Aperture's Blog, page 110

October 4, 2017

From A.P.C., an “Owner’s Manual” for Minimalist Fashion

The French brand’s new book is a collage of postcards, snapshots, and influential commissions.

By Alistair O’Neill

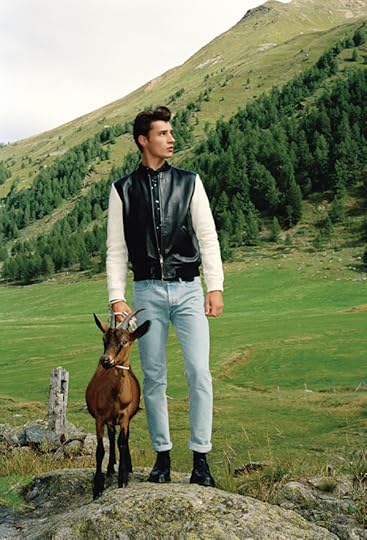

A.P.C. Fall/Winter 2015. Model: Adrien Sahores. Photograph by Collier Schorr

A.P.C. is a French clothing company known for producing well-made, casual separates which have become the choice of creative people who care what their understated, minimalist clothes say about them. Founder Jean Touitou, who started the brand in 1987, has in recent years come to front the collection presentations, offering a running commentary on the looks shown to the audience in a manner indebted to the way clothes were once introduced in couture shows. His idiosyncratic comments on a variety of subjects including normcore, yoga trousers, and the intersections between black style and brand culture have lost him collaborations and customers along the way, but it has not dimmed the broad appeal of his clothes or his take on the world.

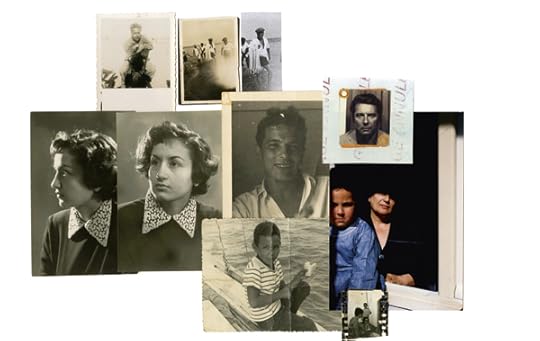

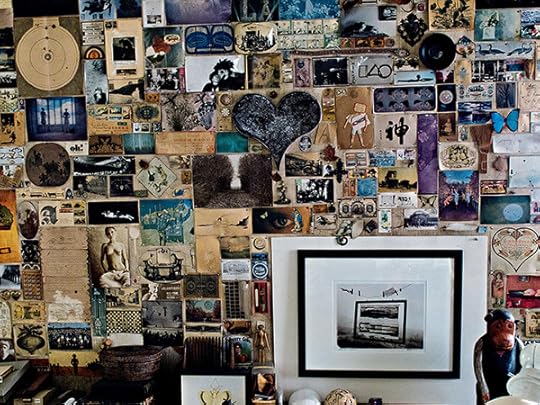

“Family,” a collage from A.P.C. Transmission, 2017

Now comes A.P.C. Transmission (2017), a deceptive book that looks like a standard survey of the brand’s output over the last thirty years. Which it is, but Transmission is also a personally-motivated project that Touitou describes as “some sort of owner’s manual of life instructions I wanted to leave to my children explaining our family’s origins and a bit of my feelings about being a human being. I had imagined that I would use a copy machine to print it, maybe fifty copies to give inside my family.” The book is split into three parts. The first pastes down Touitou’s early life, cut-out fragments of photographs, postcards, and doodles; the second reproduces typed-out texts by Touitou (including some of the presentation speeches); and the third is a chronological catalog raisonné of A.P.C. products and campaigns.

A.P.C. Fall/Winter 2001. Models from left to right: Jean-Philippe Delhomme, Lou Doillon, Nicolas Sabra, Theirry Planelle, and Christopher Niquet. Photograph by Takashi Homma

Transmission gives a sense of putting things in order, in the way a fashion brand might establish an archive, but Touitou’s impassioned address, his presence in little autoportraits and in the small details he pays attention to, override the organization. Transmission is more an ode to the materiality of print culture, as something that could be pinned to a wall—to a period when “transmission” could mean a music program listened to on a portable transistor radio, and to younger days when a favorite shirt could be worn too many times. For Touitou, this is not an exercise in nostalgia, but a means of challenging his “feeling that a machine is erasing the past,” that the digital is blurring reality. “For me, this triggers a will of surviving, and I chose to do it with a book.”

A.P.C. Spring/Summer 2001. Model: Jasmine Guiness. Photograph by Jean-Baptiste Mondino

Reading the book from front to back—the “1>2>3 way,” as Touitou describes it in the preface, or from 3>1>2, “from fashion to psychoanalysis to concepts,” or 3>2>1 “the Japanese way … going from the shallower to the deeper”—makes clear that Touitou narrates his interests and ideas by ordering images. The roll call of photographers he has keenly enlisted for A.P.C. campaigns, such as Collier Schorr, Alasdair McLellan, Inez & Vinoodh, Walter Pfeiffer, Bruce Weber, and Venetia Scott, only underscores the consistency of his way of working. Touitou is adamant that there is no strategy to how he commissions photographers: “I sort of run into people in a chaotic fashion.” And when laid out in part 3 of Transmission, the campaigns do have a collaged quality about them, as if they’re snapshots and keepsakes of a life that extends from Touitou’s own in part 1.

A.P.C. “Chiara de Sole,” Spring/Summer 2010 campaign poster. Model: Chiara Mastroianni. Photograph by Inez & Vinoodh

Transmission makes you realize that Atelier de Production et de Création is primarily a vehicle for Touitou. Its bestselling line is raw denim Japanese selvedge jeans, their slim fit reflecting Touitou’s distaste for the loose-fitting clothes of his contemporaries; the denim comes from the same factory Touitou first sourced in 1987, in Hiroshima, Japan. When I asked Touitou what fascinated him about growing up in Paris in the early ’60s, at a time of rapid change in France, he spoke of the shadow of the Second World War, growing up near the Hotel Lutecia in Saint-Germain-des-Prés on the Left Bank, once a repatriation center for concentration camp survivors. That reminded me of Chris Marker’s short film La Jetée, released in 1962 and composed from a montage of still images with a voiceover narrating a story, set in the future, of a man exploring his memories in the wake of a war. The film is a rumination on time, memory, and what the writer Brian Dillon has termed “the lure of images.” Like La Jetée, Transmission is also a sequence of still images narrated by a voice. It should be a much less compelling account of the banal nature of ordinary-looking clothes, but fashion, perversely, also marks time’s passing.

A.P.C. I was glad I gave Walter carte blanche – he came out with a goat. Spring/Summer 2014. Model: Adrien Sahores. Styling: Suzanne Koller. Photograph by Walter Pfeiffer

Alistair O’Neill is professor of fashion history and theory at Central Saint Martins, London.

A.P.C. Transmission was published by Phaidon in September 2017.

The post From A.P.C., an “Owner’s Manual” for Minimalist Fashion appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Christina Fernandez’s Lines of Sight

In two new bodies of work, the artist considers space, architecture, and the nature of collaboration.

By Jeanne Dreskin

Christina Fernandez, Steve, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

A lifelong Angeleno, Christina Fernandez has, for decades, engaged the transformations of her city’s living conditions with a steadily perspicacious eye. Fernandez’s imagery has put her own experiential narratives into conversation with those of her ancestors, historical figures, and many members of Los Angeles’s Latinx communities, and often gestures to photography’s capacity for evidentiary “truth-telling.” Part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, Christina Fernandez: Prospect, currently on view at Gallery Luisotti, presents two new bodies of work that extend these themes geographically, into multiple desert regions around Southern California, and personally, into the artist’s life as a community college art professor. View from here (2016–ongoing) presents several closely cropped photographs of windows and doorframes within historical structures across the American Southwest. These architectural interstices echo both the photographic frame itself, as well as the perspectives of the buildings’s former inhabitants. The second series, reflect/project(ion) (2016–ongoing), includes portraits of the artist’s photography students, printed on stretched canvas. Collaboratively executed by Fernandez and her subjects, the series reorients economies of prestige that have historically circulated among the Los Angeles area’s renowned art schools.

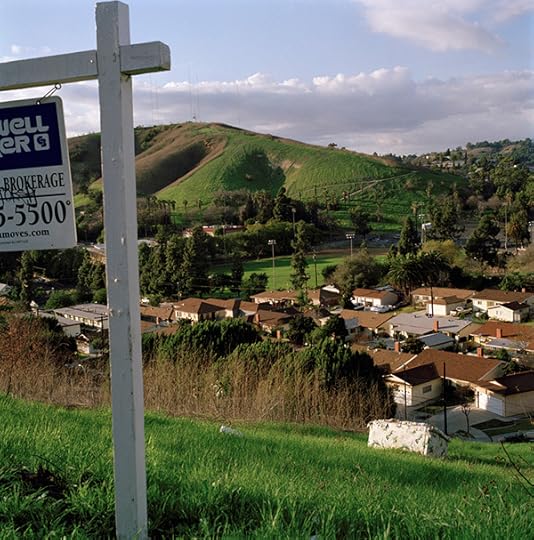

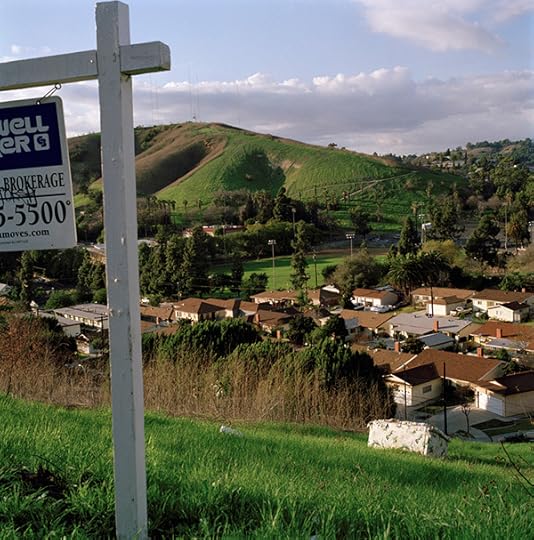

Christina Fernandez, Coldwell II, 2009, from the series Sereno

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Jeanne Dreskin: Much of your past work has drawn attention to the geographic specificities around the greater Los Angeles area. How has your relationship to the city’s social and economic concerns evolved over the course of your career, particularly in the last ten years, during which LA has seen unprecedented rates of development and gentrification?

Christina Fernandez: The Sereno series (2006), shot in El Sereno, in northeast Los Angeles, described my role as a participant rather than an observer of these phenomena you describe. There is a homelessness about the images, the sense of something lost, missing, or unattainable. El Sereno is a working-class Mexican and Mexican American neighborhood in Northeast Los Angeles. It is an enclave, a beautiful little space with rolling hills, winding streets, and modest homes with front and backyards. That is now being gentrified.

When I moved there in 2006, the gentrification process had not yet begun. It was simply a beautiful space that I could afford. But then, around 2008, the housing bubble burst and suddenly, within a few years, my home was worth far less than I had paid for it. Over the six-year period that I lived there, I photographed in these in-between spaces (of which there were many) where the refuse of outdated household items was dumped and people who could not afford even this modest community were forced to live outside. Sereno is absent of human figures and describes human presence through things left behind. By foregrounding the refuse against the backdrop of neighborhood homes, Sereno asks, “Who is this place for? Who has access? Who does not?”

Christina Fernandez, Noah (Joshua Tree), 2016, from the series View from here

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Windows and doors have consistently appeared in your work. Beyond their functionality as architectural fixtures and purveyors of directed vision, what drew you to windows and doorways in View from here and reflect/project(ion)?

Fernandez: They are passageways into another place from where we stand, and a perfect way to break up space in a flat image. For View from here, I photographed Noah (Joshua Tree) (2016) at the Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Art, and the window frames another work on view. Cabot I (Desert Hot Springs) and Cabot II (Desert Hot Springs) (both 2017) were photographed at Cabot Yerxa’s Pueblo Museum, a Hopi-inspired pueblo built with repurposed materials in the 1940s. The windows worked to create a specific flow of air for cooling by opening and closing certain windows at different times of day, so the window is almost an instrument played at different intervals to produce the “sound” of cool air.

Yerxa’s building was his penultimate creative expression as an artist, musician, and writer, completely integrated into his daily life. Purifoy’s sculptural environments evoke the idea of home. Both completely take in and acknowledge the landscape as a collaborator, a significant factor in the formation of the structures they created.

Our relation to the built environment is an ongoing negotiation; a home can be a haven or a prison. I suppose the windows can represent a type of escape, but also the prospect of another day, another life, a dream, a vision. With reflect/project(ion), I wanted to evoke the idea of transition, of being on a threshold, to visually tie the two series together, and to connect the ideas in the View from here series. The reflect/project(ion) series depicts young art students. At their age, I always felt like I was an “emerging” artist, professional, adult. When I contemplate their evolution as creative people, I admire their ability to move from one thing to another, their fluidity and depth. I wanted their portraits to reflect this.

Christina Fernandez, CCJ (Leadfield), 2016, from the series View from here

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: In View from here, material characteristics of the window and its components—pane, frame, sill, et cetera—are thrown into sharp relief, while the landscape often remains blurred. These images hint at a given site’s histories through its architecture. How do these photographs function differently than a photograph of the unobscured landscape? Do they invoke a different kind of narrative?

Fernandez: The unobscured landscape is too interesting and specific in and of itself. I am trying to point to the portent or prospect. When the artist Noah Purifoy (1917–2004) or Courtney Chauncey Julian (1885–1934), an early twentieth-century prospector who was a founder of the mining town of Leadfield, CA, arrived at their remote places, what were they hoping to build?

Many of these photographs are taken in remote desert locations. These frames are the threshold between shelter and the elements, life and death, present and future, presence and vision. Photography’s unique ability to simultaneously obfuscate and document creates this tension and abstraction between now and then, here and there, clarity and the unknown, and reveals the problem with historical narratives as truth.

Dreskin: CCJ (Leadfield) (2016), titled after Courtney Chauncey Julian, immediately reminded me of Lee Miller’s photograph Portrait of Space, created near Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert in 1937. Miller’s title raises questions about the intersections between portraiture and landscape photography. How do they intersect in your own practice?

Fernandez: I view both series as portrait works. The reflect/project(ion) series is more easily understandable as a portrait series. The View from here series—they are portraits in the sense that I imagine the people they are named after looking through these windows onto the outside and into the landscape. In View from here the view is obscured: literally obscured through a device of the camera, but, figuratively, through the passage of time and the changing landscape. Our view is also obscured through history and the formation of our understanding of these historical figures. The view is a stand-in for what they may have imagined, their vision of what they were doing, our interpretation of that moment. The window, because of its vertical orientation, is a stand-in for their bodies.

Christina Fernandez, Alice, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Thinking once more about questions of materiality, your decision to make prints of reflect/project(ion) on canvas lends them an acute tangibility. Why was this kind of tangibility important to you in this case?

Fernandez: Canvas is very different from paper in that it can be stretched over a frame and has buoyancy. I wanted to evoke skin. There is bareness to the photograph without a frame. In the image itself, I am breaking down space by using the projection in the image, but also by the use of the materials—using canvas instead of a traditional frames and matting supports.

The projections of the students’ cameras are phantom-like. At times, the projection partially obscures the photo-lab environment where I photographed. The projection bends and trails off. Because of this multilayered effect, I wanted the surface of the photographs to be more immediate, more accessible. Stretched canvas provides that effect, not only because of its materiality, but because of its familiarity, which we commonly see at coffee houses and grocery stores.

Bodies are evoked in both of these series: windows as portraits of historical figures, as imagined through the obscured views of the landscape, and portraits on canvas with the body of the “camera” projected into and onto the surfaces of the space and portrait subject.

Christina Fernandez, Joseph, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Ruin (1999–2000) and Maria’s Great Expedition (1995–96) explore your own Mexican American background and reveal how disjunctions can arise between personal narratives and the predominant “official” ones. Reconciling these contradictions can be necessarily speculative, and thus new narratives can be produced. In this context, reflect/project(ion) introduces a new structure of inheritance between yourself, a Cerritos College art professor, and your students. Why did you decide to collaborate with your students? How does this collaboration visualize a particular kind of kinship structure?

Fernandez: There is a longstanding history or tradition in the arts of the student-teacher relationship, especially here in southern California, where museum and gallery affiliations get passed down to promising graduate students at certain universities. I teach at a community college. It is a strong program; however, the opportunity for making alliances and discussing work beyond the foundation level is difficult. So, my relationships with students whose work I love have to go beyond the classroom. We keep in touch; they work for me in the lab as technicians. I see them as creative and independent. But, in many ways, they are reflections of the photographic values I taught them. They reflect back ideas and values that they are invested in; my values are translated, reinterpreted, and changed.

In reflect/project(ion), I am photographing the students, but I am also projecting an image that they created onto them. Originally, I asked them to photograph their camera in front of a light-colored background. They brought back what I asked of them, but also other types of photographs: a camera attached to a cable release with a hand depressing the cable release, the back of the camera opened with film bursting out of it, an enlarger as or instead of a camera.

There are very few Latinx Americans in university teaching positions in the arts, so the opportunity for that kind of relationship at the university level is almost nonexistent. There is something to be said about shared experiences—cultural, economic, or academic—and it is especially important for students whose families have very little or no academic or art experience. I want them to know that their ideas are valuable. They are amazing, creative people who I care for.

Jeanne Dreskin, a writer and independent curator based in Los Angeles, is a PhD candidate in history of art at the University of Pennsylvania.

Christina Fernandez: Prospect is on view at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles, through November 22, 2017. The Getty initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA is a collaboration across southern California institutions exploring Latin American and Latinx art in dialogue with Los Angeles.

The post Christina Fernandez’s Lines of Sight appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Latinx View of Los Angeles

Christina Fernandez considers space and gentrification in her native city.

By Jeanne Dreskin

Christina Fernandez, Steve, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

A lifelong Angeleno, Christina Fernandez has, for decades, engaged the transformations of her city’s living conditions with a steadily perspicacious eye. Fernandez’s imagery has put her own experiential narratives into conversation with those of her ancestors, historical figures, and many members of Los Angeles’s Latinx communities, and often gestures to photography’s capacity for evidentiary “truth-telling.” Part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, Christina Fernandez: Prospect, currently on view at Gallery Luisotti, presents two new bodies of work that extend these themes geographically, into multiple desert regions around Southern California, and personally, into the artist’s life as a community college art professor. View from here (2016–ongoing) presents several closely cropped photographs of windows and doorframes within historical structures across the American Southwest. These architectural interstices echo both the photographic frame itself, as well as the perspectives of the buildings’s former inhabitants. The second series, reflect/project(ion) (2016–ongoing), includes portraits of the artist’s photography students, printed on stretched canvas. Collaboratively executed by Fernandez and her subjects, the series reorients economies of prestige that have historically circulated among the Los Angeles area’s renowned art schools.

Christina Fernandez, Coldwell II, 2009, from the series Sereno

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Jeanne Dreskin: Much of your past work has drawn attention to the geographic specificities around the greater Los Angeles area. How has your relationship to the city’s social and economic concerns evolved over the course of your career, particularly in the last ten years, during which LA has seen unprecedented rates of development and gentrification?

Christina Fernandez: The Sereno series (2006), shot in El Sereno, in northeast Los Angeles, described my role as a participant rather than an observer of these phenomena you describe. There is a homelessness about the images, the sense of something lost, missing, or unattainable. El Sereno is a working-class Mexican and Mexican American neighborhood in Northeast Los Angeles. It is an enclave, a beautiful little space with rolling hills, winding streets, and modest homes with front and backyards. That is now being gentrified.

When I moved there in 2006, the gentrification process had not yet begun. It was simply a beautiful space that I could afford. But then, around 2008, the housing bubble burst and suddenly, within a few years, my home was worth far less than I had paid for it. Over the six-year period that I lived there, I photographed in these in-between spaces (of which there were many) where the refuse of outdated household items was dumped and people who could not afford even this modest community were forced to live outside. Sereno is absent of human figures and describes human presence through things left behind. By foregrounding the refuse against the backdrop of neighborhood homes, Sereno asks, “Who is this place for? Who has access? Who does not?”

Christina Fernandez, Noah (Joshua Tree), 2016, from the series View from here

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Windows and doors have consistently appeared in your work. Beyond their functionality as architectural fixtures and purveyors of directed vision, what drew you to windows and doorways in View from here and reflect/project(ion)?

Fernandez: They are passageways into another place from where we stand, and a perfect way to break up space in a flat image. For View from here, I photographed Noah (Joshua Tree) (2016) at the Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Art, and the window frames another work on view. Cabot I (Desert Hot Springs) and Cabot II (Desert Hot Springs) (both 2017) were photographed at Cabot Yerxa’s Pueblo Museum, a Hopi-inspired pueblo built with repurposed materials in the 1940s. The windows worked to create a specific flow of air for cooling by opening and closing certain windows at different times of day, so the window is almost an instrument played at different intervals to produce the “sound” of cool air.

Yerxa’s building was his penultimate creative expression as an artist, musician, and writer, completely integrated into his daily life. Purifoy’s sculptural environments evoke the idea of home. Both completely take in and acknowledge the landscape as a collaborator, a significant factor in the formation of the structures they created.

Our relation to the built environment is an ongoing negotiation; a home can be a haven or a prison. I suppose the windows can represent a type of escape, but also the prospect of another day, another life, a dream, a vision. With reflect/project(ion), I wanted to evoke the idea of transition, of being on a threshold, to visually tie the two series together, and to connect the ideas in the View from here series. The reflect/project(ion) series depicts young art students. At their age, I always felt like I was an “emerging” artist, professional, adult. When I contemplate their evolution as creative people, I admire their ability to move from one thing to another, their fluidity and depth. I wanted their portraits to reflect this.

Christina Fernandez, CCJ (Leadfield), 2016, from the series View from here

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: In View from here, material characteristics of the window and its components—pane, frame, sill, et cetera—are thrown into sharp relief, while the landscape often remains blurred. These images hint at a given site’s histories through its architecture. How do these photographs function differently than a photograph of the unobscured landscape? Do they invoke a different kind of narrative?

Fernandez: The unobscured landscape is too interesting and specific in and of itself. I am trying to point to the portent or prospect. When the artist Noah Purifoy (1917–2004) or Courtney Chauncey Julian (1885–1934), an early twentieth-century prospector who was a founder of the mining town of Leadfield, CA, arrived at their remote places, what were they hoping to build?

Many of these photographs are taken in remote desert locations. These frames are the threshold between shelter and the elements, life and death, present and future, presence and vision. Photography’s unique ability to simultaneously obfuscate and document creates this tension and abstraction between now and then, here and there, clarity and the unknown, and reveals the problem with historical narratives as truth.

Dreskin: CCJ (Leadfield) (2016), titled after Courtney Chauncey Julian, immediately reminded me of Lee Miller’s photograph Portrait of Space, created near Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert in 1937. Miller’s title raises questions about the intersections between portraiture and landscape photography. How do they intersect in your own practice?

Fernandez: I view both series as portrait works. The reflect/project(ion) series is more easily understandable as a portrait series. The View from here series—they are portraits in the sense that I imagine the people they are named after looking through these windows onto the outside and into the landscape. In View from here the view is obscured: literally obscured through a device of the camera, but, figuratively, through the passage of time and the changing landscape. Our view is also obscured through history and the formation of our understanding of these historical figures. The view is a stand-in for what they may have imagined, their vision of what they were doing, our interpretation of that moment. The window, because of its vertical orientation, is a stand-in for their bodies.

Christina Fernandez, Alice, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Thinking once more about questions of materiality, your decision to make prints of reflect/project(ion) on canvas lends them an acute tangibility. Why was this kind of tangibility important to you in this case?

Fernandez: Canvas is very different from paper in that it can be stretched over a frame and has buoyancy. I wanted to evoke skin. There is bareness to the photograph without a frame. In the image itself, I am breaking down space by using the projection in the image, but also by the use of the materials—using canvas instead of a traditional frames and matting supports.

The projections of the students’ cameras are phantom-like. At times, the projection partially obscures the photo-lab environment where I photographed. The projection bends and trails off. Because of this multilayered effect, I wanted the surface of the photographs to be more immediate, more accessible. Stretched canvas provides that effect, not only because of its materiality, but because of its familiarity, which we commonly see at coffee houses and grocery stores.

Bodies are evoked in both of these series: windows as portraits of historical figures, as imagined through the obscured views of the landscape, and portraits on canvas with the body of the “camera” projected into and onto the surfaces of the space and portrait subject.

Christina Fernandez, Joseph, 2017, from the series reflect/project(tion)

© the artist and courtesy Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

Dreskin: Ruin (1999–2000) and Maria’s Great Expedition (1995–96) explore your own Mexican American background and reveal how disjunctions can arise between personal narratives and the predominant “official” ones. Reconciling these contradictions can be necessarily speculative, and thus new narratives can be produced. In this context, reflect/project(ion) introduces a new structure of inheritance between yourself, a Cerritos College art professor, and your students. Why did you decide to collaborate with your students? How does this collaboration visualize a particular kind of kinship structure?

Fernandez: There is a longstanding history or tradition in the arts of the student-teacher relationship, especially here in southern California, where museum and gallery affiliations get passed down to promising graduate students at certain universities. I teach at a community college. It is a strong program; however, the opportunity for making alliances and discussing work beyond the foundation level is difficult. So, my relationships with students whose work I love have to go beyond the classroom. We keep in touch; they work for me in the lab as technicians. I see them as creative and independent. But, in many ways, they are reflections of the photographic values I taught them. They reflect back ideas and values that they are invested in; my values are translated, reinterpreted, and changed.

In reflect/project(ion), I am photographing the students, but I am also projecting an image that they created onto them. Originally, I asked them to photograph their camera in front of a light-colored background. They brought back what I asked of them, but also other types of photographs: a camera attached to a cable release with a hand depressing the cable release, the back of the camera opened with film bursting out of it, an enlarger as or instead of a camera.

There are very few Latinx Americans in university teaching positions in the arts, so the opportunity for that kind of relationship at the university level is almost nonexistent. There is something to be said about shared experiences—cultural, economic, or academic—and it is especially important for students whose families have very little or no academic or art experience. I want them to know that their ideas are valuable. They are amazing, creative people who I care for.

Jeanne Dreskin, a writer and independent curator based in Los Angeles, is a PhD candidate in history of art at the University of Pennsylvania.

Christina Fernandez: Prospect is on view at Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles, through November 22, 2017. The Getty initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA is a collaboration across southern California institutions exploring Latin American and Latinx art in dialogue with Los Angeles.

The post A Latinx View of Los Angeles appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Midcentury Style

Fatoumata Diabate’s traveling studio revives the golden age of Malian studio portraiture.

By Dagara Dakin

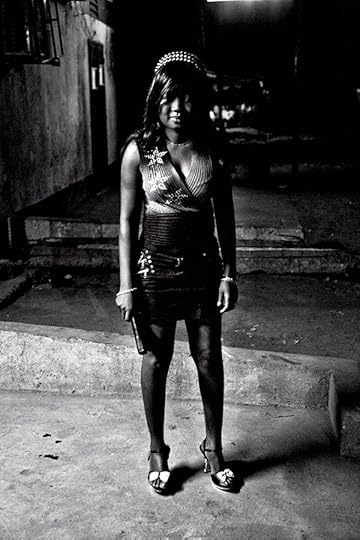

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait 03, Bamako, 2015, from the series Studio Photo de la Rue

Courtesy the artist

Fatoumata Diabate is one of a few women in Mali who practice photography professionally. Born in 1980, she first appeared on the photography scene in 2005 during the sixth edition of the venerable photography festival Rencontres de Bamako, also known as the Bamako Biennale, where her work was awarded the Afrique en Créations prize from the Institut Français. After studying at the Center for Photographic Education (Centre de formation de la photographie/CFP) from 2002 to 2004, she interned at the Center for Professional Education in Vevey (Centre d’enseignement professionel/CEPV) and another at Central DUPON’s professional printing laboratory in Paris. In 2010, following a World Press Photo training workshop in Senegal, she has undertaken various photo reporting projects.

As Franziska Jenni wrote in Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa,” Diabate’s most recent project, Studio Photo de la Rue revives Mali’s famous portraitists Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. Her mobile studio, where subjects pose in front of a textile backdrop, “is a stage-like, open-air installation” that become a performance. “The final portraits create something of a time lag: Diabate’s twenty-first-century clients enter her small time machine, which transports them back to the golden age of studio photography in Bamako.” When we spoke recently by email, I was curious to learn more about Diabate’s practice by revisiting her career and touching on her current projects.

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait of Sali, Badialan 3, Bamako, 2012, from the series Sutigui (à nous la nuit)

Courtesy the artist

Dagara Dakin: What has the Bamako Biennale meant to you?

Fatoumata Diabate: The Biennale’s role is to make young photographers known internationally. I can testify that it has opened numerous doors for me: residencies, exhibitions, publications, et cetera.

Dakin: Do you think that this event still holds the same place that it used to occupy in the West African photography scene at the beginning of the 2000s, even though it was suspended after the 2011 edition before starting again in 2015, under the artistic direction of curator Bisi Silva?

Diabate: Mali is a very large country with a lot of cultural diversity. At the same time, it is a big family. Bamako, the capital, is a city that represents this rich mix of populations: Toucouleurs, Bambaras, Bozos, Dogons, Fula, Soninkes, Mandinkas, Khassonkés, Songhais, Tuaregs.

In the same way, Americans, Europeans, and Africans from across the continent come together during the Bamako Biennale to celebrate the love of life, the beauty of the encounter, and the need for the other’s gaze, in all its diversity. So, it is a major event of our time at the national level, the West African level, and on the international stage.

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait of painter Abdoulaye Konaté, Bamako, 2015, from the series Studio Photo de la Rue

Courtesy the artist

Dakin: The Biennale is designed to serve as a showcase to the actors in the international art market. It also aims to enable healthy competition among the continent’s photographers. Do you have the sense that the Biennale is well-established at the local level, that the public supports the event?

Diabate: I can say that, thanks to the Bamako Biennale, other young people have found inspiration in me and my work, like at the presentation of the Afrique en Créations prize that I received in 2005, for example—people like Amsatou Diallo, president of the Association of Women Photographers of Mali, who, incidentally, has proposed to pass the torch to me in that position, or Bintou Camara, and so many others. All of these educational centers have been created to go along with the Bamako Biennale. In addition, to make the show even better established locally, my partners and I are in the process of setting up an “Inter-Biennale,” which will last a month and give pride of place to photography studios from Bamako’s various neighborhoods.

Dakin: You have done a number of photo reports, notably for World Press and Oxfam. Is that a way for you to take up a commitment in relation to the African continent?

Diabate: The reports for Oxfam and World Press, as well as for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Rolex, OMS, and others, allowed me to put my gaze to the service of humanist causes and to gain artistic autonomy.

Dakin: How do you reconcile the practice of photojournalism and NGO-commissioned reporting with your artistic process? What distinction do you draw between the two approaches?

Diabate: I work in and combine these two practices without difficulty. While taking into account the constraints of photo reporting, I allow myself to tell stories, to have personal points of view. The people who commission photo reports welcome so-called artistic images, such as detail-oriented work, for example, or sometimes abstract depictions.

Fatoumata Diabate, Caméleon.20, Senegal, 2015, from the series Caméléon

Courtesy the artist

Dakin: The question of the mask and, consequently, of identity reappears rather frequently in your photographic work, whether it is in the series L’homme en animal (Man as animal, 2011–13), L’homme en objet (Man as object, 2012–13), or Caméléon (Chameleon, 2015). Could you tell us more about that?

Diabate: Masks are tied to my culture and my personality. The sacred, ritual, even mystical dimensions speak to me and call me back to the world of my childhood. The tales that I have heard are still with me and are a source of creation for the series L’homme en animal or L’homme en objet.

Dakin: Do you ever establish a protocol or set rules for yourself that you force yourself to follow during a shoot, depending on whether your projects are of a documentary or artistic nature?

Diabate: For me, the protocol of a shoot comes down to respecting the main principle that I learned during my education: the subjects (the people) should recognize themselves in the image, and the image should speak to its viewers, whether it is abstract, a landscape, or a portrait.

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait in a night club, Bamako, 2012 from the series Sutigui (à nous la nuit)

Courtesy the artist

Dakin: What determines the choice of black and white or color in the treatment of your subjects?

Diabate: Before anything else, I love black and white, especially the gelatin-silver process. Obviously, I do analog photography, but that doesn’t stop me from making color photographs, especially for my latest series, Caméléon. Depending on the subject, I feel at liberty to go back and forth between black and white and color, like in the series Sutigi (à nous la Nuit) (The night is ours, 2012). With that series, I showcase a way of life, a desire to make an appearance that is characteristic of a part of the youth, a testament to my era and to the subject’s ease in front of the camera. In view of our traditions, we feel better at night than during the day.

Dakin: What place do you give in your work to the condition of women in Mali or on the continent, and what form does that take?

Diabate: I want to bear witness as an African woman who practices photography. There are a few of us (Aida Muluneh, Joana Choumali, Zanele Muholi, Nontsikelelo Veleko, Ayana V. Jackson, Hien Macline, among others) who have gotten a solid reputation on a global level, but it remains difficult to make one’s place on the African continent, outside the shows dedicated to photography. In a more general sense, in Mali, the civil service gives women roles as secretaries, accountants, and the like. In Bamako, the capital of African photography, despite our results and our commitment to the field of the image, we are hardly given any consideration for our creations. If you compare the status of women photographers in West Africa to that of their peers in South Africa, you will see that the latter enjoy a great reputation, and that that has led to the emergence of a new generation of artists in South Africa.

Fatoumata Diabate, Mah-Traoré ka boutiki, Bamako, 2012, from the series Sutigui (à nous la nuit)

Courtesy the artist

Dakin: What are your current or future projects?

Diabate: I have recreated a mobile studio, Studio Photo de la Rue, which is an installation inspired by the photography studios of the 1950s and ’60s in Mali and West Africa, and which allows everyone to see themselves through the lens, alone or in a group. The participants leave with their prints as a souvenir. I offer lots of accessories and costumes, which I use to reveal another dimension, a hidden dimension within every man and woman!

Since its creation, Studio Photo de la Rue has been regularly invited to the biggest international photography shows—the Bamako Biennale, the Rencontres d’Arles, La Gacilly Photo Festival in France, and others—to put on a performance at the exhibitions of masters who used mobile studio photography throughout their existence—Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Mama Casset, Oumar Ly, James Bernon, Samuel Fosso—whose historic work we still revere today.

Dagara Dakin is a freelance writer and curator based in Paris. Translated from the French by Matthew Brauer.

This article is produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

The post The Midcentury Style appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 3, 2017

Delirious Tokyo

In a new exhibition, Daido Moriyama returns to his icons and obsessions.

By Russet Lederman

Daido Moriyama, Color, 2017

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

In Tokyo Color at Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama revisits the themes that have consumed much of his fifty-year career—urban street life, intimacy, pattern, and light. Divided into three distinct bodies of work, the prints and projections that fill the gallery include new large-scale color images taken on his frequent nighttime walks in Tokyo’s Shinjuku neighborhood, a slideshow projection of early color works from the late 1960s through the 1980s, and an undated selection of recently printed black-and-white photographs from his erotic “tights” series. Selected and installed according to Moriyama’s specific instructions, this exhibition presents an artist’s reflections on his long-established photographic language and iconography.

Daido Moriyama, Color, 2017

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Moriyama first rose to prominence through his association with Provoke, a short-lived avant-garde publication from 1968–9 that fundamentally reshaped postwar Japanese photography. Although well-known for his grainy and blurred black-and-white photographs from the late 1960s to the ’70s, Moriyama has long included color photography in his practice. In 2008, armed with a new digital camera, his nightly Shinjuku walks began to capture a slightly different energy as a brash digital palette seeped into his images of garish signs, shop windows, tangled wires, and flamboyant urban denizens. The city and its frenetic energy collided with an immediacy that exposed an unnerving and threatening presence in everyday scenes.

Daido Moriyama, Color, 2017

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

The recent color work in Tokyo Color takes this impulse to a new level of intensity. Installed in grids on three gallery walls, Moriyama’s color photographs confront the viewer with an immersion akin to billboards: Shinjuku’s daily deluge of brightly painted faces, fanciful clothing, neon signage, and fashionable shop mannequins. Saturated colors fight for the viewer’s attention as the exponents of modern consumer culture are transformed into a collection of abstract patterns that define the texture of a bustling city. A sensation of direct experience is quickly replaced with visual overload.

Daido Moriyama, Tights, 2017

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

The jarring visual patterns of Shinjuku are both expanded and restrained on a fourth wall, which lines up a selection of sixteen black-and-white photographs from Moriyama’s ongoing “tights” series. Begun in the 1980s, these elegant portraits of curved legs and torsos enveloped in patterns of crisscrossing lines convey a subtle yet powerful eroticism. The photographs are abstract, formal compositions, directing the eye around and between undulating legs, feet, and rear ends, all highlighted against dense black backgrounds and grainy surfaces. In “tights,” Moriyama’s patterns and stark lighting simultaneously reveal and obscure a precise reading of body parts—with the only roadmap often provided by the black seam of a stocking. Earlier works printed in 2017, these highly seductive images are especially complementary when placed adjacent and opposite to the brash Shinjuku photographs. “The black-and-white tells about my inner world, my emotions and deep feelings,” Moriyama says, “whereas the color photographs are much more about the experience of being in the streets, the overload of posters and signs and advertisements as you wander through the city.”

Daido Moriyama, Color, 2017. Installation view at Luhring Augustine Bushwick

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Capturing the essence of Shinjuku has engaged Moriyama since he first arrived in Tokyo in the early 1960s from his native Osaka. As a young freelance photographer, he began his now-routine practice of nightly wanderings and bar crawls through Shinjuku’s seedier quarters. Many of his best-known photographs from the 1960s and ’70s began as color images that were later converted to black-and-white. Projected on a hanging screen that bisects the gallery space is a slideshow of 128 color photographs from his earliest wanderings. Purplish in tone and challenging to see clearly in the well-lit gallery space, these images, which were first published in Camera Mainichi magazine, offer a primer of Moriyama’s continual engagement with the city. Gritty and rundown street corners, 1970s signage, bodies in various states of undress, legs in fishnets, motorcycle gangs, and the lowlifes from Shinjuku’s notorious Kabukicho district flash across the screen. Seen together in one space, the three distinct series that comprise Tokyo Color provide a rare glimpse of a mature photographer revisiting his own history and taking stock of his lifelong thematic obsessions.

Russet Lederman teaches art writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Daido Moriyama: Tokyo Color is on view at Luhring Augustine Bushwick through October 22, 2017.

The post Delirious Tokyo appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 2, 2017

6 Men Who Think They’re the Second Coming of Jesus Christ

From Zambia to Japan, photographer Jonas Bendiksen tells their stories.

Jonas Bendiksen, Bupete Chibwe Chishimba, known as Jesus of Kitwe, Zambia, 2016

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Jesus of Kitwe

Jesus of Nazareth was a carpenter by trade. Upon his return two thousand years later, he operates two unlicensed taxis in Kitwe, Zambia. When he was twenty-four, Bupete Chibwe Chishimba received a revelation from God that he was the second coming of Jesus. Jesus also goes by the names Parent Rock of the World, Mr. Faithful, and Mr. Word of God.

Jonas Bendiksen, Disciples shut the curtains in front of INRI Cristo after he has delivered the sermon of the day, Brazil, 2014

© the artist/Magnum Photos

INRI Cristo

INRI takes his first name from the initials of the inscription Pontius Pilate placed on the cross to spite Jesus two thousand years ago: Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, or Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. His first awakening as the Christ came in 1979 during a fast in Santiago de Chile. Subsequently, INRI spent many years as a wandering preacher before settling in what he calls New Jerusalem, which is located outside of Brasília, Brazil.

Jonas Bendiksen, Dolores, David Shayler’s femme persona, in a church, Windsor, England, 2015

© Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

David Shayler/Dolores Kane

David Shayler the Christ, a former MI5 agent, had the revelation that he is Jesus in 2007. In Galatians 3:28 Paul the apostle writes, “nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Thus the Messiah today has an alter ego named Dolores Kane, who embodies the feminine aspects of divinity. Like Jesus of Nazareth, David and Dolores move in circles far outside of society’s establishment.

Jonas Bendiksen, Jesus Matayoshi holds his election sermons from the top of his campaign vehicle, Tokyo, 2016

© Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

Jesus Matayoshi

Jesus Matayoshi was born in Okinawa, Japan, in 1944. In 1997, he founded the World Economic Community Party, which bases its policies on Matayoshi’s identity as Jesus Christ reborn. Matayoshi, also known as The Only God, will bring about the End Times and God’s Kingdom through the democratic political process. Matayoshi is famous for his vigorous campaign style. He often instructs his opponents to commit suicide and threatens hellfire upon sinners.

Jonas Bendiksen, Moses Hlongwane, otherwise known simply as Jesus, on the day of his wedding to one of his disciples, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2016

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Moses Hlongwane

In 1992, when Moses was working as a small-time jewelry salesman, God came to him in a dream with the word that he is the Messiah. Now, Moses Hlongwane is known to his forty or so disciples in South Africa as The King of Kings, The Lord of Lords, or simply: Jesus. According to Moses’s teachings, Judgment Day is approaching fast. The resulting End of Days is in part triggered by the conclusion of Moses’s successful search for a wife.

Jonas Bendiksen, On January 14, Vissarion’s birthday, his disciples enter the community’s innermost and holiest village, Obitel Rassveta, or The Abode of Dawn, Russia, 2015

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Vissarion of Siberia

The man born as Sergei Torop had his first revelations that he was Jesus Christ just as the USSR collapsed around him. In the early 1990s he founded the Church of the Last Testament, renamed himself Vissarion, and settled with his disciples in an off-the-grid utopian eco-village in the Siberian woods, the Abode of Dawn. The community now numbers some five thousand followers.

Jonas Bendiksen is a photographer based in Oslo. This feature is adapted from Jonas Bendiksen: The Last Testament, published by Aperture in September 2017.

The post 6 Men Who Think They’re the Second Coming of Jesus Christ appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 29, 2017

Aperture Honors Fred Smith (1942–2017)

Memories of the late Aperture Foundation trustee.

I first took note of the voice—booming, self-assured. Then, a quick glance: polished, suit and tie, sitting next to me at the counter at Novitá, extolling the virtues of George W. Bush to the hostess over lunch. This was in 2004.

When he went outside to smoke, I shared with the hostess my own opinions of the president, which were far at the other end of the spectrum. The tall, sharp-featured, fair-haired man came back in, heard about 25 per cent of my diatribe, and in that sonorous voice demanded, “Who are you?” We started talking, or perhaps politely bickering. I discovered he was interested in photography, and had once been a subscriber to Aperture—I was the magazine’s editor-in-chief at the time. This earned him some points, for sure. He discovered that, like him, I had gone to Yale. This apparently earned me some points. As he got up to leave, he challenged me to send him a recent issue of Aperture: “Fred Smith. Park Avenue.” I laughed at that. And then, just before the door closed behind him, the chaser: “I’m the only one.”

I sent Fred Smith of Park Avenue some issues—carefully chosen issues, featuring political content that would, I was certain, provoke him. Some days later, he called me, this time extolling Aperture’s excellence (but making it clear he was not in complete agreement with our content). He proceeded to generously offer a financial contribution to the magazine. (We had, after agreeing to disagree as far as Bush was concerned, already discussed Aperture Foundation’s financial health. He knew that this would be welcome.). I told him perhaps he shouldn’t offer his money until he really knew and understood what he was giving to. He should come in, meet people, see our books, see what we really do, everything we do . . . and then we could take it from there.

At that point Fred was at Credit Suisse and Aperture was more or less around the corner, on Twenty-Third Street at the base of Madison Avenue. Shortly after, he came in and met the team. And this was, as they say, the beginning of a beautiful friendship between Fred Smith and Aperture Foundation.

As a trustee, Fred did not just want to support Aperture financially—he made this very clear to me in our early discussions. He wanted to really engage, to share his remarkable talents and perspective. He wanted to give his most valuable possession—his time. We needed, and soon came to depend on his input, no question about that. And I like to think that, in some way, Aperture benefited him, too. He seemed to have fun working with us, and we could always count on Fred’s clarity and honesty. Over more than twelve years of collaboration, Fred became an invaluable member of our family. Intelligent, judicious, ethical, articulate, open-minded, and present, Fred was not remotely censorious, understanding and believing in our strict church/state separation between funding and editorial content. I quickly came to learn that his politics were not as one-sided as they’d seemed on the day we met, when I had wanted to throw my water at him at Novitá. His mind was always open to new ideas, and he was a fervent believer in human decency, in opportunity. He was an uncompromising supporter of Aperture’s mission; indeed, I think he cared about it as much as the staff does. And in turn, Aperture’s staff loved, respected, and appreciated Fred Smith. He was truly “the only one.” He will be greatly missed.

—Melissa Harris, editor-at-large, Aperture Foundation

Fred Smith was already on the Aperture Board when I joined. As I got to know my fellow Board members Fred seemed an anomaly, a self-proclaimed non-photography person on a Board of passionate collectors. But that self description was deceiving. Fred had, through his association with Aperture, developed a respect for the history and role of photography and a love of certain photographers and had even built a small, very personal, collection of photographs. Although Fred came to Aperture after a chance encounter with then editor-in-chief Melissa Harris, he only joined the Board after study and from a sense that he could help Aperture in a significant way through his financial expertise. Fred treated his role as Treasurer with the same intensity and care that he applied to the financing transactions that he worked on during his years as an investment banker. After I became Chair of the Aperture Board I spoke to Fred frequently, consulted with him on decisions and valued his wise input.

Fred was a true humanist. He cared about the role Aperture played in the world, and the importance of the visual image. He also cared about the people who worked at Aperture. He would stop by the office frequently to check in, he knew everyone who worked there and he formed deep friendships.

In the weeks since his death, many of Aperture’s Board members have expressed how hard the news of Fred’s death hit them and how much they will miss his calm and rational presence at our meetings and how they will especially miss his deep, reassuring voice. Fred was a huge presence at Aperture.

—Cathy Kaplan, chair, Board of Trustees, Aperture Foundation

I first met Fred in 2010 when interviewing for the position of chief financial officer at Aperture. Prior to the meeting, I had reviewed the interviewers’ bios, many of which were impressively long and detailed. In contrast, Fred’s was brief: Fred Smith, Banker. The man behind the bio was equally succinct, direct, and unvarnished. During the interview, he asked penetrating questions and listened carefully to the answers. By the end of the interview, I felt strongly that here was someone with whom I would like to work. This conviction was confirmed tenfold over the following seven years as we worked closely together and became—I like to think—friends.

Fred brought wisdom and perspective to all of our interactions and projects. One of his greatest gifts was his uncanny power to distill the most complex ideas into a few simple sentences, providing clarity and direction to both Board and staff.

Although clearly knowledgeable and influential in his role as Treasurer and Finance Committee chair, Fred never pulled rank on anyone. He respected and trusted the staff’s knowledge and listened carefully to our input. He was also crystal clear about the difference between Board oversight and staff execution, which freed us to do our jobs, albeit within a clear policy framework.

Fred approached everything he did with dedication and enthusiasm. Although by profession a financier, he was passionate about music, books, his family, the English language, Aperture, and, of course, golf and politics, not necessarily in that order. Fred loved to test ideas and theories, loved to debate, loved to be challenged and learn new things. I can still hear him hoot with laughter when someone poked an indignant hole in one of his theories; or see him cock his head and concede, “Well now, that’s true”, when shown an alternative way to approach an issue. He was extraordinarily open to learning and growing, and as a result seemed perennially young and engaged.

One of my favorite memories of Fred is from Aperture’s 2014 gala. With the dinner and auction over and the tables cleared, the band’s decibel output had increased to the point where a number of the older patrons had begun an orderly rout. Not Fred. Surrounded by his children and their friends, he leaned back in his chair, pounding the table with his fist in time with the rhythm, a huge grin on his face. I do believe he closed the place down.

I miss his frequent calls (“Hi, MC, just checking in to see how things are going”), his calm, clarity, and financial acumen, his humor, and his steadfast devotion to the Aperture cause. We all miss him more than words can express.

—Mary Colman St. John, chief financial and administrative officer, Aperture Foundation

I first met with Fred Smith during interviews for the job of executive director at Aperture, in 2010, along with the then recently-appointed Chief Financial Officer, Mary Colman St. John. In the hour or two we spent together, I learned that Aperture’s finances were being looked after by sound minds and good people, and that we really liked and immediately trusted each other. Since then, apart from the couple of weeks each year that Fred disappeared to Jamaica to be with his family and play golf (always scheduled so as not to interfere with his commitments to Aperture), I worked with Fred every week. He became one of the most important business partners of my working life, parsing and re-imagining of Aperture’s economics and playing a key role in charting the institution’s path forward.

Fred was devoted to Aperture, but, unlike other supporters and trustees, wasn’t consumed with interest in art and photography. Or so we thought. Later on, I came to know him as a man of great taste and artistic judgment, but he never let that show, nor interfere with good organizational decision-making. Why did he bother? It took a while for me to understand that his devotion was a decision of heart and mind. As a retired banker, with considerable talents and experience, he needed a project to occupy him. He chose us because we believed in something and because he liked us. And having made the decision, he applied his wise counsel to our affairs for however many hours necessary, week after week, for over a decade. Thousands of hours. He scrutinized every detail of our activities and took time to understand our economics at a granular level, which he in turn interpreted to our other trustees, responsible for the organization’s governance.

Aperture’s history is publicly characterized by great artists—Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Sally Mann, among many others; by the charisma of its former directors, Minor White and Michael Hoffman, and its editors; and by the leadership of its Board chairs. Although I don’t think most people engaged with Aperture beyond our Board knew the name of Fred Smith, yet he was central to Aperture’s story, and has shaped it. We will miss him terribly.

—Chris Boot, executive director, Aperture Foundation

The post Aperture Honors Fred Smith (1942–2017) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 28, 2017

The Theater of Everyday Life

In France, photographer Alessandra Sanguinetti injects elements of fairy tales and fantasy into quotidian scenes.

By Susan Bright

Alessandra Sanguinetti, The vendor, Jardin des Tuileries, Paris, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

“Infraordinary.” This term, drawn from a 1970s essay by French experimental writer Georges Perec, requires that we pay attention to all that is considered neither ordinary nor extraordinary. It demands that we reconsider what is significant and what is not. This is what Alessandra Sanguinetti does in Le Gendarme Sur La Colline (Aperture, 2017). Through her work, a transformation takes place: she assembles a series of fragments and details from a host of different lives, showing us that what can be historic, significant, and revelatory is not the stuff of headlines, but that of the quotidian. The infraordinary becomes the key player in each scene. What is crucial is her manner of injecting the everyday with elements of fairy tales and theater—two ancient methods of storytelling. By seizing on the possibilities of the magical and the promise of performance, she takes familiar and everyday French lives and landscapes and transforms them into notable and even exotic frames, often tinged with fantasy. She evades the grotesque or judgmental in this transformation. What happens instead is a reading of heightened possibility in the minutiae of the everyday.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Matinée I, Paris, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Sanguinetti conveys the idea of theater literally as well as stylistically, with oblique hints to the charged atmosphere alongside the required equipage. We can see the lushness of the red velvet curtain suggested through textures on chairs and walls, lone drapes in tower blocks, and a tablecloth mournfully lifted to mark the end of a meal, as if in intermission. The white sheet with the reproduction Eiffel Towers becomes a stage, while the audience in the theater represents the increasingly diverse population of France. The people in several of the portraits appear to be lit by spotlight, as if they are starring in a performance of their own lives. These photographs are infused with hushed tones that recall the slight impatience and anticipation echoing the beginning of the next act. Arcane costumes highlight notions of performance that take on a mournful edge when out of context. A guard, all dressed up in his red jacket, seems to have forgotten his words and been rejected from the scene as tourists line up to enter a château, which in itself is a performance of the past.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Weighing in, 57.00 kg, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

In this work, France is also solemn, deep in contemplation. While fantastical and opaque traditions and rituals are played out in half-forgotten corners of the country, the newer developments, people, and customs contrast with and frame the theatrical reenactment of the country’s past and continuing traditions. But among the mournfulness, there is also humor in the characters, costumes, and performances. The lightweight jockeys in Chantilly look like titular kings. Perhaps they live in the model castle that follows several pages later? One puff of wind by a mythical wolf and they would all but disappear. Set in the eve of systemic shifts all across Europe, and a rise of nationalism globally, Le Gendarme Sur La Colline shows us the fragility of France—as delicate as the jigsaw on the frontispiece of the book. In the first images of a small family circus as well as the portraits throughout the book, France is depicted as both strange and mythical, and everyday and familiar.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Château de Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, 2016

© and courtesy the artist

Susan Bright is a curator and writer whose recent books include Art Photography Now and Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography. This feature is adapted from the Aperture book Le Gendarme Sur La Colline.

The post The Theater of Everyday Life appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 27, 2017

Remembering Robert Delpire, Publisher of the Greats

Aperture commemorates the life of Robert Delpire (1926–2017), the publisher, editor, and curator, whose vision defined twentieth-century photography. In this interview from 2012, Melissa Harris spoke with Delpire about his projects with luminaries including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and William Klein.

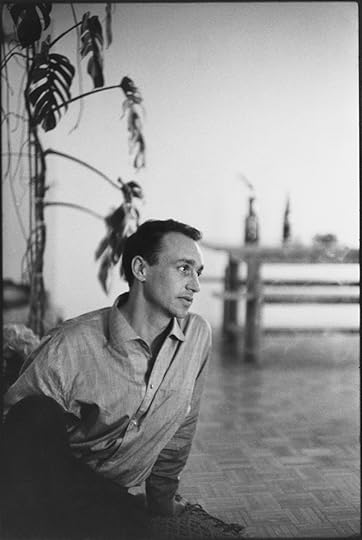

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Delpire, 1960

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Over the past sixty years, the eyes and instincts of Robert Delpire (1926–2017) have shaped much of the world’s understanding of photography. A prolific publisher and exhibition organizer, with a razor-sharp comprehension of the graphic arts, Delpire has had a defining hand in the careers of many of the master photographers of recent history. He began his own trajectory in the early 1950s—incongruously—as a student of medicine in Paris. At that time, the Maison de la Médicine (like the “houses” of other university faculties) hosted both cultural and sports activities; Delpire had a taste for competitive sports and frequented the place. The Maison—to justify itself to the ministry of education—produced a modest semiannual bulletin, and found itself in need of someone to take over the publication’s production. At the age of twenty-two, Delpire agreed to take the gig, but soon transformed the bulletin into a luxe magazine, which he called Neuf. With the brash confidence of youth, he approached and convinced a stunning array of luminaries to contribute: writers such as André Breton, Henry Miller, and Jean-Paul Sartre; photographers such as Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Werner Bischof.

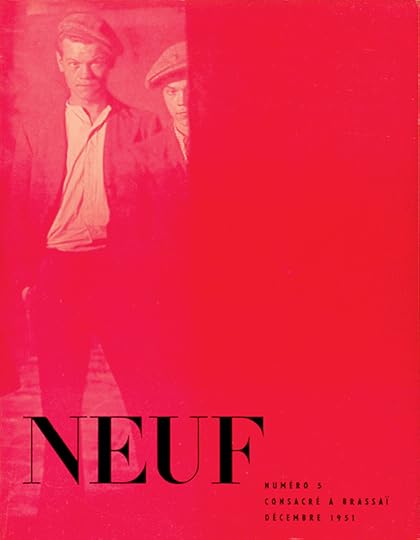

Within a few years, the former medical student realized he had found his calling and launched what would become one of the most important photography and graphic-arts publishing companies of its time: Éditions Delpire. Among its earliest ventures were the publication of Brassaï’s first-ever monograph, and several books with the Magnum pantheon, including Cartier-Bresson, whose close friendship with Delpire over the following half century resulted in countless collaborations, among them the seminal publication Henri Cartier-Bresson: Photographe (1979). In 1958 Delpire took a chance on a project by a little-known Swiss photographer named Robert Frank: that book, Les Américains—The Americans—would of course set the world of photography on fire; more than fifty years later, it remains a provoking standard of the medium. Delpire later worked with William Klein, beginning with his Moscow and Tokyo books of the mid-1960s, and with Josef Koudelka to produce numerous publications, from 1975’s Gitans (Gypsies) to 1999’s groundbreaking collection of panoramas, Chaos.

Cover of Neuf, no. 5, December 1951

Courtesy Delpire Éditeur

A perspicacious businessman, in the 1960s Delpire initiated a publicity company that soon was managing such lofty clients as Citroën, Cacharel, and L’Oréal. He also found time to art-direct magazines (notably the contemporary-arts journal L’Œil), to produce films (among them William Klein’s Cassius le grand [Cassius the Great, 1964] and Qui êtes-vous, Polly Maggoo? [Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, 1966]) and to open and run a gallery on Paris’s rue de l’Abbaye, showcasing work by photographers Koudelka, August Sander, Walt Kühn, Duane Michals, Guy Bourdin, and others, as well as a bevy of illustrators. In the following decade, working with editor/publisher of Le Nouvel Observateur Claude Perdriel, Delpire began producing photography-driven special editions of the magazine; these Spécial Photo issues featured a range of powerful images, from the antique masterpieces in the collection of André Jammes to work by more recent artists such as Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Lee Friedlander.

In 1982 French minister of culture Jack Lang invited Delpire to head the newly created Centre National de la Photographie in Paris; over the course of his fifteen years in that position, Delpire mounted more than 150 exhibitions. Also in the early 1980s, Delpire launched Photo Poche books: a series of gorgeous yet modestly tailored publications on photography and graphic arts, engaging and accessible in both price and spirit to the common reader—a milestone in the world of arts publishing.

Melissa Harris conducted this interview with Robert Delpire via correspondence, over the course of a year.

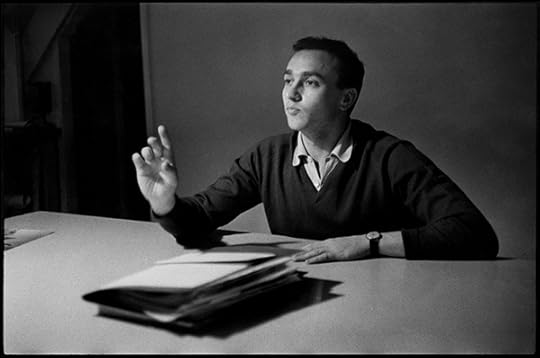

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Delpire, Paris, 1957

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Melissa Harris: What is the relationship between a book and an exhibition?

Robert Delpire: One might think that it is easy to extrapolate the organization of an exhibition from the layout made for the corresponding book. Curiously, this is wrong. The reading of photographs fixed on a wall is totally different from the one you get in turning the pages of a book. It’s a question of perspective, certainly, but also a consequence of the visitor’s position in front of a panel on a wall. But also, importantly, a photograph printed in a book is received by the reader as a unique offering. In a museum or in a gallery, the visitor’s eye is constantly solicited by prints, which are often of different sizes, and which he or she can choose to look at in a different order than the sequence proposed by the curator.

MH: How do you work with that? Do you sequence an exhibition with multiple entry points in mind?

RD: In planning an exhibition, one can work toward effecting a cinematographic vision—in a succession of images, there is often a narrative—as a way of taking advantage of the three-dimensional structure of the space. The solutions to the problem are quite traditional. In an exhibition, one has the possibility of creating a contrast between medium-size pictures and big prints. This solution is very simple to do—and so it is commonly used.

Still, there are no strict rules. One has constantly to adapt convictions or ideas to the situation, to the lighting, to the size of the room. Another interesting element that allows one to give a special ambiance to a show is the color; it is easy to paint the walls, and it is sometimes very effective. When I was in charge of the Centre National de la Photographie, I decided to paint the walls a flaming red when we presented a selection of Marc Riboud’s photographs of China (1996). The result was amazing. But it doesn’t work every time. For the Robert Frank exhibition (1983), I had the idea to cover the walls with craft paper. I liked the result, but Robert hated it and asked me to take the paper off. He wanted a classic hanging, so that’s what we did.

When possible—but it is rarely the case—it is very exciting for a curator or an art director to create the space itself, by building walls, or making them curved, for instance. It’s a privilege to think not only in terms of flat scenography but of the very architecture of the exhibition. I have had this opportunity in some circumstances. At the Palais de Tokyo, the space is large and I organized a show with this kind of freedom for William Klein’s Le commun des mortels (The common man, 1987). And also at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition (2003).

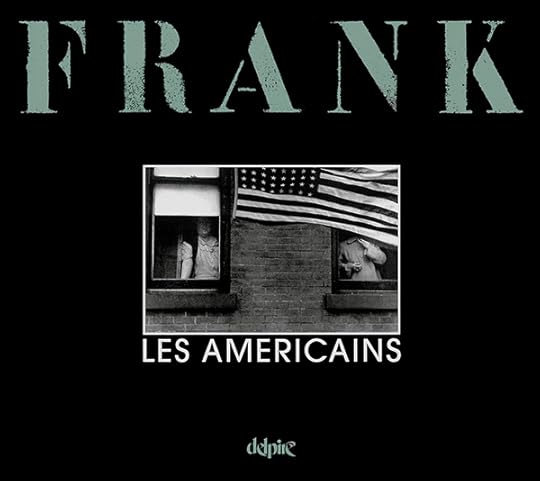

Robert Frank, Les Américains (The Americans), 1958

Courtesy Delpire Éditeur

MH: Do you feel that there are relationships among photography and painting, sculpture, music, mathematics, and so on? Or are there absolute distinctions?

RD: The absolute distinction is due to an obvious fact: photography is made from reality—no matter what distance a photographer wants to create between what he or she is photographing and what he or she has in mind. Of course the painter and the filmmaker also take advantage of a visual basis in reality, but there are many ways to transform a drawing or a film and adapt them to a concept. René Magritte said: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”—“This is not a pipe.” He was right. And a collage made by Robert Rauschenberg or John Heartfield could be said to be situated at the frontier of photography and painting. But for a photographer, it is impossible to forget about the “performance” of a negative: its first function is to register reality. Consequently there are millions of photographs carefully archived in agencies or foundations or in public repositories that are without any interest—apart from a documentary interest in lifestyles, architecture, fashion.

MH: Do you think about beauty and photography—not in terms of pretty pictures, but something more profound? What is it? Truth? Is there such a thing as a truthful photograph, an evidentiary photograph, an objective photograph?

RD: Beauty and photography. Or beauty in photography? It’s a difficult subject. All the professionals (or almost all) are aware that it is not enough to be in front of a beautiful landscape or an elegant lady to make a good photograph. In a certain sense, it’s too easy to make an image with a camera. And the digital process makes it even easier. This facility explains the enormous success of photography among amateurs.

But to make more than a simple statement in a photograph, one has to enhance the significance of a fact, the psychology of a person, the specificity of a subject. And everything becomes much more difficult. Making a good photograph requires sensitivity, patience, vivacity, graphic sense, not to mention technical knowledge. The talent is “the cherry on the cake,” as we say in French . . . We publishers are looking for the cherries.

I’m also attracted by certain authorless photographs that I’ve discovered. Among the uninteresting prints—badly developed, torn—we sometimes find marvels. Family albums, souvenirs of wars or vacations, portraits, and situations that make up a person’s intimacy, tenderness, passion—sometimes to the point of indecency, because there was no one there witnessing. But I’ve never sought to establish a connection between the work of great photographers and the naïveté of the amateur . . . it’s their status as art brut that has seduced me and not their relation to photography considered as fine art.

Presentation of the Commandeur des Arts et Lettres medal to Robert Delpire. From left to right (standing): unidentified man; French Minister of Culture Philippe Douste-Blazy; Elliott Erwitt; Sarah Moon; Robert Delpire; René Burri; Bruno Barbey; William Klein; (squatting): Sebastião Salgado; Harry Gruyaert, 1966

MH: What are the possible dynamics between photography and text—how and when do they enhance each other? And how do these considerations enter into your design and sequencing as you are working?

RD: It is generally admitted that a good photograph needs no words, not even a caption. Nevertheless, when working on a magazine or a book, the publisher often hesitates—text or no text? It seems evident that a so-called reportage photograph will benefit by being seen in context. To know that those dead bodies piled on a street curb are victims of the Mafia and not demonstrators killed by the police is no minor detail and will influence the way the image is interpreted.

And when a photograph aspires to formal artistic achievement, and when the author wants to express his or her personal emotions, a commentary may be useful to deepen the reader’s understanding of the image. Positive: it might create empathy. Critical: convincing arguments can cut down any sympathy with what is shown in the photograph.

In the Nouvel Observateur Spécial Photo we chose to accompany images with extensive captions by various writers, who, in my opinion, succeed both in giving adequate information about the photographers and in clearly pointing out the specific features of each document.

In general, I am careful to put text and image together that will function in concert with one another—not text that simply comments on the photographs. Ever since I have been involved in the making of books and magazines, I have tried to find the writer who by nature feels close to a given photographer, and whose analysis will increase the reader’s interest in the subject matter.

MH: What would you cite as a major text on the interpretation of images?

RD: The first ones that come to mind are Roland Barthes and André Jammes. I also am very interested in Susan Sontag.

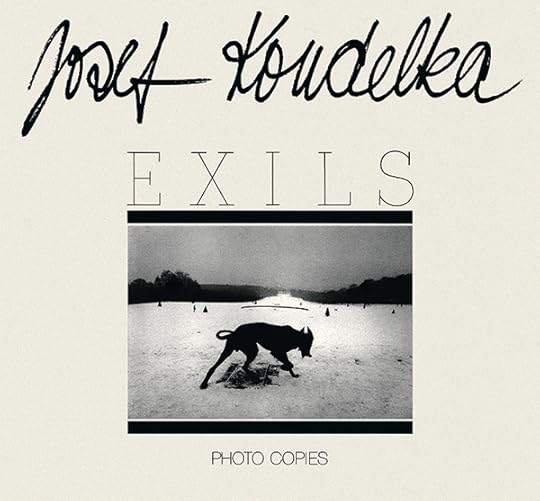

Josef Koudelka, cover of Exils (Exiles), 1988

Courtesy Delpire Éditeur

MH: When you are working, do you rely primarily on your intuition? When, if ever, is your process more intellectual? More emotional?

RD: Fundamentally, I am an intuitive person. Each time I have to make a choice, for instance to select a good photograph on a contact sheet, to build a sequence, even to make a general decision concerning a book to publish, I am always most comfortable if I follow my first impulse. It would be very pretentious to say that I am always right—but if I do make a mistake it’s always in accordance with my feelings, my deep convictions (even if I don’t express them). My way of working is much more emotional than intellectual. I feel more than I know.

MH: When does a photograph—or any kind of image or story—get under your skin?

RD: There are so many elements in a photograph that can get under your skin. Compassion, pity, empathy, seduction. It depends on your mood, on your mental state, on your physical health . . . But in fact, I am not being sincere when I say that! As far as I am concerned, when a photograph touches me profoundly, I do remember it, whatever the circumstances. When we were looking at contact sheets, Cartier-Bresson used to say ironically to me: “You are really stubborn. Twenty years after a first edit, you mark red crosses on all the same images.” My answer was: “That’s the advantage of being narrow-minded.”

But please don’t ask me to list my favorite photographers—there are too many. It’s the reason I sometimes scratch my skin. There are photographers who are mere witnesses, who see things and scoop up events. And those who say what they think in their photos—those are the artists . . . For them, the “I” is so cumbersome that they can’t separate themselves from it.

President François Mitterand at the Centre National de la Photographie after the opening of the exhibition in honor of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s eightieth birthday, December 1988

Courtesy Delpire Éditeur

MH: I interviewed William Eggleston a couple of years ago, and we ended up talking about John Cage and Bach. Music is key for many artists, although not always in a literal way. Does music enter into your process?