields probably take on new meanings for us today. I hope the show provides a variety of perspectives on suburban lifestyles.

Matsuda: And who has access to it.

Sawyer: Exactly.

Will Matsuda is the Social Media Associate at Aperture. Drew Sawyer is the William J. and Sarah Ross Soter Associate Curator of Photography at the Columbus Museum of Art and the Arts Editor at Document Journal.

Golden State is on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, through April 27, 2017.

The post On the Edge of the American Dream appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 14, 2017

Robert Adams on Gregory Halpern, ZZYZX

D. H. Lawrence admired the American Southwest but found Southern California troubling: “In a way, it has turned its back on the world, and looks into the void Pacific. It is absolutely selfish, very empty, but not false.”

Gregory Halpern records an aspect of what still seems to be its emptiness—a careless isolation from one another. The idea of community appears to be almost beyond our imagination.

Halpern’s Southern California is, however, in another sense, far from empty. Despite our neglect of what we might improve—others’ lives, and the places we share—there is frequently evident an unorthodox beauty. No matter the smog, the view from the junky chairs is one of distant harmony. The blackbird, though at risk next to the street, is for the moment a shape perfectly whole. And the young man with arms outstretched in the sun is worthy of Donatello.

Beauty and its implication of promise is the metaphor that gives art its value. It helps us rediscover some of our best intuitions—the ones that encourage caring.

Robert Adams has worked as a photographer of the changing American landscape for the last five decades. He has received numerous awards for his work, including the Deutsche Börse Prize in 2006 and the Hasselblad Award in 2009.

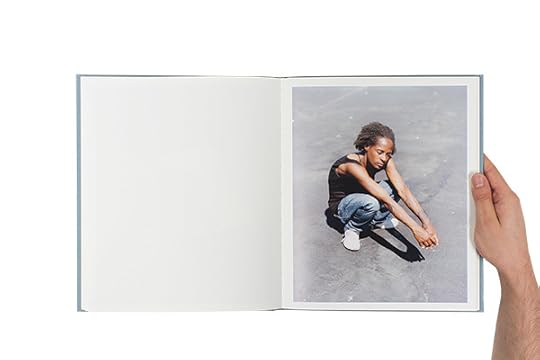

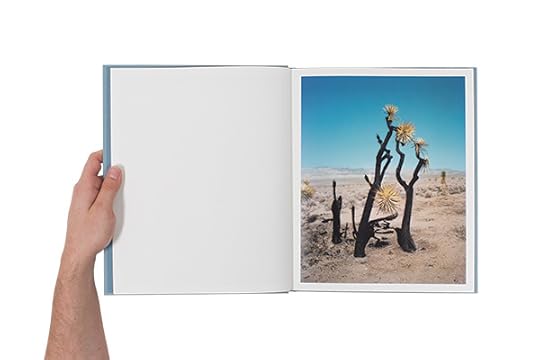

Gregory Halpern

ZZYZX

MACK • London, 2016

Designed by Lewis Chaplin

9 3/8 x 11 3/8 in. (24 x 29 cm) • 128 pages

77 color images • Silkscreened hardcover

mackbooks.co.uk

The post Robert Adams on Gregory Halpern, ZZYZX appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 13, 2017

2017 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

![Andrianjafy_OK_revised image to be used[2732]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1492238719i/22496239._SY540_.jpg)

![Andrianjafy_OK_revised image to be used[2732]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1492238719i/22496239._SY540_.jpg)

Emmanuelle Andrianjafy, Untitled, 2016, from the series Nothing's in Vain

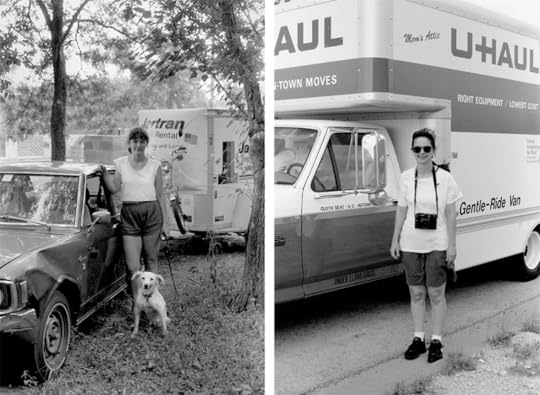

Nancy Floyd, Moving, 1983-1999, 2015, from the series Weathering Time

Kris Graves, Francis, 2016, from the series The Testament Project

Balarama Heller, Cuban Knight Anole, 2017, from the series Zero at the Bone

Natalie Krick, Me posing as Mom posing as Marilyn, 2014, from the series Natural Deceptions

We’re pleased to announce the five finalists for the 2017 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an international photography competition whose goal is to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition:

Emmanuelle Andrianjafy

Nancy Floyd

Kris Graves

Balarama Heller

Natalie Krick

This year, Aperture’s staff reviewed more than 700 portfolios. Our challenge is to select one winner and four honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. One finalist will be selected as the winner and will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore in New York.

We are delighted to welcome these five finalists to our ranks of illustrious past winners and finalists, joining such artists as Eli Durst, Drew Nikonowicz, Amy Elkins, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Alexander Gronsky, Sarah Palmer, Louie Palu, Bryan Schutmaat, and many others. The winner of the 2017 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced in May 2017, and the finalists’ portfolios and statements will be featured on aperture.org.

The post 2017 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 12, 2017

Guilty Pleasures/Hidden Treasures: Darius Himes and Frish Brandt

Darius Himes on Robert Spector

The Pizza Hut Story

Melcher Media and IPHFHA

New York and Wichita, KS, 2008

The official geographic center of the continental United States of America is in Lebanon, Kansas, a mere 199 miles from Wichita, the birthplace of Pizza Hut. It somehow seems fitting that a chain restaurant with such national (and global) reach emanated from smack-dab in the center of the country. In 1958, the Carney brothers borrowed $600 from their mother to open a restaurant after seeing an article in the Saturday Evening Post about a new phenomenon: pizza. The name? Well, the sign of the building they rented only had room for eight letters—and a classic was born!

Having survived college on two-for-one coupons for medium-sized pizzas, I readily welcomed this book into my library. The Pizza Hut Story, an illustrated history of the company, was produced for its fiftieth anniversary and released only internally. This glossy book—loaded up like a Meat Lover’s pizza with historical photos, kitschy logos, and an earnest love for building a popular business—is devoid of any irony and is the perfect way to simply celebrate their success. It comes delivered, obviously, in a cardboard pizza box. Scrumptious!

Darius Himes is the international head of photographs at Christie’s.

Frish Brandt on Paul Bertolli with Alice Waters

Chez Panisse Cooking

Random House

New York, 1988

Chez Panisse is practically an adjective, not just a proper noun. The soul of this restaurant in Berkeley, California, is in the ingredients, not the technique. It all started when the now-revolutionary food-wizardess Alice Waters simply wanted to cook for her peers while hosting political gatherings during the Free Speech Movement that rocked UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

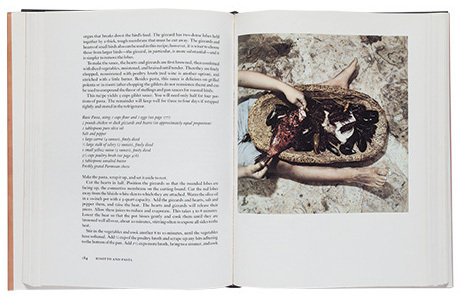

By the time this book came out in 1988, a lot of that political unrest had gone to bed, and other unrest had taken shape. But what transpired in those nearly twenty years is a completely new understanding of what we put on the table—and why. The book’s pictures, by Gail Skoff, give us this in the most elegant and elegiac way. Take the monochromatic picture of two legs straddling a wooden bowl of langostino that leads us to the lobster ravioli recipe. The picture doesn’t tell us anything about technique. There’s no photograph of shelling, or rolling, or cutting—just this: a visual poem to the ingredients, and to the participant. Or what about the picture of levain bread, from back when Wonder Bread was most prevalent? The loaf resembles a boulder in a landscape, with a snow of flour upon it. The bowl of wild mushrooms could be an ode to Proust, if only he had felt about mushrooms as he did about madeleines. But mostly the pictures are simply pure metaphor. Their ingredients drive the picture, just as they drive the kitchen of a place that has revolutionized the way we think about food. I’m not just talking about glorious palate experiences—I’m talking about politics. From UC Berkeley to Waters’s life-changing, school-based Edible Schoolyard Project, politics are where it began and where it leads.

Frish Brandt is president and co-owner of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. fraenkelgallery.com

The post Guilty Pleasures/Hidden Treasures: Darius Himes and Frish Brandt appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers