Aperture's Blog, page 114

July 12, 2017

Does the Venice Biennale Have a Problem with Photography?

At the world’s most prestigious contemporary art exhibition, photographers are on the margins.

By Annika Klein

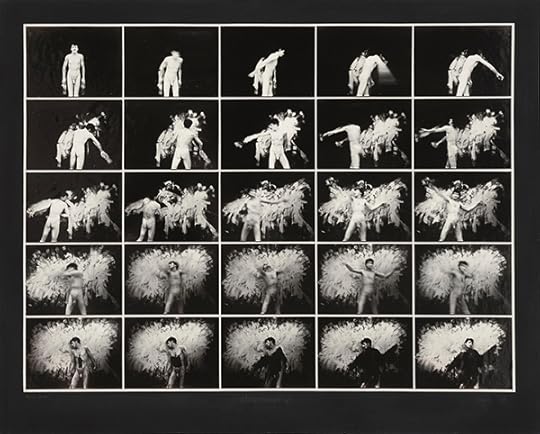

Tibor Hajas, Flesh Painting No. 4, 1978. Photography by János Vető

© Estate of Tibor Hajas and János Vető

Courtesy Ludwig Museum, Budapest

“Taking photographs is an action,” János Vető noted in 1973, referring to his collaboration with Hungarian performance artist Tibor Hajas, currently on view at the 57th Venice Biennale. In their 1970s photographic series, Surface Torture, each piece shows a gridded progression of images, invoking the narrative of a film. In a particularly unnerving sequence, a dark figure against a black background pulls white goo—a mask? paint?—off his face. The gritty, high contrast images give the illusion that Hajas is peeling away his own skin. Taking a picture is an integral part of the performance, not just a tool for documentation: each action was performed for the camera. The two mediums work well together, and neither is upstaged. The wall text, however, tells another story: Hajas’s name appears at the top, where the artists’ names are usually listed, and Vető is relegated to a secondary status, appearing, in significantly smaller type, three lines below.

Almost every time photography appears in the Venice Biennale, especially in the marquee exhibition, VIVA ARTE VIVA, it’s either in service of something else—performance, collage, film, books—or it’s one element of a larger, multimedia project. Out of eighty-seven national pavilions, only three exhibitions are dedicated solely to a photographer: Australia, Belgium, and Poland. Perhaps this dearth of photography is a reflection of a contemporary art market that favors painting and sculpture. But the argument for photography as art was made, and won, a long time ago. At the Biennale, with its multistory sculptures and flashy installations, photographs alone can’t compete with the spectacle. Which isn’t to say that photography doesn’t work well in conjunction with other modes of art making, such as with Hajas’s performances. But, too often, it gets lost in the fray. Genre-bending multimedia work—where most new art seems to be headed—can be timely and powerful, and at the Biennale, there is painting and sculpture aplenty. Why is photography still denied the same consideration?

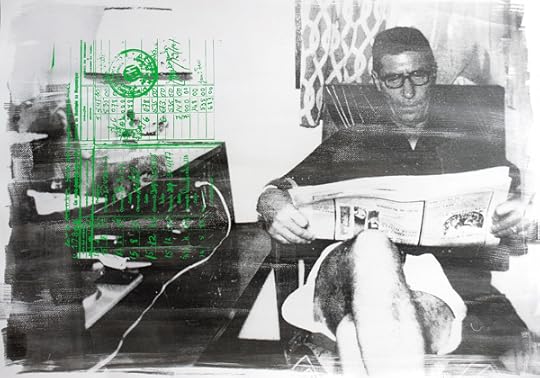

Mladen Stilinovic, Artist at Work Again, 2011

Courtesy Branka Stipancic

VIVA ARTE VIVA, a two-part extravaganza curated by Christine Macel, begins at the Giardini and continues into the Arsenale. Immediately upon entering the Giardini, visitors are faced with ten prints by Serbian artist Mladen Stilinović. In the first eight, Artist at Work (1978), Stilinović lies in bed in different positions. The last two, taken three decades later, Artist at Work Again (2011) show Stilinović slumbering on a bench in a white cube exhibition space. Stilinović appears to ask, how does a Western culture that values productivity over health and leisure affect art making? While these pictures offer a witty critique, Stilinović is a Conceptual artist, not a photographer. Conceptual art pushed for the dematerialization of the art object, to make the idea more valuable than the object. Appropriately, the prints don’t offer much in the way of formal accomplishment or visual pleasure. In 1978, this approach to photography would have been exciting. Now, it’s a one-liner, an amuse bouche for the more important work that follows.

Hajra Waheed, A Short Film 1-321 (detail), 2014

Courtesy of the Artist

Hajra Waheed’s piece A Short Film, 1–321 (2014) combines photography with archival material. Here, and in two adjacent works, the artist has collaged postcards into hundreds of blank slides, placed in neat rows on a wooden shelving unit. (A Short Film, 1–321 also includes two framed works comprised of cut photographs on cork, which are not on view.) Waheed grew up in Dhahran, a gated, residential compound for Saudi ARAMCO employees. According to the artist, the company strictly regulated civilian use of cameras and video equipment, but surveillance was pervasive. Waheed’s work often concerns geopolitics, and migration in particular, but the links to these topics can be difficult to trace. This lyrical and poignant work is part of a larger, multimedia project, Sea Change (2011–ongoing), sourced from the same set of photographic postcards from the 1930s and ’40s, and set in the Western Himalayas. A black-and-white landscape, often a lonely hill or mountain, juts into each frame; the rest is clear glass, representing the gaps in the story. The incorporation of photography works well here because the project itself is about who has the right to make images.

Thu Van Tran, Untitled, 2017. Installation at the 57th Venice Biennale

Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Elsewhere in the Biennale’s main exhibition, however, photography is often lost among the many materials in various multimedia projects. Thu-Van Tran, a French Vietnamese artist, presented an installation concerned with the global, geopolitical history of rubber trees. This topic could be a fascinating point of departure but, instead, veers into a clichés of contemporary art: large-scale installations, vaguely global projects, and a toothless critique of the West. Tran’s project is too broad in both idea and execution. Rubber casts of rubber trees lie atop coffin-like crates, and a dual projection video flickers nearby. Superficially, the installation looks polished, professional. Plus, it helpfully takes up a large amount of space in the capacious Arsenale. Candy-colored drip painted walls form the background for gigantic photograms, which resemble Anna Atkins prints from the mid-nineteenth century—but without her dexterity, grace, or eye for composition. There are too many mediums at play, and Tran has unfortunately dragged photography into the mix.

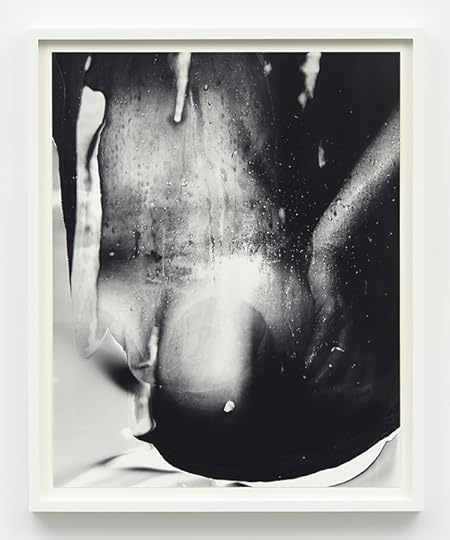

Eileen Quinlan, Super Moon, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

WithinVIVA ARTE VIVA, Eileen Quinlan’s pictures of nudes were one of the few examples of freestanding photographs meant to be seen on their own. The seven prints, which are not a formal series, show her post-pregnancy body, as well as that of another young mother. Yet the wall text apologizes for this inclusion by explaining that Quinlan and her artistic peers, “felt the urgency to free the photographic medium of its technical hyper potential,” which sounds nonsensical. The didactic reads as if a camera were a shackle, from which the artist is desperately trying to liberate herself. Pushing the boundaries of the medium, and making images that are messy and unique, are both older strategies than the crisp, consumable images of the past one hundred years: think of wet-plate daguerreotypes, or Man Ray’s Surrealist photograms. Still, Quinlan’s subject works well with the dripping, black-and-white presentation. Achieving this effect by using vintage Polaroid film, she explained in an interview with Marie Sarre, “As the bodies depicted are undergoing the ravages of time, of child-birth, and even surgery, the film itself is also being transformed by its age.”

Shirin Neshat, Ilgara, 2015, from the series, The Home of My Eyes

Courtesy Written Art Foundation, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

An official collateral exhibition at the Museo Correr, Shirin Neshat: The Home of My Eyes, presents photographs from a 2015 series of the same name, and a video, Roja (2016). Situated on St. Mark’s Square, this civil museum occupies a building known as the Napoleonic Wing, resplendent with Neoclassical treasures. Following room after room of opulent nineteenth-century furniture and gilded religious paintings, Neshat’s grid of black-and-white photographs is striking—minimal, contemporary, powerful. A large sculpture of the Virgin Mary, ostensibly part of the museum’s collection, hangs in the middle of the wall. This gesture of religious cohabitation relates to the subjects’ poses, in particular, their hand positions, which were inspired by El Greco.

Throughout her career Neshat has focused on Iran, but this expansive series of photographs show people from neighboring Azerbaijan. During the sittings, Neshat interviewed her subjects, who varied in age and ethnicity, about cultural identity and the concept of home. Each portrait is inscribed with ink, and draws from these conversations, as well as from poems by Nizami Ganjavi, a twelfth-century poet born in present-day Azerbaijan. The script is difficult to discern, as most of the pictures are hung far above eye-level, and there is no translated text on the wall, or in a booklet. For visitors lacking extraordinary vision and a grasp of Farsi, these stories will unfortunately remain unknown. Though more context would have been illuminating, Neshat’s exhibition proves that, even in Venice, photography can be relevant and contemporary—if given the chance.

Annika Klein is the editorial assistant of Aperture magazine.

The 57th Venice Biennale, including VIVA ARTE VIVA, is on view through November 27, 2017. Shirin Neshat: The Home of My Eyes is on view at the Museo Correr, Venice, through November 26, 2017.

The post Does the Venice Biennale Have a Problem with Photography? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 11, 2017

Raw Land

How are artists rethinking documentary in North Africa?

By Morad Montazami

Zineb Sedira, Haunted House, 2006

© the artist and DACS, London, and courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London

If we were to attempt to chart the photographic practices of the Maghreb region, it’s unlikely that we’d end up with the expected map, divided into three neat slices of national territory: Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Rather, we’d have an opaque diagram, tangled with intertwined roadways, hybrid landscapes, and fragments of experience to be retraced. Following Roland Barthes’s notion that “photography is unclassifiable,” it seems that a desire to classify this region geographically or culturally would lead inevitably to colonialist or neo-Orientalist stereotypes. How, then, might we avoid simply filling the need for “counterrepresentations” in the face of clichés that still feed art fairs and platforms? How might we consider the “inactive” or undesignated frontiers, rather than the current boundaries inherited from colonizers—such as the border between North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa?

Zineb Sedira (a Paris-born Algerian, now based in London) and Yto Barrada (a Paris-born Moroccan, living in New York and Tangier) are two prolific artists who are addressing the documentary image’s spaces of redefinition. They find themselves at the juncture of postcolonial studies and an aesthetic of territorial, fluvial, geological, and meteorological edges—a political ecology in which the scars of living beings are as valid as those of a country road or of an entire ecosystem. Just as Tangier and Algiers lock eyes in a vast oceanic mirror, the figures looking out at the great sea in Barrada’s 2003 triptych Belvédère seem to find their exact counterparts in Sedira’s 2006 diptych Transitional Landscape, where a figure also contemplates the sea. An encounter of two Mediterranean dreamscapes? But this dream has become a nightmare—a sea cemetery—as the migration crisis accelerates.

Yto Barrada, Ceuta Border, Illegally Crossing the Border into the Spanish Enclave of Ceuta, Tangier, 1999

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Polaris, Paris

There is another point of contact for these two artists—that of placemaking, of opening paths for a new generation of artists interested in inhabiting frontiers: of photography and film, sculpture and installation. Barrada is a cofounder, and director since 2006, of the Cinémathèque de Tanger, which has played a central role in the contemporary Arab art scene. In Algiers, in 2011, Sedira founded the Aria Artist Residency, which hosts artists from North Africa and around the world who are working across boundaries. Both ventures, as they plant the seeds of cultural development, have created new networks of practitioners, critics, and viewers in their cities through exhibitions, workshops, speaker series, and, at the Cinémathèque de Tanger, even a “viewing school” for children.

Long before the start of the 2000s, a new, medium-centered documentary photography began to emerge mainly in Morocco, less open to interdisciplinary hybridization yet symptomatic of a moment at which the photobook had a particular prestige and newness. We might cite, for example, the memorable photographs of Daoud Aoulad-Syad’s Marocains (1989) and Souad Guennoun’s Les incendiaires (2000), which had clear ties to the work of leading intellectuals and authors, such as Abdelkebir Khatibi and Zakya Daoud, respectively. Cultivating an alliance between street photography and metaphorical autobiography, these photographers were impacted by both travel literature and the haunting aura of “the decisive moment,” per Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank.

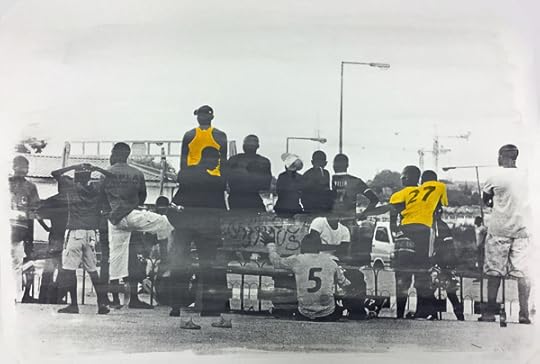

Wassim Ghozlani, Postcards from Tunisia, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Maison de l’image, Tunis

Tangier is the most captivating of “incendiary” ports of call for Guennoun, who with her camera follows Morocco’s vagabond children, without home or family, delivered into the claws of the street. Its status as a “transitional city,” a limbo zone between two worlds, attracts photographers eager to try to capture its mystique. In the same way that one never “sees” New York but can only “re-see” it (because of its innumerable photographic and filmic representations), Tangier carries the sense of déjà vu that is characteristic of particularly photogenic cities, with its teeming medina, its hushed 1970s-vintage hotels, its cinemas and abandoned theaters with their ghostly marquees, the traces of the Beat Generation and of Jean Genet, who described Tangier as a “fabulous city … the very symbol of treason.”

But the romantic myth of Tangier also warrants a more analytical gaze, as in the work of Barrada, which examines its zones of exclusion, its blind spots, its blank spaces. This task has been taken up by the new generation of Tangerine photographers, foremost among them Hicham Gardaf. Investigating the underside of urban development and the nonplaces of globalization, he seems almost to make a synthesis of photography that tells and photography that analyzes. For a bit, Gardaf manages to get us to “see” Tangier, finally. There is a connection here to Wassim Ghozlani’s 2016 series Postcards from Tunisia, which was featured at the 2016 iteration of Photomed, the annual festival of Mediterranean photography in Sanary-sur-Mer, France. Ghozlani’s antipostcards purport to show Tunisian tourist spots, but do so via mute images of nonevents: a deserted crossroads, a bottle on a shelf, a broken door, or a hostel where visitors pasted their snapshots to a wall. Whereas Gardaf takes great care in the portrayal of his characters—although their function is limited to inhabiting the landscape—Ghozlani often captures spaces devoid of human presence, evoking memories of photography’s earliest days.

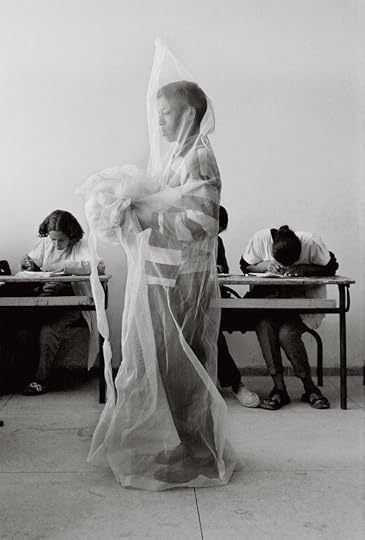

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe, 1994–2002

Courtesy the artist and Loft Art Gallery, Casablanca

These photographers’ practices—which are linked more to a fabrication of “the real” than to the documentary tradition—have an instructive model in Hicham Benohoud’s series La salle de classe (The classroom). In this long-haul project, undertaken in two stages between 1994 and 2002 when he was an art teacher in Marrakech, Benohoud used the confines of the classroom as a setting, placing his young students in situations that are incongruous to the point of surrealism. It is as if the artist were seeking to mimic the dynamics of domination that reverberate throughout the society that lies just outside the four walls. The metaphorical power of these images—and the ingenuity of the “sets” cobbled together from the accoutrements at hand in an art classroom—have brought La salle de classe much attention: it was exhibited at the 2014 Marrakech Biennale and acquired by the Marrakech Museum for Photography and Visual Arts and London’s Tate Modern.

In addition to art fairs and museums, both crucial platforms, the development of photographic practices in Morocco can be credited to new exhibition and publishing ventures. Rabat’s Kulte Gallery & Editions, by creating a proper artistic research platform, articulated through a residency program, has proved influential since it opened in 2013. Its 2014 publication New Africa, a groundbreaking overview of the continent’s impulse for photography and video, perfectly illustrates founder Yasmina Naji’s rethinking of preconceived national and cultural boundaries. “The development of photography not only as a tool for identity tracing but also a catalyst for identities in motion,” she says, “is what we hope to highlight in our program, as we also need to overcome the artificial boundary between so-called North Africa and the sub-Saharan territory.”

Carolle Bénitah, muqueuse nasale (nasal mucosa), 2012

Courtesy the artist and Sous Les Etoiles Gallery, New York

With a clear commitment to women artists, Kulte recently showcased the refinement and compelling irony with which Carolle Bénitah infuses her embroidered photographs, turning intimate memories and archives into mechanical mementos (for example, in Le désert de Sodome, 2016). Also confirming Morocco’s step forward is Galerie 127 in Marrakech, the pioneering photography venue opened by Nathalie Locatelli in 2006. Locatelli’s experience and undisputable expertise have allowed her to bring together established local photographers (Malik Nejmi, Aoulad-Syad, Benohoud) with emerging ones, such as Hicham Gardaf, but also foreigners (DaeSoo Kim, Denis Dailleux). These proactive gallery spaces have paved the path for newly established larger institutions, such as the Marrakech Museum for Photography and Visual Arts. (The latter is temporarily closed in anticipation of resettlement on a new site, after a highly promising two years.)

During the 1990s, the magazine Revue Noire helped lead the way for the boom of galleries and art spaces occurring in North Africa today. Published from 1991 to 2001, it was one of the first independent media outlets to offer African photography a distribution platform, showcasing its artistic direction and cosmopolitanism (with a focus that included everything from Abidjan, Kinshasa, Johannesburg, and Marrakech to New York, Tokyo, and beyond). Its Paris-based—and thus French-speaking—editors facilitated exchanges with the photographers of the Maghreb. It was a role that was all the more important at the time, as news agencies did not welcome Arab photographers as readily as they do today, and galleries and biennials had not yet absorbed new approaches to documentary.

Zied Ben Romdhane, Site of phosphate processing, Redeyef, Tunisia, March 21, 2015, from the series West of Life

Courtesy the artist

However, the Arab Spring of 2010–11 provided photography with a new role, accelerating the emergence of “citizen photojournalism”—by violating the long-standing taboo against photography in heavily controlled and supervised public spaces of the Maghreb countries. In Tunisia, a postrevolutionary generation of artists and photographers is only now beginning to take shape. Last year, the Washington Post published a series titled West of Life (2016) by Zied Ben Romdhane, realized in Tunisia’s Gafsa region. The project, which received an unanticipated level of attention, shows with exceptional accuracy the stigmas and other “scars” left by phosphate mines on inhabitants and workers, as on the landscape itself. It reveals not only the photographic talents of Ben Romdhane, but also his ingenuity in distributing his images on social media without passing through an agency or other intermediary.

Speaking to new forms of image distribution, the project Cairo. Open City: New Testimonies from an Ongoing Revolution began as an exhibition at the Museum für Photographie in Braunschweig, Germany, in 2012, and traveled across the country, as well as to a gallery in Dubai. Its catalog (2014), edited by Florian Ebner and Constanze Wicke, is an archive devoted to the double revolution—political and visual—that took place at Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011, including news and blog images, Flickr accounts, anonymous photographs, and works by artists such as Lara Baladi and Randa Shaath. The project shows that if indeed “photography is unclassifiable,” it must “organize” in order to better operate in the outsider zones of insurrectional imagery.

The overlap of photography’s hyperdistribution with the dizzying sociopolitics of an entire region augurs well for a very wide range of formats and platforms still to be invented. Through this acknowledgment of infinite particularities, focus shifts to the idiosyncratic, individual voice. In 2010, Zineb Sedira completed her video installation Gardiennes d’images (Image keepers), an investigation into the photographic work of Mohamed Kouaci, notably his epic experiences as a photographer during the Algerian War of Independence. What Sedira tells us through the work of Kouaci—more than half a century after his photographs were made—is that photography can no longer be defined simply as a “fine art,” nor as purely subjective evidence. In the Maghreb, at least, documentary-style and humanistic photography have given way to an art of investigation in which one author’s subjectivity calls out to those of others, seeking to join his or her solitude with the solitude of others.

Morad Montazami is Adjunct Research Curator for the Middle East and North Africa at Tate Modern and Director of Zamân Books. Translated from the French by Diana C. Stoll.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Raw Land appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 6, 2017

Aperture to honor Kwame Brathwaite, Zackary Drucker, Inez & Vinoodh

Cohosted by Edward Enninful, Susan Gutfreund, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, Hari Nef, and Anja Rubik.

October 30, 2017

IAC Building, 555 West 18th Street, New York, N.Y.

Click here to purchase tables or tickets

Aperture’s 65th Anniversary Gala celebrates the contributions of four visionary artists working at the intersection of photography, style, and human potential.

Courtesy of Kwame Brathwaite

Kwame Brathwaite popularized the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” in the late 1950s and early ’60s through his photographs, his writing, and the activities of the two organizations he helped cofound: African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS, 1956) and Grandassa Models (1962). He also photographed numerous landmark events, such as the Rumble in the Jungle, Human Kindness Day, and Nelson Mandela’s inauguration. Brathwaite’s photographs were specifically intended to shape the course of American visual discourse and to foreground the idea that artistic and political vision can effect change in popular culture—and that popular culture can effect change on culture at large. He will be profiled by Tanisha C. Ford in the “Elements of Style” issue of Aperture magazine, to be released in September.

Photo by Jaesung Lee

Courtesy of Zackary Drucker

Zackary Drucker is an independent artist, cultural producer, and trans woman who breaks down the way we think about gender, sexuality, and seeing. She has performed and exhibited her work internationally in museums, galleries, and film festivals including the Whitney Biennial 2014, MoMA PS1, Hammer Museum, Art Gallery of Ontario, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others. Drucker is an Emmy-nominated producer for the docu-series This Is Me, as well as a producer on the Golden Globe and Emmy-winning Transparent. She will be the guest editor of “Future Gender,” an issue of Aperture magazine to be released in December.

Polaroid by Eva Doll

Courtesy of Inez & Vinoodh

Inez & Vinoodh are among the most celebrated and influential photographers working within the fashion and art worlds today. In the early 1990s, they developed a signature style of visual seduction paired with provocative narratives, which infused new ideas into photography, and often upended gender conventions. They have created groundbreaking editorials for such publications as American, French, Japanese, and Italian Vogue; V Magazine; Visionaire; The Gentlewoman; W Magazine; and the New York Times Magazine, for which they recently photographed Chelsea Manning. Their innovative approach is also seen in campaigns and films for major fashion houses and their work has been exhibited in galleries and museums internationally including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; the Hayward Gallery, London; and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Inez & Vinoodh are featured on the cover of Aperture’s forthcoming publication Fashion Photography: The Story in 180 Pictures.

About Aperture

Aperture, a not-for-profit foundation, connects the photo community and its audiences with the most inspiring work, the sharpest ideas, and with each other—in print, in person, and online.

The post Aperture to honor Kwame Brathwaite, Zackary Drucker, Inez & Vinoodh appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture to honor Kwame Brathwaite, Zackary Drucker, and Inez & Vinoodh at 2017 Gala, Elements of Style

Cohosted by Edward Enninful, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, and Hari Nef

October 30, 2017

IAC Building, 555 West 18th Street, New York, N.Y.

Click here to purchase tables or tickets

Aperture’s 65th Anniversary Gala celebrates the contributions of four visionary artists working at the intersection of photography, style, and human potential.

Courtesy of Kwame Brathwaite

Kwame Brathwaite popularized the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” in the late 1950s and early ’60s through his photographs, his writing, and the activities of the two organizations he helped cofound: African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS, 1956) and Grandassa Models (1962). He also photographed numerous landmark events, such as the Rumble in the Jungle, Human Kindness Day, and Nelson Mandela’s inauguration. Brathwaite’s photographs were specifically intended to shape the course of American visual discourse and to foreground the idea that artistic and political vision can effect change in popular culture—and that popular culture can effect change on culture at large. He will be profiled by Tanisha C. Ford in the “Elements of Style” issue of Aperture magazine, to be released in September.

Photo by Jaesung Lee

Courtesy of Zackary Drucker

Zackary Drucker is an independent artist, cultural producer, and trans woman who breaks down the way we think about gender, sexuality, and seeing. She has performed and exhibited her work internationally in museums, galleries, and film festivals including the Whitney Biennial 2014, MoMA PS1, Hammer Museum, Art Gallery of Ontario, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others. Drucker is an Emmy-nominated producer for the docu-series This Is Me, as well as a producer on the Golden Globe and Emmy-winning Transparent. She will be the guest editor of “Future Gender,” an issue of Aperture magazine to be released in December.

Polaroid by Eva Doll

Courtesy of Inez & Vinoodh

Inez & Vinoodh are among the most celebrated and influential photographers working within the fashion and art worlds today. In the early 1990s, they developed a signature style of visual seduction paired with provocative narratives, which infused new ideas into photography, and often upended gender conventions. They have created groundbreaking editorials for such publications as American, French, Japanese, and Italian Vogue; V Magazine; Visionaire; The Gentlewoman; W Magazine; and the New York Times Magazine, for which they recently photographed Chelsea Manning. Their innovative approach is also seen in campaigns and films for major fashion houses and their work has been exhibited in galleries and museums internationally including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; the Hayward Gallery, London; and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Inez & Vinoodh are featured on the cover of Aperture’s forthcoming publication Fashion Photography: The Story in 180 Pictures.

The Aperture Gala is the New York photography party of the fall season and celebrates the institution that, since its inception in 1952, has served as “common ground for the advancement of photography.” Each year over 600 guests from the worlds of art, fashion, media, business, and entertainment attend the event. A cocktail preview and seated dinner for approximately 350 guests will occur from 6:00 to 8:30 p.m., followed by a Photo Party from 9:00 p.m. until midnight, with special performances by celebrated musicians, DJ sets, and dancing.

Prior to the Gala evening, Aperture programs a Gala Weekend (October 27–29) with an itinerary of activities for sponsors and ticket buyers at the highest levels. Events throughout the weekend include guided tours and cocktail receptions at artists’ studios, museum collections, archives, and private photography collections.

About Aperture

Aperture, a not-for-profit foundation, connects the photo community and its audiences with the most inspiring work, the sharpest ideas, and with each other—in print, in person, and online.

The post Aperture to honor Kwame Brathwaite, Zackary Drucker, and Inez & Vinoodh at 2017 Gala, Elements of Style appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In Praise of the Absurd

In Panama City, five photographic projects tackle the contradictions of urban life.

By Paula Kupfer

Rachelle Mozman, Yudri, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Panama City defies logic. On a bay facing the Pacific Ocean, flanked by its famous canal, the city’s steel-and-glass spires rise toward the sky. But signs of poverty and radical income disparity are conspicuous, as in the uncomfortable proximity of those high-rises to fishermen’s shacks. Lush vegetation alternates with aggressive construction, cosmopolitanism with a small-town mentality, and colonial history with the fervent wish to look forward. Vibrant yet chaotic, the place is a container for all manner of people, experiences, and journeys.

Fifteen years ago, in 2002, Panamanian art critic Adrienne Samos suggested, in Atlántica: Journal of Art and Thought, that local artists have traditionally shied away from their urban environments. Instead, she wrote, they looked toward folklore and the countryside for a common identity. By the early 2000s, however, artists and photographers, such as Gustavo Araujo, Jonathan Harker, and Brooke Alfaro, started focusing on “the city itself . . . the country’s cultural and social engine.” Still, Samos continued, “they mostly exclude overt political protest.”

In recent years, however, Panamanian artists working with photography have begun to engage in social and cultural critique. Many use humor and satire to address daily urban life, as well as of national history. The use of wit and the absurd have become important tools for artists in a city where general opinion is still conservative, money courses through the country in forms both legal and illegal, and the level of government corruption seems, at times, a joke. Artists, like most of the city’s citizens, operate in the space of contradiction between fondness and criticism for the urban space that surrounds them.

Darién Montañez, Feoclásico Punta Pacífica, 2010

Courtesy the artist

This sentiment is echoed in the work of Darién Montañez, a Panamanian artist with an expansive practice anchored in photography. Trained as an architect, Montañez coined the term feoclasicismo, or “ugly-classicism,” as a way to describe a hybrid style of architecture common in Panama City, which displays a penchant for excessive neoclassical ornamentation. He has a growing collection of photographs documenting this style. In a limited-edition photobook, he writes: “Where has this glorification of bad taste come from? Bad in its quality, bad in its malignity, and almost so bad it’s wonderful?” He wraps biting humor in a veil of tenderness for his city and its architectural acrobatics, and his fertile thinking extends across online platforms such as tumblr, WordPress, and Instagram.

Pilar Moreno, Cuatro Gatos (detail), 2015

Courtesy the artist

Pilar Moreno is also preoccupied with urban absurdity. Her collage-dioramas depict imaginary cityscapes rooted in reality and are inhabited by anthropomorphized animals. Although radically different from mass media depictions of Panama City, the dioramas are “closer to the city that I see and know,” Moreno told me. “It is a city where any juxtaposition is possible. Where the extremes share and inhabit contiguous spaces without ever mixing. Social classes, ethnicities, religions, clothing, cultures, and languages separated by chasms of different kinds.” Her animal characters make uneasy scenes, depicting poverty, as well as excess, more palatable; meanwhile, her frequent use of cats adds a tongue-in-cheek twist that resonates with the Internet’s bottomless feline love. “Humor is a useful tool to approach a dialogue about themes and situations that are difficult or conflictive,” Moreno says. “I created a series of animal characters for the pieces and I think they allow a more detailed look at situations that are in some ways quite difficult.”

Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker, Still from Under the Rug, 2015

Courtesy the artists and Diablo Rosso, Panama City

Similarly, artist team Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker use their metaphorical videos to debunk the shiny images of Panama City found in glossy local publications or travel magazines. Striking in their use of common materials—bricks as puzzle pieces, beer bottles as musical instruments, or plastic bottle caps accumulated into a giant heap—and with acute attention placed on sound, the videos may at first appear unassuming, but reveal their potency through embedded metaphors and rich references. Finding inspiration in the physical and psychological chaos of the city, Conlon told me she has “long felt that Panama City feeds that place in me where dark humor meets analytic curiosity.”

The artists’ piece Under the rug (2015) addresses how a city’s attempts at reinvention can mean pushing aside anything that doesn’t fit into the manicured image of progress. In the video, two disembodied figures clad in campy, blue-and-red suits—the colors of the Panamanian flag—sweep all manner of things under a patch of grass. The brushing away of objects—which start out as small debris like discarded lottery tickets or dominos and grow to include broken plastic guns and beheaded dolls—comments on the country’s deficient environmental policies, but also alludes to the sloppy concealment of all sorts of public information. Invisible Hands (2014), where white-gloved conjure and then make cash disappear, as if by magic, is an even more direct condemnation of the practice of making things—money—disappear. Together, the videos suggest that hidden debris as well as secret sums will ultimately, inevitably, come to light.

José Castrellón, Maria Chiquita, Colón, 2014

Courtesy the artist

The legacy of the Canal Zone, a U.S. territory until 1999, is still a subject of negotiation by historians and artists. Engaging with one chapter of its history, artist José Castrellón’s recent exhibition examined the photographs from the January 9, 1964, massacre. That day, local students who had attempted to place a Panamanian flag next to the American flag in the Canal Zone were shot and killed by U.S. military. The event marked a turning point in U.S.–Panamanian relations. Later that month, a stunning photograph by Stan Wayman from the ensuing riots was featured on the cover of Life magazine. In the photograph, students climb a lamppost to plant a flag on top. Now, over fifty years later, Castrellón juxtaposes this historic image—blown up, in a red frame—alongside his own photographs of men climbing a palo encebao’, or greased maypole, a folk custom in Panama. The photographs ask: Can the past be so easily reduced into a visual game?

Rachelle Mozman, Ivory, 2016

Courtesy the artist

In her most recent work, She, as if Gauguin (2016), artist Rachelle Mozman also considers the colonial past through satire. Using photography, drawing, collage, and video, Mozman examines the myths surrounding French painter Paul Gauguin’s short time in Panama, particularly his search for “primitive life” and “racial purity,” as described in his book Noa Noa (1901). Mozman’s staged photographs poke fun at the trope of the exotic tropical beauty and imagine subjectivities for Gauguin’s muses. In a small country with a complex relationship to its past—and where photography-as-art only entered into the conversation within the last thirty years—the artist’s turn to humor is noteworthy. “Humor,” says Mozman, “is a defense and a way to cope with something disturbing or tragic.”

Paula Kupfer is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn and Panama.

The post In Praise of the Absurd appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Délio Jasse’s Endless Archive

Looking to vintage photographs and alternative processes, an Angolan Portuguese artist engages the infinite possibilities of an image.

By Paula Nascimento

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963, 2016. Photographic emulsion and screenprint on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

“It’s as though I really knew these people and photographed them all myself,” the artist Délio Jasse said earlier this year, referring to the images from his series The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963 (2016). Featured in Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa,” Jasse’s screenprints combine 1960s-era documents, letters, and photographs that he found in a flea market in Lisbon. They depict the blithe lifestyle of a Portuguese family living in Nampula, a province in Mozambique, which at the time was still a Portuguese colony. Jasse, who was born in Luanda, Angola—another former Portuguese colony—has often used analog and historic photographic processes, such as the cyanotype, to reflect the mingling of past and present in postcolonial African culture and politics.

In the images from The Lost Chapter, the anonymous figures in family snapshots become symbolic stewards of Portuguese privilege: colonists enjoy the tropical lifestyle, but black servants are relegated to the margins. Jasse intervened further by overlaying the images with stamps and visas. “More than abstract stories, however, Jasse seems to have found that there is violence in documents,” Silas Martí writes in his introduction to Jasse’s Aperture portfolio. “Jasse makes this clear by subverting these photographs rescued from oblivion—images of nonchalant innocence are overshadowed by the fluorescent weight of authority.” Here, Jasse speaks with Paula Nascimento about archives, citizenship, and the afterimage of Portuguese colonialism in Africa.

Délio Jasse, Terreno Ocupado, 2014. Cyanotype on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Paula Nascimento: Your work is an exploration of themes of memory and identity within a context that is postcolonial by default. By interweaving disparate sources, you draw links between photography, memory, and place.

Délio Jasse: Yes, these have been key themes in my work. I like to explore the connection between photography and memory by working with archives. The issue of memory is also linked to that of photography as an expressive medium.

Nascimento: What kind of archives do you work with?

Jasse: I work both with found archives (usually I am drawn to family archives) and my own archives, the images that I shoot in Luanda and around the world. In my studio, I have many images—new, old, found, shot, et cetera—which are waiting to be processed. I would say that the archive as a concept, and how I work with archives by changing them and showing their contradictions, is quite central in my work.

Nascimento: What comes first to you, the image of a project or the concept of a series?

Jasse: The image comes first, then the concept. It is the image that finds me, but, at the same time, I often work with the same themes, so it is easy to develop the conceptual framework of a project.

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963, 2016. Photographic emulsion and screenprint on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: Some time ago, when we were talking about the role of memory in your practice, you highlighted that the most important aspect is how one decides to speak about the past. It’s about the position and the gaze. How do you start your research and approach the archives you work with?

Jasse: Well, photography isn’t objective, and the photographer’s gaze is more important than the photographed object. In my case, memory arises in the encounter between the past and the future, which isn’t always harmonious. Given that the gaze is always fragmented, rather than objective, the object—whether the past or a specific event—becomes fragile and ephemeral.

It takes me some time to create an archive of images, or as I say, a body of work of images that relate to one another. When I find some images or when I take new pictures, I let them rest for a while until I am naturally drawn to a specific image or detail. This then becomes the starting point for a new series, and from there, I start to experiment, and to decide which techniques to use.

The Nampula archive, for example, I found at Feira da Ladra, a flea market in Lisbon. At first, I was struck by the picture where you see some ladies in a car. That car reminded me of a certain type of wealth and a specific period in time. Only when I turned the paper over did I realize that the image was taken in Mozambique in 1963. The contrast between the image itself and the place in which it was taken was what interested me in this case.

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963, 2016. Photographic emulsion and screenprint on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: What do you mean by contrast? The alienation of the white settlers against the political context of the struggles for independence in Mozambique as suggested by the absence of black Mozambicans from the images?

Jasse: These images could have been taken anywhere in the Western world. They are in Africa, but there is nothing that indicates the location. Not only are there no geographical or physical signs, but there are also very few black people. And the few black people (clearly servants) are all almost hidden; it is not easy to see them. That is the contrast I was talking about: how their lives looked (totally European) versus where they were (in Mozambique). Thinking about it, I understand that the term “contrast” may be a bit ambiguous here, and maybe I should have referred to it as a “deletion” of Africa and black Africans.

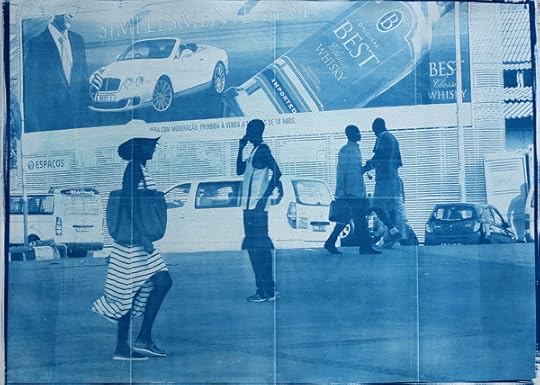

Délio Jasse, Cidade em movimento, 2016. Cyanotype on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: Let’s go back a little bit. You are part of a generation that left Angola young and moved to Portugal at a specific moment in time, around the early ’90s. How was your experience as an immigrant, and did this influence your thematic interests?

Jasse: I moved to Lisbon when I was eighteen years old. In the first years, I had all my papers, but, at a certain point, I had no work contract and I lost my legal residency. As my father has Portuguese citizenship (my great grandfather was from Northern Portugal), I then applied to become a Portuguese citizen. The process was a bit crazy. My birth certificate got lost in Luanda, Angola, and the government had to make a new one. There were always bureaucratic problems that seemed impossible to resolve. It was a grotesque situation. My brothers got their Portuguese documents very quickly but, for me, it seemed like a problem with no solution. And then, suddenly, in 2010, I got a letter saying, “Hey! You are finally Portuguese!” I still don’t know which documents or information worked.

Délio Jasse, Pontus, 2011. Watercolor and photographic emulsion on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: Clearly this narrative explains how you expose the obscurity and ambiguity of these immigration processes. Are you interested in the characters’ own stories in the images you find and collect, or only in fictionalizing and creating other signifiers?

Jasse: Both—it depends if I work with found materials or with my own images. With the found archives, I am more interested in creating new narratives; with my own images, I try to question the official version of the sources. For example, in the series Pontus (2012), you can’t say where the images were taken. I like to make a decoy for the viewer.

In most of my work, I assume the non-reality of the final images and highlight the process that created them: the manipulation or superimposition of images, whether my own or found material. The constructed images belong to space that is neither completely real nor completely fictitious, neither reality nor memory.

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963, 2016. Photographic emulsion and screenprint on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: These processes that you go through to construct the images are fascinating. How did you interest in photography start?

Jasse: I fell in love with photography after working in a screenprinting atelier. I worked at the atelier run by my uncle, in Lisbon, from 2003 until 2007. There was a photography studio within the atelier, which we used to separate the colors to create photolithographs. I developed my interest in photography from that experience.

Nascimento: Would that explain your preference for the techniques and methods you use to construct your images?

Jasse: The only element I retained from silk screen printing in my work is the use of different layers to construct the final image. Most of the time, I work with analog photography—sometimes I use digital images as a tool—and I also create my own emulsions. Once, I had to create my own camera. The first time I returned to Luanda after a long period away, I wasn’t comfortable taking my camera around town. It was a simple box, made of cardboard, with a hole in it.

Nascimento: And what did you shoot with this camera? Have you used those images?

Jasse: The camera worked but the images are quite peculiar: excessive exposure, with many nuances, and juxtapositions. I really liked the resulting images. I would say they are more like experiences or tests than real images, but I really like them. They have a dreamy look. But I haven’t worked with them yet. Who knows, maybe may next project.

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter, Nampula, 1963, 2016. Photographic emulsion and screenprint on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: Your lab must be a magical place. It is your creative space, where these processes come to live.

Jasse: The photographic lab is essential for my work. It’s where I create most of my works—to be more precise, I would use the word construct, as you’ve suggested. When I recover an old image, I have to create a new negative. I don’t only photograph the image, but I also choose to make a collage, montage, et cetera. The technique I decide to use in the beginning of a new series is very important and it will define the overall project.

Most of the techniques I use in the lab are considered “alternative.” At the moment, I am working with cyanotype, a printing technique which was initially used by botanists to register plants. The images are created with sunlight, and there is no need to have a darkroom. But I have also used other, old techniques. The type of intervention I choose depends on the found images and their state of conservation.

The stamps and documents in The Lost Chapter, for example, are also a key point in my work, and are inserted using serigraphy or photography. But there is no connection between the documents and the individuals in the images. The idea is to show the nonsense of official documents. You are not who you are just because a document states it.

Délio Jasse, Pontus, 2017. Watercolor and photographic emulsion on Fabriano paper

Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Nascimento: It is a very complex process, both technically and perhaps also symbolically.

Jasse: The methods I use have different levels of complexity depending on the expression and concept of the project. As I merge the process and the end product, I am deconstructing the image making itself. So, yes, without these alternative processes, my work wouldn’t exist. Part of my interest is in exposing these alternative processes and in making the various stages “physical,” and therefore visible. The image ends up being neither univocal nor homogeneous; each layer can be viewed individually or jointly. I like to engage with the infinite possibilities that an image, or a life, has—or could have—and for me the best way to do this is to assume the process as a fundamental part of the work.

Paula Nascimento is an architect and curator based in Luanda, Angola.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Délio Jasse’s Endless Archive appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 29, 2017

Queering “Straight” Photography

With a rush of color, David Benjamin Sherry’s new photograms gesture to abstract painting and gay history.

By William J. Simmons

David Benjamin Sherry, Submission, 0C100M160Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Rare is the artist who can surprise you with a new body of work. David Benjamin Sherry, who is known largely for his color-saturated landscapes, created a new series of photograms for his latest exhibition, Pink Genesis, at Salon 94 in New York. Though bodies do appear, the photogram, by nature, is abstract—it is an index of an object and a shadow, a semi-formless copy. Sherry’s historical references are so complex, and so joyfully filled with the often-excluded formal presence of sexuality, that revisiting Pink Genesis is like rereading Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida (1980), with its seamless integration of concept, structure, and emotion. I recently discussed with Sherry the roots of this exhibition, as well as his personal, technical, political, and artistic references.

David Benjamin Sherry, Pink Genesis (Self Portrait with Mars), 140C0M25Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

William J. Simmons: Darkroom photography often has the charge of preciousness levied against it, and you have never been afraid of that. What helps you remain steadfast in your commitment to analogue techniques, when some might see them as gimmicks?

David Benjamin Sherry: I have never once thought of darkroom photography as having a charge of preciousness. It’s a highly toxic, unstable, and intensely controlled process. For me, it’s also a strenuous, emotionally draining, bipolar performance that happens alone and in the complete darkness. It almost feels like I’m possessed in the darkroom. The entire act of printing in the dark has an aura of mystique and the unknown to it. I think people are now romanticizing the analog print and the unstable qualities of it, as well as the warmth that it exudes, versus the colder, less human, digital print. There seems to be a backlash happening in photography now, maybe against the digital image. I say this only because I love the analog process, and maybe my eyes are more attuned to it, but I have been noticing fewer digital images on gallery walls, and more human-oriented photographic work, which is often shot on film. It’s happening in Hollywood and in fashion photography.

The analog process—from shooting film to printing—satisfies many of my creative desires. A painter’s work comes to fruition through their materials, and my process is similar. I have experimented and taken courses in other forms of non-analog photography, but I am never fully satisfied with the process. It often feels too easy. Mostly my soul or hand feels out of the touch with the print in the end, and this is a crucial part of my work. There is sometimes an emotional disconnect with the physical print, and my work is often emotionally driven.

I love the instability of analog photography, the alchemical qualities of it, the dangers of it, the history of it, the mysticism tied to it, the exclusivity of it, the isolation of it, and the complete embodiment of it—meaning that once inside of a completely darkened room, using a small amount of light to expose a piece of paper, I actually become the internal workings of a sort of camera. While in the darkroom, I control the enlarger and the paper surface. My body becomes an integral part of the working machine. Through this process, I embody my print and become a working part of the camera. With Pink Genesis, I decided it was time to shed light upon my last seventeen years of working with film photography and to blow an analog kiss to all the other projects I’ve worked on. I decided it was time to let my hair down, to stop being protective of my darkroom process, and in fact celebrate it. And I wanted to do a show entirely of photograms, because they are in a sense the most primal form of the analog photographic process, hence “genesis” in the title.

David Benjamin Sherry, Empathy, 87C177M0Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: Your work has often filled up the representational with the abstract, which I have always seen as a queer strategy. How might we understand use of abstraction in Pink Genesis? Is it comparable to Hilma af Klint’s emotional, mythological abstraction, or conversely to Josef Albers’s Bauhaus-inspired, disciplined images?

Sherry: I’m glad you see this connection, Will. I think for most people, they see my interest in abstraction as a “departure,” whereas anyone familiar with my repertoire would see that my work continually investigates the various modes of the photographic image. And, absolutely, you are spot on when you see this as a queer strategy. One of my primary goals is to locate the voids I see within the history of photography and fill them, so to speak, with a queer read on landscape, for instance, or social documentary, or the photogram. And to mingle genres and degrees of abstraction and representationality reflects that queer reality of code-switching for survival—the having to be two (or more) people depending on your context.

I hope to re-contextualize queer themes within a very “straight”-forward (pun intended) medium. (Think of the term “straight photography.”) The dominant, straight, white, male gaze and the resulting interpretation of the world was, and is, at the very heart and center of the history of photography. Once I understood this, it became a turning point for my work, which is often about being in conversation with my predecessors. I was deeply moved by Hilma af Klint’s paintings, as well as a slew of other artists whose work I’ve looked at in the past year, such as Agnes Martin, Francis Picabia, Georgia O’Keeffe, Frank Stella, Carmen Herrera, and Robert Rauschenberg—to name a few. I wish I were thinking more about Albers than I actually was, but yeah, I guess he’s always been a reference for me and he’s one of the ways through which I learned about color and how to use it.

And speaking more to my genre-hopping, for my show Paradise Fire (2015) at Moran Bondaroff in Los Angeles, I exhibited a group of pictures that represent the beginning of my first social documentary project, in which I traveled throughout the Southwest and western states following wildfires. Across many years of focusing on western landscape work, I often find myself in environmental or sociological situations that are dire, as if I can see America crumbling before my camera. The reality of our grim situation here on Earth consumes me.

David Benjamin Sherry, Revelation, 0C120M95Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: A retreat from representation might emerge from the trauma of the rise of the Trump administration. Maybe you needed some time alone in the dark, to think and reflect. However, some queer and feminist artists, such as Nicole Eisenman, turn explicitly to representation in times of strife.

Sherry: I do find I need the balance that the more elemental, abstract work brings. It’s a way to ground myself while still tying in the ideas and themes that are important to me, and maybe to assuage some of the trauma I experience from my more literal, representational work about our current global circumstances. For instance, I began making photographs of pipelines inspired by the #NODAPL (No Dakota Access Pipeline) movement, which ultimately lead me to my first photogram in Pink Genesis titled Winter (2017). The work became not only a pipeline but also an escape tunnel, an evacuation route, and a portal to another place.

I began Pink Genesis while simultaneously photographing the protests immediately set off by the rise of the Trump administration. I documented with an 8-by-10-inch camera some of the major protests here in LA. I felt emotionally and psychically spent. Like you said, the darkroom offered a sense of internal solitude and helped me find my center again. So, yes, I turn to representation in these times of strife, and sometimes away from it! I also like to think of my work as a signifier of something to come. Paradise Fire was ominous. Maybe Pink Genesis is my attempt to cast a future spell upon the viewers and create a harmonious, peaceful, uplifting, self-loving balance spawned by one of the darkest years of my own and many others’ entire lives thus far. In all honesty, I believe this work saved me from completely falling to pieces in the last year.

David Benjamin Sherry, Winter, 0C160M45Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: There’s a delicacy or precariousness in the way the pieces in Pink Genesis are framed—the mounting of the photograms highlights the material presence of the image by creating distance between the paper and the backing. What was your thought process here?

Sherry: I wanted the photograms to embody the same feeling of floating that went into the work. Being in the dark while making this work really plays with one’s sense of gravity, like being in space or underwater. I worked to maintain a certain sense of disorientation and a feeling of flotation in the individual pieces. I felt it was only necessary to also “float” the works within their frames. I chose not to put glass or Plexi in front of the pieces, just for the duration of the exhibit, so the viewer can enjoy all the physical beauty in the actual print.

David Benjamin Sherry, Revolution, 0C95M100Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

For this work, I used an unusual hybrid photographic paper, which can be used in analog or digital process. Most photograms are made with glossy paper. Sometimes this can have beautiful results, but I wanted to make minimal photograms that specifically had depth, like my favorite minimal paintings. On matte paper, these works often feel like watercolors, and this was intentional. I tried to make paintings prior to making this body of work, but it somehow looped back around into my photographs.

Simmons: Leaving the edges of the negative in the photogram, complete with the word “Kodak,” could be read as either ironic branding or a sincere homage. What prompted this decision?

Sherry: I intentionally left the film edge on a handful of the works on view to expose my process and counter the misconceptions about my work being digital. I thought it may be time to give my process more glory, while also flexing my “pink analog muscles” with the intention of bringing something new and queer to the genre of photograms.

David Benjamin Sherry, Metamorphosis (Self Portrait with Wizard), 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: How might we characterize a queer iconography in this exhibition? There are some very clear references, such as Sublime Bottom I, 0C180M0Y, and Sublime Bottom II, 150C40M0Y. But there are also some more subtle references, such as your homage to—or co-opting of—both Yves Klein’s masculinist spectacle Anthropometries, and Robert Rauschenberg’s Autobiography (1968). I’m also reminded of Chicago Imagist Roger Brown’s Peach Light (1983), a surreal illustration of the soft pink and orange light used in gay bars in the ’80s to mask the skin afflictions caused by HIV/AIDS.

Sherry: There is so much queer iconography in this show! The title itself is a play on James Bidgood’s 1971 masterpiece Pink Narcissus, a film that helped shape the way I view the world. I also was thinking about Robert Rauschenberg’s collaboration with Susan Weil in Untitled (Double Rauschenberg) and Female Figure (both ca. 1950), which used exposed blueprint paper. (I wasn’t thinking of Roger Brown’s Peach Light, but what an amazing piece of art, and I love that you are reminded of it!)

I was also thinking of a Robert Gober piece I remember seeing at his 2015 MoMA retrospective The Heart Is Not a Metaphor. That entire show was profound, but this one piece, in which he combined his face with his dogs in a self-portrait mask, really resonated with me, maybe because pets for queer people really become our family, our children, which I find poignant. So, I attempted to merge my own body in one piece from Pink Genesis, with Wizard, my dog, titled Metamorphosis (Self portrait with Wizard), 150C40M0Y (2017).

David Benjamin Sherry, Sublime Bottom I, 0C180M0Y (detail), 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

My work always feels slightly indebted to AIDS-related artwork. Once, in grad school, my professor at the time, Collier Schorr, said I made my art as if I was a survivor of the AIDS crisis. At the time, I didn’t really understand what she meant. And while I can’t pretend to understand what it was like, I do feel part of the legacy of a generation of gay men, artists, and activists who were felled by the disease. I also met many of my mothers’ friends at a young age, who all had lasting impressions on me—the first gay men I ever met—and many eventually died from AIDS. This had a profound effect on me. I feared that being gay meant I would automatically have AIDS, and at age eight, I wasn’t ready to die. So, to Collier’s point, I do mourn the loss of so many great artists, and I make work from this place of queer iconography. I was always shocked by how the recent history of photography and the history of art tried to tackle AIDS-related work—or didn’t, as was too often the case. Our art history books need to be re-written.

William J. Simmons is an adjunct lecturer in art history at the City College of New York, and a PhD student in art history and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

David Benjamin Sherry: Pink Genesis is on view at Salon 94, New York, through July 28, 2017.

The post Queering “Straight” Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Malala Andrialavidrazana Redraws the Map

In photographs and photomontages, the Madagascar-born artist considers the global reverberations of African culture.

By Missla Libsekal and Sonia Recasens

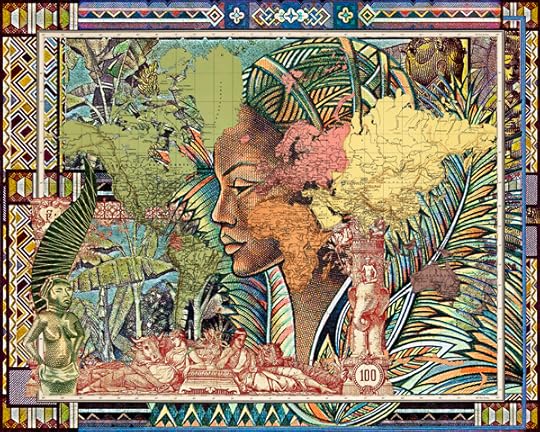

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1889, Planisferio, 2015

© and courtesy the artist; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

For the past fifteen years, the photographer Malala Andrialavidrazana has traveled to nations along the Indian Ocean, and across Asia and Latin America, to capture the cultural mutations of contemporary societies that are evolving between tradition and galloping globalization. With patience, she observes cities, their inhabitants, their ways of life, and the interiors behind the scenes, in order to overturn clichés. Her images consistently draw the contours of a plural singularity through recurrent motifs, while revealing the proximities as contradictions. In her series such as d’Outre-Monde (2003), Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land (2005), and ECHOES (from Indian Ocean) (2011–13), this is manifest through seriality of documentary-based photography. Figures (2015–ongoing), her most recent body of work, unveils a different phraseology: each photomontage in the series is composited from signs and symbols of the past—precolonial maps, bank notes, album covers, and stamps—which offer multiple readings to see the world new and again.

Born in 1971 in Madagascar, where she lived before settling in Paris at the age of twelve, Andrialavidrazana fuels her practice by moving from one country and one culture to another, taking a look with respect and sensitivity to capture, in the words of fellow Madagascan artist Joël Andrianomearisoa, “the slightest shivers of life without either geography or bias.” Andrialavidrazana’s education in architecture also informs her photographic practice. By looking at the world through three-dimensional sight, Andrialavidrazana uses her images to create new forms of circulation. At a moment when the Great Powers of the Western world are facing a rise in populism and its bedfellow, essentialism, the impetus to go beyond fear and stereotype could not be timelier. Here, Andrialavidrazana speaks about how she builds images, and her relationship to architecture, travel, and geography.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land, 2005

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Sonia Recasens: Madagascar plays a very important role in your work. There appears to be a continual back-and-forth between the intimate and the universal, the local and the global, the private and the public. These comings and goings reflect your own movements between Paris, where you live, and Madagascar, your ancestral homeland.

Malala Andrialavidrazana: I’m proud of my Malagasy roots because of the elegant way people in Madagascar consider women in social and family life, and because of the multiple connections to various cultural areas. My Malagasy roots are part of my way of thinking, so that’s why there is this back-and-forth. This is one part of me and the other is very Parisian. Nobody is perfect [laughs]. I use this dual cultural background to move from one point of view to another when I really need to think about how to tell stories about the Others.

Missla Libsekal: You came to photography by way of architecture. Could you tell us about that journey?

Andrialavidrazana: While studying at École d’Architecture de Paris-Conflans in the early 1990s, there was an optional training program in photography and video. I didn’t want to just build things; I also wanted to write and tell stories. During my childhood, I had my own camera that I used when we travelled with my dad. He was a very serious teacher; when we received the photographic prints, he always commented on the meanings within pictures. Learning to see was almost on the same level as learning to speak, to read, and to tell stories.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: When did photography replace sketching for you?

Andrialavidrazana: When I took a round-the-world trip in 2003, I thought it would be more convenient to travel with a camera than ten sketchbooks. I still take pictures in the same way as if I was drawing, to focus on details. And I can also remember telling myself in the late 1990s that I didn’t want to spend my whole life drawing lines on a computer!

Recasens: Your photographic practice feeds on architecture but also anthropology, history, and geography.

Andrialavidrazana: Architecture is generally understood as the construction of new ideas, hopefully for a better world. I felt strongly that it was possible to be an architect and construct with lighter materials—images and words.

Recasens: To construct images, but also to deconstruct the exotic clichés about the Other and the “elsewhere”?

Andrialavidrazana: Exoticism is related to the contrast between the Western and Southern world—developing countries that have less possibility to talk about themselves. So, of course, when I see it as a system of power, exoticism generally refers to the condition of master and servant. But as a kid, before moving to France, Europe used to be an exotic thing for me. It’s always a question about the point of view, which depends on where, and whom, you are talking to.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: The poet Langston Hughes called his autobiography I Wonder as I Wander. Likewise, movement has been present since the start of your career, as you produced series shot in India, Madagascar, and other locations. Can you speak about this duality of curiosity and movement as much of your image-making has happened while traveling?

Andrialavidrazana: I don’t really wander by accident … I wander where I can find attractions [laughs]. Traveling is the key to meet the Others and to better understand specificities, differences, and eventually to find commonalities between the Others and myself. In French we say, On n’apprend jamais autant qu’à travers nos propres expériences (The things that you really know are the things that you’ve learned from your own experiences).

Libsekal: But, travel photography can inadvertently encourage exoticism of the Other.

Andrialavidrazana: One of my first rules is to meet the locals. I always research in advance, planning logistics and contingencies, and I also get local contacts in order to go beyond a touristic, superficial view. I prefer to have different perspectives, to get out of my comfort zone and preconceived ways of looking at cultures or people.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, d’Outre-Monde, 2003

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Recasens: Your series on funerary burials and traditions, Tanindrazana / The Ancestors’ Land and d’Outre Monde, reveals a sensitive relationship to loss, absence, and disappearance. Where does your sensitivity come from?

Andrialavidrazana: It relates to living people. As an architect, I considered all the buildings and monuments that living people build for the dead. In French it’s said, La mort, dévoreuse d’espace (Death sucks a lot of space, and costs a lot of money). There are people who don’t even have housing! It’s not normal that many families live in tiny spaces, and that balanced solutions don’t exist. It was about getting into these questions.

Libsekal: By using spatial configurations as a photographic paradigm?

Andrialavidrazana: Rituals change depending on geography and influences. I chose cosmopolitan or multi-religious places to see how people living in the same space would get together when they die, to understand how human beings deal with heritage, globalization, and fashion. Even in funerals there are fashionable things. This is a way to embrace the complexity of the contemporary world.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), 2011–13

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Recasens: This sensitivity to worship and to the spiritual appears in d’Outre-Monde and Tanindrazana, but also in ECHOES (from Indian Ocean), with references to ritual objects and effigies. Is this your way of making a community’s portrait?

Andrialavidrazana: I observe traditions because once you go out of the big cities, that’s how people live! The smaller villages and cities are where traditions are more often upheld. This is apparent in major rites of passage including birth, weddings, and death, when ceremonies are influenced by familial heritage and local infrastructure. You cannot erase traditions from the way that you describe a country. So, talking about trendy things and new ways of living is one thing, but we also have to look at the way traditions mix with outside influences.

Recasens: In multiple series, the recurrence of familial objects—textiles, sheets, curtains, blankets, shoes, music, and religious effigies—offers a plural singularity, yet also hints to some contradictions.

Andrialavidrazana: There are some contradictions as these traditions change with globalization. In the last ten years, the ability to access news, international movies, and music from abroad has increased. Markets are more globalized. Ideas and objects move quicker than people.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1861, Natural History of Mankind, 2015

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: Representational photography, particularly portraiture in Africa and about Africans, is indeed ubiquitous. On the other hand, you and peers, such as Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, are presenting alternate subjectivities.

Andrialavidrazana: Despite the fact that I want to go beyond clichés, my projects often come from specific geographies. Instead of focusing on individuals, I try to find the commonalities—details, things, attitudes—that would speak to more people because I try to tell stories about people who are not very visible.

Libsekal: Figures, your new and ongoing series, is photographic, but it could also be considered a form of printmaking, of digital collage, and of historical recovery. You presented Figures at the 10th Bamako Biennale in 2015. What was the significance for you of showing this work in Mali?

Andrialavidrazana: “Telling Time” was the theme of the 2015 Bamako Biennale. As curator Bisi Silva noted, the exhibition was an opportunity to look back in order to move forward. Previous editions of the biennale have always paid attention both to archives and alternative identity or geographical representations. In fact, Figures combines these various fields by using materials such as precolonial maps and currency notes. We should always remember that cartography was among the most powerful political and ideological tools during the nineteenth century. In the same way, banknotes often conveyed stereotypes promoted by consecutive regimes and leaders. The roles of these printed documents are not so far from those of photography.

After completing ECHOES, I felt that something was missing in my practice. I did not want to start a new project using a camera exclusively, nor in a standard mode. I was willing to draw again, to tell stories in a different way. That is how I began exploring archives. Figures is still a camera-based project, but it’s not written in the same way.

Recasens: Yes, it has a more plastic dimension, close to drawing or collage.

Andrialavidrazana: It’s more related to drawing, and also close to writing for me. When I mix all the figures and details together, it is like writing—creating different phrases within a picture frame. I think my practice is a mix of wondering and writing, rather than just taking pictures.

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1867, Principal Countries of the World, 2015

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne, London; Afronova, Johannesburg; and Kehrer Galerie, Berlin

Libsekal: Figures reads like an exhumation of pictorial legacies, iconography embedded in the tools of modernity that historically facilitated the movement of goods and people. Given the contemporary transition to digital technologies and cashless societies, what made the past and archives so interesting?

Andrialavidrazana: The materiality of archives is really changing as many documents are now virtual, and data transmissions occur through websites more than by hand. When I decided to go back to those materials, at first I was attracted by their beauty. What is important in these documents are the messages the Great Powers used to symbolize their poetic and social values that entered into the social imaginary, to become a part of what you think the world looks like.

Recasens: How would you explain the series’ wide media coverage and critical success? Does the series reflect societal concerns and our relation to history and archives?

Andrialavidrazana: When people look at the compositions from the series, they can realize that for most of those stories written into these archives, there are multiple interpretations. The fact that Figures has become successful certainly speaks to the power of these archives.

Recasens: Coming back to your creative process, the neat framing, the usage of shadows and light or the highlighting of textures of walls, textiles, and skin is very powerful. It’s photographic, but also pictorial.

Andrialavidrazana: Critics have often said that I work like an anthropologist in the way that I capture details. When I meet a subject, I don’t remain in the same position. I really need time to take a picture, to turn around in order to go beyond appearances. I can’t be satisfied by a unique angle. I am used to thinking in a three-dimensional way; that’s why shadows, textures and light become important!

Recasens: Lastly, do you imagine “writing” in other mediums?

Andrialavidrazana: I can’t tell the future, but, that said, photography is my singular tool to write what I would like to say.

Missla Libsekal, an art writer and cultural producer based in Vancouver, is the founder and managing editor of Another Africa . Sonia Recasens is an art critic and freelance curator based in Paris, where she develops projects in France and North Africa.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives. Limited edition prints by Malala Andrialavidrazana are available from Aperture Foundation.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.