Aperture's Blog, page 108

November 14, 2017

Across a Racial Divide, Images of Daily Life under Apartheid

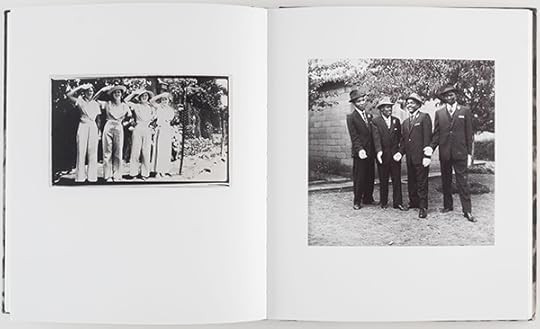

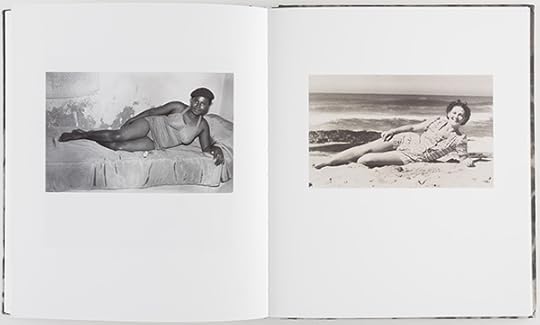

An innovative book juxtaposes images from the archives of two South African families—one black, and one white.

By Oluremi C. Onabanjo

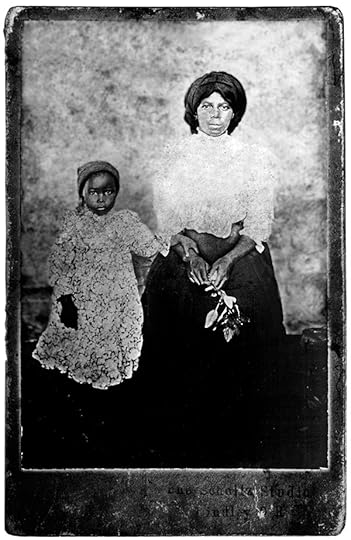

Unidentified subject, South Africa, ca. 1950s

Courtesy the Ronald Ngilima collection

Printed on tightly bound cloth, a curtain of soft ripples and floral design is rendered on the entirety of the book’s surface. A faint light emanates from the bottom left corner, infusing the texture with warmth and inviting us into Commonplace, an intimate view into the everyday lives of South Africans over the course of the twentieth century.

Authored collaboratively by Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, the book features photographs from two private collections—each informed by the movement and settling of communities within particular spaces in South Africa’s physical and social landscape: The Ngilima collection includes the combined work of two black South African photographers, Ronald Majongwa Ngilima and his son Thorence, who photographed life in the African, colored, and Indian neighborhoods in Benoni, east of Johannesburg, during the 1950s and ’60s. The other, the Drummond-Fyvie collection, dates back to the 1850s and spans 150 years of the Natal Midlands’ family history as the group settled and farmed land in Estcourt, the former Colony of Natal.

Spread from Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, Commonplace, Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg, 2016

With rich compilations from these two collections, Commonplace embraces quotidian moments, both despondent and jubilant, experienced by members of the different communities. Set against the backdrop of the social-documentary and photojournalistic heritage that often dominates South African photographic imagery, this book presents a different visual layer through which to understand the country’s complicated past. Replete with a variety of characters and compositions, Commonplace balances not only the differing social, racial, and ethnic circumstances of the apartheid era, but also the materials and objects of their lives.

Spread from Tamsyn Adams and Sophie Feyder, Commonplace, Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg, 2016

Differing in format, tonal range, and size, the photographs interact within each collection, and more subtly, in varying visual sensibilities. Occasionally a photograph is presented with its well-worn edges, borders, and jagged corners clearly visible. This appearance hints at differing temporal contexts, and provides a material reminder of the eyes and hands that engaged with these rich objects before our own—leaving behind the “trace of relatives, loved ones and friends who once, long ago, stepped out in front of a camera” (as stated in the book’s postscript)—and of those who handled the photographic products after the fact.

Sharp juxtapositions of family gatherings, intimate couples, or reclining feminine beauties across color lines and the rural-urban divide present ambivalent and, at times, beautifully fragmented representations of life within South Africa. Rhythmic echoes across a range of sartorial choices—from canes and hats or tailored suits to striped and spotted skirts—flit across decades and communities, providing playful visual cues through which to read form and self-making anew.

Undated photograph, South Africa

Courtesy the Drummond-Fyvie collection

At its core an exercise in deconstructing and parsing the components of a photo album, Commonplace elegantly destabilizes essentializing narratives of social life and subjectivity during apartheid—but to what end? With minimal, informative texts relegated to the back and printed on a thinner manila paper, the punch of the postscript and supporting essays pales in comparison to the rich, luxurious reproductions on matte paper that populate most of the publication. Through thought-provoking pairings, Adams and Feyder claim that the photographs begin “to suggest the varied ways in which lives lived in different times and places, and under very disparate circumstances, might nevertheless be tied to each other—if not in a common place then at least in their commonplaces.”

Again and again, we face these private moments of people’s lives, and yet, are left wondering how a “commonplace” can provide a prudent point of parallel, or contact, while still honoring the heartbreaking ruptures and tensions writ large throughout South African history. Perhaps Adams and Feyder prefer to leave these strings untied, as we continue to reckon with the social and spatial aftermath of the apartheid area in contemporary South Africa, and instead focus their offering on a more careful consideration of the country’s history through personal images—an exciting and worthwhile endeavor in itself.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is director of exhibitions and collections for The Walther Collection.

Commonplace was published by Fourthwall Books in 2016.

The post Across a Racial Divide, Images of Daily Life under Apartheid appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 10, 2017

Announcing the Winners of the 2017 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of the 2017 edition of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. “Each of the prizes have been awarded to very committed projects that show a dedication to and respect for the subject,” said final juror Krzysztof Candrowicz. “What I see in all of the books points to a change in traditional thinking about the photobook, blurring the boundaries and; expanding the scope what a photobook can be.”

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year

Mattie Boom, Hans Rooseboom

New Realities: Photography in the 19th Century

Publisher: Rijiksmuseum/Nai, Amsterdam, 2017

Designed by Irma Boom Office (Irma Boom/Tariq Heijboer)

“I appreciate that New Realities takes what might be considered ‘dusty’ material of the nineteenth century and brings new perspectives and fresh design to enliven this classical material. It’s important as an example of how to preserve and capture new interest in the history of photography.”—Nathalie Herschdorfer

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year

Dayanita Singh

Museum Bhavan

Publisher: Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, 2017

Designed by Dayanita Singh and Gerhard Steidl

“Dayanita Singh has extended the concept of what a book might be with Museum Bhavan: a book of books, each one exploring an Indian motif, from printing presses to the administrative archive. Her work is a sophisticated merger of East and West sensibilities, and celebrates the democratic possibilities of the offset multiple.”—Mitch Epstein

Winner of First PhotoBook ($10,000 prize)

Mathieu Asselin

Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation

Publisher: Verlag Kettler/Acte Sud, Dortmund, Germany, 2017

Designed by Ricardo Báez

“Asselin’s Monsanto is a courageous, investigative project that connects evidence-driven photography and visual research to the democratization of knowledge; it’s important that this book exists in physical form, as a document, and not just the virtual world.”—Christiano Rainondo

Juror’s Special Mention

Carlos Spottorno and Guillermo Abril

La Grieta (The Crack)

Publisher: Astiberri Ediciones, Bilbao, Spain, 2016

“Very seductive in its draw on nostalgia and forms of popular culture, it’s a very interesting strategy to bring out attention anew to a topic that we see every day in the news.”—Nathalie Herschdorfer

A final jury at Paris Photo selected this year’s winner. The jury included: Florencia Giordana Braun, director and founder of Rolf Art gallery, Buenos Aires; Krzysztof Candrowicz, the artistic director of the Triennial of Photography in Hamburg; Mitch Epstein, New York–based, award-winning photographer whose most recent book, Rocks and Clouds, will be published by Steidl this fall; Nathalie Herschdorfer, director of Museum of Fine Arts, Le Locle, Switzerland; and Cristiano Raimondi, head of development and international projects at the New National Museum of Monaco and an invited curator for Platform 2017.

This year’s shortlist selection was made by Gregory Halpern, whose ZZYZX won the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award in 2016; Lesley A. Martin, Creative Director, Aperture Foundation and Publisher, The PhotoBook Review; Kathy Ryan, longtime director of photography at the New York Times Magazine; Joel Smith, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York; and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

The shortlist was first announced at the New York Art Book Fair. The thirty-five selected photobooks are profiled in issue 013 of The PhotoBook Review, Aperture Foundation’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook. Copies will be available at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore. Subscribers to Aperture magazine receive free copies of The PhotoBook Review with their summer and winter issues.

The post Announcing the Winners of the 2017 PhotoBook Awards appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 9, 2017

An Exhibition Where Every Opinion Matters

At the Art Gallery of Ontario’s annual photography prize, four artists compete for your vote.

By Tatum Dooley

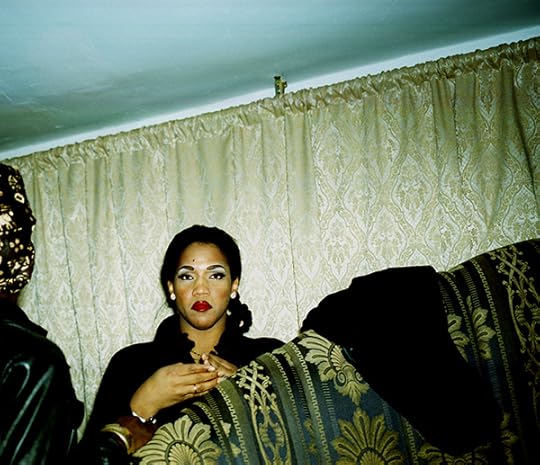

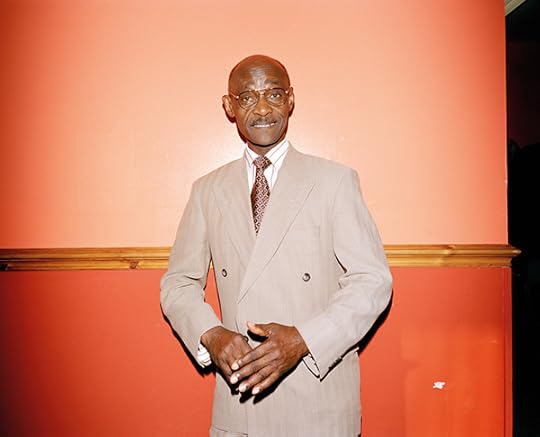

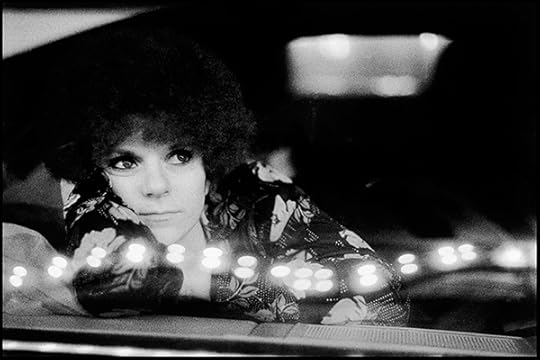

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 1986–2010, from the Black Balloon Archive

Courtesy the artist

The AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize makes a critic out of all who enter. Throughout the Art Gallery of Ontario’s annual exhibition, touchscreen monitors encourage visitors to vote for the “artist whose works speaks to you.” Handed the role of juror, viewers interact with the exhibition with a critic’s eye, forming their own responses and judgments, and assessing the work through aesthetic, concept, or both. The four finalists this year—Raymond Boisjoly, Taisuke Koyama, Liz Johnson Artur, and Hank Willis Thomas, who share an interdisciplinary approach—have already been vetted in two rounds in a nomination process led by the AGO’s photography curator Sophie Hackett.

By asking the audience to vote, the prize pits each artist against one another, resulting in four separate mini-shows rather than one unified exhibition. The transition between each artist’s area, or between each separate show, is signified by a small video screen with headphones where an “expert”—the director of a science museum, a talk show host, a curator—campaigns for why you should vote for a certain artist. These acts of rhetorical persuasion, along with the voting screens and wall text, however, are the only hints that this is not a typical museum exhibition.

Raymond Boisjoly, From age to age, as its shape slowly unraveled, 2015. Installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver

The first mini-show is Raymond Boisjoly’s installation of large-scale photographs, From age to age, as its shape slowly unravelled (2015). Printed on vinyl and placed directly on the wall, the images become part of the cavernous room. The photographs, which range from life-size to larger-than-life, often require a tilt of the head to view in their entirety. To create this series, Boisjoly scanned Statues Also Die (1953)—an anticolonial French film by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Ghislain Cloquet—while it played on his iPhone and iPad. As Boisjoly explains in a statement, “the distortions in the images result from the scanner’s inability to fix the film’s movement.” By replicating the repulsion of movement inherent in daguerreotypes, Boisjoly’s hypercontemporary images recreate technical pitfalls that existed more than a century ago.

Raymond Boisjoly, Station to Station (detail), 2014

Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver

The results of these distortions are seen in various ways. From afar, the dust particles on Boisjoly’s photographs resemble constellations, bringing attention to the physical origins of the work. In The Objects Themselves (And Now Their Image) (2015), a triptych of statues’ heads appear like mannequins detached from the rest of their bodies. The video’s rapid movement has altered one head so that it looks in both direction at the same time, a contemporary Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings. In another, Subsequent Categorizations (Institutional Framings) (2015), the scan has splintered the statues from the video, crushing them into the right side of the photograph; they appear as if they’re invading the image, an apt metaphor for the colonialism that Boisjoly grapples with. The only deviation from grayscale is a tricolor shading, the same effect of viewing a 3-D images without the requisite glasses.

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 1986–2010, from the Black Balloon Archive

Courtesy the artist

A few steps away, Liz Johnston Artur’s Black Balloon Archive (1991–ongoing) emphasizes the importance of the everyday. Instead of being mounted and framed, the photographs are displayed in vitrines, or adhered to the wall by magnets—an ode to hanging photographs on the refrigerator. And Artur’s photographs are exactly the kind you would hang on the fridge. Full of joy, Black Balloon Archive documents a broad range of Black experiences. “Whether congregating at parties or clubs, on streets, in parks or at churches, the groups in Artur’s photographs emphasize family, friendship, style, and joy without generalization,” the exhibition text explains. Artur captures her subjects in settings of celebration, where they’re looking, and maybe feeling, their best. The vitrines showing Artur’s collection of archival documents, both her own photographs as well as ephemera she has gathered, double as light boxes. The scrapbook-like documents become photographs; light shines through the newspaper image, becoming an accidental negative.

Taisuke Koyama, Rainbow Variations, 2009–ongoing. Installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario

Courtesy the artist and G/P Gallery, Tokyo

In the same room, scrolls of colorful photographs by Taisuke Koyoma are draped over black frames. To view the images themselves, visitors must weave in and out of a maze of these photo–sculptures. Unfortunately, the display is the most interesting component of the work. The aesthetically pleasing gradations—fading in and out of blue, pink, yellow, and green in vertical lines—disclose slight imperfections when inspected closely: watermarks, hair, and dust particles. Yet, Koyoma’s proposed line of inquiry, investigating the “relationship between organic processes, natural phenomena and imaging technologies,” remains ambiguous.

Hank Willis Thomas, Raise Up, 2014

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

The clear winner is Hank Willis Thomas. His work takes up the most physical space in the show, spanning two separate rooms and a hallway. In the first room is Thomas’s sculpture Raise Up (2014), from the series Punctum (2014–ongoing). Bronze heads and arms peak over a long white pedestal. Cut off at eye level, or sometimes right below, at first it might appear as if the Black men portrayed are drowning. And then you realize: maybe their arms are raised in surrender to police. Looping back, the reference for this work appears: a photograph by Ernest Cole from the early 1960s of gold mine recruits stripped down for medical evaluation. By referencing an archival photograph and using bronze, Willis creates a memorial.

One room over are seven of Thomas’s photographs, screen-printed onto retro-reflective vinyl, and activated with the flash of a camera or LED flashlight. Once hit with light, the photograph flares into focus, goes dark, and then lights back up for a final time. An artist statement reads, “When we activate the works with light, they become vivid evidence of historic moments easily forgotten in our fast-paced visual culture.” Do you look at the photograph as an image on your phone, or in the ambient light of the gallery? In mandating that these pieces be illuminated with a flash, Thomas puts the viewer in the role of the photographer, sharing some of the agency of not only viewing, but also of making the photographs, and bringing often-forgotten historical moments back into focus.

Hank Willis Thomas, Turbulence II (left), The Law of the Land is Our Demand (right), 2017

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

By allowing the audience the agency to choose which photographer they think should win, the AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize encourages visitors to actively interact with the works, as opposed to passively viewing them. Each artist mirrors this with work that also invites participation, enhancing the interactive experience. Yet whether a visitor views the art aesthetically or conceptually, Thomas is ahead on both fronts. (The official winner will be announced on December 4.) Thomas’s work requires viewers to engage with his photographs, participating in the development of the images in a novel way. The work itself is striking, and the fact that you can “develop” photographs—by taking pictures of them—means you get to revisit the images over and over again on your own camera-roll. While this exhibition’s framework turns you into a critic, Thomas turns you into a photographer.

Tatum Dooley is a writer based in Toronto.

The AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize is on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario through January 14, 2018.

The post An Exhibition Where Every Opinion Matters appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 7, 2017

In Cape Town, A New Destination for African Art

Asserting black identity, photographers take center stage at a bold new museum.

By Sean O’Toole

Thania Petersen, Flamingo (detail), 2017. Backlit photographic print in lightbox

Courtesy the artist and Everard Read, Cape Town

Photographic portraiture—of the self as much as subjects choreographed for the camera—is a central offering at the newly launched Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA), a one-hundred-gallery, nine-floor private museum that opened at a harborside address in Cape Town, South Africa’s leisure capital, and focuses exclusively on twenty-first-century art from Africa and its diaspora. Named after Jochen Zeitz, the former CEO of sportswear brand PUMA SE, whose art collection is on a twenty-year loan, the museum’s eleven inaugural exhibitions survey a broad range of contemporary artistic practices, many inventively using the camera to assert black identity and record performative engagements with social issues.

“I don’t know if I am backing the wrong horse, but I think it is going to help with public engagement,” said Mark Coetzee, Zeitz MOCAA’s executive director and chief curator, of his decision to make the figure the defining leitmotif of his museum’s opening exhibitions. Coetzee explained that his decision was influenced by two key factors: the fetish value of “selfies and the photographic image” among millennials, and the still-pressing need, in postapartheid South Africa, to offer black museumgoers work that they might identify with. “I think it is a very effective way to say to our audience that not only are they welcome here, not only does this institution belong to you, but the images that we show and celebrate are you as well,” Coetzee said.

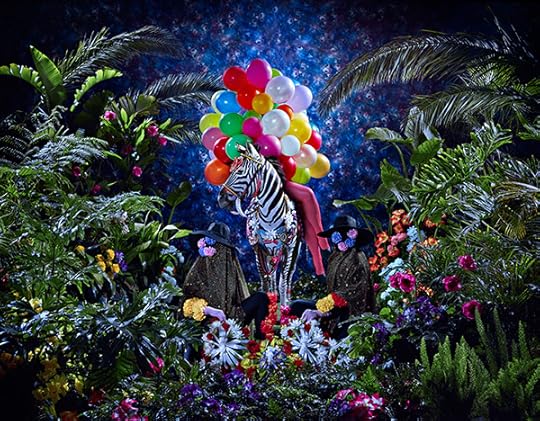

Athi-Patra Ruga, The Night of the Long Knives III, 2014

Courtesy the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Cape Town-based artist Athi-Patra Ruga’s eye-tingling triptych, The Night of the Long Knives I-III (2013), forms part of Coetzee’s group exhibition All Things Being Equal …, which also includes lens-based work by Malagasy artist Joël Andrianomearisoa, American Rashid Johnson, Briton Isaac Julien, and lesser-known South Africans such as twin brothers Hasan and Husain Essop, Mohau Modisakeng, and Thania Petersen. “I like the fact that the museum buys my black body, or the representation of it, so that it fills up these spaces,” Ruga said of his self-portraits, which portray him in a balloon costume astride a zebra in a lush tropical setting, and tell the mythical story of a future South Africa ruled by LGBTQI-friendly female monarchs. Underscoring Coetzee’s point about public engagement, Ruga added, with a seditious smile, “If a nephew walks into the space, he can send me a WhatsApp: ‘OMG, I saw your penis in Zeitz MOCAA!’”

New York-based writer Antwaun Sargent took a different view after visiting Zeitz MOCAA. Writing in an Artsy editorial, Sargent wondered if the “heavy focus on literal depictions of the black body in almost every room of the museum also runs the risk of essentializing it.” He put the question to Coetzee, who responded, “That’s a higher-level art problem.” Formerly a director at the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, Cape Town-born Coetzee joined PUMA as Chief Curator of puma.creative in 2009 and was a strategic advisor to Zeitz during a well-publicized buying spree that netted key works by Swaziland sculptor Nandipha Mntambo and South African sculptor Nicholas Hlobo, both on view in the museum.

Edson Chagas, Found Not Taken, Luanda, 2009

Courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Another of Zeitz’s key acquisitions was a photographic installation by Angolan artist Edson Chagas. In 2013, Chagas won for his country the Golden Lion for best national pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale with his exhibition, Luanda, Encyclopedic City, comprised of twenty-three stacks of mass-produced photographs of urban detritus drawn from the artist’s series Found Not Taken (2009–13). Acquired at the biennale by Zeitz, this is the work’s first public showing since 2013. The Félix González-Torres-style arrangement of Chagas’s photographs is less interesting than their insistent focus on impersonal urban spaces. Africa is the second-fastest urbanizing continent after Asia. Three untitled urban landscapes by Johannesburg photographer and Market Photo Workshop-graduate Mack Magagane, all shot at night between 2011 and 2012, are the only other works in Zeitz MOCAA addressing the experiences and realities of this difficult transition.

Mack Magagane, Untitled XII, 2011, from the series in this city

Courtesy the artist and ROOM Gallery & Projects

Zeitz MOCAA does not have traditional museum departments defined by media, concentrating instead on six “focus areas” that include costume, moving image, performative practice, curatorship, art education, and photography. Nevertheless, the museum’s photography “area” is named after the New York-born, Johannesburg-based photographer Roger Ballen, who earlier this year made a financial gift to Zeitz MOCAA’s endowment, as well as donated one signed edition of all his photographs since 1968 to the museum’s permanent collection. “If you give it to a big international museum, the work sits in a storeroom,” said Ballen, whose work is held by the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Tate in London. “It also feels appropriate,” added Ballen, who met his South African wife in Johannesburg in 1974 and has spent much of his adult life in the country.

Roger Ballen, Dove Catcher, 2009

Courtesy the artist

Ballen is a controversial figure in his adopted country: since the publication of Platteland (1994), which included many of his best-known frontal portraits of poor whites, he was dogged by persistent claims of exploitation. Ballen’s outlier status, particularly among liberal documentarians, was rehabilitated—or merely superseded—when he shot “I Fink U Freeky,” a 2012 music video for controversial rap outfit Die Antwoord. “Tens of millions of people became aware of my aesthetic,” said Ballen, who has four photographs in All Things Being Equal…, including Dove Catcher (2009). Coetzee, who first met Ballen at the 17th Biennale of Sydney in 2010, has also allowed the photographer to create a series of environments filled with animatronics, wall drawings, and props that reflect this lanky photographer’s interest in outsider art (Ballen prefers the French term art brut) and will likely provide instant recognition for fans of Die Antwoord.

Mouna Karray, 34°43’56.0″N 10°32’29.4″E, 2012–15

© the artist and courtesy Tyburn Gallery, London

The Roger Ballen Foundation Centre for Photography’s debut exhibition is devoted to the work of Tokyo-trained, Tunisian artist Mouna Karray. Curated by Gcotyelwa Mashiqa, Off-the-Air presents a series of self-portraits of the artist obscured by a white sheet and posed in various arid landscapes in her home country’s southwest, in addition to three studio portraits that follow the same setup. Karray began working on the series in 2012, a year after the revolutionary ouster of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali; the work was first exhibited at London’s Tyburn Gallery in 2016. Karray’s series is informed by a postrevolutionary anxiety: the photographer has variously described her anonymous figure as a “captive” and “a figure of resistance, a figure pushing for freedom and the re-enchantment of a forgotten land.”

![Kudzanai Chiurai, Genesis [Je n'isi isi] I, 2016 Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1510142271i/24391019._SX540_.jpg)

Kudzanai Chiurai, Genesis [Je n’isi isi] I, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Zeitz MOCAA has two full-time photography curators, Gcotyelwa Mashiqa and Bafana Zembe, assisted by a curator at large, Azu Nwagbogu. “Photography really matters today because it allows us to explore, enquire, and investigate truths,” said Nwagbogu, a Lagos-based art entrepreneur who founded LagosPhoto, an annual photography festival in Nigeria, and also heads up the nonprofit African Artists’ Foundation. Nwagbogu’s exhibition Regarding the Ease of Others offers an insightful overview of Zimbabwean multimedia artist Kudzanai Chiurai’s practice, which encompasses agitprop posters, painting, sculpture, and—since 2009, when he collaborated with fashion photographer Jurie Potgieter on bling portraits of a fictional governmental cabinet—David LaChapelle-inspired pop-political tableaus in photography and video.

Zanele Muholi, Bona, Charlottesville, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

“Photography has played a pivotal role since the liberation struggles of the 1960s up until the present,” said Coetzee during a July press conference. Despite a large showing of photography, the museum’s holdings are marked by key omissions. There are no works by South Africans Moshekwa Langa, Jo Ractliffe, and Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, all included in Okwui Enwezor’s 2006 group exhibition, Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography at the ICP in New York. Other notable absences include Pieter Hugo, Mikhael Subotzky, and Guy Tillim; as well as the Cameroonian self-portrait photographer Samuel Fosso, whose magisterial series African Spirits (2008), along with South African artist Tracey Rose’s self-portraits from her Ciao Bella (2001) video installation, underpin as much as clarify the self-reflexive, performative turn in African photography.

Absence and omission are not fatal in a new museum; indeed, they represent opportunities for future projects, or at least this is the hope. Among the highlights from Zeitz MOCAA’s debut showcase is a selection of five brooding self-portraits from Zanele Muholi’s ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail, the Dark Lioness). First exhibited at New York’s Yancey Richardson Gallery in 2014, Muholi produces her frontal self-portraits alone, at home, and on the road. The darkened skin tones are achieved in postproduction. Muholi plans to produce 365 self-portraits; in January, she had achieved 120. “It is really difficult to look at yourself,” Muholi told me. “You face your demons in ways that you might never have done before.” The self-portrait, far from being procedural or obvious, can also be a fierce act of defiance.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and editor based in Cape Town. This article is produced in collaboration with C& (Contemporary And) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

All Things Being Equal … is on view at Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, through February 19, 2018.

The post In Cape Town, A New Destination for African Art appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 2, 2017

Aperture Celebrates 65 Years at the “Elements of Style” Gala

Gigi Hadid, Iman, and Anja Rubik

Casey Kelbaugh/Aperture Foundation

Zackary Drucker with Aperture's winter 2017 issue "Future Gender"

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Elizabeth Kahane, Cathy Caplan, Chris Boot, Susan Gutfruend, Judy Glickman Lauder, Anja Rubik, and Edward Enninful

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Kwame Brathwaite, Iman, and Chris Boot

Casey Kelbaugh/Aperture Foundation

Vinoodh Matadin, Charles Star Matadin, and Inez van Lamsweerde

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Chris Boot and Edward Enninful

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Naomi Campbell and Edward Enninful

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Sherry Bronfman, Alexe Belle, Kwame Brathwaite, Tanisha C. Ford, and Isis Valentino

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Anja Rubik and Iman

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Marc Sebastian and Hari Nef

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Richie Shazam Khan and Chloe Wise

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Judith Light gives a tribute to honoree Zackary Drucker

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Inez van Lamsweerde and Naomi Campbell

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Gigi Hadid, Naomi Campbell, and Edward Enninful

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Kwame Brathwaite and Iman

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Daniel Lönnström, Richie Shazam Kahn, Chloe Wise, and Louise Parker

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Gigi Hadid

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Taia Kwinter and Uma Thurman

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Daniel Lönnström, Hari Nef, Chloe Wise, and Marc Sebastian

Casey Kelbaugh/Aperture Foundation

Zackary Drucker and Mx Justin Vivian Bond

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Stephen Galloway

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Paola Kudacki and Anja Rubik

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Sofia Sanchez de Betak

Sean Zanni ©Patrick McMullan

Kwame Brathwaite recieves a standing ovation

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Chloe Wise, Matthew Foley, Conor Lucas, Richie Shazam Kahn

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Jessica Nagle, Cathy Kaplan, and Sarah McNear

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Naomi Campbell

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Kwame Brathwaite and Dawoud Bey

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Kwame Brathwaite, Sherry Bronfman, and Kwame S. Brathwaite

Casey Kelbaugh/Aperture Foundation

Gigi Hadid and Hari Nef

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Gigi Hadid and Inez van Lamsweerde

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Richard Gregg, David Solo, Darius Himes, Michael Hoeh and guest

Casey Kelbaugh/Aperture Foundation

Nadiya Williams

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Malu Alvarez and Lindsey Butler

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Gigi Hadid and Naomi Campbell

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Kate Schelter

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Missy O'Shaughnessy and Chris Boot

Roxxe Ireland © Aperture Foundation

Bill and Elizabeth Kahane

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Inez van Lamsweerde

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Hemant Kanakia and Tony White

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Nadiya Williams and Svetlana Acquista

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Cena Jackson, Chelsea Kozak, and Kate Schelter

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Stuart Cooper

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Elaine Goldman and David Raymond

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Tom Schiff, Chris Boot, and Mary Ellen Goeke

Madison Voelkel © Aperture Foundation

Guests at the "Elements of Style" Gala

Courtesy of Max Mikulecky

Dinner scene at the "Elements of Style" Gala

Lauren Harper © Aperture Foundation

Zanele Muholi and Dawoud Bey

Lauren Harper © Aperture Foundation

Michael Famighetti and Tanisha C. Ford

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Alexe Belle and Isis Valentino of St. Beauty

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Sara Friedlander

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Matthew Foley and Kwame Brathwaite dressed in Thom Browne

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Bill Kahane, Rebecca Hayward, and Sam Lawson

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Mike Starn and Casey Weyand

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

veryAdvanced

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

On October 30, Aperture honored a group of extraordinary image-makers—Zackary Drucker, Kwame Brathwaite, and Inez & Vinoodh—who are influencing how we look, how we dress, and how we can imagine, and reimagine, ourselves. Aperture’s “Elements of Style” Gala, which took place in the Frank Gehry–designed IAC building, attracted stars of art, film, and fashion, including Edward Enninful, Uma Thurman, Naomi Campbell, Judith Light, Iman, Hari Nef, Gigi Hadid, Sofia Sanchez de Betak, Dawoud Bey, Zanele Muholi, Chloe Wise, and Jimmy Moffat. Throughout the evening, a presentation of images played on a city block–length screen. Musical entertainers included Mx Justin Vivian Bond, St. Beauty, and Anohni.

Together with more than 450 guests, Aperture celebrated its sixty-fifth anniversary of serving the art, story, and community of photography “not by looking backward to its past glories,” in the words of British Vogue’s editor-in-chief Edward Enniful, “but by celebrating photography’s role in shaping our futures. It’s a time to express ourselves in a way that reflects ourselves, our stories, our communities, to our fullest potential; to be the truest version of ourselves that we can be.” The event was cohosted by Enniful; philanthropists Susan Gutfreund, Judy Glickman Lauder, and Elizabeth Ann Kahane; Aperture’s Board Chair Cathy M. Kaplan; actress and model Hari Nef; and activist and model Anja Rubik.

“For real and lasting change, we need allies from across the cultural landscape, allies who recognize the importance of ceding control of trans narratives back to the trans people who live them. Aperture is such an ally,” said Zackary Drucker, artist, trans activist, and producer of Amazon’s Emmy-winning series Transparent. Drucker is the guest editor of Aperture’s forthcoming winter 2017 issue, “Future Gender,” which considers the power of photography to shape trans lives around the world. “I’m in awe of the work we can do together.”

Inez & Vinoodh, some of the most celebrated and influential photographers working in fashion and art today, then premiered a striking video of their fashion images, set to a previously unreleased recording by Anohni. “At the root of our work lies the wish to visualize all the options of expression that a human face and body have, and to construct a heroic image of those in front of our lens,” said Inez van Lamsweerde.

The final guest to be honored, Kwame Brathwaite, advanced the idea “Black Is Beautiful” in the 1960s through his fashion photography and social activism. As author and scholar Tanisha C. Ford noted in her tribute to the Harlem photographer, “Brathwaite’s images envisioned what black beauty might look like for those who lived in the 1960s, and they continue to do so for a generation today.”

Over the preceding Gala Weekend, the festivities kicked off with a tour of The Richard Avedon Foundation, followed by studio visits with Daniel Gordon and Alison Rossiter, as well as tours of collectors’ homes, Staley-Wise Gallery, and The Glass House.

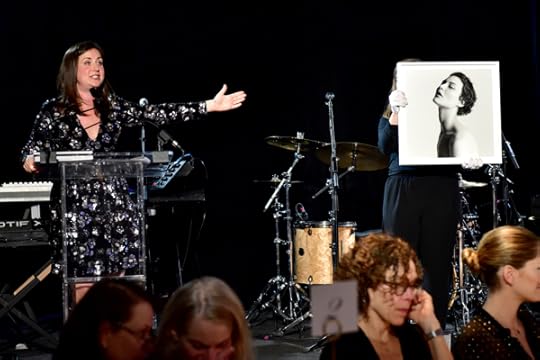

On the evening of the Gala, during a dining experience designed by Angela Dimayuga, Sara Friedlander of Christie’s presided over a live auction, which featured works by Diane Arbus, Horst P. Horst, Inez & Vinoodh, Saul Leiter, Sally Mann, Joel Meyerowitz, Richard Misrach, Sebastião Salgado, Stephen Shore, Pete Souza, and Paul Strand. Also at the venue, to mark Aperture’s sixty-fifth anniversary, the Magnum Square Print Sale in partnership with Aperture featured forty-eight museum-quality 6-by-6-inch prints for sale for $100 each, by Bruce Davidson, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Todd Hido, Mary Ellen Mark, Susan Meiselas, Alec Soth, Hank Willis Thomas, Penelope Umbrico, Alex Webb, and many others. The prints are available for sale online through Friday, November 3, 2017, 6:00 p.m. EST.

Read more about the Aperture Gala on VOGUE.

Aperture’s endeavors are only possible with the help of Gala patrons and Aperture Members. Click here to donate to Aperture’s Annual Fund or join our community as an Aperture Member.

The 2017 Aperture Gala and Auction was generously supported by:

Ingram, Christie’s, Foto Care, Artsy, Emily Thompson Flowers, Fine Art Frameworks, Hypno, photograph magazine, Patrick McMullan Company, Stella Artois, Tito’s Handmade Vodka, and Ziobaffa.

Gala Committees

Leaders

Anonymous

Sb Cooper* and R. L. Besson

Elizabeth* and William Kahane

Cathy M. Kaplan* and Renwick D. Martin

Leonard and Judy Lauder

Anne Stark Locher* and Kurt Locher

Jessica Nagle* and Roland Hartley-Urquhart

Thomas R. Schiff*

Gala Committee

Malú Alvarez

Anonymous

Rita Anthoine

Peter Barbur* and Tim Doody

Dawoud Bey*

Allan Chapin* and Anna Rachminov

Andrew Craven

Fine Art Frameworks

Foto-Care Ltd.

Annette Y. Friedland*

Elaine Goldman* and John Benis

Barbara M. Goodbody

Great Bowery

Howard Greenberg

Susan Gutfreund

Darius Himes, Christie’s

Michael Hoeh*

Ingram Content Group

Darlene Kaplan and Steve Zuckerman

Hemant Kanakia

Michèle Gerber Klein

Bonnie Englebardt Lautenberg

Raymond Learsy

Susana Torruella Leval*

Marina and Andrew Lewin

Nion McEvoy*

Patrick McMullan

Sarah Anne McNear*

Joel Meyerowitz*

Helen Nitkin*

Catherine Opie

Melissa* and James O’Shaughnessy

Louise Parker

Lori Perlow

Sarah Gore Reeves*

Leslie Simitch

David Solo*

Etheleen Staley and Taki Wise

Severn Taylor* and J. Scott Switzer

Willard Taylor* and Virginia Davies

Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont

Barbara and Donald Tober

VLM Productions

V+S Company

John C. Williams

Whit Williams

*Aperture trustee

The Photo Party Committee

Joshua Citarella

Dianna Cohen

Awol Erizku

Matthew Foley

Liz Grover

Alexander Hurst

Richie Shazam Khan

Samuel P. Lawson

Joshua Lewin

Sarah Meyohas

Antwaun Sargent

Rory Satran

Catherine Smith

Chloe Wise

Esther Zuckerman

Additional support from:

Ann Ames

Anonymous

Joe Baio and Anne Griffin

Amanda and Glenn Fuhrman

Sylvia Hemingway

Philippe Laumont

Aliya and Aren LeeKong

David Moscow

Yancey Richardson

Salon 94

Jon Stryker and Slobodan Randjelović

Casey and Lauren Weyand

Paul G. Wolf

The post Aperture Celebrates 65 Years at the “Elements of Style” Gala appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 30, 2017

15 Photographers On Their Greatest Journeys

Where can a photograph take you?

A journey implies a traversing a terrain, but photographs can also travel in time, transporting us to a distant past or an imagined future. Pictures can bring someone home, or closer to understanding themselves. Over the past sixty-five and seventy years, respectively, Aperture and Magnum photographers have demonstrated how photography moves across geography, time, space, and lives, both real and imagined.

This week, for five days only, get signed and estate stamped, museum quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by acclaimed Aperture and Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase and a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

Jacob Aue Sobol, A boy does a somersault and lands in a deep pile of snow, Tiilerilaaq, Greenland, 2001

©the artist/Magnum Photos

Jacob Aue Sobol

“I still recall my journeys to the East Coast of Greenland as the greatest and most fearless ones of my life. I was only twenty-three when I took this picture of a six-year-old boy jumping off the roof, making a summersault, and landing in a pile of snow. To me it became an image not only about the strength and courage of the children in this village, but also about what was happening inside myself. I had fallen in love with a local woman and [had] decided to live with her family to be trained as a hunter and a fisherman by the Inuits. I had started a new life, a new journey that made me feel exactly like that boy jumping off the roof.” —Jacob Aue Sobol

Hellen van Meene, Untitled, 1999

© the artist

Hellen van Meene

“The subjects of my photographs are at the cusp between childhood and adulthood. The girl here radiates a sense of ambiguity, of vulnerability, of soul-searching; it is in this fleeting in-between state of dramatic physical and emotional change, that these qualities become more visible. I’m interested in the tension between her teenage sweetness and awkwardness, made all the more palpable by her pose, and the contrasts between the textures. While this portrait shows a transitory moment of life, it is also timeless—a reminder that we are all in a state of change on life’s journey.” —Hellen van Meene

Todd Hido, Untitled, #2154-a, 1998

© the artist

Todd Hido

“This particular photo has a special meaning to me, even though it hadn’t been published in my House Hunting series, where I explored the Bay Area suburbs at night. After the completion of a body of work, I will often find things that didn’t get published because there was certain hyper sense of uniformity that I was looking for when I was making my initial choices. However, once you are able to gain some space and time to reflect, gems like this emerge and you scratch your head and ask, why haven’t I used this one before?” —Todd Hido

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Pat Brunty, the caretaker, standing behind No Contest (1994). Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum, Joshua Tree, California, 2016

© the artist

LaToya Ruby Frazier

“I took a pilgrimage out in the Mojave Desert with sculptor/installation artist Abigail DeVille to pay homage and respects to our ancestor and predecessor, artist Noah Purifoy. Born in Alabama in 1917, Noah Purifoy, after serving in World War II, spent most of his adult life in Los Angeles as an artist, activist, and educator. In 1989, he relocated near Blair Lane in Joshua Tree, High Desert. For the last fifteen years of his life, Purifoy created nearly 120 sculptures, before he passed away at eighty-six on March 5, 2004. The caretaker of Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum, Pat Brunty, a resident of Yucca Valley and also an Alabama native, worked closely with Noah during the final years of his life. She and her late husband Roger Brunty, under supervision of Noah, built his theater, Andrea’s Little Theater, in 2000. Pat is a passionate and dedicated caretaker of Noah’s work and is serious about maintaining the sculptures as he last saw them, from picking up trash to removing vandalism and greeting visitors. She believes visitors should encounter Noah’s works with an open mind of interpretation.” —LaToya Ruby Frazier

Olivia Bee, Pre-Kiss, 2010

© the artist

Olivia Bee

“This is part of my series, and book with Aperture, Kids in Love. It focuses on your internal universe expanding into the outside world, and experiencing things for the first time. They are real moments of my life that I treat with love and respect.” —Olivia Bee

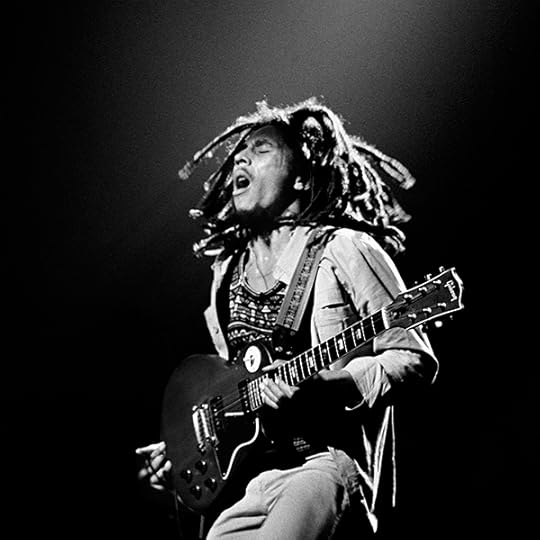

Kwame Brathwaite, Bob Marley, Beacon Theatre, 1976

© the artist

Kwame Brathwaite

“I was backstage at Madison Square Garden when I first met Bob. We started talking about Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie. He was a great storyteller. He had purpose. He talked about Rasta culture and knew a great deal about the African diaspora and the liberation struggles all over the world. Later, we spent time at his house on Hope Road in Kingston. He was great to be around and made everyone feel at home. His poetry and his music are still relevant today. He was a great voice for empowerment and freedom, and he was a friend.” —Kwame Brathwaite

Jamel Shabazz, A Time Before Crack, 1983

© the artist

Jamel Shabazz

“As the dark clouds of crack cocaine slowly casted [sic] their destructive shadows over America during the early 1980s, I saw the urgent need to take to the streets as a concerned citizen and documentarian. Already, a number of young men I knew personally were dying at the hands of other young men I also knew. I felt it was my duty both to warn the youth of the dangers that I foresaw, and to use my camera as a tool to engage and document. Anticipating more death and destruction, I found that photography was the key that allowed me entry into the lives of young people. I would venture out to the local high schools and shopping districts throughout the New York City area, searching for young people to speak to about this growing crisis. To my surprise, almost everyone seemed open to exchange thoughts and afterward stand for a portrait. Those images, in fact, became evidence of the countless exchanges I would have; many new friendships were also forged as a result of these interactions. In making these often-posed portraits, I wanted to capture a spirit of friendship and love. Today, these images serve as a constant reminder of a time before the great crack epidemic that would change life forever.” —Jamel Shabazz

Susan Meiselas, Shortie’s Dream, Barton, Vermont, 1974

©the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“The dream of the road: the place to escape, to wander, to encounter something beyond what you had imagined you’d find. That’s what led Shortie to leave home to strip in the Girl Show. We intersected while traveling through New England. Journeys are physical and emotional disruptions that involve both body and mind. For me, this journey also meant finding a new path. I followed the carnivals with the desire to make images and share the words of women whose working lives forced them to make extremely difficult choices to launch their dreams.” —Susan Meiselas

Zackary Drucker & Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #12, 2008–13

© the artists

Zackary Drucker

“Before the prevalence of selfies, or the square files of Instagram, I photographed myself into existence to fill the void of feeling that gender outlaws had been erased or only rendered by outsiders. I don’t particularly like this self-portrait, but I acknowledge this past incarnation who exists within me, and honor them for delivering me here and now.” —Zackary Drucker

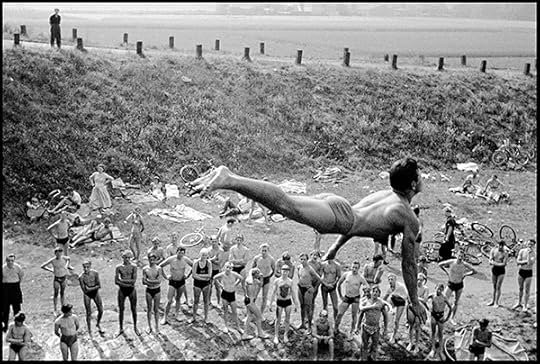

Leonard Freed, Divers on the banks of a canal near Dortmund, Dortmund, West Germany, 1965 ©the artist/Magnum Photos

Leonard Freed

“As a young photographer in the 1950s, Leonard left New York City for post-war Europe. He found devastated European nations that were in the process of rebuilding themselves. When in Rome, he met, and later married, a German woman. Together they would photograph Germans in Germany for the next ten years, creating two photobooks: Deutsche Juden heute (1965) and Made in Germany (1970).” —Elke Susannah Freed

Justine Kurland, Sea Stack, Double Mama, Ruby Beach, Washington, 2006, from the series, Of Woman Born

© the artist

Justine Kurland

“After the birth of my son, Casper, in 2004, I began a series of photographs that juxtapose radical representations of motherhood with idealized views of the American West. The project was titled after Adrienne Rich’s seminal feminist text, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976), in which she analyzes the patriarchal construct of motherhood and discusses why it is such a problematic topic for many feminists. While some theorists would prefer to do away with the body altogether, Rich envisions a new rubric in which the libidinal value of ‘tits and ass’ is replaced by the uterus and clitoris, and women are positioned as the arbiters of their own bodies. This series was my attempt to visualize what that shift might look like—women and children wandering in blissful togetherness through the social space of shared landscapes. I made them mostly for myself during my first years with a small baby, because I couldn’t relate to the depictions of motherhood available to me. These photographs opened up space for me to imagine a different way of being a mother.” —Justine Kurland

Graciela Iturbide, Cemetery, Juchitán, Mexico, 1988

© the artist

Graciela Iturbide

“Midway between the documentary and the poetic, my unusual way of looking through the lens integrates what has been experienced and what has been dreamt, into a complex web of historical, social and cultural references. The fragility of ancestral traditions and their difficult survival, the interaction between nature and culture, the importance of ritual in everyday body language and the symbolic dimension of landscapes and randomly found objects are paramount to my career. My work is characterized by an ongoing dialogue between images, time and symbols, in a poetic display in which dream, ritual, religion, travel and community all blend together.” —Graciela Iturbide

Joel Meyerowitz, Scotty’s Drive in, Florida, 1967

© the artist

Joel Meyerowitz

“Here’s Scotty’s. Sometimes when you’re traveling in the car all day, on the lookout for life on the fly, a great thirst comes over you and that desire for the next event evaporates immediately upon seeing an old-fashioned diner, I mean the real thing, not some dolled-up imitation serving prepackaged crap, but a place where some degree of reverence for the past lets you know that a milkshake from childhood can be found there. And here’s Scotty’s. Mmmmmm.”—Joel Meyerowitz

Jérôme Sessini, Caracas, Venezuela, May 27, 2013

©the artist/Magnum Photos

Enri Canaj

“This is from a journey backward, to my own homeland, to what I have kept in my memory, what I have forgotten, what I grew up away from. All of it slowly melting together into a light crystal snow ball, that I keep safe with me. To keep me safe.” —Enri Canaj

Enri Canaj, Korçë, Albania, February 2015

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Jérôme Sessini

“For most people, travel is synonymous with vacation, exoticism and relaxation. Or flight, to escape the quotidian. I understood by traveling, that there was no trip far enough to escape from oneself. Elsewhere becomes here when we are there.” —Jérôme Sessini

Support Aperture today through the Magnum Square Print Sale in Partnership with Aperture, open online October 30–November 3, 2016.

The post 15 Photographers On Their Greatest Journeys appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Elements of Style Workshop

On October 20, 2017, eleven photography students from colleges and universities in NYC were invited to Aperture Foundation’s Chelsea gallery for a workshop inspired by Aperture magazine’s fall issue, “Elements of Style.” Participants were joined by Rory Satran, editorial director for i-D US, and photographer Nadine Ijewere. The first session of the workshop was led by Satran, who presented her career path—an instructive narrative on the nature of success and how Satran’s accomplishments relied on a combination of luck, skill, and, as she put it, “chutzpah.” Satran provided students with her valuable perspective on the editorial side of fashion photography, answering questions about how to get their work seen by editors, how to collaborate with an editorial team, and how to navigate contracts. Satran discussed the differences between editorial and commercial work within the context of fashion photography, and gave students guidance about maintaining their personal creative visions while carrying out paid projects for commercial clients. Toward the end of her presentation, Satran went through a list of mistakes she made early on in her career, an illustrative lesson in what not to do, including cautionary statements such as “I thought I knew everything” and “I tried to control the outcome.” Satran emphasized the need for young photographers to take chances, to be persistent, and to advocate for themselves and their work.

The second session of the workshop was a master class by Nadine Ijewere. As a young artist whose photographs have been featured in publications such as i-D and The New York Times, as well as in ad campaigns for commercial clients, Ijewere gave helpful advice about making images for clients while continuing one’s individual, creative photographic practice. Ijewere’s style is unique in that she shoots fashion photographs that simultaneously explore issues of identity and diversity. With such specific stylistic goals, Ijewere must be careful to maintain creative control of her image-making practice, and thus she chooses to work without an agent. Ijewere explained this decision to students and discussed practical issues, such as how she gets permission from models and works with collaborators. For the remainder of the workshop, Ijewere led students through a portfolio review. She looked at each student’s body of work, asking questions and giving feedback. At the end of the day, Ijewere gave participants her contact information, stressing that she would love to see how each individual project progresses. Ijewere’s inspiring positivity encouraged students to explore their ideas and to be confident in the potential of each of their projects.

This workshop would not have been possible without a lead contribution from the Ann Levy fund. Additional public funding was provided from the National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

Thanks to its generous contributors, Aperture is able to continue with its mission to become a more inclusive arts organization, nurturing the talent of young emerging photographers and allowing us to build diverse new audiences while responding to and presenting photography’s engagement with urgent social themes.

Explore Workshops

The post Elements of Style Workshop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 27, 2017

India in Full Color

Raghubir Singh, a protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson, captured the fleeting beauty of twentieth-century India.

By Max Campbell

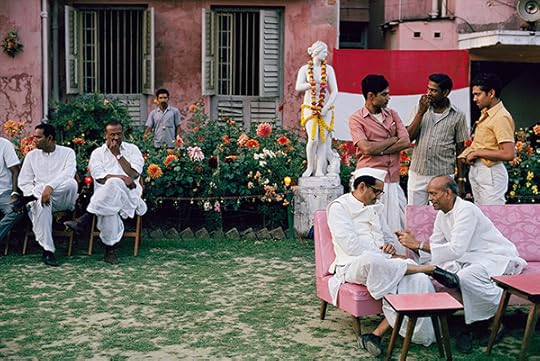

Raghubir Singh, A Marwari Wedding Reception in South Calcutta’s Singhi Park, Calcutta, West Bengal, ca. 1972

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In 1999, when photographer Raghubir Singh died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six, his work was being shown at the Art Institute of Chicago in what was intended to be a midcareer survey. He had spent his adult life living in Hong Kong, Paris, and London, but his photography, which is now the subject of Modernism on the Ganges, a comprehensive retrospective at the Met Breuer, maintained a focus on his native India. The thirteen books he published over the course of three prolific decades—a fourteenth, which took the Indian-manufactured Ambassador car as its subject, was released posthumously—were organized geographically and helped push color photography from the fringe of the art world to the center. Together, these projects form an inimitable map of Indian culture, drawn in the vivid hues of Kodachrome, and mesh modernist photography with Indian aesthetic traditions.

Raghubir Singh, Pavement Mirror Shop, Howrah, West Bengal, 1991

© Succession Raghubir Singh

Space collapses and divides itself in Singh’s photographs, and his compositions move with speed from men and women to painted and sculpted figures, to animals, to cars, and across landscapes. In some of his earliest pictures from Calcutta (now Kolkata), people on the street sink into visual arrangements, as do a statue of Subhas Chandra Bose and a mural featuring Vladimir Lenin. Similarly, in a 1991 photograph from Bombay (now Mumbai), three mannequin figures appear like members of a crowd at the Ganapati Festival. Singh held a deep admiration for Henri Cartier-Bresson and, in his early twenties, had what must have been a formative opportunity to spend a few days with the French photographer in Jaipur. Like Cartier-Bresson, he had a keen eye for striking visual parallels: a man’s net seems to take up a statue of a lion at the Victoria Terminus in Bombay; a cockeyed green door reframes a monument.

Raghubir Singh, Victoria Terminus, Bombay, Maharashtra, 1991

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In front of Singh’s lens, bustling scenes look like carefully arranged collages. The effect can be playful or ironic, but his attention to marks of the past tie each image to a place. The reflective surfaces that appear in many of the photographs are not just an opportunity to make pictures-within-pictures, but also “suggest a future not the past,” as he told the writer V.S. Naipaul. Images with multiple focal points pack frames to capacity. Instead of avoiding visual incongruity, Singh embraces it: in a 1986 photograph from Calcutta, a split-screen effect separates household employees from the gathering that they watch. Singh composites signs of India past and future, disparate political ideas, and varied moods in a single frame.

Raghubir Singh, Fruit Seller and a Boy with a Child at Zaina Kadal Bridge, Jhelum River, Srinagar, Kashmir, 1979

© Succession Raghubir Singh

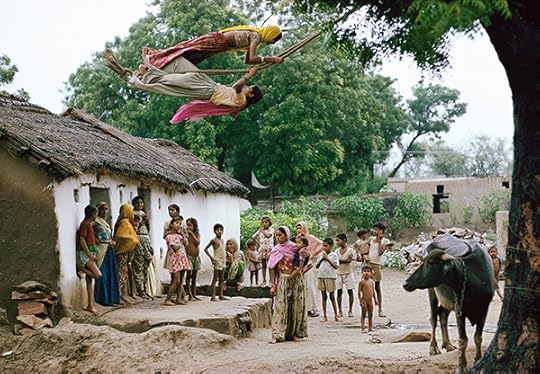

These same techniques allowed Singh to work in dialogue with of a wide range of artists, among them Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, Eugène Atget, and Ketaki Sheth. Such photographs punctuate Singh’s work on the walls at the Met Breuer. Hung among his projects are several Indian court paintings, images by other street photographers like Friedlander (whom Singh considered “the master modernist” of his time), vast landscapes of nineteenth-century British colonial photographers, and hand-painted studio portrait photography from the early twentieth century. In two comparative juxtapositions, Singh’s photograph of Holi revelers in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, from 1975, is joined by Cartier-Bresson’s depiction of dozens of refugees in Punjab, from 1947; and an eighteenth-century watercolor mirrors Singh’s photograph of two girls in Hathod Village, Jaipur, cutting through monsoon-season heat on a high-flying swing.

Raghubir Singh, Catching the Breeze, Hathod Village, Jaipur, Rajasthan, 1975

© Succession Raghubir Singh

As Singh saw it, Indian culture, with its central ideas about “the cycle of rebirth, in which color is not just an essential element but also a deep inner source” could not be coded in black and white, with its artistic modes built on the Western associations of black with “guilt, linked to death.” His undertaking required color. Novelist Amit Chaudhuri writes in the accompanying catalog that Singh’s self-assigned task as an artist was “to find a way of accommodating the joy that his cultural formation in Rajasthan gave him within modernism’s fragmentariness, its openness to texture and sensation.” This meant avoiding abjection as a subject, and opting instead to communicate what Singh called the “lyric poetry inherent in the life of India.” This accomplishment does not arrive forcefully in images that seem patriotic. Nor does color pop with oversaturation. His search for joy deals in subtleties, which allows for his photographs to appear fresh decades after they were made.

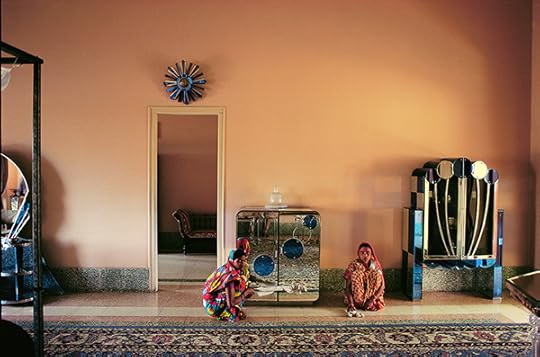

Raghubir Singh, Employees, Morvi Palace, Gujarat, 1982

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In conjunction with Modernism on the Ganges, Howard Greenberg Gallery recently opened an exhibition of Singh’s photographs from Bombay: Gateway of India (1994). In Singh’s Bombay, his interest in a changing India, which can function more as subtext in other projects, sits on the surface of the images. We see the city in the early ’90s, with its eyes turned directly at globalization. The scenes are some of the most urban in Singh’s work, and, as Chaudhuri writes, “Bombay shows how one might desire to surreptitiously linger in and inhabit the places we visit in the time of globalization.”

Raghubir Singh Man Diving, Ganges Floods, Benares, Uttar Pradesh, 1985

© Succession Raghubir Singh

While researching the exhibition, the curator Mia Fineman learned that when you were with Singh on the street, you could see his eyes marking out the four corners of frames-to-be. Modernism on the Ganges helps us begin to imagine the index of images—the worldview—that Singh used to orient his own work. And, perhaps more importantly, it highlights the humanism he maintained while taking up all of India as his material. As the art historian Partha Mitter writes in his essay for the catalog, Singh “saw himself as an Indian, with deep roots in the land.” Whether borrowing compositional forms or taking innovative steps in his use of color, working from the influence of Cartier-Bresson or Indian paintings, photographing on the street or making a formal portrait of a writer, he was, as Mitter puts it, “on a quest to delve into the inner source of India’s art and culture, its moral foundation.”

Max Campbell is a writer and photographer living in New York.

Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs is on view at The Met Breuer through January 2, 2018.

The post India in Full Color appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 26, 2017

At FotoFocus, the Radical Notion That Women Are People

Are we living in a state of emergency feminism?

By Brendan Wattenberg

Jeffrey Brandsted, Brick x Brick at D.C. Women’s March, 2017

Courtesy of FotoFocus

Two weeks before the Women’s March on January 21, 2017, Sara Vance Waddell posted a message on Facebook asking marchers to save their protest signs. Vance, a philanthropist who primarily collects art made by female-identified artists, wanted to make an exhibition of artwork from the march at the gallery in her home in Cincinnati, Ohio. When the signs that protesters sent began piling up, Waddell realized she had a bigger project on her hands. Like many Americans, prior to the 2016 presidential election, Waddell hadn’t thought of herself as an activist. But suddenly it was clear, as one participant wrote in thick black ink on a cardboard placard, that “The Future is Nasty.”

Are we living in a moment of emergency feminism? Among the gathering of artists, critics, scholars, and cultural workers at the FotoFocus symposium “Second Century: Photography, Feminism, Politics,” presented in Cincinnati in October, there was a mood of enlivened solidarity, a sense that if you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention. The symposium opened with a panel discussion by FemFour, the group that Waddell assembled to turn her Women’s March project into a traveling exhibition, but the subsequent panel discussions and keynote addresses often took on the energy of a teach-in. Although the FemFour’s project is not concerned specifically with photography, their discussion seemed an appropriate way to open FotoFocus. For curator Maria Seda-Reeder, who worked with Waddell to assemble the collection, the Women’s March project had an emotional dimension. In working with FemFour, she had connected to other women who were also “mad as hell.”

Installation view of Still They Persist: Protest Art of the 2017 Women’s March, Wave Pool Gallery, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2017

Courtesy of FotoFocus

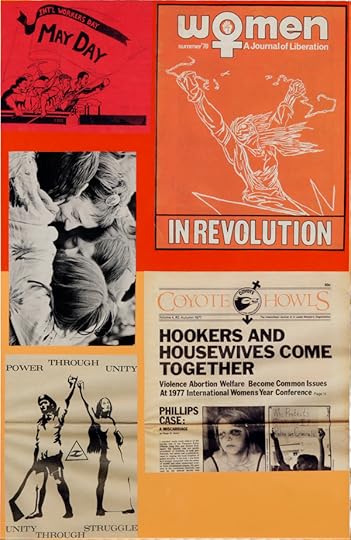

They might have been mad, but many of these women produced witty signs, ingenious sculptures, works on paper, T-shirts, pins, and, of course, knitted “pussy hats,” examples of which were hung on walls and laid out beneath glass at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in FemFour’s Still They Persist: Protest Art from the 2017 Women’s Marches. Seda-Reeder called the exhibition a “living archive,” yet at the venue, the posters looked like sacred objects. Now in a collection, these souvenirs made from humble materials are protected for posterity: they’re physical evidence of a moment widely documented in photography, on social media, and across the news. It was disarming to see signs reading “#yuge mistake” and “NOW YOU’VE PISSED OFF GRANDMA”—which might otherwise have been swept into trash piles in any number of cities around the country—neatly hung in rows in the sanctum of a white-box gallery space. Still They Persist appears to be a rejoinder to that perennial protest chant: this is what democracy looks like. Or looked like, in 2017.

The title for this edition of FotoFocus, “Second Century,” was a nod to Simone de Beauvoir’s germinal book The Second Sex, from 1949, and was meant to gesture to the next century of feminist struggles—notably those at the confluence of women’s rights, immigration, health care, LGBT equality, and racial justice—and how photography might become a visual vanguard. It’s a tall order. “Second Century” swerved across disciplines and opened up a critical space for dialogue around feminist cultural work. Panelists addressed painting, video, digital platforms, the women pioneers of Latin American film, midcentury archives of color photography, and the American Dream in images of baseball players and cross-country drifters. Pointedly, the possibilities of urgent feminist action—in art and culture, and by extension in politics—were never distant from the conversation.

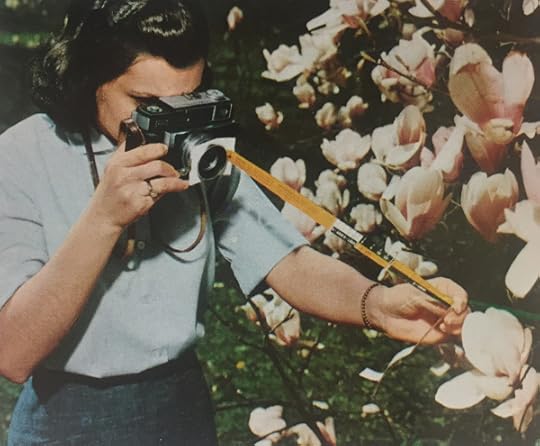

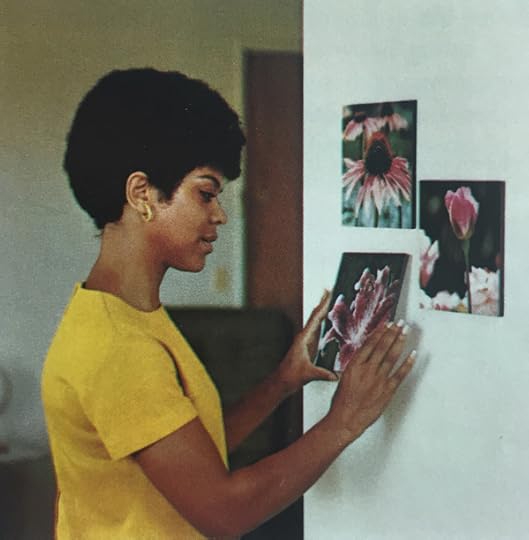

Image from Kodak instructional materials, ca. 1950s–60s

Eastman Kodak Co.

In a discussion under the banner of “Woman with a Camera,” the writer Claire Lehmann plunged into the midcentury archives of Kodak and other film companies, looking to see how women were positioned in educational materials. “It was shocking,” she said, “that women were really only pictured with a camera in hand in very specific poses”—mostly taking pictures of flowers in their backyards. (Men were pictured taking photographs of animals or butterflies.) It was only after feminism’s second wave, beginning in the 1960s, that women began to appear with cameras in titles such as Popular Photography. Lehmann, who discovered the images while researching her groundbreaking essay “Color Goes Electric” (2016), a study of the social reception of color photography in American society, noted in a bit of revisionist feminist art history that it was an exhibition at MoMA in 1966 by Marie Cosindas—not William Eggleston—that was the first moment when color photography was agreed to be “art.” Eggleston as first out of the gate is an oft-repeated myth because his exhibition, in 1976 at MoMA, made a certain kind of “splash.”

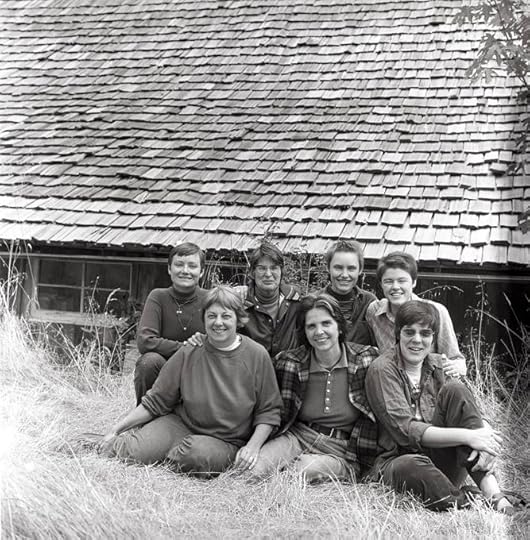

Unknown photographer, from the Ruth Mountaingrove papers (Lesbian Intentional Community), 1950–1999

Courtesy the University of Oregon

On the same panel, Carmen Winant, a critic who wrote about a strand of millennial feminism for Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue, and an artist who was recently selected for MoMA’s New Photography showcase in 2018, addressed her work in archives and collage. For the last several years, Winant has been researching ’70s-era feminist separatist communities in the United States. (Winant’s series title, The Answer Is Matriarchy, speaks for itself.) In a radical move, thousands of women left their former lives in the patriarchy behind and tried to build a world without men. But today, separatist strategies are considered dated. Winant’s project looks at a particular moment in American culture—“both utopic and exclusionary”—to ask: “Why does feminism—one of the most meaningful social movements to emerge from the twentieth century—continue to flounder, and in some ways, fail, as a political strategy?” Winant examines how, in their own pictures, separatists framed their experience, their “righteous experiment.”

Carmen Winant, Triple Jeopardy (detail), 2017

Courtesy the artist

In her solo talk “Photography in an Intersectional Field,” the writer Aruna D’Souza returned to the third rail of the art world in 2017: the controversy of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016) at the Whitney Biennial. In her painting, Schutz, a white woman, had rendered a painful depiction of Black history: the image of the teenage Emmett Till in his open casket, photographs of which were published in Jet magazine in 1955 and subsequently galvanized a sense of Black solidarity nationwide. The scorching debate around Schutz’s painting obscured what was the most diverse biennial in the Whitney’s history, but D’Souza’s point was that, if images hurt us, we have to investigate the reason why. Although D’Souza didn’t say so explicitly, it became clear that Mamie Till Mobley, who agreed to publish the images of her son’s open coffin in Jet, was in her own way an agent—a woman controlling the visual narrative in a time of extraordinary pain. Could Mobley’s framing of her son’s image be read as a feminist action? That question would merit a conference unto itself.

Tabitha Soren, Daniel Robertson, Stockton Ports dugout, Modesto, California, 2014. Professional baseball career: Oakland A’s, Tampa Bay Rays minor league teams 2012–16; current career: Durham Bulls infielder, from Fantasy Life: Baseball and the American Dream, 2017

© the artist

The final event of “Second Century,” which took place in the august setting of the Anderson Theater at Cincinnati’s Memorial Hall, brought together Tabitha Soren and Justine Kurland in conversation about their lives and work. Each opened the dialogue by reading a prepared statement. Kurland, who is known for her photographs of road trips throughout American landscapes, read from an essay originally published in Cabinet, explaining why she sold her fabled van in which she crossed the country. “I would like to publicly renounce a belief system that once seemed useful and true to me; I’ve outgrown the romantic escapism of this mode of travel.” Meandering, as her photographic essays do, Kurland described the physical and symbolic space of her van (or vans: there was a progression of them, starting with her mother’s). As a child, her mother once yanked a man from the van who was kissing Kurland’s teenage sister. That man seemed to violate not only a person, but also a territory. “I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the van was a feminist space,” Kurland said.

Justine Kurland, Claire, 8th Ward, 2012

© the artist

Kurland and Soren discussed how their work explores “masculine” themes—baseball for Soren, cars and guitars for Kurland—but from distinctly female points of view. The two photographers weren’t necessarily addressing feminist artistic action in a time of crisis, but in considering the interface between art and politics, Kurland was circumspect. Thinking about women’s art in terms of solidarity and sentiment, she referred to the scholar Lauren Berlant, and noted, “Women are really good at giving a sense of belonging, but to think about that as a political tool is weak politics.” Women’s art “can only be in proximity to politics; it can’t enact anything politically.” It’s the constant, impossible demand on artists: can art make social change? The answer is no, or at least in the utilitarian notion of change as immediate and impactful. “We’ll march at a protest,” Kurland said. “We might write to our congressmen. But there is still room in art to talk about personal expression.”

Justine Kurland, Red Couple, 2013

© the artist

At the end of her essay for the FemFour’s catalogue on protest art, Maria Seda-Reeder writes, “I need my sisters around me now more than ever.” It’s a slogan, however heartfelt and expressive of solidarity, that has become all too common in the last year. “Now more than ever” implies that we have crossed some kind of threshold. But that’s misleading. “Now” was Election Day 2016; “now” was the day when Donald Trump insulted a Gold Star family (the first time); “now” was the day that voters—men and women—defended Trump’s misogynist language in the Access Hollywood tape; “now” was the moment, in 2015, when Trump himself descended the Trump Tower escalator to declare his presidency. November 8, 2016, didn’t mark a break; it described a continuum.

Photographer unknown, Image from Kodak instructional materials, ca. 1950s–60s

Eastman Kodak Co.

Still, the arguments between second and third wave feminism, between the radical feminism of 1970s separatists and the neoliberal, one-percent, “lean in” feminism of the Sheryl Sandberg era, appear almost innocently theoretical these days. What about women living in poverty? Without access to health care? Who aren’t earning equal pay? There’s no “more than” when it comes to the truly intersectional social issues of feminism, which can’t fully be redressed by art, and which would still be with us if a woman occupied the White House. Republican women in “Trump Country” need feminism, too.

In 2000, bell hooks, as usual on point and ahead of her time, declared, “feminism is for everybody.” “Imagine living in a world where we can all be who we are,” she wrote, “a world of peace and possibility.” We have a long way to go. Whereas feminism might once have been seen as optional, as a political movement one could opt in or opt out of, or indeed be excluded from, emergency feminism—the political energy unfolding today—demands the widest possible participation. In this “second century,” we’re all feminists now, whether we like it or not.

Brendan Wattenberg is the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

The FotoFocus symposium “Second Century” took place on October 7, 2017, in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The post At FotoFocus, the Radical Notion That Women Are People appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 25, 2017

The Sound of Defiance

How can listening to images reveal the visual histories of the African diaspora?

By Brian Wallis

Martina Bacigalupo, Gulu Real Art Studio, 2011–12

Courtesy the artist and The Walther Collection

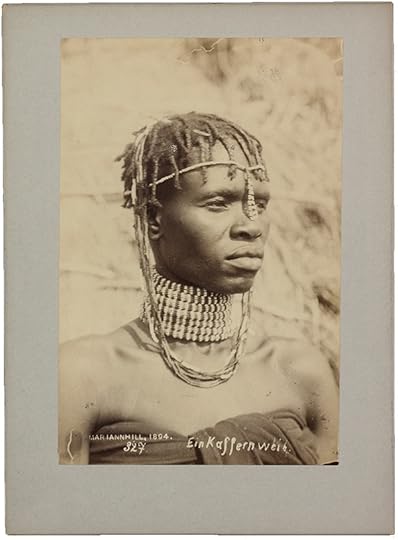

For too long, those interested in understanding the social uses of photography have lacked an adequate critical framework, beyond the stylistic and aesthetic interpretations inherited from art history. In her new book, Listening to Images (2017), theorist Tina M. Campt proposes a bold methodology for approaching previously overlooked vernacular photographs, particularly those from the neglected archives of the African diaspora. She takes seriously the latent meanings embedded in nineteenth-century ethnographic photographs from Africa, early-twentieth-century prison mugshots from Cape Town, and postwar passport photographs from Birmingham, England. Instead of just looking at these quiet documentary photographs, she listens to them, detecting in them the hum of refusal in small gestures of anticolonialist defiance and difference. By attending to the physical material of the artifacts, and by attuning all of her senses to situating these images and their subjects within specific historical contexts, Campt offers an expansive new approach to the evaluation of photographs.

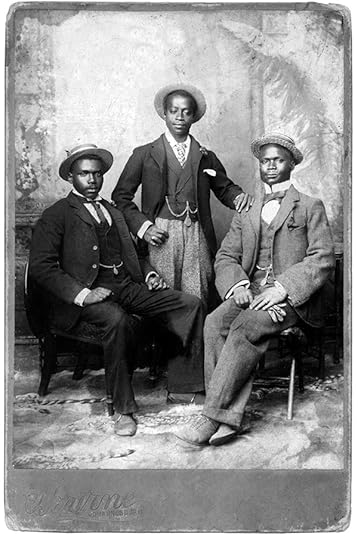

Santu Mofokeng, The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950, 1997

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy MAKER, Johannesburg

Brian Wallis: Your new book is provocatively titled Listening to Images. This implies not only a newly subjective approach but also a more physical response to images, based on touch and sound. How does your book challenge an approach to photography based primarily on vision?

Tina Campt: Photographs have an impact on us that is not solely based on seeing. And I argue that we need another approach to understanding photographs, other than simply looking at them. Listening to Images challenges us to move from vision to sound by way of touch. There is no question that images move us. But the question is, how does that happen? Photographs touch us emotionally, but also in a tactile sense through our physical encounters with them. That moment of contact is about a particular level of frequency, or resonance. But to make contact, you have to attune yourself to certain frequencies of encounter that aren’t always available to us in our normal register. This is what I mean by “listening to images.”

In my previous book, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (2012), I addressed this issue in the context of family photography. With these images we expect to be moved, emotionally, because family photographs establish a relationship between the people in the image and the viewer, even when the viewer doesn’t know the family personally. In Listening to Images, I push this idea a little bit further, to argue that it’s not only family images that touch us or have sentimental value. Photographs construct relationships through genres that are not intended to be moving, like identification photographs, which are documents produced to control, regulate, and classify individuals. The affect of such images—how they move us—can be as profound in identification photographs as in family photos. Yet these affects are even more radical in identification photographs because they work against their intended purpose, which is to control people, to track and categorize them. What I discovered in vernacular identification photography was the way their subjects—sometimes even prisoners—used these images to telegraph statements about themselves that the genre itself was trying to suppress.

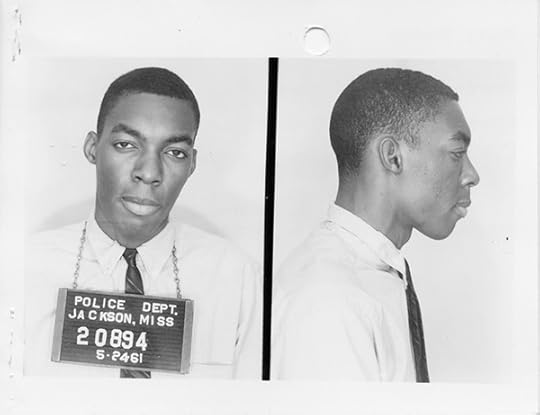

Photographer unknown, Freedom Rider mug shot, May 25, 1961

Courtesy the Archives and Records Services Division,

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Brian Wallis: Are you suggesting that prisoners, for example, could override or subvert the neutralizing power of the mugshot?